User login

Commentary: Medical educators must do more to prevent physician suicides

while describing two exemplars at providing physicians with mental health support, in a recently published commentary.

“I want to call attention to the gap between what educators think and say is available, in terms of mental health support, and what trainees experience,” Dr. Poorman said in a statement on her piece in the Journal of Patient Safety and Risk Management. She shared the results of an anonymous depression survey of interns, which showed that 41.8% of participants screened positive for depression. Dr. Poorman also provided statistics on physician suicide, including that at least 66 residents killed themselves between 2000 and 2014, according to ACGME, and that another source estimated that 300-400 physician suicide deaths occur annually.

“When it comes to mental illness and suicide, we are all at risk, but we too often lacked compassion in the way we approach our colleagues. We have lacked the courage to fight the stigma that is killing us. We have not asked whether our unwillingness to reform medical training has eroded the empathy of generations of doctors. We have not done enough to fight medical boards that ask doctors about mental health diagnoses in the same way they ask if we have domestic violence charges,” wrote Dr. Poorman, who practices at a University of Washington neighborhood clinic in Kent.

“A focus on the occupational risks we face would shift us away from ‘wellness’ and ‘resilience,’ and place the onus on schools, training programs, and hospitals to do better for providers and patients,” continued Dr. Poorman, who serves on the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News.

She commended Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, and Stanford (Calif.) University’s divisions of general surgery for providing “rigorously confidential mental health support” through a wellness and suicide prevention program for residents and faculty, and a wellness program for residents “that emphasizes relationships, structural support, and psychological safety,” respectively. Dr. Poorman also applauded both for speaking openly about physician suicides.

SOURCE: Poorman E. J Patient Saf Risk Manag. 2019 Aug 5. doi: 10.1177/2516043519866993.

This article was updated 8/5/19.

while describing two exemplars at providing physicians with mental health support, in a recently published commentary.

“I want to call attention to the gap between what educators think and say is available, in terms of mental health support, and what trainees experience,” Dr. Poorman said in a statement on her piece in the Journal of Patient Safety and Risk Management. She shared the results of an anonymous depression survey of interns, which showed that 41.8% of participants screened positive for depression. Dr. Poorman also provided statistics on physician suicide, including that at least 66 residents killed themselves between 2000 and 2014, according to ACGME, and that another source estimated that 300-400 physician suicide deaths occur annually.

“When it comes to mental illness and suicide, we are all at risk, but we too often lacked compassion in the way we approach our colleagues. We have lacked the courage to fight the stigma that is killing us. We have not asked whether our unwillingness to reform medical training has eroded the empathy of generations of doctors. We have not done enough to fight medical boards that ask doctors about mental health diagnoses in the same way they ask if we have domestic violence charges,” wrote Dr. Poorman, who practices at a University of Washington neighborhood clinic in Kent.

“A focus on the occupational risks we face would shift us away from ‘wellness’ and ‘resilience,’ and place the onus on schools, training programs, and hospitals to do better for providers and patients,” continued Dr. Poorman, who serves on the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News.

She commended Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, and Stanford (Calif.) University’s divisions of general surgery for providing “rigorously confidential mental health support” through a wellness and suicide prevention program for residents and faculty, and a wellness program for residents “that emphasizes relationships, structural support, and psychological safety,” respectively. Dr. Poorman also applauded both for speaking openly about physician suicides.

SOURCE: Poorman E. J Patient Saf Risk Manag. 2019 Aug 5. doi: 10.1177/2516043519866993.

This article was updated 8/5/19.

while describing two exemplars at providing physicians with mental health support, in a recently published commentary.

“I want to call attention to the gap between what educators think and say is available, in terms of mental health support, and what trainees experience,” Dr. Poorman said in a statement on her piece in the Journal of Patient Safety and Risk Management. She shared the results of an anonymous depression survey of interns, which showed that 41.8% of participants screened positive for depression. Dr. Poorman also provided statistics on physician suicide, including that at least 66 residents killed themselves between 2000 and 2014, according to ACGME, and that another source estimated that 300-400 physician suicide deaths occur annually.

“When it comes to mental illness and suicide, we are all at risk, but we too often lacked compassion in the way we approach our colleagues. We have lacked the courage to fight the stigma that is killing us. We have not asked whether our unwillingness to reform medical training has eroded the empathy of generations of doctors. We have not done enough to fight medical boards that ask doctors about mental health diagnoses in the same way they ask if we have domestic violence charges,” wrote Dr. Poorman, who practices at a University of Washington neighborhood clinic in Kent.

“A focus on the occupational risks we face would shift us away from ‘wellness’ and ‘resilience,’ and place the onus on schools, training programs, and hospitals to do better for providers and patients,” continued Dr. Poorman, who serves on the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News.

She commended Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, and Stanford (Calif.) University’s divisions of general surgery for providing “rigorously confidential mental health support” through a wellness and suicide prevention program for residents and faculty, and a wellness program for residents “that emphasizes relationships, structural support, and psychological safety,” respectively. Dr. Poorman also applauded both for speaking openly about physician suicides.

SOURCE: Poorman E. J Patient Saf Risk Manag. 2019 Aug 5. doi: 10.1177/2516043519866993.

This article was updated 8/5/19.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF PATIENT SAFETY AND RISK MANAGEMENT

