User login

Chronic breast rash

A punch biopsy revealed that the patient had granuloma annulare (GA).

GA is usually a self-limiting disorder that manifests as a single or, less commonly, multiple nonscaly, red, annular lesions that are typically found on the extremities. It frequently starts as a papule or cluster of papules before coalescing into its classic annular pattern. Biopsy is not usually needed to make the diagnosis when annular lesions are present. In this case, the lesions displayed the Koebner phenomenon, occurring along her areolar scar, making diagnosis more difficult and necessitating the biopsy. While the cause of GA is unknown, it has been found more often in women than men, but has no predilection for race, ethnicity, or geographic areas.1

GA is typically asymptomatic and can resolve spontaneously. Treatment is often performed for cosmetic reasons. First-line therapies include topical corticosteroids, topical tacrolimus, imiquimod cream, intralesional injections into the elevated border with 2.5 to 5 mg/mL triamcinolone acetonide, or destructive methods such as cryosurgery or pulsed dye laser therapy.1

After a discussion of treatment options, this patient chose watchful waiting.

Image courtesy of Kamini Geer, MD, and text courtesy of Kamini Geer, MD, AdventHealth East Orlando Osteopathic Family Medicine Residency and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

1. Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 6th ed. Saunders; 2015.

A punch biopsy revealed that the patient had granuloma annulare (GA).

GA is usually a self-limiting disorder that manifests as a single or, less commonly, multiple nonscaly, red, annular lesions that are typically found on the extremities. It frequently starts as a papule or cluster of papules before coalescing into its classic annular pattern. Biopsy is not usually needed to make the diagnosis when annular lesions are present. In this case, the lesions displayed the Koebner phenomenon, occurring along her areolar scar, making diagnosis more difficult and necessitating the biopsy. While the cause of GA is unknown, it has been found more often in women than men, but has no predilection for race, ethnicity, or geographic areas.1

GA is typically asymptomatic and can resolve spontaneously. Treatment is often performed for cosmetic reasons. First-line therapies include topical corticosteroids, topical tacrolimus, imiquimod cream, intralesional injections into the elevated border with 2.5 to 5 mg/mL triamcinolone acetonide, or destructive methods such as cryosurgery or pulsed dye laser therapy.1

After a discussion of treatment options, this patient chose watchful waiting.

Image courtesy of Kamini Geer, MD, and text courtesy of Kamini Geer, MD, AdventHealth East Orlando Osteopathic Family Medicine Residency and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

A punch biopsy revealed that the patient had granuloma annulare (GA).

GA is usually a self-limiting disorder that manifests as a single or, less commonly, multiple nonscaly, red, annular lesions that are typically found on the extremities. It frequently starts as a papule or cluster of papules before coalescing into its classic annular pattern. Biopsy is not usually needed to make the diagnosis when annular lesions are present. In this case, the lesions displayed the Koebner phenomenon, occurring along her areolar scar, making diagnosis more difficult and necessitating the biopsy. While the cause of GA is unknown, it has been found more often in women than men, but has no predilection for race, ethnicity, or geographic areas.1

GA is typically asymptomatic and can resolve spontaneously. Treatment is often performed for cosmetic reasons. First-line therapies include topical corticosteroids, topical tacrolimus, imiquimod cream, intralesional injections into the elevated border with 2.5 to 5 mg/mL triamcinolone acetonide, or destructive methods such as cryosurgery or pulsed dye laser therapy.1

After a discussion of treatment options, this patient chose watchful waiting.

Image courtesy of Kamini Geer, MD, and text courtesy of Kamini Geer, MD, AdventHealth East Orlando Osteopathic Family Medicine Residency and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

1. Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 6th ed. Saunders; 2015.

1. Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 6th ed. Saunders; 2015.

New-onset hirsutism

A 74-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic for follow-up 3 months after the surgical excision of a basal cell carcinoma on her left jawline. During this postop period, the patient developed new-onset hirsutism. She appeared to be in otherwise good health.

Family and personal medical history were unremarkable. Her medication regimen included aspirin 81 mg/d and a daily multivitamin. The patient was postmenopausal and had a body mass index of 28 and a history of acid reflux and osteoarthritis.

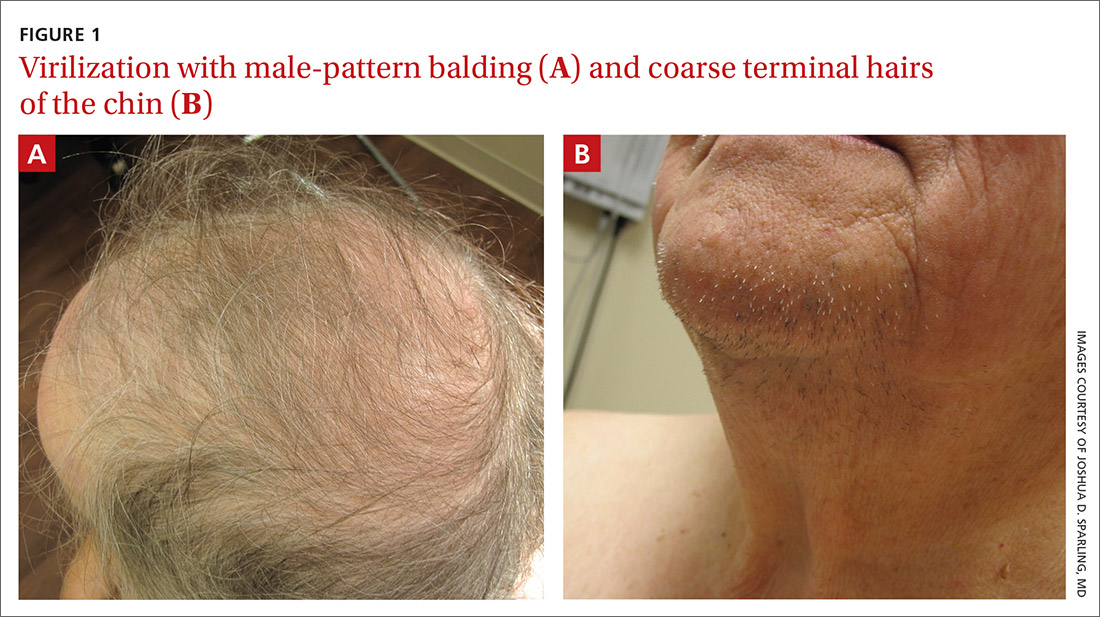

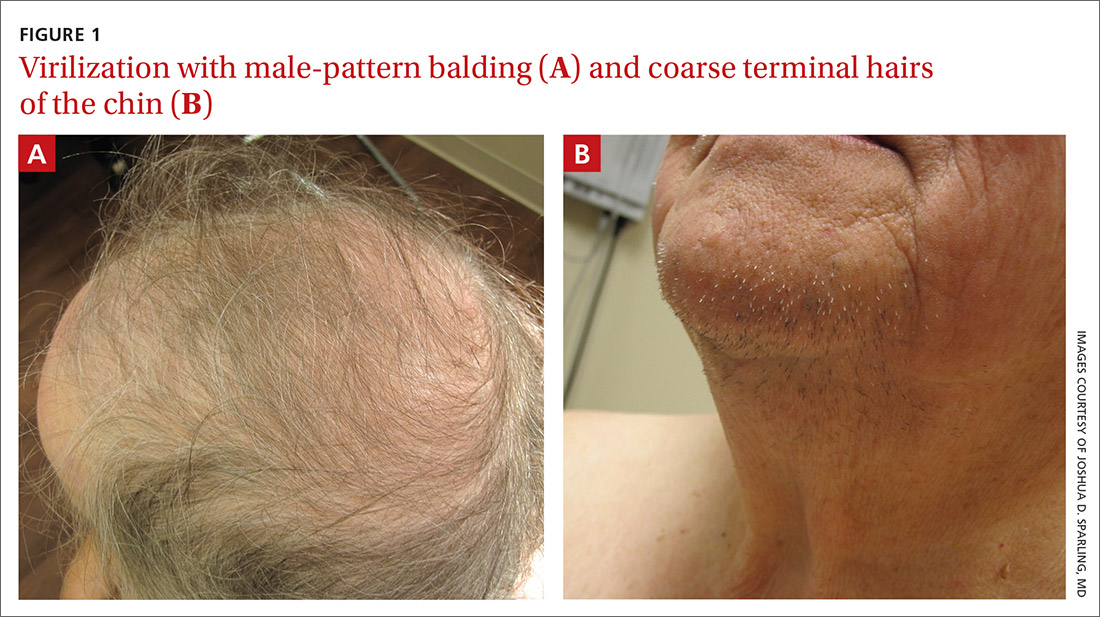

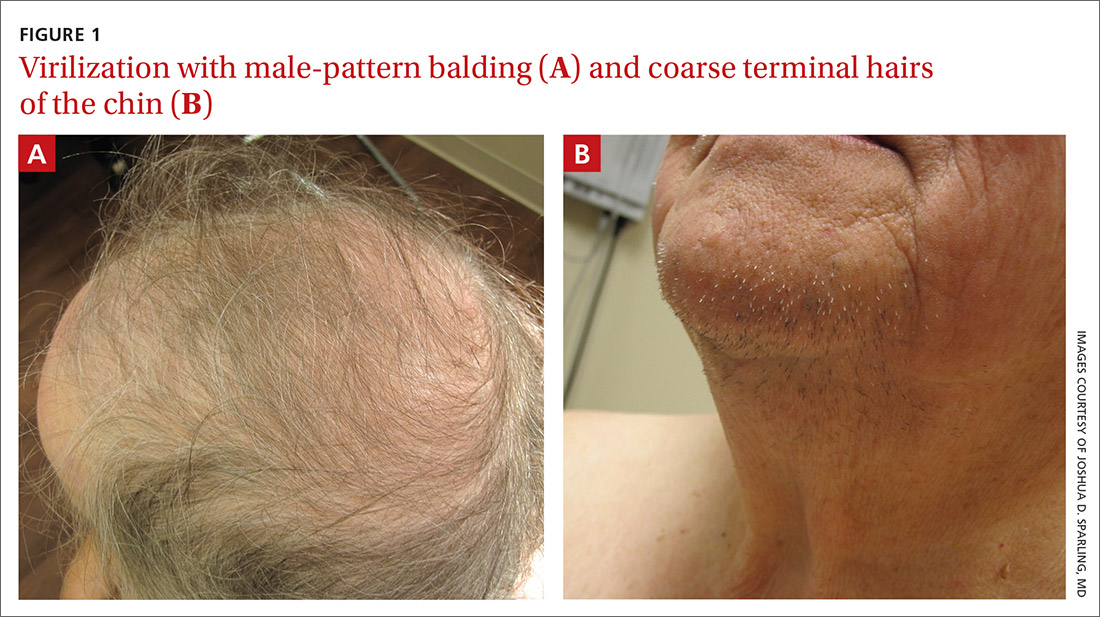

Physical examination of the patient’s scalp showed male-pattern alopecia (FIGURE 1A). She also had coarse terminal hairs on her forearms and back, as well as on her chin (FIGURE 1B).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Androgen-secreting ovarian tumor

Based on the distribution of terminal hairs and marked change over 3 months, as well as the male-pattern alopecia, a diagnosis of androgen excess was suspected. Laboratory work-up, including thyroid-stimulating hormone, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS), follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, prolactin, complete blood count, and complete metabolic panel, was within normal limits. Pelvic ultrasound of the ovaries and abdominal computed tomography (CT) of the adrenal glands were also normal.

