User login

Delayed Cutaneous Reactions to Iodinated Contrast

Case Report

A 67-year-old woman with a history of allergic rhinitis presented in the spring with a pruritic eruption of 2 days’ duration that began on the abdomen and spread to the chest, back, and bilateral arms. Six days prior to the onset of the symptoms she underwent computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis to evaluate abdominal pain and peripheral eosinophilia. Two iodinated contrast (IC) agents were used: intravenous iohexol and oral diatrizoate meglumine–diatrizoate sodium. The eruption was not preceded by fever, malaise, sore throat, rhinorrhea, cough, arthralgia, headache, diarrhea, or new medication or supplement use. The patient denied any history of drug allergy or cutaneous eruptions. Her current medications, which she had been taking long-term, were aspirin, lisinopril, diltiazem, levothyroxine, esomeprazole, paroxetine, gabapentin, and diphenhydramine.

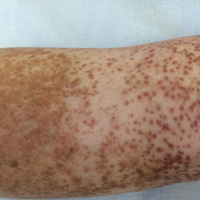

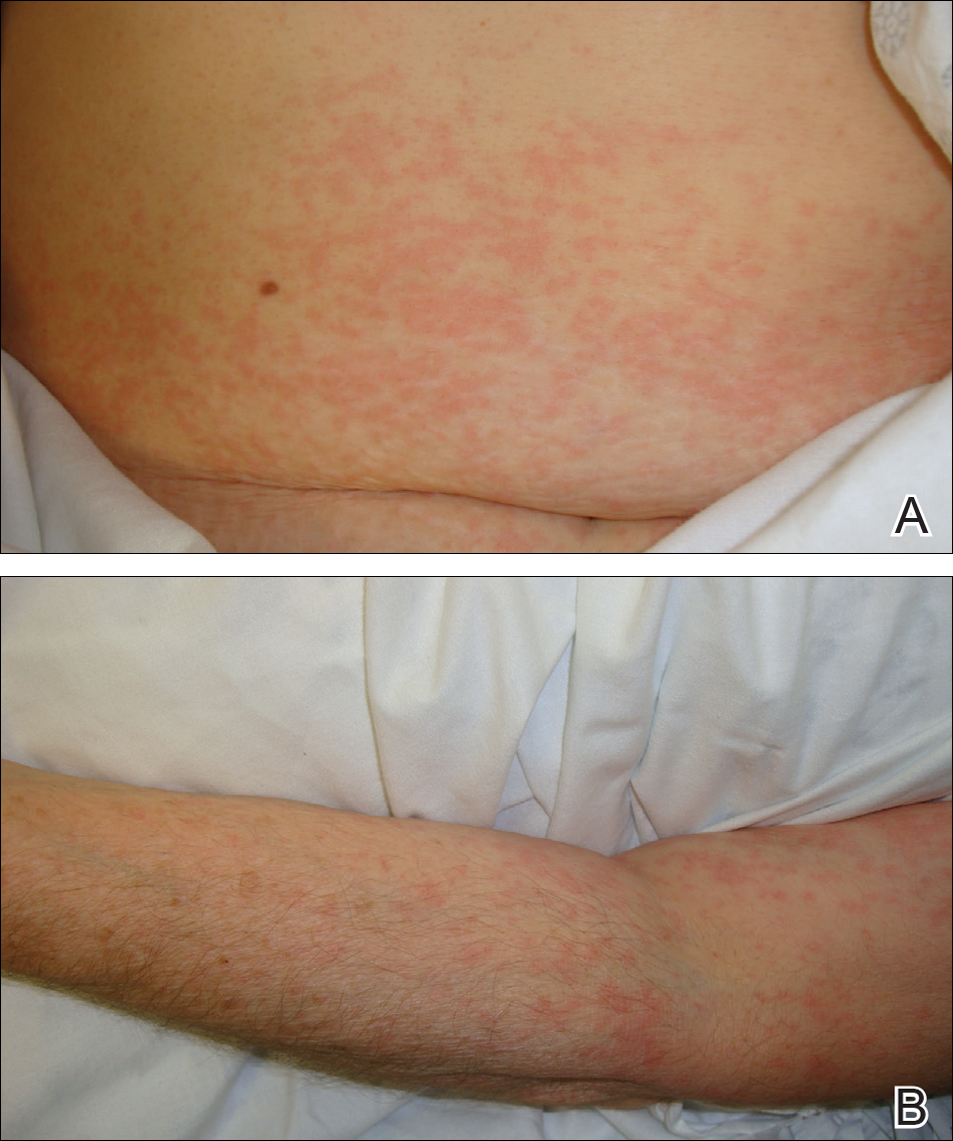

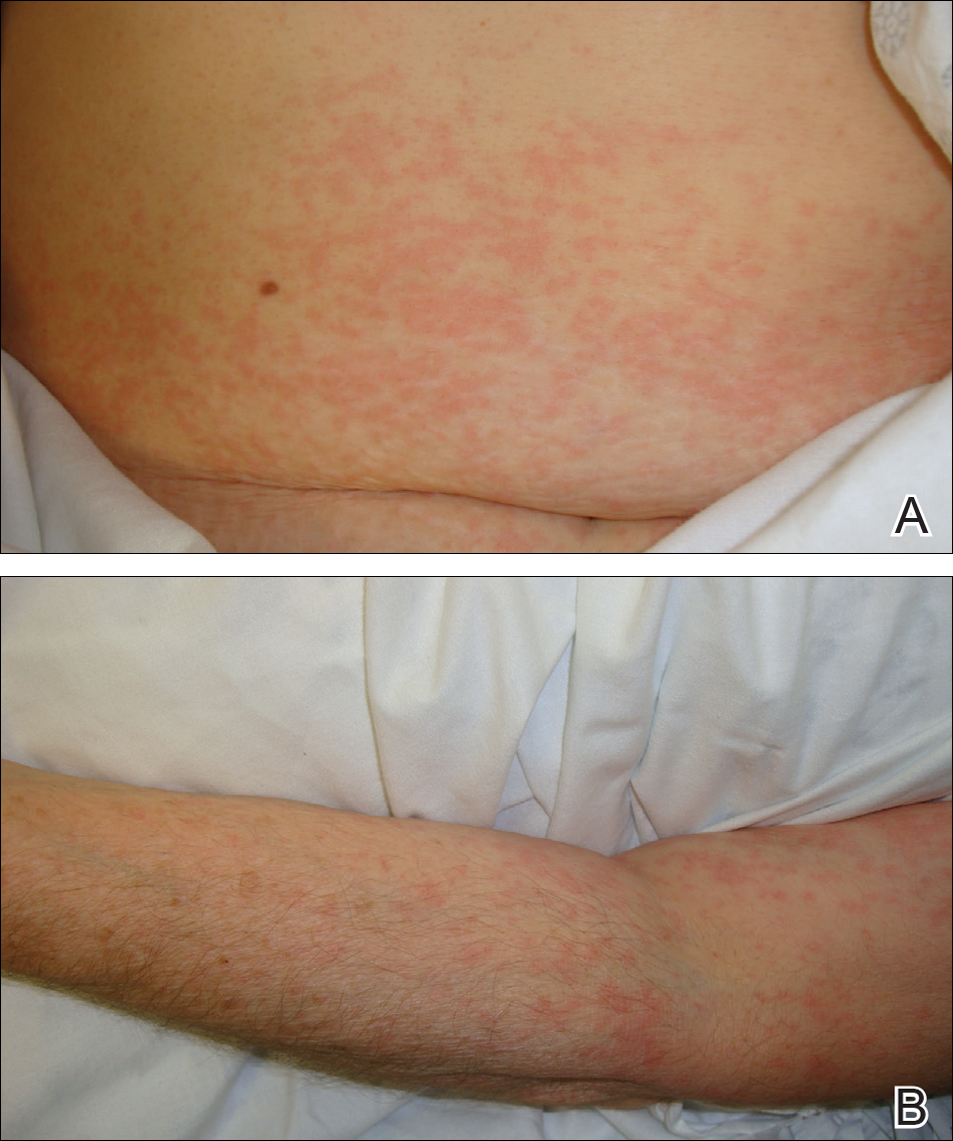

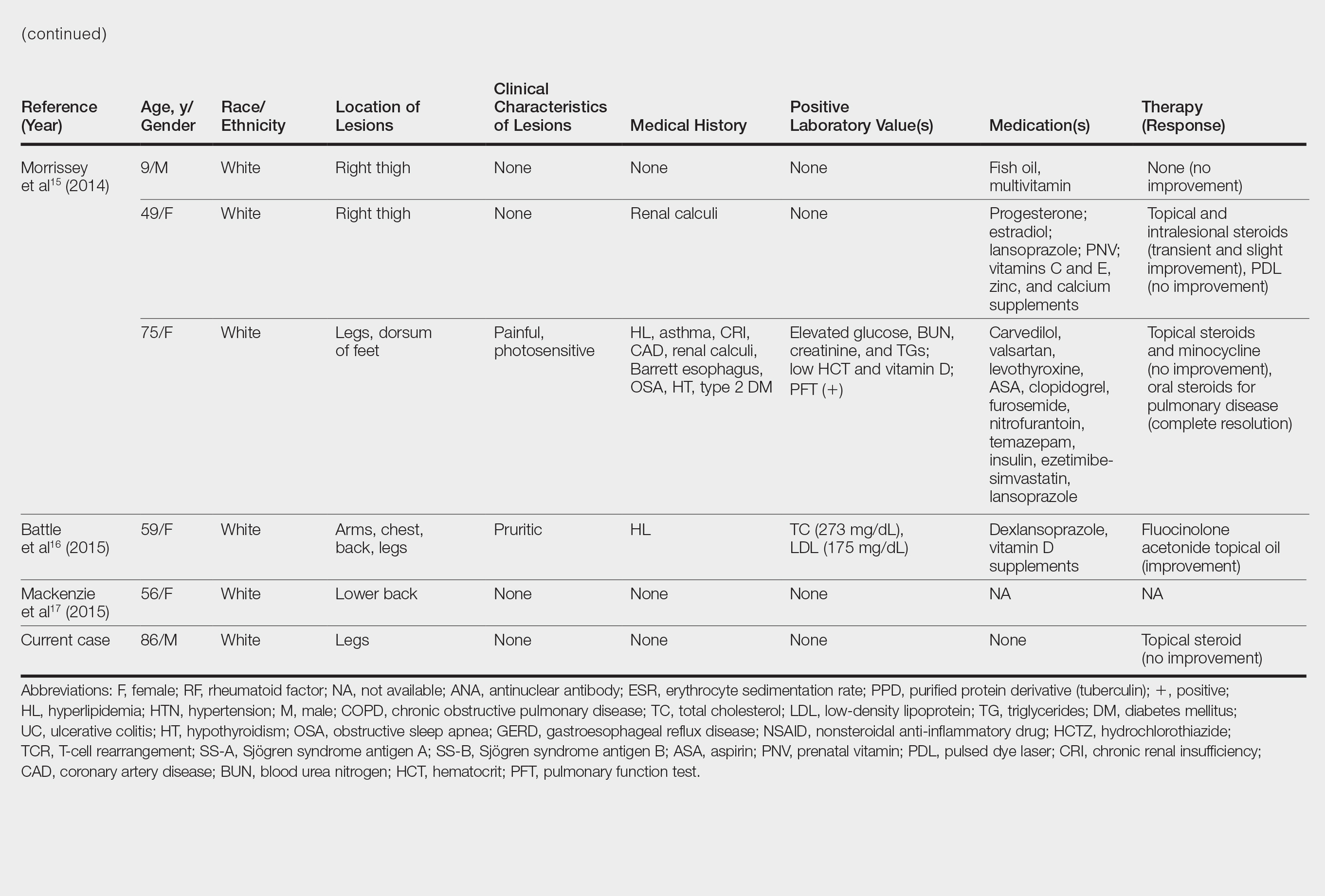

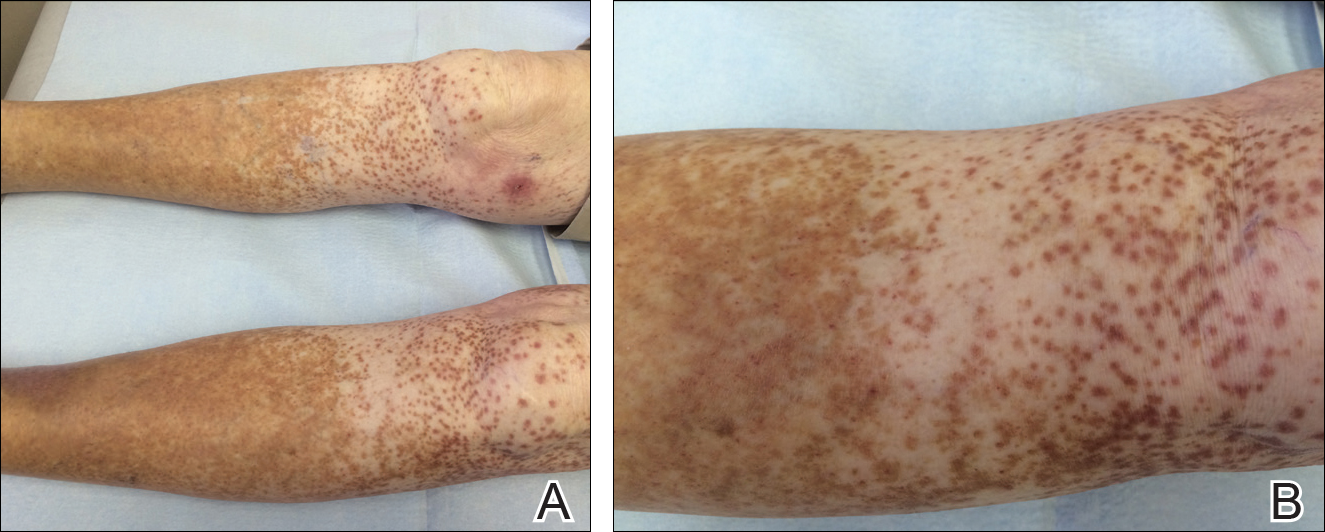

Physical examination was notable for erythematous, blanchable, nontender macules coalescing into patches on the trunk and bilateral arms (Figure). There was slight erythema on the nasolabial folds and ears. The mucosal surfaces and distal legs were clear. The patient was afebrile. Her white blood cell count was 12.5×109/L with 32.3% eosinophils (baseline: white blood cell count, 14.8×109/L; 22% eosinophils)(reference range, 4.8–10.8×109/L; 1%–4% eosinophils). Her comprehensive metabolic panel was within reference range. The human immunodeficiency virus 1/2 antibody immunoassay was nonreactive.

