User login

Do PFAs Cause Kidney Cancer? VA to Investigate

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) will conduct a scientific assessment to find out in whether kidney cancer should be considered a presumptive service-connected condition for veterans exposed to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAs). This assessment is the first step in the VA presumptive condition investigative process, which could allow exposed veterans who were exposed to PFAs during their service to access more VA services.

A class of more than 12,000 chemicals, PFAs have been used in the military since the early 1970s in many items, including military-grade firefighting foam. Studies have already suggested links between the so-called forever chemicals and cancer, particularly kidney cancer.

The US Department of Defense (DoD) is assessing contamination at hundreds of sites, while the National Defense Authorization Act in Fiscal Year 2020 mandated that DoD stop using those foams starting in October and remove all stocks from active and former installations and equipment. That may not happen until next year, though, because the DoD has requested a waiver through October 2025 and may extend it through 2026.

When a condition is considered presumptive, eligible veterans do not need to prove their service caused their disease to receive benefits. As part of the Biden Administration’s efforts to expand benefits and services for toxin-exposed veterans and their families, the VA expedited health care and benefits eligibility under the PACT Act by several years—including extending presumptions for head cancer, neck cancer, gastrointestinal cancer, reproductive cancer, lymphoma, pancreatic cancer, kidney cancer, melanoma, and hypertension for Vietnam era veterans. The VA has also extended presumptions for > 300 new conditions, most recently for male breast cancer, urethral cancer, and cancer of the paraurethral glands.

Whether a condition is an established presumptive condition or not, the VA will consider claims on a case-by-case basis and can grant disability compensation benefits if sufficient evidence of service connection is found. “[M]ake no mistake: Veterans should not wait for the outcome of this review to apply for the benefits and care they deserve,” VA Secretary Denis McDonough said in a release. “If you’re a veteran and believe your military service has negatively impacted your health, we encourage you to apply for VA care and benefits today.”

The public has 30 days to comment on the proposed scientific assessment between PFAs exposure and kidney cancer via the Federal Register. The VA is set to host a listening session on Nov. 19, 2024, to allow individuals to share research and input. Interested individuals may register to participate. The public may also comment via either forum on other conditions that would benefit from review for potential service-connection.

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) will conduct a scientific assessment to find out in whether kidney cancer should be considered a presumptive service-connected condition for veterans exposed to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAs). This assessment is the first step in the VA presumptive condition investigative process, which could allow exposed veterans who were exposed to PFAs during their service to access more VA services.

A class of more than 12,000 chemicals, PFAs have been used in the military since the early 1970s in many items, including military-grade firefighting foam. Studies have already suggested links between the so-called forever chemicals and cancer, particularly kidney cancer.

The US Department of Defense (DoD) is assessing contamination at hundreds of sites, while the National Defense Authorization Act in Fiscal Year 2020 mandated that DoD stop using those foams starting in October and remove all stocks from active and former installations and equipment. That may not happen until next year, though, because the DoD has requested a waiver through October 2025 and may extend it through 2026.

When a condition is considered presumptive, eligible veterans do not need to prove their service caused their disease to receive benefits. As part of the Biden Administration’s efforts to expand benefits and services for toxin-exposed veterans and their families, the VA expedited health care and benefits eligibility under the PACT Act by several years—including extending presumptions for head cancer, neck cancer, gastrointestinal cancer, reproductive cancer, lymphoma, pancreatic cancer, kidney cancer, melanoma, and hypertension for Vietnam era veterans. The VA has also extended presumptions for > 300 new conditions, most recently for male breast cancer, urethral cancer, and cancer of the paraurethral glands.

Whether a condition is an established presumptive condition or not, the VA will consider claims on a case-by-case basis and can grant disability compensation benefits if sufficient evidence of service connection is found. “[M]ake no mistake: Veterans should not wait for the outcome of this review to apply for the benefits and care they deserve,” VA Secretary Denis McDonough said in a release. “If you’re a veteran and believe your military service has negatively impacted your health, we encourage you to apply for VA care and benefits today.”

The public has 30 days to comment on the proposed scientific assessment between PFAs exposure and kidney cancer via the Federal Register. The VA is set to host a listening session on Nov. 19, 2024, to allow individuals to share research and input. Interested individuals may register to participate. The public may also comment via either forum on other conditions that would benefit from review for potential service-connection.

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) will conduct a scientific assessment to find out in whether kidney cancer should be considered a presumptive service-connected condition for veterans exposed to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAs). This assessment is the first step in the VA presumptive condition investigative process, which could allow exposed veterans who were exposed to PFAs during their service to access more VA services.

A class of more than 12,000 chemicals, PFAs have been used in the military since the early 1970s in many items, including military-grade firefighting foam. Studies have already suggested links between the so-called forever chemicals and cancer, particularly kidney cancer.

The US Department of Defense (DoD) is assessing contamination at hundreds of sites, while the National Defense Authorization Act in Fiscal Year 2020 mandated that DoD stop using those foams starting in October and remove all stocks from active and former installations and equipment. That may not happen until next year, though, because the DoD has requested a waiver through October 2025 and may extend it through 2026.

When a condition is considered presumptive, eligible veterans do not need to prove their service caused their disease to receive benefits. As part of the Biden Administration’s efforts to expand benefits and services for toxin-exposed veterans and their families, the VA expedited health care and benefits eligibility under the PACT Act by several years—including extending presumptions for head cancer, neck cancer, gastrointestinal cancer, reproductive cancer, lymphoma, pancreatic cancer, kidney cancer, melanoma, and hypertension for Vietnam era veterans. The VA has also extended presumptions for > 300 new conditions, most recently for male breast cancer, urethral cancer, and cancer of the paraurethral glands.

Whether a condition is an established presumptive condition or not, the VA will consider claims on a case-by-case basis and can grant disability compensation benefits if sufficient evidence of service connection is found. “[M]ake no mistake: Veterans should not wait for the outcome of this review to apply for the benefits and care they deserve,” VA Secretary Denis McDonough said in a release. “If you’re a veteran and believe your military service has negatively impacted your health, we encourage you to apply for VA care and benefits today.”

The public has 30 days to comment on the proposed scientific assessment between PFAs exposure and kidney cancer via the Federal Register. The VA is set to host a listening session on Nov. 19, 2024, to allow individuals to share research and input. Interested individuals may register to participate. The public may also comment via either forum on other conditions that would benefit from review for potential service-connection.

