User login

USPSTF update on sexually transmitted infections

In August 2020, the US Preventive Services Task Force published an update of its recommendation on preventing sexually transmitted infections (STIs) with behavioral counseling interventions.1

Whom to counsel. The USPSTF continues to recommend behavioral counseling for all sexually active adolescents and for adults at increased risk for STIs. Adults at increased risk include those who have been diagnosed with an STI in the past year, those with multiple sex partners or a sex partner at high risk for an STI, those not using condoms consistently, and those belonging to populations with high prevalence rates of STIs. These populations with high prevalence rates include1

- individuals seeking care at STI clinics,

- sexual and gender minorities, and

- those who are positive for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), use injection drugs, exchange sex for drugs or money, or have recently been in a correctional facility.

Features of effective counseling. The Task Force recommends that primary care clinicians provide behavioral counseling or refer to counseling services or suggest media-based interventions. The most effective counseling interventions are those that span more than 120 minutes over several sessions. But the Task Force also states that counseling lasting about 30 minutes in a single session can also be effective. Counseling should include information about common STIs and their modes of transmission; encouragement in the use of safer sex practices; and training in proper condom use, how to communicate with partners about safer sex practices, and problem-solving. Various approaches to this counseling can be found at https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/sexually-transmitted-infections-behavioral-counseling.

This updated recommendation is timely because most STIs in the United States have been increasing in incidence for the past decade or longer.2 Per 100,000 population, the total number of chlamydia cases since 2000 has risen from 251.4 to 539.9 (115%);gonorrhea cases since 2009 have risen from 98.1 to 179.1 (83%).3 And since 2000, the total number of reported syphilis cases per 100,000 has risen from 2.1 to 10.8 (414%).3

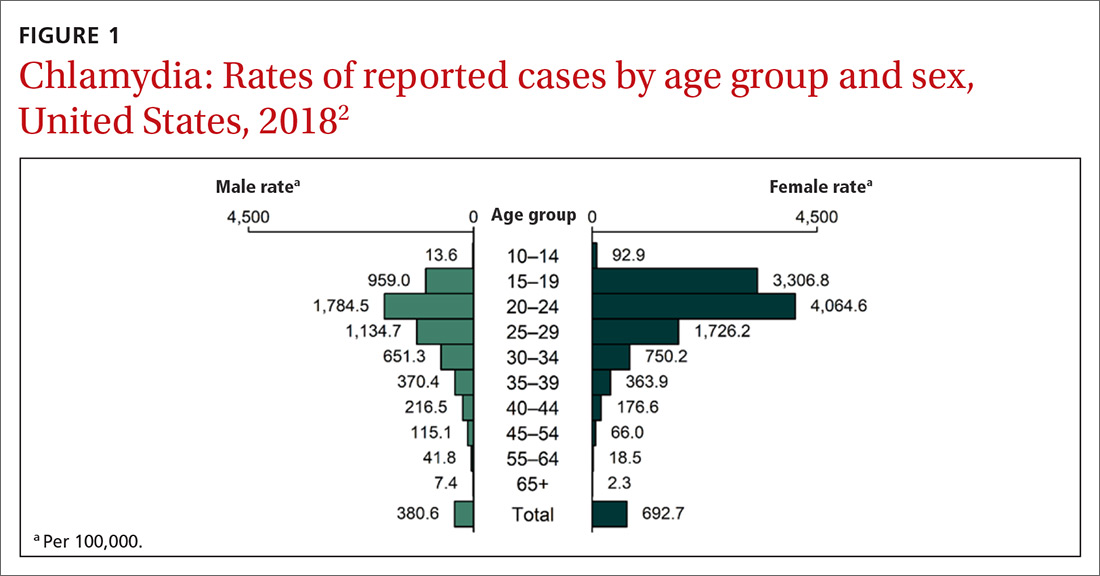

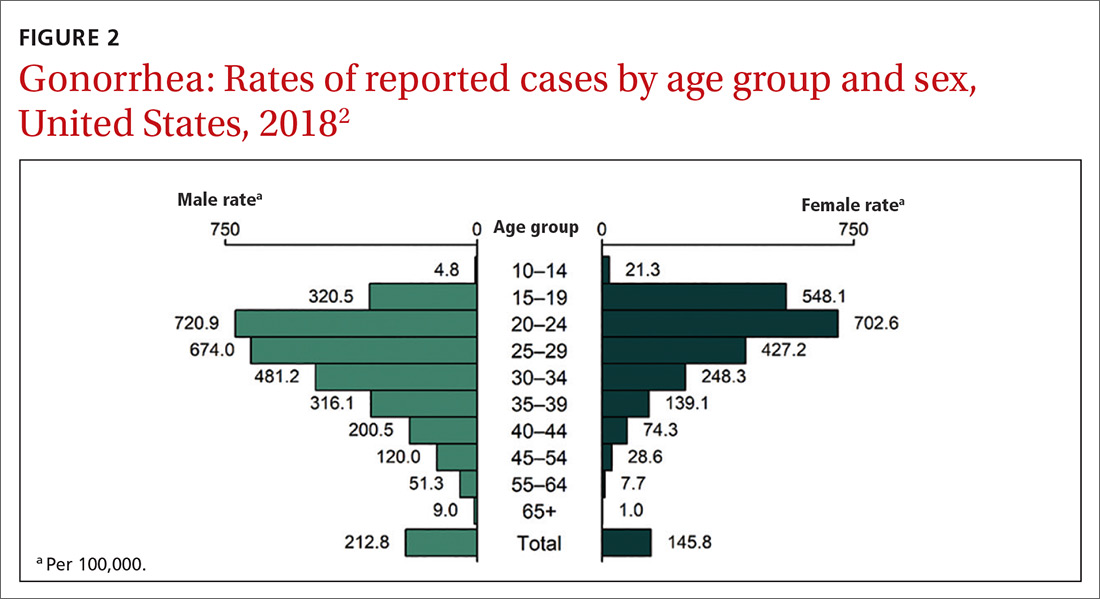

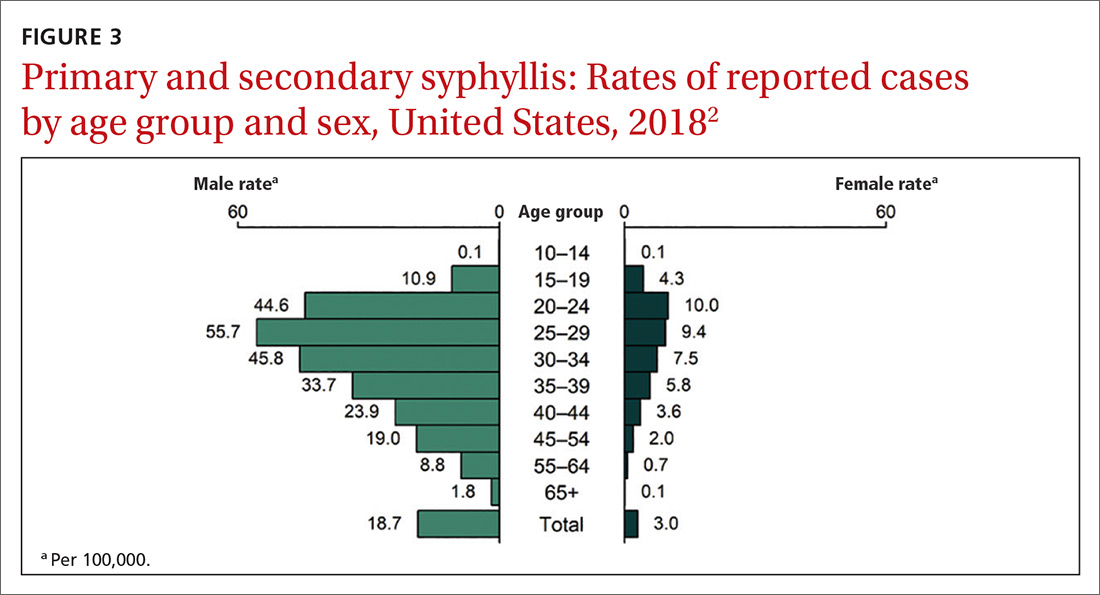

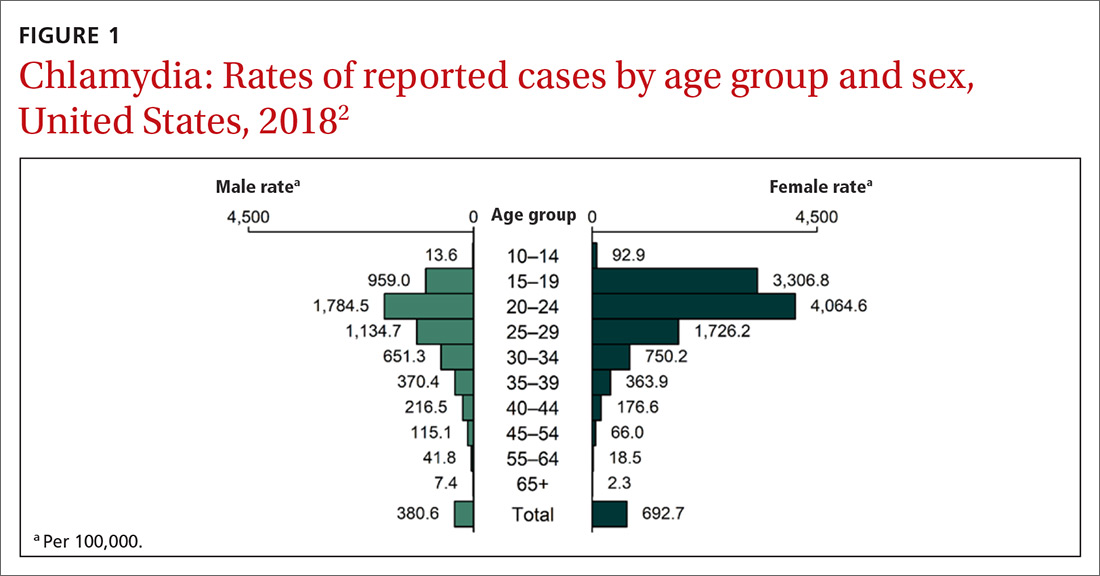

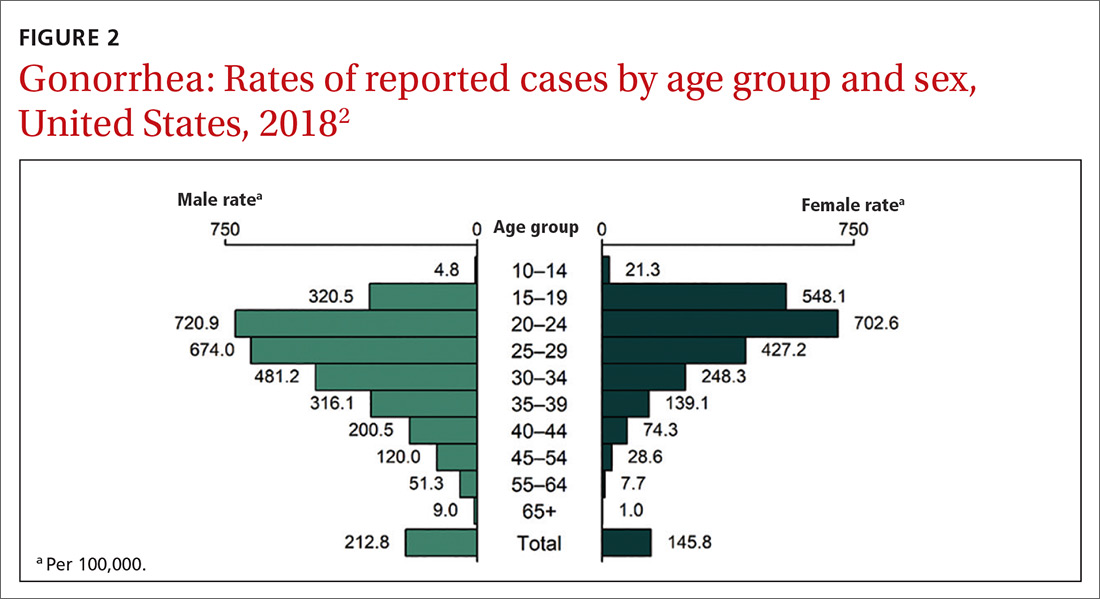

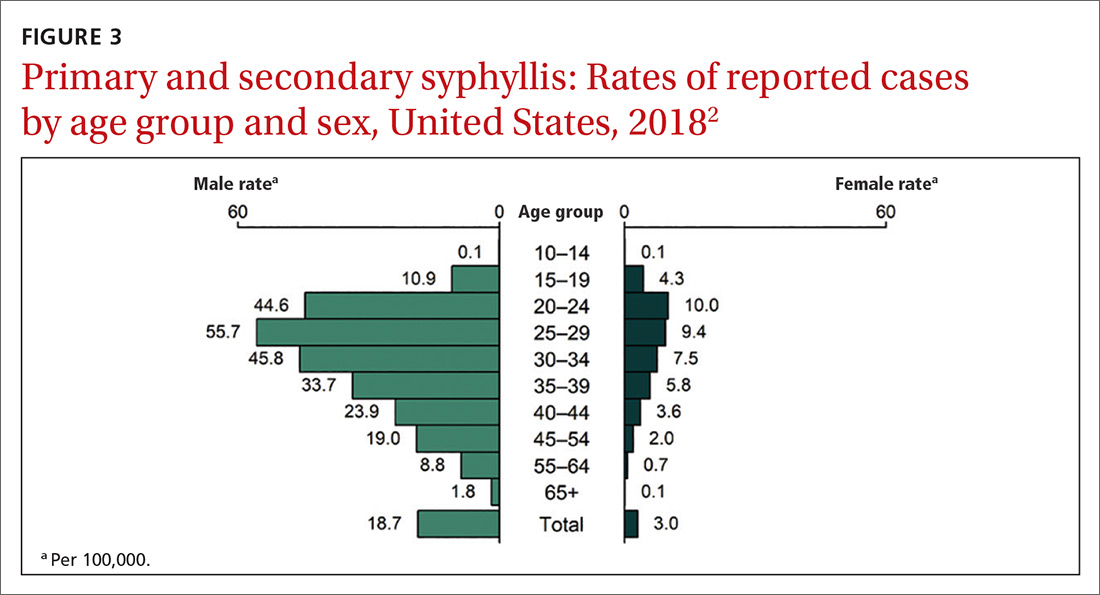

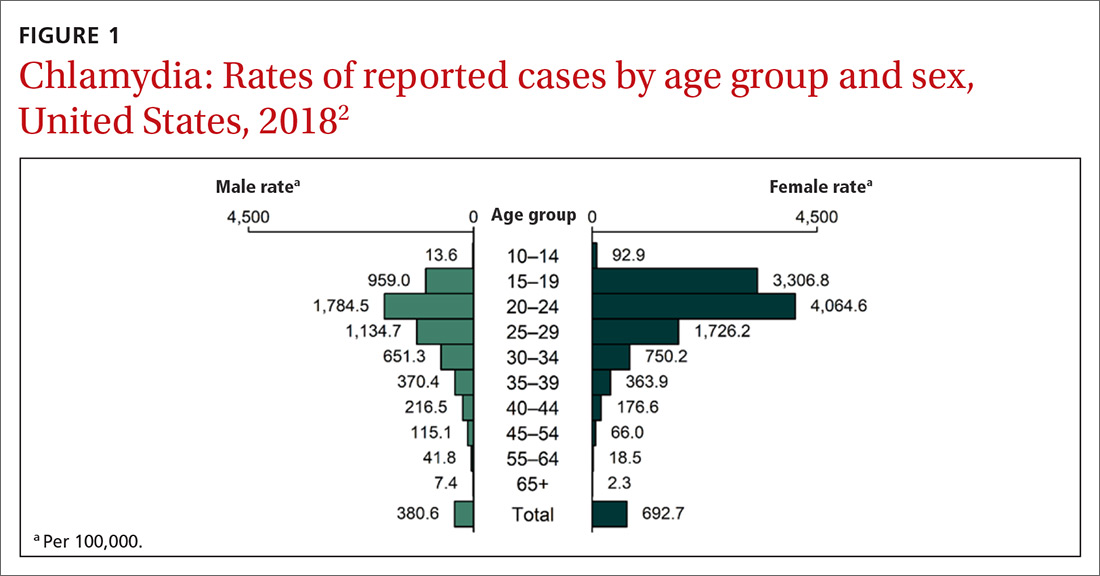

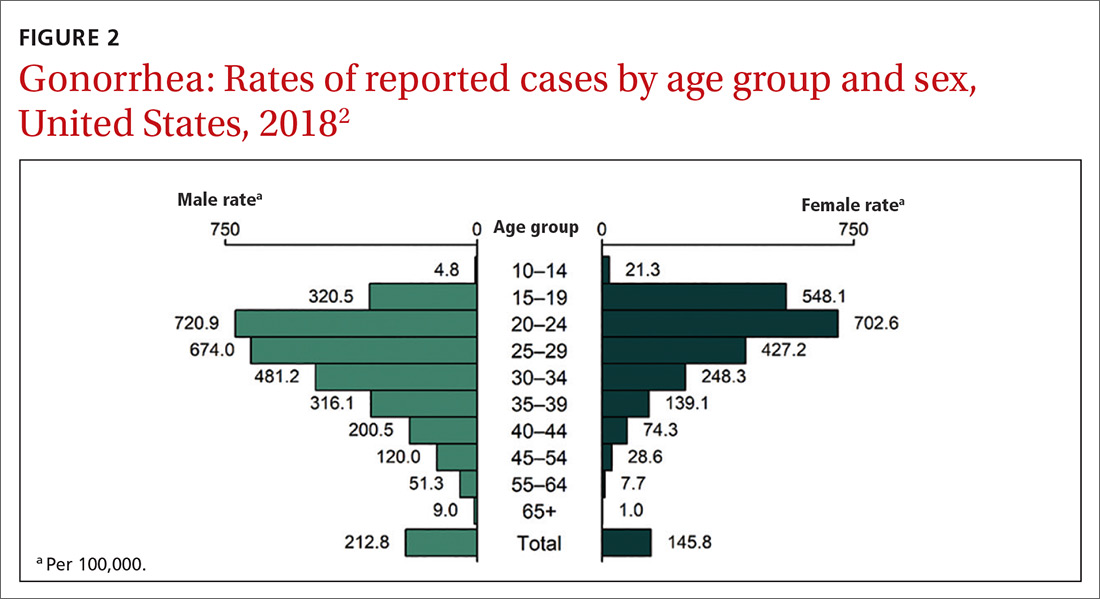

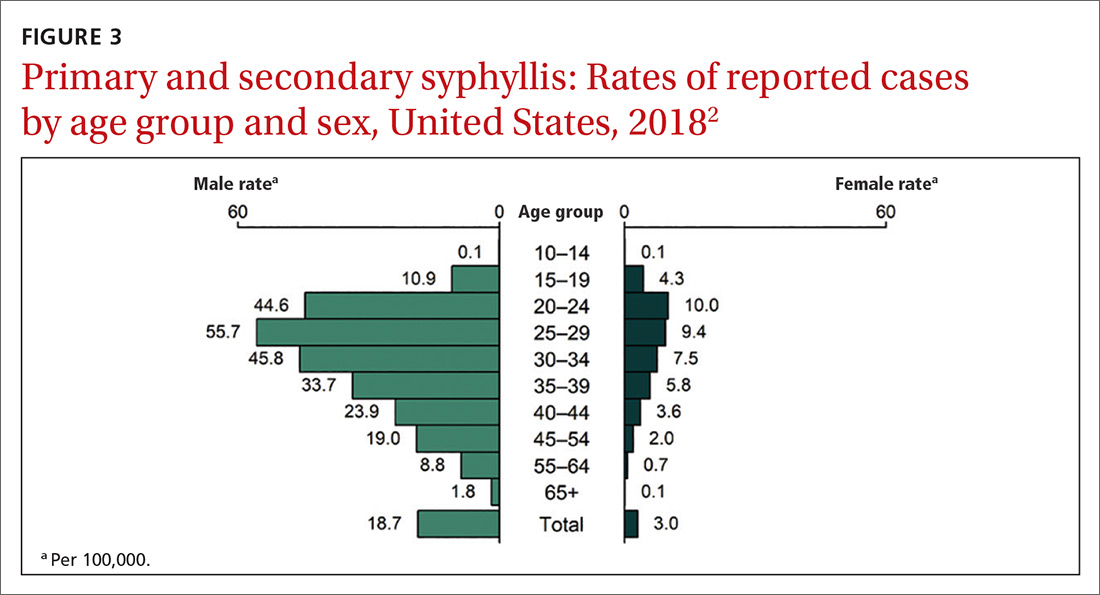

Chlamydia affects primarily those ages 15 to 24 years, with highest rates occurring in females (FIGURE 1).2 Gonorrhea affects women and men fairly evenly with slightly higher rates in men; the highest rates are seen in those ages 20 to 29 (FIGURE 2).2 Syphilis predominantly affects men who have sex with men, and the highest rates are in those ages 20 to 34 (FIGURE 3).2 In contrast to these upward trends, the number of HIV cases diagnosed has been relatively steady, with a slight downward trend over the past decade.4Other STIs that can be prevented through behavioral counseling include herpes simplex, human papillomavirus (HPV), hepatitis B virus (HBV) and trichomonas vaginalis.

Continue to: How to integrate STI preventioninto the primary care encounter

How to integrate STI preventioninto the primary care encounter

A key resource for learning to recognize the signs and symptoms of STIs, to correctly diagnose them, and to treat them according to CDC guidelines can be found at www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/default.htm.5 Equally important is to integrate the prevention of STIs into the clinical routine by using a 4-step approach: risk assessment, risk reduction (counseling and chemoprevention), screening, and vaccination.

