User login

Implementation of a VHA Virtual Oncology Training Pilot Program for Clinical Pharmacists

Purpose/Background

Oncology clinical pharmacist practitioners (CPP) play a critical role in optimizing drug therapy, managing side effects, and ensuring medication adherence. As a specialized clinical area, specific training is needed to ensure quality of care. Oncology pharmacy training programs are commercially available but pose a financial burden and are not specific to the Veterans Health Administration (VHA). A comprehensive, virtual Oncology Bootcamp series was implemented to upskill new oncology pharmacists (or pharmacists seeking to further their understanding of oncology practice), with didactic materials and clinical tools to enhance and standardize quality care delivery.

Methods

This program was comprised of an online platform of 23 one hour-long continuing education accredited sessions, delivered by leading subject matter experts. Pharmacists from two Veteran Integrated Service Networks (VISNs) were invited for the first year of the bootcamp. The curriculum encompassed fundamentals of oncology practice, patient care assessment, chemotherapy protocol review, practice management, and supportive care. Participants also received in-depth training on managing various cancer types, including but not limited to prostate, lung, gastrointestinal and hematologic malignancies. VHA specific information, including utilization of Oncology Clinical Pathways to promote standardized care was included where applicable. The interactive nature of the virtual sessions provided opportunities for real-time discussion and immediate feedback. To measure the impact of this program, a pre and post program evaluation of participants was conducted.

Results

Over the course of the program, more than 40 pharmacists across two VISNs participated in the bootcamp series. Results of the program evaluation showed an increase in self-reported comfort and skill levels in all criteria that were assessed (oncology pharmacotherapy, solid tumor malignancies, hematologic malignancies and oral anti-cancer therapy management). Additionally, 85% of respondents stated the series met their overall goals and over 90% of respondents stated they were either satisfied or very satisfied with the content, speakers and organization of the course.

Implications/Significance

This initiative has established the viability and significance of a highly accessible, VHA pathway specific and Veteran centric platform for oncology pharmacy professional development. Future directions for the program include a broader nationwide audience, increased content coverage and self-paced learning options.

Purpose/Background

Oncology clinical pharmacist practitioners (CPP) play a critical role in optimizing drug therapy, managing side effects, and ensuring medication adherence. As a specialized clinical area, specific training is needed to ensure quality of care. Oncology pharmacy training programs are commercially available but pose a financial burden and are not specific to the Veterans Health Administration (VHA). A comprehensive, virtual Oncology Bootcamp series was implemented to upskill new oncology pharmacists (or pharmacists seeking to further their understanding of oncology practice), with didactic materials and clinical tools to enhance and standardize quality care delivery.

Methods

This program was comprised of an online platform of 23 one hour-long continuing education accredited sessions, delivered by leading subject matter experts. Pharmacists from two Veteran Integrated Service Networks (VISNs) were invited for the first year of the bootcamp. The curriculum encompassed fundamentals of oncology practice, patient care assessment, chemotherapy protocol review, practice management, and supportive care. Participants also received in-depth training on managing various cancer types, including but not limited to prostate, lung, gastrointestinal and hematologic malignancies. VHA specific information, including utilization of Oncology Clinical Pathways to promote standardized care was included where applicable. The interactive nature of the virtual sessions provided opportunities for real-time discussion and immediate feedback. To measure the impact of this program, a pre and post program evaluation of participants was conducted.

Results

Over the course of the program, more than 40 pharmacists across two VISNs participated in the bootcamp series. Results of the program evaluation showed an increase in self-reported comfort and skill levels in all criteria that were assessed (oncology pharmacotherapy, solid tumor malignancies, hematologic malignancies and oral anti-cancer therapy management). Additionally, 85% of respondents stated the series met their overall goals and over 90% of respondents stated they were either satisfied or very satisfied with the content, speakers and organization of the course.

Implications/Significance

This initiative has established the viability and significance of a highly accessible, VHA pathway specific and Veteran centric platform for oncology pharmacy professional development. Future directions for the program include a broader nationwide audience, increased content coverage and self-paced learning options.

Purpose/Background

Oncology clinical pharmacist practitioners (CPP) play a critical role in optimizing drug therapy, managing side effects, and ensuring medication adherence. As a specialized clinical area, specific training is needed to ensure quality of care. Oncology pharmacy training programs are commercially available but pose a financial burden and are not specific to the Veterans Health Administration (VHA). A comprehensive, virtual Oncology Bootcamp series was implemented to upskill new oncology pharmacists (or pharmacists seeking to further their understanding of oncology practice), with didactic materials and clinical tools to enhance and standardize quality care delivery.

Methods

This program was comprised of an online platform of 23 one hour-long continuing education accredited sessions, delivered by leading subject matter experts. Pharmacists from two Veteran Integrated Service Networks (VISNs) were invited for the first year of the bootcamp. The curriculum encompassed fundamentals of oncology practice, patient care assessment, chemotherapy protocol review, practice management, and supportive care. Participants also received in-depth training on managing various cancer types, including but not limited to prostate, lung, gastrointestinal and hematologic malignancies. VHA specific information, including utilization of Oncology Clinical Pathways to promote standardized care was included where applicable. The interactive nature of the virtual sessions provided opportunities for real-time discussion and immediate feedback. To measure the impact of this program, a pre and post program evaluation of participants was conducted.

Results

Over the course of the program, more than 40 pharmacists across two VISNs participated in the bootcamp series. Results of the program evaluation showed an increase in self-reported comfort and skill levels in all criteria that were assessed (oncology pharmacotherapy, solid tumor malignancies, hematologic malignancies and oral anti-cancer therapy management). Additionally, 85% of respondents stated the series met their overall goals and over 90% of respondents stated they were either satisfied or very satisfied with the content, speakers and organization of the course.

Implications/Significance

This initiative has established the viability and significance of a highly accessible, VHA pathway specific and Veteran centric platform for oncology pharmacy professional development. Future directions for the program include a broader nationwide audience, increased content coverage and self-paced learning options.

Virtual Reality: An Innovative Approach to Cancer Distress Management

Objective

To assess the impact of virtual reality on the distress and pain levels of oncology patients in a VA outpatient infusion clinic.

Background

It is known that distress in cancer care leads to several problems including decreased survival, decreased treatment adherence, and inability to make treatment decisions. Virtual reality (VR) has proven to be beneficial to Veterans suffering from stress, anxiety, and other mental health ailments. This VA Oncology Infusion clinic is assessing the impact of VR on its Veterans’ distress and pain levels.

Methods

The pilot phase will last from 3/5/25- 9/5/25. Prior to each VR session, Veterans are administered an NCCN cancer distress screening tool and a numerical pain assessment. Post-VR session, Veterans are reassessed for distress and pain. The veterans are asked the following questions after each session: 1) Would you recommend VR to other veterans? and 2) Was the VR headset easy to use? Each VR session is approximately 10-15 minutes long, and the Veterans choose to engage in mindfulness activities, breathing exercises, or view scenery of their choice.

Results

Preliminary results indicate receptiveness and positive experiences amongst Veterans. 66% of Veterans who have used the VR headset have demonstrated a decrease in Cancer Distress by at least 2 points after a 10–15-minute VR session. 92% of Veterans that have used the VR headset report that it is easy to use and that they would recommend it to other Veterans.

Feasibility

The VA has created the Extended Reality Network (XR) to support the implementation of VR at the local site level. Resources and training are widely available to ensure program success.

Sustainability and Impact

A clearly developed standard of work and protocol that is tailored to the local site’s workflow, including a VR champion is needed to ensure sustainability. Preliminary data shows that veterans are engaged and responding positively to this innovative approach to cancer distress management, as evidenced by decreased distress levels and anxiety.

Objective

To assess the impact of virtual reality on the distress and pain levels of oncology patients in a VA outpatient infusion clinic.

Background

It is known that distress in cancer care leads to several problems including decreased survival, decreased treatment adherence, and inability to make treatment decisions. Virtual reality (VR) has proven to be beneficial to Veterans suffering from stress, anxiety, and other mental health ailments. This VA Oncology Infusion clinic is assessing the impact of VR on its Veterans’ distress and pain levels.

Methods

The pilot phase will last from 3/5/25- 9/5/25. Prior to each VR session, Veterans are administered an NCCN cancer distress screening tool and a numerical pain assessment. Post-VR session, Veterans are reassessed for distress and pain. The veterans are asked the following questions after each session: 1) Would you recommend VR to other veterans? and 2) Was the VR headset easy to use? Each VR session is approximately 10-15 minutes long, and the Veterans choose to engage in mindfulness activities, breathing exercises, or view scenery of their choice.

Results

Preliminary results indicate receptiveness and positive experiences amongst Veterans. 66% of Veterans who have used the VR headset have demonstrated a decrease in Cancer Distress by at least 2 points after a 10–15-minute VR session. 92% of Veterans that have used the VR headset report that it is easy to use and that they would recommend it to other Veterans.

Feasibility

The VA has created the Extended Reality Network (XR) to support the implementation of VR at the local site level. Resources and training are widely available to ensure program success.

Sustainability and Impact

A clearly developed standard of work and protocol that is tailored to the local site’s workflow, including a VR champion is needed to ensure sustainability. Preliminary data shows that veterans are engaged and responding positively to this innovative approach to cancer distress management, as evidenced by decreased distress levels and anxiety.

Objective

To assess the impact of virtual reality on the distress and pain levels of oncology patients in a VA outpatient infusion clinic.

Background

It is known that distress in cancer care leads to several problems including decreased survival, decreased treatment adherence, and inability to make treatment decisions. Virtual reality (VR) has proven to be beneficial to Veterans suffering from stress, anxiety, and other mental health ailments. This VA Oncology Infusion clinic is assessing the impact of VR on its Veterans’ distress and pain levels.

Methods

The pilot phase will last from 3/5/25- 9/5/25. Prior to each VR session, Veterans are administered an NCCN cancer distress screening tool and a numerical pain assessment. Post-VR session, Veterans are reassessed for distress and pain. The veterans are asked the following questions after each session: 1) Would you recommend VR to other veterans? and 2) Was the VR headset easy to use? Each VR session is approximately 10-15 minutes long, and the Veterans choose to engage in mindfulness activities, breathing exercises, or view scenery of their choice.

Results

Preliminary results indicate receptiveness and positive experiences amongst Veterans. 66% of Veterans who have used the VR headset have demonstrated a decrease in Cancer Distress by at least 2 points after a 10–15-minute VR session. 92% of Veterans that have used the VR headset report that it is easy to use and that they would recommend it to other Veterans.

Feasibility

The VA has created the Extended Reality Network (XR) to support the implementation of VR at the local site level. Resources and training are widely available to ensure program success.