Facial Angioedema, Rash, and “Mastitis” in a 31-Year-Old Female

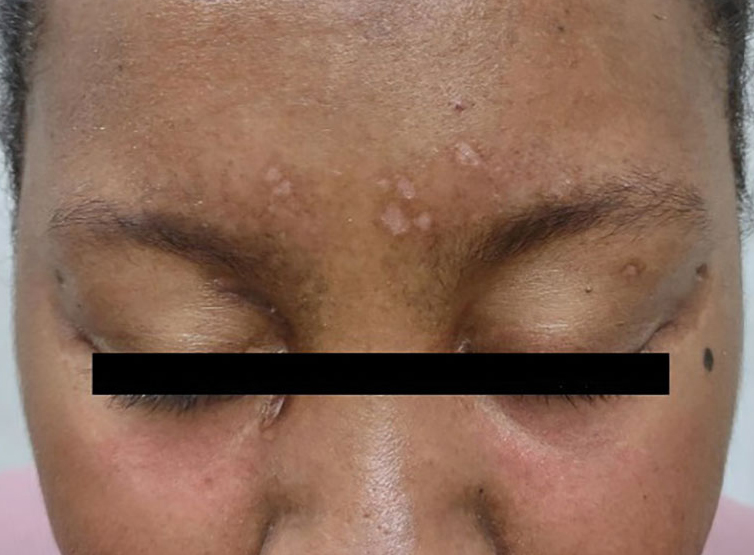

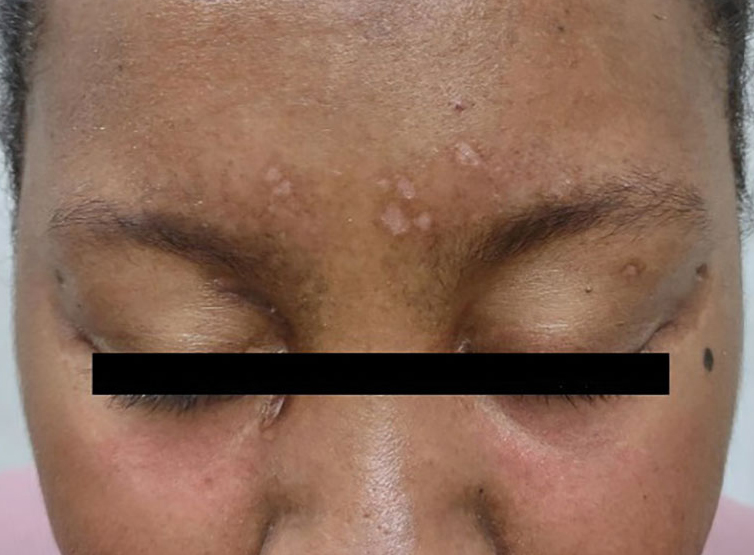

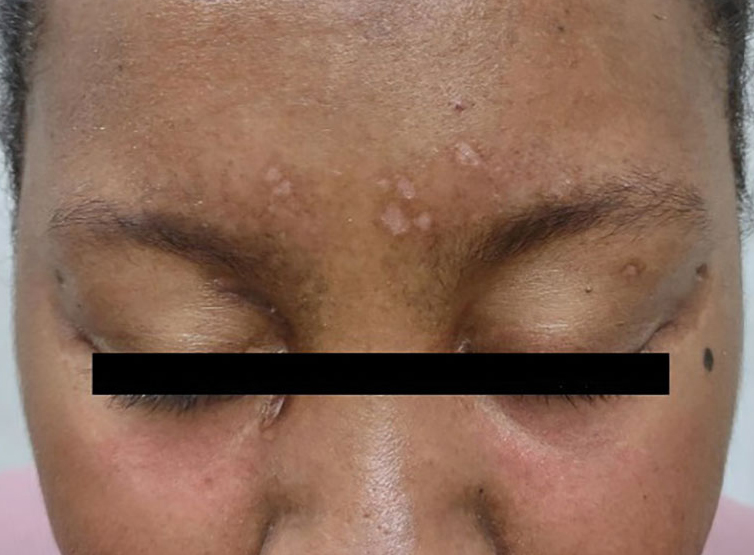

A previously healthy 31-year-old female active-duty Navy sailor working as a calibration technician developed a painful, erythematous, pruritic, indurated plaque on her left breast. The sailor was not lactating and had no known family history of malignancy. Initially, she was treated by her primary care practitioner for presumed mastitis with oral cephalexin and then with oral clindamycin with no symptom improvement. About 2 weeks after the completion of both antibiotic courses, she developed angioedema and periorbital edema (Figure 1), requiring highdose corticosteroids and antihistamines with a corticosteroid course of prednisone 40 mg daily tapered to 10 mg daily over 12 days and diphenhydramine 25 mg to use up to 4 times daily. Workup for both was acquired and hereditary angioedema was unremarkable. Two months later, the patient developed patches of alopecia, oral ulcerations, and hypopigmented plaques with a peripheral hyperpigmented rim on the central face and bilateral conchal bowls (Figure 2). She also developed hypopigmented papules with peripheral hyperpigmentation on the bilateral dorsal hands overlying the metacarpal and proximal interphalangeal joints, which eventually ulcerated (Figure 3). Laboratory evaluation, including tests for creatine kinase, aldolase, transaminases, lactate dehydrogenase, and autoantibodies (antiJo-1, anti-Mi-2, anti-MDA-5, anti-TIF-1, anti-NXP-2, and anti-SAEP), were unremarkable. A punch biopsy from a papule on the right dorsal hand showed superficial perivascular lymphohistiocytic inflammation with a subtle focal increase in dermal mucin, highlighted by the colloidal iron stain. Further evaluation of the left breast plaque revealed ER/PR+ HER2- stage IIIB inflammatory breast cancer.

DISCUSSION

Based on the clinical presentation and diagnosis of inflammatory breast cancer, the patient was diagnosed with paraneoplastic clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis (CADM). She was treated for her breast cancer with an initial chemotherapy regimen consisting of dose-dense cyclophosphamide and doxorubicin followed by paclitaxel. The patient underwent a mastectomy, axillary lymph node dissection, and 25 sessions of radiation therapy, and is currently continuing therapy with anastrozole 1 mg daily and ovarian suppression with leuprorelin 11.25 mg every 3 months. For the severe angioedema and dermatomyositis-like cutaneous findings, the patient was continued on high-dose corticosteroids at prednisone 60 mg daily with a prolonged taper to prednisone 10 mg daily. After about 10 months, she transitioned from prednisone 10 mg daily to hydrocortisone 30 mg daily and is currently tapering her hydrocortisone dosing. She was additionally started on monthly intravenous immunoglobulin, hydroxychloroquine 300 mg daily, and amlodipine 5 mg daily. The ulcerated papules on her hands were treated with topical clobetasol 0.05% ointment applied daily, topical tacrolimus 0.1% ointment applied daily, and multiple intralesional triamcinolone 5 mg/mL injections. With this regimen, the patient experienced significant improvement in her cutaneous symptoms.

CADM is a rare autoimmune inflammatory disease featuring classic dermatomyositis-like cutaneous findings such as a heliotrope rash and Gottron papules. Ulcerative Gottron papules are less common than the typical erythematous papules and are associated more strongly with amyopathic disease.1 Paraneoplastic myositis poses a diagnostic challenge because it presents like an idiopathic dermatomyositis and often has a heterogeneous clinical presentation with additional manifestations, including periorbital edema, myalgias, dysphagia, and shortness of breath. If clinically suspected, laboratory tests (eg, creatine kinase, aldolase, transaminases, and lactate dehydrogenase) can assist in diagnosing paraneoplastic myositis. Additionally, serologic testing for autoantibodies such as anti-CADM-140, anti-Jo-1, anti-Mi-2, antiMDA-5, anti-TIF-1, anti-NXP-2, and antiSAE can assist the diagnosis and predict disease phenotype.1,2

Malignancy can precede, occur during, or develop after the diagnosis of CADM.3 Malignancies most often associated with CADM include ovarian, breast, and lung cancers.4 Despite the strong correlation with malignancy, there are currently no screening guidelines for malignancy upon inflammatory myositis diagnosis. Therefore, it is important to consider the entirety of a patient’s clinical presentation in establishing further evaluation in the initial diagnostic workup.

There are numerous systemic complications associated with inflammatory myositis and imaging modalities can help to rule out some of these conditions. CADM is strongly associated with the development of interstitial lung disease, so chest radiography and pulmonary function testing are often checked.1 Though cardiac and esophageal involvement are more commonly associated with classic dermatomyositis, it may be useful to obtain an electrocardiogram to rule out conduction abnormalities from myocardial involvement, along with esophageal manometry to evaluate for esophageal dysmotility.1,5

In the management of paraneoplastic CADM, the underlying malignancy should be treated first.6 If symptoms persist after the cancer is in remission, then CADM is treated with immunosuppressive medications such as methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, or azathioprine. Physical therapy can also provide further symptom relief for those suffering from proximal weakness.

CONCLUSIONS

Presumed mastitis, angioedema, and eczematous lesions for this patient were dermatologic manifestations of an underlying inflammatory breast cancer. This case highlights the importance of early recognition, the diagnosis of CADM and awareness of its association with underlying malignancy, especially within the primary care setting where most skin concerns are addressed. Early clinical suspicion and a swift diagnostic workup can further optimize multidisciplinary management, which is often required to treat malignancies.

- Cao H, Xia Q, Pan M, et al. Gottron papules and gottron sign with ulceration: a distinctive cutaneous feature in a subset of patients with classic dermatomyositis and clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis. J Rheumatol. 2016;43(9):1735-1742. doi:10.3899/jrheum.160024

- Satoh M, Tanaka S, Ceribelli A, Calise SJ, Chan EK. A comprehensive overview on myositis-specific antibodies: new and old biomarkers in idiopathic inflammatory myopathy. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2017;52(1):1-19. doi:10.1007/s12016-015-8510-y

- Zahr ZA, Baer AN. Malignancy in myositis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2011;13(3):208-215. doi:10.1007/s11926-011-0169-7

- Udkoff J, Cohen PR. Amyopathic dermatomyositis: a concise review of clinical manifestations and associated malignancies. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016;17(5): 509-518. doi:10.1007/s40257-016-0199-z

- Fathi M, Lundberg IE, Tornling G. Pulmonary complications of polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;28(4):451-458. doi:10.1055/s-2007-985666

- Hendren E, Vinik O, Faragalla H, Haq R. Breast cancer and dermatomyositis: a case study and literature review. Curr Oncol. 2017;24(5):e429-e433. doi:10.3747/co.24.3696

A previously healthy 31-year-old female active-duty Navy sailor working as a calibration technician developed a painful, erythematous, pruritic, indurated plaque on her left breast. The sailor was not lactating and had no known family history of malignancy. Initially, she was treated by her primary care practitioner for presumed mastitis with oral cephalexin and then with oral clindamycin with no symptom improvement. About 2 weeks after the completion of both antibiotic courses, she developed angioedema and periorbital edema (Figure 1), requiring highdose corticosteroids and antihistamines with a corticosteroid course of prednisone 40 mg daily tapered to 10 mg daily over 12 days and diphenhydramine 25 mg to use up to 4 times daily. Workup for both was acquired and hereditary angioedema was unremarkable. Two months later, the patient developed patches of alopecia, oral ulcerations, and hypopigmented plaques with a peripheral hyperpigmented rim on the central face and bilateral conchal bowls (Figure 2). She also developed hypopigmented papules with peripheral hyperpigmentation on the bilateral dorsal hands overlying the metacarpal and proximal interphalangeal joints, which eventually ulcerated (Figure 3). Laboratory evaluation, including tests for creatine kinase, aldolase, transaminases, lactate dehydrogenase, and autoantibodies (antiJo-1, anti-Mi-2, anti-MDA-5, anti-TIF-1, anti-NXP-2, and anti-SAEP), were unremarkable. A punch biopsy from a papule on the right dorsal hand showed superficial perivascular lymphohistiocytic inflammation with a subtle focal increase in dermal mucin, highlighted by the colloidal iron stain. Further evaluation of the left breast plaque revealed ER/PR+ HER2- stage IIIB inflammatory breast cancer.

