User login

Transfusion doesn’t cause NEC, study suggests

Photo by Daniel Gay

Red blood cell (RBC) transfusions do not increase the risk of a serious intestinal disorder in very low-birth-weight (VLBW) infants, according to a study published in JAMA.

Past research has suggested RBC transfusions increase the risk of necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) among VLBW infants.

But other studies have shown no association between transfusions and NEC or suggested transfusions actually have a protective effect.

So researchers set out to determine whether RBC transfusions or severe anemia were associated with the rate of NEC among VLBW infants. The results suggested a significant association for severe anemia but not RBC transfusion.

To conduct this study, Ravi M. Patel, MD, of the Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, Georgia, and his colleagues assessed 598 VLBW infants from 3 neonatal intensive care units in Atlanta.

The team followed the infants for 90 days or until they were discharged from the hospital, transferred to a non-study-affiliated hospital, or died (whichever came first).

Forty-four (7.4%) infants developed NEC, and 32 (5.4%) died (of any cause). Roughly half of the infants (n=319, 53%) received RBC transfusions (n=1430).

The unadjusted cumulative incidence of NEC at week 8 was 9.9% in infants who received transfusions and 4.6% in those who did not.

However, in multivariable analysis, exposure to RBC transfusion in a given week was not significantly related to the rate of NEC. The hazard ratio was 0.44 (P=0.09).

On the other hand, the rate of NEC was significantly higher among infants with severe anemia in a given week than in those without severe anemia. The hazard ratio was 5.99 (P=0.001).

The researchers said these results suggest preventing severe anemia may be more clinically important than minimizing the use of RBC transfusion as a strategy to decrease the risk of NEC in VLBW infants.

However, such a strategy might impact other important neonatal outcomes, so further study is needed. ![]()

Photo by Daniel Gay

Red blood cell (RBC) transfusions do not increase the risk of a serious intestinal disorder in very low-birth-weight (VLBW) infants, according to a study published in JAMA.

Past research has suggested RBC transfusions increase the risk of necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) among VLBW infants.

But other studies have shown no association between transfusions and NEC or suggested transfusions actually have a protective effect.

So researchers set out to determine whether RBC transfusions or severe anemia were associated with the rate of NEC among VLBW infants. The results suggested a significant association for severe anemia but not RBC transfusion.

To conduct this study, Ravi M. Patel, MD, of the Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, Georgia, and his colleagues assessed 598 VLBW infants from 3 neonatal intensive care units in Atlanta.

The team followed the infants for 90 days or until they were discharged from the hospital, transferred to a non-study-affiliated hospital, or died (whichever came first).

Forty-four (7.4%) infants developed NEC, and 32 (5.4%) died (of any cause). Roughly half of the infants (n=319, 53%) received RBC transfusions (n=1430).

The unadjusted cumulative incidence of NEC at week 8 was 9.9% in infants who received transfusions and 4.6% in those who did not.

However, in multivariable analysis, exposure to RBC transfusion in a given week was not significantly related to the rate of NEC. The hazard ratio was 0.44 (P=0.09).

On the other hand, the rate of NEC was significantly higher among infants with severe anemia in a given week than in those without severe anemia. The hazard ratio was 5.99 (P=0.001).

The researchers said these results suggest preventing severe anemia may be more clinically important than minimizing the use of RBC transfusion as a strategy to decrease the risk of NEC in VLBW infants.

However, such a strategy might impact other important neonatal outcomes, so further study is needed. ![]()

Photo by Daniel Gay

Red blood cell (RBC) transfusions do not increase the risk of a serious intestinal disorder in very low-birth-weight (VLBW) infants, according to a study published in JAMA.

Past research has suggested RBC transfusions increase the risk of necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) among VLBW infants.

But other studies have shown no association between transfusions and NEC or suggested transfusions actually have a protective effect.

So researchers set out to determine whether RBC transfusions or severe anemia were associated with the rate of NEC among VLBW infants. The results suggested a significant association for severe anemia but not RBC transfusion.

To conduct this study, Ravi M. Patel, MD, of the Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, Georgia, and his colleagues assessed 598 VLBW infants from 3 neonatal intensive care units in Atlanta.

The team followed the infants for 90 days or until they were discharged from the hospital, transferred to a non-study-affiliated hospital, or died (whichever came first).

Forty-four (7.4%) infants developed NEC, and 32 (5.4%) died (of any cause). Roughly half of the infants (n=319, 53%) received RBC transfusions (n=1430).

The unadjusted cumulative incidence of NEC at week 8 was 9.9% in infants who received transfusions and 4.6% in those who did not.

However, in multivariable analysis, exposure to RBC transfusion in a given week was not significantly related to the rate of NEC. The hazard ratio was 0.44 (P=0.09).

On the other hand, the rate of NEC was significantly higher among infants with severe anemia in a given week than in those without severe anemia. The hazard ratio was 5.99 (P=0.001).

The researchers said these results suggest preventing severe anemia may be more clinically important than minimizing the use of RBC transfusion as a strategy to decrease the risk of NEC in VLBW infants.

However, such a strategy might impact other important neonatal outcomes, so further study is needed. ![]()

EC approves drug for iron-deficiency anemia in IBD

The European Commission (EC) has granted marketing authorization for ferric maltol (Feraccru) to treat iron-deficiency anemia in adults with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

The product can now be marketed for this indication in the 28 member countries of the European Union, as well as Iceland, Liechtenstein, and Norway.

The company developing the drug, Shield Therapeutics, said it will begin a roll-out of commercialization in the coming months.

Feraccru contains iron in a stable ferric state as a complex with a trimaltol ligand—ferric maltol. It is formulated as 30 mg of ferric iron in a hard gelatin capsule.

The complex is designed to provide iron for uptake across the intestinal wall and transfer to the iron transport and storage proteins—transferrin and ferritin, respectively. Feraccru dissociates on uptake from the gastrointestinal tract, and ferric maltol itself does not appear to enter the systemic circulation.

Phase 3 trials

The EC’s approval of ferric maltol is based on results of 2 phase 3 studies—AEGIS 1 and AEGIS 2. The results of these studies were published in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases in March 2015.

Together, the trials included 128 adult patients with IBD (ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease), iron-deficiency anemia, and recorded intolerance of ferrous sulphate. They were randomized to receive either 30 mg of ferric maltol twice a day or a matched placebo capsule for 12 weeks.

The primary efficacy endpoint was the change in hemoglobin (Hb) levels from baseline to week 12. The mean improvement in Hb in the ferric maltol group compared to the placebo group was 2.25 g/dL (P<0.0001).

The absolute mean Hb concentration improved from 11.00 g/dL at baseline to 13.20 g/dL at week 12 in the ferric maltol group. In the placebo group, the mean Hb values were similar at baseline and week 12—11.10 g/dL and 11.20 g/dL, respectively.

The incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs) was 58% in the ferric maltol group and 72% in the placebo group. However, not all of these events were considered treatment-related.

AEs that were considered treatment-related occurred in 25% of ferric maltol-treated patients and 11.7% of placebo-treated patients. The most common treatment-related AEs in the ferric maltol group were abdominal pain, constipation, and flatulence—each occurring in 6.7% of patients.

“The phase 3 clinical studies clearly demonstrated Feraccru’s effectiveness,” said Andreas Stallmach, MD, of University Clinic Jena in Germany.

“[T]his pan-European marketing authorization gives treating physicians like myself the opportunity to fulfill an important and currently unmet need for patients who are unable to tolerate other oral products, as Feraccru could provide an oral alternative to intravenous iron infusion.’’ ![]()

The European Commission (EC) has granted marketing authorization for ferric maltol (Feraccru) to treat iron-deficiency anemia in adults with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

The product can now be marketed for this indication in the 28 member countries of the European Union, as well as Iceland, Liechtenstein, and Norway.

The company developing the drug, Shield Therapeutics, said it will begin a roll-out of commercialization in the coming months.

Feraccru contains iron in a stable ferric state as a complex with a trimaltol ligand—ferric maltol. It is formulated as 30 mg of ferric iron in a hard gelatin capsule.

The complex is designed to provide iron for uptake across the intestinal wall and transfer to the iron transport and storage proteins—transferrin and ferritin, respectively. Feraccru dissociates on uptake from the gastrointestinal tract, and ferric maltol itself does not appear to enter the systemic circulation.

