User login

CDC officially endorses third dose of mRNA vaccines for immunocompromised

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, has officially signed off on a recommendation by an independent panel of 11 experts to allow people with weakened immune function to get a third dose of certain COVID-19 vaccines.

The decision follows a unanimous vote by the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), which in turn came hours after the U.S. Food and Drug Administration updated its Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) for the Pfizer and Moderna mRNA vaccines.

About 7 million adults in the United States have moderately to severely impaired immune function because of a medical condition they live with or a medication they take to manage a health condition.

People who fall into this category are at higher risk of being hospitalized or dying if they get COVID-19. They are also more likely to transmit the infection. About 40% of vaccinated patients who are hospitalized with breakthrough cases are immunocompromised.

Recent studies have shown that between one-third and one-half of immunocompromised people who didn’t develop antibodies after two doses of a vaccine do get some level of protection after a third dose.

Even then, however, the protection immunocompromised people get from vaccines is not as robust as someone who has healthy immune function, and some panel members were concerned that a third dose might come with a false sense of security.

“My only concern with adding a third dose for the immunocompromised is the impression that our immunocompromised population [will] then be safe,” said ACIP member Helen Talbot, MD, MPH, an associate professor of medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn.

“I think the reality is they’ll be safer but still at incredibly high risk for severe disease and death,” she said.

In updating its EUA, the FDA stressed that, even after a third dose, people who are immunocompromised will still need to wear a mask indoors, socially distance, and avoid large crowds. In addition, family members and other close contacts should be fully vaccinated to protect these vulnerable individuals.

Johnson & Johnson not in the mix

The boosters will be available to children as young as 12 years of age who’ve had a Pfizer vaccine or those ages 18 and older who’ve gotten the Moderna vaccine.

For now, people who’ve had the one-dose Johnson & Johnson vaccine have not been cleared to get a second dose of any vaccine.

FDA experts acknowledged the gap but said that people who had received the Johnson & Johnson vaccine represented a small slice of vaccinated Americans, and said they couldn’t act before the FDA had updated its authorization for that vaccine, which the agency is actively exploring.

“We had to do what we’re doing based on the data we have in hand,” said Peter Marks, MD, director of the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research at the FDA, the division of the agency that regulates vaccines.

“We think at least there is a solution here for the very large majority of immunocompromised individuals, and we believe we will probably have a solution for the remainder in the not-too-distant future,” Dr. Marks said.

In its updated EUA, the FDA said that the third shots were intended for people who had undergone solid organ transplants or have an “equivalent level of immunocompromise.”

The details

Clinical experts on the CDC panel spent a good deal of time trying to suss out exactly what conditions might fall under the FDA’s umbrella for a third dose.

In a presentation to the committee, Neela Goswami, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of infectious diseases at Emory University School of Medicine and of epidemiology at the Emory Rollins School of Public Health, Atlanta, stressed that the shots are intended for patients who are moderately or severely immunocompromised, in close consultation with their doctors, but that people who should qualify would include those:

- Receiving treatment for solid tumors or blood cancers

- Taking immunosuppressing medications after a solid organ transplant

- Within 2 years of receiving CAR-T therapy or a stem cell transplant

- Who have primary immunodeficiencies – rare genetic disorders that prevent the immune system from working properly

- With advanced or untreated

- Taking high-dose corticosteroids (more than 20 milligrams of or its equivalent daily), alkylating agents, antimetabolites, chemotherapy, TNF blockers, or other immunomodulating or immunosuppressing biologics

- With certain chronic medical conditions, such as or asplenia – living without a spleen

- Receiving dialysis

In discussion, CDC experts clarified that these third doses were not intended for people whose immune function had waned with age, such as elderly residents of long-term care facilities or people with chronic diseases like diabetes.

The idea is to try to get a third dose of the vaccine they’ve already had – Moderna or Pfizer – but if that’s not feasible, it’s fine for the third dose to be different from what someone has had before. The third dose should be given at least 28 days after a second dose, and, ideally, before the initiation of immunosuppressive therapy.

Participants in the meeting said that the CDC would post updated materials on its website to help guide physicians on exactly who should receive third doses.

Ultimately, however, the extra doses will be given on an honor system; no prescriptions or other kinds of clinical documentation will be required for people to get a third dose of these shots.

Tests to measure neutralizing antibodies are also not recommended before the shots are given because of differences in the types of tests used to measure these antibodies and the difficulty in interpreting them. It’s unclear right now what level of neutralizing antibodies is needed for protection.

‘Peace of mind’

In public testimony, Heather Braaten, a 44-year-old being treated for ovarian cancer, said she was grateful to have gotten two shots of the Pfizer vaccine last winter, in between rounds of chemotherapy, but she knew she was probably not well protected. She said she’d become obsessive over the past few months reading medical studies and trying to understand her risk.

“I have felt distraught over the situation. My prognosis is poor. I most likely have about two to three years left to live, so everything counts,” Ms. Braaten said.

She said her life ambitions were humble. She wants to visit with friends and family and not have to worry that she’ll be a breakthrough case. She wants to go grocery shopping again and “not panic and leave the store after five minutes.” She’d love to feel free to travel, she said.

“While I understand I still need to be cautious, I am hopeful for the peace of mind and greater freedom a third shot can provide,” Ms. Braaten said.

More boosters on the way?

In the second half of the meeting, the CDC also signaled that it was considering the use of boosters for people whose immunity might have waned in the months since they had completed their vaccine series, particularly seniors. About 75% of people hospitalized with vaccine breakthrough cases are over age 65, according to CDC data.

Those considerations are becoming more urgent as the Delta variant continues to pummel less vaccinated states and counties.

In its presentation to the ACIP, Heather Scobie, PhD, MPH, a member of the CDC’s COVID Response Team, highlighted data from Canada, Israel, Qatar, and the United Kingdom showing that, while the Pfizer vaccine was still highly effective at preventing hospitalizations and death, it’s far less likely when faced with Delta to prevent an infection that causes symptoms.

In Israel, Pfizer’s vaccine prevented symptoms an average of 41% of the time. In Qatar, which is also using the Moderna vaccine, Pfizer’s prevented symptomatic infections with Delta about 54% of the time compared with 85% with Moderna’s.

Dr. Scobie noted that Pfizer’s waning efficacy may have something to do with the fact that it uses a lower dosage than Moderna’s. Pfizer’s recommended dosing interval is also shorter – 3 weeks compared with 4 weeks for Moderna’s. Stretching the time between shots has been shown to boost vaccine effectiveness, she said.

New data from the Mayo clinic, published ahead of peer review, also suggest that Pfizer’s protection may be fading more quickly than Moderna’s.

In February, both shots were nearly 100% effective at preventing the SARS-CoV-2 infection, but by July, against Delta, Pfizer’s efficacy had dropped to somewhere between 13% and 62%, while Moderna’s was still effective at preventing infection between 58% and 87% of the time.

In July, Pfizer’s was between 24% and 94% effective at preventing hospitalization with a COVID-19 infection and Moderna’s was between 33% and 96% effective at preventing hospitalization.

While that may sound like cause for concern, Dr. Scobie noted that, as of August 2, severe COVD-19 outcomes after vaccination are still very rare. Among 164 million fully vaccinated people in the United States there have been about 7,000 hospitalizations and 1,500 deaths; nearly three out of four of these have been in people over the age of 65.

The ACIP will next meet on August 24 to focus solely on the COVID-19 vaccines.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, has officially signed off on a recommendation by an independent panel of 11 experts to allow people with weakened immune function to get a third dose of certain COVID-19 vaccines.

The decision follows a unanimous vote by the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), which in turn came hours after the U.S. Food and Drug Administration updated its Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) for the Pfizer and Moderna mRNA vaccines.

About 7 million adults in the United States have moderately to severely impaired immune function because of a medical condition they live with or a medication they take to manage a health condition.

People who fall into this category are at higher risk of being hospitalized or dying if they get COVID-19. They are also more likely to transmit the infection. About 40% of vaccinated patients who are hospitalized with breakthrough cases are immunocompromised.

