User login

Colorectal screening cost effective in cystic fibrosis patients

Screening for colorectal cancer in patients with cystic fibrosis is cost effective, and should be started at a younger age and performed more often, new research suggests.

While colorectal cancer (CRC) screening traditionally begins at age 50 years in people at average risk for the disease, those at high risk usually begin undergoing colonoscopies at an earlier age. Patients with cystic fibrosis fall under the latter category, wrote Andrea Gini, of the department of public health at Erasmus Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and colleagues, with an incidence of CRC up to 30 times higher than the general population, but their shorter lifespan has led to a “different trade-off between the benefits and harms of CRC screening.”

Between 2000 and 2015, the median predicted survival age for patients with cystic fibrosis increased from 33.3 years to 41.7 years; this increased survival has brought increased risk for other diseases, particularly in the GI tract, Mr. Gini and colleagues wrote in Gastroenterology. By using the Microsimulation Screening Analysis–Colon model – a joint project between Erasmus Medical Center and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York – the investigators assessed the cost-effectiveness of CRC screening in patients with cystic fibrosis.

Three cohorts of 10 million patients each were simulated, with one cohort having undergone transplant, one cohort not having transplant, and one cohort of individuals without cystic fibrosis. The simulated patient age was 30 years in 2017. A total of 76 different colonoscopy-screening strategies were assessed, with each differing in screening interval (3, 5, or 10 years for colonoscopy), age to start screening (30, 35, 40, 45, or 50 years), and age to end screening (55, 60, 65, 70, or 75 years). The optimal screening strategy was determined based on a willingness-to-pay threshold of $100,000 per life-year gained, the investigators wrote.

In the absence of screening, the mortality rate for nontransplant cystic fibrosis patients was 19.1 per 1,000 people, and the rate for cystic fibrosis patients who had undergone transplant was 22.3 per 1,000 people. The standard screening strategy prevented more than 73% of CRC deaths in the general population, 66% of deaths in nontransplant cystic fibrosis patients, and 36% of deaths in cystic fibrosis patients with transplant; however, the model predicted that only 22% of individuals who received a transplant and 36% of those who did not would reach the age of 50 years.

According to the model, the optimal colonoscopy-screening strategy for nontransplant patients was one screen every 5 years, starting at 40 and screening until the age of 75. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was $84,000 per life-year gained; CRC incidence was reduced by 52% and CRC mortality was reduced by 79%. For transplant patients, the best strategy was one screen every 3 years between the ages of 35 and 55, which reduced CRC mortality by 82% at an ICER of $71,000 per life-year gained.

In a separate analysis of fecal immunochemical testing, a less-demanding alternative to colonoscopy, the optimal screening strategy was an annual test between the age of 35 and 75 years for nontransplant cystic fibrosis patients, for an ICER of $47,000 per life-year gained and a CRC mortality reduction of 78%. The best strategy for transplant patients was once a year between the ages of 30 and 60, which reduced CRC mortality by 77% at an ICER of $86,000 per life-year gained. While fecal immunochemical testing may be more cost effective than colonoscopy, “specific evidence of its performance in the cystic fibrosis population is required before considering this screening modality,” the investigators noted.

“This study indicates that there is benefit to earlier CRC screening in the cystic fibrosis population and [that it] can be done at acceptable costs,” the investigators wrote. “The findings of this analysis support clinicians, researchers, and policy makers who aim to define a tailored CRC screening for individuals with cystic fibrosis in the United States.”

The study was funded by the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, the Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network consortium, and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Gini A et al. Gastroenterology. 2017 Dec 27. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.12.011.

Screening for colorectal cancer in patients with cystic fibrosis is cost effective, and should be started at a younger age and performed more often, new research suggests.

While colorectal cancer (CRC) screening traditionally begins at age 50 years in people at average risk for the disease, those at high risk usually begin undergoing colonoscopies at an earlier age. Patients with cystic fibrosis fall under the latter category, wrote Andrea Gini, of the department of public health at Erasmus Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and colleagues, with an incidence of CRC up to 30 times higher than the general population, but their shorter lifespan has led to a “different trade-off between the benefits and harms of CRC screening.”

Between 2000 and 2015, the median predicted survival age for patients with cystic fibrosis increased from 33.3 years to 41.7 years; this increased survival has brought increased risk for other diseases, particularly in the GI tract, Mr. Gini and colleagues wrote in Gastroenterology. By using the Microsimulation Screening Analysis–Colon model – a joint project between Erasmus Medical Center and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York – the investigators assessed the cost-effectiveness of CRC screening in patients with cystic fibrosis.

Three cohorts of 10 million patients each were simulated, with one cohort having undergone transplant, one cohort not having transplant, and one cohort of individuals without cystic fibrosis. The simulated patient age was 30 years in 2017. A total of 76 different colonoscopy-screening strategies were assessed, with each differing in screening interval (3, 5, or 10 years for colonoscopy), age to start screening (30, 35, 40, 45, or 50 years), and age to end screening (55, 60, 65, 70, or 75 years). The optimal screening strategy was determined based on a willingness-to-pay threshold of $100,000 per life-year gained, the investigators wrote.

In the absence of screening, the mortality rate for nontransplant cystic fibrosis patients was 19.1 per 1,000 people, and the rate for cystic fibrosis patients who had undergone transplant was 22.3 per 1,000 people. The standard screening strategy prevented more than 73% of CRC deaths in the general population, 66% of deaths in nontransplant cystic fibrosis patients, and 36% of deaths in cystic fibrosis patients with transplant; however, the model predicted that only 22% of individuals who received a transplant and 36% of those who did not would reach the age of 50 years.

According to the model, the optimal colonoscopy-screening strategy for nontransplant patients was one screen every 5 years, starting at 40 and screening until the age of 75. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was $84,000 per life-year gained; CRC incidence was reduced by 52% and CRC mortality was reduced by 79%. For transplant patients, the best strategy was one screen every 3 years between the ages of 35 and 55, which reduced CRC mortality by 82% at an ICER of $71,000 per life-year gained.

In a separate analysis of fecal immunochemical testing, a less-demanding alternative to colonoscopy, the optimal screening strategy was an annual test between the age of 35 and 75 years for nontransplant cystic fibrosis patients, for an ICER of $47,000 per life-year gained and a CRC mortality reduction of 78%. The best strategy for transplant patients was once a year between the ages of 30 and 60, which reduced CRC mortality by 77% at an ICER of $86,000 per life-year gained. While fecal immunochemical testing may be more cost effective than colonoscopy, “specific evidence of its performance in the cystic fibrosis population is required before considering this screening modality,” the investigators noted.

“This study indicates that there is benefit to earlier CRC screening in the cystic fibrosis population and [that it] can be done at acceptable costs,” the investigators wrote. “The findings of this analysis support clinicians, researchers, and policy makers who aim to define a tailored CRC screening for individuals with cystic fibrosis in the United States.”

The study was funded by the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, the Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network consortium, and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Gini A et al. Gastroenterology. 2017 Dec 27. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.12.011.

Screening for colorectal cancer in patients with cystic fibrosis is cost effective, and should be started at a younger age and performed more often, new research suggests.

While colorectal cancer (CRC) screening traditionally begins at age 50 years in people at average risk for the disease, those at high risk usually begin undergoing colonoscopies at an earlier age. Patients with cystic fibrosis fall under the latter category, wrote Andrea Gini, of the department of public health at Erasmus Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and colleagues, with an incidence of CRC up to 30 times higher than the general population, but their shorter lifespan has led to a “different trade-off between the benefits and harms of CRC screening.”

Between 2000 and 2015, the median predicted survival age for patients with cystic fibrosis increased from 33.3 years to 41.7 years; this increased survival has brought increased risk for other diseases, particularly in the GI tract, Mr. Gini and colleagues wrote in Gastroenterology. By using the Microsimulation Screening Analysis–Colon model – a joint project between Erasmus Medical Center and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York – the investigators assessed the cost-effectiveness of CRC screening in patients with cystic fibrosis.

