User login

FDA approves new antibiotic for HABP/VABP treatment

in people aged 18 years and older.

Approval for Recarbrio was based on results of a randomized, controlled clinical trial of 535 hospitalized adults with hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonia who received either Recarbrio or piperacillin-tazobactam. After 28 days, 16% of patients who received Recarbrio and 21% of patients who received piperacillin-tazobactam had died.

The most common adverse events associated with Recarbrio are increased alanine aminotransferase/ aspartate aminotransferase, anemia, diarrhea, hypokalemia, and hyponatremia. Recarbrio was previously approved by the FDA to treat patients with complicated urinary tract infections and complicated intra-abdominal infections who have limited or no alternative treatment options, according to an FDA press release.

“As a public health agency, the FDA addresses the threat of antimicrobial-resistant infections by facilitating the development of safe and effective new treatments. These efforts provide more options to fight serious bacterial infections and get new, safe and effective therapies to patients as soon as possible,” said Sumathi Nambiar, MD, MPH, director of the division of anti-infectives within the office of infectious disease at the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

in people aged 18 years and older.

Approval for Recarbrio was based on results of a randomized, controlled clinical trial of 535 hospitalized adults with hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonia who received either Recarbrio or piperacillin-tazobactam. After 28 days, 16% of patients who received Recarbrio and 21% of patients who received piperacillin-tazobactam had died.

The most common adverse events associated with Recarbrio are increased alanine aminotransferase/ aspartate aminotransferase, anemia, diarrhea, hypokalemia, and hyponatremia. Recarbrio was previously approved by the FDA to treat patients with complicated urinary tract infections and complicated intra-abdominal infections who have limited or no alternative treatment options, according to an FDA press release.

“As a public health agency, the FDA addresses the threat of antimicrobial-resistant infections by facilitating the development of safe and effective new treatments. These efforts provide more options to fight serious bacterial infections and get new, safe and effective therapies to patients as soon as possible,” said Sumathi Nambiar, MD, MPH, director of the division of anti-infectives within the office of infectious disease at the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

in people aged 18 years and older.

Approval for Recarbrio was based on results of a randomized, controlled clinical trial of 535 hospitalized adults with hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonia who received either Recarbrio or piperacillin-tazobactam. After 28 days, 16% of patients who received Recarbrio and 21% of patients who received piperacillin-tazobactam had died.

The most common adverse events associated with Recarbrio are increased alanine aminotransferase/ aspartate aminotransferase, anemia, diarrhea, hypokalemia, and hyponatremia. Recarbrio was previously approved by the FDA to treat patients with complicated urinary tract infections and complicated intra-abdominal infections who have limited or no alternative treatment options, according to an FDA press release.

“As a public health agency, the FDA addresses the threat of antimicrobial-resistant infections by facilitating the development of safe and effective new treatments. These efforts provide more options to fight serious bacterial infections and get new, safe and effective therapies to patients as soon as possible,” said Sumathi Nambiar, MD, MPH, director of the division of anti-infectives within the office of infectious disease at the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

Pulmonology, critical care earnings on the upswing before pandemic

As the COVID spring progresses, the days before the pandemic may seem like a dream: Practices were open, waiting rooms were full of unmasked people, and PPE was plentiful.

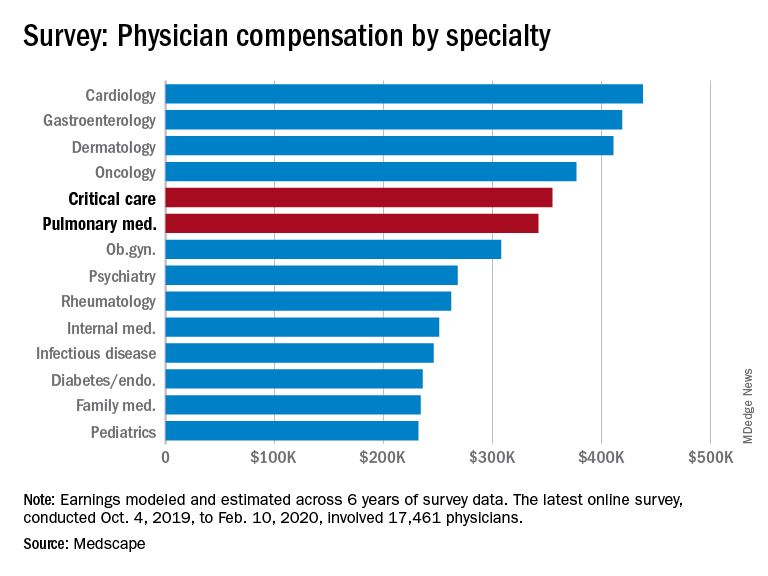

Medscape’s latest physician survey, conducted from Oct. 4, 2019, to Feb. 10, 2020, shows what pulmonology and critical care looked like just before the coronavirus arrived.

Back then, earnings were up. Average compensation reported by pulmonologists was up from $331,000 in 2019 to $342,000 this year, a 3.3% increase. For intensivists, earnings rose from $349,000 to $355,000, or 1.7%. Average income for all specialists was $346,000 in this year’s survey – 1.5% higher than the $341,000 earned in 2019, Medscape reported.

Prospects for the next year, however, are grim. “We found out that we have a 10% salary decrease effective May 2 to Dec. 25. Our bonus will be based on clinical productivity, and since our numbers are down, that is likely to go away,” a pediatric emergency physician told Medscape.

One problem area for intensivists, even before the pandemic, was paperwork and administration. Of the 26 specialties for which data are available, critical care was highest for amount of time spent on paperwork, at 19.1 hours per week. Those in pulmonary medicine spent 15.6 hours per week, which also happened to be the average for all specialists, the survey data show.

Both specialties also ranked high in denied/resubmitted claims: Intensivists were fourth among the 27 types of specialists with reliable data, with 20% of claims denied, and pulmonologists were tied for eighth at 18%, Medscape said.

Only 50% of pulmonologists surveyed said that they were being fairly compensated, putting them 26th among the 29 specialties on that list. Those in critical care medicine were 13th, with a 59% positive response, Medscape reported.

In the end, though, it looks like you can’t keep a good pulmonologist or intensivist down. When asked if they would choose medicine again, 83% of pulmonologists said yes, just one percentage point behind a three-way tie for first. Intensivists were just a little further down the list at 81%, according to the survey.

The respondents were Medscape members who had been invited to participate. The sample size was 17,461 physicians, and compensation was modeled and estimated based on a range of variables across 6 years of survey data. The sampling error was ±0.74%.

As the COVID spring progresses, the days before the pandemic may seem like a dream: Practices were open, waiting rooms were full of unmasked people, and PPE was plentiful.

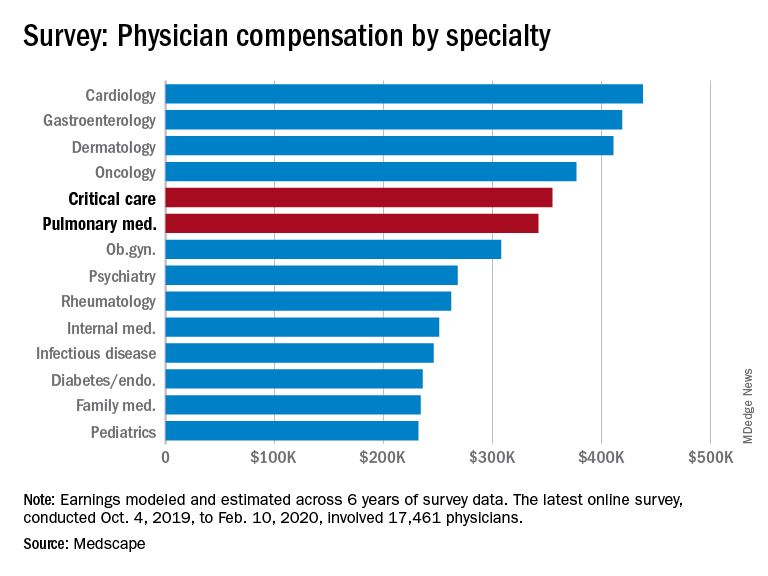

Medscape’s latest physician survey, conducted from Oct. 4, 2019, to Feb. 10, 2020, shows what pulmonology and critical care looked like just before the coronavirus arrived.

