User login

Adult ADHD: 6 studies of pharmacologic interventions

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a developmental disorder that begins in childhood and continues into adulthood. The clinical presentation is characterized by a persistent pattern of inattention, impulsivity, and/or hyperactivity that causes functional interference.1 ADHD affects patients’ interpersonal and professional lives as well as their daily functioning.2 Adults with ADHD may suffer from excessive self-criticism, low self-esteem, and sensitivity to criticism.3 The overall prevalence of adult ADHD is 4.4%.4 ADHD in adults is frequently associated with comorbid psychiatric disorders.5 The diagnosis of ADHD in adults requires the presence of ≥5 symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity that persist for ≥6 months. Patients must have first had such symptoms before age 12; symptoms need to be present in ≥2 settings and interfere with functioning.1

Treatment of ADHD includes pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions. For most patients, pharmacotherapy—specifically stimulant medications—is advised as first-line treatment,6 with adequate trials of methylphenidate and amphetamines before using second-line agents such as nonstimulants. However, despite these medications’ efficacy in randomized controlled trials (RCTs), adherence is low.7 This could be due to inadequate response or adverse effects.8 Guidelines also recommend the use of nonpharmacologic interventions for adults who cannot adhere to or tolerate medication or have an inadequate response.6 Potential nonpharmacologic interventions include transcranial direct current stimulation, mindfulness, psychoeducation, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and chronotherapy.

