User login

Sparse Hair on the Scalp

The Diagnosis: Monilethrix

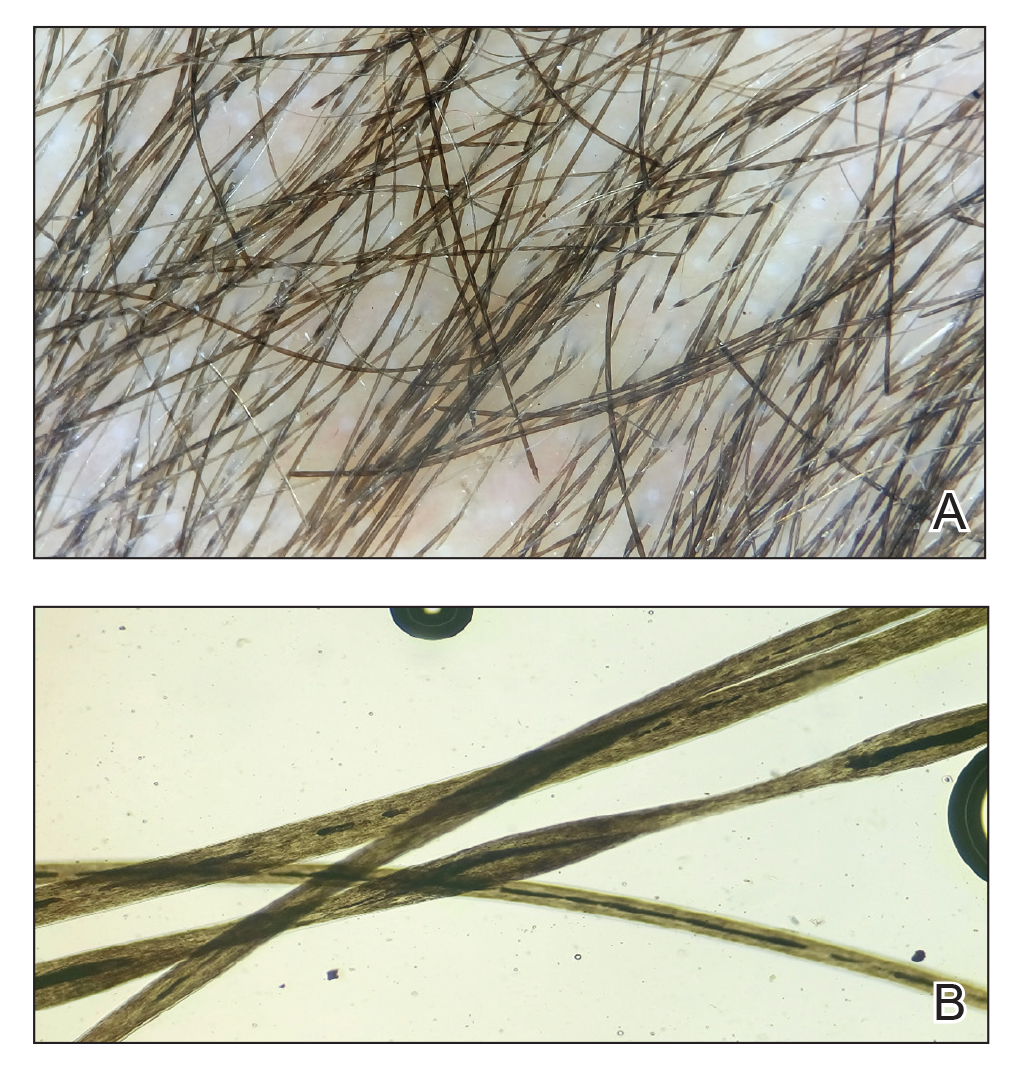

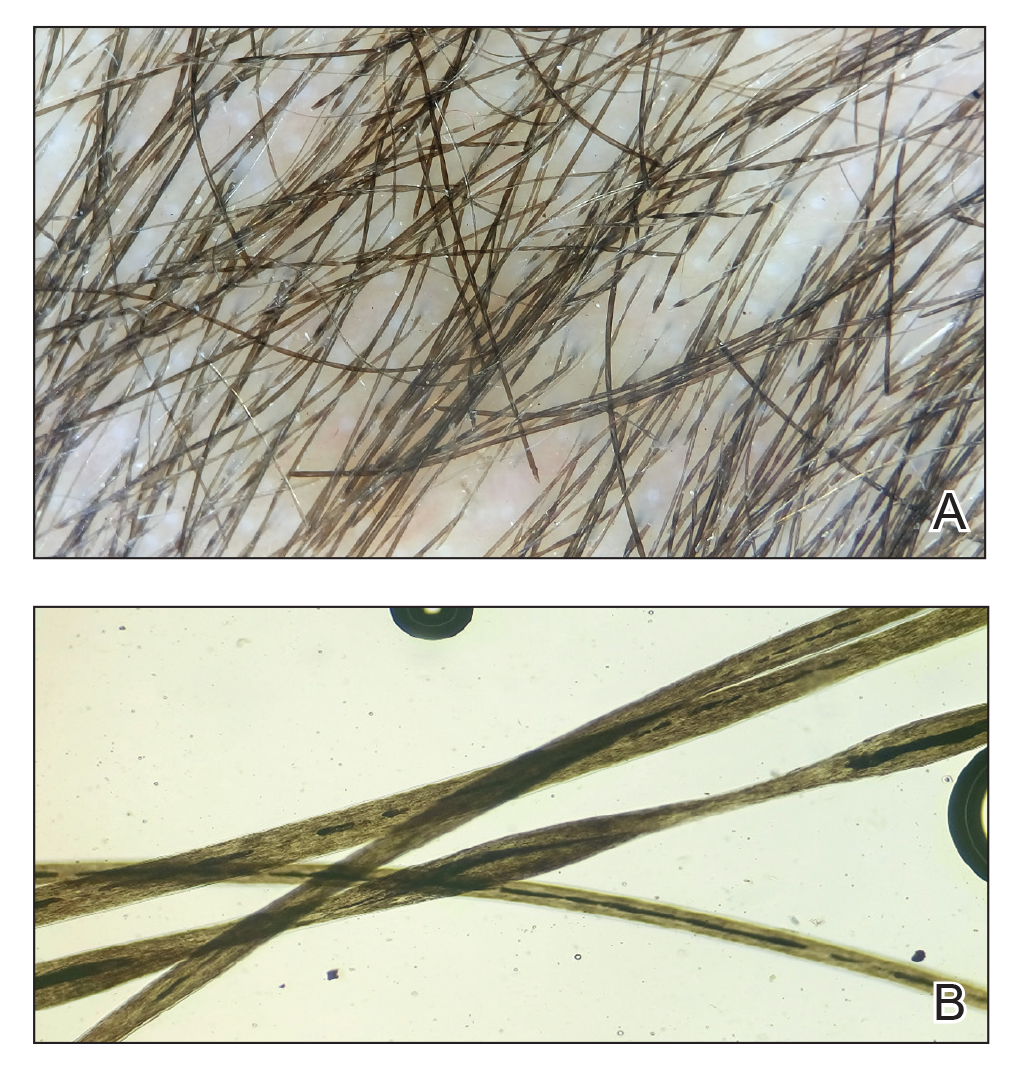

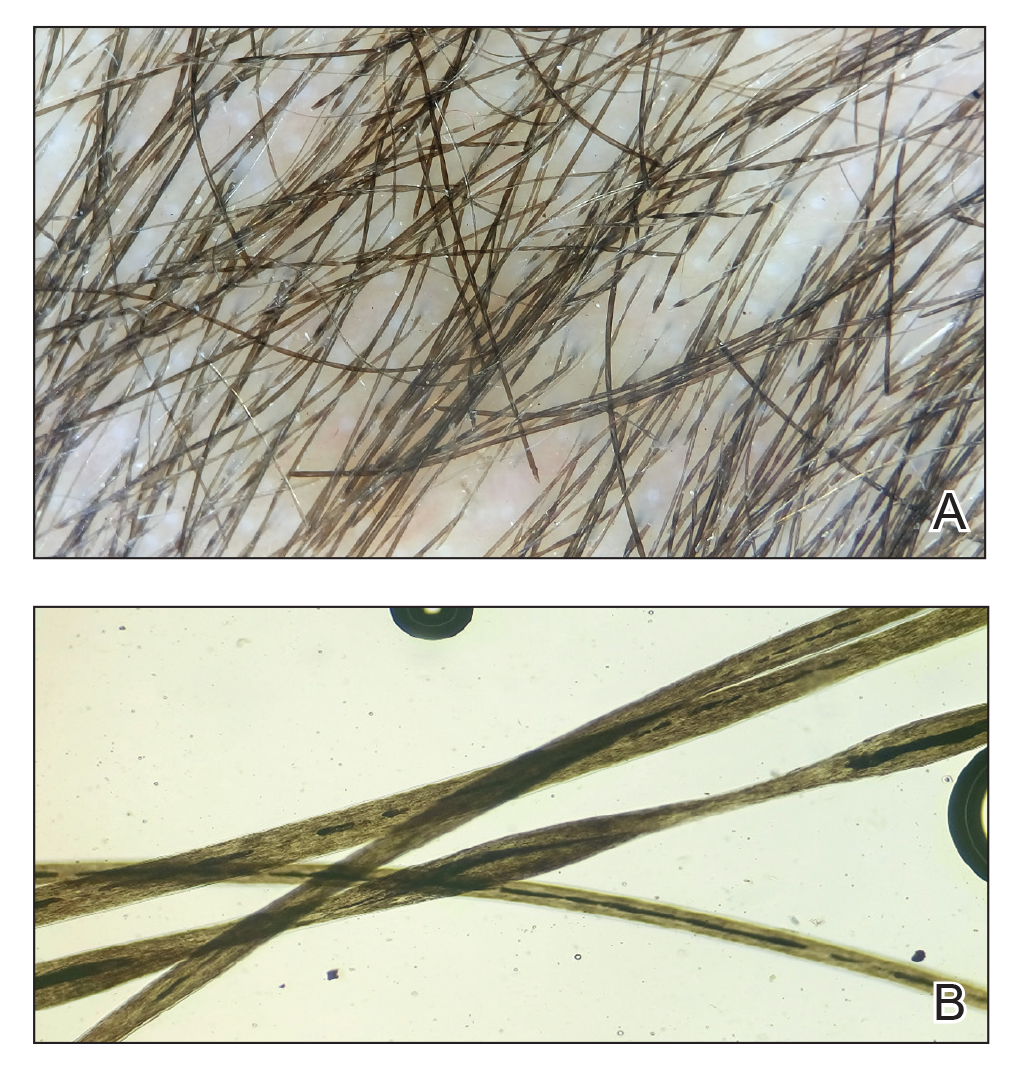

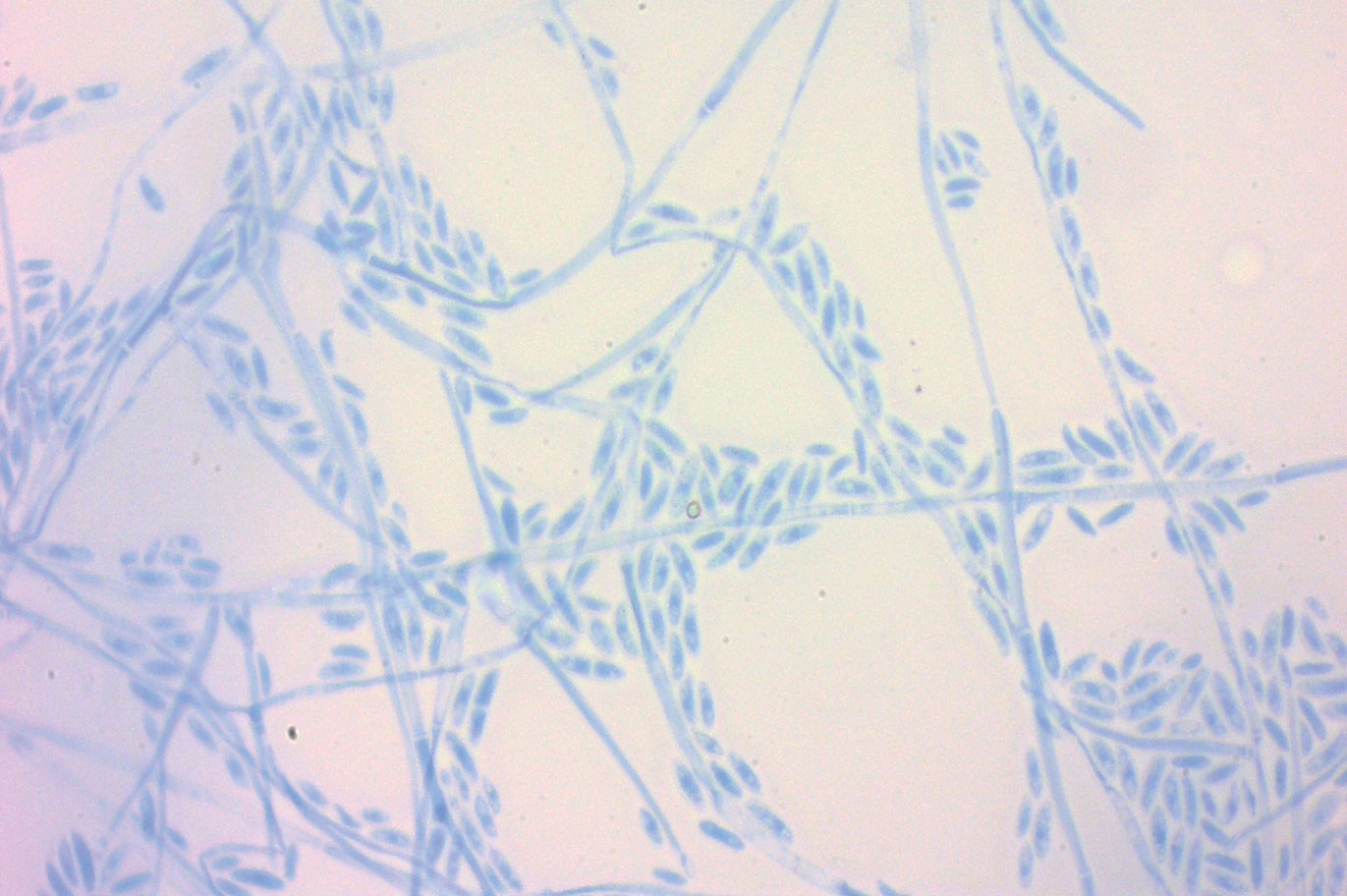

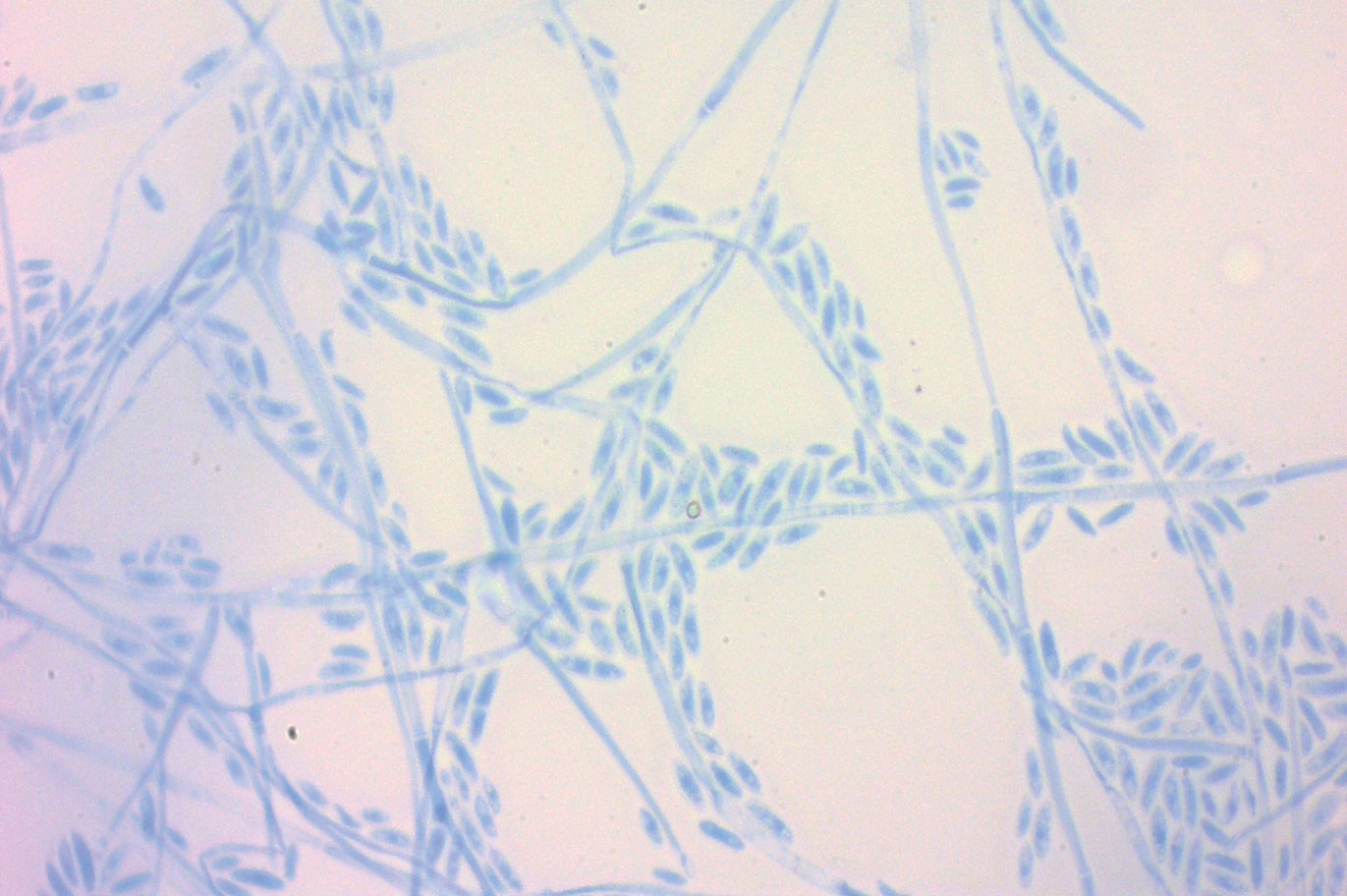

Trichoscopy showed a beaded appearance of the hair shafts (Figure, A). Light microscopy demonstrated normal medullated nodes of hair coupled with internodal, thin, nonmedullated hair at regular intervals (Figure, B). Clinical and trichoscopic findings led to a diagnosis of monilethrix.

