User login

Nonablative laser adds benefits to low-dose isotretinoin as treatment for moderate to severe acne

A combination of low-dose isotretinoin and nonablative fractional laser (NAFL) was a safe and effective treatment for moderate to severe acne and also improved acne scars in a small Chinese study, investigators reported.

In the randomized, split-face, controlled study of 18 adult Asian patients with moderate to severe acne, low-dose isotretinoin alone effectively controlled papule and pustule acne lesions, whereas NAFL had the additional effect of reducing the number of comedones and improving boxcar atrophic scars, reported Weihui Zeng, MD, and associates from the department of dermatology at the Second Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University, Shanxi, China.

The authors noted that many patients seen at their clinic cannot tolerate a 20 mg/day dose of isotretinoin because of severe mucocutaneous side effects and that treatment with nonablative lasers, which – in contrast to ablative lasers – use infrared radiation to penetrate the skin deeply and thereby selectively heat dermal tissue while sparing the epidermis, could be a treatment option for these patients.

Therefore, they set out to investigate a treatment plan combining 1,550-nm NAFL with low-dose isotretinoin (10 mg/day) in the 18 patients (mean age, 24 years; skin types II-IV) attending their outpatient dermatology clinic. Three laser treatments were administered at monthly intervals to one side of the face, with the other side of the face serving as a control. Each patient was on low-dose isotretinoin for 30-45 days before laser treatment. A revised Leeds acne-grading system was used.

At follow-up after the third treatment – 3 months after the first laser treatment – both sides of the face showed significant recovery in all participants, but there was greater improvement on the laser-treated side. The mean Leeds acne-grading scores decreased from 10.6 at baseline to 5.8 on the control side of the face, and from 10.4 at baseline to 3.5 on the laser-treated side. The changes in scores differed significantly between sides (P less than .05), and the number of comedones decreased more on the laser-treated side of the face than it did the control side.

Significant improvements were also seen with superficial scars (P less than .05) and deep boxcar atrophic scars (P less than .01) on the laser-treated sides of patients’ faces, compared with the control sides, but significant improvements were not seen with the number of papules and nodules or with icepick or rolling scars.

Patients reported discomfort after NAFL treatment, including pain (100%), sensation of heat (100%), erythema (94.5%), and edema (88.9%), which resolved spontaneously within 24 hours.

Most of the patients (n = 12; 66.7%) were satisfied after the last treatment, two (11.1%) were “very satisfied,” and four (22.2%) were neutral; none were dissatisfied.

“Low-dose isotretinoin effectively controlled papule and pustule acne lesions, whereas use of 1,550-nm Er:glass NAFL may significantly reduce the number of comedones and improve boxcar atrophic scars,” the authors wrote.

They authors reported no significant interest with commercial supporters.

SOURCE: Xia J et al. Dermatol Surg. 2018 Sep;44(9):1201-8.

A combination of low-dose isotretinoin and nonablative fractional laser (NAFL) was a safe and effective treatment for moderate to severe acne and also improved acne scars in a small Chinese study, investigators reported.

In the randomized, split-face, controlled study of 18 adult Asian patients with moderate to severe acne, low-dose isotretinoin alone effectively controlled papule and pustule acne lesions, whereas NAFL had the additional effect of reducing the number of comedones and improving boxcar atrophic scars, reported Weihui Zeng, MD, and associates from the department of dermatology at the Second Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University, Shanxi, China.

The authors noted that many patients seen at their clinic cannot tolerate a 20 mg/day dose of isotretinoin because of severe mucocutaneous side effects and that treatment with nonablative lasers, which – in contrast to ablative lasers – use infrared radiation to penetrate the skin deeply and thereby selectively heat dermal tissue while sparing the epidermis, could be a treatment option for these patients.

Therefore, they set out to investigate a treatment plan combining 1,550-nm NAFL with low-dose isotretinoin (10 mg/day) in the 18 patients (mean age, 24 years; skin types II-IV) attending their outpatient dermatology clinic. Three laser treatments were administered at monthly intervals to one side of the face, with the other side of the face serving as a control. Each patient was on low-dose isotretinoin for 30-45 days before laser treatment. A revised Leeds acne-grading system was used.

At follow-up after the third treatment – 3 months after the first laser treatment – both sides of the face showed significant recovery in all participants, but there was greater improvement on the laser-treated side. The mean Leeds acne-grading scores decreased from 10.6 at baseline to 5.8 on the control side of the face, and from 10.4 at baseline to 3.5 on the laser-treated side. The changes in scores differed significantly between sides (P less than .05), and the number of comedones decreased more on the laser-treated side of the face than it did the control side.

Significant improvements were also seen with superficial scars (P less than .05) and deep boxcar atrophic scars (P less than .01) on the laser-treated sides of patients’ faces, compared with the control sides, but significant improvements were not seen with the number of papules and nodules or with icepick or rolling scars.

Patients reported discomfort after NAFL treatment, including pain (100%), sensation of heat (100%), erythema (94.5%), and edema (88.9%), which resolved spontaneously within 24 hours.

Most of the patients (n = 12; 66.7%) were satisfied after the last treatment, two (11.1%) were “very satisfied,” and four (22.2%) were neutral; none were dissatisfied.

“Low-dose isotretinoin effectively controlled papule and pustule acne lesions, whereas use of 1,550-nm Er:glass NAFL may significantly reduce the number of comedones and improve boxcar atrophic scars,” the authors wrote.

They authors reported no significant interest with commercial supporters.

SOURCE: Xia J et al. Dermatol Surg. 2018 Sep;44(9):1201-8.

A combination of low-dose isotretinoin and nonablative fractional laser (NAFL) was a safe and effective treatment for moderate to severe acne and also improved acne scars in a small Chinese study, investigators reported.

In the randomized, split-face, controlled study of 18 adult Asian patients with moderate to severe acne, low-dose isotretinoin alone effectively controlled papule and pustule acne lesions, whereas NAFL had the additional effect of reducing the number of comedones and improving boxcar atrophic scars, reported Weihui Zeng, MD, and associates from the department of dermatology at the Second Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University, Shanxi, China.

The authors noted that many patients seen at their clinic cannot tolerate a 20 mg/day dose of isotretinoin because of severe mucocutaneous side effects and that treatment with nonablative lasers, which – in contrast to ablative lasers – use infrared radiation to penetrate the skin deeply and thereby selectively heat dermal tissue while sparing the epidermis, could be a treatment option for these patients.

Therefore, they set out to investigate a treatment plan combining 1,550-nm NAFL with low-dose isotretinoin (10 mg/day) in the 18 patients (mean age, 24 years; skin types II-IV) attending their outpatient dermatology clinic. Three laser treatments were administered at monthly intervals to one side of the face, with the other side of the face serving as a control. Each patient was on low-dose isotretinoin for 30-45 days before laser treatment. A revised Leeds acne-grading system was used.

At follow-up after the third treatment – 3 months after the first laser treatment – both sides of the face showed significant recovery in all participants, but there was greater improvement on the laser-treated side. The mean Leeds acne-grading scores decreased from 10.6 at baseline to 5.8 on the control side of the face, and from 10.4 at baseline to 3.5 on the laser-treated side. The changes in scores differed significantly between sides (P less than .05), and the number of comedones decreased more on the laser-treated side of the face than it did the control side.

Significant improvements were also seen with superficial scars (P less than .05) and deep boxcar atrophic scars (P less than .01) on the laser-treated sides of patients’ faces, compared with the control sides, but significant improvements were not seen with the number of papules and nodules or with icepick or rolling scars.

Patients reported discomfort after NAFL treatment, including pain (100%), sensation of heat (100%), erythema (94.5%), and edema (88.9%), which resolved spontaneously within 24 hours.

Most of the patients (n = 12; 66.7%) were satisfied after the last treatment, two (11.1%) were “very satisfied,” and four (22.2%) were neutral; none were dissatisfied.

“Low-dose isotretinoin effectively controlled papule and pustule acne lesions, whereas use of 1,550-nm Er:glass NAFL may significantly reduce the number of comedones and improve boxcar atrophic scars,” the authors wrote.

They authors reported no significant interest with commercial supporters.

SOURCE: Xia J et al. Dermatol Surg. 2018 Sep;44(9):1201-8.

