User login

Blood vessels injured during trocar insertion: $8.7M verdict

Blood vessels injured during trocar insertion: $8.7M verdict

PATIENT’S CLAIM:

The resident was negligent in performing trocar insertion during laparoscopic surgery by inserting the trocar too far into the abdomen. The attending ObGyn did not supervise the resident properly. There is nothing in the patient's medical records to indicate that she had abnormal anatomy. The woman's life is in turmoil after what was supposed to be a routine procedure.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE:

There was no negligence. The patient's anatomy was abnormal, making the risk of surgery higher. The injury is a known complication of laparoscopic surgery.

VERDICT:

An $8,718,848 Illinois verdict was returned.

Related article:

How to avoid major vessel injury during gynecologic laparoscopy

Wrong fallopian tube transected: $1.8M award

A 28-year-old woman underwent an appendectomy. During the operation, the surgeon saw an abscess on the patient's right fallopian tube and called in an ObGyn to remove the abscess. While doing so, the ObGyn transected the left fallopian tube. Both fallopian tubes were removed.

PATIENT’S CLAIM:

The surgeon did not tell the ObGyn which fallopian tube was abscessed and therefore the ObGyn operated on the wrong tube. In addition, the surgeon failed to obtain informed consent for bilateral salpingectomy. The patient is now unable to conceive without assisted reproductive treatment.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE:

The surgeon admitted his mistakes but disputed the informed consent claim. The patient probably would not have been able to conceive naturally due to the infection.

VERDICT:

A $1.8 million Connecticut verdict was returned.

Related article:

Elective laparoscopic appendectomy in gynecologic surgery: When, why, and how

Complications after vaginal hysterectomy

A woman underwent laparoscopic vaginal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with anterior and posterior repair using mesh in August 2010. Shortly after surgery, the patient reported vaginal discharge with pain and bleeding. She was treated with antibiotics. Results of a CT scan identified the cause of her symptoms as vaginal cuff granulations.

Her pain continued and in June 2011, she underwent vaginal tissue biopsy. After testing revealed the presence of fecal matter, a small-bowel vaginal fistula was identified. She underwent laparoscopic enterectomy, urethral lysis, an omental pedicle flap, and cystoscopy. The mesh had perforated several loops of the small bowel.

In August 2011, the patient reported spinal pain. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a new fluid abscess in a disc extending through the tract anterior to the soft tissue of the pelvis. She underwent intensive antibiotic therapy.

PATIENT’S CLAIM:

The gynecologic surgeon fell below the standard of care in his treatment of her conditions.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE:

The surgeon denied allegations.

VERDICT:

A Nevada defense verdict was returned.

Related article:

Vaginal hysterectomy with basic instrumentation

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Blood vessels injured during trocar insertion: $8.7M verdict

PATIENT’S CLAIM:

The resident was negligent in performing trocar insertion during laparoscopic surgery by inserting the trocar too far into the abdomen. The attending ObGyn did not supervise the resident properly. There is nothing in the patient's medical records to indicate that she had abnormal anatomy. The woman's life is in turmoil after what was supposed to be a routine procedure.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE:

There was no negligence. The patient's anatomy was abnormal, making the risk of surgery higher. The injury is a known complication of laparoscopic surgery.

VERDICT:

An $8,718,848 Illinois verdict was returned.

Related article:

How to avoid major vessel injury during gynecologic laparoscopy

Wrong fallopian tube transected: $1.8M award

A 28-year-old woman underwent an appendectomy. During the operation, the surgeon saw an abscess on the patient's right fallopian tube and called in an ObGyn to remove the abscess. While doing so, the ObGyn transected the left fallopian tube. Both fallopian tubes were removed.

PATIENT’S CLAIM:

The surgeon did not tell the ObGyn which fallopian tube was abscessed and therefore the ObGyn operated on the wrong tube. In addition, the surgeon failed to obtain informed consent for bilateral salpingectomy. The patient is now unable to conceive without assisted reproductive treatment.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE:

The surgeon admitted his mistakes but disputed the informed consent claim. The patient probably would not have been able to conceive naturally due to the infection.

VERDICT:

A $1.8 million Connecticut verdict was returned.

Related article:

Elective laparoscopic appendectomy in gynecologic surgery: When, why, and how

Complications after vaginal hysterectomy

A woman underwent laparoscopic vaginal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with anterior and posterior repair using mesh in August 2010. Shortly after surgery, the patient reported vaginal discharge with pain and bleeding. She was treated with antibiotics. Results of a CT scan identified the cause of her symptoms as vaginal cuff granulations.

Her pain continued and in June 2011, she underwent vaginal tissue biopsy. After testing revealed the presence of fecal matter, a small-bowel vaginal fistula was identified. She underwent laparoscopic enterectomy, urethral lysis, an omental pedicle flap, and cystoscopy. The mesh had perforated several loops of the small bowel.

In August 2011, the patient reported spinal pain. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a new fluid abscess in a disc extending through the tract anterior to the soft tissue of the pelvis. She underwent intensive antibiotic therapy.

PATIENT’S CLAIM:

The gynecologic surgeon fell below the standard of care in his treatment of her conditions.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE:

The surgeon denied allegations.

VERDICT:

A Nevada defense verdict was returned.

Related article:

Vaginal hysterectomy with basic instrumentation

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Blood vessels injured during trocar insertion: $8.7M verdict

PATIENT’S CLAIM:

The resident was negligent in performing trocar insertion during laparoscopic surgery by inserting the trocar too far into the abdomen. The attending ObGyn did not supervise the resident properly. There is nothing in the patient's medical records to indicate that she had abnormal anatomy. The woman's life is in turmoil after what was supposed to be a routine procedure.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE:

There was no negligence. The patient's anatomy was abnormal, making the risk of surgery higher. The injury is a known complication of laparoscopic surgery.

VERDICT:

An $8,718,848 Illinois verdict was returned.

Related article:

How to avoid major vessel injury during gynecologic laparoscopy

Wrong fallopian tube transected: $1.8M award

A 28-year-old woman underwent an appendectomy. During the operation, the surgeon saw an abscess on the patient's right fallopian tube and called in an ObGyn to remove the abscess. While doing so, the ObGyn transected the left fallopian tube. Both fallopian tubes were removed.

PATIENT’S CLAIM:

The surgeon did not tell the ObGyn which fallopian tube was abscessed and therefore the ObGyn operated on the wrong tube. In addition, the surgeon failed to obtain informed consent for bilateral salpingectomy. The patient is now unable to conceive without assisted reproductive treatment.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE:

The surgeon admitted his mistakes but disputed the informed consent claim. The patient probably would not have been able to conceive naturally due to the infection.

VERDICT:

A $1.8 million Connecticut verdict was returned.

Related article:

Elective laparoscopic appendectomy in gynecologic surgery: When, why, and how

Complications after vaginal hysterectomy

A woman underwent laparoscopic vaginal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with anterior and posterior repair using mesh in August 2010. Shortly after surgery, the patient reported vaginal discharge with pain and bleeding. She was treated with antibiotics. Results of a CT scan identified the cause of her symptoms as vaginal cuff granulations.

Her pain continued and in June 2011, she underwent vaginal tissue biopsy. After testing revealed the presence of fecal matter, a small-bowel vaginal fistula was identified. She underwent laparoscopic enterectomy, urethral lysis, an omental pedicle flap, and cystoscopy. The mesh had perforated several loops of the small bowel.

In August 2011, the patient reported spinal pain. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a new fluid abscess in a disc extending through the tract anterior to the soft tissue of the pelvis. She underwent intensive antibiotic therapy.

PATIENT’S CLAIM:

The gynecologic surgeon fell below the standard of care in his treatment of her conditions.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE:

The surgeon denied allegations.

VERDICT:

A Nevada defense verdict was returned.