Phase 3 trials

The EC’s approval of ferric maltol is based on results of 2 phase 3 studies—AEGIS 1 and AEGIS 2. The results of these studies were published in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases in March 2015.

Together, the trials included 128 adult patients with IBD (ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease), iron-deficiency anemia, and recorded intolerance of ferrous sulphate. They were randomized to receive either 30 mg of ferric maltol twice a day or a matched placebo capsule for 12 weeks.

The primary efficacy endpoint was the change in hemoglobin (Hb) levels from baseline to week 12. The mean improvement in Hb in the ferric maltol group compared to the placebo group was 2.25 g/dL (P<0.0001).

The absolute mean Hb concentration improved from 11.00 g/dL at baseline to 13.20 g/dL at week 12 in the ferric maltol group. In the placebo group, the mean Hb values were similar at baseline and week 12—11.10 g/dL and 11.20 g/dL, respectively.

The incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs) was 58% in the ferric maltol group and 72% in the placebo group. However, not all of these events were considered treatment-related.

AEs that were considered treatment-related occurred in 25% of ferric maltol-treated patients and 11.7% of placebo-treated patients. The most common treatment-related AEs in the ferric maltol group were abdominal pain, constipation, and flatulence—each occurring in 6.7% of patients.

“The phase 3 clinical studies clearly demonstrated Feraccru’s effectiveness,” said Andreas Stallmach, MD, of University Clinic Jena in Germany.

“[T]his pan-European marketing authorization gives treating physicians like myself the opportunity to fulfill an important and currently unmet need for patients who are unable to tolerate other oral products, as Feraccru could provide an oral alternative to intravenous iron infusion.’’ ![]()

The European Commission (EC) has granted marketing authorization for ferric maltol (Feraccru) to treat iron-deficiency anemia in adults with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

The product can now be marketed for this indication in the 28 member countries of the European Union, as well as Iceland, Liechtenstein, and Norway.

The company developing the drug, Shield Therapeutics, said it will begin a roll-out of commercialization in the coming months.

Feraccru contains iron in a stable ferric state as a complex with a trimaltol ligand—ferric maltol. It is formulated as 30 mg of ferric iron in a hard gelatin capsule.

The complex is designed to provide iron for uptake across the intestinal wall and transfer to the iron transport and storage proteins—transferrin and ferritin, respectively. Feraccru dissociates on uptake from the gastrointestinal tract, and ferric maltol itself does not appear to enter the systemic circulation.

Phase 3 trials

The EC’s approval of ferric maltol is based on results of 2 phase 3 studies—AEGIS 1 and AEGIS 2. The results of these studies were published in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases in March 2015.

Together, the trials included 128 adult patients with IBD (ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease), iron-deficiency anemia, and recorded intolerance of ferrous sulphate. They were randomized to receive either 30 mg of ferric maltol twice a day or a matched placebo capsule for 12 weeks.

The primary efficacy endpoint was the change in hemoglobin (Hb) levels from baseline to week 12. The mean improvement in Hb in the ferric maltol group compared to the placebo group was 2.25 g/dL (P<0.0001).

The absolute mean Hb concentration improved from 11.00 g/dL at baseline to 13.20 g/dL at week 12 in the ferric maltol group. In the placebo group, the mean Hb values were similar at baseline and week 12—11.10 g/dL and 11.20 g/dL, respectively.

The incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs) was 58% in the ferric maltol group and 72% in the placebo group. However, not all of these events were considered treatment-related.

AEs that were considered treatment-related occurred in 25% of ferric maltol-treated patients and 11.7% of placebo-treated patients. The most common treatment-related AEs in the ferric maltol group were abdominal pain, constipation, and flatulence—each occurring in 6.7% of patients.

“The phase 3 clinical studies clearly demonstrated Feraccru’s effectiveness,” said Andreas Stallmach, MD, of University Clinic Jena in Germany.

“[T]his pan-European marketing authorization gives treating physicians like myself the opportunity to fulfill an important and currently unmet need for patients who are unable to tolerate other oral products, as Feraccru could provide an oral alternative to intravenous iron infusion.’’ ![]()

Drug granted orphan designation for hemolytic anemia

The European Commission (EC) has granted orphan drug designation for TNT009 to treat autoimmune hemolytic anemia, including cold agglutinin disease.

TNT009 is a monoclonal antibody that selectively inhibits the classical complement pathway by targeting C1s, a serine protease within the C1-complex in the complement pathway.

The drug thereby prevents downstream disease processes involving phagocytosis, inflammation, and cell lysis.

TNT009 is being developed by True North Therapeutics.

The drug is currently in development for the treatment of autoimmune hemolytic anemia, which is characterized by the premature destruction of healthy red blood cells by autoantibodies.

In cold agglutinin disease, this destruction of red blood cells results in anemia, fatigue, and potentially fatal thrombosis.

TNT009 is also being evaluated in patients with bullous pemphigoid and end-stage renal disease.

Top-line results from a phase 1b trial of TNT009 are expected in mid-2016.

About orphan designation

The EC grants orphan designation to products intended to treat, prevent, or diagnose a life-threatening condition affecting up to 5 in 10,000 people in the European Union. The product must provide significant benefit to those affected by the condition.

Orphan drug designation from the EC provides companies with certain development incentives, including protocol assistance, a type of scientific advice specific for orphan drugs, and 10 years of market exclusivity once the drug is on the market. ![]()

The European Commission (EC) has granted orphan drug designation for TNT009 to treat autoimmune hemolytic anemia, including cold agglutinin disease.

TNT009 is a monoclonal antibody that selectively inhibits the classical complement pathway by targeting C1s, a serine protease within the C1-complex in the complement pathway.

The drug thereby prevents downstream disease processes involving phagocytosis, inflammation, and cell lysis.

TNT009 is being developed by True North Therapeutics.

The drug is currently in development for the treatment of autoimmune hemolytic anemia, which is characterized by the premature destruction of healthy red blood cells by autoantibodies.

In cold agglutinin disease, this destruction of red blood cells results in anemia, fatigue, and potentially fatal thrombosis.

TNT009 is also being evaluated in patients with bullous pemphigoid and end-stage renal disease.

Top-line results from a phase 1b trial of TNT009 are expected in mid-2016.

About orphan designation

The EC grants orphan designation to products intended to treat, prevent, or diagnose a life-threatening condition affecting up to 5 in 10,000 people in the European Union. The product must provide significant benefit to those affected by the condition.

Orphan drug designation from the EC provides companies with certain development incentives, including protocol assistance, a type of scientific advice specific for orphan drugs, and 10 years of market exclusivity once the drug is on the market. ![]()

The European Commission (EC) has granted orphan drug designation for TNT009 to treat autoimmune hemolytic anemia, including cold agglutinin disease.

TNT009 is a monoclonal antibody that selectively inhibits the classical complement pathway by targeting C1s, a serine protease within the C1-complex in the complement pathway.

The drug thereby prevents downstream disease processes involving phagocytosis, inflammation, and cell lysis.

TNT009 is being developed by True North Therapeutics.

The drug is currently in development for the treatment of autoimmune hemolytic anemia, which is characterized by the premature destruction of healthy red blood cells by autoantibodies.

In cold agglutinin disease, this destruction of red blood cells results in anemia, fatigue, and potentially fatal thrombosis.

TNT009 is also being evaluated in patients with bullous pemphigoid and end-stage renal disease.

Top-line results from a phase 1b trial of TNT009 are expected in mid-2016.

About orphan designation

The EC grants orphan designation to products intended to treat, prevent, or diagnose a life-threatening condition affecting up to 5 in 10,000 people in the European Union. The product must provide significant benefit to those affected by the condition.

