User login

Bullous Lesions in a Neonate

The Diagnosis: Incontinentia Pigmenti

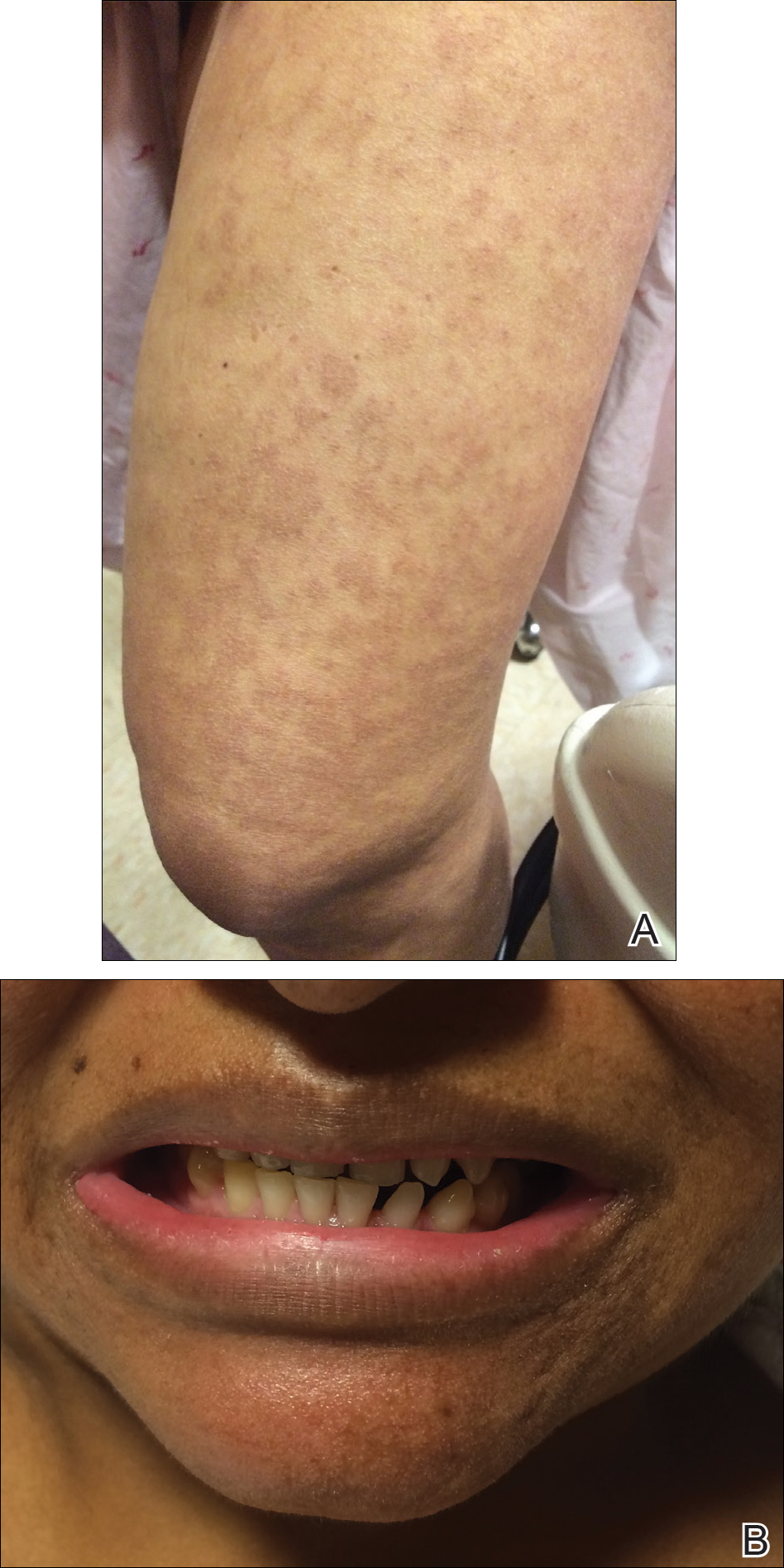

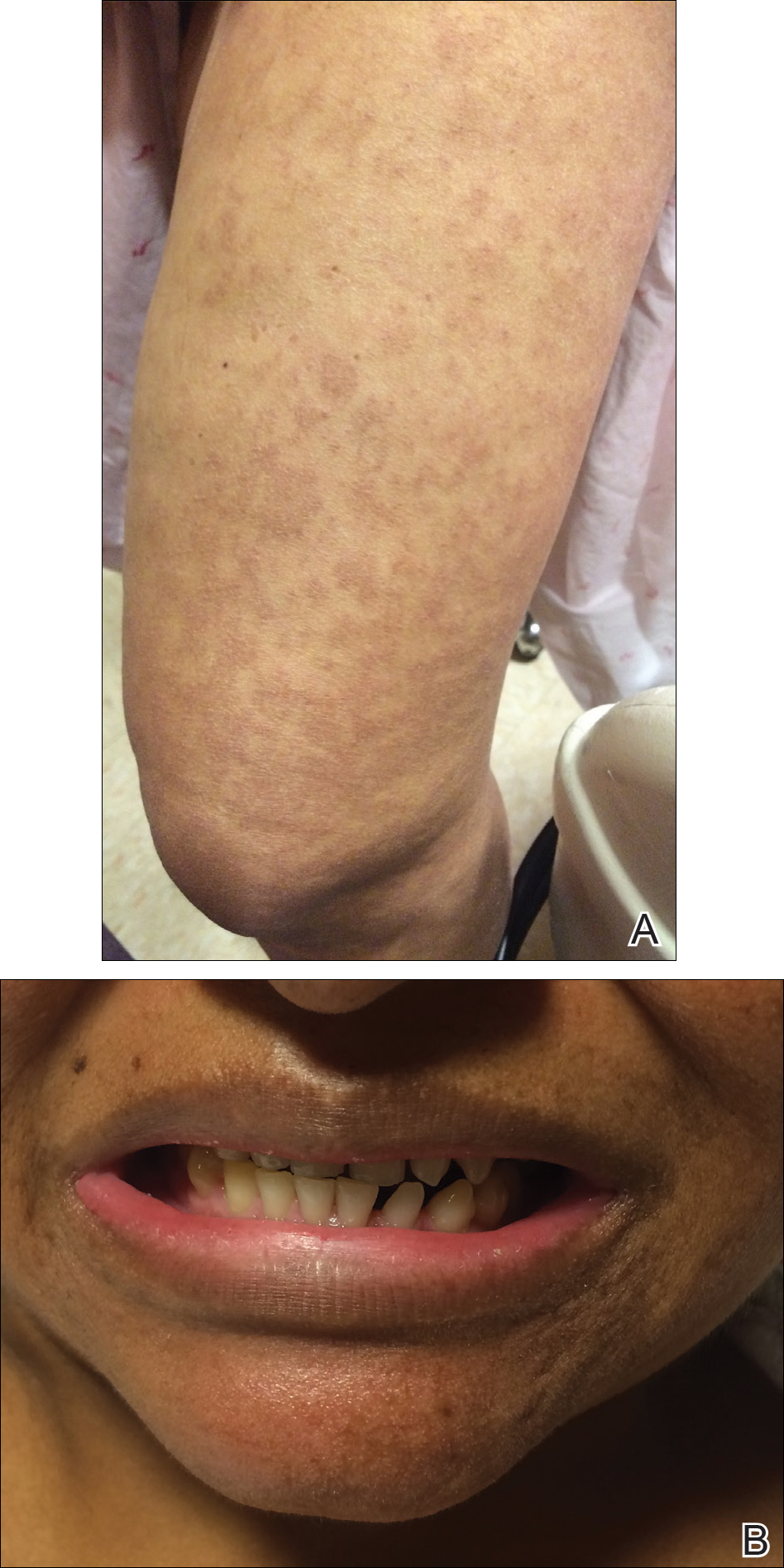

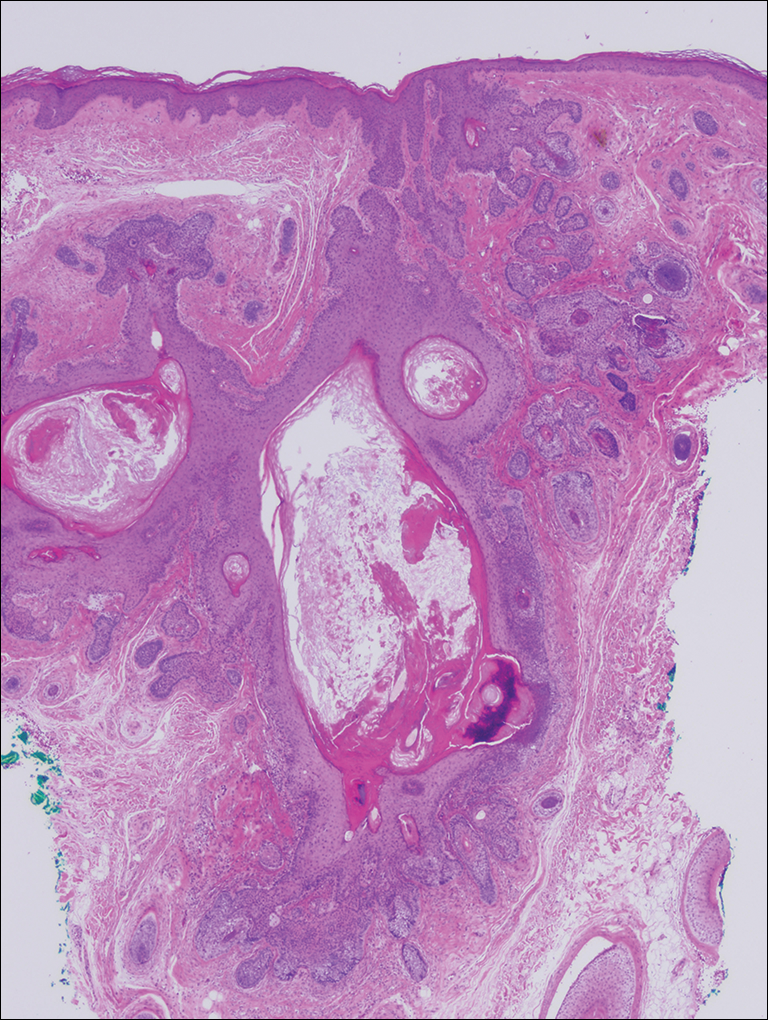

The infant's mother was noted to have diffuse hypopigmented patches over the trunk, arms, and legs (present since adolescence) with whorled cicatricial alopecia of the vertex scalp and peg-shaped teeth (Figure). Together, these findings suggested incontinentia pigmenti (IP), which the mother revealed she had been diagnosed with in childhood. The infant's characteristic lesions in the setting of her mother's diagnosed genodermatosis confirmed the diagnosis of IP.

Incontinentia pigmenti is an X-linked dominant disorder that presents with many classic dermatologic, dental, neurologic, and ophthalmologic findings. The causative mutation occurs in IKBKG/NEMO (inhibitor of κ polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells, kinase γ/nuclear factor-κB essential modulator) gene on Xq28, disabling the resultant protein that normally protects cells from tumor necrosis factor family-induced apoptosis.1 Incontinentia pigmenti usually is lethal in males and causes an unbalanced X-inactivation in surviving female IP patients. Occurring at a rate of 1.2 per 100,000 births,2 IP typically presents in female infants with skin lesions patterned along Blaschko lines that evolve in 4 stages over a lifetime.3 Stage I, presenting in the neonatal period, manifests as vesiculobullous eruptions on the limbs and scalp. Stages II to IV vary in duration from months to years and are comprised of a verrucous stage, a hyperpigmented stage, and a hypopigmented stage, respectively.3 All stages of IP can overlap and coexist.

The vesiculobullous findings in infants with IP may be mistakenly attributed to other diseases with prominent vesicular or bullous components including herpes simplex virus, epidermolysis bullosa, and infantile acropustulosis. With neonatal herpes simplex virus infection, vesicular skin or mucocutaneous lesions occur 9 to 11 days after birth and can be confirmed by specimen culture or qualitative polymerase chain reaction, while stage I of IP appears within the first 6 to 8 weeks of life and can be present at birth.4 The hallmark of epidermolysis bullosa, caused by mutations in keratins 5 and 14, is blistering erosions of the skin in response to frictional stress,1 thus these lesions do not follow Blaschko lines. Infantile acropustulosis, a nonheritable vesiculopustular eruption of the hands and feet, rarely occurs in the immediate newborn period; it most often appears in the 3- to 6-month age range with recurrent eruptions at 3- to 4-week intervals.5 Focal dermal hypoplasia is another X-linked dominant disorder with blaschkolinear findings at birth that presents with pink or red, angular, atrophic macules, in contrast to the bullous lesions of IP.6

Incontinentia pigmenti may encompass a wide range of systemic symptoms in addition to the classic dermatologic findings. Notably, central nervous system defects are concurrent in up to 40% of IP cases, with seizures, mental retardation, and spastic paresis being the most common sequelae.7 Teeth defects, seen in 35% of patients, include delayed primary dentition and peg-shaped teeth. Many patients will experience ophthalmologic defects including vision problems (16%) and retinopathy (15%).7

The cutaneous eruptions of IP may be treated with topical corticosteroids or topical tacrolimus, and vesicles should be left intact and monitored for signs of infection.8,9 Seizures, if present, should be treated with anticonvulsants, and regular neuropsychiatric monitoring and physical rehabilitation may be warranted. Patients should be regularly monitored for retinopathy beginning at the time of diagnosis. Retinal fibrovascular proliferation is treated with xenon laser photocoagulation to reduce the high risk for retinal detachment in this population.10,11 Older and younger at-risk relatives must be evaluated by genetic testing or thorough physical examination to clarify their disease status and determine the need for additional genetic counseling.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Prevalence and incidence of rare diseases: bibliographic data. Orphanet Report Series, Rare Diseases collection. http://www.orpha.net/orphacom/cahiers/docs/GB/Prevalence_of_rare_diseases_by_alphabetical_list.pdf. Published June 2017. Accessed July 13, 2017.

- Scheuerle AE, Ursini MV. Incontinentia pigmenti. In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, et al, eds. GeneReviews. Seattle, WA: University of Washington; 2015. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1472/. Accessed July 25, 2017.

- James SH, Kimberlin DW. Neonatal herpes simplex virus infection. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2015;29:391-400.

- Eichenfield LF, Frieden IJ, Mathes E, et al, eds. Neonatal and Infant Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2015.

- Temple IK, MacDowall P, Baraitser M, et al. Focal dermal hypoplasia (Goltz syndrome). J Med Genet. 1990;27:180-187.

- Fusco F, Paciolla M, Conte MI, et al. Incontinentia pigmenti: report on data from 2000 to 2013. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2014;9:93.

- Jessup CJ, Morgan SC, Cohen LM, et al. Incontinentia pigmenti: treatment of IP with topical tacrolimus. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8:944-946.

- Kaya TI, Tursen U, Ikizoglu G. Therapeutic use of topical corticosteroids in the vesiculobullous lesions of incontinentia pigmenti [published online June 1, 2009]. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:E611-E613.

- Nguyen JK, Brady-Mccreery KM. Laser photocoagulation in preproliferative retinopathy of incontinentia pigmenti. J AAPOS. 2001;5:258-259.

- Chen CJ, Han IC, Tian J, et al. Extended follow-up of treated and untreated retinopathy in incontinentia pigmenti: analysis of peripheral vascular changes and incidence of retinal detachment. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015;133:542-548.

The Diagnosis: Incontinentia Pigmenti

The infant's mother was noted to have diffuse hypopigmented patches over the trunk, arms, and legs (present since adolescence) with whorled cicatricial alopecia of the vertex scalp and peg-shaped teeth (Figure). Together, these findings suggested incontinentia pigmenti (IP), which the mother revealed she had been diagnosed with in childhood. The infant's characteristic lesions in the setting of her mother's diagnosed genodermatosis confirmed the diagnosis of IP.

Incontinentia pigmenti is an X-linked dominant disorder that presents with many classic dermatologic, dental, neurologic, and ophthalmologic findings. The causative mutation occurs in IKBKG/NEMO (inhibitor of κ polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells, kinase γ/nuclear factor-κB essential modulator) gene on Xq28, disabling the resultant protein that normally protects cells from tumor necrosis factor family-induced apoptosis.1 Incontinentia pigmenti usually is lethal in males and causes an unbalanced X-inactivation in surviving female IP patients. Occurring at a rate of 1.2 per 100,000 births,2 IP typically presents in female infants with skin lesions patterned along Blaschko lines that evolve in 4 stages over a lifetime.3 Stage I, presenting in the neonatal period, manifests as vesiculobullous eruptions on the limbs and scalp. Stages II to IV vary in duration from months to years and are comprised of a verrucous stage, a hyperpigmented stage, and a hypopigmented stage, respectively.3 All stages of IP can overlap and coexist.