Further testing showed an elevated testosterone level of 464 ng/dL (reference range: 2-45 ng/dL) and an elevated free testosterone level of 66.8 ng/dL (reference range: 0.2-3.7 ng/dL). These levels pointed to an androgen-secreting ovarian tumor; the androgen excess was likely the cause of her hirsutism.

Hirsutism or hypertrichosis?

Hirsutism, a common disorder affecting up to 8% of women, is defined by excess terminal hairs that appear in a male pattern in women due to production of excess androgens.1 This should be distinguished from hypertrichosis, which is generalized excessive hair growth not caused by androgen excess.

Testosterone and DHEAS—produced in the ovaries and adrenal glands, respectively—contribute to the development of hirsutism.1 Hirsutism is more often associated with adrenal or ovarian tumors in postmenopausal patients.2 Generalized hypertrichosis can be associated with porphyria cutanea tarda, severe anorexia nervosa, and rarely, malignancies; it also can be secondary to certain agents, such as cyclosporin, phenytoin, and minoxidil.

While hirsutism is associated with hyperandrogenemia, its degree correlates poorly with serum levels. Notably, about half of women with hirsutism have been found to have normal levels of circulating androgens.1 Severe signs of hyperandrogenemia include rapid onset of symptoms, signs of virilization, and a palpable abdominal or pelvic mass.3

Continue to: Is the patient pre- or postmenopausal?

Is the patient pre- or postmenopausal? Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) accounts for up to three-fourths of premenopausal hirsutism.3 The likelihood of hirsutism is actually decreased in postmenopausal women because estrogen levels can drop abruptly after menopause. That said, conditions linked to hirsutism in postmenopausal women include adrenal hyperplasia, thyroid dysfunction, Cushing syndrome, and least frequently, androgen-secreting tumors (seen in this patient). (Hirsutism can also be idiopathic or iatrogenic [medications].)

Methods for detection

Research suggests that when a female patient is given a diagnosis of hirsutism, it’s important to explore possible underlying ovarian and/or adrenal tumors and adult-onset adrenal hyperplasia.1 The following tests and procedure can be helpful:

Serum testosterone and DHEAS. Levels of total testosterone > 200 ng/dL and/or DHEAS > 700 ng/dL are strongly indicative of androgen-secreting tumors.1

Imaging—including ultrasound, CT, or magnetic resonance imaging—can be used for evaluation of the adrenal glands and ovaries. However, imaging is often unable to identify these small tumors.4

Selective venous catheterization can be useful in the localization and lateralization of an androgen-secreting tumor, although a nondiagnostic result with this technique is not uncommon.4

Continue to: Dynamic hormonal testing

Dynamic hormonal testing may assist in determining the pathology of disease but not laterality.2 For example, testing for gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists can be helpful because the constant administration of such agonists can lead to ovarian suppression without affecting adrenal androgen secretion.5

Testing with oral dexamethasone may induce adrenal hormonal depression of androgens and subsequent estradiol through aromatase conversion, which can help rule out an ovarian source.6 Exogenous administration of follicle-stimulating hormone or luteinizing hormone can further differentiate the source from ovarian theca or granulosa cell production.4

Treatment varies

The specific etiology of a patient’s hirsutism dictates the most appropriate treatment. For example, medication-induced hirsutism often requires discontinuation of the offending agent, whereas PCOS would necessitate appropriate nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic interventions.

For our patient, the elevated testosterone and free testosterone levels with normal DHEAS strongly suggested the presence of an androgen-secreting ovarian tumor. These findings led to a referral for bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. The surgical gross appearance of the patient’s ovaries was unremarkable, but gross dissection and pathology of the ovaries (which were not postoperatively identified to determine laterality) showed one was larger (2.7 × 1.5 × 0.8 cm vs 3.2 × 1.4 × 1.2 cm).

