User login

Three Clinical Studies Demonstrating Safety and Efficacy of Treatment for Diarrhea-Predominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS-D) in Adults

In this supplement to GI & Hepatology news, Christine Frissora, MD, provides an overview of the burdens that patients with IBS-D experience. Three clinical efficacy and safety studies surrounding an FDA-approved treatment are also examined.

Topics include:

- IBS-D diagnosis and treatment challenges

- The role of microbial imbalance and altered gut microbiota

- A treatment option for relief of IBS-D symptoms

XIFI.0273.USA.18

In this supplement to GI & Hepatology news, Christine Frissora, MD, provides an overview of the burdens that patients with IBS-D experience. Three clinical efficacy and safety studies surrounding an FDA-approved treatment are also examined.

Topics include:

- IBS-D diagnosis and treatment challenges

- The role of microbial imbalance and altered gut microbiota

- A treatment option for relief of IBS-D symptoms

XIFI.0273.USA.18

In this supplement to GI & Hepatology news, Christine Frissora, MD, provides an overview of the burdens that patients with IBS-D experience. Three clinical efficacy and safety studies surrounding an FDA-approved treatment are also examined.

Topics include:

- IBS-D diagnosis and treatment challenges

- The role of microbial imbalance and altered gut microbiota

- A treatment option for relief of IBS-D symptoms

XIFI.0273.USA.18

Hot Topics in Primary Care 2018

Click here to read Hot Topics in Primary Care.

This supplement includes 5.0 CME credits (scroll down for more information).

Topics include:

- Hepatitis C

- Migraine

- Orally Inhaled Human Insulin

- Gout

- Orthostatic Hypotension

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome with Diarrhea

- SGLT-2 Inhibitors

- Statin Therapy

- Basal Insulin/GLP-1RA Combination

- RCTs to the Real World

- Weight Management for Patients with T2DM

- NSAID OTC Formulations

- Colorectal Cancer Screening

This supplement offers the opportunity to earn a total of 5 CME credits.

Credit is awarded for successful completion of the online evaluations at the links below. These links may also be found within the supplement on the first page of each article.

- On the Front Lines: Hepatitis C Infection in Primary Care

- To complete the online evaluation and receive 1 CME credit for this article: please click on the link at the end of the article or go to www.pceconsortium.org/hepC.

- Long-term Treatment of Gout: New Opportunities for Improved Outcomes

- To complete the online evaluation and receive 1 CME credit for this article: please click on the link at the end of the article or go to www.pceconsortium.org/gout.

- Recognition and Management of Orthostatic Hypotension in Primary Care

- To complete the online evaluation and receive 1 CME credit for this article: please click on the link at the end of the article or go to www.pceconsortium.org/orthostatic.

- Practical Evaluation and Management of Irritable Bowel Syndrome with Diarrhea: A Case Study Approach

- To complete the online evaluation and receive 1 CME credit for this article: please click on the link at the end of the article or go to www.pceconsortium.org/ibs.

- Differentiating Among the SGLT-2 Inhibitors: Considering Cardiovascular and Other Safety Outcomes

- To complete the online evaluation and receive 1 CME credit for this article: please click on the link at the end of the article or go www.pceconsortium.org/sglt2.

Click here to read Hot Topics in Primary Care.

This supplement includes 5.0 CME credits (scroll down for more information).

Topics include:

- Hepatitis C

- Migraine

- Orally Inhaled Human Insulin

- Gout

- Orthostatic Hypotension

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome with Diarrhea

- SGLT-2 Inhibitors

- Statin Therapy

- Basal Insulin/GLP-1RA Combination

- RCTs to the Real World

- Weight Management for Patients with T2DM

- NSAID OTC Formulations

- Colorectal Cancer Screening

This supplement offers the opportunity to earn a total of 5 CME credits.

Credit is awarded for successful completion of the online evaluations at the links below. These links may also be found within the supplement on the first page of each article.

- On the Front Lines: Hepatitis C Infection in Primary Care

- To complete the online evaluation and receive 1 CME credit for this article: please click on the link at the end of the article or go to www.pceconsortium.org/hepC.

- Long-term Treatment of Gout: New Opportunities for Improved Outcomes

- To complete the online evaluation and receive 1 CME credit for this article: please click on the link at the end of the article or go to www.pceconsortium.org/gout.

- Recognition and Management of Orthostatic Hypotension in Primary Care

- To complete the online evaluation and receive 1 CME credit for this article: please click on the link at the end of the article or go to www.pceconsortium.org/orthostatic.

