User login

Longstanding rash

The patient was given a diagnosis of widespread tinea corporis. This diagnosis may not fit with the common paradigm of tinea as thin, scaly annular patches, often known as ringworm. However, a skin scraping was performed on the red scaly patches, and the diagnosis was confirmed.

A skin scraping is a simple procedure that takes minutes to yield actionable information. A scalpel blade is used in a scraping motion and skin flakes are caught on a slide as they fall from the skin. (Another glass slide can be used in place of the scalpel, which is slightly less frightening for children.) The sample is then covered with 1 to 2 drops of potassium hydroxide (KOH), in 1 of various available formulations, and covered with a coverslip. Gently heating the slide, or simply waiting a few minutes, will allow the KOH to begin dissolving some keratinocyte membranes and stain any fungal walls light purple.

Hyphae, which may be linear (see Figure) or branched, will cross multiple cell membranes and are themselves about the thickness of a cell membrane. A high-powered view of hyphae should reveal nuclei and septa.

Skin biopsy, culture, and a skin scraping sent to an outside lab are all alternatives to the aforementioned approach but take days or weeks to yield a result. Fungal polymerase chain reaction is a novel diagnostic approach that can be both sensitive and specific, but still requires several days for results and incurs additional cost to the patient.

In this case, the diagnosis was made at the patient’s bedside and terbinafine 250 mg/d for 3 weeks was chosen as systemic therapy because of the extent of disease. At the follow-up visit 2 months later, the patient’s rash had completely cleared.

Text and photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. (Photo copyright retained.)

Liu D, Coloe S, Baird R, et al. Application of PCR to the identification of dermatophyte fungi. J Med Microbiol. 2000;49:493-497.

The patient was given a diagnosis of widespread tinea corporis. This diagnosis may not fit with the common paradigm of tinea as thin, scaly annular patches, often known as ringworm. However, a skin scraping was performed on the red scaly patches, and the diagnosis was confirmed.

A skin scraping is a simple procedure that takes minutes to yield actionable information. A scalpel blade is used in a scraping motion and skin flakes are caught on a slide as they fall from the skin. (Another glass slide can be used in place of the scalpel, which is slightly less frightening for children.) The sample is then covered with 1 to 2 drops of potassium hydroxide (KOH), in 1 of various available formulations, and covered with a coverslip. Gently heating the slide, or simply waiting a few minutes, will allow the KOH to begin dissolving some keratinocyte membranes and stain any fungal walls light purple.

Hyphae, which may be linear (see Figure) or branched, will cross multiple cell membranes and are themselves about the thickness of a cell membrane. A high-powered view of hyphae should reveal nuclei and septa.

Skin biopsy, culture, and a skin scraping sent to an outside lab are all alternatives to the aforementioned approach but take days or weeks to yield a result. Fungal polymerase chain reaction is a novel diagnostic approach that can be both sensitive and specific, but still requires several days for results and incurs additional cost to the patient.

In this case, the diagnosis was made at the patient’s bedside and terbinafine 250 mg/d for 3 weeks was chosen as systemic therapy because of the extent of disease. At the follow-up visit 2 months later, the patient’s rash had completely cleared.

Text and photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. (Photo copyright retained.)

The patient was given a diagnosis of widespread tinea corporis. This diagnosis may not fit with the common paradigm of tinea as thin, scaly annular patches, often known as ringworm. However, a skin scraping was performed on the red scaly patches, and the diagnosis was confirmed.

A skin scraping is a simple procedure that takes minutes to yield actionable information. A scalpel blade is used in a scraping motion and skin flakes are caught on a slide as they fall from the skin. (Another glass slide can be used in place of the scalpel, which is slightly less frightening for children.) The sample is then covered with 1 to 2 drops of potassium hydroxide (KOH), in 1 of various available formulations, and covered with a coverslip. Gently heating the slide, or simply waiting a few minutes, will allow the KOH to begin dissolving some keratinocyte membranes and stain any fungal walls light purple.

Hyphae, which may be linear (see Figure) or branched, will cross multiple cell membranes and are themselves about the thickness of a cell membrane. A high-powered view of hyphae should reveal nuclei and septa.

Skin biopsy, culture, and a skin scraping sent to an outside lab are all alternatives to the aforementioned approach but take days or weeks to yield a result. Fungal polymerase chain reaction is a novel diagnostic approach that can be both sensitive and specific, but still requires several days for results and incurs additional cost to the patient.

In this case, the diagnosis was made at the patient’s bedside and terbinafine 250 mg/d for 3 weeks was chosen as systemic therapy because of the extent of disease. At the follow-up visit 2 months later, the patient’s rash had completely cleared.

Text and photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. (Photo copyright retained.)

Liu D, Coloe S, Baird R, et al. Application of PCR to the identification of dermatophyte fungi. J Med Microbiol. 2000;49:493-497.

Liu D, Coloe S, Baird R, et al. Application of PCR to the identification of dermatophyte fungi. J Med Microbiol. 2000;49:493-497.

Face masks can aggravate rosacea

The “maskne” phenomenon – that is, new onset or exacerbation of preexisting acne due to prolonged wearing of protective face masks – has become commonplace during the COVID-19 pandemic. Less well appreciated is that rosacea often markedly worsens, too, Giovanni Damiani, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

“This is particularly interesting because two inflammatory dermatoses with different pathogenesis are both mechanically and microbiologically triggered by mask use,” observed Dr. Damiani, a dermatologist at the University of Milan.

He presented . These patients – 23 with papulopustular and 13 with erythematotelangiectatic rosacea – were wearing face masks for at least 6 hours per day during quarantine. Most were using what Dr. Damiani termed “community masks,” meaning they weren’t approved by the European regulatory agency as personal protective equipment.

Every yardstick Dr. Damiani and coinvestigators employed to characterize the patients’ rosacea demonstrated that the dermatosis was significantly worse during the prolonged mask-wearing period. For example, the average prequarantine score on the Global Flushing Severity Scale was 2.56, jumping to 3.97 after a month of masked quarantine. The flushing score climbed from 1.83 to 2.78 in the subgroup with papulopustular rosacea, and from 3.85 to 6.08 in patients with erythematotelangiectatic rosacea. Scores on the Clinician’s Erythema Assessment rose from 1.09 to 1.7 in the papulopustular rosacea patients, and from 2.46 to 3.54 in those with erythematotelangiectatic rosacea.

Scores on the Dermatology Life Quality Index climbed from 7.35 prequarantine to 10.65 in the subgroup with papulopustular rosacea and from 5.15 to 8.69 in patients with erythematotelangiectatic rosacea. Investigator Global Assessment and Patient’s Self-Assessment scores also deteriorated significantly after a month in masked quarantine.

Clinically, the mask-aggravated rosacea, or “maskacea,” was mainly localized to the dorsal lower third of the nose as well as the cheeks. The ocular and perioral areas and the chin were least affected.

Dr. Damiani advised his colleagues to intensify therapy promptly when patients report any worsening of their preexisting rosacea in connection with use of face masks. He has found this condition is often relatively treatment resistant so long as affected patients continue to wear face masks as an essential tool in preventing transmission of COVID-19.

The dermatologist noted that not all face masks are equal offenders when it comes to aggravating common facial dermatoses. During the spring 2020 pandemic quarantine in Milan, 11.6% of 318 mask wearers, none health care professionals, presented to Dr. Damiani and coinvestigators for treatment of facial dermatoses. The facial dermatosis rate was 5.4% among 168 users of masks bearing the European Union CE mark signifying the devices met relevant safety and performance standards, compared with 18.7% in 150 users of community masks with no CE mark. The rate of irritant contact dermatitis was zero with the CE mark masks and 4.7% with the community masks.

During quarantine, however, these patients wore their protective face masks for only a limited time, since for the most part they were restricted to home. In contrast, during the first week after the quarantine was lifted in early May and the daily hours of mask use increased, facial dermatoses were diagnosed in 8.7% of 23 users of CE-approved masks, compared with 45% of 71 wearers of community masks. Dr. Damiani and colleagues diagnosed irritant contact dermatitis in 16% of the community mask wearers post quarantine, but in not a single user of a mask bearing the CE mark.

