User login

Allergy Testing in Dermatology and Beyond

Allergy testing typically refers to evaluation of a patient for suspected type I or type IV hypersensitivity.1,2 The possibility of type I hypersensitivity is raised in patients presenting with food allergies, allergic rhinitis, asthma, and immediate adverse reactions to medications, whereas type IV hypersensitivity is suspected in patients with eczematous eruptions, delayed adverse cutaneous reactions to medications, and failure of metallic implants (eg, metal joint replacements, cardiac stents) in conjunction with overlying skin rashes (Table 1).1-5 Type II (eg, pemphigus vulgaris) and type III (eg, IgA vasculitis) hypersensitivities are not evaluated with screening allergy tests.

Type I Sensitization

Type I hypersensitivity is an immediate hypersensitivity mediated predominantly by IgE activation of mast cells in the skin as well as the respiratory and gastric mucosa.1 Sensitization of an individual patient occurs when antigen-presenting cells induce a helper T cell (TH2) cytokine response leading to B-cell class switching and allergen-specific IgE production. Upon repeat exposure to the allergen, circulating antibodies then bind to high-affinity receptors on mast cells and basophils and initiate an allergic inflammatory response, leading to a clinical presentation of allergic rhinitis, urticaria, or immediate drug reactions. Confirming type I sensitization may be performed via serologic (in vitro) or skin testing (in vivo).5,6

Serologic Testing (In Vitro)

Serologic testing is a blood test that detects circulating IgE levels against specific allergens.5 The first such test, the radioallergosorbent test, was introduced in the 1970s but is not quantitative and is no longer used. Although common, it is inaccurate to describe current serum IgE (s-IgE) testing as radioallergosorbent testing. There are several US Food and Drug Administration-approved s-IgE assays in common use, and these tests may be helpful in elucidating relevant allergens and for tailoring therapy appropriately, which may consist of avoidance of certain foods or environmental agents and/or allergen immunotherapy.

Skin Testing (In Vivo)

Skin testing can be performed percutaneously (eg, percutaneous skin testing) or intradermally (eg, intradermal testing).6 Percutaneous skin testing is performed by placing a drop of allergen extract on the skin, after which a lancet is used to lightly scratch the skin; intradermal testing is performed by injecting a small amount of allergen extract into the dermis. In both cases, the skin is evaluated after 15 to 20 minutes for the presence and size of a cutaneous wheal. Medications with antihistaminergic activity must be discontinued prior to testing. Both s-IgE and skin testing assess for type I hypersensitivity, and factors such as extensive rash, concern for anaphylaxis, or inability to discontinue antihistamines may favor s-IgE testing versus skin testing. False-positive results can occur with both tests, and for this reason, test results should always be interpreted in conjunction with clinical examination and patient history to determine relevant allergies.

Type IV Sensitization

Type IV hypersensitivity is a delayed hypersensitivity mediated primarily by lymphocytes.2 Sensitization occurs when haptens bind to host proteins and are presented by epidermal and dermal dendritic cells to T lymphocytes in the skin. These lymphocytes then migrate to regional lymph nodes where antigen-specific T lymphocytes are produced and home back to the skin. Upon reexposure to the allergen, these memory T lymphocytes become activated and incite a delayed allergic response. Confirming type IV hypersensitivity primarily is accomplished via patch testing, though other testing modalities exist.

Skin Biopsy

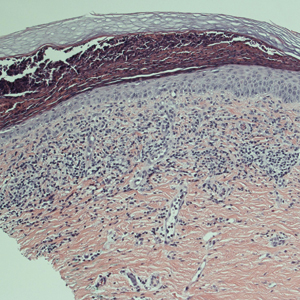

Biopsy is sometimes performed in the workup of an individual presenting with allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) and typically will show spongiosis with normal stratum corneum and epidermal thickness in the setting of acute ACD and mild to marked acanthosis and parakeratosis in chronic ACD.7 The findings, however, are nonspecific and the differential of these histopathologic findings encompasses nummular dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, irritant contact dermatitis, and dyshidrotic eczema, among others. The presence of eosinophils and Langerhans cell microabscesses may provide supportive evidence for ACD over the other spongiotic dermatitides.7,8

Patch Testing

Patch testing is the gold standard in diagnosing type IV hypersensitivities resulting in a clinical presentation of ACD. Hundreds of allergens are commercially available for patch testing, and more commonly tested allergens fall into one of several categories, such as cosmetic preservatives, rubbers, metals, textiles, fragrances, adhesives, antibiotics, plants, and even corticosteroids. Of note, a common misconception is that ACD must result from new exposures; however, patients may develop ACD secondary to an exposure or product they have been using for many years without a problem.

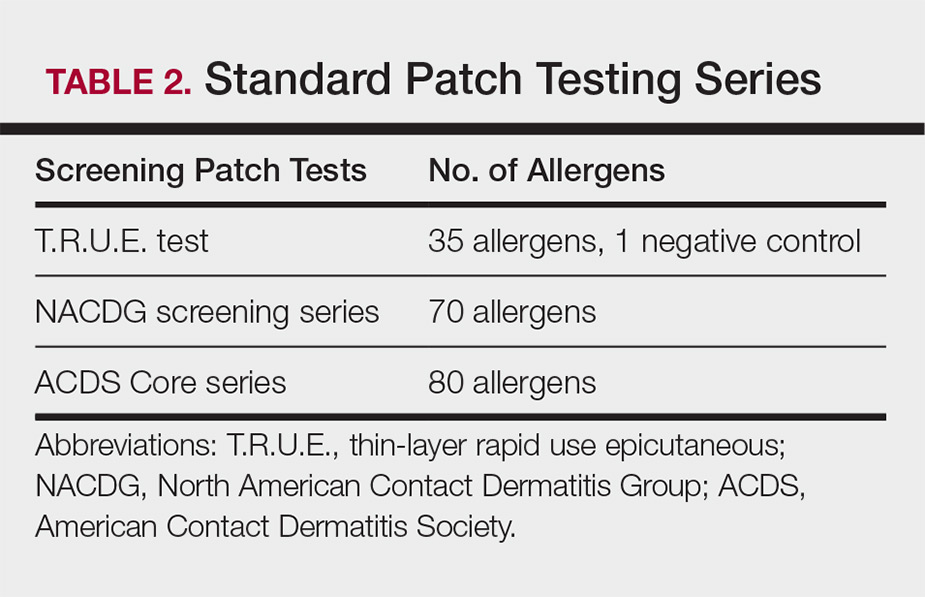

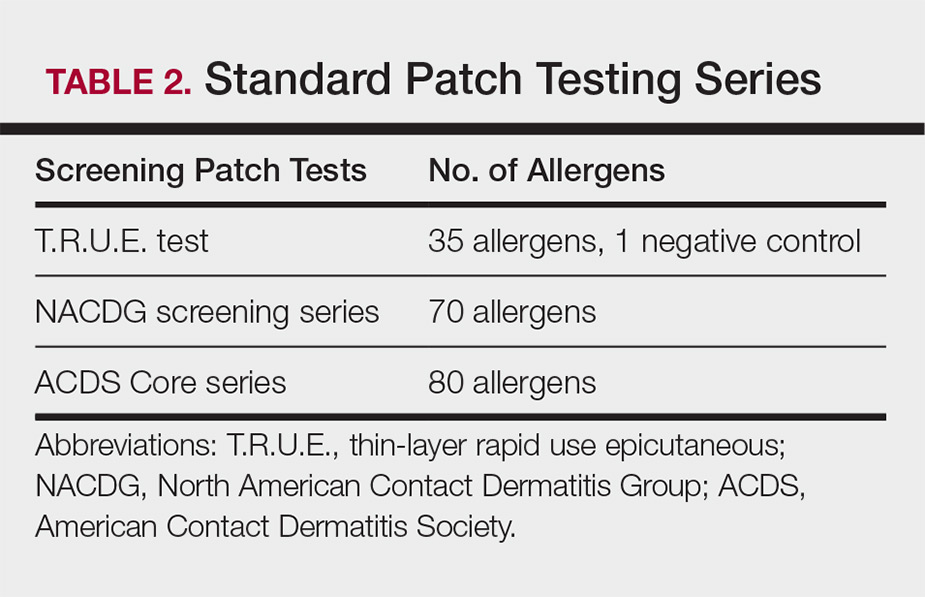

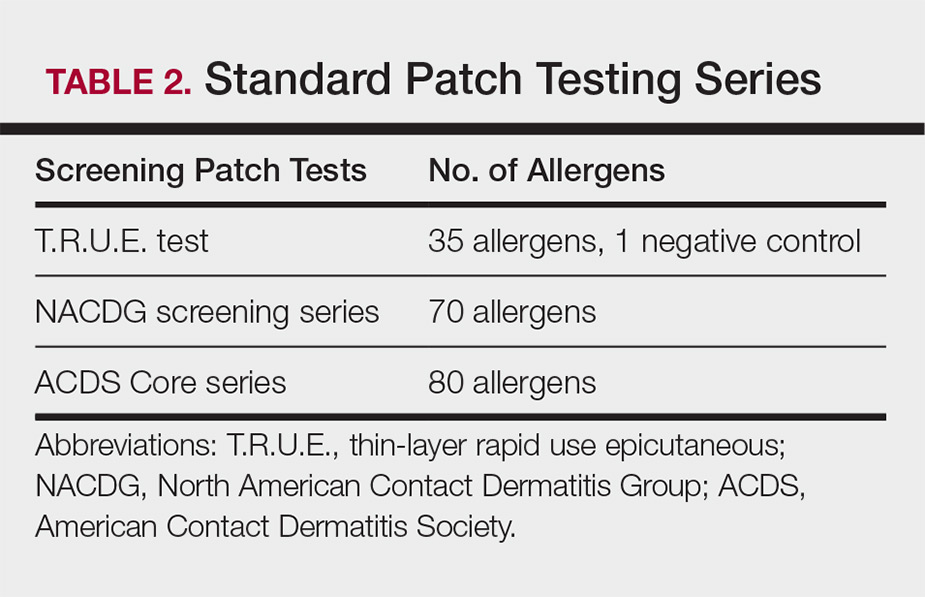

Three commonly used screening series are the thin-layer rapid use epicutaneous (T.R.U.E.) test (SmartPractice), North American Contact Dermatitis Group screening series, and American Contact Dermatitis Society Core 80 allergen series, which have some variation in the type and number of allergens included (Table 2). The T.R.U.E. test will miss a notable number of clinically relevant allergens in comparison to the North American Contact Dermatitis Group and American Contact Dermatitis Society Core series, and it may be of particularly low utility in identifying fragrance or preservative ACD.9

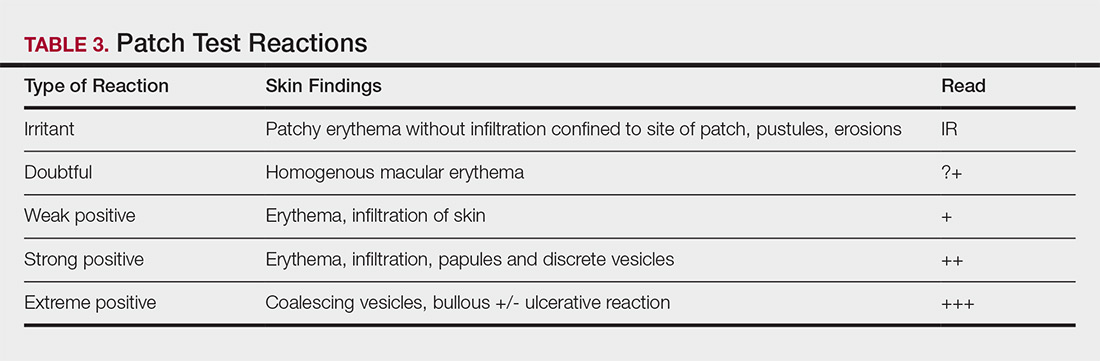

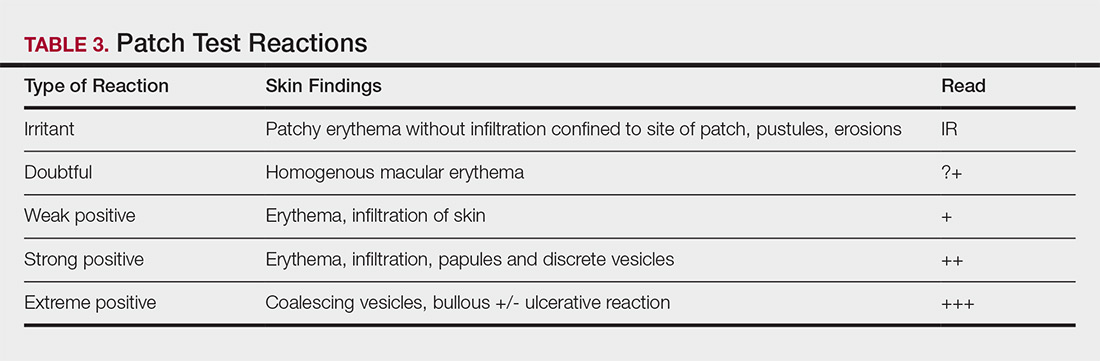

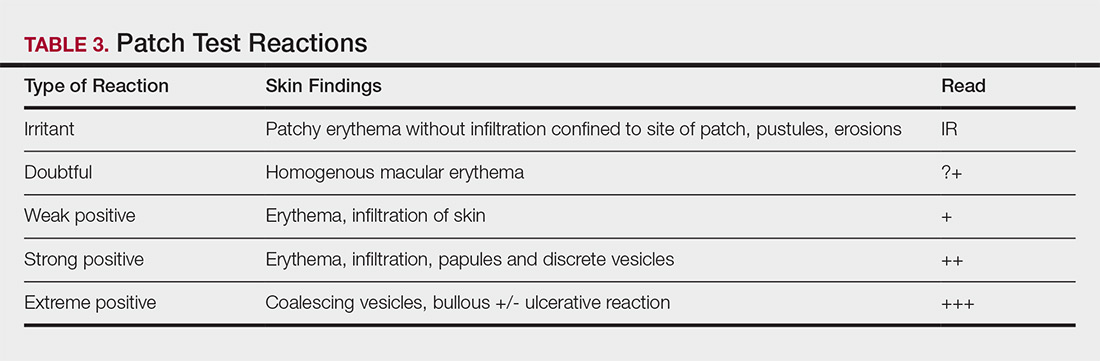

Allergens are placed on the back in chambers in a petrolatum or aqueous medium. The patches remain affixed for 48 hours, during which time the patient is asked to refrain from showering or exercising to prevent loss of patches. The patient's skin is then evaluated for reactions to allergens on 2 separate occasions: at the time of patch removal 48 hours after initial placement, then the areas of patches are marked for delayed readings at day 4 to day 7 after initial patch placement. Results are scored based on the degree of the inflammatory reaction (Table 3). Delayed readings beyond day 7 may be necessary for metals, specific preservatives (eg, dodecyl gallate, propolis), and neomycin.10