FROM DERMATOLOGIC SURGERY

Key clinical point: Adding nonablative fractional laser (NAFL) treatment to low-dose isotretinoin may reduce comedones and improve boxcar atrophic scarring in people with moderate to severe acne .

Major finding: Low-dose isotretinoin effectively controlled papule and pustule acne lesions, whereas nonablative laser also reduced the number of comedones and improved boxcar atrophic scars.

Study details: A prospective randomized, controlled, split-face study of 18 Asian adult patients with moderate to severe acne vulgaris, treated with low-dose isotretinoin, as well as NAFL to one side of the face.

Disclosures: The authors reported no significant interests with commercial supporters.

Source: Xia J et al. Dermatol Surg. 2018 Sep;44(9):1201-8.

Ablative fractional lasers treat scars like ‘a magic wand’

SAN DIEGO – .

“I tell patients it’s like boiling water in a tea kettle and watching the vapor form,” Dr. Waibel, a dermatologist with the Miami Dermatology and Laser Institute, said at the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium. “You literally ‘steam off’ their bad scar and the human body will heal that wound to almost normal skin. It’s the closest thing we have to a magic wand.”

In the not-too-distant past, dermatologists “were treating scars just to make them look better,” she said. However, thanks to groundbreaking work by clinicians at Naval Medical Center San Diego, the use of ablative fractional lasers to treat scars was found to improve range of motion in patients, as well as their pain and pruritus. “It represents a major innovation that heals in ways not previously possible,” said Dr. Waibel, who is also chief of dermatology at Baptist Hospital in Miami. “We’re not just healing the scar; we’re healing the skin back to its physiological normal place. A lot of these patients suffer quite a bit.”

Dr. Waibel likened her scar treatment approach to a three-course meal. Lesion color drives her choice of what device to use as an “appetizer” treatment. Most scars are either red (erythematous), brown (hyperpigmented), or white (hypopigmented). Though every scar is unique and individually evaluated for treatment, typically she uses pulsed dye laser, intense pulsed light, or broadband light therapy to treat erythematous/early scars; nonablative fractional lasers to treat atrophic scars, and the thulium or 1,470-nm laser to treat hyperpigmented scars. The “main course” device in her practice is an ablative fractional erbium or CO2 laser.

“Once I treat the scar three to five times, I might switch to a nonablative laser, but I’m really an ablative fractional user,” Dr. Waibel said. “Dessert” can be whatever adjunctive therapies you need, she continued. This may include triamcinolone acetonide, 5-fluorouracil, poly-l-lactic acid, hyaluronidase, Z-plasty, punch biopsies, shave biopsies, compression, chemical reconstruction of skin scars (CROSS), and subcision.

For erythematous surgical and trauma scars, she uses a combination of pulsed dye laser and ablative fractional laser. “Same day, same treatment; one after each other,” she said. She favors using intense pulsed light for donor sites because it has filters that address both melanin and hemosiderin, superiority for scar erythema, and deeper penetration with greater speed to treat large surface areas.

One recent advance in the vascular arena is the new 595-nm pulsed dye laser by Candela, known as the VBeam Prima. It features increased energy, a 15-nm spot size, a zoom hand piece, once-a-day calibration, and contact cooling, which may be better for pigmented and possibly microvascular structures. The device is cleared for treating conditions like rosacea, acne, spider veins, port-wine stains, wrinkles, warts and stretch marks, as well as photoaging and benign pigmented lesions.

Dr. Waibel’s go-to device for treating a hypertrophic, hyperpigmented surgical scar is a 1927-nm or 1470-nm nonablative fractional laser, followed by a fractional ablative laser and injection of 1-2 ccs of 5-fluorouracil only to elevated areas. Hypopigmented scars are “by far the toughest to treat,” she said. However, she has a formula for these, too, and recently conducted a trial comparing the efficacy of nonablative fractional laser, ablative fractional laser, and ablative fractional laser followed by laser-assisted delivery of bimatoprost (Latisse) to treat hypopigmentation.

Surgical scars get better on their own in many cases, but sometimes early intervention is warranted. “Most surgeons will tell patients, ‘Wait a year. What you have [in terms of scar formation] is what you have,’” Dr. Waibel said. “If a surgical scar becomes hypertrophic, it does so within a month of surgery. I don’t prophylactically treat surgical scars unless the patient has had multiple surgeries in the same location with trouble healing. But if it’s been 6 months to a year, or if the patient is developing hypertrophic scars, then I will treat.”

Acne scars are challenging, because patients want to look good right away. “With deep scars, it takes several treatments to see good improvements,” she said. “I tell all my acne scar patients it takes a year [to get good results].”

Most burn patients require three to six treatment sessions, “but sometimes you get remarkable improvement sooner,” she said. “That’s due to the patient’s healing.” She and her associates recently completed an unpublished study that examined early intervention of fractional ablative laser versus control in 20 subjects with acute burn injuries who ranged in age from 18 to 80 years. The subjects underwent treatment with an ablative fractional CO2 laser within 3 months of sustaining the burn injury, leaving an untreated control area for comparison. According to Dr. Waibel, 100% of the blinded physician evaluators graded the laser-treated area correctly, compared with the control area. In addition, a significant improvement in all points of the Manchester Scar Scale was observed in the laser-treated area. “The earlier you treat burn and trauma patients, the easier it is to get them back to normal,” she said.

Dr. Waibel disclosed that she has conducted clinical research for Aquavit, Cytrellis, Lumenis, Lutronic, Michelson Diagnostics, RegenX, Sciton, Sebacia, and Syneron/Candela. She is also a consultant for RegenX, Strata, and Syneron/Candela and is a member of the advisory board for Dominion Technologies, Sciton, and Sebacia.

SAN DIEGO – .

“I tell patients it’s like boiling water in a tea kettle and watching the vapor form,” Dr. Waibel, a dermatologist with the Miami Dermatology and Laser Institute, said at the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium. “You literally ‘steam off’ their bad scar and the human body will heal that wound to almost normal skin. It’s the closest thing we have to a magic wand.”

In the not-too-distant past, dermatologists “were treating scars just to make them look better,” she said. However, thanks to groundbreaking work by clinicians at Naval Medical Center San Diego, the use of ablative fractional lasers to treat scars was found to improve range of motion in patients, as well as their pain and pruritus. “It represents a major innovation that heals in ways not previously possible,” said Dr. Waibel, who is also chief of dermatology at Baptist Hospital in Miami. “We’re not just healing the scar; we’re healing the skin back to its physiological normal place. A lot of these patients suffer quite a bit.”

Dr. Waibel likened her scar treatment approach to a three-course meal. Lesion color drives her choice of what device to use as an “appetizer” treatment. Most scars are either red (erythematous), brown (hyperpigmented), or white (hypopigmented). Though every scar is unique and individually evaluated for treatment, typically she uses pulsed dye laser, intense pulsed light, or broadband light therapy to treat erythematous/early scars; nonablative fractional lasers to treat atrophic scars, and the thulium or 1,470-nm laser to treat hyperpigmented scars. The “main course” device in her practice is an ablative fractional erbium or CO2 laser.

“Once I treat the scar three to five times, I might switch to a nonablative laser, but I’m really an ablative fractional user,” Dr. Waibel said. “Dessert” can be whatever adjunctive therapies you need, she continued. This may include triamcinolone acetonide, 5-fluorouracil, poly-l-lactic acid, hyaluronidase, Z-plasty, punch biopsies, shave biopsies, compression, chemical reconstruction of skin scars (CROSS), and subcision.

For erythematous surgical and trauma scars, she uses a combination of pulsed dye laser and ablative fractional laser. “Same day, same treatment; one after each other,” she said. She favors using intense pulsed light for donor sites because it has filters that address both melanin and hemosiderin, superiority for scar erythema, and deeper penetration with greater speed to treat large surface areas.

One recent advance in the vascular arena is the new 595-nm pulsed dye laser by Candela, known as the VBeam Prima. It features increased energy, a 15-nm spot size, a zoom hand piece, once-a-day calibration, and contact cooling, which may be better for pigmented and possibly microvascular structures. The device is cleared for treating conditions like rosacea, acne, spider veins, port-wine stains, wrinkles, warts and stretch marks, as well as photoaging and benign pigmented lesions.