Three cohorts of 10 million patients each were simulated, with one cohort having undergone transplant, one cohort not having transplant, and one cohort of individuals without cystic fibrosis. The simulated patient age was 30 years in 2017. A total of 76 different colonoscopy-screening strategies were assessed, with each differing in screening interval (3, 5, or 10 years for colonoscopy), age to start screening (30, 35, 40, 45, or 50 years), and age to end screening (55, 60, 65, 70, or 75 years). The optimal screening strategy was determined based on a willingness-to-pay threshold of $100,000 per life-year gained, the investigators wrote.

In the absence of screening, the mortality rate for nontransplant cystic fibrosis patients was 19.1 per 1,000 people, and the rate for cystic fibrosis patients who had undergone transplant was 22.3 per 1,000 people. The standard screening strategy prevented more than 73% of CRC deaths in the general population, 66% of deaths in nontransplant cystic fibrosis patients, and 36% of deaths in cystic fibrosis patients with transplant; however, the model predicted that only 22% of individuals who received a transplant and 36% of those who did not would reach the age of 50 years.

According to the model, the optimal colonoscopy-screening strategy for nontransplant patients was one screen every 5 years, starting at 40 and screening until the age of 75. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was $84,000 per life-year gained; CRC incidence was reduced by 52% and CRC mortality was reduced by 79%. For transplant patients, the best strategy was one screen every 3 years between the ages of 35 and 55, which reduced CRC mortality by 82% at an ICER of $71,000 per life-year gained.

In a separate analysis of fecal immunochemical testing, a less-demanding alternative to colonoscopy, the optimal screening strategy was an annual test between the age of 35 and 75 years for nontransplant cystic fibrosis patients, for an ICER of $47,000 per life-year gained and a CRC mortality reduction of 78%. The best strategy for transplant patients was once a year between the ages of 30 and 60, which reduced CRC mortality by 77% at an ICER of $86,000 per life-year gained. While fecal immunochemical testing may be more cost effective than colonoscopy, “specific evidence of its performance in the cystic fibrosis population is required before considering this screening modality,” the investigators noted.

“This study indicates that there is benefit to earlier CRC screening in the cystic fibrosis population and [that it] can be done at acceptable costs,” the investigators wrote. “The findings of this analysis support clinicians, researchers, and policy makers who aim to define a tailored CRC screening for individuals with cystic fibrosis in the United States.”

The study was funded by the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, the Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network consortium, and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Gini A et al. Gastroenterology. 2017 Dec 27. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.12.011.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Key clinical point: Colorectal cancer screening in patients with cystic fibrosis is cost effective and should be performed more often and at a younger age.

Major finding:

Study details: The Microsimulation Screening Analysis–Colon, involving three simulated cohorts of 10 million people.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, the Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network consortium, and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

Source: Gini A et al. Gastroenterology. 2017 Dec 27. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.12.011.

Genetic Colorectal Cancer Risk Variants are Associated with Increasing Adenoma Counts

Background: High lifetime counts of pre-cancerous polyps, termed “adenomas,” are associated with increased risk for colorectal cancer (CRC). Given that a genetic predisposition to adenomas may increase susceptibility to CRC, further studies are needed to characterize low-penetrance germline factors in those with increased cumulative adenoma counts.

Purpose: To investigate if known CRC or adenomarisk single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are associated with increasing cumulative adenoma counts in a prospective screening cohort of veterans.

Data Analysis: The CSP #380 screening colonoscopy cohort includes a biorepository of selected individuals with baseline advanced neoplasia and matched individuals without neoplasia (n=612). Blood samples were genotyped using the Illumina Infinium Omni2.5-8 GWAS chip and associated cumulative adenoma counts were summed over 10 years. A corrected Poisson regression (adjusted for age at last colonoscopy, gender, and race) was used to evaluate associations between higher cumulative adenoma counts and 43 pre-specified CRC-risk SNPs or a subset of these SNPs shown also to be associated with adenomas in published literature. SNPs were evaluated singly or combined in a Genetic Risk Score (GRS). The GRS was constructed from only the eight adenomarisk SNPs and calculated based on the total number of present risk alleles (0-2) summed across all SNPs per individual (both weighted for published effect size and unweighted).

Results: Four CRC-risk SNPs were associated with increasing mean adenoma counts (P<0.05): rs12241008 (gene: VTI1A), rs2423279 (BMP2/HAO1), rs3184504 (SH2B3), and rs961253 (FERMT1/BMP2), with risk allele risk ratios (RR) of 1.31, 1.29, 1.24, and 1.23, respectively. Only one known adenoma-risk SNP was significant in our dataset (rs961253; OR 1.23 per risk allele; P=0.01). An increasing weighted GRS was associated with increased cumulative adenoma counts (weighted RR 1.58, P=0.03; unweighted RR 1.03, P=0.39).

Implications: In this CRC screening cohort, four known CRC-risk SNPs were found to be associated with increasing cumulative adenoma counts. Additionally, an increasing burden of adenoma-risk SNPs, as measured by a weighted GRS, was associated with higher cumulative adenoma counts. Future work will evaluate predictive tools based on a precancerous, adenoma GRS to better risk stratify patients during CRC screening, and compare to current CRC genetic risk scores.

Background: High lifetime counts of pre-cancerous polyps, termed “adenomas,” are associated with increased risk for colorectal cancer (CRC). Given that a genetic predisposition to adenomas may increase susceptibility to CRC, further studies are needed to characterize low-penetrance germline factors in those with increased cumulative adenoma counts.

Purpose: To investigate if known CRC or adenomarisk single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are associated with increasing cumulative adenoma counts in a prospective screening cohort of veterans.

Data Analysis: The CSP #380 screening colonoscopy cohort includes a biorepository of selected individuals with baseline advanced neoplasia and matched individuals without neoplasia (n=612). Blood samples were genotyped using the Illumina Infinium Omni2.5-8 GWAS chip and associated cumulative adenoma counts were summed over 10 years. A corrected Poisson regression (adjusted for age at last colonoscopy, gender, and race) was used to evaluate associations between higher cumulative adenoma counts and 43 pre-specified CRC-risk SNPs or a subset of these SNPs shown also to be associated with adenomas in published literature. SNPs were evaluated singly or combined in a Genetic Risk Score (GRS). The GRS was constructed from only the eight adenomarisk SNPs and calculated based on the total number of present risk alleles (0-2) summed across all SNPs per individual (both weighted for published effect size and unweighted).

Results: Four CRC-risk SNPs were associated with increasing mean adenoma counts (P<0.05): rs12241008 (gene: VTI1A), rs2423279 (BMP2/HAO1), rs3184504 (SH2B3), and rs961253 (FERMT1/BMP2), with risk allele risk ratios (RR) of 1.31, 1.29, 1.24, and 1.23, respectively. Only one known adenoma-risk SNP was significant in our dataset (rs961253; OR 1.23 per risk allele; P=0.01). An increasing weighted GRS was associated with increased cumulative adenoma counts (weighted RR 1.58, P=0.03; unweighted RR 1.03, P=0.39).

Implications: In this CRC screening cohort, four known CRC-risk SNPs were found to be associated with increasing cumulative adenoma counts. Additionally, an increasing burden of adenoma-risk SNPs, as measured by a weighted GRS, was associated with higher cumulative adenoma counts. Future work will evaluate predictive tools based on a precancerous, adenoma GRS to better risk stratify patients during CRC screening, and compare to current CRC genetic risk scores.