Recent studies have shown that between one-third and one-half of immunocompromised people who didn’t develop antibodies after two doses of a vaccine do get some level of protection after a third dose.

Even then, however, the protection immunocompromised people get from vaccines is not as robust as someone who has healthy immune function, and some panel members were concerned that a third dose might come with a false sense of security.

“My only concern with adding a third dose for the immunocompromised is the impression that our immunocompromised population [will] then be safe,” said ACIP member Helen Talbot, MD, MPH, an associate professor of medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn.

“I think the reality is they’ll be safer but still at incredibly high risk for severe disease and death,” she said.

In updating its EUA, the FDA stressed that, even after a third dose, people who are immunocompromised will still need to wear a mask indoors, socially distance, and avoid large crowds. In addition, family members and other close contacts should be fully vaccinated to protect these vulnerable individuals.

Johnson & Johnson not in the mix

The boosters will be available to children as young as 12 years of age who’ve had a Pfizer vaccine or those ages 18 and older who’ve gotten the Moderna vaccine.

For now, people who’ve had the one-dose Johnson & Johnson vaccine have not been cleared to get a second dose of any vaccine.

FDA experts acknowledged the gap but said that people who had received the Johnson & Johnson vaccine represented a small slice of vaccinated Americans, and said they couldn’t act before the FDA had updated its authorization for that vaccine, which the agency is actively exploring.

“We had to do what we’re doing based on the data we have in hand,” said Peter Marks, MD, director of the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research at the FDA, the division of the agency that regulates vaccines.

“We think at least there is a solution here for the very large majority of immunocompromised individuals, and we believe we will probably have a solution for the remainder in the not-too-distant future,” Dr. Marks said.

In its updated EUA, the FDA said that the third shots were intended for people who had undergone solid organ transplants or have an “equivalent level of immunocompromise.”

The details

Clinical experts on the CDC panel spent a good deal of time trying to suss out exactly what conditions might fall under the FDA’s umbrella for a third dose.

In a presentation to the committee, Neela Goswami, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of infectious diseases at Emory University School of Medicine and of epidemiology at the Emory Rollins School of Public Health, Atlanta, stressed that the shots are intended for patients who are moderately or severely immunocompromised, in close consultation with their doctors, but that people who should qualify would include those:

- Receiving treatment for solid tumors or blood cancers

- Taking immunosuppressing medications after a solid organ transplant

- Within 2 years of receiving CAR-T therapy or a stem cell transplant

- Who have primary immunodeficiencies – rare genetic disorders that prevent the immune system from working properly

- With advanced or untreated

- Taking high-dose corticosteroids (more than 20 milligrams of or its equivalent daily), alkylating agents, antimetabolites, chemotherapy, TNF blockers, or other immunomodulating or immunosuppressing biologics

- With certain chronic medical conditions, such as or asplenia – living without a spleen

- Receiving dialysis

In discussion, CDC experts clarified that these third doses were not intended for people whose immune function had waned with age, such as elderly residents of long-term care facilities or people with chronic diseases like diabetes.

The idea is to try to get a third dose of the vaccine they’ve already had – Moderna or Pfizer – but if that’s not feasible, it’s fine for the third dose to be different from what someone has had before. The third dose should be given at least 28 days after a second dose, and, ideally, before the initiation of immunosuppressive therapy.

Participants in the meeting said that the CDC would post updated materials on its website to help guide physicians on exactly who should receive third doses.

Ultimately, however, the extra doses will be given on an honor system; no prescriptions or other kinds of clinical documentation will be required for people to get a third dose of these shots.

Tests to measure neutralizing antibodies are also not recommended before the shots are given because of differences in the types of tests used to measure these antibodies and the difficulty in interpreting them. It’s unclear right now what level of neutralizing antibodies is needed for protection.

‘Peace of mind’

In public testimony, Heather Braaten, a 44-year-old being treated for ovarian cancer, said she was grateful to have gotten two shots of the Pfizer vaccine last winter, in between rounds of chemotherapy, but she knew she was probably not well protected. She said she’d become obsessive over the past few months reading medical studies and trying to understand her risk.

“I have felt distraught over the situation. My prognosis is poor. I most likely have about two to three years left to live, so everything counts,” Ms. Braaten said.

She said her life ambitions were humble. She wants to visit with friends and family and not have to worry that she’ll be a breakthrough case. She wants to go grocery shopping again and “not panic and leave the store after five minutes.” She’d love to feel free to travel, she said.

“While I understand I still need to be cautious, I am hopeful for the peace of mind and greater freedom a third shot can provide,” Ms. Braaten said.

More boosters on the way?

In the second half of the meeting, the CDC also signaled that it was considering the use of boosters for people whose immunity might have waned in the months since they had completed their vaccine series, particularly seniors. About 75% of people hospitalized with vaccine breakthrough cases are over age 65, according to CDC data.

Those considerations are becoming more urgent as the Delta variant continues to pummel less vaccinated states and counties.

In its presentation to the ACIP, Heather Scobie, PhD, MPH, a member of the CDC’s COVID Response Team, highlighted data from Canada, Israel, Qatar, and the United Kingdom showing that, while the Pfizer vaccine was still highly effective at preventing hospitalizations and death, it’s far less likely when faced with Delta to prevent an infection that causes symptoms.

In Israel, Pfizer’s vaccine prevented symptoms an average of 41% of the time. In Qatar, which is also using the Moderna vaccine, Pfizer’s prevented symptomatic infections with Delta about 54% of the time compared with 85% with Moderna’s.

Dr. Scobie noted that Pfizer’s waning efficacy may have something to do with the fact that it uses a lower dosage than Moderna’s. Pfizer’s recommended dosing interval is also shorter – 3 weeks compared with 4 weeks for Moderna’s. Stretching the time between shots has been shown to boost vaccine effectiveness, she said.

New data from the Mayo clinic, published ahead of peer review, also suggest that Pfizer’s protection may be fading more quickly than Moderna’s.

In February, both shots were nearly 100% effective at preventing the SARS-CoV-2 infection, but by July, against Delta, Pfizer’s efficacy had dropped to somewhere between 13% and 62%, while Moderna’s was still effective at preventing infection between 58% and 87% of the time.

In July, Pfizer’s was between 24% and 94% effective at preventing hospitalization with a COVID-19 infection and Moderna’s was between 33% and 96% effective at preventing hospitalization.

While that may sound like cause for concern, Dr. Scobie noted that, as of August 2, severe COVD-19 outcomes after vaccination are still very rare. Among 164 million fully vaccinated people in the United States there have been about 7,000 hospitalizations and 1,500 deaths; nearly three out of four of these have been in people over the age of 65.

The ACIP will next meet on August 24 to focus solely on the COVID-19 vaccines.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, has officially signed off on a recommendation by an independent panel of 11 experts to allow people with weakened immune function to get a third dose of certain COVID-19 vaccines.

The decision follows a unanimous vote by the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), which in turn came hours after the U.S. Food and Drug Administration updated its Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) for the Pfizer and Moderna mRNA vaccines.

About 7 million adults in the United States have moderately to severely impaired immune function because of a medical condition they live with or a medication they take to manage a health condition.

People who fall into this category are at higher risk of being hospitalized or dying if they get COVID-19. They are also more likely to transmit the infection. About 40% of vaccinated patients who are hospitalized with breakthrough cases are immunocompromised.

Recent studies have shown that between one-third and one-half of immunocompromised people who didn’t develop antibodies after two doses of a vaccine do get some level of protection after a third dose.

Even then, however, the protection immunocompromised people get from vaccines is not as robust as someone who has healthy immune function, and some panel members were concerned that a third dose might come with a false sense of security.

“My only concern with adding a third dose for the immunocompromised is the impression that our immunocompromised population [will] then be safe,” said ACIP member Helen Talbot, MD, MPH, an associate professor of medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn.

“I think the reality is they’ll be safer but still at incredibly high risk for severe disease and death,” she said.

In updating its EUA, the FDA stressed that, even after a third dose, people who are immunocompromised will still need to wear a mask indoors, socially distance, and avoid large crowds. In addition, family members and other close contacts should be fully vaccinated to protect these vulnerable individuals.