The patient was diagnosed with an exanthematous eruption caused by IC and was treated with oral hydroxyzine and triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.1%. The eruption resolved within 2 weeks without recurrence at 3-month follow-up.

Comment

Del

Clinical Presentation of Delayed Reactions

Most delayed cutaneous reactions to IC present as exanthematous eruptions in the week following a contrast-enhanced CT scan or coronary angiogram.2,12 The reactions tend to resolve within 2 weeks of onset, and the treatment is largely supportive with antihistamines and/or corticosteroids for the associated pruritus.2,5,6 In a study of 98 patients with a history of delayed reactions to IC, delayed-onset urticaria and angioedema also have been reported with incidence rates of 19% and 24%, respectively.2 Other reactions are less common. In the same study, 7% of patients developed palpable purpura; acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis; bullous, flexural, or psoriasislike exanthema; exfoliative eruptions; or purpura and a maculopapular eruption combined with eosinophilia.2 There also have been reports of IC-induced erythema multiforme,3 fixed drug eruptions,10,11 symmetrical drug-related intertriginous and flexural exanthema,13 cutaneous vasculitis,14 drug reactions with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms,15 Stevens-Johnson syndrome/TEN,7,8,16,17 and iododerma.18

IC Agents

Virtually all delayed cutaneous reactions to IC reportedly are due to intravascular rather than oral agents,1,2,19 with the exception of iododerma18 and 1 reported case of TEN.17 Intravenous iohexol was most likely the offending drug in our case. In a prospective cohort study of 539 patients undergoing CT scans, the absolute risk for developing a delayed cutaneous reaction (defined as rash, itching, or skin redness or swelling) to intravascular iohexol was 9.4%.20 Randomized, double-blind studies have found that the risk for delayed cutaneous eruptions is similar among various types of IC, except for iodixanol, which confers a higher risk.5,6,21

Risk Factors

Interestingly, analyses have shown that delayed reactions to IC are more common in atopic patients and during high pollen season.22 Our patient displayed these risk factors, as she had allergic rhinitis and presented for evaluation in late spring when local pollen counts were high. Additionally, patients who develop delayed reactions to IC are notably more likely than controls to have a history of other cutaneous drug reactions, serum creatinine levels greater than 2.0 mg/dL (reference range, 0.6–1.2 mg/dL),3 or history of treatment with recombinant interleukin 2.19

Patients with a history of delayed reactions to IC are not at increased risk for immediate reactions and vice versa.2,3 This finding is consistent with the evidence that delayed and immediate reactions to IC are mechanistically unrelated.23 Additionally, seafood allergy is not a risk factor for either immediate or delayed reactions to IC, despite a common misconception among physicians and patients because seafood is iodinated.24,25

Reexposure to IC

Patients who have had delayed cutaneous reactions to IC are at risk for similar eruptions upon reexposure. Although the reactions are believed to be cell mediated, skin testing with IC is not sensitive enough to reliably identify tolerable alternatives.12 Consequently, gadolinium-based agents have been recommended in patients with a history of reactions to IC if additional contrast-enhanced studies are needed.13,26 Iodinated and gadolinium-based contrast agents do not cross-react, and gadolinium is compatible with studies other than magnetic resonance imaging.1,27

Premedication

Despite the absence of cross-reactivity, the American College of Radiology considers patients with hypersensitivity reactions to IC to be at increased risk for reactions to gadolinium but does not make specific recommendations regarding premedication given the dearth of data.1 As a result, premedication may be considered prior to gadolinium administration depending on the severity of the delayed reaction to IC. Additionally, premedication may be beneficial in cases in which gadolinium is contraindicated and IC must be reused. In a retrospective study, all patients with suspected delayed reactions to IC tolerated IC or gadolinium contrast when pretreated with corticosteroids with or without antihistamines.28 Regimens with corticosteroids and either cyclosporine or intravenous immunoglobulin also have prevented the recurrence of IC-induced exanthematous eruptions and Stevens-Johnson syndrome.29,30 Despite these reports, delayed cutaneous reactions to IC have recurred in other patients receiving corticosteroids, antihistamines, and/or cyclosporine for premedication or concurrent treatment of an underlying condition.16,29-31

Conclusion

It is important for dermatologists to recognize IC as a cause of delayed drug reactions. Current awareness is limited, and as a result, patients often are reexposed to the offending contrast agents unsuspectingly. In addition to diagnosing these eruptions, dermatologists may help prevent their recurrence if future contrast-enhanced studies are required by recommending gadolinium-based agents and/or premedication.

- Cohan RH, Davenport MS, Dillman JR, et al; ACR Committee on Drugs and Contrast Media. ACR Manual on Contrast Media. 9th ed. Reston, VA: American College of Radiology; 2013.

- Brockow K, Romano A, Aberer W, et al; European Network of Drug Allergy and the EAACI Interest Group on Drug Hypersensitivity. Skin testing in patients with hypersensitivity reactions to iodinated contrast media—a European multicenter study. Allergy. 2009;64:234-241.

Hosoya T, Yamaguchi K, Akutsu T, et al. Delayed adverse reactions to iodinated contrast media and their risk factors. Radiat Med. 2000;18:39-45. - Rydberg J, Charles J, Aspelin P. Frequency of late allergy-like adverse reactions following injection of intravascular non-ionic contrast media: a retrospective study comparing a non-ionic monomeric contrast medium with a non-ionic dimeric contrast medium. Acta Radiol. 1998;39:219-222.

- Sutton AG, Finn P, Grech ED, et al. Early and late reactions after the use of iopamidol 340, ioxaglate 320, and iodixanol 320 in cardiac catheterization. Am Heart J. 2001;141:677-683.

- Sutton AG, Finn P, Campbell PG, et al. Early and late reactions following the use of iopamidol 340, iomeprol 350 and iodixanol 320 in cardiac catheterization. J Invasive Cardiol. 2003;15:133-138.

- Brown M, Yowler C, Brandt C. Recurrent toxic epidermal necrolysis secondary to iopromide contrast. J Burn Care Res. 2013;34:E53-E56.

- Rosado A, Canto G, Veleiro B, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis after repeated injections of iohexol. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176:262-263.

- Peterson A, Katzberg RW, Fung MA, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis as a delayed dermatotoxic reaction to IV-administered nonionic contrast media. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187:W198-W201.

- Good AE, Novak E, Sonda LP III. Fixed eruption and fever after urography. South Med J. 1980;73:948-949.

- Benson PM, Giblin WJ, Douglas DM. Transient, nonpigmenting fixed drug eruption caused by radiopaque contrast media. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23(2, pt 2):379-381.

- Torres MJ, Gomez F, Doña I, et al. Diagnostic evaluation of patients with nonimmediate cutaneous hypersensitivity reactions to iodinated contrast media. Allergy. 2012;67:929-935.

- Scherer K, Harr T, Bach S, et al. The role of iodine in hypersensitivity reactions to radio contrast media. Clin Exp Allergy. 2010;40:468-475.

- Reynolds NJ, Wallington TB, Burton JL. Hydralazine predisposes to acute cutaneous vasculitis following urography with iopamidol. Br J Dermatol. 1993;129:82-85.

- Belhadjali H, Bouzgarrou L, Youssef M, et al. DRESS syndrome induced by sodium meglumine ioxitalamate. Allergy. 2008;63:786-787.

- Baldwin BT, Lien MH, Khan H, et al. Case of fatal toxic epidermal necrolysis due to cardiac catheterization dye. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:837-840.

- Schmidt BJ, Foley WD, Bohorfoush AG. Toxic epidermal necrolysis related to oral administration of diluted diatrizoate meglumine and diatrizoate sodium. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;171:1215-1216.

- Young AL, Grossman ME. Acute iododerma secondary to iodinated contrast media. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:1377-1379.

- Choyke PL, Miller DL, Lotze MT, et al. Delayed reactions to contrast media after interleukin-2 immunotherapy. Radiology. 1992;183:111-114.

- Loh S, Bagheri S, Katzberg RW, et al. Delayed adverse reaction to contrast-enhanced CT: a prospective single-center study comparison to control group without enhancement. Radiology. 2010;255:764-771.

- Bertrand P, Delhommais A, Alison D, et al. Immediate and delayed tolerance of iohexol and ioxaglate in lower limb phlebography: a double-blind comparative study in humans. Acad Radiol. 1995;2:683-686.

- Munechika H, Hiramatsu Y, Kudo S, et al. A prospective survey of delayed adverse reactions to iohexol in urography and computed tomography. Eur Radiol. 2003;13:185-194.

- Guéant-Rodriguez RM, Romano A, Barbaud A, et al. Hypersensitivity reactions to iodinated contrast media. Curr Pharm Des. 2006;12:3359-3372.

- H

uang SW. Seafood and iodine: an analysis of a medical myth. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2005;26:468-469. - B

aig M, Farag A, Sajid J, et al. Shellfish allergy and relation to iodinated contrast media: United Kingdom survey. World J Cardiol. 2014;6:107-111. - B

öhm I, Schild HH. A practical guide to diagnose lesser-known immediate and delayed contrast media-induced adverse cutaneous reactions. Eur Radiol. 2006;16:1570-1579. - Ose K, Doue T, Zen K, et al. “Gadolinium” as an alternative to iodinated contrast media for X-ray angiography in patients with severe allergy. Circ J. 2005;69:507-509.

- Ji

ngu A, Fukuda J, Taketomi-Takahashi A, et al. Breakthrough reactions of iodinated and gadolinium contrast media after oral steroid premedication protocol. BMC Med Imaging. 2014;14:34. - Ro

mano A, Artesani MC, Andriolo M, et al. Effective prophylactic protocol in delayed hypersensitivity to contrast media: report of a case involving lymphocyte transformation studies with different compounds. Radiology. 2002;225:466-470. - He

bert AA, Bogle MA. Intravenous immunoglobulin prophylaxis for recurrent Stevens-Johnson syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:286-288. - Ha

sdenteufel F, Waton J, Cordebar V, et al. Delayed hypersensitivity reactions caused by iodixanol: an assessment of cross-reactivity in 22 patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:1356-1357.

Case Report

A 67-year-old woman with a history of allergic rhinitis presented in the spring with a pruritic eruption of 2 days’ duration that began on the abdomen and spread to the chest, back, and bilateral arms. Six days prior to the onset of the symptoms she underwent computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis to evaluate abdominal pain and peripheral eosinophilia. Two iodinated contrast (IC) agents were used: intravenous iohexol and oral diatrizoate meglumine–diatrizoate sodium. The eruption was not preceded by fever, malaise, sore throat, rhinorrhea, cough, arthralgia, headache, diarrhea, or new medication or supplement use. The patient denied any history of drug allergy or cutaneous eruptions. Her current medications, which she had been taking long-term, were aspirin, lisinopril, diltiazem, levothyroxine, esomeprazole, paroxetine, gabapentin, and diphenhydramine.

Physical examination was notable for erythematous, blanchable, nontender macules coalescing into patches on the trunk and bilateral arms (Figure). There was slight erythema on the nasolabial folds and ears. The mucosal surfaces and distal legs were clear. The patient was afebrile. Her white blood cell count was 12.5×109/L with 32.3% eosinophils (baseline: white blood cell count, 14.8×109/L; 22% eosinophils)(reference range, 4.8–10.8×109/L; 1%–4% eosinophils). Her comprehensive metabolic panel was within reference range. The human immunodeficiency virus 1/2 antibody immunoassay was nonreactive.

The patient was diagnosed with an exanthematous eruption caused by IC and was treated with oral hydroxyzine and triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.1%. The eruption resolved within 2 weeks without recurrence at 3-month follow-up.

