User login

Are antibiotics beneficial for patients with sinusitis complaints?

- If the goal of treating sinusitis with antibiotics is to cure purulent nasal discharge, we are likely over-treating; as our study showed, after 2 weeks most patients in the treatment and placebo groups still had nasal symptoms (A).

- Persons with higher scores on the clinical prediction rule for sinusitis are no more likely to improve with antibiotic treatment than are those with lower scores (A).

- Among those who did improve on antibiotics, a subgroup that could not be clinically characterized improved at a much quicker rate than the others. Until further clinical trials can describe this favorable clinical profile, routine prescribing of antibiotics for sinusitis should be avoided (A).

Background: Sinusitis is the fifth most common reason for patients to visit primary care physicians, yet clinical outcomes relevant to patients are seldom studied.

Objective To determine whether patients with purulent rhinitis, “sinusitis-type symptoms,” improved with antibiotics. Second, to examine a clinical prediction rule to provide preliminary validation data.

Methods: Prospective clinical trial, with double-blinded placebo controlled randomization. The setting was a suburb of Washington, DC, from Oct 1, 2001, to March 31, 2003. All participants were 18 years or older, presenting to a family practice clinic with a complaint of sinusitis and with pus in the nasal cavity, facial pressure, or nasal discharge lasting longer than 7 days. The main outcome measures were resolution of symptoms within a 14-day follow-up period and the time to improvement (days).

Results: After exclusion criteria, 135 patients were randomized to either placebo (n=68) or amoxicillin (n=67) for 10 days. Intention-to-treat analyses showed that 32 (48%) of the amoxicillin group vs 25 (37%) of the placebo group (P=.26) showed complete improvement by the end of the 2-week follow-up period (relative risk=1.3; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.87–1.94]). Although the rates of improvement were not statistically significantly different at the end of 2 weeks, the amoxicillin group improved significantly earlier, in the course of treatment, a median of 8 vs 12 days, than did the placebo group (P=.039).

Conclusion: For most patients with sinusitis-type complaints, no improvement was seen with antibiotics over placebo. For those who did improve, data suggested there is a subgroup of patients who may benefit from antibiotics.

It is estimated that adults have 2 to 3 colds a year, of which just 0.5% to 2% are complicated by bacterial sinusitis. However, primary care physicians treat over half of these colds with antibiotics.1 Sinusitis is the fifth most common diagnosis for which antibiotics are prescribed in the outpatient setting, with more than $6 billion spent annually in the United States on prescription and over-the-counter medications.1-3 Can we know with greater certainty when antibiotics are indicated for sinusitis?

A meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies has shown that the likelihood of bacterial sinusitis is increased (sensitivity 76%, specificity 79%) and antibiotics are helpful when a patient exhibits at least 3 of 4 cardinal clinical features: 1) purulent nasal discharge predominating on one side; 2) local facial pain predominating on one side; 3) purulent nasal discharge on both sides; and 4) pus in the nasal cavity.2 Although use of these criteria is encouraged, they are based on studies that recruited patients from subspecialty clinics and measured disease-oriented outcomes such as findings on sinus radiographs, CT scans, and sinus puncture with culture.4-12 Most cases of sinusitis, however, are treated in primary care settings where measuring such outcomes is impractical.

Given the lack of epidemiologic evidence as to which patients would benefit from treatment of sinusitis, primary care physicians face the dilemma of deciding during office encounters which patients should receive antibiotics and which have a viral infection for which symptomatic treatment is indicated.13

Our goal was to study the type of patient for whom this dilemma arises and to use clinical improvement as our primary outcome. We randomly assigned patients presenting with sinusitis complaints to receive amoxicillin or placebo, and compared the rates of improvement, time to improvement, and patient’s self-rating of sickness at the end of 2 weeks. We also tested the clinical prediction rule to see if participants with 3 or 4 signs and symptoms had different clinical outcomes than the others.

Methods

Setting

We conducted a randomized double-blind clinical trial of amoxicillin vs placebo. All patients were recruited from a suburban primary care office. Two physicians and one nurse practitioner enrolled and treated all patients over an 18-month period (Oct 1, 2001 to March 31, 2003). The clinicians involved in the study were trained to identify purulent discharge in the nasal cavity. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from Georgetown University prior to the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all participating patients.

Patients

Patients were eligible to participate if they were 18 years or older; had at least 1 cardinal feature described by the clinical prediction rule: 1) purulent nasal discharge predominating on one side, 2) local facial pain predominating on one side, 3) purulent nasal discharge on both sides, or 4) pus in the nasal cavity; and had symptoms for at least 7 days. Patients were excluded if their histories included antibiotic treatment within the past month, allergy to penicillin, sinus surgery, compromised immunity, pneumonia, or streptococcal pharyngitis.

Randomization

Permuted block randomization stratified for the 3 participating clinicians was used to determine treatment assignment. Patients were given an envelope containing 40 capsules, either a placebo medicine taken twice daily for 10 days or 1000 mg of amoxicillin (500 mg pills) taken twice daily for 10 days. The envelopes were opaque, and each had 40 identical-appearing pills (to ensure allocation concealment). The participating clinicians were naive to the treatment assignments.

Assessment of outcomes

Trained personnel, masked to treatment assignment, conducted follow-up telephone interviews on days 3, 7, and 14 following patients’ visits for sinusitis, to assess clinical improvement. Twelve follow-up questions were asked.

Sample size

The primary outcome used to determine sample size was dichotomous—either “improved” or “not improved” by the end of 2 weeks. Thus, patients were asked, “what day were you entirely improved.” The sample sizes obtained per group (67 for amoxicillin and 68 for placebo) provided 80% power for detecting a change of 25% in rates of improvement.

Statistical analysis

Basic descriptive statistics were used to describe the groups. Baseline characteristics were compared between the 2 groups using chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. For continuous variables, the Student’s t-test was used; the Wilcoxon Rank Sum test was used for ordinal or skewed variables. Similar statistical tests were used to compare baseline characteristics between the providers and also at the conclusion of the study between the responders for each group.

For the outcome variables, we hypothesized no difference between the groups either in the rates of improvement, times to improvement, or in patients’ self-rating of sickness. The actual proportions improving between the 2 groups were compared using the chi-square test. Relative risk estimates and 95% confidence intervals were calculated to provide measures of risk and precision. Multiple logistic regression was used to compare the rates of improvement adjusting for the number of signs or symptoms classified as either 1, 2, or 3–4, obtained from the clinical prediction rule (Table 1).

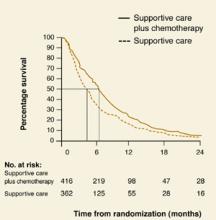

The Kaplan-Meier method was used to construct the curves showing the time until patient improvement for each treatment group. The Wilcoxon test was then used to test the statistical significance in these curves (Figure). Cox’s Proportional Hazards regression was used to test for differences in the time to improvement between the groups adjusting for the number of signs or symptoms.

Additionally, a univariate repeated measures analysis of variance model was constructed to compare the 10-point Likert scale scores for the question, “How sick do you feel today?” In this model, the number of signs and symptoms was entered as a covariate in the analysis. Orthogonal contrasts were used as post-hoc tests to compare the difference between the groups within each time point (Table 2 ).

For the subgroup of patients who improved, analysis of covariance was used to compare the mean number of days to improvement between the groups. In this case the number of signs and symptoms was used as the covariate (Table 3). The Kaplan-Meier method and the Wilcoxon test were used to compare the cumulative rates of improvement (Figure). Unadjusted P-values are reported.

Primary analyses were performed using the intention-to-treat principle. All statistical analyses were performed using JMP Software (Product of SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). Statistical significance was set at 0.05 and exact P-values are reported.

