User login

Malpractice Counsel: The Challenges of Cardioversion

Case

A 56-year-old woman presented to the ED with palpitations and lightheadedness, which began upon awakening that morning. The patient had a history of atrial fibrillation (AF), and believed this was the cause of her symptoms. Over the past 18 months, the patient had twice undergone successful cardioversion for AF with a rapid ventricular response (RVR); both cardioversions were performed by her cardiologist.

The patient denied experiencing any chest pain, shortness of breath, nausea, or vomiting. Her medical history was significant only for AF. Regarding her medication history, the patient had been prescribed metoprolol, but admitted that she frequently forgot to take it. She further stated that she was not taking aspirin or anticoagulation therapy for AF. She denied past or current alcohol consumption or tobacco use.

On physical examination, the patient’s vital signs were: heart rate (HR), 186 beats/min; blood pressure, 137/82 mm Hg; respiratory rate, 20 breaths/min, and temperature, afebrile. Oxygen saturation was 96% on room air. The head, eye, ears, nose, and throat examination was normal. Auscultation of the lungs revealed clear breath sounds bilaterally. On examination of the heart, the patient had an irregularly irregular rhythm that was tachycardic; no murmurs, rubs, or gallops were appreciated. The abdomen was soft and nontender. There was no edema or redness of the lower extremities.

The emergency physician (EP) placed the patient on a cardiac monitor and administered 2 L of oxygen via nasal cannula. An electrocardiogram (ECG), portable chest X-ray (CXR), and laboratory evaluation were ordered, and an intravenous (IV) line was established. The ECG revealed AF with RVR, without evidence of ischemia. The CXR was interpreted as normal. Laboratory studies, including complete blood count, basic metabolic profile, and serum troponin levels, were likewise within normal limits.

Based on the patient’s history and evaluation, the EP decided to cardiovert the patient rather than attempt rate control with IV medications. The patient consented to the cardioversion, based on the two previous successful cardioversions performed by her cardiologist. The EP gave the patient midazolam 2 mg IV and performed synchronized cardioversion at 200 joules. The patient converted to normal sinus rhythm with an HR of 86 beats/min. She was observed in the ED for 1 hour, given metoprolol 50 mg by mouth, and discharged home with instructions to follow up with her cardiologist the following week.

The next day, the patient suffered a large ischemic stroke in the distribution of the left middle cerebral artery, resulting in a dense right hemiparesis. The neurological deficit was significant, necessitating the patient’s placement in a nursing home.

The patient and her family sued the EP for malpractice for not anticoagulating the patient prior to and following cardioversion. A $3.3 million settlement was agreed upon prior to trial.

Discussion

Patients commonly present to the ED for complaints related to AF. In some cases, the EP is the first to diagnose the patient’s AF; in other cases, the patient has a history of AF and is presenting with a complication. The focus of this discussion is solely on the management of AF with RVR.

When managing a patient in AF with RVR, the EP must consider three issues: ventricular rate control (VRC), rhythm control, and anticoagulation. Selecting the best treatment strategy will depend on the patient’s hemodynamic stability, duration of her or his symptoms, local custom and preference, and the length of time the AF has been present.

Ventricular Rate Control and Cardioversion

For many stable patients, VRC is frequently the treatment of choice, with a goal HR of less than 100 beats/min. Intravenous diltiazem, esmolol, or metoprolol can be used to achieve VRC in patients in AF. Because these drugs only control ventricular rate and do not typically cardiovert, the risk of embolization is small.

Synchronized cardioversion has the benefit of providing both rate and rhythm control, but at the expense of the increased risk of arterial embolization. Some patients, including those with rheumatic heart disease, mitral stenosis, prosthetic heart valves, severe left ventricular dysfunction, or a history of thromboembolism, are at a constant high risk of developing a thromboembolism.1

Risk-Benefit Ratio and Anticoagulation Therapy

To help determine the risk-benefit ratio in patients without the risk factors mentioned above, the EP should calculate the CHADS2 (congestive heart failure [CHF], hypertension, age, diabetes mellitus [DM], prior stroke, transient ischemic attack [TIA], or thromboembolism [doubled]) score or CHA2DS2-VASC (CHF, hypertension, age 75 years or older [two scores], DM, previous stroke, TIA, or thromboembolism [doubled], vascular disease, age 65-74 years, sex [female]) score to help identify patients at risk for arterial embolic complications (Table).

For patients who have been in AF for less than 48 hours and who are at a very low-embolic risk (CHA2DS2-VASC score of 0), some experts suggest cardioversion without anticoagulation. However, other experts recommend anticoagulation prior to cardioversion—even in low-risk patients. Unfortunately, there is disagreement between professional organizations, with the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology/Heart Rhythm Society stating that cardioversion may be performed with or without procedural anticoagulation,2 while the 2016 European Society of Cardiology guidelines recommend immediate initiation of anticoagulants in all such patients scheduled for cardioversion.3

The reasoning in favor of anticoagulation prior to cardioversion is supported by an observational study by Airaksinen et al4 of 2,481 patients undergoing cardioversion for AF of less than 48 hours duration. This study demonstrated a definite thromboembolic event in 38 (0.7%) of the patients within 30 days (median of 2 days). The thromboembolic event was stroke in 31 of the 38 patients.4 Airaksinen et al4 found that age older than 60 years, female sex, heart failure (HF), and DM were the strongest predictors of embolization. The risk of stroke in patients without HF and those younger than age 60 years was only 0.2%.4

In a similar observational study by Hansen et al5 of 16,274 patients in AF undergoing cardioversion with and without anticoagulation therapy, the absence of postcardioversion anticoagulation increased the risk of thromboembolism 2-fold—regardless of CHA2DS2-VASC scores.

Summary

While the management of AF with a duration of more than 48 hours should always include some type of anticoagulation therapy (pre- or postcardioversion, or both), the role of anticoagulation in low-risk patients with AF of less than 48 hours is not as clear. As this situation is not uncommon, the emergency medicine and cardiology physicians should consider developing a mutually agreed upon protocol on how best to manage these patients at their institution. When considering cardioversion without pre- or postanticoagulation in low-risk patients with AF, EPs should always involve the patient in the decision-making process.

1. Phang R, Manning WJ. Prevention of embolization prior to and after restoration of sinus rhythm in atrial fibrillation. UptoDate Web site. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/prevention-of-embolization-prior-to-and-after-restoration-of-sinus-rhythm-in-atrial-fibrillation. Updated October 10, 2016. Accessed March 6, 2017.

2. January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, et al; ACC/AHA Task Force Members. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2014;130(23):e199-e267. Erratum in Circulation. 2014;130(23):e272-e274. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000041.

3. Kirchhof P, Benussi S, Kotecha D, et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Eur Heart J. 2016:37(38):2893-2962. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehw210.

4. Airaksinen KE, Grönberg T, Nuotio I, et al. Thromboembolic complications after cardioversion of acute atrial fibrillation: the FinCV (Finnish CardioVersion) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(13):1187-1192. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2013.04.089.

5. Hansen ML, Jepsen RM, Olesen JB, et al. Thromboembolic risk in 16 274 atrial fibrillation patients undergoing direct current cardioversion with and without oral anticoagulant therapy. Europace. 2015;17(1):18-23. doi:10.1093/europace/euu189.

Case

A 56-year-old woman presented to the ED with palpitations and lightheadedness, which began upon awakening that morning. The patient had a history of atrial fibrillation (AF), and believed this was the cause of her symptoms. Over the past 18 months, the patient had twice undergone successful cardioversion for AF with a rapid ventricular response (RVR); both cardioversions were performed by her cardiologist.

The patient denied experiencing any chest pain, shortness of breath, nausea, or vomiting. Her medical history was significant only for AF. Regarding her medication history, the patient had been prescribed metoprolol, but admitted that she frequently forgot to take it. She further stated that she was not taking aspirin or anticoagulation therapy for AF. She denied past or current alcohol consumption or tobacco use.

On physical examination, the patient’s vital signs were: heart rate (HR), 186 beats/min; blood pressure, 137/82 mm Hg; respiratory rate, 20 breaths/min, and temperature, afebrile. Oxygen saturation was 96% on room air. The head, eye, ears, nose, and throat examination was normal. Auscultation of the lungs revealed clear breath sounds bilaterally. On examination of the heart, the patient had an irregularly irregular rhythm that was tachycardic; no murmurs, rubs, or gallops were appreciated. The abdomen was soft and nontender. There was no edema or redness of the lower extremities.

The emergency physician (EP) placed the patient on a cardiac monitor and administered 2 L of oxygen via nasal cannula. An electrocardiogram (ECG), portable chest X-ray (CXR), and laboratory evaluation were ordered, and an intravenous (IV) line was established. The ECG revealed AF with RVR, without evidence of ischemia. The CXR was interpreted as normal. Laboratory studies, including complete blood count, basic metabolic profile, and serum troponin levels, were likewise within normal limits.

Based on the patient’s history and evaluation, the EP decided to cardiovert the patient rather than attempt rate control with IV medications. The patient consented to the cardioversion, based on the two previous successful cardioversions performed by her cardiologist. The EP gave the patient midazolam 2 mg IV and performed synchronized cardioversion at 200 joules. The patient converted to normal sinus rhythm with an HR of 86 beats/min. She was observed in the ED for 1 hour, given metoprolol 50 mg by mouth, and discharged home with instructions to follow up with her cardiologist the following week.

The next day, the patient suffered a large ischemic stroke in the distribution of the left middle cerebral artery, resulting in a dense right hemiparesis. The neurological deficit was significant, necessitating the patient’s placement in a nursing home.

The patient and her family sued the EP for malpractice for not anticoagulating the patient prior to and following cardioversion. A $3.3 million settlement was agreed upon prior to trial.

Discussion

Patients commonly present to the ED for complaints related to AF. In some cases, the EP is the first to diagnose the patient’s AF; in other cases, the patient has a history of AF and is presenting with a complication. The focus of this discussion is solely on the management of AF with RVR.

When managing a patient in AF with RVR, the EP must consider three issues: ventricular rate control (VRC), rhythm control, and anticoagulation. Selecting the best treatment strategy will depend on the patient’s hemodynamic stability, duration of her or his symptoms, local custom and preference, and the length of time the AF has been present.

Ventricular Rate Control and Cardioversion

For many stable patients, VRC is frequently the treatment of choice, with a goal HR of less than 100 beats/min. Intravenous diltiazem, esmolol, or metoprolol can be used to achieve VRC in patients in AF. Because these drugs only control ventricular rate and do not typically cardiovert, the risk of embolization is small.