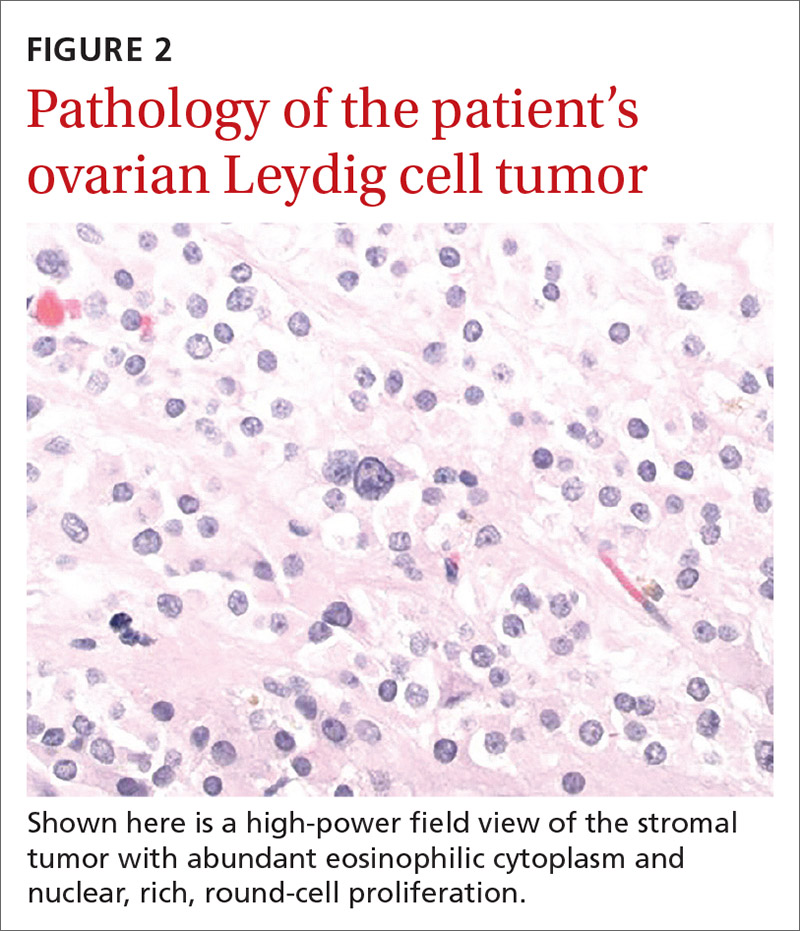

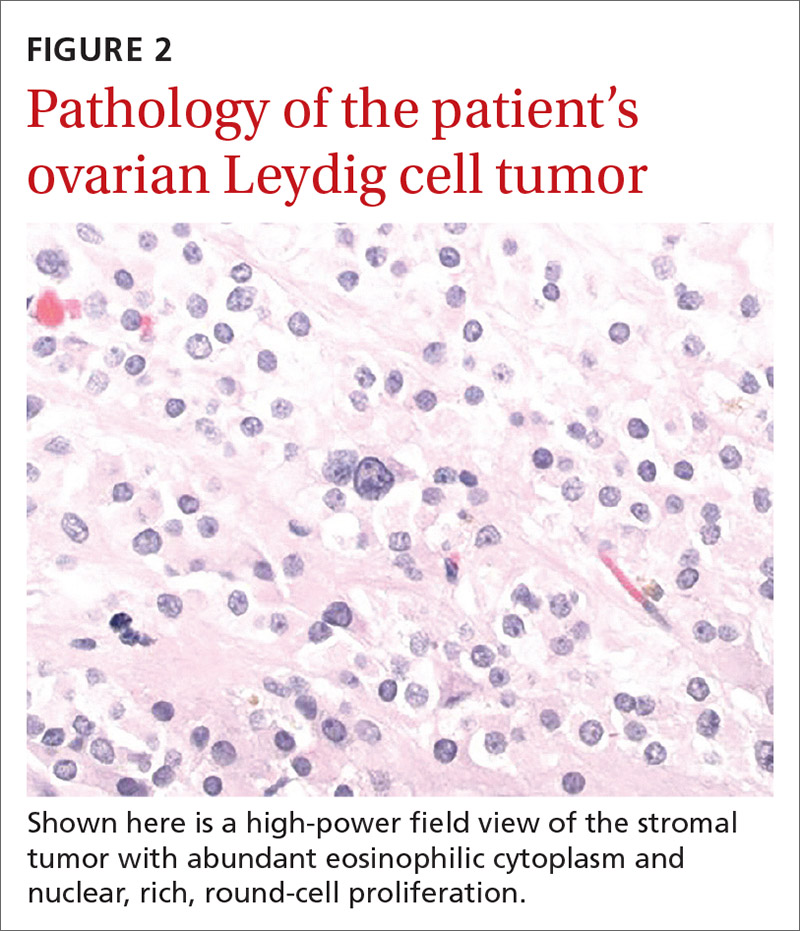

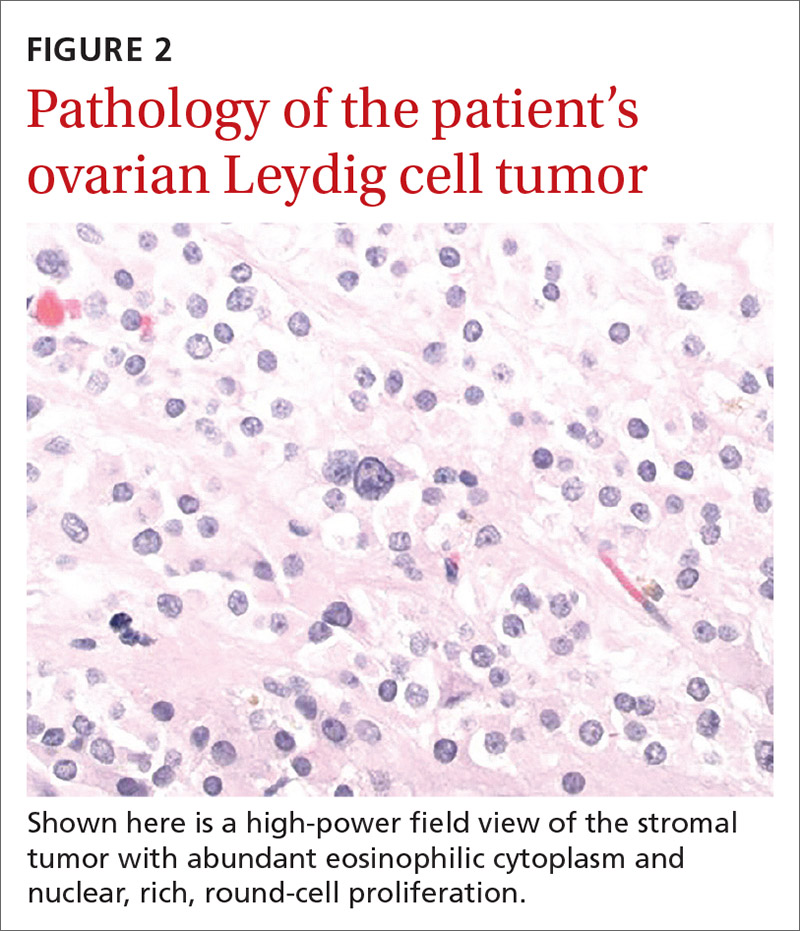

The larger ovary contained an area of brown induration measuring 2.3 × 1.1 × 1.1 cm. This area corresponded to abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm with nuclear, rich, round-cell proliferation, consistent with the diagnosis of a benign ovarian Leydig cell tumor (FIGURE 2). Thus, the bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy was both diagnostic and therapeutic.

Six weeks after the surgery, blood work showed normalization of testosterone and free testosterone levels. The patient’s hirsutism completely resolved over the course of the next several months.

1. Hunter M, Carek PJ. Evaluation and treatment of women with hirsutism. Am Fam Physician. 2003;67:2565-2572.

2. Alpañés M, González-Casbas JM, Sánchez J, et al. Management of postmenopausal virilization. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:2584-2588.

3. Bode D, Seehusen DA, Baird D. Hirsutism in women. Am Fam Physician. 2012;85:373-380.

4. Cohen I, Nabriski D, Fishman A. Noninvasive test for the diagnosis of ovarian hormone-secreting-neopolasm in postmenopausal women. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2016;15:12-15.

5. Gandrapu B, Sundar P, Phillips B. Hyperandrogenism in a postmenaupsal woman secondary to testosterone secreting ovarian stromal tumor with acoustic schwannoma. Case Rep Endocrinol. 2018;2018:8154513.

6. Curran DR, Moore C, Huber T. What is the best approach to the evaluation of hirsutism? J Fam Pract. 2005;54:458-473.

A 74-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic for follow-up 3 months after the surgical excision of a basal cell carcinoma on her left jawline. During this postop period, the patient developed new-onset hirsutism. She appeared to be in otherwise good health.

Family and personal medical history were unremarkable. Her medication regimen included aspirin 81 mg/d and a daily multivitamin. The patient was postmenopausal and had a body mass index of 28 and a history of acid reflux and osteoarthritis.

Physical examination of the patient’s scalp showed male-pattern alopecia (FIGURE 1A). She also had coarse terminal hairs on her forearms and back, as well as on her chin (FIGURE 1B).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Androgen-secreting ovarian tumor

Based on the distribution of terminal hairs and marked change over 3 months, as well as the male-pattern alopecia, a diagnosis of androgen excess was suspected. Laboratory work-up, including thyroid-stimulating hormone, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS), follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, prolactin, complete blood count, and complete metabolic panel, was within normal limits. Pelvic ultrasound of the ovaries and abdominal computed tomography (CT) of the adrenal glands were also normal.

Further testing showed an elevated testosterone level of 464 ng/dL (reference range: 2-45 ng/dL) and an elevated free testosterone level of 66.8 ng/dL (reference range: 0.2-3.7 ng/dL). These levels pointed to an androgen-secreting ovarian tumor; the androgen excess was likely the cause of her hirsutism.

Hirsutism or hypertrichosis?

Hirsutism, a common disorder affecting up to 8% of women, is defined by excess terminal hairs that appear in a male pattern in women due to production of excess androgens.1 This should be distinguished from hypertrichosis, which is generalized excessive hair growth not caused by androgen excess.

Testosterone and DHEAS—produced in the ovaries and adrenal glands, respectively—contribute to the development of hirsutism.1 Hirsutism is more often associated with adrenal or ovarian tumors in postmenopausal patients.2 Generalized hypertrichosis can be associated with porphyria cutanea tarda, severe anorexia nervosa, and rarely, malignancies; it also can be secondary to certain agents, such as cyclosporin, phenytoin, and minoxidil.

While hirsutism is associated with hyperandrogenemia, its degree correlates poorly with serum levels. Notably, about half of women with hirsutism have been found to have normal levels of circulating androgens.1 Severe signs of hyperandrogenemia include rapid onset of symptoms, signs of virilization, and a palpable abdominal or pelvic mass.3

Continue to: Is the patient pre- or postmenopausal?

Is the patient pre- or postmenopausal? Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) accounts for up to three-fourths of premenopausal hirsutism.3 The likelihood of hirsutism is actually decreased in postmenopausal women because estrogen levels can drop abruptly after menopause. That said, conditions linked to hirsutism in postmenopausal women include adrenal hyperplasia, thyroid dysfunction, Cushing syndrome, and least frequently, androgen-secreting tumors (seen in this patient). (Hirsutism can also be idiopathic or iatrogenic [medications].)

Methods for detection

Research suggests that when a female patient is given a diagnosis of hirsutism, it’s important to explore possible underlying ovarian and/or adrenal tumors and adult-onset adrenal hyperplasia.1 The following tests and procedure can be helpful:

Serum testosterone and DHEAS. Levels of total testosterone > 200 ng/dL and/or DHEAS > 700 ng/dL are strongly indicative of androgen-secreting tumors.1

Imaging—including ultrasound, CT, or magnetic resonance imaging—can be used for evaluation of the adrenal glands and ovaries. However, imaging is often unable to identify these small tumors.4

Selective venous catheterization can be useful in the localization and lateralization of an androgen-secreting tumor, although a nondiagnostic result with this technique is not uncommon.4

Continue to: Dynamic hormonal testing

Dynamic hormonal testing may assist in determining the pathology of disease but not laterality.2 For example, testing for gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists can be helpful because the constant administration of such agonists can lead to ovarian suppression without affecting adrenal androgen secretion.5

Testing with oral dexamethasone may induce adrenal hormonal depression of androgens and subsequent estradiol through aromatase conversion, which can help rule out an ovarian source.6 Exogenous administration of follicle-stimulating hormone or luteinizing hormone can further differentiate the source from ovarian theca or granulosa cell production.4

Treatment varies

The specific etiology of a patient’s hirsutism dictates the most appropriate treatment. For example, medication-induced hirsutism often requires discontinuation of the offending agent, whereas PCOS would necessitate appropriate nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic interventions.

For our patient, the elevated testosterone and free testosterone levels with normal DHEAS strongly suggested the presence of an androgen-secreting ovarian tumor. These findings led to a referral for bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. The surgical gross appearance of the patient’s ovaries was unremarkable, but gross dissection and pathology of the ovaries (which were not postoperatively identified to determine laterality) showed one was larger (2.7 × 1.5 × 0.8 cm vs 3.2 × 1.4 × 1.2 cm).

The larger ovary contained an area of brown induration measuring 2.3 × 1.1 × 1.1 cm. This area corresponded to abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm with nuclear, rich, round-cell proliferation, consistent with the diagnosis of a benign ovarian Leydig cell tumor (FIGURE 2). Thus, the bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy was both diagnostic and therapeutic.

Six weeks after the surgery, blood work showed normalization of testosterone and free testosterone levels. The patient’s hirsutism completely resolved over the course of the next several months.

A 74-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic for follow-up 3 months after the surgical excision of a basal cell carcinoma on her left jawline. During this postop period, the patient developed new-onset hirsutism. She appeared to be in otherwise good health.

Family and personal medical history were unremarkable. Her medication regimen included aspirin 81 mg/d and a daily multivitamin. The patient was postmenopausal and had a body mass index of 28 and a history of acid reflux and osteoarthritis.

Physical examination of the patient’s scalp showed male-pattern alopecia (FIGURE 1A). She also had coarse terminal hairs on her forearms and back, as well as on her chin (FIGURE 1B).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Androgen-secreting ovarian tumor

Based on the distribution of terminal hairs and marked change over 3 months, as well as the male-pattern alopecia, a diagnosis of androgen excess was suspected. Laboratory work-up, including thyroid-stimulating hormone, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS), follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, prolactin, complete blood count, and complete metabolic panel, was within normal limits. Pelvic ultrasound of the ovaries and abdominal computed tomography (CT) of the adrenal glands were also normal.

Further testing showed an elevated testosterone level of 464 ng/dL (reference range: 2-45 ng/dL) and an elevated free testosterone level of 66.8 ng/dL (reference range: 0.2-3.7 ng/dL). These levels pointed to an androgen-secreting ovarian tumor; the androgen excess was likely the cause of her hirsutism.

Hirsutism or hypertrichosis?

Hirsutism, a common disorder affecting up to 8% of women, is defined by excess terminal hairs that appear in a male pattern in women due to production of excess androgens.1 This should be distinguished from hypertrichosis, which is generalized excessive hair growth not caused by androgen excess.

Testosterone and DHEAS—produced in the ovaries and adrenal glands, respectively—contribute to the development of hirsutism.1 Hirsutism is more often associated with adrenal or ovarian tumors in postmenopausal patients.2 Generalized hypertrichosis can be associated with porphyria cutanea tarda, severe anorexia nervosa, and rarely, malignancies; it also can be secondary to certain agents, such as cyclosporin, phenytoin, and minoxidil.

While hirsutism is associated with hyperandrogenemia, its degree correlates poorly with serum levels. Notably, about half of women with hirsutism have been found to have normal levels of circulating androgens.1 Severe signs of hyperandrogenemia include rapid onset of symptoms, signs of virilization, and a palpable abdominal or pelvic mass.3

Continue to: Is the patient pre- or postmenopausal?

