User login

Mass in mouth

|

|

The diagnosis

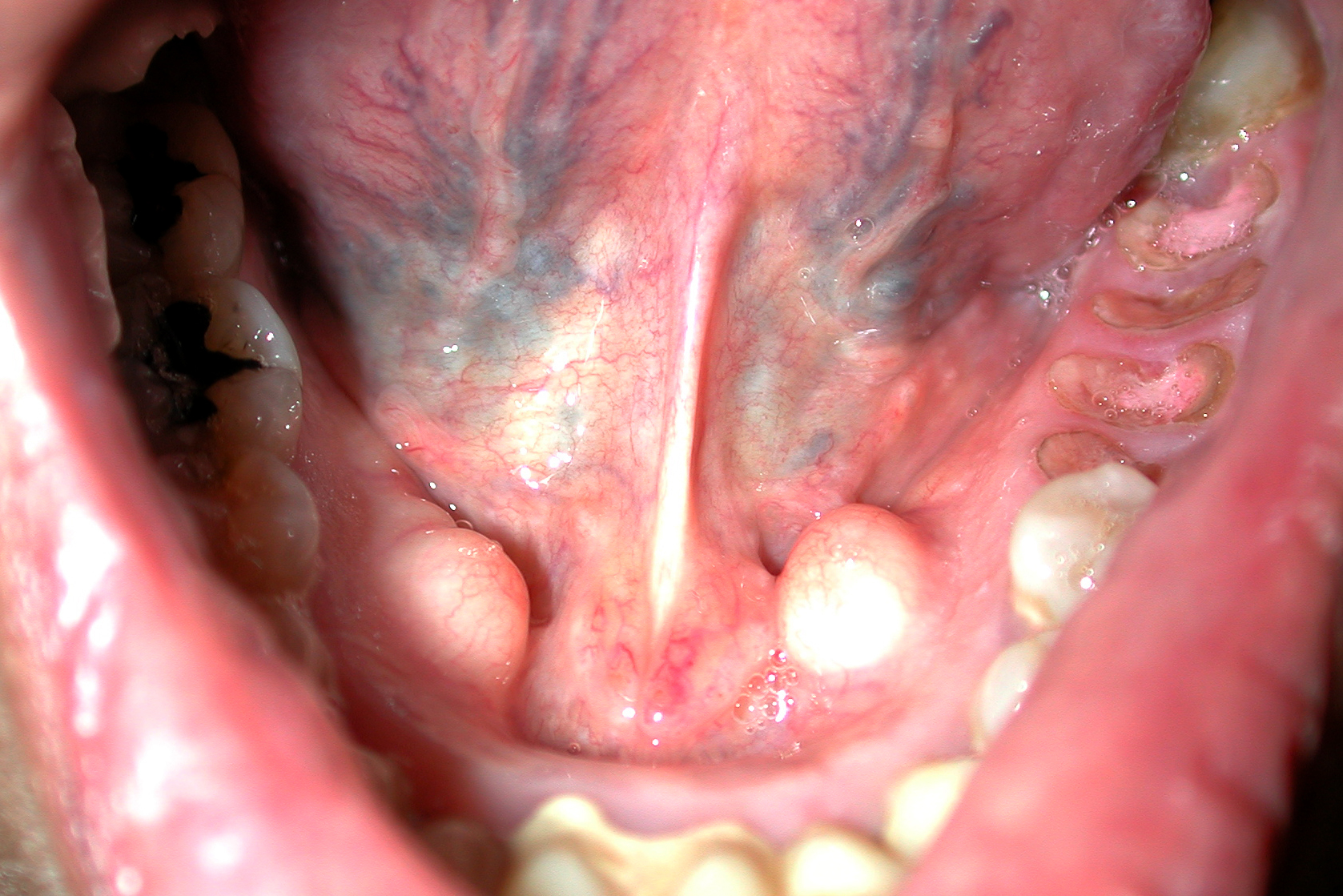

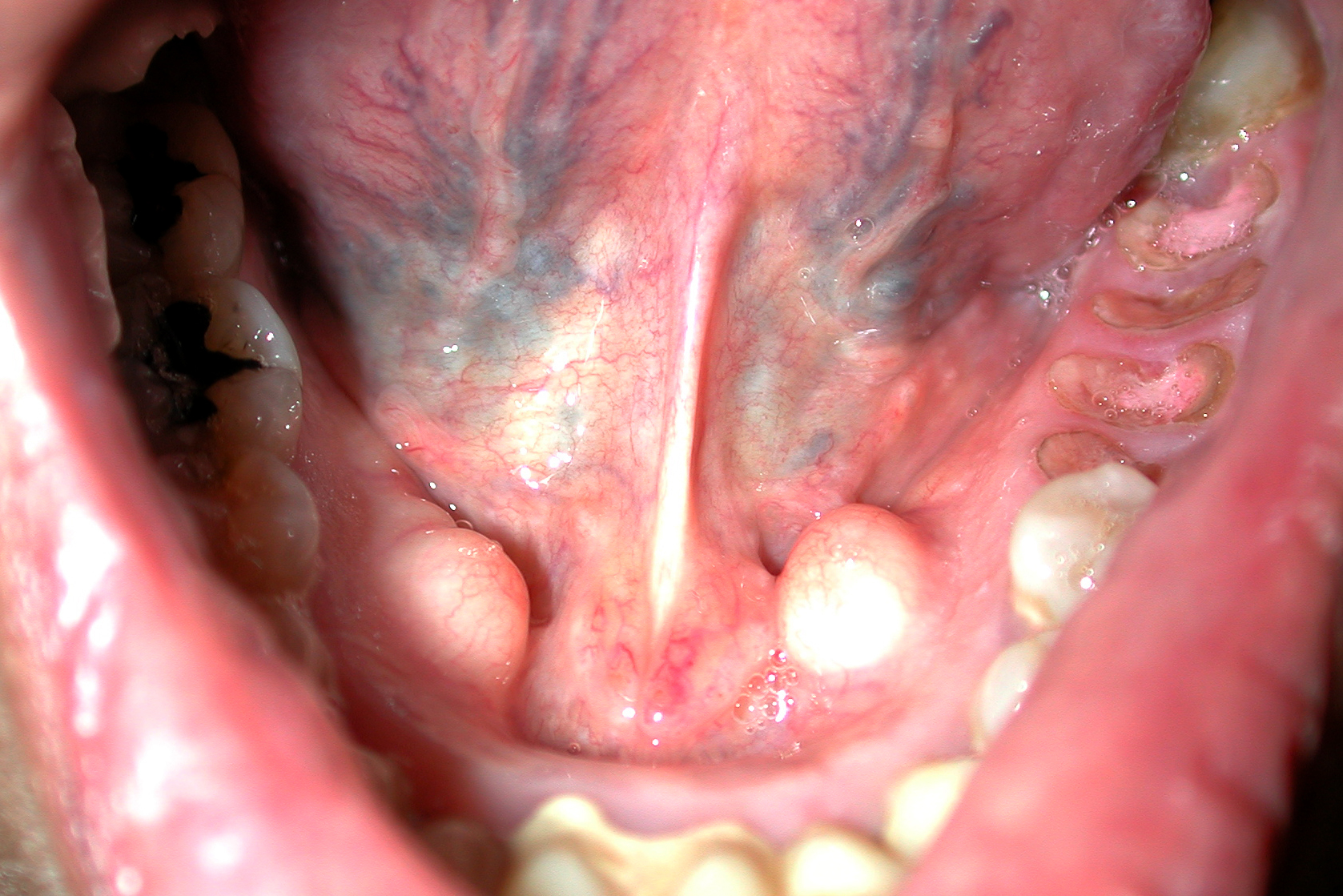

The mass in the patient’s mouth was a torus palatinus (FIGURE 1) and nothing needed to be done about it.

A torus palatinus is the most common bony maxillofacial exostosis. It is usually seen in adults over 30 years of age. It is more common in women than in men. This benign bony exostosis occurs in the midline of the hard palate. It is often noticed incidentally as a hard lump protruding from the hard palate into the mouth covered with normal mucous membrane. It is important not to miss a squamous cell carcinoma in this area, but an SCC is not as hard and the mucous membranes are usually ulcerated.

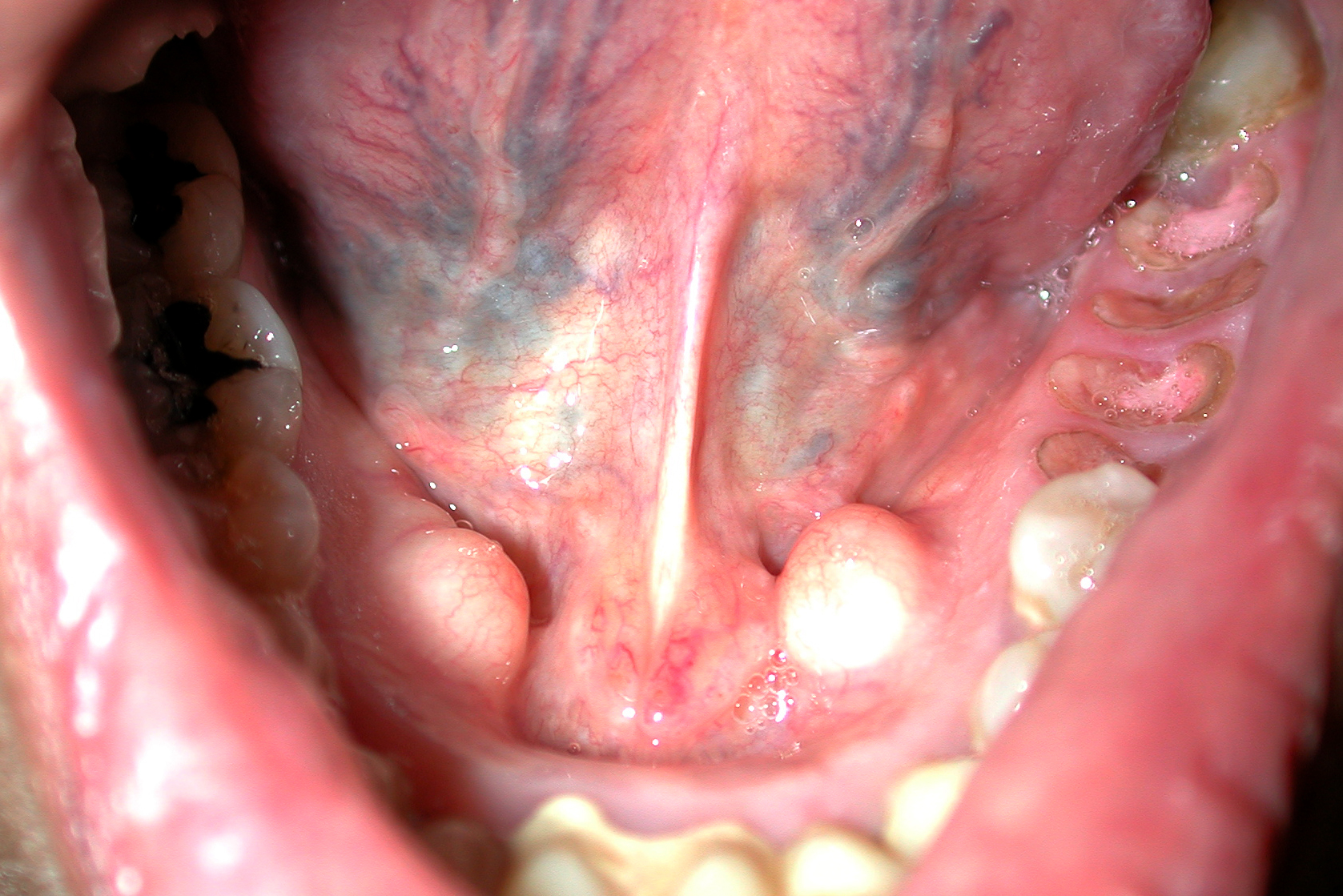

Excision can be considered if the lesion interferes with function such as the fit of dentures. A variation of this is the torus mandibularis (FIGURE 2).

