User login

Company submits supplemental NDA for topical atopic dermatitis treatment

in adults and children aged 6 years and older.

Roflumilast cream 0.3% (Zoryve) is currently approved by the FDA for the topical treatment of plaque psoriasis, including intertriginous areas, in patients 12 years of age and older. Submission of the sNDA is based on positive results from the Interventional Trial Evaluating Roflumilast Cream for the Treatment of Atopic Dermatitis (INTEGUMENT-1 and INTEGUMENT-2) trials; two identical Phase 3, vehicle-controlled trials in which roflumilast cream 0.15% or vehicle was applied once daily for 4 weeks to individuals 6 years of age and older with mild to moderate AD involving at least 3% body surface area. Roflumilast is a phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE-4) inhibitor.

According to a press release from Arcutis, both studies met the primary endpoint of IGA Success, which was defined as a validated Investigator Global Assessment – Atopic Dermatitis (vIGA-AD) score of ‘clear’ or ‘almost clear’ plus a 2-grade improvement from baseline at week 4. In INTEGUMENT-1 this endpoint was achieved by 32.0% of subjects in the roflumilast cream group vs. 15.2% of those in the vehicle group (P < .0001). In INTEGUMENT-2, this endpoint was achieved by 28.9% of subjects in the roflumilast cream group vs. 12.0% of those in the vehicle group (P < .0001). The most common adverse reactions based on data from the combined trials were headache (2.9%), nausea (1.9%), application-site pain (1.5%), diarrhea (1.5%), and vomiting (1.5%).

in adults and children aged 6 years and older.

Roflumilast cream 0.3% (Zoryve) is currently approved by the FDA for the topical treatment of plaque psoriasis, including intertriginous areas, in patients 12 years of age and older. Submission of the sNDA is based on positive results from the Interventional Trial Evaluating Roflumilast Cream for the Treatment of Atopic Dermatitis (INTEGUMENT-1 and INTEGUMENT-2) trials; two identical Phase 3, vehicle-controlled trials in which roflumilast cream 0.15% or vehicle was applied once daily for 4 weeks to individuals 6 years of age and older with mild to moderate AD involving at least 3% body surface area. Roflumilast is a phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE-4) inhibitor.

According to a press release from Arcutis, both studies met the primary endpoint of IGA Success, which was defined as a validated Investigator Global Assessment – Atopic Dermatitis (vIGA-AD) score of ‘clear’ or ‘almost clear’ plus a 2-grade improvement from baseline at week 4. In INTEGUMENT-1 this endpoint was achieved by 32.0% of subjects in the roflumilast cream group vs. 15.2% of those in the vehicle group (P < .0001). In INTEGUMENT-2, this endpoint was achieved by 28.9% of subjects in the roflumilast cream group vs. 12.0% of those in the vehicle group (P < .0001). The most common adverse reactions based on data from the combined trials were headache (2.9%), nausea (1.9%), application-site pain (1.5%), diarrhea (1.5%), and vomiting (1.5%).

in adults and children aged 6 years and older.

Roflumilast cream 0.3% (Zoryve) is currently approved by the FDA for the topical treatment of plaque psoriasis, including intertriginous areas, in patients 12 years of age and older. Submission of the sNDA is based on positive results from the Interventional Trial Evaluating Roflumilast Cream for the Treatment of Atopic Dermatitis (INTEGUMENT-1 and INTEGUMENT-2) trials; two identical Phase 3, vehicle-controlled trials in which roflumilast cream 0.15% or vehicle was applied once daily for 4 weeks to individuals 6 years of age and older with mild to moderate AD involving at least 3% body surface area. Roflumilast is a phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE-4) inhibitor.

According to a press release from Arcutis, both studies met the primary endpoint of IGA Success, which was defined as a validated Investigator Global Assessment – Atopic Dermatitis (vIGA-AD) score of ‘clear’ or ‘almost clear’ plus a 2-grade improvement from baseline at week 4. In INTEGUMENT-1 this endpoint was achieved by 32.0% of subjects in the roflumilast cream group vs. 15.2% of those in the vehicle group (P < .0001). In INTEGUMENT-2, this endpoint was achieved by 28.9% of subjects in the roflumilast cream group vs. 12.0% of those in the vehicle group (P < .0001). The most common adverse reactions based on data from the combined trials were headache (2.9%), nausea (1.9%), application-site pain (1.5%), diarrhea (1.5%), and vomiting (1.5%).