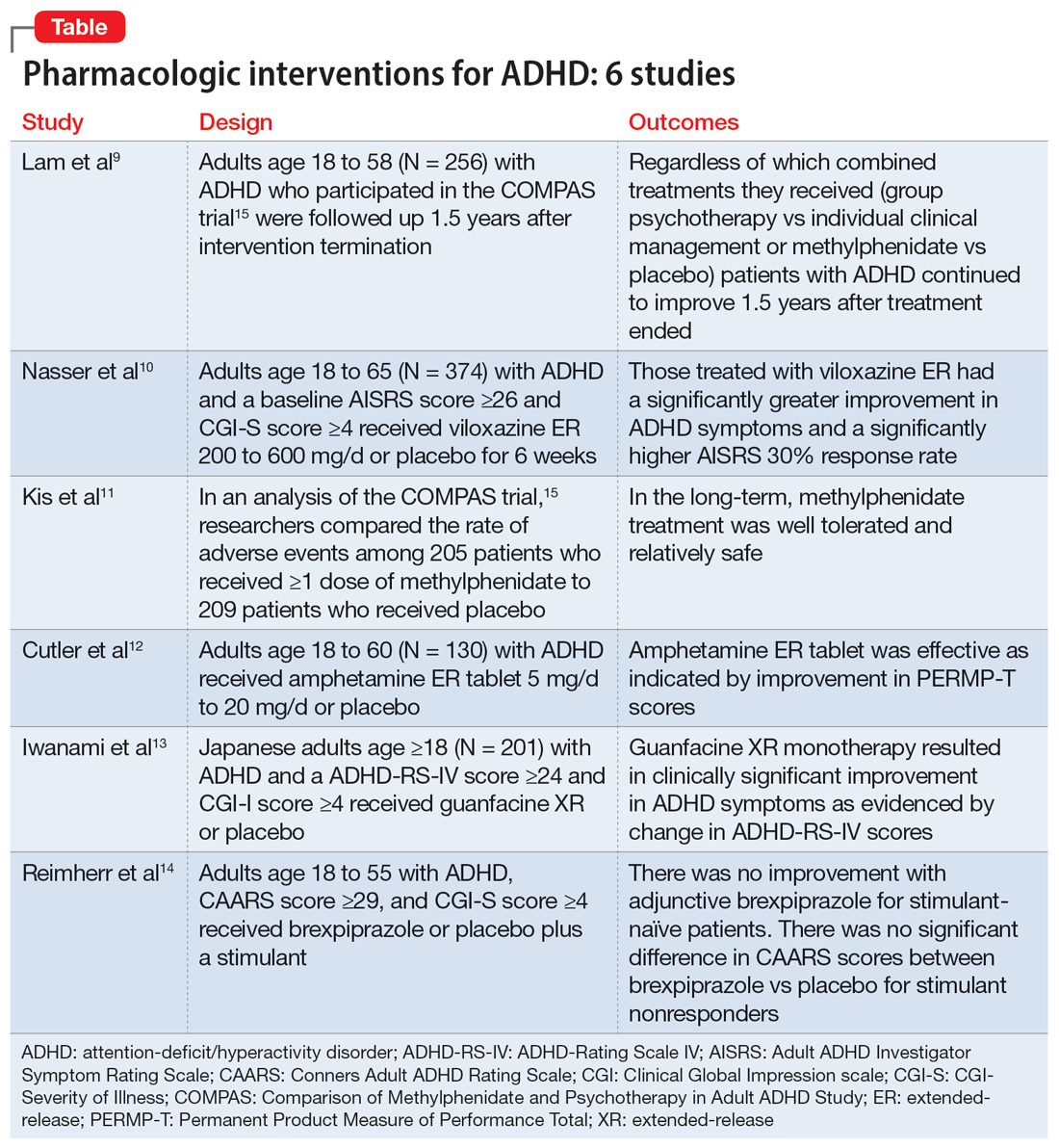

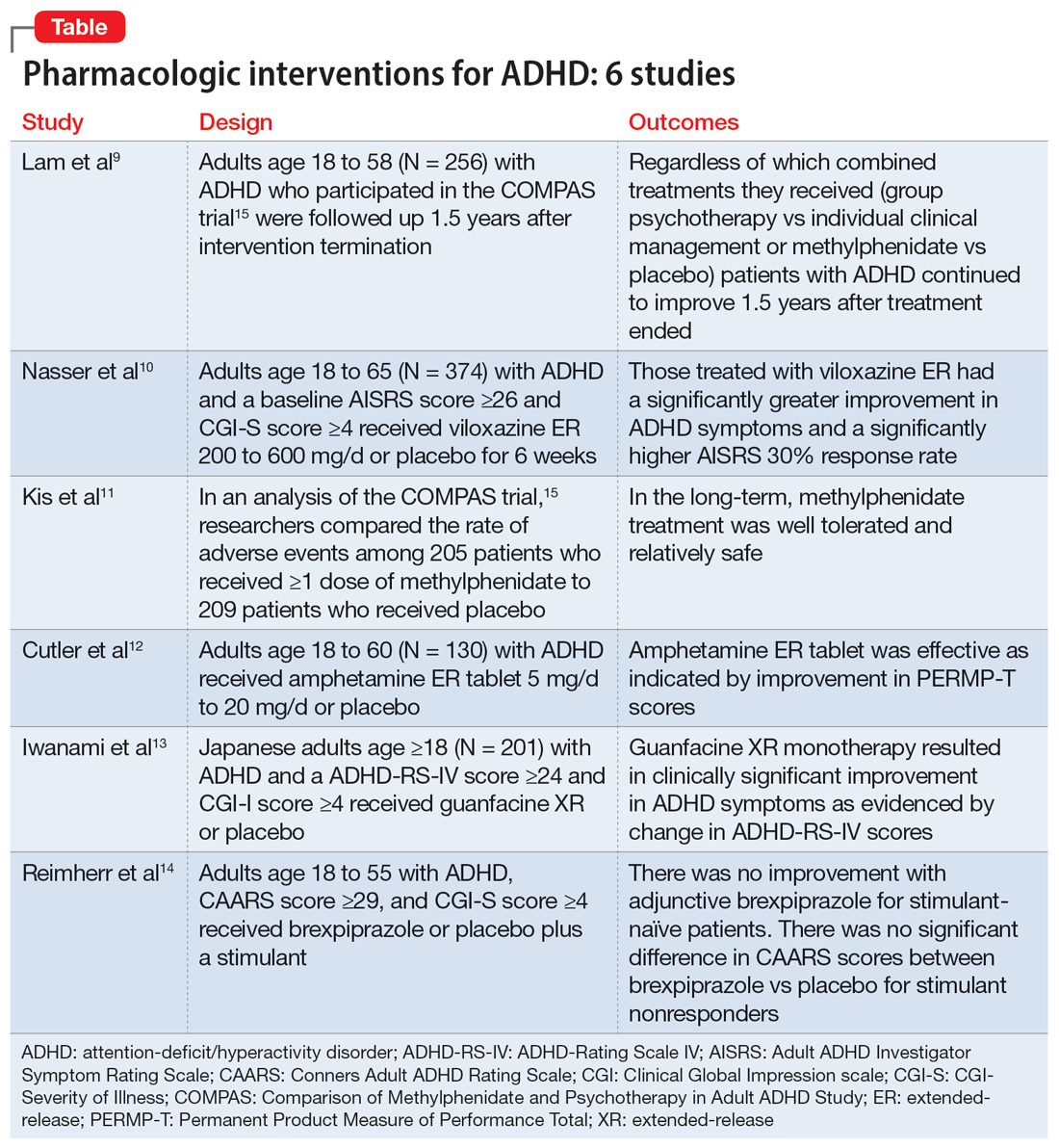

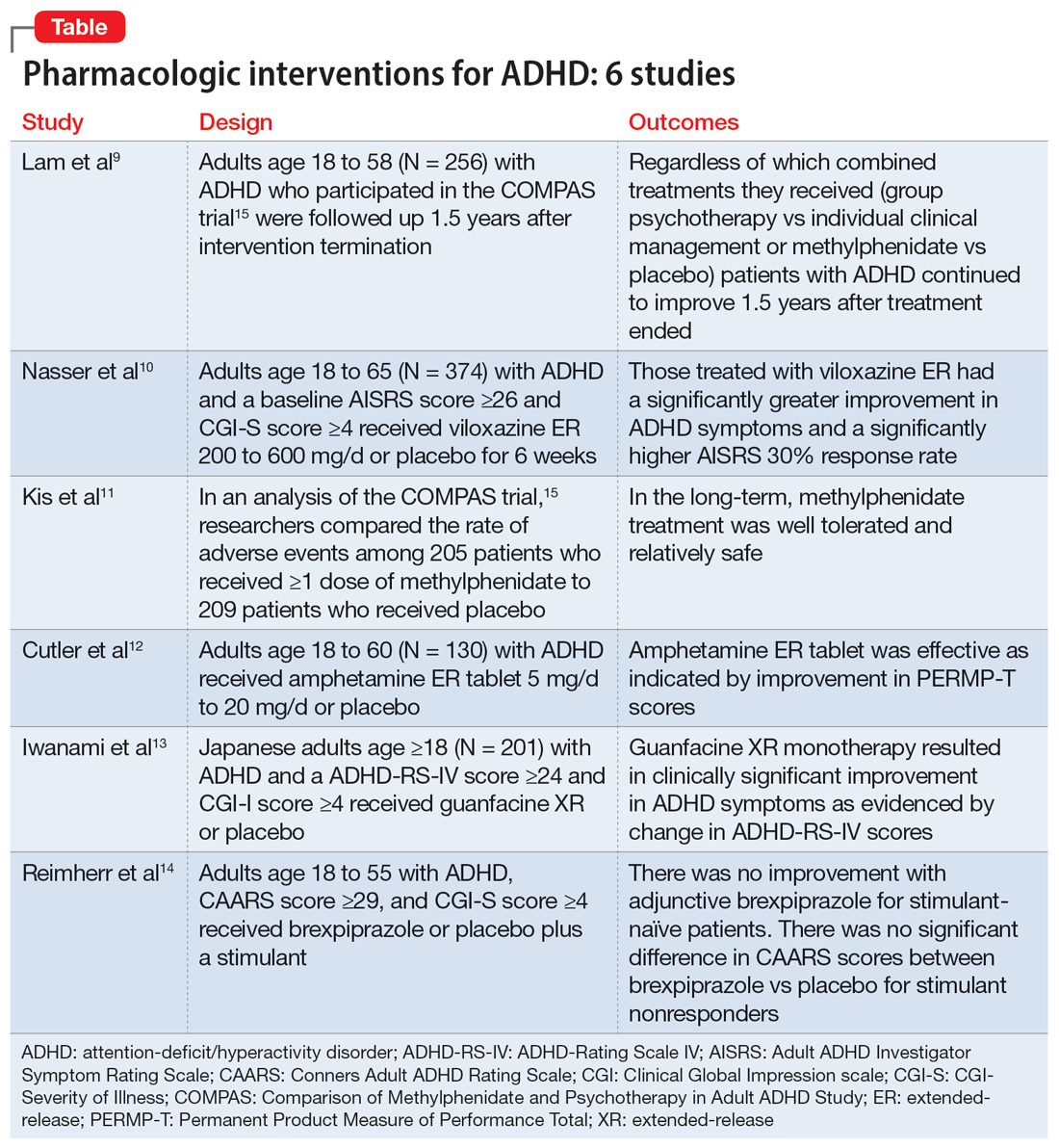

In Part 1 of this 2-part article, we review 6 RCTs of pharmacologic interventions for adult ADHD published within the last 5 years (Table9-14). Part 2 will review nonpharmacologic treatments.

1. Lam AP, Matthies S, Graf E, et al; Comparison of Methylphenidate and Psychotherapy in Adult ADHD Study (COMPAS) Consortium. Long-term effects of multimodal treatment on adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms: follow-up analysis of the COMPAS Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(5):e194980. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.4980

The Comparison of Methylphenidate and Psychotherapy in Adult ADHD Study (COMPAS) was a multicenter prospective, randomized trial of adults age 18 to 58 with ADHD.15 It compared cognitive-behavioral group psychotherapy (GPT) with individual clinical management (CM), and methylphenidate with placebo. When used in conjunction with methylphenidate, psychological treatments produced better results than placebo. However, studies on the long-term effects of multimodal treatment in ADHD are limited. Lam et al9 performed a follow-up analysis of the COMPAS trial.

Study design

- This observer-masked study involved a follow-up of participants in COMPAS 1.5 years after the interventions were terminated. Of the 433 adults with ADHD who participated in COMPAS, 256 participated in this follow-up.

- The inclusion criteria of COMPAS were age 18 to 58; diagnosis of ADHD according to DSM-IV criteria; chronic course of ADHD symptoms from childhood to adulthood; a Wender Utah Rating Scale short version score ≥30; and no pathological abnormality detected on physical examination.

- The exclusion criteria were having an IQ <85; schizophrenia, bipolar disorder (BD), borderline personality disorder, antisocial personality disorder, suicidal or self-injurious behavior, autism, motor tics, or Tourette syndrome; substance abuse/dependence within 6 months prior to screening; positive drug screening; neurologic diseases, seizures, glaucoma, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, uncontrolled arterial hypertension, angina pectoris, tachycardia arrhythmia, or arterial occlusive disease; previous stroke; current bulimia or anorexia; low weight (body mass index [BMI] <20; pregnancy (current or planned) or breastfeeding; treatment with stimulants or ADHD-specific psychotherapy in the past 6 months; methylphenidate intolerance; treatment with antidepressants, norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, bupropion, antipsychotics, theophylline, amantadine, anticoagulants derived from coumarin, antacids, or alpha-adrenergic agonists in the 2 weeks prior to baseline; and treatment with fluoxetine or monoamine oxidase inhibitors in the 4 weeks prior to baseline.

- The primary outcome was a change from baseline on the ADHD Index of Conners Adult ADHD Rating Scale (CAARS) score. Secondary outcomes were self-ratings on the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and observer-masked ratings of the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) scale and other ADHD rating scale scores, such as the Diagnostic Checklist for the diagnosis of ADHD in adults (ADHD-DC) and subscales of the CAARS.

- COMPAS was open regarding patient and therapist assignment to GPT and CM, but double-masked regarding medication. The statistical analysis focused on the 2x2 comparison of GPT vs CM and methylphenidate vs placebo.

Outcomes

- A total of 251 participants had an assessment with the observer-masked CAARS score. The baseline mean (SD) age was 36.3 (10.1), and approximately one-half (49.8%) of participants were male.

- Overall, 9.2% of patients took methylphenidate >31 days from termination of COMPAS before this study but not at the start of this study. Approximately one-third (31.1%) of patients were taking methylphenidate at follow-up. The mean (SD) daily dosage of methylphenidate was 36 (24.77) mg and 0.46 (0.27) mg/kg of body weight.

- The baseline all-group mean ADHD Index of CAARS score was 20.6. At follow-up, it was 14.7 for the CM arm and 14.2 for the GPT arm (difference not significant, P = .48). The mean score decreased to 13.8 for the methylphenidate arm and to 15.2 for the placebo (significant difference, P = .04).

- Overall, methylphenidate was associated with greater improvement in symptoms than placebo. Patients in the GPT arm had fewer severe symptoms as assessed by the self-reported ADHD Symptoms Total Score compared to the CM arm (P = .04).

- There were no significant differences in self-rating CAARS and observer-rated CAARS subscale scores. Compared to CM, GPT significantly decreased pure hyperactive symptoms on the ADHD-DC (P = .08). No significant differences were observed in BDI scores. The difference between GPT and CM remained significant at follow-up in terms of the CGI evaluation of efficacy (P = .04).

Continue to: Conclusions/limitations

Conclusions/limitations

- Regardless of which combined treatments they received, patients with ADHD continued to improve 1.5 years after the 52-week treatment phase ended.

- Patients assigned to methylphenidate performed considerably better on the observer-rated CAARS than patients assigned to placebo.

- Benefits from GPT or CM in addition to methylphenidate therapy lasted 1.5 years. Compared to CM, GPT was not linked to better scores on the CAARS.

- Limitations: Approximately 41% of patients who were recruited did not participate. Daily functioning was measured only by the CGI. There were only marginal differences among the 4 treatments, and the study compared a very regimented approach (GPT) with one that was less focused (CM).

2. Nasser A, Hull JT, Chaturvedi SA, et al. A phase III, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial assessing the efficacy and safety of viloxazine extended‐release capsules in adults with attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder. CNS Drugs. 2022;36(8): 897-915. doi:10.1007/s40263-022-00938-w

In 2021, the FDA approved viloxazine extended-release (ER) for treating ADHD in children and adolescents (age 6 to 17). Nasser et al10 reviewed the safety and efficacy of viloxazine ER in adults with ADHD.

Study design

- This phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter clinical trial included 374 adults with ADHD who received viloxazine ER or placebo.

- Participants were age 18 to 65 and had been given a primary diagnosis of ADHD according to DSM-5 criteria in the last 6 months. Other inclusion criteria were having an Adult ADHD Investigator Symptom Rating Scale (AISRS) total score ≥26 and CGI-Severity of Illness (CGI-S) score ≥4 at baseline, BMI 18 to 35 kg/m2, and being medically healthy.

- Exclusion criteria included having treatment-resistant ADHD, a current diagnosis of any psychiatric disorder other than ADHD, or a history of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, BD, autism, obsessive-compulsive disorder, personality disorder, or posttraumatic stress disorder. Individuals with any significant neurologic disorder, heart condition, arrhythmia, clinically relevant vital sign abnormality, or systemic illness were excluded, as were those with a history (within the past year) or current diagnosis of substance use disorder or a positive drug screen for a drug of abuse. Those with an allergic reaction or intolerance to viloxazine or were breastfeeding, pregnant, or refused to be abstinent or practice birth control were excluded.

- The dosage of viloxazine ER ranged from 200 to 600 mg/d for 6 weeks. This was titrated based on symptom response and adverse effects.

- All individuals received 2 capsules once a day for Week 1 and Week 2. During Week 1 and Week 2, participants in the viloxazine ER group received 200 mg (1 viloxazine ER capsule and 1 placebo capsule) and 400 mg (2 viloxazine ER capsules) of the medication, respectively. Two placebo pills were administered to those in the placebo group. From Week 3 to Week 6, the dose could be titrated or tapered at the investigator’s discretion. Compliance was assessed by comparing the number of pills dispensed vs returned.

- The primary outcome was a change in AISRS score from baselines to Week 6.

