User login

Safety and Efficacy of Combined Use of 4-Hydroxyanisole (mequinol) 2%/Tretinoin 0.01% Solution and Sunscreen in Solar Lentigines

Noxious Sensory Perceptions in Patients With Mild to Moderate Rosacea Treated With Azelaic Acid 15% Gel

Raloxifene reduces risk of vertebral fractures and breast cancer in postmenopausal women regardless of prior hormone therapy

- Consider prescribing raloxifene 60 mg/d for postmenopausal women, regardless of whether they have used hormone therapy, to reduce the incidence of vertebral fractures and breast cancer (SOR:B).

Objective: We examined whether past use of hormone therapy influences the effects of raloxifene on the risk of new vertebral fracture, cardiovascular events, or breast cancer.

Study Design: The Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation (MORE) trial examined vertebral fracture incidence as the primary endpoint, breast cancer incidence as a secondary endpoint. Cardiovascular events were collected as secondary safety endpoints.

Population: The MORE trial enrolled 7705 postmenopausal women. Of the 7682 women who reported their previous HT use status, 29% used HT before screening.

Outcomes Measured: Separate logistic regression models analyzed the relationships between prior HT use and the risk of vertebral fracture, cardiovascular events, or breast cancer. Interaction terms with P<.10 were considered to be statistically significant. Confidence intervals for relative risks (RR) were calculated using the Mantel-Haenszel method.

Results: Raloxifene 60 mg/d, the clinically approved dose for osteoporosis prevention and treatment, reduced the risk of vertebral fractures by 54% (RR=0.46) and 29% (RR=0.71) in women with and without prior HT use, respectively (interaction P=.05). A lower incidence of invasive breast cancer in women with prior HT use (RR=0.23) and in women without prior HT use [RR=0.31; interaction P=.60] was observed in women receiving raloxifene (pooled doses). Irrespective of prior HT use, women treated with raloxifene (pooled doses) had no change in incidence of cardiovascular events (interaction P=.56).

Conclusions: The risk of vertebral fractures was lower in women treated with raloxifene, regardless of prior HT use, but there was a suggestion that the effect was greater in women who had used HT. Women randomized to receive raloxifene exhibited a decreased incidence of invasive breast cancer, compared with women receiving placebo. No change occurred in the incidence of cardiovascular events, regardless of prior HT use.

Estrogen-containing hormone therapies (HT) have been used to alleviate menopausal symptoms and to prevent chronic diseases common to postmenopausal women, including osteoporosis and cardiovascular disease.1,2 In this analysis, we use the abbreviation “HT” to refer to postmenopausal hormone therapies, either estrogen alone or combined with progestin.

Based on the findings of the randomized, double-blind Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) study involving estrogen-progestin,3 the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recommends using HT to treat moderate to severe symptoms of vulvar and vaginal atrophy and vasomotor symptoms associated with the menopause, and to prevent post-menopausal osteoporosis.4 When HT is prescribed only to prevent osteoporosis in women without menopausal symptoms, the FDA recommends that other approved, non-estrogen therapies be considered and that HT be used at the lowest dose for the shortest duration to achieve treatment goals.4 Many postmenopausal women have chosen to discontinue HT in light of these recommendations.5 However, discontinuing HT may increase bone resorption and accelerate bone loss,6,7 which, if untreated, places women at risk for osteoporotic fractures.

The serum estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) raloxifene is not an estrogen, a progestin, or a hormone,8 but it binds to the estrogen receptor to exert effects in the skeletal and cardiovascular systems and in breast tissue.9 In the 4-year Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation (MORE) osteoporosis treatment trial of postmenopausal women, raloxifene 60 mg/d, the approved dose for post-menopausal osteoporosis prevention and treatment, increased bone mineral density (BMD) and significantly reduced the risk for new vertebral fractures with sustained efficacy.10 With the declining use of long-term HT,5 it is clinically relevant and important to determine whether a history of HT use has any influence on the effects of other antiresorptive agents, such as raloxifene, which may be subsequently used for postmenopausal osteoporosis prevention and treatment. The objective of this analysis is to determine the effects of raloxifene on BMD, and the risks of vertebral fractures, cardiovascular events, and breast cancer in post-menopausal women who did or did not use HT prior to screening for the MORE osteoporosis study.

Materials and methods

Subjects and treatment

Details on subject recruitment and follow-up, and complete inclusion and exclusion criteria, were previously described for the MORE study.11 The trial examined the incidence of osteoporotic fractures as a primary endpoint and the incidence of breast cancer as a prespecified secondary endpoint, and it collected reports of cardiovascular events as a secondary safety endpoint.

Researchers enrolled 7705 women up to 80 years of age who were at least 2 years post-menopausal, and who had osteoporosis as defined by radiographically apparent vertebral fractures at baseline or BMD criteria. Women were randomly assigned to receive raloxifene 60 or 120 mg/d, or an identically appearing placebo.11 All women received daily supplements of calcium (500 mg) and vitamin D (400 to 600 IU). An ethical review board at each site approved the MORE study protocol. All women gave written informed consent to participate in the study in accordance with the ethical principles stated in the Declaration of Helsinki.

At study screening, women were asked if they had ever taken HT. Women were excluded from the study if they were experiencing clinically severe menopausal symptoms at the beginning of the study that required estrogen. Women were excluded if they had been treated with therapeutic doses of androgen, calcitonin, or estrogen (>1 cycle or 28 days) alone or with progestin (>1 cycle or 28 days) within 6 months of beginning the study. Women were permitted to have used systemic (oral or transdermal) estrogen and progestin for up to 1 cycle (28 days) during the 6 months before the study. No systemic estrogen and progestin use was allowed within 2 months before study entry. Occasional use of topical estrogens (3 times per week), and oral estriol (2 mg/d) for menopausal symptoms was permitted.

A 1-year double-blind extension phase was added to the 3-year treatment phase.10 All vertebral fracture, cardiovascular, and breast cancer endpoints that occurred over the 48-month study period were included in the present analyses.

Fracture and BMD assessment

New morphometric vertebral fractures, defined using semiquantitative assessment criteria,12 were identified by comparing spinal radiographs taken at 2, 3, and 4 years with baseline radiographs. A new vertebral fracture was defined as a vertebral fracture occurring in a vertebra that was not fractured at baseline. New clinical vertebral fractures were defined as those associated with signs or symptoms suggestive of vertebral fracture, such as back pain, reported either at an interim 6-month clinic visit or at any time between clinic visits,13 and which were subsequently corroborated with radiographs and adjudicated as previously described.10

Lumbar spine and femoral neck BMD were measured annually using dual-energy x-ray densitometry, as previously described.11

Cardiovascular event assessment

Cardiovascular events were collected as a secondary safety endpoint in the MORE trial, as previously described in detail.14 Women were asked at each clinic visit if they had had a myocardial infarction (MI), coronary bypass surgery, percutaneous coronary revascularization, or a stroke since the previous visit, and unsolicited reports of adverse cardiovascular events were recorded. All summaries of reported cardiovascular events were reviewed and adjudicated by 1 board-certified cardiologist, contracted by the sponsor, who was not associated with the trial and was blinded to treatment assignment.

Women with 4 or more risk points, assessed using the same criteria as for enrollment in the Raloxifene Use for The Heart (RUTH) trial,15 were considered to be at high risk for cardiovascular events. Coronary events included MI, unstable angina, or coronary ischemia.14 Cerebrovascular events included stroke and transient ischemic attack.14

Breast cancer assessment

Assessment of breast cancer was a prespecified secondary endpoint of the MORE trial, and was previously described in detail.16 All diagnoses of breast cancer were adjudicated by an independent oncology review board consisting of 5 physician specialists in breast cancer, and chaired by a pharmacologic scientist, none of whom were employed by the sponsor. Previous publications of the MORE breast cancer data have reported 61 cases of invasive breast cancer.16 A subsequent review of the MORE dataset found 1 fewer case of invasive breast cancer in each of the placebo and pooled raloxifene groups, so that 59 cases of invasive breast cancer were confirmed, and this number will be used in the present analysis. The change in the number of cases of invasive breast cancer was small, and had no impact on the overall interpretation of the breast cancer results from the MORE trial.

Results

Characteristics for all subjects at baseline and for women in the placebo group

Of the 7705 women enrolled, 7682 (99.7%) reported their status of previous HT use, with 2235 women (29.1%) having used HT before participating in MORE ( W1, available at www.jfponline.com). Baseline characteristics that were significantly different between women who reported prior HT use and those who reported no prior HT use included age, BMD, and the incidences of vertebral fractures, coronary angioplasty, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and family histories of osteoporosis or breast cancer (Table W1, available at www.jfponline.com). In the subsets of women who did and who did not use HT previously, the baseline characteristics were not significantly different between the placebo and raloxifene groups, except for diabetes (placebo, 1.9%; raloxifene 60 mg/day, 3.3%; pooled raloxifene, 2.9%; P=.02).