Background: High lifetime counts of pre-cancerous polyps, termed “adenomas,” are associated with increased risk for colorectal cancer (CRC). Given that a genetic predisposition to adenomas may increase susceptibility to CRC, further studies are needed to characterize low-penetrance germline factors in those with increased cumulative adenoma counts.

Purpose: To investigate if known CRC or adenomarisk single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are associated with increasing cumulative adenoma counts in a prospective screening cohort of veterans.

Data Analysis: The CSP #380 screening colonoscopy cohort includes a biorepository of selected individuals with baseline advanced neoplasia and matched individuals without neoplasia (n=612). Blood samples were genotyped using the Illumina Infinium Omni2.5-8 GWAS chip and associated cumulative adenoma counts were summed over 10 years. A corrected Poisson regression (adjusted for age at last colonoscopy, gender, and race) was used to evaluate associations between higher cumulative adenoma counts and 43 pre-specified CRC-risk SNPs or a subset of these SNPs shown also to be associated with adenomas in published literature. SNPs were evaluated singly or combined in a Genetic Risk Score (GRS). The GRS was constructed from only the eight adenomarisk SNPs and calculated based on the total number of present risk alleles (0-2) summed across all SNPs per individual (both weighted for published effect size and unweighted).

Results: Four CRC-risk SNPs were associated with increasing mean adenoma counts (P<0.05): rs12241008 (gene: VTI1A), rs2423279 (BMP2/HAO1), rs3184504 (SH2B3), and rs961253 (FERMT1/BMP2), with risk allele risk ratios (RR) of 1.31, 1.29, 1.24, and 1.23, respectively. Only one known adenoma-risk SNP was significant in our dataset (rs961253; OR 1.23 per risk allele; P=0.01). An increasing weighted GRS was associated with increased cumulative adenoma counts (weighted RR 1.58, P=0.03; unweighted RR 1.03, P=0.39).

Implications: In this CRC screening cohort, four known CRC-risk SNPs were found to be associated with increasing cumulative adenoma counts. Additionally, an increasing burden of adenoma-risk SNPs, as measured by a weighted GRS, was associated with higher cumulative adenoma counts. Future work will evaluate predictive tools based on a precancerous, adenoma GRS to better risk stratify patients during CRC screening, and compare to current CRC genetic risk scores.

Clip closure reduces postop bleeding risk after proximal polyp resection

In a prospective study of almost 1,000 patients, this benefit was not influenced by polyp size, electrocautery setting, or concomitant use of antithrombotic medications, reported Heiko Pohl, MD, of Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, N.H., and colleagues.

“Endoscopic resection has replaced surgical resection as the primary treatment for large colon polyps due to a lower morbidity and less need for hospitalization,” the investigators wrote in Gastroenterology. “Postprocedure bleeding is the most common severe complication, occurring in 2%-24% of patients.” This risk is particularly common among patients with large polyps in the proximal colon.

Although previous trials have suggested that closing polyp resection sites with hemoclips could reduce the risk of postoperative bleeding, studies to date have been retrospective or uncontrolled, precluding definitive conclusions.

The prospective, controlled trial involved 44 endoscopists at 18 treatment centers. Enrollment included 919 patients with large, nonpedunculated colorectal polyps of at least 20 mm in diameter. Patients were randomized in an approximate 1:1 ratio into the clip group or control group and followed for at least 30 days after endoscopic polyp resection. The primary outcome was postoperative bleeding, defined as severe bleeding that required invasive intervention such as surgery or blood transfusion during follow-up. Subgroup analysis looked for associations between bleeding and polyp location, size, electrocautery setting, and medications.

Across the entire population, postoperative bleeding was significantly less common among patients who had their resection sites closed with clips, occurring at a rate of 3.5%, compared with 7.1% in the control group (P = .015). Serious adverse events were also less common in the clip group than the control group (4.8% vs. 9.5%; P = .006).

While the reduction of bleeding risk from clip closure was not influenced by polyp size, use of antithrombotic medications, or electrocautery setting, polyp location turned out to be a critical factor. Greatest reduction in risk of postoperative bleeding was seen among the 615 patients who had proximal polyps, based on a bleeding rate of 3.3% when clipped versus 9.6% among those who went without clips (P = .001). In contrast, clips in the distal colon were associated with a higher absolute risk of postoperative bleeding than no clips (4.0% vs. 1.4%); however, this difference was not statistically significant (P = .178).

“[T]his multicenter trial provides strong evidence that endoscopic clip closure of the mucosal defect after resection of large ... nonpedunculated colon polyps in the proximal colon significantly reduces the risk of postprocedure bleeding,” the investigators wrote.

They suggested that their study provides greater confidence in findings than similar trials previously conducted, enough to recommend that endoscopic techniques be altered accordingly. “[O]ur trial was methodologically rigorous, adequately powered, and all polyps were removed by endoscopic mucosal resection, which is considered the standard technique for large colon polyps in Western countries,” they wrote. “The results of the study are therefore broadly applicable to current practice. Furthermore, conduct of the study at different centers with multiple endoscopists strengthens generalizability of the findings.”

The investigators also speculated about why postoperative bleeding risk was increased when clips were used in the distal colon. “Potential explanations include a poorer quality of clipping, a shorter clip retention time, possible related to a thicker colon wall in the distal compared to the proximal colon,” they wrote, adding that “these considerations are worthy of further study.”

Indeed, more work remains to be done. “A formal cost-effectiveness analysis is needed to better understand the value of clip closure,” they wrote. “Such analysis can then also examine possible thresholds, for instance regarding the minimum proportion of polyp resections, for which complete closure should be achieved, or the maximum number of clips to close a defect.”

The study was funded by Boston Scientific. The investigators reported additional relationships with U.S. Endoscopy, Olympus, Medtronic, and others.

SOURCE: Pohl H et al. Gastroenterology. 2019 Mar 15. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.03.019.

In a prospective study of almost 1,000 patients, this benefit was not influenced by polyp size, electrocautery setting, or concomitant use of antithrombotic medications, reported Heiko Pohl, MD, of Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, N.H., and colleagues.

“Endoscopic resection has replaced surgical resection as the primary treatment for large colon polyps due to a lower morbidity and less need for hospitalization,” the investigators wrote in Gastroenterology. “Postprocedure bleeding is the most common severe complication, occurring in 2%-24% of patients.” This risk is particularly common among patients with large polyps in the proximal colon.

Although previous trials have suggested that closing polyp resection sites with hemoclips could reduce the risk of postoperative bleeding, studies to date have been retrospective or uncontrolled, precluding definitive conclusions.

The prospective, controlled trial involved 44 endoscopists at 18 treatment centers. Enrollment included 919 patients with large, nonpedunculated colorectal polyps of at least 20 mm in diameter. Patients were randomized in an approximate 1:1 ratio into the clip group or control group and followed for at least 30 days after endoscopic polyp resection. The primary outcome was postoperative bleeding, defined as severe bleeding that required invasive intervention such as surgery or blood transfusion during follow-up. Subgroup analysis looked for associations between bleeding and polyp location, size, electrocautery setting, and medications.

Across the entire population, postoperative bleeding was significantly less common among patients who had their resection sites closed with clips, occurring at a rate of 3.5%, compared with 7.1% in the control group (P = .015). Serious adverse events were also less common in the clip group than the control group (4.8% vs. 9.5%; P = .006).

While the reduction of bleeding risk from clip closure was not influenced by polyp size, use of antithrombotic medications, or electrocautery setting, polyp location turned out to be a critical factor. Greatest reduction in risk of postoperative bleeding was seen among the 615 patients who had proximal polyps, based on a bleeding rate of 3.3% when clipped versus 9.6% among those who went without clips (P = .001). In contrast, clips in the distal colon were associated with a higher absolute risk of postoperative bleeding than no clips (4.0% vs. 1.4%); however, this difference was not statistically significant (P = .178).

