User login

Just Minutes of Daily Vigorous Exercise Improve Heart Health

Middle-aged women who did many short bursts of vigorous-intensity exercise — amounting to as little as 3 min/d — had a 45% lower risk for major adverse cardiovascular events, reported investigators.

This doesn’t mean just a walk in the park, explained Emmanuel Stamatakis, PhD, a researcher with the University of Sydney in Australia. He said the activity can be as short as 20-30 seconds, but it must be high intensity — “movement that gets us out of breath, gets our heart rate up” — and repeated several times daily.

Stamatakis and colleagues call this type of exercise vigorous intermittent lifestyle physical activity, and it involves intense movement in very short bouts that are part of daily life, like a quick stair climb or running for a bus.

In their study, published in The British Journal of Sports Medicine, most exercise bursts were less than a minute, and few were over 2 minutes.

They are upending the common view that “any physical activity under 10 minutes doesn’t count for health,” said Stamatakis.

Bursts of Energy

The three studies looked at data for thousands of middle-aged men and women aged 40-69 years collected in the UK Biobank. Their daily activity was measured using accelerometers worn on the wrist for 7 days. This is preferable to survey data, which Stamatakis said is often unreliable.

The analysis looked at people who reported that they did not do any other exercise, taking no more than a single walk during the week. Then their cardiovascular health was tracked for almost 8 years.

Previous studies of the same data have shown benefits of vigorous physical activity for risk for cancer and for risk for death, both overall and due to cardiovascular disease or cancer.

In this study, women who did even less than 2 minutes of vigorous physical activity a day but no other exercise had a lower risk for all major cardiovascular events and for heart attack and heart failure. Women who did the median daily vigorous exercise time — 3.4 minutes — had an even lower risk. In fact, in women, there was a direct relationship between daily exercise time and risk reduction.

In men, the study showed some benefit of vigorous physical activity, but the relationship was not as clear, said Stamatakis. “The effects were much subtler and, in most cases, did not reach statistical significance.”

Good News for Women

Stamatakis said it is unclear why there was such a gap in the benefits between men and women. “Studies like ours are not designed to explain the difference,” he added.

“This study does not show that [vigorous physical activity] is effective in women but not men,” said Yasina Somani, PhD, an exercise physiology researcher at the University of Leeds in England, who was not involved in the work. Because the study just observed people’s behavior, rather than studying people in controlled conditions such as a lab, she said you cannot reach conclusions about the benefits for men. “You still need some further research.”

Somani pointed out that a study like this one cannot determine how vigorous physical activity protects the heart. In her research, she has studied the ways that exercise exerts effects on the heart. Exercise stresses the cardiovascular system, leading to physiological adaptation, and this may differ between men and women.

“Seeing this article motivates me to understand why women are responding even more than men. Do men need a greater volume of this exercise? If you’re carrying a 10-pound grocery bag up a flight of stairs, who is getting the greater stimulus?”

In fact, the study researchers think women’s exercise bursts might simply be harder for them. For some of the sample, the researchers had data on maximal oxygen consumption (VO2 max), a measure of cardiovascular fitness. During vigorous physical activity bouts, this measure showed that the effort for women averaged 83.2% of VO2 max, whereas it was 70.5% for men.

Somani said, “For men, there needs to be more clarity and more understanding of what it is that provides that stimulus — the intensity, the mode of exercise.”

“People are very surprised that 20-30 seconds of high-intensity exercise several times a day can make a difference to their health,” said Stamatakis. “They think they need to do structured exercise,” such as at a gym, to benefit.

He said the message that even quick exercise hits are beneficial can help healthcare professionals foster preventive behavior. “Any health professional who deals with patients on a regular basis knows that physical activity is important for people’s overall well-being and prevention of chronic disease.” The difficulty is that many people cannot or simply do not exercise. “Some people cannot afford it, and some do not have the motivation to stick to a structured exercise program.”

But anyone can do vigorous physical activity, he said. “The entry level is very low. There are no special preparations, no special clothes, no money to spend, no time commitment. You are interspersing exercise across your day.”

The researchers are currently studying how to foster vigorous physical activity in everyday behavior. “We are codesigning programs with participants, engaging with middle-aged people who have never exercised, so that the program has the highest chance to be successful.” Stamatakis is looking at encouraging vigorous physical activity through wearable devices and coaching, including online options.

Somani said the study adds weight to the message that any exercise is worthwhile. “These are simple choices that you can make that don’t require engaging in more structured exercise. Whatever you can do — little things outside of a gym — can have a lot of benefit for you.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Middle-aged women who did many short bursts of vigorous-intensity exercise — amounting to as little as 3 min/d — had a 45% lower risk for major adverse cardiovascular events, reported investigators.

This doesn’t mean just a walk in the park, explained Emmanuel Stamatakis, PhD, a researcher with the University of Sydney in Australia. He said the activity can be as short as 20-30 seconds, but it must be high intensity — “movement that gets us out of breath, gets our heart rate up” — and repeated several times daily.

Stamatakis and colleagues call this type of exercise vigorous intermittent lifestyle physical activity, and it involves intense movement in very short bouts that are part of daily life, like a quick stair climb or running for a bus.

In their study, published in The British Journal of Sports Medicine, most exercise bursts were less than a minute, and few were over 2 minutes.

They are upending the common view that “any physical activity under 10 minutes doesn’t count for health,” said Stamatakis.

Bursts of Energy

The three studies looked at data for thousands of middle-aged men and women aged 40-69 years collected in the UK Biobank. Their daily activity was measured using accelerometers worn on the wrist for 7 days. This is preferable to survey data, which Stamatakis said is often unreliable.

The analysis looked at people who reported that they did not do any other exercise, taking no more than a single walk during the week. Then their cardiovascular health was tracked for almost 8 years.

Previous studies of the same data have shown benefits of vigorous physical activity for risk for cancer and for risk for death, both overall and due to cardiovascular disease or cancer.

In this study, women who did even less than 2 minutes of vigorous physical activity a day but no other exercise had a lower risk for all major cardiovascular events and for heart attack and heart failure. Women who did the median daily vigorous exercise time — 3.4 minutes — had an even lower risk. In fact, in women, there was a direct relationship between daily exercise time and risk reduction.

In men, the study showed some benefit of vigorous physical activity, but the relationship was not as clear, said Stamatakis. “The effects were much subtler and, in most cases, did not reach statistical significance.”

Good News for Women

Stamatakis said it is unclear why there was such a gap in the benefits between men and women. “Studies like ours are not designed to explain the difference,” he added.

“This study does not show that [vigorous physical activity] is effective in women but not men,” said Yasina Somani, PhD, an exercise physiology researcher at the University of Leeds in England, who was not involved in the work. Because the study just observed people’s behavior, rather than studying people in controlled conditions such as a lab, she said you cannot reach conclusions about the benefits for men. “You still need some further research.”

Somani pointed out that a study like this one cannot determine how vigorous physical activity protects the heart. In her research, she has studied the ways that exercise exerts effects on the heart. Exercise stresses the cardiovascular system, leading to physiological adaptation, and this may differ between men and women.

“Seeing this article motivates me to understand why women are responding even more than men. Do men need a greater volume of this exercise? If you’re carrying a 10-pound grocery bag up a flight of stairs, who is getting the greater stimulus?”

In fact, the study researchers think women’s exercise bursts might simply be harder for them. For some of the sample, the researchers had data on maximal oxygen consumption (VO2 max), a measure of cardiovascular fitness. During vigorous physical activity bouts, this measure showed that the effort for women averaged 83.2% of VO2 max, whereas it was 70.5% for men.

Somani said, “For men, there needs to be more clarity and more understanding of what it is that provides that stimulus — the intensity, the mode of exercise.”

“People are very surprised that 20-30 seconds of high-intensity exercise several times a day can make a difference to their health,” said Stamatakis. “They think they need to do structured exercise,” such as at a gym, to benefit.

He said the message that even quick exercise hits are beneficial can help healthcare professionals foster preventive behavior. “Any health professional who deals with patients on a regular basis knows that physical activity is important for people’s overall well-being and prevention of chronic disease.” The difficulty is that many people cannot or simply do not exercise. “Some people cannot afford it, and some do not have the motivation to stick to a structured exercise program.”

But anyone can do vigorous physical activity, he said. “The entry level is very low. There are no special preparations, no special clothes, no money to spend, no time commitment. You are interspersing exercise across your day.”

The researchers are currently studying how to foster vigorous physical activity in everyday behavior. “We are codesigning programs with participants, engaging with middle-aged people who have never exercised, so that the program has the highest chance to be successful.” Stamatakis is looking at encouraging vigorous physical activity through wearable devices and coaching, including online options.

Somani said the study adds weight to the message that any exercise is worthwhile. “These are simple choices that you can make that don’t require engaging in more structured exercise. Whatever you can do — little things outside of a gym — can have a lot of benefit for you.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Middle-aged women who did many short bursts of vigorous-intensity exercise — amounting to as little as 3 min/d — had a 45% lower risk for major adverse cardiovascular events, reported investigators.

This doesn’t mean just a walk in the park, explained Emmanuel Stamatakis, PhD, a researcher with the University of Sydney in Australia. He said the activity can be as short as 20-30 seconds, but it must be high intensity — “movement that gets us out of breath, gets our heart rate up” — and repeated several times daily.

Stamatakis and colleagues call this type of exercise vigorous intermittent lifestyle physical activity, and it involves intense movement in very short bouts that are part of daily life, like a quick stair climb or running for a bus.

In their study, published in The British Journal of Sports Medicine, most exercise bursts were less than a minute, and few were over 2 minutes.

They are upending the common view that “any physical activity under 10 minutes doesn’t count for health,” said Stamatakis.

Bursts of Energy

The three studies looked at data for thousands of middle-aged men and women aged 40-69 years collected in the UK Biobank. Their daily activity was measured using accelerometers worn on the wrist for 7 days. This is preferable to survey data, which Stamatakis said is often unreliable.

The analysis looked at people who reported that they did not do any other exercise, taking no more than a single walk during the week. Then their cardiovascular health was tracked for almost 8 years.

Previous studies of the same data have shown benefits of vigorous physical activity for risk for cancer and for risk for death, both overall and due to cardiovascular disease or cancer.

In this study, women who did even less than 2 minutes of vigorous physical activity a day but no other exercise had a lower risk for all major cardiovascular events and for heart attack and heart failure. Women who did the median daily vigorous exercise time — 3.4 minutes — had an even lower risk. In fact, in women, there was a direct relationship between daily exercise time and risk reduction.