Back then, earnings were up. Average compensation reported by pulmonologists was up from $331,000 in 2019 to $342,000 this year, a 3.3% increase. For intensivists, earnings rose from $349,000 to $355,000, or 1.7%. Average income for all specialists was $346,000 in this year’s survey – 1.5% higher than the $341,000 earned in 2019, Medscape reported.

Prospects for the next year, however, are grim. “We found out that we have a 10% salary decrease effective May 2 to Dec. 25. Our bonus will be based on clinical productivity, and since our numbers are down, that is likely to go away,” a pediatric emergency physician told Medscape.

One problem area for intensivists, even before the pandemic, was paperwork and administration. Of the 26 specialties for which data are available, critical care was highest for amount of time spent on paperwork, at 19.1 hours per week. Those in pulmonary medicine spent 15.6 hours per week, which also happened to be the average for all specialists, the survey data show.

Both specialties also ranked high in denied/resubmitted claims: Intensivists were fourth among the 27 types of specialists with reliable data, with 20% of claims denied, and pulmonologists were tied for eighth at 18%, Medscape said.

Only 50% of pulmonologists surveyed said that they were being fairly compensated, putting them 26th among the 29 specialties on that list. Those in critical care medicine were 13th, with a 59% positive response, Medscape reported.

In the end, though, it looks like you can’t keep a good pulmonologist or intensivist down. When asked if they would choose medicine again, 83% of pulmonologists said yes, just one percentage point behind a three-way tie for first. Intensivists were just a little further down the list at 81%, according to the survey.

The respondents were Medscape members who had been invited to participate. The sample size was 17,461 physicians, and compensation was modeled and estimated based on a range of variables across 6 years of survey data. The sampling error was ±0.74%.

As the COVID spring progresses, the days before the pandemic may seem like a dream: Practices were open, waiting rooms were full of unmasked people, and PPE was plentiful.

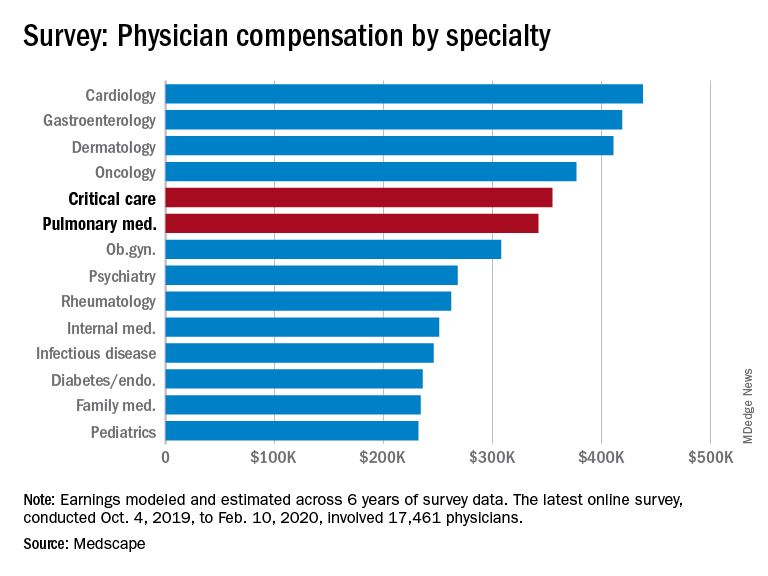

Medscape’s latest physician survey, conducted from Oct. 4, 2019, to Feb. 10, 2020, shows what pulmonology and critical care looked like just before the coronavirus arrived.

Back then, earnings were up. Average compensation reported by pulmonologists was up from $331,000 in 2019 to $342,000 this year, a 3.3% increase. For intensivists, earnings rose from $349,000 to $355,000, or 1.7%. Average income for all specialists was $346,000 in this year’s survey – 1.5% higher than the $341,000 earned in 2019, Medscape reported.

Prospects for the next year, however, are grim. “We found out that we have a 10% salary decrease effective May 2 to Dec. 25. Our bonus will be based on clinical productivity, and since our numbers are down, that is likely to go away,” a pediatric emergency physician told Medscape.

One problem area for intensivists, even before the pandemic, was paperwork and administration. Of the 26 specialties for which data are available, critical care was highest for amount of time spent on paperwork, at 19.1 hours per week. Those in pulmonary medicine spent 15.6 hours per week, which also happened to be the average for all specialists, the survey data show.

Both specialties also ranked high in denied/resubmitted claims: Intensivists were fourth among the 27 types of specialists with reliable data, with 20% of claims denied, and pulmonologists were tied for eighth at 18%, Medscape said.

Only 50% of pulmonologists surveyed said that they were being fairly compensated, putting them 26th among the 29 specialties on that list. Those in critical care medicine were 13th, with a 59% positive response, Medscape reported.

In the end, though, it looks like you can’t keep a good pulmonologist or intensivist down. When asked if they would choose medicine again, 83% of pulmonologists said yes, just one percentage point behind a three-way tie for first. Intensivists were just a little further down the list at 81%, according to the survey.

The respondents were Medscape members who had been invited to participate. The sample size was 17,461 physicians, and compensation was modeled and estimated based on a range of variables across 6 years of survey data. The sampling error was ±0.74%.

Vitamin D: A low-hanging fruit in COVID-19?

Mainstream media outlets have been flooded recently with reports speculating on what role, if any, vitamin D may play in reducing the severity of COVID-19 infection.

as well as mortality, with the further suggestion of an effect of vitamin D on the immune response to infection.

But other studies question such a link, including any association between vitamin D concentration and differences in COVID-19 severity by ethnic group.

And while some researchers and clinicians believe people should get tested to see if they have adequate vitamin D levels during this pandemic – in particular frontline health care workers – most doctors say the best way to ensure that people have adequate levels of vitamin D during COVID-19 is to simply take supplements at currently recommended levels.

This is especially important given the fact that, during “lockdown” scenarios, many people are spending more time than usual indoors.

Clifford Rosen, MD, senior scientist at Maine Medical Center’s Research Institute in Scarborough, has been researching vitamin D for 25 years.

“There’s no randomized, controlled trial for sure, and that’s the gold standard,” he said in an interview, and “the observational data are so confounded, it’s difficult to know.”

Whether from diet or supplementation, having adequate vitamin D is important, especially for those at the highest risk of COVID-19, he said. Still, robust data supporting a role of vitamin D in prevention of COVID-19, or as any kind of “therapy” for the infection, are currently lacking.

Rose Anne Kenny, MD, professor of medical gerontology at Trinity College Dublin, recently coauthored an article detailing an inverse association between vitamin D levels and mortality from COVID-19 across countries in Europe.

“At no stage are any of us saying this is a given, but there’s a probability that [vitamin D] – a low-hanging fruit – is a contributory factor and we can do something about it now,” she said in an interview.

Dr. Kenny is calling for the Irish government to formally change their recommendations. “We call on the Irish government to update guidelines as a matter of urgency and encourage all adults to take [vitamin D] supplements during the COVID-19 crisis.” Northern Ireland, part of the United Kingdom, also has not yet made this recommendation, she said.

Meanwhile, Harpreet S. Bajaj, MD, MPH, a practicing endocrinologist from Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto, said: “Vitamin D could have any of three potential roles in risk for COVID-19 and/or its severity: no role, simply a marker, or a causal factor.”

Dr. Bajaj said – as did Dr. Rosen and Dr. Kenny – that randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) are sorely needed to help ascertain whether there is a specific role of vitamin D.

“Until then, we should continue to follow established public health recommendations for vitamin D supplementation, in addition to following COVID-19 prevention guidance and evolving guidelines for COVID-19 treatment.”

What is the role of vitamin D fortification?

In their study in the Irish Medical Journal, Dr. Kenny and colleagues noted that, in Europe, despite being sunny, Spain and Northern Italy had high rates of vitamin D deficiency and have experienced some of the highest COVID-19 infection and mortality rates in the world.

But these countries do not formally fortify foods or recommend supplementation with vitamin D.

Conversely, the northern countries of Norway, Finland, and Sweden had higher vitamin D levels despite less UVB sunlight exposure, as a result of common supplementation and formal fortification of foods. These Nordic countries also had lower levels of COVID-19 infection and mortality.

Overall, the correlation between low vitamin D levels and mortality from COVID-19 was statistically significant (P = .046), the investigators reported.

“Optimizing vitamin D status to recommendations by national and international public health agencies will certainly have ... potential benefits for COVID-19,” they concluded.

“We’re not saying there aren’t any confounders. This can absolutely be the case, but this [finding] needs to be in the mix of evidence,” Dr. Kenny said.

