User login

Medication Formulation Affects Quality of Life: A Randomized Single-Blind Study of Clobetasol Propionate Foam 0.05% Compared With a Combined Program of Clobetasol Cream 0.05% and Solution 0.05% for the Treatment of Psoriasis

Can I find a doctor? Availability of primary care physicians in the San Francisco Bay Area

Objectives: Primary care physicians function as “gatekeepers” in many managed care systems. With the rapid growth of managed care enrollment, it is crucial that patients have adequate access to primary care physicians. We investigated factors associated with new-patient appointment availability of primary care physicians in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Study Design: Observational cohort.

Population: Cross-sectional survey of primary care physician offices in 2 San Francisco Bay Area counties (n=438).

Outcomes Measured: New-patient appointment availability.

Results: Seventy-five percent of primary care physicians participating in managed care had an appointment available for a new patient.

Conclusions: The limited availability of appointments for new patients may create barriers to primary care in the San Francisco Bay Area, a region with high managed-care penetration.

Recent studies and reports have examined the effect of physician supply on patient access to health care.1,2 However, physician availability is affected not only by distribution of practices, but by whether a patient can actually make an appointment with a provider.

The availability of primary care physicians is central to access to care in most managed care plans. Managed care systems often designate the primary care physician as the “gatekeeper,” the decision maker about patients’ referrals to specialists. Within this kind of system, a patient may not be able to obtain nonemergent care, including specialty care, without access to a primary care physician.

Furthermore, with at least 12% of people changing providers each year,3,4 it is not uncommon for an individual to need to find a new primary care physician who participates in their health plan. The amount of effort needed to find a primary care physician who is accepting new patients, and the possibility of waiting more than a month for an appointment, may affect an individual’s access to care.

Because access to a primary care physician may be limited by these factors, our goal was to characterize the availability of a new-patient appointment with a primary care physician in the northern California counties of Alameda and San Francisco. We further examined whether physician characteristics (eg, sex, years of experience in practice) were associated with appointment availability.

Methods

Study sample

The focus of the study was to examine the availability of primary care physicians for adults between the ages of 18 and 64 years with employer-sponsored insurance in the San Francisco Bay area. Interviewers, posing as patients, made telephone calls to primary care physician’s offices, to parallel the experience of an actual patient seeking a new primary care provider. Current print and online directories of 3 large, open managed care plans available to employees of a large employer were reviewed.

These managed care plans function through an Independent Practice Association model. Two of the 3 plans require primary care physicians to be gatekeepers for all care within the system; ie, a patient must obtain a referral from the primary care physician to have a specialist visit covered by the insurance. The third plan allows patient self-referral to a specialist, but with a higher copay and deductible than with a specialist visit that has been approved by the primary care physician. Physicians working for Kaiser Permanente, the only closed-HMO plan in the study area, were excluded because Kaiser requires a member identification number prior to making an appointment.

Physicians were chosen if they were listed in each of the 3 plan directories, if they had practice addresses in the counties of Alameda or San Francisco, if they listed specialties of internal medicine or family medicine, and if their stated primary activity was clinical care. Doctors of osteopathy were not included.

This selection process identified 469 office-based physicians. Thirty-one physicians were determined to be ineligible during the data collection process (eg, did not meet the original study criteria when the interviewer called). The final study sample was 438 physicians.

Information on 157 physicians was available from the 1997 American Medical Association (AMA) Masterfile, including sex, race/ethnicity, medical school attended, and year of graduation from medical school. For physicians not listed in this older version of the Masterfile, the physician’s sex was obtained either at the time of the interview or from an online plan directory that had this information.

For physicians not listed in the Masterfile or for those with missing information on race/ethnicity, Asian race was determined by investigator review of last names; race/ethnicity for all others was coded as “missing.” Medical school location and year of graduation from medical school for all physicians were obtained from the physician lookup feature of the Medical Board of California Web site.

Data collection

Interviewers made telephone calls to primary care providers’ offices from July 1999 to January 2000. The interviewers posed as patients new to the area, to parallel the experience of an actual patient seeking a new primary care provider.

Telephone calls were made between 9 AM and 5 PM, Monday through Friday. Once an appointment representative for the primary care physician was reached, the interviewer attempted to make an appointment for an initial physical examination, using a standard script. The interviewer stated that she was a new employee, and was in the process of choosing a health plan, based on which insurance plans the primary care physician she was calling currently accepted. If asked what her insurance choices were, the interviewer named the 3 managed care plans used for selecting physicians for the study. If asked for an insurance card number, the interviewer stated that she would bring the appropriate insurance card to the appointment, and would cancel the appointment in advance if the insurance card had not arrived in time for the appointment. If asked, the interviewer stated that she had no urgent health problems. If an appointment was available for a date more than 2 weeks away, the interviewer booked the appointment and canceled it within 1 business day of the initial call.

If the appointment date was less than 2 weeks away, the interviewer noted the time and date but did not book the appointment.

Interviewers recorded information on appointment availability, date and time of appointment, and reason for unavailability. This study was approved by the Committee on Human Research, University of California, San Francisco.

Data and statistical analysis

Several potential predictors of physician availability were examined, including physician’s sex, race/ethnicity, years since graduation from medical school, medical school location, county of practice, and median per capita income of the zip code in which the practice was located. Descriptive statistics on these demographic factors were generated according to appointment availability with Pearson χ2 tests.

We analyzed the ability to get a new-patient appointment with a given primary care physician using a multivariate logistic regression model. Variables were included in the model based on a priori hypotheses. A new race/ethnicity category was created for the logistic regression models by combining African American, Latino, and other, due to small numbers for these groups.

The length of time to an available appointment was also examined. Time to appointment was dichotomized into early appointment (within 0–30 days) and late appointment (>30 days’ wait).

Results

Of the 438 physicians included in the final sample, 328 (74.9%) had an appointment available for a new patient with managed care insurance. Availability varied by physician race/ethnicity, medical school location, years since graduation from medical school, and the median per capita income of the residents in the zip code of the primary care physician’s practice (Table 1).

Appointments were not available for several reasons. Of the 110 primary care physicians who had no appointment available to new patients, 87 (79.1%) were not accepting new patients because of a full practice. Three (2.7%) were on leave or were about to retire. Ten (9.1%) receptionists were unable to book an appointment either because they did not have access to schedules far enough in advance, or because of a basic communication difficulty during repeated calls. One (0.9%) primary care physician was only accepting referred patients. One (0.9%) primary care physician saw only monolingual Chinese-speaking patients.

Eight (7.3%) primary care physicians classed as unavailable required some form of screening, separate from inquiries about insurance or intake assessment forms, before a new patient could be considered for an appointment. Of these 8 physicians, receptionists for 5 said that the physician needed to speak directly with the patient to determine eligibility (not related to insurance), and 1 required a receptionist-administered telephone interview that would be shared with the primary care physician. One required that a written personal questionnaire be filled out and returned for this purpose. The sole remaining primary care physician did not accept current smokers as patients.

