User login

Utilization and Clinical Benefit of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor in Veterans With Microsatellite Instability-High Prostate Cancer

Background

The utilization of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) in prostate cancer (PC) can be very effective for patients with mismatch repair-deficiency (as identified by MSI-H by PCR/NGS or dMMR IHC). The use of ICI in this patient population has been associated with high rates of durable response. There is limited published data on factors that may influence patient response and outcomes. The aim of this study is to describe the utilization of and tumor response to ICI in this patient population.

Methods

This is a retrospective study of men with MSI-H PC reported by somatic genomic testing from April 1, 2015 to March 31, 2022 through the VA National Precision Oncology Program (NPOP), who received at least one dose of ICI. The primary objectives are to describe the incidence of MSI-H PC and the utilization of ICI. Descriptive statistics and Kaplan- Meier estimator were used for secondary objectives to determine the prostate-specific antigen decline of at least 50% (PSA50), clinical progression free survival (cPFS), time on ICI as a function of number of prior therapies, the extent of metastasis prior to initiation of ICI, and the correlation of MMR genetic alterations with treatment response.

Results

66 patients with MSI-H PC were identified (1.5% of a total of 4267 patients with PC tested through NPOP). 23 patients (35%) received at least one dose of ICI. 12 of 23 patients (52%) had PSA response. PSA50 responses occurred in 6 patients (50%) and 5 continued to have durable PSA50 at six months. Median cPFS was 280 days (95% CI: 105 days-not reached) and the estimated PFS at six months was 72.2% (95% CI: 35.7%-90.2%). 8 of 12 (67%) responders have received multiple lines of therapy for M1 PC. 8 of 12 patients (67%) had high-volume disease at ICI initiation. Of those patients with a MMR genetic alteration, patients with MLH1 (3/3) and MSH2 (6/8) alterations responded more frequently than those with MSH6 alterations (1/4).

Conclusions

MSI-H PC is rare but response rates to ICI are high and durable. Patients with MLH1 and MSH2 alterations appeared to respond more frequently than those with MSH6. Additional follow-up is ongoing.

Background

The utilization of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) in prostate cancer (PC) can be very effective for patients with mismatch repair-deficiency (as identified by MSI-H by PCR/NGS or dMMR IHC). The use of ICI in this patient population has been associated with high rates of durable response. There is limited published data on factors that may influence patient response and outcomes. The aim of this study is to describe the utilization of and tumor response to ICI in this patient population.

Methods

This is a retrospective study of men with MSI-H PC reported by somatic genomic testing from April 1, 2015 to March 31, 2022 through the VA National Precision Oncology Program (NPOP), who received at least one dose of ICI. The primary objectives are to describe the incidence of MSI-H PC and the utilization of ICI. Descriptive statistics and Kaplan- Meier estimator were used for secondary objectives to determine the prostate-specific antigen decline of at least 50% (PSA50), clinical progression free survival (cPFS), time on ICI as a function of number of prior therapies, the extent of metastasis prior to initiation of ICI, and the correlation of MMR genetic alterations with treatment response.

Results

66 patients with MSI-H PC were identified (1.5% of a total of 4267 patients with PC tested through NPOP). 23 patients (35%) received at least one dose of ICI. 12 of 23 patients (52%) had PSA response. PSA50 responses occurred in 6 patients (50%) and 5 continued to have durable PSA50 at six months. Median cPFS was 280 days (95% CI: 105 days-not reached) and the estimated PFS at six months was 72.2% (95% CI: 35.7%-90.2%). 8 of 12 (67%) responders have received multiple lines of therapy for M1 PC. 8 of 12 patients (67%) had high-volume disease at ICI initiation. Of those patients with a MMR genetic alteration, patients with MLH1 (3/3) and MSH2 (6/8) alterations responded more frequently than those with MSH6 alterations (1/4).

Conclusions

MSI-H PC is rare but response rates to ICI are high and durable. Patients with MLH1 and MSH2 alterations appeared to respond more frequently than those with MSH6. Additional follow-up is ongoing.

Background

The utilization of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) in prostate cancer (PC) can be very effective for patients with mismatch repair-deficiency (as identified by MSI-H by PCR/NGS or dMMR IHC). The use of ICI in this patient population has been associated with high rates of durable response. There is limited published data on factors that may influence patient response and outcomes. The aim of this study is to describe the utilization of and tumor response to ICI in this patient population.

Methods

This is a retrospective study of men with MSI-H PC reported by somatic genomic testing from April 1, 2015 to March 31, 2022 through the VA National Precision Oncology Program (NPOP), who received at least one dose of ICI. The primary objectives are to describe the incidence of MSI-H PC and the utilization of ICI. Descriptive statistics and Kaplan- Meier estimator were used for secondary objectives to determine the prostate-specific antigen decline of at least 50% (PSA50), clinical progression free survival (cPFS), time on ICI as a function of number of prior therapies, the extent of metastasis prior to initiation of ICI, and the correlation of MMR genetic alterations with treatment response.

Results

66 patients with MSI-H PC were identified (1.5% of a total of 4267 patients with PC tested through NPOP). 23 patients (35%) received at least one dose of ICI. 12 of 23 patients (52%) had PSA response. PSA50 responses occurred in 6 patients (50%) and 5 continued to have durable PSA50 at six months. Median cPFS was 280 days (95% CI: 105 days-not reached) and the estimated PFS at six months was 72.2% (95% CI: 35.7%-90.2%). 8 of 12 (67%) responders have received multiple lines of therapy for M1 PC. 8 of 12 patients (67%) had high-volume disease at ICI initiation. Of those patients with a MMR genetic alteration, patients with MLH1 (3/3) and MSH2 (6/8) alterations responded more frequently than those with MSH6 alterations (1/4).

Conclusions

MSI-H PC is rare but response rates to ICI are high and durable. Patients with MLH1 and MSH2 alterations appeared to respond more frequently than those with MSH6. Additional follow-up is ongoing.

Financial Toxicity in Colorectal Cancer Patient Who Received Localized Treatment in the Veterans Affairs Health System

Purpose

To describe patient-reported financial toxicity for patients who received localized colorectal cancer (CRC) treatment in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA).

Background

CRC is the 2nd leading cause of cancer-related death. In the private sector, many patients suffer economic hardship from CRC and its treatment. This leads to financial toxicity, or the negative impact of medical expenses, which is a strong independent predictor of quality of life. In the VHA patients access cancer care based on a sliding fee scale; however, there is a knowledge gap regarding financial toxicity for CRC patients in the VHA whose out of pocket costs have largely been subsidized.

Methods

We performed a descriptive, retrospective analysis of a survey administered at a VHA facility to patients with colorectal cancer who received localized treatment (ie, surgery or chemoradiotherapy). The survey consisted of 49 items assessing several clinical and psychosocial domains including subjective financial burden and use of financial coping strategies. Additionally, we used the validated Confusion, Hubbub and Order Scale (CHAOS) measure, which was designed to assess the level of confusion and disorganization in homes.

Results

Between November 2015 and September 2016, we mailed surveys to 265 patients diagnosed with CRC, 133 responded, for a response rate of 50%. For financial strain, 24% (n=32) of participants reported reduced spending on basics like food or clothing to pay for their cancer treatment, 17% (n=23) reported using all or a portion of their savings to pay for their cancer care,14% (n=18) noted borrowing money or using a credit card to pay for care, and 9% (n=12) of participants noted they did not fill a prescription because it was too expensive.

Conclusions/Implications

Despite policies to reduce out-of-pocket costs for VHA patients with CRC, patients reported significant financial toxicity. In the continued movement for value-based care centered on whole person care delivery, identifying persistent financial toxicity for vulnerable cancer patients is important data as we try and improve the infrastructure to impact quality of life and healthcare delivery for this population.

Purpose

To describe patient-reported financial toxicity for patients who received localized colorectal cancer (CRC) treatment in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA).

Background

CRC is the 2nd leading cause of cancer-related death. In the private sector, many patients suffer economic hardship from CRC and its treatment. This leads to financial toxicity, or the negative impact of medical expenses, which is a strong independent predictor of quality of life. In the VHA patients access cancer care based on a sliding fee scale; however, there is a knowledge gap regarding financial toxicity for CRC patients in the VHA whose out of pocket costs have largely been subsidized.

Methods

We performed a descriptive, retrospective analysis of a survey administered at a VHA facility to patients with colorectal cancer who received localized treatment (ie, surgery or chemoradiotherapy). The survey consisted of 49 items assessing several clinical and psychosocial domains including subjective financial burden and use of financial coping strategies. Additionally, we used the validated Confusion, Hubbub and Order Scale (CHAOS) measure, which was designed to assess the level of confusion and disorganization in homes.