Synchronized cardioversion has the benefit of providing both rate and rhythm control, but at the expense of the increased risk of arterial embolization. Some patients, including those with rheumatic heart disease, mitral stenosis, prosthetic heart valves, severe left ventricular dysfunction, or a history of thromboembolism, are at a constant high risk of developing a thromboembolism.1

Risk-Benefit Ratio and Anticoagulation Therapy

To help determine the risk-benefit ratio in patients without the risk factors mentioned above, the EP should calculate the CHADS2 (congestive heart failure [CHF], hypertension, age, diabetes mellitus [DM], prior stroke, transient ischemic attack [TIA], or thromboembolism [doubled]) score or CHA2DS2-VASC (CHF, hypertension, age 75 years or older [two scores], DM, previous stroke, TIA, or thromboembolism [doubled], vascular disease, age 65-74 years, sex [female]) score to help identify patients at risk for arterial embolic complications (Table).

For patients who have been in AF for less than 48 hours and who are at a very low-embolic risk (CHA2DS2-VASC score of 0), some experts suggest cardioversion without anticoagulation. However, other experts recommend anticoagulation prior to cardioversion—even in low-risk patients. Unfortunately, there is disagreement between professional organizations, with the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology/Heart Rhythm Society stating that cardioversion may be performed with or without procedural anticoagulation,2 while the 2016 European Society of Cardiology guidelines recommend immediate initiation of anticoagulants in all such patients scheduled for cardioversion.3

The reasoning in favor of anticoagulation prior to cardioversion is supported by an observational study by Airaksinen et al4 of 2,481 patients undergoing cardioversion for AF of less than 48 hours duration. This study demonstrated a definite thromboembolic event in 38 (0.7%) of the patients within 30 days (median of 2 days). The thromboembolic event was stroke in 31 of the 38 patients.4 Airaksinen et al4 found that age older than 60 years, female sex, heart failure (HF), and DM were the strongest predictors of embolization. The risk of stroke in patients without HF and those younger than age 60 years was only 0.2%.4

In a similar observational study by Hansen et al5 of 16,274 patients in AF undergoing cardioversion with and without anticoagulation therapy, the absence of postcardioversion anticoagulation increased the risk of thromboembolism 2-fold—regardless of CHA2DS2-VASC scores.

Summary

While the management of AF with a duration of more than 48 hours should always include some type of anticoagulation therapy (pre- or postcardioversion, or both), the role of anticoagulation in low-risk patients with AF of less than 48 hours is not as clear. As this situation is not uncommon, the emergency medicine and cardiology physicians should consider developing a mutually agreed upon protocol on how best to manage these patients at their institution. When considering cardioversion without pre- or postanticoagulation in low-risk patients with AF, EPs should always involve the patient in the decision-making process.

Case

A 56-year-old woman presented to the ED with palpitations and lightheadedness, which began upon awakening that morning. The patient had a history of atrial fibrillation (AF), and believed this was the cause of her symptoms. Over the past 18 months, the patient had twice undergone successful cardioversion for AF with a rapid ventricular response (RVR); both cardioversions were performed by her cardiologist.

The patient denied experiencing any chest pain, shortness of breath, nausea, or vomiting. Her medical history was significant only for AF. Regarding her medication history, the patient had been prescribed metoprolol, but admitted that she frequently forgot to take it. She further stated that she was not taking aspirin or anticoagulation therapy for AF. She denied past or current alcohol consumption or tobacco use.

On physical examination, the patient’s vital signs were: heart rate (HR), 186 beats/min; blood pressure, 137/82 mm Hg; respiratory rate, 20 breaths/min, and temperature, afebrile. Oxygen saturation was 96% on room air. The head, eye, ears, nose, and throat examination was normal. Auscultation of the lungs revealed clear breath sounds bilaterally. On examination of the heart, the patient had an irregularly irregular rhythm that was tachycardic; no murmurs, rubs, or gallops were appreciated. The abdomen was soft and nontender. There was no edema or redness of the lower extremities.

The emergency physician (EP) placed the patient on a cardiac monitor and administered 2 L of oxygen via nasal cannula. An electrocardiogram (ECG), portable chest X-ray (CXR), and laboratory evaluation were ordered, and an intravenous (IV) line was established. The ECG revealed AF with RVR, without evidence of ischemia. The CXR was interpreted as normal. Laboratory studies, including complete blood count, basic metabolic profile, and serum troponin levels, were likewise within normal limits.

Based on the patient’s history and evaluation, the EP decided to cardiovert the patient rather than attempt rate control with IV medications. The patient consented to the cardioversion, based on the two previous successful cardioversions performed by her cardiologist. The EP gave the patient midazolam 2 mg IV and performed synchronized cardioversion at 200 joules. The patient converted to normal sinus rhythm with an HR of 86 beats/min. She was observed in the ED for 1 hour, given metoprolol 50 mg by mouth, and discharged home with instructions to follow up with her cardiologist the following week.

The next day, the patient suffered a large ischemic stroke in the distribution of the left middle cerebral artery, resulting in a dense right hemiparesis. The neurological deficit was significant, necessitating the patient’s placement in a nursing home.

The patient and her family sued the EP for malpractice for not anticoagulating the patient prior to and following cardioversion. A $3.3 million settlement was agreed upon prior to trial.

Discussion

Patients commonly present to the ED for complaints related to AF. In some cases, the EP is the first to diagnose the patient’s AF; in other cases, the patient has a history of AF and is presenting with a complication. The focus of this discussion is solely on the management of AF with RVR.

When managing a patient in AF with RVR, the EP must consider three issues: ventricular rate control (VRC), rhythm control, and anticoagulation. Selecting the best treatment strategy will depend on the patient’s hemodynamic stability, duration of her or his symptoms, local custom and preference, and the length of time the AF has been present.

Ventricular Rate Control and Cardioversion

For many stable patients, VRC is frequently the treatment of choice, with a goal HR of less than 100 beats/min. Intravenous diltiazem, esmolol, or metoprolol can be used to achieve VRC in patients in AF. Because these drugs only control ventricular rate and do not typically cardiovert, the risk of embolization is small.

Synchronized cardioversion has the benefit of providing both rate and rhythm control, but at the expense of the increased risk of arterial embolization. Some patients, including those with rheumatic heart disease, mitral stenosis, prosthetic heart valves, severe left ventricular dysfunction, or a history of thromboembolism, are at a constant high risk of developing a thromboembolism.1

Risk-Benefit Ratio and Anticoagulation Therapy

To help determine the risk-benefit ratio in patients without the risk factors mentioned above, the EP should calculate the CHADS2 (congestive heart failure [CHF], hypertension, age, diabetes mellitus [DM], prior stroke, transient ischemic attack [TIA], or thromboembolism [doubled]) score or CHA2DS2-VASC (CHF, hypertension, age 75 years or older [two scores], DM, previous stroke, TIA, or thromboembolism [doubled], vascular disease, age 65-74 years, sex [female]) score to help identify patients at risk for arterial embolic complications (Table).

For patients who have been in AF for less than 48 hours and who are at a very low-embolic risk (CHA2DS2-VASC score of 0), some experts suggest cardioversion without anticoagulation. However, other experts recommend anticoagulation prior to cardioversion—even in low-risk patients. Unfortunately, there is disagreement between professional organizations, with the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology/Heart Rhythm Society stating that cardioversion may be performed with or without procedural anticoagulation,2 while the 2016 European Society of Cardiology guidelines recommend immediate initiation of anticoagulants in all such patients scheduled for cardioversion.3

The reasoning in favor of anticoagulation prior to cardioversion is supported by an observational study by Airaksinen et al4 of 2,481 patients undergoing cardioversion for AF of less than 48 hours duration. This study demonstrated a definite thromboembolic event in 38 (0.7%) of the patients within 30 days (median of 2 days). The thromboembolic event was stroke in 31 of the 38 patients.4 Airaksinen et al4 found that age older than 60 years, female sex, heart failure (HF), and DM were the strongest predictors of embolization. The risk of stroke in patients without HF and those younger than age 60 years was only 0.2%.4

In a similar observational study by Hansen et al5 of 16,274 patients in AF undergoing cardioversion with and without anticoagulation therapy, the absence of postcardioversion anticoagulation increased the risk of thromboembolism 2-fold—regardless of CHA2DS2-VASC scores.

Summary

While the management of AF with a duration of more than 48 hours should always include some type of anticoagulation therapy (pre- or postcardioversion, or both), the role of anticoagulation in low-risk patients with AF of less than 48 hours is not as clear. As this situation is not uncommon, the emergency medicine and cardiology physicians should consider developing a mutually agreed upon protocol on how best to manage these patients at their institution. When considering cardioversion without pre- or postanticoagulation in low-risk patients with AF, EPs should always involve the patient in the decision-making process.

1. Phang R, Manning WJ. Prevention of embolization prior to and after restoration of sinus rhythm in atrial fibrillation. UptoDate Web site. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/prevention-of-embolization-prior-to-and-after-restoration-of-sinus-rhythm-in-atrial-fibrillation. Updated October 10, 2016. Accessed March 6, 2017.

2. January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, et al; ACC/AHA Task Force Members. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2014;130(23):e199-e267. Erratum in Circulation. 2014;130(23):e272-e274. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000041.

3. Kirchhof P, Benussi S, Kotecha D, et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Eur Heart J. 2016:37(38):2893-2962. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehw210.

4. Airaksinen KE, Grönberg T, Nuotio I, et al. Thromboembolic complications after cardioversion of acute atrial fibrillation: the FinCV (Finnish CardioVersion) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(13):1187-1192. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2013.04.089.

5. Hansen ML, Jepsen RM, Olesen JB, et al. Thromboembolic risk in 16 274 atrial fibrillation patients undergoing direct current cardioversion with and without oral anticoagulant therapy. Europace. 2015;17(1):18-23. doi:10.1093/europace/euu189.

1. Phang R, Manning WJ. Prevention of embolization prior to and after restoration of sinus rhythm in atrial fibrillation. UptoDate Web site. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/prevention-of-embolization-prior-to-and-after-restoration-of-sinus-rhythm-in-atrial-fibrillation. Updated October 10, 2016. Accessed March 6, 2017.

2. January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, et al; ACC/AHA Task Force Members. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2014;130(23):e199-e267. Erratum in Circulation. 2014;130(23):e272-e274. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000041.

3. Kirchhof P, Benussi S, Kotecha D, et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Eur Heart J. 2016:37(38):2893-2962. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehw210.

4. Airaksinen KE, Grönberg T, Nuotio I, et al. Thromboembolic complications after cardioversion of acute atrial fibrillation: the FinCV (Finnish CardioVersion) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(13):1187-1192. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2013.04.089.