Sustainability and Impact

A clearly developed standard of work and protocol that is tailored to the local site’s workflow, including a VR champion is needed to ensure sustainability. Preliminary data shows that veterans are engaged and responding positively to this innovative approach to cancer distress management, as evidenced by decreased distress levels and anxiety.

Enhancing Veteran Access to Cutting-Edge Treatments: Launching a T Cell Engager Therapy Administration Program

Background

The rise in the number of T-cell engager therapies highlights their importance in modern cancer treatment paradigms. Having recognized the need for, and complexities of, administering these innovative medications to our patients, our team assessed our institution’s capability to provide these therapies to our patients. We identified that our facility was wellequipped for implementation of T-cell engager therapy due to inpatient administration capabilities, an outpatient infusion center, on-hand supportive care medications (tocilizumab), and access to higher levels of care. Key players included medical oncologists, pharmacists, inpatient and infusion nurses, staff physicians, critical care practitioners, and care coordinators.

Clinical Practice Initiative

Barriers identified: education, toxicity concerns, formulary management, and logistics. To overcome these obstacles, comprehensive plans for procurement, hospital admission, monitoring, and training were developed as a facility-specific standard operating procedure (SOP). All available Tcell engager therapies were presented to the formulary committee and received local approval. Physician and pharmacist champions were registered for the associated risk evaluation and mitigation strategies (REMS) programs. Recorded webinars were done to provide education on REMS requirements, medication logistics, and adverse event management.

An admission plan was formulated to outline admission criteria, medication administration, and safety logistics. Order sets created by pharmacists, encompassed pre, post, and as needed medications for cytokine release syndrome and immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome. To facilitate safe discharge and meet REMS criteria, patients received wallet cards, dexamethasone and acetaminophen PRNs with detailed instructions for use, and direction for seeking emergency care with consideration of local tocilizumab availability.

Conclusions

Our SOP has enabled administration of six T-cell engager therapies for six diseases. The primary limitation for some of these agents is the need for inpatient monitoring at initiation, which may not be available at smaller centers. Facilities that lack these capabilities could utilize community care or partner with a neighboring Veterans Affairs medical center for initial administration, then transition back for continued treatment. Facilities that lack inpatient oncology nursing could administer the drug in the infusion center followed by admission for monitoring and toxicity management. Our implementation plan serves as a scalable model for improving veteran access to novel therapies.

Background

The rise in the number of T-cell engager therapies highlights their importance in modern cancer treatment paradigms. Having recognized the need for, and complexities of, administering these innovative medications to our patients, our team assessed our institution’s capability to provide these therapies to our patients. We identified that our facility was wellequipped for implementation of T-cell engager therapy due to inpatient administration capabilities, an outpatient infusion center, on-hand supportive care medications (tocilizumab), and access to higher levels of care. Key players included medical oncologists, pharmacists, inpatient and infusion nurses, staff physicians, critical care practitioners, and care coordinators.

Clinical Practice Initiative

Barriers identified: education, toxicity concerns, formulary management, and logistics. To overcome these obstacles, comprehensive plans for procurement, hospital admission, monitoring, and training were developed as a facility-specific standard operating procedure (SOP). All available Tcell engager therapies were presented to the formulary committee and received local approval. Physician and pharmacist champions were registered for the associated risk evaluation and mitigation strategies (REMS) programs. Recorded webinars were done to provide education on REMS requirements, medication logistics, and adverse event management.

An admission plan was formulated to outline admission criteria, medication administration, and safety logistics. Order sets created by pharmacists, encompassed pre, post, and as needed medications for cytokine release syndrome and immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome. To facilitate safe discharge and meet REMS criteria, patients received wallet cards, dexamethasone and acetaminophen PRNs with detailed instructions for use, and direction for seeking emergency care with consideration of local tocilizumab availability.

Conclusions

Our SOP has enabled administration of six T-cell engager therapies for six diseases. The primary limitation for some of these agents is the need for inpatient monitoring at initiation, which may not be available at smaller centers. Facilities that lack these capabilities could utilize community care or partner with a neighboring Veterans Affairs medical center for initial administration, then transition back for continued treatment. Facilities that lack inpatient oncology nursing could administer the drug in the infusion center followed by admission for monitoring and toxicity management. Our implementation plan serves as a scalable model for improving veteran access to novel therapies.

Background

The rise in the number of T-cell engager therapies highlights their importance in modern cancer treatment paradigms. Having recognized the need for, and complexities of, administering these innovative medications to our patients, our team assessed our institution’s capability to provide these therapies to our patients. We identified that our facility was wellequipped for implementation of T-cell engager therapy due to inpatient administration capabilities, an outpatient infusion center, on-hand supportive care medications (tocilizumab), and access to higher levels of care. Key players included medical oncologists, pharmacists, inpatient and infusion nurses, staff physicians, critical care practitioners, and care coordinators.

Clinical Practice Initiative

Barriers identified: education, toxicity concerns, formulary management, and logistics. To overcome these obstacles, comprehensive plans for procurement, hospital admission, monitoring, and training were developed as a facility-specific standard operating procedure (SOP). All available Tcell engager therapies were presented to the formulary committee and received local approval. Physician and pharmacist champions were registered for the associated risk evaluation and mitigation strategies (REMS) programs. Recorded webinars were done to provide education on REMS requirements, medication logistics, and adverse event management.

An admission plan was formulated to outline admission criteria, medication administration, and safety logistics. Order sets created by pharmacists, encompassed pre, post, and as needed medications for cytokine release syndrome and immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome. To facilitate safe discharge and meet REMS criteria, patients received wallet cards, dexamethasone and acetaminophen PRNs with detailed instructions for use, and direction for seeking emergency care with consideration of local tocilizumab availability.

Conclusions

Our SOP has enabled administration of six T-cell engager therapies for six diseases. The primary limitation for some of these agents is the need for inpatient monitoring at initiation, which may not be available at smaller centers. Facilities that lack these capabilities could utilize community care or partner with a neighboring Veterans Affairs medical center for initial administration, then transition back for continued treatment. Facilities that lack inpatient oncology nursing could administer the drug in the infusion center followed by admission for monitoring and toxicity management. Our implementation plan serves as a scalable model for improving veteran access to novel therapies.

Centralized Psychosocial Distress Screening Led by RN Care Coordinator

Background

Unmet psychosocial health needs negatively impact cancer care and outcomes. The American College of Surgeons’ Commission on Cancer (CoC) accreditation requirements include Psychosocial Distress Screening (PDS) for all newly diagnosed patients. To enhance cancer care and meet CoC standards, the Tibor Rubin Veterans Affairs Medical Center (TRVAMC) developed and implemented a closed-loop, centralized PDS pathway.

Objectives

Develop processes/methods to: (1) identify all newly diagnosed cancer patients; (2) track initiation of first course of treatment; (3) offer and complete PDS at initiation of first course of treatment; and (4) ensure placement of appropriate referrals.

Methods

All staff members were trained in PDS and competency completed. A standard operating procedure (SOP) was created to identify patients meeting criteria for PDS. Newly diagnosed patients were identified from cancer registry lists, tumor boards, radiology and pathology reports. Patients were placed on a tracking tool by the nurse care coordinator (NCC) and monitored to facilitate timely workup and initiation of treatment. Nurses in the cancer program offered and completed PDS and placed all necessary referrals (to > 11 services). Patients were removed from the tracker only after confirmation of PDS and referrals.

Results

Prior to implementation of PDS, no patients received comprehensive screening and referrals. After implementation, data were collected over a 2 year period. In 2023 and 2024, 277/565 (49%) and 256/526 (48.7%) newly diagnosed patients were eligible for PDS, respectively. All eligible patients were offered PDS (100%). Of patients who underwent PDS, 37% scored their distress at a level of 4/10 or higher, underscoring the severity of distress and unmet need. Referrals to various services were indicated and made in 43.8% patients, most frequently to Social Work, Primary Care or Psychology/Mental Health. More recently, nurses in the Infusion Clinic and Radiation Oncology were trained in and also started conducting PDS on patients coming for treatment.

Conclusions

Implementation of comprehensive and timely PDS resulted in early identification and interventions to address diverse facets of distress that are known to interfere with quality of life, compliance with cancer treatments and outcomes. The program also met the CoC standard for accreditation of TRVAMC in 2024.

Background

Unmet psychosocial health needs negatively impact cancer care and outcomes. The American College of Surgeons’ Commission on Cancer (CoC) accreditation requirements include Psychosocial Distress Screening (PDS) for all newly diagnosed patients. To enhance cancer care and meet CoC standards, the Tibor Rubin Veterans Affairs Medical Center (TRVAMC) developed and implemented a closed-loop, centralized PDS pathway.

Objectives

Develop processes/methods to: (1) identify all newly diagnosed cancer patients; (2) track initiation of first course of treatment; (3) offer and complete PDS at initiation of first course of treatment; and (4) ensure placement of appropriate referrals.

Methods

All staff members were trained in PDS and competency completed. A standard operating procedure (SOP) was created to identify patients meeting criteria for PDS. Newly diagnosed patients were identified from cancer registry lists, tumor boards, radiology and pathology reports. Patients were placed on a tracking tool by the nurse care coordinator (NCC) and monitored to facilitate timely workup and initiation of treatment. Nurses in the cancer program offered and completed PDS and placed all necessary referrals (to > 11 services). Patients were removed from the tracker only after confirmation of PDS and referrals.

Results

Prior to implementation of PDS, no patients received comprehensive screening and referrals. After implementation, data were collected over a 2 year period. In 2023 and 2024, 277/565 (49%) and 256/526 (48.7%) newly diagnosed patients were eligible for PDS, respectively. All eligible patients were offered PDS (100%). Of patients who underwent PDS, 37% scored their distress at a level of 4/10 or higher, underscoring the severity of distress and unmet need. Referrals to various services were indicated and made in 43.8% patients, most frequently to Social Work, Primary Care or Psychology/Mental Health. More recently, nurses in the Infusion Clinic and Radiation Oncology were trained in and also started conducting PDS on patients coming for treatment.

Conclusions

Implementation of comprehensive and timely PDS resulted in early identification and interventions to address diverse facets of distress that are known to interfere with quality of life, compliance with cancer treatments and outcomes. The program also met the CoC standard for accreditation of TRVAMC in 2024.

Background

Unmet psychosocial health needs negatively impact cancer care and outcomes. The American College of Surgeons’ Commission on Cancer (CoC) accreditation requirements include Psychosocial Distress Screening (PDS) for all newly diagnosed patients. To enhance cancer care and meet CoC standards, the Tibor Rubin Veterans Affairs Medical Center (TRVAMC) developed and implemented a closed-loop, centralized PDS pathway.

