User login

Children and COVID-19: Decline in new cases may be leveling off

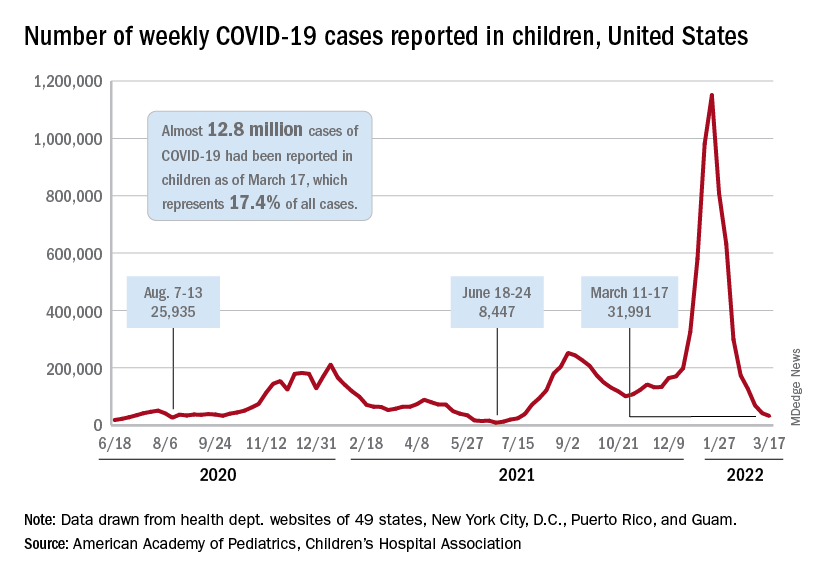

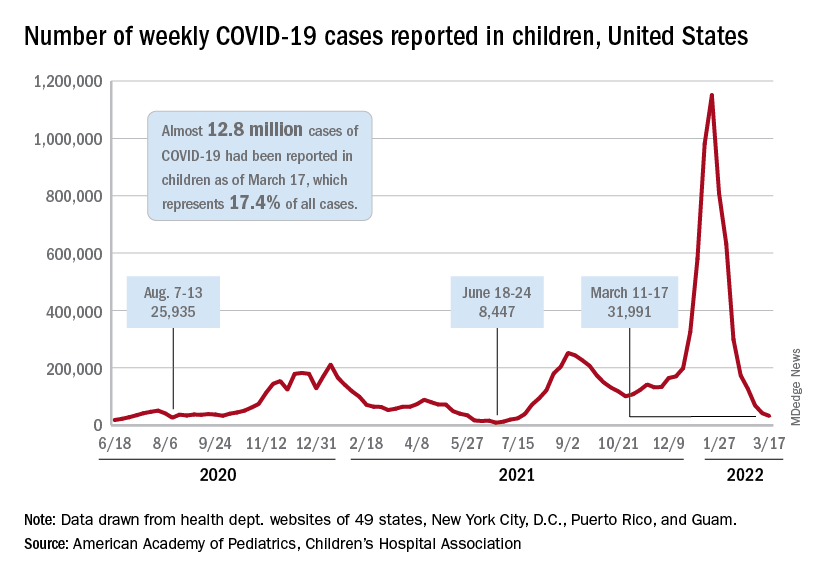

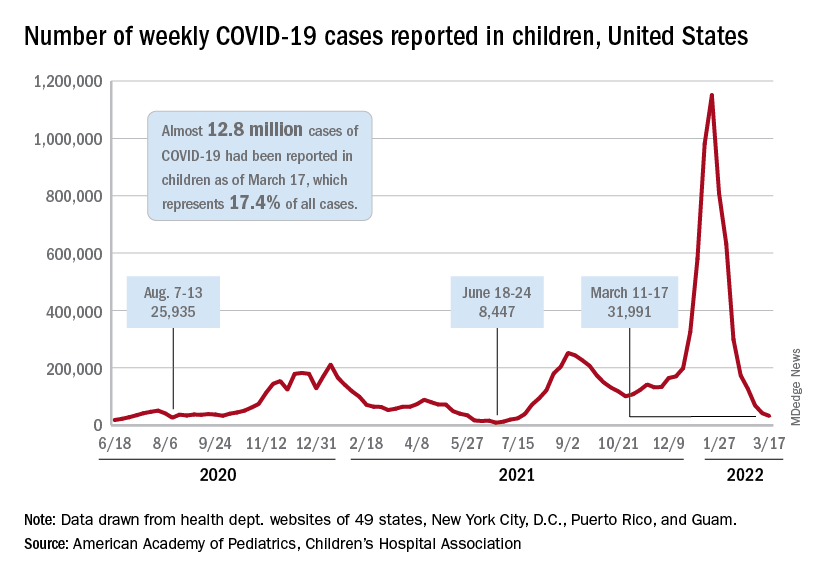

Even as a number of states see increases in new COVID-19 cases among all ages, the trend remains downward for children, albeit at a slower pace than in recent weeks, based on data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

New pediatric cases in the United States totaled 27,521 for the most recent week, March 25-31, down by 5.2% from the previous week. Earlier weekly declines, going backward through March and into late February, were 9.3%, 23%, 39.5%, and 46%, according to data collected by the AAP and CHA from state and territorial health agencies. The lowest weekly total recorded since the initial wave in 2020 was just under 8,500 during the week of June 18-24, 2021.

Reported COVID-19 cases in children now total over 12.8 million since the beginning of the pandemic in March 2020, and those infections represent 19.0% of all cases. That share of new cases has not increased in the last 7 weeks, the AAP and CHA noted in their weekly COVID report, suggesting that children have not been bearing a disproportionate share of the declining Omicron burden.

As for Omicron, the BA.2 subvariant now makes up about 55% of COVID-19 infections, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said in its COVID Data Tracker Weekly Review, and New York, Massachusetts, and New Jersey are among the states reporting BA.2-driven increases in new cases of as much as 30%, the New York Times said.

Rates of new cases for the latest week available (March 27 to April 2) and at their Omicron peaks in January were 11.3 per 100,000 and 1,011 per 100,000 (ages 0-4 years), 12.5 and 1,505 per 100,000 (5-11 years), 12.7 and 1,779 per 100,000 (12-15 years), and 13.1 and 1,982 per 100,000 (16-17 years), the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

Hospitalization rates, however, were a bit of a mixed bag. The last 2 weeks (March 13-19 and March 20-26) of data available from the CDC’s COVID-NET show that hospitalizations were up slightly in children aged 0-4 years (1.3 per 100,000 to 1.4 per 100,000), down for 5- to 11-year-olds (0.6 to 0.2), and steady for those aged 12-17 (0.4 to 0.4). COVID-NET collects data from nearly 100 counties in 10 states and from a separate four-state network.

Vaccinations got a small boost in the last week, the first one since early February. Initial doses and completions climbed slightly in the 12- to 17-year-olds, while just first doses were up a bit among the 5- to 11-year-olds during the week of March 24-30, compared with the previous week, although both groups are still well below the highest counts recorded so far in 2022, which are, in turn, far short of 2021’s peaks, according to CDC data analyzed by the AAP.

Even as a number of states see increases in new COVID-19 cases among all ages, the trend remains downward for children, albeit at a slower pace than in recent weeks, based on data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

New pediatric cases in the United States totaled 27,521 for the most recent week, March 25-31, down by 5.2% from the previous week. Earlier weekly declines, going backward through March and into late February, were 9.3%, 23%, 39.5%, and 46%, according to data collected by the AAP and CHA from state and territorial health agencies. The lowest weekly total recorded since the initial wave in 2020 was just under 8,500 during the week of June 18-24, 2021.

Reported COVID-19 cases in children now total over 12.8 million since the beginning of the pandemic in March 2020, and those infections represent 19.0% of all cases. That share of new cases has not increased in the last 7 weeks, the AAP and CHA noted in their weekly COVID report, suggesting that children have not been bearing a disproportionate share of the declining Omicron burden.

As for Omicron, the BA.2 subvariant now makes up about 55% of COVID-19 infections, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said in its COVID Data Tracker Weekly Review, and New York, Massachusetts, and New Jersey are among the states reporting BA.2-driven increases in new cases of as much as 30%, the New York Times said.