Dr. Waibel’s go-to device for treating a hypertrophic, hyperpigmented surgical scar is a 1927-nm or 1470-nm nonablative fractional laser, followed by a fractional ablative laser and injection of 1-2 ccs of 5-fluorouracil only to elevated areas. Hypopigmented scars are “by far the toughest to treat,” she said. However, she has a formula for these, too, and recently conducted a trial comparing the efficacy of nonablative fractional laser, ablative fractional laser, and ablative fractional laser followed by laser-assisted delivery of bimatoprost (Latisse) to treat hypopigmentation.

Surgical scars get better on their own in many cases, but sometimes early intervention is warranted. “Most surgeons will tell patients, ‘Wait a year. What you have [in terms of scar formation] is what you have,’” Dr. Waibel said. “If a surgical scar becomes hypertrophic, it does so within a month of surgery. I don’t prophylactically treat surgical scars unless the patient has had multiple surgeries in the same location with trouble healing. But if it’s been 6 months to a year, or if the patient is developing hypertrophic scars, then I will treat.”

Acne scars are challenging, because patients want to look good right away. “With deep scars, it takes several treatments to see good improvements,” she said. “I tell all my acne scar patients it takes a year [to get good results].”

Most burn patients require three to six treatment sessions, “but sometimes you get remarkable improvement sooner,” she said. “That’s due to the patient’s healing.” She and her associates recently completed an unpublished study that examined early intervention of fractional ablative laser versus control in 20 subjects with acute burn injuries who ranged in age from 18 to 80 years. The subjects underwent treatment with an ablative fractional CO2 laser within 3 months of sustaining the burn injury, leaving an untreated control area for comparison. According to Dr. Waibel, 100% of the blinded physician evaluators graded the laser-treated area correctly, compared with the control area. In addition, a significant improvement in all points of the Manchester Scar Scale was observed in the laser-treated area. “The earlier you treat burn and trauma patients, the easier it is to get them back to normal,” she said.

Dr. Waibel disclosed that she has conducted clinical research for Aquavit, Cytrellis, Lumenis, Lutronic, Michelson Diagnostics, RegenX, Sciton, Sebacia, and Syneron/Candela. She is also a consultant for RegenX, Strata, and Syneron/Candela and is a member of the advisory board for Dominion Technologies, Sciton, and Sebacia.

SAN DIEGO – .

“I tell patients it’s like boiling water in a tea kettle and watching the vapor form,” Dr. Waibel, a dermatologist with the Miami Dermatology and Laser Institute, said at the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium. “You literally ‘steam off’ their bad scar and the human body will heal that wound to almost normal skin. It’s the closest thing we have to a magic wand.”

In the not-too-distant past, dermatologists “were treating scars just to make them look better,” she said. However, thanks to groundbreaking work by clinicians at Naval Medical Center San Diego, the use of ablative fractional lasers to treat scars was found to improve range of motion in patients, as well as their pain and pruritus. “It represents a major innovation that heals in ways not previously possible,” said Dr. Waibel, who is also chief of dermatology at Baptist Hospital in Miami. “We’re not just healing the scar; we’re healing the skin back to its physiological normal place. A lot of these patients suffer quite a bit.”

Dr. Waibel likened her scar treatment approach to a three-course meal. Lesion color drives her choice of what device to use as an “appetizer” treatment. Most scars are either red (erythematous), brown (hyperpigmented), or white (hypopigmented). Though every scar is unique and individually evaluated for treatment, typically she uses pulsed dye laser, intense pulsed light, or broadband light therapy to treat erythematous/early scars; nonablative fractional lasers to treat atrophic scars, and the thulium or 1,470-nm laser to treat hyperpigmented scars. The “main course” device in her practice is an ablative fractional erbium or CO2 laser.

“Once I treat the scar three to five times, I might switch to a nonablative laser, but I’m really an ablative fractional user,” Dr. Waibel said. “Dessert” can be whatever adjunctive therapies you need, she continued. This may include triamcinolone acetonide, 5-fluorouracil, poly-l-lactic acid, hyaluronidase, Z-plasty, punch biopsies, shave biopsies, compression, chemical reconstruction of skin scars (CROSS), and subcision.

For erythematous surgical and trauma scars, she uses a combination of pulsed dye laser and ablative fractional laser. “Same day, same treatment; one after each other,” she said. She favors using intense pulsed light for donor sites because it has filters that address both melanin and hemosiderin, superiority for scar erythema, and deeper penetration with greater speed to treat large surface areas.

One recent advance in the vascular arena is the new 595-nm pulsed dye laser by Candela, known as the VBeam Prima. It features increased energy, a 15-nm spot size, a zoom hand piece, once-a-day calibration, and contact cooling, which may be better for pigmented and possibly microvascular structures. The device is cleared for treating conditions like rosacea, acne, spider veins, port-wine stains, wrinkles, warts and stretch marks, as well as photoaging and benign pigmented lesions.

Dr. Waibel’s go-to device for treating a hypertrophic, hyperpigmented surgical scar is a 1927-nm or 1470-nm nonablative fractional laser, followed by a fractional ablative laser and injection of 1-2 ccs of 5-fluorouracil only to elevated areas. Hypopigmented scars are “by far the toughest to treat,” she said. However, she has a formula for these, too, and recently conducted a trial comparing the efficacy of nonablative fractional laser, ablative fractional laser, and ablative fractional laser followed by laser-assisted delivery of bimatoprost (Latisse) to treat hypopigmentation.

Surgical scars get better on their own in many cases, but sometimes early intervention is warranted. “Most surgeons will tell patients, ‘Wait a year. What you have [in terms of scar formation] is what you have,’” Dr. Waibel said. “If a surgical scar becomes hypertrophic, it does so within a month of surgery. I don’t prophylactically treat surgical scars unless the patient has had multiple surgeries in the same location with trouble healing. But if it’s been 6 months to a year, or if the patient is developing hypertrophic scars, then I will treat.”

Acne scars are challenging, because patients want to look good right away. “With deep scars, it takes several treatments to see good improvements,” she said. “I tell all my acne scar patients it takes a year [to get good results].”

Most burn patients require three to six treatment sessions, “but sometimes you get remarkable improvement sooner,” she said. “That’s due to the patient’s healing.” She and her associates recently completed an unpublished study that examined early intervention of fractional ablative laser versus control in 20 subjects with acute burn injuries who ranged in age from 18 to 80 years. The subjects underwent treatment with an ablative fractional CO2 laser within 3 months of sustaining the burn injury, leaving an untreated control area for comparison. According to Dr. Waibel, 100% of the blinded physician evaluators graded the laser-treated area correctly, compared with the control area. In addition, a significant improvement in all points of the Manchester Scar Scale was observed in the laser-treated area. “The earlier you treat burn and trauma patients, the easier it is to get them back to normal,” she said.

Dr. Waibel disclosed that she has conducted clinical research for Aquavit, Cytrellis, Lumenis, Lutronic, Michelson Diagnostics, RegenX, Sciton, Sebacia, and Syneron/Candela. She is also a consultant for RegenX, Strata, and Syneron/Candela and is a member of the advisory board for Dominion Technologies, Sciton, and Sebacia.

REPORTING FROM MOAS 2018

Reflectance confocal microscopy: The future looks bright

CHICAGO – The future looks bright for to rule out malignancy, Ann M. John, MD, asserted at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery.

“With the advent of dermoscopy, dermatologists were able to elucidate both benign and malignant patterns to help further guide their decision to biopsy or not. This increased diagnostic accuracy of suspicious lesions by 30%, while reducing the benign to malignant ratio of biopsies performed from 18:1 to 4:1. However, there are still lesions that are equivocal on dermoscopy, as we all know, and for this, there’s reflectance confocal microscopy,” observed Dr. John, of Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J.

RCM is a device technology that’s been cleared by the Food and Drug Administration since 2008 for the imaging of clinically suspicious lesions. It employs laser scanning to assess the light-scattering properties of cells in the epidermis and dermis, generating images with resolution comparable to histology.

RCM took a back seat initially while American dermatologists were gradually coming to embrace dermoscopy, which their European colleagues had done years earlier. Now, with the availability of handheld RCM for use in the dermatology clinic, expect RCM to assume a growing role in daily practice.