- The key secondary outcome was the change in CGI-S score from baseline to Week 6. Scores on the AISRS inattention and hyperactive/impulsivity subscales, Behavioral Regulation Index, Metacognition Index, Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function–Adult Version (BRIEF-A), and Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 item scale (GAD-7) were also evaluated. Also, the rates of 30% and 50% responders on the AISRS (defined as ≥30% or ≥50% reduction from baseline in AISRS total score, respectively), CGI-S scores, and CGI-Improvement (CGI-I) scores were examined.

Outcomes

- Based on change in AISRS total scores, patients who received viloxazine ER had significantly greater improvement in their ADHD symptoms than those taking placebo (P = .0040). Patients in the viloxazine ER group had significantly greater improvement in AISRS hyperactive/impulsive (P = .0380) and inattentive symptoms (P = .0015).

- The decrease in CGI-S score was also significantly greater in the viloxazine ER group than in the placebo group (P = .0023). The viloxazine ER group also had significantly greater improvement in executive function as assessed by the BRIEF-A (P = .0468). The difference in GAD-7 scores between the viloxazine ER group and the placebo group was not significant.

- The viloxazine ER group had a greater AISRS 30% response rate than the placebo group (P = .0395). There were no significant differences between groups in AISRS 50% responder rate or CGI-I responder rate.

- Adverse effects related to viloxazine and occurring in ≥5% of participants included insomnia (14.8%), fatigue (11.6%), nausea, decreased appetite (10.1%), dry mouth (9.0%), and headache (9.0%). The discontinuation rate was 9.0% in the viloxazine ER group vs 4.9% in the placebo group.

Continue to: Conclusions/limitations

Conclusions/limitations

- Compared to placebo, patients treated with viloxazine ER had significantly greater improvements in ADHD symptoms, including both hyperactive/impulsive and inattentive components as well as executive function.

- The viloxazine ER group had a significantly higher AISRS 30% response rate than the placebo group, but there were no significant differences in anxiety symptoms or other measures of response.

- Viloxazine ER was well tolerated and safe.

- Limitations: There was a reduced power to detect differences in treatment due to participants dropping out or discontinuing treatment, a lack of interrater reliability data, and a lack of patient-reported outcome or satisfaction data.

3. Kis B, Lücke C, Abdel-Hamid M, et al. Safety profile of methylphenidate under long-term treatment in adult ADHD patients - results of the COMPAS study. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2020;53(6):263-271. doi:10.1055/a-1207-9851

Kis et al11 analyzed the safety results of COMPAS.15 Details of this trial, including interventions and inclusion/exclusion criteria, are described in the description of Lam et al.9

Study design

- Researchers compared the rate of adverse events (AEs) among 205 patients who received ≥1 dose of methylphenidate with 209 patients who received placebo.

- AEs were documented and analyzed on an “as received” basis during Week 0 to Week 52. Electrocardiogram (ECG) data were recorded at baseline and Week 24. Vital signs were monitored at baseline, every week for the first 12 weeks, then every 4 weeks for the next 52 weeks. Body weight was assessed at Week 6, Week 12, Week 20, Week 28, Week 40, and Week 52. A 12-lead ECG was obtained at baseline and Week 24.

- The sample size was assessed to have 80% power to detect group differences in AEs.

Outcomes

- Overall, 96% of participants in the methylphenidate group and 88% of participants in the placebo group experienced at least 1 AE (difference 8.1%; 95% CI, 2.9% to 13.5%).

- AEs that occurred more frequently with methylphenidate compared to placebo were decreased appetite (22% vs 3.8%); dry mouth (15% vs 4.8%); palpitations (13% vs 3.3%); gastrointestinal (GI) infection (11% vs 4.8%); agitation (11% vs 3.3%); restlessness (10% vs 2.9%); hyperhidrosis, tachycardia, and weight decrease (all 6.3% vs 1.9%); depressive symptoms and influenza (both 4.9% vs 1.0%); and acute tonsillitis (4.4% vs 0.5%). Serious AEs were reported by 7.3% of patients in the methylphenidate group and 4.3% of those in the placebo group, with no difference in frequency (difference 3.0%; 95% CI, 1.6% to 7.9%). The most severe AEs were aggression, depression, somnambulism, and suicidal ideation in the methylphenidate group and car accidents, epicondylitis, and a fall in the placebo group.

- There were no significant differences in AEs between the GPT and CM groups.

- The treatment combinations that included methylphenidate had higher rates of patients experiencing at least 1 AE (CM/methylphenidate 97%, GPT/methylphenidate 96%, CM/placebo 92%, GPT/placebo 84%).

- Overall, 8.8% of patients in the methylphenidate group and 4.8% in the placebo group stopped their medication treatment because of an AE (difference 4.0%; 95% CI, 0.9% to 9.1%). At least 1 dose decrease, increase, or discontinuation was made after an AE in 42% of participants in the placebo group and 69% of those in the methylphenidate group.

- There were no significant differences in clinically pertinent ECG abnormalities between methylphenidate and placebo therapy.

Continue to: Conclusions/limitations

Conclusions/limitations

- AEs were more common in the methylphenidate groups compared to placebo, but there was no significant differences for severe AEs. In the long-term, methylphenidate treatment was well tolerated and relatively safe.

- Limitations: The sample size may have been too small to detect uncommon AEs, all AEs had to be reported and may not have been caused by the treatment, and the original study’s main outcome was efficacy, not safety, which makes this an exploratory analysis of AEs.

4. Cutler AJ, Childress AC, Pardo A, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, fixed-dose study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of amphetamine extended-release tablets in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2022;83(5):22m14438. doi:10.4088/JCP.22m14438

Once-daily dosing of stimulants, which are commonly used to manage adult ADHD,16 can be beneficial because many patients have schedules that limit taking medication multiple times a day. Cutler et al12 looked at the efficacy and safety of amphetamine extended-release tablet (AMPH ER TAB), which is a 3.2:1 mixture of d- and l-amphetamine released by the LiquiXR drug delivery system. This technology allows for a continuous release following an initial quick onset of action.

Study design

- This parallel-study, double-blind study evaluated adults age 18 to 60 who had a diagnosis of ADHD according to DSM-5 criteria and the Adult ADHD Clinical Diagnostic Scale, normal-range IQ, AISRS score ≥26, and baseline CGI-S score ≥4.

- Women were not lactating or pregnant during the study.

- Exclusion criteria included a history of mental illnesses; chronic medical conditions; clinically significant abnormal ECG or cardiac findings on exam; renal or liver disease; family history of sudden death; significant vital sign findings; uncontrolled hypertension or a resting systolic blood pressure (SBP) >140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) >90 mmHg; recent history of or current alcohol or substance use disorder; use of atomoxetine, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, or tricyclic antidepressants within 14 days of study or the use of other stimulant medications within 1 week of screening; use of GI acidifying agents or urinary acidifying agents within 3 days of screening; answering “yes” to questions 4 or 5 of the Suicidal Ideation section of the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale within 2 years prior to the study; taking another investigational medication within 30 days of screening; allergic to amphetamine or components of the study drug, and a lack of prior response to amphetamine.

- Patients were randomized to receive AMPH ER TAB (n = 65) or placebo (n = 65), taken before 10

am . Participants started at 5 mg/d of the drug/placebo and then entered a 5-week titration period in which the medication was increased by 5 mg/d each week until reaching 20 mg/d, and then continued 20 mg/d for 2 weeks. - The primary outcome was the mean Permanent Product Measure of Performance Total (PERMP-T) score averaged across all time points (0.5-, 1-, 2-, 4-, 8-, 10-, 12-, 13-, and 14-hours postdose) at Visit 5.

- Participants underwent AISRS, CGI-S, and safety evaluations at baseline and at the 5 visits at the end of each treatment week.

Outcomes

- Analyses were completed on participants who received ≥1 dose of the medication and who had ≥1 PERMP-T score at Visit 5.

- Predose PERMP-T scores were similar between the AMPH ER TAB group (259.5) and placebo group (260). The mean postdose PERMP-T score in the AMPH ER TAB group (302.8) was significantly higher (P = .0043) than the placebo group (279.6).

- The PERMP-T scores were significantly different at 0.5-, 1-, 2-, 4-, 8-, and 13-hours postdose but not at 10-, 12-, and 14-hours postdose. The first Visit 5 time point at which the difference between groups was statistically different was at 0.5 hours postdose (P = .01), and the last significant time point was 13 hours (P = .006).

- The improvement in CGI-S scores was significantly greater in the AMPH ER TAB group than the placebo group. The improvement in AISRS scores was significantly greater in the AMPH ER TAB group at Visit 3, Visit 4, and Visit 5. More participants in the AMPH ER TAB group had AEs compared to the placebo group (90% vs 60%). The most common AEs (frequency ≥5% and occurring more in the intervention arm) were decreased appetite, insomnia, dry mouth, irritability, headache, anxiety, nausea, dizziness, and tachycardia.

- The AMPH ER TAB group had nonclinically significant increases in SBP (116.8 to 120.7 mmHg), DBP (74.1 to 77.1 mmHg), and heart rate (73.0 to 81.9 bpm) at Visit 5 compared to baseline.

- No serious AEs occurred. Three participants in the AMPH ER TAB group experienced AEs (increased blood pressure, CNS stimulation, and anxiety) that led them to discontinue the study.

Continue to: Conclusions/limitations

Conclusions/limitations

- AMPH ER TAB reduced symptoms in adults with ADHD as assessed by improvement in PERMP-T scores.

- The safety and tolerability profile of AMPH ER TAB were comparable to other stimulants, with expected rises in blood pressure and heart rate.

- Limitations: Patients were required to be titrated to 20 mg/d of AMPH ER TAB, instead of following a flexible titration based on an individual’s response. Some participants may have had greater improvement at a higher or lower dose. This study did not compare AMPH ER TAB to other stimulants. The 5-week duration of this study limited the ability to evaluate long-term efficacy and tolerability. Patients with a wide range of psychiatric or medical comorbidities were excluded.

5. Iwanami A, Saito K, Fujiwara M, et al. Efficacy and safety of guanfacine extended-release in the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81(3):19m12979. doi:10.4088/JCP.19m12979

Guanfacine extended-release (GXR) is a selective alpha 2A-adrenergic receptor agonist approved for treating ADHD in children and adolescents.17 Iwanami et al13 evaluated the efficacy and safety of GXR for adults.

