User login

NIAID trial to test asthma drug in disadvantaged urban children

The Prevention of Asthma Exacerbations Using Dupilumab in Urban Children and Adolescents (PANDA) trial was launched in order to examine the effects of treatment on children with poorly controlled allergic asthma who live in low-income urban environments in the United States, according to the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Black and Hispanic children who live in these environments are at particularly high risk for asthma and are prone to attacks. These children and adolescents often have many allergies and are exposed to both high levels of indoor allergens and traffic-related pollution, which can make their asthma even more difficult to control, according to a June 2 NIAID press release.

PANDA is a multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial of dupilumab adjunctive therapy for the reduction of asthma exacerbations in urban children and adolescents 6-17 years with T2-high exacerbation-prone asthma. Approximately 240 participants will be randomized 2:1 to one of two study arms: 1) guidelines-based asthma treatment plus dupilumab, or 2) guidelines-based asthma treatment plus placebo. The planned study treatment will continue for 1 year with an additional 3 months of follow-up following completion of study treatment, according to the study details.

In an earlier study, NIAID-supported investigators identified numerous networks of genes that are activated together and are associated with asthma attacks in minority children and adolescents living in low-income urban settings

“We need to find out how well approved asthma drugs work for disadvantaged children of color living in urban areas, and whether biological markers can help predict how the drugs affect their asthma,” NIAID director Anthony S. Fauci, MD, said in the release. “The PANDA trial is an important step toward these goals.”

Participant criteria for the study include children of either sex, ages 6-17 years, who live in prespecified urban areas. Participants must have a diagnosis of asthma and must have had at least two asthma exacerbations in the prior year (defined as a requirement for systemic corticosteroids and/or hospitalization). At the screening visit, participants must have the following requirements for asthma controller medication: For children ages 6-11 years: treatments with at least fluticasone 250 mcg dry powder inhaler (DPI) one puff twice daily or its equivalent; for children ages 12 years and older, treatment with at least fluticasone 250 mcg plus long-acting beta agonist (LABA) DPI one puff twice daily or its equivalent.

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT05347771Location: The NIAID-funded Childhood Asthma in Urban Settings (CAUSE) Network is conducting the study at seven medical centers located in Aurora, Colo.; Boston; Chicago; Cincinnati; New York, and Washington, D.C.

Sponsor: NIAID, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals and Sanofi are cofunding the phase 2 trial.

Study start date: April 2022

Expected completion Date: March 31, 2025

The Prevention of Asthma Exacerbations Using Dupilumab in Urban Children and Adolescents (PANDA) trial was launched in order to examine the effects of treatment on children with poorly controlled allergic asthma who live in low-income urban environments in the United States, according to the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Black and Hispanic children who live in these environments are at particularly high risk for asthma and are prone to attacks. These children and adolescents often have many allergies and are exposed to both high levels of indoor allergens and traffic-related pollution, which can make their asthma even more difficult to control, according to a June 2 NIAID press release.

PANDA is a multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial of dupilumab adjunctive therapy for the reduction of asthma exacerbations in urban children and adolescents 6-17 years with T2-high exacerbation-prone asthma. Approximately 240 participants will be randomized 2:1 to one of two study arms: 1) guidelines-based asthma treatment plus dupilumab, or 2) guidelines-based asthma treatment plus placebo. The planned study treatment will continue for 1 year with an additional 3 months of follow-up following completion of study treatment, according to the study details.

In an earlier study, NIAID-supported investigators identified numerous networks of genes that are activated together and are associated with asthma attacks in minority children and adolescents living in low-income urban settings

“We need to find out how well approved asthma drugs work for disadvantaged children of color living in urban areas, and whether biological markers can help predict how the drugs affect their asthma,” NIAID director Anthony S. Fauci, MD, said in the release. “The PANDA trial is an important step toward these goals.”

Participant criteria for the study include children of either sex, ages 6-17 years, who live in prespecified urban areas. Participants must have a diagnosis of asthma and must have had at least two asthma exacerbations in the prior year (defined as a requirement for systemic corticosteroids and/or hospitalization). At the screening visit, participants must have the following requirements for asthma controller medication: For children ages 6-11 years: treatments with at least fluticasone 250 mcg dry powder inhaler (DPI) one puff twice daily or its equivalent; for children ages 12 years and older, treatment with at least fluticasone 250 mcg plus long-acting beta agonist (LABA) DPI one puff twice daily or its equivalent.

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT05347771Location: The NIAID-funded Childhood Asthma in Urban Settings (CAUSE) Network is conducting the study at seven medical centers located in Aurora, Colo.; Boston; Chicago; Cincinnati; New York, and Washington, D.C.

Sponsor: NIAID, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals and Sanofi are cofunding the phase 2 trial.

Study start date: April 2022

Expected completion Date: March 31, 2025

The Prevention of Asthma Exacerbations Using Dupilumab in Urban Children and Adolescents (PANDA) trial was launched in order to examine the effects of treatment on children with poorly controlled allergic asthma who live in low-income urban environments in the United States, according to the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Black and Hispanic children who live in these environments are at particularly high risk for asthma and are prone to attacks. These children and adolescents often have many allergies and are exposed to both high levels of indoor allergens and traffic-related pollution, which can make their asthma even more difficult to control, according to a June 2 NIAID press release.

PANDA is a multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial of dupilumab adjunctive therapy for the reduction of asthma exacerbations in urban children and adolescents 6-17 years with T2-high exacerbation-prone asthma. Approximately 240 participants will be randomized 2:1 to one of two study arms: 1) guidelines-based asthma treatment plus dupilumab, or 2) guidelines-based asthma treatment plus placebo. The planned study treatment will continue for 1 year with an additional 3 months of follow-up following completion of study treatment, according to the study details.

In an earlier study, NIAID-supported investigators identified numerous networks of genes that are activated together and are associated with asthma attacks in minority children and adolescents living in low-income urban settings

“We need to find out how well approved asthma drugs work for disadvantaged children of color living in urban areas, and whether biological markers can help predict how the drugs affect their asthma,” NIAID director Anthony S. Fauci, MD, said in the release. “The PANDA trial is an important step toward these goals.”

Participant criteria for the study include children of either sex, ages 6-17 years, who live in prespecified urban areas. Participants must have a diagnosis of asthma and must have had at least two asthma exacerbations in the prior year (defined as a requirement for systemic corticosteroids and/or hospitalization). At the screening visit, participants must have the following requirements for asthma controller medication: For children ages 6-11 years: treatments with at least fluticasone 250 mcg dry powder inhaler (DPI) one puff twice daily or its equivalent; for children ages 12 years and older, treatment with at least fluticasone 250 mcg plus long-acting beta agonist (LABA) DPI one puff twice daily or its equivalent.

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT05347771Location: The NIAID-funded Childhood Asthma in Urban Settings (CAUSE) Network is conducting the study at seven medical centers located in Aurora, Colo.; Boston; Chicago; Cincinnati; New York, and Washington, D.C.

Sponsor: NIAID, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals and Sanofi are cofunding the phase 2 trial.

Study start date: April 2022

Expected completion Date: March 31, 2025

‘Smart inhalers’ may help diagnose and treat asthma – if used

After years going on and off medications for occasional asthma symptoms, things went downhill for Brian Blome in November 2020. The retired carpenter started feeling short of breath and wheezing during bike rides. At home, he struggled with chores.

“I was having a hard time climbing a flight of stairs, just doing laundry,” said Mr. Blome, who lives in the Chicago suburb of Palatine.

To get things under control, he saw an allergist and started regular medications – two tablets, two nasal sprays, and inhaled corticosteroids each day, plus an albuterol inhaler for flare-ups.

The inhalers have an extra feature: an electronic monitor that attaches to the device and automatically tracks where and when the medication is used. Bluetooth sends this information to an app on the patient’s mobile phone and to a dashboard where the medical team can see, at a glance, when symptoms are popping up and how regularly medications are taken – leading to the devices often being called “smart inhalers.”

At the 2022 American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology conference in Phoenix, researchers explained how digital monitoring devices can help diagnose and treat hard-to-control asthma, potentially reducing the need for oral steroids or biologic therapies.