Dr. Kenny also noted that countries in the Southern Hemisphere have been seeing a relatively low mortality from COVID-19, although she acknowledged the explanation could be that the virus spread later to those countries.

Dr. Rosen has doubts on this issue, too.

“Sure, vitamin D supplementation may have worked for [Nordic countries], their COVID-19 has been better controlled, but there’s no causality here; there’s another step to actually prove this. Other factors might be at play,” he said.

“Look at Brazil, it’s at the equator but the disease is devastating the country. Right now, I just don’t believe it.”

Does vitamin D have a role to play in immune modulation?

One theory currently circulating is that, if vitamin D does have any role to play in modulating response to COVID-19, this may be via a blunting of the immune system reaction to the virus.

In a recent preprint study, Ali Daneshkhah, PhD, and colleagues from Northwestern University, Chicago, interrogated hospital data from China, France, Germany, Italy, Iran, South Korea, Spain, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

Specifically, the risk of severe COVID-19 cases among patients with severe vitamin D deficiency was 17.3%, whereas the equivalent figure for patients with normal vitamin D levels was 14.6% (a reduction of 15.6%).

“This potential effect may be attributed to vitamin D’s ability to suppress the adaptive immune system, regulating cytokine levels and thereby reducing the risk of developing severe COVID-19,” said the researchers.

Likewise, JoAnn E. Manson, MD, chief of the division of preventive medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, in a recent commentary, noted evidence from an observational study from three South Asian hospitals, in which the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency was much higher among those with severe COVID-19 illness compared with those with mild illness.

“We also know that vitamin D has an immune-modulating effect and can lower inflammation, and this may be relevant to the respiratory response during COVID-19 and the cytokine storm that’s been demonstrated,” she noted.

Dr. Rosen said he is willing to listen on the issue of a potential role of vitamin D in immune modulation.

“I’ve been a huge skeptic from the get-go, and loudly criticized the data for doing nothing. I am surprised at myself for saying there might be some effect,” he said.

“Clearly most people don’t get this [cytokine storm] but of those that do, it’s unclear why they do. Maybe if you are vitamin D sufficient, it might have some impact down the road on your response to an infection,” Dr. Rosen said. “Vitamin D may induce proteins important in modulating the function of macrophages of the immune system.”

Ethnic minorities disproportionately affected

It is also well recognized that COVID-19 disproportionately affects black and Asian minority ethnic individuals.

But on the issue of vitamin D in this context, one recent peer-reviewed study using UK Biobank data found no evidence to support a potential role for vitamin D concentration to explain susceptibility to COVID-19 infection either overall or in explaining differences between ethnic groups.

“Vitamin D is unlikely to be the underlying mechanism for the higher risk observed in black and minority ethnic individuals, and vitamin D supplements are unlikely to provide an effective intervention,” Claire Hastie, PhD, of the University of Glasgow and colleagues concluded.

But this hasn’t stopped two endocrinologists from appealing to members of the British Association of Physicians of Indian Origin (BAPIO) to get their vitamin D levels tested.

The black and Asian minority ethnic population, “especially frontline staff, should get their Vitamin D3 levels checked and get appropriate replacement as required,” said Parag Singhal, MD, of Weston General Hospital, Weston-Super-Mare, England, and David C. Anderson, a retired endocrinologist, said in a letter to BAPIO members.

Indeed, they suggested a booster dose of 100,000 IU as a one-off for black and Asian minority ethnic health care staff that should raise vitamin D levels for 2-3 months. They referred to a systematic review that concludes that “single vitamin D3 doses ≥300,000 IU are most effective at improving vitamin D status ... for up to 3 months”.

Commenting on the idea, Dr. Rosen remarked that, in general, the high-dose 50,000-500,000 IU given as a one-off does not confer any greater benefit than a single dose of 1,000 IU per day, except that the blood levels go up quicker and higher.

“Really there is no evidence that getting to super-high levels of vitamin D confer a greater benefit than normal levels,” he said. “So if health care workers suspect vitamin D deficiency, daily doses of 1,000 IU seem reasonable; even if they miss doses, the blood levels are relatively stable.”

On the specific question of vitamin D needs in ethnic minorities, Dr. Rosen said while such individuals do have lower serum levels of vitamin D, the issue is whether there are meaningful clinical implications related to this.

“The real question is whether [ethnic minority individuals] have physiologically adapted for this in other ways because these low levels have been so for thousands of years. In fact, African Americans have lower vitamin D levels but they absolutely have better bones than [whites],” he pointed out.

Testing and governmental recommendations during COVID-19

The U.S. National Institutes of Health in general advises 400 IU to 800 IU per day intake of vitamin D, depending on age, with those over 70 years requiring the highest daily dose. This will result in blood levels that are sufficient to maintain bone health and normal calcium metabolism in healthy people. There are no additional recommendations specific to vitamin D intake during the COVID-19 pandemic, however.

And Dr. Rosen pointed out that there is no evidence for mass screening of vitamin D levels among the U.S. population.

“U.S. public health guidance was pre-COVID, and I think high-risk individuals might want to think about their levels; for example, someone with inflammatory bowel disease or liver or pancreatic disease. These people are at higher risk anyway, and it could be because their vitamin D is low,” he said.

“Skip the test and ensure you are getting adequate levels of vitamin D whether via diet or supplement [400-800 IU per day],” he suggested. “It won’t harm.”

The U.K.’s Public Health England (PHE) clarified its advice on vitamin D supplementation during COVID-19. Alison Tedstone, PhD, chief nutritionist at PHE, said: “Many people are spending more time indoors and may not get all the vitamin D they need from sunlight. To protect their bone and muscle health, they should consider taking a daily supplement containing 10 micrograms [400 IU] of vitamin D.”

However, “there is no sufficient evidence to support recommending Vitamin D for reducing the risk of COVID-19,” she stressed.

Dr. Bajaj is on the advisory board of Medscape Diabetes & Endocrinology. He has ties with Amgen, AstraZeneca Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, Eli Lilly,Valeant, Canadian Collaborative Research Network, CMS Knowledge Translation, Diabetes Canada Scientific Group, LMC Healthcare,mdBriefCase,Medscape, andMeducom. Dr. Kenny, Dr. Rosen, and Dr. Singhal have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Mainstream media outlets have been flooded recently with reports speculating on what role, if any, vitamin D may play in reducing the severity of COVID-19 infection.

as well as mortality, with the further suggestion of an effect of vitamin D on the immune response to infection.

But other studies question such a link, including any association between vitamin D concentration and differences in COVID-19 severity by ethnic group.

And while some researchers and clinicians believe people should get tested to see if they have adequate vitamin D levels during this pandemic – in particular frontline health care workers – most doctors say the best way to ensure that people have adequate levels of vitamin D during COVID-19 is to simply take supplements at currently recommended levels.

This is especially important given the fact that, during “lockdown” scenarios, many people are spending more time than usual indoors.

Clifford Rosen, MD, senior scientist at Maine Medical Center’s Research Institute in Scarborough, has been researching vitamin D for 25 years.

“There’s no randomized, controlled trial for sure, and that’s the gold standard,” he said in an interview, and “the observational data are so confounded, it’s difficult to know.”

Whether from diet or supplementation, having adequate vitamin D is important, especially for those at the highest risk of COVID-19, he said. Still, robust data supporting a role of vitamin D in prevention of COVID-19, or as any kind of “therapy” for the infection, are currently lacking.

Rose Anne Kenny, MD, professor of medical gerontology at Trinity College Dublin, recently coauthored an article detailing an inverse association between vitamin D levels and mortality from COVID-19 across countries in Europe.

“At no stage are any of us saying this is a given, but there’s a probability that [vitamin D] – a low-hanging fruit – is a contributory factor and we can do something about it now,” she said in an interview.

Dr. Kenny is calling for the Irish government to formally change their recommendations. “We call on the Irish government to update guidelines as a matter of urgency and encourage all adults to take [vitamin D] supplements during the COVID-19 crisis.” Northern Ireland, part of the United Kingdom, also has not yet made this recommendation, she said.

Meanwhile, Harpreet S. Bajaj, MD, MPH, a practicing endocrinologist from Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto, said: “Vitamin D could have any of three potential roles in risk for COVID-19 and/or its severity: no role, simply a marker, or a causal factor.”

Dr. Bajaj said – as did Dr. Rosen and Dr. Kenny – that randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) are sorely needed to help ascertain whether there is a specific role of vitamin D.

