User login

Asthma-COPD overlap linked to occupational pollutants

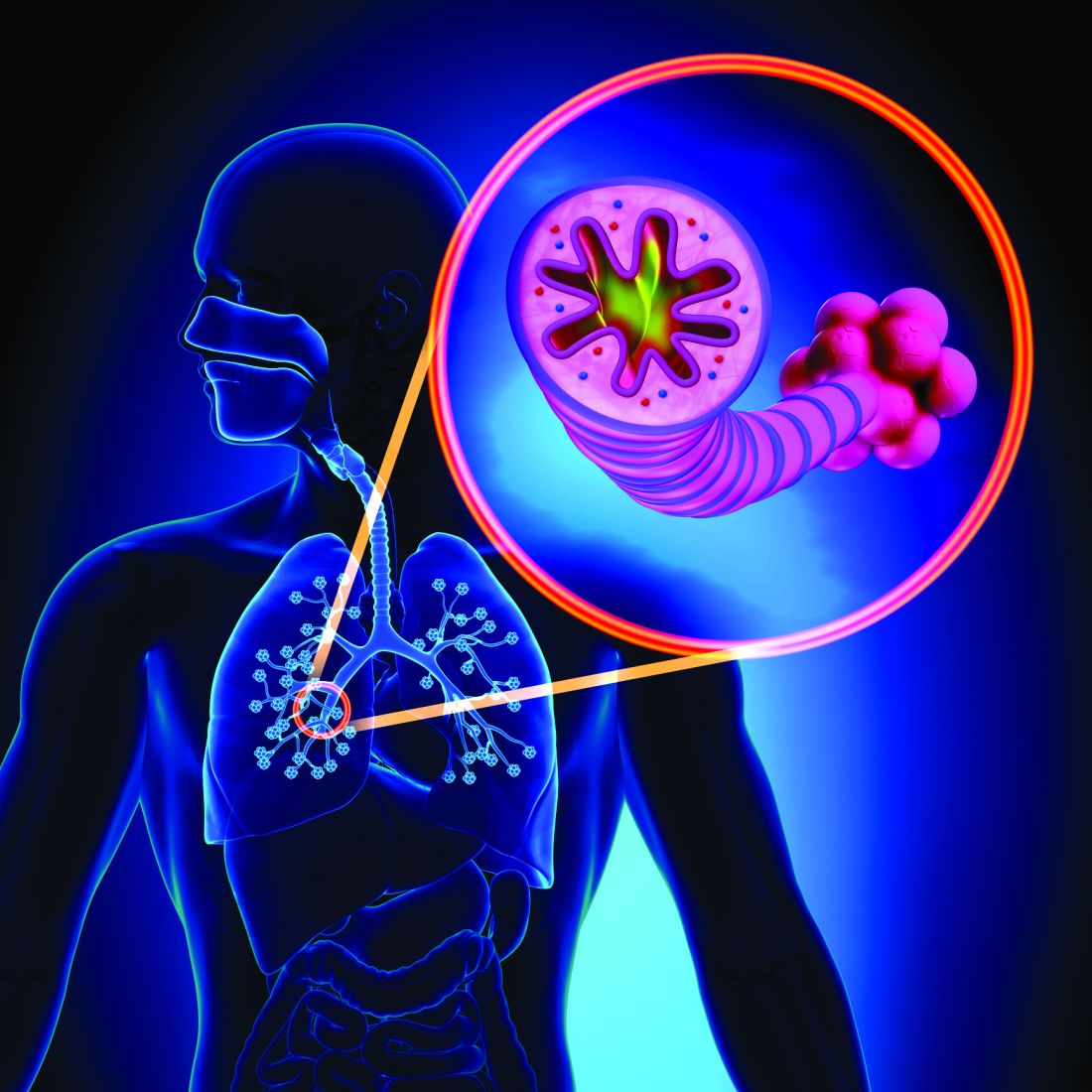

The development and worsening of overlapping asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) can be affected by pollutants found in rural and urban environments, according to a recent presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, held virtually this year.

“ features,” Jill A. Poole, MD, division chief of allergy and immunology at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, said in her presentation.

The Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) first outlined a syndrome in 2015 described as “persistent airflow limitation with several features usually associated with asthma and several features usually associated with COPD” and called asthma-COPD overlap syndrome. In 2017, a joint American Thoracic Society/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute workshop outlined knowledge gaps about asthma-COPD overlap, noting it “does not represent a single discrete disease entity.”

“This is not a single disease and should be thought of as being heterogeneous and used as a descriptive label for patients commonly seen in clinical practice,” Dr. Poole said. “Both asthma and COPD definitions are not mutually exclusive because each disease includes several phenotypes with different underlining mechanisms.” An example of how asthma-COPD overlap might present is through a patient with allergic asthma who has a history of smoking who develops airflow obstruction that isn’t fully reversible, or a patient with COPD “with high reversible airflow, obstruction, type 2 inflammation, and perhaps the presence of peripheral blood eosinophils or sputum eosinophils.”

A patient’s interaction with urban, rural, and occupational environments may additionally impact their disease, Dr. Poole explained. “The environmental factors of an urban versus rural environment may not be necessarily mutually exclusive,” she said. “It’s also important to recognize occupational exposures that can be both seen in an urban or rural environment [can] contribute to asthma-COPD overlap.”

In a study of 6,040 men and women with asthma living in Canada, 630 (10.4%) had asthma-COPD overlap, with increased air pollution raising the likelihood of developing asthma-COPD overlap (odds ratio, 2.78; 95% confidence interval, 1.62-4.78). These people experienced later onset asthma, increased emergency department visits before a diagnosis of COPD, and increased mortality. Another study in Canada of women from Ontario in the Breast Cancer Screening Study found 1,705 of 4,051 women with asthma also had COPD. While air pollution did not increase the risk of developing asthma-COPD overlap, there was an association between body mass index, low level of education, living in a rural area, and smoking status.

Among farmers in rural areas, “it has been recognized that there is something called the asthma-like syndrome that’s been reported in adult farming communities,” Dr. Poole said, which includes “some degree of airflow obstruction and reversibility” that can be worsened by smoking and could be an overlap of asthma and COPD. Farmers can also experience asthma exacerbations while working, and “livestock farmers appear more at risk of developing [chronic bronchitis and/or COPD] than do the crop farmers,” she noted.

Occupational environments outside of agriculture exposure can cause incident asthma, with high-molecular-weight antigens such as flour cereal, animal dander, latex, psyllium, crab processing products, and enzymes as well as low-molecular-weight antigens such as isocyanates, woods, antibiotics, glues, epoxies colophony products, and dyes presenting a risk. In food processing, main allergen sources can include raw and processed animal and plant products, additives and preservatives, contaminants from microbes or insects, inhaled dust particles or aerosols, which can be “IgE mediated, mixed IgE-mediated and non-lgE mediated.”

While some studies have been conducted on the prevalence of work-related asthma and asthma-COPD overlap, “in general, the prevalence and clinical features have been scarcely investigated,” Dr. Poole said. One survey of 23,137 patients found 52.9% of adults with work-related asthma also had COPD, compared with 25.6% of participants whose asthma was not work related.

To prevent asthma-COPD overlap, Dr. Poole recommended tobacco cessation, reducing indoor biomass fuel use, medical surveillance programs such as preplacement questionnaires, and considering “reducing exposure to the respiratory sensitizers with ideally monitoring the levels to keep the levels below the permissible limits.”

Dr. Poole noted there is currently no unique treatment for asthma-COPD overlap, but it is “important to fully characterize and phenotype your individual patients, looking for eosinophilia or seeing if they have more neutrophil features and whether or not the allergy features are prevalent and can be treated,” she said. “[A]wareness is really required such that counseling is encouraged for prevention and or interventional strategies as we move forward.”

For patients with features of both asthma and COPD where there is a high likelihood of asthma, treat the disease as if it were asthma, Dr. Poole said, but clinicians should follow GINA GOLD COPD treatment recommendations, adding on long-acting beta-agonists (LABAs) and long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs) when needed, but avoiding LABAs and/or LAMAs without use of inhaled corticosteroids, and avoiding oral corticosteroids entirely. Clinicians should be reviewing the treatments of patients with asthma and COPD features “every 2-3 months to see how their response is to it, and what additional therapies could be used,” she said.