To illustrate the power of RCM as a diagnostic aid, she presented a single-center retrospective study of 1,189 clinically suspicious skin lesions that were equivocal on dermoscopy and then assessed using RCM with 1 year of subsequent patient follow-up. Overall, 155 lesions were deemed positive for cancer or atypia by RCM, while 1,034 were determined to be benign. Of those 155, 46 lesions were considered false positives because of their benign appearance on histologic inspection of the biopsy sample. Only 2 of the 1,034 lesions identified as negative by RCM proved to be false negatives on the basis of clinical changes within 1 year.

The overall sensitivity and specificity of RCM was 98.2% and 99.8%, respectively, with a positive predictive value of 70.3% and a negative predictive value of 99.8%.

The entire RCM procedure takes a skilled technician 15-20 minutes per lesion. As a practical matter, other investigators have estimated that RCM results in a cost savings of about $308,000 per million health plan members per year by reducing the need for biopsies (Dermatol Clin. 2016 Oct;34[4]:367-75).

In addition to evaluating clinically suspicious lesions, other situations in which RCM offers practical value include its use directly before the first cut during Mohs surgery in order to determine the margins of atypia; ex vivo imaging of Mohs margins, which has been shown to be comparable with frozen sections in accuracy but takes only one-third of the time; and imaging of biopsied lesions in order to determine the diagnosis relatively quickly, Dr. John noted.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study.

CHICAGO – The future looks bright for to rule out malignancy, Ann M. John, MD, asserted at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery.

“With the advent of dermoscopy, dermatologists were able to elucidate both benign and malignant patterns to help further guide their decision to biopsy or not. This increased diagnostic accuracy of suspicious lesions by 30%, while reducing the benign to malignant ratio of biopsies performed from 18:1 to 4:1. However, there are still lesions that are equivocal on dermoscopy, as we all know, and for this, there’s reflectance confocal microscopy,” observed Dr. John, of Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J.

RCM is a device technology that’s been cleared by the Food and Drug Administration since 2008 for the imaging of clinically suspicious lesions. It employs laser scanning to assess the light-scattering properties of cells in the epidermis and dermis, generating images with resolution comparable to histology.

RCM took a back seat initially while American dermatologists were gradually coming to embrace dermoscopy, which their European colleagues had done years earlier. Now, with the availability of handheld RCM for use in the dermatology clinic, expect RCM to assume a growing role in daily practice.

To illustrate the power of RCM as a diagnostic aid, she presented a single-center retrospective study of 1,189 clinically suspicious skin lesions that were equivocal on dermoscopy and then assessed using RCM with 1 year of subsequent patient follow-up. Overall, 155 lesions were deemed positive for cancer or atypia by RCM, while 1,034 were determined to be benign. Of those 155, 46 lesions were considered false positives because of their benign appearance on histologic inspection of the biopsy sample. Only 2 of the 1,034 lesions identified as negative by RCM proved to be false negatives on the basis of clinical changes within 1 year.

The overall sensitivity and specificity of RCM was 98.2% and 99.8%, respectively, with a positive predictive value of 70.3% and a negative predictive value of 99.8%.

The entire RCM procedure takes a skilled technician 15-20 minutes per lesion. As a practical matter, other investigators have estimated that RCM results in a cost savings of about $308,000 per million health plan members per year by reducing the need for biopsies (Dermatol Clin. 2016 Oct;34[4]:367-75).

In addition to evaluating clinically suspicious lesions, other situations in which RCM offers practical value include its use directly before the first cut during Mohs surgery in order to determine the margins of atypia; ex vivo imaging of Mohs margins, which has been shown to be comparable with frozen sections in accuracy but takes only one-third of the time; and imaging of biopsied lesions in order to determine the diagnosis relatively quickly, Dr. John noted.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study.

CHICAGO – The future looks bright for to rule out malignancy, Ann M. John, MD, asserted at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery.

“With the advent of dermoscopy, dermatologists were able to elucidate both benign and malignant patterns to help further guide their decision to biopsy or not. This increased diagnostic accuracy of suspicious lesions by 30%, while reducing the benign to malignant ratio of biopsies performed from 18:1 to 4:1. However, there are still lesions that are equivocal on dermoscopy, as we all know, and for this, there’s reflectance confocal microscopy,” observed Dr. John, of Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J.

RCM is a device technology that’s been cleared by the Food and Drug Administration since 2008 for the imaging of clinically suspicious lesions. It employs laser scanning to assess the light-scattering properties of cells in the epidermis and dermis, generating images with resolution comparable to histology.

RCM took a back seat initially while American dermatologists were gradually coming to embrace dermoscopy, which their European colleagues had done years earlier. Now, with the availability of handheld RCM for use in the dermatology clinic, expect RCM to assume a growing role in daily practice.

To illustrate the power of RCM as a diagnostic aid, she presented a single-center retrospective study of 1,189 clinically suspicious skin lesions that were equivocal on dermoscopy and then assessed using RCM with 1 year of subsequent patient follow-up. Overall, 155 lesions were deemed positive for cancer or atypia by RCM, while 1,034 were determined to be benign. Of those 155, 46 lesions were considered false positives because of their benign appearance on histologic inspection of the biopsy sample. Only 2 of the 1,034 lesions identified as negative by RCM proved to be false negatives on the basis of clinical changes within 1 year.

The overall sensitivity and specificity of RCM was 98.2% and 99.8%, respectively, with a positive predictive value of 70.3% and a negative predictive value of 99.8%.

The entire RCM procedure takes a skilled technician 15-20 minutes per lesion. As a practical matter, other investigators have estimated that RCM results in a cost savings of about $308,000 per million health plan members per year by reducing the need for biopsies (Dermatol Clin. 2016 Oct;34[4]:367-75).

In addition to evaluating clinically suspicious lesions, other situations in which RCM offers practical value include its use directly before the first cut during Mohs surgery in order to determine the margins of atypia; ex vivo imaging of Mohs margins, which has been shown to be comparable with frozen sections in accuracy but takes only one-third of the time; and imaging of biopsied lesions in order to determine the diagnosis relatively quickly, Dr. John noted.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study.

REPORTING FROM THE ACMS ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: The future looks bright for reflectance confocal microscopy in dermatology.

Major finding: The sensitivity and specificity of reflectance confocal microscopy for diagnosis of skin cancer in patients with equivocal dermoscopic findings was 98.2% and 99.8%, respectively.

Study details: This retrospective single center study included 1,189 clinically suspicious skin lesions with equivocal dermoscopy findings, which were then evaluated using reflectance confocal microscopy.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study.

Mohs underutilized for melanoma of head and neck

CHICAGO – Contemporary national guidelines undervalue the benefits of Mohs micrographic surgery for patients with melanoma of the head and neck, William C. Fix asserted at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery.

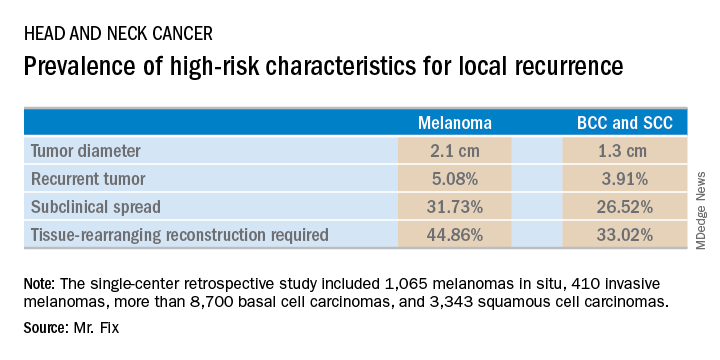

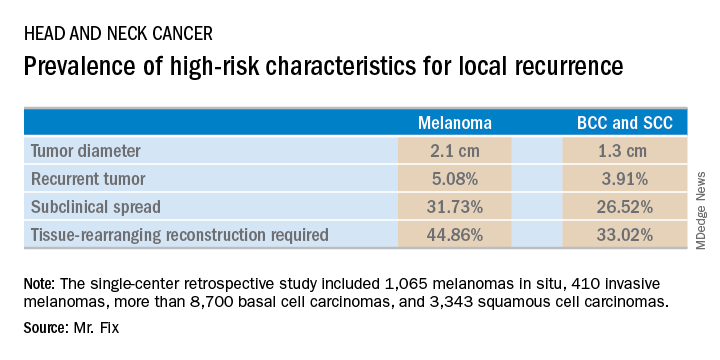

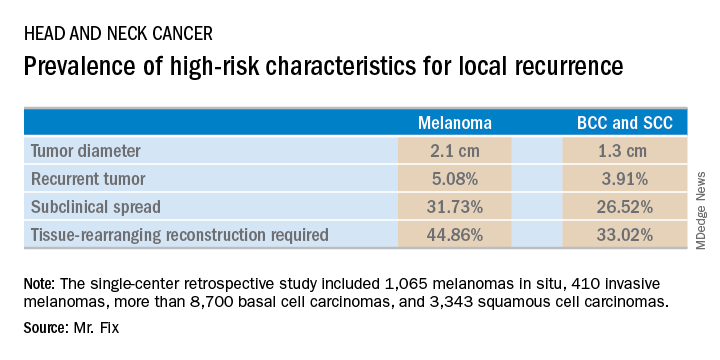

Mr. Fix, a medical student at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, presented a single-center retrospective study of 13,644 cases of head and neck skin cancer treated with Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) for margin control. The cohort included 1,065 melanomas in situ, 410 invasive melanomas, more than 8,700 basal cell carcinomas, and 3,343 squamous cell carcinomas.

