User login

Sepsis patients with hypothermia face greater mortality risk

Background: Fevers (like other vital sign abnormalities) often trigger interventions from providers. However, hypothermia (temperature under 36° C) may also be associated with higher mortality.

Study design: Retrospective subanalysis of a previous study (Focused Outcome Research on Emergency Care for Acute respiratory distress syndrome, Sepsis and Trauma [FORECAST]).

Setting: Adult patients with severe sepsis based on Sepsis-2 in 59 ICUs in Japan.

Synopsis: The study involved 1,143 patients admitted to ICUs with severe sepsis (62.6% with septic shock). The median age was 73 years with a median APACHE II and SOFA scores of 22 and 9, respectively. Core temperatures were measured on admission to ICU with patients categorized into three arms: temperature under 36° C (hypothermic), temperature 36°-38° C, and febrile patients with temperature greater than 38° C. Of studied patients, 11.1% were hypothermic on presentation. These patients were older, sicker (higher APACHE/SOFA scores), had lower body mass indexes, and had higher prevalence of septic shock than did the febrile patients. Hypothermic patients fared worse in every clinical outcome measured – in-hospital mortality, 28-day mortality, ventilator-free days, ICU-free days, length of hospital stay, and likelihood of discharge home. The odds ratio of in-hospital mortality for hypothermic patients, compared with reference febrile patients, was 1.76 (95% CI, 1.14-2.73). Patients with hypothermia were also significantly less likely to receive the entire 3-hour resuscitation bundle, including broad-spectrum antibiotics (56.3%) versus 60.8% of patients with temperature 36-38° C and 71.1% for febrile group (P = .003).

Bottom line: Hypothermia in patients with severe sepsis is associated with a significantly higher disease severity, mortality risk, and lower implementation of sepsis bundles. More emphasis on earlier identification and treatment of this specific patient population appears needed.

Citation: Kushimoto S et al. Impact of body temperature abnormalities on the implementation of sepsis bundles and outcomes in patients with severe sepsis: A retrospective sub-analysis of the focused outcome of research of emergency care for acute respiratory distress syndrome, sepsis and trauma study. Crit Care Med. 2019 May;47(5):691-9.

Dr. Sekaran is a hospitalist at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Background: Fevers (like other vital sign abnormalities) often trigger interventions from providers. However, hypothermia (temperature under 36° C) may also be associated with higher mortality.

Study design: Retrospective subanalysis of a previous study (Focused Outcome Research on Emergency Care for Acute respiratory distress syndrome, Sepsis and Trauma [FORECAST]).

Setting: Adult patients with severe sepsis based on Sepsis-2 in 59 ICUs in Japan.

Synopsis: The study involved 1,143 patients admitted to ICUs with severe sepsis (62.6% with septic shock). The median age was 73 years with a median APACHE II and SOFA scores of 22 and 9, respectively. Core temperatures were measured on admission to ICU with patients categorized into three arms: temperature under 36° C (hypothermic), temperature 36°-38° C, and febrile patients with temperature greater than 38° C. Of studied patients, 11.1% were hypothermic on presentation. These patients were older, sicker (higher APACHE/SOFA scores), had lower body mass indexes, and had higher prevalence of septic shock than did the febrile patients. Hypothermic patients fared worse in every clinical outcome measured – in-hospital mortality, 28-day mortality, ventilator-free days, ICU-free days, length of hospital stay, and likelihood of discharge home. The odds ratio of in-hospital mortality for hypothermic patients, compared with reference febrile patients, was 1.76 (95% CI, 1.14-2.73). Patients with hypothermia were also significantly less likely to receive the entire 3-hour resuscitation bundle, including broad-spectrum antibiotics (56.3%) versus 60.8% of patients with temperature 36-38° C and 71.1% for febrile group (P = .003).

Bottom line: Hypothermia in patients with severe sepsis is associated with a significantly higher disease severity, mortality risk, and lower implementation of sepsis bundles. More emphasis on earlier identification and treatment of this specific patient population appears needed.

Citation: Kushimoto S et al. Impact of body temperature abnormalities on the implementation of sepsis bundles and outcomes in patients with severe sepsis: A retrospective sub-analysis of the focused outcome of research of emergency care for acute respiratory distress syndrome, sepsis and trauma study. Crit Care Med. 2019 May;47(5):691-9.

Dr. Sekaran is a hospitalist at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Background: Fevers (like other vital sign abnormalities) often trigger interventions from providers. However, hypothermia (temperature under 36° C) may also be associated with higher mortality.

Study design: Retrospective subanalysis of a previous study (Focused Outcome Research on Emergency Care for Acute respiratory distress syndrome, Sepsis and Trauma [FORECAST]).

Setting: Adult patients with severe sepsis based on Sepsis-2 in 59 ICUs in Japan.

Synopsis: The study involved 1,143 patients admitted to ICUs with severe sepsis (62.6% with septic shock). The median age was 73 years with a median APACHE II and SOFA scores of 22 and 9, respectively. Core temperatures were measured on admission to ICU with patients categorized into three arms: temperature under 36° C (hypothermic), temperature 36°-38° C, and febrile patients with temperature greater than 38° C. Of studied patients, 11.1% were hypothermic on presentation. These patients were older, sicker (higher APACHE/SOFA scores), had lower body mass indexes, and had higher prevalence of septic shock than did the febrile patients. Hypothermic patients fared worse in every clinical outcome measured – in-hospital mortality, 28-day mortality, ventilator-free days, ICU-free days, length of hospital stay, and likelihood of discharge home. The odds ratio of in-hospital mortality for hypothermic patients, compared with reference febrile patients, was 1.76 (95% CI, 1.14-2.73). Patients with hypothermia were also significantly less likely to receive the entire 3-hour resuscitation bundle, including broad-spectrum antibiotics (56.3%) versus 60.8% of patients with temperature 36-38° C and 71.1% for febrile group (P = .003).

Bottom line: Hypothermia in patients with severe sepsis is associated with a significantly higher disease severity, mortality risk, and lower implementation of sepsis bundles. More emphasis on earlier identification and treatment of this specific patient population appears needed.

Citation: Kushimoto S et al. Impact of body temperature abnormalities on the implementation of sepsis bundles and outcomes in patients with severe sepsis: A retrospective sub-analysis of the focused outcome of research of emergency care for acute respiratory distress syndrome, sepsis and trauma study. Crit Care Med. 2019 May;47(5):691-9.

Dr. Sekaran is a hospitalist at Massachusetts General Hospital.

POPCoRN network mobilizes pediatric capacity during pandemic

Med-Peds hospitalists were an organizing force

As U.S. health care systems prepare for inpatient surges linked to hospitalizations of critically ill COVID-19 patients, two hospitalists with med-peds training (combined training in internal medicine and pediatrics) have launched an innovative solution to help facilities deal with the challenge.

The Pediatric Overflow Planning Contingency Response Network (POPCoRN network) has quickly linked almost 400 physicians and other health professionals, including hospitalists, attending physicians, residents, medical students, and nurses. The network wants to help provide more information about how pediatric-focused institutions can safely gear up to admit adult patients in children’s hospitals, in order to offset the predicted demand for hospital beds for patients with COVID-19.

According to the POPCoRN network website (www.popcornetwork.org), the majority of providers who have contacted the network say they have already started or are committed to planning for their pediatric facilities to be used for adult overflow. The Children’s Hospital Association has issued a guidance on this kind of community collaboration for children’s hospitals partnering with adult hospitals in their community and with policy makers.

“We are a network of folks from different institutions, many med-peds–trained hospitalists but quickly growing,” said Leah Ratner, MD, a second-year fellow in the Global Pediatrics Program at Boston Children’s Hospital and cofounder of the POPCoRN network. “We came together to think about how to increase capacity – both in the work force and for actual hospital space – by helping to train pediatric hospitalists and pediatrics-trained nurses to care for adult patients.”

A web-based platform filled with a rapidly expanding list of resources, an active Twitter account, and utilization of Zoom networking software for webinars and working group meetings have facilitated the network’s growth. “Social media has helped us,” Dr. Ratner said. But equally important are personal connections.

“It all started just a few weeks ago,” added cofounder Ashley Jenkins, MD, a med-peds hospital medicine and general academics research fellow in the division of hospital medicine at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. “I sent out some emails in mid-March, asking what other people were doing about these issues. Leah and I met as a result of these initial emails. We immediately started connecting with other health systems and it just expanded from there. Once we knew that enough other systems were thinking about it and trying to build capacity, we started pulling the people and information together.”