TABLE 1

Baseline characteristics for amoxicillin and placebo groups

| Characteristic | Placebo (n=68) | Amoxicillin (n=67) |

|---|---|---|

| Purulent nasal discharge predominating on 1 side (%) | 28 (41) | 33 (49) |

| Local facial pain predominating on 1 side (%) | 25 (37) | 28 (42) |

| Purulent nasal discharge on both sides (%) | 45 (66) | 49 (73) |

| Pus in the nasal cavity assessed by provider (%) | 20 (29) | 23 (34) |

| Number of symptoms (%) | ||

| 1 | 34 (50) | 29 (43) |

| 2 | 17 (25) | 11 (17) |

| 3–4 | 17 (25) | 27 (40) |

| Female (%) | 49 (73) | 44 (66) |

| Tobacco use (%) | 6 (9) | 2 (3) |

| Over-the-counter medicines used for sinusitis (%) | 55 (89) | 58 (91) |

| Age mean (SD) | 32.6 (9.5) | 35.1 (10.1) |

| Length of symptoms prior to enrollment in mean days (SD) | 11.7 (6.3) | 10.7 (5.0) |

| Temperature in Fahrenheit mean (SD) | 97.9 (.8) | 97.9 (1.0) |

| Self-rating of health* mean (SD) | 3.1 (2.6) | 3.1 (2.4) |

| Self-rating of severity of cough* mean (SD) | 5.8 (2.5) | 5.1 (2.7) |

| Self-rating of how sick patient feels at enrollment* mean (SD) | 6.3 (1.9) | 6.2 (2.0) |

| Self-rating of severity of headache* mean (SD) | 5.3 (3.1) | 5.6 (2.8) |

| Percentages not always equal to 100%, due to missing data. All P <.05 | ||

| Represents Likert scale from 1 to 10; 1 being perfect to 10 being absolute worst case. | ||

Figure

Kaplan-Meier curve for improvement—amoxicillin (n=67) vs placebo (n=68)*

TABLE 2

Comparison of mean Likert scores by group across follow-up time points Question asked at each time point:

| “On a scale of 1 to 10, How sick do you feel today?”* | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Time† | Amoxicillin (n=67) | Placebo (n=68) | P value |

| Day 0 (SD) | 6.10 (2.0) | 6.30 (1.9) | NS |

| Day 3 (SD) | 4.33 (1.8) | 4.73 (1.9) | NS |

| Day 7 (SD) | 3.15 (2.1) | 3.30 (2.0) | NS |

| Day 14 (SD) | 2.30 (1.9) | 2.80 (2.5) | NS |

| Likert score of 1 represents “perfect health” to 10 representing “worst condition.” | |||

| * Statistical tests—Orthogonal contrasts. | |||

| † Data shown represent mean and standard deviation (SD). | |||

TABLE 3

Mean number of days to improvement by group and number of signs and symptoms (at baseline) for patients who improved

| Number of signs and symptoms | Amoxicillin (n=32) | Placebo (n=25) |

|---|---|---|

| (1) Mean (n, SD) | 7.8 days (16, 3.7) | 11.0 days (10, 2.6) |

| (2) Mean (n, SD) | 7.8 days (5, 3.7) | 10.3 days (6, 3.2) |

| (3–4) Mean (n, SD) | 8.6 days (11, 3.6) | 10.6 days (9, 3.0) |

| Signs and symptoms are: purulent (yellow, thick) nasal discharge predominating on 1 side, local facial pain predominating on 1 side, purulent nasal discharge on both sides, and pus in the nasal cavity. | ||

Results

During the 18-month enrollment period, the 3 providers recorded all patients aged >18 years who had at least 1 cardinal feature described by the clinical prediction rule and had symptoms for a minimum of 7 days. Thus, initially 308 patients were approached for enrollment; 173 patients did not qualify after the exclusion criteria were applied, leaving 135 patients for randomization. Sixty-seven received amoxicillin and 68 received placebo. For 11 patients in the amoxicillin arm and 8 in the placebo arm, only baseline data were collected. These patients were then considered as lost to follow-up and were counted as “not improved” in the intention-to-treat analysis.

There were no significant differences (P >.05) in baseline characteristics of the treatment groups (Table 1). Additionally, there were no significant differences in the baseline characteristics between the providers (data not shown).

In the amoxicillin group 32 (48%) had completely improved compared with 25 (37%) in the placebo group (P=.26) after 2 weeks (relative risk of treatment failure=1.3; 95% CI, 0.87–1.94). However, individuals in the amoxicillin group did improve significantly earlier, as the Kaplan-Meier curve demonstrates (Figure). The first person in the amoxicillin group improved on day 3, compared with day 7 in the placebo group. This earlier improvement continued throughout the study (P=.039).

Subgroup analysis of the 57 who demonstrated complete recovery shows the amoxicillin group improved earlier as does the Kaplan-Meier curves in the Figure. In the amoxicillin group, the median day to any improvement was day 8 compared with day 12 for the placebo group (P=.005), while the mean day to improvement for the amoxicillin group was 8.1 days vs 10.7 days for placebo group.

When patients were asked “How sick do you feel today,” the average Likert scores decreased from 6. 1 (day 0) to 2.3 (day 14), and 6.3 (day 0) to 2.8 (day 14), in the amoxicillin and placebo groups, respectively. At each time point, there were no significant clinical or statistical differences between the 2 groups in how they rated their improvement (Table 2). Furthermore, examining only those who reported total improvement within 14 days showed no differences among groups.

No statistically significant differences were observed between the treatment groups that entailed the clinical prediction rule. However, in the patients who were improved at 14 days, the average number of days to improvement was consistently between 2 to 2.5 days shorter in the amoxicillin group compared with placebo (Table 3).

Side effects

No patients dropped out of the study due to adverse side effects (Table 4). There were no serious or unexpected side effects, with the majority related to gastrointestinal problems, such as diarrhea and abdominal pain.

TABLE 4

A Frequency of reported side effects by group

| Amoxicillin Adverse effects | Placebo (n=57) | (n=59) |

|---|---|---|

| Total number of patients with any side effects | 13 | 7 |

| Diarrhea | 4 | 1 |

| Nausea | 4 | 5 |

| Emesis | 1 | 0 |

| Abdominal pain | 2 | 1 |

| Rash | 2 | 0 |

| Hot flashes | 0 | 1 |

| Jittery | 0 | 1 |

| Dizziness | 3 | 0 |

| Dry mouth | 1 | 0 |

| Vaginal infection | 2 | 0 |

| Multiple events per patient are possible. | ||

Discussion

With respect to the patient-oriented outcome of clinical improvement, amoxicillin provided no significant benefit over placebo in the treatment of patients presenting with sinusitis complaints. On average our patients who had symptoms for 11 days prior to enrollment and are typical of patients that are often recommended for treatment with antibiotics.14,15

Our findings are consistent with others in which the overall benefit of antibiotics was minimal or nonexistent.16,18 But among individuals who did improve, those who received amoxicillin improved much earlier, both clinically and statistically. Unfortunately we were not able to specify those who are likely to improve. Clearly, further patient-oriented outcome studies are needed to help primary care physicians decide which patients may benefit from antibiotic treatment.

Antibiotics have not been shown to prevent the sequelae of acute sinusitis. One of the major difficulties in treating sinusitis is the lack of agreement about which outcomes are desired.19,20 Nearly 66% of patients diagnosed with sinusitis will get better without treatment, though nearly two thirds of patients will continue to have such symptoms as cough and nasal discharge for up to 3 weeks.21,22 Thus, we believe that to give antibiotics only to individuals who would truly benefit from them, policy makers, primary care physicians, and patients need to reassess clinically what constitutes sinusitis, and what outcomes are most desired. If the goal is to cure purulent nasal discharge, we are likely over-treating with antibiotics; as our study showed, after 2 weeks most patients in both groups still had nasal symptoms.

Our pilot of the clinical prediction rule failed to predict a proper response to antibiotics or the time to improvement. Although our numbers were not large, no trend was observed towards improvement in individuals with a higher score on the clinical prediction rule.

Our study has some important limitations. Interestingly we found different results when we used the dichotomous outcome of totally improved versus the 10-point Likert scale. A priori we decided our primary outcome was the dichotomous improvement, but which measure is more important and should be used is open to varying interpretations. Additionally, our study office unexpectedly closed and thus we could not recruit the number of patients we initially had planned. This limited our power to find differences between groups based on the number of cardinal clinical features. We encountered noncompliance with follow-up, as expected with the study design. We also arbitrarily stopped follow-up at 14 days, and cases that had not entirely improved were considered clinical failures in all but the Likert scale analysis. It is possible our results may have differed if we had continued to follow patients at 21 or 28 days, or if we had conducted the study at more than one office.

Methodologically, we conducted a rigorous study and showed that patients diagnosed with clinical sinusitis fared no better with amoxicillin or placebo, when measuring the patient-oriented outcome of complete improvement. But a subgroup of patients who were given antibiotics did improve at a much quicker rate. The difficulty is in clinically identifying this group and treating them with antibiotics. Conversely, using antibiotics in patients unnecessarily would only cause potential individual and societal harm. More clinically oriented studies need to be conducted to address this issue and elucidate what signs and symptoms these patients exhibit, to help clarify who should be treated with antibiotics.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

When this article was prepared, Dan Merenstein was an assistant professor of Family Medicine and Pediatrics at Georgetown University. This study was part of the Capricorn Research Network of Georgetown University. This projectwas supported by a grant from the American Academy ofFamily Physicians and the American Academy of FamilyPhysicians Foundation “Joint AAFP/F-AAFP Grant AwardsProgram” (JGAP). Support was also provided by the CapitolArea Primary Care Research Network. Research presentedat NAPRCG 2003, Banff, Canada.

We thank Joel Merenstein for insightful feedback and intelligent comments about study design and input with manuscript. We thank Goutham Rao and Traci Reisner for editorial help. We thank Community Drug Compounding Center of Pittsburgh and pharmacist Susan Freedenberg for drug development.