“[T]his multicenter trial provides strong evidence that endoscopic clip closure of the mucosal defect after resection of large ... nonpedunculated colon polyps in the proximal colon significantly reduces the risk of postprocedure bleeding,” the investigators wrote.

They suggested that their study provides greater confidence in findings than similar trials previously conducted, enough to recommend that endoscopic techniques be altered accordingly. “[O]ur trial was methodologically rigorous, adequately powered, and all polyps were removed by endoscopic mucosal resection, which is considered the standard technique for large colon polyps in Western countries,” they wrote. “The results of the study are therefore broadly applicable to current practice. Furthermore, conduct of the study at different centers with multiple endoscopists strengthens generalizability of the findings.”

The investigators also speculated about why postoperative bleeding risk was increased when clips were used in the distal colon. “Potential explanations include a poorer quality of clipping, a shorter clip retention time, possible related to a thicker colon wall in the distal compared to the proximal colon,” they wrote, adding that “these considerations are worthy of further study.”

Indeed, more work remains to be done. “A formal cost-effectiveness analysis is needed to better understand the value of clip closure,” they wrote. “Such analysis can then also examine possible thresholds, for instance regarding the minimum proportion of polyp resections, for which complete closure should be achieved, or the maximum number of clips to close a defect.”

The study was funded by Boston Scientific. The investigators reported additional relationships with U.S. Endoscopy, Olympus, Medtronic, and others.

SOURCE: Pohl H et al. Gastroenterology. 2019 Mar 15. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.03.019.

In a prospective study of almost 1,000 patients, this benefit was not influenced by polyp size, electrocautery setting, or concomitant use of antithrombotic medications, reported Heiko Pohl, MD, of Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, N.H., and colleagues.

“Endoscopic resection has replaced surgical resection as the primary treatment for large colon polyps due to a lower morbidity and less need for hospitalization,” the investigators wrote in Gastroenterology. “Postprocedure bleeding is the most common severe complication, occurring in 2%-24% of patients.” This risk is particularly common among patients with large polyps in the proximal colon.

Although previous trials have suggested that closing polyp resection sites with hemoclips could reduce the risk of postoperative bleeding, studies to date have been retrospective or uncontrolled, precluding definitive conclusions.

The prospective, controlled trial involved 44 endoscopists at 18 treatment centers. Enrollment included 919 patients with large, nonpedunculated colorectal polyps of at least 20 mm in diameter. Patients were randomized in an approximate 1:1 ratio into the clip group or control group and followed for at least 30 days after endoscopic polyp resection. The primary outcome was postoperative bleeding, defined as severe bleeding that required invasive intervention such as surgery or blood transfusion during follow-up. Subgroup analysis looked for associations between bleeding and polyp location, size, electrocautery setting, and medications.

Across the entire population, postoperative bleeding was significantly less common among patients who had their resection sites closed with clips, occurring at a rate of 3.5%, compared with 7.1% in the control group (P = .015). Serious adverse events were also less common in the clip group than the control group (4.8% vs. 9.5%; P = .006).

While the reduction of bleeding risk from clip closure was not influenced by polyp size, use of antithrombotic medications, or electrocautery setting, polyp location turned out to be a critical factor. Greatest reduction in risk of postoperative bleeding was seen among the 615 patients who had proximal polyps, based on a bleeding rate of 3.3% when clipped versus 9.6% among those who went without clips (P = .001). In contrast, clips in the distal colon were associated with a higher absolute risk of postoperative bleeding than no clips (4.0% vs. 1.4%); however, this difference was not statistically significant (P = .178).

“[T]his multicenter trial provides strong evidence that endoscopic clip closure of the mucosal defect after resection of large ... nonpedunculated colon polyps in the proximal colon significantly reduces the risk of postprocedure bleeding,” the investigators wrote.

They suggested that their study provides greater confidence in findings than similar trials previously conducted, enough to recommend that endoscopic techniques be altered accordingly. “[O]ur trial was methodologically rigorous, adequately powered, and all polyps were removed by endoscopic mucosal resection, which is considered the standard technique for large colon polyps in Western countries,” they wrote. “The results of the study are therefore broadly applicable to current practice. Furthermore, conduct of the study at different centers with multiple endoscopists strengthens generalizability of the findings.”

The investigators also speculated about why postoperative bleeding risk was increased when clips were used in the distal colon. “Potential explanations include a poorer quality of clipping, a shorter clip retention time, possible related to a thicker colon wall in the distal compared to the proximal colon,” they wrote, adding that “these considerations are worthy of further study.”

Indeed, more work remains to be done. “A formal cost-effectiveness analysis is needed to better understand the value of clip closure,” they wrote. “Such analysis can then also examine possible thresholds, for instance regarding the minimum proportion of polyp resections, for which complete closure should be achieved, or the maximum number of clips to close a defect.”

The study was funded by Boston Scientific. The investigators reported additional relationships with U.S. Endoscopy, Olympus, Medtronic, and others.

SOURCE: Pohl H et al. Gastroenterology. 2019 Mar 15. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.03.019.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Colorectal Cancer Awareness Fair – Make Your Bottom Your Top Priority

Background: The Comprehensive Cancer Program held a community Colorectal Cancer Awareness Fair on March 5, 2019 at the VAMC. The goal was to increase awareness of Colorectal Cancer and to engage veterans in educational opportunities about Colorectal Cancer.

Methods: The VAMC purchased an in atable “Megacolon” for veterans to walk through guided by nurses from the GI department. Cubicles were set-up for nursing education sessions, a provider station, a scheduling station, and a colonoscope table. A video loop “Before and After Colonoscopy” by Mechanisms in Medicine, Inc. (Thornhill, Ontario, Canada) played continuously in the waiting area by the provider and nurse’s cubicles. Providers in the GI department offered 2 educational presentations: “How to Stop Colon Cancer Before It Starts” by Carol Macaron, MD; and “Colonoscopy: The Good, Bad, and Ugly” by Edith Ho, MD. Additional education information was provided at staffed tables from VA General Surgery, GI, MOVE! Nutrition & Food Services, and Smoking Cessation. Also, in attendance were Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation, and the American Cancer Society. External Affairs advertised the fair on Facebook and Twitter. Medical Media created publicity posters and event flyers.

Results: The event was attended by 244 people—68 veterans, 170 employees, and 6 guests. Six colonoscopies were scheduled onsite. At least 7 veterans had questions regarding their colonoscopy surveillance in which reminder dates were given.

Background: The Comprehensive Cancer Program held a community Colorectal Cancer Awareness Fair on March 5, 2019 at the VAMC. The goal was to increase awareness of Colorectal Cancer and to engage veterans in educational opportunities about Colorectal Cancer.

Methods: The VAMC purchased an in atable “Megacolon” for veterans to walk through guided by nurses from the GI department. Cubicles were set-up for nursing education sessions, a provider station, a scheduling station, and a colonoscope table. A video loop “Before and After Colonoscopy” by Mechanisms in Medicine, Inc. (Thornhill, Ontario, Canada) played continuously in the waiting area by the provider and nurse’s cubicles. Providers in the GI department offered 2 educational presentations: “How to Stop Colon Cancer Before It Starts” by Carol Macaron, MD; and “Colonoscopy: The Good, Bad, and Ugly” by Edith Ho, MD. Additional education information was provided at staffed tables from VA General Surgery, GI, MOVE! Nutrition & Food Services, and Smoking Cessation. Also, in attendance were Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation, and the American Cancer Society. External Affairs advertised the fair on Facebook and Twitter. Medical Media created publicity posters and event flyers.

Results: The event was attended by 244 people—68 veterans, 170 employees, and 6 guests. Six colonoscopies were scheduled onsite. At least 7 veterans had questions regarding their colonoscopy surveillance in which reminder dates were given.