High-yield one-pagers

A third or more of those on the POPCoRN contact list are also participating as volunteers on its varied working groups, including health system operation groups exploring the needs of three distinct hospital models: freestanding children’s hospitals; community hospitals, which may see small numbers of children; and integrated mixed hospitals, which often means a pediatric hospital or pediatric units located within an adult hospital.

An immediate goal is to develop high-yield informational “one-pagers,” culling essential clinical facts on a variety of topics in adult inpatient medicine that may no longer be familiar to working pediatric hospitalists. These one-pagers, designed with the help of network members with graphic design skills, address topics such as syncope or chest pain or managing exacerbation of COPD in adults. They draw upon existing informational sources, encapsulating practical information tips that can be used at the bedside, including test workups, differential diagnoses, treatment approaches, and other pearls for providers. Drafts are reviewed for content by specialists, and then by pediatricians to make sure the information covers what they need.

Also under development are educational materials for nurses trained in pediatrics, a section for outpatient providers redeployed to triage or telehealth, and information for other team members including occupational, physical, and respiratory therapists. Another section offers critical care lectures for the nonintensivist. A metrics and outcomes working group is looking for ways to evaluate how the network is doing and who is being reached without having to ask frontline providers to fill out surveys.

Dr. Ratner and Dr. Jenkins have created an intentional structure for encouraging mentoring. They also call on their own mentors – Ahmet Uluer, DO, director of Weitzman Family Bridges Adult Transition Program at Boston Children’s Hospital, and Brian Herbst Jr., MD, medical director of the Hospital Medicine Adult Care Service at Cincinnati Children’s – for advice.

Beyond the silos

Pediatric hospitalists may have been doing similar things, working on similar projects, but not necessarily reaching out to each other across a system that tends to promote staying within administrative silos, Dr. Uluer said. “Through our personal contacts in POPCoRN, we’ve been able to reach beyond the silos. This network has worked like medical crowd sourcing, and the founders have been inspirational.”

Dr. Herbst added, “How do we expand bandwidth and safely expand services to take young patients and adults from other hospitals? What other populations do we need to expand to take? This network is a workplace of ideas. It’s amazing to see what has been built in a few weeks and how useful it can be.”

Med-peds hospitalists are an important resource for bridging the two specialties. Their experience with transitioning young adults with long-standing chronic conditions of childhood, who have received most of their care at a children’s hospital before reaching adulthood, offers a helpful model. “We’ve also tried to target junior physicians who could step up into leadership roles and to pull in medical students – who are the backbone of this network through their administrative support,” Dr. Jenkins said.

Marie Pfarr, MD, also a med-peds trained hospital medicine fellow at Cincinnati Children’s, was contacted in March by Dr. Jenkins. “She said they had this brainstorm, and they were getting feedback that it would be helpful to provide educational materials for pediatric providers. Because I have an interest in medical education, she asked if I wanted to help. I was at home struggling with what I could contribute during this crazy time, so I said yes.”

Dr. Pfarr leads POPCoRN’s educational working group, which came up with a list of 50 topics in need of one-pagers and people willing to create them, mostly still under development. The aim for the one-pagers is to offer a good starting point for pediatricians, helping them, for example, to ask the right questions during history and physical exams. “We also want to offer additional resources for those who want to do a deeper dive.”

Dr. Pfarr said she has enjoyed working closely with medical students, who really want to help. “That’s been great to see. We are all working toward the same goal, and we help to keep each other in check. I think there’s a future for this kind of mobilization through collaborations to connect pediatric to adult providers. A lot of good things will come out of the network, which is an example of how folks can talk to each other. It’s very dynamic and changing every day.”

One of those medical students is Chinma Onyewuenyi, finishing her fourth year at Baylor College of Medicine. Scheduled to start a med-peds residency at Geisinger Health on July 1, she had completed all of her rotations and was looking for ways to get involved in the pandemic response while respecting the shelter-in-place order. “I had heard about the network, which was recruiting medical students to play administrative roles for the working groups. I said, ‘If you have anything else you need help with, I have time on my hands.’”

Ms. Onyewuenyi says she fell into the role of a lead administrative volunteer, and her responsibilities grew from there, eventually taking charge of all the medical students’ recruiting, screening, and assignments, freeing up the project’s physician leaders from administrative tasks. “I wanted something active to do to contribute, and I appreciate all that I’m learning. With a master’s degree in public health, I have researched how health care is delivered,” she said.

“This experience has really opened my eyes to what’s required to deliver care, and just the level of collaboration that needs to go on with something like this. Even as a medical student, I felt glad to have an opportunity to contribute beyond the administrative tasks. At meetings, they ask for my opinion.”

Equitable access to resources

Another major focus for the network is promoting health equity – giving pediatric providers and health systems equitable access to information that meets their needs, Dr. Ratner said. “We’ve made a particular effort to reach out to hospitals that are the most vulnerable, including rural hospitals, and to those serving the most vulnerable patients,” she noted. These also include the homeless and refugees.

“We’ve been trying to be mindful of avoiding the sometimes-intimidating power structure that has been traditional in medicine,” Dr. Ratner said. The network’s equity working group is trying to provide content with structural competency and cultural humility. “We’re learning a lot about the ways the health care system is broken,” she added. “We all agree that we have a fragmented health care system, but there are ways to make it less fragmented and learn from each other.”

In the tragedy of the COVID epidemic, there are also unique opportunities to learn to work collaboratively and make the health care system stronger for those in greatest need, Dr. Ratner added. “What we hope is that our network becomes an example of that, even as it is moving so quickly.”

Audrey Uong, MD, an attending physician in the division of hospital medicine at Children’s Hospital at Montefiore Medical Center in New York, connected with POPCoRN for an educational presentation reviewing resuscitation in adult patients. She wanted to talk with peers about what’s going on, so as not to feel alone in her practice. She has also found the network’s website useful for identifying educational resources.

“As pediatricians, we have been asked to care for adult patients. One of our units has been admitting mostly patients under age 30, and we are accepting older patients in another unit on the pediatric wing.” This kind of thing is also happening in a lot of other places, Dr. Uong said. Keeping up with these changes in her own practice has been challenging.

She tries to take one day at a time. “Everyone at this institution feels the same – that we’re locked in on meeting the need. Even our child life specialists, when they’re not working with younger patients, have created this amazing support room for staff, with snacks and soothing music. There’s been a lot of attention paid to making us feel supported in this work.”

Med-Peds hospitalists were an organizing force

Med-Peds hospitalists were an organizing force

As U.S. health care systems prepare for inpatient surges linked to hospitalizations of critically ill COVID-19 patients, two hospitalists with med-peds training (combined training in internal medicine and pediatrics) have launched an innovative solution to help facilities deal with the challenge.

The Pediatric Overflow Planning Contingency Response Network (POPCoRN network) has quickly linked almost 400 physicians and other health professionals, including hospitalists, attending physicians, residents, medical students, and nurses. The network wants to help provide more information about how pediatric-focused institutions can safely gear up to admit adult patients in children’s hospitals, in order to offset the predicted demand for hospital beds for patients with COVID-19.

According to the POPCoRN network website (www.popcornetwork.org), the majority of providers who have contacted the network say they have already started or are committed to planning for their pediatric facilities to be used for adult overflow. The Children’s Hospital Association has issued a guidance on this kind of community collaboration for children’s hospitals partnering with adult hospitals in their community and with policy makers.

“We are a network of folks from different institutions, many med-peds–trained hospitalists but quickly growing,” said Leah Ratner, MD, a second-year fellow in the Global Pediatrics Program at Boston Children’s Hospital and cofounder of the POPCoRN network. “We came together to think about how to increase capacity – both in the work force and for actual hospital space – by helping to train pediatric hospitalists and pediatrics-trained nurses to care for adult patients.”

A web-based platform filled with a rapidly expanding list of resources, an active Twitter account, and utilization of Zoom networking software for webinars and working group meetings have facilitated the network’s growth. “Social media has helped us,” Dr. Ratner said. But equally important are personal connections.