Mr. Fix and his coinvestigators undertook this observational study because they identified a gap in current guidelines for treatment of skin cancers of the head and neck. For example, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommends margin control at the time of primary surgery for BCCs and SCCs deemed at high risk for local recurrence and defines what those high-risk features are. For melanomas, however, the guidelines recommend wide local excision, even though that approach has roughly a 10% recurrence rate, compared with less than 1% for MMS.

Moreover, the 2012 appropriate use criteria for MMS put forth by the American Academy of Dermatology in concert with several other medical societies are unclear about invasive melanoma. As a result of this lack of guidance, the use of margin control in primary surgery for melanoma is applied in less than 4% of cases, according to Mr. Fix.

The University of Pennsylvania data he presented showed that melanomas of the head and neck were significantly more likely to be large in size, to be poorly defined, and to have other high-risk features for local recurrence than were the BCCs and SCCs. In a multivariate logistic regression analysis controlling for high-risk characteristics, melanomas were independently associated with a twofold increased likelihood of requiring flap reconstruction compared with BCCs and SCCs of the head and neck.

“We’ve shown that melanomas have high-risk features for local recurrence, possibly to a greater extent than BCCs and SCCs. These features help us triage resource use for BCC and SCC. Could these same features help us make decisions for melanomas?” he asked rhetorically.

Mr. Fix reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

CHICAGO – Contemporary national guidelines undervalue the benefits of Mohs micrographic surgery for patients with melanoma of the head and neck, William C. Fix asserted at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery.

Mr. Fix, a medical student at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, presented a single-center retrospective study of 13,644 cases of head and neck skin cancer treated with Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) for margin control. The cohort included 1,065 melanomas in situ, 410 invasive melanomas, more than 8,700 basal cell carcinomas, and 3,343 squamous cell carcinomas.

Mr. Fix and his coinvestigators undertook this observational study because they identified a gap in current guidelines for treatment of skin cancers of the head and neck. For example, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommends margin control at the time of primary surgery for BCCs and SCCs deemed at high risk for local recurrence and defines what those high-risk features are. For melanomas, however, the guidelines recommend wide local excision, even though that approach has roughly a 10% recurrence rate, compared with less than 1% for MMS.

Moreover, the 2012 appropriate use criteria for MMS put forth by the American Academy of Dermatology in concert with several other medical societies are unclear about invasive melanoma. As a result of this lack of guidance, the use of margin control in primary surgery for melanoma is applied in less than 4% of cases, according to Mr. Fix.

The University of Pennsylvania data he presented showed that melanomas of the head and neck were significantly more likely to be large in size, to be poorly defined, and to have other high-risk features for local recurrence than were the BCCs and SCCs. In a multivariate logistic regression analysis controlling for high-risk characteristics, melanomas were independently associated with a twofold increased likelihood of requiring flap reconstruction compared with BCCs and SCCs of the head and neck.

“We’ve shown that melanomas have high-risk features for local recurrence, possibly to a greater extent than BCCs and SCCs. These features help us triage resource use for BCC and SCC. Could these same features help us make decisions for melanomas?” he asked rhetorically.

Mr. Fix reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

CHICAGO – Contemporary national guidelines undervalue the benefits of Mohs micrographic surgery for patients with melanoma of the head and neck, William C. Fix asserted at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery.

Mr. Fix, a medical student at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, presented a single-center retrospective study of 13,644 cases of head and neck skin cancer treated with Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) for margin control. The cohort included 1,065 melanomas in situ, 410 invasive melanomas, more than 8,700 basal cell carcinomas, and 3,343 squamous cell carcinomas.

Mr. Fix and his coinvestigators undertook this observational study because they identified a gap in current guidelines for treatment of skin cancers of the head and neck. For example, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommends margin control at the time of primary surgery for BCCs and SCCs deemed at high risk for local recurrence and defines what those high-risk features are. For melanomas, however, the guidelines recommend wide local excision, even though that approach has roughly a 10% recurrence rate, compared with less than 1% for MMS.

Moreover, the 2012 appropriate use criteria for MMS put forth by the American Academy of Dermatology in concert with several other medical societies are unclear about invasive melanoma. As a result of this lack of guidance, the use of margin control in primary surgery for melanoma is applied in less than 4% of cases, according to Mr. Fix.

The University of Pennsylvania data he presented showed that melanomas of the head and neck were significantly more likely to be large in size, to be poorly defined, and to have other high-risk features for local recurrence than were the BCCs and SCCs. In a multivariate logistic regression analysis controlling for high-risk characteristics, melanomas were independently associated with a twofold increased likelihood of requiring flap reconstruction compared with BCCs and SCCs of the head and neck.

“We’ve shown that melanomas have high-risk features for local recurrence, possibly to a greater extent than BCCs and SCCs. These features help us triage resource use for BCC and SCC. Could these same features help us make decisions for melanomas?” he asked rhetorically.

Mr. Fix reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

REPORTING FROM THE ACMS ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Margin control at the time of primary surgery for melanoma of the head and neck makes sense.

Major finding: Patients with a melanoma of the head and neck were twice as likely to require secondary flap reconstruction compared with patients with a basal cell carcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck.

Study details: A retrospective single-center study of 13,644 cases of skin cancer of the head and neck treated with Mohs surgery.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

Taking the sting out of nail surgery: Postoperative pain pearls

CHICAGO – In a busy clinic it can be hard to find the time to stop, talk, and listen. But doing so will “pay dividends in time spent later – and in reduced complications” of nail surgery, according to Molly A. Hinshaw, MD.

Dr. Hinshaw, director of the nail clinic at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, shared her

“One pearl is the importance of patient education before we start,” Dr. Hinshaw said. Preoperatively, she takes time to talk through the entire surgery and expected postoperative course. Critically, she reassures patients that pain will be controlled; she also reviews in detail what the pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic pain control strategies will be.

In addition, it’s important to address patients’ natural anxiety about what the surgical site will look and feel like and how healing will progress, particularly in those first few days after surgery. “I offer a first dressing change in my practice, either at 24 or 48 hours. This can be very anxiolytic for the patient,” she said.

At the preoperative stage, Dr. Hinshaw also tells patients that, from a healing and pain management standpoint, to make sure they plan “to have a restful 48 hours after surgery.” Her patient instructions for the immediate postoperative period include keeping the limb elevated and avoiding unnecessary activity with the affected limb while the digit, whether a finger or toe, is still anesthetized. To stay on top of the pain, the appropriate oral pain medication should be started once sensation starts to return to the digit. She recommends patients also take a dose of their pain medication at bedtime, as this will help them get a restful night of sleep.

“One thing that I’ve learned over the years is that throbbing and a little bit of swelling after surgery is not uncommon,” said Dr. Hinshaw, who uses elastic self-adherent wrap for the top layer of wound dressings after nail surgery. She tells her patients, “if you’re feeling throbbing, you’re welcome to unwrap it and rewrap it more loosely.” Just giving the patient the ability to find a comfortable level of pressure on the affected digit is often enough to alleviate the throbbing, as opposed to treating that throbbing with pain medication.

Dr. Hinshaw said she’s learned to tailor her postoperative analgesia to the surgery and to the patient. With all patients, she is sure to make medication and dosing choices that take comorbidities and potential drug-drug interactions into account. She does not ask patients to stop anticoagulation before nail procedures.