Rates of new cases for the latest week available (March 27 to April 2) and at their Omicron peaks in January were 11.3 per 100,000 and 1,011 per 100,000 (ages 0-4 years), 12.5 and 1,505 per 100,000 (5-11 years), 12.7 and 1,779 per 100,000 (12-15 years), and 13.1 and 1,982 per 100,000 (16-17 years), the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

Hospitalization rates, however, were a bit of a mixed bag. The last 2 weeks (March 13-19 and March 20-26) of data available from the CDC’s COVID-NET show that hospitalizations were up slightly in children aged 0-4 years (1.3 per 100,000 to 1.4 per 100,000), down for 5- to 11-year-olds (0.6 to 0.2), and steady for those aged 12-17 (0.4 to 0.4). COVID-NET collects data from nearly 100 counties in 10 states and from a separate four-state network.

Vaccinations got a small boost in the last week, the first one since early February. Initial doses and completions climbed slightly in the 12- to 17-year-olds, while just first doses were up a bit among the 5- to 11-year-olds during the week of March 24-30, compared with the previous week, although both groups are still well below the highest counts recorded so far in 2022, which are, in turn, far short of 2021’s peaks, according to CDC data analyzed by the AAP.

Even as a number of states see increases in new COVID-19 cases among all ages, the trend remains downward for children, albeit at a slower pace than in recent weeks, based on data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

New pediatric cases in the United States totaled 27,521 for the most recent week, March 25-31, down by 5.2% from the previous week. Earlier weekly declines, going backward through March and into late February, were 9.3%, 23%, 39.5%, and 46%, according to data collected by the AAP and CHA from state and territorial health agencies. The lowest weekly total recorded since the initial wave in 2020 was just under 8,500 during the week of June 18-24, 2021.

Reported COVID-19 cases in children now total over 12.8 million since the beginning of the pandemic in March 2020, and those infections represent 19.0% of all cases. That share of new cases has not increased in the last 7 weeks, the AAP and CHA noted in their weekly COVID report, suggesting that children have not been bearing a disproportionate share of the declining Omicron burden.

As for Omicron, the BA.2 subvariant now makes up about 55% of COVID-19 infections, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said in its COVID Data Tracker Weekly Review, and New York, Massachusetts, and New Jersey are among the states reporting BA.2-driven increases in new cases of as much as 30%, the New York Times said.

Rates of new cases for the latest week available (March 27 to April 2) and at their Omicron peaks in January were 11.3 per 100,000 and 1,011 per 100,000 (ages 0-4 years), 12.5 and 1,505 per 100,000 (5-11 years), 12.7 and 1,779 per 100,000 (12-15 years), and 13.1 and 1,982 per 100,000 (16-17 years), the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

Hospitalization rates, however, were a bit of a mixed bag. The last 2 weeks (March 13-19 and March 20-26) of data available from the CDC’s COVID-NET show that hospitalizations were up slightly in children aged 0-4 years (1.3 per 100,000 to 1.4 per 100,000), down for 5- to 11-year-olds (0.6 to 0.2), and steady for those aged 12-17 (0.4 to 0.4). COVID-NET collects data from nearly 100 counties in 10 states and from a separate four-state network.

Vaccinations got a small boost in the last week, the first one since early February. Initial doses and completions climbed slightly in the 12- to 17-year-olds, while just first doses were up a bit among the 5- to 11-year-olds during the week of March 24-30, compared with the previous week, although both groups are still well below the highest counts recorded so far in 2022, which are, in turn, far short of 2021’s peaks, according to CDC data analyzed by the AAP.

CDC recommends hep B vaccination for most adults

It also added that adults aged 60 years or older without known risk factors for hepatitis B may get vaccinated.

The agency earlier recommended the vaccination for all infants and children under the age of 19 years and for adults aged 60 years or older with known risk factors.

The CDC said it wants to expand vaccinations because, after decades of progress, the number of new hepatitis B infections is increasing among adults. Acute hepatitis B infections among adults lead to chronic hepatitis B disease in an estimated 2%-6% of cases, and can result in cirrhosis, liver cancer, and death.

Among adults aged 40-49 years, the rate of cases increased from 1.9 per 100,000 people in 2011 to 2.7 per 100,000 in 2019. Among adults aged 50-59 years, the rate increased during this period from 1.1 to 1.6 per 100,000.

Most adults aren’t vaccinated. Among adults aged 19 years or older, only 30.0% reported that they’d received at least the three recommended doses of the vaccine. The rate was 40.3% for adults aged 19-49 years, and 19.1% for adults aged 50 years or older.

Hepatitis B infection rates are particularly elevated among African Americans.

Even among adults with chronic liver disease, the vaccination rate is only 33.0%. And, among travelers to countries where the virus has been endemic since 1995, only 38.9% were vaccinated.

In a 2018 survey of internal medicine and family physicians, 68% said their patients had not told them about risk factors, making it difficult to assess whether the patients needed the vaccine according to the recommendations at the time. These risk factors include injection drug use, incarceration, and multiple sex partners, experiences the patients may not have been willing to discuss.

CDC researchers calculated that universal adult hepatitis B vaccination would cost $153,000 for every quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained. For adults aged 19-59 years, a QALY would cost $117,000 because infections are more prevalent in that age group.

The CDC specified that it intends its new guidelines to prompt physicians to offer the vaccine to adults aged 60 years or older rather than wait for them to request it.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved both three-dose and two-dose hepatitis B vaccines, with evidence showing similar seroprotection and adverse events.

People who have already completed their vaccination or have a history of hepatitis B infection should only receive additional vaccinations in specific cases, as detailed in the CDC’s 2018 recommendations.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It also added that adults aged 60 years or older without known risk factors for hepatitis B may get vaccinated.

The agency earlier recommended the vaccination for all infants and children under the age of 19 years and for adults aged 60 years or older with known risk factors.

The CDC said it wants to expand vaccinations because, after decades of progress, the number of new hepatitis B infections is increasing among adults. Acute hepatitis B infections among adults lead to chronic hepatitis B disease in an estimated 2%-6% of cases, and can result in cirrhosis, liver cancer, and death.

Among adults aged 40-49 years, the rate of cases increased from 1.9 per 100,000 people in 2011 to 2.7 per 100,000 in 2019. Among adults aged 50-59 years, the rate increased during this period from 1.1 to 1.6 per 100,000.

Most adults aren’t vaccinated. Among adults aged 19 years or older, only 30.0% reported that they’d received at least the three recommended doses of the vaccine. The rate was 40.3% for adults aged 19-49 years, and 19.1% for adults aged 50 years or older.

Hepatitis B infection rates are particularly elevated among African Americans.

Even among adults with chronic liver disease, the vaccination rate is only 33.0%. And, among travelers to countries where the virus has been endemic since 1995, only 38.9% were vaccinated.

In a 2018 survey of internal medicine and family physicians, 68% said their patients had not told them about risk factors, making it difficult to assess whether the patients needed the vaccine according to the recommendations at the time. These risk factors include injection drug use, incarceration, and multiple sex partners, experiences the patients may not have been willing to discuss.

CDC researchers calculated that universal adult hepatitis B vaccination would cost $153,000 for every quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained. For adults aged 19-59 years, a QALY would cost $117,000 because infections are more prevalent in that age group.

The CDC specified that it intends its new guidelines to prompt physicians to offer the vaccine to adults aged 60 years or older rather than wait for them to request it.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved both three-dose and two-dose hepatitis B vaccines, with evidence showing similar seroprotection and adverse events.

People who have already completed their vaccination or have a history of hepatitis B infection should only receive additional vaccinations in specific cases, as detailed in the CDC’s 2018 recommendations.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It also added that adults aged 60 years or older without known risk factors for hepatitis B may get vaccinated.

The agency earlier recommended the vaccination for all infants and children under the age of 19 years and for adults aged 60 years or older with known risk factors.

The CDC said it wants to expand vaccinations because, after decades of progress, the number of new hepatitis B infections is increasing among adults. Acute hepatitis B infections among adults lead to chronic hepatitis B disease in an estimated 2%-6% of cases, and can result in cirrhosis, liver cancer, and death.

Among adults aged 40-49 years, the rate of cases increased from 1.9 per 100,000 people in 2011 to 2.7 per 100,000 in 2019. Among adults aged 50-59 years, the rate increased during this period from 1.1 to 1.6 per 100,000.

Most adults aren’t vaccinated. Among adults aged 19 years or older, only 30.0% reported that they’d received at least the three recommended doses of the vaccine. The rate was 40.3% for adults aged 19-49 years, and 19.1% for adults aged 50 years or older.

Hepatitis B infection rates are particularly elevated among African Americans.

Even among adults with chronic liver disease, the vaccination rate is only 33.0%. And, among travelers to countries where the virus has been endemic since 1995, only 38.9% were vaccinated.