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: French L. Torus palatinus. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, Chumley H, Tysinger J, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:148-149.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

|

|

The diagnosis

The mass in the patient’s mouth was a torus palatinus (FIGURE 1) and nothing needed to be done about it.

A torus palatinus is the most common bony maxillofacial exostosis. It is usually seen in adults over 30 years of age. It is more common in women than in men. This benign bony exostosis occurs in the midline of the hard palate. It is often noticed incidentally as a hard lump protruding from the hard palate into the mouth covered with normal mucous membrane. It is important not to miss a squamous cell carcinoma in this area, but an SCC is not as hard and the mucous membranes are usually ulcerated.

Excision can be considered if the lesion interferes with function such as the fit of dentures. A variation of this is the torus mandibularis (FIGURE 2).

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: French L. Torus palatinus. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, Chumley H, Tysinger J, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:148-149.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

|

|

The diagnosis

The mass in the patient’s mouth was a torus palatinus (FIGURE 1) and nothing needed to be done about it.

A torus palatinus is the most common bony maxillofacial exostosis. It is usually seen in adults over 30 years of age. It is more common in women than in men. This benign bony exostosis occurs in the midline of the hard palate. It is often noticed incidentally as a hard lump protruding from the hard palate into the mouth covered with normal mucous membrane. It is important not to miss a squamous cell carcinoma in this area, but an SCC is not as hard and the mucous membranes are usually ulcerated.

Excision can be considered if the lesion interferes with function such as the fit of dentures. A variation of this is the torus mandibularis (FIGURE 2).

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: French L. Torus palatinus. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, Chumley H, Tysinger J, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:148-149.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

Pruritic rash

CASE 1: A 13-year-old Caucasian girl sought treatment for a pruritic, scaling patch on her right cheek. The patient had a 10-year history of atopic eczema, with rashes primarily in flexural areas, and a history of skin reactions to earrings and rivets in her blue jeans. She had gone 3 years without a rash on her earlobes and periumbilical areas by scrupulously avoiding contact with metal.

The 2 x 2-cm patch of pruritic, scaling, lichenified skin with focal excoriation that brought her in on this day had been on her right cheek for the past 3 months ( FIGURE 1 ). It had not responded to hydrocortisone 2.5% cream and desonide 0.05% cream when she applied it twice daily, nor had it responded to an intralesional injection of 2 cc of 2.5 mg/cc triamcinolone acetonide.

CASE 2: A 13-year-old African American girl with a history of atopic dermatitis went to her doctor for a rash beneath the umbilicus. She’d had the rash, which she said was extremely itchy, for 6 weeks; over the previous 10 days, it had become more widespread. A 6 x 5-cm scaling, lichenified, hyperpigmented plaque was present in the infra-umbilical region. She also had a papular rash on the dorsal hands and axillae.

CASE 3: A 15-year-old Caucasian girl sought care for a pruritic, erythematous rash circumscribing her left wrist in an 8-mm diameter band. She’d had the rash for 6 weeks.

CASE 4: A 58-year-old Caucasian woman presented with a pruritic, erythematous, scaling rash on both upper cheeks just below her lower eyelids. She told the physician that she had a similar pruritic rash on her earlobes when she wore costume jewelry.

CASE 5: A 50-year-old woman went to her doctor for a pruritic, erythematous patch on the anterior and posterior sides of her ear-lobes, bilaterally. She told the physician that her ears had been pierced 2 weeks earlier.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU MANAGE THIS CONDITION?

Diagnosis: Nickel dermatitis

Each of these 5 patients had allergic contact dermatitis caused by nickel. The cheek dermatitis was produced by contact with the circular “menu” button on the patient’s cell phone (Case 1/ FIGURE 1 ), the periumbilical rash by the rivet behind a blue jeans button (Case 2/ FIGURE 2 ), the wrist dermatitis by a bracelet (Case 3/ FIGURE 3 ), the rash on the upper cheeks by eyeglass frames (Case 4/ FIGURE 4 ), and the earlobe dermatitis by earrings (Case 5/ FIGURE 5 ). The presence of nickel in each object was confirmed with a positive dimethylglyoxime (DMG) test.

What you’ll see. Besides an erythematous, pruritic, scaling rash, other findings can include vesicles and bullae that break and form crusts at sites of contact. Extreme pruritus is also commonly seen and prompts chronic rubbing and scratching, resulting in the development of lichenification and hyper-pigmentation.

FIGURE 1

Scaling patch on cheek

FIGURE 2

Rash beneath umbilicus

The cause: The rivet on the patient’s blue jeans.

FIGURE 3

… around the wrist

The cause: The bracelet (shown), which would normally sit where the erythematous band is located.

FIGURE 4

… on the cheeks

The cause: Eyeglasses.

FIGURE 5

… on the earlobes

The cause: Nickel in pierced earrings.

Nickel dermatitis is increasingly common

Nickel is a leading cause of allergic contact dermatitis and is responsible for more cases than all other metals combined.1,2 The incidence of nickel dermatitis has been increasing in the United States for the last 15 years, annually affecting an estimated 14% to 20% of women and 2% to 4% of men.3,4 The higher percentage in women is related to nickel exposure associated with ear piercing and nickel-plated jewelry. In fact, the highest risk for nickel allergy is in young females with pierced ears.2,5,6 The number of affected males, however, is increasing, as earrings and body piercing gain popularity in this group.3

Certain occupations with high exposure to nickel, such as cashiers, hairdressers, metal workers, domestic cleaners, food handlers, bar workers, and painters, are also at risk for acquiring nickel dermatitis.7 Patients with atopic eczema are also at increased risk.8,9

Sweating may increase the severity of the dermatitis. Sodium chloride in the sweat causes corrosion of the metal and increases nickel exposure.10 Nickel release is therefore common in areas of the body that tend to be sweaty—for example, the hands, especially around the fingers, where inexpensive rings containing nickel are worn, or on the hands of individuals who carry metal key rings.

Consider oral intake of nickel, too. Another far less common, but important, nickel allergy presentation is systemic contact dermatitis from oral intake of nickel. Nuts, legumes, and chocolate can cause a flare-up reaction in a previously positive patch test site or previous site of nickel dermatitis.11 Patients can also develop a dyshidrotic eczema on the hands. Itching and general symptoms, such as headache, nausea, and malaise, have also been reported after the oral nickel exposure of nickel-sensitive individuals.12 Dietary intervention studies indicate that it is possible to reduce the activity of dermatitis in these patients by maintaining a diet low in nickel.13-16

Finally, severe local reactions to nickel and other contact allergens can lead to auto-eczematization, in which a papular or papulosquamous eruption and pruritus appear distant from the site of exposure.

Is it atopic eczema or contact dermatitis?

It can be difficult to distinguish a flare in atopic eczema from chronic allergic contact dermatitis in individuals who may display both processes concurrently. The primary clue to the diagnosis is the peculiar localization of the rash, as evidenced by the cases we have described.

Patch testing is not required for diagnosis

Nickel contact dermatitis is often suspected when patients present with an acute or sub-acute eruption characterized by erythema, vesicles, and scaling in a distribution corresponding to a metal contact allergen. Nickel allergy is one of the few types of allergic contact dermatitis where the history of exposure along with the signs and symptoms are so distinctive that patch testing is often not required.

Amelioration of the rash associated with the withdrawal of the contactant serves as adequate confirmation of the diagnosis in many cases. A DMG test is a simple, inexpensive way to determine whether the object in question contains nickel. It can be used in the physician’s office or by the patient at home. Therefore, in some clinical situations, as in the presented cases, it is appropriate to make a presumptive diagnosis of nickel dermatitis, confirm the presence of nickel with a DMG test, remove the off ending metal item, treat with topical anti-inflammatory medications, and confirm the diagnosis by monitoring the patient’s response.

When patients do not respond to withdrawal of the suspected allergen and anti-inflammatory treatment, when multiple allergens are suspected, or when a definitive diagnosis is required for legal purposes, patch testing with nickel can confirm the diagnosis. In some cases, when the distribution of the rash is not distinctive, patch test screening may elicit a positive test to nickel that prompts the physician to investigate the source of the exposure.

Tx: Remove the item, apply topical steroids

Acute episodes of nickel dermatitis are treated with topical steroid creams to break the scratch-itch cycle (which potentiates the reaction) and to reduce the inflammation. This tactic is futile, however, if the allergen remains in contact with the skin. The source of the nickel must be identified and eliminated by the patient, as was done by the 5 patients we cared for.

Clothing accessories containing nickel, such as buckles, zippers, buttons, and metal clips, must be eliminated, as well as other sources of nickel: jewelry, watches, eyeglasses, and cell phones. The situation is complicated by the fact that many patients have underlying atopic eczema/irritant dermatitis, and patients may have more than 1 form of allergic contact dermatitis. For instance, self-treatment with neomycin-containing topical antibiotics may lead to superimposed allergic contact dermatitis from this agent.

Easy preventive steps. Routine prophylactic measures should focus on eliminating exposure to nickel from all identifiable sources. You can suggest that your patient with nickel dermatitis:

- Use a clear plastic cover over the nickel-containing parts of a cell phone.

- Apply a clear coat of nail polish to the buttons and rivets on pants; this can prevent nickel release and will last through at least 2 wash and dry cycles.17 (Tucking shirts in to prevent buttons and belt buckles from touching the skin is generally ineffective; not only is the shirt unlikely to stay in place all day, but perspiration and friction can also cause problems.)

- Use other barrier coatings, such as Nickel Guard and Beauty Secrets Hardener, which may be effective in preventing contact dermatitis.18

- Replace rivets on pants with a plastic button, or cover the rivet with a sew-on denim patch. This offers a more permanent approach to eliminating nickel exposure.

- Use plastic covers for earring studs.

- Replace metal eyeglass frames with ones made out of plastic.

- Choose “hypoallergenic” or nickel-free jewelry. Of note, though: Nickel may be present in jewelry labeled hypoallergenic. The patient can perform a DMG test to verify its nickel content.