5. Hansen ML, Jepsen RM, Olesen JB, et al. Thromboembolic risk in 16 274 atrial fibrillation patients undergoing direct current cardioversion with and without oral anticoagulant therapy. Europace. 2015;17(1):18-23. doi:10.1093/europace/euu189.

Forceful use of forceps, infant dies: $10.2M verdict

Forceful use of forceps, infant dies: $10.2M verdict

A woman in her mid-20s went to the hospital in labor. After several hours, fetal heart-rate (FHR) monitor results became nonreassuring. The ObGyn and the nurse in charge disagreed on the interpretation of the FHR monitor strips. The nurse went to her supervisor, who confronted the ObGyn 2 hours later, saying that fetal distress was a serious concern and necessitated the cessation of oxytocin. The ObGyn disagreed and ordered another nurse to increase the oxytocin dose.

Three hours later, when the FHR monitoring strips showed severe distress, the ObGyn decided to undertake an operative vaginal delivery. During a 17-minute period, the ObGyn unsuccessfully used forceps 3 times. On the second attempt, a cracking noise was heard. Then a cesarean delivery was ordered; the baby was born limp, lifeless, and unresponsive. She was found to have hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy, was removed from life support, and died.

PARENTS’ CLAIM:

Oxytocin should not have been continued when the baby was clearly in distress. The supervising nurse should have contacted her supervisor and continued up the chain of command until the ObGyn was forced to stop the oxytocin.

Physicians are prohibited from using their leg muscles when applying forceps; gentle action is critical. During one attempt, the ObGyn had his leg on the bed to increase the force with which he pulled on the forceps. The ObGyn’s reckless use of forceps caused a skull fracture to depress into the brain. The ObGyn also tried to turn the baby using forceps, which is outside the standard of care because of the risk of rotational injury. A mother’s pushing rarely causes such severe damage to the baby.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE:

There was no negligence. The hypoxia was due to a hemorrhage. Natural forces of a long delivery caused the skull injury.

VERDICT:

A $10,200,575 Texas verdict was returned.

After long labor, baby has CP: $8.4M settlement

Early on March 20, a 30-year-old woman who weighed 300 lbs was admitted for delivery at 40 weeks’ gestation. Labor was induced with oxytocin. Within 30 minutes, FHR monitoring showed that the baby’s baseline began to climb, accelerations ceased, and late decelerations commenced. The oxytocin dose was steadily increased throughout the day. A nurse decided that the baby was not tolerating the contractions and discontinued oxytocin. The attending ObGyn ordered oxytocin be restarted after giving the baby a chance to recover. The mother requested a cesarean delivery, but the ObGyn refused, saying that he was concerned with the risk due to her excessive weight and prior heart surgery. When his shift ended, his partner took over.

On March 21, a nurse reported that the FHR had climbed to 160 bpm although labor had not progressed. The ObGyn ordered terbutaline to slow contractions but he did not examine the mother. An hour after terbutaline administration, the FHR showed a deceleration. An emergency cesarean delivery was performed. The baby, born severely depressed, was resuscitated. Magnetic resonance imaging performed at 23 days of life showed that the child had a hypoxic ischemic injury. She has cerebral palsy and is nonambulatory with significant cognitive deficits.

PARENTS’ CLAIM:

The care provided by 2 ObGyns, nursing staff, and hospital was negligent. A cesarean delivery should have been performed on March 20 when the nurse identified fetal distress. The nurses should have been more assertive in recommending cesarean delivery. The injury occurred 30 minutes prior to delivery and could have been prevented by an earlier cesarean delivery.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE:

FHR strips on March 20 were not as nonreassuring as claimed and did not warrant cesarean delivery, which was performed when needed.

VERDICT:

An $8.4 million Wisconsin settlement was reached by mediation.

Eclamptic seizure, twins stillborn: $4.25M

A 29-year-old woman pregnant with twins had an eclamptic seizure at 33 4/7 weeks’ gestation. The babies were stillborn.

PARENTS’ CLAIM:

The ObGyn failed to properly treat the patient’s preeclampsia for more than 11 weeks. The seizure caused hypovolemic shock, tachycardia, and massive hemorrhaging and required an emergency hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. The patient has no children and has been rendered unable to conceive. She sought to apportion 60% of the settlement proceeds to her distress claim and 20% each to wrongful-death and survival claims. She also sought to bar the twins’ biological father from sharing in the recovery due to abandonment.

HOSPITAL'S DEFENSE:

The case was settled during the trial.

VERDICT:

The mother agreed to receive 65% of the wrongful-death and survival funds, with 35% going to the father. A Pennsylvania settlement of $4.25 million was reached.

Brachial plexus injury: $4.8M verdict

A woman gave birth with assistance from a midwife. During delivery, shoulder dystocia was encountered. The baby has a permanent brachial plexus injury.

PARENTS’ CLAIM:

The midwife mismanaged shoulder dystocia by applying excessive traction to the baby’s head. The ObGyn in charge of the mother’s care did not provide adequate supervision.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE:

The hospital settled prior to trial. The midwife and ObGyn denied negligence during delivery and contended that the child’s injury occurred as a result of the natural forces of labor.

VERDICT:

The jury found the midwife 60% negligent and the ObGyn 40% negligent. A $4.82 million Florida verdict was returned.

What caused infant's death?

During prenatal care, a woman underwent weekly nonstress tests due to excessive amniotic fluid until the level returned to normal. Near the end of her pregnancy, the patient noticed a decrease in fetal movement and called her ObGyn group. She was told to perform a fetal kick count and go to the emergency department (ED) if the count was abnormal, but she fell asleep. In the morning, she presented to the ObGyns’ office and was sent to the hospital for emergency cesarean delivery, which was performed 2.5 hrs after her arrival. The infant was born in distress and died 8 hours later.

PARENTS’ CLAIM:

The ObGyns should have continued weekly tests even after the amniotic fluid level returned to normal. She should have been sent to the ED when she initially reported decreased fetal movement. Cesarean delivery should have been performed immediately upon her arrival at the hospital.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE:

Further prenatal testing for amniotic fluid levels was unwarranted. Telephone advice to count fetal kicks was appropriate. The delay in performing a cesarean delivery was beyond the ObGyns’ control. The outcome would have been the same regardless of their actions.

VERDICT:

A Michigan defense verdict was returned.

Perineal laceration during vaginal delivery

During vaginal delivery, a 27-year-old woman suffered a 4th-degree perineal laceration. She developed a retrovaginal fistula and has permanent fecal incontinence.

PARENTS’ CLAIM:

The ObGyn’s care was negligent. She failed to perform a rectal examination to assess the severity of the perineal laceration. The laceration was improperly repaired, and, as a result, the patient developed a retrovaginal fistula that persisted for 6 months until it was surgically repaired. A divot in her anal canal causes fecal incontinence.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE:

The ObGyn contended she correctly diagnosed and repaired a 3rd-degree laceration. The wound later broke down for unknown reasons.

VERDICT:

An Arizona defense verdict was returned.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Forceful use of forceps, infant dies: $10.2M verdict

A woman in her mid-20s went to the hospital in labor. After several hours, fetal heart-rate (FHR) monitor results became nonreassuring. The ObGyn and the nurse in charge disagreed on the interpretation of the FHR monitor strips. The nurse went to her supervisor, who confronted the ObGyn 2 hours later, saying that fetal distress was a serious concern and necessitated the cessation of oxytocin. The ObGyn disagreed and ordered another nurse to increase the oxytocin dose.

Three hours later, when the FHR monitoring strips showed severe distress, the ObGyn decided to undertake an operative vaginal delivery. During a 17-minute period, the ObGyn unsuccessfully used forceps 3 times. On the second attempt, a cracking noise was heard. Then a cesarean delivery was ordered; the baby was born limp, lifeless, and unresponsive. She was found to have hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy, was removed from life support, and died.

PARENTS’ CLAIM:

Oxytocin should not have been continued when the baby was clearly in distress. The supervising nurse should have contacted her supervisor and continued up the chain of command until the ObGyn was forced to stop the oxytocin.

Physicians are prohibited from using their leg muscles when applying forceps; gentle action is critical. During one attempt, the ObGyn had his leg on the bed to increase the force with which he pulled on the forceps. The ObGyn’s reckless use of forceps caused a skull fracture to depress into the brain. The ObGyn also tried to turn the baby using forceps, which is outside the standard of care because of the risk of rotational injury. A mother’s pushing rarely causes such severe damage to the baby.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE:

There was no negligence. The hypoxia was due to a hemorrhage. Natural forces of a long delivery caused the skull injury.

VERDICT:

A $10,200,575 Texas verdict was returned.

After long labor, baby has CP: $8.4M settlement

Early on March 20, a 30-year-old woman who weighed 300 lbs was admitted for delivery at 40 weeks’ gestation. Labor was induced with oxytocin. Within 30 minutes, FHR monitoring showed that the baby’s baseline began to climb, accelerations ceased, and late decelerations commenced. The oxytocin dose was steadily increased throughout the day. A nurse decided that the baby was not tolerating the contractions and discontinued oxytocin. The attending ObGyn ordered oxytocin be restarted after giving the baby a chance to recover. The mother requested a cesarean delivery, but the ObGyn refused, saying that he was concerned with the risk due to her excessive weight and prior heart surgery. When his shift ended, his partner took over.

On March 21, a nurse reported that the FHR had climbed to 160 bpm although labor had not progressed. The ObGyn ordered terbutaline to slow contractions but he did not examine the mother. An hour after terbutaline administration, the FHR showed a deceleration. An emergency cesarean delivery was performed. The baby, born severely depressed, was resuscitated. Magnetic resonance imaging performed at 23 days of life showed that the child had a hypoxic ischemic injury. She has cerebral palsy and is nonambulatory with significant cognitive deficits.

PARENTS’ CLAIM:

The care provided by 2 ObGyns, nursing staff, and hospital was negligent. A cesarean delivery should have been performed on March 20 when the nurse identified fetal distress. The nurses should have been more assertive in recommending cesarean delivery. The injury occurred 30 minutes prior to delivery and could have been prevented by an earlier cesarean delivery.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE:

FHR strips on March 20 were not as nonreassuring as claimed and did not warrant cesarean delivery, which was performed when needed.

VERDICT:

An $8.4 million Wisconsin settlement was reached by mediation.

Eclamptic seizure, twins stillborn: $4.25M

A 29-year-old woman pregnant with twins had an eclamptic seizure at 33 4/7 weeks’ gestation. The babies were stillborn.

PARENTS’ CLAIM:

The ObGyn failed to properly treat the patient’s preeclampsia for more than 11 weeks. The seizure caused hypovolemic shock, tachycardia, and massive hemorrhaging and required an emergency hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. The patient has no children and has been rendered unable to conceive. She sought to apportion 60% of the settlement proceeds to her distress claim and 20% each to wrongful-death and survival claims. She also sought to bar the twins’ biological father from sharing in the recovery due to abandonment.