In a 2018 survey of internal medicine and family physicians, 68% said their patients had not told them about risk factors, making it difficult to assess whether the patients needed the vaccine according to the recommendations at the time. These risk factors include injection drug use, incarceration, and multiple sex partners, experiences the patients may not have been willing to discuss.

CDC researchers calculated that universal adult hepatitis B vaccination would cost $153,000 for every quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained. For adults aged 19-59 years, a QALY would cost $117,000 because infections are more prevalent in that age group.

The CDC specified that it intends its new guidelines to prompt physicians to offer the vaccine to adults aged 60 years or older rather than wait for them to request it.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved both three-dose and two-dose hepatitis B vaccines, with evidence showing similar seroprotection and adverse events.

People who have already completed their vaccination or have a history of hepatitis B infection should only receive additional vaccinations in specific cases, as detailed in the CDC’s 2018 recommendations.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE MMWR

Children and COVID: The long goodbye continues

COVID-19 continues to be a diminishing issue for U.S. children, as the number of new cases declined for the ninth consecutive week, based on data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report. The most recently infected children brought the total number of COVID-19 cases to just over 12.8 million since the pandemic began.

Other measures of COVID occurrence in children, such as hospital admissions and emergency department visits, also followed recent downward trends, although the sizes of the declines are beginning to decrease. Admissions dropped by 13.3% during the week ending March 26, but that followed declines of 25%, 20%, 26.5% and 24.4% for the 4 previous weeks, data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show.

The slowdown in ED visits started a couple of weeks earlier, but the decline is still ongoing. As of March 25, ED visits with a confirmed COVID diagnosis represented just 0.4% of all visits for children aged 0-11 years, down from 1.1% on Feb. 25 and a peak of 14.3% on Jan. 15. For children aged 12-15, the latest figure is just 0.2%, compared with 0.5% on Feb. 25 and a peak of 14.3% on Jan. 9, the CDC reported on its COVID Data Tracker.

Although he was speaking of the nation as a whole and not specifically of children, Anthony Fauci, MD, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, recently told the Washington Post that, “unless something changes dramatically,” another major surge isn’t on the horizon.

That sentiment, however, was not entirely shared by Moderna’s chief medical officer, Paul Burton, MD, PhD. In an interview with WebMD, he said that another COVID wave is inevitable and that it’s too soon to dismantle the vaccine infrastructure: “We’ve come so far. We’ve put so much into this to now take our foot off the gas. I think it would be a mistake for public health worldwide.”

Disparities during the Omicron surge

As the country puts Omicron in its rear view mirror, a quick look back at the CDC data shows some differences in how children were affected. At the surge’s peak in early to mid-January, Hispanic children were the most likely to get COVID-19, with incidence highest in the older groups. (See graph.)

At their peak week of Jan. 2-8, Hispanic children aged 16-17 years had a COVID rate of 1,568 cases per 100,000 population, versus 790 per 100,000 for White children, whose peak occurred a week later, from Jan. 9 to 15. Hispanic children aged 5-11 (1,098 per 100,000) and 12-15 (1,269 per 100,000) also had the highest recorded rates of the largest racial/ethnic groups, while Black children had the highest one-week rate, 625 per 100,000, among the 0- to 4-year-olds, according to the CDC.

COVID-19 continues to be a diminishing issue for U.S. children, as the number of new cases declined for the ninth consecutive week, based on data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report. The most recently infected children brought the total number of COVID-19 cases to just over 12.8 million since the pandemic began.

Other measures of COVID occurrence in children, such as hospital admissions and emergency department visits, also followed recent downward trends, although the sizes of the declines are beginning to decrease. Admissions dropped by 13.3% during the week ending March 26, but that followed declines of 25%, 20%, 26.5% and 24.4% for the 4 previous weeks, data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show.

The slowdown in ED visits started a couple of weeks earlier, but the decline is still ongoing. As of March 25, ED visits with a confirmed COVID diagnosis represented just 0.4% of all visits for children aged 0-11 years, down from 1.1% on Feb. 25 and a peak of 14.3% on Jan. 15. For children aged 12-15, the latest figure is just 0.2%, compared with 0.5% on Feb. 25 and a peak of 14.3% on Jan. 9, the CDC reported on its COVID Data Tracker.

Although he was speaking of the nation as a whole and not specifically of children, Anthony Fauci, MD, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, recently told the Washington Post that, “unless something changes dramatically,” another major surge isn’t on the horizon.

That sentiment, however, was not entirely shared by Moderna’s chief medical officer, Paul Burton, MD, PhD. In an interview with WebMD, he said that another COVID wave is inevitable and that it’s too soon to dismantle the vaccine infrastructure: “We’ve come so far. We’ve put so much into this to now take our foot off the gas. I think it would be a mistake for public health worldwide.”

Disparities during the Omicron surge

As the country puts Omicron in its rear view mirror, a quick look back at the CDC data shows some differences in how children were affected. At the surge’s peak in early to mid-January, Hispanic children were the most likely to get COVID-19, with incidence highest in the older groups. (See graph.)

At their peak week of Jan. 2-8, Hispanic children aged 16-17 years had a COVID rate of 1,568 cases per 100,000 population, versus 790 per 100,000 for White children, whose peak occurred a week later, from Jan. 9 to 15. Hispanic children aged 5-11 (1,098 per 100,000) and 12-15 (1,269 per 100,000) also had the highest recorded rates of the largest racial/ethnic groups, while Black children had the highest one-week rate, 625 per 100,000, among the 0- to 4-year-olds, according to the CDC.

COVID-19 continues to be a diminishing issue for U.S. children, as the number of new cases declined for the ninth consecutive week, based on data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report. The most recently infected children brought the total number of COVID-19 cases to just over 12.8 million since the pandemic began.

Other measures of COVID occurrence in children, such as hospital admissions and emergency department visits, also followed recent downward trends, although the sizes of the declines are beginning to decrease. Admissions dropped by 13.3% during the week ending March 26, but that followed declines of 25%, 20%, 26.5% and 24.4% for the 4 previous weeks, data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show.

The slowdown in ED visits started a couple of weeks earlier, but the decline is still ongoing. As of March 25, ED visits with a confirmed COVID diagnosis represented just 0.4% of all visits for children aged 0-11 years, down from 1.1% on Feb. 25 and a peak of 14.3% on Jan. 15. For children aged 12-15, the latest figure is just 0.2%, compared with 0.5% on Feb. 25 and a peak of 14.3% on Jan. 9, the CDC reported on its COVID Data Tracker.

Although he was speaking of the nation as a whole and not specifically of children, Anthony Fauci, MD, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, recently told the Washington Post that, “unless something changes dramatically,” another major surge isn’t on the horizon.

That sentiment, however, was not entirely shared by Moderna’s chief medical officer, Paul Burton, MD, PhD. In an interview with WebMD, he said that another COVID wave is inevitable and that it’s too soon to dismantle the vaccine infrastructure: “We’ve come so far. We’ve put so much into this to now take our foot off the gas. I think it would be a mistake for public health worldwide.”

Disparities during the Omicron surge

As the country puts Omicron in its rear view mirror, a quick look back at the CDC data shows some differences in how children were affected. At the surge’s peak in early to mid-January, Hispanic children were the most likely to get COVID-19, with incidence highest in the older groups. (See graph.)

At their peak week of Jan. 2-8, Hispanic children aged 16-17 years had a COVID rate of 1,568 cases per 100,000 population, versus 790 per 100,000 for White children, whose peak occurred a week later, from Jan. 9 to 15. Hispanic children aged 5-11 (1,098 per 100,000) and 12-15 (1,269 per 100,000) also had the highest recorded rates of the largest racial/ethnic groups, while Black children had the highest one-week rate, 625 per 100,000, among the 0- to 4-year-olds, according to the CDC.

As FDA OKs another COVID booster, some experts question need

, even though many top infectious disease experts questioned the need before the agency’s decision.

The FDA granted emergency use authorization for both Pfizer and Moderna to offer the second booster – and fourth shot overall – for adults over 50 as well as those over 18 with compromised immune systems.

The Centers for Control and Prevention must still sign off before those doses start reaching American arms. That approval could come at any time.

“The general consensus, certainly the CDC’s consensus, is that the current vaccines are still really quite effective against Omicron and this new BA.2 variant in keeping people out of the hospital, and preventing the development of severe disease,” William Schaffner, MD, an infectious disease specialist at Vanderbilt University in Nashville said prior to the FDA’s announcement March 29.