There is a wide spectrum of cutaneous disease that should prompt consideration of patch testing, including well-circumscribed eczematous dermatitis (eg, recurrent lip, hand, and foot dermatitis); patchy or diffuse eczema, especially if recently worsened and/or unresponsive to topical steroids; lichenoid eruptions, particularly of mucosal surfaces; mucous membrane eruptions (eg, stomatitis, vulvitis); and eczematous presentations that raise concern for airborne (photodistributed) or systemic contact dermatitis.11-13 Although further studies of efficacy and safety are ongoing, patch testing also may be useful in the diagnosis of nonimmediate cutaneous adverse drug reactions, especially fixed drug eruptions, acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, systemic contact dermatitis from medications, and drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome.3 Lastly, patients with type IV hypersensitivity to metals, adhesives, or antibiotics used in metallic orthopedic or cardiac implants may experience implant failure, regional contact dermatitis, or both, and benefit from patch testing prior to implant replacement to assess for potential allergens. Of the joints that fail, it is estimated that up to 5% are due to metal hypersensitivity.4

Throughout patch testing, patients may continue to manage their skin condition with oral antihistamines and topical steroids, though application to the site at which the patches are applied should be avoided throughout patch testing and during the week prior. According to expert consensus, immunosuppressive medications that are less likely to impact patch testing and therefore may be continued include low-dose methotrexate, oral prednisone less than 10 mg daily, biologic therapy, and low-dose cyclosporine (<2 mg/kg daily). Therapeutic interventions that are more likely to impact patch testing and should be avoided include phototherapy or extensive sun exposure within a week prior to testing, oral prednisone more than 10 mg daily, intramuscular triamcinolone within the preceding month, and high-dose cyclosporine (>2 mg/kg daily).14

An important component to successful patch testing is posttest patient counseling. Providers can create a safe list of products for patients by logging onto the American Contact Dermatitis Society website and accessing the Contact Allergen Management Program (CAMP).15 All relevant allergens found on patch testing may be selected and patient-specific identification codes generated. Once these codes are entered into the CAMP app on the patient's cellular device, a personalized, regularly updated list of safe products appears for many categories of products, including shampoos, sunscreens, moisturizers, cosmetic products, and laundry or dish detergents, among others. Of note, this app is not helpful for avoidance in patients with textile allergies. Patients should be counseled that improvement occurs with avoidance, which usually occurs within weeks but may slowly occur over time in some cases.

Lymphocyte Transformation Test (In Vitro)

The lymphocyte transformation test is an experimental in vitro test for type IV hypersensitivity. This serologic test utilizes allergens to stimulate memory T lymphocytes in vitro and measures the degree of response to the allergen. Although this test has generated excitement, particularly for the potential to safely evaluate for severe adverse cutaneous drug reactions, it currently is not the standard of care and is not utilized in the United States.16

Conclusion

Dermatologists play a vital role in the workup of suspected type IV hypersensitivities. Patch testing is an important but underutilized tool in the arsenal of allergy testing and may be indicated in a wide variety of cutaneous presentations, adverse reactions to medications, and implanted device failures. Identification and avoidance of a culprit allergen has the potential to lead to complete resolution of disease and notable improvement in quality of life for patients.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Nina Botto, MD (San Francisco, California), for her mentorship in the arena of ACD as well as the Women's Dermatologic Society for the support they provided through the mentorship program.

- Oettgen H, Broide DH. Introduction to the mechanisms of allergic disease. In: Holgate ST, Church MK, Broide DH, et al, eds. Allergy. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1-32.

- Werfel T, Kapp A. Atopic dermatitis and allergic contact dermatitis. In: Holgate ST, Church MK, Broide DH, et al, eds. Allergy. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:263-286.

- Zinn A, Gayam S, Chelliah MP, et al. Patch testing for nonimmediate cutaneous adverse drug reactions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:421-423.

- Thyssen JP, Menne T, Schalock PC, et al. Pragmatic approach to the clinical work-up of patients with putative allergic disease to metallic orthopaedic implants before and after surgery. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:473-478.

- Cox L. Overview of serological-specific IgE antibody testing in children. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2011;11:447-453.

- Dolen WK. Skin testing and immunoassays for allergen-specific IgE. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2001;21:229-239.

- Keeling BH, Gavino AC, Gavino AC. Skin biopsy, the allergists' tool: how to interpret a report. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2015;15:62.

- Rosa G, Fernandez AP, Vij A, et al. Langerhans cell collections, but not eosinophils, are clues to a diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis in appropriate skin biopsies. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:498-504.

- DeKoven JG, Warshaw EM, Belsito DV. North American Contact Dermatitis Group patch test results 2013-2014. Dermatitis. 2017;28:33-46.

- Davis MD, Bhate K, Rohlinger AL, et al. Delayed patch test reading after 5 days: the Mayo Clinic experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:225-233.

- Rajagopalan R, Anderson RT. The profile of a patient with contact dermatitis and a suspicion of contact allergy (history, physical characteristics, and dermatology-specific quality of life). Am J Contact Dermat. 1997;8:26-31.

- Huygens S, Goossens A. An update on airborne contact dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 2001;44:1-6.

- Salam TN, Fowler JF. Balsam-related systemic contact dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:377-381.

- Fowler JF, Maibach HI, Zirwas M, et al. Effects of immunomodulatory agents on patch testing: expert opinion 2012. Dermatitis. 2012;23:301-303.

- ACDS CAMP. American Contact Dermatitis Society website. https://www.contactderm.org/i4a/pages/index.cfm?pageid=3489. Accessed November 14, 2018.

- Popple A, Williams J, Maxwell G, et al. The lymphocyte transformation test in allergic contact dermatitis: new opportunities. J Immunotoxicol. 2016;13:84-91.

Allergy testing typically refers to evaluation of a patient for suspected type I or type IV hypersensitivity.1,2 The possibility of type I hypersensitivity is raised in patients presenting with food allergies, allergic rhinitis, asthma, and immediate adverse reactions to medications, whereas type IV hypersensitivity is suspected in patients with eczematous eruptions, delayed adverse cutaneous reactions to medications, and failure of metallic implants (eg, metal joint replacements, cardiac stents) in conjunction with overlying skin rashes (Table 1).1-5 Type II (eg, pemphigus vulgaris) and type III (eg, IgA vasculitis) hypersensitivities are not evaluated with screening allergy tests.

Type I Sensitization

Type I hypersensitivity is an immediate hypersensitivity mediated predominantly by IgE activation of mast cells in the skin as well as the respiratory and gastric mucosa.1 Sensitization of an individual patient occurs when antigen-presenting cells induce a helper T cell (TH2) cytokine response leading to B-cell class switching and allergen-specific IgE production. Upon repeat exposure to the allergen, circulating antibodies then bind to high-affinity receptors on mast cells and basophils and initiate an allergic inflammatory response, leading to a clinical presentation of allergic rhinitis, urticaria, or immediate drug reactions. Confirming type I sensitization may be performed via serologic (in vitro) or skin testing (in vivo).5,6

Serologic Testing (In Vitro)

Serologic testing is a blood test that detects circulating IgE levels against specific allergens.5 The first such test, the radioallergosorbent test, was introduced in the 1970s but is not quantitative and is no longer used. Although common, it is inaccurate to describe current serum IgE (s-IgE) testing as radioallergosorbent testing. There are several US Food and Drug Administration-approved s-IgE assays in common use, and these tests may be helpful in elucidating relevant allergens and for tailoring therapy appropriately, which may consist of avoidance of certain foods or environmental agents and/or allergen immunotherapy.

Skin Testing (In Vivo)

Skin testing can be performed percutaneously (eg, percutaneous skin testing) or intradermally (eg, intradermal testing).6 Percutaneous skin testing is performed by placing a drop of allergen extract on the skin, after which a lancet is used to lightly scratch the skin; intradermal testing is performed by injecting a small amount of allergen extract into the dermis. In both cases, the skin is evaluated after 15 to 20 minutes for the presence and size of a cutaneous wheal. Medications with antihistaminergic activity must be discontinued prior to testing. Both s-IgE and skin testing assess for type I hypersensitivity, and factors such as extensive rash, concern for anaphylaxis, or inability to discontinue antihistamines may favor s-IgE testing versus skin testing. False-positive results can occur with both tests, and for this reason, test results should always be interpreted in conjunction with clinical examination and patient history to determine relevant allergies.

Type IV Sensitization

Type IV hypersensitivity is a delayed hypersensitivity mediated primarily by lymphocytes.2 Sensitization occurs when haptens bind to host proteins and are presented by epidermal and dermal dendritic cells to T lymphocytes in the skin. These lymphocytes then migrate to regional lymph nodes where antigen-specific T lymphocytes are produced and home back to the skin. Upon reexposure to the allergen, these memory T lymphocytes become activated and incite a delayed allergic response. Confirming type IV hypersensitivity primarily is accomplished via patch testing, though other testing modalities exist.

Skin Biopsy

Biopsy is sometimes performed in the workup of an individual presenting with allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) and typically will show spongiosis with normal stratum corneum and epidermal thickness in the setting of acute ACD and mild to marked acanthosis and parakeratosis in chronic ACD.7 The findings, however, are nonspecific and the differential of these histopathologic findings encompasses nummular dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, irritant contact dermatitis, and dyshidrotic eczema, among others. The presence of eosinophils and Langerhans cell microabscesses may provide supportive evidence for ACD over the other spongiotic dermatitides.7,8

Patch Testing

Patch testing is the gold standard in diagnosing type IV hypersensitivities resulting in a clinical presentation of ACD. Hundreds of allergens are commercially available for patch testing, and more commonly tested allergens fall into one of several categories, such as cosmetic preservatives, rubbers, metals, textiles, fragrances, adhesives, antibiotics, plants, and even corticosteroids. Of note, a common misconception is that ACD must result from new exposures; however, patients may develop ACD secondary to an exposure or product they have been using for many years without a problem.

