User login

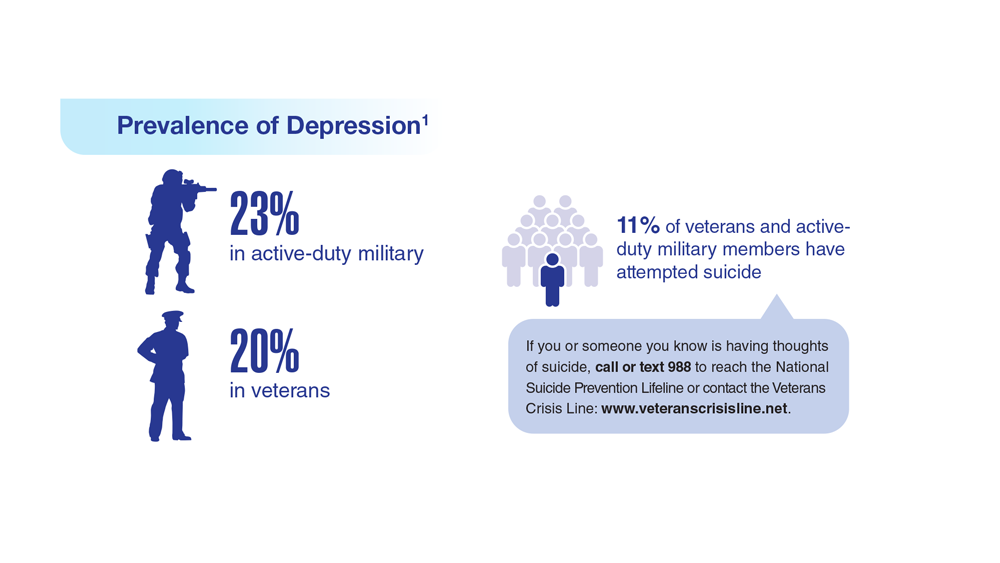

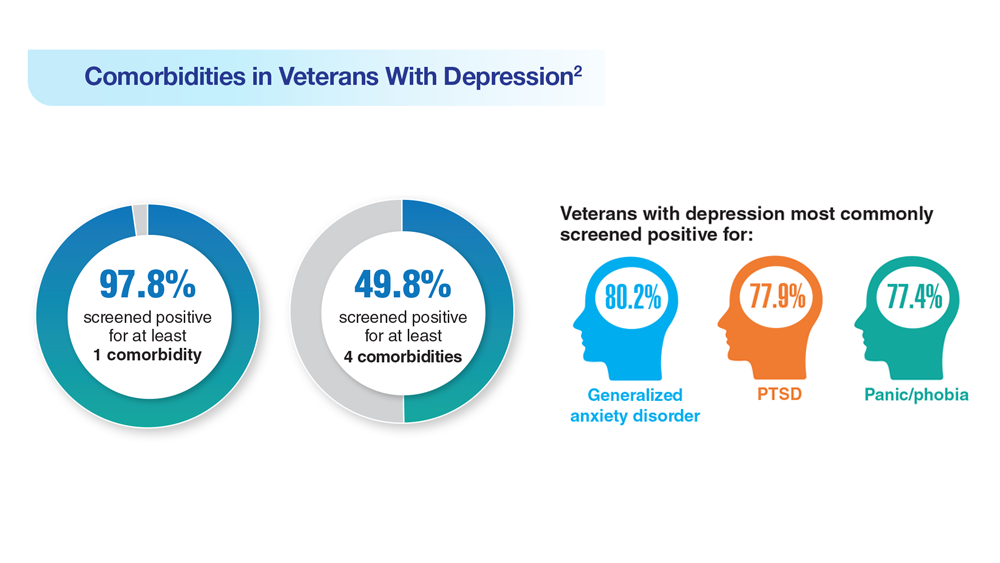

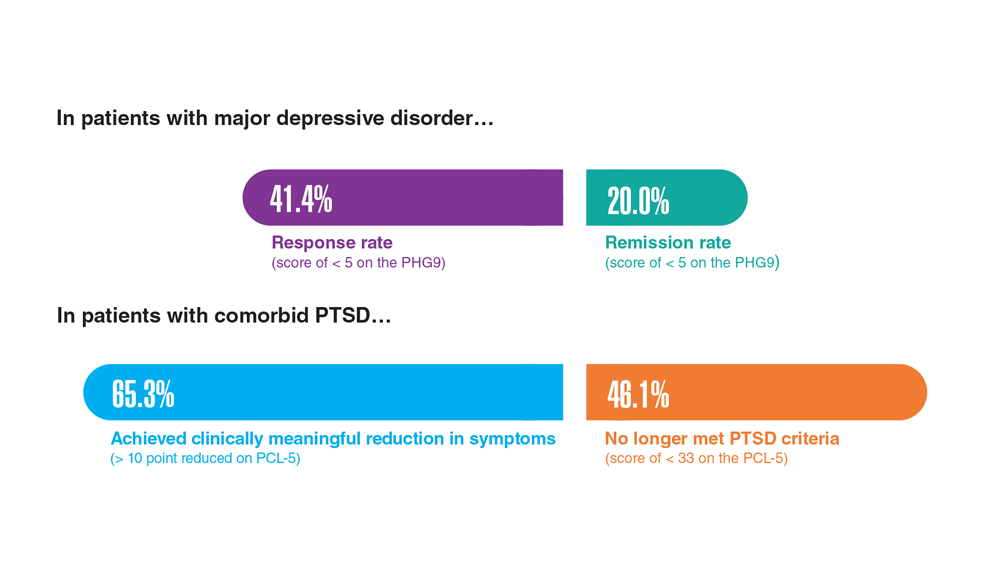

Data Trends 2023: Depression

1. Moradi Y et al. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21(1):510. doi:10.1186/s12888-021-03526-2

2. Ziobrowski HN et al. J Affect Disord. 2021;290:227-236. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2021.04.033

3. Szukis H et al. Curr Med Res Opin. 2021;37(8):1393-1401. doi:10.1080/03007995.2021.1918073

4. Levey DF et al. Nat Neurosci. 2021;24(7):954-963. doi:10.1038/s41593-021-00860-2

5. Madore MR et al. J Affect Disord. 2022;297:671-678. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2021.10.025

6. Cheng CM et al. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2021;1305:333-349. doi:10.1007/978-981-33-6044-0_18

1. Moradi Y et al. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21(1):510. doi:10.1186/s12888-021-03526-2

2. Ziobrowski HN et al. J Affect Disord. 2021;290:227-236. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2021.04.033

3. Szukis H et al. Curr Med Res Opin. 2021;37(8):1393-1401. doi:10.1080/03007995.2021.1918073

4. Levey DF et al. Nat Neurosci. 2021;24(7):954-963. doi:10.1038/s41593-021-00860-2

5. Madore MR et al. J Affect Disord. 2022;297:671-678. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2021.10.025

6. Cheng CM et al. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2021;1305:333-349. doi:10.1007/978-981-33-6044-0_18

1. Moradi Y et al. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21(1):510. doi:10.1186/s12888-021-03526-2

2. Ziobrowski HN et al. J Affect Disord. 2021;290:227-236. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2021.04.033

3. Szukis H et al. Curr Med Res Opin. 2021;37(8):1393-1401. doi:10.1080/03007995.2021.1918073

4. Levey DF et al. Nat Neurosci. 2021;24(7):954-963. doi:10.1038/s41593-021-00860-2

5. Madore MR et al. J Affect Disord. 2022;297:671-678. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2021.10.025

6. Cheng CM et al. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2021;1305:333-349. doi:10.1007/978-981-33-6044-0_18

Emotional blunting in patients taking antidepressants

When used to treat anxiety or depressive disorders, antidepressants can cause a variety of adverse effects, including emotional blunting. Emotional blunting has been described as emotional numbness, indifference, decreased responsiveness, or numbing. In a study of 669 patients who had been receiving antidepressants (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs], serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors [SNRIs], or other antidepressants), 46% said they had experienced emotional blunting.1 A 2019 study found that approximately one-third of patients with unipolar depression or bipolar depression stopped taking their antidepressant due to emotional blunting.2

Historically, there has been difficulty parsing out emotional blunting (a general decrease of all range of emotions) from anhedonia (a restriction of positive emotions). Additionally, some researchers have questioned if the blunting of emotions is part of depressive symptomatology. In a study of 38 adults, most felt able to differentiate emotional blunting due to antidepressants by considering the resolution of other depressive symptoms and timeline of onset.3

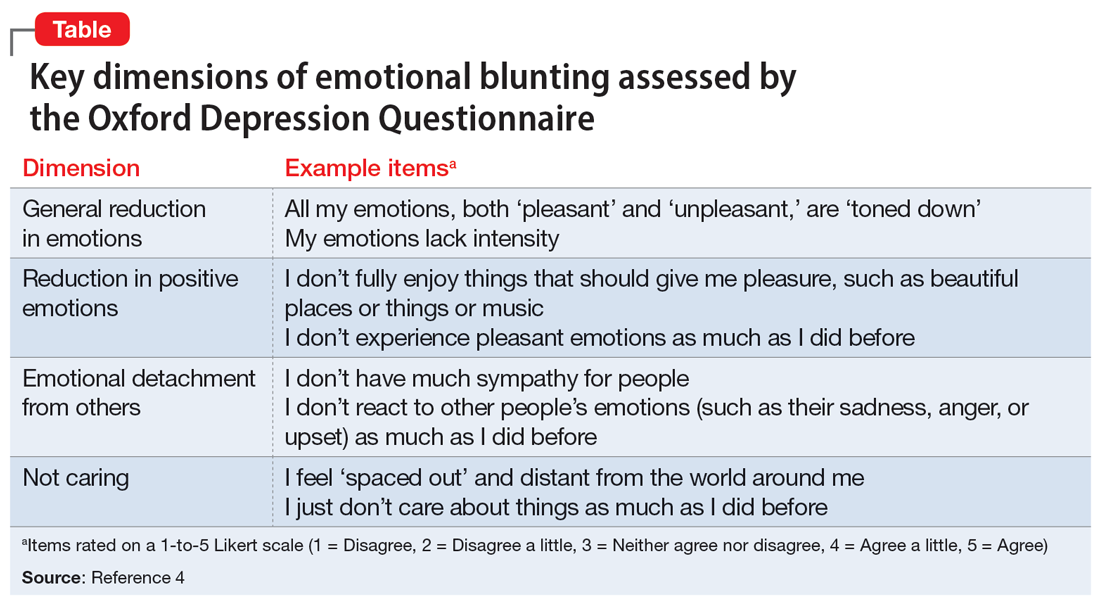

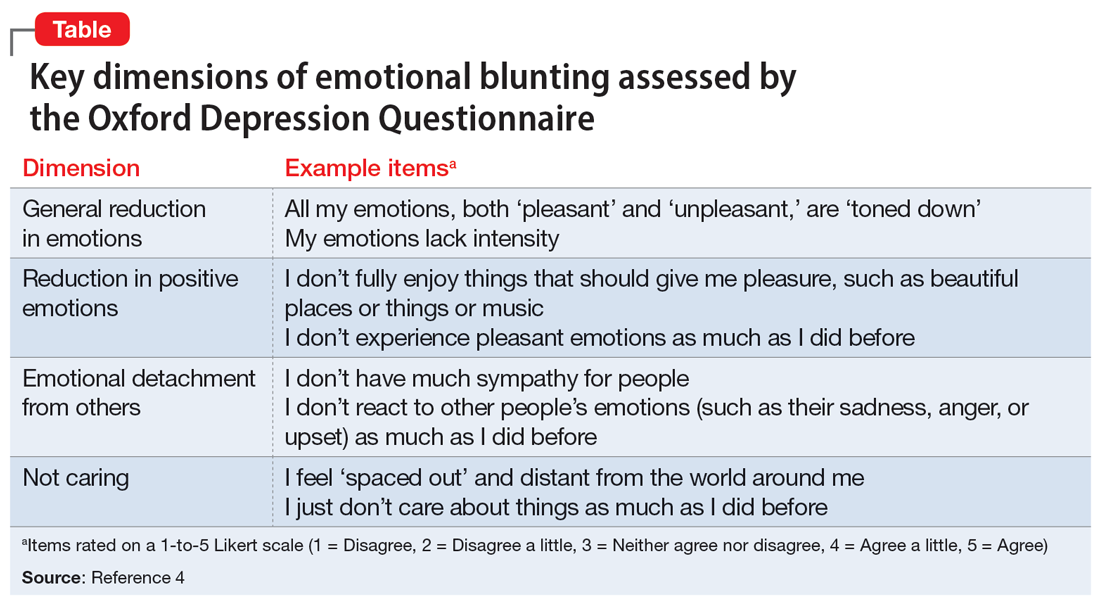

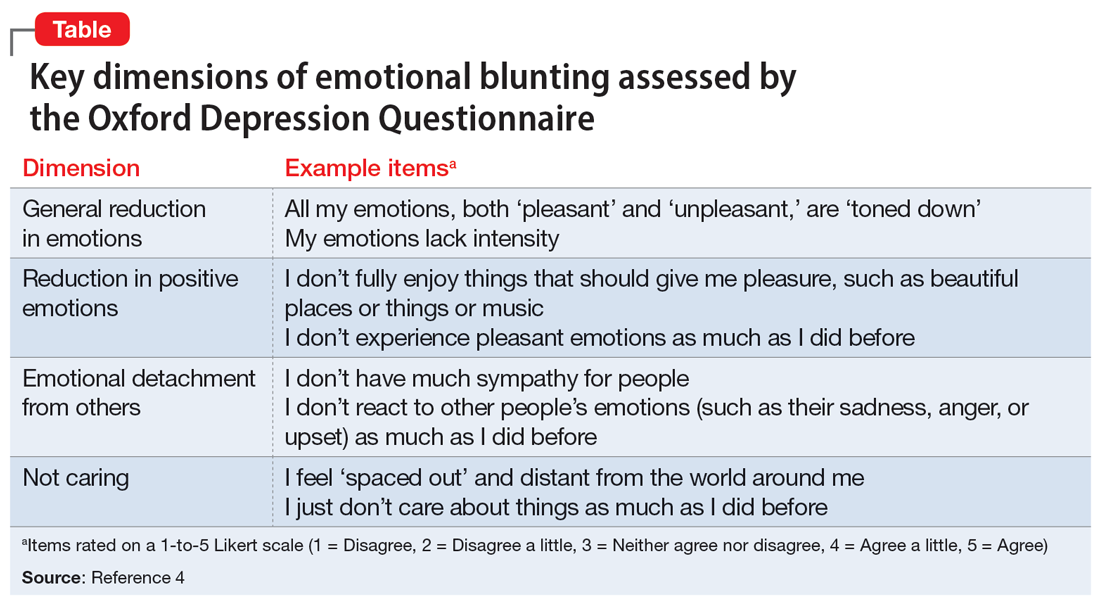

A significant limitation has been how clinicians measure or assess emotional blunting. The Oxford Depression Questionnaire (ODQ), previously known as the Oxford Questionnaire on the Emotional Side-effects of Antidepressants, was created based on a qualitative survey of patients who endorsed emotional blunting.4 A validated scale, the ODQ divides emotional blunting into 4 dimensions:

- general reduction in emotions

- reduction in positive emotions

- emotional detachment from others

- not caring.4

The sections of ODQ focus on exploring specific aspects of patients’ emotional experiences, comparing experiences in the past week to before the development of illness/emotional blunting, and patients’ opinions about antidepressants. Example statements from the ODQ (Table4) may help clinicians better understand and explore emotional blunting with their patients.

