User login

House bill would allow corrective action plan for DEA violators

A new bill aims to clarify the rules of the Controlled Substances Act to ensure that legitimate operators stay in business and patients get needed medication, according to congressional backers of the bill, which was approved by the House of Representatives on July 29.

The bill still has to be taken up by the Senate, where there is no companion legislation.

The Ensuring Patient Access and Effective Drug Enforcement Act of 2014 (H.R. 4709) would ensure that restrictions on distribution of controlled substances are not so onerous as to inhibit access for patients, would require the U.S. Attorney General to give DEA registrant pharmacies and physicians who violate the rules an opportunity to submit a corrective action plan that might defer suspension of their registration, and would establish a working group to make recommendations to Congress on federal policies to reduce prescription drug diversion and abuse.

These measures are among the major policy goals of the Alliance to Prevent the Abuse of Medicines. The Washington, D.C.–based group includes among its members the American Medical Association, Cardinal Health, CVS Caremark, the Health Industry Distributors Association, and Teva.

The National Association of Chain Drug Stores "and chain pharmacy are committed to partnering with federal and state agencies, law enforcement personnel, policymakers, and other stakeholders to work on viable strategies to simultaneously advance patient health and prevent prescription drug abuse," NACDS President and CEO Steven C. Anderson, said in a statement regarding the bill.

Rep. Marsha Blackburn (R-Tenn.), a cosponsor of the bill, said in a statement that simply acknowledging the epidemic of prescription drug abuse isn’t enough. "Congress has a responsibility to make sure the law is crystal clear for both the DEA and legitimate businesses who want to understand what the rules are so they can do the right thing."

In House testimony last April, DEA Deputy Assistant Administrator Joseph Rannazzisi said the agency’s job is getting tougher. The number of registrants that the DEA regulates has mushroomed from 480,000 in 1973 to 1.5 million today, he said. At the same time, diversion and abuse have risen steeply, with opioids selling on the black market for 5-10 times their retail value.

In the last 3 years, the DEA’s Tactical Diversion Squads have increased from 37 to 66, and the agency has been applying its stiffest penalty – an immediate suspension order – in a judicious manner, according to Mr. Rannazzisi. From October 2013 through March 2014, 20 suspensions were ordered.

On Twitter @aliciaault

A new bill aims to clarify the rules of the Controlled Substances Act to ensure that legitimate operators stay in business and patients get needed medication, according to congressional backers of the bill, which was approved by the House of Representatives on July 29.

The bill still has to be taken up by the Senate, where there is no companion legislation.

The Ensuring Patient Access and Effective Drug Enforcement Act of 2014 (H.R. 4709) would ensure that restrictions on distribution of controlled substances are not so onerous as to inhibit access for patients, would require the U.S. Attorney General to give DEA registrant pharmacies and physicians who violate the rules an opportunity to submit a corrective action plan that might defer suspension of their registration, and would establish a working group to make recommendations to Congress on federal policies to reduce prescription drug diversion and abuse.

These measures are among the major policy goals of the Alliance to Prevent the Abuse of Medicines. The Washington, D.C.–based group includes among its members the American Medical Association, Cardinal Health, CVS Caremark, the Health Industry Distributors Association, and Teva.

The National Association of Chain Drug Stores "and chain pharmacy are committed to partnering with federal and state agencies, law enforcement personnel, policymakers, and other stakeholders to work on viable strategies to simultaneously advance patient health and prevent prescription drug abuse," NACDS President and CEO Steven C. Anderson, said in a statement regarding the bill.

Rep. Marsha Blackburn (R-Tenn.), a cosponsor of the bill, said in a statement that simply acknowledging the epidemic of prescription drug abuse isn’t enough. "Congress has a responsibility to make sure the law is crystal clear for both the DEA and legitimate businesses who want to understand what the rules are so they can do the right thing."

In House testimony last April, DEA Deputy Assistant Administrator Joseph Rannazzisi said the agency’s job is getting tougher. The number of registrants that the DEA regulates has mushroomed from 480,000 in 1973 to 1.5 million today, he said. At the same time, diversion and abuse have risen steeply, with opioids selling on the black market for 5-10 times their retail value.

In the last 3 years, the DEA’s Tactical Diversion Squads have increased from 37 to 66, and the agency has been applying its stiffest penalty – an immediate suspension order – in a judicious manner, according to Mr. Rannazzisi. From October 2013 through March 2014, 20 suspensions were ordered.

On Twitter @aliciaault

A new bill aims to clarify the rules of the Controlled Substances Act to ensure that legitimate operators stay in business and patients get needed medication, according to congressional backers of the bill, which was approved by the House of Representatives on July 29.

The bill still has to be taken up by the Senate, where there is no companion legislation.

The Ensuring Patient Access and Effective Drug Enforcement Act of 2014 (H.R. 4709) would ensure that restrictions on distribution of controlled substances are not so onerous as to inhibit access for patients, would require the U.S. Attorney General to give DEA registrant pharmacies and physicians who violate the rules an opportunity to submit a corrective action plan that might defer suspension of their registration, and would establish a working group to make recommendations to Congress on federal policies to reduce prescription drug diversion and abuse.

These measures are among the major policy goals of the Alliance to Prevent the Abuse of Medicines. The Washington, D.C.–based group includes among its members the American Medical Association, Cardinal Health, CVS Caremark, the Health Industry Distributors Association, and Teva.

The National Association of Chain Drug Stores "and chain pharmacy are committed to partnering with federal and state agencies, law enforcement personnel, policymakers, and other stakeholders to work on viable strategies to simultaneously advance patient health and prevent prescription drug abuse," NACDS President and CEO Steven C. Anderson, said in a statement regarding the bill.

Rep. Marsha Blackburn (R-Tenn.), a cosponsor of the bill, said in a statement that simply acknowledging the epidemic of prescription drug abuse isn’t enough. "Congress has a responsibility to make sure the law is crystal clear for both the DEA and legitimate businesses who want to understand what the rules are so they can do the right thing."

In House testimony last April, DEA Deputy Assistant Administrator Joseph Rannazzisi said the agency’s job is getting tougher. The number of registrants that the DEA regulates has mushroomed from 480,000 in 1973 to 1.5 million today, he said. At the same time, diversion and abuse have risen steeply, with opioids selling on the black market for 5-10 times their retail value.

In the last 3 years, the DEA’s Tactical Diversion Squads have increased from 37 to 66, and the agency has been applying its stiffest penalty – an immediate suspension order – in a judicious manner, according to Mr. Rannazzisi. From October 2013 through March 2014, 20 suspensions were ordered.

On Twitter @aliciaault

Hearing Impaired Have Fewer Barriers to Healthcare Careers

Since 2008, the American Community Survey, conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau, has queried respondents regarding deafness or hearing difficulties. According to these data, about 3.5% of the U.S. population has serious difficulty hearing. Other estimates vary, putting the number higher, especially those that include the numbers of elderly who experience hearing difficulties.

People who are deaf and hard of hearing (DHoH) work in diverse areas of the healthcare field, according to Samuel Atcherson, PhD, associate professor of audiology at the University of Arkansas in Little Rock and registry co-chair for the Association of Medical Professionals with Hearing Losses (www.amphl.org). AMPHL does not have statistics to report on the numbers of DHoH individuals practicing in medical occupations, but Dr. Atcherson noted that, as of 2011, there were 55 physicians, 41 nurses, and eight physician assistants in the membership.

