User login

Mapping Pathology Work Associated With Precision Oncology Testing

Mapping Pathology Work Associated With Precision Oncology Testing

Comprehensive genomic profiling (CGP) is becoming progressively common and appropriate as the array of molecular targets expands. However, most hospital laboratories in the United States do not perform CGP assays in-house; instead, these tests are sent to reference laboratories. As evidenced by Inal et al, only a minority of guideline-indicated molecular testing is performed.1

The workload associated with referral testing is a barrier to increased use of such tests; streamlined processes in pathology might increase molecular test use. At 6 high-complexity US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers (VAMCs) (Manhattan, Los Angeles, San Diego, Denver, Kansas City, and Salisbury, Maryland) ranging from 150 to 750 beds, a consult process for anatomic pathology molecular testing has increased test utilization, appropriateness of orders, standardization of reporting, and efficiency of care. This report comprehensively describes and maps the anatomic pathology molecular testing consult process at a VAMC. We present areas of inefficiency and a target state process map that incorporates best practices.

MOLECULAR TESTING CONSULT PROCESS

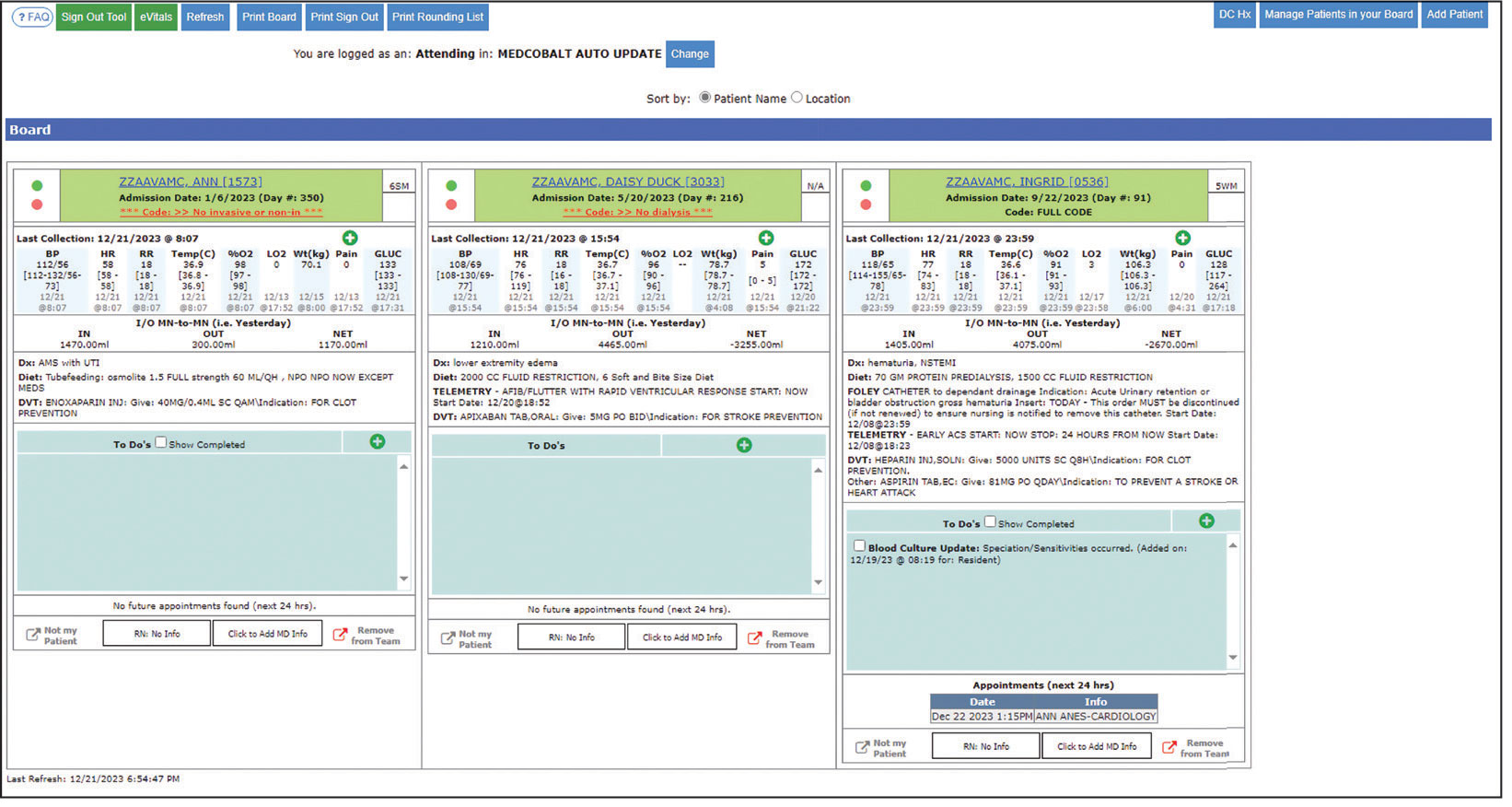

At the Kansas City VAMC (KCVAMC), a consult process for anatomic pathology molecular testing was introduced in 2021. Prior to this, requesting anatomic pathology molecular testing was not standardized. A variety of opportunities and methods were used for requests (eg, phone, page, Teams message, email, Computerized Patient Record System alert; or in-person during tumor board, an office meeting, or in passing). Requests were not documented in a standardized way, resulting in duplicate requests. Testing status and updates were documented outside the medical record, so requests for status updates (via various opportunities and methods) were common and redundant. Data from the year preceding consult implementation and the year following consult implementation have demonstrated increased test utilization, appropriateness of orders, standardization of reporting, and efficiency of care.