Three commonly used screening series are the thin-layer rapid use epicutaneous (T.R.U.E.) test (SmartPractice), North American Contact Dermatitis Group screening series, and American Contact Dermatitis Society Core 80 allergen series, which have some variation in the type and number of allergens included (Table 2). The T.R.U.E. test will miss a notable number of clinically relevant allergens in comparison to the North American Contact Dermatitis Group and American Contact Dermatitis Society Core series, and it may be of particularly low utility in identifying fragrance or preservative ACD.9

Allergens are placed on the back in chambers in a petrolatum or aqueous medium. The patches remain affixed for 48 hours, during which time the patient is asked to refrain from showering or exercising to prevent loss of patches. The patient's skin is then evaluated for reactions to allergens on 2 separate occasions: at the time of patch removal 48 hours after initial placement, then the areas of patches are marked for delayed readings at day 4 to day 7 after initial patch placement. Results are scored based on the degree of the inflammatory reaction (Table 3). Delayed readings beyond day 7 may be necessary for metals, specific preservatives (eg, dodecyl gallate, propolis), and neomycin.10

There is a wide spectrum of cutaneous disease that should prompt consideration of patch testing, including well-circumscribed eczematous dermatitis (eg, recurrent lip, hand, and foot dermatitis); patchy or diffuse eczema, especially if recently worsened and/or unresponsive to topical steroids; lichenoid eruptions, particularly of mucosal surfaces; mucous membrane eruptions (eg, stomatitis, vulvitis); and eczematous presentations that raise concern for airborne (photodistributed) or systemic contact dermatitis.11-13 Although further studies of efficacy and safety are ongoing, patch testing also may be useful in the diagnosis of nonimmediate cutaneous adverse drug reactions, especially fixed drug eruptions, acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, systemic contact dermatitis from medications, and drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome.3 Lastly, patients with type IV hypersensitivity to metals, adhesives, or antibiotics used in metallic orthopedic or cardiac implants may experience implant failure, regional contact dermatitis, or both, and benefit from patch testing prior to implant replacement to assess for potential allergens. Of the joints that fail, it is estimated that up to 5% are due to metal hypersensitivity.4

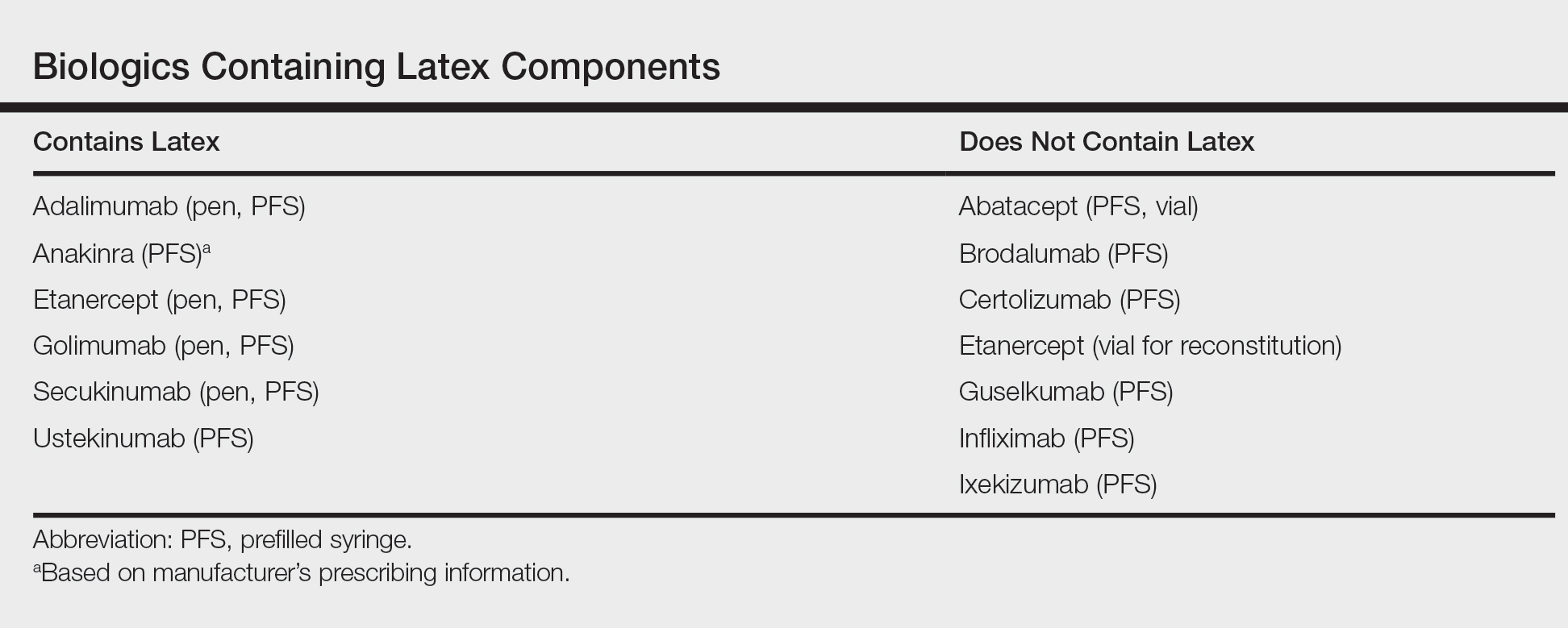

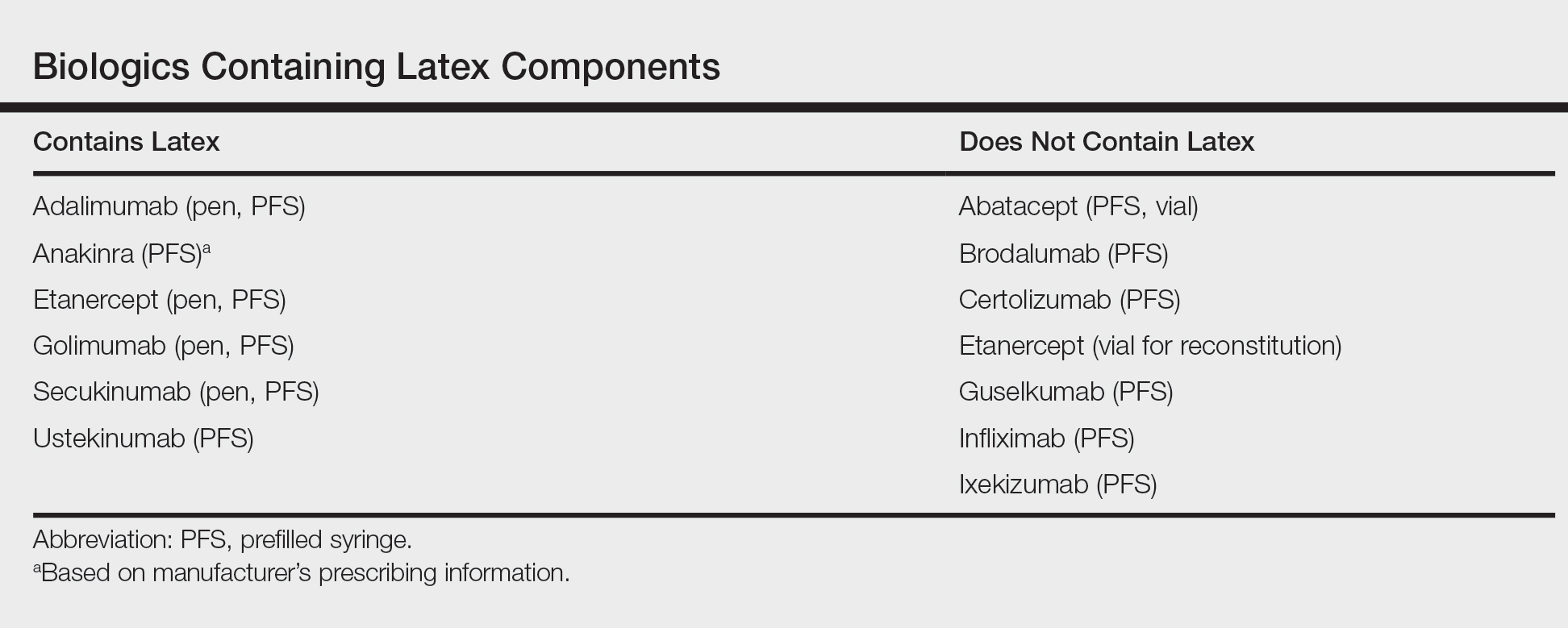

Throughout patch testing, patients may continue to manage their skin condition with oral antihistamines and topical steroids, though application to the site at which the patches are applied should be avoided throughout patch testing and during the week prior. According to expert consensus, immunosuppressive medications that are less likely to impact patch testing and therefore may be continued include low-dose methotrexate, oral prednisone less than 10 mg daily, biologic therapy, and low-dose cyclosporine (<2 mg/kg daily). Therapeutic interventions that are more likely to impact patch testing and should be avoided include phototherapy or extensive sun exposure within a week prior to testing, oral prednisone more than 10 mg daily, intramuscular triamcinolone within the preceding month, and high-dose cyclosporine (>2 mg/kg daily).14

An important component to successful patch testing is posttest patient counseling. Providers can create a safe list of products for patients by logging onto the American Contact Dermatitis Society website and accessing the Contact Allergen Management Program (CAMP).15 All relevant allergens found on patch testing may be selected and patient-specific identification codes generated. Once these codes are entered into the CAMP app on the patient's cellular device, a personalized, regularly updated list of safe products appears for many categories of products, including shampoos, sunscreens, moisturizers, cosmetic products, and laundry or dish detergents, among others. Of note, this app is not helpful for avoidance in patients with textile allergies. Patients should be counseled that improvement occurs with avoidance, which usually occurs within weeks but may slowly occur over time in some cases.

Lymphocyte Transformation Test (In Vitro)

The lymphocyte transformation test is an experimental in vitro test for type IV hypersensitivity. This serologic test utilizes allergens to stimulate memory T lymphocytes in vitro and measures the degree of response to the allergen. Although this test has generated excitement, particularly for the potential to safely evaluate for severe adverse cutaneous drug reactions, it currently is not the standard of care and is not utilized in the United States.16

Conclusion

Dermatologists play a vital role in the workup of suspected type IV hypersensitivities. Patch testing is an important but underutilized tool in the arsenal of allergy testing and may be indicated in a wide variety of cutaneous presentations, adverse reactions to medications, and implanted device failures. Identification and avoidance of a culprit allergen has the potential to lead to complete resolution of disease and notable improvement in quality of life for patients.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Nina Botto, MD (San Francisco, California), for her mentorship in the arena of ACD as well as the Women's Dermatologic Society for the support they provided through the mentorship program.

Allergy testing typically refers to evaluation of a patient for suspected type I or type IV hypersensitivity.1,2 The possibility of type I hypersensitivity is raised in patients presenting with food allergies, allergic rhinitis, asthma, and immediate adverse reactions to medications, whereas type IV hypersensitivity is suspected in patients with eczematous eruptions, delayed adverse cutaneous reactions to medications, and failure of metallic implants (eg, metal joint replacements, cardiac stents) in conjunction with overlying skin rashes (Table 1).1-5 Type II (eg, pemphigus vulgaris) and type III (eg, IgA vasculitis) hypersensitivities are not evaluated with screening allergy tests.

Type I Sensitization

Type I hypersensitivity is an immediate hypersensitivity mediated predominantly by IgE activation of mast cells in the skin as well as the respiratory and gastric mucosa.1 Sensitization of an individual patient occurs when antigen-presenting cells induce a helper T cell (TH2) cytokine response leading to B-cell class switching and allergen-specific IgE production. Upon repeat exposure to the allergen, circulating antibodies then bind to high-affinity receptors on mast cells and basophils and initiate an allergic inflammatory response, leading to a clinical presentation of allergic rhinitis, urticaria, or immediate drug reactions. Confirming type I sensitization may be performed via serologic (in vitro) or skin testing (in vivo).5,6

Serologic Testing (In Vitro)

Serologic testing is a blood test that detects circulating IgE levels against specific allergens.5 The first such test, the radioallergosorbent test, was introduced in the 1970s but is not quantitative and is no longer used. Although common, it is inaccurate to describe current serum IgE (s-IgE) testing as radioallergosorbent testing. There are several US Food and Drug Administration-approved s-IgE assays in common use, and these tests may be helpful in elucidating relevant allergens and for tailoring therapy appropriately, which may consist of avoidance of certain foods or environmental agents and/or allergen immunotherapy.

Skin Testing (In Vivo)

Skin testing can be performed percutaneously (eg, percutaneous skin testing) or intradermally (eg, intradermal testing).6 Percutaneous skin testing is performed by placing a drop of allergen extract on the skin, after which a lancet is used to lightly scratch the skin; intradermal testing is performed by injecting a small amount of allergen extract into the dermis. In both cases, the skin is evaluated after 15 to 20 minutes for the presence and size of a cutaneous wheal. Medications with antihistaminergic activity must be discontinued prior to testing. Both s-IgE and skin testing assess for type I hypersensitivity, and factors such as extensive rash, concern for anaphylaxis, or inability to discontinue antihistamines may favor s-IgE testing versus skin testing. False-positive results can occur with both tests, and for this reason, test results should always be interpreted in conjunction with clinical examination and patient history to determine relevant allergies.

Type IV Sensitization

Type IV hypersensitivity is a delayed hypersensitivity mediated primarily by lymphocytes.2 Sensitization occurs when haptens bind to host proteins and are presented by epidermal and dermal dendritic cells to T lymphocytes in the skin. These lymphocytes then migrate to regional lymph nodes where antigen-specific T lymphocytes are produced and home back to the skin. Upon reexposure to the allergen, these memory T lymphocytes become activated and incite a delayed allergic response. Confirming type IV hypersensitivity primarily is accomplished via patch testing, though other testing modalities exist.

Skin Biopsy

Biopsy is sometimes performed in the workup of an individual presenting with allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) and typically will show spongiosis with normal stratum corneum and epidermal thickness in the setting of acute ACD and mild to marked acanthosis and parakeratosis in chronic ACD.7 The findings, however, are nonspecific and the differential of these histopathologic findings encompasses nummular dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, irritant contact dermatitis, and dyshidrotic eczema, among others. The presence of eosinophils and Langerhans cell microabscesses may provide supportive evidence for ACD over the other spongiotic dermatitides.7,8

Patch Testing

Patch testing is the gold standard in diagnosing type IV hypersensitivities resulting in a clinical presentation of ACD. Hundreds of allergens are commercially available for patch testing, and more commonly tested allergens fall into one of several categories, such as cosmetic preservatives, rubbers, metals, textiles, fragrances, adhesives, antibiotics, plants, and even corticosteroids. Of note, a common misconception is that ACD must result from new exposures; however, patients may develop ACD secondary to an exposure or product they have been using for many years without a problem.