TABLE 1

Characteristics of physicians in study

| Characteristic | N (%) | Appointment available (% of total) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 328 (74.9) | 74.7 |

| Female | 110 (25.1) | 75.5 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | 170 (38.8) | 68.8 |

| Asian | 117 (26.7) | 74.4 |

| African American | 7 (1.6) | 85.7 |

| Latino | 4 (0.9) | 100 |

| Other | 8 (1.8) | 100 |

| Missing | 132 (30.1) | 80.3 |

| County | ||

| Alameda | 217 (49.5) | 74.7 |

| San Francisco | 221 (50.5) | 75.1 |

| Years since graduation from medical school | ||

| ≤10 | 61 (13.9) | 88.5* |

| 11–20 | 123 (28.1) | 74.8 |

| >20 | 254 (58.0) | 71.7 |

| Medical school location | ||

| US | 344 (78.5) | 71.5† |

| Foreign | 94 (21.5) | 87.2 |

| Yearly median income of residents in zip code of practice‡ | ||

| Low | 148 (33.8) | 75.7§ |

| Middle | 144 (32.9) | 81.3 |

| High | 146 (33.3) | 67.8 |

| Total | 438 (100) | 74.9 |

| *P=.02 for x2 comparing differences in appointment availability by years since graduation from medical school. | ||

| † P<.01 for x2 comparing differences in appointment availability by medical school location. | ||

| ‡ Low: $5,106–$22,370; middle: $22,371–$36,507; high: $36,508–$51,926. | ||

| § P=.03 for x2 comparing differences in appointment availability by yearly median income of residents in zip code of primary care physician’s practice. | ||

Predictors of appointment availability

Recent graduates were more likely to have an appointment available than more established physicians (OR=4.2; 95% CI, 1.7–10.3) ( Table 2). Foreign medical school graduates were also more likely to have an appointment available than US-educated physicians (OR=3.5; 95% CI, 1.7–7.3). Primary care physicians practicing in middle-income zip codes were more likely to have a new-patient appointment than those with offices in high-income zip codes (OR=2.1; 95% CI, 1.1–4.0).

TABLE 2

Characteristics associated with appointment availability (multivariate logistic regression)

| Characteristic N=438 | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | – | – |

| Female | 0.7 | 0.4–1.3 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | – | – |

| Asian | 0.8 | 0.4–1.5 |

| African American/Latino/other | 6.5 | 0.8–52.7 |

| Missing | 1.7 | 1.0–3.0 |

| County | ||

| Alameda | – | – |

| San Francisco | 1.7 | 1.0–2.8 |

| Years since graduation | ||

| ≤10 | 4.2 | 1.7–10.3 |

| 11–20 | 1.1 | 0.6–1.9 |

| >20 | – | – |

| Medical school location | ||

| US | – | – |

| Foreign | 3.5 | 1.7–7.3 |

| Yearly median income of residents in zip code of practice* | ||

| Low | 1.7 | 0.9–3.1 |

| Middle | 2.1 | 1.1–4.0 |

| High | – | – |

| OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval | ||

| * Low: $5,106–$22,370; middle: $22,371–$36,507; high: $36,508–$51,926 | ||

Predictors of length of time to appointment

The length of time to appointment among those primary care physicians with an available appointment ranged from 0 (same-day appointment) to 151 days; the median was 13 days. Seventy-five percent of appointments were available within 30 days. As shown in Table 3, female primary care physicians were significantly less likely than male primary care physicians to have an appointment available within 30 days (OR=0.4; 95% CI, 0.2–0.7).

TABLE 3

Physician characteristics associated with early appointment availability* (multivariate logistic regression)

| Characteristic N=309 | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | – | – |

| Female | 0.4 | 0.2–0.7 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | – | – |

| Asian | 1.5 | 0.7–3.3 |

| African American/Latino/other | 0.4 | 0.1–1.6 |

| Missing | 1.0 | 0.5–2.0 |

| County | ||

| Alameda | – | – |

| San Francisco | 0.8 | 0.4–1.5 |

| Years since graduation | ||

| ≤10 | 0.5 | 0.2–1.1 |

| 11–20 | 0.9 | 0.4–1.6 |

| >20 | – | – |

| Medical school location | ||

| US | – | – |

| Foreign | 2.0 | 0.9–4.5 |

| Yearly median income of residents in zip code of practice† | ||

| Low | 1.0 | 0.5–2.1 |

| Middle | 0.7 | 0.3–1.6 |

| High | – | – |

| OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval | ||

| * Early appointment is within 0–30 days; late appointment is over 30 days’ wait | ||

| † Low: $5,106–$22,370; middle: $22,371–$36,507; high: $36,508–$51,926. | ||

Discussion

These results suggest that in a highly capitated urban area in California, access to primary care physicians may be restricted for patients seeking a new provider. The median waiting time for a new-patient appointment was 13 days, but the range was wide, from same-day appointments to 151 days of waiting time.

The most common reason for primary care physician unavailability was a “full practice.” In addition, a few primary care physicians required some form of screening before they would consider accepting a new patient into their practice. These screening practices may be a barrier to care. Under current managed care systems, appointment unavailability and long length of wait affect not only primary care services, but also access to specialty care.

This study gathered information on physician availability by means of research assistants posing as patients. We believe that surveying physicians using concealed intent was necessary to directly assess the experience of patients. This design was chosen to minimize inaccurate and potentially biased information.

Similar studies

At least 3 previous studies have used this method to obtain direct information on physician availability. After surveying ambulatory care clinics in 10 US cities, the Medicaid Access Study Group reported a difference in the length of waiting time to an appointment according to insurance status.5 Schwartz et al,6 who studied New York City obstetricians, found that only 42% of pregnant women were able to obtain a prenatal appointment with a physician, with waiting times ranging from 2 days to 7 weeks. Gifford,7 in a survey of Chicago area obstetricians, found that 36% accepted new Medicaid patients, and that fewer obstetricians worked in the poorest zip codes.

Physicians’ characteristics

Certain characteristics of the physicians were associated with availability or time to appointment. Female primary care physicians were significantly less likely to have an “early” appointment (within 30 days) available compared with male primary care physicians. Primary care physicians who had graduated from a medical school outside the US were more available than those who had attended a school in the US. Less experienced primary care physicians were more available than more experienced providers.

We were not able to analyze the availability of African American and Latino physicians separately due to their small numbers. When physicians identifying themselves as African American, Latino, or “other” were combined, the result did not significantly predict availability. The dearth of African American and Latino primary care physicians was striking: these 2 groups comprised only 2.5% of the study sample (n=11).

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. By excluding pediatricians, we were unable to determine primary care physician availability in Independent Practice Association plans for children in the study area. Osteopathic and general practitioners were also excluded; however, these practitioners comprise only a small percentage of primary care physicians in the study area. Information about physician race/ethnicity was frequently unavailable, which limits our ability to make conclusions about the effect of race/ethnicity. Moreover, to minimize missing data on race, we assumed Asian ethnicity for primary care physicians with Asian-origin surnames, and these assumptions may be a source of bias. We repeated analyses without the Asian race assumptions and found a similar lack of association for race in the multivariate models.

Also, we examined only new-patient availability. We do not know what proportion of adults in the study area have an established primary care provider. However, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey data have shown that 73% of the US population has an office-based usual source of health care, and almost 12% of families have members who change their usual source of care each year.3

If these figures are similar for the San Francisco Bay Area population, then finding a new primary care physician is important for a significant number of people in our study area each year. Because this study dealt only with primary care providers in 2 counties of the San Francisco Bay Area, the results may not be generalizable to other regions.

Because our study goal was to characterize the availability of primary care physicians who were gatekeepers in open managed care plans, we obtained information on appointment availability for routine examinations. Results may have differed if we had sought appointments for an urgent health care issue. Finally, we examined access to care in an Independent Practice Association–model managed care system. These findings may not be generalizable to other types of managed care models.

Conclusions

Physician availability is necessary for access to care within managed care plans. By defining primary care physician availability not only as presence in an area, but also as willingness to accept new patients, we are able to better identify potentially unmet needs for primary care. This study demonstrates that in the San Francisco Bay area, patients may experience moderate difficulty in obtaining access to primary care because practices are “closed” to new patients. Managed care plans should consider whether provider availability limits access to medical services in a specific region.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Annamarie Stehli Nguyen, MPH, and Debbie Jaffe for assisting in data collection; Peter Bacchetti, PhD for statistical consultation; and Karen Vranizan, MA, Alicia Fernandez, MD, and Dean Schillinger, MD, for review of a previous version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Jennifer Haas, MD, MSPH, Division of General Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, 75 Francis Street, Boston, MA 02115. E-mail: [email protected].