For phenolization procedures and punch biopsies, she’ll advise patients to use acetaminophen or NSAIDs. Some procedures are going to have a more painful recovery course, said Dr. Hinshaw, so she’ll use an opioid such as hydrocodone with acetaminophen for shave excisions and fusiform longitudinal excisions.

The physician and patient can also plan ahead for a brief course of more potent opioids for some procedures. “Certainly for lateral longitudinal excisions, they will need narcotic pain management for at least 48 hours after surgery,” she noted. “It’s a painful surgery.”

Other procedures that will need more postoperative analgesia include flaps and nail unit grafts, she said. In general, NSAIDs are useful to add after the first 24 hours. In addition, “I always call my patients the day after surgery to see how they’re doing. This helps identify any issues and questions early and is comforting to the patient,” she added.

Dr. Hinshaw disclosed that she has an ownership stake in and sits on the board of directors of Accure Medical.

CHICAGO – In a busy clinic it can be hard to find the time to stop, talk, and listen. But doing so will “pay dividends in time spent later – and in reduced complications” of nail surgery, according to Molly A. Hinshaw, MD.

Dr. Hinshaw, director of the nail clinic at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, shared her

“One pearl is the importance of patient education before we start,” Dr. Hinshaw said. Preoperatively, she takes time to talk through the entire surgery and expected postoperative course. Critically, she reassures patients that pain will be controlled; she also reviews in detail what the pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic pain control strategies will be.

In addition, it’s important to address patients’ natural anxiety about what the surgical site will look and feel like and how healing will progress, particularly in those first few days after surgery. “I offer a first dressing change in my practice, either at 24 or 48 hours. This can be very anxiolytic for the patient,” she said.

At the preoperative stage, Dr. Hinshaw also tells patients that, from a healing and pain management standpoint, to make sure they plan “to have a restful 48 hours after surgery.” Her patient instructions for the immediate postoperative period include keeping the limb elevated and avoiding unnecessary activity with the affected limb while the digit, whether a finger or toe, is still anesthetized. To stay on top of the pain, the appropriate oral pain medication should be started once sensation starts to return to the digit. She recommends patients also take a dose of their pain medication at bedtime, as this will help them get a restful night of sleep.

“One thing that I’ve learned over the years is that throbbing and a little bit of swelling after surgery is not uncommon,” said Dr. Hinshaw, who uses elastic self-adherent wrap for the top layer of wound dressings after nail surgery. She tells her patients, “if you’re feeling throbbing, you’re welcome to unwrap it and rewrap it more loosely.” Just giving the patient the ability to find a comfortable level of pressure on the affected digit is often enough to alleviate the throbbing, as opposed to treating that throbbing with pain medication.

Dr. Hinshaw said she’s learned to tailor her postoperative analgesia to the surgery and to the patient. With all patients, she is sure to make medication and dosing choices that take comorbidities and potential drug-drug interactions into account. She does not ask patients to stop anticoagulation before nail procedures.

For phenolization procedures and punch biopsies, she’ll advise patients to use acetaminophen or NSAIDs. Some procedures are going to have a more painful recovery course, said Dr. Hinshaw, so she’ll use an opioid such as hydrocodone with acetaminophen for shave excisions and fusiform longitudinal excisions.

The physician and patient can also plan ahead for a brief course of more potent opioids for some procedures. “Certainly for lateral longitudinal excisions, they will need narcotic pain management for at least 48 hours after surgery,” she noted. “It’s a painful surgery.”

Other procedures that will need more postoperative analgesia include flaps and nail unit grafts, she said. In general, NSAIDs are useful to add after the first 24 hours. In addition, “I always call my patients the day after surgery to see how they’re doing. This helps identify any issues and questions early and is comforting to the patient,” she added.

Dr. Hinshaw disclosed that she has an ownership stake in and sits on the board of directors of Accure Medical.

CHICAGO – In a busy clinic it can be hard to find the time to stop, talk, and listen. But doing so will “pay dividends in time spent later – and in reduced complications” of nail surgery, according to Molly A. Hinshaw, MD.

Dr. Hinshaw, director of the nail clinic at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, shared her

“One pearl is the importance of patient education before we start,” Dr. Hinshaw said. Preoperatively, she takes time to talk through the entire surgery and expected postoperative course. Critically, she reassures patients that pain will be controlled; she also reviews in detail what the pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic pain control strategies will be.

In addition, it’s important to address patients’ natural anxiety about what the surgical site will look and feel like and how healing will progress, particularly in those first few days after surgery. “I offer a first dressing change in my practice, either at 24 or 48 hours. This can be very anxiolytic for the patient,” she said.

At the preoperative stage, Dr. Hinshaw also tells patients that, from a healing and pain management standpoint, to make sure they plan “to have a restful 48 hours after surgery.” Her patient instructions for the immediate postoperative period include keeping the limb elevated and avoiding unnecessary activity with the affected limb while the digit, whether a finger or toe, is still anesthetized. To stay on top of the pain, the appropriate oral pain medication should be started once sensation starts to return to the digit. She recommends patients also take a dose of their pain medication at bedtime, as this will help them get a restful night of sleep.

“One thing that I’ve learned over the years is that throbbing and a little bit of swelling after surgery is not uncommon,” said Dr. Hinshaw, who uses elastic self-adherent wrap for the top layer of wound dressings after nail surgery. She tells her patients, “if you’re feeling throbbing, you’re welcome to unwrap it and rewrap it more loosely.” Just giving the patient the ability to find a comfortable level of pressure on the affected digit is often enough to alleviate the throbbing, as opposed to treating that throbbing with pain medication.

Dr. Hinshaw said she’s learned to tailor her postoperative analgesia to the surgery and to the patient. With all patients, she is sure to make medication and dosing choices that take comorbidities and potential drug-drug interactions into account. She does not ask patients to stop anticoagulation before nail procedures.

For phenolization procedures and punch biopsies, she’ll advise patients to use acetaminophen or NSAIDs. Some procedures are going to have a more painful recovery course, said Dr. Hinshaw, so she’ll use an opioid such as hydrocodone with acetaminophen for shave excisions and fusiform longitudinal excisions.

The physician and patient can also plan ahead for a brief course of more potent opioids for some procedures. “Certainly for lateral longitudinal excisions, they will need narcotic pain management for at least 48 hours after surgery,” she noted. “It’s a painful surgery.”

Other procedures that will need more postoperative analgesia include flaps and nail unit grafts, she said. In general, NSAIDs are useful to add after the first 24 hours. In addition, “I always call my patients the day after surgery to see how they’re doing. This helps identify any issues and questions early and is comforting to the patient,” she added.

Dr. Hinshaw disclosed that she has an ownership stake in and sits on the board of directors of Accure Medical.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM SUMMER AAD 2018

Cost-effective wound healing described with fetal bovine collagen matrix

CHICAGO – A novel, commercially available fetal bovine collagen matrix provides “an ideal wound healing environment” for outpatient treatment of partial and full thickness wounds, ulcers, burns, and surgical wounds, Katarina R. Kesty, MD, declared at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery.

“. We applied this product to 46 patients over 10 months and have observed favorable healing times and good cosmesis,” said Dr. Kesty, a dermatology resident at Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C.

She shared the clinical experience she and her colleagues have accrued with this product, which is called PriMatrix and is manufactured by Integra LifeSciences. She also explained how to successfully code and bill for its use.

“In-office application of this product is cost-effective when compared to similar products applied in the operating room by plastic surgeons and other specialists,” Dr. Kesty noted.

How cost-effective? She provided one example of a patient with a 12.6-cm2 defect on the scalp repaired with fetal bovine collagen matrix. Upon application of the appropriate billing codes, this repair was reimbursed by Medicare to the tune of $1,208. In contrast, another patient at Wake Forest had a 16.6-cm2 Mohs defect on the scalp repaired in the operating room by an oculoplastic surgeon who used split thickness skin grafts. For this procedure, Medicare was billed $30,805.11, and the medical center received $9,241.53 in reimbursement.

“An office repair using this fetal bovine collagen matrix is much more cost-effective,” she observed. “It also saves the patient from the risks of general anesthesia or conscious sedation.”