DISCUSSION

Based on the clinical presentation and diagnosis of inflammatory breast cancer, the patient was diagnosed with paraneoplastic clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis (CADM). She was treated for her breast cancer with an initial chemotherapy regimen consisting of dose-dense cyclophosphamide and doxorubicin followed by paclitaxel. The patient underwent a mastectomy, axillary lymph node dissection, and 25 sessions of radiation therapy, and is currently continuing therapy with anastrozole 1 mg daily and ovarian suppression with leuprorelin 11.25 mg every 3 months. For the severe angioedema and dermatomyositis-like cutaneous findings, the patient was continued on high-dose corticosteroids at prednisone 60 mg daily with a prolonged taper to prednisone 10 mg daily. After about 10 months, she transitioned from prednisone 10 mg daily to hydrocortisone 30 mg daily and is currently tapering her hydrocortisone dosing. She was additionally started on monthly intravenous immunoglobulin, hydroxychloroquine 300 mg daily, and amlodipine 5 mg daily. The ulcerated papules on her hands were treated with topical clobetasol 0.05% ointment applied daily, topical tacrolimus 0.1% ointment applied daily, and multiple intralesional triamcinolone 5 mg/mL injections. With this regimen, the patient experienced significant improvement in her cutaneous symptoms.

CADM is a rare autoimmune inflammatory disease featuring classic dermatomyositis-like cutaneous findings such as a heliotrope rash and Gottron papules. Ulcerative Gottron papules are less common than the typical erythematous papules and are associated more strongly with amyopathic disease.1 Paraneoplastic myositis poses a diagnostic challenge because it presents like an idiopathic dermatomyositis and often has a heterogeneous clinical presentation with additional manifestations, including periorbital edema, myalgias, dysphagia, and shortness of breath. If clinically suspected, laboratory tests (eg, creatine kinase, aldolase, transaminases, and lactate dehydrogenase) can assist in diagnosing paraneoplastic myositis. Additionally, serologic testing for autoantibodies such as anti-CADM-140, anti-Jo-1, anti-Mi-2, antiMDA-5, anti-TIF-1, anti-NXP-2, and antiSAE can assist the diagnosis and predict disease phenotype.1,2

Malignancy can precede, occur during, or develop after the diagnosis of CADM.3 Malignancies most often associated with CADM include ovarian, breast, and lung cancers.4 Despite the strong correlation with malignancy, there are currently no screening guidelines for malignancy upon inflammatory myositis diagnosis. Therefore, it is important to consider the entirety of a patient’s clinical presentation in establishing further evaluation in the initial diagnostic workup.

There are numerous systemic complications associated with inflammatory myositis and imaging modalities can help to rule out some of these conditions. CADM is strongly associated with the development of interstitial lung disease, so chest radiography and pulmonary function testing are often checked.1 Though cardiac and esophageal involvement are more commonly associated with classic dermatomyositis, it may be useful to obtain an electrocardiogram to rule out conduction abnormalities from myocardial involvement, along with esophageal manometry to evaluate for esophageal dysmotility.1,5

In the management of paraneoplastic CADM, the underlying malignancy should be treated first.6 If symptoms persist after the cancer is in remission, then CADM is treated with immunosuppressive medications such as methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, or azathioprine. Physical therapy can also provide further symptom relief for those suffering from proximal weakness.

CONCLUSIONS

Presumed mastitis, angioedema, and eczematous lesions for this patient were dermatologic manifestations of an underlying inflammatory breast cancer. This case highlights the importance of early recognition, the diagnosis of CADM and awareness of its association with underlying malignancy, especially within the primary care setting where most skin concerns are addressed. Early clinical suspicion and a swift diagnostic workup can further optimize multidisciplinary management, which is often required to treat malignancies.

A previously healthy 31-year-old female active-duty Navy sailor working as a calibration technician developed a painful, erythematous, pruritic, indurated plaque on her left breast. The sailor was not lactating and had no known family history of malignancy. Initially, she was treated by her primary care practitioner for presumed mastitis with oral cephalexin and then with oral clindamycin with no symptom improvement. About 2 weeks after the completion of both antibiotic courses, she developed angioedema and periorbital edema (Figure 1), requiring highdose corticosteroids and antihistamines with a corticosteroid course of prednisone 40 mg daily tapered to 10 mg daily over 12 days and diphenhydramine 25 mg to use up to 4 times daily. Workup for both was acquired and hereditary angioedema was unremarkable. Two months later, the patient developed patches of alopecia, oral ulcerations, and hypopigmented plaques with a peripheral hyperpigmented rim on the central face and bilateral conchal bowls (Figure 2). She also developed hypopigmented papules with peripheral hyperpigmentation on the bilateral dorsal hands overlying the metacarpal and proximal interphalangeal joints, which eventually ulcerated (Figure 3). Laboratory evaluation, including tests for creatine kinase, aldolase, transaminases, lactate dehydrogenase, and autoantibodies (antiJo-1, anti-Mi-2, anti-MDA-5, anti-TIF-1, anti-NXP-2, and anti-SAEP), were unremarkable. A punch biopsy from a papule on the right dorsal hand showed superficial perivascular lymphohistiocytic inflammation with a subtle focal increase in dermal mucin, highlighted by the colloidal iron stain. Further evaluation of the left breast plaque revealed ER/PR+ HER2- stage IIIB inflammatory breast cancer.

DISCUSSION

Based on the clinical presentation and diagnosis of inflammatory breast cancer, the patient was diagnosed with paraneoplastic clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis (CADM). She was treated for her breast cancer with an initial chemotherapy regimen consisting of dose-dense cyclophosphamide and doxorubicin followed by paclitaxel. The patient underwent a mastectomy, axillary lymph node dissection, and 25 sessions of radiation therapy, and is currently continuing therapy with anastrozole 1 mg daily and ovarian suppression with leuprorelin 11.25 mg every 3 months. For the severe angioedema and dermatomyositis-like cutaneous findings, the patient was continued on high-dose corticosteroids at prednisone 60 mg daily with a prolonged taper to prednisone 10 mg daily. After about 10 months, she transitioned from prednisone 10 mg daily to hydrocortisone 30 mg daily and is currently tapering her hydrocortisone dosing. She was additionally started on monthly intravenous immunoglobulin, hydroxychloroquine 300 mg daily, and amlodipine 5 mg daily. The ulcerated papules on her hands were treated with topical clobetasol 0.05% ointment applied daily, topical tacrolimus 0.1% ointment applied daily, and multiple intralesional triamcinolone 5 mg/mL injections. With this regimen, the patient experienced significant improvement in her cutaneous symptoms.

CADM is a rare autoimmune inflammatory disease featuring classic dermatomyositis-like cutaneous findings such as a heliotrope rash and Gottron papules. Ulcerative Gottron papules are less common than the typical erythematous papules and are associated more strongly with amyopathic disease.1 Paraneoplastic myositis poses a diagnostic challenge because it presents like an idiopathic dermatomyositis and often has a heterogeneous clinical presentation with additional manifestations, including periorbital edema, myalgias, dysphagia, and shortness of breath. If clinically suspected, laboratory tests (eg, creatine kinase, aldolase, transaminases, and lactate dehydrogenase) can assist in diagnosing paraneoplastic myositis. Additionally, serologic testing for autoantibodies such as anti-CADM-140, anti-Jo-1, anti-Mi-2, antiMDA-5, anti-TIF-1, anti-NXP-2, and antiSAE can assist the diagnosis and predict disease phenotype.1,2

Malignancy can precede, occur during, or develop after the diagnosis of CADM.3 Malignancies most often associated with CADM include ovarian, breast, and lung cancers.4 Despite the strong correlation with malignancy, there are currently no screening guidelines for malignancy upon inflammatory myositis diagnosis. Therefore, it is important to consider the entirety of a patient’s clinical presentation in establishing further evaluation in the initial diagnostic workup.