Risk assessment. The first step in prevention is taking a sexual history to accurately assess a patient’s risk for STIs. The CDC provides a tool (www.cdc.gov/std/products/provider-pocket-guides.htm) that can assist in gathering information in a nonjudgmental fashion about 5 Ps: partners, practices, protection from STIs, past history of STIs, and prevention of pregnancy.

Risk reduction. Following STI risk assessment, recommend risk-reduction interventions, as appropriate. Notable in the new Task Force recommendation are behavioral counseling methods that work. Additionally, when needed, pre-exposure prophylaxis with effective antiretroviral agents can be offered to those at high risk of HIV.6

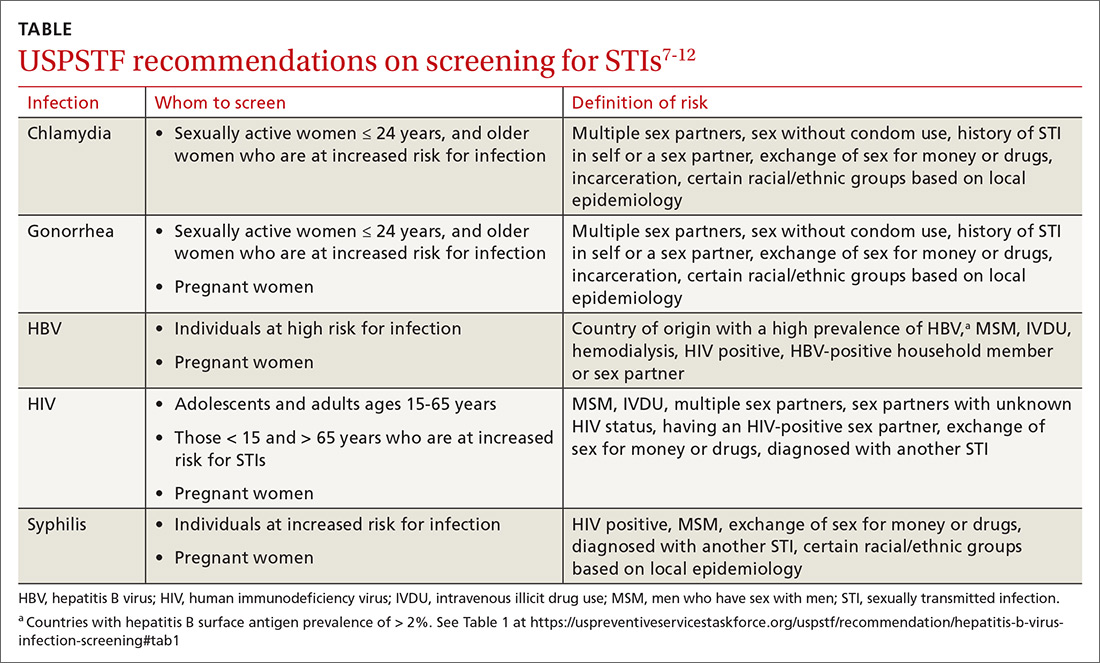

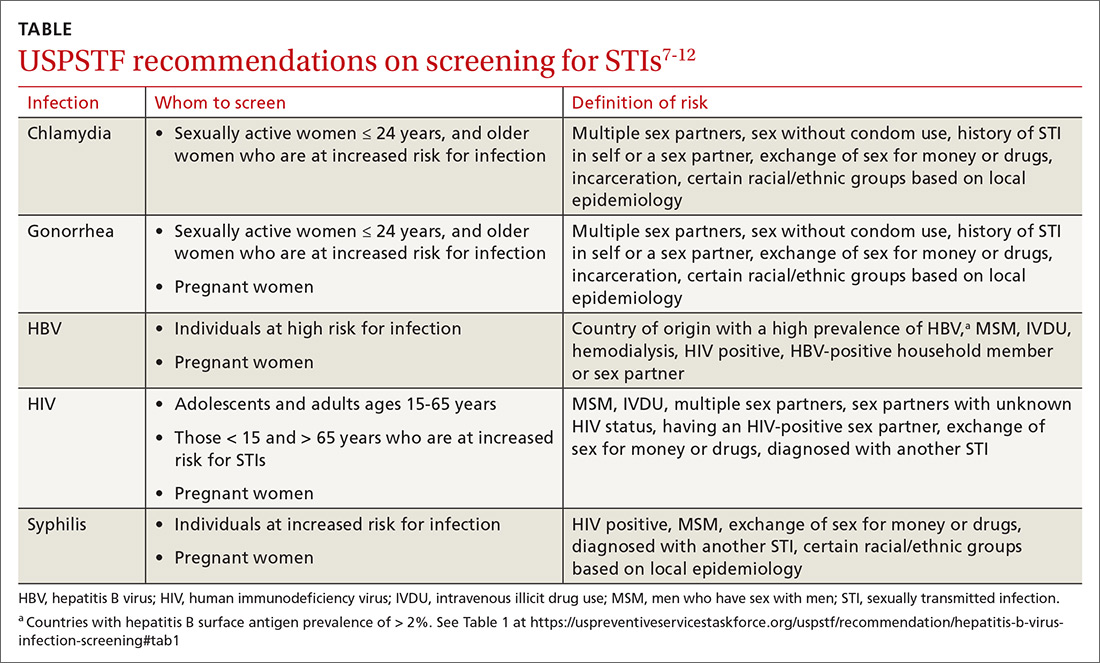

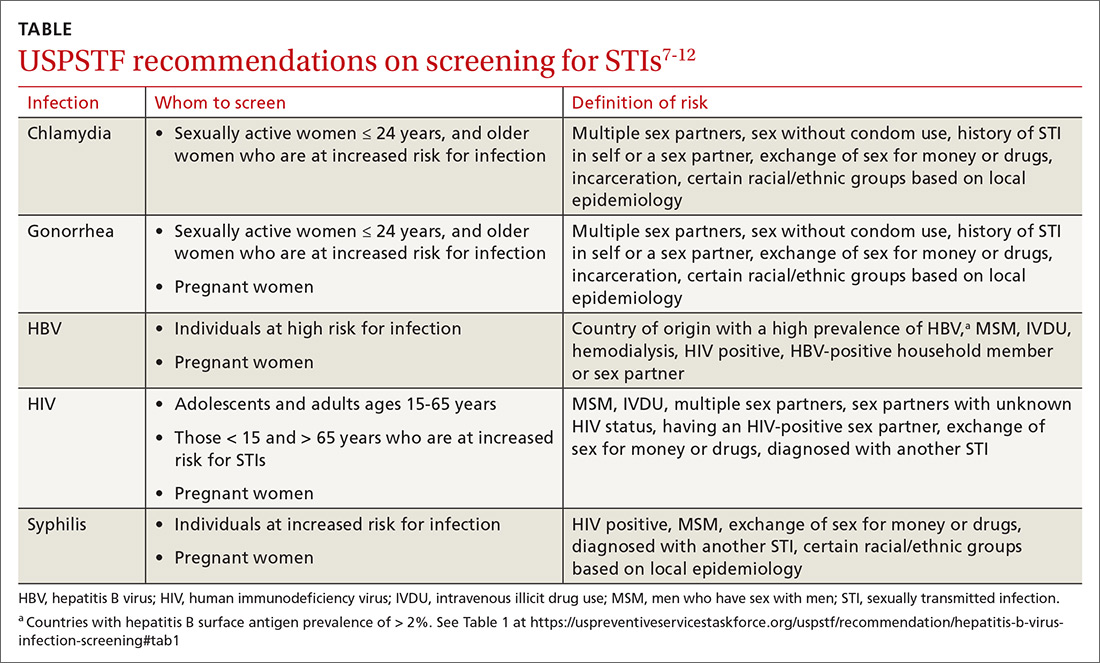

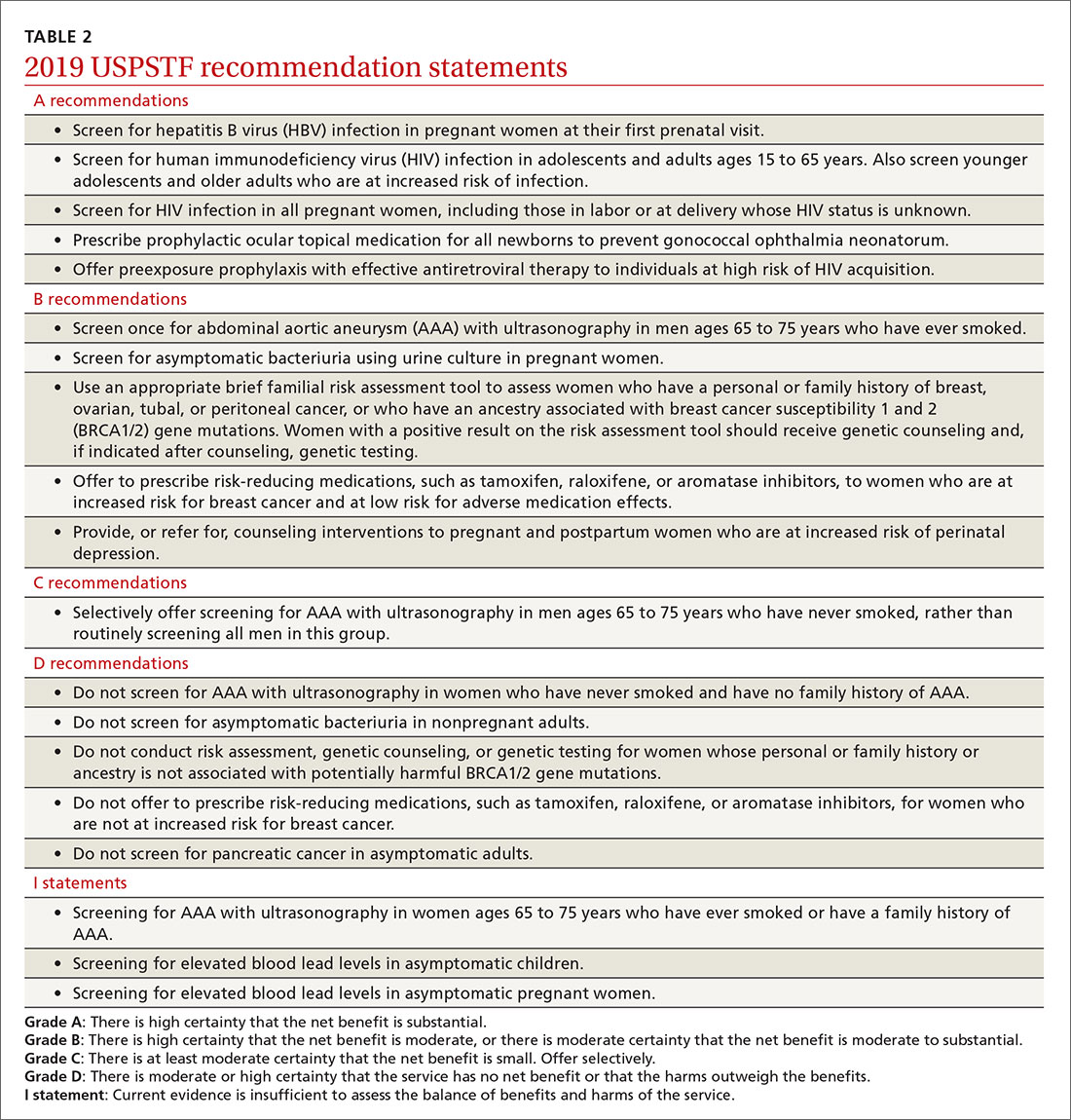

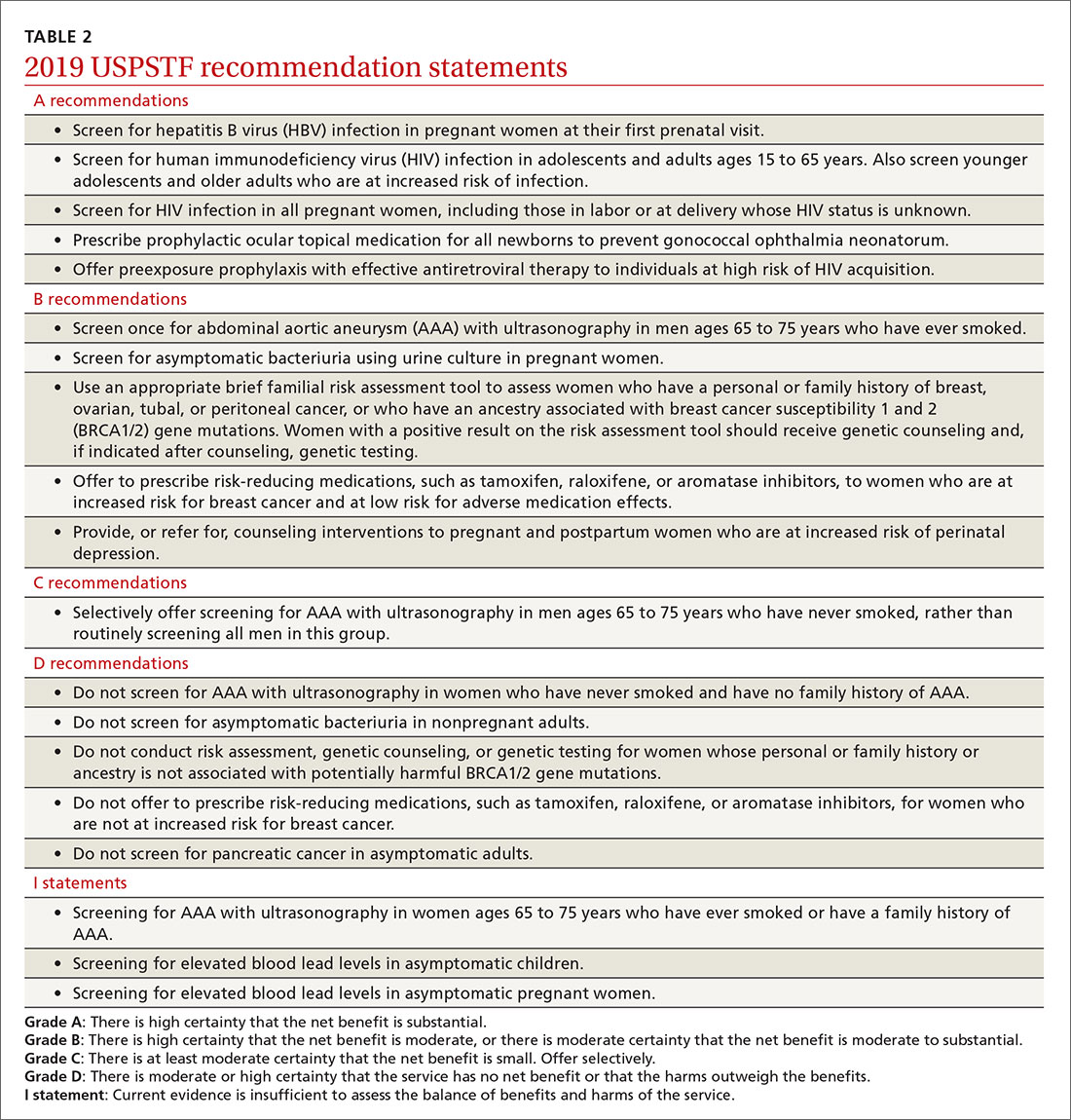

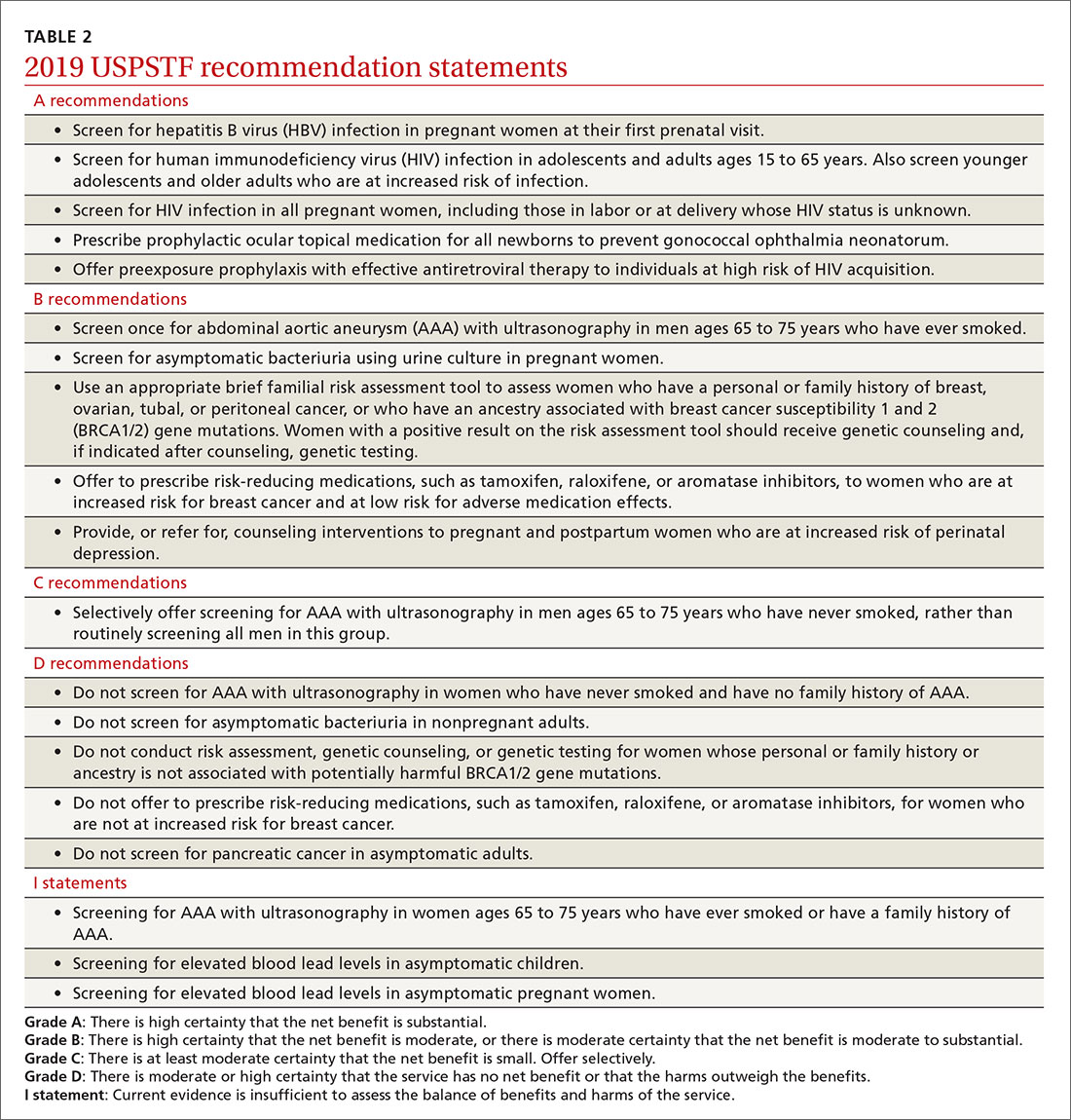

Screening. Task Force recommendations for STI screening are described in the TABLE.7-12 Screening for HIV, chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, and HBV are also recommended for pregnant women. And, although pregnant women are not specifically mentioned in the recommendation on chlamydia screening, it is reasonable to include it in prenatal care testing for STIs.

The Task Force has made an “I” statement regarding screening for gonorrhea and chlamydia in males. This does not mean that screening should be avoided, but only that there is insufficient evidence to support a firm statement regarding the harms and benefits in males. Keep in mind that this applies to asymptomatic males, and that testing and preventive treatment are warranted after documented exposure to either infection.

The Task Force recommends against screening for genital herpes, including in pregnant women, because of a lack of evidence of benefit from such screening, the high rate of false-positive tests, and the potential to cause anxiety and harm to personal relationships.

Continue to: Although hepatitis C virus...