Related article:

Vaginal hysterectomy with basic instrumentation

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Labor and delivery mismanaged, child has CP: $30.5M award

Labor and delivery mismanaged, child has CP: $30.5M award

Two days later, the mother reported decreased fetal movement; she was admitted to the hospital for continuous fetal heart-rate (FHR) monitoring, and a maternal-fetal medicine (MFM) specialist was consulted. The mother was not placed on FHR monitoring until 2 hours after admission. Three hours after admission, the MFM, by phone, recommended further testing and later, cesarean delivery.

The child was found to have spastic quadriplegic cerebral palsy, profound developmental delays, a seizure disorder, and cortical blindness.

PARENTS' CLAIM:

The child's injuries were due to mismanagement of labor and delivery. The MFM prescribed ultrasonographic biophysical profiles, but they were not performed until 2 hours after ordered. There were 3 ultrasonography (US) technicians at the hospital when the mother was admitted: 1 was on break, another was performing other tests, and the third was not notified because the hospital's computer system was down. When test results were unfavorable, the MFM recommended emergency cesarean delivery. An earlier delivery could have prevented the child's injuries.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE:

The infant's injuries were a result of her mother's failure to keep her GDM under control.

VERDICT:

A $30,545,655 Georgia verdict was returned.

Related article:

10 tips for overcoming common challenges of intrapartum fetal monitoring

Did oxytocin cause child's spastic CP? $14.4M verdict

When a woman went to the hospital in labor, her ObGyn ordered oxytocin to enhance delivery. The FHR monitor showed repetitive decelerations for the next hour, dropping to 60 bpm by 8:00 pm, when the ObGyn expedited delivery but did not stop the oxytocin. By 8:20 pm, the baby's head was crowning, but the ObGyn waited another 10 minutes before performing an episiotomy and delivering the baby.

The child, intubated 5 minutes after birth, was found to have spastic tetraparesis cerebral palsy (CP) with impaired cognition, seizures, and global aphasia.

PARENTS' CLAIM:

The ObGyn and nurses failed to properly monitor labor and delivery. The ObGyn should not have started oxytocin because the patient's labor was progressing normally. He should have taken the mother off oxytocin at 8:00 pm when the FHR dropped to 60 bpm. He should have performed an operative delivery at 8:20 pm when the baby's head crowned. An earlier delivery would have prevented injury.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE:

The ObGyn's treatment was within the standard of care. He properly determined that vaginal delivery would be the quickest. It is his practice to stop oxytocin when the FHR slows, though he had no memory of halting oxytocin administration in this case. The baby's CP stemmed from insufficiencies in the placenta, seizures, and meconium aspiration syndrome.

VERDICT:

A $14.4 million Pennsylvania verdict was returned. The ObGyn was found 60% liable for the baby's injuries and the hospital 40% responsible.

Related article:

Q: Following cesarean delivery, what is the optimal oxytocin infusion duration to prevent postpartum bleeding?

Woman with preeclampsia dies: $6M verdict

A 34-year-old woman had been a patient of her family practitioner (FP) for many years. Her blood pressure (BP) averaged 105/63 mm Hg over that time. At a regular prenatal visit on February 26, the patient reported a headache and cough. Her BP was 130/90 mm Hg and she had gained 8.6 lb since her last visit 4 weeks earlier. She was told to return in 2 weeks.

She contacted her FP 2 days later to report acute vaginal bleeding and a severe headache. The FP sent her to the hospital, where potential placental abruption was considered. Two US studies demonstrated oligohydramnios, intrauterine growth restriction, and a grade II placenta. She continued to have repeated high BP readings, headaches, variable and late decelerations, and a dropping platelet count.

She was discharged on the morning of March 3 and sent to another hospital for a specialized US. The FP spoke to the physician who was to perform the US, advising him by phone and in writing to evaluate the oligohydramnios and intrauterine growth restriction. No other information was provided.

At 6:00 pm on March 3, the patient's husband called the FP to report that his wife was vomiting, reporting abdominal pain and intense headache. He was advised to call back in 1 hour, and when he did, he was told to take his wife to the hospital. At the hospital at 8:50 pm on March 3, her BP was 128/103 mm Hg. She reported throbbing headache, vomiting, and facial edema. She was admitted for observation.

At 9:30 pm, when the patient's BP was 155/100 mm Hg, a nurse contacted the FP to report the patient's continued throbbing headache and elevated, labile BP. The FP neither requested a consultation with an attending ObGyn nor went to the hospital until 4:31 am on March 4.

At 3:15 am on March 4, a nurse found the patient with her head hanging over the side of the bed in an obtunded state, having vomited. The rapid response team and an attending ObGyn were called. The ObGyn diagnosed eclampsia, ordered magnesium sulfate and hydralazine and immediately transported her to the operating room for an emergency cesarean delivery. Although the baby was healthy, the mother remained unresponsive. A computed tomography (CT) scan confirmed a massive intracranial hemorrhage. She was pronounced dead at 5:10 pm.

ESTATE'S CLAIM:

The FP negligently deviated from the standard of care, leading to the mother's death. The FP fraudulently misrepresented her experience and training for obstetric conditions. She was negligent for failing to adequately diagnose and react to the patient's condition or refer her to an ObGyn, per hospital policy.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE:

The patient's treatment met the standard of care. The FP was credentialed to practice obstetrics at the hospital. The patient's BP never reached or sustained a level that would require the FP to consult an ObGyn until 3:15 am on March 4. When the patient first presented with a headache, the FP had consulted a board-certified ObGyn and an MFM, who suggested continued antepartum testing and induction at 39 weeks. The patient's death was unforeseeable because her BP values were inconsistent; the FP had no knowledge of a family history of stroke. The autopsy reported that a ruptured aneurysm was the cause of death.

VERDICT:

A $6,067,830 Ohio verdict was returned. The award was reduced to $900,000 due to a high/low agreement.

Related article:

Start offering aspirin to pregnant women at high risk for preeclampsia

Fetal abnormalities not diagnosed: Baby has Down syndrome

On September 6, at 10 weeks' gestation, a woman began prenatal care at a clinic with Dr. A, an ObGyn. The mother participated in the California Prenatal Screening Program and received test results on October 23 that showed normal risk for birth defects. On November 1, she saw Dr. B, another ObGyn, who confirmed the negative prenatal screening and ordered an US. A radiologist reported to Dr. Bthat the fetal anatomy was not well visualized. When the mother was at 23 2/7 weeks' gestation (December 6), Dr. B told the parents that the US results were normal.

On January 2, the parents saw Dr. A, who disclosed that the US radiology report indicated an incomplete fetal anatomy scan and ordered a repeat US. The US performed on January 17 showed a cardiac defect. Further testing confirmed that the fetus had Down syndrome. The parents scheduled but did not appear for a late-term abortion because they feared that the procedure was illegal.

PARENTS' CLAIM:

The parents told both ObGyns that they wanted extensive prenatal testing because of a family history of birth defects and that they would terminate the pregnancy if birth defects were discovered. Because Dr. B did not discuss prenatal testing, the parents did not know their child had Down syndrome until it was too late to legally terminate the pregnancy. The mother testified that she had never heard of amniocentesis until mid-January, when a perinatologist confirmed that the baby had Down syndrome.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE:

The ObGyns denied having any discussions with the parents about their request for extensive prenatal tests or desire for termination. Difficulty in visualizing the fetus is common in second trimester US, and therefore Dr. B routinely performs another US later in the pregnancy. He also denied responsibility for discussing prenatal testing with the parents, stating that such discussions should happen in the first trimester. Since the parents saw Dr. A during that time, Dr. B believed that those conversations had already taken place. The prenatal screening pamphlet that the mother signed on September 6 discussed amniocentesis. The child's grandmother testified that she had discussed amniocentesis with the parents early in the pregnancy. A clinic employee testified that in January she asked the mother why she had not chosen amniocentesis earlier in the pregnancy; the mother replied that she had decided against it because her prenatal screening test was normal.