Dr. Moreland and co-authors recently published a national survey that queried deaf physicians and trainees on a variety of subjects (e.g. career satisfaction, satisfaction with education, workplace accommodations). Due to the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, more people with hearing impairments are entering healthcare professions. Technological advances, such as electronic stethoscopes, also contribute to this surge.

The authors found that DHoH physicians and trainees responding to their survey were satisfied with multimodal employment and educational accommodations. Based on these results, they surmise, there might be an opportunity to recruit these individuals and further reach the underserved DHoH patient population.

—Gretchen Henkel

Since 2008, the American Community Survey, conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau, has queried respondents regarding deafness or hearing difficulties. According to these data, about 3.5% of the U.S. population has serious difficulty hearing. Other estimates vary, putting the number higher, especially those that include the numbers of elderly who experience hearing difficulties.

People who are deaf and hard of hearing (DHoH) work in diverse areas of the healthcare field, according to Samuel Atcherson, PhD, associate professor of audiology at the University of Arkansas in Little Rock and registry co-chair for the Association of Medical Professionals with Hearing Losses (www.amphl.org). AMPHL does not have statistics to report on the numbers of DHoH individuals practicing in medical occupations, but Dr. Atcherson noted that, as of 2011, there were 55 physicians, 41 nurses, and eight physician assistants in the membership.

Dr. Moreland and co-authors recently published a national survey that queried deaf physicians and trainees on a variety of subjects (e.g. career satisfaction, satisfaction with education, workplace accommodations). Due to the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, more people with hearing impairments are entering healthcare professions. Technological advances, such as electronic stethoscopes, also contribute to this surge.

The authors found that DHoH physicians and trainees responding to their survey were satisfied with multimodal employment and educational accommodations. Based on these results, they surmise, there might be an opportunity to recruit these individuals and further reach the underserved DHoH patient population.

—Gretchen Henkel

Since 2008, the American Community Survey, conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau, has queried respondents regarding deafness or hearing difficulties. According to these data, about 3.5% of the U.S. population has serious difficulty hearing. Other estimates vary, putting the number higher, especially those that include the numbers of elderly who experience hearing difficulties.

People who are deaf and hard of hearing (DHoH) work in diverse areas of the healthcare field, according to Samuel Atcherson, PhD, associate professor of audiology at the University of Arkansas in Little Rock and registry co-chair for the Association of Medical Professionals with Hearing Losses (www.amphl.org). AMPHL does not have statistics to report on the numbers of DHoH individuals practicing in medical occupations, but Dr. Atcherson noted that, as of 2011, there were 55 physicians, 41 nurses, and eight physician assistants in the membership.

Dr. Moreland and co-authors recently published a national survey that queried deaf physicians and trainees on a variety of subjects (e.g. career satisfaction, satisfaction with education, workplace accommodations). Due to the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, more people with hearing impairments are entering healthcare professions. Technological advances, such as electronic stethoscopes, also contribute to this surge.

The authors found that DHoH physicians and trainees responding to their survey were satisfied with multimodal employment and educational accommodations. Based on these results, they surmise, there might be an opportunity to recruit these individuals and further reach the underserved DHoH patient population.

—Gretchen Henkel

Physician Burnout Reduced with Intervention Groups

Clinical question: Does an intervention involving a facilitated physician small group result in improvement in well-being and reduction in burnout?

Background: Burnout affects nearly half of medical students, residents, and practicing physicians in the U.S.; however, very few interventions have been tested to address this problem.

Study design: Randomized controlled trial (RCT).

Setting: Department of Medicine at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

Synopsis: Practicing physicians were randomly assigned to facilitated, small-group intervention curriculum for one hour every two weeks (N=37) or control with unstructured, protected time for one hour every two weeks (N=37). A non-trial cohort of 350 practicing physicians was surveyed annually. This study showed a significant increase in empowerment and engagement at three months that was sustained for 12 months, and a significant decrease in high depersonalization scores was seen at both three and 12 months in the intervention group. There were no significant differences in stress, depression, quality of life, or job satisfaction.

Compared to the non-trial cohort, depersonalization, emotional exhaustion, and overall burnout decreased substantially in the intervention arm and slightly in the control arm.

Sample size was small and results may not be generalizable. Topics covered included reflection, self-awareness, and mindfulness, with a combination of community building and skill acquisition to promote connectedness and meaning in work. It is not clear which elements of the curriculum were most effective.

Bottom line: A facilitated, small-group intervention with institution-provided protected time can improve physician empowerment and engagement and reduce depersonalization, an important component of burnout.

Citation: West CP, Dyrbye LN, Rabatin JT, et al. Intervention to promote physician well-being, job satisfaction, and professionalism: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(4):527-533.

Clinical question: Does an intervention involving a facilitated physician small group result in improvement in well-being and reduction in burnout?

Background: Burnout affects nearly half of medical students, residents, and practicing physicians in the U.S.; however, very few interventions have been tested to address this problem.

Study design: Randomized controlled trial (RCT).

Setting: Department of Medicine at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

Synopsis: Practicing physicians were randomly assigned to facilitated, small-group intervention curriculum for one hour every two weeks (N=37) or control with unstructured, protected time for one hour every two weeks (N=37). A non-trial cohort of 350 practicing physicians was surveyed annually. This study showed a significant increase in empowerment and engagement at three months that was sustained for 12 months, and a significant decrease in high depersonalization scores was seen at both three and 12 months in the intervention group. There were no significant differences in stress, depression, quality of life, or job satisfaction.

Compared to the non-trial cohort, depersonalization, emotional exhaustion, and overall burnout decreased substantially in the intervention arm and slightly in the control arm.

Sample size was small and results may not be generalizable. Topics covered included reflection, self-awareness, and mindfulness, with a combination of community building and skill acquisition to promote connectedness and meaning in work. It is not clear which elements of the curriculum were most effective.

Bottom line: A facilitated, small-group intervention with institution-provided protected time can improve physician empowerment and engagement and reduce depersonalization, an important component of burnout.

Citation: West CP, Dyrbye LN, Rabatin JT, et al. Intervention to promote physician well-being, job satisfaction, and professionalism: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(4):527-533.

Clinical question: Does an intervention involving a facilitated physician small group result in improvement in well-being and reduction in burnout?

Background: Burnout affects nearly half of medical students, residents, and practicing physicians in the U.S.; however, very few interventions have been tested to address this problem.

Study design: Randomized controlled trial (RCT).

Setting: Department of Medicine at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

Synopsis: Practicing physicians were randomly assigned to facilitated, small-group intervention curriculum for one hour every two weeks (N=37) or control with unstructured, protected time for one hour every two weeks (N=37). A non-trial cohort of 350 practicing physicians was surveyed annually. This study showed a significant increase in empowerment and engagement at three months that was sustained for 12 months, and a significant decrease in high depersonalization scores was seen at both three and 12 months in the intervention group. There were no significant differences in stress, depression, quality of life, or job satisfaction.

Compared to the non-trial cohort, depersonalization, emotional exhaustion, and overall burnout decreased substantially in the intervention arm and slightly in the control arm.

Sample size was small and results may not be generalizable. Topics covered included reflection, self-awareness, and mindfulness, with a combination of community building and skill acquisition to promote connectedness and meaning in work. It is not clear which elements of the curriculum were most effective.

Bottom line: A facilitated, small-group intervention with institution-provided protected time can improve physician empowerment and engagement and reduce depersonalization, an important component of burnout.

Citation: West CP, Dyrbye LN, Rabatin JT, et al. Intervention to promote physician well-being, job satisfaction, and professionalism: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(4):527-533.