“It all started just a few weeks ago,” added cofounder Ashley Jenkins, MD, a med-peds hospital medicine and general academics research fellow in the division of hospital medicine at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. “I sent out some emails in mid-March, asking what other people were doing about these issues. Leah and I met as a result of these initial emails. We immediately started connecting with other health systems and it just expanded from there. Once we knew that enough other systems were thinking about it and trying to build capacity, we started pulling the people and information together.”

High-yield one-pagers

A third or more of those on the POPCoRN contact list are also participating as volunteers on its varied working groups, including health system operation groups exploring the needs of three distinct hospital models: freestanding children’s hospitals; community hospitals, which may see small numbers of children; and integrated mixed hospitals, which often means a pediatric hospital or pediatric units located within an adult hospital.

An immediate goal is to develop high-yield informational “one-pagers,” culling essential clinical facts on a variety of topics in adult inpatient medicine that may no longer be familiar to working pediatric hospitalists. These one-pagers, designed with the help of network members with graphic design skills, address topics such as syncope or chest pain or managing exacerbation of COPD in adults. They draw upon existing informational sources, encapsulating practical information tips that can be used at the bedside, including test workups, differential diagnoses, treatment approaches, and other pearls for providers. Drafts are reviewed for content by specialists, and then by pediatricians to make sure the information covers what they need.

Also under development are educational materials for nurses trained in pediatrics, a section for outpatient providers redeployed to triage or telehealth, and information for other team members including occupational, physical, and respiratory therapists. Another section offers critical care lectures for the nonintensivist. A metrics and outcomes working group is looking for ways to evaluate how the network is doing and who is being reached without having to ask frontline providers to fill out surveys.

Dr. Ratner and Dr. Jenkins have created an intentional structure for encouraging mentoring. They also call on their own mentors – Ahmet Uluer, DO, director of Weitzman Family Bridges Adult Transition Program at Boston Children’s Hospital, and Brian Herbst Jr., MD, medical director of the Hospital Medicine Adult Care Service at Cincinnati Children’s – for advice.

Beyond the silos

Pediatric hospitalists may have been doing similar things, working on similar projects, but not necessarily reaching out to each other across a system that tends to promote staying within administrative silos, Dr. Uluer said. “Through our personal contacts in POPCoRN, we’ve been able to reach beyond the silos. This network has worked like medical crowd sourcing, and the founders have been inspirational.”

Dr. Herbst added, “How do we expand bandwidth and safely expand services to take young patients and adults from other hospitals? What other populations do we need to expand to take? This network is a workplace of ideas. It’s amazing to see what has been built in a few weeks and how useful it can be.”

Med-peds hospitalists are an important resource for bridging the two specialties. Their experience with transitioning young adults with long-standing chronic conditions of childhood, who have received most of their care at a children’s hospital before reaching adulthood, offers a helpful model. “We’ve also tried to target junior physicians who could step up into leadership roles and to pull in medical students – who are the backbone of this network through their administrative support,” Dr. Jenkins said.

Marie Pfarr, MD, also a med-peds trained hospital medicine fellow at Cincinnati Children’s, was contacted in March by Dr. Jenkins. “She said they had this brainstorm, and they were getting feedback that it would be helpful to provide educational materials for pediatric providers. Because I have an interest in medical education, she asked if I wanted to help. I was at home struggling with what I could contribute during this crazy time, so I said yes.”

Dr. Pfarr leads POPCoRN’s educational working group, which came up with a list of 50 topics in need of one-pagers and people willing to create them, mostly still under development. The aim for the one-pagers is to offer a good starting point for pediatricians, helping them, for example, to ask the right questions during history and physical exams. “We also want to offer additional resources for those who want to do a deeper dive.”

Dr. Pfarr said she has enjoyed working closely with medical students, who really want to help. “That’s been great to see. We are all working toward the same goal, and we help to keep each other in check. I think there’s a future for this kind of mobilization through collaborations to connect pediatric to adult providers. A lot of good things will come out of the network, which is an example of how folks can talk to each other. It’s very dynamic and changing every day.”

One of those medical students is Chinma Onyewuenyi, finishing her fourth year at Baylor College of Medicine. Scheduled to start a med-peds residency at Geisinger Health on July 1, she had completed all of her rotations and was looking for ways to get involved in the pandemic response while respecting the shelter-in-place order. “I had heard about the network, which was recruiting medical students to play administrative roles for the working groups. I said, ‘If you have anything else you need help with, I have time on my hands.’”

Ms. Onyewuenyi says she fell into the role of a lead administrative volunteer, and her responsibilities grew from there, eventually taking charge of all the medical students’ recruiting, screening, and assignments, freeing up the project’s physician leaders from administrative tasks. “I wanted something active to do to contribute, and I appreciate all that I’m learning. With a master’s degree in public health, I have researched how health care is delivered,” she said.

“This experience has really opened my eyes to what’s required to deliver care, and just the level of collaboration that needs to go on with something like this. Even as a medical student, I felt glad to have an opportunity to contribute beyond the administrative tasks. At meetings, they ask for my opinion.”

Equitable access to resources

Another major focus for the network is promoting health equity – giving pediatric providers and health systems equitable access to information that meets their needs, Dr. Ratner said. “We’ve made a particular effort to reach out to hospitals that are the most vulnerable, including rural hospitals, and to those serving the most vulnerable patients,” she noted. These also include the homeless and refugees.

“We’ve been trying to be mindful of avoiding the sometimes-intimidating power structure that has been traditional in medicine,” Dr. Ratner said. The network’s equity working group is trying to provide content with structural competency and cultural humility. “We’re learning a lot about the ways the health care system is broken,” she added. “We all agree that we have a fragmented health care system, but there are ways to make it less fragmented and learn from each other.”

In the tragedy of the COVID epidemic, there are also unique opportunities to learn to work collaboratively and make the health care system stronger for those in greatest need, Dr. Ratner added. “What we hope is that our network becomes an example of that, even as it is moving so quickly.”

Audrey Uong, MD, an attending physician in the division of hospital medicine at Children’s Hospital at Montefiore Medical Center in New York, connected with POPCoRN for an educational presentation reviewing resuscitation in adult patients. She wanted to talk with peers about what’s going on, so as not to feel alone in her practice. She has also found the network’s website useful for identifying educational resources.

“As pediatricians, we have been asked to care for adult patients. One of our units has been admitting mostly patients under age 30, and we are accepting older patients in another unit on the pediatric wing.” This kind of thing is also happening in a lot of other places, Dr. Uong said. Keeping up with these changes in her own practice has been challenging.

She tries to take one day at a time. “Everyone at this institution feels the same – that we’re locked in on meeting the need. Even our child life specialists, when they’re not working with younger patients, have created this amazing support room for staff, with snacks and soothing music. There’s been a lot of attention paid to making us feel supported in this work.”

As U.S. health care systems prepare for inpatient surges linked to hospitalizations of critically ill COVID-19 patients, two hospitalists with med-peds training (combined training in internal medicine and pediatrics) have launched an innovative solution to help facilities deal with the challenge.

The Pediatric Overflow Planning Contingency Response Network (POPCoRN network) has quickly linked almost 400 physicians and other health professionals, including hospitalists, attending physicians, residents, medical students, and nurses. The network wants to help provide more information about how pediatric-focused institutions can safely gear up to admit adult patients in children’s hospitals, in order to offset the predicted demand for hospital beds for patients with COVID-19.

According to the POPCoRN network website (www.popcornetwork.org), the majority of providers who have contacted the network say they have already started or are committed to planning for their pediatric facilities to be used for adult overflow. The Children’s Hospital Association has issued a guidance on this kind of community collaboration for children’s hospitals partnering with adult hospitals in their community and with policy makers.

“We are a network of folks from different institutions, many med-peds–trained hospitalists but quickly growing,” said Leah Ratner, MD, a second-year fellow in the Global Pediatrics Program at Boston Children’s Hospital and cofounder of the POPCoRN network. “We came together to think about how to increase capacity – both in the work force and for actual hospital space – by helping to train pediatric hospitalists and pediatrics-trained nurses to care for adult patients.”

A web-based platform filled with a rapidly expanding list of resources, an active Twitter account, and utilization of Zoom networking software for webinars and working group meetings have facilitated the network’s growth. “Social media has helped us,” Dr. Ratner said. But equally important are personal connections.

