User login

AI-Enhanced ECG Used to Predict Hypertension and Associated Risks

TOPLINE:

in addition to traditional markers.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a development and external validation prognostic cohort study in a secondary care setting to identify individuals at risk for incident hypertension.

- They developed AIRE-HTN, which was trained on a derivation cohort from the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, involving 1,163,401 ECGs from 189,539 patients (mean age, 57.7 years; 52.1% women; 64.5% White individuals).

- External validation was conducted on 65,610 ECGs from a UK-based volunteer cohort, drawn from an equal number of patients (mean age, 65.4 years; 51.5% women; 96.3% White individuals).

- Incident hypertension was evaluated in 19,423 individuals without hypertension from the medical center cohort and in 35,806 individuals without hypertension from the UK cohort.

TAKEAWAY:

- AIRE-HTN predicted incident hypertension with a C-index of 0.70 (95% CI, 0.69-0.71) in both the cohorts. Those in the quartile with the highest AIRE-HTN scores had a fourfold increased risk for incident hypertension (P < .001).

- The model’s predictive accuracy was maintained in individuals without left ventricular hypertrophy and those with normal ECGs and baseline blood pressure, indicating its robustness.

- The model was significantly additive to traditional clinical markers, with a continuous net reclassification index of 0.44 for the medical center cohort and 0.32 for the UK cohort.

- AIRE-HTN was an independent predictor of cardiovascular death (hazard ratio per 1-SD increase in score [HR], 2.24), heart failure (HR, 2.60), myocardial infarction (HR, 3.13), ischemic stroke (HR, 1.23), and chronic kidney disease (HR, 1.89) in outpatients from the medical center cohort (all P < .001), with largely consistent findings in the UK cohort.

IN PRACTICE:

“Results of exploratory and phenotypic analyses suggest the biological plausibility of these findings. Enhanced predictability could influence surveillance programs and primordial prevention,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Arunashis Sau, PhD, and Joseph Barker, MRes, National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College London, England. It was published online on January 2, 2025, in JAMA Cardiology.

LIMITATIONS:

In one cohort, hypertension was defined using International Classification of Diseases codes, which may lack granularity and not align with contemporary guidelines. The findings were not validated against ambulatory monitoring standards. The performance of the model in different populations and clinical settings remains to be explored.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors acknowledged receiving support from Imperial’s British Heart Foundation Centre for Excellence Award and disclosed receiving support from the British Heart Foundation, the National Institute for Health Research Imperial College Biomedical Research Centre, the EJP RD Research Mobility Fellowship, the Medical Research Council, and the Sir Jules Thorn Charitable Trust. Some authors reported receiving grants, personal fees, advisory fees, or laboratory work fees outside the submitted work.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

in addition to traditional markers.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a development and external validation prognostic cohort study in a secondary care setting to identify individuals at risk for incident hypertension.

- They developed AIRE-HTN, which was trained on a derivation cohort from the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, involving 1,163,401 ECGs from 189,539 patients (mean age, 57.7 years; 52.1% women; 64.5% White individuals).

- External validation was conducted on 65,610 ECGs from a UK-based volunteer cohort, drawn from an equal number of patients (mean age, 65.4 years; 51.5% women; 96.3% White individuals).

- Incident hypertension was evaluated in 19,423 individuals without hypertension from the medical center cohort and in 35,806 individuals without hypertension from the UK cohort.

TAKEAWAY:

- AIRE-HTN predicted incident hypertension with a C-index of 0.70 (95% CI, 0.69-0.71) in both the cohorts. Those in the quartile with the highest AIRE-HTN scores had a fourfold increased risk for incident hypertension (P < .001).

- The model’s predictive accuracy was maintained in individuals without left ventricular hypertrophy and those with normal ECGs and baseline blood pressure, indicating its robustness.

- The model was significantly additive to traditional clinical markers, with a continuous net reclassification index of 0.44 for the medical center cohort and 0.32 for the UK cohort.

- AIRE-HTN was an independent predictor of cardiovascular death (hazard ratio per 1-SD increase in score [HR], 2.24), heart failure (HR, 2.60), myocardial infarction (HR, 3.13), ischemic stroke (HR, 1.23), and chronic kidney disease (HR, 1.89) in outpatients from the medical center cohort (all P < .001), with largely consistent findings in the UK cohort.

IN PRACTICE:

“Results of exploratory and phenotypic analyses suggest the biological plausibility of these findings. Enhanced predictability could influence surveillance programs and primordial prevention,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Arunashis Sau, PhD, and Joseph Barker, MRes, National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College London, England. It was published online on January 2, 2025, in JAMA Cardiology.

LIMITATIONS:

In one cohort, hypertension was defined using International Classification of Diseases codes, which may lack granularity and not align with contemporary guidelines. The findings were not validated against ambulatory monitoring standards. The performance of the model in different populations and clinical settings remains to be explored.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors acknowledged receiving support from Imperial’s British Heart Foundation Centre for Excellence Award and disclosed receiving support from the British Heart Foundation, the National Institute for Health Research Imperial College Biomedical Research Centre, the EJP RD Research Mobility Fellowship, the Medical Research Council, and the Sir Jules Thorn Charitable Trust. Some authors reported receiving grants, personal fees, advisory fees, or laboratory work fees outside the submitted work.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

in addition to traditional markers.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a development and external validation prognostic cohort study in a secondary care setting to identify individuals at risk for incident hypertension.

- They developed AIRE-HTN, which was trained on a derivation cohort from the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, involving 1,163,401 ECGs from 189,539 patients (mean age, 57.7 years; 52.1% women; 64.5% White individuals).

- External validation was conducted on 65,610 ECGs from a UK-based volunteer cohort, drawn from an equal number of patients (mean age, 65.4 years; 51.5% women; 96.3% White individuals).

- Incident hypertension was evaluated in 19,423 individuals without hypertension from the medical center cohort and in 35,806 individuals without hypertension from the UK cohort.

TAKEAWAY:

- AIRE-HTN predicted incident hypertension with a C-index of 0.70 (95% CI, 0.69-0.71) in both the cohorts. Those in the quartile with the highest AIRE-HTN scores had a fourfold increased risk for incident hypertension (P < .001).

- The model’s predictive accuracy was maintained in individuals without left ventricular hypertrophy and those with normal ECGs and baseline blood pressure, indicating its robustness.

- The model was significantly additive to traditional clinical markers, with a continuous net reclassification index of 0.44 for the medical center cohort and 0.32 for the UK cohort.

- AIRE-HTN was an independent predictor of cardiovascular death (hazard ratio per 1-SD increase in score [HR], 2.24), heart failure (HR, 2.60), myocardial infarction (HR, 3.13), ischemic stroke (HR, 1.23), and chronic kidney disease (HR, 1.89) in outpatients from the medical center cohort (all P < .001), with largely consistent findings in the UK cohort.

IN PRACTICE:

“Results of exploratory and phenotypic analyses suggest the biological plausibility of these findings. Enhanced predictability could influence surveillance programs and primordial prevention,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Arunashis Sau, PhD, and Joseph Barker, MRes, National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College London, England. It was published online on January 2, 2025, in JAMA Cardiology.

LIMITATIONS:

In one cohort, hypertension was defined using International Classification of Diseases codes, which may lack granularity and not align with contemporary guidelines. The findings were not validated against ambulatory monitoring standards. The performance of the model in different populations and clinical settings remains to be explored.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors acknowledged receiving support from Imperial’s British Heart Foundation Centre for Excellence Award and disclosed receiving support from the British Heart Foundation, the National Institute for Health Research Imperial College Biomedical Research Centre, the EJP RD Research Mobility Fellowship, the Medical Research Council, and the Sir Jules Thorn Charitable Trust. Some authors reported receiving grants, personal fees, advisory fees, or laboratory work fees outside the submitted work.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Intensive BP Control May Benefit CKD Patients in Real World

TOPLINE:

The cardiovascular benefits observed with intensive blood pressure (BP) control in patients with hypertension and elevated cardiovascular risk from the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) can be largely replicated in real-world settings among patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), highlighting the advantages of adopting intensive BP targets.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a comparative effectiveness study to determine if the beneficial and adverse effects of intensive vs standard BP control observed in SPRINT were replicable in patients with CKD and hypertension in clinical practice.

- They identified 85,938 patients (mean age, 75.7 years; 95.0% men) and 13,983 patients (mean age, 77.4 years; 38.4% men) from the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) and Kaiser Permanente of Southern California (KPSC) databases, respectively.

- The treatment effect was estimated by combining baseline covariate, treatment, and outcome data of participants from the SPRINT with covariate data from the VHA and KPSC databases.

- The primary outcomes included major cardiovascular events, all-cause death, cognitive impairment, CKD progression, and adverse events at 4 years.

TAKEAWAY:

- Compared with SPRINT participants, those in the VHA and KPSC databases were older, had less prevalent cardiovascular disease, higher albuminuria, and used more statins.

- The benefits of intensive vs standard BP control on major cardiovascular events, all-cause mortality, and certain adverse events (hypotension, syncope, bradycardia, acute kidney injury, and electrolyte abnormality) were transferable from the trial to the VHA and KPSC populations.

- The treatment effect of intensive BP management on CKD progression was transportable to the KPSC population but not to the VHA population. However, the trial’s impact on cognitive outcomes, such as dementia, was not transportable to either the VHA or KPSC populations.

- On the absolute scale, intensive vs standard BP treatment showed greater cardiovascular benefits and fewer safety concerns in the VHA and KPSC populations than in the SPRINT.

IN PRACTICE:

“This example highlights the potential for transportability methods to provide insights that can bridge evidence gaps and inform the application of novel therapies to patients with CKD who are treated in everyday practice,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Manjula Kurella Tamura, MD, MPH, Division of Nephrology, Department of Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, California. It was published online on January 7, 2025, in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

Transportability analyses could not account for characteristics that were not well-documented in electronic health records, such as limited life expectancy. The study was conducted before the widespread use of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors, glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists, and nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, making it unclear whether intensive BP treatment would result in similar benefits with current pharmacotherapy regimens. Eligibility for this study was based on BP measurements in routine practice, which tend to be more variable than those collected in research settings.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health. Some authors disclosed serving as a consultant and receiving grants, personal fees, and consulting fees from pharmaceutical companies and other sources.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

The cardiovascular benefits observed with intensive blood pressure (BP) control in patients with hypertension and elevated cardiovascular risk from the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) can be largely replicated in real-world settings among patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), highlighting the advantages of adopting intensive BP targets.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a comparative effectiveness study to determine if the beneficial and adverse effects of intensive vs standard BP control observed in SPRINT were replicable in patients with CKD and hypertension in clinical practice.

- They identified 85,938 patients (mean age, 75.7 years; 95.0% men) and 13,983 patients (mean age, 77.4 years; 38.4% men) from the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) and Kaiser Permanente of Southern California (KPSC) databases, respectively.

- The treatment effect was estimated by combining baseline covariate, treatment, and outcome data of participants from the SPRINT with covariate data from the VHA and KPSC databases.

- The primary outcomes included major cardiovascular events, all-cause death, cognitive impairment, CKD progression, and adverse events at 4 years.

TAKEAWAY:

- Compared with SPRINT participants, those in the VHA and KPSC databases were older, had less prevalent cardiovascular disease, higher albuminuria, and used more statins.

- The benefits of intensive vs standard BP control on major cardiovascular events, all-cause mortality, and certain adverse events (hypotension, syncope, bradycardia, acute kidney injury, and electrolyte abnormality) were transferable from the trial to the VHA and KPSC populations.

- The treatment effect of intensive BP management on CKD progression was transportable to the KPSC population but not to the VHA population. However, the trial’s impact on cognitive outcomes, such as dementia, was not transportable to either the VHA or KPSC populations.

- On the absolute scale, intensive vs standard BP treatment showed greater cardiovascular benefits and fewer safety concerns in the VHA and KPSC populations than in the SPRINT.

IN PRACTICE:

“This example highlights the potential for transportability methods to provide insights that can bridge evidence gaps and inform the application of novel therapies to patients with CKD who are treated in everyday practice,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Manjula Kurella Tamura, MD, MPH, Division of Nephrology, Department of Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, California. It was published online on January 7, 2025, in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

Transportability analyses could not account for characteristics that were not well-documented in electronic health records, such as limited life expectancy. The study was conducted before the widespread use of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors, glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists, and nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, making it unclear whether intensive BP treatment would result in similar benefits with current pharmacotherapy regimens. Eligibility for this study was based on BP measurements in routine practice, which tend to be more variable than those collected in research settings.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health. Some authors disclosed serving as a consultant and receiving grants, personal fees, and consulting fees from pharmaceutical companies and other sources.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

The cardiovascular benefits observed with intensive blood pressure (BP) control in patients with hypertension and elevated cardiovascular risk from the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) can be largely replicated in real-world settings among patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), highlighting the advantages of adopting intensive BP targets.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a comparative effectiveness study to determine if the beneficial and adverse effects of intensive vs standard BP control observed in SPRINT were replicable in patients with CKD and hypertension in clinical practice.