In patients who continue to react in the absence of nickel jewelry, co-sensitization to gold must be considered, as many patients do react to multiple metals. Gold is a more common allergen than previously reported and is statistically linked to allergic reactions to nickel and cobalt metals.19 Unlike nickel dermatitis, the clinical relevance of a positive gold patch test is harder to ascertain because rashing distant from areas in direct contact with gold jewelry often occurs. In fact, in some cases of eyelid dermatitis induced by contact allergy to gold, titanium dioxide particles on the skin from cosmetics and sunscreen are thought to adsorb gold particles and carry them to the eyelids.

Disclosure

Dr. Brodell reports that he receives grants/research support from Amgen Inc., Doak Dermatologics, Galderma, and OrthoNeutrogena. He serves as a consultant for, or is on the speakers bureau of, 3M/Graceway Pharmaceuticals, Allergan, CollagGenex Pharmaceuticals, Connetics Corp., Dermik/BenzaClin, Galderma, Genentech, Inc., Genentech/ Raptiva, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, MDsConnect.net, Medicis, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp., Pedinol Pharmacal, Inc., Roerig-Pfizer, Sandoz/Novartis, sanofi-aventis, Sirius Laboratories, Stiefel, Westwood-Squibb, and Upjohn. Ms. Uhlenhake and Dr. Nedorost reported no potential conflict of interest relevant to this article.

CORRESPONDENCE

Robert Brodell, MD, 2660 East Market Street, Warren, OH 44483; [email protected]

1. Arnold HL, Odom RB, James WD. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 8th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: W.B. Saunders Co.; 1990.

2. Thyssen JP, Linneberg A, Menne T, et al. The epidemiology of contact allergy in the general population—prevalence and main findings. Contact Dermatitis. 2007;57:287-299.

3. Rietschel RL, Fowler JF, Warshaw EM, et al. Detection of nickel sensitivity has increased in North American patch-test patients. Dermatitis. 2008;19:16-19.

4. Belsito DV. Allergic contact dermatitis. In: Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, et al. Fitzpatrick’s dermatology in general medicine. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1999:1447-1461.

5. McDonagh AJG, Wright AL, Cork MJ, et al. Nickel sensitivity: the influence of ear piercing and atopy. Br J Dermatol. 1992;126:16-18

6. Larsson-Stymne B, Widstrom L. Ear piercing: a cause of nickel allergy in school girls? Contact Dermatitis. 1985;13:289-293.

7. Shah M, Lewis F, Gawkrodger DJ. Nickel as an occupational allergen. A survey of 368 nickel-sensitive subjects. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:1231-1236.

8. De Groot AC. The frequency of contact allergy in atopic patients with dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 1990;22:273-277.

9. Cronin E, McFadden JP. Patients with atopic eczema do become sensitized to contact allergens. Contact Dermatitis. 1993;28:225-228.

10. Suchoski JP. Allergic contact dermatitis. J Assoc Milit Dermatol. 1983;9:65-8.

11. Veien NK, Hattel T, Justesen O, Norholm A. Diagnostic procedures for eczema patients. Contact Dermatitis. 1987;17:35-40.

12. Jensen CS, Menne T, Lisby S, et al. Experimental systemic contact dermatitis from nickel: a dose-response study. Contact Dermatitis. 2003;49:124-132.

13. Kaaber K, Veien NK, Tjell JC. Low nickel diet in the treatment of patients with chronic nickel dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 1978;98:197-200.

14. Veien NK, Hattel T, Justesen O, et al. Dietary treatment of nickel dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1985;65:138-142.

15. Veien NK, Hattel T, Laurberg G. Low nickel diet: an open, prospective trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:1002-1007.

16. Antico A, Soana R. Chronic allergic-like dermatopathies in nickel-sensitive patients. Results of dietary restrictions and challenge with nickel salts. Allergy Asthma Proc. 1999;20:235-242.

17. Suneja T, Flanagan KH, Glaser DA. Blue-jean button nickel: prevalence and prevention of its release from buttons. Dermatitis. 2007;18:208-211.

18. Sprigle AM, Marks JG, Jr. Anderson BE. Prevention of nickel release with barrier coatings. Dermatitis. 2008;19:28-31.

19. Fowler J, Jr, Taylor J, Storrs F, et al. Gold allergy in North America. Am J Contact Dermat. 2001;12:3-5.

CASE 1: A 13-year-old Caucasian girl sought treatment for a pruritic, scaling patch on her right cheek. The patient had a 10-year history of atopic eczema, with rashes primarily in flexural areas, and a history of skin reactions to earrings and rivets in her blue jeans. She had gone 3 years without a rash on her earlobes and periumbilical areas by scrupulously avoiding contact with metal.

The 2 x 2-cm patch of pruritic, scaling, lichenified skin with focal excoriation that brought her in on this day had been on her right cheek for the past 3 months ( FIGURE 1 ). It had not responded to hydrocortisone 2.5% cream and desonide 0.05% cream when she applied it twice daily, nor had it responded to an intralesional injection of 2 cc of 2.5 mg/cc triamcinolone acetonide.

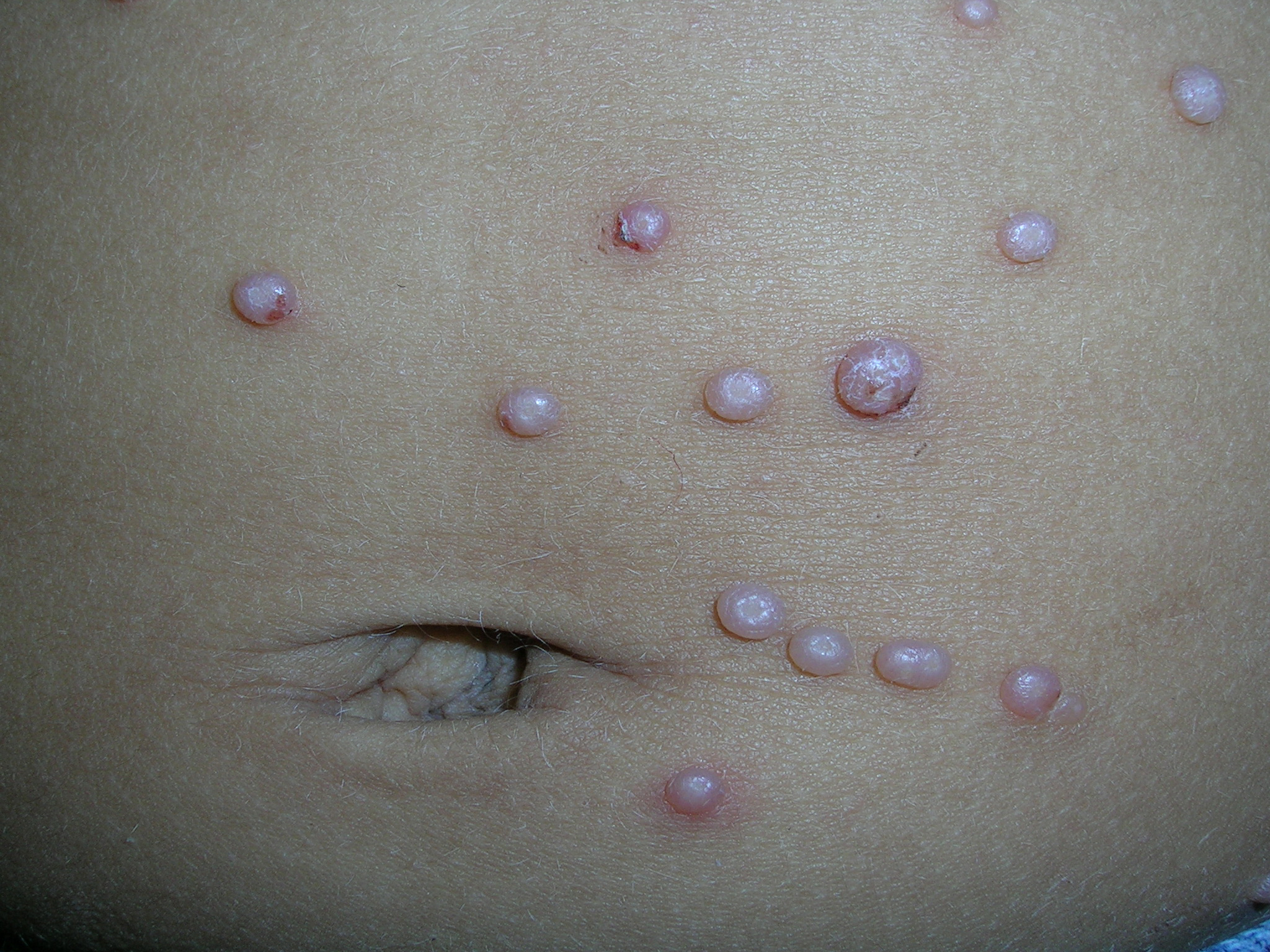

CASE 2: A 13-year-old African American girl with a history of atopic dermatitis went to her doctor for a rash beneath the umbilicus. She’d had the rash, which she said was extremely itchy, for 6 weeks; over the previous 10 days, it had become more widespread. A 6 x 5-cm scaling, lichenified, hyperpigmented plaque was present in the infra-umbilical region. She also had a papular rash on the dorsal hands and axillae.

CASE 3: A 15-year-old Caucasian girl sought care for a pruritic, erythematous rash circumscribing her left wrist in an 8-mm diameter band. She’d had the rash for 6 weeks.

CASE 4: A 58-year-old Caucasian woman presented with a pruritic, erythematous, scaling rash on both upper cheeks just below her lower eyelids. She told the physician that she had a similar pruritic rash on her earlobes when she wore costume jewelry.

CASE 5: A 50-year-old woman went to her doctor for a pruritic, erythematous patch on the anterior and posterior sides of her ear-lobes, bilaterally. She told the physician that her ears had been pierced 2 weeks earlier.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU MANAGE THIS CONDITION?

Diagnosis: Nickel dermatitis

Each of these 5 patients had allergic contact dermatitis caused by nickel. The cheek dermatitis was produced by contact with the circular “menu” button on the patient’s cell phone (Case 1/ FIGURE 1 ), the periumbilical rash by the rivet behind a blue jeans button (Case 2/ FIGURE 2 ), the wrist dermatitis by a bracelet (Case 3/ FIGURE 3 ), the rash on the upper cheeks by eyeglass frames (Case 4/ FIGURE 4 ), and the earlobe dermatitis by earrings (Case 5/ FIGURE 5 ). The presence of nickel in each object was confirmed with a positive dimethylglyoxime (DMG) test.

What you’ll see. Besides an erythematous, pruritic, scaling rash, other findings can include vesicles and bullae that break and form crusts at sites of contact. Extreme pruritus is also commonly seen and prompts chronic rubbing and scratching, resulting in the development of lichenification and hyper-pigmentation.

FIGURE 1

Scaling patch on cheek

FIGURE 2

Rash beneath umbilicus

The cause: The rivet on the patient’s blue jeans.

FIGURE 3

… around the wrist

The cause: The bracelet (shown), which would normally sit where the erythematous band is located.

FIGURE 4

… on the cheeks

The cause: Eyeglasses.

