User login

Acne before puberty: When to treat, when to worry

NEWPORT BEACH, CALIF. – according to Sheila Fallon Friedlander, MD.

“This is something you are going to see in your practice,” said Dr. Friedlander, a pediatric dermatologists at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. It’s important to know when it’s time to be concerned and when another condition may be masquerading as acne, she said at the at Skin Disease Education Foundation’s Women’s & Pediatric Dermatology Seminar.

Dr. Friedlander, who is professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, talked about treating acne in the following prepubertal age groups:

Neonatal acne (ages birth to 4 weeks)

Acne appears in this population up to 20% of the time, according to research, and it is much more common in males than in females, at a ratio of five to one.

The cause is “most likely the relationship between placental androgens and the baby’s adrenal glands,” Dr. Friedlander said. However, something more serious could be going on. “Look at the child and see if he’s sick. If he looks sick, then we need to worry.”

Hormonal abnormalities also could be a cause, she said. Refer a baby to a specialist if there are other signs of hyperandrogenism. However, “the likelihood is very low,” and she’s never needed to refer a neonate with acne for evaluation.

As for treatment, she said, “Mainly, I’m using tincture of time.” However, “many of my mothers have told me that topical yogurt application will work.” Why yogurt? It’s possible that its bacteria could play a role in combating acne, she said.

Masquerader alert! Beware of neonatal cephalic pustulosis, Dr. Friedlander cautioned, which may be an inflammatory response to yeast. Ketoconazole cream may be helpful.

Infantile acne (ages 0-12 months)

This form of acne is more common in males and may hint at the future development of severe adolescent acne. It does resolve but it may take months or years, Dr. Friedlander said.

In general, this acne isn’t a sign of something more serious. “You do not need to go crazy with the work-up,” she said. “With mild to moderate disease, with nothing else suspicious, I don’t do a big work-up.”

However, do consider whether the child is undergoing precocious puberty, Dr. Friedlander said. Signs include axillary hair, pubic hair, and body odor.

As for treatment of infantile acne, “start out topically” and consider options such as Bactrim (sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim) and erythromycin.

Masquerader alert! Idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma can be mistaken for acne and abscess, and ultrasound is helpful to confirm it. “It’s not so easy to treat,” she said. “Ivermectin may be helpful. Sometimes you do cultures and make sure something else isn’t going on.”

Midchildhood (ages 1-7 years)

“It’s not as common to have acne develop in this age group, but when it develops you need to be concerned,” Dr. Friedlander said. “This is the age period when there is more often something really wrong.”

Be on the lookout for a family history of hormonal abnormalities, and check if the child is on medication. “You need to look carefully,” she said, adding that it’s important to check for signs of premature puberty such as giant spikes in growth, abnormally large hands and feet, genital changes, and body odor. Check blood pressure if you’re worried about an adrenal tumor.

It’s possible for children to develop precocious puberty – with acne – because of exposure to testosterone gel used by a father. Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) creams also may cause the condition. “The more creams out there with androgenic effects, the more we may see it,” Dr. Friedlander said. “This is something to ask about because families may not be forthcoming.”

Masquerader alert! Perioral dermatitis may look like acne, and it may be linked to inhaled or topical steroids, she said.

Other masqueraders include demodex folliculitis, angiofibromas (think tuberous sclerosis), and keratosis pilaris (the most common type of bump on a children aged 1-7 years). The latter condition “is not the end of the world,” said Dr. Friedlander, who added that “I’ve never cured anyone of it.”

Prepubertal acne (ages 7 years to puberty)

Acne in this group is generally not worrisome, Dr. Friedlander said, but investigate further if there’s significant inflammation and signs of early sexual development or virilization.

Benzoyl peroxide wash may be enough to help the condition initially, and consider topical clindamycin or a combination product. “Start out slow,” she said. Twice a week to start might be appropriate. Moisturizers can be helpful, as can topical adapalene.

Also, keep in mind that even mild acne can be emotionally devastating to a child in this age group and worthy of treatment. “Your assessment may be very different than hers,” she said. It’s possible that “she has a few lesions, but she feels like an outcast.”

Dr. Friedlander reported no relevant financial disclosures. SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

NEWPORT BEACH, CALIF. – according to Sheila Fallon Friedlander, MD.

“This is something you are going to see in your practice,” said Dr. Friedlander, a pediatric dermatologists at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. It’s important to know when it’s time to be concerned and when another condition may be masquerading as acne, she said at the at Skin Disease Education Foundation’s Women’s & Pediatric Dermatology Seminar.

Dr. Friedlander, who is professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, talked about treating acne in the following prepubertal age groups:

Neonatal acne (ages birth to 4 weeks)

Acne appears in this population up to 20% of the time, according to research, and it is much more common in males than in females, at a ratio of five to one.

The cause is “most likely the relationship between placental androgens and the baby’s adrenal glands,” Dr. Friedlander said. However, something more serious could be going on. “Look at the child and see if he’s sick. If he looks sick, then we need to worry.”

Hormonal abnormalities also could be a cause, she said. Refer a baby to a specialist if there are other signs of hyperandrogenism. However, “the likelihood is very low,” and she’s never needed to refer a neonate with acne for evaluation.

As for treatment, she said, “Mainly, I’m using tincture of time.” However, “many of my mothers have told me that topical yogurt application will work.” Why yogurt? It’s possible that its bacteria could play a role in combating acne, she said.

Masquerader alert! Beware of neonatal cephalic pustulosis, Dr. Friedlander cautioned, which may be an inflammatory response to yeast. Ketoconazole cream may be helpful.

Infantile acne (ages 0-12 months)

This form of acne is more common in males and may hint at the future development of severe adolescent acne. It does resolve but it may take months or years, Dr. Friedlander said.

In general, this acne isn’t a sign of something more serious. “You do not need to go crazy with the work-up,” she said. “With mild to moderate disease, with nothing else suspicious, I don’t do a big work-up.”

However, do consider whether the child is undergoing precocious puberty, Dr. Friedlander said. Signs include axillary hair, pubic hair, and body odor.

As for treatment of infantile acne, “start out topically” and consider options such as Bactrim (sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim) and erythromycin.

Masquerader alert! Idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma can be mistaken for acne and abscess, and ultrasound is helpful to confirm it. “It’s not so easy to treat,” she said. “Ivermectin may be helpful. Sometimes you do cultures and make sure something else isn’t going on.”

Midchildhood (ages 1-7 years)

“It’s not as common to have acne develop in this age group, but when it develops you need to be concerned,” Dr. Friedlander said. “This is the age period when there is more often something really wrong.”

Be on the lookout for a family history of hormonal abnormalities, and check if the child is on medication. “You need to look carefully,” she said, adding that it’s important to check for signs of premature puberty such as giant spikes in growth, abnormally large hands and feet, genital changes, and body odor. Check blood pressure if you’re worried about an adrenal tumor.

It’s possible for children to develop precocious puberty – with acne – because of exposure to testosterone gel used by a father. Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) creams also may cause the condition. “The more creams out there with androgenic effects, the more we may see it,” Dr. Friedlander said. “This is something to ask about because families may not be forthcoming.”

Masquerader alert! Perioral dermatitis may look like acne, and it may be linked to inhaled or topical steroids, she said.

Other masqueraders include demodex folliculitis, angiofibromas (think tuberous sclerosis), and keratosis pilaris (the most common type of bump on a children aged 1-7 years). The latter condition “is not the end of the world,” said Dr. Friedlander, who added that “I’ve never cured anyone of it.”

Prepubertal acne (ages 7 years to puberty)

Acne in this group is generally not worrisome, Dr. Friedlander said, but investigate further if there’s significant inflammation and signs of early sexual development or virilization.

Benzoyl peroxide wash may be enough to help the condition initially, and consider topical clindamycin or a combination product. “Start out slow,” she said. Twice a week to start might be appropriate. Moisturizers can be helpful, as can topical adapalene.

Also, keep in mind that even mild acne can be emotionally devastating to a child in this age group and worthy of treatment. “Your assessment may be very different than hers,” she said. It’s possible that “she has a few lesions, but she feels like an outcast.”

Dr. Friedlander reported no relevant financial disclosures. SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

NEWPORT BEACH, CALIF. – according to Sheila Fallon Friedlander, MD.

“This is something you are going to see in your practice,” said Dr. Friedlander, a pediatric dermatologists at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. It’s important to know when it’s time to be concerned and when another condition may be masquerading as acne, she said at the at Skin Disease Education Foundation’s Women’s & Pediatric Dermatology Seminar.

Dr. Friedlander, who is professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, talked about treating acne in the following prepubertal age groups:

Neonatal acne (ages birth to 4 weeks)

Acne appears in this population up to 20% of the time, according to research, and it is much more common in males than in females, at a ratio of five to one.

The cause is “most likely the relationship between placental androgens and the baby’s adrenal glands,” Dr. Friedlander said. However, something more serious could be going on. “Look at the child and see if he’s sick. If he looks sick, then we need to worry.”

Hormonal abnormalities also could be a cause, she said. Refer a baby to a specialist if there are other signs of hyperandrogenism. However, “the likelihood is very low,” and she’s never needed to refer a neonate with acne for evaluation.

As for treatment, she said, “Mainly, I’m using tincture of time.” However, “many of my mothers have told me that topical yogurt application will work.” Why yogurt? It’s possible that its bacteria could play a role in combating acne, she said.

Masquerader alert! Beware of neonatal cephalic pustulosis, Dr. Friedlander cautioned, which may be an inflammatory response to yeast. Ketoconazole cream may be helpful.

