User login

CDC defends new COVID guidance as doctors raise concerns

, Director Rochelle Walenksy, MD, said during a White House briefing Jan. 5.

Health officials recently shortened the recommended COVID-19 isolation and quarantine period from 10 days to 5, creating confusion amid an outbreak of the highly transmissible Omicron variant, which now accounts for 95% of cases in the United States.

Then, in slightly updated guidance, the CDC recommended using an at-home antigen test after 5 days of isolation if possible, even though these tests having aren’t as sensitive to the Omicron variant, according to the FDA.

“After we released our recs early last week, it became very clear people were interested in using the rapid test, though not authorized for this purpose after the end of their isolation period,” Dr. Walensky said. “We then provided guidance on how they should be used.”

“If that test is negative, people really do need to understand they must continue to wear their mask for those 5 days,” Dr. Walensky said.

But for many, the CDC guidelines are murky and seem to always change.

“Nearly 2 years into this pandemic, with Omicron cases surging across the country, the American people should be able to count on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for timely, accurate, clear guidance to protect themselves, their loved ones, and their communities,” American Medical Association president Gerald Harmon, MD, said in a statement. “Instead, the new recommendations on quarantine and isolation are not only confusing, but are risking further spread of the virus.”

About 31% of people remain infectious 5 days after a positive COVID-19 test, Dr. Harmon said, quoting the CDC’s own rationale for changing its guidance.

“With hundreds of thousands of new cases daily and more than a million positive reported cases on January 3, tens of thousands – potentially hundreds of thousands of people – could return to work and school infectious if they follow the CDC’s new guidance on ending isolation after 5 days without a negative test,” he said. “Physicians are concerned that these recommendations put our patients at risk and could further overwhelm our health care system.”

Instead, Dr. Harmon said a negative test should be required for ending isolation.

“Reemerging without knowing one’s status unnecessarily risks further transmission of the virus,” he said.

Meanwhile, also during the White House briefing, officials said that early data continue to show that Omicron infections are less severe than those from other variants, but skyrocketing cases will still put a strain on the health care system.

“The big caveat is we should not be complacent,” presidential Chief Medical Adviser Anthony Fauci, MD, said a White House briefing Jan. 5.

He added that Omicron “could still stress our hospital system because a certain proportion of a large volume of cases, no matter what, are going to be severe.”

Cases continue to increase greatly. This week’s 7-day daily average of infections is 491,700 -- an increase of 98% over last week, Dr. Walensky said. Hospitalizations, while lagging behind case numbers, are still rising significantly: The daily average is 14,800 admissions, up 63% from last week. Daily deaths this week are 1,200, an increase of only 5%.

Dr. Walensky continues to encourage vaccinations, boosters, and other precautions.

“Vaccines and boosters are protecting people from the severe and tragic outcomes that can occur from COVID-19 infection,” she said. “Get vaccinated and get boosted if eligible, wear a mask, stay home when you’re sick, and take a test if you have symptoms or are looking for greater reassurance before you gather with others.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

, Director Rochelle Walenksy, MD, said during a White House briefing Jan. 5.

Health officials recently shortened the recommended COVID-19 isolation and quarantine period from 10 days to 5, creating confusion amid an outbreak of the highly transmissible Omicron variant, which now accounts for 95% of cases in the United States.

Then, in slightly updated guidance, the CDC recommended using an at-home antigen test after 5 days of isolation if possible, even though these tests having aren’t as sensitive to the Omicron variant, according to the FDA.

“After we released our recs early last week, it became very clear people were interested in using the rapid test, though not authorized for this purpose after the end of their isolation period,” Dr. Walensky said. “We then provided guidance on how they should be used.”

“If that test is negative, people really do need to understand they must continue to wear their mask for those 5 days,” Dr. Walensky said.

But for many, the CDC guidelines are murky and seem to always change.

“Nearly 2 years into this pandemic, with Omicron cases surging across the country, the American people should be able to count on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for timely, accurate, clear guidance to protect themselves, their loved ones, and their communities,” American Medical Association president Gerald Harmon, MD, said in a statement. “Instead, the new recommendations on quarantine and isolation are not only confusing, but are risking further spread of the virus.”

About 31% of people remain infectious 5 days after a positive COVID-19 test, Dr. Harmon said, quoting the CDC’s own rationale for changing its guidance.

“With hundreds of thousands of new cases daily and more than a million positive reported cases on January 3, tens of thousands – potentially hundreds of thousands of people – could return to work and school infectious if they follow the CDC’s new guidance on ending isolation after 5 days without a negative test,” he said. “Physicians are concerned that these recommendations put our patients at risk and could further overwhelm our health care system.”

Instead, Dr. Harmon said a negative test should be required for ending isolation.

“Reemerging without knowing one’s status unnecessarily risks further transmission of the virus,” he said.

Meanwhile, also during the White House briefing, officials said that early data continue to show that Omicron infections are less severe than those from other variants, but skyrocketing cases will still put a strain on the health care system.

“The big caveat is we should not be complacent,” presidential Chief Medical Adviser Anthony Fauci, MD, said a White House briefing Jan. 5.

He added that Omicron “could still stress our hospital system because a certain proportion of a large volume of cases, no matter what, are going to be severe.”

Cases continue to increase greatly. This week’s 7-day daily average of infections is 491,700 -- an increase of 98% over last week, Dr. Walensky said. Hospitalizations, while lagging behind case numbers, are still rising significantly: The daily average is 14,800 admissions, up 63% from last week. Daily deaths this week are 1,200, an increase of only 5%.

Dr. Walensky continues to encourage vaccinations, boosters, and other precautions.

“Vaccines and boosters are protecting people from the severe and tragic outcomes that can occur from COVID-19 infection,” she said. “Get vaccinated and get boosted if eligible, wear a mask, stay home when you’re sick, and take a test if you have symptoms or are looking for greater reassurance before you gather with others.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

, Director Rochelle Walenksy, MD, said during a White House briefing Jan. 5.

Health officials recently shortened the recommended COVID-19 isolation and quarantine period from 10 days to 5, creating confusion amid an outbreak of the highly transmissible Omicron variant, which now accounts for 95% of cases in the United States.

Then, in slightly updated guidance, the CDC recommended using an at-home antigen test after 5 days of isolation if possible, even though these tests having aren’t as sensitive to the Omicron variant, according to the FDA.

“After we released our recs early last week, it became very clear people were interested in using the rapid test, though not authorized for this purpose after the end of their isolation period,” Dr. Walensky said. “We then provided guidance on how they should be used.”

“If that test is negative, people really do need to understand they must continue to wear their mask for those 5 days,” Dr. Walensky said.

But for many, the CDC guidelines are murky and seem to always change.

“Nearly 2 years into this pandemic, with Omicron cases surging across the country, the American people should be able to count on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for timely, accurate, clear guidance to protect themselves, their loved ones, and their communities,” American Medical Association president Gerald Harmon, MD, said in a statement. “Instead, the new recommendations on quarantine and isolation are not only confusing, but are risking further spread of the virus.”

About 31% of people remain infectious 5 days after a positive COVID-19 test, Dr. Harmon said, quoting the CDC’s own rationale for changing its guidance.

“With hundreds of thousands of new cases daily and more than a million positive reported cases on January 3, tens of thousands – potentially hundreds of thousands of people – could return to work and school infectious if they follow the CDC’s new guidance on ending isolation after 5 days without a negative test,” he said. “Physicians are concerned that these recommendations put our patients at risk and could further overwhelm our health care system.”

Instead, Dr. Harmon said a negative test should be required for ending isolation.

“Reemerging without knowing one’s status unnecessarily risks further transmission of the virus,” he said.

Meanwhile, also during the White House briefing, officials said that early data continue to show that Omicron infections are less severe than those from other variants, but skyrocketing cases will still put a strain on the health care system.

“The big caveat is we should not be complacent,” presidential Chief Medical Adviser Anthony Fauci, MD, said a White House briefing Jan. 5.

He added that Omicron “could still stress our hospital system because a certain proportion of a large volume of cases, no matter what, are going to be severe.”

Cases continue to increase greatly. This week’s 7-day daily average of infections is 491,700 -- an increase of 98% over last week, Dr. Walensky said. Hospitalizations, while lagging behind case numbers, are still rising significantly: The daily average is 14,800 admissions, up 63% from last week. Daily deaths this week are 1,200, an increase of only 5%.

Dr. Walensky continues to encourage vaccinations, boosters, and other precautions.

“Vaccines and boosters are protecting people from the severe and tragic outcomes that can occur from COVID-19 infection,” she said. “Get vaccinated and get boosted if eligible, wear a mask, stay home when you’re sick, and take a test if you have symptoms or are looking for greater reassurance before you gather with others.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Children and COVID: New cases, admissions are higher than ever