The 10 Commandments of Internships

Patients concerned about clinician burnout

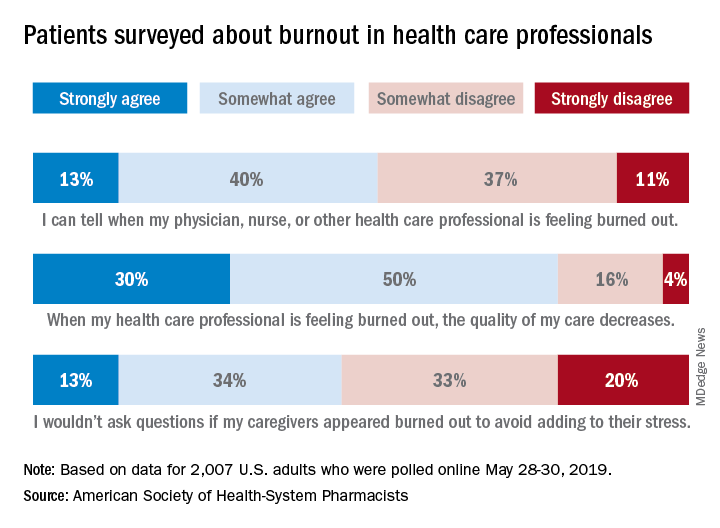

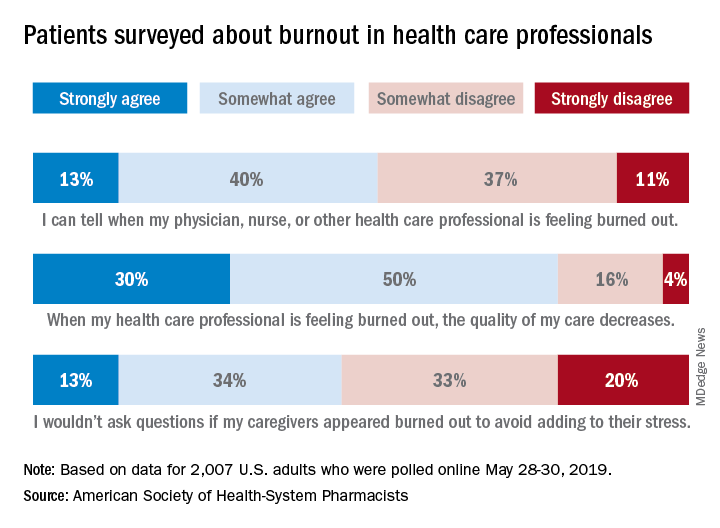

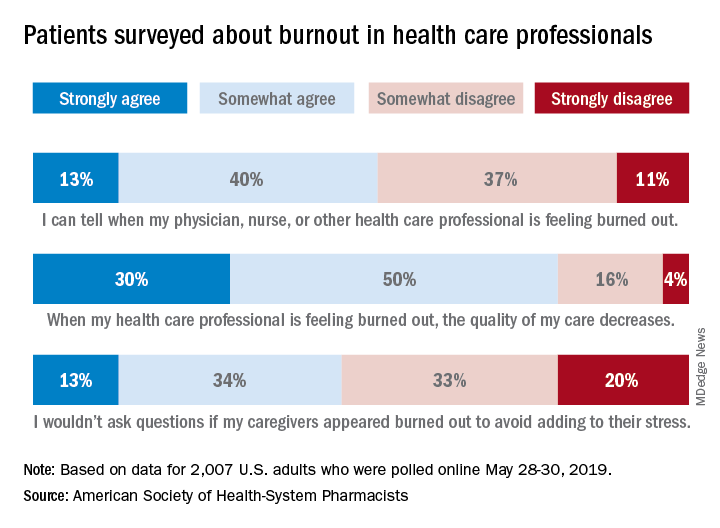

Almost three-quarters of Americans are concerned about burnout among health care professionals, according to the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists.

The public is aware “that burnout among pharmacists, physicians, nurses, and other professionals can lead to impaired attention and decreased functioning that threatens to cause medical errors and reduce safety,” the ASHP said when it released data from a survey conducted May 28-30, 2019, by the Harris Poll.

Those data show that 23% of respondents were very concerned and 51% were somewhat concerned about burnout among health care providers. Just over half (53%) of the 2,007 adults involved said that they could tell when a provider was burned out, suggesting that health care professionals “may be conveying signs of burnout to their patients without knowing it,” the society noted.

A majority of respondents (80%) felt that the quality of their care was affected when their physician, nurse, pharmacist, or other health care professional was burned out, and almost half (47%) said that they would avoid asking questions if their provider appeared burned out because they wouldn’t want to add to that person’s stress, the ASHP said.

“A healthy and thriving clinician workforce is essential to ensure optimal patient health outcomes and safety,” said Paul W. Abramowitz, PharmD, chief executive officer of the ASHP. “Within the healthcare industry, we are working to help build a culture of resilience and well-being to ensure that no patient or clinician is harmed due to burnout; but it takes a concerted effort from all entities involved – providers and healthcare organizations.”

Almost three-quarters of Americans are concerned about burnout among health care professionals, according to the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists.

The public is aware “that burnout among pharmacists, physicians, nurses, and other professionals can lead to impaired attention and decreased functioning that threatens to cause medical errors and reduce safety,” the ASHP said when it released data from a survey conducted May 28-30, 2019, by the Harris Poll.

Those data show that 23% of respondents were very concerned and 51% were somewhat concerned about burnout among health care providers. Just over half (53%) of the 2,007 adults involved said that they could tell when a provider was burned out, suggesting that health care professionals “may be conveying signs of burnout to their patients without knowing it,” the society noted.

A majority of respondents (80%) felt that the quality of their care was affected when their physician, nurse, pharmacist, or other health care professional was burned out, and almost half (47%) said that they would avoid asking questions if their provider appeared burned out because they wouldn’t want to add to that person’s stress, the ASHP said.

“A healthy and thriving clinician workforce is essential to ensure optimal patient health outcomes and safety,” said Paul W. Abramowitz, PharmD, chief executive officer of the ASHP. “Within the healthcare industry, we are working to help build a culture of resilience and well-being to ensure that no patient or clinician is harmed due to burnout; but it takes a concerted effort from all entities involved – providers and healthcare organizations.”

Almost three-quarters of Americans are concerned about burnout among health care professionals, according to the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists.

The public is aware “that burnout among pharmacists, physicians, nurses, and other professionals can lead to impaired attention and decreased functioning that threatens to cause medical errors and reduce safety,” the ASHP said when it released data from a survey conducted May 28-30, 2019, by the Harris Poll.

Those data show that 23% of respondents were very concerned and 51% were somewhat concerned about burnout among health care providers. Just over half (53%) of the 2,007 adults involved said that they could tell when a provider was burned out, suggesting that health care professionals “may be conveying signs of burnout to their patients without knowing it,” the society noted.

A majority of respondents (80%) felt that the quality of their care was affected when their physician, nurse, pharmacist, or other health care professional was burned out, and almost half (47%) said that they would avoid asking questions if their provider appeared burned out because they wouldn’t want to add to that person’s stress, the ASHP said.

“A healthy and thriving clinician workforce is essential to ensure optimal patient health outcomes and safety,” said Paul W. Abramowitz, PharmD, chief executive officer of the ASHP. “Within the healthcare industry, we are working to help build a culture of resilience and well-being to ensure that no patient or clinician is harmed due to burnout; but it takes a concerted effort from all entities involved – providers and healthcare organizations.”

