User login

Risk calculator for early-stage CKD may soon enter U.S. market

PHILADELPHIA – The analyses offer the possibility of focusing intensified medical management of early-stage CKD on those patients who could potentially receive the most benefit.

The Klinrisk model predicts the risk of an adult with early-stage CKD developing either a 40% or greater drop in estimated glomerular filtration rate or kidney failure. It calculates risk based on 20 lab-measured variables that include serum creatinine, urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio, and other values taken from routinely ordered tests such as complete blood cell counts, chemistry panels, comprehensive metabolic panels, and urinalysis.

In the most recent and largest external validation study using data from 4.6 million American adults enrolled in commercial and Medicare insurance plans, the results showed Klinrisk correctly predicted CKD progression in 80%-83% of individuals over 2 years and in 78%-83% of individuals over 5 years, depending on the insurance provider, Navdeep Tangri, MD, PhD, reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Nephrology. When urinalysis data were available, the model correctly predicted CKD progression in 81%-87% of individuals over 2 years and in 80%-87% of individuals over 5 years. These results follow prior reports of several other successful validations of Klinrisk.

‘Ready to implement’

“The Klinrisk model is ready to implement by any payer, health system, or clinic where the needed lab data are available,” said Dr. Tangri, a nephrologist and professor at the University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, and founder of Klinrisk Inc., the company developing and commercializing the Klinrisk assessment tool.

For the time being, Dr. Tangri sees Klinrisk as a population health device that can allow insurers and health systems to track management quality and quality improvement and to target patients who stand to benefit most from relatively expensive resources. This includes prescriptions for finerenone (Kerendia, Bayer) for people who also have type 2 diabetes, and agents from the class of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors such as dapagliflozin (Farxiga, AstraZeneca) and empagliflozin (Jardiance, Boehringer Ingelheim and Lilly).

He has also begun discussions with the Food and Drug Administration about the data the agency will need to consider Klinrisk for potential approval as a new medical device, perhaps in 2025. That’s how he envisions getting a Klinrisk assessment into the hands of caregivers that they could use with individual patients to create an appropriate treatment plan.

Results from his new analysis showed that “all the kidney disease action is in the 10%-20% of people with the highest risk on Klinrisk, while not much happens in those in the bottom half,” Dr. Tangri said during his presentation.

“We’re trying to find the patients who get the largest [absolute] benefit from intensified treatment,” he added in an interview. “Klinrisk finds people with high-risk kidney disease early on, when kidney function is still normal or near normal. High-risk patients are often completely unrecognized. Risk-based management” that identifies the early-stage CKD patients who would benefit most from treatment with an SGLT2 inhibitor, finerenone, and other foundational treatments to slow CKD progression “is better than the free-for-all that occurs today.”

Simplified data collection

“Klinrisk is very effective,” but requires follow-up by clinicians and health systems to implement its findings, commented Josef Coresh, MD, a professor of clinical epidemiology at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg, Baltimore. Dr. Coresh compared it with a free equation that estimates a person’s risk for a 40% drop in kidney function over the next 3 years developed by Dr. Tangri, Dr. Coresh, and many collaborators led by Morgan C. Grams, MD, PhD, of New York University that they published in 2022, and posted on a website of the CKD Prognosis Consortium.

The CKD Prognosis Consortium formula “takes a different approach” from Klinrisk. The commercial formula “is simpler, only using lab measures, and avoids inputs taken from physical examination such as systolic blood pressure and body mass index and health history data such as smoking, noted Dr. Coresh. He also speculated that “a commercial formula that must be paid for may counterintuitively result in better follow-up for making management changes if it uses some of the resources for education and system changes.”

Using data from multiple sources, like the CKD Prognosis Consortium equation, can create implementation challenges, said Dr. Tangri. “Lab results don’t vary much,” which makes Klinrisk “quite an improvement for implementation. It’s easier to implement.”

Other findings from the newest validation study that Dr. Tangri presented were that the people studied with Klinrisk scores in the top 10% had, over the next 2 years of follow-up and compared with people in the bottom half for Klinrisk staging, a 3- to 5-fold higher rate of all-cause medical costs, a 13-30-fold increase in CKD-related costs, and a 5- to 10-fold increase in hospitalizations and ED visits.

Early identification of CKD and early initiation of intensified treatment for high-risk patients can reduce the rate of progression to dialysis, reduce hospitalizations for heart failure, and lower the cost of care, Dr. Tangri said.

The validation study in 4.6 million Americans was sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim. Dr. Tangri founded and has an ownership interest in Klinrisk. He has also received honoraria from, has ownership interests in, and has been a consultant to multiple pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Coresh had no disclosures.

PHILADELPHIA – The analyses offer the possibility of focusing intensified medical management of early-stage CKD on those patients who could potentially receive the most benefit.

The Klinrisk model predicts the risk of an adult with early-stage CKD developing either a 40% or greater drop in estimated glomerular filtration rate or kidney failure. It calculates risk based on 20 lab-measured variables that include serum creatinine, urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio, and other values taken from routinely ordered tests such as complete blood cell counts, chemistry panels, comprehensive metabolic panels, and urinalysis.

In the most recent and largest external validation study using data from 4.6 million American adults enrolled in commercial and Medicare insurance plans, the results showed Klinrisk correctly predicted CKD progression in 80%-83% of individuals over 2 years and in 78%-83% of individuals over 5 years, depending on the insurance provider, Navdeep Tangri, MD, PhD, reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Nephrology. When urinalysis data were available, the model correctly predicted CKD progression in 81%-87% of individuals over 2 years and in 80%-87% of individuals over 5 years. These results follow prior reports of several other successful validations of Klinrisk.

‘Ready to implement’

“The Klinrisk model is ready to implement by any payer, health system, or clinic where the needed lab data are available,” said Dr. Tangri, a nephrologist and professor at the University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, and founder of Klinrisk Inc., the company developing and commercializing the Klinrisk assessment tool.

For the time being, Dr. Tangri sees Klinrisk as a population health device that can allow insurers and health systems to track management quality and quality improvement and to target patients who stand to benefit most from relatively expensive resources. This includes prescriptions for finerenone (Kerendia, Bayer) for people who also have type 2 diabetes, and agents from the class of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors such as dapagliflozin (Farxiga, AstraZeneca) and empagliflozin (Jardiance, Boehringer Ingelheim and Lilly).

He has also begun discussions with the Food and Drug Administration about the data the agency will need to consider Klinrisk for potential approval as a new medical device, perhaps in 2025. That’s how he envisions getting a Klinrisk assessment into the hands of caregivers that they could use with individual patients to create an appropriate treatment plan.

Results from his new analysis showed that “all the kidney disease action is in the 10%-20% of people with the highest risk on Klinrisk, while not much happens in those in the bottom half,” Dr. Tangri said during his presentation.

“We’re trying to find the patients who get the largest [absolute] benefit from intensified treatment,” he added in an interview. “Klinrisk finds people with high-risk kidney disease early on, when kidney function is still normal or near normal. High-risk patients are often completely unrecognized. Risk-based management” that identifies the early-stage CKD patients who would benefit most from treatment with an SGLT2 inhibitor, finerenone, and other foundational treatments to slow CKD progression “is better than the free-for-all that occurs today.”

Simplified data collection

“Klinrisk is very effective,” but requires follow-up by clinicians and health systems to implement its findings, commented Josef Coresh, MD, a professor of clinical epidemiology at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg, Baltimore. Dr. Coresh compared it with a free equation that estimates a person’s risk for a 40% drop in kidney function over the next 3 years developed by Dr. Tangri, Dr. Coresh, and many collaborators led by Morgan C. Grams, MD, PhD, of New York University that they published in 2022, and posted on a website of the CKD Prognosis Consortium.

The CKD Prognosis Consortium formula “takes a different approach” from Klinrisk. The commercial formula “is simpler, only using lab measures, and avoids inputs taken from physical examination such as systolic blood pressure and body mass index and health history data such as smoking, noted Dr. Coresh. He also speculated that “a commercial formula that must be paid for may counterintuitively result in better follow-up for making management changes if it uses some of the resources for education and system changes.”

Using data from multiple sources, like the CKD Prognosis Consortium equation, can create implementation challenges, said Dr. Tangri. “Lab results don’t vary much,” which makes Klinrisk “quite an improvement for implementation. It’s easier to implement.”

Other findings from the newest validation study that Dr. Tangri presented were that the people studied with Klinrisk scores in the top 10% had, over the next 2 years of follow-up and compared with people in the bottom half for Klinrisk staging, a 3- to 5-fold higher rate of all-cause medical costs, a 13-30-fold increase in CKD-related costs, and a 5- to 10-fold increase in hospitalizations and ED visits.