Results

Between November 2015 and September 2016, we mailed surveys to 265 patients diagnosed with CRC, 133 responded, for a response rate of 50%. For financial strain, 24% (n=32) of participants reported reduced spending on basics like food or clothing to pay for their cancer treatment, 17% (n=23) reported using all or a portion of their savings to pay for their cancer care,14% (n=18) noted borrowing money or using a credit card to pay for care, and 9% (n=12) of participants noted they did not fill a prescription because it was too expensive.

Conclusions/Implications

Despite policies to reduce out-of-pocket costs for VHA patients with CRC, patients reported significant financial toxicity. In the continued movement for value-based care centered on whole person care delivery, identifying persistent financial toxicity for vulnerable cancer patients is important data as we try and improve the infrastructure to impact quality of life and healthcare delivery for this population.

Purpose

To describe patient-reported financial toxicity for patients who received localized colorectal cancer (CRC) treatment in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA).

Background

CRC is the 2nd leading cause of cancer-related death. In the private sector, many patients suffer economic hardship from CRC and its treatment. This leads to financial toxicity, or the negative impact of medical expenses, which is a strong independent predictor of quality of life. In the VHA patients access cancer care based on a sliding fee scale; however, there is a knowledge gap regarding financial toxicity for CRC patients in the VHA whose out of pocket costs have largely been subsidized.

Methods

We performed a descriptive, retrospective analysis of a survey administered at a VHA facility to patients with colorectal cancer who received localized treatment (ie, surgery or chemoradiotherapy). The survey consisted of 49 items assessing several clinical and psychosocial domains including subjective financial burden and use of financial coping strategies. Additionally, we used the validated Confusion, Hubbub and Order Scale (CHAOS) measure, which was designed to assess the level of confusion and disorganization in homes.

Results

Between November 2015 and September 2016, we mailed surveys to 265 patients diagnosed with CRC, 133 responded, for a response rate of 50%. For financial strain, 24% (n=32) of participants reported reduced spending on basics like food or clothing to pay for their cancer treatment, 17% (n=23) reported using all or a portion of their savings to pay for their cancer care,14% (n=18) noted borrowing money or using a credit card to pay for care, and 9% (n=12) of participants noted they did not fill a prescription because it was too expensive.

Conclusions/Implications

Despite policies to reduce out-of-pocket costs for VHA patients with CRC, patients reported significant financial toxicity. In the continued movement for value-based care centered on whole person care delivery, identifying persistent financial toxicity for vulnerable cancer patients is important data as we try and improve the infrastructure to impact quality of life and healthcare delivery for this population.

Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer—Not Only Challenging to Treat, but Difficult to Define

Purpose

Examine the impact of different definitions of castration resistance used to identify patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) using electronic health records (EHR).

Background

CRPC is a form of prostate cancer that is resistant to treatment with androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) and is associated with higher morbidity and mortality. Widely used guidelines like the Prostate Cancer Working Group 3 (PCWG 3), the American Urological Association (AUA), and many others differ in their definitions of castration-resistance. Until now, the feasibility of identifying CRPC using different definitions from EHR data has not been studied.

Methods/Data Analyisis

EHR data from the Veterans Health Administration (01/2006-12/2020) were used to identify veterans with CRPC according to the following criteria: 1) PCWG 3—a PSA increase ?25% from the nadir with a minimum rise of 2 ng/mL, while castrate (testosterone < 50 ng/mL); 2) AUA—2 consecutive PSA rises of ?0.2 ng/mL; 3) CRPC screening—a PSA rise of > 0.0 ng/mL within a window of 7–90 days.

Results

36,101 unique patients were identified using 1 of (or a combination of) the 3 CRPC criteria. Approximately 12,775 (35%) patients met all 3 criteria, while 8,589 (24%) were identified by AUA, 4,785 (13%) by CRPC screening, and 145 (0.4%) by PCWG3. A total of 8,377 (23%) patients met both the AUA and CRPC screening criteria, 1,219 (3%) patients met the AUA and PCWG3 criteria, and 211 (1%) met the PCWG3 and CRPC screening criteria.

Conculsions/Implications

Although several definitions can be used to identify CRPC patients, a combination of these definitions results in the greatest yield of CRPC patients identified using EHR data. Even though the PCWG3 criterion is frequently used in both clinical trials research and retrospective observational research, PCWG3 may miss many patients meeting other criteria and should not be used by itself when studying patients with CRPC identified from EHR data.

Purpose

Examine the impact of different definitions of castration resistance used to identify patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) using electronic health records (EHR).

Background

CRPC is a form of prostate cancer that is resistant to treatment with androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) and is associated with higher morbidity and mortality. Widely used guidelines like the Prostate Cancer Working Group 3 (PCWG 3), the American Urological Association (AUA), and many others differ in their definitions of castration-resistance. Until now, the feasibility of identifying CRPC using different definitions from EHR data has not been studied.

Methods/Data Analyisis

EHR data from the Veterans Health Administration (01/2006-12/2020) were used to identify veterans with CRPC according to the following criteria: 1) PCWG 3—a PSA increase ?25% from the nadir with a minimum rise of 2 ng/mL, while castrate (testosterone < 50 ng/mL); 2) AUA—2 consecutive PSA rises of ?0.2 ng/mL; 3) CRPC screening—a PSA rise of > 0.0 ng/mL within a window of 7–90 days.

Results

36,101 unique patients were identified using 1 of (or a combination of) the 3 CRPC criteria. Approximately 12,775 (35%) patients met all 3 criteria, while 8,589 (24%) were identified by AUA, 4,785 (13%) by CRPC screening, and 145 (0.4%) by PCWG3. A total of 8,377 (23%) patients met both the AUA and CRPC screening criteria, 1,219 (3%) patients met the AUA and PCWG3 criteria, and 211 (1%) met the PCWG3 and CRPC screening criteria.

Conculsions/Implications

Although several definitions can be used to identify CRPC patients, a combination of these definitions results in the greatest yield of CRPC patients identified using EHR data. Even though the PCWG3 criterion is frequently used in both clinical trials research and retrospective observational research, PCWG3 may miss many patients meeting other criteria and should not be used by itself when studying patients with CRPC identified from EHR data.

Purpose

Examine the impact of different definitions of castration resistance used to identify patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) using electronic health records (EHR).

Background

CRPC is a form of prostate cancer that is resistant to treatment with androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) and is associated with higher morbidity and mortality. Widely used guidelines like the Prostate Cancer Working Group 3 (PCWG 3), the American Urological Association (AUA), and many others differ in their definitions of castration-resistance. Until now, the feasibility of identifying CRPC using different definitions from EHR data has not been studied.

Methods/Data Analyisis

EHR data from the Veterans Health Administration (01/2006-12/2020) were used to identify veterans with CRPC according to the following criteria: 1) PCWG 3—a PSA increase ?25% from the nadir with a minimum rise of 2 ng/mL, while castrate (testosterone < 50 ng/mL); 2) AUA—2 consecutive PSA rises of ?0.2 ng/mL; 3) CRPC screening—a PSA rise of > 0.0 ng/mL within a window of 7–90 days.

Results

36,101 unique patients were identified using 1 of (or a combination of) the 3 CRPC criteria. Approximately 12,775 (35%) patients met all 3 criteria, while 8,589 (24%) were identified by AUA, 4,785 (13%) by CRPC screening, and 145 (0.4%) by PCWG3. A total of 8,377 (23%) patients met both the AUA and CRPC screening criteria, 1,219 (3%) patients met the AUA and PCWG3 criteria, and 211 (1%) met the PCWG3 and CRPC screening criteria.

Conculsions/Implications

Although several definitions can be used to identify CRPC patients, a combination of these definitions results in the greatest yield of CRPC patients identified using EHR data. Even though the PCWG3 criterion is frequently used in both clinical trials research and retrospective observational research, PCWG3 may miss many patients meeting other criteria and should not be used by itself when studying patients with CRPC identified from EHR data.

Identification of Clinically Actionable Genomic Alterations in Colorectal Cancer Patients From the VA National Precision Oncology Program (NPOP)

Purpose

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the fourth most common cancer at VA and the third leading cause of cancer-related death in the USA. The VA National Precision Oncology Program (NPOP) was established in 2016 with the goal of implementing standardized, streamlined methods for molecular testing of veterans with cancer and has enabled comprehensive genomic profiling (CGP) and precision medicine as part of routine cancer care. Obtaining CGP of predictive biomarkers in cancer tissue, including mutations in genes (e.g., KRAS, NRAS and BRAF), tumor mutation burden (TMB) and microsatellite instability status (MSI) can be used to support treatment decisions with targeted and immunotherapies.