Dr. Poole reports receiving grant support from National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, and the Central States Center for Agricultural Safety and Health at the University of Nebraska Medical Center.

The development and worsening of overlapping asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) can be affected by pollutants found in rural and urban environments, according to a recent presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, held virtually this year.

“ features,” Jill A. Poole, MD, division chief of allergy and immunology at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, said in her presentation.

The Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) first outlined a syndrome in 2015 described as “persistent airflow limitation with several features usually associated with asthma and several features usually associated with COPD” and called asthma-COPD overlap syndrome. In 2017, a joint American Thoracic Society/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute workshop outlined knowledge gaps about asthma-COPD overlap, noting it “does not represent a single discrete disease entity.”

“This is not a single disease and should be thought of as being heterogeneous and used as a descriptive label for patients commonly seen in clinical practice,” Dr. Poole said. “Both asthma and COPD definitions are not mutually exclusive because each disease includes several phenotypes with different underlining mechanisms.” An example of how asthma-COPD overlap might present is through a patient with allergic asthma who has a history of smoking who develops airflow obstruction that isn’t fully reversible, or a patient with COPD “with high reversible airflow, obstruction, type 2 inflammation, and perhaps the presence of peripheral blood eosinophils or sputum eosinophils.”

A patient’s interaction with urban, rural, and occupational environments may additionally impact their disease, Dr. Poole explained. “The environmental factors of an urban versus rural environment may not be necessarily mutually exclusive,” she said. “It’s also important to recognize occupational exposures that can be both seen in an urban or rural environment [can] contribute to asthma-COPD overlap.”

In a study of 6,040 men and women with asthma living in Canada, 630 (10.4%) had asthma-COPD overlap, with increased air pollution raising the likelihood of developing asthma-COPD overlap (odds ratio, 2.78; 95% confidence interval, 1.62-4.78). These people experienced later onset asthma, increased emergency department visits before a diagnosis of COPD, and increased mortality. Another study in Canada of women from Ontario in the Breast Cancer Screening Study found 1,705 of 4,051 women with asthma also had COPD. While air pollution did not increase the risk of developing asthma-COPD overlap, there was an association between body mass index, low level of education, living in a rural area, and smoking status.

Among farmers in rural areas, “it has been recognized that there is something called the asthma-like syndrome that’s been reported in adult farming communities,” Dr. Poole said, which includes “some degree of airflow obstruction and reversibility” that can be worsened by smoking and could be an overlap of asthma and COPD. Farmers can also experience asthma exacerbations while working, and “livestock farmers appear more at risk of developing [chronic bronchitis and/or COPD] than do the crop farmers,” she noted.

Occupational environments outside of agriculture exposure can cause incident asthma, with high-molecular-weight antigens such as flour cereal, animal dander, latex, psyllium, crab processing products, and enzymes as well as low-molecular-weight antigens such as isocyanates, woods, antibiotics, glues, epoxies colophony products, and dyes presenting a risk. In food processing, main allergen sources can include raw and processed animal and plant products, additives and preservatives, contaminants from microbes or insects, inhaled dust particles or aerosols, which can be “IgE mediated, mixed IgE-mediated and non-lgE mediated.”

While some studies have been conducted on the prevalence of work-related asthma and asthma-COPD overlap, “in general, the prevalence and clinical features have been scarcely investigated,” Dr. Poole said. One survey of 23,137 patients found 52.9% of adults with work-related asthma also had COPD, compared with 25.6% of participants whose asthma was not work related.

To prevent asthma-COPD overlap, Dr. Poole recommended tobacco cessation, reducing indoor biomass fuel use, medical surveillance programs such as preplacement questionnaires, and considering “reducing exposure to the respiratory sensitizers with ideally monitoring the levels to keep the levels below the permissible limits.”

Dr. Poole noted there is currently no unique treatment for asthma-COPD overlap, but it is “important to fully characterize and phenotype your individual patients, looking for eosinophilia or seeing if they have more neutrophil features and whether or not the allergy features are prevalent and can be treated,” she said. “[A]wareness is really required such that counseling is encouraged for prevention and or interventional strategies as we move forward.”

For patients with features of both asthma and COPD where there is a high likelihood of asthma, treat the disease as if it were asthma, Dr. Poole said, but clinicians should follow GINA GOLD COPD treatment recommendations, adding on long-acting beta-agonists (LABAs) and long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs) when needed, but avoiding LABAs and/or LAMAs without use of inhaled corticosteroids, and avoiding oral corticosteroids entirely. Clinicians should be reviewing the treatments of patients with asthma and COPD features “every 2-3 months to see how their response is to it, and what additional therapies could be used,” she said.

Dr. Poole reports receiving grant support from National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, and the Central States Center for Agricultural Safety and Health at the University of Nebraska Medical Center.

The development and worsening of overlapping asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) can be affected by pollutants found in rural and urban environments, according to a recent presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, held virtually this year.

“ features,” Jill A. Poole, MD, division chief of allergy and immunology at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, said in her presentation.

The Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) first outlined a syndrome in 2015 described as “persistent airflow limitation with several features usually associated with asthma and several features usually associated with COPD” and called asthma-COPD overlap syndrome. In 2017, a joint American Thoracic Society/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute workshop outlined knowledge gaps about asthma-COPD overlap, noting it “does not represent a single discrete disease entity.”

“This is not a single disease and should be thought of as being heterogeneous and used as a descriptive label for patients commonly seen in clinical practice,” Dr. Poole said. “Both asthma and COPD definitions are not mutually exclusive because each disease includes several phenotypes with different underlining mechanisms.” An example of how asthma-COPD overlap might present is through a patient with allergic asthma who has a history of smoking who develops airflow obstruction that isn’t fully reversible, or a patient with COPD “with high reversible airflow, obstruction, type 2 inflammation, and perhaps the presence of peripheral blood eosinophils or sputum eosinophils.”

A patient’s interaction with urban, rural, and occupational environments may additionally impact their disease, Dr. Poole explained. “The environmental factors of an urban versus rural environment may not be necessarily mutually exclusive,” she said. “It’s also important to recognize occupational exposures that can be both seen in an urban or rural environment [can] contribute to asthma-COPD overlap.”

In a study of 6,040 men and women with asthma living in Canada, 630 (10.4%) had asthma-COPD overlap, with increased air pollution raising the likelihood of developing asthma-COPD overlap (odds ratio, 2.78; 95% confidence interval, 1.62-4.78). These people experienced later onset asthma, increased emergency department visits before a diagnosis of COPD, and increased mortality. Another study in Canada of women from Ontario in the Breast Cancer Screening Study found 1,705 of 4,051 women with asthma also had COPD. While air pollution did not increase the risk of developing asthma-COPD overlap, there was an association between body mass index, low level of education, living in a rural area, and smoking status.

Among farmers in rural areas, “it has been recognized that there is something called the asthma-like syndrome that’s been reported in adult farming communities,” Dr. Poole said, which includes “some degree of airflow obstruction and reversibility” that can be worsened by smoking and could be an overlap of asthma and COPD. Farmers can also experience asthma exacerbations while working, and “livestock farmers appear more at risk of developing [chronic bronchitis and/or COPD] than do the crop farmers,” she noted.

Occupational environments outside of agriculture exposure can cause incident asthma, with high-molecular-weight antigens such as flour cereal, animal dander, latex, psyllium, crab processing products, and enzymes as well as low-molecular-weight antigens such as isocyanates, woods, antibiotics, glues, epoxies colophony products, and dyes presenting a risk. In food processing, main allergen sources can include raw and processed animal and plant products, additives and preservatives, contaminants from microbes or insects, inhaled dust particles or aerosols, which can be “IgE mediated, mixed IgE-mediated and non-lgE mediated.”

While some studies have been conducted on the prevalence of work-related asthma and asthma-COPD overlap, “in general, the prevalence and clinical features have been scarcely investigated,” Dr. Poole said. One survey of 23,137 patients found 52.9% of adults with work-related asthma also had COPD, compared with 25.6% of participants whose asthma was not work related.

