User login

CDC panel backs mRNA COVID vaccines over J&J because of clot risk

because the Johnson & Johnson shot carries the risk of a rare but potentially fatal side effect that causes blood clots and bleeding in the brain.

In an emergency meeting on December 16, the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, or ACIP, voted unanimously (15-0) to state a preference for the mRNA vaccines over the Johnson & Johnson shot. The vote came after the panel heard a safety update on cases of thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome, or TTS, a condition that causes large clots that deplete the blood of platelets, resulting in uncontrolled bleeding.

The move brings the United States in line with other wealthy countries. In May, Denmark dropped the Johnson & Johnson shot from its vaccination program because of this risk. Australia and Greece have limited the use of a similar vaccine, made by AstraZeneca, in younger people because of the TTS risk. Both vaccines use the envelope of a different kind of virus, called an adenovirus, to sneak the vaccine instructions into cells. On Dec. 16, health officials said they had determined that TTS was likely due to a class effect, meaning it happens with all adenovirus vector vaccines.

The risk of dying from TTS after a Johnson & Johnson shot is extremely rare. There is an estimated 1 death for every 2 million doses of the vaccine given in the general population. That risk is higher for women ages 30 to 49, rising to about 2 deaths for every 1 million doses given in this age group. There’s no question that the Johnson & Johnson shot has saved many more lives than it has taken, experts said

Still, the committee previously paused the use of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine in April after the first cases of TTS came to light. That pause was lifted just 10 days later, after a new warning was added to the vaccine’s label to raise awareness of the risk.

In updating the safety information on Johnson & Johnson, the panel noted that the warning label had not sufficiently lowered the risk of death from TTS. Doctors seem to be aware of the condition because none of the patients who had developed TTS had been treated with the blood thinner heparin, which can make the syndrome worse. But patients continued to die even after the label was added, the panel noted, because TTS can progress so quickly that doctors simply don’t have time to treat it.

For that reason, and because there are other, safer vaccines available, the panel decided to make what’s called a preferential statement, saying the Pfizer and Moderna mRNA vaccines should be preferred over Johnson & Johnson.

The statement leaves the J&J vaccine on the market and available to patients who are at risk of a severe allergic reaction to the mRNA vaccines. It also means that people can still choose the J&J vaccine if they still want it after being informed about the risks.

About 17 million first doses and 900,000 second doses of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine have been given in the United States. Through the end of August, 54 cases of thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome (TTS) have occurred after the J&J shots in the United States. Nearly half of those were in women ages 30 to 49. There have been nine deaths from TTS after Johnson & Johnson shots.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

because the Johnson & Johnson shot carries the risk of a rare but potentially fatal side effect that causes blood clots and bleeding in the brain.

In an emergency meeting on December 16, the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, or ACIP, voted unanimously (15-0) to state a preference for the mRNA vaccines over the Johnson & Johnson shot. The vote came after the panel heard a safety update on cases of thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome, or TTS, a condition that causes large clots that deplete the blood of platelets, resulting in uncontrolled bleeding.

The move brings the United States in line with other wealthy countries. In May, Denmark dropped the Johnson & Johnson shot from its vaccination program because of this risk. Australia and Greece have limited the use of a similar vaccine, made by AstraZeneca, in younger people because of the TTS risk. Both vaccines use the envelope of a different kind of virus, called an adenovirus, to sneak the vaccine instructions into cells. On Dec. 16, health officials said they had determined that TTS was likely due to a class effect, meaning it happens with all adenovirus vector vaccines.

The risk of dying from TTS after a Johnson & Johnson shot is extremely rare. There is an estimated 1 death for every 2 million doses of the vaccine given in the general population. That risk is higher for women ages 30 to 49, rising to about 2 deaths for every 1 million doses given in this age group. There’s no question that the Johnson & Johnson shot has saved many more lives than it has taken, experts said

Still, the committee previously paused the use of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine in April after the first cases of TTS came to light. That pause was lifted just 10 days later, after a new warning was added to the vaccine’s label to raise awareness of the risk.

In updating the safety information on Johnson & Johnson, the panel noted that the warning label had not sufficiently lowered the risk of death from TTS. Doctors seem to be aware of the condition because none of the patients who had developed TTS had been treated with the blood thinner heparin, which can make the syndrome worse. But patients continued to die even after the label was added, the panel noted, because TTS can progress so quickly that doctors simply don’t have time to treat it.

For that reason, and because there are other, safer vaccines available, the panel decided to make what’s called a preferential statement, saying the Pfizer and Moderna mRNA vaccines should be preferred over Johnson & Johnson.

The statement leaves the J&J vaccine on the market and available to patients who are at risk of a severe allergic reaction to the mRNA vaccines. It also means that people can still choose the J&J vaccine if they still want it after being informed about the risks.

About 17 million first doses and 900,000 second doses of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine have been given in the United States. Through the end of August, 54 cases of thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome (TTS) have occurred after the J&J shots in the United States. Nearly half of those were in women ages 30 to 49. There have been nine deaths from TTS after Johnson & Johnson shots.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

because the Johnson & Johnson shot carries the risk of a rare but potentially fatal side effect that causes blood clots and bleeding in the brain.

In an emergency meeting on December 16, the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, or ACIP, voted unanimously (15-0) to state a preference for the mRNA vaccines over the Johnson & Johnson shot. The vote came after the panel heard a safety update on cases of thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome, or TTS, a condition that causes large clots that deplete the blood of platelets, resulting in uncontrolled bleeding.

The move brings the United States in line with other wealthy countries. In May, Denmark dropped the Johnson & Johnson shot from its vaccination program because of this risk. Australia and Greece have limited the use of a similar vaccine, made by AstraZeneca, in younger people because of the TTS risk. Both vaccines use the envelope of a different kind of virus, called an adenovirus, to sneak the vaccine instructions into cells. On Dec. 16, health officials said they had determined that TTS was likely due to a class effect, meaning it happens with all adenovirus vector vaccines.

The risk of dying from TTS after a Johnson & Johnson shot is extremely rare. There is an estimated 1 death for every 2 million doses of the vaccine given in the general population. That risk is higher for women ages 30 to 49, rising to about 2 deaths for every 1 million doses given in this age group. There’s no question that the Johnson & Johnson shot has saved many more lives than it has taken, experts said

Still, the committee previously paused the use of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine in April after the first cases of TTS came to light. That pause was lifted just 10 days later, after a new warning was added to the vaccine’s label to raise awareness of the risk.

In updating the safety information on Johnson & Johnson, the panel noted that the warning label had not sufficiently lowered the risk of death from TTS. Doctors seem to be aware of the condition because none of the patients who had developed TTS had been treated with the blood thinner heparin, which can make the syndrome worse. But patients continued to die even after the label was added, the panel noted, because TTS can progress so quickly that doctors simply don’t have time to treat it.

For that reason, and because there are other, safer vaccines available, the panel decided to make what’s called a preferential statement, saying the Pfizer and Moderna mRNA vaccines should be preferred over Johnson & Johnson.

The statement leaves the J&J vaccine on the market and available to patients who are at risk of a severe allergic reaction to the mRNA vaccines. It also means that people can still choose the J&J vaccine if they still want it after being informed about the risks.

About 17 million first doses and 900,000 second doses of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine have been given in the United States. Through the end of August, 54 cases of thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome (TTS) have occurred after the J&J shots in the United States. Nearly half of those were in women ages 30 to 49. There have been nine deaths from TTS after Johnson & Johnson shots.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Tofacitinib approved for new ankylosing spondylitis indication

The Food and Drug Administration approved a supplemental new drug application for tofacitinib (Xeljanz, Xeljanz XR) that adds active ankylosing spondylitis in adults to its list of indications, according to a Dec. 14 announcement from manufacturer Pfizer.

The approval makes the drug the first Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor to be approved for ankylosing spondylitis, joining tofacitinib’s other indications of rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ulcerative colitis, and polyarticular-course juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

Like other JAK inhibitors that are indicated for immune-mediated inflammatory diseases, tofacitinib’s use for all indications is limited to patients who have had an inadequate response or intolerance to one or more tumor necrosis factor (TNF) blockers.

The agency based its decision on the results of a phase 3, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in 269 adults with active ankylosing spondylitis that tested tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily.

The study met its primary endpoint showing that at week 16 the percentage of tofacitinib-treated patients who achieved 20% improvement in Assessment in SpondyloArthritis International Society response criteria (ASAS20) was significantly greater than with placebo (56.4% vs. 29.4%; P < .0001). The percentage of responders for ASAS40 criteria was likewise significantly greater with tofacitinib vs. placebo (40.6% vs. 12.5%; P < .0001). Pfizer said that the safety profile of tofacitinib observed in patients with ankylosing spondylitis was consistent with the safety profile observed in patients with either rheumatoid arthritis or psoriatic arthritis.