The vesiculobullous findings in infants with IP may be mistakenly attributed to other diseases with prominent vesicular or bullous components including herpes simplex virus, epidermolysis bullosa, and infantile acropustulosis. With neonatal herpes simplex virus infection, vesicular skin or mucocutaneous lesions occur 9 to 11 days after birth and can be confirmed by specimen culture or qualitative polymerase chain reaction, while stage I of IP appears within the first 6 to 8 weeks of life and can be present at birth.4 The hallmark of epidermolysis bullosa, caused by mutations in keratins 5 and 14, is blistering erosions of the skin in response to frictional stress,1 thus these lesions do not follow Blaschko lines. Infantile acropustulosis, a nonheritable vesiculopustular eruption of the hands and feet, rarely occurs in the immediate newborn period; it most often appears in the 3- to 6-month age range with recurrent eruptions at 3- to 4-week intervals.5 Focal dermal hypoplasia is another X-linked dominant disorder with blaschkolinear findings at birth that presents with pink or red, angular, atrophic macules, in contrast to the bullous lesions of IP.6

Incontinentia pigmenti may encompass a wide range of systemic symptoms in addition to the classic dermatologic findings. Notably, central nervous system defects are concurrent in up to 40% of IP cases, with seizures, mental retardation, and spastic paresis being the most common sequelae.7 Teeth defects, seen in 35% of patients, include delayed primary dentition and peg-shaped teeth. Many patients will experience ophthalmologic defects including vision problems (16%) and retinopathy (15%).7

The cutaneous eruptions of IP may be treated with topical corticosteroids or topical tacrolimus, and vesicles should be left intact and monitored for signs of infection.8,9 Seizures, if present, should be treated with anticonvulsants, and regular neuropsychiatric monitoring and physical rehabilitation may be warranted. Patients should be regularly monitored for retinopathy beginning at the time of diagnosis. Retinal fibrovascular proliferation is treated with xenon laser photocoagulation to reduce the high risk for retinal detachment in this population.10,11 Older and younger at-risk relatives must be evaluated by genetic testing or thorough physical examination to clarify their disease status and determine the need for additional genetic counseling.

The Diagnosis: Incontinentia Pigmenti

The infant's mother was noted to have diffuse hypopigmented patches over the trunk, arms, and legs (present since adolescence) with whorled cicatricial alopecia of the vertex scalp and peg-shaped teeth (Figure). Together, these findings suggested incontinentia pigmenti (IP), which the mother revealed she had been diagnosed with in childhood. The infant's characteristic lesions in the setting of her mother's diagnosed genodermatosis confirmed the diagnosis of IP.

Incontinentia pigmenti is an X-linked dominant disorder that presents with many classic dermatologic, dental, neurologic, and ophthalmologic findings. The causative mutation occurs in IKBKG/NEMO (inhibitor of κ polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells, kinase γ/nuclear factor-κB essential modulator) gene on Xq28, disabling the resultant protein that normally protects cells from tumor necrosis factor family-induced apoptosis.1 Incontinentia pigmenti usually is lethal in males and causes an unbalanced X-inactivation in surviving female IP patients. Occurring at a rate of 1.2 per 100,000 births,2 IP typically presents in female infants with skin lesions patterned along Blaschko lines that evolve in 4 stages over a lifetime.3 Stage I, presenting in the neonatal period, manifests as vesiculobullous eruptions on the limbs and scalp. Stages II to IV vary in duration from months to years and are comprised of a verrucous stage, a hyperpigmented stage, and a hypopigmented stage, respectively.3 All stages of IP can overlap and coexist.

The vesiculobullous findings in infants with IP may be mistakenly attributed to other diseases with prominent vesicular or bullous components including herpes simplex virus, epidermolysis bullosa, and infantile acropustulosis. With neonatal herpes simplex virus infection, vesicular skin or mucocutaneous lesions occur 9 to 11 days after birth and can be confirmed by specimen culture or qualitative polymerase chain reaction, while stage I of IP appears within the first 6 to 8 weeks of life and can be present at birth.4 The hallmark of epidermolysis bullosa, caused by mutations in keratins 5 and 14, is blistering erosions of the skin in response to frictional stress,1 thus these lesions do not follow Blaschko lines. Infantile acropustulosis, a nonheritable vesiculopustular eruption of the hands and feet, rarely occurs in the immediate newborn period; it most often appears in the 3- to 6-month age range with recurrent eruptions at 3- to 4-week intervals.5 Focal dermal hypoplasia is another X-linked dominant disorder with blaschkolinear findings at birth that presents with pink or red, angular, atrophic macules, in contrast to the bullous lesions of IP.6

Incontinentia pigmenti may encompass a wide range of systemic symptoms in addition to the classic dermatologic findings. Notably, central nervous system defects are concurrent in up to 40% of IP cases, with seizures, mental retardation, and spastic paresis being the most common sequelae.7 Teeth defects, seen in 35% of patients, include delayed primary dentition and peg-shaped teeth. Many patients will experience ophthalmologic defects including vision problems (16%) and retinopathy (15%).7

The cutaneous eruptions of IP may be treated with topical corticosteroids or topical tacrolimus, and vesicles should be left intact and monitored for signs of infection.8,9 Seizures, if present, should be treated with anticonvulsants, and regular neuropsychiatric monitoring and physical rehabilitation may be warranted. Patients should be regularly monitored for retinopathy beginning at the time of diagnosis. Retinal fibrovascular proliferation is treated with xenon laser photocoagulation to reduce the high risk for retinal detachment in this population.10,11 Older and younger at-risk relatives must be evaluated by genetic testing or thorough physical examination to clarify their disease status and determine the need for additional genetic counseling.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Prevalence and incidence of rare diseases: bibliographic data. Orphanet Report Series, Rare Diseases collection. http://www.orpha.net/orphacom/cahiers/docs/GB/Prevalence_of_rare_diseases_by_alphabetical_list.pdf. Published June 2017. Accessed July 13, 2017.

- Scheuerle AE, Ursini MV. Incontinentia pigmenti. In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, et al, eds. GeneReviews. Seattle, WA: University of Washington; 2015. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1472/. Accessed July 25, 2017.

- James SH, Kimberlin DW. Neonatal herpes simplex virus infection. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2015;29:391-400.

- Eichenfield LF, Frieden IJ, Mathes E, et al, eds. Neonatal and Infant Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2015.

- Temple IK, MacDowall P, Baraitser M, et al. Focal dermal hypoplasia (Goltz syndrome). J Med Genet. 1990;27:180-187.

- Fusco F, Paciolla M, Conte MI, et al. Incontinentia pigmenti: report on data from 2000 to 2013. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2014;9:93.

- Jessup CJ, Morgan SC, Cohen LM, et al. Incontinentia pigmenti: treatment of IP with topical tacrolimus. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8:944-946.

- Kaya TI, Tursen U, Ikizoglu G. Therapeutic use of topical corticosteroids in the vesiculobullous lesions of incontinentia pigmenti [published online June 1, 2009]. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:E611-E613.

- Nguyen JK, Brady-Mccreery KM. Laser photocoagulation in preproliferative retinopathy of incontinentia pigmenti. J AAPOS. 2001;5:258-259.

- Chen CJ, Han IC, Tian J, et al. Extended follow-up of treated and untreated retinopathy in incontinentia pigmenti: analysis of peripheral vascular changes and incidence of retinal detachment. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015;133:542-548.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Prevalence and incidence of rare diseases: bibliographic data. Orphanet Report Series, Rare Diseases collection. http://www.orpha.net/orphacom/cahiers/docs/GB/Prevalence_of_rare_diseases_by_alphabetical_list.pdf. Published June 2017. Accessed July 13, 2017.

- Scheuerle AE, Ursini MV. Incontinentia pigmenti. In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, et al, eds. GeneReviews. Seattle, WA: University of Washington; 2015. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1472/. Accessed July 25, 2017.

- James SH, Kimberlin DW. Neonatal herpes simplex virus infection. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2015;29:391-400.

- Eichenfield LF, Frieden IJ, Mathes E, et al, eds. Neonatal and Infant Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2015.

- Temple IK, MacDowall P, Baraitser M, et al. Focal dermal hypoplasia (Goltz syndrome). J Med Genet. 1990;27:180-187.

- Fusco F, Paciolla M, Conte MI, et al. Incontinentia pigmenti: report on data from 2000 to 2013. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2014;9:93.

- Jessup CJ, Morgan SC, Cohen LM, et al. Incontinentia pigmenti: treatment of IP with topical tacrolimus. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8:944-946.

- Kaya TI, Tursen U, Ikizoglu G. Therapeutic use of topical corticosteroids in the vesiculobullous lesions of incontinentia pigmenti [published online June 1, 2009]. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:E611-E613.

- Nguyen JK, Brady-Mccreery KM. Laser photocoagulation in preproliferative retinopathy of incontinentia pigmenti. J AAPOS. 2001;5:258-259.

- Chen CJ, Han IC, Tian J, et al. Extended follow-up of treated and untreated retinopathy in incontinentia pigmenti: analysis of peripheral vascular changes and incidence of retinal detachment. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015;133:542-548.

A 1-day-old Hispanic female infant was born via uncomplicated vaginal delivery at 41 weeks' gestation after a normal pregnancy. Linear plaques containing multiple ruptured vesicles and bullae following Blaschko lines were noted on the right medial thigh and anterior arm. The infant was afebrile and generally well-appearing.