To prevent asthma-COPD overlap, Dr. Poole recommended tobacco cessation, reducing indoor biomass fuel use, medical surveillance programs such as preplacement questionnaires, and considering “reducing exposure to the respiratory sensitizers with ideally monitoring the levels to keep the levels below the permissible limits.”

Dr. Poole noted there is currently no unique treatment for asthma-COPD overlap, but it is “important to fully characterize and phenotype your individual patients, looking for eosinophilia or seeing if they have more neutrophil features and whether or not the allergy features are prevalent and can be treated,” she said. “[A]wareness is really required such that counseling is encouraged for prevention and or interventional strategies as we move forward.”

For patients with features of both asthma and COPD where there is a high likelihood of asthma, treat the disease as if it were asthma, Dr. Poole said, but clinicians should follow GINA GOLD COPD treatment recommendations, adding on long-acting beta-agonists (LABAs) and long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs) when needed, but avoiding LABAs and/or LAMAs without use of inhaled corticosteroids, and avoiding oral corticosteroids entirely. Clinicians should be reviewing the treatments of patients with asthma and COPD features “every 2-3 months to see how their response is to it, and what additional therapies could be used,” she said.

Dr. Poole reports receiving grant support from National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, and the Central States Center for Agricultural Safety and Health at the University of Nebraska Medical Center.

FROM AAAAI 2021

Patients with asthma and COPD lost ground in accessing care

Over the past 20 years, patients with asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) have seen next to no improvement in problems of delayed care because of cost or unaffordable medications, despite wider insurance coverage since the passage of the Affordable Care Act, a new analysis shows.

The long-view analysis illuminates the ongoing problem for people with these chronic diseases despite health care legislation that was considered historic.

“That long-term scope puts recent improvements in better context – whereas we have made improvements in coverage in recent years due to the Affordable Care Act, the longer-term picture is that people with asthma and COPD are struggling to obtain needed medical care and medications despite a substantial reduction in the uninsurance rate,” said Adam Gaffney, MD, MPH, assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston who authored the paper with David Himmelstein, MD, professor of public health at City University of New York–Hunter College. The findings were published in Chest.

Researchers examined data from 1997 to 2018 for 76,843 adults with asthma and 30,548 adults with COPD, from the National Health Interview Survey, an annual survey by the Centers for Disease Control that is based on in-person interviews and health questionnaires completed by an adult in each family.

Insurance coverage up, patients losing ground

During 1997 and 2018, there was an overall 9.3% decrease in the rate of adults with asthma who were uninsured, a significant improvement (P < .001). Between the pre- and post-ACA years, there was modest improvement in those putting off care because of cost, a drop of 3.8%, or going without prescriptions, a drop of 4.0%. But those improvements didn’t correspond to the 7.2% drop in the uninsured rate after the AC , contributing to the finding that there was no significant improvement over the 20 years.

For adults with COPD, it was a slightly different story. Over those 2 decades, the uninsured rate dropped by 9.5%. But the number of patients foregoing care due to cost actually rose by 3.4%, which wasn’t statistically significant, but the rate of those unable to afford needed medications rose significantly by 7.8%.

Researchers found there was improvement between the pre- and post-ACA years among COPD patients putting off care and going without medications (decreases of 6.9% and 4.5%, respectively). That adhered fairly closely with the improvement in the uninsured rate, which fell by 7.1%. But over the 20-year study period, the percentage of those needing medications they couldn’t afford increased significantly by 7.8%. The rate of those delaying or foregoing care also increased, though this amount was not statistically significant.

After the ACA was created, Blacks and Hispanics with asthma had greater improvement in obtaining insurance, compared with other racial and ethnic groups. But over the 20 years, like all racial and ethnic groups, they saw no statistically significant improvement in rates of “inadequate coverage,” defined in this study as either being uninsured, having to delay care because of cost, or being unable to afford needed medications.

For those with COPD, only Whites had statistically significant improvement in the number of patients with inadequate coverage after the ACA, researchers found.

So despite obtaining insurance, patients lost ground in managing their disease because of the growing cost of care and medication.

“Medication affordability has actually worsened for those with COPD – a worrisome development given that medication nonadherence worsens outcomes for these vulnerable patients,” Dr. Gaffney said. “Policy makers should return to the issue of national health care reform. Both uninsurance and underinsurance undermines pulmonologists’ ability to care for their patients with chronic disease. A health care system without financial barriers, in contrast, might well improve these patients’ outcomes, and advance health equity.”

Insurance is no guarantee to access

Daniel Ouellette, MD, FCCP, a pulmonary and critical care specialist at Henry Ford Health System in Detroit, said it’s not surprising that access to care remains a problem despite the Affordable Care Act.

“It covers the hospitalizations and ER visits – patients in this segment of society were getting cared for there anyway,” he said. “And what the ACA didn’t always do was provide adequate prescription coverage or cover these outpatient gaps. So even though the patients have the ACA they still have unaffordable prescriptions, they still can’t buy them, and they still can’t pay for their outpatient clinic if they have a $500 or $1,000 deductible.” These patients also continue to struggle with more fundamental issues that affect access to care, such as lack of transportation and poor health literacy.

At Henry Ford, pharmacists work with patients to identify medications covered by their insurance and work to find discounts and coupons, he said. As for the ACA, “it’s a good first start, but we really need to identify what its limitations are.” Locally driven, less expensive solutions might be a better way forward than costly federal initiatives.

Brandon M. Seay, MD, a pediatric pulmonologist and sleep specialist at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, said the findings dovetail with what he has seen in the pediatric population.

“From my experience, the ACA has helped patients get their foot in the door and has helped patients decrease the possibility of serious financial burden in emergency situations, but the ability to afford medications has not changed very much,” he said. When patients struggle with sufficient prescription coverage, he helps patients fight for coverage and connects them with prescription assistance programs such as GoodRx.

“Instead of focusing on the access of insurance to patients, the goal of the system should be to make care as affordable as possible,” Dr. Seay said. “Access does not meet the needs of a patient if they cannot afford what they have access to. Transition to a nationalized health system where there is no question of access could help to drive down prescription drug prices by allowing the government to negotiate with pharmaceutical companies more adequately by removing the ‘middle man’ of the private insurance industry.”

The investigators reported no financial conflicts. Dr. Ouellette and Dr. Seay reported no financial conflicts.

Over the past 20 years, patients with asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) have seen next to no improvement in problems of delayed care because of cost or unaffordable medications, despite wider insurance coverage since the passage of the Affordable Care Act, a new analysis shows.

The long-view analysis illuminates the ongoing problem for people with these chronic diseases despite health care legislation that was considered historic.

“That long-term scope puts recent improvements in better context – whereas we have made improvements in coverage in recent years due to the Affordable Care Act, the longer-term picture is that people with asthma and COPD are struggling to obtain needed medical care and medications despite a substantial reduction in the uninsurance rate,” said Adam Gaffney, MD, MPH, assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston who authored the paper with David Himmelstein, MD, professor of public health at City University of New York–Hunter College. The findings were published in Chest.

Researchers examined data from 1997 to 2018 for 76,843 adults with asthma and 30,548 adults with COPD, from the National Health Interview Survey, an annual survey by the Centers for Disease Control that is based on in-person interviews and health questionnaires completed by an adult in each family.

Insurance coverage up, patients losing ground

During 1997 and 2018, there was an overall 9.3% decrease in the rate of adults with asthma who were uninsured, a significant improvement (P < .001). Between the pre- and post-ACA years, there was modest improvement in those putting off care because of cost, a drop of 3.8%, or going without prescriptions, a drop of 4.0%. But those improvements didn’t correspond to the 7.2% drop in the uninsured rate after the AC , contributing to the finding that there was no significant improvement over the 20 years.

For adults with COPD, it was a slightly different story. Over those 2 decades, the uninsured rate dropped by 9.5%. But the number of patients foregoing care due to cost actually rose by 3.4%, which wasn’t statistically significant, but the rate of those unable to afford needed medications rose significantly by 7.8%.

Researchers found there was improvement between the pre- and post-ACA years among COPD patients putting off care and going without medications (decreases of 6.9% and 4.5%, respectively). That adhered fairly closely with the improvement in the uninsured rate, which fell by 7.1%. But over the 20-year study period, the percentage of those needing medications they couldn’t afford increased significantly by 7.8%. The rate of those delaying or foregoing care also increased, though this amount was not statistically significant.