Early identification of CKD and early initiation of intensified treatment for high-risk patients can reduce the rate of progression to dialysis, reduce hospitalizations for heart failure, and lower the cost of care, Dr. Tangri said.

The validation study in 4.6 million Americans was sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim. Dr. Tangri founded and has an ownership interest in Klinrisk. He has also received honoraria from, has ownership interests in, and has been a consultant to multiple pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Coresh had no disclosures.

PHILADELPHIA – The analyses offer the possibility of focusing intensified medical management of early-stage CKD on those patients who could potentially receive the most benefit.

The Klinrisk model predicts the risk of an adult with early-stage CKD developing either a 40% or greater drop in estimated glomerular filtration rate or kidney failure. It calculates risk based on 20 lab-measured variables that include serum creatinine, urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio, and other values taken from routinely ordered tests such as complete blood cell counts, chemistry panels, comprehensive metabolic panels, and urinalysis.

In the most recent and largest external validation study using data from 4.6 million American adults enrolled in commercial and Medicare insurance plans, the results showed Klinrisk correctly predicted CKD progression in 80%-83% of individuals over 2 years and in 78%-83% of individuals over 5 years, depending on the insurance provider, Navdeep Tangri, MD, PhD, reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Nephrology. When urinalysis data were available, the model correctly predicted CKD progression in 81%-87% of individuals over 2 years and in 80%-87% of individuals over 5 years. These results follow prior reports of several other successful validations of Klinrisk.

‘Ready to implement’

“The Klinrisk model is ready to implement by any payer, health system, or clinic where the needed lab data are available,” said Dr. Tangri, a nephrologist and professor at the University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, and founder of Klinrisk Inc., the company developing and commercializing the Klinrisk assessment tool.

For the time being, Dr. Tangri sees Klinrisk as a population health device that can allow insurers and health systems to track management quality and quality improvement and to target patients who stand to benefit most from relatively expensive resources. This includes prescriptions for finerenone (Kerendia, Bayer) for people who also have type 2 diabetes, and agents from the class of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors such as dapagliflozin (Farxiga, AstraZeneca) and empagliflozin (Jardiance, Boehringer Ingelheim and Lilly).

He has also begun discussions with the Food and Drug Administration about the data the agency will need to consider Klinrisk for potential approval as a new medical device, perhaps in 2025. That’s how he envisions getting a Klinrisk assessment into the hands of caregivers that they could use with individual patients to create an appropriate treatment plan.

Results from his new analysis showed that “all the kidney disease action is in the 10%-20% of people with the highest risk on Klinrisk, while not much happens in those in the bottom half,” Dr. Tangri said during his presentation.

“We’re trying to find the patients who get the largest [absolute] benefit from intensified treatment,” he added in an interview. “Klinrisk finds people with high-risk kidney disease early on, when kidney function is still normal or near normal. High-risk patients are often completely unrecognized. Risk-based management” that identifies the early-stage CKD patients who would benefit most from treatment with an SGLT2 inhibitor, finerenone, and other foundational treatments to slow CKD progression “is better than the free-for-all that occurs today.”

Simplified data collection

“Klinrisk is very effective,” but requires follow-up by clinicians and health systems to implement its findings, commented Josef Coresh, MD, a professor of clinical epidemiology at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg, Baltimore. Dr. Coresh compared it with a free equation that estimates a person’s risk for a 40% drop in kidney function over the next 3 years developed by Dr. Tangri, Dr. Coresh, and many collaborators led by Morgan C. Grams, MD, PhD, of New York University that they published in 2022, and posted on a website of the CKD Prognosis Consortium.

The CKD Prognosis Consortium formula “takes a different approach” from Klinrisk. The commercial formula “is simpler, only using lab measures, and avoids inputs taken from physical examination such as systolic blood pressure and body mass index and health history data such as smoking, noted Dr. Coresh. He also speculated that “a commercial formula that must be paid for may counterintuitively result in better follow-up for making management changes if it uses some of the resources for education and system changes.”

Using data from multiple sources, like the CKD Prognosis Consortium equation, can create implementation challenges, said Dr. Tangri. “Lab results don’t vary much,” which makes Klinrisk “quite an improvement for implementation. It’s easier to implement.”

Other findings from the newest validation study that Dr. Tangri presented were that the people studied with Klinrisk scores in the top 10% had, over the next 2 years of follow-up and compared with people in the bottom half for Klinrisk staging, a 3- to 5-fold higher rate of all-cause medical costs, a 13-30-fold increase in CKD-related costs, and a 5- to 10-fold increase in hospitalizations and ED visits.

Early identification of CKD and early initiation of intensified treatment for high-risk patients can reduce the rate of progression to dialysis, reduce hospitalizations for heart failure, and lower the cost of care, Dr. Tangri said.

The validation study in 4.6 million Americans was sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim. Dr. Tangri founded and has an ownership interest in Klinrisk. He has also received honoraria from, has ownership interests in, and has been a consultant to multiple pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Coresh had no disclosures.

AT KIDNEY WEEK 2023

Not enough evidence for primary care to routinely conduct dental screenings

Routine screenings for signs of cavities and gum disease by primary care clinicians may not catch patients most at risk of these conditions, according to a statement by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) that was published in JAMA.

Suggesting ways to improve oral health also may fail to engage the patients who most need the message, the group said in its statement.

The task force is not suggesting that primary care providers stop all oral health screening of adults or that they never discuss ways to improve oral health. But the current evidence of the most effective oral health screenings or enhancement strategies in primary care settings received an “I” rating, for “Inconclusive.” The highest ranking a screening can receive is an “A” or “B,” which indicate that there is strong evidence for conducting a screening, while a “C” would indicate that clinicians could rarely provide a screening, and a “D” would indicate not to, given the current evidence.

Primary care clinicians should immediately refer any patients with apparent caries or gum disease to a dentist, the USPSTF noted. But what clinicians should do for patients who have no obvious oral health problems is up for debate.

“The ‘I’ is a note about where the evidence is at this point and then a call for more research to see if we can’t get some more clarity for next time,” said John Ruiz, PhD, professor of clinical psychology at the University of Arizona, Tucson, who is a member of the task force.

More than 90% of U.S. adults may have caries, including 26% with untreated caries that can cause serious infections or tooth loss. In addition, 42% of adults have some type of gum disease. More than two-thirds of Americans aged 65 or older have gum disease, and it is the leading cause of tooth loss in this population. People earning low incomes and those who do not have health insurance or who belong to a marginalized racial or ethnic group are at greater risk of the harms of caries and gum disease.

“Oral health care is important to overall health,” and any new research on oral health screening and enhancement efforts should be demographically representative of adults affected by these conditions, Dr. Ruiz said.

In an accompanying editorial, oral health researchers from the National Institutes of Health and the University of California, San Francisco, echoed the call for representative research and encouraged closer collaboration between primary care providers and dentists to promote oral health.

“Oral health screening and referral by medical primary care clinicians can help ensure that individuals get to the dental chair to receive needed interventions that can benefit both oral and potentially overall health,” the authors wrote. “Likewise, medical challenges and oral mucosal manifestations of chronic health conditions detected at a dental visit should result in medical referral, allowing prompt evaluation and treatment.”

Lack of data

The USPSTF defined oral health screenings for patients older than 18 who have no obvious signs of caries or gum disease as looking at a patient’s mouth during physical exams. Additionally, clinicians might use prediction models to identify patients at greater risk of facing these problems.

Strategies to improve oral health include providing encouragement to patients to reduce intake of refined sugar, to floss and brush effectively to reduce bacteria, and to use fluoride gels, fluoride varnishes, or other kinds of sealants to make caries harder to form.

A literature review found that there has been limited analysis of primary care clinicians performing these tasks. Perhaps unsurprisingly, more such studies about dentists existed, leaving an open field for dedicated studies about what primary care clinicians should do to optimize oral health with patients.

“Clinicians, in the absence of clear guidelines, should continue to use their best judgment,” Dr. Ruiz said.

One dentist interviewed said screening could be as simple as doctors asking patients how often they brush their teeth and giving patients a toothbrush as part of the office visit.

“It all comes down to, ‘Is the person brushing their teeth?’ ” said Jennifer Hartshorn, DDS, who specializes in community and preventive dentistry at the University of Iowa, Iowa City.