In the placebo group, the incidence of new vertebral fractures, cardiovascular events, and breast cancer at 4 years were not significantly different in women with prior HT use compared with women without prior HT use.

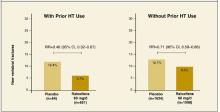

Vertebral fracture events and bone mineral density

After 4 years of treatment with raloxifene 60 mg/d, women with and without prior HT use exhibited significant reductions in new vertebral fractures compared with those taking placebo ( Figure ). Vertebral fracture risk reductions between treatment groups were also statistically significant in subgroups of women with and without prevalent vertebral fractures ( Table1 ). Raloxifene 60 mg/d also reduced the risk of new clinically-apparent vertebral fractures, compared with placebo, in women with prior HT use (absolute risk reduction (ARR)=1.8%; RR=0.52 [95% CI, 0.28–0.96]), and in women without prior HT use (ARR=1.7%; RR=0.61 [95% CI, 0.43–0.87]; interaction P=.66]. The interaction P-values remained similar after adjusting for the baseline fracture risk factors (TableW1 , at www.jfponline.com) that were significantly different between women with and women without prior HT use. Women with and without prior HT use treated with raloxifene 60 mg/d had significant increases in BMD, at the lumbar spine (2.7% and 2.5%, respectively; interaction P=.54), and femoral neck (2.6% and 1.9% respectively; interaction P=.06), compared with placebo. Similar results were observed for fracture and BMD in women treated with the pooled raloxifene doses.

TABLE 1

Absolute and relative risks of new vertebral fractures with raloxifene 60 mg/d compared with placeboa

| Women who had used HT (n=1305) | Women who had notused HT (n=3232) | Overall study population d | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n=654) | Raloxifene 60 mg/d(n=651) | RR (95% CI)b [ARR] | Placebo (n=1634) | Raloxifene 60 md/d (n=1598) | RR (95% CI)[ARR] | Interaction P-valuec | RR (95% CI) | ||

| Women with prevalent fractures | 25.36% | 13.68% | 0.54(0.36–0.81)[11.68%] | 24.24% | 17.11% | 0.71(0.57–0.88)[7.13%] | .27 | 0.66(0.55–0.81) | |

| Women without prevalent vertebral | 6.29% | 1.82% | 0.29(0.13–0.63) [4.47%] | 5.54% | 3.46% | 0.62(0.41–0.95)[2.08%] | .09 | 0.51(0.35–0.73) | |

| a Results with raloxifene 60 mg/d are shown since this is the clinically approved dose for osteoporosis prevention and treatment. Results with pooled raloxifene doses were similar. Data from women with at least one post-baseline follow-up spinal radiograph were included in this table. | |||||||||

| b RR (95% CI) denotes relative risk (95% confidence interval) Absolute risk reductions, denoted [ARR], are the differences between the placebo and raloxifene groups. Similar results were observed with raloxifene (pooled 60 mg/d and 120 mg/d doses) on vertebral fracture risk, in women who previously used HT [ARR=6.6%; RR=0.47 (95% CI, 0.35–0.63)], and in women without prior HT use [ARR=4.4%; RR=0.66 (95% CI, 0.55–0.78); interaction P=.06] | |||||||||

| c Results for the overall study population would be used unless the interaction effects between therapy group and prior HT use were statistically significant (P<.10), in which case, the results in the subgroups of women with and women without prior HT use should be used. | |||||||||

| d Delmas et al10 published the results for the overall study population, regardless of whether or not information on the participants’ HT use was available. | |||||||||

FIGURE

Percentage of women with and without prior HT use who experienced new vertebral fractures in the 4-year MORE study

This analysis included all women with at least 1 post-baseline follow-up vertebral radiograph, who reported their status of prior HT use. The relative risks (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) are shown for women treated with either placebo or raloxifene 60 mg/d. The absolute risk reductions were 6.7% in women with prior HT use and 3.7% in women without prior HT use. The interaction P-value was .05.

Cardiovascular events

In women with and without prior HT use, treatment with raloxifene (pooled doses) did not result in statistically significant changes in the incidence of new cardiovascular, coronary, or cerebrovascu-lar events, compared with placebo ( Table2 ). In a subgroup of women who were at high risk of cardiovascular disease,15 prior HT use had no effect on the incidence of new cardiovascular events with raloxifene (pooled doses) treatment ( Table 2 ). The interaction P-values remained similar after adjusting for the baseline cardiovascular risk factors (Table W1, at www.jfponline.com) that were significantly different between women with and without prior HT use.

TABLE 2

Absolute and relative risks of cardiovascular events with raloxifene (pooled doses) compared with placeboa

| Women who had used HT (n=2235) | Women who had not used HT (n=5447) | Overall studypopulation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo(n=738) | Pooled raloxifene(n=1497) | RR (95% CI)b [ARR] | Placebo (n=1833) | Pooled raloxifene (n=3614) | RR(95% CI)[ARR] | Interaction P-valuec | RR(95% CI) | |

| Cardiovascular events | 2.71% | 2.87% | 1.06(0.63–1.79)[–0.16%] | 4.15% | 3.68% | 0.89(0.67–1.17) [0.47%] | .56 | 0.92(0.72–1.18) |

| Coronary events | 1.49% | 1.74% | 1.17 (0.58–2.35)[–0.25%] | 2.40% | 2.08% | 0.87 (0.60–1.25) [0.32%] | .46 | 0.92(0.67–1.28) |

| Cerebrovascularevents | 1.22% | 1.14% | 0.93(0.42–2.08)[0.08%] | 1.75% | 1.63% | 0.94 (0.61–1.43)[.012%] | .99 | 0.93(0.64–1.36) |

| Cardiovascularevents in high-risk subgroupd | 12.66% | 5.91% | .047(0.21–1.06)[6.75%] | 13.08% | 8.54% | 0.65 (0.42–1.01)[4.54%] | .49 | 0.60(0.41–0.88) [4.54%] |

| a Pooled raloxifene doses were used in this analysis, since there were few events. There were no differences in the incidence of events between the raloxifene doses. | ||||||||

| b Relative risk (RR), 95% confidence interval (95% CI). Absolute risk reductions, denoted [ARR], are the differences between the placebo and raloxifene groups. | ||||||||

| c The interaction effects between therapy group and prior HT use were not statistically significant (P>.10), so results from the overall study population would be used. Barrett-Connor et al14 reported the results for raloxifene 60 mg/d and raloxifene 120 mg/d in the overall study population, regardless of whether or not information on the participants’ HT use was available. | ||||||||

| d Of the 1029 women in the high-risk subgroup, 764 women had no prior history of HT use (placebo, n=237; raloxifene, n=527), and 265 women reported prior HT use (placebo, n=79; raloxifene, n=186). | ||||||||

Breast cancer

In women with and without prior HT use, similar reductions in the incidence of breast cancer (regardless of invasiveness), invasive breast cancer, and estrogen-receptor positive invasive breast cancer, were observed after raloxifene treatment (pooled doses) compared with placebo ( Table 3 ). The interaction P-values remained similar after adjusting for the baseline breast cancer risk factors (Table W1) that were significantly different between women with and without prior HT use.

TABLE 3

Absolute and relative risks of breast cancer with raloxifene (pooled doses) compared with placeboa

| Women who had used HT (n=2235) | Women who had notused HT (n=5447) | Overall study population | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo(n=738) | Pooledraloxifene(n=1497) | RR(95% CI)b [ARR] | Placebo(n=1833) | Pooled raloxifene(n=3614) | RR(95% CI)[ARR] | InteractionP-valuec | RR(95% CI) | |

| Breast cancer d | 2.30% | 0.73% | 0.32(0.15–0.68)[1.57%] | 1.47% | 0.64% | 0.43(0.25–0.75)[0.83%] | .52 | 0.38 (0.24–0.58) |

| Invasivebreast cancer | 2.03% | 0.47% | 0.23(0.09–0.56)[1.56%] | 1.25% | 0.39% | 0.31(0.16–0.60) [0.86%] | .60 | 0.28(0.17–0.46) |

| Invasiveestrogen-receptorpositive breastcancer | 1.76% | 0.27% | 0.15(0.05–0.46)[1.49%] | 0.87% | 0.17% | 0.19(0.08–0.49)[0.70%] | .75 | 0.16(0.09–0.30) |

| a Pooled raloxifene doses were used in this analysis, since there were few events. There were no differences in the incidence of events between the raloxifene doses. | ||||||||

| b Relative risk (RR), 95% confidence interval (95% CI). Absolute risk reductions, denoted [ARR], are the differences between the placebo and raloxifene groups. | ||||||||

| c The interaction effects between therapy group and prior HT use were not statistically significant (P>.10), so results from the overall study population would be used. Cauley et al16 reported the results for in the overall study population, regardless of whether or not information on the participants’ HT use was available. | ||||||||

| d All breast cancer, regardless of invasiveness. | ||||||||

Discussion

This analysis examined the effects of raloxifene in women who reported their use of postmenopausal hormone therapies before enrolling in the MORE osteoporosis trial. Compared with placebo, women treated with raloxifene experienced significant decreases in the risks for new vertebral fractures and the incidence of breast cancer, without significant changes in the incidence of cardiovascular events, regardless of previous HT use. These analyses provide further information on the effects of raloxifene on the risks of vertebral fractures,10 cardiovascular events,14 and breast cancer16 seen in the overall MORE study population at 4 years.