After the ACA was created, Blacks and Hispanics with asthma had greater improvement in obtaining insurance, compared with other racial and ethnic groups. But over the 20 years, like all racial and ethnic groups, they saw no statistically significant improvement in rates of “inadequate coverage,” defined in this study as either being uninsured, having to delay care because of cost, or being unable to afford needed medications.

For those with COPD, only Whites had statistically significant improvement in the number of patients with inadequate coverage after the ACA, researchers found.

So despite obtaining insurance, patients lost ground in managing their disease because of the growing cost of care and medication.

“Medication affordability has actually worsened for those with COPD – a worrisome development given that medication nonadherence worsens outcomes for these vulnerable patients,” Dr. Gaffney said. “Policy makers should return to the issue of national health care reform. Both uninsurance and underinsurance undermines pulmonologists’ ability to care for their patients with chronic disease. A health care system without financial barriers, in contrast, might well improve these patients’ outcomes, and advance health equity.”

Insurance is no guarantee to access

Daniel Ouellette, MD, FCCP, a pulmonary and critical care specialist at Henry Ford Health System in Detroit, said it’s not surprising that access to care remains a problem despite the Affordable Care Act.

“It covers the hospitalizations and ER visits – patients in this segment of society were getting cared for there anyway,” he said. “And what the ACA didn’t always do was provide adequate prescription coverage or cover these outpatient gaps. So even though the patients have the ACA they still have unaffordable prescriptions, they still can’t buy them, and they still can’t pay for their outpatient clinic if they have a $500 or $1,000 deductible.” These patients also continue to struggle with more fundamental issues that affect access to care, such as lack of transportation and poor health literacy.

At Henry Ford, pharmacists work with patients to identify medications covered by their insurance and work to find discounts and coupons, he said. As for the ACA, “it’s a good first start, but we really need to identify what its limitations are.” Locally driven, less expensive solutions might be a better way forward than costly federal initiatives.

Brandon M. Seay, MD, a pediatric pulmonologist and sleep specialist at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, said the findings dovetail with what he has seen in the pediatric population.

“From my experience, the ACA has helped patients get their foot in the door and has helped patients decrease the possibility of serious financial burden in emergency situations, but the ability to afford medications has not changed very much,” he said. When patients struggle with sufficient prescription coverage, he helps patients fight for coverage and connects them with prescription assistance programs such as GoodRx.

“Instead of focusing on the access of insurance to patients, the goal of the system should be to make care as affordable as possible,” Dr. Seay said. “Access does not meet the needs of a patient if they cannot afford what they have access to. Transition to a nationalized health system where there is no question of access could help to drive down prescription drug prices by allowing the government to negotiate with pharmaceutical companies more adequately by removing the ‘middle man’ of the private insurance industry.”

The investigators reported no financial conflicts. Dr. Ouellette and Dr. Seay reported no financial conflicts.

Over the past 20 years, patients with asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) have seen next to no improvement in problems of delayed care because of cost or unaffordable medications, despite wider insurance coverage since the passage of the Affordable Care Act, a new analysis shows.

The long-view analysis illuminates the ongoing problem for people with these chronic diseases despite health care legislation that was considered historic.

“That long-term scope puts recent improvements in better context – whereas we have made improvements in coverage in recent years due to the Affordable Care Act, the longer-term picture is that people with asthma and COPD are struggling to obtain needed medical care and medications despite a substantial reduction in the uninsurance rate,” said Adam Gaffney, MD, MPH, assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston who authored the paper with David Himmelstein, MD, professor of public health at City University of New York–Hunter College. The findings were published in Chest.

Researchers examined data from 1997 to 2018 for 76,843 adults with asthma and 30,548 adults with COPD, from the National Health Interview Survey, an annual survey by the Centers for Disease Control that is based on in-person interviews and health questionnaires completed by an adult in each family.

Insurance coverage up, patients losing ground

During 1997 and 2018, there was an overall 9.3% decrease in the rate of adults with asthma who were uninsured, a significant improvement (P < .001). Between the pre- and post-ACA years, there was modest improvement in those putting off care because of cost, a drop of 3.8%, or going without prescriptions, a drop of 4.0%. But those improvements didn’t correspond to the 7.2% drop in the uninsured rate after the AC , contributing to the finding that there was no significant improvement over the 20 years.

For adults with COPD, it was a slightly different story. Over those 2 decades, the uninsured rate dropped by 9.5%. But the number of patients foregoing care due to cost actually rose by 3.4%, which wasn’t statistically significant, but the rate of those unable to afford needed medications rose significantly by 7.8%.

Researchers found there was improvement between the pre- and post-ACA years among COPD patients putting off care and going without medications (decreases of 6.9% and 4.5%, respectively). That adhered fairly closely with the improvement in the uninsured rate, which fell by 7.1%. But over the 20-year study period, the percentage of those needing medications they couldn’t afford increased significantly by 7.8%. The rate of those delaying or foregoing care also increased, though this amount was not statistically significant.

After the ACA was created, Blacks and Hispanics with asthma had greater improvement in obtaining insurance, compared with other racial and ethnic groups. But over the 20 years, like all racial and ethnic groups, they saw no statistically significant improvement in rates of “inadequate coverage,” defined in this study as either being uninsured, having to delay care because of cost, or being unable to afford needed medications.

For those with COPD, only Whites had statistically significant improvement in the number of patients with inadequate coverage after the ACA, researchers found.

So despite obtaining insurance, patients lost ground in managing their disease because of the growing cost of care and medication.

“Medication affordability has actually worsened for those with COPD – a worrisome development given that medication nonadherence worsens outcomes for these vulnerable patients,” Dr. Gaffney said. “Policy makers should return to the issue of national health care reform. Both uninsurance and underinsurance undermines pulmonologists’ ability to care for their patients with chronic disease. A health care system without financial barriers, in contrast, might well improve these patients’ outcomes, and advance health equity.”

Insurance is no guarantee to access

Daniel Ouellette, MD, FCCP, a pulmonary and critical care specialist at Henry Ford Health System in Detroit, said it’s not surprising that access to care remains a problem despite the Affordable Care Act.

“It covers the hospitalizations and ER visits – patients in this segment of society were getting cared for there anyway,” he said. “And what the ACA didn’t always do was provide adequate prescription coverage or cover these outpatient gaps. So even though the patients have the ACA they still have unaffordable prescriptions, they still can’t buy them, and they still can’t pay for their outpatient clinic if they have a $500 or $1,000 deductible.” These patients also continue to struggle with more fundamental issues that affect access to care, such as lack of transportation and poor health literacy.

At Henry Ford, pharmacists work with patients to identify medications covered by their insurance and work to find discounts and coupons, he said. As for the ACA, “it’s a good first start, but we really need to identify what its limitations are.” Locally driven, less expensive solutions might be a better way forward than costly federal initiatives.

Brandon M. Seay, MD, a pediatric pulmonologist and sleep specialist at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, said the findings dovetail with what he has seen in the pediatric population.

“From my experience, the ACA has helped patients get their foot in the door and has helped patients decrease the possibility of serious financial burden in emergency situations, but the ability to afford medications has not changed very much,” he said. When patients struggle with sufficient prescription coverage, he helps patients fight for coverage and connects them with prescription assistance programs such as GoodRx.

“Instead of focusing on the access of insurance to patients, the goal of the system should be to make care as affordable as possible,” Dr. Seay said. “Access does not meet the needs of a patient if they cannot afford what they have access to. Transition to a nationalized health system where there is no question of access could help to drive down prescription drug prices by allowing the government to negotiate with pharmaceutical companies more adequately by removing the ‘middle man’ of the private insurance industry.”

The investigators reported no financial conflicts. Dr. Ouellette and Dr. Seay reported no financial conflicts.

FROM CHEST

Inhaled hyaluronan may bring sigh of relief to COPD patients

(COPD), findings of a new study suggest.

HMW-HA was associated with a significantly shorter duration of noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation (NIPPV), lower systemic inflammatory markers, and lower measured peak airway pressure, compared with placebo, reported lead author Flavia Galdi, MD, of Campus Bio-Medico University Hospital, Rome, and colleagues.