Monilethrix is a genetic hair disorder characterized by regular periodic thinning of the hair shafts, giving the strands a beaded appearance. The hair tends to break at these constricted parts, resulting in short hairs. Nodosities represent the normal hair shaft, whereas the constricted points are the site of the defect. The hair tends to be normal at birth and then becomes short, fragile, and brittle within months, leading to hypotrichosis, particularly on the occipital scalp.1 Monilethrix also may involve the eyebrows and eyelashes in addition to scalp hair. Follicular hyperkeratotic papules with perifollicular erythema frequently are noted on the occipital area. Monilethrix can be inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion with mutations involving KRT81, KRT83, and KRT86, which code for the type II hair keratins Hb1, Hb3, and Hb6, respectively. The autosomal-recessive form is caused by mutations in the DSG4 gene, coding for the desmoglein 4 protein.2 Trichoscopy or light microscopy is essential to establish a diagnosis of monilethrix. Trichoscopy is an easy and rapid tool that is utilized to illustrate the beaded appearance of the hair shafts.3 Light microscopy shows the distinctive nodes that are medullated, with a normal hair diameter alternating with the internodes, or constrictions, that are nonmedullated and represent the sites of fracture.1 Monilethrix can improve by puberty. There is no definitive treatment; however, some patients show considerable improvement on minoxidil.4 Treatment with minoxidil was initiated in this patient; however, she was lost to follow-up.

Genetic hair disorders are rare and can be an isolated phenomenon or part of concurrent genetic syndromes. Therefore, thorough clinical examination of other ectodermal structures such as the nails and teeth is crucial as well as obtaining a detailed family history and review of systems to exclude other syndromes.2 Hypotrichosis simplex is characterized by hair loss exclusively on the scalp, sparing other ectodermal structures and with no systemic abnormalities. Ectodermal dysplasia is a heterogeneous group of disorders affecting not only the hair but also the teeth, nails, and sweat glands.2 Pili torti is another rare genetic hair disorder that is characterized by twisting of the hair fiber on its own axis. It presents clinically as sparse, depigmented, lusterless hair that is easily broken. Light microscopy demonstrates twists of hair at irregular intervals. Pili annulati is characterized by bright and dark bands when viewed with reflected light. Unlike monilethrix, there is no fragility, and the hair can grow long.5

- Mirmirani P, Huang KP, Price VH. A practical, algorithmic approach to diagnosing hair shaft disorders. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:1-12.

- Ahmed A, Almohanna H, Griggs J, et al. Genetic hair disorders: a review. Dermatol Ther. 2019;9:421-448.

- Liu C-I, Hsu C-H. Rapid diagnosis of monilethrix using dermoscopy. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:741-743.

- Rossi A, Iorio A, Fortuna MC, et al. Monilethrix treated with minoxidil. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2011;24:239-242.

- Singh G, Miteva M. Prognosis and management of congenital hair shaft disorders with fragility—part I. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:473-480.

The Diagnosis: Monilethrix

Trichoscopy showed a beaded appearance of the hair shafts (Figure, A). Light microscopy demonstrated normal medullated nodes of hair coupled with internodal, thin, nonmedullated hair at regular intervals (Figure, B). Clinical and trichoscopic findings led to a diagnosis of monilethrix.

Monilethrix is a genetic hair disorder characterized by regular periodic thinning of the hair shafts, giving the strands a beaded appearance. The hair tends to break at these constricted parts, resulting in short hairs. Nodosities represent the normal hair shaft, whereas the constricted points are the site of the defect. The hair tends to be normal at birth and then becomes short, fragile, and brittle within months, leading to hypotrichosis, particularly on the occipital scalp.1 Monilethrix also may involve the eyebrows and eyelashes in addition to scalp hair. Follicular hyperkeratotic papules with perifollicular erythema frequently are noted on the occipital area. Monilethrix can be inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion with mutations involving KRT81, KRT83, and KRT86, which code for the type II hair keratins Hb1, Hb3, and Hb6, respectively. The autosomal-recessive form is caused by mutations in the DSG4 gene, coding for the desmoglein 4 protein.2 Trichoscopy or light microscopy is essential to establish a diagnosis of monilethrix. Trichoscopy is an easy and rapid tool that is utilized to illustrate the beaded appearance of the hair shafts.3 Light microscopy shows the distinctive nodes that are medullated, with a normal hair diameter alternating with the internodes, or constrictions, that are nonmedullated and represent the sites of fracture.1 Monilethrix can improve by puberty. There is no definitive treatment; however, some patients show considerable improvement on minoxidil.4 Treatment with minoxidil was initiated in this patient; however, she was lost to follow-up.

Genetic hair disorders are rare and can be an isolated phenomenon or part of concurrent genetic syndromes. Therefore, thorough clinical examination of other ectodermal structures such as the nails and teeth is crucial as well as obtaining a detailed family history and review of systems to exclude other syndromes.2 Hypotrichosis simplex is characterized by hair loss exclusively on the scalp, sparing other ectodermal structures and with no systemic abnormalities. Ectodermal dysplasia is a heterogeneous group of disorders affecting not only the hair but also the teeth, nails, and sweat glands.2 Pili torti is another rare genetic hair disorder that is characterized by twisting of the hair fiber on its own axis. It presents clinically as sparse, depigmented, lusterless hair that is easily broken. Light microscopy demonstrates twists of hair at irregular intervals. Pili annulati is characterized by bright and dark bands when viewed with reflected light. Unlike monilethrix, there is no fragility, and the hair can grow long.5

The Diagnosis: Monilethrix

Trichoscopy showed a beaded appearance of the hair shafts (Figure, A). Light microscopy demonstrated normal medullated nodes of hair coupled with internodal, thin, nonmedullated hair at regular intervals (Figure, B). Clinical and trichoscopic findings led to a diagnosis of monilethrix.

Monilethrix is a genetic hair disorder characterized by regular periodic thinning of the hair shafts, giving the strands a beaded appearance. The hair tends to break at these constricted parts, resulting in short hairs. Nodosities represent the normal hair shaft, whereas the constricted points are the site of the defect. The hair tends to be normal at birth and then becomes short, fragile, and brittle within months, leading to hypotrichosis, particularly on the occipital scalp.1 Monilethrix also may involve the eyebrows and eyelashes in addition to scalp hair. Follicular hyperkeratotic papules with perifollicular erythema frequently are noted on the occipital area. Monilethrix can be inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion with mutations involving KRT81, KRT83, and KRT86, which code for the type II hair keratins Hb1, Hb3, and Hb6, respectively. The autosomal-recessive form is caused by mutations in the DSG4 gene, coding for the desmoglein 4 protein.2 Trichoscopy or light microscopy is essential to establish a diagnosis of monilethrix. Trichoscopy is an easy and rapid tool that is utilized to illustrate the beaded appearance of the hair shafts.3 Light microscopy shows the distinctive nodes that are medullated, with a normal hair diameter alternating with the internodes, or constrictions, that are nonmedullated and represent the sites of fracture.1 Monilethrix can improve by puberty. There is no definitive treatment; however, some patients show considerable improvement on minoxidil.4 Treatment with minoxidil was initiated in this patient; however, she was lost to follow-up.

Genetic hair disorders are rare and can be an isolated phenomenon or part of concurrent genetic syndromes. Therefore, thorough clinical examination of other ectodermal structures such as the nails and teeth is crucial as well as obtaining a detailed family history and review of systems to exclude other syndromes.2 Hypotrichosis simplex is characterized by hair loss exclusively on the scalp, sparing other ectodermal structures and with no systemic abnormalities. Ectodermal dysplasia is a heterogeneous group of disorders affecting not only the hair but also the teeth, nails, and sweat glands.2 Pili torti is another rare genetic hair disorder that is characterized by twisting of the hair fiber on its own axis. It presents clinically as sparse, depigmented, lusterless hair that is easily broken. Light microscopy demonstrates twists of hair at irregular intervals. Pili annulati is characterized by bright and dark bands when viewed with reflected light. Unlike monilethrix, there is no fragility, and the hair can grow long.5

- Mirmirani P, Huang KP, Price VH. A practical, algorithmic approach to diagnosing hair shaft disorders. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:1-12.

- Ahmed A, Almohanna H, Griggs J, et al. Genetic hair disorders: a review. Dermatol Ther. 2019;9:421-448.

- Liu C-I, Hsu C-H. Rapid diagnosis of monilethrix using dermoscopy. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:741-743.

- Rossi A, Iorio A, Fortuna MC, et al. Monilethrix treated with minoxidil. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2011;24:239-242.

- Singh G, Miteva M. Prognosis and management of congenital hair shaft disorders with fragility—part I. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:473-480.

- Mirmirani P, Huang KP, Price VH. A practical, algorithmic approach to diagnosing hair shaft disorders. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:1-12.

- Ahmed A, Almohanna H, Griggs J, et al. Genetic hair disorders: a review. Dermatol Ther. 2019;9:421-448.

- Liu C-I, Hsu C-H. Rapid diagnosis of monilethrix using dermoscopy. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:741-743.

- Rossi A, Iorio A, Fortuna MC, et al. Monilethrix treated with minoxidil. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2011;24:239-242.

- Singh G, Miteva M. Prognosis and management of congenital hair shaft disorders with fragility—part I. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:473-480.

A 5-year-old girl presented to our clinic with sparse scalp hair. Her mother reported thinning of the hair and breakage that appeared shortly after birth. She also reported that the patient’s hair was dull, dry, and unable to be grown long. The patient was otherwise healthy. She was born to nonconsanguineous parents, and her family history was unremarkable. Physical examination revealed dry, brittle, and short hairs. The hair was sparser on the occipital area of the scalp, and multiple keratotic papules were noted in this area. No abnormalities were detected on the teeth or nails, and a review of systems was unremarkable. Trichoscopy and light microscopy were performed.