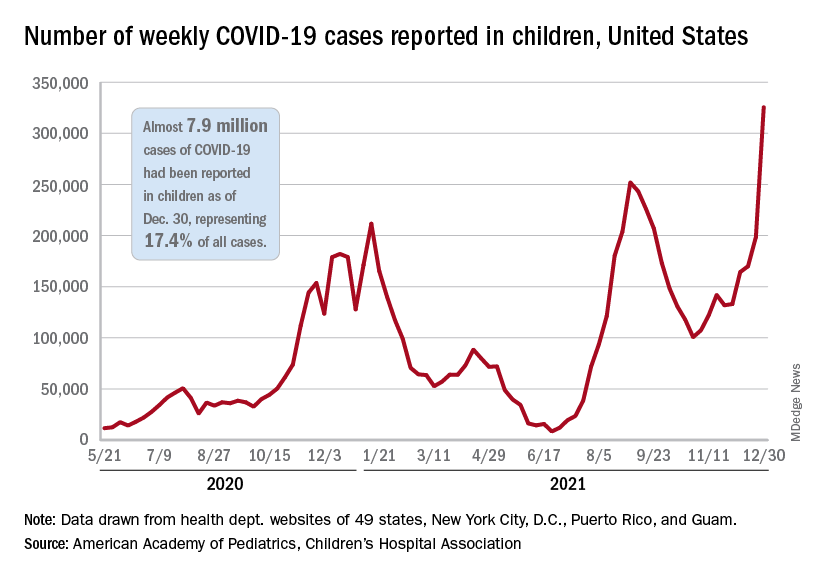

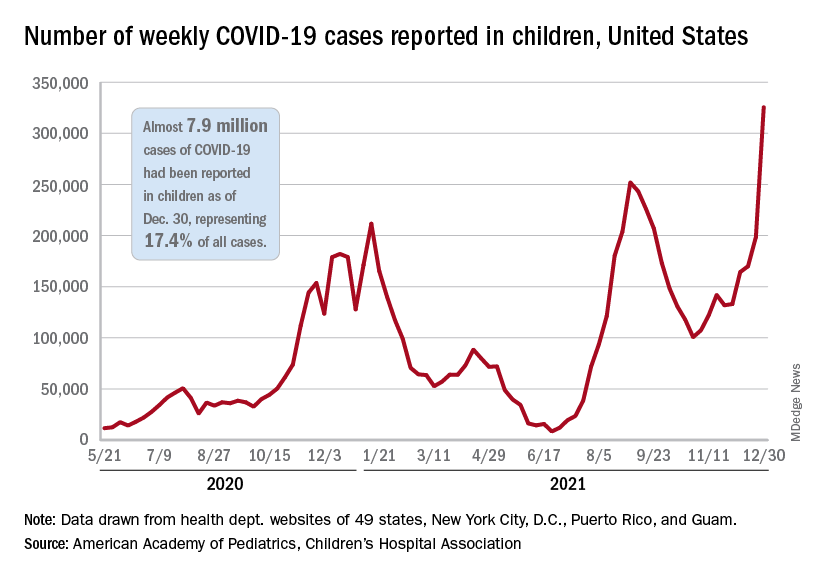

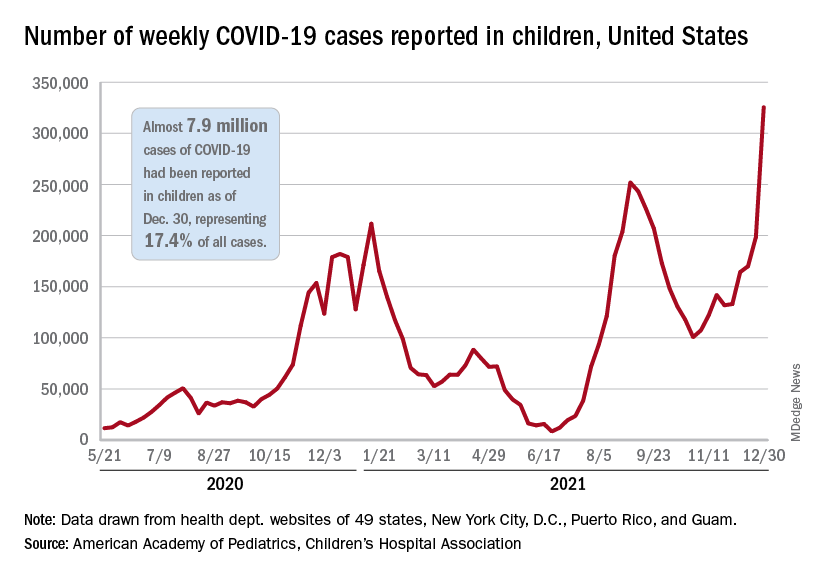

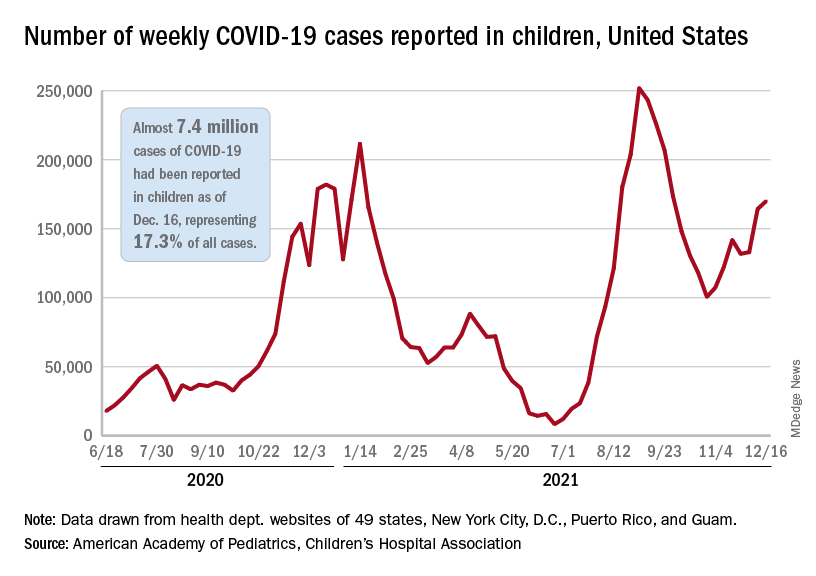

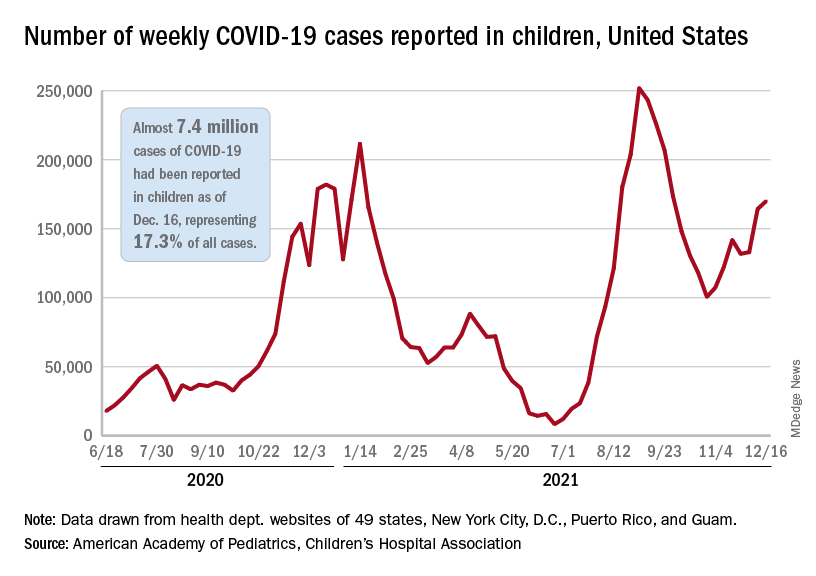

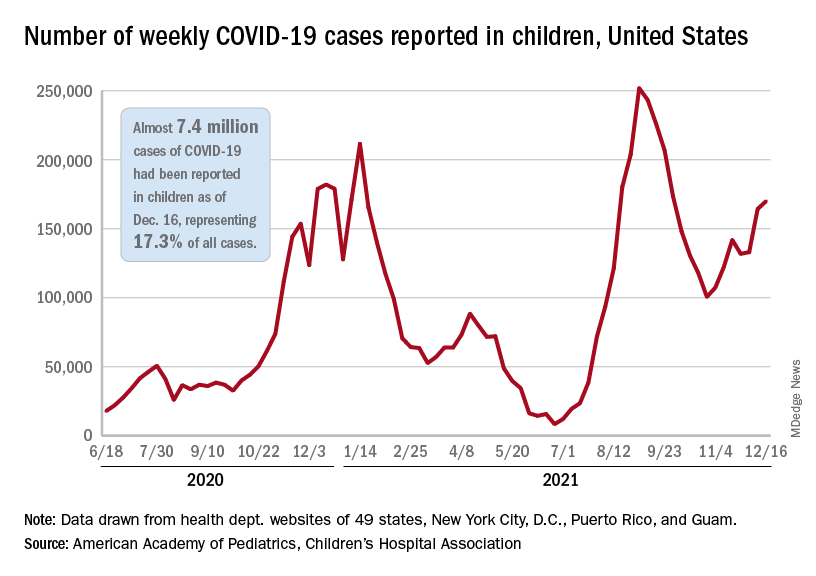

Weekly COVID-19 cases in children passed 300,000 for the first time since the pandemic started, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The rate of new COVID-related hospital admissions also reached a new high of 0.74 per 100,000 children as of Dec. 31. The highest rate seen before the current Omicron-fueled surge was 0.47 per 100,000 in early September, data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show.

and exceeding the previous week’s count by almost 64%, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report.

New cases were up in all four regions of the United States, with the Northeast adding the most newly infected children while setting a new high for the fifth consecutive week. The South was just behind for the week but still well off the record it reached in September, the Midwest was third but recorded its busiest week ever, and the West was fourth and nowhere near its previous high, the AAP/CHA report indicated.

The total number of child cases since the pandemic began is almost 7.9 million, they said based on data collected from 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam. That figure represents 17.4% of all cases reported in the United States, and the cumulative rate of COVID infection is up to almost 10,500 per 100,000 children, meaning that 1 in 10 children have been infected.