Pfizer noted in its announcement that the FDA updated the prescribing information this month for tofacitinib (and other JAK inhibitors approved for immune-mediated inflammatory conditions, upadacitinib [Rinvoq] and baricitinib [Olumiant]). This update included a new boxed warning for major adverse cardiovascular events and updated boxed warnings regarding mortality, malignancies, and thrombosis. These changes were made in light of results from the ORAL Surveillance postmarketing study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis aged 50 years and older with at least one cardiovascular risk factor. That study found an association between tofacitinib and increased risk of heart attack or stroke, cancer, blood clots, and death in comparison with patients who took the TNF blockers adalimumab or etanercept.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration approved a supplemental new drug application for tofacitinib (Xeljanz, Xeljanz XR) that adds active ankylosing spondylitis in adults to its list of indications, according to a Dec. 14 announcement from manufacturer Pfizer.

The approval makes the drug the first Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor to be approved for ankylosing spondylitis, joining tofacitinib’s other indications of rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ulcerative colitis, and polyarticular-course juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

Like other JAK inhibitors that are indicated for immune-mediated inflammatory diseases, tofacitinib’s use for all indications is limited to patients who have had an inadequate response or intolerance to one or more tumor necrosis factor (TNF) blockers.

The agency based its decision on the results of a phase 3, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in 269 adults with active ankylosing spondylitis that tested tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily.

The study met its primary endpoint showing that at week 16 the percentage of tofacitinib-treated patients who achieved 20% improvement in Assessment in SpondyloArthritis International Society response criteria (ASAS20) was significantly greater than with placebo (56.4% vs. 29.4%; P < .0001). The percentage of responders for ASAS40 criteria was likewise significantly greater with tofacitinib vs. placebo (40.6% vs. 12.5%; P < .0001). Pfizer said that the safety profile of tofacitinib observed in patients with ankylosing spondylitis was consistent with the safety profile observed in patients with either rheumatoid arthritis or psoriatic arthritis.

Pfizer noted in its announcement that the FDA updated the prescribing information this month for tofacitinib (and other JAK inhibitors approved for immune-mediated inflammatory conditions, upadacitinib [Rinvoq] and baricitinib [Olumiant]). This update included a new boxed warning for major adverse cardiovascular events and updated boxed warnings regarding mortality, malignancies, and thrombosis. These changes were made in light of results from the ORAL Surveillance postmarketing study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis aged 50 years and older with at least one cardiovascular risk factor. That study found an association between tofacitinib and increased risk of heart attack or stroke, cancer, blood clots, and death in comparison with patients who took the TNF blockers adalimumab or etanercept.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration approved a supplemental new drug application for tofacitinib (Xeljanz, Xeljanz XR) that adds active ankylosing spondylitis in adults to its list of indications, according to a Dec. 14 announcement from manufacturer Pfizer.

The approval makes the drug the first Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor to be approved for ankylosing spondylitis, joining tofacitinib’s other indications of rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ulcerative colitis, and polyarticular-course juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

Like other JAK inhibitors that are indicated for immune-mediated inflammatory diseases, tofacitinib’s use for all indications is limited to patients who have had an inadequate response or intolerance to one or more tumor necrosis factor (TNF) blockers.

The agency based its decision on the results of a phase 3, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in 269 adults with active ankylosing spondylitis that tested tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily.

The study met its primary endpoint showing that at week 16 the percentage of tofacitinib-treated patients who achieved 20% improvement in Assessment in SpondyloArthritis International Society response criteria (ASAS20) was significantly greater than with placebo (56.4% vs. 29.4%; P < .0001). The percentage of responders for ASAS40 criteria was likewise significantly greater with tofacitinib vs. placebo (40.6% vs. 12.5%; P < .0001). Pfizer said that the safety profile of tofacitinib observed in patients with ankylosing spondylitis was consistent with the safety profile observed in patients with either rheumatoid arthritis or psoriatic arthritis.

Pfizer noted in its announcement that the FDA updated the prescribing information this month for tofacitinib (and other JAK inhibitors approved for immune-mediated inflammatory conditions, upadacitinib [Rinvoq] and baricitinib [Olumiant]). This update included a new boxed warning for major adverse cardiovascular events and updated boxed warnings regarding mortality, malignancies, and thrombosis. These changes were made in light of results from the ORAL Surveillance postmarketing study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis aged 50 years and older with at least one cardiovascular risk factor. That study found an association between tofacitinib and increased risk of heart attack or stroke, cancer, blood clots, and death in comparison with patients who took the TNF blockers adalimumab or etanercept.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FDA updates risks, cautions for clotting-bleeding disorder on Janssen COVID-19 vaccine

Updated Janssen/Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccine fact sheets for health care professionals and the general public now include a contraindication to its use in persons with a history of thrombosis with thrombocytopenia after receiving it “or any other adenovirus-vectored COVID-19 vaccine,” the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has announced.

Thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome (TTS) – thrombocytopenia and increased bleeding risk along with documented thrombosis – after administration of the Janssen Ad26.COV2.S vaccine remains rare. But over all age groups, about one in seven cases have been fatal, said the agency.

the provider fact sheet states.

Although TTS associated with the Janssen COVID-19 vaccine has been reported in men and women aged 18 and older, the highest reported rate has been for women aged 30-49, the agency states. The rate in that group has been about 1 case per 100,000 doses administered.

Symptoms of TTS may occur 1-2 weeks after administration of the Janssen COVID-19 vaccine, the FDA says, based on data from the Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System (VAERS).

Its clinical course shares features with autoimmune heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. In individuals with suspected TTS following receipt of the Janssen COVID-19 vaccine, the agency cautions, the use of heparin “may be harmful and alternative treatments may be needed. Consultation with hematology specialists is strongly recommended.”

The apparent excess risk of TTS remains under investigation, but “the FDA continues to find that the known and potential benefits of the Janssen COVID-19 vaccine outweigh its known and potential risks in individuals 18 years of age and older,” the agency states.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Updated Janssen/Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccine fact sheets for health care professionals and the general public now include a contraindication to its use in persons with a history of thrombosis with thrombocytopenia after receiving it “or any other adenovirus-vectored COVID-19 vaccine,” the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has announced.

Thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome (TTS) – thrombocytopenia and increased bleeding risk along with documented thrombosis – after administration of the Janssen Ad26.COV2.S vaccine remains rare. But over all age groups, about one in seven cases have been fatal, said the agency.

the provider fact sheet states.

Although TTS associated with the Janssen COVID-19 vaccine has been reported in men and women aged 18 and older, the highest reported rate has been for women aged 30-49, the agency states. The rate in that group has been about 1 case per 100,000 doses administered.

Symptoms of TTS may occur 1-2 weeks after administration of the Janssen COVID-19 vaccine, the FDA says, based on data from the Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System (VAERS).

Its clinical course shares features with autoimmune heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. In individuals with suspected TTS following receipt of the Janssen COVID-19 vaccine, the agency cautions, the use of heparin “may be harmful and alternative treatments may be needed. Consultation with hematology specialists is strongly recommended.”

The apparent excess risk of TTS remains under investigation, but “the FDA continues to find that the known and potential benefits of the Janssen COVID-19 vaccine outweigh its known and potential risks in individuals 18 years of age and older,” the agency states.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Updated Janssen/Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccine fact sheets for health care professionals and the general public now include a contraindication to its use in persons with a history of thrombosis with thrombocytopenia after receiving it “or any other adenovirus-vectored COVID-19 vaccine,” the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has announced.

Thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome (TTS) – thrombocytopenia and increased bleeding risk along with documented thrombosis – after administration of the Janssen Ad26.COV2.S vaccine remains rare. But over all age groups, about one in seven cases have been fatal, said the agency.

the provider fact sheet states.

Although TTS associated with the Janssen COVID-19 vaccine has been reported in men and women aged 18 and older, the highest reported rate has been for women aged 30-49, the agency states. The rate in that group has been about 1 case per 100,000 doses administered.

Symptoms of TTS may occur 1-2 weeks after administration of the Janssen COVID-19 vaccine, the FDA says, based on data from the Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System (VAERS).

Its clinical course shares features with autoimmune heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. In individuals with suspected TTS following receipt of the Janssen COVID-19 vaccine, the agency cautions, the use of heparin “may be harmful and alternative treatments may be needed. Consultation with hematology specialists is strongly recommended.”