Although hepatitis C virus (HCV) is transmitted mainly through intravenous drug use, it can also be transmitted sexually. The Task Force recommends screening for HCV in all adults ages 18 to 79 years.13

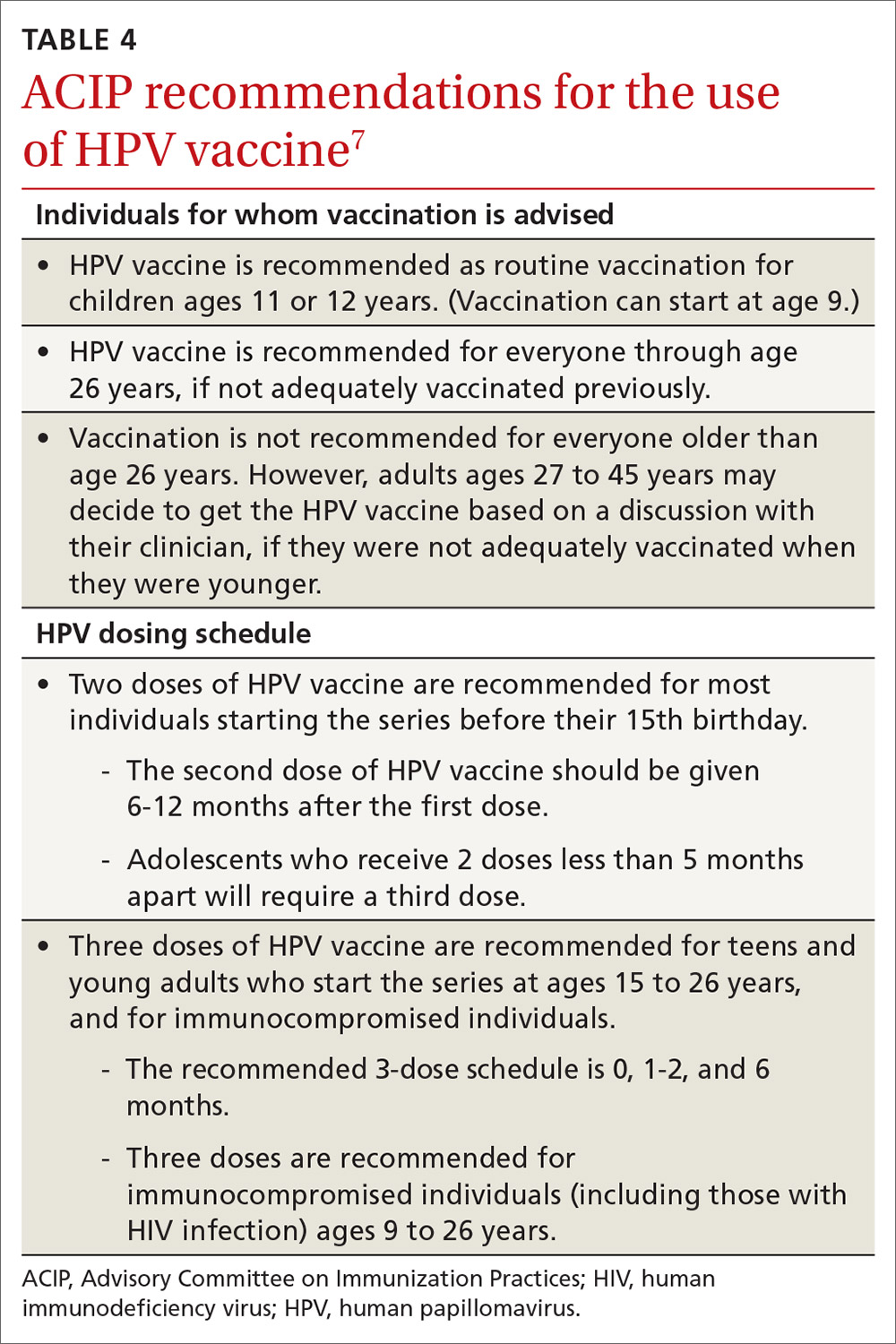

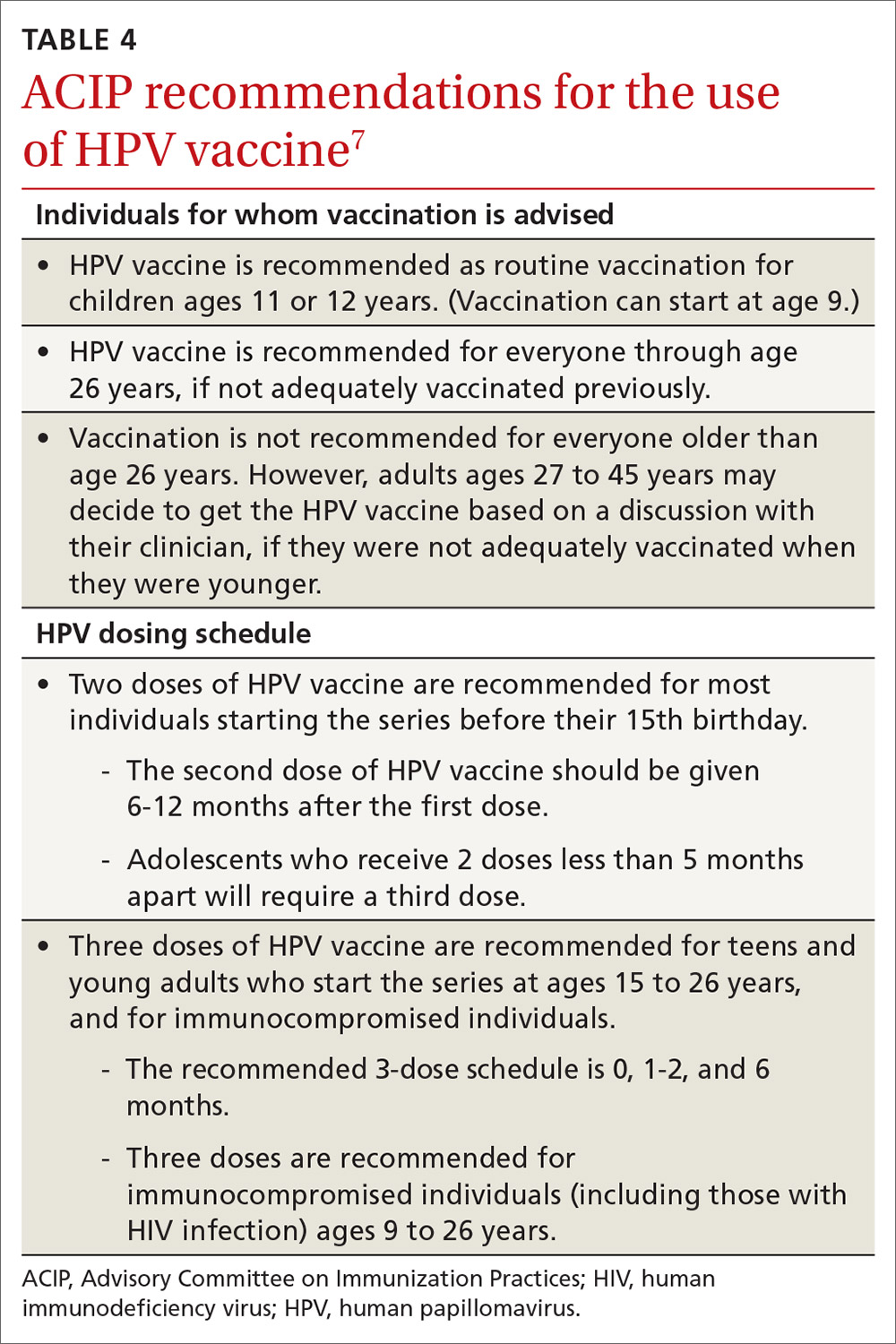

Vaccination. Two STIs can be prevented by immunizations: HPV and HBV. The current recommendations by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) are to vaccinate all infants with HBV vaccine and all unvaccinated children and adolescents through age 18.14 Unvaccinated adults who are at risk for HBV infection, including those at risk through sexual practices, should also be vaccinated.14

ACIP recommends routine HPV vaccination at age 11 or 12 years, but it can be started as early as 9 years.15 Catch-up vaccination is recommended for males and females through age 26 years.15 The vaccine is approved for use in individuals ages 27 through 45 years, but ACIP has not recommended it for routine use in this age group, and has instead recommended shared clinical decision-making to evaluate whether there is potential individual benefit from the vaccine.15

Public health implications

All STIs are reportable to local or state health departments. This is important for tracking community infection trends and, if resources are available, for contact notification and testing. In most jurisdictions, local health department resources are limited and contact tracing may be restricted to syphilis and HIV infections. When this is the case, it is especially important to instruct patients in whom STIs have been detected to notify their recent sex partners and advise them to be tested or preventively treated.

Expedited partner therapy (EPT)—providing treatment for exposed sexual contacts without a clinical encounter—is allowed in some states and is a tool that can prevent re-infection in the treated patient and suppress spread in the community. This is most useful for partners of those with gonorrhea, chlamydia, or trichomonas. The CDC has published guidance on how to implement EPT in a clinical setting if state law allows it.16

1. Henderson JT, Senger CA, Henninger M, et al. Behavioral counseling interventions to prevent sexually transmitted infections. JAMA. 2020;324:682-699.

2. CDC. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance, 2018. www.cdc.gov/std/stats18/slides.htm. Accessed November 25, 2020.

3. CDC. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2018. www.cdc.gov/std/stats18/tables/1.htm. Accessed November 25, 2020.

4. CDC. Estimated HIV incidence and prevalence in the United States (2010-2018). www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/slidesets/cdc-hiv-surveillance-epidemiology-2018.pdf. Accessed November 25, 2020.

5. CDC. 2015 sexually transmitted disease treatment guidelines. www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/default.htm. Accessed November 25, 2020.

6. USPSTF. Prevention of human immunodeficiency (HIV) infection: pre-exposure prophylaxis. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/prevention-of-human-immunodeficiency-virus-hiv-infection-pre-exposure-prophylaxis. Accessed November 25, 2020.

7. LeFevre ML, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for chlamydia and gonorrhea: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:902-910. 8. USPSTF. Syphilis infection in nonpregnant adults and adolescents: screening. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/syphilis-infection-in-nonpregnant-adults-and-adolescents. Accessed November 25, 2020.

9. Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, et al. Screening for syphilis in pregnant women: US Preventive Services Task Force reaffirmation recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320:911-917.

10. Owens DK, Davidson KW, Krist AH, et al; US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for HIV infection: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2019;321:2326-2336.

11. USPSTF. US Preventive Services Task Force issues draft recommendation statement on screening for hepatitis B virus infection in adolescents and adults. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/sites/default/files/file/supporting_documents/hepatitis-b-nonpregnant-adults-draft-rs-bulletin.pdf. Accessed November 25, 2020.

12. Owens DK, Davidson KW, Krist AH, et al. Screening for Hepatitis B Virus Infection in Pregnant Women: US Preventive Services Task Force reaffirmation recommendation statement. JAMA. 2019;322:349-354.

13. USPSTF. Hepatitis C virus infection in adolescents and adults: screening. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/hepatitis-c-screening. Accessed November 25, 2020. 14. Schillie S, Vellozzi C, Reingold A, et al. Prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2018;67;1-31.

15. Meites E, Szilagyi PG, Chesson HW, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination for adults: updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:698-702.

16. CDC. Expedited partner therapy in the management of sexually transmitted diseases. www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/eptfinalreport2006.pdf. Accessed November 25, 2020.

In August 2020, the US Preventive Services Task Force published an update of its recommendation on preventing sexually transmitted infections (STIs) with behavioral counseling interventions.1

Whom to counsel. The USPSTF continues to recommend behavioral counseling for all sexually active adolescents and for adults at increased risk for STIs. Adults at increased risk include those who have been diagnosed with an STI in the past year, those with multiple sex partners or a sex partner at high risk for an STI, those not using condoms consistently, and those belonging to populations with high prevalence rates of STIs. These populations with high prevalence rates include1

- individuals seeking care at STI clinics,

- sexual and gender minorities, and

- those who are positive for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), use injection drugs, exchange sex for drugs or money, or have recently been in a correctional facility.

Features of effective counseling. The Task Force recommends that primary care clinicians provide behavioral counseling or refer to counseling services or suggest media-based interventions. The most effective counseling interventions are those that span more than 120 minutes over several sessions. But the Task Force also states that counseling lasting about 30 minutes in a single session can also be effective. Counseling should include information about common STIs and their modes of transmission; encouragement in the use of safer sex practices; and training in proper condom use, how to communicate with partners about safer sex practices, and problem-solving. Various approaches to this counseling can be found at https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/sexually-transmitted-infections-behavioral-counseling.

This updated recommendation is timely because most STIs in the United States have been increasing in incidence for the past decade or longer.2 Per 100,000 population, the total number of chlamydia cases since 2000 has risen from 251.4 to 539.9 (115%);gonorrhea cases since 2009 have risen from 98.1 to 179.1 (83%).3 And since 2000, the total number of reported syphilis cases per 100,000 has risen from 2.1 to 10.8 (414%).3

Chlamydia affects primarily those ages 15 to 24 years, with highest rates occurring in females (FIGURE 1).2 Gonorrhea affects women and men fairly evenly with slightly higher rates in men; the highest rates are seen in those ages 20 to 29 (FIGURE 2).2 Syphilis predominantly affects men who have sex with men, and the highest rates are in those ages 20 to 34 (FIGURE 3).2 In contrast to these upward trends, the number of HIV cases diagnosed has been relatively steady, with a slight downward trend over the past decade.4Other STIs that can be prevented through behavioral counseling include herpes simplex, human papillomavirus (HPV), hepatitis B virus (HBV) and trichomonas vaginalis.

Continue to: How to integrate STI preventioninto the primary care encounter

How to integrate STI preventioninto the primary care encounter

A key resource for learning to recognize the signs and symptoms of STIs, to correctly diagnose them, and to treat them according to CDC guidelines can be found at www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/default.htm.5 Equally important is to integrate the prevention of STIs into the clinical routine by using a 4-step approach: risk assessment, risk reduction (counseling and chemoprevention), screening, and vaccination.

Risk assessment. The first step in prevention is taking a sexual history to accurately assess a patient’s risk for STIs. The CDC provides a tool (www.cdc.gov/std/products/provider-pocket-guides.htm) that can assist in gathering information in a nonjudgmental fashion about 5 Ps: partners, practices, protection from STIs, past history of STIs, and prevention of pregnancy.

Risk reduction. Following STI risk assessment, recommend risk-reduction interventions, as appropriate. Notable in the new Task Force recommendation are behavioral counseling methods that work. Additionally, when needed, pre-exposure prophylaxis with effective antiretroviral agents can be offered to those at high risk of HIV.6

Screening. Task Force recommendations for STI screening are described in the TABLE.7-12 Screening for HIV, chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, and HBV are also recommended for pregnant women. And, although pregnant women are not specifically mentioned in the recommendation on chlamydia screening, it is reasonable to include it in prenatal care testing for STIs.

The Task Force has made an “I” statement regarding screening for gonorrhea and chlamydia in males. This does not mean that screening should be avoided, but only that there is insufficient evidence to support a firm statement regarding the harms and benefits in males. Keep in mind that this applies to asymptomatic males, and that testing and preventive treatment are warranted after documented exposure to either infection.

The Task Force recommends against screening for genital herpes, including in pregnant women, because of a lack of evidence of benefit from such screening, the high rate of false-positive tests, and the potential to cause anxiety and harm to personal relationships.

Continue to: Although hepatitis C virus...

Although hepatitis C virus (HCV) is transmitted mainly through intravenous drug use, it can also be transmitted sexually. The Task Force recommends screening for HCV in all adults ages 18 to 79 years.13

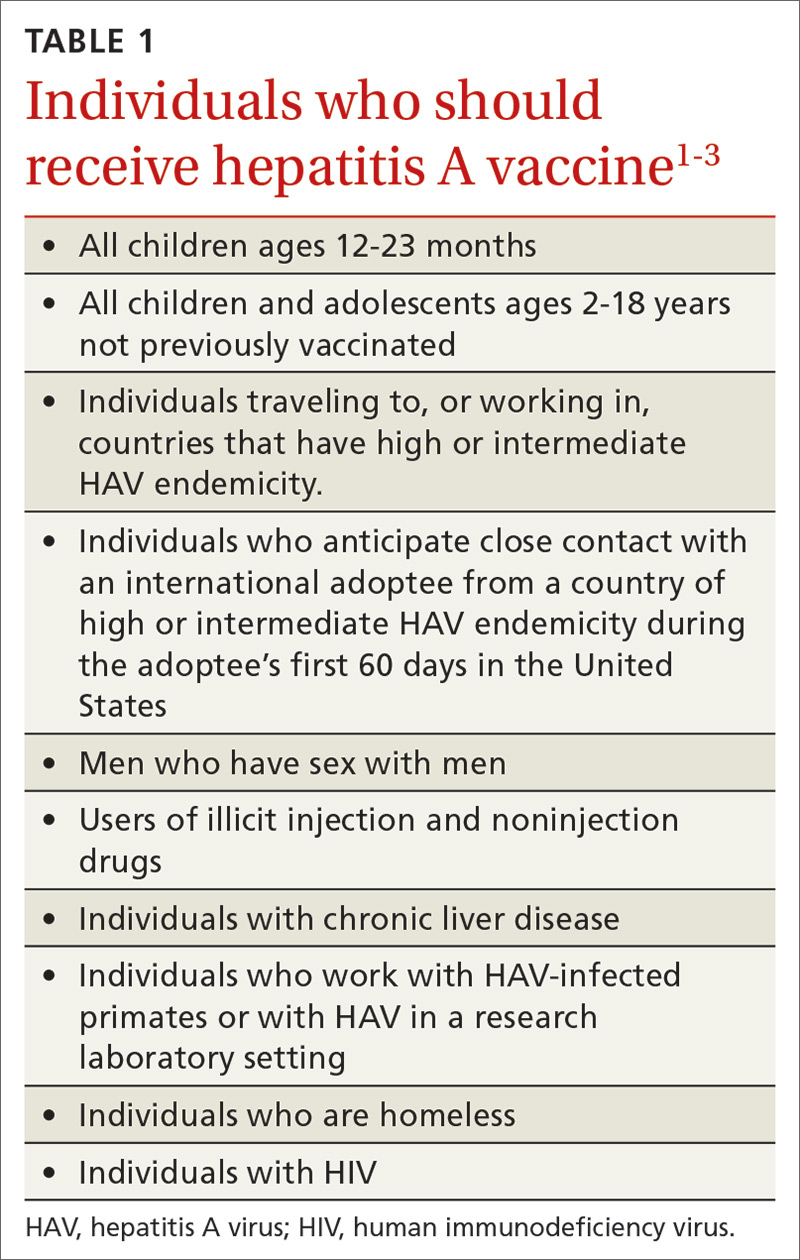

Vaccination. Two STIs can be prevented by immunizations: HPV and HBV. The current recommendations by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) are to vaccinate all infants with HBV vaccine and all unvaccinated children and adolescents through age 18.14 Unvaccinated adults who are at risk for HBV infection, including those at risk through sexual practices, should also be vaccinated.14

ACIP recommends routine HPV vaccination at age 11 or 12 years, but it can be started as early as 9 years.15 Catch-up vaccination is recommended for males and females through age 26 years.15 The vaccine is approved for use in individuals ages 27 through 45 years, but ACIP has not recommended it for routine use in this age group, and has instead recommended shared clinical decision-making to evaluate whether there is potential individual benefit from the vaccine.15

Public health implications

All STIs are reportable to local or state health departments. This is important for tracking community infection trends and, if resources are available, for contact notification and testing. In most jurisdictions, local health department resources are limited and contact tracing may be restricted to syphilis and HIV infections. When this is the case, it is especially important to instruct patients in whom STIs have been detected to notify their recent sex partners and advise them to be tested or preventively treated.

Expedited partner therapy (EPT)—providing treatment for exposed sexual contacts without a clinical encounter—is allowed in some states and is a tool that can prevent re-infection in the treated patient and suppress spread in the community. This is most useful for partners of those with gonorrhea, chlamydia, or trichomonas. The CDC has published guidance on how to implement EPT in a clinical setting if state law allows it.16

In August 2020, the US Preventive Services Task Force published an update of its recommendation on preventing sexually transmitted infections (STIs) with behavioral counseling interventions.1

Whom to counsel. The USPSTF continues to recommend behavioral counseling for all sexually active adolescents and for adults at increased risk for STIs. Adults at increased risk include those who have been diagnosed with an STI in the past year, those with multiple sex partners or a sex partner at high risk for an STI, those not using condoms consistently, and those belonging to populations with high prevalence rates of STIs. These populations with high prevalence rates include1

- individuals seeking care at STI clinics,

- sexual and gender minorities, and

- those who are positive for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), use injection drugs, exchange sex for drugs or money, or have recently been in a correctional facility.

Features of effective counseling. The Task Force recommends that primary care clinicians provide behavioral counseling or refer to counseling services or suggest media-based interventions. The most effective counseling interventions are those that span more than 120 minutes over several sessions. But the Task Force also states that counseling lasting about 30 minutes in a single session can also be effective. Counseling should include information about common STIs and their modes of transmission; encouragement in the use of safer sex practices; and training in proper condom use, how to communicate with partners about safer sex practices, and problem-solving. Various approaches to this counseling can be found at https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/sexually-transmitted-infections-behavioral-counseling.

This updated recommendation is timely because most STIs in the United States have been increasing in incidence for the past decade or longer.2 Per 100,000 population, the total number of chlamydia cases since 2000 has risen from 251.4 to 539.9 (115%);gonorrhea cases since 2009 have risen from 98.1 to 179.1 (83%).3 And since 2000, the total number of reported syphilis cases per 100,000 has risen from 2.1 to 10.8 (414%).3

Chlamydia affects primarily those ages 15 to 24 years, with highest rates occurring in females (FIGURE 1).2 Gonorrhea affects women and men fairly evenly with slightly higher rates in men; the highest rates are seen in those ages 20 to 29 (FIGURE 2).2 Syphilis predominantly affects men who have sex with men, and the highest rates are in those ages 20 to 34 (FIGURE 3).2 In contrast to these upward trends, the number of HIV cases diagnosed has been relatively steady, with a slight downward trend over the past decade.4Other STIs that can be prevented through behavioral counseling include herpes simplex, human papillomavirus (HPV), hepatitis B virus (HBV) and trichomonas vaginalis.

Continue to: How to integrate STI preventioninto the primary care encounter

How to integrate STI preventioninto the primary care encounter

A key resource for learning to recognize the signs and symptoms of STIs, to correctly diagnose them, and to treat them according to CDC guidelines can be found at www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/default.htm.5 Equally important is to integrate the prevention of STIs into the clinical routine by using a 4-step approach: risk assessment, risk reduction (counseling and chemoprevention), screening, and vaccination.

Risk assessment. The first step in prevention is taking a sexual history to accurately assess a patient’s risk for STIs. The CDC provides a tool (www.cdc.gov/std/products/provider-pocket-guides.htm) that can assist in gathering information in a nonjudgmental fashion about 5 Ps: partners, practices, protection from STIs, past history of STIs, and prevention of pregnancy.

Risk reduction. Following STI risk assessment, recommend risk-reduction interventions, as appropriate. Notable in the new Task Force recommendation are behavioral counseling methods that work. Additionally, when needed, pre-exposure prophylaxis with effective antiretroviral agents can be offered to those at high risk of HIV.6

Screening. Task Force recommendations for STI screening are described in the TABLE.7-12 Screening for HIV, chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, and HBV are also recommended for pregnant women. And, although pregnant women are not specifically mentioned in the recommendation on chlamydia screening, it is reasonable to include it in prenatal care testing for STIs.

The Task Force has made an “I” statement regarding screening for gonorrhea and chlamydia in males. This does not mean that screening should be avoided, but only that there is insufficient evidence to support a firm statement regarding the harms and benefits in males. Keep in mind that this applies to asymptomatic males, and that testing and preventive treatment are warranted after documented exposure to either infection.