Is the patient pre- or postmenopausal? Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) accounts for up to three-fourths of premenopausal hirsutism.3 The likelihood of hirsutism is actually decreased in postmenopausal women because estrogen levels can drop abruptly after menopause. That said, conditions linked to hirsutism in postmenopausal women include adrenal hyperplasia, thyroid dysfunction, Cushing syndrome, and least frequently, androgen-secreting tumors (seen in this patient). (Hirsutism can also be idiopathic or iatrogenic [medications].)

Methods for detection

Research suggests that when a female patient is given a diagnosis of hirsutism, it’s important to explore possible underlying ovarian and/or adrenal tumors and adult-onset adrenal hyperplasia.1 The following tests and procedure can be helpful:

Serum testosterone and DHEAS. Levels of total testosterone > 200 ng/dL and/or DHEAS > 700 ng/dL are strongly indicative of androgen-secreting tumors.1

Imaging—including ultrasound, CT, or magnetic resonance imaging—can be used for evaluation of the adrenal glands and ovaries. However, imaging is often unable to identify these small tumors.4

Selective venous catheterization can be useful in the localization and lateralization of an androgen-secreting tumor, although a nondiagnostic result with this technique is not uncommon.4

Continue to: Dynamic hormonal testing

Dynamic hormonal testing may assist in determining the pathology of disease but not laterality.2 For example, testing for gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists can be helpful because the constant administration of such agonists can lead to ovarian suppression without affecting adrenal androgen secretion.5

Testing with oral dexamethasone may induce adrenal hormonal depression of androgens and subsequent estradiol through aromatase conversion, which can help rule out an ovarian source.6 Exogenous administration of follicle-stimulating hormone or luteinizing hormone can further differentiate the source from ovarian theca or granulosa cell production.4

Treatment varies

The specific etiology of a patient’s hirsutism dictates the most appropriate treatment. For example, medication-induced hirsutism often requires discontinuation of the offending agent, whereas PCOS would necessitate appropriate nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic interventions.

For our patient, the elevated testosterone and free testosterone levels with normal DHEAS strongly suggested the presence of an androgen-secreting ovarian tumor. These findings led to a referral for bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. The surgical gross appearance of the patient’s ovaries was unremarkable, but gross dissection and pathology of the ovaries (which were not postoperatively identified to determine laterality) showed one was larger (2.7 × 1.5 × 0.8 cm vs 3.2 × 1.4 × 1.2 cm).

The larger ovary contained an area of brown induration measuring 2.3 × 1.1 × 1.1 cm. This area corresponded to abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm with nuclear, rich, round-cell proliferation, consistent with the diagnosis of a benign ovarian Leydig cell tumor (FIGURE 2). Thus, the bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy was both diagnostic and therapeutic.

Six weeks after the surgery, blood work showed normalization of testosterone and free testosterone levels. The patient’s hirsutism completely resolved over the course of the next several months.

1. Hunter M, Carek PJ. Evaluation and treatment of women with hirsutism. Am Fam Physician. 2003;67:2565-2572.

2. Alpañés M, González-Casbas JM, Sánchez J, et al. Management of postmenopausal virilization. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:2584-2588.

3. Bode D, Seehusen DA, Baird D. Hirsutism in women. Am Fam Physician. 2012;85:373-380.

4. Cohen I, Nabriski D, Fishman A. Noninvasive test for the diagnosis of ovarian hormone-secreting-neopolasm in postmenopausal women. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2016;15:12-15.

5. Gandrapu B, Sundar P, Phillips B. Hyperandrogenism in a postmenaupsal woman secondary to testosterone secreting ovarian stromal tumor with acoustic schwannoma. Case Rep Endocrinol. 2018;2018:8154513.

6. Curran DR, Moore C, Huber T. What is the best approach to the evaluation of hirsutism? J Fam Pract. 2005;54:458-473.

1. Hunter M, Carek PJ. Evaluation and treatment of women with hirsutism. Am Fam Physician. 2003;67:2565-2572.

2. Alpañés M, González-Casbas JM, Sánchez J, et al. Management of postmenopausal virilization. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:2584-2588.

3. Bode D, Seehusen DA, Baird D. Hirsutism in women. Am Fam Physician. 2012;85:373-380.

4. Cohen I, Nabriski D, Fishman A. Noninvasive test for the diagnosis of ovarian hormone-secreting-neopolasm in postmenopausal women. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2016;15:12-15.

5. Gandrapu B, Sundar P, Phillips B. Hyperandrogenism in a postmenaupsal woman secondary to testosterone secreting ovarian stromal tumor with acoustic schwannoma. Case Rep Endocrinol. 2018;2018:8154513.

6. Curran DR, Moore C, Huber T. What is the best approach to the evaluation of hirsutism? J Fam Pract. 2005;54:458-473.

Itchy rash on back

A unilateral, neuropathic itch accompanied by postinflammatory pigmentation changes or lichenification at the medial inferior tip of the scapula are the hallmarks of notalgia paresthetica (NP).

NP is thought to result from nerve impingement or chronic nerve trauma to the posterior rami of the upper thoracic spinal nerves. The hyperpigmentation and lichenification arise from repeated scratching or rubbing of the skin.

NP is a clinical diagnosis and does not require biopsy or imaging. The differential diagnosis includes brachioradial pruritus, postherpetic neuralgia, multiple sclerosis, and other small fiber neuropathies.

The standard treatment is topical capsaicin 0.025% tid for 5 weeks, with repeat treatments (for a few days or weeks) if there are relapses. Higher doses (0.075%) may work more quickly but may also lead to more burning. A lidocaine 5% patch bid can also be considered. Second-line treatment options include cutaneous electrical field stimulation or transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, gabapentin, or oxcarbazepine. Topical steroids are considered ineffective for this condition.1

The patient in this case was started on capsaicin 0.025%. She was encouraged to keep her skin moisturized and well hydrated because dyshidrosis can exacerbate itching. A prescription for gabapentin was offered in case topical treatments were unsuccessful, but she declined after she weighed the risks of adverse effects against her current symptoms.

Photo courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, and text courtesy of Nathan Birnbaum, MD, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque

1. Lebwohl MG, Heymann WR, Berth-Jones J, et al, eds. Treatment of Skin Disease: Comprehensive Therapeutic Strategies. 5th ed. Elsevier; 2017.

A unilateral, neuropathic itch accompanied by postinflammatory pigmentation changes or lichenification at the medial inferior tip of the scapula are the hallmarks of notalgia paresthetica (NP).

NP is thought to result from nerve impingement or chronic nerve trauma to the posterior rami of the upper thoracic spinal nerves. The hyperpigmentation and lichenification arise from repeated scratching or rubbing of the skin.

NP is a clinical diagnosis and does not require biopsy or imaging. The differential diagnosis includes brachioradial pruritus, postherpetic neuralgia, multiple sclerosis, and other small fiber neuropathies.

The standard treatment is topical capsaicin 0.025% tid for 5 weeks, with repeat treatments (for a few days or weeks) if there are relapses. Higher doses (0.075%) may work more quickly but may also lead to more burning. A lidocaine 5% patch bid can also be considered. Second-line treatment options include cutaneous electrical field stimulation or transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, gabapentin, or oxcarbazepine. Topical steroids are considered ineffective for this condition.1

The patient in this case was started on capsaicin 0.025%. She was encouraged to keep her skin moisturized and well hydrated because dyshidrosis can exacerbate itching. A prescription for gabapentin was offered in case topical treatments were unsuccessful, but she declined after she weighed the risks of adverse effects against her current symptoms.

Photo courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, and text courtesy of Nathan Birnbaum, MD, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque

A unilateral, neuropathic itch accompanied by postinflammatory pigmentation changes or lichenification at the medial inferior tip of the scapula are the hallmarks of notalgia paresthetica (NP).

NP is thought to result from nerve impingement or chronic nerve trauma to the posterior rami of the upper thoracic spinal nerves. The hyperpigmentation and lichenification arise from repeated scratching or rubbing of the skin.

NP is a clinical diagnosis and does not require biopsy or imaging. The differential diagnosis includes brachioradial pruritus, postherpetic neuralgia, multiple sclerosis, and other small fiber neuropathies.

The standard treatment is topical capsaicin 0.025% tid for 5 weeks, with repeat treatments (for a few days or weeks) if there are relapses. Higher doses (0.075%) may work more quickly but may also lead to more burning. A lidocaine 5% patch bid can also be considered. Second-line treatment options include cutaneous electrical field stimulation or transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, gabapentin, or oxcarbazepine. Topical steroids are considered ineffective for this condition.1

The patient in this case was started on capsaicin 0.025%. She was encouraged to keep her skin moisturized and well hydrated because dyshidrosis can exacerbate itching. A prescription for gabapentin was offered in case topical treatments were unsuccessful, but she declined after she weighed the risks of adverse effects against her current symptoms.

Photo courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, and text courtesy of Nathan Birnbaum, MD, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque

1. Lebwohl MG, Heymann WR, Berth-Jones J, et al, eds. Treatment of Skin Disease: Comprehensive Therapeutic Strategies. 5th ed. Elsevier; 2017.

1. Lebwohl MG, Heymann WR, Berth-Jones J, et al, eds. Treatment of Skin Disease: Comprehensive Therapeutic Strategies. 5th ed. Elsevier; 2017.

Painful thickened breast lesion

Treatment was attempted for both a suspected spider bite (2 weeks of topical triamcinolone 0.1%) and presumed cellulitis (oral doxycycline 100 mg bid/5 d), but neither improved her condition. Concerned for the possibility of cutaneous breast cancer, a punch biopsy was ordered and revealed diffuse dermal angiomatosis (DDA).

DDA is an uncommon proliferation of cutaneous blood vessels causing a reticular blood vessel pattern, as seen in this image. Typically, DDA is associated with tissue hypoxia due to arterial insufficiency from peripheral artery disease. In recent years, there have been numerous case reports of painful ulcerated lesions and reticular blood vessels occurring in women with large, pendulous breasts, increased body mass index, and a history of smoking. One theory suggests that the weight of the breasts causes tissue to stretch, compressing the blood vessels. This, combined with smoking, leads to localized hypoxia and DDA.