Methods

In this study we describe the frequencies of these clinical biomarkers in colon adenocarcinoma (COAD), rectal adenocarcinoma (READ), and other colon or rectum histologies (CROT); and compare these frequencies to a published cohort of metastatic CRC using Chi-square test (Yaeger et al., 2018).

Results

A total of 1802 patients with CRC were included in this study. COAD was the most frequent disease site (76.9%) followed by READ (19.1%). Approximately 52.9% of COAD patients harbored at least one highly actionable biomarker (defined as having an FDA-approved indication) including NRAS/ KRAS/BRAF wildtype (38.0%), TMB-H (12.9%), BRAF V600E (9.7%), MSI-H (8.9%), and NTRK fusion or rearrangement (0.3%). About 52.0% of patients with READ had these biomarkers, while this rate was (16.4%) in CROT. Among patients with COAD and READ, those with BRAF V600E mutations were more likely to be older, White, not Hispanic or Latino, and lived in urban areas compared to those without BRAF V600E. Relative to those with NRAS/KRAS/BRAF mutations, patients with NRAS/KRAS/BRAF wildtype were frequently younger. Relative to the frequency of biomarkers from a cBioPortal cohort of metastatic CRC, the frequency of NRAS wildtype was significantly lower in patients with COAD and READ tested through NPOP.

Consulsions

In this cohort, ~53 % of patients with COAD and 52% of patients with READ have highly actionable biomarkers and are potentially eligible for FDAapproved targeted therapies. Future studies examining cancer outcomes with regard to the use of targeted therapies in the setting of actionable gene alterations, TMB, and MSI are warranted.

Purpose

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the fourth most common cancer at VA and the third leading cause of cancer-related death in the USA. The VA National Precision Oncology Program (NPOP) was established in 2016 with the goal of implementing standardized, streamlined methods for molecular testing of veterans with cancer and has enabled comprehensive genomic profiling (CGP) and precision medicine as part of routine cancer care. Obtaining CGP of predictive biomarkers in cancer tissue, including mutations in genes (e.g., KRAS, NRAS and BRAF), tumor mutation burden (TMB) and microsatellite instability status (MSI) can be used to support treatment decisions with targeted and immunotherapies.

Methods

In this study we describe the frequencies of these clinical biomarkers in colon adenocarcinoma (COAD), rectal adenocarcinoma (READ), and other colon or rectum histologies (CROT); and compare these frequencies to a published cohort of metastatic CRC using Chi-square test (Yaeger et al., 2018).

Results

A total of 1802 patients with CRC were included in this study. COAD was the most frequent disease site (76.9%) followed by READ (19.1%). Approximately 52.9% of COAD patients harbored at least one highly actionable biomarker (defined as having an FDA-approved indication) including NRAS/ KRAS/BRAF wildtype (38.0%), TMB-H (12.9%), BRAF V600E (9.7%), MSI-H (8.9%), and NTRK fusion or rearrangement (0.3%). About 52.0% of patients with READ had these biomarkers, while this rate was (16.4%) in CROT. Among patients with COAD and READ, those with BRAF V600E mutations were more likely to be older, White, not Hispanic or Latino, and lived in urban areas compared to those without BRAF V600E. Relative to those with NRAS/KRAS/BRAF mutations, patients with NRAS/KRAS/BRAF wildtype were frequently younger. Relative to the frequency of biomarkers from a cBioPortal cohort of metastatic CRC, the frequency of NRAS wildtype was significantly lower in patients with COAD and READ tested through NPOP.

Consulsions

In this cohort, ~53 % of patients with COAD and 52% of patients with READ have highly actionable biomarkers and are potentially eligible for FDAapproved targeted therapies. Future studies examining cancer outcomes with regard to the use of targeted therapies in the setting of actionable gene alterations, TMB, and MSI are warranted.

Purpose

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the fourth most common cancer at VA and the third leading cause of cancer-related death in the USA. The VA National Precision Oncology Program (NPOP) was established in 2016 with the goal of implementing standardized, streamlined methods for molecular testing of veterans with cancer and has enabled comprehensive genomic profiling (CGP) and precision medicine as part of routine cancer care. Obtaining CGP of predictive biomarkers in cancer tissue, including mutations in genes (e.g., KRAS, NRAS and BRAF), tumor mutation burden (TMB) and microsatellite instability status (MSI) can be used to support treatment decisions with targeted and immunotherapies.

Methods

In this study we describe the frequencies of these clinical biomarkers in colon adenocarcinoma (COAD), rectal adenocarcinoma (READ), and other colon or rectum histologies (CROT); and compare these frequencies to a published cohort of metastatic CRC using Chi-square test (Yaeger et al., 2018).

Results

A total of 1802 patients with CRC were included in this study. COAD was the most frequent disease site (76.9%) followed by READ (19.1%). Approximately 52.9% of COAD patients harbored at least one highly actionable biomarker (defined as having an FDA-approved indication) including NRAS/ KRAS/BRAF wildtype (38.0%), TMB-H (12.9%), BRAF V600E (9.7%), MSI-H (8.9%), and NTRK fusion or rearrangement (0.3%). About 52.0% of patients with READ had these biomarkers, while this rate was (16.4%) in CROT. Among patients with COAD and READ, those with BRAF V600E mutations were more likely to be older, White, not Hispanic or Latino, and lived in urban areas compared to those without BRAF V600E. Relative to those with NRAS/KRAS/BRAF mutations, patients with NRAS/KRAS/BRAF wildtype were frequently younger. Relative to the frequency of biomarkers from a cBioPortal cohort of metastatic CRC, the frequency of NRAS wildtype was significantly lower in patients with COAD and READ tested through NPOP.

Consulsions

In this cohort, ~53 % of patients with COAD and 52% of patients with READ have highly actionable biomarkers and are potentially eligible for FDAapproved targeted therapies. Future studies examining cancer outcomes with regard to the use of targeted therapies in the setting of actionable gene alterations, TMB, and MSI are warranted.

Evaluation of the Prostate Cancer Molecular Testing Pathway (PCMTP) Within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA)

Purpose

The PCMTP was developed to provide standardized decision support for molecular testing for veterans with prostate cancer.

Background

Prior to the precision medicine era, molecular tumor testing in prostate cancer was not standard of care. Field practitioners were unfamiliar with the role of molecular testing in clinical care. The PCMTP provides direction for germline and tumor testing in appropriate patients with prostate cancer. The expectation is that at least 80% of veterans will be pathway adherent. The PCMTP is an Oncology Clinical Pathway (OCP) that supports evidence-based practice providing highquality, safe, and cost-effective care for veterans reducing variability of care in the VHA.

Methods

The National Oncology Program Office assembled a Prostate Cancer Team (PCT) to develop OCPs. The pathways were incorporated into note templates that record clinical decisions using text and metadata (Health Factors [HF]), and record pathway adherence for the 4 key nodes of the PCMTP. The templates were pilot-tested and improved using an iterative process over a 3-month period. Further evaluation was conducted by the Office of Human Factors Engineering and the National Clinical Template Workgroup, utilizing a heuristic evaluation to ensure standardization, interoperability, and reduce duplication. HF data were retrieved from the Corporate Data Warehouse using a custom-built dashboard. Descriptive statistics of PCMTP use are presented.

Results

Between 4/1/2021 and 6/22/2022, 6276 health factors were generated from 1707 unique veterans in whom this clinical pathway was accessed. 328 distinct providers participated at 61 sites. Average veteran age was 73 years. (range 45-100) including 42% Black and 56% White. Of 1243 veterans considered for germline testing, 96.6% had germline testing ordered and for 1102 veterans considered for tumor testing, 93.3% had tumor testing ordered.

Conclusions

Pathway adherence exceeded the 80% benchmark. Race representation was diverse and reflective of the VA prostate cancer population. About 46% of VA oncology practices have used the PCMTP for ~11% of the estimated 15,000 veterans with metastatic prostate cancer in VHA. Increased use of this pathway is expected to improve outcomes for veterans with prostate cancer

Purpose

The PCMTP was developed to provide standardized decision support for molecular testing for veterans with prostate cancer.