Solitary Nodule With White Hairs

The Diagnosis: Trichofolliculoma

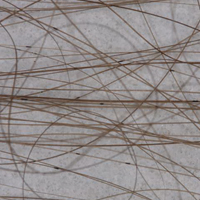

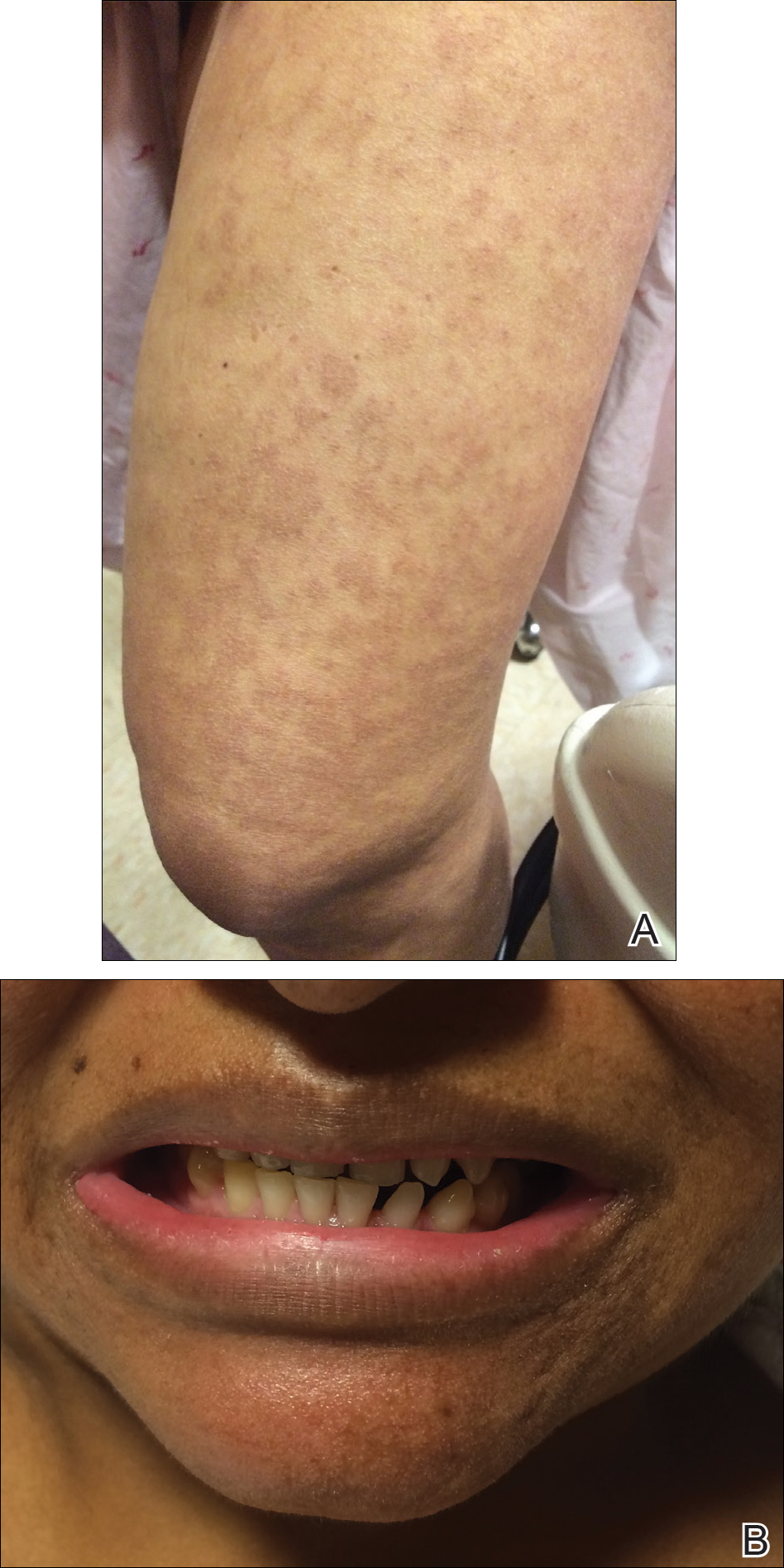

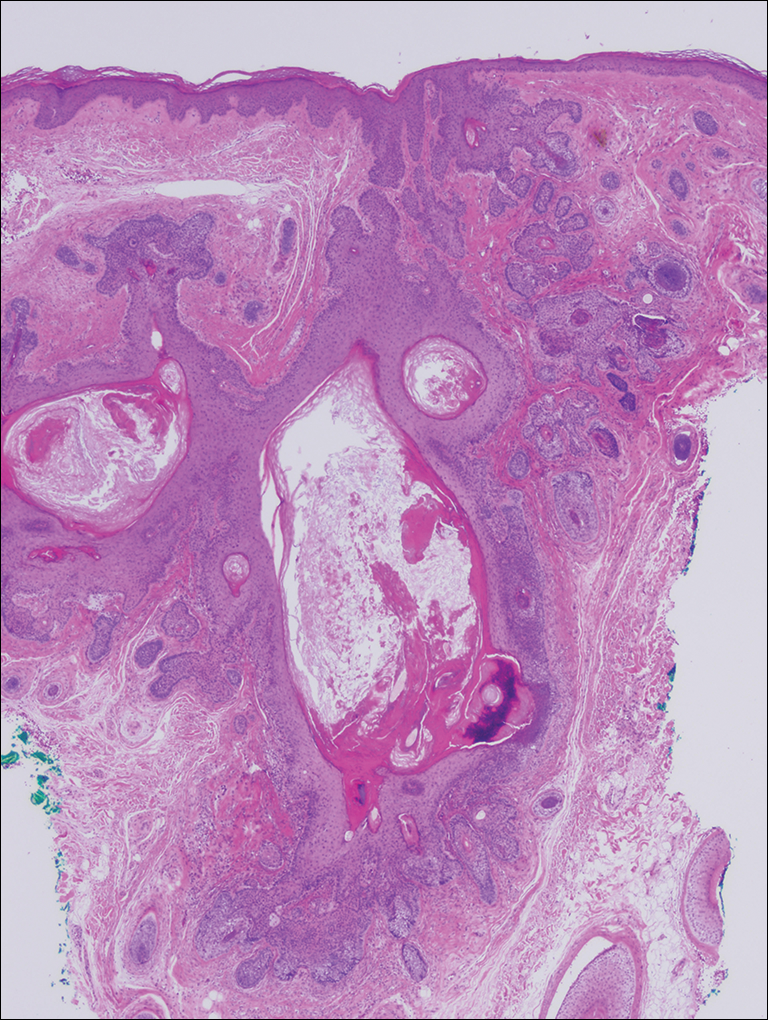

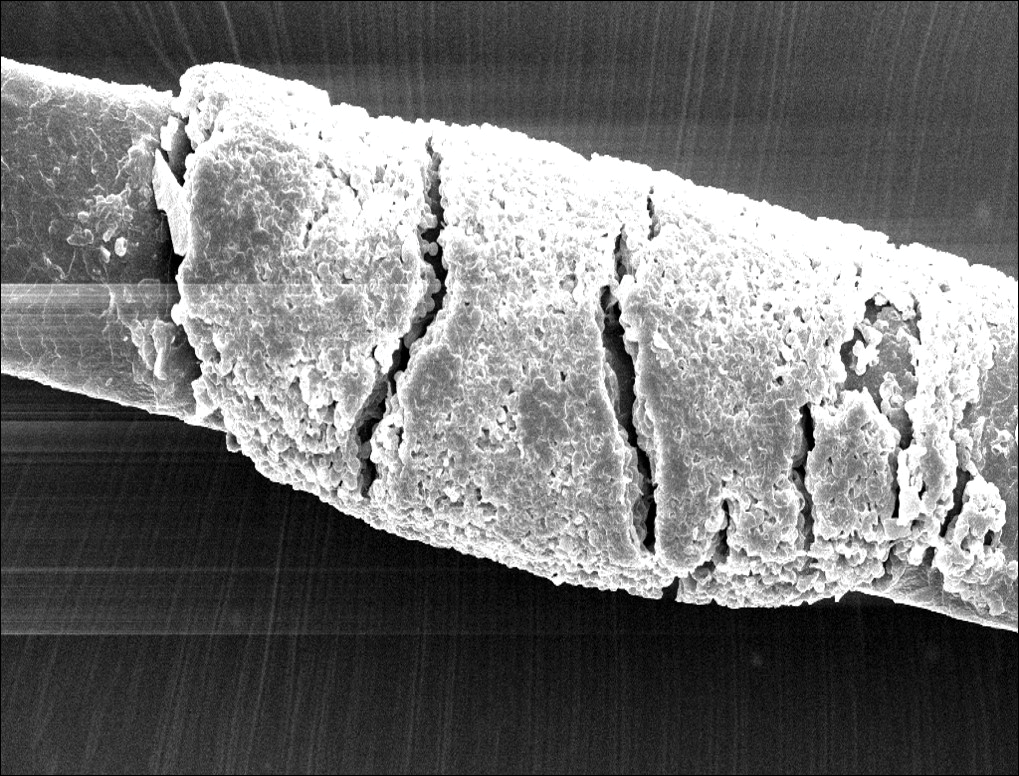

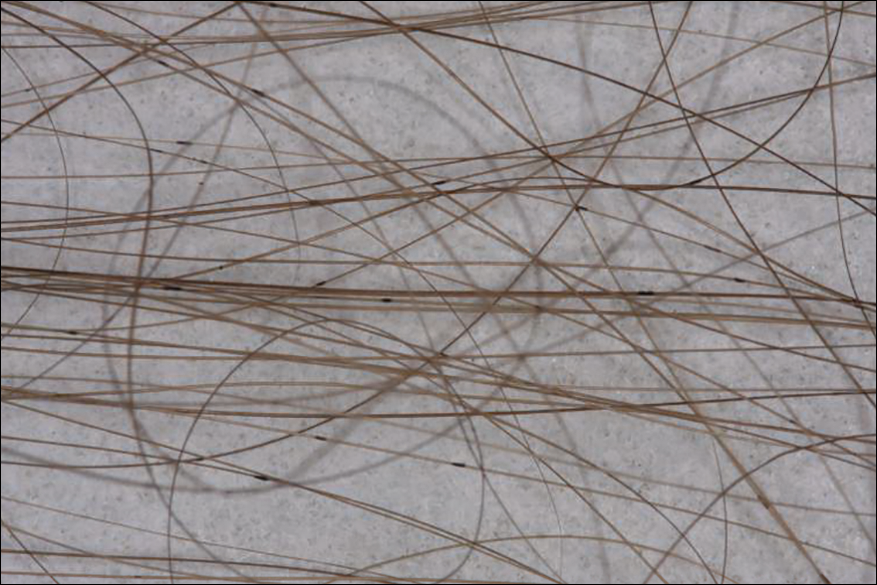

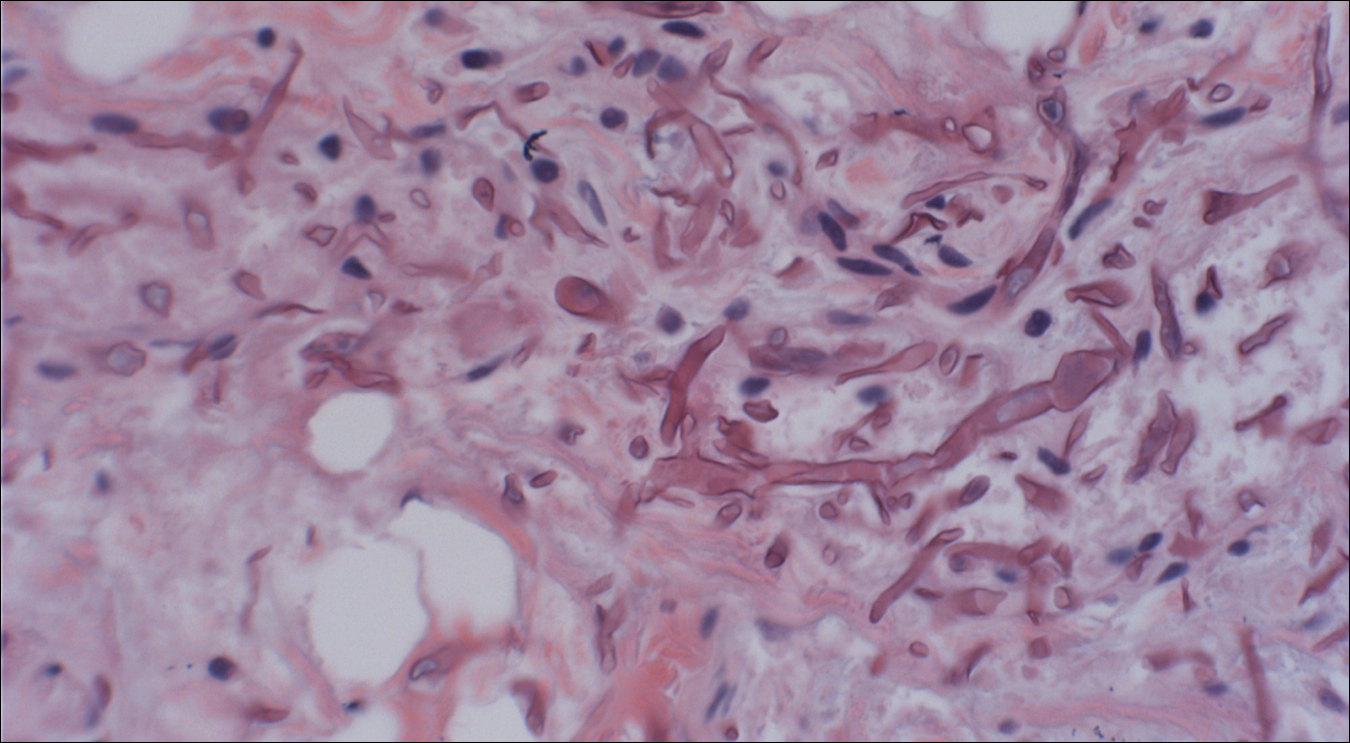

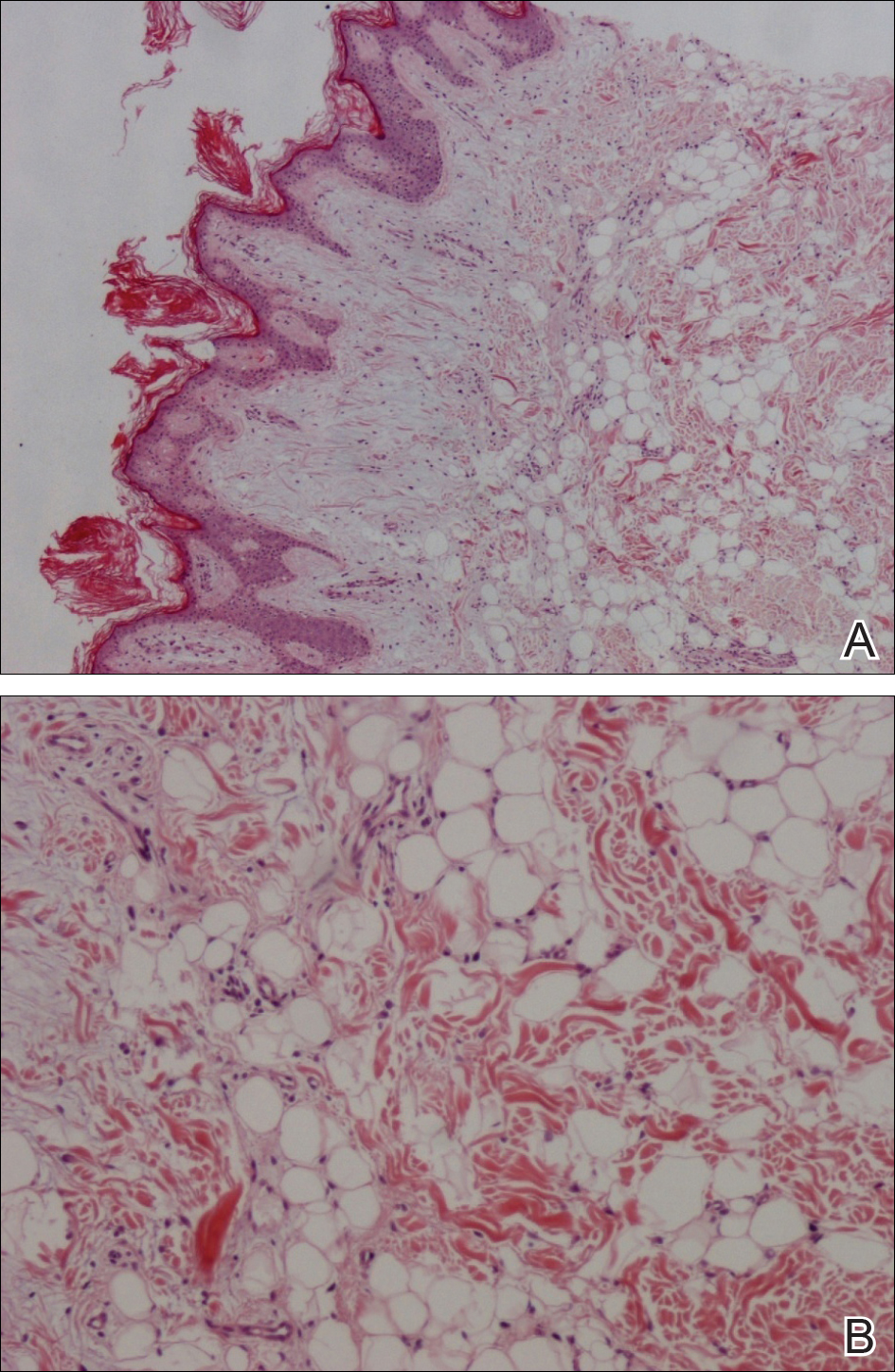

Microscopic examination revealed a dilated cystic follicle that communicated with the skin surface (Figure). The follicle was lined with squamous epithelium and surrounded by numerous secondary follicles, many of which contained a hair shaft. A diagnosis of trichofolliculoma was made.

Clinically, the differential diagnosis of a flesh-colored papule on the scalp with prominent follicle includes dilated pore of Winer, epidermoid cyst, pilar sheath acanthoma, and trichoepithelioma.1,2 Multiple hair shafts present in a single follicle may be seen in pili multigemini, tufted folliculitis, trichostasis spinulosa, and trichofolliculoma. On histopathologic examination, a dilated central follicle surrounded with smaller secondary follicles was identified, consistent with trichofolliculoma.

Trichofolliculoma is a rare follicular hamartoma typically occurring on the face, scalp, or trunk as a solitary papule or nodule due to the proliferation of abnormal hair follicle stem cells.3,4 It may present as a flesh-colored nodule with a central pore that may drain sebum or contain white vellus hairs. Trichofolliculoma is considered a benign entity, despite one case report of malignant transformation.5 Biopsy is diagnostic and no further treatment is needed. Recurrence rarely occurs at the primary site after surgical excision, which may be performed for cosmetic purposes or to alleviate functional impairment.

- Ghosh SK, Bandyopadhyay D, Barma KD. Perifollicular nodule on the face of a young man. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:531-533.

- Gokalp H, Gurer MA, Alan S. Trichofolliculoma: a rare variant of hair follicle hamartoma. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:19264.

- Choi CM, Lew BL, Sim WY. Multiple trichofolliculomas on unusual sites: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:87-89.

- Misago N, Kimura T, Toda S, et al. A revaluation of trichofolliculoma: the histopathological and immunohistochemical features. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:35-43.

- Stem JB, Stout DA. Trichofolliculoma showing perineural invasion. trichofolliculocarcinoma? Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:1003-1004.

The Diagnosis: Trichofolliculoma

Microscopic examination revealed a dilated cystic follicle that communicated with the skin surface (Figure). The follicle was lined with squamous epithelium and surrounded by numerous secondary follicles, many of which contained a hair shaft. A diagnosis of trichofolliculoma was made.

Clinically, the differential diagnosis of a flesh-colored papule on the scalp with prominent follicle includes dilated pore of Winer, epidermoid cyst, pilar sheath acanthoma, and trichoepithelioma.1,2 Multiple hair shafts present in a single follicle may be seen in pili multigemini, tufted folliculitis, trichostasis spinulosa, and trichofolliculoma. On histopathologic examination, a dilated central follicle surrounded with smaller secondary follicles was identified, consistent with trichofolliculoma.

Trichofolliculoma is a rare follicular hamartoma typically occurring on the face, scalp, or trunk as a solitary papule or nodule due to the proliferation of abnormal hair follicle stem cells.3,4 It may present as a flesh-colored nodule with a central pore that may drain sebum or contain white vellus hairs. Trichofolliculoma is considered a benign entity, despite one case report of malignant transformation.5 Biopsy is diagnostic and no further treatment is needed. Recurrence rarely occurs at the primary site after surgical excision, which may be performed for cosmetic purposes or to alleviate functional impairment.

The Diagnosis: Trichofolliculoma

Microscopic examination revealed a dilated cystic follicle that communicated with the skin surface (Figure). The follicle was lined with squamous epithelium and surrounded by numerous secondary follicles, many of which contained a hair shaft. A diagnosis of trichofolliculoma was made.

Clinically, the differential diagnosis of a flesh-colored papule on the scalp with prominent follicle includes dilated pore of Winer, epidermoid cyst, pilar sheath acanthoma, and trichoepithelioma.1,2 Multiple hair shafts present in a single follicle may be seen in pili multigemini, tufted folliculitis, trichostasis spinulosa, and trichofolliculoma. On histopathologic examination, a dilated central follicle surrounded with smaller secondary follicles was identified, consistent with trichofolliculoma.

Trichofolliculoma is a rare follicular hamartoma typically occurring on the face, scalp, or trunk as a solitary papule or nodule due to the proliferation of abnormal hair follicle stem cells.3,4 It may present as a flesh-colored nodule with a central pore that may drain sebum or contain white vellus hairs. Trichofolliculoma is considered a benign entity, despite one case report of malignant transformation.5 Biopsy is diagnostic and no further treatment is needed. Recurrence rarely occurs at the primary site after surgical excision, which may be performed for cosmetic purposes or to alleviate functional impairment.

- Ghosh SK, Bandyopadhyay D, Barma KD. Perifollicular nodule on the face of a young man. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:531-533.

- Gokalp H, Gurer MA, Alan S. Trichofolliculoma: a rare variant of hair follicle hamartoma. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:19264.

- Choi CM, Lew BL, Sim WY. Multiple trichofolliculomas on unusual sites: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:87-89.

- Misago N, Kimura T, Toda S, et al. A revaluation of trichofolliculoma: the histopathological and immunohistochemical features. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:35-43.

- Stem JB, Stout DA. Trichofolliculoma showing perineural invasion. trichofolliculocarcinoma? Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:1003-1004.

- Ghosh SK, Bandyopadhyay D, Barma KD. Perifollicular nodule on the face of a young man. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:531-533.

- Gokalp H, Gurer MA, Alan S. Trichofolliculoma: a rare variant of hair follicle hamartoma. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:19264.

- Choi CM, Lew BL, Sim WY. Multiple trichofolliculomas on unusual sites: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:87-89.

- Misago N, Kimura T, Toda S, et al. A revaluation of trichofolliculoma: the histopathological and immunohistochemical features. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:35-43.

- Stem JB, Stout DA. Trichofolliculoma showing perineural invasion. trichofolliculocarcinoma? Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:1003-1004.

A 72-year-old man presented with a new asymptomatic 0.7-cm flesh-colored papule with a central tuft of white hairs on the posterior scalp. The remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable. Biopsy for histopathologic examination was performed to confirm diagnosis.