There are 2 leading theories behind the mechanism of emotional blunting on antidepressants, both focused on serotonin. The first theory offers that SSRIs alter frontal lobe activity through serotonergic effects. The second theory is focused on the downward effects of serotonin on dopamine in reward pathways.5

Treatment options: Limited evidence

Data on how to address antidepressant-induced emotional blunting are limited and based largely on case reports. One open-label study (N = 143) found that patients experiencing emotional blunting while taking SSRIs and SNRIs who were switched to vortioxetine had a statistically significant decrease in ODQ total score; 50% reported no emotional blunting.6 Options to address emotional blunting include decreasing the antidepressant dose, augmenting with or switching to another agent, or considering other treatments such as neuromodulation.5 Further research is necessary to clarify which intervention is best.

Clinicians will encounter emotional blunting in patients who are taking antidepressants. It is important to recognize and address these symptoms to help improve patients’ adherence and overall quality of life.

1. Goodwin GM, Price J, De Bodinat C, et al. Emotional blunting with antidepressant treatments: a survey among depressed patients. J Affect Disord. 2017;221:31-35.

2. Rosenblat JD, Simon GE, Sachs GS, et al. Treatment effectiveness and tolerability outcomes that are most important to individuals with bipolar and unipolar depression. J Affect Disord. 2019;243:116-120.

3. Price J, Cole V, Goodwin GM. Emotional side-effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: qualitative study. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;195(3):211-217.

4. Price J, Cole V, Doll H, et al. The Oxford Questionnaire on the Emotional Side-effects of Antidepressants (OQuESA): development, validity, reliability and sensitivity to change. J Affect Disord. 2012;140(1):66-74.

5. Ma H, Cai M, Wang H. Emotional blunting in patients with major depressive disorder: a brief non-systematic review of current research. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:792960. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.792960

6. Fagiolini A, Florea I, Loft H, et al. Effectiveness of vortioxetine on emotional blunting in patients with major depressive disorder with inadequate response to SSRI/SNRI treatment. J Affect Disord. 2021;283:472-479.

When used to treat anxiety or depressive disorders, antidepressants can cause a variety of adverse effects, including emotional blunting. Emotional blunting has been described as emotional numbness, indifference, decreased responsiveness, or numbing. In a study of 669 patients who had been receiving antidepressants (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs], serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors [SNRIs], or other antidepressants), 46% said they had experienced emotional blunting.1 A 2019 study found that approximately one-third of patients with unipolar depression or bipolar depression stopped taking their antidepressant due to emotional blunting.2

Historically, there has been difficulty parsing out emotional blunting (a general decrease of all range of emotions) from anhedonia (a restriction of positive emotions). Additionally, some researchers have questioned if the blunting of emotions is part of depressive symptomatology. In a study of 38 adults, most felt able to differentiate emotional blunting due to antidepressants by considering the resolution of other depressive symptoms and timeline of onset.3

A significant limitation has been how clinicians measure or assess emotional blunting. The Oxford Depression Questionnaire (ODQ), previously known as the Oxford Questionnaire on the Emotional Side-effects of Antidepressants, was created based on a qualitative survey of patients who endorsed emotional blunting.4 A validated scale, the ODQ divides emotional blunting into 4 dimensions:

- general reduction in emotions

- reduction in positive emotions

- emotional detachment from others

- not caring.4

The sections of ODQ focus on exploring specific aspects of patients’ emotional experiences, comparing experiences in the past week to before the development of illness/emotional blunting, and patients’ opinions about antidepressants. Example statements from the ODQ (Table4) may help clinicians better understand and explore emotional blunting with their patients.

There are 2 leading theories behind the mechanism of emotional blunting on antidepressants, both focused on serotonin. The first theory offers that SSRIs alter frontal lobe activity through serotonergic effects. The second theory is focused on the downward effects of serotonin on dopamine in reward pathways.5

Treatment options: Limited evidence

Data on how to address antidepressant-induced emotional blunting are limited and based largely on case reports. One open-label study (N = 143) found that patients experiencing emotional blunting while taking SSRIs and SNRIs who were switched to vortioxetine had a statistically significant decrease in ODQ total score; 50% reported no emotional blunting.6 Options to address emotional blunting include decreasing the antidepressant dose, augmenting with or switching to another agent, or considering other treatments such as neuromodulation.5 Further research is necessary to clarify which intervention is best.

Clinicians will encounter emotional blunting in patients who are taking antidepressants. It is important to recognize and address these symptoms to help improve patients’ adherence and overall quality of life.

When used to treat anxiety or depressive disorders, antidepressants can cause a variety of adverse effects, including emotional blunting. Emotional blunting has been described as emotional numbness, indifference, decreased responsiveness, or numbing. In a study of 669 patients who had been receiving antidepressants (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs], serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors [SNRIs], or other antidepressants), 46% said they had experienced emotional blunting.1 A 2019 study found that approximately one-third of patients with unipolar depression or bipolar depression stopped taking their antidepressant due to emotional blunting.2

Historically, there has been difficulty parsing out emotional blunting (a general decrease of all range of emotions) from anhedonia (a restriction of positive emotions). Additionally, some researchers have questioned if the blunting of emotions is part of depressive symptomatology. In a study of 38 adults, most felt able to differentiate emotional blunting due to antidepressants by considering the resolution of other depressive symptoms and timeline of onset.3

A significant limitation has been how clinicians measure or assess emotional blunting. The Oxford Depression Questionnaire (ODQ), previously known as the Oxford Questionnaire on the Emotional Side-effects of Antidepressants, was created based on a qualitative survey of patients who endorsed emotional blunting.4 A validated scale, the ODQ divides emotional blunting into 4 dimensions:

- general reduction in emotions

- reduction in positive emotions

- emotional detachment from others

- not caring.4

The sections of ODQ focus on exploring specific aspects of patients’ emotional experiences, comparing experiences in the past week to before the development of illness/emotional blunting, and patients’ opinions about antidepressants. Example statements from the ODQ (Table4) may help clinicians better understand and explore emotional blunting with their patients.

There are 2 leading theories behind the mechanism of emotional blunting on antidepressants, both focused on serotonin. The first theory offers that SSRIs alter frontal lobe activity through serotonergic effects. The second theory is focused on the downward effects of serotonin on dopamine in reward pathways.5

Treatment options: Limited evidence

Data on how to address antidepressant-induced emotional blunting are limited and based largely on case reports. One open-label study (N = 143) found that patients experiencing emotional blunting while taking SSRIs and SNRIs who were switched to vortioxetine had a statistically significant decrease in ODQ total score; 50% reported no emotional blunting.6 Options to address emotional blunting include decreasing the antidepressant dose, augmenting with or switching to another agent, or considering other treatments such as neuromodulation.5 Further research is necessary to clarify which intervention is best.

Clinicians will encounter emotional blunting in patients who are taking antidepressants. It is important to recognize and address these symptoms to help improve patients’ adherence and overall quality of life.

1. Goodwin GM, Price J, De Bodinat C, et al. Emotional blunting with antidepressant treatments: a survey among depressed patients. J Affect Disord. 2017;221:31-35.

2. Rosenblat JD, Simon GE, Sachs GS, et al. Treatment effectiveness and tolerability outcomes that are most important to individuals with bipolar and unipolar depression. J Affect Disord. 2019;243:116-120.

3. Price J, Cole V, Goodwin GM. Emotional side-effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: qualitative study. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;195(3):211-217.

4. Price J, Cole V, Doll H, et al. The Oxford Questionnaire on the Emotional Side-effects of Antidepressants (OQuESA): development, validity, reliability and sensitivity to change. J Affect Disord. 2012;140(1):66-74.

5. Ma H, Cai M, Wang H. Emotional blunting in patients with major depressive disorder: a brief non-systematic review of current research. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:792960. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.792960

6. Fagiolini A, Florea I, Loft H, et al. Effectiveness of vortioxetine on emotional blunting in patients with major depressive disorder with inadequate response to SSRI/SNRI treatment. J Affect Disord. 2021;283:472-479.

1. Goodwin GM, Price J, De Bodinat C, et al. Emotional blunting with antidepressant treatments: a survey among depressed patients. J Affect Disord. 2017;221:31-35.

2. Rosenblat JD, Simon GE, Sachs GS, et al. Treatment effectiveness and tolerability outcomes that are most important to individuals with bipolar and unipolar depression. J Affect Disord. 2019;243:116-120.

3. Price J, Cole V, Goodwin GM. Emotional side-effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: qualitative study. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;195(3):211-217.

4. Price J, Cole V, Doll H, et al. The Oxford Questionnaire on the Emotional Side-effects of Antidepressants (OQuESA): development, validity, reliability and sensitivity to change. J Affect Disord. 2012;140(1):66-74.

5. Ma H, Cai M, Wang H. Emotional blunting in patients with major depressive disorder: a brief non-systematic review of current research. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:792960. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.792960

6. Fagiolini A, Florea I, Loft H, et al. Effectiveness of vortioxetine on emotional blunting in patients with major depressive disorder with inadequate response to SSRI/SNRI treatment. J Affect Disord. 2021;283:472-479.

Neuropsychiatric aspects of Parkinson’s disease: Practical considerations

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative condition diagnosed pathologically by alpha synuclein–containing Lewy bodies and dopaminergic cell loss in the substantia nigra pars compacta of the midbrain. Loss of dopaminergic input to the caudate and putamen disrupts the direct and indirect basal ganglia pathways for motor control and contributes to the motor symptoms of PD.1 According to the Movement Disorder Society criteria, PD is diagnosed clinically by bradykinesia (slowness of movement) plus resting tremor and/or rigidity in the presence of supportive criteria, such as levodopa responsiveness and hyposmia, and in the absence of exclusion criteria and red flags that would suggest atypical parkinsonism or an alternative diagnosis.2

Although the diagnosis and treatment of PD focus heavily on the motor symptoms, nonmotor symptoms can arise decades before the onset of motor symptoms and continue throughout the lifespan. Nonmotor symptoms affect patients from head (ie, cognition and mood) to toe (ie, striatal toe pain) and multiple organ systems in between, including the olfactory, integumentary, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, and autonomic nervous systems. Thus, it is not surprising that nonmotor symptoms of PD impact health-related quality of life more substantially than motor symptoms.3 A helpful analogy is to consider the motor symptoms of PD as the tip of the iceberg and the nonmotor symptoms as the larger, submerged portions of the iceberg.4

Nonmotor symptoms can negatively impact the treatment of motor symptoms. For example, imagine a patient who is very rigid and dyscoordinated in the arms and legs, which limits their ability to dress and walk. If this patient also suffers from nonmotor symptoms of orthostatic hypotension and psychosis—both of which can be exacerbated by levodopa—dose escalation of levodopa for the rigidity and dyscoordination could be compromised, rendering the patient undertreated and less mobile.