Infantile acne (ages 0-12 months)

This form of acne is more common in males and may hint at the future development of severe adolescent acne. It does resolve but it may take months or years, Dr. Friedlander said.

In general, this acne isn’t a sign of something more serious. “You do not need to go crazy with the work-up,” she said. “With mild to moderate disease, with nothing else suspicious, I don’t do a big work-up.”

However, do consider whether the child is undergoing precocious puberty, Dr. Friedlander said. Signs include axillary hair, pubic hair, and body odor.

As for treatment of infantile acne, “start out topically” and consider options such as Bactrim (sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim) and erythromycin.

Masquerader alert! Idiopathic facial aseptic granuloma can be mistaken for acne and abscess, and ultrasound is helpful to confirm it. “It’s not so easy to treat,” she said. “Ivermectin may be helpful. Sometimes you do cultures and make sure something else isn’t going on.”

Midchildhood (ages 1-7 years)

“It’s not as common to have acne develop in this age group, but when it develops you need to be concerned,” Dr. Friedlander said. “This is the age period when there is more often something really wrong.”

Be on the lookout for a family history of hormonal abnormalities, and check if the child is on medication. “You need to look carefully,” she said, adding that it’s important to check for signs of premature puberty such as giant spikes in growth, abnormally large hands and feet, genital changes, and body odor. Check blood pressure if you’re worried about an adrenal tumor.

It’s possible for children to develop precocious puberty – with acne – because of exposure to testosterone gel used by a father. Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) creams also may cause the condition. “The more creams out there with androgenic effects, the more we may see it,” Dr. Friedlander said. “This is something to ask about because families may not be forthcoming.”

Masquerader alert! Perioral dermatitis may look like acne, and it may be linked to inhaled or topical steroids, she said.

Other masqueraders include demodex folliculitis, angiofibromas (think tuberous sclerosis), and keratosis pilaris (the most common type of bump on a children aged 1-7 years). The latter condition “is not the end of the world,” said Dr. Friedlander, who added that “I’ve never cured anyone of it.”

Prepubertal acne (ages 7 years to puberty)

Acne in this group is generally not worrisome, Dr. Friedlander said, but investigate further if there’s significant inflammation and signs of early sexual development or virilization.

Benzoyl peroxide wash may be enough to help the condition initially, and consider topical clindamycin or a combination product. “Start out slow,” she said. Twice a week to start might be appropriate. Moisturizers can be helpful, as can topical adapalene.

Also, keep in mind that even mild acne can be emotionally devastating to a child in this age group and worthy of treatment. “Your assessment may be very different than hers,” she said. It’s possible that “she has a few lesions, but she feels like an outcast.”

Dr. Friedlander reported no relevant financial disclosures. SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

REPORTING FROM SDEF WOMEN’S & PEDIATRIC DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

Update on Diet and Acne

Acne is a common condition that most often affects adolescents but is not uncommon in adults. It can result in considerable anxiety, depression, and medical and pharmaceutical costs. Additionally, oral antibiotics, the standard treatment for acne, are increasingly under suspicion for causing bacterial resistance as well as disruption of the cutaneous and gut microbiomes.1,2 These factors are among those that often drive patients and physicians to search for alternative and complementary treatments, including dietary modification.

Over the last few decades, the interaction between diet and acne has been one of the most fluid areas of research in dermatology. The role of diet in acne incidence and presentation has evolved from the general view in the 1970s that there was no connection to today’s more data-driven understanding that the acne disease course likely is modified by specific dietary components. Better designed and more rigorous studies have supported a link between acne severity and glycemic index (GI)/glycemic load (GL) and possibly dairy consumption. The ability to use data-driven evidence to counsel patients regarding dietary treatment of acne is increasingly important to counteract the pseudoadvice that patients can easily find on the Internet.

This article summarizes the history of beliefs about diet and acne, reviews more recent published data regarding dietary components that can modify acne severity, and outlines the current American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) guidelines and recommendations for diet and acne.

History of Diet and Acne

In most of the current literature, acne frequently is referred to as a disease of modern civilization or a consequence of the typical Western diet.3 For clarity, the Western diet is most commonly described as “a dietary regimen characterized by high amounts of sugary desserts, refined grains, high protein, high-fat dairy products, and high-sugar drinks.”4 The role of dairy in the etiology of acne typically is discussed separately from the Western diet. It has been reported that acne is not found in nonwesternized populations where a Paleolithic diet, which does not include consumption of high-GI carbohydrates, milk, or other dairy products, is common.5

Extending this line of argument, acne vulgaris has been called a metabolic syndrome of the sebaceous follicle and one of the mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1–driven diseases of civilization, along with cancer, obesity, and diabetes mellitus.3 This view seems somewhat extreme and discounts other drivers of acne incidence and severity. Twin studies have shown that acne is highly heritable, with 81% of the population variance attributed to genetic factors.6 Similar incidence numbers for acne vulgaris have been reported worldwide, and global incidence in late adolescence is rising; however, it is unknown whether this increase is a result of the adoption of the Western diet, which is thought to encourage early onset of puberty; genetic drift; changes in regional and cultural understanding and reporting of acne; or a byproduct of unknown environmental factors.4 More nuanced views acknowledge that acne is a multifactorial disease,7 and therefore genetic and possibly epigenetic factors as well as the cutaneous and gut microbiomes also must be taken into account. An interesting historical perspective on acne by Mahmood and Shipman8 outlined acne descriptions, diagnoses, topical treatments, and dietary advice going back to ancient Greek and Egyptian civilizations. They also cited recommendations from the 1930s that suggested avoiding “starchy foods, bread rolls, noodles, spaghetti, potatoes, oily nuts, chop suey, chow mein, and waffles” and listed the following foods as suitable to cure acne: “cooked and raw fruit, farina, rice, wheat, oatmeal, green vegetables, boiled or broiled meat and poultry, clear soup, vegetable soup, and an abundance of water.”8

More Recent Evidence of Dietary Influence on Acne

Importantly, the available research does not demonstrate that diet causes acne but rather that it may influence or aggravate existing acne. Data collection for acne studies also can be confounded by the interplay of many factors, such as increased access to health care, socioeconomic status, and shifting cultural perceptions of skin care and beauty.4 An important facet of any therapeutic recommendation is that it should be supported by confirmable mechanistic pathways.

GI and GL

Over the last few decades, a number of observational and intervention studies have focused on the possible influence of the GI/GL of foods on acne incidence and/or severity. A high GI diet is characterized by a relatively high intake of carbohydrate-containing foods that are quickly digested and absorbed, increasing blood glucose and insulin concentrations. Glycemic load takes the portion size of dietary carbohydrates into consideration and therefore is a measure of both the quality and quantity of carbohydrate-containing foods.9 TheGI/GL values of more than 2480 food items are available in the literature.10

Evidence from several studies supports the role of high GI/GL diets in exacerbating acne and suggests that transitioning to low GI/GL diets may lead to decreased lesion counts after 12 weeks.11-13 In one randomized controlled trial, male participants aged 15 to 25 years with mild to moderate facial acne were instructed either to eat a high protein/low GI diet or a conventional high GL control diet.13 After 12 weeks, total lesion counts had decreased more in the low GI diet group than the control. As partial confirmation of a mechanistic pathway for a high GI diet and acne, the low GI group demonstrated lower free androgen index and insulin levels than the control group.13 In a Korean study, a 10-week low GL regimen led to a reduction in acne lesion count, a decrease in sebaceous gland size, decreased inflammation, and reduced expression of sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 and IL-8.14

More recent studies have further solidified the role of high GI/GL diets in acne severity.9,15,16 High GI/GL diets are believed to stimulate acne pathways by stimulating insulinlike growth factor 1 (IGF-1), which induces proliferation of both keratinocytes and sebocytes and simulates androgen production.17 An excellent diagram showing the connection between high GI diets (and dairy) and IGF-1, insulin and its receptors, androgen and its receptors, mammalian target of rapamycin, and the pilosebaceous unit was published in the literature in 2016.4 Interestingly, metformin has been shown to be an effective adjunctive therapy in the treatment of moderate to severe acne vulgaris.18,19

Milk and Dairy Consumption

Milk consumption also has been examined for its potential role in the pathogenesis of acne, including its ability to increase insulin and IGF-1 levels and bind to the human IGF-1 receptor as well as the fact that it contains bovine IGF-1 and dihydrotestosterone precursors.20 Although not studied quite as extensively or rigorously as GI/GL, consumption of milk and dairy products does appear to have the potential to exacerbate acne lesions. Beginning with a series of retrospective and prospective epidemiologic studies published from 2005 to 2008,21-23 a link between clinical acne and milk or dairy consumption in adolescent subjects was reported. A recent meta-analysis found a positive relationship between dairy, total milk, whole milk, low-fat milk, and skim milk consumption and acne occurrence but no significant association between yogurt/cheese consumption and acne development.24

AAD Guidelines

In their public forum, the AAD has advised that a low-glycemic diet may reduce the number of lesions in acne patients and highlighted data from around the world that support the concept that a high-glycemic diet and dairy are correlated with acne severity. They stated that consumption of milk—whole, low fat, and skim—may be linked to an increase in acne breakouts but that no studies have found that products made from milk, such as yogurt or cheese, lead to more breakouts.25

Other Considerations

Acne can be a serious quality-of-life issue with considerable psychological distress, physical morbidity, and social prejudice.9 Consequently, acne patients may be more willing to accept nonprofessional treatment advice, and there is no shortage of non–health care “experts” willing to provide an array of unfounded and fantastical advice. Dietary recommendations found online range from specific “miracle” foods to the more data-driven suggestions to “avoid dairy” or “eat low GI foods.” An important study recently published in Cutis concluded that most of the information found online regarding diet and acne is unfounded and/or misleading.26

Two additional reasons for recommending that acne patients consider dietary modification are not directly related to the disease: (1) the general health benefits of a lower GI/GL diet, and (2) the potential for decreasing the use of antibiotics. Antibiotic resistance is a growing problem across medicine, and dermatologists prescribe more antibiotics per provider than any other specialty.17 Dietary modification, where appropriate, could provide an approach to limiting the use of antibiotics in acne.