The National Rosacea Society has issued patient guidance on avoiding rosacea flare-ups during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Dr. Damiani reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study.

The “maskne” phenomenon – that is, new onset or exacerbation of preexisting acne due to prolonged wearing of protective face masks – has become commonplace during the COVID-19 pandemic. Less well appreciated is that rosacea often markedly worsens, too, Giovanni Damiani, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

“This is particularly interesting because two inflammatory dermatoses with different pathogenesis are both mechanically and microbiologically triggered by mask use,” observed Dr. Damiani, a dermatologist at the University of Milan.

He presented . These patients – 23 with papulopustular and 13 with erythematotelangiectatic rosacea – were wearing face masks for at least 6 hours per day during quarantine. Most were using what Dr. Damiani termed “community masks,” meaning they weren’t approved by the European regulatory agency as personal protective equipment.

Every yardstick Dr. Damiani and coinvestigators employed to characterize the patients’ rosacea demonstrated that the dermatosis was significantly worse during the prolonged mask-wearing period. For example, the average prequarantine score on the Global Flushing Severity Scale was 2.56, jumping to 3.97 after a month of masked quarantine. The flushing score climbed from 1.83 to 2.78 in the subgroup with papulopustular rosacea, and from 3.85 to 6.08 in patients with erythematotelangiectatic rosacea. Scores on the Clinician’s Erythema Assessment rose from 1.09 to 1.7 in the papulopustular rosacea patients, and from 2.46 to 3.54 in those with erythematotelangiectatic rosacea.

Scores on the Dermatology Life Quality Index climbed from 7.35 prequarantine to 10.65 in the subgroup with papulopustular rosacea and from 5.15 to 8.69 in patients with erythematotelangiectatic rosacea. Investigator Global Assessment and Patient’s Self-Assessment scores also deteriorated significantly after a month in masked quarantine.

Clinically, the mask-aggravated rosacea, or “maskacea,” was mainly localized to the dorsal lower third of the nose as well as the cheeks. The ocular and perioral areas and the chin were least affected.

Dr. Damiani advised his colleagues to intensify therapy promptly when patients report any worsening of their preexisting rosacea in connection with use of face masks. He has found this condition is often relatively treatment resistant so long as affected patients continue to wear face masks as an essential tool in preventing transmission of COVID-19.

The dermatologist noted that not all face masks are equal offenders when it comes to aggravating common facial dermatoses. During the spring 2020 pandemic quarantine in Milan, 11.6% of 318 mask wearers, none health care professionals, presented to Dr. Damiani and coinvestigators for treatment of facial dermatoses. The facial dermatosis rate was 5.4% among 168 users of masks bearing the European Union CE mark signifying the devices met relevant safety and performance standards, compared with 18.7% in 150 users of community masks with no CE mark. The rate of irritant contact dermatitis was zero with the CE mark masks and 4.7% with the community masks.

During quarantine, however, these patients wore their protective face masks for only a limited time, since for the most part they were restricted to home. In contrast, during the first week after the quarantine was lifted in early May and the daily hours of mask use increased, facial dermatoses were diagnosed in 8.7% of 23 users of CE-approved masks, compared with 45% of 71 wearers of community masks. Dr. Damiani and colleagues diagnosed irritant contact dermatitis in 16% of the community mask wearers post quarantine, but in not a single user of a mask bearing the CE mark.

The National Rosacea Society has issued patient guidance on avoiding rosacea flare-ups during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Dr. Damiani reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study.

The “maskne” phenomenon – that is, new onset or exacerbation of preexisting acne due to prolonged wearing of protective face masks – has become commonplace during the COVID-19 pandemic. Less well appreciated is that rosacea often markedly worsens, too, Giovanni Damiani, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

“This is particularly interesting because two inflammatory dermatoses with different pathogenesis are both mechanically and microbiologically triggered by mask use,” observed Dr. Damiani, a dermatologist at the University of Milan.

He presented . These patients – 23 with papulopustular and 13 with erythematotelangiectatic rosacea – were wearing face masks for at least 6 hours per day during quarantine. Most were using what Dr. Damiani termed “community masks,” meaning they weren’t approved by the European regulatory agency as personal protective equipment.

Every yardstick Dr. Damiani and coinvestigators employed to characterize the patients’ rosacea demonstrated that the dermatosis was significantly worse during the prolonged mask-wearing period. For example, the average prequarantine score on the Global Flushing Severity Scale was 2.56, jumping to 3.97 after a month of masked quarantine. The flushing score climbed from 1.83 to 2.78 in the subgroup with papulopustular rosacea, and from 3.85 to 6.08 in patients with erythematotelangiectatic rosacea. Scores on the Clinician’s Erythema Assessment rose from 1.09 to 1.7 in the papulopustular rosacea patients, and from 2.46 to 3.54 in those with erythematotelangiectatic rosacea.

Scores on the Dermatology Life Quality Index climbed from 7.35 prequarantine to 10.65 in the subgroup with papulopustular rosacea and from 5.15 to 8.69 in patients with erythematotelangiectatic rosacea. Investigator Global Assessment and Patient’s Self-Assessment scores also deteriorated significantly after a month in masked quarantine.

Clinically, the mask-aggravated rosacea, or “maskacea,” was mainly localized to the dorsal lower third of the nose as well as the cheeks. The ocular and perioral areas and the chin were least affected.

Dr. Damiani advised his colleagues to intensify therapy promptly when patients report any worsening of their preexisting rosacea in connection with use of face masks. He has found this condition is often relatively treatment resistant so long as affected patients continue to wear face masks as an essential tool in preventing transmission of COVID-19.

The dermatologist noted that not all face masks are equal offenders when it comes to aggravating common facial dermatoses. During the spring 2020 pandemic quarantine in Milan, 11.6% of 318 mask wearers, none health care professionals, presented to Dr. Damiani and coinvestigators for treatment of facial dermatoses. The facial dermatosis rate was 5.4% among 168 users of masks bearing the European Union CE mark signifying the devices met relevant safety and performance standards, compared with 18.7% in 150 users of community masks with no CE mark. The rate of irritant contact dermatitis was zero with the CE mark masks and 4.7% with the community masks.

During quarantine, however, these patients wore their protective face masks for only a limited time, since for the most part they were restricted to home. In contrast, during the first week after the quarantine was lifted in early May and the daily hours of mask use increased, facial dermatoses were diagnosed in 8.7% of 23 users of CE-approved masks, compared with 45% of 71 wearers of community masks. Dr. Damiani and colleagues diagnosed irritant contact dermatitis in 16% of the community mask wearers post quarantine, but in not a single user of a mask bearing the CE mark.

The National Rosacea Society has issued patient guidance on avoiding rosacea flare-ups during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Dr. Damiani reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study.

FROM THE EADV CONGRESS

What's the diagnosis?

Nipple eczema is a dermatitis of the nipple and areola with clinical features such as erythema, fissures, scaling, pruritus, and crusting.1,2 It is classically associated with atopic dermatitis (AD), though it may occur as an isolated condition less commonly. While it may affect female adolescents, nipple eczema has also been reported in boys and breastfeeding women.3,4 The overall risk of incidence of nipple dermatitis has also been shown to increase with age.5 Nipple eczema is considered a cutaneous finding of AD, and is listed as a minor diagnostic criteria for AD in the Hanifin-Rajka criteria.6 The patient had not related his history of AD, which was elicited after finding typical antecubital eczematous dermatitis, and he had not been actively treating it.

Diagnosis and differential

Nipple eczema may be a challenging diagnosis for various reasons. For example, a unilateral presentation and the changes in the eczematous lesions overlying the nipple and areola’s varying textures and colors can make it difficult for clinicians to identify.3 Many children and adolescents, including our patient, are initially diagnosed as having impetigo and treated with antibiotics. The diagnosis of nipple eczema is made clinically, and management straightforward (see below). However, additional testing may be appropriate including patch testing for allergic contact dermatitis or bacterial cultures if bacterial infection or superinfection is considered.7,8 The differential diagnosis for nipple eczema includes impetigo, gynecomastia, scabies, and allergic contact dermatitis.