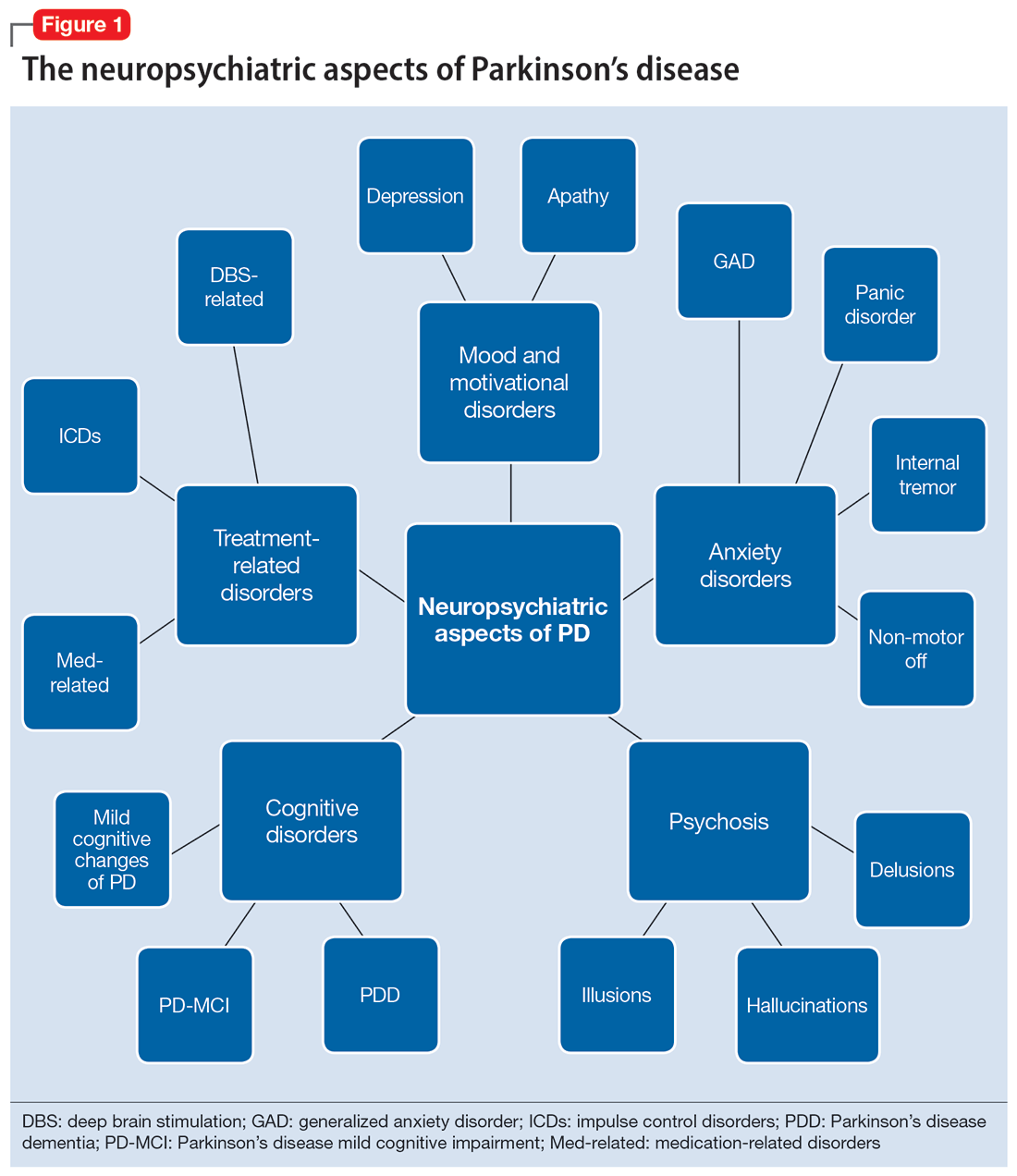

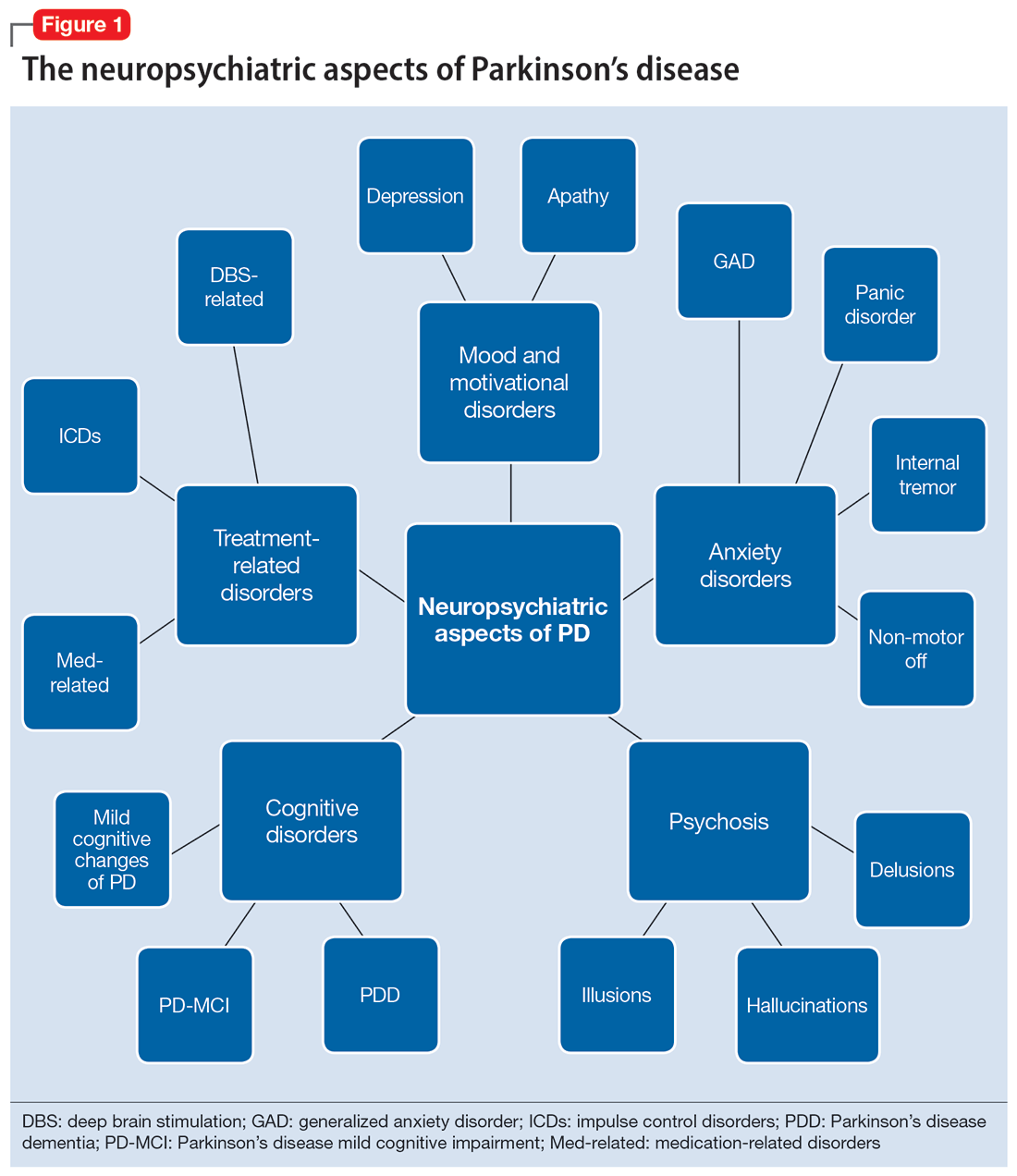

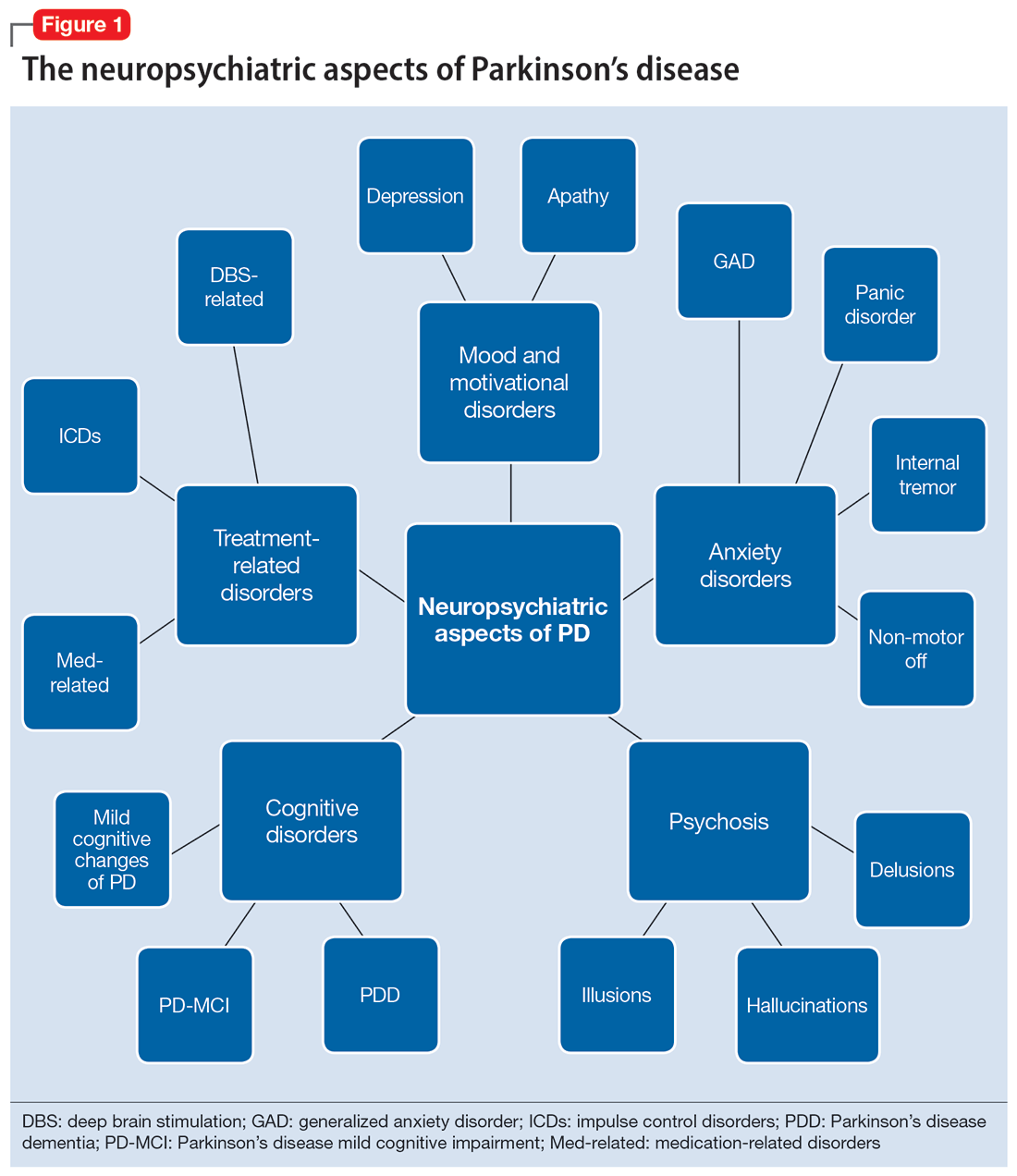

In this review, we focus on identifying and managing nonmotor symptoms of PD that are relevant to psychiatric practice, including mood and motivational disorders, anxiety disorders, psychosis, cognitive disorders, and disorders related to the pharmacologic and surgical treatment of PD (Figure 1).

Mood and motivational disorders

Depression

Depression is a common symptom in PD that can occur in the prodromal period years to decades before the onset of motor symptoms, as well as throughout the disease course.5 The prevalence of depression in PD varies from 3% to 90%, depending on the methods of assessment, clinical setting of assessment, motor symptom severity, and other factors; clinically significant depression likely affects approximately 35% to 38% of patients.5,6 How depression in patients with PD differs from depression in the general population is not entirely understood, but there does seem to be less guilt and suicidal ideation and a substantial component of negative affect, including dysphoria and anxiety.7 Practically speaking, depression is treated similarly in PD and general populations, with a few considerations.

Despite limited randomized controlled trials (RCTs) for efficacy specifically in patients with PD, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are generally considered first-line treatments. There is also evidence for tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), but due to potential worsening of orthostatic hypotension and cognition, TCAs may not be a favorable option for certain patients with PD.8,9 All antidepressants have the potential to worsen tremor. Theoretically, SNRIs, with noradrenergic activity, may be less tolerable than SSRIs in patients with PD. However, worsening tremor generally has not been a clinically significant adverse event reported in PD depression clinical trials, although it was seen in 17% of patients receiving paroxetine and 21% of patients receiving venlafaxine compared to 7% of patients receiving placebo.9-11 If tremor worsens, mirtazapine could be considered because it has been reported to cause less tremor than SSRIs or TCAs.12

Among medications for PD, pramipexole, a dopamine agonist, may have a beneficial effect on depression.13 Additionally, some evidence supports rasagiline, a monoamine oxidase type B inhibitor, as an adjunctive medication for depression in PD.14 Nevertheless, antidepressant medications remain the standard pharmacologic treatment for PD depression.

Continue to: In terms of nonpharmacologic options...

In terms of nonpharmacologic options, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is likely efficacious, exercise (especially yoga) is likely efficacious, and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation may be efficacious.15,16 While further high-quality trials are needed, these treatments are low-risk and can be considered, especially for patients who cannot tolerate medications.

Apathy

Apathy—a loss of motivation and goal-directed behavior—can occur in up to 30% of patients during the prodromal period of PD, and in up to 70% of patients throughout the disease course.17 Apathy can coexist with depression, which can make apathy difficult to diagnose.17 Given the time constraints of a clinic visit, a practical approach would be to first screen for depression and cognitive impairment. If there is continued suspicion of apathy, the Movement Disorder Society-Sponsored Revision of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale part I question (“In the past week have you felt indifferent to doing activities or being with people?”) can be used to screen for apathy, and more detailed scales, such as the Apathy Scale (AS) or Lille Apathy Rating Scale (LARS), could be used if indicated.18

There are limited high-quality positive trials of apathy-specific treatments in PD. In an RCT of patients with PD who did not have depression or dementia, rivastigmine improved LARS scores compared to placebo.15 Piribedil, a D2/D3 receptor agonist, improved apathy in patients who underwent subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation (STN DBS).15 Exercise such as individualized physical therapy programs, dance, and Nordic walking as well as mindfulness interventions were shown to significantly reduce apathy scale scores.19 SSRIs, SNRIs, and rotigotine showed a trend toward reducing AS scores in RCTs.10,20

Larger, high-quality studies are needed to clarify the treatment of apathy in PD. In the meantime, a reasonable approach is to first treat any comorbid psychiatric or cognitive disorders, since apathy can be associated with these conditions, and to optimize antiparkinsonian medications for motor symptoms, motor fluctuations, and nonmotor fluctuations. Then, the investigational apathy treatments described in this section could be considered on an individual basis.

Anxiety disorders

Anxiety is seen throughout the disease course of PD in approximately 30% to 50% of patients.21 It can manifest as generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and other anxiety disorders. There are no high-quality RCTs of pharmacologic treatments of anxiety specifically in patients with PD, except for a negative safety and tolerability study of buspirone in which one-half of patients experienced worsening motor symptoms.15,22 Thus, the treatment of anxiety in patients with PD is similar to treatments in the general population. SSRIs and SNRIs are typically considered first-line, benzodiazepines are sometimes used with caution (although cognitive adverse effects and fall risk need to be considered), and nonpharmacologic treatments such as mindfulness yoga, exercise, CBT, and psychotherapy can be effective.16,21,23

Continue to: Because there is the lack...

Because there is the lack of evidence-based treatments for anxiety in PD, we highlight 2 PD-specific anxiety disorders: internal tremor, and nonmotor “off” anxiety.

Internal tremor

Internal tremor is a sense of vibration in the axial and/or appendicular muscles that cannot be seen externally by the patient or examiner. It is not yet fully understood if this phenomenon is sensory, anxiety-related, related to subclinical tremor, or the result of a combination of these factors (ie, sensory awareness of a subclinical tremor that triggers or is worsened by anxiety). There is some evidence for subclinical tremor on electromyography, but internal tremor does not respond to antiparkinsonian medications in 70% of patients.24 More electrophysiological research is needed to clarify this phenomenon. Internal tremor has been associated with anxiety in 64% of patients and often improves with anxiolytic therapies.24

Although poorly understood, internal tremor is a documented phenomenon in 33% to 44% of patients with PD, and in some cases, it may be an initial symptom that motivates a patient to seek medical attention for the first time.24,25 Internal tremor has also been reported in patients with essential tremor and multiple sclerosis.25 Therefore, physicians should be aware of internal tremor because this symptom could herald an underlying neurological disease.

Nonmotor ‘off’ anxiety

Patients with PD are commonly prescribed carbidopa-levodopa, a dopamine precursor, at least 3 times daily. Initially, this medication controls motor symptoms well from 1 dose to the next. However, as the disease progresses, some patients report motor fluctuations in which an individual dose of carbidopa-levodopa may wear off early, take longer than usual to take effect, or not take effect at all. Patients describe these periods as an “off” state in which they do not feel their medications are working. Such motor fluctuations can lead to anxiety and avoidance behaviors, because patients fear being in public at times when the medication does not adequately control their motor symptoms.