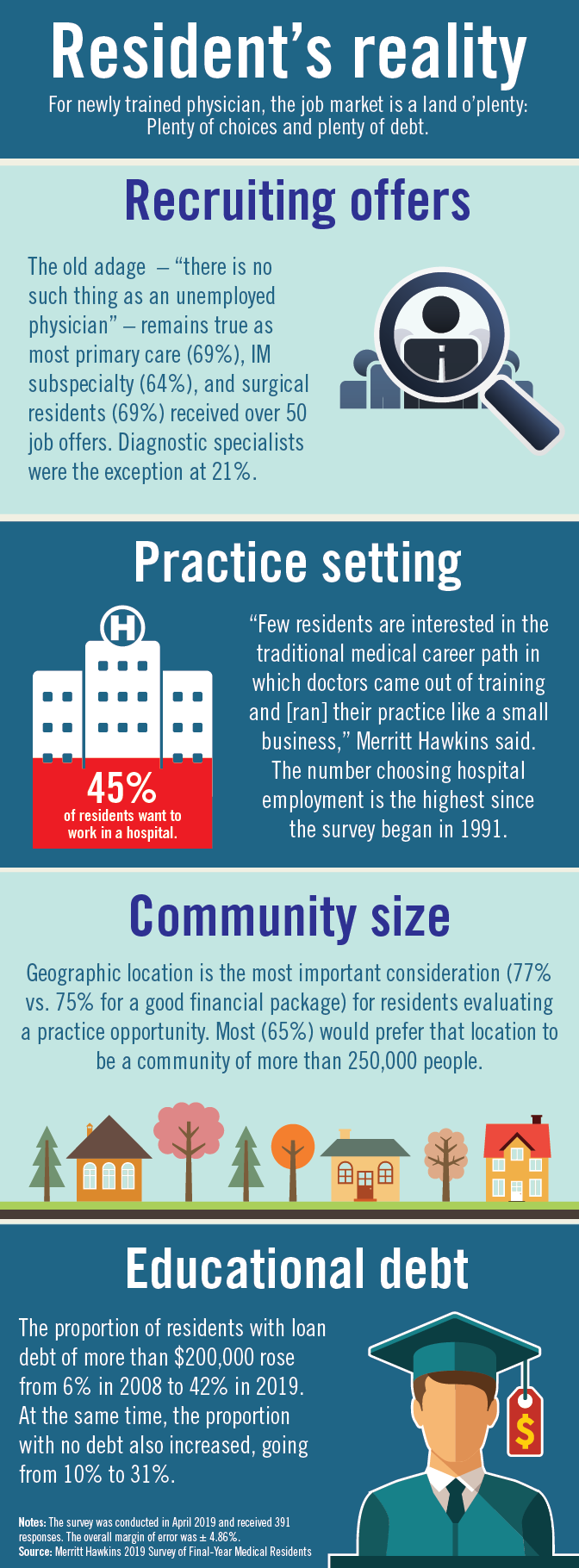

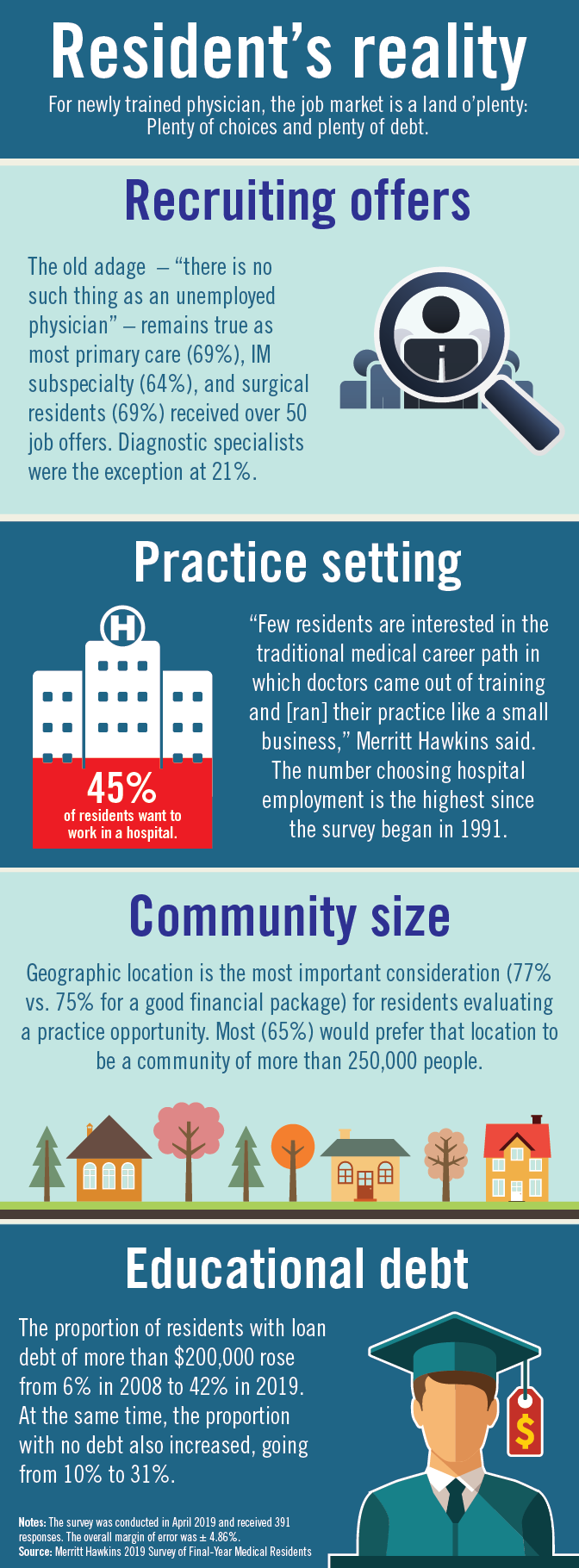

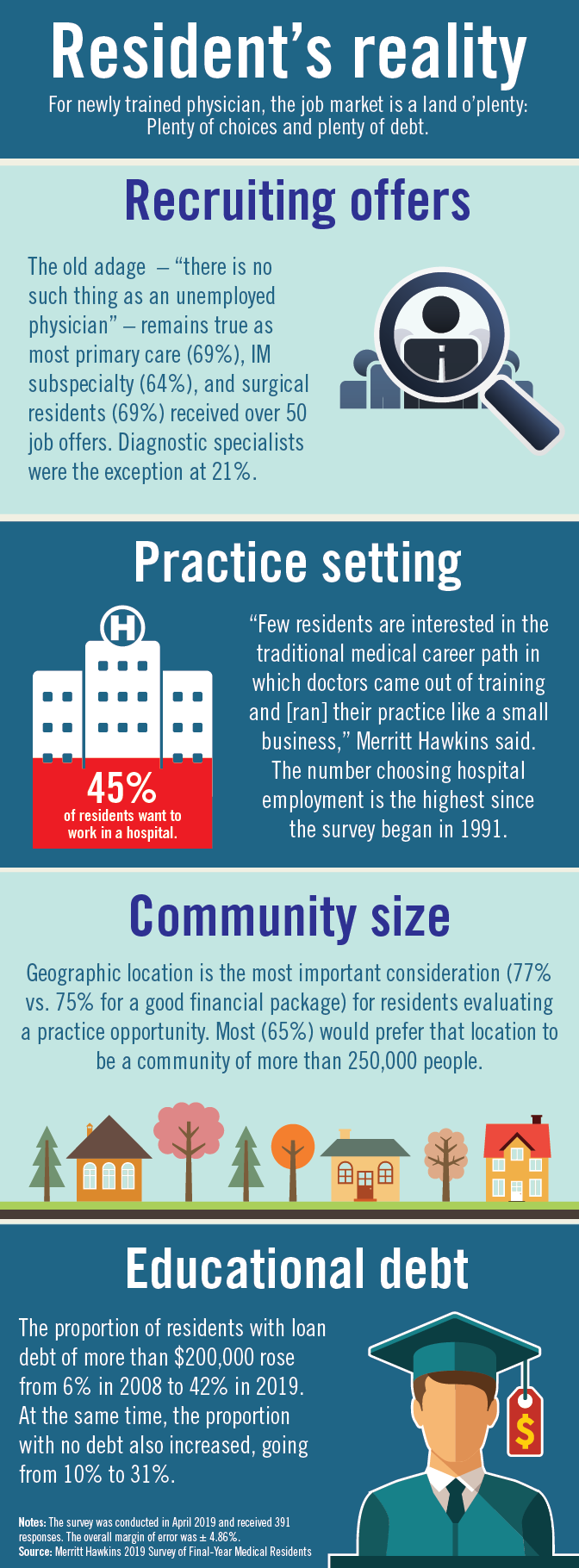

Residents are drowning in job offers – and debt

Physician search firm Merritt Hawkins did – actually, they heard from 391 residents – and 64% said that they had been contacted too many times by recruiters.

“Physicians coming out of training are being recruited like blue-chip athletes,” Travis Singleton, executive vice president of Merritt Hawkins, said in a statement. “There are simply not enough new doctors to go around.”

Merritt Hawkins asked physicians in their final year of residency about career choices, practice plans, and finances. Most said that they would prefer to be employed by a hospital or group practice, and a majority want to practice in a community with a population of 250,000 or more. More than half of the residents owed over $150,000 in student loans, but there were considerable debt differences between U.S. and international medical graduates.

The specialty distribution of respondents was 50% primary care, 30% internal medicine subspecialty/other, 15% surgical, and 5% diagnostic. About three-quarters were U.S. graduates and one-quarter of the residents were international medical graduates in this latest survey in a series that has been conducted periodically since 1991.

The survey was conducted in April 2018.

Physician search firm Merritt Hawkins did – actually, they heard from 391 residents – and 64% said that they had been contacted too many times by recruiters.

“Physicians coming out of training are being recruited like blue-chip athletes,” Travis Singleton, executive vice president of Merritt Hawkins, said in a statement. “There are simply not enough new doctors to go around.”

Merritt Hawkins asked physicians in their final year of residency about career choices, practice plans, and finances. Most said that they would prefer to be employed by a hospital or group practice, and a majority want to practice in a community with a population of 250,000 or more. More than half of the residents owed over $150,000 in student loans, but there were considerable debt differences between U.S. and international medical graduates.

The specialty distribution of respondents was 50% primary care, 30% internal medicine subspecialty/other, 15% surgical, and 5% diagnostic. About three-quarters were U.S. graduates and one-quarter of the residents were international medical graduates in this latest survey in a series that has been conducted periodically since 1991.

The survey was conducted in April 2018.

Physician search firm Merritt Hawkins did – actually, they heard from 391 residents – and 64% said that they had been contacted too many times by recruiters.

“Physicians coming out of training are being recruited like blue-chip athletes,” Travis Singleton, executive vice president of Merritt Hawkins, said in a statement. “There are simply not enough new doctors to go around.”

Merritt Hawkins asked physicians in their final year of residency about career choices, practice plans, and finances. Most said that they would prefer to be employed by a hospital or group practice, and a majority want to practice in a community with a population of 250,000 or more. More than half of the residents owed over $150,000 in student loans, but there were considerable debt differences between U.S. and international medical graduates.

The specialty distribution of respondents was 50% primary care, 30% internal medicine subspecialty/other, 15% surgical, and 5% diagnostic. About three-quarters were U.S. graduates and one-quarter of the residents were international medical graduates in this latest survey in a series that has been conducted periodically since 1991.