Consult Request

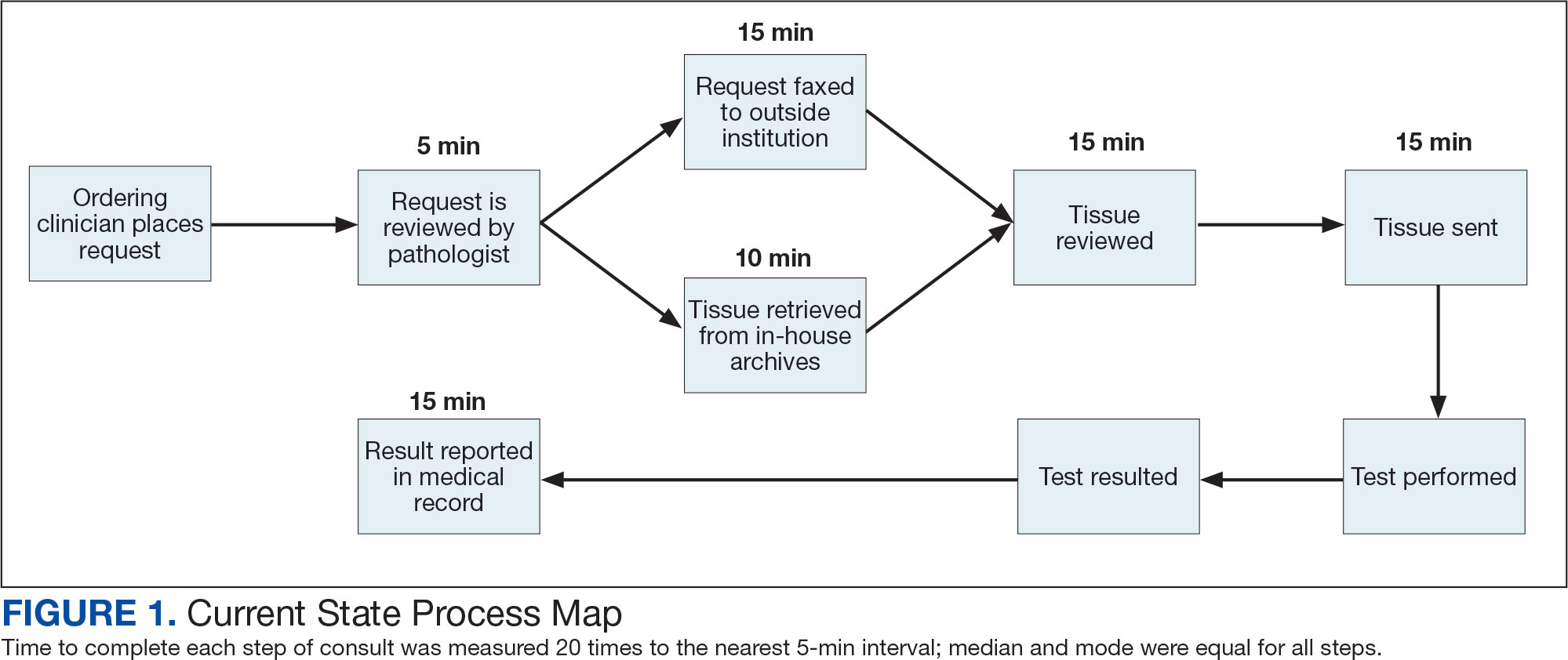

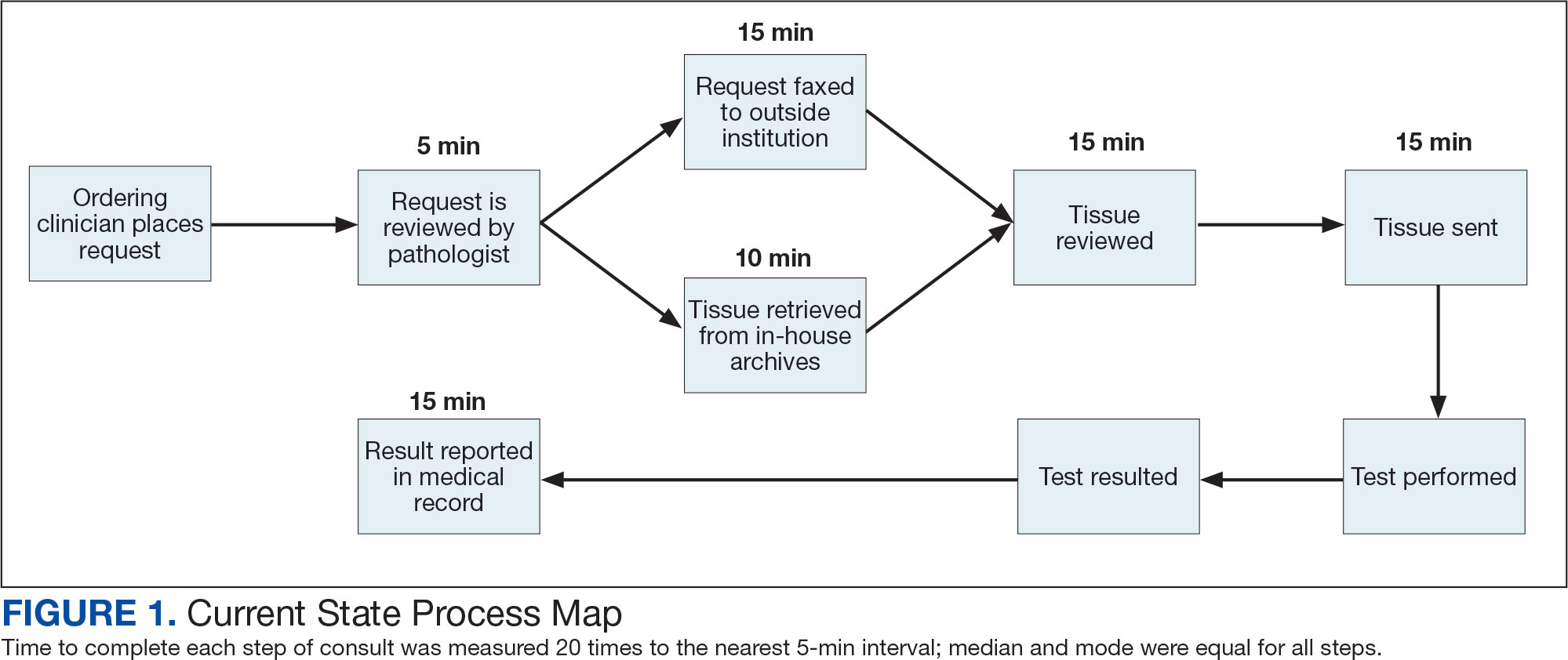

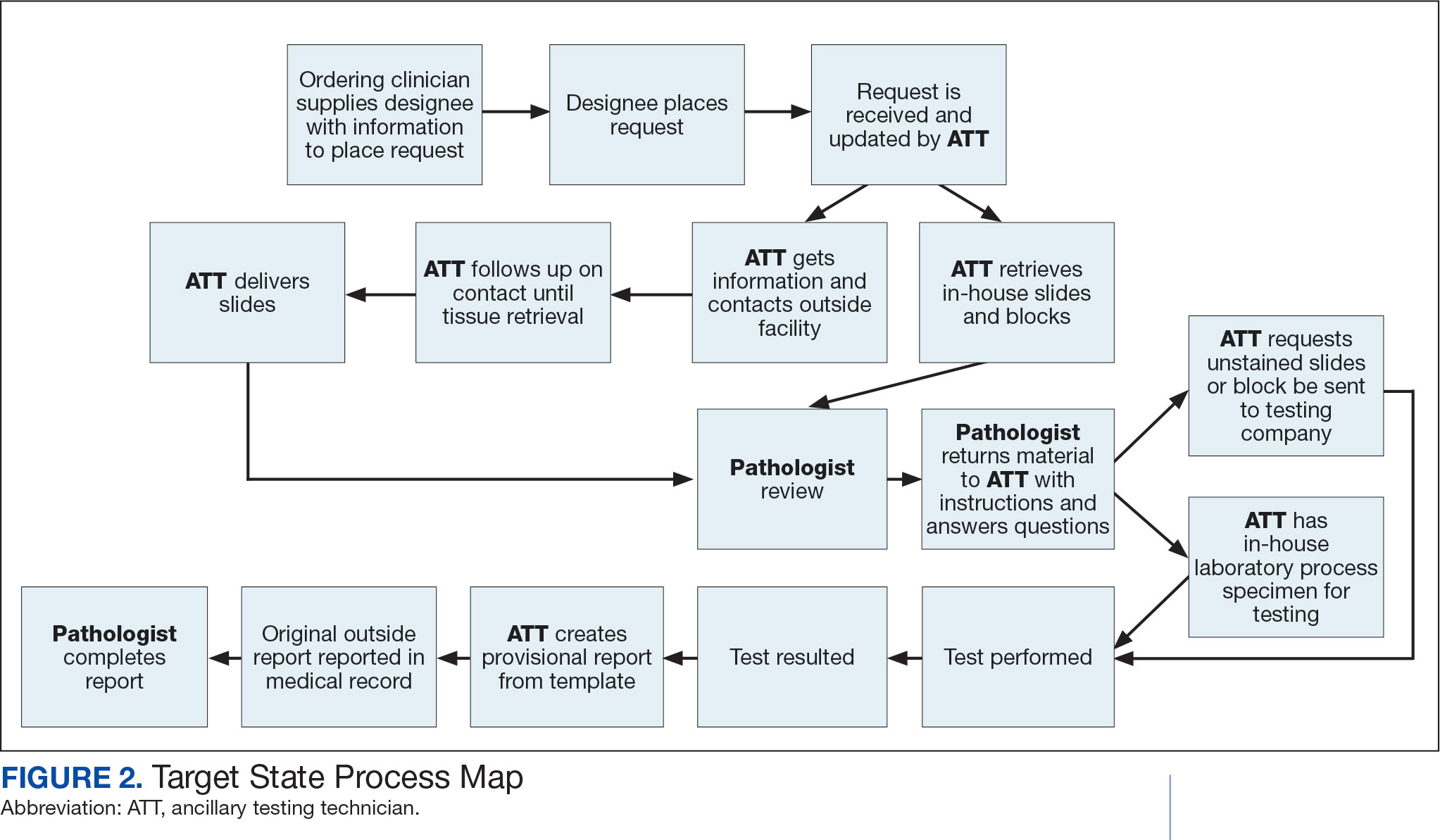

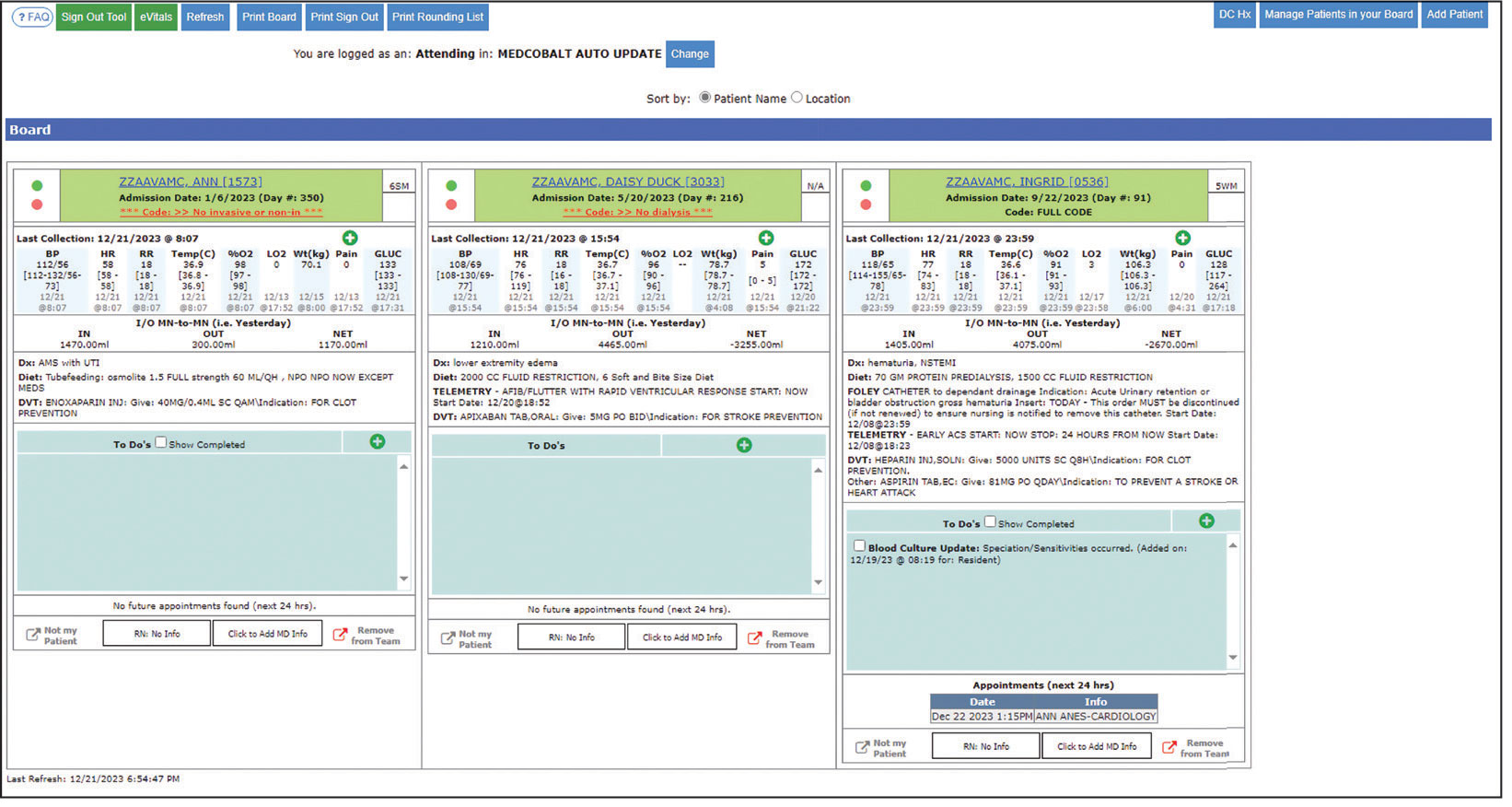

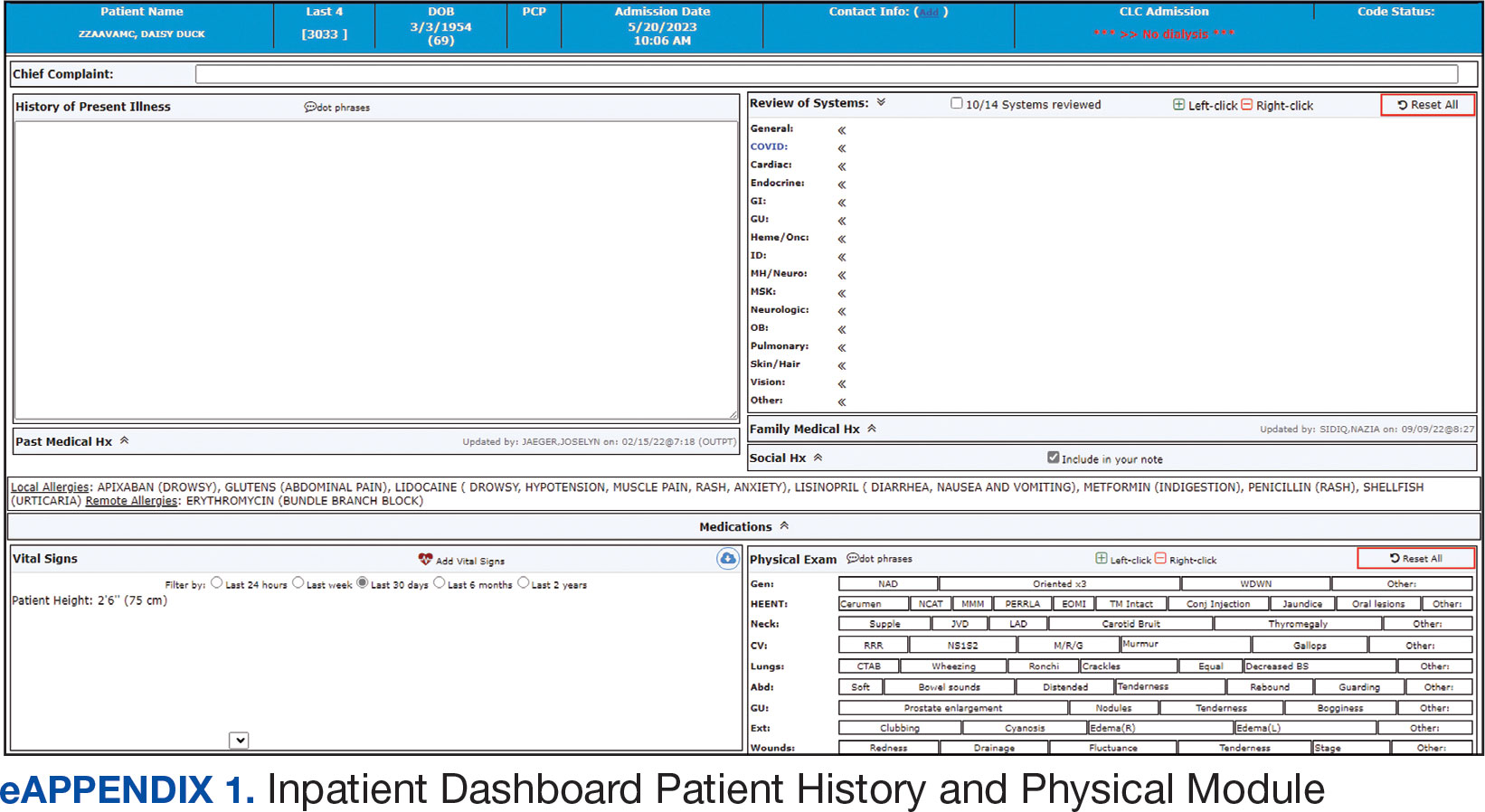

The precision oncology testing process starts with a health care practitioner (HCP) request on behalf of any physician or advanced practice registered nurse. It can be placed by any health care employee and directed to a designated employee in the pathology department. The request is ultimately reviewed by a pathologist (Figure 1). At KCVAMC, this request comes in the form of a consult in the electronic health record (EHR) from the ordering HCP to a pathologist. The KCVAMC pathology consult form was previously published with a discussion of the rationale for this process as opposed to a laboratory order process.2 This consult form ensures ordering HCPs supply all necessary information for the pathologist to approve the request and order the test without needing to, in most cases, contact the ordering HCP for clarification or additional information. The form asks the ordering HCP to specify which test is being requested and why. Within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) there are local and national contracts with many laboratories with hundreds of precision oncology tests to choose from. Consulting with a pathologist is necessary to determine which test is most appropriate.

The precision oncology consult form cannot be submitted without completing all required fields. It also contains indications for the test the ordering HCP selects to minimize unintentionally inappropriate orders. The form asks which tissue the requestor expects the test to be performed on. The requestor must provide contact information for the originating institution when the tissue was collected outside the VHA. The consult form also asks whether another anatomic site is accessible and could be biopsied without unacceptable risk or impracticality, should all previously collected tissue be insufficient. For CGP requests, this allows the pathologist to determine the appropriateness of liquid biopsy without having to reach out to the ordering HCP or wait for the question to be addressed at a tumor board. When a companion diagnostic is available for a test, the ordering HCP is asked which drug will be used so that the most appropriate assay is chosen.

Consult Review

Pathology service involvement begins with pathologist review of the consult form to ensure that the correct test is indicated. Depending on the resources and preferences at a site, consults can be directed to and reviewed by the pathologist associated with the corresponding pathology specimen or to a single pathologist or group of pathologists charged with attending to consults.

The patient’s EHR is reviewed to verify that the test has not already been performed and to determine which tissue to review. Previous surgical pathology reports are examined to assess whether sufficient tissue is available for testing, which may be determined without the need for direct slide examination. Pathologists often use wording such as “rare cells” or in some cases specify that there are not enough lesional cells for ancillary testing. In biopsy reports, the percentage of tissue occupied by lesional cells or the greatest linear length of tumor cells is often documented. As for quality, pathologists may note that a specimen is largely necrotic, and gross descriptions will indicate if a specimen was compromised for molecular analysis by exposure to fixatives such as Bouin’s solution, B-5, or decalcifying agents that contain strong acids.

Tissue Retrieval

If, after such evaluation, the test is indicated and there is tissue that could be sufficient for testing, retrieval of the tissue is pursued. For in-house cases, the pathologist reviews the corresponding surgical pathology report to determine which blocks and slides to pull from the archives. In the cancer checklist, some pathologists specify the best block for subsequent ancillary studies. From the final diagnosis and gross description, the pathologist can determine which blocks are most likely to contain lesional tissue. These slides are retrieved from the archives.

For cases collected at an outside institution (other VHA facility or non-VHA facility/institution), the outside institution must be contacted to retrieve the needed slides and blocks. The phone numbers, fax numbers, email addresses, and mailing addresses for outside institutions are housed in an electronic file and are specific to the point of contact for such requests. Maintaining a record of contacts increases efficiency of the overall process; gathering contact information and successfully requesting tissue often involves multiple automated answering systems, misdirected calls, and failed attempts.

Tissue Review

After retrieving in-house tissue, the pathologist can proceed directly to slide review. For outside cases, the case must first be accessioned so that after review of the slides the pathologist can issue a report to confirm the outside diagnosis. In reviewing the slides, the pathologist looks to see that the diagnosis is correct, that there is a sufficient number of lesional cells in a section, that the lesional cells are of a sufficient concentration in a section, or subsection of the section that could be dissected, and that the cells are viable. Depending on the requested assay and the familiarity of the pathologist with that assay, the pathologist may need to look up the technical requirements of the assay and capabilities of the testing company. Assays vary in sensitivity and require differing amounts and concentrations of tumor. Some companies will dissect tissue, others will not.

If there is sufficient tissue in the material reviewed, the corresponding blocks are retrieved from in-house archives or requests are placed for outside blocks or unstained slides. If there was not enough tissue for testing, the same process is repeated to retrieve and evaluate any other specimens the patient may have. If there are no other specimens to review, this is simply communicated to the ordering HCP via the consult. If the patient is a candidate for liquid biopsy—ie, current specimens are of insufficient quality and/or quantity and a new tissue sample cannot be obtained due to unacceptable risk or impracticality—the order is placed at this time.

Tissue Transport and Testing

Unstained slides need to be cut unless blocks are sent. Slides, blocks, reports, and requisition forms are packaged for transport. An accession number is created for the precision oncology molecular laboratory test in the clinical laboratory section of the EHR system. The clinical laboratory accession number provides a way of tracking sendout testing status. The case is accessioned just prior to placement in the mail so that when an accession number appears in the EHR, the ordering HCP knows the case has been sent out. When results are received, the clinical laboratory accession is completed and a comment is added to indicate where in the EHR to find the report or, when applicable, notes that testing failed.

RESULT REPORTING

When a result becomes available, the report file is downloaded from the vendor portal. This full report is securely transmitted to the ordering HCP. The file is then scanned into the EHR. Additionally, salient findings from the report are abstracted by the pathologist for inclusion as a supplement to the anatomic pathology case. This step ensures that this information travels with the anatomic pathology report if the patient’s care is transferred elsewhere. Templates are used to ensure essential data is captured based on the type of test. The template reminds the pathologist to comment on things such as variants that may represent clonal hematopoiesis, variants that may be germline, and variants that qualify a patient for germline testing. Even with the template, the pathologist must spend significant time reviewing the chart for things such as personal cancer history, other medical history, other masses on imaging, family history, previous surgical pathology reports, and previous molecular testing.

If results are suboptimal, recommendations for repeat testing are made based on the consult response to the question of repeat biopsy feasibility and review of previous pathology reports. The final consult report is added as a consult note, the consult is completed, and the original vendor report file is associated with the consult note in the EHR.