“Until then, we should continue to follow established public health recommendations for vitamin D supplementation, in addition to following COVID-19 prevention guidance and evolving guidelines for COVID-19 treatment.”

What is the role of vitamin D fortification?

In their study in the Irish Medical Journal, Dr. Kenny and colleagues noted that, in Europe, despite being sunny, Spain and Northern Italy had high rates of vitamin D deficiency and have experienced some of the highest COVID-19 infection and mortality rates in the world.

But these countries do not formally fortify foods or recommend supplementation with vitamin D.

Conversely, the northern countries of Norway, Finland, and Sweden had higher vitamin D levels despite less UVB sunlight exposure, as a result of common supplementation and formal fortification of foods. These Nordic countries also had lower levels of COVID-19 infection and mortality.

Overall, the correlation between low vitamin D levels and mortality from COVID-19 was statistically significant (P = .046), the investigators reported.

“Optimizing vitamin D status to recommendations by national and international public health agencies will certainly have ... potential benefits for COVID-19,” they concluded.

“We’re not saying there aren’t any confounders. This can absolutely be the case, but this [finding] needs to be in the mix of evidence,” Dr. Kenny said.

Dr. Kenny also noted that countries in the Southern Hemisphere have been seeing a relatively low mortality from COVID-19, although she acknowledged the explanation could be that the virus spread later to those countries.

Dr. Rosen has doubts on this issue, too.

“Sure, vitamin D supplementation may have worked for [Nordic countries], their COVID-19 has been better controlled, but there’s no causality here; there’s another step to actually prove this. Other factors might be at play,” he said.

“Look at Brazil, it’s at the equator but the disease is devastating the country. Right now, I just don’t believe it.”

Does vitamin D have a role to play in immune modulation?

One theory currently circulating is that, if vitamin D does have any role to play in modulating response to COVID-19, this may be via a blunting of the immune system reaction to the virus.

In a recent preprint study, Ali Daneshkhah, PhD, and colleagues from Northwestern University, Chicago, interrogated hospital data from China, France, Germany, Italy, Iran, South Korea, Spain, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

Specifically, the risk of severe COVID-19 cases among patients with severe vitamin D deficiency was 17.3%, whereas the equivalent figure for patients with normal vitamin D levels was 14.6% (a reduction of 15.6%).

“This potential effect may be attributed to vitamin D’s ability to suppress the adaptive immune system, regulating cytokine levels and thereby reducing the risk of developing severe COVID-19,” said the researchers.

Likewise, JoAnn E. Manson, MD, chief of the division of preventive medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, in a recent commentary, noted evidence from an observational study from three South Asian hospitals, in which the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency was much higher among those with severe COVID-19 illness compared with those with mild illness.

“We also know that vitamin D has an immune-modulating effect and can lower inflammation, and this may be relevant to the respiratory response during COVID-19 and the cytokine storm that’s been demonstrated,” she noted.

Dr. Rosen said he is willing to listen on the issue of a potential role of vitamin D in immune modulation.

“I’ve been a huge skeptic from the get-go, and loudly criticized the data for doing nothing. I am surprised at myself for saying there might be some effect,” he said.

“Clearly most people don’t get this [cytokine storm] but of those that do, it’s unclear why they do. Maybe if you are vitamin D sufficient, it might have some impact down the road on your response to an infection,” Dr. Rosen said. “Vitamin D may induce proteins important in modulating the function of macrophages of the immune system.”

Ethnic minorities disproportionately affected

It is also well recognized that COVID-19 disproportionately affects black and Asian minority ethnic individuals.

But on the issue of vitamin D in this context, one recent peer-reviewed study using UK Biobank data found no evidence to support a potential role for vitamin D concentration to explain susceptibility to COVID-19 infection either overall or in explaining differences between ethnic groups.

“Vitamin D is unlikely to be the underlying mechanism for the higher risk observed in black and minority ethnic individuals, and vitamin D supplements are unlikely to provide an effective intervention,” Claire Hastie, PhD, of the University of Glasgow and colleagues concluded.

But this hasn’t stopped two endocrinologists from appealing to members of the British Association of Physicians of Indian Origin (BAPIO) to get their vitamin D levels tested.

The black and Asian minority ethnic population, “especially frontline staff, should get their Vitamin D3 levels checked and get appropriate replacement as required,” said Parag Singhal, MD, of Weston General Hospital, Weston-Super-Mare, England, and David C. Anderson, a retired endocrinologist, said in a letter to BAPIO members.

Indeed, they suggested a booster dose of 100,000 IU as a one-off for black and Asian minority ethnic health care staff that should raise vitamin D levels for 2-3 months. They referred to a systematic review that concludes that “single vitamin D3 doses ≥300,000 IU are most effective at improving vitamin D status ... for up to 3 months”.

Commenting on the idea, Dr. Rosen remarked that, in general, the high-dose 50,000-500,000 IU given as a one-off does not confer any greater benefit than a single dose of 1,000 IU per day, except that the blood levels go up quicker and higher.

“Really there is no evidence that getting to super-high levels of vitamin D confer a greater benefit than normal levels,” he said. “So if health care workers suspect vitamin D deficiency, daily doses of 1,000 IU seem reasonable; even if they miss doses, the blood levels are relatively stable.”

On the specific question of vitamin D needs in ethnic minorities, Dr. Rosen said while such individuals do have lower serum levels of vitamin D, the issue is whether there are meaningful clinical implications related to this.

“The real question is whether [ethnic minority individuals] have physiologically adapted for this in other ways because these low levels have been so for thousands of years. In fact, African Americans have lower vitamin D levels but they absolutely have better bones than [whites],” he pointed out.

Testing and governmental recommendations during COVID-19

The U.S. National Institutes of Health in general advises 400 IU to 800 IU per day intake of vitamin D, depending on age, with those over 70 years requiring the highest daily dose. This will result in blood levels that are sufficient to maintain bone health and normal calcium metabolism in healthy people. There are no additional recommendations specific to vitamin D intake during the COVID-19 pandemic, however.

And Dr. Rosen pointed out that there is no evidence for mass screening of vitamin D levels among the U.S. population.

“U.S. public health guidance was pre-COVID, and I think high-risk individuals might want to think about their levels; for example, someone with inflammatory bowel disease or liver or pancreatic disease. These people are at higher risk anyway, and it could be because their vitamin D is low,” he said.

“Skip the test and ensure you are getting adequate levels of vitamin D whether via diet or supplement [400-800 IU per day],” he suggested. “It won’t harm.”

The U.K.’s Public Health England (PHE) clarified its advice on vitamin D supplementation during COVID-19. Alison Tedstone, PhD, chief nutritionist at PHE, said: “Many people are spending more time indoors and may not get all the vitamin D they need from sunlight. To protect their bone and muscle health, they should consider taking a daily supplement containing 10 micrograms [400 IU] of vitamin D.”

However, “there is no sufficient evidence to support recommending Vitamin D for reducing the risk of COVID-19,” she stressed.

Dr. Bajaj is on the advisory board of Medscape Diabetes & Endocrinology. He has ties with Amgen, AstraZeneca Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, Eli Lilly,Valeant, Canadian Collaborative Research Network, CMS Knowledge Translation, Diabetes Canada Scientific Group, LMC Healthcare,mdBriefCase,Medscape, andMeducom. Dr. Kenny, Dr. Rosen, and Dr. Singhal have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Mainstream media outlets have been flooded recently with reports speculating on what role, if any, vitamin D may play in reducing the severity of COVID-19 infection.

as well as mortality, with the further suggestion of an effect of vitamin D on the immune response to infection.

But other studies question such a link, including any association between vitamin D concentration and differences in COVID-19 severity by ethnic group.

And while some researchers and clinicians believe people should get tested to see if they have adequate vitamin D levels during this pandemic – in particular frontline health care workers – most doctors say the best way to ensure that people have adequate levels of vitamin D during COVID-19 is to simply take supplements at currently recommended levels.

This is especially important given the fact that, during “lockdown” scenarios, many people are spending more time than usual indoors.

Clifford Rosen, MD, senior scientist at Maine Medical Center’s Research Institute in Scarborough, has been researching vitamin D for 25 years.

“There’s no randomized, controlled trial for sure, and that’s the gold standard,” he said in an interview, and “the observational data are so confounded, it’s difficult to know.”

Whether from diet or supplementation, having adequate vitamin D is important, especially for those at the highest risk of COVID-19, he said. Still, robust data supporting a role of vitamin D in prevention of COVID-19, or as any kind of “therapy” for the infection, are currently lacking.