This analysis found a differential reduction in vertebral fracture risk with raloxifene between women who did and did not have prior HT use, which may result from possible differences in women who chose to use HT before participating in MORE. In women with previous HT use, a greater proportion had a family history of osteo-porosis and a lower proportion had prevalent ver-tebral fractures at baseline, compared with women who had not used HT. Other unidentified confounding factors, such as the “healthy user” bias commonly associated with women who chose to use HT,17 may also contribute to the differential vertebral fracture risk reduction with raloxifene treatment. The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures showed that women with current estrogen use had significantly decreased fracture risks, but the risk reduction waned in women who discontinued estrogen.18 After HT discontinuation, BMD loss resumes at a rate similar to that seen in women shortly after menopause, suggesting that prior HT use may have limited residual effects on maintaining BMD.7,19 Such findings raise the urgency of evaluating the risk for osteoporosis in women who discontinue HT.

Women treated with raloxifene had no significant changes in the incidence of cardiovascular events, with no differential treatment effect based on prior HT use. In the HERS20 and WHI3 trials, which studied the outcomes of estrogen-progestin therapy in postmenopausal women, similar analyses did not show any significant differential effects of prior HT use on the incidence of cardiovascular events with estrogen-progestin during the respective trials.

In this analysis, women treated with raloxifene had a significantly lower incidence of breast cancer compared with those who received placebo, and this incidence was comparable between women with and without prior HT use. In contrast, women who had used HT before the WHI study had a significant increase in the risk of breast cancer with estrogen-progestin therapy during the study, compared with those who had not used HT.3

A limitation of our analysis that a history of HT use was based on participants’ self-report, which depended on their ability to recall medication they may have taken years earlier. Also, no information was obtained on therapy duration and the doses and formulations of HT. Since the MORE trial was conducted in 25 countries, the patterns and types of HT regimens are expected to be different. The strength of our analysis is that the MORE population was large enough to prospectively collect data on multiple clinical outcomes.

In summary, postmenopausal women treated with raloxifene experienced a significant risk reduction for vertebral fractures, regardless of prior HT use, but women who had used HT may exhibit greater reductions. Women who used raloxifene had no change in the incidence of cardiovascular events and a lower incidence of breast cancer, compared with placebo, regardless of their history of HT use. Since HT is becoming increasingly limited to short-term use for menopausal symptoms, women and their physicians may consider several other therapeutic options to address postmenopausal health concerns.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions of Leo Plouffe Jr., MD, and Somnath Sarkar, PhD, for suggestions on manuscript content, and Sharon Xiaohan Zou, MS, for statistical programming. A complete list of all investigators in the MORE trial is found in J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002; 87:3609–3617. Portions of this work were presented at the following meetings: Third European Symposium on Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis, Barcelona, Spain, 2002; International Society for Clinical Densitometry (ISCD), Los Angeles, USA,2003; European Calcified Tissue Society (ECTS), Rome, Italy, 2003; International Bone and Mineral Society (IBMS), Osaka, Japan, 2003; European Menopause and Andropause Society (EMAS), Bucharest, Romania, 2003; Ninth Bath Conference on Osteoporosis, Bath, UK, 2003. Eli Lilly and Company sponsored the Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation (MORE) Trial.

Corresponding author

Olof Johnell, MD, PhD, Department of Orthopedics, Universitetssjukhuset MAS, Malmo, SE-20502, Sweden. E-mail: [email protected].

1. Greendale GA, Lee NP, Arriola ER. The menopause. Lancet 1999;353:571-580.

2. Grady D, Rubin SM, Petitti DB, et al. Hormone therapy to prevent disease and prolong life in postmenopausal women. Ann Intern Med 1992;117:1016-1037.

3. Writing Group for the Women’s Health Initiative Investigators. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women. Principal results from the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002;288:321-333.

4. Bren L. The estrogen and progestin dilemma: New advice, labeling and guidelines. FDA Consumer 2003;37:10-11.

5. Haas JS, Kaplan CP, Gerstenberger EP, Kerlikowske K. Changes in the use of postmenopausal hormone therapy after the publication of clinical trial results. Ann Intern Med 2004;140:184-188.

6. Gallagher JC, Rapuri PB, Haynatzki G, Detter JR. Effect of discontinuation of estrogen, calcitriol, and the combination of both on bone density and bone markers. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002;87:4914-4923.

7. Tremollieres FA, Pouilles JM, Ribot C. Withdrawal of hormone replacement therapy is associated with significant ver-tebral bone loss in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int 2001;12:385-390.

8. Riggs BL, Hartmann LC. Selective estrogen-receptor modulators —mechanisms of action and application to clinical practice. N Engl J Med 2003;348:618-629.

9. Maricic M, Gluck O. Review of raloxifene and its clinical applications in osteoporosis. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2002;3:767-775.

10. Delmas PD, Ensrud KE, Adachi JD, et al. Efficacy of raloxifene on vertebral fracture risk reduction in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: four-year results from a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002;87:3609-3617.

11. Ettinger B, Black DM, Mitlak BH, et al. Reduction of verte-bral fracture risk in postmenopausal women with osteo-porosis treated with raloxifene: Results from a 3-year randomized clinical trial. JAMA 1999;282:637-645.

12. Genant HK, Wu CY, van Kuijk C, Nevitt MC. Vertebral fracture assessment using a semiquantitative technique. J Bone Miner Res 1993;8:1137-1148.

13. Maricic M, Adachi JD, Sarkar S, Wu W, Wong M, Harper KD. Early effects of raloxifene on clinical vertebral fractures at 12 months in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:1140-1143.

14. Barrett-Connor E, Grady D, Sashegyi A, et al. Raloxifene and cardiovascular events in osteoporotic postmenopausal women: four-year results from the MORE (Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation) randomized trial. JAMA 2002;287:847-857.

15. Mosca L, Barrett-Connor E, Wenger NK, et al. Design and methods of the Raloxifene Use for The Heart (RUTH) study. Am J Cardiol 2001;88:392-395.

16. Cauley J, Norton L, Lippman ME, et al. Continued breast cancer risk reduction in postmenopausal women treated with raloxifene: 4-year Results from the MORE Trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2001;65:125-134.

17. Grodstein F, Clarkson TB, Manson JE. Understanding the divergent data on postmenopausal hormone therapy. N Engl J Med 2003;348:645-650.

18. Cauley J, Seeley DG, Ensrud K, Ettinger B, Black D, Cummings SR. Estrogen replacement therapy and fractures in older women. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Ann Intern Med 1995;122:9-16.

19. Greendale GA, Espeland M, Slone S, Marcus R, Barrett-Connor E. Bone mass response to discontinuation of long-term hormone replacement therapy: results from the Postmenopausal Estrogen/Progestin Interventions (PEPI) Safety Follow-up Study. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:665-672.

20. Grady D, Herrington D, Bittner V, et al. Cardiovascular disease outcomes during 6.8 years of hormone therapy: Heart and Estrogen/Progestin Replacement Study Follow-up (HERS II). JAMA 2002;288:49-57.

21. Looker AC, Wahner HW, Dunn WL, et al. Updated data on proximal femur bone mineral levels of US adults. Osteoporos Int 1998;8:468-489.

- Consider prescribing raloxifene 60 mg/d for postmenopausal women, regardless of whether they have used hormone therapy, to reduce the incidence of vertebral fractures and breast cancer (SOR:B).

Objective: We examined whether past use of hormone therapy influences the effects of raloxifene on the risk of new vertebral fracture, cardiovascular events, or breast cancer.

Study Design: The Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation (MORE) trial examined vertebral fracture incidence as the primary endpoint, breast cancer incidence as a secondary endpoint. Cardiovascular events were collected as secondary safety endpoints.

Population: The MORE trial enrolled 7705 postmenopausal women. Of the 7682 women who reported their previous HT use status, 29% used HT before screening.

Outcomes Measured: Separate logistic regression models analyzed the relationships between prior HT use and the risk of vertebral fracture, cardiovascular events, or breast cancer. Interaction terms with P<.10 were considered to be statistically significant. Confidence intervals for relative risks (RR) were calculated using the Mantel-Haenszel method.