“By all means look in their mouth, ask how much they are brushing, and urge them to find a dental home if at all possible,” Dr. Hartshorn said, especially for patients who smoke or have conditions such as dry mouth, which can increase the risk of oral disease.

Dr. Ruiz and Dr. Hartshorn report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Routine screenings for signs of cavities and gum disease by primary care clinicians may not catch patients most at risk of these conditions, according to a statement by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) that was published in JAMA.

Suggesting ways to improve oral health also may fail to engage the patients who most need the message, the group said in its statement.

The task force is not suggesting that primary care providers stop all oral health screening of adults or that they never discuss ways to improve oral health. But the current evidence of the most effective oral health screenings or enhancement strategies in primary care settings received an “I” rating, for “Inconclusive.” The highest ranking a screening can receive is an “A” or “B,” which indicate that there is strong evidence for conducting a screening, while a “C” would indicate that clinicians could rarely provide a screening, and a “D” would indicate not to, given the current evidence.

Primary care clinicians should immediately refer any patients with apparent caries or gum disease to a dentist, the USPSTF noted. But what clinicians should do for patients who have no obvious oral health problems is up for debate.

“The ‘I’ is a note about where the evidence is at this point and then a call for more research to see if we can’t get some more clarity for next time,” said John Ruiz, PhD, professor of clinical psychology at the University of Arizona, Tucson, who is a member of the task force.

More than 90% of U.S. adults may have caries, including 26% with untreated caries that can cause serious infections or tooth loss. In addition, 42% of adults have some type of gum disease. More than two-thirds of Americans aged 65 or older have gum disease, and it is the leading cause of tooth loss in this population. People earning low incomes and those who do not have health insurance or who belong to a marginalized racial or ethnic group are at greater risk of the harms of caries and gum disease.

“Oral health care is important to overall health,” and any new research on oral health screening and enhancement efforts should be demographically representative of adults affected by these conditions, Dr. Ruiz said.

In an accompanying editorial, oral health researchers from the National Institutes of Health and the University of California, San Francisco, echoed the call for representative research and encouraged closer collaboration between primary care providers and dentists to promote oral health.

“Oral health screening and referral by medical primary care clinicians can help ensure that individuals get to the dental chair to receive needed interventions that can benefit both oral and potentially overall health,” the authors wrote. “Likewise, medical challenges and oral mucosal manifestations of chronic health conditions detected at a dental visit should result in medical referral, allowing prompt evaluation and treatment.”

Lack of data

The USPSTF defined oral health screenings for patients older than 18 who have no obvious signs of caries or gum disease as looking at a patient’s mouth during physical exams. Additionally, clinicians might use prediction models to identify patients at greater risk of facing these problems.

Strategies to improve oral health include providing encouragement to patients to reduce intake of refined sugar, to floss and brush effectively to reduce bacteria, and to use fluoride gels, fluoride varnishes, or other kinds of sealants to make caries harder to form.

A literature review found that there has been limited analysis of primary care clinicians performing these tasks. Perhaps unsurprisingly, more such studies about dentists existed, leaving an open field for dedicated studies about what primary care clinicians should do to optimize oral health with patients.

“Clinicians, in the absence of clear guidelines, should continue to use their best judgment,” Dr. Ruiz said.

One dentist interviewed said screening could be as simple as doctors asking patients how often they brush their teeth and giving patients a toothbrush as part of the office visit.

“It all comes down to, ‘Is the person brushing their teeth?’ ” said Jennifer Hartshorn, DDS, who specializes in community and preventive dentistry at the University of Iowa, Iowa City.

“By all means look in their mouth, ask how much they are brushing, and urge them to find a dental home if at all possible,” Dr. Hartshorn said, especially for patients who smoke or have conditions such as dry mouth, which can increase the risk of oral disease.

Dr. Ruiz and Dr. Hartshorn report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Routine screenings for signs of cavities and gum disease by primary care clinicians may not catch patients most at risk of these conditions, according to a statement by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) that was published in JAMA.

Suggesting ways to improve oral health also may fail to engage the patients who most need the message, the group said in its statement.

The task force is not suggesting that primary care providers stop all oral health screening of adults or that they never discuss ways to improve oral health. But the current evidence of the most effective oral health screenings or enhancement strategies in primary care settings received an “I” rating, for “Inconclusive.” The highest ranking a screening can receive is an “A” or “B,” which indicate that there is strong evidence for conducting a screening, while a “C” would indicate that clinicians could rarely provide a screening, and a “D” would indicate not to, given the current evidence.

Primary care clinicians should immediately refer any patients with apparent caries or gum disease to a dentist, the USPSTF noted. But what clinicians should do for patients who have no obvious oral health problems is up for debate.

“The ‘I’ is a note about where the evidence is at this point and then a call for more research to see if we can’t get some more clarity for next time,” said John Ruiz, PhD, professor of clinical psychology at the University of Arizona, Tucson, who is a member of the task force.

More than 90% of U.S. adults may have caries, including 26% with untreated caries that can cause serious infections or tooth loss. In addition, 42% of adults have some type of gum disease. More than two-thirds of Americans aged 65 or older have gum disease, and it is the leading cause of tooth loss in this population. People earning low incomes and those who do not have health insurance or who belong to a marginalized racial or ethnic group are at greater risk of the harms of caries and gum disease.

“Oral health care is important to overall health,” and any new research on oral health screening and enhancement efforts should be demographically representative of adults affected by these conditions, Dr. Ruiz said.

In an accompanying editorial, oral health researchers from the National Institutes of Health and the University of California, San Francisco, echoed the call for representative research and encouraged closer collaboration between primary care providers and dentists to promote oral health.

“Oral health screening and referral by medical primary care clinicians can help ensure that individuals get to the dental chair to receive needed interventions that can benefit both oral and potentially overall health,” the authors wrote. “Likewise, medical challenges and oral mucosal manifestations of chronic health conditions detected at a dental visit should result in medical referral, allowing prompt evaluation and treatment.”

Lack of data

The USPSTF defined oral health screenings for patients older than 18 who have no obvious signs of caries or gum disease as looking at a patient’s mouth during physical exams. Additionally, clinicians might use prediction models to identify patients at greater risk of facing these problems.

Strategies to improve oral health include providing encouragement to patients to reduce intake of refined sugar, to floss and brush effectively to reduce bacteria, and to use fluoride gels, fluoride varnishes, or other kinds of sealants to make caries harder to form.

A literature review found that there has been limited analysis of primary care clinicians performing these tasks. Perhaps unsurprisingly, more such studies about dentists existed, leaving an open field for dedicated studies about what primary care clinicians should do to optimize oral health with patients.

“Clinicians, in the absence of clear guidelines, should continue to use their best judgment,” Dr. Ruiz said.

One dentist interviewed said screening could be as simple as doctors asking patients how often they brush their teeth and giving patients a toothbrush as part of the office visit.

“It all comes down to, ‘Is the person brushing their teeth?’ ” said Jennifer Hartshorn, DDS, who specializes in community and preventive dentistry at the University of Iowa, Iowa City.

“By all means look in their mouth, ask how much they are brushing, and urge them to find a dental home if at all possible,” Dr. Hartshorn said, especially for patients who smoke or have conditions such as dry mouth, which can increase the risk of oral disease.

Dr. Ruiz and Dr. Hartshorn report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA

AHA joins new cardiovascular certification group ABCVM

T to be known as the American Board of Cardiovascular Medicine (ABCVM).

The ABCVM would be independent of the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM), the current organization providing maintenance of certification for cardiologists along with 20 other internal medicine subspecialties. The ABIM’s maintenance of certification process has been widely criticized for many years and has been described as “needlessly burdensome and expensive.”

The AHA will be joining the American College of Cardiology (ACC), Heart Failure Society of America (HFSA), Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), and Society for Cardiovascular Angiography & Interventions (SCAI) in forming the ABCVM.

These four other societies issued a joint statement in September saying that they will apply to the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) to request an independent cardiology board that follows a “new competency-based approach to continuous certification — one that harnesses the knowledge, skills, and attitudes required to sustain professional excellence and care for cardiovascular patients effectively.”

The new board requirements will “de-emphasize timed, high stakes performance exams in the continuous certification process and instead will focus on learning assessments to identify gaps in current knowledge or skills,” the statement noted.

At the time the September statement was issued, the AHA was said to be supportive of the move but was waiting for formal endorsement to join the effort by its board of directors.

That has now happened, with the AHA’s national board of directors voting to provide “full support” for the creation of the proposed ABCVM.