VERDICT:

A California defense verdict was returned.

Related article:

When is cell-free DNA best used as a primary screen?

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Labor and delivery mismanaged, child has CP: $30.5M award

Two days later, the mother reported decreased fetal movement; she was admitted to the hospital for continuous fetal heart-rate (FHR) monitoring, and a maternal-fetal medicine (MFM) specialist was consulted. The mother was not placed on FHR monitoring until 2 hours after admission. Three hours after admission, the MFM, by phone, recommended further testing and later, cesarean delivery.

The child was found to have spastic quadriplegic cerebral palsy, profound developmental delays, a seizure disorder, and cortical blindness.

PARENTS' CLAIM:

The child's injuries were due to mismanagement of labor and delivery. The MFM prescribed ultrasonographic biophysical profiles, but they were not performed until 2 hours after ordered. There were 3 ultrasonography (US) technicians at the hospital when the mother was admitted: 1 was on break, another was performing other tests, and the third was not notified because the hospital's computer system was down. When test results were unfavorable, the MFM recommended emergency cesarean delivery. An earlier delivery could have prevented the child's injuries.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE:

The infant's injuries were a result of her mother's failure to keep her GDM under control.

VERDICT:

A $30,545,655 Georgia verdict was returned.

Related article:

10 tips for overcoming common challenges of intrapartum fetal monitoring

Did oxytocin cause child's spastic CP? $14.4M verdict

When a woman went to the hospital in labor, her ObGyn ordered oxytocin to enhance delivery. The FHR monitor showed repetitive decelerations for the next hour, dropping to 60 bpm by 8:00 pm, when the ObGyn expedited delivery but did not stop the oxytocin. By 8:20 pm, the baby's head was crowning, but the ObGyn waited another 10 minutes before performing an episiotomy and delivering the baby.

The child, intubated 5 minutes after birth, was found to have spastic tetraparesis cerebral palsy (CP) with impaired cognition, seizures, and global aphasia.

PARENTS' CLAIM:

The ObGyn and nurses failed to properly monitor labor and delivery. The ObGyn should not have started oxytocin because the patient's labor was progressing normally. He should have taken the mother off oxytocin at 8:00 pm when the FHR dropped to 60 bpm. He should have performed an operative delivery at 8:20 pm when the baby's head crowned. An earlier delivery would have prevented injury.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE:

The ObGyn's treatment was within the standard of care. He properly determined that vaginal delivery would be the quickest. It is his practice to stop oxytocin when the FHR slows, though he had no memory of halting oxytocin administration in this case. The baby's CP stemmed from insufficiencies in the placenta, seizures, and meconium aspiration syndrome.

VERDICT:

A $14.4 million Pennsylvania verdict was returned. The ObGyn was found 60% liable for the baby's injuries and the hospital 40% responsible.

Related article:

Q: Following cesarean delivery, what is the optimal oxytocin infusion duration to prevent postpartum bleeding?

Woman with preeclampsia dies: $6M verdict

A 34-year-old woman had been a patient of her family practitioner (FP) for many years. Her blood pressure (BP) averaged 105/63 mm Hg over that time. At a regular prenatal visit on February 26, the patient reported a headache and cough. Her BP was 130/90 mm Hg and she had gained 8.6 lb since her last visit 4 weeks earlier. She was told to return in 2 weeks.

She contacted her FP 2 days later to report acute vaginal bleeding and a severe headache. The FP sent her to the hospital, where potential placental abruption was considered. Two US studies demonstrated oligohydramnios, intrauterine growth restriction, and a grade II placenta. She continued to have repeated high BP readings, headaches, variable and late decelerations, and a dropping platelet count.

She was discharged on the morning of March 3 and sent to another hospital for a specialized US. The FP spoke to the physician who was to perform the US, advising him by phone and in writing to evaluate the oligohydramnios and intrauterine growth restriction. No other information was provided.

At 6:00 pm on March 3, the patient's husband called the FP to report that his wife was vomiting, reporting abdominal pain and intense headache. He was advised to call back in 1 hour, and when he did, he was told to take his wife to the hospital. At the hospital at 8:50 pm on March 3, her BP was 128/103 mm Hg. She reported throbbing headache, vomiting, and facial edema. She was admitted for observation.

At 9:30 pm, when the patient's BP was 155/100 mm Hg, a nurse contacted the FP to report the patient's continued throbbing headache and elevated, labile BP. The FP neither requested a consultation with an attending ObGyn nor went to the hospital until 4:31 am on March 4.

At 3:15 am on March 4, a nurse found the patient with her head hanging over the side of the bed in an obtunded state, having vomited. The rapid response team and an attending ObGyn were called. The ObGyn diagnosed eclampsia, ordered magnesium sulfate and hydralazine and immediately transported her to the operating room for an emergency cesarean delivery. Although the baby was healthy, the mother remained unresponsive. A computed tomography (CT) scan confirmed a massive intracranial hemorrhage. She was pronounced dead at 5:10 pm.

ESTATE'S CLAIM:

The FP negligently deviated from the standard of care, leading to the mother's death. The FP fraudulently misrepresented her experience and training for obstetric conditions. She was negligent for failing to adequately diagnose and react to the patient's condition or refer her to an ObGyn, per hospital policy.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE:

The patient's treatment met the standard of care. The FP was credentialed to practice obstetrics at the hospital. The patient's BP never reached or sustained a level that would require the FP to consult an ObGyn until 3:15 am on March 4. When the patient first presented with a headache, the FP had consulted a board-certified ObGyn and an MFM, who suggested continued antepartum testing and induction at 39 weeks. The patient's death was unforeseeable because her BP values were inconsistent; the FP had no knowledge of a family history of stroke. The autopsy reported that a ruptured aneurysm was the cause of death.

VERDICT:

A $6,067,830 Ohio verdict was returned. The award was reduced to $900,000 due to a high/low agreement.

Related article:

Start offering aspirin to pregnant women at high risk for preeclampsia

Fetal abnormalities not diagnosed: Baby has Down syndrome

On September 6, at 10 weeks' gestation, a woman began prenatal care at a clinic with Dr. A, an ObGyn. The mother participated in the California Prenatal Screening Program and received test results on October 23 that showed normal risk for birth defects. On November 1, she saw Dr. B, another ObGyn, who confirmed the negative prenatal screening and ordered an US. A radiologist reported to Dr. Bthat the fetal anatomy was not well visualized. When the mother was at 23 2/7 weeks' gestation (December 6), Dr. B told the parents that the US results were normal.

On January 2, the parents saw Dr. A, who disclosed that the US radiology report indicated an incomplete fetal anatomy scan and ordered a repeat US. The US performed on January 17 showed a cardiac defect. Further testing confirmed that the fetus had Down syndrome. The parents scheduled but did not appear for a late-term abortion because they feared that the procedure was illegal.

PARENTS' CLAIM:

The parents told both ObGyns that they wanted extensive prenatal testing because of a family history of birth defects and that they would terminate the pregnancy if birth defects were discovered. Because Dr. B did not discuss prenatal testing, the parents did not know their child had Down syndrome until it was too late to legally terminate the pregnancy. The mother testified that she had never heard of amniocentesis until mid-January, when a perinatologist confirmed that the baby had Down syndrome.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE:

The ObGyns denied having any discussions with the parents about their request for extensive prenatal tests or desire for termination. Difficulty in visualizing the fetus is common in second trimester US, and therefore Dr. B routinely performs another US later in the pregnancy. He also denied responsibility for discussing prenatal testing with the parents, stating that such discussions should happen in the first trimester. Since the parents saw Dr. A during that time, Dr. B believed that those conversations had already taken place. The prenatal screening pamphlet that the mother signed on September 6 discussed amniocentesis. The child's grandmother testified that she had discussed amniocentesis with the parents early in the pregnancy. A clinic employee testified that in January she asked the mother why she had not chosen amniocentesis earlier in the pregnancy; the mother replied that she had decided against it because her prenatal screening test was normal.