Results: Raloxifene 60 mg/d, the clinically approved dose for osteoporosis prevention and treatment, reduced the risk of vertebral fractures by 54% (RR=0.46) and 29% (RR=0.71) in women with and without prior HT use, respectively (interaction P=.05). A lower incidence of invasive breast cancer in women with prior HT use (RR=0.23) and in women without prior HT use [RR=0.31; interaction P=.60] was observed in women receiving raloxifene (pooled doses). Irrespective of prior HT use, women treated with raloxifene (pooled doses) had no change in incidence of cardiovascular events (interaction P=.56).

Conclusions: The risk of vertebral fractures was lower in women treated with raloxifene, regardless of prior HT use, but there was a suggestion that the effect was greater in women who had used HT. Women randomized to receive raloxifene exhibited a decreased incidence of invasive breast cancer, compared with women receiving placebo. No change occurred in the incidence of cardiovascular events, regardless of prior HT use.

Estrogen-containing hormone therapies (HT) have been used to alleviate menopausal symptoms and to prevent chronic diseases common to postmenopausal women, including osteoporosis and cardiovascular disease.1,2 In this analysis, we use the abbreviation “HT” to refer to postmenopausal hormone therapies, either estrogen alone or combined with progestin.

Based on the findings of the randomized, double-blind Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) study involving estrogen-progestin,3 the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recommends using HT to treat moderate to severe symptoms of vulvar and vaginal atrophy and vasomotor symptoms associated with the menopause, and to prevent post-menopausal osteoporosis.4 When HT is prescribed only to prevent osteoporosis in women without menopausal symptoms, the FDA recommends that other approved, non-estrogen therapies be considered and that HT be used at the lowest dose for the shortest duration to achieve treatment goals.4 Many postmenopausal women have chosen to discontinue HT in light of these recommendations.5 However, discontinuing HT may increase bone resorption and accelerate bone loss,6,7 which, if untreated, places women at risk for osteoporotic fractures.

The serum estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) raloxifene is not an estrogen, a progestin, or a hormone,8 but it binds to the estrogen receptor to exert effects in the skeletal and cardiovascular systems and in breast tissue.9 In the 4-year Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation (MORE) osteoporosis treatment trial of postmenopausal women, raloxifene 60 mg/d, the approved dose for post-menopausal osteoporosis prevention and treatment, increased bone mineral density (BMD) and significantly reduced the risk for new vertebral fractures with sustained efficacy.10 With the declining use of long-term HT,5 it is clinically relevant and important to determine whether a history of HT use has any influence on the effects of other antiresorptive agents, such as raloxifene, which may be subsequently used for postmenopausal osteoporosis prevention and treatment. The objective of this analysis is to determine the effects of raloxifene on BMD, and the risks of vertebral fractures, cardiovascular events, and breast cancer in post-menopausal women who did or did not use HT prior to screening for the MORE osteoporosis study.

Materials and methods

Subjects and treatment

Details on subject recruitment and follow-up, and complete inclusion and exclusion criteria, were previously described for the MORE study.11 The trial examined the incidence of osteoporotic fractures as a primary endpoint and the incidence of breast cancer as a prespecified secondary endpoint, and it collected reports of cardiovascular events as a secondary safety endpoint.

Researchers enrolled 7705 women up to 80 years of age who were at least 2 years post-menopausal, and who had osteoporosis as defined by radiographically apparent vertebral fractures at baseline or BMD criteria. Women were randomly assigned to receive raloxifene 60 or 120 mg/d, or an identically appearing placebo.11 All women received daily supplements of calcium (500 mg) and vitamin D (400 to 600 IU). An ethical review board at each site approved the MORE study protocol. All women gave written informed consent to participate in the study in accordance with the ethical principles stated in the Declaration of Helsinki.

At study screening, women were asked if they had ever taken HT. Women were excluded from the study if they were experiencing clinically severe menopausal symptoms at the beginning of the study that required estrogen. Women were excluded if they had been treated with therapeutic doses of androgen, calcitonin, or estrogen (>1 cycle or 28 days) alone or with progestin (>1 cycle or 28 days) within 6 months of beginning the study. Women were permitted to have used systemic (oral or transdermal) estrogen and progestin for up to 1 cycle (28 days) during the 6 months before the study. No systemic estrogen and progestin use was allowed within 2 months before study entry. Occasional use of topical estrogens (3 times per week), and oral estriol (2 mg/d) for menopausal symptoms was permitted.

A 1-year double-blind extension phase was added to the 3-year treatment phase.10 All vertebral fracture, cardiovascular, and breast cancer endpoints that occurred over the 48-month study period were included in the present analyses.

Fracture and BMD assessment

New morphometric vertebral fractures, defined using semiquantitative assessment criteria,12 were identified by comparing spinal radiographs taken at 2, 3, and 4 years with baseline radiographs. A new vertebral fracture was defined as a vertebral fracture occurring in a vertebra that was not fractured at baseline. New clinical vertebral fractures were defined as those associated with signs or symptoms suggestive of vertebral fracture, such as back pain, reported either at an interim 6-month clinic visit or at any time between clinic visits,13 and which were subsequently corroborated with radiographs and adjudicated as previously described.10

Lumbar spine and femoral neck BMD were measured annually using dual-energy x-ray densitometry, as previously described.11

Cardiovascular event assessment

Cardiovascular events were collected as a secondary safety endpoint in the MORE trial, as previously described in detail.14 Women were asked at each clinic visit if they had had a myocardial infarction (MI), coronary bypass surgery, percutaneous coronary revascularization, or a stroke since the previous visit, and unsolicited reports of adverse cardiovascular events were recorded. All summaries of reported cardiovascular events were reviewed and adjudicated by 1 board-certified cardiologist, contracted by the sponsor, who was not associated with the trial and was blinded to treatment assignment.

Women with 4 or more risk points, assessed using the same criteria as for enrollment in the Raloxifene Use for The Heart (RUTH) trial,15 were considered to be at high risk for cardiovascular events. Coronary events included MI, unstable angina, or coronary ischemia.14 Cerebrovascular events included stroke and transient ischemic attack.14

Breast cancer assessment

Assessment of breast cancer was a prespecified secondary endpoint of the MORE trial, and was previously described in detail.16 All diagnoses of breast cancer were adjudicated by an independent oncology review board consisting of 5 physician specialists in breast cancer, and chaired by a pharmacologic scientist, none of whom were employed by the sponsor. Previous publications of the MORE breast cancer data have reported 61 cases of invasive breast cancer.16 A subsequent review of the MORE dataset found 1 fewer case of invasive breast cancer in each of the placebo and pooled raloxifene groups, so that 59 cases of invasive breast cancer were confirmed, and this number will be used in the present analysis. The change in the number of cases of invasive breast cancer was small, and had no impact on the overall interpretation of the breast cancer results from the MORE trial.

Results

Characteristics for all subjects at baseline and for women in the placebo group

Of the 7705 women enrolled, 7682 (99.7%) reported their status of previous HT use, with 2235 women (29.1%) having used HT before participating in MORE ( W1, available at www.jfponline.com). Baseline characteristics that were significantly different between women who reported prior HT use and those who reported no prior HT use included age, BMD, and the incidences of vertebral fractures, coronary angioplasty, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and family histories of osteoporosis or breast cancer (Table W1, available at www.jfponline.com). In the subsets of women who did and who did not use HT previously, the baseline characteristics were not significantly different between the placebo and raloxifene groups, except for diabetes (placebo, 1.9%; raloxifene 60 mg/day, 3.3%; pooled raloxifene, 2.9%; P=.02).

In the placebo group, the incidence of new vertebral fractures, cardiovascular events, and breast cancer at 4 years were not significantly different in women with prior HT use compared with women without prior HT use.

Vertebral fracture events and bone mineral density

After 4 years of treatment with raloxifene 60 mg/d, women with and without prior HT use exhibited significant reductions in new vertebral fractures compared with those taking placebo ( Figure ). Vertebral fracture risk reductions between treatment groups were also statistically significant in subgroups of women with and without prevalent vertebral fractures ( Table1 ). Raloxifene 60 mg/d also reduced the risk of new clinically-apparent vertebral fractures, compared with placebo, in women with prior HT use (absolute risk reduction (ARR)=1.8%; RR=0.52 [95% CI, 0.28–0.96]), and in women without prior HT use (ARR=1.7%; RR=0.61 [95% CI, 0.43–0.87]; interaction P=.66]. The interaction P-values remained similar after adjusting for the baseline fracture risk factors (TableW1 , at www.jfponline.com) that were significantly different between women with and women without prior HT use. Women with and without prior HT use treated with raloxifene 60 mg/d had significant increases in BMD, at the lumbar spine (2.7% and 2.5%, respectively; interaction P=.54), and femoral neck (2.6% and 1.9% respectively; interaction P=.06), compared with placebo. Similar results were observed for fracture and BMD in women treated with the pooled raloxifene doses.