Hospital Medicine Upcoming Events, Meetings, Symposiums

Safety and Brazilian Hospital

Medicine 2014

August 6-8

Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

SHM’s Glycemic Control Program Informational Webinar

August 14, 2 p.m.

https://www4.gotomeeting.com/register/907579183

Palliative Medicine and Supportive Oncology 2014, The 17th International Symposium

September 18-20

Green Valley Ranch, Las Vegas

Society of OB/GYN Hospitalists Annual Clinical Meeting OB/GYN Hospitalists: Recognition, Response, Results

September 18-20

Embassy Suites Downtown, Denver

www.societyofobgynhospitalists.com

Academic Hospitalist Academy

October 20-23

Inverness Hotel and Conference

Center, Englewood, Colo.

Adult Hospital Medicine Boot Camp

October 1-5

The Westin Peachtree Plaza, Atlanta, Ga.

SHM Leadership Academy

November 3-6

Hilton Hawaiian Village Waikiki Beach Resort, Honolulu

www.hospitalmedicine.org/leadership

Hospital Medicine 2015

March 29-April 1, 2015

Gaylord National Resort & Convention Center, National Harbor, Md.

Safety and Brazilian Hospital

Medicine 2014

August 6-8

Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

SHM’s Glycemic Control Program Informational Webinar

August 14, 2 p.m.

https://www4.gotomeeting.com/register/907579183

Palliative Medicine and Supportive Oncology 2014, The 17th International Symposium

September 18-20

Green Valley Ranch, Las Vegas

Society of OB/GYN Hospitalists Annual Clinical Meeting OB/GYN Hospitalists: Recognition, Response, Results

September 18-20

Embassy Suites Downtown, Denver

www.societyofobgynhospitalists.com

Academic Hospitalist Academy

October 20-23

Inverness Hotel and Conference

Center, Englewood, Colo.

Adult Hospital Medicine Boot Camp

October 1-5

The Westin Peachtree Plaza, Atlanta, Ga.

SHM Leadership Academy

November 3-6

Hilton Hawaiian Village Waikiki Beach Resort, Honolulu

www.hospitalmedicine.org/leadership

Hospital Medicine 2015

March 29-April 1, 2015

Gaylord National Resort & Convention Center, National Harbor, Md.

Safety and Brazilian Hospital

Medicine 2014

August 6-8

Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

SHM’s Glycemic Control Program Informational Webinar

August 14, 2 p.m.

https://www4.gotomeeting.com/register/907579183

Palliative Medicine and Supportive Oncology 2014, The 17th International Symposium

September 18-20

Green Valley Ranch, Las Vegas

Society of OB/GYN Hospitalists Annual Clinical Meeting OB/GYN Hospitalists: Recognition, Response, Results

September 18-20

Embassy Suites Downtown, Denver

www.societyofobgynhospitalists.com

Academic Hospitalist Academy

October 20-23

Inverness Hotel and Conference

Center, Englewood, Colo.

Adult Hospital Medicine Boot Camp

October 1-5

The Westin Peachtree Plaza, Atlanta, Ga.

SHM Leadership Academy

November 3-6

Hilton Hawaiian Village Waikiki Beach Resort, Honolulu

www.hospitalmedicine.org/leadership

Hospital Medicine 2015

March 29-April 1, 2015

Gaylord National Resort & Convention Center, National Harbor, Md.

Common Coding Mistakes Hospitalists Should Avoid

Medical decision-making (MDM) mistakes are common. Here are the coding and documentation mistakes hospitalists make most often, along with some tips on how to avoid them.

Listing the problem without a plan. Healthcare professionals are able to infer the acuity and severity of a case without superfluous or redundant documentation, but auditors may not have this ability. Adequate documentation for every service date helps to convey patient complexity during a medical record review. Although the problem list may not change dramatically from day to day during a hospitalization, the auditor only reviews the service date in question, not the entire medical record.

Hospitalists should be sure to formulate a complete and accurate description of the patient’s condition with an analogous plan of care for each encounter. Listing problems without a corresponding plan of care does not corroborate physician management of that problem and could cause a downgrade of complexity. Listing problems with a brief, generalized comment (e.g. “DM, CKD, CHF: Continue current treatment plan”) equally diminishes the complexity and effort put forth by the physician.

Clearly document the plan. The care plan represents problems the physician personally manages, along with those that must also be considered when he or she formulates the management options, even if another physician is primarily managing the problem. For example, the hospitalist can monitor the patient’s diabetic management while the nephrologist oversees the chronic kidney disease (CKD). Since the CKD impacts the hospitalist’s diabetic care plan, the hospitalist may also receive credit for any CKD consideration if the documentation supports a hospitalist-related care plan, or comment about CKD that does not overlap or replicate the nephrologist’s plan. In other words, there must be some “value-added” input by the hospitalist.

Credit is given for the quantity of problems addressed as well as the quality. For inpatient care, an established problem is defined as one in which a care plan has been generated by the physician (or same specialty group practice member) during the current hospitalization. Established problems are less complex than new problems, for which a diagnosis, prognosis, or care plan has not been developed. Severity of the problem also influences complexity. A “worsening” problem is considered more complex than an “improving” problem, since the worsening problem likely requires revisions to the current care plan and, thus, more physician effort. Physician documentation should always:

- Identify all problems managed or addressed during each encounter;

- Identify problems as stable or progressing, when appropriate;

- Indicate differential diagnoses when the problem remains undefined;

- Indicate the management/treatment option(s) for each problem; and

- Note management options to be continued somewhere in the progress note for that encounter (e.g. medication list) when documentation indicates a continuation of current management options (e.g. “continue meds”).

Considering relevant data. “Data” is organized as pathology/laboratory testing, radiology, and medicine-based diagnostic testing that contributes to diagnosing or managing patient problems. Pertinent orders or results may appear in the medical record, but most of the background interactions and communications involving testing are undetected when reviewing the progress note. To receive credit:

- Specify tests ordered and rationale in the physician’s progress note, or make an entry that refers to another auditor-accessible location for ordered tests and studies; however, this latter option jeopardizes a medical record review due to potential lack of awareness of the need to submit this extraneous information during a payer record request or appeal.

- Document test review by including a brief entry in the progress note (e.g. “elevated glucose levels” or “CXR shows RLL infiltrates”); credit is not given for entries lacking a comment on the findings (e.g. “CXR reviewed”).

- Summarize key points when reviewing old records or obtaining history from someone other than the patient, as necessary; be sure to identify the increased efforts of reviewing the considerable number of old records by stating, “OSH (outside hospital) records reviewed and shows…” or “Records from previous hospitalization(s) reveal….”

- Indicate when images, tracings, or specimens are “personally reviewed,” or the auditor will assume the physician merely reviewed the written report; be sure to include a comment on the findings.

- Summarize any discussions of unexpected or contradictory test results with the physician performing the procedure or diagnostic study.

Data credit may be more substantial during the initial investigative phase of the hospitalization, before diagnoses or treatment options have been confirmed. Routine monitoring of the stabilized patient may not yield as many “points.”

Undervaluing the patient’s complexity. A general lack of understanding of the MDM component of the documentation guidelines often results in physicians undervaluing their services. Some physicians may consider a case “low complexity” simply because of the frequency with which they encounter the case type. The speed with which the care plan is developed should have no bearing on how complex the patient’s condition really is. Hospitalists need to better identify the risk involved for the patient.