“We enthusiastically join with our colleagues in proposing a new professional certification body to accredit cardiovascular professionals called the American Board of Cardiovascular Medicine,” said the association’s volunteer president Joseph C. Wu, MD. “The new ABCVM will be independent of the ABIM and focus on the specific competency-based trainings and appropriate ongoing certifications that align with and strengthen skills for cardiovascular physicians and enhance quality of care for people with cardiovascular disease,” Wu said.

“The AHA joins the consortium to submit the application to the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) requesting an independent medical board for cardiovascular medicine. The consortium’s robust proposal harnesses the knowledge, skills, and benchmarks appropriate for professional excellence and delivery of effective, high-quality cardiovascular care,” Wu added.

The leaders of the ABCVM will include professional representatives from the consortium of member organizations, with a specific focus on relevant education, trainings, and supports that recognize the increasing specialization in cardiology and the latest advances in the various subspecialties of cardiovascular medicine, the AHA notes in a statement.

Professional certification by ABIM is a condition of employment for physicians practicing in large hospitals or health systems. A dedicated certification board separate from ABIM will help to ensure that cardiovascular professionals are maintaining the expertise appropriate to high-quality care and improved outcomes for their patients, the AHA said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

T to be known as the American Board of Cardiovascular Medicine (ABCVM).

The ABCVM would be independent of the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM), the current organization providing maintenance of certification for cardiologists along with 20 other internal medicine subspecialties. The ABIM’s maintenance of certification process has been widely criticized for many years and has been described as “needlessly burdensome and expensive.”

The AHA will be joining the American College of Cardiology (ACC), Heart Failure Society of America (HFSA), Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), and Society for Cardiovascular Angiography & Interventions (SCAI) in forming the ABCVM.

These four other societies issued a joint statement in September saying that they will apply to the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) to request an independent cardiology board that follows a “new competency-based approach to continuous certification — one that harnesses the knowledge, skills, and attitudes required to sustain professional excellence and care for cardiovascular patients effectively.”

The new board requirements will “de-emphasize timed, high stakes performance exams in the continuous certification process and instead will focus on learning assessments to identify gaps in current knowledge or skills,” the statement noted.

At the time the September statement was issued, the AHA was said to be supportive of the move but was waiting for formal endorsement to join the effort by its board of directors.

That has now happened, with the AHA’s national board of directors voting to provide “full support” for the creation of the proposed ABCVM.

“We enthusiastically join with our colleagues in proposing a new professional certification body to accredit cardiovascular professionals called the American Board of Cardiovascular Medicine,” said the association’s volunteer president Joseph C. Wu, MD. “The new ABCVM will be independent of the ABIM and focus on the specific competency-based trainings and appropriate ongoing certifications that align with and strengthen skills for cardiovascular physicians and enhance quality of care for people with cardiovascular disease,” Wu said.

“The AHA joins the consortium to submit the application to the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) requesting an independent medical board for cardiovascular medicine. The consortium’s robust proposal harnesses the knowledge, skills, and benchmarks appropriate for professional excellence and delivery of effective, high-quality cardiovascular care,” Wu added.

The leaders of the ABCVM will include professional representatives from the consortium of member organizations, with a specific focus on relevant education, trainings, and supports that recognize the increasing specialization in cardiology and the latest advances in the various subspecialties of cardiovascular medicine, the AHA notes in a statement.

Professional certification by ABIM is a condition of employment for physicians practicing in large hospitals or health systems. A dedicated certification board separate from ABIM will help to ensure that cardiovascular professionals are maintaining the expertise appropriate to high-quality care and improved outcomes for their patients, the AHA said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

T to be known as the American Board of Cardiovascular Medicine (ABCVM).

The ABCVM would be independent of the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM), the current organization providing maintenance of certification for cardiologists along with 20 other internal medicine subspecialties. The ABIM’s maintenance of certification process has been widely criticized for many years and has been described as “needlessly burdensome and expensive.”

The AHA will be joining the American College of Cardiology (ACC), Heart Failure Society of America (HFSA), Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), and Society for Cardiovascular Angiography & Interventions (SCAI) in forming the ABCVM.

These four other societies issued a joint statement in September saying that they will apply to the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) to request an independent cardiology board that follows a “new competency-based approach to continuous certification — one that harnesses the knowledge, skills, and attitudes required to sustain professional excellence and care for cardiovascular patients effectively.”

The new board requirements will “de-emphasize timed, high stakes performance exams in the continuous certification process and instead will focus on learning assessments to identify gaps in current knowledge or skills,” the statement noted.

At the time the September statement was issued, the AHA was said to be supportive of the move but was waiting for formal endorsement to join the effort by its board of directors.

That has now happened, with the AHA’s national board of directors voting to provide “full support” for the creation of the proposed ABCVM.

“We enthusiastically join with our colleagues in proposing a new professional certification body to accredit cardiovascular professionals called the American Board of Cardiovascular Medicine,” said the association’s volunteer president Joseph C. Wu, MD. “The new ABCVM will be independent of the ABIM and focus on the specific competency-based trainings and appropriate ongoing certifications that align with and strengthen skills for cardiovascular physicians and enhance quality of care for people with cardiovascular disease,” Wu said.

“The AHA joins the consortium to submit the application to the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) requesting an independent medical board for cardiovascular medicine. The consortium’s robust proposal harnesses the knowledge, skills, and benchmarks appropriate for professional excellence and delivery of effective, high-quality cardiovascular care,” Wu added.

The leaders of the ABCVM will include professional representatives from the consortium of member organizations, with a specific focus on relevant education, trainings, and supports that recognize the increasing specialization in cardiology and the latest advances in the various subspecialties of cardiovascular medicine, the AHA notes in a statement.

Professional certification by ABIM is a condition of employment for physicians practicing in large hospitals or health systems. A dedicated certification board separate from ABIM will help to ensure that cardiovascular professionals are maintaining the expertise appropriate to high-quality care and improved outcomes for their patients, the AHA said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Even one night in the ED raises risk for death

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

As a consulting nephrologist, I go all over the hospital. Medicine floors, surgical floors, the ICU – I’ve even done consults in the operating room. And more and more, I do consults in the emergency department.

The reason I am doing more consults in the ED is not because the ED docs are getting gun shy with creatinine increases; it’s because patients are staying for extended periods in the ED despite being formally admitted to the hospital. It’s a phenomenon known as boarding, because there are simply not enough beds. You know the scene if you have ever been to a busy hospital: The ED is full to breaking, with patients on stretchers in hallways. It can often feel more like a warzone than a place for healing.

This is a huge problem.

The Joint Commission specifies that admitted patients should spend no more than 4 hours in the ED waiting for a bed in the hospital.

That is, based on what I’ve seen, hugely ambitious. But I should point out that I work in a hospital that runs near capacity all the time, and studies – from some of my Yale colleagues, actually – have shown that once hospital capacity exceeds 85%, boarding rates skyrocket.

I want to discuss some of the causes of extended boarding and some solutions. But before that, I should prove to you that this really matters, and for that we are going to dig in to a new study which suggests that ED boarding kills.

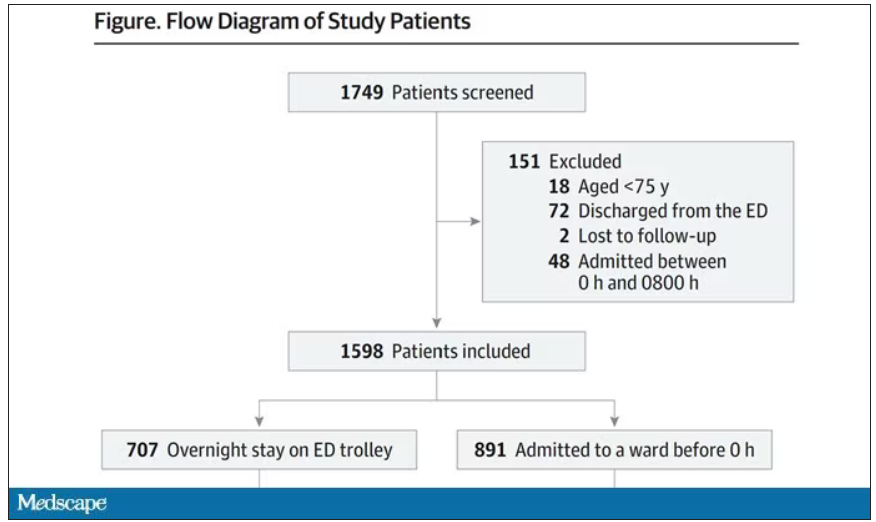

To put some hard numbers to the boarding problem, we turn to this paper out of France, appearing in JAMA Internal Medicine.