Of the 217.4 million Americans who are “fully vaccinated,” i.e., received two doses of either Pfizer or Moderna’s vaccines or one dose of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine, only 45% have also received a booster shot, according to the CDC.

“Given that, there’s no need at the moment for the general population to get a fourth inoculation,” Dr. Schaffner says. “Our current focus ought to be on making sure that as many people as possible get that [first] booster who are eligible.”

Monica Gandhi, MD, an infectious disease specialist at the University of California, San Francisco, agreed that another booster for everyone was unnecessary. The only people who would need a fourth shot (or third, if they had the Johnson & Johnson vaccine initially) are those over age 65 or 70 years, Dr. Gandhi says.

“Older people need those antibodies up high because they’re more susceptible to severe breakthroughs,” she said, also before the latest development.

To boost or not to boost

Daniel Kuritzkes, MD, chief of infectious diseases at Brigham & Women’s Hospital in Boston, said the timing of a booster and who should be eligible depends on what the nation is trying to achieve with its vaccination strategy.

“Is the goal to prevent any symptomatic infection with COVID-19, is the goal to prevent the spread of COVID-19, or is the goal to prevent severe disease that requires hospitalization?” asked Dr. Kuritzkes.

The current vaccine — with a booster — has prevented severe disease, he said.

An Israeli study showed, for instance, that a third Pfizer dose was 93% effective against hospitalization, 92% effective against severe illness, and 81% effective against death.

A just-published study in the New England Journal of Medicine found that a booster of the Pfizer vaccine was 95% effective against COVID-19 infection and that it did not raise any new safety issues.

A small Israeli study, also published in NEJM, of a fourth Pfizer dose given to health care workers found that it prevented symptomatic infection and illness, but that it was much less effective than previous doses — maybe 65% effective against symptomatic illness, the authors write.

Giving Americans another booster now — which has been shown to lose some effectiveness after about 4 months — means it might not offer protection this fall and winter, when there could be a seasonal surge of the virus, Dr. Kuritzkes says.

And, even if people receive boosters every few months, they are still likely to get a mild respiratory virus infection, he said.

“I’m pretty convinced that we cannot boost ourselves out of this pandemic,” said Dr. Kuritzkes. “We need to first of all ensure there’s global immunization so that all the people who have not been vaccinated at all get vaccinated. That’s far more important than boosting people a fourth time.”

Booster confusion

The April 6 FDA meeting of the agency’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee comes as the two major COVID vaccine makers — Pfizer and Moderna — have applied for emergency use authorization for an additional booster.

Pfizer had asked for authorization for a fourth shot in patients over age 65 years, while Moderna wanted a booster to be available to all Americans over 18. The FDA instead granted authorization to both companies for those over 50 and anyone 18 or older who is immunocompromised.

What this means for the committee’s April 6 meeting is not clear. The original agenda says the committee will consider the evidence on safety and effectiveness of the additional vaccine doses and discuss how to set up a process — similar to that used for the influenza vaccine — to be able to determine the makeup of COVID vaccines as new variants emerge. That could lay the groundwork for an annual COVID shot, if needed.

The FDA advisers will not make recommendations nor vote on whether — and which — Americans should get a COVID booster. That is the job of the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP).

The last time a booster was considered, CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, overrode the committee and recommended that all Americans — not just older individuals — get an additional COVID shot, which became the first booster.

That past action worries Dr. Gandhi, who calls it confusing, and says it may have contributed to the fact that less than half of Americans have since chosen to get a booster.

Dr. Schaffner says he expects the FDA to authorize emergency use for fourth doses of the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, but he doesn’t think the CDC committee will recommend routine use. As was seen before, however, the CDC director does not have to follow the committee’s advice.

The members of ACIP “might be more conservative or narrower in scope in terms of recommending who needs to be boosted and when boosting is appropriate,” Dr. Kuritzkes says.

Dr. Gandhi says she’s concerned the FDA’s deliberations could be swayed by Moderna and Pfizer’s influence and that “pharmaceutical companies are going to have more of a say than they should in the scientific process.”

There are similar worries for Dr. Schaffner. He says he’s “a bit grumpy” that the vaccine makers have been using press releases to argue for boosters.

“Press releases are no way to make vaccine recommendations,” Dr. Schaffner said, adding that he “would advise [vaccine makers] to sit down and be quiet and let the FDA and CDC advisory committee do their thing.”

Moderna Chief Medical Officer Paul Burton, MD, however, told WebMD last week that the signs point to why a fourth shot may be needed.

“We see waning of effectiveness, antibody levels come down, and certainly effectiveness against Omicron comes down in 3 to 6 months,” Burton said. “The natural history, from what we’re seeing around the world, is that BA.2 is definitely here, it’s highly transmissible, and I think we are going to get an additional wave of BA.2 here in the United States.”

Another wave is coming, he said, and “I think there will be waning of effectiveness. We need to be prepared for that, so that’s why we need the fourth dose.”

Supply issues?

Meanwhile, the United Kingdom has begun offering boosters to anyone over 75, and Sweden’s health authority has recommended a fourth shot to people over age 80.

That puts pressure on the United States — at least on its politicians and policymakers — to, in a sense, keep up, said the infectious disease specialists.

Indeed, the White House has been keeping fourth shots in the news, warning that it is running out of money to ensure that all Americans would have access to one, if recommended.

On March 23, outgoing White House COVID-19 Response Coordinator Jeff Zients said the federal government had enough vaccine for the immunocompromised to get a fourth dose “and, if authorized in the coming weeks, enough supply for fourth doses for our most vulnerable, including seniors.”

But he warned that without congressional approval of a COVID-19 funding package, “We can’t procure the necessary vaccine supply to support fourth shots for all Americans.”

Mr. Zients also noted that other countries, including Japan, Vietnam, and the Philippines had already secured future booster doses and added, “We should be securing additional supply right now.”

Dr. Schaffner says that while it would be nice to “have a booster on the shelf,” the United States needs to put more effort into creating a globally-coordinated process for ensuring that vaccines match circulating strains and that they are manufactured on a timely basis.

He says he and others “have been reminding the public that the COVID pandemic may indeed be diminishing and moving into the endemic, but that doesn’t mean COVID is over or finished or disappeared.”

Dr. Schaffner says that it may be that “perhaps we’d need a periodic reminder to our immune system to remain protected. In other words, we might have to get boosted perhaps annually like we do with influenza.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

, even though many top infectious disease experts questioned the need before the agency’s decision.

The FDA granted emergency use authorization for both Pfizer and Moderna to offer the second booster – and fourth shot overall – for adults over 50 as well as those over 18 with compromised immune systems.

The Centers for Control and Prevention must still sign off before those doses start reaching American arms. That approval could come at any time.

“The general consensus, certainly the CDC’s consensus, is that the current vaccines are still really quite effective against Omicron and this new BA.2 variant in keeping people out of the hospital, and preventing the development of severe disease,” William Schaffner, MD, an infectious disease specialist at Vanderbilt University in Nashville said prior to the FDA’s announcement March 29.

Of the 217.4 million Americans who are “fully vaccinated,” i.e., received two doses of either Pfizer or Moderna’s vaccines or one dose of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine, only 45% have also received a booster shot, according to the CDC.

“Given that, there’s no need at the moment for the general population to get a fourth inoculation,” Dr. Schaffner says. “Our current focus ought to be on making sure that as many people as possible get that [first] booster who are eligible.”

Monica Gandhi, MD, an infectious disease specialist at the University of California, San Francisco, agreed that another booster for everyone was unnecessary. The only people who would need a fourth shot (or third, if they had the Johnson & Johnson vaccine initially) are those over age 65 or 70 years, Dr. Gandhi says.

“Older people need those antibodies up high because they’re more susceptible to severe breakthroughs,” she said, also before the latest development.

To boost or not to boost

Daniel Kuritzkes, MD, chief of infectious diseases at Brigham & Women’s Hospital in Boston, said the timing of a booster and who should be eligible depends on what the nation is trying to achieve with its vaccination strategy.

“Is the goal to prevent any symptomatic infection with COVID-19, is the goal to prevent the spread of COVID-19, or is the goal to prevent severe disease that requires hospitalization?” asked Dr. Kuritzkes.

The current vaccine — with a booster — has prevented severe disease, he said.

An Israeli study showed, for instance, that a third Pfizer dose was 93% effective against hospitalization, 92% effective against severe illness, and 81% effective against death.