The apparent excess risk of TTS remains under investigation, but “the FDA continues to find that the known and potential benefits of the Janssen COVID-19 vaccine outweigh its known and potential risks in individuals 18 years of age and older,” the agency states.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Upadacitinib (Rinvoq) gains psoriatic arthritis as second FDA-approved indication

upadacitinib (Rinvoq) for adults with psoriatic arthritis who had an inadequate response or intolerance to one or more anti-tumor necrosis factor drugs, manufacturer AbbVie announced December 14.

The approval is the second indication given by the agency for the selective Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor upadacitinib, which was previously approved for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in 2019.

Upadacitinib 15 mg is also approved by the European Commission for adults with RA, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis. The European Commission also approved the drug for moderate to severe atopic dermatitis at both 15- and 30-mg doses for adults and at 15 mg for adolescents.

The approval is based on two phase 3 trials, SELECT-PsA 1 and SELECT-PsA 2, which together randomized more than 2,300 patients with psoriatic arthritis. In the trials, significantly more patients who took upadacitinib 15 mg met their primary endpoint of 20% improvement in American College of Rheumatology response criteria (ACR20) at week 12 (71% in SELECT-PsA 1 and 57% in SELECT-PsA 2) vs placebo (36% and 24%, respectively). Both trials also included treatment arms for upadacitinib at 30 mg, but the FDA approved only the 15-mg dose.

In the announcement, AbbVie noted that significantly higher percentages of patients treated with upadacitinib 15 mg in the SELECT-PSA 1 and 2 trials, respectively, met ACR50 (38% and 32%) and ACR70 (16% and 9%) criteria than did patients on placebo (13% and 5% for ACR50 and 2% and 1% for ACR70). Symptoms of dactylitis and enthesitis improved with upadacitinib for patients who had them at baseline.

The trials’ 12-week results also indicated that upadacitinib significantly improved physical function relative to placebo at baseline, based on the Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index, as well as fatigue, according to Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy – Fatigue (FACIT-F) scores. Skin manifestations also improved during the trial, but upadacitinib has not been studied for treating plaque psoriasis.

AbbVie reported that the safety results of upadacitinib in the trials were consistent with the results seen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, and during the trials’ 24-week placebo-controlled period, the most common adverse events reported with upadacitinib were upper respiratory tract infection and blood creatine phosphokinase elevations.

Upadacitinib comes with a boxed warning that was formally placed on the drug’s label this month after data from a postmarketing trial of the JAK inhibitor tofacitinib (Xeljanz and Xeljanz XR) in patients with RA aged 50 years and older with at least one cardiovascular risk factor showed numerically higher risks for all-cause mortality; lymphoma and other malignancies; major adverse cardiovascular events (cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, and stroke); and thrombosis, including deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and arterial thrombosis.

Upadacitinib also carries a boxed warning for an elevated risk of serious infection leading to hospitalization or death. In the SELECT-PsA 1 and 2 trials overall, rates of herpes zoster and herpes simplex were 1.1% and 1.4% with upadacitinib, compared with 0.8% and 1.3% with placebo.

Phase 3 trials of upadacitinib in RA, atopic dermatitis, psoriatic arthritis, axial spondyloarthritis, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, giant cell arteritis, and Takayasu arteritis are ongoing, according to AbbVie.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

upadacitinib (Rinvoq) for adults with psoriatic arthritis who had an inadequate response or intolerance to one or more anti-tumor necrosis factor drugs, manufacturer AbbVie announced December 14.

The approval is the second indication given by the agency for the selective Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor upadacitinib, which was previously approved for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in 2019.

Upadacitinib 15 mg is also approved by the European Commission for adults with RA, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis. The European Commission also approved the drug for moderate to severe atopic dermatitis at both 15- and 30-mg doses for adults and at 15 mg for adolescents.

The approval is based on two phase 3 trials, SELECT-PsA 1 and SELECT-PsA 2, which together randomized more than 2,300 patients with psoriatic arthritis. In the trials, significantly more patients who took upadacitinib 15 mg met their primary endpoint of 20% improvement in American College of Rheumatology response criteria (ACR20) at week 12 (71% in SELECT-PsA 1 and 57% in SELECT-PsA 2) vs placebo (36% and 24%, respectively). Both trials also included treatment arms for upadacitinib at 30 mg, but the FDA approved only the 15-mg dose.

In the announcement, AbbVie noted that significantly higher percentages of patients treated with upadacitinib 15 mg in the SELECT-PSA 1 and 2 trials, respectively, met ACR50 (38% and 32%) and ACR70 (16% and 9%) criteria than did patients on placebo (13% and 5% for ACR50 and 2% and 1% for ACR70). Symptoms of dactylitis and enthesitis improved with upadacitinib for patients who had them at baseline.

The trials’ 12-week results also indicated that upadacitinib significantly improved physical function relative to placebo at baseline, based on the Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index, as well as fatigue, according to Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy – Fatigue (FACIT-F) scores. Skin manifestations also improved during the trial, but upadacitinib has not been studied for treating plaque psoriasis.

AbbVie reported that the safety results of upadacitinib in the trials were consistent with the results seen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, and during the trials’ 24-week placebo-controlled period, the most common adverse events reported with upadacitinib were upper respiratory tract infection and blood creatine phosphokinase elevations.

Upadacitinib comes with a boxed warning that was formally placed on the drug’s label this month after data from a postmarketing trial of the JAK inhibitor tofacitinib (Xeljanz and Xeljanz XR) in patients with RA aged 50 years and older with at least one cardiovascular risk factor showed numerically higher risks for all-cause mortality; lymphoma and other malignancies; major adverse cardiovascular events (cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, and stroke); and thrombosis, including deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and arterial thrombosis.

Upadacitinib also carries a boxed warning for an elevated risk of serious infection leading to hospitalization or death. In the SELECT-PsA 1 and 2 trials overall, rates of herpes zoster and herpes simplex were 1.1% and 1.4% with upadacitinib, compared with 0.8% and 1.3% with placebo.

Phase 3 trials of upadacitinib in RA, atopic dermatitis, psoriatic arthritis, axial spondyloarthritis, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, giant cell arteritis, and Takayasu arteritis are ongoing, according to AbbVie.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

upadacitinib (Rinvoq) for adults with psoriatic arthritis who had an inadequate response or intolerance to one or more anti-tumor necrosis factor drugs, manufacturer AbbVie announced December 14.

The approval is the second indication given by the agency for the selective Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor upadacitinib, which was previously approved for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in 2019.

Upadacitinib 15 mg is also approved by the European Commission for adults with RA, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis. The European Commission also approved the drug for moderate to severe atopic dermatitis at both 15- and 30-mg doses for adults and at 15 mg for adolescents.

The approval is based on two phase 3 trials, SELECT-PsA 1 and SELECT-PsA 2, which together randomized more than 2,300 patients with psoriatic arthritis. In the trials, significantly more patients who took upadacitinib 15 mg met their primary endpoint of 20% improvement in American College of Rheumatology response criteria (ACR20) at week 12 (71% in SELECT-PsA 1 and 57% in SELECT-PsA 2) vs placebo (36% and 24%, respectively). Both trials also included treatment arms for upadacitinib at 30 mg, but the FDA approved only the 15-mg dose.

In the announcement, AbbVie noted that significantly higher percentages of patients treated with upadacitinib 15 mg in the SELECT-PSA 1 and 2 trials, respectively, met ACR50 (38% and 32%) and ACR70 (16% and 9%) criteria than did patients on placebo (13% and 5% for ACR50 and 2% and 1% for ACR70). Symptoms of dactylitis and enthesitis improved with upadacitinib for patients who had them at baseline.

The trials’ 12-week results also indicated that upadacitinib significantly improved physical function relative to placebo at baseline, based on the Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index, as well as fatigue, according to Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy – Fatigue (FACIT-F) scores. Skin manifestations also improved during the trial, but upadacitinib has not been studied for treating plaque psoriasis.

AbbVie reported that the safety results of upadacitinib in the trials were consistent with the results seen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, and during the trials’ 24-week placebo-controlled period, the most common adverse events reported with upadacitinib were upper respiratory tract infection and blood creatine phosphokinase elevations.

Upadacitinib comes with a boxed warning that was formally placed on the drug’s label this month after data from a postmarketing trial of the JAK inhibitor tofacitinib (Xeljanz and Xeljanz XR) in patients with RA aged 50 years and older with at least one cardiovascular risk factor showed numerically higher risks for all-cause mortality; lymphoma and other malignancies; major adverse cardiovascular events (cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, and stroke); and thrombosis, including deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and arterial thrombosis.

Upadacitinib also carries a boxed warning for an elevated risk of serious infection leading to hospitalization or death. In the SELECT-PsA 1 and 2 trials overall, rates of herpes zoster and herpes simplex were 1.1% and 1.4% with upadacitinib, compared with 0.8% and 1.3% with placebo.