Background

Prior to the precision medicine era, molecular tumor testing in prostate cancer was not standard of care. Field practitioners were unfamiliar with the role of molecular testing in clinical care. The PCMTP provides direction for germline and tumor testing in appropriate patients with prostate cancer. The expectation is that at least 80% of veterans will be pathway adherent. The PCMTP is an Oncology Clinical Pathway (OCP) that supports evidence-based practice providing highquality, safe, and cost-effective care for veterans reducing variability of care in the VHA.

Methods

The National Oncology Program Office assembled a Prostate Cancer Team (PCT) to develop OCPs. The pathways were incorporated into note templates that record clinical decisions using text and metadata (Health Factors [HF]), and record pathway adherence for the 4 key nodes of the PCMTP. The templates were pilot-tested and improved using an iterative process over a 3-month period. Further evaluation was conducted by the Office of Human Factors Engineering and the National Clinical Template Workgroup, utilizing a heuristic evaluation to ensure standardization, interoperability, and reduce duplication. HF data were retrieved from the Corporate Data Warehouse using a custom-built dashboard. Descriptive statistics of PCMTP use are presented.

Results

Between 4/1/2021 and 6/22/2022, 6276 health factors were generated from 1707 unique veterans in whom this clinical pathway was accessed. 328 distinct providers participated at 61 sites. Average veteran age was 73 years. (range 45-100) including 42% Black and 56% White. Of 1243 veterans considered for germline testing, 96.6% had germline testing ordered and for 1102 veterans considered for tumor testing, 93.3% had tumor testing ordered.

Conclusions

Pathway adherence exceeded the 80% benchmark. Race representation was diverse and reflective of the VA prostate cancer population. About 46% of VA oncology practices have used the PCMTP for ~11% of the estimated 15,000 veterans with metastatic prostate cancer in VHA. Increased use of this pathway is expected to improve outcomes for veterans with prostate cancer

Purpose

The PCMTP was developed to provide standardized decision support for molecular testing for veterans with prostate cancer.

Background

Prior to the precision medicine era, molecular tumor testing in prostate cancer was not standard of care. Field practitioners were unfamiliar with the role of molecular testing in clinical care. The PCMTP provides direction for germline and tumor testing in appropriate patients with prostate cancer. The expectation is that at least 80% of veterans will be pathway adherent. The PCMTP is an Oncology Clinical Pathway (OCP) that supports evidence-based practice providing highquality, safe, and cost-effective care for veterans reducing variability of care in the VHA.

Methods

The National Oncology Program Office assembled a Prostate Cancer Team (PCT) to develop OCPs. The pathways were incorporated into note templates that record clinical decisions using text and metadata (Health Factors [HF]), and record pathway adherence for the 4 key nodes of the PCMTP. The templates were pilot-tested and improved using an iterative process over a 3-month period. Further evaluation was conducted by the Office of Human Factors Engineering and the National Clinical Template Workgroup, utilizing a heuristic evaluation to ensure standardization, interoperability, and reduce duplication. HF data were retrieved from the Corporate Data Warehouse using a custom-built dashboard. Descriptive statistics of PCMTP use are presented.

Results

Between 4/1/2021 and 6/22/2022, 6276 health factors were generated from 1707 unique veterans in whom this clinical pathway was accessed. 328 distinct providers participated at 61 sites. Average veteran age was 73 years. (range 45-100) including 42% Black and 56% White. Of 1243 veterans considered for germline testing, 96.6% had germline testing ordered and for 1102 veterans considered for tumor testing, 93.3% had tumor testing ordered.

Conclusions

Pathway adherence exceeded the 80% benchmark. Race representation was diverse and reflective of the VA prostate cancer population. About 46% of VA oncology practices have used the PCMTP for ~11% of the estimated 15,000 veterans with metastatic prostate cancer in VHA. Increased use of this pathway is expected to improve outcomes for veterans with prostate cancer

New Delivery Models Improve Access to Germline Testing for Patients With Advanced Prostate Cancer

Objectives

The VA Oncology Clinical Pathway for Prostate Cancer is the first to include both tumor and germline testing to inform treatment and clinical trial eligibility for advanced disease. Anticipating increased germline testing demand, new germline testing delivery models were created to augment the existing traditional model of referring patients to genetics providers (VA or non-VA) for germline testing. The new models include: a non-traditional model where oncology clinicians perform all pre- and post-test activities and consult genetics when needed, and a hybrid model where oncology clinicians obtain informed consent and place e-consults for germline test ordering, results disclosure, and genetics follow-up, as needed. We sought to assess germline testing by delivery model.

Methods

Data sources included the National Precision Oncology Program (NPOP) dashboard and NPOP-contracted germline testing laboratories. Patient inclusion criteria: living as of 5/2/2021 with VA oncology or urology visits after 5/2/2021. We used multivariate regression to assess associations between patient characteristics and germline testing between 5/3/2021 (pathway launch) and 5/2/2022, accounting for clustering of patients within ordering clinicians.

Results

We identified 16,041 patients from 129 VA facilities with average age 75 years (SD, 8.2; range, 36- 102), 28.7% Black and 60.0% White. Only 5.6% had germline testing ordered by 60 clinicians at 67 facilities with 52.2% of orders by the hybrid model, 32.1% the non-traditional model, and 15.4% the traditional model. Patient characteristics positively associated with germline testing included care at hybrid model (OR, 6.03; 95% CI, 4.62-7.88) or non-traditional model facilities (OR, 5.66; 95% CI, 4.24-7.56) compared to the traditional model, completing tumor molecular testing (OR, 5.80; 95%CI, 4.98-6.75), and Black compared with White race (OR, 1.24; 95%CI, 1.06-1.45). Compared to patients aged < 66 years, patients aged 66-75 years and 76-85 years were less likely to have germline testing (OR, 0.74; 95%CI, 0.60-0.90; and OR, 0.67; 95%CI, 0.53-0.84, respectively).

Conclusions/Implications

Though only a small percentage of patients with advanced prostate cancer had NPOP-supported germline testing since the pathway launch, the new delivery models were instrumental to improving access to germline testing. Ongoing evaluation will help to understand observed demographic differences in germline testing. Implementation and evaluation of strategies that promote adoption of the new germline testing delivery models is needed. 0922FED AVAHO_Abstracts.indd 15 8

Objectives

The VA Oncology Clinical Pathway for Prostate Cancer is the first to include both tumor and germline testing to inform treatment and clinical trial eligibility for advanced disease. Anticipating increased germline testing demand, new germline testing delivery models were created to augment the existing traditional model of referring patients to genetics providers (VA or non-VA) for germline testing. The new models include: a non-traditional model where oncology clinicians perform all pre- and post-test activities and consult genetics when needed, and a hybrid model where oncology clinicians obtain informed consent and place e-consults for germline test ordering, results disclosure, and genetics follow-up, as needed. We sought to assess germline testing by delivery model.

Methods

Data sources included the National Precision Oncology Program (NPOP) dashboard and NPOP-contracted germline testing laboratories. Patient inclusion criteria: living as of 5/2/2021 with VA oncology or urology visits after 5/2/2021. We used multivariate regression to assess associations between patient characteristics and germline testing between 5/3/2021 (pathway launch) and 5/2/2022, accounting for clustering of patients within ordering clinicians.

Results

We identified 16,041 patients from 129 VA facilities with average age 75 years (SD, 8.2; range, 36- 102), 28.7% Black and 60.0% White. Only 5.6% had germline testing ordered by 60 clinicians at 67 facilities with 52.2% of orders by the hybrid model, 32.1% the non-traditional model, and 15.4% the traditional model. Patient characteristics positively associated with germline testing included care at hybrid model (OR, 6.03; 95% CI, 4.62-7.88) or non-traditional model facilities (OR, 5.66; 95% CI, 4.24-7.56) compared to the traditional model, completing tumor molecular testing (OR, 5.80; 95%CI, 4.98-6.75), and Black compared with White race (OR, 1.24; 95%CI, 1.06-1.45). Compared to patients aged < 66 years, patients aged 66-75 years and 76-85 years were less likely to have germline testing (OR, 0.74; 95%CI, 0.60-0.90; and OR, 0.67; 95%CI, 0.53-0.84, respectively).

Conclusions/Implications

Though only a small percentage of patients with advanced prostate cancer had NPOP-supported germline testing since the pathway launch, the new delivery models were instrumental to improving access to germline testing. Ongoing evaluation will help to understand observed demographic differences in germline testing. Implementation and evaluation of strategies that promote adoption of the new germline testing delivery models is needed. 0922FED AVAHO_Abstracts.indd 15 8

Objectives

The VA Oncology Clinical Pathway for Prostate Cancer is the first to include both tumor and germline testing to inform treatment and clinical trial eligibility for advanced disease. Anticipating increased germline testing demand, new germline testing delivery models were created to augment the existing traditional model of referring patients to genetics providers (VA or non-VA) for germline testing. The new models include: a non-traditional model where oncology clinicians perform all pre- and post-test activities and consult genetics when needed, and a hybrid model where oncology clinicians obtain informed consent and place e-consults for germline test ordering, results disclosure, and genetics follow-up, as needed. We sought to assess germline testing by delivery model.