- They identified 85,938 patients (mean age, 75.7 years; 95.0% men) and 13,983 patients (mean age, 77.4 years; 38.4% men) from the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) and Kaiser Permanente of Southern California (KPSC) databases, respectively.

- The treatment effect was estimated by combining baseline covariate, treatment, and outcome data of participants from the SPRINT with covariate data from the VHA and KPSC databases.

- The primary outcomes included major cardiovascular events, all-cause death, cognitive impairment, CKD progression, and adverse events at 4 years.

TAKEAWAY:

- Compared with SPRINT participants, those in the VHA and KPSC databases were older, had less prevalent cardiovascular disease, higher albuminuria, and used more statins.

- The benefits of intensive vs standard BP control on major cardiovascular events, all-cause mortality, and certain adverse events (hypotension, syncope, bradycardia, acute kidney injury, and electrolyte abnormality) were transferable from the trial to the VHA and KPSC populations.

- The treatment effect of intensive BP management on CKD progression was transportable to the KPSC population but not to the VHA population. However, the trial’s impact on cognitive outcomes, such as dementia, was not transportable to either the VHA or KPSC populations.

- On the absolute scale, intensive vs standard BP treatment showed greater cardiovascular benefits and fewer safety concerns in the VHA and KPSC populations than in the SPRINT.

IN PRACTICE:

“This example highlights the potential for transportability methods to provide insights that can bridge evidence gaps and inform the application of novel therapies to patients with CKD who are treated in everyday practice,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Manjula Kurella Tamura, MD, MPH, Division of Nephrology, Department of Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, California. It was published online on January 7, 2025, in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

Transportability analyses could not account for characteristics that were not well-documented in electronic health records, such as limited life expectancy. The study was conducted before the widespread use of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors, glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists, and nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, making it unclear whether intensive BP treatment would result in similar benefits with current pharmacotherapy regimens. Eligibility for this study was based on BP measurements in routine practice, which tend to be more variable than those collected in research settings.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health. Some authors disclosed serving as a consultant and receiving grants, personal fees, and consulting fees from pharmaceutical companies and other sources.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Pharmacist-Led Deprescribing of Aspirin for Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease Among Geriatric Veterans

Pharmacist-Led Deprescribing of Aspirin for Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease Among Geriatric Veterans

Low-dose aspirin commonly is used for the prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD) but is associated with an increased risk of major bleeding.1 The use of aspirin for primary prevention is largely extrapolated from clinical trials showing benefit in the secondary prevention of myocardial infarction and ischemic stroke. However, results from the Aspirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly (ASPREE) trial challenged this practice.2 The ASPREE trial, conducted in the United States and Australia from 2010 to 2014, sought to determine whether daily 100 mg aspirin, was superior to placebo in promoting disability-free survival among older adults. Participants were aged ≥ 70 years (≥ 65 years for Hispanic and Black US participants), living in the community, and were free from preexisting CVD, cerebrovascular disease, or any chronic condition likely to limit survival to < 5 years. The study found no significant difference in the primary endpoints of death, dementia, or persistent physical disability, but there was a significantly higher risk of major hemorrhage in the aspirin group (3.8% vs 2.8%; hazard ratio, 1.38; 95% CI, 1.18-1.62; P < .001).

Several medical societies have updated their guideline recommendations for aspirin for primary prevention of CVD. The 2022 United States Public Service Task Force (USPSTF) provides a grade C recommendation (at least moderate certainty that the net benefit is small) to consider low-dose aspirin for the primary prevention of CVD on an individual patient basis for adults aged 40 to 59 years who have a ≥ 10% 10-year CVD risk. For adults aged ≥ 60 years, the USPSTF recommendation is grade D (moderate or high certainty that the practice has no net benefit or that harms outweigh the benefits) for low-dose aspirin use.1,3 The American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) recommend considering low-dose aspirin for primary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) among select adults aged 40 to 70 years at higher CVD risk but not at increased risk of bleeding.4 The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommends low-dose aspirin for primary prevention of CVD in patients with diabetes and additional risk factors such as family history of premature ASCVD, hypertension, dyslipidemia, smoking, or chronic kidney disease, and who are not at higher risk of bleeding.5 The ADA standards also caution against the use of aspirin as primary prevention in patients aged > 70 years. Low-dose aspirin use is not recommended for the primary prevention of CVD in older adults or adults of any age who are at increased risk of bleeding.

Recent literature using the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Corporate Data Warehouse database confirms 86,555 of 1.8 million veterans aged > 70 years (5%) were taking low-dose aspirin for primary prevention of ASCVD despite guideline recommendations.6 Higher risk of gastrointestinal and other major bleeding from low-dose aspirin has been reported in the literature.1 Major bleeds represent a significant burden to the health care system with an estimated mean $13,093 cost for gastrointestinal bleed hospitalization.7

Considering the large scale aspirin use without appropriate indication within the veteran population, the risk of adverse effects, and the significant cost to patients and the health care system, it is imperative to determine the best approach to efficiently deprescribe aspirin for primary prevention among geriatric patients. Deprescribing refers to the systematic and supervised process of dose reduction or drug discontinuation with the goal of improving health and/or reducing the risk of adverse effects.8 During patient visits, primary care practitioners (PCPs) have opportunities to discontinue aspirin, but these encounters are time-limited and deprescribing might be secondary to more acute primary care needs. The shortage of PCPs is expected to worsen in coming years, which could further reduce their availability to assess inappropriate aspirin use.9

VA clinical pharmacist practitioners (CPPs) serve as medication experts and work autonomously under a broad scope of practice as part of the patient aligned care team.10-12 CPPs can free up time for PCPs and facilitate deprescribing efforts, especially for older adults. One retrospective cohort study conducted at a VA medical center found that CPPs deprescribed more potentially inappropriate medications among individuals aged ≥ 80 years compared with usual care with PCPs (26.8% vs 16.1%; P < .001).12,13 An aspirin deprescribing protocol conducted in 2022 resulted in nearly half of veterans aged ≥ 70 years contacted by phone agreeing to stop aspirin. Although this study supports the role pharmacists can play in reducing aspirin use in accordance with guidelines, the authors acknowledge that their interventions had a mean time of 12 minutes per patient and would require workflow changes.14 The purpose of this study is to evaluate the efficiency of aspirin deprescribing through 2 approaches: direct deprescribing by pharmacists using populationlevel review compared with clinicians following a pharmacist-led education.

Methods

This was a single-center quality improvement cohort study at the Durham VA Health Care System (DVAHCS) in North Carolina. Patients included were aged ≥ 70 years without known ASCVD who received care at any of 3 DVAHCS community-based outpatient clinics and prescribed aspirin. Patient data was obtained using the VIONE (Deprescribing Dashboard called Vital, Important, Optional, Not indicated, and Every medication has a specific indication or diagnosis) dashboard.15 VIONE was developed to identify potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) that are eligible to deprescribe based on Beers Criteria, Screening Tool of Older Personsf Prescriptions criteria, and common clinical scenarios when clinicians determine the risk outweighs the benefit to continue a specific medication. 16,17 VIONE is used to reduce polypharmacy and improve patient safety, comfort, and medication adherence. Aspirin for patients aged ≥ 70 years without a history of ASCVD is a PIM identified by VIONE. Patients aged ≥ 70 years were chosen as an inclusion criteria in this study to match the ASPREE trial inclusion criteria and age inclusion criteria in the VIONE dashboard for aspirin deprescribing.2 Patient lists were generated for these potentially inappropriate aspirin prescriptions for 3 months before clinician staff education presentations, the day of the presentations, and 3 months after.

The primary endpoint was the number of veterans with aspirin deprescribed directly by 2 pharmacists over 12 weeks, divided by total patient care time spent, compared with the change in number of veterans with aspirin deprescribed by any DVAHCS physician, nurse practitioner, physician assistant, or CPP over 12 weeks, divided by the total pharmacist time spent on PCP education. Secondary endpoints were the number of aspirin orders discontinued by pharmacists and CPPs, the number of aspirin orders discontinued 12 weeks before pharmacist-led education compared with the number of aspirin orders discontinued 12 weeks after CPP-led education, average and median pharmacist time spent per patient encounter, and time of direct patient encounters vs time spent on PCP education.

Pharmacists reviewed each patient who met the inclusion criteria from the list generated by VIONE on December 1, 2022, for aspirin appropriateness according to the ACC/AHA and USPSTF guidelines, with the goal to discontinue aspirin for primary prevention of ASCVD and no other indications.1,4 Pharmacists documented their visits using VIONE methodology in the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) using a polypharmacy review note. CPPs contacted patients who were taking aspirin for primary prevention by unscheduled telephone call to assess for aspirin adherence, undocumented history of ASCVD, cardiovascular risk factors, and history of bleeding. Aspirin was discontinued if patients met guideline criteria recommendations and agreed to discontinuation. Risk-benefit discussions were completed when patients without known ASCVD were considered high risk because the ACC/AHA guidelines mention there is insufficient evidence of safety and efficacy of aspirin for primary prevention for patients with other known ASCVD risk factors (eg, strong family history of premature myocardial infarction, inability to achieve lipid, blood pressure, or glucose targets, or significant elevation in coronary artery calcium score).

High risk was defined as family history of premature ASCVD (in a male first-degree relative aged < 55 years or a female first-degree relative aged < 65 years), most recent blood pressure or 2 blood pressure results in the last 12 months > 160/100 mm Hg, recent hemoglobin A1c > 9%, and/or low-density lipoprotein > 190 mg/dL or not prescribed an indicated statin.3 Aspirin was continued or discontinued according to patient preference after the personalized risk-benefit discussion.

For patients with a clinical indication for aspirin use other than ASCVD (eg, atrial fibrillation not on anticoagulation, venous thromboembolism prophylaxis, carotid artery disease), CPPs documented their assessment and when appropriate deferred to the PCP for consideration of stopping aspirin. For patients with undocumented ASCVD, CPPs added their ASCVD history to their problem list and aspirin was continued. PCPs were notified by alert when aspirin was discontinued and when patients could not be reached by telephone.

presented a review of recent guideline updates and supporting literature at 2 online staff meetings. The education sessions lasted about 10 minutes and were presented to PCPs across 3 community-based outpatient clinics. An estimated 40 minutes were spent creating the PowerPoint education materials, seeking feedback, making edits, and answering questions or emails from PCPs after the presentation. During the presentation, pharmacists encouraged PCPs to discontinue aspirin (active VA prescriptions and reported over-the-counter use) for primary prevention of ASCVD in patients aged ≥ 70 years during their upcoming appointments and consider risk factors recommended by the ACC/AHA guidelines when applicable. PCPs were notified that CPPs planned to start a population review for discontinuing active VA aspirin prescriptions on December 1, 2022. The primary endpoint and secondary endpoints were analyzed using descriptive statistics. All data were analyzed using Microsoft Excel.