A just-published study in the New England Journal of Medicine found that a booster of the Pfizer vaccine was 95% effective against COVID-19 infection and that it did not raise any new safety issues.

A small Israeli study, also published in NEJM, of a fourth Pfizer dose given to health care workers found that it prevented symptomatic infection and illness, but that it was much less effective than previous doses — maybe 65% effective against symptomatic illness, the authors write.

Giving Americans another booster now — which has been shown to lose some effectiveness after about 4 months — means it might not offer protection this fall and winter, when there could be a seasonal surge of the virus, Dr. Kuritzkes says.

And, even if people receive boosters every few months, they are still likely to get a mild respiratory virus infection, he said.

“I’m pretty convinced that we cannot boost ourselves out of this pandemic,” said Dr. Kuritzkes. “We need to first of all ensure there’s global immunization so that all the people who have not been vaccinated at all get vaccinated. That’s far more important than boosting people a fourth time.”

Booster confusion

The April 6 FDA meeting of the agency’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee comes as the two major COVID vaccine makers — Pfizer and Moderna — have applied for emergency use authorization for an additional booster.

Pfizer had asked for authorization for a fourth shot in patients over age 65 years, while Moderna wanted a booster to be available to all Americans over 18. The FDA instead granted authorization to both companies for those over 50 and anyone 18 or older who is immunocompromised.

What this means for the committee’s April 6 meeting is not clear. The original agenda says the committee will consider the evidence on safety and effectiveness of the additional vaccine doses and discuss how to set up a process — similar to that used for the influenza vaccine — to be able to determine the makeup of COVID vaccines as new variants emerge. That could lay the groundwork for an annual COVID shot, if needed.

The FDA advisers will not make recommendations nor vote on whether — and which — Americans should get a COVID booster. That is the job of the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP).

The last time a booster was considered, CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, overrode the committee and recommended that all Americans — not just older individuals — get an additional COVID shot, which became the first booster.

That past action worries Dr. Gandhi, who calls it confusing, and says it may have contributed to the fact that less than half of Americans have since chosen to get a booster.

Dr. Schaffner says he expects the FDA to authorize emergency use for fourth doses of the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, but he doesn’t think the CDC committee will recommend routine use. As was seen before, however, the CDC director does not have to follow the committee’s advice.

The members of ACIP “might be more conservative or narrower in scope in terms of recommending who needs to be boosted and when boosting is appropriate,” Dr. Kuritzkes says.

Dr. Gandhi says she’s concerned the FDA’s deliberations could be swayed by Moderna and Pfizer’s influence and that “pharmaceutical companies are going to have more of a say than they should in the scientific process.”

There are similar worries for Dr. Schaffner. He says he’s “a bit grumpy” that the vaccine makers have been using press releases to argue for boosters.

“Press releases are no way to make vaccine recommendations,” Dr. Schaffner said, adding that he “would advise [vaccine makers] to sit down and be quiet and let the FDA and CDC advisory committee do their thing.”

Moderna Chief Medical Officer Paul Burton, MD, however, told WebMD last week that the signs point to why a fourth shot may be needed.

“We see waning of effectiveness, antibody levels come down, and certainly effectiveness against Omicron comes down in 3 to 6 months,” Burton said. “The natural history, from what we’re seeing around the world, is that BA.2 is definitely here, it’s highly transmissible, and I think we are going to get an additional wave of BA.2 here in the United States.”

Another wave is coming, he said, and “I think there will be waning of effectiveness. We need to be prepared for that, so that’s why we need the fourth dose.”

Supply issues?

Meanwhile, the United Kingdom has begun offering boosters to anyone over 75, and Sweden’s health authority has recommended a fourth shot to people over age 80.

That puts pressure on the United States — at least on its politicians and policymakers — to, in a sense, keep up, said the infectious disease specialists.

Indeed, the White House has been keeping fourth shots in the news, warning that it is running out of money to ensure that all Americans would have access to one, if recommended.

On March 23, outgoing White House COVID-19 Response Coordinator Jeff Zients said the federal government had enough vaccine for the immunocompromised to get a fourth dose “and, if authorized in the coming weeks, enough supply for fourth doses for our most vulnerable, including seniors.”

But he warned that without congressional approval of a COVID-19 funding package, “We can’t procure the necessary vaccine supply to support fourth shots for all Americans.”

Mr. Zients also noted that other countries, including Japan, Vietnam, and the Philippines had already secured future booster doses and added, “We should be securing additional supply right now.”

Dr. Schaffner says that while it would be nice to “have a booster on the shelf,” the United States needs to put more effort into creating a globally-coordinated process for ensuring that vaccines match circulating strains and that they are manufactured on a timely basis.

He says he and others “have been reminding the public that the COVID pandemic may indeed be diminishing and moving into the endemic, but that doesn’t mean COVID is over or finished or disappeared.”

Dr. Schaffner says that it may be that “perhaps we’d need a periodic reminder to our immune system to remain protected. In other words, we might have to get boosted perhaps annually like we do with influenza.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

, even though many top infectious disease experts questioned the need before the agency’s decision.

The FDA granted emergency use authorization for both Pfizer and Moderna to offer the second booster – and fourth shot overall – for adults over 50 as well as those over 18 with compromised immune systems.

The Centers for Control and Prevention must still sign off before those doses start reaching American arms. That approval could come at any time.

“The general consensus, certainly the CDC’s consensus, is that the current vaccines are still really quite effective against Omicron and this new BA.2 variant in keeping people out of the hospital, and preventing the development of severe disease,” William Schaffner, MD, an infectious disease specialist at Vanderbilt University in Nashville said prior to the FDA’s announcement March 29.

Of the 217.4 million Americans who are “fully vaccinated,” i.e., received two doses of either Pfizer or Moderna’s vaccines or one dose of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine, only 45% have also received a booster shot, according to the CDC.

“Given that, there’s no need at the moment for the general population to get a fourth inoculation,” Dr. Schaffner says. “Our current focus ought to be on making sure that as many people as possible get that [first] booster who are eligible.”

Monica Gandhi, MD, an infectious disease specialist at the University of California, San Francisco, agreed that another booster for everyone was unnecessary. The only people who would need a fourth shot (or third, if they had the Johnson & Johnson vaccine initially) are those over age 65 or 70 years, Dr. Gandhi says.

“Older people need those antibodies up high because they’re more susceptible to severe breakthroughs,” she said, also before the latest development.

To boost or not to boost

Daniel Kuritzkes, MD, chief of infectious diseases at Brigham & Women’s Hospital in Boston, said the timing of a booster and who should be eligible depends on what the nation is trying to achieve with its vaccination strategy.

“Is the goal to prevent any symptomatic infection with COVID-19, is the goal to prevent the spread of COVID-19, or is the goal to prevent severe disease that requires hospitalization?” asked Dr. Kuritzkes.

The current vaccine — with a booster — has prevented severe disease, he said.

An Israeli study showed, for instance, that a third Pfizer dose was 93% effective against hospitalization, 92% effective against severe illness, and 81% effective against death.

A just-published study in the New England Journal of Medicine found that a booster of the Pfizer vaccine was 95% effective against COVID-19 infection and that it did not raise any new safety issues.

A small Israeli study, also published in NEJM, of a fourth Pfizer dose given to health care workers found that it prevented symptomatic infection and illness, but that it was much less effective than previous doses — maybe 65% effective against symptomatic illness, the authors write.

Giving Americans another booster now — which has been shown to lose some effectiveness after about 4 months — means it might not offer protection this fall and winter, when there could be a seasonal surge of the virus, Dr. Kuritzkes says.

And, even if people receive boosters every few months, they are still likely to get a mild respiratory virus infection, he said.

“I’m pretty convinced that we cannot boost ourselves out of this pandemic,” said Dr. Kuritzkes. “We need to first of all ensure there’s global immunization so that all the people who have not been vaccinated at all get vaccinated. That’s far more important than boosting people a fourth time.”

Booster confusion

The April 6 FDA meeting of the agency’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee comes as the two major COVID vaccine makers — Pfizer and Moderna — have applied for emergency use authorization for an additional booster.

Pfizer had asked for authorization for a fourth shot in patients over age 65 years, while Moderna wanted a booster to be available to all Americans over 18. The FDA instead granted authorization to both companies for those over 50 and anyone 18 or older who is immunocompromised.

What this means for the committee’s April 6 meeting is not clear. The original agenda says the committee will consider the evidence on safety and effectiveness of the additional vaccine doses and discuss how to set up a process — similar to that used for the influenza vaccine — to be able to determine the makeup of COVID vaccines as new variants emerge. That could lay the groundwork for an annual COVID shot, if needed.