The survey was conducted in April 2018.

Patient-centered care in clinic

Almost 30 years ago a young woman made an appointment to see me. I had just started my internal medicine practice and almost all the patients who saw me were new to me. I assumed she was establishing care with me. Her first words to me were “Hello Dr. Paauw, I would like to interview you to see if you will be a good fit as my doctor.” We talked for the 40-minute appointment time. I asked her about her health, her life, and what she wanted out of both. We shared with each other that we both were parents of young children. When the appointment was over, she said she would really like for me to be her doctor. She told me that the main thing she appreciated about me was that I listened, and that her previous physician never sat down at her appointments and often had his hand on the door handle for much of the visit. Physicians and patients both agree that compassionate care is essential for good patient care, yet about half of patients and 60% of doctors believe it is lacking in our medical system.1

Remember the golden first minutes

I often start by asking the patient to give me an update on how they are doing. This lets me know what is important to them. I do not touch the computer until after this initial check-in.

Use the computer as a bond to strengthen your patient relationship

Many studies have shown patients find the computer gets between the doctor and patient. It is especially problematic if it breaks eye contact with the patient. People are less likely to share scary, sensitive, or embarrassing information if someone is looking at a computer and typing. As you look up tests, radiology reports, or consultant notes, let the patient in on what you are doing. Explain why you are searching in the record, and if it helps make an important point, show your findings to the patient. Offer to print out results, so they have something to carry with them.

Explain what you are looking for and what you find on the physical exam

Being a patient is scary. We all want reassurance that our fears are not true. When you find normal findings on exam, share those with the patient. Hearing “your heart sounds good, your pulses are strong” really helps patients. Explaining what we are doing when we examine is also helpful. Explain why you are feeling for lymph nodes in the neck, why we percuss the abdomen. Patients are often fascinated by getting a window into how we are thinking. I usually have medical students with me, which offers another avenue to explaining the how and why behind the exam. In asking and explaining to students, the patient is also taught why we do what we do.

Make sure that we cover what they are afraid of, not just what their symptom is

Patients come in not just to get symptom relief but to rest their mind from their fears of what it could be. I find it helpful to ask the patient what they think is the cause of the problem, or if they are worried about any specific diagnosis. With certain symptoms this is particularly important (for example, headaches, fatigue, or abdominal pain).

None of these suggestions are easy to do in busy, time-pressured clinic visits. I have found though that when patients feel cared about, listened to and can have their fears addressed they value our advice more, and less time is needed to negotiate the plan, as it has been developed together.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

Reference

Lown BA et al. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011 Sep;30(9):1772-8.