HOSPITAL'S DEFENSE:

The case was settled during the trial.

VERDICT:

The mother agreed to receive 65% of the wrongful-death and survival funds, with 35% going to the father. A Pennsylvania settlement of $4.25 million was reached.

Brachial plexus injury: $4.8M verdict

A woman gave birth with assistance from a midwife. During delivery, shoulder dystocia was encountered. The baby has a permanent brachial plexus injury.

PARENTS’ CLAIM:

The midwife mismanaged shoulder dystocia by applying excessive traction to the baby’s head. The ObGyn in charge of the mother’s care did not provide adequate supervision.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE:

The hospital settled prior to trial. The midwife and ObGyn denied negligence during delivery and contended that the child’s injury occurred as a result of the natural forces of labor.

VERDICT:

The jury found the midwife 60% negligent and the ObGyn 40% negligent. A $4.82 million Florida verdict was returned.

What caused infant's death?

During prenatal care, a woman underwent weekly nonstress tests due to excessive amniotic fluid until the level returned to normal. Near the end of her pregnancy, the patient noticed a decrease in fetal movement and called her ObGyn group. She was told to perform a fetal kick count and go to the emergency department (ED) if the count was abnormal, but she fell asleep. In the morning, she presented to the ObGyns’ office and was sent to the hospital for emergency cesarean delivery, which was performed 2.5 hrs after her arrival. The infant was born in distress and died 8 hours later.

PARENTS’ CLAIM:

The ObGyns should have continued weekly tests even after the amniotic fluid level returned to normal. She should have been sent to the ED when she initially reported decreased fetal movement. Cesarean delivery should have been performed immediately upon her arrival at the hospital.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE:

Further prenatal testing for amniotic fluid levels was unwarranted. Telephone advice to count fetal kicks was appropriate. The delay in performing a cesarean delivery was beyond the ObGyns’ control. The outcome would have been the same regardless of their actions.

VERDICT:

A Michigan defense verdict was returned.

Perineal laceration during vaginal delivery

During vaginal delivery, a 27-year-old woman suffered a 4th-degree perineal laceration. She developed a retrovaginal fistula and has permanent fecal incontinence.

PARENTS’ CLAIM:

The ObGyn’s care was negligent. She failed to perform a rectal examination to assess the severity of the perineal laceration. The laceration was improperly repaired, and, as a result, the patient developed a retrovaginal fistula that persisted for 6 months until it was surgically repaired. A divot in her anal canal causes fecal incontinence.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE:

The ObGyn contended she correctly diagnosed and repaired a 3rd-degree laceration. The wound later broke down for unknown reasons.

VERDICT:

An Arizona defense verdict was returned.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Forceful use of forceps, infant dies: $10.2M verdict

A woman in her mid-20s went to the hospital in labor. After several hours, fetal heart-rate (FHR) monitor results became nonreassuring. The ObGyn and the nurse in charge disagreed on the interpretation of the FHR monitor strips. The nurse went to her supervisor, who confronted the ObGyn 2 hours later, saying that fetal distress was a serious concern and necessitated the cessation of oxytocin. The ObGyn disagreed and ordered another nurse to increase the oxytocin dose.

Three hours later, when the FHR monitoring strips showed severe distress, the ObGyn decided to undertake an operative vaginal delivery. During a 17-minute period, the ObGyn unsuccessfully used forceps 3 times. On the second attempt, a cracking noise was heard. Then a cesarean delivery was ordered; the baby was born limp, lifeless, and unresponsive. She was found to have hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy, was removed from life support, and died.

PARENTS’ CLAIM:

Oxytocin should not have been continued when the baby was clearly in distress. The supervising nurse should have contacted her supervisor and continued up the chain of command until the ObGyn was forced to stop the oxytocin.

Physicians are prohibited from using their leg muscles when applying forceps; gentle action is critical. During one attempt, the ObGyn had his leg on the bed to increase the force with which he pulled on the forceps. The ObGyn’s reckless use of forceps caused a skull fracture to depress into the brain. The ObGyn also tried to turn the baby using forceps, which is outside the standard of care because of the risk of rotational injury. A mother’s pushing rarely causes such severe damage to the baby.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE:

There was no negligence. The hypoxia was due to a hemorrhage. Natural forces of a long delivery caused the skull injury.

VERDICT:

A $10,200,575 Texas verdict was returned.

After long labor, baby has CP: $8.4M settlement

Early on March 20, a 30-year-old woman who weighed 300 lbs was admitted for delivery at 40 weeks’ gestation. Labor was induced with oxytocin. Within 30 minutes, FHR monitoring showed that the baby’s baseline began to climb, accelerations ceased, and late decelerations commenced. The oxytocin dose was steadily increased throughout the day. A nurse decided that the baby was not tolerating the contractions and discontinued oxytocin. The attending ObGyn ordered oxytocin be restarted after giving the baby a chance to recover. The mother requested a cesarean delivery, but the ObGyn refused, saying that he was concerned with the risk due to her excessive weight and prior heart surgery. When his shift ended, his partner took over.

On March 21, a nurse reported that the FHR had climbed to 160 bpm although labor had not progressed. The ObGyn ordered terbutaline to slow contractions but he did not examine the mother. An hour after terbutaline administration, the FHR showed a deceleration. An emergency cesarean delivery was performed. The baby, born severely depressed, was resuscitated. Magnetic resonance imaging performed at 23 days of life showed that the child had a hypoxic ischemic injury. She has cerebral palsy and is nonambulatory with significant cognitive deficits.

PARENTS’ CLAIM:

The care provided by 2 ObGyns, nursing staff, and hospital was negligent. A cesarean delivery should have been performed on March 20 when the nurse identified fetal distress. The nurses should have been more assertive in recommending cesarean delivery. The injury occurred 30 minutes prior to delivery and could have been prevented by an earlier cesarean delivery.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE:

FHR strips on March 20 were not as nonreassuring as claimed and did not warrant cesarean delivery, which was performed when needed.

VERDICT:

An $8.4 million Wisconsin settlement was reached by mediation.

Eclamptic seizure, twins stillborn: $4.25M

A 29-year-old woman pregnant with twins had an eclamptic seizure at 33 4/7 weeks’ gestation. The babies were stillborn.

PARENTS’ CLAIM:

The ObGyn failed to properly treat the patient’s preeclampsia for more than 11 weeks. The seizure caused hypovolemic shock, tachycardia, and massive hemorrhaging and required an emergency hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. The patient has no children and has been rendered unable to conceive. She sought to apportion 60% of the settlement proceeds to her distress claim and 20% each to wrongful-death and survival claims. She also sought to bar the twins’ biological father from sharing in the recovery due to abandonment.

HOSPITAL'S DEFENSE:

The case was settled during the trial.

VERDICT:

The mother agreed to receive 65% of the wrongful-death and survival funds, with 35% going to the father. A Pennsylvania settlement of $4.25 million was reached.

Brachial plexus injury: $4.8M verdict

A woman gave birth with assistance from a midwife. During delivery, shoulder dystocia was encountered. The baby has a permanent brachial plexus injury.

PARENTS’ CLAIM:

The midwife mismanaged shoulder dystocia by applying excessive traction to the baby’s head. The ObGyn in charge of the mother’s care did not provide adequate supervision.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE:

The hospital settled prior to trial. The midwife and ObGyn denied negligence during delivery and contended that the child’s injury occurred as a result of the natural forces of labor.

VERDICT:

The jury found the midwife 60% negligent and the ObGyn 40% negligent. A $4.82 million Florida verdict was returned.

What caused infant's death?

During prenatal care, a woman underwent weekly nonstress tests due to excessive amniotic fluid until the level returned to normal. Near the end of her pregnancy, the patient noticed a decrease in fetal movement and called her ObGyn group. She was told to perform a fetal kick count and go to the emergency department (ED) if the count was abnormal, but she fell asleep. In the morning, she presented to the ObGyns’ office and was sent to the hospital for emergency cesarean delivery, which was performed 2.5 hrs after her arrival. The infant was born in distress and died 8 hours later.

PARENTS’ CLAIM:

The ObGyns should have continued weekly tests even after the amniotic fluid level returned to normal. She should have been sent to the ED when she initially reported decreased fetal movement. Cesarean delivery should have been performed immediately upon her arrival at the hospital.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE:

Further prenatal testing for amniotic fluid levels was unwarranted. Telephone advice to count fetal kicks was appropriate. The delay in performing a cesarean delivery was beyond the ObGyns’ control. The outcome would have been the same regardless of their actions.

VERDICT:

A Michigan defense verdict was returned.

Perineal laceration during vaginal delivery

During vaginal delivery, a 27-year-old woman suffered a 4th-degree perineal laceration. She developed a retrovaginal fistula and has permanent fecal incontinence.

PARENTS’ CLAIM:

The ObGyn’s care was negligent. She failed to perform a rectal examination to assess the severity of the perineal laceration. The laceration was improperly repaired, and, as a result, the patient developed a retrovaginal fistula that persisted for 6 months until it was surgically repaired. A divot in her anal canal causes fecal incontinence.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE:

The ObGyn contended she correctly diagnosed and repaired a 3rd-degree laceration. The wound later broke down for unknown reasons.

VERDICT:

An Arizona defense verdict was returned.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Did posthysterectomy hemorrhage cause woman’s brain damage?

Did posthysterectomy hemorrhage cause woman’s brain damage?

A 42-year-old woman underwent elective subtotal hysterectomy to treat a large uterine fibroid. In the recovery unit, she had extremely low blood pressure and tachycardia and lost consciousness for 15 minutes. She was given a blood transfusion, but was not returned to the operating room for emergency exploratory laparotomy until 3 hours later. Surgery revealed a hemorrhage from the left uterine artery requiring ligation.

PATIENT’S CLAIM:

The hemorrhage caused hypoxia resulting in an anoxic brain injury with memory and concentration difficulties. The gynecologist and hospital staff were negligent in delaying emergency treatment.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE:

Postoperative bleeding is a known complication of hysterectomy. The patient was at increased risk of bleeding because of the numerous blood vessels feeding the fibroid. A morphine reaction is believed to be the cause of her becoming unconscious. The patient had not sustained an anoxic or hypoxic brain damage because she was alert and oriented immediately after the damage allegedly occurred.

VERDICT:

The Illinois jury deadlocked. The parties entered into a settlement agreement for a confidential sum before a mistrial was declared.

Related article:

7 Myomectomy myths debunked

Choriocarcinoma diagnosis missed

A 25-year-old woman had a miscarriage. A follow-up test to measure the patient’s human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) hormone level test was not performed. The patient died from choriocarcinoma.