- Practical Evaluation and Management of Irritable Bowel Syndrome with Diarrhea: A Case Study Approach

- To complete the online evaluation and receive 1 CME credit for this article: please click on the link at the end of the article or go to www.pceconsortium.org/ibs.

- Differentiating Among the SGLT-2 Inhibitors: Considering Cardiovascular and Other Safety Outcomes

- To complete the online evaluation and receive 1 CME credit for this article: please click on the link at the end of the article or go www.pceconsortium.org/sglt2.

Click here to read Hot Topics in Primary Care.

This supplement includes 5.0 CME credits (scroll down for more information).

Topics include:

- Hepatitis C

- Migraine

- Orally Inhaled Human Insulin

- Gout

- Orthostatic Hypotension

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome with Diarrhea

- SGLT-2 Inhibitors

- Statin Therapy

- Basal Insulin/GLP-1RA Combination

- RCTs to the Real World

- Weight Management for Patients with T2DM

- NSAID OTC Formulations

- Colorectal Cancer Screening

This supplement offers the opportunity to earn a total of 5 CME credits.

Credit is awarded for successful completion of the online evaluations at the links below. These links may also be found within the supplement on the first page of each article.

- On the Front Lines: Hepatitis C Infection in Primary Care

- To complete the online evaluation and receive 1 CME credit for this article: please click on the link at the end of the article or go to www.pceconsortium.org/hepC.

- Long-term Treatment of Gout: New Opportunities for Improved Outcomes

- To complete the online evaluation and receive 1 CME credit for this article: please click on the link at the end of the article or go to www.pceconsortium.org/gout.

- Recognition and Management of Orthostatic Hypotension in Primary Care

- To complete the online evaluation and receive 1 CME credit for this article: please click on the link at the end of the article or go to www.pceconsortium.org/orthostatic.

- Practical Evaluation and Management of Irritable Bowel Syndrome with Diarrhea: A Case Study Approach

- To complete the online evaluation and receive 1 CME credit for this article: please click on the link at the end of the article or go to www.pceconsortium.org/ibs.

- Differentiating Among the SGLT-2 Inhibitors: Considering Cardiovascular and Other Safety Outcomes

- To complete the online evaluation and receive 1 CME credit for this article: please click on the link at the end of the article or go www.pceconsortium.org/sglt2.

MS News From 2018 AAN & CMSC Meetings

The Science Behind Monoclonal Antibodies: Practical Applications

Click the link above to review hypothetical case studies that explore different monoclonal antibody (mAb) properties and the practical applications for clinical decision making.

For more information on mAbs, please read "The Science Behind Monoclonal Antibodies: What Neurologists Need to Know"

USA-334-81078

Click the link above to review hypothetical case studies that explore different monoclonal antibody (mAb) properties and the practical applications for clinical decision making.

For more information on mAbs, please read "The Science Behind Monoclonal Antibodies: What Neurologists Need to Know"

USA-334-81078

Click the link above to review hypothetical case studies that explore different monoclonal antibody (mAb) properties and the practical applications for clinical decision making.

For more information on mAbs, please read "The Science Behind Monoclonal Antibodies: What Neurologists Need to Know"

USA-334-81078

A New Treatment Option for Epidermolysis Bullosa Simplex

Walter J. Hamlin Professor and Chair, Department of Dermatology, and Professor of Pediatrics

Director, Northwestern University Skin Disease Research Center (SDRC)

Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine

Chicago, Illinois

Dr. Paller reports that she has received an honorarium for consultation for Castle Creek Pharmaceuticals LLC. She also reports that she is an investigator for a diacerein trial.

What is EBS and what is the DELIVERS Study?

DR. AMY PALLER: Epidermolysis bullosa simplex (EBS) is the most common type of epidermolysis bullosa, which is a genetic blistering disorder that can start early in childhood, or sometimes be present at birth. EBS is particularly difficult during the first decade of life, with extensive blistering and great discomfort.

DELIVERS is an ongoing multicenter, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group phase 2 study evaluating the safety and efficacy of diacerein 1% ointment. In this study, patients are randomized to either the active treatment with the diacerein 1% or its vehicle ointment. Patients apply the ointment once a day for 8 weeks with follow up that can be as long as 20 weeks.

Patient-reported outcomes are being assessed include blistering, itch, pain, and decreased mobility, all of which affect the patient's quality of life.

How many centers are currently recruiting patients and who can qualify?