1. Grumbach K, Vranizan K, Bindman AB. Physician supply and access to care in urban communities. Health Aff (Millwood) 1997;16:71-86.

2. Knapp KK, Paavola FG, Maine LL, Sorofman B, Politzer RM. Availability of primary care providers and pharmacists in the United States. J Am Pharm Assoc (Wash) 1999;39:127-135.

3. Weinick RM, Zuvekas SH, Drilea SK. Access to health care–sources and barriers, 1996. MEPS Research Findings No. 3. Rockville, Md: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1997. AHCPR publication 98-0001.

4. Reed MC. Why people change their health care providers. Washington, DC: Center for Studying Health System Change; 2000. Data Bulletin No. 16. Available at: http://www.hschange.org/CONTENT/81/. Accessed on July 28, 2003.

5. Access of Medicaid recipients to outpatient care N Engl J Med 1994;330:1426-1430.

6. Schwartz LR, Heagarty M, Graham EH, Pirani S. Measuring access to prenatal care in New York City: a telephone survey of prenatal clinics. Am J Public Health 1996;86:1474-1475.

7. Gifford B. Obstetricians’ receptiveness to teen prenatal patients who are Medicaid recipients. Health Serv Res 1997;32:265-282.

Objectives: Primary care physicians function as “gatekeepers” in many managed care systems. With the rapid growth of managed care enrollment, it is crucial that patients have adequate access to primary care physicians. We investigated factors associated with new-patient appointment availability of primary care physicians in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Study Design: Observational cohort.

Population: Cross-sectional survey of primary care physician offices in 2 San Francisco Bay Area counties (n=438).

Outcomes Measured: New-patient appointment availability.

Results: Seventy-five percent of primary care physicians participating in managed care had an appointment available for a new patient.

Conclusions: The limited availability of appointments for new patients may create barriers to primary care in the San Francisco Bay Area, a region with high managed-care penetration.

Recent studies and reports have examined the effect of physician supply on patient access to health care.1,2 However, physician availability is affected not only by distribution of practices, but by whether a patient can actually make an appointment with a provider.

The availability of primary care physicians is central to access to care in most managed care plans. Managed care systems often designate the primary care physician as the “gatekeeper,” the decision maker about patients’ referrals to specialists. Within this kind of system, a patient may not be able to obtain nonemergent care, including specialty care, without access to a primary care physician.

Furthermore, with at least 12% of people changing providers each year,3,4 it is not uncommon for an individual to need to find a new primary care physician who participates in their health plan. The amount of effort needed to find a primary care physician who is accepting new patients, and the possibility of waiting more than a month for an appointment, may affect an individual’s access to care.

Because access to a primary care physician may be limited by these factors, our goal was to characterize the availability of a new-patient appointment with a primary care physician in the northern California counties of Alameda and San Francisco. We further examined whether physician characteristics (eg, sex, years of experience in practice) were associated with appointment availability.

Methods

Study sample

The focus of the study was to examine the availability of primary care physicians for adults between the ages of 18 and 64 years with employer-sponsored insurance in the San Francisco Bay area. Interviewers, posing as patients, made telephone calls to primary care physician’s offices, to parallel the experience of an actual patient seeking a new primary care provider. Current print and online directories of 3 large, open managed care plans available to employees of a large employer were reviewed.

These managed care plans function through an Independent Practice Association model. Two of the 3 plans require primary care physicians to be gatekeepers for all care within the system; ie, a patient must obtain a referral from the primary care physician to have a specialist visit covered by the insurance. The third plan allows patient self-referral to a specialist, but with a higher copay and deductible than with a specialist visit that has been approved by the primary care physician. Physicians working for Kaiser Permanente, the only closed-HMO plan in the study area, were excluded because Kaiser requires a member identification number prior to making an appointment.

Physicians were chosen if they were listed in each of the 3 plan directories, if they had practice addresses in the counties of Alameda or San Francisco, if they listed specialties of internal medicine or family medicine, and if their stated primary activity was clinical care. Doctors of osteopathy were not included.

This selection process identified 469 office-based physicians. Thirty-one physicians were determined to be ineligible during the data collection process (eg, did not meet the original study criteria when the interviewer called). The final study sample was 438 physicians.

Information on 157 physicians was available from the 1997 American Medical Association (AMA) Masterfile, including sex, race/ethnicity, medical school attended, and year of graduation from medical school. For physicians not listed in this older version of the Masterfile, the physician’s sex was obtained either at the time of the interview or from an online plan directory that had this information.

For physicians not listed in the Masterfile or for those with missing information on race/ethnicity, Asian race was determined by investigator review of last names; race/ethnicity for all others was coded as “missing.” Medical school location and year of graduation from medical school for all physicians were obtained from the physician lookup feature of the Medical Board of California Web site.

Data collection

Interviewers made telephone calls to primary care providers’ offices from July 1999 to January 2000. The interviewers posed as patients new to the area, to parallel the experience of an actual patient seeking a new primary care provider.

Telephone calls were made between 9 AM and 5 PM, Monday through Friday. Once an appointment representative for the primary care physician was reached, the interviewer attempted to make an appointment for an initial physical examination, using a standard script. The interviewer stated that she was a new employee, and was in the process of choosing a health plan, based on which insurance plans the primary care physician she was calling currently accepted. If asked what her insurance choices were, the interviewer named the 3 managed care plans used for selecting physicians for the study. If asked for an insurance card number, the interviewer stated that she would bring the appropriate insurance card to the appointment, and would cancel the appointment in advance if the insurance card had not arrived in time for the appointment. If asked, the interviewer stated that she had no urgent health problems. If an appointment was available for a date more than 2 weeks away, the interviewer booked the appointment and canceled it within 1 business day of the initial call.

If the appointment date was less than 2 weeks away, the interviewer noted the time and date but did not book the appointment.

Interviewers recorded information on appointment availability, date and time of appointment, and reason for unavailability. This study was approved by the Committee on Human Research, University of California, San Francisco.

Data and statistical analysis

Several potential predictors of physician availability were examined, including physician’s sex, race/ethnicity, years since graduation from medical school, medical school location, county of practice, and median per capita income of the zip code in which the practice was located. Descriptive statistics on these demographic factors were generated according to appointment availability with Pearson χ2 tests.

We analyzed the ability to get a new-patient appointment with a given primary care physician using a multivariate logistic regression model. Variables were included in the model based on a priori hypotheses. A new race/ethnicity category was created for the logistic regression models by combining African American, Latino, and other, due to small numbers for these groups.

The length of time to an available appointment was also examined. Time to appointment was dichotomized into early appointment (within 0–30 days) and late appointment (>30 days’ wait).

Results

Of the 438 physicians included in the final sample, 328 (74.9%) had an appointment available for a new patient with managed care insurance. Availability varied by physician race/ethnicity, medical school location, years since graduation from medical school, and the median per capita income of the residents in the zip code of the primary care physician’s practice (Table 1).

Appointments were not available for several reasons. Of the 110 primary care physicians who had no appointment available to new patients, 87 (79.1%) were not accepting new patients because of a full practice. Three (2.7%) were on leave or were about to retire. Ten (9.1%) receptionists were unable to book an appointment either because they did not have access to schedules far enough in advance, or because of a basic communication difficulty during repeated calls. One (0.9%) primary care physician was only accepting referred patients. One (0.9%) primary care physician saw only monolingual Chinese-speaking patients.

Eight (7.3%) primary care physicians classed as unavailable required some form of screening, separate from inquiries about insurance or intake assessment forms, before a new patient could be considered for an appointment. Of these 8 physicians, receptionists for 5 said that the physician needed to speak directly with the patient to determine eligibility (not related to insurance), and 1 required a receptionist-administered telephone interview that would be shared with the primary care physician. One required that a written personal questionnaire be filled out and returned for this purpose. The sole remaining primary care physician did not accept current smokers as patients.