Phase 3 trials of upadacitinib in RA, atopic dermatitis, psoriatic arthritis, axial spondyloarthritis, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, giant cell arteritis, and Takayasu arteritis are ongoing, according to AbbVie.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

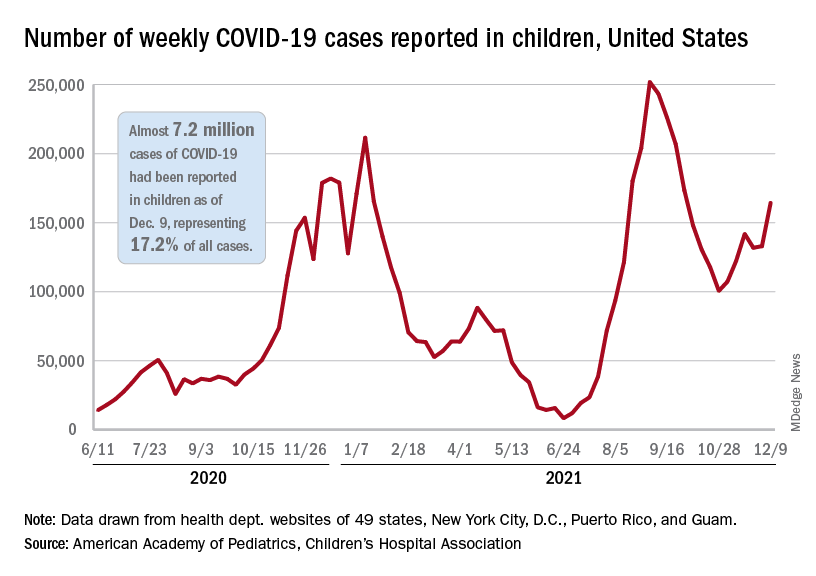

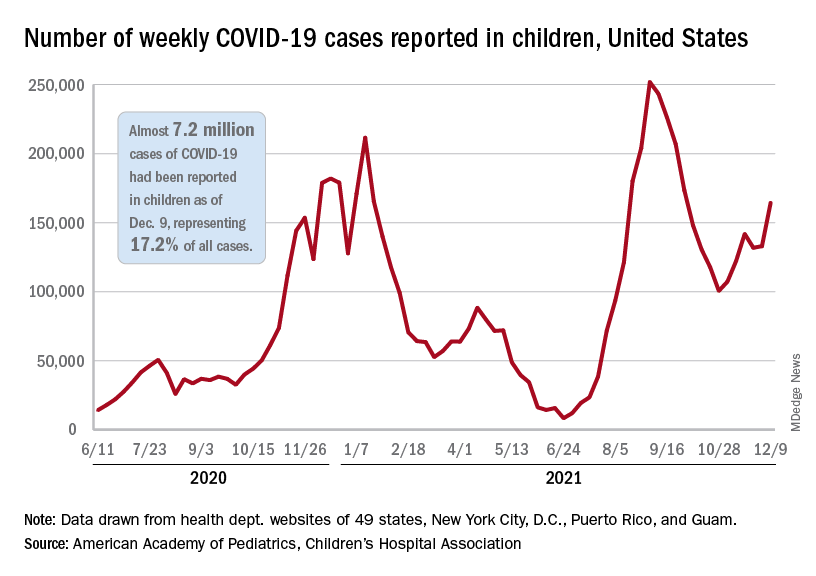

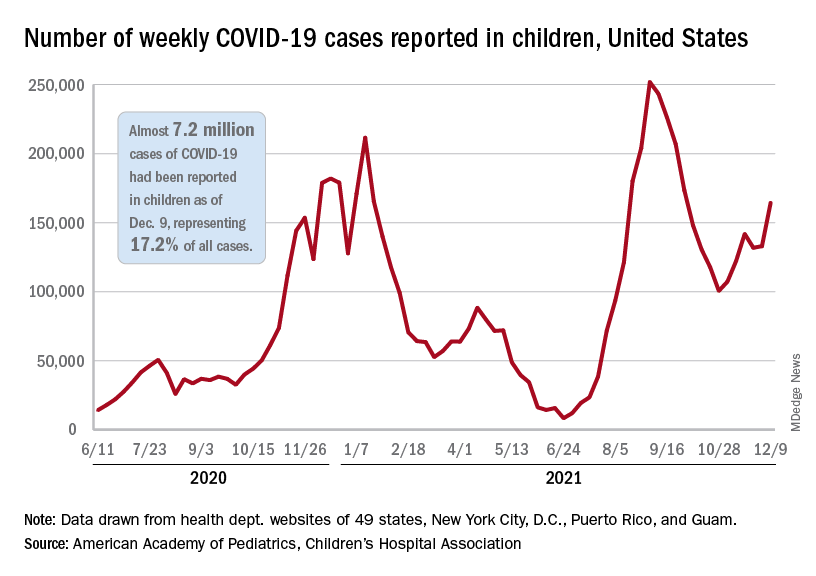

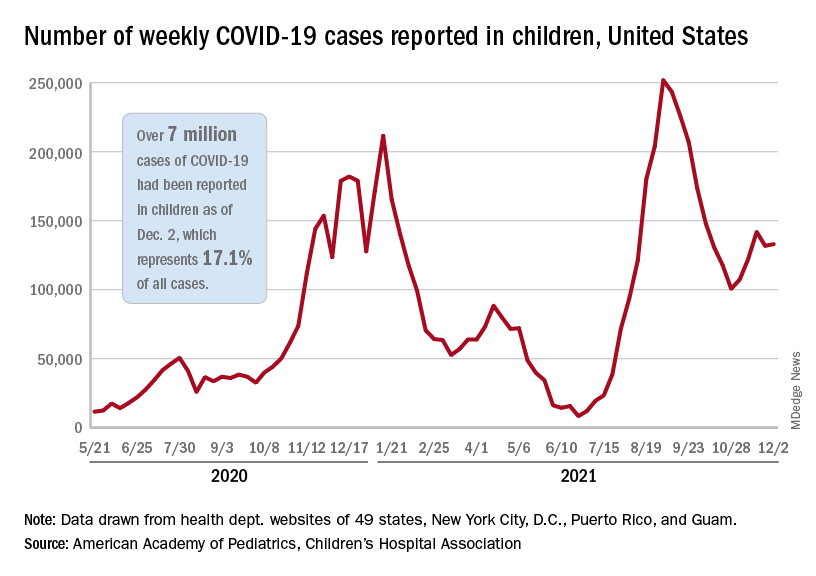

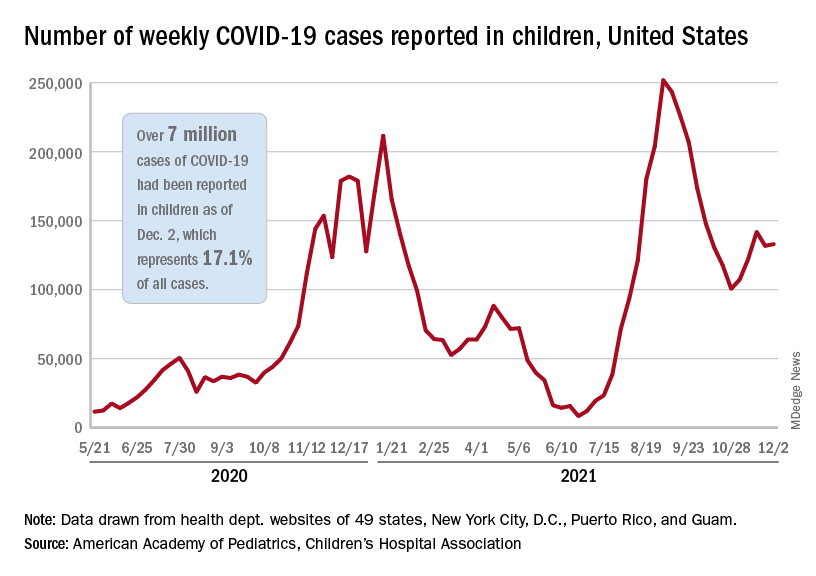

Children and COVID: Weekly cases resume their climb

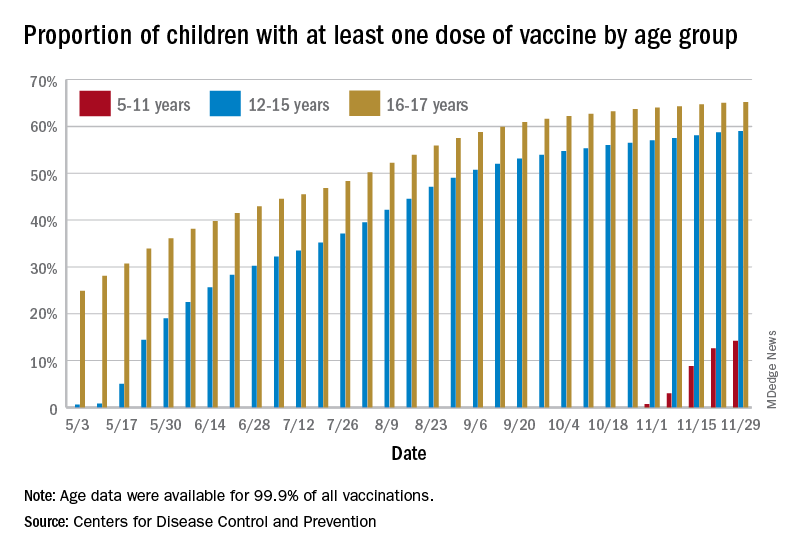

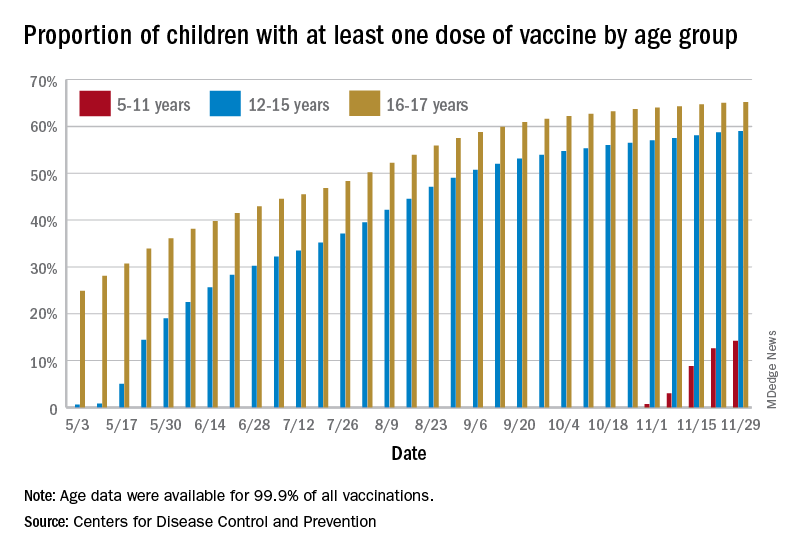

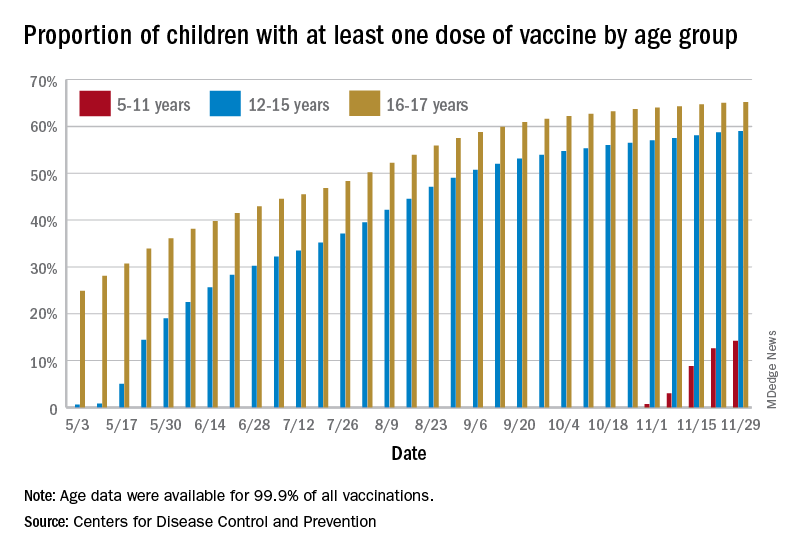

After a brief lull in activity, weekly COVID-19 cases in children returned to the upward trend that began in early November, based on data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

New COVID-19 cases were up by 23.5% for the week of Dec. 3-9, after a 2-week period that saw a drop and then just a slight increase, the AAP and CHA said in their latest weekly COVID report. There were 164,000 new cases from Dec. 3 to Dec. 9 in 46 states (Alabama, Nebraska, and Texas stopped reporting over the summer of 2021 and New York has never reported by age), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

The increase occurred across all four regions of the country, but the largest share came in the Midwest, with over 65,000 new cases, followed by the West (just over 35,000), the Northeast (just under 35,000), and the South (close to 28,000), the AAP/CHA data show.

The 7.2 million cumulative cases in children as of Dec. 9 represent 17.2% of all cases reported in the United States since the start of the pandemic, with available state reports showing that proportion ranges from 12.3% in Florida to 26.1% in Vermont. Alaska has the highest incidence of COVID at 19,000 cases per 100,000 children, and Hawaii has the lowest (5,300 per 100,000) among the states currently reporting, the AAP and CHA said.

State reporting on vaccinations shows that 37% of children aged 5-11 years in Massachusetts have received at least one dose, the highest of any state, while West Virginia is lowest at just 4%. The highest vaccination rate for children aged 12-17 goes to Massachusetts at 84%, with Wyoming lowest at 37%, the AAP said in a separate report.

Nationally, new vaccinations fell by a third during the week of Dec. 7-13, compared with the previous week, with the largest decline (34.7%) coming from the 5- to 11-year-olds, who still represented the majority (almost 84%) of the 430,000 new child vaccinations received, according to the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker. Corresponding declines for the last week were 27.5% for 12- to 15-year-olds and 22.7% for those aged 16-17.

Altogether, 21.2 million children aged 5-17 had received at least one dose and 16.0 million were fully vaccinated as of Dec. 13. By age group, 19.2% of children aged 5-11 years have gotten at least one dose and 9.6% are fully vaccinated, compared with 62.1% and 52.3%, respectively, among children aged 12-17, the CDC said.

After a brief lull in activity, weekly COVID-19 cases in children returned to the upward trend that began in early November, based on data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