Ancillary Testing Technician

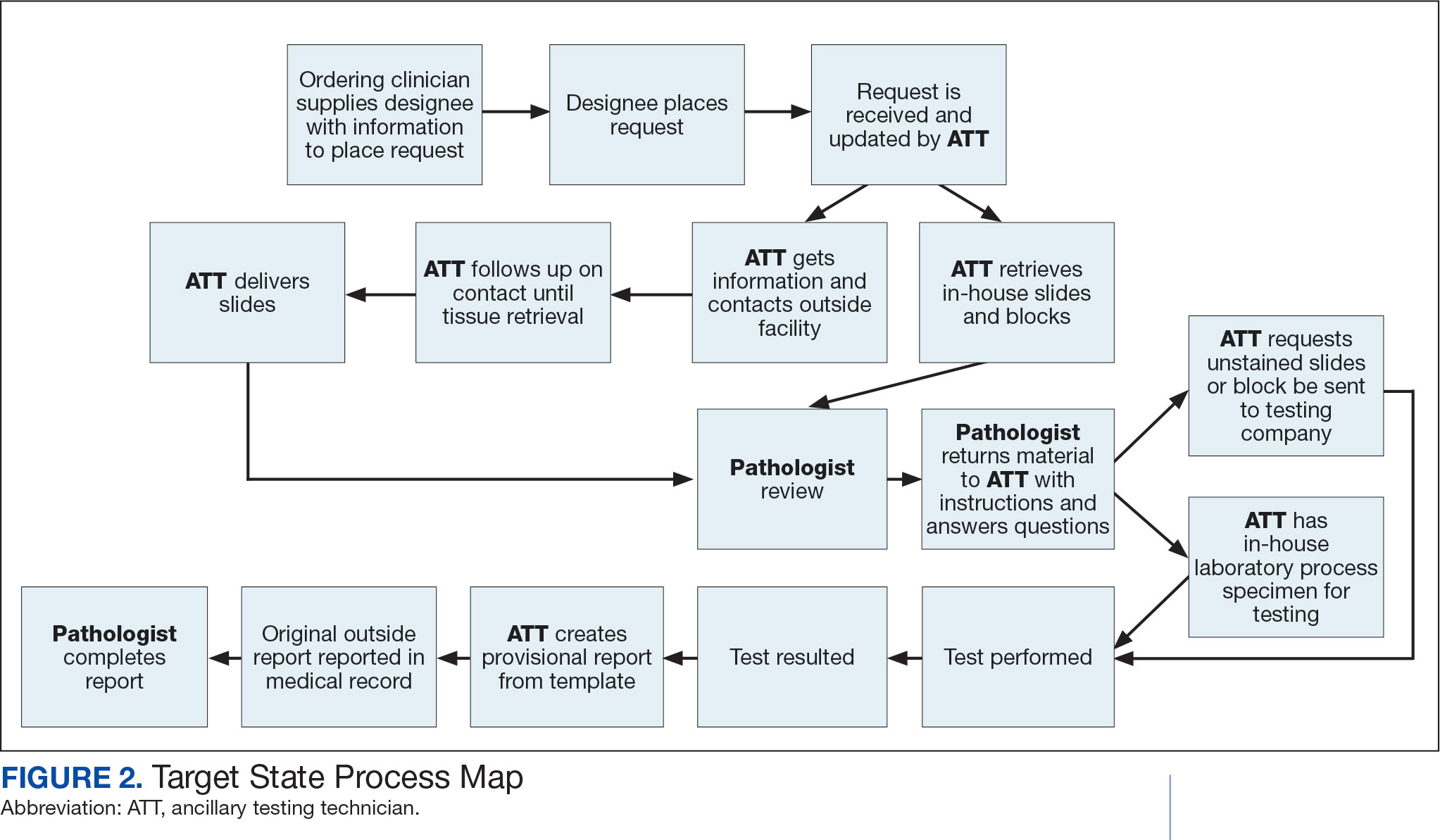

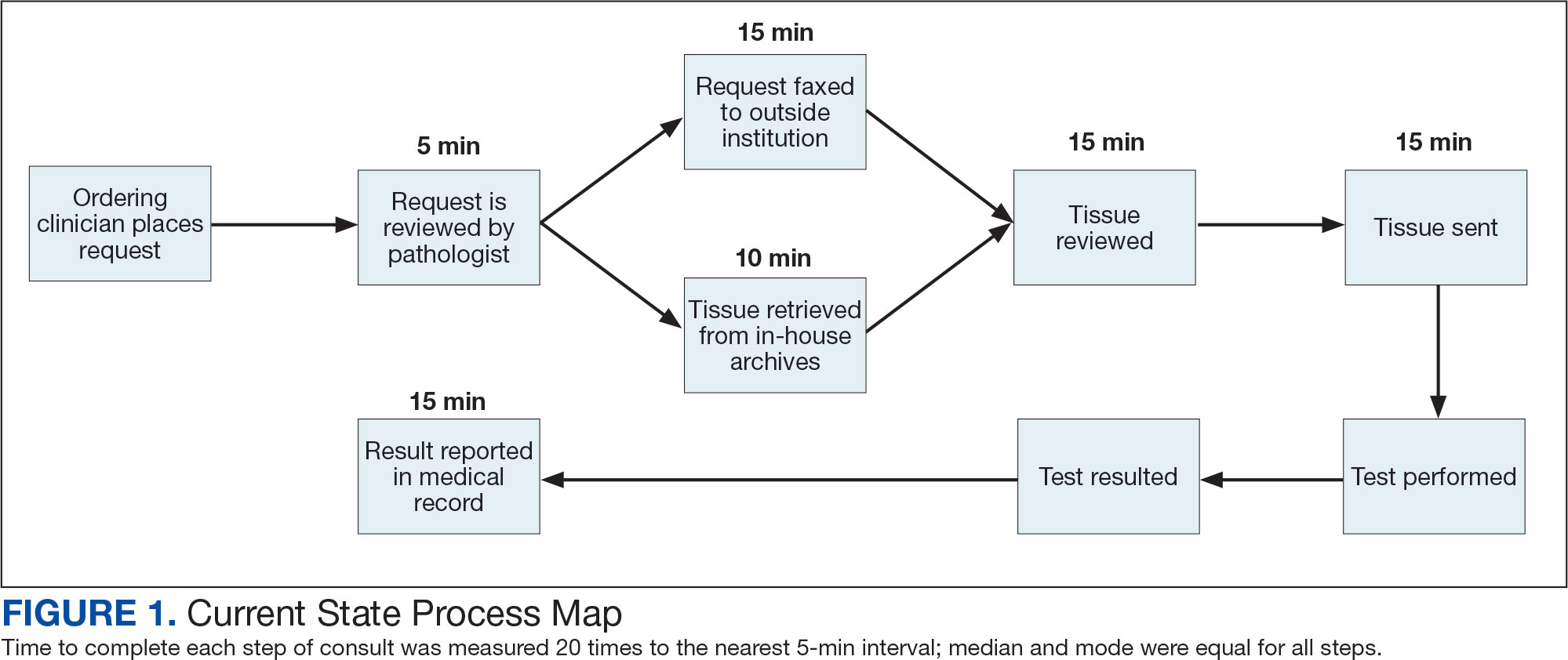

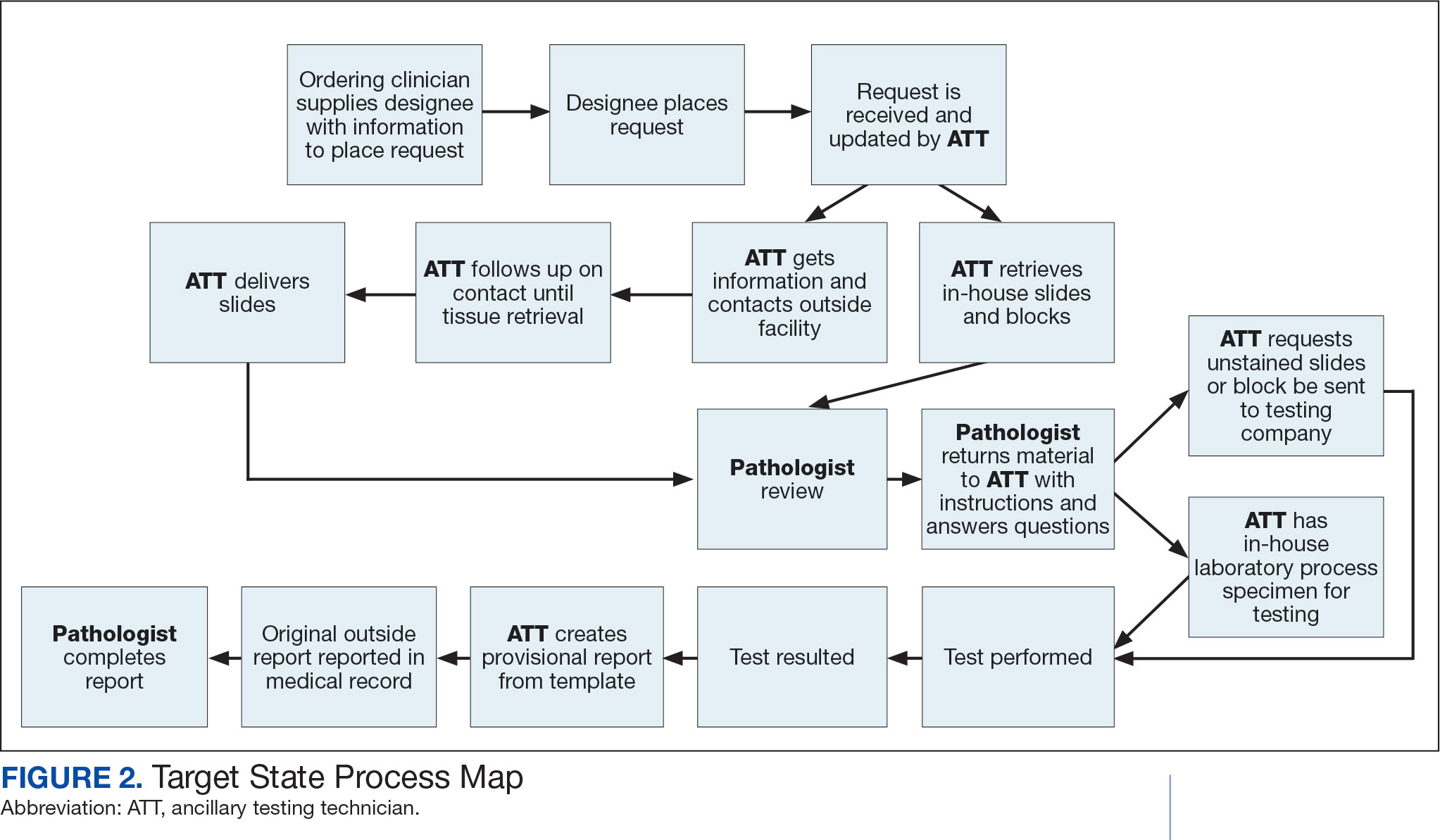

Due to chronic KCVAMC understaffing in the clerical office, gross room, and histology, most of the consult tasks are performed by a pathologist. In an ideal scenario, the pathology staff would divide its time between a pathologist and another dedicated laboratory position, such as an ancillary testing technician (ATT). The ATT can assume responsibilities that do not require the expertise of a pathologist (Figure 2). In such a process, the only steps that would require a pathologist would be review of requests and slides and completion of the interpretive report. All other steps could be accomplished by someone who lacks certifications, laboratory experience, or postsecondary education.

The ATT can receive the requests and retrieve slides and blocks. After slides have been reviewed by a pathologist, the pathologist can inform the ATT which slides or blocks testing will be performed on, provide any additional necessary information for completing the order, and answer any questions. For send-out tests, this allows the ATT to independently complete online portal forms and all other physical requirements prior to delivery of the slides and blocks to specimen processors in the laboratory.

ATTs can keep the ordering HCPs informed of status and be identified as the point of contact for all status inquiries. ATTs can receive results and get outside reports scanned into the EHR. Finally, ATTs can use pathologistdesigned templates to transpose information from outside reports such that a provisional report is prepared and a pathologist does not spend time duplicating information from the outside report. The pathologist can then complete the report with information requiring medical judgment that enhances care.

Optimal Pathologist Involvement

Only 3 steps in the process (request review, tissue review, and completion of an interpretive report) require a pathologist, which are necessary for optimal care and to address barriers to precision oncology.3 While the laboratory may consume only 5% of a health system budget, optimal laboratory use could prevent as much as 30% of avoidable costs.4 These estimates are widely recognized and addressed by campaigns such as Choosing Wisely, as well as programming of alerts and hard stops in EHR systems to reduce duplicate or otherwise inappropriate orders. The tests associated with precision oncology, such as CGP assays, require more nuanced consideration that is best achieved through pathology consultation. In vetting requests for such tests, the pathologist needs information that ordering HCPs do not routinely provide when ordering other tests. A consult asking for such information allows an ordering HCP to efficiently convey this information without having to call the laboratory to circumvent a hard stop.

Regardless of whether a formal electronic consult is used, pathologists must be involved in the review of requests. Creation of an original in-house report also provides an opportunity for pathologists to offer their expertise and maximize the contribution of pathology to patient care. If outside (other VHA facility or non-VHA facility/institution) reports are simply scanned into the EHR without review and issuance of an interpretive report by an in-house pathologist, then an interpretation by a pathologist with access to the patient’s complete chart is never provided. Testing companies are not provided with every patient diagnosis, so in patients with multiple neoplastic conditions, a report may seem to indicate that a detected mutation is from 1 tumor when it is actually from another. Even when all known diagnoses are considered, a variant may be detected that the medical record could reveal to indicate a new diagnosis.

Variation in reporting between companies necessitates pathologist review to standardize care. Some companies indicate which variants may represent clonal hematopoiesis, while others will simply list the pathogenic variants. An oncologist who sees a high volume of hematolymphoid neoplasia may recognize which variants may represent clonal hematopoiesis, but others may not. Reports from the same company may vary, and their interpretation often requires a pathologist's expertise. For example, even if a sample meets the technical requirements for analysis, the report may indicate that the quality or quantity of DNA has reduced the sensitivity for genomic alteration detection. A pathologist would know how to use this information in deciding how to proceed. In a situation where quantity was the issue, the pathologist may know there is additional tissue that could be sent for testing. If quality is the issue, the pathologist may know that additional blocks from the same case likely have the same quality of DNA and would also be unsuitable for testing.

Pathologist input is necessary for precision oncology testing. Some tasks that would ideally be completed by a molecular pathologist (eg, creation of reports to indicate which variants may represent clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential) may be sufficiently completed by a pathologist without fellowship training in molecular pathology.

There are about 15,000 full-time pathologists in the US.4 In the 20 years since molecular genetic pathology was formally recognized as a specialty, there have been < 500 pathologists who have pursued fellowship training in this specialty.5 With the inundation of molecular variants uncovered by routine next-generation sequencing (NGS), there are too few fellowship-trained molecular pathologists to provide all such aforementioned input; it is incumbent on surgical pathologists in general to take on such responsibilities.

Consult Implementation Data

These results support the feasibility and effectiveness of the consult process. Prior to consult implementation, many requests were not compliant with VHA National Precision Oncology Program (NPOP) testing guidelines. Since enactment of the consult, > 90% of requests have been in compliance. In the year preceding the consult (January 2020 to December 2021), 55 of 211 (26.1%) metastatic lung and prostate cancers samples eligible for NGS were tested and 126 (59.7%) NGS vendor reports were scanned into the EHR. The mean time from metastasis to NGS result was 151 days. In the year following enactment of the consult (January 2021 to December 2022), 168 of 224 (75.0%) of metastatic lung and prostate cancers eligible for NGS were tested and all 224 NGS vendor reports were scanned into the EHR. The mean time from metastasis to NGS result was 83 days. These data indicate that the practices recommended increase test use, appropriateness of orders, standardization of reporting, and efficiency of care.

CONCLUSIONS

Processing precision oncology testing requires substantial work for pathology departments. Laboratory workforce shortages and ever-expanding indications necessitate additional study of pathology processes to manage increasing workload and maintain the highest quality of cancer care through maximal efficiency and the development of appropriate staffing models. The use of a consult for anatomic pathology molecular testing is one process that can increase test use, appropriateness of orders, standardization of reporting, and efficiency of care. This report provides a comprehensive description and mapping of the process, highlights best practices, identifies inefficiencies, and provides a description and mapping of a target state.

- Inal C, Yilmaz E, Cheng H, et al. Effect of reflex testing by pathologists on molecular testing rates in lung cancer patients: experience from a community-based academic center. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(15 suppl):8098. doi:10.1200/jco.2014.32.15_suppl.8098

- Mettman D, Goodman M, Modzelewski J, et al. Streamlining institutional pathway processes: the development and implementation of a pathology molecular consult to facilitate convenient and efficient ordering, fulfillment, and reporting for tissue molecular tests. J Clin Pathw.Ersek JL, Black LJ, Thompson MA, Kim ES. Implementing precision medicine programs and clinical trials in the community-based oncology practice: barriers and best practices. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2018;38:188- 196. doi:10.1200/EDBK_200633 2022;8(1):28-33.