In addition to these motor symptom fluctuations and related anxiety, patients can also experience nonmotor symptom fluctuations. A wide variety of nonmotor symptoms, such as mood, cognitive, and behavioral symptoms, have been reported to fluctuate in parallel with motor symptoms.26,27 One study reported fluctuating restlessness in 39% of patients with PD, excessive worry in 17%, shortness of breath in 13%, excessive sweating and fear in 12%, and palpitations in 10%.27 A patient with fluctuating shortness of breath, sweating, and palpitations (for example) may repeatedly present to the emergency department with a negative cardiac workup and eventually be diagnosed with panic disorder, whereas the patient is truly experiencing nonmotor “off” symptoms. Thus, it is important to be aware of nonmotor fluctuations so this diagnosis can be made and the symptoms appropriately treated. The first step in treating nonmotor fluctuations is to optimize the antiparkinsonian regimen to minimize fluctuations. If “off” anxiety symptoms persist, anxiolytic medications can be prescribed.21

Continue to: Psychosis

Psychosis

Psychosis can occur in prodromal and early PD but is most common in advanced PD.28 One study reported that 60% of patients developed hallucinations or delusions after 12 years of follow-up.29 Disease duration, disease severity, dementia, and rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder are significant risk factors for psychosis in PD.30 Well-formed visual hallucinations are the most common manifestation of psychosis in patients with PD. Auditory hallucinations and delusions are less common. Delusions are usually seen in patients with dementia and are often paranoid delusions, such as of spousal infidelity.30 Sensory hallucinations can occur, but should not be mistaken with formication, a central pain syndrome in PD that can represent a nonmotor “off” symptom that may respond to dopaminergic medication.31 Other more mild psychotic symptoms include illusions or misinterpretation of stimuli, false sense of presence, and passage hallucinations of fleeting figures in the peripheral vision.30

The pathophysiology of PD psychosis is not entirely understood but differs from psychosis in other disorders. It can occur in the absence of antiparkinsonian medication exposure and is thought to be a consequence of the underlying disease process of PD involving neurodegeneration in certain brain regions and aberrant neurotransmission of not only dopamine but also serotonin, acetylcholine, and glutamate.30

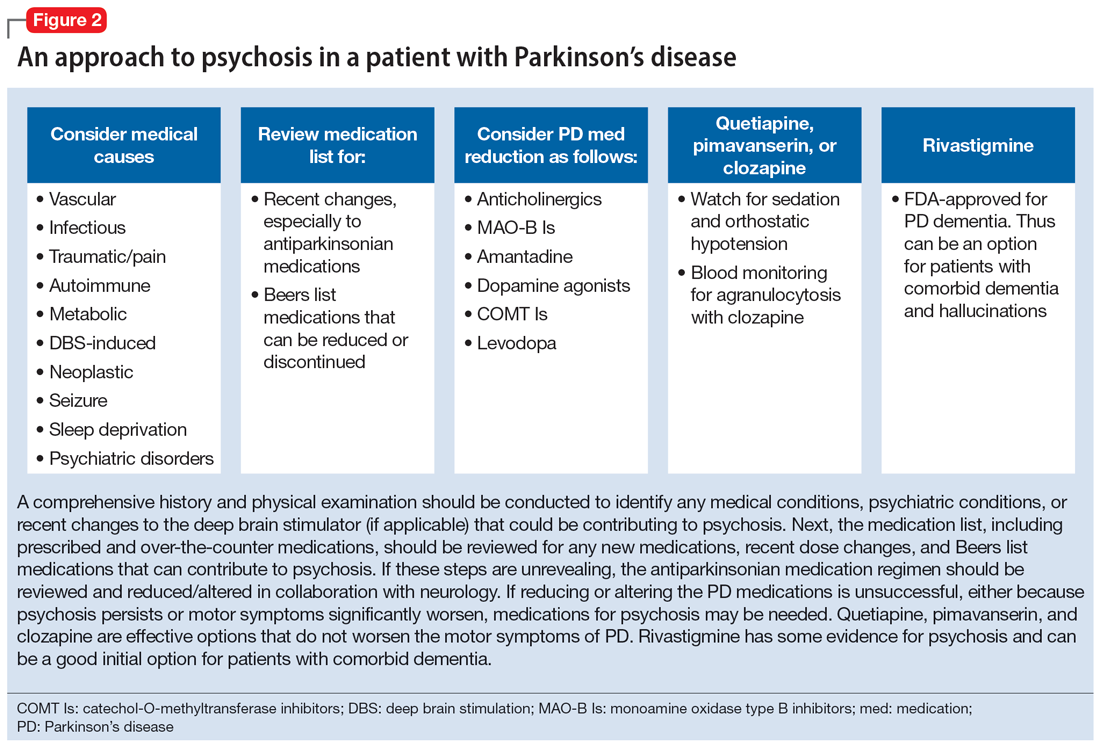

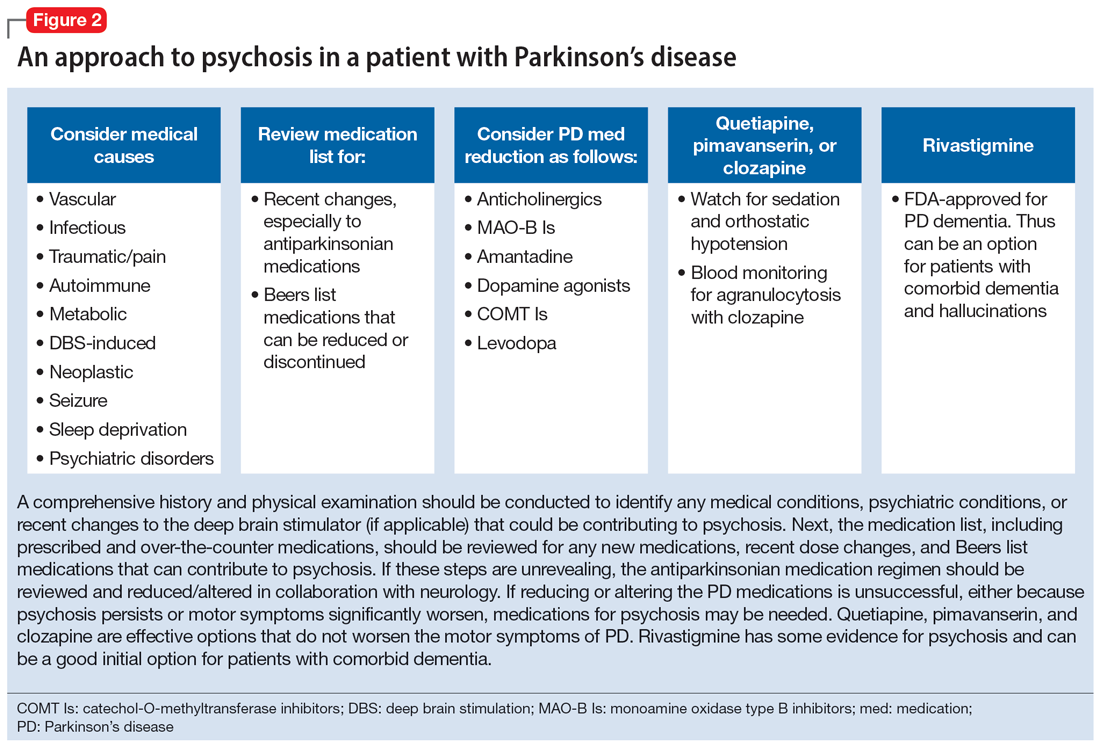

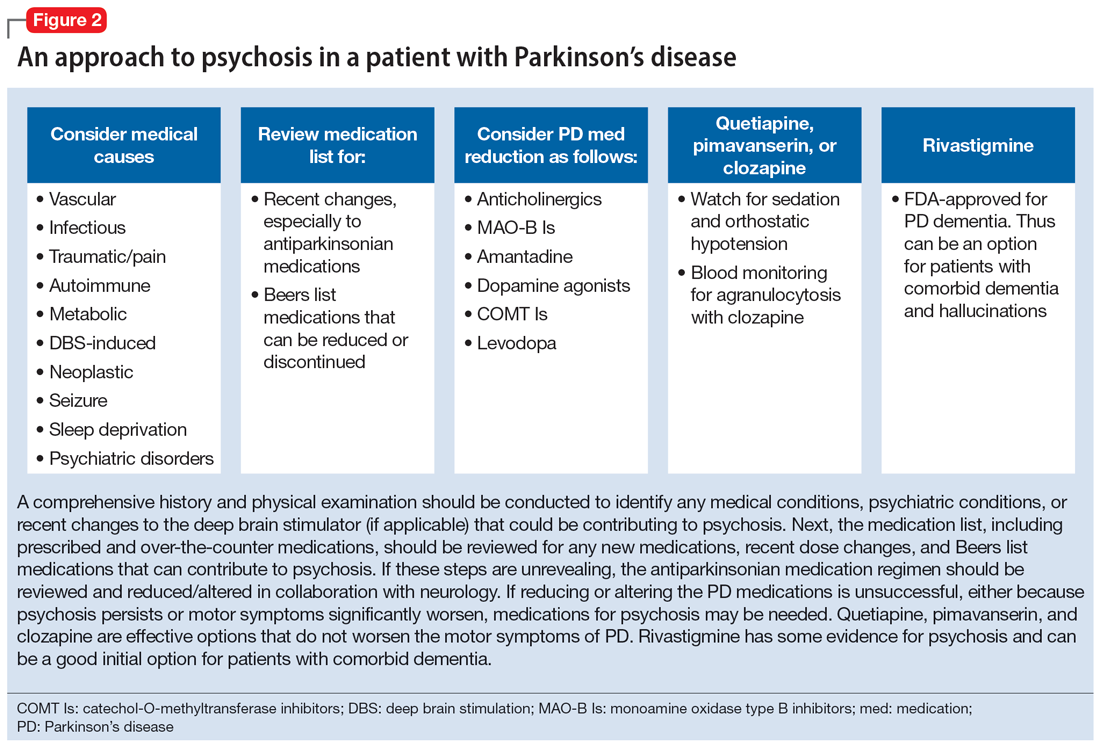

Figure 2 outlines the management of psychosis in PD. After addressing medical and medication-related causes, it is important to determine if the psychotic symptom is sufficiently bothersome to and/or potentially dangerous for the patient to warrant treatment. If treatment is indicated, pimavanserin and clozapine are efficacious for psychosis in PD without worsening motor symptoms, and quetiapine is possibly efficacious with a low risk of worsening motor symptoms.15 Other antipsychotics, such as olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol, can substantially worsen motor symptoms.15 Both second-generation antipsychotics and pimavanserin have an FDA black-box warning for a higher risk of all-cause mortality in older patients with dementia; however, because psychosis is associated with early mortality in PD, the risk/benefit ratio should be discussed with the patient and family for shared decision-making.30 If the patient also has dementia, rivastigmine—which is FDA-approved for PD dementia (PDD)—may also improve hallucinations.32