The DELIVERS study has been open since June of 2017 and the study is currently being conducted in 20 sites throughout the United States and Europe, Israel, and Australia, so it's truly international. It is enrolling patients who have a documented genetic mutation consistent with any form of EBS with at least 2% body involvement (that documentation is done as part of the study). Patients must be at least 4 years of age.

In addition, we are conducting another study to better understand the safety and absorption of diacerein 1% ointment under maximum use conditions.

What exactly is a pharmacokinetic (PK) study and why is it needed for regulatory approval?

DR. AMY PALLER: With any new drug it's important to determine systemic absorption and how long the medication stays in the circulation. This is particularly important in EBS because of the blistering and reduced epidermal barrier. And the greater the extent of skin blistering, the greater the chance of systemic exposure through their use of higher doses and frequency of application. The FDA wants a better understanding of plasma concentrations in this subset of patients, which is valuable by helping establish dosing recommendations or identifying potential systemic adverse effects. A maximal use PK study is conducted to increase the systemic exposure through the use of higher concentration, frequency of dose, or greater body surface area involvement under controlled conditions.

Are there any blood draws and how many patient visits are needed for this study?

DR. AMY PALLER: The PK study is being conducted at 8 locations in the United States and Europe, where patients are applying 1% diacerein for 10 days (active medication only). There are 2 patient visits (Day 1 and Day 10) with a series of blood draws at each of those visits. Patients have a preapplication draw, and then a series of subsequent draws: a half hour, 1 hour, 2 hours, 3 hours, 4 hours, 6 hours, and 8 hours. This is so we can look at what is getting into the bloodstream in that period of time after the daily application.

Are there additional benefits for patients participating in these studies?

DR. AMY PALLER: First, there's the potential benefit of improvement. This is a medication that targets interleukin 1 beta, which has been shown to be increased in the disease. Also, the sponsor will cover all expenses for eligible patients participating and, once patients have successfully completed the study, they will also receive free medication for up to 2 additional treatment cycles totaling 8 months. Patients that complete the double-blind DELIVERS study or participate in the open-label PK study may be eligible to enter an open-label extension study.

This interview was produced by the Custom Programs division of Frontline Medical Communications. The editorial staff of Pediatric News and Dermatology News was not involved in the content development.

Walter J. Hamlin Professor and Chair, Department of Dermatology, and Professor of Pediatrics

Director, Northwestern University Skin Disease Research Center (SDRC)

Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine

Chicago, Illinois

Dr. Paller reports that she has received an honorarium for consultation for Castle Creek Pharmaceuticals LLC. She also reports that she is an investigator for a diacerein trial.

What is EBS and what is the DELIVERS Study?

DR. AMY PALLER: Epidermolysis bullosa simplex (EBS) is the most common type of epidermolysis bullosa, which is a genetic blistering disorder that can start early in childhood, or sometimes be present at birth. EBS is particularly difficult during the first decade of life, with extensive blistering and great discomfort.

DELIVERS is an ongoing multicenter, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group phase 2 study evaluating the safety and efficacy of diacerein 1% ointment. In this study, patients are randomized to either the active treatment with the diacerein 1% or its vehicle ointment. Patients apply the ointment once a day for 8 weeks with follow up that can be as long as 20 weeks.

Patient-reported outcomes are being assessed include blistering, itch, pain, and decreased mobility, all of which affect the patient's quality of life.

How many centers are currently recruiting patients and who can qualify?

The DELIVERS study has been open since June of 2017 and the study is currently being conducted in 20 sites throughout the United States and Europe, Israel, and Australia, so it's truly international. It is enrolling patients who have a documented genetic mutation consistent with any form of EBS with at least 2% body involvement (that documentation is done as part of the study). Patients must be at least 4 years of age.

In addition, we are conducting another study to better understand the safety and absorption of diacerein 1% ointment under maximum use conditions.

What exactly is a pharmacokinetic (PK) study and why is it needed for regulatory approval?

DR. AMY PALLER: With any new drug it's important to determine systemic absorption and how long the medication stays in the circulation. This is particularly important in EBS because of the blistering and reduced epidermal barrier. And the greater the extent of skin blistering, the greater the chance of systemic exposure through their use of higher doses and frequency of application. The FDA wants a better understanding of plasma concentrations in this subset of patients, which is valuable by helping establish dosing recommendations or identifying potential systemic adverse effects. A maximal use PK study is conducted to increase the systemic exposure through the use of higher concentration, frequency of dose, or greater body surface area involvement under controlled conditions.