New COVID-19 cases were up by 23.5% for the week of Dec. 3-9, after a 2-week period that saw a drop and then just a slight increase, the AAP and CHA said in their latest weekly COVID report. There were 164,000 new cases from Dec. 3 to Dec. 9 in 46 states (Alabama, Nebraska, and Texas stopped reporting over the summer of 2021 and New York has never reported by age), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

The increase occurred across all four regions of the country, but the largest share came in the Midwest, with over 65,000 new cases, followed by the West (just over 35,000), the Northeast (just under 35,000), and the South (close to 28,000), the AAP/CHA data show.

The 7.2 million cumulative cases in children as of Dec. 9 represent 17.2% of all cases reported in the United States since the start of the pandemic, with available state reports showing that proportion ranges from 12.3% in Florida to 26.1% in Vermont. Alaska has the highest incidence of COVID at 19,000 cases per 100,000 children, and Hawaii has the lowest (5,300 per 100,000) among the states currently reporting, the AAP and CHA said.

State reporting on vaccinations shows that 37% of children aged 5-11 years in Massachusetts have received at least one dose, the highest of any state, while West Virginia is lowest at just 4%. The highest vaccination rate for children aged 12-17 goes to Massachusetts at 84%, with Wyoming lowest at 37%, the AAP said in a separate report.

Nationally, new vaccinations fell by a third during the week of Dec. 7-13, compared with the previous week, with the largest decline (34.7%) coming from the 5- to 11-year-olds, who still represented the majority (almost 84%) of the 430,000 new child vaccinations received, according to the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker. Corresponding declines for the last week were 27.5% for 12- to 15-year-olds and 22.7% for those aged 16-17.

Altogether, 21.2 million children aged 5-17 had received at least one dose and 16.0 million were fully vaccinated as of Dec. 13. By age group, 19.2% of children aged 5-11 years have gotten at least one dose and 9.6% are fully vaccinated, compared with 62.1% and 52.3%, respectively, among children aged 12-17, the CDC said.

After a brief lull in activity, weekly COVID-19 cases in children returned to the upward trend that began in early November, based on data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

New COVID-19 cases were up by 23.5% for the week of Dec. 3-9, after a 2-week period that saw a drop and then just a slight increase, the AAP and CHA said in their latest weekly COVID report. There were 164,000 new cases from Dec. 3 to Dec. 9 in 46 states (Alabama, Nebraska, and Texas stopped reporting over the summer of 2021 and New York has never reported by age), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

The increase occurred across all four regions of the country, but the largest share came in the Midwest, with over 65,000 new cases, followed by the West (just over 35,000), the Northeast (just under 35,000), and the South (close to 28,000), the AAP/CHA data show.

The 7.2 million cumulative cases in children as of Dec. 9 represent 17.2% of all cases reported in the United States since the start of the pandemic, with available state reports showing that proportion ranges from 12.3% in Florida to 26.1% in Vermont. Alaska has the highest incidence of COVID at 19,000 cases per 100,000 children, and Hawaii has the lowest (5,300 per 100,000) among the states currently reporting, the AAP and CHA said.