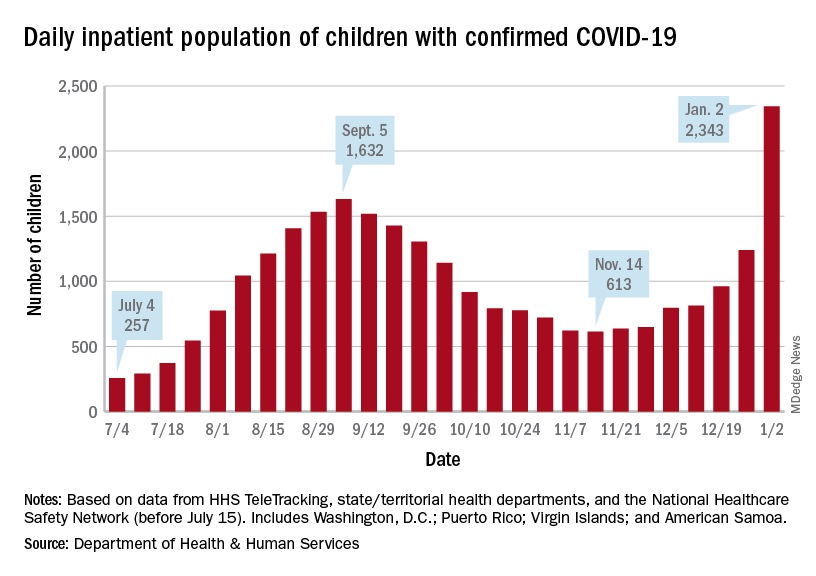

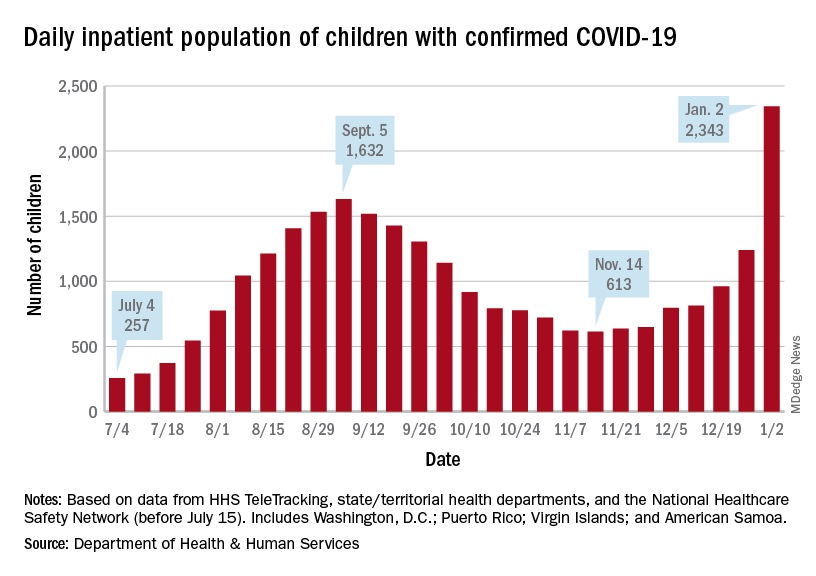

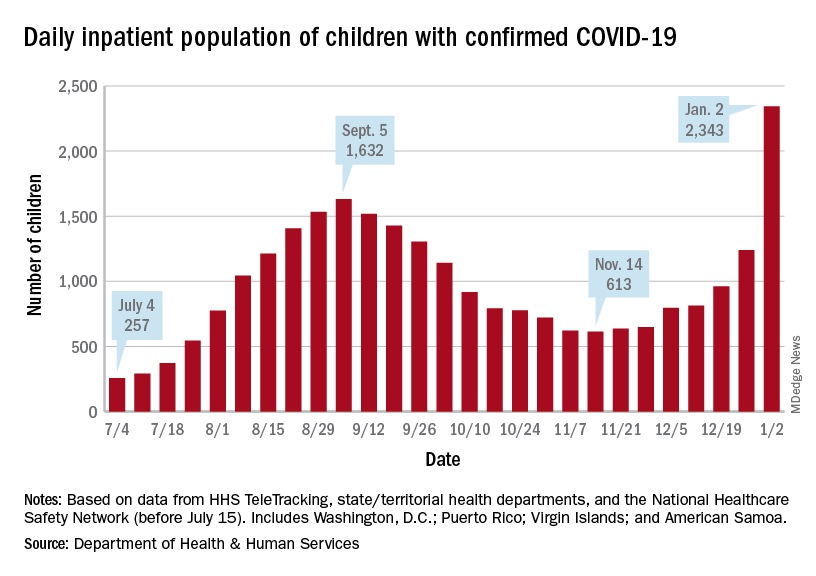

Children are still less likely to be hospitalized than adults, but the gap appears to be closing. On Jan. 2 there were 2,343 children and 87,690 adults in the hospital with confirmed COVID, a ratio of 37 adults for each child, but on Sept. 5, at the height of the previous surge, the ratio of hospitalized adults (93,647) to children (1,632) was 57:1, according to data from the Department of Health & Human Services.

New admissions show a similar pattern: The 0.74 admissions per 100,000 children recorded on Dec. 31 was lower than, for example, adults aged 30-39 years (2.7 per 100,000) or 50-59 years (4.25 per 100,000), but on Sept. 5 the corresponding figures were 0.46 (children), 2.74 (ages 30-39), and 5.03 (aged 50-59), based on the HHS data.

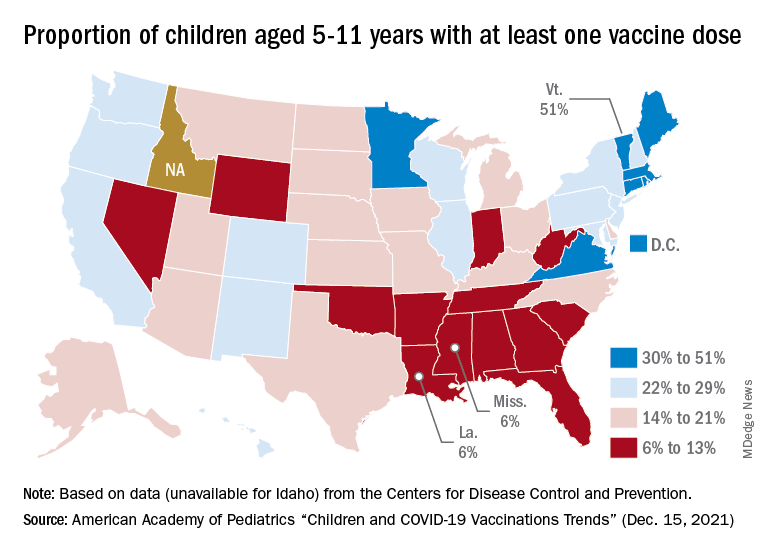

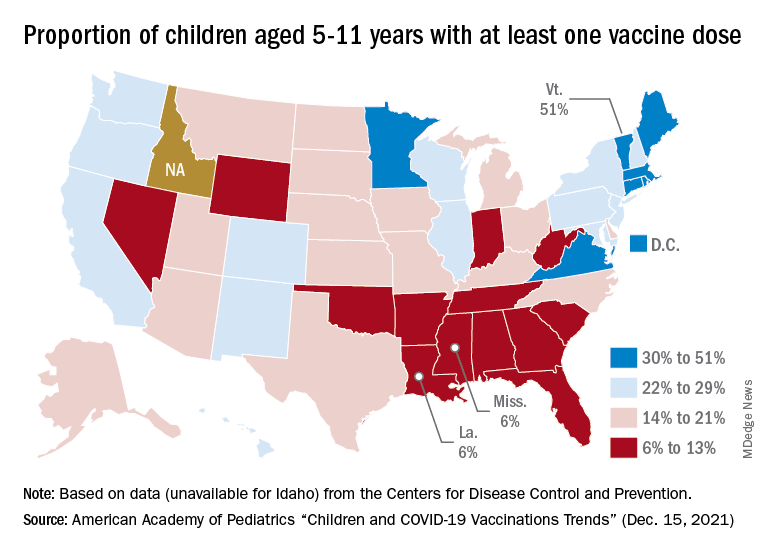

A look at vaccinations

The vaccination response to Omicron, however, has been more subdued and somewhat inconsistent. Vaccine initiation, not surprisingly, was down among eligible children for the week of Dec. 23-29. Before that, both the 5- to 11-year-olds and 12- to 15-year-olds were down for the second week of December and then up a bit (5.6% and 14.3%, respectively) during the third week, while the 16- to 17-year-olds, increased initiation by 63.2%, CDC’s COVID Data Tracker shows.

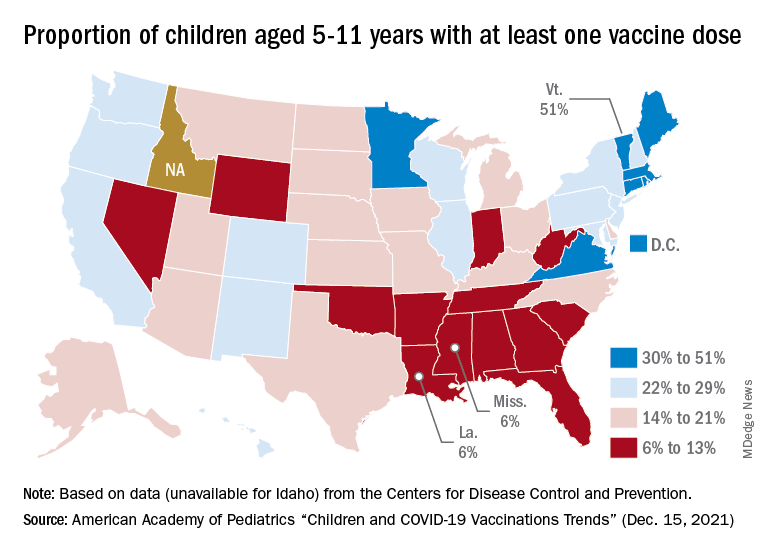

Less than a quarter (23.5%) of children aged 5-11 received at least one dose of the vaccine in the first 2 months of their eligibility, and only 14.7% are fully vaccinated. Among the older children, coverage looks like this: at least one dose for 61.2% of 12- to 15-year-olds and 67.4% of 16- to 17-year-olds and full vaccination for 51.3% and 57.6%, respectively, the CDC said.

At the state level, Massachusetts and Hawaii have the highest rates for children aged 12-17 years, with 86% having received a least one dose, and Vermont is highest for children aged 5-11 at 56%. The lowest rates can be found in Wyoming (38%) for 12- to 17-year-olds and in Mississippi (6%) for 5- to 11-year-olds, the AAP said in a separate report.

Weekly COVID-19 cases in children passed 300,000 for the first time since the pandemic started, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The rate of new COVID-related hospital admissions also reached a new high of 0.74 per 100,000 children as of Dec. 31. The highest rate seen before the current Omicron-fueled surge was 0.47 per 100,000 in early September, data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show.

and exceeding the previous week’s count by almost 64%, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report.

New cases were up in all four regions of the United States, with the Northeast adding the most newly infected children while setting a new high for the fifth consecutive week. The South was just behind for the week but still well off the record it reached in September, the Midwest was third but recorded its busiest week ever, and the West was fourth and nowhere near its previous high, the AAP/CHA report indicated.

The total number of child cases since the pandemic began is almost 7.9 million, they said based on data collected from 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam. That figure represents 17.4% of all cases reported in the United States, and the cumulative rate of COVID infection is up to almost 10,500 per 100,000 children, meaning that 1 in 10 children have been infected.

Children are still less likely to be hospitalized than adults, but the gap appears to be closing. On Jan. 2 there were 2,343 children and 87,690 adults in the hospital with confirmed COVID, a ratio of 37 adults for each child, but on Sept. 5, at the height of the previous surge, the ratio of hospitalized adults (93,647) to children (1,632) was 57:1, according to data from the Department of Health & Human Services.

New admissions show a similar pattern: The 0.74 admissions per 100,000 children recorded on Dec. 31 was lower than, for example, adults aged 30-39 years (2.7 per 100,000) or 50-59 years (4.25 per 100,000), but on Sept. 5 the corresponding figures were 0.46 (children), 2.74 (ages 30-39), and 5.03 (aged 50-59), based on the HHS data.

A look at vaccinations

The vaccination response to Omicron, however, has been more subdued and somewhat inconsistent. Vaccine initiation, not surprisingly, was down among eligible children for the week of Dec. 23-29. Before that, both the 5- to 11-year-olds and 12- to 15-year-olds were down for the second week of December and then up a bit (5.6% and 14.3%, respectively) during the third week, while the 16- to 17-year-olds, increased initiation by 63.2%, CDC’s COVID Data Tracker shows.