“HMW-HA is a naturally occurring sugar that is abundant in the extracellular matrix, including in the lung,” the investigators wrote in Respiratory Research. “[It] has been used routinely, together with hypertonic saline, in cystic fibrosis patients [for several years] with no reported side effects; rather, it improves tolerability and decreases the need for bronchodilators in these patients.”

According to Robert A. Sandhaus, MD, PhD, FCCP, of National Jewish Health, Denver, the role of hyaluronan in lung disease was first recognized decades ago.

“Data stretching back into the 1970s has identified decreases in hyaluronan content in emphysematous lung tissue, protection of lung connective tissue from proteolysis by hyaluronan, and potential therapeutic roles for hyaluronan in a variety of disease, especially of the lungs,” he said in an interview.

For patients with COPD, treatment with HMW-HA may provide benefit by counteracting an imbalance in diseased lung tissue, wrote Dr. Galdi and colleagues.

“Emerging evidence suggests that imbalance between declining HMW-HA levels, and increasing smaller fragments of hyaluronan may contribute to chronic airway disease pathogenesis,” they wrote. “This has led to the hypothesis that exogenous supplementation of HMW-HA may restore hyaluronan homeostasis in favor of undegraded molecules, inhibit inflammation and loss of lung function, and ameliorate COPD progression.”

To test this hypothesis, the investigators screened 44 patients with a history of acute exacerbations of COPD necessitating NIPPV, ultimately excluding 3 patients because of heart failure. Following 1:1 randomization, 20 patients received HMW-HA while 21 received placebo, each twice daily, in conjunction with NIPPV and standard medical therapy. Treatment continued until NIPPV failure or liberation from NIPPV. Most patients received NIPPV in the hospital; however, home/chronic NIPPV was given to four patients in the placebo group and three patients in the HMW-HA group.

The primary outcome was duration of NIPPV. Secondary outcomes included markers of systemic inflammation associated with acute exacerbations of COPD and respiratory physiology parameters. Adverse events were also reported.

Results showed that patients treated with HMW-HA were liberated sooner from NIPPV than were those who received placebo (mean, 5.2 vs 6.4 days; P < .037). Similarly, patients in the HMW-HA group had significantly shorter hospital stay, on average, than those in the placebo group (mean, 7.2 vs 10.2 days; P = .039). Median values followed a similar pattern.

“These data suggest that HMW-HA shortened the duration of acute respiratory failure, need for NIPPV and, consequently, hospital length of stay in these patients,” the investigators wrote.

Secondary outcomes further supported these therapeutic benefits. Compared with placebo, HMW-HA was associated with significantly lower peak pressure and greater improvements in both pCO2/FiO2 ratio and inflammatory markers. No adverse events were reported.

Further analyses involving human bronchial epithelial cell cultures offered some mechanistic insight. Using micro-optical coherence tomography imaging, the investigators found that HMW-HA treatment was associated with “a prominent effect on mucociliary transport” in cell cultures derived from COPD patients and in healthy nonsmoker cell cultures exposed to cigarette smoke extract.

“Our study shows for the first time the therapeutic potential of an extracellular matrix molecule in acute exacerbation of human lung disease,” the investigators concluded, noting a “clinically meaningful salutary effect” on duration of NIPPV.

Dr. Galdi and colleagues went on to predict that benefits in a real-world patient population could be even more meaningful.

“Since the serum samples were collected at the end of NIPPV, HMW-HA–treated patients were on average sampled a day earlier than placebo-treated patients (because they were liberated from NIPPV a day earlier on average),” the investigators wrote. “Thus, HMW-HA treatment effects may have been underestimated in our study.”

According to Dr. Sandhaus, “The current report, while a relatively small single-center study, is well controlled and the results suggest that inhaled hyaluronan decreased time on noninvasive ventilation, decreased hospital stay duration, and decreased some mediators of inflammation.”

He also suggested that HMW-HA may have a role in the prophylactic setting.

“The limitations of this pilot study are appropriately explored by the authors but do not dampen the exciting possibility that this therapeutic approach may hold promise not only in severe exacerbations of COPD but potentially for the prevention of such exacerbations,” Dr. Sandhaus said.

Jerome O. Cantor, MD, FCCP, of St. John’s University, New York, who previously conducted a pilot study for using lower molecular weight hyaluronan in COPD and published a review on the subject, said that more studies are necessary.

“Further clinical trials are needed to better determine the role of hyaluronan as an adjunct to existing therapies for COPD exacerbations,” he said.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health. The investigators and Dr. Sandhaus declared no conflicts of interest. Dr. Cantor disclosed a relationship with MatRx Therapeutics.

(COPD), findings of a new study suggest.

HMW-HA was associated with a significantly shorter duration of noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation (NIPPV), lower systemic inflammatory markers, and lower measured peak airway pressure, compared with placebo, reported lead author Flavia Galdi, MD, of Campus Bio-Medico University Hospital, Rome, and colleagues.

“HMW-HA is a naturally occurring sugar that is abundant in the extracellular matrix, including in the lung,” the investigators wrote in Respiratory Research. “[It] has been used routinely, together with hypertonic saline, in cystic fibrosis patients [for several years] with no reported side effects; rather, it improves tolerability and decreases the need for bronchodilators in these patients.”

According to Robert A. Sandhaus, MD, PhD, FCCP, of National Jewish Health, Denver, the role of hyaluronan in lung disease was first recognized decades ago.

“Data stretching back into the 1970s has identified decreases in hyaluronan content in emphysematous lung tissue, protection of lung connective tissue from proteolysis by hyaluronan, and potential therapeutic roles for hyaluronan in a variety of disease, especially of the lungs,” he said in an interview.

For patients with COPD, treatment with HMW-HA may provide benefit by counteracting an imbalance in diseased lung tissue, wrote Dr. Galdi and colleagues.

“Emerging evidence suggests that imbalance between declining HMW-HA levels, and increasing smaller fragments of hyaluronan may contribute to chronic airway disease pathogenesis,” they wrote. “This has led to the hypothesis that exogenous supplementation of HMW-HA may restore hyaluronan homeostasis in favor of undegraded molecules, inhibit inflammation and loss of lung function, and ameliorate COPD progression.”

To test this hypothesis, the investigators screened 44 patients with a history of acute exacerbations of COPD necessitating NIPPV, ultimately excluding 3 patients because of heart failure. Following 1:1 randomization, 20 patients received HMW-HA while 21 received placebo, each twice daily, in conjunction with NIPPV and standard medical therapy. Treatment continued until NIPPV failure or liberation from NIPPV. Most patients received NIPPV in the hospital; however, home/chronic NIPPV was given to four patients in the placebo group and three patients in the HMW-HA group.

The primary outcome was duration of NIPPV. Secondary outcomes included markers of systemic inflammation associated with acute exacerbations of COPD and respiratory physiology parameters. Adverse events were also reported.

Results showed that patients treated with HMW-HA were liberated sooner from NIPPV than were those who received placebo (mean, 5.2 vs 6.4 days; P < .037). Similarly, patients in the HMW-HA group had significantly shorter hospital stay, on average, than those in the placebo group (mean, 7.2 vs 10.2 days; P = .039). Median values followed a similar pattern.

“These data suggest that HMW-HA shortened the duration of acute respiratory failure, need for NIPPV and, consequently, hospital length of stay in these patients,” the investigators wrote.

Secondary outcomes further supported these therapeutic benefits. Compared with placebo, HMW-HA was associated with significantly lower peak pressure and greater improvements in both pCO2/FiO2 ratio and inflammatory markers. No adverse events were reported.

Further analyses involving human bronchial epithelial cell cultures offered some mechanistic insight. Using micro-optical coherence tomography imaging, the investigators found that HMW-HA treatment was associated with “a prominent effect on mucociliary transport” in cell cultures derived from COPD patients and in healthy nonsmoker cell cultures exposed to cigarette smoke extract.

“Our study shows for the first time the therapeutic potential of an extracellular matrix molecule in acute exacerbation of human lung disease,” the investigators concluded, noting a “clinically meaningful salutary effect” on duration of NIPPV.