Objectives

Develop processes/methods to: (1) identify all newly diagnosed cancer patients; (2) track initiation of first course of treatment; (3) offer and complete PDS at initiation of first course of treatment; and (4) ensure placement of appropriate referrals.

Methods

All staff members were trained in PDS and competency completed. A standard operating procedure (SOP) was created to identify patients meeting criteria for PDS. Newly diagnosed patients were identified from cancer registry lists, tumor boards, radiology and pathology reports. Patients were placed on a tracking tool by the nurse care coordinator (NCC) and monitored to facilitate timely workup and initiation of treatment. Nurses in the cancer program offered and completed PDS and placed all necessary referrals (to > 11 services). Patients were removed from the tracker only after confirmation of PDS and referrals.

Results

Prior to implementation of PDS, no patients received comprehensive screening and referrals. After implementation, data were collected over a 2 year period. In 2023 and 2024, 277/565 (49%) and 256/526 (48.7%) newly diagnosed patients were eligible for PDS, respectively. All eligible patients were offered PDS (100%). Of patients who underwent PDS, 37% scored their distress at a level of 4/10 or higher, underscoring the severity of distress and unmet need. Referrals to various services were indicated and made in 43.8% patients, most frequently to Social Work, Primary Care or Psychology/Mental Health. More recently, nurses in the Infusion Clinic and Radiation Oncology were trained in and also started conducting PDS on patients coming for treatment.

Conclusions

Implementation of comprehensive and timely PDS resulted in early identification and interventions to address diverse facets of distress that are known to interfere with quality of life, compliance with cancer treatments and outcomes. The program also met the CoC standard for accreditation of TRVAMC in 2024.

Access to Germline Genetic Testing through Clinical Pathways in Veterans With Prostate Cancer

Background

Germline genetic testing (GGT) is essential in prostate cancer care, informing clinical decisions. The Veterans Affairs National Oncology Program (VA NOP) recommends GGT for patients with specific risk factors in non-metastatic prostate cancer and all patients with metastatic disease. Understanding GGT access helps evaluate care quality and guide improvements. Since 2021, VA NOP has implemented pathway health factor (HF) templates to standardize cancer care documentation, including GGT status, enabling data extraction from the Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) rather than requiring manual review of clinical notes. This work aims to evaluate Veterans’ access to GGT in prostate cancer care by leveraging pathway HF templates, and to assess the feasibility of using structured electronic health record (EHR) data to monitor adherence to GGT recommendations.

Methods

Process delivery diagrams (PDDs) were used to map data flow from prostate cancer clinical pathways to the VA CDW. We identified and categorized HFs related to prostate cancer GGT through the computerized patient record system (CPRS). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize access, ordering, and consent rates.

Results

We identified 5,744 Veterans with at least one prostate cancer GGT-relevant HF entered between 02/01/2021 and 12/31/2024. Of these, 5,125 (89.2%) had access to GGT, with 4,569 (89.2%) consenting to or having GGT ordered, while 556 (10.8%) declined testing. Among the 619 (10.8%) Veterans without GGT access, providers reported plans to discuss GGT in the future for 528 (85.3%) patients, while 91 (14.7%) were off pathway.

Conclusions

NOP-developed HF templates enabled extraction of GGT information from structured EHR data, eliminating manual extraction from clinical notes. We observed high GGT utilization among Veterans with pathway-entered HFs. However, low overall HF utilization may introduce selection bias. Future work includes developing a Natural Language Processing pipeline using large language models to automatically extract GGT information from clinical notes, with HF data serving as ground truth.

Background

Germline genetic testing (GGT) is essential in prostate cancer care, informing clinical decisions. The Veterans Affairs National Oncology Program (VA NOP) recommends GGT for patients with specific risk factors in non-metastatic prostate cancer and all patients with metastatic disease. Understanding GGT access helps evaluate care quality and guide improvements. Since 2021, VA NOP has implemented pathway health factor (HF) templates to standardize cancer care documentation, including GGT status, enabling data extraction from the Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) rather than requiring manual review of clinical notes. This work aims to evaluate Veterans’ access to GGT in prostate cancer care by leveraging pathway HF templates, and to assess the feasibility of using structured electronic health record (EHR) data to monitor adherence to GGT recommendations.

Methods

Process delivery diagrams (PDDs) were used to map data flow from prostate cancer clinical pathways to the VA CDW. We identified and categorized HFs related to prostate cancer GGT through the computerized patient record system (CPRS). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize access, ordering, and consent rates.

Results

We identified 5,744 Veterans with at least one prostate cancer GGT-relevant HF entered between 02/01/2021 and 12/31/2024. Of these, 5,125 (89.2%) had access to GGT, with 4,569 (89.2%) consenting to or having GGT ordered, while 556 (10.8%) declined testing. Among the 619 (10.8%) Veterans without GGT access, providers reported plans to discuss GGT in the future for 528 (85.3%) patients, while 91 (14.7%) were off pathway.

Conclusions

NOP-developed HF templates enabled extraction of GGT information from structured EHR data, eliminating manual extraction from clinical notes. We observed high GGT utilization among Veterans with pathway-entered HFs. However, low overall HF utilization may introduce selection bias. Future work includes developing a Natural Language Processing pipeline using large language models to automatically extract GGT information from clinical notes, with HF data serving as ground truth.

Background

Germline genetic testing (GGT) is essential in prostate cancer care, informing clinical decisions. The Veterans Affairs National Oncology Program (VA NOP) recommends GGT for patients with specific risk factors in non-metastatic prostate cancer and all patients with metastatic disease. Understanding GGT access helps evaluate care quality and guide improvements. Since 2021, VA NOP has implemented pathway health factor (HF) templates to standardize cancer care documentation, including GGT status, enabling data extraction from the Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) rather than requiring manual review of clinical notes. This work aims to evaluate Veterans’ access to GGT in prostate cancer care by leveraging pathway HF templates, and to assess the feasibility of using structured electronic health record (EHR) data to monitor adherence to GGT recommendations.

Methods

Process delivery diagrams (PDDs) were used to map data flow from prostate cancer clinical pathways to the VA CDW. We identified and categorized HFs related to prostate cancer GGT through the computerized patient record system (CPRS). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize access, ordering, and consent rates.

Results

We identified 5,744 Veterans with at least one prostate cancer GGT-relevant HF entered between 02/01/2021 and 12/31/2024. Of these, 5,125 (89.2%) had access to GGT, with 4,569 (89.2%) consenting to or having GGT ordered, while 556 (10.8%) declined testing. Among the 619 (10.8%) Veterans without GGT access, providers reported plans to discuss GGT in the future for 528 (85.3%) patients, while 91 (14.7%) were off pathway.

Conclusions

NOP-developed HF templates enabled extraction of GGT information from structured EHR data, eliminating manual extraction from clinical notes. We observed high GGT utilization among Veterans with pathway-entered HFs. However, low overall HF utilization may introduce selection bias. Future work includes developing a Natural Language Processing pipeline using large language models to automatically extract GGT information from clinical notes, with HF data serving as ground truth.

VA Ann Arbor Immunotherapy Stewardship Program

Purpose

To compare vial utilization and spending between fixed and weight-based dosing of pembrolizumab in Veterans. Promote and assess pembrolizumab extended interval dosing.

Background

FDA approved pembrolizumab label change from weight-based to fixed dosing without evidence of fixed-dosing’s superiority. Retrospective studies demonstrate equivalent outcomes for 2 mg/kg every 3 weeks (Q3W), 200 mg Q3W, 4 mg/kg every 6 weeks (Q6W), and 400 mg Q6W.

Methods

In July 2024 VAAAHS (VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System) initiated an immunotherapy stewardship quality improvement program to deprescribe unnecessary pembrolizumab units and promote extended-interval dosing. Specific interventions included order template modification and targeted outreach to key stakeholders.

Data Analysis

All pembrolizumab doses administered at VAAAHS between July 1, 2024 (launch) and March 31, 2025 (data cutoff) were extracted from EHR. Drug utilization, spending, and healthcare contact hours averted were compared to a fixed-dosing counterfactual.

Results

Sixty-three Veterans received 286 total pembrolizumab doses, of which 107 (37.4%) were Q6W and 179 (62.6%) were Q3W. In total, 741 vials were utilized, against expectation of 786 (5.7% reduction), reflecting approximately $182,000 in savings (annualized, $243,000) and 86.5% of the theoretical maximum savings were captured. Q6W’s share of all doses rose from 27.3% in July 2024 to 53.8% in March 2025. Amongst monotherapy, Q6W’s share rose from 60.0% in July 2024 to 86.7% in March 2025. Q6W adoption saved 381 Veteran-healthcare contact hours, not including travel time.

Conclusions

Stewardship efforts reduced unnecessary pembrolizumab utilization and spending while saving Veterans and VAAAHS providers’ time. Continued provider reinforcement, preparation for Oracle/ Cerner implementation, VISN expansion, refinement of pembrolizumab dose-banding, and development of dose bands for other immunotherapies are underway.

Significance

National implementation would improve Veteran convenience and quality of life, enable reductions in drug and resource costs, and enhance clinic throughput.

Purpose

To compare vial utilization and spending between fixed and weight-based dosing of pembrolizumab in Veterans. Promote and assess pembrolizumab extended interval dosing.

Background

FDA approved pembrolizumab label change from weight-based to fixed dosing without evidence of fixed-dosing’s superiority. Retrospective studies demonstrate equivalent outcomes for 2 mg/kg every 3 weeks (Q3W), 200 mg Q3W, 4 mg/kg every 6 weeks (Q6W), and 400 mg Q6W.

Methods

In July 2024 VAAAHS (VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System) initiated an immunotherapy stewardship quality improvement program to deprescribe unnecessary pembrolizumab units and promote extended-interval dosing. Specific interventions included order template modification and targeted outreach to key stakeholders.

Data Analysis

All pembrolizumab doses administered at VAAAHS between July 1, 2024 (launch) and March 31, 2025 (data cutoff) were extracted from EHR. Drug utilization, spending, and healthcare contact hours averted were compared to a fixed-dosing counterfactual.

Results

Sixty-three Veterans received 286 total pembrolizumab doses, of which 107 (37.4%) were Q6W and 179 (62.6%) were Q3W. In total, 741 vials were utilized, against expectation of 786 (5.7% reduction), reflecting approximately $182,000 in savings (annualized, $243,000) and 86.5% of the theoretical maximum savings were captured. Q6W’s share of all doses rose from 27.3% in July 2024 to 53.8% in March 2025. Amongst monotherapy, Q6W’s share rose from 60.0% in July 2024 to 86.7% in March 2025. Q6W adoption saved 381 Veteran-healthcare contact hours, not including travel time.