Corresponding author

Dan Merenstein, MD, Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholar, The Johns Hopkins Hospital, 600 North Wolfe St., Carnegie 291, Baltimore, MD 21287-6220. E-mail: [email protected].

1. Leggett JE. Acute sinusitis. When—and when not—to prescribe antibiotics. Postgrad Med 2004;115(1):13-19.

2. Lau J, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of acute bacterial rhinosinusitis. Evidence Report #9. Rockville, Md: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1999.

3. Brooks I, Gooch WM, 3rd, Jenkins SG, et al. Medical management of acute bacterial sinusitis. Recommendations of a clinical advisory committee on pediatric and adult sinusitis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol Suppl 2000;182:2-20.

4. Williams JW, Jr, Holleman DR, Jr, Samsa GP, Simel DL. Randomized controlled trial of 3 vs 10 days of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole for acute maxillary sinusitis. JAMA 1995;273:1015-1021.

5. Williams JW, Jr, Simel DL. Does this patient have sinusitis? Diagnosing acute sinusitis by history and physical examination. JAMA 1993;270:1242-1246.

6. Williams JW, Jr, Simel DL, Roberts L, Samsa GP. Clinical evaluation for sinusitis. Making the diagnosis by history and physical examination. Ann Intern Med 1992;117:705-710.

7. Wald ER, Chiponis D, Ledesma-Medina J. Comparative effectiveness of amoxicillin and amoxicillin-clavulanate potassium in acute paranasal sinus infections in children: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Pediatrics 1986;77:795-800.

8. van Duijn NP, Brouwer HJ, Lamberts H. Use of symptoms and signs to diagnose maxillary sinusitis in general practice: comparison with ultrasonography. BMJ 1992;305:684-687.

9. Alho OP, Ylitalo K, Jokinen K, et al. The common cold in patients with a history of recurrent sinusitis: increased symptoms and radiologic sinusitislike findings. J Fam Pract 2001;50:26-31.

10. Berg O, Carenfelt C. Analysis of symptoms and clinical signs in the maxillary sinus empyema. Acta Otolaryngol 1988;105:343-349.

11. Okuyemi KS, Tsue TT. Radiologic imaging in the management of sinusitis. Am Fam Physician 2002;66:1882-1886.

12. Engels EA, Terrin N, Barza M, Lau J. Meta-analysis of diagnostic tests for acute sinusitis. J Clin Epidemiol 2000;53:852-862.

13. Poole MD. A focus on acute sinusitis in adults: changes in disease management. Am J Med 1999;106:38S-47S;discussion 48S-52S.

14. Desrosiers M, Frankiel S, Hamid QA, et al. Acute bacterial sinusitis in adults: management in the primary care setting. J Otolaryngol 2002;31 Suppl 2:2S2-14.

15. Lindbaek M. Acute sinusitis: guide to selection of anti-bacterial therapy. Drugs 2004;64:805-819.

16. De Sutter AI, De Meyere MJ, Christiaens TC, Van Driel ML, Peersman W, De Maeseneer JM. Does amoxicillin improve outcomes in patients with purulent rhinorrhea? J Fam Pract 2002;51:317-323.

17. Bucher HC, Tschudi P, Young J, et al. BASINUS (Basel Sinusitis Study) Investigators Effect of amoxicillin-clavulanate in clinically diagnosed acute rhinosinusitis: a placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized trial in general practice. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:1793-1798.

18. Varonen H, Kunnamo I, Savolainen S, et al. Treatment of acute rhinosinusitis diagnosed by clinical criteria or ultrasound in primary care. A placebo-controlled randomised trial. Scand J Prim Health Care 2003;21:121-126.

19. Linder JA, Singer DE, Ancker M, Atlas SJ. Measures of health-related quality of life for adults with acute sinusitis. A systematic review. J Gen Intern Med 2003;18:390-401.

20. Theis J, Oubichon T. Are antibiotics helpful for acute maxillary sinusitis? J Fam Pract 2003;52:490-492;discussion 491.-

21. de Ferranti SD, Ioannidis JP, Lau J, Anninger WV, Barza M. Are amoxycillin and folate inhibitors as effective as other antibiotics for acute sinusitis? A meta-analysis. BMJ 1998;317:632-637.

22. Scott J, Orzano AJ. Evaluation and treatment of the patient with acute undifferentiated respiratory tract infection. J Fam Pract 2001;50:1070-1077.

- If the goal of treating sinusitis with antibiotics is to cure purulent nasal discharge, we are likely over-treating; as our study showed, after 2 weeks most patients in the treatment and placebo groups still had nasal symptoms (A).

- Persons with higher scores on the clinical prediction rule for sinusitis are no more likely to improve with antibiotic treatment than are those with lower scores (A).

- Among those who did improve on antibiotics, a subgroup that could not be clinically characterized improved at a much quicker rate than the others. Until further clinical trials can describe this favorable clinical profile, routine prescribing of antibiotics for sinusitis should be avoided (A).

Background: Sinusitis is the fifth most common reason for patients to visit primary care physicians, yet clinical outcomes relevant to patients are seldom studied.

Objective To determine whether patients with purulent rhinitis, “sinusitis-type symptoms,” improved with antibiotics. Second, to examine a clinical prediction rule to provide preliminary validation data.

Methods: Prospective clinical trial, with double-blinded placebo controlled randomization. The setting was a suburb of Washington, DC, from Oct 1, 2001, to March 31, 2003. All participants were 18 years or older, presenting to a family practice clinic with a complaint of sinusitis and with pus in the nasal cavity, facial pressure, or nasal discharge lasting longer than 7 days. The main outcome measures were resolution of symptoms within a 14-day follow-up period and the time to improvement (days).

Results: After exclusion criteria, 135 patients were randomized to either placebo (n=68) or amoxicillin (n=67) for 10 days. Intention-to-treat analyses showed that 32 (48%) of the amoxicillin group vs 25 (37%) of the placebo group (P=.26) showed complete improvement by the end of the 2-week follow-up period (relative risk=1.3; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.87–1.94]). Although the rates of improvement were not statistically significantly different at the end of 2 weeks, the amoxicillin group improved significantly earlier, in the course of treatment, a median of 8 vs 12 days, than did the placebo group (P=.039).

Conclusion: For most patients with sinusitis-type complaints, no improvement was seen with antibiotics over placebo. For those who did improve, data suggested there is a subgroup of patients who may benefit from antibiotics.

It is estimated that adults have 2 to 3 colds a year, of which just 0.5% to 2% are complicated by bacterial sinusitis. However, primary care physicians treat over half of these colds with antibiotics.1 Sinusitis is the fifth most common diagnosis for which antibiotics are prescribed in the outpatient setting, with more than $6 billion spent annually in the United States on prescription and over-the-counter medications.1-3 Can we know with greater certainty when antibiotics are indicated for sinusitis?

A meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies has shown that the likelihood of bacterial sinusitis is increased (sensitivity 76%, specificity 79%) and antibiotics are helpful when a patient exhibits at least 3 of 4 cardinal clinical features: 1) purulent nasal discharge predominating on one side; 2) local facial pain predominating on one side; 3) purulent nasal discharge on both sides; and 4) pus in the nasal cavity.2 Although use of these criteria is encouraged, they are based on studies that recruited patients from subspecialty clinics and measured disease-oriented outcomes such as findings on sinus radiographs, CT scans, and sinus puncture with culture.4-12 Most cases of sinusitis, however, are treated in primary care settings where measuring such outcomes is impractical.

Given the lack of epidemiologic evidence as to which patients would benefit from treatment of sinusitis, primary care physicians face the dilemma of deciding during office encounters which patients should receive antibiotics and which have a viral infection for which symptomatic treatment is indicated.13

Our goal was to study the type of patient for whom this dilemma arises and to use clinical improvement as our primary outcome. We randomly assigned patients presenting with sinusitis complaints to receive amoxicillin or placebo, and compared the rates of improvement, time to improvement, and patient’s self-rating of sickness at the end of 2 weeks. We also tested the clinical prediction rule to see if participants with 3 or 4 signs and symptoms had different clinical outcomes than the others.

Methods

Setting

We conducted a randomized double-blind clinical trial of amoxicillin vs placebo. All patients were recruited from a suburban primary care office. Two physicians and one nurse practitioner enrolled and treated all patients over an 18-month period (Oct 1, 2001 to March 31, 2003). The clinicians involved in the study were trained to identify purulent discharge in the nasal cavity. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from Georgetown University prior to the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all participating patients.

Patients

Patients were eligible to participate if they were 18 years or older; had at least 1 cardinal feature described by the clinical prediction rule: 1) purulent nasal discharge predominating on one side, 2) local facial pain predominating on one side, 3) purulent nasal discharge on both sides, or 4) pus in the nasal cavity; and had symptoms for at least 7 days. Patients were excluded if their histories included antibiotic treatment within the past month, allergy to penicillin, sinus surgery, compromised immunity, pneumonia, or streptococcal pharyngitis.