FIGURE 5

… on the earlobes

The cause: Nickel in pierced earrings.

Nickel dermatitis is increasingly common

Nickel is a leading cause of allergic contact dermatitis and is responsible for more cases than all other metals combined.1,2 The incidence of nickel dermatitis has been increasing in the United States for the last 15 years, annually affecting an estimated 14% to 20% of women and 2% to 4% of men.3,4 The higher percentage in women is related to nickel exposure associated with ear piercing and nickel-plated jewelry. In fact, the highest risk for nickel allergy is in young females with pierced ears.2,5,6 The number of affected males, however, is increasing, as earrings and body piercing gain popularity in this group.3

Certain occupations with high exposure to nickel, such as cashiers, hairdressers, metal workers, domestic cleaners, food handlers, bar workers, and painters, are also at risk for acquiring nickel dermatitis.7 Patients with atopic eczema are also at increased risk.8,9

Sweating may increase the severity of the dermatitis. Sodium chloride in the sweat causes corrosion of the metal and increases nickel exposure.10 Nickel release is therefore common in areas of the body that tend to be sweaty—for example, the hands, especially around the fingers, where inexpensive rings containing nickel are worn, or on the hands of individuals who carry metal key rings.

Consider oral intake of nickel, too. Another far less common, but important, nickel allergy presentation is systemic contact dermatitis from oral intake of nickel. Nuts, legumes, and chocolate can cause a flare-up reaction in a previously positive patch test site or previous site of nickel dermatitis.11 Patients can also develop a dyshidrotic eczema on the hands. Itching and general symptoms, such as headache, nausea, and malaise, have also been reported after the oral nickel exposure of nickel-sensitive individuals.12 Dietary intervention studies indicate that it is possible to reduce the activity of dermatitis in these patients by maintaining a diet low in nickel.13-16

Finally, severe local reactions to nickel and other contact allergens can lead to auto-eczematization, in which a papular or papulosquamous eruption and pruritus appear distant from the site of exposure.

Is it atopic eczema or contact dermatitis?

It can be difficult to distinguish a flare in atopic eczema from chronic allergic contact dermatitis in individuals who may display both processes concurrently. The primary clue to the diagnosis is the peculiar localization of the rash, as evidenced by the cases we have described.

Patch testing is not required for diagnosis

Nickel contact dermatitis is often suspected when patients present with an acute or sub-acute eruption characterized by erythema, vesicles, and scaling in a distribution corresponding to a metal contact allergen. Nickel allergy is one of the few types of allergic contact dermatitis where the history of exposure along with the signs and symptoms are so distinctive that patch testing is often not required.

Amelioration of the rash associated with the withdrawal of the contactant serves as adequate confirmation of the diagnosis in many cases. A DMG test is a simple, inexpensive way to determine whether the object in question contains nickel. It can be used in the physician’s office or by the patient at home. Therefore, in some clinical situations, as in the presented cases, it is appropriate to make a presumptive diagnosis of nickel dermatitis, confirm the presence of nickel with a DMG test, remove the off ending metal item, treat with topical anti-inflammatory medications, and confirm the diagnosis by monitoring the patient’s response.

When patients do not respond to withdrawal of the suspected allergen and anti-inflammatory treatment, when multiple allergens are suspected, or when a definitive diagnosis is required for legal purposes, patch testing with nickel can confirm the diagnosis. In some cases, when the distribution of the rash is not distinctive, patch test screening may elicit a positive test to nickel that prompts the physician to investigate the source of the exposure.

Tx: Remove the item, apply topical steroids

Acute episodes of nickel dermatitis are treated with topical steroid creams to break the scratch-itch cycle (which potentiates the reaction) and to reduce the inflammation. This tactic is futile, however, if the allergen remains in contact with the skin. The source of the nickel must be identified and eliminated by the patient, as was done by the 5 patients we cared for.

Clothing accessories containing nickel, such as buckles, zippers, buttons, and metal clips, must be eliminated, as well as other sources of nickel: jewelry, watches, eyeglasses, and cell phones. The situation is complicated by the fact that many patients have underlying atopic eczema/irritant dermatitis, and patients may have more than 1 form of allergic contact dermatitis. For instance, self-treatment with neomycin-containing topical antibiotics may lead to superimposed allergic contact dermatitis from this agent.

Easy preventive steps. Routine prophylactic measures should focus on eliminating exposure to nickel from all identifiable sources. You can suggest that your patient with nickel dermatitis:

- Use a clear plastic cover over the nickel-containing parts of a cell phone.

- Apply a clear coat of nail polish to the buttons and rivets on pants; this can prevent nickel release and will last through at least 2 wash and dry cycles.17 (Tucking shirts in to prevent buttons and belt buckles from touching the skin is generally ineffective; not only is the shirt unlikely to stay in place all day, but perspiration and friction can also cause problems.)

- Use other barrier coatings, such as Nickel Guard and Beauty Secrets Hardener, which may be effective in preventing contact dermatitis.18

- Replace rivets on pants with a plastic button, or cover the rivet with a sew-on denim patch. This offers a more permanent approach to eliminating nickel exposure.

- Use plastic covers for earring studs.

- Replace metal eyeglass frames with ones made out of plastic.

- Choose “hypoallergenic” or nickel-free jewelry. Of note, though: Nickel may be present in jewelry labeled hypoallergenic. The patient can perform a DMG test to verify its nickel content.

In patients who continue to react in the absence of nickel jewelry, co-sensitization to gold must be considered, as many patients do react to multiple metals. Gold is a more common allergen than previously reported and is statistically linked to allergic reactions to nickel and cobalt metals.19 Unlike nickel dermatitis, the clinical relevance of a positive gold patch test is harder to ascertain because rashing distant from areas in direct contact with gold jewelry often occurs. In fact, in some cases of eyelid dermatitis induced by contact allergy to gold, titanium dioxide particles on the skin from cosmetics and sunscreen are thought to adsorb gold particles and carry them to the eyelids.

Disclosure

Dr. Brodell reports that he receives grants/research support from Amgen Inc., Doak Dermatologics, Galderma, and OrthoNeutrogena. He serves as a consultant for, or is on the speakers bureau of, 3M/Graceway Pharmaceuticals, Allergan, CollagGenex Pharmaceuticals, Connetics Corp., Dermik/BenzaClin, Galderma, Genentech, Inc., Genentech/ Raptiva, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, MDsConnect.net, Medicis, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp., Pedinol Pharmacal, Inc., Roerig-Pfizer, Sandoz/Novartis, sanofi-aventis, Sirius Laboratories, Stiefel, Westwood-Squibb, and Upjohn. Ms. Uhlenhake and Dr. Nedorost reported no potential conflict of interest relevant to this article.

CORRESPONDENCE

Robert Brodell, MD, 2660 East Market Street, Warren, OH 44483; [email protected]

CASE 1: A 13-year-old Caucasian girl sought treatment for a pruritic, scaling patch on her right cheek. The patient had a 10-year history of atopic eczema, with rashes primarily in flexural areas, and a history of skin reactions to earrings and rivets in her blue jeans. She had gone 3 years without a rash on her earlobes and periumbilical areas by scrupulously avoiding contact with metal.

The 2 x 2-cm patch of pruritic, scaling, lichenified skin with focal excoriation that brought her in on this day had been on her right cheek for the past 3 months ( FIGURE 1 ). It had not responded to hydrocortisone 2.5% cream and desonide 0.05% cream when she applied it twice daily, nor had it responded to an intralesional injection of 2 cc of 2.5 mg/cc triamcinolone acetonide.

CASE 2: A 13-year-old African American girl with a history of atopic dermatitis went to her doctor for a rash beneath the umbilicus. She’d had the rash, which she said was extremely itchy, for 6 weeks; over the previous 10 days, it had become more widespread. A 6 x 5-cm scaling, lichenified, hyperpigmented plaque was present in the infra-umbilical region. She also had a papular rash on the dorsal hands and axillae.

CASE 3: A 15-year-old Caucasian girl sought care for a pruritic, erythematous rash circumscribing her left wrist in an 8-mm diameter band. She’d had the rash for 6 weeks.

CASE 4: A 58-year-old Caucasian woman presented with a pruritic, erythematous, scaling rash on both upper cheeks just below her lower eyelids. She told the physician that she had a similar pruritic rash on her earlobes when she wore costume jewelry.

CASE 5: A 50-year-old woman went to her doctor for a pruritic, erythematous patch on the anterior and posterior sides of her ear-lobes, bilaterally. She told the physician that her ears had been pierced 2 weeks earlier.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU MANAGE THIS CONDITION?

Diagnosis: Nickel dermatitis

Each of these 5 patients had allergic contact dermatitis caused by nickel. The cheek dermatitis was produced by contact with the circular “menu” button on the patient’s cell phone (Case 1/ FIGURE 1 ), the periumbilical rash by the rivet behind a blue jeans button (Case 2/ FIGURE 2 ), the wrist dermatitis by a bracelet (Case 3/ FIGURE 3 ), the rash on the upper cheeks by eyeglass frames (Case 4/ FIGURE 4 ), and the earlobe dermatitis by earrings (Case 5/ FIGURE 5 ). The presence of nickel in each object was confirmed with a positive dimethylglyoxime (DMG) test.

What you’ll see. Besides an erythematous, pruritic, scaling rash, other findings can include vesicles and bullae that break and form crusts at sites of contact. Extreme pruritus is also commonly seen and prompts chronic rubbing and scratching, resulting in the development of lichenification and hyper-pigmentation.

FIGURE 1

Scaling patch on cheek

FIGURE 2

Rash beneath umbilicus

The cause: The rivet on the patient’s blue jeans.

FIGURE 3

… around the wrist

The cause: The bracelet (shown), which would normally sit where the erythematous band is located.

FIGURE 4

… on the cheeks

The cause: Eyeglasses.

FIGURE 5

… on the earlobes

The cause: Nickel in pierced earrings.

Nickel dermatitis is increasingly common

Nickel is a leading cause of allergic contact dermatitis and is responsible for more cases than all other metals combined.1,2 The incidence of nickel dermatitis has been increasing in the United States for the last 15 years, annually affecting an estimated 14% to 20% of women and 2% to 4% of men.3,4 The higher percentage in women is related to nickel exposure associated with ear piercing and nickel-plated jewelry. In fact, the highest risk for nickel allergy is in young females with pierced ears.2,5,6 The number of affected males, however, is increasing, as earrings and body piercing gain popularity in this group.3

Certain occupations with high exposure to nickel, such as cashiers, hairdressers, metal workers, domestic cleaners, food handlers, bar workers, and painters, are also at risk for acquiring nickel dermatitis.7 Patients with atopic eczema are also at increased risk.8,9

Sweating may increase the severity of the dermatitis. Sodium chloride in the sweat causes corrosion of the metal and increases nickel exposure.10 Nickel release is therefore common in areas of the body that tend to be sweaty—for example, the hands, especially around the fingers, where inexpensive rings containing nickel are worn, or on the hands of individuals who carry metal key rings.