In men, the study showed some benefit of vigorous physical activity, but the relationship was not as clear, said Stamatakis. “The effects were much subtler and, in most cases, did not reach statistical significance.”

Good News for Women

Stamatakis said it is unclear why there was such a gap in the benefits between men and women. “Studies like ours are not designed to explain the difference,” he added.

“This study does not show that [vigorous physical activity] is effective in women but not men,” said Yasina Somani, PhD, an exercise physiology researcher at the University of Leeds in England, who was not involved in the work. Because the study just observed people’s behavior, rather than studying people in controlled conditions such as a lab, she said you cannot reach conclusions about the benefits for men. “You still need some further research.”

Somani pointed out that a study like this one cannot determine how vigorous physical activity protects the heart. In her research, she has studied the ways that exercise exerts effects on the heart. Exercise stresses the cardiovascular system, leading to physiological adaptation, and this may differ between men and women.

“Seeing this article motivates me to understand why women are responding even more than men. Do men need a greater volume of this exercise? If you’re carrying a 10-pound grocery bag up a flight of stairs, who is getting the greater stimulus?”

In fact, the study researchers think women’s exercise bursts might simply be harder for them. For some of the sample, the researchers had data on maximal oxygen consumption (VO2 max), a measure of cardiovascular fitness. During vigorous physical activity bouts, this measure showed that the effort for women averaged 83.2% of VO2 max, whereas it was 70.5% for men.

Somani said, “For men, there needs to be more clarity and more understanding of what it is that provides that stimulus — the intensity, the mode of exercise.”

“People are very surprised that 20-30 seconds of high-intensity exercise several times a day can make a difference to their health,” said Stamatakis. “They think they need to do structured exercise,” such as at a gym, to benefit.

He said the message that even quick exercise hits are beneficial can help healthcare professionals foster preventive behavior. “Any health professional who deals with patients on a regular basis knows that physical activity is important for people’s overall well-being and prevention of chronic disease.” The difficulty is that many people cannot or simply do not exercise. “Some people cannot afford it, and some do not have the motivation to stick to a structured exercise program.”

But anyone can do vigorous physical activity, he said. “The entry level is very low. There are no special preparations, no special clothes, no money to spend, no time commitment. You are interspersing exercise across your day.”

The researchers are currently studying how to foster vigorous physical activity in everyday behavior. “We are codesigning programs with participants, engaging with middle-aged people who have never exercised, so that the program has the highest chance to be successful.” Stamatakis is looking at encouraging vigorous physical activity through wearable devices and coaching, including online options.

Somani said the study adds weight to the message that any exercise is worthwhile. “These are simple choices that you can make that don’t require engaging in more structured exercise. Whatever you can do — little things outside of a gym — can have a lot of benefit for you.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE BRITISH JOURNAL OF SPORTS MEDICINE

Cardiovascular Risk in T1D: LDL Focus and Beyond

Estimation of cardiovascular risk (CVR) in individuals living with type 1 diabetes (T1D) was a key topic presented by Sophie Borot, MD, from Besançon University Hospital, Besançon, France, at the 40th congress of the French Society of Endocrinology. Borot highlighted the complexities of this subject, outlining several factors that contribute to its challenges.

A Heterogeneous Disease

T1D is a highly heterogeneous condition, and the patients included in studies reflect this diversity:

- The impact of blood glucose levels on CVR changes depending on diabetes duration, its history, the frequency of hypoglycemic episodes, average A1c levels over several years, and the patient’s age at diagnosis.

- A T1D diagnosis from the 1980s involved different management strategies compared with a diagnosis today.

- Patient profiles also vary based on complications such as nephropathy or cardiac autonomic neuropathy.

- Diffuse and distal arterial damage in T1D leads to more subtle and delayed pathologic events than in type 2 diabetes (T2D).

- Most clinical studies assess CVR over 10 years, but a 20- or 30-year evaluation would be more relevant.

- Patients may share CVR factors with the general population (eg, family history, smoking, sedentary lifestyle, obesity, hypertension, or elevated low-density lipoprotein [LDL] levels), raising questions about possible overlap with metabolic syndrome.

- Study criteria differ, with a focus on outcomes such as cardiovascular death, major adverse cardiovascular events like myocardial infarction and stroke, or other endpoints.

- CVR is measured using either absolute or relative values, with varying units of measurement.

A Recent Awareness

The concept of CVR in T1D is relatively new. Until the publication of the prospective Diabetes Control and Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications study in 2005, it was believed that T1D control had no impact on CVR. However, follow-up results from the same cohort of 50,000 patients, published in 2022 after 30 years of observation, revealed that CVR was 20% higher in patients who received conventional hyperglycemia-targeted treatment than those undergoing intensive treatment. The CVR increases in conjunction with diabetes duration. The study also showed that even well-controlled glycemia in T1D carries CVR (primarily due to microangiopathy), and that the most critical factor for CVR is not A1c control but rather LDL cholesterol levels.

These findings were corroborated by a Danish prospective study, which demonstrated that while CVR increased in conjunction with the number of risk factors, it was 82% higher in patients with T1D than in a control group — even in the absence of risk factors.

Key Takeaways

At diagnosis, a fundamental difference exists between T1D and T2D in terms of the urgency to address CVR. In T2D, diabetes may have progressed for years before diagnosis, necessitating immediate CVR reduction efforts. In contrast, T1D is often diagnosed in younger patients with initially low CVR, raising questions about the optimal timing for interventions such as statin prescriptions.

Recommendations

The American Diabetes Association/European Association for the Study of Diabetes guidelines (2024) include the following recommendations:

- Between ages 20 and 40, statins are recommended if at least one CVR factor is present.

- For children 10 years of age or older with T1D, the LDL target is < 1.0 g/L. Statins are prescribed if LDL exceeds 1.6 g/L without CVR factors or 1.3 g/L with at least one CVR factor.

The European Society of Cardiology guidelines (2023) include the following:

- For the first time, a dedicated chapter addresses T1D. Like the American guidelines, routine statin use after age 40 is recommended.

- Before age 40, statins are prescribed if there is at least one CVR factor (microangiopathy) or a 10-year CVR ≥ 10% (based on a CVR calculator).

The International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes guidelines (2022) recommend:

- For children 10 years of age or older, the LDL target is < 1.0 g/L. Statins are recommended if LDL exceeds 1.3 g/L.

CAC Score in High CVR

The French Society of Cardiology and the French-speaking Society of Diabetology recommend incorporating the coronary artery calcium (CAC) score to refine CVR classification in high-risk patients. For those without prior cardiovascular events, LDL targets vary based on CAC and age. For example:

- High-risk patients with a CAC of 0-10 are reclassified as moderate risk, with an LDL target of < 1 g/L.

- A CAC ≥ 400 indicates very high risk, warranting coronary exploration.

- Patients under 50 years of age with a CAC of 11-100 remain high risk, with an LDL target of 0.7 g/L.

Conclusion

CVR in patients with T1D remains challenging to define. However, it is essential to consider long-term outcomes, planning for 30 or 40 years into the future. This involves educating patients about the importance of prevention, even when reassuring numbers are seen in their youth.

This story was translated from Univadis France using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Estimation of cardiovascular risk (CVR) in individuals living with type 1 diabetes (T1D) was a key topic presented by Sophie Borot, MD, from Besançon University Hospital, Besançon, France, at the 40th congress of the French Society of Endocrinology. Borot highlighted the complexities of this subject, outlining several factors that contribute to its challenges.

A Heterogeneous Disease

T1D is a highly heterogeneous condition, and the patients included in studies reflect this diversity:

- The impact of blood glucose levels on CVR changes depending on diabetes duration, its history, the frequency of hypoglycemic episodes, average A1c levels over several years, and the patient’s age at diagnosis.

- A T1D diagnosis from the 1980s involved different management strategies compared with a diagnosis today.

- Patient profiles also vary based on complications such as nephropathy or cardiac autonomic neuropathy.

- Diffuse and distal arterial damage in T1D leads to more subtle and delayed pathologic events than in type 2 diabetes (T2D).

- Most clinical studies assess CVR over 10 years, but a 20- or 30-year evaluation would be more relevant.

- Patients may share CVR factors with the general population (eg, family history, smoking, sedentary lifestyle, obesity, hypertension, or elevated low-density lipoprotein [LDL] levels), raising questions about possible overlap with metabolic syndrome.

- Study criteria differ, with a focus on outcomes such as cardiovascular death, major adverse cardiovascular events like myocardial infarction and stroke, or other endpoints.

- CVR is measured using either absolute or relative values, with varying units of measurement.

A Recent Awareness

The concept of CVR in T1D is relatively new. Until the publication of the prospective Diabetes Control and Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications study in 2005, it was believed that T1D control had no impact on CVR. However, follow-up results from the same cohort of 50,000 patients, published in 2022 after 30 years of observation, revealed that CVR was 20% higher in patients who received conventional hyperglycemia-targeted treatment than those undergoing intensive treatment. The CVR increases in conjunction with diabetes duration. The study also showed that even well-controlled glycemia in T1D carries CVR (primarily due to microangiopathy), and that the most critical factor for CVR is not A1c control but rather LDL cholesterol levels.

These findings were corroborated by a Danish prospective study, which demonstrated that while CVR increased in conjunction with the number of risk factors, it was 82% higher in patients with T1D than in a control group — even in the absence of risk factors.

Key Takeaways

At diagnosis, a fundamental difference exists between T1D and T2D in terms of the urgency to address CVR. In T2D, diabetes may have progressed for years before diagnosis, necessitating immediate CVR reduction efforts. In contrast, T1D is often diagnosed in younger patients with initially low CVR, raising questions about the optimal timing for interventions such as statin prescriptions.

Recommendations

The American Diabetes Association/European Association for the Study of Diabetes guidelines (2024) include the following recommendations:

- Between ages 20 and 40, statins are recommended if at least one CVR factor is present.

- For children 10 years of age or older with T1D, the LDL target is < 1.0 g/L. Statins are prescribed if LDL exceeds 1.6 g/L without CVR factors or 1.3 g/L with at least one CVR factor.

The European Society of Cardiology guidelines (2023) include the following:

- For the first time, a dedicated chapter addresses T1D. Like the American guidelines, routine statin use after age 40 is recommended.

- Before age 40, statins are prescribed if there is at least one CVR factor (microangiopathy) or a 10-year CVR ≥ 10% (based on a CVR calculator).

The International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes guidelines (2022) recommend:

- For children 10 years of age or older, the LDL target is < 1.0 g/L. Statins are recommended if LDL exceeds 1.3 g/L.