Randomization

Permuted block randomization stratified for the 3 participating clinicians was used to determine treatment assignment. Patients were given an envelope containing 40 capsules, either a placebo medicine taken twice daily for 10 days or 1000 mg of amoxicillin (500 mg pills) taken twice daily for 10 days. The envelopes were opaque, and each had 40 identical-appearing pills (to ensure allocation concealment). The participating clinicians were naive to the treatment assignments.

Assessment of outcomes

Trained personnel, masked to treatment assignment, conducted follow-up telephone interviews on days 3, 7, and 14 following patients’ visits for sinusitis, to assess clinical improvement. Twelve follow-up questions were asked.

Sample size

The primary outcome used to determine sample size was dichotomous—either “improved” or “not improved” by the end of 2 weeks. Thus, patients were asked, “what day were you entirely improved.” The sample sizes obtained per group (67 for amoxicillin and 68 for placebo) provided 80% power for detecting a change of 25% in rates of improvement.

Statistical analysis

Basic descriptive statistics were used to describe the groups. Baseline characteristics were compared between the 2 groups using chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. For continuous variables, the Student’s t-test was used; the Wilcoxon Rank Sum test was used for ordinal or skewed variables. Similar statistical tests were used to compare baseline characteristics between the providers and also at the conclusion of the study between the responders for each group.

For the outcome variables, we hypothesized no difference between the groups either in the rates of improvement, times to improvement, or in patients’ self-rating of sickness. The actual proportions improving between the 2 groups were compared using the chi-square test. Relative risk estimates and 95% confidence intervals were calculated to provide measures of risk and precision. Multiple logistic regression was used to compare the rates of improvement adjusting for the number of signs or symptoms classified as either 1, 2, or 3–4, obtained from the clinical prediction rule (Table 1).

The Kaplan-Meier method was used to construct the curves showing the time until patient improvement for each treatment group. The Wilcoxon test was then used to test the statistical significance in these curves (Figure). Cox’s Proportional Hazards regression was used to test for differences in the time to improvement between the groups adjusting for the number of signs or symptoms.

Additionally, a univariate repeated measures analysis of variance model was constructed to compare the 10-point Likert scale scores for the question, “How sick do you feel today?” In this model, the number of signs and symptoms was entered as a covariate in the analysis. Orthogonal contrasts were used as post-hoc tests to compare the difference between the groups within each time point (Table 2 ).

For the subgroup of patients who improved, analysis of covariance was used to compare the mean number of days to improvement between the groups. In this case the number of signs and symptoms was used as the covariate (Table 3). The Kaplan-Meier method and the Wilcoxon test were used to compare the cumulative rates of improvement (Figure). Unadjusted P-values are reported.

Primary analyses were performed using the intention-to-treat principle. All statistical analyses were performed using JMP Software (Product of SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). Statistical significance was set at 0.05 and exact P-values are reported.

TABLE 1

Baseline characteristics for amoxicillin and placebo groups

| Characteristic | Placebo (n=68) | Amoxicillin (n=67) |

|---|---|---|

| Purulent nasal discharge predominating on 1 side (%) | 28 (41) | 33 (49) |

| Local facial pain predominating on 1 side (%) | 25 (37) | 28 (42) |

| Purulent nasal discharge on both sides (%) | 45 (66) | 49 (73) |

| Pus in the nasal cavity assessed by provider (%) | 20 (29) | 23 (34) |

| Number of symptoms (%) | ||

| 1 | 34 (50) | 29 (43) |

| 2 | 17 (25) | 11 (17) |

| 3–4 | 17 (25) | 27 (40) |

| Female (%) | 49 (73) | 44 (66) |

| Tobacco use (%) | 6 (9) | 2 (3) |

| Over-the-counter medicines used for sinusitis (%) | 55 (89) | 58 (91) |

| Age mean (SD) | 32.6 (9.5) | 35.1 (10.1) |

| Length of symptoms prior to enrollment in mean days (SD) | 11.7 (6.3) | 10.7 (5.0) |

| Temperature in Fahrenheit mean (SD) | 97.9 (.8) | 97.9 (1.0) |

| Self-rating of health* mean (SD) | 3.1 (2.6) | 3.1 (2.4) |

| Self-rating of severity of cough* mean (SD) | 5.8 (2.5) | 5.1 (2.7) |

| Self-rating of how sick patient feels at enrollment* mean (SD) | 6.3 (1.9) | 6.2 (2.0) |

| Self-rating of severity of headache* mean (SD) | 5.3 (3.1) | 5.6 (2.8) |

| Percentages not always equal to 100%, due to missing data. All P <.05 | ||

| Represents Likert scale from 1 to 10; 1 being perfect to 10 being absolute worst case. | ||

Figure

Kaplan-Meier curve for improvement—amoxicillin (n=67) vs placebo (n=68)*

TABLE 2

Comparison of mean Likert scores by group across follow-up time points Question asked at each time point:

| “On a scale of 1 to 10, How sick do you feel today?”* | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Time† | Amoxicillin (n=67) | Placebo (n=68) | P value |

| Day 0 (SD) | 6.10 (2.0) | 6.30 (1.9) | NS |

| Day 3 (SD) | 4.33 (1.8) | 4.73 (1.9) | NS |

| Day 7 (SD) | 3.15 (2.1) | 3.30 (2.0) | NS |

| Day 14 (SD) | 2.30 (1.9) | 2.80 (2.5) | NS |

| Likert score of 1 represents “perfect health” to 10 representing “worst condition.” | |||

| * Statistical tests—Orthogonal contrasts. | |||

| † Data shown represent mean and standard deviation (SD). | |||

TABLE 3

Mean number of days to improvement by group and number of signs and symptoms (at baseline) for patients who improved

| Number of signs and symptoms | Amoxicillin (n=32) | Placebo (n=25) |

|---|---|---|

| (1) Mean (n, SD) | 7.8 days (16, 3.7) | 11.0 days (10, 2.6) |

| (2) Mean (n, SD) | 7.8 days (5, 3.7) | 10.3 days (6, 3.2) |

| (3–4) Mean (n, SD) | 8.6 days (11, 3.6) | 10.6 days (9, 3.0) |

| Signs and symptoms are: purulent (yellow, thick) nasal discharge predominating on 1 side, local facial pain predominating on 1 side, purulent nasal discharge on both sides, and pus in the nasal cavity. | ||

Results

During the 18-month enrollment period, the 3 providers recorded all patients aged >18 years who had at least 1 cardinal feature described by the clinical prediction rule and had symptoms for a minimum of 7 days. Thus, initially 308 patients were approached for enrollment; 173 patients did not qualify after the exclusion criteria were applied, leaving 135 patients for randomization. Sixty-seven received amoxicillin and 68 received placebo. For 11 patients in the amoxicillin arm and 8 in the placebo arm, only baseline data were collected. These patients were then considered as lost to follow-up and were counted as “not improved” in the intention-to-treat analysis.

There were no significant differences (P >.05) in baseline characteristics of the treatment groups (Table 1). Additionally, there were no significant differences in the baseline characteristics between the providers (data not shown).

In the amoxicillin group 32 (48%) had completely improved compared with 25 (37%) in the placebo group (P=.26) after 2 weeks (relative risk of treatment failure=1.3; 95% CI, 0.87–1.94). However, individuals in the amoxicillin group did improve significantly earlier, as the Kaplan-Meier curve demonstrates (Figure). The first person in the amoxicillin group improved on day 3, compared with day 7 in the placebo group. This earlier improvement continued throughout the study (P=.039).

Subgroup analysis of the 57 who demonstrated complete recovery shows the amoxicillin group improved earlier as does the Kaplan-Meier curves in the Figure. In the amoxicillin group, the median day to any improvement was day 8 compared with day 12 for the placebo group (P=.005), while the mean day to improvement for the amoxicillin group was 8.1 days vs 10.7 days for placebo group.

When patients were asked “How sick do you feel today,” the average Likert scores decreased from 6. 1 (day 0) to 2.3 (day 14), and 6.3 (day 0) to 2.8 (day 14), in the amoxicillin and placebo groups, respectively. At each time point, there were no significant clinical or statistical differences between the 2 groups in how they rated their improvement (Table 2). Furthermore, examining only those who reported total improvement within 14 days showed no differences among groups.

No statistically significant differences were observed between the treatment groups that entailed the clinical prediction rule. However, in the patients who were improved at 14 days, the average number of days to improvement was consistently between 2 to 2.5 days shorter in the amoxicillin group compared with placebo (Table 3).

Side effects

No patients dropped out of the study due to adverse side effects (Table 4). There were no serious or unexpected side effects, with the majority related to gastrointestinal problems, such as diarrhea and abdominal pain.