The Task Force recommends against screening for genital herpes, including in pregnant women, because of a lack of evidence of benefit from such screening, the high rate of false-positive tests, and the potential to cause anxiety and harm to personal relationships.

Continue to: Although hepatitis C virus...

Although hepatitis C virus (HCV) is transmitted mainly through intravenous drug use, it can also be transmitted sexually. The Task Force recommends screening for HCV in all adults ages 18 to 79 years.13

Vaccination. Two STIs can be prevented by immunizations: HPV and HBV. The current recommendations by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) are to vaccinate all infants with HBV vaccine and all unvaccinated children and adolescents through age 18.14 Unvaccinated adults who are at risk for HBV infection, including those at risk through sexual practices, should also be vaccinated.14

ACIP recommends routine HPV vaccination at age 11 or 12 years, but it can be started as early as 9 years.15 Catch-up vaccination is recommended for males and females through age 26 years.15 The vaccine is approved for use in individuals ages 27 through 45 years, but ACIP has not recommended it for routine use in this age group, and has instead recommended shared clinical decision-making to evaluate whether there is potential individual benefit from the vaccine.15

Public health implications

All STIs are reportable to local or state health departments. This is important for tracking community infection trends and, if resources are available, for contact notification and testing. In most jurisdictions, local health department resources are limited and contact tracing may be restricted to syphilis and HIV infections. When this is the case, it is especially important to instruct patients in whom STIs have been detected to notify their recent sex partners and advise them to be tested or preventively treated.

Expedited partner therapy (EPT)—providing treatment for exposed sexual contacts without a clinical encounter—is allowed in some states and is a tool that can prevent re-infection in the treated patient and suppress spread in the community. This is most useful for partners of those with gonorrhea, chlamydia, or trichomonas. The CDC has published guidance on how to implement EPT in a clinical setting if state law allows it.16

1. Henderson JT, Senger CA, Henninger M, et al. Behavioral counseling interventions to prevent sexually transmitted infections. JAMA. 2020;324:682-699.

2. CDC. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance, 2018. www.cdc.gov/std/stats18/slides.htm. Accessed November 25, 2020.

3. CDC. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2018. www.cdc.gov/std/stats18/tables/1.htm. Accessed November 25, 2020.

4. CDC. Estimated HIV incidence and prevalence in the United States (2010-2018). www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/slidesets/cdc-hiv-surveillance-epidemiology-2018.pdf. Accessed November 25, 2020.

5. CDC. 2015 sexually transmitted disease treatment guidelines. www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/default.htm. Accessed November 25, 2020.

6. USPSTF. Prevention of human immunodeficiency (HIV) infection: pre-exposure prophylaxis. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/prevention-of-human-immunodeficiency-virus-hiv-infection-pre-exposure-prophylaxis. Accessed November 25, 2020.

7. LeFevre ML, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for chlamydia and gonorrhea: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:902-910. 8. USPSTF. Syphilis infection in nonpregnant adults and adolescents: screening. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/syphilis-infection-in-nonpregnant-adults-and-adolescents. Accessed November 25, 2020.

9. Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, et al. Screening for syphilis in pregnant women: US Preventive Services Task Force reaffirmation recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320:911-917.

10. Owens DK, Davidson KW, Krist AH, et al; US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for HIV infection: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2019;321:2326-2336.

11. USPSTF. US Preventive Services Task Force issues draft recommendation statement on screening for hepatitis B virus infection in adolescents and adults. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/sites/default/files/file/supporting_documents/hepatitis-b-nonpregnant-adults-draft-rs-bulletin.pdf. Accessed November 25, 2020.

12. Owens DK, Davidson KW, Krist AH, et al. Screening for Hepatitis B Virus Infection in Pregnant Women: US Preventive Services Task Force reaffirmation recommendation statement. JAMA. 2019;322:349-354.

13. USPSTF. Hepatitis C virus infection in adolescents and adults: screening. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/hepatitis-c-screening. Accessed November 25, 2020. 14. Schillie S, Vellozzi C, Reingold A, et al. Prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2018;67;1-31.

15. Meites E, Szilagyi PG, Chesson HW, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination for adults: updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:698-702.

16. CDC. Expedited partner therapy in the management of sexually transmitted diseases. www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/eptfinalreport2006.pdf. Accessed November 25, 2020.

1. Henderson JT, Senger CA, Henninger M, et al. Behavioral counseling interventions to prevent sexually transmitted infections. JAMA. 2020;324:682-699.

2. CDC. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance, 2018. www.cdc.gov/std/stats18/slides.htm. Accessed November 25, 2020.

3. CDC. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2018. www.cdc.gov/std/stats18/tables/1.htm. Accessed November 25, 2020.

4. CDC. Estimated HIV incidence and prevalence in the United States (2010-2018). www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/slidesets/cdc-hiv-surveillance-epidemiology-2018.pdf. Accessed November 25, 2020.

5. CDC. 2015 sexually transmitted disease treatment guidelines. www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/default.htm. Accessed November 25, 2020.

6. USPSTF. Prevention of human immunodeficiency (HIV) infection: pre-exposure prophylaxis. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/prevention-of-human-immunodeficiency-virus-hiv-infection-pre-exposure-prophylaxis. Accessed November 25, 2020.

7. LeFevre ML, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for chlamydia and gonorrhea: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:902-910. 8. USPSTF. Syphilis infection in nonpregnant adults and adolescents: screening. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/syphilis-infection-in-nonpregnant-adults-and-adolescents. Accessed November 25, 2020.

9. Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, et al. Screening for syphilis in pregnant women: US Preventive Services Task Force reaffirmation recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320:911-917.

10. Owens DK, Davidson KW, Krist AH, et al; US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for HIV infection: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2019;321:2326-2336.

11. USPSTF. US Preventive Services Task Force issues draft recommendation statement on screening for hepatitis B virus infection in adolescents and adults. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/sites/default/files/file/supporting_documents/hepatitis-b-nonpregnant-adults-draft-rs-bulletin.pdf. Accessed November 25, 2020.

12. Owens DK, Davidson KW, Krist AH, et al. Screening for Hepatitis B Virus Infection in Pregnant Women: US Preventive Services Task Force reaffirmation recommendation statement. JAMA. 2019;322:349-354.

13. USPSTF. Hepatitis C virus infection in adolescents and adults: screening. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/hepatitis-c-screening. Accessed November 25, 2020. 14. Schillie S, Vellozzi C, Reingold A, et al. Prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2018;67;1-31.

15. Meites E, Szilagyi PG, Chesson HW, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination for adults: updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:698-702.

16. CDC. Expedited partner therapy in the management of sexually transmitted diseases. www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/eptfinalreport2006.pdf. Accessed November 25, 2020.

Prospects and challenges for the upcoming influenza season

The 2020-2021 influenza season is shaping up to be challenging. Its likely concurrence with the ongoing severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus 2 (SARS-coV-2) pandemic (COVID-19) will pose diagnostic and therapeutic dilemmas and could overload the hospital system. But there could also be potential synergies in preventing morbidity and mortality from each disease.

A consistent pattern overthe past few influenza seasons

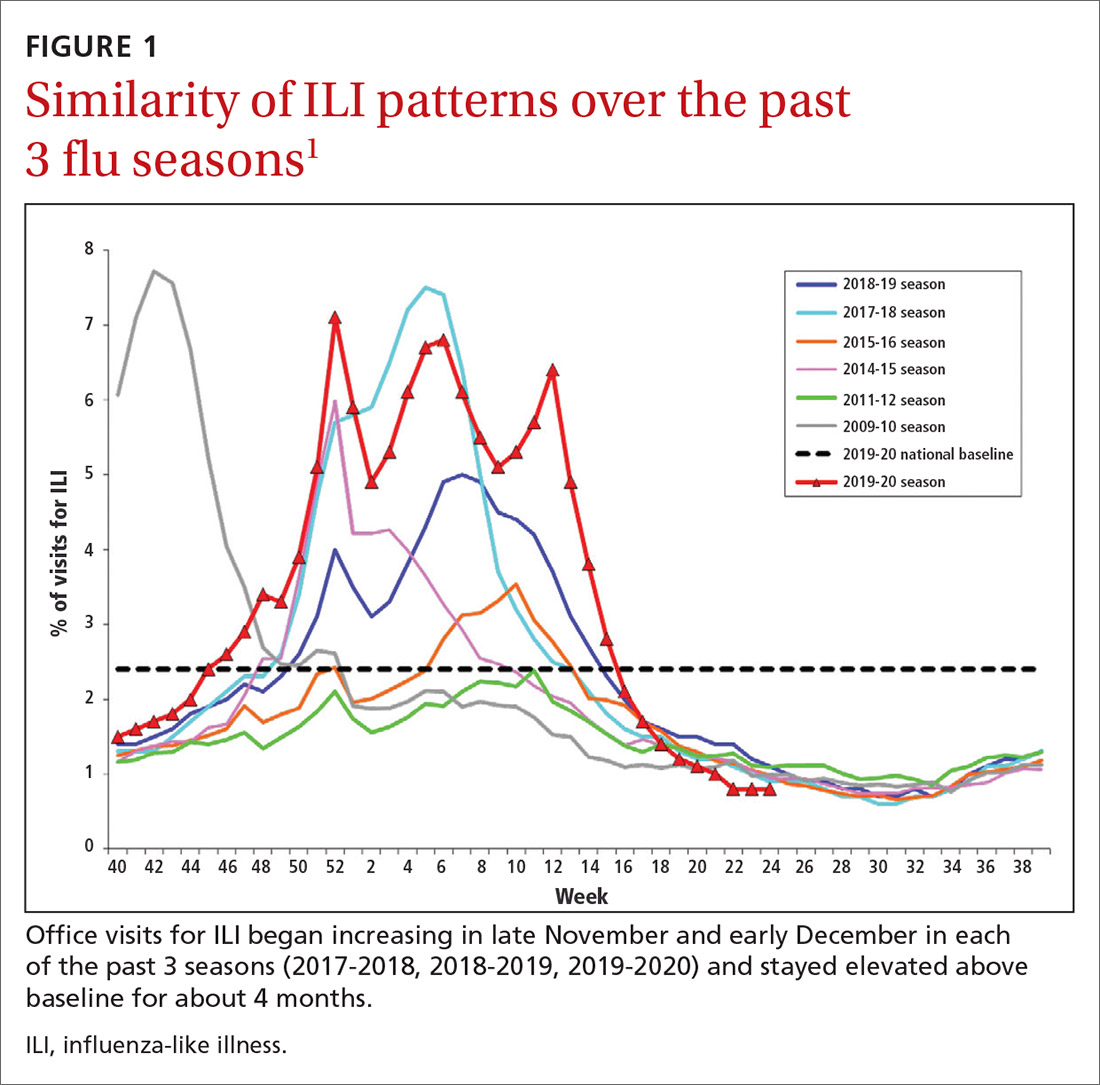

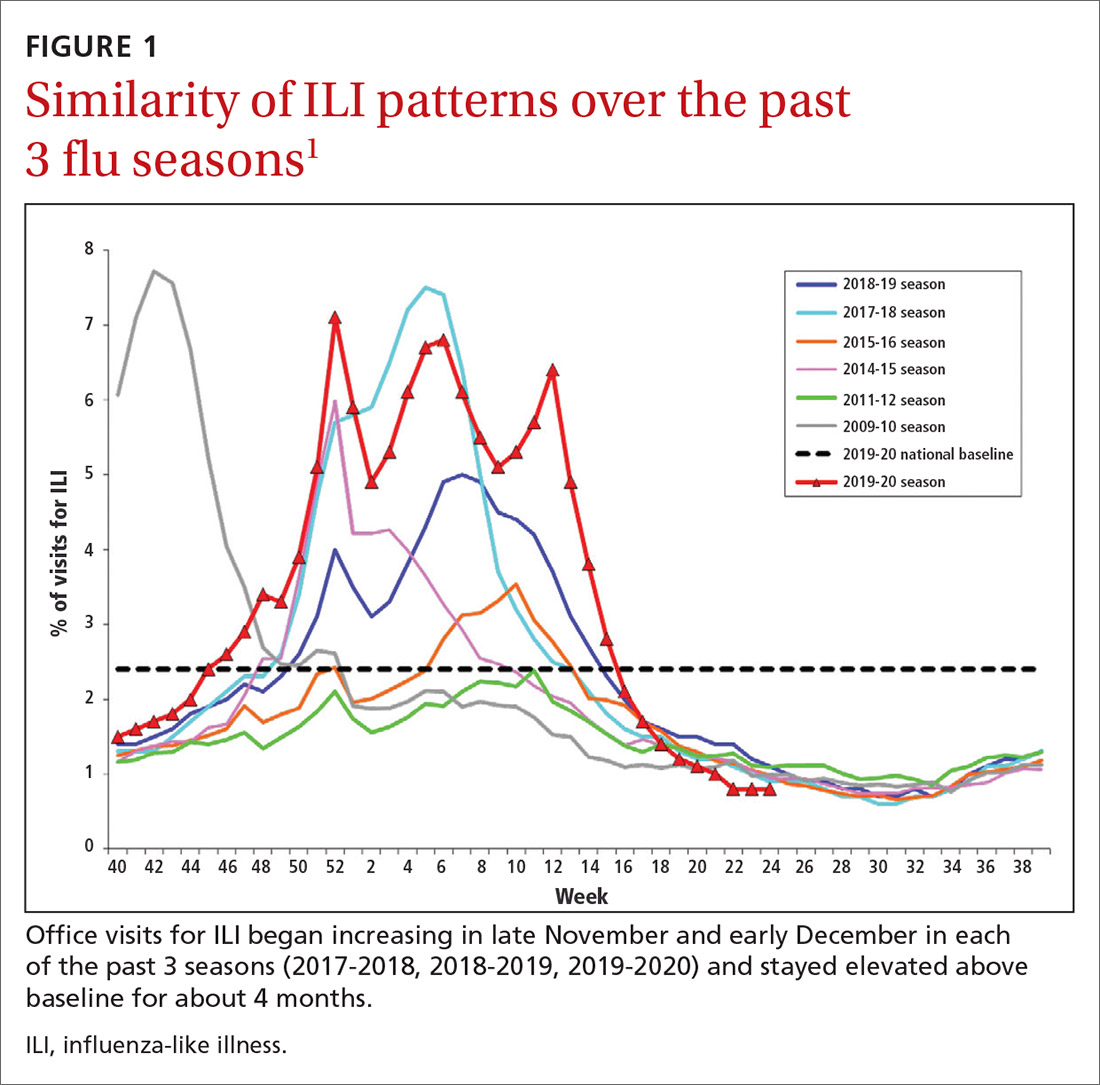

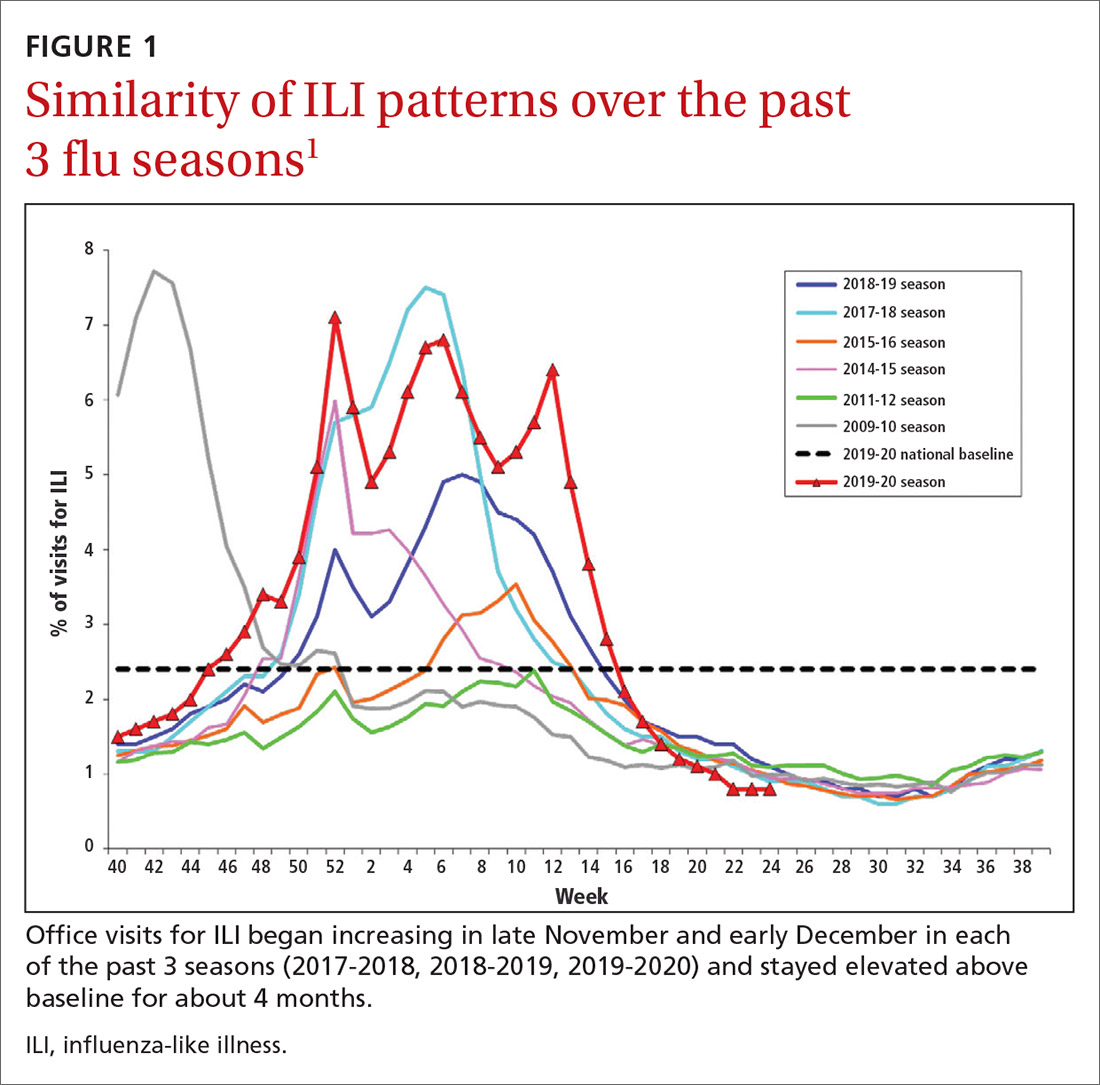

During the 2019-2020 flu season, there were an estimated 410,000 to 740,000 hospitalizations and 24,000 to 62,000 deaths attributed to influenza.1 As seen in FIGURE 1, office visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) began to increase in late November and early December in each of the last 3 years (2017-2018, 2018-2019, 2019-2020) and stayed elevated above baseline for about 4 months each season.1