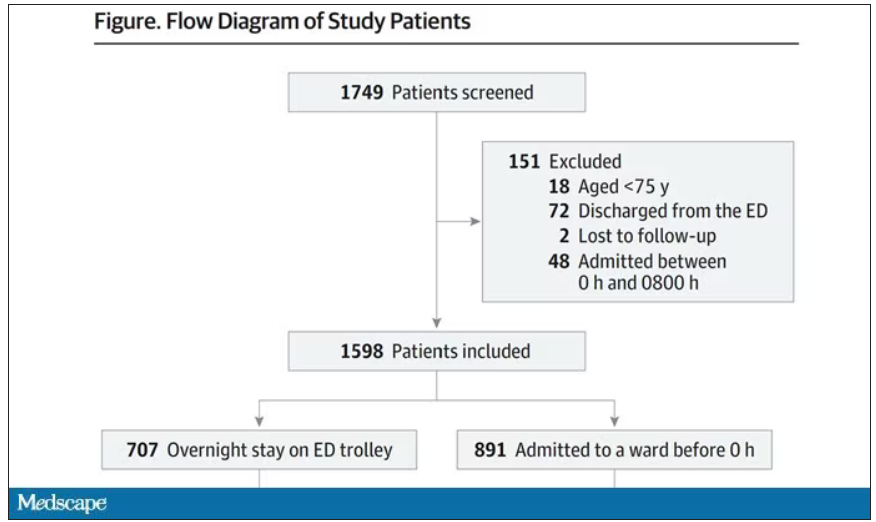

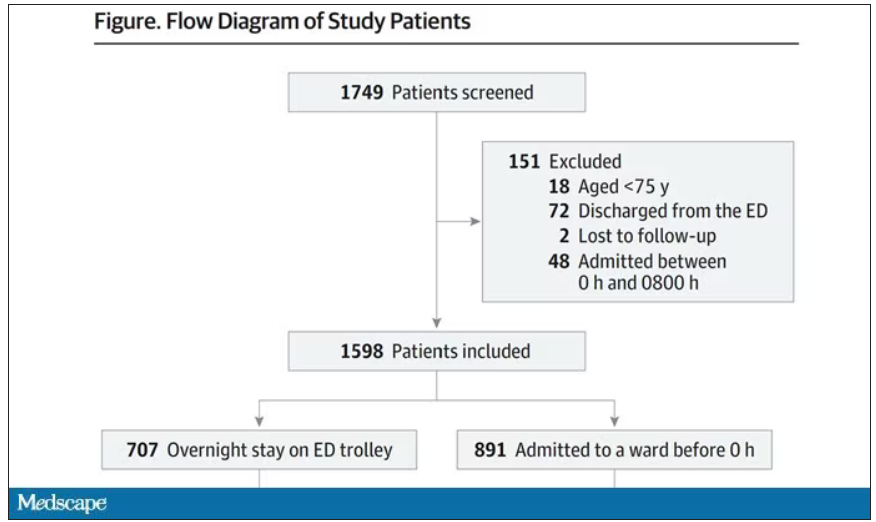

This is a unique study design. Basically, on a single day – Dec. 12, 2022 – researchers fanned out across France to 97 EDs and started counting patients. The study focused on those older than age 75 who were admitted to a hospital ward from the ED. The researchers then defined two groups: those who were sent up to the hospital floor before midnight, and those who spent at least from midnight until 8 AM in the ED (basically, people forced to sleep in the ED for a night). The middle-ground people who were sent up between midnight and 8 AM were excluded.

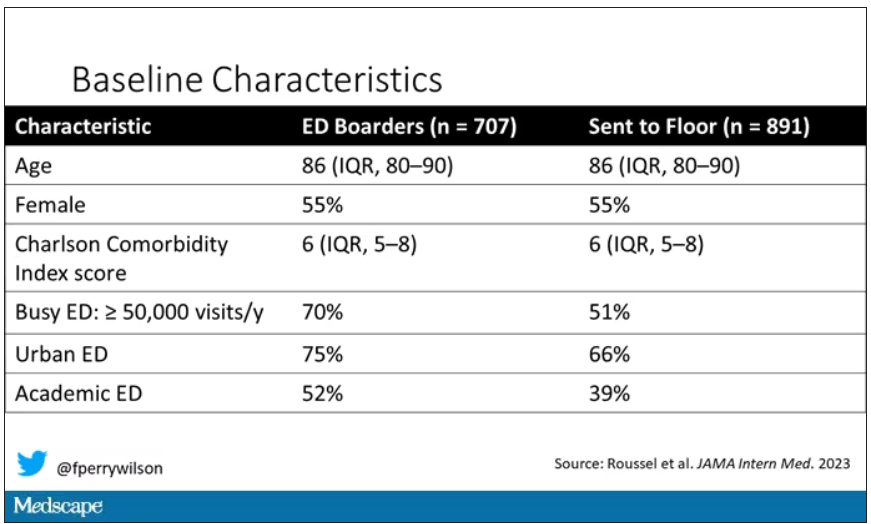

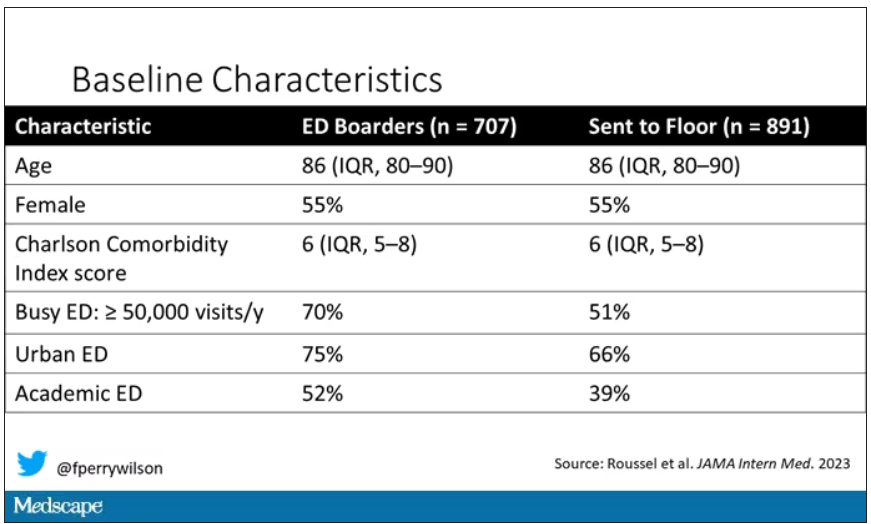

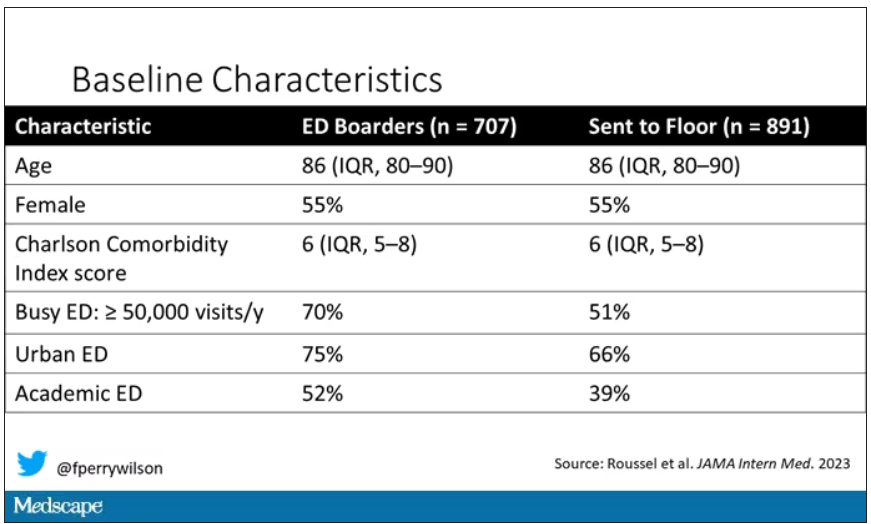

The baseline characteristics between the two groups of patients were pretty similar: median age around 86, 55% female. There were no significant differences in comorbidities. That said, comporting with previous studies, people in an urban ED, an academic ED, or a busy ED were much more likely to board overnight.

So, what we have are two similar groups of patients treated quite differently. Not quite a randomized trial, given the hospital differences, but not bad for purposes of analysis.

Here are the most important numbers from the trial:

This difference held up even after adjustment for patient and hospital characteristics. Put another way, you’d need to send 22 patients to the floor instead of boarding in the ED to save one life. Not a bad return on investment.