Study design

- This randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial enrolled Japanese adults age ≥18 who were diagnosed with ADHD according to DSM-5 criteria and scored ≥24 on the ADHD-Rating Scale IV (ADHD-RS-IV) and ≥4 on CGI- I.

- Exclusion criteria included having anxiety, depression, substance use disorder, tic disorder, BD, personality disorder, schizophrenia, or intellectual disability; a moderate or severe psychiatric disorder requiring treatment other than counseling; seizures; increased risk for suicide; a history of cardiovascular disease, including prolonged QTc/abnormal ECG/abnormal labs, orthostatic hypotension, or continuous bradycardia; or taking medications that affect blood pressure or heart rate.

- Overall, 101 participants were randomized to the GXR group and 100 to the placebo group. Approximately two-thirds of the study population was male. Patients received GXR or placebo once daily at approximately the same time.

- There were 5 phases to the trial. The screening period occurred over 1 to 4 weeks. Part 1 of the treatment period consisted of 5 weeks of medication optimization. Participants were started on GXR 2 mg/d and were required to be receiving a minimum dose of 4 mg/d starting at Week 3. Clinicians were allowed to increase the dose 1 mg/d per week starting at Week 4 based on clinical response to a maximum dosage of 6 mg/d. Part 2 of the treatment period consisted of 5 weeks of maintenance at 4 to 6 mg/d. The tapering period to 2 mg/d occurred over 2 weeks. The follow-up period lasted 1 week.

- Efficacy measurements included the Japanese version of the ADHD-RS-IV and translations of the English-language CAARS, CGI-I, and CGI-S. Participant-reported measures included the Patient Global Impression-Improvement scale (PGI-I), Adult ADHD Quality of Life Questionnaire (AAQoL), and BRIEF-A.

- The primary outcome was the difference in ADHD-RS-IV total score from baseline to the end of the maintenance period (Week 10).

- Safety assessments were completed at Week 5 (end of dose optimization period), Week 10 (end of dose maintenance period), and Week 12 (tapering period).

Outcomes

- The average GXR dose during the maintenance period was 5.07 mg/d.

- Compared to the placebo group, the GXR group had more patients age <30 (47% vs 39%) and fewer patients age ≥40 (17% vs 27%). Baseline ADHD-RS-IV scores in both groups were comparable. At baseline, 51% in the GXR group had a combined inattentive/hyperactive-impulsive presentation and 47% had a predominately inattention presentation, with similar characteristics in the placebo group (49% combined, 49% inattention).

- At Week 10, the least squares mean change from baseline on the ADHD-RS-IV total score was significantly greater in the GXR group than in the placebo group (-11.55 ± 1.10 vs -7.27 ± 1.07; P = .0005), with an effect size of 0.52. There was a greater decrease in the ADHD-RS-IV scores starting at Week 4 and continuing to Week 10 (P < .005).

- There were also significant differences favoring GXR on the ADHD-RS-IV hyperactivity-impulsivity subscale score (P = .0021) and ADHD-RS-IV inattention subscale score (P = .0032).

- There were significant differences in the CAARS total ADHD score (P = .0029) and BRIEF-A scores on the inhibit (P = .0173), initiate (P = .0406), plan/organize (P = .174), and global executive composite index (P = .0404) scales. There was no significant difference in the total AAQoL score (P = .0691), but there was a significant improvement in the AAQoL life productivity subscore (P = .0072).

- At Week 10, there were also significant improvements in the CGI-I scores (P = .0007) and PGI-I scores (P = .0283). The CGI-S scores were similar at all time points.

- Overall, 81.2% of GXR patients reported AEs compared to 62% in the placebo group. There was 1 serious treatment-emergent AE (a suicide attempt) that the authors concluded was unrelated to the study drug. No deaths occurred. The most common AEs (incidence ≥10% in either group) included somnolence, thirst, nasopharyngitis (occurring more in the placebo group), blood pressure decrease, postural dizziness, and constipation. The main AEs leading to discontinuation were somnolence and blood pressure decrease. Overall, 19.8% of patients receiving GXR discontinued treatment due to AEs, compared to 3% in the placebo group.

- Heart rate, blood pressure, and QTc (corrected by the Bazett formula) were decreased in the GXR group at Week 10 while QT and RR intervals increased, and most returned to normal by Week 12.

Continue to: Conclusions/limitations

Conclusions/limitations

- Compared to placebo, GXR monotherapy resulted in clinical improvement in ADHD symptoms, with a moderate effect size.

- The most common AEs were mild to moderate and congruent with known adverse effects of guanfacine. Sedation effects mostly transpired within the first week of medication administration and were transient.

- Limitations: The findings might not be generalizable to non-Japanese patients. The duration of the study was short. Patients with a wide range of psychiatric and medical comorbidities were excluded. Two-thirds of the participants were male, and there was a disparity in participant age in the GXR and placebo groups.

6. Reimherr FW, Gift TE, Steans TA, et al. The use of brexpiprazole combined with a stimulant in adults with treatment-resistant attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2022;42(5):445-453. doi:10.1097/JCP.0000000000001592

While stimulants are a mainstay ADHD treatment, some patients have a partial response or do not respond to amphetamines or methylphenidate. Reimherr et el14 assessed the efficacy and safety of adding brexpiprazole (BXP) to a stimulant.

Study design

- This randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial recruited 559 stimulant-naive patients and 174 patients who had not responded to previous stimulant therapy.

- Participants were adults age 18 to 55 with a primary diagnosis of ADHD according to DSM-IV-TR criteria and the Conners Adult ADHD Diagnostic Interview. Other inclusion criteria were having a CAARS score ≥29 and a CGI-S score ≥4.

- Exclusion criteria included being at risk for suicide; having current substance abuse or positive alcohol/drug screens; a history of good response to prestudy treatment; a clinically significant medical condition; fasting blood glucose >200 mg/dL or hemoglobin A1C >7%; and hospitalization in past 12 months from a diabetic complication, uncontrolled hypertension, ischemic heart disease, or epilepsy. Further exclusion criteria included a history of psychosis, current MDD or BD, current panic disorder, uncontrolled comorbid psychiatric condition, or clinically significant personality disorder. Investigators excluded any patient with severe DSM-IV axis I or II disorders or abnormal/psychopathological behaviors.

- The trial consisted of 3 segments. Part 1 was screening. If the patient was currently receiving a stimulant but not fully responding, the medication was discontinued for at least 5 half-lives.

- Part 2 (5 weeks) involved administering a stimulant plus a single-blind placebo (597 patients completed this phase). The stimulant was chosen by the investigator, who had the option of using 1 of 2 amphetamine derivatives (mixed amphetamine salts capsules or lisdexamfetamine dimesylate capsules) or 1 of 2 methylphenidate derivatives (methylphenidate hydrochloride ER tabs or dexmethylphenidate HCl ER capsules). If a patient did not respond to a particular stimulant prior to the study, they were given a different stimulant from the list. Patients continued the same stimulant throughout the trial. Patients were monitored for a response, defined as a ≥30% decrease in CAARS score or a CAARS score <24, or a CGI-I score of 1 or 2 at Week 5. Patients who did not show this improvement were categorized as open-label nonresponders.

- Part 3 (6 weeks) involved administering a stimulant plus double-blind BXP vs placebo (stimulant-naive n = 167, stimulant nonresponders n = 68). Nonresponders continued the stimulant (at the same dose reached at the end of Part 2) and added either BXP (n = 155) or continued placebo (n = 80). Patients who responded in Part 2 were continued on the stimulant plus placebo and were not randomized. Patients were started on BXP 0.25 mg/d, and the medication could be titrated to 2 mg/d during the following 3 weeks, depending on the benefit vs AE profile. After the third week, the dose could be decreased but not increased.

- The primary outcome was a change in CAARS score. Secondary measurements included the CGI-S, Wender-Reimherr Adult Attention Deficit Disorder Scale (WRAADDS), Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS), and BDI.

Outcomes

- Stimulant-naive patients were equally divided among the 4 stimulant groups, and previous nonresponders who continued to not respond in Part 2 were more likely to be given methylphenidate HCl or lisdexamfetamine dimesylate.

- Patients with a history of nonresponse had less response to stimulants in Part 2 compared to stimulant-naive patients, as seen by 27% (n = 167) of stimulant-naive patients entering Part 3 compared to 39% of prior nonresponders (n = 68; P = .0249).

- ADHD improvement with BXP appeared to be greater among pretrial nonresponders.

- For stimulant nonresponders before and during the study, at the end of the double-blind endpoint (Part 3; Week 11), WRAADDS total score was significantly improved in the BXP group compared to the placebo group (P = .013; d = 0.74), with most beneficial effects seen in the hyperactivity/restlessness, emotional dysregulation factor, and impulsivity categories.

- For stimulant nonresponders before and during the study, there was no significant difference at the end of Week 11 on the CAARS (P = .64), MADRS (P = .37), or BDI (P = .73). There was a trend toward significance on the CAARS subscale for hyperactive/impulsive (P = .09).

- For prestudy stimulant-naive patients who did not respond to stimulants in Part 2 and were randomized in Part 3, there was not a significant difference between BXP and placebo at Week 11 as assessed on WRAADDS, CAARS, MADRS, or BDI.

- As assessed on WRAADDS, 50% in the BXP group had a response compared to 41% in the placebo group (Fisher exact = 0.334). Under the emotional dysregulation factor category of the WRAADDS, 64% in the BXP group had a response compared to 41% in the placebo group (Fisher exact = 0.064). The attention factor category showed a 40% improvement in the BXP group compared to 32% in the placebo group (Fisher exact = 0.344).

- There were 2 serious AEs in the BXP group (gall bladder inflammation and diarrhea) and 2 in the placebo group (pneumonia and urinary tract infection). There was no statistically significant difference between groups with regards to common AEs (ie, fatigue, heartburn/nausea/stomachache, weight loss), although there was a trend to significant for insomnia in the BXP group (P = .083).

Conclusions/limitations

- Stimulant-naive patients experienced no improvement with adjunctive BXP.