State reporting on vaccinations shows that 37% of children aged 5-11 years in Massachusetts have received at least one dose, the highest of any state, while West Virginia is lowest at just 4%. The highest vaccination rate for children aged 12-17 goes to Massachusetts at 84%, with Wyoming lowest at 37%, the AAP said in a separate report.

Nationally, new vaccinations fell by a third during the week of Dec. 7-13, compared with the previous week, with the largest decline (34.7%) coming from the 5- to 11-year-olds, who still represented the majority (almost 84%) of the 430,000 new child vaccinations received, according to the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker. Corresponding declines for the last week were 27.5% for 12- to 15-year-olds and 22.7% for those aged 16-17.

Altogether, 21.2 million children aged 5-17 had received at least one dose and 16.0 million were fully vaccinated as of Dec. 13. By age group, 19.2% of children aged 5-11 years have gotten at least one dose and 9.6% are fully vaccinated, compared with 62.1% and 52.3%, respectively, among children aged 12-17, the CDC said.

FDA expands pembrolizumab approval for advanced melanoma

The over age 12 years. The FDA also extended the approval to those with stage III disease.

The FDA approval on Dec. 3 was based on first interim findings from the randomized, placebo-controlled KEYNOTE-716 trial, which evaluated patients with stage IIB and IIC disease.

Since the anti-PD-1 therapy was approved in metastatic melanoma 7 years ago, “we have built on this foundation in melanoma and have expanded the use of KEYTRUDA into earlier stages of this disease,” said Scot Ebbinghaus, MD, vice president, clinical research, Merck Research Laboratories, in a press release. “With today’s approval, we can now offer health care providers and patients 12 years and older the opportunity to help prevent melanoma recurrence with Keytruda across resected stage IIB, stage IIC, and stage III melanoma.”

In KEYNOTE-716, patients with completely resected stage IIB or IIC melanoma were randomly assigned to receive 200 mg of intravenous pembrolizumab, the pediatric dose 2 mg/kg (up to a maximum of 200 mg) every 3 weeks, or placebo for up to 1 year until disease recurrence or unacceptable toxicity.

After a median follow-up of 14.4 months, investigators reported a statistically significant 35% improvement in recurrence-free survival (RFS) in those treated with pembrolizumab, compared with those who received placebo (hazard ratio, 0.65).

The most common adverse reactions reported in patients receiving pembrolizumab in KEYNOTE-716 were fatigue, diarrhea, pruritus, and arthralgia, each occurring in at least 20% of patients.

“Early identification and management of immune-mediated adverse reactions are essential to ensure safe use of Keytruda,” according to Merck.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The over age 12 years. The FDA also extended the approval to those with stage III disease.

The FDA approval on Dec. 3 was based on first interim findings from the randomized, placebo-controlled KEYNOTE-716 trial, which evaluated patients with stage IIB and IIC disease.

Since the anti-PD-1 therapy was approved in metastatic melanoma 7 years ago, “we have built on this foundation in melanoma and have expanded the use of KEYTRUDA into earlier stages of this disease,” said Scot Ebbinghaus, MD, vice president, clinical research, Merck Research Laboratories, in a press release. “With today’s approval, we can now offer health care providers and patients 12 years and older the opportunity to help prevent melanoma recurrence with Keytruda across resected stage IIB, stage IIC, and stage III melanoma.”

In KEYNOTE-716, patients with completely resected stage IIB or IIC melanoma were randomly assigned to receive 200 mg of intravenous pembrolizumab, the pediatric dose 2 mg/kg (up to a maximum of 200 mg) every 3 weeks, or placebo for up to 1 year until disease recurrence or unacceptable toxicity.

After a median follow-up of 14.4 months, investigators reported a statistically significant 35% improvement in recurrence-free survival (RFS) in those treated with pembrolizumab, compared with those who received placebo (hazard ratio, 0.65).

The most common adverse reactions reported in patients receiving pembrolizumab in KEYNOTE-716 were fatigue, diarrhea, pruritus, and arthralgia, each occurring in at least 20% of patients.

“Early identification and management of immune-mediated adverse reactions are essential to ensure safe use of Keytruda,” according to Merck.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The over age 12 years. The FDA also extended the approval to those with stage III disease.

The FDA approval on Dec. 3 was based on first interim findings from the randomized, placebo-controlled KEYNOTE-716 trial, which evaluated patients with stage IIB and IIC disease.

Since the anti-PD-1 therapy was approved in metastatic melanoma 7 years ago, “we have built on this foundation in melanoma and have expanded the use of KEYTRUDA into earlier stages of this disease,” said Scot Ebbinghaus, MD, vice president, clinical research, Merck Research Laboratories, in a press release. “With today’s approval, we can now offer health care providers and patients 12 years and older the opportunity to help prevent melanoma recurrence with Keytruda across resected stage IIB, stage IIC, and stage III melanoma.”

In KEYNOTE-716, patients with completely resected stage IIB or IIC melanoma were randomly assigned to receive 200 mg of intravenous pembrolizumab, the pediatric dose 2 mg/kg (up to a maximum of 200 mg) every 3 weeks, or placebo for up to 1 year until disease recurrence or unacceptable toxicity.

After a median follow-up of 14.4 months, investigators reported a statistically significant 35% improvement in recurrence-free survival (RFS) in those treated with pembrolizumab, compared with those who received placebo (hazard ratio, 0.65).

The most common adverse reactions reported in patients receiving pembrolizumab in KEYNOTE-716 were fatigue, diarrhea, pruritus, and arthralgia, each occurring in at least 20% of patients.

“Early identification and management of immune-mediated adverse reactions are essential to ensure safe use of Keytruda,” according to Merck.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

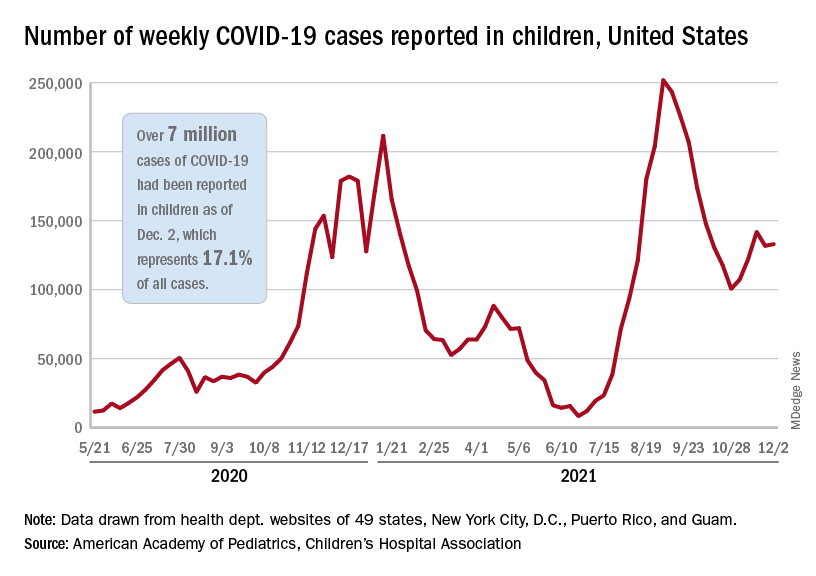

Children and COVID-19: 7 million cases and still counting

Total COVID-19 cases in children surpassed the 7-million mark as new cases rose slightly after the previous week’s decline, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report. New cases had dropped the previous week after 3 straight weeks of increases since late October.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention puts the total number of child COVID-19 cases at 6.2 million, but both estimates are based on all-age totals – 40 million for the CDC and 41 million for the AAP/CHA – that are well short of the CDC’s latest cumulative figure, which is now just over 49 million, so the actual figures are undoubtedly higher.

Meanwhile, the 1-month anniversary of 5- to 11-year-olds’ vaccine eligibility brought many completions: 923,000 received their second dose during the week ending Dec. 6, compared with 405,000 the previous week. About 16.9% (4.9 million) of children aged 5-11 have gotten at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine thus far, of whom almost 1.5 million children (5.1% of the age group) are now fully vaccinated, the CDC said on its COVID-19 Data Tracker.

The pace of vaccinations, however, is much lower for older children. Weekly numbers for all COVID-19 vaccinations, both first and second doses, dropped from 84,000 (Nov. 23-29) to 70,000 (Nov. 30 to Dec. 6), for those aged 12-17 years. In that group, 61.6% have received at least one dose and 51.8% are fully vaccinated, the CDC said.