Comment

Del

Clinical Presentation of Delayed Reactions

Most delayed cutaneous reactions to IC present as exanthematous eruptions in the week following a contrast-enhanced CT scan or coronary angiogram.2,12 The reactions tend to resolve within 2 weeks of onset, and the treatment is largely supportive with antihistamines and/or corticosteroids for the associated pruritus.2,5,6 In a study of 98 patients with a history of delayed reactions to IC, delayed-onset urticaria and angioedema also have been reported with incidence rates of 19% and 24%, respectively.2 Other reactions are less common. In the same study, 7% of patients developed palpable purpura; acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis; bullous, flexural, or psoriasislike exanthema; exfoliative eruptions; or purpura and a maculopapular eruption combined with eosinophilia.2 There also have been reports of IC-induced erythema multiforme,3 fixed drug eruptions,10,11 symmetrical drug-related intertriginous and flexural exanthema,13 cutaneous vasculitis,14 drug reactions with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms,15 Stevens-Johnson syndrome/TEN,7,8,16,17 and iododerma.18

IC Agents

Virtually all delayed cutaneous reactions to IC reportedly are due to intravascular rather than oral agents,1,2,19 with the exception of iododerma18 and 1 reported case of TEN.17 Intravenous iohexol was most likely the offending drug in our case. In a prospective cohort study of 539 patients undergoing CT scans, the absolute risk for developing a delayed cutaneous reaction (defined as rash, itching, or skin redness or swelling) to intravascular iohexol was 9.4%.20 Randomized, double-blind studies have found that the risk for delayed cutaneous eruptions is similar among various types of IC, except for iodixanol, which confers a higher risk.5,6,21

Risk Factors

Interestingly, analyses have shown that delayed reactions to IC are more common in atopic patients and during high pollen season.22 Our patient displayed these risk factors, as she had allergic rhinitis and presented for evaluation in late spring when local pollen counts were high. Additionally, patients who develop delayed reactions to IC are notably more likely than controls to have a history of other cutaneous drug reactions, serum creatinine levels greater than 2.0 mg/dL (reference range, 0.6–1.2 mg/dL),3 or history of treatment with recombinant interleukin 2.19

Patients with a history of delayed reactions to IC are not at increased risk for immediate reactions and vice versa.2,3 This finding is consistent with the evidence that delayed and immediate reactions to IC are mechanistically unrelated.23 Additionally, seafood allergy is not a risk factor for either immediate or delayed reactions to IC, despite a common misconception among physicians and patients because seafood is iodinated.24,25

Reexposure to IC

Patients who have had delayed cutaneous reactions to IC are at risk for similar eruptions upon reexposure. Although the reactions are believed to be cell mediated, skin testing with IC is not sensitive enough to reliably identify tolerable alternatives.12 Consequently, gadolinium-based agents have been recommended in patients with a history of reactions to IC if additional contrast-enhanced studies are needed.13,26 Iodinated and gadolinium-based contrast agents do not cross-react, and gadolinium is compatible with studies other than magnetic resonance imaging.1,27

Premedication

Despite the absence of cross-reactivity, the American College of Radiology considers patients with hypersensitivity reactions to IC to be at increased risk for reactions to gadolinium but does not make specific recommendations regarding premedication given the dearth of data.1 As a result, premedication may be considered prior to gadolinium administration depending on the severity of the delayed reaction to IC. Additionally, premedication may be beneficial in cases in which gadolinium is contraindicated and IC must be reused. In a retrospective study, all patients with suspected delayed reactions to IC tolerated IC or gadolinium contrast when pretreated with corticosteroids with or without antihistamines.28 Regimens with corticosteroids and either cyclosporine or intravenous immunoglobulin also have prevented the recurrence of IC-induced exanthematous eruptions and Stevens-Johnson syndrome.29,30 Despite these reports, delayed cutaneous reactions to IC have recurred in other patients receiving corticosteroids, antihistamines, and/or cyclosporine for premedication or concurrent treatment of an underlying condition.16,29-31

Conclusion

It is important for dermatologists to recognize IC as a cause of delayed drug reactions. Current awareness is limited, and as a result, patients often are reexposed to the offending contrast agents unsuspectingly. In addition to diagnosing these eruptions, dermatologists may help prevent their recurrence if future contrast-enhanced studies are required by recommending gadolinium-based agents and/or premedication.

Case Report

A 67-year-old woman with a history of allergic rhinitis presented in the spring with a pruritic eruption of 2 days’ duration that began on the abdomen and spread to the chest, back, and bilateral arms. Six days prior to the onset of the symptoms she underwent computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis to evaluate abdominal pain and peripheral eosinophilia. Two iodinated contrast (IC) agents were used: intravenous iohexol and oral diatrizoate meglumine–diatrizoate sodium. The eruption was not preceded by fever, malaise, sore throat, rhinorrhea, cough, arthralgia, headache, diarrhea, or new medication or supplement use. The patient denied any history of drug allergy or cutaneous eruptions. Her current medications, which she had been taking long-term, were aspirin, lisinopril, diltiazem, levothyroxine, esomeprazole, paroxetine, gabapentin, and diphenhydramine.

Physical examination was notable for erythematous, blanchable, nontender macules coalescing into patches on the trunk and bilateral arms (Figure). There was slight erythema on the nasolabial folds and ears. The mucosal surfaces and distal legs were clear. The patient was afebrile. Her white blood cell count was 12.5×109/L with 32.3% eosinophils (baseline: white blood cell count, 14.8×109/L; 22% eosinophils)(reference range, 4.8–10.8×109/L; 1%–4% eosinophils). Her comprehensive metabolic panel was within reference range. The human immunodeficiency virus 1/2 antibody immunoassay was nonreactive.

The patient was diagnosed with an exanthematous eruption caused by IC and was treated with oral hydroxyzine and triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.1%. The eruption resolved within 2 weeks without recurrence at 3-month follow-up.

Comment

Del

Clinical Presentation of Delayed Reactions

Most delayed cutaneous reactions to IC present as exanthematous eruptions in the week following a contrast-enhanced CT scan or coronary angiogram.2,12 The reactions tend to resolve within 2 weeks of onset, and the treatment is largely supportive with antihistamines and/or corticosteroids for the associated pruritus.2,5,6 In a study of 98 patients with a history of delayed reactions to IC, delayed-onset urticaria and angioedema also have been reported with incidence rates of 19% and 24%, respectively.2 Other reactions are less common. In the same study, 7% of patients developed palpable purpura; acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis; bullous, flexural, or psoriasislike exanthema; exfoliative eruptions; or purpura and a maculopapular eruption combined with eosinophilia.2 There also have been reports of IC-induced erythema multiforme,3 fixed drug eruptions,10,11 symmetrical drug-related intertriginous and flexural exanthema,13 cutaneous vasculitis,14 drug reactions with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms,15 Stevens-Johnson syndrome/TEN,7,8,16,17 and iododerma.18

IC Agents

Virtually all delayed cutaneous reactions to IC reportedly are due to intravascular rather than oral agents,1,2,19 with the exception of iododerma18 and 1 reported case of TEN.17 Intravenous iohexol was most likely the offending drug in our case. In a prospective cohort study of 539 patients undergoing CT scans, the absolute risk for developing a delayed cutaneous reaction (defined as rash, itching, or skin redness or swelling) to intravascular iohexol was 9.4%.20 Randomized, double-blind studies have found that the risk for delayed cutaneous eruptions is similar among various types of IC, except for iodixanol, which confers a higher risk.5,6,21

Risk Factors

Interestingly, analyses have shown that delayed reactions to IC are more common in atopic patients and during high pollen season.22 Our patient displayed these risk factors, as she had allergic rhinitis and presented for evaluation in late spring when local pollen counts were high. Additionally, patients who develop delayed reactions to IC are notably more likely than controls to have a history of other cutaneous drug reactions, serum creatinine levels greater than 2.0 mg/dL (reference range, 0.6–1.2 mg/dL),3 or history of treatment with recombinant interleukin 2.19

Patients with a history of delayed reactions to IC are not at increased risk for immediate reactions and vice versa.2,3 This finding is consistent with the evidence that delayed and immediate reactions to IC are mechanistically unrelated.23 Additionally, seafood allergy is not a risk factor for either immediate or delayed reactions to IC, despite a common misconception among physicians and patients because seafood is iodinated.24,25

Reexposure to IC

Patients who have had delayed cutaneous reactions to IC are at risk for similar eruptions upon reexposure. Although the reactions are believed to be cell mediated, skin testing with IC is not sensitive enough to reliably identify tolerable alternatives.12 Consequently, gadolinium-based agents have been recommended in patients with a history of reactions to IC if additional contrast-enhanced studies are needed.13,26 Iodinated and gadolinium-based contrast agents do not cross-react, and gadolinium is compatible with studies other than magnetic resonance imaging.1,27

Premedication

Despite the absence of cross-reactivity, the American College of Radiology considers patients with hypersensitivity reactions to IC to be at increased risk for reactions to gadolinium but does not make specific recommendations regarding premedication given the dearth of data.1 As a result, premedication may be considered prior to gadolinium administration depending on the severity of the delayed reaction to IC. Additionally, premedication may be beneficial in cases in which gadolinium is contraindicated and IC must be reused. In a retrospective study, all patients with suspected delayed reactions to IC tolerated IC or gadolinium contrast when pretreated with corticosteroids with or without antihistamines.28 Regimens with corticosteroids and either cyclosporine or intravenous immunoglobulin also have prevented the recurrence of IC-induced exanthematous eruptions and Stevens-Johnson syndrome.29,30 Despite these reports, delayed cutaneous reactions to IC have recurred in other patients receiving corticosteroids, antihistamines, and/or cyclosporine for premedication or concurrent treatment of an underlying condition.16,29-31

Conclusion

It is important for dermatologists to recognize IC as a cause of delayed drug reactions. Current awareness is limited, and as a result, patients often are reexposed to the offending contrast agents unsuspectingly. In addition to diagnosing these eruptions, dermatologists may help prevent their recurrence if future contrast-enhanced studies are required by recommending gadolinium-based agents and/or premedication.

- Cohan RH, Davenport MS, Dillman JR, et al; ACR Committee on Drugs and Contrast Media. ACR Manual on Contrast Media. 9th ed. Reston, VA: American College of Radiology; 2013.

- Brockow K, Romano A, Aberer W, et al; European Network of Drug Allergy and the EAACI Interest Group on Drug Hypersensitivity. Skin testing in patients with hypersensitivity reactions to iodinated contrast media—a European multicenter study. Allergy. 2009;64:234-241.

Hosoya T, Yamaguchi K, Akutsu T, et al. Delayed adverse reactions to iodinated contrast media and their risk factors. Radiat Med. 2000;18:39-45. - Rydberg J, Charles J, Aspelin P. Frequency of late allergy-like adverse reactions following injection of intravascular non-ionic contrast media: a retrospective study comparing a non-ionic monomeric contrast medium with a non-ionic dimeric contrast medium. Acta Radiol. 1998;39:219-222.

- Sutton AG, Finn P, Grech ED, et al. Early and late reactions after the use of iopamidol 340, ioxaglate 320, and iodixanol 320 in cardiac catheterization. Am Heart J. 2001;141:677-683.

- Sutton AG, Finn P, Campbell PG, et al. Early and late reactions following the use of iopamidol 340, iomeprol 350 and iodixanol 320 in cardiac catheterization. J Invasive Cardiol. 2003;15:133-138.

- Brown M, Yowler C, Brandt C. Recurrent toxic epidermal necrolysis secondary to iopromide contrast. J Burn Care Res. 2013;34:E53-E56.

- Rosado A, Canto G, Veleiro B, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis after repeated injections of iohexol. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176:262-263.

- Peterson A, Katzberg RW, Fung MA, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis as a delayed dermatotoxic reaction to IV-administered nonionic contrast media. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187:W198-W201.

- Good AE, Novak E, Sonda LP III. Fixed eruption and fever after urography. South Med J. 1980;73:948-949.

- Benson PM, Giblin WJ, Douglas DM. Transient, nonpigmenting fixed drug eruption caused by radiopaque contrast media. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23(2, pt 2):379-381.

- Torres MJ, Gomez F, Doña I, et al. Diagnostic evaluation of patients with nonimmediate cutaneous hypersensitivity reactions to iodinated contrast media. Allergy. 2012;67:929-935.

- Scherer K, Harr T, Bach S, et al. The role of iodine in hypersensitivity reactions to radio contrast media. Clin Exp Allergy. 2010;40:468-475.

- Reynolds NJ, Wallington TB, Burton JL. Hydralazine predisposes to acute cutaneous vasculitis following urography with iopamidol. Br J Dermatol. 1993;129:82-85.

- Belhadjali H, Bouzgarrou L, Youssef M, et al. DRESS syndrome induced by sodium meglumine ioxitalamate. Allergy. 2008;63:786-787.

- Baldwin BT, Lien MH, Khan H, et al. Case of fatal toxic epidermal necrolysis due to cardiac catheterization dye. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:837-840.

- Schmidt BJ, Foley WD, Bohorfoush AG. Toxic epidermal necrolysis related to oral administration of diluted diatrizoate meglumine and diatrizoate sodium. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;171:1215-1216.

- Young AL, Grossman ME. Acute iododerma secondary to iodinated contrast media. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:1377-1379.

- Choyke PL, Miller DL, Lotze MT, et al. Delayed reactions to contrast media after interleukin-2 immunotherapy. Radiology. 1992;183:111-114.

- Loh S, Bagheri S, Katzberg RW, et al. Delayed adverse reaction to contrast-enhanced CT: a prospective single-center study comparison to control group without enhancement. Radiology. 2010;255:764-771.

- Bertrand P, Delhommais A, Alison D, et al. Immediate and delayed tolerance of iohexol and ioxaglate in lower limb phlebography: a double-blind comparative study in humans. Acad Radiol. 1995;2:683-686.

- Munechika H, Hiramatsu Y, Kudo S, et al. A prospective survey of delayed adverse reactions to iohexol in urography and computed tomography. Eur Radiol. 2003;13:185-194.

- Guéant-Rodriguez RM, Romano A, Barbaud A, et al. Hypersensitivity reactions to iodinated contrast media. Curr Pharm Des. 2006;12:3359-3372.