- For prior stimulant nonresponders, there was no significant difference between BXP vs placebo on the primary outcome of the CAARS score, but there was an improvement as observed by assessment with the WRAADDS.

- The largest change in the WRAADDS occurred in the emotional dysregulation factor compared to the attention factor.

- BXP appeared to be well tolerated.

- Limitations: The WRAADDS was administered without the patients’ significant other/collateral. Raters were not trained in the use of the WRAADDS. Patients with a wide range of psychiatric and medical comorbidities were excluded. Fewer patients were recruited in the prior stimulant nonresponder group.

Bottom Line

Recent randomized controlled trials suggest that methylphenidate, amphetamine extended-release, viloxazine extended-release, and guanfacine extended-release improved symptoms of adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). There were no improvements in ADHD symptoms with adjunctive brexpiprazole.

Related Resources

- Parikh AR, Baker SA. Adult ADHD: pharmacologic treatment in the DSM-5 era. Current Psychiatry. 2016;15(10):18-25.

- Akbar HN. Why we should be scrutinizing the rising prevalence of adult ADHD. Current Psychiatry. 2022; 21(7):e1-e2. doi:10.12788/cp.0268

Drug Brand Names

Amantadine • Gocovri

Amphetamine extended-release tablet • Dyanavel XR

Atomoxetine • Strattera

Brexpiprazole • Rexulti

Bupropion • Wellbutrin

Dexmethylphenidate • Focalin

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Guanfacine extended- release • Intuniv

Lisdexamfetamine • Vyvanse

Methylphenidate • Concerta, Methylin

Theophylline • Elixophyllin

Viloxazine • Qelbree

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed, text revision. American Psychiatric Association; 2022.

2. Harpin V, Mazzone L, Raynaud JP, et al. Long-term outcomes of ADHD: a systematic review of self-esteem and social function. J Atten Disord. 2016;20(4):295-305. doi:10.1177/1087054713486516

3. Beaton DM, Sirois F, Milne E. Experiences of criticism in adults with ADHD: a qualitative study. PLoS One. 2022;17(2):e0263366. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0263366

4. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). National Institute of Mental Health. Accessed February 9, 2023. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/attention-deficit-hyperactivity-disorder-adhd

5. Katzman MA, Bilkey TS, Chokka PR, et al. Adult ADHD and comorbid disorders: clinical implications of a dimensional approach. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):302. doi:10.1186/s12888-017-1463-3

6. Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: Diagnosis and Management. NICE Guideline No. 87. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2019. Accessed February 9, 2023. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493361/

7. Adler LD, Nierenberg AA. Review of medication adherence in children and adults with ADHD. Postgrad Med. 2010;122(1):184-191. doi:10.3810/pgm.2010.01.2112

8. Cunill R, Castells X, Tobias A, et al. Efficacy, safety and variability in pharmacotherapy for adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analysis and meta-regression in over 9000 patients. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2016;233(2):187-197. doi:10.1007/s00213-015-4099-3

9. Lam AP, Matthies S, Graf E, et al; Comparison of Methylphenidate and Psychotherapy in Adult ADHD Study (COMPAS) Consortium. Long-term effects of multimodal treatment on adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms: follow-up analysis of the COMPAS Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(5):e194980. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.4980

10. Nasser A, Hull JT, Chaturvedi SA, et al. A phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial assessing the efficacy and safety of viloxazine extended-release capsules in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. CNS Drugs. 2022;36(8):897-915. doi:10.1007/s40263-022-00938-w

11. Kis B, Lücke C, Abdel-Hamid M, et al. Safety profile of methylphenidate under long-term treatment in adult ADHD patients - results of the COMPAS study. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2020;53(6):263-271. doi:10.1055/a-1207-9851

12. Cutler AJ, Childress AC, Pardo A, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, fixed-dose study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of amphetamine extended-release tablets in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2022;83(5):22m14438. doi:10.4088/JCP.22m14438

13. Iwanami A, Saito K, Fujiwara M, et al. Efficacy and safety of guanfacine extended-release in the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81(3):19m12979. doi:10.4088/JCP.19m12979

14. Reimherr FW, Gift TE, Steans TA, et al. The use of brexpiprazole combined with a stimulant in adults with treatment-resistant attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2022;42(5):445-453. doi:10.1097/JCP.0000000000001592

15. Philipsen A, Jans T, Graf E, et al; Comparison of Methylphenidate and Psychotherapy in Adult ADHD Study (COMPAS) Consortium. Effects of group psychotherapy, individual counseling, methylphenidate, and placebo in the treatment of adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(12):1199-1210.

16. McGough JJ. Treatment controversies in adult ADHD. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(10):960-966. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.15091207

17. Cruz MP. Guanfacine extended-release tablets (Intuniv), a nonstimulant selective alpha2a-adrenergic receptor agonist for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. P T. 2010;35(8):448-451.

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a developmental disorder that begins in childhood and continues into adulthood. The clinical presentation is characterized by a persistent pattern of inattention, impulsivity, and/or hyperactivity that causes functional interference.1 ADHD affects patients’ interpersonal and professional lives as well as their daily functioning.2 Adults with ADHD may suffer from excessive self-criticism, low self-esteem, and sensitivity to criticism.3 The overall prevalence of adult ADHD is 4.4%.4 ADHD in adults is frequently associated with comorbid psychiatric disorders.5 The diagnosis of ADHD in adults requires the presence of ≥5 symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity that persist for ≥6 months. Patients must have first had such symptoms before age 12; symptoms need to be present in ≥2 settings and interfere with functioning.1

Treatment of ADHD includes pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions. For most patients, pharmacotherapy—specifically stimulant medications—is advised as first-line treatment,6 with adequate trials of methylphenidate and amphetamines before using second-line agents such as nonstimulants. However, despite these medications’ efficacy in randomized controlled trials (RCTs), adherence is low.7 This could be due to inadequate response or adverse effects.8 Guidelines also recommend the use of nonpharmacologic interventions for adults who cannot adhere to or tolerate medication or have an inadequate response.6 Potential nonpharmacologic interventions include transcranial direct current stimulation, mindfulness, psychoeducation, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and chronotherapy.

In Part 1 of this 2-part article, we review 6 RCTs of pharmacologic interventions for adult ADHD published within the last 5 years (Table9-14). Part 2 will review nonpharmacologic treatments.

1. Lam AP, Matthies S, Graf E, et al; Comparison of Methylphenidate and Psychotherapy in Adult ADHD Study (COMPAS) Consortium. Long-term effects of multimodal treatment on adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms: follow-up analysis of the COMPAS Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(5):e194980. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.4980

The Comparison of Methylphenidate and Psychotherapy in Adult ADHD Study (COMPAS) was a multicenter prospective, randomized trial of adults age 18 to 58 with ADHD.15 It compared cognitive-behavioral group psychotherapy (GPT) with individual clinical management (CM), and methylphenidate with placebo. When used in conjunction with methylphenidate, psychological treatments produced better results than placebo. However, studies on the long-term effects of multimodal treatment in ADHD are limited. Lam et al9 performed a follow-up analysis of the COMPAS trial.

Study design

- This observer-masked study involved a follow-up of participants in COMPAS 1.5 years after the interventions were terminated. Of the 433 adults with ADHD who participated in COMPAS, 256 participated in this follow-up.

- The inclusion criteria of COMPAS were age 18 to 58; diagnosis of ADHD according to DSM-IV criteria; chronic course of ADHD symptoms from childhood to adulthood; a Wender Utah Rating Scale short version score ≥30; and no pathological abnormality detected on physical examination.

- The exclusion criteria were having an IQ <85; schizophrenia, bipolar disorder (BD), borderline personality disorder, antisocial personality disorder, suicidal or self-injurious behavior, autism, motor tics, or Tourette syndrome; substance abuse/dependence within 6 months prior to screening; positive drug screening; neurologic diseases, seizures, glaucoma, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, uncontrolled arterial hypertension, angina pectoris, tachycardia arrhythmia, or arterial occlusive disease; previous stroke; current bulimia or anorexia; low weight (body mass index [BMI] <20; pregnancy (current or planned) or breastfeeding; treatment with stimulants or ADHD-specific psychotherapy in the past 6 months; methylphenidate intolerance; treatment with antidepressants, norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, bupropion, antipsychotics, theophylline, amantadine, anticoagulants derived from coumarin, antacids, or alpha-adrenergic agonists in the 2 weeks prior to baseline; and treatment with fluoxetine or monoamine oxidase inhibitors in the 4 weeks prior to baseline.

- The primary outcome was a change from baseline on the ADHD Index of Conners Adult ADHD Rating Scale (CAARS) score. Secondary outcomes were self-ratings on the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and observer-masked ratings of the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) scale and other ADHD rating scale scores, such as the Diagnostic Checklist for the diagnosis of ADHD in adults (ADHD-DC) and subscales of the CAARS.

- COMPAS was open regarding patient and therapist assignment to GPT and CM, but double-masked regarding medication. The statistical analysis focused on the 2x2 comparison of GPT vs CM and methylphenidate vs placebo.

Outcomes

- A total of 251 participants had an assessment with the observer-masked CAARS score. The baseline mean (SD) age was 36.3 (10.1), and approximately one-half (49.8%) of participants were male.

- Overall, 9.2% of patients took methylphenidate >31 days from termination of COMPAS before this study but not at the start of this study. Approximately one-third (31.1%) of patients were taking methylphenidate at follow-up. The mean (SD) daily dosage of methylphenidate was 36 (24.77) mg and 0.46 (0.27) mg/kg of body weight.

- The baseline all-group mean ADHD Index of CAARS score was 20.6. At follow-up, it was 14.7 for the CM arm and 14.2 for the GPT arm (difference not significant, P = .48). The mean score decreased to 13.8 for the methylphenidate arm and to 15.2 for the placebo (significant difference, P = .04).

- Overall, methylphenidate was associated with greater improvement in symptoms than placebo. Patients in the GPT arm had fewer severe symptoms as assessed by the self-reported ADHD Symptoms Total Score compared to the CM arm (P = .04).