Patient risk is categorized as minimal, low, moderate, or high based on pre-assigned items pertaining to the presenting problem, diagnostic procedures ordered, and management options selected. The single highest-rated item detected on the Table of Risk determines the overall patient risk for an encounter.1 Chronic conditions with exacerbations and invasive procedures offer more patient risk than acute, uncomplicated illnesses or noninvasive procedures. Stable or improving problems are considered “less risky” than progressing problems; conditions that pose a threat to life/bodily function outweigh undiagnosed problems where it is difficult to determine the patient’s prognosis; and medication risk varies with the administration (e.g. oral vs. parenteral), type, and potential for adverse effects. Medication risk for a particular drug is invariable whether the dosage is increased, decreased, or continued without change. Physicians should:

- Provide status for all problems in the plan of care and identify them as stable, worsening, or progressing (mild or severe), when applicable; don’t assume that the auditor can infer this from the documentation details.

- Document all diagnostic or therapeutic procedures considered.

- Identify surgical risk factors involving co-morbid conditions that place the patient at greater risk than the average patient, when appropriate.

- Associate the labs ordered to monitor for medication toxicity with the corresponding medication; don’t assume that the auditor knows which labs are used to check for toxicity.

Varying levels of complexity. Remember that decision-making is just one of three components in evaluation and management (E&M) services, along with history and exam. MDM is identical for both the 1995 and 1997 guidelines, rooted in the complexity of the patient’s problem(s) addressed during a given encounter.1,2 Complexity is categorized as straightforward, low, moderate, or high, and directly correlates to the content of physician documentation.

Each visit level represents a particular level of complexity (see Table 1). Auditors only consider the care plan for a given service date when reviewing MDM. More specifically, the auditor reviews three areas of MDM for each encounter (see Table 2), and the physician receives credit for: a) the number of diagnoses and/or treatment options; b) the amount and/or complexity of data ordered/reviewed; c) the risk of complications/morbidity/mortality.

To determine MDM complexity, each MDM category is assigned a point level. Complexity correlates to the second-highest MDM category. For example, if the auditor assigns “multiple” diagnoses/treatment options, “minimal” data, and “high” risk, the physician attains moderate complexity decision-making (see Table 3).

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 1995 Documentation Guidelines for Evaluation and Management Services. Available at: www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNEdWebGuide/Downloads/95Docguidelines.pdf. Accessed July 7, 2014.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 1997 Documentation Guidelines for Evaluation and Management Services. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNEdWebGuide/Downloads/97Docguidelines.pdf. Accessed July 7, 2014.

- American Medical Association. Current Procedural Terminology: 2014 Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association; 2013:14-21.

- Novitas Solutions. Novitas Solutions documentation worksheet. Available at: www.novitas-solutions.com/webcenter/content/conn/UCM_Repository/uuid/dDocName:00004966. Accessed July 7, 2014.

Medical decision-making (MDM) mistakes are common. Here are the coding and documentation mistakes hospitalists make most often, along with some tips on how to avoid them.

Listing the problem without a plan. Healthcare professionals are able to infer the acuity and severity of a case without superfluous or redundant documentation, but auditors may not have this ability. Adequate documentation for every service date helps to convey patient complexity during a medical record review. Although the problem list may not change dramatically from day to day during a hospitalization, the auditor only reviews the service date in question, not the entire medical record.

Hospitalists should be sure to formulate a complete and accurate description of the patient’s condition with an analogous plan of care for each encounter. Listing problems without a corresponding plan of care does not corroborate physician management of that problem and could cause a downgrade of complexity. Listing problems with a brief, generalized comment (e.g. “DM, CKD, CHF: Continue current treatment plan”) equally diminishes the complexity and effort put forth by the physician.

Clearly document the plan. The care plan represents problems the physician personally manages, along with those that must also be considered when he or she formulates the management options, even if another physician is primarily managing the problem. For example, the hospitalist can monitor the patient’s diabetic management while the nephrologist oversees the chronic kidney disease (CKD). Since the CKD impacts the hospitalist’s diabetic care plan, the hospitalist may also receive credit for any CKD consideration if the documentation supports a hospitalist-related care plan, or comment about CKD that does not overlap or replicate the nephrologist’s plan. In other words, there must be some “value-added” input by the hospitalist.

Credit is given for the quantity of problems addressed as well as the quality. For inpatient care, an established problem is defined as one in which a care plan has been generated by the physician (or same specialty group practice member) during the current hospitalization. Established problems are less complex than new problems, for which a diagnosis, prognosis, or care plan has not been developed. Severity of the problem also influences complexity. A “worsening” problem is considered more complex than an “improving” problem, since the worsening problem likely requires revisions to the current care plan and, thus, more physician effort. Physician documentation should always:

- Identify all problems managed or addressed during each encounter;

- Identify problems as stable or progressing, when appropriate;

- Indicate differential diagnoses when the problem remains undefined;

- Indicate the management/treatment option(s) for each problem; and

- Note management options to be continued somewhere in the progress note for that encounter (e.g. medication list) when documentation indicates a continuation of current management options (e.g. “continue meds”).

Considering relevant data. “Data” is organized as pathology/laboratory testing, radiology, and medicine-based diagnostic testing that contributes to diagnosing or managing patient problems. Pertinent orders or results may appear in the medical record, but most of the background interactions and communications involving testing are undetected when reviewing the progress note. To receive credit:

- Specify tests ordered and rationale in the physician’s progress note, or make an entry that refers to another auditor-accessible location for ordered tests and studies; however, this latter option jeopardizes a medical record review due to potential lack of awareness of the need to submit this extraneous information during a payer record request or appeal.

- Document test review by including a brief entry in the progress note (e.g. “elevated glucose levels” or “CXR shows RLL infiltrates”); credit is not given for entries lacking a comment on the findings (e.g. “CXR reviewed”).

- Summarize key points when reviewing old records or obtaining history from someone other than the patient, as necessary; be sure to identify the increased efforts of reviewing the considerable number of old records by stating, “OSH (outside hospital) records reviewed and shows…” or “Records from previous hospitalization(s) reveal….”

- Indicate when images, tracings, or specimens are “personally reviewed,” or the auditor will assume the physician merely reviewed the written report; be sure to include a comment on the findings.

- Summarize any discussions of unexpected or contradictory test results with the physician performing the procedure or diagnostic study.

Data credit may be more substantial during the initial investigative phase of the hospitalization, before diagnoses or treatment options have been confirmed. Routine monitoring of the stabilized patient may not yield as many “points.”

Undervaluing the patient’s complexity. A general lack of understanding of the MDM component of the documentation guidelines often results in physicians undervaluing their services. Some physicians may consider a case “low complexity” simply because of the frequency with which they encounter the case type. The speed with which the care plan is developed should have no bearing on how complex the patient’s condition really is. Hospitalists need to better identify the risk involved for the patient.

Patient risk is categorized as minimal, low, moderate, or high based on pre-assigned items pertaining to the presenting problem, diagnostic procedures ordered, and management options selected. The single highest-rated item detected on the Table of Risk determines the overall patient risk for an encounter.1 Chronic conditions with exacerbations and invasive procedures offer more patient risk than acute, uncomplicated illnesses or noninvasive procedures. Stable or improving problems are considered “less risky” than progressing problems; conditions that pose a threat to life/bodily function outweigh undiagnosed problems where it is difficult to determine the patient’s prognosis; and medication risk varies with the administration (e.g. oral vs. parenteral), type, and potential for adverse effects. Medication risk for a particular drug is invariable whether the dosage is increased, decreased, or continued without change. Physicians should:

- Provide status for all problems in the plan of care and identify them as stable, worsening, or progressing (mild or severe), when applicable; don’t assume that the auditor can infer this from the documentation details.