- H

uang SW. Seafood and iodine: an analysis of a medical myth. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2005;26:468-469. - B

aig M, Farag A, Sajid J, et al. Shellfish allergy and relation to iodinated contrast media: United Kingdom survey. World J Cardiol. 2014;6:107-111. - B

öhm I, Schild HH. A practical guide to diagnose lesser-known immediate and delayed contrast media-induced adverse cutaneous reactions. Eur Radiol. 2006;16:1570-1579. - Ose K, Doue T, Zen K, et al. “Gadolinium” as an alternative to iodinated contrast media for X-ray angiography in patients with severe allergy. Circ J. 2005;69:507-509.

- Ji

ngu A, Fukuda J, Taketomi-Takahashi A, et al. Breakthrough reactions of iodinated and gadolinium contrast media after oral steroid premedication protocol. BMC Med Imaging. 2014;14:34. - Ro

mano A, Artesani MC, Andriolo M, et al. Effective prophylactic protocol in delayed hypersensitivity to contrast media: report of a case involving lymphocyte transformation studies with different compounds. Radiology. 2002;225:466-470. - He

bert AA, Bogle MA. Intravenous immunoglobulin prophylaxis for recurrent Stevens-Johnson syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:286-288. - Ha

sdenteufel F, Waton J, Cordebar V, et al. Delayed hypersensitivity reactions caused by iodixanol: an assessment of cross-reactivity in 22 patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:1356-1357.

- Cohan RH, Davenport MS, Dillman JR, et al; ACR Committee on Drugs and Contrast Media. ACR Manual on Contrast Media. 9th ed. Reston, VA: American College of Radiology; 2013.

- Brockow K, Romano A, Aberer W, et al; European Network of Drug Allergy and the EAACI Interest Group on Drug Hypersensitivity. Skin testing in patients with hypersensitivity reactions to iodinated contrast media—a European multicenter study. Allergy. 2009;64:234-241.

Hosoya T, Yamaguchi K, Akutsu T, et al. Delayed adverse reactions to iodinated contrast media and their risk factors. Radiat Med. 2000;18:39-45. - Rydberg J, Charles J, Aspelin P. Frequency of late allergy-like adverse reactions following injection of intravascular non-ionic contrast media: a retrospective study comparing a non-ionic monomeric contrast medium with a non-ionic dimeric contrast medium. Acta Radiol. 1998;39:219-222.

- Sutton AG, Finn P, Grech ED, et al. Early and late reactions after the use of iopamidol 340, ioxaglate 320, and iodixanol 320 in cardiac catheterization. Am Heart J. 2001;141:677-683.

- Sutton AG, Finn P, Campbell PG, et al. Early and late reactions following the use of iopamidol 340, iomeprol 350 and iodixanol 320 in cardiac catheterization. J Invasive Cardiol. 2003;15:133-138.

- Brown M, Yowler C, Brandt C. Recurrent toxic epidermal necrolysis secondary to iopromide contrast. J Burn Care Res. 2013;34:E53-E56.

- Rosado A, Canto G, Veleiro B, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis after repeated injections of iohexol. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176:262-263.

- Peterson A, Katzberg RW, Fung MA, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis as a delayed dermatotoxic reaction to IV-administered nonionic contrast media. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187:W198-W201.

- Good AE, Novak E, Sonda LP III. Fixed eruption and fever after urography. South Med J. 1980;73:948-949.

- Benson PM, Giblin WJ, Douglas DM. Transient, nonpigmenting fixed drug eruption caused by radiopaque contrast media. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23(2, pt 2):379-381.

- Torres MJ, Gomez F, Doña I, et al. Diagnostic evaluation of patients with nonimmediate cutaneous hypersensitivity reactions to iodinated contrast media. Allergy. 2012;67:929-935.

- Scherer K, Harr T, Bach S, et al. The role of iodine in hypersensitivity reactions to radio contrast media. Clin Exp Allergy. 2010;40:468-475.

- Reynolds NJ, Wallington TB, Burton JL. Hydralazine predisposes to acute cutaneous vasculitis following urography with iopamidol. Br J Dermatol. 1993;129:82-85.

- Belhadjali H, Bouzgarrou L, Youssef M, et al. DRESS syndrome induced by sodium meglumine ioxitalamate. Allergy. 2008;63:786-787.

- Baldwin BT, Lien MH, Khan H, et al. Case of fatal toxic epidermal necrolysis due to cardiac catheterization dye. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:837-840.

- Schmidt BJ, Foley WD, Bohorfoush AG. Toxic epidermal necrolysis related to oral administration of diluted diatrizoate meglumine and diatrizoate sodium. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;171:1215-1216.

- Young AL, Grossman ME. Acute iododerma secondary to iodinated contrast media. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:1377-1379.

- Choyke PL, Miller DL, Lotze MT, et al. Delayed reactions to contrast media after interleukin-2 immunotherapy. Radiology. 1992;183:111-114.

- Loh S, Bagheri S, Katzberg RW, et al. Delayed adverse reaction to contrast-enhanced CT: a prospective single-center study comparison to control group without enhancement. Radiology. 2010;255:764-771.

- Bertrand P, Delhommais A, Alison D, et al. Immediate and delayed tolerance of iohexol and ioxaglate in lower limb phlebography: a double-blind comparative study in humans. Acad Radiol. 1995;2:683-686.

- Munechika H, Hiramatsu Y, Kudo S, et al. A prospective survey of delayed adverse reactions to iohexol in urography and computed tomography. Eur Radiol. 2003;13:185-194.

- Guéant-Rodriguez RM, Romano A, Barbaud A, et al. Hypersensitivity reactions to iodinated contrast media. Curr Pharm Des. 2006;12:3359-3372.

- H

uang SW. Seafood and iodine: an analysis of a medical myth. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2005;26:468-469. - B

aig M, Farag A, Sajid J, et al. Shellfish allergy and relation to iodinated contrast media: United Kingdom survey. World J Cardiol. 2014;6:107-111. - B

öhm I, Schild HH. A practical guide to diagnose lesser-known immediate and delayed contrast media-induced adverse cutaneous reactions. Eur Radiol. 2006;16:1570-1579. - Ose K, Doue T, Zen K, et al. “Gadolinium” as an alternative to iodinated contrast media for X-ray angiography in patients with severe allergy. Circ J. 2005;69:507-509.

- Ji

ngu A, Fukuda J, Taketomi-Takahashi A, et al. Breakthrough reactions of iodinated and gadolinium contrast media after oral steroid premedication protocol. BMC Med Imaging. 2014;14:34. - Ro

mano A, Artesani MC, Andriolo M, et al. Effective prophylactic protocol in delayed hypersensitivity to contrast media: report of a case involving lymphocyte transformation studies with different compounds. Radiology. 2002;225:466-470. - He

bert AA, Bogle MA. Intravenous immunoglobulin prophylaxis for recurrent Stevens-Johnson syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:286-288. - Ha

sdenteufel F, Waton J, Cordebar V, et al. Delayed hypersensitivity reactions caused by iodixanol: an assessment of cross-reactivity in 22 patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:1356-1357.

Practice Points

- Delayed cutaneous reactions to iodinated contrast (IC) are common, but patients frequently are misdiagnosed and inadvertently readministered the offending agent.

- The most common IC-induced delayed reactions are self-limited exanthematous eruptions that develop within 1 week of exposure.

- Risk factors for delayed reactions to IC include atopy, contrast exposure during high pollen season, use of the agent iodixanol, a history of other cutaneous drug eruptions, elevated serum creatinine levels, and treatment with recombinant interleukin 2.

- Dermatologists can help prevent recurrent reactions in patients who require repeated exposure to IC by recommending gadolinium-based contrast agents and/or premedication.

Drug-induced Linear IgA Bullous Dermatosis in a Patient With a Vancomycin-impregnated Cement Spacer