Less than a quarter (23.5%) of children aged 5-11 received at least one dose of the vaccine in the first 2 months of their eligibility, and only 14.7% are fully vaccinated. Among the older children, coverage looks like this: at least one dose for 61.2% of 12- to 15-year-olds and 67.4% of 16- to 17-year-olds and full vaccination for 51.3% and 57.6%, respectively, the CDC said.

At the state level, Massachusetts and Hawaii have the highest rates for children aged 12-17 years, with 86% having received a least one dose, and Vermont is highest for children aged 5-11 at 56%. The lowest rates can be found in Wyoming (38%) for 12- to 17-year-olds and in Mississippi (6%) for 5- to 11-year-olds, the AAP said in a separate report.

Weekly COVID-19 cases in children passed 300,000 for the first time since the pandemic started, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The rate of new COVID-related hospital admissions also reached a new high of 0.74 per 100,000 children as of Dec. 31. The highest rate seen before the current Omicron-fueled surge was 0.47 per 100,000 in early September, data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show.

and exceeding the previous week’s count by almost 64%, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report.

New cases were up in all four regions of the United States, with the Northeast adding the most newly infected children while setting a new high for the fifth consecutive week. The South was just behind for the week but still well off the record it reached in September, the Midwest was third but recorded its busiest week ever, and the West was fourth and nowhere near its previous high, the AAP/CHA report indicated.

The total number of child cases since the pandemic began is almost 7.9 million, they said based on data collected from 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam. That figure represents 17.4% of all cases reported in the United States, and the cumulative rate of COVID infection is up to almost 10,500 per 100,000 children, meaning that 1 in 10 children have been infected.

Children are still less likely to be hospitalized than adults, but the gap appears to be closing. On Jan. 2 there were 2,343 children and 87,690 adults in the hospital with confirmed COVID, a ratio of 37 adults for each child, but on Sept. 5, at the height of the previous surge, the ratio of hospitalized adults (93,647) to children (1,632) was 57:1, according to data from the Department of Health & Human Services.

New admissions show a similar pattern: The 0.74 admissions per 100,000 children recorded on Dec. 31 was lower than, for example, adults aged 30-39 years (2.7 per 100,000) or 50-59 years (4.25 per 100,000), but on Sept. 5 the corresponding figures were 0.46 (children), 2.74 (ages 30-39), and 5.03 (aged 50-59), based on the HHS data.

A look at vaccinations

The vaccination response to Omicron, however, has been more subdued and somewhat inconsistent. Vaccine initiation, not surprisingly, was down among eligible children for the week of Dec. 23-29. Before that, both the 5- to 11-year-olds and 12- to 15-year-olds were down for the second week of December and then up a bit (5.6% and 14.3%, respectively) during the third week, while the 16- to 17-year-olds, increased initiation by 63.2%, CDC’s COVID Data Tracker shows.

Less than a quarter (23.5%) of children aged 5-11 received at least one dose of the vaccine in the first 2 months of their eligibility, and only 14.7% are fully vaccinated. Among the older children, coverage looks like this: at least one dose for 61.2% of 12- to 15-year-olds and 67.4% of 16- to 17-year-olds and full vaccination for 51.3% and 57.6%, respectively, the CDC said.

At the state level, Massachusetts and Hawaii have the highest rates for children aged 12-17 years, with 86% having received a least one dose, and Vermont is highest for children aged 5-11 at 56%. The lowest rates can be found in Wyoming (38%) for 12- to 17-year-olds and in Mississippi (6%) for 5- to 11-year-olds, the AAP said in a separate report.

COVID-19–positive or exposed? What to do next

With new cases of COVID-19 skyrocketing to more than 240,000 a day recently in the U.S., many people are facing the same situation: A family member or friend tests positive or was exposed to someone who did, and the holiday gathering, visit, or return to work is just days or hours away. Now what?

New guidance issued Dec. 27 by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shortens the recommended isolation and quarantine period for the general population, coming after the agency shortened the isolation period for health care workers.

This news organization reached out to two infectious disease specialists to get answers to questions that are frequently asked in these situations.

If you have tested positive for COVID-19, what do you do next?

“If you have tested positive, you are infected. At the moment, you are [either] symptomatically affected or presymptomatically infected,’’ said Paul A. Offit, MD, director of the Vaccine Education Center and professor of pediatrics at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. At that point, you need to isolate for 5 days, according to the new CDC guidance. (That period has been shortened from 10 days.)

Isolation means separating the infected person from others. Quarantine refers to things you should do if you’re exposed to the virus or you have a close contact infected with COVID-19.

Under the new CDC guidelines, after the 5-day isolation, if the infected person then has no symptoms, he or she can leave isolation and then wear a mask for 5 days.

Those who test positive also need to tell their close contacts they are positive, said Amesh Adalja, MD, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security.

According to the CDC, the change to a shortened quarantine time is motivated by science ‘’demonstrating that the majority of SARS-CoV-2 transmission occurs early in the course of the illness, generally in the 1-2 days prior to onset of symptoms and the 2-3 days after.”

If you have been exposed to someone with COVID-19, what do you do next?

“If they are vaccinated and boosted, the guidance says there is no need to quarantine,” Dr. Adalja said. But the CDC guidance does recommend these people wear a well-fitting mask at all times when around others for 10 days after exposure.

For everyone else, including the unvaccinated and those who are more than 6 months out from their second Pfizer or Moderna vaccine dose, or more than 2 months from their J&J dose, the CDC recommends a quarantine for 5 days – and wearing a mask for the 5 days after that.

On a practical level, Dr. Adalja said he thinks those who are vaccinated but not boosted could also skip the quarantine and wear a mask for 10 days. Dr. Offit agrees. Because many people exposed have trouble quarantining, Dr. Offit advises those exposed who can’t follow that guidance to be sure to wear a mask for 10 days when indoors. The CDC guidance also offers that as another strategy – that if a 5-day quarantine is not feasible, the exposed person should wear a mask for 10 days when around others.

But if someone who was exposed gets symptoms, that person then enters the infected category and follows that guidance, Dr. Offit said.

When should the person who has been exposed get tested?

After the exposure, ‘’you should probably wait 2-3 days,” Dr. Offit said. “The virus has to reproduce itself.”

Testing should be done by those exposed at least once, Dr. Adalja said.

“But there’s data to support daily testing to guide their activities, but this is not CDC guidance. Home tests are sufficient for this purpose.”

At what point can the infected person mingle safely with others?

“Technically, if asymptomatic, 10 days without a mask, 5 days with a mask,” said Dr. Adalja. “I think this could also be guided with home test negativity being a gauge [as to whether to mingle].”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

With new cases of COVID-19 skyrocketing to more than 240,000 a day recently in the U.S., many people are facing the same situation: A family member or friend tests positive or was exposed to someone who did, and the holiday gathering, visit, or return to work is just days or hours away. Now what?

New guidance issued Dec. 27 by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shortens the recommended isolation and quarantine period for the general population, coming after the agency shortened the isolation period for health care workers.

This news organization reached out to two infectious disease specialists to get answers to questions that are frequently asked in these situations.

If you have tested positive for COVID-19, what do you do next?

“If you have tested positive, you are infected. At the moment, you are [either] symptomatically affected or presymptomatically infected,’’ said Paul A. Offit, MD, director of the Vaccine Education Center and professor of pediatrics at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. At that point, you need to isolate for 5 days, according to the new CDC guidance. (That period has been shortened from 10 days.)

Isolation means separating the infected person from others. Quarantine refers to things you should do if you’re exposed to the virus or you have a close contact infected with COVID-19.

Under the new CDC guidelines, after the 5-day isolation, if the infected person then has no symptoms, he or she can leave isolation and then wear a mask for 5 days.

Those who test positive also need to tell their close contacts they are positive, said Amesh Adalja, MD, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security.

According to the CDC, the change to a shortened quarantine time is motivated by science ‘’demonstrating that the majority of SARS-CoV-2 transmission occurs early in the course of the illness, generally in the 1-2 days prior to onset of symptoms and the 2-3 days after.”

If you have been exposed to someone with COVID-19, what do you do next?

“If they are vaccinated and boosted, the guidance says there is no need to quarantine,” Dr. Adalja said. But the CDC guidance does recommend these people wear a well-fitting mask at all times when around others for 10 days after exposure.

For everyone else, including the unvaccinated and those who are more than 6 months out from their second Pfizer or Moderna vaccine dose, or more than 2 months from their J&J dose, the CDC recommends a quarantine for 5 days – and wearing a mask for the 5 days after that.

On a practical level, Dr. Adalja said he thinks those who are vaccinated but not boosted could also skip the quarantine and wear a mask for 10 days. Dr. Offit agrees. Because many people exposed have trouble quarantining, Dr. Offit advises those exposed who can’t follow that guidance to be sure to wear a mask for 10 days when indoors. The CDC guidance also offers that as another strategy – that if a 5-day quarantine is not feasible, the exposed person should wear a mask for 10 days when around others.

But if someone who was exposed gets symptoms, that person then enters the infected category and follows that guidance, Dr. Offit said.

When should the person who has been exposed get tested?

After the exposure, ‘’you should probably wait 2-3 days,” Dr. Offit said. “The virus has to reproduce itself.”

Testing should be done by those exposed at least once, Dr. Adalja said.

“But there’s data to support daily testing to guide their activities, but this is not CDC guidance. Home tests are sufficient for this purpose.”

At what point can the infected person mingle safely with others?

“Technically, if asymptomatic, 10 days without a mask, 5 days with a mask,” said Dr. Adalja. “I think this could also be guided with home test negativity being a gauge [as to whether to mingle].”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

With new cases of COVID-19 skyrocketing to more than 240,000 a day recently in the U.S., many people are facing the same situation: A family member or friend tests positive or was exposed to someone who did, and the holiday gathering, visit, or return to work is just days or hours away. Now what?

New guidance issued Dec. 27 by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shortens the recommended isolation and quarantine period for the general population, coming after the agency shortened the isolation period for health care workers.

This news organization reached out to two infectious disease specialists to get answers to questions that are frequently asked in these situations.

If you have tested positive for COVID-19, what do you do next?

“If you have tested positive, you are infected. At the moment, you are [either] symptomatically affected or presymptomatically infected,’’ said Paul A. Offit, MD, director of the Vaccine Education Center and professor of pediatrics at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. At that point, you need to isolate for 5 days, according to the new CDC guidance. (That period has been shortened from 10 days.)

Isolation means separating the infected person from others. Quarantine refers to things you should do if you’re exposed to the virus or you have a close contact infected with COVID-19.

Under the new CDC guidelines, after the 5-day isolation, if the infected person then has no symptoms, he or she can leave isolation and then wear a mask for 5 days.

Those who test positive also need to tell their close contacts they are positive, said Amesh Adalja, MD, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security.