CAC Score in High CVR

The French Society of Cardiology and the French-speaking Society of Diabetology recommend incorporating the coronary artery calcium (CAC) score to refine CVR classification in high-risk patients. For those without prior cardiovascular events, LDL targets vary based on CAC and age. For example:

- High-risk patients with a CAC of 0-10 are reclassified as moderate risk, with an LDL target of < 1 g/L.

- A CAC ≥ 400 indicates very high risk, warranting coronary exploration.

- Patients under 50 years of age with a CAC of 11-100 remain high risk, with an LDL target of 0.7 g/L.

Conclusion

CVR in patients with T1D remains challenging to define. However, it is essential to consider long-term outcomes, planning for 30 or 40 years into the future. This involves educating patients about the importance of prevention, even when reassuring numbers are seen in their youth.

This story was translated from Univadis France using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Estimation of cardiovascular risk (CVR) in individuals living with type 1 diabetes (T1D) was a key topic presented by Sophie Borot, MD, from Besançon University Hospital, Besançon, France, at the 40th congress of the French Society of Endocrinology. Borot highlighted the complexities of this subject, outlining several factors that contribute to its challenges.

A Heterogeneous Disease

T1D is a highly heterogeneous condition, and the patients included in studies reflect this diversity:

- The impact of blood glucose levels on CVR changes depending on diabetes duration, its history, the frequency of hypoglycemic episodes, average A1c levels over several years, and the patient’s age at diagnosis.

- A T1D diagnosis from the 1980s involved different management strategies compared with a diagnosis today.

- Patient profiles also vary based on complications such as nephropathy or cardiac autonomic neuropathy.

- Diffuse and distal arterial damage in T1D leads to more subtle and delayed pathologic events than in type 2 diabetes (T2D).

- Most clinical studies assess CVR over 10 years, but a 20- or 30-year evaluation would be more relevant.

- Patients may share CVR factors with the general population (eg, family history, smoking, sedentary lifestyle, obesity, hypertension, or elevated low-density lipoprotein [LDL] levels), raising questions about possible overlap with metabolic syndrome.

- Study criteria differ, with a focus on outcomes such as cardiovascular death, major adverse cardiovascular events like myocardial infarction and stroke, or other endpoints.

- CVR is measured using either absolute or relative values, with varying units of measurement.

A Recent Awareness

The concept of CVR in T1D is relatively new. Until the publication of the prospective Diabetes Control and Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications study in 2005, it was believed that T1D control had no impact on CVR. However, follow-up results from the same cohort of 50,000 patients, published in 2022 after 30 years of observation, revealed that CVR was 20% higher in patients who received conventional hyperglycemia-targeted treatment than those undergoing intensive treatment. The CVR increases in conjunction with diabetes duration. The study also showed that even well-controlled glycemia in T1D carries CVR (primarily due to microangiopathy), and that the most critical factor for CVR is not A1c control but rather LDL cholesterol levels.

These findings were corroborated by a Danish prospective study, which demonstrated that while CVR increased in conjunction with the number of risk factors, it was 82% higher in patients with T1D than in a control group — even in the absence of risk factors.

Key Takeaways

At diagnosis, a fundamental difference exists between T1D and T2D in terms of the urgency to address CVR. In T2D, diabetes may have progressed for years before diagnosis, necessitating immediate CVR reduction efforts. In contrast, T1D is often diagnosed in younger patients with initially low CVR, raising questions about the optimal timing for interventions such as statin prescriptions.

Recommendations

The American Diabetes Association/European Association for the Study of Diabetes guidelines (2024) include the following recommendations:

- Between ages 20 and 40, statins are recommended if at least one CVR factor is present.

- For children 10 years of age or older with T1D, the LDL target is < 1.0 g/L. Statins are prescribed if LDL exceeds 1.6 g/L without CVR factors or 1.3 g/L with at least one CVR factor.

The European Society of Cardiology guidelines (2023) include the following:

- For the first time, a dedicated chapter addresses T1D. Like the American guidelines, routine statin use after age 40 is recommended.

- Before age 40, statins are prescribed if there is at least one CVR factor (microangiopathy) or a 10-year CVR ≥ 10% (based on a CVR calculator).

The International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes guidelines (2022) recommend:

- For children 10 years of age or older, the LDL target is < 1.0 g/L. Statins are recommended if LDL exceeds 1.3 g/L.

CAC Score in High CVR

The French Society of Cardiology and the French-speaking Society of Diabetology recommend incorporating the coronary artery calcium (CAC) score to refine CVR classification in high-risk patients. For those without prior cardiovascular events, LDL targets vary based on CAC and age. For example:

- High-risk patients with a CAC of 0-10 are reclassified as moderate risk, with an LDL target of < 1 g/L.

- A CAC ≥ 400 indicates very high risk, warranting coronary exploration.

- Patients under 50 years of age with a CAC of 11-100 remain high risk, with an LDL target of 0.7 g/L.

Conclusion

CVR in patients with T1D remains challenging to define. However, it is essential to consider long-term outcomes, planning for 30 or 40 years into the future. This involves educating patients about the importance of prevention, even when reassuring numbers are seen in their youth.

This story was translated from Univadis France using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Fifty Years Later: Preterm Birth Shows Complex Pattern of Cardiovascular Outcomes

TOPLINE:

Adults aged 50 years who were born preterm have a higher risk for hypertension but lower risk for cardiovascular events than those born at term, with similar risks for diabetes, prediabetes, and dyslipidemia between groups.

METHODOLOGY:

- The researchers conducted a prospective cohort study of the Auckland Steroid Trial — the first randomized trial of antenatal corticosteroids (betamethasone) for women who were at risk for preterm birth, conducted in Auckland, New Zealand, between December 1969 and February 1974.

- They analyzed 470 participants, including 424 survivors recruited between January 2020 and May 2022 and 46 participants who died after infancy.

- The outcomes for 326 participants born preterm (mean age, 49.4 years) and 144 participants born at term (mean age, 49.2 years) were assessed using either a questionnaire, administrative datasets, or both.

- The primary outcome was a composite of cardiovascular events or risk factors, defined as a history of a major adverse cardiovascular event or the presence of at least one cardiovascular risk factor, including diabetes mellitus, prediabetes, treated dyslipidemia, and treated hypertension.

- The secondary outcomes included respiratory, mental health, educational, and other health outcomes, as well as components of the primary outcomes.

TAKEAWAY:

- The composite of cardiovascular events or risk factors occurred in 34.5% of participants born preterm and 29.9% of participants born at term, with no differences in the risk factor components.

- The risk for cardiovascular events was lower in participants born preterm than in those born at term (adjusted relative risk [aRR], 0.33; P = .013).

- The participants born preterm had a higher risk for high blood pressure (aRR, 1.74; P = .007) and the composite of treated hypertension or self-reported diagnosis of high blood pressure (aRR, 1.63; P = .010) than those born at term.

- From randomization to the 50-year follow-up, death from any cause was more common in those born preterm than in those born at term (aRR, 2.29; P < .0001), whereas the diagnosis or treatment of a mental health disorder was less common (P = .007); no differences were observed between the groups for other outcomes.

IN PRACTICE:

“Those aware of being born preterm also may be more likely to seek preventive treatments, potentially resulting in a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease but a greater prevalence of risk factors if defined by a treatment such as treated dyslipidemia or treated hypertension,” the authors wrote.

“In this cohort, the survival advantage of the term-born control group abated after infancy, with a higher all-cause mortality rate, compared with that of the group born preterm,” wrote Jonathan S. Litt, MD, MPH, ScD, and Henning Tiemeier, MD, PhD, in a related commentary published in Pediatrics.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Anthony G. B. Walters, MBChB, Liggins Institute, Auckland, New Zealand. It was published online on December 16, 2024, in Pediatrics .

LIMITATIONS:

The small sample size limited the ability to detect subtle differences between groups and the validity of subgroup analyses. Attrition bias may have occurred because of low follow-up rates among presumed survivors. Bias could have been introduced because of lack of consent for access to the administrative dataset or from missing data from the participants in the questionnaire. The lack of in-person assessments for blood pressure and blood tests, resulting from geographical dispersion over 50 years, may have led to underestimation of some outcomes. Additionally, as most participants were born moderately or late preterm, with a median gestational age of 34.1 weeks, findings may not be generalizable to those born preterm at earlier gestational ages.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported in part by the Aotearoa Foundation, the Auckland Medical Research Foundation, Cure Kids New Zealand, and the Health Research Council of New Zealand. The authors of both the study and the commentary reported no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Adults aged 50 years who were born preterm have a higher risk for hypertension but lower risk for cardiovascular events than those born at term, with similar risks for diabetes, prediabetes, and dyslipidemia between groups.

METHODOLOGY:

- The researchers conducted a prospective cohort study of the Auckland Steroid Trial — the first randomized trial of antenatal corticosteroids (betamethasone) for women who were at risk for preterm birth, conducted in Auckland, New Zealand, between December 1969 and February 1974.

- They analyzed 470 participants, including 424 survivors recruited between January 2020 and May 2022 and 46 participants who died after infancy.

- The outcomes for 326 participants born preterm (mean age, 49.4 years) and 144 participants born at term (mean age, 49.2 years) were assessed using either a questionnaire, administrative datasets, or both.

- The primary outcome was a composite of cardiovascular events or risk factors, defined as a history of a major adverse cardiovascular event or the presence of at least one cardiovascular risk factor, including diabetes mellitus, prediabetes, treated dyslipidemia, and treated hypertension.

- The secondary outcomes included respiratory, mental health, educational, and other health outcomes, as well as components of the primary outcomes.

TAKEAWAY:

- The composite of cardiovascular events or risk factors occurred in 34.5% of participants born preterm and 29.9% of participants born at term, with no differences in the risk factor components.

- The risk for cardiovascular events was lower in participants born preterm than in those born at term (adjusted relative risk [aRR], 0.33; P = .013).

- The participants born preterm had a higher risk for high blood pressure (aRR, 1.74; P = .007) and the composite of treated hypertension or self-reported diagnosis of high blood pressure (aRR, 1.63; P = .010) than those born at term.

- From randomization to the 50-year follow-up, death from any cause was more common in those born preterm than in those born at term (aRR, 2.29; P < .0001), whereas the diagnosis or treatment of a mental health disorder was less common (P = .007); no differences were observed between the groups for other outcomes.

IN PRACTICE:

“Those aware of being born preterm also may be more likely to seek preventive treatments, potentially resulting in a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease but a greater prevalence of risk factors if defined by a treatment such as treated dyslipidemia or treated hypertension,” the authors wrote.