It’s not entirely clear what the mechanism for the excess mortality might be, but the researchers note that patients kept in the ED overnight were about twice as likely to have a fall during their hospital stay – not surprising, given the dangers of gurneys in hallways and the sleep deprivation that trying to rest in a busy ED engenders.

I should point out that this could be worse in the United States. French ED doctors continue to care for admitted patients boarding in the ED, whereas in many hospitals in the United States, admitted patients are the responsibility of the floor team, regardless of where they are, making it more likely that these individuals may be neglected.

So, if boarding in the ED is a life-threatening situation, why do we do it? What conditions predispose to this?

You’ll hear a lot of talk, mostly from hospital administrators, saying that this is simply a problem of supply and demand. There are not enough beds for the number of patients who need beds. And staffing shortages don’t help either.

However, they never want to talk about the reasons for the staffing shortages, like poor pay, poor support, and, of course, the moral injury of treating patients in hallways.

The issue of volume is real. We could do a lot to prevent ED visits and hospital admissions by providing better access to preventive and primary care and improving our outpatient mental health infrastructure. But I think this framing passes the buck a little.

Another reason ED boarding occurs is the way our health care system is paid for. If you are building a hospital, you have little incentive to build in excess capacity. The most efficient hospital, from a profit-and-loss standpoint, is one that is 100% full as often as possible. That may be fine at times, but throw in a respiratory virus or even a pandemic, and those systems fracture under the pressure.

Let us also remember that not all hospital beds are given to patients who acutely need hospital beds. Many beds, in many hospitals, are necessary to handle postoperative patients undergoing elective procedures. Those patients having a knee replacement or abdominoplasty don’t spend the night in the ED when they leave the OR; they go to a hospital bed. And those procedures are – let’s face it – more profitable than an ED admission for a medical issue. That’s why, even when hospitals expand the number of beds they have, they do it with an eye toward increasing the rate of those profitable procedures, not decreasing the burden faced by their ED.

For now, the band-aid to the solution might be to better triage individuals boarding in the ED for floor access, prioritizing those of older age, greater frailty, or more medical complexity. But it feels like a stop-gap measure as long as the incentives are aligned to view an empty hospital bed as a sign of failure in the health system instead of success.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

As a consulting nephrologist, I go all over the hospital. Medicine floors, surgical floors, the ICU – I’ve even done consults in the operating room. And more and more, I do consults in the emergency department.

The reason I am doing more consults in the ED is not because the ED docs are getting gun shy with creatinine increases; it’s because patients are staying for extended periods in the ED despite being formally admitted to the hospital. It’s a phenomenon known as boarding, because there are simply not enough beds. You know the scene if you have ever been to a busy hospital: The ED is full to breaking, with patients on stretchers in hallways. It can often feel more like a warzone than a place for healing.

This is a huge problem.

The Joint Commission specifies that admitted patients should spend no more than 4 hours in the ED waiting for a bed in the hospital.

That is, based on what I’ve seen, hugely ambitious. But I should point out that I work in a hospital that runs near capacity all the time, and studies – from some of my Yale colleagues, actually – have shown that once hospital capacity exceeds 85%, boarding rates skyrocket.

I want to discuss some of the causes of extended boarding and some solutions. But before that, I should prove to you that this really matters, and for that we are going to dig in to a new study which suggests that ED boarding kills.

To put some hard numbers to the boarding problem, we turn to this paper out of France, appearing in JAMA Internal Medicine.

This is a unique study design. Basically, on a single day – Dec. 12, 2022 – researchers fanned out across France to 97 EDs and started counting patients. The study focused on those older than age 75 who were admitted to a hospital ward from the ED. The researchers then defined two groups: those who were sent up to the hospital floor before midnight, and those who spent at least from midnight until 8 AM in the ED (basically, people forced to sleep in the ED for a night). The middle-ground people who were sent up between midnight and 8 AM were excluded.

The baseline characteristics between the two groups of patients were pretty similar: median age around 86, 55% female. There were no significant differences in comorbidities. That said, comporting with previous studies, people in an urban ED, an academic ED, or a busy ED were much more likely to board overnight.

So, what we have are two similar groups of patients treated quite differently. Not quite a randomized trial, given the hospital differences, but not bad for purposes of analysis.

Here are the most important numbers from the trial:

This difference held up even after adjustment for patient and hospital characteristics. Put another way, you’d need to send 22 patients to the floor instead of boarding in the ED to save one life. Not a bad return on investment.

It’s not entirely clear what the mechanism for the excess mortality might be, but the researchers note that patients kept in the ED overnight were about twice as likely to have a fall during their hospital stay – not surprising, given the dangers of gurneys in hallways and the sleep deprivation that trying to rest in a busy ED engenders.

I should point out that this could be worse in the United States. French ED doctors continue to care for admitted patients boarding in the ED, whereas in many hospitals in the United States, admitted patients are the responsibility of the floor team, regardless of where they are, making it more likely that these individuals may be neglected.

So, if boarding in the ED is a life-threatening situation, why do we do it? What conditions predispose to this?

You’ll hear a lot of talk, mostly from hospital administrators, saying that this is simply a problem of supply and demand. There are not enough beds for the number of patients who need beds. And staffing shortages don’t help either.

However, they never want to talk about the reasons for the staffing shortages, like poor pay, poor support, and, of course, the moral injury of treating patients in hallways.

The issue of volume is real. We could do a lot to prevent ED visits and hospital admissions by providing better access to preventive and primary care and improving our outpatient mental health infrastructure. But I think this framing passes the buck a little.

Another reason ED boarding occurs is the way our health care system is paid for. If you are building a hospital, you have little incentive to build in excess capacity. The most efficient hospital, from a profit-and-loss standpoint, is one that is 100% full as often as possible. That may be fine at times, but throw in a respiratory virus or even a pandemic, and those systems fracture under the pressure.

Let us also remember that not all hospital beds are given to patients who acutely need hospital beds. Many beds, in many hospitals, are necessary to handle postoperative patients undergoing elective procedures. Those patients having a knee replacement or abdominoplasty don’t spend the night in the ED when they leave the OR; they go to a hospital bed. And those procedures are – let’s face it – more profitable than an ED admission for a medical issue. That’s why, even when hospitals expand the number of beds they have, they do it with an eye toward increasing the rate of those profitable procedures, not decreasing the burden faced by their ED.

For now, the band-aid to the solution might be to better triage individuals boarding in the ED for floor access, prioritizing those of older age, greater frailty, or more medical complexity. But it feels like a stop-gap measure as long as the incentives are aligned to view an empty hospital bed as a sign of failure in the health system instead of success.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

As a consulting nephrologist, I go all over the hospital. Medicine floors, surgical floors, the ICU – I’ve even done consults in the operating room. And more and more, I do consults in the emergency department.

The reason I am doing more consults in the ED is not because the ED docs are getting gun shy with creatinine increases; it’s because patients are staying for extended periods in the ED despite being formally admitted to the hospital. It’s a phenomenon known as boarding, because there are simply not enough beds. You know the scene if you have ever been to a busy hospital: The ED is full to breaking, with patients on stretchers in hallways. It can often feel more like a warzone than a place for healing.

This is a huge problem.

The Joint Commission specifies that admitted patients should spend no more than 4 hours in the ED waiting for a bed in the hospital.

That is, based on what I’ve seen, hugely ambitious. But I should point out that I work in a hospital that runs near capacity all the time, and studies – from some of my Yale colleagues, actually – have shown that once hospital capacity exceeds 85%, boarding rates skyrocket.

I want to discuss some of the causes of extended boarding and some solutions. But before that, I should prove to you that this really matters, and for that we are going to dig in to a new study which suggests that ED boarding kills.

To put some hard numbers to the boarding problem, we turn to this paper out of France, appearing in JAMA Internal Medicine.

This is a unique study design. Basically, on a single day – Dec. 12, 2022 – researchers fanned out across France to 97 EDs and started counting patients. The study focused on those older than age 75 who were admitted to a hospital ward from the ED. The researchers then defined two groups: those who were sent up to the hospital floor before midnight, and those who spent at least from midnight until 8 AM in the ED (basically, people forced to sleep in the ED for a night). The middle-ground people who were sent up between midnight and 8 AM were excluded.

The baseline characteristics between the two groups of patients were pretty similar: median age around 86, 55% female. There were no significant differences in comorbidities. That said, comporting with previous studies, people in an urban ED, an academic ED, or a busy ED were much more likely to board overnight.