TABLE 4

A Frequency of reported side effects by group

| Amoxicillin Adverse effects | Placebo (n=57) | (n=59) |

|---|---|---|

| Total number of patients with any side effects | 13 | 7 |

| Diarrhea | 4 | 1 |

| Nausea | 4 | 5 |

| Emesis | 1 | 0 |

| Abdominal pain | 2 | 1 |

| Rash | 2 | 0 |

| Hot flashes | 0 | 1 |

| Jittery | 0 | 1 |

| Dizziness | 3 | 0 |

| Dry mouth | 1 | 0 |

| Vaginal infection | 2 | 0 |

| Multiple events per patient are possible. | ||

Discussion

With respect to the patient-oriented outcome of clinical improvement, amoxicillin provided no significant benefit over placebo in the treatment of patients presenting with sinusitis complaints. On average our patients who had symptoms for 11 days prior to enrollment and are typical of patients that are often recommended for treatment with antibiotics.14,15

Our findings are consistent with others in which the overall benefit of antibiotics was minimal or nonexistent.16,18 But among individuals who did improve, those who received amoxicillin improved much earlier, both clinically and statistically. Unfortunately we were not able to specify those who are likely to improve. Clearly, further patient-oriented outcome studies are needed to help primary care physicians decide which patients may benefit from antibiotic treatment.

Antibiotics have not been shown to prevent the sequelae of acute sinusitis. One of the major difficulties in treating sinusitis is the lack of agreement about which outcomes are desired.19,20 Nearly 66% of patients diagnosed with sinusitis will get better without treatment, though nearly two thirds of patients will continue to have such symptoms as cough and nasal discharge for up to 3 weeks.21,22 Thus, we believe that to give antibiotics only to individuals who would truly benefit from them, policy makers, primary care physicians, and patients need to reassess clinically what constitutes sinusitis, and what outcomes are most desired. If the goal is to cure purulent nasal discharge, we are likely over-treating with antibiotics; as our study showed, after 2 weeks most patients in both groups still had nasal symptoms.

Our pilot of the clinical prediction rule failed to predict a proper response to antibiotics or the time to improvement. Although our numbers were not large, no trend was observed towards improvement in individuals with a higher score on the clinical prediction rule.

Our study has some important limitations. Interestingly we found different results when we used the dichotomous outcome of totally improved versus the 10-point Likert scale. A priori we decided our primary outcome was the dichotomous improvement, but which measure is more important and should be used is open to varying interpretations. Additionally, our study office unexpectedly closed and thus we could not recruit the number of patients we initially had planned. This limited our power to find differences between groups based on the number of cardinal clinical features. We encountered noncompliance with follow-up, as expected with the study design. We also arbitrarily stopped follow-up at 14 days, and cases that had not entirely improved were considered clinical failures in all but the Likert scale analysis. It is possible our results may have differed if we had continued to follow patients at 21 or 28 days, or if we had conducted the study at more than one office.

Methodologically, we conducted a rigorous study and showed that patients diagnosed with clinical sinusitis fared no better with amoxicillin or placebo, when measuring the patient-oriented outcome of complete improvement. But a subgroup of patients who were given antibiotics did improve at a much quicker rate. The difficulty is in clinically identifying this group and treating them with antibiotics. Conversely, using antibiotics in patients unnecessarily would only cause potential individual and societal harm. More clinically oriented studies need to be conducted to address this issue and elucidate what signs and symptoms these patients exhibit, to help clarify who should be treated with antibiotics.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

When this article was prepared, Dan Merenstein was an assistant professor of Family Medicine and Pediatrics at Georgetown University. This study was part of the Capricorn Research Network of Georgetown University. This projectwas supported by a grant from the American Academy ofFamily Physicians and the American Academy of FamilyPhysicians Foundation “Joint AAFP/F-AAFP Grant AwardsProgram” (JGAP). Support was also provided by the CapitolArea Primary Care Research Network. Research presentedat NAPRCG 2003, Banff, Canada.

We thank Joel Merenstein for insightful feedback and intelligent comments about study design and input with manuscript. We thank Goutham Rao and Traci Reisner for editorial help. We thank Community Drug Compounding Center of Pittsburgh and pharmacist Susan Freedenberg for drug development.

Corresponding author

Dan Merenstein, MD, Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholar, The Johns Hopkins Hospital, 600 North Wolfe St., Carnegie 291, Baltimore, MD 21287-6220. E-mail: [email protected].

- If the goal of treating sinusitis with antibiotics is to cure purulent nasal discharge, we are likely over-treating; as our study showed, after 2 weeks most patients in the treatment and placebo groups still had nasal symptoms (A).

- Persons with higher scores on the clinical prediction rule for sinusitis are no more likely to improve with antibiotic treatment than are those with lower scores (A).

- Among those who did improve on antibiotics, a subgroup that could not be clinically characterized improved at a much quicker rate than the others. Until further clinical trials can describe this favorable clinical profile, routine prescribing of antibiotics for sinusitis should be avoided (A).

Background: Sinusitis is the fifth most common reason for patients to visit primary care physicians, yet clinical outcomes relevant to patients are seldom studied.

Objective To determine whether patients with purulent rhinitis, “sinusitis-type symptoms,” improved with antibiotics. Second, to examine a clinical prediction rule to provide preliminary validation data.

Methods: Prospective clinical trial, with double-blinded placebo controlled randomization. The setting was a suburb of Washington, DC, from Oct 1, 2001, to March 31, 2003. All participants were 18 years or older, presenting to a family practice clinic with a complaint of sinusitis and with pus in the nasal cavity, facial pressure, or nasal discharge lasting longer than 7 days. The main outcome measures were resolution of symptoms within a 14-day follow-up period and the time to improvement (days).

Results: After exclusion criteria, 135 patients were randomized to either placebo (n=68) or amoxicillin (n=67) for 10 days. Intention-to-treat analyses showed that 32 (48%) of the amoxicillin group vs 25 (37%) of the placebo group (P=.26) showed complete improvement by the end of the 2-week follow-up period (relative risk=1.3; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.87–1.94]). Although the rates of improvement were not statistically significantly different at the end of 2 weeks, the amoxicillin group improved significantly earlier, in the course of treatment, a median of 8 vs 12 days, than did the placebo group (P=.039).

Conclusion: For most patients with sinusitis-type complaints, no improvement was seen with antibiotics over placebo. For those who did improve, data suggested there is a subgroup of patients who may benefit from antibiotics.

It is estimated that adults have 2 to 3 colds a year, of which just 0.5% to 2% are complicated by bacterial sinusitis. However, primary care physicians treat over half of these colds with antibiotics.1 Sinusitis is the fifth most common diagnosis for which antibiotics are prescribed in the outpatient setting, with more than $6 billion spent annually in the United States on prescription and over-the-counter medications.1-3 Can we know with greater certainty when antibiotics are indicated for sinusitis?

A meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies has shown that the likelihood of bacterial sinusitis is increased (sensitivity 76%, specificity 79%) and antibiotics are helpful when a patient exhibits at least 3 of 4 cardinal clinical features: 1) purulent nasal discharge predominating on one side; 2) local facial pain predominating on one side; 3) purulent nasal discharge on both sides; and 4) pus in the nasal cavity.2 Although use of these criteria is encouraged, they are based on studies that recruited patients from subspecialty clinics and measured disease-oriented outcomes such as findings on sinus radiographs, CT scans, and sinus puncture with culture.4-12 Most cases of sinusitis, however, are treated in primary care settings where measuring such outcomes is impractical.

Given the lack of epidemiologic evidence as to which patients would benefit from treatment of sinusitis, primary care physicians face the dilemma of deciding during office encounters which patients should receive antibiotics and which have a viral infection for which symptomatic treatment is indicated.13

Our goal was to study the type of patient for whom this dilemma arises and to use clinical improvement as our primary outcome. We randomly assigned patients presenting with sinusitis complaints to receive amoxicillin or placebo, and compared the rates of improvement, time to improvement, and patient’s self-rating of sickness at the end of 2 weeks. We also tested the clinical prediction rule to see if participants with 3 or 4 signs and symptoms had different clinical outcomes than the others.

Methods

Setting

We conducted a randomized double-blind clinical trial of amoxicillin vs placebo. All patients were recruited from a suburban primary care office. Two physicians and one nurse practitioner enrolled and treated all patients over an 18-month period (Oct 1, 2001 to March 31, 2003). The clinicians involved in the study were trained to identify purulent discharge in the nasal cavity. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from Georgetown University prior to the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all participating patients.

Patients

Patients were eligible to participate if they were 18 years or older; had at least 1 cardinal feature described by the clinical prediction rule: 1) purulent nasal discharge predominating on one side, 2) local facial pain predominating on one side, 3) purulent nasal discharge on both sides, or 4) pus in the nasal cavity; and had symptoms for at least 7 days. Patients were excluded if their histories included antibiotic treatment within the past month, allergy to penicillin, sinus surgery, compromised immunity, pneumonia, or streptococcal pharyngitis.