Conclusions

Stewardship efforts reduced unnecessary pembrolizumab utilization and spending while saving Veterans and VAAAHS providers’ time. Continued provider reinforcement, preparation for Oracle/ Cerner implementation, VISN expansion, refinement of pembrolizumab dose-banding, and development of dose bands for other immunotherapies are underway.

Significance

National implementation would improve Veteran convenience and quality of life, enable reductions in drug and resource costs, and enhance clinic throughput.

Purpose

To compare vial utilization and spending between fixed and weight-based dosing of pembrolizumab in Veterans. Promote and assess pembrolizumab extended interval dosing.

Background

FDA approved pembrolizumab label change from weight-based to fixed dosing without evidence of fixed-dosing’s superiority. Retrospective studies demonstrate equivalent outcomes for 2 mg/kg every 3 weeks (Q3W), 200 mg Q3W, 4 mg/kg every 6 weeks (Q6W), and 400 mg Q6W.

Methods

In July 2024 VAAAHS (VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System) initiated an immunotherapy stewardship quality improvement program to deprescribe unnecessary pembrolizumab units and promote extended-interval dosing. Specific interventions included order template modification and targeted outreach to key stakeholders.

Data Analysis

All pembrolizumab doses administered at VAAAHS between July 1, 2024 (launch) and March 31, 2025 (data cutoff) were extracted from EHR. Drug utilization, spending, and healthcare contact hours averted were compared to a fixed-dosing counterfactual.

Results

Sixty-three Veterans received 286 total pembrolizumab doses, of which 107 (37.4%) were Q6W and 179 (62.6%) were Q3W. In total, 741 vials were utilized, against expectation of 786 (5.7% reduction), reflecting approximately $182,000 in savings (annualized, $243,000) and 86.5% of the theoretical maximum savings were captured. Q6W’s share of all doses rose from 27.3% in July 2024 to 53.8% in March 2025. Amongst monotherapy, Q6W’s share rose from 60.0% in July 2024 to 86.7% in March 2025. Q6W adoption saved 381 Veteran-healthcare contact hours, not including travel time.

Conclusions

Stewardship efforts reduced unnecessary pembrolizumab utilization and spending while saving Veterans and VAAAHS providers’ time. Continued provider reinforcement, preparation for Oracle/ Cerner implementation, VISN expansion, refinement of pembrolizumab dose-banding, and development of dose bands for other immunotherapies are underway.

Significance

National implementation would improve Veteran convenience and quality of life, enable reductions in drug and resource costs, and enhance clinic throughput.

From Screening to Support: Enhancing Cancer Care Through eScreener Technology

Background

Addressing cancer-related distress is a critical component of comprehensive oncology care. In alignment with the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines, which advocate for routine distress screening as a standard of care, our institution aimed to enhance a previously underutilized paper-based screening process by implementing a more efficient and accessible solution.

Objective

To improve screening rates and streamline the identification of psychosocial needs of Veterans who have cancer.

Population

This initiative was conducted in an outpatient Hematology/Oncology clinic at a Midwest Federal Healthcare Center.

Methods

The Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) quality improvement model was used to guide the implementation of the electronic screener. The eScreener was integrated into routine clinical workflow and staff received training to facilitate implementation. Veterans self-identified their needs through the screener, which included a range of practical, family/social, physical, religious or emotional concerns. Clinical staff then review the responses, assessed the identified needs, and entered appropriate referrals into the electronic health record. A dedicated certified nursing assistant (CNA) was incorporated into the workflow to support implementation efforts. As part of their role, the CNA was tasked with ensuring that all Veterans completed the distress screener either electronically or on paper during their visit

Results

Between January 2025 and March 2025, a total of 180 distress screens were completed using the newly implement method. During the same period in the previous year, only 60 screens were completed, representing a 200% increase. The new process enabled timely referrals based on identified needs, resulting in 39 referrals to physicians, 32 to psychologists, 10 to social work, 7 to dieticians, 6 to nurses, and 1 to pastoral care. These outcomes reflect a significant improvement in both accessibility and patient engagement.

Conclusions

The implementation of an electronic cancer distress screener, along with a dedicated staff member resulted in a substantial increase in screening completion rates and multidisciplinary referrals. These preliminary finds suggest that digital tools can significantly enhance psychosocial assessment, improve coordination, and support the delivery of timely, patient-centered oncology care.

Background

Addressing cancer-related distress is a critical component of comprehensive oncology care. In alignment with the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines, which advocate for routine distress screening as a standard of care, our institution aimed to enhance a previously underutilized paper-based screening process by implementing a more efficient and accessible solution.

Objective

To improve screening rates and streamline the identification of psychosocial needs of Veterans who have cancer.

Population

This initiative was conducted in an outpatient Hematology/Oncology clinic at a Midwest Federal Healthcare Center.

Methods

The Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) quality improvement model was used to guide the implementation of the electronic screener. The eScreener was integrated into routine clinical workflow and staff received training to facilitate implementation. Veterans self-identified their needs through the screener, which included a range of practical, family/social, physical, religious or emotional concerns. Clinical staff then review the responses, assessed the identified needs, and entered appropriate referrals into the electronic health record. A dedicated certified nursing assistant (CNA) was incorporated into the workflow to support implementation efforts. As part of their role, the CNA was tasked with ensuring that all Veterans completed the distress screener either electronically or on paper during their visit

Results

Between January 2025 and March 2025, a total of 180 distress screens were completed using the newly implement method. During the same period in the previous year, only 60 screens were completed, representing a 200% increase. The new process enabled timely referrals based on identified needs, resulting in 39 referrals to physicians, 32 to psychologists, 10 to social work, 7 to dieticians, 6 to nurses, and 1 to pastoral care. These outcomes reflect a significant improvement in both accessibility and patient engagement.

Conclusions

The implementation of an electronic cancer distress screener, along with a dedicated staff member resulted in a substantial increase in screening completion rates and multidisciplinary referrals. These preliminary finds suggest that digital tools can significantly enhance psychosocial assessment, improve coordination, and support the delivery of timely, patient-centered oncology care.

Background

Addressing cancer-related distress is a critical component of comprehensive oncology care. In alignment with the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines, which advocate for routine distress screening as a standard of care, our institution aimed to enhance a previously underutilized paper-based screening process by implementing a more efficient and accessible solution.

Objective

To improve screening rates and streamline the identification of psychosocial needs of Veterans who have cancer.

Population

This initiative was conducted in an outpatient Hematology/Oncology clinic at a Midwest Federal Healthcare Center.

Methods

The Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) quality improvement model was used to guide the implementation of the electronic screener. The eScreener was integrated into routine clinical workflow and staff received training to facilitate implementation. Veterans self-identified their needs through the screener, which included a range of practical, family/social, physical, religious or emotional concerns. Clinical staff then review the responses, assessed the identified needs, and entered appropriate referrals into the electronic health record. A dedicated certified nursing assistant (CNA) was incorporated into the workflow to support implementation efforts. As part of their role, the CNA was tasked with ensuring that all Veterans completed the distress screener either electronically or on paper during their visit

Results

Between January 2025 and March 2025, a total of 180 distress screens were completed using the newly implement method. During the same period in the previous year, only 60 screens were completed, representing a 200% increase. The new process enabled timely referrals based on identified needs, resulting in 39 referrals to physicians, 32 to psychologists, 10 to social work, 7 to dieticians, 6 to nurses, and 1 to pastoral care. These outcomes reflect a significant improvement in both accessibility and patient engagement.

Conclusions

The implementation of an electronic cancer distress screener, along with a dedicated staff member resulted in a substantial increase in screening completion rates and multidisciplinary referrals. These preliminary finds suggest that digital tools can significantly enhance psychosocial assessment, improve coordination, and support the delivery of timely, patient-centered oncology care.

COPD CARE Academy: Design of Purposeful Training Guided by Implementation Strategies

COPD CARE Academy: Design of Purposeful Training Guided by Implementation Strategies

Quality improvement (QI) initiatives within the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) play an important role in enhancing health care for veterans.1,2 While effective QI programs are often developed, veterans benefit only if they receive care at sites where the program is offered.3 It is estimated only 1% to 5% of patients receive benefit from evidence-based programs, limiting the opportunity for widespread impact.4,5

The Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) Coordinated Access to Reduce Exacerbations (CARE) Academy is a national training program designed to promote the adoption of a COPD primary care service.6 The Academy was created and iteratively refined by VA staff to include both clinical training emphasizing COPD management and program implementation strategies. Training programs such as COPD CARE are commonly described as a method to support adoption of health care services, but there is no consensus on a universal approach to training design.

This article describes COPD CARE training and implementation strategies (Table). The Academy began as a training program at 1 VA medical center (VAMC) and has expanded to 49 diverse VAMCs. The Academy illustrates how implementation strategies can be leveraged to develop pragmatic and impactful training. Highlights from the Academy's 9-year history are outlined in this article.

COPD CARE

One in 4 veterans have a COPD diagnosis, and the 5-year mortality rate following a COPD flare is ≥ 50%.7,8 In 2015, a pharmacy resident designed and piloted COPD CARE, a program that used evidence-based practice to optimize management of the disease.9,10

The COPD CARE program is delivered by interprofessional team members. It includes a postacute care call completed 48 hours postdischarge, a wellness visit (face-to-face or virtual) 1 month postdischarge, and a follow-up visit scheduled 2 months postdischarge. Clinical pharmacist practitioners (CPPs) prescribe and collaborate with the COPD CARE health care team. Evidence-based practices embedded within COPD CARE include treatment optimization, symptom evaluation, severity staging, vaccination promotion, referrals, tobacco treatment, and comorbidity management.11-16 The initial COPD CARE pilot demonstrated promising results; patients received timely care and high rates of COPD best practices.11

Academy Design and Implementation

Initial COPD CARE training was tailored to the culture, context, and workflow of the William S. Middleton Memorial Veteran’s Hospital in Madison, Wisconsin. Further service expansion required integration of implementation strategies that enable learners to apply and adapt content to fit different processes, staffing, and patient needs.