Almost 30 years ago a young woman made an appointment to see me. I had just started my internal medicine practice and almost all the patients who saw me were new to me. I assumed she was establishing care with me. Her first words to me were “Hello Dr. Paauw, I would like to interview you to see if you will be a good fit as my doctor.” We talked for the 40-minute appointment time. I asked her about her health, her life, and what she wanted out of both. We shared with each other that we both were parents of young children. When the appointment was over, she said she would really like for me to be her doctor. She told me that the main thing she appreciated about me was that I listened, and that her previous physician never sat down at her appointments and often had his hand on the door handle for much of the visit. Physicians and patients both agree that compassionate care is essential for good patient care, yet about half of patients and 60% of doctors believe it is lacking in our medical system.1

Remember the golden first minutes

I often start by asking the patient to give me an update on how they are doing. This lets me know what is important to them. I do not touch the computer until after this initial check-in.

Use the computer as a bond to strengthen your patient relationship

Many studies have shown patients find the computer gets between the doctor and patient. It is especially problematic if it breaks eye contact with the patient. People are less likely to share scary, sensitive, or embarrassing information if someone is looking at a computer and typing. As you look up tests, radiology reports, or consultant notes, let the patient in on what you are doing. Explain why you are searching in the record, and if it helps make an important point, show your findings to the patient. Offer to print out results, so they have something to carry with them.

Explain what you are looking for and what you find on the physical exam

Being a patient is scary. We all want reassurance that our fears are not true. When you find normal findings on exam, share those with the patient. Hearing “your heart sounds good, your pulses are strong” really helps patients. Explaining what we are doing when we examine is also helpful. Explain why you are feeling for lymph nodes in the neck, why we percuss the abdomen. Patients are often fascinated by getting a window into how we are thinking. I usually have medical students with me, which offers another avenue to explaining the how and why behind the exam. In asking and explaining to students, the patient is also taught why we do what we do.

Make sure that we cover what they are afraid of, not just what their symptom is

Patients come in not just to get symptom relief but to rest their mind from their fears of what it could be. I find it helpful to ask the patient what they think is the cause of the problem, or if they are worried about any specific diagnosis. With certain symptoms this is particularly important (for example, headaches, fatigue, or abdominal pain).

None of these suggestions are easy to do in busy, time-pressured clinic visits. I have found though that when patients feel cared about, listened to and can have their fears addressed they value our advice more, and less time is needed to negotiate the plan, as it has been developed together.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

Reference

Lown BA et al. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011 Sep;30(9):1772-8.

Almost 30 years ago a young woman made an appointment to see me. I had just started my internal medicine practice and almost all the patients who saw me were new to me. I assumed she was establishing care with me. Her first words to me were “Hello Dr. Paauw, I would like to interview you to see if you will be a good fit as my doctor.” We talked for the 40-minute appointment time. I asked her about her health, her life, and what she wanted out of both. We shared with each other that we both were parents of young children. When the appointment was over, she said she would really like for me to be her doctor. She told me that the main thing she appreciated about me was that I listened, and that her previous physician never sat down at her appointments and often had his hand on the door handle for much of the visit. Physicians and patients both agree that compassionate care is essential for good patient care, yet about half of patients and 60% of doctors believe it is lacking in our medical system.1

Remember the golden first minutes

I often start by asking the patient to give me an update on how they are doing. This lets me know what is important to them. I do not touch the computer until after this initial check-in.

Use the computer as a bond to strengthen your patient relationship

Many studies have shown patients find the computer gets between the doctor and patient. It is especially problematic if it breaks eye contact with the patient. People are less likely to share scary, sensitive, or embarrassing information if someone is looking at a computer and typing. As you look up tests, radiology reports, or consultant notes, let the patient in on what you are doing. Explain why you are searching in the record, and if it helps make an important point, show your findings to the patient. Offer to print out results, so they have something to carry with them.

Explain what you are looking for and what you find on the physical exam

Being a patient is scary. We all want reassurance that our fears are not true. When you find normal findings on exam, share those with the patient. Hearing “your heart sounds good, your pulses are strong” really helps patients. Explaining what we are doing when we examine is also helpful. Explain why you are feeling for lymph nodes in the neck, why we percuss the abdomen. Patients are often fascinated by getting a window into how we are thinking. I usually have medical students with me, which offers another avenue to explaining the how and why behind the exam. In asking and explaining to students, the patient is also taught why we do what we do.

Make sure that we cover what they are afraid of, not just what their symptom is

Patients come in not just to get symptom relief but to rest their mind from their fears of what it could be. I find it helpful to ask the patient what they think is the cause of the problem, or if they are worried about any specific diagnosis. With certain symptoms this is particularly important (for example, headaches, fatigue, or abdominal pain).

None of these suggestions are easy to do in busy, time-pressured clinic visits. I have found though that when patients feel cared about, listened to and can have their fears addressed they value our advice more, and less time is needed to negotiate the plan, as it has been developed together.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

Reference

Lown BA et al. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011 Sep;30(9):1772-8.

Physicians discuss bringing cultural humility to medicine

PHILADELPHIA – during a panel discussion moderated by Sarah Candler, MD, an internist in Houston.

Dr. Candler, former chair, Council of Resident and Fellow Members, Board of Regents, American College of Physicians, began the discussion by asking Dr. DeLisser, to describe his role in teaching medical students about the social determinants of health, at the annual Internal Medicine meeting of the ACP.

Dr. DeLisser, associate dean for professionalism and humanism at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said he focuses on a number of issues, including social medicine, cultural competency, and cultural humility.

“We look at health care disparities and try to do a lot of innovation around service learning that will bring our students into the community, one to learn about these determinants but more importantly to be able to see how these issues can be addressed both on a provider level but also on a more structural systemic level,” he noted.

Dr. Poorman, an internist at the University of Washington, later discussed the importance of practicing cultural humility as it related to her experience providing care to migrant workers while she was a medical school student.

Dr. Candler, an internist in Houston, concluded the discussion by describing some of the ACP’s newest resources designed to address the social determinants of health for specific groups of patients.

The full panel discussion was recorded as a video.

PHILADELPHIA – during a panel discussion moderated by Sarah Candler, MD, an internist in Houston.

Dr. Candler, former chair, Council of Resident and Fellow Members, Board of Regents, American College of Physicians, began the discussion by asking Dr. DeLisser, to describe his role in teaching medical students about the social determinants of health, at the annual Internal Medicine meeting of the ACP.

Dr. DeLisser, associate dean for professionalism and humanism at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said he focuses on a number of issues, including social medicine, cultural competency, and cultural humility.

“We look at health care disparities and try to do a lot of innovation around service learning that will bring our students into the community, one to learn about these determinants but more importantly to be able to see how these issues can be addressed both on a provider level but also on a more structural systemic level,” he noted.

Dr. Poorman, an internist at the University of Washington, later discussed the importance of practicing cultural humility as it related to her experience providing care to migrant workers while she was a medical school student.

Dr. Candler, an internist in Houston, concluded the discussion by describing some of the ACP’s newest resources designed to address the social determinants of health for specific groups of patients.