Orphan drug designation from the EC provides companies with certain development incentives, including protocol assistance, a type of scientific advice specific for orphan drugs, and 10 years of market exclusivity once the drug is on the market. ![]()

Gene therapy could treat aplastic anemia

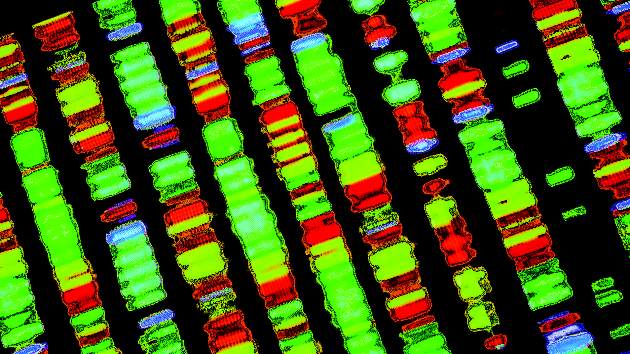

with telomeres in green

Image by Claus Azzalin

Researchers say they have found a new way to fight aplastic anemia—using a therapy designed to delay aging.

Four years ago, the group created telomerase gene therapy, an antiaging treatment based on repairing telomeres.

Now, they have found evidence to suggest this therapy can be effective against both acquired and inherited aplastic anemia.

The team reported preclinical results with the treatment in Blood.

In 2012, Maria A. Blasco, PhD, of Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Oncologicas in Madrid, Spain, and her colleagues described a strategy to repair telomeres.

They used adeno-associated virus (AAV9) vectors to deliver telomerase (Tert) gene therapy, which attenuated or reverted aging-associated telomere erosion in peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

For the current study, the researchers tested the therapy in a mouse model of acquired aplastic anemia and one of inherited aplastic anemia.

Acquired aplastic anemia

For the model of acquired aplastic anemia, the researchers depleted the TRF1 shelterin protein in the bone marrow. The team said this causes severe telomere uncapping and provokes a persistent DNA damage response at telomeres, which leads to fast clearance of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) deficient for Trf1.

The remaining HSPCs then undergo additional rounds of compensatory proliferation to regenerate the bone marrow, which leads to rapid telomere attrition. So this model recapitulates the compensatory hyperproliferation and short-telomere phenotype observed in acquired aplastic anemia.

The researchers induced Trf1 deletion with polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid injections given 3 times a week for 5 weeks. At that point, the mice began to show signs of aplastic anemia. A week after the last injection, the mice received either AAV9-Tert or AAV9-empty vectors.

Eighty-seven percent of the AAV9-Tert mice were still alive at 100 days, compared to 55% of mice in the empty vector group (P=0.0025).

In addition, 13% (4/31) of the mice treated with AAV9-Tert actually developed aplastic anemia, while 44% (16/36) of the control mice died showing “clear signs” of aplastic anemia (P=0.0006).

Finally, the researchers found that AAV9-Tert reversed telomere shortening in peripheral blood and bone marrow cells.

Inherited aplastic anemia

For the model of inherited aplastic anemia, the researchers transplanted irradiated wild-type mice with bone marrow from third-generation telomerase-deficient Tert knockout mice. These mice have short telomeres resulting from telomerase deficiency over 3 generations.

As with the previous model, these mice received AAV9-Tert or AAV9-empty vectors. The AAV9-Tert mice had a superior survival rate that nearly reached statistical significance (P=0.058).

The researchers also found that, compared to controls, AAV9-Tert-treated mice had significant increases in hemoglobin levels (P=0.003), erythrocyte counts (P=0.006), and platelet counts (P=0.035), as well as a trend toward an increase in leukocyte counts (P=0.09).

In addition, AAV9-Tert treatment led to a net increase in average telomere length of 5.18Kb, while control mice had a slight telomere shortening of 1.76Kb.

The researchers noted that there are types of aplastic anemia not associated with short telomeres. However, they believe these results provide proof of concept that gene therapy is a valid strategy for treating aplastic anemia. ![]()

with telomeres in green

Image by Claus Azzalin

Researchers say they have found a new way to fight aplastic anemia—using a therapy designed to delay aging.

Four years ago, the group created telomerase gene therapy, an antiaging treatment based on repairing telomeres.

Now, they have found evidence to suggest this therapy can be effective against both acquired and inherited aplastic anemia.

The team reported preclinical results with the treatment in Blood.

In 2012, Maria A. Blasco, PhD, of Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Oncologicas in Madrid, Spain, and her colleagues described a strategy to repair telomeres.

They used adeno-associated virus (AAV9) vectors to deliver telomerase (Tert) gene therapy, which attenuated or reverted aging-associated telomere erosion in peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

For the current study, the researchers tested the therapy in a mouse model of acquired aplastic anemia and one of inherited aplastic anemia.

Acquired aplastic anemia

For the model of acquired aplastic anemia, the researchers depleted the TRF1 shelterin protein in the bone marrow. The team said this causes severe telomere uncapping and provokes a persistent DNA damage response at telomeres, which leads to fast clearance of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) deficient for Trf1.

The remaining HSPCs then undergo additional rounds of compensatory proliferation to regenerate the bone marrow, which leads to rapid telomere attrition. So this model recapitulates the compensatory hyperproliferation and short-telomere phenotype observed in acquired aplastic anemia.

The researchers induced Trf1 deletion with polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid injections given 3 times a week for 5 weeks. At that point, the mice began to show signs of aplastic anemia. A week after the last injection, the mice received either AAV9-Tert or AAV9-empty vectors.

Eighty-seven percent of the AAV9-Tert mice were still alive at 100 days, compared to 55% of mice in the empty vector group (P=0.0025).

In addition, 13% (4/31) of the mice treated with AAV9-Tert actually developed aplastic anemia, while 44% (16/36) of the control mice died showing “clear signs” of aplastic anemia (P=0.0006).

Finally, the researchers found that AAV9-Tert reversed telomere shortening in peripheral blood and bone marrow cells.

Inherited aplastic anemia

For the model of inherited aplastic anemia, the researchers transplanted irradiated wild-type mice with bone marrow from third-generation telomerase-deficient Tert knockout mice. These mice have short telomeres resulting from telomerase deficiency over 3 generations.

As with the previous model, these mice received AAV9-Tert or AAV9-empty vectors. The AAV9-Tert mice had a superior survival rate that nearly reached statistical significance (P=0.058).

The researchers also found that, compared to controls, AAV9-Tert-treated mice had significant increases in hemoglobin levels (P=0.003), erythrocyte counts (P=0.006), and platelet counts (P=0.035), as well as a trend toward an increase in leukocyte counts (P=0.09).

In addition, AAV9-Tert treatment led to a net increase in average telomere length of 5.18Kb, while control mice had a slight telomere shortening of 1.76Kb.

The researchers noted that there are types of aplastic anemia not associated with short telomeres. However, they believe these results provide proof of concept that gene therapy is a valid strategy for treating aplastic anemia. ![]()

with telomeres in green

Image by Claus Azzalin

Researchers say they have found a new way to fight aplastic anemia—using a therapy designed to delay aging.

Four years ago, the group created telomerase gene therapy, an antiaging treatment based on repairing telomeres.

Now, they have found evidence to suggest this therapy can be effective against both acquired and inherited aplastic anemia.

The team reported preclinical results with the treatment in Blood.

In 2012, Maria A. Blasco, PhD, of Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Oncologicas in Madrid, Spain, and her colleagues described a strategy to repair telomeres.

They used adeno-associated virus (AAV9) vectors to deliver telomerase (Tert) gene therapy, which attenuated or reverted aging-associated telomere erosion in peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

For the current study, the researchers tested the therapy in a mouse model of acquired aplastic anemia and one of inherited aplastic anemia.

Acquired aplastic anemia

For the model of acquired aplastic anemia, the researchers depleted the TRF1 shelterin protein in the bone marrow. The team said this causes severe telomere uncapping and provokes a persistent DNA damage response at telomeres, which leads to fast clearance of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) deficient for Trf1.

The remaining HSPCs then undergo additional rounds of compensatory proliferation to regenerate the bone marrow, which leads to rapid telomere attrition. So this model recapitulates the compensatory hyperproliferation and short-telomere phenotype observed in acquired aplastic anemia.

The researchers induced Trf1 deletion with polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid injections given 3 times a week for 5 weeks. At that point, the mice began to show signs of aplastic anemia. A week after the last injection, the mice received either AAV9-Tert or AAV9-empty vectors.

Eighty-seven percent of the AAV9-Tert mice were still alive at 100 days, compared to 55% of mice in the empty vector group (P=0.0025).

In addition, 13% (4/31) of the mice treated with AAV9-Tert actually developed aplastic anemia, while 44% (16/36) of the control mice died showing “clear signs” of aplastic anemia (P=0.0006).