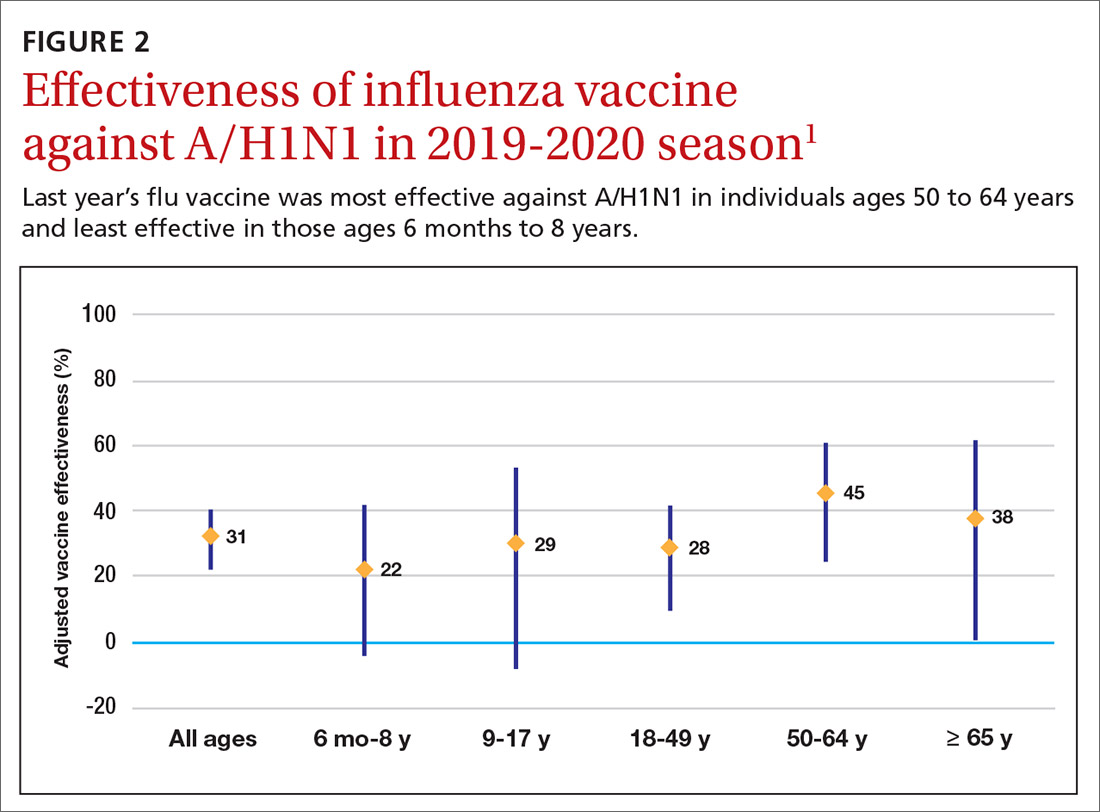

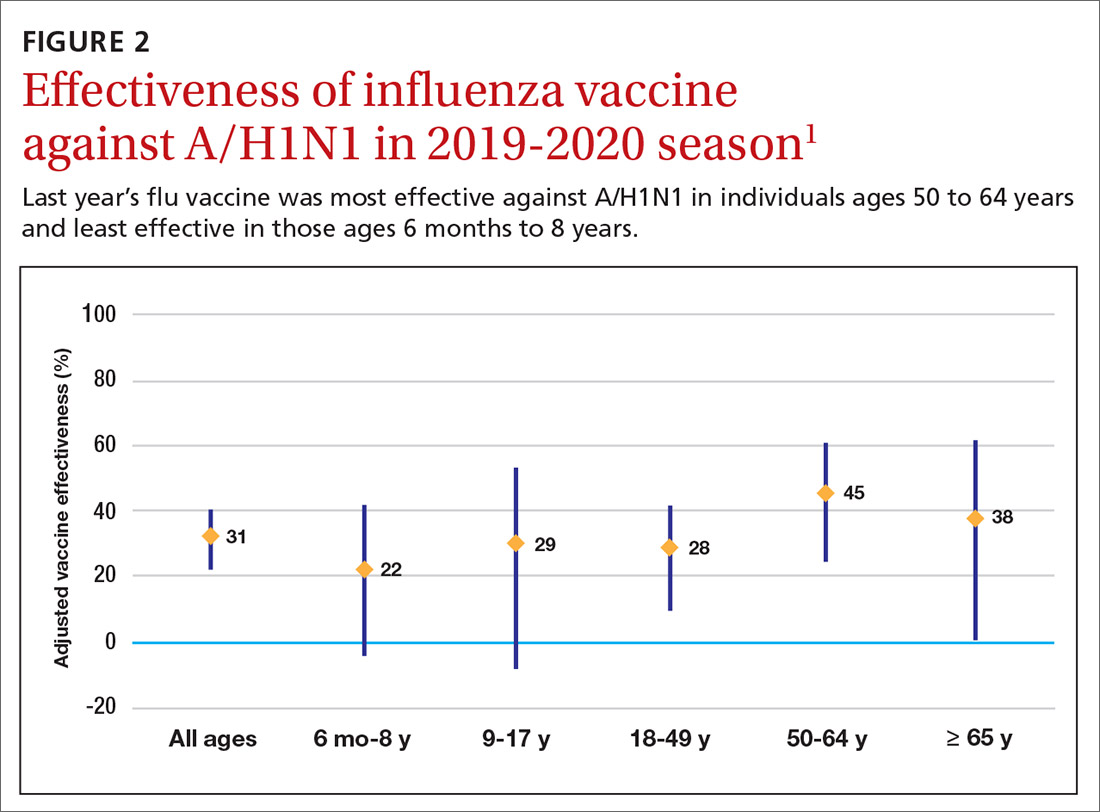

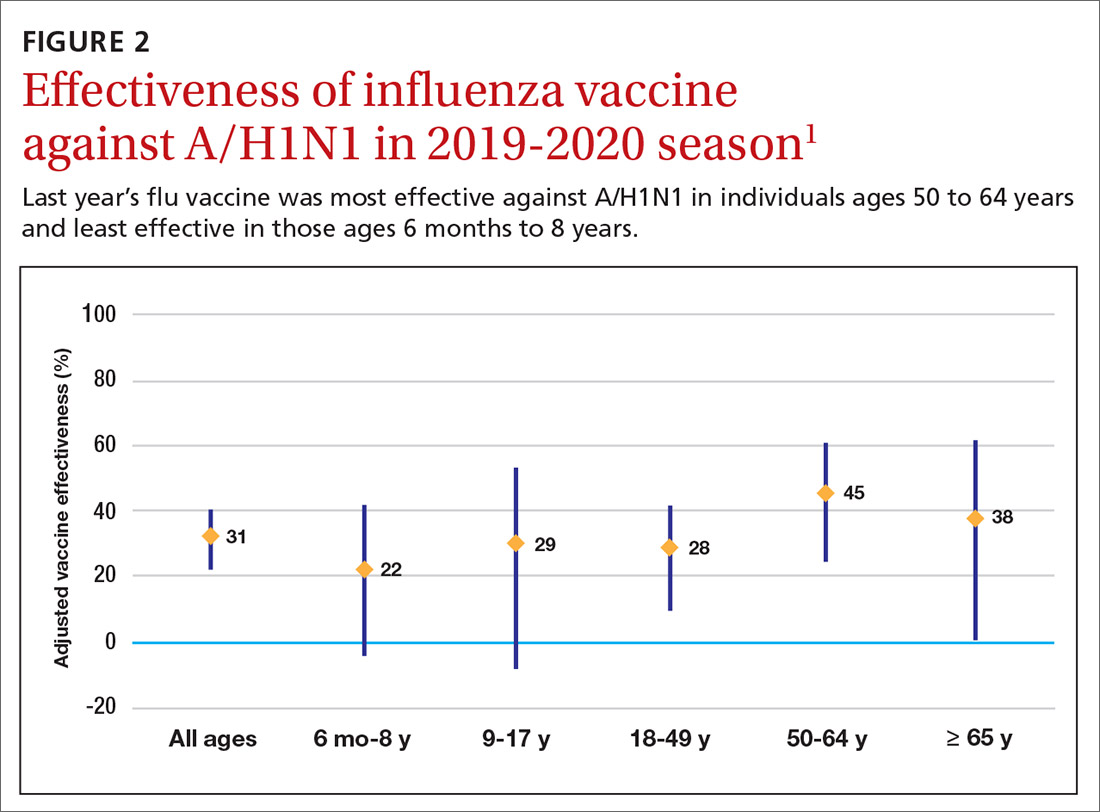

The effectiveness of influenza vaccine during the 2019-2020 season is being estimated using the US Flu Vaccine Effectiveness Network, which has close to 9000 enrollees. Overall, it appears the vaccine was 39% effective against medically attended influenza, with a higher effectiveness against influenza B (44%) than against A/H1N1 (31%). Effectiveness against influenza B was similar in all age groups, but effectiveness against A/H1N1 was highest for those ages 50 to 64 years (45%) and lowest for those ages 6 months through 8 years (22%), although 95% confidence intervals overlapped for all age groups (FIGURE 2). These preliminary effectiveness rates were presented at the summer meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP).1

Influenza vaccine safety data for 2019-2020 were based on the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), a passive surveillance system, and on the Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD) system, an active surveillance system involving close to 6 million doses administered at VSD sites. No safety concerns were identified for any of the different vaccine types. Both the VAERS and VSD surveillance systems have been described in more detail in a previous Practice Alert.2

Recommendations for 2020-2021

The composition of the influenza vaccines for this year’s flu season will be different for 3 of the 4 antigens: A/H1N1, A/H2N2 and B/Victoria.3 The antigens included in the influenza vaccines each year are decided on in the spring, based on surveillance of circulating strains around the world. The effectiveness of the vaccine each year largely depends on how well the strains included in the vaccine match those circulating in the United States during the influenza season.

The main immunization recommendation for preventing morbidity and mortality from influenza has not changed: All individuals ages 6 months and older without a contraindication should receive an influenza vaccine.4 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that patients receive the vaccine by the end of October.4 This includes the second dose for those children younger than 9 years who need 2 doses—ie, those who have received fewer than 2 doses of influenza vaccine prior to July 2020. Vaccination should continue through the end of the season for anyone who has not received a 2020-2021 influenza vaccine.

Two new influenza vaccine products are available for use in those ages 65 years and older: Fluzone high-dose quadrivalent and Fluad Quadrivalent (adjuvanted).4 Both of these products were available last year as trivalent options. Currently no specific vaccine product is listed as preferred by ACIP for those ages 65 and older.

Continue to: New vaccine contraindications

New vaccine contraindications. Four medical conditions have been added to the list of contraindications for quadrivalent live, attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV4): cochlear implant, cerebrospinal fluid leak, asplenia (anatomic and functional), and sickle cell anemia.4 In addition, those who receive LAIV4 should not be prescribed an influenza antiviral until 2 weeks after receiving the vaccine. And the vaccine should not be administered for 48 hours after receipt of oseltamivir or zanamivir, 5 days after peramivir, and 17 days after baloxavir marboxil.4 This is to prevent possible antiviral inactivation of the live attenuated influenza viruses in the vaccine.

For those who have a history of severe allergic reaction to eggs, there are now 2 egg-free options: cell-culture-based inactivated vaccine (ccIIV4) and recombinant influenza vaccine (RIV4).3,4 Urticaria alone is not considered a severe reaction. If neither of these egg-free options is available, a vaccine may still be administered in a medical setting supervised by a provider who is able to manage a severe allergic reaction (which rarely occurs).

All vaccine products available for the upcoming influenza season are listed and described on the CDC Web site, as is a summary of related recommendations.4 Particular attention should be paid to the dose of vaccine administered, as it differs by product for those ages 6 through 35 months of age and those ages 65 years and older.

Use of antiviral medications

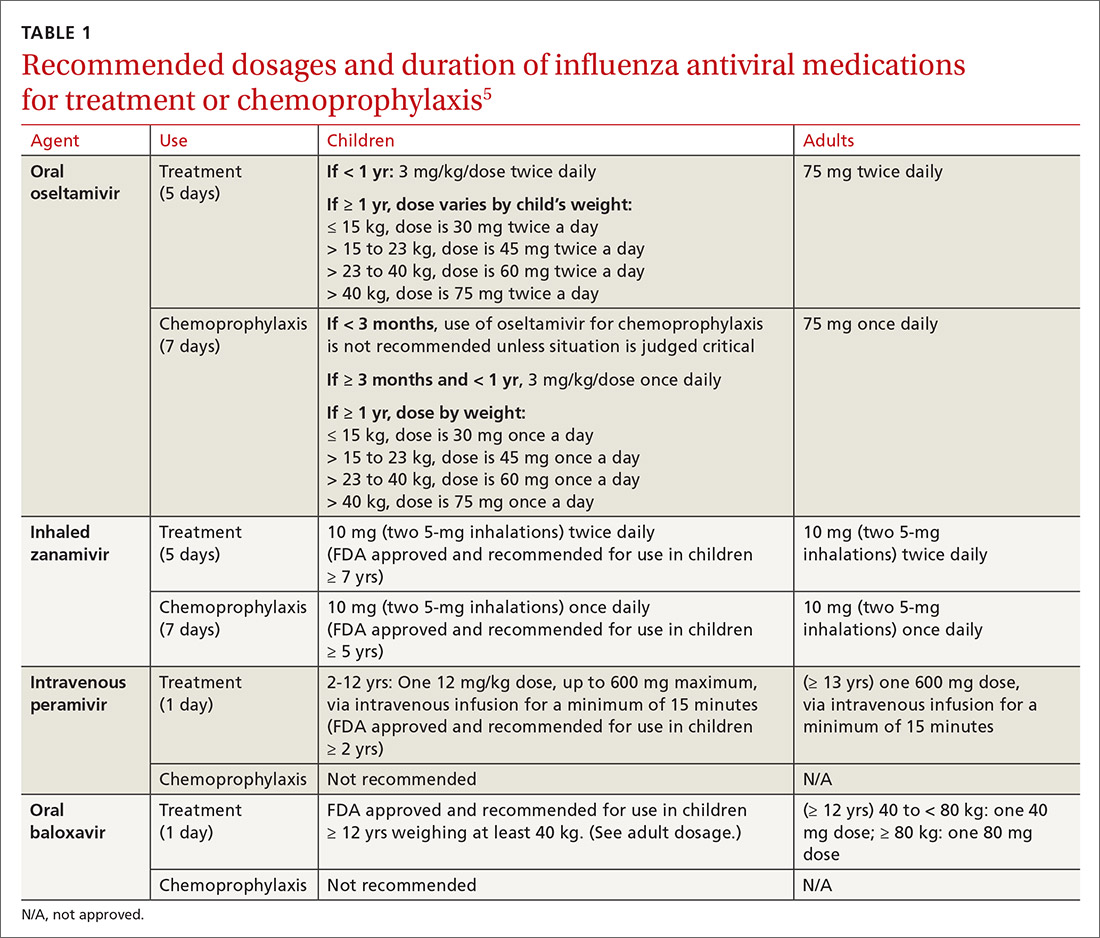

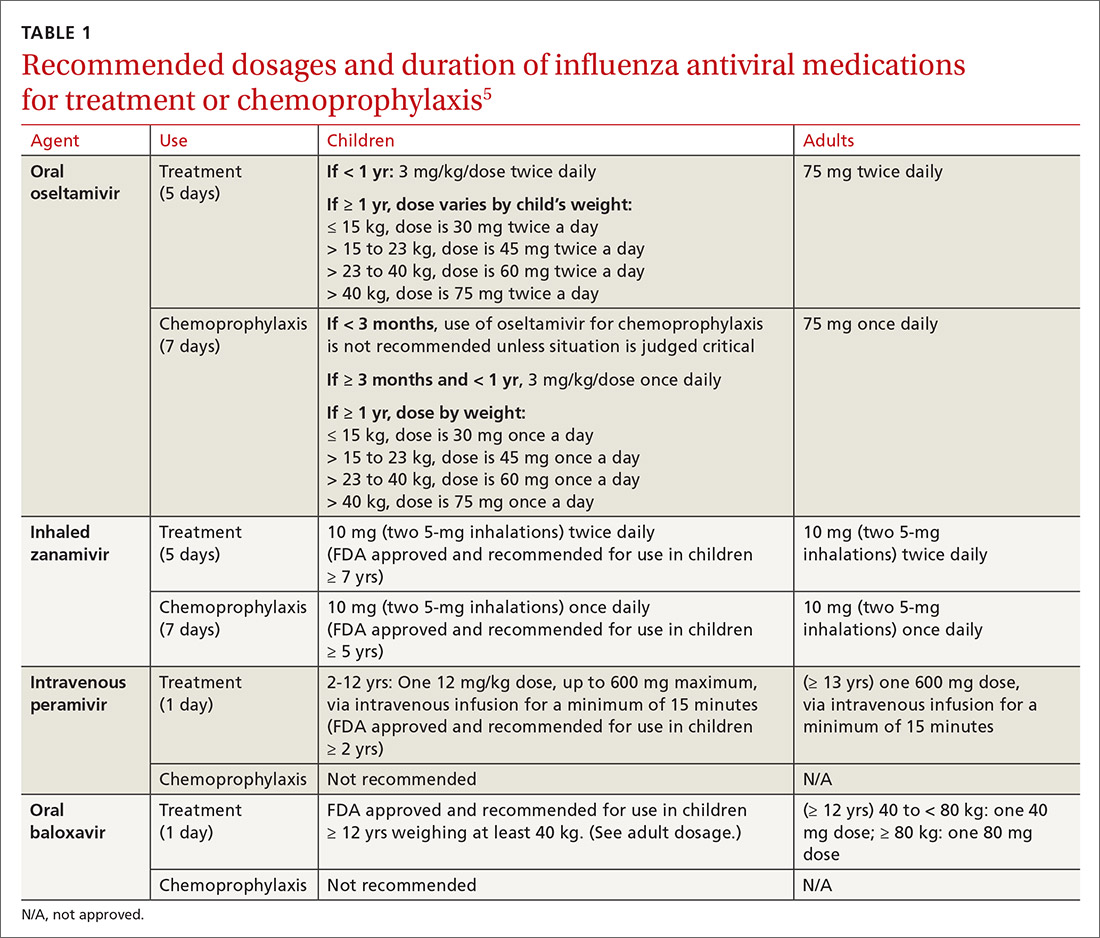

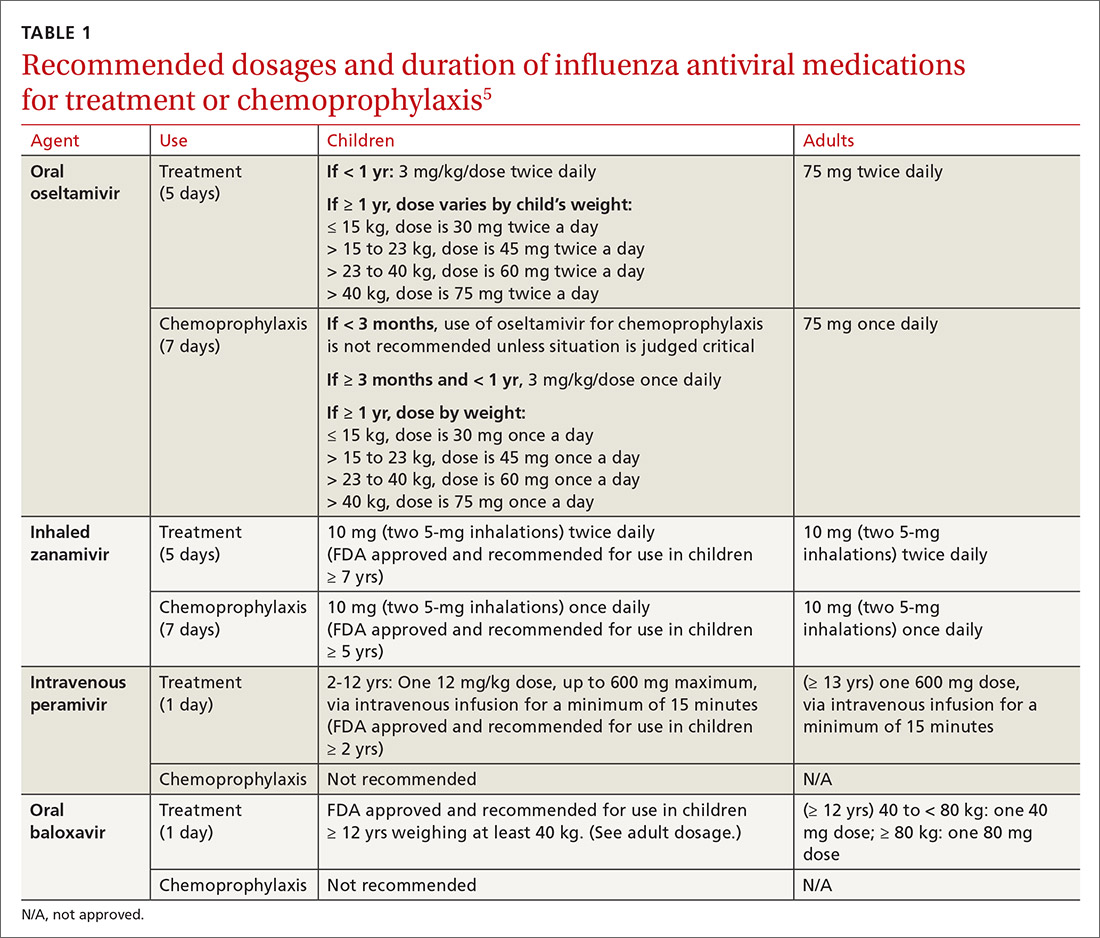

Four antiviral medications are now available for treating influenza (3 neuraminidase inhibitors and 1 endonuclease inhibitor), and there are 2 agents for preventing influenza, both neuraminidase inhibitors (TABLE 1).5 The CDC recommends treating with antivirals as soon as possible if individuals with confirmed or suspected influenza require hospitalization; have severe, complicated, or progressive illness; or are at high risk for complications. Use antivirals based on clinical judgment if previously healthy individuals do not have severe complications and are not at increased risk for complications, and only if the medication can be started within 48 hours of symptom onset.