Even though electric monitors have been on the market for years, their use has been slow to catch on because of uncertainties around insurance coverage, liability, and how to manage and best use the data. One recent study said these devices cost $100-$500, but that price depends on many things, such as insurance.

About 17% of adult asthma patients have “difficult-to-control” asthma, meaning they limit their activity because of breathing symptoms and use reliever medications multiple times a week.

But research suggests that correcting inhaling technique and sticking to the use of the medications can cut that 17% down to just 3.7%, said Mr. Blome’s allergist, Giselle Mosnaim, MD, of NorthShore University HealthSystem in Glenview, Ill. Dr. Mosnaim spoke about digital monitoring at a conference session on digital technologies for asthma management.

A study of more than 5,000 asthma patients “showed that, if you have critical errors in inhaler technique, this leads to worse asthma outcomes and increased asthma exacerbations,” she said. It also shows that, despite new devices and new technologies, “we still have poor inhaler technique.”

Yet adherence is poorly gauged by doctors and patient self-reporting. “The ideal measure of adherence should be objective, accurate, and unobtrusive to minimize impact on patient behavior and allow reliable data collection in real-world settings,” Dr. Mosnaim said. “So electronic medication monitors are the gold standard.”

Improving use

Patients not following instructions or guidelines “is something we saw nonstop with kids,” said Caroline Moassessi, founder of the allergy and asthma blog Gratefulfoodie.com who formerly served on a regional board of the American Lung Association. She’s also the mother of two asthmatic children, now in college, who years ago used electronic medication monitors as part of a research trial.

They were “unimpressed – mostly since I think they thought their asthma was controlled,” she said. “When patients are not in crisis, they don’t manage their asthma well.”

Even in research studies such as the one Rachelle Ramsey, PhD, presented at the conference, it’s not only hard to determine if better adherence leads to improved health, but when.

“For example, does your adherence this week impact your asthma control this week, or does it impact your asthma control next week? Or is it even further out? Do you need to have some level of adherence over the course of a month in order to have better outcomes at the end of that month?” said Dr. Ramsey, a pediatric research psychologist at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. “I think it’s a little complicated.”

That said, results from several small studies do show a connection between remote monitoring and better clinical outcomes. One study enrolled asthma patients in the United Kingdom, and another was done by Dr. Mosnaim with Chicago-area patients.

In the U.K. quality improvement project, nurses asked patients with difficult-to-control asthma if they knew how to use their inhalers and were following treatment guidelines.

Those who said “yes” were invited to swap their steroid/inhalers for a controller fitted with a device that tracks use and measures acoustics to test inhaler technique. After 28 days of monitoring, many people in the study had better clinical outcomes.

And after 3 months of digital monitoring, patients didn’t use their rescue medication quite as often.

Mr. Blome has seen a marked improvement in his asthma since starting regular appointments and getting back on daily medications a year and a half ago. He says that now and then, he has wheezing and shortness of breath, usually while biking or exercising. But those symptoms aren’t as severe or frequent as before.

From a doctor’s perspective, “digital inhaler systems allow me to discern patterns in order to determine what triggers his asthma symptoms and to adjust medications at different times of the year,” Dr. Mosnaim said.

Electronic systems can monitor pollen counts and air quality as well as how often a patient uses a quick reliever medication. Thus, she said, tracking these measures year-round could raise attention to impending asthma attacks and suggest when to increase the dose of controller medications or add other treatments.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

After years going on and off medications for occasional asthma symptoms, things went downhill for Brian Blome in November 2020. The retired carpenter started feeling short of breath and wheezing during bike rides. At home, he struggled with chores.

“I was having a hard time climbing a flight of stairs, just doing laundry,” said Mr. Blome, who lives in the Chicago suburb of Palatine.

To get things under control, he saw an allergist and started regular medications – two tablets, two nasal sprays, and inhaled corticosteroids each day, plus an albuterol inhaler for flare-ups.

The inhalers have an extra feature: an electronic monitor that attaches to the device and automatically tracks where and when the medication is used. Bluetooth sends this information to an app on the patient’s mobile phone and to a dashboard where the medical team can see, at a glance, when symptoms are popping up and how regularly medications are taken – leading to the devices often being called “smart inhalers.”

At the 2022 American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology conference in Phoenix, researchers explained how digital monitoring devices can help diagnose and treat hard-to-control asthma, potentially reducing the need for oral steroids or biologic therapies.

Even though electric monitors have been on the market for years, their use has been slow to catch on because of uncertainties around insurance coverage, liability, and how to manage and best use the data. One recent study said these devices cost $100-$500, but that price depends on many things, such as insurance.

About 17% of adult asthma patients have “difficult-to-control” asthma, meaning they limit their activity because of breathing symptoms and use reliever medications multiple times a week.

But research suggests that correcting inhaling technique and sticking to the use of the medications can cut that 17% down to just 3.7%, said Mr. Blome’s allergist, Giselle Mosnaim, MD, of NorthShore University HealthSystem in Glenview, Ill. Dr. Mosnaim spoke about digital monitoring at a conference session on digital technologies for asthma management.

A study of more than 5,000 asthma patients “showed that, if you have critical errors in inhaler technique, this leads to worse asthma outcomes and increased asthma exacerbations,” she said. It also shows that, despite new devices and new technologies, “we still have poor inhaler technique.”

Yet adherence is poorly gauged by doctors and patient self-reporting. “The ideal measure of adherence should be objective, accurate, and unobtrusive to minimize impact on patient behavior and allow reliable data collection in real-world settings,” Dr. Mosnaim said. “So electronic medication monitors are the gold standard.”

Improving use

Patients not following instructions or guidelines “is something we saw nonstop with kids,” said Caroline Moassessi, founder of the allergy and asthma blog Gratefulfoodie.com who formerly served on a regional board of the American Lung Association. She’s also the mother of two asthmatic children, now in college, who years ago used electronic medication monitors as part of a research trial.

They were “unimpressed – mostly since I think they thought their asthma was controlled,” she said. “When patients are not in crisis, they don’t manage their asthma well.”

Even in research studies such as the one Rachelle Ramsey, PhD, presented at the conference, it’s not only hard to determine if better adherence leads to improved health, but when.

“For example, does your adherence this week impact your asthma control this week, or does it impact your asthma control next week? Or is it even further out? Do you need to have some level of adherence over the course of a month in order to have better outcomes at the end of that month?” said Dr. Ramsey, a pediatric research psychologist at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. “I think it’s a little complicated.”

That said, results from several small studies do show a connection between remote monitoring and better clinical outcomes. One study enrolled asthma patients in the United Kingdom, and another was done by Dr. Mosnaim with Chicago-area patients.

In the U.K. quality improvement project, nurses asked patients with difficult-to-control asthma if they knew how to use their inhalers and were following treatment guidelines.

Those who said “yes” were invited to swap their steroid/inhalers for a controller fitted with a device that tracks use and measures acoustics to test inhaler technique. After 28 days of monitoring, many people in the study had better clinical outcomes.

And after 3 months of digital monitoring, patients didn’t use their rescue medication quite as often.

Mr. Blome has seen a marked improvement in his asthma since starting regular appointments and getting back on daily medications a year and a half ago. He says that now and then, he has wheezing and shortness of breath, usually while biking or exercising. But those symptoms aren’t as severe or frequent as before.

From a doctor’s perspective, “digital inhaler systems allow me to discern patterns in order to determine what triggers his asthma symptoms and to adjust medications at different times of the year,” Dr. Mosnaim said.

Electronic systems can monitor pollen counts and air quality as well as how often a patient uses a quick reliever medication. Thus, she said, tracking these measures year-round could raise attention to impending asthma attacks and suggest when to increase the dose of controller medications or add other treatments.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

After years going on and off medications for occasional asthma symptoms, things went downhill for Brian Blome in November 2020. The retired carpenter started feeling short of breath and wheezing during bike rides. At home, he struggled with chores.

“I was having a hard time climbing a flight of stairs, just doing laundry,” said Mr. Blome, who lives in the Chicago suburb of Palatine.

To get things under control, he saw an allergist and started regular medications – two tablets, two nasal sprays, and inhaled corticosteroids each day, plus an albuterol inhaler for flare-ups.

The inhalers have an extra feature: an electronic monitor that attaches to the device and automatically tracks where and when the medication is used. Bluetooth sends this information to an app on the patient’s mobile phone and to a dashboard where the medical team can see, at a glance, when symptoms are popping up and how regularly medications are taken – leading to the devices often being called “smart inhalers.”