Cognitive disorders

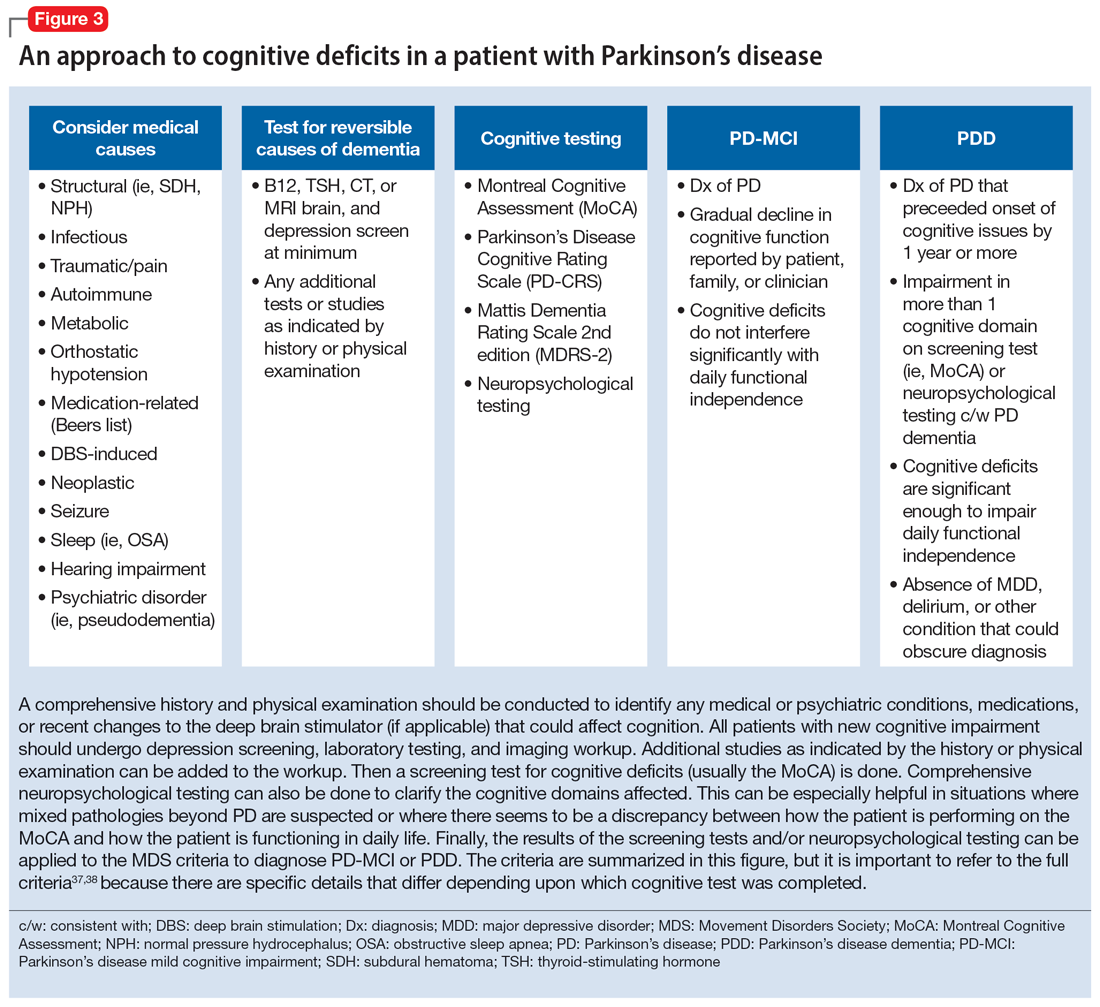

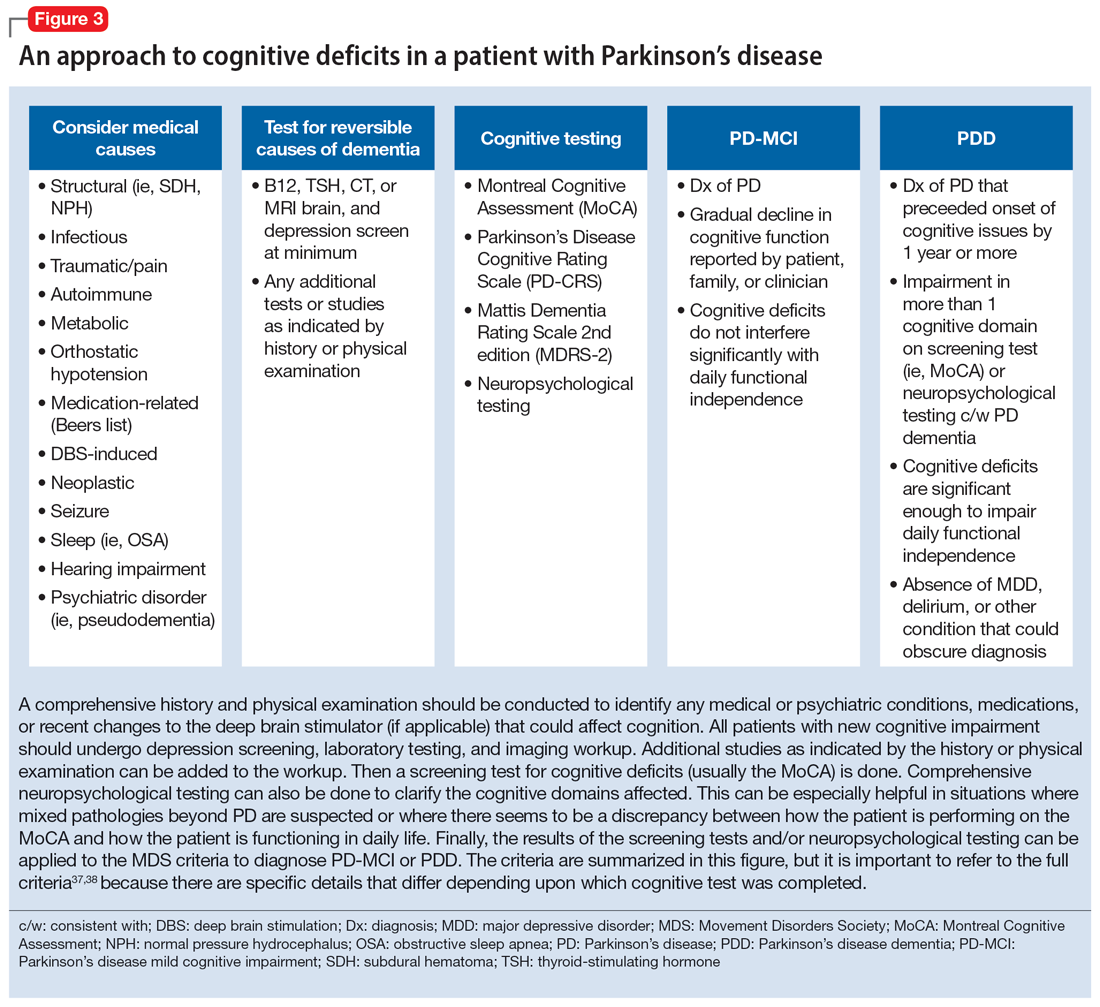

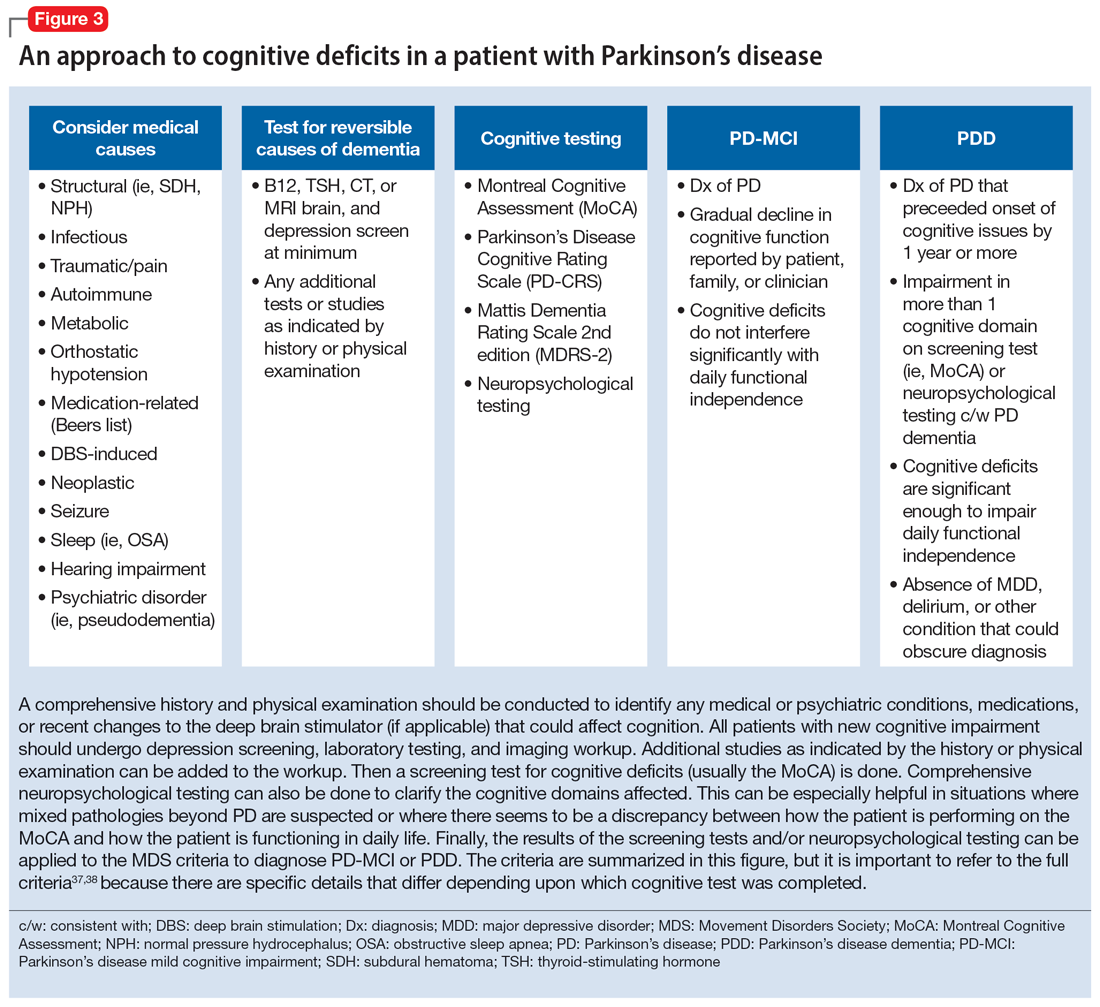

This section focuses on PD mild cognitive impairment (PD-MCI) and PDD. When a patient with PD reports cognitive concerns, the approach outlined in Figure 3 can be used to diagnose the cognitive disorder. A detailed history, medication review, and physical examination can identify any medical or psychiatric conditions that could affect cognition. The American Academy of Neurology recommends screening for depression, obtaining blood levels of vitamin B12 and thyroid-stimulating hormone, and obtaining a CT or MRI of the brain to rule out reversible causes of dementia.33 A validated screening test such as the Montreal Cognitive Assessment, which has higher sensitivity for PD-MCI than the Mini-Mental State Examination, is used to identify and quantify cognitive impairment.34 Neuropsychological testing is the gold standard and can be used to confirm and/or better quantify the degree and domains of cognitive impairment.35 Typically, cognitive deficits in PD affect executive function, attention, and/or visuospatial domains more than memory and language early on, and deficits in visuospatial and language domains have the highest sensitivity for predicting progression to PDD.36

Once reversible causes of dementia are addressed or ruled out and cognitive testing is completed, the Movement Disorder Society (MDS) criteria for PD-MCI and PDD summarized in Figure 3 can be used to diagnose the cognitive disorder.37,38 The MDS criteria for PDD require a diagnosis of PD for ≥1 year prior to the onset of dementia to differentiate PDD from dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB). If the dementia starts within 1 year of the onset of parkinsonism, the diagnosis would be DLB. PDD and DLB are on the spectrum of Lewy body dementia, with the same Lewy body pathology in different temporal and spatial distributions in the brain.38

Continue to: PD-MCI is present in...

PD-MCI is present in approximately 25% of patients.35 PD-MCI does not always progress to dementia but increases the risk of dementia 6-fold. The prevalence of PDD increases with disease duration; it is present in approximately 50% of patients at 10 years and 80% of patients at 20 years of disease.35 Rivastigmine is the only FDA-approved medication to slow progression of PDD. There is insufficient evidence for other acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and memantine.15 Unfortunately, RCTs of pharmacotherapy for PD-MCI have failed to show efficacy. However, exercise, cognitive rehabilitation, and neuromodulation are being studied. In the meantime, addressing modifiable risk factors (such as vascular risk factors and alcohol consumption) and treating comorbid orthostatic hypotension, obstructive sleep apnea, and depression may improve cognition.35,39