Necrotic Ulcer on the Thigh

The Diagnosis: Disseminated Cryptococcosis

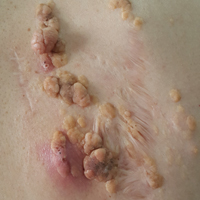

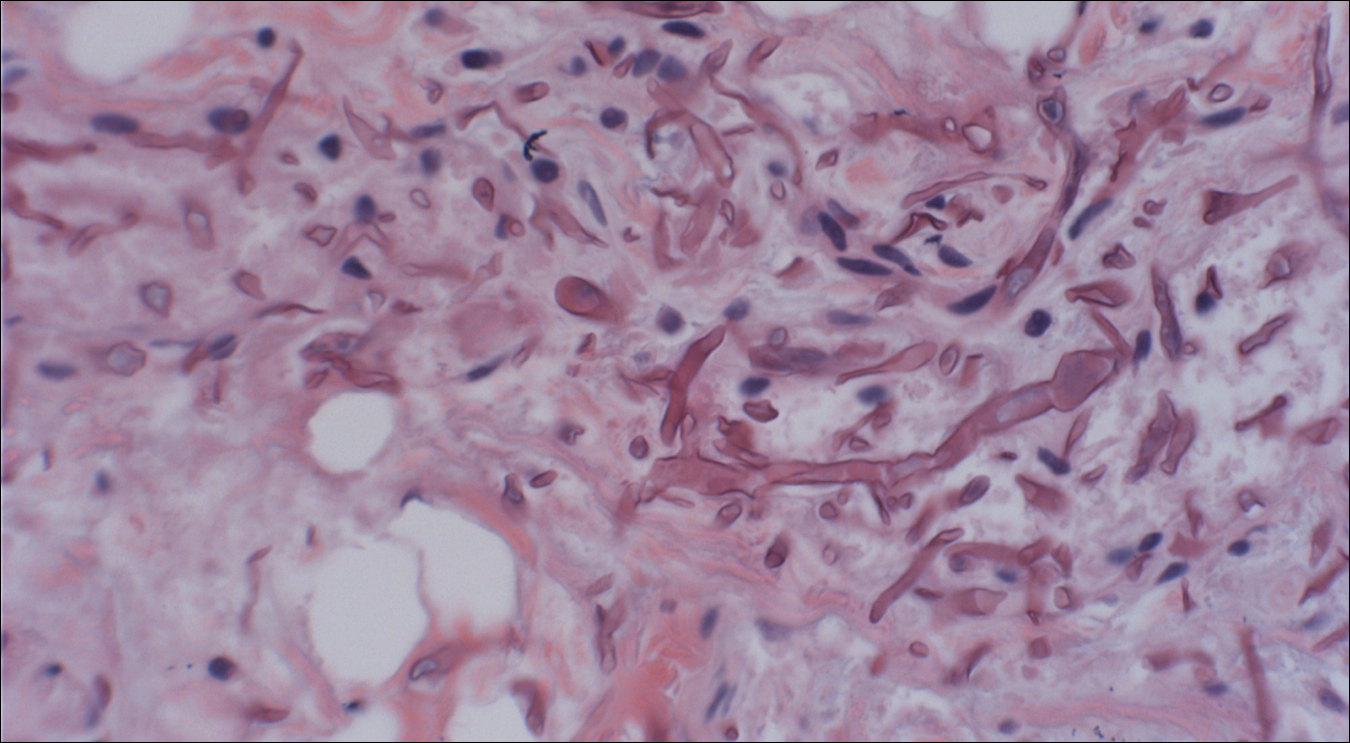

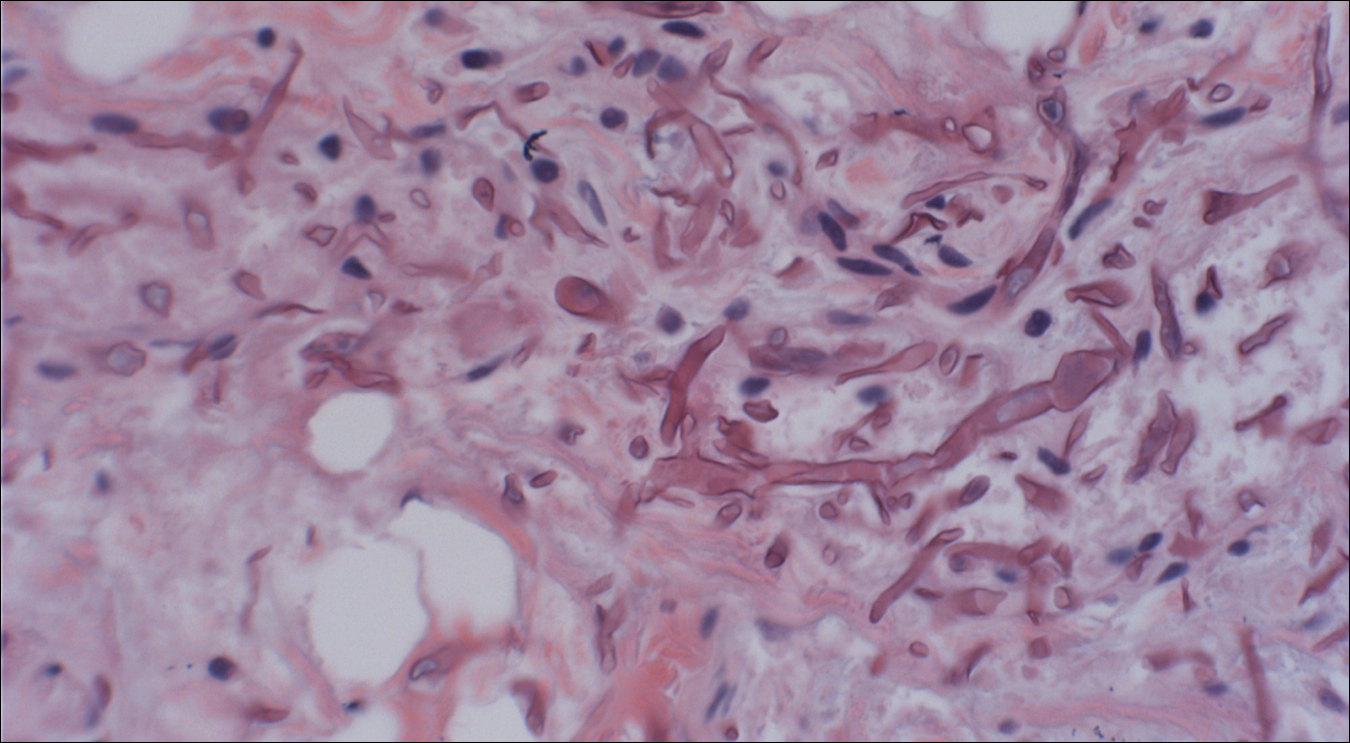

Histopathologic examination of a 3-mm punch biopsy showed a diffuse dermal neutrophilic infiltrate with necrosis and subcutaneous tissue with round yeast surrounded by a prominent halo staining bright red with mucicarmine, representing a thick mucinous capsule (Figure). Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver and periodic acid-Schiff stains also demonstrated fungal spores morphologically. Cerebrospinal fluid culture grew Cryptococcus neoformans, and cryptococcal antigen titers were positive in both serum and cerebrospinal fluid samples (>1:4096). The patient had autolytic debridement of the ulcer after completing a 4-week induction course of intravenous liposomal amphotericin B with oral flucytosine. He was transitioned to oral fluconazole for the consolidation phase of treatment.

Cryptococcus is an opportunistic basidiomycetous yeast with worldwide distribution and 2 primary pathogenic species in humans: C neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii. It is associated with bird feces, composted food, and decayed wood.1,2 A predilection toward an immunosuppressed host is recognized in 70% to 90% of the infections caused by C neoformans; however, C gattii commonly affects individuals with apparently intact immune systems.1,3 Risk factors for infection include advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection, solid organ transplantation, chronic liver disease, autoimmune disease, hematological malignancy, and underlying genetic susceptibility.1,2

Initial exposure is through the respiratory tract with formation of latent reservoirs in the pulmonary lymph nodes with subsequent reactivation that can result in hematogenous dissemination.1,2 Cutaneous involvement was described in 108 patients (5%) in a large review of 1974 cases in France.4 Among those with cutaneous involvement, disseminated disease was diagnosed in 80 cases (74%), and 28 cases (26%) were considered primary cutaneous cryptococcosis. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis typically presents as a single lesion, predominantly on the hand, with whitlow and more rarely with extensive cellulitis or necrotizing fasciitis.4 In disseminated cutaneous disease, there is no pathognomonic single lesion; however, it is commonly associated with multiple cutaneous lesions predominantly involving the head and neck. Plaques, abscesses, nodules, and pustular or umbilicated papules have been reported.1,5 There are few case reports that describe a single isolated necrotic ulcer with disseminated disease similar to our presented case, and more typically the necrotic ulcer is seen in transplanted patients.6 The differential diagnosis of a necrotic thigh ulcer includes pseudomonal ecthyma gangrenosum, cutaneous anthrax and aspergillosis, fusariosis, and a bite from the brown recluse spider.7 Our patient had an increased susceptibility to infection from his ongoing chemotherapy, a risk previously described in oncology patients with cell-mediated immunosuppression.8

Management for disseminated cryptococcosis is a 3-phase therapy including induction with intravenous amphotericin B and oral flucytosine for a minimum of 2 weeks, with consolidation and maintenance phases both with oral fluconazole for a length depending on underlying immunosuppression.9

- Chen SC, Meyer W, Sorrell TC. Cryptococcus gattii infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2014;27:980-1024.

- Williamson PR, Jarvis JN, Panackal AA, et al. Cryptococcal meningitis: epidemiology, immunology, diagnosis, and therapy [published online November 25, 2016]. Nat Rev Neurol. 2017;13:13-24.

- Speed B, Dunt D. Clinical and host differences between infections with the two varieties of Cryptococcus neoformans. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:28-34.

- Neuville S, Dromer F, Morin O, et al; French Cryptococcosis Study Group. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis: a distinct clinical entity [published online January 17, 2003]. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:337-347.

- Murakawa GJ, Kerschmann R, Berger T. Cutaneous cryptococcus infection and AIDS: report of 12 cases and review of the literature. JAMA Dermatol. 1996;132:545-548.

- Sun HY, Alexander BD, Lortholary O, et al. Cutaneous cryptococcosis in solid organ transplant recipients. Med Mycol. 2010;48:785-791.

- Grossman ME, Fox LP, Kovarik C, et al. Cutaneous Manifestations of Infection in the Immunocompromised Host. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 2012.

- Korfel A, Menssen HD, Schwartz S, et al. Cryptococcosis in Hodgkin's disease: description of two cases and review of the literature. Ann Hematol. 1998;76:283-286.

- Perfect JR, Dismukes WE, Dromer F. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of cryptococcal disease: 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:291-322.

The Diagnosis: Disseminated Cryptococcosis

Histopathologic examination of a 3-mm punch biopsy showed a diffuse dermal neutrophilic infiltrate with necrosis and subcutaneous tissue with round yeast surrounded by a prominent halo staining bright red with mucicarmine, representing a thick mucinous capsule (Figure). Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver and periodic acid-Schiff stains also demonstrated fungal spores morphologically. Cerebrospinal fluid culture grew Cryptococcus neoformans, and cryptococcal antigen titers were positive in both serum and cerebrospinal fluid samples (>1:4096). The patient had autolytic debridement of the ulcer after completing a 4-week induction course of intravenous liposomal amphotericin B with oral flucytosine. He was transitioned to oral fluconazole for the consolidation phase of treatment.

Cryptococcus is an opportunistic basidiomycetous yeast with worldwide distribution and 2 primary pathogenic species in humans: C neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii. It is associated with bird feces, composted food, and decayed wood.1,2 A predilection toward an immunosuppressed host is recognized in 70% to 90% of the infections caused by C neoformans; however, C gattii commonly affects individuals with apparently intact immune systems.1,3 Risk factors for infection include advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection, solid organ transplantation, chronic liver disease, autoimmune disease, hematological malignancy, and underlying genetic susceptibility.1,2

Initial exposure is through the respiratory tract with formation of latent reservoirs in the pulmonary lymph nodes with subsequent reactivation that can result in hematogenous dissemination.1,2 Cutaneous involvement was described in 108 patients (5%) in a large review of 1974 cases in France.4 Among those with cutaneous involvement, disseminated disease was diagnosed in 80 cases (74%), and 28 cases (26%) were considered primary cutaneous cryptococcosis. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis typically presents as a single lesion, predominantly on the hand, with whitlow and more rarely with extensive cellulitis or necrotizing fasciitis.4 In disseminated cutaneous disease, there is no pathognomonic single lesion; however, it is commonly associated with multiple cutaneous lesions predominantly involving the head and neck. Plaques, abscesses, nodules, and pustular or umbilicated papules have been reported.1,5 There are few case reports that describe a single isolated necrotic ulcer with disseminated disease similar to our presented case, and more typically the necrotic ulcer is seen in transplanted patients.6 The differential diagnosis of a necrotic thigh ulcer includes pseudomonal ecthyma gangrenosum, cutaneous anthrax and aspergillosis, fusariosis, and a bite from the brown recluse spider.7 Our patient had an increased susceptibility to infection from his ongoing chemotherapy, a risk previously described in oncology patients with cell-mediated immunosuppression.8

Management for disseminated cryptococcosis is a 3-phase therapy including induction with intravenous amphotericin B and oral flucytosine for a minimum of 2 weeks, with consolidation and maintenance phases both with oral fluconazole for a length depending on underlying immunosuppression.9

The Diagnosis: Disseminated Cryptococcosis

Histopathologic examination of a 3-mm punch biopsy showed a diffuse dermal neutrophilic infiltrate with necrosis and subcutaneous tissue with round yeast surrounded by a prominent halo staining bright red with mucicarmine, representing a thick mucinous capsule (Figure). Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver and periodic acid-Schiff stains also demonstrated fungal spores morphologically. Cerebrospinal fluid culture grew Cryptococcus neoformans, and cryptococcal antigen titers were positive in both serum and cerebrospinal fluid samples (>1:4096). The patient had autolytic debridement of the ulcer after completing a 4-week induction course of intravenous liposomal amphotericin B with oral flucytosine. He was transitioned to oral fluconazole for the consolidation phase of treatment.

Cryptococcus is an opportunistic basidiomycetous yeast with worldwide distribution and 2 primary pathogenic species in humans: C neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii. It is associated with bird feces, composted food, and decayed wood.1,2 A predilection toward an immunosuppressed host is recognized in 70% to 90% of the infections caused by C neoformans; however, C gattii commonly affects individuals with apparently intact immune systems.1,3 Risk factors for infection include advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection, solid organ transplantation, chronic liver disease, autoimmune disease, hematological malignancy, and underlying genetic susceptibility.1,2

Initial exposure is through the respiratory tract with formation of latent reservoirs in the pulmonary lymph nodes with subsequent reactivation that can result in hematogenous dissemination.1,2 Cutaneous involvement was described in 108 patients (5%) in a large review of 1974 cases in France.4 Among those with cutaneous involvement, disseminated disease was diagnosed in 80 cases (74%), and 28 cases (26%) were considered primary cutaneous cryptococcosis. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis typically presents as a single lesion, predominantly on the hand, with whitlow and more rarely with extensive cellulitis or necrotizing fasciitis.4 In disseminated cutaneous disease, there is no pathognomonic single lesion; however, it is commonly associated with multiple cutaneous lesions predominantly involving the head and neck. Plaques, abscesses, nodules, and pustular or umbilicated papules have been reported.1,5 There are few case reports that describe a single isolated necrotic ulcer with disseminated disease similar to our presented case, and more typically the necrotic ulcer is seen in transplanted patients.6 The differential diagnosis of a necrotic thigh ulcer includes pseudomonal ecthyma gangrenosum, cutaneous anthrax and aspergillosis, fusariosis, and a bite from the brown recluse spider.7 Our patient had an increased susceptibility to infection from his ongoing chemotherapy, a risk previously described in oncology patients with cell-mediated immunosuppression.8

Management for disseminated cryptococcosis is a 3-phase therapy including induction with intravenous amphotericin B and oral flucytosine for a minimum of 2 weeks, with consolidation and maintenance phases both with oral fluconazole for a length depending on underlying immunosuppression.9

- Chen SC, Meyer W, Sorrell TC. Cryptococcus gattii infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2014;27:980-1024.

- Williamson PR, Jarvis JN, Panackal AA, et al. Cryptococcal meningitis: epidemiology, immunology, diagnosis, and therapy [published online November 25, 2016]. Nat Rev Neurol. 2017;13:13-24.

- Speed B, Dunt D. Clinical and host differences between infections with the two varieties of Cryptococcus neoformans. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:28-34.

- Neuville S, Dromer F, Morin O, et al; French Cryptococcosis Study Group. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis: a distinct clinical entity [published online January 17, 2003]. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:337-347.

- Murakawa GJ, Kerschmann R, Berger T. Cutaneous cryptococcus infection and AIDS: report of 12 cases and review of the literature. JAMA Dermatol. 1996;132:545-548.

- Sun HY, Alexander BD, Lortholary O, et al. Cutaneous cryptococcosis in solid organ transplant recipients. Med Mycol. 2010;48:785-791.