Johnson & Johnson not in the mix

The boosters will be available to children as young as 12 years of age who’ve had a Pfizer vaccine or those ages 18 and older who’ve gotten the Moderna vaccine.

For now, people who’ve had the one-dose Johnson & Johnson vaccine have not been cleared to get a second dose of any vaccine.

FDA experts acknowledged the gap but said that people who had received the Johnson & Johnson vaccine represented a small slice of vaccinated Americans, and said they couldn’t act before the FDA had updated its authorization for that vaccine, which the agency is actively exploring.

“We had to do what we’re doing based on the data we have in hand,” said Peter Marks, MD, director of the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research at the FDA, the division of the agency that regulates vaccines.

“We think at least there is a solution here for the very large majority of immunocompromised individuals, and we believe we will probably have a solution for the remainder in the not-too-distant future,” Dr. Marks said.

In its updated EUA, the FDA said that the third shots were intended for people who had undergone solid organ transplants or have an “equivalent level of immunocompromise.”

The details

Clinical experts on the CDC panel spent a good deal of time trying to suss out exactly what conditions might fall under the FDA’s umbrella for a third dose.

In a presentation to the committee, Neela Goswami, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of infectious diseases at Emory University School of Medicine and of epidemiology at the Emory Rollins School of Public Health, Atlanta, stressed that the shots are intended for patients who are moderately or severely immunocompromised, in close consultation with their doctors, but that people who should qualify would include those:

- Receiving treatment for solid tumors or blood cancers

- Taking immunosuppressing medications after a solid organ transplant

- Within 2 years of receiving CAR-T therapy or a stem cell transplant

- Who have primary immunodeficiencies – rare genetic disorders that prevent the immune system from working properly

- With advanced or untreated

- Taking high-dose corticosteroids (more than 20 milligrams of or its equivalent daily), alkylating agents, antimetabolites, chemotherapy, TNF blockers, or other immunomodulating or immunosuppressing biologics

- With certain chronic medical conditions, such as or asplenia – living without a spleen

- Receiving dialysis

In discussion, CDC experts clarified that these third doses were not intended for people whose immune function had waned with age, such as elderly residents of long-term care facilities or people with chronic diseases like diabetes.

The idea is to try to get a third dose of the vaccine they’ve already had – Moderna or Pfizer – but if that’s not feasible, it’s fine for the third dose to be different from what someone has had before. The third dose should be given at least 28 days after a second dose, and, ideally, before the initiation of immunosuppressive therapy.

Participants in the meeting said that the CDC would post updated materials on its website to help guide physicians on exactly who should receive third doses.

Ultimately, however, the extra doses will be given on an honor system; no prescriptions or other kinds of clinical documentation will be required for people to get a third dose of these shots.

Tests to measure neutralizing antibodies are also not recommended before the shots are given because of differences in the types of tests used to measure these antibodies and the difficulty in interpreting them. It’s unclear right now what level of neutralizing antibodies is needed for protection.

‘Peace of mind’

In public testimony, Heather Braaten, a 44-year-old being treated for ovarian cancer, said she was grateful to have gotten two shots of the Pfizer vaccine last winter, in between rounds of chemotherapy, but she knew she was probably not well protected. She said she’d become obsessive over the past few months reading medical studies and trying to understand her risk.

“I have felt distraught over the situation. My prognosis is poor. I most likely have about two to three years left to live, so everything counts,” Ms. Braaten said.

She said her life ambitions were humble. She wants to visit with friends and family and not have to worry that she’ll be a breakthrough case. She wants to go grocery shopping again and “not panic and leave the store after five minutes.” She’d love to feel free to travel, she said.

“While I understand I still need to be cautious, I am hopeful for the peace of mind and greater freedom a third shot can provide,” Ms. Braaten said.

More boosters on the way?

In the second half of the meeting, the CDC also signaled that it was considering the use of boosters for people whose immunity might have waned in the months since they had completed their vaccine series, particularly seniors. About 75% of people hospitalized with vaccine breakthrough cases are over age 65, according to CDC data.

Those considerations are becoming more urgent as the Delta variant continues to pummel less vaccinated states and counties.

In its presentation to the ACIP, Heather Scobie, PhD, MPH, a member of the CDC’s COVID Response Team, highlighted data from Canada, Israel, Qatar, and the United Kingdom showing that, while the Pfizer vaccine was still highly effective at preventing hospitalizations and death, it’s far less likely when faced with Delta to prevent an infection that causes symptoms.

In Israel, Pfizer’s vaccine prevented symptoms an average of 41% of the time. In Qatar, which is also using the Moderna vaccine, Pfizer’s prevented symptomatic infections with Delta about 54% of the time compared with 85% with Moderna’s.

Dr. Scobie noted that Pfizer’s waning efficacy may have something to do with the fact that it uses a lower dosage than Moderna’s. Pfizer’s recommended dosing interval is also shorter – 3 weeks compared with 4 weeks for Moderna’s. Stretching the time between shots has been shown to boost vaccine effectiveness, she said.

New data from the Mayo clinic, published ahead of peer review, also suggest that Pfizer’s protection may be fading more quickly than Moderna’s.

In February, both shots were nearly 100% effective at preventing the SARS-CoV-2 infection, but by July, against Delta, Pfizer’s efficacy had dropped to somewhere between 13% and 62%, while Moderna’s was still effective at preventing infection between 58% and 87% of the time.

In July, Pfizer’s was between 24% and 94% effective at preventing hospitalization with a COVID-19 infection and Moderna’s was between 33% and 96% effective at preventing hospitalization.

While that may sound like cause for concern, Dr. Scobie noted that, as of August 2, severe COVD-19 outcomes after vaccination are still very rare. Among 164 million fully vaccinated people in the United States there have been about 7,000 hospitalizations and 1,500 deaths; nearly three out of four of these have been in people over the age of 65.

The ACIP will next meet on August 24 to focus solely on the COVID-19 vaccines.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

CDC reports Burkholderia cepacia and B. pseudomallei outbreaks

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Food and Drug Administration have announced an outbreak of at least 15 Burkholderia cepacia infections associated with contaminated ultrasound gel used to guide invasive procedures as well as an unrelated outbreak of Burkholderia pseudomallei that caused two deaths.

The procedures involved in the B. cepacia outbreak included placement of both central and peripheral intravenous catheters and paracentesis (removal of peritoneal fluid from the abdominal cavity). Cases have occurred in several states.

Further testing has shown the presence of Burkholderia stabilis, a member of B. cepacia complex (Bcc), in four lots of unopened bottles of MediChoice M500812 ultrasound gel. Eco-Med Pharmaceuticals of Etobicoke, Ont., the parent manufacturer, has issued a recall of MediChoice M500812 or Eco-Gel 200 with the following lot numbers: B029, B030, B031, B032, B040, B041, B048, B055. A similar outbreak occurred in Canada.

Some of these cases resulted in bloodstream infections. Further details are not yet available. Bcc infections have ranged from asymptomatic to life-threatening pneumonias, particularly in patients with cystic fibrosis. Other risk factors include immunosuppression, mechanical ventilation, and the use of other invasive venous or urinary catheters.

Kiran M. Perkins, MD, MPH, outbreak lead with the CDC’s Prevention Research Branch, said in an interview via email that automated systems such as Vitek might have trouble identifying the organism as “the system may only reveal the microbial species at the genus level but not at the species level, and/or it may have difficulty distinguishing between members of closely related group members.”

In the CDC’s experience, “most facilities do not conduct further species identification.” The agency added that it cannot tell if there has been any increase in cases associated with COVID-19, as they are not notifiable diseases and the “CDC does not systematically collect information on B. cepacia complex infections.”

Rodney Rohde, PhD, professor of clinical laboratory science and chair of the clinical laboratory science program, Texas State University, San Marcos, told this news organization via email that Burkholderia’s “detection in the manufacturing process is difficult, and product recalls are frequent.” He added, “A recent review by the Food and Drug Administration in the U.S. found that almost 40% of contamination reports in both sterile and nonsterile pharmaceutical products were caused by Bcc bacteria.” Another problem is that they often create biofilms, so “they are tenacious environmental colonizers of medical equipment and surfaces in general.”