Consider oral intake of nickel, too. Another far less common, but important, nickel allergy presentation is systemic contact dermatitis from oral intake of nickel. Nuts, legumes, and chocolate can cause a flare-up reaction in a previously positive patch test site or previous site of nickel dermatitis.11 Patients can also develop a dyshidrotic eczema on the hands. Itching and general symptoms, such as headache, nausea, and malaise, have also been reported after the oral nickel exposure of nickel-sensitive individuals.12 Dietary intervention studies indicate that it is possible to reduce the activity of dermatitis in these patients by maintaining a diet low in nickel.13-16

Finally, severe local reactions to nickel and other contact allergens can lead to auto-eczematization, in which a papular or papulosquamous eruption and pruritus appear distant from the site of exposure.

Is it atopic eczema or contact dermatitis?

It can be difficult to distinguish a flare in atopic eczema from chronic allergic contact dermatitis in individuals who may display both processes concurrently. The primary clue to the diagnosis is the peculiar localization of the rash, as evidenced by the cases we have described.

Patch testing is not required for diagnosis

Nickel contact dermatitis is often suspected when patients present with an acute or sub-acute eruption characterized by erythema, vesicles, and scaling in a distribution corresponding to a metal contact allergen. Nickel allergy is one of the few types of allergic contact dermatitis where the history of exposure along with the signs and symptoms are so distinctive that patch testing is often not required.

Amelioration of the rash associated with the withdrawal of the contactant serves as adequate confirmation of the diagnosis in many cases. A DMG test is a simple, inexpensive way to determine whether the object in question contains nickel. It can be used in the physician’s office or by the patient at home. Therefore, in some clinical situations, as in the presented cases, it is appropriate to make a presumptive diagnosis of nickel dermatitis, confirm the presence of nickel with a DMG test, remove the off ending metal item, treat with topical anti-inflammatory medications, and confirm the diagnosis by monitoring the patient’s response.

When patients do not respond to withdrawal of the suspected allergen and anti-inflammatory treatment, when multiple allergens are suspected, or when a definitive diagnosis is required for legal purposes, patch testing with nickel can confirm the diagnosis. In some cases, when the distribution of the rash is not distinctive, patch test screening may elicit a positive test to nickel that prompts the physician to investigate the source of the exposure.

Tx: Remove the item, apply topical steroids

Acute episodes of nickel dermatitis are treated with topical steroid creams to break the scratch-itch cycle (which potentiates the reaction) and to reduce the inflammation. This tactic is futile, however, if the allergen remains in contact with the skin. The source of the nickel must be identified and eliminated by the patient, as was done by the 5 patients we cared for.

Clothing accessories containing nickel, such as buckles, zippers, buttons, and metal clips, must be eliminated, as well as other sources of nickel: jewelry, watches, eyeglasses, and cell phones. The situation is complicated by the fact that many patients have underlying atopic eczema/irritant dermatitis, and patients may have more than 1 form of allergic contact dermatitis. For instance, self-treatment with neomycin-containing topical antibiotics may lead to superimposed allergic contact dermatitis from this agent.

Easy preventive steps. Routine prophylactic measures should focus on eliminating exposure to nickel from all identifiable sources. You can suggest that your patient with nickel dermatitis:

- Use a clear plastic cover over the nickel-containing parts of a cell phone.

- Apply a clear coat of nail polish to the buttons and rivets on pants; this can prevent nickel release and will last through at least 2 wash and dry cycles.17 (Tucking shirts in to prevent buttons and belt buckles from touching the skin is generally ineffective; not only is the shirt unlikely to stay in place all day, but perspiration and friction can also cause problems.)

- Use other barrier coatings, such as Nickel Guard and Beauty Secrets Hardener, which may be effective in preventing contact dermatitis.18

- Replace rivets on pants with a plastic button, or cover the rivet with a sew-on denim patch. This offers a more permanent approach to eliminating nickel exposure.

- Use plastic covers for earring studs.

- Replace metal eyeglass frames with ones made out of plastic.

- Choose “hypoallergenic” or nickel-free jewelry. Of note, though: Nickel may be present in jewelry labeled hypoallergenic. The patient can perform a DMG test to verify its nickel content.

In patients who continue to react in the absence of nickel jewelry, co-sensitization to gold must be considered, as many patients do react to multiple metals. Gold is a more common allergen than previously reported and is statistically linked to allergic reactions to nickel and cobalt metals.19 Unlike nickel dermatitis, the clinical relevance of a positive gold patch test is harder to ascertain because rashing distant from areas in direct contact with gold jewelry often occurs. In fact, in some cases of eyelid dermatitis induced by contact allergy to gold, titanium dioxide particles on the skin from cosmetics and sunscreen are thought to adsorb gold particles and carry them to the eyelids.

Disclosure

Dr. Brodell reports that he receives grants/research support from Amgen Inc., Doak Dermatologics, Galderma, and OrthoNeutrogena. He serves as a consultant for, or is on the speakers bureau of, 3M/Graceway Pharmaceuticals, Allergan, CollagGenex Pharmaceuticals, Connetics Corp., Dermik/BenzaClin, Galderma, Genentech, Inc., Genentech/ Raptiva, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, MDsConnect.net, Medicis, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp., Pedinol Pharmacal, Inc., Roerig-Pfizer, Sandoz/Novartis, sanofi-aventis, Sirius Laboratories, Stiefel, Westwood-Squibb, and Upjohn. Ms. Uhlenhake and Dr. Nedorost reported no potential conflict of interest relevant to this article.

CORRESPONDENCE

Robert Brodell, MD, 2660 East Market Street, Warren, OH 44483; [email protected]

1. Arnold HL, Odom RB, James WD. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 8th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: W.B. Saunders Co.; 1990.

2. Thyssen JP, Linneberg A, Menne T, et al. The epidemiology of contact allergy in the general population—prevalence and main findings. Contact Dermatitis. 2007;57:287-299.

3. Rietschel RL, Fowler JF, Warshaw EM, et al. Detection of nickel sensitivity has increased in North American patch-test patients. Dermatitis. 2008;19:16-19.

4. Belsito DV. Allergic contact dermatitis. In: Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, et al. Fitzpatrick’s dermatology in general medicine. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1999:1447-1461.

5. McDonagh AJG, Wright AL, Cork MJ, et al. Nickel sensitivity: the influence of ear piercing and atopy. Br J Dermatol. 1992;126:16-18

6. Larsson-Stymne B, Widstrom L. Ear piercing: a cause of nickel allergy in school girls? Contact Dermatitis. 1985;13:289-293.

7. Shah M, Lewis F, Gawkrodger DJ. Nickel as an occupational allergen. A survey of 368 nickel-sensitive subjects. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:1231-1236.

8. De Groot AC. The frequency of contact allergy in atopic patients with dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 1990;22:273-277.

9. Cronin E, McFadden JP. Patients with atopic eczema do become sensitized to contact allergens. Contact Dermatitis. 1993;28:225-228.

10. Suchoski JP. Allergic contact dermatitis. J Assoc Milit Dermatol. 1983;9:65-8.

11. Veien NK, Hattel T, Justesen O, Norholm A. Diagnostic procedures for eczema patients. Contact Dermatitis. 1987;17:35-40.

12. Jensen CS, Menne T, Lisby S, et al. Experimental systemic contact dermatitis from nickel: a dose-response study. Contact Dermatitis. 2003;49:124-132.

13. Kaaber K, Veien NK, Tjell JC. Low nickel diet in the treatment of patients with chronic nickel dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 1978;98:197-200.

14. Veien NK, Hattel T, Justesen O, et al. Dietary treatment of nickel dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1985;65:138-142.

15. Veien NK, Hattel T, Laurberg G. Low nickel diet: an open, prospective trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:1002-1007.

16. Antico A, Soana R. Chronic allergic-like dermatopathies in nickel-sensitive patients. Results of dietary restrictions and challenge with nickel salts. Allergy Asthma Proc. 1999;20:235-242.

17. Suneja T, Flanagan KH, Glaser DA. Blue-jean button nickel: prevalence and prevention of its release from buttons. Dermatitis. 2007;18:208-211.

18. Sprigle AM, Marks JG, Jr. Anderson BE. Prevention of nickel release with barrier coatings. Dermatitis. 2008;19:28-31.

19. Fowler J, Jr, Taylor J, Storrs F, et al. Gold allergy in North America. Am J Contact Dermat. 2001;12:3-5.

1. Arnold HL, Odom RB, James WD. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 8th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: W.B. Saunders Co.; 1990.

2. Thyssen JP, Linneberg A, Menne T, et al. The epidemiology of contact allergy in the general population—prevalence and main findings. Contact Dermatitis. 2007;57:287-299.

3. Rietschel RL, Fowler JF, Warshaw EM, et al. Detection of nickel sensitivity has increased in North American patch-test patients. Dermatitis. 2008;19:16-19.

4. Belsito DV. Allergic contact dermatitis. In: Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, et al. Fitzpatrick’s dermatology in general medicine. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1999:1447-1461.

5. McDonagh AJG, Wright AL, Cork MJ, et al. Nickel sensitivity: the influence of ear piercing and atopy. Br J Dermatol. 1992;126:16-18

6. Larsson-Stymne B, Widstrom L. Ear piercing: a cause of nickel allergy in school girls? Contact Dermatitis. 1985;13:289-293.

7. Shah M, Lewis F, Gawkrodger DJ. Nickel as an occupational allergen. A survey of 368 nickel-sensitive subjects. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:1231-1236.

8. De Groot AC. The frequency of contact allergy in atopic patients with dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 1990;22:273-277.

9. Cronin E, McFadden JP. Patients with atopic eczema do become sensitized to contact allergens. Contact Dermatitis. 1993;28:225-228.

10. Suchoski JP. Allergic contact dermatitis. J Assoc Milit Dermatol. 1983;9:65-8.

11. Veien NK, Hattel T, Justesen O, Norholm A. Diagnostic procedures for eczema patients. Contact Dermatitis. 1987;17:35-40.

12. Jensen CS, Menne T, Lisby S, et al. Experimental systemic contact dermatitis from nickel: a dose-response study. Contact Dermatitis. 2003;49:124-132.

13. Kaaber K, Veien NK, Tjell JC. Low nickel diet in the treatment of patients with chronic nickel dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 1978;98:197-200.

14. Veien NK, Hattel T, Justesen O, et al. Dietary treatment of nickel dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1985;65:138-142.

15. Veien NK, Hattel T, Laurberg G. Low nickel diet: an open, prospective trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:1002-1007.

16. Antico A, Soana R. Chronic allergic-like dermatopathies in nickel-sensitive patients. Results of dietary restrictions and challenge with nickel salts. Allergy Asthma Proc. 1999;20:235-242.

17. Suneja T, Flanagan KH, Glaser DA. Blue-jean button nickel: prevalence and prevention of its release from buttons. Dermatitis. 2007;18:208-211.

18. Sprigle AM, Marks JG, Jr. Anderson BE. Prevention of nickel release with barrier coatings. Dermatitis. 2008;19:28-31.