Methods

Data sources included the National Precision Oncology Program (NPOP) dashboard and NPOP-contracted germline testing laboratories. Patient inclusion criteria: living as of 5/2/2021 with VA oncology or urology visits after 5/2/2021. We used multivariate regression to assess associations between patient characteristics and germline testing between 5/3/2021 (pathway launch) and 5/2/2022, accounting for clustering of patients within ordering clinicians.

Results

We identified 16,041 patients from 129 VA facilities with average age 75 years (SD, 8.2; range, 36- 102), 28.7% Black and 60.0% White. Only 5.6% had germline testing ordered by 60 clinicians at 67 facilities with 52.2% of orders by the hybrid model, 32.1% the non-traditional model, and 15.4% the traditional model. Patient characteristics positively associated with germline testing included care at hybrid model (OR, 6.03; 95% CI, 4.62-7.88) or non-traditional model facilities (OR, 5.66; 95% CI, 4.24-7.56) compared to the traditional model, completing tumor molecular testing (OR, 5.80; 95%CI, 4.98-6.75), and Black compared with White race (OR, 1.24; 95%CI, 1.06-1.45). Compared to patients aged < 66 years, patients aged 66-75 years and 76-85 years were less likely to have germline testing (OR, 0.74; 95%CI, 0.60-0.90; and OR, 0.67; 95%CI, 0.53-0.84, respectively).

Conclusions/Implications

Though only a small percentage of patients with advanced prostate cancer had NPOP-supported germline testing since the pathway launch, the new delivery models were instrumental to improving access to germline testing. Ongoing evaluation will help to understand observed demographic differences in germline testing. Implementation and evaluation of strategies that promote adoption of the new germline testing delivery models is needed. 0922FED AVAHO_Abstracts.indd 15 8

Utilization of Next Generation Sequencing in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer

Introduction

Metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) is one of the most common and lethal cancers. Nextgeneration sequencing (NGS) has been recommended as a tool to help guide treatment by identifying actionable genetic mutations. However, data regarding realworld usage of NGS in a Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system is lacking. We conducted a retrospective observational study of the patterns of NGS usage in patients with mCRC at the South Texas Veterans Affairs Healthcare System (STVAHCS).

Methods

We identified patients with a diagnosis of mCRC evaluated and treated at STVAHCS between January 1, 2018 and June 1, 2022. We assessed the prevalence of utilizing NGS on solid tumor samples performed by Foundation One and identified the presence of different molecular aberrations detected by NGS.

Results

65 patients were identified. Median age was 68 years. 63 (96.9%) were males and 2 (3.1%) were females. 29 (44.6%) were Hispanic, 25 (38.5%) were White, 10 (15.4%) were African American and 1 (1.5%) was Pacific Islander. NGS was performed in 34 (52.3%) patients. The most common reasons for not performing NGS were unknown/not documented (54.8%), early mortality (29%), lack of adequate tissue (12.9%) and patient refusal of treatment (3.2%). The most common molecular aberrations identified in patients who had NGS were TP53 (73.5%), APC (64.7%), KRAS (47.1%), ATM (20.6%), SMAD4 (14.7%) and BRAF (14.7%). All patients who had NGS were found to have at least one identifiable mutation.

Conclusions

Approximately 50% of patients with mCRC did not have NGS performed on their tissue sample. This rate is similar to other real-world studies in non-VA settings. Documented reasons for lack of NGS testing included inadequate tissue and early patient mortality. Other potential reasons could be lack of efficient VA clinical testing protocols, use of simple molecular testing rather than comprehensive NGS testing and limited knowledge of availability of NGS among providers. Measures that can be taken to increase utilization of NGS include incorporating NGS testing early in the disease course, incorporating testing into VA clinical pathways, improving physician education, increasing the size of solid tissue samples and ordering liquid biopsies where solid tissue is deficient.

Introduction

Metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) is one of the most common and lethal cancers. Nextgeneration sequencing (NGS) has been recommended as a tool to help guide treatment by identifying actionable genetic mutations. However, data regarding realworld usage of NGS in a Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system is lacking. We conducted a retrospective observational study of the patterns of NGS usage in patients with mCRC at the South Texas Veterans Affairs Healthcare System (STVAHCS).

Methods

We identified patients with a diagnosis of mCRC evaluated and treated at STVAHCS between January 1, 2018 and June 1, 2022. We assessed the prevalence of utilizing NGS on solid tumor samples performed by Foundation One and identified the presence of different molecular aberrations detected by NGS.

Results

65 patients were identified. Median age was 68 years. 63 (96.9%) were males and 2 (3.1%) were females. 29 (44.6%) were Hispanic, 25 (38.5%) were White, 10 (15.4%) were African American and 1 (1.5%) was Pacific Islander. NGS was performed in 34 (52.3%) patients. The most common reasons for not performing NGS were unknown/not documented (54.8%), early mortality (29%), lack of adequate tissue (12.9%) and patient refusal of treatment (3.2%). The most common molecular aberrations identified in patients who had NGS were TP53 (73.5%), APC (64.7%), KRAS (47.1%), ATM (20.6%), SMAD4 (14.7%) and BRAF (14.7%). All patients who had NGS were found to have at least one identifiable mutation.

Conclusions

Approximately 50% of patients with mCRC did not have NGS performed on their tissue sample. This rate is similar to other real-world studies in non-VA settings. Documented reasons for lack of NGS testing included inadequate tissue and early patient mortality. Other potential reasons could be lack of efficient VA clinical testing protocols, use of simple molecular testing rather than comprehensive NGS testing and limited knowledge of availability of NGS among providers. Measures that can be taken to increase utilization of NGS include incorporating NGS testing early in the disease course, incorporating testing into VA clinical pathways, improving physician education, increasing the size of solid tissue samples and ordering liquid biopsies where solid tissue is deficient.

Introduction

Metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) is one of the most common and lethal cancers. Nextgeneration sequencing (NGS) has been recommended as a tool to help guide treatment by identifying actionable genetic mutations. However, data regarding realworld usage of NGS in a Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system is lacking. We conducted a retrospective observational study of the patterns of NGS usage in patients with mCRC at the South Texas Veterans Affairs Healthcare System (STVAHCS).

Methods

We identified patients with a diagnosis of mCRC evaluated and treated at STVAHCS between January 1, 2018 and June 1, 2022. We assessed the prevalence of utilizing NGS on solid tumor samples performed by Foundation One and identified the presence of different molecular aberrations detected by NGS.

Results

65 patients were identified. Median age was 68 years. 63 (96.9%) were males and 2 (3.1%) were females. 29 (44.6%) were Hispanic, 25 (38.5%) were White, 10 (15.4%) were African American and 1 (1.5%) was Pacific Islander. NGS was performed in 34 (52.3%) patients. The most common reasons for not performing NGS were unknown/not documented (54.8%), early mortality (29%), lack of adequate tissue (12.9%) and patient refusal of treatment (3.2%). The most common molecular aberrations identified in patients who had NGS were TP53 (73.5%), APC (64.7%), KRAS (47.1%), ATM (20.6%), SMAD4 (14.7%) and BRAF (14.7%). All patients who had NGS were found to have at least one identifiable mutation.

Conclusions

Approximately 50% of patients with mCRC did not have NGS performed on their tissue sample. This rate is similar to other real-world studies in non-VA settings. Documented reasons for lack of NGS testing included inadequate tissue and early patient mortality. Other potential reasons could be lack of efficient VA clinical testing protocols, use of simple molecular testing rather than comprehensive NGS testing and limited knowledge of availability of NGS among providers. Measures that can be taken to increase utilization of NGS include incorporating NGS testing early in the disease course, incorporating testing into VA clinical pathways, improving physician education, increasing the size of solid tissue samples and ordering liquid biopsies where solid tissue is deficient.