Rose Anne Kenny, MD, professor of medical gerontology at Trinity College Dublin, recently coauthored an article detailing an inverse association between vitamin D levels and mortality from COVID-19 across countries in Europe.

“At no stage are any of us saying this is a given, but there’s a probability that [vitamin D] – a low-hanging fruit – is a contributory factor and we can do something about it now,” she said in an interview.

Dr. Kenny is calling for the Irish government to formally change their recommendations. “We call on the Irish government to update guidelines as a matter of urgency and encourage all adults to take [vitamin D] supplements during the COVID-19 crisis.” Northern Ireland, part of the United Kingdom, also has not yet made this recommendation, she said.

Meanwhile, Harpreet S. Bajaj, MD, MPH, a practicing endocrinologist from Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto, said: “Vitamin D could have any of three potential roles in risk for COVID-19 and/or its severity: no role, simply a marker, or a causal factor.”

Dr. Bajaj said – as did Dr. Rosen and Dr. Kenny – that randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) are sorely needed to help ascertain whether there is a specific role of vitamin D.

“Until then, we should continue to follow established public health recommendations for vitamin D supplementation, in addition to following COVID-19 prevention guidance and evolving guidelines for COVID-19 treatment.”

What is the role of vitamin D fortification?

In their study in the Irish Medical Journal, Dr. Kenny and colleagues noted that, in Europe, despite being sunny, Spain and Northern Italy had high rates of vitamin D deficiency and have experienced some of the highest COVID-19 infection and mortality rates in the world.

But these countries do not formally fortify foods or recommend supplementation with vitamin D.

Conversely, the northern countries of Norway, Finland, and Sweden had higher vitamin D levels despite less UVB sunlight exposure, as a result of common supplementation and formal fortification of foods. These Nordic countries also had lower levels of COVID-19 infection and mortality.

Overall, the correlation between low vitamin D levels and mortality from COVID-19 was statistically significant (P = .046), the investigators reported.

“Optimizing vitamin D status to recommendations by national and international public health agencies will certainly have ... potential benefits for COVID-19,” they concluded.

“We’re not saying there aren’t any confounders. This can absolutely be the case, but this [finding] needs to be in the mix of evidence,” Dr. Kenny said.

Dr. Kenny also noted that countries in the Southern Hemisphere have been seeing a relatively low mortality from COVID-19, although she acknowledged the explanation could be that the virus spread later to those countries.

Dr. Rosen has doubts on this issue, too.

“Sure, vitamin D supplementation may have worked for [Nordic countries], their COVID-19 has been better controlled, but there’s no causality here; there’s another step to actually prove this. Other factors might be at play,” he said.

“Look at Brazil, it’s at the equator but the disease is devastating the country. Right now, I just don’t believe it.”

Does vitamin D have a role to play in immune modulation?

One theory currently circulating is that, if vitamin D does have any role to play in modulating response to COVID-19, this may be via a blunting of the immune system reaction to the virus.

In a recent preprint study, Ali Daneshkhah, PhD, and colleagues from Northwestern University, Chicago, interrogated hospital data from China, France, Germany, Italy, Iran, South Korea, Spain, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

Specifically, the risk of severe COVID-19 cases among patients with severe vitamin D deficiency was 17.3%, whereas the equivalent figure for patients with normal vitamin D levels was 14.6% (a reduction of 15.6%).

“This potential effect may be attributed to vitamin D’s ability to suppress the adaptive immune system, regulating cytokine levels and thereby reducing the risk of developing severe COVID-19,” said the researchers.

Likewise, JoAnn E. Manson, MD, chief of the division of preventive medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, in a recent commentary, noted evidence from an observational study from three South Asian hospitals, in which the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency was much higher among those with severe COVID-19 illness compared with those with mild illness.

“We also know that vitamin D has an immune-modulating effect and can lower inflammation, and this may be relevant to the respiratory response during COVID-19 and the cytokine storm that’s been demonstrated,” she noted.

Dr. Rosen said he is willing to listen on the issue of a potential role of vitamin D in immune modulation.

“I’ve been a huge skeptic from the get-go, and loudly criticized the data for doing nothing. I am surprised at myself for saying there might be some effect,” he said.

“Clearly most people don’t get this [cytokine storm] but of those that do, it’s unclear why they do. Maybe if you are vitamin D sufficient, it might have some impact down the road on your response to an infection,” Dr. Rosen said. “Vitamin D may induce proteins important in modulating the function of macrophages of the immune system.”

Ethnic minorities disproportionately affected

It is also well recognized that COVID-19 disproportionately affects black and Asian minority ethnic individuals.

But on the issue of vitamin D in this context, one recent peer-reviewed study using UK Biobank data found no evidence to support a potential role for vitamin D concentration to explain susceptibility to COVID-19 infection either overall or in explaining differences between ethnic groups.

“Vitamin D is unlikely to be the underlying mechanism for the higher risk observed in black and minority ethnic individuals, and vitamin D supplements are unlikely to provide an effective intervention,” Claire Hastie, PhD, of the University of Glasgow and colleagues concluded.

But this hasn’t stopped two endocrinologists from appealing to members of the British Association of Physicians of Indian Origin (BAPIO) to get their vitamin D levels tested.

The black and Asian minority ethnic population, “especially frontline staff, should get their Vitamin D3 levels checked and get appropriate replacement as required,” said Parag Singhal, MD, of Weston General Hospital, Weston-Super-Mare, England, and David C. Anderson, a retired endocrinologist, said in a letter to BAPIO members.

Indeed, they suggested a booster dose of 100,000 IU as a one-off for black and Asian minority ethnic health care staff that should raise vitamin D levels for 2-3 months. They referred to a systematic review that concludes that “single vitamin D3 doses ≥300,000 IU are most effective at improving vitamin D status ... for up to 3 months”.

Commenting on the idea, Dr. Rosen remarked that, in general, the high-dose 50,000-500,000 IU given as a one-off does not confer any greater benefit than a single dose of 1,000 IU per day, except that the blood levels go up quicker and higher.

“Really there is no evidence that getting to super-high levels of vitamin D confer a greater benefit than normal levels,” he said. “So if health care workers suspect vitamin D deficiency, daily doses of 1,000 IU seem reasonable; even if they miss doses, the blood levels are relatively stable.”

On the specific question of vitamin D needs in ethnic minorities, Dr. Rosen said while such individuals do have lower serum levels of vitamin D, the issue is whether there are meaningful clinical implications related to this.

“The real question is whether [ethnic minority individuals] have physiologically adapted for this in other ways because these low levels have been so for thousands of years. In fact, African Americans have lower vitamin D levels but they absolutely have better bones than [whites],” he pointed out.

Testing and governmental recommendations during COVID-19

The U.S. National Institutes of Health in general advises 400 IU to 800 IU per day intake of vitamin D, depending on age, with those over 70 years requiring the highest daily dose. This will result in blood levels that are sufficient to maintain bone health and normal calcium metabolism in healthy people. There are no additional recommendations specific to vitamin D intake during the COVID-19 pandemic, however.

And Dr. Rosen pointed out that there is no evidence for mass screening of vitamin D levels among the U.S. population.

“U.S. public health guidance was pre-COVID, and I think high-risk individuals might want to think about their levels; for example, someone with inflammatory bowel disease or liver or pancreatic disease. These people are at higher risk anyway, and it could be because their vitamin D is low,” he said.

“Skip the test and ensure you are getting adequate levels of vitamin D whether via diet or supplement [400-800 IU per day],” he suggested. “It won’t harm.”

The U.K.’s Public Health England (PHE) clarified its advice on vitamin D supplementation during COVID-19. Alison Tedstone, PhD, chief nutritionist at PHE, said: “Many people are spending more time indoors and may not get all the vitamin D they need from sunlight. To protect their bone and muscle health, they should consider taking a daily supplement containing 10 micrograms [400 IU] of vitamin D.”

However, “there is no sufficient evidence to support recommending Vitamin D for reducing the risk of COVID-19,” she stressed.

Dr. Bajaj is on the advisory board of Medscape Diabetes & Endocrinology. He has ties with Amgen, AstraZeneca Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, Eli Lilly,Valeant, Canadian Collaborative Research Network, CMS Knowledge Translation, Diabetes Canada Scientific Group, LMC Healthcare,mdBriefCase,Medscape, andMeducom. Dr. Kenny, Dr. Rosen, and Dr. Singhal have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Hazard pay included in new COVID-19 relief bill

Hazard pay for frontline health care workers – an idea that has been championed by President Donald J. Trump and Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer, among others – is included in a just-released COVID-19 relief package assembled by Democrats in the House of Representatives.

according to a report in the Washington Post.