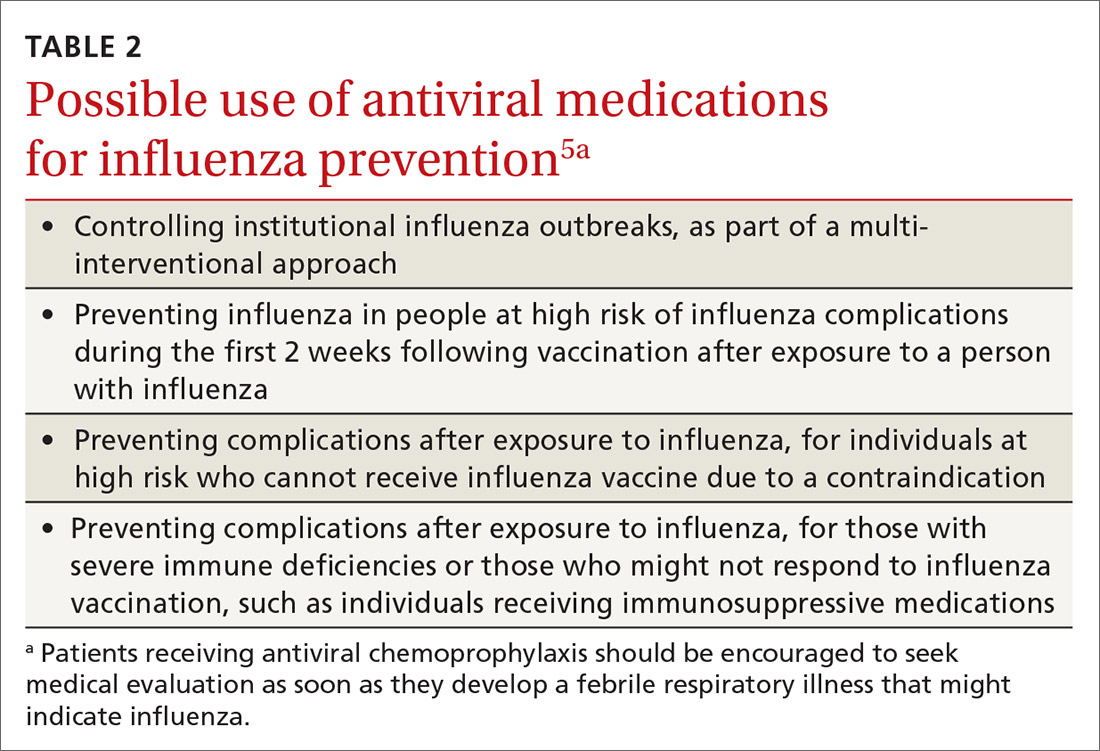

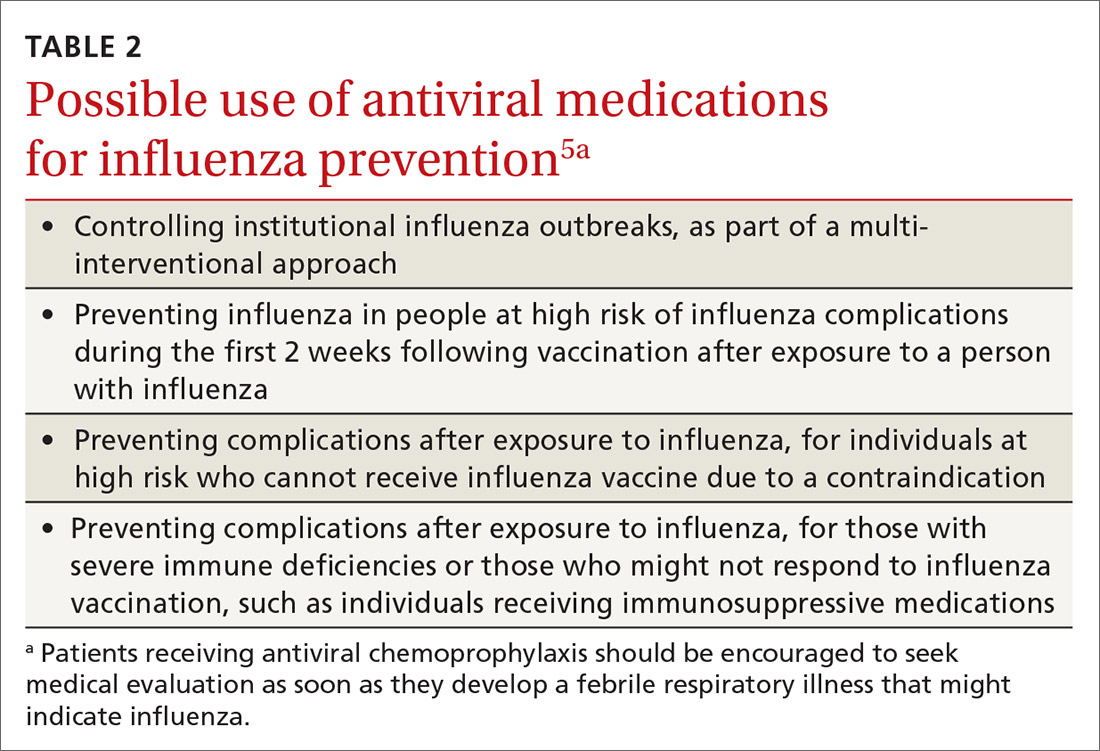

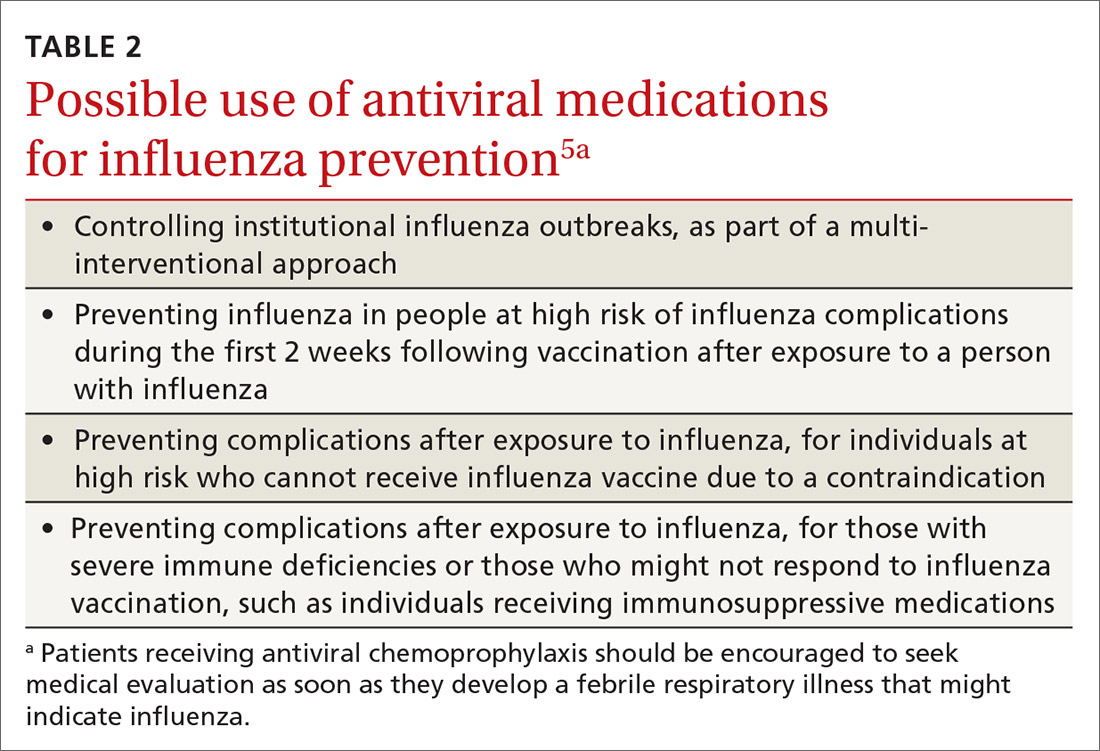

The CDC discourages widespread use of antivirals to prevent influenza, either pre- or postexposure, although it specifies certain situations in which usage would be acceptable (TABLE 2).5 There is some concern that widespread use could lead to the emergence of drug-resistant strains and that using postexposure dosing could lead to suboptimal treatment if influenza infection occurred before the start of prophylaxis. If postexposure antivirals are prescribed, they should be started within 48 hours of exposure and continued for 7 days after the last exposure.

Continue to: A potential perfect storm

A potential perfect storm: Concurrence of influenza and SARS-coV-19

While we have vaccines and antivirals to prevent influenza, and have effective antivirals for treatment, no prevention or treatment options exist for COVID-19, except, possibly, dexamethasone to reduce mortality among those seriously ill.6 The concurrence of influenza and COVID-19 will present unique challenges for the health care system.

Action steps. Keep abreast of the incidences of circulating SARS-coV-19 and influenza viruses in your community. The similar signs and symptoms of these 2 infectious agents will complicate diagnosis. Rapid, or point-of-care, tests for influenza are widely available, but their accuracy varies and not all tests detect both influenza A and B. The CDC lists approved point-of-care tests at www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/diagnosis/table-ridt.html and advises on how to interpret these test results when influenza is and is not circulating in the community, at www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/diagnosis/clinician_guidance_ridt.htm.

Clinical practice advice for both conditions should be implemented when any patient presents with ILI:7

- Most patients who are not seriously ill and have no conditions that place them at high risk for adverse outcomes can be treated symptomatically at home.

- Those with ILI should be tested for both influenza virus and SARS-CoV-2 if testing is available. It is possible to be co-infected.

- Sick patients should self-isolate at home for the duration of their symptoms.

- If others live in the house, the sick person should stay in a separate room and wear a mask. Everyone in the house should cover coughs and sneezes (if not wearing a mask), dispose of used tissues in a trash can (rather than leaving them on night stands and countertops), and wash hands frequently.

- All household members should be vaccinated against influenza. Those who are unvaccinated, and those at high risk who have been recently vaccinated, can consider influenza antiviral prophylaxis. If the sick family member is confirmed to have COVID-19, with no co-existing influenza, anti-influenza antiviral prophylaxis may be discontinued.

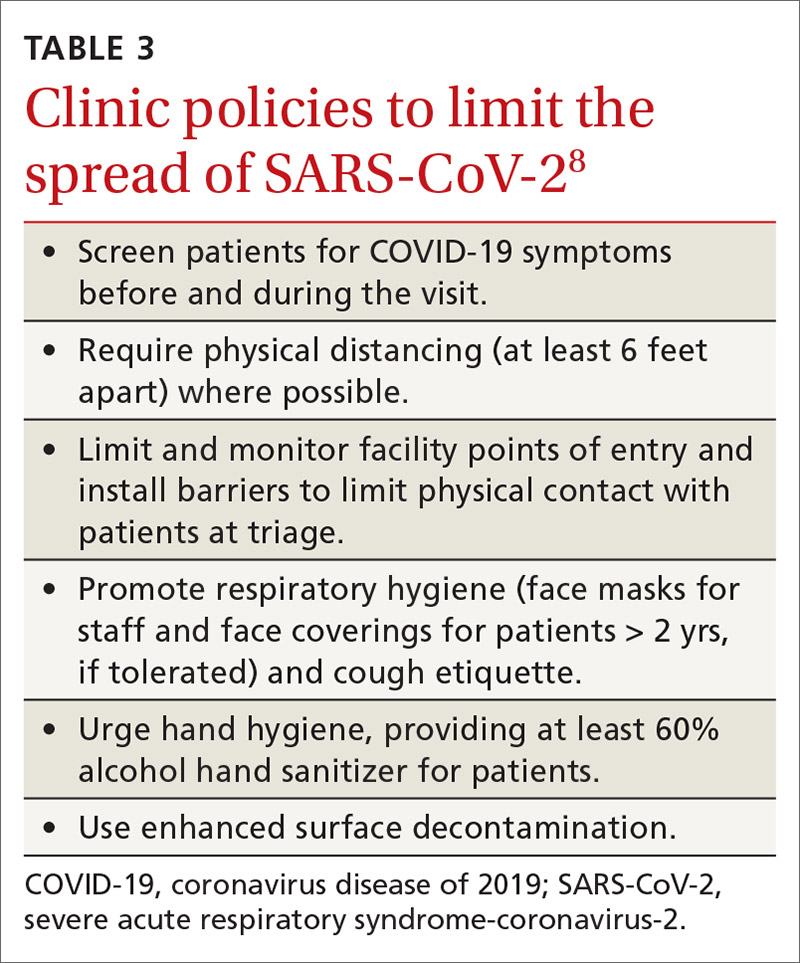

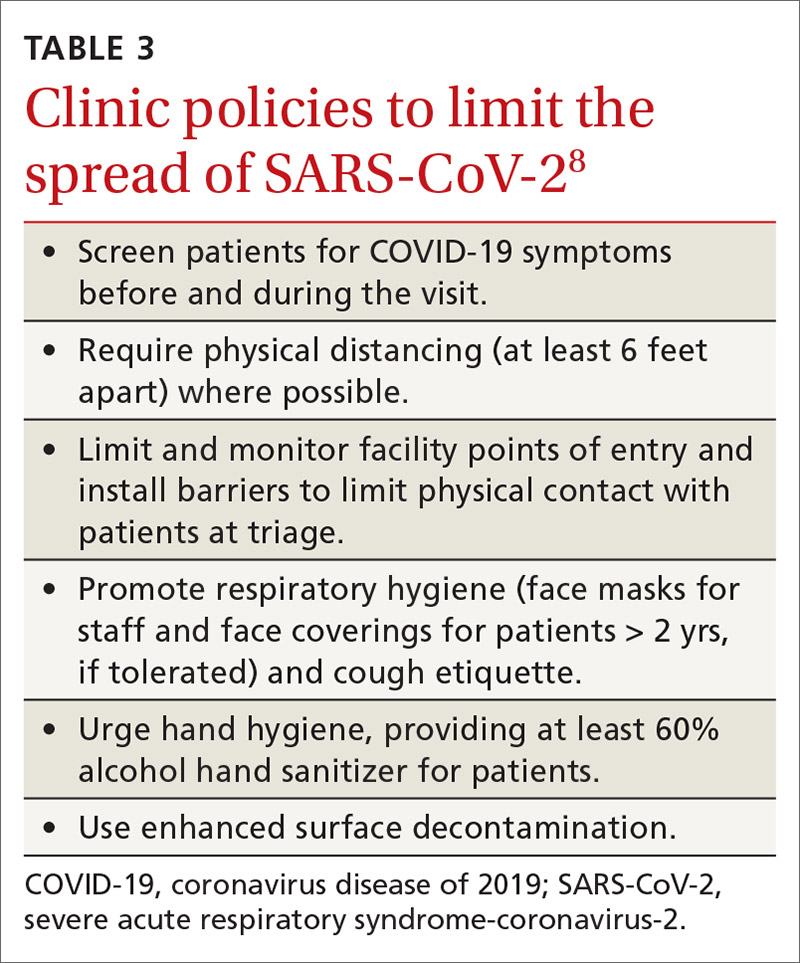

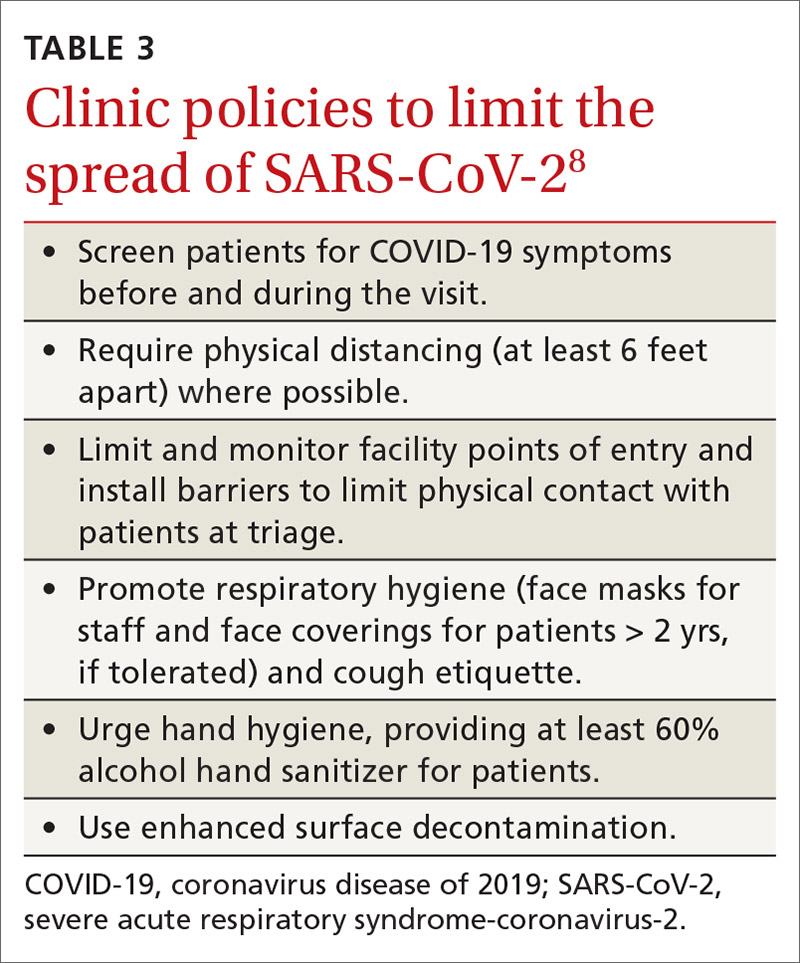

- Clinical infection control practices should be the same for anyone presenting with ILI.7 Enhanced clinic-based infection control practices to prevent spread of SARS-CoV-2 are listed in TABLE 3.8

Since there currently are no preventive medications proven to work for COVID-19, the main clinical decision physicians will have to make when a patient presents with ILI is whether to use antivirals to treat those who are at risk for complications based on the result of rapid, on-site influenza testing, or clinical presentation, or both. In this situation, knowledge of which viruses are circulating at high rates in the community could be valuable.

Milder season or perfect storm? The society-wide interventions that have been encouraged (although not mandated everywhere) to prevent community spread of SARS-CoV-2 should help prevent the community spread of influenza as well, and, if adhered to, may lead to a milder influenza season than would otherwise have occurred. However, given the uncertainties, the combination of influenza and coronavirus could present a perfect storm for the health care system and result in higher-than-normal morbidity and mortality from ILI and pneumonia overall.

Continue to: The possibility that one or more vaccines...

The possibility that one or more vaccines to prevent COVID-19 may be available in late 2020 or early 2021 offers hope. However, in current testing, the vaccine is not being given simultaneously with the influenza vaccine. If the potential for adverse interaction exists between the vaccines, it is important that influenza vaccine be given by mid- to late-October to avoid such an interaction if and when the new SARS-CoV-2 vaccine becomes available. Individuals who have symptoms of COVID-19 should not be vaccinated with influenza vaccine until they are considered noninfectious.

Encourage influenza vaccination. The COVID-19 pandemic may make it difficult to achieve desired community influenza vaccine levels because of decreased visits to medical facilities for preventive care, possible lower insurance coverage due to loss of employment, and a decrease in worksite mass vaccination programs. This makes it important for family physicians to encourage and offer influenza vaccines at their clinical sites.

Several evidence-based practices have been shown to improve vaccine uptake. Examples of such practices include patient reminder and recall systems that provide feedback to clinicians about rates of vaccination among patients, and establishing standing orders for vaccine administration that allow other health care providers to assess a patient’s immunization status and administer vaccinations according to a protocol.9 Finally, the CDC provides a video on how to recommend influenza vaccine to those who may be resistant (www.cdc.gov/vaccines/howirecommend/adult-vacc-videos.html).

SIDEBAR

CDC influenza resources

Point-of-care tests that detect both influenza A and B viruses approved by the CDC

www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/diagnosis/table-ridt.html

Advice on how to interpret the test results

www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/diagnosis/clinician_guidance_ridt.htm

How to recommend influenza vaccine to reluctant patients

www.cdc.gov/vaccines/howirecommend/adult-vacc-videos.html

CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

1. Grohskopf L. Influenza work groups: updates, considerations, and proposed recommendations for the 2020-2021 season. Presented at the ACIP meeting June 24, 2020. www.youtube.com/watch?v=W1SV2DSJsaQ&list=PLvrp9iOILTQb6D9e1YZWpbUvzfptNMKx2&index=8&t=0s. [Time stamp: 1:26:48] Accessed Septemeber 29, 2020.

2. Campos-Outcalt D. Facts to help you keep pace with the vaccine conversation. J Fam Pract. 2019;68:341-346.

3. Grohskopf L, Alyanak E, Broder KR, et al. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2020-21 Influenza Season. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2020;69:1-24.

4. Prevention and Control of Seasonal Influenza with Vaccines: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP)—United States, 2020-21 Summary of Recommendations. www.cdc.gov/flu/pdf/professionals/acip/acip-2020-21-summary-of-recommendations.pdf. Accessed September 29, 2020.

5. CDC. Influenza antiviral medications: summary for clinicians. www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/antivirals/summary-clinicians.htm. Accessed September 29, 2020.

6. NIH. COVID-19 treatment guidelines. Corticosteroids. www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/immune-based-therapy/immunomodulators/corticosteroids/. Accessed September 29, 2020.

7. CDC. Infection control. www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/. Accessed September 29, 2020.

8. CDC. Interim infection prevention and control recommendations for healthcare personnel during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/infection-control.html. Accessed September 29, 2020.

9. HHS. CPSTF findings for increasing vaccination. www.thecommunityguide.org/content/task-force-findings-increasing-vaccination. Accessed September 29, 2020.

The 2020-2021 influenza season is shaping up to be challenging. Its likely concurrence with the ongoing severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus 2 (SARS-coV-2) pandemic (COVID-19) will pose diagnostic and therapeutic dilemmas and could overload the hospital system. But there could also be potential synergies in preventing morbidity and mortality from each disease.

A consistent pattern overthe past few influenza seasons

During the 2019-2020 flu season, there were an estimated 410,000 to 740,000 hospitalizations and 24,000 to 62,000 deaths attributed to influenza.1 As seen in FIGURE 1, office visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) began to increase in late November and early December in each of the last 3 years (2017-2018, 2018-2019, 2019-2020) and stayed elevated above baseline for about 4 months each season.1

The effectiveness of influenza vaccine during the 2019-2020 season is being estimated using the US Flu Vaccine Effectiveness Network, which has close to 9000 enrollees. Overall, it appears the vaccine was 39% effective against medically attended influenza, with a higher effectiveness against influenza B (44%) than against A/H1N1 (31%). Effectiveness against influenza B was similar in all age groups, but effectiveness against A/H1N1 was highest for those ages 50 to 64 years (45%) and lowest for those ages 6 months through 8 years (22%), although 95% confidence intervals overlapped for all age groups (FIGURE 2). These preliminary effectiveness rates were presented at the summer meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP).1

Influenza vaccine safety data for 2019-2020 were based on the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), a passive surveillance system, and on the Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD) system, an active surveillance system involving close to 6 million doses administered at VSD sites. No safety concerns were identified for any of the different vaccine types. Both the VAERS and VSD surveillance systems have been described in more detail in a previous Practice Alert.2

Recommendations for 2020-2021

The composition of the influenza vaccines for this year’s flu season will be different for 3 of the 4 antigens: A/H1N1, A/H2N2 and B/Victoria.3 The antigens included in the influenza vaccines each year are decided on in the spring, based on surveillance of circulating strains around the world. The effectiveness of the vaccine each year largely depends on how well the strains included in the vaccine match those circulating in the United States during the influenza season.

The main immunization recommendation for preventing morbidity and mortality from influenza has not changed: All individuals ages 6 months and older without a contraindication should receive an influenza vaccine.4 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that patients receive the vaccine by the end of October.4 This includes the second dose for those children younger than 9 years who need 2 doses—ie, those who have received fewer than 2 doses of influenza vaccine prior to July 2020. Vaccination should continue through the end of the season for anyone who has not received a 2020-2021 influenza vaccine.

Two new influenza vaccine products are available for use in those ages 65 years and older: Fluzone high-dose quadrivalent and Fluad Quadrivalent (adjuvanted).4 Both of these products were available last year as trivalent options. Currently no specific vaccine product is listed as preferred by ACIP for those ages 65 and older.

Continue to: New vaccine contraindications

New vaccine contraindications. Four medical conditions have been added to the list of contraindications for quadrivalent live, attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV4): cochlear implant, cerebrospinal fluid leak, asplenia (anatomic and functional), and sickle cell anemia.4 In addition, those who receive LAIV4 should not be prescribed an influenza antiviral until 2 weeks after receiving the vaccine. And the vaccine should not be administered for 48 hours after receipt of oseltamivir or zanamivir, 5 days after peramivir, and 17 days after baloxavir marboxil.4 This is to prevent possible antiviral inactivation of the live attenuated influenza viruses in the vaccine.