Impetigo typically presents with honey-colored crusts or pustules caused by infection with Staphylococcus aureus or Streptococcus. Patients with AD have higher rates of colonization with S. aureus and impetiginized eczema in common. Impetigo of the nipple and areola is more common in breastfeeding women as skin cracking from lactation can lead to exposure to bacteria from the infant’s mouth.9 Treatments involve topical or oral antibiotics.

Gynecomastia is the development of male breast tissue with most cases hypothesized to be caused by an imbalance between androgens and estrogens.10 Some other causes include direct skin contact with topical estrogen sprays and recreational use of marijuana and heroin.11 It is usually a benign exam finding in adolescent boys. However, clinical findings such as overlying skin changes, rapidly enlarging masses, and constitutional symptoms are concerning in the setting of gynecomastia and warrant further evaluation.

Scabies, which is caused by the infestation of scabies mites, is a common infectious skin disease. The classic presentation includes a rash that is intensely itchy, especially at night. Crusted scabies of the nipples may be difficult to distinguish from nipple eczema. Areas of frequent involvement of scabies include palms, between fingers, armpits, groin, between toes, and feet. Treatments include treating all household members with permethrin cream and washing all clothes and bedding in contact with a scabies-infected patient in high heat, or oral ivermectin in certain circumstances.12

Allergic contact dermatitis is a common cause of breast and nipple dermatitis and should be considered within the differential diagnosis of nipple eczema with atopic dermatitis, or as an exacerbator.7,9 Patients in particular who present with bilateral involvement extending to the periareolar skin, or unusual bilateral focal patterns suggestive for contact allergy should be considered for allergic contact dermatitis evaluation with patch tests. A common causative agent for allergic contact dermatitis of the breast and nipple includes Cl+Me-isothiazolinone, commonly found in detergents and fabric softeners.7 Primary treatment includes avoidance of the offending agents.

Treatment

Topical corticosteroids are first-line treatment for treating nipple eczema. Low-potency topical steroids can be used for maintenance and mild eczema while more potent steroids are useful for more severe cases. In addition to topical medication therapy, frequent emollient use to protect the skin barrier and the elimination of any irritants are essential to a successful treatment course. Unilateral nipple eczema can also be secondary to inadequate treatment of AD, demonstrating the importance of addressing the underlying AD with therapy.3

Our patient was diagnosed with nipple eczema based on clinical presentation of an eczematous left nipple in the setting of active atopic dermatitis and minimal improvement on topical antibiotic. He was started on a 3-week course of fluocinonide 0.05% topical ointment (a potent topical corticosteroid) twice daily for 2 weeks with plans to transition to triamcinolone 0.1% topical ointment several times a week.

Ms. Park is a pediatric dermatology research associate in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology, University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital. Neither Ms. Park nor Dr. Eichenfield have any relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22(1):64-6.

2. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37(4):284-8.

3. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32(5):718-22.

4. J Cutan Med Surg. 2004;8(2):126-30.

5. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29(5):580-3.

6. Dermatologica. 1988;177(6):360-4.

7. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26(3):413-4.

8. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13(8).

9. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(6):1483-94.

10. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2017;14(4):371-7.

11. JAMA. 2010;304(9):953.

12. JAMA. 2018;320(6):612.

Nipple eczema is a dermatitis of the nipple and areola with clinical features such as erythema, fissures, scaling, pruritus, and crusting.1,2 It is classically associated with atopic dermatitis (AD), though it may occur as an isolated condition less commonly. While it may affect female adolescents, nipple eczema has also been reported in boys and breastfeeding women.3,4 The overall risk of incidence of nipple dermatitis has also been shown to increase with age.5 Nipple eczema is considered a cutaneous finding of AD, and is listed as a minor diagnostic criteria for AD in the Hanifin-Rajka criteria.6 The patient had not related his history of AD, which was elicited after finding typical antecubital eczematous dermatitis, and he had not been actively treating it.

Diagnosis and differential

Nipple eczema may be a challenging diagnosis for various reasons. For example, a unilateral presentation and the changes in the eczematous lesions overlying the nipple and areola’s varying textures and colors can make it difficult for clinicians to identify.3 Many children and adolescents, including our patient, are initially diagnosed as having impetigo and treated with antibiotics. The diagnosis of nipple eczema is made clinically, and management straightforward (see below). However, additional testing may be appropriate including patch testing for allergic contact dermatitis or bacterial cultures if bacterial infection or superinfection is considered.7,8 The differential diagnosis for nipple eczema includes impetigo, gynecomastia, scabies, and allergic contact dermatitis.

Impetigo typically presents with honey-colored crusts or pustules caused by infection with Staphylococcus aureus or Streptococcus. Patients with AD have higher rates of colonization with S. aureus and impetiginized eczema in common. Impetigo of the nipple and areola is more common in breastfeeding women as skin cracking from lactation can lead to exposure to bacteria from the infant’s mouth.9 Treatments involve topical or oral antibiotics.

Gynecomastia is the development of male breast tissue with most cases hypothesized to be caused by an imbalance between androgens and estrogens.10 Some other causes include direct skin contact with topical estrogen sprays and recreational use of marijuana and heroin.11 It is usually a benign exam finding in adolescent boys. However, clinical findings such as overlying skin changes, rapidly enlarging masses, and constitutional symptoms are concerning in the setting of gynecomastia and warrant further evaluation.

Scabies, which is caused by the infestation of scabies mites, is a common infectious skin disease. The classic presentation includes a rash that is intensely itchy, especially at night. Crusted scabies of the nipples may be difficult to distinguish from nipple eczema. Areas of frequent involvement of scabies include palms, between fingers, armpits, groin, between toes, and feet. Treatments include treating all household members with permethrin cream and washing all clothes and bedding in contact with a scabies-infected patient in high heat, or oral ivermectin in certain circumstances.12

Allergic contact dermatitis is a common cause of breast and nipple dermatitis and should be considered within the differential diagnosis of nipple eczema with atopic dermatitis, or as an exacerbator.7,9 Patients in particular who present with bilateral involvement extending to the periareolar skin, or unusual bilateral focal patterns suggestive for contact allergy should be considered for allergic contact dermatitis evaluation with patch tests. A common causative agent for allergic contact dermatitis of the breast and nipple includes Cl+Me-isothiazolinone, commonly found in detergents and fabric softeners.7 Primary treatment includes avoidance of the offending agents.

Treatment

Topical corticosteroids are first-line treatment for treating nipple eczema. Low-potency topical steroids can be used for maintenance and mild eczema while more potent steroids are useful for more severe cases. In addition to topical medication therapy, frequent emollient use to protect the skin barrier and the elimination of any irritants are essential to a successful treatment course. Unilateral nipple eczema can also be secondary to inadequate treatment of AD, demonstrating the importance of addressing the underlying AD with therapy.3

Our patient was diagnosed with nipple eczema based on clinical presentation of an eczematous left nipple in the setting of active atopic dermatitis and minimal improvement on topical antibiotic. He was started on a 3-week course of fluocinonide 0.05% topical ointment (a potent topical corticosteroid) twice daily for 2 weeks with plans to transition to triamcinolone 0.1% topical ointment several times a week.

Ms. Park is a pediatric dermatology research associate in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology, University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital. Neither Ms. Park nor Dr. Eichenfield have any relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22(1):64-6.

2. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37(4):284-8.

3. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32(5):718-22.

4. J Cutan Med Surg. 2004;8(2):126-30.

5. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29(5):580-3.

6. Dermatologica. 1988;177(6):360-4.

7. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26(3):413-4.

8. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13(8).

9. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(6):1483-94.

10. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2017;14(4):371-7.

11. JAMA. 2010;304(9):953.

12. JAMA. 2018;320(6):612.

Nipple eczema is a dermatitis of the nipple and areola with clinical features such as erythema, fissures, scaling, pruritus, and crusting.1,2 It is classically associated with atopic dermatitis (AD), though it may occur as an isolated condition less commonly. While it may affect female adolescents, nipple eczema has also been reported in boys and breastfeeding women.3,4 The overall risk of incidence of nipple dermatitis has also been shown to increase with age.5 Nipple eczema is considered a cutaneous finding of AD, and is listed as a minor diagnostic criteria for AD in the Hanifin-Rajka criteria.6 The patient had not related his history of AD, which was elicited after finding typical antecubital eczematous dermatitis, and he had not been actively treating it.