Treatments have included oral isotretinoin, calcium channel blockers, aspirin, or pentoxifylline to help circulation. Smoking cessation is recommended, as well as reduction mammoplasty to decrease the stretch on the tissues and relieve the local hypoxia. Although invasive, breast reduction surgery has moved to the forefront of therapy, with reports having shown resolution of the ulcers and pain.1

Two important aspects of clinical medicine are highlighted by this case. First, nonhealing lesions that are not responding to prescribed therapies may require biopsy to rule out malignancy. Second, when there is difficulty making a diagnosis, especially with uncommon diseases, biopsy and input from a pathologist can be extremely helpful.

In this case, the patient was referred to Plastic Surgery and scheduled for reduction mammoplasty. The patient was advised to stop smoking for at least 4 weeks prior to the surgery to possibly improve her condition and reduce the likelihood of postoperative complications.

Photo courtesy of Michael Louie, MD, and text courtesy of Michael Louie, MD, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque

Galambos J, Meuli-Simmen C, Schmid R, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis of the breast: a distinct entity in the spectrum of cutaneous reactive angiomatoses—clinicopathologic study of two cases and comprehensive review of the literature. Case Rep Dermatol 2017;9:194-205. https://doi.org/10.1159/000480721

Treatment was attempted for both a suspected spider bite (2 weeks of topical triamcinolone 0.1%) and presumed cellulitis (oral doxycycline 100 mg bid/5 d), but neither improved her condition. Concerned for the possibility of cutaneous breast cancer, a punch biopsy was ordered and revealed diffuse dermal angiomatosis (DDA).

DDA is an uncommon proliferation of cutaneous blood vessels causing a reticular blood vessel pattern, as seen in this image. Typically, DDA is associated with tissue hypoxia due to arterial insufficiency from peripheral artery disease. In recent years, there have been numerous case reports of painful ulcerated lesions and reticular blood vessels occurring in women with large, pendulous breasts, increased body mass index, and a history of smoking. One theory suggests that the weight of the breasts causes tissue to stretch, compressing the blood vessels. This, combined with smoking, leads to localized hypoxia and DDA.

Treatments have included oral isotretinoin, calcium channel blockers, aspirin, or pentoxifylline to help circulation. Smoking cessation is recommended, as well as reduction mammoplasty to decrease the stretch on the tissues and relieve the local hypoxia. Although invasive, breast reduction surgery has moved to the forefront of therapy, with reports having shown resolution of the ulcers and pain.1

Two important aspects of clinical medicine are highlighted by this case. First, nonhealing lesions that are not responding to prescribed therapies may require biopsy to rule out malignancy. Second, when there is difficulty making a diagnosis, especially with uncommon diseases, biopsy and input from a pathologist can be extremely helpful.

In this case, the patient was referred to Plastic Surgery and scheduled for reduction mammoplasty. The patient was advised to stop smoking for at least 4 weeks prior to the surgery to possibly improve her condition and reduce the likelihood of postoperative complications.

Photo courtesy of Michael Louie, MD, and text courtesy of Michael Louie, MD, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque

Treatment was attempted for both a suspected spider bite (2 weeks of topical triamcinolone 0.1%) and presumed cellulitis (oral doxycycline 100 mg bid/5 d), but neither improved her condition. Concerned for the possibility of cutaneous breast cancer, a punch biopsy was ordered and revealed diffuse dermal angiomatosis (DDA).

DDA is an uncommon proliferation of cutaneous blood vessels causing a reticular blood vessel pattern, as seen in this image. Typically, DDA is associated with tissue hypoxia due to arterial insufficiency from peripheral artery disease. In recent years, there have been numerous case reports of painful ulcerated lesions and reticular blood vessels occurring in women with large, pendulous breasts, increased body mass index, and a history of smoking. One theory suggests that the weight of the breasts causes tissue to stretch, compressing the blood vessels. This, combined with smoking, leads to localized hypoxia and DDA.

Treatments have included oral isotretinoin, calcium channel blockers, aspirin, or pentoxifylline to help circulation. Smoking cessation is recommended, as well as reduction mammoplasty to decrease the stretch on the tissues and relieve the local hypoxia. Although invasive, breast reduction surgery has moved to the forefront of therapy, with reports having shown resolution of the ulcers and pain.1

Two important aspects of clinical medicine are highlighted by this case. First, nonhealing lesions that are not responding to prescribed therapies may require biopsy to rule out malignancy. Second, when there is difficulty making a diagnosis, especially with uncommon diseases, biopsy and input from a pathologist can be extremely helpful.

In this case, the patient was referred to Plastic Surgery and scheduled for reduction mammoplasty. The patient was advised to stop smoking for at least 4 weeks prior to the surgery to possibly improve her condition and reduce the likelihood of postoperative complications.

Photo courtesy of Michael Louie, MD, and text courtesy of Michael Louie, MD, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque

Galambos J, Meuli-Simmen C, Schmid R, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis of the breast: a distinct entity in the spectrum of cutaneous reactive angiomatoses—clinicopathologic study of two cases and comprehensive review of the literature. Case Rep Dermatol 2017;9:194-205. https://doi.org/10.1159/000480721

Galambos J, Meuli-Simmen C, Schmid R, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis of the breast: a distinct entity in the spectrum of cutaneous reactive angiomatoses—clinicopathologic study of two cases and comprehensive review of the literature. Case Rep Dermatol 2017;9:194-205. https://doi.org/10.1159/000480721

Pink plaque on the ear

A 4-mm punch biopsy was performed and revealed B-cell lymphoma, consistent with extranodal marginal zone lymphoma. The plaque was palpated carefully and the location of branches of the superficial temporal artery, which usually course anterior to the helix, were mapped, and avoided as a biopsy site.

Marginal zone lymphoma is a relatively indolent B-cell lymphoma that occurs in adults in mucosal associated lymphoid tissue, most often in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Neoplasms also occur in the lungs, eyes, and skin. Initial symptoms vary according to the site of manifestation. Patients with GI tumors may present with GI bleeding, abdominal pain, and weight loss. Pulmonary lesions are often asymptomatic and picked up on chest imaging for other indications. Chronic gastritis associated with Helicobacter pylori contributes to cases and occasionally eradication of H. pylori may clear patients of disease. Autoimmune diseases, particularly Sjögren disease and Hashimoto thyroiditis, also have a causative association. Rarely, transformation into high-grade disease occurs.

On the skin, marginal zone lymphoma may be exhibited as soft salmon-colored patches with serpentine vascular markings, as seen here on dermoscopy.1 The differential diagnosis includes keloid scar, basal cell carcinoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, arthropod bites, and amelanotic melanoma.

This patient had been under the care of Medical Oncology for surveillance and was offered observation as a potential treatment strategy because of the relatively indolent nature of the tumor. However, because the tumor was painful and growing, she opted for focal palliative radiation therapy.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Geller S, Marghoob AA, Scope A, et al. Dermoscopy and the diagnosis of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:53-56. doi:10.1111/jdv.14549

A 4-mm punch biopsy was performed and revealed B-cell lymphoma, consistent with extranodal marginal zone lymphoma. The plaque was palpated carefully and the location of branches of the superficial temporal artery, which usually course anterior to the helix, were mapped, and avoided as a biopsy site.

Marginal zone lymphoma is a relatively indolent B-cell lymphoma that occurs in adults in mucosal associated lymphoid tissue, most often in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Neoplasms also occur in the lungs, eyes, and skin. Initial symptoms vary according to the site of manifestation. Patients with GI tumors may present with GI bleeding, abdominal pain, and weight loss. Pulmonary lesions are often asymptomatic and picked up on chest imaging for other indications. Chronic gastritis associated with Helicobacter pylori contributes to cases and occasionally eradication of H. pylori may clear patients of disease. Autoimmune diseases, particularly Sjögren disease and Hashimoto thyroiditis, also have a causative association. Rarely, transformation into high-grade disease occurs.

On the skin, marginal zone lymphoma may be exhibited as soft salmon-colored patches with serpentine vascular markings, as seen here on dermoscopy.1 The differential diagnosis includes keloid scar, basal cell carcinoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, arthropod bites, and amelanotic melanoma.

This patient had been under the care of Medical Oncology for surveillance and was offered observation as a potential treatment strategy because of the relatively indolent nature of the tumor. However, because the tumor was painful and growing, she opted for focal palliative radiation therapy.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

A 4-mm punch biopsy was performed and revealed B-cell lymphoma, consistent with extranodal marginal zone lymphoma. The plaque was palpated carefully and the location of branches of the superficial temporal artery, which usually course anterior to the helix, were mapped, and avoided as a biopsy site.

Marginal zone lymphoma is a relatively indolent B-cell lymphoma that occurs in adults in mucosal associated lymphoid tissue, most often in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Neoplasms also occur in the lungs, eyes, and skin. Initial symptoms vary according to the site of manifestation. Patients with GI tumors may present with GI bleeding, abdominal pain, and weight loss. Pulmonary lesions are often asymptomatic and picked up on chest imaging for other indications. Chronic gastritis associated with Helicobacter pylori contributes to cases and occasionally eradication of H. pylori may clear patients of disease. Autoimmune diseases, particularly Sjögren disease and Hashimoto thyroiditis, also have a causative association. Rarely, transformation into high-grade disease occurs.

On the skin, marginal zone lymphoma may be exhibited as soft salmon-colored patches with serpentine vascular markings, as seen here on dermoscopy.1 The differential diagnosis includes keloid scar, basal cell carcinoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, arthropod bites, and amelanotic melanoma.

This patient had been under the care of Medical Oncology for surveillance and was offered observation as a potential treatment strategy because of the relatively indolent nature of the tumor. However, because the tumor was painful and growing, she opted for focal palliative radiation therapy.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Geller S, Marghoob AA, Scope A, et al. Dermoscopy and the diagnosis of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:53-56. doi:10.1111/jdv.14549

1. Geller S, Marghoob AA, Scope A, et al. Dermoscopy and the diagnosis of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:53-56. doi:10.1111/jdv.14549

Pink papule on thigh

A deep-shave biopsy indicated that this was an inflamed/irritated solitary neurofibroma. Basal cell carcinoma, inflamed nevus, and Merkel cell carcinoma were also considered.

Most often manifesting in adults, solitary neurofibromas are common nonencapsulated, soft to firm papules that range in size from 2 mm to 2 cm. Solitary neurofibromas are benign and work-up for systemic neurofibromatosis is not indicated. However, if a patient presents with multiple neurofibromas, axillary freckling, or multiple café au lait macules, systemic disease should be considered, followed by molecular testing and/or referral to a medical geneticist or neurofibromatosis clinic.