TABLE 1

Characteristics of physicians in study

| Characteristic | N (%) | Appointment available (% of total) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 328 (74.9) | 74.7 |

| Female | 110 (25.1) | 75.5 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | 170 (38.8) | 68.8 |

| Asian | 117 (26.7) | 74.4 |

| African American | 7 (1.6) | 85.7 |

| Latino | 4 (0.9) | 100 |

| Other | 8 (1.8) | 100 |

| Missing | 132 (30.1) | 80.3 |

| County | ||

| Alameda | 217 (49.5) | 74.7 |

| San Francisco | 221 (50.5) | 75.1 |

| Years since graduation from medical school | ||

| ≤10 | 61 (13.9) | 88.5* |

| 11–20 | 123 (28.1) | 74.8 |

| >20 | 254 (58.0) | 71.7 |

| Medical school location | ||

| US | 344 (78.5) | 71.5† |

| Foreign | 94 (21.5) | 87.2 |

| Yearly median income of residents in zip code of practice‡ | ||

| Low | 148 (33.8) | 75.7§ |

| Middle | 144 (32.9) | 81.3 |

| High | 146 (33.3) | 67.8 |

| Total | 438 (100) | 74.9 |

| *P=.02 for x2 comparing differences in appointment availability by years since graduation from medical school. | ||

| † P<.01 for x2 comparing differences in appointment availability by medical school location. | ||

| ‡ Low: $5,106–$22,370; middle: $22,371–$36,507; high: $36,508–$51,926. | ||

| § P=.03 for x2 comparing differences in appointment availability by yearly median income of residents in zip code of primary care physician’s practice. | ||

Predictors of appointment availability

Recent graduates were more likely to have an appointment available than more established physicians (OR=4.2; 95% CI, 1.7–10.3) ( Table 2). Foreign medical school graduates were also more likely to have an appointment available than US-educated physicians (OR=3.5; 95% CI, 1.7–7.3). Primary care physicians practicing in middle-income zip codes were more likely to have a new-patient appointment than those with offices in high-income zip codes (OR=2.1; 95% CI, 1.1–4.0).

TABLE 2

Characteristics associated with appointment availability (multivariate logistic regression)

| Characteristic N=438 | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | – | – |

| Female | 0.7 | 0.4–1.3 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | – | – |

| Asian | 0.8 | 0.4–1.5 |

| African American/Latino/other | 6.5 | 0.8–52.7 |

| Missing | 1.7 | 1.0–3.0 |

| County | ||

| Alameda | – | – |

| San Francisco | 1.7 | 1.0–2.8 |

| Years since graduation | ||

| ≤10 | 4.2 | 1.7–10.3 |

| 11–20 | 1.1 | 0.6–1.9 |

| >20 | – | – |

| Medical school location | ||

| US | – | – |

| Foreign | 3.5 | 1.7–7.3 |

| Yearly median income of residents in zip code of practice* | ||

| Low | 1.7 | 0.9–3.1 |

| Middle | 2.1 | 1.1–4.0 |

| High | – | – |

| OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval | ||

| * Low: $5,106–$22,370; middle: $22,371–$36,507; high: $36,508–$51,926 | ||

Predictors of length of time to appointment

The length of time to appointment among those primary care physicians with an available appointment ranged from 0 (same-day appointment) to 151 days; the median was 13 days. Seventy-five percent of appointments were available within 30 days. As shown in Table 3, female primary care physicians were significantly less likely than male primary care physicians to have an appointment available within 30 days (OR=0.4; 95% CI, 0.2–0.7).

TABLE 3

Physician characteristics associated with early appointment availability* (multivariate logistic regression)

| Characteristic N=309 | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | – | – |

| Female | 0.4 | 0.2–0.7 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | – | – |

| Asian | 1.5 | 0.7–3.3 |

| African American/Latino/other | 0.4 | 0.1–1.6 |

| Missing | 1.0 | 0.5–2.0 |

| County | ||

| Alameda | – | – |

| San Francisco | 0.8 | 0.4–1.5 |

| Years since graduation | ||

| ≤10 | 0.5 | 0.2–1.1 |

| 11–20 | 0.9 | 0.4–1.6 |

| >20 | – | – |

| Medical school location | ||

| US | – | – |

| Foreign | 2.0 | 0.9–4.5 |

| Yearly median income of residents in zip code of practice† | ||

| Low | 1.0 | 0.5–2.1 |

| Middle | 0.7 | 0.3–1.6 |

| High | – | – |

| OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval | ||

| * Early appointment is within 0–30 days; late appointment is over 30 days’ wait | ||

| † Low: $5,106–$22,370; middle: $22,371–$36,507; high: $36,508–$51,926. | ||

Discussion

These results suggest that in a highly capitated urban area in California, access to primary care physicians may be restricted for patients seeking a new provider. The median waiting time for a new-patient appointment was 13 days, but the range was wide, from same-day appointments to 151 days of waiting time.

The most common reason for primary care physician unavailability was a “full practice.” In addition, a few primary care physicians required some form of screening before they would consider accepting a new patient into their practice. These screening practices may be a barrier to care. Under current managed care systems, appointment unavailability and long length of wait affect not only primary care services, but also access to specialty care.

This study gathered information on physician availability by means of research assistants posing as patients. We believe that surveying physicians using concealed intent was necessary to directly assess the experience of patients. This design was chosen to minimize inaccurate and potentially biased information.

Similar studies

At least 3 previous studies have used this method to obtain direct information on physician availability. After surveying ambulatory care clinics in 10 US cities, the Medicaid Access Study Group reported a difference in the length of waiting time to an appointment according to insurance status.5 Schwartz et al,6 who studied New York City obstetricians, found that only 42% of pregnant women were able to obtain a prenatal appointment with a physician, with waiting times ranging from 2 days to 7 weeks. Gifford,7 in a survey of Chicago area obstetricians, found that 36% accepted new Medicaid patients, and that fewer obstetricians worked in the poorest zip codes.

Physicians’ characteristics

Certain characteristics of the physicians were associated with availability or time to appointment. Female primary care physicians were significantly less likely to have an “early” appointment (within 30 days) available compared with male primary care physicians. Primary care physicians who had graduated from a medical school outside the US were more available than those who had attended a school in the US. Less experienced primary care physicians were more available than more experienced providers.

We were not able to analyze the availability of African American and Latino physicians separately due to their small numbers. When physicians identifying themselves as African American, Latino, or “other” were combined, the result did not significantly predict availability. The dearth of African American and Latino primary care physicians was striking: these 2 groups comprised only 2.5% of the study sample (n=11).

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. By excluding pediatricians, we were unable to determine primary care physician availability in Independent Practice Association plans for children in the study area. Osteopathic and general practitioners were also excluded; however, these practitioners comprise only a small percentage of primary care physicians in the study area. Information about physician race/ethnicity was frequently unavailable, which limits our ability to make conclusions about the effect of race/ethnicity. Moreover, to minimize missing data on race, we assumed Asian ethnicity for primary care physicians with Asian-origin surnames, and these assumptions may be a source of bias. We repeated analyses without the Asian race assumptions and found a similar lack of association for race in the multivariate models.

Also, we examined only new-patient availability. We do not know what proportion of adults in the study area have an established primary care provider. However, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey data have shown that 73% of the US population has an office-based usual source of health care, and almost 12% of families have members who change their usual source of care each year.3

If these figures are similar for the San Francisco Bay Area population, then finding a new primary care physician is important for a significant number of people in our study area each year. Because this study dealt only with primary care providers in 2 counties of the San Francisco Bay Area, the results may not be generalizable to other regions.

Because our study goal was to characterize the availability of primary care physicians who were gatekeepers in open managed care plans, we obtained information on appointment availability for routine examinations. Results may have differed if we had sought appointments for an urgent health care issue. Finally, we examined access to care in an Independent Practice Association–model managed care system. These findings may not be generalizable to other types of managed care models.