Randomization

Permuted block randomization stratified for the 3 participating clinicians was used to determine treatment assignment. Patients were given an envelope containing 40 capsules, either a placebo medicine taken twice daily for 10 days or 1000 mg of amoxicillin (500 mg pills) taken twice daily for 10 days. The envelopes were opaque, and each had 40 identical-appearing pills (to ensure allocation concealment). The participating clinicians were naive to the treatment assignments.

Assessment of outcomes

Trained personnel, masked to treatment assignment, conducted follow-up telephone interviews on days 3, 7, and 14 following patients’ visits for sinusitis, to assess clinical improvement. Twelve follow-up questions were asked.

Sample size

The primary outcome used to determine sample size was dichotomous—either “improved” or “not improved” by the end of 2 weeks. Thus, patients were asked, “what day were you entirely improved.” The sample sizes obtained per group (67 for amoxicillin and 68 for placebo) provided 80% power for detecting a change of 25% in rates of improvement.

Statistical analysis

Basic descriptive statistics were used to describe the groups. Baseline characteristics were compared between the 2 groups using chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. For continuous variables, the Student’s t-test was used; the Wilcoxon Rank Sum test was used for ordinal or skewed variables. Similar statistical tests were used to compare baseline characteristics between the providers and also at the conclusion of the study between the responders for each group.

For the outcome variables, we hypothesized no difference between the groups either in the rates of improvement, times to improvement, or in patients’ self-rating of sickness. The actual proportions improving between the 2 groups were compared using the chi-square test. Relative risk estimates and 95% confidence intervals were calculated to provide measures of risk and precision. Multiple logistic regression was used to compare the rates of improvement adjusting for the number of signs or symptoms classified as either 1, 2, or 3–4, obtained from the clinical prediction rule (Table 1).

The Kaplan-Meier method was used to construct the curves showing the time until patient improvement for each treatment group. The Wilcoxon test was then used to test the statistical significance in these curves (Figure). Cox’s Proportional Hazards regression was used to test for differences in the time to improvement between the groups adjusting for the number of signs or symptoms.

Additionally, a univariate repeated measures analysis of variance model was constructed to compare the 10-point Likert scale scores for the question, “How sick do you feel today?” In this model, the number of signs and symptoms was entered as a covariate in the analysis. Orthogonal contrasts were used as post-hoc tests to compare the difference between the groups within each time point (Table 2 ).

For the subgroup of patients who improved, analysis of covariance was used to compare the mean number of days to improvement between the groups. In this case the number of signs and symptoms was used as the covariate (Table 3). The Kaplan-Meier method and the Wilcoxon test were used to compare the cumulative rates of improvement (Figure). Unadjusted P-values are reported.

Primary analyses were performed using the intention-to-treat principle. All statistical analyses were performed using JMP Software (Product of SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). Statistical significance was set at 0.05 and exact P-values are reported.

TABLE 1

Baseline characteristics for amoxicillin and placebo groups

| Characteristic | Placebo (n=68) | Amoxicillin (n=67) |

|---|---|---|

| Purulent nasal discharge predominating on 1 side (%) | 28 (41) | 33 (49) |

| Local facial pain predominating on 1 side (%) | 25 (37) | 28 (42) |

| Purulent nasal discharge on both sides (%) | 45 (66) | 49 (73) |

| Pus in the nasal cavity assessed by provider (%) | 20 (29) | 23 (34) |

| Number of symptoms (%) | ||

| 1 | 34 (50) | 29 (43) |

| 2 | 17 (25) | 11 (17) |

| 3–4 | 17 (25) | 27 (40) |

| Female (%) | 49 (73) | 44 (66) |

| Tobacco use (%) | 6 (9) | 2 (3) |

| Over-the-counter medicines used for sinusitis (%) | 55 (89) | 58 (91) |

| Age mean (SD) | 32.6 (9.5) | 35.1 (10.1) |

| Length of symptoms prior to enrollment in mean days (SD) | 11.7 (6.3) | 10.7 (5.0) |

| Temperature in Fahrenheit mean (SD) | 97.9 (.8) | 97.9 (1.0) |

| Self-rating of health* mean (SD) | 3.1 (2.6) | 3.1 (2.4) |

| Self-rating of severity of cough* mean (SD) | 5.8 (2.5) | 5.1 (2.7) |

| Self-rating of how sick patient feels at enrollment* mean (SD) | 6.3 (1.9) | 6.2 (2.0) |

| Self-rating of severity of headache* mean (SD) | 5.3 (3.1) | 5.6 (2.8) |

| Percentages not always equal to 100%, due to missing data. All P <.05 | ||

| Represents Likert scale from 1 to 10; 1 being perfect to 10 being absolute worst case. | ||

Figure

Kaplan-Meier curve for improvement—amoxicillin (n=67) vs placebo (n=68)*

TABLE 2

Comparison of mean Likert scores by group across follow-up time points Question asked at each time point:

| “On a scale of 1 to 10, How sick do you feel today?”* | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Time† | Amoxicillin (n=67) | Placebo (n=68) | P value |

| Day 0 (SD) | 6.10 (2.0) | 6.30 (1.9) | NS |

| Day 3 (SD) | 4.33 (1.8) | 4.73 (1.9) | NS |

| Day 7 (SD) | 3.15 (2.1) | 3.30 (2.0) | NS |

| Day 14 (SD) | 2.30 (1.9) | 2.80 (2.5) | NS |

| Likert score of 1 represents “perfect health” to 10 representing “worst condition.” | |||

| * Statistical tests—Orthogonal contrasts. | |||

| † Data shown represent mean and standard deviation (SD). | |||

TABLE 3

Mean number of days to improvement by group and number of signs and symptoms (at baseline) for patients who improved

| Number of signs and symptoms | Amoxicillin (n=32) | Placebo (n=25) |

|---|---|---|

| (1) Mean (n, SD) | 7.8 days (16, 3.7) | 11.0 days (10, 2.6) |

| (2) Mean (n, SD) | 7.8 days (5, 3.7) | 10.3 days (6, 3.2) |

| (3–4) Mean (n, SD) | 8.6 days (11, 3.6) | 10.6 days (9, 3.0) |

| Signs and symptoms are: purulent (yellow, thick) nasal discharge predominating on 1 side, local facial pain predominating on 1 side, purulent nasal discharge on both sides, and pus in the nasal cavity. | ||

Results

During the 18-month enrollment period, the 3 providers recorded all patients aged >18 years who had at least 1 cardinal feature described by the clinical prediction rule and had symptoms for a minimum of 7 days. Thus, initially 308 patients were approached for enrollment; 173 patients did not qualify after the exclusion criteria were applied, leaving 135 patients for randomization. Sixty-seven received amoxicillin and 68 received placebo. For 11 patients in the amoxicillin arm and 8 in the placebo arm, only baseline data were collected. These patients were then considered as lost to follow-up and were counted as “not improved” in the intention-to-treat analysis.

There were no significant differences (P >.05) in baseline characteristics of the treatment groups (Table 1). Additionally, there were no significant differences in the baseline characteristics between the providers (data not shown).

In the amoxicillin group 32 (48%) had completely improved compared with 25 (37%) in the placebo group (P=.26) after 2 weeks (relative risk of treatment failure=1.3; 95% CI, 0.87–1.94). However, individuals in the amoxicillin group did improve significantly earlier, as the Kaplan-Meier curve demonstrates (Figure). The first person in the amoxicillin group improved on day 3, compared with day 7 in the placebo group. This earlier improvement continued throughout the study (P=.039).

Subgroup analysis of the 57 who demonstrated complete recovery shows the amoxicillin group improved earlier as does the Kaplan-Meier curves in the Figure. In the amoxicillin group, the median day to any improvement was day 8 compared with day 12 for the placebo group (P=.005), while the mean day to improvement for the amoxicillin group was 8.1 days vs 10.7 days for placebo group.

When patients were asked “How sick do you feel today,” the average Likert scores decreased from 6. 1 (day 0) to 2.3 (day 14), and 6.3 (day 0) to 2.8 (day 14), in the amoxicillin and placebo groups, respectively. At each time point, there were no significant clinical or statistical differences between the 2 groups in how they rated their improvement (Table 2). Furthermore, examining only those who reported total improvement within 14 days showed no differences among groups.

No statistically significant differences were observed between the treatment groups that entailed the clinical prediction rule. However, in the patients who were improved at 14 days, the average number of days to improvement was consistently between 2 to 2.5 days shorter in the amoxicillin group compared with placebo (Table 3).

Side effects

No patients dropped out of the study due to adverse side effects (Table 4). There were no serious or unexpected side effects, with the majority related to gastrointestinal problems, such as diarrhea and abdominal pain.