TABLE 1

Absolute and relative risks of new vertebral fractures with raloxifene 60 mg/d compared with placeboa

| Women who had used HT (n=1305) | Women who had notused HT (n=3232) | Overall study population d | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n=654) | Raloxifene 60 mg/d(n=651) | RR (95% CI)b [ARR] | Placebo (n=1634) | Raloxifene 60 md/d (n=1598) | RR (95% CI)[ARR] | Interaction P-valuec | RR (95% CI) | ||

| Women with prevalent fractures | 25.36% | 13.68% | 0.54(0.36–0.81)[11.68%] | 24.24% | 17.11% | 0.71(0.57–0.88)[7.13%] | .27 | 0.66(0.55–0.81) | |

| Women without prevalent vertebral | 6.29% | 1.82% | 0.29(0.13–0.63) [4.47%] | 5.54% | 3.46% | 0.62(0.41–0.95)[2.08%] | .09 | 0.51(0.35–0.73) | |

| a Results with raloxifene 60 mg/d are shown since this is the clinically approved dose for osteoporosis prevention and treatment. Results with pooled raloxifene doses were similar. Data from women with at least one post-baseline follow-up spinal radiograph were included in this table. | |||||||||

| b RR (95% CI) denotes relative risk (95% confidence interval) Absolute risk reductions, denoted [ARR], are the differences between the placebo and raloxifene groups. Similar results were observed with raloxifene (pooled 60 mg/d and 120 mg/d doses) on vertebral fracture risk, in women who previously used HT [ARR=6.6%; RR=0.47 (95% CI, 0.35–0.63)], and in women without prior HT use [ARR=4.4%; RR=0.66 (95% CI, 0.55–0.78); interaction P=.06] | |||||||||

| c Results for the overall study population would be used unless the interaction effects between therapy group and prior HT use were statistically significant (P<.10), in which case, the results in the subgroups of women with and women without prior HT use should be used. | |||||||||

| d Delmas et al10 published the results for the overall study population, regardless of whether or not information on the participants’ HT use was available. | |||||||||

FIGURE

Percentage of women with and without prior HT use who experienced new vertebral fractures in the 4-year MORE study

This analysis included all women with at least 1 post-baseline follow-up vertebral radiograph, who reported their status of prior HT use. The relative risks (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) are shown for women treated with either placebo or raloxifene 60 mg/d. The absolute risk reductions were 6.7% in women with prior HT use and 3.7% in women without prior HT use. The interaction P-value was .05.

Cardiovascular events

In women with and without prior HT use, treatment with raloxifene (pooled doses) did not result in statistically significant changes in the incidence of new cardiovascular, coronary, or cerebrovascu-lar events, compared with placebo ( Table2 ). In a subgroup of women who were at high risk of cardiovascular disease,15 prior HT use had no effect on the incidence of new cardiovascular events with raloxifene (pooled doses) treatment ( Table 2 ). The interaction P-values remained similar after adjusting for the baseline cardiovascular risk factors (Table W1, at www.jfponline.com) that were significantly different between women with and without prior HT use.

TABLE 2

Absolute and relative risks of cardiovascular events with raloxifene (pooled doses) compared with placeboa

| Women who had used HT (n=2235) | Women who had not used HT (n=5447) | Overall studypopulation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo(n=738) | Pooled raloxifene(n=1497) | RR (95% CI)b [ARR] | Placebo (n=1833) | Pooled raloxifene (n=3614) | RR(95% CI)[ARR] | Interaction P-valuec | RR(95% CI) | |

| Cardiovascular events | 2.71% | 2.87% | 1.06(0.63–1.79)[–0.16%] | 4.15% | 3.68% | 0.89(0.67–1.17) [0.47%] | .56 | 0.92(0.72–1.18) |

| Coronary events | 1.49% | 1.74% | 1.17 (0.58–2.35)[–0.25%] | 2.40% | 2.08% | 0.87 (0.60–1.25) [0.32%] | .46 | 0.92(0.67–1.28) |

| Cerebrovascularevents | 1.22% | 1.14% | 0.93(0.42–2.08)[0.08%] | 1.75% | 1.63% | 0.94 (0.61–1.43)[.012%] | .99 | 0.93(0.64–1.36) |

| Cardiovascularevents in high-risk subgroupd | 12.66% | 5.91% | .047(0.21–1.06)[6.75%] | 13.08% | 8.54% | 0.65 (0.42–1.01)[4.54%] | .49 | 0.60(0.41–0.88) [4.54%] |

| a Pooled raloxifene doses were used in this analysis, since there were few events. There were no differences in the incidence of events between the raloxifene doses. | ||||||||

| b Relative risk (RR), 95% confidence interval (95% CI). Absolute risk reductions, denoted [ARR], are the differences between the placebo and raloxifene groups. | ||||||||

| c The interaction effects between therapy group and prior HT use were not statistically significant (P>.10), so results from the overall study population would be used. Barrett-Connor et al14 reported the results for raloxifene 60 mg/d and raloxifene 120 mg/d in the overall study population, regardless of whether or not information on the participants’ HT use was available. | ||||||||

| d Of the 1029 women in the high-risk subgroup, 764 women had no prior history of HT use (placebo, n=237; raloxifene, n=527), and 265 women reported prior HT use (placebo, n=79; raloxifene, n=186). | ||||||||

Breast cancer

In women with and without prior HT use, similar reductions in the incidence of breast cancer (regardless of invasiveness), invasive breast cancer, and estrogen-receptor positive invasive breast cancer, were observed after raloxifene treatment (pooled doses) compared with placebo ( Table 3 ). The interaction P-values remained similar after adjusting for the baseline breast cancer risk factors (Table W1) that were significantly different between women with and without prior HT use.

TABLE 3

Absolute and relative risks of breast cancer with raloxifene (pooled doses) compared with placeboa

| Women who had used HT (n=2235) | Women who had notused HT (n=5447) | Overall study population | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo(n=738) | Pooledraloxifene(n=1497) | RR(95% CI)b [ARR] | Placebo(n=1833) | Pooled raloxifene(n=3614) | RR(95% CI)[ARR] | InteractionP-valuec | RR(95% CI) | |

| Breast cancer d | 2.30% | 0.73% | 0.32(0.15–0.68)[1.57%] | 1.47% | 0.64% | 0.43(0.25–0.75)[0.83%] | .52 | 0.38 (0.24–0.58) |

| Invasivebreast cancer | 2.03% | 0.47% | 0.23(0.09–0.56)[1.56%] | 1.25% | 0.39% | 0.31(0.16–0.60) [0.86%] | .60 | 0.28(0.17–0.46) |

| Invasiveestrogen-receptorpositive breastcancer | 1.76% | 0.27% | 0.15(0.05–0.46)[1.49%] | 0.87% | 0.17% | 0.19(0.08–0.49)[0.70%] | .75 | 0.16(0.09–0.30) |

| a Pooled raloxifene doses were used in this analysis, since there were few events. There were no differences in the incidence of events between the raloxifene doses. | ||||||||

| b Relative risk (RR), 95% confidence interval (95% CI). Absolute risk reductions, denoted [ARR], are the differences between the placebo and raloxifene groups. | ||||||||

| c The interaction effects between therapy group and prior HT use were not statistically significant (P>.10), so results from the overall study population would be used. Cauley et al16 reported the results for in the overall study population, regardless of whether or not information on the participants’ HT use was available. | ||||||||

| d All breast cancer, regardless of invasiveness. | ||||||||

Discussion

This analysis examined the effects of raloxifene in women who reported their use of postmenopausal hormone therapies before enrolling in the MORE osteoporosis trial. Compared with placebo, women treated with raloxifene experienced significant decreases in the risks for new vertebral fractures and the incidence of breast cancer, without significant changes in the incidence of cardiovascular events, regardless of previous HT use. These analyses provide further information on the effects of raloxifene on the risks of vertebral fractures,10 cardiovascular events,14 and breast cancer16 seen in the overall MORE study population at 4 years.

This analysis found a differential reduction in vertebral fracture risk with raloxifene between women who did and did not have prior HT use, which may result from possible differences in women who chose to use HT before participating in MORE. In women with previous HT use, a greater proportion had a family history of osteo-porosis and a lower proportion had prevalent ver-tebral fractures at baseline, compared with women who had not used HT. Other unidentified confounding factors, such as the “healthy user” bias commonly associated with women who chose to use HT,17 may also contribute to the differential vertebral fracture risk reduction with raloxifene treatment. The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures showed that women with current estrogen use had significantly decreased fracture risks, but the risk reduction waned in women who discontinued estrogen.18 After HT discontinuation, BMD loss resumes at a rate similar to that seen in women shortly after menopause, suggesting that prior HT use may have limited residual effects on maintaining BMD.7,19 Such findings raise the urgency of evaluating the risk for osteoporosis in women who discontinue HT.