Results

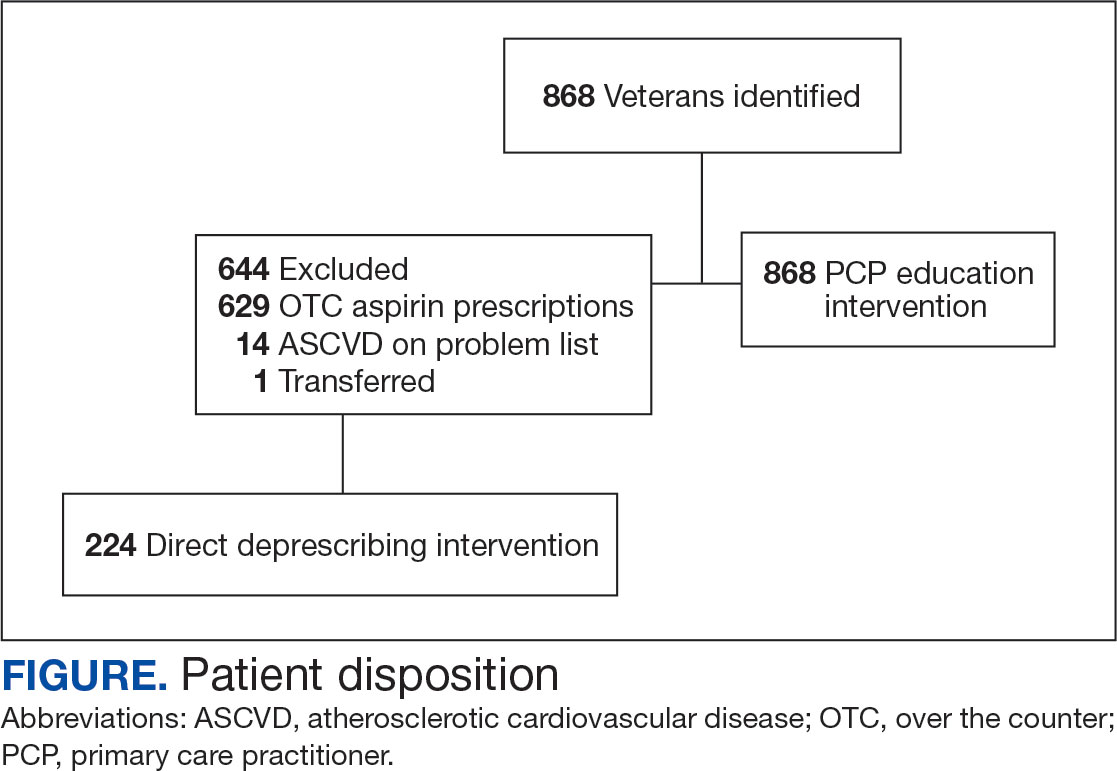

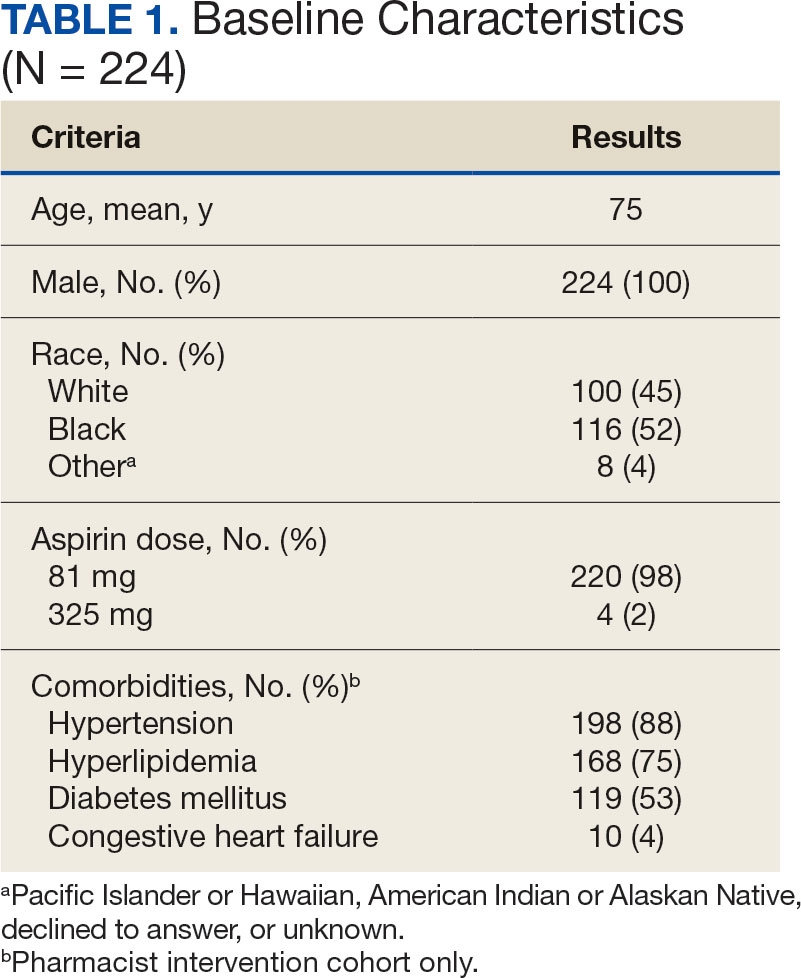

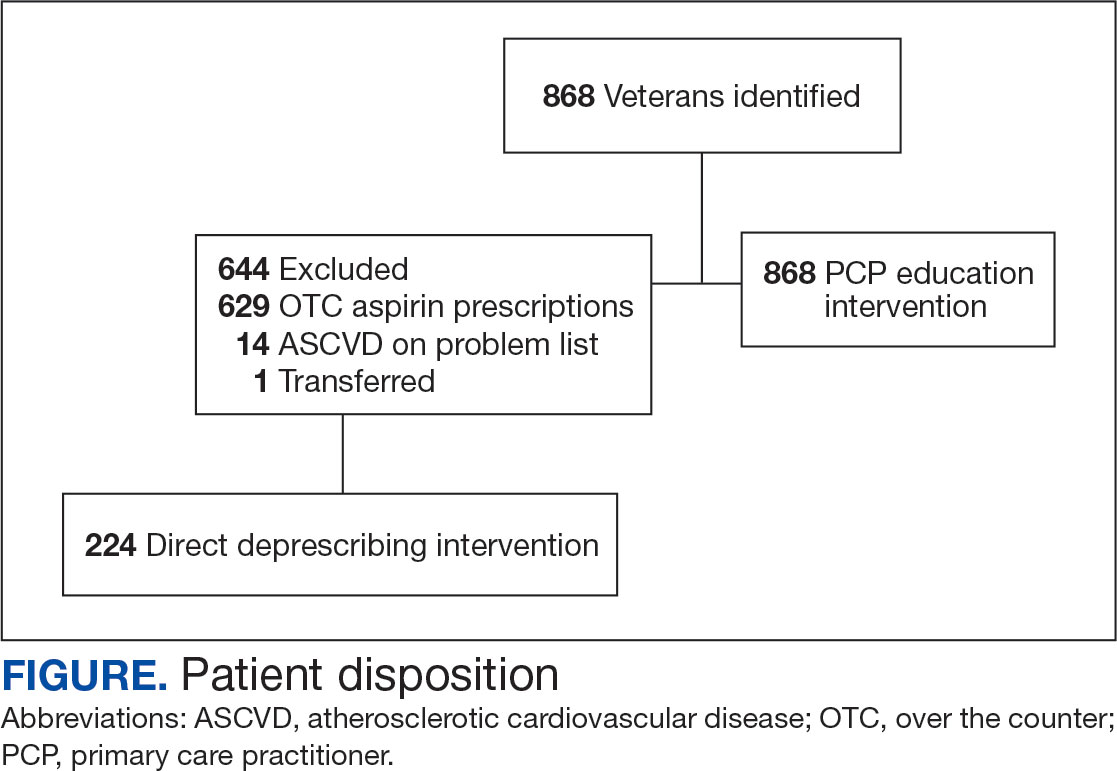

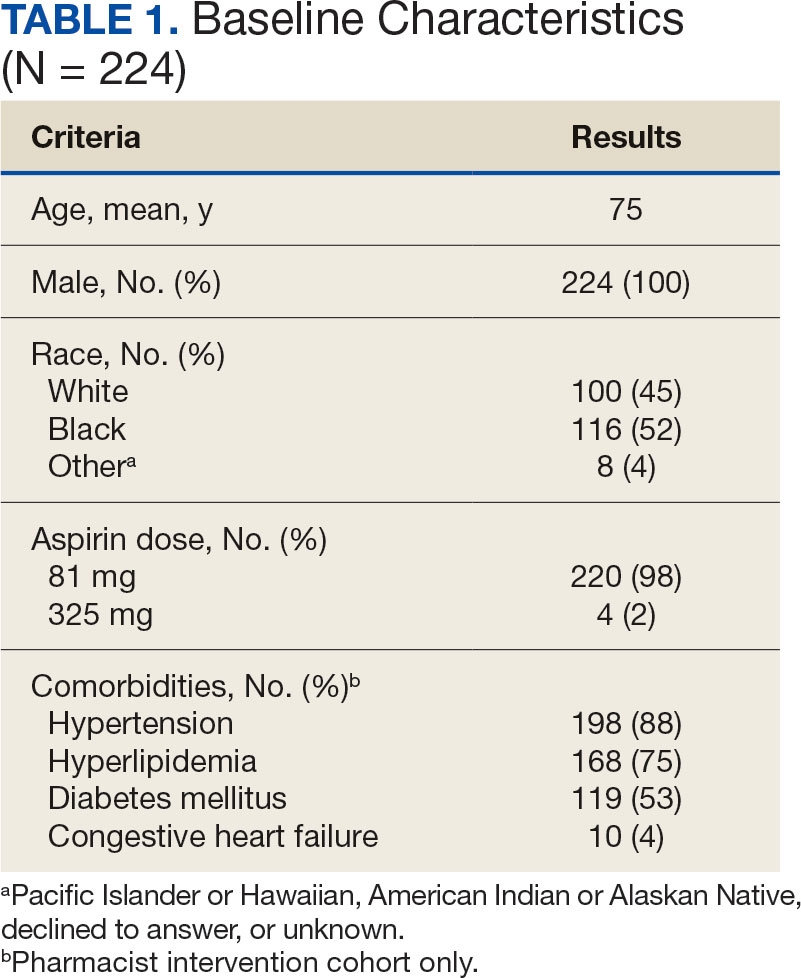

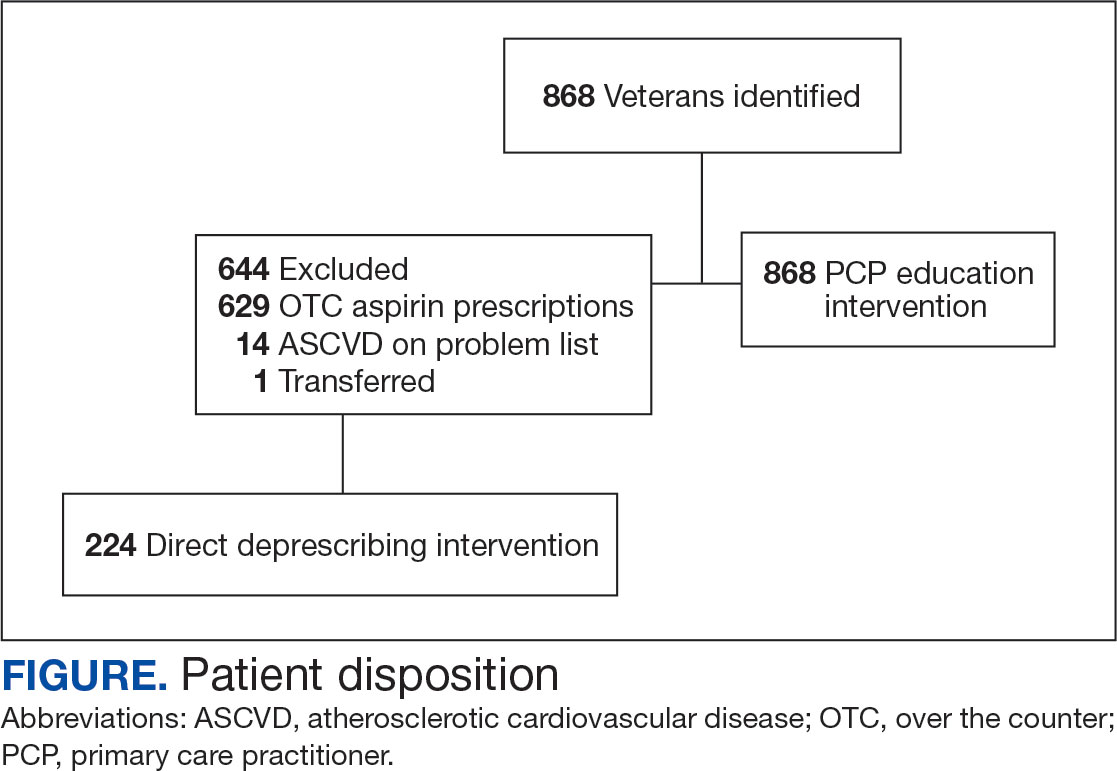

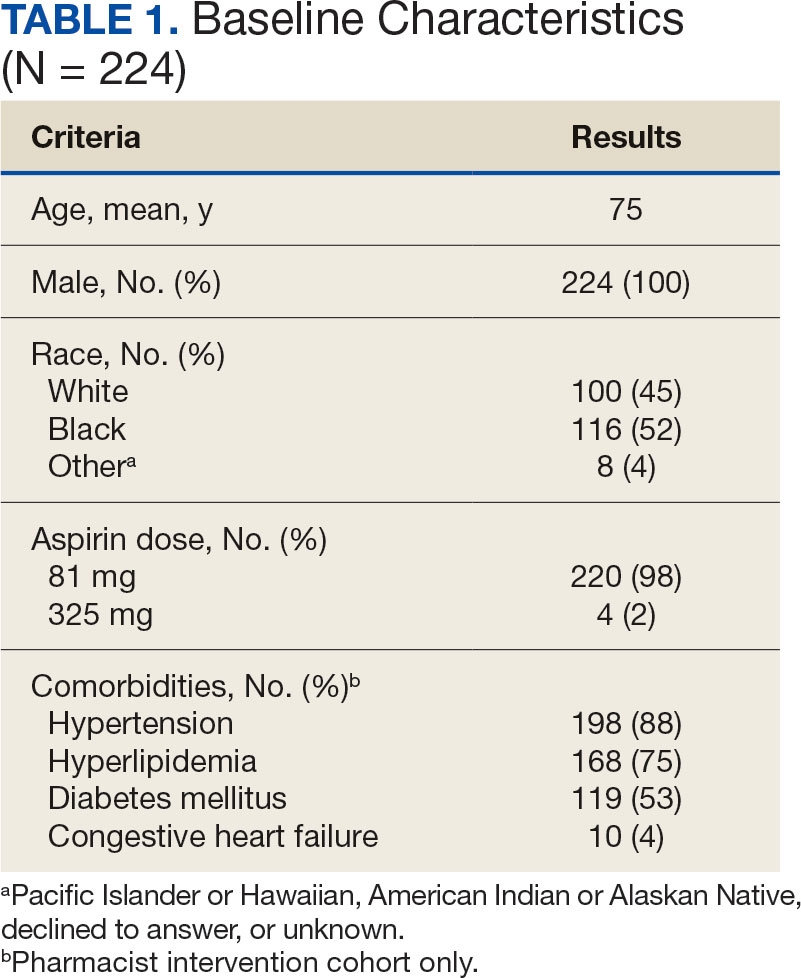

A total of 868 patients aged ≥ 70 years with active prescriptions for aspirin were identified on December 1, 2022. After applying inclusion and exclusion criteria for the pharmacist population review, 224 patients were included for cohort final analysis (Figure). All 868 patients were eligible for the CPP intervention. Primary reasons for exclusion from the CPP population included over-thecounter aspirin and a history of ASCVD in the patient’s problem list. All patients were male, with a mean (SD) age of 75 (4.4) years (Table 1). Most patients were prescribed aspirin, 81 mg daily (n = 220; 98%).