Conclusions

Physician availability is necessary for access to care within managed care plans. By defining primary care physician availability not only as presence in an area, but also as willingness to accept new patients, we are able to better identify potentially unmet needs for primary care. This study demonstrates that in the San Francisco Bay area, patients may experience moderate difficulty in obtaining access to primary care because practices are “closed” to new patients. Managed care plans should consider whether provider availability limits access to medical services in a specific region.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Annamarie Stehli Nguyen, MPH, and Debbie Jaffe for assisting in data collection; Peter Bacchetti, PhD for statistical consultation; and Karen Vranizan, MA, Alicia Fernandez, MD, and Dean Schillinger, MD, for review of a previous version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Jennifer Haas, MD, MSPH, Division of General Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, 75 Francis Street, Boston, MA 02115. E-mail: [email protected].

Objectives: Primary care physicians function as “gatekeepers” in many managed care systems. With the rapid growth of managed care enrollment, it is crucial that patients have adequate access to primary care physicians. We investigated factors associated with new-patient appointment availability of primary care physicians in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Study Design: Observational cohort.

Population: Cross-sectional survey of primary care physician offices in 2 San Francisco Bay Area counties (n=438).

Outcomes Measured: New-patient appointment availability.

Results: Seventy-five percent of primary care physicians participating in managed care had an appointment available for a new patient.

Conclusions: The limited availability of appointments for new patients may create barriers to primary care in the San Francisco Bay Area, a region with high managed-care penetration.

Recent studies and reports have examined the effect of physician supply on patient access to health care.1,2 However, physician availability is affected not only by distribution of practices, but by whether a patient can actually make an appointment with a provider.

The availability of primary care physicians is central to access to care in most managed care plans. Managed care systems often designate the primary care physician as the “gatekeeper,” the decision maker about patients’ referrals to specialists. Within this kind of system, a patient may not be able to obtain nonemergent care, including specialty care, without access to a primary care physician.

Furthermore, with at least 12% of people changing providers each year,3,4 it is not uncommon for an individual to need to find a new primary care physician who participates in their health plan. The amount of effort needed to find a primary care physician who is accepting new patients, and the possibility of waiting more than a month for an appointment, may affect an individual’s access to care.

Because access to a primary care physician may be limited by these factors, our goal was to characterize the availability of a new-patient appointment with a primary care physician in the northern California counties of Alameda and San Francisco. We further examined whether physician characteristics (eg, sex, years of experience in practice) were associated with appointment availability.

Methods

Study sample

The focus of the study was to examine the availability of primary care physicians for adults between the ages of 18 and 64 years with employer-sponsored insurance in the San Francisco Bay area. Interviewers, posing as patients, made telephone calls to primary care physician’s offices, to parallel the experience of an actual patient seeking a new primary care provider. Current print and online directories of 3 large, open managed care plans available to employees of a large employer were reviewed.

These managed care plans function through an Independent Practice Association model. Two of the 3 plans require primary care physicians to be gatekeepers for all care within the system; ie, a patient must obtain a referral from the primary care physician to have a specialist visit covered by the insurance. The third plan allows patient self-referral to a specialist, but with a higher copay and deductible than with a specialist visit that has been approved by the primary care physician. Physicians working for Kaiser Permanente, the only closed-HMO plan in the study area, were excluded because Kaiser requires a member identification number prior to making an appointment.

Physicians were chosen if they were listed in each of the 3 plan directories, if they had practice addresses in the counties of Alameda or San Francisco, if they listed specialties of internal medicine or family medicine, and if their stated primary activity was clinical care. Doctors of osteopathy were not included.

This selection process identified 469 office-based physicians. Thirty-one physicians were determined to be ineligible during the data collection process (eg, did not meet the original study criteria when the interviewer called). The final study sample was 438 physicians.

Information on 157 physicians was available from the 1997 American Medical Association (AMA) Masterfile, including sex, race/ethnicity, medical school attended, and year of graduation from medical school. For physicians not listed in this older version of the Masterfile, the physician’s sex was obtained either at the time of the interview or from an online plan directory that had this information.

For physicians not listed in the Masterfile or for those with missing information on race/ethnicity, Asian race was determined by investigator review of last names; race/ethnicity for all others was coded as “missing.” Medical school location and year of graduation from medical school for all physicians were obtained from the physician lookup feature of the Medical Board of California Web site.

Data collection

Interviewers made telephone calls to primary care providers’ offices from July 1999 to January 2000. The interviewers posed as patients new to the area, to parallel the experience of an actual patient seeking a new primary care provider.

Telephone calls were made between 9 AM and 5 PM, Monday through Friday. Once an appointment representative for the primary care physician was reached, the interviewer attempted to make an appointment for an initial physical examination, using a standard script. The interviewer stated that she was a new employee, and was in the process of choosing a health plan, based on which insurance plans the primary care physician she was calling currently accepted. If asked what her insurance choices were, the interviewer named the 3 managed care plans used for selecting physicians for the study. If asked for an insurance card number, the interviewer stated that she would bring the appropriate insurance card to the appointment, and would cancel the appointment in advance if the insurance card had not arrived in time for the appointment. If asked, the interviewer stated that she had no urgent health problems. If an appointment was available for a date more than 2 weeks away, the interviewer booked the appointment and canceled it within 1 business day of the initial call.

If the appointment date was less than 2 weeks away, the interviewer noted the time and date but did not book the appointment.

Interviewers recorded information on appointment availability, date and time of appointment, and reason for unavailability. This study was approved by the Committee on Human Research, University of California, San Francisco.

Data and statistical analysis

Several potential predictors of physician availability were examined, including physician’s sex, race/ethnicity, years since graduation from medical school, medical school location, county of practice, and median per capita income of the zip code in which the practice was located. Descriptive statistics on these demographic factors were generated according to appointment availability with Pearson χ2 tests.

We analyzed the ability to get a new-patient appointment with a given primary care physician using a multivariate logistic regression model. Variables were included in the model based on a priori hypotheses. A new race/ethnicity category was created for the logistic regression models by combining African American, Latino, and other, due to small numbers for these groups.

The length of time to an available appointment was also examined. Time to appointment was dichotomized into early appointment (within 0–30 days) and late appointment (>30 days’ wait).

Results

Of the 438 physicians included in the final sample, 328 (74.9%) had an appointment available for a new patient with managed care insurance. Availability varied by physician race/ethnicity, medical school location, years since graduation from medical school, and the median per capita income of the residents in the zip code of the primary care physician’s practice (Table 1).

Appointments were not available for several reasons. Of the 110 primary care physicians who had no appointment available to new patients, 87 (79.1%) were not accepting new patients because of a full practice. Three (2.7%) were on leave or were about to retire. Ten (9.1%) receptionists were unable to book an appointment either because they did not have access to schedules far enough in advance, or because of a basic communication difficulty during repeated calls. One (0.9%) primary care physician was only accepting referred patients. One (0.9%) primary care physician saw only monolingual Chinese-speaking patients.

Eight (7.3%) primary care physicians classed as unavailable required some form of screening, separate from inquiries about insurance or intake assessment forms, before a new patient could be considered for an appointment. Of these 8 physicians, receptionists for 5 said that the physician needed to speak directly with the patient to determine eligibility (not related to insurance), and 1 required a receptionist-administered telephone interview that would be shared with the primary care physician. One required that a written personal questionnaire be filled out and returned for this purpose. The sole remaining primary care physician did not accept current smokers as patients.