There are numerous systemic complications associated with inflammatory myositis and imaging modalities can help to rule out some of these conditions. CADM is strongly associated with the development of interstitial lung disease, so chest radiography and pulmonary function testing are often checked.1 Though cardiac and esophageal involvement are more commonly associated with classic dermatomyositis, it may be useful to obtain an electrocardiogram to rule out conduction abnormalities from myocardial involvement, along with esophageal manometry to evaluate for esophageal dysmotility.1,5

In the management of paraneoplastic CADM, the underlying malignancy should be treated first.6 If symptoms persist after the cancer is in remission, then CADM is treated with immunosuppressive medications such as methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, or azathioprine. Physical therapy can also provide further symptom relief for those suffering from proximal weakness.

CONCLUSIONS

Presumed mastitis, angioedema, and eczematous lesions for this patient were dermatologic manifestations of an underlying inflammatory breast cancer. This case highlights the importance of early recognition, the diagnosis of CADM and awareness of its association with underlying malignancy, especially within the primary care setting where most skin concerns are addressed. Early clinical suspicion and a swift diagnostic workup can further optimize multidisciplinary management, which is often required to treat malignancies.

- Cao H, Xia Q, Pan M, et al. Gottron papules and gottron sign with ulceration: a distinctive cutaneous feature in a subset of patients with classic dermatomyositis and clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis. J Rheumatol. 2016;43(9):1735-1742. doi:10.3899/jrheum.160024

- Satoh M, Tanaka S, Ceribelli A, Calise SJ, Chan EK. A comprehensive overview on myositis-specific antibodies: new and old biomarkers in idiopathic inflammatory myopathy. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2017;52(1):1-19. doi:10.1007/s12016-015-8510-y

- Zahr ZA, Baer AN. Malignancy in myositis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2011;13(3):208-215. doi:10.1007/s11926-011-0169-7

- Udkoff J, Cohen PR. Amyopathic dermatomyositis: a concise review of clinical manifestations and associated malignancies. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016;17(5): 509-518. doi:10.1007/s40257-016-0199-z

- Fathi M, Lundberg IE, Tornling G. Pulmonary complications of polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;28(4):451-458. doi:10.1055/s-2007-985666

- Hendren E, Vinik O, Faragalla H, Haq R. Breast cancer and dermatomyositis: a case study and literature review. Curr Oncol. 2017;24(5):e429-e433. doi:10.3747/co.24.3696

- Cao H, Xia Q, Pan M, et al. Gottron papules and gottron sign with ulceration: a distinctive cutaneous feature in a subset of patients with classic dermatomyositis and clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis. J Rheumatol. 2016;43(9):1735-1742. doi:10.3899/jrheum.160024

- Satoh M, Tanaka S, Ceribelli A, Calise SJ, Chan EK. A comprehensive overview on myositis-specific antibodies: new and old biomarkers in idiopathic inflammatory myopathy. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2017;52(1):1-19. doi:10.1007/s12016-015-8510-y

- Zahr ZA, Baer AN. Malignancy in myositis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2011;13(3):208-215. doi:10.1007/s11926-011-0169-7

- Udkoff J, Cohen PR. Amyopathic dermatomyositis: a concise review of clinical manifestations and associated malignancies. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016;17(5): 509-518. doi:10.1007/s40257-016-0199-z

- Fathi M, Lundberg IE, Tornling G. Pulmonary complications of polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;28(4):451-458. doi:10.1055/s-2007-985666

- Hendren E, Vinik O, Faragalla H, Haq R. Breast cancer and dermatomyositis: a case study and literature review. Curr Oncol. 2017;24(5):e429-e433. doi:10.3747/co.24.3696

Implementation of a Prior Authorization Drug Review Process for Care in the Community Oncology Prescriptions

Background

Veterans receiving care in the community (CITC) are prescribed oral oncology medications to be filled at VA pharmacies. Many of the outpatient prescriptions written for oncology medications require a prior authorization review by a pharmacist. A standardized workflow to obtain outside records to ensure patient safety, appropriate therapeutic selections, and maximize cost avoidance was established in March 2023. This quality improvement project evaluated the implementation of a clinical peer-to-peer prescription referral process between operational and oncology clinical pharmacists (CPS) to include a prior authorization drug request (PADR) review.

Methods

A retrospective chart review was completed to assess the effectiveness of the CITC Rx review process. Patients who had a CITC PADR consult entered between April 2023 and March 2024 were included. Metrics obtained included medication ordered, diagnosis, line of treatment, date prescription received, time to PADR completion, PADR outcome, FDA approval status, and conformity to VA National Oncology Program (NOP) disease pathway. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the data.

Results

Top reasons for referral for CITC included best medical interest and drive time. Fifty-one PADR requests were submitted for 41 patients. Forty-six PADR consults were completed. Approval rate was 85%. Consults involved 32 different oncolytics, 78% had VA Pharmacy Benefits Manager criteria for use. Thirty-seven percent of the PADR requests adhered to the NOP pathways. Approximately 30% of PADR requests did not have an associated NOP pathway. Seventy-four percent of drugs had an associated FDA approval. On average, two calls were made to CITC provider by the operational pharmacist to obtain necessary information for clinical review, resulting in a 5 day time to PADR entry. The average time to PADR consult completion was 9.5 hours. Four interventions addressed drug interactions or dosing adjustments.

Conclusions

This review demonstrated the feasibility and framework for implementing a standardized peer-to-peer PADR consult review process for CITC prescriptions requiring prior authorization. Having separate intake of CITC prescriptions by the operational pharmacist who is responsible for obtaining outside records, the CPS provided a timely clinical review of PADR consults, assuring appropriate therapeutic selections to maximize cost avoidance while maintaining patient safety.

Background

Veterans receiving care in the community (CITC) are prescribed oral oncology medications to be filled at VA pharmacies. Many of the outpatient prescriptions written for oncology medications require a prior authorization review by a pharmacist. A standardized workflow to obtain outside records to ensure patient safety, appropriate therapeutic selections, and maximize cost avoidance was established in March 2023. This quality improvement project evaluated the implementation of a clinical peer-to-peer prescription referral process between operational and oncology clinical pharmacists (CPS) to include a prior authorization drug request (PADR) review.

Methods

A retrospective chart review was completed to assess the effectiveness of the CITC Rx review process. Patients who had a CITC PADR consult entered between April 2023 and March 2024 were included. Metrics obtained included medication ordered, diagnosis, line of treatment, date prescription received, time to PADR completion, PADR outcome, FDA approval status, and conformity to VA National Oncology Program (NOP) disease pathway. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the data.

Results

Top reasons for referral for CITC included best medical interest and drive time. Fifty-one PADR requests were submitted for 41 patients. Forty-six PADR consults were completed. Approval rate was 85%. Consults involved 32 different oncolytics, 78% had VA Pharmacy Benefits Manager criteria for use. Thirty-seven percent of the PADR requests adhered to the NOP pathways. Approximately 30% of PADR requests did not have an associated NOP pathway. Seventy-four percent of drugs had an associated FDA approval. On average, two calls were made to CITC provider by the operational pharmacist to obtain necessary information for clinical review, resulting in a 5 day time to PADR entry. The average time to PADR consult completion was 9.5 hours. Four interventions addressed drug interactions or dosing adjustments.

Conclusions

This review demonstrated the feasibility and framework for implementing a standardized peer-to-peer PADR consult review process for CITC prescriptions requiring prior authorization. Having separate intake of CITC prescriptions by the operational pharmacist who is responsible for obtaining outside records, the CPS provided a timely clinical review of PADR consults, assuring appropriate therapeutic selections to maximize cost avoidance while maintaining patient safety.

Background

Veterans receiving care in the community (CITC) are prescribed oral oncology medications to be filled at VA pharmacies. Many of the outpatient prescriptions written for oncology medications require a prior authorization review by a pharmacist. A standardized workflow to obtain outside records to ensure patient safety, appropriate therapeutic selections, and maximize cost avoidance was established in March 2023. This quality improvement project evaluated the implementation of a clinical peer-to-peer prescription referral process between operational and oncology clinical pharmacists (CPS) to include a prior authorization drug request (PADR) review.

Methods

A retrospective chart review was completed to assess the effectiveness of the CITC Rx review process. Patients who had a CITC PADR consult entered between April 2023 and March 2024 were included. Metrics obtained included medication ordered, diagnosis, line of treatment, date prescription received, time to PADR completion, PADR outcome, FDA approval status, and conformity to VA National Oncology Program (NOP) disease pathway. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the data.