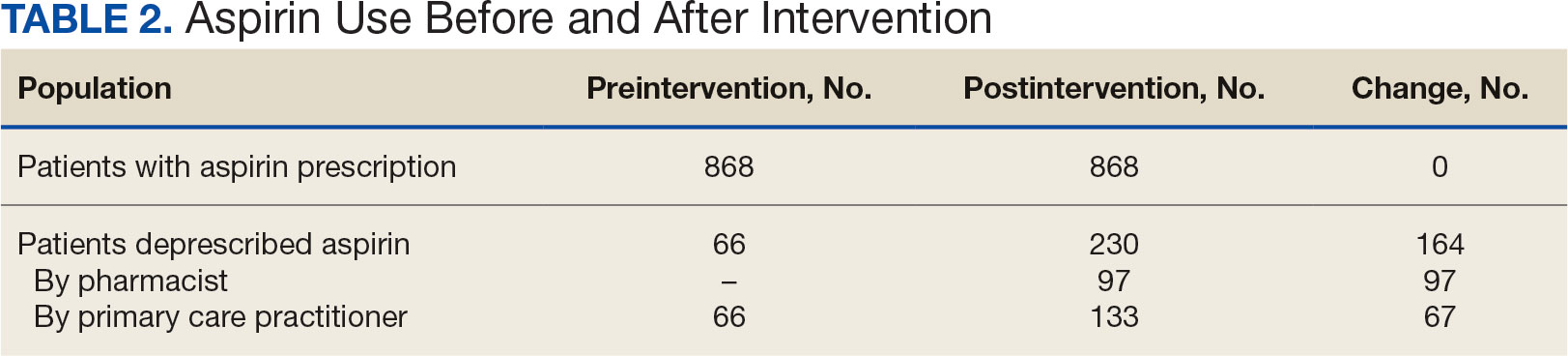

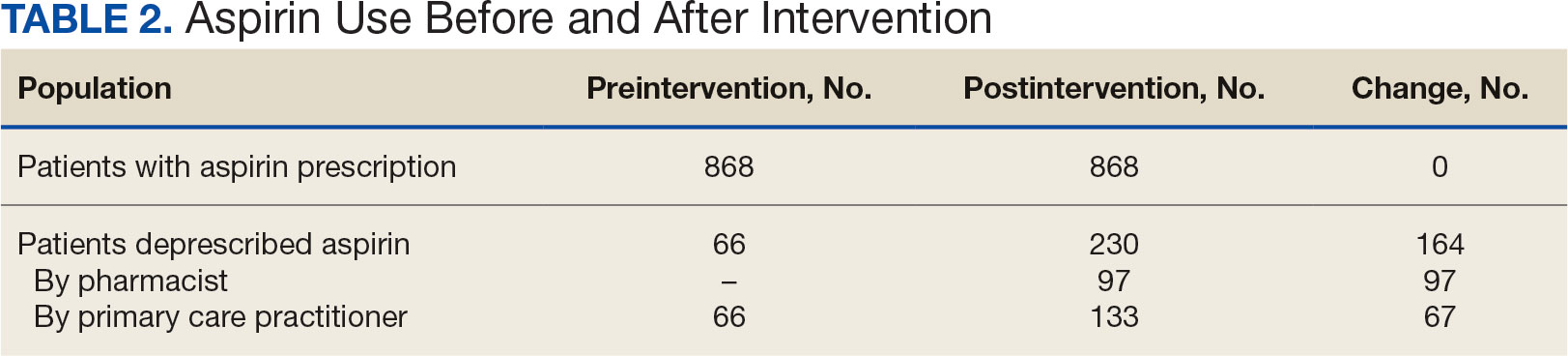

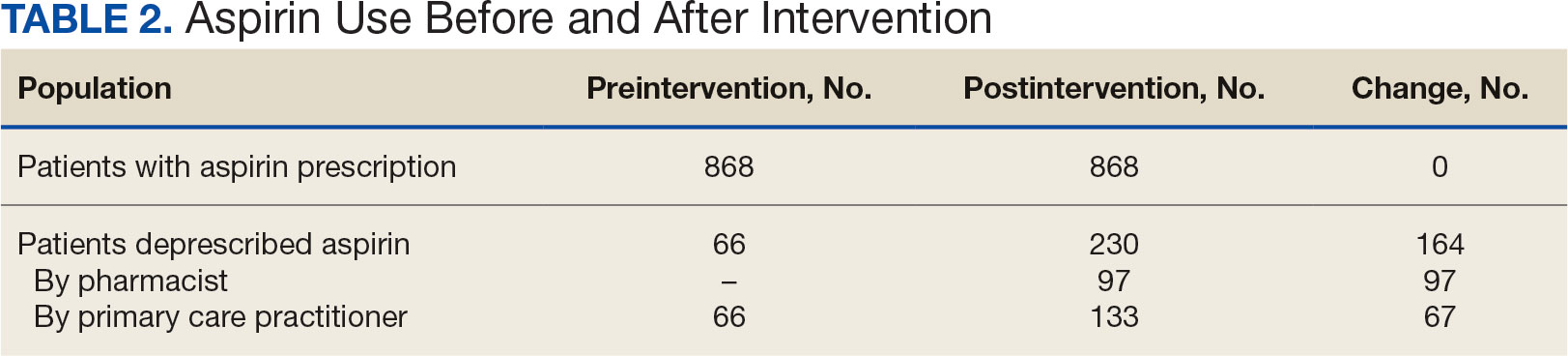

The direct CPP deprescribing intervention resulted in 2 aspirin prescriptions discontinued per hour of pharmacist time and 67 aspirin prescriptions discontinued per hour of pharmacist time via the PCP education intervention. CPPs discontinued 66 aspirin orders in the 12 weeks before the PCP education sessions. A total of 230 aspirin prescriptions were discontinued in the 12 weeks following the PCP education sessions, with 97 discontinued directly by CPPs and 133 discontinued by PCPs. The PCP education session yielded an additional 67 discontinued aspirin orders compared with the 12 weeks before the education sessions (Table 2).