Are there any blood draws and how many patient visits are needed for this study?

DR. AMY PALLER: The PK study is being conducted at 8 locations in the United States and Europe, where patients are applying 1% diacerein for 10 days (active medication only). There are 2 patient visits (Day 1 and Day 10) with a series of blood draws at each of those visits. Patients have a preapplication draw, and then a series of subsequent draws: a half hour, 1 hour, 2 hours, 3 hours, 4 hours, 6 hours, and 8 hours. This is so we can look at what is getting into the bloodstream in that period of time after the daily application.

Are there additional benefits for patients participating in these studies?

DR. AMY PALLER: First, there's the potential benefit of improvement. This is a medication that targets interleukin 1 beta, which has been shown to be increased in the disease. Also, the sponsor will cover all expenses for eligible patients participating and, once patients have successfully completed the study, they will also receive free medication for up to 2 additional treatment cycles totaling 8 months. Patients that complete the double-blind DELIVERS study or participate in the open-label PK study may be eligible to enter an open-label extension study.

This interview was produced by the Custom Programs division of Frontline Medical Communications. The editorial staff of Pediatric News and Dermatology News was not involved in the content development.

Walter J. Hamlin Professor and Chair, Department of Dermatology, and Professor of Pediatrics

Director, Northwestern University Skin Disease Research Center (SDRC)

Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine

Chicago, Illinois

Dr. Paller reports that she has received an honorarium for consultation for Castle Creek Pharmaceuticals LLC. She also reports that she is an investigator for a diacerein trial.

What is EBS and what is the DELIVERS Study?

DR. AMY PALLER: Epidermolysis bullosa simplex (EBS) is the most common type of epidermolysis bullosa, which is a genetic blistering disorder that can start early in childhood, or sometimes be present at birth. EBS is particularly difficult during the first decade of life, with extensive blistering and great discomfort.

DELIVERS is an ongoing multicenter, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group phase 2 study evaluating the safety and efficacy of diacerein 1% ointment. In this study, patients are randomized to either the active treatment with the diacerein 1% or its vehicle ointment. Patients apply the ointment once a day for 8 weeks with follow up that can be as long as 20 weeks.

Patient-reported outcomes are being assessed include blistering, itch, pain, and decreased mobility, all of which affect the patient's quality of life.

How many centers are currently recruiting patients and who can qualify?

The DELIVERS study has been open since June of 2017 and the study is currently being conducted in 20 sites throughout the United States and Europe, Israel, and Australia, so it's truly international. It is enrolling patients who have a documented genetic mutation consistent with any form of EBS with at least 2% body involvement (that documentation is done as part of the study). Patients must be at least 4 years of age.

In addition, we are conducting another study to better understand the safety and absorption of diacerein 1% ointment under maximum use conditions.

What exactly is a pharmacokinetic (PK) study and why is it needed for regulatory approval?

DR. AMY PALLER: With any new drug it's important to determine systemic absorption and how long the medication stays in the circulation. This is particularly important in EBS because of the blistering and reduced epidermal barrier. And the greater the extent of skin blistering, the greater the chance of systemic exposure through their use of higher doses and frequency of application. The FDA wants a better understanding of plasma concentrations in this subset of patients, which is valuable by helping establish dosing recommendations or identifying potential systemic adverse effects. A maximal use PK study is conducted to increase the systemic exposure through the use of higher concentration, frequency of dose, or greater body surface area involvement under controlled conditions.

Are there any blood draws and how many patient visits are needed for this study?

DR. AMY PALLER: The PK study is being conducted at 8 locations in the United States and Europe, where patients are applying 1% diacerein for 10 days (active medication only). There are 2 patient visits (Day 1 and Day 10) with a series of blood draws at each of those visits. Patients have a preapplication draw, and then a series of subsequent draws: a half hour, 1 hour, 2 hours, 3 hours, 4 hours, 6 hours, and 8 hours. This is so we can look at what is getting into the bloodstream in that period of time after the daily application.

Are there additional benefits for patients participating in these studies?

DR. AMY PALLER: First, there's the potential benefit of improvement. This is a medication that targets interleukin 1 beta, which has been shown to be increased in the disease. Also, the sponsor will cover all expenses for eligible patients participating and, once patients have successfully completed the study, they will also receive free medication for up to 2 additional treatment cycles totaling 8 months. Patients that complete the double-blind DELIVERS study or participate in the open-label PK study may be eligible to enter an open-label extension study.