There have been many other outbreaks as a result to B. cepacia complex. Because it is often in the water supply used in pharmaceutical manufacturing and is resistant to preservatives, the FDA cautions that it poses a risk of contamination in all nonsterile, water-based drug products.

Recalls have included contaminated antiseptics, such as povidone iodine, benzalkonium chloride, and chlorhexidine gluconate. Contamination in manufacturing may not be uniform, and only some samples may be affected. Antiseptic mouthwashes have also been affected. So have nonbacterial soaps and docusate (a stool softener) solutions, and various personal care products, including nasal sprays, lotions, simethicone gas relief drops (Mylicon), and baby wipes.

Although Bcc are considered “objectionable organisms,” there have been no strong or consistent standards for their detection from the U.S. Pharmacopeia, and some manufacturers reportedly underestimate the consequences of contamination. The FDA issued a guidance to manufacturers in 2017 on quality assurance and cleaning procedures. This is particularly important since preservatives are ineffective against Bcc, and sterility has to be insured at each step of production.

Burkholderia isolates are generally resistant to commonly used antibiotics. Treatment might therefore include a combination of two drugs (to try to limit the emergence of more resistance) such as ceftazidime, piperacillin, meropenem with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, or a beta-lactam plus aminoglycoside.

Interestingly, an outbreak of Burkholderia pseudomallei was just reported by the CDC as well. This is a related gram-negative bacillus which is quite uncommon in the United States. It causes melioidosis, usually a tropical infection, which presents with nonspecific symptoms or serious pneumonia, abscesses, or bloodstream infections.

Four cases have been identified this year in Georgia, Kansas, Minnesota, and Texas, two of them fatal. It is usually acquired from soil or water. By genomic analysis, the four cases are felt to be related, but no common source of exposure has been identified. They also appear to be closely related to South Asian strains, although none of the patients had traveled internationally. Prolonged antibiotic therapy with ceftazidime or meropenem, followed by 3-6 months of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, is often required.

In his email, Dr. Rohde stated, “Melioidosis causes cough, chest pain, high fever, headache or unexplained weight loss, but it may take 2-3 weeks for symptoms of melioidosis to appear after a person’s initial exposure to the bacteria. So, one could see how this might be overlooked as COVID per symptoms and per the limitations of laboratory identification.”

It’s essential for clinicians to recognize that automated microbiology identification systems can misidentify B. pseudomallei as B. cepacia and to ask the lab for more specialized molecular diagnostics, particularly when relatively unusual organisms are isolated.

Candice Hoffmann, a public affairs specialist at the CDC, told this news organization that “clinicians should consider melioidosis as a differential diagnosis in both adult and pediatric patients who are suspected to have a bacterial infection (pneumonia, sepsis, meningitis, wound) and are not responding to antibacterial treatment, even if they have not traveled outside of the continental United States.”

Dr. Rohde has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Food and Drug Administration have announced an outbreak of at least 15 Burkholderia cepacia infections associated with contaminated ultrasound gel used to guide invasive procedures as well as an unrelated outbreak of Burkholderia pseudomallei that caused two deaths.

The procedures involved in the B. cepacia outbreak included placement of both central and peripheral intravenous catheters and paracentesis (removal of peritoneal fluid from the abdominal cavity). Cases have occurred in several states.

Further testing has shown the presence of Burkholderia stabilis, a member of B. cepacia complex (Bcc), in four lots of unopened bottles of MediChoice M500812 ultrasound gel. Eco-Med Pharmaceuticals of Etobicoke, Ont., the parent manufacturer, has issued a recall of MediChoice M500812 or Eco-Gel 200 with the following lot numbers: B029, B030, B031, B032, B040, B041, B048, B055. A similar outbreak occurred in Canada.

Some of these cases resulted in bloodstream infections. Further details are not yet available. Bcc infections have ranged from asymptomatic to life-threatening pneumonias, particularly in patients with cystic fibrosis. Other risk factors include immunosuppression, mechanical ventilation, and the use of other invasive venous or urinary catheters.

Kiran M. Perkins, MD, MPH, outbreak lead with the CDC’s Prevention Research Branch, said in an interview via email that automated systems such as Vitek might have trouble identifying the organism as “the system may only reveal the microbial species at the genus level but not at the species level, and/or it may have difficulty distinguishing between members of closely related group members.”

In the CDC’s experience, “most facilities do not conduct further species identification.” The agency added that it cannot tell if there has been any increase in cases associated with COVID-19, as they are not notifiable diseases and the “CDC does not systematically collect information on B. cepacia complex infections.”

Rodney Rohde, PhD, professor of clinical laboratory science and chair of the clinical laboratory science program, Texas State University, San Marcos, told this news organization via email that Burkholderia’s “detection in the manufacturing process is difficult, and product recalls are frequent.” He added, “A recent review by the Food and Drug Administration in the U.S. found that almost 40% of contamination reports in both sterile and nonsterile pharmaceutical products were caused by Bcc bacteria.” Another problem is that they often create biofilms, so “they are tenacious environmental colonizers of medical equipment and surfaces in general.”

There have been many other outbreaks as a result to B. cepacia complex. Because it is often in the water supply used in pharmaceutical manufacturing and is resistant to preservatives, the FDA cautions that it poses a risk of contamination in all nonsterile, water-based drug products.

Recalls have included contaminated antiseptics, such as povidone iodine, benzalkonium chloride, and chlorhexidine gluconate. Contamination in manufacturing may not be uniform, and only some samples may be affected. Antiseptic mouthwashes have also been affected. So have nonbacterial soaps and docusate (a stool softener) solutions, and various personal care products, including nasal sprays, lotions, simethicone gas relief drops (Mylicon), and baby wipes.

Although Bcc are considered “objectionable organisms,” there have been no strong or consistent standards for their detection from the U.S. Pharmacopeia, and some manufacturers reportedly underestimate the consequences of contamination. The FDA issued a guidance to manufacturers in 2017 on quality assurance and cleaning procedures. This is particularly important since preservatives are ineffective against Bcc, and sterility has to be insured at each step of production.

Burkholderia isolates are generally resistant to commonly used antibiotics. Treatment might therefore include a combination of two drugs (to try to limit the emergence of more resistance) such as ceftazidime, piperacillin, meropenem with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, or a beta-lactam plus aminoglycoside.

Interestingly, an outbreak of Burkholderia pseudomallei was just reported by the CDC as well. This is a related gram-negative bacillus which is quite uncommon in the United States. It causes melioidosis, usually a tropical infection, which presents with nonspecific symptoms or serious pneumonia, abscesses, or bloodstream infections.

Four cases have been identified this year in Georgia, Kansas, Minnesota, and Texas, two of them fatal. It is usually acquired from soil or water. By genomic analysis, the four cases are felt to be related, but no common source of exposure has been identified. They also appear to be closely related to South Asian strains, although none of the patients had traveled internationally. Prolonged antibiotic therapy with ceftazidime or meropenem, followed by 3-6 months of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, is often required.

In his email, Dr. Rohde stated, “Melioidosis causes cough, chest pain, high fever, headache or unexplained weight loss, but it may take 2-3 weeks for symptoms of melioidosis to appear after a person’s initial exposure to the bacteria. So, one could see how this might be overlooked as COVID per symptoms and per the limitations of laboratory identification.”

It’s essential for clinicians to recognize that automated microbiology identification systems can misidentify B. pseudomallei as B. cepacia and to ask the lab for more specialized molecular diagnostics, particularly when relatively unusual organisms are isolated.

Candice Hoffmann, a public affairs specialist at the CDC, told this news organization that “clinicians should consider melioidosis as a differential diagnosis in both adult and pediatric patients who are suspected to have a bacterial infection (pneumonia, sepsis, meningitis, wound) and are not responding to antibacterial treatment, even if they have not traveled outside of the continental United States.”

Dr. Rohde has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Food and Drug Administration have announced an outbreak of at least 15 Burkholderia cepacia infections associated with contaminated ultrasound gel used to guide invasive procedures as well as an unrelated outbreak of Burkholderia pseudomallei that caused two deaths.