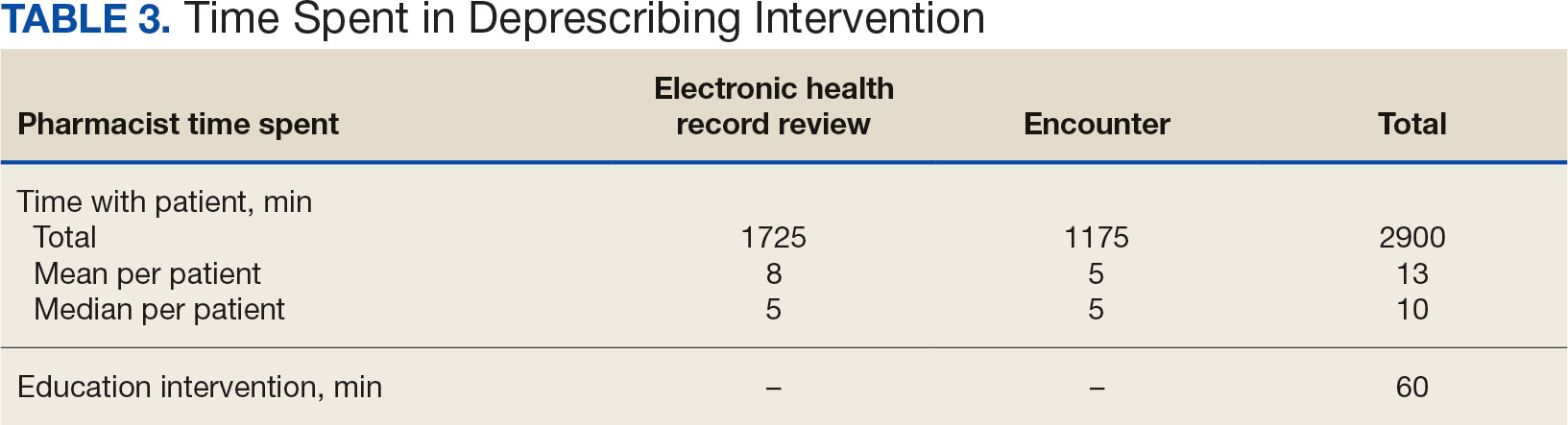

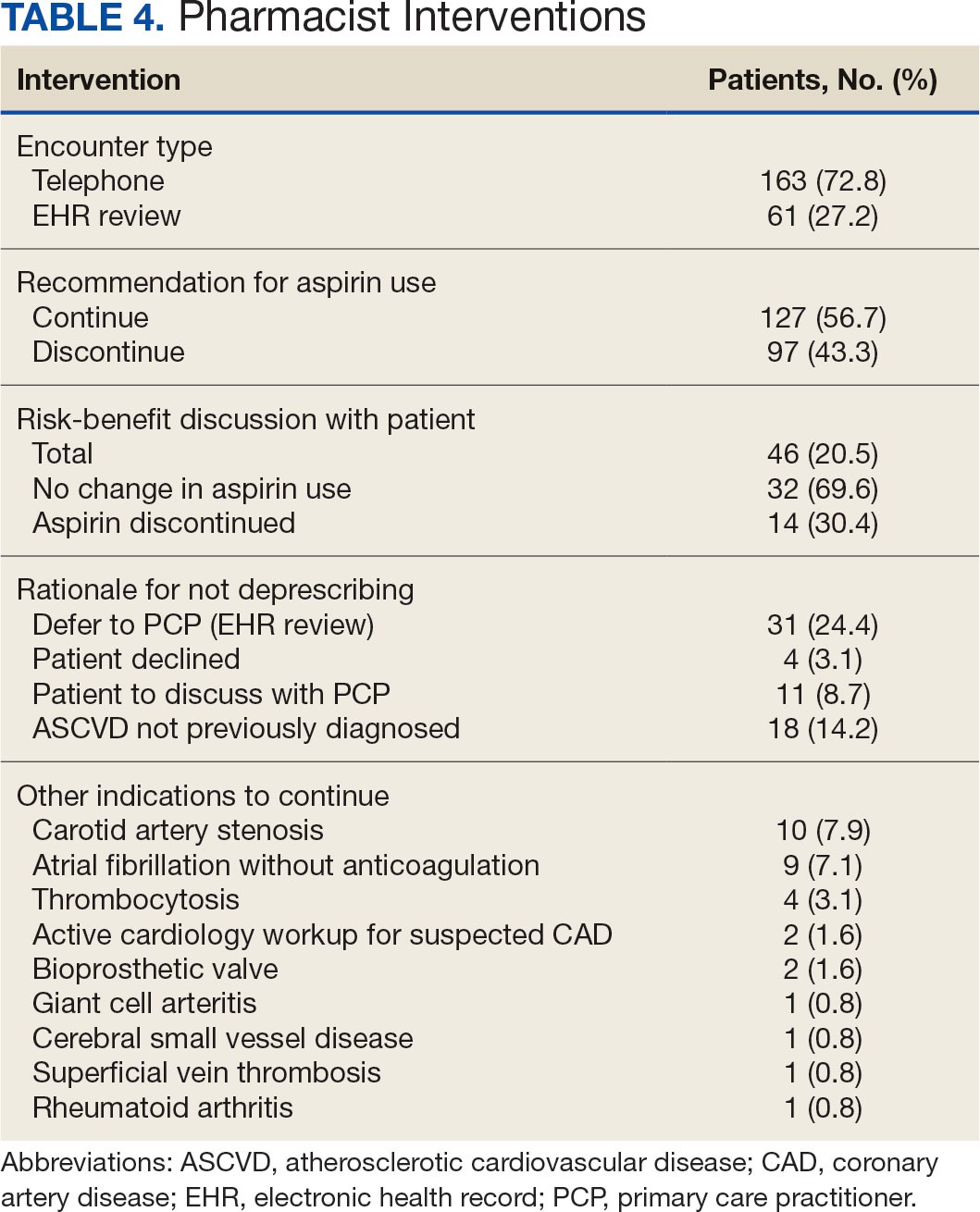

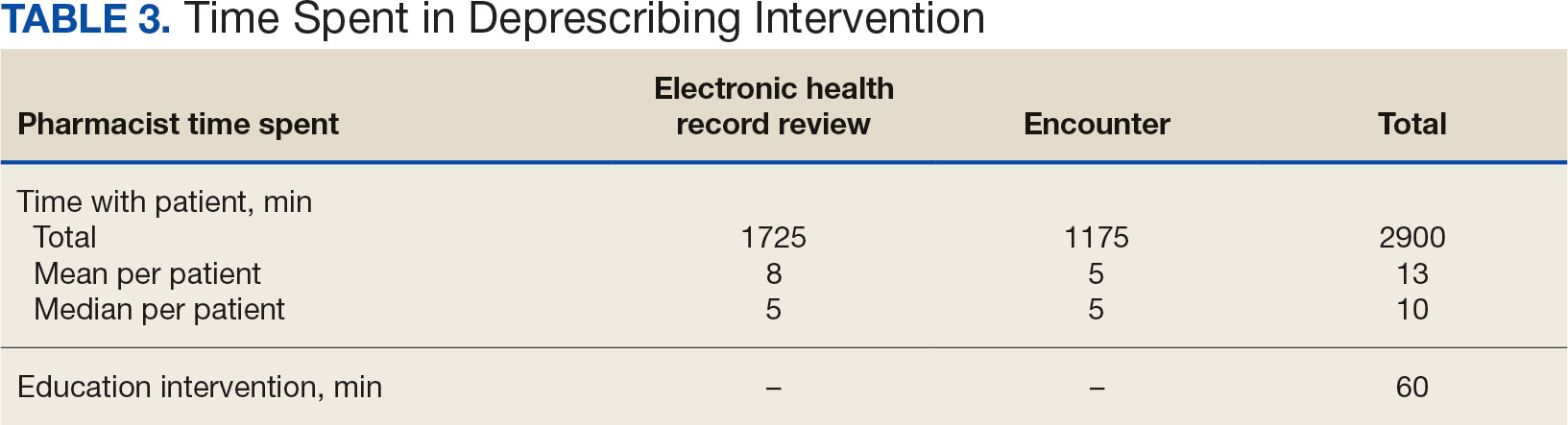

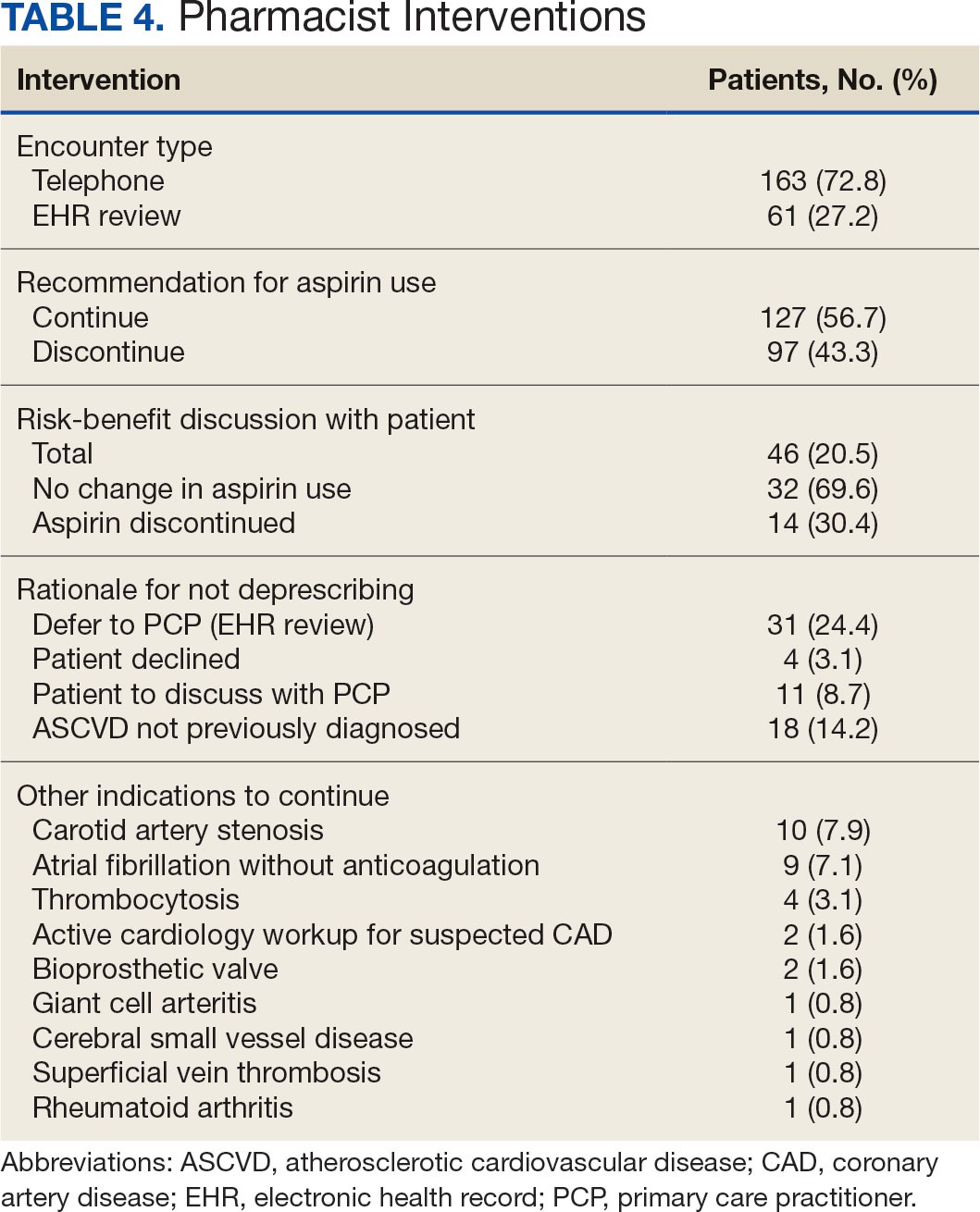

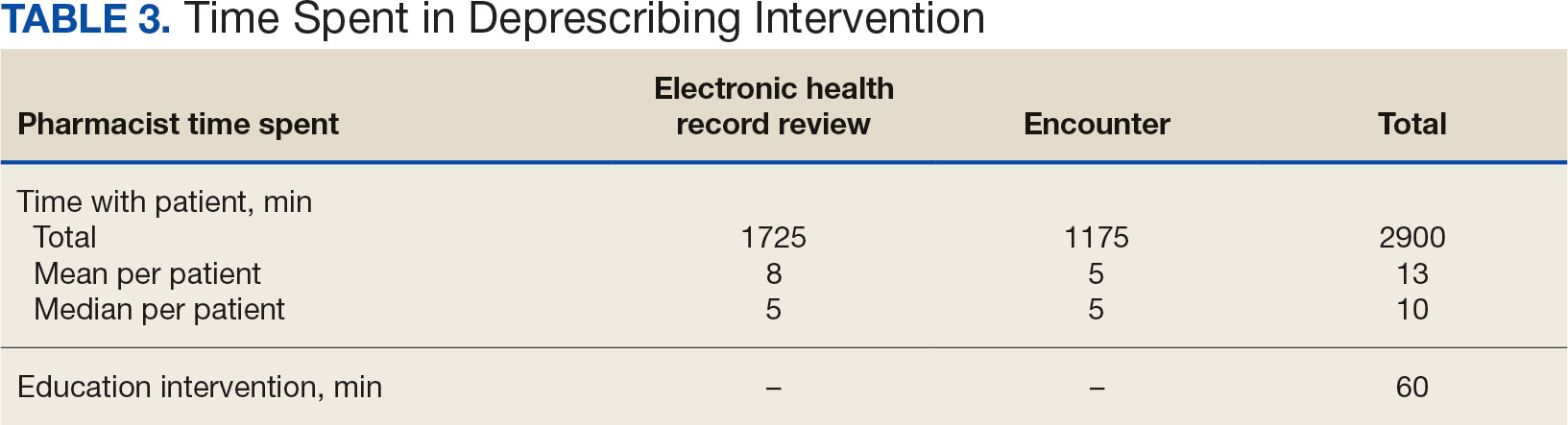

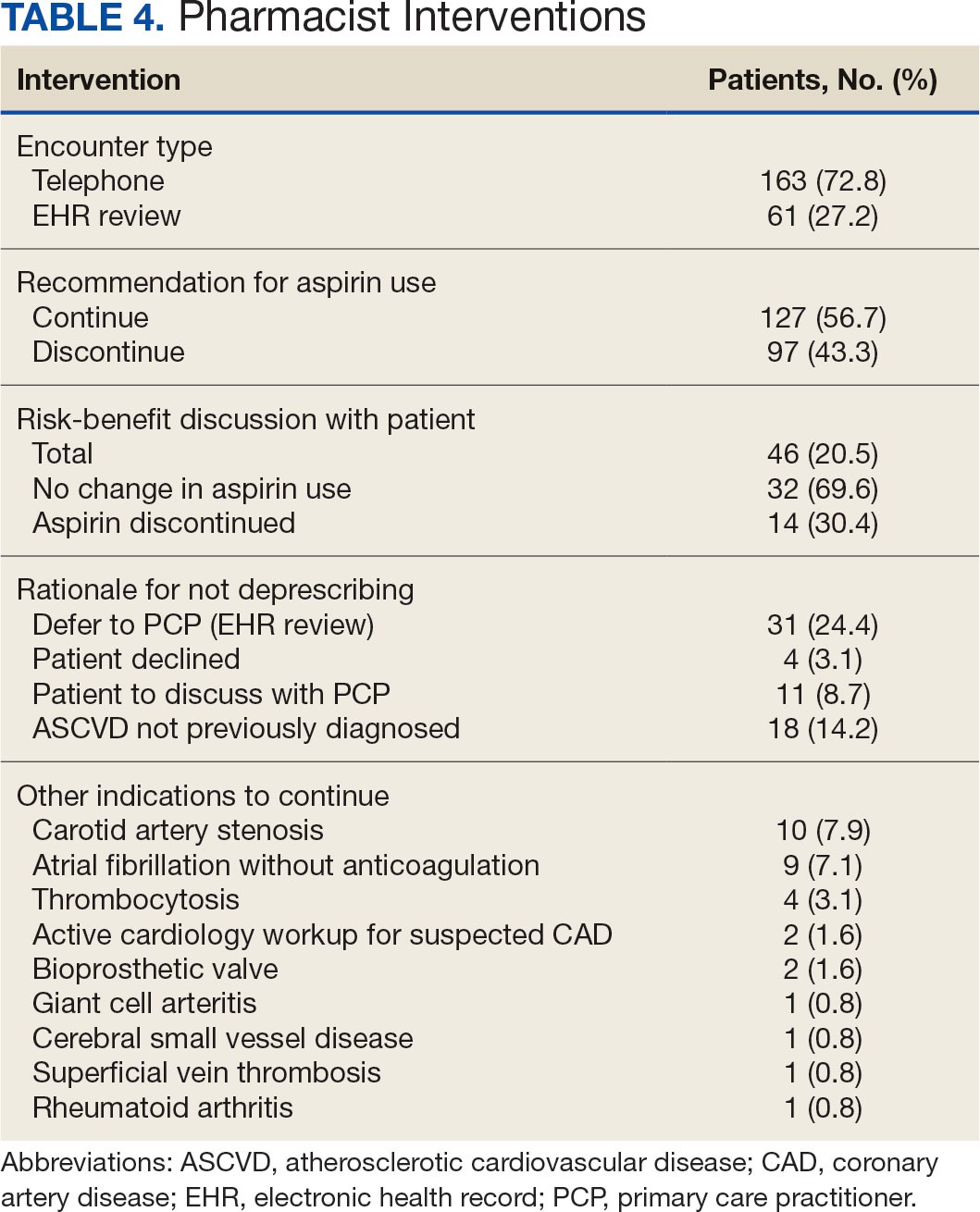

The CPP direct deprescribing intervention took about 48.3 hours, accounting for health record review and time interacting with patients. The PCP education intervention took about 60 minutes, which included time for preparing and delivering education materials (Table 3). CPP deprescribing encounter types, interventions, and related subcategories, and other identified indications to continue aspirin are listed in Table 4.