Women treated with raloxifene had no significant changes in the incidence of cardiovascular events, with no differential treatment effect based on prior HT use. In the HERS20 and WHI3 trials, which studied the outcomes of estrogen-progestin therapy in postmenopausal women, similar analyses did not show any significant differential effects of prior HT use on the incidence of cardiovascular events with estrogen-progestin during the respective trials.

In this analysis, women treated with raloxifene had a significantly lower incidence of breast cancer compared with those who received placebo, and this incidence was comparable between women with and without prior HT use. In contrast, women who had used HT before the WHI study had a significant increase in the risk of breast cancer with estrogen-progestin therapy during the study, compared with those who had not used HT.3

A limitation of our analysis that a history of HT use was based on participants’ self-report, which depended on their ability to recall medication they may have taken years earlier. Also, no information was obtained on therapy duration and the doses and formulations of HT. Since the MORE trial was conducted in 25 countries, the patterns and types of HT regimens are expected to be different. The strength of our analysis is that the MORE population was large enough to prospectively collect data on multiple clinical outcomes.

In summary, postmenopausal women treated with raloxifene experienced a significant risk reduction for vertebral fractures, regardless of prior HT use, but women who had used HT may exhibit greater reductions. Women who used raloxifene had no change in the incidence of cardiovascular events and a lower incidence of breast cancer, compared with placebo, regardless of their history of HT use. Since HT is becoming increasingly limited to short-term use for menopausal symptoms, women and their physicians may consider several other therapeutic options to address postmenopausal health concerns.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions of Leo Plouffe Jr., MD, and Somnath Sarkar, PhD, for suggestions on manuscript content, and Sharon Xiaohan Zou, MS, for statistical programming. A complete list of all investigators in the MORE trial is found in J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002; 87:3609–3617. Portions of this work were presented at the following meetings: Third European Symposium on Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis, Barcelona, Spain, 2002; International Society for Clinical Densitometry (ISCD), Los Angeles, USA,2003; European Calcified Tissue Society (ECTS), Rome, Italy, 2003; International Bone and Mineral Society (IBMS), Osaka, Japan, 2003; European Menopause and Andropause Society (EMAS), Bucharest, Romania, 2003; Ninth Bath Conference on Osteoporosis, Bath, UK, 2003. Eli Lilly and Company sponsored the Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation (MORE) Trial.

Corresponding author

Olof Johnell, MD, PhD, Department of Orthopedics, Universitetssjukhuset MAS, Malmo, SE-20502, Sweden. E-mail: [email protected].

- Consider prescribing raloxifene 60 mg/d for postmenopausal women, regardless of whether they have used hormone therapy, to reduce the incidence of vertebral fractures and breast cancer (SOR:B).

Objective: We examined whether past use of hormone therapy influences the effects of raloxifene on the risk of new vertebral fracture, cardiovascular events, or breast cancer.

Study Design: The Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation (MORE) trial examined vertebral fracture incidence as the primary endpoint, breast cancer incidence as a secondary endpoint. Cardiovascular events were collected as secondary safety endpoints.

Population: The MORE trial enrolled 7705 postmenopausal women. Of the 7682 women who reported their previous HT use status, 29% used HT before screening.

Outcomes Measured: Separate logistic regression models analyzed the relationships between prior HT use and the risk of vertebral fracture, cardiovascular events, or breast cancer. Interaction terms with P<.10 were considered to be statistically significant. Confidence intervals for relative risks (RR) were calculated using the Mantel-Haenszel method.

Results: Raloxifene 60 mg/d, the clinically approved dose for osteoporosis prevention and treatment, reduced the risk of vertebral fractures by 54% (RR=0.46) and 29% (RR=0.71) in women with and without prior HT use, respectively (interaction P=.05). A lower incidence of invasive breast cancer in women with prior HT use (RR=0.23) and in women without prior HT use [RR=0.31; interaction P=.60] was observed in women receiving raloxifene (pooled doses). Irrespective of prior HT use, women treated with raloxifene (pooled doses) had no change in incidence of cardiovascular events (interaction P=.56).

Conclusions: The risk of vertebral fractures was lower in women treated with raloxifene, regardless of prior HT use, but there was a suggestion that the effect was greater in women who had used HT. Women randomized to receive raloxifene exhibited a decreased incidence of invasive breast cancer, compared with women receiving placebo. No change occurred in the incidence of cardiovascular events, regardless of prior HT use.

Estrogen-containing hormone therapies (HT) have been used to alleviate menopausal symptoms and to prevent chronic diseases common to postmenopausal women, including osteoporosis and cardiovascular disease.1,2 In this analysis, we use the abbreviation “HT” to refer to postmenopausal hormone therapies, either estrogen alone or combined with progestin.

Based on the findings of the randomized, double-blind Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) study involving estrogen-progestin,3 the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recommends using HT to treat moderate to severe symptoms of vulvar and vaginal atrophy and vasomotor symptoms associated with the menopause, and to prevent post-menopausal osteoporosis.4 When HT is prescribed only to prevent osteoporosis in women without menopausal symptoms, the FDA recommends that other approved, non-estrogen therapies be considered and that HT be used at the lowest dose for the shortest duration to achieve treatment goals.4 Many postmenopausal women have chosen to discontinue HT in light of these recommendations.5 However, discontinuing HT may increase bone resorption and accelerate bone loss,6,7 which, if untreated, places women at risk for osteoporotic fractures.

The serum estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) raloxifene is not an estrogen, a progestin, or a hormone,8 but it binds to the estrogen receptor to exert effects in the skeletal and cardiovascular systems and in breast tissue.9 In the 4-year Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation (MORE) osteoporosis treatment trial of postmenopausal women, raloxifene 60 mg/d, the approved dose for post-menopausal osteoporosis prevention and treatment, increased bone mineral density (BMD) and significantly reduced the risk for new vertebral fractures with sustained efficacy.10 With the declining use of long-term HT,5 it is clinically relevant and important to determine whether a history of HT use has any influence on the effects of other antiresorptive agents, such as raloxifene, which may be subsequently used for postmenopausal osteoporosis prevention and treatment. The objective of this analysis is to determine the effects of raloxifene on BMD, and the risks of vertebral fractures, cardiovascular events, and breast cancer in post-menopausal women who did or did not use HT prior to screening for the MORE osteoporosis study.

Materials and methods

Subjects and treatment

Details on subject recruitment and follow-up, and complete inclusion and exclusion criteria, were previously described for the MORE study.11 The trial examined the incidence of osteoporotic fractures as a primary endpoint and the incidence of breast cancer as a prespecified secondary endpoint, and it collected reports of cardiovascular events as a secondary safety endpoint.

Researchers enrolled 7705 women up to 80 years of age who were at least 2 years post-menopausal, and who had osteoporosis as defined by radiographically apparent vertebral fractures at baseline or BMD criteria. Women were randomly assigned to receive raloxifene 60 or 120 mg/d, or an identically appearing placebo.11 All women received daily supplements of calcium (500 mg) and vitamin D (400 to 600 IU). An ethical review board at each site approved the MORE study protocol. All women gave written informed consent to participate in the study in accordance with the ethical principles stated in the Declaration of Helsinki.

At study screening, women were asked if they had ever taken HT. Women were excluded from the study if they were experiencing clinically severe menopausal symptoms at the beginning of the study that required estrogen. Women were excluded if they had been treated with therapeutic doses of androgen, calcitonin, or estrogen (>1 cycle or 28 days) alone or with progestin (>1 cycle or 28 days) within 6 months of beginning the study. Women were permitted to have used systemic (oral or transdermal) estrogen and progestin for up to 1 cycle (28 days) during the 6 months before the study. No systemic estrogen and progestin use was allowed within 2 months before study entry. Occasional use of topical estrogens (3 times per week), and oral estriol (2 mg/d) for menopausal symptoms was permitted.

A 1-year double-blind extension phase was added to the 3-year treatment phase.10 All vertebral fracture, cardiovascular, and breast cancer endpoints that occurred over the 48-month study period were included in the present analyses.

Fracture and BMD assessment

New morphometric vertebral fractures, defined using semiquantitative assessment criteria,12 were identified by comparing spinal radiographs taken at 2, 3, and 4 years with baseline radiographs. A new vertebral fracture was defined as a vertebral fracture occurring in a vertebra that was not fractured at baseline. New clinical vertebral fractures were defined as those associated with signs or symptoms suggestive of vertebral fracture, such as back pain, reported either at an interim 6-month clinic visit or at any time between clinic visits,13 and which were subsequently corroborated with radiographs and adjudicated as previously described.10

Lumbar spine and femoral neck BMD were measured annually using dual-energy x-ray densitometry, as previously described.11

Cardiovascular event assessment

Cardiovascular events were collected as a secondary safety endpoint in the MORE trial, as previously described in detail.14 Women were asked at each clinic visit if they had had a myocardial infarction (MI), coronary bypass surgery, percutaneous coronary revascularization, or a stroke since the previous visit, and unsolicited reports of adverse cardiovascular events were recorded. All summaries of reported cardiovascular events were reviewed and adjudicated by 1 board-certified cardiologist, contracted by the sponsor, who was not associated with the trial and was blinded to treatment assignment.