At the 2022 American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology conference in Phoenix, researchers explained how digital monitoring devices can help diagnose and treat hard-to-control asthma, potentially reducing the need for oral steroids or biologic therapies.

Even though electric monitors have been on the market for years, their use has been slow to catch on because of uncertainties around insurance coverage, liability, and how to manage and best use the data. One recent study said these devices cost $100-$500, but that price depends on many things, such as insurance.

About 17% of adult asthma patients have “difficult-to-control” asthma, meaning they limit their activity because of breathing symptoms and use reliever medications multiple times a week.

But research suggests that correcting inhaling technique and sticking to the use of the medications can cut that 17% down to just 3.7%, said Mr. Blome’s allergist, Giselle Mosnaim, MD, of NorthShore University HealthSystem in Glenview, Ill. Dr. Mosnaim spoke about digital monitoring at a conference session on digital technologies for asthma management.

A study of more than 5,000 asthma patients “showed that, if you have critical errors in inhaler technique, this leads to worse asthma outcomes and increased asthma exacerbations,” she said. It also shows that, despite new devices and new technologies, “we still have poor inhaler technique.”

Yet adherence is poorly gauged by doctors and patient self-reporting. “The ideal measure of adherence should be objective, accurate, and unobtrusive to minimize impact on patient behavior and allow reliable data collection in real-world settings,” Dr. Mosnaim said. “So electronic medication monitors are the gold standard.”

Improving use

Patients not following instructions or guidelines “is something we saw nonstop with kids,” said Caroline Moassessi, founder of the allergy and asthma blog Gratefulfoodie.com who formerly served on a regional board of the American Lung Association. She’s also the mother of two asthmatic children, now in college, who years ago used electronic medication monitors as part of a research trial.

They were “unimpressed – mostly since I think they thought their asthma was controlled,” she said. “When patients are not in crisis, they don’t manage their asthma well.”

Even in research studies such as the one Rachelle Ramsey, PhD, presented at the conference, it’s not only hard to determine if better adherence leads to improved health, but when.

“For example, does your adherence this week impact your asthma control this week, or does it impact your asthma control next week? Or is it even further out? Do you need to have some level of adherence over the course of a month in order to have better outcomes at the end of that month?” said Dr. Ramsey, a pediatric research psychologist at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. “I think it’s a little complicated.”

That said, results from several small studies do show a connection between remote monitoring and better clinical outcomes. One study enrolled asthma patients in the United Kingdom, and another was done by Dr. Mosnaim with Chicago-area patients.

In the U.K. quality improvement project, nurses asked patients with difficult-to-control asthma if they knew how to use their inhalers and were following treatment guidelines.

Those who said “yes” were invited to swap their steroid/inhalers for a controller fitted with a device that tracks use and measures acoustics to test inhaler technique. After 28 days of monitoring, many people in the study had better clinical outcomes.

And after 3 months of digital monitoring, patients didn’t use their rescue medication quite as often.

Mr. Blome has seen a marked improvement in his asthma since starting regular appointments and getting back on daily medications a year and a half ago. He says that now and then, he has wheezing and shortness of breath, usually while biking or exercising. But those symptoms aren’t as severe or frequent as before.

From a doctor’s perspective, “digital inhaler systems allow me to discern patterns in order to determine what triggers his asthma symptoms and to adjust medications at different times of the year,” Dr. Mosnaim said.

Electronic systems can monitor pollen counts and air quality as well as how often a patient uses a quick reliever medication. Thus, she said, tracking these measures year-round could raise attention to impending asthma attacks and suggest when to increase the dose of controller medications or add other treatments.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Food allergy risk not greater in C-section infants

Cesarean births are not likely linked to an elevated risk of food allergy during the first year of life, an Australian study found.

Published online in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, the findings may help assess the risks and benefits of cesarean delivery and reassure women who require it that their babies are not more likely to develop food allergy, according to Rachel L. Peters, PhD, an epidemiologist at the Murdoch Child Research Institute (MCRI) in Melbourne, and colleagues.

Dr. Peters’ group undertook the analysis to clarify a possible association between mode of delivery and food allergy risk, which has remained unclear owing to the absence of studies with both challenge-proven food allergy outcomes and detailed information on the type and timing of cesarean delivery.

“The infant immune system undergoes rapid development during the neonatal period,” Dr. Peters said in an MCRI press release, and the mode of delivery may interfere with the normal development of the immune system. “Babies born by cesarean have less exposure to the bacteria from the mother’s gut and vagina, which influence the composition of the baby’s microbiome and immune system development. However, this doesn’t appear to play a major role in the development of food allergy,” she said.

The HealthNuts study

In the period 2007-2011, the longitudinal population-based HealthNuts cohort study enrolled 5,276 12-month-olds who underwent skin prick testing and oral food challenge for sensitization to egg, peanut, sesame, and either shellfish or cow’s milk. It linked the resulting data to additional birth statistics from the Victorian Perinatal Data Collection when children turned 6.

Birth data were obtained on 2,045 babies, and in this subgroup with linked data, 30% were born by cesarean – similar to the 31.7% of U.S. cesarean births in 2019 – and 12.7% of these had food allergy versus 13.2% of those delivered vaginally.

Compared with vaginal birth, C-section was not associated with the risk of food allergy (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 0.95, 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.70-0.30).

Nor did the timing of the C-section have an effect. Cesarean delivery either before labor or after onset of labor was not associated with the risk of food allergy (aOR, 0.83, 95% CI, 0.55-1.23) and aOR, 1.13, 95% CI, 0.75-1.72), respectively.

Compared with vaginal delivery, elective or emergency cesarean was not associated with food allergy risk (aOR, 1.05, 95% CI, 0.71-1.55, and aOR, 0.86, 95% CI, 0.56-1.31).

Similarly, no evidence emerged of an effect modification by breastfeeding, older siblings, pet dog ownership, or maternal allergy.

“This study is helpful because in addition to blood and skin tests, it also used food challenge, which is the gold standard,” Terri Brown-Whitehorn, MD, an attending physician in the division of allergy and immunology at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, said in an interview. “If no actual food is given, the other tests could lead to false positives.”

Dr. Brown-Whitehorn, who was not involved in the MCRI research, said the findings are not likely to affect most decisions about C-sections because most are not voluntary. “But if a mother had a first baby by emergency cesarean section, she might be given the option of having the next one by the same method.”

She said the current advice is to introduce even high-risk foods to a child’s diet early on to ward off the development of food allergies.

According to the microbial exposure hypothesis, it was previously thought that a potential link between cesarean birth and allergy might reflect differences in early exposure to maternal flora beneficial to the immune system in the vagina during delivery. A C-section might bypass the opportunity for neonatal gut colonization with maternal gut and vaginal flora, thereby raising allergy risk. A 2018 meta-analysis, for example, suggested cesarean birth could raise the risk for food allergies by 21%.

In other research from HealthNuts, 30% of child peanut allergy and 90% of egg allergy appear to resolve naturally by age 6. These numbers are somewhat higher than what Dr. Brown-Whitehorn sees. “We find that about 20% of peanut allergies and about 70% or 80% – maybe a bit less – of egg allergies resolve by age 6.”

This research was supported by the National Health & Medical Research Council of Australia, the Ilhan Food Allergy Foundation, AnaphylaxiStop, the Charles and Sylvia Viertel Medical Research Foundation, the Victorian Government’s Operational Infrastructure Support Program, and the Melbourne Children’s Clinician-Scientist Fellowship.

Dr. Peters disclosed no competing interests. Several coauthors reported research support or employment with private companies and one is the inventor of an MCRI-held patent. Dr. Brown-Whitehorn had no competing interests to disclose.

Cesarean births are not likely linked to an elevated risk of food allergy during the first year of life, an Australian study found.

Published online in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, the findings may help assess the risks and benefits of cesarean delivery and reassure women who require it that their babies are not more likely to develop food allergy, according to Rachel L. Peters, PhD, an epidemiologist at the Murdoch Child Research Institute (MCRI) in Melbourne, and colleagues.