- There were no significant differences in self-rating CAARS and observer-rated CAARS subscale scores. Compared to CM, GPT significantly decreased pure hyperactive symptoms on the ADHD-DC (P = .08). No significant differences were observed in BDI scores. The difference between GPT and CM remained significant at follow-up in terms of the CGI evaluation of efficacy (P = .04).

Continue to: Conclusions/limitations

Conclusions/limitations

- Regardless of which combined treatments they received, patients with ADHD continued to improve 1.5 years after the 52-week treatment phase ended.

- Patients assigned to methylphenidate performed considerably better on the observer-rated CAARS than patients assigned to placebo.

- Benefits from GPT or CM in addition to methylphenidate therapy lasted 1.5 years. Compared to CM, GPT was not linked to better scores on the CAARS.

- Limitations: Approximately 41% of patients who were recruited did not participate. Daily functioning was measured only by the CGI. There were only marginal differences among the 4 treatments, and the study compared a very regimented approach (GPT) with one that was less focused (CM).

2. Nasser A, Hull JT, Chaturvedi SA, et al. A phase III, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial assessing the efficacy and safety of viloxazine extended‐release capsules in adults with attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder. CNS Drugs. 2022;36(8): 897-915. doi:10.1007/s40263-022-00938-w

In 2021, the FDA approved viloxazine extended-release (ER) for treating ADHD in children and adolescents (age 6 to 17). Nasser et al10 reviewed the safety and efficacy of viloxazine ER in adults with ADHD.

Study design

- This phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter clinical trial included 374 adults with ADHD who received viloxazine ER or placebo.

- Participants were age 18 to 65 and had been given a primary diagnosis of ADHD according to DSM-5 criteria in the last 6 months. Other inclusion criteria were having an Adult ADHD Investigator Symptom Rating Scale (AISRS) total score ≥26 and CGI-Severity of Illness (CGI-S) score ≥4 at baseline, BMI 18 to 35 kg/m2, and being medically healthy.

- Exclusion criteria included having treatment-resistant ADHD, a current diagnosis of any psychiatric disorder other than ADHD, or a history of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, BD, autism, obsessive-compulsive disorder, personality disorder, or posttraumatic stress disorder. Individuals with any significant neurologic disorder, heart condition, arrhythmia, clinically relevant vital sign abnormality, or systemic illness were excluded, as were those with a history (within the past year) or current diagnosis of substance use disorder or a positive drug screen for a drug of abuse. Those with an allergic reaction or intolerance to viloxazine or were breastfeeding, pregnant, or refused to be abstinent or practice birth control were excluded.

- The dosage of viloxazine ER ranged from 200 to 600 mg/d for 6 weeks. This was titrated based on symptom response and adverse effects.

- All individuals received 2 capsules once a day for Week 1 and Week 2. During Week 1 and Week 2, participants in the viloxazine ER group received 200 mg (1 viloxazine ER capsule and 1 placebo capsule) and 400 mg (2 viloxazine ER capsules) of the medication, respectively. Two placebo pills were administered to those in the placebo group. From Week 3 to Week 6, the dose could be titrated or tapered at the investigator’s discretion. Compliance was assessed by comparing the number of pills dispensed vs returned.

- The primary outcome was a change in AISRS score from baselines to Week 6.

- The key secondary outcome was the change in CGI-S score from baseline to Week 6. Scores on the AISRS inattention and hyperactive/impulsivity subscales, Behavioral Regulation Index, Metacognition Index, Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function–Adult Version (BRIEF-A), and Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 item scale (GAD-7) were also evaluated. Also, the rates of 30% and 50% responders on the AISRS (defined as ≥30% or ≥50% reduction from baseline in AISRS total score, respectively), CGI-S scores, and CGI-Improvement (CGI-I) scores were examined.

Outcomes

- Based on change in AISRS total scores, patients who received viloxazine ER had significantly greater improvement in their ADHD symptoms than those taking placebo (P = .0040). Patients in the viloxazine ER group had significantly greater improvement in AISRS hyperactive/impulsive (P = .0380) and inattentive symptoms (P = .0015).

- The decrease in CGI-S score was also significantly greater in the viloxazine ER group than in the placebo group (P = .0023). The viloxazine ER group also had significantly greater improvement in executive function as assessed by the BRIEF-A (P = .0468). The difference in GAD-7 scores between the viloxazine ER group and the placebo group was not significant.

- The viloxazine ER group had a greater AISRS 30% response rate than the placebo group (P = .0395). There were no significant differences between groups in AISRS 50% responder rate or CGI-I responder rate.

- Adverse effects related to viloxazine and occurring in ≥5% of participants included insomnia (14.8%), fatigue (11.6%), nausea, decreased appetite (10.1%), dry mouth (9.0%), and headache (9.0%). The discontinuation rate was 9.0% in the viloxazine ER group vs 4.9% in the placebo group.

Continue to: Conclusions/limitations

Conclusions/limitations

- Compared to placebo, patients treated with viloxazine ER had significantly greater improvements in ADHD symptoms, including both hyperactive/impulsive and inattentive components as well as executive function.

- The viloxazine ER group had a significantly higher AISRS 30% response rate than the placebo group, but there were no significant differences in anxiety symptoms or other measures of response.

- Viloxazine ER was well tolerated and safe.

- Limitations: There was a reduced power to detect differences in treatment due to participants dropping out or discontinuing treatment, a lack of interrater reliability data, and a lack of patient-reported outcome or satisfaction data.

3. Kis B, Lücke C, Abdel-Hamid M, et al. Safety profile of methylphenidate under long-term treatment in adult ADHD patients - results of the COMPAS study. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2020;53(6):263-271. doi:10.1055/a-1207-9851

Kis et al11 analyzed the safety results of COMPAS.15 Details of this trial, including interventions and inclusion/exclusion criteria, are described in the description of Lam et al.9

Study design

- Researchers compared the rate of adverse events (AEs) among 205 patients who received ≥1 dose of methylphenidate with 209 patients who received placebo.

- AEs were documented and analyzed on an “as received” basis during Week 0 to Week 52. Electrocardiogram (ECG) data were recorded at baseline and Week 24. Vital signs were monitored at baseline, every week for the first 12 weeks, then every 4 weeks for the next 52 weeks. Body weight was assessed at Week 6, Week 12, Week 20, Week 28, Week 40, and Week 52. A 12-lead ECG was obtained at baseline and Week 24.

- The sample size was assessed to have 80% power to detect group differences in AEs.

Outcomes

- Overall, 96% of participants in the methylphenidate group and 88% of participants in the placebo group experienced at least 1 AE (difference 8.1%; 95% CI, 2.9% to 13.5%).

- AEs that occurred more frequently with methylphenidate compared to placebo were decreased appetite (22% vs 3.8%); dry mouth (15% vs 4.8%); palpitations (13% vs 3.3%); gastrointestinal (GI) infection (11% vs 4.8%); agitation (11% vs 3.3%); restlessness (10% vs 2.9%); hyperhidrosis, tachycardia, and weight decrease (all 6.3% vs 1.9%); depressive symptoms and influenza (both 4.9% vs 1.0%); and acute tonsillitis (4.4% vs 0.5%). Serious AEs were reported by 7.3% of patients in the methylphenidate group and 4.3% of those in the placebo group, with no difference in frequency (difference 3.0%; 95% CI, 1.6% to 7.9%). The most severe AEs were aggression, depression, somnambulism, and suicidal ideation in the methylphenidate group and car accidents, epicondylitis, and a fall in the placebo group.

- There were no significant differences in AEs between the GPT and CM groups.

- The treatment combinations that included methylphenidate had higher rates of patients experiencing at least 1 AE (CM/methylphenidate 97%, GPT/methylphenidate 96%, CM/placebo 92%, GPT/placebo 84%).

- Overall, 8.8% of patients in the methylphenidate group and 4.8% in the placebo group stopped their medication treatment because of an AE (difference 4.0%; 95% CI, 0.9% to 9.1%). At least 1 dose decrease, increase, or discontinuation was made after an AE in 42% of participants in the placebo group and 69% of those in the methylphenidate group.

- There were no significant differences in clinically pertinent ECG abnormalities between methylphenidate and placebo therapy.

Continue to: Conclusions/limitations

Conclusions/limitations

- AEs were more common in the methylphenidate groups compared to placebo, but there was no significant differences for severe AEs. In the long-term, methylphenidate treatment was well tolerated and relatively safe.

- Limitations: The sample size may have been too small to detect uncommon AEs, all AEs had to be reported and may not have been caused by the treatment, and the original study’s main outcome was efficacy, not safety, which makes this an exploratory analysis of AEs.

4. Cutler AJ, Childress AC, Pardo A, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, fixed-dose study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of amphetamine extended-release tablets in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2022;83(5):22m14438. doi:10.4088/JCP.22m14438

Once-daily dosing of stimulants, which are commonly used to manage adult ADHD,16 can be beneficial because many patients have schedules that limit taking medication multiple times a day. Cutler et al12 looked at the efficacy and safety of amphetamine extended-release tablet (AMPH ER TAB), which is a 3.2:1 mixture of d- and l-amphetamine released by the LiquiXR drug delivery system. This technology allows for a continuous release following an initial quick onset of action.

Study design

- This parallel-study, double-blind study evaluated adults age 18 to 60 who had a diagnosis of ADHD according to DSM-5 criteria and the Adult ADHD Clinical Diagnostic Scale, normal-range IQ, AISRS score ≥26, and baseline CGI-S score ≥4.

- Women were not lactating or pregnant during the study.

- Exclusion criteria included a history of mental illnesses; chronic medical conditions; clinically significant abnormal ECG or cardiac findings on exam; renal or liver disease; family history of sudden death; significant vital sign findings; uncontrolled hypertension or a resting systolic blood pressure (SBP) >140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) >90 mmHg; recent history of or current alcohol or substance use disorder; use of atomoxetine, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, or tricyclic antidepressants within 14 days of study or the use of other stimulant medications within 1 week of screening; use of GI acidifying agents or urinary acidifying agents within 3 days of screening; answering “yes” to questions 4 or 5 of the Suicidal Ideation section of the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale within 2 years prior to the study; taking another investigational medication within 30 days of screening; allergic to amphetamine or components of the study drug, and a lack of prior response to amphetamine.