So, what we have are two similar groups of patients treated quite differently. Not quite a randomized trial, given the hospital differences, but not bad for purposes of analysis.

Here are the most important numbers from the trial:

This difference held up even after adjustment for patient and hospital characteristics. Put another way, you’d need to send 22 patients to the floor instead of boarding in the ED to save one life. Not a bad return on investment.

It’s not entirely clear what the mechanism for the excess mortality might be, but the researchers note that patients kept in the ED overnight were about twice as likely to have a fall during their hospital stay – not surprising, given the dangers of gurneys in hallways and the sleep deprivation that trying to rest in a busy ED engenders.

I should point out that this could be worse in the United States. French ED doctors continue to care for admitted patients boarding in the ED, whereas in many hospitals in the United States, admitted patients are the responsibility of the floor team, regardless of where they are, making it more likely that these individuals may be neglected.

So, if boarding in the ED is a life-threatening situation, why do we do it? What conditions predispose to this?

You’ll hear a lot of talk, mostly from hospital administrators, saying that this is simply a problem of supply and demand. There are not enough beds for the number of patients who need beds. And staffing shortages don’t help either.

However, they never want to talk about the reasons for the staffing shortages, like poor pay, poor support, and, of course, the moral injury of treating patients in hallways.

The issue of volume is real. We could do a lot to prevent ED visits and hospital admissions by providing better access to preventive and primary care and improving our outpatient mental health infrastructure. But I think this framing passes the buck a little.

Another reason ED boarding occurs is the way our health care system is paid for. If you are building a hospital, you have little incentive to build in excess capacity. The most efficient hospital, from a profit-and-loss standpoint, is one that is 100% full as often as possible. That may be fine at times, but throw in a respiratory virus or even a pandemic, and those systems fracture under the pressure.

Let us also remember that not all hospital beds are given to patients who acutely need hospital beds. Many beds, in many hospitals, are necessary to handle postoperative patients undergoing elective procedures. Those patients having a knee replacement or abdominoplasty don’t spend the night in the ED when they leave the OR; they go to a hospital bed. And those procedures are – let’s face it – more profitable than an ED admission for a medical issue. That’s why, even when hospitals expand the number of beds they have, they do it with an eye toward increasing the rate of those profitable procedures, not decreasing the burden faced by their ED.

For now, the band-aid to the solution might be to better triage individuals boarding in the ED for floor access, prioritizing those of older age, greater frailty, or more medical complexity. But it feels like a stop-gap measure as long as the incentives are aligned to view an empty hospital bed as a sign of failure in the health system instead of success.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The placebo effect

As I noted in my last column, I recently had a generic cold.

One of the more irritating aspects is that I usually get a cough that lasts a few weeks afterwards, and, like most people, I try to do something about it. So I load up on various over-the-counter remedies.

I have no idea if they work, or if I’m shelling out for a placebo. I’m not alone in buying these, or they wouldn’t be on the market, or making money, at all.

But the placebo effect is pretty strong. Phenylephrine has been around since 1938. It’s sold on its own and is an ingredient in almost every anti-cough/cold combination medication out there (NyQuil, DayQuil, Robitussin Multi-Symptom, and their many generic store brands). Millions of people use it every year.

Yet, after sifting through piles of accumulated data, the Food and Drug Administration announced earlier this year that phenylephrine ... doesn’t do anything. Zip. Zero. Nada. When compared with a placebo in controlled trials, you couldn’t tell the difference between them. So now the use of it is being questioned. CVS has started pulling it off their shelves, and I suspect other pharmacies will follow.

But back to my cough. A time-honored tradition in American childhood is having to cram down Robitussin and gagging from its nasty taste (the cherry and orange flavoring don’t make a difference, it tastes terrible no matter what you do). So that gets ingrained into us, and to this day I, and most adults, reach for a bottle of dextromethorphan when they have a cough.

But the evidence for that is spotty, too. Several studies have shown equivocal, if any, evidence to suggest it helps with coughs, though others have shown some. Nothing really amazing though.

But we still buy it by the gallon when we’re sick, because we want something, anything, that will make us better. Even if we’re doing so more from hope than conviction.

There’s also the old standby of cough drops, which have been used for more than 3,000 years. Ingredients vary, but menthol is probably the most common one. I go through those, too. I keep a bag in my desk at work. In medical school, during cold season, it was in my backpack. I remember sitting in the Creighton library to study, quietly sucking on a lozenge to keep my cough from disturbing other students.

But even then, the evidence is iffy as to whether they do anything. In fact, one interesting (though small) study in 2018 suggested they may actually prolong coughs.

The fact is that we are all susceptible to the placebo effect, regardless of how much we know about illness and medication. Maybe these things work, maybe they don’t, but it’s a valid question. How often do we let wishful thinking beat objective data?

Probably more often than we want to admit.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

As I noted in my last column, I recently had a generic cold.

One of the more irritating aspects is that I usually get a cough that lasts a few weeks afterwards, and, like most people, I try to do something about it. So I load up on various over-the-counter remedies.

I have no idea if they work, or if I’m shelling out for a placebo. I’m not alone in buying these, or they wouldn’t be on the market, or making money, at all.

But the placebo effect is pretty strong. Phenylephrine has been around since 1938. It’s sold on its own and is an ingredient in almost every anti-cough/cold combination medication out there (NyQuil, DayQuil, Robitussin Multi-Symptom, and their many generic store brands). Millions of people use it every year.

Yet, after sifting through piles of accumulated data, the Food and Drug Administration announced earlier this year that phenylephrine ... doesn’t do anything. Zip. Zero. Nada. When compared with a placebo in controlled trials, you couldn’t tell the difference between them. So now the use of it is being questioned. CVS has started pulling it off their shelves, and I suspect other pharmacies will follow.

But back to my cough. A time-honored tradition in American childhood is having to cram down Robitussin and gagging from its nasty taste (the cherry and orange flavoring don’t make a difference, it tastes terrible no matter what you do). So that gets ingrained into us, and to this day I, and most adults, reach for a bottle of dextromethorphan when they have a cough.

But the evidence for that is spotty, too. Several studies have shown equivocal, if any, evidence to suggest it helps with coughs, though others have shown some. Nothing really amazing though.

But we still buy it by the gallon when we’re sick, because we want something, anything, that will make us better. Even if we’re doing so more from hope than conviction.

There’s also the old standby of cough drops, which have been used for more than 3,000 years. Ingredients vary, but menthol is probably the most common one. I go through those, too. I keep a bag in my desk at work. In medical school, during cold season, it was in my backpack. I remember sitting in the Creighton library to study, quietly sucking on a lozenge to keep my cough from disturbing other students.

But even then, the evidence is iffy as to whether they do anything. In fact, one interesting (though small) study in 2018 suggested they may actually prolong coughs.

The fact is that we are all susceptible to the placebo effect, regardless of how much we know about illness and medication. Maybe these things work, maybe they don’t, but it’s a valid question. How often do we let wishful thinking beat objective data?

Probably more often than we want to admit.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

As I noted in my last column, I recently had a generic cold.

One of the more irritating aspects is that I usually get a cough that lasts a few weeks afterwards, and, like most people, I try to do something about it. So I load up on various over-the-counter remedies.

I have no idea if they work, or if I’m shelling out for a placebo. I’m not alone in buying these, or they wouldn’t be on the market, or making money, at all.

But the placebo effect is pretty strong. Phenylephrine has been around since 1938. It’s sold on its own and is an ingredient in almost every anti-cough/cold combination medication out there (NyQuil, DayQuil, Robitussin Multi-Symptom, and their many generic store brands). Millions of people use it every year.

Yet, after sifting through piles of accumulated data, the Food and Drug Administration announced earlier this year that phenylephrine ... doesn’t do anything. Zip. Zero. Nada. When compared with a placebo in controlled trials, you couldn’t tell the difference between them. So now the use of it is being questioned. CVS has started pulling it off their shelves, and I suspect other pharmacies will follow.

But back to my cough. A time-honored tradition in American childhood is having to cram down Robitussin and gagging from its nasty taste (the cherry and orange flavoring don’t make a difference, it tastes terrible no matter what you do). So that gets ingrained into us, and to this day I, and most adults, reach for a bottle of dextromethorphan when they have a cough.

But the evidence for that is spotty, too. Several studies have shown equivocal, if any, evidence to suggest it helps with coughs, though others have shown some. Nothing really amazing though.

But we still buy it by the gallon when we’re sick, because we want something, anything, that will make us better. Even if we’re doing so more from hope than conviction.