Final Thoughts

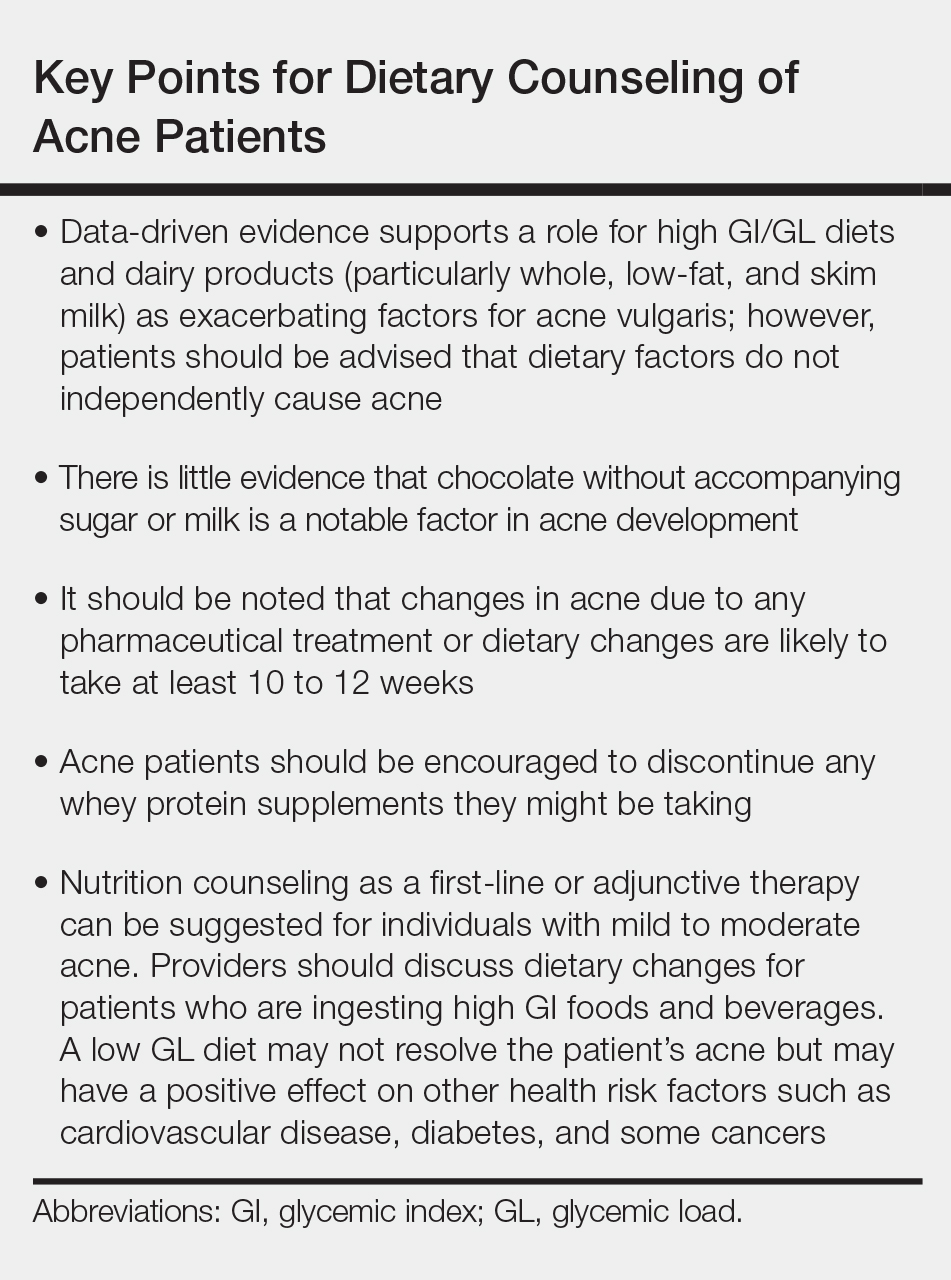

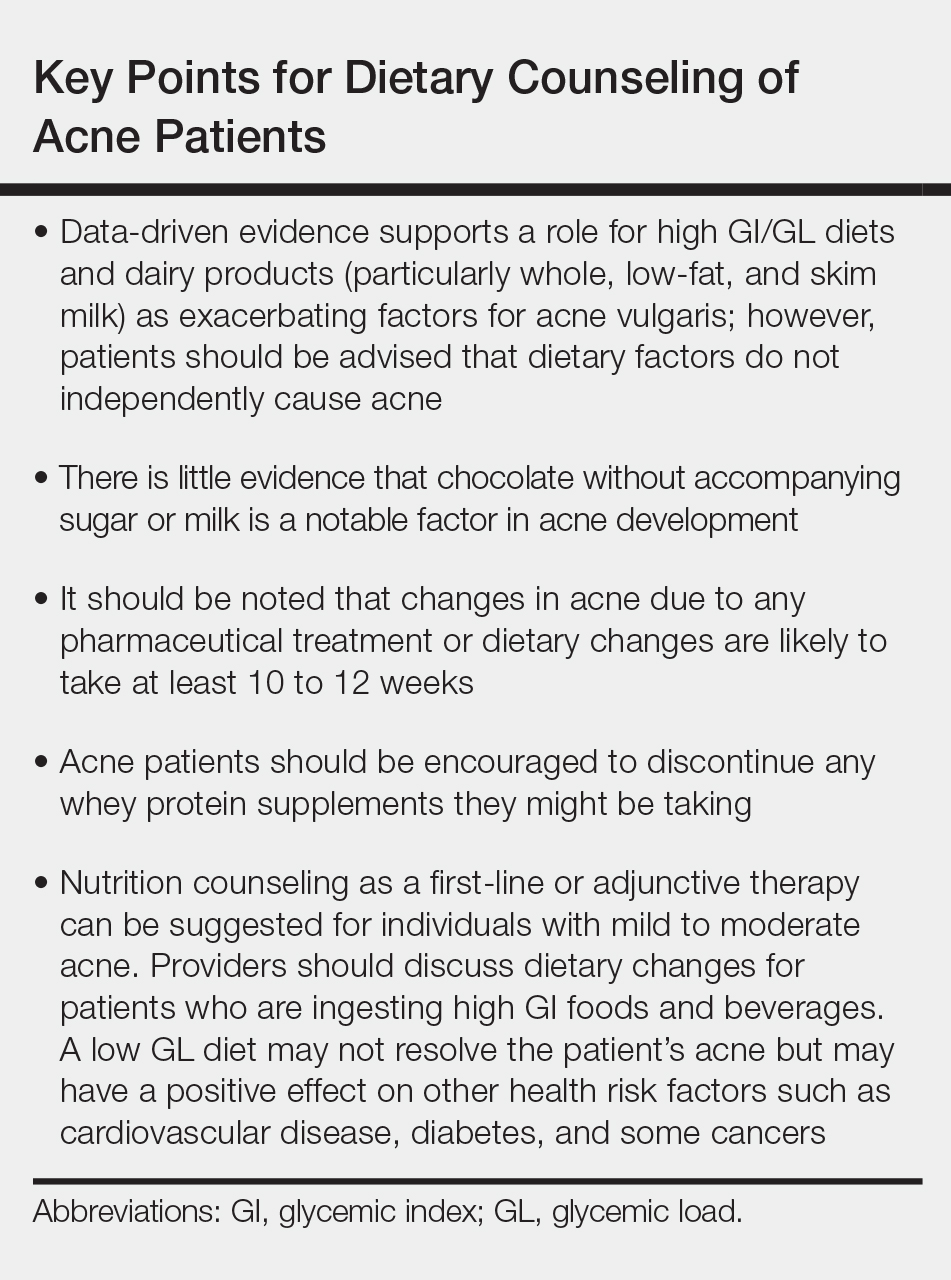

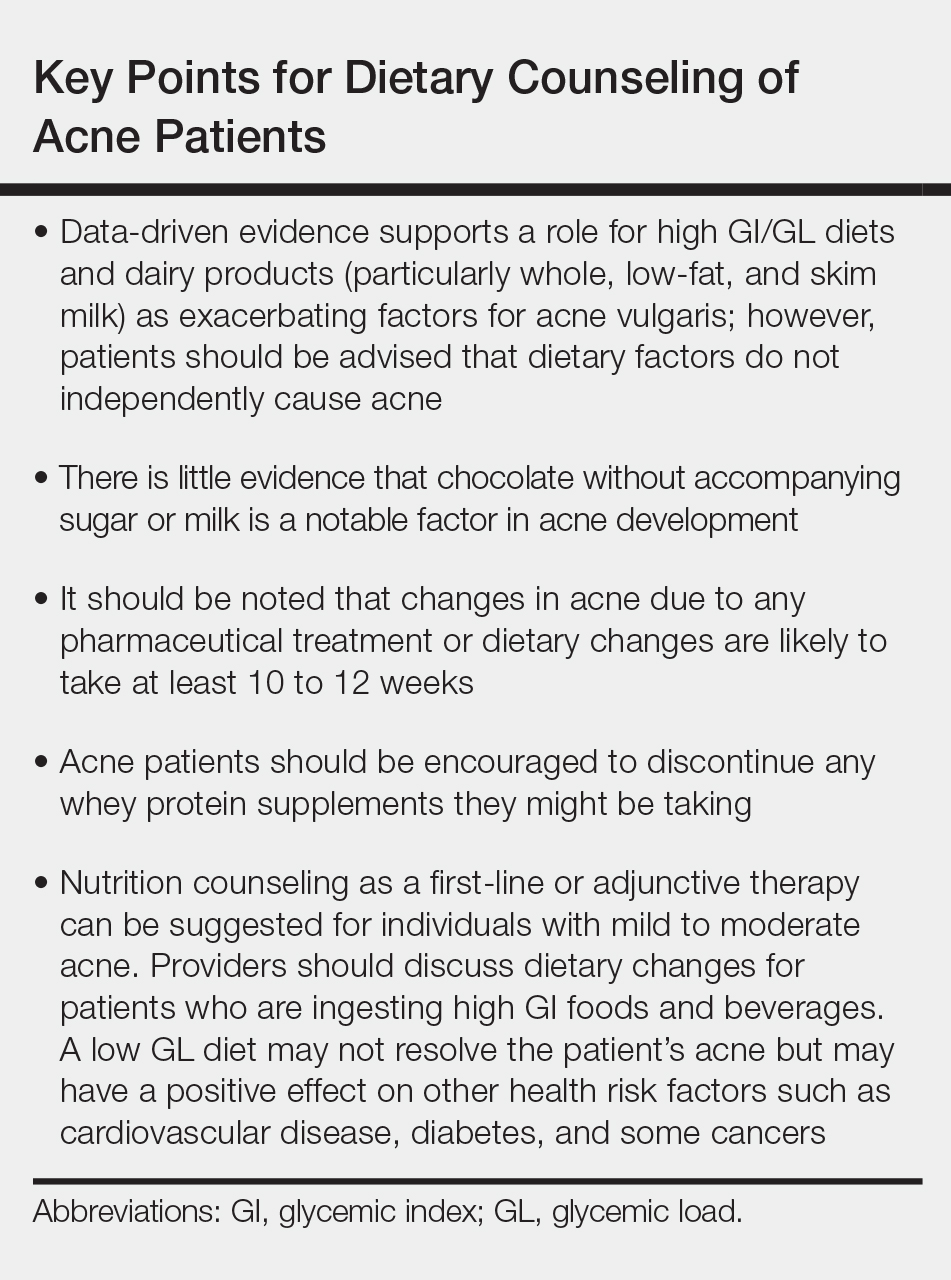

When advising acne patients, dermatologists can refer to the Table for general guidelines that incorporate the most current data-driven information on the relationship between diet and acne. Dietary modification, of course, will not work for all but can be safely recommended in cases of mild to moderate acne.

- Barbieri JS, Bhate K, Hartnett KP, et al. Trends in oral antibiotic prescription in dermatology, 2008 to 2016 [published online January 16, 2019]. JAMA Dermatol. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4944.

- Barbieri JS, Spaccarelli N, Margolis DJ, et al. Approaches to limit systemic antibiotic use in acne: systemic alternatives, emerging topical therapies, dietary modification, and laser and light-based treatments. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:538-549.

- Melnik BC. Acne vulgaris: the metabolic syndrome of the pilosebaceous follicle [published online September 8, 2017]. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:29-40.

- Lynn DD, Umari T, Dunnick CA, et al. The epidemiology of acne vulgaris in late adolescence. Adolesc Health Med Ther. 2016;7:13-25.

- Cordain L, Lindeberg S, Hurtado M, et al. Acne vulgaris: a disease of Western civilization. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1584-1590.

- Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris [published online February 17, 2016]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:945.e33-973.e33.

- Rezakovic´ S, Bukvic´ Mokos Z, Basta-Juzbašic´ A. Acne and diet: facts and controversies. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2012;20:170-174.

- Mahmood NF, Shipman AR. The age-old problem of acne. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2017;3:71-76.

- Burris J, Shikany JM, Rietkerk W, et al. A low glycemic index and glycemic load diet decreases insulin-like growth factor-1 among adults with moderate and severe acne: a short-duration, 2-week randomized controlled trial. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2018;118:1874-1885.

- Atkinson FS, Foster-Powell K, Brand-Miller JC. International tables of glycemic index and glycemic load values: 2008 [published online October 3, 2008]. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:2281-2283.

- Smith RN, Braue A, Varigos GA, et al. The effect of a low glycemic load diet on acne vulgaris and the fatty acid composition of skin surface triglycerides. J Dermatol Sci. 2008;50:41-52

- Smith RN, Braue A, Varigos GA, et al. A low-glycemic-load diet improves symptoms in acne vulgaris patients: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86:107-115.

- Smith RN, Mann NJ, Braue A, et al. The effect of a high-protein, low glycemic-load diet versus a conventional, high glycemic-load diet on biochemical parameters associated with acne vulgaris: a randomized, investigator-masked, controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:247-256.

- Kwon HH, Yoon JY, Hong JS, et al. Clinical and histological effect of a low glycaemic load diet in treatment of acne vulgaris in Korean patients: a randomized, controlled trial. Acta Derm Venereol. 2012;92:241-246.

- Burris J, Rietkerk W, Woolf K. Differences in dietary glycemic load and hormones in New York City adults with no and moderate/severe acne. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2017;117:1375-1383.

- Burris J, Rietkerk W, Woolf K. Relationships of self-reported dietary factors and perceived acne severity in a cohort of New York young adults [published online January 9, 2014]. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2014;114:384-392.

- Barbieri JS, Bhate K, Hartnett KP, et al. Trends in oral antibiotic prescription in dermatology, 2008 to 2016 [published online January 16, 2019]. JAMA Dermatol. 2019. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4944.

- Lee JK, Smith AD. Metformin as an adjunct therapy for the treatment of moderate to severe acne vulgaris [published online November 15, 2017]. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23. pii:13030/qt53m2q13s.

- Robinson S, Kwan Z, Tang MM. Metformin as an adjunct therapy for the treatment of moderate to severe acne vulgaris: a randomized open-labeled study [published online May 1, 2019]. Dermatol Ther. 2019. doi:10.1111/dth.12953.

- Barbieri JS, Spaccarelli N, Margolis DJ, et al. Approaches to limitsystemic antibiotic use in acne: systemic alternatives, emerging topical therapies, dietary modification, and laser and light-based treatments [published online October 5, 2018]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:538-549.

- Adebamowo CA, Spiegelman D, Berkey CS, et al. Milk consumption and acne in adolescent girls. Dermatol Online J. 2006;12:1.

- Adebamowo CA, Spiegelman D, Berkey CS, et al. Milk consumption and acne in teenaged boys. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:787-793.

- Adebamowo CA, Spiegelman D, Danby FW, et al. High school dietary dairy intake and teenage acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:207-214.