According to the CDC, the change to a shortened quarantine time is motivated by science ‘’demonstrating that the majority of SARS-CoV-2 transmission occurs early in the course of the illness, generally in the 1-2 days prior to onset of symptoms and the 2-3 days after.”

If you have been exposed to someone with COVID-19, what do you do next?

“If they are vaccinated and boosted, the guidance says there is no need to quarantine,” Dr. Adalja said. But the CDC guidance does recommend these people wear a well-fitting mask at all times when around others for 10 days after exposure.

For everyone else, including the unvaccinated and those who are more than 6 months out from their second Pfizer or Moderna vaccine dose, or more than 2 months from their J&J dose, the CDC recommends a quarantine for 5 days – and wearing a mask for the 5 days after that.

On a practical level, Dr. Adalja said he thinks those who are vaccinated but not boosted could also skip the quarantine and wear a mask for 10 days. Dr. Offit agrees. Because many people exposed have trouble quarantining, Dr. Offit advises those exposed who can’t follow that guidance to be sure to wear a mask for 10 days when indoors. The CDC guidance also offers that as another strategy – that if a 5-day quarantine is not feasible, the exposed person should wear a mask for 10 days when around others.

But if someone who was exposed gets symptoms, that person then enters the infected category and follows that guidance, Dr. Offit said.

When should the person who has been exposed get tested?

After the exposure, ‘’you should probably wait 2-3 days,” Dr. Offit said. “The virus has to reproduce itself.”

Testing should be done by those exposed at least once, Dr. Adalja said.

“But there’s data to support daily testing to guide their activities, but this is not CDC guidance. Home tests are sufficient for this purpose.”

At what point can the infected person mingle safely with others?

“Technically, if asymptomatic, 10 days without a mask, 5 days with a mask,” said Dr. Adalja. “I think this could also be guided with home test negativity being a gauge [as to whether to mingle].”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

COVID-19 antigen tests may be less sensitive to Omicron: FDA

Rapid antigen tests for COVID-19 might be less effective at detecting the Omicron variant that is spreading rapidly across the United States, according to the Food and Drug Administration.

Early data suggest that COVID-19 antigen tests “do detect the Omicron variant but may have reduced sensitivity,” the FDA said in a statement posted Dec. 28 on its website.

The FDA is working with the National Institutes of Health’s Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostics (RADx) initiative to assess the performance of antigen tests with patient samples that have the Omicron variant.

The potential for antigen tests to be less sensitive for the Omicron variant emerged in tests using patient samples containing live virus, “which represents the best way to evaluate true test performance in the short term,” the FDA said.

Initial laboratory tests using heat-activated (killed) virus samples found that antigen tests were able to detect the Omicron variant.

“It is important to note that these laboratory data are not a replacement for clinical study evaluations using patient samples with live virus, which are ongoing. The FDA and RADx are continuing to further evaluate the performance of antigen tests using patient samples with live virus,” the FDA said.

Testing still important

The agency continues to recommend use of antigen tests as directed in the authorized labeling and in accordance with the instructions included with the tests.

They note that antigen tests are generally less sensitive and less likely to pick up very early infections, compared with molecular tests.

The FDA continues to recommend that an individual with a negative antigen test who has symptoms or a high likelihood of infection because of exposure follow-up with a molecular test to determine if they have COVID-19.

An individual with a positive antigen test should self-isolate and seek follow-up care with a health care provider to determine the next steps.

The FDA, with partners and test developers, are continuing to evaluate test sensitivity, as well as the best timing and frequency of antigen testing.

The agency said that it will provide updated information and any needed recommendations when appropriate.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Rapid antigen tests for COVID-19 might be less effective at detecting the Omicron variant that is spreading rapidly across the United States, according to the Food and Drug Administration.

Early data suggest that COVID-19 antigen tests “do detect the Omicron variant but may have reduced sensitivity,” the FDA said in a statement posted Dec. 28 on its website.

The FDA is working with the National Institutes of Health’s Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostics (RADx) initiative to assess the performance of antigen tests with patient samples that have the Omicron variant.

The potential for antigen tests to be less sensitive for the Omicron variant emerged in tests using patient samples containing live virus, “which represents the best way to evaluate true test performance in the short term,” the FDA said.

Initial laboratory tests using heat-activated (killed) virus samples found that antigen tests were able to detect the Omicron variant.

“It is important to note that these laboratory data are not a replacement for clinical study evaluations using patient samples with live virus, which are ongoing. The FDA and RADx are continuing to further evaluate the performance of antigen tests using patient samples with live virus,” the FDA said.

Testing still important

The agency continues to recommend use of antigen tests as directed in the authorized labeling and in accordance with the instructions included with the tests.

They note that antigen tests are generally less sensitive and less likely to pick up very early infections, compared with molecular tests.

The FDA continues to recommend that an individual with a negative antigen test who has symptoms or a high likelihood of infection because of exposure follow-up with a molecular test to determine if they have COVID-19.

An individual with a positive antigen test should self-isolate and seek follow-up care with a health care provider to determine the next steps.

The FDA, with partners and test developers, are continuing to evaluate test sensitivity, as well as the best timing and frequency of antigen testing.

The agency said that it will provide updated information and any needed recommendations when appropriate.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Rapid antigen tests for COVID-19 might be less effective at detecting the Omicron variant that is spreading rapidly across the United States, according to the Food and Drug Administration.

Early data suggest that COVID-19 antigen tests “do detect the Omicron variant but may have reduced sensitivity,” the FDA said in a statement posted Dec. 28 on its website.

The FDA is working with the National Institutes of Health’s Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostics (RADx) initiative to assess the performance of antigen tests with patient samples that have the Omicron variant.

The potential for antigen tests to be less sensitive for the Omicron variant emerged in tests using patient samples containing live virus, “which represents the best way to evaluate true test performance in the short term,” the FDA said.

Initial laboratory tests using heat-activated (killed) virus samples found that antigen tests were able to detect the Omicron variant.

“It is important to note that these laboratory data are not a replacement for clinical study evaluations using patient samples with live virus, which are ongoing. The FDA and RADx are continuing to further evaluate the performance of antigen tests using patient samples with live virus,” the FDA said.

Testing still important

The agency continues to recommend use of antigen tests as directed in the authorized labeling and in accordance with the instructions included with the tests.

They note that antigen tests are generally less sensitive and less likely to pick up very early infections, compared with molecular tests.

The FDA continues to recommend that an individual with a negative antigen test who has symptoms or a high likelihood of infection because of exposure follow-up with a molecular test to determine if they have COVID-19.

An individual with a positive antigen test should self-isolate and seek follow-up care with a health care provider to determine the next steps.

The FDA, with partners and test developers, are continuing to evaluate test sensitivity, as well as the best timing and frequency of antigen testing.

The agency said that it will provide updated information and any needed recommendations when appropriate.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Children and COVID: Nearly 200,000 new cases reported in 1 week

, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

Available state data show that 198,551 child COVID cases were added during the week of Dec. 17-23 – up by 16.8% from the nearly 170,000 new cases reported the previous week and the highest 7-day figure since Sept. 17-23, when 207,000 cases were reported, the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly COVID report. Since Oct. 22-28, when the weekly count dropped to a seasonal low, the weekly count has nearly doubled.

The largest shares of the nearly 199,000 new cases were divided pretty equally between the Northeast and the South, while the West had just a small bump in cases and the Midwest was in the middle. The largest statewide percent increases came in the New England states, along with New Jersey, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. New York State does not report age ranges for COVID cases, the AAP/CHA report noted.

Emergency department visits and hospital admissions are following a similar trend, as both have risen considerably over the last 2 months, data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show.

COVID-related ED visits for children aged 0-11 years – measured as a proportion of all ED visits – are nearing the pandemic high of 4.1% set in late August, while visits in 12- to 15-year-olds have risen from 1.4% in early November to 5.6% on Dec. 24 and 16- to 17-year-olds have gone from 1.5% to 6% over the same period of time, the CDC reported on its COVID Data Tracker.

As for hospital admissions in children aged 0-17 years, the rate was down to 0.19 per 100,000 population on Nov. 11 but had risen to 0.38 per 100,000 as of Dec. 24. The highest point reached in children during the pandemic was 0.46 per 100,000 in early September, the CDC said.

On Dec. 23, 367 children were admitted to hospitals in the United States, the highest number since Sept. 7, when 374 were hospitalized. The highest 1-day total over the course of the pandemic, 394, came just a week before that, Aug. 31, according to the Department of Health & Human Services.