Results

Top reasons for referral for CITC included best medical interest and drive time. Fifty-one PADR requests were submitted for 41 patients. Forty-six PADR consults were completed. Approval rate was 85%. Consults involved 32 different oncolytics, 78% had VA Pharmacy Benefits Manager criteria for use. Thirty-seven percent of the PADR requests adhered to the NOP pathways. Approximately 30% of PADR requests did not have an associated NOP pathway. Seventy-four percent of drugs had an associated FDA approval. On average, two calls were made to CITC provider by the operational pharmacist to obtain necessary information for clinical review, resulting in a 5 day time to PADR entry. The average time to PADR consult completion was 9.5 hours. Four interventions addressed drug interactions or dosing adjustments.

Conclusions

This review demonstrated the feasibility and framework for implementing a standardized peer-to-peer PADR consult review process for CITC prescriptions requiring prior authorization. Having separate intake of CITC prescriptions by the operational pharmacist who is responsible for obtaining outside records, the CPS provided a timely clinical review of PADR consults, assuring appropriate therapeutic selections to maximize cost avoidance while maintaining patient safety.

The OCTAGON Project: A Novel VA-Based Telehealth Intervention for Oral Chemotherapy Monitoring

Background

Many Veterans with cancer experience substantial side effects related to their chemotherapy treatments resulting in impaired quality of life. Prompt management of such symptoms can improve adherence to therapy and potentially clinical outcomes. Previous studies in cancer patients have shown that mobile apps can improve symptom management and quality of life, though there are limited studies using oncology-focused apps in the VA population. The VA Annie App is an optimal platform for Veterans since it relies primarily on SMS-based texting and not on internet capabilities. This would address several well-known barriers to Veterans’ care access (limited internet connectivity, transportation) and enhance symptom reporting between infrequent provider visits. Providers can securely collect app responses within the VA system and there is already considerable VA developer experience with designing complex protocols. The OCTAGON project (Optimizing Cancer Care with Telehealth Assessment for Goal-Oriented Needs) will have the following goals: 1) To develop Annie App protocols to assist in management of cancer and/or chemotherapy-related symptoms (OCTAGON intervention), 2) To examine initial acceptability, feasibility, and Veteran-reported outcomes, 3) To explore short term effects on the utilization of VA encounters.

Methods

All patients who are primarily being managed at the VA Ann Arbor for their cancer therapy and are receiving one of the following therapies are considered eligible: EGFR inhibitors (lung cancer), antiandrogen therapies (prostate cancer), BTK inhibitors (lymphoma).

Discussion

Drug-specific protocols will be developed in conjunction with clinical pharmacists with experience in outpatient oral chemotherapy toxicity monitoring. Questions will have either a Yes/No, or numerical response. Interventions will be administered weekly for the first 3 months after enrollment, then decrease to monthly for a total of 6 months on protocol. Patients will be directed to contact their providers with any significant changes in tolerability. Planned data collected will include intervention question responses, adverse events, demographics, diagnosis, disease response, hospitalizations, treatment dose reductions or interruptions, provider and staff utilization. Survey responses to assess treatment acceptability (Treatment Acceptability/Adherence Scale), usability (System Usability Scale), general health (PROMIS-GH), and patient satisfaction will also be collected. Funding: VA Telehealth Research and Innovation for Veterans with Cancer (THRIVE).

Background

Many Veterans with cancer experience substantial side effects related to their chemotherapy treatments resulting in impaired quality of life. Prompt management of such symptoms can improve adherence to therapy and potentially clinical outcomes. Previous studies in cancer patients have shown that mobile apps can improve symptom management and quality of life, though there are limited studies using oncology-focused apps in the VA population. The VA Annie App is an optimal platform for Veterans since it relies primarily on SMS-based texting and not on internet capabilities. This would address several well-known barriers to Veterans’ care access (limited internet connectivity, transportation) and enhance symptom reporting between infrequent provider visits. Providers can securely collect app responses within the VA system and there is already considerable VA developer experience with designing complex protocols. The OCTAGON project (Optimizing Cancer Care with Telehealth Assessment for Goal-Oriented Needs) will have the following goals: 1) To develop Annie App protocols to assist in management of cancer and/or chemotherapy-related symptoms (OCTAGON intervention), 2) To examine initial acceptability, feasibility, and Veteran-reported outcomes, 3) To explore short term effects on the utilization of VA encounters.

Methods

All patients who are primarily being managed at the VA Ann Arbor for their cancer therapy and are receiving one of the following therapies are considered eligible: EGFR inhibitors (lung cancer), antiandrogen therapies (prostate cancer), BTK inhibitors (lymphoma).

Discussion

Drug-specific protocols will be developed in conjunction with clinical pharmacists with experience in outpatient oral chemotherapy toxicity monitoring. Questions will have either a Yes/No, or numerical response. Interventions will be administered weekly for the first 3 months after enrollment, then decrease to monthly for a total of 6 months on protocol. Patients will be directed to contact their providers with any significant changes in tolerability. Planned data collected will include intervention question responses, adverse events, demographics, diagnosis, disease response, hospitalizations, treatment dose reductions or interruptions, provider and staff utilization. Survey responses to assess treatment acceptability (Treatment Acceptability/Adherence Scale), usability (System Usability Scale), general health (PROMIS-GH), and patient satisfaction will also be collected. Funding: VA Telehealth Research and Innovation for Veterans with Cancer (THRIVE).

Background

Many Veterans with cancer experience substantial side effects related to their chemotherapy treatments resulting in impaired quality of life. Prompt management of such symptoms can improve adherence to therapy and potentially clinical outcomes. Previous studies in cancer patients have shown that mobile apps can improve symptom management and quality of life, though there are limited studies using oncology-focused apps in the VA population. The VA Annie App is an optimal platform for Veterans since it relies primarily on SMS-based texting and not on internet capabilities. This would address several well-known barriers to Veterans’ care access (limited internet connectivity, transportation) and enhance symptom reporting between infrequent provider visits. Providers can securely collect app responses within the VA system and there is already considerable VA developer experience with designing complex protocols. The OCTAGON project (Optimizing Cancer Care with Telehealth Assessment for Goal-Oriented Needs) will have the following goals: 1) To develop Annie App protocols to assist in management of cancer and/or chemotherapy-related symptoms (OCTAGON intervention), 2) To examine initial acceptability, feasibility, and Veteran-reported outcomes, 3) To explore short term effects on the utilization of VA encounters.

Methods

All patients who are primarily being managed at the VA Ann Arbor for their cancer therapy and are receiving one of the following therapies are considered eligible: EGFR inhibitors (lung cancer), antiandrogen therapies (prostate cancer), BTK inhibitors (lymphoma).

Discussion

Drug-specific protocols will be developed in conjunction with clinical pharmacists with experience in outpatient oral chemotherapy toxicity monitoring. Questions will have either a Yes/No, or numerical response. Interventions will be administered weekly for the first 3 months after enrollment, then decrease to monthly for a total of 6 months on protocol. Patients will be directed to contact their providers with any significant changes in tolerability. Planned data collected will include intervention question responses, adverse events, demographics, diagnosis, disease response, hospitalizations, treatment dose reductions or interruptions, provider and staff utilization. Survey responses to assess treatment acceptability (Treatment Acceptability/Adherence Scale), usability (System Usability Scale), general health (PROMIS-GH), and patient satisfaction will also be collected. Funding: VA Telehealth Research and Innovation for Veterans with Cancer (THRIVE).

How to Make Keeping Up With the Drugs as Easy as Keeping Up With the Kardashians: Implementing a Local Oncology Drug Review Committee

Background

From 2000-2022 there were over 200 new drug and over 500 indication approvals specific to oncology. The rate of approvals has increased exponentially, making it difficult to maintain an up-to-date, standardized practice. Nationally, Veterans Affairs (VA) formulary decisions can take time given a lengthy approval process. Locally, the need was identified to incorporate new drugs and data into practice more rapidly. When bringing requests to the facility Pharmacy and Therapeutics (P&T) Committee, it was recognized that the membership consisting of non-oncology practitioners did not allow for meaningful discussion of utilization. In 2017, a dedicated oncology drug review committee (DRC) comprised of oncology practitioners and a facility formulary representative was created as a P&T workgroup. Purpose: Evaluate and describe the utility of forming a local oncology DRC to incorporate new drugs and data into practice.

Methods

DRC minutes from December 2017 to May 2023 were reviewed. Discussion items were categorized into type of review. Date of local review was compared to national formulary criteria for use publication dates, and date of FDA approval for new drugs or publication date for new data, where applicable. Items were excluded if crucial information was missing from minutes. Descriptive statistics were used.