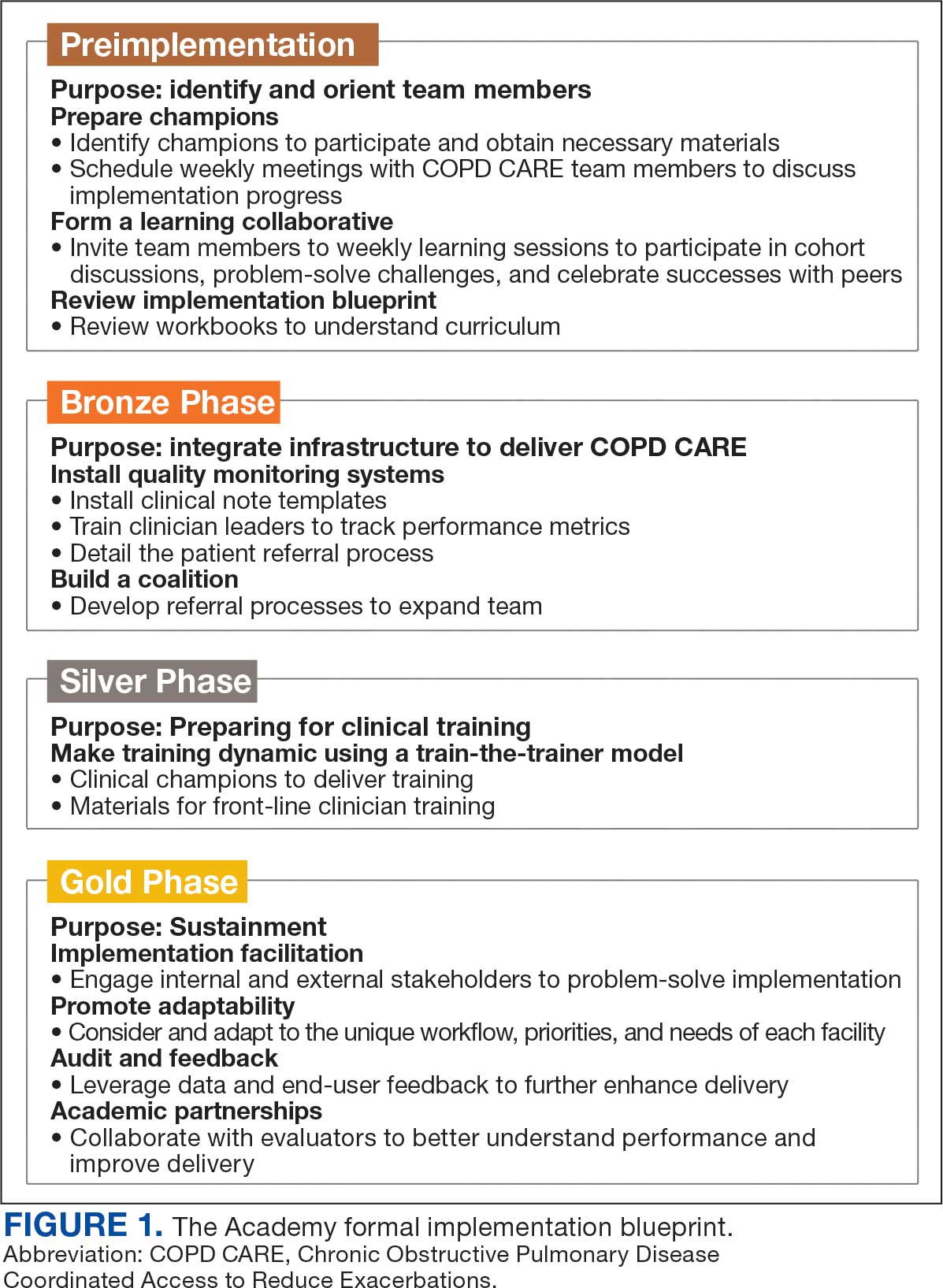

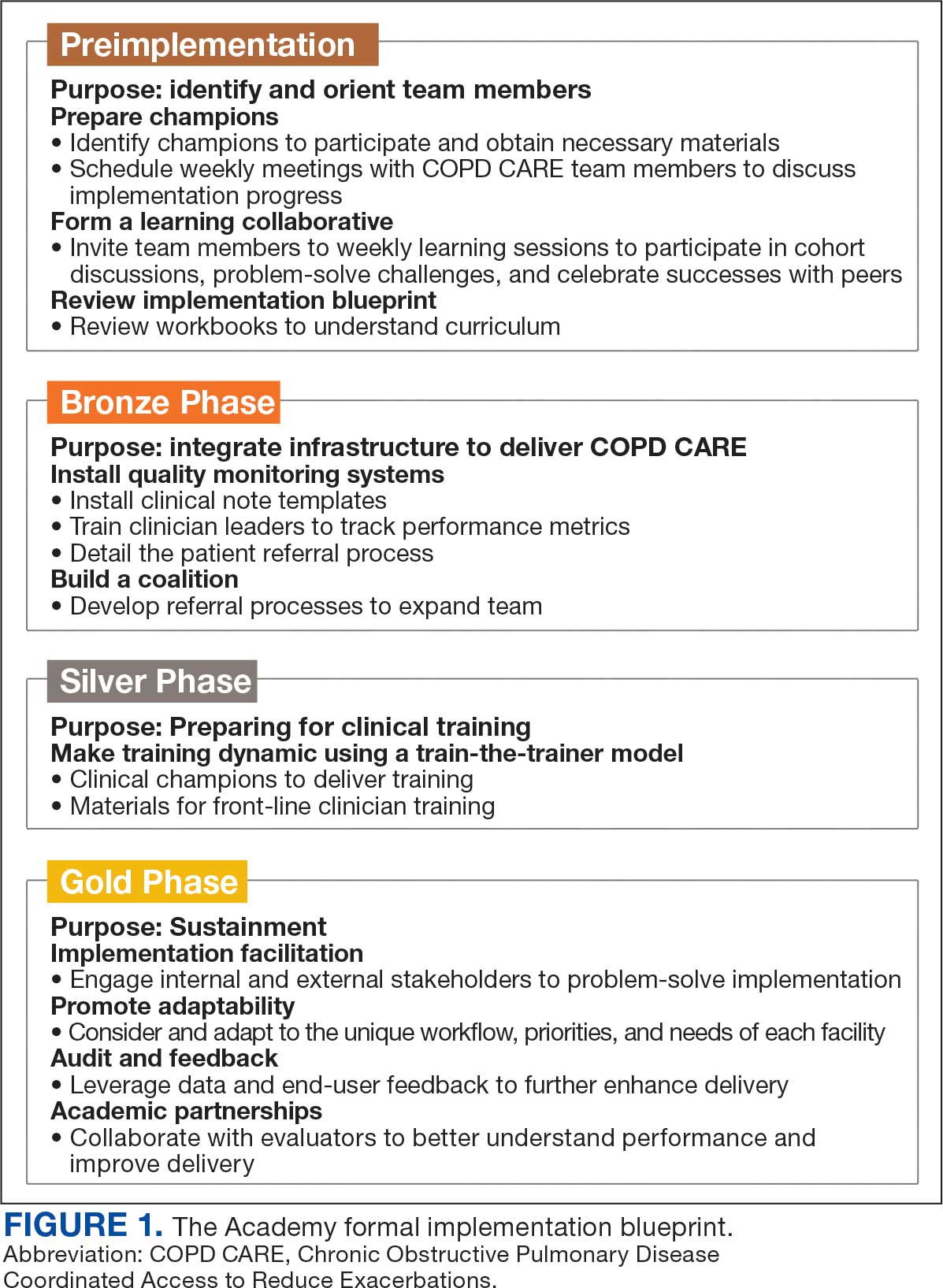

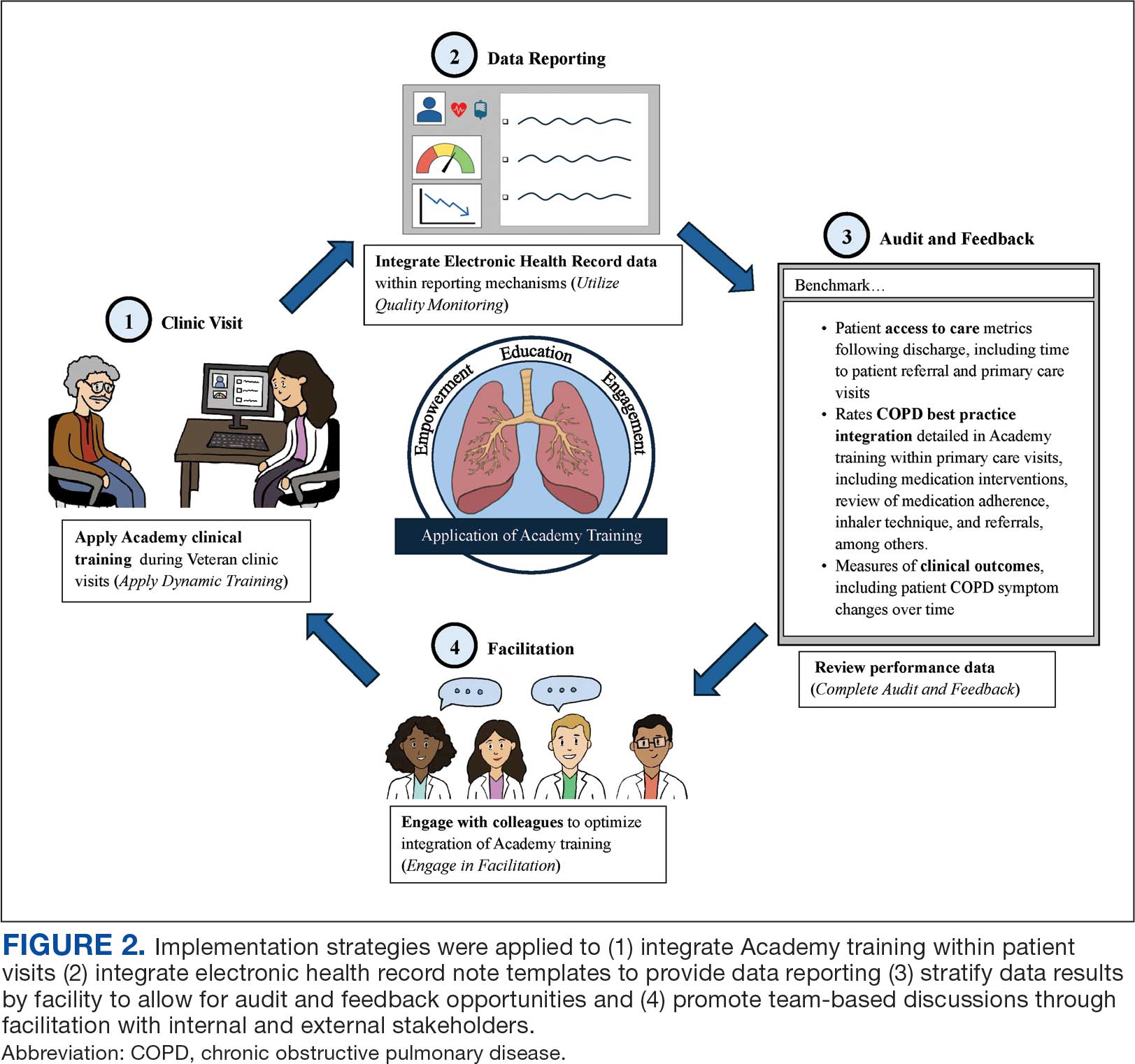

Formal Implementation Blueprint

A key aspect of the Academy is the integration of a formal implementation blueprint that includes training goals, scope, and key milestones to guide implementation. The Academy blueprint includes 4 phased training workbooks: (1) preimplementation support from local stakeholders; (2) integration of COPD CARE operational infrastructure into workflows; (3) preparing clinical champions; and (4) leading clinical training (Figure 1). Five weekly 1-hour synchronous virtual discussions are used for learning the workbook content that include learning objectives and opportunities to strategize how to overcome implementation barriers.