- Ersek JL, Black LJ, Thompson MA, Kim ES. Implementing precision medicine programs and clinical trials in the community-based oncology practice: barriers and best practices. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2018;38:188- 196. doi:10.1200/EDBK_200633

- Robboy SJ, Gupta S, Crawford JM, et al. The pathologist workforce in the United States: II. An interactive modeling tool for analyzing future qualitative and quantitative staffing demands for services. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2015;139(11):1413-1430. doi:10.5858/arpa.2014-0559-OA doi:10.25270/jcp.2022.02.1

- Robboy SJ, Gross D, Park JY, et al. Reevaluation of the US pathologist workforce size. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(7): e2010648. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.10648

Comprehensive genomic profiling (CGP) is becoming progressively common and appropriate as the array of molecular targets expands. However, most hospital laboratories in the United States do not perform CGP assays in-house; instead, these tests are sent to reference laboratories. As evidenced by Inal et al, only a minority of guideline-indicated molecular testing is performed.1

The workload associated with referral testing is a barrier to increased use of such tests; streamlined processes in pathology might increase molecular test use. At 6 high-complexity US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers (VAMCs) (Manhattan, Los Angeles, San Diego, Denver, Kansas City, and Salisbury, Maryland) ranging from 150 to 750 beds, a consult process for anatomic pathology molecular testing has increased test utilization, appropriateness of orders, standardization of reporting, and efficiency of care. This report comprehensively describes and maps the anatomic pathology molecular testing consult process at a VAMC. We present areas of inefficiency and a target state process map that incorporates best practices.

MOLECULAR TESTING CONSULT PROCESS

At the Kansas City VAMC (KCVAMC), a consult process for anatomic pathology molecular testing was introduced in 2021. Prior to this, requesting anatomic pathology molecular testing was not standardized. A variety of opportunities and methods were used for requests (eg, phone, page, Teams message, email, Computerized Patient Record System alert; or in-person during tumor board, an office meeting, or in passing). Requests were not documented in a standardized way, resulting in duplicate requests. Testing status and updates were documented outside the medical record, so requests for status updates (via various opportunities and methods) were common and redundant. Data from the year preceding consult implementation and the year following consult implementation have demonstrated increased test utilization, appropriateness of orders, standardization of reporting, and efficiency of care.

Consult Request

The precision oncology testing process starts with a health care practitioner (HCP) request on behalf of any physician or advanced practice registered nurse. It can be placed by any health care employee and directed to a designated employee in the pathology department. The request is ultimately reviewed by a pathologist (Figure 1). At KCVAMC, this request comes in the form of a consult in the electronic health record (EHR) from the ordering HCP to a pathologist. The KCVAMC pathology consult form was previously published with a discussion of the rationale for this process as opposed to a laboratory order process.2 This consult form ensures ordering HCPs supply all necessary information for the pathologist to approve the request and order the test without needing to, in most cases, contact the ordering HCP for clarification or additional information. The form asks the ordering HCP to specify which test is being requested and why. Within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) there are local and national contracts with many laboratories with hundreds of precision oncology tests to choose from. Consulting with a pathologist is necessary to determine which test is most appropriate.

The precision oncology consult form cannot be submitted without completing all required fields. It also contains indications for the test the ordering HCP selects to minimize unintentionally inappropriate orders. The form asks which tissue the requestor expects the test to be performed on. The requestor must provide contact information for the originating institution when the tissue was collected outside the VHA. The consult form also asks whether another anatomic site is accessible and could be biopsied without unacceptable risk or impracticality, should all previously collected tissue be insufficient. For CGP requests, this allows the pathologist to determine the appropriateness of liquid biopsy without having to reach out to the ordering HCP or wait for the question to be addressed at a tumor board. When a companion diagnostic is available for a test, the ordering HCP is asked which drug will be used so that the most appropriate assay is chosen.

Consult Review

Pathology service involvement begins with pathologist review of the consult form to ensure that the correct test is indicated. Depending on the resources and preferences at a site, consults can be directed to and reviewed by the pathologist associated with the corresponding pathology specimen or to a single pathologist or group of pathologists charged with attending to consults.

The patient’s EHR is reviewed to verify that the test has not already been performed and to determine which tissue to review. Previous surgical pathology reports are examined to assess whether sufficient tissue is available for testing, which may be determined without the need for direct slide examination. Pathologists often use wording such as “rare cells” or in some cases specify that there are not enough lesional cells for ancillary testing. In biopsy reports, the percentage of tissue occupied by lesional cells or the greatest linear length of tumor cells is often documented. As for quality, pathologists may note that a specimen is largely necrotic, and gross descriptions will indicate if a specimen was compromised for molecular analysis by exposure to fixatives such as Bouin’s solution, B-5, or decalcifying agents that contain strong acids.

Tissue Retrieval

If, after such evaluation, the test is indicated and there is tissue that could be sufficient for testing, retrieval of the tissue is pursued. For in-house cases, the pathologist reviews the corresponding surgical pathology report to determine which blocks and slides to pull from the archives. In the cancer checklist, some pathologists specify the best block for subsequent ancillary studies. From the final diagnosis and gross description, the pathologist can determine which blocks are most likely to contain lesional tissue. These slides are retrieved from the archives.

For cases collected at an outside institution (other VHA facility or non-VHA facility/institution), the outside institution must be contacted to retrieve the needed slides and blocks. The phone numbers, fax numbers, email addresses, and mailing addresses for outside institutions are housed in an electronic file and are specific to the point of contact for such requests. Maintaining a record of contacts increases efficiency of the overall process; gathering contact information and successfully requesting tissue often involves multiple automated answering systems, misdirected calls, and failed attempts.

Tissue Review

After retrieving in-house tissue, the pathologist can proceed directly to slide review. For outside cases, the case must first be accessioned so that after review of the slides the pathologist can issue a report to confirm the outside diagnosis. In reviewing the slides, the pathologist looks to see that the diagnosis is correct, that there is a sufficient number of lesional cells in a section, that the lesional cells are of a sufficient concentration in a section, or subsection of the section that could be dissected, and that the cells are viable. Depending on the requested assay and the familiarity of the pathologist with that assay, the pathologist may need to look up the technical requirements of the assay and capabilities of the testing company. Assays vary in sensitivity and require differing amounts and concentrations of tumor. Some companies will dissect tissue, others will not.

If there is sufficient tissue in the material reviewed, the corresponding blocks are retrieved from in-house archives or requests are placed for outside blocks or unstained slides. If there was not enough tissue for testing, the same process is repeated to retrieve and evaluate any other specimens the patient may have. If there are no other specimens to review, this is simply communicated to the ordering HCP via the consult. If the patient is a candidate for liquid biopsy—ie, current specimens are of insufficient quality and/or quantity and a new tissue sample cannot be obtained due to unacceptable risk or impracticality—the order is placed at this time.

Tissue Transport and Testing

Unstained slides need to be cut unless blocks are sent. Slides, blocks, reports, and requisition forms are packaged for transport. An accession number is created for the precision oncology molecular laboratory test in the clinical laboratory section of the EHR system. The clinical laboratory accession number provides a way of tracking sendout testing status. The case is accessioned just prior to placement in the mail so that when an accession number appears in the EHR, the ordering HCP knows the case has been sent out. When results are received, the clinical laboratory accession is completed and a comment is added to indicate where in the EHR to find the report or, when applicable, notes that testing failed.

RESULT REPORTING

When a result becomes available, the report file is downloaded from the vendor portal. This full report is securely transmitted to the ordering HCP. The file is then scanned into the EHR. Additionally, salient findings from the report are abstracted by the pathologist for inclusion as a supplement to the anatomic pathology case. This step ensures that this information travels with the anatomic pathology report if the patient’s care is transferred elsewhere. Templates are used to ensure essential data is captured based on the type of test. The template reminds the pathologist to comment on things such as variants that may represent clonal hematopoiesis, variants that may be germline, and variants that qualify a patient for germline testing. Even with the template, the pathologist must spend significant time reviewing the chart for things such as personal cancer history, other medical history, other masses on imaging, family history, previous surgical pathology reports, and previous molecular testing.

If results are suboptimal, recommendations for repeat testing are made based on the consult response to the question of repeat biopsy feasibility and review of previous pathology reports. The final consult report is added as a consult note, the consult is completed, and the original vendor report file is associated with the consult note in the EHR.

Ancillary Testing Technician

Due to chronic KCVAMC understaffing in the clerical office, gross room, and histology, most of the consult tasks are performed by a pathologist. In an ideal scenario, the pathology staff would divide its time between a pathologist and another dedicated laboratory position, such as an ancillary testing technician (ATT). The ATT can assume responsibilities that do not require the expertise of a pathologist (Figure 2). In such a process, the only steps that would require a pathologist would be review of requests and slides and completion of the interpretive report. All other steps could be accomplished by someone who lacks certifications, laboratory experience, or postsecondary education.

The ATT can receive the requests and retrieve slides and blocks. After slides have been reviewed by a pathologist, the pathologist can inform the ATT which slides or blocks testing will be performed on, provide any additional necessary information for completing the order, and answer any questions. For send-out tests, this allows the ATT to independently complete online portal forms and all other physical requirements prior to delivery of the slides and blocks to specimen processors in the laboratory.

ATTs can keep the ordering HCPs informed of status and be identified as the point of contact for all status inquiries. ATTs can receive results and get outside reports scanned into the EHR. Finally, ATTs can use pathologistdesigned templates to transpose information from outside reports such that a provisional report is prepared and a pathologist does not spend time duplicating information from the outside report. The pathologist can then complete the report with information requiring medical judgment that enhances care.

Optimal Pathologist Involvement

Only 3 steps in the process (request review, tissue review, and completion of an interpretive report) require a pathologist, which are necessary for optimal care and to address barriers to precision oncology.3 While the laboratory may consume only 5% of a health system budget, optimal laboratory use could prevent as much as 30% of avoidable costs.4 These estimates are widely recognized and addressed by campaigns such as Choosing Wisely, as well as programming of alerts and hard stops in EHR systems to reduce duplicate or otherwise inappropriate orders. The tests associated with precision oncology, such as CGP assays, require more nuanced consideration that is best achieved through pathology consultation. In vetting requests for such tests, the pathologist needs information that ordering HCPs do not routinely provide when ordering other tests. A consult asking for such information allows an ordering HCP to efficiently convey this information without having to call the laboratory to circumvent a hard stop.

Regardless of whether a formal electronic consult is used, pathologists must be involved in the review of requests. Creation of an original in-house report also provides an opportunity for pathologists to offer their expertise and maximize the contribution of pathology to patient care. If outside (other VHA facility or non-VHA facility/institution) reports are simply scanned into the EHR without review and issuance of an interpretive report by an in-house pathologist, then an interpretation by a pathologist with access to the patient’s complete chart is never provided. Testing companies are not provided with every patient diagnosis, so in patients with multiple neoplastic conditions, a report may seem to indicate that a detected mutation is from 1 tumor when it is actually from another. Even when all known diagnoses are considered, a variant may be detected that the medical record could reveal to indicate a new diagnosis.

Variation in reporting between companies necessitates pathologist review to standardize care. Some companies indicate which variants may represent clonal hematopoiesis, while others will simply list the pathogenic variants. An oncologist who sees a high volume of hematolymphoid neoplasia may recognize which variants may represent clonal hematopoiesis, but others may not. Reports from the same company may vary, and their interpretation often requires a pathologist's expertise. For example, even if a sample meets the technical requirements for analysis, the report may indicate that the quality or quantity of DNA has reduced the sensitivity for genomic alteration detection. A pathologist would know how to use this information in deciding how to proceed. In a situation where quantity was the issue, the pathologist may know there is additional tissue that could be sent for testing. If quality is the issue, the pathologist may know that additional blocks from the same case likely have the same quality of DNA and would also be unsuitable for testing.

Pathologist input is necessary for precision oncology testing. Some tasks that would ideally be completed by a molecular pathologist (eg, creation of reports to indicate which variants may represent clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential) may be sufficiently completed by a pathologist without fellowship training in molecular pathology.

There are about 15,000 full-time pathologists in the US.4 In the 20 years since molecular genetic pathology was formally recognized as a specialty, there have been < 500 pathologists who have pursued fellowship training in this specialty.5 With the inundation of molecular variants uncovered by routine next-generation sequencing (NGS), there are too few fellowship-trained molecular pathologists to provide all such aforementioned input; it is incumbent on surgical pathologists in general to take on such responsibilities.

Consult Implementation Data

These results support the feasibility and effectiveness of the consult process. Prior to consult implementation, many requests were not compliant with VHA National Precision Oncology Program (NPOP) testing guidelines. Since enactment of the consult, > 90% of requests have been in compliance. In the year preceding the consult (January 2020 to December 2021), 55 of 211 (26.1%) metastatic lung and prostate cancers samples eligible for NGS were tested and 126 (59.7%) NGS vendor reports were scanned into the EHR. The mean time from metastasis to NGS result was 151 days. In the year following enactment of the consult (January 2021 to December 2022), 168 of 224 (75.0%) of metastatic lung and prostate cancers eligible for NGS were tested and all 224 NGS vendor reports were scanned into the EHR. The mean time from metastasis to NGS result was 83 days. These data indicate that the practices recommended increase test use, appropriateness of orders, standardization of reporting, and efficiency of care.

CONCLUSIONS

Processing precision oncology testing requires substantial work for pathology departments. Laboratory workforce shortages and ever-expanding indications necessitate additional study of pathology processes to manage increasing workload and maintain the highest quality of cancer care through maximal efficiency and the development of appropriate staffing models. The use of a consult for anatomic pathology molecular testing is one process that can increase test use, appropriateness of orders, standardization of reporting, and efficiency of care. This report provides a comprehensive description and mapping of the process, highlights best practices, identifies inefficiencies, and provides a description and mapping of a target state.

Comprehensive genomic profiling (CGP) is becoming progressively common and appropriate as the array of molecular targets expands. However, most hospital laboratories in the United States do not perform CGP assays in-house; instead, these tests are sent to reference laboratories. As evidenced by Inal et al, only a minority of guideline-indicated molecular testing is performed.1

The workload associated with referral testing is a barrier to increased use of such tests; streamlined processes in pathology might increase molecular test use. At 6 high-complexity US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers (VAMCs) (Manhattan, Los Angeles, San Diego, Denver, Kansas City, and Salisbury, Maryland) ranging from 150 to 750 beds, a consult process for anatomic pathology molecular testing has increased test utilization, appropriateness of orders, standardization of reporting, and efficiency of care. This report comprehensively describes and maps the anatomic pathology molecular testing consult process at a VAMC. We present areas of inefficiency and a target state process map that incorporates best practices.

MOLECULAR TESTING CONSULT PROCESS

At the Kansas City VAMC (KCVAMC), a consult process for anatomic pathology molecular testing was introduced in 2021. Prior to this, requesting anatomic pathology molecular testing was not standardized. A variety of opportunities and methods were used for requests (eg, phone, page, Teams message, email, Computerized Patient Record System alert; or in-person during tumor board, an office meeting, or in passing). Requests were not documented in a standardized way, resulting in duplicate requests. Testing status and updates were documented outside the medical record, so requests for status updates (via various opportunities and methods) were common and redundant. Data from the year preceding consult implementation and the year following consult implementation have demonstrated increased test utilization, appropriateness of orders, standardization of reporting, and efficiency of care.

Consult Request

The precision oncology testing process starts with a health care practitioner (HCP) request on behalf of any physician or advanced practice registered nurse. It can be placed by any health care employee and directed to a designated employee in the pathology department. The request is ultimately reviewed by a pathologist (Figure 1). At KCVAMC, this request comes in the form of a consult in the electronic health record (EHR) from the ordering HCP to a pathologist. The KCVAMC pathology consult form was previously published with a discussion of the rationale for this process as opposed to a laboratory order process.2 This consult form ensures ordering HCPs supply all necessary information for the pathologist to approve the request and order the test without needing to, in most cases, contact the ordering HCP for clarification or additional information. The form asks the ordering HCP to specify which test is being requested and why. Within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) there are local and national contracts with many laboratories with hundreds of precision oncology tests to choose from. Consulting with a pathologist is necessary to determine which test is most appropriate.