Results

Over 65 months, 38 meetings were held. Thirty total members include: pharmacists, physicians, fellows, and advanced practice providers. Items reviewed included: 36 new drugs (ND), 36 new indications/data (NI), 14 institutional preferences, 10 new dosage form/biosimilars, 4 drug shortages and 2 others. The median time from ND approval to discussion was 3 months (n= 36, IQR 3-6) and NI from publication was 3 months (n=30, IQR 1-8). Nearly all (34/36, 94%) ND were reviewed prior to national review. Local review was a median of 7 months before national, with 11 drugs currently having no published national criteria for use (n=25, IQR 2-12).

Conclusions

DRC formation has enabled faster incorporation of new drugs/indications into practice. It has also created an appropriate forum for in-depth utilization discussions, pharmacoeconomic stewardship, and sharing of formulary and medication related information. VA Health Systems could consider implementing similar committees to review and implement up-to-date oncology practices.

Background

From 2000-2022 there were over 200 new drug and over 500 indication approvals specific to oncology. The rate of approvals has increased exponentially, making it difficult to maintain an up-to-date, standardized practice. Nationally, Veterans Affairs (VA) formulary decisions can take time given a lengthy approval process. Locally, the need was identified to incorporate new drugs and data into practice more rapidly. When bringing requests to the facility Pharmacy and Therapeutics (P&T) Committee, it was recognized that the membership consisting of non-oncology practitioners did not allow for meaningful discussion of utilization. In 2017, a dedicated oncology drug review committee (DRC) comprised of oncology practitioners and a facility formulary representative was created as a P&T workgroup. Purpose: Evaluate and describe the utility of forming a local oncology DRC to incorporate new drugs and data into practice.

Methods

DRC minutes from December 2017 to May 2023 were reviewed. Discussion items were categorized into type of review. Date of local review was compared to national formulary criteria for use publication dates, and date of FDA approval for new drugs or publication date for new data, where applicable. Items were excluded if crucial information was missing from minutes. Descriptive statistics were used.

Results

Over 65 months, 38 meetings were held. Thirty total members include: pharmacists, physicians, fellows, and advanced practice providers. Items reviewed included: 36 new drugs (ND), 36 new indications/data (NI), 14 institutional preferences, 10 new dosage form/biosimilars, 4 drug shortages and 2 others. The median time from ND approval to discussion was 3 months (n= 36, IQR 3-6) and NI from publication was 3 months (n=30, IQR 1-8). Nearly all (34/36, 94%) ND were reviewed prior to national review. Local review was a median of 7 months before national, with 11 drugs currently having no published national criteria for use (n=25, IQR 2-12).

Conclusions

DRC formation has enabled faster incorporation of new drugs/indications into practice. It has also created an appropriate forum for in-depth utilization discussions, pharmacoeconomic stewardship, and sharing of formulary and medication related information. VA Health Systems could consider implementing similar committees to review and implement up-to-date oncology practices.

Background

From 2000-2022 there were over 200 new drug and over 500 indication approvals specific to oncology. The rate of approvals has increased exponentially, making it difficult to maintain an up-to-date, standardized practice. Nationally, Veterans Affairs (VA) formulary decisions can take time given a lengthy approval process. Locally, the need was identified to incorporate new drugs and data into practice more rapidly. When bringing requests to the facility Pharmacy and Therapeutics (P&T) Committee, it was recognized that the membership consisting of non-oncology practitioners did not allow for meaningful discussion of utilization. In 2017, a dedicated oncology drug review committee (DRC) comprised of oncology practitioners and a facility formulary representative was created as a P&T workgroup. Purpose: Evaluate and describe the utility of forming a local oncology DRC to incorporate new drugs and data into practice.

Methods

DRC minutes from December 2017 to May 2023 were reviewed. Discussion items were categorized into type of review. Date of local review was compared to national formulary criteria for use publication dates, and date of FDA approval for new drugs or publication date for new data, where applicable. Items were excluded if crucial information was missing from minutes. Descriptive statistics were used.

Results

Over 65 months, 38 meetings were held. Thirty total members include: pharmacists, physicians, fellows, and advanced practice providers. Items reviewed included: 36 new drugs (ND), 36 new indications/data (NI), 14 institutional preferences, 10 new dosage form/biosimilars, 4 drug shortages and 2 others. The median time from ND approval to discussion was 3 months (n= 36, IQR 3-6) and NI from publication was 3 months (n=30, IQR 1-8). Nearly all (34/36, 94%) ND were reviewed prior to national review. Local review was a median of 7 months before national, with 11 drugs currently having no published national criteria for use (n=25, IQR 2-12).

Conclusions

DRC formation has enabled faster incorporation of new drugs/indications into practice. It has also created an appropriate forum for in-depth utilization discussions, pharmacoeconomic stewardship, and sharing of formulary and medication related information. VA Health Systems could consider implementing similar committees to review and implement up-to-date oncology practices.

PHASER Testing Initiative for Patients Newly Diagnosed With a GI Malignancy

Background

In December of 2023, the Survivorship Coordinator at VA Connecticut spearheaded a multidisciplinary collaboration to offer PHASER testing to all patients newly diagnosed with a GI malignancy and/ or patients with a known GI malignancy and a new recurrence that might necessitate chemotherapy. The PHASER panel includes two genes that are involved in the metabolism of two commonly used chemotherapy drugs in this patient population.

Methods

By identifying patients who may have impaired metabolism prior to starting treatment, the doses of the appropriate drugs, 5FU and irinotecan, can be adjusted if appropriate, leading to less toxicity for patients while on treatment and fewer lingering side-effects from treatment. We are tracking all of the patients who are being tested and will report quarterly to the Cancer Committee on any findings with a specific focus on whether any dose-adjustments were made to Veteran’s chemotherapy regimens as the result of this testing.

Discussion

We have developed a systematic process centered around GI tumor boards to ensure that testing is done at least two weeks prior to planned chemotherapy start-date to ensure adequate time for testing results to be received. We have developed a systematic process whereby primary care providers and pharmacists are alerted to the PHASER results and patients’ non-oncology medications are reviewed for any recommended adjustments. We will have 9 months of data to report on at AVAHO as well as lessons learned from this new quality improvement process. Despite access to pharmacogenomic testing at VA, there can be variations between VA sites in terms of uptake of this new testing. VA Connecticut’s PHASER testing initiative for patients with GI malignancies is a model that can be replicated throughout the VA. This initiative is part of a broader focus at VA Connecticut on “pre-habilitation” and pre-treatment testing that is designed to reduce toxicity of treatment and improve quality of life for cancer survivors.

Background

In December of 2023, the Survivorship Coordinator at VA Connecticut spearheaded a multidisciplinary collaboration to offer PHASER testing to all patients newly diagnosed with a GI malignancy and/ or patients with a known GI malignancy and a new recurrence that might necessitate chemotherapy. The PHASER panel includes two genes that are involved in the metabolism of two commonly used chemotherapy drugs in this patient population.

Methods

By identifying patients who may have impaired metabolism prior to starting treatment, the doses of the appropriate drugs, 5FU and irinotecan, can be adjusted if appropriate, leading to less toxicity for patients while on treatment and fewer lingering side-effects from treatment. We are tracking all of the patients who are being tested and will report quarterly to the Cancer Committee on any findings with a specific focus on whether any dose-adjustments were made to Veteran’s chemotherapy regimens as the result of this testing.

Discussion

We have developed a systematic process centered around GI tumor boards to ensure that testing is done at least two weeks prior to planned chemotherapy start-date to ensure adequate time for testing results to be received. We have developed a systematic process whereby primary care providers and pharmacists are alerted to the PHASER results and patients’ non-oncology medications are reviewed for any recommended adjustments. We will have 9 months of data to report on at AVAHO as well as lessons learned from this new quality improvement process. Despite access to pharmacogenomic testing at VA, there can be variations between VA sites in terms of uptake of this new testing. VA Connecticut’s PHASER testing initiative for patients with GI malignancies is a model that can be replicated throughout the VA. This initiative is part of a broader focus at VA Connecticut on “pre-habilitation” and pre-treatment testing that is designed to reduce toxicity of treatment and improve quality of life for cancer survivors.

Background

In December of 2023, the Survivorship Coordinator at VA Connecticut spearheaded a multidisciplinary collaboration to offer PHASER testing to all patients newly diagnosed with a GI malignancy and/ or patients with a known GI malignancy and a new recurrence that might necessitate chemotherapy. The PHASER panel includes two genes that are involved in the metabolism of two commonly used chemotherapy drugs in this patient population.

Methods

By identifying patients who may have impaired metabolism prior to starting treatment, the doses of the appropriate drugs, 5FU and irinotecan, can be adjusted if appropriate, leading to less toxicity for patients while on treatment and fewer lingering side-effects from treatment. We are tracking all of the patients who are being tested and will report quarterly to the Cancer Committee on any findings with a specific focus on whether any dose-adjustments were made to Veteran’s chemotherapy regimens as the result of this testing.