Three commonly used screening series are the thin-layer rapid use epicutaneous (T.R.U.E.) test (SmartPractice), North American Contact Dermatitis Group screening series, and American Contact Dermatitis Society Core 80 allergen series, which have some variation in the type and number of allergens included (Table 2). The T.R.U.E. test will miss a notable number of clinically relevant allergens in comparison to the North American Contact Dermatitis Group and American Contact Dermatitis Society Core series, and it may be of particularly low utility in identifying fragrance or preservative ACD.9

Allergens are placed on the back in chambers in a petrolatum or aqueous medium. The patches remain affixed for 48 hours, during which time the patient is asked to refrain from showering or exercising to prevent loss of patches. The patient's skin is then evaluated for reactions to allergens on 2 separate occasions: at the time of patch removal 48 hours after initial placement, then the areas of patches are marked for delayed readings at day 4 to day 7 after initial patch placement. Results are scored based on the degree of the inflammatory reaction (Table 3). Delayed readings beyond day 7 may be necessary for metals, specific preservatives (eg, dodecyl gallate, propolis), and neomycin.10

There is a wide spectrum of cutaneous disease that should prompt consideration of patch testing, including well-circumscribed eczematous dermatitis (eg, recurrent lip, hand, and foot dermatitis); patchy or diffuse eczema, especially if recently worsened and/or unresponsive to topical steroids; lichenoid eruptions, particularly of mucosal surfaces; mucous membrane eruptions (eg, stomatitis, vulvitis); and eczematous presentations that raise concern for airborne (photodistributed) or systemic contact dermatitis.11-13 Although further studies of efficacy and safety are ongoing, patch testing also may be useful in the diagnosis of nonimmediate cutaneous adverse drug reactions, especially fixed drug eruptions, acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, systemic contact dermatitis from medications, and drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome.3 Lastly, patients with type IV hypersensitivity to metals, adhesives, or antibiotics used in metallic orthopedic or cardiac implants may experience implant failure, regional contact dermatitis, or both, and benefit from patch testing prior to implant replacement to assess for potential allergens. Of the joints that fail, it is estimated that up to 5% are due to metal hypersensitivity.4

Throughout patch testing, patients may continue to manage their skin condition with oral antihistamines and topical steroids, though application to the site at which the patches are applied should be avoided throughout patch testing and during the week prior. According to expert consensus, immunosuppressive medications that are less likely to impact patch testing and therefore may be continued include low-dose methotrexate, oral prednisone less than 10 mg daily, biologic therapy, and low-dose cyclosporine (<2 mg/kg daily). Therapeutic interventions that are more likely to impact patch testing and should be avoided include phototherapy or extensive sun exposure within a week prior to testing, oral prednisone more than 10 mg daily, intramuscular triamcinolone within the preceding month, and high-dose cyclosporine (>2 mg/kg daily).14

An important component to successful patch testing is posttest patient counseling. Providers can create a safe list of products for patients by logging onto the American Contact Dermatitis Society website and accessing the Contact Allergen Management Program (CAMP).15 All relevant allergens found on patch testing may be selected and patient-specific identification codes generated. Once these codes are entered into the CAMP app on the patient's cellular device, a personalized, regularly updated list of safe products appears for many categories of products, including shampoos, sunscreens, moisturizers, cosmetic products, and laundry or dish detergents, among others. Of note, this app is not helpful for avoidance in patients with textile allergies. Patients should be counseled that improvement occurs with avoidance, which usually occurs within weeks but may slowly occur over time in some cases.

Lymphocyte Transformation Test (In Vitro)

The lymphocyte transformation test is an experimental in vitro test for type IV hypersensitivity. This serologic test utilizes allergens to stimulate memory T lymphocytes in vitro and measures the degree of response to the allergen. Although this test has generated excitement, particularly for the potential to safely evaluate for severe adverse cutaneous drug reactions, it currently is not the standard of care and is not utilized in the United States.16

Conclusion

Dermatologists play a vital role in the workup of suspected type IV hypersensitivities. Patch testing is an important but underutilized tool in the arsenal of allergy testing and may be indicated in a wide variety of cutaneous presentations, adverse reactions to medications, and implanted device failures. Identification and avoidance of a culprit allergen has the potential to lead to complete resolution of disease and notable improvement in quality of life for patients.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Nina Botto, MD (San Francisco, California), for her mentorship in the arena of ACD as well as the Women's Dermatologic Society for the support they provided through the mentorship program.

- Oettgen H, Broide DH. Introduction to the mechanisms of allergic disease. In: Holgate ST, Church MK, Broide DH, et al, eds. Allergy. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1-32.

- Werfel T, Kapp A. Atopic dermatitis and allergic contact dermatitis. In: Holgate ST, Church MK, Broide DH, et al, eds. Allergy. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:263-286.

- Zinn A, Gayam S, Chelliah MP, et al. Patch testing for nonimmediate cutaneous adverse drug reactions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:421-423.

- Thyssen JP, Menne T, Schalock PC, et al. Pragmatic approach to the clinical work-up of patients with putative allergic disease to metallic orthopaedic implants before and after surgery. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:473-478.

- Cox L. Overview of serological-specific IgE antibody testing in children. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2011;11:447-453.

- Dolen WK. Skin testing and immunoassays for allergen-specific IgE. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2001;21:229-239.

- Keeling BH, Gavino AC, Gavino AC. Skin biopsy, the allergists' tool: how to interpret a report. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2015;15:62.

- Rosa G, Fernandez AP, Vij A, et al. Langerhans cell collections, but not eosinophils, are clues to a diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis in appropriate skin biopsies. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:498-504.

- DeKoven JG, Warshaw EM, Belsito DV. North American Contact Dermatitis Group patch test results 2013-2014. Dermatitis. 2017;28:33-46.

- Davis MD, Bhate K, Rohlinger AL, et al. Delayed patch test reading after 5 days: the Mayo Clinic experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:225-233.

- Rajagopalan R, Anderson RT. The profile of a patient with contact dermatitis and a suspicion of contact allergy (history, physical characteristics, and dermatology-specific quality of life). Am J Contact Dermat. 1997;8:26-31.

- Huygens S, Goossens A. An update on airborne contact dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 2001;44:1-6.

- Salam TN, Fowler JF. Balsam-related systemic contact dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:377-381.

- Fowler JF, Maibach HI, Zirwas M, et al. Effects of immunomodulatory agents on patch testing: expert opinion 2012. Dermatitis. 2012;23:301-303.

- ACDS CAMP. American Contact Dermatitis Society website. https://www.contactderm.org/i4a/pages/index.cfm?pageid=3489. Accessed November 14, 2018.

- Popple A, Williams J, Maxwell G, et al. The lymphocyte transformation test in allergic contact dermatitis: new opportunities. J Immunotoxicol. 2016;13:84-91.

- Oettgen H, Broide DH. Introduction to the mechanisms of allergic disease. In: Holgate ST, Church MK, Broide DH, et al, eds. Allergy. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1-32.

- Werfel T, Kapp A. Atopic dermatitis and allergic contact dermatitis. In: Holgate ST, Church MK, Broide DH, et al, eds. Allergy. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:263-286.

- Zinn A, Gayam S, Chelliah MP, et al. Patch testing for nonimmediate cutaneous adverse drug reactions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:421-423.

- Thyssen JP, Menne T, Schalock PC, et al. Pragmatic approach to the clinical work-up of patients with putative allergic disease to metallic orthopaedic implants before and after surgery. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:473-478.

- Cox L. Overview of serological-specific IgE antibody testing in children. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2011;11:447-453.

- Dolen WK. Skin testing and immunoassays for allergen-specific IgE. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2001;21:229-239.

- Keeling BH, Gavino AC, Gavino AC. Skin biopsy, the allergists' tool: how to interpret a report. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2015;15:62.

- Rosa G, Fernandez AP, Vij A, et al. Langerhans cell collections, but not eosinophils, are clues to a diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis in appropriate skin biopsies. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:498-504.

- DeKoven JG, Warshaw EM, Belsito DV. North American Contact Dermatitis Group patch test results 2013-2014. Dermatitis. 2017;28:33-46.

- Davis MD, Bhate K, Rohlinger AL, et al. Delayed patch test reading after 5 days: the Mayo Clinic experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:225-233.

- Rajagopalan R, Anderson RT. The profile of a patient with contact dermatitis and a suspicion of contact allergy (history, physical characteristics, and dermatology-specific quality of life). Am J Contact Dermat. 1997;8:26-31.

- Huygens S, Goossens A. An update on airborne contact dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 2001;44:1-6.

- Salam TN, Fowler JF. Balsam-related systemic contact dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:377-381.

- Fowler JF, Maibach HI, Zirwas M, et al. Effects of immunomodulatory agents on patch testing: expert opinion 2012. Dermatitis. 2012;23:301-303.

- ACDS CAMP. American Contact Dermatitis Society website. https://www.contactderm.org/i4a/pages/index.cfm?pageid=3489. Accessed November 14, 2018.

- Popple A, Williams J, Maxwell G, et al. The lymphocyte transformation test in allergic contact dermatitis: new opportunities. J Immunotoxicol. 2016;13:84-91.