The precision oncology consult form cannot be submitted without completing all required fields. It also contains indications for the test the ordering HCP selects to minimize unintentionally inappropriate orders. The form asks which tissue the requestor expects the test to be performed on. The requestor must provide contact information for the originating institution when the tissue was collected outside the VHA. The consult form also asks whether another anatomic site is accessible and could be biopsied without unacceptable risk or impracticality, should all previously collected tissue be insufficient. For CGP requests, this allows the pathologist to determine the appropriateness of liquid biopsy without having to reach out to the ordering HCP or wait for the question to be addressed at a tumor board. When a companion diagnostic is available for a test, the ordering HCP is asked which drug will be used so that the most appropriate assay is chosen.

Consult Review

Pathology service involvement begins with pathologist review of the consult form to ensure that the correct test is indicated. Depending on the resources and preferences at a site, consults can be directed to and reviewed by the pathologist associated with the corresponding pathology specimen or to a single pathologist or group of pathologists charged with attending to consults.

The patient’s EHR is reviewed to verify that the test has not already been performed and to determine which tissue to review. Previous surgical pathology reports are examined to assess whether sufficient tissue is available for testing, which may be determined without the need for direct slide examination. Pathologists often use wording such as “rare cells” or in some cases specify that there are not enough lesional cells for ancillary testing. In biopsy reports, the percentage of tissue occupied by lesional cells or the greatest linear length of tumor cells is often documented. As for quality, pathologists may note that a specimen is largely necrotic, and gross descriptions will indicate if a specimen was compromised for molecular analysis by exposure to fixatives such as Bouin’s solution, B-5, or decalcifying agents that contain strong acids.

Tissue Retrieval

If, after such evaluation, the test is indicated and there is tissue that could be sufficient for testing, retrieval of the tissue is pursued. For in-house cases, the pathologist reviews the corresponding surgical pathology report to determine which blocks and slides to pull from the archives. In the cancer checklist, some pathologists specify the best block for subsequent ancillary studies. From the final diagnosis and gross description, the pathologist can determine which blocks are most likely to contain lesional tissue. These slides are retrieved from the archives.

For cases collected at an outside institution (other VHA facility or non-VHA facility/institution), the outside institution must be contacted to retrieve the needed slides and blocks. The phone numbers, fax numbers, email addresses, and mailing addresses for outside institutions are housed in an electronic file and are specific to the point of contact for such requests. Maintaining a record of contacts increases efficiency of the overall process; gathering contact information and successfully requesting tissue often involves multiple automated answering systems, misdirected calls, and failed attempts.

Tissue Review

After retrieving in-house tissue, the pathologist can proceed directly to slide review. For outside cases, the case must first be accessioned so that after review of the slides the pathologist can issue a report to confirm the outside diagnosis. In reviewing the slides, the pathologist looks to see that the diagnosis is correct, that there is a sufficient number of lesional cells in a section, that the lesional cells are of a sufficient concentration in a section, or subsection of the section that could be dissected, and that the cells are viable. Depending on the requested assay and the familiarity of the pathologist with that assay, the pathologist may need to look up the technical requirements of the assay and capabilities of the testing company. Assays vary in sensitivity and require differing amounts and concentrations of tumor. Some companies will dissect tissue, others will not.

If there is sufficient tissue in the material reviewed, the corresponding blocks are retrieved from in-house archives or requests are placed for outside blocks or unstained slides. If there was not enough tissue for testing, the same process is repeated to retrieve and evaluate any other specimens the patient may have. If there are no other specimens to review, this is simply communicated to the ordering HCP via the consult. If the patient is a candidate for liquid biopsy—ie, current specimens are of insufficient quality and/or quantity and a new tissue sample cannot be obtained due to unacceptable risk or impracticality—the order is placed at this time.

Tissue Transport and Testing

Unstained slides need to be cut unless blocks are sent. Slides, blocks, reports, and requisition forms are packaged for transport. An accession number is created for the precision oncology molecular laboratory test in the clinical laboratory section of the EHR system. The clinical laboratory accession number provides a way of tracking sendout testing status. The case is accessioned just prior to placement in the mail so that when an accession number appears in the EHR, the ordering HCP knows the case has been sent out. When results are received, the clinical laboratory accession is completed and a comment is added to indicate where in the EHR to find the report or, when applicable, notes that testing failed.

RESULT REPORTING

When a result becomes available, the report file is downloaded from the vendor portal. This full report is securely transmitted to the ordering HCP. The file is then scanned into the EHR. Additionally, salient findings from the report are abstracted by the pathologist for inclusion as a supplement to the anatomic pathology case. This step ensures that this information travels with the anatomic pathology report if the patient’s care is transferred elsewhere. Templates are used to ensure essential data is captured based on the type of test. The template reminds the pathologist to comment on things such as variants that may represent clonal hematopoiesis, variants that may be germline, and variants that qualify a patient for germline testing. Even with the template, the pathologist must spend significant time reviewing the chart for things such as personal cancer history, other medical history, other masses on imaging, family history, previous surgical pathology reports, and previous molecular testing.

If results are suboptimal, recommendations for repeat testing are made based on the consult response to the question of repeat biopsy feasibility and review of previous pathology reports. The final consult report is added as a consult note, the consult is completed, and the original vendor report file is associated with the consult note in the EHR.

Ancillary Testing Technician

Due to chronic KCVAMC understaffing in the clerical office, gross room, and histology, most of the consult tasks are performed by a pathologist. In an ideal scenario, the pathology staff would divide its time between a pathologist and another dedicated laboratory position, such as an ancillary testing technician (ATT). The ATT can assume responsibilities that do not require the expertise of a pathologist (Figure 2). In such a process, the only steps that would require a pathologist would be review of requests and slides and completion of the interpretive report. All other steps could be accomplished by someone who lacks certifications, laboratory experience, or postsecondary education.

The ATT can receive the requests and retrieve slides and blocks. After slides have been reviewed by a pathologist, the pathologist can inform the ATT which slides or blocks testing will be performed on, provide any additional necessary information for completing the order, and answer any questions. For send-out tests, this allows the ATT to independently complete online portal forms and all other physical requirements prior to delivery of the slides and blocks to specimen processors in the laboratory.

ATTs can keep the ordering HCPs informed of status and be identified as the point of contact for all status inquiries. ATTs can receive results and get outside reports scanned into the EHR. Finally, ATTs can use pathologistdesigned templates to transpose information from outside reports such that a provisional report is prepared and a pathologist does not spend time duplicating information from the outside report. The pathologist can then complete the report with information requiring medical judgment that enhances care.

Optimal Pathologist Involvement

Only 3 steps in the process (request review, tissue review, and completion of an interpretive report) require a pathologist, which are necessary for optimal care and to address barriers to precision oncology.3 While the laboratory may consume only 5% of a health system budget, optimal laboratory use could prevent as much as 30% of avoidable costs.4 These estimates are widely recognized and addressed by campaigns such as Choosing Wisely, as well as programming of alerts and hard stops in EHR systems to reduce duplicate or otherwise inappropriate orders. The tests associated with precision oncology, such as CGP assays, require more nuanced consideration that is best achieved through pathology consultation. In vetting requests for such tests, the pathologist needs information that ordering HCPs do not routinely provide when ordering other tests. A consult asking for such information allows an ordering HCP to efficiently convey this information without having to call the laboratory to circumvent a hard stop.

Regardless of whether a formal electronic consult is used, pathologists must be involved in the review of requests. Creation of an original in-house report also provides an opportunity for pathologists to offer their expertise and maximize the contribution of pathology to patient care. If outside (other VHA facility or non-VHA facility/institution) reports are simply scanned into the EHR without review and issuance of an interpretive report by an in-house pathologist, then an interpretation by a pathologist with access to the patient’s complete chart is never provided. Testing companies are not provided with every patient diagnosis, so in patients with multiple neoplastic conditions, a report may seem to indicate that a detected mutation is from 1 tumor when it is actually from another. Even when all known diagnoses are considered, a variant may be detected that the medical record could reveal to indicate a new diagnosis.

Variation in reporting between companies necessitates pathologist review to standardize care. Some companies indicate which variants may represent clonal hematopoiesis, while others will simply list the pathogenic variants. An oncologist who sees a high volume of hematolymphoid neoplasia may recognize which variants may represent clonal hematopoiesis, but others may not. Reports from the same company may vary, and their interpretation often requires a pathologist's expertise. For example, even if a sample meets the technical requirements for analysis, the report may indicate that the quality or quantity of DNA has reduced the sensitivity for genomic alteration detection. A pathologist would know how to use this information in deciding how to proceed. In a situation where quantity was the issue, the pathologist may know there is additional tissue that could be sent for testing. If quality is the issue, the pathologist may know that additional blocks from the same case likely have the same quality of DNA and would also be unsuitable for testing.

Pathologist input is necessary for precision oncology testing. Some tasks that would ideally be completed by a molecular pathologist (eg, creation of reports to indicate which variants may represent clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential) may be sufficiently completed by a pathologist without fellowship training in molecular pathology.

There are about 15,000 full-time pathologists in the US.4 In the 20 years since molecular genetic pathology was formally recognized as a specialty, there have been < 500 pathologists who have pursued fellowship training in this specialty.5 With the inundation of molecular variants uncovered by routine next-generation sequencing (NGS), there are too few fellowship-trained molecular pathologists to provide all such aforementioned input; it is incumbent on surgical pathologists in general to take on such responsibilities.

Consult Implementation Data

These results support the feasibility and effectiveness of the consult process. Prior to consult implementation, many requests were not compliant with VHA National Precision Oncology Program (NPOP) testing guidelines. Since enactment of the consult, > 90% of requests have been in compliance. In the year preceding the consult (January 2020 to December 2021), 55 of 211 (26.1%) metastatic lung and prostate cancers samples eligible for NGS were tested and 126 (59.7%) NGS vendor reports were scanned into the EHR. The mean time from metastasis to NGS result was 151 days. In the year following enactment of the consult (January 2021 to December 2022), 168 of 224 (75.0%) of metastatic lung and prostate cancers eligible for NGS were tested and all 224 NGS vendor reports were scanned into the EHR. The mean time from metastasis to NGS result was 83 days. These data indicate that the practices recommended increase test use, appropriateness of orders, standardization of reporting, and efficiency of care.

CONCLUSIONS

Processing precision oncology testing requires substantial work for pathology departments. Laboratory workforce shortages and ever-expanding indications necessitate additional study of pathology processes to manage increasing workload and maintain the highest quality of cancer care through maximal efficiency and the development of appropriate staffing models. The use of a consult for anatomic pathology molecular testing is one process that can increase test use, appropriateness of orders, standardization of reporting, and efficiency of care. This report provides a comprehensive description and mapping of the process, highlights best practices, identifies inefficiencies, and provides a description and mapping of a target state.

- Inal C, Yilmaz E, Cheng H, et al. Effect of reflex testing by pathologists on molecular testing rates in lung cancer patients: experience from a community-based academic center. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(15 suppl):8098. doi:10.1200/jco.2014.32.15_suppl.8098

- Mettman D, Goodman M, Modzelewski J, et al. Streamlining institutional pathway processes: the development and implementation of a pathology molecular consult to facilitate convenient and efficient ordering, fulfillment, and reporting for tissue molecular tests. J Clin Pathw.Ersek JL, Black LJ, Thompson MA, Kim ES. Implementing precision medicine programs and clinical trials in the community-based oncology practice: barriers and best practices. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2018;38:188- 196. doi:10.1200/EDBK_200633 2022;8(1):28-33.

- Ersek JL, Black LJ, Thompson MA, Kim ES. Implementing precision medicine programs and clinical trials in the community-based oncology practice: barriers and best practices. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2018;38:188- 196. doi:10.1200/EDBK_200633

- Robboy SJ, Gupta S, Crawford JM, et al. The pathologist workforce in the United States: II. An interactive modeling tool for analyzing future qualitative and quantitative staffing demands for services. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2015;139(11):1413-1430. doi:10.5858/arpa.2014-0559-OA doi:10.25270/jcp.2022.02.1

- Robboy SJ, Gross D, Park JY, et al. Reevaluation of the US pathologist workforce size. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(7): e2010648. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.10648

- Inal C, Yilmaz E, Cheng H, et al. Effect of reflex testing by pathologists on molecular testing rates in lung cancer patients: experience from a community-based academic center. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(15 suppl):8098. doi:10.1200/jco.2014.32.15_suppl.8098

- Mettman D, Goodman M, Modzelewski J, et al. Streamlining institutional pathway processes: the development and implementation of a pathology molecular consult to facilitate convenient and efficient ordering, fulfillment, and reporting for tissue molecular tests. J Clin Pathw.Ersek JL, Black LJ, Thompson MA, Kim ES. Implementing precision medicine programs and clinical trials in the community-based oncology practice: barriers and best practices. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2018;38:188- 196. doi:10.1200/EDBK_200633 2022;8(1):28-33.

- Ersek JL, Black LJ, Thompson MA, Kim ES. Implementing precision medicine programs and clinical trials in the community-based oncology practice: barriers and best practices. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2018;38:188- 196. doi:10.1200/EDBK_200633

- Robboy SJ, Gupta S, Crawford JM, et al. The pathologist workforce in the United States: II. An interactive modeling tool for analyzing future qualitative and quantitative staffing demands for services. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2015;139(11):1413-1430. doi:10.5858/arpa.2014-0559-OA doi:10.25270/jcp.2022.02.1

- Robboy SJ, Gross D, Park JY, et al. Reevaluation of the US pathologist workforce size. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(7): e2010648. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.10648

Mapping Pathology Work Associated With Precision Oncology Testing

Mapping Pathology Work Associated With Precision Oncology Testing

Leveraging Community Asset Mapping to Improve Suicide Prevention for Veterans

Leveraging Community Asset Mapping to Improve Suicide Prevention for Veterans

Suicide prevention is the leading clinical priority for the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA).1 An average of 18 veterans died by suicide each day in 2021.2 Numerous risk factors for veteran suicide have been identified, including mental health disorders, comorbidities, access to firearms, and potentially lethal medications.3-5 To better understand groups of patients at risk of suicide in medical settings, the authors have previously compared demographic and clinical risk factors between patients who died by suicide by using firearms or other means with matched patients who did not die by suicide (control group) to examine the impact of lack of social support, financial stress,6 legal problems,7 homelessness,8 and discrimination.9 The number of cooccurring risk factors a veteran experiences is associated with a greater likelihood of suicide attempts over time.10 In addition, some risk factors are social and environmental risk factors known as social determinants of health (SDoH), including financial stability and access to health care, food, housing, and education. 11 SDoH may influence health outcomes more broadly and are associated with greater risk of suicide.12,13

The VA offers programming to address suicide risk factors. However, not all veterans are eligible for VA care. Further, some veterans prefer to obtain non-VA services in their communities. Providing veterans with community resources that address risk factors, particularly SDoH, may be a worthwhile strategy for reducing suicide. Such resources have demonstrated success; for example, greater use of housing services was associated with a reduced risk for suicide-related mortality among unhoused veterans.12

The challenges that veterans experience can go beyond the scope of services the VA provides. For example, while the VA provides some services related to homelessness, justice involvement, and assistance with home loans, these services are often limited. Other services for veterans to address SDoH may require access to community resources, including food banks, employment assistance, respite and childcare services, and transportation assistance. Some veterans also may have experienced institutional betrayal, which could be a barrier to VA care and may motivate veterans to address their needs in the community.14 Veterans therefore may need a range of services beyond those within the VA. Leveraging community resources for veterans at risk for suicide is critical, as these resources may help to mitigate suicide risk.