TABLE 4

A Frequency of reported side effects by group

| Amoxicillin Adverse effects | Placebo (n=57) | (n=59) |

|---|---|---|

| Total number of patients with any side effects | 13 | 7 |

| Diarrhea | 4 | 1 |

| Nausea | 4 | 5 |

| Emesis | 1 | 0 |

| Abdominal pain | 2 | 1 |

| Rash | 2 | 0 |

| Hot flashes | 0 | 1 |

| Jittery | 0 | 1 |

| Dizziness | 3 | 0 |

| Dry mouth | 1 | 0 |

| Vaginal infection | 2 | 0 |

| Multiple events per patient are possible. | ||

Discussion

With respect to the patient-oriented outcome of clinical improvement, amoxicillin provided no significant benefit over placebo in the treatment of patients presenting with sinusitis complaints. On average our patients who had symptoms for 11 days prior to enrollment and are typical of patients that are often recommended for treatment with antibiotics.14,15

Our findings are consistent with others in which the overall benefit of antibiotics was minimal or nonexistent.16,18 But among individuals who did improve, those who received amoxicillin improved much earlier, both clinically and statistically. Unfortunately we were not able to specify those who are likely to improve. Clearly, further patient-oriented outcome studies are needed to help primary care physicians decide which patients may benefit from antibiotic treatment.

Antibiotics have not been shown to prevent the sequelae of acute sinusitis. One of the major difficulties in treating sinusitis is the lack of agreement about which outcomes are desired.19,20 Nearly 66% of patients diagnosed with sinusitis will get better without treatment, though nearly two thirds of patients will continue to have such symptoms as cough and nasal discharge for up to 3 weeks.21,22 Thus, we believe that to give antibiotics only to individuals who would truly benefit from them, policy makers, primary care physicians, and patients need to reassess clinically what constitutes sinusitis, and what outcomes are most desired. If the goal is to cure purulent nasal discharge, we are likely over-treating with antibiotics; as our study showed, after 2 weeks most patients in both groups still had nasal symptoms.

Our pilot of the clinical prediction rule failed to predict a proper response to antibiotics or the time to improvement. Although our numbers were not large, no trend was observed towards improvement in individuals with a higher score on the clinical prediction rule.

Our study has some important limitations. Interestingly we found different results when we used the dichotomous outcome of totally improved versus the 10-point Likert scale. A priori we decided our primary outcome was the dichotomous improvement, but which measure is more important and should be used is open to varying interpretations. Additionally, our study office unexpectedly closed and thus we could not recruit the number of patients we initially had planned. This limited our power to find differences between groups based on the number of cardinal clinical features. We encountered noncompliance with follow-up, as expected with the study design. We also arbitrarily stopped follow-up at 14 days, and cases that had not entirely improved were considered clinical failures in all but the Likert scale analysis. It is possible our results may have differed if we had continued to follow patients at 21 or 28 days, or if we had conducted the study at more than one office.

Methodologically, we conducted a rigorous study and showed that patients diagnosed with clinical sinusitis fared no better with amoxicillin or placebo, when measuring the patient-oriented outcome of complete improvement. But a subgroup of patients who were given antibiotics did improve at a much quicker rate. The difficulty is in clinically identifying this group and treating them with antibiotics. Conversely, using antibiotics in patients unnecessarily would only cause potential individual and societal harm. More clinically oriented studies need to be conducted to address this issue and elucidate what signs and symptoms these patients exhibit, to help clarify who should be treated with antibiotics.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

When this article was prepared, Dan Merenstein was an assistant professor of Family Medicine and Pediatrics at Georgetown University. This study was part of the Capricorn Research Network of Georgetown University. This projectwas supported by a grant from the American Academy ofFamily Physicians and the American Academy of FamilyPhysicians Foundation “Joint AAFP/F-AAFP Grant AwardsProgram” (JGAP). Support was also provided by the CapitolArea Primary Care Research Network. Research presentedat NAPRCG 2003, Banff, Canada.

We thank Joel Merenstein for insightful feedback and intelligent comments about study design and input with manuscript. We thank Goutham Rao and Traci Reisner for editorial help. We thank Community Drug Compounding Center of Pittsburgh and pharmacist Susan Freedenberg for drug development.

Corresponding author

Dan Merenstein, MD, Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholar, The Johns Hopkins Hospital, 600 North Wolfe St., Carnegie 291, Baltimore, MD 21287-6220. E-mail: [email protected].

1. Leggett JE. Acute sinusitis. When—and when not—to prescribe antibiotics. Postgrad Med 2004;115(1):13-19.

2. Lau J, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of acute bacterial rhinosinusitis. Evidence Report #9. Rockville, Md: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1999.

3. Brooks I, Gooch WM, 3rd, Jenkins SG, et al. Medical management of acute bacterial sinusitis. Recommendations of a clinical advisory committee on pediatric and adult sinusitis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol Suppl 2000;182:2-20.

4. Williams JW, Jr, Holleman DR, Jr, Samsa GP, Simel DL. Randomized controlled trial of 3 vs 10 days of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole for acute maxillary sinusitis. JAMA 1995;273:1015-1021.

5. Williams JW, Jr, Simel DL. Does this patient have sinusitis? Diagnosing acute sinusitis by history and physical examination. JAMA 1993;270:1242-1246.

6. Williams JW, Jr, Simel DL, Roberts L, Samsa GP. Clinical evaluation for sinusitis. Making the diagnosis by history and physical examination. Ann Intern Med 1992;117:705-710.

7. Wald ER, Chiponis D, Ledesma-Medina J. Comparative effectiveness of amoxicillin and amoxicillin-clavulanate potassium in acute paranasal sinus infections in children: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Pediatrics 1986;77:795-800.

8. van Duijn NP, Brouwer HJ, Lamberts H. Use of symptoms and signs to diagnose maxillary sinusitis in general practice: comparison with ultrasonography. BMJ 1992;305:684-687.

9. Alho OP, Ylitalo K, Jokinen K, et al. The common cold in patients with a history of recurrent sinusitis: increased symptoms and radiologic sinusitislike findings. J Fam Pract 2001;50:26-31.

10. Berg O, Carenfelt C. Analysis of symptoms and clinical signs in the maxillary sinus empyema. Acta Otolaryngol 1988;105:343-349.

11. Okuyemi KS, Tsue TT. Radiologic imaging in the management of sinusitis. Am Fam Physician 2002;66:1882-1886.

12. Engels EA, Terrin N, Barza M, Lau J. Meta-analysis of diagnostic tests for acute sinusitis. J Clin Epidemiol 2000;53:852-862.

13. Poole MD. A focus on acute sinusitis in adults: changes in disease management. Am J Med 1999;106:38S-47S;discussion 48S-52S.

14. Desrosiers M, Frankiel S, Hamid QA, et al. Acute bacterial sinusitis in adults: management in the primary care setting. J Otolaryngol 2002;31 Suppl 2:2S2-14.

15. Lindbaek M. Acute sinusitis: guide to selection of anti-bacterial therapy. Drugs 2004;64:805-819.

16. De Sutter AI, De Meyere MJ, Christiaens TC, Van Driel ML, Peersman W, De Maeseneer JM. Does amoxicillin improve outcomes in patients with purulent rhinorrhea? J Fam Pract 2002;51:317-323.

17. Bucher HC, Tschudi P, Young J, et al. BASINUS (Basel Sinusitis Study) Investigators Effect of amoxicillin-clavulanate in clinically diagnosed acute rhinosinusitis: a placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized trial in general practice. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:1793-1798.

18. Varonen H, Kunnamo I, Savolainen S, et al. Treatment of acute rhinosinusitis diagnosed by clinical criteria or ultrasound in primary care. A placebo-controlled randomised trial. Scand J Prim Health Care 2003;21:121-126.

19. Linder JA, Singer DE, Ancker M, Atlas SJ. Measures of health-related quality of life for adults with acute sinusitis. A systematic review. J Gen Intern Med 2003;18:390-401.

20. Theis J, Oubichon T. Are antibiotics helpful for acute maxillary sinusitis? J Fam Pract 2003;52:490-492;discussion 491.-

21. de Ferranti SD, Ioannidis JP, Lau J, Anninger WV, Barza M. Are amoxycillin and folate inhibitors as effective as other antibiotics for acute sinusitis? A meta-analysis. BMJ 1998;317:632-637.

22. Scott J, Orzano AJ. Evaluation and treatment of the patient with acute undifferentiated respiratory tract infection. J Fam Pract 2001;50:1070-1077.

1. Leggett JE. Acute sinusitis. When—and when not—to prescribe antibiotics. Postgrad Med 2004;115(1):13-19.

2. Lau J, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of acute bacterial rhinosinusitis. Evidence Report #9. Rockville, Md: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1999.

3. Brooks I, Gooch WM, 3rd, Jenkins SG, et al. Medical management of acute bacterial sinusitis. Recommendations of a clinical advisory committee on pediatric and adult sinusitis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol Suppl 2000;182:2-20.