Lesions With a Distinct Black Pigment

The Diagnosis: Black-Spot Poison Ivy

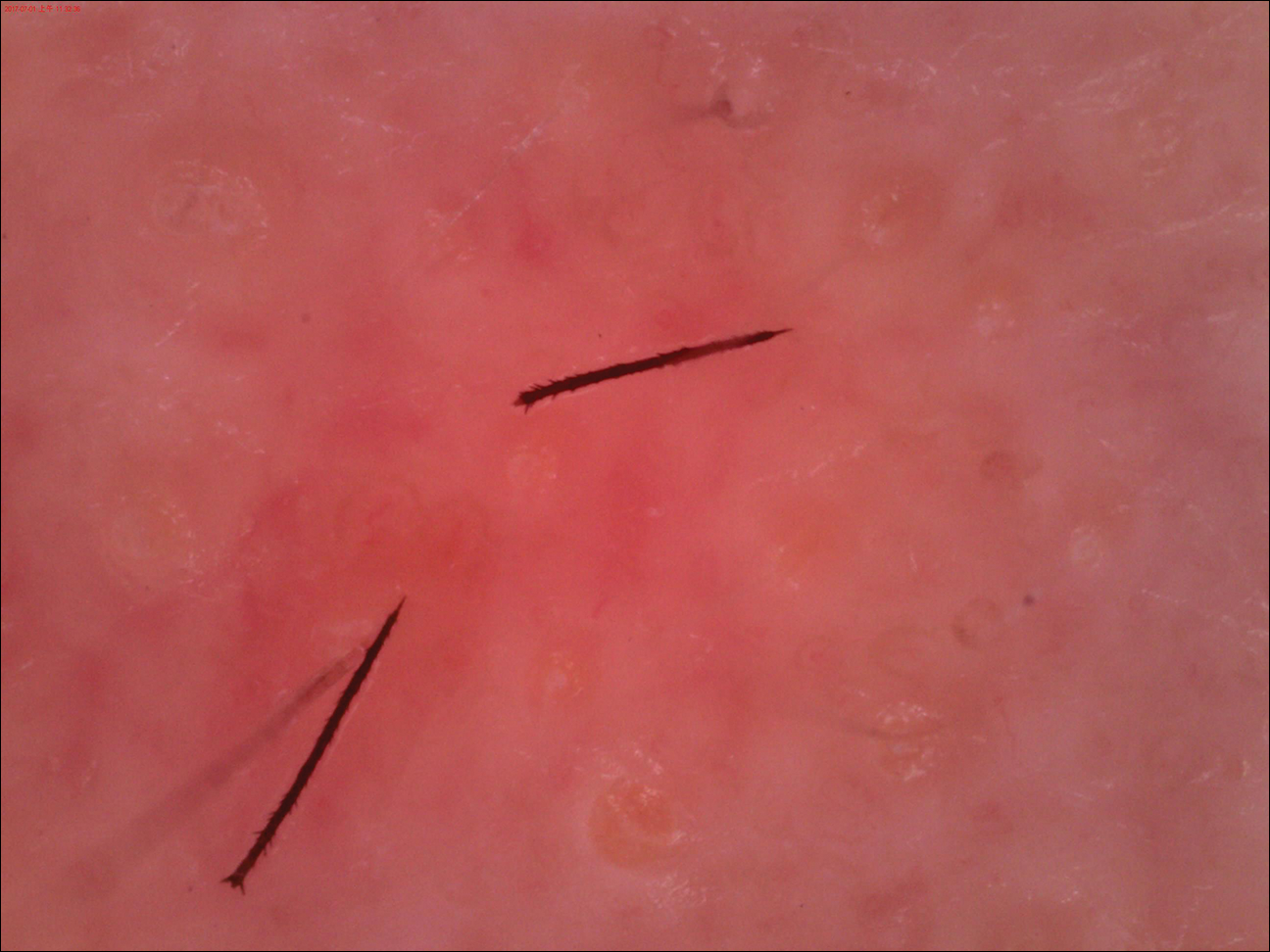

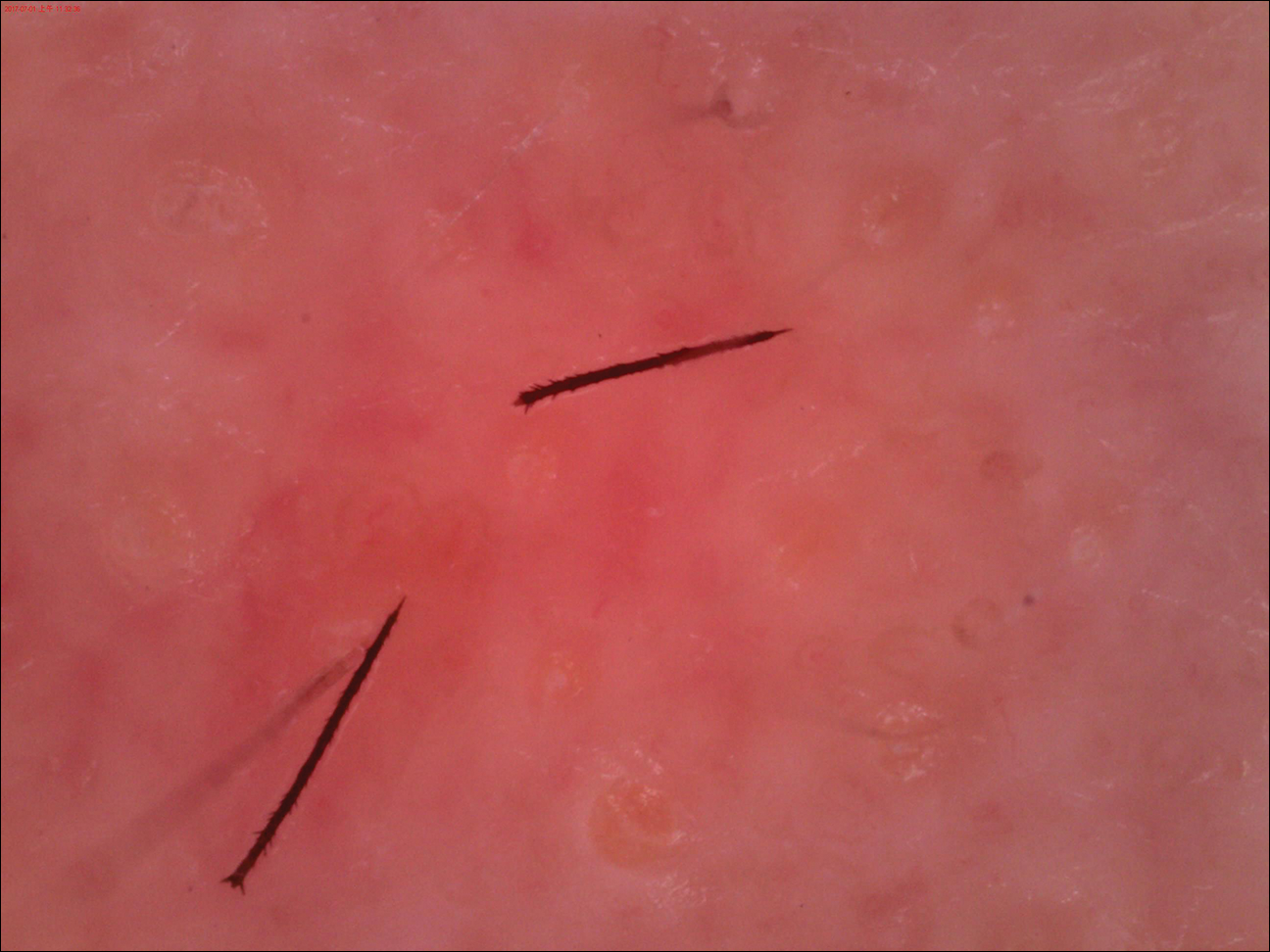

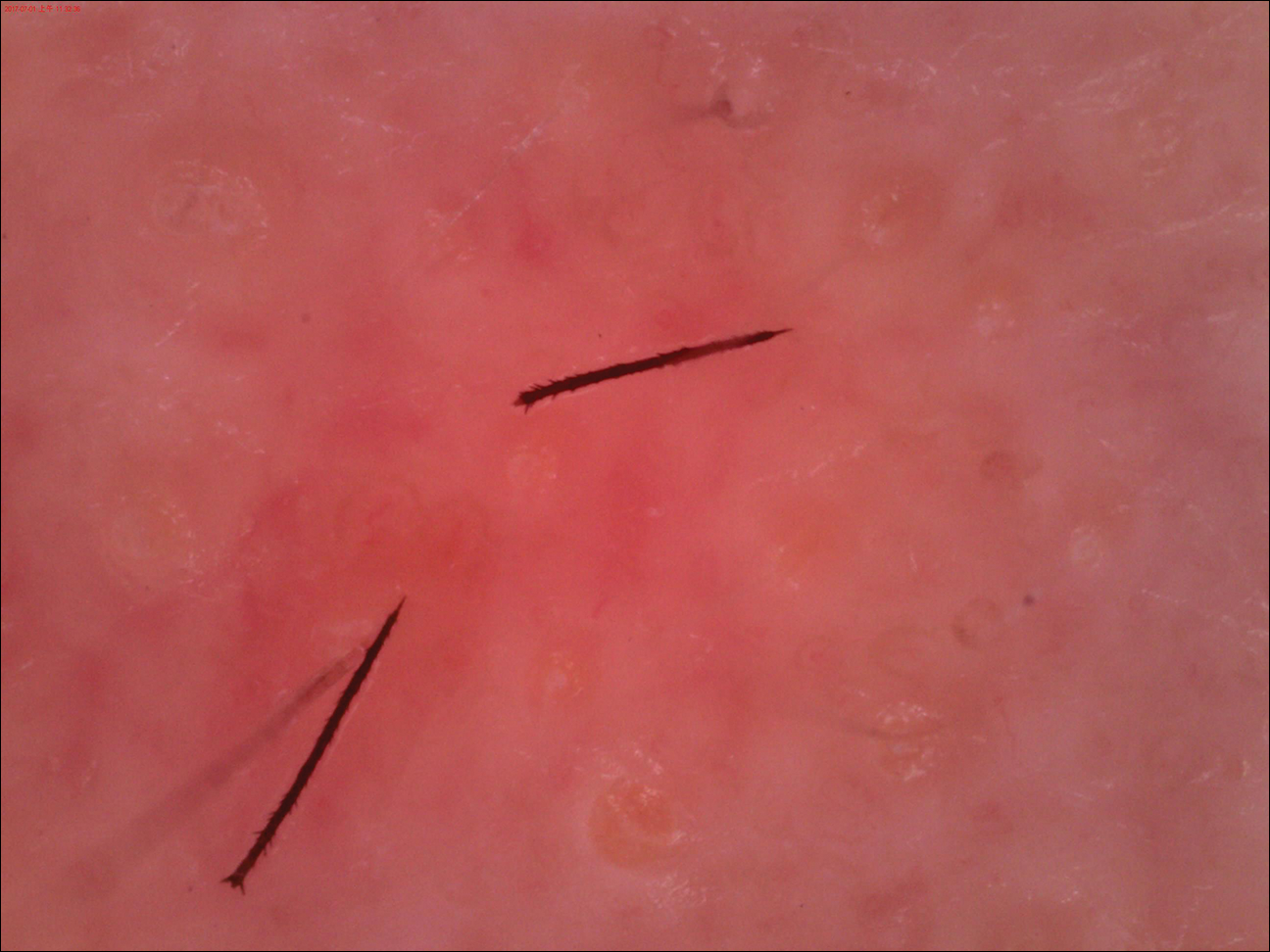

Due to the detailed account of the patient's history including acuity of current presentation, history of recent activities, travel history, and recent exposures, as well as a thorough skin examination, a diagnosis of black-spot poison ivy was made. In this case, the linear distribution of the lesions with overlying black pigment that could not be removed (Figures 1 and 2) provided important clues to diagnosis.

Poison ivy is an allergic contact dermatitis that affects an estimated 25 to 40 million Americans annually who are exposed to its resin. Poison ivy is a plant from the Toxicodendron genus, and an estimated 85% of the North American population report sensitivity to these plants, of which poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans) is the most common.1 Other related plants include poison sumac and poison oak. Poison ivy and other Toxicodendron plants produce urushiol, the oleoresin responsible for one of the most common allergic contact dermatitides in the United States.2 Black-spot poison ivy is an uncommon presentation following exposure to urushiol or oleoresin,3 as sufficient concentration of urushiol on the skin rarely is achieved.3,4 This plant's resin oxidizes and turns coal black when exposed to air.5 Contact with enough of this oleoresin will produce black-spot poison ivy.6 Patients with sufficient concentrations of oleoresin on their skin to cause this black oxidation usually have similar black spots on their clothing.7 Interestingly, some Toxicodendron species, such as the Japanese lacquer tree, Toxicodendron vernicifluum, have a black lacquer sap that was historically used as ink.8 This ink was used on Chinese and Japanese jars and has caused contact dermatitis hundreds of years after they were created.7

Poison ivy is characterized by a generalized, pruritic, erythematous rash with vesicles and papules in a linear distribution.9 Black-spot poison ivy presents the same with the addition of black lacquer-like macules with surrounding erythema.10 The skin lesions usually appear on exposed areas 24 to 48 hours after contact.11 Histology of black-spot poison ivy lesions should reveal yellow material in the stratum corneum with epidermal necrosis, in addition to classic features of acute allergic contact dermatitis.3 Interestingly, because these lesions occur with the first exposure to poison ivy, a patient may not develop the typical itchy eczematous eruption characteristic of poison ivy dermatitis. Differential diagnosis includes superficial purpura; exogenous pigment such as marker, ink, or tattoo pigment; tinea nigra; purpuric allergic contact dermatitis to resins or dyes; arthropod assault; irritant contact dermatitis; and infectious and noninfectious vasculitis.11

Similar to poison ivy, treatment of black-spot poison ivy involves oral and topical steroids combined with antihistamines if the patient continues to experience pruritus.6,12 It was recommended to our patient to apply cool compresses with water or Burow solution to alleviate itching and promote drying of the lesions. Calamine lotion can provide similar outcomes.13 Once the oleoresin is oxidized and bound to skin, the black spots cannot be removed with soap, water, or alcohol. The black spots gradually desquamate 1 to 2 weeks after formation without scarring,11 and patients do not require further monitoring.1 Patients should clean or discard clothing and evaluate for possible sources of poison ivy exposure. Because this type of poison ivy dermatitis is rare, most health care workers likely have never seen black-spot poison ivy, and it is an important diagnosis to consider.13

- Baer RL. Poison ivy dermatitis. Cutis. 1990;46:34-36.

- Usatine RP, Riojas M. Diagnosis and management of contact dermatitis. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82:249-255.

- Hurwitz RM, Rivera HP, Guin JD. Black-spot poison ivy dermatitis. an acute irritant contact dermatitis superimposed upon an allergic contact dermatitis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1984;6:319-322.

- Kurlan JG, Lucky AW. Black spot poison ivy: a report of 5 cases and a review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:246-249.

- Guin JD. The black spot test for recognizing poison ivy and related species. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;2:332-333.

- Mallory SB, Hurwitz RM. Black-spot poison-ivy dermatitis. Clin Dermatol. 1986;4:149-151.

- Mallory SB, Miller OF, Tyler WB. Toxicodendron radicans dermatitis with black lacquer deposit on the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1982;6:363-368.

- Rietschel R, Fowler J. Toxicodendron plants and species. Fisher's Contact Dermatitis. 4th ed. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1995:469-472.

- Fisher AA. Poison ivy/oak dermatitis. part I: prevention--soap and water, topical barriers, hyposensitization. Cutis. 1996;57:384-386.

- McClanahan C, Asarch A, Swick BL. Black spot poison ivy. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:752-753.

- Mu EW, Capell BC, Castelo-Soccio L. Black spots on a toddler's skin. Contemp Pediatr. 2013;30:31-32.

- Schram SE, Willey A, Lee PK, et al. Black-spot poison ivy. Dermatitis. 2008;19:48-51.

- Paniagua CT, Bean AS. Black-spot poison ivy: a rare phenomenon. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2011;23:275-277.

The Diagnosis: Black-Spot Poison Ivy

Due to the detailed account of the patient's history including acuity of current presentation, history of recent activities, travel history, and recent exposures, as well as a thorough skin examination, a diagnosis of black-spot poison ivy was made. In this case, the linear distribution of the lesions with overlying black pigment that could not be removed (Figures 1 and 2) provided important clues to diagnosis.