Impact of Race on Outcomes of High-Risk Patients With Prostate Cancer Treated With Moderately Hypofractionated Radiotherapy in an Equal Access Setting

Although moderately hypofractionated radiotherapy (MHRT) is an accepted treatment for localized prostate cancer, its adaptation remains limited in the United States.1,2 MHRT theoretically exploits α/β ratio differences between the prostate (1.5 Gy), bladder (5-10 Gy), and rectum (3 Gy), thereby reducing late treatment-related adverse effects compared with those of conventional fractionation at biologically equivalent doses.3-8 Multiple randomized noninferiority trials have demonstrated equivalent outcomes between MHRT and conventional fraction with no appreciable increase in patient-reported toxicity.9-14 Although these studies have led to the acceptance of MHRT as a standard treatment, the majority of these trials involve individuals with low- and intermediate-risk disease.

There are less phase 3 data addressing MHRT for high-risk prostate cancer (HRPC).10,12,14-17 Only 2 studies examined predominately high-risk populations, accounting for 83 and 292 patients, respectively.15,16 Additional phase 3 trials with small proportions of high-risk patients (n = 126, 12%; n = 53, 35%) offer limited additional information regarding clinical outcomes and toxicity rates specific to high-risk disease.10-12 Numerous phase 1 and 2 studies report various field designs and fractionation plans for MHRT in the context of high-risk disease, although the applicability of these data to off-trial populations remains limited.18-20

Furthermore, African American individuals are underrepresented in the trials establishing the role of MHRT despite higher rates of prostate cancer incidence, more advanced disease stage at diagnosis, and higher rates of prostate cancer–specific survival (PCSS) when compared with White patients.21 Racial disparities across patients with prostate cancer and their management are multifactorial across health care literacy, education level, access to care (including transportation issues), and issues of adherence and distrust.22-25 Correlation of patient race to prostate cancer outcomes varies greatly across health care systems, with the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) equal access system providing robust mental health services and transportation services for some patients, while demonstrating similar rates of stage-adjusted PCSS between African American and White patients across a broad range of treatment modalities.26-28 Given the paucity of data exploring outcomes following MHRT for African American patients with HRPC, the present analysis provides long-term clinical outcomes and toxicity profiles for an off-trial majority African American population with HRPC treated with MHRT within the VA.

Methods

Records were retrospectively reviewed under an institutional review board–approved protocol for all patients with HRPC treated with definitive MHRT at the Durham Veterans Affairs Healthcare System in North Carolina between November 2008 and August 2018. Exclusion criteria included < 12 months of follow-up or elective nodal irradiation. Demographic variables obtained included age at diagnosis, race, clinical T stage, pre-MHRT prostate-specific antigen (PSA), Gleason grade group at diagnosis, favorable vs unfavorable high-risk disease, pre-MHRT international prostate symptom score (IPSS), and pre-MHRT urinary medication usage (yes/no).29

Concurrent androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) was initiated 6 to 8 weeks before MHRT unless medically contraindicated per the discretion of the treating radiation oncologist. Patients generally received 18 to 24 months of ADT, with those with favorable HRPC (ie, T1c disease with either Gleason 4+4 and PSA < 10 mg/mL or Gleason 3+3 and PSA > 20 ng/mL) receiving 6 months after 2015.29 Patients were simulated supine in either standard or custom immobilization with a full bladder and empty rectum. MHRT fractionation plans included 70 Gy at 2.5 Gy per fraction and 60 Gy at 3 Gy per fraction. Radiotherapy targets included the prostate and seminal vesicles without elective nodal coverage per institutional practice. Treatments were delivered following image guidance, either prostate matching with cone beam computed tomography or fiducial matching with kilo voltage imaging. All patients received intensity-modulated radiotherapy. For plans delivering 70 Gy at 2.5 Gy per fraction, constraints included bladder V (volume receiving) 70 < 10 cc, V65 ≤ 15%, V40 ≤ 35%, rectum V70 < 10 cc, V65 ≤ 10%, V40 ≤ 35%, femoral heads maximum point dose ≤ 40 Gy, penile bulb mean dose ≤ 50 Gy, and small bowel V40 ≤ 1%. For plans delivering 60 Gy at 3 Gy per fraction, constraints included rectum V57 ≤ 15%, V46 ≤ 30%, V37 ≤ 50%, bladder V60 ≤ 5%, V46 ≤ 30%, V37 ≤ 50%, and femoral heads V43 ≤ 5%.

Gastrointestinal (GI) and genitourinary (GU) toxicities were graded using Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE), version 5.0, with acute toxicity defined as on-treatment < 3 months following completion of MHRT. Late toxicity was defined as ≥ 3 months following completion of MHRT. Individuals were seen in follow-up at 6 weeks and 3 months with PSA and testosterone after MHRT completion, then every 6 to 12 months for 5 years and annually thereafter. Each follow-up visit included history, physical examination, IPSS, and CTCAE grading for GI and GU toxicity.

The Wilcoxon rank sum test and χ2 test were used to compare differences in demographic data, dosimetric parameters, and frequency of toxicity events with respect to patient race. Clinical endpoints including biochemical recurrence-free survival (BRFS; defined by Phoenix criteria as 2.0 above PSA nadir), distant metastases-free survival (DMFS), PCSS, and overall survival (OS) were estimated from time of radiotherapy completion by the Kaplan-Meier method and compared between African American and White race by log-rank testing.30 Late GI and GU toxicity-free survival were estimated by Kaplan-Meier plots and compared between African American and White patients by the log-rank test. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS 9.4.

Results

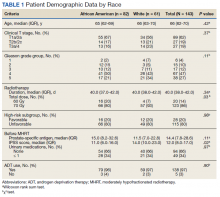

We identified 143 patients with HRPC treated with definitive MHRT between November 2008 and August 2018 (Table 1). Mean age was 65 years (range, 36-80 years); 57% were African American men. Eighty percent of individuals had unfavorable high-risk disease. Median (IQR) PSA was 14.4 (7.8-28.6). Twenty-six percent had grade group 1-3 disease, 47% had grade group 4 disease, and 27% had grade group 5 disease. African American patients had significantly lower pre-MHRT IPSS scores than White patients (mean IPSS, 11 vs 14, respectively; P = .02) despite similar rates of preradiotherapy urinary medication usage (66% and 66%, respectively).

Eighty-six percent received 70 Gy over 28 fractions, with institutional protocol shifting to 60 Gy over 20 fractions (14%) in June 2017. The median (IQR) duration of radiotherapy was 39 (38-42) days, with 97% of individuals undergoing ADT for a median (IQR) duration of 24 (24-36) months. The median follow-up time was 38 months, with 57 (40%) patients followed for at least 60 months.

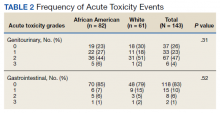

Grade 3 GI and GU acute toxicity events were observed in 1% and 4% of all individuals, respectively (Table 2). No acute GI or GU grade 4+ events were observed. No significant differences in acute GU or GI toxicity were observed between African American and White patients.

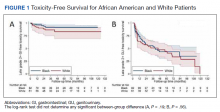

No significant differences between African American and White patients were observed for late grade 2+ GI (P = .19) or GU (P = .55) toxicity. Late grade 2+ GI toxicity was observed in 17 (12%) patients overall (Figure 1A). One grade 3 and 1 grade 4 late GI event were observed following MHRT completion: The latter involved hospitalization for bleeding secondary to radiation proctitis in the context of cirrhosis predating MHRT. Late grade 2+ GU toxicity was observed in 80 (56%) patients, with late grade 2 events steadily increasing over time (Figure 1B). Nine late grade 3 GU toxicity events were observed at a median of 13 months following completion of MHRT, 2 of which occurred more than 24 months after MHRT completion. No late grade 4 or 5 GU events were observed. IPSS values both before MHRT and at time of last follow-up were available for 65 (40%) patients, with a median (IQR) IPSS of 10 (6-16) before MHRT and 12 (8-16) at last follow-up at a median (IQR) interval of 36 months (26-76) from radiation completion.

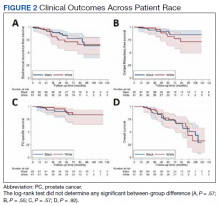

No significant differences were observed between African American and White patients with respect to BRFS, DMFS, PCSS, or OS (Figure 2). Overall, 21 of 143 (15%) patients experienced biochemical recurrence: 5-year BRFS was 77% (95% CI, 67%-85%) for all patients, 83% (95% CI, 70%-91%) for African American patients, and 71% (95% CI, 53%-82%) for White patients. Five-year DMFS was 87% (95% CI, 77%-92%) for all individuals, 91% (95% CI, 80%-96%) for African American patients, and 81% (95% CI, 62%-91%) for White patients. Five-year PCSS was 89% (95% CI, 80%-94%) for all patients, with 5-year PCSS rates of 90% (95% CI, 79%-95%) for African American patients and 87% (95% CI, 70%-95%) for White patients. Five-year OS was 75% overall (95% CI, 64%-82%), with 5-year OS rates of 73% (95% CI, 58%-83%) for African American patients and 77% (95% CI, 60%-87%) for White patients.