- Aghasi M, Golzarand M, Shab-Bidar S, et al. Dairy intake and acne development: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Clin Nutr. 2019;38:1067-1075.

- Can the right diet get rid of acne? American Academy of Dermatology website. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/acne-and-rosacea/can-the-right-diet-get-rid-of-acne. Accessed June 13, 2019.

- Khanna R, Shifrin N, Nektalova T, et al. Diet and dermatology: Google search results for acne, psoriasis, and eczema. Cutis. 2018;102:44-46, 48.

Acne is a common condition that most often affects adolescents but is not uncommon in adults. It can result in considerable anxiety, depression, and medical and pharmaceutical costs. Additionally, oral antibiotics, the standard treatment for acne, are increasingly under suspicion for causing bacterial resistance as well as disruption of the cutaneous and gut microbiomes.1,2 These factors are among those that often drive patients and physicians to search for alternative and complementary treatments, including dietary modification.

Over the last few decades, the interaction between diet and acne has been one of the most fluid areas of research in dermatology. The role of diet in acne incidence and presentation has evolved from the general view in the 1970s that there was no connection to today’s more data-driven understanding that the acne disease course likely is modified by specific dietary components. Better designed and more rigorous studies have supported a link between acne severity and glycemic index (GI)/glycemic load (GL) and possibly dairy consumption. The ability to use data-driven evidence to counsel patients regarding dietary treatment of acne is increasingly important to counteract the pseudoadvice that patients can easily find on the Internet.

This article summarizes the history of beliefs about diet and acne, reviews more recent published data regarding dietary components that can modify acne severity, and outlines the current American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) guidelines and recommendations for diet and acne.

History of Diet and Acne

In most of the current literature, acne frequently is referred to as a disease of modern civilization or a consequence of the typical Western diet.3 For clarity, the Western diet is most commonly described as “a dietary regimen characterized by high amounts of sugary desserts, refined grains, high protein, high-fat dairy products, and high-sugar drinks.”4 The role of dairy in the etiology of acne typically is discussed separately from the Western diet. It has been reported that acne is not found in nonwesternized populations where a Paleolithic diet, which does not include consumption of high-GI carbohydrates, milk, or other dairy products, is common.5

Extending this line of argument, acne vulgaris has been called a metabolic syndrome of the sebaceous follicle and one of the mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1–driven diseases of civilization, along with cancer, obesity, and diabetes mellitus.3 This view seems somewhat extreme and discounts other drivers of acne incidence and severity. Twin studies have shown that acne is highly heritable, with 81% of the population variance attributed to genetic factors.6 Similar incidence numbers for acne vulgaris have been reported worldwide, and global incidence in late adolescence is rising; however, it is unknown whether this increase is a result of the adoption of the Western diet, which is thought to encourage early onset of puberty; genetic drift; changes in regional and cultural understanding and reporting of acne; or a byproduct of unknown environmental factors.4 More nuanced views acknowledge that acne is a multifactorial disease,7 and therefore genetic and possibly epigenetic factors as well as the cutaneous and gut microbiomes also must be taken into account. An interesting historical perspective on acne by Mahmood and Shipman8 outlined acne descriptions, diagnoses, topical treatments, and dietary advice going back to ancient Greek and Egyptian civilizations. They also cited recommendations from the 1930s that suggested avoiding “starchy foods, bread rolls, noodles, spaghetti, potatoes, oily nuts, chop suey, chow mein, and waffles” and listed the following foods as suitable to cure acne: “cooked and raw fruit, farina, rice, wheat, oatmeal, green vegetables, boiled or broiled meat and poultry, clear soup, vegetable soup, and an abundance of water.”8

More Recent Evidence of Dietary Influence on Acne

Importantly, the available research does not demonstrate that diet causes acne but rather that it may influence or aggravate existing acne. Data collection for acne studies also can be confounded by the interplay of many factors, such as increased access to health care, socioeconomic status, and shifting cultural perceptions of skin care and beauty.4 An important facet of any therapeutic recommendation is that it should be supported by confirmable mechanistic pathways.