Hemorrhagic Papular Eruption on the Dorsal Hands

The Diagnosis: Heparin-Induced Bullous Hemorrhagic Dermatosis

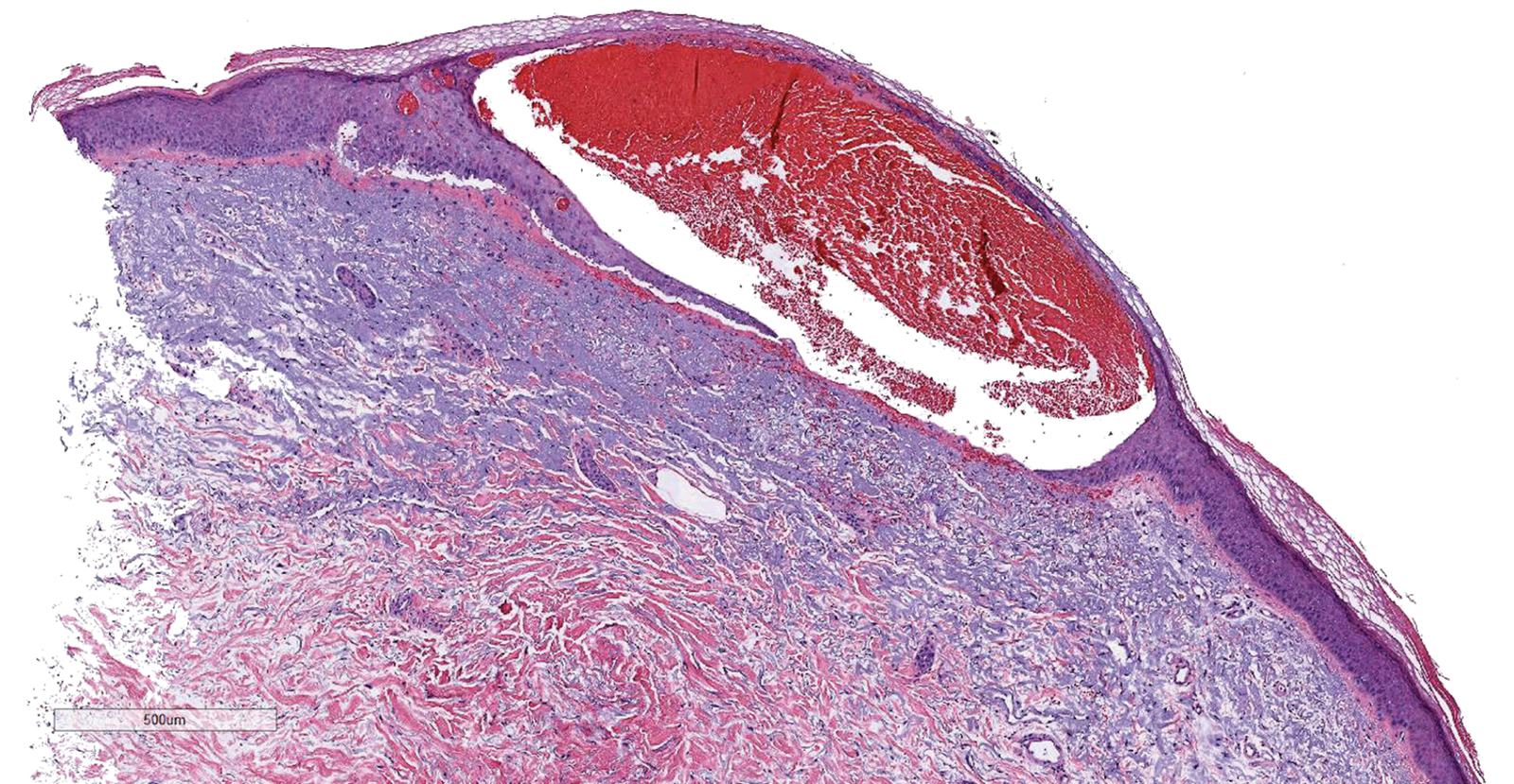

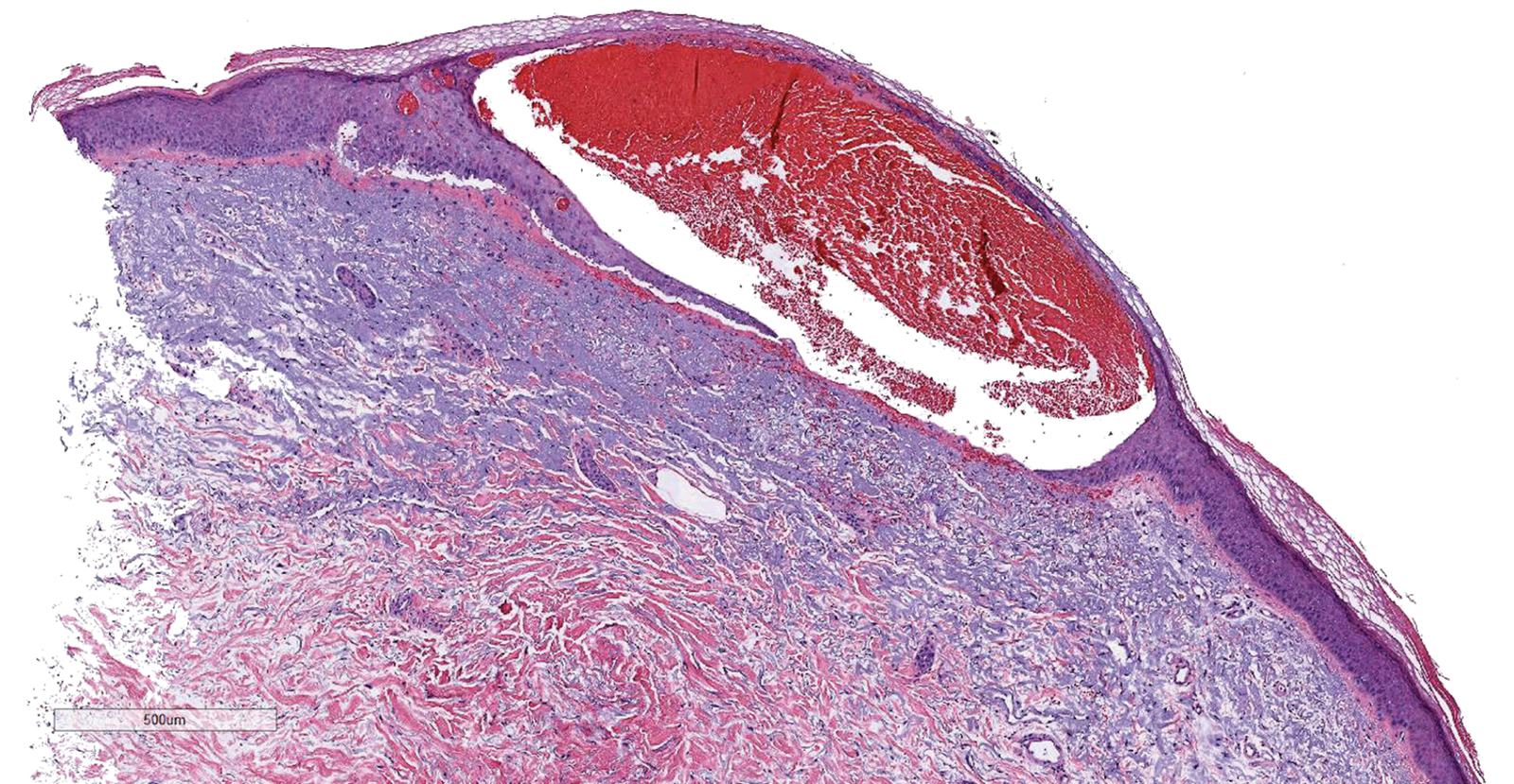

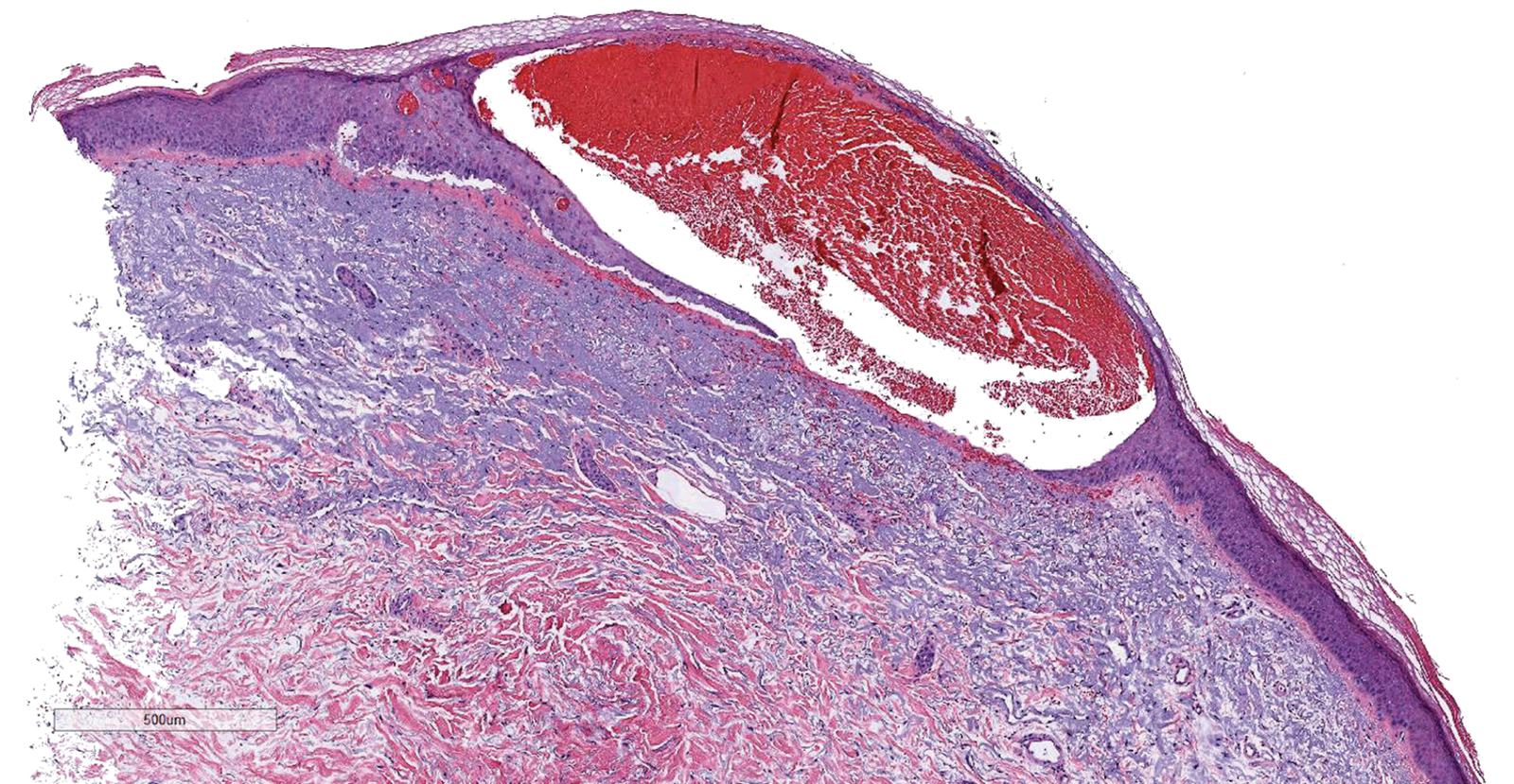

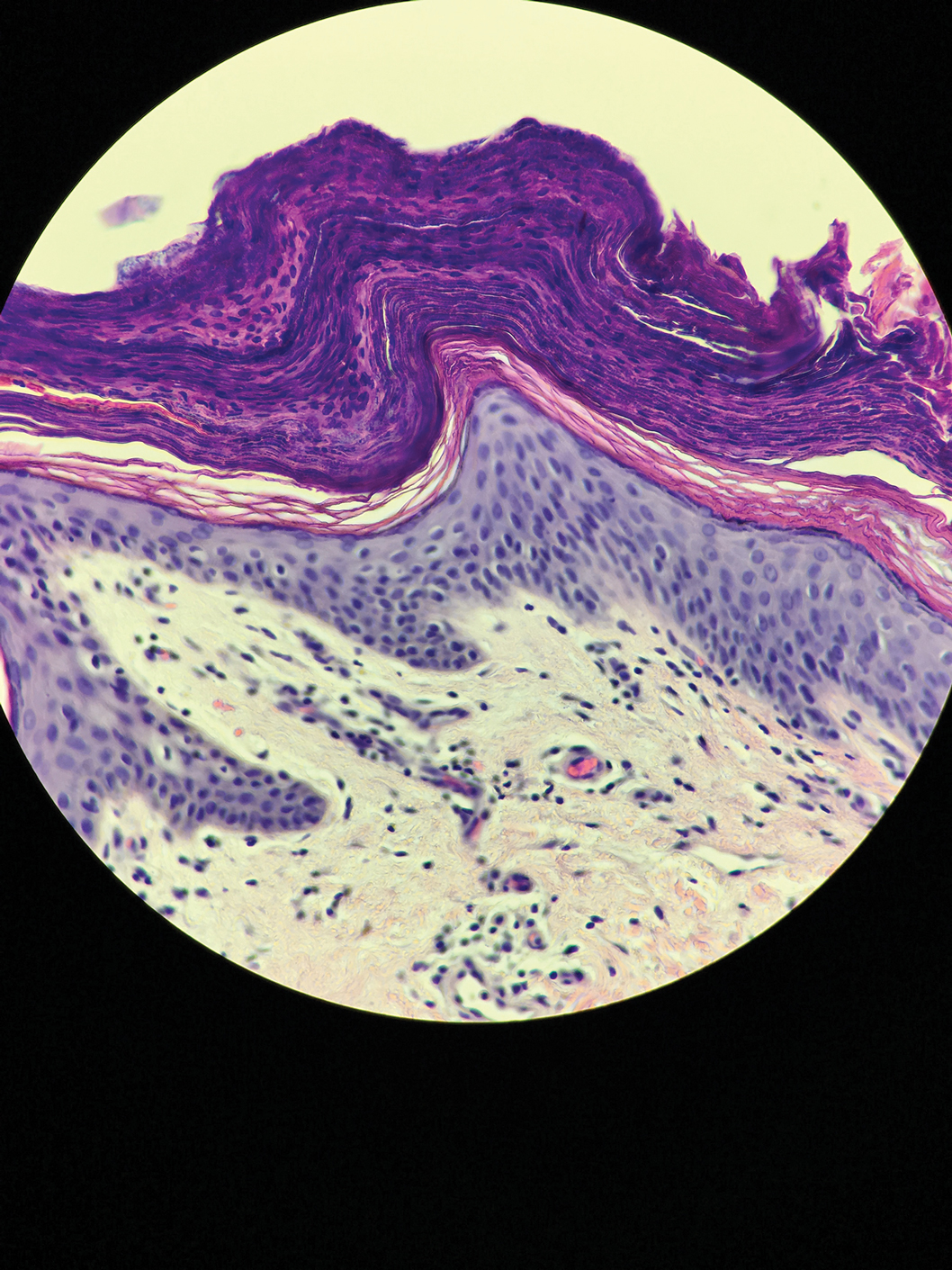

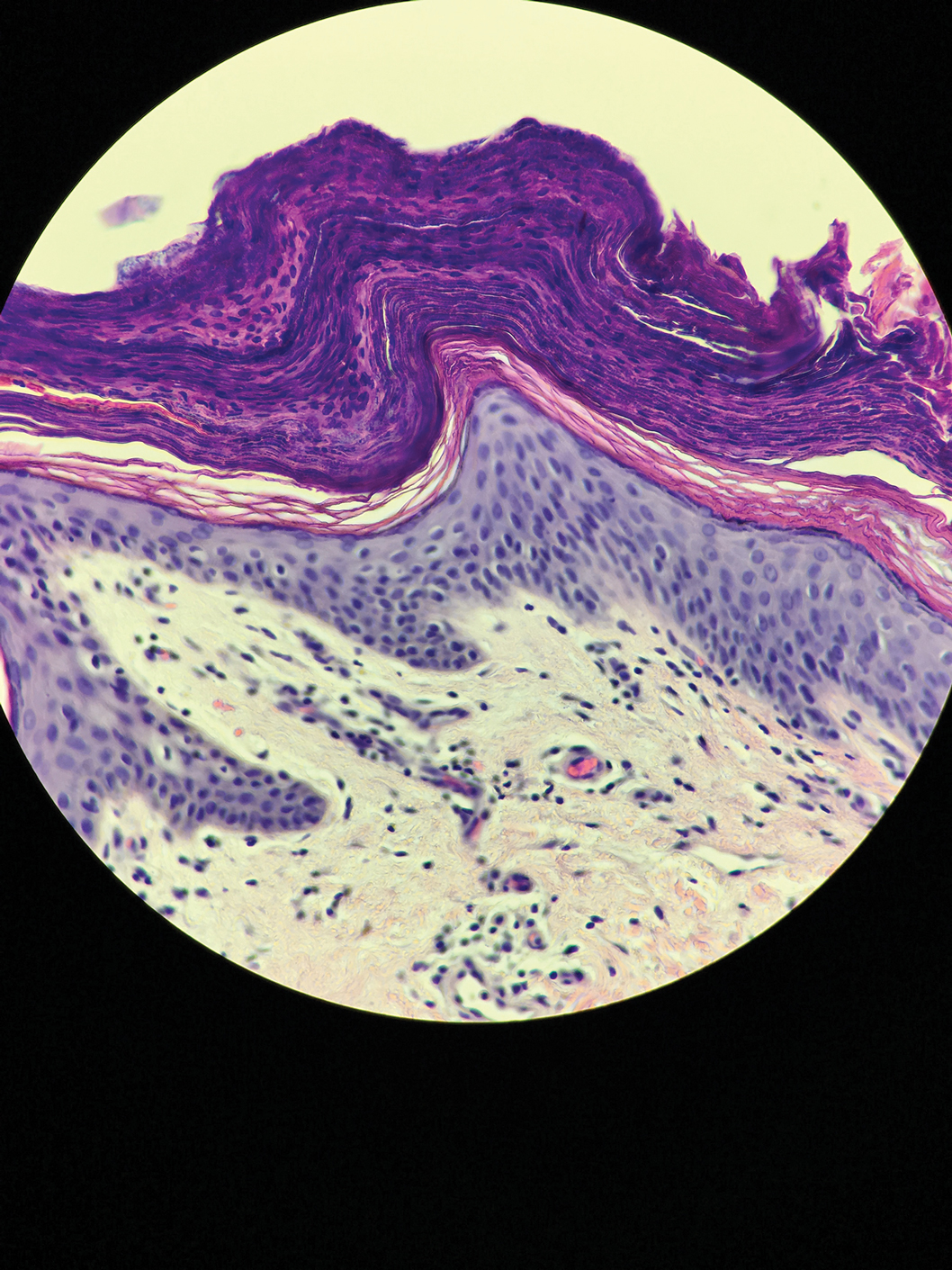

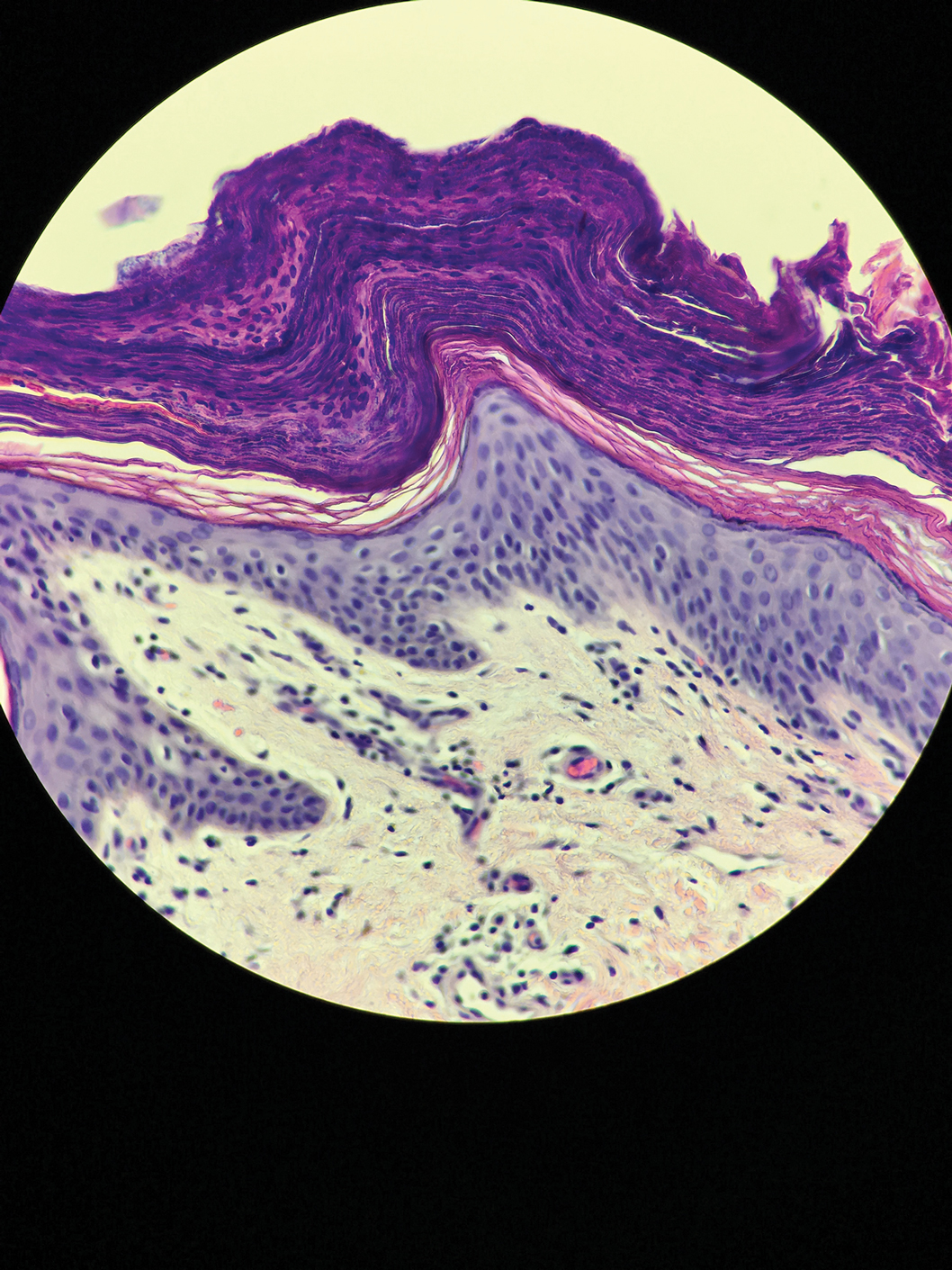

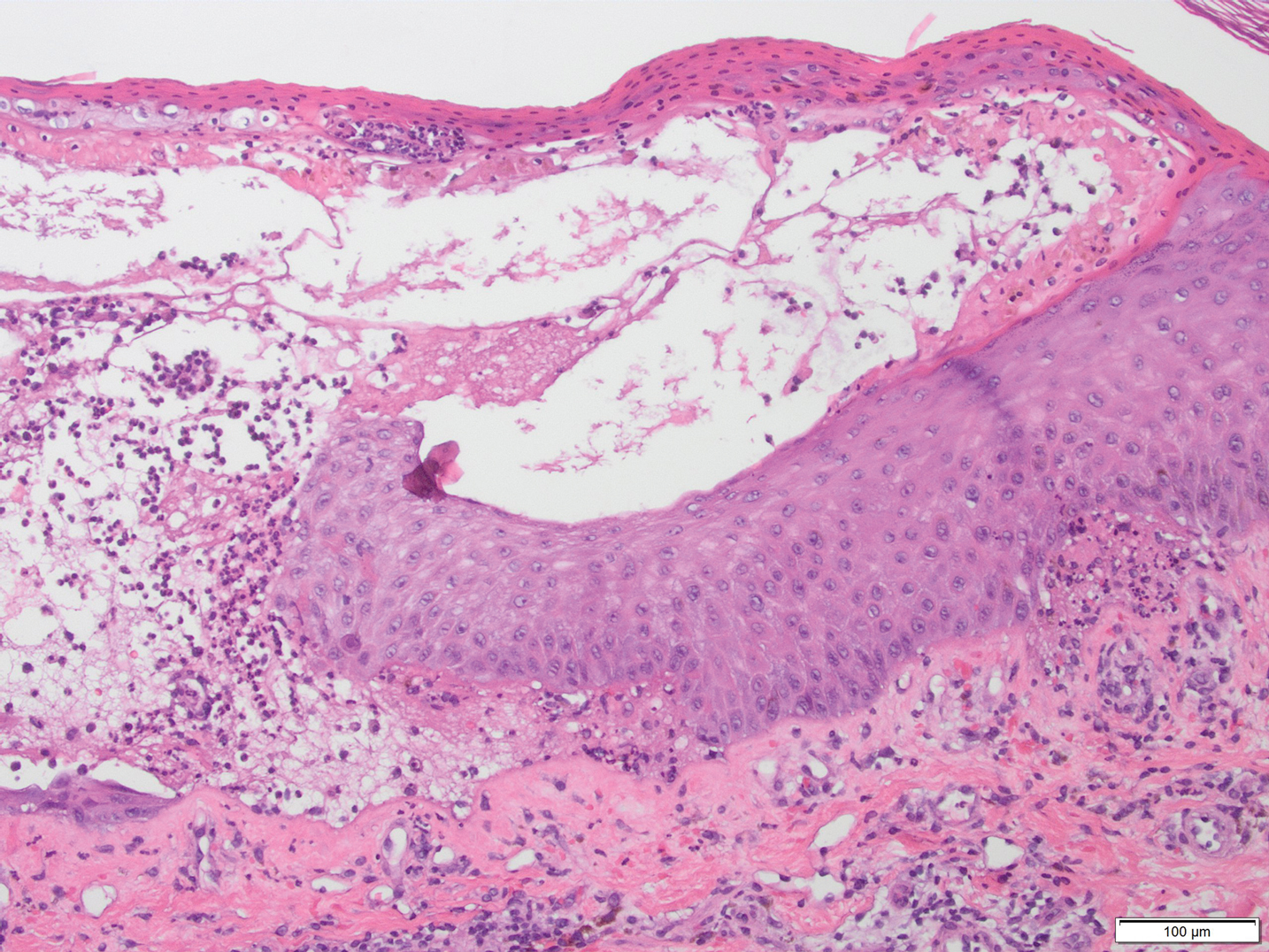

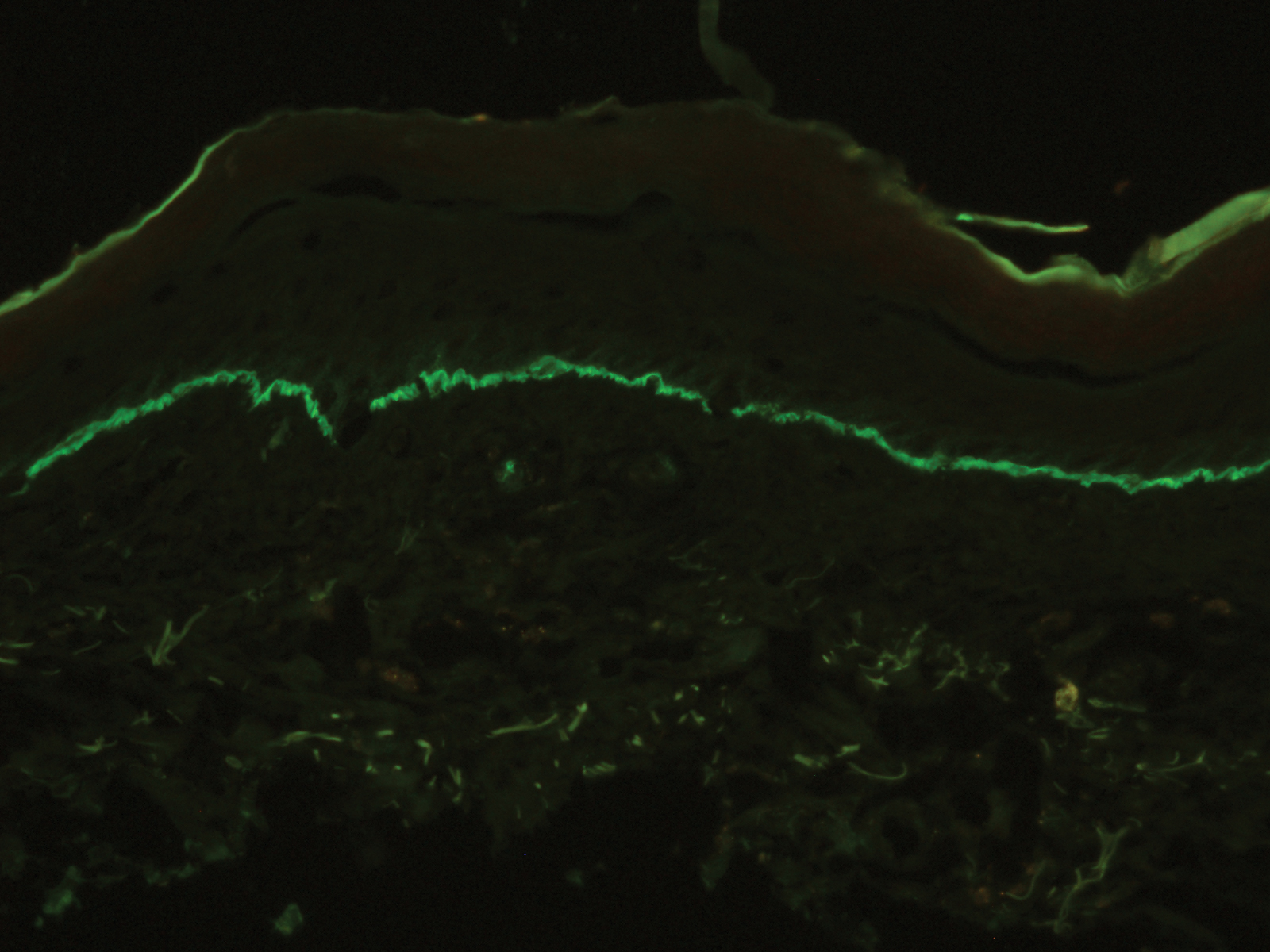

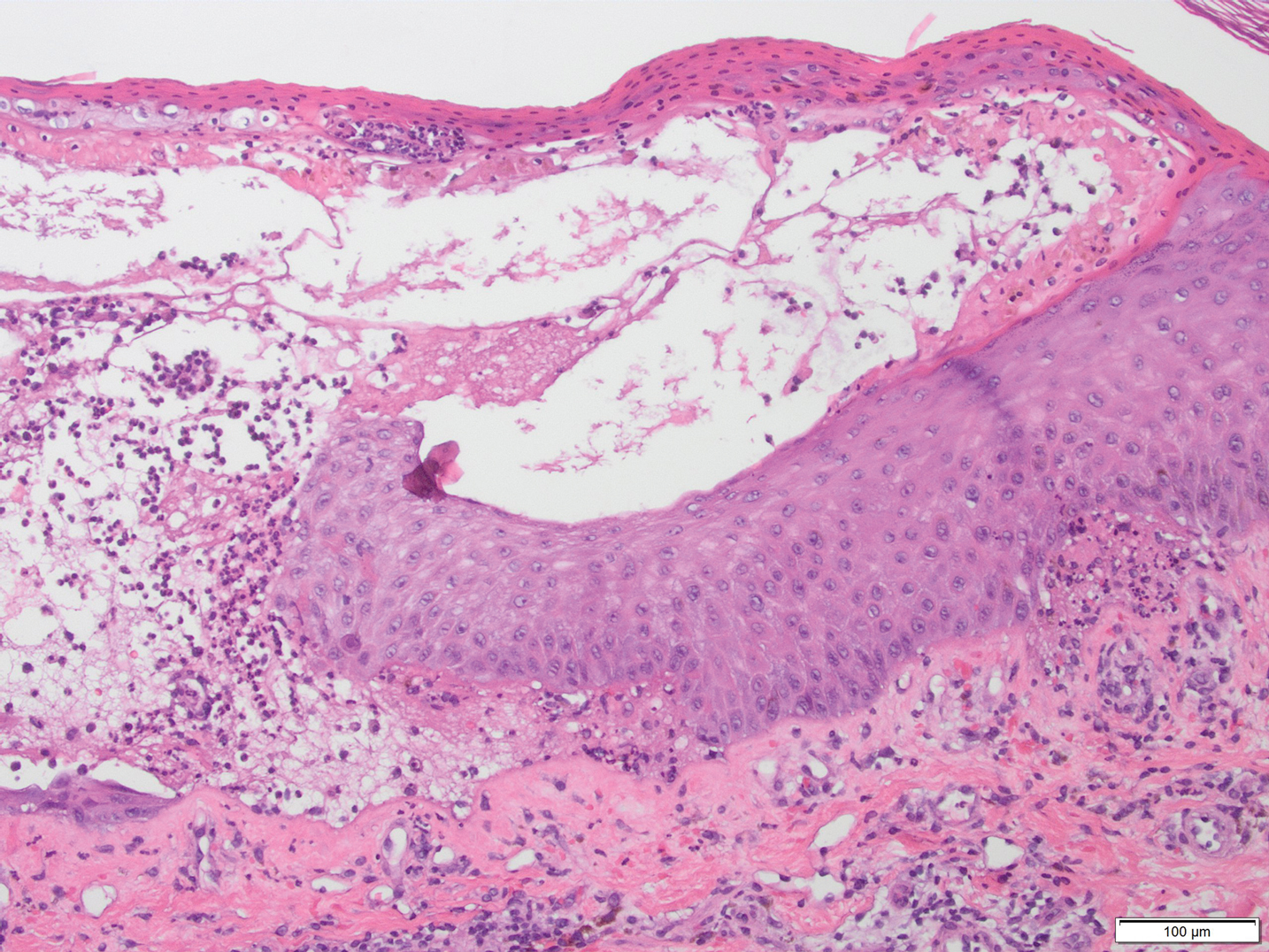

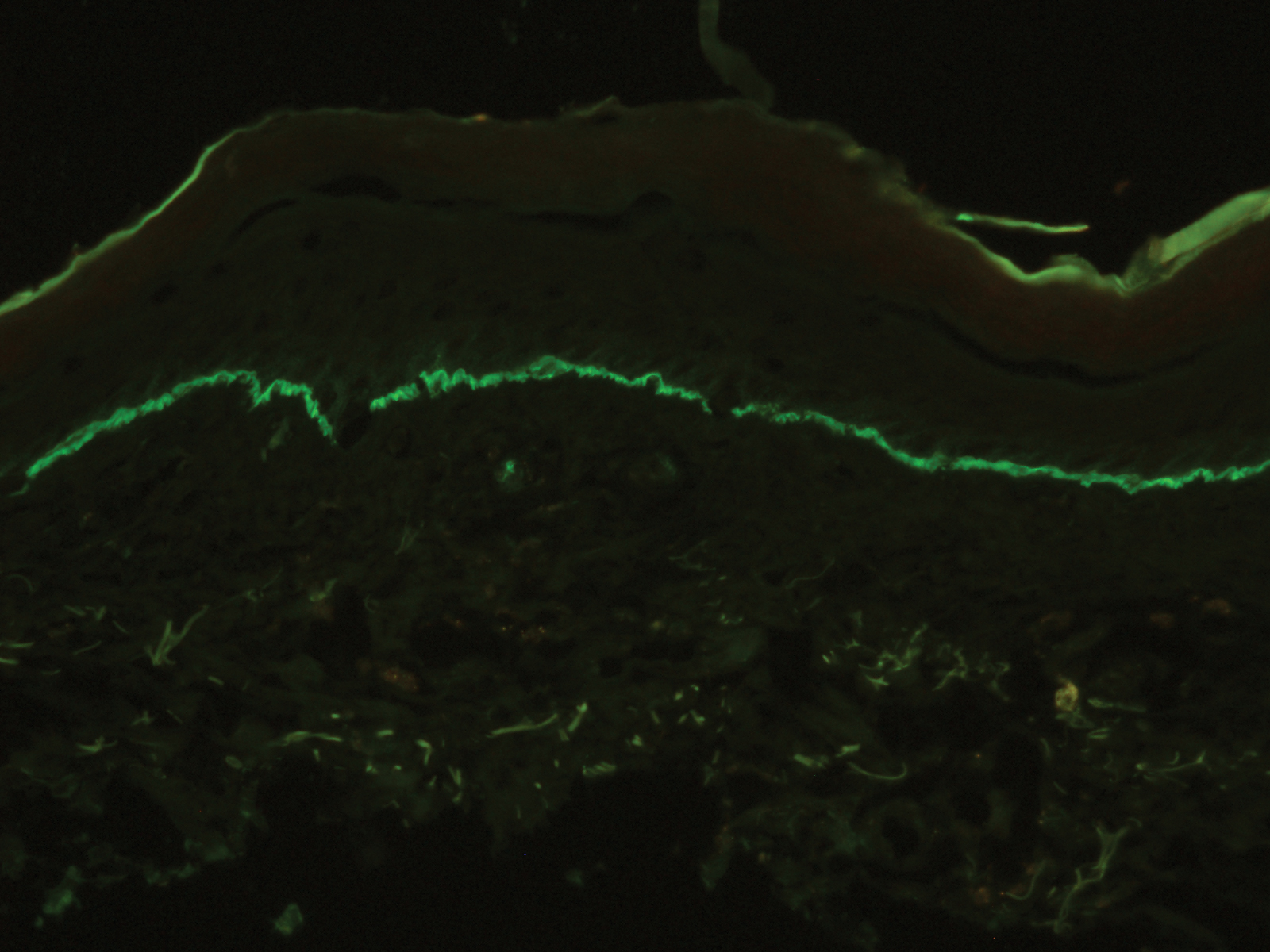

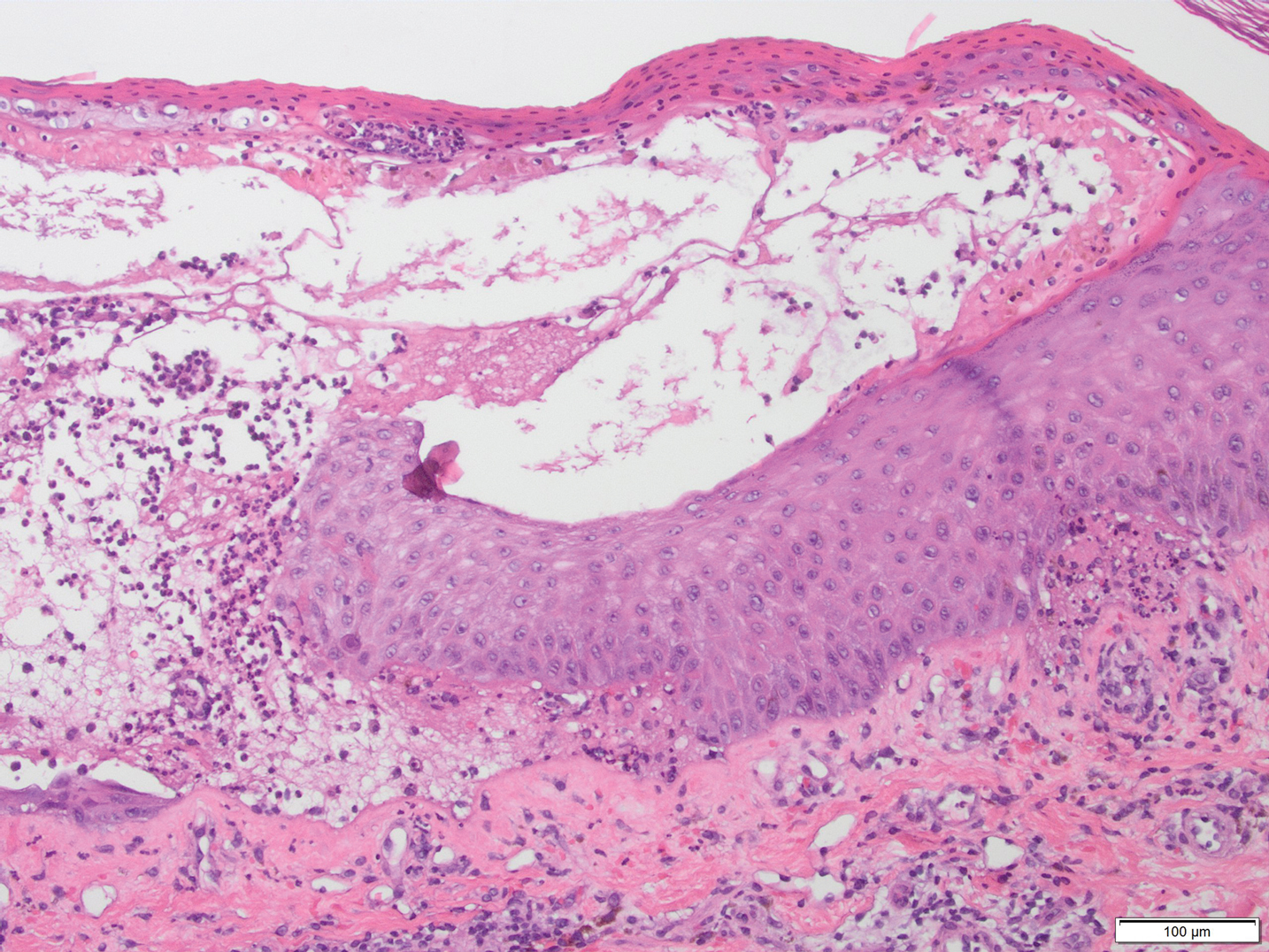

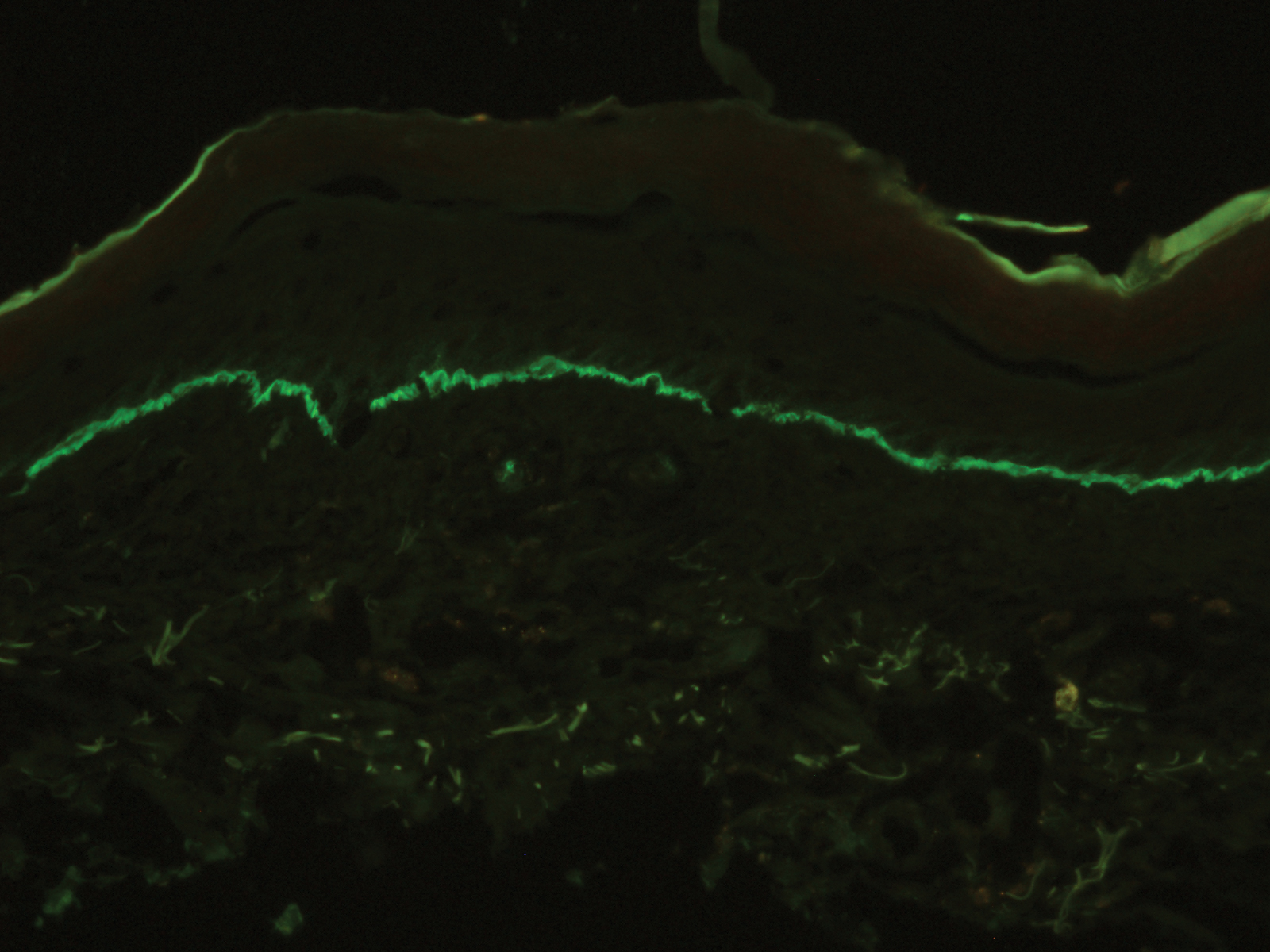

Results of a punch biopsy of one of the hemorrhagic papules revealed a subcorneal hemorrhagic vesicle without underlying vasculitis, vasculopathy, inflammation, or viral changes (Figure). Tissue and blood cultures were sterile. Heparin and platelet factor 4 antibody testing was negative. The patient was diagnosed with heparin induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis (BHD). After chest imaging ruled out a pulmonary embolism, anticoagulation therapy was discontinued. Respiratory symptoms improved on antibiotics, and the skin lesions resolved completely within 2 weeks.

Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis is an uncommon and underrecognized reaction to various anticoagulants. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis presents with painless, noninflammatory, hemorrhagic vesicles and bullae occurring at sites distant from anticoagulant administration. The condition was first characterized in 2006 by Perrinaud et al,1 who presented 3 cases in patients treated with heparin and low-molecular-weight heparin. Since then, there have been at least 90 cases reported in the international literature, with elderly men found to be the more affected demographic (male to female ratio, 1.9:1).2 Typically, BHD presents within 1 week of administration of an anticoagulant, but delayed onset has been reported.2 Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis is most commonly observed with enoxaparin use but also has been described in association with unfractionated heparin, low-molecular-weight heparin products, and warfarin.2

The noninflammatory-appearing hemorrhagic papules and small plaques of BHD generally are seen on the extremities but can occur anywhere on the body including the oral mucosa.3 The differential diagnosis of BHD may include autoimmune vesiculobullous conditions, bullous drug eruptions, herpetic infection, supratherapeutic anticoagulation, porphyria cutanea tarda, amyloidosis, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, angioinvasive infections, and heparin necrosis. Diagnosis of BHD can be made clinically, but a biopsy is useful to exclude other conditions.

Histologically, BHD is characterized by the presence of intraepidermal hemorrhagic bullae without thrombotic, inflammatory, or vasculitic changes. Although heparinrelated skin lesions have been attributed to various mechanisms, including immune-mediated thrombocytopenia, type IV hypersensitivity reactions, type I allergic hypersensitivity reactions, pustulosis, and skin necrosis, the pathogenesis of BHD remains poorly understood.4 The condition has demonstrated koebnerization in some cases.5

In our patient, the absence of histologic inflammation, viral changes, vasculitis, and amyloid deposition helped rule out the other entities in the differential. The absence of heparin and platelet factor 4 antibodies helped exclude heparin necrosis. Direct immunofluorescence testing was not obtained in our patient but may be used to evaluate for an immunobullous etiology.

Management strategies for BHD are variable, and associated evidence is lacking. Treatment of BHD should be considered in the clinical context based on the necessity for anticoagulation and the severity of the eruption. Discontinuation of anticoagulation therapy, if possible, may prevent morbidity in some cases.6 If it is necessary to continue anticoagulation therapy, changing the drug or decreasing the dose are reasonable options. Skin lesions may resolve even if anticoagulation therapy is continued at the same dose.7,8 Concurrent supportive wound care is beneficial.

- Perrinaud A, Jacobi D, Machet MC, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis occurring at sites distant from subcutaneous injections of heparin: three cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(suppl):S5-S7.

- Russo A, Curtis S, Balbuena-Merle R, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis is an under-recognized side effect of full dose low-molecular weight heparin: a case report and review of the literature [published online July 6, 2018]. Exp Hematol. 2018;7:15.

- Harris HB, Kurth BJ, Lam TK, et al. Heparin-induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis confined to the oral mucosa. Cutis. 2019;103:365-366, 370.

- Schindewolf M, Schwaner S, Wolter M, et al. Incidence and causes of heparin-induced skin lesions. CMAJ. 2009;181:477-481.

- Gargallo V, Romero FT, Rodríguez-Peralto JL, et al. Heparin induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis at a site distant from the injection. a report of five cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:857-859.

- Choudhry S, Fishman PM, Hernandez C. Heparin-induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis. Cutis. 2013;91:93-98.

- Maldonado Cid P, Moreno Alonso de Celada R, Herranz Pinto P, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis at sites distant from subcutaneous injections of heparin: a report of 5 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:E220-E222.

- Snow SC, Pearson DR, Fathi R, et al. Heparin-induced haemorrhagic bullous dermatosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2018;43:393-398.

The Diagnosis: Heparin-Induced Bullous Hemorrhagic Dermatosis

Results of a punch biopsy of one of the hemorrhagic papules revealed a subcorneal hemorrhagic vesicle without underlying vasculitis, vasculopathy, inflammation, or viral changes (Figure). Tissue and blood cultures were sterile. Heparin and platelet factor 4 antibody testing was negative. The patient was diagnosed with heparin induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis (BHD). After chest imaging ruled out a pulmonary embolism, anticoagulation therapy was discontinued. Respiratory symptoms improved on antibiotics, and the skin lesions resolved completely within 2 weeks.

Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis is an uncommon and underrecognized reaction to various anticoagulants. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis presents with painless, noninflammatory, hemorrhagic vesicles and bullae occurring at sites distant from anticoagulant administration. The condition was first characterized in 2006 by Perrinaud et al,1 who presented 3 cases in patients treated with heparin and low-molecular-weight heparin. Since then, there have been at least 90 cases reported in the international literature, with elderly men found to be the more affected demographic (male to female ratio, 1.9:1).2 Typically, BHD presents within 1 week of administration of an anticoagulant, but delayed onset has been reported.2 Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis is most commonly observed with enoxaparin use but also has been described in association with unfractionated heparin, low-molecular-weight heparin products, and warfarin.2

The noninflammatory-appearing hemorrhagic papules and small plaques of BHD generally are seen on the extremities but can occur anywhere on the body including the oral mucosa.3 The differential diagnosis of BHD may include autoimmune vesiculobullous conditions, bullous drug eruptions, herpetic infection, supratherapeutic anticoagulation, porphyria cutanea tarda, amyloidosis, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, angioinvasive infections, and heparin necrosis. Diagnosis of BHD can be made clinically, but a biopsy is useful to exclude other conditions.

Histologically, BHD is characterized by the presence of intraepidermal hemorrhagic bullae without thrombotic, inflammatory, or vasculitic changes. Although heparinrelated skin lesions have been attributed to various mechanisms, including immune-mediated thrombocytopenia, type IV hypersensitivity reactions, type I allergic hypersensitivity reactions, pustulosis, and skin necrosis, the pathogenesis of BHD remains poorly understood.4 The condition has demonstrated koebnerization in some cases.5

In our patient, the absence of histologic inflammation, viral changes, vasculitis, and amyloid deposition helped rule out the other entities in the differential. The absence of heparin and platelet factor 4 antibodies helped exclude heparin necrosis. Direct immunofluorescence testing was not obtained in our patient but may be used to evaluate for an immunobullous etiology.

Management strategies for BHD are variable, and associated evidence is lacking. Treatment of BHD should be considered in the clinical context based on the necessity for anticoagulation and the severity of the eruption. Discontinuation of anticoagulation therapy, if possible, may prevent morbidity in some cases.6 If it is necessary to continue anticoagulation therapy, changing the drug or decreasing the dose are reasonable options. Skin lesions may resolve even if anticoagulation therapy is continued at the same dose.7,8 Concurrent supportive wound care is beneficial.

The Diagnosis: Heparin-Induced Bullous Hemorrhagic Dermatosis

Results of a punch biopsy of one of the hemorrhagic papules revealed a subcorneal hemorrhagic vesicle without underlying vasculitis, vasculopathy, inflammation, or viral changes (Figure). Tissue and blood cultures were sterile. Heparin and platelet factor 4 antibody testing was negative. The patient was diagnosed with heparin induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis (BHD). After chest imaging ruled out a pulmonary embolism, anticoagulation therapy was discontinued. Respiratory symptoms improved on antibiotics, and the skin lesions resolved completely within 2 weeks.

Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis is an uncommon and underrecognized reaction to various anticoagulants. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis presents with painless, noninflammatory, hemorrhagic vesicles and bullae occurring at sites distant from anticoagulant administration. The condition was first characterized in 2006 by Perrinaud et al,1 who presented 3 cases in patients treated with heparin and low-molecular-weight heparin. Since then, there have been at least 90 cases reported in the international literature, with elderly men found to be the more affected demographic (male to female ratio, 1.9:1).2 Typically, BHD presents within 1 week of administration of an anticoagulant, but delayed onset has been reported.2 Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis is most commonly observed with enoxaparin use but also has been described in association with unfractionated heparin, low-molecular-weight heparin products, and warfarin.2

The noninflammatory-appearing hemorrhagic papules and small plaques of BHD generally are seen on the extremities but can occur anywhere on the body including the oral mucosa.3 The differential diagnosis of BHD may include autoimmune vesiculobullous conditions, bullous drug eruptions, herpetic infection, supratherapeutic anticoagulation, porphyria cutanea tarda, amyloidosis, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, angioinvasive infections, and heparin necrosis. Diagnosis of BHD can be made clinically, but a biopsy is useful to exclude other conditions.

Histologically, BHD is characterized by the presence of intraepidermal hemorrhagic bullae without thrombotic, inflammatory, or vasculitic changes. Although heparinrelated skin lesions have been attributed to various mechanisms, including immune-mediated thrombocytopenia, type IV hypersensitivity reactions, type I allergic hypersensitivity reactions, pustulosis, and skin necrosis, the pathogenesis of BHD remains poorly understood.4 The condition has demonstrated koebnerization in some cases.5

In our patient, the absence of histologic inflammation, viral changes, vasculitis, and amyloid deposition helped rule out the other entities in the differential. The absence of heparin and platelet factor 4 antibodies helped exclude heparin necrosis. Direct immunofluorescence testing was not obtained in our patient but may be used to evaluate for an immunobullous etiology.

Management strategies for BHD are variable, and associated evidence is lacking. Treatment of BHD should be considered in the clinical context based on the necessity for anticoagulation and the severity of the eruption. Discontinuation of anticoagulation therapy, if possible, may prevent morbidity in some cases.6 If it is necessary to continue anticoagulation therapy, changing the drug or decreasing the dose are reasonable options. Skin lesions may resolve even if anticoagulation therapy is continued at the same dose.7,8 Concurrent supportive wound care is beneficial.

- Perrinaud A, Jacobi D, Machet MC, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis occurring at sites distant from subcutaneous injections of heparin: three cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(suppl):S5-S7.

- Russo A, Curtis S, Balbuena-Merle R, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis is an under-recognized side effect of full dose low-molecular weight heparin: a case report and review of the literature [published online July 6, 2018]. Exp Hematol. 2018;7:15.

- Harris HB, Kurth BJ, Lam TK, et al. Heparin-induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis confined to the oral mucosa. Cutis. 2019;103:365-366, 370.

- Schindewolf M, Schwaner S, Wolter M, et al. Incidence and causes of heparin-induced skin lesions. CMAJ. 2009;181:477-481.

- Gargallo V, Romero FT, Rodríguez-Peralto JL, et al. Heparin induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis at a site distant from the injection. a report of five cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:857-859.

- Choudhry S, Fishman PM, Hernandez C. Heparin-induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis. Cutis. 2013;91:93-98.

- Maldonado Cid P, Moreno Alonso de Celada R, Herranz Pinto P, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis at sites distant from subcutaneous injections of heparin: a report of 5 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:E220-E222.

- Snow SC, Pearson DR, Fathi R, et al. Heparin-induced haemorrhagic bullous dermatosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2018;43:393-398.

- Perrinaud A, Jacobi D, Machet MC, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis occurring at sites distant from subcutaneous injections of heparin: three cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(suppl):S5-S7.

- Russo A, Curtis S, Balbuena-Merle R, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis is an under-recognized side effect of full dose low-molecular weight heparin: a case report and review of the literature [published online July 6, 2018]. Exp Hematol. 2018;7:15.

- Harris HB, Kurth BJ, Lam TK, et al. Heparin-induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis confined to the oral mucosa. Cutis. 2019;103:365-366, 370.

- Schindewolf M, Schwaner S, Wolter M, et al. Incidence and causes of heparin-induced skin lesions. CMAJ. 2009;181:477-481.

- Gargallo V, Romero FT, Rodríguez-Peralto JL, et al. Heparin induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis at a site distant from the injection. a report of five cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:857-859.

- Choudhry S, Fishman PM, Hernandez C. Heparin-induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis. Cutis. 2013;91:93-98.

- Maldonado Cid P, Moreno Alonso de Celada R, Herranz Pinto P, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis at sites distant from subcutaneous injections of heparin: a report of 5 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:E220-E222.

- Snow SC, Pearson DR, Fathi R, et al. Heparin-induced haemorrhagic bullous dermatosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2018;43:393-398.

A 66-year-old woman with a history of granulomatous lung disease managed with methotrexate and prednisone, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and Grave disease was admitted to the hospital for hypoxic respiratory failure. At admission, treatment was empirically initiated for pneumonia with intravenous ceftriaxone and azithromycin. Given the concern of a pulmonary embolism, intravenous heparin also was initiated. Dermatology was consulted for multiple painless blood blisters that erupted on the hands within 24 hours of admission. Physical examination revealed numerous firm hemorrhagic papules on the dorsal hands. Laboratory workup revealed a slightly elevated white blood cell count (11,800/µL [reference range, 4500–11,000/µL]), a normal stable platelet count (231,000/µL [reference range, 150,000– 350,000/µL]), and a normal international normalized ratio.

Red, Swollen, Tender Ear

The Diagnosis: Relapsing Polychondritis

Due to suspicion of relapsing polychondritis (RP), we also performed an audiometric evaluation, which demonstrated bilateral sensorineural hearing loss. Echocardiography highlighted mild to moderate mitralic and tricuspidal insufficiency without hemodynamic impairment (ejection fraction, 50%). Corticosteroid therapy was started (prednisone 0.5 mg/kg/d). After 7 days of treatment, inflammation was remarkably reduced, and the patient no longer reported pain.

Relapsing polychondritis is a rare noninfective condition characterized by focal inflammatory destruction of ear cartilage, followed by fibroblastic regeneration. It often is associated with ocular inflammation, including conjunctivitis, scleritis, and episcleritis; cochlear or vestibular lesions; and seronegative nonerosive inflammatory arthritis.1 Clinical examination of the affected area shows swelling, redness, and tenderness of the ear, which could lead to a misdiagnosis of cellulitis. A typical and useful differentiating sign is the sparing of the noncartilaginous parts of the ear lobule. If not promptly diagnosed and treated, the destructive process can cause thinning of the cartilage, leading to deformities of the external ear.

The differential diagnosis includes erysipelas, which presents as a rapidly appearing inflammatory patch with sharply defined borders, accompanied by regional lymphadenopathy or skin streaking as well as fever. Sweet syndrome usually presents with tender erythematous or violaceous skin papules, plaques, or nodules, frequently with a pseudovesicular appearance; patients generally present with a classic fever and peripheral neutrophilia.2 The localized cutaneous form of leishmaniasis usually appears with a papule that generally develops into an ulcerative nodular lesion. Our patient did not have a history of exposure to topical substances that could point to photocontact dermatitis.

Dion et al3 proposed 3 distinct clinical phenotypes of RP: (1) patients with concomitant myelodysplastic syndrome or other hematologic malignancy (<10% of patients), mostly older men with a poor prognosis; (2) patients with tracheobronchial involvement (approximately 25% of patients); and (3) patients who do not have hematologic or tracheobronchial involvement (approximately 65% of patients) with a good prognosis.

Two sets of diagnostic criteria have been proposed. The criteria from McAdam et al4 required the presence of 3 or more of the following clinical features: bilateral auricular chondritis, nonerosive seronegative inflammatory polyarthritis, nasal chondritis, ocular inflammation (eg, conjunctivitis, keratitis, scleritis/episcleritis, uveitis), respiratory tract chondritis (laryngeal and/or tracheal cartilages), and cochlear and/or vestibular dysfunction (eg, neurosensory hearing loss, tinnitus, vertigo). These criteria were modified by Damiani and Levine.5 According to the latter, all patients were required to have one of the following: at least 4 of the McAdam et al4 diagnostic criteria; 1 or more of the clinical findings included in the McAdam et al4 criteria with histologic features suggestive for RP; or chondritis at 2 or more separate anatomic locations with a response to glucocorticoids and/or dapsone.

No laboratory findings are specific for RP, and nonspecific indicators of inflammation--elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein--often are present.

The cause of RP is unknown. Familial clustering has not been observed. Terao et al6 found that HLA-DRB1*1602, -DQB1*0502, and -B*6701, in linkage disequilibrium with each other, are associated with susceptibility to RP.

There is no universal consensus about treatment, but a course of steroids leads to the resolution of the acute phase. Maintenance treatment can include dapsone, azathioprine, methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, and cyclosporine.7,8 Some studies have described the successful use of anti-tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors and rituximab.9,10

- Borgia F, Giuffrida R, Guarneri F, et al. Relapsing polychondritis: an updated review. Biomedicines. 2018;6:84.

- Rednic S, Damian L, Talarico R, et al. Relapsing polychondritis: state of the art on clinical practice guidelines. RMD Open. 2018:4(suppl 1)e000788.

- Dion J, Costedoat-Chalumeau N, Sène D, et al. Relapsing polychondritis can be characterized by three different clinical phenotypes: analysis of a recent series of 142 patients. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:2992-3001.

- McAdam LP, O'Hanlan MA, Bluestone R, et al. Relapsing polychondritis: prospective study of 23 patients and a review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1976;55:193.

- Damiani JM, Levine HL. Relapsing polychondritis--report of ten cases. Laryngoscope. 1979;89:929-946.

- Terao C, Yoshifuji H, Yamano Y, et al. Genotyping of relapsing polychondritis identified novel susceptibility HLA alleles and distinct genetic characteristics from other rheumatic diseases. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2016;55:1686.016-82

- Goldenberg G, Sangueza OP, Jorizzo JL. Successful treatment of relapsing polychondritis with mycophenolate mofetil. J Dermatolog Treat. 2006;17:158-159.