Background: The Comprehensive Cancer Program held a community Colorectal Cancer Awareness Fair on March 5, 2019 at the VAMC. The goal was to increase awareness of Colorectal Cancer and to engage veterans in educational opportunities about Colorectal Cancer.

Methods: The VAMC purchased an in atable “Megacolon” for veterans to walk through guided by nurses from the GI department. Cubicles were set-up for nursing education sessions, a provider station, a scheduling station, and a colonoscope table. A video loop “Before and After Colonoscopy” by Mechanisms in Medicine, Inc. (Thornhill, Ontario, Canada) played continuously in the waiting area by the provider and nurse’s cubicles. Providers in the GI department offered 2 educational presentations: “How to Stop Colon Cancer Before It Starts” by Carol Macaron, MD; and “Colonoscopy: The Good, Bad, and Ugly” by Edith Ho, MD. Additional education information was provided at staffed tables from VA General Surgery, GI, MOVE! Nutrition & Food Services, and Smoking Cessation. Also, in attendance were Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation, and the American Cancer Society. External Affairs advertised the fair on Facebook and Twitter. Medical Media created publicity posters and event flyers.

Results: The event was attended by 244 people—68 veterans, 170 employees, and 6 guests. Six colonoscopies were scheduled onsite. At least 7 veterans had questions regarding their colonoscopy surveillance in which reminder dates were given.

Surviving Colorectal Cancer, Now at Risk for Hypertension

Colorectal cancer (CRC) survivor rates are improving, which means people are living long enough after the cancer to have other chronic conditions. CRC is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer among users of the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system, according to VA researchers, and there is a high prevalence of cardiovascular disease (CVD). The researchers also say emerging evidence suggests that survivors of CRC may be more likely to develop diabetes mellitus (DM) in the 5 years following their cancer diagnosis. But they add that there is a paucity of research about control of CVD-related chronic conditions among survivors of CRC.

In a retrospective study, the researchers compared 9,758 nonmetastatic patients with CRC with 29,066 people who had not had cancer. At baseline, 69% of the survivors of CRC and the matched controls were diagnosed with hypertension, 52% with hyperlipidemia, and 37% with DM.

But somewhat contrary to expectations, the researchers found no significant differences between the 2 groups for DM in the year following the baseline assessment. The researchers point to the VA’s “strong history” of DM risk reduction research and 2 national programs targeting DM, although they do not know whether the people in their study participated in those.

The survivors of CRC also had half the odds of being diagnosed with hyperlipidemia. However, they did have 57% higher odds of being diagnosed with hypertension.

Although the researchers acknowledge that hypertension is a transient adverse effect of certain chemotherapy regimens, they found only 7 survivors of CRC and 11 controls were treated with bevacizumab during their first year postanchor date.

The relationship between nonmetastatic CRC and CVD risk-related chronic conditions is complex, the researchers say. But they share risk factors, including obesity, physical inactivity, and diet.

The researchers call behavioral change interventions that improve survivors of CRC physical activity, dietary habits, and body mass index a “promising beginning” but call for other similar interventions, particularly those targeting blood pressure management and adherence to antihypertensive medications (which was significantly lower among the survivors).

While the magnitude of the effect regarding hypertension seems relatively small, the researchers say, they believe it is still an important difference when considered from a population health perspective—and one that should be addressed. The researchers also note that nonmetastatic survivors of CRC and controls had very similar rates of primary care visits in the 3 years postanchor date and as a result similar opportunities to receive a hypertension diagnosis.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) survivor rates are improving, which means people are living long enough after the cancer to have other chronic conditions. CRC is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer among users of the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system, according to VA researchers, and there is a high prevalence of cardiovascular disease (CVD). The researchers also say emerging evidence suggests that survivors of CRC may be more likely to develop diabetes mellitus (DM) in the 5 years following their cancer diagnosis. But they add that there is a paucity of research about control of CVD-related chronic conditions among survivors of CRC.

In a retrospective study, the researchers compared 9,758 nonmetastatic patients with CRC with 29,066 people who had not had cancer. At baseline, 69% of the survivors of CRC and the matched controls were diagnosed with hypertension, 52% with hyperlipidemia, and 37% with DM.

But somewhat contrary to expectations, the researchers found no significant differences between the 2 groups for DM in the year following the baseline assessment. The researchers point to the VA’s “strong history” of DM risk reduction research and 2 national programs targeting DM, although they do not know whether the people in their study participated in those.

The survivors of CRC also had half the odds of being diagnosed with hyperlipidemia. However, they did have 57% higher odds of being diagnosed with hypertension.

Although the researchers acknowledge that hypertension is a transient adverse effect of certain chemotherapy regimens, they found only 7 survivors of CRC and 11 controls were treated with bevacizumab during their first year postanchor date.

The relationship between nonmetastatic CRC and CVD risk-related chronic conditions is complex, the researchers say. But they share risk factors, including obesity, physical inactivity, and diet.

The researchers call behavioral change interventions that improve survivors of CRC physical activity, dietary habits, and body mass index a “promising beginning” but call for other similar interventions, particularly those targeting blood pressure management and adherence to antihypertensive medications (which was significantly lower among the survivors).

While the magnitude of the effect regarding hypertension seems relatively small, the researchers say, they believe it is still an important difference when considered from a population health perspective—and one that should be addressed. The researchers also note that nonmetastatic survivors of CRC and controls had very similar rates of primary care visits in the 3 years postanchor date and as a result similar opportunities to receive a hypertension diagnosis.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) survivor rates are improving, which means people are living long enough after the cancer to have other chronic conditions. CRC is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer among users of the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system, according to VA researchers, and there is a high prevalence of cardiovascular disease (CVD). The researchers also say emerging evidence suggests that survivors of CRC may be more likely to develop diabetes mellitus (DM) in the 5 years following their cancer diagnosis. But they add that there is a paucity of research about control of CVD-related chronic conditions among survivors of CRC.

In a retrospective study, the researchers compared 9,758 nonmetastatic patients with CRC with 29,066 people who had not had cancer. At baseline, 69% of the survivors of CRC and the matched controls were diagnosed with hypertension, 52% with hyperlipidemia, and 37% with DM.

But somewhat contrary to expectations, the researchers found no significant differences between the 2 groups for DM in the year following the baseline assessment. The researchers point to the VA’s “strong history” of DM risk reduction research and 2 national programs targeting DM, although they do not know whether the people in their study participated in those.

The survivors of CRC also had half the odds of being diagnosed with hyperlipidemia. However, they did have 57% higher odds of being diagnosed with hypertension.

Although the researchers acknowledge that hypertension is a transient adverse effect of certain chemotherapy regimens, they found only 7 survivors of CRC and 11 controls were treated with bevacizumab during their first year postanchor date.

The relationship between nonmetastatic CRC and CVD risk-related chronic conditions is complex, the researchers say. But they share risk factors, including obesity, physical inactivity, and diet.

The researchers call behavioral change interventions that improve survivors of CRC physical activity, dietary habits, and body mass index a “promising beginning” but call for other similar interventions, particularly those targeting blood pressure management and adherence to antihypertensive medications (which was significantly lower among the survivors).

While the magnitude of the effect regarding hypertension seems relatively small, the researchers say, they believe it is still an important difference when considered from a population health perspective—and one that should be addressed. The researchers also note that nonmetastatic survivors of CRC and controls had very similar rates of primary care visits in the 3 years postanchor date and as a result similar opportunities to receive a hypertension diagnosis.

Coordination of Care Between Primary Care and Oncology for Patients With Prostate Cancer (FULL)

The following is a lightly edited transcript of a teleconference recorded in July 2018. The teleconference brought together health care providers from the Greater Los Angeles VA Health Care System (GLAVAHCS) to discuss the real-world processes for managing the treatment of patients with prostate cancer as they move between primary and specialist care.