The full panel discussion was recorded as a video.

PHILADELPHIA – during a panel discussion moderated by Sarah Candler, MD, an internist in Houston.

Dr. Candler, former chair, Council of Resident and Fellow Members, Board of Regents, American College of Physicians, began the discussion by asking Dr. DeLisser, to describe his role in teaching medical students about the social determinants of health, at the annual Internal Medicine meeting of the ACP.

Dr. DeLisser, associate dean for professionalism and humanism at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said he focuses on a number of issues, including social medicine, cultural competency, and cultural humility.

“We look at health care disparities and try to do a lot of innovation around service learning that will bring our students into the community, one to learn about these determinants but more importantly to be able to see how these issues can be addressed both on a provider level but also on a more structural systemic level,” he noted.

Dr. Poorman, an internist at the University of Washington, later discussed the importance of practicing cultural humility as it related to her experience providing care to migrant workers while she was a medical school student.

Dr. Candler, an internist in Houston, concluded the discussion by describing some of the ACP’s newest resources designed to address the social determinants of health for specific groups of patients.

The full panel discussion was recorded as a video.

REPORTING FROM INTERNAL MEDICINE 2019

Volunteerism: How and why to do it, according to Dr. Eileen Barrett

PHILADELPHIA –

“I think what we get out of it is the feeling of our commitment to our sense of purpose and mission, and you just feel great when you’re giving, and then you meet these really remarkable people who do really, really remarkable things. ... It’s tremendously inspiring,” Dr. Barrett said in a video interview at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians. She is a hospitalist at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, and serves on the ACP Board of Regents.

In addition, Dr. Barrett has done disaster relief work in West Africa, provided patient care to refugees in a hospital on the Thailand side of the Thailand-Myanmar border, and even helped bring organization to a public radio station in rural New Mexico.

She also described some opportunities available to internists who are trying to get their feet wet in volunteering that are available through the organizations, Health Volunteers Overseas and the Maven Project.

PHILADELPHIA –

“I think what we get out of it is the feeling of our commitment to our sense of purpose and mission, and you just feel great when you’re giving, and then you meet these really remarkable people who do really, really remarkable things. ... It’s tremendously inspiring,” Dr. Barrett said in a video interview at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians. She is a hospitalist at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, and serves on the ACP Board of Regents.

In addition, Dr. Barrett has done disaster relief work in West Africa, provided patient care to refugees in a hospital on the Thailand side of the Thailand-Myanmar border, and even helped bring organization to a public radio station in rural New Mexico.

She also described some opportunities available to internists who are trying to get their feet wet in volunteering that are available through the organizations, Health Volunteers Overseas and the Maven Project.

PHILADELPHIA –

“I think what we get out of it is the feeling of our commitment to our sense of purpose and mission, and you just feel great when you’re giving, and then you meet these really remarkable people who do really, really remarkable things. ... It’s tremendously inspiring,” Dr. Barrett said in a video interview at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians. She is a hospitalist at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, and serves on the ACP Board of Regents.

In addition, Dr. Barrett has done disaster relief work in West Africa, provided patient care to refugees in a hospital on the Thailand side of the Thailand-Myanmar border, and even helped bring organization to a public radio station in rural New Mexico.

She also described some opportunities available to internists who are trying to get their feet wet in volunteering that are available through the organizations, Health Volunteers Overseas and the Maven Project.

REPORTING FROM INTERNAL MEDICINE 2019

ACP launches program to better implement QI projects

PHILADELPHIA – .

The program includes 12 months of virtual coaching for a cost, and free online module training, according to Daisy Smith, MD, FACP, who spoke at a press conference at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians.

Dr. Smith, the ACP’s vice president of clinical programs, discussed additional aspects of ACP Advance with Selam Wubu, director of the ACP’s Center for Quality, in a video interview.

“We launched ACP Advance to engage physicians and their teams [and] empower them to engage and implement quality improvement that results in meaningful improvement for them and their patients,” Ms. Wubu said.

Dr. Smith and Ms. Wubu have no relevant disclosures.

PHILADELPHIA – .

The program includes 12 months of virtual coaching for a cost, and free online module training, according to Daisy Smith, MD, FACP, who spoke at a press conference at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians.

Dr. Smith, the ACP’s vice president of clinical programs, discussed additional aspects of ACP Advance with Selam Wubu, director of the ACP’s Center for Quality, in a video interview.

“We launched ACP Advance to engage physicians and their teams [and] empower them to engage and implement quality improvement that results in meaningful improvement for them and their patients,” Ms. Wubu said.

Dr. Smith and Ms. Wubu have no relevant disclosures.

PHILADELPHIA – .

The program includes 12 months of virtual coaching for a cost, and free online module training, according to Daisy Smith, MD, FACP, who spoke at a press conference at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians.

Dr. Smith, the ACP’s vice president of clinical programs, discussed additional aspects of ACP Advance with Selam Wubu, director of the ACP’s Center for Quality, in a video interview.

“We launched ACP Advance to engage physicians and their teams [and] empower them to engage and implement quality improvement that results in meaningful improvement for them and their patients,” Ms. Wubu said.

Dr. Smith and Ms. Wubu have no relevant disclosures.

REPORTING FROM INTERNAL MEDICINE 2019

Groups of physicians produce more accurate diagnoses than individuals

Groups of physicians and trainees diagnose clinical cases with more accuracy than individuals, according to a study of solo and aggregate diagnoses collected through an online medical teaching platform.

“These findings suggest that using the concept of collective intelligence to pool many physicians’ diagnoses could be a scalable approach to improve diagnostic accuracy,” wrote lead author Michael L. Barnett, MD, of Harvard University in Boston and his coauthors, adding that “groups of all sizes outperformed individual subspecialists on cases in their own subspecialty.” The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

This cross-sectional study examined 1,572 cases solved within the Human Diagnosis Project (Human Dx) system, an online platform for authoring and diagnosing teaching cases. The system presents real-life cases from clinical practices and asks respondents to generate ranked differential diagnoses. Cases are tagged for specialties based on both intended diagnoses and the top diagnoses chosen by respondents. All cases used in this study were authored between May 7, 2014, and October 5, 2016, and had 10 or more respondents.

Of the 2,069 attending physicians and fellows, residents, and medical students (users) who solved cases within the Human Dx system, 1,452 (70.2%) were trained in internal medicine, 1,228 (59.4%) were residents or fellows, 431 (20.8%) were attending physicians, and 410 (19.8%) were medical students. To create a collective differential, Dr. Barnett and his colleagues aggregated the responses of up to nine participants via a weighted combination of each clinician’s top three diagnoses, which they dubbed “collective intelligence.”