GI and GL

Over the last few decades, a number of observational and intervention studies have focused on the possible influence of the GI/GL of foods on acne incidence and/or severity. A high GI diet is characterized by a relatively high intake of carbohydrate-containing foods that are quickly digested and absorbed, increasing blood glucose and insulin concentrations. Glycemic load takes the portion size of dietary carbohydrates into consideration and therefore is a measure of both the quality and quantity of carbohydrate-containing foods.9 TheGI/GL values of more than 2480 food items are available in the literature.10

Evidence from several studies supports the role of high GI/GL diets in exacerbating acne and suggests that transitioning to low GI/GL diets may lead to decreased lesion counts after 12 weeks.11-13 In one randomized controlled trial, male participants aged 15 to 25 years with mild to moderate facial acne were instructed either to eat a high protein/low GI diet or a conventional high GL control diet.13 After 12 weeks, total lesion counts had decreased more in the low GI diet group than the control. As partial confirmation of a mechanistic pathway for a high GI diet and acne, the low GI group demonstrated lower free androgen index and insulin levels than the control group.13 In a Korean study, a 10-week low GL regimen led to a reduction in acne lesion count, a decrease in sebaceous gland size, decreased inflammation, and reduced expression of sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 and IL-8.14

More recent studies have further solidified the role of high GI/GL diets in acne severity.9,15,16 High GI/GL diets are believed to stimulate acne pathways by stimulating insulinlike growth factor 1 (IGF-1), which induces proliferation of both keratinocytes and sebocytes and simulates androgen production.17 An excellent diagram showing the connection between high GI diets (and dairy) and IGF-1, insulin and its receptors, androgen and its receptors, mammalian target of rapamycin, and the pilosebaceous unit was published in the literature in 2016.4 Interestingly, metformin has been shown to be an effective adjunctive therapy in the treatment of moderate to severe acne vulgaris.18,19

Milk and Dairy Consumption

Milk consumption also has been examined for its potential role in the pathogenesis of acne, including its ability to increase insulin and IGF-1 levels and bind to the human IGF-1 receptor as well as the fact that it contains bovine IGF-1 and dihydrotestosterone precursors.20 Although not studied quite as extensively or rigorously as GI/GL, consumption of milk and dairy products does appear to have the potential to exacerbate acne lesions. Beginning with a series of retrospective and prospective epidemiologic studies published from 2005 to 2008,21-23 a link between clinical acne and milk or dairy consumption in adolescent subjects was reported. A recent meta-analysis found a positive relationship between dairy, total milk, whole milk, low-fat milk, and skim milk consumption and acne occurrence but no significant association between yogurt/cheese consumption and acne development.24

AAD Guidelines

In their public forum, the AAD has advised that a low-glycemic diet may reduce the number of lesions in acne patients and highlighted data from around the world that support the concept that a high-glycemic diet and dairy are correlated with acne severity. They stated that consumption of milk—whole, low fat, and skim—may be linked to an increase in acne breakouts but that no studies have found that products made from milk, such as yogurt or cheese, lead to more breakouts.25

Other Considerations

Acne can be a serious quality-of-life issue with considerable psychological distress, physical morbidity, and social prejudice.9 Consequently, acne patients may be more willing to accept nonprofessional treatment advice, and there is no shortage of non–health care “experts” willing to provide an array of unfounded and fantastical advice. Dietary recommendations found online range from specific “miracle” foods to the more data-driven suggestions to “avoid dairy” or “eat low GI foods.” An important study recently published in Cutis concluded that most of the information found online regarding diet and acne is unfounded and/or misleading.26

Two additional reasons for recommending that acne patients consider dietary modification are not directly related to the disease: (1) the general health benefits of a lower GI/GL diet, and (2) the potential for decreasing the use of antibiotics. Antibiotic resistance is a growing problem across medicine, and dermatologists prescribe more antibiotics per provider than any other specialty.17 Dietary modification, where appropriate, could provide an approach to limiting the use of antibiotics in acne.

Final Thoughts

When advising acne patients, dermatologists can refer to the Table for general guidelines that incorporate the most current data-driven information on the relationship between diet and acne. Dietary modification, of course, will not work for all but can be safely recommended in cases of mild to moderate acne.

Acne is a common condition that most often affects adolescents but is not uncommon in adults. It can result in considerable anxiety, depression, and medical and pharmaceutical costs. Additionally, oral antibiotics, the standard treatment for acne, are increasingly under suspicion for causing bacterial resistance as well as disruption of the cutaneous and gut microbiomes.1,2 These factors are among those that often drive patients and physicians to search for alternative and complementary treatments, including dietary modification.

Over the last few decades, the interaction between diet and acne has been one of the most fluid areas of research in dermatology. The role of diet in acne incidence and presentation has evolved from the general view in the 1970s that there was no connection to today’s more data-driven understanding that the acne disease course likely is modified by specific dietary components. Better designed and more rigorous studies have supported a link between acne severity and glycemic index (GI)/glycemic load (GL) and possibly dairy consumption. The ability to use data-driven evidence to counsel patients regarding dietary treatment of acne is increasingly important to counteract the pseudoadvice that patients can easily find on the Internet.

This article summarizes the history of beliefs about diet and acne, reviews more recent published data regarding dietary components that can modify acne severity, and outlines the current American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) guidelines and recommendations for diet and acne.

History of Diet and Acne

In most of the current literature, acne frequently is referred to as a disease of modern civilization or a consequence of the typical Western diet.3 For clarity, the Western diet is most commonly described as “a dietary regimen characterized by high amounts of sugary desserts, refined grains, high protein, high-fat dairy products, and high-sugar drinks.”4 The role of dairy in the etiology of acne typically is discussed separately from the Western diet. It has been reported that acne is not found in nonwesternized populations where a Paleolithic diet, which does not include consumption of high-GI carbohydrates, milk, or other dairy products, is common.5

Extending this line of argument, acne vulgaris has been called a metabolic syndrome of the sebaceous follicle and one of the mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1–driven diseases of civilization, along with cancer, obesity, and diabetes mellitus.3 This view seems somewhat extreme and discounts other drivers of acne incidence and severity. Twin studies have shown that acne is highly heritable, with 81% of the population variance attributed to genetic factors.6 Similar incidence numbers for acne vulgaris have been reported worldwide, and global incidence in late adolescence is rising; however, it is unknown whether this increase is a result of the adoption of the Western diet, which is thought to encourage early onset of puberty; genetic drift; changes in regional and cultural understanding and reporting of acne; or a byproduct of unknown environmental factors.4 More nuanced views acknowledge that acne is a multifactorial disease,7 and therefore genetic and possibly epigenetic factors as well as the cutaneous and gut microbiomes also must be taken into account. An interesting historical perspective on acne by Mahmood and Shipman8 outlined acne descriptions, diagnoses, topical treatments, and dietary advice going back to ancient Greek and Egyptian civilizations. They also cited recommendations from the 1930s that suggested avoiding “starchy foods, bread rolls, noodles, spaghetti, potatoes, oily nuts, chop suey, chow mein, and waffles” and listed the following foods as suitable to cure acne: “cooked and raw fruit, farina, rice, wheat, oatmeal, green vegetables, boiled or broiled meat and poultry, clear soup, vegetable soup, and an abundance of water.”8

More Recent Evidence of Dietary Influence on Acne

Importantly, the available research does not demonstrate that diet causes acne but rather that it may influence or aggravate existing acne. Data collection for acne studies also can be confounded by the interplay of many factors, such as increased access to health care, socioeconomic status, and shifting cultural perceptions of skin care and beauty.4 An important facet of any therapeutic recommendation is that it should be supported by confirmable mechanistic pathways.