Promoting and Facilitating Implementation

As clinicians apply content from the Academy to install informatics tools, coordinate clinical training, and build relationships across service lines, implementation barriers may occur. A learning collaborative allows peer-mentorship and shared problem solving. The Academy learning collaborative includes attendees across multiple VAMCs, allowing for diverse perspectives and cross-site learning. Within the field of dissemination and implementation science, this process of shared problem-solving to support individuals is referred to as implementation facilitation.17 Academy facilitators with prior experience provide a unique perspective and external facilitation from outside local VAMCs. Academy learners form local teams to engage in shared decision-making when applying Academy content. Following Academy completion, learning collaboratives continue to meet monthly to share clinical insights and operational updates.

Local Champions Promote Adaptability

One or more local champions were identified at each VAMC who were focused on the implementation of clinical training content and operational implementation of Academy content.18 Champions have helped develop adaptations of Academy content, such as integrating telehealth nursing within the COPD CARE referral process, which have become new best practices. Champions attend Academy sessions, which provide an opportunity to share adaptations to meet local needs.19

Using a Train-The-Trainer Model

Clinical training was designed to be dynamic and included video modeling, such as recorded examples of CPPs conducting COPD CARE visits and video clips highlighting clinical content. Each learner received a clinical workbook summarizing the content. The champion shares discussion questions to relate training content to the local clinical practice setting. The combination of live training, with videos of clinic visits and case-based discussion was intended to address differing learning styles. Clinical training was delivered using a train-the-trainer model led by the local champion, which allows clinicians with expertise to tailor their training. The use of a train-the-trainer model was intended to promote local buy-in and was often completed by frontline clinicians.

Informatics note templates provide clinicians with information needed to deliver training content during clinic visits. Direct hyperlinks to symptomatic scoring tools, resources to promote evidence-based medication optimization, and patient education resources were embedded within the electronic health record note templates. Direct links to consults for COPD referrals services discussed during clinical training were also included to promote ease of care coordination and awareness of referral opportunities. The integration of clinical training with informatics note template support was intentional to directly relate clinical training to clinical care delivery.

Audit and Feedback

To inform COPD CARE practice, the Academy included informatics infrastructure that allowed for timely local quality monitoring. Electronic health record note templates with embedded data fields track COPD CARE service implementation, including timely completion of patient visits, completion of patient medication reviews, appropriate testing, symptom assessment, and interventions made. Champions can organize template installation and integrate templates into COPD CARE clinical training. Data are included on a COPD CARE implementation dashboard.

An audit and feedback process is allows for the review of performance metrics and development of action plans.20,21 Data reports from note templates are described during the Academy, along with resources to help teams enhance delivery of their program based on performance metrics.

Building a Coalition

Within VA primary care, clinical care delivery is optimized through a team-based coalition of clinicians using the patient aligned care team (PACT) framework. The VA patient-centered team-based care delivery model, patient facilitates coordination of patient referrals, including patient review, scheduling, and completion of patient visits.22

Partnerships with VA Pharmacy Benefits Manager, VA Diffusion of Excellence, VA Quality Enhancement Research Initiative, VA Office of Pulmonary Medicine, and the VA Office of Rural Health have facilitated COPD CARE successes. Collaborations with VA Centers of Innovation helped benchmark the Academy’s impact. An academic partnership with the University of Wisconsin-Madison was established in 2017 and has provided evaluation expertise and leadership as the Academy has been iteratively developed, and revised.

Preliminary Metrics

COPD CARE has delivered > 2000 visits. CPPs have delivered COPD care, with a mean 9.4 of 10 best practices per patient visit. Improvements in veteran COPD symptoms have also been observed following COPD CARE patient visits.

DISCUSSION

The COPD CARE Academy was developed to promote rapid scale-up of a complex, team-based COPD service delivered during veteran care transitions. The implementation blueprint for the Academy is multifaceted and integrates both clinical-focused and implementation-focused infrastructure to apply training content.23 A randomized control trial evaluating the efficacy of training modalities found a need to expand implementation blueprints beyond clinical training alone, as training by itself may not be sufficient to change behavior.24 VA staff designed the Academy using clinical- and implementation-focused content within its implementation blueprint. Key components included leveraging clinical champions, using a train-the-trainer approach, and incorporating facilitation strategies to overcome adoption barriers.