Finally, the researchers found that AAV9-Tert reversed telomere shortening in peripheral blood and bone marrow cells.

Inherited aplastic anemia

For the model of inherited aplastic anemia, the researchers transplanted irradiated wild-type mice with bone marrow from third-generation telomerase-deficient Tert knockout mice. These mice have short telomeres resulting from telomerase deficiency over 3 generations.

As with the previous model, these mice received AAV9-Tert or AAV9-empty vectors. The AAV9-Tert mice had a superior survival rate that nearly reached statistical significance (P=0.058).

The researchers also found that, compared to controls, AAV9-Tert-treated mice had significant increases in hemoglobin levels (P=0.003), erythrocyte counts (P=0.006), and platelet counts (P=0.035), as well as a trend toward an increase in leukocyte counts (P=0.09).

In addition, AAV9-Tert treatment led to a net increase in average telomere length of 5.18Kb, while control mice had a slight telomere shortening of 1.76Kb.

The researchers noted that there are types of aplastic anemia not associated with short telomeres. However, they believe these results provide proof of concept that gene therapy is a valid strategy for treating aplastic anemia. ![]()

Histone levels may predict thrombocytopenia

Image by Eric Smith

Measuring circulating histones may help physicians predict the onset of thrombocytopenia or allow them to monitor the condition in patients who are critically ill, according to researchers.

They noted that histones induce profound thrombocytopenia in mice and are associated with organ injury when released after extensive cell damage in patients who are critically ill.

So the team decided to examine the association between circulating histones and thrombocytopenia in patients in the intensive care unit (ICU).

Cheng-Hock Toh, MD, of the University of Liverpool in the UK, and his colleagues conducted this research and reported the results in a letter to JAMA.

The researchers analyzed 56 patients with thrombocytopenia and 56 controls with normal platelet counts who were admitted to the ICU at Royal Liverpool University Hospital between June 2013 and January 2014.

Thrombocytopenia was defined as a platelet count less than 150 × 103/µL, a 25% or greater decrease in platelet count, or both within the first 96 hours of ICU admission.

The researchers noted that, at approximately 30 µg/mL, histones bind platelets and cause platelet aggregation, which results in profound thrombocytopenia in mice.

So the team used this as a cutoff to stratify thrombocytopenic patients. A “high” level of histones was 30 µg/mL or greater, and a “low” level was below 30 µg/mL.

The researchers detected circulating histones in 51 of the thrombocytopenic patients and 31 controls—91% and 55%, respectively (P<0.001). Histone levels were 2.5- to 5.5-fold higher in thrombocytopenic patients than in controls.

Thrombocytopenic patients with high histone levels at ICU admission had significantly lower platelet counts and a significantly higher percentage of decrease in platelet counts at 24 hours (P=0.02 and P=0.04, respectively) and 48 hours (P=0.003 and P=0.005, respectively) after admission.

High admission histone levels were associated with moderate to severe thrombocytopenia and the development of clinically important thrombocytopenia (P<0.001).

A 30 µg/mL histone concentration was able to predict thrombocytopenia with 76% sensitivity and 91% specificity. The positive predictive value was 79.4%, and the negative predictive value was 89.2%. ![]()

Image by Eric Smith

Measuring circulating histones may help physicians predict the onset of thrombocytopenia or allow them to monitor the condition in patients who are critically ill, according to researchers.

They noted that histones induce profound thrombocytopenia in mice and are associated with organ injury when released after extensive cell damage in patients who are critically ill.

So the team decided to examine the association between circulating histones and thrombocytopenia in patients in the intensive care unit (ICU).

Cheng-Hock Toh, MD, of the University of Liverpool in the UK, and his colleagues conducted this research and reported the results in a letter to JAMA.

The researchers analyzed 56 patients with thrombocytopenia and 56 controls with normal platelet counts who were admitted to the ICU at Royal Liverpool University Hospital between June 2013 and January 2014.

Thrombocytopenia was defined as a platelet count less than 150 × 103/µL, a 25% or greater decrease in platelet count, or both within the first 96 hours of ICU admission.

The researchers noted that, at approximately 30 µg/mL, histones bind platelets and cause platelet aggregation, which results in profound thrombocytopenia in mice.

So the team used this as a cutoff to stratify thrombocytopenic patients. A “high” level of histones was 30 µg/mL or greater, and a “low” level was below 30 µg/mL.

The researchers detected circulating histones in 51 of the thrombocytopenic patients and 31 controls—91% and 55%, respectively (P<0.001). Histone levels were 2.5- to 5.5-fold higher in thrombocytopenic patients than in controls.

Thrombocytopenic patients with high histone levels at ICU admission had significantly lower platelet counts and a significantly higher percentage of decrease in platelet counts at 24 hours (P=0.02 and P=0.04, respectively) and 48 hours (P=0.003 and P=0.005, respectively) after admission.

High admission histone levels were associated with moderate to severe thrombocytopenia and the development of clinically important thrombocytopenia (P<0.001).

A 30 µg/mL histone concentration was able to predict thrombocytopenia with 76% sensitivity and 91% specificity. The positive predictive value was 79.4%, and the negative predictive value was 89.2%. ![]()

Image by Eric Smith

Measuring circulating histones may help physicians predict the onset of thrombocytopenia or allow them to monitor the condition in patients who are critically ill, according to researchers.

They noted that histones induce profound thrombocytopenia in mice and are associated with organ injury when released after extensive cell damage in patients who are critically ill.

So the team decided to examine the association between circulating histones and thrombocytopenia in patients in the intensive care unit (ICU).

Cheng-Hock Toh, MD, of the University of Liverpool in the UK, and his colleagues conducted this research and reported the results in a letter to JAMA.

The researchers analyzed 56 patients with thrombocytopenia and 56 controls with normal platelet counts who were admitted to the ICU at Royal Liverpool University Hospital between June 2013 and January 2014.

Thrombocytopenia was defined as a platelet count less than 150 × 103/µL, a 25% or greater decrease in platelet count, or both within the first 96 hours of ICU admission.

The researchers noted that, at approximately 30 µg/mL, histones bind platelets and cause platelet aggregation, which results in profound thrombocytopenia in mice.

So the team used this as a cutoff to stratify thrombocytopenic patients. A “high” level of histones was 30 µg/mL or greater, and a “low” level was below 30 µg/mL.

The researchers detected circulating histones in 51 of the thrombocytopenic patients and 31 controls—91% and 55%, respectively (P<0.001). Histone levels were 2.5- to 5.5-fold higher in thrombocytopenic patients than in controls.

Thrombocytopenic patients with high histone levels at ICU admission had significantly lower platelet counts and a significantly higher percentage of decrease in platelet counts at 24 hours (P=0.02 and P=0.04, respectively) and 48 hours (P=0.003 and P=0.005, respectively) after admission.

High admission histone levels were associated with moderate to severe thrombocytopenia and the development of clinically important thrombocytopenia (P<0.001).

A 30 µg/mL histone concentration was able to predict thrombocytopenia with 76% sensitivity and 91% specificity. The positive predictive value was 79.4%, and the negative predictive value was 89.2%. ![]()

Human gene editing consensus study underway

A consensus study of the scientific underpinnings of human gene editing technologies is underway, and the committee of experts behind the effort will independently review potential applications for those technologies, as well as the clinical, ethical, legal, and social implications of their use.

The multidisciplinary committee met Feb. 11 to receive input from select stakeholders as it launches its review, the results of which will represent the official views of the National Academy of Sciences and the National Academy of Medicine.

Among those stakeholders were representatives from several companies commercializing gene editing, a representative from the National Institutes of Health, and patient advocacy groups.

With some caveats, participants lobbied to maintain the existing regulatory framework related to gene therapy.

Michael Werner, cofounder and executive director of the Alliance for Regenerative Medicine, which advocates globally for regenerative medicine and advanced therapies, said his organization believes “the existing regulatory framework overall works for these technologies.”

“We don’t believe the [Food and Drug Administration], for example, needs to create a whole separate oversight process in addition to the process we already have now for gene therapy,” he said, adding that “the ultimate goal here is not to have regulatory action or legislative action that will hinder or delay the development of these technologies.”