The pace of vaccinations varies for younger children as well, when geography is considered. The AAP analyzed the CDC’s data and found that 42% of all 5- to 11-year-olds in Vermont had received at least one dose as of Dec. 1, followed by Massachusetts (33%), Maine (30%), and Rhode Island (28%). At the other end of the vaccination scale are Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, and West Virginia, all with 4%, the AAP reported.

As the United States puts 7 million children infected with COVID-19 in its rear view mirror, another milestone is looming ahead: The CDC’s current count of deaths in children is 974.

Total COVID-19 cases in children surpassed the 7-million mark as new cases rose slightly after the previous week’s decline, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report. New cases had dropped the previous week after 3 straight weeks of increases since late October.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention puts the total number of child COVID-19 cases at 6.2 million, but both estimates are based on all-age totals – 40 million for the CDC and 41 million for the AAP/CHA – that are well short of the CDC’s latest cumulative figure, which is now just over 49 million, so the actual figures are undoubtedly higher.

Meanwhile, the 1-month anniversary of 5- to 11-year-olds’ vaccine eligibility brought many completions: 923,000 received their second dose during the week ending Dec. 6, compared with 405,000 the previous week. About 16.9% (4.9 million) of children aged 5-11 have gotten at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine thus far, of whom almost 1.5 million children (5.1% of the age group) are now fully vaccinated, the CDC said on its COVID-19 Data Tracker.

The pace of vaccinations, however, is much lower for older children. Weekly numbers for all COVID-19 vaccinations, both first and second doses, dropped from 84,000 (Nov. 23-29) to 70,000 (Nov. 30 to Dec. 6), for those aged 12-17 years. In that group, 61.6% have received at least one dose and 51.8% are fully vaccinated, the CDC said.

The pace of vaccinations varies for younger children as well, when geography is considered. The AAP analyzed the CDC’s data and found that 42% of all 5- to 11-year-olds in Vermont had received at least one dose as of Dec. 1, followed by Massachusetts (33%), Maine (30%), and Rhode Island (28%). At the other end of the vaccination scale are Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, and West Virginia, all with 4%, the AAP reported.

As the United States puts 7 million children infected with COVID-19 in its rear view mirror, another milestone is looming ahead: The CDC’s current count of deaths in children is 974.

Total COVID-19 cases in children surpassed the 7-million mark as new cases rose slightly after the previous week’s decline, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report. New cases had dropped the previous week after 3 straight weeks of increases since late October.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention puts the total number of child COVID-19 cases at 6.2 million, but both estimates are based on all-age totals – 40 million for the CDC and 41 million for the AAP/CHA – that are well short of the CDC’s latest cumulative figure, which is now just over 49 million, so the actual figures are undoubtedly higher.

Meanwhile, the 1-month anniversary of 5- to 11-year-olds’ vaccine eligibility brought many completions: 923,000 received their second dose during the week ending Dec. 6, compared with 405,000 the previous week. About 16.9% (4.9 million) of children aged 5-11 have gotten at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine thus far, of whom almost 1.5 million children (5.1% of the age group) are now fully vaccinated, the CDC said on its COVID-19 Data Tracker.

The pace of vaccinations, however, is much lower for older children. Weekly numbers for all COVID-19 vaccinations, both first and second doses, dropped from 84,000 (Nov. 23-29) to 70,000 (Nov. 30 to Dec. 6), for those aged 12-17 years. In that group, 61.6% have received at least one dose and 51.8% are fully vaccinated, the CDC said.

The pace of vaccinations varies for younger children as well, when geography is considered. The AAP analyzed the CDC’s data and found that 42% of all 5- to 11-year-olds in Vermont had received at least one dose as of Dec. 1, followed by Massachusetts (33%), Maine (30%), and Rhode Island (28%). At the other end of the vaccination scale are Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, and West Virginia, all with 4%, the AAP reported.

As the United States puts 7 million children infected with COVID-19 in its rear view mirror, another milestone is looming ahead: The CDC’s current count of deaths in children is 974.

First Omicron variant case identified in U.S.

He or she was fully vaccinated against COVID-19 and experienced only “mild symptoms that are improving,” officials with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said.

The patient, who was not named in the CDC’s announcement of the first U.S. case of the Omicron variant Dec. 1, is self-quarantining.

“All close contacts have been contacted and have tested negative,” officials said.

The announcement comes as no surprise to many as the Omicron variant, first identified in South Africa, has been reported in countries around the world in recent days. Hong Kong, the United Kingdom, and Germany each reported this variant, as have Italy and the Netherlands. Over the weekend, the first North American cases were identified in Canada.

Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, announced over the weekend that this newest variant was likely already in the United States, telling ABC’s This Week its appearance here was “inevitable.”

Similar to previous variants, this new strain likely started circulating in the United States before scientists could do genetic tests to confirm its presence.

The World Health Organization named Omicron a “variant of concern” on Nov. 26, even though much remains unknown about how well it spreads, how severe it can be, and how it may resist vaccines. In the meantime, the United States enacted travel bans from multiple South African countries.

It remains to be seen if Omicron will follow the pattern of the Delta variant, which was first identified in the United States in May and became the dominant strain by July. It’s also possible it will follow the path taken by the Mu variant. Mu emerged in March and April to much concern, only to fizzle out by September because it was unable to compete with the Delta variant.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

He or she was fully vaccinated against COVID-19 and experienced only “mild symptoms that are improving,” officials with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said.

The patient, who was not named in the CDC’s announcement of the first U.S. case of the Omicron variant Dec. 1, is self-quarantining.

“All close contacts have been contacted and have tested negative,” officials said.

The announcement comes as no surprise to many as the Omicron variant, first identified in South Africa, has been reported in countries around the world in recent days. Hong Kong, the United Kingdom, and Germany each reported this variant, as have Italy and the Netherlands. Over the weekend, the first North American cases were identified in Canada.

Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, announced over the weekend that this newest variant was likely already in the United States, telling ABC’s This Week its appearance here was “inevitable.”

Similar to previous variants, this new strain likely started circulating in the United States before scientists could do genetic tests to confirm its presence.

The World Health Organization named Omicron a “variant of concern” on Nov. 26, even though much remains unknown about how well it spreads, how severe it can be, and how it may resist vaccines. In the meantime, the United States enacted travel bans from multiple South African countries.

It remains to be seen if Omicron will follow the pattern of the Delta variant, which was first identified in the United States in May and became the dominant strain by July. It’s also possible it will follow the path taken by the Mu variant. Mu emerged in March and April to much concern, only to fizzle out by September because it was unable to compete with the Delta variant.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

He or she was fully vaccinated against COVID-19 and experienced only “mild symptoms that are improving,” officials with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said.

The patient, who was not named in the CDC’s announcement of the first U.S. case of the Omicron variant Dec. 1, is self-quarantining.

“All close contacts have been contacted and have tested negative,” officials said.

The announcement comes as no surprise to many as the Omicron variant, first identified in South Africa, has been reported in countries around the world in recent days. Hong Kong, the United Kingdom, and Germany each reported this variant, as have Italy and the Netherlands. Over the weekend, the first North American cases were identified in Canada.

Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, announced over the weekend that this newest variant was likely already in the United States, telling ABC’s This Week its appearance here was “inevitable.”

Similar to previous variants, this new strain likely started circulating in the United States before scientists could do genetic tests to confirm its presence.

The World Health Organization named Omicron a “variant of concern” on Nov. 26, even though much remains unknown about how well it spreads, how severe it can be, and how it may resist vaccines. In the meantime, the United States enacted travel bans from multiple South African countries.

It remains to be seen if Omicron will follow the pattern of the Delta variant, which was first identified in the United States in May and became the dominant strain by July. It’s also possible it will follow the path taken by the Mu variant. Mu emerged in March and April to much concern, only to fizzle out by September because it was unable to compete with the Delta variant.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Children and COVID: New cases, vaccinations both decline

States reported 131,828 new pediatric cases for the week of Nov. 19-25, a decline of 7.1% over the previous week but still enough to surpass 100,000 for the 16th consecutive week. The weekly count had risen for 3 straight weeks since the last decrease in late October, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said Nov. 30 in their weekly COVID report.

The AAP/CHA analysis, based on data from state and territorial health departments, puts the total number of cases in children at 6.9 million since the pandemic began, representing 17.0% of cases in Americans of all ages. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which uses an age limit of 18 years to define a child, unlike some states, reports numbers of 6.1 million and 15.5%.

New vaccinations among the youngest eligible children, those aged 5-11 years, were down for the second week in a row after reaching almost 1.7 million during the first full week after approval on Nov. 2. Since then, the vaccination counts have been 1.2 million (Nov. 16-22) and 333,000 (Nov. 23-29), the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker. A similar drop in the last week – from 127,000 to just 50,000 – also was seen for those aged 12-17 years.