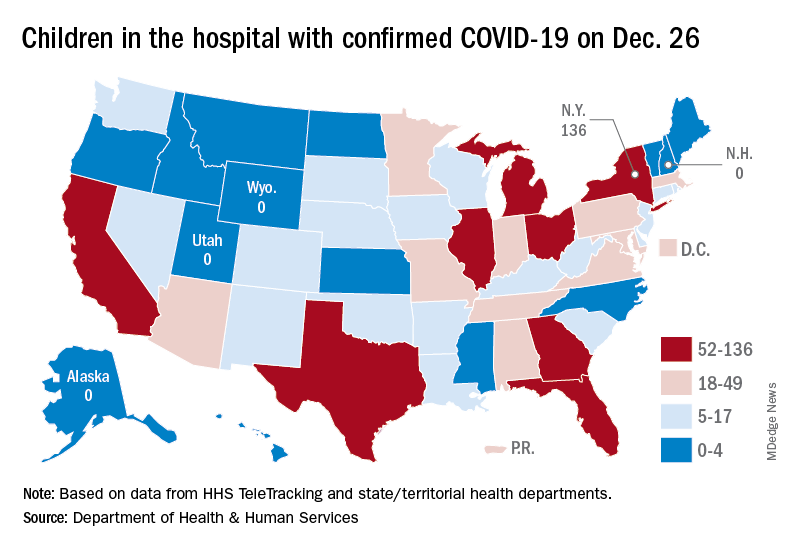

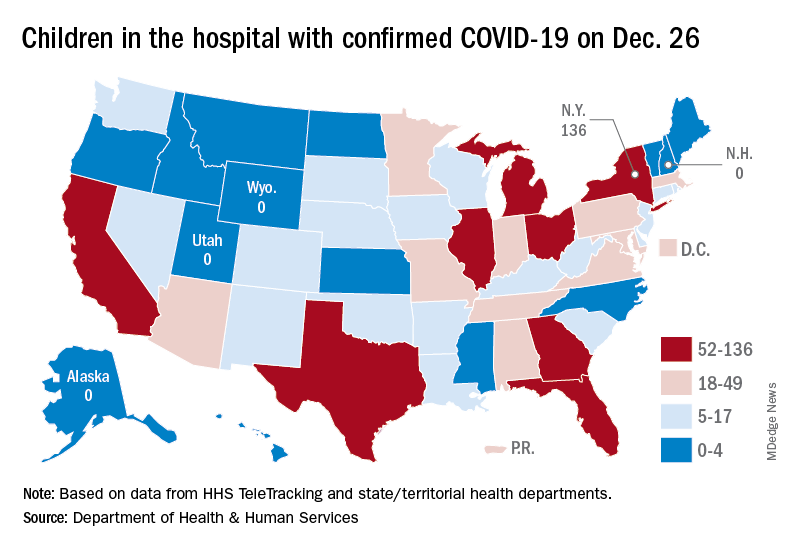

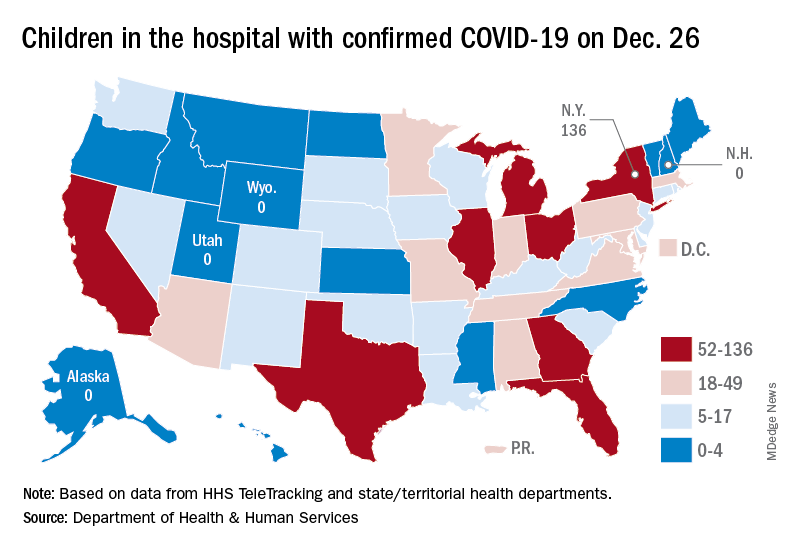

A look at the most recent HHS data shows that 1,161 children were being hospitalized in pediatric inpatient beds with confirmed COVID-19 on Dec. 26. The highest number by state was in New York (136), followed by Texas (90) and Illinois and Ohio, both with 83. There were four states – Alaska, New Hampshire, Utah, and Wyoming – with no hospitalized children, the HHS said. Puerto Rico, meanwhile, had 28 children in the hospital with COVID, more than 38 states.

, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

Available state data show that 198,551 child COVID cases were added during the week of Dec. 17-23 – up by 16.8% from the nearly 170,000 new cases reported the previous week and the highest 7-day figure since Sept. 17-23, when 207,000 cases were reported, the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly COVID report. Since Oct. 22-28, when the weekly count dropped to a seasonal low, the weekly count has nearly doubled.

The largest shares of the nearly 199,000 new cases were divided pretty equally between the Northeast and the South, while the West had just a small bump in cases and the Midwest was in the middle. The largest statewide percent increases came in the New England states, along with New Jersey, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. New York State does not report age ranges for COVID cases, the AAP/CHA report noted.

Emergency department visits and hospital admissions are following a similar trend, as both have risen considerably over the last 2 months, data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show.

COVID-related ED visits for children aged 0-11 years – measured as a proportion of all ED visits – are nearing the pandemic high of 4.1% set in late August, while visits in 12- to 15-year-olds have risen from 1.4% in early November to 5.6% on Dec. 24 and 16- to 17-year-olds have gone from 1.5% to 6% over the same period of time, the CDC reported on its COVID Data Tracker.

As for hospital admissions in children aged 0-17 years, the rate was down to 0.19 per 100,000 population on Nov. 11 but had risen to 0.38 per 100,000 as of Dec. 24. The highest point reached in children during the pandemic was 0.46 per 100,000 in early September, the CDC said.

On Dec. 23, 367 children were admitted to hospitals in the United States, the highest number since Sept. 7, when 374 were hospitalized. The highest 1-day total over the course of the pandemic, 394, came just a week before that, Aug. 31, according to the Department of Health & Human Services.

A look at the most recent HHS data shows that 1,161 children were being hospitalized in pediatric inpatient beds with confirmed COVID-19 on Dec. 26. The highest number by state was in New York (136), followed by Texas (90) and Illinois and Ohio, both with 83. There were four states – Alaska, New Hampshire, Utah, and Wyoming – with no hospitalized children, the HHS said. Puerto Rico, meanwhile, had 28 children in the hospital with COVID, more than 38 states.

, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

Available state data show that 198,551 child COVID cases were added during the week of Dec. 17-23 – up by 16.8% from the nearly 170,000 new cases reported the previous week and the highest 7-day figure since Sept. 17-23, when 207,000 cases were reported, the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly COVID report. Since Oct. 22-28, when the weekly count dropped to a seasonal low, the weekly count has nearly doubled.

The largest shares of the nearly 199,000 new cases were divided pretty equally between the Northeast and the South, while the West had just a small bump in cases and the Midwest was in the middle. The largest statewide percent increases came in the New England states, along with New Jersey, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. New York State does not report age ranges for COVID cases, the AAP/CHA report noted.

Emergency department visits and hospital admissions are following a similar trend, as both have risen considerably over the last 2 months, data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show.

COVID-related ED visits for children aged 0-11 years – measured as a proportion of all ED visits – are nearing the pandemic high of 4.1% set in late August, while visits in 12- to 15-year-olds have risen from 1.4% in early November to 5.6% on Dec. 24 and 16- to 17-year-olds have gone from 1.5% to 6% over the same period of time, the CDC reported on its COVID Data Tracker.

As for hospital admissions in children aged 0-17 years, the rate was down to 0.19 per 100,000 population on Nov. 11 but had risen to 0.38 per 100,000 as of Dec. 24. The highest point reached in children during the pandemic was 0.46 per 100,000 in early September, the CDC said.

On Dec. 23, 367 children were admitted to hospitals in the United States, the highest number since Sept. 7, when 374 were hospitalized. The highest 1-day total over the course of the pandemic, 394, came just a week before that, Aug. 31, according to the Department of Health & Human Services.

A look at the most recent HHS data shows that 1,161 children were being hospitalized in pediatric inpatient beds with confirmed COVID-19 on Dec. 26. The highest number by state was in New York (136), followed by Texas (90) and Illinois and Ohio, both with 83. There were four states – Alaska, New Hampshire, Utah, and Wyoming – with no hospitalized children, the HHS said. Puerto Rico, meanwhile, had 28 children in the hospital with COVID, more than 38 states.

FDA gives nod to tralokinumab for adults with moderate to severe AD

whose disease is not well controlled with topical prescription therapies or when those therapies are not advisable.

Administered subcutaneously, tralokinumab is a fully human IgG4 monoclonal antibody that specifically binds to interleukin-13, a key driver of underlying inflammation in AD. The drug, which has been developed by LEO Pharma, comes as a single-dose (150 mg) prefilled syringe with needle guard.

In two pivotal phase 3 trials, ECZTRA 1 and ECZTRA 2, tralokinumab monotherapy was superior to placebo at week 16 for all primary and secondary endpoints. For example, at week 16, for the ECZTRA 1 and 2 monotherapy trials, respectively, 16% and 21% of patients treated with tralokinumab 300 mg every other week achieved clear or almost clear skin (IGA 0/1) versus 7% and 9% with placebo.

In addition, 25% and 33% of patients treated with tralokinumab 300 mg every other week achieved an improvement of 75% or more in the Eczema Area and Severity Index score (EASI-75) versus 13% and 10% with placebo. At 52 weeks, 51% and 60% of patients who responded at week 16 maintained IGA 0/1 response with tralokinumab 300 mg every other week in ECZTRA 1 and 2, respectively.

Finally, 60% and 57% of patients who responded at week 16 maintained EASI-75 response with tralokinumab 300 mg every other week.

In the drug’s third pivotal trial, ECZTRA 3, researchers evaluated the efficacy and safety of tralokinumab 300 mg in combination with topical corticosteroids (TCS) as needed in adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis who are candidates for systemic therapy. At week 16, 38% of patients treated with tralokinumab 300 mg every other week plus TCS achieved clear or almost clear skin (IGA 0/1) versus 27% with placebo plus TCS. In addition, 56% of patients treated with tralokinumab 300 mg every other week plus TCS achieved an improvement of 75% or more in the EASI-75 versus 37% with placebo plus TCS. At 32 weeks, 89% and 92% of patients who responded at week 16 maintained response (IGA 0/1 and EASI-75, respectively) with tralokinumab 300 mg every other week.

A link to prescribing information can be found here. Tralokinumab is expected to be available by February 2022.

whose disease is not well controlled with topical prescription therapies or when those therapies are not advisable.

Administered subcutaneously, tralokinumab is a fully human IgG4 monoclonal antibody that specifically binds to interleukin-13, a key driver of underlying inflammation in AD. The drug, which has been developed by LEO Pharma, comes as a single-dose (150 mg) prefilled syringe with needle guard.

In two pivotal phase 3 trials, ECZTRA 1 and ECZTRA 2, tralokinumab monotherapy was superior to placebo at week 16 for all primary and secondary endpoints. For example, at week 16, for the ECZTRA 1 and 2 monotherapy trials, respectively, 16% and 21% of patients treated with tralokinumab 300 mg every other week achieved clear or almost clear skin (IGA 0/1) versus 7% and 9% with placebo.

In addition, 25% and 33% of patients treated with tralokinumab 300 mg every other week achieved an improvement of 75% or more in the Eczema Area and Severity Index score (EASI-75) versus 13% and 10% with placebo. At 52 weeks, 51% and 60% of patients who responded at week 16 maintained IGA 0/1 response with tralokinumab 300 mg every other week in ECZTRA 1 and 2, respectively.

Finally, 60% and 57% of patients who responded at week 16 maintained EASI-75 response with tralokinumab 300 mg every other week.

In the drug’s third pivotal trial, ECZTRA 3, researchers evaluated the efficacy and safety of tralokinumab 300 mg in combination with topical corticosteroids (TCS) as needed in adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis who are candidates for systemic therapy. At week 16, 38% of patients treated with tralokinumab 300 mg every other week plus TCS achieved clear or almost clear skin (IGA 0/1) versus 27% with placebo plus TCS. In addition, 56% of patients treated with tralokinumab 300 mg every other week plus TCS achieved an improvement of 75% or more in the EASI-75 versus 37% with placebo plus TCS. At 32 weeks, 89% and 92% of patients who responded at week 16 maintained response (IGA 0/1 and EASI-75, respectively) with tralokinumab 300 mg every other week.