The procedures involved in the B. cepacia outbreak included placement of both central and peripheral intravenous catheters and paracentesis (removal of peritoneal fluid from the abdominal cavity). Cases have occurred in several states.

Further testing has shown the presence of Burkholderia stabilis, a member of B. cepacia complex (Bcc), in four lots of unopened bottles of MediChoice M500812 ultrasound gel. Eco-Med Pharmaceuticals of Etobicoke, Ont., the parent manufacturer, has issued a recall of MediChoice M500812 or Eco-Gel 200 with the following lot numbers: B029, B030, B031, B032, B040, B041, B048, B055. A similar outbreak occurred in Canada.

Some of these cases resulted in bloodstream infections. Further details are not yet available. Bcc infections have ranged from asymptomatic to life-threatening pneumonias, particularly in patients with cystic fibrosis. Other risk factors include immunosuppression, mechanical ventilation, and the use of other invasive venous or urinary catheters.

Kiran M. Perkins, MD, MPH, outbreak lead with the CDC’s Prevention Research Branch, said in an interview via email that automated systems such as Vitek might have trouble identifying the organism as “the system may only reveal the microbial species at the genus level but not at the species level, and/or it may have difficulty distinguishing between members of closely related group members.”

In the CDC’s experience, “most facilities do not conduct further species identification.” The agency added that it cannot tell if there has been any increase in cases associated with COVID-19, as they are not notifiable diseases and the “CDC does not systematically collect information on B. cepacia complex infections.”

Rodney Rohde, PhD, professor of clinical laboratory science and chair of the clinical laboratory science program, Texas State University, San Marcos, told this news organization via email that Burkholderia’s “detection in the manufacturing process is difficult, and product recalls are frequent.” He added, “A recent review by the Food and Drug Administration in the U.S. found that almost 40% of contamination reports in both sterile and nonsterile pharmaceutical products were caused by Bcc bacteria.” Another problem is that they often create biofilms, so “they are tenacious environmental colonizers of medical equipment and surfaces in general.”

There have been many other outbreaks as a result to B. cepacia complex. Because it is often in the water supply used in pharmaceutical manufacturing and is resistant to preservatives, the FDA cautions that it poses a risk of contamination in all nonsterile, water-based drug products.

Recalls have included contaminated antiseptics, such as povidone iodine, benzalkonium chloride, and chlorhexidine gluconate. Contamination in manufacturing may not be uniform, and only some samples may be affected. Antiseptic mouthwashes have also been affected. So have nonbacterial soaps and docusate (a stool softener) solutions, and various personal care products, including nasal sprays, lotions, simethicone gas relief drops (Mylicon), and baby wipes.

Although Bcc are considered “objectionable organisms,” there have been no strong or consistent standards for their detection from the U.S. Pharmacopeia, and some manufacturers reportedly underestimate the consequences of contamination. The FDA issued a guidance to manufacturers in 2017 on quality assurance and cleaning procedures. This is particularly important since preservatives are ineffective against Bcc, and sterility has to be insured at each step of production.

Burkholderia isolates are generally resistant to commonly used antibiotics. Treatment might therefore include a combination of two drugs (to try to limit the emergence of more resistance) such as ceftazidime, piperacillin, meropenem with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, or a beta-lactam plus aminoglycoside.

Interestingly, an outbreak of Burkholderia pseudomallei was just reported by the CDC as well. This is a related gram-negative bacillus which is quite uncommon in the United States. It causes melioidosis, usually a tropical infection, which presents with nonspecific symptoms or serious pneumonia, abscesses, or bloodstream infections.

Four cases have been identified this year in Georgia, Kansas, Minnesota, and Texas, two of them fatal. It is usually acquired from soil or water. By genomic analysis, the four cases are felt to be related, but no common source of exposure has been identified. They also appear to be closely related to South Asian strains, although none of the patients had traveled internationally. Prolonged antibiotic therapy with ceftazidime or meropenem, followed by 3-6 months of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, is often required.

In his email, Dr. Rohde stated, “Melioidosis causes cough, chest pain, high fever, headache or unexplained weight loss, but it may take 2-3 weeks for symptoms of melioidosis to appear after a person’s initial exposure to the bacteria. So, one could see how this might be overlooked as COVID per symptoms and per the limitations of laboratory identification.”

It’s essential for clinicians to recognize that automated microbiology identification systems can misidentify B. pseudomallei as B. cepacia and to ask the lab for more specialized molecular diagnostics, particularly when relatively unusual organisms are isolated.

Candice Hoffmann, a public affairs specialist at the CDC, told this news organization that “clinicians should consider melioidosis as a differential diagnosis in both adult and pediatric patients who are suspected to have a bacterial infection (pneumonia, sepsis, meningitis, wound) and are not responding to antibacterial treatment, even if they have not traveled outside of the continental United States.”

Dr. Rohde has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Surge of new child COVID cases continues for 6th consecutive week

The current COVID-19 surge has brought new cases in children to their highest level since February, according to a new report.

New pediatric cases rose for the 6th straight week, with almost 94,000 reported for the week ending Aug. 5.

That weekly total was up by 31% over the previous week and by over 1,000% since late June, when the new-case figure was at its lowest point (8,447) since early in the pandemic, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said. COVID-related deaths – 13 for the week – were also higher than at any time since March 2021.

Almost 4.3 million children have been infected with SARS-CoV-2, which is 14.3% of all cases reported in 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam. Children represented 15.0% of the new cases reported in those jurisdictions during the week ending Aug. 5, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly report.

Another measure that has been trending upward recently is vaccine initiation among 12- to 15-year-olds, although the latest weekly total is still well below the high of 1.4 million seen in May. First-time vaccinations reached almost 411,000 for the week of Aug. 3-9, marking the fourth consecutive increase in that age group, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said on its COVID Data Tracker. Vaccinations also increased, although more modestly, for 16- and 17-year-olds in the most recent week.

Cumulative figures for children aged 12-17 show that almost 10.4 million have received at least one dose and that 7.7 million are fully vaccinated as of Aug. 9. By age group, 42.2% of those aged 12-15 have received at least one dose, and 30.4% have completed the vaccine regimen. Among those aged 16-17 years, 52.2% have gotten their first dose, and 41.4% are fully vaccinated, according to the COVID Data Tracker.