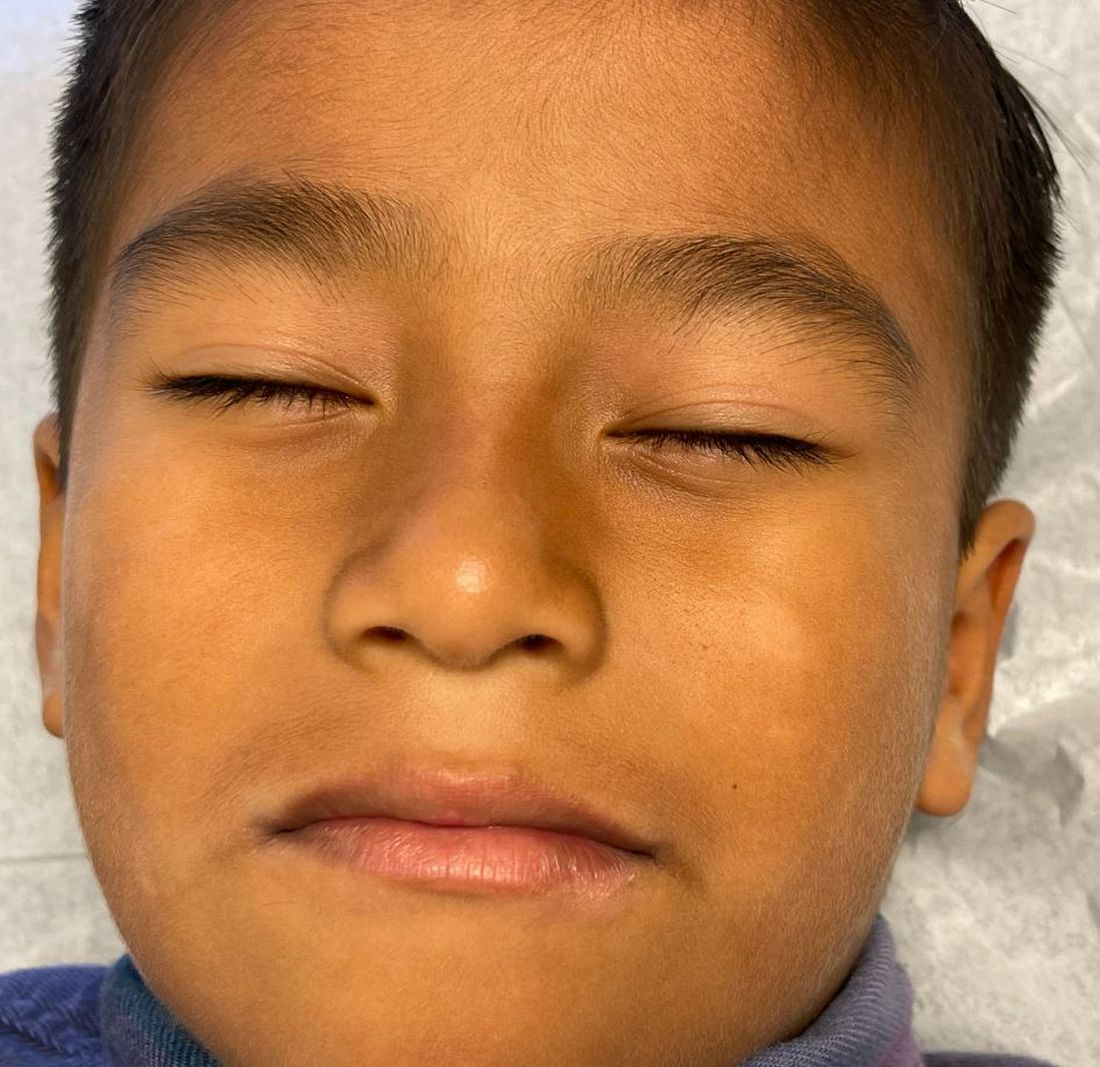

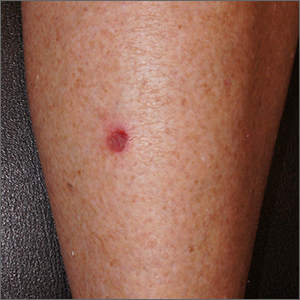

A White male presented with a purulent erythematous edematous plaque with central necrosis and ulceration on his right flank

Lyme disease is the most commonly transmitted tick-borne illness in the United States. This infection is typically transmitted through a bite by the Ixodes tick commonly found in the Midwest, Northeast, and mid-Atlantic regions; however, the geographical distribution continues to expand over time in the United States. Ticks must be attached for 24-48 hours to transmit the pathogen. There are three general stages of the disease: early localized, early disseminated, and late disseminated.