“In this cohort, the survival advantage of the term-born control group abated after infancy, with a higher all-cause mortality rate, compared with that of the group born preterm,” wrote Jonathan S. Litt, MD, MPH, ScD, and Henning Tiemeier, MD, PhD, in a related commentary published in Pediatrics.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Anthony G. B. Walters, MBChB, Liggins Institute, Auckland, New Zealand. It was published online on December 16, 2024, in Pediatrics .

LIMITATIONS:

The small sample size limited the ability to detect subtle differences between groups and the validity of subgroup analyses. Attrition bias may have occurred because of low follow-up rates among presumed survivors. Bias could have been introduced because of lack of consent for access to the administrative dataset or from missing data from the participants in the questionnaire. The lack of in-person assessments for blood pressure and blood tests, resulting from geographical dispersion over 50 years, may have led to underestimation of some outcomes. Additionally, as most participants were born moderately or late preterm, with a median gestational age of 34.1 weeks, findings may not be generalizable to those born preterm at earlier gestational ages.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported in part by the Aotearoa Foundation, the Auckland Medical Research Foundation, Cure Kids New Zealand, and the Health Research Council of New Zealand. The authors of both the study and the commentary reported no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Adults aged 50 years who were born preterm have a higher risk for hypertension but lower risk for cardiovascular events than those born at term, with similar risks for diabetes, prediabetes, and dyslipidemia between groups.

METHODOLOGY:

- The researchers conducted a prospective cohort study of the Auckland Steroid Trial — the first randomized trial of antenatal corticosteroids (betamethasone) for women who were at risk for preterm birth, conducted in Auckland, New Zealand, between December 1969 and February 1974.

- They analyzed 470 participants, including 424 survivors recruited between January 2020 and May 2022 and 46 participants who died after infancy.

- The outcomes for 326 participants born preterm (mean age, 49.4 years) and 144 participants born at term (mean age, 49.2 years) were assessed using either a questionnaire, administrative datasets, or both.

- The primary outcome was a composite of cardiovascular events or risk factors, defined as a history of a major adverse cardiovascular event or the presence of at least one cardiovascular risk factor, including diabetes mellitus, prediabetes, treated dyslipidemia, and treated hypertension.

- The secondary outcomes included respiratory, mental health, educational, and other health outcomes, as well as components of the primary outcomes.

TAKEAWAY:

- The composite of cardiovascular events or risk factors occurred in 34.5% of participants born preterm and 29.9% of participants born at term, with no differences in the risk factor components.

- The risk for cardiovascular events was lower in participants born preterm than in those born at term (adjusted relative risk [aRR], 0.33; P = .013).

- The participants born preterm had a higher risk for high blood pressure (aRR, 1.74; P = .007) and the composite of treated hypertension or self-reported diagnosis of high blood pressure (aRR, 1.63; P = .010) than those born at term.

- From randomization to the 50-year follow-up, death from any cause was more common in those born preterm than in those born at term (aRR, 2.29; P < .0001), whereas the diagnosis or treatment of a mental health disorder was less common (P = .007); no differences were observed between the groups for other outcomes.

IN PRACTICE:

“Those aware of being born preterm also may be more likely to seek preventive treatments, potentially resulting in a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease but a greater prevalence of risk factors if defined by a treatment such as treated dyslipidemia or treated hypertension,” the authors wrote.

“In this cohort, the survival advantage of the term-born control group abated after infancy, with a higher all-cause mortality rate, compared with that of the group born preterm,” wrote Jonathan S. Litt, MD, MPH, ScD, and Henning Tiemeier, MD, PhD, in a related commentary published in Pediatrics.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Anthony G. B. Walters, MBChB, Liggins Institute, Auckland, New Zealand. It was published online on December 16, 2024, in Pediatrics .

LIMITATIONS:

The small sample size limited the ability to detect subtle differences between groups and the validity of subgroup analyses. Attrition bias may have occurred because of low follow-up rates among presumed survivors. Bias could have been introduced because of lack of consent for access to the administrative dataset or from missing data from the participants in the questionnaire. The lack of in-person assessments for blood pressure and blood tests, resulting from geographical dispersion over 50 years, may have led to underestimation of some outcomes. Additionally, as most participants were born moderately or late preterm, with a median gestational age of 34.1 weeks, findings may not be generalizable to those born preterm at earlier gestational ages.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported in part by the Aotearoa Foundation, the Auckland Medical Research Foundation, Cure Kids New Zealand, and the Health Research Council of New Zealand. The authors of both the study and the commentary reported no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Popular Diabetes Drug May Raise Vascular Surgery Risk

TOPLINE:

Among older veterans with type 2 diabetes (T2D), the use of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors as an add-on therapy is associated with a higher risk for peripheral artery disease (PAD)-related surgical events than the use of dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors.

METHODOLOGY:

- Some placebo-controlled randomized trials have reported an increased risk for amputation with the use of SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with underlying cardiovascular diseases; however, the evidence remains unconfirmed by other subsequent trials.

- Researchers conducted a retrospective study of US veterans with T2D initiating SGLT2 inhibitors or DPP-4 inhibitors (a reference drug) as an add-on to metformin, sulfonylurea, or insulin treatment alone or in combination.

- The primary outcome was the time to the first surgical event for PAD (amputation, peripheral revascularization and bypass, or peripheral vascular stent).

- A Cox proportional hazards model was used to compare PAD event risk between the SGLT2 inhibitor and DPP-4 inhibitor groups, allowing events up to 90 days or 360 days after stopping SGLT2 inhibitors.

TAKEAWAY:

- After propensity score weighting, 76,072 episodes of SGLT2 inhibitor use (94% empagliflozin, 4% canagliflozin, and 2% dapagliflozin) and 75,833 episodes of DPP-4 inhibitor use (45% saxagliptin, 34% alogliptin, 15% sitagliptin, and 6% linagliptin) were included.

- Participants had a median age of 69 years and a median duration of diabetes of 10.1 years.

- SGLT2 inhibitor users had higher PAD-related surgical events than DPP-4 inhibitor users (874 vs 780), with event rates of 11.2 vs 10.0 per 1000 person-years (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.18).

- The results remained consistent after 90 and 360 days of stopping SGLT2 inhibitors.

- SGLT2 inhibitor use was also associated with a higher risk for amputation (aHR, 1.15) and revascularization (aHR, 1.25) events than DPP-4 inhibitor use.

IN PRACTICE:

“These results underscore the need to determine the safety of [SGLT2 inhibitor] use among patients with diabetes who remain at very high risk for PAD,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Katherine E. Griffin, Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center, Tennessee Valley Healthcare System, Nashville, and published online in Diabetes Care.

LIMITATIONS:

The study excluded patients whose initial diabetes treatment was not metformin, insulin, or sulfonylurea, which might have influenced the interpretation of the results. The median follow-up period of approximately 0.7 years for both groups may have affected the number of amputations and revascularization events observed. The study population primarily comprised White men, limiting generalizability to women and other demographic groups.

DISCLOSURES:

The study received funding through an investigator-initiated grant from the Veterans Affairs Clinical Science Research and Development. Two authors received partial research support through a grant from the Center for Diabetes Translation Research. All authors received partial support from the VETWISE-LHS Center of Innovation. No potential conflicts of interest relevant to the article were reported.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including artificial intelligence, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Among older veterans with type 2 diabetes (T2D), the use of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors as an add-on therapy is associated with a higher risk for peripheral artery disease (PAD)-related surgical events than the use of dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors.

METHODOLOGY:

- Some placebo-controlled randomized trials have reported an increased risk for amputation with the use of SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with underlying cardiovascular diseases; however, the evidence remains unconfirmed by other subsequent trials.

- Researchers conducted a retrospective study of US veterans with T2D initiating SGLT2 inhibitors or DPP-4 inhibitors (a reference drug) as an add-on to metformin, sulfonylurea, or insulin treatment alone or in combination.

- The primary outcome was the time to the first surgical event for PAD (amputation, peripheral revascularization and bypass, or peripheral vascular stent).

- A Cox proportional hazards model was used to compare PAD event risk between the SGLT2 inhibitor and DPP-4 inhibitor groups, allowing events up to 90 days or 360 days after stopping SGLT2 inhibitors.

TAKEAWAY:

- After propensity score weighting, 76,072 episodes of SGLT2 inhibitor use (94% empagliflozin, 4% canagliflozin, and 2% dapagliflozin) and 75,833 episodes of DPP-4 inhibitor use (45% saxagliptin, 34% alogliptin, 15% sitagliptin, and 6% linagliptin) were included.

- Participants had a median age of 69 years and a median duration of diabetes of 10.1 years.

- SGLT2 inhibitor users had higher PAD-related surgical events than DPP-4 inhibitor users (874 vs 780), with event rates of 11.2 vs 10.0 per 1000 person-years (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.18).

- The results remained consistent after 90 and 360 days of stopping SGLT2 inhibitors.

- SGLT2 inhibitor use was also associated with a higher risk for amputation (aHR, 1.15) and revascularization (aHR, 1.25) events than DPP-4 inhibitor use.

IN PRACTICE:

“These results underscore the need to determine the safety of [SGLT2 inhibitor] use among patients with diabetes who remain at very high risk for PAD,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Katherine E. Griffin, Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center, Tennessee Valley Healthcare System, Nashville, and published online in Diabetes Care.

LIMITATIONS:

The study excluded patients whose initial diabetes treatment was not metformin, insulin, or sulfonylurea, which might have influenced the interpretation of the results. The median follow-up period of approximately 0.7 years for both groups may have affected the number of amputations and revascularization events observed. The study population primarily comprised White men, limiting generalizability to women and other demographic groups.

DISCLOSURES:

The study received funding through an investigator-initiated grant from the Veterans Affairs Clinical Science Research and Development. Two authors received partial research support through a grant from the Center for Diabetes Translation Research. All authors received partial support from the VETWISE-LHS Center of Innovation. No potential conflicts of interest relevant to the article were reported.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including artificial intelligence, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Among older veterans with type 2 diabetes (T2D), the use of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors as an add-on therapy is associated with a higher risk for peripheral artery disease (PAD)-related surgical events than the use of dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors.

METHODOLOGY:

- Some placebo-controlled randomized trials have reported an increased risk for amputation with the use of SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with underlying cardiovascular diseases; however, the evidence remains unconfirmed by other subsequent trials.

- Researchers conducted a retrospective study of US veterans with T2D initiating SGLT2 inhibitors or DPP-4 inhibitors (a reference drug) as an add-on to metformin, sulfonylurea, or insulin treatment alone or in combination.