William J. Aronson, MD. We are fortunate in having a superb medical record system at the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) where we can all communicate with each other through a number of methods. Let’s start our discussion by reviewing an index patient that we see in our practice who has been treated with either radical prostatectomy or radiation therapy. One question to address is: Is there a point when the Urology or Radiation Oncology service can transition the patient’s entire care back to the primary care team? And if so, what would be the optimal way to accomplish this?

Nick, is there some point at which you discharge the patient from the radiation oncology service and give specific directions to primary care, or is it primarily just back to urology in your case?

Nicholas G. Nickols, MD, PhD. I have not discharged any patient from my clinic after definitive prostate cancer treatment. During treatment, patients are seen every week. Subsequently, I see them 6 weeks posttreatment, and then every 4 months for the first year, then every 6 months for the next 4 years, and then yearly after that. Although I never formally discharged a patient from my clinic, you can see based on the frequency of visits, that the patient will see more often than their primary care provider (PCP) toward the beginning. And then, after some years, the patient sees their primary more than they me. So it’s not an immediate hand off but rather a gradual transition. It’s important that the PCP is aware of what to look for especially for the late recurrences, late potential side effects, probably more significantly than the early side effects, how to manage them when appropriate, and when to ask the patient to see our team more frequently in follow-up.

William Aronson. We have a number of patients who travel tremendous distances to see us, and I tend to think that many of our follow-up patients, once things are stabilized with regards to management of their side effects, really could see their primary care doctors if we can give them specific instructions on, for example, when to get a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test and when to refer back to us.

Alison, can you think of some specific cases where you feel like we’ve successfully done that?

Alison Neymark, MS. For the most part we haven’t discharged people, either. What we have done is transitioned them over to a phone clinic. In our department, we have 4 nurse practitioners (NPs) who each have a half-day of phone clinic where they call patients with their test results. Some of those patients are prostate cancer patients that we have been following for years. We schedule them for a phone call, whether it’s every 3 months, every 6 months or every year, to review the updated PSA level and to just check in with them by phone. It’s a win-win because it’s a really quick phone call to reassure the veteran that the PSA level is being followed, and it frees up an in-person appointment slot for another veteran.

We still have patients that prefer face-to-face visits, even though they know we’re not doing anything except discussing a PSA level with them—they just want that security of seeing our face. Some patients are very nervous, and they don’t necessarily want to be discharged, so to speak, back to primary care. Also, for those patients that travel a long distance to clinic, we offer an appointment in the video chat clinic, with the community-based outpatient clinics in Bakersfield and Santa Maria, California.

PSA Levels

William Aronson. I probably see a patient about every 4 to 6 weeks who has a low PSA after about 10 years and has a long distance to travel and mobility and other problems that make it difficult to come in.

The challenge that I have is, what is that specific guideline to give with regards to the rise in PSA? I think it all depends on the patients prostate cancer clinical features and comorbidities.

Nicholas Nickols. If a patient has been seen by me in follow-up a number of times and there’s really no active issues and there’s a low suspicion of recurrence, then I offer the patient the option of a phone follow-up as an alternative to face to face. Some of them accept that, but I ask that they agree to also see either urology or their PCP face to face. I will also remotely ensure that they’re getting the right laboratory tests, and if not, I’ll put those orders in.

With regard to when to refer a patient back for a suspected recurrence after definitive radiation therapy, there is an accepted definition of biochemical failure called the Phoenix definition, which is an absolute rise in 2 ng/mL of PSA over their posttreatment nadir. Often the posttreatment nadir, especially if they were on hormone therapy, will be close to 0. If the PSA gets to 2, that is a good trigger for a referral back to me and/or urology to discuss restaging and workup for a suspected recurrence.

For patients that are postsurgery and then subsequently get salvage radiation, it is not as clear when a restaging workup should be initiated. Currently, the imaging that is routine care is not very sensitive for detecting PSA in that setting until the PSA is around 0.8 ng/mL, and that’s with the most modern imaging available. Over time that may improve.

William Aronson. The other index patient to think about would be the patient who is on watchful waiting for their prostate cancer, which is to be distinguished from active surveillance. If someone’s on active surveillance, we’re regularly doing prostate biopsies and doing very close monitoring; but we also have patients who have multiple other medical problems, have a limited life expectancy, don’t have aggressive prostate cancer, and it’s extremely reasonable not to do a biopsy in those patients.

Again, those are patients where we do follow the PSA generally every 6 months. And I think there’s also scenarios there where it’s reasonable to refer back to primary care with specific instructions. These, again, are patients who had difficulty getting in to see us or have mobility issues, but it is also a way to limit patient visits if that’s their desire.

Peter Glassman, MBBS, MSc: I’m trained as both a general internist and board certified in hospice and palliative medicine. I currently provide primary care as well as palliative care. I view prostate cancer from the diagnosis through the treatment spectrum as a continuum. It starts with the PCP with an elevated PSA level or if the digital rectal exam has an abnormality, and then the role of the genitourinary (GU) practitioner becomes more significant during the active treatment and diagnostic phases.

Primary care doesn’t disappear, and I think there are 2 major issues that go along with that. First of all, we in primary care, because we take care of patients that often have other comorbidities, need to work with the patient on those comorbidities. Secondly, we need the information shared between the GU and primary care providers so that we can answer questions from our patients and have an understanding of what they’re going through and when.

As time goes on, we go through various phases: We may reach a cure, a quiescent period, active therapy, watchful waiting, or recurrence. Primary care gets involved as time goes on when the disease either becomes quiescent, is just being followed, or is considered cured. Clearly when you have watchful waiting, active treatment, or are in a recurrence, then GU takes the forefront.

I view it as a wave function. Primary care to GU with primary in smaller letters and then primary, if you will, in larger letters, GU becomes a lesser participant unless there is active therapy, watchful waiting or recurrence.

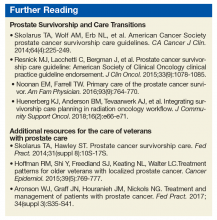

In doing a little bit of research, I found 2 very good and very helpful documents. One is the American Cancer Society (ACS) prostate cancer survivorship care guidelines (Box). And the other is a synopsis of the guidelines. What I liked was that the guidelines focused not only on what should be done for the initial period of prostate cancer, but also for many of the ancillary issues which we often don’t give voice to. The guidelines provide a structure, a foundation to work with our patients over time on their prostate cancer-related issues while, at the same time, being cognizant that we need to deal with their other comorbid conditions.

Modes of Communication

Alison Neymark. We find that including parameters for PSA monitoring in our Progress Notes in the electronic health record (EHR) the best way to communicate with other providers. We’ll say, “If PSA gets to this level, please refer back.” We try to make it clear because with the VA being a training facility, it could be a different resident/attending physician team that’s going to see the patient the next time he is in primary care.

Peter Glassman. Yes, we’re very lucky, as Bill talked about earlier and Alison just mentioned. We have the EHR, and Bill may remember this. Before the EHR, we were constantly fishing to find the most relevant notes. If a patient saw a GU practitioner the day before they saw me, I was often asking the patient what was said. Now we can just review the notes.

It’s a double-edged sword though because there are, of course, many notes in a medical record; and you have to look for the specific items. The EHR and documenting the medical record probably plays the primary role in getting information across. When you want to have an active handoff, or you need to communicate with each other, we have a variety of mechanisms, ranging from the phone to the Microsoft Skype Link (Redmond, WA) system that allows us to tap a message to a colleague.

And I’ve been here long enough that I’ve seen most permutations of how prostate cancer is diagnosed as well as shared among providers. Bill and I have shared patients. Alison and I have shared patients, not necessarily with prostate cancer, although that too. But we know how to communicate with each other. And of course, there’s paging if you need something more urgently.