ESTATE’S CLAIM:

The ObGyn did not follow the standard of care: the patient’s hCG level should have been tested after the miscarriage. It is a well-known fact that an hCG level that does not return to zero after a miscarriage is cause for concern, especially from choriocarcinoma.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE:

There was nothing that could have been done to save the woman’s life; choriocarcinoma is a quickly spreading cancer.

VERDICT:

A $1,800,000 Massachusetts settlement was reached.

Related article:

Manual vacuum aspiration: A safe and effective treatment for early miscarriage

Bowel perforation during hysterectomy: $860,000 verdict

A 58-year-old woman underwent laparoscopic hysterectomy and was discharged the next day although she had not urinated or defecated. After eating solid food that evening, she experienced immediate vomiting, nausea, and abdominal pain. When she saw her ObGyn the next morning, he immediately hospitalized her. During the next 8 days in the hospital, she was unable to pass gas, was febrile, and was given antibiotics. On postoperative day 11, a general surgeon transferred her to the intensive care unit due to shortness of breath and tachycardia. During exploratory abdominal surgery, several abscesses and a 1-cm injury to the rectosigmoid colon were discovered necessitating a colostomy. The patient underwent 5 additional abdominal washout procedures and was hospitalized for 40 days. Colostomy reversal surgery occurred 8 months later.

PATIENT’S CLAIM:

The ObGyn never provided an explanation of what went wrong; the patient was told the hysterectomy was accomplished without incident. An expert colorectal surgeon stated that the perforation likely occurred within 24 hours of surgery and was probably caused by the electromechanical device used during surgery.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE:

The perforation was caused by a sudden rupture of a diverticulum 10 days after hysterectomy. The injury was treated in a timely manner.

VERDICT:

An $860,000 Virginia verdict was returned.

Related article:

How to avoid intestinal and urinary tract injuries during gynecologic laparoscopy

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Did posthysterectomy hemorrhage cause woman’s brain damage?

A 42-year-old woman underwent elective subtotal hysterectomy to treat a large uterine fibroid. In the recovery unit, she had extremely low blood pressure and tachycardia and lost consciousness for 15 minutes. She was given a blood transfusion, but was not returned to the operating room for emergency exploratory laparotomy until 3 hours later. Surgery revealed a hemorrhage from the left uterine artery requiring ligation.

PATIENT’S CLAIM:

The hemorrhage caused hypoxia resulting in an anoxic brain injury with memory and concentration difficulties. The gynecologist and hospital staff were negligent in delaying emergency treatment.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE:

Postoperative bleeding is a known complication of hysterectomy. The patient was at increased risk of bleeding because of the numerous blood vessels feeding the fibroid. A morphine reaction is believed to be the cause of her becoming unconscious. The patient had not sustained an anoxic or hypoxic brain damage because she was alert and oriented immediately after the damage allegedly occurred.

VERDICT:

The Illinois jury deadlocked. The parties entered into a settlement agreement for a confidential sum before a mistrial was declared.

Related article:

7 Myomectomy myths debunked

Choriocarcinoma diagnosis missed

A 25-year-old woman had a miscarriage. A follow-up test to measure the patient’s human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) hormone level test was not performed. The patient died from choriocarcinoma.

ESTATE’S CLAIM:

The ObGyn did not follow the standard of care: the patient’s hCG level should have been tested after the miscarriage. It is a well-known fact that an hCG level that does not return to zero after a miscarriage is cause for concern, especially from choriocarcinoma.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE:

There was nothing that could have been done to save the woman’s life; choriocarcinoma is a quickly spreading cancer.

VERDICT:

A $1,800,000 Massachusetts settlement was reached.

Related article:

Manual vacuum aspiration: A safe and effective treatment for early miscarriage

Bowel perforation during hysterectomy: $860,000 verdict

A 58-year-old woman underwent laparoscopic hysterectomy and was discharged the next day although she had not urinated or defecated. After eating solid food that evening, she experienced immediate vomiting, nausea, and abdominal pain. When she saw her ObGyn the next morning, he immediately hospitalized her. During the next 8 days in the hospital, she was unable to pass gas, was febrile, and was given antibiotics. On postoperative day 11, a general surgeon transferred her to the intensive care unit due to shortness of breath and tachycardia. During exploratory abdominal surgery, several abscesses and a 1-cm injury to the rectosigmoid colon were discovered necessitating a colostomy. The patient underwent 5 additional abdominal washout procedures and was hospitalized for 40 days. Colostomy reversal surgery occurred 8 months later.

PATIENT’S CLAIM:

The ObGyn never provided an explanation of what went wrong; the patient was told the hysterectomy was accomplished without incident. An expert colorectal surgeon stated that the perforation likely occurred within 24 hours of surgery and was probably caused by the electromechanical device used during surgery.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE:

The perforation was caused by a sudden rupture of a diverticulum 10 days after hysterectomy. The injury was treated in a timely manner.

VERDICT:

An $860,000 Virginia verdict was returned.

Related article:

How to avoid intestinal and urinary tract injuries during gynecologic laparoscopy

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Did posthysterectomy hemorrhage cause woman’s brain damage?

A 42-year-old woman underwent elective subtotal hysterectomy to treat a large uterine fibroid. In the recovery unit, she had extremely low blood pressure and tachycardia and lost consciousness for 15 minutes. She was given a blood transfusion, but was not returned to the operating room for emergency exploratory laparotomy until 3 hours later. Surgery revealed a hemorrhage from the left uterine artery requiring ligation.

PATIENT’S CLAIM:

The hemorrhage caused hypoxia resulting in an anoxic brain injury with memory and concentration difficulties. The gynecologist and hospital staff were negligent in delaying emergency treatment.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE:

Postoperative bleeding is a known complication of hysterectomy. The patient was at increased risk of bleeding because of the numerous blood vessels feeding the fibroid. A morphine reaction is believed to be the cause of her becoming unconscious. The patient had not sustained an anoxic or hypoxic brain damage because she was alert and oriented immediately after the damage allegedly occurred.

VERDICT:

The Illinois jury deadlocked. The parties entered into a settlement agreement for a confidential sum before a mistrial was declared.

Related article:

7 Myomectomy myths debunked

Choriocarcinoma diagnosis missed

A 25-year-old woman had a miscarriage. A follow-up test to measure the patient’s human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) hormone level test was not performed. The patient died from choriocarcinoma.

ESTATE’S CLAIM:

The ObGyn did not follow the standard of care: the patient’s hCG level should have been tested after the miscarriage. It is a well-known fact that an hCG level that does not return to zero after a miscarriage is cause for concern, especially from choriocarcinoma.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE:

There was nothing that could have been done to save the woman’s life; choriocarcinoma is a quickly spreading cancer.

VERDICT:

A $1,800,000 Massachusetts settlement was reached.

Related article:

Manual vacuum aspiration: A safe and effective treatment for early miscarriage

Bowel perforation during hysterectomy: $860,000 verdict

A 58-year-old woman underwent laparoscopic hysterectomy and was discharged the next day although she had not urinated or defecated. After eating solid food that evening, she experienced immediate vomiting, nausea, and abdominal pain. When she saw her ObGyn the next morning, he immediately hospitalized her. During the next 8 days in the hospital, she was unable to pass gas, was febrile, and was given antibiotics. On postoperative day 11, a general surgeon transferred her to the intensive care unit due to shortness of breath and tachycardia. During exploratory abdominal surgery, several abscesses and a 1-cm injury to the rectosigmoid colon were discovered necessitating a colostomy. The patient underwent 5 additional abdominal washout procedures and was hospitalized for 40 days. Colostomy reversal surgery occurred 8 months later.

PATIENT’S CLAIM:

The ObGyn never provided an explanation of what went wrong; the patient was told the hysterectomy was accomplished without incident. An expert colorectal surgeon stated that the perforation likely occurred within 24 hours of surgery and was probably caused by the electromechanical device used during surgery.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE:

The perforation was caused by a sudden rupture of a diverticulum 10 days after hysterectomy. The injury was treated in a timely manner.

VERDICT:

An $860,000 Virginia verdict was returned.

Related article:

How to avoid intestinal and urinary tract injuries during gynecologic laparoscopy

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

What is your liability for involuntary commitment based on faulty information?

Dear Dr. Mossman,

Last week, I hospitalized a patient against her will, based in part on what her family members told me she had threatened to do. The patient threatened to sue me and said I should have known that her relatives were lying. What if my patient is right? Could I face liability if I involuntarily hospitalized her based on bad collateral information?

Submitted by “Dr. R”

In all U.S. states, laws permit psychiatrists to involuntarily hospitalize persons who pose a danger to themselves or others because of mental illness.1 But taking this step can be tough. Deciding to hospitalize a patient against her will involves weighing her wants and freedom against your duty to look out for her long-term welfare and the community’s safety.2,3 Often, psychiatrists make these decisions under pressure because the family wants something done immediately, other patients also need attention, the clinical picture is incomplete, or potential dispositions (eg, crisis care and inpatient beds) are limited.3 Given such constraints, you can’t always make perfect decisions.

Dr. R’s question has 2 parts:

- What liabilities can a clinician face if a patient is wrongfully committed?

- What liabilities could arise from relying on inaccurate information or making a false petition in order to hospitalize a patient?

We hope that as you and Dr. R read our answers, you’ll have a clearer understanding of:

- the rationale for civil commitment

- how patients, doctors, and courts view civil commitment

- the role of collateral information in decision-making

- relevant legal concepts and case law.