- The primary outcome was the time to the first surgical event for PAD (amputation, peripheral revascularization and bypass, or peripheral vascular stent).

- A Cox proportional hazards model was used to compare PAD event risk between the SGLT2 inhibitor and DPP-4 inhibitor groups, allowing events up to 90 days or 360 days after stopping SGLT2 inhibitors.

TAKEAWAY:

- After propensity score weighting, 76,072 episodes of SGLT2 inhibitor use (94% empagliflozin, 4% canagliflozin, and 2% dapagliflozin) and 75,833 episodes of DPP-4 inhibitor use (45% saxagliptin, 34% alogliptin, 15% sitagliptin, and 6% linagliptin) were included.

- Participants had a median age of 69 years and a median duration of diabetes of 10.1 years.

- SGLT2 inhibitor users had higher PAD-related surgical events than DPP-4 inhibitor users (874 vs 780), with event rates of 11.2 vs 10.0 per 1000 person-years (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.18).

- The results remained consistent after 90 and 360 days of stopping SGLT2 inhibitors.

- SGLT2 inhibitor use was also associated with a higher risk for amputation (aHR, 1.15) and revascularization (aHR, 1.25) events than DPP-4 inhibitor use.

IN PRACTICE:

“These results underscore the need to determine the safety of [SGLT2 inhibitor] use among patients with diabetes who remain at very high risk for PAD,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Katherine E. Griffin, Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center, Tennessee Valley Healthcare System, Nashville, and published online in Diabetes Care.

LIMITATIONS:

The study excluded patients whose initial diabetes treatment was not metformin, insulin, or sulfonylurea, which might have influenced the interpretation of the results. The median follow-up period of approximately 0.7 years for both groups may have affected the number of amputations and revascularization events observed. The study population primarily comprised White men, limiting generalizability to women and other demographic groups.

DISCLOSURES:

The study received funding through an investigator-initiated grant from the Veterans Affairs Clinical Science Research and Development. Two authors received partial research support through a grant from the Center for Diabetes Translation Research. All authors received partial support from the VETWISE-LHS Center of Innovation. No potential conflicts of interest relevant to the article were reported.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including artificial intelligence, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Impact of NSAID Use on Bleeding Rates for Patients Taking Rivaroxaban or Apixaban

Impact of NSAID Use on Bleeding Rates for Patients Taking Rivaroxaban or Apixaban

Clinical practice has shifted from vitamin K antagonists to direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) for atrial fibrillation treatment due to their more favorable risk-benefit profile and less lifestyle modification required.1,2 However, the advantage of a lower bleeding risk with DOACs could be compromised by potentially problematic pharmacokinetic interactions like those conferred by antiplatelets or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).3,4 Treating a patient needing anticoagulation with a DOAC who has comorbidities may introduce unavoidable drug-drug interactions. This particularly happens with over-the-counter and prescription NSAIDs used for the management of pain and inflammatory conditions.5

NSAIDs primarily affect 2 cyclooxygenase (COX) enzyme isomers, COX-1 and COX-2.6 COX-1 helps maintain gastrointestinal (GI) mucosa integrity and platelet aggregation processes, whereas COX-2 is engaged in pain signaling and inflammation mediation. COX-1 inhibition is associated with more bleeding-related adverse events (AEs), especially in the GI tract. COX-2 inhibition is thought to provide analgesia and anti-inflammatory properties without elevating bleeding risk. This premise is responsible for the preferential use of celecoxib, a COX-2 selective NSAID, which should confer a lower bleeding risk compared to nonselective NSAIDs such as ibuprofen and naproxen.7 NSAIDs have been documented as independent risk factors for bleeding. NSAID users are about 3 times as likely to develop GI AEs compared to nonNSAID users.8

Many clinicians aim to further mitigate NSAID-associated bleeding risk by coprescribing a proton pump inhibitor (PPI). PPIs provide gastroprotection against NSAID-induced mucosal injury and sequential complication of GI bleeding. In a multicenter randomized control trial, patients who received concomitant PPI therapy while undergoing chronic NSAID therapy—including nonselective and COX-2 selective NSAIDs—had a significantly lower risk of GI ulcer development (placebo, 17.0%; 20 mg esomeprazole, 5.2%; 40 mg esomeprazole, 4.6%).9 Current clinical guidelines for preventing NSAIDassociated bleeding complications recommend using a COX-2 selective NSAID in combination with PPI therapy for patients at high risk for GI-related bleeding, including the concomitant use of anticoagulants.10

There is evidence suggesting an increased bleeding risk with NSAIDs when used in combination with vitamin K antagonists such as warfarin.11,12 A systematic review of warfarin and concomitant NSAID use found an increased risk of overall bleeding with NSAID use in combination with warfarin (odds ratio 1.58; 95% CI, 1.18-2.12), compared to warfarin alone.12

Posthoc analyses of randomized clinical trials have also demonstrated an increased bleeding risk with oral anticoagulation and concomitant NSAID use.13,14 In the RE-LY trial, NSAID users on warfarin or dabigatran had a statistically significant increased risk of major bleeding compared to non-NSAID users (hazard ratio [HR] 1.68; 95% CI, 1.40- 2.02; P < .001).13 In the ARISTOTLE trial, patients on warfarin or apixaban who were incident NSAID users were found to have an increased risk of major bleeding (HR 1.61; 95% CI, 1.11-2.33) and clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding (HR 1.70; 95% CI, 1.16- 2.48).14 These trials found a statistically significant increased bleeding risk associated with NSAID use, though the populations evaluated included patients taking warfarin and patients taking DOACs. These trials did not evaluate the bleeding risk of concomitant NSAID use among DOACs alone.

Evidence on NSAID-associated bleeding risk with DOACs is lacking in settings where the patient population, prescribing practices, and monitoring levels are variable. Within the Veterans Health Administration, clinical pharmacist practitioners (CPPs) in anticoagulation clinics oversee DOAC therapy management. CPPs monitor safety and efficacy of DOAC therapies through a population health management tool, the DOAC Dashboard.15 The DOAC Dashboard creates alerts for patients who may require an intervention based on certain clinical parameters, such as drug-drug interactions.16 Whenever a patient on a DOAC is prescribed an NSAID, an alert is generated on the DOAC Dashboard to flag the CPPs for the potential need for an intervention. If NSAID therapy remains clinically indicated, CPPs may recommend risk reduction strategies such as a COX-2 selective NSAID or coprescribing a PPI.10

The DOAC Dashboard provides an ideal setting for investigating the effects of NSAID use, NSAID selectivity, and PPI coprescribing on DOAC bleeding rates. With an increasing population of patients receiving anticoagulation therapy with a DOAC, more guidance regarding the bleeding risk of concomitant NSAID use with DOACs is needed. Studies evaluating the bleeding risk with concomitant NSAID use in patients on a DOAC alone are limited. This is the first study to date to compare bleeding risk with concomitant NSAID use between DOACs. This study provides information on bleeding risk with NSAID use among commonly prescribed DOACs, rivaroxaban and apixaban, and the potential impacts of current risk reduction strategies.

METHODS

This single-center retrospective cohort review was performed using the electronic health records (EHRs) of patients enrolled in the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Mountain Home Healthcare System who received rivaroxaban or apixaban from December 2020 to December 2022. This study received approval from the East Tennessee State University/VA Institutional Review Board committee.

Patients were identified through the DOAC Dashboard, aged 21 to 100 years, and received rivaroxaban or apixaban at a therapeutic dose: rivaroxaban 10 to 20 mg daily or apixaban 2.5 to 5 mg twice daily. Patients were excluded if they were prescribed dual antiplatelet therapy, received rivaroxaban at dosing indicated for peripheral vascular disease, were undergoing dialysis, had evidence of moderate to severe hepatic impairment or any hepatic disease with coagulopathy, were undergoing chemotherapy or radiation, or had hematological conditions with predisposed bleeding risk. These patients were excluded to mitigate the potential confounding impact from nontherapeutic DOAC dosing strategies and conditions associated with an increased bleeding risk.

Eligible patients were stratified based on NSAID use. NSAID users were defined as patients prescribed an oral NSAID, including both acute and chronic courses, at any point during the study time frame while actively on a DOAC. Bleeding events were reviewed to evaluate rates between rivaroxaban and apixaban among NSAID and nonNSAID users. Identified NSAID users were further assessed for NSAID selectivity and PPI coprescribing as a subgroup analysis for the secondary assessment.

Data Collection

Baseline data were collected, including age, body mass index, anticoagulation indication, DOAC agent, DOAC dose, and DOAC total daily dose. Baseline serum creatinine levels, liver function tests, hemoglobin levels, and platelet counts were collected from the most recent data available immediately prior to the bleeding event, if applicable.

The DOAC Dashboard was reviewed for active and dismissed drug interaction alerts to identify patients taking rivaroxaban or apixaban who were prescribed an NSAID. Patients were categorized in the NSAID group if an interacting drug alert with an NSAID was reported during the study time frame. Data available through the interacting drug alerts on NSAID use were limited to the interacting drug name and date of the reported flag. Manual EHR review was required to confirm dates of NSAID therapy initiation and NSAID discontinuation, if applicable.

Data regarding concomitant antiplatelet use were obtained through review of the active and dismissed drug interaction alerts on the DOAC Dashboard. Concomitant antiplatelet use was defined as the prescribing of a single antiplatelet agent at any point while receiving DOAC therapy. Data on concomitant antiplatelets were collected regardless of NSAID status.

Data on coprescribed PPI therapy were obtained through manual EHR review of identified NSAID users. Coprescribed PPI therapy was defined as the prescribing of a PPI at any point during NSAID therapy. Data regarding PPI use among non-NSAID users were not collected because the secondary endpoint was designed to assess PPI use only among patients coprescribed a DOAC and NSAID.

Outcomes

Bleeding events were identified through an outcomes report generated by the DOAC Dashboard based on International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision diagnosis codes associated with a bleeding event. The outcomes report captures diagnoses from the outpatient and inpatient care settings. Reported bleeding events were limited to patients who received a DOAC at any point in the 6 months prior to the event and excluded patients with recent DOAC initiation within 7 days of the event, as these patients are not captured on the DOAC Dashboard.

All reported bleeding events were manually reviewed in the EHR and categorized as a major or clinically relevant nonmajor bleed, according to International Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis criteria. Validated bleeding events were then crossreferenced with the interacting drug alerts report to identify events with potentially overlapping NSAID therapy at the time of the event. Overlapping NSAID therapy was defined as the prescribing of an NSAID at any point in the 6 months prior to the event. All events with potential overlapping NSAID therapies were manually reviewed for confirmation of NSAID status at the time of the event.