Dr. Galdi and colleagues went on to predict that benefits in a real-world patient population could be even more meaningful.

“Since the serum samples were collected at the end of NIPPV, HMW-HA–treated patients were on average sampled a day earlier than placebo-treated patients (because they were liberated from NIPPV a day earlier on average),” the investigators wrote. “Thus, HMW-HA treatment effects may have been underestimated in our study.”

According to Dr. Sandhaus, “The current report, while a relatively small single-center study, is well controlled and the results suggest that inhaled hyaluronan decreased time on noninvasive ventilation, decreased hospital stay duration, and decreased some mediators of inflammation.”

He also suggested that HMW-HA may have a role in the prophylactic setting.

“The limitations of this pilot study are appropriately explored by the authors but do not dampen the exciting possibility that this therapeutic approach may hold promise not only in severe exacerbations of COPD but potentially for the prevention of such exacerbations,” Dr. Sandhaus said.

Jerome O. Cantor, MD, FCCP, of St. John’s University, New York, who previously conducted a pilot study for using lower molecular weight hyaluronan in COPD and published a review on the subject, said that more studies are necessary.

“Further clinical trials are needed to better determine the role of hyaluronan as an adjunct to existing therapies for COPD exacerbations,” he said.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health. The investigators and Dr. Sandhaus declared no conflicts of interest. Dr. Cantor disclosed a relationship with MatRx Therapeutics.

(COPD), findings of a new study suggest.

HMW-HA was associated with a significantly shorter duration of noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation (NIPPV), lower systemic inflammatory markers, and lower measured peak airway pressure, compared with placebo, reported lead author Flavia Galdi, MD, of Campus Bio-Medico University Hospital, Rome, and colleagues.

“HMW-HA is a naturally occurring sugar that is abundant in the extracellular matrix, including in the lung,” the investigators wrote in Respiratory Research. “[It] has been used routinely, together with hypertonic saline, in cystic fibrosis patients [for several years] with no reported side effects; rather, it improves tolerability and decreases the need for bronchodilators in these patients.”

According to Robert A. Sandhaus, MD, PhD, FCCP, of National Jewish Health, Denver, the role of hyaluronan in lung disease was first recognized decades ago.

“Data stretching back into the 1970s has identified decreases in hyaluronan content in emphysematous lung tissue, protection of lung connective tissue from proteolysis by hyaluronan, and potential therapeutic roles for hyaluronan in a variety of disease, especially of the lungs,” he said in an interview.

For patients with COPD, treatment with HMW-HA may provide benefit by counteracting an imbalance in diseased lung tissue, wrote Dr. Galdi and colleagues.

“Emerging evidence suggests that imbalance between declining HMW-HA levels, and increasing smaller fragments of hyaluronan may contribute to chronic airway disease pathogenesis,” they wrote. “This has led to the hypothesis that exogenous supplementation of HMW-HA may restore hyaluronan homeostasis in favor of undegraded molecules, inhibit inflammation and loss of lung function, and ameliorate COPD progression.”

To test this hypothesis, the investigators screened 44 patients with a history of acute exacerbations of COPD necessitating NIPPV, ultimately excluding 3 patients because of heart failure. Following 1:1 randomization, 20 patients received HMW-HA while 21 received placebo, each twice daily, in conjunction with NIPPV and standard medical therapy. Treatment continued until NIPPV failure or liberation from NIPPV. Most patients received NIPPV in the hospital; however, home/chronic NIPPV was given to four patients in the placebo group and three patients in the HMW-HA group.

The primary outcome was duration of NIPPV. Secondary outcomes included markers of systemic inflammation associated with acute exacerbations of COPD and respiratory physiology parameters. Adverse events were also reported.

Results showed that patients treated with HMW-HA were liberated sooner from NIPPV than were those who received placebo (mean, 5.2 vs 6.4 days; P < .037). Similarly, patients in the HMW-HA group had significantly shorter hospital stay, on average, than those in the placebo group (mean, 7.2 vs 10.2 days; P = .039). Median values followed a similar pattern.

“These data suggest that HMW-HA shortened the duration of acute respiratory failure, need for NIPPV and, consequently, hospital length of stay in these patients,” the investigators wrote.

Secondary outcomes further supported these therapeutic benefits. Compared with placebo, HMW-HA was associated with significantly lower peak pressure and greater improvements in both pCO2/FiO2 ratio and inflammatory markers. No adverse events were reported.

Further analyses involving human bronchial epithelial cell cultures offered some mechanistic insight. Using micro-optical coherence tomography imaging, the investigators found that HMW-HA treatment was associated with “a prominent effect on mucociliary transport” in cell cultures derived from COPD patients and in healthy nonsmoker cell cultures exposed to cigarette smoke extract.

“Our study shows for the first time the therapeutic potential of an extracellular matrix molecule in acute exacerbation of human lung disease,” the investigators concluded, noting a “clinically meaningful salutary effect” on duration of NIPPV.

Dr. Galdi and colleagues went on to predict that benefits in a real-world patient population could be even more meaningful.

“Since the serum samples were collected at the end of NIPPV, HMW-HA–treated patients were on average sampled a day earlier than placebo-treated patients (because they were liberated from NIPPV a day earlier on average),” the investigators wrote. “Thus, HMW-HA treatment effects may have been underestimated in our study.”

According to Dr. Sandhaus, “The current report, while a relatively small single-center study, is well controlled and the results suggest that inhaled hyaluronan decreased time on noninvasive ventilation, decreased hospital stay duration, and decreased some mediators of inflammation.”

He also suggested that HMW-HA may have a role in the prophylactic setting.

“The limitations of this pilot study are appropriately explored by the authors but do not dampen the exciting possibility that this therapeutic approach may hold promise not only in severe exacerbations of COPD but potentially for the prevention of such exacerbations,” Dr. Sandhaus said.

Jerome O. Cantor, MD, FCCP, of St. John’s University, New York, who previously conducted a pilot study for using lower molecular weight hyaluronan in COPD and published a review on the subject, said that more studies are necessary.

“Further clinical trials are needed to better determine the role of hyaluronan as an adjunct to existing therapies for COPD exacerbations,” he said.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health. The investigators and Dr. Sandhaus declared no conflicts of interest. Dr. Cantor disclosed a relationship with MatRx Therapeutics.

FROM RESPIRATORY RESEARCH

New COPD mortality risk model includes imaging-derived variables

All-cause mortality in patients with COPD over 10 years of follow-up was accurately predicted by a newly developed model based on a point system incorporating imaging-derived variables.

Identifying risk factors is important to develop treatments and preventive strategies, but the role of imaging variables in COPD mortality among smokers has not been well studied, wrote investigator Matthew Strand, PhD, of National Jewish Health in Denver, and colleagues.

An established risk model is the body mass index–airflow Obstruction-Dyspnea-Exercise capacity (BODE) index, developed to predict mortality in COPD patients over a 4-year period. The investigators noted that while models such as BODE provide useful information about predictors of mortality in COPD, they were developed using participants in the Global initiative for obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) spirometry grades 1-4, and have been largely constructed without quantitative computed tomography (CT) imaging variables until recently.

“The BODE index was created as a simple point scoring system to predict risk of all-cause mortality within 4 years, and is based on FEV1 [forced expiratory volume at 1 second], [6-minute walk test], dyspnea and BMI, a subset of predictors we considered in our model,” the investigators noted. The new model includes data from pulmonary function tests and volumetric CT scans.

In a study published in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Diseases, the researchers identified 9,074 current and past smokers in the COPD Genetic Epidemiology study (COPDGene) for whom complete data were available. They developed a point system to determine mortality risk in current and former smokers after controlling for multiple risk factors. The average age of the study population was 60 years. All participants were current or former smokers with a smoking history of at least 10 pack-years.

Assessments of the study participants included a medical history, pre- and post-bronchodilator spirometry, a 6-minute walk distance test, and inspiratory and expiratory CT scans. The researchers analyzed mortality risk in the context of Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) classifications of patients in the sample.

Overall, the average 10-year mortality risk was 18% for women and 25% for men. Performance on the 6-minute walk test (distances less than 500 feet), FEV1 (less than 20), and older age (80 years and older) were the strongest predictors of mortality.