Discussion

We have developed a systematic process centered around GI tumor boards to ensure that testing is done at least two weeks prior to planned chemotherapy start-date to ensure adequate time for testing results to be received. We have developed a systematic process whereby primary care providers and pharmacists are alerted to the PHASER results and patients’ non-oncology medications are reviewed for any recommended adjustments. We will have 9 months of data to report on at AVAHO as well as lessons learned from this new quality improvement process. Despite access to pharmacogenomic testing at VA, there can be variations between VA sites in terms of uptake of this new testing. VA Connecticut’s PHASER testing initiative for patients with GI malignancies is a model that can be replicated throughout the VA. This initiative is part of a broader focus at VA Connecticut on “pre-habilitation” and pre-treatment testing that is designed to reduce toxicity of treatment and improve quality of life for cancer survivors.

Rare Gems: Navigating Goblet Cell Appendiceal Cancer

Background

Goblet cell adenocarcinoma (GCA), also known as goblet cell carcinoid, is a rare and distinct type of cancer originating from the appendix. It is characterized by cells that exhibit both mucinous and neuroendocrine differentiation, presenting a more aggressive nature compared to conventional carcinoids and a higher propensity for metastasis.

Case Presentation

A 60-year-old male presented with complaints of abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, constipation, and weight loss worsening in the last month. He had a history of heavy alcohol intake, smoking, and family history of colon cancer in his grandfather. Initial workup with abdominal CT revealed findings suggestive of early bowel obstruction and possible malignancy. Subsequent EGD showed esophagitis, and colonoscopy identified a cecal mass. Biopsies confirmed malignant cells of enteric type with goblet cell features. Staging CT during hospitalization did not reveal distant metastasis initially. However, diagnostic laparoscopy later identified widespread peritoneal carcinomatosis, precluding surgical intervention. The case was discussed in tumor boards, leading to the initiation of palliative FOLFOX + Bevacizumab chemotherapy. After completing 7 cycles, restaging imaging showed stable disease. Subsequently, the patient experienced worsening obstructive symptoms with CT abdomen and pelvis demonstrating disease progression. Given his condition, decompressive gastrostomy was not feasible. The patient decided to transition to comfort measures only.

Discussion

Goblet cell adenocarcinoma is a rare appendiceal tumor with amphicrine differentiation, occurring at a rate of 0.01–0.05 per 100,000 individuals annually and comprising approximately 15% of all appendiceal neoplasms. These tumors often disseminate within the peritoneum, contributing to their aggressive behavior and challenging management.

Conclusions

Metastatic goblet cell adenocarcinoma presents significant treatment challenges and is associated with a poor prognosis. Tailored treatment strategies, vigilant monitoring, and ongoing research efforts are essential for optimizing patient outcomes and enhancing quality of life in this aggressive cancer

Background

Goblet cell adenocarcinoma (GCA), also known as goblet cell carcinoid, is a rare and distinct type of cancer originating from the appendix. It is characterized by cells that exhibit both mucinous and neuroendocrine differentiation, presenting a more aggressive nature compared to conventional carcinoids and a higher propensity for metastasis.

Case Presentation

A 60-year-old male presented with complaints of abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, constipation, and weight loss worsening in the last month. He had a history of heavy alcohol intake, smoking, and family history of colon cancer in his grandfather. Initial workup with abdominal CT revealed findings suggestive of early bowel obstruction and possible malignancy. Subsequent EGD showed esophagitis, and colonoscopy identified a cecal mass. Biopsies confirmed malignant cells of enteric type with goblet cell features. Staging CT during hospitalization did not reveal distant metastasis initially. However, diagnostic laparoscopy later identified widespread peritoneal carcinomatosis, precluding surgical intervention. The case was discussed in tumor boards, leading to the initiation of palliative FOLFOX + Bevacizumab chemotherapy. After completing 7 cycles, restaging imaging showed stable disease. Subsequently, the patient experienced worsening obstructive symptoms with CT abdomen and pelvis demonstrating disease progression. Given his condition, decompressive gastrostomy was not feasible. The patient decided to transition to comfort measures only.

Discussion

Goblet cell adenocarcinoma is a rare appendiceal tumor with amphicrine differentiation, occurring at a rate of 0.01–0.05 per 100,000 individuals annually and comprising approximately 15% of all appendiceal neoplasms. These tumors often disseminate within the peritoneum, contributing to their aggressive behavior and challenging management.

Conclusions

Metastatic goblet cell adenocarcinoma presents significant treatment challenges and is associated with a poor prognosis. Tailored treatment strategies, vigilant monitoring, and ongoing research efforts are essential for optimizing patient outcomes and enhancing quality of life in this aggressive cancer

Background

Goblet cell adenocarcinoma (GCA), also known as goblet cell carcinoid, is a rare and distinct type of cancer originating from the appendix. It is characterized by cells that exhibit both mucinous and neuroendocrine differentiation, presenting a more aggressive nature compared to conventional carcinoids and a higher propensity for metastasis.

Case Presentation

A 60-year-old male presented with complaints of abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, constipation, and weight loss worsening in the last month. He had a history of heavy alcohol intake, smoking, and family history of colon cancer in his grandfather. Initial workup with abdominal CT revealed findings suggestive of early bowel obstruction and possible malignancy. Subsequent EGD showed esophagitis, and colonoscopy identified a cecal mass. Biopsies confirmed malignant cells of enteric type with goblet cell features. Staging CT during hospitalization did not reveal distant metastasis initially. However, diagnostic laparoscopy later identified widespread peritoneal carcinomatosis, precluding surgical intervention. The case was discussed in tumor boards, leading to the initiation of palliative FOLFOX + Bevacizumab chemotherapy. After completing 7 cycles, restaging imaging showed stable disease. Subsequently, the patient experienced worsening obstructive symptoms with CT abdomen and pelvis demonstrating disease progression. Given his condition, decompressive gastrostomy was not feasible. The patient decided to transition to comfort measures only.

Discussion

Goblet cell adenocarcinoma is a rare appendiceal tumor with amphicrine differentiation, occurring at a rate of 0.01–0.05 per 100,000 individuals annually and comprising approximately 15% of all appendiceal neoplasms. These tumors often disseminate within the peritoneum, contributing to their aggressive behavior and challenging management.

Conclusions

Metastatic goblet cell adenocarcinoma presents significant treatment challenges and is associated with a poor prognosis. Tailored treatment strategies, vigilant monitoring, and ongoing research efforts are essential for optimizing patient outcomes and enhancing quality of life in this aggressive cancer

Anchors Aweigh, Clinical Trial Navigation at the VA!

Background

Despite the benefit of cancer clinical trials (CTs) in increasing medical knowledge and broadening treatment options, VA oncologists face challenges referring or enrolling Veterans in CTs including identifying appropriate CTs and navigating the referral process especially for non-VA CTs. To address these challenges, the VA National Oncology Program (NOP) provided guidance regarding community care referral for CT participation and established the Cancer Clinical Trial Nurse Navigation (CTN) service.

Methods

Referrals to CTN occur via Precision Oncology consult or email to [email protected]. The CT nurse navigator educates Veterans about CTs, identifies CTs for Veterans based on disease and geographic area, provides written summaries to Veterans and VA oncologists, and facilitates communication between clinical and research teams. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize characteristics of Veterans referred to CTN and results of the CTN searches. A semi-structured survey was used to assess satisfaction from 50 VA oncologists who had used the CTN service.

Results

Between June 2023 and May 2024, 72 Veterans were referred to CTN. Patient characteristics include male (94%), non-rural (65%), median age 66.5 (range 27-80), self-reported race as White (74%) and Black (22%), cancer type as solid tumor (73%) and blood cancer (27%). The median number of CTs found for each Veteran was two (range 0 - 12). No referred Veterans enrolled in CTs, with the most common causes being CT ineligibility and desire to receive standard therapy in the VA. Twenty oncologists were educated about NOP CT guidance. The response rate to the feedback survey was modest (34%) but 94% of survey respondents rated their overall satisfaction as highly satisfied or satisfied.

Conclusions

The CTN assists Veterans and VA oncologists in connecting with CTs. The high satisfaction rate and ability to reach a racially and geographically diverse Veteran population are measures of early program success. By lowering the barriers for VA oncologists to consider CTs for their patients, the CTN expects increased and earlier referrals of Veterans, which may improve CT eligibility and participation. Future efforts to provide disease-directed education about CTs to Veterans and VA oncologists is intended to encourage early consideration of CTs.