VERDICT:

A California defense verdict was returned.

Related article:

When is cell-free DNA best used as a primary screen?

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Labor and delivery mismanaged, child has CP: $30.5M award

Two days later, the mother reported decreased fetal movement; she was admitted to the hospital for continuous fetal heart-rate (FHR) monitoring, and a maternal-fetal medicine (MFM) specialist was consulted. The mother was not placed on FHR monitoring until 2 hours after admission. Three hours after admission, the MFM, by phone, recommended further testing and later, cesarean delivery.

The child was found to have spastic quadriplegic cerebral palsy, profound developmental delays, a seizure disorder, and cortical blindness.

PARENTS' CLAIM:

The child's injuries were due to mismanagement of labor and delivery. The MFM prescribed ultrasonographic biophysical profiles, but they were not performed until 2 hours after ordered. There were 3 ultrasonography (US) technicians at the hospital when the mother was admitted: 1 was on break, another was performing other tests, and the third was not notified because the hospital's computer system was down. When test results were unfavorable, the MFM recommended emergency cesarean delivery. An earlier delivery could have prevented the child's injuries.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE:

The infant's injuries were a result of her mother's failure to keep her GDM under control.

VERDICT:

A $30,545,655 Georgia verdict was returned.

Related article:

10 tips for overcoming common challenges of intrapartum fetal monitoring

Did oxytocin cause child's spastic CP? $14.4M verdict

When a woman went to the hospital in labor, her ObGyn ordered oxytocin to enhance delivery. The FHR monitor showed repetitive decelerations for the next hour, dropping to 60 bpm by 8:00 pm, when the ObGyn expedited delivery but did not stop the oxytocin. By 8:20 pm, the baby's head was crowning, but the ObGyn waited another 10 minutes before performing an episiotomy and delivering the baby.

The child, intubated 5 minutes after birth, was found to have spastic tetraparesis cerebral palsy (CP) with impaired cognition, seizures, and global aphasia.

PARENTS' CLAIM:

The ObGyn and nurses failed to properly monitor labor and delivery. The ObGyn should not have started oxytocin because the patient's labor was progressing normally. He should have taken the mother off oxytocin at 8:00 pm when the FHR dropped to 60 bpm. He should have performed an operative delivery at 8:20 pm when the baby's head crowned. An earlier delivery would have prevented injury.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE:

The ObGyn's treatment was within the standard of care. He properly determined that vaginal delivery would be the quickest. It is his practice to stop oxytocin when the FHR slows, though he had no memory of halting oxytocin administration in this case. The baby's CP stemmed from insufficiencies in the placenta, seizures, and meconium aspiration syndrome.

VERDICT:

A $14.4 million Pennsylvania verdict was returned. The ObGyn was found 60% liable for the baby's injuries and the hospital 40% responsible.

Related article:

Q: Following cesarean delivery, what is the optimal oxytocin infusion duration to prevent postpartum bleeding?

Woman with preeclampsia dies: $6M verdict

A 34-year-old woman had been a patient of her family practitioner (FP) for many years. Her blood pressure (BP) averaged 105/63 mm Hg over that time. At a regular prenatal visit on February 26, the patient reported a headache and cough. Her BP was 130/90 mm Hg and she had gained 8.6 lb since her last visit 4 weeks earlier. She was told to return in 2 weeks.

She contacted her FP 2 days later to report acute vaginal bleeding and a severe headache. The FP sent her to the hospital, where potential placental abruption was considered. Two US studies demonstrated oligohydramnios, intrauterine growth restriction, and a grade II placenta. She continued to have repeated high BP readings, headaches, variable and late decelerations, and a dropping platelet count.

She was discharged on the morning of March 3 and sent to another hospital for a specialized US. The FP spoke to the physician who was to perform the US, advising him by phone and in writing to evaluate the oligohydramnios and intrauterine growth restriction. No other information was provided.

At 6:00 pm on March 3, the patient's husband called the FP to report that his wife was vomiting, reporting abdominal pain and intense headache. He was advised to call back in 1 hour, and when he did, he was told to take his wife to the hospital. At the hospital at 8:50 pm on March 3, her BP was 128/103 mm Hg. She reported throbbing headache, vomiting, and facial edema. She was admitted for observation.

At 9:30 pm, when the patient's BP was 155/100 mm Hg, a nurse contacted the FP to report the patient's continued throbbing headache and elevated, labile BP. The FP neither requested a consultation with an attending ObGyn nor went to the hospital until 4:31 am on March 4.

At 3:15 am on March 4, a nurse found the patient with her head hanging over the side of the bed in an obtunded state, having vomited. The rapid response team and an attending ObGyn were called. The ObGyn diagnosed eclampsia, ordered magnesium sulfate and hydralazine and immediately transported her to the operating room for an emergency cesarean delivery. Although the baby was healthy, the mother remained unresponsive. A computed tomography (CT) scan confirmed a massive intracranial hemorrhage. She was pronounced dead at 5:10 pm.

ESTATE'S CLAIM:

The FP negligently deviated from the standard of care, leading to the mother's death. The FP fraudulently misrepresented her experience and training for obstetric conditions. She was negligent for failing to adequately diagnose and react to the patient's condition or refer her to an ObGyn, per hospital policy.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE:

The patient's treatment met the standard of care. The FP was credentialed to practice obstetrics at the hospital. The patient's BP never reached or sustained a level that would require the FP to consult an ObGyn until 3:15 am on March 4. When the patient first presented with a headache, the FP had consulted a board-certified ObGyn and an MFM, who suggested continued antepartum testing and induction at 39 weeks. The patient's death was unforeseeable because her BP values were inconsistent; the FP had no knowledge of a family history of stroke. The autopsy reported that a ruptured aneurysm was the cause of death.

VERDICT:

A $6,067,830 Ohio verdict was returned. The award was reduced to $900,000 due to a high/low agreement.

Related article:

Start offering aspirin to pregnant women at high risk for preeclampsia

Fetal abnormalities not diagnosed: Baby has Down syndrome

On September 6, at 10 weeks' gestation, a woman began prenatal care at a clinic with Dr. A, an ObGyn. The mother participated in the California Prenatal Screening Program and received test results on October 23 that showed normal risk for birth defects. On November 1, she saw Dr. B, another ObGyn, who confirmed the negative prenatal screening and ordered an US. A radiologist reported to Dr. Bthat the fetal anatomy was not well visualized. When the mother was at 23 2/7 weeks' gestation (December 6), Dr. B told the parents that the US results were normal.

On January 2, the parents saw Dr. A, who disclosed that the US radiology report indicated an incomplete fetal anatomy scan and ordered a repeat US. The US performed on January 17 showed a cardiac defect. Further testing confirmed that the fetus had Down syndrome. The parents scheduled but did not appear for a late-term abortion because they feared that the procedure was illegal.

PARENTS' CLAIM:

The parents told both ObGyns that they wanted extensive prenatal testing because of a family history of birth defects and that they would terminate the pregnancy if birth defects were discovered. Because Dr. B did not discuss prenatal testing, the parents did not know their child had Down syndrome until it was too late to legally terminate the pregnancy. The mother testified that she had never heard of amniocentesis until mid-January, when a perinatologist confirmed that the baby had Down syndrome.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE:

The ObGyns denied having any discussions with the parents about their request for extensive prenatal tests or desire for termination. Difficulty in visualizing the fetus is common in second trimester US, and therefore Dr. B routinely performs another US later in the pregnancy. He also denied responsibility for discussing prenatal testing with the parents, stating that such discussions should happen in the first trimester. Since the parents saw Dr. A during that time, Dr. B believed that those conversations had already taken place. The prenatal screening pamphlet that the mother signed on September 6 discussed amniocentesis. The child's grandmother testified that she had discussed amniocentesis with the parents early in the pregnancy. A clinic employee testified that in January she asked the mother why she had not chosen amniocentesis earlier in the pregnancy; the mother replied that she had decided against it because her prenatal screening test was normal.