The consensus study follows an International Summit on Human Gene Editing held in December, and is the next component of the Human Gene Editing Initiative. The committee will study the potential for gene editing in biomedical research and medicine – including human germline editing – although representatives from each of the companies represented at the meeting noted that they are not currently focused on germline applications.

Rather, the commercial focus is on other areas, such as correcting genes in somatic cells.

“We start with medical need. We want to work on things where there is not currently a therapy that addresses adequately the medical need, and we need the ability to generate a differentiated product,” said Vic Myer, Ph.D., of Editas Medicine in Cambridge, Mass.

The company has projects underway for opthalmologic applications, sickle cell anemia, beta-thalassemia, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, cystic fibrosis, alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency in the liver, and others.

“We are working on a number of different types of edits in a number of different tissues with a number of delivery modalities,” Dr. Myer said, noting that some programs will move quickly, while others will not.

Similarly, Intellia Therapeutics, also of Cambridge, Mass., is “focusing very much on what we hope will be curative products for somatic gene-based disorders,” said Dr. John Leonard, the company’s chief medical officer.

“We limit our work to somatic cells. We thought very carefully about that and that is what we do,” he added, noting that a recently launched division of Intellia is focused on autoimmune oncology opportunities (ex vivo), and on liver disease (in vivo).

The committee of experts conducting the consensus study, which began its information-gathering process in December at the International Summit on Human Gene Editing, will take these and other views expressed at the meeting into consideration during its work over the next year. The study will include a literature review and data gathering via meetings in the United States and abroad. The committee will continue to seek input from researchers, clinicians, policy makers, and the public.

“The committee will also monitor in real time the latest scientific achievements of importance in this rapidly developing field,” according to information from the National Academies.

The field has enormous potential, according to Mr. Werner, who explained that combined, the various types of gene editing technology available are “pretty powerful” in terms of an approach for targeting and changing DNA sequences in human cells.

“We’re talking about the potential to durably treat and potentially even cure diseases that currently represent unmet medical needs,” he said. “We could, in theory, be talking about millions of patients worldwide.”

A consensus study of the scientific underpinnings of human gene editing technologies is underway, and the committee of experts behind the effort will independently review potential applications for those technologies, as well as the clinical, ethical, legal, and social implications of their use.

The multidisciplinary committee met Feb. 11 to receive input from select stakeholders as it launches its review, the results of which will represent the official views of the National Academy of Sciences and the National Academy of Medicine.

Among those stakeholders were representatives from several companies commercializing gene editing, a representative from the National Institutes of Health, and patient advocacy groups.

With some caveats, participants lobbied to maintain the existing regulatory framework related to gene therapy.

Michael Werner, cofounder and executive director of the Alliance for Regenerative Medicine, which advocates globally for regenerative medicine and advanced therapies, said his organization believes “the existing regulatory framework overall works for these technologies.”

“We don’t believe the [Food and Drug Administration], for example, needs to create a whole separate oversight process in addition to the process we already have now for gene therapy,” he said, adding that “the ultimate goal here is not to have regulatory action or legislative action that will hinder or delay the development of these technologies.”

The consensus study follows an International Summit on Human Gene Editing held in December, and is the next component of the Human Gene Editing Initiative. The committee will study the potential for gene editing in biomedical research and medicine – including human germline editing – although representatives from each of the companies represented at the meeting noted that they are not currently focused on germline applications.

Rather, the commercial focus is on other areas, such as correcting genes in somatic cells.

“We start with medical need. We want to work on things where there is not currently a therapy that addresses adequately the medical need, and we need the ability to generate a differentiated product,” said Vic Myer, Ph.D., of Editas Medicine in Cambridge, Mass.

The company has projects underway for opthalmologic applications, sickle cell anemia, beta-thalassemia, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, cystic fibrosis, alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency in the liver, and others.

“We are working on a number of different types of edits in a number of different tissues with a number of delivery modalities,” Dr. Myer said, noting that some programs will move quickly, while others will not.

Similarly, Intellia Therapeutics, also of Cambridge, Mass., is “focusing very much on what we hope will be curative products for somatic gene-based disorders,” said Dr. John Leonard, the company’s chief medical officer.

“We limit our work to somatic cells. We thought very carefully about that and that is what we do,” he added, noting that a recently launched division of Intellia is focused on autoimmune oncology opportunities (ex vivo), and on liver disease (in vivo).

The committee of experts conducting the consensus study, which began its information-gathering process in December at the International Summit on Human Gene Editing, will take these and other views expressed at the meeting into consideration during its work over the next year. The study will include a literature review and data gathering via meetings in the United States and abroad. The committee will continue to seek input from researchers, clinicians, policy makers, and the public.

“The committee will also monitor in real time the latest scientific achievements of importance in this rapidly developing field,” according to information from the National Academies.

The field has enormous potential, according to Mr. Werner, who explained that combined, the various types of gene editing technology available are “pretty powerful” in terms of an approach for targeting and changing DNA sequences in human cells.

“We’re talking about the potential to durably treat and potentially even cure diseases that currently represent unmet medical needs,” he said. “We could, in theory, be talking about millions of patients worldwide.”

A consensus study of the scientific underpinnings of human gene editing technologies is underway, and the committee of experts behind the effort will independently review potential applications for those technologies, as well as the clinical, ethical, legal, and social implications of their use.

The multidisciplinary committee met Feb. 11 to receive input from select stakeholders as it launches its review, the results of which will represent the official views of the National Academy of Sciences and the National Academy of Medicine.

Among those stakeholders were representatives from several companies commercializing gene editing, a representative from the National Institutes of Health, and patient advocacy groups.

With some caveats, participants lobbied to maintain the existing regulatory framework related to gene therapy.

Michael Werner, cofounder and executive director of the Alliance for Regenerative Medicine, which advocates globally for regenerative medicine and advanced therapies, said his organization believes “the existing regulatory framework overall works for these technologies.”

“We don’t believe the [Food and Drug Administration], for example, needs to create a whole separate oversight process in addition to the process we already have now for gene therapy,” he said, adding that “the ultimate goal here is not to have regulatory action or legislative action that will hinder or delay the development of these technologies.”

The consensus study follows an International Summit on Human Gene Editing held in December, and is the next component of the Human Gene Editing Initiative. The committee will study the potential for gene editing in biomedical research and medicine – including human germline editing – although representatives from each of the companies represented at the meeting noted that they are not currently focused on germline applications.

Rather, the commercial focus is on other areas, such as correcting genes in somatic cells.

“We start with medical need. We want to work on things where there is not currently a therapy that addresses adequately the medical need, and we need the ability to generate a differentiated product,” said Vic Myer, Ph.D., of Editas Medicine in Cambridge, Mass.

The company has projects underway for opthalmologic applications, sickle cell anemia, beta-thalassemia, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, cystic fibrosis, alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency in the liver, and others.

“We are working on a number of different types of edits in a number of different tissues with a number of delivery modalities,” Dr. Myer said, noting that some programs will move quickly, while others will not.

Similarly, Intellia Therapeutics, also of Cambridge, Mass., is “focusing very much on what we hope will be curative products for somatic gene-based disorders,” said Dr. John Leonard, the company’s chief medical officer.

“We limit our work to somatic cells. We thought very carefully about that and that is what we do,” he added, noting that a recently launched division of Intellia is focused on autoimmune oncology opportunities (ex vivo), and on liver disease (in vivo).

The committee of experts conducting the consensus study, which began its information-gathering process in December at the International Summit on Human Gene Editing, will take these and other views expressed at the meeting into consideration during its work over the next year. The study will include a literature review and data gathering via meetings in the United States and abroad. The committee will continue to seek input from researchers, clinicians, policy makers, and the public.

“The committee will also monitor in real time the latest scientific achievements of importance in this rapidly developing field,” according to information from the National Academies.

The field has enormous potential, according to Mr. Werner, who explained that combined, the various types of gene editing technology available are “pretty powerful” in terms of an approach for targeting and changing DNA sequences in human cells.

“We’re talking about the potential to durably treat and potentially even cure diseases that currently represent unmet medical needs,” he said. “We could, in theory, be talking about millions of patients worldwide.”

Drug could aid standard care for aTTP

Results of a phase 2 trial suggest an investigational agent may improve upon standard care for acquired thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (aTTP).