“It all started just a few weeks ago,” added cofounder Ashley Jenkins, MD, a med-peds hospital medicine and general academics research fellow in the division of hospital medicine at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. “I sent out some emails in mid-March, asking what other people were doing about these issues. Leah and I met as a result of these initial emails. We immediately started connecting with other health systems and it just expanded from there. Once we knew that enough other systems were thinking about it and trying to build capacity, we started pulling the people and information together.”

High-yield one-pagers

A third or more of those on the POPCoRN contact list are also participating as volunteers on its varied working groups, including health system operation groups exploring the needs of three distinct hospital models: freestanding children’s hospitals; community hospitals, which may see small numbers of children; and integrated mixed hospitals, which often means a pediatric hospital or pediatric units located within an adult hospital.

An immediate goal is to develop high-yield informational “one-pagers,” culling essential clinical facts on a variety of topics in adult inpatient medicine that may no longer be familiar to working pediatric hospitalists. These one-pagers, designed with the help of network members with graphic design skills, address topics such as syncope or chest pain or managing exacerbation of COPD in adults. They draw upon existing informational sources, encapsulating practical information tips that can be used at the bedside, including test workups, differential diagnoses, treatment approaches, and other pearls for providers. Drafts are reviewed for content by specialists, and then by pediatricians to make sure the information covers what they need.

Also under development are educational materials for nurses trained in pediatrics, a section for outpatient providers redeployed to triage or telehealth, and information for other team members including occupational, physical, and respiratory therapists. Another section offers critical care lectures for the nonintensivist. A metrics and outcomes working group is looking for ways to evaluate how the network is doing and who is being reached without having to ask frontline providers to fill out surveys.

Dr. Ratner and Dr. Jenkins have created an intentional structure for encouraging mentoring. They also call on their own mentors – Ahmet Uluer, DO, director of Weitzman Family Bridges Adult Transition Program at Boston Children’s Hospital, and Brian Herbst Jr., MD, medical director of the Hospital Medicine Adult Care Service at Cincinnati Children’s – for advice.

Beyond the silos

Pediatric hospitalists may have been doing similar things, working on similar projects, but not necessarily reaching out to each other across a system that tends to promote staying within administrative silos, Dr. Uluer said. “Through our personal contacts in POPCoRN, we’ve been able to reach beyond the silos. This network has worked like medical crowd sourcing, and the founders have been inspirational.”

Dr. Herbst added, “How do we expand bandwidth and safely expand services to take young patients and adults from other hospitals? What other populations do we need to expand to take? This network is a workplace of ideas. It’s amazing to see what has been built in a few weeks and how useful it can be.”

Med-peds hospitalists are an important resource for bridging the two specialties. Their experience with transitioning young adults with long-standing chronic conditions of childhood, who have received most of their care at a children’s hospital before reaching adulthood, offers a helpful model. “We’ve also tried to target junior physicians who could step up into leadership roles and to pull in medical students – who are the backbone of this network through their administrative support,” Dr. Jenkins said.

Marie Pfarr, MD, also a med-peds trained hospital medicine fellow at Cincinnati Children’s, was contacted in March by Dr. Jenkins. “She said they had this brainstorm, and they were getting feedback that it would be helpful to provide educational materials for pediatric providers. Because I have an interest in medical education, she asked if I wanted to help. I was at home struggling with what I could contribute during this crazy time, so I said yes.”

Dr. Pfarr leads POPCoRN’s educational working group, which came up with a list of 50 topics in need of one-pagers and people willing to create them, mostly still under development. The aim for the one-pagers is to offer a good starting point for pediatricians, helping them, for example, to ask the right questions during history and physical exams. “We also want to offer additional resources for those who want to do a deeper dive.”

Dr. Pfarr said she has enjoyed working closely with medical students, who really want to help. “That’s been great to see. We are all working toward the same goal, and we help to keep each other in check. I think there’s a future for this kind of mobilization through collaborations to connect pediatric to adult providers. A lot of good things will come out of the network, which is an example of how folks can talk to each other. It’s very dynamic and changing every day.”

One of those medical students is Chinma Onyewuenyi, finishing her fourth year at Baylor College of Medicine. Scheduled to start a med-peds residency at Geisinger Health on July 1, she had completed all of her rotations and was looking for ways to get involved in the pandemic response while respecting the shelter-in-place order. “I had heard about the network, which was recruiting medical students to play administrative roles for the working groups. I said, ‘If you have anything else you need help with, I have time on my hands.’”

Ms. Onyewuenyi says she fell into the role of a lead administrative volunteer, and her responsibilities grew from there, eventually taking charge of all the medical students’ recruiting, screening, and assignments, freeing up the project’s physician leaders from administrative tasks. “I wanted something active to do to contribute, and I appreciate all that I’m learning. With a master’s degree in public health, I have researched how health care is delivered,” she said.

“This experience has really opened my eyes to what’s required to deliver care, and just the level of collaboration that needs to go on with something like this. Even as a medical student, I felt glad to have an opportunity to contribute beyond the administrative tasks. At meetings, they ask for my opinion.”

Equitable access to resources

Another major focus for the network is promoting health equity – giving pediatric providers and health systems equitable access to information that meets their needs, Dr. Ratner said. “We’ve made a particular effort to reach out to hospitals that are the most vulnerable, including rural hospitals, and to those serving the most vulnerable patients,” she noted. These also include the homeless and refugees.

“We’ve been trying to be mindful of avoiding the sometimes-intimidating power structure that has been traditional in medicine,” Dr. Ratner said. The network’s equity working group is trying to provide content with structural competency and cultural humility. “We’re learning a lot about the ways the health care system is broken,” she added. “We all agree that we have a fragmented health care system, but there are ways to make it less fragmented and learn from each other.”

In the tragedy of the COVID epidemic, there are also unique opportunities to learn to work collaboratively and make the health care system stronger for those in greatest need, Dr. Ratner added. “What we hope is that our network becomes an example of that, even as it is moving so quickly.”

Audrey Uong, MD, an attending physician in the division of hospital medicine at Children’s Hospital at Montefiore Medical Center in New York, connected with POPCoRN for an educational presentation reviewing resuscitation in adult patients. She wanted to talk with peers about what’s going on, so as not to feel alone in her practice. She has also found the network’s website useful for identifying educational resources.

“As pediatricians, we have been asked to care for adult patients. One of our units has been admitting mostly patients under age 30, and we are accepting older patients in another unit on the pediatric wing.” This kind of thing is also happening in a lot of other places, Dr. Uong said. Keeping up with these changes in her own practice has been challenging.

She tries to take one day at a time. “Everyone at this institution feels the same – that we’re locked in on meeting the need. Even our child life specialists, when they’re not working with younger patients, have created this amazing support room for staff, with snacks and soothing music. There’s been a lot of attention paid to making us feel supported in this work.”

Volunteer surgeon describes working at a New York hospital

In an April 18 Twitter post, Dr. Salles wrote that her unit had experienced three code blues and two deaths in a single night.

“I don’t know how many times I’ve called to tell someone their loved one has died,” she wrote in the post. “I had to do it again last night. ... Of the five patients I’ve personally been responsible for in the past two nights, two have come so close to dying that we called a code blue. That means 40% of my patients have coded. Never in my life has anything close to that happened,” she continued in the thread.

Dr. Salles, a minimally invasive and bariatric surgeon and scholar in residence at Stanford (Calif.) University, headed to New York in mid-April to assist with COVID-19 treatment efforts. Before the trip, she collected as many supplies and as much personal protective equipment as she could acquire, some of which were donated by Good Samaritans. On her first day as a volunteer, Dr. Salles recounted the stark differences between what she is used to seeing and her new environment and the novel challenges she has encountered in New York.

“Things that were not normal now seem normal,” she wrote in an April 15 Twitter post. “ICU patients in [a postanesthesia care unit] and Preop is the new normal. Patients satting in the 70s and 80s seems normal. ICU docs managing [continuous veno-venous hemodialysis] seems normal. Working with strangers seems normal. ... Obviously everyone walking around with barely any skin exposed is also the new normal.”

Similar to a “normal” ICU, new patients are admitted daily, Dr. Salles noted. However, the majority of those who leave the ICU do not go home, she wrote.

“Almost all of the ones who leave are doing so because they’ve died rather than getting better,” she wrote in the same April 19 Twitter thread. “There is a pervasive feeling of helplessness. ... The tools we are working with seem insufficient. For the sickest patients, there are no ventilator settings that seem to work, there are no medications that seem to help. I am not used to this.”