TABLE 1

Characteristics of physicians in study

| Characteristic | N (%) | Appointment available (% of total) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 328 (74.9) | 74.7 |

| Female | 110 (25.1) | 75.5 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | 170 (38.8) | 68.8 |

| Asian | 117 (26.7) | 74.4 |

| African American | 7 (1.6) | 85.7 |

| Latino | 4 (0.9) | 100 |

| Other | 8 (1.8) | 100 |

| Missing | 132 (30.1) | 80.3 |

| County | ||

| Alameda | 217 (49.5) | 74.7 |

| San Francisco | 221 (50.5) | 75.1 |

| Years since graduation from medical school | ||

| ≤10 | 61 (13.9) | 88.5* |

| 11–20 | 123 (28.1) | 74.8 |

| >20 | 254 (58.0) | 71.7 |

| Medical school location | ||

| US | 344 (78.5) | 71.5† |

| Foreign | 94 (21.5) | 87.2 |

| Yearly median income of residents in zip code of practice‡ | ||

| Low | 148 (33.8) | 75.7§ |

| Middle | 144 (32.9) | 81.3 |

| High | 146 (33.3) | 67.8 |

| Total | 438 (100) | 74.9 |

| *P=.02 for x2 comparing differences in appointment availability by years since graduation from medical school. | ||

| † P<.01 for x2 comparing differences in appointment availability by medical school location. | ||

| ‡ Low: $5,106–$22,370; middle: $22,371–$36,507; high: $36,508–$51,926. | ||

| § P=.03 for x2 comparing differences in appointment availability by yearly median income of residents in zip code of primary care physician’s practice. | ||

Predictors of appointment availability

Recent graduates were more likely to have an appointment available than more established physicians (OR=4.2; 95% CI, 1.7–10.3) ( Table 2). Foreign medical school graduates were also more likely to have an appointment available than US-educated physicians (OR=3.5; 95% CI, 1.7–7.3). Primary care physicians practicing in middle-income zip codes were more likely to have a new-patient appointment than those with offices in high-income zip codes (OR=2.1; 95% CI, 1.1–4.0).

TABLE 2

Characteristics associated with appointment availability (multivariate logistic regression)

| Characteristic N=438 | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | – | – |

| Female | 0.7 | 0.4–1.3 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | – | – |

| Asian | 0.8 | 0.4–1.5 |

| African American/Latino/other | 6.5 | 0.8–52.7 |

| Missing | 1.7 | 1.0–3.0 |

| County | ||

| Alameda | – | – |

| San Francisco | 1.7 | 1.0–2.8 |

| Years since graduation | ||

| ≤10 | 4.2 | 1.7–10.3 |

| 11–20 | 1.1 | 0.6–1.9 |

| >20 | – | – |

| Medical school location | ||

| US | – | – |

| Foreign | 3.5 | 1.7–7.3 |

| Yearly median income of residents in zip code of practice* | ||

| Low | 1.7 | 0.9–3.1 |

| Middle | 2.1 | 1.1–4.0 |

| High | – | – |

| OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval | ||

| * Low: $5,106–$22,370; middle: $22,371–$36,507; high: $36,508–$51,926 | ||

Predictors of length of time to appointment

The length of time to appointment among those primary care physicians with an available appointment ranged from 0 (same-day appointment) to 151 days; the median was 13 days. Seventy-five percent of appointments were available within 30 days. As shown in Table 3, female primary care physicians were significantly less likely than male primary care physicians to have an appointment available within 30 days (OR=0.4; 95% CI, 0.2–0.7).

TABLE 3

Physician characteristics associated with early appointment availability* (multivariate logistic regression)

| Characteristic N=309 | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | – | – |

| Female | 0.4 | 0.2–0.7 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | – | – |

| Asian | 1.5 | 0.7–3.3 |

| African American/Latino/other | 0.4 | 0.1–1.6 |

| Missing | 1.0 | 0.5–2.0 |

| County | ||

| Alameda | – | – |

| San Francisco | 0.8 | 0.4–1.5 |

| Years since graduation | ||

| ≤10 | 0.5 | 0.2–1.1 |

| 11–20 | 0.9 | 0.4–1.6 |

| >20 | – | – |

| Medical school location | ||

| US | – | – |

| Foreign | 2.0 | 0.9–4.5 |

| Yearly median income of residents in zip code of practice† | ||

| Low | 1.0 | 0.5–2.1 |

| Middle | 0.7 | 0.3–1.6 |

| High | – | – |

| OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval | ||

| * Early appointment is within 0–30 days; late appointment is over 30 days’ wait | ||

| † Low: $5,106–$22,370; middle: $22,371–$36,507; high: $36,508–$51,926. | ||

Discussion

These results suggest that in a highly capitated urban area in California, access to primary care physicians may be restricted for patients seeking a new provider. The median waiting time for a new-patient appointment was 13 days, but the range was wide, from same-day appointments to 151 days of waiting time.

The most common reason for primary care physician unavailability was a “full practice.” In addition, a few primary care physicians required some form of screening before they would consider accepting a new patient into their practice. These screening practices may be a barrier to care. Under current managed care systems, appointment unavailability and long length of wait affect not only primary care services, but also access to specialty care.

This study gathered information on physician availability by means of research assistants posing as patients. We believe that surveying physicians using concealed intent was necessary to directly assess the experience of patients. This design was chosen to minimize inaccurate and potentially biased information.

Similar studies

At least 3 previous studies have used this method to obtain direct information on physician availability. After surveying ambulatory care clinics in 10 US cities, the Medicaid Access Study Group reported a difference in the length of waiting time to an appointment according to insurance status.5 Schwartz et al,6 who studied New York City obstetricians, found that only 42% of pregnant women were able to obtain a prenatal appointment with a physician, with waiting times ranging from 2 days to 7 weeks. Gifford,7 in a survey of Chicago area obstetricians, found that 36% accepted new Medicaid patients, and that fewer obstetricians worked in the poorest zip codes.

Physicians’ characteristics

Certain characteristics of the physicians were associated with availability or time to appointment. Female primary care physicians were significantly less likely to have an “early” appointment (within 30 days) available compared with male primary care physicians. Primary care physicians who had graduated from a medical school outside the US were more available than those who had attended a school in the US. Less experienced primary care physicians were more available than more experienced providers.

We were not able to analyze the availability of African American and Latino physicians separately due to their small numbers. When physicians identifying themselves as African American, Latino, or “other” were combined, the result did not significantly predict availability. The dearth of African American and Latino primary care physicians was striking: these 2 groups comprised only 2.5% of the study sample (n=11).

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. By excluding pediatricians, we were unable to determine primary care physician availability in Independent Practice Association plans for children in the study area. Osteopathic and general practitioners were also excluded; however, these practitioners comprise only a small percentage of primary care physicians in the study area. Information about physician race/ethnicity was frequently unavailable, which limits our ability to make conclusions about the effect of race/ethnicity. Moreover, to minimize missing data on race, we assumed Asian ethnicity for primary care physicians with Asian-origin surnames, and these assumptions may be a source of bias. We repeated analyses without the Asian race assumptions and found a similar lack of association for race in the multivariate models.

Also, we examined only new-patient availability. We do not know what proportion of adults in the study area have an established primary care provider. However, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey data have shown that 73% of the US population has an office-based usual source of health care, and almost 12% of families have members who change their usual source of care each year.3

If these figures are similar for the San Francisco Bay Area population, then finding a new primary care physician is important for a significant number of people in our study area each year. Because this study dealt only with primary care providers in 2 counties of the San Francisco Bay Area, the results may not be generalizable to other regions.

Because our study goal was to characterize the availability of primary care physicians who were gatekeepers in open managed care plans, we obtained information on appointment availability for routine examinations. Results may have differed if we had sought appointments for an urgent health care issue. Finally, we examined access to care in an Independent Practice Association–model managed care system. These findings may not be generalizable to other types of managed care models.