Treatment-related disorders

Impulse control disorders

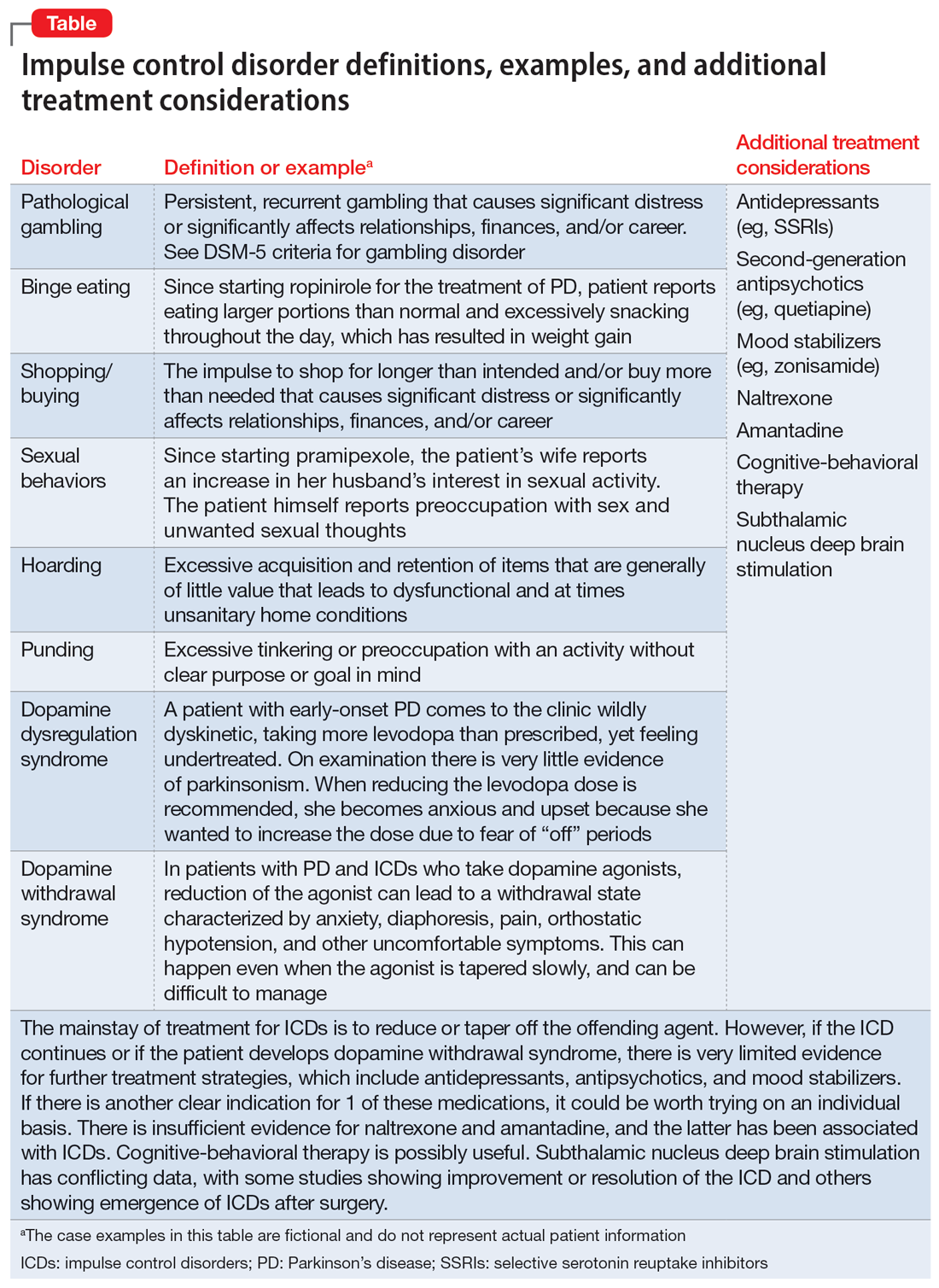

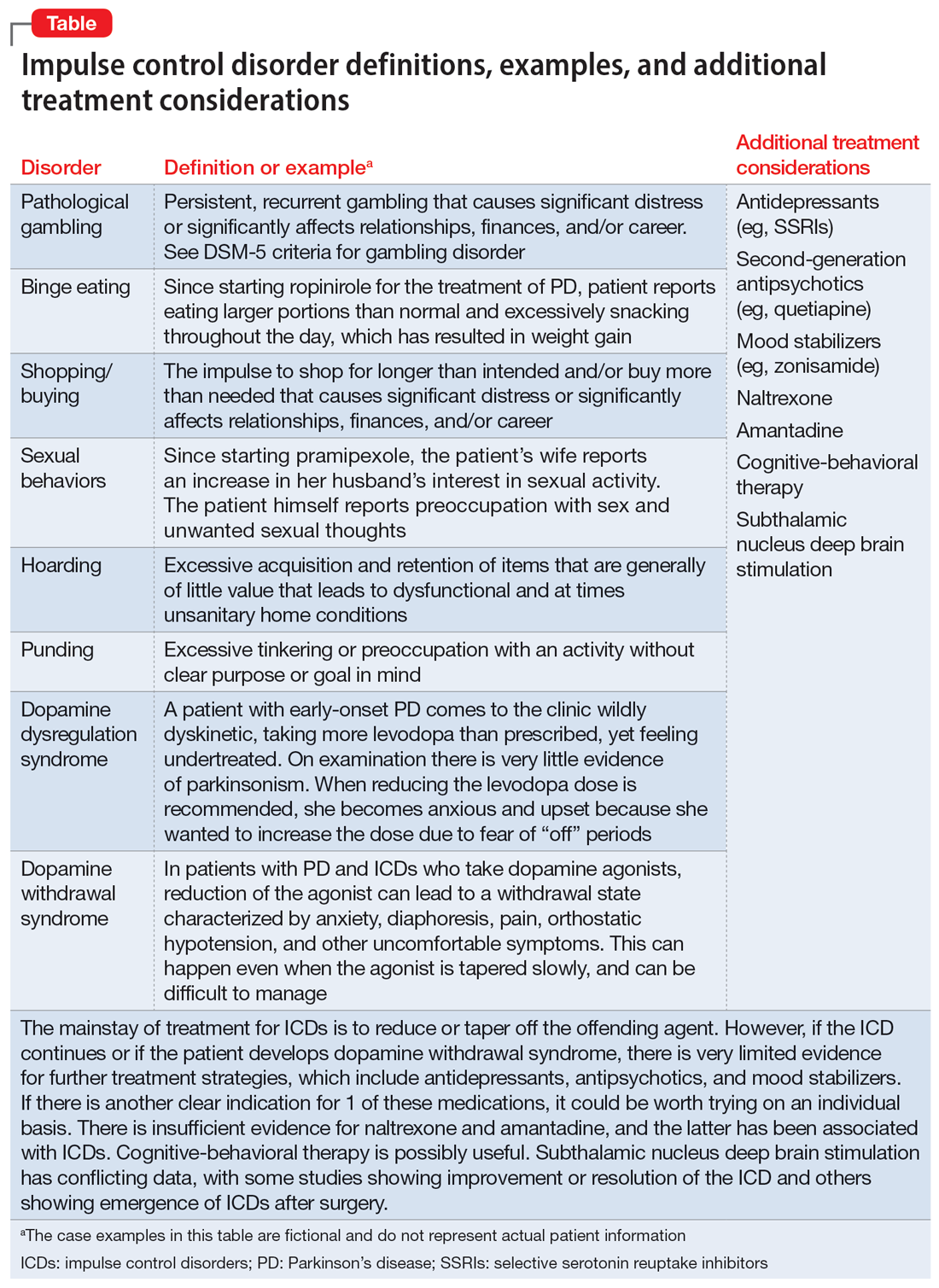

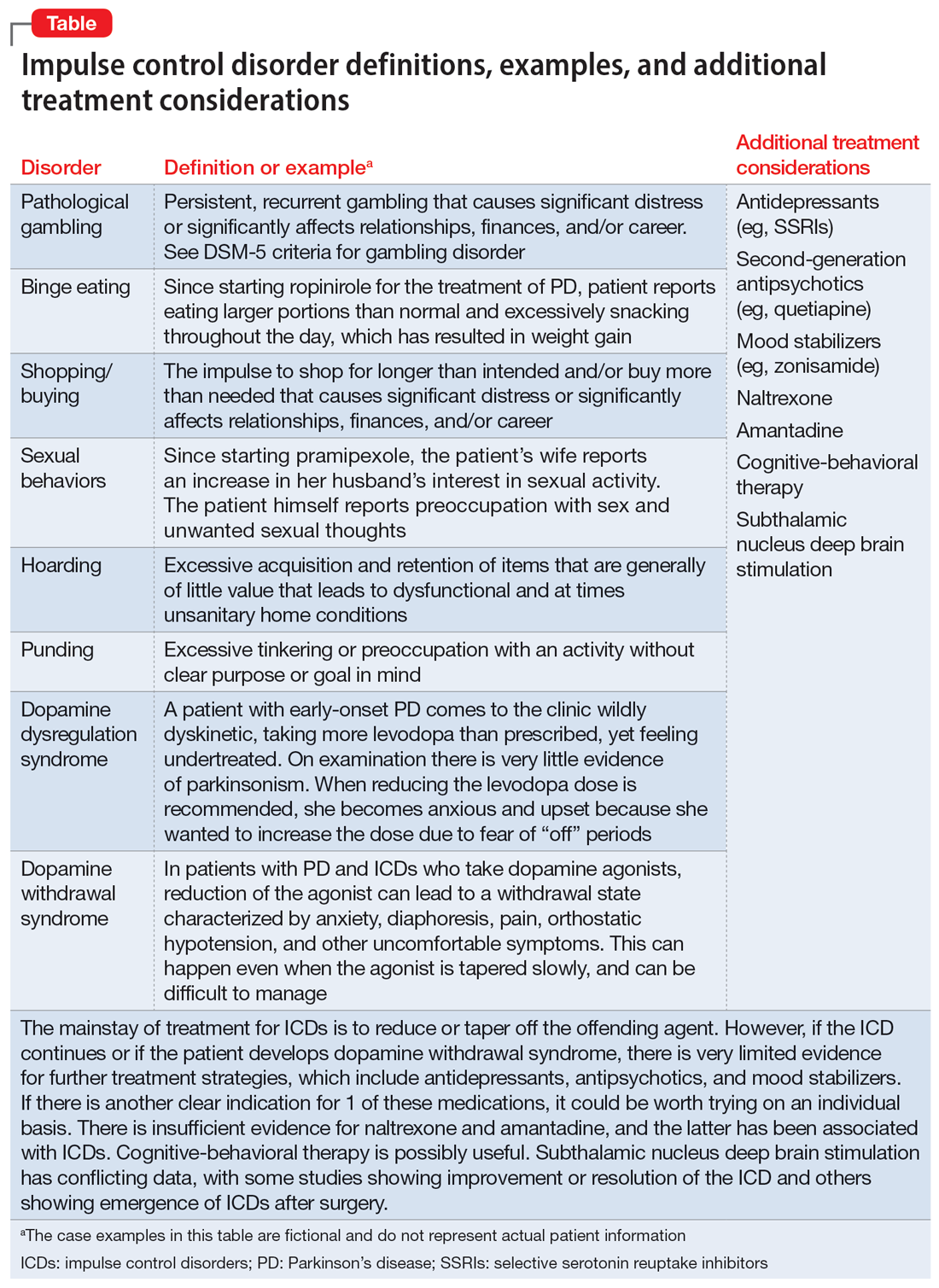

Impulse control disorders (ICDs) are an important medication-related consideration in patients with PD. The ICDs seen in PD include pathological gambling, binge eating, excessive shopping, hypersexual behaviors, and dopamine dysregulation syndrome (Table). These disorders are more common in younger patients with a history of impulsive personality traits and addictive behaviors (eg, history of tobacco or alcohol abuse), and are most strongly associated with dopaminergic therapies, particularly the dopamine agonists.40,41 In the DOMINION study, the odds of ICDs were 2- to 3.5-fold higher in patients taking dopamine agonists.42 This is mainly thought to be due to stimulation of D2/D3 receptors in the mesolimbic system.40 High doses of levodopa, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, and amantadine are also associated with ICDs.40-42

The first step in managing ICDs is diagnosing them, which can be difficult because patients often are not forthcoming about these problems due to embarrassment or failure to recognize that the ICD is related to PD medications. If a family member accompanies the patient at the visit, the patient may not want to disclose the amount of money they spend or the extent to which the behavior is a problem. Thus, a screening questionnaire, such as the Questionnaire for Impulsive-Compulsive Disorders in Parkinson’s Disease (QUIP) can be a helpful way for patients to alert the clinician to the issue.41 Education for the patient and family is crucial before the ICD causes significant financial, health, or relationship problems.

The mainstay of treatment is to reduce or taper off the dopamine agonist or other offending agent while monitoring for worsening motor symptoms and dopamine withdrawal syndrome. If this is unsuccessful, there is very limited evidence for further treatment strategies (Table), including antidepressants, antipsychotics, and mood stabilizers.40,43,44 There is insufficient evidence for naltrexone based on an RCT that failed to meet its primary endpoint, although naltrexone did significantly reduce QUIP scores.15,44 There is also insufficient evidence for amantadine, which showed benefit in some studies but was associated with ICDs in the DOMINION study.15,40,42 In terms of nonpharmacologic treatments, CBT is likely efficacious.15,40 There are mixed results for STN DBS. Some studies showed improvement in the ICD, due at least in part to dopaminergic medication reduction postoperatively, but this treatment has also been reported to increase impulsivity.40,45

Deep brain stimulation–related disorders

For patients with PD, the ideal lead location for STN DBS is the dorsolateral aspect of the STN, as this is the motor region of the nucleus. The STN functions in indirect and hyperdirect pathways to put the brake on certain motor programs so only the desired movement can be executed. Its function is clinically demonstrated by patients with STN stroke who develop excessive ballistic movements. Adjacent to the motor region of the STN is a centrally located associative region and a medially located limbic region. Thus, when stimulating the dorsolateral STN, current can spread to those regions as well, and the STN’s ability to put the brake on behavioral and emotional programs can be affected.46 Stimulation of the STN has been associated with mania, euphoria, new-onset ICDs, decreased verbal fluency, and executive dysfunction. Depression, apathy, and anxiety can also occur, but more commonly result from rapid withdrawal of antiparkinsonian medications after DBS surgery.46,47 Therefore, for PD patients with DBS with new or worsening psychiatric or cognitive symptoms, it is important to inquire about any recent programming sessions with neurology as well as recent self-increases in stimulation by the patient using their controller. Collaboration with neurology is important to troubleshoot whether stimulation could be contributing to the patient’s psychiatric or cognitive symptoms.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Mood, anxiety, psychotic, and cognitive symptoms and disorders are common psychiatric manifestations associated with Parkinson’s disease (PD). In addition, patients with PD may experience impulsive control disorders and other symptoms related to treatments they receive for PD. Careful assessment and collaboration with neurology is crucial to alleviating the effects of these conditions.

Related Resources

- Weintraub D, Aarsland D, Chaudhuri KR, et al. The neuropsychiatry of Parkinson’s disease: advances and challenges. Lancet Neurology. 2022;21(1):89-102. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(21)00330-6

- Goldman JG, Guerra CM. Treatment of nonmotor symptoms associated with Parkinson disease. Neurologic Clinics. 2020;38(2):269-292. doi:10.1016/j.ncl.2019.12.003

- Castrioto A, Lhommee E, Moro E et al. Mood and behavioral effects of subthalamic stimulation in Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurology. 2014;13(3):287-305. doi:10.1016/ S1474-4422(13)70294-1

Drug Brand Names

Amantadine • Gocovri

Carbidopa-levodopa • Sinemet

Clozapine • Clozaril

Haloperidol • Haldol

Memantine • Namenda

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Naltrexone • Vivitrol

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Paroxetine • Paxil

Pimavanserin • Nuplazid

Piribedil • Pronoran

Pramipexole • Mirapex

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Rasagiline • Azilect

Risperidone • Risperdal

Rivastigmine • Exelon

Ropinirole • Requip

Rotigotine • Neupro

Venlafaxine • Effexor

Zonisamide • Zonegran

1. Bloem BR, Okun MS, Klein C. Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurology. 2021;397(10291):2284-2303.

2. Postuma RB, Berg D, Stern M, et al. MDS clinical diagnostic criteria for Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders. 2015;30(12):1591-1601.

3. Martinez-Martin P, Rodriguez-Blazquez C, Kurtiz MM, et al. The impact of non-motor symptoms on health-related quality of life of patients with Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2011;26(3):399-406.

4. Langston WJ. The Parkinson’s complex: parkinsonism is just the tip of the iceberg. Ann Neurol. 2006;59(4):591-596.

5. Cong S, Xiang C, Zhang S, et al. Prevalence and clinical aspects of depression in Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and meta‑analysis of 129 studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2022;141:104749. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2022.104749

6. Reijnders JS, Ehrt U, Weber WE, et al. A systematic review of prevalence studies in depression in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2008;23(2):183-189.

7. Zahodne LB, Marsiske M, Okun MS, et al. Components of depression in Parkinson disease. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2012;25(3):131-137.

8. Skapinakis P, Bakola E, Salanti G, et al. Efficacy and acceptability of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for the treatment of depression in Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Neurology. 2010;10:49. doi:10.1186/1471-2377-10-49

9. Richard IH, McDermott MP, Kurlan R, et al; SAD-PD Study Group. A randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled trial of antidepressants in Parkinson’s disease. Neurology. 2012;78(16):1229-1236.

10. Takahashi M, Tabu H, Ozaki A, et al. Antidepressants for depression, apathy, and gait instability in Parkinson’s disease: a multicenter randomized study. Intern Med. 2019;58(3):361-368.

11. Bonuccelli U, Mecco G, Fabrini G, et al. A non-comparative assessment of tolerability and efficacy of duloxetine in the treatment of depressed patients with Parkinson’s disease. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2012;13(16):2269-2280.

12. Wantanabe N, Omorio IM, Nakagawa A, et al; MANGA (Meta-Analysis of New Generation Antidepressants) Study Group. Safety reporting and adverse-event profile of mirtazapine described in randomized controlled trials in comparison with other classes of antidepressants in the acute-phase treatment of adults with depression. CNS Drugs. 2010;24(1):35-53.

13. Barone P, Scarzella L, Marconi R, et al; Depression/Parkinson Italian Study Group. Pramipexole versus sertraline in the treatment of depression in Parkinson’s disease: a national multicenter parallel-group randomized study. J Neurol. 2006;253(5):601-607.

14. Smith KM, Eyal E, Weintraub D, et al; ADAGIO Investigators. Combined rasagiline and anti-depressant use in Parkinson’s disease in the ADAGIO study: effects on non-motor symptoms and tolerability. JAMA Neurology. 2015;72(1):88-95.

15. Seppi K, Chaudhuri R, Coelho M, et al; the collaborators of the Parkinson’s Disease Update on Non-Motor Symptoms Study Group on behalf of the Movement Disorders Society Evidence-Based Medicine Committee. Update on treatments for nonmotor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease--an evidence-based medicine review. Mov Disord. 2019;34(2):180-198.

16. Kwok JYY, Kwan JCY, Auyeung M, et al. Effects of mindfulness yoga vs stretching and resistance training exercises on anxiety and depression for people with Parkinson disease: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(7):755-763.

17. De Waele S, Cras P, Crosiers D. Apathy in Parkinson’s disease: defining the Park apathy subtype. Brain Sci. 2022;12(7):923.

18. Mele B, Van S, Holroyd-Leduc J, et al. Diagnosis, treatment and management of apathy in Parkinson’s disease: a scoping review. BMJ Open. 2020;10(9):037632. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-037632

19. Mele B, Ismail Z, Goodarzi Z, et al. Non-pharmacological interventions to treat apathy in Parkinson’s disease: a realist review. Clin Park Relat Disord. 2021;4:100096. doi:10.1016/j.prdoa.2021.100096

20. Chung SJ, Asgharnejad M, Bauer L, et al. Evaluation of rotigotine transdermal patch for the treatment of depressive symptoms in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2016;(17)11:1453-1461.

21. Goldman JG, Guerra CM. Treatment of nonmotor symptoms associated with Parkinson disease. Neurol Clin. 2020;38(2):269-292.

22. Schneider RB, Auinger P, Tarolli CG, et al. A trial of buspirone for anxiety in Parkinson’s disease: safety and tolerability. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2020;81:69-74.

23. Moonen AJH, Mulders AEP, Defebvre L, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety in Parkinson’s disease: a randomized controlled trial. Mov Disord. 2021;36(11):2539-2548.

24. Shulman LM, Singer C, Bean JA, et al. Internal tremor in patient with Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 1996;11(1):3-7.

25. Cochrane GD, Rizvi S, Abrantes A, et al. Internal tremor in Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, and essential tremor. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2015;21(10):1145-1147.

26. Del Prete E, Schmitt E, Meoni S, et al. Do neuropsychiatric fluctuations temporally match motor fluctuations in Parkinson’s disease? Neurol Sci. 2022;43(6):3641-3647.

27. Kleiner G, Fernandez HH, Chou KL, et al. Non-motor fluctuations in Parkinson’s disease: validation of the non-motor fluctuation assessment questionnaire. Mov Disord. 2021;36(6):1392-1400.

28. Pachi I, Maraki MI, Giagkou N, et al. Late life psychotic features in prodromal Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2021;86:67-73.

29. Forsaa EB, Larsen JP, Wentzel-Larsen T, et al. A 12-year population-based study of psychosis in Parkinson’s disease. Arch Neurol. 2010;67(8):996-1001.

30. Chang A, Fox SH. Psychosis in Parkinson’s disease: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management. Drugs. 2016;76(11):1093-1118.

31. Kasunich A, Kilbane C, Wiggins R. Movement disorders moment: pain and palliative care in movement disorders. Practical Neurology. 2021;20(4):63-67.

32. Burn D, Emre M, McKeith I, et al. Effects of rivastigmine in patients with and without visual hallucinations in dementia associated with Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2006;21(11):1899-1907.