When patients are close to dying, health care workers do their best to connect the patient to loved ones through video calls, watching as family members say their last goodbyes through a screen, Dr. Salles detailed in a later post.

“Their voices cracked, and though they weren’t speaking English, I could hear their pain,” she wrote in an April 20 Twitter post. “For a moment, I imagined having to say goodbye to my mother this way. To not be able to be there, to not be able to hold her hand, to not be able to hug her. And I watched my colleague, who amazingly kept her composure until they had said everything they wanted to say. It was only after they hung up that I saw the tears well up in her eyes.”

But amid the dark days and bleak outcomes, Dr. Salles has found silver linings, humor, and gifts for which to be thankful.

“People are really generous,” she wrote in an April 15 post. “So many have offered to pay for transportation. Other docs in NY have offered to help me with supplies (and I am paying it forward). Grateful to you all!”

In another post, Dr. Salles joked that her “small head” makes it difficult to wear PPE.

“Wearing an N95 for hours really sucks,” she wrote. “It rides up, I pull it down. It digs into my cheeks, I pull it up. Repeat.”

The volunteer experience thus far has also made Dr. Salles question the future and worry about the mental health of her fellow health care professionals.

“The people who have been in NYC since the beginning of this, and those who work in Lombardy, Italy, and in Wuhan, China have faced loss for weeks to months,” she wrote in an April 18 Twitter post. “Not only do we not know when this will end, but it is likely that after it fades, it will come back in a second wave. I am lucky. I’m just a visitor here. I have the privilege to observe and learn and hopefully help, knowing I will be able to walk away. But what about those who can’t walk away? Social distancing is starting to work. But for healthcare workers, the ongoing devastation is very real. What is our long term plan?”

Dr. Salles expressed concern for health care workers who are witnessing “horrible things” with little time to process the experiences.

“It may be especially hard for those who are now working in specialties they are not used to, having to provide care they are not familiar with. They are all doing their best, but inevitably mistakes will be made, and they will likely blame themselves,” she wrote. “How do we best support them?”

Stay tuned for upcoming commentaries from Dr. Salles on her COVID-19 volunteer experience in New York City.

In an April 18 Twitter post, Dr. Salles wrote that her unit had experienced three code blues and two deaths in a single night.

“I don’t know how many times I’ve called to tell someone their loved one has died,” she wrote in the post. “I had to do it again last night. ... Of the five patients I’ve personally been responsible for in the past two nights, two have come so close to dying that we called a code blue. That means 40% of my patients have coded. Never in my life has anything close to that happened,” she continued in the thread.

Dr. Salles, a minimally invasive and bariatric surgeon and scholar in residence at Stanford (Calif.) University, headed to New York in mid-April to assist with COVID-19 treatment efforts. Before the trip, she collected as many supplies and as much personal protective equipment as she could acquire, some of which were donated by Good Samaritans. On her first day as a volunteer, Dr. Salles recounted the stark differences between what she is used to seeing and her new environment and the novel challenges she has encountered in New York.

“Things that were not normal now seem normal,” she wrote in an April 15 Twitter post. “ICU patients in [a postanesthesia care unit] and Preop is the new normal. Patients satting in the 70s and 80s seems normal. ICU docs managing [continuous veno-venous hemodialysis] seems normal. Working with strangers seems normal. ... Obviously everyone walking around with barely any skin exposed is also the new normal.”

Similar to a “normal” ICU, new patients are admitted daily, Dr. Salles noted. However, the majority of those who leave the ICU do not go home, she wrote.

“Almost all of the ones who leave are doing so because they’ve died rather than getting better,” she wrote in the same April 19 Twitter thread. “There is a pervasive feeling of helplessness. ... The tools we are working with seem insufficient. For the sickest patients, there are no ventilator settings that seem to work, there are no medications that seem to help. I am not used to this.”

When patients are close to dying, health care workers do their best to connect the patient to loved ones through video calls, watching as family members say their last goodbyes through a screen, Dr. Salles detailed in a later post.

“Their voices cracked, and though they weren’t speaking English, I could hear their pain,” she wrote in an April 20 Twitter post. “For a moment, I imagined having to say goodbye to my mother this way. To not be able to be there, to not be able to hold her hand, to not be able to hug her. And I watched my colleague, who amazingly kept her composure until they had said everything they wanted to say. It was only after they hung up that I saw the tears well up in her eyes.”

But amid the dark days and bleak outcomes, Dr. Salles has found silver linings, humor, and gifts for which to be thankful.

“People are really generous,” she wrote in an April 15 post. “So many have offered to pay for transportation. Other docs in NY have offered to help me with supplies (and I am paying it forward). Grateful to you all!”

In another post, Dr. Salles joked that her “small head” makes it difficult to wear PPE.

“Wearing an N95 for hours really sucks,” she wrote. “It rides up, I pull it down. It digs into my cheeks, I pull it up. Repeat.”

The volunteer experience thus far has also made Dr. Salles question the future and worry about the mental health of her fellow health care professionals.

“The people who have been in NYC since the beginning of this, and those who work in Lombardy, Italy, and in Wuhan, China have faced loss for weeks to months,” she wrote in an April 18 Twitter post. “Not only do we not know when this will end, but it is likely that after it fades, it will come back in a second wave. I am lucky. I’m just a visitor here. I have the privilege to observe and learn and hopefully help, knowing I will be able to walk away. But what about those who can’t walk away? Social distancing is starting to work. But for healthcare workers, the ongoing devastation is very real. What is our long term plan?”

Dr. Salles expressed concern for health care workers who are witnessing “horrible things” with little time to process the experiences.

“It may be especially hard for those who are now working in specialties they are not used to, having to provide care they are not familiar with. They are all doing their best, but inevitably mistakes will be made, and they will likely blame themselves,” she wrote. “How do we best support them?”

Stay tuned for upcoming commentaries from Dr. Salles on her COVID-19 volunteer experience in New York City.

In an April 18 Twitter post, Dr. Salles wrote that her unit had experienced three code blues and two deaths in a single night.

“I don’t know how many times I’ve called to tell someone their loved one has died,” she wrote in the post. “I had to do it again last night. ... Of the five patients I’ve personally been responsible for in the past two nights, two have come so close to dying that we called a code blue. That means 40% of my patients have coded. Never in my life has anything close to that happened,” she continued in the thread.

Dr. Salles, a minimally invasive and bariatric surgeon and scholar in residence at Stanford (Calif.) University, headed to New York in mid-April to assist with COVID-19 treatment efforts. Before the trip, she collected as many supplies and as much personal protective equipment as she could acquire, some of which were donated by Good Samaritans. On her first day as a volunteer, Dr. Salles recounted the stark differences between what she is used to seeing and her new environment and the novel challenges she has encountered in New York.

“Things that were not normal now seem normal,” she wrote in an April 15 Twitter post. “ICU patients in [a postanesthesia care unit] and Preop is the new normal. Patients satting in the 70s and 80s seems normal. ICU docs managing [continuous veno-venous hemodialysis] seems normal. Working with strangers seems normal. ... Obviously everyone walking around with barely any skin exposed is also the new normal.”

Similar to a “normal” ICU, new patients are admitted daily, Dr. Salles noted. However, the majority of those who leave the ICU do not go home, she wrote.

“Almost all of the ones who leave are doing so because they’ve died rather than getting better,” she wrote in the same April 19 Twitter thread. “There is a pervasive feeling of helplessness. ... The tools we are working with seem insufficient. For the sickest patients, there are no ventilator settings that seem to work, there are no medications that seem to help. I am not used to this.”

When patients are close to dying, health care workers do their best to connect the patient to loved ones through video calls, watching as family members say their last goodbyes through a screen, Dr. Salles detailed in a later post.

“Their voices cracked, and though they weren’t speaking English, I could hear their pain,” she wrote in an April 20 Twitter post. “For a moment, I imagined having to say goodbye to my mother this way. To not be able to be there, to not be able to hold her hand, to not be able to hug her. And I watched my colleague, who amazingly kept her composure until they had said everything they wanted to say. It was only after they hung up that I saw the tears well up in her eyes.”

But amid the dark days and bleak outcomes, Dr. Salles has found silver linings, humor, and gifts for which to be thankful.

“People are really generous,” she wrote in an April 15 post. “So many have offered to pay for transportation. Other docs in NY have offered to help me with supplies (and I am paying it forward). Grateful to you all!”