Conclusions

Physician availability is necessary for access to care within managed care plans. By defining primary care physician availability not only as presence in an area, but also as willingness to accept new patients, we are able to better identify potentially unmet needs for primary care. This study demonstrates that in the San Francisco Bay area, patients may experience moderate difficulty in obtaining access to primary care because practices are “closed” to new patients. Managed care plans should consider whether provider availability limits access to medical services in a specific region.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Annamarie Stehli Nguyen, MPH, and Debbie Jaffe for assisting in data collection; Peter Bacchetti, PhD for statistical consultation; and Karen Vranizan, MA, Alicia Fernandez, MD, and Dean Schillinger, MD, for review of a previous version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Jennifer Haas, MD, MSPH, Division of General Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, 75 Francis Street, Boston, MA 02115. E-mail: [email protected].

1. Grumbach K, Vranizan K, Bindman AB. Physician supply and access to care in urban communities. Health Aff (Millwood) 1997;16:71-86.

2. Knapp KK, Paavola FG, Maine LL, Sorofman B, Politzer RM. Availability of primary care providers and pharmacists in the United States. J Am Pharm Assoc (Wash) 1999;39:127-135.

3. Weinick RM, Zuvekas SH, Drilea SK. Access to health care–sources and barriers, 1996. MEPS Research Findings No. 3. Rockville, Md: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1997. AHCPR publication 98-0001.

4. Reed MC. Why people change their health care providers. Washington, DC: Center for Studying Health System Change; 2000. Data Bulletin No. 16. Available at: http://www.hschange.org/CONTENT/81/. Accessed on July 28, 2003.

5. Access of Medicaid recipients to outpatient care N Engl J Med 1994;330:1426-1430.

6. Schwartz LR, Heagarty M, Graham EH, Pirani S. Measuring access to prenatal care in New York City: a telephone survey of prenatal clinics. Am J Public Health 1996;86:1474-1475.

7. Gifford B. Obstetricians’ receptiveness to teen prenatal patients who are Medicaid recipients. Health Serv Res 1997;32:265-282.

1. Grumbach K, Vranizan K, Bindman AB. Physician supply and access to care in urban communities. Health Aff (Millwood) 1997;16:71-86.

2. Knapp KK, Paavola FG, Maine LL, Sorofman B, Politzer RM. Availability of primary care providers and pharmacists in the United States. J Am Pharm Assoc (Wash) 1999;39:127-135.

3. Weinick RM, Zuvekas SH, Drilea SK. Access to health care–sources and barriers, 1996. MEPS Research Findings No. 3. Rockville, Md: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1997. AHCPR publication 98-0001.

4. Reed MC. Why people change their health care providers. Washington, DC: Center for Studying Health System Change; 2000. Data Bulletin No. 16. Available at: http://www.hschange.org/CONTENT/81/. Accessed on July 28, 2003.

5. Access of Medicaid recipients to outpatient care N Engl J Med 1994;330:1426-1430.

6. Schwartz LR, Heagarty M, Graham EH, Pirani S. Measuring access to prenatal care in New York City: a telephone survey of prenatal clinics. Am J Public Health 1996;86:1474-1475.

7. Gifford B. Obstetricians’ receptiveness to teen prenatal patients who are Medicaid recipients. Health Serv Res 1997;32:265-282.

Herpes Simplex Virus Prophylaxis With Famciclovir in Patients Undergoing Aesthetic Facial CO2 Laser Resurfacing

Comparison of Azithromycin and Cefadroxil for the Treatment of Uncomplicated Skin and Skin Structure Infections

What is an ROC curve?

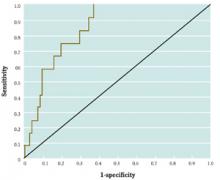

Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curves were developed to assess the quality of radar. In medicine, ROC curves are a way to analyze the accuracy of diagnostic tests and to determine the best threshold or “cutoff” value for distinguishing between positive and negative test results.

Diagnostic testing is almost always a tradeoff between sensitivity and specificity. ROC curves provide a graphic representation of this tradeoff. Setting a cutoff value too low may yield a very high sensitivity (ie, no disease would be missed) but at the expense of specificity (ie, a lot of false-positive results). Setting a cutoff too high would yield high specificity at the expense of sensitivity.

Consider a study by Smith et al,1 who measured the accuracy of B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) as a test for impaired left ventricular function. They measured BNP levels in 155 elderly patients, who also underwent echocardiography (the diagnostic gold standard). An ROC curve was created by plotting the sensitivity against 1–specificity for different cutoff values of BNP (Figure). For example, the sensitivity and specificity of the BNP test were calculated and plotted, assuming a level of 19.8 pmol/L as a cutoff for a positive test.

The best cutoff has the highest sensitivity and lowest 1–specificity, and is therefore located as high up on the vertical axis and as far left on the horizontal axis as possible (upper left corner). The area under an ROC curve is a measure of the usefulness or “discriminative ” value of a test in general. The greater the area, the more useful the test. The maximum possible area under the curve is simply a perfect square and has an area of 1.0. Smith et al’s1 curve has an area of 0.85. The diagonal 45° line represents a test that has no discriminative value—ie, it’s completely useless.

FIGURE 1

Sample ROC curve

An ROC curve for the accuracy of B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) as a test for impaired left ventricular function, which plots the sensitivity against 1–specificity for different cutoff values of BNP.

Correspondence

Goutham Rao, MD, 3518 Fifth Avenue, Pittsburgh, PA 15261. E-mail: [email protected].

REFERENCE

1. Smith H, Pickering RM, Struthers A, Simpson I, Mant D. Biochemical diagnosis of ventricular dysfunction in elderly patients in general practice: an observational study. BMJ 2000;320:906-908.

Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curves were developed to assess the quality of radar. In medicine, ROC curves are a way to analyze the accuracy of diagnostic tests and to determine the best threshold or “cutoff” value for distinguishing between positive and negative test results.

Diagnostic testing is almost always a tradeoff between sensitivity and specificity. ROC curves provide a graphic representation of this tradeoff. Setting a cutoff value too low may yield a very high sensitivity (ie, no disease would be missed) but at the expense of specificity (ie, a lot of false-positive results). Setting a cutoff too high would yield high specificity at the expense of sensitivity.

Consider a study by Smith et al,1 who measured the accuracy of B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) as a test for impaired left ventricular function. They measured BNP levels in 155 elderly patients, who also underwent echocardiography (the diagnostic gold standard). An ROC curve was created by plotting the sensitivity against 1–specificity for different cutoff values of BNP (Figure). For example, the sensitivity and specificity of the BNP test were calculated and plotted, assuming a level of 19.8 pmol/L as a cutoff for a positive test.

The best cutoff has the highest sensitivity and lowest 1–specificity, and is therefore located as high up on the vertical axis and as far left on the horizontal axis as possible (upper left corner). The area under an ROC curve is a measure of the usefulness or “discriminative ” value of a test in general. The greater the area, the more useful the test. The maximum possible area under the curve is simply a perfect square and has an area of 1.0. Smith et al’s1 curve has an area of 0.85. The diagonal 45° line represents a test that has no discriminative value—ie, it’s completely useless.

FIGURE 1

Sample ROC curve

An ROC curve for the accuracy of B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) as a test for impaired left ventricular function, which plots the sensitivity against 1–specificity for different cutoff values of BNP.

Correspondence

Goutham Rao, MD, 3518 Fifth Avenue, Pittsburgh, PA 15261. E-mail: [email protected].

Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curves were developed to assess the quality of radar. In medicine, ROC curves are a way to analyze the accuracy of diagnostic tests and to determine the best threshold or “cutoff” value for distinguishing between positive and negative test results.

Diagnostic testing is almost always a tradeoff between sensitivity and specificity. ROC curves provide a graphic representation of this tradeoff. Setting a cutoff value too low may yield a very high sensitivity (ie, no disease would be missed) but at the expense of specificity (ie, a lot of false-positive results). Setting a cutoff too high would yield high specificity at the expense of sensitivity.