Although both the triage amalgamated diagnostic algorithm and the 2-step dermoscopy algorithm suggested this lesion was higher risk, it was ultimately found to be benign. This case highlights areas in which dermoscopy and physical exam lack specificity, but this trade-off increases the sensitivity of an algorithmic approach. Solitary pink papules can include some subtle, but fearsome, diagnoses and deserve close attention. In this case, the biopsy not only helped confirm the diagnosis, but it also alleviated the discomfort caused by the neurofibroma.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Geller S, Pulitzer M, Brady MS, et al. Dermoscopic assessment of vascular structures in solitary small pink lesions—differentiating between good and evil. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2017;7:47-50. doi: 10.5826/dpc.0703a10

A deep-shave biopsy indicated that this was an inflamed/irritated solitary neurofibroma. Basal cell carcinoma, inflamed nevus, and Merkel cell carcinoma were also considered.

Most often manifesting in adults, solitary neurofibromas are common nonencapsulated, soft to firm papules that range in size from 2 mm to 2 cm. Solitary neurofibromas are benign and work-up for systemic neurofibromatosis is not indicated. However, if a patient presents with multiple neurofibromas, axillary freckling, or multiple café au lait macules, systemic disease should be considered, followed by molecular testing and/or referral to a medical geneticist or neurofibromatosis clinic.

Although both the triage amalgamated diagnostic algorithm and the 2-step dermoscopy algorithm suggested this lesion was higher risk, it was ultimately found to be benign. This case highlights areas in which dermoscopy and physical exam lack specificity, but this trade-off increases the sensitivity of an algorithmic approach. Solitary pink papules can include some subtle, but fearsome, diagnoses and deserve close attention. In this case, the biopsy not only helped confirm the diagnosis, but it also alleviated the discomfort caused by the neurofibroma.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

A deep-shave biopsy indicated that this was an inflamed/irritated solitary neurofibroma. Basal cell carcinoma, inflamed nevus, and Merkel cell carcinoma were also considered.

Most often manifesting in adults, solitary neurofibromas are common nonencapsulated, soft to firm papules that range in size from 2 mm to 2 cm. Solitary neurofibromas are benign and work-up for systemic neurofibromatosis is not indicated. However, if a patient presents with multiple neurofibromas, axillary freckling, or multiple café au lait macules, systemic disease should be considered, followed by molecular testing and/or referral to a medical geneticist or neurofibromatosis clinic.

Although both the triage amalgamated diagnostic algorithm and the 2-step dermoscopy algorithm suggested this lesion was higher risk, it was ultimately found to be benign. This case highlights areas in which dermoscopy and physical exam lack specificity, but this trade-off increases the sensitivity of an algorithmic approach. Solitary pink papules can include some subtle, but fearsome, diagnoses and deserve close attention. In this case, the biopsy not only helped confirm the diagnosis, but it also alleviated the discomfort caused by the neurofibroma.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Geller S, Pulitzer M, Brady MS, et al. Dermoscopic assessment of vascular structures in solitary small pink lesions—differentiating between good and evil. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2017;7:47-50. doi: 10.5826/dpc.0703a10

1. Geller S, Pulitzer M, Brady MS, et al. Dermoscopic assessment of vascular structures in solitary small pink lesions—differentiating between good and evil. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2017;7:47-50. doi: 10.5826/dpc.0703a10

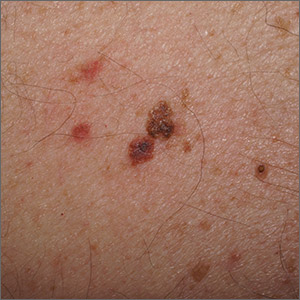

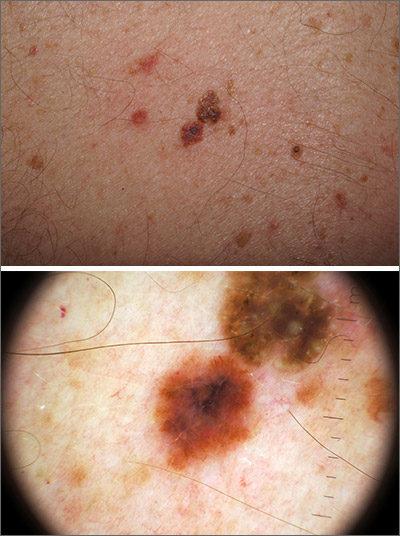

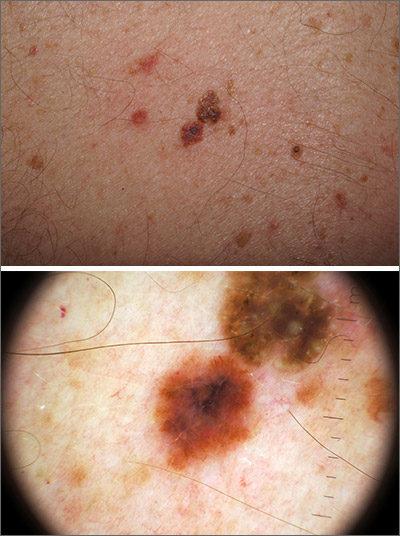

Outlier lesion on the back

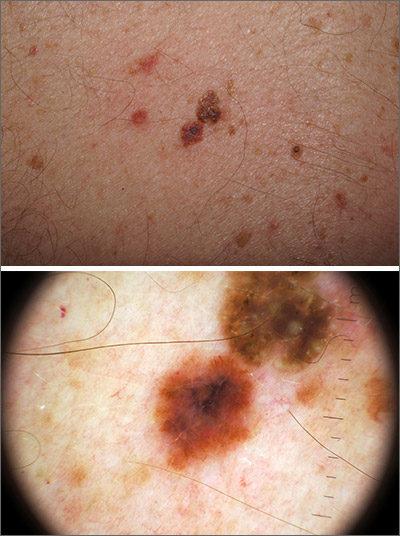

In addition to the patient’s SK, the second finding was diagnosed as a thin melanoma. The clinical appearance of SKs and nevi or melanoma can overlap. Dermoscopy is a helpful tool in distinguishing between them, even when juxtaposed in a collision lesion such as this.1

Dermoscopy of the superior portion of the lesion demonstrated a well-demarcated brown, waxy papule with milia-like cysts, consistent with an SK. Inferiorly, the dermoscopic features included atypical pigment network, asymmetrical streaks, and blue-white veil, suggestive of melanoma or an atypical melanocytic neoplasm. A deep-shave biopsy was performed of the lower section, aiming for a narrow margin (1-3 mm) of normal skin. The biopsy confirmed a superficial spreading melanoma with a Breslow depth of 0.5 mm with 0 mitoses per high-power field.

A deep-shave biopsy was chosen over a punch biopsy because the latter would be unlikely to sample the entire lesion.

One month after the initial biopsy, a wide local excision with a 1-cm margin was performed. The planned follow-up for the patient was skin exams every 3 months for the first year, every 6 months for the next 4 years, and then annually for life.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Blum A, Siggs G, Marghoob AA, et al. Collision skin lesions-results of a multicenter study of the International Dermoscopy Society (IDS). Dermatol Pract Concept. 2017;7:51-62. doi:10.5826/dpc.0704a12

In addition to the patient’s SK, the second finding was diagnosed as a thin melanoma. The clinical appearance of SKs and nevi or melanoma can overlap. Dermoscopy is a helpful tool in distinguishing between them, even when juxtaposed in a collision lesion such as this.1

Dermoscopy of the superior portion of the lesion demonstrated a well-demarcated brown, waxy papule with milia-like cysts, consistent with an SK. Inferiorly, the dermoscopic features included atypical pigment network, asymmetrical streaks, and blue-white veil, suggestive of melanoma or an atypical melanocytic neoplasm. A deep-shave biopsy was performed of the lower section, aiming for a narrow margin (1-3 mm) of normal skin. The biopsy confirmed a superficial spreading melanoma with a Breslow depth of 0.5 mm with 0 mitoses per high-power field.

A deep-shave biopsy was chosen over a punch biopsy because the latter would be unlikely to sample the entire lesion.

One month after the initial biopsy, a wide local excision with a 1-cm margin was performed. The planned follow-up for the patient was skin exams every 3 months for the first year, every 6 months for the next 4 years, and then annually for life.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

In addition to the patient’s SK, the second finding was diagnosed as a thin melanoma. The clinical appearance of SKs and nevi or melanoma can overlap. Dermoscopy is a helpful tool in distinguishing between them, even when juxtaposed in a collision lesion such as this.1

Dermoscopy of the superior portion of the lesion demonstrated a well-demarcated brown, waxy papule with milia-like cysts, consistent with an SK. Inferiorly, the dermoscopic features included atypical pigment network, asymmetrical streaks, and blue-white veil, suggestive of melanoma or an atypical melanocytic neoplasm. A deep-shave biopsy was performed of the lower section, aiming for a narrow margin (1-3 mm) of normal skin. The biopsy confirmed a superficial spreading melanoma with a Breslow depth of 0.5 mm with 0 mitoses per high-power field.

A deep-shave biopsy was chosen over a punch biopsy because the latter would be unlikely to sample the entire lesion.

One month after the initial biopsy, a wide local excision with a 1-cm margin was performed. The planned follow-up for the patient was skin exams every 3 months for the first year, every 6 months for the next 4 years, and then annually for life.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Blum A, Siggs G, Marghoob AA, et al. Collision skin lesions-results of a multicenter study of the International Dermoscopy Society (IDS). Dermatol Pract Concept. 2017;7:51-62. doi:10.5826/dpc.0704a12

1. Blum A, Siggs G, Marghoob AA, et al. Collision skin lesions-results of a multicenter study of the International Dermoscopy Society (IDS). Dermatol Pract Concept. 2017;7:51-62. doi:10.5826/dpc.0704a12

Slow-growing lesion on eyebrow

A 51-year-old woman presented to the family medicine clinic for evaluation of a slightly tender skin lesion on her left eyebrow. The lesion had been slowly growing for a year.

The patient’s family history included multiple family members with colon or breast cancer and other relatives with pancreatic and prostate cancer. A colonoscopy performed a year earlier on the patient was negative. The patient’s past medical history included hypertension, major depressive disorder, hyperlipidemia, and venous insufficiency. She also had a colon polyp history.