The agent, caplacizumab, is an anti-von Willebrand factor, humanized, single-variable-domain immunoglobulin that works by inhibiting the interaction between ultralarge von Willebrand factor multimers and platelets.

In the phase 2 TITAN trial, caplacizumab plus standard care induced a faster resolution of aTTP episodes when compared to placebo plus standard care. However, caplacizumab was also associated with a higher risk of bleeding.

Flora Peyvandi, MD, PhD, of the University of Milan in Italy, and her colleagues reported these results in The New England Journal of Medicine. The study was supported by Ablynx, the company developing caplacizumab.

“Caplacizumab has the potential to become an important new component in the standard of care for patients with acquired TTP,” Dr Peyvandi said. “The results from the phase 2 TITAN study showed that caplacizumab acts quickly to control the critical acute phase of the disease and protects patients until immunosuppressive treatments take effect.”

TITAN was a single-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled study conducted at 56 centers around the world. The trial included 75 aTTP patients who were randomized to caplacizumab (n=36) or placebo (n=39), with all patients receiving the current standard of care (daily plasma exchange and immunosuppressive therapy).

Patients in the caplacizumab arm immediately received an intravenous bolus dose of caplacizumab at 10 mg and then a 10 mg subcutaneous dose of the drug daily until 30 days had elapsed after the final plasma exchange. Patients in the control arm received placebo at the same time points.

Response, recurrence, and relapse

The study’s primary endpoint was time to response (platelet count normalization). Patients in the caplacizumab arm had a 39% reduction in the median time to response compared to patients in the placebo arm (P=0.005).

Among the 69 patients who had not undergone a plasma-exchange session before enrollment, the median time to response was 3.0 days in the caplacizumab arm and 4.9 days in the placebo arm.

Among the 6 patients who did undergo a plasma-exchange session before enrollment, the median time to a response was 2.4 days in the caplacizumab arm and 4.3 days in the placebo arm.

The rate of confirmed response was 86.1% (n=31) in the caplacizumab arm and 71.8% (n=28) in the placebo arm.

One of the study’s secondary endpoints was exacerbation, which was defined as recurrent thrombocytopenia within 30 days of the end of daily plasma exchange that required reinitiation of daily exchange.

There were fewer exacerbations in the caplacizumab arm than the placebo arm—3 (8.3%) and 11 (28.2%), respectively.

Another secondary endpoint was relapse, which was defined as a TTP event occurring more than 30 days after the end of daily plasma exchange.

There were more relapses in the caplacizumab arm than the placebo arm—8 (22.2%) and 0, respectively. The investigators noted that 7 of the 8 patients had ADAMTS13 activity that remained below 10%, which suggests unresolved autoimmune activity.

Adverse events

There were 541 adverse events (AEs) in 34 of the 35 evaluable patients receiving caplacizumab (97%) and 522 AEs in all 37 evaluable patients receiving placebo (100%). TTP exacerbations and relapses were not included as AEs.

The rate of AEs thought to be related to the study drug was 17% in the caplacizumab arm and 11% in the placebo arm. The rate of AEs that were possibly related was 54% and 8%, respectively. And the rate of serious AEs was 37% and 32%, respectively.

The rate of bleeding-related AEs was 54% in the caplacizumab arm and 38% in the placebo arm. Of the 101 bleeding-related AEs, 84 (83%) were reported as mild, 14 (14%) as moderate, and 3 (3%) as severe.

There were no deaths in the caplacizumab arm and 2 in the placebo arm. One death was due to severe, refractory TTP, and the other was due to cerebral hemorrhage.

Caplacizumab development

The results of this trial will serve as the basis for filing for conditional approval of caplacizumab in Europe in the first half of 2017, according to Ablynx. The company is planning to file in the US in 2018.

Ablynx has started a phase 3 trial of caplacizumab known as the HERCULES study. In this double-blind, placebo-controlled study, investigators are evaluating the safety and efficacy of caplacizumab, in conjunction with the standard of care, in patients with aTTP.

The study is expected to enroll 92 patients at clinical sites across 17 countries. Recruitment is expected to be complete by the end of 2017. ![]()

Results of a phase 2 trial suggest an investigational agent may improve upon standard care for acquired thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (aTTP).

The agent, caplacizumab, is an anti-von Willebrand factor, humanized, single-variable-domain immunoglobulin that works by inhibiting the interaction between ultralarge von Willebrand factor multimers and platelets.

In the phase 2 TITAN trial, caplacizumab plus standard care induced a faster resolution of aTTP episodes when compared to placebo plus standard care. However, caplacizumab was also associated with a higher risk of bleeding.

Flora Peyvandi, MD, PhD, of the University of Milan in Italy, and her colleagues reported these results in The New England Journal of Medicine. The study was supported by Ablynx, the company developing caplacizumab.

“Caplacizumab has the potential to become an important new component in the standard of care for patients with acquired TTP,” Dr Peyvandi said. “The results from the phase 2 TITAN study showed that caplacizumab acts quickly to control the critical acute phase of the disease and protects patients until immunosuppressive treatments take effect.”

TITAN was a single-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled study conducted at 56 centers around the world. The trial included 75 aTTP patients who were randomized to caplacizumab (n=36) or placebo (n=39), with all patients receiving the current standard of care (daily plasma exchange and immunosuppressive therapy).

Patients in the caplacizumab arm immediately received an intravenous bolus dose of caplacizumab at 10 mg and then a 10 mg subcutaneous dose of the drug daily until 30 days had elapsed after the final plasma exchange. Patients in the control arm received placebo at the same time points.

Response, recurrence, and relapse

The study’s primary endpoint was time to response (platelet count normalization). Patients in the caplacizumab arm had a 39% reduction in the median time to response compared to patients in the placebo arm (P=0.005).

Among the 69 patients who had not undergone a plasma-exchange session before enrollment, the median time to response was 3.0 days in the caplacizumab arm and 4.9 days in the placebo arm.

Among the 6 patients who did undergo a plasma-exchange session before enrollment, the median time to a response was 2.4 days in the caplacizumab arm and 4.3 days in the placebo arm.

The rate of confirmed response was 86.1% (n=31) in the caplacizumab arm and 71.8% (n=28) in the placebo arm.

One of the study’s secondary endpoints was exacerbation, which was defined as recurrent thrombocytopenia within 30 days of the end of daily plasma exchange that required reinitiation of daily exchange.

There were fewer exacerbations in the caplacizumab arm than the placebo arm—3 (8.3%) and 11 (28.2%), respectively.

Another secondary endpoint was relapse, which was defined as a TTP event occurring more than 30 days after the end of daily plasma exchange.

There were more relapses in the caplacizumab arm than the placebo arm—8 (22.2%) and 0, respectively. The investigators noted that 7 of the 8 patients had ADAMTS13 activity that remained below 10%, which suggests unresolved autoimmune activity.

Adverse events

There were 541 adverse events (AEs) in 34 of the 35 evaluable patients receiving caplacizumab (97%) and 522 AEs in all 37 evaluable patients receiving placebo (100%). TTP exacerbations and relapses were not included as AEs.

The rate of AEs thought to be related to the study drug was 17% in the caplacizumab arm and 11% in the placebo arm. The rate of AEs that were possibly related was 54% and 8%, respectively. And the rate of serious AEs was 37% and 32%, respectively.

The rate of bleeding-related AEs was 54% in the caplacizumab arm and 38% in the placebo arm. Of the 101 bleeding-related AEs, 84 (83%) were reported as mild, 14 (14%) as moderate, and 3 (3%) as severe.

There were no deaths in the caplacizumab arm and 2 in the placebo arm. One death was due to severe, refractory TTP, and the other was due to cerebral hemorrhage.

Caplacizumab development

The results of this trial will serve as the basis for filing for conditional approval of caplacizumab in Europe in the first half of 2017, according to Ablynx. The company is planning to file in the US in 2018.

Ablynx has started a phase 3 trial of caplacizumab known as the HERCULES study. In this double-blind, placebo-controlled study, investigators are evaluating the safety and efficacy of caplacizumab, in conjunction with the standard of care, in patients with aTTP.

The study is expected to enroll 92 patients at clinical sites across 17 countries. Recruitment is expected to be complete by the end of 2017. ![]()

Results of a phase 2 trial suggest an investigational agent may improve upon standard care for acquired thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (aTTP).