Altogether, 14.2% of children aged 5-11, almost 4.1 million individuals, have received at least one dose of the vaccine, compared with 59.0% (10 million) of the 12- to 15-year-olds and 65.2% (5.5 million) of those aged 16-17. Just under 1% of the youngest group has been fully vaccinated, versus 49.0% and 55.8% for the older children, the CDC said.

It has been reported that Pfizer and BioNTech, which produce the only COVID vaccine approved for children, are planning to apply to the Food and Drug Administration during the first week of December for authorization for a booster dose for 16- and 17-year-olds.

States reported 131,828 new pediatric cases for the week of Nov. 19-25, a decline of 7.1% over the previous week but still enough to surpass 100,000 for the 16th consecutive week. The weekly count had risen for 3 straight weeks since the last decrease in late October, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said Nov. 30 in their weekly COVID report.

The AAP/CHA analysis, based on data from state and territorial health departments, puts the total number of cases in children at 6.9 million since the pandemic began, representing 17.0% of cases in Americans of all ages. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which uses an age limit of 18 years to define a child, unlike some states, reports numbers of 6.1 million and 15.5%.

New vaccinations among the youngest eligible children, those aged 5-11 years, were down for the second week in a row after reaching almost 1.7 million during the first full week after approval on Nov. 2. Since then, the vaccination counts have been 1.2 million (Nov. 16-22) and 333,000 (Nov. 23-29), the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker. A similar drop in the last week – from 127,000 to just 50,000 – also was seen for those aged 12-17 years.

Altogether, 14.2% of children aged 5-11, almost 4.1 million individuals, have received at least one dose of the vaccine, compared with 59.0% (10 million) of the 12- to 15-year-olds and 65.2% (5.5 million) of those aged 16-17. Just under 1% of the youngest group has been fully vaccinated, versus 49.0% and 55.8% for the older children, the CDC said.

It has been reported that Pfizer and BioNTech, which produce the only COVID vaccine approved for children, are planning to apply to the Food and Drug Administration during the first week of December for authorization for a booster dose for 16- and 17-year-olds.

States reported 131,828 new pediatric cases for the week of Nov. 19-25, a decline of 7.1% over the previous week but still enough to surpass 100,000 for the 16th consecutive week. The weekly count had risen for 3 straight weeks since the last decrease in late October, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said Nov. 30 in their weekly COVID report.

The AAP/CHA analysis, based on data from state and territorial health departments, puts the total number of cases in children at 6.9 million since the pandemic began, representing 17.0% of cases in Americans of all ages. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which uses an age limit of 18 years to define a child, unlike some states, reports numbers of 6.1 million and 15.5%.

New vaccinations among the youngest eligible children, those aged 5-11 years, were down for the second week in a row after reaching almost 1.7 million during the first full week after approval on Nov. 2. Since then, the vaccination counts have been 1.2 million (Nov. 16-22) and 333,000 (Nov. 23-29), the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker. A similar drop in the last week – from 127,000 to just 50,000 – also was seen for those aged 12-17 years.

Altogether, 14.2% of children aged 5-11, almost 4.1 million individuals, have received at least one dose of the vaccine, compared with 59.0% (10 million) of the 12- to 15-year-olds and 65.2% (5.5 million) of those aged 16-17. Just under 1% of the youngest group has been fully vaccinated, versus 49.0% and 55.8% for the older children, the CDC said.

It has been reported that Pfizer and BioNTech, which produce the only COVID vaccine approved for children, are planning to apply to the Food and Drug Administration during the first week of December for authorization for a booster dose for 16- and 17-year-olds.

FDA approves first drug for treatment of resistant cytomegalovirus infection

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the first treatment for posttransplant cytomegalovirus (CMV) that is resistant to other drugs.

There are an estimated 200,000 adult transplants every year globally. CMV, a type of herpes virus, is one of the most common infections in transplant patients, occurring in 16%-56% of solid organ transplant recipients and 30%-70% of hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients, according to Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited, the company that manufactures Livtencity. For immunosuppressed transplant patients, CMV infection can lead to complications that include loss of the transplanted or organ or even death.

“Cytomegalovirus infections that are resistant or do not respond to available drugs are of even greater concern,” John Farley, MD, MPH, the director of the Office of Infectious Diseases in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a statement. “Today’s approval helps meet a significant unmet medical need by providing a treatment option for this patient population.”

Livtencity, which is taken orally, works by preventing the activity of the enzyme responsible for virus replication. The approval, announced Nov. 23, was based on a phase 3 clinical trial that compared Livtencity with conventional antiviral treatments in the achievement of CMV DNA concentration levels below what is measurable in transplant patients with CMV infection that is refractory or treatment-resistant. After 8 weeks, of the 235 patients who received Livtencity, 56% achieved this primary endpoint, compared with 24% of the 117 patients who received conventional antiviral treatments, the press release says.

The most reported adverse reactions of Livtencity were taste disturbance, nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, and fatigue.

“We are grateful for the contributions of the patients and clinicians who participated in our clinical trials, as well as the dedication of our scientists and researchers,” Ramona Sequeira, president of the Takeda’s U.S. Business Unit and Global Portfolio Commercialization, said in a statement. “People undergoing transplants have a lengthy and complex health care journey; with the approval of this treatment, we’re proud to offer these individuals a new oral antiviral to fight CMV infection and disease.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the first treatment for posttransplant cytomegalovirus (CMV) that is resistant to other drugs.

There are an estimated 200,000 adult transplants every year globally. CMV, a type of herpes virus, is one of the most common infections in transplant patients, occurring in 16%-56% of solid organ transplant recipients and 30%-70% of hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients, according to Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited, the company that manufactures Livtencity. For immunosuppressed transplant patients, CMV infection can lead to complications that include loss of the transplanted or organ or even death.

“Cytomegalovirus infections that are resistant or do not respond to available drugs are of even greater concern,” John Farley, MD, MPH, the director of the Office of Infectious Diseases in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a statement. “Today’s approval helps meet a significant unmet medical need by providing a treatment option for this patient population.”

Livtencity, which is taken orally, works by preventing the activity of the enzyme responsible for virus replication. The approval, announced Nov. 23, was based on a phase 3 clinical trial that compared Livtencity with conventional antiviral treatments in the achievement of CMV DNA concentration levels below what is measurable in transplant patients with CMV infection that is refractory or treatment-resistant. After 8 weeks, of the 235 patients who received Livtencity, 56% achieved this primary endpoint, compared with 24% of the 117 patients who received conventional antiviral treatments, the press release says.

The most reported adverse reactions of Livtencity were taste disturbance, nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, and fatigue.

“We are grateful for the contributions of the patients and clinicians who participated in our clinical trials, as well as the dedication of our scientists and researchers,” Ramona Sequeira, president of the Takeda’s U.S. Business Unit and Global Portfolio Commercialization, said in a statement. “People undergoing transplants have a lengthy and complex health care journey; with the approval of this treatment, we’re proud to offer these individuals a new oral antiviral to fight CMV infection and disease.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the first treatment for posttransplant cytomegalovirus (CMV) that is resistant to other drugs.

There are an estimated 200,000 adult transplants every year globally. CMV, a type of herpes virus, is one of the most common infections in transplant patients, occurring in 16%-56% of solid organ transplant recipients and 30%-70% of hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients, according to Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited, the company that manufactures Livtencity. For immunosuppressed transplant patients, CMV infection can lead to complications that include loss of the transplanted or organ or even death.

“Cytomegalovirus infections that are resistant or do not respond to available drugs are of even greater concern,” John Farley, MD, MPH, the director of the Office of Infectious Diseases in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a statement. “Today’s approval helps meet a significant unmet medical need by providing a treatment option for this patient population.”

Livtencity, which is taken orally, works by preventing the activity of the enzyme responsible for virus replication. The approval, announced Nov. 23, was based on a phase 3 clinical trial that compared Livtencity with conventional antiviral treatments in the achievement of CMV DNA concentration levels below what is measurable in transplant patients with CMV infection that is refractory or treatment-resistant. After 8 weeks, of the 235 patients who received Livtencity, 56% achieved this primary endpoint, compared with 24% of the 117 patients who received conventional antiviral treatments, the press release says.

The most reported adverse reactions of Livtencity were taste disturbance, nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, and fatigue.

“We are grateful for the contributions of the patients and clinicians who participated in our clinical trials, as well as the dedication of our scientists and researchers,” Ramona Sequeira, president of the Takeda’s U.S. Business Unit and Global Portfolio Commercialization, said in a statement. “People undergoing transplants have a lengthy and complex health care journey; with the approval of this treatment, we’re proud to offer these individuals a new oral antiviral to fight CMV infection and disease.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.