The FDA advisers will not make recommendations nor vote on whether — and which — Americans should get a COVID booster. That is the job of the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP).

The last time a booster was considered, CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, overrode the committee and recommended that all Americans — not just older individuals — get an additional COVID shot, which became the first booster.

That past action worries Dr. Gandhi, who calls it confusing, and says it may have contributed to the fact that less than half of Americans have since chosen to get a booster.

Dr. Schaffner says he expects the FDA to authorize emergency use for fourth doses of the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, but he doesn’t think the CDC committee will recommend routine use. As was seen before, however, the CDC director does not have to follow the committee’s advice.

The members of ACIP “might be more conservative or narrower in scope in terms of recommending who needs to be boosted and when boosting is appropriate,” Dr. Kuritzkes says.

Dr. Gandhi says she’s concerned the FDA’s deliberations could be swayed by Moderna and Pfizer’s influence and that “pharmaceutical companies are going to have more of a say than they should in the scientific process.”

There are similar worries for Dr. Schaffner. He says he’s “a bit grumpy” that the vaccine makers have been using press releases to argue for boosters.

“Press releases are no way to make vaccine recommendations,” Dr. Schaffner said, adding that he “would advise [vaccine makers] to sit down and be quiet and let the FDA and CDC advisory committee do their thing.”

Moderna Chief Medical Officer Paul Burton, MD, however, told WebMD last week that the signs point to why a fourth shot may be needed.

“We see waning of effectiveness, antibody levels come down, and certainly effectiveness against Omicron comes down in 3 to 6 months,” Burton said. “The natural history, from what we’re seeing around the world, is that BA.2 is definitely here, it’s highly transmissible, and I think we are going to get an additional wave of BA.2 here in the United States.”

Another wave is coming, he said, and “I think there will be waning of effectiveness. We need to be prepared for that, so that’s why we need the fourth dose.”

Supply issues?

Meanwhile, the United Kingdom has begun offering boosters to anyone over 75, and Sweden’s health authority has recommended a fourth shot to people over age 80.

That puts pressure on the United States — at least on its politicians and policymakers — to, in a sense, keep up, said the infectious disease specialists.

Indeed, the White House has been keeping fourth shots in the news, warning that it is running out of money to ensure that all Americans would have access to one, if recommended.

On March 23, outgoing White House COVID-19 Response Coordinator Jeff Zients said the federal government had enough vaccine for the immunocompromised to get a fourth dose “and, if authorized in the coming weeks, enough supply for fourth doses for our most vulnerable, including seniors.”

But he warned that without congressional approval of a COVID-19 funding package, “We can’t procure the necessary vaccine supply to support fourth shots for all Americans.”

Mr. Zients also noted that other countries, including Japan, Vietnam, and the Philippines had already secured future booster doses and added, “We should be securing additional supply right now.”

Dr. Schaffner says that while it would be nice to “have a booster on the shelf,” the United States needs to put more effort into creating a globally-coordinated process for ensuring that vaccines match circulating strains and that they are manufactured on a timely basis.

He says he and others “have been reminding the public that the COVID pandemic may indeed be diminishing and moving into the endemic, but that doesn’t mean COVID is over or finished or disappeared.”

Dr. Schaffner says that it may be that “perhaps we’d need a periodic reminder to our immune system to remain protected. In other words, we might have to get boosted perhaps annually like we do with influenza.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

FDA approves HIV injectable Cabenuva initiation without oral lead-in

Initiating treatment may become easier for adults living with HIV. a combination injectable, without a lead-in period of oral tablets, according to a press release from Janssen Pharmaceuticals.

Cabenuva combines rilpivirine (Janssen) and cabotegravir (ViiV Healthcare). The change offers patients and clinicians an option for a streamlined entry to treatment without the burden of daily pill taking, according to the release.

Cabenuva injections may be given as few as six times a year to manage HIV, according to Janssen. HIV patients with viral suppression previously had to complete an oral treatment regimen before starting monthly or bimonthly injections.

The injectable combination of cabotegravir, an HIV-1 integrase strand transfer inhibitor, and rilpivirine, an HIV-1 nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, is currently indicated as a complete treatment regimen to replace the current antiretroviral regimen for adults with HIV who are virologically suppressed,” according to the press release.

“Janssen and ViiV are exploring the future possibility of an ultra–long-acting version of Cabenuva, which could reduce the frequency of injections even further, according to the press release.

Access may improve, but barriers persist

“Despite advances in HIV care, many barriers remain, particularly for the most vulnerable populations,” Lina Rosengren-Hovee, MD, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, said in an interview.

“Care engagement has improved with the use of bridge counselors, rapid ART [antiretroviral therapy] initiation policies, and contact tracing,” she said. “Similarly, increasing access to multiple modalities of HIV treatment is critical to increase engagement in care.

“For patients, removing the oral lead-in primarily reduces the number of clinical visits to start injectable ART,” Dr. Rosengren-Hovee added. “It may also remove adherence barriers for patients who have difficulty taking a daily oral medication.”

But Dr. Rosengren-Hovee (who has no financial connection to the manufacturers) pointed out that access to Cabenuva may not be seamless. “Unless the medication is stocked in clinics, patients are not likely to receive their first injection during the initial visit. Labs are also required prior to initiation to ensure there is no contraindication to the medication, such as viral resistance to one of its components. Cost and insurance coverage are also likely to remain major obstacles.”

Dr. Rosengren-Hovee has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Initiating treatment may become easier for adults living with HIV. a combination injectable, without a lead-in period of oral tablets, according to a press release from Janssen Pharmaceuticals.

Cabenuva combines rilpivirine (Janssen) and cabotegravir (ViiV Healthcare). The change offers patients and clinicians an option for a streamlined entry to treatment without the burden of daily pill taking, according to the release.

Cabenuva injections may be given as few as six times a year to manage HIV, according to Janssen. HIV patients with viral suppression previously had to complete an oral treatment regimen before starting monthly or bimonthly injections.

The injectable combination of cabotegravir, an HIV-1 integrase strand transfer inhibitor, and rilpivirine, an HIV-1 nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, is currently indicated as a complete treatment regimen to replace the current antiretroviral regimen for adults with HIV who are virologically suppressed,” according to the press release.

“Janssen and ViiV are exploring the future possibility of an ultra–long-acting version of Cabenuva, which could reduce the frequency of injections even further, according to the press release.

Access may improve, but barriers persist

“Despite advances in HIV care, many barriers remain, particularly for the most vulnerable populations,” Lina Rosengren-Hovee, MD, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, said in an interview.

“Care engagement has improved with the use of bridge counselors, rapid ART [antiretroviral therapy] initiation policies, and contact tracing,” she said. “Similarly, increasing access to multiple modalities of HIV treatment is critical to increase engagement in care.

“For patients, removing the oral lead-in primarily reduces the number of clinical visits to start injectable ART,” Dr. Rosengren-Hovee added. “It may also remove adherence barriers for patients who have difficulty taking a daily oral medication.”

But Dr. Rosengren-Hovee (who has no financial connection to the manufacturers) pointed out that access to Cabenuva may not be seamless. “Unless the medication is stocked in clinics, patients are not likely to receive their first injection during the initial visit. Labs are also required prior to initiation to ensure there is no contraindication to the medication, such as viral resistance to one of its components. Cost and insurance coverage are also likely to remain major obstacles.”

Dr. Rosengren-Hovee has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Initiating treatment may become easier for adults living with HIV. a combination injectable, without a lead-in period of oral tablets, according to a press release from Janssen Pharmaceuticals.

Cabenuva combines rilpivirine (Janssen) and cabotegravir (ViiV Healthcare). The change offers patients and clinicians an option for a streamlined entry to treatment without the burden of daily pill taking, according to the release.

Cabenuva injections may be given as few as six times a year to manage HIV, according to Janssen. HIV patients with viral suppression previously had to complete an oral treatment regimen before starting monthly or bimonthly injections.

The injectable combination of cabotegravir, an HIV-1 integrase strand transfer inhibitor, and rilpivirine, an HIV-1 nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, is currently indicated as a complete treatment regimen to replace the current antiretroviral regimen for adults with HIV who are virologically suppressed,” according to the press release.

“Janssen and ViiV are exploring the future possibility of an ultra–long-acting version of Cabenuva, which could reduce the frequency of injections even further, according to the press release.