The agent, caplacizumab, is an anti-von Willebrand factor, humanized, single-variable-domain immunoglobulin that works by inhibiting the interaction between ultralarge von Willebrand factor multimers and platelets.

In the phase 2 TITAN trial, caplacizumab plus standard care induced a faster resolution of aTTP episodes when compared to placebo plus standard care. However, caplacizumab was also associated with a higher risk of bleeding.

Flora Peyvandi, MD, PhD, of the University of Milan in Italy, and her colleagues reported these results in The New England Journal of Medicine. The study was supported by Ablynx, the company developing caplacizumab.

“Caplacizumab has the potential to become an important new component in the standard of care for patients with acquired TTP,” Dr Peyvandi said. “The results from the phase 2 TITAN study showed that caplacizumab acts quickly to control the critical acute phase of the disease and protects patients until immunosuppressive treatments take effect.”

TITAN was a single-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled study conducted at 56 centers around the world. The trial included 75 aTTP patients who were randomized to caplacizumab (n=36) or placebo (n=39), with all patients receiving the current standard of care (daily plasma exchange and immunosuppressive therapy).

Patients in the caplacizumab arm immediately received an intravenous bolus dose of caplacizumab at 10 mg and then a 10 mg subcutaneous dose of the drug daily until 30 days had elapsed after the final plasma exchange. Patients in the control arm received placebo at the same time points.

Response, recurrence, and relapse

The study’s primary endpoint was time to response (platelet count normalization). Patients in the caplacizumab arm had a 39% reduction in the median time to response compared to patients in the placebo arm (P=0.005).

Among the 69 patients who had not undergone a plasma-exchange session before enrollment, the median time to response was 3.0 days in the caplacizumab arm and 4.9 days in the placebo arm.

Among the 6 patients who did undergo a plasma-exchange session before enrollment, the median time to a response was 2.4 days in the caplacizumab arm and 4.3 days in the placebo arm.

The rate of confirmed response was 86.1% (n=31) in the caplacizumab arm and 71.8% (n=28) in the placebo arm.

One of the study’s secondary endpoints was exacerbation, which was defined as recurrent thrombocytopenia within 30 days of the end of daily plasma exchange that required reinitiation of daily exchange.

There were fewer exacerbations in the caplacizumab arm than the placebo arm—3 (8.3%) and 11 (28.2%), respectively.

Another secondary endpoint was relapse, which was defined as a TTP event occurring more than 30 days after the end of daily plasma exchange.

There were more relapses in the caplacizumab arm than the placebo arm—8 (22.2%) and 0, respectively. The investigators noted that 7 of the 8 patients had ADAMTS13 activity that remained below 10%, which suggests unresolved autoimmune activity.

Adverse events

There were 541 adverse events (AEs) in 34 of the 35 evaluable patients receiving caplacizumab (97%) and 522 AEs in all 37 evaluable patients receiving placebo (100%). TTP exacerbations and relapses were not included as AEs.

The rate of AEs thought to be related to the study drug was 17% in the caplacizumab arm and 11% in the placebo arm. The rate of AEs that were possibly related was 54% and 8%, respectively. And the rate of serious AEs was 37% and 32%, respectively.

The rate of bleeding-related AEs was 54% in the caplacizumab arm and 38% in the placebo arm. Of the 101 bleeding-related AEs, 84 (83%) were reported as mild, 14 (14%) as moderate, and 3 (3%) as severe.

There were no deaths in the caplacizumab arm and 2 in the placebo arm. One death was due to severe, refractory TTP, and the other was due to cerebral hemorrhage.

Caplacizumab development

The results of this trial will serve as the basis for filing for conditional approval of caplacizumab in Europe in the first half of 2017, according to Ablynx. The company is planning to file in the US in 2018.

Ablynx has started a phase 3 trial of caplacizumab known as the HERCULES study. In this double-blind, placebo-controlled study, investigators are evaluating the safety and efficacy of caplacizumab, in conjunction with the standard of care, in patients with aTTP.

The study is expected to enroll 92 patients at clinical sites across 17 countries. Recruitment is expected to be complete by the end of 2017. ![]()

Do we give too much iron?

A 69-year-old man is evaluated for fatigue. He undergoes a colonoscopy and is found to have a right-sided colon cancer. His hematocrit is 33 with an MCV of 72. His ferritin level is 3. What do you recommend to help with his iron deficiency?

A. Ferrous sulfate 325 mg daily.

B. Ferrous sulfate 325 mg b.i.d.

C. Ferrous sulfate 325 mg t.i.d.

Treatment of iron deficiency with oral iron has traditionally been done by giving 150-200 mg of elemental iron (which is equal to three 325 mg tablets of iron sulfate).1 This dosing regimen has considerable gastrointestinal side effects. Recent research into iron absorption suggests that the higher the dose of iron given, the more absorption may be hindered. In a study of 54 women who had low ferritin levels, lower daily doses of iron – and not giving it multiple times a day – led to better iron absorption.2

In a study of elderly patients with iron deficiency, 90 hospitalized elderly patients older than 80 years with iron deficiency anemia were randomized to receive elemental iron as 15 mg or 50 mg of liquid ferrous gluconate, or 150 mg of ferrous calcium citrate for 60 days.3 Two months of iron treatment raised hemoglobin and ferritin levels to a similar degree in all groups, with no significant differences between the 15-mg, 50-mg, and 150-mg groups.

There was a significant difference in abdominal discomfort, with much less (20%) in the patients who received 15 mg of ferrous gluconate, compared with 60% in those who received 50 mg and 70% in those receiving 150 mg (P less than .05 comparing 15 mg with 50 mg and 150 mg). Statistically significant differences were also seen for nausea/vomiting, constipation, and dropout, with much lower rates seen in the low-dose (15-mg) group.

In a study of iron supplementation in individuals undergoing blood donation, a single daily dose of iron was used (37.5 mg of elemental iron) in half of the subjects, with the rest of the subjects receiving no iron.4 The mean age of the participants was 48 years.

Subjects who received the once-daily low-dose iron recovered much more quickly toward predonation hematocrit than did those who did not receive the low-dose iron (time to 80% hemoglobin recovery, 32 days vs. 92 days in the non–iron treated patients, P = .02). The effect was more dramatic in subjects who started with a low ferritin level (defined as less than 26), where time to 80% hemoglobin recovery was 36 days in the iron-treated patients vs. 153 days for the no-iron group.

The results of this study are in line with what we know about avid iron absorption in iron deficient patients, and the success of low doses in a younger patient population is encouraging.

In a small study looking at two different doses of elemental iron for the treatment of iron deficiency, 24 women (ages 18-35 years) with iron deficiency were randomized to 60 mg or 80 mg of elemental iron or placebo for 16 weeks.5 There was no difference in normalization of ferritin levels in the women who received either dose of iron. There was also no difference in side effects between the groups.

This study is small and had minimal difference in iron dose. In addition, the dosing was given once a day for both groups. I suspect that the lack of difference in side effects was due to both the small size of the study and the minimal difference in iron dose.

What does this all mean? I think that the most appropriate dosing for oral iron replacement is a single daily low-dose iron preparation. Whether that dose is 15 mg of elemental iron to 68 mg of elemental iron (the amount in a 325-mg ferrous sulfate tablet) isn’t clear. Low doses appear to be effective, and avoiding high doses likely decreases side effects without sacrificing efficacy.

References

1. Fairbanks V.F., Beutler E. Iron deficiency, in “Williams Textbook of Hematology, 6th ed. Beutler E., Coller B.S., Lichtman M.A., Kipps T.J., eds. (New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001, pp. 460-2).

2. Blood. 2015 Oct 22;126(17):1981-9.

3. Am J Med. 2005 Oct;118(10):1142-7.

4. JAMA. 2015 Feb 10;313(6):575-83.

5. Nutrients. 2014 Apr 4;6(4):1394-405.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

A 69-year-old man is evaluated for fatigue. He undergoes a colonoscopy and is found to have a right-sided colon cancer. His hematocrit is 33 with an MCV of 72. His ferritin level is 3. What do you recommend to help with his iron deficiency?