- Grossman ME, Fox LP, Kovarik C, et al. Cutaneous Manifestations of Infection in the Immunocompromised Host. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 2012.

- Korfel A, Menssen HD, Schwartz S, et al. Cryptococcosis in Hodgkin's disease: description of two cases and review of the literature. Ann Hematol. 1998;76:283-286.

- Perfect JR, Dismukes WE, Dromer F. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of cryptococcal disease: 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:291-322.

- Chen SC, Meyer W, Sorrell TC. Cryptococcus gattii infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2014;27:980-1024.

- Williamson PR, Jarvis JN, Panackal AA, et al. Cryptococcal meningitis: epidemiology, immunology, diagnosis, and therapy [published online November 25, 2016]. Nat Rev Neurol. 2017;13:13-24.

- Speed B, Dunt D. Clinical and host differences between infections with the two varieties of Cryptococcus neoformans. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:28-34.

- Neuville S, Dromer F, Morin O, et al; French Cryptococcosis Study Group. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis: a distinct clinical entity [published online January 17, 2003]. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:337-347.

- Murakawa GJ, Kerschmann R, Berger T. Cutaneous cryptococcus infection and AIDS: report of 12 cases and review of the literature. JAMA Dermatol. 1996;132:545-548.

- Sun HY, Alexander BD, Lortholary O, et al. Cutaneous cryptococcosis in solid organ transplant recipients. Med Mycol. 2010;48:785-791.

- Grossman ME, Fox LP, Kovarik C, et al. Cutaneous Manifestations of Infection in the Immunocompromised Host. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 2012.

- Korfel A, Menssen HD, Schwartz S, et al. Cryptococcosis in Hodgkin's disease: description of two cases and review of the literature. Ann Hematol. 1998;76:283-286.

- Perfect JR, Dismukes WE, Dromer F. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of cryptococcal disease: 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:291-322.

A 29-year-old man with a history of acute lymphoblastic leukemia was admitted for acute encephalopathy and a necrotic ulcer on the right thigh of 2 weeks' duration. He had received chemotherapy with pegaspargase and vincristine 6 weeks prior to admission. He reported headache with nausea and vomiting of 2 weeks' duration and had sustained a fall in the bathtub a week prior that initially resulted in a right thigh abrasion. He denied recent travel, unusual food consumption, animal exposure, exposure to sick persons, and alcohol or other drug use. On examination the patient was alert but was not oriented to person, place, or time. A 10.2 ×10-cm necrotic ulcer with surrounding mild erythema and tenderness was noted on the right inner thigh.

Chronic Diffuse Erythematous Papulonodules

The Diagnosis: Lymphomatoid Papulosis

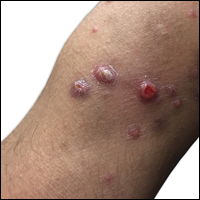

A shave biopsy of an established lesion on the volar aspect of the left wrist was performed (Figure 1). The biopsy showed an ulcerated nodular lesion characterized by a dense mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate in the dermis composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes, scattered neutrophils, and numerous eosinophils (Figure 2). Notably there was a minor population of large atypical cells with immunoblastic and anaplastic morphology present individually and in small clusters most prominently within the upper dermis (Figures 3 and 4). Immunohistochemistry of the anaplastic cells revealed a CD30+, CD3−, CD4+, CD5−, CD8−, CD2−, CD7−, CD56−, ALK1− (anaplastic lymphoma kinase-1), PAX5− (paired box protein-5), CD20−, and CD15− phenotype. These morphologic and immunohistochemical features suggested a CD30+ cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorder. The clinical history of recurrent self-healing papulonodules in an otherwise-healthy patient established the diagnosis of lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP).

Lymphomatoid papulosis is a lymphoproliferative disorder characterized by recurrent crops of self-resolving eruptive papulonodular skin lesions that may show a variety of histologic features including a CD30+ malignant T-cell lymphoma.1 Lymphomatoid papulosis was first described in 19681 but debate continues whether the condition should be considered malignant or benign.2 Although the prognosis is excellent, LyP is characterized by a protracted course, often lasting many years. Additionally, these patients have a lifelong increased risk for development of a second cutaneous or systemic lymphoma such as mycosis fungoides (MF), cutaneous or nodal anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL), or Hodgkin lymphoma, among others.

Lymphomatoid papulosis is a rare disease occurring in all ethnic groups and at any age, though most commonly presenting in the fifth decade of life. Finding large atypical T cells expressing CD30 in recurring skin lesions is highly suggestive of LyP; however, large CD30+ cells also can be seen in numerous benign reactive processes such as arthropod assault, drug eruption, viral skin infections, and other dermatoses, thus clinical correlation is always paramount. The cause of LyP is largely unknown; however, spontaneous regression may be explained by CD30-CD30 ligand interaction3 as well as an increased proapoptotic milieu.4 Specific translocations such as interferon regulatory factor-4 have been hypothesized as a risk factor for malignant progression.5-7 Additionally, an inactivating gene mutation resulting in loss of transforming growth factor β1 receptor expression and subsequent unresponsiveness to the growth inhibitory effect of transforming growth factor β may play a role in progression of LyP to ALCL.8

Clinically, LyP consists of red-brown papules and nodules generally smaller than 2 cm, often with central hemorrhage, necrosis, and crusting. Lesions are at different stages of eruption and resolution. They are often grouped but may be disseminated. Spontaneous regression typically occurs within 3 to 8 weeks. Pruritus or mild tenderness may occur as well as residual hyperpigmentation or scarring. Systemic symptoms are notably absent.

The histologic features of LyP vary according to the age of the lesion and subtype.2 Early lesions may only show a few inflammatory cells, but as lesions evolve, larger immunoblastlike CD30+ atypical cells accumulate that may resemble the Reed-Sternberg cells of Hodgkin lymphoma. Of the 5 subtypes, the most common is type A. It is characterized by a wedge-shaped infiltrate with a mixed population of scattered or clustered, large, atypical CD30+ cells, lymphocytes, neutrophils, eosinophils, and histiocytes.9 Frequent mitoses often are seen. Type B appears similar to MF due to a predominantly epidermotropic infiltrate of CD3+ and often CD30− atypical cells. Spontaneously regressing papules favor LyP, whereas persistent patches or plaques favor MF. Type C appears identical to ALCL with diffuse sheets of large atypical CD30+ cells and relatively few inflammatory cells, but spontaneously regressing lesions again favor LyP, whereas persistent tumors favor ALCL. Type D appears similar to primary cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ cytotoxic T cell lymphoma due to a markedly epidermotropic infiltrate of small atypical CD8+ and CD30+ lymphocytes, often TIA-1+ (T-cell intracytoplasmic antigen-1) or granzyme B+, but CD30 positivity and self-resolving lesions favor LyP. Type E mimics extranodal natural killer/T cell lymphoma (nasal type) due to angioinvasive CD30+ and beta F1+ T lymphocytes, often CD8+ and/or TIA-1+, but self-resolving lesions again favor LyP, as well as absence of Epstein-Barr virus and CD56−.9

The most common therapeutic approaches to LyP include topical steroids, phototherapy, and low-dose methotrexate.10 However, treatment does not change overall disease course or reduce the future risk for developing an associated lymphoma. Accordingly, abstaining from active therapeutic intervention is reasonable, especially in patients with only a few asymptomatic lesions.

- Macaulay WL. Lymphomatoid papulosis: a continuing self-healing eruption, clinically benign--histologically malignant. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:23-30.

- Slater DN. The new World Health Organization-European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer classification for cutaneous lymphomas: a practical marriage of two giants. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:874-880.

- Mori M, Manuelli C, Pimpinelli N, et al. CD30-CD30 ligand interaction in primary cutaneous CD30(+) T-cell lymphomas: a clue to the pathophysiology of clinical regression. Blood. 1999;94:3077-3083.

- Greisser J, Doebbeling U, Roos M, et al. Apoptosis in CD30-positive lymphoproliferative disorders of the skin. Exp Dermatol. 2005;14:380-385.

- Kiran T, Demirkesen C, Eker C, et al. The significance of MUM1/IRF4 protein expression and IRF4 translocation of CD30(+) cutaneous T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders: a study of 53 cases. Leuk Res. 2013;37:396-400.

- Wada DA, Law ME, Hsi ED, et al. Specificity of IRF4 translocations for primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma: a multicenter study of 204 skin biopsies. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:596-605.

- Pham-Ledard A, Prochazkova-Carlotti M, Laharanne E, et al. IRF4 gene rearrangements define a subgroup of CD30-positive cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: a study of 54 cases. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:816-825.

- Schiemann WP, Pfeifer WM, Levi E, et al. A deletion in the gene for transforming growth factor β type I receptor abolishes growth regulation by transforming growth factor β in a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Blood. 1999;94:2854-2861.

- Kempf W, Kazakov DV, Schärer L, et al. Angioinvasive lymphomatoid papulosis: a new variant simulating aggressive lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:1-13.

- Kempf W, Pfaltz K, Vermeer MH, et al. EORTC, ISCL, and USCLC consensus recommendations for the treatment of primary cutaneous CD30-positive lymphoproliferative disorders: lymphomatoid papulosis and primary cutaneous anaplastic large-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2011;118:4024-4035.

The Diagnosis: Lymphomatoid Papulosis

A shave biopsy of an established lesion on the volar aspect of the left wrist was performed (Figure 1). The biopsy showed an ulcerated nodular lesion characterized by a dense mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate in the dermis composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes, scattered neutrophils, and numerous eosinophils (Figure 2). Notably there was a minor population of large atypical cells with immunoblastic and anaplastic morphology present individually and in small clusters most prominently within the upper dermis (Figures 3 and 4). Immunohistochemistry of the anaplastic cells revealed a CD30+, CD3−, CD4+, CD5−, CD8−, CD2−, CD7−, CD56−, ALK1− (anaplastic lymphoma kinase-1), PAX5− (paired box protein-5), CD20−, and CD15− phenotype. These morphologic and immunohistochemical features suggested a CD30+ cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorder. The clinical history of recurrent self-healing papulonodules in an otherwise-healthy patient established the diagnosis of lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP).

Lymphomatoid papulosis is a lymphoproliferative disorder characterized by recurrent crops of self-resolving eruptive papulonodular skin lesions that may show a variety of histologic features including a CD30+ malignant T-cell lymphoma.1 Lymphomatoid papulosis was first described in 19681 but debate continues whether the condition should be considered malignant or benign.2 Although the prognosis is excellent, LyP is characterized by a protracted course, often lasting many years. Additionally, these patients have a lifelong increased risk for development of a second cutaneous or systemic lymphoma such as mycosis fungoides (MF), cutaneous or nodal anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL), or Hodgkin lymphoma, among others.

Lymphomatoid papulosis is a rare disease occurring in all ethnic groups and at any age, though most commonly presenting in the fifth decade of life. Finding large atypical T cells expressing CD30 in recurring skin lesions is highly suggestive of LyP; however, large CD30+ cells also can be seen in numerous benign reactive processes such as arthropod assault, drug eruption, viral skin infections, and other dermatoses, thus clinical correlation is always paramount. The cause of LyP is largely unknown; however, spontaneous regression may be explained by CD30-CD30 ligand interaction3 as well as an increased proapoptotic milieu.4 Specific translocations such as interferon regulatory factor-4 have been hypothesized as a risk factor for malignant progression.5-7 Additionally, an inactivating gene mutation resulting in loss of transforming growth factor β1 receptor expression and subsequent unresponsiveness to the growth inhibitory effect of transforming growth factor β may play a role in progression of LyP to ALCL.8

Clinically, LyP consists of red-brown papules and nodules generally smaller than 2 cm, often with central hemorrhage, necrosis, and crusting. Lesions are at different stages of eruption and resolution. They are often grouped but may be disseminated. Spontaneous regression typically occurs within 3 to 8 weeks. Pruritus or mild tenderness may occur as well as residual hyperpigmentation or scarring. Systemic symptoms are notably absent.

The histologic features of LyP vary according to the age of the lesion and subtype.2 Early lesions may only show a few inflammatory cells, but as lesions evolve, larger immunoblastlike CD30+ atypical cells accumulate that may resemble the Reed-Sternberg cells of Hodgkin lymphoma. Of the 5 subtypes, the most common is type A. It is characterized by a wedge-shaped infiltrate with a mixed population of scattered or clustered, large, atypical CD30+ cells, lymphocytes, neutrophils, eosinophils, and histiocytes.9 Frequent mitoses often are seen. Type B appears similar to MF due to a predominantly epidermotropic infiltrate of CD3+ and often CD30− atypical cells. Spontaneously regressing papules favor LyP, whereas persistent patches or plaques favor MF. Type C appears identical to ALCL with diffuse sheets of large atypical CD30+ cells and relatively few inflammatory cells, but spontaneously regressing lesions again favor LyP, whereas persistent tumors favor ALCL. Type D appears similar to primary cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ cytotoxic T cell lymphoma due to a markedly epidermotropic infiltrate of small atypical CD8+ and CD30+ lymphocytes, often TIA-1+ (T-cell intracytoplasmic antigen-1) or granzyme B+, but CD30 positivity and self-resolving lesions favor LyP. Type E mimics extranodal natural killer/T cell lymphoma (nasal type) due to angioinvasive CD30+ and beta F1+ T lymphocytes, often CD8+ and/or TIA-1+, but self-resolving lesions again favor LyP, as well as absence of Epstein-Barr virus and CD56−.9

The most common therapeutic approaches to LyP include topical steroids, phototherapy, and low-dose methotrexate.10 However, treatment does not change overall disease course or reduce the future risk for developing an associated lymphoma. Accordingly, abstaining from active therapeutic intervention is reasonable, especially in patients with only a few asymptomatic lesions.

The Diagnosis: Lymphomatoid Papulosis

A shave biopsy of an established lesion on the volar aspect of the left wrist was performed (Figure 1). The biopsy showed an ulcerated nodular lesion characterized by a dense mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate in the dermis composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes, scattered neutrophils, and numerous eosinophils (Figure 2). Notably there was a minor population of large atypical cells with immunoblastic and anaplastic morphology present individually and in small clusters most prominently within the upper dermis (Figures 3 and 4). Immunohistochemistry of the anaplastic cells revealed a CD30+, CD3−, CD4+, CD5−, CD8−, CD2−, CD7−, CD56−, ALK1− (anaplastic lymphoma kinase-1), PAX5− (paired box protein-5), CD20−, and CD15− phenotype. These morphologic and immunohistochemical features suggested a CD30+ cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorder. The clinical history of recurrent self-healing papulonodules in an otherwise-healthy patient established the diagnosis of lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP).

Lymphomatoid papulosis is a lymphoproliferative disorder characterized by recurrent crops of self-resolving eruptive papulonodular skin lesions that may show a variety of histologic features including a CD30+ malignant T-cell lymphoma.1 Lymphomatoid papulosis was first described in 19681 but debate continues whether the condition should be considered malignant or benign.2 Although the prognosis is excellent, LyP is characterized by a protracted course, often lasting many years. Additionally, these patients have a lifelong increased risk for development of a second cutaneous or systemic lymphoma such as mycosis fungoides (MF), cutaneous or nodal anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL), or Hodgkin lymphoma, among others.

Lymphomatoid papulosis is a rare disease occurring in all ethnic groups and at any age, though most commonly presenting in the fifth decade of life. Finding large atypical T cells expressing CD30 in recurring skin lesions is highly suggestive of LyP; however, large CD30+ cells also can be seen in numerous benign reactive processes such as arthropod assault, drug eruption, viral skin infections, and other dermatoses, thus clinical correlation is always paramount. The cause of LyP is largely unknown; however, spontaneous regression may be explained by CD30-CD30 ligand interaction3 as well as an increased proapoptotic milieu.4 Specific translocations such as interferon regulatory factor-4 have been hypothesized as a risk factor for malignant progression.5-7 Additionally, an inactivating gene mutation resulting in loss of transforming growth factor β1 receptor expression and subsequent unresponsiveness to the growth inhibitory effect of transforming growth factor β may play a role in progression of LyP to ALCL.8

Clinically, LyP consists of red-brown papules and nodules generally smaller than 2 cm, often with central hemorrhage, necrosis, and crusting. Lesions are at different stages of eruption and resolution. They are often grouped but may be disseminated. Spontaneous regression typically occurs within 3 to 8 weeks. Pruritus or mild tenderness may occur as well as residual hyperpigmentation or scarring. Systemic symptoms are notably absent.