But it is far from a done deal. “The Democrats’ spending bill is a Pelosi-led pipe dream written in private,” said House Republican Leader Kevin McCarthy (Calif.) in a Fox News interview posted May 12 on Facebook.

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell condemned the package. “This is exactly the wrong approach,” he said in a prepared statement that instead laid out a variety of liability protections, which he said should be the first priority.

“We are not going to let health care heroes emerge from this crisis facing a tidal wave of medical malpractice lawsuits so that trial lawyers can line their pockets,” said Sen. McConnell, adding that his plan would “raise the liability threshold for COVID-related malpractice lawsuits.”

Ingrida Lusis, vice president of government affairs and health policy at the American Nurses Association, said in an interview that the ANA had lobbied for hazard pay and was told it would be in the next relief package.

“Though there is an inherent risk in the nursing profession, we think that this is really critical to ensuring that we have a workforce to meet the intense demands of this pandemic,” said Ms. Lusis.

“If health care workers are not treated and compensated appropriately for what they’re going through right now, then we may not have a next generation that will want to enter the field,” she said.

Various nursing organizations, nurses’ unions, and health care unions, such as the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) and the Service Employees International Union, have advocated for hazard pay.

Physicians’ organizations have not been vocal on the issue, however. The American Medical Association, for instance, pushed for hazard pay for residents but has not made any further public statements. An AMA spokesman said that the group was monitoring the situation but declined further comment.

Multiple online petitions seeking hazard pay for health care workers have been circulated, including one seeking the same $600 bump for essential workers that was given out as part of unemployment benefits in the first COVID-19 relief package. More than 1.2 million had signed the petition as of May 12.

‘Heroes fund’

The president first suggested hazard pay for health care workers on March 30 Fox News broadcast. “These are really brave people,” he said, adding that the administration was considering different ways of boosting pay, primarily through hospitals.

“We are asking the hospitals to do it and to consider something, including bonuses,” said Trump. “If anybody’s entitled to it, they are.”

On April 7, Sen. Schumer proposed a “Heroes Fund.” It would give public, private, and tribal frontline employees – including doctors, nurses, first responders, and transit, grocery, and postal workers – a $13 per hour raise up to $25,000 in additional pay through Dec. 31 for workers earning up to $200,000 and $5,000 in additional pay for those earning more than $200,000. It would also provide a $15,000 signing bonus to those who agree to take on such a position.

Rep. Matt Cartwright (D-Pa.) introduced a bill in mid-April, the Coronavirus Frontline Workers Fair Pay Act (HR 6709), that would provide similar pay increases. Health care workers would receive an additional $13 per hour. It would be retroactive to Jan. 31, 2020, and would be available through the end of 2020.

Molly Kinder of the Brookings Institution, a self-described nonpartisan Washington policy institute, estimates that Sen. Schumer’s proposal would represent the equivalent of double-time pay for the average low-wage worker, a 50% pay increase for a mail carrier, a 20% boost for a pharmacist, and less than a 15% increase for a surgeon, as determined from median 2018 wages.

Before the House Democrats unveiled their bill, Isabel Soto of the center-right group American Action Forum estimated that a $13 per hour wage increase could cost $398.9 billion just from the end of March to the end of September. A great proportion of that amount – $264 billion – would go to some 10 million health care workers, Ms. Soto calculated.

Some already offering pay boost

A few states and hospital systems are already offering hazard pay.

On April 12, Massachusetts agreed to give about 6,500 AFSCME union members who work at state human services facilities and group homes a $5 or a $10 per hour pay increase, depending on duties. It was to stay in effect until at least May 30.

Maine Governor Janet Mills (D) also agreed to increase pay by $3-$5 an hour for AFSCME workers in state correctional and mental health facilities beginning March 29.

In New York City, the biggest hospital network, Northwell Health, in late April gave 45,000 workers – including nurses, physicians, respiratory therapists, environmental services workers, housekeepers, and people in outpatient and corporate roles – a lump sum bonus payment of up to $2,500 and 1 week of paid time off. The money came out of the system’s general fund.

“As an organization, we want to continue to support, motivate and inspire our team members,” said Northwell President and CEO Michael Dowling in a statement at the time.

On April 2, New York–Presbyterian Hospital’s chair of the department of surgery, Craig Smith, MD, announced that the facility was “providing a $1,250 bonus for everyone who has worked in or supported the COVID-19 front lines, for at least 1 week.”

Advocate Aurora, with 15 hospitals and 32,000 employees in Wisconsin, said in early April that it was giving increases of $6.25-$15.00 an hour at least through the end of May.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Hazard pay for frontline health care workers – an idea that has been championed by President Donald J. Trump and Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer, among others – is included in a just-released COVID-19 relief package assembled by Democrats in the House of Representatives.

according to a report in the Washington Post.

But it is far from a done deal. “The Democrats’ spending bill is a Pelosi-led pipe dream written in private,” said House Republican Leader Kevin McCarthy (Calif.) in a Fox News interview posted May 12 on Facebook.

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell condemned the package. “This is exactly the wrong approach,” he said in a prepared statement that instead laid out a variety of liability protections, which he said should be the first priority.

“We are not going to let health care heroes emerge from this crisis facing a tidal wave of medical malpractice lawsuits so that trial lawyers can line their pockets,” said Sen. McConnell, adding that his plan would “raise the liability threshold for COVID-related malpractice lawsuits.”

Ingrida Lusis, vice president of government affairs and health policy at the American Nurses Association, said in an interview that the ANA had lobbied for hazard pay and was told it would be in the next relief package.

“Though there is an inherent risk in the nursing profession, we think that this is really critical to ensuring that we have a workforce to meet the intense demands of this pandemic,” said Ms. Lusis.

“If health care workers are not treated and compensated appropriately for what they’re going through right now, then we may not have a next generation that will want to enter the field,” she said.

Various nursing organizations, nurses’ unions, and health care unions, such as the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) and the Service Employees International Union, have advocated for hazard pay.

Physicians’ organizations have not been vocal on the issue, however. The American Medical Association, for instance, pushed for hazard pay for residents but has not made any further public statements. An AMA spokesman said that the group was monitoring the situation but declined further comment.

Multiple online petitions seeking hazard pay for health care workers have been circulated, including one seeking the same $600 bump for essential workers that was given out as part of unemployment benefits in the first COVID-19 relief package. More than 1.2 million had signed the petition as of May 12.

‘Heroes fund’

The president first suggested hazard pay for health care workers on March 30 Fox News broadcast. “These are really brave people,” he said, adding that the administration was considering different ways of boosting pay, primarily through hospitals.

“We are asking the hospitals to do it and to consider something, including bonuses,” said Trump. “If anybody’s entitled to it, they are.”

On April 7, Sen. Schumer proposed a “Heroes Fund.” It would give public, private, and tribal frontline employees – including doctors, nurses, first responders, and transit, grocery, and postal workers – a $13 per hour raise up to $25,000 in additional pay through Dec. 31 for workers earning up to $200,000 and $5,000 in additional pay for those earning more than $200,000. It would also provide a $15,000 signing bonus to those who agree to take on such a position.

Rep. Matt Cartwright (D-Pa.) introduced a bill in mid-April, the Coronavirus Frontline Workers Fair Pay Act (HR 6709), that would provide similar pay increases. Health care workers would receive an additional $13 per hour. It would be retroactive to Jan. 31, 2020, and would be available through the end of 2020.

Molly Kinder of the Brookings Institution, a self-described nonpartisan Washington policy institute, estimates that Sen. Schumer’s proposal would represent the equivalent of double-time pay for the average low-wage worker, a 50% pay increase for a mail carrier, a 20% boost for a pharmacist, and less than a 15% increase for a surgeon, as determined from median 2018 wages.

Before the House Democrats unveiled their bill, Isabel Soto of the center-right group American Action Forum estimated that a $13 per hour wage increase could cost $398.9 billion just from the end of March to the end of September. A great proportion of that amount – $264 billion – would go to some 10 million health care workers, Ms. Soto calculated.

Some already offering pay boost

A few states and hospital systems are already offering hazard pay.

On April 12, Massachusetts agreed to give about 6,500 AFSCME union members who work at state human services facilities and group homes a $5 or a $10 per hour pay increase, depending on duties. It was to stay in effect until at least May 30.