In another post, Dr. Salles joked that her “small head” makes it difficult to wear PPE.

“Wearing an N95 for hours really sucks,” she wrote. “It rides up, I pull it down. It digs into my cheeks, I pull it up. Repeat.”

The volunteer experience thus far has also made Dr. Salles question the future and worry about the mental health of her fellow health care professionals.

“The people who have been in NYC since the beginning of this, and those who work in Lombardy, Italy, and in Wuhan, China have faced loss for weeks to months,” she wrote in an April 18 Twitter post. “Not only do we not know when this will end, but it is likely that after it fades, it will come back in a second wave. I am lucky. I’m just a visitor here. I have the privilege to observe and learn and hopefully help, knowing I will be able to walk away. But what about those who can’t walk away? Social distancing is starting to work. But for healthcare workers, the ongoing devastation is very real. What is our long term plan?”

Dr. Salles expressed concern for health care workers who are witnessing “horrible things” with little time to process the experiences.

“It may be especially hard for those who are now working in specialties they are not used to, having to provide care they are not familiar with. They are all doing their best, but inevitably mistakes will be made, and they will likely blame themselves,” she wrote. “How do we best support them?”

Stay tuned for upcoming commentaries from Dr. Salles on her COVID-19 volunteer experience in New York City.

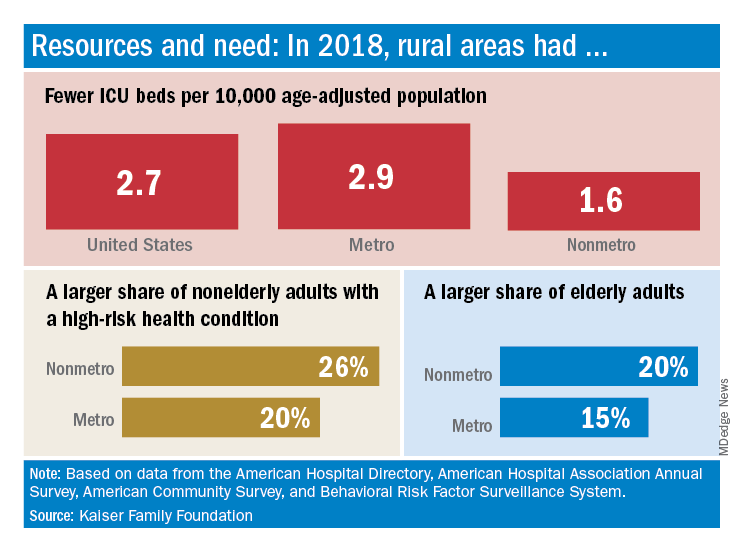

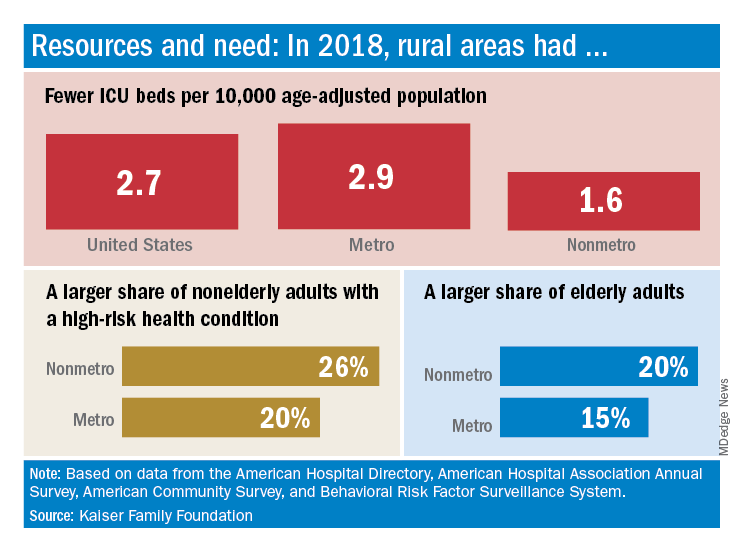

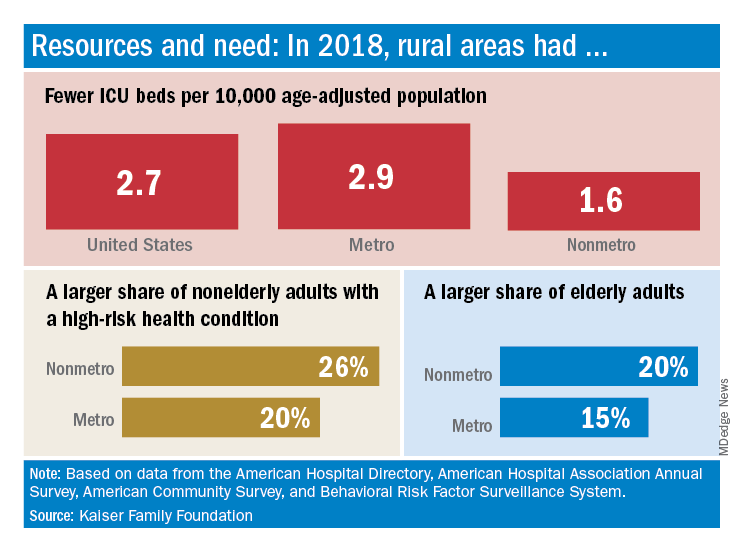

Rural ICU capacity could be strained by COVID-19

The nonmetropolitan, largely rural, areas of the United States have fewer ICU beds than do urban areas, but their populations may be at higher risk for COVID-19 complications, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

In 2018, the United States had 2.7 ICU beds per 10,000 age-adjusted population, but that number drops to 1.6 beds per 10,000 in nonmetro America and rises to 2.9 per 10,000 in metro areas. Counts for all hospital beds were much closer: 21.6 per 10,000 (rural) and 23.9 per 10,000 (urban), Kaiser investigators reported.

“The novel coronavirus was slower to spread to rural areas in the U.S., but that appears to be changing, with new outbreaks becoming evident in less densely populated parts of the country,” Kendal Orgera and associates said in a recent analysis.

Those rural areas have COVID-19 issues beyond ICU bed counts. Populations in nonmetro areas are less healthy – 26% of adults under age 65 years had a preexisting medical condition in 2018, compared with 20% in metro areas – and older – 20% of people are 65 and older, versus 15% in metro areas, they said.

“If coronavirus continues to spread in rural communities across the U.S., it is possible many [nonmetro] areas will face shortages of ICU beds with limited options to adapt. Patients in rural areas experiencing more severe illnesses may be transferred to hospitals with greater capacity, but if nearby urban areas are also overwhelmed, transfer may not be an option,” Ms. Orgera and associates wrote.

They defined nonmetro counties as those with rural towns of fewer than 2,500 people and/or “urban areas with populations ranging from 2,500 to 49,999 that are not part of larger labor market areas.” The Kaiser analysis involved 2018 data from the American Hospital Association, American Hospital Directory, American Community Survey, and the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System.

The nonmetropolitan, largely rural, areas of the United States have fewer ICU beds than do urban areas, but their populations may be at higher risk for COVID-19 complications, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

In 2018, the United States had 2.7 ICU beds per 10,000 age-adjusted population, but that number drops to 1.6 beds per 10,000 in nonmetro America and rises to 2.9 per 10,000 in metro areas. Counts for all hospital beds were much closer: 21.6 per 10,000 (rural) and 23.9 per 10,000 (urban), Kaiser investigators reported.

“The novel coronavirus was slower to spread to rural areas in the U.S., but that appears to be changing, with new outbreaks becoming evident in less densely populated parts of the country,” Kendal Orgera and associates said in a recent analysis.

Those rural areas have COVID-19 issues beyond ICU bed counts. Populations in nonmetro areas are less healthy – 26% of adults under age 65 years had a preexisting medical condition in 2018, compared with 20% in metro areas – and older – 20% of people are 65 and older, versus 15% in metro areas, they said.

“If coronavirus continues to spread in rural communities across the U.S., it is possible many [nonmetro] areas will face shortages of ICU beds with limited options to adapt. Patients in rural areas experiencing more severe illnesses may be transferred to hospitals with greater capacity, but if nearby urban areas are also overwhelmed, transfer may not be an option,” Ms. Orgera and associates wrote.