Diagnosis and differential

Nipple eczema may be a challenging diagnosis for various reasons. For example, a unilateral presentation and the changes in the eczematous lesions overlying the nipple and areola’s varying textures and colors can make it difficult for clinicians to identify.3 Many children and adolescents, including our patient, are initially diagnosed as having impetigo and treated with antibiotics. The diagnosis of nipple eczema is made clinically, and management straightforward (see below). However, additional testing may be appropriate including patch testing for allergic contact dermatitis or bacterial cultures if bacterial infection or superinfection is considered.7,8 The differential diagnosis for nipple eczema includes impetigo, gynecomastia, scabies, and allergic contact dermatitis.

Impetigo typically presents with honey-colored crusts or pustules caused by infection with Staphylococcus aureus or Streptococcus. Patients with AD have higher rates of colonization with S. aureus and impetiginized eczema in common. Impetigo of the nipple and areola is more common in breastfeeding women as skin cracking from lactation can lead to exposure to bacteria from the infant’s mouth.9 Treatments involve topical or oral antibiotics.

Gynecomastia is the development of male breast tissue with most cases hypothesized to be caused by an imbalance between androgens and estrogens.10 Some other causes include direct skin contact with topical estrogen sprays and recreational use of marijuana and heroin.11 It is usually a benign exam finding in adolescent boys. However, clinical findings such as overlying skin changes, rapidly enlarging masses, and constitutional symptoms are concerning in the setting of gynecomastia and warrant further evaluation.

Scabies, which is caused by the infestation of scabies mites, is a common infectious skin disease. The classic presentation includes a rash that is intensely itchy, especially at night. Crusted scabies of the nipples may be difficult to distinguish from nipple eczema. Areas of frequent involvement of scabies include palms, between fingers, armpits, groin, between toes, and feet. Treatments include treating all household members with permethrin cream and washing all clothes and bedding in contact with a scabies-infected patient in high heat, or oral ivermectin in certain circumstances.12

Allergic contact dermatitis is a common cause of breast and nipple dermatitis and should be considered within the differential diagnosis of nipple eczema with atopic dermatitis, or as an exacerbator.7,9 Patients in particular who present with bilateral involvement extending to the periareolar skin, or unusual bilateral focal patterns suggestive for contact allergy should be considered for allergic contact dermatitis evaluation with patch tests. A common causative agent for allergic contact dermatitis of the breast and nipple includes Cl+Me-isothiazolinone, commonly found in detergents and fabric softeners.7 Primary treatment includes avoidance of the offending agents.

Treatment

Topical corticosteroids are first-line treatment for treating nipple eczema. Low-potency topical steroids can be used for maintenance and mild eczema while more potent steroids are useful for more severe cases. In addition to topical medication therapy, frequent emollient use to protect the skin barrier and the elimination of any irritants are essential to a successful treatment course. Unilateral nipple eczema can also be secondary to inadequate treatment of AD, demonstrating the importance of addressing the underlying AD with therapy.3

Our patient was diagnosed with nipple eczema based on clinical presentation of an eczematous left nipple in the setting of active atopic dermatitis and minimal improvement on topical antibiotic. He was started on a 3-week course of fluocinonide 0.05% topical ointment (a potent topical corticosteroid) twice daily for 2 weeks with plans to transition to triamcinolone 0.1% topical ointment several times a week.

Ms. Park is a pediatric dermatology research associate in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology, University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital. Neither Ms. Park nor Dr. Eichenfield have any relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22(1):64-6.

2. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37(4):284-8.

3. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32(5):718-22.

4. J Cutan Med Surg. 2004;8(2):126-30.

5. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29(5):580-3.

6. Dermatologica. 1988;177(6):360-4.

7. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26(3):413-4.

8. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13(8).

9. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(6):1483-94.

10. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2017;14(4):371-7.

11. JAMA. 2010;304(9):953.

12. JAMA. 2018;320(6):612.

A 12-year-old boy presents to the dermatology clinic with a 1-month history of crusting and watery sticky drainage from the left nipple. Given concern for a possible skin infection, the patient was initially treated with mupirocin ointment for several weeks but without improvement. The affected area is sometimes itchy but not painful. He reports no prior history of similar problems.

On physical exam, he is noted to have an eczematous left nipple with edema, xerosis, and scaling overlying the entire areola. There is no evidence of visible discharge, pustules, or honey-colored crusts in the area. The extensor surfaces of his arms bilaterally have skin-colored follicular papules, and his antecubital fossa display erythematous scaling plaques with mild lichenification and excoriations.

Sticking His Neck Out Leads to Diagnosis

ANSWER

The correct answer is all of the above (choice “d”).

DISCUSSION

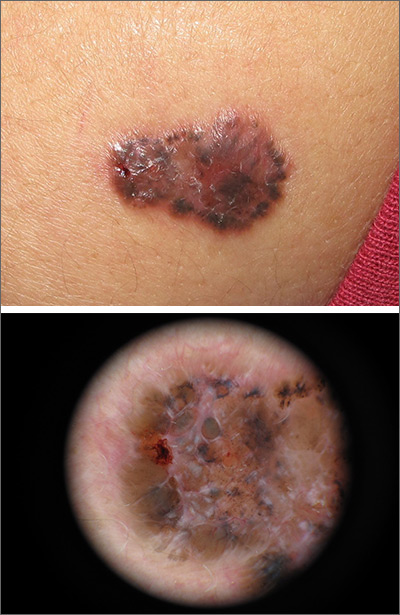

For this patient, there could have been even more items in the differential, including melanoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, or even metastatic (from lung, colon, etc) origin. Dermatofibroma sarcoma protuberans is another possibility because it is rarely aggressive, though it is seldom as exophytic as this lesion. However, the prolonged, indolent course of the patient’s lesion was more consistent with the 3 choices listed. The overarching point is this: Why guess when the diagnosis is easily obtained by biopsy?

Biopsy of the lesion was ordered at the patient's first visit to dermatology. It revealed an invasive basal cell carcinoma (BCC), which almost never metastasizes. BCC requires extensive surgical removal and closure.

TREATMENT

The patient’s lesion needed a total excision with margins. Its size, location, and longevity called for the Mohs technique to assure clear margins and optimal closure.

Because of the findings and the patient’s history, he would also need to see dermatology every 6 months because he is a prime candidate for developing other skin cancers.

ANSWER

The correct answer is all of the above (choice “d”).

DISCUSSION

For this patient, there could have been even more items in the differential, including melanoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, or even metastatic (from lung, colon, etc) origin. Dermatofibroma sarcoma protuberans is another possibility because it is rarely aggressive, though it is seldom as exophytic as this lesion. However, the prolonged, indolent course of the patient’s lesion was more consistent with the 3 choices listed. The overarching point is this: Why guess when the diagnosis is easily obtained by biopsy?

Biopsy of the lesion was ordered at the patient's first visit to dermatology. It revealed an invasive basal cell carcinoma (BCC), which almost never metastasizes. BCC requires extensive surgical removal and closure.

TREATMENT

The patient’s lesion needed a total excision with margins. Its size, location, and longevity called for the Mohs technique to assure clear margins and optimal closure.

Because of the findings and the patient’s history, he would also need to see dermatology every 6 months because he is a prime candidate for developing other skin cancers.

ANSWER

The correct answer is all of the above (choice “d”).

DISCUSSION

For this patient, there could have been even more items in the differential, including melanoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, or even metastatic (from lung, colon, etc) origin. Dermatofibroma sarcoma protuberans is another possibility because it is rarely aggressive, though it is seldom as exophytic as this lesion. However, the prolonged, indolent course of the patient’s lesion was more consistent with the 3 choices listed. The overarching point is this: Why guess when the diagnosis is easily obtained by biopsy?

Biopsy of the lesion was ordered at the patient's first visit to dermatology. It revealed an invasive basal cell carcinoma (BCC), which almost never metastasizes. BCC requires extensive surgical removal and closure.

TREATMENT

The patient’s lesion needed a total excision with margins. Its size, location, and longevity called for the Mohs technique to assure clear margins and optimal closure.