33. Tripathi M, Vibha D. Reversible dementias. Indian J Psychiatry. 2009; 51 Suppl 1(Suppl 1): S52-S55.

34. Dalrymple-Alford JC, MacAskill MR, Nakas CT, et al. The MoCA: well-suited screen for cognitive impairment in Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2010;75(19):1717-1725.

35. Goldman J, Sieg, E. Cognitive impairment and dementia in Parkinson disease. Clin Geriatr Med. 2020;36(2):365-377.

36. Gonzalez-Latapi P, Bayram E, Litvan I, et al. Cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease: epidemiology, clinical profile, protective and risk factors. Behav Sci (Basel). 2021;11(5):74.

37. Litvan I, Goldman JG, Tröster AI, et al. Diagnostic criteria for mild cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease: Movement Disorder Society Task Force Guidelines. Mov Disord. 2012;27(3):349-356.

38. Dubois B, Burn D, Goetz C, et al. Diagnostic procedures for Parkinson’s disease dementia: recommendations from the movement disorder society task force. Mov Disord. 2007;22(16):2314-2324.

39. Aarsland D, Batzu L, Halliday GM, et al. Parkinson disease-associated cognitive impairment. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7(1):47. doi:10.1038/s41572-021-00280-3

40. Weintraub D, Claassen DO. Impulse control and related disorders in Parkinson’s disease. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2017;133:679-717.

41. Vilas D, Pont-Sunyer C, Tolosa E. Impulse control disorders in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2012;18 Suppl 1:S80-S84.

42. Weintraub D, Koester J, Potenza MN, et al. Impulse control disorders in Parkinson disease: a cross-sectional study of 3090 patients. Arch Neurol. 2010;67(5):589-595.

43. Faouzi J, Corvol JC, Mariani LL. Impulse control disorders and related behaviors in Parkinson’s disease: risk factors, clinical and genetic aspects, and management. Curr Opin Neurol. 2021;34(4):547-555.

44. Samuel M, Rodriguez-Oroz M, Antonini A, et al. Impulse control disorders in Parkinson’s disease: management, controversies, and potential approaches. Mov Disord. 2015;30(2):150-159.

45. Frank MJ, Samanta J, Moustafa AA, et al. Hold your horses: impulsivity, deep brain stimulation and medication in Parkinsonism. Science. 2007;318(5854):1309-1312.

46. Jahanshahi M, Obeso I, Baunez C, et al. Parkinson’s disease, the subthalamic nucleus, inhibition, and impulsivity. Mov Disord. 2015;30(2):128-140.

47. Castrioto A, Lhommée E, Moro E, et al. Mood and behavioral effects of subthalamic stimulation in Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(3):287-305.

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative condition diagnosed pathologically by alpha synuclein–containing Lewy bodies and dopaminergic cell loss in the substantia nigra pars compacta of the midbrain. Loss of dopaminergic input to the caudate and putamen disrupts the direct and indirect basal ganglia pathways for motor control and contributes to the motor symptoms of PD.1 According to the Movement Disorder Society criteria, PD is diagnosed clinically by bradykinesia (slowness of movement) plus resting tremor and/or rigidity in the presence of supportive criteria, such as levodopa responsiveness and hyposmia, and in the absence of exclusion criteria and red flags that would suggest atypical parkinsonism or an alternative diagnosis.2

Although the diagnosis and treatment of PD focus heavily on the motor symptoms, nonmotor symptoms can arise decades before the onset of motor symptoms and continue throughout the lifespan. Nonmotor symptoms affect patients from head (ie, cognition and mood) to toe (ie, striatal toe pain) and multiple organ systems in between, including the olfactory, integumentary, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, and autonomic nervous systems. Thus, it is not surprising that nonmotor symptoms of PD impact health-related quality of life more substantially than motor symptoms.3 A helpful analogy is to consider the motor symptoms of PD as the tip of the iceberg and the nonmotor symptoms as the larger, submerged portions of the iceberg.4

Nonmotor symptoms can negatively impact the treatment of motor symptoms. For example, imagine a patient who is very rigid and dyscoordinated in the arms and legs, which limits their ability to dress and walk. If this patient also suffers from nonmotor symptoms of orthostatic hypotension and psychosis—both of which can be exacerbated by levodopa—dose escalation of levodopa for the rigidity and dyscoordination could be compromised, rendering the patient undertreated and less mobile.

In this review, we focus on identifying and managing nonmotor symptoms of PD that are relevant to psychiatric practice, including mood and motivational disorders, anxiety disorders, psychosis, cognitive disorders, and disorders related to the pharmacologic and surgical treatment of PD (Figure 1).

Mood and motivational disorders

Depression

Depression is a common symptom in PD that can occur in the prodromal period years to decades before the onset of motor symptoms, as well as throughout the disease course.5 The prevalence of depression in PD varies from 3% to 90%, depending on the methods of assessment, clinical setting of assessment, motor symptom severity, and other factors; clinically significant depression likely affects approximately 35% to 38% of patients.5,6 How depression in patients with PD differs from depression in the general population is not entirely understood, but there does seem to be less guilt and suicidal ideation and a substantial component of negative affect, including dysphoria and anxiety.7 Practically speaking, depression is treated similarly in PD and general populations, with a few considerations.

Despite limited randomized controlled trials (RCTs) for efficacy specifically in patients with PD, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are generally considered first-line treatments. There is also evidence for tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), but due to potential worsening of orthostatic hypotension and cognition, TCAs may not be a favorable option for certain patients with PD.8,9 All antidepressants have the potential to worsen tremor. Theoretically, SNRIs, with noradrenergic activity, may be less tolerable than SSRIs in patients with PD. However, worsening tremor generally has not been a clinically significant adverse event reported in PD depression clinical trials, although it was seen in 17% of patients receiving paroxetine and 21% of patients receiving venlafaxine compared to 7% of patients receiving placebo.9-11 If tremor worsens, mirtazapine could be considered because it has been reported to cause less tremor than SSRIs or TCAs.12

Among medications for PD, pramipexole, a dopamine agonist, may have a beneficial effect on depression.13 Additionally, some evidence supports rasagiline, a monoamine oxidase type B inhibitor, as an adjunctive medication for depression in PD.14 Nevertheless, antidepressant medications remain the standard pharmacologic treatment for PD depression.

Continue to: In terms of nonpharmacologic options...

In terms of nonpharmacologic options, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is likely efficacious, exercise (especially yoga) is likely efficacious, and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation may be efficacious.15,16 While further high-quality trials are needed, these treatments are low-risk and can be considered, especially for patients who cannot tolerate medications.

Apathy

Apathy—a loss of motivation and goal-directed behavior—can occur in up to 30% of patients during the prodromal period of PD, and in up to 70% of patients throughout the disease course.17 Apathy can coexist with depression, which can make apathy difficult to diagnose.17 Given the time constraints of a clinic visit, a practical approach would be to first screen for depression and cognitive impairment. If there is continued suspicion of apathy, the Movement Disorder Society-Sponsored Revision of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale part I question (“In the past week have you felt indifferent to doing activities or being with people?”) can be used to screen for apathy, and more detailed scales, such as the Apathy Scale (AS) or Lille Apathy Rating Scale (LARS), could be used if indicated.18

There are limited high-quality positive trials of apathy-specific treatments in PD. In an RCT of patients with PD who did not have depression or dementia, rivastigmine improved LARS scores compared to placebo.15 Piribedil, a D2/D3 receptor agonist, improved apathy in patients who underwent subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation (STN DBS).15 Exercise such as individualized physical therapy programs, dance, and Nordic walking as well as mindfulness interventions were shown to significantly reduce apathy scale scores.19 SSRIs, SNRIs, and rotigotine showed a trend toward reducing AS scores in RCTs.10,20

Larger, high-quality studies are needed to clarify the treatment of apathy in PD. In the meantime, a reasonable approach is to first treat any comorbid psychiatric or cognitive disorders, since apathy can be associated with these conditions, and to optimize antiparkinsonian medications for motor symptoms, motor fluctuations, and nonmotor fluctuations. Then, the investigational apathy treatments described in this section could be considered on an individual basis.

Anxiety disorders

Anxiety is seen throughout the disease course of PD in approximately 30% to 50% of patients.21 It can manifest as generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and other anxiety disorders. There are no high-quality RCTs of pharmacologic treatments of anxiety specifically in patients with PD, except for a negative safety and tolerability study of buspirone in which one-half of patients experienced worsening motor symptoms.15,22 Thus, the treatment of anxiety in patients with PD is similar to treatments in the general population. SSRIs and SNRIs are typically considered first-line, benzodiazepines are sometimes used with caution (although cognitive adverse effects and fall risk need to be considered), and nonpharmacologic treatments such as mindfulness yoga, exercise, CBT, and psychotherapy can be effective.16,21,23

Continue to: Because there is the lack...

Because there is the lack of evidence-based treatments for anxiety in PD, we highlight 2 PD-specific anxiety disorders: internal tremor, and nonmotor “off” anxiety.

Internal tremor

Internal tremor is a sense of vibration in the axial and/or appendicular muscles that cannot be seen externally by the patient or examiner. It is not yet fully understood if this phenomenon is sensory, anxiety-related, related to subclinical tremor, or the result of a combination of these factors (ie, sensory awareness of a subclinical tremor that triggers or is worsened by anxiety). There is some evidence for subclinical tremor on electromyography, but internal tremor does not respond to antiparkinsonian medications in 70% of patients.24 More electrophysiological research is needed to clarify this phenomenon. Internal tremor has been associated with anxiety in 64% of patients and often improves with anxiolytic therapies.24

Although poorly understood, internal tremor is a documented phenomenon in 33% to 44% of patients with PD, and in some cases, it may be an initial symptom that motivates a patient to seek medical attention for the first time.24,25 Internal tremor has also been reported in patients with essential tremor and multiple sclerosis.25 Therefore, physicians should be aware of internal tremor because this symptom could herald an underlying neurological disease.

Nonmotor ‘off’ anxiety

Patients with PD are commonly prescribed carbidopa-levodopa, a dopamine precursor, at least 3 times daily. Initially, this medication controls motor symptoms well from 1 dose to the next. However, as the disease progresses, some patients report motor fluctuations in which an individual dose of carbidopa-levodopa may wear off early, take longer than usual to take effect, or not take effect at all. Patients describe these periods as an “off” state in which they do not feel their medications are working. Such motor fluctuations can lead to anxiety and avoidance behaviors, because patients fear being in public at times when the medication does not adequately control their motor symptoms.

In addition to these motor symptom fluctuations and related anxiety, patients can also experience nonmotor symptom fluctuations. A wide variety of nonmotor symptoms, such as mood, cognitive, and behavioral symptoms, have been reported to fluctuate in parallel with motor symptoms.26,27 One study reported fluctuating restlessness in 39% of patients with PD, excessive worry in 17%, shortness of breath in 13%, excessive sweating and fear in 12%, and palpitations in 10%.27 A patient with fluctuating shortness of breath, sweating, and palpitations (for example) may repeatedly present to the emergency department with a negative cardiac workup and eventually be diagnosed with panic disorder, whereas the patient is truly experiencing nonmotor “off” symptoms. Thus, it is important to be aware of nonmotor fluctuations so this diagnosis can be made and the symptoms appropriately treated. The first step in treating nonmotor fluctuations is to optimize the antiparkinsonian regimen to minimize fluctuations. If “off” anxiety symptoms persist, anxiolytic medications can be prescribed.21

Continue to: Psychosis

Psychosis

Psychosis can occur in prodromal and early PD but is most common in advanced PD.28 One study reported that 60% of patients developed hallucinations or delusions after 12 years of follow-up.29 Disease duration, disease severity, dementia, and rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder are significant risk factors for psychosis in PD.30 Well-formed visual hallucinations are the most common manifestation of psychosis in patients with PD. Auditory hallucinations and delusions are less common. Delusions are usually seen in patients with dementia and are often paranoid delusions, such as of spousal infidelity.30 Sensory hallucinations can occur, but should not be mistaken with formication, a central pain syndrome in PD that can represent a nonmotor “off” symptom that may respond to dopaminergic medication.31 Other more mild psychotic symptoms include illusions or misinterpretation of stimuli, false sense of presence, and passage hallucinations of fleeting figures in the peripheral vision.30

The pathophysiology of PD psychosis is not entirely understood but differs from psychosis in other disorders. It can occur in the absence of antiparkinsonian medication exposure and is thought to be a consequence of the underlying disease process of PD involving neurodegeneration in certain brain regions and aberrant neurotransmission of not only dopamine but also serotonin, acetylcholine, and glutamate.30

Figure 2 outlines the management of psychosis in PD. After addressing medical and medication-related causes, it is important to determine if the psychotic symptom is sufficiently bothersome to and/or potentially dangerous for the patient to warrant treatment. If treatment is indicated, pimavanserin and clozapine are efficacious for psychosis in PD without worsening motor symptoms, and quetiapine is possibly efficacious with a low risk of worsening motor symptoms.15 Other antipsychotics, such as olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol, can substantially worsen motor symptoms.15 Both second-generation antipsychotics and pimavanserin have an FDA black-box warning for a higher risk of all-cause mortality in older patients with dementia; however, because psychosis is associated with early mortality in PD, the risk/benefit ratio should be discussed with the patient and family for shared decision-making.30 If the patient also has dementia, rivastigmine—which is FDA-approved for PD dementia (PDD)—may also improve hallucinations.32

Cognitive disorders

This section focuses on PD mild cognitive impairment (PD-MCI) and PDD. When a patient with PD reports cognitive concerns, the approach outlined in Figure 3 can be used to diagnose the cognitive disorder. A detailed history, medication review, and physical examination can identify any medical or psychiatric conditions that could affect cognition. The American Academy of Neurology recommends screening for depression, obtaining blood levels of vitamin B12 and thyroid-stimulating hormone, and obtaining a CT or MRI of the brain to rule out reversible causes of dementia.33 A validated screening test such as the Montreal Cognitive Assessment, which has higher sensitivity for PD-MCI than the Mini-Mental State Examination, is used to identify and quantify cognitive impairment.34 Neuropsychological testing is the gold standard and can be used to confirm and/or better quantify the degree and domains of cognitive impairment.35 Typically, cognitive deficits in PD affect executive function, attention, and/or visuospatial domains more than memory and language early on, and deficits in visuospatial and language domains have the highest sensitivity for predicting progression to PDD.36

Once reversible causes of dementia are addressed or ruled out and cognitive testing is completed, the Movement Disorder Society (MDS) criteria for PD-MCI and PDD summarized in Figure 3 can be used to diagnose the cognitive disorder.37,38 The MDS criteria for PDD require a diagnosis of PD for ≥1 year prior to the onset of dementia to differentiate PDD from dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB). If the dementia starts within 1 year of the onset of parkinsonism, the diagnosis would be DLB. PDD and DLB are on the spectrum of Lewy body dementia, with the same Lewy body pathology in different temporal and spatial distributions in the brain.38

Continue to: PD-MCI is present in...