Case Report

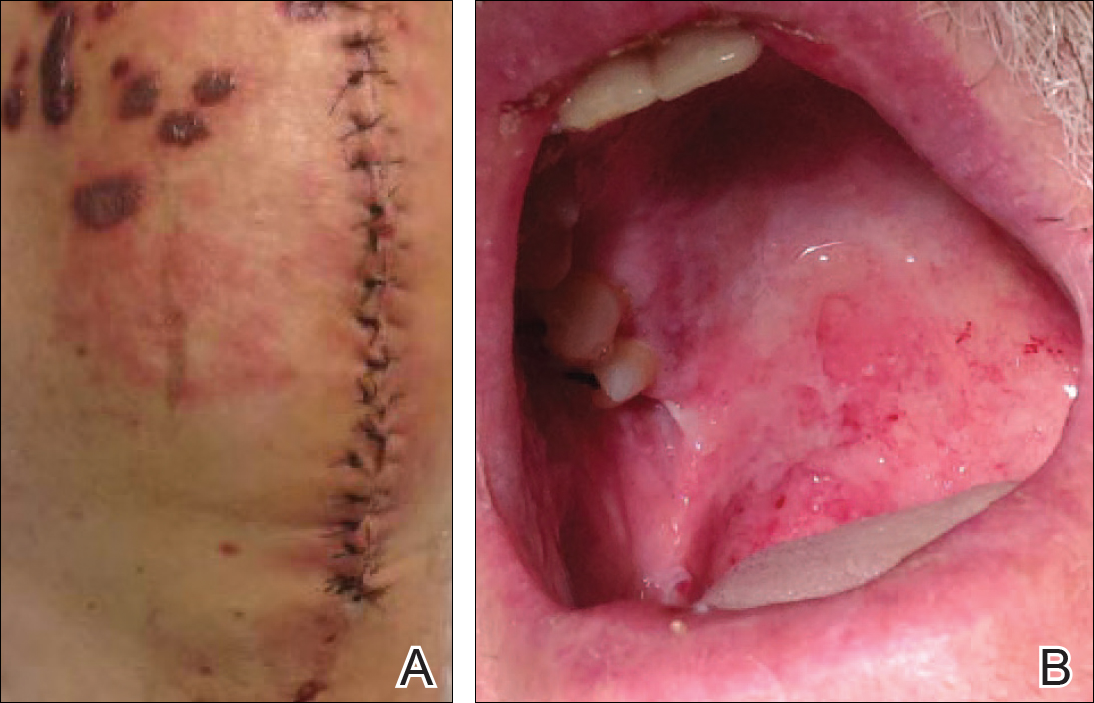

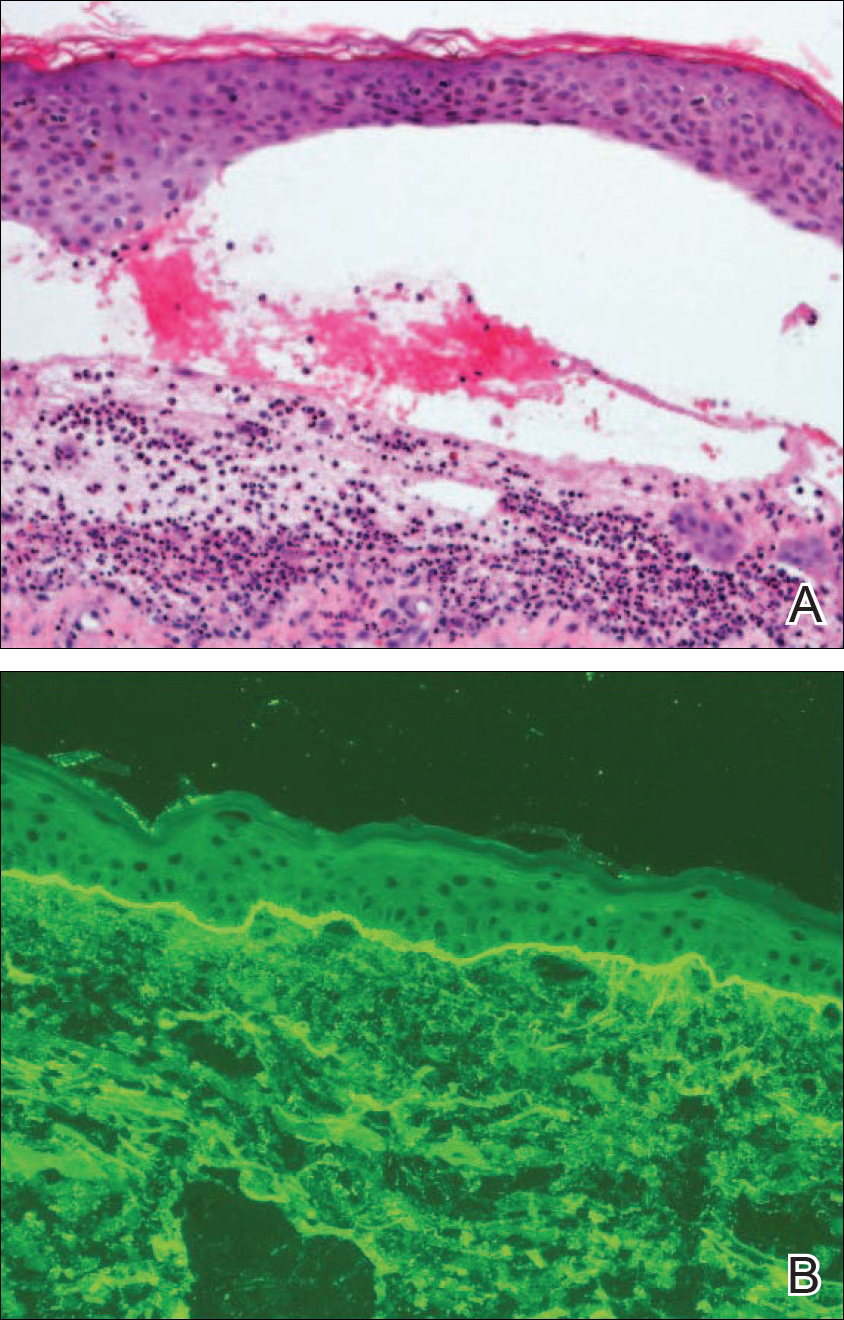

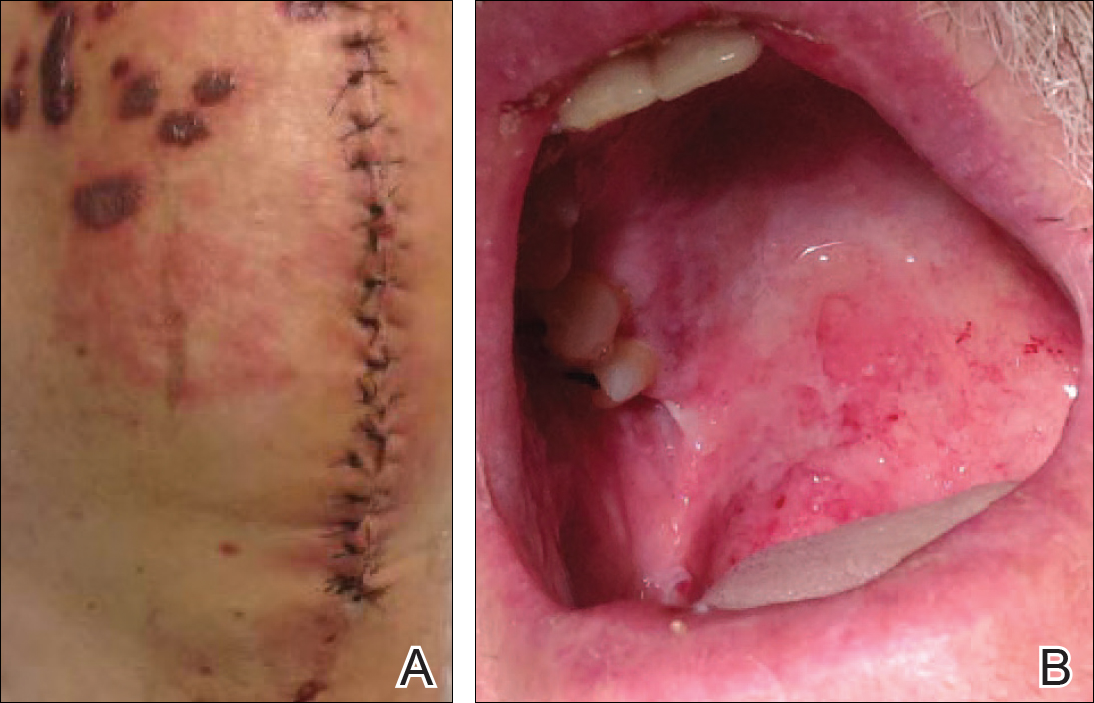

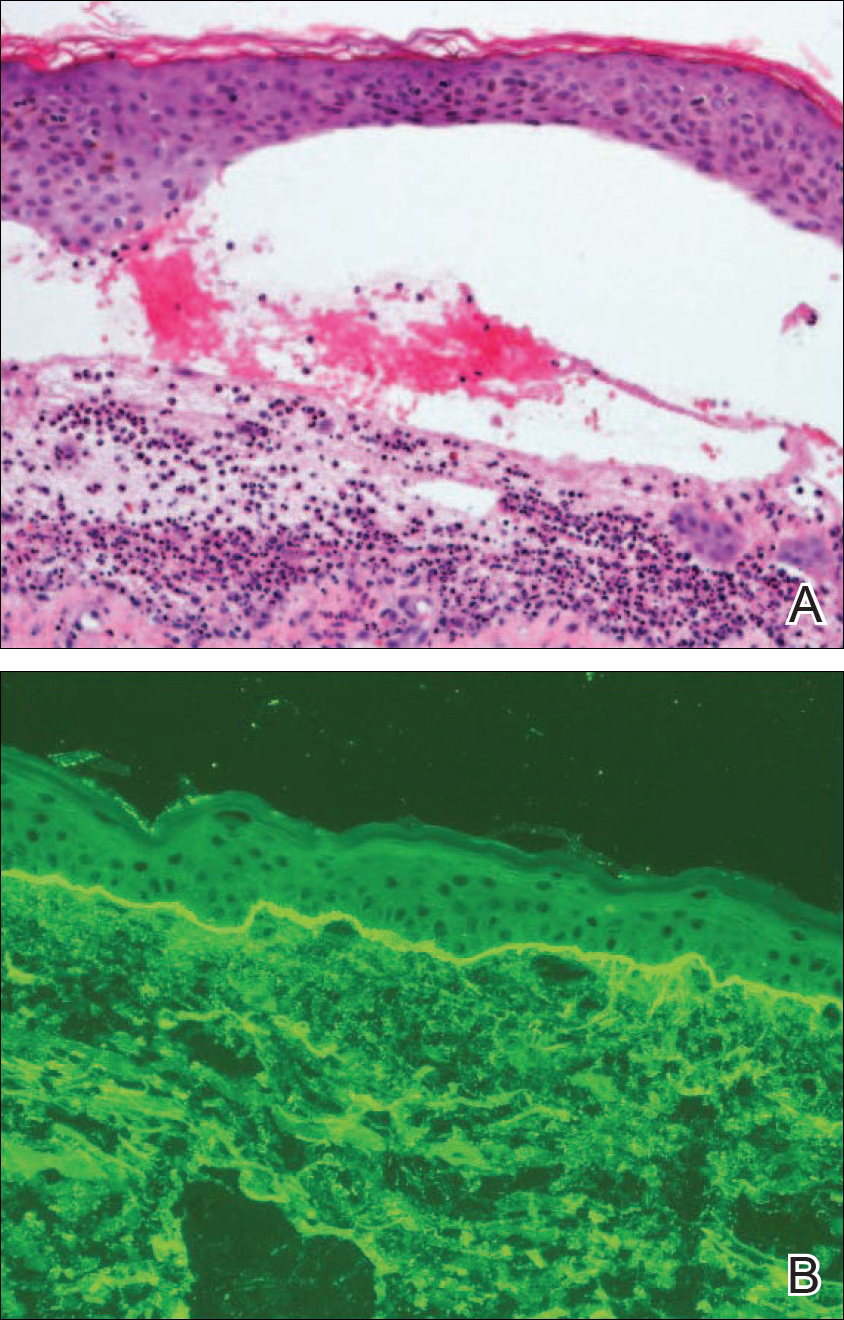

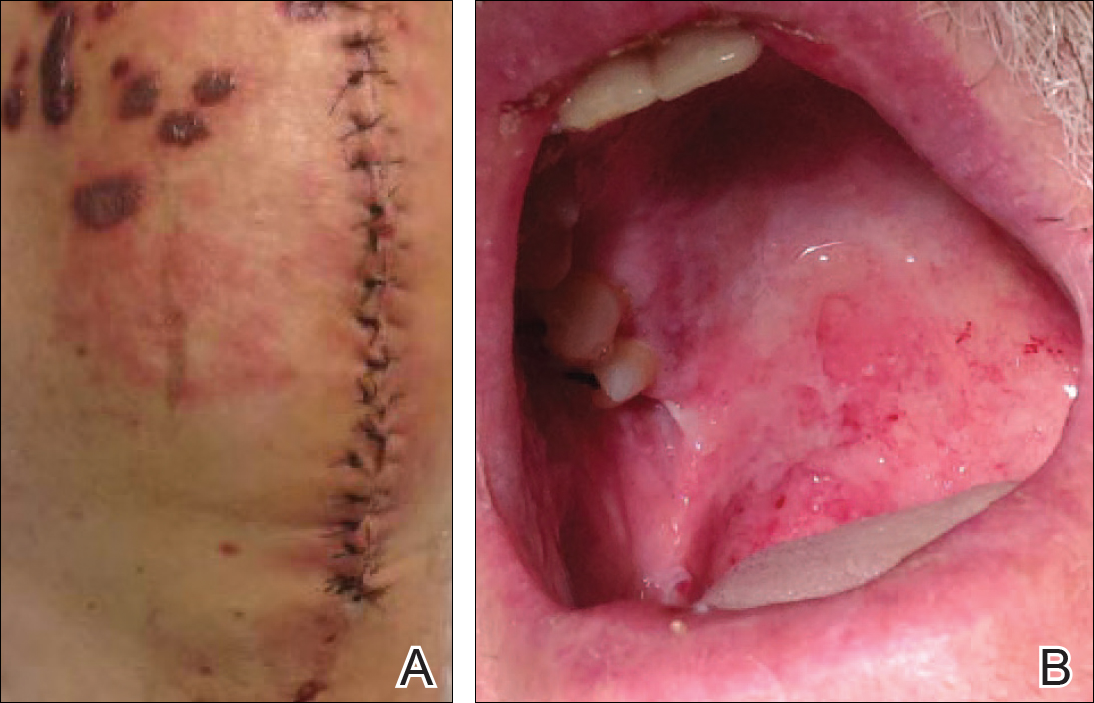

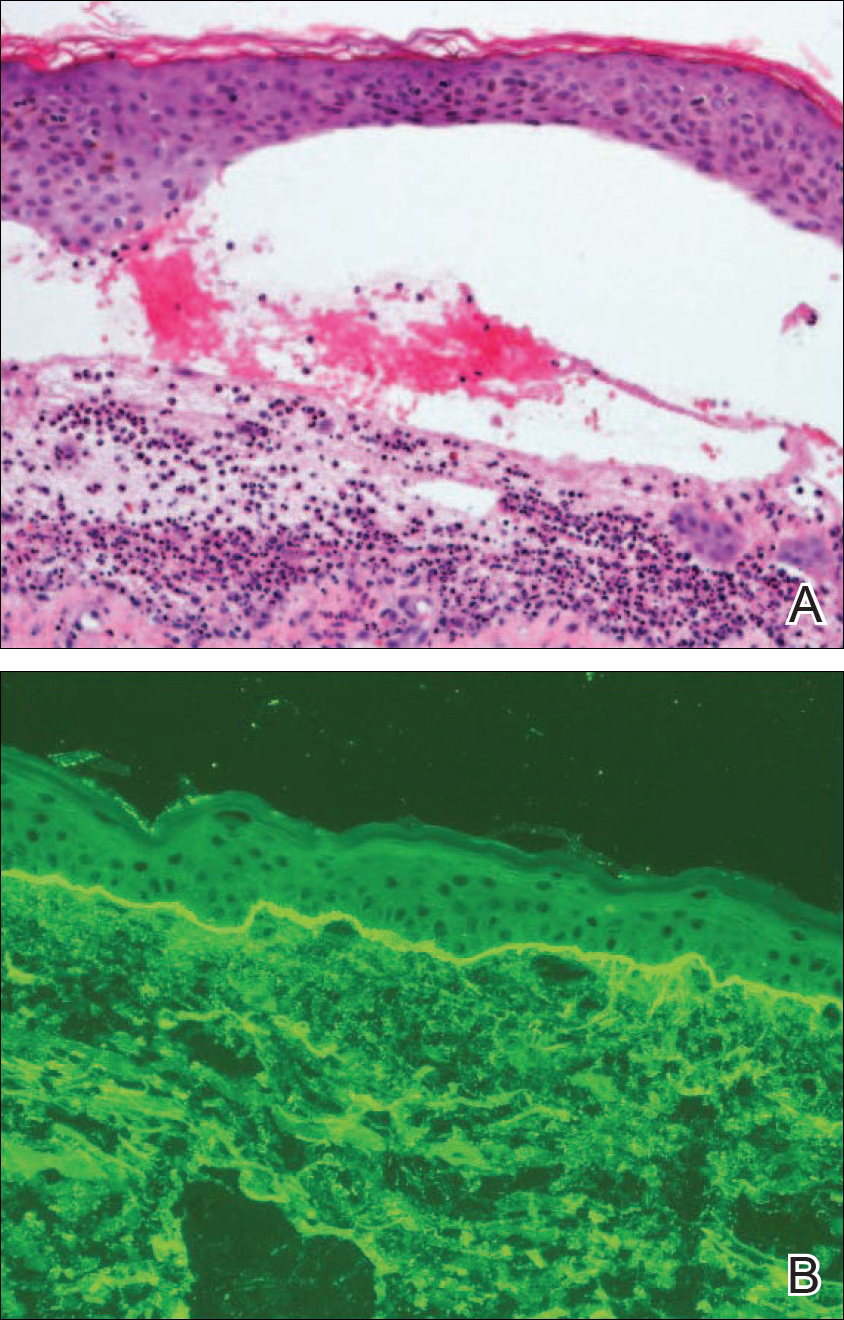

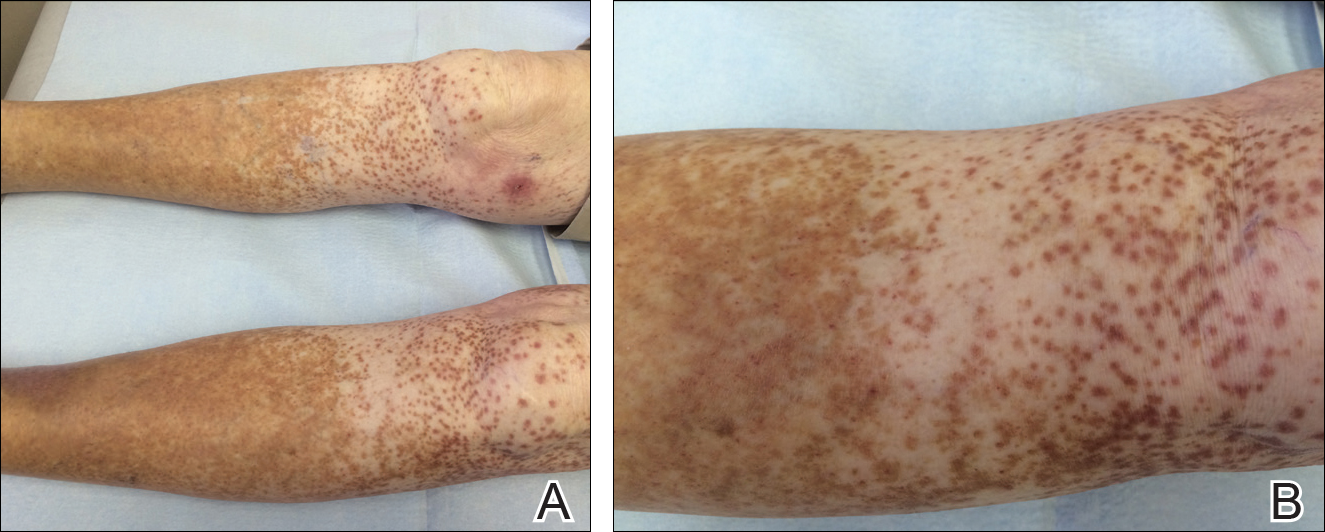

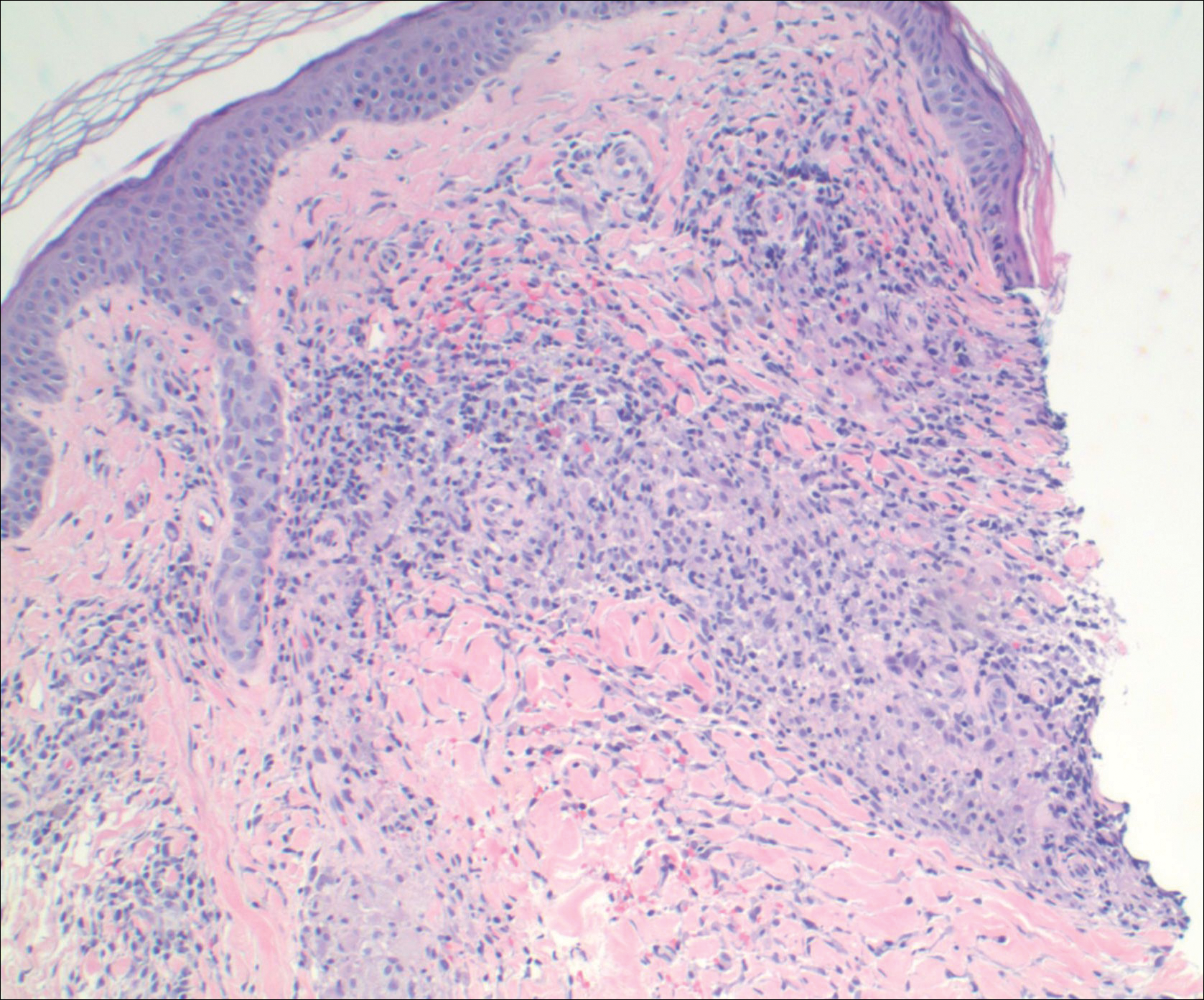

A 77-year-old man was admitted to the general medicine service at our institution for treatment of a diffuse macular eruption and hemorrhagic bullae 12 days after undergoing left-knee revision arthroplasty during which a cement spacer impregnated with vancomycin and tobramycin was placed. At the time of the surgery, the patient also received intravenous (IV) vancomycin and oral ciprofloxacin, which were continued postoperatively until his hospital presentation. The patient was recovering well until postoperative day 7, when he developed painful swelling and erythema surrounding the surgical wound on the left knee. Concerned that his symptoms indicated a flare of gout, he restarted a former allopurinol prescription from an outside physician after 2 years of nonuse. The skin changes progressed distally on the left leg over the next 48 hours. By postoperative day 10, he had developed serosanguinous blisters on the left knee (Figure 1A) and oral mucosa (Figure 1B), as well as erythematous nodules on the bilateral palms. He presented to our institution for emergent care on postoperative day 12 following progression of the eruption to the inguinal region (Figure 2A), buttocks (Figure 2B), and abdominal region.

Due to concerns about a potential drug reaction, the IV vancomycin, oral ciprofloxacin, and oral allopurinol were discontinued on hospital admission.

Oral prednisone 60 mg once daily and oral dapsone 25 mg once daily were initiated on hospital days 4 and 6 (postoperative days 15 and 17), respectively. A 6-week course of oral ciprofloxacin 750 mg twice daily and daptomycin 8 mg/kg once daily was initiated for bacterial coverage on hospital day 5 (postoperative day 16). Topical triamcinolone and an anesthetic mouthwash also were used to treat the mucosal involvement. The lesions stabilized on the third day of steroid therapy, and the patient was discharged 7 days after hospital admission (postoperative day 18). Dapsone was rapidly increased to 100 mg once daily over the next week for Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia prophylaxis. An increase in prednisone to 80 mg once daily was required 3 days after the patient was discharged due to worsening oral lesions. Five days after discharge, the patient was readmitted to the hospital for 3 days due to acute kidney injury (AKI) in which his baseline creatinine level tripled. The cause of renal impairment was unknown, resulting in empiric discontinuation of dapsone on postoperative day 27. Prophylaxis for P jirovecii pneumonia was replaced with once-monthly inhaled pentamidine. Prednisone was tapered 20 days after the original presentation (postoperative day 32) following gradual improvement of both the skin and oral lesions. At dermatology follow-up 2 weeks later, doxycycline 100 mg twice daily was added for residual inflammation of the left leg. A deep vein thrombosis was discovered in the left leg 10 days later, and 3 months of anticoagulation therapy was initiated with discontinuation of the doxycycline. The patient continued to have renal insufficiency several weeks after dapsone discontinuation and developed prominent peripheral motor neuropathy with bilateral thenar atrophy. He did not experience any skin eruptions or relapses in the weeks following prednisone cessation and underwent successful removal of the cement spacer with full left-knee reconstruction 4 months after his initial presentation to our institution. At 9-month dermatology follow-up, the LABD remained in remission.

Comment

Linear IgA bullous dermatosis is a well-documented autoimmune mucocutaneous disorder characterized by linear IgA deposits at the dermoepidermal junction. The development of autoantibodies to antigens within the basement membrane zone leads to both cellular and humoral immune responses that facilitate the subepidermal blistering rash in LABD.2,3 Linear IgA bullous dermatosis affects all ages and races with a bimodal epidemiology. The adult form typically appears after 60 years of age, whereas the childhood form (chronic bullous disease of childhood) appears between 6 months and 6 years of age.3 Medications—particularly vancomycin—are responsible for a substantial portion of cases.1-4 In one review, vancomycin was implicated in almost half (22/52 [42.3%]) of drug-related cases of LABD.4 Other associated medications include captopril, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, phenytoin, and diclo-fenac.3,4 Vancomycin-associated LABD has a substantially shorter time to onset of symptoms, with a mean of 8.6 days compared to 63.8 days for other causative agents.4