The diagnostic accuracy for groups of nine was 85.6% (95% confidence interval, 83.9%-87.4%), compared with individual users at 62.5% (95% CI, 60.1%-64.9%), a difference of 23% (95% CI, 14.9%-31.2%; P less than .001). Groups of five saw a 17.8% difference in accuracy versus an individual (95% CI, 14.0%-21.6%; P less than .001), compared with 12.5% for groups of two (95% CI, 9.3%-15.8%; P less than .001). Taken together, these seem to underline an association between larger groups and increased accuracy.

Individual specialists solved cases in their particular areas with a diagnostic accuracy of 66.3% (95% CI, 59.1%-73.5%), compared with nonmatched specialty accuracy of 63.9% (95% CI, 56.6%-71.2%). Groups, however, outperformed specialists across the board: 77.7% accuracy for a group of 2 (95% CI, 70.1%-84.6%; P less than .001) and 85.5% accuracy for a group of 9 (95% CI, 75.1%-95.9%; P less than .001).

The coauthors shared the limitations of their study, including the possibility that the users who contributed these cases to Human Dx may not be representative of the medical community as a whole. They also noted that, while their 431 attending physicians constituted the “largest number ... to date in a study of collective intelligence,” trainees still made up almost 80% of users. In addition, they acknowledged that Human Dx was not designed to generate collective diagnoses nor assess collective intelligence; another platform created with that ability in mind may have returned different results. Finally, they were unable to assess how exactly greater accuracy would have been linked to changes in treatment, calling it “an important question for future work.”

The authors disclosed several conflicts of interest. One doctor reported receiving personal fees from Greylock McKinnon Associates; another reported receiving personal fees from the Human Diagnosis Project and serving as their nonprofit director during the study. A third doctor reported consulting for a company that makes patient-safety monitoring systems and receiving compensation from a not-for-profit incubator, along with having equity in three medical data and software companies.

SOURCE: Barnett ML et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Mar 1. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.0096.

Although this study from Barnett et al. is not the silver bullet for misdiagnosis, better understanding why physicians make mistakes is a necessary and valuable undertaking, according to Stephan D. Fihn, MD, of the University of Washington, Seattle.

In the past, the “correct” diagnostic approach included making a list of potential diagnoses and systematically ruling them out one by one, a process conveyed via clinicopathologic conferences in teaching hospitals. These, Dr. Fihn recalled, lasted until medical educators recognized them as “more ... theatrical events than meaningful teaching exercises” and understood that master clinicians did not actually think in the manner this approach modeled. Since then, the maturation of cognitive psychology and “a growing literature” have made diagnostic error seem like a common, sometimes unavoidable element of being human.

What can be done? Computers have always been a possibility, but “none have achieved the breadth of content and accuracy necessary to be adopted to any great extent,” Dr. Fihn wrote. Another option is crowdsourcing, as described in this study from Barnett and colleagues. Their approach has its pitfalls: A 62.5% level of diagnostic accuracy from individuals is not very high, which suggests either difficult cases or a preponderance of inexperienced clinicians who may benefit from collective intelligence even more. Regardless, he stated, “clinicians need to be cognizant of their own inherent limitations and acknowledge fallibility”; being humble and willing to seek advice “remain important, albeit imperfect, antidotes to misdiagnosis.”

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Mar 1. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.1071 ). No conflicts of interest were reported.

Although this study from Barnett et al. is not the silver bullet for misdiagnosis, better understanding why physicians make mistakes is a necessary and valuable undertaking, according to Stephan D. Fihn, MD, of the University of Washington, Seattle.

In the past, the “correct” diagnostic approach included making a list of potential diagnoses and systematically ruling them out one by one, a process conveyed via clinicopathologic conferences in teaching hospitals. These, Dr. Fihn recalled, lasted until medical educators recognized them as “more ... theatrical events than meaningful teaching exercises” and understood that master clinicians did not actually think in the manner this approach modeled. Since then, the maturation of cognitive psychology and “a growing literature” have made diagnostic error seem like a common, sometimes unavoidable element of being human.

What can be done? Computers have always been a possibility, but “none have achieved the breadth of content and accuracy necessary to be adopted to any great extent,” Dr. Fihn wrote. Another option is crowdsourcing, as described in this study from Barnett and colleagues. Their approach has its pitfalls: A 62.5% level of diagnostic accuracy from individuals is not very high, which suggests either difficult cases or a preponderance of inexperienced clinicians who may benefit from collective intelligence even more. Regardless, he stated, “clinicians need to be cognizant of their own inherent limitations and acknowledge fallibility”; being humble and willing to seek advice “remain important, albeit imperfect, antidotes to misdiagnosis.”

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Mar 1. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.1071 ). No conflicts of interest were reported.

Although this study from Barnett et al. is not the silver bullet for misdiagnosis, better understanding why physicians make mistakes is a necessary and valuable undertaking, according to Stephan D. Fihn, MD, of the University of Washington, Seattle.

In the past, the “correct” diagnostic approach included making a list of potential diagnoses and systematically ruling them out one by one, a process conveyed via clinicopathologic conferences in teaching hospitals. These, Dr. Fihn recalled, lasted until medical educators recognized them as “more ... theatrical events than meaningful teaching exercises” and understood that master clinicians did not actually think in the manner this approach modeled. Since then, the maturation of cognitive psychology and “a growing literature” have made diagnostic error seem like a common, sometimes unavoidable element of being human.

What can be done? Computers have always been a possibility, but “none have achieved the breadth of content and accuracy necessary to be adopted to any great extent,” Dr. Fihn wrote. Another option is crowdsourcing, as described in this study from Barnett and colleagues. Their approach has its pitfalls: A 62.5% level of diagnostic accuracy from individuals is not very high, which suggests either difficult cases or a preponderance of inexperienced clinicians who may benefit from collective intelligence even more. Regardless, he stated, “clinicians need to be cognizant of their own inherent limitations and acknowledge fallibility”; being humble and willing to seek advice “remain important, albeit imperfect, antidotes to misdiagnosis.”

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Mar 1. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.1071 ). No conflicts of interest were reported.

Groups of physicians and trainees diagnose clinical cases with more accuracy than individuals, according to a study of solo and aggregate diagnoses collected through an online medical teaching platform.

“These findings suggest that using the concept of collective intelligence to pool many physicians’ diagnoses could be a scalable approach to improve diagnostic accuracy,” wrote lead author Michael L. Barnett, MD, of Harvard University in Boston and his coauthors, adding that “groups of all sizes outperformed individual subspecialists on cases in their own subspecialty.” The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

This cross-sectional study examined 1,572 cases solved within the Human Diagnosis Project (Human Dx) system, an online platform for authoring and diagnosing teaching cases. The system presents real-life cases from clinical practices and asks respondents to generate ranked differential diagnoses. Cases are tagged for specialties based on both intended diagnoses and the top diagnoses chosen by respondents. All cases used in this study were authored between May 7, 2014, and October 5, 2016, and had 10 or more respondents.