Dr. Peters’ group undertook the analysis to clarify a possible association between mode of delivery and food allergy risk, which has remained unclear owing to the absence of studies with both challenge-proven food allergy outcomes and detailed information on the type and timing of cesarean delivery.

“The infant immune system undergoes rapid development during the neonatal period,” Dr. Peters said in an MCRI press release, and the mode of delivery may interfere with the normal development of the immune system. “Babies born by cesarean have less exposure to the bacteria from the mother’s gut and vagina, which influence the composition of the baby’s microbiome and immune system development. However, this doesn’t appear to play a major role in the development of food allergy,” she said.

The HealthNuts study

In the period 2007-2011, the longitudinal population-based HealthNuts cohort study enrolled 5,276 12-month-olds who underwent skin prick testing and oral food challenge for sensitization to egg, peanut, sesame, and either shellfish or cow’s milk. It linked the resulting data to additional birth statistics from the Victorian Perinatal Data Collection when children turned 6.

Birth data were obtained on 2,045 babies, and in this subgroup with linked data, 30% were born by cesarean – similar to the 31.7% of U.S. cesarean births in 2019 – and 12.7% of these had food allergy versus 13.2% of those delivered vaginally.

Compared with vaginal birth, C-section was not associated with the risk of food allergy (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 0.95, 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.70-0.30).

Nor did the timing of the C-section have an effect. Cesarean delivery either before labor or after onset of labor was not associated with the risk of food allergy (aOR, 0.83, 95% CI, 0.55-1.23) and aOR, 1.13, 95% CI, 0.75-1.72), respectively.

Compared with vaginal delivery, elective or emergency cesarean was not associated with food allergy risk (aOR, 1.05, 95% CI, 0.71-1.55, and aOR, 0.86, 95% CI, 0.56-1.31).

Similarly, no evidence emerged of an effect modification by breastfeeding, older siblings, pet dog ownership, or maternal allergy.

“This study is helpful because in addition to blood and skin tests, it also used food challenge, which is the gold standard,” Terri Brown-Whitehorn, MD, an attending physician in the division of allergy and immunology at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, said in an interview. “If no actual food is given, the other tests could lead to false positives.”

Dr. Brown-Whitehorn, who was not involved in the MCRI research, said the findings are not likely to affect most decisions about C-sections because most are not voluntary. “But if a mother had a first baby by emergency cesarean section, she might be given the option of having the next one by the same method.”

She said the current advice is to introduce even high-risk foods to a child’s diet early on to ward off the development of food allergies.

According to the microbial exposure hypothesis, it was previously thought that a potential link between cesarean birth and allergy might reflect differences in early exposure to maternal flora beneficial to the immune system in the vagina during delivery. A C-section might bypass the opportunity for neonatal gut colonization with maternal gut and vaginal flora, thereby raising allergy risk. A 2018 meta-analysis, for example, suggested cesarean birth could raise the risk for food allergies by 21%.

In other research from HealthNuts, 30% of child peanut allergy and 90% of egg allergy appear to resolve naturally by age 6. These numbers are somewhat higher than what Dr. Brown-Whitehorn sees. “We find that about 20% of peanut allergies and about 70% or 80% – maybe a bit less – of egg allergies resolve by age 6.”

This research was supported by the National Health & Medical Research Council of Australia, the Ilhan Food Allergy Foundation, AnaphylaxiStop, the Charles and Sylvia Viertel Medical Research Foundation, the Victorian Government’s Operational Infrastructure Support Program, and the Melbourne Children’s Clinician-Scientist Fellowship.

Dr. Peters disclosed no competing interests. Several coauthors reported research support or employment with private companies and one is the inventor of an MCRI-held patent. Dr. Brown-Whitehorn had no competing interests to disclose.

Cesarean births are not likely linked to an elevated risk of food allergy during the first year of life, an Australian study found.

Published online in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, the findings may help assess the risks and benefits of cesarean delivery and reassure women who require it that their babies are not more likely to develop food allergy, according to Rachel L. Peters, PhD, an epidemiologist at the Murdoch Child Research Institute (MCRI) in Melbourne, and colleagues.

Dr. Peters’ group undertook the analysis to clarify a possible association between mode of delivery and food allergy risk, which has remained unclear owing to the absence of studies with both challenge-proven food allergy outcomes and detailed information on the type and timing of cesarean delivery.

“The infant immune system undergoes rapid development during the neonatal period,” Dr. Peters said in an MCRI press release, and the mode of delivery may interfere with the normal development of the immune system. “Babies born by cesarean have less exposure to the bacteria from the mother’s gut and vagina, which influence the composition of the baby’s microbiome and immune system development. However, this doesn’t appear to play a major role in the development of food allergy,” she said.

The HealthNuts study

In the period 2007-2011, the longitudinal population-based HealthNuts cohort study enrolled 5,276 12-month-olds who underwent skin prick testing and oral food challenge for sensitization to egg, peanut, sesame, and either shellfish or cow’s milk. It linked the resulting data to additional birth statistics from the Victorian Perinatal Data Collection when children turned 6.

Birth data were obtained on 2,045 babies, and in this subgroup with linked data, 30% were born by cesarean – similar to the 31.7% of U.S. cesarean births in 2019 – and 12.7% of these had food allergy versus 13.2% of those delivered vaginally.

Compared with vaginal birth, C-section was not associated with the risk of food allergy (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 0.95, 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.70-0.30).

Nor did the timing of the C-section have an effect. Cesarean delivery either before labor or after onset of labor was not associated with the risk of food allergy (aOR, 0.83, 95% CI, 0.55-1.23) and aOR, 1.13, 95% CI, 0.75-1.72), respectively.

Compared with vaginal delivery, elective or emergency cesarean was not associated with food allergy risk (aOR, 1.05, 95% CI, 0.71-1.55, and aOR, 0.86, 95% CI, 0.56-1.31).

Similarly, no evidence emerged of an effect modification by breastfeeding, older siblings, pet dog ownership, or maternal allergy.

“This study is helpful because in addition to blood and skin tests, it also used food challenge, which is the gold standard,” Terri Brown-Whitehorn, MD, an attending physician in the division of allergy and immunology at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, said in an interview. “If no actual food is given, the other tests could lead to false positives.”

Dr. Brown-Whitehorn, who was not involved in the MCRI research, said the findings are not likely to affect most decisions about C-sections because most are not voluntary. “But if a mother had a first baby by emergency cesarean section, she might be given the option of having the next one by the same method.”

She said the current advice is to introduce even high-risk foods to a child’s diet early on to ward off the development of food allergies.

According to the microbial exposure hypothesis, it was previously thought that a potential link between cesarean birth and allergy might reflect differences in early exposure to maternal flora beneficial to the immune system in the vagina during delivery. A C-section might bypass the opportunity for neonatal gut colonization with maternal gut and vaginal flora, thereby raising allergy risk. A 2018 meta-analysis, for example, suggested cesarean birth could raise the risk for food allergies by 21%.

In other research from HealthNuts, 30% of child peanut allergy and 90% of egg allergy appear to resolve naturally by age 6. These numbers are somewhat higher than what Dr. Brown-Whitehorn sees. “We find that about 20% of peanut allergies and about 70% or 80% – maybe a bit less – of egg allergies resolve by age 6.”

This research was supported by the National Health & Medical Research Council of Australia, the Ilhan Food Allergy Foundation, AnaphylaxiStop, the Charles and Sylvia Viertel Medical Research Foundation, the Victorian Government’s Operational Infrastructure Support Program, and the Melbourne Children’s Clinician-Scientist Fellowship.

Dr. Peters disclosed no competing interests. Several coauthors reported research support or employment with private companies and one is the inventor of an MCRI-held patent. Dr. Brown-Whitehorn had no competing interests to disclose.