The initial treatment of drug-induced LABD is immediate discontinuation of the suspected agent(s) and supportive care.9 Although future avoidance of vancomycin is recommended in patients with a history of LABD, there are reported cases of successful rechallenges.4,10 The early removal of our patient’s cement spacer was discouraged by both the orthopedics and infectious disease consultation services due to potential complications as well as the patient’s gradual improvement during his hospital course.

Dapsone is considered the standard systemic treatment for LABD. Sulfapyridine is an alternative to dapsone, or a combination of these 2 drugs may be used. Corticosteroids can be added to each of these regimens to achieve remission, as in our case.2 Although dapsone was discontinued in the setting of the patient’s AKI, the vancomycin in the dual-eluting spacer was more likely the culprit. A review of 544 postoperative outcomes following the use of an antibiotic-impregnated cement spacer (AICS) during 2-stage arthroplasty displayed an 8- to 10-fold increase in the development of AKIs compared to the rate of AKIs following primary joint arthroplasty.10 While our patient’s AKI was not attributed to dapsone, his prominent peripheral motor neuropathy with resultant bilateral thenar atrophy was a rare complication of dapsone use. While dapsone-associated neuropathy has been reported in daily dosages of as low as 75 mg, it typically is seen in doses of at least 300 mg per day and in larger cumulative dosages.11

Despite having a well-characterized vancomycin-induced LABD in the setting of known vancomycin exposure, our patient’s case was particularly challenging given the continued presence of the vancomycin-impregnated cement spacer (VICS) in the left knee, resulting in vancomycin levels at admission and during subsequent measurements over 2 weeks that were all several-fold higher than the renal clearance predicted.

Vancomycin-associated LABD does not appear to be dose dependent and has been reported at both subtherapeutic1-3 and supratherapeutic levels,5-9 whereas toxicity reactions are more common at supratherapeutic levels.9 The literature on AICS use suggests that drug elution occurs at relatively unpredictable rates based on a variety of factors, including the type of cement used and the initial antibiotic concentration.12,13 Furthermore, the addition of tobramycin to VICSs has been found to increase the rate of vancomycin delivery through a phenomenon known as passive opportunism.14

As AICS devices allow for the delivery of higher concentrations of antibiotics to a localized area, systemic complications are considered rare but have been reported.13 Our report describes a rare case of LABD in the setting of a VICS. One clinical aspect of our case that supports the implication of VICS as the cause of the patient’s LABD is the concentration of bullae overlying the incision site on the left knee. A case of a desquamating rash in a patient with an implanted VICS has been documented in which the early lesions were localized to the surgical leg, as in our case.15 Unlike our case, there was a history of Stevens-Johnson syndrome following previous vancomycin exposure. A case of a gentamicin-impregnated cement spacer causing allergic dermatitis that was most prominent in the surgical leg also has been reported.16 An isomorphic phenomenon (Köbner phenomenon) has been suggested in the setting of

- Plunkett RW, Chiarello SE, Beutner EH. Linear IgA bullous dermatosis in one of two piroxicam-induced eruptions: a distinct direct immunofluorescence trend revealed by the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:691-696.

- Guide SV, Marinkovich MP. Linear IgA bullous dermatosis. Clin Dermatol. 2001;19:719-727.

- Fortuna G, Marinkovich MP. Linear immunoglobulin A bullous dermatosis. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:38-50.

- Fortuna G, Salas-Alanis JC, Guidetti E, et al. A critical reappraisal of the current data on drug-induced linear immunoglobulin A bullous dermatosis: a real and separate nosological entity? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:988-994.

- Kuechle MK, Stegemeir E, Maynard B, et al. Drug-induced linear IgA bullous dermatosis: report of six cases and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30(2, pt 1):187-192.

- Neughebauer BI, Negron G, Pelton S, et al. Bullous skin disease: an unusual allergic reaction to vancomycin. Am J Med Sci. 2002;323:273-278.

- Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30:239-245.

- Wiadrowski TP, Reid CM. Drug-induced linear IgA bullous disease following antibiotics. Australas J Dermatol. 2001;42:196-199.

- Dang LV, Byrom L, Muir J, et al. Vancomycin-induced linear IgA with mucosal and ocular involvement: a case report. Infect Dis Clin Pract. 2014;22:e119-e121.

- Luu A, Syed F, Raman G, et al. Two-stage arthroplasty for prosthetic joint infection: a systematic review of acute kidney injury, systemic toxicity and infection control [published online April 8, 2013]. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28:1490.e1-1498.e1.

- Daneshmend TK. The neurotoxicity of dapsone. Adverse Drug React Acute Poisoning Rev. 1984;3:43-58.