Because of the findings and the patient’s history, he would also need to see dermatology every 6 months because he is a prime candidate for developing other skin cancers.

For 5 years, a lesion has been slowly growing on this 50-year-old man’s neck. He has seen several primary care providers who had provided different diagnoses, including wart, seborrheic keratosis, and keratoacanthoma. Throughout these visits, the only treatment he was offered was cryotherapy, but this was not effective at clearing the lesion. One family member convinced him it was time to try a dermatology provider.

In his lifetime, the patient has been exposed to a great deal of UV light. He has had several basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas removed from his face and arms.

He claims to be in otherwise good health, but further questioning reveals a > 40 pack-year history of smoking. He also has a recent diagnosis of early chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Physical examination of the lesion reveals a 4-x-3.5-cm sessile mass located on the left lateral neck. Its surface is rough and irregular, but there is no break in the skin.

On palpation, the lesion is quite firm and only partially mobile. No tenderness is detected. There are no palpable nodes in the region. There is evidence of advanced chronic sun damage on all sun-exposed areas, but especially on the head and neck. The rest of skin has no lesions.

A 67-year-old White woman presented with 2 weeks of bullae on her lower feet

Bullous arthropod assault

Insect-bite reactions are commonly seen in dermatology practice. Most often, they present as pruritic papules. Vesicles and bullae can be seen as well but are less common. Flea bites are the most likely to cause blisters.1 Lesions may be grouped or in a linear pattern. Children tend to have more severe reactions than adults. Body temperature and odor may make some people more susceptible than others to bites. Of note, patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia tend to have more severe, bullous reactions.2 The differential diagnosis includes bullous pemphigoid, bullous impetigo, bullous tinea, bullous fixed drug, and bullous diabeticorum.

In general, bullous arthropod reactions begin as intraepidermal vesicles that can progress to subepidermal blisters. Eosinophils can be present. Flame figures are often seen in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia.3 Histopathology in this patient revealed a subepidermal vesicular dermatitis with minimal inflammation. Periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) stain was negative. Direct immunofluorescence was negative for IgG, C3, IgA, IgM, and fibrinogen. Of note, systemic steroids may alter histologic and immunologic findings.

Bullous pemphigoid is an autoimmune blistering disorder where patients develop widespread tense bullae. Histopathology revealed a subepidermal blister with numerous eosinophils. Direct immunofluorescence study of perilesional skin showed linear IgG and C3 deposits at the basal membrane level. Systemic steroids, tetracyclines, and immunosuppressive medications are a mainstay of treatment. In bullous impetigo, the toxin of Staphylococcus aureus causes blister formation. It is treated with antistaphylococcal antibiotics. Bullous tinea reveals hyphae with PAS staining. Topical or systemic antifungals are used for treatment.

In severe cases, systemic steroids can be used as well. Bacterial culture was negative in this patient. The patient was treated with 1 week of oral prednisone prior to biopsy and topical betamethasone ointment. Her lesions subsequently resolved with no recurrence.

This case and photo were submitted by Brooke Resh Sateesh, MD, San Diego Family Dermatology.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

1-3. “Dermatology” 2nd ed. (Maryland Heights, Mo.: Mosby, 2008).

Bullous arthropod assault

Insect-bite reactions are commonly seen in dermatology practice. Most often, they present as pruritic papules. Vesicles and bullae can be seen as well but are less common. Flea bites are the most likely to cause blisters.1 Lesions may be grouped or in a linear pattern. Children tend to have more severe reactions than adults. Body temperature and odor may make some people more susceptible than others to bites. Of note, patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia tend to have more severe, bullous reactions.2 The differential diagnosis includes bullous pemphigoid, bullous impetigo, bullous tinea, bullous fixed drug, and bullous diabeticorum.

In general, bullous arthropod reactions begin as intraepidermal vesicles that can progress to subepidermal blisters. Eosinophils can be present. Flame figures are often seen in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia.3 Histopathology in this patient revealed a subepidermal vesicular dermatitis with minimal inflammation. Periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) stain was negative. Direct immunofluorescence was negative for IgG, C3, IgA, IgM, and fibrinogen. Of note, systemic steroids may alter histologic and immunologic findings.

Bullous pemphigoid is an autoimmune blistering disorder where patients develop widespread tense bullae. Histopathology revealed a subepidermal blister with numerous eosinophils. Direct immunofluorescence study of perilesional skin showed linear IgG and C3 deposits at the basal membrane level. Systemic steroids, tetracyclines, and immunosuppressive medications are a mainstay of treatment. In bullous impetigo, the toxin of Staphylococcus aureus causes blister formation. It is treated with antistaphylococcal antibiotics. Bullous tinea reveals hyphae with PAS staining. Topical or systemic antifungals are used for treatment.

In severe cases, systemic steroids can be used as well. Bacterial culture was negative in this patient. The patient was treated with 1 week of oral prednisone prior to biopsy and topical betamethasone ointment. Her lesions subsequently resolved with no recurrence.

This case and photo were submitted by Brooke Resh Sateesh, MD, San Diego Family Dermatology.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

1-3. “Dermatology” 2nd ed. (Maryland Heights, Mo.: Mosby, 2008).

Bullous arthropod assault

Insect-bite reactions are commonly seen in dermatology practice. Most often, they present as pruritic papules. Vesicles and bullae can be seen as well but are less common. Flea bites are the most likely to cause blisters.1 Lesions may be grouped or in a linear pattern. Children tend to have more severe reactions than adults. Body temperature and odor may make some people more susceptible than others to bites. Of note, patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia tend to have more severe, bullous reactions.2 The differential diagnosis includes bullous pemphigoid, bullous impetigo, bullous tinea, bullous fixed drug, and bullous diabeticorum.

In general, bullous arthropod reactions begin as intraepidermal vesicles that can progress to subepidermal blisters. Eosinophils can be present. Flame figures are often seen in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia.3 Histopathology in this patient revealed a subepidermal vesicular dermatitis with minimal inflammation. Periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) stain was negative. Direct immunofluorescence was negative for IgG, C3, IgA, IgM, and fibrinogen. Of note, systemic steroids may alter histologic and immunologic findings.

Bullous pemphigoid is an autoimmune blistering disorder where patients develop widespread tense bullae. Histopathology revealed a subepidermal blister with numerous eosinophils. Direct immunofluorescence study of perilesional skin showed linear IgG and C3 deposits at the basal membrane level. Systemic steroids, tetracyclines, and immunosuppressive medications are a mainstay of treatment. In bullous impetigo, the toxin of Staphylococcus aureus causes blister formation. It is treated with antistaphylococcal antibiotics. Bullous tinea reveals hyphae with PAS staining. Topical or systemic antifungals are used for treatment.

In severe cases, systemic steroids can be used as well. Bacterial culture was negative in this patient. The patient was treated with 1 week of oral prednisone prior to biopsy and topical betamethasone ointment. Her lesions subsequently resolved with no recurrence.

This case and photo were submitted by Brooke Resh Sateesh, MD, San Diego Family Dermatology.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

1-3. “Dermatology” 2nd ed. (Maryland Heights, Mo.: Mosby, 2008).

Neck papules in a young man

The findings of follicular-based papules, pustules, and scars led to the diagnosis of early folliculitis keloidalis nuchae (FKN).

FKN, also called acne keloidalis nuchae, is more common in patients with darker skin types (Fitzpatrick skin types IV-VI) and is the most common form of scarring alopecia in men of African descent. The pathogenesis is unclear, but the condition may arise from mechanical occlusion with a retained short hair that leads to follicular destruction. Patients should lengthen their hair to at least a quarter of an inch to minimize this process. Military personnel may receive a waiver from standard grooming requirements. FKN may also occur as a primary disorder arising from bacterial infection and subsequent vigorous inflammation.

For early disease, topical therapy with either clindamycin 1% lotion or chlorhexidine solution are acceptable options. Should these options and hair lengthening fail over 3 to 4 months, consider a 6- to 12-week course of doxycycline or minocycline 100 mg once or twice daily. Intralesional triamcinolone with 5 to 10 mg/mL injected into fixed papules every 4 to 8 weeks is another option to reduce scar formation. The most severe cases may require combination oral antibiotics, isotretinoin, or plastic surgery.