Women with 4 or more risk points, assessed using the same criteria as for enrollment in the Raloxifene Use for The Heart (RUTH) trial,15 were considered to be at high risk for cardiovascular events. Coronary events included MI, unstable angina, or coronary ischemia.14 Cerebrovascular events included stroke and transient ischemic attack.14

Breast cancer assessment

Assessment of breast cancer was a prespecified secondary endpoint of the MORE trial, and was previously described in detail.16 All diagnoses of breast cancer were adjudicated by an independent oncology review board consisting of 5 physician specialists in breast cancer, and chaired by a pharmacologic scientist, none of whom were employed by the sponsor. Previous publications of the MORE breast cancer data have reported 61 cases of invasive breast cancer.16 A subsequent review of the MORE dataset found 1 fewer case of invasive breast cancer in each of the placebo and pooled raloxifene groups, so that 59 cases of invasive breast cancer were confirmed, and this number will be used in the present analysis. The change in the number of cases of invasive breast cancer was small, and had no impact on the overall interpretation of the breast cancer results from the MORE trial.

Results

Characteristics for all subjects at baseline and for women in the placebo group

Of the 7705 women enrolled, 7682 (99.7%) reported their status of previous HT use, with 2235 women (29.1%) having used HT before participating in MORE ( W1, available at www.jfponline.com). Baseline characteristics that were significantly different between women who reported prior HT use and those who reported no prior HT use included age, BMD, and the incidences of vertebral fractures, coronary angioplasty, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and family histories of osteoporosis or breast cancer (Table W1, available at www.jfponline.com). In the subsets of women who did and who did not use HT previously, the baseline characteristics were not significantly different between the placebo and raloxifene groups, except for diabetes (placebo, 1.9%; raloxifene 60 mg/day, 3.3%; pooled raloxifene, 2.9%; P=.02).

In the placebo group, the incidence of new vertebral fractures, cardiovascular events, and breast cancer at 4 years were not significantly different in women with prior HT use compared with women without prior HT use.

Vertebral fracture events and bone mineral density

After 4 years of treatment with raloxifene 60 mg/d, women with and without prior HT use exhibited significant reductions in new vertebral fractures compared with those taking placebo ( Figure ). Vertebral fracture risk reductions between treatment groups were also statistically significant in subgroups of women with and without prevalent vertebral fractures ( Table1 ). Raloxifene 60 mg/d also reduced the risk of new clinically-apparent vertebral fractures, compared with placebo, in women with prior HT use (absolute risk reduction (ARR)=1.8%; RR=0.52 [95% CI, 0.28–0.96]), and in women without prior HT use (ARR=1.7%; RR=0.61 [95% CI, 0.43–0.87]; interaction P=.66]. The interaction P-values remained similar after adjusting for the baseline fracture risk factors (TableW1 , at www.jfponline.com) that were significantly different between women with and women without prior HT use. Women with and without prior HT use treated with raloxifene 60 mg/d had significant increases in BMD, at the lumbar spine (2.7% and 2.5%, respectively; interaction P=.54), and femoral neck (2.6% and 1.9% respectively; interaction P=.06), compared with placebo. Similar results were observed for fracture and BMD in women treated with the pooled raloxifene doses.

TABLE 1

Absolute and relative risks of new vertebral fractures with raloxifene 60 mg/d compared with placeboa

| Women who had used HT (n=1305) | Women who had notused HT (n=3232) | Overall study population d | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n=654) | Raloxifene 60 mg/d(n=651) | RR (95% CI)b [ARR] | Placebo (n=1634) | Raloxifene 60 md/d (n=1598) | RR (95% CI)[ARR] | Interaction P-valuec | RR (95% CI) | ||

| Women with prevalent fractures | 25.36% | 13.68% | 0.54(0.36–0.81)[11.68%] | 24.24% | 17.11% | 0.71(0.57–0.88)[7.13%] | .27 | 0.66(0.55–0.81) | |

| Women without prevalent vertebral | 6.29% | 1.82% | 0.29(0.13–0.63) [4.47%] | 5.54% | 3.46% | 0.62(0.41–0.95)[2.08%] | .09 | 0.51(0.35–0.73) | |

| a Results with raloxifene 60 mg/d are shown since this is the clinically approved dose for osteoporosis prevention and treatment. Results with pooled raloxifene doses were similar. Data from women with at least one post-baseline follow-up spinal radiograph were included in this table. | |||||||||

| b RR (95% CI) denotes relative risk (95% confidence interval) Absolute risk reductions, denoted [ARR], are the differences between the placebo and raloxifene groups. Similar results were observed with raloxifene (pooled 60 mg/d and 120 mg/d doses) on vertebral fracture risk, in women who previously used HT [ARR=6.6%; RR=0.47 (95% CI, 0.35–0.63)], and in women without prior HT use [ARR=4.4%; RR=0.66 (95% CI, 0.55–0.78); interaction P=.06] | |||||||||

| c Results for the overall study population would be used unless the interaction effects between therapy group and prior HT use were statistically significant (P<.10), in which case, the results in the subgroups of women with and women without prior HT use should be used. | |||||||||

| d Delmas et al10 published the results for the overall study population, regardless of whether or not information on the participants’ HT use was available. | |||||||||

FIGURE

Percentage of women with and without prior HT use who experienced new vertebral fractures in the 4-year MORE study

This analysis included all women with at least 1 post-baseline follow-up vertebral radiograph, who reported their status of prior HT use. The relative risks (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) are shown for women treated with either placebo or raloxifene 60 mg/d. The absolute risk reductions were 6.7% in women with prior HT use and 3.7% in women without prior HT use. The interaction P-value was .05.

Cardiovascular events

In women with and without prior HT use, treatment with raloxifene (pooled doses) did not result in statistically significant changes in the incidence of new cardiovascular, coronary, or cerebrovascu-lar events, compared with placebo ( Table2 ). In a subgroup of women who were at high risk of cardiovascular disease,15 prior HT use had no effect on the incidence of new cardiovascular events with raloxifene (pooled doses) treatment ( Table 2 ). The interaction P-values remained similar after adjusting for the baseline cardiovascular risk factors (Table W1, at www.jfponline.com) that were significantly different between women with and without prior HT use.

TABLE 2

Absolute and relative risks of cardiovascular events with raloxifene (pooled doses) compared with placeboa

| Women who had used HT (n=2235) | Women who had not used HT (n=5447) | Overall studypopulation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo(n=738) | Pooled raloxifene(n=1497) | RR (95% CI)b [ARR] | Placebo (n=1833) | Pooled raloxifene (n=3614) | RR(95% CI)[ARR] | Interaction P-valuec | RR(95% CI) | |

| Cardiovascular events | 2.71% | 2.87% | 1.06(0.63–1.79)[–0.16%] | 4.15% | 3.68% | 0.89(0.67–1.17) [0.47%] | .56 | 0.92(0.72–1.18) |

| Coronary events | 1.49% | 1.74% | 1.17 (0.58–2.35)[–0.25%] | 2.40% | 2.08% | 0.87 (0.60–1.25) [0.32%] | .46 | 0.92(0.67–1.28) |

| Cerebrovascularevents | 1.22% | 1.14% | 0.93(0.42–2.08)[0.08%] | 1.75% | 1.63% | 0.94 (0.61–1.43)[.012%] | .99 | 0.93(0.64–1.36) |

| Cardiovascularevents in high-risk subgroupd | 12.66% | 5.91% | .047(0.21–1.06)[6.75%] | 13.08% | 8.54% | 0.65 (0.42–1.01)[4.54%] | .49 | 0.60(0.41–0.88) [4.54%] |

| a Pooled raloxifene doses were used in this analysis, since there were few events. There were no differences in the incidence of events between the raloxifene doses. | ||||||||

| b Relative risk (RR), 95% confidence interval (95% CI). Absolute risk reductions, denoted [ARR], are the differences between the placebo and raloxifene groups. | ||||||||

| c The interaction effects between therapy group and prior HT use were not statistically significant (P>.10), so results from the overall study population would be used. Barrett-Connor et al14 reported the results for raloxifene 60 mg/d and raloxifene 120 mg/d in the overall study population, regardless of whether or not information on the participants’ HT use was available. | ||||||||

| d Of the 1029 women in the high-risk subgroup, 764 women had no prior history of HT use (placebo, n=237; raloxifene, n=527), and 265 women reported prior HT use (placebo, n=79; raloxifene, n=186). | ||||||||

Breast cancer

In women with and without prior HT use, similar reductions in the incidence of breast cancer (regardless of invasiveness), invasive breast cancer, and estrogen-receptor positive invasive breast cancer, were observed after raloxifene treatment (pooled doses) compared with placebo ( Table 3 ). The interaction P-values remained similar after adjusting for the baseline breast cancer risk factors (Table W1) that were significantly different between women with and without prior HT use.