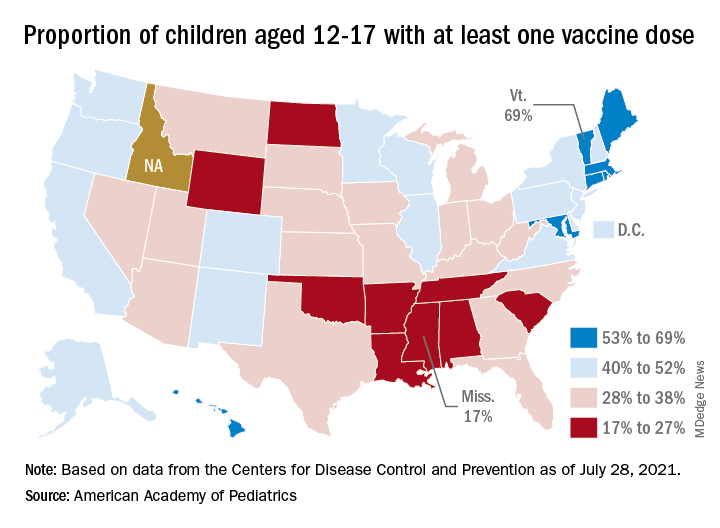

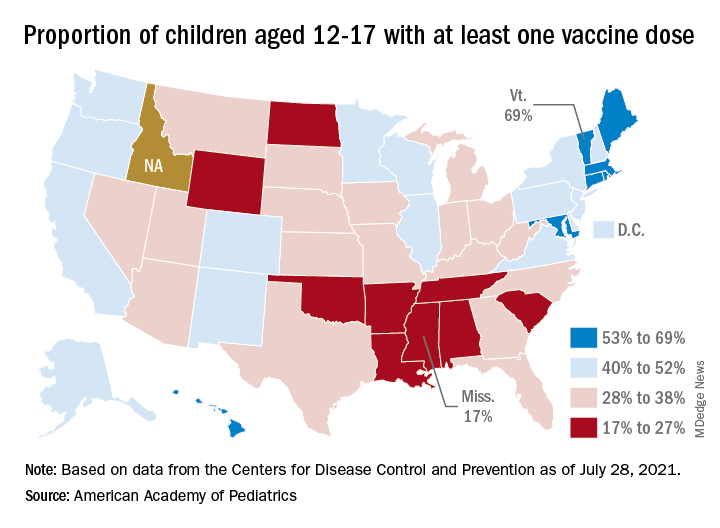

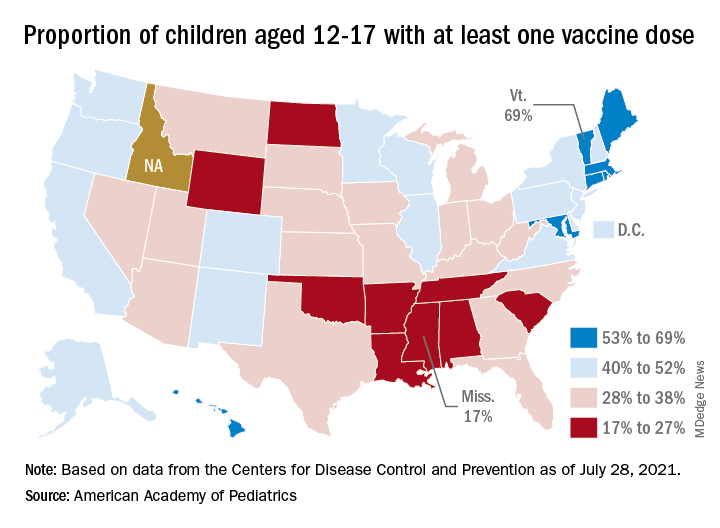

Looking at vaccination rates on the state level shows that only 20% of children aged 12-17 in Wyoming and 21% in Mississippi have gotten at least one dose as of Aug. 4, while Massachusetts is up to 68% and Vermont reports 70%. Rates for full vaccination range from 11% in Mississippi and Alabama to 61% in Vermont, based on an AAP analysis of CDC data, which is not available for Idaho.

The current COVID-19 surge has brought new cases in children to their highest level since February, according to a new report.

New pediatric cases rose for the 6th straight week, with almost 94,000 reported for the week ending Aug. 5.

That weekly total was up by 31% over the previous week and by over 1,000% since late June, when the new-case figure was at its lowest point (8,447) since early in the pandemic, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said. COVID-related deaths – 13 for the week – were also higher than at any time since March 2021.

Almost 4.3 million children have been infected with SARS-CoV-2, which is 14.3% of all cases reported in 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam. Children represented 15.0% of the new cases reported in those jurisdictions during the week ending Aug. 5, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly report.

Another measure that has been trending upward recently is vaccine initiation among 12- to 15-year-olds, although the latest weekly total is still well below the high of 1.4 million seen in May. First-time vaccinations reached almost 411,000 for the week of Aug. 3-9, marking the fourth consecutive increase in that age group, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said on its COVID Data Tracker. Vaccinations also increased, although more modestly, for 16- and 17-year-olds in the most recent week.

Cumulative figures for children aged 12-17 show that almost 10.4 million have received at least one dose and that 7.7 million are fully vaccinated as of Aug. 9. By age group, 42.2% of those aged 12-15 have received at least one dose, and 30.4% have completed the vaccine regimen. Among those aged 16-17 years, 52.2% have gotten their first dose, and 41.4% are fully vaccinated, according to the COVID Data Tracker.

Looking at vaccination rates on the state level shows that only 20% of children aged 12-17 in Wyoming and 21% in Mississippi have gotten at least one dose as of Aug. 4, while Massachusetts is up to 68% and Vermont reports 70%. Rates for full vaccination range from 11% in Mississippi and Alabama to 61% in Vermont, based on an AAP analysis of CDC data, which is not available for Idaho.

The current COVID-19 surge has brought new cases in children to their highest level since February, according to a new report.

New pediatric cases rose for the 6th straight week, with almost 94,000 reported for the week ending Aug. 5.

That weekly total was up by 31% over the previous week and by over 1,000% since late June, when the new-case figure was at its lowest point (8,447) since early in the pandemic, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said. COVID-related deaths – 13 for the week – were also higher than at any time since March 2021.

Almost 4.3 million children have been infected with SARS-CoV-2, which is 14.3% of all cases reported in 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam. Children represented 15.0% of the new cases reported in those jurisdictions during the week ending Aug. 5, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly report.

Another measure that has been trending upward recently is vaccine initiation among 12- to 15-year-olds, although the latest weekly total is still well below the high of 1.4 million seen in May. First-time vaccinations reached almost 411,000 for the week of Aug. 3-9, marking the fourth consecutive increase in that age group, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said on its COVID Data Tracker. Vaccinations also increased, although more modestly, for 16- and 17-year-olds in the most recent week.

Cumulative figures for children aged 12-17 show that almost 10.4 million have received at least one dose and that 7.7 million are fully vaccinated as of Aug. 9. By age group, 42.2% of those aged 12-15 have received at least one dose, and 30.4% have completed the vaccine regimen. Among those aged 16-17 years, 52.2% have gotten their first dose, and 41.4% are fully vaccinated, according to the COVID Data Tracker.

Looking at vaccination rates on the state level shows that only 20% of children aged 12-17 in Wyoming and 21% in Mississippi have gotten at least one dose as of Aug. 4, while Massachusetts is up to 68% and Vermont reports 70%. Rates for full vaccination range from 11% in Mississippi and Alabama to 61% in Vermont, based on an AAP analysis of CDC data, which is not available for Idaho.

CDC: Vaccination may cut risk of COVID reinfection in half

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has recommended that everyone get a COVID-19 vaccine, even if they’ve had the virus before. Yet many skeptics have held off getting the shots, believing that immunity generated by their previous infection will protect them if they should encounter the virus again.

A new study published in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report pokes holes in this notion. It shows people who have recovered from COVID-19 but haven’t been vaccinated have more than double the risk of testing positive for the virus again, compared with someone who was vaccinated after an initial infection.

The study looked at 738 Kentucky residents who had an initial bout of COVID-19 in 2020. About 250 of them tested positive for COVID-19 a second time between May and July of 2021, when the Delta variant became dominant in the United States.

The study matched each person who’d been reinfected with two people of the same sex and roughly the same age who had caught their initial COVID infection within the same week. The researchers then cross-matched those cases with data from Kentucky’s Immunization Registry.

They found that those who were unvaccinated had more than double the risk of being reinfected during the Delta wave. Partial vaccination appeared to have no significant impact on the risk of reinfection.

Among those who were reinfected, 20% were fully vaccinated, while 34% of those who did not get reinfected were fully vaccinated.

The study is observational, meaning it can’t show cause and effect; and the researchers had no information on the severity of the infections. Alyson Cavanaugh, PhD, a member of the CDC’s Epidemic Intelligence Service who led the study, said it is possible that some of the people who tested positive a second time had asymptomatic infections that were picked up through routine screening.

Still, the study backs up previous research and suggests that vaccination offers important additional protection.

“Our laboratory studies have shown that there’s an added benefit of vaccine for people who’ve had previous COVID-19. This is a real-world, epidemiologic study that found that among people who’d previously already had COVID-19, those who were vaccinated had lower odds of being reinfected,” Dr. Cavanaugh said.

“If you have had COVID-19 before, please still get vaccinated,” said CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, in a written media statement. “This study shows you are twice as likely to get infected again if you are unvaccinated. Getting the vaccine is the best way to protect yourself and others around you, especially as the more contagious Delta variant spreads around the country.”

In a White House COVID-19 Response Team briefing in May, Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, explained why vaccines create stronger immunity than infection. He highlighted new research showing that two doses of an mRNA vaccine produce levels of neutralizing antibodies that are up to 10 times higher than the levels found in the blood of people who’ve recovered from COVID-19. Vaccines also enhance B cells and T cells in people who’ve recovered from COVID-19, which broadens the spectrum of protection and helps to fend off variants.