The histologic features of LyP vary according to the age of the lesion and subtype.2 Early lesions may only show a few inflammatory cells, but as lesions evolve, larger immunoblastlike CD30+ atypical cells accumulate that may resemble the Reed-Sternberg cells of Hodgkin lymphoma. Of the 5 subtypes, the most common is type A. It is characterized by a wedge-shaped infiltrate with a mixed population of scattered or clustered, large, atypical CD30+ cells, lymphocytes, neutrophils, eosinophils, and histiocytes.9 Frequent mitoses often are seen. Type B appears similar to MF due to a predominantly epidermotropic infiltrate of CD3+ and often CD30− atypical cells. Spontaneously regressing papules favor LyP, whereas persistent patches or plaques favor MF. Type C appears identical to ALCL with diffuse sheets of large atypical CD30+ cells and relatively few inflammatory cells, but spontaneously regressing lesions again favor LyP, whereas persistent tumors favor ALCL. Type D appears similar to primary cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ cytotoxic T cell lymphoma due to a markedly epidermotropic infiltrate of small atypical CD8+ and CD30+ lymphocytes, often TIA-1+ (T-cell intracytoplasmic antigen-1) or granzyme B+, but CD30 positivity and self-resolving lesions favor LyP. Type E mimics extranodal natural killer/T cell lymphoma (nasal type) due to angioinvasive CD30+ and beta F1+ T lymphocytes, often CD8+ and/or TIA-1+, but self-resolving lesions again favor LyP, as well as absence of Epstein-Barr virus and CD56−.9

The most common therapeutic approaches to LyP include topical steroids, phototherapy, and low-dose methotrexate.10 However, treatment does not change overall disease course or reduce the future risk for developing an associated lymphoma. Accordingly, abstaining from active therapeutic intervention is reasonable, especially in patients with only a few asymptomatic lesions.

- Macaulay WL. Lymphomatoid papulosis: a continuing self-healing eruption, clinically benign--histologically malignant. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:23-30.

- Slater DN. The new World Health Organization-European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer classification for cutaneous lymphomas: a practical marriage of two giants. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:874-880.

- Mori M, Manuelli C, Pimpinelli N, et al. CD30-CD30 ligand interaction in primary cutaneous CD30(+) T-cell lymphomas: a clue to the pathophysiology of clinical regression. Blood. 1999;94:3077-3083.

- Greisser J, Doebbeling U, Roos M, et al. Apoptosis in CD30-positive lymphoproliferative disorders of the skin. Exp Dermatol. 2005;14:380-385.

- Kiran T, Demirkesen C, Eker C, et al. The significance of MUM1/IRF4 protein expression and IRF4 translocation of CD30(+) cutaneous T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders: a study of 53 cases. Leuk Res. 2013;37:396-400.

- Wada DA, Law ME, Hsi ED, et al. Specificity of IRF4 translocations for primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma: a multicenter study of 204 skin biopsies. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:596-605.

- Pham-Ledard A, Prochazkova-Carlotti M, Laharanne E, et al. IRF4 gene rearrangements define a subgroup of CD30-positive cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: a study of 54 cases. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:816-825.

- Schiemann WP, Pfeifer WM, Levi E, et al. A deletion in the gene for transforming growth factor β type I receptor abolishes growth regulation by transforming growth factor β in a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Blood. 1999;94:2854-2861.

- Kempf W, Kazakov DV, Schärer L, et al. Angioinvasive lymphomatoid papulosis: a new variant simulating aggressive lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:1-13.

- Kempf W, Pfaltz K, Vermeer MH, et al. EORTC, ISCL, and USCLC consensus recommendations for the treatment of primary cutaneous CD30-positive lymphoproliferative disorders: lymphomatoid papulosis and primary cutaneous anaplastic large-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2011;118:4024-4035.

- Macaulay WL. Lymphomatoid papulosis: a continuing self-healing eruption, clinically benign--histologically malignant. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:23-30.

- Slater DN. The new World Health Organization-European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer classification for cutaneous lymphomas: a practical marriage of two giants. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:874-880.

- Mori M, Manuelli C, Pimpinelli N, et al. CD30-CD30 ligand interaction in primary cutaneous CD30(+) T-cell lymphomas: a clue to the pathophysiology of clinical regression. Blood. 1999;94:3077-3083.

- Greisser J, Doebbeling U, Roos M, et al. Apoptosis in CD30-positive lymphoproliferative disorders of the skin. Exp Dermatol. 2005;14:380-385.

- Kiran T, Demirkesen C, Eker C, et al. The significance of MUM1/IRF4 protein expression and IRF4 translocation of CD30(+) cutaneous T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders: a study of 53 cases. Leuk Res. 2013;37:396-400.

- Wada DA, Law ME, Hsi ED, et al. Specificity of IRF4 translocations for primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma: a multicenter study of 204 skin biopsies. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:596-605.

- Pham-Ledard A, Prochazkova-Carlotti M, Laharanne E, et al. IRF4 gene rearrangements define a subgroup of CD30-positive cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: a study of 54 cases. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:816-825.

- Schiemann WP, Pfeifer WM, Levi E, et al. A deletion in the gene for transforming growth factor β type I receptor abolishes growth regulation by transforming growth factor β in a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Blood. 1999;94:2854-2861.

- Kempf W, Kazakov DV, Schärer L, et al. Angioinvasive lymphomatoid papulosis: a new variant simulating aggressive lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:1-13.

- Kempf W, Pfaltz K, Vermeer MH, et al. EORTC, ISCL, and USCLC consensus recommendations for the treatment of primary cutaneous CD30-positive lymphoproliferative disorders: lymphomatoid papulosis and primary cutaneous anaplastic large-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2011;118:4024-4035.

A 29-year-old man from Saudi Arabia presented with slightly tender skin lesions occurring in crops every few months over the last 7 years. The lesions typically would occur on the inguinal area, lower abdomen, buttocks, thighs, or arms, resolving within a few weeks despite no treatment. The patient denied having systemic symptoms such as fevers, chills, sweats, chest pain, shortness of breath, or unexpected weight loss. Physical examination revealed multiple erythematous papulonodules, some ulcerated with a superficial crust, grouped predominantly on the medial aspect of the right upper arm and left lower inguinal region. Isolated lesions also were present on the forearms, dorsal aspects of the hands, abdomen, and thighs. The grouped papulonodules were intermixed with faint hyperpigmented macules indicative of prior lesions. No oral lesions were noted, and there was no marked axillary or inguinal lymphadenopathy.

Eroded Plaque on the Lower Lip

The Diagnosis: Squamous Cell Carcinoma

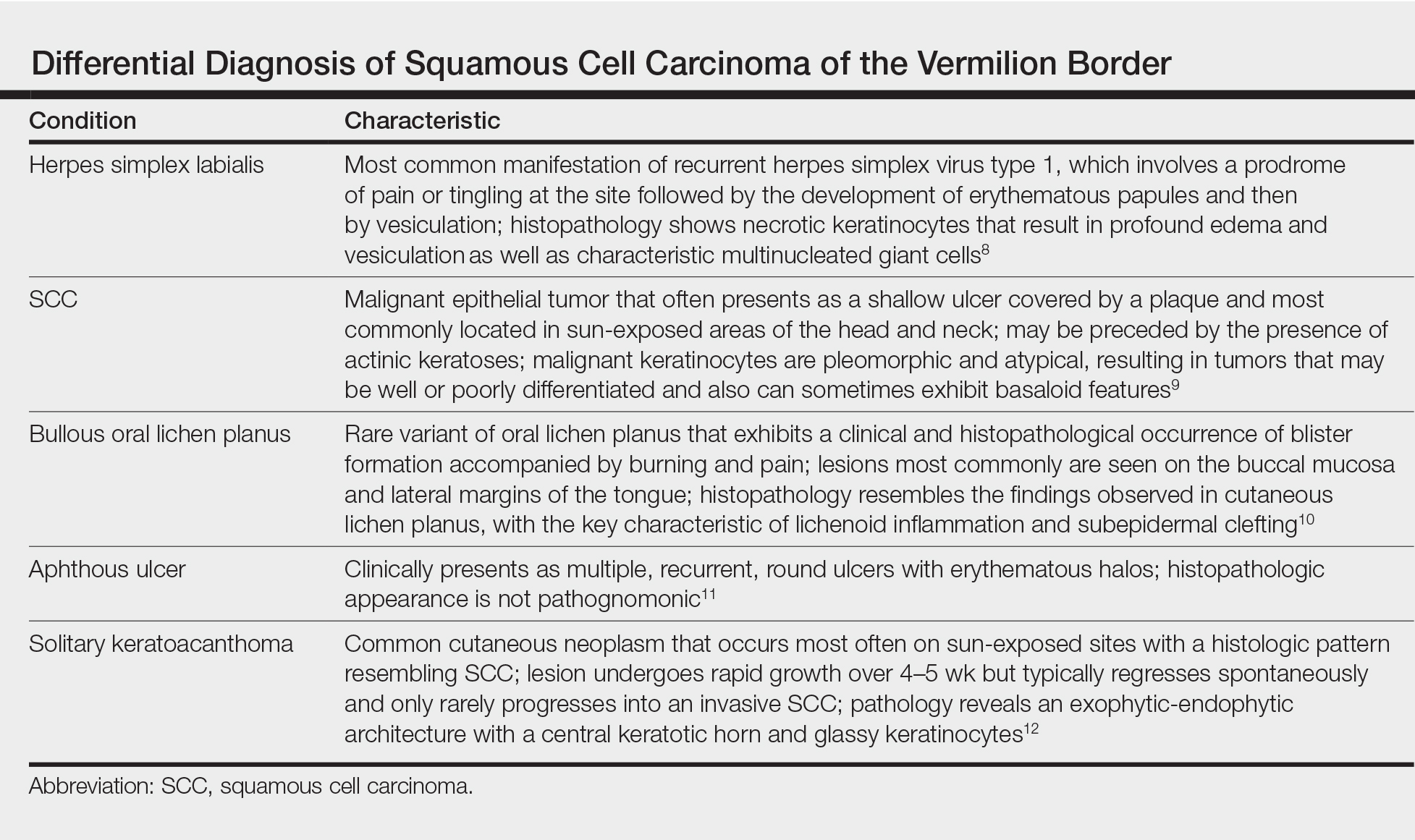

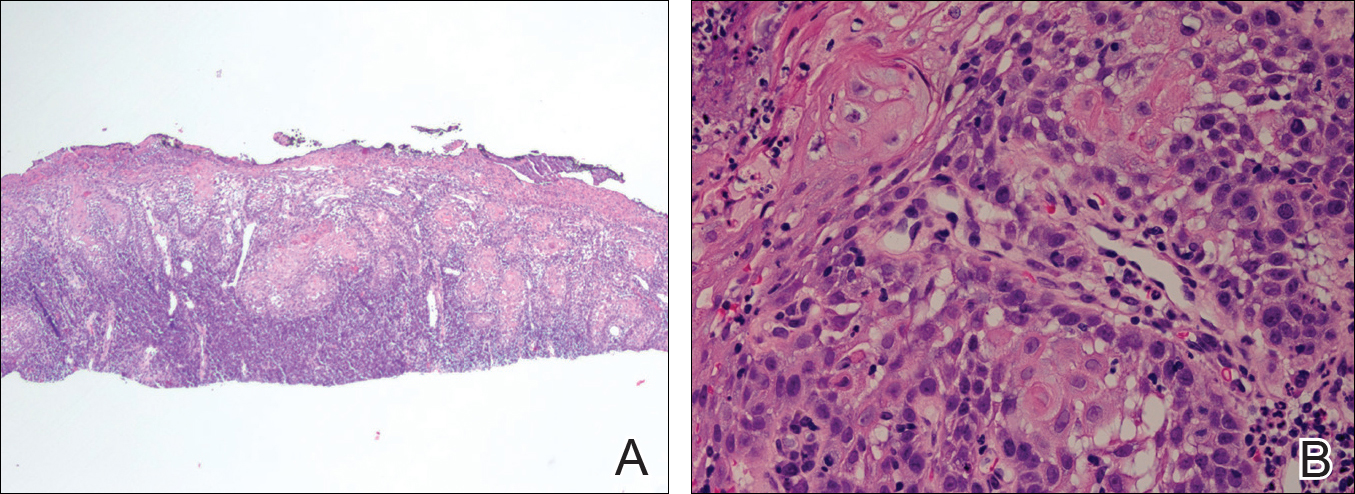

The initial clinical presentation suggested a diagnosis of herpes simplex labialis. The patient reported no response to topical acyclovir, and because the plaque persisted, a biopsy was performed. Pathology demonstrated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) that was moderately well differentiated and invasive (Figure).

Approximately 38% of all oral SCCs in the United States occur on the lower lip and typically are solar-related cancers developing within the epidermis.1 Oral lesions initially may be asymptomatic and may not be of concern to the patient; however, it is important to recognize SCC early, as invasive lesions have the potential to metastasize. Some factors that increase the chance for the development of metastases include tumor size larger than 2 cm; location on the ear, lip, or other sites on the head and neck; and history of prior unsuccessful treatment.2 Any solitary ulcer, lump, wound, or lesion that will not heal and persists for more than 3 weeks should be regarded as cancer until proven otherwise. Although few oral SCCs are detected by clinicians at an early stage, diagnostic aids such as vital staining and molecular markers in tissues and saliva may be implemented.3 Toluidine blue is a simple, fast, and inexpensive technique that stains the nuclear material of malignant lesions, but not normal mucosa, and may be a worthwhile diagnostic adjunct to clinical inspection.4

Our patient presented with a lesion that clinically looked herpetic, though he reported no prodromal signs of tingling, burning, or pain before the occurrence of the lesion. Due to the persistence of the lesion and lack of response to treatment, a biopsy was indicated. The differential diagnoses include aphthous ulcers, which may occasionally extend on to the vermilion border of the lip and exhibit nondiagnostic histology.5 Bullous oral lichen planus is the least common variant of oral lichen planus, is unlikely to present as a solitary lesion, and is rarely seen on the lips. Histologically, the lesion demonstrated lichenoid inflammation.6 Solitary keratoacanthoma, though histologically similar to SCC, typically presents as a rapidly growing crateriform nodule without erosion or ulceration.7 The differential diagnoses are summarized in the Table.

The patient underwent wide excision with repair by mucosal advancement flap. He continues to be regularly seen in the clinic for monitoring of other skin cancers and is doing well. Clinicians encountering any wound or ulcer that does not show signs of healing should be wary of underlying malignancy and be prompted to perform a biopsy.

- Fehrenbach MJ. Extraoral and intraoral clinical assessment. In: Darby ML, Walsh MM, eds. Dental Hygiene: Theory and Practice. 4th ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2014:214-233.

- Hawrot A, Alam M, Ratner D. Squamous cell carcinoma. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2003;15:91-133.

- Scully C, Bagan J. Oral squamous cell carcinoma overview. Oral Oncol. 2009;45:301-308.

- Chhabra N, Chhabra S, Sapra N. Diagnostic modalities for squamous cell carcinoma: an extensive review of literature considering toluidine blue as a useful adjunct. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;14:188-200.

- Porter SR, Scully C, Pedersen A. Recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2003;9:1499-1505.

- Bricker SL. Oral lichen planus: a review. Semin Dermatol. 1994;13:87-90.

- Cabrijan L, Lipozencic´ J, Batinac T, et al. Differences between keratoacanthoma and squamous cell carcinoma using TGF-alpha. Coll Antropol. 2013;37:147-150.

- Douglas GD, Couch RB. A prospective study of chronic herpes simplex virus infection and recurrent herpes labialis in humans. J Immunol. 1970;104:289-295.

- Alam M, Ratner D. Cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:976-983.

- van Tuyll van Serooskerken AM, van Marion AM, de Zwart-Storm E, et al. Lichen planus with bullous manifestation on the lip. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46(suppl 3):25-26.

- Messadi DV, Younai F. Apthous ulcers. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:281-290.

- Ko CJ. Keratoacanthoma: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:254-261.

The Diagnosis: Squamous Cell Carcinoma

The initial clinical presentation suggested a diagnosis of herpes simplex labialis. The patient reported no response to topical acyclovir, and because the plaque persisted, a biopsy was performed. Pathology demonstrated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) that was moderately well differentiated and invasive (Figure).

Approximately 38% of all oral SCCs in the United States occur on the lower lip and typically are solar-related cancers developing within the epidermis.1 Oral lesions initially may be asymptomatic and may not be of concern to the patient; however, it is important to recognize SCC early, as invasive lesions have the potential to metastasize. Some factors that increase the chance for the development of metastases include tumor size larger than 2 cm; location on the ear, lip, or other sites on the head and neck; and history of prior unsuccessful treatment.2 Any solitary ulcer, lump, wound, or lesion that will not heal and persists for more than 3 weeks should be regarded as cancer until proven otherwise. Although few oral SCCs are detected by clinicians at an early stage, diagnostic aids such as vital staining and molecular markers in tissues and saliva may be implemented.3 Toluidine blue is a simple, fast, and inexpensive technique that stains the nuclear material of malignant lesions, but not normal mucosa, and may be a worthwhile diagnostic adjunct to clinical inspection.4

Our patient presented with a lesion that clinically looked herpetic, though he reported no prodromal signs of tingling, burning, or pain before the occurrence of the lesion. Due to the persistence of the lesion and lack of response to treatment, a biopsy was indicated. The differential diagnoses include aphthous ulcers, which may occasionally extend on to the vermilion border of the lip and exhibit nondiagnostic histology.5 Bullous oral lichen planus is the least common variant of oral lichen planus, is unlikely to present as a solitary lesion, and is rarely seen on the lips. Histologically, the lesion demonstrated lichenoid inflammation.6 Solitary keratoacanthoma, though histologically similar to SCC, typically presents as a rapidly growing crateriform nodule without erosion or ulceration.7 The differential diagnoses are summarized in the Table.