FROM JOURNAL OF ALLERGY AND CLINICAL IMMUNOLOGY

NAVIGATOR steers uncontrolled asthma toward calmer seas

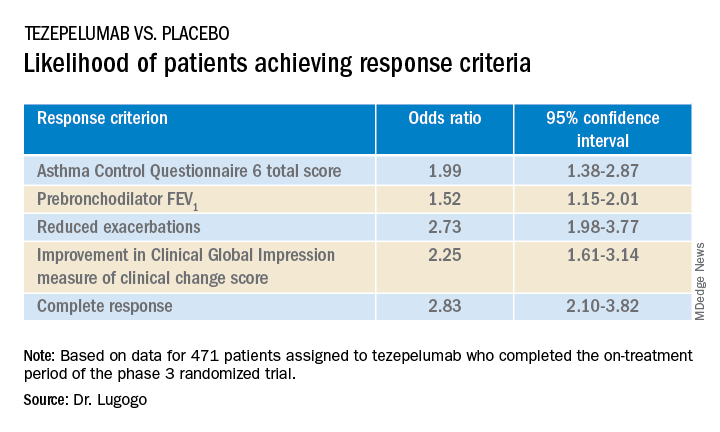

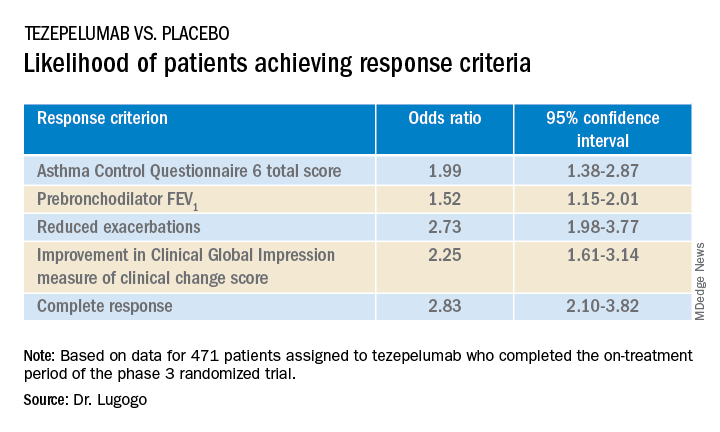

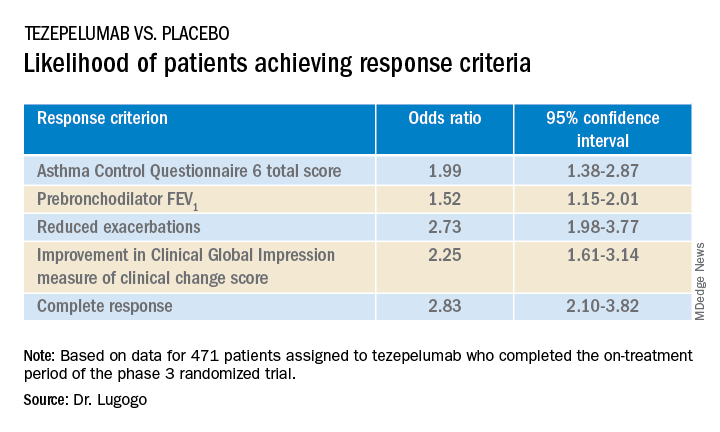

SAN FRANCISCO – Nearly half of all patients with severe, uncontrolled asthma who received a full course of the biologic agent tezepelumab (Tezspire) in the NAVIGATOR trial had a complete response to treatment at 1 year, results of a prespecified exploratory analysis indicated.

Among 471 patients assigned to tezepelumab who completed the on-treatment period of the phase 3 randomized trial, 46% had a complete response at 52 weeks, compared with 24% of patients assigned to placebo.

Complete response was defined as reduction in exacerbations of at least 50% over the previous year, improvement from baseline in Asthma Control Questionnaire 6 (ACQ-6) total score of at least 0.5 points, improvement in prebronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 second (pre-BD FEV1), and physician-assessed Clinical Global Impression measure of clinical change (CGI-C) score.

“These data further support the efficacy of tezepelumab in a broad population of patients with severe, uncontrolled asthma,” said Njira Lugogo, MD, of the division of pulmonary and critical care medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Dr. Lugogo presented results of the exploratory analysis at the American Thoracic Society’s international conference.

Exacerbations reduced, lung function improved

Primary results from NAVIGATOR, published in The New England Journal of Medicine, showed that patients with severe, uncontrolled asthma randomly assigned to tezepelumab had fewer exacerbations and better lung function, asthma control, and health-related quality of life compared with patients assigned to placebo.

The investigators noted that approximately 10% of patients with asthma have symptoms and exacerbations despite maximal standard-of-care controller therapy.

Tezepelumab is a human monoclonal antibody that inhibits action of thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), an epithelial cytokine that is released in response to airborne triggers of asthma. TSLP is a major contributor to initiation and persistence of airway inflammation, Dr. Lugogo said.

The on-treatment analysis looked at all patients in the trial who completed 52 weeks of treatment and had complete data for all criteria studied.

The odds ratios (OR) for patients on tezepelumab achieving each of the response criteria are shown in the table.

Exacerbations explored

In a separate presentation, Christopher S. Ambrose, MD, MBA, of AstraZeneca in Gaithersburg, Md., presented information from investigator-narrative descriptions of all hospitalization events related to asthma exacerbations (mild, moderate, or severe) that occurred while the investigator was blinded to each patient’s treatment assignment in NAVIGATOR.

In all, 39 of 531 patients (7.3%) assigned to placebo had a total of 78 exacerbations requiring hospitalization, compared with 13 of 528 patients (2.5%) assigned to tezepelumab. The latter group had a total of 14 exacerbations requiring hospitalization during the study.

Among hospitalized patients, 32 of the 39 assigned to placebo had severe, incapacitating exacerbations, compared with 5 of 13 assigned to tezepelumab.

Reported symptoms were generally similar between hospitalized patients in the two treatment groups, although there appeared to be trends toward lower incidence of dyspnea, fever, and tachycardia with tezepelumab.

Health care resource utilization, a surrogate marker for disease burden, was substantially lower for patients assigned to tezepelumab.

Infections were the most common triggers of exacerbations in both groups.

“These data provide further evidence that tezepelumab can reduce the burden of disease of severe uncontrolled asthma, both to patients and to health care systems,” Dr. Ambrose said.

Head-to-head studies needed

Although there have been no head-to-head comparisons of biologic agents for asthma to date, results of these studies suggest that tezepelumab has efficacy similar to that of other agents for reducing exacerbation, said Fernando Holguin, MD, MPH, from the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, who comoderated the oral session where the data were presented but was not involved in the study.

Biologic agents appear to be slightly more effective against type 2 inflammation in asthma, “but in general I think we give it to a broader severe population, so that’s exciting,” he told this news organization.

Comoderator Amisha Barochia, MBBS, MHS, of the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md., told this news organization that head-to-head trials of biologic agents would provide important clinical information going forward.

“Should we switch to a different biologic or add a second biologic? Those are questions we need answers for,” she said.

The NAVIGATOR trial is funded by AstraZeneca and Amgen. Dr. Lugogo disclosed financial relationships with both companies. Dr. Holguin and Dr. Barochia have disclosed no financial relationships relevant to the studies presented.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN FRANCISCO – Nearly half of all patients with severe, uncontrolled asthma who received a full course of the biologic agent tezepelumab (Tezspire) in the NAVIGATOR trial had a complete response to treatment at 1 year, results of a prespecified exploratory analysis indicated.

Among 471 patients assigned to tezepelumab who completed the on-treatment period of the phase 3 randomized trial, 46% had a complete response at 52 weeks, compared with 24% of patients assigned to placebo.

Complete response was defined as reduction in exacerbations of at least 50% over the previous year, improvement from baseline in Asthma Control Questionnaire 6 (ACQ-6) total score of at least 0.5 points, improvement in prebronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 second (pre-BD FEV1), and physician-assessed Clinical Global Impression measure of clinical change (CGI-C) score.

“These data further support the efficacy of tezepelumab in a broad population of patients with severe, uncontrolled asthma,” said Njira Lugogo, MD, of the division of pulmonary and critical care medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Dr. Lugogo presented results of the exploratory analysis at the American Thoracic Society’s international conference.

Exacerbations reduced, lung function improved

Primary results from NAVIGATOR, published in The New England Journal of Medicine, showed that patients with severe, uncontrolled asthma randomly assigned to tezepelumab had fewer exacerbations and better lung function, asthma control, and health-related quality of life compared with patients assigned to placebo.

The investigators noted that approximately 10% of patients with asthma have symptoms and exacerbations despite maximal standard-of-care controller therapy.