In this case, the patient grew out his hair and applied clindamycin 1% lotion twice daily for a year. As a result, he had no further disease.

Text and photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. (Photo copyright retained.)

The findings of follicular-based papules, pustules, and scars led to the diagnosis of early folliculitis keloidalis nuchae (FKN).

FKN, also called acne keloidalis nuchae, is more common in patients with darker skin types (Fitzpatrick skin types IV-VI) and is the most common form of scarring alopecia in men of African descent. The pathogenesis is unclear, but the condition may arise from mechanical occlusion with a retained short hair that leads to follicular destruction. Patients should lengthen their hair to at least a quarter of an inch to minimize this process. Military personnel may receive a waiver from standard grooming requirements. FKN may also occur as a primary disorder arising from bacterial infection and subsequent vigorous inflammation.

For early disease, topical therapy with either clindamycin 1% lotion or chlorhexidine solution are acceptable options. Should these options and hair lengthening fail over 3 to 4 months, consider a 6- to 12-week course of doxycycline or minocycline 100 mg once or twice daily. Intralesional triamcinolone with 5 to 10 mg/mL injected into fixed papules every 4 to 8 weeks is another option to reduce scar formation. The most severe cases may require combination oral antibiotics, isotretinoin, or plastic surgery.

In this case, the patient grew out his hair and applied clindamycin 1% lotion twice daily for a year. As a result, he had no further disease.

Text and photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. (Photo copyright retained.)

The findings of follicular-based papules, pustules, and scars led to the diagnosis of early folliculitis keloidalis nuchae (FKN).

FKN, also called acne keloidalis nuchae, is more common in patients with darker skin types (Fitzpatrick skin types IV-VI) and is the most common form of scarring alopecia in men of African descent. The pathogenesis is unclear, but the condition may arise from mechanical occlusion with a retained short hair that leads to follicular destruction. Patients should lengthen their hair to at least a quarter of an inch to minimize this process. Military personnel may receive a waiver from standard grooming requirements. FKN may also occur as a primary disorder arising from bacterial infection and subsequent vigorous inflammation.

For early disease, topical therapy with either clindamycin 1% lotion or chlorhexidine solution are acceptable options. Should these options and hair lengthening fail over 3 to 4 months, consider a 6- to 12-week course of doxycycline or minocycline 100 mg once or twice daily. Intralesional triamcinolone with 5 to 10 mg/mL injected into fixed papules every 4 to 8 weeks is another option to reduce scar formation. The most severe cases may require combination oral antibiotics, isotretinoin, or plastic surgery.

In this case, the patient grew out his hair and applied clindamycin 1% lotion twice daily for a year. As a result, he had no further disease.

Text and photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. (Photo copyright retained.)

Baseline body surface area may drive optimal baricitinib responses

results from an analysis of phase 3 data showed.

“This proposed clinical tailoring approach for baricitinib 2 mg allows for treatment of patients who are more likely to respond to therapy and rapid decision on discontinuation of treatment for those who are not likely to benefit from baricitinib 2 mg,” Eric L. Simpson, MD, said during a late-breaking abstract session at the Revolutionizing Atopic Dermatitis virtual symposium.

Baricitinib is an oral, reversible and selective Janus kinase 1/JAK2 inhibitor that is approved in Europe for the treatment of moderate to severe AD in adults who are candidates for systemic therapy. In the United States, it is approved for treating rheumatoid arthritis, and is currently under Food and Drug Administration review in the United States for AD.

For the current analysis, Dr. Simpson, professor of dermatology at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, and colleagues set out to identify responders to baricitinib 2 mg using a tailored approach based on baseline BSA affected and early clinical improvement in the phase 3 monotherapy trial BREEZE-AD5. The trial enrolled 440 patients: 147 to placebo, 147 to baricitinib 1 mg once daily, and 146 to baricitinib 2 mg once daily. The primary endpoint was Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI)–75 at week 16.

“Understanding which patients can benefit most from this treatment was our goal,” Dr. Simpson said. “By tailoring your therapy, you can significantly improve the patient experience, increase the cost-effectiveness of a therapy, and you can ensure that only patients who are likely to benefit are exposed to a drug.”

The researchers used a classification and regression tree algorithm that identified baseline BSA as the strongest predictor of EASI-75 response at week 16. A BSA cutoff of 50% was established as the optimal cutoff for sensitivity and negative predictive value. Results for EASI-75 and Validated Investigator Global Assessment for Atopic Dermatitis (vIGA-AD) scores of 0 or 1 were confirmed using a BSA of 10%-50% at baseline to predict response, compared with a BSA or greater than 50% at baseline.

Sensitivity analyses revealed that about 90% of patients with an EASI-75 response were in the BSA 10%-50% group. Conversely, among patients with a BSA greater than 50%, the negative predictive value was greater than 90%, “so there’s a 90% chance you’re not going to hit that EASI-75 at week 16 if your BSA is greater than 50%,” Dr. Simpson explained. “The same holds true for vIGA-AD, so that 50% cutoff is important for understanding whether someone is going to respond or not.”

On the EASI-75, 38% of patients in the BSA 10%-50% group responded to baricitinib at week 16, compared with 10% in the BSA greater than 50% group. A similar association was observed on the vIGA-AD, where 32% of patients in the BSA 10%-50% group responded to baricitinib at week 16, compared with 5% in the BSA greater than 50% group.

When stratified by early response assessed at week 4, based on a 4-point improvement or greater on the Itch Numeric Rating Scale, 55% of those patients became EASI-75 responders, compared with 17% who were not. A similar association was observed by early response assessed at week 8.

“Due to the rapid onset of response, clinical assessment of patients after 4-8 weeks of initiation of baricitinib 2 mg treatment provided a positive feedback to patients who are likely to benefit from long-term therapy,” Dr. Simpson said. “This analysis may allow for a precision-medicine approach to therapy in moderate to severe AD.”

The study was supported by Eli Lilly, and was under license from Incyte. Dr. Simpson reported serving as an investigator for and consultant to numerous pharmaceutical companies.

results from an analysis of phase 3 data showed.

“This proposed clinical tailoring approach for baricitinib 2 mg allows for treatment of patients who are more likely to respond to therapy and rapid decision on discontinuation of treatment for those who are not likely to benefit from baricitinib 2 mg,” Eric L. Simpson, MD, said during a late-breaking abstract session at the Revolutionizing Atopic Dermatitis virtual symposium.

Baricitinib is an oral, reversible and selective Janus kinase 1/JAK2 inhibitor that is approved in Europe for the treatment of moderate to severe AD in adults who are candidates for systemic therapy. In the United States, it is approved for treating rheumatoid arthritis, and is currently under Food and Drug Administration review in the United States for AD.

For the current analysis, Dr. Simpson, professor of dermatology at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, and colleagues set out to identify responders to baricitinib 2 mg using a tailored approach based on baseline BSA affected and early clinical improvement in the phase 3 monotherapy trial BREEZE-AD5. The trial enrolled 440 patients: 147 to placebo, 147 to baricitinib 1 mg once daily, and 146 to baricitinib 2 mg once daily. The primary endpoint was Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI)–75 at week 16.

“Understanding which patients can benefit most from this treatment was our goal,” Dr. Simpson said. “By tailoring your therapy, you can significantly improve the patient experience, increase the cost-effectiveness of a therapy, and you can ensure that only patients who are likely to benefit are exposed to a drug.”

The researchers used a classification and regression tree algorithm that identified baseline BSA as the strongest predictor of EASI-75 response at week 16. A BSA cutoff of 50% was established as the optimal cutoff for sensitivity and negative predictive value. Results for EASI-75 and Validated Investigator Global Assessment for Atopic Dermatitis (vIGA-AD) scores of 0 or 1 were confirmed using a BSA of 10%-50% at baseline to predict response, compared with a BSA or greater than 50% at baseline.

Sensitivity analyses revealed that about 90% of patients with an EASI-75 response were in the BSA 10%-50% group. Conversely, among patients with a BSA greater than 50%, the negative predictive value was greater than 90%, “so there’s a 90% chance you’re not going to hit that EASI-75 at week 16 if your BSA is greater than 50%,” Dr. Simpson explained. “The same holds true for vIGA-AD, so that 50% cutoff is important for understanding whether someone is going to respond or not.”