An emerging emphasis of the VA is improving coordination with community partners to prevent veteran suicide. In 2019, the VA launched an improved Veterans Community Care Program, which implemented portions of the VA MISSION Act of 2018 to create additional connection to community care for VA-enrolled veterans. This includes assisting veterans in gaining access to specialty services not offered at a local VA medical center (VAMC), getting access to services sooner, and receiving care if they do not live near a VAMC.15 In addition, the COMPACT Act allows veterans in acute suicidal crisis to receive emergency health care through either VA or non-VA facilities at no cost.16 The VA National Strategy for Preventing Veteran Suicide 2018-2028 is a 10-year plan to reduce veteran suicide rates that includes initiatives to increase connections between VA and community agencies.17 A suicide prevention community toolkit is available online for health care professionals (HCPs) (and others, including employers) outside of the VA who may be unfamiliar with best practices for working with veterans at risk for suicide.18

The challenge, however, is that there is often a lack of “connectedness” between VA suicide prevention coordinators and community resources to address suicide risk factors and related social determinants of health. These services include, but are not limited to suicide prevention, mental health counseling (particularly no/low-cost services), unemployment resources, financial assistance and counseling, housing assistance, and identity-related supportive spaces. A major stumbling block in connecting resources with veterans (regardless of discharge status) who need them is there is no single, national organization with a comprehensive, community-based network that can serve in this intermediary role.

Community asset mapping (CAM), also known as asset mapping or environmental scanning, is a way to bridge the gap.19 CAM provides a method for identifying and aligning community resources relative to a specific need.20 CAM may be used to build community relationships in service of veteran suicide prevention. This process can help individuals learn about and make use of organizations and services within their communities. CAM also helps connect HCPs so they can network, exchange ideas, and collaborate with an eye toward increasing the availability of services and enhancing care coordination. CAM also allows community members (eg, leaders, organizations, individuals) to identify possible gaps in services that address suicide risk factors and solve these problems.

This article details CAM for suicide prevention, which can be utilized by the VA and community organizations alike. Within the VA, CAM can be used by HCPs and administrators, such as VA community engagement and partnership coordinators, to identify potential partnering organizations. For those who serve veterans outside of the VA, CAM can be used to connect at-risk individuals to resources that can enhance their care. This process can help increase the overall knowledge of, and access to, community resources.

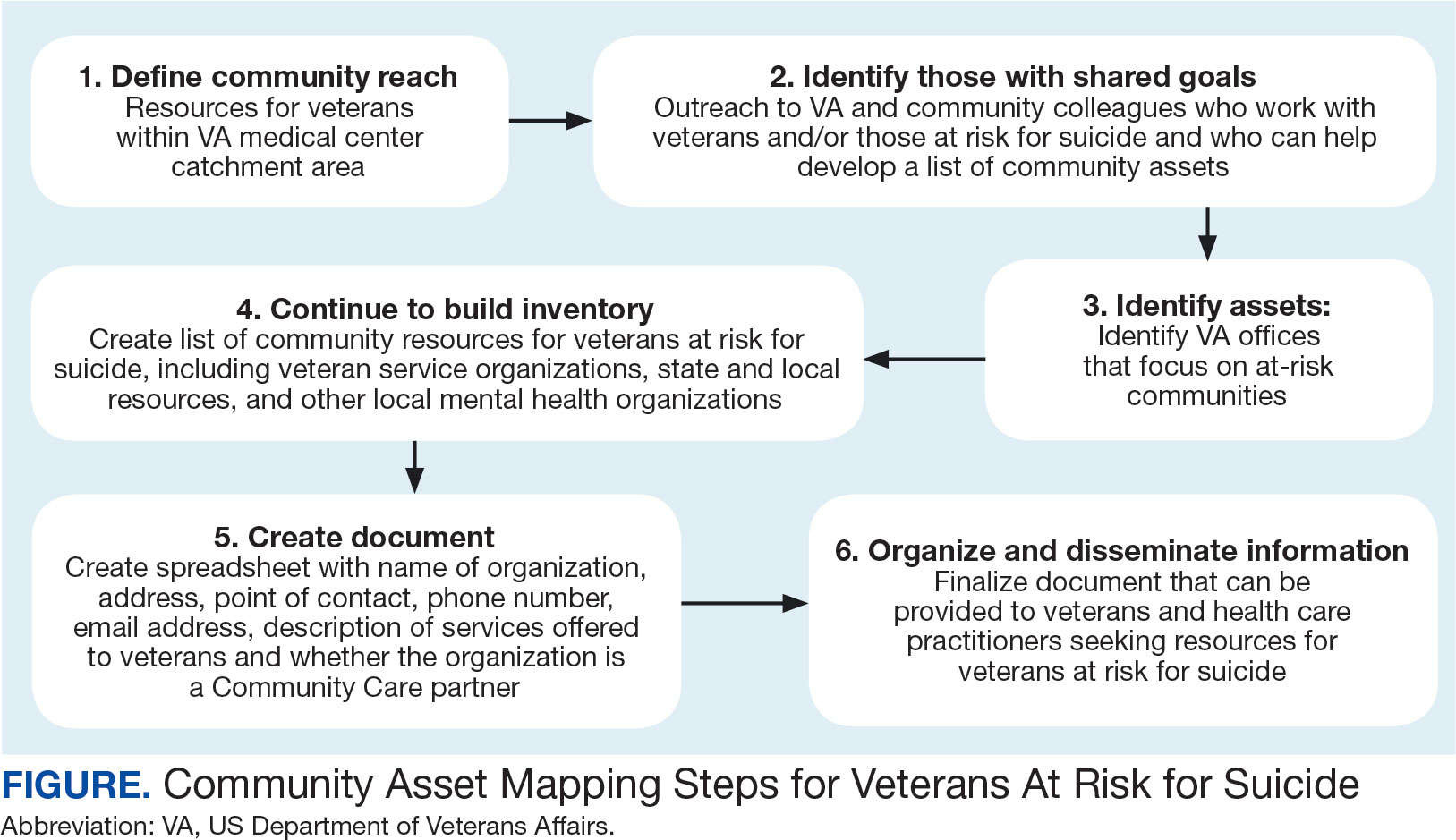

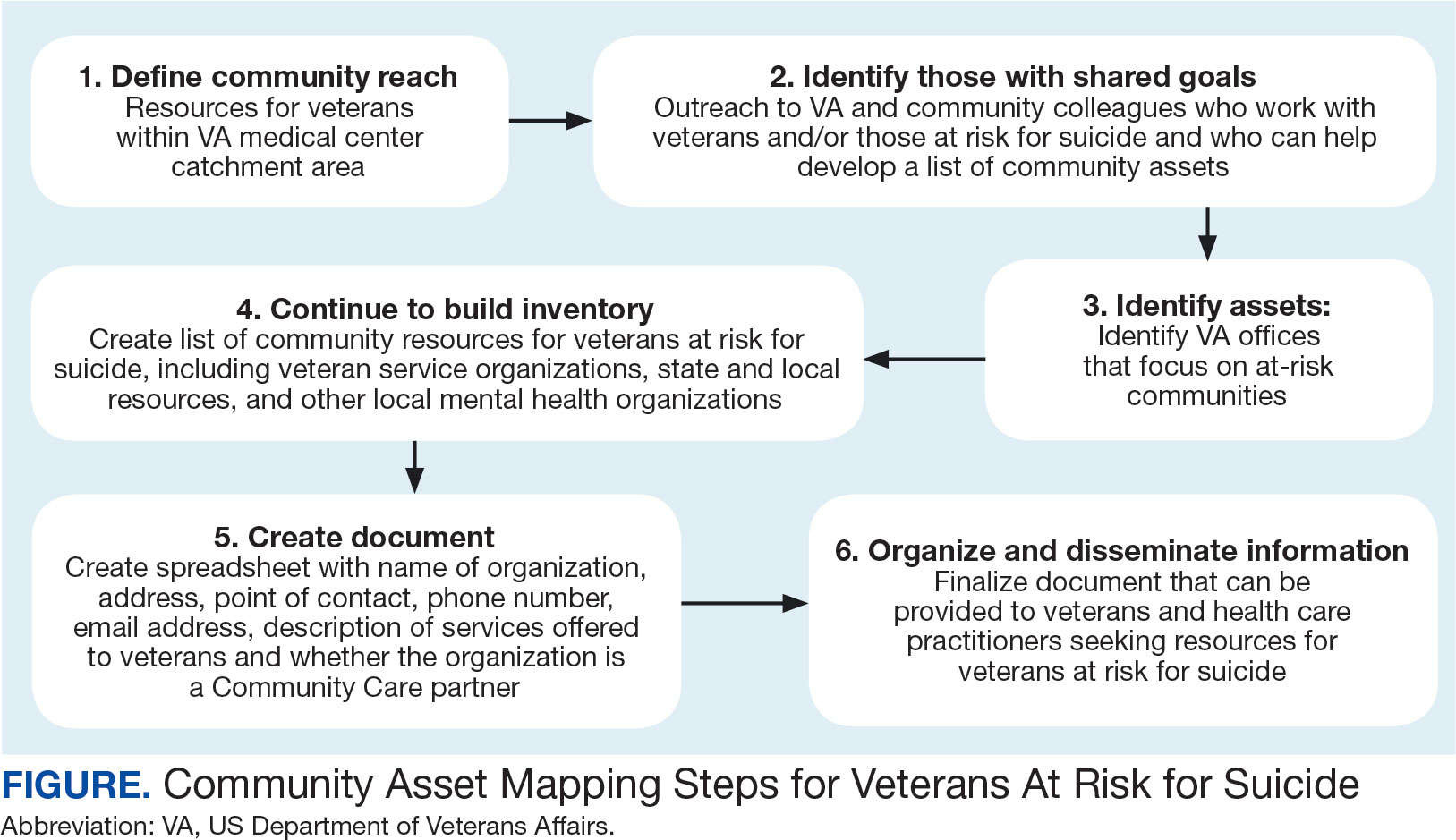

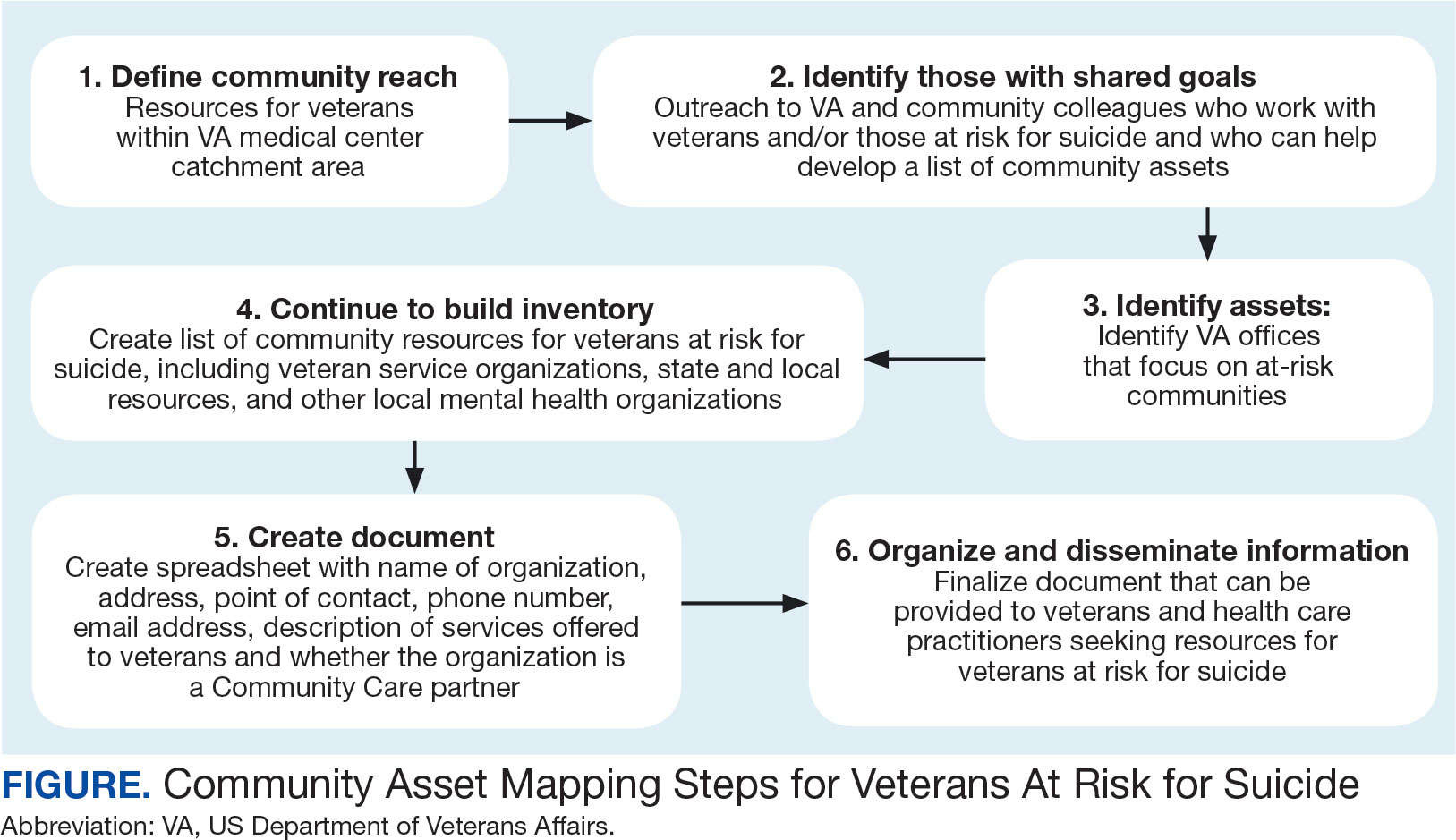

COMMUNITY ASSET MAPPING

The University of California, Los Angeles Center for Health Policy Research provides 6 steps for the CAM process.21 These steps include: (1) defining the boundaries of people and places that comprise the community; (2) identifying people and organizations who share similar interests and goals; (3) determining the assets to include; (4) creating an inventory of all organizations’ assets; (5) creating an inventory of individuals’ assets; and (6) organizing the assets on a map. To address the needs of the veteran population, we’ve taken these 6 steps and adapted them to create a CAM for veterans at risk for suicide (Figure). The discussion that follows details how these steps can be implemented to identify community resources that address social determinants of health that may contribute to suicide risk. The goal is to prevent veteran suicide.

Step 1: Define Community Reach. The first step is to identify the geographical boundaries of the community. This may include all veterans within a catchment area (eg, veterans within 60 miles of a VAMC). Defining the geographical parameters of the community will provide structure to the effort so that the resource list is as comprehensive as possible.

Steps 2 and 3: Identify Community Members with Shared Goals; Identify Assets. It is important to identify community members who share similar interests and goals, including people with specific knowledge and skills, organizations with particular goals, and community partners with a broad reach. To begin building a list of referrals, reach out to colleagues within the VA system who are familiar with community resources for those with suicide risk factors. The local VA Transition and Care Management (TCM) office is a resource that connects those transitioning from military to civilian sectors with needed resources, and thus may be a helpful resource while building a CAM. Additionally, each office has a transition patient advocate, who is trained to resolve care-related concerns and may be familiar with community resources.

VA HCPs that can assist include Community Engagement and Partnership Coordinators, Suicide Prevention Coordinators, Local Recovery Coordinators, and substance abuse counselors. In addition, VA patient services, patient safety, and public affairs office staff—as well as VA Homeless Programs—may be good resources. Every VA health care system has care coordinators focused on military sexual trauma, intimate partner violence, and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer+ care. These care coordinators may be able to provide information on community resources that address social determinants of health (eg, discrimination, violence).

Reaching out to key community resources and asking for recommendations of other groups that provide assistance to veterans can also be productive. You can start by connecting with veterans service organizations (VSOs), Vet Centers, Veterans Experience Offices (VEO), and Community Veterans Engagement Boards (CVEBs). The VEO is an office designed around VA and community engagement efforts. This office utilizes the CVEBs to foster a 2-way communication feedback loop between veterans and local VA facilities regarding community engagement efforts and outreach.22 CVEBs are particularly valuable sources of information because veterans directly contribute to the conversation about community engagement by describing the difficulties and successes they’ve experienced. Veteran feedback about how a particular resource met their needs can inform which community services are prioritized for inclusion in the resource list. In addition, CVEBs may have a listing of local government, military, and/or community resources that provide services for veterans. Consider, too, organizations that are unrelated to an individual’s veteran status, but speak to their race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity, spirituality, socioeconomic status, or disability.