Access may improve, but barriers persist

“Despite advances in HIV care, many barriers remain, particularly for the most vulnerable populations,” Lina Rosengren-Hovee, MD, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, said in an interview.

“Care engagement has improved with the use of bridge counselors, rapid ART [antiretroviral therapy] initiation policies, and contact tracing,” she said. “Similarly, increasing access to multiple modalities of HIV treatment is critical to increase engagement in care.

“For patients, removing the oral lead-in primarily reduces the number of clinical visits to start injectable ART,” Dr. Rosengren-Hovee added. “It may also remove adherence barriers for patients who have difficulty taking a daily oral medication.”

But Dr. Rosengren-Hovee (who has no financial connection to the manufacturers) pointed out that access to Cabenuva may not be seamless. “Unless the medication is stocked in clinics, patients are not likely to receive their first injection during the initial visit. Labs are also required prior to initiation to ensure there is no contraindication to the medication, such as viral resistance to one of its components. Cost and insurance coverage are also likely to remain major obstacles.”

Dr. Rosengren-Hovee has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Children and COVID: CDC gives perspective on hospitalizations

New COVID-19 cases in children fell by 23% as the latest weekly count dropped to its lowest level since July of 2021, based on data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

, when the early stages of the Delta surge led to 23,551 cases, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report.

The two organizations put the total number of cases at nearly 12.8 million from the start of the pandemic to March 17, with children representing 19.0% of cases among all ages. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention puts the cumulative number of COVID-19 cases at almost 12.0 million as of March 21, or 17.5% of the nationwide total.

COVID-related hospitalizations also continue to fall, and two new studies from the CDC put children’s experiences during the Omicron surge and the larger pandemic into perspective.

One study showed that hospitalization rates for children aged 4 years and younger during the Omicron surge were five times higher than at the peak of the Delta surge, with the highest rates occurring in infants under 6 months of age. That report was based on the CDC’s COVID-19–Associated Hospitalization Surveillance Network (COVID-NET), which covers 99 counties across 14 states (MMWR. 2022 March 18;71[11]:429-36).

The second study compared child hospitalizations during 1 year of the COVID pandemic (Oct. 1, 2020, to Sept. 30, 2021) with three influenza seasons (2017-2018 through 2019-2020). The pre-Omicron hospitalization rate for those under age 18 years, 48.2 per 100,000 children, was higher than any of the three flu seasons: 33.5 per 100,000 in 2017-2018, 33.8 in 2018-2019, and 41.7 for 2019-2020, the investigators said in a medRxiv preprint.

Most of the increased COVID burden fell on adolescents aged 12-17, they said. The COVID hospitalization rate for that age group was 59.9 per 100,000, versus 12.2-14.1 for influenza, while children aged 5-11 had a COVID-related rate of 25.0 and flu-related rates of 24.3-31.7, and those aged 0-4 had rates of 66.8 for COVID and 70.9-91.5 for the flu, Miranda J. Delahoy of the CDC’s COVID-19 Response Team and associates reported.

New COVID-19 cases in children fell by 23% as the latest weekly count dropped to its lowest level since July of 2021, based on data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

, when the early stages of the Delta surge led to 23,551 cases, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report.

The two organizations put the total number of cases at nearly 12.8 million from the start of the pandemic to March 17, with children representing 19.0% of cases among all ages. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention puts the cumulative number of COVID-19 cases at almost 12.0 million as of March 21, or 17.5% of the nationwide total.

COVID-related hospitalizations also continue to fall, and two new studies from the CDC put children’s experiences during the Omicron surge and the larger pandemic into perspective.

One study showed that hospitalization rates for children aged 4 years and younger during the Omicron surge were five times higher than at the peak of the Delta surge, with the highest rates occurring in infants under 6 months of age. That report was based on the CDC’s COVID-19–Associated Hospitalization Surveillance Network (COVID-NET), which covers 99 counties across 14 states (MMWR. 2022 March 18;71[11]:429-36).

The second study compared child hospitalizations during 1 year of the COVID pandemic (Oct. 1, 2020, to Sept. 30, 2021) with three influenza seasons (2017-2018 through 2019-2020). The pre-Omicron hospitalization rate for those under age 18 years, 48.2 per 100,000 children, was higher than any of the three flu seasons: 33.5 per 100,000 in 2017-2018, 33.8 in 2018-2019, and 41.7 for 2019-2020, the investigators said in a medRxiv preprint.

Most of the increased COVID burden fell on adolescents aged 12-17, they said. The COVID hospitalization rate for that age group was 59.9 per 100,000, versus 12.2-14.1 for influenza, while children aged 5-11 had a COVID-related rate of 25.0 and flu-related rates of 24.3-31.7, and those aged 0-4 had rates of 66.8 for COVID and 70.9-91.5 for the flu, Miranda J. Delahoy of the CDC’s COVID-19 Response Team and associates reported.

New COVID-19 cases in children fell by 23% as the latest weekly count dropped to its lowest level since July of 2021, based on data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

, when the early stages of the Delta surge led to 23,551 cases, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report.

The two organizations put the total number of cases at nearly 12.8 million from the start of the pandemic to March 17, with children representing 19.0% of cases among all ages. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention puts the cumulative number of COVID-19 cases at almost 12.0 million as of March 21, or 17.5% of the nationwide total.

COVID-related hospitalizations also continue to fall, and two new studies from the CDC put children’s experiences during the Omicron surge and the larger pandemic into perspective.

One study showed that hospitalization rates for children aged 4 years and younger during the Omicron surge were five times higher than at the peak of the Delta surge, with the highest rates occurring in infants under 6 months of age. That report was based on the CDC’s COVID-19–Associated Hospitalization Surveillance Network (COVID-NET), which covers 99 counties across 14 states (MMWR. 2022 March 18;71[11]:429-36).

The second study compared child hospitalizations during 1 year of the COVID pandemic (Oct. 1, 2020, to Sept. 30, 2021) with three influenza seasons (2017-2018 through 2019-2020). The pre-Omicron hospitalization rate for those under age 18 years, 48.2 per 100,000 children, was higher than any of the three flu seasons: 33.5 per 100,000 in 2017-2018, 33.8 in 2018-2019, and 41.7 for 2019-2020, the investigators said in a medRxiv preprint.

Most of the increased COVID burden fell on adolescents aged 12-17, they said. The COVID hospitalization rate for that age group was 59.9 per 100,000, versus 12.2-14.1 for influenza, while children aged 5-11 had a COVID-related rate of 25.0 and flu-related rates of 24.3-31.7, and those aged 0-4 had rates of 66.8 for COVID and 70.9-91.5 for the flu, Miranda J. Delahoy of the CDC’s COVID-19 Response Team and associates reported.

FDA approves generic Symbicort for asthma, COPD

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the first generic of Symbicort (budesonide and formoterol fumarate dihydrate) inhalation aerosol for the treatment of asthma in patients 6 years of age and older and for the maintenance treatment of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), including chronic bronchitis and/or emphysema.

The approval was given for a complex generic drug-device combination product – a metered-dose inhaler that contains both budesonide (a corticosteroid that reduces inflammation) and formoterol (a long-acting bronchodilator that relaxes muscles in the airways to improve breathing). It is intended to be used as two inhalations, two times a day (usually morning and night, about 12 hours apart), to treat both diseases by preventing symptoms, such as wheezing for those with asthma and for improved breathing for patients with COPD.

The inhaler is approved at two strengths (160/4.5 mcg/actuation and 80/4.5 mcg/actuation), according to the March 15 FDA announcement. The device is not intended for the treatment of acute asthma.

“Today’s approval of the first generic for one of the most commonly prescribed complex drug-device combination products to treat asthma and COPD is another step forward in our commitment to bring generic copies of complex drugs to the market, which can improve quality of life and help reduce the cost of treatment,” said Sally Choe, PhD, director of the Office of Generic Drugs in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

The most common side effects associated with budesonide and formoterol fumarate dihydrate oral inhalation aerosol for those with asthma are nasopharyngitis pain, sinusitis, influenza, back pain, nasal congestion, stomach discomfort, vomiting, and oral candidiasis (thrush). For those with COPD, the most common side effects are nasopharyngitis, oral candidiasis, bronchitis, sinusitis, and upper respiratory tract infection, the FDA reported.

The approval of this generic drug-device combination was granted to Mylan Pharmaceuticals.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the first generic of Symbicort (budesonide and formoterol fumarate dihydrate) inhalation aerosol for the treatment of asthma in patients 6 years of age and older and for the maintenance treatment of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), including chronic bronchitis and/or emphysema.