- Document all diagnostic or therapeutic procedures considered.

- Identify surgical risk factors involving co-morbid conditions that place the patient at greater risk than the average patient, when appropriate.

- Associate the labs ordered to monitor for medication toxicity with the corresponding medication; don’t assume that the auditor knows which labs are used to check for toxicity.

Varying levels of complexity. Remember that decision-making is just one of three components in evaluation and management (E&M) services, along with history and exam. MDM is identical for both the 1995 and 1997 guidelines, rooted in the complexity of the patient’s problem(s) addressed during a given encounter.1,2 Complexity is categorized as straightforward, low, moderate, or high, and directly correlates to the content of physician documentation.

Each visit level represents a particular level of complexity (see Table 1). Auditors only consider the care plan for a given service date when reviewing MDM. More specifically, the auditor reviews three areas of MDM for each encounter (see Table 2), and the physician receives credit for: a) the number of diagnoses and/or treatment options; b) the amount and/or complexity of data ordered/reviewed; c) the risk of complications/morbidity/mortality.

To determine MDM complexity, each MDM category is assigned a point level. Complexity correlates to the second-highest MDM category. For example, if the auditor assigns “multiple” diagnoses/treatment options, “minimal” data, and “high” risk, the physician attains moderate complexity decision-making (see Table 3).

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 1995 Documentation Guidelines for Evaluation and Management Services. Available at: www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNEdWebGuide/Downloads/95Docguidelines.pdf. Accessed July 7, 2014.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 1997 Documentation Guidelines for Evaluation and Management Services. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNEdWebGuide/Downloads/97Docguidelines.pdf. Accessed July 7, 2014.

- American Medical Association. Current Procedural Terminology: 2014 Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association; 2013:14-21.

- Novitas Solutions. Novitas Solutions documentation worksheet. Available at: www.novitas-solutions.com/webcenter/content/conn/UCM_Repository/uuid/dDocName:00004966. Accessed July 7, 2014.

Medical decision-making (MDM) mistakes are common. Here are the coding and documentation mistakes hospitalists make most often, along with some tips on how to avoid them.

Listing the problem without a plan. Healthcare professionals are able to infer the acuity and severity of a case without superfluous or redundant documentation, but auditors may not have this ability. Adequate documentation for every service date helps to convey patient complexity during a medical record review. Although the problem list may not change dramatically from day to day during a hospitalization, the auditor only reviews the service date in question, not the entire medical record.

Hospitalists should be sure to formulate a complete and accurate description of the patient’s condition with an analogous plan of care for each encounter. Listing problems without a corresponding plan of care does not corroborate physician management of that problem and could cause a downgrade of complexity. Listing problems with a brief, generalized comment (e.g. “DM, CKD, CHF: Continue current treatment plan”) equally diminishes the complexity and effort put forth by the physician.

Clearly document the plan. The care plan represents problems the physician personally manages, along with those that must also be considered when he or she formulates the management options, even if another physician is primarily managing the problem. For example, the hospitalist can monitor the patient’s diabetic management while the nephrologist oversees the chronic kidney disease (CKD). Since the CKD impacts the hospitalist’s diabetic care plan, the hospitalist may also receive credit for any CKD consideration if the documentation supports a hospitalist-related care plan, or comment about CKD that does not overlap or replicate the nephrologist’s plan. In other words, there must be some “value-added” input by the hospitalist.

Credit is given for the quantity of problems addressed as well as the quality. For inpatient care, an established problem is defined as one in which a care plan has been generated by the physician (or same specialty group practice member) during the current hospitalization. Established problems are less complex than new problems, for which a diagnosis, prognosis, or care plan has not been developed. Severity of the problem also influences complexity. A “worsening” problem is considered more complex than an “improving” problem, since the worsening problem likely requires revisions to the current care plan and, thus, more physician effort. Physician documentation should always:

- Identify all problems managed or addressed during each encounter;

- Identify problems as stable or progressing, when appropriate;

- Indicate differential diagnoses when the problem remains undefined;

- Indicate the management/treatment option(s) for each problem; and

- Note management options to be continued somewhere in the progress note for that encounter (e.g. medication list) when documentation indicates a continuation of current management options (e.g. “continue meds”).

Considering relevant data. “Data” is organized as pathology/laboratory testing, radiology, and medicine-based diagnostic testing that contributes to diagnosing or managing patient problems. Pertinent orders or results may appear in the medical record, but most of the background interactions and communications involving testing are undetected when reviewing the progress note. To receive credit:

- Specify tests ordered and rationale in the physician’s progress note, or make an entry that refers to another auditor-accessible location for ordered tests and studies; however, this latter option jeopardizes a medical record review due to potential lack of awareness of the need to submit this extraneous information during a payer record request or appeal.

- Document test review by including a brief entry in the progress note (e.g. “elevated glucose levels” or “CXR shows RLL infiltrates”); credit is not given for entries lacking a comment on the findings (e.g. “CXR reviewed”).

- Summarize key points when reviewing old records or obtaining history from someone other than the patient, as necessary; be sure to identify the increased efforts of reviewing the considerable number of old records by stating, “OSH (outside hospital) records reviewed and shows…” or “Records from previous hospitalization(s) reveal….”

- Indicate when images, tracings, or specimens are “personally reviewed,” or the auditor will assume the physician merely reviewed the written report; be sure to include a comment on the findings.

- Summarize any discussions of unexpected or contradictory test results with the physician performing the procedure or diagnostic study.

Data credit may be more substantial during the initial investigative phase of the hospitalization, before diagnoses or treatment options have been confirmed. Routine monitoring of the stabilized patient may not yield as many “points.”

Undervaluing the patient’s complexity. A general lack of understanding of the MDM component of the documentation guidelines often results in physicians undervaluing their services. Some physicians may consider a case “low complexity” simply because of the frequency with which they encounter the case type. The speed with which the care plan is developed should have no bearing on how complex the patient’s condition really is. Hospitalists need to better identify the risk involved for the patient.

Patient risk is categorized as minimal, low, moderate, or high based on pre-assigned items pertaining to the presenting problem, diagnostic procedures ordered, and management options selected. The single highest-rated item detected on the Table of Risk determines the overall patient risk for an encounter.1 Chronic conditions with exacerbations and invasive procedures offer more patient risk than acute, uncomplicated illnesses or noninvasive procedures. Stable or improving problems are considered “less risky” than progressing problems; conditions that pose a threat to life/bodily function outweigh undiagnosed problems where it is difficult to determine the patient’s prognosis; and medication risk varies with the administration (e.g. oral vs. parenteral), type, and potential for adverse effects. Medication risk for a particular drug is invariable whether the dosage is increased, decreased, or continued without change. Physicians should:

- Provide status for all problems in the plan of care and identify them as stable, worsening, or progressing (mild or severe), when applicable; don’t assume that the auditor can infer this from the documentation details.

- Document all diagnostic or therapeutic procedures considered.

- Identify surgical risk factors involving co-morbid conditions that place the patient at greater risk than the average patient, when appropriate.

- Associate the labs ordered to monitor for medication toxicity with the corresponding medication; don’t assume that the auditor knows which labs are used to check for toxicity.

Varying levels of complexity. Remember that decision-making is just one of three components in evaluation and management (E&M) services, along with history and exam. MDM is identical for both the 1995 and 1997 guidelines, rooted in the complexity of the patient’s problem(s) addressed during a given encounter.1,2 Complexity is categorized as straightforward, low, moderate, or high, and directly correlates to the content of physician documentation.