They defined nonmetro counties as those with rural towns of fewer than 2,500 people and/or “urban areas with populations ranging from 2,500 to 49,999 that are not part of larger labor market areas.” The Kaiser analysis involved 2018 data from the American Hospital Association, American Hospital Directory, American Community Survey, and the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System.

The nonmetropolitan, largely rural, areas of the United States have fewer ICU beds than do urban areas, but their populations may be at higher risk for COVID-19 complications, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

In 2018, the United States had 2.7 ICU beds per 10,000 age-adjusted population, but that number drops to 1.6 beds per 10,000 in nonmetro America and rises to 2.9 per 10,000 in metro areas. Counts for all hospital beds were much closer: 21.6 per 10,000 (rural) and 23.9 per 10,000 (urban), Kaiser investigators reported.

“The novel coronavirus was slower to spread to rural areas in the U.S., but that appears to be changing, with new outbreaks becoming evident in less densely populated parts of the country,” Kendal Orgera and associates said in a recent analysis.

Those rural areas have COVID-19 issues beyond ICU bed counts. Populations in nonmetro areas are less healthy – 26% of adults under age 65 years had a preexisting medical condition in 2018, compared with 20% in metro areas – and older – 20% of people are 65 and older, versus 15% in metro areas, they said.

“If coronavirus continues to spread in rural communities across the U.S., it is possible many [nonmetro] areas will face shortages of ICU beds with limited options to adapt. Patients in rural areas experiencing more severe illnesses may be transferred to hospitals with greater capacity, but if nearby urban areas are also overwhelmed, transfer may not be an option,” Ms. Orgera and associates wrote.

They defined nonmetro counties as those with rural towns of fewer than 2,500 people and/or “urban areas with populations ranging from 2,500 to 49,999 that are not part of larger labor market areas.” The Kaiser analysis involved 2018 data from the American Hospital Association, American Hospital Directory, American Community Survey, and the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System.

Seniors with COVID-19 show unusual symptoms, doctors say

complicating efforts to ensure they get timely and appropriate treatment, according to physicians.

COVID-19 is typically signaled by three symptoms: a fever, an insistent cough, and shortness of breath. But older adults – the age group most at risk of severe complications or death from this condition – may have none of these characteristics.

Instead, seniors may seem “off” – not acting like themselves – early on after being infected by the coronavirus. They may sleep more than usual or stop eating. They may seem unusually apathetic or confused, losing orientation to their surroundings. They may become dizzy and fall. Sometimes, seniors stop speaking or simply collapse.

“With a lot of conditions, older adults don’t present in a typical way, and we’re seeing that with COVID-19 as well,” said Camille Vaughan, MD, section chief of geriatrics and gerontology at Emory University, Atlanta.

The reason has to do with how older bodies respond to illness and infection.

At advanced ages, “someone’s immune response may be blunted and their ability to regulate temperature may be altered,” said Dr. Joseph Ouslander, a professor of geriatric medicine at Florida Atlantic University in Boca Raton.

“Underlying chronic illnesses can mask or interfere with signs of infection,” he said. “Some older people, whether from age-related changes or previous neurologic issues such as a stroke, may have altered cough reflexes. Others with cognitive impairment may not be able to communicate their symptoms.”

Recognizing danger signs is important: If early signs of COVID-19 are missed, seniors may deteriorate before getting needed care. And people may go in and out of their homes without adequate protective measures, risking the spread of infection.

Quratulain Syed, MD, an Atlanta geriatrician, describes a man in his 80s whom she treated in mid-March. Over a period of days, this patient, who had heart disease, diabetes and moderate cognitive impairment, stopped walking and became incontinent and profoundly lethargic. But he didn’t have a fever or a cough. His only respiratory symptom: sneezing off and on.

The man’s elderly spouse called 911 twice. Both times, paramedics checked his vital signs and declared he was OK. After another worried call from the overwhelmed spouse, Dr. Syed insisted the patient be taken to the hospital, where he tested positive for COVID-19.

“I was quite concerned about the paramedics and health aides who’d been in the house and who hadn’t used PPE [personal protective equipment],” Dr. Syed said.

Dr. Sam Torbati, medical director of the emergency department at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, describes treating seniors who initially appear to be trauma patients but are found to have COVID-19.

“They get weak and dehydrated,” he said, “and when they stand to walk, they collapse and injure themselves badly.”

Dr. Torbati has seen older adults who are profoundly disoriented and unable to speak and who appear at first to have suffered strokes.

“When we test them, we discover that what’s producing these changes is a central nervous system effect of coronavirus,” he said.

Laura Perry, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, saw a patient like this several weeks ago. The woman, in her 80s, had what seemed to be a cold before becoming very confused. In the hospital, she couldn’t identify where she was or stay awake during an examination. Dr. Perry diagnosed hypoactive delirium, an altered mental state in which people become inactive and drowsy. The patient tested positive for coronavirus and is still in the ICU.

Anthony Perry, MD, of the department of geriatric medicine at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, tells of an 81-year-old woman with nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea who tested positive for COVID-19 in the emergency room. After receiving intravenous fluids, oxygen, and medication for her intestinal upset, she returned home after 2 days and is doing well.

Another 80-year-old Rush patient with similar symptoms – nausea and vomiting, but no cough, fever, or shortness of breath – is in intensive care after getting a positive COVID-19 test and due to be put on a ventilator. The difference? This patient is frail with “a lot of cardiovascular disease,” Dr. Perry said. Other than that, it’s not yet clear why some older patients do well while others do not.

So far, reports of cases like these have been anecdotal. But a few physicians are trying to gather more systematic information.

In Switzerland, Sylvain Nguyen, MD, a geriatrician at the University of Lausanne Hospital Center, put together a list of typical and atypical symptoms in older COVID-19 patients for a paper to be published in the Revue Médicale Suisse. Included on the atypical list are changes in a patient’s usual status, delirium, falls, fatigue, lethargy, low blood pressure, painful swallowing, fainting, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and the loss of smell and taste.

Data come from hospitals and nursing homes in Switzerland, Italy, and France, Dr. Nguyen said in an email.

On the front lines, physicians need to make sure they carefully assess an older patient’s symptoms.

“While we have to have a high suspicion of COVID-19 because it’s so dangerous in the older population, there are many other things to consider,” said Kathleen Unroe, MD, a geriatrician at Indiana University, Indianapolis.

Seniors may also do poorly because their routines have changed. In nursing homes and most assisted living centers, activities have stopped and “residents are going to get weaker and more deconditioned because they’re not walking to and from the dining hall,” she said.

At home, isolated seniors may not be getting as much help with medication management or other essential needs from family members who are keeping their distance, other experts suggested. Or they may have become apathetic or depressed.

“I’d want to know ‘What’s the potential this person has had an exposure [to the coronavirus], especially in the last 2 weeks?’ ” said Dr. Vaughan of Emory. “Do they have home health personnel coming in? Have they gotten together with other family members? Are chronic conditions being controlled? Is there another diagnosis that seems more likely?”

“Someone may be just having a bad day. But if they’re not themselves for a couple of days, absolutely reach out to a primary care doctor or a local health system hotline to see if they meet the threshold for [coronavirus] testing,” Dr. Vaughan advised. “Be persistent. If you get a ‘no’ the first time and things aren’t improving, call back and ask again.”

Kaiser Health News (khn.org) is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

complicating efforts to ensure they get timely and appropriate treatment, according to physicians.

COVID-19 is typically signaled by three symptoms: a fever, an insistent cough, and shortness of breath. But older adults – the age group most at risk of severe complications or death from this condition – may have none of these characteristics.

Instead, seniors may seem “off” – not acting like themselves – early on after being infected by the coronavirus. They may sleep more than usual or stop eating. They may seem unusually apathetic or confused, losing orientation to their surroundings. They may become dizzy and fall. Sometimes, seniors stop speaking or simply collapse.

“With a lot of conditions, older adults don’t present in a typical way, and we’re seeing that with COVID-19 as well,” said Camille Vaughan, MD, section chief of geriatrics and gerontology at Emory University, Atlanta.

The reason has to do with how older bodies respond to illness and infection.

At advanced ages, “someone’s immune response may be blunted and their ability to regulate temperature may be altered,” said Dr. Joseph Ouslander, a professor of geriatric medicine at Florida Atlantic University in Boca Raton.