VERDICT:

A California defense verdict was returned.

Related article:

When is cell-free DNA best used as a primary screen?

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Malpractice Counsel: Missed Eye Injury: The Importance of the Visual Examination

Case

A 61-year-old woman presented to the ED for evaluation of left-side facial pain following a fall. The patient stated that she lost her balance as she was getting out of her car and fell to the ground, striking her left face and head. She denied any loss of consciousness, and complained of primarily left periorbital pain and swelling. She also denied neck or extremity pain, and was ambulatory after the fall. Her medical history was significant for hypertension and gastroesophageal reflux disease, for which she took medications. She admitted to a modest use of alcohol but denied tobacco use.

On physical examination, the patient’s vital signs were: blood pressure, 148/92 mm Hg; heart rate, 104 beats/min; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min; and temperature, 98.8oF. Oxygen saturation was 98% on room air. Examination of the head and face revealed marked left periorbital bruising and swelling, and abrasions to the left forehead and anterior temporal area. The left eye was swollen shut. The right pupil was round and reactive to light, with intact extraocular muscle movement. The patient was tender to palpation around the left periorbital area, but not on any other areas of her face or cranium. The neck was nontender in the midline posteriorly, and the patient’s neurological examination was normal. Examination of the lungs, heart, and abdomen were likewise normal. No measurement of visual acuity was obtained.

The emergency physician (EP) ordered a computed tomography (CT) scan of the head and face without contrast. Because the patient could not remember the date of her last tetanus shot, a tetanus immunization was administered. The EP made several attempts to open the patient’s left eye to examine the pupil and anterior chamber, but was unable to do so because of the marked swelling and the patient’s discomfort.

Radiology services reported that the CT scan of the head was normal, while the CT scan of the face revealed a left orbital floor fracture. The patient was discharged home with instructions to place ice on the areas of swelling and to avoid blowing her nose. She was also given a prescription for hydrocodone/acetaminophen and instructed to follow-up with an ophthalmologist in 1 week.

Unfortunately, the patient suffered permanent and complete loss of sight in the left eye. She sued the hospital and the EP for failure to perform a complete physical examination and consult with an ophthalmologist to determine the extent of her injuries. In addition, an overread of the CT scan of the face revealed entrapment of the left inferior rectus muscle, which the original radiologist did not include in his report. The jury returned a defense verdict.

Discussion

This case is unfortunate because the critical injury, entrapment of the inferior rectus muscle, was missed by two physicians—the EP and the radiologist. While this injury can sometimes be detected on CT, most clinicians agree that orbital muscle entrapment is a clinical diagnosis. The most significant omission in this case is that the EP neither examined the affected eye nor tested the extraocular muscles. If the EP had done so, then in all likelihood this injury would have been identified and ophthalmology services would have been consulted.

Visual acuity should be considered a sixth vital sign in patients who present with an eye injury. This test can be performed using a wall, pocket, or mobile-app Snellen chart.1 If the patient is unable to perform an eye examination, the EP should assess for light and color perception.1 A complete loss of vision implies injury to the optic nerve or globe.1

When possible, it is best to attempt to examine the eyes prior to the onset of significant eyelid swelling. In the presence of significant swelling, lid retractors (eg, paper clip retractors) can be used to allow proper examination of the eye. The pupil, sclera, anterior chamber, and eye movement should all be assessed. Limited vertical movement of the globe, vertical diplopia, and pain in the inferior orbit on attempted vertical movement are consistent with entrapment of the inferior rectus muscle.2 The presence of enophthalmos (posterior displacement of the globe within the orbit) and globe ptosis (downward displacement of the globe within the orbit) should be noted because these often indicate a significant fracture.2

The majority of orbital floor fractures do not require surgical repair. Most are followed for 5 to 10 days to allow swelling and orbital hemorrhage to subside.2 Prednisone (1 mg/kg/d for 7 days) can decrease edema and may limit the risk of diplopia from inferior rectus muscle contractions and fibrosis. However, the presence of tight entrapment of the inferior rectus muscle, or CT scan demonstration of the inferior rectus muscle within the maxillary sinus, is an indication for immediate surgical intervention.2

As physicians, it is imperative that we thoroughly examine the area of primary complaint which, as this case demonstrates, is not always easy.

1. Walker RA, Adhikari S. Eye emergencies. In

2. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Orbital floor fractures. www.aao.org/bcscsnippetdetail.aspx?id=415cdb9b-3308-4f90-bc33-dac1ebd676ce. Accessed May 3, 2017.

Case

A 61-year-old woman presented to the ED for evaluation of left-side facial pain following a fall. The patient stated that she lost her balance as she was getting out of her car and fell to the ground, striking her left face and head. She denied any loss of consciousness, and complained of primarily left periorbital pain and swelling. She also denied neck or extremity pain, and was ambulatory after the fall. Her medical history was significant for hypertension and gastroesophageal reflux disease, for which she took medications. She admitted to a modest use of alcohol but denied tobacco use.

On physical examination, the patient’s vital signs were: blood pressure, 148/92 mm Hg; heart rate, 104 beats/min; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min; and temperature, 98.8oF. Oxygen saturation was 98% on room air. Examination of the head and face revealed marked left periorbital bruising and swelling, and abrasions to the left forehead and anterior temporal area. The left eye was swollen shut. The right pupil was round and reactive to light, with intact extraocular muscle movement. The patient was tender to palpation around the left periorbital area, but not on any other areas of her face or cranium. The neck was nontender in the midline posteriorly, and the patient’s neurological examination was normal. Examination of the lungs, heart, and abdomen were likewise normal. No measurement of visual acuity was obtained.

The emergency physician (EP) ordered a computed tomography (CT) scan of the head and face without contrast. Because the patient could not remember the date of her last tetanus shot, a tetanus immunization was administered. The EP made several attempts to open the patient’s left eye to examine the pupil and anterior chamber, but was unable to do so because of the marked swelling and the patient’s discomfort.

Radiology services reported that the CT scan of the head was normal, while the CT scan of the face revealed a left orbital floor fracture. The patient was discharged home with instructions to place ice on the areas of swelling and to avoid blowing her nose. She was also given a prescription for hydrocodone/acetaminophen and instructed to follow-up with an ophthalmologist in 1 week.

Unfortunately, the patient suffered permanent and complete loss of sight in the left eye. She sued the hospital and the EP for failure to perform a complete physical examination and consult with an ophthalmologist to determine the extent of her injuries. In addition, an overread of the CT scan of the face revealed entrapment of the left inferior rectus muscle, which the original radiologist did not include in his report. The jury returned a defense verdict.

Discussion

This case is unfortunate because the critical injury, entrapment of the inferior rectus muscle, was missed by two physicians—the EP and the radiologist. While this injury can sometimes be detected on CT, most clinicians agree that orbital muscle entrapment is a clinical diagnosis. The most significant omission in this case is that the EP neither examined the affected eye nor tested the extraocular muscles. If the EP had done so, then in all likelihood this injury would have been identified and ophthalmology services would have been consulted.