On the EASI-75, 38% of patients in the BSA 10%-50% group responded to baricitinib at week 16, compared with 10% in the BSA greater than 50% group. A similar association was observed on the vIGA-AD, where 32% of patients in the BSA 10%-50% group responded to baricitinib at week 16, compared with 5% in the BSA greater than 50% group.

When stratified by early response assessed at week 4, based on a 4-point improvement or greater on the Itch Numeric Rating Scale, 55% of those patients became EASI-75 responders, compared with 17% who were not. A similar association was observed by early response assessed at week 8.

“Due to the rapid onset of response, clinical assessment of patients after 4-8 weeks of initiation of baricitinib 2 mg treatment provided a positive feedback to patients who are likely to benefit from long-term therapy,” Dr. Simpson said. “This analysis may allow for a precision-medicine approach to therapy in moderate to severe AD.”

The study was supported by Eli Lilly, and was under license from Incyte. Dr. Simpson reported serving as an investigator for and consultant to numerous pharmaceutical companies.

results from an analysis of phase 3 data showed.

“This proposed clinical tailoring approach for baricitinib 2 mg allows for treatment of patients who are more likely to respond to therapy and rapid decision on discontinuation of treatment for those who are not likely to benefit from baricitinib 2 mg,” Eric L. Simpson, MD, said during a late-breaking abstract session at the Revolutionizing Atopic Dermatitis virtual symposium.

Baricitinib is an oral, reversible and selective Janus kinase 1/JAK2 inhibitor that is approved in Europe for the treatment of moderate to severe AD in adults who are candidates for systemic therapy. In the United States, it is approved for treating rheumatoid arthritis, and is currently under Food and Drug Administration review in the United States for AD.

For the current analysis, Dr. Simpson, professor of dermatology at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, and colleagues set out to identify responders to baricitinib 2 mg using a tailored approach based on baseline BSA affected and early clinical improvement in the phase 3 monotherapy trial BREEZE-AD5. The trial enrolled 440 patients: 147 to placebo, 147 to baricitinib 1 mg once daily, and 146 to baricitinib 2 mg once daily. The primary endpoint was Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI)–75 at week 16.

“Understanding which patients can benefit most from this treatment was our goal,” Dr. Simpson said. “By tailoring your therapy, you can significantly improve the patient experience, increase the cost-effectiveness of a therapy, and you can ensure that only patients who are likely to benefit are exposed to a drug.”

The researchers used a classification and regression tree algorithm that identified baseline BSA as the strongest predictor of EASI-75 response at week 16. A BSA cutoff of 50% was established as the optimal cutoff for sensitivity and negative predictive value. Results for EASI-75 and Validated Investigator Global Assessment for Atopic Dermatitis (vIGA-AD) scores of 0 or 1 were confirmed using a BSA of 10%-50% at baseline to predict response, compared with a BSA or greater than 50% at baseline.

Sensitivity analyses revealed that about 90% of patients with an EASI-75 response were in the BSA 10%-50% group. Conversely, among patients with a BSA greater than 50%, the negative predictive value was greater than 90%, “so there’s a 90% chance you’re not going to hit that EASI-75 at week 16 if your BSA is greater than 50%,” Dr. Simpson explained. “The same holds true for vIGA-AD, so that 50% cutoff is important for understanding whether someone is going to respond or not.”

On the EASI-75, 38% of patients in the BSA 10%-50% group responded to baricitinib at week 16, compared with 10% in the BSA greater than 50% group. A similar association was observed on the vIGA-AD, where 32% of patients in the BSA 10%-50% group responded to baricitinib at week 16, compared with 5% in the BSA greater than 50% group.

When stratified by early response assessed at week 4, based on a 4-point improvement or greater on the Itch Numeric Rating Scale, 55% of those patients became EASI-75 responders, compared with 17% who were not. A similar association was observed by early response assessed at week 8.

“Due to the rapid onset of response, clinical assessment of patients after 4-8 weeks of initiation of baricitinib 2 mg treatment provided a positive feedback to patients who are likely to benefit from long-term therapy,” Dr. Simpson said. “This analysis may allow for a precision-medicine approach to therapy in moderate to severe AD.”

The study was supported by Eli Lilly, and was under license from Incyte. Dr. Simpson reported serving as an investigator for and consultant to numerous pharmaceutical companies.

FROM REVOLUTIONIZING AD 2020

Avoiding atopic dermatitis triggers easier said than done

“Guidelines on trigger avoidance are written as if it’s easy to do,” Jonathan I. Silverberg, MD, PhD, MPH, said during the Revolutionizing Atopic Dermatitis virtual symposium. “It turns out that trigger avoidance is really complicated.”

He and his colleagues conducted a study of most common triggers for itch based on a prospective dermatology practice–based study of 587 adults with AD . About two-thirds (65%) reported one or more itch trigger in the past week and 36% had three or more itch triggers in the past week. The two most common triggers were stress (35%) and sweat (31%).

“To me, this is provocative, because this is not how I was trained in residency,” said Dr. Silverberg, director of clinical research in the division of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington. “I was trained that it’s all about excess showering, dry air, or cold temperature. Those are important, but the most common triggers are stress and sweat.”

AD triggers are also commonly linked to seasonality. “If you ask patients when their AD is worse, sometimes it’s winter,” he said. “Sometimes it’s spring. Sometimes it’s summer. It turns out that there is a distinct set of triggers that are associated with AD seasonality.” Wintertime worsening of disease is associated with cold temperature and weather change, he continued, while springtime worsening of disease is often linked to weather change and dry air. Common summertime triggers for flares include hot temperature, heat, sweat, weather change, sunlight, humid air, and dry air. “In the fall, the weather change again comes up as a trigger. Humid air does as well.”

In their prospective study, Dr. Silverberg and colleagues found that 90% of those who had at least three itch triggers reported 3 months or less of AD remission in the past year, “meaning that 90% are reporting persistent disease when they have multiple itch triggers,” he said. In addition, 78% reported two or more flares per year and 61% reported that AD is worse during certain seasons.

Potential mitigation strategies for stress include stress management, biofeedback, meditation, relaxation training, and mindfulness. “These don’t necessarily require expensive psychotherapy,” he said. Freely available iPhone apps can be incorporated into daily practice, such as Calm, Relax with Andrew Johnson, Nature Sounds Relax and Sleep, Breathe2Relax, and Headspace.

Many AD patients are sedentary and avoid vigorous physical activity owing to heat and sweat as triggers. Simple solutions include exercising in a cooler temperature environment, “not just using fans,” he said. “Take a quick shower right after working out and consider pre- and/or post treatment with topical medication.”

High temperature and sweating can be problematic at bedtime, he continued. Even if the indoor temperature is 70° F, that might jump to 85° F or 90° F under a thick blanket. “That heat can trigger itch and may cause sweating, which can trigger itch,” said Dr. Silverberg, who has AD and is director of patch testing at George Washington University. Potential solutions include using a lighter blanket, lowering the indoor temperature, and wearing breathable pajamas.

Dryness, another common AD trigger, can be secondary to a combination of low outdoor and/or indoor humidity. “Lower outdoor humidity is a particular problem in the wintertime, because cold air doesn’t hold moisture as well,” he said. “That’s why the air feels much dryer in the wintertime. There’s also a problem of indoor heating and cooling. Sometimes central air systems can lower humidity to the point where it’s bone dry.”

In an effort to determine the impact of specific climatic factors on the U.S. prevalence of AD, Dr. Silverberg and colleagues conducted a study using a merged analysis of the 2007 National Survey of Children’s Health from a representative sample of 91,642 children aged 0-17 years and 2006-2007 measurements from the National Climate Data Center and Weather Service. They found that childhood AD prevalence was increased in geographical areas that use more indoor heat and cooling and had lower outdoor humidity. “So, we see that there’s a direct correlate of this dryness issue that is leading to more AD throughout the U.S.,” he said.