Maine Governor Janet Mills (D) also agreed to increase pay by $3-$5 an hour for AFSCME workers in state correctional and mental health facilities beginning March 29.

In New York City, the biggest hospital network, Northwell Health, in late April gave 45,000 workers – including nurses, physicians, respiratory therapists, environmental services workers, housekeepers, and people in outpatient and corporate roles – a lump sum bonus payment of up to $2,500 and 1 week of paid time off. The money came out of the system’s general fund.

“As an organization, we want to continue to support, motivate and inspire our team members,” said Northwell President and CEO Michael Dowling in a statement at the time.

On April 2, New York–Presbyterian Hospital’s chair of the department of surgery, Craig Smith, MD, announced that the facility was “providing a $1,250 bonus for everyone who has worked in or supported the COVID-19 front lines, for at least 1 week.”

Advocate Aurora, with 15 hospitals and 32,000 employees in Wisconsin, said in early April that it was giving increases of $6.25-$15.00 an hour at least through the end of May.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Hazard pay for frontline health care workers – an idea that has been championed by President Donald J. Trump and Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer, among others – is included in a just-released COVID-19 relief package assembled by Democrats in the House of Representatives.

according to a report in the Washington Post.

But it is far from a done deal. “The Democrats’ spending bill is a Pelosi-led pipe dream written in private,” said House Republican Leader Kevin McCarthy (Calif.) in a Fox News interview posted May 12 on Facebook.

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell condemned the package. “This is exactly the wrong approach,” he said in a prepared statement that instead laid out a variety of liability protections, which he said should be the first priority.

“We are not going to let health care heroes emerge from this crisis facing a tidal wave of medical malpractice lawsuits so that trial lawyers can line their pockets,” said Sen. McConnell, adding that his plan would “raise the liability threshold for COVID-related malpractice lawsuits.”

Ingrida Lusis, vice president of government affairs and health policy at the American Nurses Association, said in an interview that the ANA had lobbied for hazard pay and was told it would be in the next relief package.

“Though there is an inherent risk in the nursing profession, we think that this is really critical to ensuring that we have a workforce to meet the intense demands of this pandemic,” said Ms. Lusis.

“If health care workers are not treated and compensated appropriately for what they’re going through right now, then we may not have a next generation that will want to enter the field,” she said.

Various nursing organizations, nurses’ unions, and health care unions, such as the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) and the Service Employees International Union, have advocated for hazard pay.

Physicians’ organizations have not been vocal on the issue, however. The American Medical Association, for instance, pushed for hazard pay for residents but has not made any further public statements. An AMA spokesman said that the group was monitoring the situation but declined further comment.

Multiple online petitions seeking hazard pay for health care workers have been circulated, including one seeking the same $600 bump for essential workers that was given out as part of unemployment benefits in the first COVID-19 relief package. More than 1.2 million had signed the petition as of May 12.

‘Heroes fund’

The president first suggested hazard pay for health care workers on March 30 Fox News broadcast. “These are really brave people,” he said, adding that the administration was considering different ways of boosting pay, primarily through hospitals.

“We are asking the hospitals to do it and to consider something, including bonuses,” said Trump. “If anybody’s entitled to it, they are.”

On April 7, Sen. Schumer proposed a “Heroes Fund.” It would give public, private, and tribal frontline employees – including doctors, nurses, first responders, and transit, grocery, and postal workers – a $13 per hour raise up to $25,000 in additional pay through Dec. 31 for workers earning up to $200,000 and $5,000 in additional pay for those earning more than $200,000. It would also provide a $15,000 signing bonus to those who agree to take on such a position.

Rep. Matt Cartwright (D-Pa.) introduced a bill in mid-April, the Coronavirus Frontline Workers Fair Pay Act (HR 6709), that would provide similar pay increases. Health care workers would receive an additional $13 per hour. It would be retroactive to Jan. 31, 2020, and would be available through the end of 2020.

Molly Kinder of the Brookings Institution, a self-described nonpartisan Washington policy institute, estimates that Sen. Schumer’s proposal would represent the equivalent of double-time pay for the average low-wage worker, a 50% pay increase for a mail carrier, a 20% boost for a pharmacist, and less than a 15% increase for a surgeon, as determined from median 2018 wages.

Before the House Democrats unveiled their bill, Isabel Soto of the center-right group American Action Forum estimated that a $13 per hour wage increase could cost $398.9 billion just from the end of March to the end of September. A great proportion of that amount – $264 billion – would go to some 10 million health care workers, Ms. Soto calculated.

Some already offering pay boost

A few states and hospital systems are already offering hazard pay.

On April 12, Massachusetts agreed to give about 6,500 AFSCME union members who work at state human services facilities and group homes a $5 or a $10 per hour pay increase, depending on duties. It was to stay in effect until at least May 30.

Maine Governor Janet Mills (D) also agreed to increase pay by $3-$5 an hour for AFSCME workers in state correctional and mental health facilities beginning March 29.

In New York City, the biggest hospital network, Northwell Health, in late April gave 45,000 workers – including nurses, physicians, respiratory therapists, environmental services workers, housekeepers, and people in outpatient and corporate roles – a lump sum bonus payment of up to $2,500 and 1 week of paid time off. The money came out of the system’s general fund.

“As an organization, we want to continue to support, motivate and inspire our team members,” said Northwell President and CEO Michael Dowling in a statement at the time.

On April 2, New York–Presbyterian Hospital’s chair of the department of surgery, Craig Smith, MD, announced that the facility was “providing a $1,250 bonus for everyone who has worked in or supported the COVID-19 front lines, for at least 1 week.”

Advocate Aurora, with 15 hospitals and 32,000 employees in Wisconsin, said in early April that it was giving increases of $6.25-$15.00 an hour at least through the end of May.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

ER docs ask, “Where are our patients?”

according to an expert panel on unanticipated consequences of pandemic care hosted by the presidents of the Society of Critical Care Medicine and the American College of Emergency Physicians.*

“At the peak of exposure to COVID-19 illness or infection, ED volumes in my system, which are really not much different from others across the country, were cut in half, if not more. And those changes happened across virtually every form of ED presentation, from the highest acuity to the lowest. We’re now beyond our highest level of exposure to COVID-19 clinically symptomatic patients in western Pennsylvania, but that recovery in volume hasn’t occurred yet, although there are some embers,” explained Donald M. Yealy, MD, professor and chair of the department of emergency medicine at the University of Pittsburgh.

He and other panelists also addressed some of the other unanticipated developments in the COVID-19 pandemic, including a recently recognized childhood manifestation called for now COVID-associated pediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome, an anticipated massive second wave of non-COVID patients expected to present late to EDs and primary care clinics after having avoided needed medical care out of fear of infection, and the pandemic’s negative impact upon medical education.

Who’s not showing up in the ED

Dr. Yealy said that across the country, the number of patients arriving in EDs with acute ST-elevation MI, stroke, trauma, and other highest-acuity presentations is down substantially. But the volume of patients with more routine, bread-and-butter conditions typically seen in EDs is down even more.

“You might say, if I was designing from the insurance side, this is exactly what I’d hope for. I’ve heard that some people on the insurance-only side of the business really are experiencing a pretty good deal right now: They’re collecting premiums and not having to pay out on the ED or hospital side,” he said.

Tweaking the public health message on seeking medical care

“One of the unanticipated casualties of the pandemic are the patients who don’t have it. It will take a whole lot of work and coordinated effort to re-engage with those patients,” predicted SCCM President Lewis J. Kaplan, MD, professor of surgery at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Evie G. Marcolini, MD, described what she believes is necessary now: “We need to have a big focus on getting the word out to the public that acute MI, stroke, and other acute injuries are still a time-sensitive problem and they warrant at least a call to their physician or consideration of coming in to the ED.

“I think when we started out, we were telling people, ‘Don’t come in.’ Now we’re trying to dial it back a little bit and say, ‘Listen, there are things you really do need to come in for. And we will keep you safe,’” said Dr. Marcolini, an emergency medicine and neurocritical care specialist at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Hanover, N.H.

“It is safe,” Dr. Yealy agreed. “The safest place in the world to be right now is the ED. Everybody’s cordoned off. There’s way more PPE [personal protective equipment]. There’s a level of precision now that should have existed but never did in our previous influenza seasons. So we have something very unique to offer, and we can put people’s minds at rest.”

He spoke of a coming “tsunami of untreated illness.”