Background

Despite the benefit of cancer clinical trials (CTs) in increasing medical knowledge and broadening treatment options, VA oncologists face challenges referring or enrolling Veterans in CTs including identifying appropriate CTs and navigating the referral process especially for non-VA CTs. To address these challenges, the VA National Oncology Program (NOP) provided guidance regarding community care referral for CT participation and established the Cancer Clinical Trial Nurse Navigation (CTN) service.

Methods

Referrals to CTN occur via Precision Oncology consult or email to [email protected]. The CT nurse navigator educates Veterans about CTs, identifies CTs for Veterans based on disease and geographic area, provides written summaries to Veterans and VA oncologists, and facilitates communication between clinical and research teams. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize characteristics of Veterans referred to CTN and results of the CTN searches. A semi-structured survey was used to assess satisfaction from 50 VA oncologists who had used the CTN service.

Results

Between June 2023 and May 2024, 72 Veterans were referred to CTN. Patient characteristics include male (94%), non-rural (65%), median age 66.5 (range 27-80), self-reported race as White (74%) and Black (22%), cancer type as solid tumor (73%) and blood cancer (27%). The median number of CTs found for each Veteran was two (range 0 - 12). No referred Veterans enrolled in CTs, with the most common causes being CT ineligibility and desire to receive standard therapy in the VA. Twenty oncologists were educated about NOP CT guidance. The response rate to the feedback survey was modest (34%) but 94% of survey respondents rated their overall satisfaction as highly satisfied or satisfied.

Conclusions

The CTN assists Veterans and VA oncologists in connecting with CTs. The high satisfaction rate and ability to reach a racially and geographically diverse Veteran population are measures of early program success. By lowering the barriers for VA oncologists to consider CTs for their patients, the CTN expects increased and earlier referrals of Veterans, which may improve CT eligibility and participation. Future efforts to provide disease-directed education about CTs to Veterans and VA oncologists is intended to encourage early consideration of CTs.

Background

Despite the benefit of cancer clinical trials (CTs) in increasing medical knowledge and broadening treatment options, VA oncologists face challenges referring or enrolling Veterans in CTs including identifying appropriate CTs and navigating the referral process especially for non-VA CTs. To address these challenges, the VA National Oncology Program (NOP) provided guidance regarding community care referral for CT participation and established the Cancer Clinical Trial Nurse Navigation (CTN) service.

Methods

Referrals to CTN occur via Precision Oncology consult or email to [email protected]. The CT nurse navigator educates Veterans about CTs, identifies CTs for Veterans based on disease and geographic area, provides written summaries to Veterans and VA oncologists, and facilitates communication between clinical and research teams. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize characteristics of Veterans referred to CTN and results of the CTN searches. A semi-structured survey was used to assess satisfaction from 50 VA oncologists who had used the CTN service.

Results

Between June 2023 and May 2024, 72 Veterans were referred to CTN. Patient characteristics include male (94%), non-rural (65%), median age 66.5 (range 27-80), self-reported race as White (74%) and Black (22%), cancer type as solid tumor (73%) and blood cancer (27%). The median number of CTs found for each Veteran was two (range 0 - 12). No referred Veterans enrolled in CTs, with the most common causes being CT ineligibility and desire to receive standard therapy in the VA. Twenty oncologists were educated about NOP CT guidance. The response rate to the feedback survey was modest (34%) but 94% of survey respondents rated their overall satisfaction as highly satisfied or satisfied.

Conclusions

The CTN assists Veterans and VA oncologists in connecting with CTs. The high satisfaction rate and ability to reach a racially and geographically diverse Veteran population are measures of early program success. By lowering the barriers for VA oncologists to consider CTs for their patients, the CTN expects increased and earlier referrals of Veterans, which may improve CT eligibility and participation. Future efforts to provide disease-directed education about CTs to Veterans and VA oncologists is intended to encourage early consideration of CTs.

Variation in Cardiovascular Risk Assessment Status in Patients Receiving Oral Anti-Cancer Therapies: A Focus on Equity throughout VISN (Veteran Integrated Service Network) 12

Background

Oral anti-cancer therapies have quickly moved to the forefront of cancer treatment for several oncologic disease states. While these treatments have led to improvements in prognosis and ease of administration, many of these agents carry the risk of serious short- and long-term toxicities affecting the cardiovascular system. This prompted the Journal of the American Heart Association (JAHA) to release special guidance focused on cardiovascular monitoring strategies for anti-cancer agents. The primary objective of this retrospective review was to evaluate compliance with cardiovascular monitoring based on JAHA cardio-oncologic guidelines. The secondary objective was to assess disparities in cardiovascular monitoring based on markers of equity such as race/ ethnicity, rurality, socioeconomic status and gender.

Methods

Patients who initiated pazopanib, cabozantinib, lenvatinib, axitinib, regorafenib, nilotinib, ibrutinib, sorafenib, sunitinib, ponatinib or everolimus between January 1, 2019 and December 31, 2022 at a VHA VISN 12 site with oncology services were followed forward until treatment discontinuation or 12 months of therapy had been completed. Data was acquired utilizing the VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure (VINCI) and the Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW). The following cardiovascular monitoring markers were recorded at baseline and months 3, 6, 9 and 12 after initiation anti-cancer therapy: blood pressure, blood glucose, cholesterol, ECG and echocardiogram. Descriptive statistics were used to examine all continuous variables, while frequencies were used to examine categorical variables. Univariate statistics were performed on all items respectively.

Results

A total of 219 patients were identified initiating pre-specified oral anti-cancer therapies during the study time period. Of these, a total of n=145 met study inclusion criteria. 97% were male (n=141), 80% (n=116) had a racial background of white, 36% (n=52) live in rural or highly rural locations and 23% (n=34) lived in a high poverty area. Based on the primary endpoint, the mean compliance with recommended cardiovascular monitoring was 44.95% [IQR 12]. There was no statistically significant difference in cardiovascular monitoring based on equity.

Conclusions

Overall uptake of cardiovascular monitoring markers recommended by JAHA guidance is low. We plan to evaluate methods to increase these measures, utilizing clinical pharmacy provider support throughout VISN 12.

Background

Oral anti-cancer therapies have quickly moved to the forefront of cancer treatment for several oncologic disease states. While these treatments have led to improvements in prognosis and ease of administration, many of these agents carry the risk of serious short- and long-term toxicities affecting the cardiovascular system. This prompted the Journal of the American Heart Association (JAHA) to release special guidance focused on cardiovascular monitoring strategies for anti-cancer agents. The primary objective of this retrospective review was to evaluate compliance with cardiovascular monitoring based on JAHA cardio-oncologic guidelines. The secondary objective was to assess disparities in cardiovascular monitoring based on markers of equity such as race/ ethnicity, rurality, socioeconomic status and gender.

Methods

Patients who initiated pazopanib, cabozantinib, lenvatinib, axitinib, regorafenib, nilotinib, ibrutinib, sorafenib, sunitinib, ponatinib or everolimus between January 1, 2019 and December 31, 2022 at a VHA VISN 12 site with oncology services were followed forward until treatment discontinuation or 12 months of therapy had been completed. Data was acquired utilizing the VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure (VINCI) and the Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW). The following cardiovascular monitoring markers were recorded at baseline and months 3, 6, 9 and 12 after initiation anti-cancer therapy: blood pressure, blood glucose, cholesterol, ECG and echocardiogram. Descriptive statistics were used to examine all continuous variables, while frequencies were used to examine categorical variables. Univariate statistics were performed on all items respectively.

Results

A total of 219 patients were identified initiating pre-specified oral anti-cancer therapies during the study time period. Of these, a total of n=145 met study inclusion criteria. 97% were male (n=141), 80% (n=116) had a racial background of white, 36% (n=52) live in rural or highly rural locations and 23% (n=34) lived in a high poverty area. Based on the primary endpoint, the mean compliance with recommended cardiovascular monitoring was 44.95% [IQR 12]. There was no statistically significant difference in cardiovascular monitoring based on equity.

Conclusions

Overall uptake of cardiovascular monitoring markers recommended by JAHA guidance is low. We plan to evaluate methods to increase these measures, utilizing clinical pharmacy provider support throughout VISN 12.

Background

Oral anti-cancer therapies have quickly moved to the forefront of cancer treatment for several oncologic disease states. While these treatments have led to improvements in prognosis and ease of administration, many of these agents carry the risk of serious short- and long-term toxicities affecting the cardiovascular system. This prompted the Journal of the American Heart Association (JAHA) to release special guidance focused on cardiovascular monitoring strategies for anti-cancer agents. The primary objective of this retrospective review was to evaluate compliance with cardiovascular monitoring based on JAHA cardio-oncologic guidelines. The secondary objective was to assess disparities in cardiovascular monitoring based on markers of equity such as race/ ethnicity, rurality, socioeconomic status and gender.

Methods