A. Ferrous sulfate 325 mg daily.

B. Ferrous sulfate 325 mg b.i.d.

C. Ferrous sulfate 325 mg t.i.d.

Treatment of iron deficiency with oral iron has traditionally been done by giving 150-200 mg of elemental iron (which is equal to three 325 mg tablets of iron sulfate).1 This dosing regimen has considerable gastrointestinal side effects. Recent research into iron absorption suggests that the higher the dose of iron given, the more absorption may be hindered. In a study of 54 women who had low ferritin levels, lower daily doses of iron – and not giving it multiple times a day – led to better iron absorption.2

In a study of elderly patients with iron deficiency, 90 hospitalized elderly patients older than 80 years with iron deficiency anemia were randomized to receive elemental iron as 15 mg or 50 mg of liquid ferrous gluconate, or 150 mg of ferrous calcium citrate for 60 days.3 Two months of iron treatment raised hemoglobin and ferritin levels to a similar degree in all groups, with no significant differences between the 15-mg, 50-mg, and 150-mg groups.

There was a significant difference in abdominal discomfort, with much less (20%) in the patients who received 15 mg of ferrous gluconate, compared with 60% in those who received 50 mg and 70% in those receiving 150 mg (P less than .05 comparing 15 mg with 50 mg and 150 mg). Statistically significant differences were also seen for nausea/vomiting, constipation, and dropout, with much lower rates seen in the low-dose (15-mg) group.

In a study of iron supplementation in individuals undergoing blood donation, a single daily dose of iron was used (37.5 mg of elemental iron) in half of the subjects, with the rest of the subjects receiving no iron.4 The mean age of the participants was 48 years.

Subjects who received the once-daily low-dose iron recovered much more quickly toward predonation hematocrit than did those who did not receive the low-dose iron (time to 80% hemoglobin recovery, 32 days vs. 92 days in the non–iron treated patients, P = .02). The effect was more dramatic in subjects who started with a low ferritin level (defined as less than 26), where time to 80% hemoglobin recovery was 36 days in the iron-treated patients vs. 153 days for the no-iron group.

The results of this study are in line with what we know about avid iron absorption in iron deficient patients, and the success of low doses in a younger patient population is encouraging.

In a small study looking at two different doses of elemental iron for the treatment of iron deficiency, 24 women (ages 18-35 years) with iron deficiency were randomized to 60 mg or 80 mg of elemental iron or placebo for 16 weeks.5 There was no difference in normalization of ferritin levels in the women who received either dose of iron. There was also no difference in side effects between the groups.

This study is small and had minimal difference in iron dose. In addition, the dosing was given once a day for both groups. I suspect that the lack of difference in side effects was due to both the small size of the study and the minimal difference in iron dose.

What does this all mean? I think that the most appropriate dosing for oral iron replacement is a single daily low-dose iron preparation. Whether that dose is 15 mg of elemental iron to 68 mg of elemental iron (the amount in a 325-mg ferrous sulfate tablet) isn’t clear. Low doses appear to be effective, and avoiding high doses likely decreases side effects without sacrificing efficacy.

References

1. Fairbanks V.F., Beutler E. Iron deficiency, in “Williams Textbook of Hematology, 6th ed. Beutler E., Coller B.S., Lichtman M.A., Kipps T.J., eds. (New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001, pp. 460-2).

2. Blood. 2015 Oct 22;126(17):1981-9.

3. Am J Med. 2005 Oct;118(10):1142-7.

4. JAMA. 2015 Feb 10;313(6):575-83.

5. Nutrients. 2014 Apr 4;6(4):1394-405.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

A 69-year-old man is evaluated for fatigue. He undergoes a colonoscopy and is found to have a right-sided colon cancer. His hematocrit is 33 with an MCV of 72. His ferritin level is 3. What do you recommend to help with his iron deficiency?

A. Ferrous sulfate 325 mg daily.

B. Ferrous sulfate 325 mg b.i.d.

C. Ferrous sulfate 325 mg t.i.d.

Treatment of iron deficiency with oral iron has traditionally been done by giving 150-200 mg of elemental iron (which is equal to three 325 mg tablets of iron sulfate).1 This dosing regimen has considerable gastrointestinal side effects. Recent research into iron absorption suggests that the higher the dose of iron given, the more absorption may be hindered. In a study of 54 women who had low ferritin levels, lower daily doses of iron – and not giving it multiple times a day – led to better iron absorption.2

In a study of elderly patients with iron deficiency, 90 hospitalized elderly patients older than 80 years with iron deficiency anemia were randomized to receive elemental iron as 15 mg or 50 mg of liquid ferrous gluconate, or 150 mg of ferrous calcium citrate for 60 days.3 Two months of iron treatment raised hemoglobin and ferritin levels to a similar degree in all groups, with no significant differences between the 15-mg, 50-mg, and 150-mg groups.

There was a significant difference in abdominal discomfort, with much less (20%) in the patients who received 15 mg of ferrous gluconate, compared with 60% in those who received 50 mg and 70% in those receiving 150 mg (P less than .05 comparing 15 mg with 50 mg and 150 mg). Statistically significant differences were also seen for nausea/vomiting, constipation, and dropout, with much lower rates seen in the low-dose (15-mg) group.

In a study of iron supplementation in individuals undergoing blood donation, a single daily dose of iron was used (37.5 mg of elemental iron) in half of the subjects, with the rest of the subjects receiving no iron.4 The mean age of the participants was 48 years.

Subjects who received the once-daily low-dose iron recovered much more quickly toward predonation hematocrit than did those who did not receive the low-dose iron (time to 80% hemoglobin recovery, 32 days vs. 92 days in the non–iron treated patients, P = .02). The effect was more dramatic in subjects who started with a low ferritin level (defined as less than 26), where time to 80% hemoglobin recovery was 36 days in the iron-treated patients vs. 153 days for the no-iron group.

The results of this study are in line with what we know about avid iron absorption in iron deficient patients, and the success of low doses in a younger patient population is encouraging.

In a small study looking at two different doses of elemental iron for the treatment of iron deficiency, 24 women (ages 18-35 years) with iron deficiency were randomized to 60 mg or 80 mg of elemental iron or placebo for 16 weeks.5 There was no difference in normalization of ferritin levels in the women who received either dose of iron. There was also no difference in side effects between the groups.

This study is small and had minimal difference in iron dose. In addition, the dosing was given once a day for both groups. I suspect that the lack of difference in side effects was due to both the small size of the study and the minimal difference in iron dose.

What does this all mean? I think that the most appropriate dosing for oral iron replacement is a single daily low-dose iron preparation. Whether that dose is 15 mg of elemental iron to 68 mg of elemental iron (the amount in a 325-mg ferrous sulfate tablet) isn’t clear. Low doses appear to be effective, and avoiding high doses likely decreases side effects without sacrificing efficacy.

References

1. Fairbanks V.F., Beutler E. Iron deficiency, in “Williams Textbook of Hematology, 6th ed. Beutler E., Coller B.S., Lichtman M.A., Kipps T.J., eds. (New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001, pp. 460-2).

2. Blood. 2015 Oct 22;126(17):1981-9.

3. Am J Med. 2005 Oct;118(10):1142-7.

4. JAMA. 2015 Feb 10;313(6):575-83.

5. Nutrients. 2014 Apr 4;6(4):1394-405.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

Generic imatinib launched with savings program

Photo by Rhoda Baer

Sun Pharma has announced the US launch of imatinib mesylate tablets, which are a generic version of Novartis’s Gleevec, for indications approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

As part of this launch, Sun Pharma has rolled out a savings card program. The goal is to provide greater access to imatinib mesylate tablets for patients who have commercial insurance, but their out-of-pocket cost may exceed an affordable amount.

Sun Pharma’s Imatinib Mesylate Savings Card will reduce patient’s co-payment to $10. The card will also offer patients an additional savings benefit of up to $700 for a 30-day fill to offset any additional out-of-pocket cost should they be required to meet their deductible or co-insurance.

Participating pharmacies across the US can use the patient’s card as part of this program.

Eligible patients can participate in Sun Pharma’s Imatinib Mesylate Savings Card program by registering at www.imatinibrx.com or by requesting a savings card from their oncologist. Sun Pharma will be supplying its Imatinib Mesylate Savings Cards to more than 4500 oncologists.

Sun Pharma has established a Hub service so patients can call and speak with a trained healthcare professional about imatinib mesylate. The number is 1-844-502-5950.