Discussion

Compared with direct deprescribing by pharmacists, the PCP education intervention was more efficient based on number of aspirin orders discontinued by pharmacist time. PCPs discontinued twice as many aspirin prescriptions in the 12 weeks after pharmacist-led education compared with the 12 weeks before.

Patients were primarily contacted by telephone (73%) for deprescribing. Among the 163 patients reached by phone and encouraged to discontinue aspirin, 97 patients (60%) accepted the recommendation, which was similar to the acceptance rates found in the literature (48% to 55%).14,18 Although many veterans continued taking aspirin (78%), most had indications for its continued use, such as a history of ASCVD, atrial fibrillation without anticoagulation, and carotid artery stenosis, and complex comorbidities that required further discussion with their PCP. Less common uses for aspirin were identified through CPRS review or patient reports included cerebral small vessel disease without history of ASCVD, subclavian artery stenosis, thrombocytosis, bioprosthetic valve replacement, giant cell arteritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and prevention of second eye involvement of ischemic optic neuropathy.

to describe the benefit of clinical pharmacy services for deprescribing aspirin for primary prevention of ASCVD through PCP education. Previously published literature has assessed alternative ways to identify or discontinue PIMs—including aspirin—among geriatric patients. One study evaluated the use of marking inappropriate aspirin prescriptions in the electronic health database, leading to a significant reduction in incidence of inappropriate aspirin prescribing; however, it did not assess changes in discontinuation rates of existing aspirin prescriptions.19 The previous VA pharmacist aspirin deprescribing protocol demonstrated pharmacists’ aptitude at discontinuing aspirin for primary prevention but only used direct patient contact and did not compare efficiency with other methods, including PCP education.14

This quality improvement project contributes new data to the existing literature to support the use of clinical pharmacists to discontinue aspirin for primary prevention and suggests a strong role for pharmacists as educators on clinical guidelines, in addition to their roles directly deprescribing PIMs in clinical practice. This study is further strengthened by its use of VIONE, which previously has demonstrated effectiveness in deprescribing a variety of PIMs in primary care settings.20

Despite using VIONE for generating a list of patients eligible for deprescription, our CPRS review found that this list was frequently inaccurate. For example, a small portion of patients were on the VIONE generated list indicating they had no ASCVD history, but had transient ischemic attack listed in their problem lists. Patient problem lists often were missing documented ASCVD history that was revealed by patient interview or CPRS review. It is possible that patients interviewed might have omitted relevant ASCVD history because of low health literacy, conditions affecting memory, or use of health care services outside the VA system.

There were several instances of aspirin used for other non-ASCVD indications, such as primary stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. The ACC/AHA atrial fibrillation guidelines previously provided a Class IIb recommendation (benefit is greater than risk but additional studies are needed) for considering no antithrombic therapy or treatment with oral anticoagulant or aspirin for nonvalvular atrial fibrillation with CHA2DS2-VASc (Congestive heart failure, Hypertension, Age [> 65 y, 1 point; > 75 y, 2 points], Diabetes, previous Stroke/transient ischemic attack [2 points]) score of 1.21 The ACC/ AHA guidelines were updated in 2023 to recommend against antiplatelet therapy as an alternative to anticoagulation for reducing cardioembolic stroke risk among patients with atrial fibrillation with no indication for antiplatelet therapy because of risk of harm.22 If a patient has no risk factors for stroke, aspirin is not recommended to prevent thromboembolic events because of a lack of benefit. Interventions from this quality improvement study were completed before the 2023 atrial fibrillation guideline was published and therefore in this study aspirin was not discontinued when used for atrial fibrillation. Aspirin use for atrial fibrillation might benefit from similar discontinuation efforts analyzed within this study. Beyond atrial fibrillation, major guidelines do not comment on the use of aspirin for any other indications in the absence of clinical ASCVD.

Limitations

This study is limited by the lack of clinical consensus for complex patients and demonstrates the importance of individualized patient assessment when considering discontinuing aspirin. Because of the project’s relatively short intervention period, aspirin deprescribing rates could decrease over time and repeated education efforts might be necessary to see lasting impact. Health care professionals from services outside of primary care also might have discontinued aspirin during the study period unrelated to the education and these discontinued aspirin prescriptions could contribute to the higher rate observed among PCPs. This study included a specific population cohort of male, US veterans and might not reflect other populations where these interventions could be implemented.

The measurement of time spent by pharmacists and PCPs is an additional limitation. Although it is expected that PCPs attempt to discontinue aspirin during their existing patient care appointments, the time spent during visits was not measured or documented. Direct deprescribing by pharmacist CPRS review required a significant amount of time and could be a barrier to successful intervention by CPPs in patient aligned care teams.

To reduce the time pharmacists spent completing CPRS reviews, an aspirin deprescribing clinical reminder tool could be used to assess use and appropriate indication quickly during any primary care visit led by a PCP or CPP. In addition, it is recommended that pharmacists regularly educate health care professionals on guideline recommendations for aspirin use among geriatric patients. Future studies of the incidence of major cardiovascular events after aspirin deprescribing among geriatric patients and a longitudinal cost/benefit analysis could support these initiatives.

Conclusions

In this study, pharmacists successfully deprescribed inappropriate medications, such as aspirin. However, pharmacist-led PCP education is more efficient compared with direct deprescribing using a population-level review. PCP education requires less time and could allow ambulatory care pharmacists to spend more time on other direct patient care interventions to improve quality and access to care in primary care clinics. This study’s results further support the role of pharmacists in deprescribing PIMs for older adults and the use of a deprescribing tool, such as VIONE, in a primary care setting.

- US Preventive Services Task Force; Davidson KW, Barry MJ, et al. Aspirin use to prevent cardiovascular disease: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2022;327(16):1577-1584. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.4983

- McNeil JJ, Nelson MR, Woods RL, et al. Effect of aspirin on all-cause mortality in the healthy elderly. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(16):1519-1528. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1803955

- Barry MJ, Wolff TA, Pbert L, et al. Putting evidence into practice: an update on the US Preventive Services Task Force methods for developing recommendations for preventive services. Ann Fam Med. 2023;21(2):165-171. doi:10.1370/afm.2946

- Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al. 2019 ACC/ AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: A report of the American College of Cardiology/ American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019;140(11):e596-e646. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000678

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 10. Cardiovascular disease and risk management: Standards of care in diabetes-2024. Diabetes Care. 2024;47(Suppl 1):S179-S218. doi:10.2337/dc24-S010

- Ong SY, Chui P, Bhargava A, Justice A, Hauser RG. Estimating aspirin overuse for primary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (from a nationwide healthcare system). Am J Cardiol. 2020;137:25-30. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2020.09.042

- Weiss AJ, Jiang HJ. Overview of clinical conditions with frequent and costly hospital readmissions by payer, 2018. In: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); July 20, 2021.

- Krishnaswami A, Steinman MA, Goyal P, et al. Deprescribing in older adults with cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(20):2584-2595. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2019.03.467

- Association of American Medical Colleges. The complexities of physician supply and demand: projections from 2019 to 2034. Accessed March 17, 2024. https://www.aamc.org/media/54681/download

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. VHA Directive 1108.07(1): General pharmacy service requirements. November 28, 2022. Accessed March 17, 2024. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=10045

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. VHA Handbook 1108.11(3): Clinical pharmacy services. July 1, 2015. Accessed March 17, 2024. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=3120

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Clinical pharmacist practitioner (CPP) to improve access to and quality of care August 2021. August 2021. Accessed May 19, 2023. https://www.pbm.va.gov/PBM/CPPO/Documents/ExternalFactSheet_OptimizingtheCPPToImproveAccess_508.pdf

- Ammerman CA, Simpkins BA, Warman N, Downs TN. Potentially inappropriate medications in older adults: Deprescribing with a clinical pharmacist. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(1):115-118. doi:10.1111/jgs.15623

- Rothbauer K, Siodlak M, Dreischmeier E, Ranola TS, Welch L. Evaluation of a pharmacist-driven ambulatory aspirin deprescribing protocol. Fed Pract. 2022;39(suppl 5):S37- S41a. doi:10.12788/fp.0294

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. VIONE changes the way VA handles prescriptions. January 25, 2020. Accessed May 21, 2023. https://news.va.gov/70709/vione-changes-way-va-handles-prescriptions/

- 2023 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2023 updated AGS Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2023;71(7):2052- 2081. doi:10.1111/jgs.18372

- O’Mahony D, Cherubini A, Guiteras AR, et al. STOPP/ START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 3. Eur Geriatr Med. 2023;14(4):625- 632. doi:10.1007/s41999-023-00777-y

- Draeger C, Lodhi F, Geissinger N, Larson T, Griesbach S. Interdisciplinary deprescribing of aspirin through prescriber education and provision of patient-specific recommendations. WMJ. 2022;121(3):220-225

- de Lusignan S, Hinton W, Seidu S, et al. Dashboards to reduce inappropriate prescribing of metformin and aspirin: A quality assurance programme in a primary care sentinel network. Prim Care Diabetes. 2021;15(6):1075-1079. doi:10.1016/j.pcd.2021.06.003

- Nelson MW, Downs TN, Puglisi GM, Simpkins BA, Collier AS. Use of a deprescribing tool in an interdisciplinary primary-care patient-aligned care team. Sr Care Pharm. 2022;37(1):34-43. doi:10.4140/TCP.n.2022.34

- January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, et al. 2014 AHA/ ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2014;130(23):e199-e267. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000041

- Joglar JA, Chung MK, Armbruster AL, et al. 2023 ACC/ AHA/ACCP/HRS Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Atrial Fibrillation: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines Circulation. 2024;149(1):e1- e156. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001193

Low-dose aspirin commonly is used for the prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD) but is associated with an increased risk of major bleeding.1 The use of aspirin for primary prevention is largely extrapolated from clinical trials showing benefit in the secondary prevention of myocardial infarction and ischemic stroke. However, results from the Aspirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly (ASPREE) trial challenged this practice.2 The ASPREE trial, conducted in the United States and Australia from 2010 to 2014, sought to determine whether daily 100 mg aspirin, was superior to placebo in promoting disability-free survival among older adults. Participants were aged ≥ 70 years (≥ 65 years for Hispanic and Black US participants), living in the community, and were free from preexisting CVD, cerebrovascular disease, or any chronic condition likely to limit survival to < 5 years. The study found no significant difference in the primary endpoints of death, dementia, or persistent physical disability, but there was a significantly higher risk of major hemorrhage in the aspirin group (3.8% vs 2.8%; hazard ratio, 1.38; 95% CI, 1.18-1.62; P < .001).