- Jacobs C, Christensen CP, Berend ME. Static and mobile antibiotic-impregnated cement spacers for the management of prosthetic joint infection. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2009;17:356-368.

- Springer BD, Lee GC, Osmon D, et al. Systemic safety of high-dose antibiotic-loaded cement spacers after resection of an infected total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;427:47-51.

- Penner MJ, Masri BA, Duncan CP. Elution characteristics of vancomycin and tobramycin combined in acrylic bone-cement. J Arthroplasty. 1996;11:939-944.

- Williams B, Hanson A, Sha B. Diffuse desquamating rash following exposure to vancomycin-impregnated bone cement. Ann Pharmacother. 2014;48:1061-1065.

- Haeberle M, Wittner B. Is gentamicin-loaded bone cement a risk for developing systemic allergic dermatitis? Contact Dermatitis. 2009;60:176-177.

- McDonald HC, York NR, Pandya AG. Drug-induced linear IgA bullous dermatosis demonstrating the isomorphic phenomenon. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:897-898.

Case Report

A 77-year-old man was admitted to the general medicine service at our institution for treatment of a diffuse macular eruption and hemorrhagic bullae 12 days after undergoing left-knee revision arthroplasty during which a cement spacer impregnated with vancomycin and tobramycin was placed. At the time of the surgery, the patient also received intravenous (IV) vancomycin and oral ciprofloxacin, which were continued postoperatively until his hospital presentation. The patient was recovering well until postoperative day 7, when he developed painful swelling and erythema surrounding the surgical wound on the left knee. Concerned that his symptoms indicated a flare of gout, he restarted a former allopurinol prescription from an outside physician after 2 years of nonuse. The skin changes progressed distally on the left leg over the next 48 hours. By postoperative day 10, he had developed serosanguinous blisters on the left knee (Figure 1A) and oral mucosa (Figure 1B), as well as erythematous nodules on the bilateral palms. He presented to our institution for emergent care on postoperative day 12 following progression of the eruption to the inguinal region (Figure 2A), buttocks (Figure 2B), and abdominal region.

Due to concerns about a potential drug reaction, the IV vancomycin, oral ciprofloxacin, and oral allopurinol were discontinued on hospital admission.

Oral prednisone 60 mg once daily and oral dapsone 25 mg once daily were initiated on hospital days 4 and 6 (postoperative days 15 and 17), respectively. A 6-week course of oral ciprofloxacin 750 mg twice daily and daptomycin 8 mg/kg once daily was initiated for bacterial coverage on hospital day 5 (postoperative day 16). Topical triamcinolone and an anesthetic mouthwash also were used to treat the mucosal involvement. The lesions stabilized on the third day of steroid therapy, and the patient was discharged 7 days after hospital admission (postoperative day 18). Dapsone was rapidly increased to 100 mg once daily over the next week for Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia prophylaxis. An increase in prednisone to 80 mg once daily was required 3 days after the patient was discharged due to worsening oral lesions. Five days after discharge, the patient was readmitted to the hospital for 3 days due to acute kidney injury (AKI) in which his baseline creatinine level tripled. The cause of renal impairment was unknown, resulting in empiric discontinuation of dapsone on postoperative day 27. Prophylaxis for P jirovecii pneumonia was replaced with once-monthly inhaled pentamidine. Prednisone was tapered 20 days after the original presentation (postoperative day 32) following gradual improvement of both the skin and oral lesions. At dermatology follow-up 2 weeks later, doxycycline 100 mg twice daily was added for residual inflammation of the left leg. A deep vein thrombosis was discovered in the left leg 10 days later, and 3 months of anticoagulation therapy was initiated with discontinuation of the doxycycline. The patient continued to have renal insufficiency several weeks after dapsone discontinuation and developed prominent peripheral motor neuropathy with bilateral thenar atrophy. He did not experience any skin eruptions or relapses in the weeks following prednisone cessation and underwent successful removal of the cement spacer with full left-knee reconstruction 4 months after his initial presentation to our institution. At 9-month dermatology follow-up, the LABD remained in remission.

Comment

Linear IgA bullous dermatosis is a well-documented autoimmune mucocutaneous disorder characterized by linear IgA deposits at the dermoepidermal junction. The development of autoantibodies to antigens within the basement membrane zone leads to both cellular and humoral immune responses that facilitate the subepidermal blistering rash in LABD.2,3 Linear IgA bullous dermatosis affects all ages and races with a bimodal epidemiology. The adult form typically appears after 60 years of age, whereas the childhood form (chronic bullous disease of childhood) appears between 6 months and 6 years of age.3 Medications—particularly vancomycin—are responsible for a substantial portion of cases.1-4 In one review, vancomycin was implicated in almost half (22/52 [42.3%]) of drug-related cases of LABD.4 Other associated medications include captopril, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, phenytoin, and diclo-fenac.3,4 Vancomycin-associated LABD has a substantially shorter time to onset of symptoms, with a mean of 8.6 days compared to 63.8 days for other causative agents.4

The initial treatment of drug-induced LABD is immediate discontinuation of the suspected agent(s) and supportive care.9 Although future avoidance of vancomycin is recommended in patients with a history of LABD, there are reported cases of successful rechallenges.4,10 The early removal of our patient’s cement spacer was discouraged by both the orthopedics and infectious disease consultation services due to potential complications as well as the patient’s gradual improvement during his hospital course.

Dapsone is considered the standard systemic treatment for LABD. Sulfapyridine is an alternative to dapsone, or a combination of these 2 drugs may be used. Corticosteroids can be added to each of these regimens to achieve remission, as in our case.2 Although dapsone was discontinued in the setting of the patient’s AKI, the vancomycin in the dual-eluting spacer was more likely the culprit. A review of 544 postoperative outcomes following the use of an antibiotic-impregnated cement spacer (AICS) during 2-stage arthroplasty displayed an 8- to 10-fold increase in the development of AKIs compared to the rate of AKIs following primary joint arthroplasty.10 While our patient’s AKI was not attributed to dapsone, his prominent peripheral motor neuropathy with resultant bilateral thenar atrophy was a rare complication of dapsone use. While dapsone-associated neuropathy has been reported in daily dosages of as low as 75 mg, it typically is seen in doses of at least 300 mg per day and in larger cumulative dosages.11

Despite having a well-characterized vancomycin-induced LABD in the setting of known vancomycin exposure, our patient’s case was particularly challenging given the continued presence of the vancomycin-impregnated cement spacer (VICS) in the left knee, resulting in vancomycin levels at admission and during subsequent measurements over 2 weeks that were all several-fold higher than the renal clearance predicted.

Vancomycin-associated LABD does not appear to be dose dependent and has been reported at both subtherapeutic1-3 and supratherapeutic levels,5-9 whereas toxicity reactions are more common at supratherapeutic levels.9 The literature on AICS use suggests that drug elution occurs at relatively unpredictable rates based on a variety of factors, including the type of cement used and the initial antibiotic concentration.12,13 Furthermore, the addition of tobramycin to VICSs has been found to increase the rate of vancomycin delivery through a phenomenon known as passive opportunism.14

As AICS devices allow for the delivery of higher concentrations of antibiotics to a localized area, systemic complications are considered rare but have been reported.13 Our report describes a rare case of LABD in the setting of a VICS. One clinical aspect of our case that supports the implication of VICS as the cause of the patient’s LABD is the concentration of bullae overlying the incision site on the left knee. A case of a desquamating rash in a patient with an implanted VICS has been documented in which the early lesions were localized to the surgical leg, as in our case.15 Unlike our case, there was a history of Stevens-Johnson syndrome following previous vancomycin exposure. A case of a gentamicin-impregnated cement spacer causing allergic dermatitis that was most prominent in the surgical leg also has been reported.16 An isomorphic phenomenon (Köbner phenomenon) has been suggested in the setting of

Case Report

A 77-year-old man was admitted to the general medicine service at our institution for treatment of a diffuse macular eruption and hemorrhagic bullae 12 days after undergoing left-knee revision arthroplasty during which a cement spacer impregnated with vancomycin and tobramycin was placed. At the time of the surgery, the patient also received intravenous (IV) vancomycin and oral ciprofloxacin, which were continued postoperatively until his hospital presentation. The patient was recovering well until postoperative day 7, when he developed painful swelling and erythema surrounding the surgical wound on the left knee. Concerned that his symptoms indicated a flare of gout, he restarted a former allopurinol prescription from an outside physician after 2 years of nonuse. The skin changes progressed distally on the left leg over the next 48 hours. By postoperative day 10, he had developed serosanguinous blisters on the left knee (Figure 1A) and oral mucosa (Figure 1B), as well as erythematous nodules on the bilateral palms. He presented to our institution for emergent care on postoperative day 12 following progression of the eruption to the inguinal region (Figure 2A), buttocks (Figure 2B), and abdominal region.

Due to concerns about a potential drug reaction, the IV vancomycin, oral ciprofloxacin, and oral allopurinol were discontinued on hospital admission.

Oral prednisone 60 mg once daily and oral dapsone 25 mg once daily were initiated on hospital days 4 and 6 (postoperative days 15 and 17), respectively. A 6-week course of oral ciprofloxacin 750 mg twice daily and daptomycin 8 mg/kg once daily was initiated for bacterial coverage on hospital day 5 (postoperative day 16). Topical triamcinolone and an anesthetic mouthwash also were used to treat the mucosal involvement. The lesions stabilized on the third day of steroid therapy, and the patient was discharged 7 days after hospital admission (postoperative day 18). Dapsone was rapidly increased to 100 mg once daily over the next week for Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia prophylaxis. An increase in prednisone to 80 mg once daily was required 3 days after the patient was discharged due to worsening oral lesions. Five days after discharge, the patient was readmitted to the hospital for 3 days due to acute kidney injury (AKI) in which his baseline creatinine level tripled. The cause of renal impairment was unknown, resulting in empiric discontinuation of dapsone on postoperative day 27. Prophylaxis for P jirovecii pneumonia was replaced with once-monthly inhaled pentamidine. Prednisone was tapered 20 days after the original presentation (postoperative day 32) following gradual improvement of both the skin and oral lesions. At dermatology follow-up 2 weeks later, doxycycline 100 mg twice daily was added for residual inflammation of the left leg. A deep vein thrombosis was discovered in the left leg 10 days later, and 3 months of anticoagulation therapy was initiated with discontinuation of the doxycycline. The patient continued to have renal insufficiency several weeks after dapsone discontinuation and developed prominent peripheral motor neuropathy with bilateral thenar atrophy. He did not experience any skin eruptions or relapses in the weeks following prednisone cessation and underwent successful removal of the cement spacer with full left-knee reconstruction 4 months after his initial presentation to our institution. At 9-month dermatology follow-up, the LABD remained in remission.

Comment

Linear IgA bullous dermatosis is a well-documented autoimmune mucocutaneous disorder characterized by linear IgA deposits at the dermoepidermal junction. The development of autoantibodies to antigens within the basement membrane zone leads to both cellular and humoral immune responses that facilitate the subepidermal blistering rash in LABD.2,3 Linear IgA bullous dermatosis affects all ages and races with a bimodal epidemiology. The adult form typically appears after 60 years of age, whereas the childhood form (chronic bullous disease of childhood) appears between 6 months and 6 years of age.3 Medications—particularly vancomycin—are responsible for a substantial portion of cases.1-4 In one review, vancomycin was implicated in almost half (22/52 [42.3%]) of drug-related cases of LABD.4 Other associated medications include captopril, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, phenytoin, and diclo-fenac.3,4 Vancomycin-associated LABD has a substantially shorter time to onset of symptoms, with a mean of 8.6 days compared to 63.8 days for other causative agents.4

The initial treatment of drug-induced LABD is immediate discontinuation of the suspected agent(s) and supportive care.9 Although future avoidance of vancomycin is recommended in patients with a history of LABD, there are reported cases of successful rechallenges.4,10 The early removal of our patient’s cement spacer was discouraged by both the orthopedics and infectious disease consultation services due to potential complications as well as the patient’s gradual improvement during his hospital course.

Dapsone is considered the standard systemic treatment for LABD. Sulfapyridine is an alternative to dapsone, or a combination of these 2 drugs may be used. Corticosteroids can be added to each of these regimens to achieve remission, as in our case.2 Although dapsone was discontinued in the setting of the patient’s AKI, the vancomycin in the dual-eluting spacer was more likely the culprit. A review of 544 postoperative outcomes following the use of an antibiotic-impregnated cement spacer (AICS) during 2-stage arthroplasty displayed an 8- to 10-fold increase in the development of AKIs compared to the rate of AKIs following primary joint arthroplasty.10 While our patient’s AKI was not attributed to dapsone, his prominent peripheral motor neuropathy with resultant bilateral thenar atrophy was a rare complication of dapsone use. While dapsone-associated neuropathy has been reported in daily dosages of as low as 75 mg, it typically is seen in doses of at least 300 mg per day and in larger cumulative dosages.11

Despite having a well-characterized vancomycin-induced LABD in the setting of known vancomycin exposure, our patient’s case was particularly challenging given the continued presence of the vancomycin-impregnated cement spacer (VICS) in the left knee, resulting in vancomycin levels at admission and during subsequent measurements over 2 weeks that were all several-fold higher than the renal clearance predicted.