Poison ivy is an allergic contact dermatitis that affects an estimated 25 to 40 million Americans annually who are exposed to its resin. Poison ivy is a plant from the Toxicodendron genus, and an estimated 85% of the North American population report sensitivity to these plants, of which poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans) is the most common.1 Other related plants include poison sumac and poison oak. Poison ivy and other Toxicodendron plants produce urushiol, the oleoresin responsible for one of the most common allergic contact dermatitides in the United States.2 Black-spot poison ivy is an uncommon presentation following exposure to urushiol or oleoresin,3 as sufficient concentration of urushiol on the skin rarely is achieved.3,4 This plant's resin oxidizes and turns coal black when exposed to air.5 Contact with enough of this oleoresin will produce black-spot poison ivy.6 Patients with sufficient concentrations of oleoresin on their skin to cause this black oxidation usually have similar black spots on their clothing.7 Interestingly, some Toxicodendron species, such as the Japanese lacquer tree, Toxicodendron vernicifluum, have a black lacquer sap that was historically used as ink.8 This ink was used on Chinese and Japanese jars and has caused contact dermatitis hundreds of years after they were created.7

Poison ivy is characterized by a generalized, pruritic, erythematous rash with vesicles and papules in a linear distribution.9 Black-spot poison ivy presents the same with the addition of black lacquer-like macules with surrounding erythema.10 The skin lesions usually appear on exposed areas 24 to 48 hours after contact.11 Histology of black-spot poison ivy lesions should reveal yellow material in the stratum corneum with epidermal necrosis, in addition to classic features of acute allergic contact dermatitis.3 Interestingly, because these lesions occur with the first exposure to poison ivy, a patient may not develop the typical itchy eczematous eruption characteristic of poison ivy dermatitis. Differential diagnosis includes superficial purpura; exogenous pigment such as marker, ink, or tattoo pigment; tinea nigra; purpuric allergic contact dermatitis to resins or dyes; arthropod assault; irritant contact dermatitis; and infectious and noninfectious vasculitis.11

Similar to poison ivy, treatment of black-spot poison ivy involves oral and topical steroids combined with antihistamines if the patient continues to experience pruritus.6,12 It was recommended to our patient to apply cool compresses with water or Burow solution to alleviate itching and promote drying of the lesions. Calamine lotion can provide similar outcomes.13 Once the oleoresin is oxidized and bound to skin, the black spots cannot be removed with soap, water, or alcohol. The black spots gradually desquamate 1 to 2 weeks after formation without scarring,11 and patients do not require further monitoring.1 Patients should clean or discard clothing and evaluate for possible sources of poison ivy exposure. Because this type of poison ivy dermatitis is rare, most health care workers likely have never seen black-spot poison ivy, and it is an important diagnosis to consider.13

The Diagnosis: Black-Spot Poison Ivy

Due to the detailed account of the patient's history including acuity of current presentation, history of recent activities, travel history, and recent exposures, as well as a thorough skin examination, a diagnosis of black-spot poison ivy was made. In this case, the linear distribution of the lesions with overlying black pigment that could not be removed (Figures 1 and 2) provided important clues to diagnosis.

Poison ivy is an allergic contact dermatitis that affects an estimated 25 to 40 million Americans annually who are exposed to its resin. Poison ivy is a plant from the Toxicodendron genus, and an estimated 85% of the North American population report sensitivity to these plants, of which poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans) is the most common.1 Other related plants include poison sumac and poison oak. Poison ivy and other Toxicodendron plants produce urushiol, the oleoresin responsible for one of the most common allergic contact dermatitides in the United States.2 Black-spot poison ivy is an uncommon presentation following exposure to urushiol or oleoresin,3 as sufficient concentration of urushiol on the skin rarely is achieved.3,4 This plant's resin oxidizes and turns coal black when exposed to air.5 Contact with enough of this oleoresin will produce black-spot poison ivy.6 Patients with sufficient concentrations of oleoresin on their skin to cause this black oxidation usually have similar black spots on their clothing.7 Interestingly, some Toxicodendron species, such as the Japanese lacquer tree, Toxicodendron vernicifluum, have a black lacquer sap that was historically used as ink.8 This ink was used on Chinese and Japanese jars and has caused contact dermatitis hundreds of years after they were created.7

Poison ivy is characterized by a generalized, pruritic, erythematous rash with vesicles and papules in a linear distribution.9 Black-spot poison ivy presents the same with the addition of black lacquer-like macules with surrounding erythema.10 The skin lesions usually appear on exposed areas 24 to 48 hours after contact.11 Histology of black-spot poison ivy lesions should reveal yellow material in the stratum corneum with epidermal necrosis, in addition to classic features of acute allergic contact dermatitis.3 Interestingly, because these lesions occur with the first exposure to poison ivy, a patient may not develop the typical itchy eczematous eruption characteristic of poison ivy dermatitis. Differential diagnosis includes superficial purpura; exogenous pigment such as marker, ink, or tattoo pigment; tinea nigra; purpuric allergic contact dermatitis to resins or dyes; arthropod assault; irritant contact dermatitis; and infectious and noninfectious vasculitis.11

Similar to poison ivy, treatment of black-spot poison ivy involves oral and topical steroids combined with antihistamines if the patient continues to experience pruritus.6,12 It was recommended to our patient to apply cool compresses with water or Burow solution to alleviate itching and promote drying of the lesions. Calamine lotion can provide similar outcomes.13 Once the oleoresin is oxidized and bound to skin, the black spots cannot be removed with soap, water, or alcohol. The black spots gradually desquamate 1 to 2 weeks after formation without scarring,11 and patients do not require further monitoring.1 Patients should clean or discard clothing and evaluate for possible sources of poison ivy exposure. Because this type of poison ivy dermatitis is rare, most health care workers likely have never seen black-spot poison ivy, and it is an important diagnosis to consider.13

- Baer RL. Poison ivy dermatitis. Cutis. 1990;46:34-36.

- Usatine RP, Riojas M. Diagnosis and management of contact dermatitis. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82:249-255.

- Hurwitz RM, Rivera HP, Guin JD. Black-spot poison ivy dermatitis. an acute irritant contact dermatitis superimposed upon an allergic contact dermatitis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1984;6:319-322.

- Kurlan JG, Lucky AW. Black spot poison ivy: a report of 5 cases and a review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:246-249.

- Guin JD. The black spot test for recognizing poison ivy and related species. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;2:332-333.

- Mallory SB, Hurwitz RM. Black-spot poison-ivy dermatitis. Clin Dermatol. 1986;4:149-151.

- Mallory SB, Miller OF, Tyler WB. Toxicodendron radicans dermatitis with black lacquer deposit on the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1982;6:363-368.

- Rietschel R, Fowler J. Toxicodendron plants and species. Fisher's Contact Dermatitis. 4th ed. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1995:469-472.

- Fisher AA. Poison ivy/oak dermatitis. part I: prevention--soap and water, topical barriers, hyposensitization. Cutis. 1996;57:384-386.

- McClanahan C, Asarch A, Swick BL. Black spot poison ivy. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:752-753.

- Mu EW, Capell BC, Castelo-Soccio L. Black spots on a toddler's skin. Contemp Pediatr. 2013;30:31-32.

- Schram SE, Willey A, Lee PK, et al. Black-spot poison ivy. Dermatitis. 2008;19:48-51.

- Paniagua CT, Bean AS. Black-spot poison ivy: a rare phenomenon. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2011;23:275-277.

- Baer RL. Poison ivy dermatitis. Cutis. 1990;46:34-36.

- Usatine RP, Riojas M. Diagnosis and management of contact dermatitis. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82:249-255.

- Hurwitz RM, Rivera HP, Guin JD. Black-spot poison ivy dermatitis. an acute irritant contact dermatitis superimposed upon an allergic contact dermatitis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1984;6:319-322.

- Kurlan JG, Lucky AW. Black spot poison ivy: a report of 5 cases and a review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:246-249.

- Guin JD. The black spot test for recognizing poison ivy and related species. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;2:332-333.

- Mallory SB, Hurwitz RM. Black-spot poison-ivy dermatitis. Clin Dermatol. 1986;4:149-151.

- Mallory SB, Miller OF, Tyler WB. Toxicodendron radicans dermatitis with black lacquer deposit on the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1982;6:363-368.

- Rietschel R, Fowler J. Toxicodendron plants and species. Fisher's Contact Dermatitis. 4th ed. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1995:469-472.

- Fisher AA. Poison ivy/oak dermatitis. part I: prevention--soap and water, topical barriers, hyposensitization. Cutis. 1996;57:384-386.

- McClanahan C, Asarch A, Swick BL. Black spot poison ivy. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:752-753.

- Mu EW, Capell BC, Castelo-Soccio L. Black spots on a toddler's skin. Contemp Pediatr. 2013;30:31-32.

- Schram SE, Willey A, Lee PK, et al. Black-spot poison ivy. Dermatitis. 2008;19:48-51.

- Paniagua CT, Bean AS. Black-spot poison ivy: a rare phenomenon. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2011;23:275-277.

A 17-year-old adolescent boy presented to urgent care with a pruritic eruption on the bilateral arms of 1 day's duration. He was camping in the woods the night prior to presentation. On physical examination linear, erythematous, edematous plaques were observed bilaterally with overlying brown and black pigment on the arms. The pigment could not be removed with alcohol or vigorous scrubbing. The patient's condition improved with prednisone.

DRESS Syndrome: Clinical Myths and Pearls

Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS syndrome), also known as drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome, is an uncommon severe systemic hypersensitivity drug reaction. It is estimated to occur in 1 in every 1000 to 10,000 drug exposures.1 It can affect patients of all ages and typically presents 2 to 6 weeks after exposure to a culprit medication. Classically, DRESS syndrome presents with often widespread rash, facial edema, systemic symptoms such as fever, lymphadenopathy, and evidence of visceral organ involvement. Peripheral blood eosinophilia is frequently but not universally observed.1,2

Even with proper management, reported DRESS syndrome mortality rates worldwide are approximately 10%2 or higher depending on the degree and type of other organ involvement (eg, cardiac).3 Beyond the acute manifestations of DRESS syndrome, this condition is unique in that some patients develop late-onset sequelae such as myocarditis or autoimmune conditions even years after the initial cutaneous eruption.4 Therefore, longitudinal evaluation is a key component of management.