Physical examination of the eyebrow showed a 3-mm papule that was firm on palpation. Dermoscopy of the lesion revealed a yellow papule with

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Sebaceous carcinoma

A rapid teledermatology consultation helped us to determine that this was a sebaceous lesion, but its location and the overlying telangiectasia raised concerns for malignancy. After shared decision-making with the patient, she agreed to proceed with a biopsy. We first made an incision into the lesion, which was hard, demonstrating that it was not cystic. A shave biopsy was then completed. The dermatopathology findings showed clear-cell change consisting of bubbly or foamy cytoplasm, with scalloping of the nuclei, which is characteristic of a sebaceous origin. There were tumor cells that were enlarged with pleomorphism, multiple nucleoli, and scattered mitotic figures. These findings pointed to a diagnosis of sebaceous carcinoma.

Sebaceous carcinomas most commonly manifest on the eyelids. They can originate from the Meibomian glands as well as from pilosebaceous glands at other sites on the body.1 They are rare, accounting for only 1% to 5% of eyelid malignancies, and occur in approximately 2 per 1 million people.1 Tumors can invade locally and metastasize, particularly to surrounding lymph nodes. Periocular pathology may sometimes lead to misdiagnosis, which contributes to a mortality rate that has been reported as high as 20%.1 Suspicion for malignancy may arise due to ulceration, bleeding, pain, or rapid growth.

A lesson in considering the full differential

While sebaceous lesions on the eyelid and eyebrow are often benign, this case underscored the importance of considering the more worrisome elements in the differential. The differential diagnosis for lesions in the area of the eye include the following:

Sebaceous hyperplasia is a common condition (typically among older patients) in which sebaceous glands increase in size and number.2 The classic clinical feature is yellow or skin-colored papules. The lesions typically manifest on the face—particularly on the forehead. They are benign and often have a central umbilication.2

Sebaceous adenomas are benign tumors that may manifest as tan, skin-colored, pink, or yellow papules or nodules.2 The lesions are usually asymptomatic, small, and slow growing.2

Continue to: Basal and squamous cell carcinomas

Basal and squamous cell carcinomas. Basal cell carcinomas often feature translucent lesions on areas of the skin that are exposed to sunlight. These lesions often have slightly rolled border edges or overlying branching telangiectasia and may be nodular.3 Squamous cell carcinomas often feature scaled, reddened patches that may become tender and ulcerate.4

Hordeolums and chalazions. A hordeolum (or stye) is a painful, acute, localized swelling of the eyelid.5 These often develop externally at the lid margin from infection of the follicle. A chalazion is characterized by a persistent, nontender mass that results from small, noninfectious obstruction of the Meibomian glands with secondary granulomatous inflammation.5

Dermoscopy can (and did) help with the Dx

Dermoscopy can help confirm whether a lesion has a sebaceous origin because it would show yellow globules with “crown vessel” telangiectasias that classically do not cross midline.6 Unfortunately, the findings of yellow globules and dermal vessels do not adequately differentiate benign from malignant lesions.6 Carcinomas can manifest in an undifferentiated way early in their course.

Sebaceous carcinomas can be associated with the autosomal dominant Muir-Torre syndrome, a subset of the Lynch syndrome.7,8 Colorectal and genitourinary carcinomas are the most common internal malignancies seen in patients with Muir-Torre syndrome.9

Patients benefit from Mohs surgery

Treatment outcomes for sebaceous carcinoma appear to be improved by Mohs surgery. In a recent review of 1265 patients with early-stage sebaceous carcinomas, Su et al found that 234 patients who were treated with Mohs surgery had improved overall survival, compared with 1031 who were treated with surgical excision.10

Continue to: Our patient

Our patient was referred to a Mohs surgeon who removed the lesion (FIGURES 2 and 3). Given the overall small tumor size, a sentinel lymph node biopsy was not necessary. Because of the patient’s family history, which was suggestive of a genetic predisposition to cancer, she requested a clinical genetics consultation for definitive testing. She went on to pursue genetic testing, which came back negative for Lynch syndrome genes.

The dermatologist recommended yearly skin examination for 5 years for the patient.

1. Kahana A, Pribila HT, Nelson CC, et al. Sebaceous cell carcinoma. In: Levin LA, Albert DM, eds. Ocular Disease: Mechanisms and Management. Saunders/Elsevier; 2010:396-407.

2. Iacobelli J, Harvey NT, Wood BA. Sebaceous lesions of the skin. Pathology. 2017;49:688-697.

3. Marzuka AG, Book SE. Basal cell carcinoma: pathogenesis, epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis, histopathology, and management. Yale J Biol Med. 2015;88:167-179.

4. Smith H, Patel A. When to suspect a non-melanoma skin cancer. BMJ. 2020;368:m692.

5. Sun MT, Huang S, Huilgol SC, et al. Eyelid lesions in general practice. Aust J Gen Pract. 2019;48:509-514.

6. Kim NH, Zell DS, Kolm I, et al. The dermoscopic differential diagnosis of yellow lobularlike structures. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:962.

7. EG, Bell AJY, Barlow KA. Multiple primary carcinomata of the colon, duodenum, and larynx associated with kerato-acanthomata of the face. Br J Surg. 1967;54:191-195.

8. Torre D. Multiple sebaceous tumors. Arch Dermatol. 1968;98:549-55.

9. Cohen PR, Kohn SR, Kurzrock R. Association of sebaceous gland tumors and internal malignancy: the Muir-Torre syndrome. Am J Med. 1991;90:606-613.

10. Su C, Nguyen KA, Bai HX, et al. Comparison of Mohs surgery and surgical excision in the treatment of localized sebaceous carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:1125-1135.

A 51-year-old woman presented to the family medicine clinic for evaluation of a slightly tender skin lesion on her left eyebrow. The lesion had been slowly growing for a year.

The patient’s family history included multiple family members with colon or breast cancer and other relatives with pancreatic and prostate cancer. A colonoscopy performed a year earlier on the patient was negative. The patient’s past medical history included hypertension, major depressive disorder, hyperlipidemia, and venous insufficiency. She also had a colon polyp history.

Physical examination of the eyebrow showed a 3-mm papule that was firm on palpation. Dermoscopy of the lesion revealed a yellow papule with

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Sebaceous carcinoma

A rapid teledermatology consultation helped us to determine that this was a sebaceous lesion, but its location and the overlying telangiectasia raised concerns for malignancy. After shared decision-making with the patient, she agreed to proceed with a biopsy. We first made an incision into the lesion, which was hard, demonstrating that it was not cystic. A shave biopsy was then completed. The dermatopathology findings showed clear-cell change consisting of bubbly or foamy cytoplasm, with scalloping of the nuclei, which is characteristic of a sebaceous origin. There were tumor cells that were enlarged with pleomorphism, multiple nucleoli, and scattered mitotic figures. These findings pointed to a diagnosis of sebaceous carcinoma.

Sebaceous carcinomas most commonly manifest on the eyelids. They can originate from the Meibomian glands as well as from pilosebaceous glands at other sites on the body.1 They are rare, accounting for only 1% to 5% of eyelid malignancies, and occur in approximately 2 per 1 million people.1 Tumors can invade locally and metastasize, particularly to surrounding lymph nodes. Periocular pathology may sometimes lead to misdiagnosis, which contributes to a mortality rate that has been reported as high as 20%.1 Suspicion for malignancy may arise due to ulceration, bleeding, pain, or rapid growth.

A lesson in considering the full differential

While sebaceous lesions on the eyelid and eyebrow are often benign, this case underscored the importance of considering the more worrisome elements in the differential. The differential diagnosis for lesions in the area of the eye include the following:

Sebaceous hyperplasia is a common condition (typically among older patients) in which sebaceous glands increase in size and number.2 The classic clinical feature is yellow or skin-colored papules. The lesions typically manifest on the face—particularly on the forehead. They are benign and often have a central umbilication.2

Sebaceous adenomas are benign tumors that may manifest as tan, skin-colored, pink, or yellow papules or nodules.2 The lesions are usually asymptomatic, small, and slow growing.2

Continue to: Basal and squamous cell carcinomas

Basal and squamous cell carcinomas. Basal cell carcinomas often feature translucent lesions on areas of the skin that are exposed to sunlight. These lesions often have slightly rolled border edges or overlying branching telangiectasia and may be nodular.3 Squamous cell carcinomas often feature scaled, reddened patches that may become tender and ulcerate.4

Hordeolums and chalazions. A hordeolum (or stye) is a painful, acute, localized swelling of the eyelid.5 These often develop externally at the lid margin from infection of the follicle. A chalazion is characterized by a persistent, nontender mass that results from small, noninfectious obstruction of the Meibomian glands with secondary granulomatous inflammation.5

Dermoscopy can (and did) help with the Dx

Dermoscopy can help confirm whether a lesion has a sebaceous origin because it would show yellow globules with “crown vessel” telangiectasias that classically do not cross midline.6 Unfortunately, the findings of yellow globules and dermal vessels do not adequately differentiate benign from malignant lesions.6 Carcinomas can manifest in an undifferentiated way early in their course.

Sebaceous carcinomas can be associated with the autosomal dominant Muir-Torre syndrome, a subset of the Lynch syndrome.7,8 Colorectal and genitourinary carcinomas are the most common internal malignancies seen in patients with Muir-Torre syndrome.9

Patients benefit from Mohs surgery

Treatment outcomes for sebaceous carcinoma appear to be improved by Mohs surgery. In a recent review of 1265 patients with early-stage sebaceous carcinomas, Su et al found that 234 patients who were treated with Mohs surgery had improved overall survival, compared with 1031 who were treated with surgical excision.10

Continue to: Our patient

Our patient was referred to a Mohs surgeon who removed the lesion (FIGURES 2 and 3). Given the overall small tumor size, a sentinel lymph node biopsy was not necessary. Because of the patient’s family history, which was suggestive of a genetic predisposition to cancer, she requested a clinical genetics consultation for definitive testing. She went on to pursue genetic testing, which came back negative for Lynch syndrome genes.

The dermatologist recommended yearly skin examination for 5 years for the patient.

A 51-year-old woman presented to the family medicine clinic for evaluation of a slightly tender skin lesion on her left eyebrow. The lesion had been slowly growing for a year.

The patient’s family history included multiple family members with colon or breast cancer and other relatives with pancreatic and prostate cancer. A colonoscopy performed a year earlier on the patient was negative. The patient’s past medical history included hypertension, major depressive disorder, hyperlipidemia, and venous insufficiency. She also had a colon polyp history.