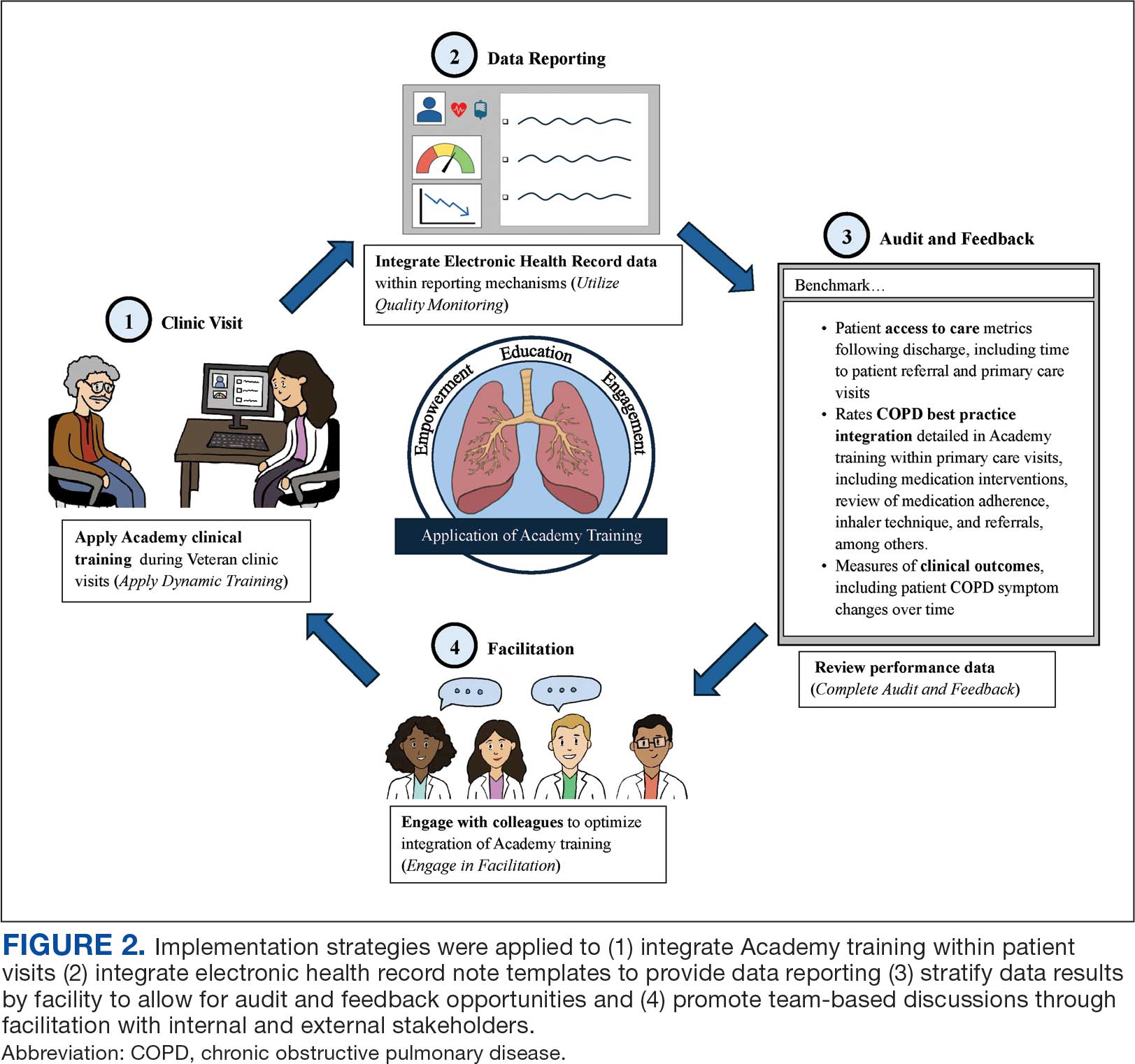

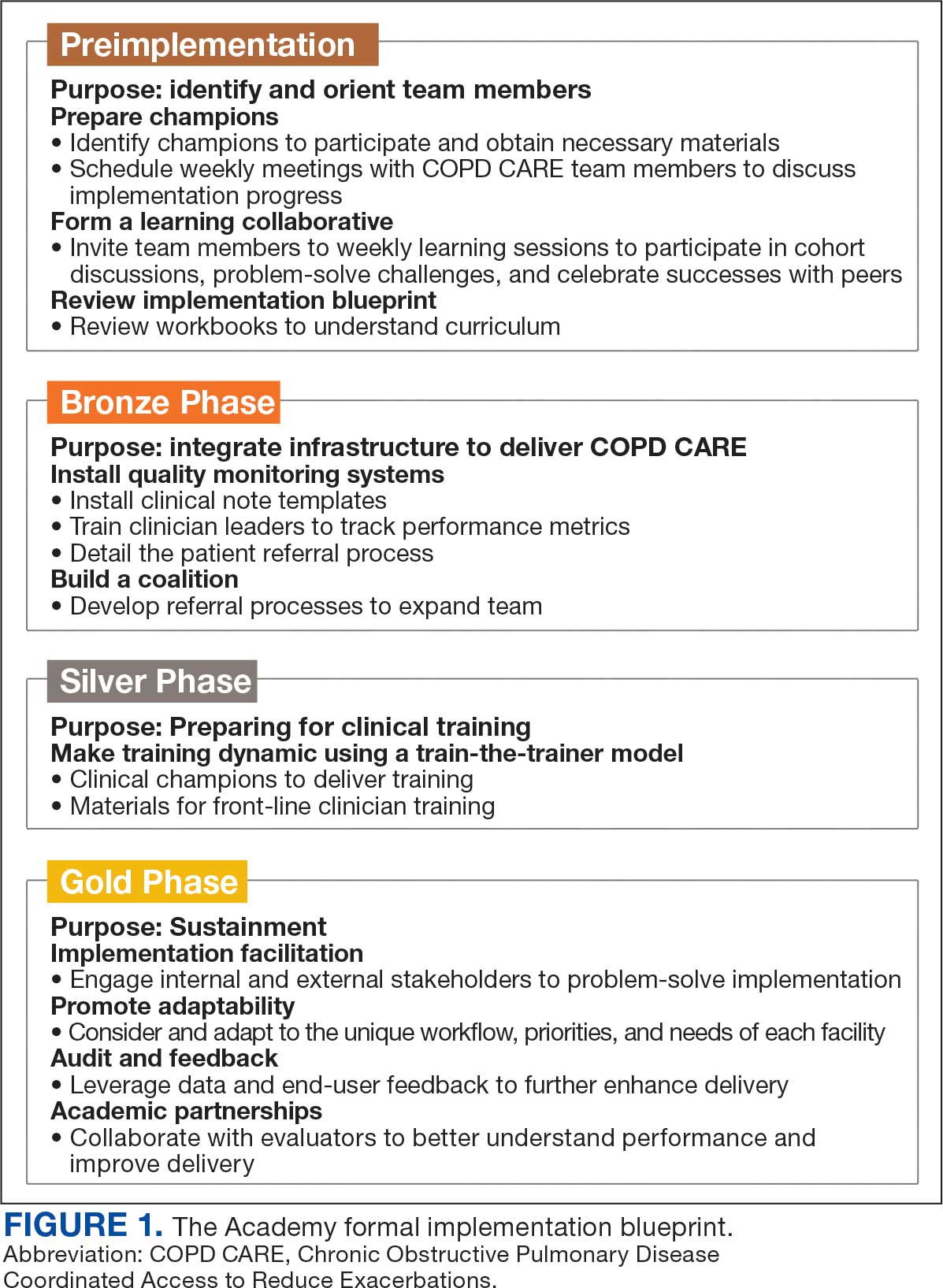

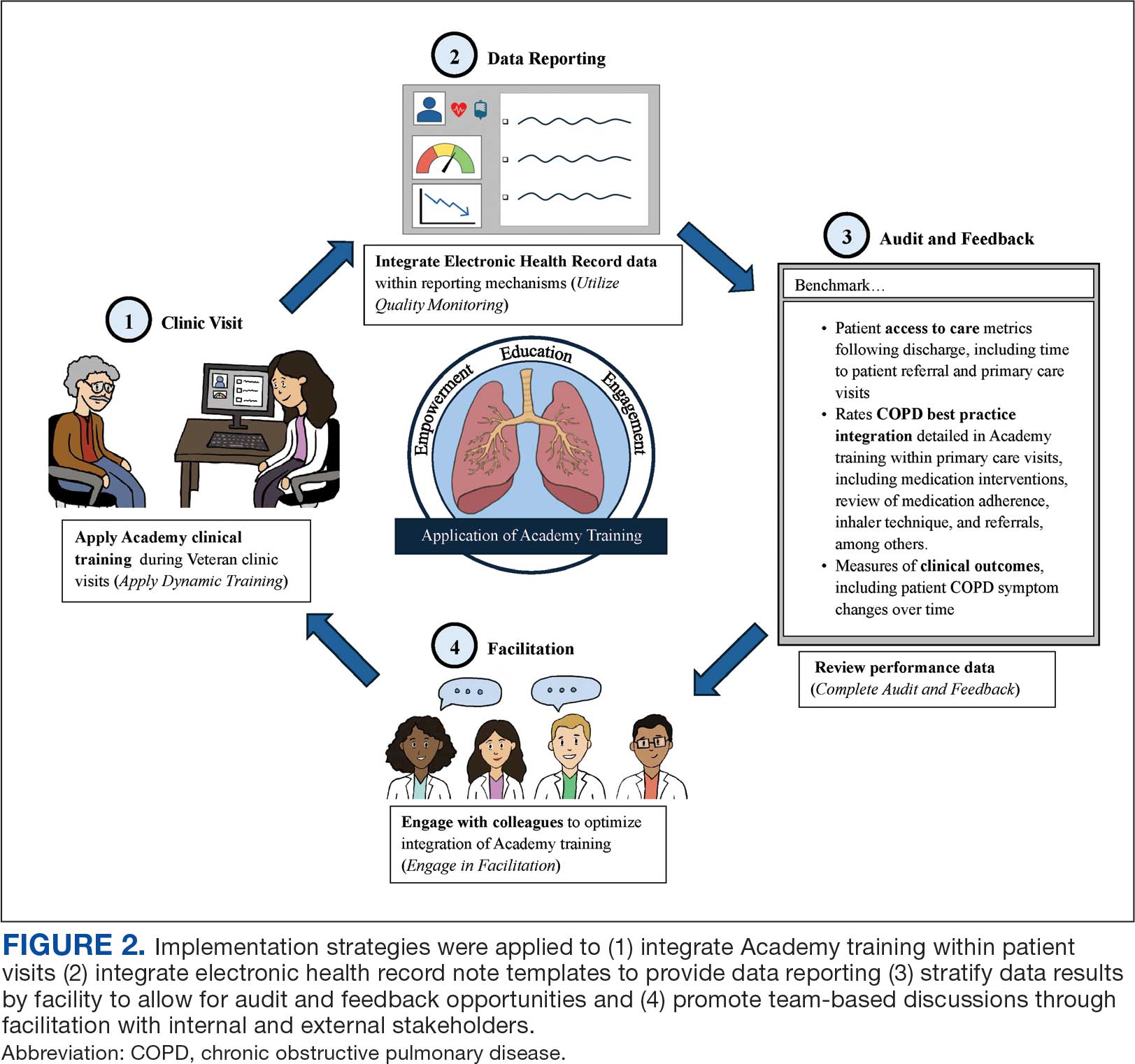

Lewis et al emphasize matching implementation strategies to barriers within VA staff who identify care coordination as a key challenge.23 The informatics infrastructure developed for Academy learners, including standardized note templates, video modeling examples of clinic visits, and data capture for audit and feedback, was designed to complement clinical training and standardize service workflows (Figure 2). There are opportunities to explore how to optimize technology in the Academy.

While Academy clinical training specifically focuses on COPD management, many implementation strategies can be considered to promote care delivery services for other chronic conditions. The Academy blueprint and implementation infrastructure, are strategies that may be considered within and outside the federal health care system. The opportunity for adaptations to Academy training enables clinical champions to promote tailored content to the needs of each unique VAMC. The translation of Academy implementation strategies for new chronic conditions will similarly require adaptations at each VAMC to promote adoption of content.

CONCLUSIONS

COPD CARE Academy is an example of the collaborative spirit within VA, and the opportunity for further advancement of health care programs. The VA is a national leader in Learning Health Systems implementation, in which “science, informatics, incentives and culture are aligned for continuous improvement and innovation.”25,26 There are many opportunities for VA staff to learn from one another to form partnerships between leaders, clinicians, and scientists to optimize health care delivery and further the VA’s work as a learning health system.

- Robinson CH, Thompto AJ, Lima EN, Damschroder LJ. Continuous quality improvement at the frontline: one interdisciplinary clinical team's four-year journey after completing a virtual learning program. Learn Health Syst. 2022;6(4):e10345. doi:10.1002/lrh2.10345

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Continuous quality improvement (CQI) for clinical teams: a systematic review of reviews. Accessed July 24, 2025. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/for_researchers/cyber_seminars/archives/video_archive.cfm?SessionID=4151

- Dondanville KA, Fina BA, Straud CL, et al. Launching a competency-based training program in evidence-based treatments for PTSD: supporting veteran-serving mental health providers in Texas. Community Ment Health J. 2021;57(5):910-919. doi:10.1007/S10597-020-00676-7

- Abildso CG, Zizzi SJ, Reger-Nash B. Evaluating an insurance- sponsored weight management program with the RE-AIM model, West Virginia, 2004-2008. Prev Chronic Dis. 2010;7(3):A46.

- Glasgow RE, Vinson C, Chambers D, Khoury MJ, Kaplan RM, Hunter C. National institutes of health approaches to dissemination and implementation science: current and future directions. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(7):1274- 1281. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.300755

- Portillo EC, Maurer MA, Kettner JT, et al. Applying RE-AIM to examine the impact of an implementation facilitation package to scale up a program for veterans with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Implement Sci Commun. 2023;4(1):143. doi:10.1186/S43058-023-00520-5

- McGhan R, Radcliff T, Fish R, Sutherland ER, Welsh C, Make B. Predictors of rehospitalization and death after a severe exacerbation of COPD. Chest. 2007;132(6):1748- 1755. doi:10.1378/chest.06-3018

- Anderson E, Wiener RS, Resnick K, Elwy AR, Rinne ST. Care coordination for veterans with COPD: a positive deviance study. Am J Manag Care. 2020;26(2):63-68. doi:10.37765/AJMC.2020.42394

- 2024 GOLD Report. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease - GOLD. Accessed July 24, 2025. https://goldcopd.org/2024-gold-report/

- Nici L, Mammen MJ, Charbek E, et al. Pharmacologic management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. An official American Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(9):e56-e69. doi:10.1164/rccm.202003-0625ST

- Portillo EC, Wilcox A, Seckel E, et al. Reducing COPD readmission rates: using a COPD care service during care transitions. Fed Pract. 2018;35(11):30-36.

- Portillo EC, Gruber S, Lehmann M, et al. Application of the replicating effective programs framework to design a COPD training program. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2021;61(2):e129-e135. doi:10.1016/J.JAPH.2020.10.023

- Portillo EC, Lehmann MR, Hagen TL, et al. Integration of the patient-centered medical home to deliver a care bundle for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease management. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2023;63(1):212-219. doi:10.1016/j.japh.2022.10.003

- Portillo E, Lehmann M, Hagen T, et al. Evaluation of an implementation package to deliver the COPD CARE service. BMJ Open Qual. 2023;12(1). doi:10.1136/BMJOQ-2022-002074

- Portillo E, Lehmann M, Maurer M, et al. Barriers to implementing a pharmacist-led COPD care bundle in rural settings: A qualitative evaluation. 2025 (under review).