- Patients were randomized to receive AMPH ER TAB (n = 65) or placebo (n = 65), taken before 10

am . Participants started at 5 mg/d of the drug/placebo and then entered a 5-week titration period in which the medication was increased by 5 mg/d each week until reaching 20 mg/d, and then continued 20 mg/d for 2 weeks. - The primary outcome was the mean Permanent Product Measure of Performance Total (PERMP-T) score averaged across all time points (0.5-, 1-, 2-, 4-, 8-, 10-, 12-, 13-, and 14-hours postdose) at Visit 5.

- Participants underwent AISRS, CGI-S, and safety evaluations at baseline and at the 5 visits at the end of each treatment week.

Outcomes

- Analyses were completed on participants who received ≥1 dose of the medication and who had ≥1 PERMP-T score at Visit 5.

- Predose PERMP-T scores were similar between the AMPH ER TAB group (259.5) and placebo group (260). The mean postdose PERMP-T score in the AMPH ER TAB group (302.8) was significantly higher (P = .0043) than the placebo group (279.6).

- The PERMP-T scores were significantly different at 0.5-, 1-, 2-, 4-, 8-, and 13-hours postdose but not at 10-, 12-, and 14-hours postdose. The first Visit 5 time point at which the difference between groups was statistically different was at 0.5 hours postdose (P = .01), and the last significant time point was 13 hours (P = .006).

- The improvement in CGI-S scores was significantly greater in the AMPH ER TAB group than the placebo group. The improvement in AISRS scores was significantly greater in the AMPH ER TAB group at Visit 3, Visit 4, and Visit 5. More participants in the AMPH ER TAB group had AEs compared to the placebo group (90% vs 60%). The most common AEs (frequency ≥5% and occurring more in the intervention arm) were decreased appetite, insomnia, dry mouth, irritability, headache, anxiety, nausea, dizziness, and tachycardia.

- The AMPH ER TAB group had nonclinically significant increases in SBP (116.8 to 120.7 mmHg), DBP (74.1 to 77.1 mmHg), and heart rate (73.0 to 81.9 bpm) at Visit 5 compared to baseline.

- No serious AEs occurred. Three participants in the AMPH ER TAB group experienced AEs (increased blood pressure, CNS stimulation, and anxiety) that led them to discontinue the study.

Continue to: Conclusions/limitations

Conclusions/limitations

- AMPH ER TAB reduced symptoms in adults with ADHD as assessed by improvement in PERMP-T scores.

- The safety and tolerability profile of AMPH ER TAB were comparable to other stimulants, with expected rises in blood pressure and heart rate.

- Limitations: Patients were required to be titrated to 20 mg/d of AMPH ER TAB, instead of following a flexible titration based on an individual’s response. Some participants may have had greater improvement at a higher or lower dose. This study did not compare AMPH ER TAB to other stimulants. The 5-week duration of this study limited the ability to evaluate long-term efficacy and tolerability. Patients with a wide range of psychiatric or medical comorbidities were excluded.

5. Iwanami A, Saito K, Fujiwara M, et al. Efficacy and safety of guanfacine extended-release in the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81(3):19m12979. doi:10.4088/JCP.19m12979

Guanfacine extended-release (GXR) is a selective alpha 2A-adrenergic receptor agonist approved for treating ADHD in children and adolescents.17 Iwanami et al13 evaluated the efficacy and safety of GXR for adults.

Study design

- This randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial enrolled Japanese adults age ≥18 who were diagnosed with ADHD according to DSM-5 criteria and scored ≥24 on the ADHD-Rating Scale IV (ADHD-RS-IV) and ≥4 on CGI- I.

- Exclusion criteria included having anxiety, depression, substance use disorder, tic disorder, BD, personality disorder, schizophrenia, or intellectual disability; a moderate or severe psychiatric disorder requiring treatment other than counseling; seizures; increased risk for suicide; a history of cardiovascular disease, including prolonged QTc/abnormal ECG/abnormal labs, orthostatic hypotension, or continuous bradycardia; or taking medications that affect blood pressure or heart rate.

- Overall, 101 participants were randomized to the GXR group and 100 to the placebo group. Approximately two-thirds of the study population was male. Patients received GXR or placebo once daily at approximately the same time.

- There were 5 phases to the trial. The screening period occurred over 1 to 4 weeks. Part 1 of the treatment period consisted of 5 weeks of medication optimization. Participants were started on GXR 2 mg/d and were required to be receiving a minimum dose of 4 mg/d starting at Week 3. Clinicians were allowed to increase the dose 1 mg/d per week starting at Week 4 based on clinical response to a maximum dosage of 6 mg/d. Part 2 of the treatment period consisted of 5 weeks of maintenance at 4 to 6 mg/d. The tapering period to 2 mg/d occurred over 2 weeks. The follow-up period lasted 1 week.

- Efficacy measurements included the Japanese version of the ADHD-RS-IV and translations of the English-language CAARS, CGI-I, and CGI-S. Participant-reported measures included the Patient Global Impression-Improvement scale (PGI-I), Adult ADHD Quality of Life Questionnaire (AAQoL), and BRIEF-A.

- The primary outcome was the difference in ADHD-RS-IV total score from baseline to the end of the maintenance period (Week 10).

- Safety assessments were completed at Week 5 (end of dose optimization period), Week 10 (end of dose maintenance period), and Week 12 (tapering period).

Outcomes

- The average GXR dose during the maintenance period was 5.07 mg/d.

- Compared to the placebo group, the GXR group had more patients age <30 (47% vs 39%) and fewer patients age ≥40 (17% vs 27%). Baseline ADHD-RS-IV scores in both groups were comparable. At baseline, 51% in the GXR group had a combined inattentive/hyperactive-impulsive presentation and 47% had a predominately inattention presentation, with similar characteristics in the placebo group (49% combined, 49% inattention).

- At Week 10, the least squares mean change from baseline on the ADHD-RS-IV total score was significantly greater in the GXR group than in the placebo group (-11.55 ± 1.10 vs -7.27 ± 1.07; P = .0005), with an effect size of 0.52. There was a greater decrease in the ADHD-RS-IV scores starting at Week 4 and continuing to Week 10 (P < .005).

- There were also significant differences favoring GXR on the ADHD-RS-IV hyperactivity-impulsivity subscale score (P = .0021) and ADHD-RS-IV inattention subscale score (P = .0032).

- There were significant differences in the CAARS total ADHD score (P = .0029) and BRIEF-A scores on the inhibit (P = .0173), initiate (P = .0406), plan/organize (P = .174), and global executive composite index (P = .0404) scales. There was no significant difference in the total AAQoL score (P = .0691), but there was a significant improvement in the AAQoL life productivity subscore (P = .0072).

- At Week 10, there were also significant improvements in the CGI-I scores (P = .0007) and PGI-I scores (P = .0283). The CGI-S scores were similar at all time points.

- Overall, 81.2% of GXR patients reported AEs compared to 62% in the placebo group. There was 1 serious treatment-emergent AE (a suicide attempt) that the authors concluded was unrelated to the study drug. No deaths occurred. The most common AEs (incidence ≥10% in either group) included somnolence, thirst, nasopharyngitis (occurring more in the placebo group), blood pressure decrease, postural dizziness, and constipation. The main AEs leading to discontinuation were somnolence and blood pressure decrease. Overall, 19.8% of patients receiving GXR discontinued treatment due to AEs, compared to 3% in the placebo group.

- Heart rate, blood pressure, and QTc (corrected by the Bazett formula) were decreased in the GXR group at Week 10 while QT and RR intervals increased, and most returned to normal by Week 12.

Continue to: Conclusions/limitations

Conclusions/limitations

- Compared to placebo, GXR monotherapy resulted in clinical improvement in ADHD symptoms, with a moderate effect size.

- The most common AEs were mild to moderate and congruent with known adverse effects of guanfacine. Sedation effects mostly transpired within the first week of medication administration and were transient.

- Limitations: The findings might not be generalizable to non-Japanese patients. The duration of the study was short. Patients with a wide range of psychiatric and medical comorbidities were excluded. Two-thirds of the participants were male, and there was a disparity in participant age in the GXR and placebo groups.

6. Reimherr FW, Gift TE, Steans TA, et al. The use of brexpiprazole combined with a stimulant in adults with treatment-resistant attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2022;42(5):445-453. doi:10.1097/JCP.0000000000001592

While stimulants are a mainstay ADHD treatment, some patients have a partial response or do not respond to amphetamines or methylphenidate. Reimherr et el14 assessed the efficacy and safety of adding brexpiprazole (BXP) to a stimulant.

Study design

- This randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial recruited 559 stimulant-naive patients and 174 patients who had not responded to previous stimulant therapy.

- Participants were adults age 18 to 55 with a primary diagnosis of ADHD according to DSM-IV-TR criteria and the Conners Adult ADHD Diagnostic Interview. Other inclusion criteria were having a CAARS score ≥29 and a CGI-S score ≥4.

- Exclusion criteria included being at risk for suicide; having current substance abuse or positive alcohol/drug screens; a history of good response to prestudy treatment; a clinically significant medical condition; fasting blood glucose >200 mg/dL or hemoglobin A1C >7%; and hospitalization in past 12 months from a diabetic complication, uncontrolled hypertension, ischemic heart disease, or epilepsy. Further exclusion criteria included a history of psychosis, current MDD or BD, current panic disorder, uncontrolled comorbid psychiatric condition, or clinically significant personality disorder. Investigators excluded any patient with severe DSM-IV axis I or II disorders or abnormal/psychopathological behaviors.

- The trial consisted of 3 segments. Part 1 was screening. If the patient was currently receiving a stimulant but not fully responding, the medication was discontinued for at least 5 half-lives.

- Part 2 (5 weeks) involved administering a stimulant plus a single-blind placebo (597 patients completed this phase). The stimulant was chosen by the investigator, who had the option of using 1 of 2 amphetamine derivatives (mixed amphetamine salts capsules or lisdexamfetamine dimesylate capsules) or 1 of 2 methylphenidate derivatives (methylphenidate hydrochloride ER tabs or dexmethylphenidate HCl ER capsules). If a patient did not respond to a particular stimulant prior to the study, they were given a different stimulant from the list. Patients continued the same stimulant throughout the trial. Patients were monitored for a response, defined as a ≥30% decrease in CAARS score or a CAARS score <24, or a CGI-I score of 1 or 2 at Week 5. Patients who did not show this improvement were categorized as open-label nonresponders.