The model showed strong predictive accuracy, with an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve averaging 0.797 that was validated in an external cohort, the researchers said.

The study findings were limited by the observational design that does not allow for estimating the causal effects of such modifiable factors as smoking cessation, that might impact the walking test and FEV1 values, the researchers noted. In addition, the model did not allow for testing the effects of smoking vs. not smoking.

However, the model developed in the study “will allow physicians and patients to better understand factors affecting risk of an adverse event, some of which may be modifiable,” the researchers said. “The risk estimates can be used to target groups of individuals for future clinical trials, including those not currently classified as having COPD based on GOLD criteria,” they said.

The study was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and by the COPD Foundation through contributions to an industry advisory committee including AstraZeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Pfizer, Siemens, and Sunovion.

All-cause mortality in patients with COPD over 10 years of follow-up was accurately predicted by a newly developed model based on a point system incorporating imaging-derived variables.

Identifying risk factors is important to develop treatments and preventive strategies, but the role of imaging variables in COPD mortality among smokers has not been well studied, wrote investigator Matthew Strand, PhD, of National Jewish Health in Denver, and colleagues.

An established risk model is the body mass index–airflow Obstruction-Dyspnea-Exercise capacity (BODE) index, developed to predict mortality in COPD patients over a 4-year period. The investigators noted that while models such as BODE provide useful information about predictors of mortality in COPD, they were developed using participants in the Global initiative for obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) spirometry grades 1-4, and have been largely constructed without quantitative computed tomography (CT) imaging variables until recently.

“The BODE index was created as a simple point scoring system to predict risk of all-cause mortality within 4 years, and is based on FEV1 [forced expiratory volume at 1 second], [6-minute walk test], dyspnea and BMI, a subset of predictors we considered in our model,” the investigators noted. The new model includes data from pulmonary function tests and volumetric CT scans.

In a study published in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Diseases, the researchers identified 9,074 current and past smokers in the COPD Genetic Epidemiology study (COPDGene) for whom complete data were available. They developed a point system to determine mortality risk in current and former smokers after controlling for multiple risk factors. The average age of the study population was 60 years. All participants were current or former smokers with a smoking history of at least 10 pack-years.

Assessments of the study participants included a medical history, pre- and post-bronchodilator spirometry, a 6-minute walk distance test, and inspiratory and expiratory CT scans. The researchers analyzed mortality risk in the context of Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) classifications of patients in the sample.

Overall, the average 10-year mortality risk was 18% for women and 25% for men. Performance on the 6-minute walk test (distances less than 500 feet), FEV1 (less than 20), and older age (80 years and older) were the strongest predictors of mortality.

The model showed strong predictive accuracy, with an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve averaging 0.797 that was validated in an external cohort, the researchers said.

The study findings were limited by the observational design that does not allow for estimating the causal effects of such modifiable factors as smoking cessation, that might impact the walking test and FEV1 values, the researchers noted. In addition, the model did not allow for testing the effects of smoking vs. not smoking.

However, the model developed in the study “will allow physicians and patients to better understand factors affecting risk of an adverse event, some of which may be modifiable,” the researchers said. “The risk estimates can be used to target groups of individuals for future clinical trials, including those not currently classified as having COPD based on GOLD criteria,” they said.

The study was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and by the COPD Foundation through contributions to an industry advisory committee including AstraZeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Pfizer, Siemens, and Sunovion.

All-cause mortality in patients with COPD over 10 years of follow-up was accurately predicted by a newly developed model based on a point system incorporating imaging-derived variables.

Identifying risk factors is important to develop treatments and preventive strategies, but the role of imaging variables in COPD mortality among smokers has not been well studied, wrote investigator Matthew Strand, PhD, of National Jewish Health in Denver, and colleagues.

An established risk model is the body mass index–airflow Obstruction-Dyspnea-Exercise capacity (BODE) index, developed to predict mortality in COPD patients over a 4-year period. The investigators noted that while models such as BODE provide useful information about predictors of mortality in COPD, they were developed using participants in the Global initiative for obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) spirometry grades 1-4, and have been largely constructed without quantitative computed tomography (CT) imaging variables until recently.

“The BODE index was created as a simple point scoring system to predict risk of all-cause mortality within 4 years, and is based on FEV1 [forced expiratory volume at 1 second], [6-minute walk test], dyspnea and BMI, a subset of predictors we considered in our model,” the investigators noted. The new model includes data from pulmonary function tests and volumetric CT scans.

In a study published in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Diseases, the researchers identified 9,074 current and past smokers in the COPD Genetic Epidemiology study (COPDGene) for whom complete data were available. They developed a point system to determine mortality risk in current and former smokers after controlling for multiple risk factors. The average age of the study population was 60 years. All participants were current or former smokers with a smoking history of at least 10 pack-years.

Assessments of the study participants included a medical history, pre- and post-bronchodilator spirometry, a 6-minute walk distance test, and inspiratory and expiratory CT scans. The researchers analyzed mortality risk in the context of Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) classifications of patients in the sample.

Overall, the average 10-year mortality risk was 18% for women and 25% for men. Performance on the 6-minute walk test (distances less than 500 feet), FEV1 (less than 20), and older age (80 years and older) were the strongest predictors of mortality.

The model showed strong predictive accuracy, with an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve averaging 0.797 that was validated in an external cohort, the researchers said.

The study findings were limited by the observational design that does not allow for estimating the causal effects of such modifiable factors as smoking cessation, that might impact the walking test and FEV1 values, the researchers noted. In addition, the model did not allow for testing the effects of smoking vs. not smoking.

However, the model developed in the study “will allow physicians and patients to better understand factors affecting risk of an adverse event, some of which may be modifiable,” the researchers said. “The risk estimates can be used to target groups of individuals for future clinical trials, including those not currently classified as having COPD based on GOLD criteria,” they said.

The study was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and by the COPD Foundation through contributions to an industry advisory committee including AstraZeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Pfizer, Siemens, and Sunovion.

FROM CHRONIC OBSTRUCTIVE PULMONARY DISEASES

Lung disease raises mortality risk in older RA patients

Patients with rheumatoid arthritis–associated interstitial lung disease showed increases in overall mortality, respiratory mortality, and cancer mortality, compared with RA patients without interstitial lung disease, based on data from more than 500,000 patients in a nationwide cohort study.

RA-associated interstitial lung disease (RA-ILD) has been associated with worse survival rates as well as reduced quality of life, functional impairment, and increased health care use and costs, wrote Jeffrey A. Sparks, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and colleagues. However, data on the incidence and prevalence of RA-ILD have been inconsistent and large studies are lacking.

In a study published online in Rheumatology, the researchers identified 509,787 RA patients aged 65 years and older from Medicare claims data. The average age of the patients was 72.6 years, and 76.2% were women.

At baseline, 10,306 (2%) of the study population had RA-ILD, and 13,372 (2.7%) developed RA-ILD over an average of 3.8 years’ follow-up per person (total of 1,873,127 person-years of follow-up). The overall incidence of RA-ILD was 7.14 per 1,000 person-years.

Overall mortality was significantly higher among RA-ILD patients than in those with RA alone in a multivariate analysis (38.7% vs. 20.7%; hazard ratio, 1.66).

In addition, RA-ILD was associated with an increased risk of respiratory mortality (HR, 4.39) and cancer mortality (HR, 1.56), compared with RA without ILD. For these hazard regression analyses, the researchers used Fine and Gray subdistribution HRs “to handle competing risks of alternative causes of mortality. For example, the risk of respiratory mortality for patients with RA-ILD, compared with RA without ILD also accounted for the competing risk of cardiovascular, cancer, infection and other types of mortality.”

In another multivariate analysis, male gender, smoking, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder, and medication use (specifically biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, targeted synthetic DMARDs, and glucocorticoids) were independently associated with increased incident RA-ILD at baseline. However, “the associations of RA-related medications with incident RA-ILD risk should be interpreted with caution since they may be explained by unmeasured factors, including RA disease activity, severity, comorbidities, and prior or concomitant medication use,” the researchers noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the lack of data on disease activity, disease duration, disease severity, and RA-related autoantibodies, the researchers noted. However, the results support data from previous studies and were strengthened by the large sample size and data on demographics and health care use.