- Handler RP. Leflunomide for relapsing polychondritis: successful longterm treatment. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:1916; author reply 1916-1917.

- Carter JD. Treatment of relapsing polychondritis with a TNF antagonist. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:1413.

- Leroux G, Costedoat-Chalumeau N, Brihaye B, et al. Treatment of relapsing polychondritis with rituximab: a retrospective study of nine patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:577-582.

The Diagnosis: Relapsing Polychondritis

Due to suspicion of relapsing polychondritis (RP), we also performed an audiometric evaluation, which demonstrated bilateral sensorineural hearing loss. Echocardiography highlighted mild to moderate mitralic and tricuspidal insufficiency without hemodynamic impairment (ejection fraction, 50%). Corticosteroid therapy was started (prednisone 0.5 mg/kg/d). After 7 days of treatment, inflammation was remarkably reduced, and the patient no longer reported pain.

Relapsing polychondritis is a rare noninfective condition characterized by focal inflammatory destruction of ear cartilage, followed by fibroblastic regeneration. It often is associated with ocular inflammation, including conjunctivitis, scleritis, and episcleritis; cochlear or vestibular lesions; and seronegative nonerosive inflammatory arthritis.1 Clinical examination of the affected area shows swelling, redness, and tenderness of the ear, which could lead to a misdiagnosis of cellulitis. A typical and useful differentiating sign is the sparing of the noncartilaginous parts of the ear lobule. If not promptly diagnosed and treated, the destructive process can cause thinning of the cartilage, leading to deformities of the external ear.

The differential diagnosis includes erysipelas, which presents as a rapidly appearing inflammatory patch with sharply defined borders, accompanied by regional lymphadenopathy or skin streaking as well as fever. Sweet syndrome usually presents with tender erythematous or violaceous skin papules, plaques, or nodules, frequently with a pseudovesicular appearance; patients generally present with a classic fever and peripheral neutrophilia.2 The localized cutaneous form of leishmaniasis usually appears with a papule that generally develops into an ulcerative nodular lesion. Our patient did not have a history of exposure to topical substances that could point to photocontact dermatitis.

Dion et al3 proposed 3 distinct clinical phenotypes of RP: (1) patients with concomitant myelodysplastic syndrome or other hematologic malignancy (<10% of patients), mostly older men with a poor prognosis; (2) patients with tracheobronchial involvement (approximately 25% of patients); and (3) patients who do not have hematologic or tracheobronchial involvement (approximately 65% of patients) with a good prognosis.

Two sets of diagnostic criteria have been proposed. The criteria from McAdam et al4 required the presence of 3 or more of the following clinical features: bilateral auricular chondritis, nonerosive seronegative inflammatory polyarthritis, nasal chondritis, ocular inflammation (eg, conjunctivitis, keratitis, scleritis/episcleritis, uveitis), respiratory tract chondritis (laryngeal and/or tracheal cartilages), and cochlear and/or vestibular dysfunction (eg, neurosensory hearing loss, tinnitus, vertigo). These criteria were modified by Damiani and Levine.5 According to the latter, all patients were required to have one of the following: at least 4 of the McAdam et al4 diagnostic criteria; 1 or more of the clinical findings included in the McAdam et al4 criteria with histologic features suggestive for RP; or chondritis at 2 or more separate anatomic locations with a response to glucocorticoids and/or dapsone.

No laboratory findings are specific for RP, and nonspecific indicators of inflammation--elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein--often are present.

The cause of RP is unknown. Familial clustering has not been observed. Terao et al6 found that HLA-DRB1*1602, -DQB1*0502, and -B*6701, in linkage disequilibrium with each other, are associated with susceptibility to RP.

There is no universal consensus about treatment, but a course of steroids leads to the resolution of the acute phase. Maintenance treatment can include dapsone, azathioprine, methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, and cyclosporine.7,8 Some studies have described the successful use of anti-tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors and rituximab.9,10

The Diagnosis: Relapsing Polychondritis

Due to suspicion of relapsing polychondritis (RP), we also performed an audiometric evaluation, which demonstrated bilateral sensorineural hearing loss. Echocardiography highlighted mild to moderate mitralic and tricuspidal insufficiency without hemodynamic impairment (ejection fraction, 50%). Corticosteroid therapy was started (prednisone 0.5 mg/kg/d). After 7 days of treatment, inflammation was remarkably reduced, and the patient no longer reported pain.

Relapsing polychondritis is a rare noninfective condition characterized by focal inflammatory destruction of ear cartilage, followed by fibroblastic regeneration. It often is associated with ocular inflammation, including conjunctivitis, scleritis, and episcleritis; cochlear or vestibular lesions; and seronegative nonerosive inflammatory arthritis.1 Clinical examination of the affected area shows swelling, redness, and tenderness of the ear, which could lead to a misdiagnosis of cellulitis. A typical and useful differentiating sign is the sparing of the noncartilaginous parts of the ear lobule. If not promptly diagnosed and treated, the destructive process can cause thinning of the cartilage, leading to deformities of the external ear.

The differential diagnosis includes erysipelas, which presents as a rapidly appearing inflammatory patch with sharply defined borders, accompanied by regional lymphadenopathy or skin streaking as well as fever. Sweet syndrome usually presents with tender erythematous or violaceous skin papules, plaques, or nodules, frequently with a pseudovesicular appearance; patients generally present with a classic fever and peripheral neutrophilia.2 The localized cutaneous form of leishmaniasis usually appears with a papule that generally develops into an ulcerative nodular lesion. Our patient did not have a history of exposure to topical substances that could point to photocontact dermatitis.

Dion et al3 proposed 3 distinct clinical phenotypes of RP: (1) patients with concomitant myelodysplastic syndrome or other hematologic malignancy (<10% of patients), mostly older men with a poor prognosis; (2) patients with tracheobronchial involvement (approximately 25% of patients); and (3) patients who do not have hematologic or tracheobronchial involvement (approximately 65% of patients) with a good prognosis.

Two sets of diagnostic criteria have been proposed. The criteria from McAdam et al4 required the presence of 3 or more of the following clinical features: bilateral auricular chondritis, nonerosive seronegative inflammatory polyarthritis, nasal chondritis, ocular inflammation (eg, conjunctivitis, keratitis, scleritis/episcleritis, uveitis), respiratory tract chondritis (laryngeal and/or tracheal cartilages), and cochlear and/or vestibular dysfunction (eg, neurosensory hearing loss, tinnitus, vertigo). These criteria were modified by Damiani and Levine.5 According to the latter, all patients were required to have one of the following: at least 4 of the McAdam et al4 diagnostic criteria; 1 or more of the clinical findings included in the McAdam et al4 criteria with histologic features suggestive for RP; or chondritis at 2 or more separate anatomic locations with a response to glucocorticoids and/or dapsone.

No laboratory findings are specific for RP, and nonspecific indicators of inflammation--elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein--often are present.

The cause of RP is unknown. Familial clustering has not been observed. Terao et al6 found that HLA-DRB1*1602, -DQB1*0502, and -B*6701, in linkage disequilibrium with each other, are associated with susceptibility to RP.

There is no universal consensus about treatment, but a course of steroids leads to the resolution of the acute phase. Maintenance treatment can include dapsone, azathioprine, methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, and cyclosporine.7,8 Some studies have described the successful use of anti-tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors and rituximab.9,10

- Borgia F, Giuffrida R, Guarneri F, et al. Relapsing polychondritis: an updated review. Biomedicines. 2018;6:84.

- Rednic S, Damian L, Talarico R, et al. Relapsing polychondritis: state of the art on clinical practice guidelines. RMD Open. 2018:4(suppl 1)e000788.

- Dion J, Costedoat-Chalumeau N, Sène D, et al. Relapsing polychondritis can be characterized by three different clinical phenotypes: analysis of a recent series of 142 patients. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:2992-3001.

- McAdam LP, O'Hanlan MA, Bluestone R, et al. Relapsing polychondritis: prospective study of 23 patients and a review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1976;55:193.

- Damiani JM, Levine HL. Relapsing polychondritis--report of ten cases. Laryngoscope. 1979;89:929-946.

- Terao C, Yoshifuji H, Yamano Y, et al. Genotyping of relapsing polychondritis identified novel susceptibility HLA alleles and distinct genetic characteristics from other rheumatic diseases. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2016;55:1686.016-82

- Goldenberg G, Sangueza OP, Jorizzo JL. Successful treatment of relapsing polychondritis with mycophenolate mofetil. J Dermatolog Treat. 2006;17:158-159.

- Handler RP. Leflunomide for relapsing polychondritis: successful longterm treatment. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:1916; author reply 1916-1917.

- Carter JD. Treatment of relapsing polychondritis with a TNF antagonist. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:1413.

- Leroux G, Costedoat-Chalumeau N, Brihaye B, et al. Treatment of relapsing polychondritis with rituximab: a retrospective study of nine patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:577-582.

- Borgia F, Giuffrida R, Guarneri F, et al. Relapsing polychondritis: an updated review. Biomedicines. 2018;6:84.

- Rednic S, Damian L, Talarico R, et al. Relapsing polychondritis: state of the art on clinical practice guidelines. RMD Open. 2018:4(suppl 1)e000788.

- Dion J, Costedoat-Chalumeau N, Sène D, et al. Relapsing polychondritis can be characterized by three different clinical phenotypes: analysis of a recent series of 142 patients. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:2992-3001.

- McAdam LP, O'Hanlan MA, Bluestone R, et al. Relapsing polychondritis: prospective study of 23 patients and a review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1976;55:193.

- Damiani JM, Levine HL. Relapsing polychondritis--report of ten cases. Laryngoscope. 1979;89:929-946.

- Terao C, Yoshifuji H, Yamano Y, et al. Genotyping of relapsing polychondritis identified novel susceptibility HLA alleles and distinct genetic characteristics from other rheumatic diseases. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2016;55:1686.016-82

- Goldenberg G, Sangueza OP, Jorizzo JL. Successful treatment of relapsing polychondritis with mycophenolate mofetil. J Dermatolog Treat. 2006;17:158-159.

- Handler RP. Leflunomide for relapsing polychondritis: successful longterm treatment. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:1916; author reply 1916-1917.

- Carter JD. Treatment of relapsing polychondritis with a TNF antagonist. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:1413.

- Leroux G, Costedoat-Chalumeau N, Brihaye B, et al. Treatment of relapsing polychondritis with rituximab: a retrospective study of nine patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:577-582.

A 67-year-old woman presented with severe pain of the left external ear. She explained that similar episodes had occurred 2 years prior and affected the right ear and the nose. Her general practitioner prescribed topical and systemic antibiotic treatment, but there was no improvement. The patient also reported diffuse small joint pain without any radiologic sign of erosive arthritis. Physical examination revealed a red swollen external ear that was tender to the touch from the helix to the antitragus; conversely, the earlobe did not present any sign of inflammation. Redness of the left eye also was noticed, and a slit-lamp examination confirmed our suspect of scleritis. Results from routine blood tests, including an autoimmune panel, were within reference range, except for a nonspecific increase of inflammatory markers (erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 43 mm/h [reference range, 0–20 mm/h]; C-reactive protein, 5.65 mg/L [reference range, 0.08–3.1 mg/L]).

Irritable Baby With Weight Loss and a Periorificial and Truncal Rash

The Diagnosis: Acrodermatitis Enteropathica

Acrodermatitis enteropathica (AE) was the presumptive diagnosis. Oral supplementation with zinc sulfate 3 mg/kg/d was started immediately after a zinc level was ordered. A low zinc level of 15 µg/dL (reference range, 56-134 µg/dL) eventually was obtained. The lesions began to fade in 2 days along with return of normal feeding and disposition, and the patient was discharged with continued zinc supplementation.

Acrodermatitis enteropathica is an autosomal-recessive condition resulting in severe zinc deficiency caused by a defect of dietary zinc absorption in the duodenum and jejunum.1 It occurs in 1 in 500,000 individuals with no gender or racial predilection. It can be acquired or inherited.2 Recognition of clinical symptoms is essential due to potential death if untreated. Zinc is an important trace element required for the proper functioning of all cells and plays a large role in the metabolism of protein, carbohydrates, and vitamin A. Zinc deficiency impairs immune function, leading to bacterial infections. It also is a cofactor of numerous metal enzymes such as alkaline phosphatase, RNA polymerase, and numerous digestive enzymes.3

Our laboratory analysis revealed low alkaline phosphatase and zinc levels, which led to the diagnosis of AE; unfortunately, these levels can be ambiguous.4 There are many causes of acquired zinc deficiency, including premature birth, low birth weight, zinc deficiency in maternal milk, exclusive parenteral nutrition, malabsorption syndromes such as Crohn disease and celiac disease, alcoholism, low calcium and phytate (cereal grain) diet, and kwashiorkor.5 The hereditary deficiency of zinc classically is known as AE and is caused by an autosomal-recessive mutation of the SLC39A4 gene on chromosome arm 8q24.3, which determines a congenital partial or total deficiency of the zinc transporter protein ZIP4.6

The clinical manifestations of acquired zinc deficiency and AE are similar and consist of 3 essential symptoms: periorificial dermatitis, alopecia, and diarrhea. Unfortunately, this clinical triad is complete in only 20% of patients with AE.3 For example, our patient was too young for an alopecia determination. The disease typically presents with eczematous papules and sometimes vesiculobullous or pustular lesions located around perioral and acral areas (Figure 1) as well as the anogenital region (Figures 2 and 3). The severity of the skin lesions is variable.7 Our patient also presented with eczematous truncal papules on the chest (Figure 4). Acrodermatitis enteropathica usually presents during childhood after weaning. Along with the aforementioned skin findings, other symptoms in infancy can include diarrhea, mood changes, and anorexia. In school-aged children and toddlers, zinc deficiency is characterized by growth retardation, alopecia, weight loss, and recurrent infections.

In the differential diagnosis, the clinical presentation of biotin deficiency involves abnormalities of the hair, skin, nails, and central nervous system (eg, seizures, ataxia, deafness).8 Cystic fibrosis presentation depends on the multiorgan involvement, but neonates often present with failure to thrive.9 Essential fatty acid deficiency presents clinically as dermatitis, alopecia, and thrombocytopenia, but a complete blood cell count with platelets was within reference range in our patient.10 Langerhans cell histiocytosis presents with perineal and postauricular lesions, but the skin biopsy did not confirm this diagnosis in our patient.11 Histopathologic examination of the buttock biopsy in our patient revealed nonspecific epidermal hyperplasia with acanthosis as well as clustered necrotic keratinocytes with vacuolization and parakeratosis.

Most clinicians who suspect AE treat with a therapeutic supplementation of zinc sulfate 3 mg/kg/d while awaiting laboratory results. Acrodermatitis enteropathica is a rare condition, and early recognition of skin findings is important because misdiagnosis can lead to infections, malnutrition, and possibly death.

- Sehgal VN, Jain S. Acrodermatitis enteropathica. Clin Dermatol. 2000;18:745-748.

- Van Wouwe JP. Clinical and laboratory assessment of zinc deficiency in Dutch children: a review. Biol Trace Elem Res. 1995;49:211-225.

- Maverakis E, Fung MA, Lynch PJ, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica and an overview of zinc metabolism. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:116-124.

- Van Wouwe JP. Clinical and laboratory diagnosis of acrodermatitis enteropathica. Eur J Pediatr. 1989;149:2-8.

- Perafán-Riveros C, França LF, Alves AC, et al. Acrodermatitisenteropathica: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:426-431.

- Kury S, Dréno B, Bézieau S, et al. Identification of SLC39A4, a gene involved in acrodermatitis enteropathica. Nat Genet. 2002;31:239-240.

- Nistor N, Ciontu L, Frasinariu OE, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica: a case report. Medicine. 2016;95:E3553.

- Gratias T. Biotin deficiency. Medscape website. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/984803-overview. Updated October 22, 2018. Accessed October 15, 2020.

- Sharma G. Cystic fibrosis. Medscape website. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1001602-overview. Updated September 28, 2018. Accessed October 15, 2020.

- Morley JE. Essential fatty acid deficiency. Merck Manual website. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/nutritional-disorders/undernutrition/essential-fatty-acid-deficiency. Updated January 2020. Accessed October 15, 2020.

- Shea CR. Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Medscape website. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1100579-overview. Updated June 12, 2020. Accessed October 15, 2020.

The Diagnosis: Acrodermatitis Enteropathica

Acrodermatitis enteropathica (AE) was the presumptive diagnosis. Oral supplementation with zinc sulfate 3 mg/kg/d was started immediately after a zinc level was ordered. A low zinc level of 15 µg/dL (reference range, 56-134 µg/dL) eventually was obtained. The lesions began to fade in 2 days along with return of normal feeding and disposition, and the patient was discharged with continued zinc supplementation.