PriMatrix is a porous acellular collagen matrix derived from fetal bovine dermis. It contains type I and type III collagen, with the latter being particularly effective at attracting growth factors, blood, and angiogenic cytokines in support of dermal regeneration and revascularization. The product is available in solid sheets, mesh, and fenestrated forms in a variety of sizes. It needs to be rehydrated for 1 minute in room temperature saline. It can then be cut to the size of the wound and secured to the wound bed, periosteum, fascia, or cartilage with sutures or staples. The site is then covered with a thick layer of petrolatum and a tie-over bolster.

Dr. Kesty and her dermatology colleagues have applied the matrix to surgical defects ranging in size from 0.2 cm2 to 70 cm2, with an average area of 19 cm2. They have utilized the mesh format most often in order to allow drainage. They found the average healing time when the matrix was applied to exposed bone, periosteum, or perichondrium was 13.8 weeks, compared with 10.8 weeks for subcutaneous wounds.

With the use of the fetal bovine collagen matrix, wounds less than 10 cm2 in size healed in an average of 9.3 weeks, those from 10 cm2 to 25 cm2 in size healed in an average of 10.4 weeks, and wounds larger than 25 cm2 healed in an average of 15.7 weeks.

Coding and reimbursement

PriMatrix has been available for outpatient office use and reimbursement by Medicare since January 2017. Successful reimbursement requires completion of a preauthorization form, which is typically approved on the same day by Medicare and other payers. The proper CPT codes are 1527x, signifying a skin substitute graft less than 100 cm2 in size; Q4110 times the number of 1-cm2 units of PriMatrix utilized; and, when appropriate, ICD10 code Z85.828, for personal history of nonmelanoma skin cancer.

Dr. Kesty reported no financial conflicts of interest.

CHICAGO – A novel, commercially available fetal bovine collagen matrix provides “an ideal wound healing environment” for outpatient treatment of partial and full thickness wounds, ulcers, burns, and surgical wounds, Katarina R. Kesty, MD, declared at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery.

“. We applied this product to 46 patients over 10 months and have observed favorable healing times and good cosmesis,” said Dr. Kesty, a dermatology resident at Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C.

She shared the clinical experience she and her colleagues have accrued with this product, which is called PriMatrix and is manufactured by Integra LifeSciences. She also explained how to successfully code and bill for its use.

“In-office application of this product is cost-effective when compared to similar products applied in the operating room by plastic surgeons and other specialists,” Dr. Kesty noted.

How cost-effective? She provided one example of a patient with a 12.6-cm2 defect on the scalp repaired with fetal bovine collagen matrix. Upon application of the appropriate billing codes, this repair was reimbursed by Medicare to the tune of $1,208. In contrast, another patient at Wake Forest had a 16.6-cm2 Mohs defect on the scalp repaired in the operating room by an oculoplastic surgeon who used split thickness skin grafts. For this procedure, Medicare was billed $30,805.11, and the medical center received $9,241.53 in reimbursement.

“An office repair using this fetal bovine collagen matrix is much more cost-effective,” she observed. “It also saves the patient from the risks of general anesthesia or conscious sedation.”

PriMatrix is a porous acellular collagen matrix derived from fetal bovine dermis. It contains type I and type III collagen, with the latter being particularly effective at attracting growth factors, blood, and angiogenic cytokines in support of dermal regeneration and revascularization. The product is available in solid sheets, mesh, and fenestrated forms in a variety of sizes. It needs to be rehydrated for 1 minute in room temperature saline. It can then be cut to the size of the wound and secured to the wound bed, periosteum, fascia, or cartilage with sutures or staples. The site is then covered with a thick layer of petrolatum and a tie-over bolster.

Dr. Kesty and her dermatology colleagues have applied the matrix to surgical defects ranging in size from 0.2 cm2 to 70 cm2, with an average area of 19 cm2. They have utilized the mesh format most often in order to allow drainage. They found the average healing time when the matrix was applied to exposed bone, periosteum, or perichondrium was 13.8 weeks, compared with 10.8 weeks for subcutaneous wounds.

With the use of the fetal bovine collagen matrix, wounds less than 10 cm2 in size healed in an average of 9.3 weeks, those from 10 cm2 to 25 cm2 in size healed in an average of 10.4 weeks, and wounds larger than 25 cm2 healed in an average of 15.7 weeks.

Coding and reimbursement

PriMatrix has been available for outpatient office use and reimbursement by Medicare since January 2017. Successful reimbursement requires completion of a preauthorization form, which is typically approved on the same day by Medicare and other payers. The proper CPT codes are 1527x, signifying a skin substitute graft less than 100 cm2 in size; Q4110 times the number of 1-cm2 units of PriMatrix utilized; and, when appropriate, ICD10 code Z85.828, for personal history of nonmelanoma skin cancer.

Dr. Kesty reported no financial conflicts of interest.

CHICAGO – A novel, commercially available fetal bovine collagen matrix provides “an ideal wound healing environment” for outpatient treatment of partial and full thickness wounds, ulcers, burns, and surgical wounds, Katarina R. Kesty, MD, declared at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery.

“. We applied this product to 46 patients over 10 months and have observed favorable healing times and good cosmesis,” said Dr. Kesty, a dermatology resident at Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C.

She shared the clinical experience she and her colleagues have accrued with this product, which is called PriMatrix and is manufactured by Integra LifeSciences. She also explained how to successfully code and bill for its use.

“In-office application of this product is cost-effective when compared to similar products applied in the operating room by plastic surgeons and other specialists,” Dr. Kesty noted.

How cost-effective? She provided one example of a patient with a 12.6-cm2 defect on the scalp repaired with fetal bovine collagen matrix. Upon application of the appropriate billing codes, this repair was reimbursed by Medicare to the tune of $1,208. In contrast, another patient at Wake Forest had a 16.6-cm2 Mohs defect on the scalp repaired in the operating room by an oculoplastic surgeon who used split thickness skin grafts. For this procedure, Medicare was billed $30,805.11, and the medical center received $9,241.53 in reimbursement.

“An office repair using this fetal bovine collagen matrix is much more cost-effective,” she observed. “It also saves the patient from the risks of general anesthesia or conscious sedation.”

PriMatrix is a porous acellular collagen matrix derived from fetal bovine dermis. It contains type I and type III collagen, with the latter being particularly effective at attracting growth factors, blood, and angiogenic cytokines in support of dermal regeneration and revascularization. The product is available in solid sheets, mesh, and fenestrated forms in a variety of sizes. It needs to be rehydrated for 1 minute in room temperature saline. It can then be cut to the size of the wound and secured to the wound bed, periosteum, fascia, or cartilage with sutures or staples. The site is then covered with a thick layer of petrolatum and a tie-over bolster.

Dr. Kesty and her dermatology colleagues have applied the matrix to surgical defects ranging in size from 0.2 cm2 to 70 cm2, with an average area of 19 cm2. They have utilized the mesh format most often in order to allow drainage. They found the average healing time when the matrix was applied to exposed bone, periosteum, or perichondrium was 13.8 weeks, compared with 10.8 weeks for subcutaneous wounds.

With the use of the fetal bovine collagen matrix, wounds less than 10 cm2 in size healed in an average of 9.3 weeks, those from 10 cm2 to 25 cm2 in size healed in an average of 10.4 weeks, and wounds larger than 25 cm2 healed in an average of 15.7 weeks.

Coding and reimbursement

PriMatrix has been available for outpatient office use and reimbursement by Medicare since January 2017. Successful reimbursement requires completion of a preauthorization form, which is typically approved on the same day by Medicare and other payers. The proper CPT codes are 1527x, signifying a skin substitute graft less than 100 cm2 in size; Q4110 times the number of 1-cm2 units of PriMatrix utilized; and, when appropriate, ICD10 code Z85.828, for personal history of nonmelanoma skin cancer.

Dr. Kesty reported no financial conflicts of interest.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE ACMS ANNUAL MEETING

Stress balls, hand-holding no help during dermatology procedures

according to a randomized trial of 135 patients at Northwestern University, Chicago.

In all three groups, anxiety levels were a little over 3 points on a 10-point Visual Analog Scale (VAS) before surgery and around 2 points during it. The 6-item State Trait Anxiety Inventory score was just under 9 in all three groups right after the procedure, meaning patients weren’t very anxious. Physiological measures did not change from before to after the procedure or between groups. Postoperative pain scores were all under 1 on a 10-point scale, and patients in all three groups were highly satisfied with their encounter, the researchers said in JAMA Dermatology.