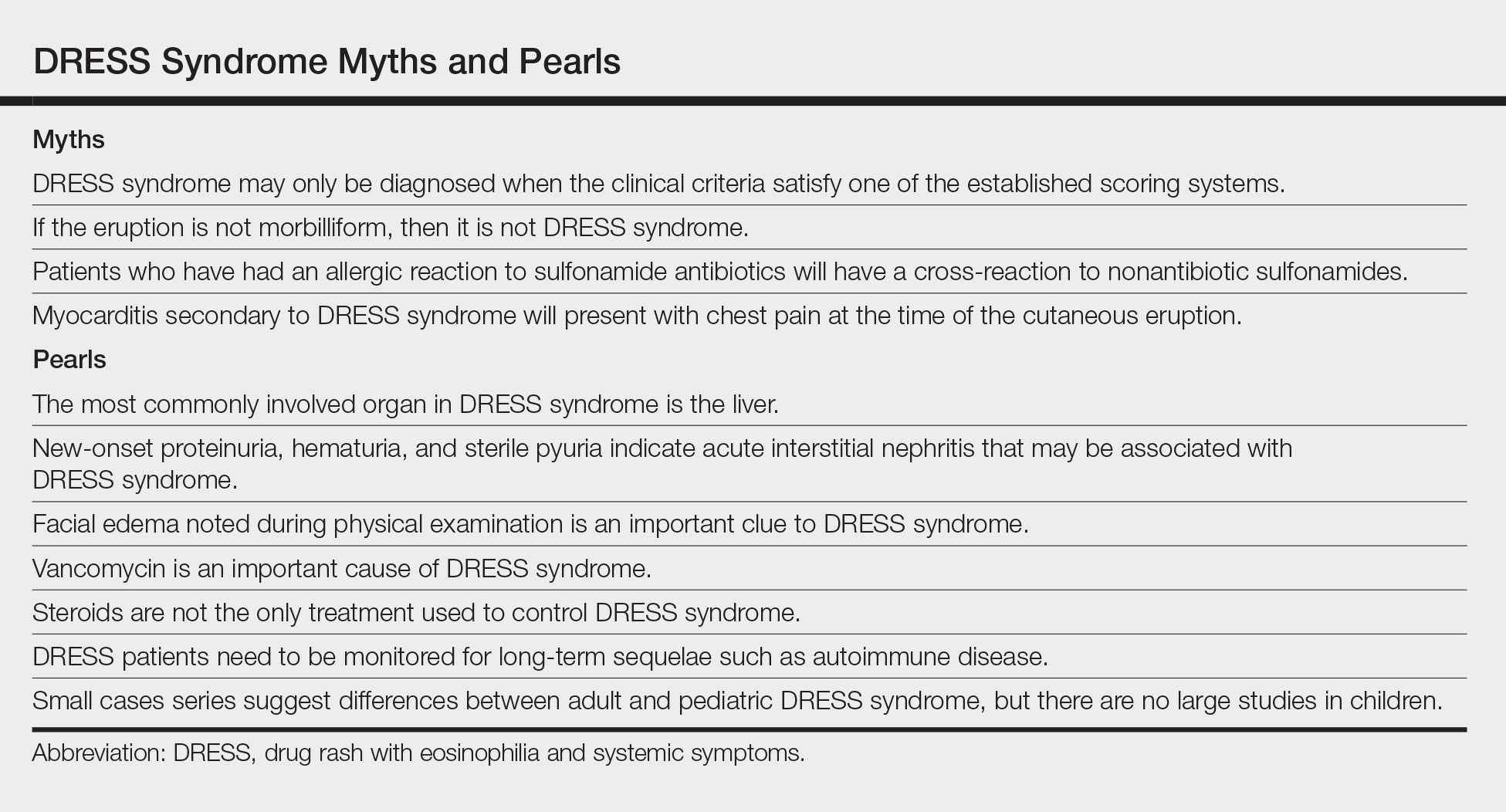

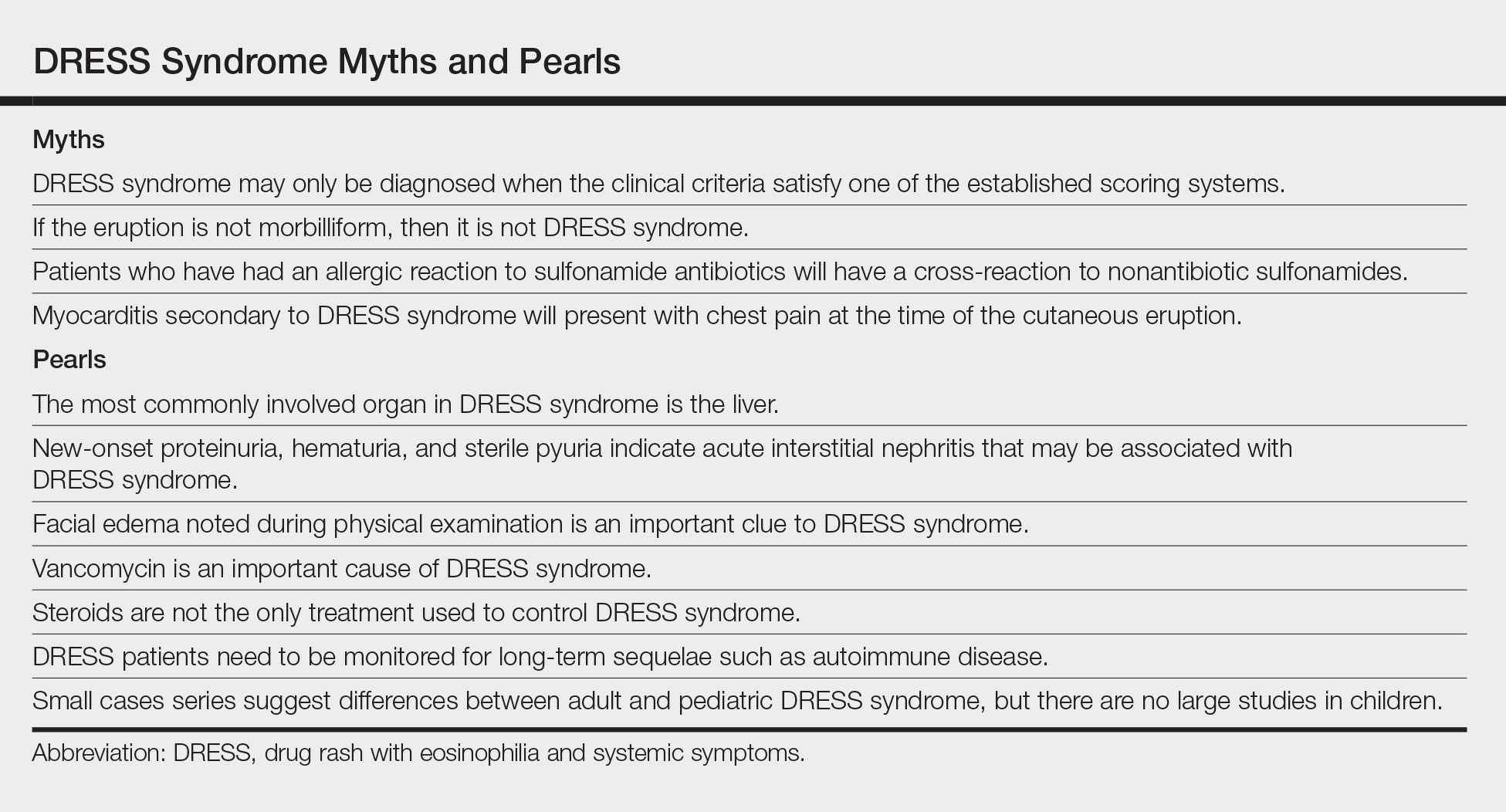

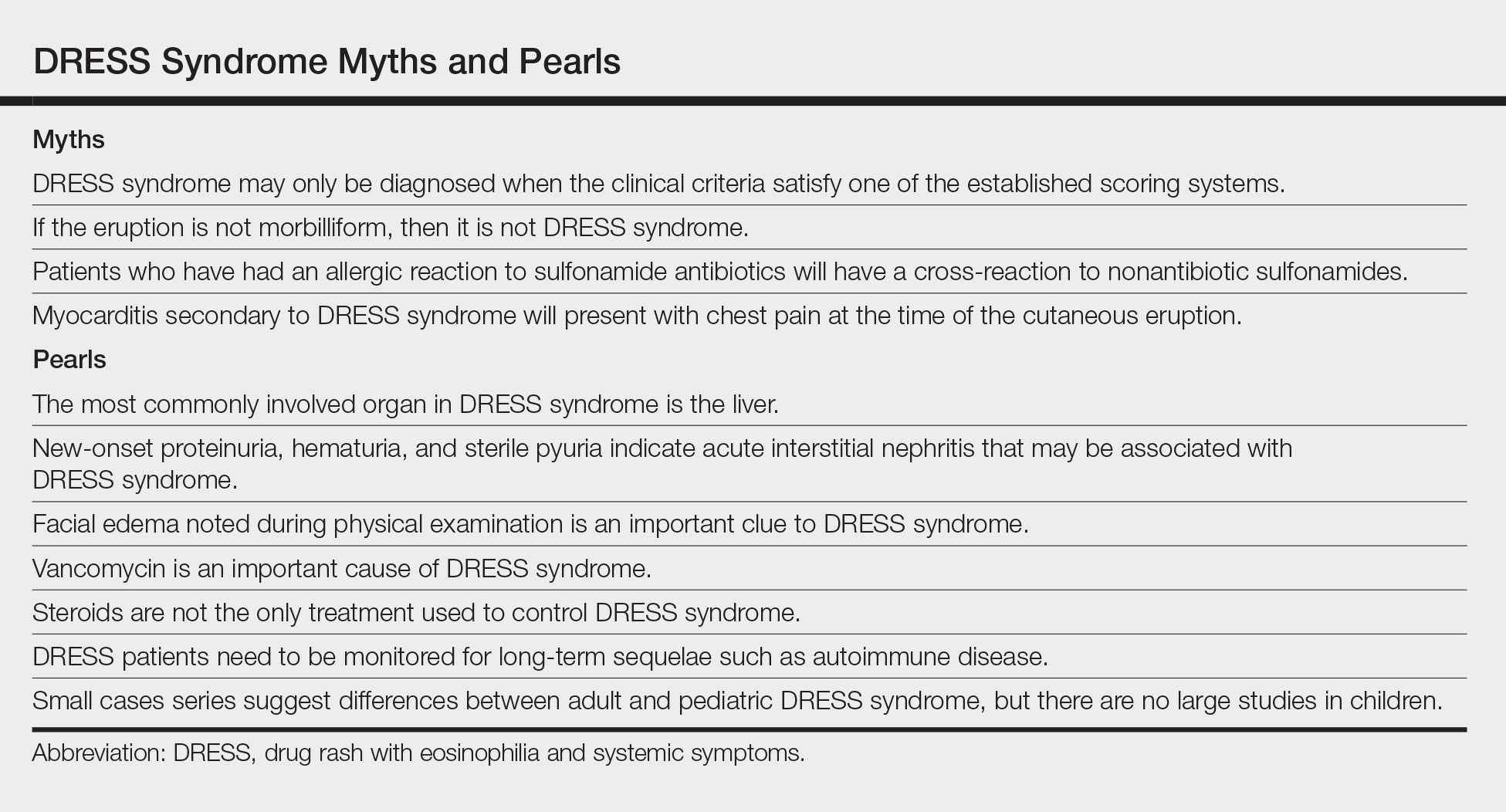

The clinical myths and pearls presented here highlight some of the commonly held assumptions regarding DRESS syndrome in an effort to illuminate subtleties of managing patients with this condition (Table).

Myth: DRESS syndrome may only be diagnosed when the clinical criteria satisfy one of the established scoring systems.

Patients with DRESS syndrome can have heterogeneous manifestations. As a result, patients may develop a drug hypersensitivity with biological behavior and a natural history compatible with DRESS syndrome that does not fulfill published diagnostic criteria.5 The syndrome also may reveal its component manifestations gradually, thus delaying the diagnosis. The terms mini-DRESS and skirt syndrome have been employed to describe drug eruptions that clearly have systemic symptoms and more complex and pernicious biologic behavior than a simple drug exanthema but do not meet DRESS syndrome criteria. Ultimately, it is important to note that in clinical practice, DRESS syndrome exists on a spectrum of severity and the diagnosis remains a clinical one.

Pearl: The most commonly involved organ in DRESS syndrome is the liver.

Liver involvement is the most common visceral organ involved in DRESS syndrome and is estimated to occur in approximately 45.0% to 86.1% of cases.6,7 If a patient develops the characteristic rash, peripheral blood eosinophilia, and evidence of liver injury, DRESS syndrome must be included in the differential diagnosis.

Hepatitis presenting in DRESS syndrome can be hepatocellular, cholestatic, or mixed.6,7 Case series are varied in whether the transaminitis of DRESS syndrome tends to be more hepatocellular8 or cholestatic.7 Liver dysfunction in DRESS syndrome often lasts longer than in other severe cutaneous adverse drug reactions, and patients may improve anywhere from a few days in milder cases to months to achieve resolution of abnormalities.6,7 Severe hepatic involvement is thought to be the most notable cause of mortality.9

Pearl: New-onset proteinuria, hematuria, and sterile pyuria indicate acute interstitial nephritis that may be associated with DRESS syndrome.

Acute interstitial nephritis (AIN) is a drug-induced form of acute kidney injury that can co-occur with DRESS syndrome. Acute interstitial nephritis can present with some combination of acute kidney injury, morbilliform eruption, eosinophilia, fever, and sometimes eosinophiluria. Although AIN can be distinct from DRESS syndrome, there are cases of DRESS syndrome associated with AIN.10 In the correct clinical context, urinalysis may help by showing new-onset proteinuria, new-onset hematuria, and sterile pyuria. More common causes of acute kidney injury such as prerenal etiologies and acute tubular necrosis have a bland urinary sediment.

Myth: If the eruption is not morbilliform, then it is not DRESS syndrome.

The most common morphology of DRESS syndrome is a morbilliform eruption (Figure 1), but urticarial and atypical targetoid (erythema multiforme–like) eruptions also have been described.9 Rarely, DRESS syndrome secondary to use of allopurinol or anticonvulsants may have a pustular morphology (Figure 2), which is distinguished from acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis by its delayed onset, more severe visceral involvement, and prolonged course.11

Another reported variant demonstrates overlapping features between Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis and DRESS syndrome. It may present with mucositis, atypical targetoid lesions, and vesiculobullous lesions.12 It is unclear whether this reported variant is indeed a true subtype of DRESS syndrome, as Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis may present with systemic symptoms, lymphadenopathy, hepatic, renal, and pulmonary complications, among other systemic disturbances.12

Pearl: Facial edema noted during physical examination is an important clue of DRESS syndrome.

Perhaps the most helpful findings in the diagnosis of DRESS syndrome are facial edema and anasarca (Figure 3), as facial edema is not a usual finding in sepsis. Facial edema can be severe enough that the patient’s features are dramatically altered. It may be useful to ask family members if the patient’s face appears swollen or to compare the current appearance to the patient’s driver’s license photograph. An important complication to note is laryngeal edema, which may complicate airway management and may manifest as respiratory distress, stridor, and the need for emergent intubation.13

Myth: Patients who have had an allergic reaction to sulfonamide antibiotics will have a cross-reaction to nonantibiotic sulfonamides.

A common question is, if a patient has had a prior allergy to sulfonamide antibiotics, then are nonantibiotic sulfones such as a sulfonylurea, thiazide diuretic, or furosemide likely to cause a a cross-reaction? In one study (N=969), only 9.9% of patients with a prior sulfone antibiotic allergy developed hypersensitivity when exposed to a nonantibiotic sulfone, which is thought to be due to an overall increased propensity for hypersensitivity rather than a true cross-reaction. In fact, the risk for developing a hypersensitivity reaction to penicillin (14.0% [717/5115]) was higher than the risk for developing a reaction from a nonantibiotic sulfone among these patients.14 This study bolsters the argument that if there are other potential culprit medications and the time course for a patient’s nonantibiotic sulfone is not consistent with the timeline for DRESS syndrome, it may be beneficial to look for a different causative agent.

Pearl: Vancomycin is an important cause of DRESS syndrome.

Guidelines for treating endocarditis and osteomyelitis caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection recommend intravenous vancomycin for 4 to 6 weeks.15 This duration is within the relevant time frame of exposure for the development of DRESS syndrome de novo.

One case series noted that 37.5% (12/32) of DRESS syndrome cases in a 3-year period were caused by vancomycin, which notably was the most common medication associated with DRESS syndrome.16 There were caveats to this case series in that no standardized drug causality score was used and the sample size over the 3-year period was small; however, the increased use (and misuse) of antibiotics and perhaps increased recognition of rash in outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy clinics may play a role if vancomycin-induced DRESS syndrome is indeed becoming more common.

Myth: Myocarditis secondary to DRESS syndrome will present with chest pain at the time of the cutaneous eruption.

Few patients with DRESS syndrome–associated myocarditis actually are symptomatic during their hospitalization.4 In asymptomatic patients, the primary team and consultants should be vigilant for the potential of subclinical myocarditis or the possibility of developing cardiac involvement after discharge, as myocarditis secondary to DRESS syndrome may present any time from rash onset up to 4 months later.4 Therefore, DRESS patients should be especially attentive to any new cardiac symptoms and notify their provider if any develop.