Discussion

In this study, we reported acute and late GI and GU toxicity rates as well as clinical outcomes for a majority African American population with predominately unfavorable HRPC treated with MHRT in an equal access health care environment. We found that MHRT was well tolerated with high rates of biochemical control, PCSS, and OS. Additionally, outcomes were not significantly different across patient race. To our knowledge, this is the first report of MHRT for HRPC in a majority African American population.

We found that MHRT was an effective treatment for patients with HRPC, in particular those with unfavorable high-risk disease. While prior prospective and randomized studies have investigated the use of MHRT, our series was larger than most and had a predominately unfavorable high-risk population.12,15-17 Our biochemical and PCSS rates compare favorably with those of HRPC trial populations, particularly given the high proportion of unfavorable high-risk disease.12,15,16 Despite similar rates of biochemical control, OS was lower in the present cohort than in HRPC trial populations, even with a younger median age at diagnosis. The similarly high rates of non–HRPC-related death across race may reflect differences in baseline comorbidities compared with trial populations as well as reported differences between individuals in the VA and the private sector.31 This suggests that MHRT can be an effective treatment for patients with unfavorable HRPC.

We did not find any differences in outcomes between African American and White individuals with HRPC treated with MHRT. Furthermore, our study demonstrates long-term rates of BRFS and PCSS in a majority African American population with predominately unfavorable HRPC that are comparable with those of prior randomized MHRT studies in high-risk, predominately White populations.12,15,16 Prior reports have found that African American men with HRPC may be at increased risk for inferior clinical outcomes due to a number of socioeconomic, biologic, and cultural mediators.26,27,32 Such individuals may disproportionally benefit from shorter treatment courses that improve access to radiotherapy, a well-documented disparity for African American men with localized prostate cancer.33-36 The VA is an ideal system for studying racial disparities within prostate cancer, as accessibility of mental health and transportation services, income, and insurance status are not barriers to preventative or acute care.37 Our results are concordant with those previously seen for African American patients with prostate cancer seen in the VA, which similarly demonstrate equal outcomes with those of other races.28,36 Incorporation of the earlier mentioned VA services into oncologic care across other health care systems could better characterize determinants of racial disparities in prostate cancer, including the prognostic significance of shortening treatment duration and number of patient visits via MHRT.

Despite widespread acceptance in prostate cancer radiotherapy guidelines, routine use of MHRT seems limited across all stages of localized prostate cancer.1,2 Late toxicity is a frequently noted concern regarding MHRT use. Higher rates of late grade 2+ GI toxicity were observed in the hypofractionation arm of the HYPRO trial.17 While RTOG 0415 did not include patients with HRPC, significantly higher rates of physician-reported (but not patient-reported) late grade 2+ GI and GU toxicity were observed using the same MHRT fractionation regimen used for the majority of individuals in our cohort.9 In our study, the steady increase in late grade 2 GU toxicity is consistent with what is seen following conventionally fractionated radiotherapy and is likely multifactorial.38 The mean IPSS difference of 2/35 from pre-MHRT baseline to the time of last follow-up suggests minimal quality of life decline. The relatively stable IPSSs over time alongside the > 50% prevalence of late grade 2 GU toxicity per CTCAE grading seems consistent with the discrepancy noted in RTOG 0415 between increased physician-reported late toxicity and favorable patient-reported quality of life scores.9 Moreover, significant variance exists in toxicity grading across scoring systems, revised editions of CTCAE, and physician-specific toxicity classification, particularly with regard to the use of adrenergic receptor blocker medications. In light of these factors, the high rate of late grade 2 GU toxicity in our study should be interpreted in the context of largely stable post-MHRT IPSSs and favorable rates of late GI grade 2+ and late GU grade 3+ toxicity.

Limitations

This study has several inherent limitations. While the size of the current HRPC cohort is notably larger than similar populations within the majority of phase 3 MHRT trials, these data derive from a single VA hospital. It is unclear whether these outcomes would be representative in a similar high-risk population receiving care outside of the VA equal access system. Follow-up data beyond 5 years was available for less than half of patients, partially due to nonprostate cancer–related mortality at a higher rate than observed in HRPC trial populations.12,15,16 Furthermore, all GI toxicity events were exclusively physician reported, and GU toxicity reporting was limited in the off-trial setting with not all patients routinely completing IPSS questionnaires following MHRT completion. However, all patients were treated similarly, and radiation quality was verified over the treatment period with mandated accreditation, frequent standardized output checks, and systematic treatment review.39

Conclusions

Patients with HRPC treated with MHRT in an equal access, off-trial setting demonstrated favorable rates of biochemical control with acceptable rates of acute and late GI and GU toxicities. Clinical outcomes, including biochemical control, were not significantly different between African American and White patients, which may reflect equal access to care within the VA irrespective of income and insurance status. Incorporating VA services, such as access to primary care, mental health services, and transportation across other health care systems may aid in characterizing and mitigating racial and gender disparities in oncologic care.

Acknowledgments

Portions of this work were presented at the November 2020 ASTRO conference. 40

1. Stokes WA, Kavanagh BD, Raben D, Pugh TJ. Implementation of hypofractionated prostate radiation therapy in the United States: a National Cancer Database analysis. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2017;7:270-278. doi:10.1016/j.prro.2017.03.011

2. Jaworski L, Dominello MM, Heimburger DK, et al. Contemporary practice patterns for intact and post-operative prostate cancer: results from a statewide collaborative. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2019;105(1):E282. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2019.06.1915

3. Miralbell R, Roberts SA, Zubizarreta E, Hendry JH. Dose-fractionation sensitivity of prostate cancer deduced from radiotherapy outcomes of 5,969 patients in seven international institutional datasets: α/β = 1.4 (0.9-2.2) Gy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82(1):e17-e24. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.10.075

4. Tree AC, Khoo VS, van As NJ, Partridge M. Is biochemical relapse-free survival after profoundly hypofractionated radiotherapy consistent with current radiobiological models? Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2014;26(4):216-229. doi:10.1016/j.clon.2014.01.008

5. Brenner DJ. Fractionation and late rectal toxicity. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;60(4):1013-1015. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.04.014

6. Tucker SL, Thames HD, Michalski JM, et al. Estimation of α/β for late rectal toxicity based on RTOG 94-06. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;81(2):600-605. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.11.080

7. Dasu A, Toma-Dasu I. Prostate alpha/beta revisited—an analysis of clinical results from 14 168 patients. Acta Oncol. 2012;51(8):963-974. doi:10.3109/0284186X.2012.719635 start

8. Proust-Lima C, Taylor JMG, Sécher S, et al. Confirmation of a Low α/β ratio for prostate cancer treated by external beam radiation therapy alone using a post-treatment repeated-measures model for PSA dynamics. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;79(1):195-201. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.10.008

9. Lee WR, Dignam JJ, Amin MB, et al. Randomized phase III noninferiority study comparing two radiotherapy fractionation schedules in patients with low-risk prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(20): 2325-2332. doi:10.1200/JCO.2016.67.0448

10. Dearnaley D, Syndikus I, Mossop H, et al. Conventional versus hypofractionated high-dose intensity-modulated radiotherapy for prostate cancer: 5-year outcomes of the randomised, non-inferiority, phase 3 CHHiP trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(8):1047-1060. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30102-4

11. Catton CN, Lukka H, Gu C-S, et al. Randomized trial of a hypofractionated radiation regimen for the treatment of localized prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(17):1884-1890. doi:10.1200/JCO.2016.71.7397

12. Pollack A, Walker G, Horwitz EM, et al. Randomized trial of hypofractionated external-beam radiotherapy for prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(31):3860-3868. doi:10.1200/JCO.2013.51.1972

13. Hoffman KE, Voong KR, Levy LB, et al. Randomized trial of hypofractionated, dose-escalated, intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) versus conventionally fractionated IMRT for localized prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(29):2943-2949. doi:10.1200/JCO.2018.77.9868

14. Wilkins A, Mossop H, Syndikus I, et al. Hypofractionated radiotherapy versus conventionally fractionated radiotherapy for patients with intermediate-risk localised prostate cancer: 2-year patient-reported outcomes of the randomised, non-inferiority, phase 3 CHHiP trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(16):1605-1616. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00280-6