“My concern is there is a significant subset of people who are not only eschewing ED care but staying away from their primary care provider. My fear is that we’re not as well aware of this,” he said. “Together with our primary care partners, we have to figure out ways to reach the people who are ignoring illnesses and injuries that they’re making long-term decisions about without realizing it. We have to find a way to reach those people and say it’s okay to reach for care.”

SCCM Immediate Past President Heatherlee Bailey, MD, also sees a problematic looming wave.

“I’m quite concerned about the coming second wave of non-COVID patients who’ve sat home with their worsening renal failure that’s gone from 2 to 5 because they’ve been taking a lot of NSAIDs, or the individual who’s had several TIAs that self-resolved, and we’ve missed an opportunity to prevent some significant disease. At some point they’re going to come back, and we need to figure out how to get these individuals hooked up with care, either through the ED or with their primary care provider, to prevent these potential bad outcomes,” said Dr. Bailey of the Durham (N.C.) Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

Interim guidance for pediatricians on an alarming new syndrome

Edward E. Conway Jr., MD, recalled that early in the U.S. pandemic, pediatricians felt a sense of relief that children appeared to be spared from severe COVID-19 disease. But, in just the past few weeks, a new syndrome has emerged. New York City has recorded more than 100 cases of what’s provisionally being called COVID-associated pediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome. Dr. Conway and others are working with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to develop a case definition for the syndrome, first reported by pediatricians in Italy and the United Kingdom.

“We’re trying to get the word out to general pediatricians as to the common signs and symptoms that should prompt parents to bring their children in for medical care,” according to Dr. Conway, chief of pediatric critical care medicine and vice-chair of pediatrics at Jacobi Medical Center in New York.

Ninety percent of affected children have abdominal symptoms early on, including abdominal pain, diarrhea, emesis, or enteritis upon imaging. A nondescript rash, headache, conjunctivitis, and irritability are common, cough much less so – under 25%.

“The thought is that if any one of these is associated with a fever lasting more than 4 days, we suggest these children be brought in and seen by a pediatrician. We don’t have a formal guideline – we’re working on that – but basically the current recommendation is to screen them initially with a CBC with differential, a chem 10, and liver function tests, but also to look for inflammatory markers that we see in our COVID patients. We’ve been quite surprised: These patients have C-reactive proteins of about 240 mg/L on average, ferritin is quite high at around 1,200 ng/mL, and d-dimers of 2,300 ng/mL. We’ve also found very high brain natriuretic peptides and troponins in these patients,” according to Dr. Conway.

Analogies have been made between this COVID-19 pediatric syndrome and Kawasaki disease. Dr. Conway is unconvinced.

“This is quite different from Kawasaki in that these children are usually thrombocytopenic and usually present with DIC [disseminated intravascular coagulation], and the d-dimers are extraordinarily high, compared to what we’re used to seeing in pediatric patients,” he said.

Symptomatic children with laboratory red flags should be hospitalized. Most of the affected New York City children have recovered after 5 or 6 days in the pediatric ICU with empiric treatment using intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), corticosteroids, and/or interleukin-6 inhibitors. However, five recent deaths are now under study.

Dr. Yealy commented that this new pediatric syndrome is “really interesting,” but to date, it affects only a very small percentage of children, and children overall have been much less affected by the pandemic than are adults.

“The populations being disproportionately impacted are the elderly, the elderly, the elderly, and then other vulnerable populations, particularly congregants and the poor,” he said. “At my site, three-quarters of the patients coming in are either patients at assisted-living facilities or work at one of those congregant facilities.”

The pandemic’s impact on medical education

In many hospitals, grand rounds are being done virtually via videoconferencing, often with attendant challenges in asking and answering questions. Hospital patient volumes are diminished. Medical students aren’t coming in to do clinical rotations. Medical students and residents can’t travel to interview for future residencies or jobs.

“It’s affecting education across all of the components of medicine. It’s hard to say how long this pandemic is going to last. We’re all trying to be innovative in using online tools, but I believe it’s going to have a long-lasting effect on our education system,” Dr. Marcolini predicted.

Remote interface while working from home has become frustrating, especially during peak Internet use hours.

“It’s staggering how slow my home system has become in comparison to what’s wired at work. Now many times when you try to get into your work system from home, you time out while you’re waiting for the next piece of information to come across,” Dr. Kaplan commented.

All panel participants reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

*Correction, 5/15/20: An earlier version of this article misstated the name of the American College of Emergency Physicians.)

according to an expert panel on unanticipated consequences of pandemic care hosted by the presidents of the Society of Critical Care Medicine and the American College of Emergency Physicians.*

“At the peak of exposure to COVID-19 illness or infection, ED volumes in my system, which are really not much different from others across the country, were cut in half, if not more. And those changes happened across virtually every form of ED presentation, from the highest acuity to the lowest. We’re now beyond our highest level of exposure to COVID-19 clinically symptomatic patients in western Pennsylvania, but that recovery in volume hasn’t occurred yet, although there are some embers,” explained Donald M. Yealy, MD, professor and chair of the department of emergency medicine at the University of Pittsburgh.

He and other panelists also addressed some of the other unanticipated developments in the COVID-19 pandemic, including a recently recognized childhood manifestation called for now COVID-associated pediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome, an anticipated massive second wave of non-COVID patients expected to present late to EDs and primary care clinics after having avoided needed medical care out of fear of infection, and the pandemic’s negative impact upon medical education.

Who’s not showing up in the ED

Dr. Yealy said that across the country, the number of patients arriving in EDs with acute ST-elevation MI, stroke, trauma, and other highest-acuity presentations is down substantially. But the volume of patients with more routine, bread-and-butter conditions typically seen in EDs is down even more.

“You might say, if I was designing from the insurance side, this is exactly what I’d hope for. I’ve heard that some people on the insurance-only side of the business really are experiencing a pretty good deal right now: They’re collecting premiums and not having to pay out on the ED or hospital side,” he said.

Tweaking the public health message on seeking medical care

“One of the unanticipated casualties of the pandemic are the patients who don’t have it. It will take a whole lot of work and coordinated effort to re-engage with those patients,” predicted SCCM President Lewis J. Kaplan, MD, professor of surgery at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Evie G. Marcolini, MD, described what she believes is necessary now: “We need to have a big focus on getting the word out to the public that acute MI, stroke, and other acute injuries are still a time-sensitive problem and they warrant at least a call to their physician or consideration of coming in to the ED.

“I think when we started out, we were telling people, ‘Don’t come in.’ Now we’re trying to dial it back a little bit and say, ‘Listen, there are things you really do need to come in for. And we will keep you safe,’” said Dr. Marcolini, an emergency medicine and neurocritical care specialist at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Hanover, N.H.

“It is safe,” Dr. Yealy agreed. “The safest place in the world to be right now is the ED. Everybody’s cordoned off. There’s way more PPE [personal protective equipment]. There’s a level of precision now that should have existed but never did in our previous influenza seasons. So we have something very unique to offer, and we can put people’s minds at rest.”

He spoke of a coming “tsunami of untreated illness.”

“My concern is there is a significant subset of people who are not only eschewing ED care but staying away from their primary care provider. My fear is that we’re not as well aware of this,” he said. “Together with our primary care partners, we have to figure out ways to reach the people who are ignoring illnesses and injuries that they’re making long-term decisions about without realizing it. We have to find a way to reach those people and say it’s okay to reach for care.”

SCCM Immediate Past President Heatherlee Bailey, MD, also sees a problematic looming wave.

“I’m quite concerned about the coming second wave of non-COVID patients who’ve sat home with their worsening renal failure that’s gone from 2 to 5 because they’ve been taking a lot of NSAIDs, or the individual who’s had several TIAs that self-resolved, and we’ve missed an opportunity to prevent some significant disease. At some point they’re going to come back, and we need to figure out how to get these individuals hooked up with care, either through the ED or with their primary care provider, to prevent these potential bad outcomes,” said Dr. Bailey of the Durham (N.C.) Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

Interim guidance for pediatricians on an alarming new syndrome

Edward E. Conway Jr., MD, recalled that early in the U.S. pandemic, pediatricians felt a sense of relief that children appeared to be spared from severe COVID-19 disease. But, in just the past few weeks, a new syndrome has emerged. New York City has recorded more than 100 cases of what’s provisionally being called COVID-associated pediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome. Dr. Conway and others are working with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to develop a case definition for the syndrome, first reported by pediatricians in Italy and the United Kingdom.