The primary endpoint was a composite of any bleeding event per International Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis criteria. The secondary endpoint evaluated the potential impact of NSAID selectivity or PPI coprescribing on the bleeding rate among the NSAID user groups.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were performed consistent with the methods used in the ARISTOTLE and RE-LY trials. It was determined that a sample size of 504 patients, with ≥ 168 patients in each group, would provide 80% power using a 2-sided a of 0.05. HRs with 95% CIs and respective P values were calculated using a SPSS-adapted online calculator.

RESULTS

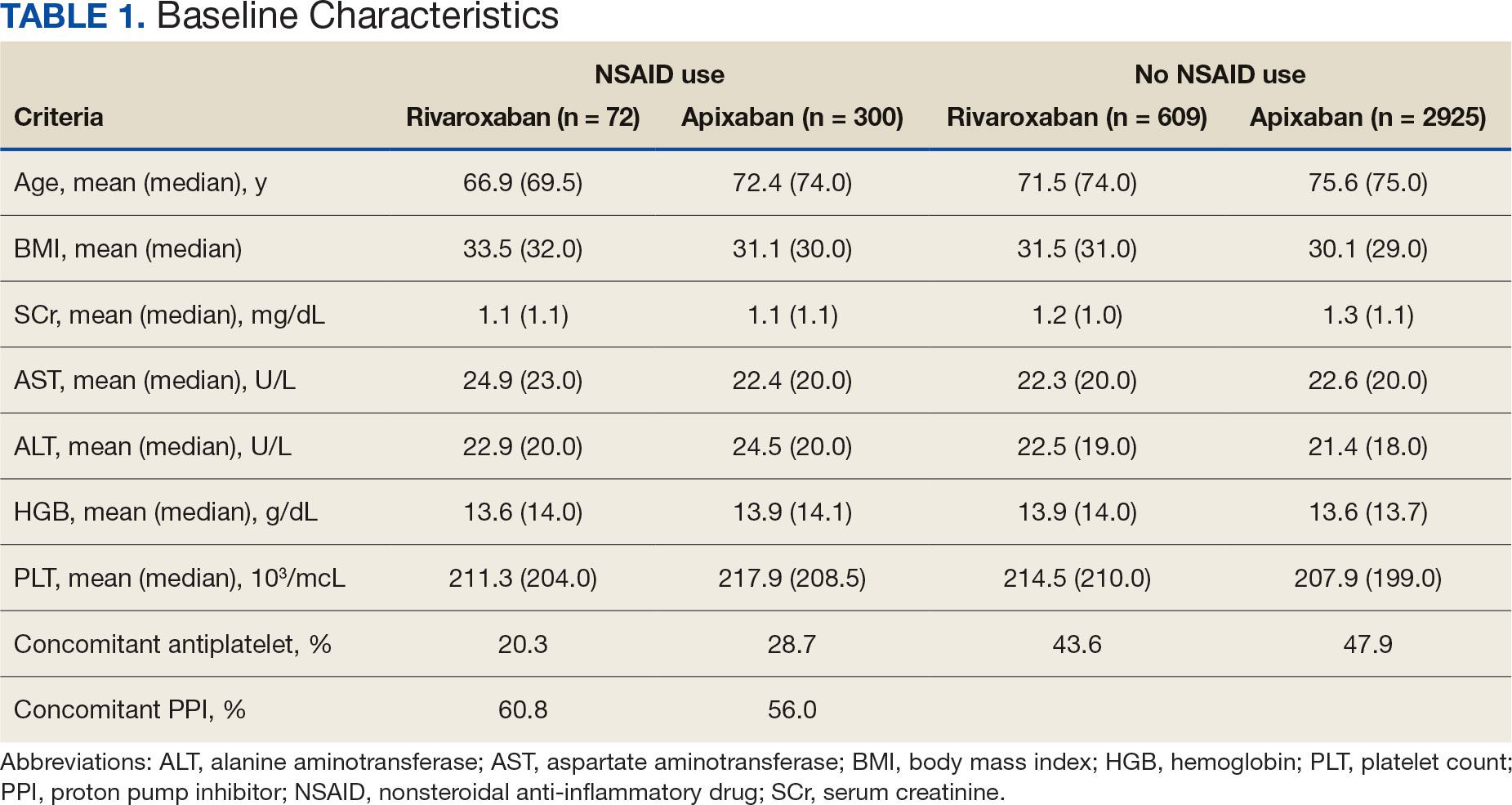

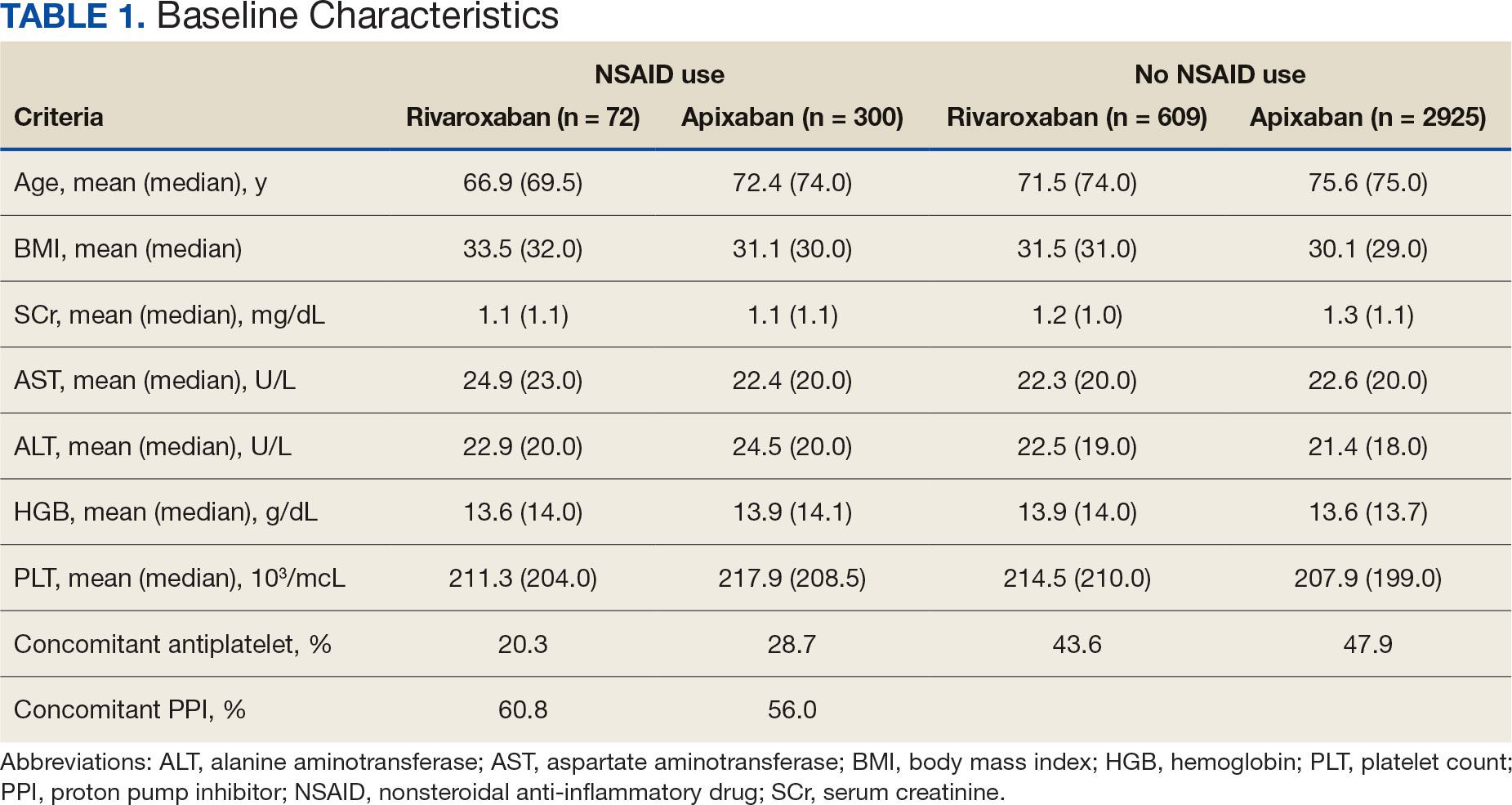

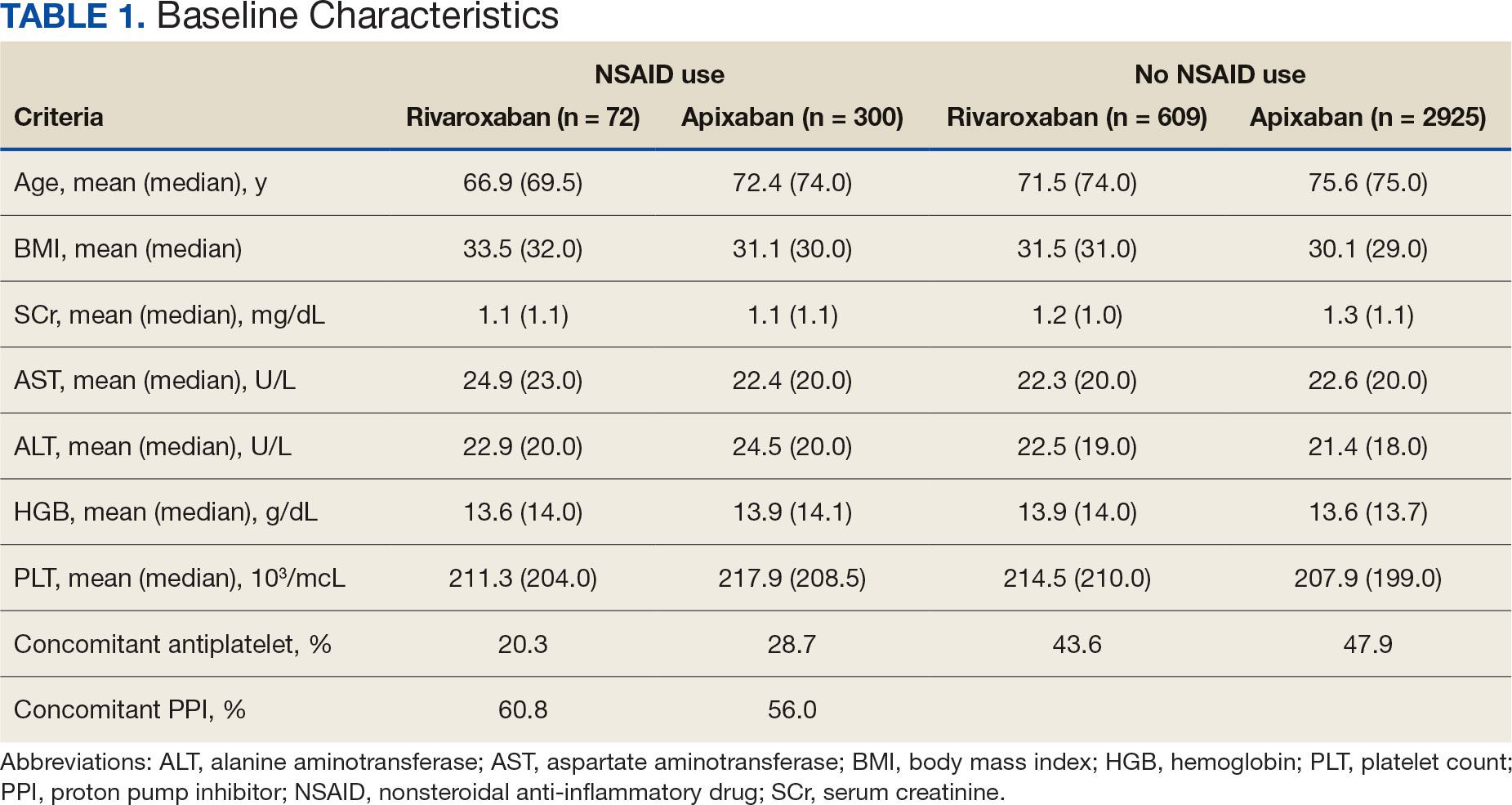

The DOAC Dashboard identified 681 patients on rivaroxaban and 3225 patients on apixaban; 72 patients on rivaroxaban (10.6%) and 300 patients on apixaban (9.3%) were NSAID users. The mean age of NSAID users was 66.9 years in the rivaroxaban group and 72.4 years in the apixaban group. The mean age of non-NSAID users was 71.5 years in the rivaroxaban group and 75.6 years in the apixaban group. No appreciable differences were observed among subgroups in body mass index, renal function, hepatic function, hemoglobin, or platelet counts, and no statistically significant differences were identified (Table 1). Antiplatelet agents identified included aspirin, clopidogrel, prasugrel, and ticagrelor. Fifteen patients (20.3%) in the rivaroxaban group and 87 patients (28.7%) in the apixaban group had concomitant antiplatelet and NSAID use. Forty-five patients on rivaroxaban (60.8%) and 170 (55.9%) on apixaban were prescribed concomitant PPI and NSAID at baseline. Among non-NSAID users, there was concomitant antiplatelet use for 265 patients (43.6%) in the rivaroxaban group and 1401 patients (47.9%) in the apixaban group. Concomitant PPI use was identified among 63 patients (60.0%) taking selective NSAIDs and 182 (57.2%) taking nonselective NSAIDs.

A total of 423 courses of NSAIDs were identified: 85 NSAID courses in the rivaroxaban group and 338 NSAID courses in the apixaban group. Most NSAID courses involved a nonselective NSAID in the rivaroxaban and apixaban NSAID user groups: 75.2% (n = 318) aggregately compared to 71.8% (n = 61) and 76.0% (n = 257) in the rivaroxaban and apixaban groups, respectively. The most frequent NSAID courses identified were meloxicam (26.7%; n = 113), celecoxib (24.8%; n = 105), ibuprofen (19.1%; n = 81), and naproxen (13.5%; n = 57). Data regarding NSAID therapy initiation and discontinuation dates were not readily available. As a result, the duration of NSAID courses was not captured.