Acrodermatitis enteropathica is an autosomal-recessive condition resulting in severe zinc deficiency caused by a defect of dietary zinc absorption in the duodenum and jejunum.1 It occurs in 1 in 500,000 individuals with no gender or racial predilection. It can be acquired or inherited.2 Recognition of clinical symptoms is essential due to potential death if untreated. Zinc is an important trace element required for the proper functioning of all cells and plays a large role in the metabolism of protein, carbohydrates, and vitamin A. Zinc deficiency impairs immune function, leading to bacterial infections. It also is a cofactor of numerous metal enzymes such as alkaline phosphatase, RNA polymerase, and numerous digestive enzymes.3

Our laboratory analysis revealed low alkaline phosphatase and zinc levels, which led to the diagnosis of AE; unfortunately, these levels can be ambiguous.4 There are many causes of acquired zinc deficiency, including premature birth, low birth weight, zinc deficiency in maternal milk, exclusive parenteral nutrition, malabsorption syndromes such as Crohn disease and celiac disease, alcoholism, low calcium and phytate (cereal grain) diet, and kwashiorkor.5 The hereditary deficiency of zinc classically is known as AE and is caused by an autosomal-recessive mutation of the SLC39A4 gene on chromosome arm 8q24.3, which determines a congenital partial or total deficiency of the zinc transporter protein ZIP4.6

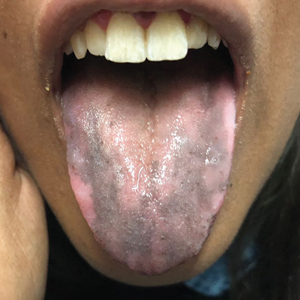

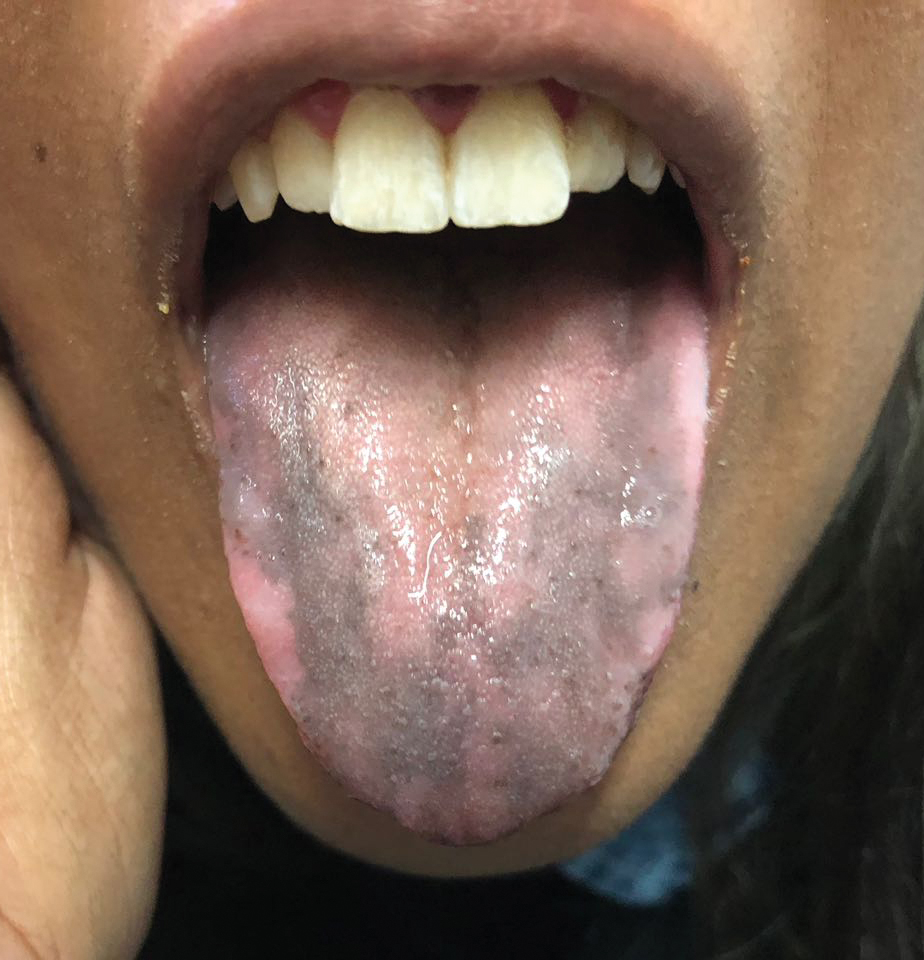

The clinical manifestations of acquired zinc deficiency and AE are similar and consist of 3 essential symptoms: periorificial dermatitis, alopecia, and diarrhea. Unfortunately, this clinical triad is complete in only 20% of patients with AE.3 For example, our patient was too young for an alopecia determination. The disease typically presents with eczematous papules and sometimes vesiculobullous or pustular lesions located around perioral and acral areas (Figure 1) as well as the anogenital region (Figures 2 and 3). The severity of the skin lesions is variable.7 Our patient also presented with eczematous truncal papules on the chest (Figure 4). Acrodermatitis enteropathica usually presents during childhood after weaning. Along with the aforementioned skin findings, other symptoms in infancy can include diarrhea, mood changes, and anorexia. In school-aged children and toddlers, zinc deficiency is characterized by growth retardation, alopecia, weight loss, and recurrent infections.

In the differential diagnosis, the clinical presentation of biotin deficiency involves abnormalities of the hair, skin, nails, and central nervous system (eg, seizures, ataxia, deafness).8 Cystic fibrosis presentation depends on the multiorgan involvement, but neonates often present with failure to thrive.9 Essential fatty acid deficiency presents clinically as dermatitis, alopecia, and thrombocytopenia, but a complete blood cell count with platelets was within reference range in our patient.10 Langerhans cell histiocytosis presents with perineal and postauricular lesions, but the skin biopsy did not confirm this diagnosis in our patient.11 Histopathologic examination of the buttock biopsy in our patient revealed nonspecific epidermal hyperplasia with acanthosis as well as clustered necrotic keratinocytes with vacuolization and parakeratosis.

Most clinicians who suspect AE treat with a therapeutic supplementation of zinc sulfate 3 mg/kg/d while awaiting laboratory results. Acrodermatitis enteropathica is a rare condition, and early recognition of skin findings is important because misdiagnosis can lead to infections, malnutrition, and possibly death.

The Diagnosis: Acrodermatitis Enteropathica

Acrodermatitis enteropathica (AE) was the presumptive diagnosis. Oral supplementation with zinc sulfate 3 mg/kg/d was started immediately after a zinc level was ordered. A low zinc level of 15 µg/dL (reference range, 56-134 µg/dL) eventually was obtained. The lesions began to fade in 2 days along with return of normal feeding and disposition, and the patient was discharged with continued zinc supplementation.

Acrodermatitis enteropathica is an autosomal-recessive condition resulting in severe zinc deficiency caused by a defect of dietary zinc absorption in the duodenum and jejunum.1 It occurs in 1 in 500,000 individuals with no gender or racial predilection. It can be acquired or inherited.2 Recognition of clinical symptoms is essential due to potential death if untreated. Zinc is an important trace element required for the proper functioning of all cells and plays a large role in the metabolism of protein, carbohydrates, and vitamin A. Zinc deficiency impairs immune function, leading to bacterial infections. It also is a cofactor of numerous metal enzymes such as alkaline phosphatase, RNA polymerase, and numerous digestive enzymes.3

Our laboratory analysis revealed low alkaline phosphatase and zinc levels, which led to the diagnosis of AE; unfortunately, these levels can be ambiguous.4 There are many causes of acquired zinc deficiency, including premature birth, low birth weight, zinc deficiency in maternal milk, exclusive parenteral nutrition, malabsorption syndromes such as Crohn disease and celiac disease, alcoholism, low calcium and phytate (cereal grain) diet, and kwashiorkor.5 The hereditary deficiency of zinc classically is known as AE and is caused by an autosomal-recessive mutation of the SLC39A4 gene on chromosome arm 8q24.3, which determines a congenital partial or total deficiency of the zinc transporter protein ZIP4.6

The clinical manifestations of acquired zinc deficiency and AE are similar and consist of 3 essential symptoms: periorificial dermatitis, alopecia, and diarrhea. Unfortunately, this clinical triad is complete in only 20% of patients with AE.3 For example, our patient was too young for an alopecia determination. The disease typically presents with eczematous papules and sometimes vesiculobullous or pustular lesions located around perioral and acral areas (Figure 1) as well as the anogenital region (Figures 2 and 3). The severity of the skin lesions is variable.7 Our patient also presented with eczematous truncal papules on the chest (Figure 4). Acrodermatitis enteropathica usually presents during childhood after weaning. Along with the aforementioned skin findings, other symptoms in infancy can include diarrhea, mood changes, and anorexia. In school-aged children and toddlers, zinc deficiency is characterized by growth retardation, alopecia, weight loss, and recurrent infections.

In the differential diagnosis, the clinical presentation of biotin deficiency involves abnormalities of the hair, skin, nails, and central nervous system (eg, seizures, ataxia, deafness).8 Cystic fibrosis presentation depends on the multiorgan involvement, but neonates often present with failure to thrive.9 Essential fatty acid deficiency presents clinically as dermatitis, alopecia, and thrombocytopenia, but a complete blood cell count with platelets was within reference range in our patient.10 Langerhans cell histiocytosis presents with perineal and postauricular lesions, but the skin biopsy did not confirm this diagnosis in our patient.11 Histopathologic examination of the buttock biopsy in our patient revealed nonspecific epidermal hyperplasia with acanthosis as well as clustered necrotic keratinocytes with vacuolization and parakeratosis.

Most clinicians who suspect AE treat with a therapeutic supplementation of zinc sulfate 3 mg/kg/d while awaiting laboratory results. Acrodermatitis enteropathica is a rare condition, and early recognition of skin findings is important because misdiagnosis can lead to infections, malnutrition, and possibly death.

- Sehgal VN, Jain S. Acrodermatitis enteropathica. Clin Dermatol. 2000;18:745-748.

- Van Wouwe JP. Clinical and laboratory assessment of zinc deficiency in Dutch children: a review. Biol Trace Elem Res. 1995;49:211-225.

- Maverakis E, Fung MA, Lynch PJ, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica and an overview of zinc metabolism. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:116-124.

- Van Wouwe JP. Clinical and laboratory diagnosis of acrodermatitis enteropathica. Eur J Pediatr. 1989;149:2-8.

- Perafán-Riveros C, França LF, Alves AC, et al. Acrodermatitisenteropathica: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:426-431.

- Kury S, Dréno B, Bézieau S, et al. Identification of SLC39A4, a gene involved in acrodermatitis enteropathica. Nat Genet. 2002;31:239-240.

- Nistor N, Ciontu L, Frasinariu OE, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica: a case report. Medicine. 2016;95:E3553.

- Gratias T. Biotin deficiency. Medscape website. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/984803-overview. Updated October 22, 2018. Accessed October 15, 2020.

- Sharma G. Cystic fibrosis. Medscape website. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1001602-overview. Updated September 28, 2018. Accessed October 15, 2020.

- Morley JE. Essential fatty acid deficiency. Merck Manual website. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/nutritional-disorders/undernutrition/essential-fatty-acid-deficiency. Updated January 2020. Accessed October 15, 2020.

- Shea CR. Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Medscape website. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1100579-overview. Updated June 12, 2020. Accessed October 15, 2020.

- Sehgal VN, Jain S. Acrodermatitis enteropathica. Clin Dermatol. 2000;18:745-748.

- Van Wouwe JP. Clinical and laboratory assessment of zinc deficiency in Dutch children: a review. Biol Trace Elem Res. 1995;49:211-225.

- Maverakis E, Fung MA, Lynch PJ, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica and an overview of zinc metabolism. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:116-124.

- Van Wouwe JP. Clinical and laboratory diagnosis of acrodermatitis enteropathica. Eur J Pediatr. 1989;149:2-8.

- Perafán-Riveros C, França LF, Alves AC, et al. Acrodermatitisenteropathica: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:426-431.

- Kury S, Dréno B, Bézieau S, et al. Identification of SLC39A4, a gene involved in acrodermatitis enteropathica. Nat Genet. 2002;31:239-240.

- Nistor N, Ciontu L, Frasinariu OE, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica: a case report. Medicine. 2016;95:E3553.

- Gratias T. Biotin deficiency. Medscape website. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/984803-overview. Updated October 22, 2018. Accessed October 15, 2020.

- Sharma G. Cystic fibrosis. Medscape website. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1001602-overview. Updated September 28, 2018. Accessed October 15, 2020.

- Morley JE. Essential fatty acid deficiency. Merck Manual website. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/nutritional-disorders/undernutrition/essential-fatty-acid-deficiency. Updated January 2020. Accessed October 15, 2020.

- Shea CR. Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Medscape website. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1100579-overview. Updated June 12, 2020. Accessed October 15, 2020.

A 4-month-old infant boy presented to the pediatric hospital unit with a rash, fever, and failure to thrive. Prior to admission, the patient was treated for impetigo by a community dermatologist. After not responding to treatment, he was admitted and given intravenous acyclovir for 1 day by the pediatric hospitalist, and the dermatology service was consulted. The parents reported the patient had diarrhea for 1 month and a worsening rash over the last 2 weeks. The mother was breastfeeding. Physical examination revealed a fever (temperature, 38.9°C [102°F]) and an irritable infant whose growth curve had fallen from the 50th to 15th percentile since the 2-month well-baby examination. He had a fine, red, papular truncal rash with confluent plaques in a periorificial distribution that spared the inguinal skin folds, with some vesicles in a herpetiform presentation on the thighs as well as inflammation on the feet and hands. A complete blood cell count was within reference range, but the alkaline phosphatase level was low at 53 U/L (reference range, 72–307 U/L). A herpes simplex virus test was negative. A human immunodeficiency virus test and skin biopsy were performed.