19. Fowler J, Jr, Taylor J, Storrs F, et al. Gold allergy in North America. Am J Contact Dermat. 2001;12:3-5.

Pustules on arms and thigh

The acute nature of the process led the physician to favor a diagnosis of bacterial folliculitis; the culture came back positive for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) sensitive to doxycycline.

Community-acquired MRSA outbreaks have been associated with participation in team sports, living in prison, dormitory or group home settings, IV drug use, sharing personal items, and men who have sex with men. However, the prevalence of MRSA infections in patients without any recognized risk factors, like this patient, is increasing.

Initial empiric treatment for the patient included doxycycline 100 mg daily and topical treatment with clindamycin 1% lotion twice a day. Once the culture came back, the physician instructed the patient to continue the initial medications and apply mupirocin 2% ointment to the nares twice a day for 1 week to eliminate the possibility of a staphylococcal carrier state.

At follow-up 2 weeks later, only a few excoriated papules and some post-inflammatory erythema remained. The topical clindamycin lotion and the doxycycline were continued for an additional 30 days, at which time the patient was clear and treatment was discontinued.

Adapted from:

Plotner AN, Brodell RT. Photo rounds: bilateral axillary pustules. J Fam Pract. 2008;57:253-255.

The acute nature of the process led the physician to favor a diagnosis of bacterial folliculitis; the culture came back positive for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) sensitive to doxycycline.

Community-acquired MRSA outbreaks have been associated with participation in team sports, living in prison, dormitory or group home settings, IV drug use, sharing personal items, and men who have sex with men. However, the prevalence of MRSA infections in patients without any recognized risk factors, like this patient, is increasing.

Initial empiric treatment for the patient included doxycycline 100 mg daily and topical treatment with clindamycin 1% lotion twice a day. Once the culture came back, the physician instructed the patient to continue the initial medications and apply mupirocin 2% ointment to the nares twice a day for 1 week to eliminate the possibility of a staphylococcal carrier state.

At follow-up 2 weeks later, only a few excoriated papules and some post-inflammatory erythema remained. The topical clindamycin lotion and the doxycycline were continued for an additional 30 days, at which time the patient was clear and treatment was discontinued.

Adapted from:

Plotner AN, Brodell RT. Photo rounds: bilateral axillary pustules. J Fam Pract. 2008;57:253-255.

The acute nature of the process led the physician to favor a diagnosis of bacterial folliculitis; the culture came back positive for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) sensitive to doxycycline.

Community-acquired MRSA outbreaks have been associated with participation in team sports, living in prison, dormitory or group home settings, IV drug use, sharing personal items, and men who have sex with men. However, the prevalence of MRSA infections in patients without any recognized risk factors, like this patient, is increasing.

Initial empiric treatment for the patient included doxycycline 100 mg daily and topical treatment with clindamycin 1% lotion twice a day. Once the culture came back, the physician instructed the patient to continue the initial medications and apply mupirocin 2% ointment to the nares twice a day for 1 week to eliminate the possibility of a staphylococcal carrier state.

At follow-up 2 weeks later, only a few excoriated papules and some post-inflammatory erythema remained. The topical clindamycin lotion and the doxycycline were continued for an additional 30 days, at which time the patient was clear and treatment was discontinued.

Adapted from:

Plotner AN, Brodell RT. Photo rounds: bilateral axillary pustules. J Fam Pract. 2008;57:253-255.

Body rash

The biopsy ultimately indicated that the patient had eczematous dermatitis.

The treating physician had initially considered erythroderma from psoriasis, eczema, a drug reaction, fungal infection, seborrheic dermatitis, and mycosis fungoides as part of the differential. The physician had also suggested the patient be hospitalization for detox and dermatologic treatment, but he declined.

Given that the lab work would not be ready for a few days, the physician sent the patient home with a 1-pound tub of 0.1% triamcinolone ointment to apply to the affected areas twice daily. For the first few days, the patient was to apply the triamcinolone extensively, soak cotton pajamas in warm water and put those on, and wrap himself in a blanket. He was told to remove the pajamas in 15 minutes. The physician also told the patient to cut back on his alcohol intake, drink plenty of fluids, and return the following day. When the patient returned, the appearance of his skin had improved.

The biopsy results followed, and confirmed that he had eczematous dermatitis.

Knowing this was not psoriasis, the physician prescribed a course of systemic steroids along with the topical ointment. The patient continued to improve, but reached a plateau at 3 weeks. Again, the physician urged the patient to enter the hospital for detoxification. He agreed, and after a rocky period in the intensive care unit, left the hospital sober, and with almost completely clear skin.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Henderson D. Erythroderma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, Chumley H, Tysinger J, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:643-647.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

The biopsy ultimately indicated that the patient had eczematous dermatitis.

The treating physician had initially considered erythroderma from psoriasis, eczema, a drug reaction, fungal infection, seborrheic dermatitis, and mycosis fungoides as part of the differential. The physician had also suggested the patient be hospitalization for detox and dermatologic treatment, but he declined.

Given that the lab work would not be ready for a few days, the physician sent the patient home with a 1-pound tub of 0.1% triamcinolone ointment to apply to the affected areas twice daily. For the first few days, the patient was to apply the triamcinolone extensively, soak cotton pajamas in warm water and put those on, and wrap himself in a blanket. He was told to remove the pajamas in 15 minutes. The physician also told the patient to cut back on his alcohol intake, drink plenty of fluids, and return the following day. When the patient returned, the appearance of his skin had improved.

The biopsy results followed, and confirmed that he had eczematous dermatitis.

Knowing this was not psoriasis, the physician prescribed a course of systemic steroids along with the topical ointment. The patient continued to improve, but reached a plateau at 3 weeks. Again, the physician urged the patient to enter the hospital for detoxification. He agreed, and after a rocky period in the intensive care unit, left the hospital sober, and with almost completely clear skin.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Henderson D. Erythroderma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, Chumley H, Tysinger J, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:643-647.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

The biopsy ultimately indicated that the patient had eczematous dermatitis.

The treating physician had initially considered erythroderma from psoriasis, eczema, a drug reaction, fungal infection, seborrheic dermatitis, and mycosis fungoides as part of the differential. The physician had also suggested the patient be hospitalization for detox and dermatologic treatment, but he declined.

Given that the lab work would not be ready for a few days, the physician sent the patient home with a 1-pound tub of 0.1% triamcinolone ointment to apply to the affected areas twice daily. For the first few days, the patient was to apply the triamcinolone extensively, soak cotton pajamas in warm water and put those on, and wrap himself in a blanket. He was told to remove the pajamas in 15 minutes. The physician also told the patient to cut back on his alcohol intake, drink plenty of fluids, and return the following day. When the patient returned, the appearance of his skin had improved.

The biopsy results followed, and confirmed that he had eczematous dermatitis.

Knowing this was not psoriasis, the physician prescribed a course of systemic steroids along with the topical ointment. The patient continued to improve, but reached a plateau at 3 weeks. Again, the physician urged the patient to enter the hospital for detoxification. He agreed, and after a rocky period in the intensive care unit, left the hospital sober, and with almost completely clear skin.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Henderson D. Erythroderma. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, Chumley H, Tysinger J, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:643-647.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