4. Williams JW, Jr, Holleman DR, Jr, Samsa GP, Simel DL. Randomized controlled trial of 3 vs 10 days of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole for acute maxillary sinusitis. JAMA 1995;273:1015-1021.

5. Williams JW, Jr, Simel DL. Does this patient have sinusitis? Diagnosing acute sinusitis by history and physical examination. JAMA 1993;270:1242-1246.

6. Williams JW, Jr, Simel DL, Roberts L, Samsa GP. Clinical evaluation for sinusitis. Making the diagnosis by history and physical examination. Ann Intern Med 1992;117:705-710.

7. Wald ER, Chiponis D, Ledesma-Medina J. Comparative effectiveness of amoxicillin and amoxicillin-clavulanate potassium in acute paranasal sinus infections in children: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Pediatrics 1986;77:795-800.

8. van Duijn NP, Brouwer HJ, Lamberts H. Use of symptoms and signs to diagnose maxillary sinusitis in general practice: comparison with ultrasonography. BMJ 1992;305:684-687.

9. Alho OP, Ylitalo K, Jokinen K, et al. The common cold in patients with a history of recurrent sinusitis: increased symptoms and radiologic sinusitislike findings. J Fam Pract 2001;50:26-31.

10. Berg O, Carenfelt C. Analysis of symptoms and clinical signs in the maxillary sinus empyema. Acta Otolaryngol 1988;105:343-349.

11. Okuyemi KS, Tsue TT. Radiologic imaging in the management of sinusitis. Am Fam Physician 2002;66:1882-1886.

12. Engels EA, Terrin N, Barza M, Lau J. Meta-analysis of diagnostic tests for acute sinusitis. J Clin Epidemiol 2000;53:852-862.

13. Poole MD. A focus on acute sinusitis in adults: changes in disease management. Am J Med 1999;106:38S-47S;discussion 48S-52S.

14. Desrosiers M, Frankiel S, Hamid QA, et al. Acute bacterial sinusitis in adults: management in the primary care setting. J Otolaryngol 2002;31 Suppl 2:2S2-14.

15. Lindbaek M. Acute sinusitis: guide to selection of anti-bacterial therapy. Drugs 2004;64:805-819.

16. De Sutter AI, De Meyere MJ, Christiaens TC, Van Driel ML, Peersman W, De Maeseneer JM. Does amoxicillin improve outcomes in patients with purulent rhinorrhea? J Fam Pract 2002;51:317-323.

17. Bucher HC, Tschudi P, Young J, et al. BASINUS (Basel Sinusitis Study) Investigators Effect of amoxicillin-clavulanate in clinically diagnosed acute rhinosinusitis: a placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized trial in general practice. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:1793-1798.

18. Varonen H, Kunnamo I, Savolainen S, et al. Treatment of acute rhinosinusitis diagnosed by clinical criteria or ultrasound in primary care. A placebo-controlled randomised trial. Scand J Prim Health Care 2003;21:121-126.

19. Linder JA, Singer DE, Ancker M, Atlas SJ. Measures of health-related quality of life for adults with acute sinusitis. A systematic review. J Gen Intern Med 2003;18:390-401.

20. Theis J, Oubichon T. Are antibiotics helpful for acute maxillary sinusitis? J Fam Pract 2003;52:490-492;discussion 491.-

21. de Ferranti SD, Ioannidis JP, Lau J, Anninger WV, Barza M. Are amoxycillin and folate inhibitors as effective as other antibiotics for acute sinusitis? A meta-analysis. BMJ 1998;317:632-637.

22. Scott J, Orzano AJ. Evaluation and treatment of the patient with acute undifferentiated respiratory tract infection. J Fam Pract 2001;50:1070-1077.

Second thoughts on integrative medicine

Integrative medicine is a new concept of healthcare.1,2 Confusingly, the term has 2 definitions. The first definition is a healthcare system “that selectively incorporates elements of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) into comprehensive treatment plans….”1 The second definition is an approach that emphasizes “health and healing rather than disease and treatment. It views patients as whole people with minds and spirits as well as bodies….”1

I would argue that the whole-person concept has always been at the core of good medicine, particularly primary care, and that coining a new name for an old value is counterproductive. If we can agree that the whole-person concept needs no other name, we can greatly simplify matters by letting integrative medicine stand for just one thing—incorporating elements of CAM into routine health care. Let’s consider the implications of this thinking.

The arguments for integrative medicine

Proponents of integrating CAM into routine medical care point to its increasing popularity3 and to the satisfaction of most CAM users.4 They also argue that CAM has largely been a privilege of the affluent class,3 and, to achieve equity in health care, we should integrate CAM across all of society. This line of argument seems logical and well intentioned. But is it convincing?

Just because the affluent are the primary recipients of CAM does not necessarily recommend it to everyone. Their lifestyle choices also put them at greater risk for cancer and gout, and they undergo liposuction more often. That the affluent can afford to pay for CAM does not mean it’s good for them.

The evidence for benefits vs risks

The assumption we should really mistrust is that satisfaction with CAM services is the same as a demonstration of efficacy. The missing link in the logic of integrated medicine is the evidence that CAM does more good than harm. Integrating therapies with uncertain risk-benefit profiles (eg, upper spinal manipulation) or modalities that are pleasant but of dubious value (eg, aromatherapy) would render health care less evidence-based and more expensive but not necessarily more effective.

Of course, not all CAM is ineffective or unsafe.5 CAM interventions that demonstrably do more good than harm should be integrated; those that don’t should not be. Research into CAM is in its infancy, and the area of uncertainty remains huge. For most forms of CAM, we simply cannot be sure about the balance of risk and benefit. To integrate such CAM would be counterproductive. To integrate those therapies that are supported by good data is not integrative medicine but simply evidence-based medicine.

Patient choice and responsible decisions

And what about patient choice? This concept is well-founded in our legal system. As physicians, we are just advisors trying to guide patient choice. Creating a new type of medicine that stands for incorporation of unproven practices into medical routine would, however, be a violation of our duty to be responsible advisors to patients. Responsible advice has to be based on evidence, not on ideology. Decision-makers rightly insist on data, not anecdote.6

In conclusion, the term integrative medicine is superfluous since it stands either for whole-person medicine (a concept already a part of primary care) or for the promotion of integrating well-documented CAM modalities (already being done with evidence-based medicine). The danger of integrative medicine lies in creating a smokescreen behind which dubious practices are pushed into routine healthcare. I believe this would be a serious disservice to all involved—not least, to our patients.

Correspondence

Edzard Ernst, MD, PhD, FRCP, FRCPEd, Complementary Medicine, Peninsula Medical School, Universities of Exeter & Plymouth, 25 Victoria Park Road, Exeter EX2 4NT UK. E-mail: [email protected].

1. Rees L, Weil A. Integrated medicine. BMJ 2001;322:119-120.

2. Caspi O, Bell IR, Rychener D, Gaudet TW, Weil A. The tower of Babel: communication and medicine - an essay on medical education and complementary/alternative medicine. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:3193-3195

3. Eisenberg DM, David RB, Ettner SL, et al. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States. JAMA 1998;280:1569-1575.

4. Mahady GB, Parrot J, Lee C, Yun GS, Dan A. Botanical dietary supplement use in peri- and postmenopausal women. Menopause 2003;10:65-72.

5. Ernst E, Pittler MH, Stevinson C, White AR. The Desktop Guide to Complementary and Alternative Medicine. Edinburgh: Mosby; 2001.

6. Van Haselen R, Fisher P. Evidence influencing British Health Authorities decisions in purchasing complementary medicine. JAMA 1998;290:1564.-

Integrative medicine is a new concept of healthcare.1,2 Confusingly, the term has 2 definitions. The first definition is a healthcare system “that selectively incorporates elements of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) into comprehensive treatment plans….”1 The second definition is an approach that emphasizes “health and healing rather than disease and treatment. It views patients as whole people with minds and spirits as well as bodies….”1

I would argue that the whole-person concept has always been at the core of good medicine, particularly primary care, and that coining a new name for an old value is counterproductive. If we can agree that the whole-person concept needs no other name, we can greatly simplify matters by letting integrative medicine stand for just one thing—incorporating elements of CAM into routine health care. Let’s consider the implications of this thinking.

The arguments for integrative medicine

Proponents of integrating CAM into routine medical care point to its increasing popularity3 and to the satisfaction of most CAM users.4 They also argue that CAM has largely been a privilege of the affluent class,3 and, to achieve equity in health care, we should integrate CAM across all of society. This line of argument seems logical and well intentioned. But is it convincing?

Just because the affluent are the primary recipients of CAM does not necessarily recommend it to everyone. Their lifestyle choices also put them at greater risk for cancer and gout, and they undergo liposuction more often. That the affluent can afford to pay for CAM does not mean it’s good for them.

The evidence for benefits vs risks