Of the 2,069 attending physicians and fellows, residents, and medical students (users) who solved cases within the Human Dx system, 1,452 (70.2%) were trained in internal medicine, 1,228 (59.4%) were residents or fellows, 431 (20.8%) were attending physicians, and 410 (19.8%) were medical students. To create a collective differential, Dr. Barnett and his colleagues aggregated the responses of up to nine participants via a weighted combination of each clinician’s top three diagnoses, which they dubbed “collective intelligence.”

The diagnostic accuracy for groups of nine was 85.6% (95% confidence interval, 83.9%-87.4%), compared with individual users at 62.5% (95% CI, 60.1%-64.9%), a difference of 23% (95% CI, 14.9%-31.2%; P less than .001). Groups of five saw a 17.8% difference in accuracy versus an individual (95% CI, 14.0%-21.6%; P less than .001), compared with 12.5% for groups of two (95% CI, 9.3%-15.8%; P less than .001). Taken together, these seem to underline an association between larger groups and increased accuracy.

Individual specialists solved cases in their particular areas with a diagnostic accuracy of 66.3% (95% CI, 59.1%-73.5%), compared with nonmatched specialty accuracy of 63.9% (95% CI, 56.6%-71.2%). Groups, however, outperformed specialists across the board: 77.7% accuracy for a group of 2 (95% CI, 70.1%-84.6%; P less than .001) and 85.5% accuracy for a group of 9 (95% CI, 75.1%-95.9%; P less than .001).

The coauthors shared the limitations of their study, including the possibility that the users who contributed these cases to Human Dx may not be representative of the medical community as a whole. They also noted that, while their 431 attending physicians constituted the “largest number ... to date in a study of collective intelligence,” trainees still made up almost 80% of users. In addition, they acknowledged that Human Dx was not designed to generate collective diagnoses nor assess collective intelligence; another platform created with that ability in mind may have returned different results. Finally, they were unable to assess how exactly greater accuracy would have been linked to changes in treatment, calling it “an important question for future work.”

The authors disclosed several conflicts of interest. One doctor reported receiving personal fees from Greylock McKinnon Associates; another reported receiving personal fees from the Human Diagnosis Project and serving as their nonprofit director during the study. A third doctor reported consulting for a company that makes patient-safety monitoring systems and receiving compensation from a not-for-profit incubator, along with having equity in three medical data and software companies.

SOURCE: Barnett ML et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Mar 1. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.0096.

Groups of physicians and trainees diagnose clinical cases with more accuracy than individuals, according to a study of solo and aggregate diagnoses collected through an online medical teaching platform.

“These findings suggest that using the concept of collective intelligence to pool many physicians’ diagnoses could be a scalable approach to improve diagnostic accuracy,” wrote lead author Michael L. Barnett, MD, of Harvard University in Boston and his coauthors, adding that “groups of all sizes outperformed individual subspecialists on cases in their own subspecialty.” The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

This cross-sectional study examined 1,572 cases solved within the Human Diagnosis Project (Human Dx) system, an online platform for authoring and diagnosing teaching cases. The system presents real-life cases from clinical practices and asks respondents to generate ranked differential diagnoses. Cases are tagged for specialties based on both intended diagnoses and the top diagnoses chosen by respondents. All cases used in this study were authored between May 7, 2014, and October 5, 2016, and had 10 or more respondents.

Of the 2,069 attending physicians and fellows, residents, and medical students (users) who solved cases within the Human Dx system, 1,452 (70.2%) were trained in internal medicine, 1,228 (59.4%) were residents or fellows, 431 (20.8%) were attending physicians, and 410 (19.8%) were medical students. To create a collective differential, Dr. Barnett and his colleagues aggregated the responses of up to nine participants via a weighted combination of each clinician’s top three diagnoses, which they dubbed “collective intelligence.”

The diagnostic accuracy for groups of nine was 85.6% (95% confidence interval, 83.9%-87.4%), compared with individual users at 62.5% (95% CI, 60.1%-64.9%), a difference of 23% (95% CI, 14.9%-31.2%; P less than .001). Groups of five saw a 17.8% difference in accuracy versus an individual (95% CI, 14.0%-21.6%; P less than .001), compared with 12.5% for groups of two (95% CI, 9.3%-15.8%; P less than .001). Taken together, these seem to underline an association between larger groups and increased accuracy.

Individual specialists solved cases in their particular areas with a diagnostic accuracy of 66.3% (95% CI, 59.1%-73.5%), compared with nonmatched specialty accuracy of 63.9% (95% CI, 56.6%-71.2%). Groups, however, outperformed specialists across the board: 77.7% accuracy for a group of 2 (95% CI, 70.1%-84.6%; P less than .001) and 85.5% accuracy for a group of 9 (95% CI, 75.1%-95.9%; P less than .001).

The coauthors shared the limitations of their study, including the possibility that the users who contributed these cases to Human Dx may not be representative of the medical community as a whole. They also noted that, while their 431 attending physicians constituted the “largest number ... to date in a study of collective intelligence,” trainees still made up almost 80% of users. In addition, they acknowledged that Human Dx was not designed to generate collective diagnoses nor assess collective intelligence; another platform created with that ability in mind may have returned different results. Finally, they were unable to assess how exactly greater accuracy would have been linked to changes in treatment, calling it “an important question for future work.”

The authors disclosed several conflicts of interest. One doctor reported receiving personal fees from Greylock McKinnon Associates; another reported receiving personal fees from the Human Diagnosis Project and serving as their nonprofit director during the study. A third doctor reported consulting for a company that makes patient-safety monitoring systems and receiving compensation from a not-for-profit incubator, along with having equity in three medical data and software companies.

SOURCE: Barnett ML et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Mar 1. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.0096.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

500 Women in Medicine: Part I

Ms. Gerull and Ms. Loe are third-year medical students at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

Their aim is to create a network of support and advancement for women in medicine. 500 Women in Medicine is a pod of the organization 500 Women Scientists.

In this episode, Nick Andrews speaks with the two innovators about their motivation to found this organization.

Correction, 3/12/19: An earlier version of this article misstated Kate Gerull's name.

Ms. Gerull and Ms. Loe are third-year medical students at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

Their aim is to create a network of support and advancement for women in medicine. 500 Women in Medicine is a pod of the organization 500 Women Scientists.

In this episode, Nick Andrews speaks with the two innovators about their motivation to found this organization.

Correction, 3/12/19: An earlier version of this article misstated Kate Gerull's name.

Ms. Gerull and Ms. Loe are third-year medical students at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

Their aim is to create a network of support and advancement for women in medicine. 500 Women in Medicine is a pod of the organization 500 Women Scientists.

In this episode, Nick Andrews speaks with the two innovators about their motivation to found this organization.

Correction, 3/12/19: An earlier version of this article misstated Kate Gerull's name.