- Part 3 (6 weeks) involved administering a stimulant plus double-blind BXP vs placebo (stimulant-naive n = 167, stimulant nonresponders n = 68). Nonresponders continued the stimulant (at the same dose reached at the end of Part 2) and added either BXP (n = 155) or continued placebo (n = 80). Patients who responded in Part 2 were continued on the stimulant plus placebo and were not randomized. Patients were started on BXP 0.25 mg/d, and the medication could be titrated to 2 mg/d during the following 3 weeks, depending on the benefit vs AE profile. After the third week, the dose could be decreased but not increased.

- The primary outcome was a change in CAARS score. Secondary measurements included the CGI-S, Wender-Reimherr Adult Attention Deficit Disorder Scale (WRAADDS), Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS), and BDI.

Outcomes

- Stimulant-naive patients were equally divided among the 4 stimulant groups, and previous nonresponders who continued to not respond in Part 2 were more likely to be given methylphenidate HCl or lisdexamfetamine dimesylate.

- Patients with a history of nonresponse had less response to stimulants in Part 2 compared to stimulant-naive patients, as seen by 27% (n = 167) of stimulant-naive patients entering Part 3 compared to 39% of prior nonresponders (n = 68; P = .0249).

- ADHD improvement with BXP appeared to be greater among pretrial nonresponders.

- For stimulant nonresponders before and during the study, at the end of the double-blind endpoint (Part 3; Week 11), WRAADDS total score was significantly improved in the BXP group compared to the placebo group (P = .013; d = 0.74), with most beneficial effects seen in the hyperactivity/restlessness, emotional dysregulation factor, and impulsivity categories.

- For stimulant nonresponders before and during the study, there was no significant difference at the end of Week 11 on the CAARS (P = .64), MADRS (P = .37), or BDI (P = .73). There was a trend toward significance on the CAARS subscale for hyperactive/impulsive (P = .09).

- For prestudy stimulant-naive patients who did not respond to stimulants in Part 2 and were randomized in Part 3, there was not a significant difference between BXP and placebo at Week 11 as assessed on WRAADDS, CAARS, MADRS, or BDI.

- As assessed on WRAADDS, 50% in the BXP group had a response compared to 41% in the placebo group (Fisher exact = 0.334). Under the emotional dysregulation factor category of the WRAADDS, 64% in the BXP group had a response compared to 41% in the placebo group (Fisher exact = 0.064). The attention factor category showed a 40% improvement in the BXP group compared to 32% in the placebo group (Fisher exact = 0.344).

- There were 2 serious AEs in the BXP group (gall bladder inflammation and diarrhea) and 2 in the placebo group (pneumonia and urinary tract infection). There was no statistically significant difference between groups with regards to common AEs (ie, fatigue, heartburn/nausea/stomachache, weight loss), although there was a trend to significant for insomnia in the BXP group (P = .083).

Conclusions/limitations

- Stimulant-naive patients experienced no improvement with adjunctive BXP.

- For prior stimulant nonresponders, there was no significant difference between BXP vs placebo on the primary outcome of the CAARS score, but there was an improvement as observed by assessment with the WRAADDS.

- The largest change in the WRAADDS occurred in the emotional dysregulation factor compared to the attention factor.

- BXP appeared to be well tolerated.

- Limitations: The WRAADDS was administered without the patients’ significant other/collateral. Raters were not trained in the use of the WRAADDS. Patients with a wide range of psychiatric and medical comorbidities were excluded. Fewer patients were recruited in the prior stimulant nonresponder group.

Bottom Line

Recent randomized controlled trials suggest that methylphenidate, amphetamine extended-release, viloxazine extended-release, and guanfacine extended-release improved symptoms of adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). There were no improvements in ADHD symptoms with adjunctive brexpiprazole.

Related Resources

- Parikh AR, Baker SA. Adult ADHD: pharmacologic treatment in the DSM-5 era. Current Psychiatry. 2016;15(10):18-25.

- Akbar HN. Why we should be scrutinizing the rising prevalence of adult ADHD. Current Psychiatry. 2022; 21(7):e1-e2. doi:10.12788/cp.0268

Drug Brand Names

Amantadine • Gocovri

Amphetamine extended-release tablet • Dyanavel XR

Atomoxetine • Strattera

Brexpiprazole • Rexulti

Bupropion • Wellbutrin

Dexmethylphenidate • Focalin

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Guanfacine extended- release • Intuniv

Lisdexamfetamine • Vyvanse

Methylphenidate • Concerta, Methylin

Theophylline • Elixophyllin

Viloxazine • Qelbree

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a developmental disorder that begins in childhood and continues into adulthood. The clinical presentation is characterized by a persistent pattern of inattention, impulsivity, and/or hyperactivity that causes functional interference.1 ADHD affects patients’ interpersonal and professional lives as well as their daily functioning.2 Adults with ADHD may suffer from excessive self-criticism, low self-esteem, and sensitivity to criticism.3 The overall prevalence of adult ADHD is 4.4%.4 ADHD in adults is frequently associated with comorbid psychiatric disorders.5 The diagnosis of ADHD in adults requires the presence of ≥5 symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity that persist for ≥6 months. Patients must have first had such symptoms before age 12; symptoms need to be present in ≥2 settings and interfere with functioning.1

Treatment of ADHD includes pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions. For most patients, pharmacotherapy—specifically stimulant medications—is advised as first-line treatment,6 with adequate trials of methylphenidate and amphetamines before using second-line agents such as nonstimulants. However, despite these medications’ efficacy in randomized controlled trials (RCTs), adherence is low.7 This could be due to inadequate response or adverse effects.8 Guidelines also recommend the use of nonpharmacologic interventions for adults who cannot adhere to or tolerate medication or have an inadequate response.6 Potential nonpharmacologic interventions include transcranial direct current stimulation, mindfulness, psychoeducation, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and chronotherapy.

In Part 1 of this 2-part article, we review 6 RCTs of pharmacologic interventions for adult ADHD published within the last 5 years (Table9-14). Part 2 will review nonpharmacologic treatments.

1. Lam AP, Matthies S, Graf E, et al; Comparison of Methylphenidate and Psychotherapy in Adult ADHD Study (COMPAS) Consortium. Long-term effects of multimodal treatment on adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms: follow-up analysis of the COMPAS Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(5):e194980. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.4980

The Comparison of Methylphenidate and Psychotherapy in Adult ADHD Study (COMPAS) was a multicenter prospective, randomized trial of adults age 18 to 58 with ADHD.15 It compared cognitive-behavioral group psychotherapy (GPT) with individual clinical management (CM), and methylphenidate with placebo. When used in conjunction with methylphenidate, psychological treatments produced better results than placebo. However, studies on the long-term effects of multimodal treatment in ADHD are limited. Lam et al9 performed a follow-up analysis of the COMPAS trial.

Study design

- This observer-masked study involved a follow-up of participants in COMPAS 1.5 years after the interventions were terminated. Of the 433 adults with ADHD who participated in COMPAS, 256 participated in this follow-up.

- The inclusion criteria of COMPAS were age 18 to 58; diagnosis of ADHD according to DSM-IV criteria; chronic course of ADHD symptoms from childhood to adulthood; a Wender Utah Rating Scale short version score ≥30; and no pathological abnormality detected on physical examination.

- The exclusion criteria were having an IQ <85; schizophrenia, bipolar disorder (BD), borderline personality disorder, antisocial personality disorder, suicidal or self-injurious behavior, autism, motor tics, or Tourette syndrome; substance abuse/dependence within 6 months prior to screening; positive drug screening; neurologic diseases, seizures, glaucoma, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, uncontrolled arterial hypertension, angina pectoris, tachycardia arrhythmia, or arterial occlusive disease; previous stroke; current bulimia or anorexia; low weight (body mass index [BMI] <20; pregnancy (current or planned) or breastfeeding; treatment with stimulants or ADHD-specific psychotherapy in the past 6 months; methylphenidate intolerance; treatment with antidepressants, norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, bupropion, antipsychotics, theophylline, amantadine, anticoagulants derived from coumarin, antacids, or alpha-adrenergic agonists in the 2 weeks prior to baseline; and treatment with fluoxetine or monoamine oxidase inhibitors in the 4 weeks prior to baseline.

- The primary outcome was a change from baseline on the ADHD Index of Conners Adult ADHD Rating Scale (CAARS) score. Secondary outcomes were self-ratings on the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and observer-masked ratings of the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) scale and other ADHD rating scale scores, such as the Diagnostic Checklist for the diagnosis of ADHD in adults (ADHD-DC) and subscales of the CAARS.

- COMPAS was open regarding patient and therapist assignment to GPT and CM, but double-masked regarding medication. The statistical analysis focused on the 2x2 comparison of GPT vs CM and methylphenidate vs placebo.

Outcomes

- A total of 251 participants had an assessment with the observer-masked CAARS score. The baseline mean (SD) age was 36.3 (10.1), and approximately one-half (49.8%) of participants were male.

- Overall, 9.2% of patients took methylphenidate >31 days from termination of COMPAS before this study but not at the start of this study. Approximately one-third (31.1%) of patients were taking methylphenidate at follow-up. The mean (SD) daily dosage of methylphenidate was 36 (24.77) mg and 0.46 (0.27) mg/kg of body weight.

- The baseline all-group mean ADHD Index of CAARS score was 20.6. At follow-up, it was 14.7 for the CM arm and 14.2 for the GPT arm (difference not significant, P = .48). The mean score decreased to 13.8 for the methylphenidate arm and to 15.2 for the placebo (significant difference, P = .04).

- Overall, methylphenidate was associated with greater improvement in symptoms than placebo. Patients in the GPT arm had fewer severe symptoms as assessed by the self-reported ADHD Symptoms Total Score compared to the CM arm (P = .04).