A link to prescribing information can be found here. Tralokinumab is expected to be available by February 2022.

whose disease is not well controlled with topical prescription therapies or when those therapies are not advisable.

Administered subcutaneously, tralokinumab is a fully human IgG4 monoclonal antibody that specifically binds to interleukin-13, a key driver of underlying inflammation in AD. The drug, which has been developed by LEO Pharma, comes as a single-dose (150 mg) prefilled syringe with needle guard.

In two pivotal phase 3 trials, ECZTRA 1 and ECZTRA 2, tralokinumab monotherapy was superior to placebo at week 16 for all primary and secondary endpoints. For example, at week 16, for the ECZTRA 1 and 2 monotherapy trials, respectively, 16% and 21% of patients treated with tralokinumab 300 mg every other week achieved clear or almost clear skin (IGA 0/1) versus 7% and 9% with placebo.

In addition, 25% and 33% of patients treated with tralokinumab 300 mg every other week achieved an improvement of 75% or more in the Eczema Area and Severity Index score (EASI-75) versus 13% and 10% with placebo. At 52 weeks, 51% and 60% of patients who responded at week 16 maintained IGA 0/1 response with tralokinumab 300 mg every other week in ECZTRA 1 and 2, respectively.

Finally, 60% and 57% of patients who responded at week 16 maintained EASI-75 response with tralokinumab 300 mg every other week.

In the drug’s third pivotal trial, ECZTRA 3, researchers evaluated the efficacy and safety of tralokinumab 300 mg in combination with topical corticosteroids (TCS) as needed in adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis who are candidates for systemic therapy. At week 16, 38% of patients treated with tralokinumab 300 mg every other week plus TCS achieved clear or almost clear skin (IGA 0/1) versus 27% with placebo plus TCS. In addition, 56% of patients treated with tralokinumab 300 mg every other week plus TCS achieved an improvement of 75% or more in the EASI-75 versus 37% with placebo plus TCS. At 32 weeks, 89% and 92% of patients who responded at week 16 maintained response (IGA 0/1 and EASI-75, respectively) with tralokinumab 300 mg every other week.

A link to prescribing information can be found here. Tralokinumab is expected to be available by February 2022.

FDA authorizes Pfizer antiviral pill for COVID-19

The Food and Drug Administration on Dec. 22, 2021, granted emergency use authorization (EUA) for a new antiviral pill to treat people with symptomatic COVID-19.

Pfizer’s ritonavir, name brand Paxlovid, can now be taken by patients ages 12 and up who weigh at least 88 pounds.

The antiviral is only for people who test positive for the coronavirus and who are at high risk for severe COVID-19, including hospitalization or death. It is available by prescription only and should be taken as soon as possible after diagnosis and within 5 days of the start of symptoms.

Paxlovid is taken as three tablets together orally twice a day for 5 days, for a total of 30 tablets.

Possible side effects include a reduced sense of taste, diarrhea, high blood pressure, and muscle aches.

The authorization arrives as U.S. cases of the Omicron variant are surging, some monoclonal antibody treatments are becoming less effective, and Americans struggle to maintain some sense of tradition and normalcy around the holidays.

Paxlovid joins remdesivir as an available antiviral to treat COVID-19. Remdesivir is fully approved by the FDA but is given only intravenously in a hospital.

The COVID-19 antiviral pills come with some obvious advantages, including greater convenience for consumers – such as home use – and the potential to expand treatment for people in low- and middle-income countries.

‘An exciting step forward’

The EUA for Pfizer’s new drug has been highly anticipated, and news of its impending authorization circulated on social media on Tuesday. Eric Topol, MD, called the development an “exciting step forward.” Dr. Topol is editor in chief of Medscape, the parent company of MDedge.

He and many others also expected the FDA to grant emergency use authorization for an antiviral from Merck. But there was no immediate word Wednesday if that was still going to happen.

An accelerated authorization?

The FDA’s authorization for Pfizer’s antiviral comes about 5 weeks after the company submitted an application to the agency. In its submission, the company said a study showed the pill reduced by 89% the rate of hospitalization and death for people with mild to moderate COVID-19 illness.

In April 2021, Pfizer announced its antiviral pill for COVID-19 could be available by year’s end. In September, an official at the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases seconded the prediction.

Merck filed its EUA application with the FDA in October. The company included results of its phase 3 study showing the treatment was linked to a 50% reduction in COVID-19 hospitalizations.

Interestingly, in September, Merck announced the findings of laboratory studies suggesting that molnupiravir would work against variants of the coronavirus because the agent does not target the virus’s spike protein. At the time, Delta was the dominant variant in the United States.

Faith-based purchasing

The U.S. government has already recognized the potential of these oral therapies, at least in terms of preorders.

Last month, it announced intentions to purchase $1 billion worth of Merck’s molnupiravir, adding to the $1.2 billion worth of the pills the U.S. ordered in June 2021. Also in November, the government announced it would purchase 10 million courses of the Pfizer pill at an estimated cost of $5.3 billion.

The government preorders of the antiviral pills for COVID-19 are separate from the orders for COVID-19 vaccines. Most recently, the Biden administration announced it will make 500 million tests for coronavirus infection available to Americans for free in early 2022.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The Food and Drug Administration on Dec. 22, 2021, granted emergency use authorization (EUA) for a new antiviral pill to treat people with symptomatic COVID-19.

Pfizer’s ritonavir, name brand Paxlovid, can now be taken by patients ages 12 and up who weigh at least 88 pounds.

The antiviral is only for people who test positive for the coronavirus and who are at high risk for severe COVID-19, including hospitalization or death. It is available by prescription only and should be taken as soon as possible after diagnosis and within 5 days of the start of symptoms.

Paxlovid is taken as three tablets together orally twice a day for 5 days, for a total of 30 tablets.

Possible side effects include a reduced sense of taste, diarrhea, high blood pressure, and muscle aches.

The authorization arrives as U.S. cases of the Omicron variant are surging, some monoclonal antibody treatments are becoming less effective, and Americans struggle to maintain some sense of tradition and normalcy around the holidays.

Paxlovid joins remdesivir as an available antiviral to treat COVID-19. Remdesivir is fully approved by the FDA but is given only intravenously in a hospital.

The COVID-19 antiviral pills come with some obvious advantages, including greater convenience for consumers – such as home use – and the potential to expand treatment for people in low- and middle-income countries.

‘An exciting step forward’

The EUA for Pfizer’s new drug has been highly anticipated, and news of its impending authorization circulated on social media on Tuesday. Eric Topol, MD, called the development an “exciting step forward.” Dr. Topol is editor in chief of Medscape, the parent company of MDedge.

He and many others also expected the FDA to grant emergency use authorization for an antiviral from Merck. But there was no immediate word Wednesday if that was still going to happen.

An accelerated authorization?

The FDA’s authorization for Pfizer’s antiviral comes about 5 weeks after the company submitted an application to the agency. In its submission, the company said a study showed the pill reduced by 89% the rate of hospitalization and death for people with mild to moderate COVID-19 illness.

In April 2021, Pfizer announced its antiviral pill for COVID-19 could be available by year’s end. In September, an official at the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases seconded the prediction.

Merck filed its EUA application with the FDA in October. The company included results of its phase 3 study showing the treatment was linked to a 50% reduction in COVID-19 hospitalizations.

Interestingly, in September, Merck announced the findings of laboratory studies suggesting that molnupiravir would work against variants of the coronavirus because the agent does not target the virus’s spike protein. At the time, Delta was the dominant variant in the United States.

Faith-based purchasing

The U.S. government has already recognized the potential of these oral therapies, at least in terms of preorders.

Last month, it announced intentions to purchase $1 billion worth of Merck’s molnupiravir, adding to the $1.2 billion worth of the pills the U.S. ordered in June 2021. Also in November, the government announced it would purchase 10 million courses of the Pfizer pill at an estimated cost of $5.3 billion.

The government preorders of the antiviral pills for COVID-19 are separate from the orders for COVID-19 vaccines. Most recently, the Biden administration announced it will make 500 million tests for coronavirus infection available to Americans for free in early 2022.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The Food and Drug Administration on Dec. 22, 2021, granted emergency use authorization (EUA) for a new antiviral pill to treat people with symptomatic COVID-19.

Pfizer’s ritonavir, name brand Paxlovid, can now be taken by patients ages 12 and up who weigh at least 88 pounds.

The antiviral is only for people who test positive for the coronavirus and who are at high risk for severe COVID-19, including hospitalization or death. It is available by prescription only and should be taken as soon as possible after diagnosis and within 5 days of the start of symptoms.

Paxlovid is taken as three tablets together orally twice a day for 5 days, for a total of 30 tablets.

Possible side effects include a reduced sense of taste, diarrhea, high blood pressure, and muscle aches.

The authorization arrives as U.S. cases of the Omicron variant are surging, some monoclonal antibody treatments are becoming less effective, and Americans struggle to maintain some sense of tradition and normalcy around the holidays.

Paxlovid joins remdesivir as an available antiviral to treat COVID-19. Remdesivir is fully approved by the FDA but is given only intravenously in a hospital.

The COVID-19 antiviral pills come with some obvious advantages, including greater convenience for consumers – such as home use – and the potential to expand treatment for people in low- and middle-income countries.

‘An exciting step forward’

The EUA for Pfizer’s new drug has been highly anticipated, and news of its impending authorization circulated on social media on Tuesday. Eric Topol, MD, called the development an “exciting step forward.” Dr. Topol is editor in chief of Medscape, the parent company of MDedge.

He and many others also expected the FDA to grant emergency use authorization for an antiviral from Merck. But there was no immediate word Wednesday if that was still going to happen.

An accelerated authorization?

The FDA’s authorization for Pfizer’s antiviral comes about 5 weeks after the company submitted an application to the agency. In its submission, the company said a study showed the pill reduced by 89% the rate of hospitalization and death for people with mild to moderate COVID-19 illness.

In April 2021, Pfizer announced its antiviral pill for COVID-19 could be available by year’s end. In September, an official at the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases seconded the prediction.

Merck filed its EUA application with the FDA in October. The company included results of its phase 3 study showing the treatment was linked to a 50% reduction in COVID-19 hospitalizations.

Interestingly, in September, Merck announced the findings of laboratory studies suggesting that molnupiravir would work against variants of the coronavirus because the agent does not target the virus’s spike protein. At the time, Delta was the dominant variant in the United States.

Faith-based purchasing

The U.S. government has already recognized the potential of these oral therapies, at least in terms of preorders.