GI and GL

Over the last few decades, a number of observational and intervention studies have focused on the possible influence of the GI/GL of foods on acne incidence and/or severity. A high GI diet is characterized by a relatively high intake of carbohydrate-containing foods that are quickly digested and absorbed, increasing blood glucose and insulin concentrations. Glycemic load takes the portion size of dietary carbohydrates into consideration and therefore is a measure of both the quality and quantity of carbohydrate-containing foods.9 TheGI/GL values of more than 2480 food items are available in the literature.10

Evidence from several studies supports the role of high GI/GL diets in exacerbating acne and suggests that transitioning to low GI/GL diets may lead to decreased lesion counts after 12 weeks.11-13 In one randomized controlled trial, male participants aged 15 to 25 years with mild to moderate facial acne were instructed either to eat a high protein/low GI diet or a conventional high GL control diet.13 After 12 weeks, total lesion counts had decreased more in the low GI diet group than the control. As partial confirmation of a mechanistic pathway for a high GI diet and acne, the low GI group demonstrated lower free androgen index and insulin levels than the control group.13 In a Korean study, a 10-week low GL regimen led to a reduction in acne lesion count, a decrease in sebaceous gland size, decreased inflammation, and reduced expression of sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 and IL-8.14

More recent studies have further solidified the role of high GI/GL diets in acne severity.9,15,16 High GI/GL diets are believed to stimulate acne pathways by stimulating insulinlike growth factor 1 (IGF-1), which induces proliferation of both keratinocytes and sebocytes and simulates androgen production.17 An excellent diagram showing the connection between high GI diets (and dairy) and IGF-1, insulin and its receptors, androgen and its receptors, mammalian target of rapamycin, and the pilosebaceous unit was published in the literature in 2016.4 Interestingly, metformin has been shown to be an effective adjunctive therapy in the treatment of moderate to severe acne vulgaris.18,19

Milk and Dairy Consumption

Milk consumption also has been examined for its potential role in the pathogenesis of acne, including its ability to increase insulin and IGF-1 levels and bind to the human IGF-1 receptor as well as the fact that it contains bovine IGF-1 and dihydrotestosterone precursors.20 Although not studied quite as extensively or rigorously as GI/GL, consumption of milk and dairy products does appear to have the potential to exacerbate acne lesions. Beginning with a series of retrospective and prospective epidemiologic studies published from 2005 to 2008,21-23 a link between clinical acne and milk or dairy consumption in adolescent subjects was reported. A recent meta-analysis found a positive relationship between dairy, total milk, whole milk, low-fat milk, and skim milk consumption and acne occurrence but no significant association between yogurt/cheese consumption and acne development.24

AAD Guidelines

In their public forum, the AAD has advised that a low-glycemic diet may reduce the number of lesions in acne patients and highlighted data from around the world that support the concept that a high-glycemic diet and dairy are correlated with acne severity. They stated that consumption of milk—whole, low fat, and skim—may be linked to an increase in acne breakouts but that no studies have found that products made from milk, such as yogurt or cheese, lead to more breakouts.25

Other Considerations

Acne can be a serious quality-of-life issue with considerable psychological distress, physical morbidity, and social prejudice.9 Consequently, acne patients may be more willing to accept nonprofessional treatment advice, and there is no shortage of non–health care “experts” willing to provide an array of unfounded and fantastical advice. Dietary recommendations found online range from specific “miracle” foods to the more data-driven suggestions to “avoid dairy” or “eat low GI foods.” An important study recently published in Cutis concluded that most of the information found online regarding diet and acne is unfounded and/or misleading.26

Two additional reasons for recommending that acne patients consider dietary modification are not directly related to the disease: (1) the general health benefits of a lower GI/GL diet, and (2) the potential for decreasing the use of antibiotics. Antibiotic resistance is a growing problem across medicine, and dermatologists prescribe more antibiotics per provider than any other specialty.17 Dietary modification, where appropriate, could provide an approach to limiting the use of antibiotics in acne.

Final Thoughts

When advising acne patients, dermatologists can refer to the Table for general guidelines that incorporate the most current data-driven information on the relationship between diet and acne. Dietary modification, of course, will not work for all but can be safely recommended in cases of mild to moderate acne.

- Barbieri JS, Bhate K, Hartnett KP, et al. Trends in oral antibiotic prescription in dermatology, 2008 to 2016 [published online January 16, 2019]. JAMA Dermatol. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4944.

- Barbieri JS, Spaccarelli N, Margolis DJ, et al. Approaches to limit systemic antibiotic use in acne: systemic alternatives, emerging topical therapies, dietary modification, and laser and light-based treatments. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:538-549.

- Melnik BC. Acne vulgaris: the metabolic syndrome of the pilosebaceous follicle [published online September 8, 2017]. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:29-40.

- Lynn DD, Umari T, Dunnick CA, et al. The epidemiology of acne vulgaris in late adolescence. Adolesc Health Med Ther. 2016;7:13-25.

- Cordain L, Lindeberg S, Hurtado M, et al. Acne vulgaris: a disease of Western civilization. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1584-1590.

- Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris [published online February 17, 2016]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:945.e33-973.e33.

- Rezakovic´ S, Bukvic´ Mokos Z, Basta-Juzbašic´ A. Acne and diet: facts and controversies. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2012;20:170-174.

- Mahmood NF, Shipman AR. The age-old problem of acne. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2017;3:71-76.

- Burris J, Shikany JM, Rietkerk W, et al. A low glycemic index and glycemic load diet decreases insulin-like growth factor-1 among adults with moderate and severe acne: a short-duration, 2-week randomized controlled trial. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2018;118:1874-1885.

- Atkinson FS, Foster-Powell K, Brand-Miller JC. International tables of glycemic index and glycemic load values: 2008 [published online October 3, 2008]. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:2281-2283.

- Smith RN, Braue A, Varigos GA, et al. The effect of a low glycemic load diet on acne vulgaris and the fatty acid composition of skin surface triglycerides. J Dermatol Sci. 2008;50:41-52

- Smith RN, Braue A, Varigos GA, et al. A low-glycemic-load diet improves symptoms in acne vulgaris patients: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86:107-115.

- Smith RN, Mann NJ, Braue A, et al. The effect of a high-protein, low glycemic-load diet versus a conventional, high glycemic-load diet on biochemical parameters associated with acne vulgaris: a randomized, investigator-masked, controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:247-256.

- Kwon HH, Yoon JY, Hong JS, et al. Clinical and histological effect of a low glycaemic load diet in treatment of acne vulgaris in Korean patients: a randomized, controlled trial. Acta Derm Venereol. 2012;92:241-246.

- Burris J, Rietkerk W, Woolf K. Differences in dietary glycemic load and hormones in New York City adults with no and moderate/severe acne. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2017;117:1375-1383.

- Burris J, Rietkerk W, Woolf K. Relationships of self-reported dietary factors and perceived acne severity in a cohort of New York young adults [published online January 9, 2014]. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2014;114:384-392.

- Barbieri JS, Bhate K, Hartnett KP, et al. Trends in oral antibiotic prescription in dermatology, 2008 to 2016 [published online January 16, 2019]. JAMA Dermatol. 2019. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4944.

- Lee JK, Smith AD. Metformin as an adjunct therapy for the treatment of moderate to severe acne vulgaris [published online November 15, 2017]. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23. pii:13030/qt53m2q13s.

- Robinson S, Kwan Z, Tang MM. Metformin as an adjunct therapy for the treatment of moderate to severe acne vulgaris: a randomized open-labeled study [published online May 1, 2019]. Dermatol Ther. 2019. doi:10.1111/dth.12953.

- Barbieri JS, Spaccarelli N, Margolis DJ, et al. Approaches to limitsystemic antibiotic use in acne: systemic alternatives, emerging topical therapies, dietary modification, and laser and light-based treatments [published online October 5, 2018]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:538-549.

- Adebamowo CA, Spiegelman D, Berkey CS, et al. Milk consumption and acne in adolescent girls. Dermatol Online J. 2006;12:1.

- Adebamowo CA, Spiegelman D, Berkey CS, et al. Milk consumption and acne in teenaged boys. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:787-793.

- Adebamowo CA, Spiegelman D, Danby FW, et al. High school dietary dairy intake and teenage acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:207-214.

- Aghasi M, Golzarand M, Shab-Bidar S, et al. Dairy intake and acne development: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Clin Nutr. 2019;38:1067-1075.

- Can the right diet get rid of acne? American Academy of Dermatology website. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/acne-and-rosacea/can-the-right-diet-get-rid-of-acne. Accessed June 13, 2019.

- Khanna R, Shifrin N, Nektalova T, et al. Diet and dermatology: Google search results for acne, psoriasis, and eczema. Cutis. 2018;102:44-46, 48.

- Barbieri JS, Bhate K, Hartnett KP, et al. Trends in oral antibiotic prescription in dermatology, 2008 to 2016 [published online January 16, 2019]. JAMA Dermatol. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4944.

- Barbieri JS, Spaccarelli N, Margolis DJ, et al. Approaches to limit systemic antibiotic use in acne: systemic alternatives, emerging topical therapies, dietary modification, and laser and light-based treatments. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:538-549.

- Melnik BC. Acne vulgaris: the metabolic syndrome of the pilosebaceous follicle [published online September 8, 2017]. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:29-40.

- Lynn DD, Umari T, Dunnick CA, et al. The epidemiology of acne vulgaris in late adolescence. Adolesc Health Med Ther. 2016;7:13-25.

- Cordain L, Lindeberg S, Hurtado M, et al. Acne vulgaris: a disease of Western civilization. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1584-1590.

- Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris [published online February 17, 2016]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:945.e33-973.e33.

- Rezakovic´ S, Bukvic´ Mokos Z, Basta-Juzbašic´ A. Acne and diet: facts and controversies. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2012;20:170-174.

- Mahmood NF, Shipman AR. The age-old problem of acne. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2017;3:71-76.

- Burris J, Shikany JM, Rietkerk W, et al. A low glycemic index and glycemic load diet decreases insulin-like growth factor-1 among adults with moderate and severe acne: a short-duration, 2-week randomized controlled trial. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2018;118:1874-1885.

- Atkinson FS, Foster-Powell K, Brand-Miller JC. International tables of glycemic index and glycemic load values: 2008 [published online October 3, 2008]. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:2281-2283.