This interview was produced by the Custom Programs division of Frontline Medical Communications. The editorial staff of Pediatric News and Dermatology News was not involved in the content development.

Federal Health Care Data Trends 2018

Pediatric Dermatology: Summer 2018

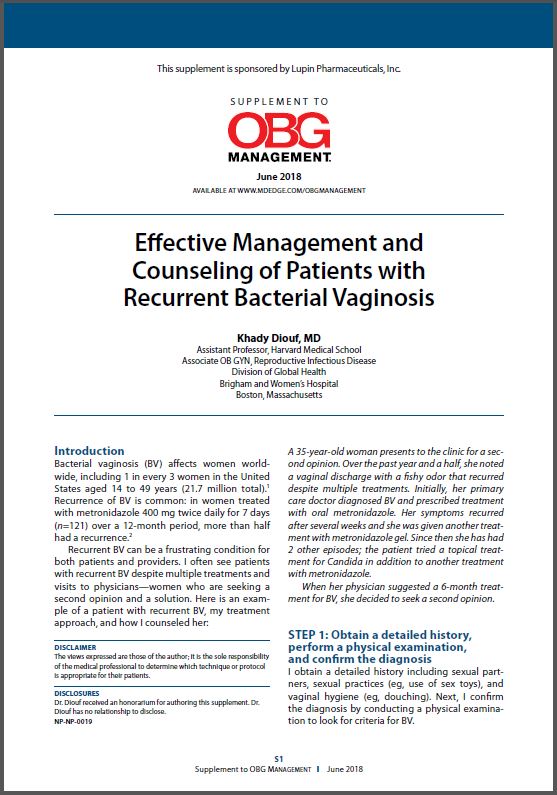

Effective Management and Counseling of Patients with Recurrent Bacterial Vaginosis

Click Here to Read Supplement.

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) affects women worldwide and recurrent BV can be a frustrating condition for both patients and providers. In this new supplement, expert Khady Diouf, MD, discusses her treatment approach and suggested counseling for patients with recurrent BV.

Click Here to Read Supplement.

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) affects women worldwide and recurrent BV can be a frustrating condition for both patients and providers. In this new supplement, expert Khady Diouf, MD, discusses her treatment approach and suggested counseling for patients with recurrent BV.

Click Here to Read Supplement.

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) affects women worldwide and recurrent BV can be a frustrating condition for both patients and providers. In this new supplement, expert Khady Diouf, MD, discusses her treatment approach and suggested counseling for patients with recurrent BV.

Neurology Board Review: Epilepsy

Click here to read Neurology Board Review: Epilepsy

Neurology Board Review: Epilepsy is a resource developed by leading clinical educators for studying for board certification and maintenance of certification exams.

After reading the article, Click Here to Access the Board Review Questions

About the Authors

Shavonne L. Massey, MD

Clinical Instructor

Departments of Neurology and Pediatrics

Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia

University of Pennsylvania

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Hannah C. Glass, MDCM, MAS

Associate Professor

Departments of Neurology, Pediatrics, and

Epidemiology & Biostatistics

University of California, San Francisco

San Francisco, California

Click here to read Neurology Board Review: Epilepsy

After reading the article, Click Here to Access the Board Review Questions

Click here to read Neurology Board Review: Epilepsy

Neurology Board Review: Epilepsy is a resource developed by leading clinical educators for studying for board certification and maintenance of certification exams.

After reading the article, Click Here to Access the Board Review Questions

About the Authors

Shavonne L. Massey, MD

Clinical Instructor

Departments of Neurology and Pediatrics

Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia

University of Pennsylvania

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Hannah C. Glass, MDCM, MAS

Associate Professor

Departments of Neurology, Pediatrics, and

Epidemiology & Biostatistics

University of California, San Francisco

San Francisco, California

Click here to read Neurology Board Review: Epilepsy

After reading the article, Click Here to Access the Board Review Questions

Click here to read Neurology Board Review: Epilepsy

Neurology Board Review: Epilepsy is a resource developed by leading clinical educators for studying for board certification and maintenance of certification exams.

After reading the article, Click Here to Access the Board Review Questions

About the Authors

Shavonne L. Massey, MD

Clinical Instructor

Departments of Neurology and Pediatrics

Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia

University of Pennsylvania

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Hannah C. Glass, MDCM, MAS

Associate Professor

Departments of Neurology, Pediatrics, and

Epidemiology & Biostatistics

University of California, San Francisco

San Francisco, California