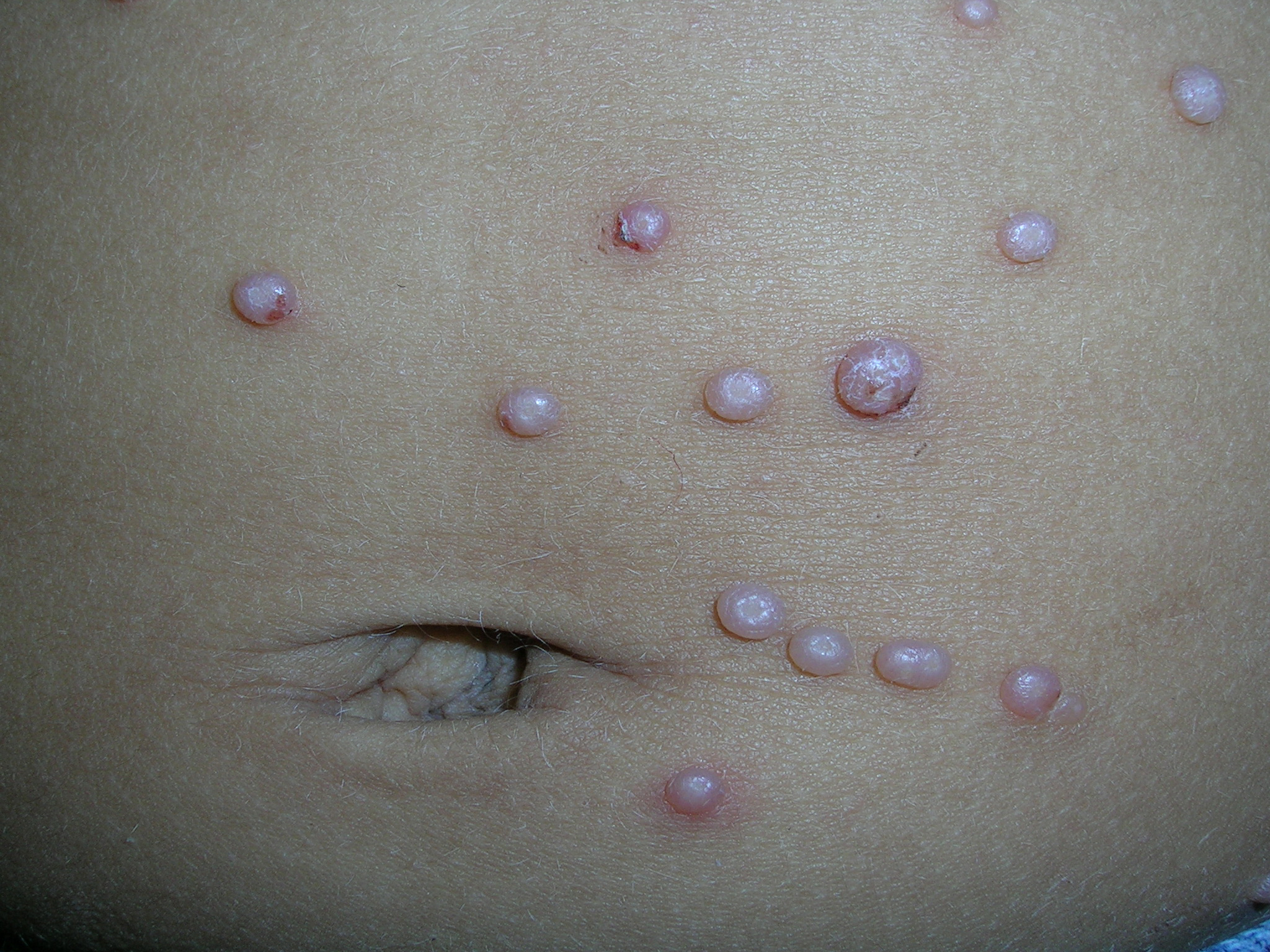

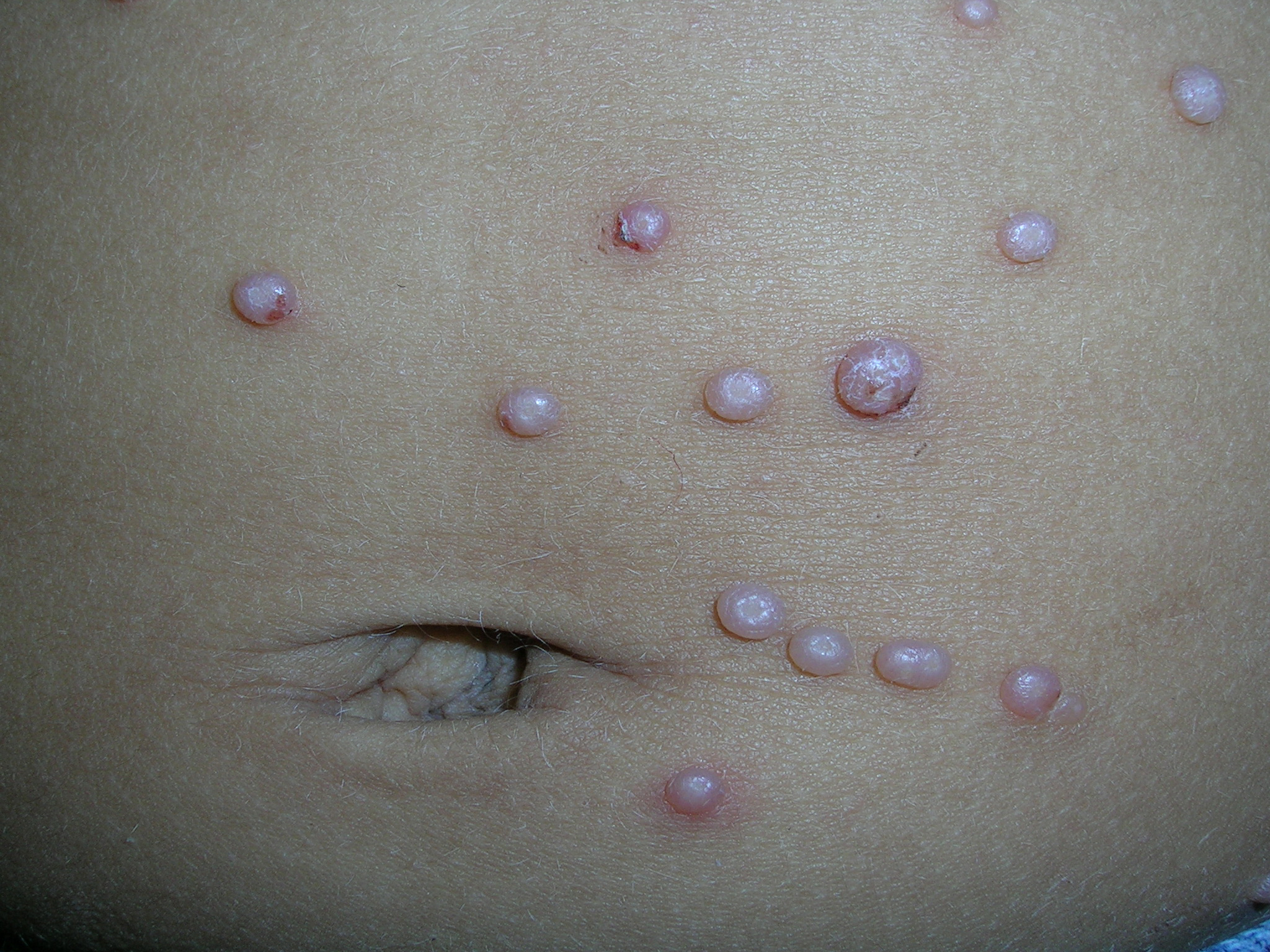

Bumps on abdomen

|

|

The physician diagnosed molluscum contagiosum. FIGURE 1 shows multiple firm 2- to 5-mm pearly dome-shaped papules. Some of them have a characteristic umbilicated center (FIGURE 2). Not all of the papules, though, have a central umbilication, so when confronted with this possible diagnosis, it helps to take a moment and look for a papule that has this characteristic morphology.

Molluscum contagiosum is a benign condition that is often transmitted through close contact in children and through sexual contact in adults. Molluscum contagiosum is a large DNA virus of the Poxviridae family of poxvirus. Treatment of nongenital lesions is usually unnecessary since the infection tends to be self-limited and spontaneously resolves after a few months. Patients and parents of children often want treatment for cosmetic reasons and when watchful waiting fails.

Excisional curettage or cryotherapy can be effective. Genital lesions should be treated to prevent spread by sexual contact. Curettage, cryotherapy, imiquimod 5%, cantharidin, tretinoin cream 0.1% or gel 0.025%, trichloroacetic acid, and laser therapies are commonly used. Note, though, that there are no medications that are FDA-approved for molluscum.

In this case, the mother was not willing to wait for the molluscum to resolve on its own, so the physician gave the patient a prescription for topical tretinoin cream to be applied nightly until resolution. While the evidence for imiquimod is stronger, the cost is over $500 for treatment.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ. Molluscum contagiosum. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, Chumley H, Tysinger J, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:518-521.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

|

|

The physician diagnosed molluscum contagiosum. FIGURE 1 shows multiple firm 2- to 5-mm pearly dome-shaped papules. Some of them have a characteristic umbilicated center (FIGURE 2). Not all of the papules, though, have a central umbilication, so when confronted with this possible diagnosis, it helps to take a moment and look for a papule that has this characteristic morphology.

Molluscum contagiosum is a benign condition that is often transmitted through close contact in children and through sexual contact in adults. Molluscum contagiosum is a large DNA virus of the Poxviridae family of poxvirus. Treatment of nongenital lesions is usually unnecessary since the infection tends to be self-limited and spontaneously resolves after a few months. Patients and parents of children often want treatment for cosmetic reasons and when watchful waiting fails.

Excisional curettage or cryotherapy can be effective. Genital lesions should be treated to prevent spread by sexual contact. Curettage, cryotherapy, imiquimod 5%, cantharidin, tretinoin cream 0.1% or gel 0.025%, trichloroacetic acid, and laser therapies are commonly used. Note, though, that there are no medications that are FDA-approved for molluscum.

In this case, the mother was not willing to wait for the molluscum to resolve on its own, so the physician gave the patient a prescription for topical tretinoin cream to be applied nightly until resolution. While the evidence for imiquimod is stronger, the cost is over $500 for treatment.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ. Molluscum contagiosum. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, Chumley H, Tysinger J, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:518-521.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

|

|

The physician diagnosed molluscum contagiosum. FIGURE 1 shows multiple firm 2- to 5-mm pearly dome-shaped papules. Some of them have a characteristic umbilicated center (FIGURE 2). Not all of the papules, though, have a central umbilication, so when confronted with this possible diagnosis, it helps to take a moment and look for a papule that has this characteristic morphology.

Molluscum contagiosum is a benign condition that is often transmitted through close contact in children and through sexual contact in adults. Molluscum contagiosum is a large DNA virus of the Poxviridae family of poxvirus. Treatment of nongenital lesions is usually unnecessary since the infection tends to be self-limited and spontaneously resolves after a few months. Patients and parents of children often want treatment for cosmetic reasons and when watchful waiting fails.

Excisional curettage or cryotherapy can be effective. Genital lesions should be treated to prevent spread by sexual contact. Curettage, cryotherapy, imiquimod 5%, cantharidin, tretinoin cream 0.1% or gel 0.025%, trichloroacetic acid, and laser therapies are commonly used. Note, though, that there are no medications that are FDA-approved for molluscum.

In this case, the mother was not willing to wait for the molluscum to resolve on its own, so the physician gave the patient a prescription for topical tretinoin cream to be applied nightly until resolution. While the evidence for imiquimod is stronger, the cost is over $500 for treatment.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ. Molluscum contagiosum. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, Chumley H, Tysinger J, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:518-521.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

Growths on penis

The Diagnosis

A shave biopsy of the pink lesion was positive for condylomata acuminata. (The differential diagnosis also included seborrheic keratoses.) The patient consented to blood tests for human immunodeficiency virus and syphilis; he was negative for both. The benefits and costs of urine screening for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhea were discussed and the patient decided that he would forego that test.

Condyloma acuminata is caused by human papillomavirus (HPV) infection and is the most common STD in the United States. HPV types 6 and 11 account for most external genital warts and are rarely associated with invasive carcinoma of the external genitalia. Most infections are transient and clear within 2 years, but many infections persist.

The shave biopsy that was done for diagnostic purposes also served as partial treatment. The remaining lesion was treated successfully with 2 courses of cryotherapy. Other treatment choices include topical imiquimod and podofilox.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ. Usatine R. Genital warts. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, Chumley H, Tysinger J, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:530-534.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

The Diagnosis

A shave biopsy of the pink lesion was positive for condylomata acuminata. (The differential diagnosis also included seborrheic keratoses.) The patient consented to blood tests for human immunodeficiency virus and syphilis; he was negative for both. The benefits and costs of urine screening for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhea were discussed and the patient decided that he would forego that test.

Condyloma acuminata is caused by human papillomavirus (HPV) infection and is the most common STD in the United States. HPV types 6 and 11 account for most external genital warts and are rarely associated with invasive carcinoma of the external genitalia. Most infections are transient and clear within 2 years, but many infections persist.

The shave biopsy that was done for diagnostic purposes also served as partial treatment. The remaining lesion was treated successfully with 2 courses of cryotherapy. Other treatment choices include topical imiquimod and podofilox.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ. Usatine R. Genital warts. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, Chumley H, Tysinger J, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:530-534.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

The Diagnosis

A shave biopsy of the pink lesion was positive for condylomata acuminata. (The differential diagnosis also included seborrheic keratoses.) The patient consented to blood tests for human immunodeficiency virus and syphilis; he was negative for both. The benefits and costs of urine screening for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhea were discussed and the patient decided that he would forego that test.

Condyloma acuminata is caused by human papillomavirus (HPV) infection and is the most common STD in the United States. HPV types 6 and 11 account for most external genital warts and are rarely associated with invasive carcinoma of the external genitalia. Most infections are transient and clear within 2 years, but many infections persist.

The shave biopsy that was done for diagnostic purposes also served as partial treatment. The remaining lesion was treated successfully with 2 courses of cryotherapy. Other treatment choices include topical imiquimod and podofilox.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ. Usatine R. Genital warts. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, Chumley H, Tysinger J, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:530-534.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

Pain in abdomen and shoulder

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

A 26-YEAR-OLD MAN came into the emergency department for treatment of vomiting, and pain in his abdomen and right shoulder. His vital signs were normal, with the exception of his heart rate, which was 109 bpm. His oxygen saturation was 96% on room air. The patient, a smoker, did not complain of any difficulty breathing, despite having diminished breath sounds over the left lung fields and absent breath sounds over the right. The rest of the exam was normal.

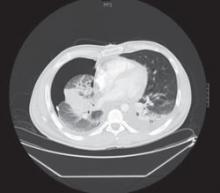

The patient’s initial blood work was within normal limits. We ordered a chest x-ray (FIGURE 1) and a chest computed tomography (CT) scan to further assess his decreased breath sounds.