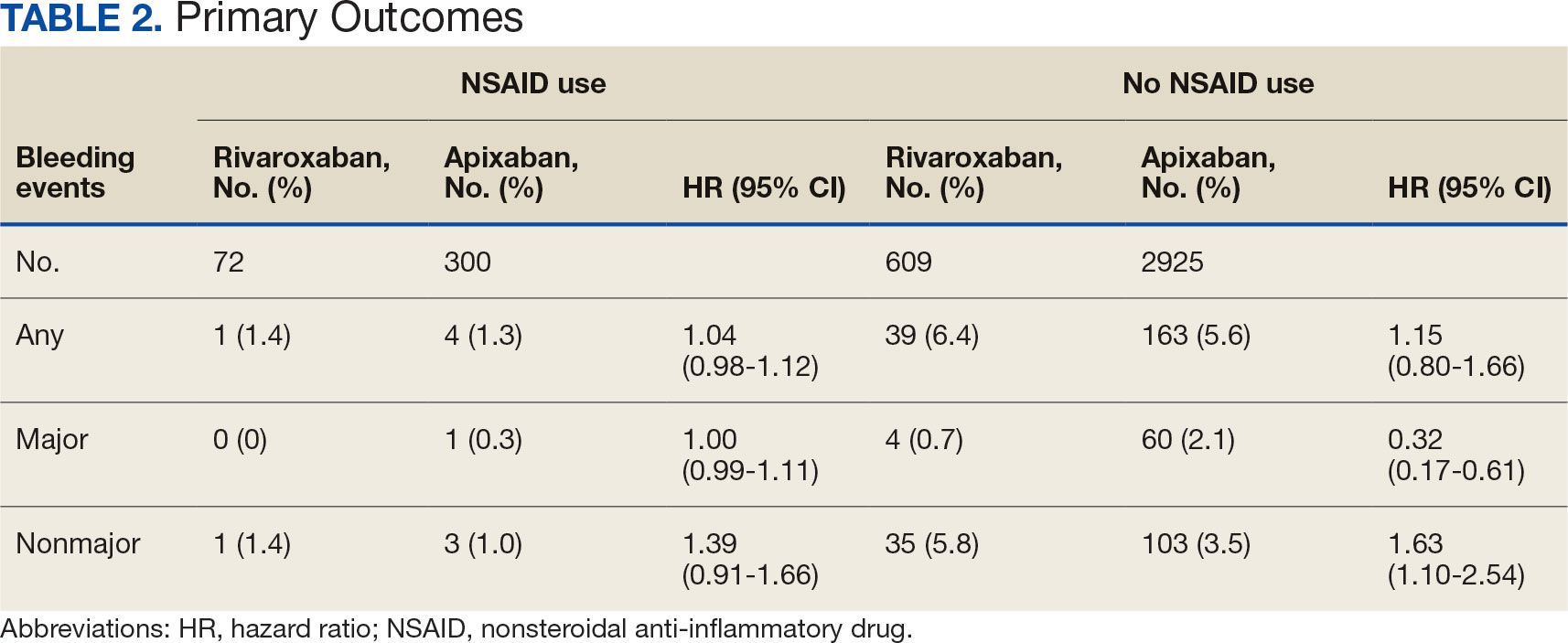

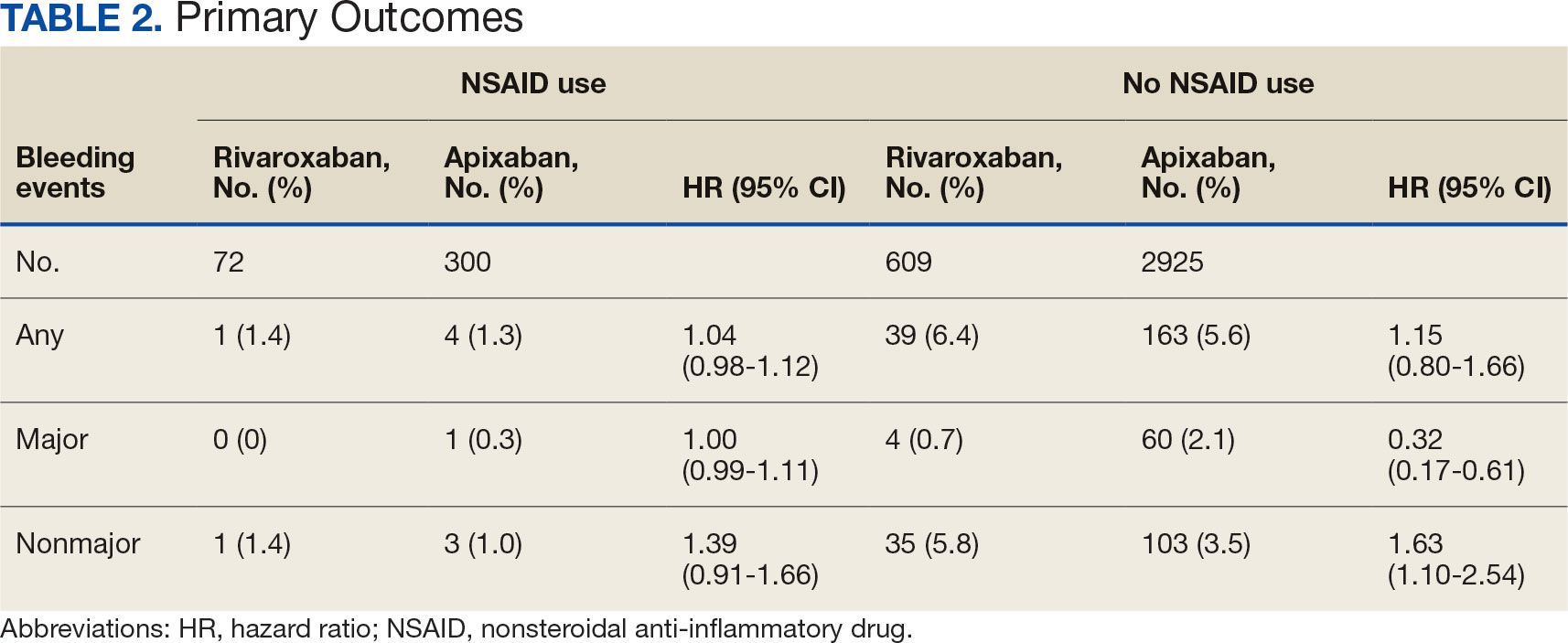

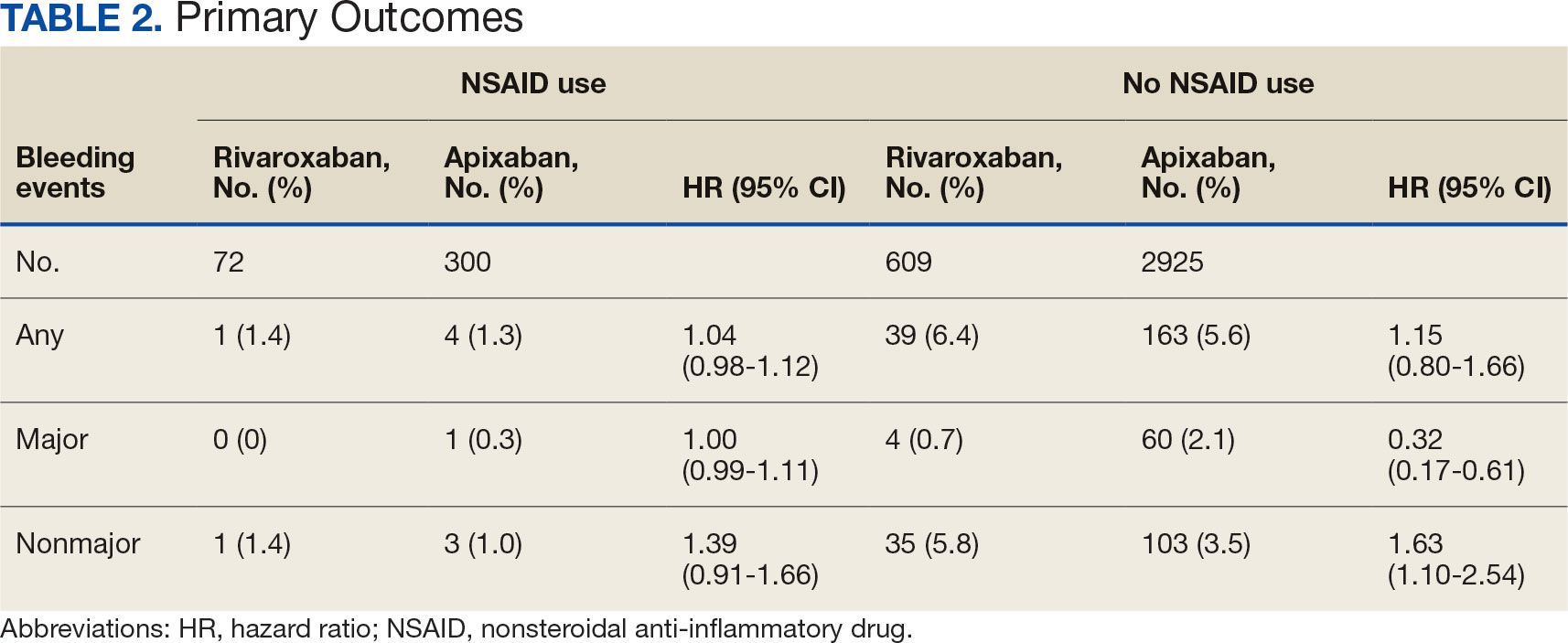

There was no statistically significant difference in bleeding rates between rivaroxaban and apixaban among NSAID users (HR 1.04; 95% CI, 0.98-1.12) or non-NSAID users (HR 1.15; 95% CI, 0.80-1.66) (Table 2). Apixaban non-NSAID users had a higher rate of major bleeds (HR 0.32; 95% CI, 0.17-0.61) while rivaroxaban non-NSAID users had a higher rate of clinically relevant nonmajor bleeds (HR 1.63; 95% CI, 1.10-2.54).

The sample size for the secondary endpoint consisted of bleeding events that were confirmed to have had an overlapping NSAID prescribed at the time of the event. For this secondary assessment, there was 1 rivaroxaban NSAID user bleeding event and 4 apixaban NSAID user bleeding events. For the rivaroxaban NSAID user bleeding event, the NSAID was nonselective and a PPI was not coprescribed. For the apixaban NSAID user bleeding events, 2 NSAIDs were nonselective and 2 were selective. All patients with apixaban and NSAID bleeding events had a coprescribed PPI. There was no clinically significant difference in the bleeding rates observed for NSAID selectivity or PPI coprescribing among the NSAID user subgroups.

DISCUSSION

This study found that there was no statistically significant difference for bleeding rates of major and nonmajor bleeding events between rivaroxaban and apixaban among NSAID users and non-NSAID users. This study did not identify a clinically significant impact on bleeding rates from NSAID selectivity or PPI coprescribing among the NSAID users.

There were notable but not statistically significant differences in baseline characteristics observed between the NSAID and non-NSAID user groups. On average, the rivaroxaban and apixaban NSAID users were younger compared with those not taking NSAIDs. NSAIDs, specifically nonselective NSAIDs, are recognized as potentially inappropriate medications for older adults given that this population is at an increased risk for GI ulcer development and/or GI bleeding.17 The non-NSAID user group likely consisted of older patients compared to the NSAID user group as clinicians may avoid prescribing NSAIDs to older adults regardless of concomitant DOAC therapy.

In addition to having an older patient population, non-NSAID users were more frequently prescribed a concomitant antiplatelet when compared with NSAID users. This prescribing pattern may be due to clinicians avoiding the use of NSAIDs in patients receiving DOAC therapy in combination with antiplatelet therapy, as these patients have been found to have an increased bleeding rate compared to DOAC therapy alone.18

Non-NSAID users had an overall higher bleeding rate for both major and nonmajor bleeding events. Based on this observation, it could be hypothesized that antiplatelet agents have a higher risk of bleeding in comparison to NSAIDs. In a subanalysis of the EXPAND study evaluating risk factors of major bleeding in patients receiving rivaroxaban, concomitant use of antiplatelet agents demonstrated a statistically significant increased risk of bleeding (HR 1.6; 95% CI, 1.2-2.3; P = .003) while concomitant use of NSAIDs did not (HR 0.8; 95% CI, 0.3-2.2; P = .67).19

In assessing PPI status at baseline, a majority of both rivaroxaban and apixaban NSAID users were coprescribed a PPI. This trend aligns with current clinical guideline recommendations for the prescribing of PPI therapy for GI protection in high-risk patients, such as those on DOAC therapy and concomitant NSAID therapy.10 Given the high proportion of NSAID users coprescribed a PPI at baseline, it may be possible that the true incidence of NSAID-associated bleeding events was higher than what this study found. This observation may reflect the impact from timely implementation of risk mitigation strategies by CPPs in the anticoagulation clinic. However, this study was not constructed to assess the efficacy of PPI use in this manner.

It is important to note the patients included in this study were followed by a pharmacist in an anticoagulation clinic using the DOAC Dashboard.15 This population management tool allows CPPs to make proactive interventions when a patient taking a DOAC receives an NSAID prescription, such as recommending the coprescribing of a PPI or use of a selective NSAID.10,16 These standards of care may have contributed to an overall reduced bleeding rate among the NSAID user group and may not be reflective of private practice.