Consider a study by Smith et al,1 who measured the accuracy of B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) as a test for impaired left ventricular function. They measured BNP levels in 155 elderly patients, who also underwent echocardiography (the diagnostic gold standard). An ROC curve was created by plotting the sensitivity against 1–specificity for different cutoff values of BNP (Figure). For example, the sensitivity and specificity of the BNP test were calculated and plotted, assuming a level of 19.8 pmol/L as a cutoff for a positive test.

The best cutoff has the highest sensitivity and lowest 1–specificity, and is therefore located as high up on the vertical axis and as far left on the horizontal axis as possible (upper left corner). The area under an ROC curve is a measure of the usefulness or “discriminative ” value of a test in general. The greater the area, the more useful the test. The maximum possible area under the curve is simply a perfect square and has an area of 1.0. Smith et al’s1 curve has an area of 0.85. The diagonal 45° line represents a test that has no discriminative value—ie, it’s completely useless.

FIGURE 1

Sample ROC curve

An ROC curve for the accuracy of B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) as a test for impaired left ventricular function, which plots the sensitivity against 1–specificity for different cutoff values of BNP.

Correspondence

Goutham Rao, MD, 3518 Fifth Avenue, Pittsburgh, PA 15261. E-mail: [email protected].

REFERENCE

1. Smith H, Pickering RM, Struthers A, Simpson I, Mant D. Biochemical diagnosis of ventricular dysfunction in elderly patients in general practice: an observational study. BMJ 2000;320:906-908.

REFERENCE

1. Smith H, Pickering RM, Struthers A, Simpson I, Mant D. Biochemical diagnosis of ventricular dysfunction in elderly patients in general practice: an observational study. BMJ 2000;320:906-908.

Water versus gel lubricant for cervical cytology specimens

- Gel should be considered a viable option in obtaining Pap smears to ease insertion, minimize discomfort, and perhaps help maintain regular interval sampling compliance. Physicians choosing to use gel should be careful to apply only a thin layer to the outer blades of the speculum.

- Because approximately two thirds of false-negative smears are related to inadequate sampling, be sure to obtain cells from the transformational zone, where cancer is known to develop.

The medical literature generally recommends moistening the speculum with water for performance of a Papanicolaou (Pap) test, because gel lubricants interfere with specimen analysis and assessment of vaginal secretions.1,2 After an extensive literature search, we found little information that identified or substantiated the type or frequency of interference or distortion in analysis or assessment with regard to gel lubricants on cervical cytologic evaluation. The only study of gel lubricant use that we found recommended further study because surprisingly few Pap smears are rendered inadequate despite the high prevalence of gel use.3

Due to these findings and the lack of literature substantiating interference or distortion with gel lubricants, we investigated whether there is a difference in Pap smear obscuration rates with gellubricated vs water-lubricated speculum samples.

Methods

Target population

The target population consisted of all women who received Pap smears between 1995 and 1999 at the University of Tennessee Health Sciences Center HealthPlex Family Medicine Residency Program in Memphis, Tennessee. Pap smears were obtained by resident physicians in the Department of Family Medicine, University of Tennessee Health Science Center. The specific technique used by the residents was left to their discretion and each was asked to describe the usual use of lubricants.

More than 4169 Pap smears were identified via Current Procedural Terminology codes (A88141, A88155, A88164, and/or A88167). Of these, 649 charts were selected by using every sixth record. From those selected, 615 contained adequate information to be included in the study.

Data collection

We gathered medical record data by using a retrospective review of medical records, including the medical record number, date of birth, date of service, provider performing pelvic examination or obtaining cervical cytology smear, identification of the laboratory processing and reporting each cytology report, and insurance coverage (Medicare, private, self-payer, and TennCare/ Medicaid). Cervical cytology report information retrieved included sample adequacy (satisfactory or unsatisfactory), whether the sample was identified as obscured, and whether obscuration was caused by blood.

We also collected data from the medical record on potential confounders, including socioeconomic status (determined by insurance source) and reproductive status (currently pregnant, menopausal, or posthysterectomy). Medical records containing incomplete documentation of any portion of the review criteria were excluded.

Analysis

Statistical analysis was completed with SAS 8.1. Simple χ2 analysis was used where appropriate to demonstrate associations. A stepwise regression model was considered, but none of the χ2 statistics were significant, which eliminated the need for a modeling procedure.

Results

Of the 615 participants, 50 were pregnant, 49 were menopausal, and 42 had undergone a hysterectomy. By matching clinicians’ survey responses to the cytology specimens they collected, we determined that 379 were acquired with water, 81 with gel, and 155 without lubricant.

We reviewed cytology reports for the documented level of adequacy, the presence of any obscuration, and the type of obscuration (see Table). for cytology findings). All 27 obscured and 4 inadequate specimens (5% of the 615 cytology reports reviewed) were reported among women who were pregnant, menopausal, or posthysterectomy. Menopausal women accounted for 89% (24) of obscured specimens and 100% (4) of inadequate specimens. Within the menopausal group, 63% (15) of the specimens were obscured by blood and 37% (9) were obscured by “other.” The term “other” was not defined further or explained on any cytology report. The 5 laboratories reporting obscuration by “other” were contacted, and all reported that this term defines obscuration by nonblood contaminants. Pregnant women accounted for 7% (2) of the obscured specimens, with 1 obscured by blood and 1 obscured by “other.” Women identified as posthysterectomy contributed 4% (1) of the obscured specimens; it was reported as obscured by “other.”

Reports identifying obscured or inadequate specimens and socioeconomic status were also cross-tabulated against type of lubricant used in consideration for possible bias. The outcome showed no identified indication.

No statistically significant difference was found in the likelihood of specimen obscuration or adequacy vs inadequacy between water, gel, or no lubricant. The occurrence of obscuration was lower with the use of water lubricant (3.2%) than with gel lubricant (6.2%) or no lubricant (6.5%). However, this difference was not statistically significant (P<.20).

TABLE

Lubricant use and cytology findings

| Total no. | Water lubricant, % (n) | Gel lubricant, % (n) | No lubricant, % (n) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lubricant use reported | 615 | 62 (379) | 13 (81) | 25 (155) |

| Adequate sample | 611 | 99.2 (376) | 98.8 (80) | 100 (155) |

| Inadequate sample | 4 | 0.08 (3) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Not obscured | 588 | 96.8 (367) | 93.8 (76) | 93.5 (145) |

| Obscured | 27 | 3 (12) | 6.2 (5) | 6.5 (10) |

| By blood | 16 | 58 (7) | 20 (1) | 80 (8) |

| By other* | 11 | 42 (5) | 80 (4) | 20 (2) |

| *Defined as obscuration by nonblood contaminant(s). | ||||

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to identify any differences in the occurrence of contamination or distortion of cervical cytology test results between water and gel as the lubricant. With a sample size that allowed us to detect an absolute difference as small as 7%, we found no significant difference between the use of gel or water lubricant in the likelihood of cell obscuration or inadequacy. These findings did not support current data reported in several publications and may explain the lack of publications describing specific adverse gel effects on sampling collection.

Inadequate specimens in postmenopausal women

The number of obscured and inadequate specimens found within the group of women who had reached menopause was not unexpected because of hormonal changes in cervical cells and the physical structure of the uterus. Although not unexpected, it is of concern that this group includes many older women who constitute an underscreened subgroup who frequently forego routine cervical cancer screening unless they have gynecologic problems.4

In recognizing the need for this group to obtain testing and maintain routine screening compliance, minimizing discomfort related to cervical cell acquisition procedure should be a primary consideration. Because lubricant minimizes friction and optimizes the ease of speculum insertion, gel can be considered an effective choice for these women.

Sampling errors

Nationally, approximately two thirds of false-negative smears are related to inadequate sampling, and the primary sampling error is the failure to obtain cells from the transformational zone, where cancer is known to develop.5,6 The high percentage of specimen adequacy (99% for the water and gel groups and 100% for the no-lubricant group) found during this study may be attributed to the homogeneity in clinical training of the participating residents.