FIGURE 1

A revealing X-ray

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU MANAGE THIS CONDITION?

Diagnosis: Adenocarcinoma

The chest x-ray revealed a massive right-sided pleural effusion resulting in a hemothorax, tense mediastinum, and partial collapse of the left lung. A CT scan (FIGURE 2) of the chest revealed a 5-cm mass in the right lung. Thoracocentesis was performed and 11 liters of pleural fluid were removed.

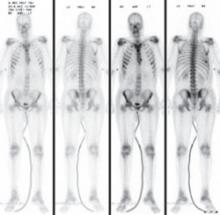

Cytological examination of the pleural fluid revealed adenocarcinoma of the lung. A diagnosis of adenocarcinoma of pulmonary origin was supported by immunohistochemical tests that were positive for thyroid transcription factor 1, cytokeratin 7, carcinoembryonic antigen, and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), which made findings from other sites of adenocarcinoma less likely. A bone scan revealed metastases to the sixth rib and sternum, indicating stage IV adenocarcinoma (FIGURE 3).

FIGURE 2

Mass in lung

FIGURE 3

Bone scan reveals metastases

A cancer that presents at advanced stages

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in the United States in both men and women. The National Cancer Institute estimates that 159,390 people will die of lung cancer this year.1

More than 219,000 cases of lung cancer will be diagnosed this year;1 primary adenocarcinoma, a subtype of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), is the most commonly diagnosed form of lung cancer.2 Most NSCLC cases will present at advanced stages, which limits treatment options and leads to a poor prognosis.

Cigarette smoking remains the most significant risk factor for lung cancer and, according to the American Cancer Society, smoking is responsible for at least 30% of all cancer deaths.3 Moreover, the US Department of Health and Human Services has found that 80% of lung cancers are attributable to smoking.4

What was unusual here? Although our patient had a 16-pack-year history of smoking, it is unusual for the disease to present in adolescents and young adults. The youngest reported case of primary adenocarcinoma of the lung involved a 15 year old, leading researchers to believe that genetic mutation may play a role. In addition, researchers have identified a mutation involving the EGFR gene that may predispose an individual to developing NSCLC.5 Trials are now underway using tyrosine kinase inhibitors, such as gefitinib and erlotinib, to target the tyrosine kinase domain on EGFR.6,7

Differential Dx includes a variety of infections

The differential diagnosis of a lung mass is broad and includes bacterial, fungal, pneumocystic, and granulomatous infections. Cancer, connective tissue diseases, and vascular malformations may also present in this manner. However, our patient also had a pleural effusion, which would lead one to consider cancer or a bacterial infection as a more likely etiology.

In a 26-year-old man, the most common metastatic cancers would include testicular, melanoma, and thyroid cancers. In addition, the typical pattern of metastatic disease of these cancers on chest x-ray is that of bilateral, multiple, round, and well-circumscribed lesions, which was not the case with our patient.

Pleural fluid analysis holds key to diagnosis

Making the diagnosis of lung cancer—particularly in a younger population—requires a high level of suspicion. A delay in diagnosis leads to a poor prognosis. Symptoms and clinical findings should direct the diagnostic process.

In our patient, the diagnosis was particularly challenging because he had no presenting pulmonary symptoms and the work-up was directed by findings on exam. Pleural effusions are present in up to one-third of patients with NSCLC at the time of presentation,8 as was the case with our patient. Analysis of pleural fluid or tissue is required to confirm the diagnosis of NSCLC.

Surgery? Chemo? What’s best and when

Most (55%) NSCLC patients present at advanced stages,1 limiting recommended treatment options. Treatment and management considerations are as follows:

Surgical resection is considered the treatment of choice for patients with local disease if pulmonary function is adequate and comorbidities do not preclude surgery (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B).9

Radical radiotherapy may be considered as a primary treatment modality for patients who refuse surgery or those with comorbid conditions that preclude safe resection (SOR: C).10

Platinum-based combination chemotherapy may be used as a first-line therapy to prolong survival in patients with advanced disease (SOR: B).11

Surgery wasn’t an option for our patient

Through pleural fluid analysis, we confirmed our patient’s diagnosis of primary pulmonary adenocarcinoma. A subsequent bone scan (FIGURE 3) showed metastases to the sixth rib and sternum, indicating that he had stage IV pulmonary adenocarcinoma.

Due to this advanced stage, surgery was not practical. The patient’s oncologist started him on 2 chemotherapy agents, cisplatin and paclitaxel.

The 5-year survival rate with treatment for patients with advanced stage pulmonary adenocarcinoma is approximately 1%.12 Our patient was expected to live another 9 to 12 months.

CORRESPONDENCE Robert Garcia, MD, Associate Director, Family Medicine Residency Program, St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center, 2927 N. 7th Avenue, Phoenix, AZ 85013; [email protected]

1. National Cancer Institute. Surveillance epidemiology and end results (SEER) stat fact sheet. Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/lungb.html. Accessed August 27, 2009.

2. Homer MJ, Ries LAG, Krapcho M, et al (eds). SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2006, National Cancer Institute. Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2006/results_merged/sect_15_lung_bronchus.pdf. Accessed August 27, 2009.

3. American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2009. Page 47. Available at: www.cancer.org/downloads/STT/500809web.pdf. Accessed August 27, 2009.

4. US Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, Ga: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office of Smoking and Health; 2004.

5. Sharma SV, Gajowniczek P, Way IP, et al. A common signaling cascade may underlie “addiction” to the Src, BCR-ABL, and EGF receptor oncogenes. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:425-435.

6. Inoue A, Suzuki T, Fukuhara T, et al. Prospective phase II study of gefitinib for chemotherapy-naïve patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer with epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3340-3346.

7. Paz-Ares L, Sanchez JM, Garcia-Velasco A, et al. A prospective phase II trial of erlotinib in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients (p) with mutations in the tyrosine kinase (TK) domain of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). Paper presented at the 2006 American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting; June 2-6, 2006; Atlanta, Ga.

8. The American Thoracic Society and The European Respiratory Society. Pretreatment evaluation of non-small cell lung cancer. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 1997;156:320-332.

9. Manser R, Wright G, Byrnes G, et al. Surgery for early stage non-small cell lung cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(1):CD004699.-

10. Rowell NP, Williams CJ. Radical radiotherapy for stage I/II non-small cell lung cancer in patients not sufficiently fit for or declining surgery (medically inoperable): a systematic review. Thorax. 2001;56:628-638.

11. Pfister DG, Johnson DH, Azzoli CG, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology treatment of unresectable non-small cell lung cancer guideline: update 2003. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:330-353.

12. Lung carcinoma: tumors of the lungs. Merck Manual Professional Edition. Available at: http://www.merck.com/mmpe/sec05/ch062/ch062b.html#. Accessed August 27, 2009.

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

A 26-YEAR-OLD MAN came into the emergency department for treatment of vomiting, and pain in his abdomen and right shoulder. His vital signs were normal, with the exception of his heart rate, which was 109 bpm. His oxygen saturation was 96% on room air. The patient, a smoker, did not complain of any difficulty breathing, despite having diminished breath sounds over the left lung fields and absent breath sounds over the right. The rest of the exam was normal.

The patient’s initial blood work was within normal limits. We ordered a chest x-ray (FIGURE 1) and a chest computed tomography (CT) scan to further assess his decreased breath sounds.

FIGURE 1

A revealing X-ray

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU MANAGE THIS CONDITION?

Diagnosis: Adenocarcinoma

The chest x-ray revealed a massive right-sided pleural effusion resulting in a hemothorax, tense mediastinum, and partial collapse of the left lung. A CT scan (FIGURE 2) of the chest revealed a 5-cm mass in the right lung. Thoracocentesis was performed and 11 liters of pleural fluid were removed.

Cytological examination of the pleural fluid revealed adenocarcinoma of the lung. A diagnosis of adenocarcinoma of pulmonary origin was supported by immunohistochemical tests that were positive for thyroid transcription factor 1, cytokeratin 7, carcinoembryonic antigen, and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), which made findings from other sites of adenocarcinoma less likely. A bone scan revealed metastases to the sixth rib and sternum, indicating stage IV adenocarcinoma (FIGURE 3).

FIGURE 2

Mass in lung

FIGURE 3

Bone scan reveals metastases

A cancer that presents at advanced stages

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in the United States in both men and women. The National Cancer Institute estimates that 159,390 people will die of lung cancer this year.1

More than 219,000 cases of lung cancer will be diagnosed this year;1 primary adenocarcinoma, a subtype of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), is the most commonly diagnosed form of lung cancer.2 Most NSCLC cases will present at advanced stages, which limits treatment options and leads to a poor prognosis.

Cigarette smoking remains the most significant risk factor for lung cancer and, according to the American Cancer Society, smoking is responsible for at least 30% of all cancer deaths.3 Moreover, the US Department of Health and Human Services has found that 80% of lung cancers are attributable to smoking.4

What was unusual here? Although our patient had a 16-pack-year history of smoking, it is unusual for the disease to present in adolescents and young adults. The youngest reported case of primary adenocarcinoma of the lung involved a 15 year old, leading researchers to believe that genetic mutation may play a role. In addition, researchers have identified a mutation involving the EGFR gene that may predispose an individual to developing NSCLC.5 Trials are now underway using tyrosine kinase inhibitors, such as gefitinib and erlotinib, to target the tyrosine kinase domain on EGFR.6,7

Differential Dx includes a variety of infections

The differential diagnosis of a lung mass is broad and includes bacterial, fungal, pneumocystic, and granulomatous infections. Cancer, connective tissue diseases, and vascular malformations may also present in this manner. However, our patient also had a pleural effusion, which would lead one to consider cancer or a bacterial infection as a more likely etiology.

In a 26-year-old man, the most common metastatic cancers would include testicular, melanoma, and thyroid cancers. In addition, the typical pattern of metastatic disease of these cancers on chest x-ray is that of bilateral, multiple, round, and well-circumscribed lesions, which was not the case with our patient.

Pleural fluid analysis holds key to diagnosis

Making the diagnosis of lung cancer—particularly in a younger population—requires a high level of suspicion. A delay in diagnosis leads to a poor prognosis. Symptoms and clinical findings should direct the diagnostic process.

In our patient, the diagnosis was particularly challenging because he had no presenting pulmonary symptoms and the work-up was directed by findings on exam. Pleural effusions are present in up to one-third of patients with NSCLC at the time of presentation,8 as was the case with our patient. Analysis of pleural fluid or tissue is required to confirm the diagnosis of NSCLC.

Surgery? Chemo? What’s best and when

Most (55%) NSCLC patients present at advanced stages,1 limiting recommended treatment options. Treatment and management considerations are as follows:

Surgical resection is considered the treatment of choice for patients with local disease if pulmonary function is adequate and comorbidities do not preclude surgery (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B).9

Radical radiotherapy may be considered as a primary treatment modality for patients who refuse surgery or those with comorbid conditions that preclude safe resection (SOR: C).10