Tezepelumab is a human monoclonal antibody that inhibits action of thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), an epithelial cytokine that is released in response to airborne triggers of asthma. TSLP is a major contributor to initiation and persistence of airway inflammation, Dr. Lugogo said.

The on-treatment analysis looked at all patients in the trial who completed 52 weeks of treatment and had complete data for all criteria studied.

The odds ratios (OR) for patients on tezepelumab achieving each of the response criteria are shown in the table.

Exacerbations explored

In a separate presentation, Christopher S. Ambrose, MD, MBA, of AstraZeneca in Gaithersburg, Md., presented information from investigator-narrative descriptions of all hospitalization events related to asthma exacerbations (mild, moderate, or severe) that occurred while the investigator was blinded to each patient’s treatment assignment in NAVIGATOR.

In all, 39 of 531 patients (7.3%) assigned to placebo had a total of 78 exacerbations requiring hospitalization, compared with 13 of 528 patients (2.5%) assigned to tezepelumab. The latter group had a total of 14 exacerbations requiring hospitalization during the study.

Among hospitalized patients, 32 of the 39 assigned to placebo had severe, incapacitating exacerbations, compared with 5 of 13 assigned to tezepelumab.

Reported symptoms were generally similar between hospitalized patients in the two treatment groups, although there appeared to be trends toward lower incidence of dyspnea, fever, and tachycardia with tezepelumab.

Health care resource utilization, a surrogate marker for disease burden, was substantially lower for patients assigned to tezepelumab.

Infections were the most common triggers of exacerbations in both groups.

“These data provide further evidence that tezepelumab can reduce the burden of disease of severe uncontrolled asthma, both to patients and to health care systems,” Dr. Ambrose said.

Head-to-head studies needed

Although there have been no head-to-head comparisons of biologic agents for asthma to date, results of these studies suggest that tezepelumab has efficacy similar to that of other agents for reducing exacerbation, said Fernando Holguin, MD, MPH, from the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, who comoderated the oral session where the data were presented but was not involved in the study.

Biologic agents appear to be slightly more effective against type 2 inflammation in asthma, “but in general I think we give it to a broader severe population, so that’s exciting,” he told this news organization.

Comoderator Amisha Barochia, MBBS, MHS, of the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md., told this news organization that head-to-head trials of biologic agents would provide important clinical information going forward.

“Should we switch to a different biologic or add a second biologic? Those are questions we need answers for,” she said.

The NAVIGATOR trial is funded by AstraZeneca and Amgen. Dr. Lugogo disclosed financial relationships with both companies. Dr. Holguin and Dr. Barochia have disclosed no financial relationships relevant to the studies presented.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN FRANCISCO – Nearly half of all patients with severe, uncontrolled asthma who received a full course of the biologic agent tezepelumab (Tezspire) in the NAVIGATOR trial had a complete response to treatment at 1 year, results of a prespecified exploratory analysis indicated.

Among 471 patients assigned to tezepelumab who completed the on-treatment period of the phase 3 randomized trial, 46% had a complete response at 52 weeks, compared with 24% of patients assigned to placebo.

Complete response was defined as reduction in exacerbations of at least 50% over the previous year, improvement from baseline in Asthma Control Questionnaire 6 (ACQ-6) total score of at least 0.5 points, improvement in prebronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 second (pre-BD FEV1), and physician-assessed Clinical Global Impression measure of clinical change (CGI-C) score.

“These data further support the efficacy of tezepelumab in a broad population of patients with severe, uncontrolled asthma,” said Njira Lugogo, MD, of the division of pulmonary and critical care medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Dr. Lugogo presented results of the exploratory analysis at the American Thoracic Society’s international conference.

Exacerbations reduced, lung function improved

Primary results from NAVIGATOR, published in The New England Journal of Medicine, showed that patients with severe, uncontrolled asthma randomly assigned to tezepelumab had fewer exacerbations and better lung function, asthma control, and health-related quality of life compared with patients assigned to placebo.

The investigators noted that approximately 10% of patients with asthma have symptoms and exacerbations despite maximal standard-of-care controller therapy.

Tezepelumab is a human monoclonal antibody that inhibits action of thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), an epithelial cytokine that is released in response to airborne triggers of asthma. TSLP is a major contributor to initiation and persistence of airway inflammation, Dr. Lugogo said.

The on-treatment analysis looked at all patients in the trial who completed 52 weeks of treatment and had complete data for all criteria studied.

The odds ratios (OR) for patients on tezepelumab achieving each of the response criteria are shown in the table.

Exacerbations explored

In a separate presentation, Christopher S. Ambrose, MD, MBA, of AstraZeneca in Gaithersburg, Md., presented information from investigator-narrative descriptions of all hospitalization events related to asthma exacerbations (mild, moderate, or severe) that occurred while the investigator was blinded to each patient’s treatment assignment in NAVIGATOR.

In all, 39 of 531 patients (7.3%) assigned to placebo had a total of 78 exacerbations requiring hospitalization, compared with 13 of 528 patients (2.5%) assigned to tezepelumab. The latter group had a total of 14 exacerbations requiring hospitalization during the study.

Among hospitalized patients, 32 of the 39 assigned to placebo had severe, incapacitating exacerbations, compared with 5 of 13 assigned to tezepelumab.

Reported symptoms were generally similar between hospitalized patients in the two treatment groups, although there appeared to be trends toward lower incidence of dyspnea, fever, and tachycardia with tezepelumab.

Health care resource utilization, a surrogate marker for disease burden, was substantially lower for patients assigned to tezepelumab.

Infections were the most common triggers of exacerbations in both groups.

“These data provide further evidence that tezepelumab can reduce the burden of disease of severe uncontrolled asthma, both to patients and to health care systems,” Dr. Ambrose said.

Head-to-head studies needed

Although there have been no head-to-head comparisons of biologic agents for asthma to date, results of these studies suggest that tezepelumab has efficacy similar to that of other agents for reducing exacerbation, said Fernando Holguin, MD, MPH, from the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, who comoderated the oral session where the data were presented but was not involved in the study.

Biologic agents appear to be slightly more effective against type 2 inflammation in asthma, “but in general I think we give it to a broader severe population, so that’s exciting,” he told this news organization.

Comoderator Amisha Barochia, MBBS, MHS, of the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md., told this news organization that head-to-head trials of biologic agents would provide important clinical information going forward.

“Should we switch to a different biologic or add a second biologic? Those are questions we need answers for,” she said.

The NAVIGATOR trial is funded by AstraZeneca and Amgen. Dr. Lugogo disclosed financial relationships with both companies. Dr. Holguin and Dr. Barochia have disclosed no financial relationships relevant to the studies presented.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT ATS 2022

More evidence links asthma severity to age of onset

A recently published multinational cohort study may be the largest to date that’s found the age of asthma onset is an integral factor in defining the severity of disease and the frequency of comorbidities.

“It’s very simple to ask your patient: ‘Did you have asthma as a child? When did your asthma start?’ ” coauthor Guy Brusselle, MD, a professor at the University of Ghent (Belgium), said in an interview. “You do not need expensive investigations, CT scans or proteomics or genomics; just two simple questions.”

The retrospective cohort study, published in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice, combined national electronic health records databases from five different countries – the United Kingdom, Spain, Italy, the Netherlands, and Denmark – that included 586,436 adult asthma patients. The study divided the patients into three subtypes: childhood-onset asthma, meaning a diagnosis before age 18 (n = 81,691); adult-onset disease, defined as a diagnosis between ages 18 and 40 (n = 218,184); and late onset, defined as a diagnosis made after age 40 (n = 286,561).

Dr. Brusselle said the study found stark differences in characteristics between the three subtypes, including an increasing risk for women with later age of onset. Across the five databases, females comprised approximately 45% of those with childhood-onset asthma, but about 60% of those with later-onset disease, Dr. Brusselle said.

As for characteristics of asthma, 7.2% of the cohort (n = 42,611) had severe asthma, but the proportion was highest in late-onset asthma, 10% versus 5% in adult onset and 3% in childhood onset. The percentage of uncontrolled asthma followed a similar trend: 8%, 6%, and 0.4% in the respective treatment groups.

The most common comorbidities were atopic disorders (31%) and overweight/obesity (50%). The prevalence of atopic disorders was highest in the childhood-onset group, 45% versus 35%, and 25% in the adult-onset and late-onset patients. However, the trend for overweight/obesity was reversed: 30%, 43%, and 61%, respectively.