Each visit level represents a particular level of complexity (see Table 1). Auditors only consider the care plan for a given service date when reviewing MDM. More specifically, the auditor reviews three areas of MDM for each encounter (see Table 2), and the physician receives credit for: a) the number of diagnoses and/or treatment options; b) the amount and/or complexity of data ordered/reviewed; c) the risk of complications/morbidity/mortality.

To determine MDM complexity, each MDM category is assigned a point level. Complexity correlates to the second-highest MDM category. For example, if the auditor assigns “multiple” diagnoses/treatment options, “minimal” data, and “high” risk, the physician attains moderate complexity decision-making (see Table 3).

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 1995 Documentation Guidelines for Evaluation and Management Services. Available at: www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNEdWebGuide/Downloads/95Docguidelines.pdf. Accessed July 7, 2014.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 1997 Documentation Guidelines for Evaluation and Management Services. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNEdWebGuide/Downloads/97Docguidelines.pdf. Accessed July 7, 2014.

- American Medical Association. Current Procedural Terminology: 2014 Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association; 2013:14-21.

- Novitas Solutions. Novitas Solutions documentation worksheet. Available at: www.novitas-solutions.com/webcenter/content/conn/UCM_Repository/uuid/dDocName:00004966. Accessed July 7, 2014.

CODE-H Medical Coding Education Program Becomes Interactive

SHM’s coding education program, CODE-H, now has an interactive component through the SHM Learning Portal. CODE-H originally was developed as a series of live and on-demand webinars complemented by online forums; today, CODE-H Interactive brings the same expertise to an interactive platform ideal for new hospitalists learning the nuances of coding, hospital medicine groups assessing the coding skills of their caregivers, or even coders using it as a training tool for conducting audits of hospital medicine groups.

To learn more about CODE-H and CODE-H Interactive, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/codeh.

SHM’s coding education program, CODE-H, now has an interactive component through the SHM Learning Portal. CODE-H originally was developed as a series of live and on-demand webinars complemented by online forums; today, CODE-H Interactive brings the same expertise to an interactive platform ideal for new hospitalists learning the nuances of coding, hospital medicine groups assessing the coding skills of their caregivers, or even coders using it as a training tool for conducting audits of hospital medicine groups.

To learn more about CODE-H and CODE-H Interactive, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/codeh.

SHM’s coding education program, CODE-H, now has an interactive component through the SHM Learning Portal. CODE-H originally was developed as a series of live and on-demand webinars complemented by online forums; today, CODE-H Interactive brings the same expertise to an interactive platform ideal for new hospitalists learning the nuances of coding, hospital medicine groups assessing the coding skills of their caregivers, or even coders using it as a training tool for conducting audits of hospital medicine groups.

To learn more about CODE-H and CODE-H Interactive, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/codeh.

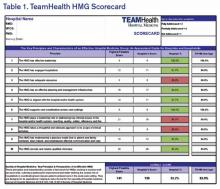

TeamHealth Hospital Medicine Shares Performance Stats

In February, SHM published the first performance assessment tool for HM groups. Now, HMGs across the country are using the “Key Principles and Characteristics of an Effective Hospital Medicine Group” to better understand their organizations’ strengths and areas needing improvement. Knoxville-based TeamHealth is the first to share its findings with SHM and The Hospitalist.

Before SHM published the assessment tool, there were very few objective attempts to provide guidelines that define an effective HMG. At TeamHealth, we viewed this tool as a way to proactively analyze our HMGs—a starting point if you will, to measure our performance against the principles identified in this assessment.

To this end, we allocated an internal analyst to work with our regional leadership teams. We felt it was important to have one person coordinating the analysis in order to ensure consistency with regard to how performance was defined. The analyst, along with the regional medical director and vice president of client services, went through each of the 47 key characteristics and identified the program’s status by evaluating the following statements:

- This characteristic does not apply to our HMG;

- Yes, we fully address the characteristic;

- Yes, we partially address the characteristic; or

- No, we do not materially address the characteristic.

For purposes of scoring, we then assigned a weight to each of the characteristics: three points if “fully addressed”; two points if “partially addressed”; one point if not addressed. We did not find that any of the characteristics fell under the “does not apply to our HMG” category.

A “100% effective” HMG was defined as scoring the highest possible score of 141 (i.e., three points for “fully addressing” each of the 47 characteristics).

We are currently at the next step in our assessment process. This step involves completion of a scorecard for each individual HMG (see Table 1). Additionally, the individual HMG score will be benchmarked against TeamHealth Hospital Medicine performance overall.

Finally, our regional teams will take the scorecard and meet with their hospital administrators to review the assessment tool, our methodology for completion, and the hospital’s performance.

We fully recognize that some of our hospital partners have measurement standards that differ from those presented by SHM in this assessment; nonetheless, TeamHealth feels the tool in its present state is a significant first step toward quantifying a high-functioning HMG—and will ultimately help improve both hospitalists and hospital performance.

Roberta P. Himebaugh is executive vice president of TeamHealth Hospital Medicine.

In February, SHM published the first performance assessment tool for HM groups. Now, HMGs across the country are using the “Key Principles and Characteristics of an Effective Hospital Medicine Group” to better understand their organizations’ strengths and areas needing improvement. Knoxville-based TeamHealth is the first to share its findings with SHM and The Hospitalist.

Before SHM published the assessment tool, there were very few objective attempts to provide guidelines that define an effective HMG. At TeamHealth, we viewed this tool as a way to proactively analyze our HMGs—a starting point if you will, to measure our performance against the principles identified in this assessment.

To this end, we allocated an internal analyst to work with our regional leadership teams. We felt it was important to have one person coordinating the analysis in order to ensure consistency with regard to how performance was defined. The analyst, along with the regional medical director and vice president of client services, went through each of the 47 key characteristics and identified the program’s status by evaluating the following statements:

- This characteristic does not apply to our HMG;

- Yes, we fully address the characteristic;

- Yes, we partially address the characteristic; or

- No, we do not materially address the characteristic.

For purposes of scoring, we then assigned a weight to each of the characteristics: three points if “fully addressed”; two points if “partially addressed”; one point if not addressed. We did not find that any of the characteristics fell under the “does not apply to our HMG” category.

A “100% effective” HMG was defined as scoring the highest possible score of 141 (i.e., three points for “fully addressing” each of the 47 characteristics).

We are currently at the next step in our assessment process. This step involves completion of a scorecard for each individual HMG (see Table 1). Additionally, the individual HMG score will be benchmarked against TeamHealth Hospital Medicine performance overall.

Finally, our regional teams will take the scorecard and meet with their hospital administrators to review the assessment tool, our methodology for completion, and the hospital’s performance.

We fully recognize that some of our hospital partners have measurement standards that differ from those presented by SHM in this assessment; nonetheless, TeamHealth feels the tool in its present state is a significant first step toward quantifying a high-functioning HMG—and will ultimately help improve both hospitalists and hospital performance.

Roberta P. Himebaugh is executive vice president of TeamHealth Hospital Medicine.

In February, SHM published the first performance assessment tool for HM groups. Now, HMGs across the country are using the “Key Principles and Characteristics of an Effective Hospital Medicine Group” to better understand their organizations’ strengths and areas needing improvement. Knoxville-based TeamHealth is the first to share its findings with SHM and The Hospitalist.