- Population Health Management. American Hospital Association. Accessed July 24, 2025. https://www.aha.org/center/population-health-management

- Ritchie MJ, Dollar KM, Miller CK, et al. Using implementation facilitation to improve healthcare: implementation facilitation training manual. Accessed July 11, 2024. https:// www.queri.research.va.gov/tools/Facilitation-Manual.pdf

- Morena AL, Gaias LM, Larkin C. Understanding the role of clinical champions and their impact on clinician behavior change: the need for causal pathway mechanisms. Front Health Serv. 2022;2:896885. doi:10.3389/FRHS.2022.896885

- Ayele RA, Rabin BA, McCreight M, Battaglia C. Editorial: understanding, assessing, and guiding adaptations in public health and health systems interventions: current and future directions. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1228437. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2023.1228437

- Jamtvedt G, Flottorp S, Ivers N. Audit and feedback as a quality strategy. In: Improving Healthcare Services. World Health Organization; 2019. Accessed July 24, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK549284/

- Snider MDH, Boyd MR, Walker MR, Powell BJ, Lewis CC. Using audit and feedback to guide tailored implementations of measurement-based care in community mental health: a multiple case study. Implement Sci Commun. 2023;4(1):94. doi:10.1186/s43058-023-00474-8

- Patient Aligned Care Team (PACT) – Patient Care Services. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Accessed July 24, 2025. https://www.patientcare.va.gov/primarycare/PACT.asp

- Lewis CC, Scott K, Marriott BR. A methodology for generating a tailored implementation blueprint: an exemplar from a youth residential setting. Implementat Sci. 2018;13(1):68. doi:10.1186/s13012-018-0761-6

- Beidas RS, Edmunds JM, Marcus SC, Kendall PC. Training and consultation to promote implementation of an empirically supported treatment: a randomized trial. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63(7):660-665. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201100401

- Kilbourne AM, Schmidt J, Edmunds M, Vega R, Bowersox N, Atkins D. How the VA is training the next-generation workforce for learning health systems. Learn Health Syst. 2022;6(4):e10333. doi:10.1002/LRH2.10333

- Easterling D, Perry AC, Woodside R, Patel T, Gesell SB. Clarifying the concept of a learning health system for healthcare delivery organizations: implications from a qualitative analysis of the scientific literature. Learn Health Syst. 2021;6(2):e10287. doi:10.1002/LRH2.10287

Quality improvement (QI) initiatives within the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) play an important role in enhancing health care for veterans.1,2 While effective QI programs are often developed, veterans benefit only if they receive care at sites where the program is offered.3 It is estimated only 1% to 5% of patients receive benefit from evidence-based programs, limiting the opportunity for widespread impact.4,5

The Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) Coordinated Access to Reduce Exacerbations (CARE) Academy is a national training program designed to promote the adoption of a COPD primary care service.6 The Academy was created and iteratively refined by VA staff to include both clinical training emphasizing COPD management and program implementation strategies. Training programs such as COPD CARE are commonly described as a method to support adoption of health care services, but there is no consensus on a universal approach to training design.

This article describes COPD CARE training and implementation strategies (Table). The Academy began as a training program at 1 VA medical center (VAMC) and has expanded to 49 diverse VAMCs. The Academy illustrates how implementation strategies can be leveraged to develop pragmatic and impactful training. Highlights from the Academy's 9-year history are outlined in this article.

COPD CARE

One in 4 veterans have a COPD diagnosis, and the 5-year mortality rate following a COPD flare is ≥ 50%.7,8 In 2015, a pharmacy resident designed and piloted COPD CARE, a program that used evidence-based practice to optimize management of the disease.9,10

The COPD CARE program is delivered by interprofessional team members. It includes a postacute care call completed 48 hours postdischarge, a wellness visit (face-to-face or virtual) 1 month postdischarge, and a follow-up visit scheduled 2 months postdischarge. Clinical pharmacist practitioners (CPPs) prescribe and collaborate with the COPD CARE health care team. Evidence-based practices embedded within COPD CARE include treatment optimization, symptom evaluation, severity staging, vaccination promotion, referrals, tobacco treatment, and comorbidity management.11-16 The initial COPD CARE pilot demonstrated promising results; patients received timely care and high rates of COPD best practices.11

Academy Design and Implementation

Initial COPD CARE training was tailored to the culture, context, and workflow of the William S. Middleton Memorial Veteran’s Hospital in Madison, Wisconsin. Further service expansion required integration of implementation strategies that enable learners to apply and adapt content to fit different processes, staffing, and patient needs.

Formal Implementation Blueprint

A key aspect of the Academy is the integration of a formal implementation blueprint that includes training goals, scope, and key milestones to guide implementation. The Academy blueprint includes 4 phased training workbooks: (1) preimplementation support from local stakeholders; (2) integration of COPD CARE operational infrastructure into workflows; (3) preparing clinical champions; and (4) leading clinical training (Figure 1). Five weekly 1-hour synchronous virtual discussions are used for learning the workbook content that include learning objectives and opportunities to strategize how to overcome implementation barriers.

Promoting and Facilitating Implementation

As clinicians apply content from the Academy to install informatics tools, coordinate clinical training, and build relationships across service lines, implementation barriers may occur. A learning collaborative allows peer-mentorship and shared problem solving. The Academy learning collaborative includes attendees across multiple VAMCs, allowing for diverse perspectives and cross-site learning. Within the field of dissemination and implementation science, this process of shared problem-solving to support individuals is referred to as implementation facilitation.17 Academy facilitators with prior experience provide a unique perspective and external facilitation from outside local VAMCs. Academy learners form local teams to engage in shared decision-making when applying Academy content. Following Academy completion, learning collaboratives continue to meet monthly to share clinical insights and operational updates.

Local Champions Promote Adaptability

One or more local champions were identified at each VAMC who were focused on the implementation of clinical training content and operational implementation of Academy content.18 Champions have helped develop adaptations of Academy content, such as integrating telehealth nursing within the COPD CARE referral process, which have become new best practices. Champions attend Academy sessions, which provide an opportunity to share adaptations to meet local needs.19

Using a Train-The-Trainer Model

Clinical training was designed to be dynamic and included video modeling, such as recorded examples of CPPs conducting COPD CARE visits and video clips highlighting clinical content. Each learner received a clinical workbook summarizing the content. The champion shares discussion questions to relate training content to the local clinical practice setting. The combination of live training, with videos of clinic visits and case-based discussion was intended to address differing learning styles. Clinical training was delivered using a train-the-trainer model led by the local champion, which allows clinicians with expertise to tailor their training. The use of a train-the-trainer model was intended to promote local buy-in and was often completed by frontline clinicians.

Informatics note templates provide clinicians with information needed to deliver training content during clinic visits. Direct hyperlinks to symptomatic scoring tools, resources to promote evidence-based medication optimization, and patient education resources were embedded within the electronic health record note templates. Direct links to consults for COPD referrals services discussed during clinical training were also included to promote ease of care coordination and awareness of referral opportunities. The integration of clinical training with informatics note template support was intentional to directly relate clinical training to clinical care delivery.

Audit and Feedback

To inform COPD CARE practice, the Academy included informatics infrastructure that allowed for timely local quality monitoring. Electronic health record note templates with embedded data fields track COPD CARE service implementation, including timely completion of patient visits, completion of patient medication reviews, appropriate testing, symptom assessment, and interventions made. Champions can organize template installation and integrate templates into COPD CARE clinical training. Data are included on a COPD CARE implementation dashboard.

An audit and feedback process is allows for the review of performance metrics and development of action plans.20,21 Data reports from note templates are described during the Academy, along with resources to help teams enhance delivery of their program based on performance metrics.

Building a Coalition

Within VA primary care, clinical care delivery is optimized through a team-based coalition of clinicians using the patient aligned care team (PACT) framework. The VA patient-centered team-based care delivery model, patient facilitates coordination of patient referrals, including patient review, scheduling, and completion of patient visits.22

Partnerships with VA Pharmacy Benefits Manager, VA Diffusion of Excellence, VA Quality Enhancement Research Initiative, VA Office of Pulmonary Medicine, and the VA Office of Rural Health have facilitated COPD CARE successes. Collaborations with VA Centers of Innovation helped benchmark the Academy’s impact. An academic partnership with the University of Wisconsin-Madison was established in 2017 and has provided evaluation expertise and leadership as the Academy has been iteratively developed, and revised.

Preliminary Metrics

COPD CARE has delivered > 2000 visits. CPPs have delivered COPD care, with a mean 9.4 of 10 best practices per patient visit. Improvements in veteran COPD symptoms have also been observed following COPD CARE patient visits.

DISCUSSION

The COPD CARE Academy was developed to promote rapid scale-up of a complex, team-based COPD service delivered during veteran care transitions. The implementation blueprint for the Academy is multifaceted and integrates both clinical-focused and implementation-focused infrastructure to apply training content.23 A randomized control trial evaluating the efficacy of training modalities found a need to expand implementation blueprints beyond clinical training alone, as training by itself may not be sufficient to change behavior.24 VA staff designed the Academy using clinical- and implementation-focused content within its implementation blueprint. Key components included leveraging clinical champions, using a train-the-trainer approach, and incorporating facilitation strategies to overcome adoption barriers.

Lewis et al emphasize matching implementation strategies to barriers within VA staff who identify care coordination as a key challenge.23 The informatics infrastructure developed for Academy learners, including standardized note templates, video modeling examples of clinic visits, and data capture for audit and feedback, was designed to complement clinical training and standardize service workflows (Figure 2). There are opportunities to explore how to optimize technology in the Academy.

While Academy clinical training specifically focuses on COPD management, many implementation strategies can be considered to promote care delivery services for other chronic conditions. The Academy blueprint and implementation infrastructure, are strategies that may be considered within and outside the federal health care system. The opportunity for adaptations to Academy training enables clinical champions to promote tailored content to the needs of each unique VAMC. The translation of Academy implementation strategies for new chronic conditions will similarly require adaptations at each VAMC to promote adoption of content.

CONCLUSIONS

COPD CARE Academy is an example of the collaborative spirit within VA, and the opportunity for further advancement of health care programs. The VA is a national leader in Learning Health Systems implementation, in which “science, informatics, incentives and culture are aligned for continuous improvement and innovation.”25,26 There are many opportunities for VA staff to learn from one another to form partnerships between leaders, clinicians, and scientists to optimize health care delivery and further the VA’s work as a learning health system.

Quality improvement (QI) initiatives within the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) play an important role in enhancing health care for veterans.1,2 While effective QI programs are often developed, veterans benefit only if they receive care at sites where the program is offered.3 It is estimated only 1% to 5% of patients receive benefit from evidence-based programs, limiting the opportunity for widespread impact.4,5

The Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) Coordinated Access to Reduce Exacerbations (CARE) Academy is a national training program designed to promote the adoption of a COPD primary care service.6 The Academy was created and iteratively refined by VA staff to include both clinical training emphasizing COPD management and program implementation strategies. Training programs such as COPD CARE are commonly described as a method to support adoption of health care services, but there is no consensus on a universal approach to training design.