- Smith RN, Braue A, Varigos GA, et al. The effect of a low glycemic load diet on acne vulgaris and the fatty acid composition of skin surface triglycerides. J Dermatol Sci. 2008;50:41-52

- Smith RN, Braue A, Varigos GA, et al. A low-glycemic-load diet improves symptoms in acne vulgaris patients: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86:107-115.

- Smith RN, Mann NJ, Braue A, et al. The effect of a high-protein, low glycemic-load diet versus a conventional, high glycemic-load diet on biochemical parameters associated with acne vulgaris: a randomized, investigator-masked, controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:247-256.

- Kwon HH, Yoon JY, Hong JS, et al. Clinical and histological effect of a low glycaemic load diet in treatment of acne vulgaris in Korean patients: a randomized, controlled trial. Acta Derm Venereol. 2012;92:241-246.

- Burris J, Rietkerk W, Woolf K. Differences in dietary glycemic load and hormones in New York City adults with no and moderate/severe acne. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2017;117:1375-1383.

- Burris J, Rietkerk W, Woolf K. Relationships of self-reported dietary factors and perceived acne severity in a cohort of New York young adults [published online January 9, 2014]. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2014;114:384-392.

- Barbieri JS, Bhate K, Hartnett KP, et al. Trends in oral antibiotic prescription in dermatology, 2008 to 2016 [published online January 16, 2019]. JAMA Dermatol. 2019. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4944.

- Lee JK, Smith AD. Metformin as an adjunct therapy for the treatment of moderate to severe acne vulgaris [published online November 15, 2017]. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23. pii:13030/qt53m2q13s.

- Robinson S, Kwan Z, Tang MM. Metformin as an adjunct therapy for the treatment of moderate to severe acne vulgaris: a randomized open-labeled study [published online May 1, 2019]. Dermatol Ther. 2019. doi:10.1111/dth.12953.

- Barbieri JS, Spaccarelli N, Margolis DJ, et al. Approaches to limitsystemic antibiotic use in acne: systemic alternatives, emerging topical therapies, dietary modification, and laser and light-based treatments [published online October 5, 2018]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:538-549.

- Adebamowo CA, Spiegelman D, Berkey CS, et al. Milk consumption and acne in adolescent girls. Dermatol Online J. 2006;12:1.

- Adebamowo CA, Spiegelman D, Berkey CS, et al. Milk consumption and acne in teenaged boys. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:787-793.

- Adebamowo CA, Spiegelman D, Danby FW, et al. High school dietary dairy intake and teenage acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:207-214.

- Aghasi M, Golzarand M, Shab-Bidar S, et al. Dairy intake and acne development: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Clin Nutr. 2019;38:1067-1075.

- Can the right diet get rid of acne? American Academy of Dermatology website. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/acne-and-rosacea/can-the-right-diet-get-rid-of-acne. Accessed June 13, 2019.

- Khanna R, Shifrin N, Nektalova T, et al. Diet and dermatology: Google search results for acne, psoriasis, and eczema. Cutis. 2018;102:44-46, 48.

The Role of Adolescent Acne Treatment in Formation of Scars Among Patients With Persistent Adult Acne: Evidence From an Observational Study

In the last 20 years, the incidence of acne lesions in adults has markedly increased. 1 Acne affects adults (individuals older than 25 years) and is no longer a condition limited to adolescents and young adults (individuals younger than 25 years). According to Dreno et al, 2 the accepted age threshold for the onset of adult acne is 25 years. 1-3 In 2013, the term adult acne was defined. 2 Among patients with adult acne, there are 2 subtypes: (1) persistent adult acne, which is a continuation or recurrence of adolescent acne, affecting approximately 80% of patients, and (2) late-onset acne, affecting approximately 20% of patients. 4

Clinical symptoms of adult acne and available treatment modalities have been explored in the literature. Daily clinical experience shows that additional difficulties involved in the management of adult acne patients are related mainly to a high therapeutic failure rate in acne patients older than 25 years. 5 Persistent adult acne seems to be noteworthy because it causes long-term symptoms, and patients experience uncontrollable recurrences.

It is believed that adult acne often is resistant to treatment. 2 Adult skin is more sensitive to topical agents, leading to more irritation by medications intended for external use and cosmetics. 6 Scars in these patients are a frequent and undesirable consequence. 3

Effective treatment of acne encompasses oral antibiotics, topical and systemic retinoids, and oral contraceptive pills (OCPs). For years, oral subantimicrobial doses of cyclines have been recommended for acne treatment. Topical and oral retinoids have been successfully used for more than 30 years as important therapeutic options. 7 More recent evidence-based guidelines for acne issued by the American Academy of Dermatology 8 and the European Dermatology Forum 9 also show that retinoids play an important role in acne therapy. Their anti-inflammatory activity acts against comedones and their precursors (microcomedones). Successful antiacne therapy not only achieves a smooth face without comedones but also minimizes scar formation, postinflammatory discoloration, and long-lasting postinflammatory erythema. 10 Oral contraceptives have a mainly antiseborrheic effect. 11

Our study sought to analyze the potential influence of therapy during adolescent acne on patients who later developed adult acne. Particular attention was given to the use of oral antibiotics, isotretinoin, and topical retinoids for adolescent acne and their potential role in diminishing scar formation in adult acne.

Materials and Methods

Patient Demographics and Selection

A population-based study of Polish patients with adult acne was conducted. Patients were included in the study group on a consecutive basis from among those who visited our outpatient dermatology center from May 2015 to January 2016. A total of 111 patients (101 women [90.99%] and 10 men [9.01%]) were examined. The study group comprised patients aged 25 years and older who were treated for adult acne (20 patients [18.02%] were aged 25–29 years, 61 [54.95%] were aged 30–39 years, and 30 [27.02%] were 40 years or older).

The following inclusion criteria were used: observation period of at least 6 months in our dermatologic center for patients diagnosed with adult acne, at least 2 dermatologic visits for adult acne prior to the study, written informed consent for study participation and data processing (the aim of the study was explained to each participant by a dermatologist), and age 25 years or older. Exclusion criteria included those who were younger than 25 years, those who had only 1 dermatologic visit at our dermatology center, and those who were unwilling to participate or did not provide written informed consent. Our study was conducted according to Good Clinical Practice.

Data Collection

To obtain data with the highest degree of reliability, 3 sources of information were used: (1) a detailed medical interview conducted by one experienced dermatologist (E.C.) at our dermatology center at the first visit in all study participants, (2) a clinical examination that yielded results necessary for the assessment of scars using a method outlined by Jacob et al, 12 and (3) information included in available medical records. These data were then statistically analyzed.

Statistical Analysis

The results were presented as frequency plots, and a Fisher exact test was conducted to obtain a statistical comparison of the distributions of analyzed data. Unless otherwise indicated, 5% was adopted as the significance level. The statistical analysis was performed using Stata 14 software (StataCorp LLC, College Station, Texas).

Results

Incidence of Different Forms of Adult Acne

To analyze the onset of acne, patients were categorized into 1 of 2 groups: those with persistent adult acne (81.98%) and those with late-onset adult acne (ie, developed after 25 years of age)(18.02%).

Age at Initiation of Dermatologic Treatment

Of the patients with persistent adult acne, 31.87% first visited a dermatologist the same year that the first acne lesions appeared, 36.26% postponed the first visit by at least 5 years (Figure 1), and 23.08% started treatment at least 10 years after acne first appeared. Among patients with persistent adult acne, 76.92% began dermatologic treatment before 25 years of age, and 23.08% began treatment after 25 years of age. Of the latter, 28.57% did not start therapy until they were older than 35 years.

Severity of Adolescent Acne

In the persistent adult acne group, the severity of adolescent acne was assessed during the medical interview as well as detailed histories in medical records. The activity of acne was evaluated at 2-year intervals with the use of a 10-point scale: 1 to 3 points indicated mild acne (7.69% of patients), 4 to 6 points indicated moderate acne (24.18%), and 7 to 10 points indicated severe acne (68.13%).

Treatment of Persistent Acne in Adolescence

Treatment was comprised of oral therapy with antibiotics, isotretinoin, and/or application of topical retinoids (sometimes supported with OCPs). Monotherapy was the standard of treatment more than 25 years ago when patients with persistent adult acne were treated as adolescents or young adults. As many as 43.96% of patients with persistent adult acne did not receive any of these therapies before 25 years of age; rather, they used antiacne cosmetics or beauty procedures. Furthermore, 50.55% of patients were treated with oral antibiotics (Figure 2). Topical retinoids were used in 19.78% of patients and isotretinoin was used in 16.48%. Incidentally, OCPs were given to 26.5%. In the course of adolescent acne, 31.87% of patients received 2 to 4 courses of treatment with either antibiotics or retinoids (oral or topical), and 5.49% were treated with 5 or more courses of treatment (Figure 3). The analysis of each treatment revealed that only 1 patient received 4 courses of isotretinoin. Five courses of oral antibiotics were given in 1 patient, and 3 courses of topical retinoids were given in the same patient.

Topical Retinoids

In an analysis of the number of treatments with topical retinoids completed by patients with persistent adult acne, it was established that 80.22% of patients never used topical retinoids for acne during adolescence. Additionally, 12.08% of these patients completed 1 course of treatment, and 7.69% completed 2 to 4 treatments. However, after 25 years of age, only 25.27% of the patients with persistent adult acne were not treated with topical retinoids, and 35.16% completed more than 2 courses of treatment.