Before SHM published the assessment tool, there were very few objective attempts to provide guidelines that define an effective HMG. At TeamHealth, we viewed this tool as a way to proactively analyze our HMGs—a starting point if you will, to measure our performance against the principles identified in this assessment.

To this end, we allocated an internal analyst to work with our regional leadership teams. We felt it was important to have one person coordinating the analysis in order to ensure consistency with regard to how performance was defined. The analyst, along with the regional medical director and vice president of client services, went through each of the 47 key characteristics and identified the program’s status by evaluating the following statements:

- This characteristic does not apply to our HMG;

- Yes, we fully address the characteristic;

- Yes, we partially address the characteristic; or

- No, we do not materially address the characteristic.

For purposes of scoring, we then assigned a weight to each of the characteristics: three points if “fully addressed”; two points if “partially addressed”; one point if not addressed. We did not find that any of the characteristics fell under the “does not apply to our HMG” category.

A “100% effective” HMG was defined as scoring the highest possible score of 141 (i.e., three points for “fully addressing” each of the 47 characteristics).

We are currently at the next step in our assessment process. This step involves completion of a scorecard for each individual HMG (see Table 1). Additionally, the individual HMG score will be benchmarked against TeamHealth Hospital Medicine performance overall.

Finally, our regional teams will take the scorecard and meet with their hospital administrators to review the assessment tool, our methodology for completion, and the hospital’s performance.

We fully recognize that some of our hospital partners have measurement standards that differ from those presented by SHM in this assessment; nonetheless, TeamHealth feels the tool in its present state is a significant first step toward quantifying a high-functioning HMG—and will ultimately help improve both hospitalists and hospital performance.

Roberta P. Himebaugh is executive vice president of TeamHealth Hospital Medicine.

Medical Decision-Making: Avoid These Common Coding & Documentation Mistakes

Medical decision-making (MDM) mistakes are common. Here are the coding and documentation mistakes hospitalists make most often, along with some tips on how to avoid them.

Listing the problem without a plan. Healthcare professionals are able to infer the acuity and severity of a case without superfluous or redundant documentation, but auditors may not have this ability. Adequate documentation for every service date helps to convey patient complexity during a medical record review. Although the problem list may not change dramatically from day to day during a hospitalization, the auditor only reviews the service date in question, not the entire medical record.

Hospitalists should be sure to formulate a complete and accurate description of the patient’s condition with an analogous plan of care for each encounter. Listing problems without a corresponding plan of care does not corroborate physician management of that problem and could cause a downgrade of complexity. Listing problems with a brief, generalized comment (e.g. “DM, CKD, CHF: Continue current treatment plan”) equally diminishes the complexity and effort put forth by the physician.

Clearly document the plan. The care plan represents problems the physician personally manages, along with those that must also be considered when he or she formulates the management options, even if another physician is primarily managing the problem. For example, the hospitalist can monitor the patient’s diabetic management while the nephrologist oversees the chronic kidney disease (CKD). Since the CKD impacts the hospitalist’s diabetic care plan, the hospitalist may also receive credit for any CKD consideration if the documentation supports a hospitalist-related care plan, or comment about CKD that does not overlap or replicate the nephrologist’s plan. In other words, there must be some “value-added” input by the hospitalist.

Credit is given for the quantity of problems addressed as well as the quality. For inpatient care, an established problem is defined as one in which a care plan has been generated by the physician (or same specialty group practice member) during the current hospitalization. Established problems are less complex than new problems, for which a diagnosis, prognosis, or care plan has not been developed. Severity of the problem also influences complexity. A “worsening” problem is considered more complex than an “improving” problem, since the worsening problem likely requires revisions to the current care plan and, thus, more physician effort. Physician documentation should always:

- Identify all problems managed or addressed during each encounter;

- Identify problems as stable or progressing, when appropriate;

- Indicate differential diagnoses when the problem remains undefined;

- Indicate the management/treatment option(s) for each problem; and

- Note management options to be continued somewhere in the progress note for that encounter (e.g. medication list) when documentation indicates a continuation of current management options (e.g. “continue meds”).

Considering relevant data. “Data” is organized as pathology/laboratory testing, radiology, and medicine-based diagnostic testing that contributes to diagnosing or managing patient problems. Pertinent orders or results may appear in the medical record, but most of the background interactions and communications involving testing are undetected when reviewing the progress note. To receive credit:

- Specify tests ordered and rationale in the physician’s progress note, or make an entry that refers to another auditor-accessible location for ordered tests and studies; however, this latter option jeopardizes a medical record review due to potential lack of awareness of the need to submit this extraneous information during a payer record request or appeal.

- Document test review by including a brief entry in the progress note (e.g. “elevated glucose levels” or “CXR shows RLL infiltrates”); credit is not given for entries lacking a comment on the findings (e.g. “CXR reviewed”).

- Summarize key points when reviewing old records or obtaining history from someone other than the patient, as necessary; be sure to identify the increased efforts of reviewing the considerable number of old records by stating, “OSH (outside hospital) records reviewed and shows…” or “Records from previous hospitalization(s) reveal….”

- Indicate when images, tracings, or specimens are “personally reviewed,” or the auditor will assume the physician merely reviewed the written report; be sure to include a comment on the findings.

- Summarize any discussions of unexpected or contradictory test results with the physician performing the procedure or diagnostic study.

Data credit may be more substantial during the initial investigative phase of the hospitalization, before diagnoses or treatment options have been confirmed. Routine monitoring of the stabilized patient may not yield as many “points.”

Undervaluing the patient’s complexity. A general lack of understanding of the MDM component of the documentation guidelines often results in physicians undervaluing their services. Some physicians may consider a case “low complexity” simply because of the frequency with which they encounter the case type. The speed with which the care plan is developed should have no bearing on how complex the patient’s condition really is. Hospitalists need to better identify the risk involved for the patient.

Patient risk is categorized as minimal, low, moderate, or high based on pre-assigned items pertaining to the presenting problem, diagnostic procedures ordered, and management options selected. The single highest-rated item detected on the Table of Risk determines the overall patient risk for an encounter.1 Chronic conditions with exacerbations and invasive procedures offer more patient risk than acute, uncomplicated illnesses or noninvasive procedures. Stable or improving problems are considered “less risky” than progressing problems; conditions that pose a threat to life/bodily function outweigh undiagnosed problems where it is difficult to determine the patient’s prognosis; and medication risk varies with the administration (e.g. oral vs. parenteral), type, and potential for adverse effects. Medication risk for a particular drug is invariable whether the dosage is increased, decreased, or continued without change. Physicians should:

- Provide status for all problems in the plan of care and identify them as stable, worsening, or progressing (mild or severe), when applicable; don’t assume that the auditor can infer this from the documentation details.

- Document all diagnostic or therapeutic procedures considered.

- Identify surgical risk factors involving co-morbid conditions that place the patient at greater risk than the average patient, when appropriate.

- Associate the labs ordered to monitor for medication toxicity with the corresponding medication; don’t assume that the auditor knows which labs are used to check for toxicity.

Varying levels of complexity. Remember that decision-making is just one of three components in evaluation and management (E&M) services, along with history and exam. MDM is identical for both the 1995 and 1997 guidelines, rooted in the complexity of the patient’s problem(s) addressed during a given encounter.1,2 Complexity is categorized as straightforward, low, moderate, or high, and directly correlates to the content of physician documentation.