Practical solutions to mitigate the effect of dry air on AD include opening windows to allow entry of moist air, “which can be particularly helpful in residences that are overheated,” he said. “I deal with this a lot in patients who live in dormitories. Use humidifiers to add moisture back into the air. Aim for 40%-50% indoor humidity to avoid mold and dust mites. It’s better to use demineralized water to reduce bacterial growth. This can be helpful for aeroallergies. Of note, there are really no well-done studies that have examined the efficacy of humidifiers in AD, but based on our anecdotal experience, this is a good way to go.”

Cold temperatures and trigger intense itch, even in the setting of high humidity. “For me personally, this is one of my most brutal triggers,” Dr. Silverberg said. “When I’m in a place with extremes of cold, I get a rapid onset of itch, a mix of itch and pain, particularly on the dorsal hands. For solutions, you can encourage patients to avoid extremely low temperatures, to bundle up, and to potentially use hand warmers or other heating devices.”

Clothing can be a trigger as well, especially tight-fitting clothes, hot and nonbreathable clothes, and large-diameter wool, which has been shown to induce itching and irritation. Mitigation strategies include wearing loose-fitting, lightweight, nonirritating fabric. “Traditional cotton and silk fabrics have mixed evidence in improving AD but are generally safe,” he said. “Ultra- or superfine merino wool has been shown to be nonpruritic. There is sparse evidence to support chemically treated/coated clothing for AD, but this may be an emerging area.”

Dr. Silverberg pointed out variability of cultural perspectives and preferences for bathing practices, including temperature, duration, frequency, optimal bathing products, and the use of loofahs and other scrubbing products. “This stems from different perceptions of what it means to be clean, and how dry our skin should feel after a shower,” he said. “Many clinicians and patients were taught that regular bathing is harmful in AD. It turns out that’s not true.”

In a recently published systematic review and meta-analysis of 13 studies, he and his colleagues examined efficacy outcomes of different bathing/showering regimens in AD. All 13 studies showed numerically reduced AD severity with any bathing regimen in at least one time point. Numerical decreases over time were observed for body surface area (BSA), Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI), and/or SCORAD measures for daily and less than daily bathing, with or without application of emollients or topical corticosteroids. In random effects regression models, taking baths more than or less than seven times per week were not associated with significant differences of Cohen’s D scores for EASI, SCORAD, or BSA. “The take-home message here is, let your AD patients bathe,” Dr. Silverberg said. “Bathing is good. It can be channeled to help the eczema, but it has to be done the right way.”

Patients should be counseled to use nonirritating cleansers and shampoos, avoid excessively long baths/showers, avoid excessively hot baths/showers, avoid excessive rubbing or scrubbing of skin, and to apply emollients and/or topical corticosteroids immediately after the bath/shower.

PROMIS Itch-Triggers is a simple and feasible checklist to screen for the most common itch triggers in AD in clinical practice (patients are asked to check off which of the following have caused their itch in the previous 7 days: cold temperature, hot temperature, heat, sweat, tight clothing, fragrances, boredom, talking about itch, stress, weather change, sunlight, humid air, dry air). “It takes less than 1 minute to complete,” he said. “Additional testing with skin patch and/or prick testing may be warranted to identify allergenic triggers.”

Dr. Silverberg reported that he is a consultant to and/or an advisory board member for several pharmaceutical companies. He is also a speaker for Regeneron and Sanofi and has received a grant from Galderma.

“Guidelines on trigger avoidance are written as if it’s easy to do,” Jonathan I. Silverberg, MD, PhD, MPH, said during the Revolutionizing Atopic Dermatitis virtual symposium. “It turns out that trigger avoidance is really complicated.”

He and his colleagues conducted a study of most common triggers for itch based on a prospective dermatology practice–based study of 587 adults with AD . About two-thirds (65%) reported one or more itch trigger in the past week and 36% had three or more itch triggers in the past week. The two most common triggers were stress (35%) and sweat (31%).

“To me, this is provocative, because this is not how I was trained in residency,” said Dr. Silverberg, director of clinical research in the division of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington. “I was trained that it’s all about excess showering, dry air, or cold temperature. Those are important, but the most common triggers are stress and sweat.”

AD triggers are also commonly linked to seasonality. “If you ask patients when their AD is worse, sometimes it’s winter,” he said. “Sometimes it’s spring. Sometimes it’s summer. It turns out that there is a distinct set of triggers that are associated with AD seasonality.” Wintertime worsening of disease is associated with cold temperature and weather change, he continued, while springtime worsening of disease is often linked to weather change and dry air. Common summertime triggers for flares include hot temperature, heat, sweat, weather change, sunlight, humid air, and dry air. “In the fall, the weather change again comes up as a trigger. Humid air does as well.”

In their prospective study, Dr. Silverberg and colleagues found that 90% of those who had at least three itch triggers reported 3 months or less of AD remission in the past year, “meaning that 90% are reporting persistent disease when they have multiple itch triggers,” he said. In addition, 78% reported two or more flares per year and 61% reported that AD is worse during certain seasons.

Potential mitigation strategies for stress include stress management, biofeedback, meditation, relaxation training, and mindfulness. “These don’t necessarily require expensive psychotherapy,” he said. Freely available iPhone apps can be incorporated into daily practice, such as Calm, Relax with Andrew Johnson, Nature Sounds Relax and Sleep, Breathe2Relax, and Headspace.

Many AD patients are sedentary and avoid vigorous physical activity owing to heat and sweat as triggers. Simple solutions include exercising in a cooler temperature environment, “not just using fans,” he said. “Take a quick shower right after working out and consider pre- and/or post treatment with topical medication.”

High temperature and sweating can be problematic at bedtime, he continued. Even if the indoor temperature is 70° F, that might jump to 85° F or 90° F under a thick blanket. “That heat can trigger itch and may cause sweating, which can trigger itch,” said Dr. Silverberg, who has AD and is director of patch testing at George Washington University. Potential solutions include using a lighter blanket, lowering the indoor temperature, and wearing breathable pajamas.

Dryness, another common AD trigger, can be secondary to a combination of low outdoor and/or indoor humidity. “Lower outdoor humidity is a particular problem in the wintertime, because cold air doesn’t hold moisture as well,” he said. “That’s why the air feels much dryer in the wintertime. There’s also a problem of indoor heating and cooling. Sometimes central air systems can lower humidity to the point where it’s bone dry.”

In an effort to determine the impact of specific climatic factors on the U.S. prevalence of AD, Dr. Silverberg and colleagues conducted a study using a merged analysis of the 2007 National Survey of Children’s Health from a representative sample of 91,642 children aged 0-17 years and 2006-2007 measurements from the National Climate Data Center and Weather Service. They found that childhood AD prevalence was increased in geographical areas that use more indoor heat and cooling and had lower outdoor humidity. “So, we see that there’s a direct correlate of this dryness issue that is leading to more AD throughout the U.S.,” he said.

Practical solutions to mitigate the effect of dry air on AD include opening windows to allow entry of moist air, “which can be particularly helpful in residences that are overheated,” he said. “I deal with this a lot in patients who live in dormitories. Use humidifiers to add moisture back into the air. Aim for 40%-50% indoor humidity to avoid mold and dust mites. It’s better to use demineralized water to reduce bacterial growth. This can be helpful for aeroallergies. Of note, there are really no well-done studies that have examined the efficacy of humidifiers in AD, but based on our anecdotal experience, this is a good way to go.”

Cold temperatures and trigger intense itch, even in the setting of high humidity. “For me personally, this is one of my most brutal triggers,” Dr. Silverberg said. “When I’m in a place with extremes of cold, I get a rapid onset of itch, a mix of itch and pain, particularly on the dorsal hands. For solutions, you can encourage patients to avoid extremely low temperatures, to bundle up, and to potentially use hand warmers or other heating devices.”

Clothing can be a trigger as well, especially tight-fitting clothes, hot and nonbreathable clothes, and large-diameter wool, which has been shown to induce itching and irritation. Mitigation strategies include wearing loose-fitting, lightweight, nonirritating fabric. “Traditional cotton and silk fabrics have mixed evidence in improving AD but are generally safe,” he said. “Ultra- or superfine merino wool has been shown to be nonpruritic. There is sparse evidence to support chemically treated/coated clothing for AD, but this may be an emerging area.”