For those who have a history of severe allergic reaction to eggs, there are now 2 egg-free options: cell-culture-based inactivated vaccine (ccIIV4) and recombinant influenza vaccine (RIV4).3,4 Urticaria alone is not considered a severe reaction. If neither of these egg-free options is available, a vaccine may still be administered in a medical setting supervised by a provider who is able to manage a severe allergic reaction (which rarely occurs).

All vaccine products available for the upcoming influenza season are listed and described on the CDC Web site, as is a summary of related recommendations.4 Particular attention should be paid to the dose of vaccine administered, as it differs by product for those ages 6 through 35 months of age and those ages 65 years and older.

Use of antiviral medications

Four antiviral medications are now available for treating influenza (3 neuraminidase inhibitors and 1 endonuclease inhibitor), and there are 2 agents for preventing influenza, both neuraminidase inhibitors (TABLE 1).5 The CDC recommends treating with antivirals as soon as possible if individuals with confirmed or suspected influenza require hospitalization; have severe, complicated, or progressive illness; or are at high risk for complications. Use antivirals based on clinical judgment if previously healthy individuals do not have severe complications and are not at increased risk for complications, and only if the medication can be started within 48 hours of symptom onset.

The CDC discourages widespread use of antivirals to prevent influenza, either pre- or postexposure, although it specifies certain situations in which usage would be acceptable (TABLE 2).5 There is some concern that widespread use could lead to the emergence of drug-resistant strains and that using postexposure dosing could lead to suboptimal treatment if influenza infection occurred before the start of prophylaxis. If postexposure antivirals are prescribed, they should be started within 48 hours of exposure and continued for 7 days after the last exposure.

Continue to: A potential perfect storm

A potential perfect storm: Concurrence of influenza and SARS-coV-19

While we have vaccines and antivirals to prevent influenza, and have effective antivirals for treatment, no prevention or treatment options exist for COVID-19, except, possibly, dexamethasone to reduce mortality among those seriously ill.6 The concurrence of influenza and COVID-19 will present unique challenges for the health care system.

Action steps. Keep abreast of the incidences of circulating SARS-coV-19 and influenza viruses in your community. The similar signs and symptoms of these 2 infectious agents will complicate diagnosis. Rapid, or point-of-care, tests for influenza are widely available, but their accuracy varies and not all tests detect both influenza A and B. The CDC lists approved point-of-care tests at www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/diagnosis/table-ridt.html and advises on how to interpret these test results when influenza is and is not circulating in the community, at www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/diagnosis/clinician_guidance_ridt.htm.

Clinical practice advice for both conditions should be implemented when any patient presents with ILI:7

- Most patients who are not seriously ill and have no conditions that place them at high risk for adverse outcomes can be treated symptomatically at home.

- Those with ILI should be tested for both influenza virus and SARS-CoV-2 if testing is available. It is possible to be co-infected.

- Sick patients should self-isolate at home for the duration of their symptoms.

- If others live in the house, the sick person should stay in a separate room and wear a mask. Everyone in the house should cover coughs and sneezes (if not wearing a mask), dispose of used tissues in a trash can (rather than leaving them on night stands and countertops), and wash hands frequently.

- All household members should be vaccinated against influenza. Those who are unvaccinated, and those at high risk who have been recently vaccinated, can consider influenza antiviral prophylaxis. If the sick family member is confirmed to have COVID-19, with no co-existing influenza, anti-influenza antiviral prophylaxis may be discontinued.

- Clinical infection control practices should be the same for anyone presenting with ILI.7 Enhanced clinic-based infection control practices to prevent spread of SARS-CoV-2 are listed in TABLE 3.8

Since there currently are no preventive medications proven to work for COVID-19, the main clinical decision physicians will have to make when a patient presents with ILI is whether to use antivirals to treat those who are at risk for complications based on the result of rapid, on-site influenza testing, or clinical presentation, or both. In this situation, knowledge of which viruses are circulating at high rates in the community could be valuable.

Milder season or perfect storm? The society-wide interventions that have been encouraged (although not mandated everywhere) to prevent community spread of SARS-CoV-2 should help prevent the community spread of influenza as well, and, if adhered to, may lead to a milder influenza season than would otherwise have occurred. However, given the uncertainties, the combination of influenza and coronavirus could present a perfect storm for the health care system and result in higher-than-normal morbidity and mortality from ILI and pneumonia overall.

Continue to: The possibility that one or more vaccines...

The possibility that one or more vaccines to prevent COVID-19 may be available in late 2020 or early 2021 offers hope. However, in current testing, the vaccine is not being given simultaneously with the influenza vaccine. If the potential for adverse interaction exists between the vaccines, it is important that influenza vaccine be given by mid- to late-October to avoid such an interaction if and when the new SARS-CoV-2 vaccine becomes available. Individuals who have symptoms of COVID-19 should not be vaccinated with influenza vaccine until they are considered noninfectious.

Encourage influenza vaccination. The COVID-19 pandemic may make it difficult to achieve desired community influenza vaccine levels because of decreased visits to medical facilities for preventive care, possible lower insurance coverage due to loss of employment, and a decrease in worksite mass vaccination programs. This makes it important for family physicians to encourage and offer influenza vaccines at their clinical sites.

Several evidence-based practices have been shown to improve vaccine uptake. Examples of such practices include patient reminder and recall systems that provide feedback to clinicians about rates of vaccination among patients, and establishing standing orders for vaccine administration that allow other health care providers to assess a patient’s immunization status and administer vaccinations according to a protocol.9 Finally, the CDC provides a video on how to recommend influenza vaccine to those who may be resistant (www.cdc.gov/vaccines/howirecommend/adult-vacc-videos.html).

SIDEBAR

CDC influenza resources

Point-of-care tests that detect both influenza A and B viruses approved by the CDC

www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/diagnosis/table-ridt.html

Advice on how to interpret the test results

www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/diagnosis/clinician_guidance_ridt.htm

How to recommend influenza vaccine to reluctant patients

www.cdc.gov/vaccines/howirecommend/adult-vacc-videos.html

CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The 2020-2021 influenza season is shaping up to be challenging. Its likely concurrence with the ongoing severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus 2 (SARS-coV-2) pandemic (COVID-19) will pose diagnostic and therapeutic dilemmas and could overload the hospital system. But there could also be potential synergies in preventing morbidity and mortality from each disease.

A consistent pattern overthe past few influenza seasons

During the 2019-2020 flu season, there were an estimated 410,000 to 740,000 hospitalizations and 24,000 to 62,000 deaths attributed to influenza.1 As seen in FIGURE 1, office visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) began to increase in late November and early December in each of the last 3 years (2017-2018, 2018-2019, 2019-2020) and stayed elevated above baseline for about 4 months each season.1

The effectiveness of influenza vaccine during the 2019-2020 season is being estimated using the US Flu Vaccine Effectiveness Network, which has close to 9000 enrollees. Overall, it appears the vaccine was 39% effective against medically attended influenza, with a higher effectiveness against influenza B (44%) than against A/H1N1 (31%). Effectiveness against influenza B was similar in all age groups, but effectiveness against A/H1N1 was highest for those ages 50 to 64 years (45%) and lowest for those ages 6 months through 8 years (22%), although 95% confidence intervals overlapped for all age groups (FIGURE 2). These preliminary effectiveness rates were presented at the summer meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP).1

Influenza vaccine safety data for 2019-2020 were based on the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), a passive surveillance system, and on the Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD) system, an active surveillance system involving close to 6 million doses administered at VSD sites. No safety concerns were identified for any of the different vaccine types. Both the VAERS and VSD surveillance systems have been described in more detail in a previous Practice Alert.2

Recommendations for 2020-2021

The composition of the influenza vaccines for this year’s flu season will be different for 3 of the 4 antigens: A/H1N1, A/H2N2 and B/Victoria.3 The antigens included in the influenza vaccines each year are decided on in the spring, based on surveillance of circulating strains around the world. The effectiveness of the vaccine each year largely depends on how well the strains included in the vaccine match those circulating in the United States during the influenza season.

The main immunization recommendation for preventing morbidity and mortality from influenza has not changed: All individuals ages 6 months and older without a contraindication should receive an influenza vaccine.4 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that patients receive the vaccine by the end of October.4 This includes the second dose for those children younger than 9 years who need 2 doses—ie, those who have received fewer than 2 doses of influenza vaccine prior to July 2020. Vaccination should continue through the end of the season for anyone who has not received a 2020-2021 influenza vaccine.

Two new influenza vaccine products are available for use in those ages 65 years and older: Fluzone high-dose quadrivalent and Fluad Quadrivalent (adjuvanted).4 Both of these products were available last year as trivalent options. Currently no specific vaccine product is listed as preferred by ACIP for those ages 65 and older.

Continue to: New vaccine contraindications

New vaccine contraindications. Four medical conditions have been added to the list of contraindications for quadrivalent live, attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV4): cochlear implant, cerebrospinal fluid leak, asplenia (anatomic and functional), and sickle cell anemia.4 In addition, those who receive LAIV4 should not be prescribed an influenza antiviral until 2 weeks after receiving the vaccine. And the vaccine should not be administered for 48 hours after receipt of oseltamivir or zanamivir, 5 days after peramivir, and 17 days after baloxavir marboxil.4 This is to prevent possible antiviral inactivation of the live attenuated influenza viruses in the vaccine.

For those who have a history of severe allergic reaction to eggs, there are now 2 egg-free options: cell-culture-based inactivated vaccine (ccIIV4) and recombinant influenza vaccine (RIV4).3,4 Urticaria alone is not considered a severe reaction. If neither of these egg-free options is available, a vaccine may still be administered in a medical setting supervised by a provider who is able to manage a severe allergic reaction (which rarely occurs).

All vaccine products available for the upcoming influenza season are listed and described on the CDC Web site, as is a summary of related recommendations.4 Particular attention should be paid to the dose of vaccine administered, as it differs by product for those ages 6 through 35 months of age and those ages 65 years and older.

Use of antiviral medications

Four antiviral medications are now available for treating influenza (3 neuraminidase inhibitors and 1 endonuclease inhibitor), and there are 2 agents for preventing influenza, both neuraminidase inhibitors (TABLE 1).5 The CDC recommends treating with antivirals as soon as possible if individuals with confirmed or suspected influenza require hospitalization; have severe, complicated, or progressive illness; or are at high risk for complications. Use antivirals based on clinical judgment if previously healthy individuals do not have severe complications and are not at increased risk for complications, and only if the medication can be started within 48 hours of symptom onset.

The CDC discourages widespread use of antivirals to prevent influenza, either pre- or postexposure, although it specifies certain situations in which usage would be acceptable (TABLE 2).5 There is some concern that widespread use could lead to the emergence of drug-resistant strains and that using postexposure dosing could lead to suboptimal treatment if influenza infection occurred before the start of prophylaxis. If postexposure antivirals are prescribed, they should be started within 48 hours of exposure and continued for 7 days after the last exposure.

Continue to: A potential perfect storm

A potential perfect storm: Concurrence of influenza and SARS-coV-19

While we have vaccines and antivirals to prevent influenza, and have effective antivirals for treatment, no prevention or treatment options exist for COVID-19, except, possibly, dexamethasone to reduce mortality among those seriously ill.6 The concurrence of influenza and COVID-19 will present unique challenges for the health care system.

Action steps. Keep abreast of the incidences of circulating SARS-coV-19 and influenza viruses in your community. The similar signs and symptoms of these 2 infectious agents will complicate diagnosis. Rapid, or point-of-care, tests for influenza are widely available, but their accuracy varies and not all tests detect both influenza A and B. The CDC lists approved point-of-care tests at www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/diagnosis/table-ridt.html and advises on how to interpret these test results when influenza is and is not circulating in the community, at www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/diagnosis/clinician_guidance_ridt.htm.

Clinical practice advice for both conditions should be implemented when any patient presents with ILI:7

- Most patients who are not seriously ill and have no conditions that place them at high risk for adverse outcomes can be treated symptomatically at home.

- Those with ILI should be tested for both influenza virus and SARS-CoV-2 if testing is available. It is possible to be co-infected.

- Sick patients should self-isolate at home for the duration of their symptoms.

- If others live in the house, the sick person should stay in a separate room and wear a mask. Everyone in the house should cover coughs and sneezes (if not wearing a mask), dispose of used tissues in a trash can (rather than leaving them on night stands and countertops), and wash hands frequently.

- All household members should be vaccinated against influenza. Those who are unvaccinated, and those at high risk who have been recently vaccinated, can consider influenza antiviral prophylaxis. If the sick family member is confirmed to have COVID-19, with no co-existing influenza, anti-influenza antiviral prophylaxis may be discontinued.

- Clinical infection control practices should be the same for anyone presenting with ILI.7 Enhanced clinic-based infection control practices to prevent spread of SARS-CoV-2 are listed in TABLE 3.8

Since there currently are no preventive medications proven to work for COVID-19, the main clinical decision physicians will have to make when a patient presents with ILI is whether to use antivirals to treat those who are at risk for complications based on the result of rapid, on-site influenza testing, or clinical presentation, or both. In this situation, knowledge of which viruses are circulating at high rates in the community could be valuable.

Milder season or perfect storm? The society-wide interventions that have been encouraged (although not mandated everywhere) to prevent community spread of SARS-CoV-2 should help prevent the community spread of influenza as well, and, if adhered to, may lead to a milder influenza season than would otherwise have occurred. However, given the uncertainties, the combination of influenza and coronavirus could present a perfect storm for the health care system and result in higher-than-normal morbidity and mortality from ILI and pneumonia overall.

Continue to: The possibility that one or more vaccines...

The possibility that one or more vaccines to prevent COVID-19 may be available in late 2020 or early 2021 offers hope. However, in current testing, the vaccine is not being given simultaneously with the influenza vaccine. If the potential for adverse interaction exists between the vaccines, it is important that influenza vaccine be given by mid- to late-October to avoid such an interaction if and when the new SARS-CoV-2 vaccine becomes available. Individuals who have symptoms of COVID-19 should not be vaccinated with influenza vaccine until they are considered noninfectious.

Encourage influenza vaccination. The COVID-19 pandemic may make it difficult to achieve desired community influenza vaccine levels because of decreased visits to medical facilities for preventive care, possible lower insurance coverage due to loss of employment, and a decrease in worksite mass vaccination programs. This makes it important for family physicians to encourage and offer influenza vaccines at their clinical sites.

Several evidence-based practices have been shown to improve vaccine uptake. Examples of such practices include patient reminder and recall systems that provide feedback to clinicians about rates of vaccination among patients, and establishing standing orders for vaccine administration that allow other health care providers to assess a patient’s immunization status and administer vaccinations according to a protocol.9 Finally, the CDC provides a video on how to recommend influenza vaccine to those who may be resistant (www.cdc.gov/vaccines/howirecommend/adult-vacc-videos.html).

SIDEBAR

CDC influenza resources

Point-of-care tests that detect both influenza A and B viruses approved by the CDC

www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/diagnosis/table-ridt.html

Advice on how to interpret the test results

www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/diagnosis/clinician_guidance_ridt.htm

How to recommend influenza vaccine to reluctant patients

www.cdc.gov/vaccines/howirecommend/adult-vacc-videos.html

CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

1. Grohskopf L. Influenza work groups: updates, considerations, and proposed recommendations for the 2020-2021 season. Presented at the ACIP meeting June 24, 2020. www.youtube.com/watch?v=W1SV2DSJsaQ&list=PLvrp9iOILTQb6D9e1YZWpbUvzfptNMKx2&index=8&t=0s. [Time stamp: 1:26:48] Accessed Septemeber 29, 2020.

2. Campos-Outcalt D. Facts to help you keep pace with the vaccine conversation. J Fam Pract. 2019;68:341-346.

3. Grohskopf L, Alyanak E, Broder KR, et al. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2020-21 Influenza Season. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2020;69:1-24.

4. Prevention and Control of Seasonal Influenza with Vaccines: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP)—United States, 2020-21 Summary of Recommendations. www.cdc.gov/flu/pdf/professionals/acip/acip-2020-21-summary-of-recommendations.pdf. Accessed September 29, 2020.

5. CDC. Influenza antiviral medications: summary for clinicians. www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/antivirals/summary-clinicians.htm. Accessed September 29, 2020.

6. NIH. COVID-19 treatment guidelines. Corticosteroids. www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/immune-based-therapy/immunomodulators/corticosteroids/. Accessed September 29, 2020.

7. CDC. Infection control. www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/. Accessed September 29, 2020.

8. CDC. Interim infection prevention and control recommendations for healthcare personnel during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/infection-control.html. Accessed September 29, 2020.

9. HHS. CPSTF findings for increasing vaccination. www.thecommunityguide.org/content/task-force-findings-increasing-vaccination. Accessed September 29, 2020.

1. Grohskopf L. Influenza work groups: updates, considerations, and proposed recommendations for the 2020-2021 season. Presented at the ACIP meeting June 24, 2020. www.youtube.com/watch?v=W1SV2DSJsaQ&list=PLvrp9iOILTQb6D9e1YZWpbUvzfptNMKx2&index=8&t=0s. [Time stamp: 1:26:48] Accessed Septemeber 29, 2020.

2. Campos-Outcalt D. Facts to help you keep pace with the vaccine conversation. J Fam Pract. 2019;68:341-346.

3. Grohskopf L, Alyanak E, Broder KR, et al. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2020-21 Influenza Season. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2020;69:1-24.

4. Prevention and Control of Seasonal Influenza with Vaccines: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP)—United States, 2020-21 Summary of Recommendations. www.cdc.gov/flu/pdf/professionals/acip/acip-2020-21-summary-of-recommendations.pdf. Accessed September 29, 2020.

5. CDC. Influenza antiviral medications: summary for clinicians. www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/antivirals/summary-clinicians.htm. Accessed September 29, 2020.

6. NIH. COVID-19 treatment guidelines. Corticosteroids. www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/immune-based-therapy/immunomodulators/corticosteroids/. Accessed September 29, 2020.

7. CDC. Infection control. www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/. Accessed September 29, 2020.

8. CDC. Interim infection prevention and control recommendations for healthcare personnel during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/infection-control.html. Accessed September 29, 2020.

9. HHS. CPSTF findings for increasing vaccination. www.thecommunityguide.org/content/task-force-findings-increasing-vaccination. Accessed September 29, 2020.

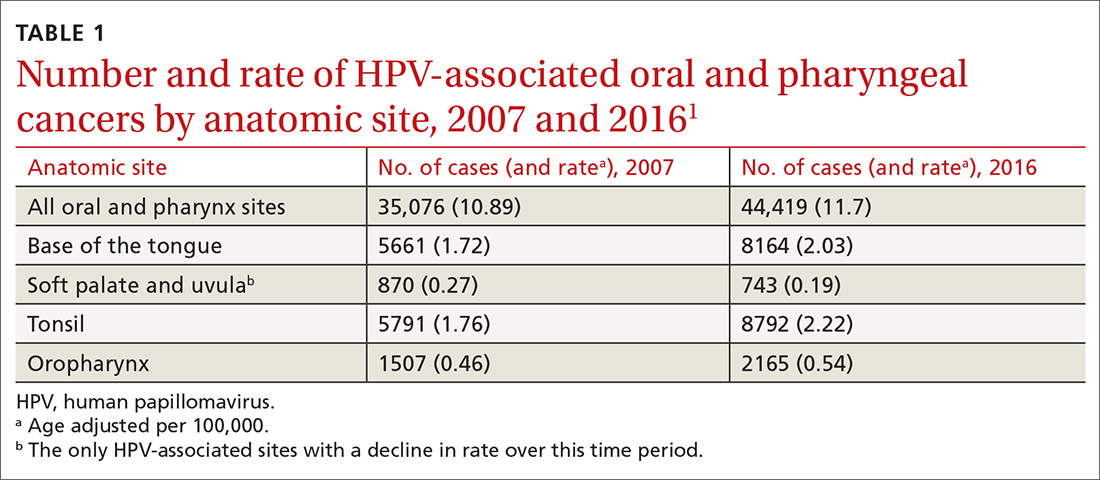

Taking steps to slow the upswing in oral and pharyngeal cancers

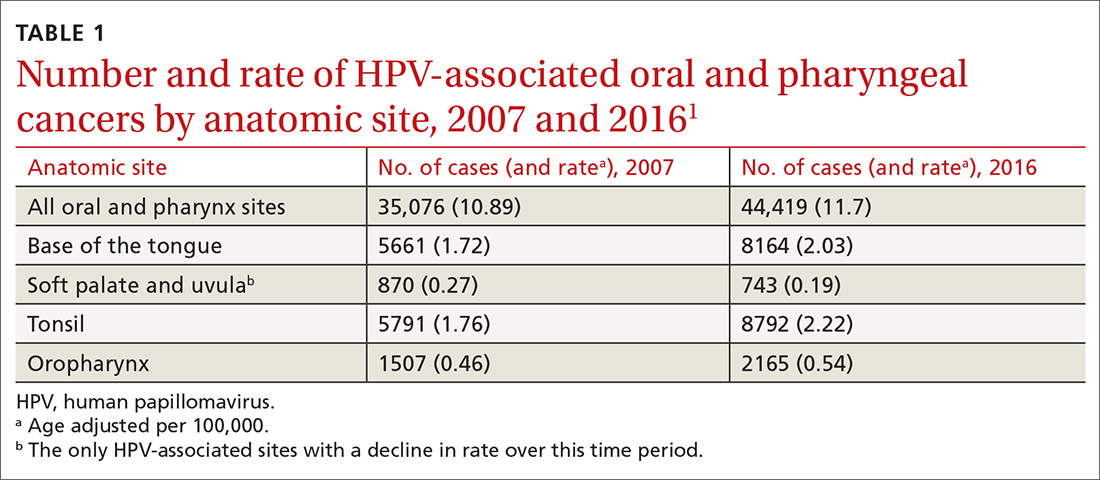

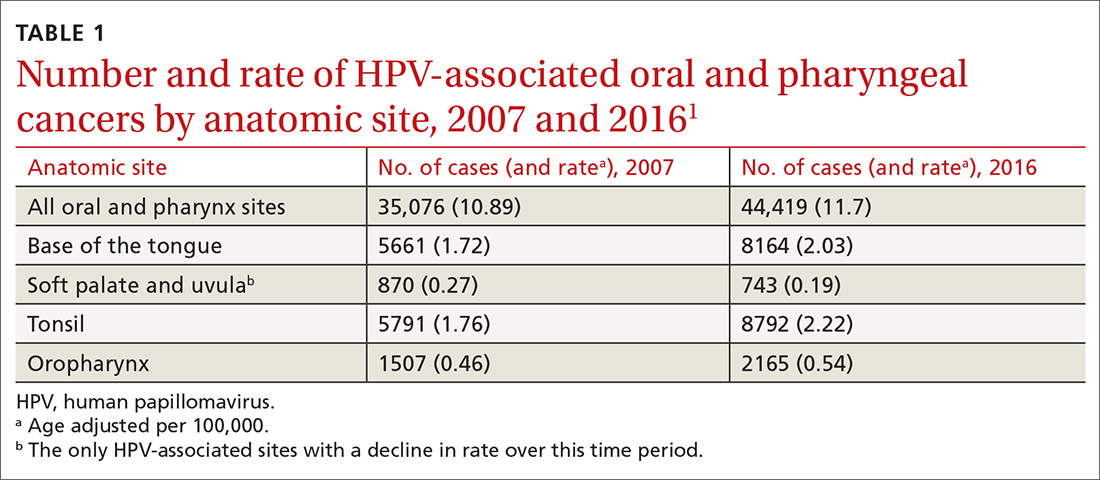

A recent report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) documents the trends in oral and pharyngeal cancers (OPC) in the United States over a 10-year period, 2007-2016.1 The rate of OPC began to increase in 1999 and has been increasing ever since. The age-adjusted rate in 2007 was 10.89/100,000 compared with 11.7/100,000 in 2016 (TABLE 11). This is an annual relative increase of about 6% per year. In absolute numbers, there were 35,076 cases in 2007 and 44,419 in 2016.1 The trends in incidence of OPC vary by anatomical site, with some increasing and others declining.