The study has some important limitations, which the authors acknowledged. The first is that second infections weren’t confirmed with genetic sequencing, so the researchers couldn’t definitively tell if a person tested positive a second time because they caught a new virus, or if they were somehow still shedding virus from their first infection. Given that the tests were at least 5 months apart, though, the researchers think reinfection is the most likely explanation.

Another bias in the study could have something to do with vaccination. Vaccinated people may have been less likely to be tested for COVID-19 after their vaccines, so the association or reinfection with a lack of vaccination may be overestimated.

Also, people who were vaccinated at federal sites or in another state were not logged in the state’s immunization registry, which may have skewed the data.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has recommended that everyone get a COVID-19 vaccine, even if they’ve had the virus before. Yet many skeptics have held off getting the shots, believing that immunity generated by their previous infection will protect them if they should encounter the virus again.

A new study published in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report pokes holes in this notion. It shows people who have recovered from COVID-19 but haven’t been vaccinated have more than double the risk of testing positive for the virus again, compared with someone who was vaccinated after an initial infection.

The study looked at 738 Kentucky residents who had an initial bout of COVID-19 in 2020. About 250 of them tested positive for COVID-19 a second time between May and July of 2021, when the Delta variant became dominant in the United States.

The study matched each person who’d been reinfected with two people of the same sex and roughly the same age who had caught their initial COVID infection within the same week. The researchers then cross-matched those cases with data from Kentucky’s Immunization Registry.

They found that those who were unvaccinated had more than double the risk of being reinfected during the Delta wave. Partial vaccination appeared to have no significant impact on the risk of reinfection.

Among those who were reinfected, 20% were fully vaccinated, while 34% of those who did not get reinfected were fully vaccinated.

The study is observational, meaning it can’t show cause and effect; and the researchers had no information on the severity of the infections. Alyson Cavanaugh, PhD, a member of the CDC’s Epidemic Intelligence Service who led the study, said it is possible that some of the people who tested positive a second time had asymptomatic infections that were picked up through routine screening.

Still, the study backs up previous research and suggests that vaccination offers important additional protection.

“Our laboratory studies have shown that there’s an added benefit of vaccine for people who’ve had previous COVID-19. This is a real-world, epidemiologic study that found that among people who’d previously already had COVID-19, those who were vaccinated had lower odds of being reinfected,” Dr. Cavanaugh said.

“If you have had COVID-19 before, please still get vaccinated,” said CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, in a written media statement. “This study shows you are twice as likely to get infected again if you are unvaccinated. Getting the vaccine is the best way to protect yourself and others around you, especially as the more contagious Delta variant spreads around the country.”

In a White House COVID-19 Response Team briefing in May, Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, explained why vaccines create stronger immunity than infection. He highlighted new research showing that two doses of an mRNA vaccine produce levels of neutralizing antibodies that are up to 10 times higher than the levels found in the blood of people who’ve recovered from COVID-19. Vaccines also enhance B cells and T cells in people who’ve recovered from COVID-19, which broadens the spectrum of protection and helps to fend off variants.

The study has some important limitations, which the authors acknowledged. The first is that second infections weren’t confirmed with genetic sequencing, so the researchers couldn’t definitively tell if a person tested positive a second time because they caught a new virus, or if they were somehow still shedding virus from their first infection. Given that the tests were at least 5 months apart, though, the researchers think reinfection is the most likely explanation.

Another bias in the study could have something to do with vaccination. Vaccinated people may have been less likely to be tested for COVID-19 after their vaccines, so the association or reinfection with a lack of vaccination may be overestimated.

Also, people who were vaccinated at federal sites or in another state were not logged in the state’s immunization registry, which may have skewed the data.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has recommended that everyone get a COVID-19 vaccine, even if they’ve had the virus before. Yet many skeptics have held off getting the shots, believing that immunity generated by their previous infection will protect them if they should encounter the virus again.

A new study published in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report pokes holes in this notion. It shows people who have recovered from COVID-19 but haven’t been vaccinated have more than double the risk of testing positive for the virus again, compared with someone who was vaccinated after an initial infection.

The study looked at 738 Kentucky residents who had an initial bout of COVID-19 in 2020. About 250 of them tested positive for COVID-19 a second time between May and July of 2021, when the Delta variant became dominant in the United States.

The study matched each person who’d been reinfected with two people of the same sex and roughly the same age who had caught their initial COVID infection within the same week. The researchers then cross-matched those cases with data from Kentucky’s Immunization Registry.

They found that those who were unvaccinated had more than double the risk of being reinfected during the Delta wave. Partial vaccination appeared to have no significant impact on the risk of reinfection.

Among those who were reinfected, 20% were fully vaccinated, while 34% of those who did not get reinfected were fully vaccinated.

The study is observational, meaning it can’t show cause and effect; and the researchers had no information on the severity of the infections. Alyson Cavanaugh, PhD, a member of the CDC’s Epidemic Intelligence Service who led the study, said it is possible that some of the people who tested positive a second time had asymptomatic infections that were picked up through routine screening.

Still, the study backs up previous research and suggests that vaccination offers important additional protection.

“Our laboratory studies have shown that there’s an added benefit of vaccine for people who’ve had previous COVID-19. This is a real-world, epidemiologic study that found that among people who’d previously already had COVID-19, those who were vaccinated had lower odds of being reinfected,” Dr. Cavanaugh said.

“If you have had COVID-19 before, please still get vaccinated,” said CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, in a written media statement. “This study shows you are twice as likely to get infected again if you are unvaccinated. Getting the vaccine is the best way to protect yourself and others around you, especially as the more contagious Delta variant spreads around the country.”

In a White House COVID-19 Response Team briefing in May, Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, explained why vaccines create stronger immunity than infection. He highlighted new research showing that two doses of an mRNA vaccine produce levels of neutralizing antibodies that are up to 10 times higher than the levels found in the blood of people who’ve recovered from COVID-19. Vaccines also enhance B cells and T cells in people who’ve recovered from COVID-19, which broadens the spectrum of protection and helps to fend off variants.

The study has some important limitations, which the authors acknowledged. The first is that second infections weren’t confirmed with genetic sequencing, so the researchers couldn’t definitively tell if a person tested positive a second time because they caught a new virus, or if they were somehow still shedding virus from their first infection. Given that the tests were at least 5 months apart, though, the researchers think reinfection is the most likely explanation.

Another bias in the study could have something to do with vaccination. Vaccinated people may have been less likely to be tested for COVID-19 after their vaccines, so the association or reinfection with a lack of vaccination may be overestimated.

Also, people who were vaccinated at federal sites or in another state were not logged in the state’s immunization registry, which may have skewed the data.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Treating bioterrorism-related plague: CDC issues new guidelines

The Centers for Disease Control has issued the first recommendations for the prevention and treatment of plague since 2000. The new guidelines focus on the possibility of bioterrorism with mass casualty events from an intentional release of Yersinia pestis.

Plague, a deadly infection caused by Y. pestis, has been feared throughout history because of large pandemics. The most well-known pandemic was the so-called Black Death in the fourteenth century, during which more than 50 million Europeans died. The biggest concern now is the spread of the bacteria by bioterrorism.

The CDC based their revised guidelines on an extensive systematic review of the literature and multiple sessions with about 90 experts in infectious disease, public health, emergency medicine, obgyn, maternal-fetal health, and pediatrics, in addition to representatives from a wide range of federal agencies.

Key changes

Christina Nelson, a medical officer with the CDC’s Division of Vector-Borne Diseases, told this news organization that now “we have been fortunate to have extended options for treatment.” Previously, “streptomycin and gentamicin were the first-line options for adults,” she said. Now, on the basis of additional evidence, “[we’re] able to … elevate the fluoroquinolones to first-line treatments.”

On the basis of the Animal Rule, which allows approval of antibiotics without human testing if such testing is not possible, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved several quinolones for both treatment and prophylaxis of plague.

The guidelines offer same-class alternative antibiotics to meet surge capacity. Similarly, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is now an alternative for prophylaxis.

There are additional oral options to conserve IV medications and supplies in a mass casualty event.