Rationale for civil commitment

For centuries, society has used civil commitment as one of its legal methods for intervening when persons pose a danger to themselves or others because of their mental illness.4 Because incapacitation or death could result from a “false-negative” decision to release a dangerous patient, psychiatrists err on the side of caution and tolerate many “false-positive” hospitalizations of persons who wouldn’t have hurt anyone.5

We can never know if a patient would have done harm had she not been hospitalized. Measures of suicidality and hostility tend to subside during involuntary hospital treatment.6 After hospitalization, many patients cite protection from harm as a reason they are thankful for their treatment.7-9 Some involuntary inpatients want to be hospitalized but hide this for conscious or unconscious reasons,10,11 and involuntary treatment sometimes is the only way to help persons whose illness-induced anosognosia12 prevents them from understanding why they need treatment.13 Involuntary inpatient care leads to modest symptom reduction14,15 and produces treatment outcomes no worse than those of non-coerced patients.10

Patients’ views

Patients often view commitment as unjustified.16 They and their advocates object to what some view as the ultimate infringement on civil liberty.7,17 By its nature, involuntary commitment eliminates patients’ involvement in a major treatment decision,8 disempowers them,18 and influences their relationship with the treatment team.15

Some involuntary patients feel disrespected by staff members8 or experience inadvertent psychological harm, including “loss of self-esteem, identity, self-control, and self-efficacy, as well as diminished hope in the possibility of recovery.”15 Involuntary hospitalization also can have serious practical consequences. Commitment can lead to social stigma, loss of gun rights, increased risks of losing child custody, housing problems, and possible disqualification from some professions.19

Having seen many involuntary patients undergo a change of heart after treatment, psychiatrist Alan Stone proposed the “Thank You Theory” of civil commitment: involuntary hospitalization can be justified by showing that the patient is grateful after recovering.20 Studies show, however, that gratitude is far from universal.1

How coercion is experienced often depends on how it is communicated. The less coercion patients perceive, the better they feel about the treatment they received.21 Satisfaction is important because it leads to less compulsory readmission,22 and dissatisfaction makes malpractice lawsuits more likely.23

Commitment decision-making

States’ laws, judges’ attitudes, and court decisions establish each jurisdiction’s legal methods for instituting emergency holds and willingness to tolerate “false-positive” involuntary hospitalization,4,24 all of which create variation between and within states in how civil commitment laws are applied. As a result, clinicians’ decisions are influenced “by a range of social, political, and economic factors,”25 including patients’ sex, race, age, homelessness, employment status, living situation, diagnoses, previous involuntary treatment, and dissatisfaction with mental health treatment.22,26-32 Furthermore, the potential for coercion often blurs the line between an offer of voluntary admission and an involuntary hospitalization.18

Collateral information

Psychiatrists owe each patient a sound clinical assessment before deciding to initiate involuntarily hospitalization. During a psychiatric crisis, a patient might not be forthcoming or could have impaired memory or judgment. Information from friends or family can help fill in gaps in a patient’s self-report.33 As Dr. R’s question illustrates, adequate assessment often includes seeking information from persons familiar with the patient.1 A report on the Virginia Tech shootings by the Virginia Office of the Inspector General describes how collateral sources can provide otherwise missing evidence of dangerousness,34 and it often leads clinicians toward favoring admission.35

Yet clinicians should regard third-party reports with caution.36 As one attorney warns, “Psychiatrists should be cautious of the underlying motives of well-meaning family members and relatives.”37 If you make a decision to hospitalize a patient involuntarily based on collateral information that turns out to be flawed, are you at fault and potentially liable for harm to the patient?