Visual acuity should be considered a sixth vital sign in patients who present with an eye injury. This test can be performed using a wall, pocket, or mobile-app Snellen chart.1 If the patient is unable to perform an eye examination, the EP should assess for light and color perception.1 A complete loss of vision implies injury to the optic nerve or globe.1

When possible, it is best to attempt to examine the eyes prior to the onset of significant eyelid swelling. In the presence of significant swelling, lid retractors (eg, paper clip retractors) can be used to allow proper examination of the eye. The pupil, sclera, anterior chamber, and eye movement should all be assessed. Limited vertical movement of the globe, vertical diplopia, and pain in the inferior orbit on attempted vertical movement are consistent with entrapment of the inferior rectus muscle.2 The presence of enophthalmos (posterior displacement of the globe within the orbit) and globe ptosis (downward displacement of the globe within the orbit) should be noted because these often indicate a significant fracture.2

The majority of orbital floor fractures do not require surgical repair. Most are followed for 5 to 10 days to allow swelling and orbital hemorrhage to subside.2 Prednisone (1 mg/kg/d for 7 days) can decrease edema and may limit the risk of diplopia from inferior rectus muscle contractions and fibrosis. However, the presence of tight entrapment of the inferior rectus muscle, or CT scan demonstration of the inferior rectus muscle within the maxillary sinus, is an indication for immediate surgical intervention.2

As physicians, it is imperative that we thoroughly examine the area of primary complaint which, as this case demonstrates, is not always easy.

Case

A 61-year-old woman presented to the ED for evaluation of left-side facial pain following a fall. The patient stated that she lost her balance as she was getting out of her car and fell to the ground, striking her left face and head. She denied any loss of consciousness, and complained of primarily left periorbital pain and swelling. She also denied neck or extremity pain, and was ambulatory after the fall. Her medical history was significant for hypertension and gastroesophageal reflux disease, for which she took medications. She admitted to a modest use of alcohol but denied tobacco use.

On physical examination, the patient’s vital signs were: blood pressure, 148/92 mm Hg; heart rate, 104 beats/min; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min; and temperature, 98.8oF. Oxygen saturation was 98% on room air. Examination of the head and face revealed marked left periorbital bruising and swelling, and abrasions to the left forehead and anterior temporal area. The left eye was swollen shut. The right pupil was round and reactive to light, with intact extraocular muscle movement. The patient was tender to palpation around the left periorbital area, but not on any other areas of her face or cranium. The neck was nontender in the midline posteriorly, and the patient’s neurological examination was normal. Examination of the lungs, heart, and abdomen were likewise normal. No measurement of visual acuity was obtained.

The emergency physician (EP) ordered a computed tomography (CT) scan of the head and face without contrast. Because the patient could not remember the date of her last tetanus shot, a tetanus immunization was administered. The EP made several attempts to open the patient’s left eye to examine the pupil and anterior chamber, but was unable to do so because of the marked swelling and the patient’s discomfort.

Radiology services reported that the CT scan of the head was normal, while the CT scan of the face revealed a left orbital floor fracture. The patient was discharged home with instructions to place ice on the areas of swelling and to avoid blowing her nose. She was also given a prescription for hydrocodone/acetaminophen and instructed to follow-up with an ophthalmologist in 1 week.

Unfortunately, the patient suffered permanent and complete loss of sight in the left eye. She sued the hospital and the EP for failure to perform a complete physical examination and consult with an ophthalmologist to determine the extent of her injuries. In addition, an overread of the CT scan of the face revealed entrapment of the left inferior rectus muscle, which the original radiologist did not include in his report. The jury returned a defense verdict.

Discussion

This case is unfortunate because the critical injury, entrapment of the inferior rectus muscle, was missed by two physicians—the EP and the radiologist. While this injury can sometimes be detected on CT, most clinicians agree that orbital muscle entrapment is a clinical diagnosis. The most significant omission in this case is that the EP neither examined the affected eye nor tested the extraocular muscles. If the EP had done so, then in all likelihood this injury would have been identified and ophthalmology services would have been consulted.

Visual acuity should be considered a sixth vital sign in patients who present with an eye injury. This test can be performed using a wall, pocket, or mobile-app Snellen chart.1 If the patient is unable to perform an eye examination, the EP should assess for light and color perception.1 A complete loss of vision implies injury to the optic nerve or globe.1

When possible, it is best to attempt to examine the eyes prior to the onset of significant eyelid swelling. In the presence of significant swelling, lid retractors (eg, paper clip retractors) can be used to allow proper examination of the eye. The pupil, sclera, anterior chamber, and eye movement should all be assessed. Limited vertical movement of the globe, vertical diplopia, and pain in the inferior orbit on attempted vertical movement are consistent with entrapment of the inferior rectus muscle.2 The presence of enophthalmos (posterior displacement of the globe within the orbit) and globe ptosis (downward displacement of the globe within the orbit) should be noted because these often indicate a significant fracture.2

The majority of orbital floor fractures do not require surgical repair. Most are followed for 5 to 10 days to allow swelling and orbital hemorrhage to subside.2 Prednisone (1 mg/kg/d for 7 days) can decrease edema and may limit the risk of diplopia from inferior rectus muscle contractions and fibrosis. However, the presence of tight entrapment of the inferior rectus muscle, or CT scan demonstration of the inferior rectus muscle within the maxillary sinus, is an indication for immediate surgical intervention.2

As physicians, it is imperative that we thoroughly examine the area of primary complaint which, as this case demonstrates, is not always easy.

1. Walker RA, Adhikari S. Eye emergencies. In

2. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Orbital floor fractures. www.aao.org/bcscsnippetdetail.aspx?id=415cdb9b-3308-4f90-bc33-dac1ebd676ce. Accessed May 3, 2017.

1. Walker RA, Adhikari S. Eye emergencies. In

2. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Orbital floor fractures. www.aao.org/bcscsnippetdetail.aspx?id=415cdb9b-3308-4f90-bc33-dac1ebd676ce. Accessed May 3, 2017.

‘3 Strikes ‘n’ yer out’: Dismissing no-show patients

Dear Dr. Mossman,

The clinic where I work initiated a “3 misses and out” policy: If a patient doesn’t show for 3 appointments in a 12-month period, the clinic removes him from the patient rolls. I’ve heard such policies are common, but I worry: Is this abandonment?

Submitted by “Dr. C”

The short answer to Dr. C’s question is, “Handled properly, it’s not abandonment.” But if this response really was satisfactory, Dr. C probably would not have asked the question. Dealing with no-show patients has bothered psychiatrists, other mental health professionals, and other physicians for decades.1

Clinicians worry when patients miss important follow-up, and unreimbursed office time won’t help pay a clinician’s salary or office expenses.2 But a policy such as the one Dr. C describes may not be the best response—clinically or financially—for many patients who miss appointments repeatedly.

If no-show patients worry you or cause problems where you practice, read on as I cover:

- charging for missed appointments

- why patients miss appointments

- evidence-based methods to improve show-up rates

- when ending a treatment relationship unilaterally is not abandonment

- how to dismiss no-show patients from a practice properly.

Before the mid-1980s, most office-based psychiatrists worked in solo or small group and required patients to pay cash for treatment; approximately 40% of psychiatrists still practice this way.3 Often, private practice clinicians require payment for appointments missed without 24 hours’ notice. This well-accepted practice2,4,5 reinforces the notion that psychotherapy involves making a commitment to work on problems. It also protects clinicians’ financial interests and mitigates possible resentment that might arise if office time committed to a patient went unreimbursed.6 Clinicians who charge for missed appointments should inform patients of this at the beginning of treatment, explaining clearly that the patient—not the insurer—will be paying for unused treatment time.2,4

Since the 1980s, outpatient psychiatrists have increasingly worked in public agencies or other organizational practice settings7 where patients—whose care is funded by public monies or third-party payors—cannot afford to pay for missed appointments. If you work in a clinic such as the one where Dr. C provides services, you probably are paid an hourly wage whether your patients show up or not. To pay you and remain solvent, your clinic must find ways other than charging patients to address and reduce no-shows.