“The larger differences were when late-onset asthma was compared to adult-onset asthma with respect to comorbidities,” Dr. Brusselle said. “The late-onset asthma patients more frequently had nasal polyposis.” These patients typically lose their sense of smell, as in COVID-19. However, in nasal polyposis the loss is chronic rather than transient.

Pulmonologists should be attuned to the prevalence of overweight/obesity in the late-onset group, Dr. Brusselle said. “We know that obesity is an important risk factor for diabetes, and then obesity is also associated with gastroesophageal reflux – and we know that gastroesophageal reflux is a risk factor for asthma exacerbations.”

Smaller studies have arrived at the same conclusions regarding the relationships between asthma severity and age of onset, Dr. Brusselle said. What’s notable about this study is its size and the consistency of findings across different national databases.

“In childhood onset you need to watch for different allergies – atopic dermatitis and allergic rhinitis – but in late-onset asthma look for obesity, diabetes and reflux disease, and nasal polyposis,” he said.

Sally E. Wenzel, MD, professor at the University of Pittsburgh and director of the Asthma and Environmental Lung Health Institute at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, concurred that the size of this study makes it noteworthy.

“It’s certainly far and away the largest study of its kind that’s ever been done, and it’s multinational,” she said in an interview. “Just doing a study like this with thousands and thousands of patients is a step in the right direction. That’s probably what’s very unique about it, to bring all of these clinical cohorts as it were together and to look at what is the relationship of the age of onset.”

She also said the study is unique in how it delineates the groups by age of onset.

“In addition to this concept that there’s a difference in asthma by the age that you got diagnosed with it, I think it’s also important to just remember that when any physician, be they a specialist or nonspecialist, sees a patient with asthma, they should ask them when did their symptoms develop,” she said. “These are really simple questions that don’t take any sophisticated training and don’t take any sophisticated instruments to measure, but they can be really helpful.”

GlaxoSmithKline supplied a grant for the study. Dr. Brusselle disclosed relationships with AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GSK, Novartis, Sanofi, and Teva. A study coauthor is an employee of GSK. Dr. Wenzel reported no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A recently published multinational cohort study may be the largest to date that’s found the age of asthma onset is an integral factor in defining the severity of disease and the frequency of comorbidities.

“It’s very simple to ask your patient: ‘Did you have asthma as a child? When did your asthma start?’ ” coauthor Guy Brusselle, MD, a professor at the University of Ghent (Belgium), said in an interview. “You do not need expensive investigations, CT scans or proteomics or genomics; just two simple questions.”

The retrospective cohort study, published in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice, combined national electronic health records databases from five different countries – the United Kingdom, Spain, Italy, the Netherlands, and Denmark – that included 586,436 adult asthma patients. The study divided the patients into three subtypes: childhood-onset asthma, meaning a diagnosis before age 18 (n = 81,691); adult-onset disease, defined as a diagnosis between ages 18 and 40 (n = 218,184); and late onset, defined as a diagnosis made after age 40 (n = 286,561).

Dr. Brusselle said the study found stark differences in characteristics between the three subtypes, including an increasing risk for women with later age of onset. Across the five databases, females comprised approximately 45% of those with childhood-onset asthma, but about 60% of those with later-onset disease, Dr. Brusselle said.

As for characteristics of asthma, 7.2% of the cohort (n = 42,611) had severe asthma, but the proportion was highest in late-onset asthma, 10% versus 5% in adult onset and 3% in childhood onset. The percentage of uncontrolled asthma followed a similar trend: 8%, 6%, and 0.4% in the respective treatment groups.

The most common comorbidities were atopic disorders (31%) and overweight/obesity (50%). The prevalence of atopic disorders was highest in the childhood-onset group, 45% versus 35%, and 25% in the adult-onset and late-onset patients. However, the trend for overweight/obesity was reversed: 30%, 43%, and 61%, respectively.

“The larger differences were when late-onset asthma was compared to adult-onset asthma with respect to comorbidities,” Dr. Brusselle said. “The late-onset asthma patients more frequently had nasal polyposis.” These patients typically lose their sense of smell, as in COVID-19. However, in nasal polyposis the loss is chronic rather than transient.

Pulmonologists should be attuned to the prevalence of overweight/obesity in the late-onset group, Dr. Brusselle said. “We know that obesity is an important risk factor for diabetes, and then obesity is also associated with gastroesophageal reflux – and we know that gastroesophageal reflux is a risk factor for asthma exacerbations.”

Smaller studies have arrived at the same conclusions regarding the relationships between asthma severity and age of onset, Dr. Brusselle said. What’s notable about this study is its size and the consistency of findings across different national databases.

“In childhood onset you need to watch for different allergies – atopic dermatitis and allergic rhinitis – but in late-onset asthma look for obesity, diabetes and reflux disease, and nasal polyposis,” he said.

Sally E. Wenzel, MD, professor at the University of Pittsburgh and director of the Asthma and Environmental Lung Health Institute at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, concurred that the size of this study makes it noteworthy.

“It’s certainly far and away the largest study of its kind that’s ever been done, and it’s multinational,” she said in an interview. “Just doing a study like this with thousands and thousands of patients is a step in the right direction. That’s probably what’s very unique about it, to bring all of these clinical cohorts as it were together and to look at what is the relationship of the age of onset.”

She also said the study is unique in how it delineates the groups by age of onset.

“In addition to this concept that there’s a difference in asthma by the age that you got diagnosed with it, I think it’s also important to just remember that when any physician, be they a specialist or nonspecialist, sees a patient with asthma, they should ask them when did their symptoms develop,” she said. “These are really simple questions that don’t take any sophisticated training and don’t take any sophisticated instruments to measure, but they can be really helpful.”

GlaxoSmithKline supplied a grant for the study. Dr. Brusselle disclosed relationships with AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GSK, Novartis, Sanofi, and Teva. A study coauthor is an employee of GSK. Dr. Wenzel reported no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A recently published multinational cohort study may be the largest to date that’s found the age of asthma onset is an integral factor in defining the severity of disease and the frequency of comorbidities.

“It’s very simple to ask your patient: ‘Did you have asthma as a child? When did your asthma start?’ ” coauthor Guy Brusselle, MD, a professor at the University of Ghent (Belgium), said in an interview. “You do not need expensive investigations, CT scans or proteomics or genomics; just two simple questions.”

The retrospective cohort study, published in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice, combined national electronic health records databases from five different countries – the United Kingdom, Spain, Italy, the Netherlands, and Denmark – that included 586,436 adult asthma patients. The study divided the patients into three subtypes: childhood-onset asthma, meaning a diagnosis before age 18 (n = 81,691); adult-onset disease, defined as a diagnosis between ages 18 and 40 (n = 218,184); and late onset, defined as a diagnosis made after age 40 (n = 286,561).

Dr. Brusselle said the study found stark differences in characteristics between the three subtypes, including an increasing risk for women with later age of onset. Across the five databases, females comprised approximately 45% of those with childhood-onset asthma, but about 60% of those with later-onset disease, Dr. Brusselle said.

As for characteristics of asthma, 7.2% of the cohort (n = 42,611) had severe asthma, but the proportion was highest in late-onset asthma, 10% versus 5% in adult onset and 3% in childhood onset. The percentage of uncontrolled asthma followed a similar trend: 8%, 6%, and 0.4% in the respective treatment groups.

The most common comorbidities were atopic disorders (31%) and overweight/obesity (50%). The prevalence of atopic disorders was highest in the childhood-onset group, 45% versus 35%, and 25% in the adult-onset and late-onset patients. However, the trend for overweight/obesity was reversed: 30%, 43%, and 61%, respectively.

“The larger differences were when late-onset asthma was compared to adult-onset asthma with respect to comorbidities,” Dr. Brusselle said. “The late-onset asthma patients more frequently had nasal polyposis.” These patients typically lose their sense of smell, as in COVID-19. However, in nasal polyposis the loss is chronic rather than transient.

Pulmonologists should be attuned to the prevalence of overweight/obesity in the late-onset group, Dr. Brusselle said. “We know that obesity is an important risk factor for diabetes, and then obesity is also associated with gastroesophageal reflux – and we know that gastroesophageal reflux is a risk factor for asthma exacerbations.”