Paronychia and Target Lesions After Hematopoietic Cell Transplant

The Diagnosis: Fusariosis

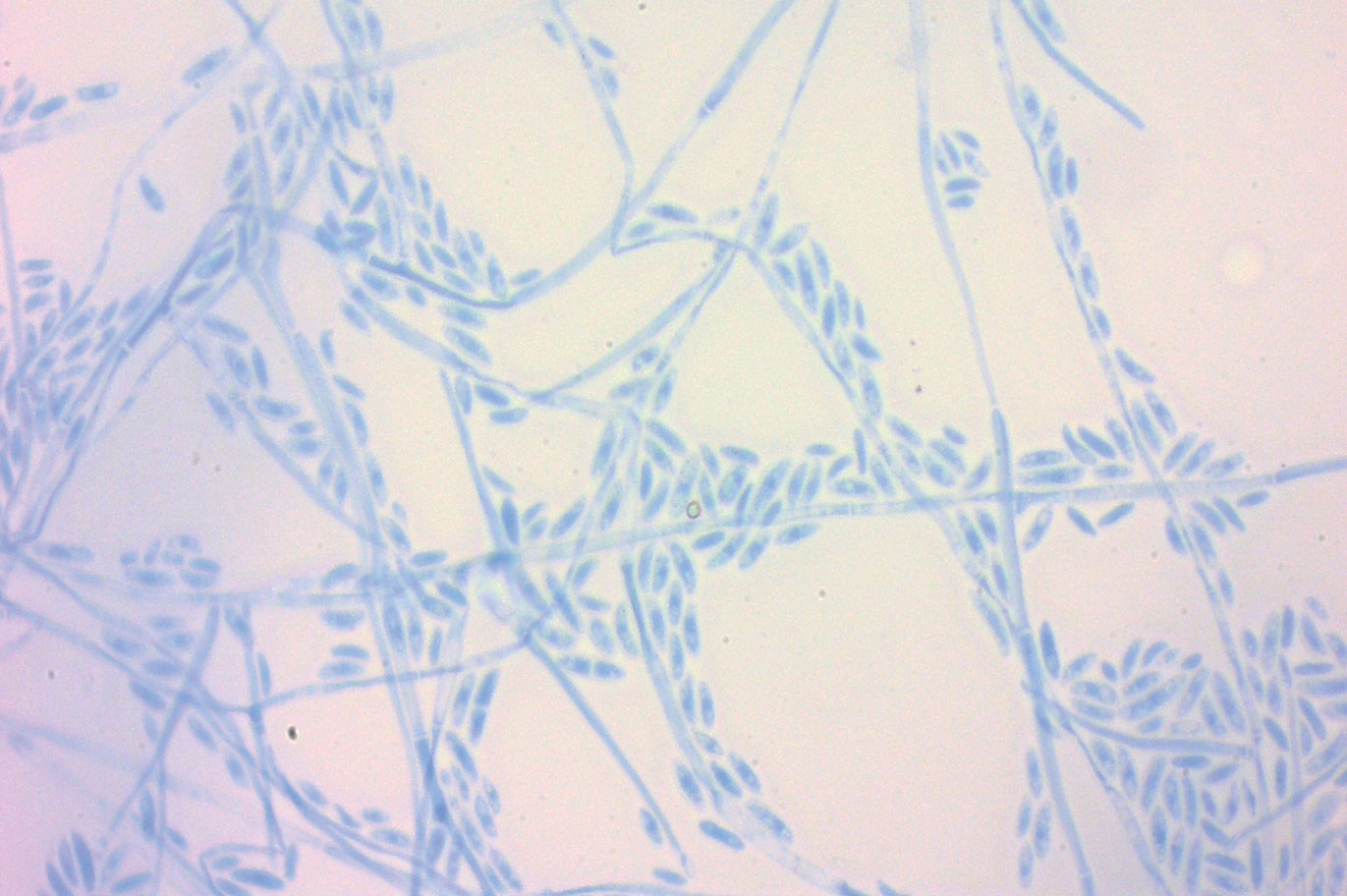

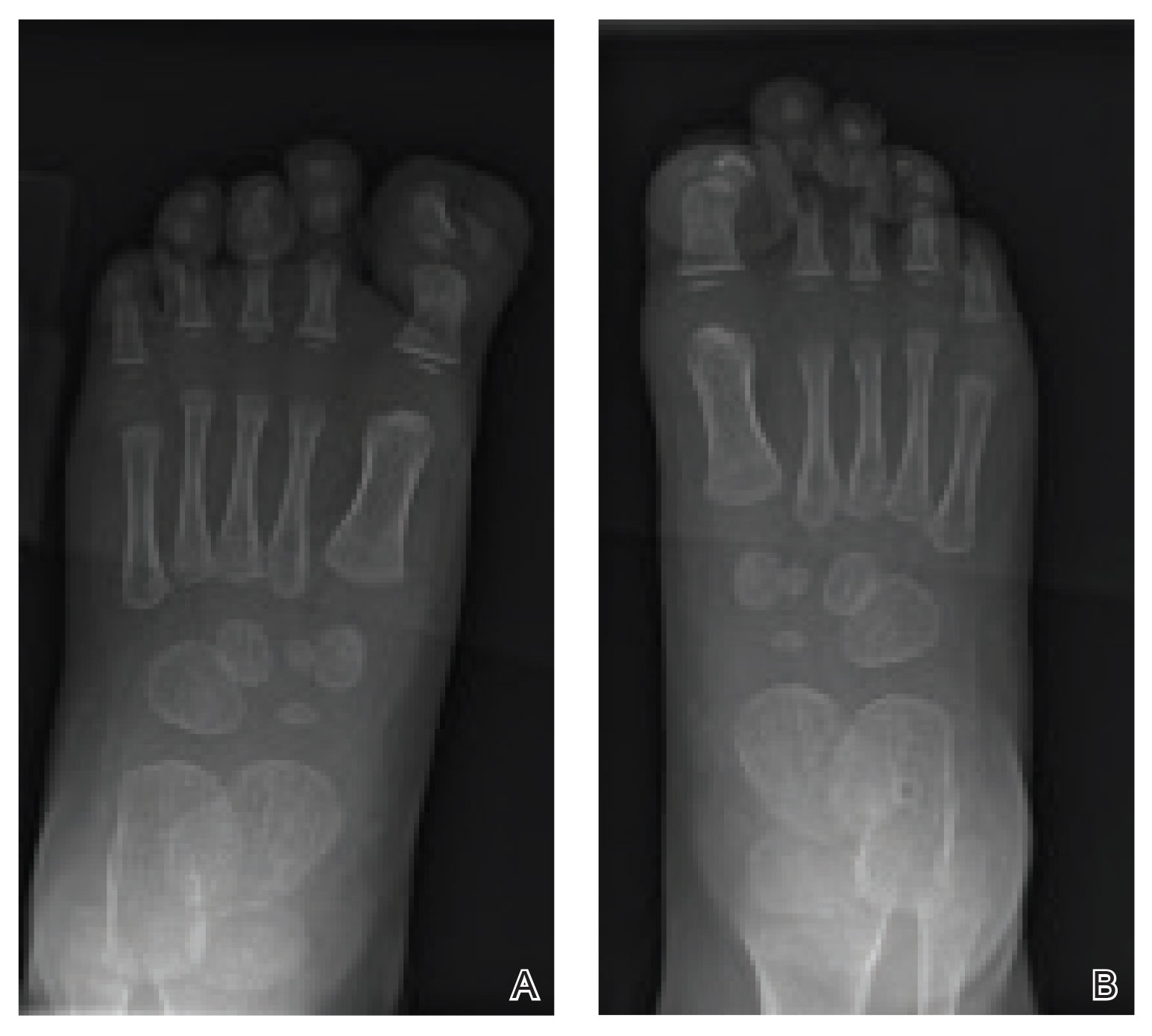

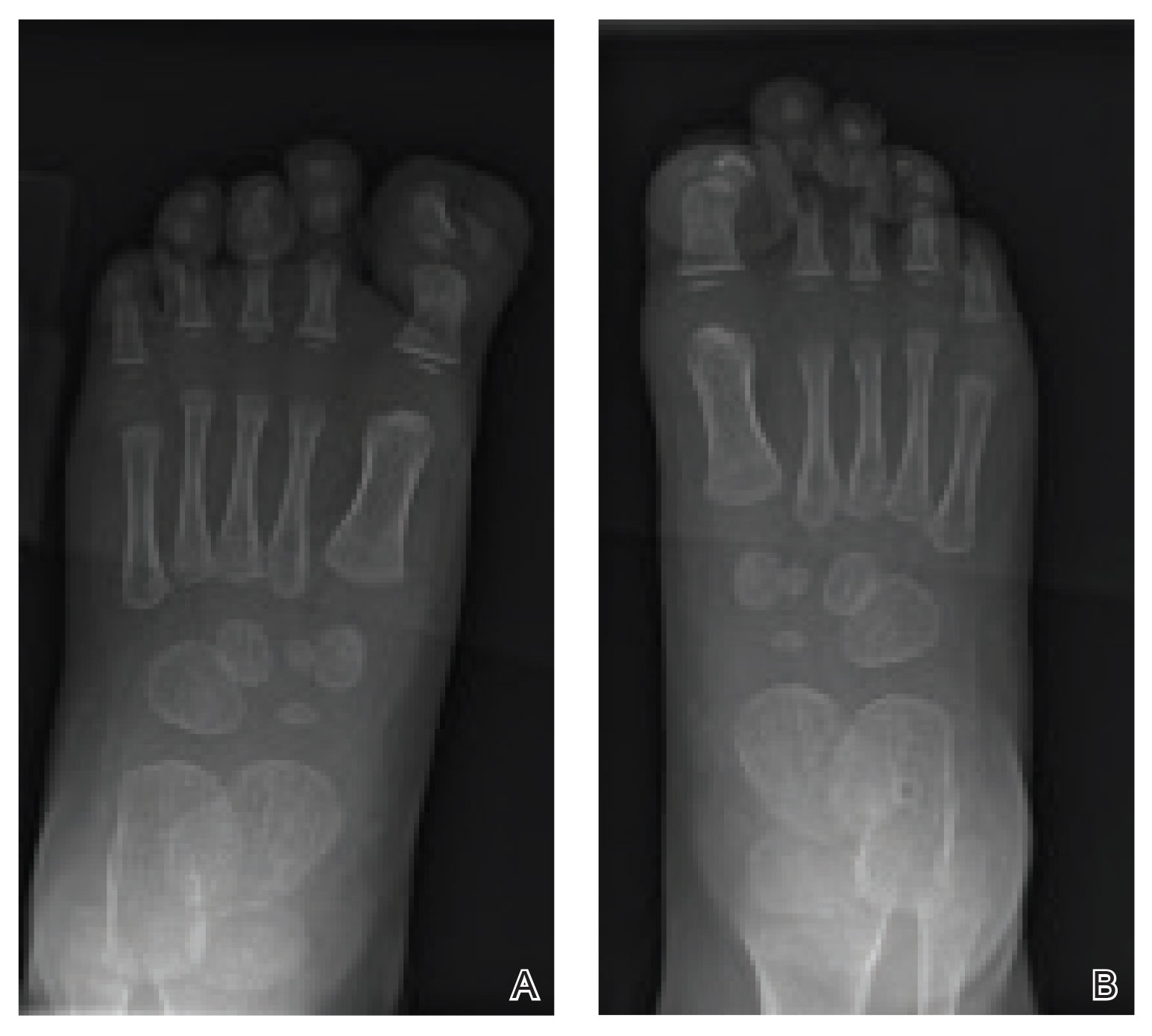

A periodic acid-Schiff stain of the seropurulent drainage from a skin nodule revealed neutrophils and scarce branching hyaline hyphae. Skin and blood cultures grew a white cottony colony. Microscopic examination showed sickle-shaped macroconidia and septate hyaline hyphae with branching acute angles (Figure). Molecular analysis by polymerase chain reaction yielded Fusarium solani species complex. Histopathology as well as culture and molecular findings were consistent with a diagnosis of disseminated fusariosis. Amphotericin B was started with rapid clinical improvement. The patient was asymptomatic upon discharge with voriconazole 200 mg twice daily.

Fusariosis is an emerging, opportunistic, and life-threatening mycosis. In immunocompetent patients it may cause onychomycosis and keratitis.1 Invasive fusariosis predominantly is caused by the F solani species complex and affects immunocompromised patients, especially those with neutropenia or acute leukemia or hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients.2

Before invasion, the infection frequently may begin by affecting the nail apparatus as onychomycosis or paronychia of the skin. As in our case, trauma or manipulation of the nail favors dissemination.3 Skin manifestations include erythematous to violaceous papules, macules, and nodules with central necrosis or crust; some may exhibit target morphology. Other organs may be affected, including the sinuses, lungs, liver, spleen, and kidneys. A comprehensive clinical examination before hematopoietic cell transplant and during fever and neutropenia may opportunely identify these potential infective foci.3,4

The differential diagnosis of disseminated fusariosis includes bacterial infections, especially Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and other invasive fungal infections, particularly aspergillosis, mucormycosis, and candidiasis.5 Symptom persistence after broad-spectrum antibiotic initiation should raise diagnostic suspicion of systemic mycosis or mycobacterial infection. Mucormycosis and candidiasis have histopathologic profiles that differ from fusariosis, presenting with broad ribbonlike hyphae with 90° angulation and pseudohyphae with budding yeast cells, respectively. Differentiation of disseminated fusariosis and aspergillosis in neutropenic patients is difficult. Hyphae cannot be differentiated from those of Aspergillus species on histology.6 Furthermore, serologic assays, such as galactomannan and (1,3)-β-D-glucan, cross-react with both genera. Clinically, Fusarium species exhibit metastatic skin lesions, cellulitis, and positive blood cultures due to adventitious sporulation more frequently than Aspergillus species. Patients with aspergillosis more commonly present with sinusitis, pneumonia, and pulmonary macronodules with the halo sign.6 Although nocardiosis presents with disseminated subcutaneous nodules with pulmonary affection in immunocompromised patients, its morphology is very different from fusariosis. Nocardia presents with a gram-positive bacillus with the microscopic appearance of branching filaments. Yeastlike microorganisms with morphology ranging from oval to sausagelike are found in talaromycosis, an uncommon fungal infection predominantly caused by Talaromyces marneffei. Fusarium species culture reveals white cottony colonies with characteristic hyaline, canoe-shaped or sickle-shaped (banana-shaped), multicellular macroconidia, and microconidia. Precise species identification requires molecular analyses such as polymerase chain reaction.

Mortality is high, ranging from 50% to 70% of cases.5 Voriconazole or lipid-based amphotericin B are considered first-line treatments. Posaconazole may be employed as a second-line alternative. Surgical debridement of infected tissues and removal of colonized venous catheters is recommended. Secondary prophylaxis should be considered with agents such as voriconazole, posaconazole, or amphotericin B.5 Resolution of immunosuppression and neutropenia is an important factor to reduce the mortality rate.

- Ranawaka RR, Nagahawatte A, Gunasekara TA. Fusarium onychomycosis: prevalence, clinical presentations, response toitraconazole and terbinafine pulse therapy, and 1-year follow-up in nine cases. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:1275-1282.

- Nucci F, Nouer SA, Capone D, et al. Fusariosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;36:706-714.

- Varon AG, Nouer SA, Barreiros G, et al. Superficial skin lesions positive for Fusarium are associated with subsequent development of invasive fusariosis. J Infect. 2014;68:85-89.

- Hay RJ. Fusarium infections of the skin. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2007;20:115-117.

- Tortorano AM, Richardson M, Roilides E, et al. ESCMID and ECMM joint guidelines on diagnosis and management of hyalohyphomycosis: Fusarium spp., Scedosporium spp. and others. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20:27-46.

- Nucci F, Nouer SA, Capone D, et al. Invasive mould disease in haematologic patients: comparison between fusariosis and aspergillosis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2018;24:1105.e1-1105.e4.

The Diagnosis: Fusariosis

A periodic acid-Schiff stain of the seropurulent drainage from a skin nodule revealed neutrophils and scarce branching hyaline hyphae. Skin and blood cultures grew a white cottony colony. Microscopic examination showed sickle-shaped macroconidia and septate hyaline hyphae with branching acute angles (Figure). Molecular analysis by polymerase chain reaction yielded Fusarium solani species complex. Histopathology as well as culture and molecular findings were consistent with a diagnosis of disseminated fusariosis. Amphotericin B was started with rapid clinical improvement. The patient was asymptomatic upon discharge with voriconazole 200 mg twice daily.

Fusariosis is an emerging, opportunistic, and life-threatening mycosis. In immunocompetent patients it may cause onychomycosis and keratitis.1 Invasive fusariosis predominantly is caused by the F solani species complex and affects immunocompromised patients, especially those with neutropenia or acute leukemia or hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients.2

Before invasion, the infection frequently may begin by affecting the nail apparatus as onychomycosis or paronychia of the skin. As in our case, trauma or manipulation of the nail favors dissemination.3 Skin manifestations include erythematous to violaceous papules, macules, and nodules with central necrosis or crust; some may exhibit target morphology. Other organs may be affected, including the sinuses, lungs, liver, spleen, and kidneys. A comprehensive clinical examination before hematopoietic cell transplant and during fever and neutropenia may opportunely identify these potential infective foci.3,4

The differential diagnosis of disseminated fusariosis includes bacterial infections, especially Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and other invasive fungal infections, particularly aspergillosis, mucormycosis, and candidiasis.5 Symptom persistence after broad-spectrum antibiotic initiation should raise diagnostic suspicion of systemic mycosis or mycobacterial infection. Mucormycosis and candidiasis have histopathologic profiles that differ from fusariosis, presenting with broad ribbonlike hyphae with 90° angulation and pseudohyphae with budding yeast cells, respectively. Differentiation of disseminated fusariosis and aspergillosis in neutropenic patients is difficult. Hyphae cannot be differentiated from those of Aspergillus species on histology.6 Furthermore, serologic assays, such as galactomannan and (1,3)-β-D-glucan, cross-react with both genera. Clinically, Fusarium species exhibit metastatic skin lesions, cellulitis, and positive blood cultures due to adventitious sporulation more frequently than Aspergillus species. Patients with aspergillosis more commonly present with sinusitis, pneumonia, and pulmonary macronodules with the halo sign.6 Although nocardiosis presents with disseminated subcutaneous nodules with pulmonary affection in immunocompromised patients, its morphology is very different from fusariosis. Nocardia presents with a gram-positive bacillus with the microscopic appearance of branching filaments. Yeastlike microorganisms with morphology ranging from oval to sausagelike are found in talaromycosis, an uncommon fungal infection predominantly caused by Talaromyces marneffei. Fusarium species culture reveals white cottony colonies with characteristic hyaline, canoe-shaped or sickle-shaped (banana-shaped), multicellular macroconidia, and microconidia. Precise species identification requires molecular analyses such as polymerase chain reaction.

Mortality is high, ranging from 50% to 70% of cases.5 Voriconazole or lipid-based amphotericin B are considered first-line treatments. Posaconazole may be employed as a second-line alternative. Surgical debridement of infected tissues and removal of colonized venous catheters is recommended. Secondary prophylaxis should be considered with agents such as voriconazole, posaconazole, or amphotericin B.5 Resolution of immunosuppression and neutropenia is an important factor to reduce the mortality rate.

The Diagnosis: Fusariosis

A periodic acid-Schiff stain of the seropurulent drainage from a skin nodule revealed neutrophils and scarce branching hyaline hyphae. Skin and blood cultures grew a white cottony colony. Microscopic examination showed sickle-shaped macroconidia and septate hyaline hyphae with branching acute angles (Figure). Molecular analysis by polymerase chain reaction yielded Fusarium solani species complex. Histopathology as well as culture and molecular findings were consistent with a diagnosis of disseminated fusariosis. Amphotericin B was started with rapid clinical improvement. The patient was asymptomatic upon discharge with voriconazole 200 mg twice daily.

Fusariosis is an emerging, opportunistic, and life-threatening mycosis. In immunocompetent patients it may cause onychomycosis and keratitis.1 Invasive fusariosis predominantly is caused by the F solani species complex and affects immunocompromised patients, especially those with neutropenia or acute leukemia or hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients.2

Before invasion, the infection frequently may begin by affecting the nail apparatus as onychomycosis or paronychia of the skin. As in our case, trauma or manipulation of the nail favors dissemination.3 Skin manifestations include erythematous to violaceous papules, macules, and nodules with central necrosis or crust; some may exhibit target morphology. Other organs may be affected, including the sinuses, lungs, liver, spleen, and kidneys. A comprehensive clinical examination before hematopoietic cell transplant and during fever and neutropenia may opportunely identify these potential infective foci.3,4

The differential diagnosis of disseminated fusariosis includes bacterial infections, especially Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and other invasive fungal infections, particularly aspergillosis, mucormycosis, and candidiasis.5 Symptom persistence after broad-spectrum antibiotic initiation should raise diagnostic suspicion of systemic mycosis or mycobacterial infection. Mucormycosis and candidiasis have histopathologic profiles that differ from fusariosis, presenting with broad ribbonlike hyphae with 90° angulation and pseudohyphae with budding yeast cells, respectively. Differentiation of disseminated fusariosis and aspergillosis in neutropenic patients is difficult. Hyphae cannot be differentiated from those of Aspergillus species on histology.6 Furthermore, serologic assays, such as galactomannan and (1,3)-β-D-glucan, cross-react with both genera. Clinically, Fusarium species exhibit metastatic skin lesions, cellulitis, and positive blood cultures due to adventitious sporulation more frequently than Aspergillus species. Patients with aspergillosis more commonly present with sinusitis, pneumonia, and pulmonary macronodules with the halo sign.6 Although nocardiosis presents with disseminated subcutaneous nodules with pulmonary affection in immunocompromised patients, its morphology is very different from fusariosis. Nocardia presents with a gram-positive bacillus with the microscopic appearance of branching filaments. Yeastlike microorganisms with morphology ranging from oval to sausagelike are found in talaromycosis, an uncommon fungal infection predominantly caused by Talaromyces marneffei. Fusarium species culture reveals white cottony colonies with characteristic hyaline, canoe-shaped or sickle-shaped (banana-shaped), multicellular macroconidia, and microconidia. Precise species identification requires molecular analyses such as polymerase chain reaction.

Mortality is high, ranging from 50% to 70% of cases.5 Voriconazole or lipid-based amphotericin B are considered first-line treatments. Posaconazole may be employed as a second-line alternative. Surgical debridement of infected tissues and removal of colonized venous catheters is recommended. Secondary prophylaxis should be considered with agents such as voriconazole, posaconazole, or amphotericin B.5 Resolution of immunosuppression and neutropenia is an important factor to reduce the mortality rate.

- Ranawaka RR, Nagahawatte A, Gunasekara TA. Fusarium onychomycosis: prevalence, clinical presentations, response toitraconazole and terbinafine pulse therapy, and 1-year follow-up in nine cases. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:1275-1282.

- Nucci F, Nouer SA, Capone D, et al. Fusariosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;36:706-714.

- Varon AG, Nouer SA, Barreiros G, et al. Superficial skin lesions positive for Fusarium are associated with subsequent development of invasive fusariosis. J Infect. 2014;68:85-89.

- Hay RJ. Fusarium infections of the skin. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2007;20:115-117.

- Tortorano AM, Richardson M, Roilides E, et al. ESCMID and ECMM joint guidelines on diagnosis and management of hyalohyphomycosis: Fusarium spp., Scedosporium spp. and others. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20:27-46.

- Nucci F, Nouer SA, Capone D, et al. Invasive mould disease in haematologic patients: comparison between fusariosis and aspergillosis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2018;24:1105.e1-1105.e4.

- Ranawaka RR, Nagahawatte A, Gunasekara TA. Fusarium onychomycosis: prevalence, clinical presentations, response toitraconazole and terbinafine pulse therapy, and 1-year follow-up in nine cases. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:1275-1282.

- Nucci F, Nouer SA, Capone D, et al. Fusariosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;36:706-714.

- Varon AG, Nouer SA, Barreiros G, et al. Superficial skin lesions positive for Fusarium are associated with subsequent development of invasive fusariosis. J Infect. 2014;68:85-89.

- Hay RJ. Fusarium infections of the skin. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2007;20:115-117.

- Tortorano AM, Richardson M, Roilides E, et al. ESCMID and ECMM joint guidelines on diagnosis and management of hyalohyphomycosis: Fusarium spp., Scedosporium spp. and others. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20:27-46.

- Nucci F, Nouer SA, Capone D, et al. Invasive mould disease in haematologic patients: comparison between fusariosis and aspergillosis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2018;24:1105.e1-1105.e4.