Several medical societies have updated their guideline recommendations for aspirin for primary prevention of CVD. The 2022 United States Public Service Task Force (USPSTF) provides a grade C recommendation (at least moderate certainty that the net benefit is small) to consider low-dose aspirin for the primary prevention of CVD on an individual patient basis for adults aged 40 to 59 years who have a ≥ 10% 10-year CVD risk. For adults aged ≥ 60 years, the USPSTF recommendation is grade D (moderate or high certainty that the practice has no net benefit or that harms outweigh the benefits) for low-dose aspirin use.1,3 The American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) recommend considering low-dose aspirin for primary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) among select adults aged 40 to 70 years at higher CVD risk but not at increased risk of bleeding.4 The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommends low-dose aspirin for primary prevention of CVD in patients with diabetes and additional risk factors such as family history of premature ASCVD, hypertension, dyslipidemia, smoking, or chronic kidney disease, and who are not at higher risk of bleeding.5 The ADA standards also caution against the use of aspirin as primary prevention in patients aged > 70 years. Low-dose aspirin use is not recommended for the primary prevention of CVD in older adults or adults of any age who are at increased risk of bleeding.

Recent literature using the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Corporate Data Warehouse database confirms 86,555 of 1.8 million veterans aged > 70 years (5%) were taking low-dose aspirin for primary prevention of ASCVD despite guideline recommendations.6 Higher risk of gastrointestinal and other major bleeding from low-dose aspirin has been reported in the literature.1 Major bleeds represent a significant burden to the health care system with an estimated mean $13,093 cost for gastrointestinal bleed hospitalization.7

Considering the large scale aspirin use without appropriate indication within the veteran population, the risk of adverse effects, and the significant cost to patients and the health care system, it is imperative to determine the best approach to efficiently deprescribe aspirin for primary prevention among geriatric patients. Deprescribing refers to the systematic and supervised process of dose reduction or drug discontinuation with the goal of improving health and/or reducing the risk of adverse effects.8 During patient visits, primary care practitioners (PCPs) have opportunities to discontinue aspirin, but these encounters are time-limited and deprescribing might be secondary to more acute primary care needs. The shortage of PCPs is expected to worsen in coming years, which could further reduce their availability to assess inappropriate aspirin use.9

VA clinical pharmacist practitioners (CPPs) serve as medication experts and work autonomously under a broad scope of practice as part of the patient aligned care team.10-12 CPPs can free up time for PCPs and facilitate deprescribing efforts, especially for older adults. One retrospective cohort study conducted at a VA medical center found that CPPs deprescribed more potentially inappropriate medications among individuals aged ≥ 80 years compared with usual care with PCPs (26.8% vs 16.1%; P < .001).12,13 An aspirin deprescribing protocol conducted in 2022 resulted in nearly half of veterans aged ≥ 70 years contacted by phone agreeing to stop aspirin. Although this study supports the role pharmacists can play in reducing aspirin use in accordance with guidelines, the authors acknowledge that their interventions had a mean time of 12 minutes per patient and would require workflow changes.14 The purpose of this study is to evaluate the efficiency of aspirin deprescribing through 2 approaches: direct deprescribing by pharmacists using populationlevel review compared with clinicians following a pharmacist-led education.

Methods

This was a single-center quality improvement cohort study at the Durham VA Health Care System (DVAHCS) in North Carolina. Patients included were aged ≥ 70 years without known ASCVD who received care at any of 3 DVAHCS community-based outpatient clinics and prescribed aspirin. Patient data was obtained using the VIONE (Deprescribing Dashboard called Vital, Important, Optional, Not indicated, and Every medication has a specific indication or diagnosis) dashboard.15 VIONE was developed to identify potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) that are eligible to deprescribe based on Beers Criteria, Screening Tool of Older Personsf Prescriptions criteria, and common clinical scenarios when clinicians determine the risk outweighs the benefit to continue a specific medication. 16,17 VIONE is used to reduce polypharmacy and improve patient safety, comfort, and medication adherence. Aspirin for patients aged ≥ 70 years without a history of ASCVD is a PIM identified by VIONE. Patients aged ≥ 70 years were chosen as an inclusion criteria in this study to match the ASPREE trial inclusion criteria and age inclusion criteria in the VIONE dashboard for aspirin deprescribing.2 Patient lists were generated for these potentially inappropriate aspirin prescriptions for 3 months before clinician staff education presentations, the day of the presentations, and 3 months after.

The primary endpoint was the number of veterans with aspirin deprescribed directly by 2 pharmacists over 12 weeks, divided by total patient care time spent, compared with the change in number of veterans with aspirin deprescribed by any DVAHCS physician, nurse practitioner, physician assistant, or CPP over 12 weeks, divided by the total pharmacist time spent on PCP education. Secondary endpoints were the number of aspirin orders discontinued by pharmacists and CPPs, the number of aspirin orders discontinued 12 weeks before pharmacist-led education compared with the number of aspirin orders discontinued 12 weeks after CPP-led education, average and median pharmacist time spent per patient encounter, and time of direct patient encounters vs time spent on PCP education.

Pharmacists reviewed each patient who met the inclusion criteria from the list generated by VIONE on December 1, 2022, for aspirin appropriateness according to the ACC/AHA and USPSTF guidelines, with the goal to discontinue aspirin for primary prevention of ASCVD and no other indications.1,4 Pharmacists documented their visits using VIONE methodology in the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) using a polypharmacy review note. CPPs contacted patients who were taking aspirin for primary prevention by unscheduled telephone call to assess for aspirin adherence, undocumented history of ASCVD, cardiovascular risk factors, and history of bleeding. Aspirin was discontinued if patients met guideline criteria recommendations and agreed to discontinuation. Risk-benefit discussions were completed when patients without known ASCVD were considered high risk because the ACC/AHA guidelines mention there is insufficient evidence of safety and efficacy of aspirin for primary prevention for patients with other known ASCVD risk factors (eg, strong family history of premature myocardial infarction, inability to achieve lipid, blood pressure, or glucose targets, or significant elevation in coronary artery calcium score).

High risk was defined as family history of premature ASCVD (in a male first-degree relative aged < 55 years or a female first-degree relative aged < 65 years), most recent blood pressure or 2 blood pressure results in the last 12 months > 160/100 mm Hg, recent hemoglobin A1c > 9%, and/or low-density lipoprotein > 190 mg/dL or not prescribed an indicated statin.3 Aspirin was continued or discontinued according to patient preference after the personalized risk-benefit discussion.

For patients with a clinical indication for aspirin use other than ASCVD (eg, atrial fibrillation not on anticoagulation, venous thromboembolism prophylaxis, carotid artery disease), CPPs documented their assessment and when appropriate deferred to the PCP for consideration of stopping aspirin. For patients with undocumented ASCVD, CPPs added their ASCVD history to their problem list and aspirin was continued. PCPs were notified by alert when aspirin was discontinued and when patients could not be reached by telephone.

presented a review of recent guideline updates and supporting literature at 2 online staff meetings. The education sessions lasted about 10 minutes and were presented to PCPs across 3 community-based outpatient clinics. An estimated 40 minutes were spent creating the PowerPoint education materials, seeking feedback, making edits, and answering questions or emails from PCPs after the presentation. During the presentation, pharmacists encouraged PCPs to discontinue aspirin (active VA prescriptions and reported over-the-counter use) for primary prevention of ASCVD in patients aged ≥ 70 years during their upcoming appointments and consider risk factors recommended by the ACC/AHA guidelines when applicable. PCPs were notified that CPPs planned to start a population review for discontinuing active VA aspirin prescriptions on December 1, 2022. The primary endpoint and secondary endpoints were analyzed using descriptive statistics. All data were analyzed using Microsoft Excel.

Results

A total of 868 patients aged ≥ 70 years with active prescriptions for aspirin were identified on December 1, 2022. After applying inclusion and exclusion criteria for the pharmacist population review, 224 patients were included for cohort final analysis (Figure). All 868 patients were eligible for the CPP intervention. Primary reasons for exclusion from the CPP population included over-thecounter aspirin and a history of ASCVD in the patient’s problem list. All patients were male, with a mean (SD) age of 75 (4.4) years (Table 1). Most patients were prescribed aspirin, 81 mg daily (n = 220; 98%).

The direct CPP deprescribing intervention resulted in 2 aspirin prescriptions discontinued per hour of pharmacist time and 67 aspirin prescriptions discontinued per hour of pharmacist time via the PCP education intervention. CPPs discontinued 66 aspirin orders in the 12 weeks before the PCP education sessions. A total of 230 aspirin prescriptions were discontinued in the 12 weeks following the PCP education sessions, with 97 discontinued directly by CPPs and 133 discontinued by PCPs. The PCP education session yielded an additional 67 discontinued aspirin orders compared with the 12 weeks before the education sessions (Table 2).

The CPP direct deprescribing intervention took about 48.3 hours, accounting for health record review and time interacting with patients. The PCP education intervention took about 60 minutes, which included time for preparing and delivering education materials (Table 3). CPP deprescribing encounter types, interventions, and related subcategories, and other identified indications to continue aspirin are listed in Table 4.

Discussion

Compared with direct deprescribing by pharmacists, the PCP education intervention was more efficient based on number of aspirin orders discontinued by pharmacist time. PCPs discontinued twice as many aspirin prescriptions in the 12 weeks after pharmacist-led education compared with the 12 weeks before.

Patients were primarily contacted by telephone (73%) for deprescribing. Among the 163 patients reached by phone and encouraged to discontinue aspirin, 97 patients (60%) accepted the recommendation, which was similar to the acceptance rates found in the literature (48% to 55%).14,18 Although many veterans continued taking aspirin (78%), most had indications for its continued use, such as a history of ASCVD, atrial fibrillation without anticoagulation, and carotid artery stenosis, and complex comorbidities that required further discussion with their PCP. Less common uses for aspirin were identified through CPRS review or patient reports included cerebral small vessel disease without history of ASCVD, subclavian artery stenosis, thrombocytosis, bioprosthetic valve replacement, giant cell arteritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and prevention of second eye involvement of ischemic optic neuropathy.

to describe the benefit of clinical pharmacy services for deprescribing aspirin for primary prevention of ASCVD through PCP education. Previously published literature has assessed alternative ways to identify or discontinue PIMs—including aspirin—among geriatric patients. One study evaluated the use of marking inappropriate aspirin prescriptions in the electronic health database, leading to a significant reduction in incidence of inappropriate aspirin prescribing; however, it did not assess changes in discontinuation rates of existing aspirin prescriptions.19 The previous VA pharmacist aspirin deprescribing protocol demonstrated pharmacists’ aptitude at discontinuing aspirin for primary prevention but only used direct patient contact and did not compare efficiency with other methods, including PCP education.14

This quality improvement project contributes new data to the existing literature to support the use of clinical pharmacists to discontinue aspirin for primary prevention and suggests a strong role for pharmacists as educators on clinical guidelines, in addition to their roles directly deprescribing PIMs in clinical practice. This study is further strengthened by its use of VIONE, which previously has demonstrated effectiveness in deprescribing a variety of PIMs in primary care settings.20

Despite using VIONE for generating a list of patients eligible for deprescription, our CPRS review found that this list was frequently inaccurate. For example, a small portion of patients were on the VIONE generated list indicating they had no ASCVD history, but had transient ischemic attack listed in their problem lists. Patient problem lists often were missing documented ASCVD history that was revealed by patient interview or CPRS review. It is possible that patients interviewed might have omitted relevant ASCVD history because of low health literacy, conditions affecting memory, or use of health care services outside the VA system.

There were several instances of aspirin used for other non-ASCVD indications, such as primary stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. The ACC/AHA atrial fibrillation guidelines previously provided a Class IIb recommendation (benefit is greater than risk but additional studies are needed) for considering no antithrombic therapy or treatment with oral anticoagulant or aspirin for nonvalvular atrial fibrillation with CHA2DS2-VASc (Congestive heart failure, Hypertension, Age [> 65 y, 1 point; > 75 y, 2 points], Diabetes, previous Stroke/transient ischemic attack [2 points]) score of 1.21 The ACC/ AHA guidelines were updated in 2023 to recommend against antiplatelet therapy as an alternative to anticoagulation for reducing cardioembolic stroke risk among patients with atrial fibrillation with no indication for antiplatelet therapy because of risk of harm.22 If a patient has no risk factors for stroke, aspirin is not recommended to prevent thromboembolic events because of a lack of benefit. Interventions from this quality improvement study were completed before the 2023 atrial fibrillation guideline was published and therefore in this study aspirin was not discontinued when used for atrial fibrillation. Aspirin use for atrial fibrillation might benefit from similar discontinuation efforts analyzed within this study. Beyond atrial fibrillation, major guidelines do not comment on the use of aspirin for any other indications in the absence of clinical ASCVD.