“Many patients commented anecdotally on the calming effect of hand-holding or stress ball use,” so “it was surprising that the total data did not show these interventions to preferentially decrease anxiety or alleviate pain,” Arianna F. Yanes, a medical student at Northwestern University, and her coinvestigators said.

It could be that standard measures – giving patients an opportunity to ask questions, making sure they feel comfortable, and the like – are enough. However, “hand-holding and stress balls may still provide stress relief in patients who are particularly anxious before the procedure.” Perhaps patients would have preferred having their hand held by a loved one instead of a stranger, the investigators said.

Meanwhile, patients who researched their operation online beforehand had higher preoperative anxiety scores (3.84 vs. 2.62 points on the VAS; P = .04), but they could have been more anxious from the start.

The mean subject age was 66 years, and 62% were men.

The work was funded by Northwestern University and a grant from Merz. The investigators had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Yanes AF et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2018 Jul 18. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.1783.

according to a randomized trial of 135 patients at Northwestern University, Chicago.

In all three groups, anxiety levels were a little over 3 points on a 10-point Visual Analog Scale (VAS) before surgery and around 2 points during it. The 6-item State Trait Anxiety Inventory score was just under 9 in all three groups right after the procedure, meaning patients weren’t very anxious. Physiological measures did not change from before to after the procedure or between groups. Postoperative pain scores were all under 1 on a 10-point scale, and patients in all three groups were highly satisfied with their encounter, the researchers said in JAMA Dermatology.

“Many patients commented anecdotally on the calming effect of hand-holding or stress ball use,” so “it was surprising that the total data did not show these interventions to preferentially decrease anxiety or alleviate pain,” Arianna F. Yanes, a medical student at Northwestern University, and her coinvestigators said.

It could be that standard measures – giving patients an opportunity to ask questions, making sure they feel comfortable, and the like – are enough. However, “hand-holding and stress balls may still provide stress relief in patients who are particularly anxious before the procedure.” Perhaps patients would have preferred having their hand held by a loved one instead of a stranger, the investigators said.

Meanwhile, patients who researched their operation online beforehand had higher preoperative anxiety scores (3.84 vs. 2.62 points on the VAS; P = .04), but they could have been more anxious from the start.

The mean subject age was 66 years, and 62% were men.

The work was funded by Northwestern University and a grant from Merz. The investigators had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Yanes AF et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2018 Jul 18. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.1783.

according to a randomized trial of 135 patients at Northwestern University, Chicago.

In all three groups, anxiety levels were a little over 3 points on a 10-point Visual Analog Scale (VAS) before surgery and around 2 points during it. The 6-item State Trait Anxiety Inventory score was just under 9 in all three groups right after the procedure, meaning patients weren’t very anxious. Physiological measures did not change from before to after the procedure or between groups. Postoperative pain scores were all under 1 on a 10-point scale, and patients in all three groups were highly satisfied with their encounter, the researchers said in JAMA Dermatology.

“Many patients commented anecdotally on the calming effect of hand-holding or stress ball use,” so “it was surprising that the total data did not show these interventions to preferentially decrease anxiety or alleviate pain,” Arianna F. Yanes, a medical student at Northwestern University, and her coinvestigators said.

It could be that standard measures – giving patients an opportunity to ask questions, making sure they feel comfortable, and the like – are enough. However, “hand-holding and stress balls may still provide stress relief in patients who are particularly anxious before the procedure.” Perhaps patients would have preferred having their hand held by a loved one instead of a stranger, the investigators said.

Meanwhile, patients who researched their operation online beforehand had higher preoperative anxiety scores (3.84 vs. 2.62 points on the VAS; P = .04), but they could have been more anxious from the start.

The mean subject age was 66 years, and 62% were men.

The work was funded by Northwestern University and a grant from Merz. The investigators had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Yanes AF et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2018 Jul 18. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.1783.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

Unlikely mentors

Mentorship is a hot topic. Mentors are generally perceived as knowledgeable, kind, generous souls who will guide mentees through tough challenges and be your pal. I suggest to you that while such encounters are marvelous, and to be sought out, some of the most important lessons are taught by members of the opposite cast.

The presiding secretary of the Ohio state medical board was a brigadier general, still active reserve, tall with a bristling countenance. I was president of the Ohio Dermatological Association and was accompanied by Mark Bechtel, MD, who was our chair of state legislation. We had been invited to , and that there had not been any deaths related to local anesthesia administered by dermatologists in Ohio (or anywhere else). We expected to tell the medical board there was nothing to worry about, and we could all go home. This was 17 years ago.

It quickly became apparent that there had been an extensive prior dialogue between the medical board and representatives of the American College of Surgeons and the American Society of Anesthesiologists. They sat at the head table with the secretary of the medical board.

“In our experience, there are really some dangerous procedures going on in the office setting under local anesthesia, and this area desperately needs regulation,” the anesthesiologist’s representative said. The surgeon’s representative chimed in: “From what I’ve heard, office surgery is a ticking time bomb and needs regulation, and as soon as possible.” This prattle went on and on, with the medical board secretary sympathetically nodding his head. I raised my hand and was ignored – and ignored. It became apparent that this was a show trial, and our opinion was not really wanted, just our attendance noted in the minutes. Finally, I stood up and protested, and pointed out that all of this “testimony” was conjecture and personal opinion, and that there was no factual basis for their claims. The president stiffened, stood up, and started barking orders.He told me to “sit down and not speak unless I was called on.” I sat down and shut up. And I was never called on. Mark Bechtel put a calming hand on my arm. Goodness, I had not been treated like that since junior high.

I soon realized that dermatologists were not at all important to the medical board, and that the medical board had no idea about our safety and efficiency and really did not care.

Following the meeting, I was told by Larry Lanier (the American Academy of Dermatology state legislative liaison at the time) that Ohio was to be the test state to restrict local anesthesia and tumescent anesthesia nationwide. He explained that some widely reported liposuction-related deaths in Florida had given the medical board the “justification” to act. He went on to explain that yes, there were no data either way, but we had better hire a lobbyist and hope for the best.

I was stunned by what I now call (in this case, rough) “mentorship” by the medical board secretary. I understood I could meekly go along – or get angry. I chose the latter, and it has greatly changed my career.

Now, this was not a hot, red, foam-at-the-mouth mad, but a slow burn, the kind that sustains, not consumes.

I went home and did a literature review and was disheartened to find absolutely nothing in the literature on the safety record of dermatologists in the office setting or on the safety of office surgery in general under local anesthesia. We had nothing to back us up.

I looked up the liposuction deaths in Florida and discovered the procedures were all done under general anesthesia or deep sedation by surgeons of one type or another. I also discovered that Florida had enacted mandatory reporting, and the reports could be had for copying costs. I ordered all available, 9 months of data.

We dermatologists passed a special assessment and hired a lobbyist who told us we were too late to have any impact on the impending restrictions. We took a resolution opposing the medical board rules – which would have eliminated using any sedation in the office, even haloperidol and tumescent anesthesia – to the state medical society and got it passed despite the medical board secretary (who was a former president of the society) testifying against us. The Florida data showed no deaths or injuries from using local anesthesia in the office by anyone, and I succeeded in getting a letter addressing that data published expeditiously in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA 2001;285[20]:2582).

The president of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery at that time, Stephen Mandy, MD, came to town and testified against the proposed restrictions along with about 60 physicians, including dermatologists, plastic surgeons, and other physicians who perform office-based surgery who we had rallied to join us from across the state. So many colleagues joined us, in fact, that some of us had to sit on the floor during the proceedings.

The proposed restrictions evaporated. I and many others have since devoted our research efforts to solidifying dermatology’s safety and quality record. Dr. Bechtel, professor of dermatology at Ohio State University, Columbus, is now secretary of the state medical board. At the last annual state meeting, I thanked the brigadier general, the former secretary of the medical board, for his unlikely mentorship. He smiled and we got our picture taken together.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at [email protected].

Mentorship is a hot topic. Mentors are generally perceived as knowledgeable, kind, generous souls who will guide mentees through tough challenges and be your pal. I suggest to you that while such encounters are marvelous, and to be sought out, some of the most important lessons are taught by members of the opposite cast.