The literature abounds with research on why no-shows occur. But no-shows seem to be more common in psychiatry than in other medical specialties.8 The frequency of no-shows varies considerably, but it’s a big problem in some mental health treatment contexts, with reported rates ranging from 12% to 60%.9 A recent, comprehensive review reported that approximately 30% of patients refuse, drop out, or prematurely disengage from services after first-episode psychosis.10 No-shows and drop outs are linked to clinical deterioration11 and heightened risk of hospitalization.12

Jaeschke et al15 suggests that no-shows, dropping out of treatment, and other forms of what doctors call “noncompliance” or “nonadherence” might be better conceptualized as a lack of “concordance,” “mutuality,” or “shared ideology” about what ails patients and the role of their physicians. For this reason, striving for a “partnership between a physician and a patient,” with the patient “fully engaged in the two-way communication with a doctor … seems to be a much more suitable way of achieving therapeutic progress in the discipline of psychiatry.”15

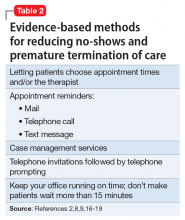

Reducing no-shows: Evidence-based methods

Many medical and mental health articles describe evidence-based methods for lowering no-show rates. Studies document the value of assertive outreach, home visits, avoiding scheduling on religious holidays, scheduling appointments in the afternoon rather than the morning, providing assistance with transportation,8 sending reminder letters,16 or making telephone calls.17 Growing evidence suggests that text messages reduce missed appointments, even among patients with severe disorders (eg, schizophrenia) that compromise cognitive functioning.18

The measures I’ve described won’t prevent every patient from no-showing repeatedly. If you or your employer have tried some of these proven methods and they haven’t reduced a patient’s persistent no-shows, and if it makes sense from a clinical and financial standpoint, then it’s all right to dismiss the patient.

To understand why you are permitted to dismiss a patient from your practice, it helps to understand how the law views the doctor–patient relationship. A doctor has no legal duty to treat anyone—even someone who desperately needs care—unless the doctor has taken some action to establish a treatment relationship with that person. Having previously treated the patient establishes a treatment relationship, as could other actions such as giving specific advice or (in some cases) making an appointment for a person. Once you have a treatment relationship with someone, you usually must continue to provide necessary medical attention until either the treatment episode has concluded or you and the patient agree to end treatment.20

For many chronic mental illnesses, a treatment episode could last years. But this does not force you to continue caring for a patient indefinitely if your circumstances change or if the patient’s behavior causes you to want to withdraw from providing care.

To ethically end care of a patient while a treatment episode is ongoing, you must either transfer care to another competent physician, or give your patient adequate notice and opportunity to obtain appropriate treatment elsewhere.20 If you fail to do either, however, you are guilty of “abandonment” and potentially subject to discipline by state licensing authorities21 or, if harm results, a malpractice lawsuit.22

In many states, statutes or regulations describe what you must do to end a treatment relationship properly. Ohio’s rule is typical: You must send the patient a certified letter explaining that the treatment relationship is ending, that you will remain available to provide care for 30 days, and that you will send treatment records to another provider upon receiving the patient’s signed authorization.21

One note of caution, however: If you practice in hospitals or groups, or if you or the agency where you work has signed provider contracts, you may have agreed to terms of practice that make dismissing a patient more complicated.23 Whether you practice individually or in a large organization, it’s usually wise to get advice from an attorney and/or your malpractice carrier to make sure you’re handling a patient dismissal the right way.

1. Adler LM, Yamamoto J, Goin M. Failed psychiatric clinic appointments. Relationship to social class. Calif Med. 1963;99:388-392.

2. Buppert C. How to deal with missed appointments. Dermatol Nurs 2009;21(4):207-208.

3. National Council Medical Director Institute. The psychiatric shortage: causes and solutions. https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Psychiatric-Shortage_National-Council-.pdf. Published March 28, 2017. Accessed April 6, 2017.

4. Legal & Regulatory Affairs staff. Practitioner pointer: how to handle late and missed appointments. http://www.apapracticecentral.org/update/2014/11-06/late-missed-appoitments.aspx. Published November 6, 2004. Accessed April 7, 2017.

5. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. MLN Matters Number: MM5613. https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNMattersArticles/downloads/MM5613.pdf. Updated November 12, 2014. Accessed April 7, 2017.

6. MacCutcheon M. Why I charge for late cancellations and no-shows to therapy. http://www.goodtherapy.org/blog/why-i-charge-for-late-cancellations-no-shows-to-therapy-0921164. Published September 21, 2016. Accessed April 6, 2017.

7. Kalman TP, Goldstein MA. Satisfaction of Manhattan psychiatrists with private practice: assessing the impact of managed care. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/430759_4. Accessed April 6, 2017.

8. Mitchell AJ, Selmes T. Why don’t patients attend their appointments? Maintaining engagement with psychiatric services. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2007;13(6):423-434.

9. Long J, Sakauye K, Chisty K, et al. The empty chair appointment. SAGE Open. 2016;6:1-5.

10. Doyle R, Turner N, Fanning F, et al. First-episode psychosis and disengagement from treatment: a systematic review. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(5):603-611.

11. Nelson EA, Maruish ME, Axler JL. Effects of discharge planning and compliance with outpatient appointments on readmission rates. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51(7):885-889.

12. Killaspy H, Banerjee S, King M, et al. Prospective controlled study of psychiatric out-patient non-attendance. Characteristics and outcome. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;176:160-165.

13. Williamson AE, Ellis DA, Wilson P, et al. Understanding repeated non-attendance in health services: a pilot analysis of administrative data and full study protocol for a national retrospective cohort. BMJ Open. 2017;7(2):e014120. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014120.

14. Binnie J, Boden Z. Non-attendance at psychological therapy appointments. Mental Health Rev J. 2016;21(3):231-248.

15. Jaeschke R, Siwek M, Dudek D. Various ways of understanding compliance: a psychiatrist’s view. Arch Psychiatr Psychother. 2011;13(3):49-55.

16. Boland B, Burnett F. Optimising outpatient efficiency – development of an innovative ‘Did Not Attend’ management approach. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2014;18(3):217-219.

17. Pennington D, Hodgson J. Non‐attendance and invitation methods within a CBT service. Mental Health Rev J. 2012;17(3):145-151.

18. Sims H, Sanghara H, Hayes D, et al. Text message reminders of appointments: a pilot intervention at four community mental health clinics in London. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63(2):161-168.

19. Oldham M, Kellett S, Miles E, et al. Interventions to increase attendance at psychotherapy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80(5):928-939.

20. Gore AG, Grossman EL, Martin L, et al. Physicians, surgeons, and other healers. In: American Jurisprudence. 2nd ed, §130. Eagan, MN: West Publishing; 2017:61.

21. Ohio Administrative Code §4731-27-02.

22. Lowery v Miller, 157 Wis 2d 503, 460 N.W. 2d 446 (Wis App 1990).

23. Brockway LH. Terminating patient relationships: how to dismiss without abandoning. TMLT. https://www.tmlt.org/tmlt/tmlt-resources/newscenter/blog/2009/Terminating-patient-relationships.html. Published June 19, 2009. Accessed April 3, 2017.

Dear Dr. Mossman,

The clinic where I work initiated a “3 misses and out” policy: If a patient doesn’t show for 3 appointments in a 12-month period, the clinic removes him from the patient rolls. I’ve heard such policies are common, but I worry: Is this abandonment?

Submitted by “Dr. C”

The short answer to Dr. C’s question is, “Handled properly, it’s not abandonment.” But if this response really was satisfactory, Dr. C probably would not have asked the question. Dealing with no-show patients has bothered psychiatrists, other mental health professionals, and other physicians for decades.1

Clinicians worry when patients miss important follow-up, and unreimbursed office time won’t help pay a clinician’s salary or office expenses.2 But a policy such as the one Dr. C describes may not be the best response—clinically or financially—for many patients who miss appointments repeatedly.