Limitations

This study is limited by the lack of clinical consensus for complex patients and demonstrates the importance of individualized patient assessment when considering discontinuing aspirin. Because of the project’s relatively short intervention period, aspirin deprescribing rates could decrease over time and repeated education efforts might be necessary to see lasting impact. Health care professionals from services outside of primary care also might have discontinued aspirin during the study period unrelated to the education and these discontinued aspirin prescriptions could contribute to the higher rate observed among PCPs. This study included a specific population cohort of male, US veterans and might not reflect other populations where these interventions could be implemented.

The measurement of time spent by pharmacists and PCPs is an additional limitation. Although it is expected that PCPs attempt to discontinue aspirin during their existing patient care appointments, the time spent during visits was not measured or documented. Direct deprescribing by pharmacist CPRS review required a significant amount of time and could be a barrier to successful intervention by CPPs in patient aligned care teams.

To reduce the time pharmacists spent completing CPRS reviews, an aspirin deprescribing clinical reminder tool could be used to assess use and appropriate indication quickly during any primary care visit led by a PCP or CPP. In addition, it is recommended that pharmacists regularly educate health care professionals on guideline recommendations for aspirin use among geriatric patients. Future studies of the incidence of major cardiovascular events after aspirin deprescribing among geriatric patients and a longitudinal cost/benefit analysis could support these initiatives.

Conclusions

In this study, pharmacists successfully deprescribed inappropriate medications, such as aspirin. However, pharmacist-led PCP education is more efficient compared with direct deprescribing using a population-level review. PCP education requires less time and could allow ambulatory care pharmacists to spend more time on other direct patient care interventions to improve quality and access to care in primary care clinics. This study’s results further support the role of pharmacists in deprescribing PIMs for older adults and the use of a deprescribing tool, such as VIONE, in a primary care setting.

Low-dose aspirin commonly is used for the prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD) but is associated with an increased risk of major bleeding.1 The use of aspirin for primary prevention is largely extrapolated from clinical trials showing benefit in the secondary prevention of myocardial infarction and ischemic stroke. However, results from the Aspirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly (ASPREE) trial challenged this practice.2 The ASPREE trial, conducted in the United States and Australia from 2010 to 2014, sought to determine whether daily 100 mg aspirin, was superior to placebo in promoting disability-free survival among older adults. Participants were aged ≥ 70 years (≥ 65 years for Hispanic and Black US participants), living in the community, and were free from preexisting CVD, cerebrovascular disease, or any chronic condition likely to limit survival to < 5 years. The study found no significant difference in the primary endpoints of death, dementia, or persistent physical disability, but there was a significantly higher risk of major hemorrhage in the aspirin group (3.8% vs 2.8%; hazard ratio, 1.38; 95% CI, 1.18-1.62; P < .001).

Several medical societies have updated their guideline recommendations for aspirin for primary prevention of CVD. The 2022 United States Public Service Task Force (USPSTF) provides a grade C recommendation (at least moderate certainty that the net benefit is small) to consider low-dose aspirin for the primary prevention of CVD on an individual patient basis for adults aged 40 to 59 years who have a ≥ 10% 10-year CVD risk. For adults aged ≥ 60 years, the USPSTF recommendation is grade D (moderate or high certainty that the practice has no net benefit or that harms outweigh the benefits) for low-dose aspirin use.1,3 The American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) recommend considering low-dose aspirin for primary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) among select adults aged 40 to 70 years at higher CVD risk but not at increased risk of bleeding.4 The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommends low-dose aspirin for primary prevention of CVD in patients with diabetes and additional risk factors such as family history of premature ASCVD, hypertension, dyslipidemia, smoking, or chronic kidney disease, and who are not at higher risk of bleeding.5 The ADA standards also caution against the use of aspirin as primary prevention in patients aged > 70 years. Low-dose aspirin use is not recommended for the primary prevention of CVD in older adults or adults of any age who are at increased risk of bleeding.

Recent literature using the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Corporate Data Warehouse database confirms 86,555 of 1.8 million veterans aged > 70 years (5%) were taking low-dose aspirin for primary prevention of ASCVD despite guideline recommendations.6 Higher risk of gastrointestinal and other major bleeding from low-dose aspirin has been reported in the literature.1 Major bleeds represent a significant burden to the health care system with an estimated mean $13,093 cost for gastrointestinal bleed hospitalization.7

Considering the large scale aspirin use without appropriate indication within the veteran population, the risk of adverse effects, and the significant cost to patients and the health care system, it is imperative to determine the best approach to efficiently deprescribe aspirin for primary prevention among geriatric patients. Deprescribing refers to the systematic and supervised process of dose reduction or drug discontinuation with the goal of improving health and/or reducing the risk of adverse effects.8 During patient visits, primary care practitioners (PCPs) have opportunities to discontinue aspirin, but these encounters are time-limited and deprescribing might be secondary to more acute primary care needs. The shortage of PCPs is expected to worsen in coming years, which could further reduce their availability to assess inappropriate aspirin use.9

VA clinical pharmacist practitioners (CPPs) serve as medication experts and work autonomously under a broad scope of practice as part of the patient aligned care team.10-12 CPPs can free up time for PCPs and facilitate deprescribing efforts, especially for older adults. One retrospective cohort study conducted at a VA medical center found that CPPs deprescribed more potentially inappropriate medications among individuals aged ≥ 80 years compared with usual care with PCPs (26.8% vs 16.1%; P < .001).12,13 An aspirin deprescribing protocol conducted in 2022 resulted in nearly half of veterans aged ≥ 70 years contacted by phone agreeing to stop aspirin. Although this study supports the role pharmacists can play in reducing aspirin use in accordance with guidelines, the authors acknowledge that their interventions had a mean time of 12 minutes per patient and would require workflow changes.14 The purpose of this study is to evaluate the efficiency of aspirin deprescribing through 2 approaches: direct deprescribing by pharmacists using populationlevel review compared with clinicians following a pharmacist-led education.

Methods

This was a single-center quality improvement cohort study at the Durham VA Health Care System (DVAHCS) in North Carolina. Patients included were aged ≥ 70 years without known ASCVD who received care at any of 3 DVAHCS community-based outpatient clinics and prescribed aspirin. Patient data was obtained using the VIONE (Deprescribing Dashboard called Vital, Important, Optional, Not indicated, and Every medication has a specific indication or diagnosis) dashboard.15 VIONE was developed to identify potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) that are eligible to deprescribe based on Beers Criteria, Screening Tool of Older Personsf Prescriptions criteria, and common clinical scenarios when clinicians determine the risk outweighs the benefit to continue a specific medication. 16,17 VIONE is used to reduce polypharmacy and improve patient safety, comfort, and medication adherence. Aspirin for patients aged ≥ 70 years without a history of ASCVD is a PIM identified by VIONE. Patients aged ≥ 70 years were chosen as an inclusion criteria in this study to match the ASPREE trial inclusion criteria and age inclusion criteria in the VIONE dashboard for aspirin deprescribing.2 Patient lists were generated for these potentially inappropriate aspirin prescriptions for 3 months before clinician staff education presentations, the day of the presentations, and 3 months after.

The primary endpoint was the number of veterans with aspirin deprescribed directly by 2 pharmacists over 12 weeks, divided by total patient care time spent, compared with the change in number of veterans with aspirin deprescribed by any DVAHCS physician, nurse practitioner, physician assistant, or CPP over 12 weeks, divided by the total pharmacist time spent on PCP education. Secondary endpoints were the number of aspirin orders discontinued by pharmacists and CPPs, the number of aspirin orders discontinued 12 weeks before pharmacist-led education compared with the number of aspirin orders discontinued 12 weeks after CPP-led education, average and median pharmacist time spent per patient encounter, and time of direct patient encounters vs time spent on PCP education.

Pharmacists reviewed each patient who met the inclusion criteria from the list generated by VIONE on December 1, 2022, for aspirin appropriateness according to the ACC/AHA and USPSTF guidelines, with the goal to discontinue aspirin for primary prevention of ASCVD and no other indications.1,4 Pharmacists documented their visits using VIONE methodology in the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) using a polypharmacy review note. CPPs contacted patients who were taking aspirin for primary prevention by unscheduled telephone call to assess for aspirin adherence, undocumented history of ASCVD, cardiovascular risk factors, and history of bleeding. Aspirin was discontinued if patients met guideline criteria recommendations and agreed to discontinuation. Risk-benefit discussions were completed when patients without known ASCVD were considered high risk because the ACC/AHA guidelines mention there is insufficient evidence of safety and efficacy of aspirin for primary prevention for patients with other known ASCVD risk factors (eg, strong family history of premature myocardial infarction, inability to achieve lipid, blood pressure, or glucose targets, or significant elevation in coronary artery calcium score).

High risk was defined as family history of premature ASCVD (in a male first-degree relative aged < 55 years or a female first-degree relative aged < 65 years), most recent blood pressure or 2 blood pressure results in the last 12 months > 160/100 mm Hg, recent hemoglobin A1c > 9%, and/or low-density lipoprotein > 190 mg/dL or not prescribed an indicated statin.3 Aspirin was continued or discontinued according to patient preference after the personalized risk-benefit discussion.

For patients with a clinical indication for aspirin use other than ASCVD (eg, atrial fibrillation not on anticoagulation, venous thromboembolism prophylaxis, carotid artery disease), CPPs documented their assessment and when appropriate deferred to the PCP for consideration of stopping aspirin. For patients with undocumented ASCVD, CPPs added their ASCVD history to their problem list and aspirin was continued. PCPs were notified by alert when aspirin was discontinued and when patients could not be reached by telephone.

presented a review of recent guideline updates and supporting literature at 2 online staff meetings. The education sessions lasted about 10 minutes and were presented to PCPs across 3 community-based outpatient clinics. An estimated 40 minutes were spent creating the PowerPoint education materials, seeking feedback, making edits, and answering questions or emails from PCPs after the presentation. During the presentation, pharmacists encouraged PCPs to discontinue aspirin (active VA prescriptions and reported over-the-counter use) for primary prevention of ASCVD in patients aged ≥ 70 years during their upcoming appointments and consider risk factors recommended by the ACC/AHA guidelines when applicable. PCPs were notified that CPPs planned to start a population review for discontinuing active VA aspirin prescriptions on December 1, 2022. The primary endpoint and secondary endpoints were analyzed using descriptive statistics. All data were analyzed using Microsoft Excel.

Results

A total of 868 patients aged ≥ 70 years with active prescriptions for aspirin were identified on December 1, 2022. After applying inclusion and exclusion criteria for the pharmacist population review, 224 patients were included for cohort final analysis (Figure). All 868 patients were eligible for the CPP intervention. Primary reasons for exclusion from the CPP population included over-thecounter aspirin and a history of ASCVD in the patient’s problem list. All patients were male, with a mean (SD) age of 75 (4.4) years (Table 1). Most patients were prescribed aspirin, 81 mg daily (n = 220; 98%).

The direct CPP deprescribing intervention resulted in 2 aspirin prescriptions discontinued per hour of pharmacist time and 67 aspirin prescriptions discontinued per hour of pharmacist time via the PCP education intervention. CPPs discontinued 66 aspirin orders in the 12 weeks before the PCP education sessions. A total of 230 aspirin prescriptions were discontinued in the 12 weeks following the PCP education sessions, with 97 discontinued directly by CPPs and 133 discontinued by PCPs. The PCP education session yielded an additional 67 discontinued aspirin orders compared with the 12 weeks before the education sessions (Table 2).

The CPP direct deprescribing intervention took about 48.3 hours, accounting for health record review and time interacting with patients. The PCP education intervention took about 60 minutes, which included time for preparing and delivering education materials (Table 3). CPP deprescribing encounter types, interventions, and related subcategories, and other identified indications to continue aspirin are listed in Table 4.

Discussion

Compared with direct deprescribing by pharmacists, the PCP education intervention was more efficient based on number of aspirin orders discontinued by pharmacist time. PCPs discontinued twice as many aspirin prescriptions in the 12 weeks after pharmacist-led education compared with the 12 weeks before.

Patients were primarily contacted by telephone (73%) for deprescribing. Among the 163 patients reached by phone and encouraged to discontinue aspirin, 97 patients (60%) accepted the recommendation, which was similar to the acceptance rates found in the literature (48% to 55%).14,18 Although many veterans continued taking aspirin (78%), most had indications for its continued use, such as a history of ASCVD, atrial fibrillation without anticoagulation, and carotid artery stenosis, and complex comorbidities that required further discussion with their PCP. Less common uses for aspirin were identified through CPRS review or patient reports included cerebral small vessel disease without history of ASCVD, subclavian artery stenosis, thrombocytosis, bioprosthetic valve replacement, giant cell arteritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and prevention of second eye involvement of ischemic optic neuropathy.