“Ours is the first to study the epidemiology and mortality outcomes of RA-ILD using a validated claims algorithm to identify RA and RA-ILD,” and “to quantify the mortality burden of RA-ILD and to identify a potentially novel association of RA-ILD with cancer mortality,” they noted.

The study was supported by an investigator-initiated grant from Bristol-Myers Squibb. Lead author Dr. Sparks disclosed support from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, the Rheumatology Research Foundation, the Brigham Research Institute, and the R. Bruce and Joan M. Mickey Research Scholar Fund. Dr. Sparks also disclosed serving as a consultant to Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Inova Diagnostics, Janssen, Optum, and Pfizer for work unrelated to the current study. Other authors reported research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb, involvement in a clinical trial funded by Genentech and Bristol-Myers Squibb, and receiving research support to Brigham and Women’s Hospital for other studies from AbbVie, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, and Vertex.

Patients with rheumatoid arthritis–associated interstitial lung disease showed increases in overall mortality, respiratory mortality, and cancer mortality, compared with RA patients without interstitial lung disease, based on data from more than 500,000 patients in a nationwide cohort study.

RA-associated interstitial lung disease (RA-ILD) has been associated with worse survival rates as well as reduced quality of life, functional impairment, and increased health care use and costs, wrote Jeffrey A. Sparks, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and colleagues. However, data on the incidence and prevalence of RA-ILD have been inconsistent and large studies are lacking.

In a study published online in Rheumatology, the researchers identified 509,787 RA patients aged 65 years and older from Medicare claims data. The average age of the patients was 72.6 years, and 76.2% were women.

At baseline, 10,306 (2%) of the study population had RA-ILD, and 13,372 (2.7%) developed RA-ILD over an average of 3.8 years’ follow-up per person (total of 1,873,127 person-years of follow-up). The overall incidence of RA-ILD was 7.14 per 1,000 person-years.

Overall mortality was significantly higher among RA-ILD patients than in those with RA alone in a multivariate analysis (38.7% vs. 20.7%; hazard ratio, 1.66).

In addition, RA-ILD was associated with an increased risk of respiratory mortality (HR, 4.39) and cancer mortality (HR, 1.56), compared with RA without ILD. For these hazard regression analyses, the researchers used Fine and Gray subdistribution HRs “to handle competing risks of alternative causes of mortality. For example, the risk of respiratory mortality for patients with RA-ILD, compared with RA without ILD also accounted for the competing risk of cardiovascular, cancer, infection and other types of mortality.”

In another multivariate analysis, male gender, smoking, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder, and medication use (specifically biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, targeted synthetic DMARDs, and glucocorticoids) were independently associated with increased incident RA-ILD at baseline. However, “the associations of RA-related medications with incident RA-ILD risk should be interpreted with caution since they may be explained by unmeasured factors, including RA disease activity, severity, comorbidities, and prior or concomitant medication use,” the researchers noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the lack of data on disease activity, disease duration, disease severity, and RA-related autoantibodies, the researchers noted. However, the results support data from previous studies and were strengthened by the large sample size and data on demographics and health care use.

“Ours is the first to study the epidemiology and mortality outcomes of RA-ILD using a validated claims algorithm to identify RA and RA-ILD,” and “to quantify the mortality burden of RA-ILD and to identify a potentially novel association of RA-ILD with cancer mortality,” they noted.

The study was supported by an investigator-initiated grant from Bristol-Myers Squibb. Lead author Dr. Sparks disclosed support from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, the Rheumatology Research Foundation, the Brigham Research Institute, and the R. Bruce and Joan M. Mickey Research Scholar Fund. Dr. Sparks also disclosed serving as a consultant to Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Inova Diagnostics, Janssen, Optum, and Pfizer for work unrelated to the current study. Other authors reported research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb, involvement in a clinical trial funded by Genentech and Bristol-Myers Squibb, and receiving research support to Brigham and Women’s Hospital for other studies from AbbVie, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, and Vertex.

Patients with rheumatoid arthritis–associated interstitial lung disease showed increases in overall mortality, respiratory mortality, and cancer mortality, compared with RA patients without interstitial lung disease, based on data from more than 500,000 patients in a nationwide cohort study.

RA-associated interstitial lung disease (RA-ILD) has been associated with worse survival rates as well as reduced quality of life, functional impairment, and increased health care use and costs, wrote Jeffrey A. Sparks, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and colleagues. However, data on the incidence and prevalence of RA-ILD have been inconsistent and large studies are lacking.

In a study published online in Rheumatology, the researchers identified 509,787 RA patients aged 65 years and older from Medicare claims data. The average age of the patients was 72.6 years, and 76.2% were women.

At baseline, 10,306 (2%) of the study population had RA-ILD, and 13,372 (2.7%) developed RA-ILD over an average of 3.8 years’ follow-up per person (total of 1,873,127 person-years of follow-up). The overall incidence of RA-ILD was 7.14 per 1,000 person-years.

Overall mortality was significantly higher among RA-ILD patients than in those with RA alone in a multivariate analysis (38.7% vs. 20.7%; hazard ratio, 1.66).

In addition, RA-ILD was associated with an increased risk of respiratory mortality (HR, 4.39) and cancer mortality (HR, 1.56), compared with RA without ILD. For these hazard regression analyses, the researchers used Fine and Gray subdistribution HRs “to handle competing risks of alternative causes of mortality. For example, the risk of respiratory mortality for patients with RA-ILD, compared with RA without ILD also accounted for the competing risk of cardiovascular, cancer, infection and other types of mortality.”

In another multivariate analysis, male gender, smoking, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder, and medication use (specifically biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, targeted synthetic DMARDs, and glucocorticoids) were independently associated with increased incident RA-ILD at baseline. However, “the associations of RA-related medications with incident RA-ILD risk should be interpreted with caution since they may be explained by unmeasured factors, including RA disease activity, severity, comorbidities, and prior or concomitant medication use,” the researchers noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the lack of data on disease activity, disease duration, disease severity, and RA-related autoantibodies, the researchers noted. However, the results support data from previous studies and were strengthened by the large sample size and data on demographics and health care use.

“Ours is the first to study the epidemiology and mortality outcomes of RA-ILD using a validated claims algorithm to identify RA and RA-ILD,” and “to quantify the mortality burden of RA-ILD and to identify a potentially novel association of RA-ILD with cancer mortality,” they noted.

The study was supported by an investigator-initiated grant from Bristol-Myers Squibb. Lead author Dr. Sparks disclosed support from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, the Rheumatology Research Foundation, the Brigham Research Institute, and the R. Bruce and Joan M. Mickey Research Scholar Fund. Dr. Sparks also disclosed serving as a consultant to Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Inova Diagnostics, Janssen, Optum, and Pfizer for work unrelated to the current study. Other authors reported research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb, involvement in a clinical trial funded by Genentech and Bristol-Myers Squibb, and receiving research support to Brigham and Women’s Hospital for other studies from AbbVie, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, and Vertex.

FROM RHEUMATOLOGY

Asthma-COPD overlap: Patients have high disease burden

Patients with asthma–chronic obstructive pulmonary disease overlap (ACO) experienced a higher burden of disease than patients with either asthma or COPD alone, a recent study has found.

Approximately 20% of chronic obstructive airway disease cases are ACO, but data on these patients are limited, as they are often excluded from clinical trials, wrote Sarah A. Hiles, MD, of the University of Newcastle (Australia) and colleagues.

“Comparing the burden of eosinophilic ACO, eosinophilic severe asthma, and eosinophilic COPD may also help contextualize findings from phenotype-targeted treatments in different diagnostic groups, such as the limited success of anti-IL [interleukin]–5 monoclonal antibodies as therapy in eosinophilic COPD,” they said.

In a cross-sectional, observational study published in Respirology the researchers recruited patients aged 18 years and older with a confirmed diagnosis of COPD only (153) severe asthma only (64), or ACO (106). Patients were assessed for demographic and clinical factors including health-related quality of life, past-year exacerbation, and other indicators of disease burden. In addition, patients were identified as having eosinophilic airway disease based on a blood eosinophil count of at least 0.3x109/L.