TABLE 3

Absolute and relative risks of breast cancer with raloxifene (pooled doses) compared with placeboa

| Women who had used HT (n=2235) | Women who had notused HT (n=5447) | Overall study population | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo(n=738) | Pooledraloxifene(n=1497) | RR(95% CI)b [ARR] | Placebo(n=1833) | Pooled raloxifene(n=3614) | RR(95% CI)[ARR] | InteractionP-valuec | RR(95% CI) | |

| Breast cancer d | 2.30% | 0.73% | 0.32(0.15–0.68)[1.57%] | 1.47% | 0.64% | 0.43(0.25–0.75)[0.83%] | .52 | 0.38 (0.24–0.58) |

| Invasivebreast cancer | 2.03% | 0.47% | 0.23(0.09–0.56)[1.56%] | 1.25% | 0.39% | 0.31(0.16–0.60) [0.86%] | .60 | 0.28(0.17–0.46) |

| Invasiveestrogen-receptorpositive breastcancer | 1.76% | 0.27% | 0.15(0.05–0.46)[1.49%] | 0.87% | 0.17% | 0.19(0.08–0.49)[0.70%] | .75 | 0.16(0.09–0.30) |

| a Pooled raloxifene doses were used in this analysis, since there were few events. There were no differences in the incidence of events between the raloxifene doses. | ||||||||

| b Relative risk (RR), 95% confidence interval (95% CI). Absolute risk reductions, denoted [ARR], are the differences between the placebo and raloxifene groups. | ||||||||

| c The interaction effects between therapy group and prior HT use were not statistically significant (P>.10), so results from the overall study population would be used. Cauley et al16 reported the results for in the overall study population, regardless of whether or not information on the participants’ HT use was available. | ||||||||

| d All breast cancer, regardless of invasiveness. | ||||||||

Discussion

This analysis examined the effects of raloxifene in women who reported their use of postmenopausal hormone therapies before enrolling in the MORE osteoporosis trial. Compared with placebo, women treated with raloxifene experienced significant decreases in the risks for new vertebral fractures and the incidence of breast cancer, without significant changes in the incidence of cardiovascular events, regardless of previous HT use. These analyses provide further information on the effects of raloxifene on the risks of vertebral fractures,10 cardiovascular events,14 and breast cancer16 seen in the overall MORE study population at 4 years.

This analysis found a differential reduction in vertebral fracture risk with raloxifene between women who did and did not have prior HT use, which may result from possible differences in women who chose to use HT before participating in MORE. In women with previous HT use, a greater proportion had a family history of osteo-porosis and a lower proportion had prevalent ver-tebral fractures at baseline, compared with women who had not used HT. Other unidentified confounding factors, such as the “healthy user” bias commonly associated with women who chose to use HT,17 may also contribute to the differential vertebral fracture risk reduction with raloxifene treatment. The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures showed that women with current estrogen use had significantly decreased fracture risks, but the risk reduction waned in women who discontinued estrogen.18 After HT discontinuation, BMD loss resumes at a rate similar to that seen in women shortly after menopause, suggesting that prior HT use may have limited residual effects on maintaining BMD.7,19 Such findings raise the urgency of evaluating the risk for osteoporosis in women who discontinue HT.

Women treated with raloxifene had no significant changes in the incidence of cardiovascular events, with no differential treatment effect based on prior HT use. In the HERS20 and WHI3 trials, which studied the outcomes of estrogen-progestin therapy in postmenopausal women, similar analyses did not show any significant differential effects of prior HT use on the incidence of cardiovascular events with estrogen-progestin during the respective trials.

In this analysis, women treated with raloxifene had a significantly lower incidence of breast cancer compared with those who received placebo, and this incidence was comparable between women with and without prior HT use. In contrast, women who had used HT before the WHI study had a significant increase in the risk of breast cancer with estrogen-progestin therapy during the study, compared with those who had not used HT.3

A limitation of our analysis that a history of HT use was based on participants’ self-report, which depended on their ability to recall medication they may have taken years earlier. Also, no information was obtained on therapy duration and the doses and formulations of HT. Since the MORE trial was conducted in 25 countries, the patterns and types of HT regimens are expected to be different. The strength of our analysis is that the MORE population was large enough to prospectively collect data on multiple clinical outcomes.

In summary, postmenopausal women treated with raloxifene experienced a significant risk reduction for vertebral fractures, regardless of prior HT use, but women who had used HT may exhibit greater reductions. Women who used raloxifene had no change in the incidence of cardiovascular events and a lower incidence of breast cancer, compared with placebo, regardless of their history of HT use. Since HT is becoming increasingly limited to short-term use for menopausal symptoms, women and their physicians may consider several other therapeutic options to address postmenopausal health concerns.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions of Leo Plouffe Jr., MD, and Somnath Sarkar, PhD, for suggestions on manuscript content, and Sharon Xiaohan Zou, MS, for statistical programming. A complete list of all investigators in the MORE trial is found in J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002; 87:3609–3617. Portions of this work were presented at the following meetings: Third European Symposium on Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis, Barcelona, Spain, 2002; International Society for Clinical Densitometry (ISCD), Los Angeles, USA,2003; European Calcified Tissue Society (ECTS), Rome, Italy, 2003; International Bone and Mineral Society (IBMS), Osaka, Japan, 2003; European Menopause and Andropause Society (EMAS), Bucharest, Romania, 2003; Ninth Bath Conference on Osteoporosis, Bath, UK, 2003. Eli Lilly and Company sponsored the Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation (MORE) Trial.

Corresponding author

Olof Johnell, MD, PhD, Department of Orthopedics, Universitetssjukhuset MAS, Malmo, SE-20502, Sweden. E-mail: [email protected].

1. Greendale GA, Lee NP, Arriola ER. The menopause. Lancet 1999;353:571-580.

2. Grady D, Rubin SM, Petitti DB, et al. Hormone therapy to prevent disease and prolong life in postmenopausal women. Ann Intern Med 1992;117:1016-1037.

3. Writing Group for the Women’s Health Initiative Investigators. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women. Principal results from the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002;288:321-333.

4. Bren L. The estrogen and progestin dilemma: New advice, labeling and guidelines. FDA Consumer 2003;37:10-11.

5. Haas JS, Kaplan CP, Gerstenberger EP, Kerlikowske K. Changes in the use of postmenopausal hormone therapy after the publication of clinical trial results. Ann Intern Med 2004;140:184-188.

6. Gallagher JC, Rapuri PB, Haynatzki G, Detter JR. Effect of discontinuation of estrogen, calcitriol, and the combination of both on bone density and bone markers. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002;87:4914-4923.

7. Tremollieres FA, Pouilles JM, Ribot C. Withdrawal of hormone replacement therapy is associated with significant ver-tebral bone loss in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int 2001;12:385-390.

8. Riggs BL, Hartmann LC. Selective estrogen-receptor modulators —mechanisms of action and application to clinical practice. N Engl J Med 2003;348:618-629.

9. Maricic M, Gluck O. Review of raloxifene and its clinical applications in osteoporosis. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2002;3:767-775.

10. Delmas PD, Ensrud KE, Adachi JD, et al. Efficacy of raloxifene on vertebral fracture risk reduction in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: four-year results from a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002;87:3609-3617.

11. Ettinger B, Black DM, Mitlak BH, et al. Reduction of verte-bral fracture risk in postmenopausal women with osteo-porosis treated with raloxifene: Results from a 3-year randomized clinical trial. JAMA 1999;282:637-645.

12. Genant HK, Wu CY, van Kuijk C, Nevitt MC. Vertebral fracture assessment using a semiquantitative technique. J Bone Miner Res 1993;8:1137-1148.

13. Maricic M, Adachi JD, Sarkar S, Wu W, Wong M, Harper KD. Early effects of raloxifene on clinical vertebral fractures at 12 months in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:1140-1143.

14. Barrett-Connor E, Grady D, Sashegyi A, et al. Raloxifene and cardiovascular events in osteoporotic postmenopausal women: four-year results from the MORE (Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation) randomized trial. JAMA 2002;287:847-857.

15. Mosca L, Barrett-Connor E, Wenger NK, et al. Design and methods of the Raloxifene Use for The Heart (RUTH) study. Am J Cardiol 2001;88:392-395.

16. Cauley J, Norton L, Lippman ME, et al. Continued breast cancer risk reduction in postmenopausal women treated with raloxifene: 4-year Results from the MORE Trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2001;65:125-134.