False petitions and liability

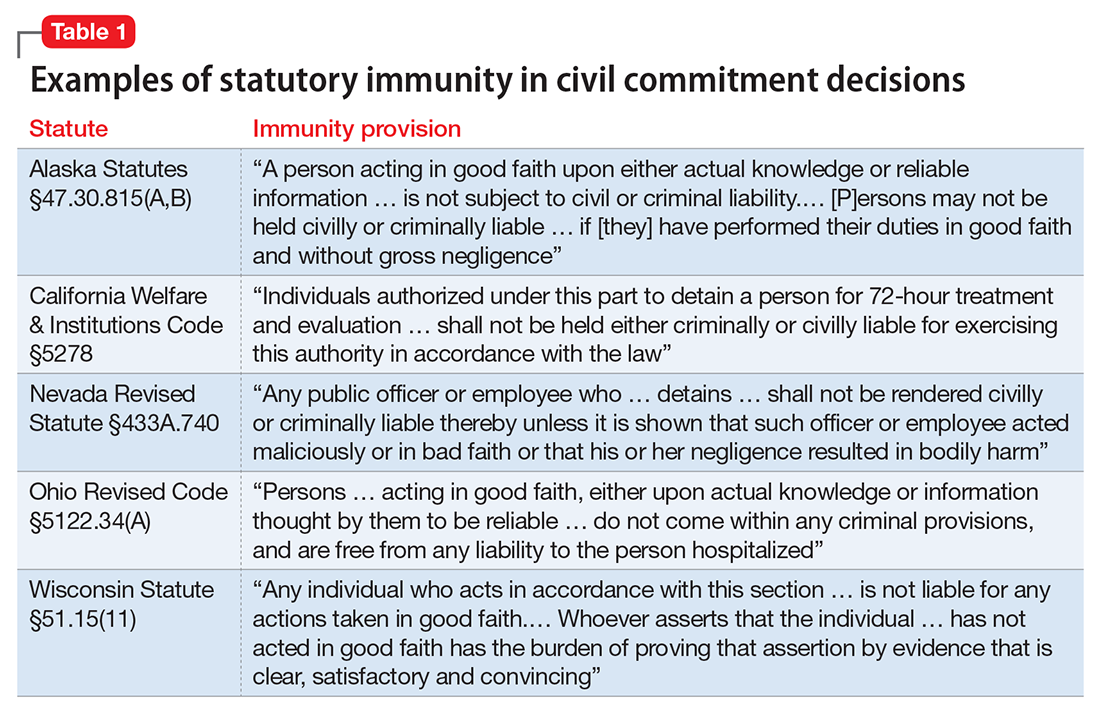

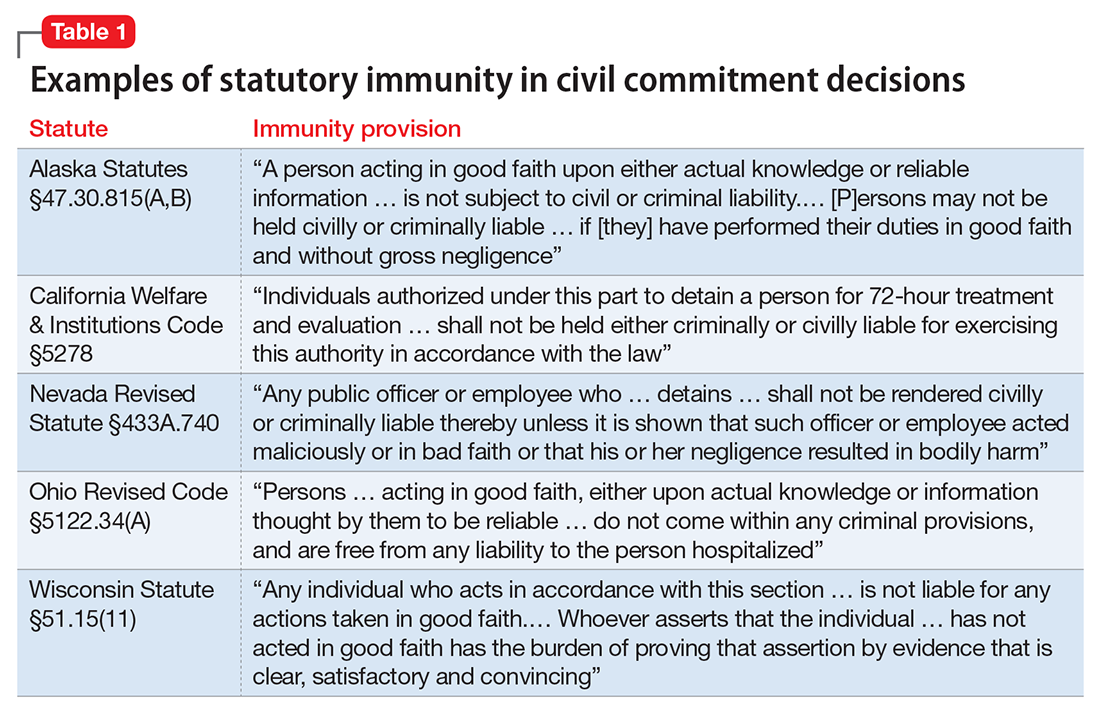

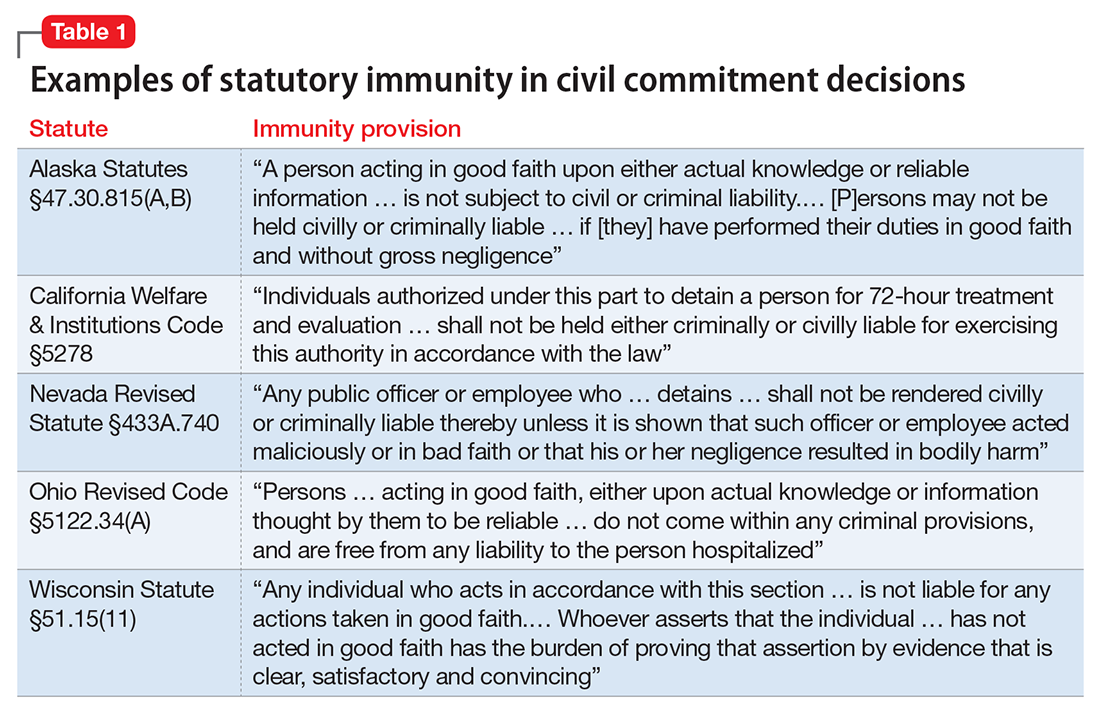

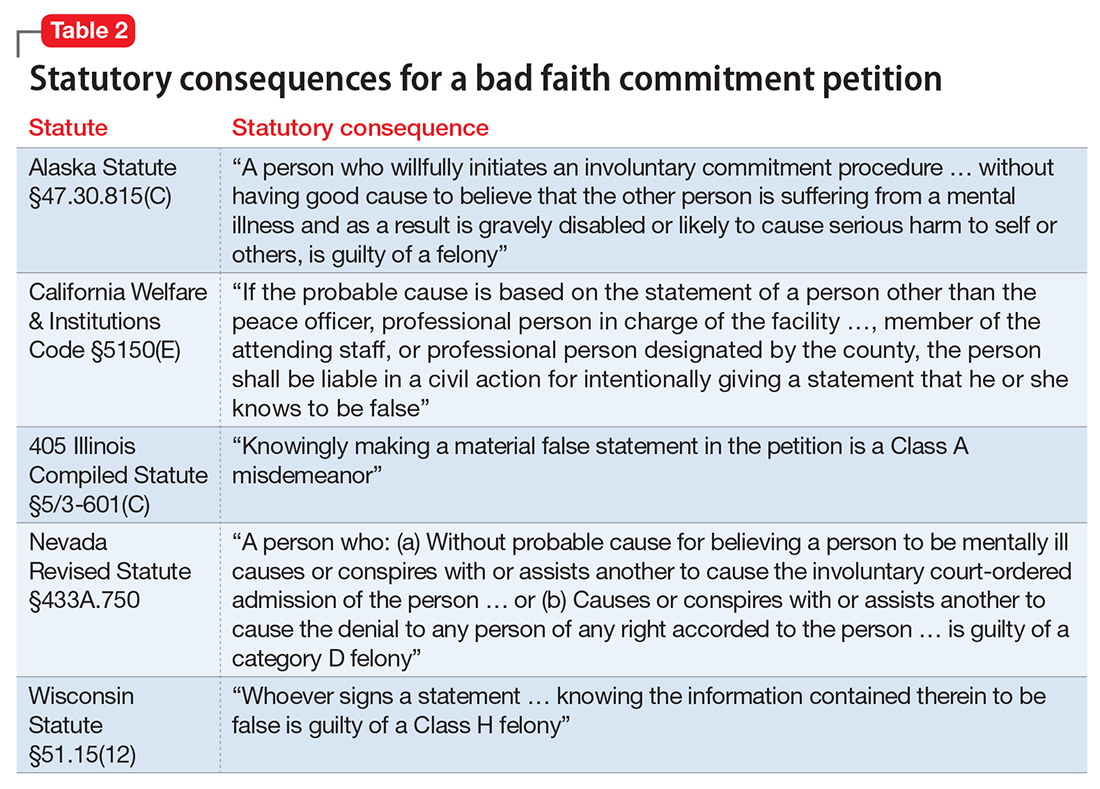

If you’re in a situation similar to the one Dr. R describes, you can take solace in knowing that courts generally provide immunity to a psychiatrist who makes a reasonable, well-intentioned decision to commit someone. The degree of immunity offered varies by jurisdiction. Table 1 provides examples of immunity language from several states’ statutes.

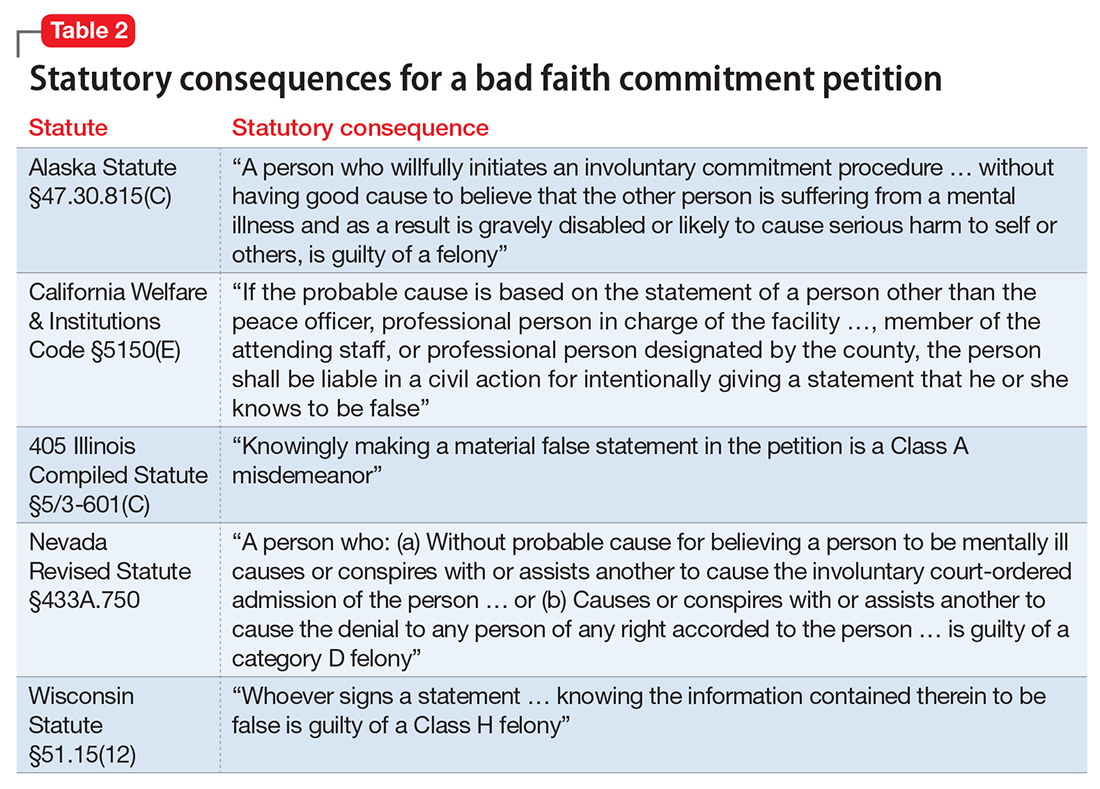

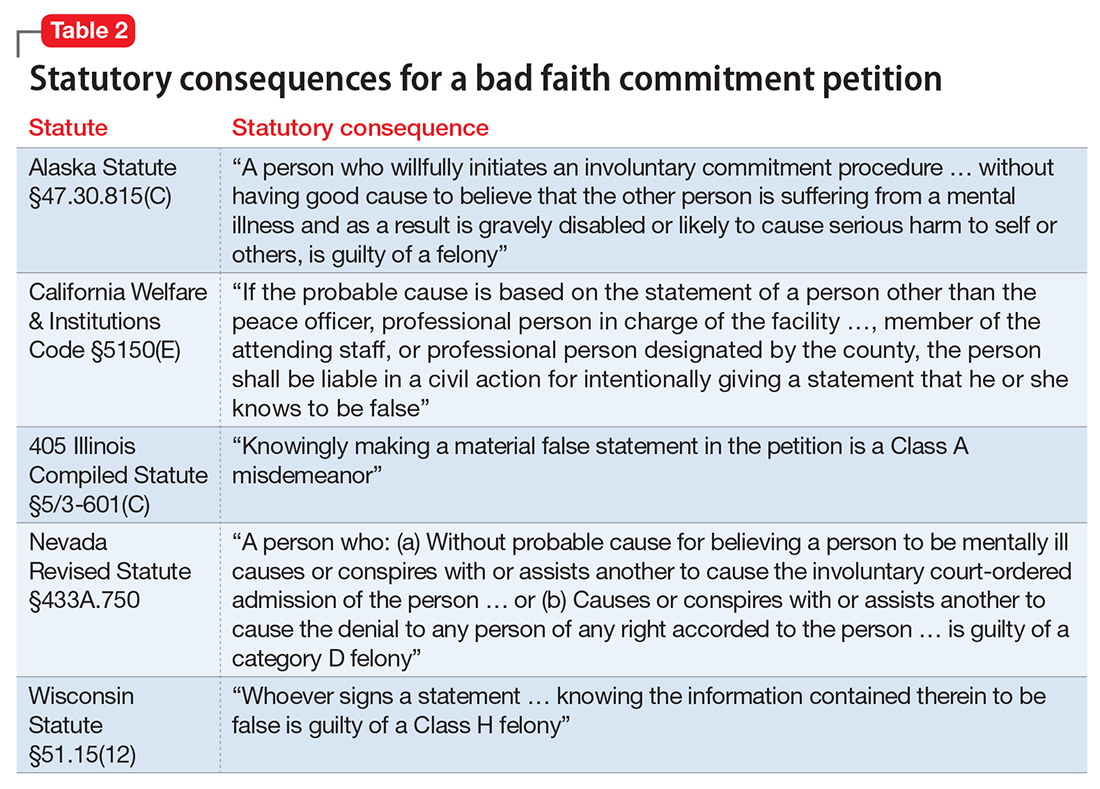

Many states’ statutes also lay out the potential consequences if a psychiatrist takes action to involuntarily hospitalize someone in bad faith or with malicious intent. In some jurisdictions, such actions can lead to criminal sanctions against the doctor or against the party who made a false petition (eg, a devious family member) (Table 2). Commenting on Texas’s statute, attorney Jeffrey Anderson explains, “The touchstone for causes of action based upon a wrongful civil commitment require that the psychiatrist[’s] conduct be found to be unreasonable and negligent. [Immunity…] still requires that a psychiatrist[’s] diagnosis of a patient[’s] threat to harm himself or others be a reasonable and prudent one.”37

The immunity extended through such statutes usually is limited to claims arising directly from the detention. For example, in the California case of Jacobs v Grossmont Hospital, a patient under a 72-hour hold fell and fractured her leg, and she sought damages. The trial court dismissed the suit under the immunity statute applicable to commitment decisions, but the appellate court held that “the immunity did not extend to other negligent acts.… The trial court erred in assuming that … the hospital was exempt from all liability for any negligence that occurred during the lawful hold.”38

Bingham v Cedars-Sinai Health Systems illustrates how physicians can lose immunity.39 A nurse contacted her supervisor to report a colleague who had stolen narcotics from work and compromised patient care. In response, the supervisor, hospital, and several physicians agreed to have her involuntarily committed. Later, it was confirmed that the colleague had taken the narcotics. She later sued the hospital system, claiming—in addition to malpractice—retaliation, invasion of privacy, assault and battery, false imprisonment, defamation, intentional infliction of emotional distress, disability-based harassment, and violation of her civil rights. Citing California’s immunity statute, the trial court granted summary judgment to the clinicians and hospital system. On appeal, however, the appellate court reversed the judgment, holding that the defendants had not shown that “the decision to detain Bingham was based on probable cause, a prerequisite to the exemption from liability,” and that Bingham had some legitimate grounds for her lawsuit.