Duration of Treatment

Because adult acne is a chronic disease, the mean number of years that patients received treatment over the disease course was analyzed. In the case of persistent adult acne, the mean duration of treatment, including therapy received during adolescence, was more than 13 years. At the time of the study, more than 30% of patients had been undergoing treatment of adult acne for more than 20 years. Scars— The proportion of patients with persistent adult acne who experienced scarring was evaluated. In the persistent adult acne group, scars were identified in 53.85% of patients. Scars appeared only during adolescence in 26.37% of patients with persistent adult acne, scars appeared only after 25 years of age in 21.97% of patients, and scars appeared in adolescence as well as adulthood in 30.77% of patients.

In an analysis of patients with persistent adult acne who experienced scarring after 25 years of age, the proportion of patients with untreated adolescent acne and those who were treated with antibiotics only was not significantly different (60% vs 64%; P = .478)(Table). The inclusion of topical retinoids into treatment decreased the proportion of scars (isotretinoin: 20%, P = .009; topical retinoids: 38.89%, P = .114).

Comment

Persistent Adult Acne

Patients with symptoms of persistent adult acne represented 81.98% of the study population, which was similar to a 1999 study by Goulden et al, 1 a 2001 study by Shaw and White, 13 and a 2009 report by Schmidt et al. 14 Of these patients with persistent adult acne, 23.08% initiated therapy after 25 years of age, and 23.08% started treatment at least 10 years after acne lesions first appeared. However, it is noteworthy that 68.13% of all patients with persistent adult acne assessed their disease as severe.

Treatment Modalities for Adult Acne

Over the last 5 years, some researchers have attempted to make recommendations for the treatment of adult acne based on standards adopted for the treatment of adolescent acne. 2,9,15 First-line treatment of patients with adult comedonal acne is topical retinoids. 9 The recommended treatment of mild to moderate adult inflammatory acne involves topical drugs, including retinoids, azelaic acid, or benzoyl peroxide, or oral medications, including antibiotics, OCPs, or antiandrogens. In severe inflammatory acne, the recommended treatment involves oral isotretinoin or combined therapies; the latter seems to be the most effective. 16 Furthermore, this therapy has been adjusted to the patient’s current clinical condition; general individual sensitivity of the skin to irritation and the risk for irritant activity of topical medications; and life situation, such as planned pregnancies and intended use of OCPs due to the risk for teratogenic effects of drugs. 17

To assess available treatment modalities, oral therapy with antibiotics or isotretinoin as well as topical retinoids were selected for our analysis. It is difficult to determine an exclusive impact of OCPs as acne treatment; according to our study, many female patients use hormone therapy for other medical conditions or contraception, and only a small proportion of these patients are prescribed hormone treatment for acne. We found that 43.96% of patients with persistent adult acne underwent no treatment with antibiotics, isotretinoin, or topical retinoids in adolescence. Patients who did not receive any of these treatments came only for single visits to a dermatologist, did not comply to a recommended therapy, or used only cosmetics or beauty procedures. We found that 80.22% of patients with persistent adult acne never used topical retinoids during adolescence and did not receive maintenance therapy, which may be attributed to the fact that there were no strict recommendations regarding retinoid treatment when these patients were adolescents or young adults. Published data indicate that retinoid use for acne treatment is not common. 18 Conversely, among patients older than 25 years with late-onset adult acne, there was only 1 patient (ie, < 1%) who had never received any oral antibiotic or isotretinoin treatment or therapy with topical retinoids. The reason for the lack of medical treatment is unknown. Only 25.27% of patients were not treated with topical retinoids, and 35.16% completed at least 2 courses of treatment.

Acne Scarring

The worst complication of acne is scarring. Scars develop for the duration of the disease, during both adolescent and adult acne. In the group with persistent adult acne, scarring was found in 53.85% of patients. Scar formation has been previously reported as a common complication of acne. 19 The effects of skin lesions that remain after acne are not only limited to impaired cosmetic appearance; they also negatively affect mental health and impair quality of life. 20 The aim of our study was to analyze types of treatment for adolescent acne in patients who later had persistent adult acne. Postacne scars observed later are objective evidence of the severity of disease. We found that using oral antibiotics did not diminish the number of scars among persistent adult acne patients in adulthood. In contrast, isotretinoin or topical retinoid treatment during adolescence decreased the risk for scars occurring during adulthood. In our opinion, these findings emphasize the role of this type of treatment among adolescents or young adults. The decrease of scar formation in adult acne due to retinoid treatment in adolescence indirectly justifies the role of maintenance therapy with topical retinoids. 21,22

- Goulden V, Stables GI, Cunliffe WJ. Prevalence of facial acne in adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:577-580.

- Dreno B, Layton A, Zouboulis CC, et al. Adult female acne: a new paradigm. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1063-1070.

- Preneau S, Dreno B. Female acne--a different subtype of teenager acne? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:277-282.

- Goulden V, Clark SM, Cunliffe WJ. Post-adolescent acne: a review of clinical features. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:66-70.

- Kamangar F, Shinkai K. Acne in the adult female patient: a practical approach. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:1162-1174.

- Choi CW, Lee DH, Kim HS, et al. The clinical features of late onset acne compared with early onset acne in women. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:454-461.

- Kligman AM, Fulton JE Jr, Plewig G. Topical vitamin A acid in acne vulgaris. Arch Dermatol. 1969;99:469-476.

- Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:945.e33-973.e33.

- Nast A, Dreno B, Bettoli V, et al. European evidence-based guidelines for the treatment of acne. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26(suppl 1):1-29.

- Levin J. The relationship of proper skin cleansing to pathophysiology, clinical benefits, and the concomitant use of prescription topical therapies in patients with acne vulgaris. Dermatol Clin. 2016;34:133-145.

- Savage LJ, Layton AM. Treating acne vulgaris: systemic, local and combination therapy. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2010;3:563-580.

- Jacob CL, Dover JS, Kaminer MS. Acne scarring: a classification system and review of treatment options. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:109-117.

- Shaw JC, White LE. Persistent acne in adult women. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:1252-1253.

- Schmidt JV, Masuda PY, Miot HA. Acne in women: clinical patterns in different age groups. An Bras Dermatol. 2009;84:349-354.

- Thiboutot D, Gollnick H, Bettoli V, et al. New insights into the management of acne: an update from the Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne group. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60(5 suppl):1-50.

- Williams C, Layton AM. Persistent acne in women: implications for the patient and for therapy. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006;7:281-290.

- Holzmann R, Shakery K. Postadolescent acne in females. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2014;27(suppl 1):3-8.

- Pena S, Hill D, Feldman SR. Use of topical retinoids by dermatologist and non-dermatologist in the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1252-1254.

- Layton AM, Henderson CA, Cunliffe WJ. A clinical evaluation of acne scarring and its incidence. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19;303-308.

- Halvorsen JA, Stern RS, Dalgard F, et al. Suicidal ideation, mental health problems, and social impairment are increased in adolescents with acne: a population-based study. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:363-370.

- Thielitz A, Sidou F, Gollnick H. Control of microcomedone formation throughout a maintenance treatment with adapalene gel, 0.1%. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:747-753.

- Leyden J, Thiboutot DM, Shalita R, et al. Comparison of tazarotene and minocycline maintenance therapies in acne vulgaris: a multicenter, double-blind, randomized, parallel-group study. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:605-612.

In the last 20 years, the incidence of acne lesions in adults has markedly increased. 1 Acne affects adults (individuals older than 25 years) and is no longer a condition limited to adolescents and young adults (individuals younger than 25 years). According to Dreno et al, 2 the accepted age threshold for the onset of adult acne is 25 years. 1-3 In 2013, the term adult acne was defined. 2 Among patients with adult acne, there are 2 subtypes: (1) persistent adult acne, which is a continuation or recurrence of adolescent acne, affecting approximately 80% of patients, and (2) late-onset acne, affecting approximately 20% of patients. 4

Clinical symptoms of adult acne and available treatment modalities have been explored in the literature. Daily clinical experience shows that additional difficulties involved in the management of adult acne patients are related mainly to a high therapeutic failure rate in acne patients older than 25 years. 5 Persistent adult acne seems to be noteworthy because it causes long-term symptoms, and patients experience uncontrollable recurrences.

It is believed that adult acne often is resistant to treatment. 2 Adult skin is more sensitive to topical agents, leading to more irritation by medications intended for external use and cosmetics. 6 Scars in these patients are a frequent and undesirable consequence. 3

Effective treatment of acne encompasses oral antibiotics, topical and systemic retinoids, and oral contraceptive pills (OCPs). For years, oral subantimicrobial doses of cyclines have been recommended for acne treatment. Topical and oral retinoids have been successfully used for more than 30 years as important therapeutic options. 7 More recent evidence-based guidelines for acne issued by the American Academy of Dermatology 8 and the European Dermatology Forum 9 also show that retinoids play an important role in acne therapy. Their anti-inflammatory activity acts against comedones and their precursors (microcomedones). Successful antiacne therapy not only achieves a smooth face without comedones but also minimizes scar formation, postinflammatory discoloration, and long-lasting postinflammatory erythema. 10 Oral contraceptives have a mainly antiseborrheic effect. 11

Our study sought to analyze the potential influence of therapy during adolescent acne on patients who later developed adult acne. Particular attention was given to the use of oral antibiotics, isotretinoin, and topical retinoids for adolescent acne and their potential role in diminishing scar formation in adult acne.

Materials and Methods

Patient Demographics and Selection

A population-based study of Polish patients with adult acne was conducted. Patients were included in the study group on a consecutive basis from among those who visited our outpatient dermatology center from May 2015 to January 2016. A total of 111 patients (101 women [90.99%] and 10 men [9.01%]) were examined. The study group comprised patients aged 25 years and older who were treated for adult acne (20 patients [18.02%] were aged 25–29 years, 61 [54.95%] were aged 30–39 years, and 30 [27.02%] were 40 years or older).