The patient underwent wide excision with repair by mucosal advancement flap. He continues to be regularly seen in the clinic for monitoring of other skin cancers and is doing well. Clinicians encountering any wound or ulcer that does not show signs of healing should be wary of underlying malignancy and be prompted to perform a biopsy.

The Diagnosis: Squamous Cell Carcinoma

The initial clinical presentation suggested a diagnosis of herpes simplex labialis. The patient reported no response to topical acyclovir, and because the plaque persisted, a biopsy was performed. Pathology demonstrated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) that was moderately well differentiated and invasive (Figure).

Approximately 38% of all oral SCCs in the United States occur on the lower lip and typically are solar-related cancers developing within the epidermis.1 Oral lesions initially may be asymptomatic and may not be of concern to the patient; however, it is important to recognize SCC early, as invasive lesions have the potential to metastasize. Some factors that increase the chance for the development of metastases include tumor size larger than 2 cm; location on the ear, lip, or other sites on the head and neck; and history of prior unsuccessful treatment.2 Any solitary ulcer, lump, wound, or lesion that will not heal and persists for more than 3 weeks should be regarded as cancer until proven otherwise. Although few oral SCCs are detected by clinicians at an early stage, diagnostic aids such as vital staining and molecular markers in tissues and saliva may be implemented.3 Toluidine blue is a simple, fast, and inexpensive technique that stains the nuclear material of malignant lesions, but not normal mucosa, and may be a worthwhile diagnostic adjunct to clinical inspection.4

Our patient presented with a lesion that clinically looked herpetic, though he reported no prodromal signs of tingling, burning, or pain before the occurrence of the lesion. Due to the persistence of the lesion and lack of response to treatment, a biopsy was indicated. The differential diagnoses include aphthous ulcers, which may occasionally extend on to the vermilion border of the lip and exhibit nondiagnostic histology.5 Bullous oral lichen planus is the least common variant of oral lichen planus, is unlikely to present as a solitary lesion, and is rarely seen on the lips. Histologically, the lesion demonstrated lichenoid inflammation.6 Solitary keratoacanthoma, though histologically similar to SCC, typically presents as a rapidly growing crateriform nodule without erosion or ulceration.7 The differential diagnoses are summarized in the Table.

The patient underwent wide excision with repair by mucosal advancement flap. He continues to be regularly seen in the clinic for monitoring of other skin cancers and is doing well. Clinicians encountering any wound or ulcer that does not show signs of healing should be wary of underlying malignancy and be prompted to perform a biopsy.

- Fehrenbach MJ. Extraoral and intraoral clinical assessment. In: Darby ML, Walsh MM, eds. Dental Hygiene: Theory and Practice. 4th ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2014:214-233.

- Hawrot A, Alam M, Ratner D. Squamous cell carcinoma. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2003;15:91-133.

- Scully C, Bagan J. Oral squamous cell carcinoma overview. Oral Oncol. 2009;45:301-308.

- Chhabra N, Chhabra S, Sapra N. Diagnostic modalities for squamous cell carcinoma: an extensive review of literature considering toluidine blue as a useful adjunct. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;14:188-200.

- Porter SR, Scully C, Pedersen A. Recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2003;9:1499-1505.

- Bricker SL. Oral lichen planus: a review. Semin Dermatol. 1994;13:87-90.

- Cabrijan L, Lipozencic´ J, Batinac T, et al. Differences between keratoacanthoma and squamous cell carcinoma using TGF-alpha. Coll Antropol. 2013;37:147-150.

- Douglas GD, Couch RB. A prospective study of chronic herpes simplex virus infection and recurrent herpes labialis in humans. J Immunol. 1970;104:289-295.

- Alam M, Ratner D. Cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:976-983.

- van Tuyll van Serooskerken AM, van Marion AM, de Zwart-Storm E, et al. Lichen planus with bullous manifestation on the lip. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46(suppl 3):25-26.

- Messadi DV, Younai F. Apthous ulcers. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:281-290.

- Ko CJ. Keratoacanthoma: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:254-261.

- Fehrenbach MJ. Extraoral and intraoral clinical assessment. In: Darby ML, Walsh MM, eds. Dental Hygiene: Theory and Practice. 4th ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2014:214-233.

- Hawrot A, Alam M, Ratner D. Squamous cell carcinoma. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2003;15:91-133.

- Scully C, Bagan J. Oral squamous cell carcinoma overview. Oral Oncol. 2009;45:301-308.

- Chhabra N, Chhabra S, Sapra N. Diagnostic modalities for squamous cell carcinoma: an extensive review of literature considering toluidine blue as a useful adjunct. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;14:188-200.

- Porter SR, Scully C, Pedersen A. Recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2003;9:1499-1505.

- Bricker SL. Oral lichen planus: a review. Semin Dermatol. 1994;13:87-90.

- Cabrijan L, Lipozencic´ J, Batinac T, et al. Differences between keratoacanthoma and squamous cell carcinoma using TGF-alpha. Coll Antropol. 2013;37:147-150.

- Douglas GD, Couch RB. A prospective study of chronic herpes simplex virus infection and recurrent herpes labialis in humans. J Immunol. 1970;104:289-295.

- Alam M, Ratner D. Cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:976-983.

- van Tuyll van Serooskerken AM, van Marion AM, de Zwart-Storm E, et al. Lichen planus with bullous manifestation on the lip. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46(suppl 3):25-26.

- Messadi DV, Younai F. Apthous ulcers. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:281-290.

- Ko CJ. Keratoacanthoma: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:254-261.

An 83-year-old man presented with a new-onset 1.2-cm eroded plaque on the vermilion border of the right lower lip that reportedly developed 2 weeks prior and was increasing in size. The plaque was moist and was composed of confluent glistening papules. Medical history was notable for the presence of both basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas.