For the first time, the CDC added specific recommendations for pregnant women. Gigi Kwik Gronvall, PhD, senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, Baltimore, told this news organization that she was pleased to see this addition, because “effects on women and during pregnancy are not fully addressed, and it leads to problems down the road, like with COVID, [for which] they didn’t include pregnant people in their clinical trials for the vaccines [and] don’t have enough data to convince pregnant women to actually get the vaccine.”

Bubonic plague

Plague occurs globally, with natural sylvatic (wild animal) outbreaks occurring among rodents and small mammals. It is spread by fleas. When an infected flea bites a human, the person can become infected, most commonly as “bubonic” plague, with swollen lymph nodes, called buboes. Transmission can also occur between people by contact with infected fluids or inhalation of infectious droplets.

Gentamicin or streptomycin remain first-line agents for treating bubonic plague. When used as monotherapy, the survival rate is 91%. They have to be given parenterally and are associated with both nephroroxicity and ototoxicity; patients require monitoring.

Alternative first-line drugs now include high-dose ciprofloxicin, levofloxacin, moxifloxacin, and doxycycline. Each is administered either intravenously or orally.

Physicians should consider dual therapy and drainage for patients with large buboes. Treatment is for 10 to 14 days.

Pneumonic and septicemic plague

The pneumonic and septicemic forms of infection are deadlier than the bubonic. Pneumonic plague can be acquired from inhalation of infected bacteria from animals or people, from lab accidents, or from intentional aerosolization. Without treatment, these forms are almost always fatal. With treatment with aminoglycosides, fluoroquinolones, or tetracyclines, alone or in combination, survival is 82% to 83%. With naturally occurring pneumonic plague, the CDC now recommends levofloxacin or moxifloxacin to cover for community-acquired pneumonia if the source of the infection is uncertain.

Because plague is life threatening, doxycycline is not considered contraindicated in children. It has not been shown to cause tooth staining, unlike other tetracyclines, which should still be avoided if possible.

Meningitis

About 10% of people infected with bubonic plague develop plague meningitis. Symptoms are stiff neck, fever, headache, and coma. The current recommendation for treating plague meningitis is chloramphenicol and moxifloxacin or levofloxacin. However, quinolones can cause seizures, and clinicians should take that into account.

Infection control

Plague is transmitted between people by droplets, so caretakers should wear a mask in addition to taking standard precautions. They should add eye protection and a face shield if splashing is likely. Airborne precautions are not needed. Plague is not very transmissible from person to person; each infected person on average infects only 1.18 other people. In comparison, someone with chicken pox infects 9 to 10 people on average.

Bioterrorism

A deliberate attack would likely go undetected until a cluster or unusual pattern of disease became evident. With Y. pestis, the infectious dose is low. According to the guidelines, modeling suggests that a “release of 50 kg of Y. pestis into the air over a city of 5 million persons could result in 150,000 cases of pneumonic plague and 36,000 deaths.”

Because the former Union of the Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) engineered antibiotic-resistant Y. pestis, antibiotics from two different classes should be used empirically until sensitivity tests become available.

Antibiotic prophylaxis would also have to be considered for exposed individuals. Recommendations would be developed at the time by federal and state experts, based in part on the magnitude of the event and the availability of masks and different classes of antibiotics.

Dr. Gronvall stressed the need for awareness, saying, “It’s important for people to remember that the first sign of the potential attack could be somebody coming into your hospital.”

Dr. Nelson added, “One of the main take-home messages ... is that plague still happens, it still happens in the western United States, it still happens around the world ... It’s not just a relic of history.” She emphasized that clinicians need to be thinking about it, because “it’s very important to get antibiotics on board early ... Then patients generally have a good prognosis.”

Dr. Nelson and Dr. Gronvall have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Centers for Disease Control has issued the first recommendations for the prevention and treatment of plague since 2000. The new guidelines focus on the possibility of bioterrorism with mass casualty events from an intentional release of Yersinia pestis.

Plague, a deadly infection caused by Y. pestis, has been feared throughout history because of large pandemics. The most well-known pandemic was the so-called Black Death in the fourteenth century, during which more than 50 million Europeans died. The biggest concern now is the spread of the bacteria by bioterrorism.

The CDC based their revised guidelines on an extensive systematic review of the literature and multiple sessions with about 90 experts in infectious disease, public health, emergency medicine, obgyn, maternal-fetal health, and pediatrics, in addition to representatives from a wide range of federal agencies.

Key changes

Christina Nelson, a medical officer with the CDC’s Division of Vector-Borne Diseases, told this news organization that now “we have been fortunate to have extended options for treatment.” Previously, “streptomycin and gentamicin were the first-line options for adults,” she said. Now, on the basis of additional evidence, “[we’re] able to … elevate the fluoroquinolones to first-line treatments.”

On the basis of the Animal Rule, which allows approval of antibiotics without human testing if such testing is not possible, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved several quinolones for both treatment and prophylaxis of plague.

The guidelines offer same-class alternative antibiotics to meet surge capacity. Similarly, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is now an alternative for prophylaxis.

There are additional oral options to conserve IV medications and supplies in a mass casualty event.

For the first time, the CDC added specific recommendations for pregnant women. Gigi Kwik Gronvall, PhD, senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, Baltimore, told this news organization that she was pleased to see this addition, because “effects on women and during pregnancy are not fully addressed, and it leads to problems down the road, like with COVID, [for which] they didn’t include pregnant people in their clinical trials for the vaccines [and] don’t have enough data to convince pregnant women to actually get the vaccine.”

Bubonic plague

Plague occurs globally, with natural sylvatic (wild animal) outbreaks occurring among rodents and small mammals. It is spread by fleas. When an infected flea bites a human, the person can become infected, most commonly as “bubonic” plague, with swollen lymph nodes, called buboes. Transmission can also occur between people by contact with infected fluids or inhalation of infectious droplets.

Gentamicin or streptomycin remain first-line agents for treating bubonic plague. When used as monotherapy, the survival rate is 91%. They have to be given parenterally and are associated with both nephroroxicity and ototoxicity; patients require monitoring.

Alternative first-line drugs now include high-dose ciprofloxicin, levofloxacin, moxifloxacin, and doxycycline. Each is administered either intravenously or orally.

Physicians should consider dual therapy and drainage for patients with large buboes. Treatment is for 10 to 14 days.

Pneumonic and septicemic plague

The pneumonic and septicemic forms of infection are deadlier than the bubonic. Pneumonic plague can be acquired from inhalation of infected bacteria from animals or people, from lab accidents, or from intentional aerosolization. Without treatment, these forms are almost always fatal. With treatment with aminoglycosides, fluoroquinolones, or tetracyclines, alone or in combination, survival is 82% to 83%. With naturally occurring pneumonic plague, the CDC now recommends levofloxacin or moxifloxacin to cover for community-acquired pneumonia if the source of the infection is uncertain.

Because plague is life threatening, doxycycline is not considered contraindicated in children. It has not been shown to cause tooth staining, unlike other tetracyclines, which should still be avoided if possible.

Meningitis

About 10% of people infected with bubonic plague develop plague meningitis. Symptoms are stiff neck, fever, headache, and coma. The current recommendation for treating plague meningitis is chloramphenicol and moxifloxacin or levofloxacin. However, quinolones can cause seizures, and clinicians should take that into account.

Infection control

Plague is transmitted between people by droplets, so caretakers should wear a mask in addition to taking standard precautions. They should add eye protection and a face shield if splashing is likely. Airborne precautions are not needed. Plague is not very transmissible from person to person; each infected person on average infects only 1.18 other people. In comparison, someone with chicken pox infects 9 to 10 people on average.

Bioterrorism

A deliberate attack would likely go undetected until a cluster or unusual pattern of disease became evident. With Y. pestis, the infectious dose is low. According to the guidelines, modeling suggests that a “release of 50 kg of Y. pestis into the air over a city of 5 million persons could result in 150,000 cases of pneumonic plague and 36,000 deaths.”

Because the former Union of the Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) engineered antibiotic-resistant Y. pestis, antibiotics from two different classes should be used empirically until sensitivity tests become available.