15. Incrocci L, Wortel RC, Alemayehu WG, et al. Hypofractionated versus conventionally fractionated radiotherapy for patients with localised prostate cancer (HYPRO): final efficacy results from a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(8):1061-1069. doi.10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30070-5

16. Arcangeli G, Saracino B, Arcangeli S, et al. Moderate hypofractionation in high-risk, organ-confined prostate cancer: final results of a phase III randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(17):1891-1897. doi:10.1200/JCO.2016.70.4189

17. Aluwini S, Pos F, Schimmel E, et al. Hypofractionated versus conventionally fractionated radiotherapy for patients with prostate cancer (HYPRO): late toxicity results from a randomised, non-inferiority, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(4):464-474. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00567-7

18. Pervez N, Small C, MacKenzie M, et al. Acute toxicity in high-risk prostate cancer patients treated with androgen suppression and hypofractionated intensity-modulated radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76(1):57-64. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.01.048

19. Magli A, Moretti E, Tullio A, Giannarini G. Hypofractionated simultaneous integrated boost (IMRT- cancer: results of a prospective phase II trial SIB) with pelvic nodal irradiation and concurrent androgen deprivation therapy for high-risk prostate cancer: results of a prospective phase II trial. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2018;21(2):269-276. doi:10.1038/s41391-018-0034-0

20. Di Muzio NG, Fodor A, Noris Chiorda B, et al. Moderate hypofractionation with simultaneous integrated boost in prostate cancer: long-term results of a phase I–II study. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2016;28(8):490-500. doi:10.1016/j.clon.2016.02.005

21. DeSantis CE, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Jemal A, Siegel RL. Cancer statistics for African Americans, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(3):21-233. doi:10.3322/caac.21555

22. Wolf MS, Knight SJ, Lyons EA, et al. Literacy, race, and PSA level among low-income men newly diagnosed with prostate cancer. Urology. 2006(1);68:89-93. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2006.01.064

23. Rebbeck TR. Prostate cancer disparities by race and ethnicity: from nucleotide to neighborhood. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2018;8(9):a030387. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a030387

24. Guidry JJ, Aday LA, Zhang D, Winn RJ. Transportation as a barrier to cancer treatment. Cancer Pract. 1997;5(6):361-366.

25. Friedman DB, Corwin SJ, Dominick GM, Rose ID. African American men’s understanding and perceptions about prostate cancer: why multiple dimensions of health literacy are important in cancer communication. J Community Health. 2009;34(5):449-460. doi:10.1007/s10900-009-9167-3

26. Connell PP, Ignacio L, Haraf D, et al. Equivalent racial outcome after conformal radiotherapy for prostate cancer: a single departmental experience. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(1):54-61. doi:10.1200/JCO.2001.19.1.54

27. Dess RT, Hartman HE, Mahal BA, et al. Association of black race with prostate cancer-specific and other-cause mortality. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(1):975-983. doi:10.1200/JCO.2001.19.1.54

28. McKay RR, Sarkar RR, Kumar A, et al. Outcomes of Black men with prostate cancer treated with radiation therapy in the Veterans Health Administration. Cancer. 2021;127(3):403-411. doi:10.1002/cncr.33224

29. Muralidhar V, Chen M-H, Reznor G, et al. Definition and validation of “favorable high-risk prostate cancer”: implications for personalizing treatment of radiation-managed patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015;93(4):828-835. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2015.07.2281

30. Roach M 3rd, Hanks G, Thames H Jr, et al. Defining biochemical failure following radiotherapy with or without hormonal therapy in men with clinically localized prostate cancer: recommendations of the RTOG-ASTRO Phoenix Consensus Conference. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65(4):965-974. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.04.029

31. Freeman VL, Durazo-Arvizu R, Arozullah AM, Keys LC. Determinants of mortality following a diagnosis of prostate cancer in Veterans Affairs and private sector health care systems. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(100):1706-1712. doi:10.2105/ajph.93.10.1706

32. Ward E, Jemal A, Cokkinides V, et al. Cancer disparities by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54(2):78-93. doi:10.3322/canjclin.54.2.78

33. Zemplenyi AT, Kaló Z, Kovacs G, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of intensity-modulated radiation therapy with normal and hypofractionated schemes for the treatment of localised prostate cancer. Eur J Cancer Care. 2018;27(1):e12430. doi:10.1111/ecc.12430

34. Klabunde CN, Potosky AL, Harlan LC, Kramer BS. Trends and black/white differences in treatment for nonmetastatic prostate cancer. Med Care. 1998;36(9):1337-1348. doi:10.1097/00005650-199809000-00006

35. Harlan L, Brawley O, Pommerenke F, Wali P, Kramer B. Geographic, age, and racial variation in the treatment of local/regional carcinoma of the prostate. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13(1):93-100. doi:10.1200/JCO.1995.13.1.93

36. Riviere P, Luterstein E, Kumar A, et al. Racial equity among African-American and non-Hispanic white men diagnosed with prostate cancer in the veterans affairs healthcare system. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2019;105:E305.

37. Peterson K, Anderson J, Boundy E, Ferguson L, McCleery E, Waldrip K. Mortality disparities in racial/ethnic minority groups in the Veterans Health Administration: an evidence review and map. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(3):e1-e11. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2017.304246

38. Zietman AL, DeSilvio ML, Slater JD, et al. Comparison of conventional-dose vs high-dose conformal radiation therapy in clinically localized adenocarcinoma of the prostate: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;294(10):1233-1239. doi:10.1001/jama.294.10.1233

39. Hagan M, Kapoor R, Michalski J, et al. VA-Radiation Oncology Quality Surveillance program. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2020;106(3):639-647. doi.10.1016/j.ijrobp.2019.08.064

40. Carpenter DJ, Natesan D, Floyd W, et al. Long-term experience in an equal access health care system using moderately hypofractionated radiotherapy for high risk prostate cancer in a predominately African American population with unfavorable disease. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2020;108(3):E417. https://www.redjournal.org/article/S0360-3016(20)33923-7/fulltext

Although moderately hypofractionated radiotherapy (MHRT) is an accepted treatment for localized prostate cancer, its adaptation remains limited in the United States.1,2 MHRT theoretically exploits α/β ratio differences between the prostate (1.5 Gy), bladder (5-10 Gy), and rectum (3 Gy), thereby reducing late treatment-related adverse effects compared with those of conventional fractionation at biologically equivalent doses.3-8 Multiple randomized noninferiority trials have demonstrated equivalent outcomes between MHRT and conventional fraction with no appreciable increase in patient-reported toxicity.9-14 Although these studies have led to the acceptance of MHRT as a standard treatment, the majority of these trials involve individuals with low- and intermediate-risk disease.

There are less phase 3 data addressing MHRT for high-risk prostate cancer (HRPC).10,12,14-17 Only 2 studies examined predominately high-risk populations, accounting for 83 and 292 patients, respectively.15,16 Additional phase 3 trials with small proportions of high-risk patients (n = 126, 12%; n = 53, 35%) offer limited additional information regarding clinical outcomes and toxicity rates specific to high-risk disease.10-12 Numerous phase 1 and 2 studies report various field designs and fractionation plans for MHRT in the context of high-risk disease, although the applicability of these data to off-trial populations remains limited.18-20

Furthermore, African American individuals are underrepresented in the trials establishing the role of MHRT despite higher rates of prostate cancer incidence, more advanced disease stage at diagnosis, and higher rates of prostate cancer–specific survival (PCSS) when compared with White patients.21 Racial disparities across patients with prostate cancer and their management are multifactorial across health care literacy, education level, access to care (including transportation issues), and issues of adherence and distrust.22-25 Correlation of patient race to prostate cancer outcomes varies greatly across health care systems, with the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) equal access system providing robust mental health services and transportation services for some patients, while demonstrating similar rates of stage-adjusted PCSS between African American and White patients across a broad range of treatment modalities.26-28 Given the paucity of data exploring outcomes following MHRT for African American patients with HRPC, the present analysis provides long-term clinical outcomes and toxicity profiles for an off-trial majority African American population with HRPC treated with MHRT within the VA.

Methods

Records were retrospectively reviewed under an institutional review board–approved protocol for all patients with HRPC treated with definitive MHRT at the Durham Veterans Affairs Healthcare System in North Carolina between November 2008 and August 2018. Exclusion criteria included < 12 months of follow-up or elective nodal irradiation. Demographic variables obtained included age at diagnosis, race, clinical T stage, pre-MHRT prostate-specific antigen (PSA), Gleason grade group at diagnosis, favorable vs unfavorable high-risk disease, pre-MHRT international prostate symptom score (IPSS), and pre-MHRT urinary medication usage (yes/no).29