The approval was given for a complex generic drug-device combination product – a metered-dose inhaler that contains both budesonide (a corticosteroid that reduces inflammation) and formoterol (a long-acting bronchodilator that relaxes muscles in the airways to improve breathing). It is intended to be used as two inhalations, two times a day (usually morning and night, about 12 hours apart), to treat both diseases by preventing symptoms, such as wheezing for those with asthma and for improved breathing for patients with COPD.

The inhaler is approved at two strengths (160/4.5 mcg/actuation and 80/4.5 mcg/actuation), according to the March 15 FDA announcement. The device is not intended for the treatment of acute asthma.

“Today’s approval of the first generic for one of the most commonly prescribed complex drug-device combination products to treat asthma and COPD is another step forward in our commitment to bring generic copies of complex drugs to the market, which can improve quality of life and help reduce the cost of treatment,” said Sally Choe, PhD, director of the Office of Generic Drugs in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

The most common side effects associated with budesonide and formoterol fumarate dihydrate oral inhalation aerosol for those with asthma are nasopharyngitis pain, sinusitis, influenza, back pain, nasal congestion, stomach discomfort, vomiting, and oral candidiasis (thrush). For those with COPD, the most common side effects are nasopharyngitis, oral candidiasis, bronchitis, sinusitis, and upper respiratory tract infection, the FDA reported.

The approval of this generic drug-device combination was granted to Mylan Pharmaceuticals.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the first generic of Symbicort (budesonide and formoterol fumarate dihydrate) inhalation aerosol for the treatment of asthma in patients 6 years of age and older and for the maintenance treatment of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), including chronic bronchitis and/or emphysema.

The approval was given for a complex generic drug-device combination product – a metered-dose inhaler that contains both budesonide (a corticosteroid that reduces inflammation) and formoterol (a long-acting bronchodilator that relaxes muscles in the airways to improve breathing). It is intended to be used as two inhalations, two times a day (usually morning and night, about 12 hours apart), to treat both diseases by preventing symptoms, such as wheezing for those with asthma and for improved breathing for patients with COPD.

The inhaler is approved at two strengths (160/4.5 mcg/actuation and 80/4.5 mcg/actuation), according to the March 15 FDA announcement. The device is not intended for the treatment of acute asthma.

“Today’s approval of the first generic for one of the most commonly prescribed complex drug-device combination products to treat asthma and COPD is another step forward in our commitment to bring generic copies of complex drugs to the market, which can improve quality of life and help reduce the cost of treatment,” said Sally Choe, PhD, director of the Office of Generic Drugs in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

The most common side effects associated with budesonide and formoterol fumarate dihydrate oral inhalation aerosol for those with asthma are nasopharyngitis pain, sinusitis, influenza, back pain, nasal congestion, stomach discomfort, vomiting, and oral candidiasis (thrush). For those with COPD, the most common side effects are nasopharyngitis, oral candidiasis, bronchitis, sinusitis, and upper respiratory tract infection, the FDA reported.

The approval of this generic drug-device combination was granted to Mylan Pharmaceuticals.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Children and COVID: Decline in new cases reaches 7th week

New cases of COVID-19 in U.S. children have fallen to their lowest level since the beginning of the Delta surge in July of 2021, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

. Over those 7 weeks, new cases dropped over 96% from the 1.15 million reported for Jan. 14-20, based on data collected by the AAP and CHA from state and territorial health departments.

The last time that the weekly count was below 42,000 was July 16-22, 2021, when almost 39,000 cases were reported in the midst of the Delta upsurge. That was shortly after cases had reached their lowest point, 8,447, since the early stages of the pandemic in 2020, the AAP/CHA data show.

The cumulative number of pediatric cases is now up to 12.7 million, while the overall proportion of cases occurring in children held steady at 19.0% for the 4th week in a row, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, using an age range of 0-18 versus the states’ variety of ages, puts total cases at 11.7 million and deaths at 1,656 as of March 14.

Data from the CDC’s COVID-19–Associated Hospitalization Surveillance Network show that hospitalizations with laboratory-confirmed infection were down by 50% in children aged 0-4 years, by 63% among 5- to 11-year-olds, and by 58% in those aged 12-17 years for the week of Feb. 27 to March 5, compared with the week before.

The pace of vaccination continues to follow a similar trend, as the declines seen through February have continued into March. Cumulatively, 33.7% of children aged 5-11 have received at least one dose, and 26.8% are fully vaccinated, with corresponding numbers of 68.0% and 58.0% for children aged 12-17, the CDC reported on its COVID Data Tracker.

State-level data show that children aged 5-11 in Vermont, with a rate of 65%, are the most likely to have received at least one dose of COVID vaccine, while just 15% of 5- to 11-year-olds in Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi have gotten their first dose. Among children aged 12-17, that rate ranges from 40% in Wyoming to 94% in Hawaii, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island, the AAP said in a separate report based on CDC data.

In a recent report involving 1,364 children aged 5-15 years, two doses of the COVID-19 vaccine reduced the risk of infection from the Omicron variant by 31% in children aged 5-11 years and by 59% among children aged 12-15 years, said Ashley L. Fowlkes, ScD, of the CDC’s COVID-19 Emergency Response Team, and associates (MMWR 2022 Mar 11;71).

New cases of COVID-19 in U.S. children have fallen to their lowest level since the beginning of the Delta surge in July of 2021, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

. Over those 7 weeks, new cases dropped over 96% from the 1.15 million reported for Jan. 14-20, based on data collected by the AAP and CHA from state and territorial health departments.

The last time that the weekly count was below 42,000 was July 16-22, 2021, when almost 39,000 cases were reported in the midst of the Delta upsurge. That was shortly after cases had reached their lowest point, 8,447, since the early stages of the pandemic in 2020, the AAP/CHA data show.

The cumulative number of pediatric cases is now up to 12.7 million, while the overall proportion of cases occurring in children held steady at 19.0% for the 4th week in a row, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, using an age range of 0-18 versus the states’ variety of ages, puts total cases at 11.7 million and deaths at 1,656 as of March 14.

Data from the CDC’s COVID-19–Associated Hospitalization Surveillance Network show that hospitalizations with laboratory-confirmed infection were down by 50% in children aged 0-4 years, by 63% among 5- to 11-year-olds, and by 58% in those aged 12-17 years for the week of Feb. 27 to March 5, compared with the week before.

The pace of vaccination continues to follow a similar trend, as the declines seen through February have continued into March. Cumulatively, 33.7% of children aged 5-11 have received at least one dose, and 26.8% are fully vaccinated, with corresponding numbers of 68.0% and 58.0% for children aged 12-17, the CDC reported on its COVID Data Tracker.

State-level data show that children aged 5-11 in Vermont, with a rate of 65%, are the most likely to have received at least one dose of COVID vaccine, while just 15% of 5- to 11-year-olds in Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi have gotten their first dose. Among children aged 12-17, that rate ranges from 40% in Wyoming to 94% in Hawaii, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island, the AAP said in a separate report based on CDC data.

In a recent report involving 1,364 children aged 5-15 years, two doses of the COVID-19 vaccine reduced the risk of infection from the Omicron variant by 31% in children aged 5-11 years and by 59% among children aged 12-15 years, said Ashley L. Fowlkes, ScD, of the CDC’s COVID-19 Emergency Response Team, and associates (MMWR 2022 Mar 11;71).

New cases of COVID-19 in U.S. children have fallen to their lowest level since the beginning of the Delta surge in July of 2021, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

. Over those 7 weeks, new cases dropped over 96% from the 1.15 million reported for Jan. 14-20, based on data collected by the AAP and CHA from state and territorial health departments.

The last time that the weekly count was below 42,000 was July 16-22, 2021, when almost 39,000 cases were reported in the midst of the Delta upsurge. That was shortly after cases had reached their lowest point, 8,447, since the early stages of the pandemic in 2020, the AAP/CHA data show.

The cumulative number of pediatric cases is now up to 12.7 million, while the overall proportion of cases occurring in children held steady at 19.0% for the 4th week in a row, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, using an age range of 0-18 versus the states’ variety of ages, puts total cases at 11.7 million and deaths at 1,656 as of March 14.

Data from the CDC’s COVID-19–Associated Hospitalization Surveillance Network show that hospitalizations with laboratory-confirmed infection were down by 50% in children aged 0-4 years, by 63% among 5- to 11-year-olds, and by 58% in those aged 12-17 years for the week of Feb. 27 to March 5, compared with the week before.