Physical examination of the eyebrow showed a 3-mm papule that was firm on palpation. Dermoscopy of the lesion revealed a yellow papule with

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Sebaceous carcinoma

A rapid teledermatology consultation helped us to determine that this was a sebaceous lesion, but its location and the overlying telangiectasia raised concerns for malignancy. After shared decision-making with the patient, she agreed to proceed with a biopsy. We first made an incision into the lesion, which was hard, demonstrating that it was not cystic. A shave biopsy was then completed. The dermatopathology findings showed clear-cell change consisting of bubbly or foamy cytoplasm, with scalloping of the nuclei, which is characteristic of a sebaceous origin. There were tumor cells that were enlarged with pleomorphism, multiple nucleoli, and scattered mitotic figures. These findings pointed to a diagnosis of sebaceous carcinoma.

Sebaceous carcinomas most commonly manifest on the eyelids. They can originate from the Meibomian glands as well as from pilosebaceous glands at other sites on the body.1 They are rare, accounting for only 1% to 5% of eyelid malignancies, and occur in approximately 2 per 1 million people.1 Tumors can invade locally and metastasize, particularly to surrounding lymph nodes. Periocular pathology may sometimes lead to misdiagnosis, which contributes to a mortality rate that has been reported as high as 20%.1 Suspicion for malignancy may arise due to ulceration, bleeding, pain, or rapid growth.

A lesson in considering the full differential

While sebaceous lesions on the eyelid and eyebrow are often benign, this case underscored the importance of considering the more worrisome elements in the differential. The differential diagnosis for lesions in the area of the eye include the following:

Sebaceous hyperplasia is a common condition (typically among older patients) in which sebaceous glands increase in size and number.2 The classic clinical feature is yellow or skin-colored papules. The lesions typically manifest on the face—particularly on the forehead. They are benign and often have a central umbilication.2

Sebaceous adenomas are benign tumors that may manifest as tan, skin-colored, pink, or yellow papules or nodules.2 The lesions are usually asymptomatic, small, and slow growing.2

Continue to: Basal and squamous cell carcinomas

Basal and squamous cell carcinomas. Basal cell carcinomas often feature translucent lesions on areas of the skin that are exposed to sunlight. These lesions often have slightly rolled border edges or overlying branching telangiectasia and may be nodular.3 Squamous cell carcinomas often feature scaled, reddened patches that may become tender and ulcerate.4

Hordeolums and chalazions. A hordeolum (or stye) is a painful, acute, localized swelling of the eyelid.5 These often develop externally at the lid margin from infection of the follicle. A chalazion is characterized by a persistent, nontender mass that results from small, noninfectious obstruction of the Meibomian glands with secondary granulomatous inflammation.5

Dermoscopy can (and did) help with the Dx

Dermoscopy can help confirm whether a lesion has a sebaceous origin because it would show yellow globules with “crown vessel” telangiectasias that classically do not cross midline.6 Unfortunately, the findings of yellow globules and dermal vessels do not adequately differentiate benign from malignant lesions.6 Carcinomas can manifest in an undifferentiated way early in their course.

Sebaceous carcinomas can be associated with the autosomal dominant Muir-Torre syndrome, a subset of the Lynch syndrome.7,8 Colorectal and genitourinary carcinomas are the most common internal malignancies seen in patients with Muir-Torre syndrome.9

Patients benefit from Mohs surgery

Treatment outcomes for sebaceous carcinoma appear to be improved by Mohs surgery. In a recent review of 1265 patients with early-stage sebaceous carcinomas, Su et al found that 234 patients who were treated with Mohs surgery had improved overall survival, compared with 1031 who were treated with surgical excision.10

Continue to: Our patient

Our patient was referred to a Mohs surgeon who removed the lesion (FIGURES 2 and 3). Given the overall small tumor size, a sentinel lymph node biopsy was not necessary. Because of the patient’s family history, which was suggestive of a genetic predisposition to cancer, she requested a clinical genetics consultation for definitive testing. She went on to pursue genetic testing, which came back negative for Lynch syndrome genes.

The dermatologist recommended yearly skin examination for 5 years for the patient.

1. Kahana A, Pribila HT, Nelson CC, et al. Sebaceous cell carcinoma. In: Levin LA, Albert DM, eds. Ocular Disease: Mechanisms and Management. Saunders/Elsevier; 2010:396-407.

2. Iacobelli J, Harvey NT, Wood BA. Sebaceous lesions of the skin. Pathology. 2017;49:688-697.

3. Marzuka AG, Book SE. Basal cell carcinoma: pathogenesis, epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis, histopathology, and management. Yale J Biol Med. 2015;88:167-179.

4. Smith H, Patel A. When to suspect a non-melanoma skin cancer. BMJ. 2020;368:m692.

5. Sun MT, Huang S, Huilgol SC, et al. Eyelid lesions in general practice. Aust J Gen Pract. 2019;48:509-514.

6. Kim NH, Zell DS, Kolm I, et al. The dermoscopic differential diagnosis of yellow lobularlike structures. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:962.

7. EG, Bell AJY, Barlow KA. Multiple primary carcinomata of the colon, duodenum, and larynx associated with kerato-acanthomata of the face. Br J Surg. 1967;54:191-195.

8. Torre D. Multiple sebaceous tumors. Arch Dermatol. 1968;98:549-55.

9. Cohen PR, Kohn SR, Kurzrock R. Association of sebaceous gland tumors and internal malignancy: the Muir-Torre syndrome. Am J Med. 1991;90:606-613.

10. Su C, Nguyen KA, Bai HX, et al. Comparison of Mohs surgery and surgical excision in the treatment of localized sebaceous carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:1125-1135.

1. Kahana A, Pribila HT, Nelson CC, et al. Sebaceous cell carcinoma. In: Levin LA, Albert DM, eds. Ocular Disease: Mechanisms and Management. Saunders/Elsevier; 2010:396-407.

2. Iacobelli J, Harvey NT, Wood BA. Sebaceous lesions of the skin. Pathology. 2017;49:688-697.

3. Marzuka AG, Book SE. Basal cell carcinoma: pathogenesis, epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis, histopathology, and management. Yale J Biol Med. 2015;88:167-179.

4. Smith H, Patel A. When to suspect a non-melanoma skin cancer. BMJ. 2020;368:m692.

5. Sun MT, Huang S, Huilgol SC, et al. Eyelid lesions in general practice. Aust J Gen Pract. 2019;48:509-514.

6. Kim NH, Zell DS, Kolm I, et al. The dermoscopic differential diagnosis of yellow lobularlike structures. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:962.

7. EG, Bell AJY, Barlow KA. Multiple primary carcinomata of the colon, duodenum, and larynx associated with kerato-acanthomata of the face. Br J Surg. 1967;54:191-195.

8. Torre D. Multiple sebaceous tumors. Arch Dermatol. 1968;98:549-55.

9. Cohen PR, Kohn SR, Kurzrock R. Association of sebaceous gland tumors and internal malignancy: the Muir-Torre syndrome. Am J Med. 1991;90:606-613.

10. Su C, Nguyen KA, Bai HX, et al. Comparison of Mohs surgery and surgical excision in the treatment of localized sebaceous carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:1125-1135.

New skin papules

A 49-year-old woman with a history of end-stage renal disease, uncontrolled type 2 diabetes, and congestive heart failure visited the hospital for an acute heart failure exacerbation secondary to missed dialysis appointments. On admission, her provider noted that she had tender, pruritic lesions on the extensor surface of her arms. She said they had appeared 2 to 3 months after she started dialysis. She had attempted to control the pain and pruritus with over-the-counter topical hydrocortisone and oral diphenhydramine but nothing provided relief. She was recommended for follow-up at the hospital for further examination and biopsy of one of her lesions.

At this follow-up visit, the patient noted that the lesions had spread to her left knee. Multiple firm discrete papules and nodules, with central hyperkeratotic plugs, were noted along the extensor surfaces of her forearms, left extensor knee, and around her ankles (FIGURES 1A and 1B). Some of the lesions were tender. Examination of the rest of her skin was normal. A punch biopsy was obtained.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Kyrle disease

The patient’s end-stage renal disease and type 2 diabetes—along with findings from the physical examination—led us to suspect Kyrle disease. The punch biopsy, as well as the characteristic keratotic plugs (FIGURE 2) within epidermal invagination that was bordered by hyperkeratotic epidermis, confirmed the diagnosis.

Kyrle disease (also known as hyperkeratosis follicularis et follicularis in cutem penetrans) is a rare skin condition. It is 1 of 4 skin conditions that are classified as perforating skin disorders; the other 3 are elastosis perforans serpiginosa, reactive perforating collagenosis, and perforating folliculitis (TABLE1,2).3 Perforating skin disorders share the common characteristic of transepidermal elimination of material from the upper dermis.4 These disorders are typically classified based on the nature of the eliminated material and the type of epidermal disruption.5

There are 2 forms of Kyrle disease: an inherited form often seen in childhood that is not associated with systemic disease and an acquired form that occurs in adulthood, most commonly among women ages 35 to 70 years who have systemic disease.3,4,6 The acquired form of Kyrle disease is associated with diabetes and renal failure, but there is a lack of data on its pathogenesis.7,8

Characteristic findings include discrete pruritic, dry papules and nodules with central keratotic plugs that are occasionally tender. These can manifest over the extensor surface of the extremities, trunk, face, and scalp.4,7,9 Lesions most commonly manifest on the extensor surfaces of the lower extremities.

Other conditions that feature pruritic lesions

In addition to the other perforating skin disorders described in the TABLE,1,2 the differential for Kyrle disease includes the following:

Prurigo nodularis (PN) is a skin disorder in which the manifestation of extremely pruritic nodules leads to vigorous scratching and secondary infections. These lesions typically have a grouped and symmetrically distributed appearance. They often appear on extensor surfaces of upper and lower extremities.10 PN has no known etiology, but like Kyrle disease, is associated with renal failure. Biopsy can help to distinguish PN from Kyrle disease.

Continue to: Hypertrophic lichen planus

Hypertrophic lichen planus is a pruritic skin disorder characterized by the “6 Ps”: planar, purple, polygonal, pruritic, papules, and plaques. These lesions can mimic the early stages of Kyrle disease.11 However, in the later stages of Kyrle disease, discrete papules with hyperkeratotic plugs develop, whereas large plaques will be seen with lichen planus.

Keratosis pilaris (KP) is an extremely common, yet benign, disorder in which hair follicles become keratinized.12 KP can feature rough papules that are often described as “goosebumps” or having a sandpaper–like appearance. These papules often affect the upper arms. KP usually manifests in adolescents or young adults and tends to improve with age.12 The lesions are typically smaller than those seen in Kyrle disease and are asymptomatic. In addition, KP is not associated with systemic disease.