Smaller studies have arrived at the same conclusions regarding the relationships between asthma severity and age of onset, Dr. Brusselle said. What’s notable about this study is its size and the consistency of findings across different national databases.

“In childhood onset you need to watch for different allergies – atopic dermatitis and allergic rhinitis – but in late-onset asthma look for obesity, diabetes and reflux disease, and nasal polyposis,” he said.

Sally E. Wenzel, MD, professor at the University of Pittsburgh and director of the Asthma and Environmental Lung Health Institute at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, concurred that the size of this study makes it noteworthy.

“It’s certainly far and away the largest study of its kind that’s ever been done, and it’s multinational,” she said in an interview. “Just doing a study like this with thousands and thousands of patients is a step in the right direction. That’s probably what’s very unique about it, to bring all of these clinical cohorts as it were together and to look at what is the relationship of the age of onset.”

She also said the study is unique in how it delineates the groups by age of onset.

“In addition to this concept that there’s a difference in asthma by the age that you got diagnosed with it, I think it’s also important to just remember that when any physician, be they a specialist or nonspecialist, sees a patient with asthma, they should ask them when did their symptoms develop,” she said. “These are really simple questions that don’t take any sophisticated training and don’t take any sophisticated instruments to measure, but they can be really helpful.”

GlaxoSmithKline supplied a grant for the study. Dr. Brusselle disclosed relationships with AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GSK, Novartis, Sanofi, and Teva. A study coauthor is an employee of GSK. Dr. Wenzel reported no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF ALLERGY AND CLINICAL IMMUNOLOGY: IN PRACTICE

Probiotic LGG doesn’t lessen eczema, asthma, or rhinitis risk by age 7

Giving the probiotic supplement Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG) to high-risk infants in the first 6 months of life is not effective in lessening incidence of eczema, asthma, or rhinitis in later childhood, researchers have found.

The researchers, led by Michael D. Cabana, MD, MPH, with the Children’s Hospital of Montefiore, New York, said they cannot support its use in this population of children at high risk for allergic disease. Findings were published in Pediatrics.

Jonathan Spergel, MD, PhD, chief of the allergy program at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, who was not part of the study, said the “small, but very interesting study adds to the literature indicating that allergy prevention needs to be a multifactorial approach and simply adding LGG in a select population makes no difference.”

He noted that the study of probiotics for allergic conditions is complex as it depends on many factors, such as the child’s environment, including exposure to pets and pollution, and whether the child was delivered vaginally or by cesarean section.

Study builds on previous work

The new study builds on the same researchers’ randomized, double-masked, parallel-arm, controlled Trial of Infant Probiotic Supplementation (TIPS). That study investigated whether daily administration of LGG in the first 6 months to children at high risk for allergic disease because of asthma in a parent, could decrease their cumulative incidence of eczema. Investigators found LGG had no effect.

These additional results included participants at least 7 years old and also included physician-diagnosed asthma and physician-diagnosed rhinitis as secondary outcomes.

Retention rate over the 7-year follow-up was 56%; 49 (53%) of 92 in the intervention group and 54 (59%) of 92 in the control group.

The researchers performed modified intention-to-treat analyses with all children who received treatment in the study arm to which they had been randomized.

Eczema was diagnosed in 78 participants, asthma in 32, and rhinitis in 15. Incidence of eczema was high in infancy, but low thereafter. Incidence rates for asthma and rhinitis were constant throughout childhood.

The researchers used modeling to compare the incidence of each outcome between the intervention and control groups, adjusting for mode of delivery and how long a child was breastfed.

Cesarean delivery was linked to a greater incidence of rhinitis, with a hazard ratio of 3.33 (95% confidence interval, 1.21-9.21).

Finding the right strain

Heather Cassell, MD, a pediatric allergist and immunologist at University of Arizona, Tucson, who was not part of the study, said in an interview that many researchers, including those at her institution, are trying to find which strain of probiotic might be beneficial in lowering risk for allergic disease.

Though it appears LGG doesn’t have an effect, she said, another strain might be successful and this helps zero in on the right one.

The TIPS trial showed that there were no significant side effects from giving LGG early, which is good information to have as the search resumes for the right strain, she said.

“We know that there’s probably some immune dysregulation in kids with asthma, eczema, other allergies, but we don’t fully know the extent of it,” she said, adding that it may be that skin flora or respiratory flora and microbiomes in other parts of the body play a role.

“We don’t have bacteria just in our guts,” she noted. “It may be a combination of strains or a combination of bacteria.”

The authors, Dr. Spergel, and Dr. Cassell reported no relevant financial relationships.

Giving the probiotic supplement Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG) to high-risk infants in the first 6 months of life is not effective in lessening incidence of eczema, asthma, or rhinitis in later childhood, researchers have found.

The researchers, led by Michael D. Cabana, MD, MPH, with the Children’s Hospital of Montefiore, New York, said they cannot support its use in this population of children at high risk for allergic disease. Findings were published in Pediatrics.

Jonathan Spergel, MD, PhD, chief of the allergy program at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, who was not part of the study, said the “small, but very interesting study adds to the literature indicating that allergy prevention needs to be a multifactorial approach and simply adding LGG in a select population makes no difference.”

He noted that the study of probiotics for allergic conditions is complex as it depends on many factors, such as the child’s environment, including exposure to pets and pollution, and whether the child was delivered vaginally or by cesarean section.

Study builds on previous work

The new study builds on the same researchers’ randomized, double-masked, parallel-arm, controlled Trial of Infant Probiotic Supplementation (TIPS). That study investigated whether daily administration of LGG in the first 6 months to children at high risk for allergic disease because of asthma in a parent, could decrease their cumulative incidence of eczema. Investigators found LGG had no effect.

These additional results included participants at least 7 years old and also included physician-diagnosed asthma and physician-diagnosed rhinitis as secondary outcomes.

Retention rate over the 7-year follow-up was 56%; 49 (53%) of 92 in the intervention group and 54 (59%) of 92 in the control group.

The researchers performed modified intention-to-treat analyses with all children who received treatment in the study arm to which they had been randomized.

Eczema was diagnosed in 78 participants, asthma in 32, and rhinitis in 15. Incidence of eczema was high in infancy, but low thereafter. Incidence rates for asthma and rhinitis were constant throughout childhood.

The researchers used modeling to compare the incidence of each outcome between the intervention and control groups, adjusting for mode of delivery and how long a child was breastfed.

Cesarean delivery was linked to a greater incidence of rhinitis, with a hazard ratio of 3.33 (95% confidence interval, 1.21-9.21).

Finding the right strain

Heather Cassell, MD, a pediatric allergist and immunologist at University of Arizona, Tucson, who was not part of the study, said in an interview that many researchers, including those at her institution, are trying to find which strain of probiotic might be beneficial in lowering risk for allergic disease.

Though it appears LGG doesn’t have an effect, she said, another strain might be successful and this helps zero in on the right one.

The TIPS trial showed that there were no significant side effects from giving LGG early, which is good information to have as the search resumes for the right strain, she said.

“We know that there’s probably some immune dysregulation in kids with asthma, eczema, other allergies, but we don’t fully know the extent of it,” she said, adding that it may be that skin flora or respiratory flora and microbiomes in other parts of the body play a role.

“We don’t have bacteria just in our guts,” she noted. “It may be a combination of strains or a combination of bacteria.”

The authors, Dr. Spergel, and Dr. Cassell reported no relevant financial relationships.

Giving the probiotic supplement Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG) to high-risk infants in the first 6 months of life is not effective in lessening incidence of eczema, asthma, or rhinitis in later childhood, researchers have found.

The researchers, led by Michael D. Cabana, MD, MPH, with the Children’s Hospital of Montefiore, New York, said they cannot support its use in this population of children at high risk for allergic disease. Findings were published in Pediatrics.

Jonathan Spergel, MD, PhD, chief of the allergy program at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, who was not part of the study, said the “small, but very interesting study adds to the literature indicating that allergy prevention needs to be a multifactorial approach and simply adding LGG in a select population makes no difference.”

He noted that the study of probiotics for allergic conditions is complex as it depends on many factors, such as the child’s environment, including exposure to pets and pollution, and whether the child was delivered vaginally or by cesarean section.

Study builds on previous work