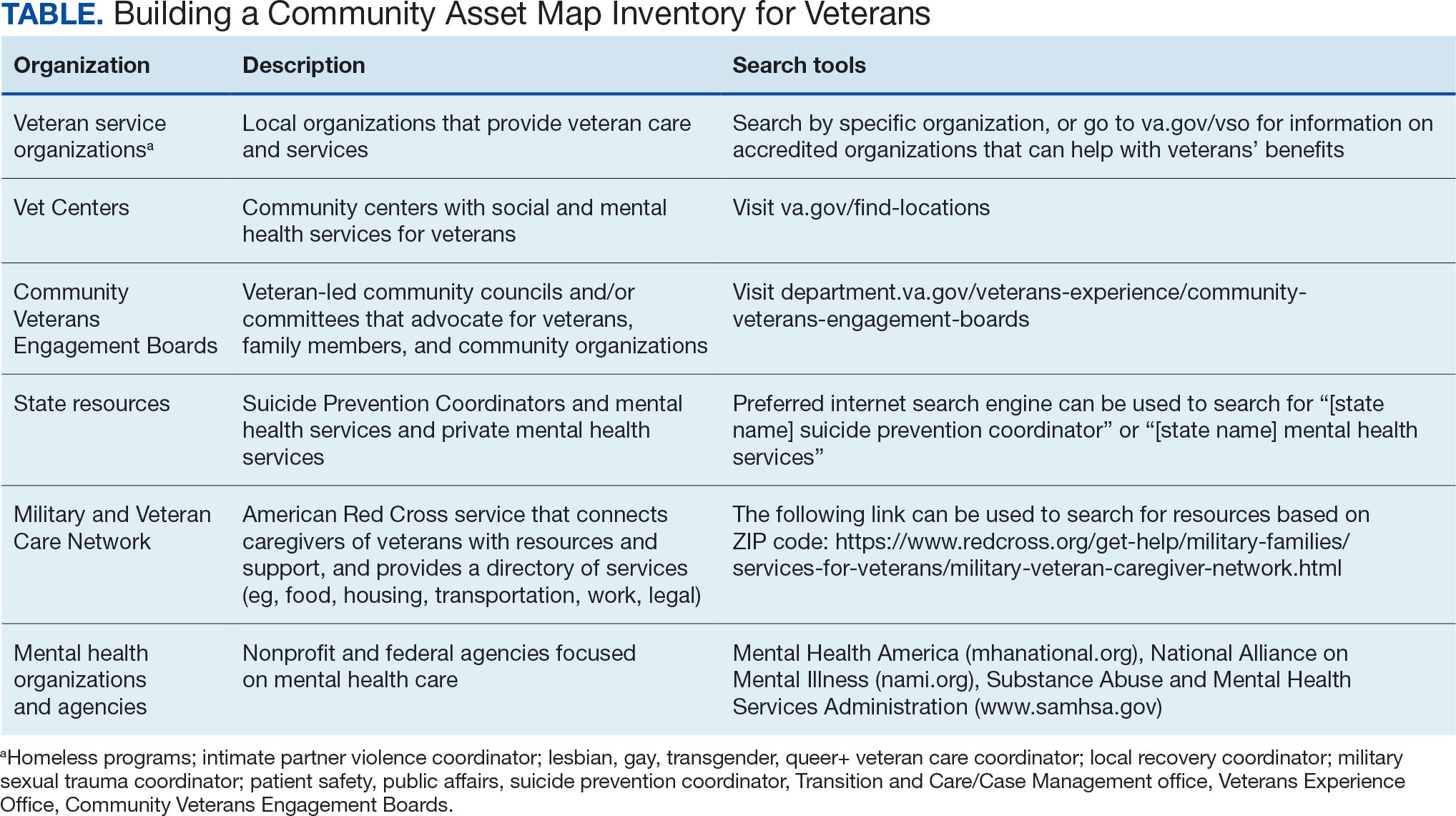

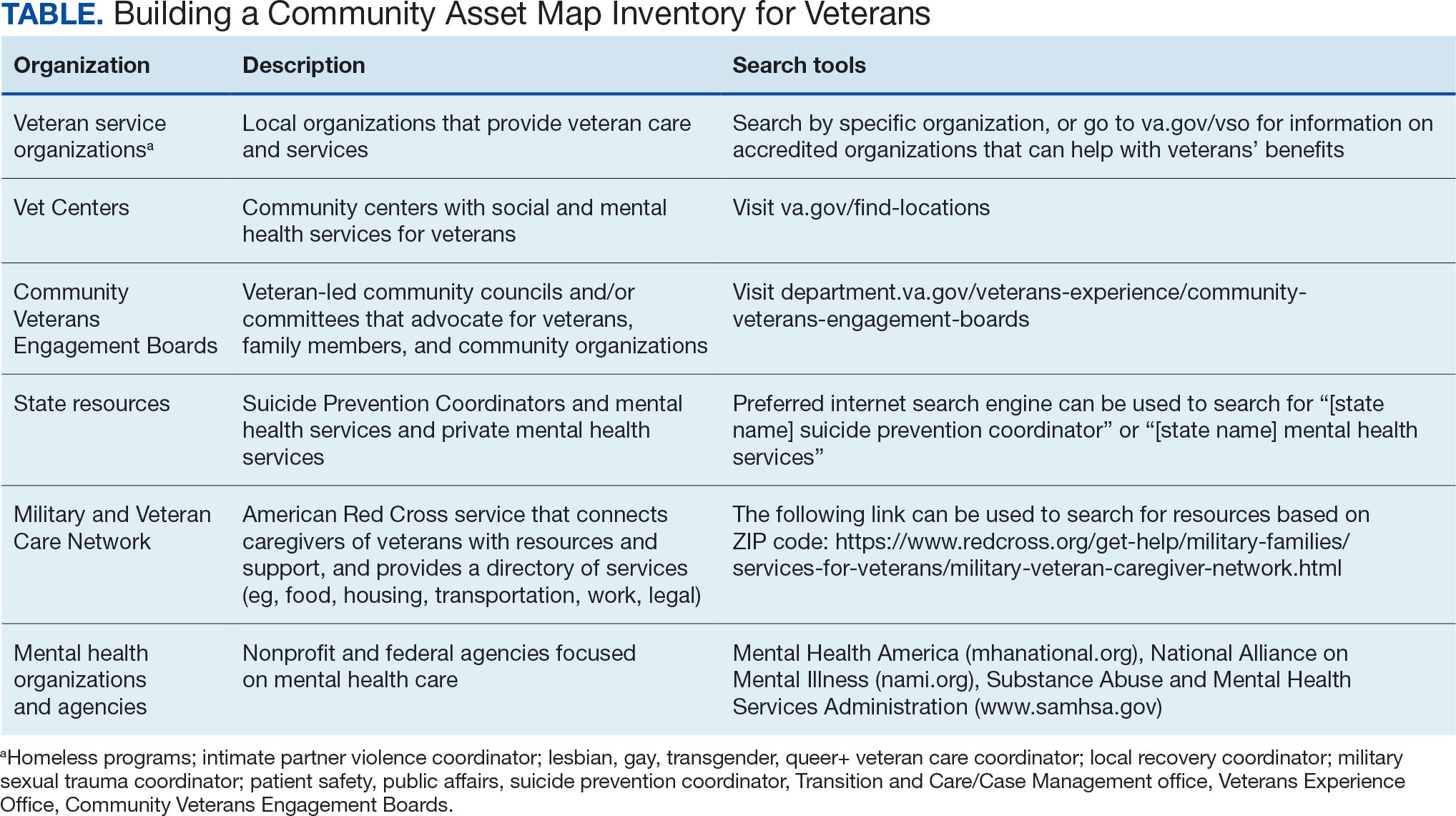

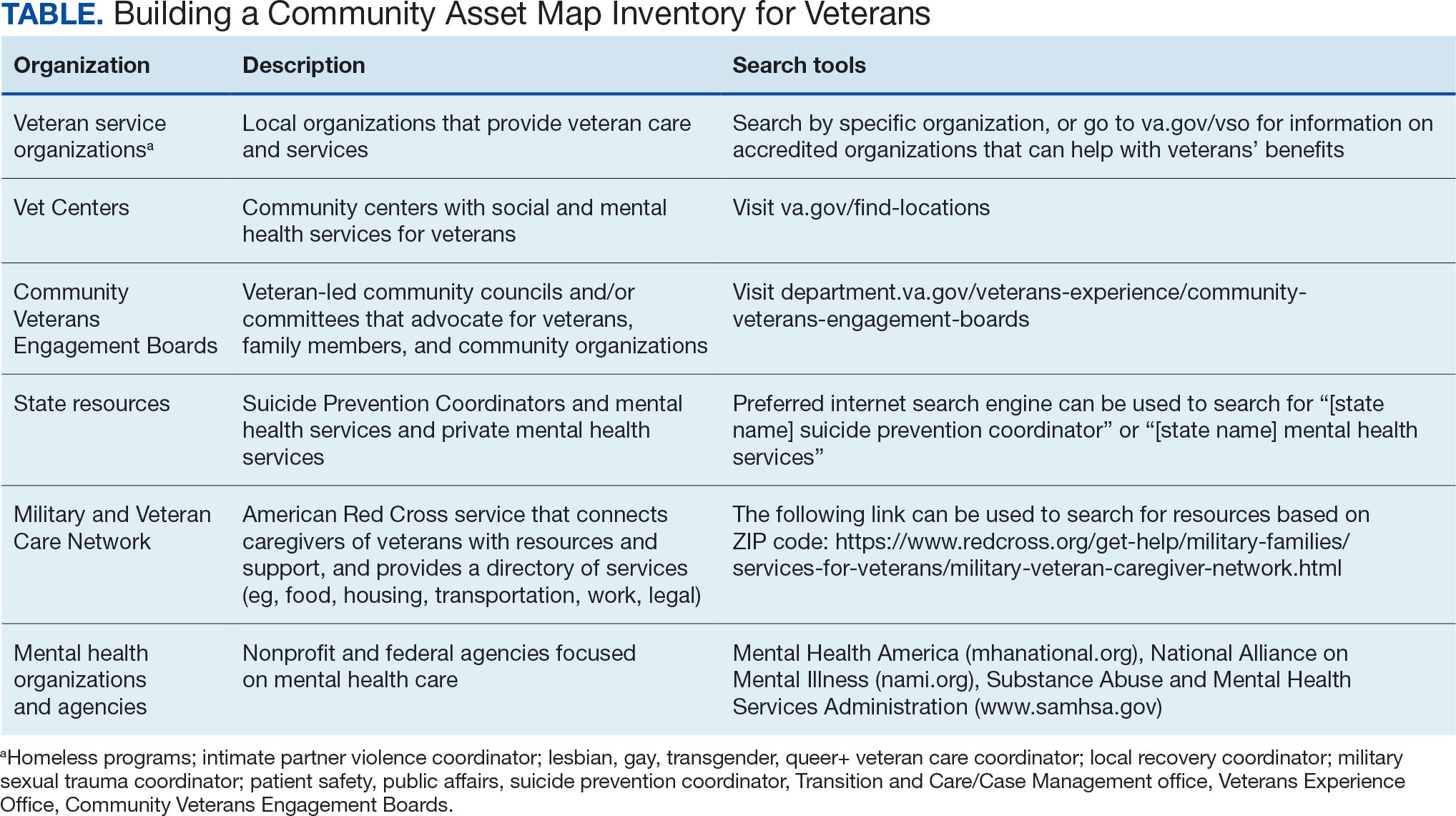

Step 4: Continue to Build Inventory. Use online searches to identify additional resources in the community that are known to have local relationships. These include state suicide prevention coordinators, mental health organizations, and other resources that address social determinants of health (eg, public health and human service organizations, faith-based organizations, collegial organizations). A list of links and search tips are available in the Table.