Black Adherence Nodules on the Scalp Hair Shaft

The Diagnosis: Piedra

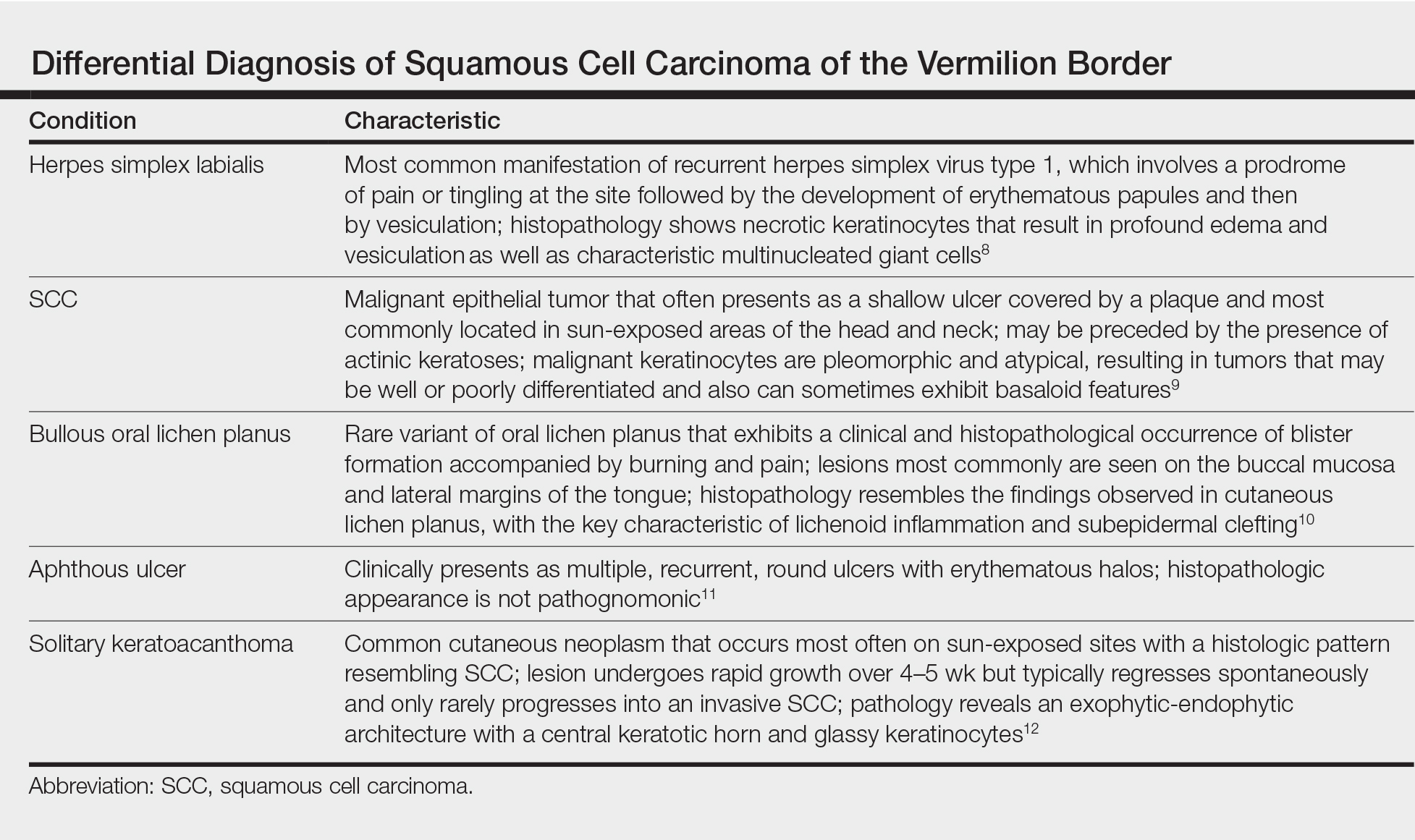

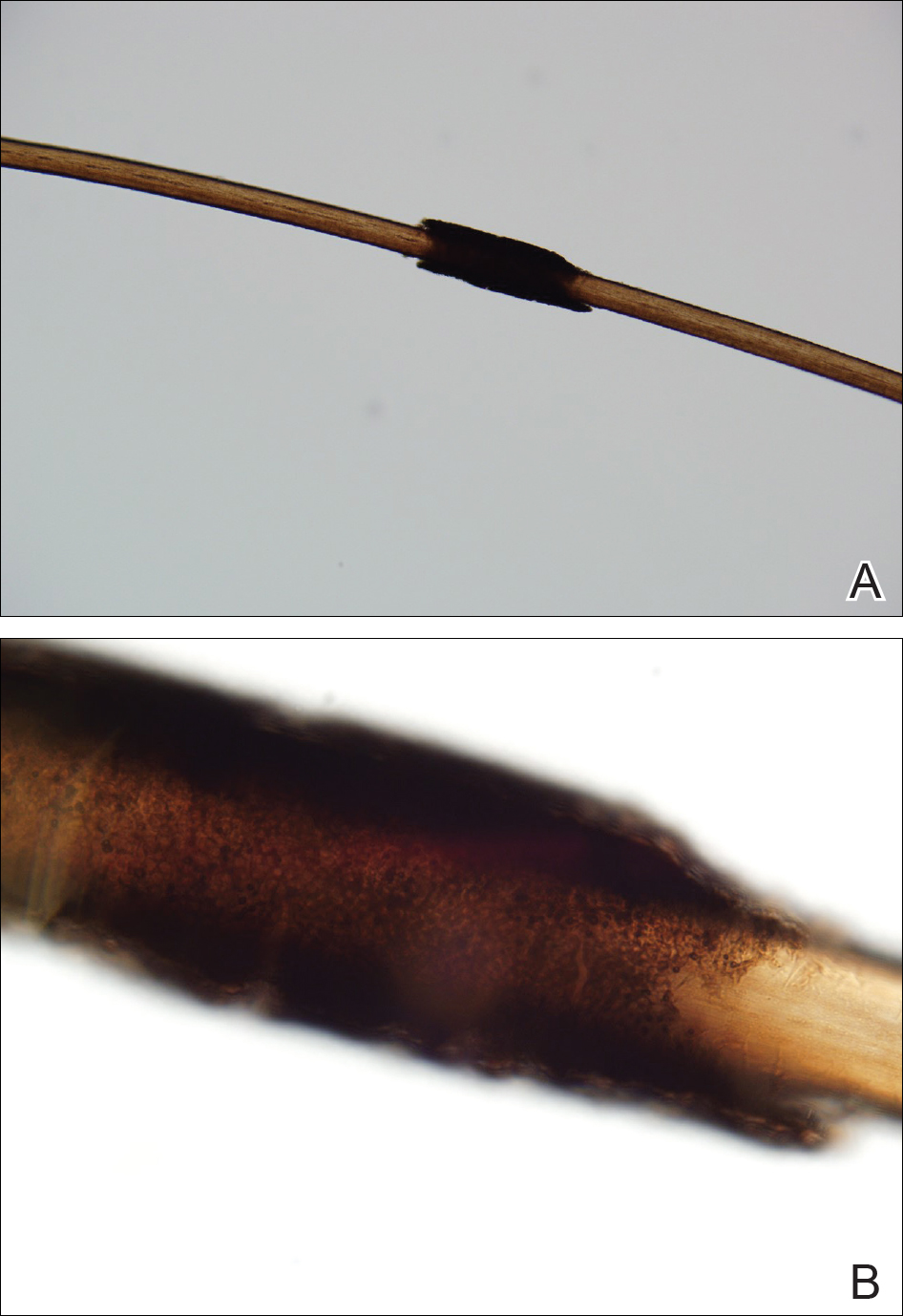

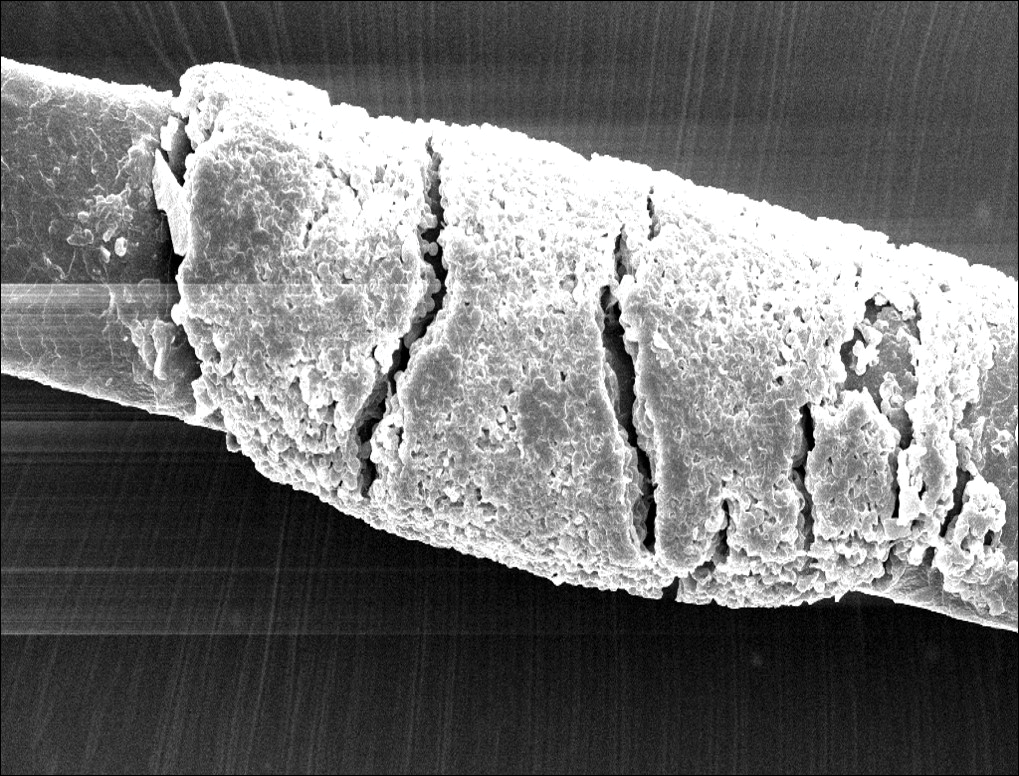

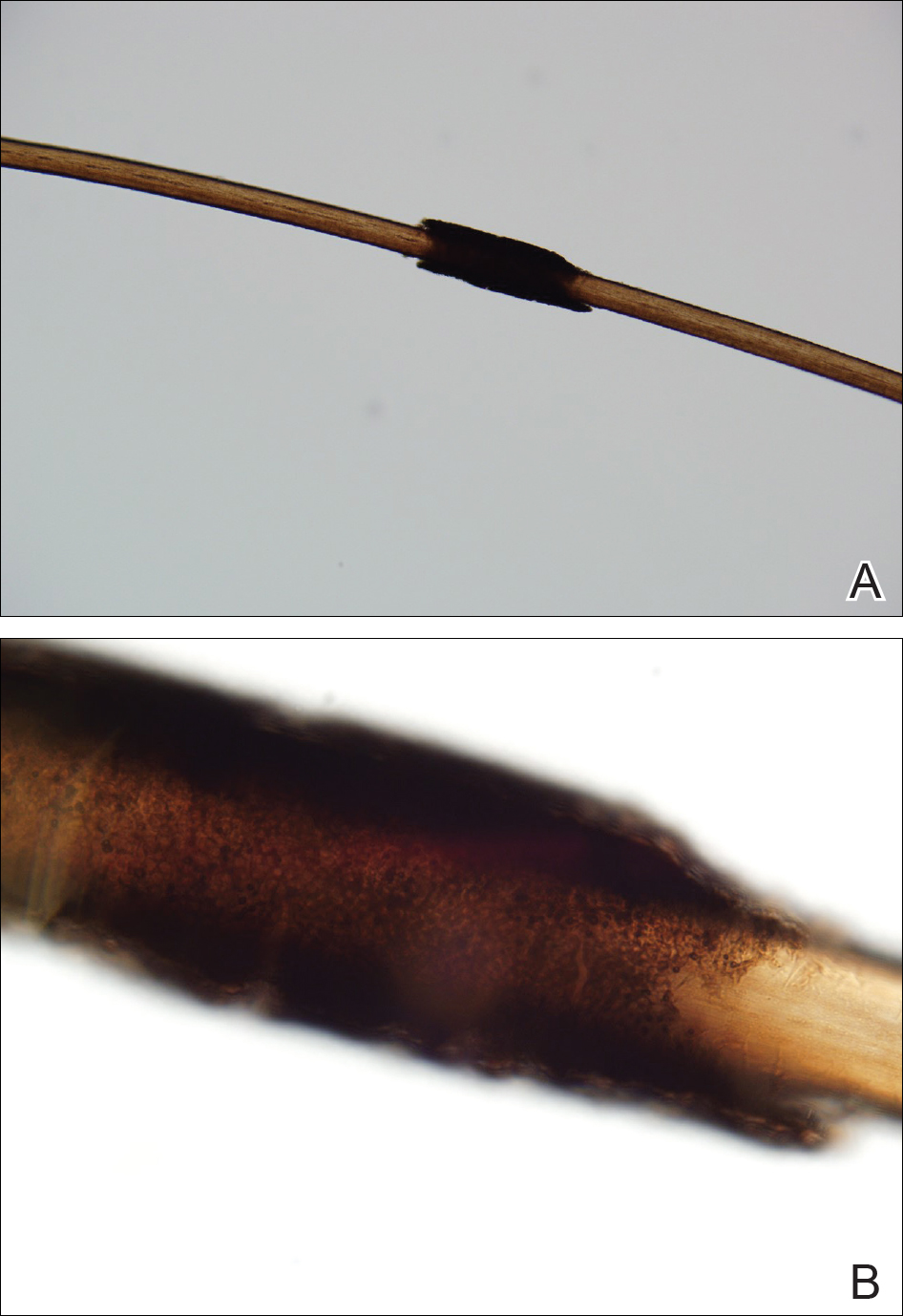

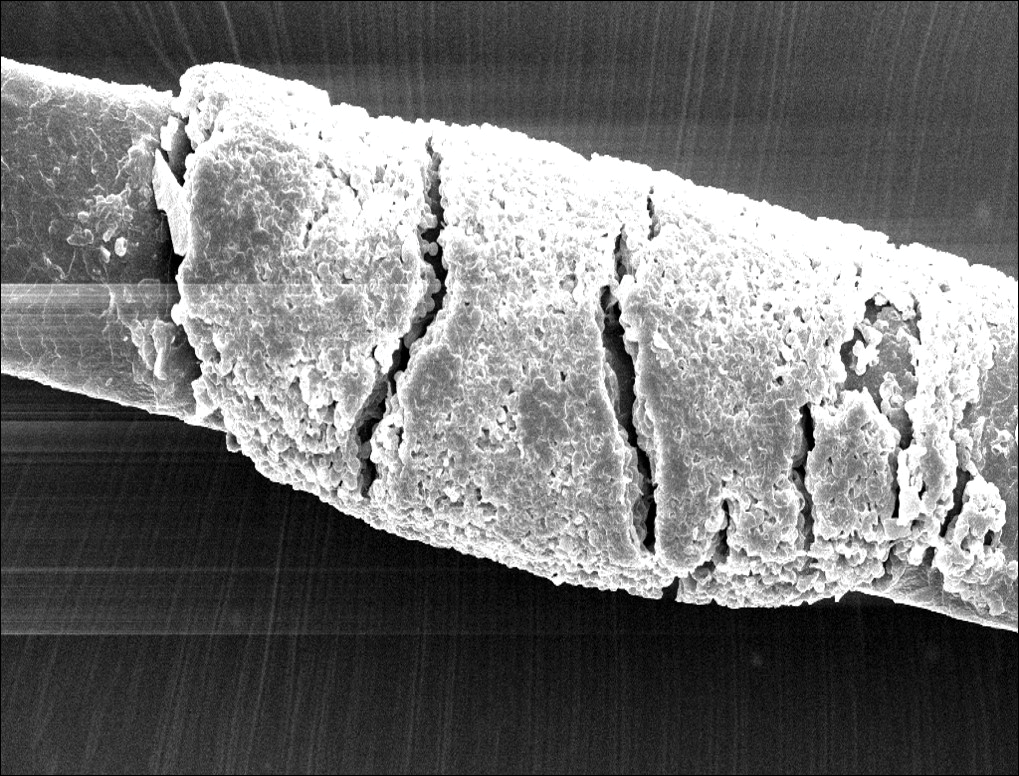

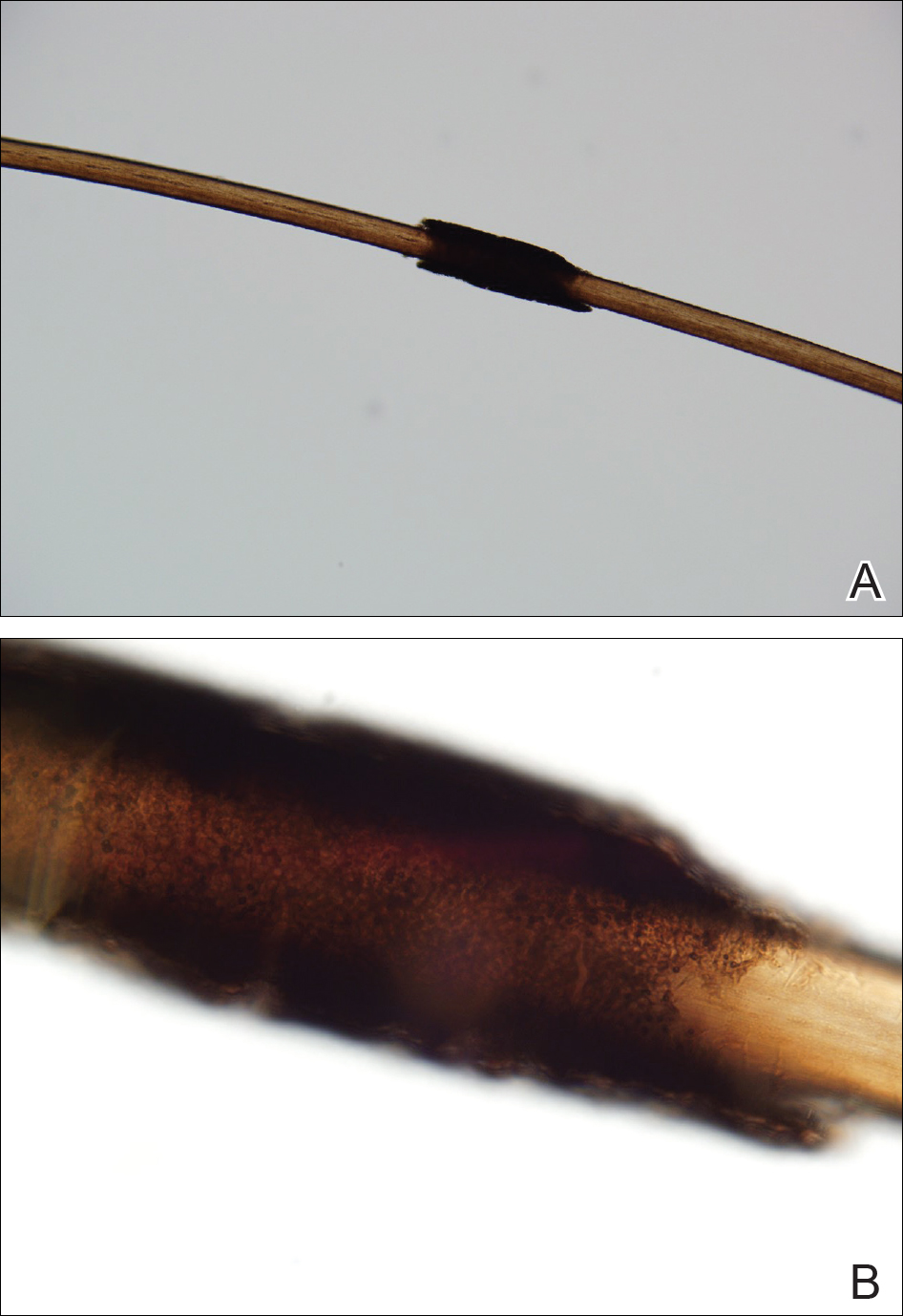

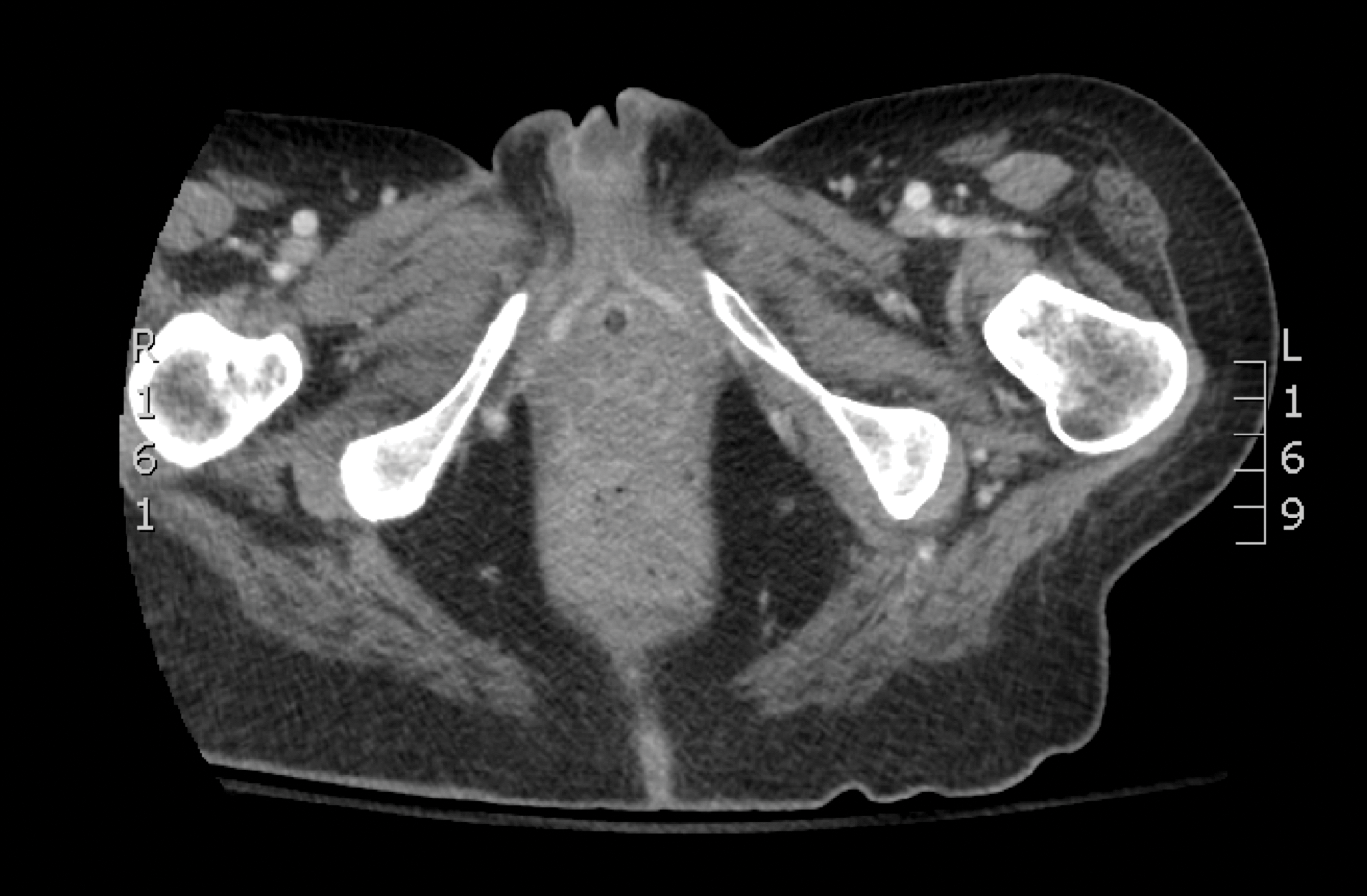

Microscopic examination of the hair shafts revealed brown to black, firmly adherent concretions (Figure 1). Scanning electron microscopy of the nodules was performed, which allowed for greater definition of the constituent hyphae and arthrospores (Figure 2).

Fungal cultures grew Trichosporon inkin along with other dematiaceous molds. The patient initially was treated with a combination of ketoconazole shampoo and weekly application of topical terbinafine. She trimmed 15.2 cm of the hair of her own volition. At 2-month follow-up the nodules were still present, though smaller and less numerous. Repeat cultures were obtained, which again grew T inkin. She then began taking oral terbinafine 250 mg daily for 6 weeks.

This case of piedra is unique in that our patient presented with black nodules clinically, but cultures grew only the causative agent of white piedra, T inkin. A search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms black piedra, white piedra, or piedra, and mixed infection or coinfection yielded one other similar case.1 Kanitakis et al1 speculated that perhaps there was coinfection of black and white piedra and that Piedraia hortae, the causative agent of black piedra, was unable to flourish in culture facing competition from other fungi. This scenario also could apply to our patient. However, the original culture taken from our patient also grew other dematiaceous molds including Cladosporium and Exophiala species. It also is possible that these other fungi could have contributed pigment to the nodules, giving it the appearance of black piedra when only T inkin was present as the true pathogen.

White piedra is a rare fungal infection of the hair shaft caused by organisms of the genus Trichosporon, with Trichosporon ovoides most likely to infect the scalp.2 Black piedra is a similar fungal infection caused by P hortae. Piedra means stone in Spanish, reflecting the appearance of these organisms on the hair shaft. It is common in tropical regions of the world such as Southeast Asia and South America, flourishing in the high temperatures and humidity.2 Both infectious agents are found in the soil or in standing water.3 White piedra most commonly is found in facial, axilla, or pubic hair, while black piedra most often is found in the hair of the scalp.2,4 Local cultural practices may contribute to transfer of Trichosporon or P hortae to the scalp, including the use of Brazilian plant oils in the hair or tying a veil or hijab to wet hair. Interestingly, some groups intentionally introduce the fungus to their hair for cosmetic reasons in endemic areas.2,3,5

Patients with white or black piedra generally are asymptomatic.4 Some may notice a rough texture to the hair or hear a characteristic metallic rattling sound as the nodules make contact with brush bristles.2,3 On inspection of the scalp, white piedra will appear to be white to light brown nodules, while black piedra presents as brown to black in color. The nodules are often firm on palpation.2,3 The nodules of white piedra generally are easy to remove in contrast to black piedra, which involves nodules that securely attach to the hair shaft but can be removed with pressure.3,5 Piedra has natural keratolytic activities and with prolonged infection can penetrate the hair cuticle, causing weakness and eventual breakage of the hair. This invasion into the hair cortex also can complicate treatment regimens, contributing to the chronic course of these infections.6

Diagnosis is based on clinical and microscopic findings. Nodules on hair shafts can be prepared with potassium hydroxide and placed on glass slides for examination.4 Dyes such as toluidine blue or chlorazol black E stain can be used to assist in identifying fungal structures.2 Sabouraud agar with cycloheximide may be the best choice for culture medium.2 Black piedra slowly grows into small dome-shaped colonies. White piedra will grow more quickly into cream-colored colonies with wrinkles and sometimes mucinous characteristics.3