William Aronson. We also use Microsoft Outlook e-mail, and encrypt the messages to keep them confidential and private. The other nice thing we have is there is a nationwide urology Outlook e-mail, so if any of us have any specific questions, through one e-mail we can send it around the country; and there’s usually multiple very useful responses. That’s another real strength of our system within the VA that helps patient care enormously.

Nicholas Nickols. Sometimes, if there’s a critical note that I absolutely want someone on the care team to read, I’ll add them as a cosigner; and that will pop up when they log in to the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) as something that they need to read.

If the patient lives particularly far or gets his care at another VA medical center and laboratory tests are needed, then I will reach out to their PCP via e-mail. If contact is not confirmed, I will reach out via phone or Skype.

Peter Glassman. The most helpful notes are those that are very specific as to what primary care is being asked to do and/or what urology is going to be doing. So, the more specific we get in the notes as to what is being addressed, I think that’s very helpful.

I have been here long enough that I’ve known both Alison and Bill; and if they have an issue, they will tap me a message. It wasn’t long ago that Bill sent a message to me, and we worked on a patient with prostate cancer who was going to be on long-term hormone therapy. We talked about osteoporosis management, and between us we worked out who was going to do what. Those are the kind of shared decision-making situations that are very, very helpful.

Alison Neymark. Also, GLAVAHCS has a home-based primary care team (HBPC), and a lot of the PCPs for that team are NPs. They know that they can contact me for their patients because a lot of those patients are on watchful waiting, and we do not necessarily need to see them face to face in clinic. Our urology team just needs to review updated lab results and how they are doing clinically. The HBPC NP who knows them best can contact me every 6 months or so, and we’ll discuss the case, which avoids making the patient come in, especially when they’re homebound. Those of us that have been working at the VA for many years have established good relationships. We feel very comfortable reaching out and talking to each other about these patients

Peter Glassman. Alison, I agree. When I can talk to my patients and say, “You know, we had that question about,” whatever the question might be, “and I contacted urology, and this is what they said.” It gives the patient confidence that we’re following up on the issues that they have and that we’re communicating with each other in a way that is to their benefit. And I think it’s very appreciated both by the provider as well as the patient.

William Aronson. Not infrequently I’ll have patients who have nonurologic issues, which I may first detect, or who have specific issues with their prostate cancer that can be comanaged. And I have found that when I send an encrypted e-mail to the PCP, it has been an extremely satisfying interaction; and we really get to the heart of the matter quickly for the sake of the veteran.

Veterans With Comorbidities

William Aronson. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a very significant and unique aspect of our patients, which is enormously important to recognize. For example, the side effects of prostate treatments can be very significant, whether radiation or surgery. Our patients understandably can be very fearful of the prostate cancer diagnosis and treatment side effects.

We know, for example, after a patient gets a diagnosis of prostate cancer, they’re at increased risk of cardiac death. That’s an especially important issue for our patients that there be an ongoing interaction between urology and primary care.

The ACS guidelines that Dr. Glassman referred to were enlightening. In many cases, primary care can look at the whole patient and their circumstances better than we can and may detect, for example, specific psychological issues that either they can manage or refer to other specialists.

Peter Glassman. One of the things that was highlighted in the ACS guideline is that in any population of men who have this disease, there’s going to be distress, anxiety, and full-fledged depression. Of course, there are psychosocial aspects of prostate cancer, such as sexual activity and intimacy with a partner that we often don’t explore but are probably playing an important role in the overall health of our patients. We need to be mindful of these psychosocial aspects and at least periodically ask them, “How are you doing with this? How are things at home?” And of course, we already use screeners for depression. As the article noted, distress and anxiety and other factors can make somebody’s life less optimal with poorer quality of life.

Dual Care Patients

Alison Neymark. Many patients whether they have Medicare, insurance through their spouse, or Kaiser Permanente through their job, choose to go to both places. The challenge is communicating with the non-VA providers because here at the VA we can communicate easily through Skype, Outlook e-mail, or CPRS, but for dual care patients who’s in charge? I encourage the veterans to choose whom they want to manage their care; we’re always here and happy to treat them, but they need to decide who’s in charge because I don’t want them to get into a situation where the differing opinions lead to a delay in care.

Nicholas Nickols. The communication when the patient is receiving care outside VA, either on a continuous basis or temporarily, is more of a challenge. We obviously can’t rely upon the messaging system, face-to-face contact is difficult, and they may not be able to use e-mail as well. So in those situations, usually a phone call is the best approach. I have found that the outside providers are happy to speak on the phone to coordinate care.

Peter Glassman. I agree, it does add a layer of complexity because we don’t readily have the notes, any information in front of us. That said, a lot of our patients can and do bring in information from outside specialists, and I’m hopeful that they share the information that we provide back to their outside doctors as well.

William Aronson. Some patient get nervous. They might decide they want care elsewhere, but they still want the VA available for them. I always let them know they should proceed in whatever way they prefer, but we’re always available and here for them. I try to empower them to make their own decisions and feel comfortable with them.

Nicholas Nickols. Notes from the outside, if they’re being referred for VA Choice or community care, do get uploaded into VistA Imaging and can be accessed, although it’s not instantaneous. Sometimes there’s a delay, but I have been able to access outside notes most of the time. If a patient goes through a clinic at the VA, the note is written in real time, and you can read it immediately.

Peter Glassman. That is true for patients that are within the VA system who receive contracted care either through Choice or through non-VA care that is contracted through VA. For somebody who is choosing to use 2 health care systems, that can provide more of a challenge because those notes don’t come to us. Over time, most of my patients have brought test results to me.

The thing with oncologic care, of course, is it’s a lot more complex. And it’s hard to know without reasonable documentation what’s been going on. At some level, you have to trust that the outside provider is doing whatever they need to do, or you have to take it upon yourself to do it within the system.

Alison Neymark. In my experience with the Choice Program, it really depends on the outside providers and how comfortable they are with the system that has been established to share records. Not all providers are going into that system and accessing it. I have had cases where I will see the non-VA provider’s note and it’ll say, “No documentation available for this consultation.” It just happens that they didn’t go into the system to review it. So it can be a challenge.

I’ve had good communication with the providers who use the system correctly. In some cases, just to make it easier, I will go ahead and communicate with them through encrypted e-mail, or I’ll talk to their care coordinators directly by phone.

Peter Glassman. Many, if not most, PCPs are going to take care of these patients, certainly within the VA, with their GU colleagues. And most of us feel comfortable using the current documentation system in a way that allows us to share information or at least to gather information about these patients.

One of the things that I think came out for me in looking at this was that there are guidelines or there are ideas out there on how to take better care of these patients. And I for one learned a fair bit just by going through these documents, which I’m very appreciative of. But it does highlight to me that we can give good care and provide good shared care for prostate cancer survivors. I think that is something that perhaps this discussion will highlight that not only are people doing that, but there are resources they can utilize that will help them get a more comprehensive picture of taking care of prostate cancer survivors in the primary care clinic.

The beauty of the VA system as a system is that as these issues come up that might affect the overall health of the veteran with prostate cancer, for example, psychosocial issues, we have many people that can address this that are experts in their area. And one of the great beauties of having an all-encompassing healthcare system is being able to use resources within the system, whether that be for other medical problems or other social or other psychological issues, that we ourselves are not expert in. We can reach out to our other colleagues and ask them for assistance. We have that available to help the patients. It’s really holistic.

We even have integrated medicine where we can help patients, hopefully, get back into a healthy lifestyle, for example, whereas we may not have that expertise or knowledge. We often think of this as sort of a shared decision between GU and primary care. But, in fact, it’s really the responsibility of many, many people of the system at large. We are very lucky to have that.