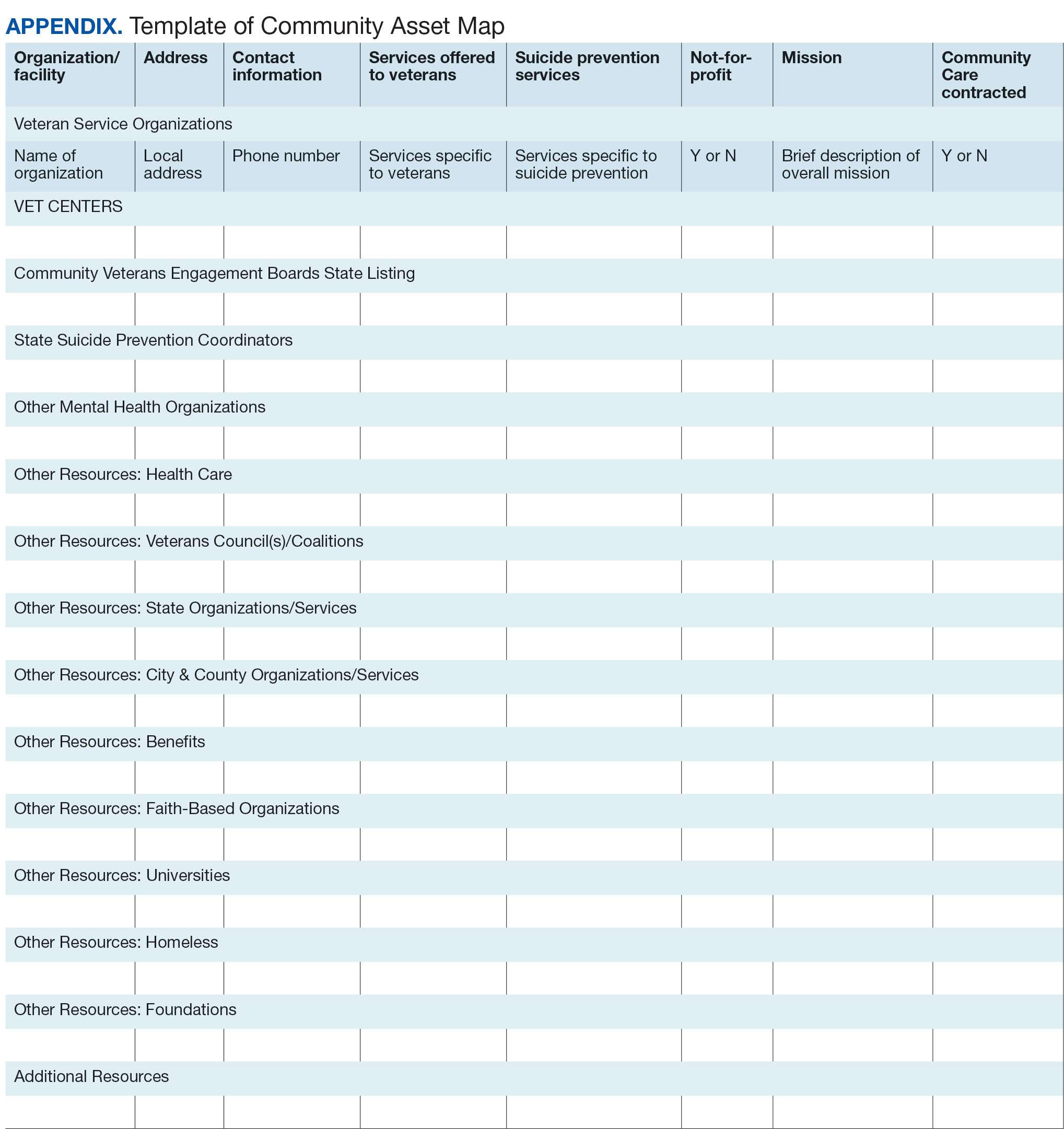

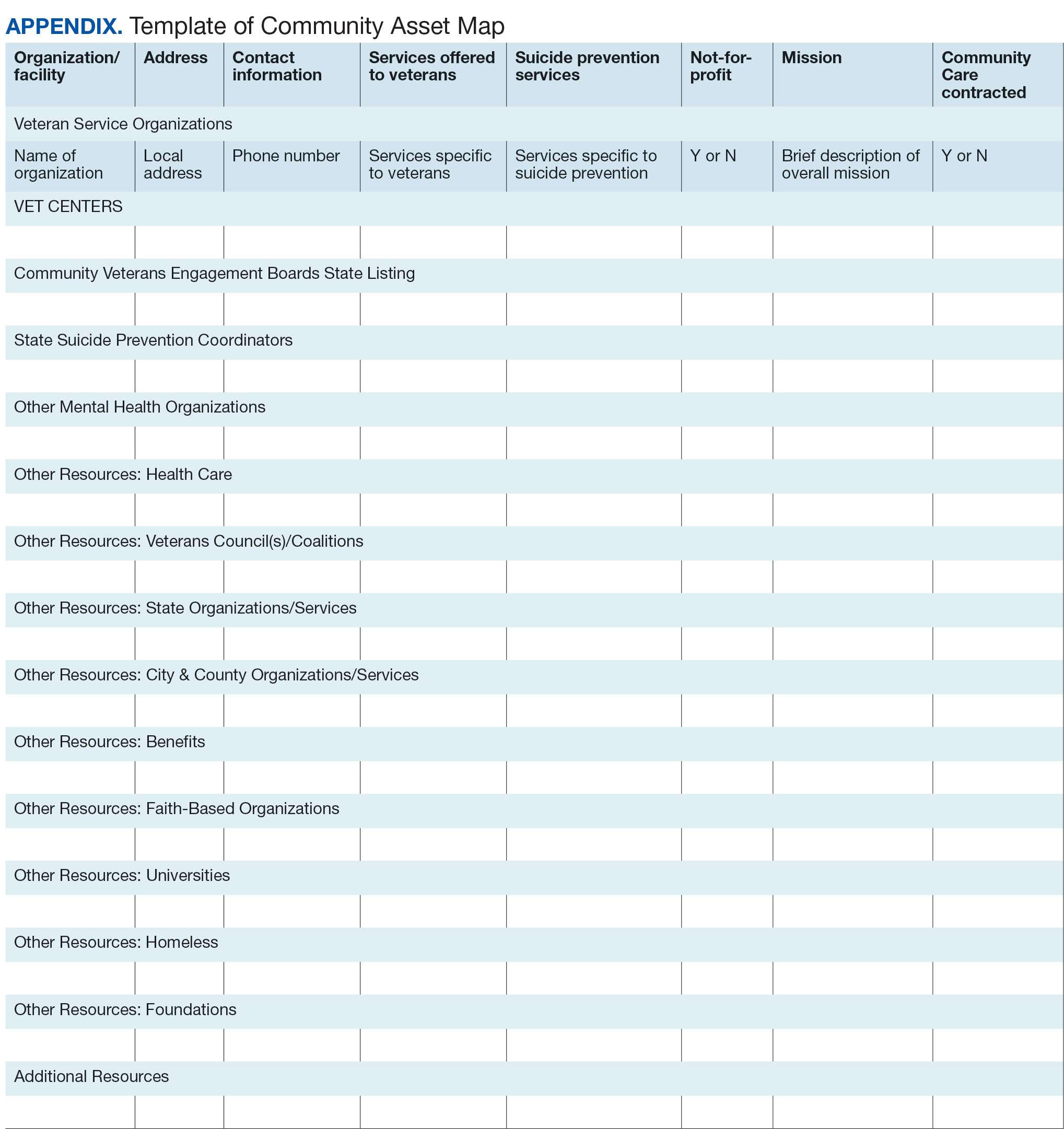

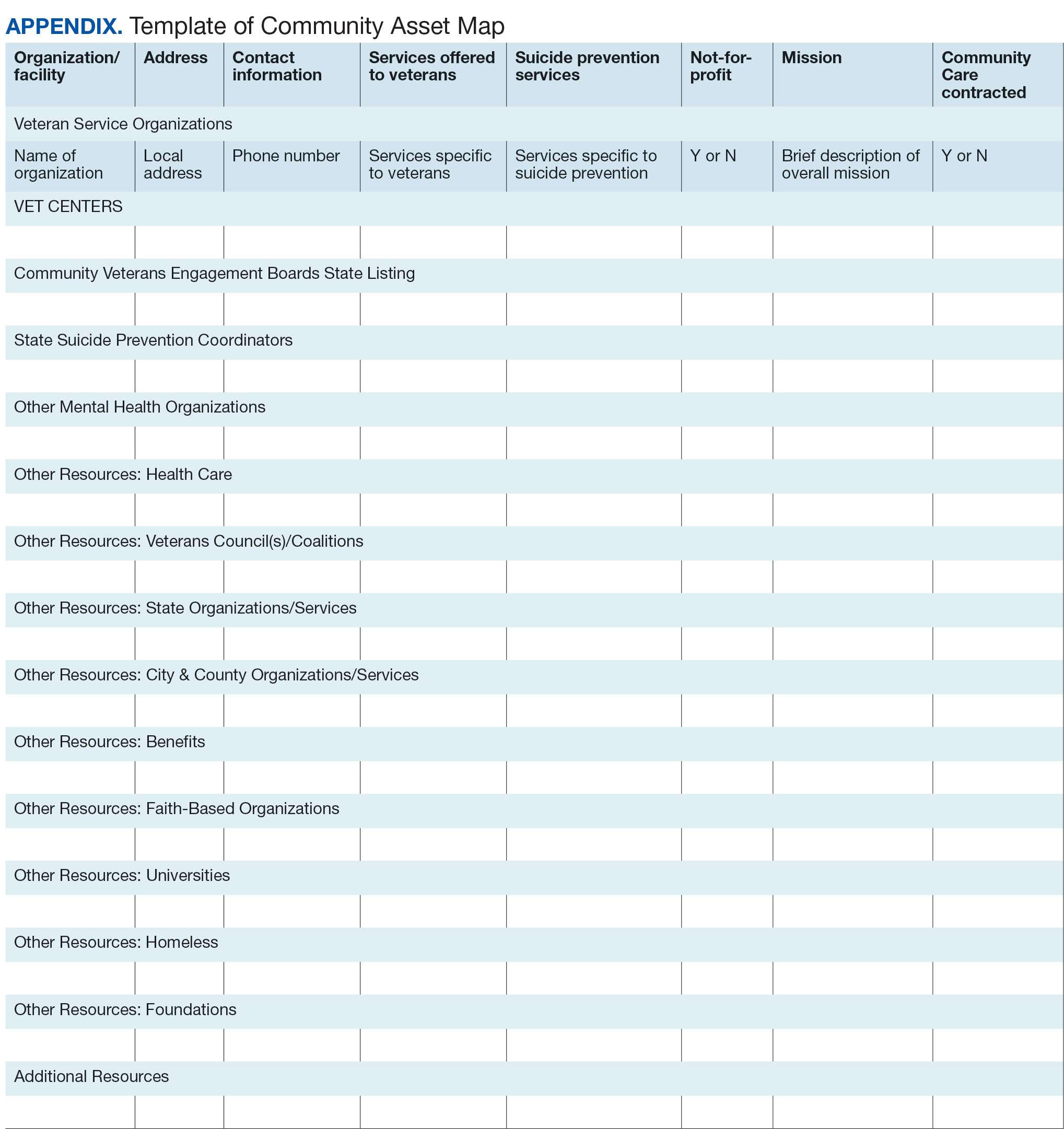

Steps 5 and 6: Create Document; Organize and Disseminate Information. A spreadsheet can be used to document organization information (Appendix). It is critical to record: (1) the name of the organization or individual; (2) the local address and a point of contact with contact information; (3) services offered to veterans; (4) services specific to suicide prevention, or that address risk factors for suicide; and (5) whether the referral organization is partnered with the VA Community Care Network, which is comprised of contracted HCPs who contract with the VA to provide care to veterans.23

Once a document is created, it can be disseminated through VA offices and among community partners who work with veterans at risk for suicide. It should also be stored in a centralized location such as a shared folder so that it can be continuously updated.

Regularly updating the list is vital so the resource list can continue to be helpful in addressing veterans’ needs and reducing suicide risk factors. Continued collaboration with those in the community can help ensure the resource list is up to date with all available services and pertinent contact information. It can also go far in strengthening collaborative bonds.

IMPLEMENTATION

To illustrate the use of CAM for veteran suicide prevention, we offer a case example of CAM conducted by the VA Patient Safety Center of Inquiry — Suicide Prevention Collaborative (VA PSCI-SPC) team, consisting of 4 team members. A veteran was included as a team member and assisted with the CAM process.

The VA PSCI-SPC sought to identify community services for veterans in Colorado who were not enrolled in VA health care and had risk factors for suicide. Next, the team reached out to colleagues and asked about community organizations that work with individuals at risk for suicide. VA PSCI-SPC outreach resulted in a list of assets that included resources to address mental health, legal concerns, employment, homelessness/housing, finances, religion, peer support, food insecurity, exercise, intimate partner violence, sexual and gender identity needs, and peer support. VSOs and CVEBs were also added to the list.

Next, the team continued to build on the inventory and identified state suicide prevention coordinators; health care systems; regional suicide prevention commissions; Colorado Department of Health and Human Services; program coordinators for Governor’s and Mayor’s Challenges to Prevent Suicide Among Service Members, Veterans, and their Families; veterans councils; universities (eg, counseling clinics, legal clinics); and foundations devoted to general and veteran-specific suicide prevention within the region.

All the identified resources were inventoried. Details were gathered about each of the organizations, including addresses, points of contact and phone numbers, descriptions of services offered for veterans, descriptions of suicide prevention services offered, whether or not organizations were not-for-profit, the mission of the organizations, and whether or not the organizations were under contract for VA Community Care. Finally, the resource spreadsheet was created and disseminated among stakeholders to be used to enhance veteran suicide care. Stakeholders included social workers, psychologists, and nurse practitioners working with veterans. The list was circulated to VA and community partners as needed.

The VA PSCI-SPC resource document was only 1 benefit of CAM. The asset mapping also resulted in the creation of a learning collaborative comprised of VA and community partners, designed to share knowledge of best practices in suicide prevention and create an established referral network for veterans at risk for suicide.24 Ultimately, the goal of the CAM and the creation of the learning collaborative was to better connect veterans to care in order to decrease suicide risk. A secondary benefit of this community connectedness is that the list of resources produced by CAM became a living document that was, and continues to be, updated as the network became aware of new resources and resources that were no longer available. The VA PSCI-SPC learning collaborative met quarterly to discuss implementation of suicide prevention best practices within their organization.

Data from the VA PSCI-SPC learning collaborative via CAM revealed that organizations felt more efficacious in implementing suicide prevention best practices, noticed increased connections and collaborations with community organizations with the goal of providing services to veterans, and resulted in staff training that improved services provided to veterans.24 This is supported by other findings of a literature review of suicide prevention interventions, which indicated that programs with an established community support network were more effective at reducing suicide rates.25 CAM therefore may be a process through which greater community connection and increased knowledge of resources may help prevent suicide among veterans.

It seems reasonable that the CAM processes used by the VA PSCI-SPC can be implemented within the regional Veterans Integrated Service Networks to identify assets in a specific geographical area to address challenges with social determinants of health and potentially decrease veteran suicide risk.

CONCLUSIONS

CAM can be used to identify and build relationships with community resources that address the stressors that place veterans at risk for suicide. Six proposed steps to CAM for veterans at risk for suicide include: defining community reach (the map); identifying community members and organizations with shared goals; identifying assets within the community; continuing to build inventory; creating a document; and organizing and disseminating the information (while continuing to update the resources).21

CAM can be used to connect veterans with resources to address needs related to adverse social determinants of health that may heighten their risk for suicide. For example, veterans facing legal challenges can connect with a legal clinic; those having difficulties paying bills can obtain financial assistance; those who need help completing their VA claims can connect with the Veterans Benefits Administration or VSOs to assist them with their claims; and those experiencing discrimination can connect with organizations where they may experience acceptance, safety, and support. Broad community support surrounding suicide risk factors can be critical for effective suicide prevention.25

CAM may also be helpful for HCPs and others involved in veteran health care. For example, community mapping can be utilized by newly hired community engagement and partnership coordinators as a tool for outlining resources available for veterans in their community and as a framework to continually update their resource network. CAM develops community awareness, integrates resources, and enhances service utilization, which may assist in veteran suicide prevention by increasing care coordination.17 Finally, mapping community resources can create awareness of the many resources available to help veterans, even before suicide becomes a consideration.

- Rice L. VA Secretary Robert Wilkie says suicide prevention is his agency’s top ‘clinical’ priority. June 17, 2019. Accessed January 30, 2025. https://www.kut.org/post/va-secretary-robert-wilkie-says-suicide-prevention-his-agencys-top-clinical-priority

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. 2023 national veteran suicide prevention annual report. November 2023. Accessed January 30, 2025. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/data-sheets/2023/2023-National-Veteran-Suicide-Prevention-Annual-Report-FINAL-508.pdf

- DeBeer BB, Meyer EC, Kimbrel NA, Kittel JA, Gulliver SB, Morissette SB. Psychological inflexibility predicts of suicidal ideation over time in veterans of the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2018;48(6):627–641. doi:10.1111/sltb.12388

- Ilgen MA, Bohnert ASB, Ignacio RV, et al. Psychiatric diagnoses and risk of suicide in veterans. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(11):1152–1158. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.129

- Kimbrel NA, Meyer EC, DeBeer BB, Gulliver SB, Morissette SB. A 12-month prospective study of the effects of PTSD-depression comorbidity on suicidal behavior in Iraq/ Afghanistan-era veterans. Psychiatry Res. 2016;243:97–99. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2016.06.011

- Hoffmire CA, Borowski S, Vogt D. Contribution of veterans’ initial post-separation vocational, financial, and social experiences to their suicidal ideation trajectories following military service. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2023;53(3):443- 456. doi:10.1111/sltb.12955

- Holliday R, Martin WB, Monteith LL, Clark SC, LePage JP. Suicide among justice-involved veterans: a brief overview of extant research, theoretical conceptualization, and recommendations for future research. J Soc Distress Homeless. 2020;30(1):41-49. doi:10.1080/10530789.2019.1711306

- Holliday R, Liu S, Brenner LA, et al. Preventing suicide among homeless veterans: a consensus statement by the Veterans Affairs suicide prevention among veterans experiencing homelessness workgroup. Med Care. 2021;59(Suppl 2):S103- S105. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001399

- Carter SP, Allred KM, Tucker RP, Simpson TL, Shipherd JC, Lehavot K. Discrimination and suicidal ideation among transgender veterans: The role of social supsupport and connection. LGBT Health. 2019;6(2):43-50. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2018.0239

- Lee DJ, Kearns JC, Wisco BE, et al. A longitudinal study of risk factors for suicide attempts among Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom veterans. Depress Anxiety. 2018;35(7): 609-618. doi:10.1002/da.22736

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Social determinants of health (SDOH). Accessed January 30, 2025. https://odphp.health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health

- Montgomery AE, Dichter M, Byrne T, Blosnich J. Intervention to address homelessness and all-cause and suicide mortality among unstably housed US veterans, 2012- 2016. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2021;75:380-386. doi: 10.1136/jech-2020-214664

- Llamocca EN, Yeh HH, Miller-Matero LR, et al. Association between adverse social determinants of health and suicide death. Med Care. 2023;61(11):744-749. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001918

- Monteith LL, Holliday R, Schneider AL, et al. Institutional betrayal and help-seeking among women survivors of military sexual trauma. Psychol Trauma. 2021;13(7):814-823. doi:10.1037/tra0001027