Each visit level represents a particular level of complexity (see Table 1). Auditors only consider the care plan for a given service date when reviewing MDM. More specifically, the auditor reviews three areas of MDM for each encounter (see Table 2), and the physician receives credit for: a) the number of diagnoses and/or treatment options; b) the amount and/or complexity of data ordered/reviewed; c) the risk of complications/morbidity/mortality.

To determine MDM complexity, each MDM category is assigned a point level. Complexity correlates to the second-highest MDM category. For example, if the auditor assigns “multiple” diagnoses/treatment options, “minimal” data, and “high” risk, the physician attains moderate complexity decision-making (see Table 3).

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 1995 Documentation Guidelines for Evaluation and Management Services. Available at: www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNEdWebGuide/Downloads/95Docguidelines.pdf. Accessed July 7, 2014.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 1997 Documentation Guidelines for Evaluation and Management Services. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNEdWebGuide/Downloads/97Docguidelines.pdf. Accessed July 7, 2014.

- American Medical Association. Current Procedural Terminology: 2014 Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association; 2013:14-21.

- Novitas Solutions. Novitas Solutions documentation worksheet. Available at: www.novitas-solutions.com/webcenter/content/conn/UCM_Repository/uuid/dDocName:00004966. Accessed July 7, 2014.

Medical decision-making (MDM) mistakes are common. Here are the coding and documentation mistakes hospitalists make most often, along with some tips on how to avoid them.

Listing the problem without a plan. Healthcare professionals are able to infer the acuity and severity of a case without superfluous or redundant documentation, but auditors may not have this ability. Adequate documentation for every service date helps to convey patient complexity during a medical record review. Although the problem list may not change dramatically from day to day during a hospitalization, the auditor only reviews the service date in question, not the entire medical record.

Hospitalists should be sure to formulate a complete and accurate description of the patient’s condition with an analogous plan of care for each encounter. Listing problems without a corresponding plan of care does not corroborate physician management of that problem and could cause a downgrade of complexity. Listing problems with a brief, generalized comment (e.g. “DM, CKD, CHF: Continue current treatment plan”) equally diminishes the complexity and effort put forth by the physician.

Clearly document the plan. The care plan represents problems the physician personally manages, along with those that must also be considered when he or she formulates the management options, even if another physician is primarily managing the problem. For example, the hospitalist can monitor the patient’s diabetic management while the nephrologist oversees the chronic kidney disease (CKD). Since the CKD impacts the hospitalist’s diabetic care plan, the hospitalist may also receive credit for any CKD consideration if the documentation supports a hospitalist-related care plan, or comment about CKD that does not overlap or replicate the nephrologist’s plan. In other words, there must be some “value-added” input by the hospitalist.

Credit is given for the quantity of problems addressed as well as the quality. For inpatient care, an established problem is defined as one in which a care plan has been generated by the physician (or same specialty group practice member) during the current hospitalization. Established problems are less complex than new problems, for which a diagnosis, prognosis, or care plan has not been developed. Severity of the problem also influences complexity. A “worsening” problem is considered more complex than an “improving” problem, since the worsening problem likely requires revisions to the current care plan and, thus, more physician effort. Physician documentation should always:

- Identify all problems managed or addressed during each encounter;

- Identify problems as stable or progressing, when appropriate;

- Indicate differential diagnoses when the problem remains undefined;

- Indicate the management/treatment option(s) for each problem; and

- Note management options to be continued somewhere in the progress note for that encounter (e.g. medication list) when documentation indicates a continuation of current management options (e.g. “continue meds”).

Considering relevant data. “Data” is organized as pathology/laboratory testing, radiology, and medicine-based diagnostic testing that contributes to diagnosing or managing patient problems. Pertinent orders or results may appear in the medical record, but most of the background interactions and communications involving testing are undetected when reviewing the progress note. To receive credit:

- Specify tests ordered and rationale in the physician’s progress note, or make an entry that refers to another auditor-accessible location for ordered tests and studies; however, this latter option jeopardizes a medical record review due to potential lack of awareness of the need to submit this extraneous information during a payer record request or appeal.

- Document test review by including a brief entry in the progress note (e.g. “elevated glucose levels” or “CXR shows RLL infiltrates”); credit is not given for entries lacking a comment on the findings (e.g. “CXR reviewed”).

- Summarize key points when reviewing old records or obtaining history from someone other than the patient, as necessary; be sure to identify the increased efforts of reviewing the considerable number of old records by stating, “OSH (outside hospital) records reviewed and shows…” or “Records from previous hospitalization(s) reveal….”

- Indicate when images, tracings, or specimens are “personally reviewed,” or the auditor will assume the physician merely reviewed the written report; be sure to include a comment on the findings.

- Summarize any discussions of unexpected or contradictory test results with the physician performing the procedure or diagnostic study.

Data credit may be more substantial during the initial investigative phase of the hospitalization, before diagnoses or treatment options have been confirmed. Routine monitoring of the stabilized patient may not yield as many “points.”

Undervaluing the patient’s complexity. A general lack of understanding of the MDM component of the documentation guidelines often results in physicians undervaluing their services. Some physicians may consider a case “low complexity” simply because of the frequency with which they encounter the case type. The speed with which the care plan is developed should have no bearing on how complex the patient’s condition really is. Hospitalists need to better identify the risk involved for the patient.

Patient risk is categorized as minimal, low, moderate, or high based on pre-assigned items pertaining to the presenting problem, diagnostic procedures ordered, and management options selected. The single highest-rated item detected on the Table of Risk determines the overall patient risk for an encounter.1 Chronic conditions with exacerbations and invasive procedures offer more patient risk than acute, uncomplicated illnesses or noninvasive procedures. Stable or improving problems are considered “less risky” than progressing problems; conditions that pose a threat to life/bodily function outweigh undiagnosed problems where it is difficult to determine the patient’s prognosis; and medication risk varies with the administration (e.g. oral vs. parenteral), type, and potential for adverse effects. Medication risk for a particular drug is invariable whether the dosage is increased, decreased, or continued without change. Physicians should:

- Provide status for all problems in the plan of care and identify them as stable, worsening, or progressing (mild or severe), when applicable; don’t assume that the auditor can infer this from the documentation details.

- Document all diagnostic or therapeutic procedures considered.

- Identify surgical risk factors involving co-morbid conditions that place the patient at greater risk than the average patient, when appropriate.

- Associate the labs ordered to monitor for medication toxicity with the corresponding medication; don’t assume that the auditor knows which labs are used to check for toxicity.

Varying levels of complexity. Remember that decision-making is just one of three components in evaluation and management (E&M) services, along with history and exam. MDM is identical for both the 1995 and 1997 guidelines, rooted in the complexity of the patient’s problem(s) addressed during a given encounter.1,2 Complexity is categorized as straightforward, low, moderate, or high, and directly correlates to the content of physician documentation.

Each visit level represents a particular level of complexity (see Table 1). Auditors only consider the care plan for a given service date when reviewing MDM. More specifically, the auditor reviews three areas of MDM for each encounter (see Table 2), and the physician receives credit for: a) the number of diagnoses and/or treatment options; b) the amount and/or complexity of data ordered/reviewed; c) the risk of complications/morbidity/mortality.

To determine MDM complexity, each MDM category is assigned a point level. Complexity correlates to the second-highest MDM category. For example, if the auditor assigns “multiple” diagnoses/treatment options, “minimal” data, and “high” risk, the physician attains moderate complexity decision-making (see Table 3).

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 1995 Documentation Guidelines for Evaluation and Management Services. Available at: www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNEdWebGuide/Downloads/95Docguidelines.pdf. Accessed July 7, 2014.