The planned analysis of this study was modeled after the posthoc analysis of the RE-LY and ARISTOTLE trials. Both trials demonstrated an increased risk of bleeding with oral anticoagulation, including DOAC and warfarin, in combination with NSAID use. However, both trials found that NSAID use in patients treated with a DOAC was not independently associated with increased bleeding events compared with warfarin.13,14 The results of this study are comparable to the RE-LY and ARISTOTLE findings that NSAID use among patients treated with rivaroxaban or apixaban did not demonstrate a statistically significant increased bleeding risk.

Studies of NSAID use in combination with DOAC therapy have been limited to patient populations consisting of both DOAC and warfarin. Evidence from these trials outlines the increased bleeding risk associated with NSAID use in combination with oral anticoagulation; however, these patient populations include those on a DOAC and warfarin.13,14,19,20 Given the limited evidence on NSAID use among DOACs alone, it is assumed NSAID use in combination with DOACs has a similar risk of bleeding as warfarin use. This may cause clinicians to automatically exclude NSAID therapy as a treatment option for patients on a DOAC who are otherwise clinically appropriate candidates, such as those with underlying inflammatory conditions. Avoiding NSAID therapy in this patient population may lead to suboptimal pain management and increase the risk of patient harm from methods such as inappropriate opioid therapy prescribing.

DOAC therapy should not be a universal limitation to the use of NSAIDs. Although the risk of bleeding with NSAID therapy is always present, deliberate NSAID prescribing in addition to the timely implementation of risk mitigation strategies may provide an avenue for safe NSAID prescribing in patients receiving a DOAC. A population health-based approach to DOAC management, such as the DOAC Dashboard, appears to be effective at preventing patient harm when NSAIDs are prescribed in conjunction with DOACs.

Limitations

The DOAC Dashboard has been shown to be effective and efficient at monitoring DOAC therapy from a population-based approach.16 Reports generated through the DOAC Dashboard provide convenient access to patient data which allows for timely interventions; however, there are limits to its use for data collection. All the data elements necessary to properly assess bleeding risk with validated tools, such as HAS-BLED (hypertension, abnormal renal/liver function, stroke, bleeding history or predisposition, labile international normalized ratio, elderly, drugs/ alcohol concomitantly), are not available on DOAC Dashboard reports. Due to this constraint, bleeding risk assessments were not conducted at baseline and this study was unable to include risk modeling. Additionally, data elements like initiation and discontinuation dates and duration of therapies were not readily available. As a result, this study was unable to incorporate time as a data point.

This was a retrospective study that relied on manual review of chart documentation to verify bleeding events, but data obtained through the DOAC Dashboard were transferred directly from the EHR.15 Bleeding events available for evaluation were restricted to those that occurred at a VA facility. Additionally, the sample size within the rivaroxaban NSAID user group did not reach the predefined sample size required to reach power and may have been too small to detect a difference if one did exist. The secondary assessment had a low sample size of NSAID user bleeding events, making it difficult to fully assess its impact on NSAID selectivity and PPI coprescribing on bleeding rates. All courses of NSAIDs were equally valued regardless of the dose or therapy duration; however, this is consistent with how NSAID use was defined in the RE-LY and ARISTOTLE trials.

CONCLUSIONS

This retrospective cohort review found no statistically significant difference in the composite bleeding rates between rivaroxaban and apixaban among NSAID users and non-NSAID users. Moreover, there was no clinically significant impact observed for bleeding rates in regard to NSAID selectivity and PPI coprescribing among NSAID users. However, coprescribing of PPI therapy to patients on a DOAC who are clinically indicated for an NSAID may reduce the risk of bleeding. Population health management tools, such as the DOAC Dashboard, may also allow clinicians to safely prescribe NSAIDs to patients on a DOAC. Further large-scale observational studies are needed to quantify the real-world risk of bleeding with concomitant NSAID use among DOACs alone and to evaluate the impact from NSAID selectivity or PPI coprescribing.

- Ruff CT, Giugliano RP, Braunwald E, et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2014;383(9921):955-962. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62343-0