A key point for Dr. R to consider is that, although some states provide immunity if the psychiatrist’s admitting decision was based on an evaluation “performed in good faith,”40 other states’ immunity provisions apply only if the psychiatrist had probable cause to make a decision to detain.41

Ways to reduce liability risk

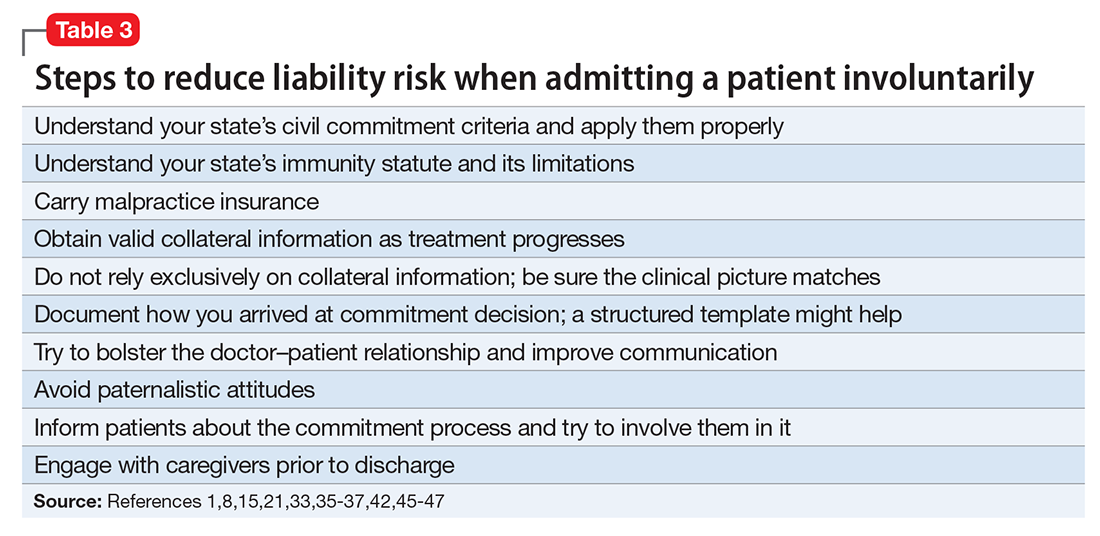

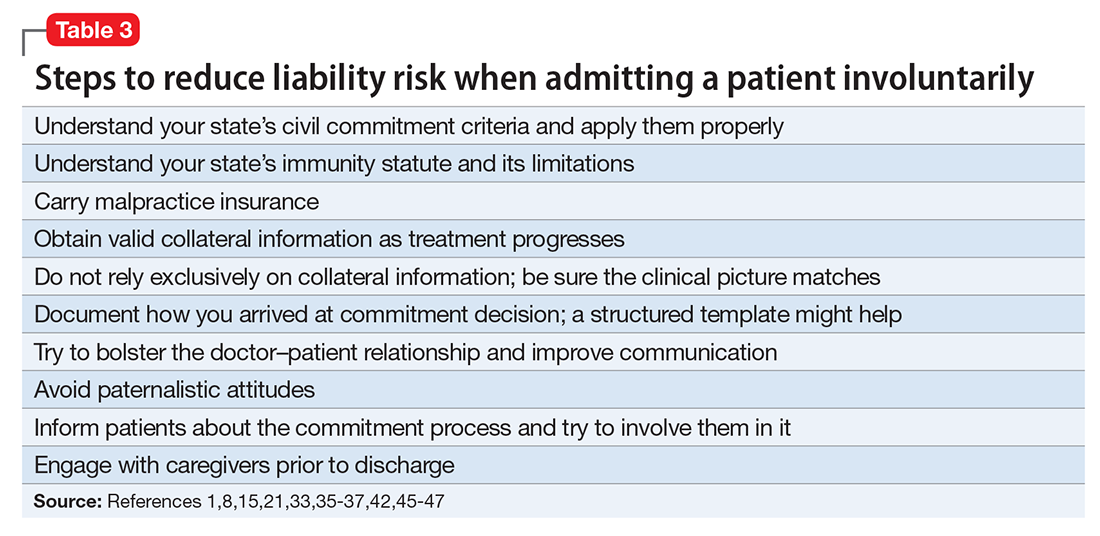

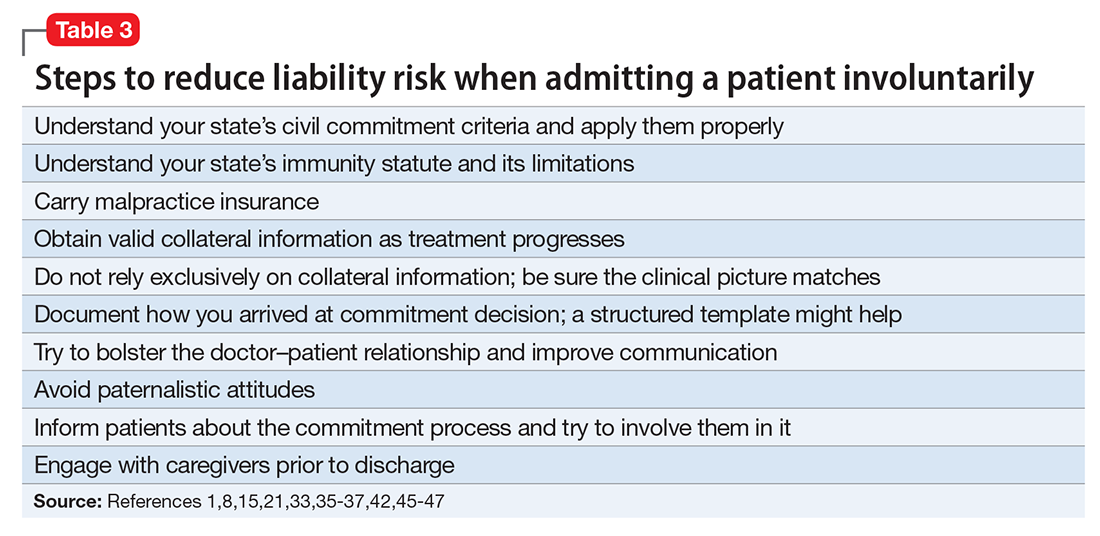

Although an involuntary hospitalization could have an uncertain basis, psychiatrists can reduce the risk of legal liability for their decisions. Good documentation is important. Admitting psychiatrists usually make sound decisions, but the corresponding documentation frequently lacks clinical justification.42-44 As the rate of appropriate documentation of admission decision-making improves, the rate of commitment falls,44 and patients’ legal rights enjoy greater protection.43 Poor communication can decrease the quality of care and increase the risk of a malpractice lawsuit.45 This is just one of many reasons why you should explain your reasons for involuntary hospitalization and inform patients of the procedures for judicial review.8,9 Table 3 summarizes other steps to reduce liability risk when committing patients to the hospital.1,8,15,21,33,35-37,42,45-47

1. Pinals DA, Mossman D. Evaluation for civil commitment: best practices for forensic mental health assessments. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2011.

2. Testa M, West SG. Civil commitment in the United States. Psychiatry (Edgemont). 2010;7(10):30-40.

3. Hedman LC, Petrila J, Fisher WH, et al. State laws on emergency holds for mental health stabilization. Psychiatr Serv. 2016;67(5):529-535.

4. Groendyk Z. “It takes a lot to get into Bellevue”: a pro-rights critique of New York’s involuntary commitment law. Fordham Urban Law J. 2013;40(1):548-585.

5. Brooks RA. U.S. psychiatrists’ beliefs and wants about involuntary civil commitment grounds. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2006;29(1):13-21.

6. Giacco D, Priebe S. Suicidality and hostility following involuntary hospital treatment. PLoS One. 2016;11(5):e0154458. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154458.

7. Wyder M, Bland R, Herriot A, et al. The experiences of the legal processes of involuntary treatment orders: tension between the legal and medical frameworks. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2015;38:44-50.

8. Valenti E, Giacco D, Katasakou C, et al. Which values are important for patients during involuntary treatment? A qualitative study with psychiatric inpatients. J Med Ethics. 2014;40(12):832-836.

9. Katsakou C, Rose D, Amos T, et al. Psychiatric patients’ views on why their involuntary hospitalisation was right or wrong: a qualitative study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012;42(7):1169-1179.

10. Kaltiala-Heino R, Laippala P, Salokangas RK. Impact of coercion on treatment outcome. Int J Law Psychiatry. 1997;20(3):311-322.

11. Hoge SK, Lidz CW, Eisenberg M, et al. Perceptions of coercion in the admission of voluntary and involuntary psychiatric patients. Int J Law Psychiatry. 1997;20(2):167-181.

12. Lehrer DS, Lorenz J. Anosognosia in schizophrenia: hidden in plain sight. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2014;11(5-6):10-17. 13. Gordon S. The danger zone: how the dangerousness standard in civil commitment proceedings harms people with serious mental illness. Case Western Reserve Law Review. 2016;66(3):657-700.

14. Kallert TW, Katsakou C, Adamowski T, et al. Coerced hospital admission and symptom change—a prospective observational multi-centre study. PLoS One. 2011;6(11):e28191. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028191.

15. Danzer G, Wilkus-Stone A. The give and take of freedom: the role of involuntary hospitalization and treatment in recovery from mental illness. Bull Menninger Clin. 2015;79(3):255-280.

16. Roe D, Weishut DJ, Jaglom M, et al. Patients’ and staff members’ attitudes about the rights of hospitalized psychiatric patients. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53(1):87-91.

17. Amidov T. Involuntary commitment is unnecessary and discriminatory. In: Berlatsky N, ed. Mental illness. Farmington Hills, MI: Greenhaven Press; 2016;140-145.

18. Monahan J, Hoge SK, Lidz C, et al. Coercion and commitment: understanding involuntary mental hospital admission. Int J Law Psychiatry. 1995;18(3):249-263.

19. Guest Pryal KR. Heller’s scapegoats. North Carolina Law Review. 2015;93(5):1439-1473.

20. Stone AA. Mental health and law: a system in transition. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1975:75-176.

21. Katsakou C, Bowers L, Amos T, et al. Coercion and treatment satisfaction among involuntary patients. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61(3):286-292.

22. Setkowski K, van der Post LF, Peen J, et al. Changing patient perspectives after compulsory admission and the risk of re-admission during 5 years of follow-up: the Amsterdam study of acute psychiatry IX. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2016;62(6):578-588.

23. Stelfox HT, Gandhi TK, Orav EJ, et al. The relation of patient satisfaction with complaints against physicians and malpractice lawsuits. Am J Med. 2005;118(10):1126-1133.

24. Goldman A. Continued overreliance on involuntary commitment: the need for a less restrictive alternative. J Leg Med. 2015;36(2):233-251.

25. Fisher WH, Grisso T. Commentary: civil commitment statutes—40 years of circumvention. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2010;38(3):365-368.

26. Curley A, Agada E, Emechebe A, et al. Exploring and explaining involuntary care: the relationship between psychiatric admission status, gender and other demographic and clinical variables. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2016;47:53-59.