Last month, it announced intentions to purchase $1 billion worth of Merck’s molnupiravir, adding to the $1.2 billion worth of the pills the U.S. ordered in June 2021. Also in November, the government announced it would purchase 10 million courses of the Pfizer pill at an estimated cost of $5.3 billion.

The government preorders of the antiviral pills for COVID-19 are separate from the orders for COVID-19 vaccines. Most recently, the Biden administration announced it will make 500 million tests for coronavirus infection available to Americans for free in early 2022.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Children and COVID: New cases up slightly, vaccinations continue to slow

New COVID-19 vaccinations in children were down by almost 24% in the last week as new cases rose by just 3.5%, based on new data.

That fairly low number suggests the latest case count from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association has not caught up yet to the reality of the Omicron variant, which has sent new cases climbing among all ages and now represents the majority of COVID-19 infections nationwide, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said.

Meanwhile, in the midst of the latest surge, the United States just passed yet another sobering COVID milestone: 1,000 deaths in children aged 17 and under. The total as of Dec. 20 was 1,015, according to the CDC, with the largest share, almost 32%, occurring in children less than 5 years of age.

Regionally, the majority of that increase came in the Northeast, with a small rise in the South and decreases in the Midwest and West, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report.

At the state level, the largest percent increases in cases over the past 2 weeks were seen in Maine and New Hampshire, as well as Vermont, which has the nation’s highest vaccination rates for children aged 5-11 (51%) and 12-17 (84%), the AAP said in its vaccination trends report.

Nationally, new COVID vaccinations in children continue to trend downward. The number of children aged 5-17 years who had received at least one dose increased by about 498,000 for the week of Dec. 13-19, down from 654,000 (–23.9%) the previous week. Children aged 5-11 years still represented the largest share (22.7%) of all vaccine initiators in the last 2 weeks, but that proportion was 42.8% just before Thanksgiving, according to data from the CDC.

On a more positive note, children aged 5-11 made up 51% of all Americans who completed the vaccine regimen during the 2 weeks ending Dec. 20. The cumulative completion count is 3.6 million in that age group, along with almost 13.4 million children aged 12-17, and the CDC data show that 6.1 million children aged 5-11 and 15.9 million children aged 12-17 have received at least one dose.

On a less positive note, however, that means almost half (47%) of 12- to 17-year-olds still are not fully vaccinated and that over a third (37%) have received no vaccine at all, according to the COVID Data Tracker.

New COVID-19 vaccinations in children were down by almost 24% in the last week as new cases rose by just 3.5%, based on new data.

That fairly low number suggests the latest case count from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association has not caught up yet to the reality of the Omicron variant, which has sent new cases climbing among all ages and now represents the majority of COVID-19 infections nationwide, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said.

Meanwhile, in the midst of the latest surge, the United States just passed yet another sobering COVID milestone: 1,000 deaths in children aged 17 and under. The total as of Dec. 20 was 1,015, according to the CDC, with the largest share, almost 32%, occurring in children less than 5 years of age.

Regionally, the majority of that increase came in the Northeast, with a small rise in the South and decreases in the Midwest and West, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report.

At the state level, the largest percent increases in cases over the past 2 weeks were seen in Maine and New Hampshire, as well as Vermont, which has the nation’s highest vaccination rates for children aged 5-11 (51%) and 12-17 (84%), the AAP said in its vaccination trends report.

Nationally, new COVID vaccinations in children continue to trend downward. The number of children aged 5-17 years who had received at least one dose increased by about 498,000 for the week of Dec. 13-19, down from 654,000 (–23.9%) the previous week. Children aged 5-11 years still represented the largest share (22.7%) of all vaccine initiators in the last 2 weeks, but that proportion was 42.8% just before Thanksgiving, according to data from the CDC.

On a more positive note, children aged 5-11 made up 51% of all Americans who completed the vaccine regimen during the 2 weeks ending Dec. 20. The cumulative completion count is 3.6 million in that age group, along with almost 13.4 million children aged 12-17, and the CDC data show that 6.1 million children aged 5-11 and 15.9 million children aged 12-17 have received at least one dose.

On a less positive note, however, that means almost half (47%) of 12- to 17-year-olds still are not fully vaccinated and that over a third (37%) have received no vaccine at all, according to the COVID Data Tracker.

New COVID-19 vaccinations in children were down by almost 24% in the last week as new cases rose by just 3.5%, based on new data.

That fairly low number suggests the latest case count from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association has not caught up yet to the reality of the Omicron variant, which has sent new cases climbing among all ages and now represents the majority of COVID-19 infections nationwide, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said.

Meanwhile, in the midst of the latest surge, the United States just passed yet another sobering COVID milestone: 1,000 deaths in children aged 17 and under. The total as of Dec. 20 was 1,015, according to the CDC, with the largest share, almost 32%, occurring in children less than 5 years of age.

Regionally, the majority of that increase came in the Northeast, with a small rise in the South and decreases in the Midwest and West, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report.

At the state level, the largest percent increases in cases over the past 2 weeks were seen in Maine and New Hampshire, as well as Vermont, which has the nation’s highest vaccination rates for children aged 5-11 (51%) and 12-17 (84%), the AAP said in its vaccination trends report.

Nationally, new COVID vaccinations in children continue to trend downward. The number of children aged 5-17 years who had received at least one dose increased by about 498,000 for the week of Dec. 13-19, down from 654,000 (–23.9%) the previous week. Children aged 5-11 years still represented the largest share (22.7%) of all vaccine initiators in the last 2 weeks, but that proportion was 42.8% just before Thanksgiving, according to data from the CDC.

On a more positive note, children aged 5-11 made up 51% of all Americans who completed the vaccine regimen during the 2 weeks ending Dec. 20. The cumulative completion count is 3.6 million in that age group, along with almost 13.4 million children aged 12-17, and the CDC data show that 6.1 million children aged 5-11 and 15.9 million children aged 12-17 have received at least one dose.

On a less positive note, however, that means almost half (47%) of 12- to 17-year-olds still are not fully vaccinated and that over a third (37%) have received no vaccine at all, according to the COVID Data Tracker.

Voxelotor for sickle cell anemia now down to 4-year-olds

The indication had previously been for patients 12 years old and up, the FDA said in an announcement.

Voxelotor (Oxbryta) was originally approved for sickle cell disease in November 2019 and was described as the first drug that directly inhibits sickle hemoglobin polymerization, the root cause of the disease. It binds and stabilizes hemoglobin to prevent red blood cells from sickling and being destroyed.

Approval for the new indication of use in children down to age 4 was based on data from a phase 2 trial that involved 45 children aged 4-11 years; the results show that 36% had an increase in hemoglobin greater than 1 g/dL by week 24, the FDA said.

“Complications of [sickle cell disease] that can cause irreversible organ damage are known to begin in the first few years of life, which is why earlier intervention is critical,” commented Ted Love, MD, president and CEO of Global Blood Therapeutics, the manufacturer, in a press release.

The company is studying voxelotor in children as young as 9 months old.

The agent was granted an accelerated approval by the FDA, so continued approval depends on additional data to confirm that increases in hemoglobin have clinical benefit.

With the new approvals, voxelotor is now available in 500-mg tablets and the 300-mg tablets for oral suspension. Dosing for ages 12 years and up is 1,500 mg once daily. Dosing for children 4 to up to 12 years old is weight based.

The most common side effects are headache, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, nausea, rash, and fever.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The indication had previously been for patients 12 years old and up, the FDA said in an announcement.

Voxelotor (Oxbryta) was originally approved for sickle cell disease in November 2019 and was described as the first drug that directly inhibits sickle hemoglobin polymerization, the root cause of the disease. It binds and stabilizes hemoglobin to prevent red blood cells from sickling and being destroyed.

Approval for the new indication of use in children down to age 4 was based on data from a phase 2 trial that involved 45 children aged 4-11 years; the results show that 36% had an increase in hemoglobin greater than 1 g/dL by week 24, the FDA said.

“Complications of [sickle cell disease] that can cause irreversible organ damage are known to begin in the first few years of life, which is why earlier intervention is critical,” commented Ted Love, MD, president and CEO of Global Blood Therapeutics, the manufacturer, in a press release.

The company is studying voxelotor in children as young as 9 months old.

The agent was granted an accelerated approval by the FDA, so continued approval depends on additional data to confirm that increases in hemoglobin have clinical benefit.

With the new approvals, voxelotor is now available in 500-mg tablets and the 300-mg tablets for oral suspension. Dosing for ages 12 years and up is 1,500 mg once daily. Dosing for children 4 to up to 12 years old is weight based.

The most common side effects are headache, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, nausea, rash, and fever.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The indication had previously been for patients 12 years old and up, the FDA said in an announcement.

Voxelotor (Oxbryta) was originally approved for sickle cell disease in November 2019 and was described as the first drug that directly inhibits sickle hemoglobin polymerization, the root cause of the disease. It binds and stabilizes hemoglobin to prevent red blood cells from sickling and being destroyed.

Approval for the new indication of use in children down to age 4 was based on data from a phase 2 trial that involved 45 children aged 4-11 years; the results show that 36% had an increase in hemoglobin greater than 1 g/dL by week 24, the FDA said.

“Complications of [sickle cell disease] that can cause irreversible organ damage are known to begin in the first few years of life, which is why earlier intervention is critical,” commented Ted Love, MD, president and CEO of Global Blood Therapeutics, the manufacturer, in a press release.

The company is studying voxelotor in children as young as 9 months old.

The agent was granted an accelerated approval by the FDA, so continued approval depends on additional data to confirm that increases in hemoglobin have clinical benefit.

With the new approvals, voxelotor is now available in 500-mg tablets and the 300-mg tablets for oral suspension. Dosing for ages 12 years and up is 1,500 mg once daily. Dosing for children 4 to up to 12 years old is weight based.

The most common side effects are headache, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, nausea, rash, and fever.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FDA approves tezepelumab-ekko (Tezspire) for severe asthma

The Food and Drug Administration has approved tezepelumab-ekko (Tezspire) as a first-in-class treatment for severe asthma in adults and pediatric patients aged 12 years and older. It is not recommended for the relief of acute bronchospasm or status asthmaticus.

Tezepelumab-ekko is a human monoclonal antibody that acts as a thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) blocker. TSLP is an epithelial cell–derived cytokine implicated in the pathogenesis of asthma. Tezepelumab-ekko is administered by subcutaneous injection at a recommended dosage of 210 mg given once every 4 weeks.

“Tezspire represents a much-needed new treatment for the many patients who remain underserved and continue to struggle with severe, uncontrolled asthma,” said professor Andrew Menzies-Gow, MD, PhD, director of the lung division, Royal Brompton Hospital, London, and the principal investigator of the pivotal NAVIGATOR trial, in a Dec. 17 Amgen press release.

Trial results