“Underlying chronic illnesses can mask or interfere with signs of infection,” he said. “Some older people, whether from age-related changes or previous neurologic issues such as a stroke, may have altered cough reflexes. Others with cognitive impairment may not be able to communicate their symptoms.”

Recognizing danger signs is important: If early signs of COVID-19 are missed, seniors may deteriorate before getting needed care. And people may go in and out of their homes without adequate protective measures, risking the spread of infection.

Quratulain Syed, MD, an Atlanta geriatrician, describes a man in his 80s whom she treated in mid-March. Over a period of days, this patient, who had heart disease, diabetes and moderate cognitive impairment, stopped walking and became incontinent and profoundly lethargic. But he didn’t have a fever or a cough. His only respiratory symptom: sneezing off and on.

The man’s elderly spouse called 911 twice. Both times, paramedics checked his vital signs and declared he was OK. After another worried call from the overwhelmed spouse, Dr. Syed insisted the patient be taken to the hospital, where he tested positive for COVID-19.

“I was quite concerned about the paramedics and health aides who’d been in the house and who hadn’t used PPE [personal protective equipment],” Dr. Syed said.

Dr. Sam Torbati, medical director of the emergency department at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, describes treating seniors who initially appear to be trauma patients but are found to have COVID-19.

“They get weak and dehydrated,” he said, “and when they stand to walk, they collapse and injure themselves badly.”

Dr. Torbati has seen older adults who are profoundly disoriented and unable to speak and who appear at first to have suffered strokes.

“When we test them, we discover that what’s producing these changes is a central nervous system effect of coronavirus,” he said.

Laura Perry, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, saw a patient like this several weeks ago. The woman, in her 80s, had what seemed to be a cold before becoming very confused. In the hospital, she couldn’t identify where she was or stay awake during an examination. Dr. Perry diagnosed hypoactive delirium, an altered mental state in which people become inactive and drowsy. The patient tested positive for coronavirus and is still in the ICU.

Anthony Perry, MD, of the department of geriatric medicine at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, tells of an 81-year-old woman with nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea who tested positive for COVID-19 in the emergency room. After receiving intravenous fluids, oxygen, and medication for her intestinal upset, she returned home after 2 days and is doing well.

Another 80-year-old Rush patient with similar symptoms – nausea and vomiting, but no cough, fever, or shortness of breath – is in intensive care after getting a positive COVID-19 test and due to be put on a ventilator. The difference? This patient is frail with “a lot of cardiovascular disease,” Dr. Perry said. Other than that, it’s not yet clear why some older patients do well while others do not.

So far, reports of cases like these have been anecdotal. But a few physicians are trying to gather more systematic information.

In Switzerland, Sylvain Nguyen, MD, a geriatrician at the University of Lausanne Hospital Center, put together a list of typical and atypical symptoms in older COVID-19 patients for a paper to be published in the Revue Médicale Suisse. Included on the atypical list are changes in a patient’s usual status, delirium, falls, fatigue, lethargy, low blood pressure, painful swallowing, fainting, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and the loss of smell and taste.

Data come from hospitals and nursing homes in Switzerland, Italy, and France, Dr. Nguyen said in an email.

On the front lines, physicians need to make sure they carefully assess an older patient’s symptoms.

“While we have to have a high suspicion of COVID-19 because it’s so dangerous in the older population, there are many other things to consider,” said Kathleen Unroe, MD, a geriatrician at Indiana University, Indianapolis.

Seniors may also do poorly because their routines have changed. In nursing homes and most assisted living centers, activities have stopped and “residents are going to get weaker and more deconditioned because they’re not walking to and from the dining hall,” she said.

At home, isolated seniors may not be getting as much help with medication management or other essential needs from family members who are keeping their distance, other experts suggested. Or they may have become apathetic or depressed.

“I’d want to know ‘What’s the potential this person has had an exposure [to the coronavirus], especially in the last 2 weeks?’ ” said Dr. Vaughan of Emory. “Do they have home health personnel coming in? Have they gotten together with other family members? Are chronic conditions being controlled? Is there another diagnosis that seems more likely?”

“Someone may be just having a bad day. But if they’re not themselves for a couple of days, absolutely reach out to a primary care doctor or a local health system hotline to see if they meet the threshold for [coronavirus] testing,” Dr. Vaughan advised. “Be persistent. If you get a ‘no’ the first time and things aren’t improving, call back and ask again.”

Kaiser Health News (khn.org) is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

complicating efforts to ensure they get timely and appropriate treatment, according to physicians.

COVID-19 is typically signaled by three symptoms: a fever, an insistent cough, and shortness of breath. But older adults – the age group most at risk of severe complications or death from this condition – may have none of these characteristics.

Instead, seniors may seem “off” – not acting like themselves – early on after being infected by the coronavirus. They may sleep more than usual or stop eating. They may seem unusually apathetic or confused, losing orientation to their surroundings. They may become dizzy and fall. Sometimes, seniors stop speaking or simply collapse.

“With a lot of conditions, older adults don’t present in a typical way, and we’re seeing that with COVID-19 as well,” said Camille Vaughan, MD, section chief of geriatrics and gerontology at Emory University, Atlanta.

The reason has to do with how older bodies respond to illness and infection.

At advanced ages, “someone’s immune response may be blunted and their ability to regulate temperature may be altered,” said Dr. Joseph Ouslander, a professor of geriatric medicine at Florida Atlantic University in Boca Raton.

“Underlying chronic illnesses can mask or interfere with signs of infection,” he said. “Some older people, whether from age-related changes or previous neurologic issues such as a stroke, may have altered cough reflexes. Others with cognitive impairment may not be able to communicate their symptoms.”

Recognizing danger signs is important: If early signs of COVID-19 are missed, seniors may deteriorate before getting needed care. And people may go in and out of their homes without adequate protective measures, risking the spread of infection.

Quratulain Syed, MD, an Atlanta geriatrician, describes a man in his 80s whom she treated in mid-March. Over a period of days, this patient, who had heart disease, diabetes and moderate cognitive impairment, stopped walking and became incontinent and profoundly lethargic. But he didn’t have a fever or a cough. His only respiratory symptom: sneezing off and on.

The man’s elderly spouse called 911 twice. Both times, paramedics checked his vital signs and declared he was OK. After another worried call from the overwhelmed spouse, Dr. Syed insisted the patient be taken to the hospital, where he tested positive for COVID-19.

“I was quite concerned about the paramedics and health aides who’d been in the house and who hadn’t used PPE [personal protective equipment],” Dr. Syed said.

Dr. Sam Torbati, medical director of the emergency department at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, describes treating seniors who initially appear to be trauma patients but are found to have COVID-19.

“They get weak and dehydrated,” he said, “and when they stand to walk, they collapse and injure themselves badly.”

Dr. Torbati has seen older adults who are profoundly disoriented and unable to speak and who appear at first to have suffered strokes.

“When we test them, we discover that what’s producing these changes is a central nervous system effect of coronavirus,” he said.

Laura Perry, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, saw a patient like this several weeks ago. The woman, in her 80s, had what seemed to be a cold before becoming very confused. In the hospital, she couldn’t identify where she was or stay awake during an examination. Dr. Perry diagnosed hypoactive delirium, an altered mental state in which people become inactive and drowsy. The patient tested positive for coronavirus and is still in the ICU.

Anthony Perry, MD, of the department of geriatric medicine at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, tells of an 81-year-old woman with nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea who tested positive for COVID-19 in the emergency room. After receiving intravenous fluids, oxygen, and medication for her intestinal upset, she returned home after 2 days and is doing well.

Another 80-year-old Rush patient with similar symptoms – nausea and vomiting, but no cough, fever, or shortness of breath – is in intensive care after getting a positive COVID-19 test and due to be put on a ventilator. The difference? This patient is frail with “a lot of cardiovascular disease,” Dr. Perry said. Other than that, it’s not yet clear why some older patients do well while others do not.

So far, reports of cases like these have been anecdotal. But a few physicians are trying to gather more systematic information.

In Switzerland, Sylvain Nguyen, MD, a geriatrician at the University of Lausanne Hospital Center, put together a list of typical and atypical symptoms in older COVID-19 patients for a paper to be published in the Revue Médicale Suisse. Included on the atypical list are changes in a patient’s usual status, delirium, falls, fatigue, lethargy, low blood pressure, painful swallowing, fainting, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and the loss of smell and taste.