If no-show patients worry you or cause problems where you practice, read on as I cover:

- charging for missed appointments

- why patients miss appointments

- evidence-based methods to improve show-up rates

- when ending a treatment relationship unilaterally is not abandonment

- how to dismiss no-show patients from a practice properly.

Before the mid-1980s, most office-based psychiatrists worked in solo or small group and required patients to pay cash for treatment; approximately 40% of psychiatrists still practice this way.3 Often, private practice clinicians require payment for appointments missed without 24 hours’ notice. This well-accepted practice2,4,5 reinforces the notion that psychotherapy involves making a commitment to work on problems. It also protects clinicians’ financial interests and mitigates possible resentment that might arise if office time committed to a patient went unreimbursed.6 Clinicians who charge for missed appointments should inform patients of this at the beginning of treatment, explaining clearly that the patient—not the insurer—will be paying for unused treatment time.2,4

Since the 1980s, outpatient psychiatrists have increasingly worked in public agencies or other organizational practice settings7 where patients—whose care is funded by public monies or third-party payors—cannot afford to pay for missed appointments. If you work in a clinic such as the one where Dr. C provides services, you probably are paid an hourly wage whether your patients show up or not. To pay you and remain solvent, your clinic must find ways other than charging patients to address and reduce no-shows.

The literature abounds with research on why no-shows occur. But no-shows seem to be more common in psychiatry than in other medical specialties.8 The frequency of no-shows varies considerably, but it’s a big problem in some mental health treatment contexts, with reported rates ranging from 12% to 60%.9 A recent, comprehensive review reported that approximately 30% of patients refuse, drop out, or prematurely disengage from services after first-episode psychosis.10 No-shows and drop outs are linked to clinical deterioration11 and heightened risk of hospitalization.12

Jaeschke et al15 suggests that no-shows, dropping out of treatment, and other forms of what doctors call “noncompliance” or “nonadherence” might be better conceptualized as a lack of “concordance,” “mutuality,” or “shared ideology” about what ails patients and the role of their physicians. For this reason, striving for a “partnership between a physician and a patient,” with the patient “fully engaged in the two-way communication with a doctor … seems to be a much more suitable way of achieving therapeutic progress in the discipline of psychiatry.”15

Reducing no-shows: Evidence-based methods

Many medical and mental health articles describe evidence-based methods for lowering no-show rates. Studies document the value of assertive outreach, home visits, avoiding scheduling on religious holidays, scheduling appointments in the afternoon rather than the morning, providing assistance with transportation,8 sending reminder letters,16 or making telephone calls.17 Growing evidence suggests that text messages reduce missed appointments, even among patients with severe disorders (eg, schizophrenia) that compromise cognitive functioning.18

The measures I’ve described won’t prevent every patient from no-showing repeatedly. If you or your employer have tried some of these proven methods and they haven’t reduced a patient’s persistent no-shows, and if it makes sense from a clinical and financial standpoint, then it’s all right to dismiss the patient.

To understand why you are permitted to dismiss a patient from your practice, it helps to understand how the law views the doctor–patient relationship. A doctor has no legal duty to treat anyone—even someone who desperately needs care—unless the doctor has taken some action to establish a treatment relationship with that person. Having previously treated the patient establishes a treatment relationship, as could other actions such as giving specific advice or (in some cases) making an appointment for a person. Once you have a treatment relationship with someone, you usually must continue to provide necessary medical attention until either the treatment episode has concluded or you and the patient agree to end treatment.20

For many chronic mental illnesses, a treatment episode could last years. But this does not force you to continue caring for a patient indefinitely if your circumstances change or if the patient’s behavior causes you to want to withdraw from providing care.

To ethically end care of a patient while a treatment episode is ongoing, you must either transfer care to another competent physician, or give your patient adequate notice and opportunity to obtain appropriate treatment elsewhere.20 If you fail to do either, however, you are guilty of “abandonment” and potentially subject to discipline by state licensing authorities21 or, if harm results, a malpractice lawsuit.22

In many states, statutes or regulations describe what you must do to end a treatment relationship properly. Ohio’s rule is typical: You must send the patient a certified letter explaining that the treatment relationship is ending, that you will remain available to provide care for 30 days, and that you will send treatment records to another provider upon receiving the patient’s signed authorization.21

One note of caution, however: If you practice in hospitals or groups, or if you or the agency where you work has signed provider contracts, you may have agreed to terms of practice that make dismissing a patient more complicated.23 Whether you practice individually or in a large organization, it’s usually wise to get advice from an attorney and/or your malpractice carrier to make sure you’re handling a patient dismissal the right way.

Dear Dr. Mossman,

The clinic where I work initiated a “3 misses and out” policy: If a patient doesn’t show for 3 appointments in a 12-month period, the clinic removes him from the patient rolls. I’ve heard such policies are common, but I worry: Is this abandonment?

Submitted by “Dr. C”

The short answer to Dr. C’s question is, “Handled properly, it’s not abandonment.” But if this response really was satisfactory, Dr. C probably would not have asked the question. Dealing with no-show patients has bothered psychiatrists, other mental health professionals, and other physicians for decades.1

Clinicians worry when patients miss important follow-up, and unreimbursed office time won’t help pay a clinician’s salary or office expenses.2 But a policy such as the one Dr. C describes may not be the best response—clinically or financially—for many patients who miss appointments repeatedly.

If no-show patients worry you or cause problems where you practice, read on as I cover:

- charging for missed appointments

- why patients miss appointments

- evidence-based methods to improve show-up rates

- when ending a treatment relationship unilaterally is not abandonment

- how to dismiss no-show patients from a practice properly.

Before the mid-1980s, most office-based psychiatrists worked in solo or small group and required patients to pay cash for treatment; approximately 40% of psychiatrists still practice this way.3 Often, private practice clinicians require payment for appointments missed without 24 hours’ notice. This well-accepted practice2,4,5 reinforces the notion that psychotherapy involves making a commitment to work on problems. It also protects clinicians’ financial interests and mitigates possible resentment that might arise if office time committed to a patient went unreimbursed.6 Clinicians who charge for missed appointments should inform patients of this at the beginning of treatment, explaining clearly that the patient—not the insurer—will be paying for unused treatment time.2,4

Since the 1980s, outpatient psychiatrists have increasingly worked in public agencies or other organizational practice settings7 where patients—whose care is funded by public monies or third-party payors—cannot afford to pay for missed appointments. If you work in a clinic such as the one where Dr. C provides services, you probably are paid an hourly wage whether your patients show up or not. To pay you and remain solvent, your clinic must find ways other than charging patients to address and reduce no-shows.

The literature abounds with research on why no-shows occur. But no-shows seem to be more common in psychiatry than in other medical specialties.8 The frequency of no-shows varies considerably, but it’s a big problem in some mental health treatment contexts, with reported rates ranging from 12% to 60%.9 A recent, comprehensive review reported that approximately 30% of patients refuse, drop out, or prematurely disengage from services after first-episode psychosis.10 No-shows and drop outs are linked to clinical deterioration11 and heightened risk of hospitalization.12

Jaeschke et al15 suggests that no-shows, dropping out of treatment, and other forms of what doctors call “noncompliance” or “nonadherence” might be better conceptualized as a lack of “concordance,” “mutuality,” or “shared ideology” about what ails patients and the role of their physicians. For this reason, striving for a “partnership between a physician and a patient,” with the patient “fully engaged in the two-way communication with a doctor … seems to be a much more suitable way of achieving therapeutic progress in the discipline of psychiatry.”15

Reducing no-shows: Evidence-based methods