Although no standard cardiac screening guidelines exist for DRESS syndrome, some have recommended that baseline cardiac screening tests including electrocardiogram, troponin levels, and echocardiogram be considered at the time of diagnosis.5 If any testing is abnormal, DRESS syndrome–associated myocarditis should be suspected and an endomyocardial biopsy, which is the diagnostic gold standard, may be necessary.4 If the cardiac screening tests are normal, some investigators recommend serial outpatient echocardiograms for all DRESS patients, even those who remain asymptomatic.17 An alternative is an empiric approach in which a thorough review of systems is performed and testing is done if patients develop symptoms that are concerning for myocarditis.

Pearl: Steroids are not the only treatment used to control DRESS syndrome.

A prolonged taper of systemic steroids is the first-line treatment of DRESS syndrome. Steroids at the equivalent of 1 to 2 mg/kg daily (once or divided into 2 doses) of prednisone typically are used. For severe and/or recalcitrant DRESS syndrome, 2 mg/kg daily (once or divided into 2 doses) typically is used, and less than 1 mg/kg daily may be used for mini-DRESS syndrome.

Clinical improvement of DRESS syndrome has been demonstrated in several case reports with intravenous immunoglobulin, cyclosporine, cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate mofetil, and plasmapheresis.18-21 Each of these therapies typically were initiated as second-line therapeutic agents when initial treatment with steroids failed. It is important to note that large prospective studies regarding these treatments are lacking; however, there have been case reports of acute necrotizing eosinophilic myocarditis that did not respond to the combination of steroids and cyclosporine.4,22

Although there have been successful case reports using intravenous immunoglobulin, a 2012 prospective open-label clinical trial reported notable side effects in 5 of 6 (83.3%) patients with only 1 of 6 (16.6%) achieving the primary end point of control of fever/symptoms at day 7 and clinical remission without steroids on day 30.23

Pearl: DRESS patients need to be monitored for long-term sequelae such as autoimmune disease.

Several autoimmune conditions may develop as a delayed complication of DRESS syndrome, including autoimmune thyroiditis, systemic lupus erythematosus, type 1 diabetes mellitus, and autoimmune hemolytic anemia.24-26 Incidence rates of autoimmunity following DRESS syndrome range from 3% to 5% among small case series.24,25

Autoimmune thyroiditis, which may present as Graves disease, Hashimoto thyroiditis, or painless thyroiditis, is the most common autoimmune disorder to develop in DRESS patients and appears from several weeks to up to 3 years after DRESS.24 Therefore, all DRESS patients should be monitored longitudinally for several years for signs or symptoms suggestive of an autoimmune condition.5,24,26

Because no guidelines exist regarding serial monitoring for autoimmune sequelae, it may be reasonable to check thyroid function tests at the time of diagnosis and regularly for at least 2 years after diagnosis.5 Alternatively, clinicians may consider an empiric approach to laboratory testing that is guided by the development of clinical symptoms.

Pearl: Small cases series suggest differences between adult and pediatric DRESS syndrome, but there are no large studies in children.

Small case series have suggested there may be noteworthy differences between DRESS syndrome in adults and children. Although human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) positivity in DRESS syndrome in adults may be as high as 80%, 13% of pediatric patients in one cohort tested positive for HHV-6, though the study size was limited at 29 total patients.27 In children, DRESS syndrome secondary to antibiotics was associated with a shorter latency time as compared to cases secondary to nonantibiotics. In contrast to the typical 2- to 6-week timeline, Sasidharanpillai et al28 reported an average onset 5.8 days after drug administration in antibiotic-associated DRESS syndrome compared to 23.9 days for anticonvulsants, though this study only included 11 total patients. Other reports have suggested a similar trend.27

The role of HHV-6 positivity in pediatric DRESS syndrome and its influence on prognosis remains unclear. One study showed a worse prognosis for pediatric patients with positive HHV-6 antibodies.27 However, with such a small sample size—only 4 HHV-6–positive patients of 29 pediatric DRESS cases—larger studies are needed to better characterize the relationship between HHV-6 positivity and prognosis.

- Cacoub P, Musette P, Descamps V, et al. The DRESS syndrome: a literature review. Am J Med, 2011;124:588-597.

- Kardaun SH, Sekula P, Valeyrie-Allanore L, et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): an original multisystem adverse drug reaction. results from the prospective RegiSCAR study. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:1071-1080.

- Intarasupht J, Kanchanomai A, Leelasattakul W, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and mortality outcome in the drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms patients with cardiac involvement. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:1187-1191.

- Bourgeois GP, Cafardi JA, Groysman V, et al. A review of DRESS-associated myocarditis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:E229-E236.

- Husain Z, Reddy BY, Schwartz RA. DRESS syndrome: part I. clinical perspectives. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:693.e1-693.e14; quiz 706-708.

- Lee T, Lee YS, Yoon SY, et al. Characteristics of liver injury in drug-induced systemic hypersensitivity reactions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:407-415.

- Lin IC, Yang HC, Strong C, et al. Liver injury in patients with DRESS: a clinical study of 72 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:984-991.

- Peyrière H, Dereure O, Breton H, et al. Variability in the clinical pattern of cutaneous side-effects of drugs with systemic symptoms: does a DRESS syndrome really exist? Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:422-428.

- Walsh S, Diaz-Cano S, Higgins E, et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms: is cutaneous phenotype a prognostic marker for outcome? a review of clinicopathological features of 27 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:391-401.

- Raghavan R, Eknoyan G. Acute interstitial nephritis—a reappraisal and update. Clin Nephrol. 2014;82:149-162.

- Matsuda H, Saito K, Takayanagi Y, et al. Pustular-type drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome/drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms due to carbamazepine with systemic muscle involvement. J Dermatol. 2013;40:118-122.

- Wolf R, Davidovici B, Matz H, et al. Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms versus Stevens-Johnson Syndrome—a case that indicates a stumbling block in the current classification. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2006;141:308-310.

- Kumar A, Goldfarb JW, Bittner EA. A case of drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome complicating airway management. Can J Anaesth. 2012;59:295-298.

- Strom BL, Schinnar R, Apter AJ, et al. Absence of cross-reactivity between sulfonamide antibiotics and sulfonamide nonantibiotics. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1628-1635.

- Berbari EF, Kanj SS, Kowalski TJ, et al; Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2015 Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of native vertebral osteomyelitis in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61:E26-E46.

- Lam BD, Miller MM, Sutton AV, et al. Vancomycin and DRESS: a retrospective chart review of 32 cases in Los Angeles, California. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:973-975.

- Eppenberger M, Hack D, Ammann P, et al. Acute eosinophilic myocarditis with dramatic response to steroid therapy: the central role of echocardiography in diagnosis and follow-up. Tex Heart Inst J. 2013;40:326-330.

- Kirchhof MG, Wong A, Dutz JP. Cyclosporine treatment of drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1254-1257.

- Singer EM, Wanat KA, Rosenbach MA. A case of recalcitrant DRESS syndrome with multiple autoimmune sequelae treated with intravenous immunoglobulins. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:494-495.

- Bommersbach TJ, Lapid MI, Leung JG, et al. Management of psychotropic drug-induced DRESS syndrome: a systematic review. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91:787-801.

- Alexander T, Iglesia E, Park Y, et al. Severe DRESS syndrome managed with therapeutic plasma exchange. Pediatrics. 2013;131:E945-E949.

- Daoulah A, Alqahtani AA, Ocheltree SR, et al. Acute myocardial infarction in a 56-year-old female patient treated with sulfasalazine. Am J Emerg Med. 2012;30:638.e1-638.e3.

- Joly P, Janela B, Tetart F, et al. Poor benefit/risk balance of intravenous immunoglobulins in DRESS. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:543-544.

- Kano Y, Tohyama M, Aihara M, et al. Sequelae in 145 patients with drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome/drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms: survey conducted by the Asian Research Committee on Severe Cutaneous Adverse Reactions (ASCAR). J Dermatol. 2015;42:276-282.

- Ushigome Y, Kano Y, Ishida T, et al. Short- and long-term outcomes of 34 patients with drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome in a single institution. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:721-728.

- Matta JM, Flores SM, Cherit JD. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) and its relation with autoimmunity in a reference center in Mexico. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:30-33.

- Ahluwalia J, Abuabara K, Perman MJ, et al. Human herpesvirus 6 involvement in paediatric drug hypersensitivity syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:1090-1095.

- Sasidharanpillai S, Sabitha S, Riyaz N, et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms in children: a prospective study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:E162-E165.

Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS syndrome), also known as drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome, is an uncommon severe systemic hypersensitivity drug reaction. It is estimated to occur in 1 in every 1000 to 10,000 drug exposures.1 It can affect patients of all ages and typically presents 2 to 6 weeks after exposure to a culprit medication. Classically, DRESS syndrome presents with often widespread rash, facial edema, systemic symptoms such as fever, lymphadenopathy, and evidence of visceral organ involvement. Peripheral blood eosinophilia is frequently but not universally observed.1,2

Even with proper management, reported DRESS syndrome mortality rates worldwide are approximately 10%2 or higher depending on the degree and type of other organ involvement (eg, cardiac).3 Beyond the acute manifestations of DRESS syndrome, this condition is unique in that some patients develop late-onset sequelae such as myocarditis or autoimmune conditions even years after the initial cutaneous eruption.4 Therefore, longitudinal evaluation is a key component of management.

The clinical myths and pearls presented here highlight some of the commonly held assumptions regarding DRESS syndrome in an effort to illuminate subtleties of managing patients with this condition (Table).

Myth: DRESS syndrome may only be diagnosed when the clinical criteria satisfy one of the established scoring systems.

Patients with DRESS syndrome can have heterogeneous manifestations. As a result, patients may develop a drug hypersensitivity with biological behavior and a natural history compatible with DRESS syndrome that does not fulfill published diagnostic criteria.5 The syndrome also may reveal its component manifestations gradually, thus delaying the diagnosis. The terms mini-DRESS and skirt syndrome have been employed to describe drug eruptions that clearly have systemic symptoms and more complex and pernicious biologic behavior than a simple drug exanthema but do not meet DRESS syndrome criteria. Ultimately, it is important to note that in clinical practice, DRESS syndrome exists on a spectrum of severity and the diagnosis remains a clinical one.

Pearl: The most commonly involved organ in DRESS syndrome is the liver.

Liver involvement is the most common visceral organ involved in DRESS syndrome and is estimated to occur in approximately 45.0% to 86.1% of cases.6,7 If a patient develops the characteristic rash, peripheral blood eosinophilia, and evidence of liver injury, DRESS syndrome must be included in the differential diagnosis.

Hepatitis presenting in DRESS syndrome can be hepatocellular, cholestatic, or mixed.6,7 Case series are varied in whether the transaminitis of DRESS syndrome tends to be more hepatocellular8 or cholestatic.7 Liver dysfunction in DRESS syndrome often lasts longer than in other severe cutaneous adverse drug reactions, and patients may improve anywhere from a few days in milder cases to months to achieve resolution of abnormalities.6,7 Severe hepatic involvement is thought to be the most notable cause of mortality.9

Pearl: New-onset proteinuria, hematuria, and sterile pyuria indicate acute interstitial nephritis that may be associated with DRESS syndrome.

Acute interstitial nephritis (AIN) is a drug-induced form of acute kidney injury that can co-occur with DRESS syndrome. Acute interstitial nephritis can present with some combination of acute kidney injury, morbilliform eruption, eosinophilia, fever, and sometimes eosinophiluria. Although AIN can be distinct from DRESS syndrome, there are cases of DRESS syndrome associated with AIN.10 In the correct clinical context, urinalysis may help by showing new-onset proteinuria, new-onset hematuria, and sterile pyuria. More common causes of acute kidney injury such as prerenal etiologies and acute tubular necrosis have a bland urinary sediment.

Myth: If the eruption is not morbilliform, then it is not DRESS syndrome.

The most common morphology of DRESS syndrome is a morbilliform eruption (Figure 1), but urticarial and atypical targetoid (erythema multiforme–like) eruptions also have been described.9 Rarely, DRESS syndrome secondary to use of allopurinol or anticonvulsants may have a pustular morphology (Figure 2), which is distinguished from acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis by its delayed onset, more severe visceral involvement, and prolonged course.11

Another reported variant demonstrates overlapping features between Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis and DRESS syndrome. It may present with mucositis, atypical targetoid lesions, and vesiculobullous lesions.12 It is unclear whether this reported variant is indeed a true subtype of DRESS syndrome, as Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis may present with systemic symptoms, lymphadenopathy, hepatic, renal, and pulmonary complications, among other systemic disturbances.12

Pearl: Facial edema noted during physical examination is an important clue of DRESS syndrome.

Perhaps the most helpful findings in the diagnosis of DRESS syndrome are facial edema and anasarca (Figure 3), as facial edema is not a usual finding in sepsis. Facial edema can be severe enough that the patient’s features are dramatically altered. It may be useful to ask family members if the patient’s face appears swollen or to compare the current appearance to the patient’s driver’s license photograph. An important complication to note is laryngeal edema, which may complicate airway management and may manifest as respiratory distress, stridor, and the need for emergent intubation.13