The following is a lightly edited transcript of a teleconference recorded in July 2018. The teleconference brought together health care providers from the Greater Los Angeles VA Health Care System (GLAVAHCS) to discuss the real-world processes for managing the treatment of patients with prostate cancer as they move between primary and specialist care.

William J. Aronson, MD. We are fortunate in having a superb medical record system at the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) where we can all communicate with each other through a number of methods. Let’s start our discussion by reviewing an index patient that we see in our practice who has been treated with either radical prostatectomy or radiation therapy. One question to address is: Is there a point when the Urology or Radiation Oncology service can transition the patient’s entire care back to the primary care team? And if so, what would be the optimal way to accomplish this?

Nick, is there some point at which you discharge the patient from the radiation oncology service and give specific directions to primary care, or is it primarily just back to urology in your case?

Nicholas G. Nickols, MD, PhD. I have not discharged any patient from my clinic after definitive prostate cancer treatment. During treatment, patients are seen every week. Subsequently, I see them 6 weeks posttreatment, and then every 4 months for the first year, then every 6 months for the next 4 years, and then yearly after that. Although I never formally discharged a patient from my clinic, you can see based on the frequency of visits, that the patient will see more often than their primary care provider (PCP) toward the beginning. And then, after some years, the patient sees their primary more than they me. So it’s not an immediate hand off but rather a gradual transition. It’s important that the PCP is aware of what to look for especially for the late recurrences, late potential side effects, probably more significantly than the early side effects, how to manage them when appropriate, and when to ask the patient to see our team more frequently in follow-up.

William Aronson. We have a number of patients who travel tremendous distances to see us, and I tend to think that many of our follow-up patients, once things are stabilized with regards to management of their side effects, really could see their primary care doctors if we can give them specific instructions on, for example, when to get a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test and when to refer back to us.

Alison, can you think of some specific cases where you feel like we’ve successfully done that?

Alison Neymark, MS. For the most part we haven’t discharged people, either. What we have done is transitioned them over to a phone clinic. In our department, we have 4 nurse practitioners (NPs) who each have a half-day of phone clinic where they call patients with their test results. Some of those patients are prostate cancer patients that we have been following for years. We schedule them for a phone call, whether it’s every 3 months, every 6 months or every year, to review the updated PSA level and to just check in with them by phone. It’s a win-win because it’s a really quick phone call to reassure the veteran that the PSA level is being followed, and it frees up an in-person appointment slot for another veteran.

We still have patients that prefer face-to-face visits, even though they know we’re not doing anything except discussing a PSA level with them—they just want that security of seeing our face. Some patients are very nervous, and they don’t necessarily want to be discharged, so to speak, back to primary care. Also, for those patients that travel a long distance to clinic, we offer an appointment in the video chat clinic, with the community-based outpatient clinics in Bakersfield and Santa Maria, California.

PSA Levels

William Aronson. I probably see a patient about every 4 to 6 weeks who has a low PSA after about 10 years and has a long distance to travel and mobility and other problems that make it difficult to come in.

The challenge that I have is, what is that specific guideline to give with regards to the rise in PSA? I think it all depends on the patients prostate cancer clinical features and comorbidities.

Nicholas Nickols. If a patient has been seen by me in follow-up a number of times and there’s really no active issues and there’s a low suspicion of recurrence, then I offer the patient the option of a phone follow-up as an alternative to face to face. Some of them accept that, but I ask that they agree to also see either urology or their PCP face to face. I will also remotely ensure that they’re getting the right laboratory tests, and if not, I’ll put those orders in.

With regard to when to refer a patient back for a suspected recurrence after definitive radiation therapy, there is an accepted definition of biochemical failure called the Phoenix definition, which is an absolute rise in 2 ng/mL of PSA over their posttreatment nadir. Often the posttreatment nadir, especially if they were on hormone therapy, will be close to 0. If the PSA gets to 2, that is a good trigger for a referral back to me and/or urology to discuss restaging and workup for a suspected recurrence.

For patients that are postsurgery and then subsequently get salvage radiation, it is not as clear when a restaging workup should be initiated. Currently, the imaging that is routine care is not very sensitive for detecting PSA in that setting until the PSA is around 0.8 ng/mL, and that’s with the most modern imaging available. Over time that may improve.

William Aronson. The other index patient to think about would be the patient who is on watchful waiting for their prostate cancer, which is to be distinguished from active surveillance. If someone’s on active surveillance, we’re regularly doing prostate biopsies and doing very close monitoring; but we also have patients who have multiple other medical problems, have a limited life expectancy, don’t have aggressive prostate cancer, and it’s extremely reasonable not to do a biopsy in those patients.

Again, those are patients where we do follow the PSA generally every 6 months. And I think there’s also scenarios there where it’s reasonable to refer back to primary care with specific instructions. These, again, are patients who had difficulty getting in to see us or have mobility issues, but it is also a way to limit patient visits if that’s their desire.

Peter Glassman, MBBS, MSc: I’m trained as both a general internist and board certified in hospice and palliative medicine. I currently provide primary care as well as palliative care. I view prostate cancer from the diagnosis through the treatment spectrum as a continuum. It starts with the PCP with an elevated PSA level or if the digital rectal exam has an abnormality, and then the role of the genitourinary (GU) practitioner becomes more significant during the active treatment and diagnostic phases.

Primary care doesn’t disappear, and I think there are 2 major issues that go along with that. First of all, we in primary care, because we take care of patients that often have other comorbidities, need to work with the patient on those comorbidities. Secondly, we need the information shared between the GU and primary care providers so that we can answer questions from our patients and have an understanding of what they’re going through and when.

As time goes on, we go through various phases: We may reach a cure, a quiescent period, active therapy, watchful waiting, or recurrence. Primary care gets involved as time goes on when the disease either becomes quiescent, is just being followed, or is considered cured. Clearly when you have watchful waiting, active treatment, or are in a recurrence, then GU takes the forefront.

I view it as a wave function. Primary care to GU with primary in smaller letters and then primary, if you will, in larger letters, GU becomes a lesser participant unless there is active therapy, watchful waiting or recurrence.

In doing a little bit of research, I found 2 very good and very helpful documents. One is the American Cancer Society (ACS) prostate cancer survivorship care guidelines (Box). And the other is a synopsis of the guidelines. What I liked was that the guidelines focused not only on what should be done for the initial period of prostate cancer, but also for many of the ancillary issues which we often don’t give voice to. The guidelines provide a structure, a foundation to work with our patients over time on their prostate cancer-related issues while, at the same time, being cognizant that we need to deal with their other comorbid conditions.

Modes of Communication

Alison Neymark. We find that including parameters for PSA monitoring in our Progress Notes in the electronic health record (EHR) the best way to communicate with other providers. We’ll say, “If PSA gets to this level, please refer back.” We try to make it clear because with the VA being a training facility, it could be a different resident/attending physician team that’s going to see the patient the next time he is in primary care.

Peter Glassman. Yes, we’re very lucky, as Bill talked about earlier and Alison just mentioned. We have the EHR, and Bill may remember this. Before the EHR, we were constantly fishing to find the most relevant notes. If a patient saw a GU practitioner the day before they saw me, I was often asking the patient what was said. Now we can just review the notes.

It’s a double-edged sword though because there are, of course, many notes in a medical record; and you have to look for the specific items. The EHR and documenting the medical record probably plays the primary role in getting information across. When you want to have an active handoff, or you need to communicate with each other, we have a variety of mechanisms, ranging from the phone to the Microsoft Skype Link (Redmond, WA) system that allows us to tap a message to a colleague.

And I’ve been here long enough that I’ve seen most permutations of how prostate cancer is diagnosed as well as shared among providers. Bill and I have shared patients. Alison and I have shared patients, not necessarily with prostate cancer, although that too. But we know how to communicate with each other. And of course, there’s paging if you need something more urgently.