There’s also the old standby of cough drops, which have been used for more than 3,000 years. Ingredients vary, but menthol is probably the most common one. I go through those, too. I keep a bag in my desk at work. In medical school, during cold season, it was in my backpack. I remember sitting in the Creighton library to study, quietly sucking on a lozenge to keep my cough from disturbing other students.

But even then, the evidence is iffy as to whether they do anything. In fact, one interesting (though small) study in 2018 suggested they may actually prolong coughs.

The fact is that we are all susceptible to the placebo effect, regardless of how much we know about illness and medication. Maybe these things work, maybe they don’t, but it’s a valid question. How often do we let wishful thinking beat objective data?

Probably more often than we want to admit.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Psychological safety in cardiology training

Training in medicine has long been thought of as a tough process, but the issue of creating a psychologically safe environment for young doctors is now being highlighted as an important way of providing an improved learning environment, which will ultimately lead to better patient care. And cardiology is one field that needs to work harder on this.

“We all remember attendings who made our training experience memorable, who made us excited to come to work and learn, and who inspired us to become better,” Vivek Kulkarni, MD, wrote in a recent commentary. “Unfortunately, we also all remember the learning environments where we were terrified, where thriving took a backseat to surviving, and where learning was an afterthought.”

Writing in an article in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, Dr. Kulkarni asked the question: “Why are some learning environments better than others, and what can we do to improve the learning environment for our trainees?”

Dr. Kulkarni, director of the training program for cardiology fellows at Cooper University Hospital, Camden, New Jersey, said “There may be some people in some institutions that do pay attention to this but as wider field we could do better.”

Dr. Kulkarni explained that psychological safety is the comfort to engage with others genuinely, with honesty and without fear.

It has been defined as a “willingness to take interpersonal risks at work, whether to admit error, ask a question, seek help, or simply say ‘I don’t know,’ ” or as “the perception that a working environment is safe for team members to express a concern, ask a question, or acknowledge a mistake without fear of humiliation, retaliation, blame, or being ignored.”

“In the medical environment we usually work in teams: older doctors, younger doctors, nurses, other staff,” Dr. Kulkarni said in an interview. “A psychologically safe environment would be one where a trainee feels comfortable so that they can ask a question about something that they don’t understand. That comfort comes from the idea that it is okay to get something wrong or to not know something and to ask for help.

“The flip side of that is an environment in which people are so afraid to make a mistake out of fear of retribution or punishment that they don’t take risks, or they don’t openly acknowledge when they might need help with something,” he said. “That would be a psychologically unsafe environment.”

What exactly this looks like varies in different environments and culture of the group, he noted, “but in general, you can tell if you are part of a psychologically safe environment because you are excited to come to work and feel comfortable at work.”

Dr. Kulkarni added that a growing body of literature now shows that psychological safety is critical for optimal learning but that cardiovascular fellowship training poses unique barriers to psychological safety.

‘Arrogant, unkind, and unwelcoming’

First, he said that the “high-stakes” nature of cardiology, in which decisions often must be made quickly and can have life-or-death consequences, can create fear about making mistakes and that some trainees may be so afraid that they cannot speak up and ask for help when struggling or cannot incorporate feedback in real time.

Second, in medicine at large, there is a stereotype that cardiologists can be “arrogant, unkind, and unwelcoming,” which may discourage new fellows from honest interaction.

Third, cardiology involves many different technical skills that fellows have little to no previous experience with; this may contribute to a perceived sense of being judged when making mistakes or asking for help.

Finally, demographics may be a factor, with only one in eight cardiologists in the United States being women and only 7.5% of cardiologists being from traditionally underrepresented racial and ethnic minority groups, which Dr. Kulkarni said may lead to a lack of psychological safety because of “bias, microaggressions, or even just a lack of mentors of similar backgrounds.”

But he believes that the cardiology training culture is improving.

“I think it is getting better. Even the fact that I can publish this article is a positive sign. I think there’s an audience for this type of thing now.”

He believes that part of the reason for this is the availability of research and evidence showing there are better ways to teach than the old traditional approaches.

He noted that some teaching physicians receive training on how to teach and some don’t, and this is an area that could be improved.

“I think the knowledge of how to produce psychologically safe environments is already there,” he said. “It just has to be standardized and publicized. That would make the learning environment better.”

“Nothing about this is groundbreaking,” he added. “We all know psychologically unsafe environments exist. The novelty is just that it is now starting to be discussed. It’s one of those things that we can likely improve the ways our trainees learn and the kind of doctors we produce just by thinking a little bit more carefully about the way we interact with each other.”

Dr. Kulkarni said trainees often drop out because they have had a negative experience of feeling psychologically unsafe. “They may drop out of medicine all together or they may choose to pursue a career in a different part of medicine, where they perceive a more psychologically safe environment.”

He also suggested that this issue can affect patient care.

“If the medical team does not provide a psychologically safe environment for trainees, it is very likely that that team is not operating as effectively as it could, and it is very likely that patients being taken care of by that team may have missed opportunities for better care,” he concluded. Examples could include trainees recognizing errors and bringing things that might not be right to the attention of their superiors. “That is something that requires some degree of psychological safety.”

Action for improvement

Dr. Kulkarni suggested several strategies to promote psychological safety in cardiology training.

As a first step, institutions should investigate the culture of learning within their fellowship programs and gather feedback from anonymous surveys of fellows. They can then implement policies to address gaps.

He noted that, at Cooper University Hospital, standardized documents have been created that explicitly outline policies for attendings on teaching services, which establish expectations for all team members, encourage fellows to ask for help, set guidelines for feedback conversations with fellows, and delineate situations when calling the attending is expected.

Dr. Kulkarni also suggested that cardiologists involved in teaching fellows can try several strategies to promote psychological safety. These include setting clear expectations on their tasks and graded autonomy, inviting participation in decisions, acknowledging that gaps in knowledge are not a personal failure but rather a normal part of the growth process, encouraging fellows to seek help when they need it, fostering collegial relationships with fellows, acknowledging your own uncertainty in difficult situations, checking in about emotions after challenging situations, and seeking feedback on your own performance.

He added that changes on a larger scale are also needed, such as training for cardiology program directors including more on this issue as well as developing best practices.

“If we as a community could come together and agree on the things needed to create a psychologically safe environment for training, that would be a big improvement.”

Addressing the challenges of different generations

In a response to Dr. Kulkarni’s article, Margo Vassar, MD, The Queen’s Medical Center, Honolulu, and Sandra Lewis, MD, Legacy Health System, Portland, Ore., make the case that to succeed in providing psychological safety, the cardiovascular community also needs to address intergenerational cultural challenges.

“Twenty years ago, to have raised the idea of psychological safety in any phase of training would likely have been met with intergenerational pushback and complete disregard,” they say, adding that: “Asking senior Baby Boomer cardiologists to develop skills to implement psychological safety, with just a list of action items, to suddenly create safe environments, belies the challenges inherent in intergenerational understanding and collaboration.”

In an interview, Dr. Lewis elaborated: “Many cardiology training program directors are Baby Boomers, but there is a whole new group of younger people moving in, and the way they deal with things and communicate is quite different.”

Dr. Lewis gave an example of when she was in training the attending was the “be all and end all,” and it was not expected that fellows would ask questions. “I think there is more communication now and a willingness to take risks and ask questions.”

But she said because everyone is so busy now, building relationships within a team can be difficult.

“We don’t have the doctors’ lounge anymore. We don’t sit and have lunch together. Computers are taking over now, no one actually talks to each other anymore,” she said. “We need to try to get to know each other and become colleagues. It’s easy when you don’t know somebody to be abrupt or brusque; it’s harder when you’re friends.”

She noted that the Mayo Clinic is one institution that is doing a lot of work on this, arranging for groups of doctors to go out for dinner together to get to know each other.

“This bringing people together socially happens in a lot of workplaces, and it can happen in medicine.”

Dr. Lewis, who has some leadership positions at the American College of Cardiology, said the organization is focusing on “intergenerational opportunities and challenges” to help improve psychological safety for trainees.

Noting that a recent survey of medical residents found that “contemporary residents were more likely than their predecessors to agree with negative perceptions of cardiology,” Lewis said the ACC is also reaching out to medical residents who may think that cardiology is an unwelcoming environment to enter and to minority groups of medical residents such as women and ethnic minorities to try and attract them to become cardiology fellows.

“If fellows find in hard to speak up because they are in this hierarchical learning situation, that can be even more difficult if you feel you’re in a minority group. ... We need to create a culture of colleagues rather than perpetuating a culture of us and them, to provide a safe and thriving cardiovascular community,” she added.