PD-MCI is present in approximately 25% of patients.35 PD-MCI does not always progress to dementia but increases the risk of dementia 6-fold. The prevalence of PDD increases with disease duration; it is present in approximately 50% of patients at 10 years and 80% of patients at 20 years of disease.35 Rivastigmine is the only FDA-approved medication to slow progression of PDD. There is insufficient evidence for other acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and memantine.15 Unfortunately, RCTs of pharmacotherapy for PD-MCI have failed to show efficacy. However, exercise, cognitive rehabilitation, and neuromodulation are being studied. In the meantime, addressing modifiable risk factors (such as vascular risk factors and alcohol consumption) and treating comorbid orthostatic hypotension, obstructive sleep apnea, and depression may improve cognition.35,39

Treatment-related disorders

Impulse control disorders

Impulse control disorders (ICDs) are an important medication-related consideration in patients with PD. The ICDs seen in PD include pathological gambling, binge eating, excessive shopping, hypersexual behaviors, and dopamine dysregulation syndrome (Table). These disorders are more common in younger patients with a history of impulsive personality traits and addictive behaviors (eg, history of tobacco or alcohol abuse), and are most strongly associated with dopaminergic therapies, particularly the dopamine agonists.40,41 In the DOMINION study, the odds of ICDs were 2- to 3.5-fold higher in patients taking dopamine agonists.42 This is mainly thought to be due to stimulation of D2/D3 receptors in the mesolimbic system.40 High doses of levodopa, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, and amantadine are also associated with ICDs.40-42

The first step in managing ICDs is diagnosing them, which can be difficult because patients often are not forthcoming about these problems due to embarrassment or failure to recognize that the ICD is related to PD medications. If a family member accompanies the patient at the visit, the patient may not want to disclose the amount of money they spend or the extent to which the behavior is a problem. Thus, a screening questionnaire, such as the Questionnaire for Impulsive-Compulsive Disorders in Parkinson’s Disease (QUIP) can be a helpful way for patients to alert the clinician to the issue.41 Education for the patient and family is crucial before the ICD causes significant financial, health, or relationship problems.

The mainstay of treatment is to reduce or taper off the dopamine agonist or other offending agent while monitoring for worsening motor symptoms and dopamine withdrawal syndrome. If this is unsuccessful, there is very limited evidence for further treatment strategies (Table), including antidepressants, antipsychotics, and mood stabilizers.40,43,44 There is insufficient evidence for naltrexone based on an RCT that failed to meet its primary endpoint, although naltrexone did significantly reduce QUIP scores.15,44 There is also insufficient evidence for amantadine, which showed benefit in some studies but was associated with ICDs in the DOMINION study.15,40,42 In terms of nonpharmacologic treatments, CBT is likely efficacious.15,40 There are mixed results for STN DBS. Some studies showed improvement in the ICD, due at least in part to dopaminergic medication reduction postoperatively, but this treatment has also been reported to increase impulsivity.40,45

Deep brain stimulation–related disorders

For patients with PD, the ideal lead location for STN DBS is the dorsolateral aspect of the STN, as this is the motor region of the nucleus. The STN functions in indirect and hyperdirect pathways to put the brake on certain motor programs so only the desired movement can be executed. Its function is clinically demonstrated by patients with STN stroke who develop excessive ballistic movements. Adjacent to the motor region of the STN is a centrally located associative region and a medially located limbic region. Thus, when stimulating the dorsolateral STN, current can spread to those regions as well, and the STN’s ability to put the brake on behavioral and emotional programs can be affected.46 Stimulation of the STN has been associated with mania, euphoria, new-onset ICDs, decreased verbal fluency, and executive dysfunction. Depression, apathy, and anxiety can also occur, but more commonly result from rapid withdrawal of antiparkinsonian medications after DBS surgery.46,47 Therefore, for PD patients with DBS with new or worsening psychiatric or cognitive symptoms, it is important to inquire about any recent programming sessions with neurology as well as recent self-increases in stimulation by the patient using their controller. Collaboration with neurology is important to troubleshoot whether stimulation could be contributing to the patient’s psychiatric or cognitive symptoms.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Mood, anxiety, psychotic, and cognitive symptoms and disorders are common psychiatric manifestations associated with Parkinson’s disease (PD). In addition, patients with PD may experience impulsive control disorders and other symptoms related to treatments they receive for PD. Careful assessment and collaboration with neurology is crucial to alleviating the effects of these conditions.

Related Resources

- Weintraub D, Aarsland D, Chaudhuri KR, et al. The neuropsychiatry of Parkinson’s disease: advances and challenges. Lancet Neurology. 2022;21(1):89-102. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(21)00330-6

- Goldman JG, Guerra CM. Treatment of nonmotor symptoms associated with Parkinson disease. Neurologic Clinics. 2020;38(2):269-292. doi:10.1016/j.ncl.2019.12.003

- Castrioto A, Lhommee E, Moro E et al. Mood and behavioral effects of subthalamic stimulation in Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurology. 2014;13(3):287-305. doi:10.1016/ S1474-4422(13)70294-1

Drug Brand Names

Amantadine • Gocovri

Carbidopa-levodopa • Sinemet

Clozapine • Clozaril

Haloperidol • Haldol

Memantine • Namenda

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Naltrexone • Vivitrol

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Paroxetine • Paxil

Pimavanserin • Nuplazid

Piribedil • Pronoran

Pramipexole • Mirapex

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Rasagiline • Azilect

Risperidone • Risperdal

Rivastigmine • Exelon

Ropinirole • Requip

Rotigotine • Neupro

Venlafaxine • Effexor

Zonisamide • Zonegran

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative condition diagnosed pathologically by alpha synuclein–containing Lewy bodies and dopaminergic cell loss in the substantia nigra pars compacta of the midbrain. Loss of dopaminergic input to the caudate and putamen disrupts the direct and indirect basal ganglia pathways for motor control and contributes to the motor symptoms of PD.1 According to the Movement Disorder Society criteria, PD is diagnosed clinically by bradykinesia (slowness of movement) plus resting tremor and/or rigidity in the presence of supportive criteria, such as levodopa responsiveness and hyposmia, and in the absence of exclusion criteria and red flags that would suggest atypical parkinsonism or an alternative diagnosis.2

Although the diagnosis and treatment of PD focus heavily on the motor symptoms, nonmotor symptoms can arise decades before the onset of motor symptoms and continue throughout the lifespan. Nonmotor symptoms affect patients from head (ie, cognition and mood) to toe (ie, striatal toe pain) and multiple organ systems in between, including the olfactory, integumentary, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, and autonomic nervous systems. Thus, it is not surprising that nonmotor symptoms of PD impact health-related quality of life more substantially than motor symptoms.3 A helpful analogy is to consider the motor symptoms of PD as the tip of the iceberg and the nonmotor symptoms as the larger, submerged portions of the iceberg.4

Nonmotor symptoms can negatively impact the treatment of motor symptoms. For example, imagine a patient who is very rigid and dyscoordinated in the arms and legs, which limits their ability to dress and walk. If this patient also suffers from nonmotor symptoms of orthostatic hypotension and psychosis—both of which can be exacerbated by levodopa—dose escalation of levodopa for the rigidity and dyscoordination could be compromised, rendering the patient undertreated and less mobile.

In this review, we focus on identifying and managing nonmotor symptoms of PD that are relevant to psychiatric practice, including mood and motivational disorders, anxiety disorders, psychosis, cognitive disorders, and disorders related to the pharmacologic and surgical treatment of PD (Figure 1).

Mood and motivational disorders

Depression

Depression is a common symptom in PD that can occur in the prodromal period years to decades before the onset of motor symptoms, as well as throughout the disease course.5 The prevalence of depression in PD varies from 3% to 90%, depending on the methods of assessment, clinical setting of assessment, motor symptom severity, and other factors; clinically significant depression likely affects approximately 35% to 38% of patients.5,6 How depression in patients with PD differs from depression in the general population is not entirely understood, but there does seem to be less guilt and suicidal ideation and a substantial component of negative affect, including dysphoria and anxiety.7 Practically speaking, depression is treated similarly in PD and general populations, with a few considerations.

Despite limited randomized controlled trials (RCTs) for efficacy specifically in patients with PD, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are generally considered first-line treatments. There is also evidence for tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), but due to potential worsening of orthostatic hypotension and cognition, TCAs may not be a favorable option for certain patients with PD.8,9 All antidepressants have the potential to worsen tremor. Theoretically, SNRIs, with noradrenergic activity, may be less tolerable than SSRIs in patients with PD. However, worsening tremor generally has not been a clinically significant adverse event reported in PD depression clinical trials, although it was seen in 17% of patients receiving paroxetine and 21% of patients receiving venlafaxine compared to 7% of patients receiving placebo.9-11 If tremor worsens, mirtazapine could be considered because it has been reported to cause less tremor than SSRIs or TCAs.12

Among medications for PD, pramipexole, a dopamine agonist, may have a beneficial effect on depression.13 Additionally, some evidence supports rasagiline, a monoamine oxidase type B inhibitor, as an adjunctive medication for depression in PD.14 Nevertheless, antidepressant medications remain the standard pharmacologic treatment for PD depression.

Continue to: In terms of nonpharmacologic options...

In terms of nonpharmacologic options, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is likely efficacious, exercise (especially yoga) is likely efficacious, and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation may be efficacious.15,16 While further high-quality trials are needed, these treatments are low-risk and can be considered, especially for patients who cannot tolerate medications.

Apathy

Apathy—a loss of motivation and goal-directed behavior—can occur in up to 30% of patients during the prodromal period of PD, and in up to 70% of patients throughout the disease course.17 Apathy can coexist with depression, which can make apathy difficult to diagnose.17 Given the time constraints of a clinic visit, a practical approach would be to first screen for depression and cognitive impairment. If there is continued suspicion of apathy, the Movement Disorder Society-Sponsored Revision of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale part I question (“In the past week have you felt indifferent to doing activities or being with people?”) can be used to screen for apathy, and more detailed scales, such as the Apathy Scale (AS) or Lille Apathy Rating Scale (LARS), could be used if indicated.18

There are limited high-quality positive trials of apathy-specific treatments in PD. In an RCT of patients with PD who did not have depression or dementia, rivastigmine improved LARS scores compared to placebo.15 Piribedil, a D2/D3 receptor agonist, improved apathy in patients who underwent subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation (STN DBS).15 Exercise such as individualized physical therapy programs, dance, and Nordic walking as well as mindfulness interventions were shown to significantly reduce apathy scale scores.19 SSRIs, SNRIs, and rotigotine showed a trend toward reducing AS scores in RCTs.10,20

Larger, high-quality studies are needed to clarify the treatment of apathy in PD. In the meantime, a reasonable approach is to first treat any comorbid psychiatric or cognitive disorders, since apathy can be associated with these conditions, and to optimize antiparkinsonian medications for motor symptoms, motor fluctuations, and nonmotor fluctuations. Then, the investigational apathy treatments described in this section could be considered on an individual basis.

Anxiety disorders

Anxiety is seen throughout the disease course of PD in approximately 30% to 50% of patients.21 It can manifest as generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and other anxiety disorders. There are no high-quality RCTs of pharmacologic treatments of anxiety specifically in patients with PD, except for a negative safety and tolerability study of buspirone in which one-half of patients experienced worsening motor symptoms.15,22 Thus, the treatment of anxiety in patients with PD is similar to treatments in the general population. SSRIs and SNRIs are typically considered first-line, benzodiazepines are sometimes used with caution (although cognitive adverse effects and fall risk need to be considered), and nonpharmacologic treatments such as mindfulness yoga, exercise, CBT, and psychotherapy can be effective.16,21,23

Continue to: Because there is the lack...

Because there is the lack of evidence-based treatments for anxiety in PD, we highlight 2 PD-specific anxiety disorders: internal tremor, and nonmotor “off” anxiety.

Internal tremor

Internal tremor is a sense of vibration in the axial and/or appendicular muscles that cannot be seen externally by the patient or examiner. It is not yet fully understood if this phenomenon is sensory, anxiety-related, related to subclinical tremor, or the result of a combination of these factors (ie, sensory awareness of a subclinical tremor that triggers or is worsened by anxiety). There is some evidence for subclinical tremor on electromyography, but internal tremor does not respond to antiparkinsonian medications in 70% of patients.24 More electrophysiological research is needed to clarify this phenomenon. Internal tremor has been associated with anxiety in 64% of patients and often improves with anxiolytic therapies.24

Although poorly understood, internal tremor is a documented phenomenon in 33% to 44% of patients with PD, and in some cases, it may be an initial symptom that motivates a patient to seek medical attention for the first time.24,25 Internal tremor has also been reported in patients with essential tremor and multiple sclerosis.25 Therefore, physicians should be aware of internal tremor because this symptom could herald an underlying neurological disease.

Nonmotor ‘off’ anxiety

Patients with PD are commonly prescribed carbidopa-levodopa, a dopamine precursor, at least 3 times daily. Initially, this medication controls motor symptoms well from 1 dose to the next. However, as the disease progresses, some patients report motor fluctuations in which an individual dose of carbidopa-levodopa may wear off early, take longer than usual to take effect, or not take effect at all. Patients describe these periods as an “off” state in which they do not feel their medications are working. Such motor fluctuations can lead to anxiety and avoidance behaviors, because patients fear being in public at times when the medication does not adequately control their motor symptoms.

In addition to these motor symptom fluctuations and related anxiety, patients can also experience nonmotor symptom fluctuations. A wide variety of nonmotor symptoms, such as mood, cognitive, and behavioral symptoms, have been reported to fluctuate in parallel with motor symptoms.26,27 One study reported fluctuating restlessness in 39% of patients with PD, excessive worry in 17%, shortness of breath in 13%, excessive sweating and fear in 12%, and palpitations in 10%.27 A patient with fluctuating shortness of breath, sweating, and palpitations (for example) may repeatedly present to the emergency department with a negative cardiac workup and eventually be diagnosed with panic disorder, whereas the patient is truly experiencing nonmotor “off” symptoms. Thus, it is important to be aware of nonmotor fluctuations so this diagnosis can be made and the symptoms appropriately treated. The first step in treating nonmotor fluctuations is to optimize the antiparkinsonian regimen to minimize fluctuations. If “off” anxiety symptoms persist, anxiolytic medications can be prescribed.21

Continue to: Psychosis

Psychosis

Psychosis can occur in prodromal and early PD but is most common in advanced PD.28 One study reported that 60% of patients developed hallucinations or delusions after 12 years of follow-up.29 Disease duration, disease severity, dementia, and rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder are significant risk factors for psychosis in PD.30 Well-formed visual hallucinations are the most common manifestation of psychosis in patients with PD. Auditory hallucinations and delusions are less common. Delusions are usually seen in patients with dementia and are often paranoid delusions, such as of spousal infidelity.30 Sensory hallucinations can occur, but should not be mistaken with formication, a central pain syndrome in PD that can represent a nonmotor “off” symptom that may respond to dopaminergic medication.31 Other more mild psychotic symptoms include illusions or misinterpretation of stimuli, false sense of presence, and passage hallucinations of fleeting figures in the peripheral vision.30