Vancomycin-associated LABD does not appear to be dose dependent and has been reported at both subtherapeutic1-3 and supratherapeutic levels,5-9 whereas toxicity reactions are more common at supratherapeutic levels.9 The literature on AICS use suggests that drug elution occurs at relatively unpredictable rates based on a variety of factors, including the type of cement used and the initial antibiotic concentration.12,13 Furthermore, the addition of tobramycin to VICSs has been found to increase the rate of vancomycin delivery through a phenomenon known as passive opportunism.14

As AICS devices allow for the delivery of higher concentrations of antibiotics to a localized area, systemic complications are considered rare but have been reported.13 Our report describes a rare case of LABD in the setting of a VICS. One clinical aspect of our case that supports the implication of VICS as the cause of the patient’s LABD is the concentration of bullae overlying the incision site on the left knee. A case of a desquamating rash in a patient with an implanted VICS has been documented in which the early lesions were localized to the surgical leg, as in our case.15 Unlike our case, there was a history of Stevens-Johnson syndrome following previous vancomycin exposure. A case of a gentamicin-impregnated cement spacer causing allergic dermatitis that was most prominent in the surgical leg also has been reported.16 An isomorphic phenomenon (Köbner phenomenon) has been suggested in the setting of

- Plunkett RW, Chiarello SE, Beutner EH. Linear IgA bullous dermatosis in one of two piroxicam-induced eruptions: a distinct direct immunofluorescence trend revealed by the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:691-696.

- Guide SV, Marinkovich MP. Linear IgA bullous dermatosis. Clin Dermatol. 2001;19:719-727.

- Fortuna G, Marinkovich MP. Linear immunoglobulin A bullous dermatosis. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:38-50.

- Fortuna G, Salas-Alanis JC, Guidetti E, et al. A critical reappraisal of the current data on drug-induced linear immunoglobulin A bullous dermatosis: a real and separate nosological entity? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:988-994.

- Kuechle MK, Stegemeir E, Maynard B, et al. Drug-induced linear IgA bullous dermatosis: report of six cases and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30(2, pt 1):187-192.

- Neughebauer BI, Negron G, Pelton S, et al. Bullous skin disease: an unusual allergic reaction to vancomycin. Am J Med Sci. 2002;323:273-278.

- Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30:239-245.

- Wiadrowski TP, Reid CM. Drug-induced linear IgA bullous disease following antibiotics. Australas J Dermatol. 2001;42:196-199.

- Dang LV, Byrom L, Muir J, et al. Vancomycin-induced linear IgA with mucosal and ocular involvement: a case report. Infect Dis Clin Pract. 2014;22:e119-e121.

- Luu A, Syed F, Raman G, et al. Two-stage arthroplasty for prosthetic joint infection: a systematic review of acute kidney injury, systemic toxicity and infection control [published online April 8, 2013]. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28:1490.e1-1498.e1.

- Daneshmend TK. The neurotoxicity of dapsone. Adverse Drug React Acute Poisoning Rev. 1984;3:43-58.

- Jacobs C, Christensen CP, Berend ME. Static and mobile antibiotic-impregnated cement spacers for the management of prosthetic joint infection. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2009;17:356-368.

- Springer BD, Lee GC, Osmon D, et al. Systemic safety of high-dose antibiotic-loaded cement spacers after resection of an infected total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;427:47-51.

- Penner MJ, Masri BA, Duncan CP. Elution characteristics of vancomycin and tobramycin combined in acrylic bone-cement. J Arthroplasty. 1996;11:939-944.

- Williams B, Hanson A, Sha B. Diffuse desquamating rash following exposure to vancomycin-impregnated bone cement. Ann Pharmacother. 2014;48:1061-1065.

- Haeberle M, Wittner B. Is gentamicin-loaded bone cement a risk for developing systemic allergic dermatitis? Contact Dermatitis. 2009;60:176-177.

- McDonald HC, York NR, Pandya AG. Drug-induced linear IgA bullous dermatosis demonstrating the isomorphic phenomenon. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:897-898.

- Plunkett RW, Chiarello SE, Beutner EH. Linear IgA bullous dermatosis in one of two piroxicam-induced eruptions: a distinct direct immunofluorescence trend revealed by the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:691-696.

- Guide SV, Marinkovich MP. Linear IgA bullous dermatosis. Clin Dermatol. 2001;19:719-727.

- Fortuna G, Marinkovich MP. Linear immunoglobulin A bullous dermatosis. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:38-50.

- Fortuna G, Salas-Alanis JC, Guidetti E, et al. A critical reappraisal of the current data on drug-induced linear immunoglobulin A bullous dermatosis: a real and separate nosological entity? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:988-994.

- Kuechle MK, Stegemeir E, Maynard B, et al. Drug-induced linear IgA bullous dermatosis: report of six cases and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30(2, pt 1):187-192.

- Neughebauer BI, Negron G, Pelton S, et al. Bullous skin disease: an unusual allergic reaction to vancomycin. Am J Med Sci. 2002;323:273-278.

- Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30:239-245.

- Wiadrowski TP, Reid CM. Drug-induced linear IgA bullous disease following antibiotics. Australas J Dermatol. 2001;42:196-199.

- Dang LV, Byrom L, Muir J, et al. Vancomycin-induced linear IgA with mucosal and ocular involvement: a case report. Infect Dis Clin Pract. 2014;22:e119-e121.

- Luu A, Syed F, Raman G, et al. Two-stage arthroplasty for prosthetic joint infection: a systematic review of acute kidney injury, systemic toxicity and infection control [published online April 8, 2013]. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28:1490.e1-1498.e1.

- Daneshmend TK. The neurotoxicity of dapsone. Adverse Drug React Acute Poisoning Rev. 1984;3:43-58.

- Jacobs C, Christensen CP, Berend ME. Static and mobile antibiotic-impregnated cement spacers for the management of prosthetic joint infection. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2009;17:356-368.

- Springer BD, Lee GC, Osmon D, et al. Systemic safety of high-dose antibiotic-loaded cement spacers after resection of an infected total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;427:47-51.

- Penner MJ, Masri BA, Duncan CP. Elution characteristics of vancomycin and tobramycin combined in acrylic bone-cement. J Arthroplasty. 1996;11:939-944.

- Williams B, Hanson A, Sha B. Diffuse desquamating rash following exposure to vancomycin-impregnated bone cement. Ann Pharmacother. 2014;48:1061-1065.

- Haeberle M, Wittner B. Is gentamicin-loaded bone cement a risk for developing systemic allergic dermatitis? Contact Dermatitis. 2009;60:176-177.

- McDonald HC, York NR, Pandya AG. Drug-induced linear IgA bullous dermatosis demonstrating the isomorphic phenomenon. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:897-898.

Practice Points

- Linear IgA bullous dermatosis (LABD) is an autoimmune mucocutaneous disorder characterized by linear IgA deposits at the dermoepidermal junction.

- A substantial number of cases of LABD are drug related, with vancomycin most commonly implicated.

- While antibiotic-impregnated cement spacers deliver high concentrations of local medications, systemic reactions are still possible.

- Dapsone is the first-line treatment for LABD.

VIDEO: Select atopic dermatitis patients need patch testing

SAN DIEGO – Patch testing may be in order for some patients with atopic dermatitis, according to Jonathan Silverberg, MD, PhD, of the department of dermatology, Northwestern University, Chicago.

Allergic contact dermatitis is a common comorbid condition in people with AD “and sometimes, can flare up the severity of the disease,” he said in a video interview at the American Academy of Dermatology annual meeting.

Patch testing can ferret out a trigger in atopic dermatitis patients with atypical disease distribution or refractory disease, and help avoid the need for systemic therapy, Dr. Silverman pointed out.

In the interview, he discussed these and other clinical scenarios, as well as how patch testing differs in these patients and what screening series to consider using.

Dr. Silverberg had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Silverberg, J. et al, Session 061.

SAN DIEGO – Patch testing may be in order for some patients with atopic dermatitis, according to Jonathan Silverberg, MD, PhD, of the department of dermatology, Northwestern University, Chicago.

Allergic contact dermatitis is a common comorbid condition in people with AD “and sometimes, can flare up the severity of the disease,” he said in a video interview at the American Academy of Dermatology annual meeting.

Patch testing can ferret out a trigger in atopic dermatitis patients with atypical disease distribution or refractory disease, and help avoid the need for systemic therapy, Dr. Silverman pointed out.

In the interview, he discussed these and other clinical scenarios, as well as how patch testing differs in these patients and what screening series to consider using.

Dr. Silverberg had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Silverberg, J. et al, Session 061.

SAN DIEGO – Patch testing may be in order for some patients with atopic dermatitis, according to Jonathan Silverberg, MD, PhD, of the department of dermatology, Northwestern University, Chicago.

Allergic contact dermatitis is a common comorbid condition in people with AD “and sometimes, can flare up the severity of the disease,” he said in a video interview at the American Academy of Dermatology annual meeting.

Patch testing can ferret out a trigger in atopic dermatitis patients with atypical disease distribution or refractory disease, and help avoid the need for systemic therapy, Dr. Silverman pointed out.

In the interview, he discussed these and other clinical scenarios, as well as how patch testing differs in these patients and what screening series to consider using.

Dr. Silverberg had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Silverberg, J. et al, Session 061.

REPORTING FROM AAD 18

VIDEO: Parabens named ‘nonallergen’ of the year

SAN DIEGO – With propylene glycol already declared 2018 Allergen of the Year in a published journal article, the news at the Allergen of the Year session of the American Contact Dermatitis Society was announcement of the 2019 pick, parabens.

From a skin perspective, parabens are “perhaps the safest” preservative, but despite that they have a bad public reputation Donald V. Belsito, MD, said in his Allergen of the Year talk during the Society’s annual meeting held the day before the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

There is an unfounded public perception that parabens cause endocrine disruption. Naming parabens the “nonallergen” of the year for 2019 is an effort to dispel this myth, Dr. Belsito said in a video interview.

The public prejudice against parabens, exacerbated by many products that tout being paraben free, has helped cause a crisis because preservative systems in general have been under attack and facing restrictions. Dr. Belsito cited European limitations on the preservative methylisothiazolinone (Allergen of the Year in 2013) and withdrawal of formaldehyde (2015 Allergen of the Year) from many products.

Dr. Belsito also highlighted why propylene glycol received the nod as 2018’s Allergen of the Year (Dermatitis. 2018 Jan/Feb;29[1]:3-5). Propylene glycol is a very ubiquitous emulsifier found in cosmetics, foods, and both topical and oral medications. Caution is needed when running a patch test on the agent to distinguish an irritation reaction from an allergic reaction. Interpreting the test result correctly is very important, said Dr. Belsito, professor of dermatology at Columbia University in New York.

Parabens is the 20th Allergen of the Year named by the Society, an annual event since 2000.

Dr. Belsito has participated in the program since its start.

SAN DIEGO – With propylene glycol already declared 2018 Allergen of the Year in a published journal article, the news at the Allergen of the Year session of the American Contact Dermatitis Society was announcement of the 2019 pick, parabens.

From a skin perspective, parabens are “perhaps the safest” preservative, but despite that they have a bad public reputation Donald V. Belsito, MD, said in his Allergen of the Year talk during the Society’s annual meeting held the day before the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

There is an unfounded public perception that parabens cause endocrine disruption. Naming parabens the “nonallergen” of the year for 2019 is an effort to dispel this myth, Dr. Belsito said in a video interview.

The public prejudice against parabens, exacerbated by many products that tout being paraben free, has helped cause a crisis because preservative systems in general have been under attack and facing restrictions. Dr. Belsito cited European limitations on the preservative methylisothiazolinone (Allergen of the Year in 2013) and withdrawal of formaldehyde (2015 Allergen of the Year) from many products.

Dr. Belsito also highlighted why propylene glycol received the nod as 2018’s Allergen of the Year (Dermatitis. 2018 Jan/Feb;29[1]:3-5). Propylene glycol is a very ubiquitous emulsifier found in cosmetics, foods, and both topical and oral medications. Caution is needed when running a patch test on the agent to distinguish an irritation reaction from an allergic reaction. Interpreting the test result correctly is very important, said Dr. Belsito, professor of dermatology at Columbia University in New York.

Parabens is the 20th Allergen of the Year named by the Society, an annual event since 2000.

Dr. Belsito has participated in the program since its start.

SAN DIEGO – With propylene glycol already declared 2018 Allergen of the Year in a published journal article, the news at the Allergen of the Year session of the American Contact Dermatitis Society was announcement of the 2019 pick, parabens.

From a skin perspective, parabens are “perhaps the safest” preservative, but despite that they have a bad public reputation Donald V. Belsito, MD, said in his Allergen of the Year talk during the Society’s annual meeting held the day before the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

There is an unfounded public perception that parabens cause endocrine disruption. Naming parabens the “nonallergen” of the year for 2019 is an effort to dispel this myth, Dr. Belsito said in a video interview.

The public prejudice against parabens, exacerbated by many products that tout being paraben free, has helped cause a crisis because preservative systems in general have been under attack and facing restrictions. Dr. Belsito cited European limitations on the preservative methylisothiazolinone (Allergen of the Year in 2013) and withdrawal of formaldehyde (2015 Allergen of the Year) from many products.

Dr. Belsito also highlighted why propylene glycol received the nod as 2018’s Allergen of the Year (Dermatitis. 2018 Jan/Feb;29[1]:3-5). Propylene glycol is a very ubiquitous emulsifier found in cosmetics, foods, and both topical and oral medications. Caution is needed when running a patch test on the agent to distinguish an irritation reaction from an allergic reaction. Interpreting the test result correctly is very important, said Dr. Belsito, professor of dermatology at Columbia University in New York.

Parabens is the 20th Allergen of the Year named by the Society, an annual event since 2000.

Dr. Belsito has participated in the program since its start.

FROM ACDS 18

VIDEO: The skinny on patch testing

KAUAI, HAWAII – .