There are 3 known causal factors related to OPC: tobacco use, alcohol use, and human papillomavirus (HPV) infection. The CDC estimates that, overall, 70% of OPCs are caused by HPV.2 However, while cancers at some oropharyngeal sites are likely related to HPV infection, cancers at other sites are not. The rising overall incidence of OPC is being driven by increases in HPV-related cancers at an average rate of 2.1% per year, while the rates at non-HPV-associated sites have been declining by 0.4% per year.1 It is also important to appreciate that HPV causes cancer at other anatomical sites (TABLE 22) and is responsible for an estimated 35,000 cancers per year.2

Other trends of note in all OPCs combined are increasing rates among non-Hispanic whites and Asian-Pacific Islanders; decreasing rates among Hispanics and African Americans; increasing rates among males with no real change in rates among females; increasing rates in those 50 to 79 years of age; decreasing rates among those 40 to 49 years of age; and unchanged rates in other age groups.1

The role of the family physician

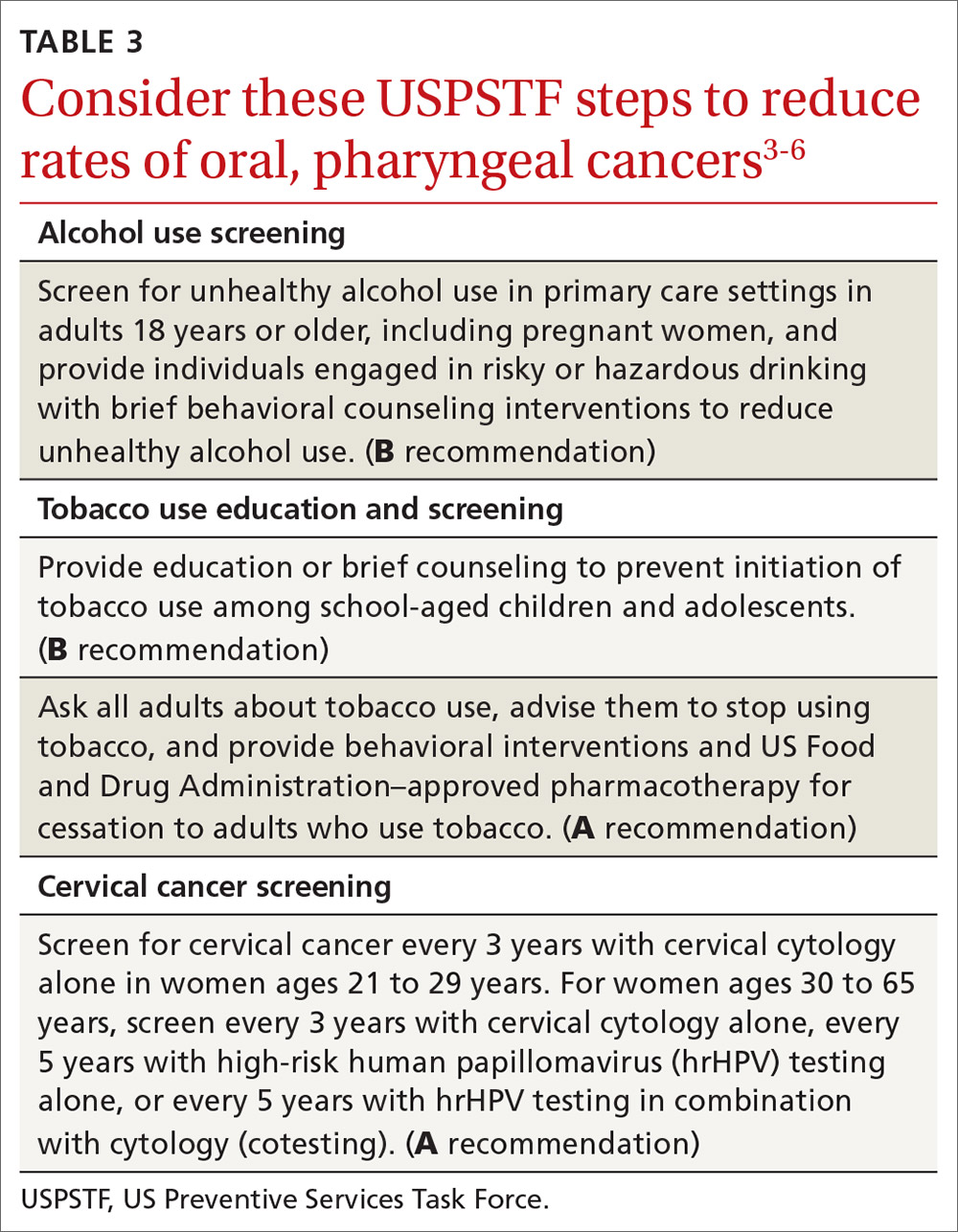

Preventing OPC and all HPV-related cancers begins by encouraging patients to reduce alcohol and tobacco use and by emphasizing the importance of HPV vaccination. Educate teens and parents/guardians about HPV vaccine and its safety. Screen for tobacco and alcohol use, and offer brief clinical interventions as needed to decrease usage.

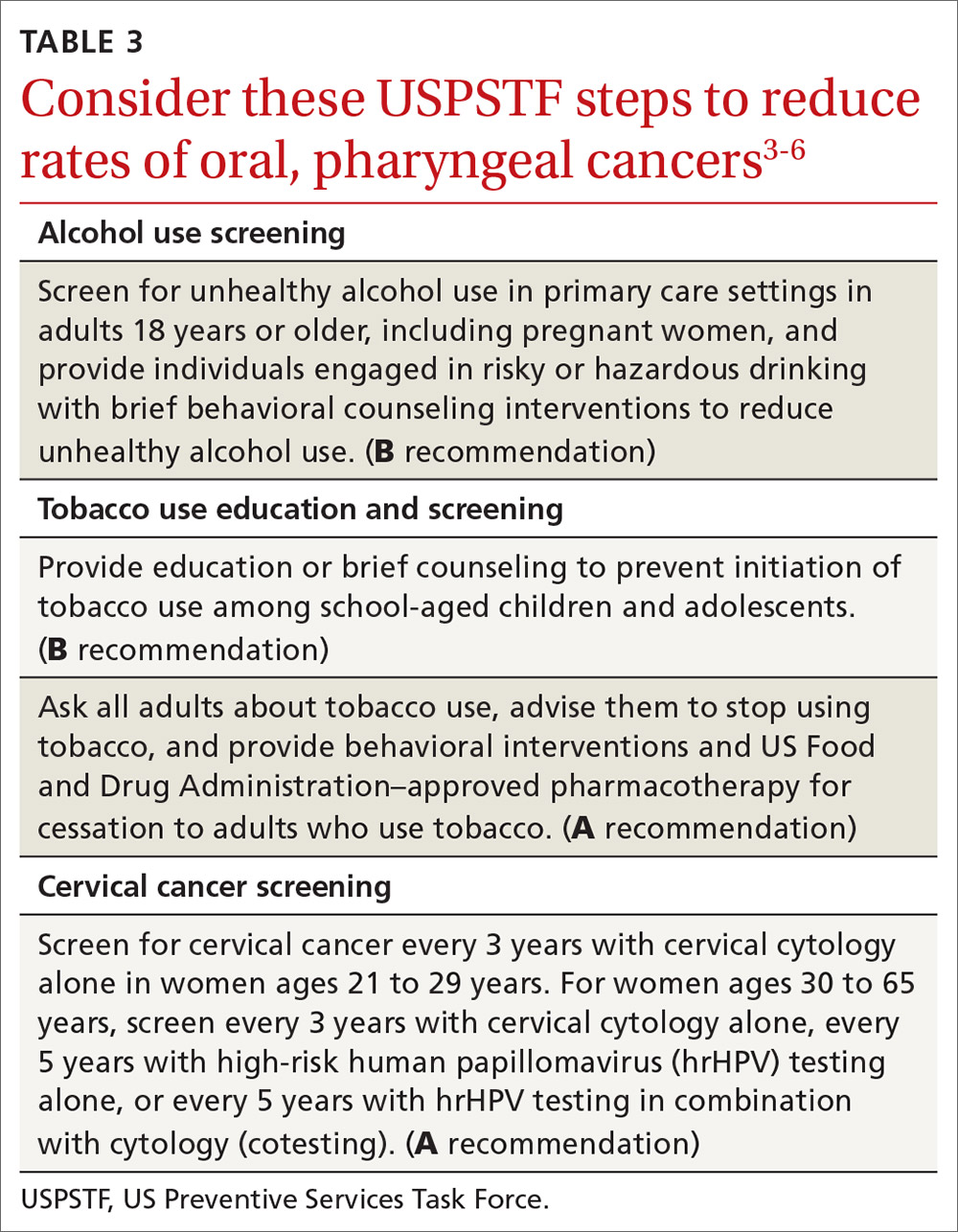

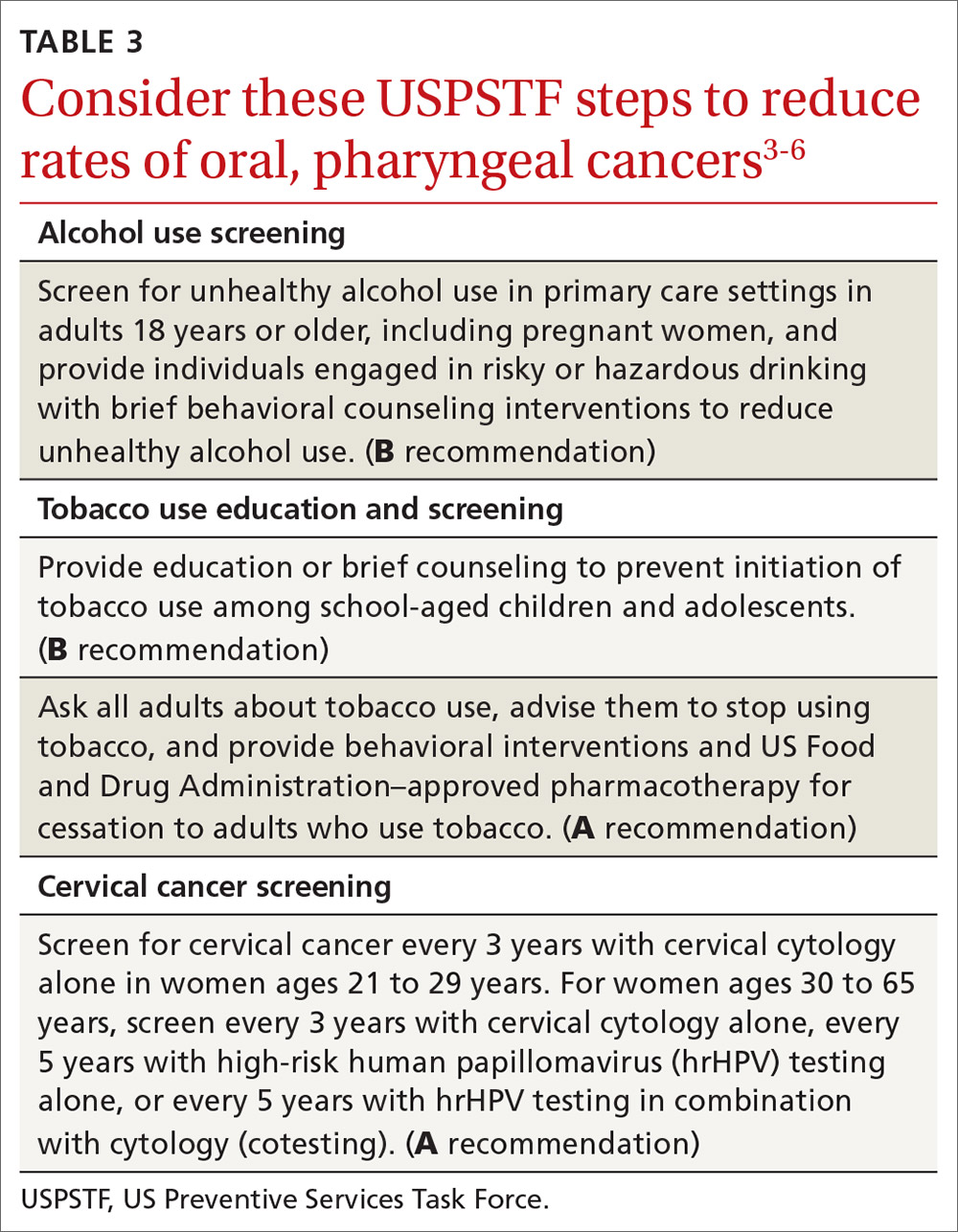

Recommendations by the US Preventive Services Task Force regarding screening for, and reducing use of, tobacco and alcohol, as well as screening for cervical cancer, are listed in TABLE 3.3-6 Remember that cervical cancer screening is both a primary and secondary intervention: It can reduce mortality by preventing cervical cancer (via treatment of precancerous lesions) and by detecting cervical cancer early at more treatable stages.

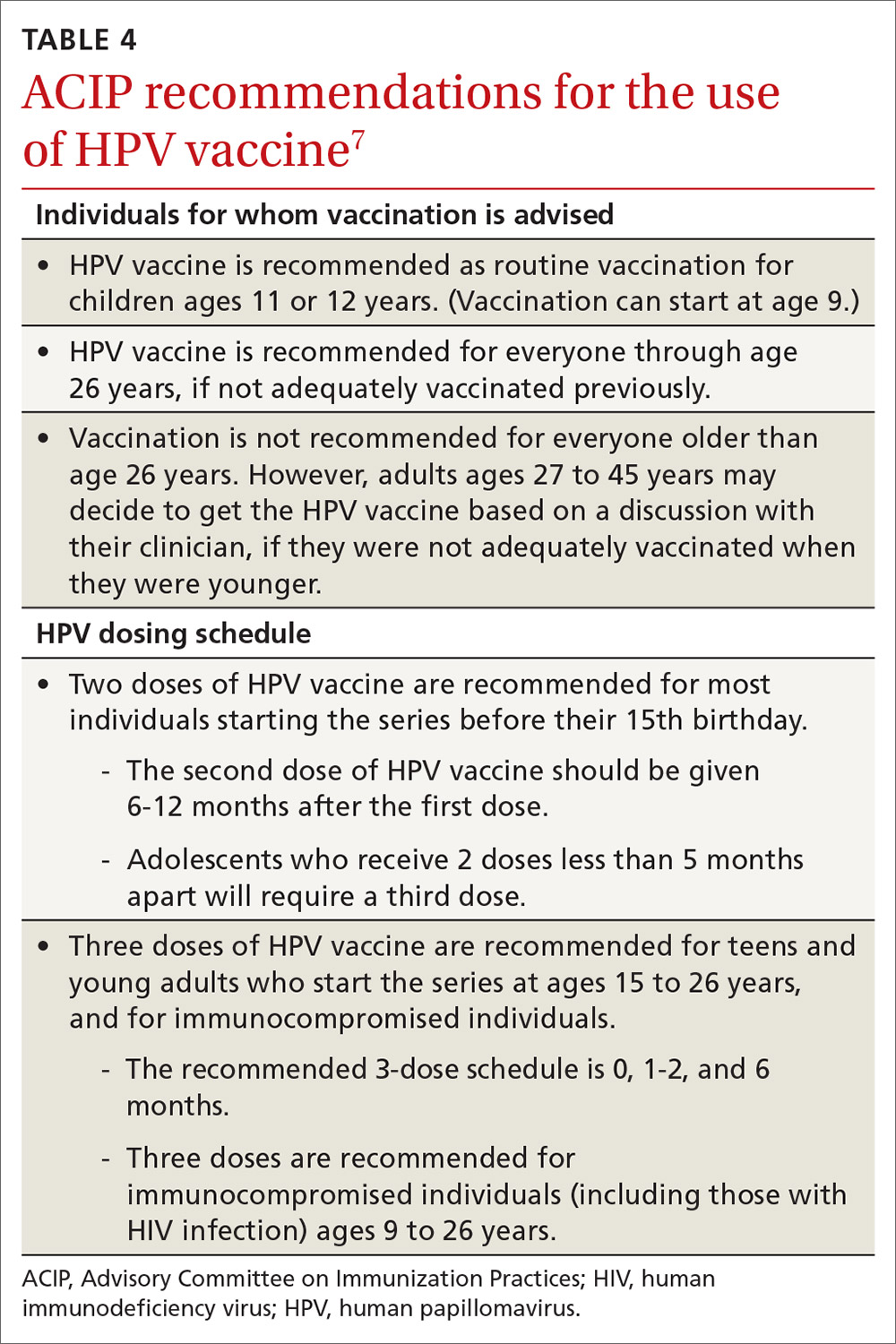

HPV vaccination essentials. CDC recommendations for the use of HPV vaccine and the vaccine dosing schedule appear in TABLE 4.7 While it is true that the best evidence for HPV vaccine’s prevention of cancer comes from the study of cervical and anal cancers, it is reasonable to expect that it will also be proven over time to prevent other HPV-caused cancers as the rate of HPV infections declines.

HPV vaccine is underused. In a 2018 survey, only 68.1% of adolescents had received 1 or more doses of HPV vaccine, and only 51.1% were up to date.8 In contrast, 86.6% had received 1 or more doses of quadrivalent meningococcal vaccine; 88.9% had received 1 or more doses of tetanus, diphtheria & acellular pertussis vaccine; 91.9% were up to date with 2 or more doses of measles, mumps & rubella vaccine; and 92.1% were up to date with hepatitis B vaccine, with 3 or more doses.8

Continue to: Address parental concerns, including these 5 false beliefs

Address parental concerns, including these 5 false beliefs

One study found 5 major false beliefs parents hold about HPV vaccine9:

- Vaccination is not effective at preventing cancer.

- Pap smears are sufficient to prevent cervical cancer.

- HPV vaccination is not safe.

- HPV vaccination is not needed since most infections are naturally cleared by the immune system.

- Eleven to 12 years of age is too young to vaccinate.

There is some evidence that if clinicians actively engage with parents about these concerns and address them head on, same-day vaccination rates can improve.10

We can expect to see HPV-associated OPC decline in the coming years due to the delayed effects on cancer incidence by the HPV vaccine. These anticipated declines will be more dramatic if we can increase the uptake of the HPV vaccine.

1. Ellington TD, Henley SJ, Senkomago V, et al. Trends in the incidence of cancers of the oral cavity and pharynx—United States 2007-2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:433-438.

2. CDC. HPV and cancer. 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/statistics/cases.htm. Accessed June 29, 2020.

3. USPSTF. Unhealthy alcohol use in adolescents and adults: screening and behavioral counseling interventions. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/unhealthy-alcohol-use-in-adolescents-and-adults-screening-and-behavioral-counseling-interventions. Accessed June 29, 2020.

4. USPSTF. Prevention and cessation of tobacco use in children and adolescents: primary care interventions. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/tobacco-and-nicotine-use-prevention-in-children-and-adolescents-primary-care-interventions. Accessed June 29, 2020.

5. USPSTF. Tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant women: behavioral and pharmacotherapy interventions. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/tobacco-use-in-adults-and-pregnant-women-counseling-and-interventions. Accessed June 29, 2020.

6. USPSTF. Cervical cancer: screening. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/cervical-cancer-screening. Accessed June 29, 2020.

7. CDC. Vaccines and preventable diseases. HPV vaccine recommendations. 2020. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/hpv/hcp/recommendations.html. Accessed June 29, 2020.

8. Walker TY, Elam-Evans LD, Yankey D, et al. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13-17 years-United States, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019:68:718-723.

9. Bednarczyk RA. Addressing HPV vaccine myths: practical information for healthcare providers. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15:1628-1638.

10. Shay LA, Baldwin AS, Betts AC, et al. Parent-provider communication of HPV vaccine hesitancy. Pediatrics 2018;141:e20172312.