The most common presentation is the early localized disease, which manifests between 3 and 30 days after an infected tick bite. Approximately 70%-80% of cases feature a targetlike lesion that expands centrifugally at the site of the bite. Most commonly, lesions appear on the abdomen, groin, axilla, and popliteal fossa. The diagnosis of ECM requires lesions at least 5 cm in size. Lesions may be asymptomatic, although burning may occur in half of patients. Atypical presentations include bullous, vesicular, hemorrhagic, or necrotic lesions. Up to half of patients may develop multiple ECM lesions. Palms and soles are spared. Differential diagnoses include arthropod reactions, pyoderma gangrenosum, cellulitis, herpes simplex virus and varicella zoster virus, contact dermatitis, or granuloma annulare. The rash is often accompanied by systemic symptoms including fatigue, myalgia, headache, and fever.

The next two stages include early and late disseminated infection. Early disseminated infection often occurs 3-12 weeks after infection and is characterized by muscle pain, dizziness, headache, and cardiac symptoms. CNS involvement occurs in about 20% of patients. Joint involvement may include the knee, ankle, and wrist. If symptoms are only in one joint, septic arthritis is part of the differential diagnosis, so clinical correlation and labs must be considered. Late disseminated infection occurs months or years after initial infection and includes neurologic and rheumatologic symptoms including meningitis, Bell’s palsy, arthritis, and dysesthesia. Knee arthritis is a key feature of this stage. Patients commonly have radicular pain and fibromyalgia-type pain. More severe disease processes include encephalomyelitis, arrhythmias, and heart block.

ECM is often a clinical diagnosis because serologic testing may not be positive during the first 2 weeks of infection. The screening serologic test is the ELISA, and a Western blot confirms the results. Skin histopathology for Lyme disease is often nonspecific and reveals a perivascular infiltrate of histiocytes, plasma cells, and lymphocytes. Silver stain or antibody testing may be used to identify the spirochete. In acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans, late Lyme disease presenting on the distal extremities, lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltrates are present. In borrelial lymphocytoma, a dense dermal lymphocytic infiltrate is present.

The standard for treatment of early localized disease is oral doxycycline in adults. Alternatives may be used if a patient is allergic or for children under 9. Disseminated disease may be treated with IV ceftriaxone and topical steroids are used if ocular symptoms are involved. Early treatment is often curative.

This patient’s antibodies were negative initially, but became positive after 6 weeks. He was treated empirically at the time of his office visit with doxycycline for 1 month.

This case and the photo were submitted by Lucas Shapiro, BS, of Nova Southeastern University College of Osteopathic Medicine, Fort Lauderdale, Fla., and Susannah Berke, MD, Three Rivers Dermatology, Coraopolis, Pa. The column was edited by Donna Bilu Martin, MD.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at MDedge.com/Dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

Carriveau A et al. Nurs Clin North Am. 2019 Jun;54(2):261-75.

Skar GL and Simonsen KA. Lyme Disease. [Updated 2023 May 31]. In: “StatPearls” [Internet]. Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan.

Tiger JB et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014 Oct;71(4):e133-4.

Lyme disease is the most commonly transmitted tick-borne illness in the United States. This infection is typically transmitted through a bite by the Ixodes tick commonly found in the Midwest, Northeast, and mid-Atlantic regions; however, the geographical distribution continues to expand over time in the United States. Ticks must be attached for 24-48 hours to transmit the pathogen. There are three general stages of the disease: early localized, early disseminated, and late disseminated.

The most common presentation is the early localized disease, which manifests between 3 and 30 days after an infected tick bite. Approximately 70%-80% of cases feature a targetlike lesion that expands centrifugally at the site of the bite. Most commonly, lesions appear on the abdomen, groin, axilla, and popliteal fossa. The diagnosis of ECM requires lesions at least 5 cm in size. Lesions may be asymptomatic, although burning may occur in half of patients. Atypical presentations include bullous, vesicular, hemorrhagic, or necrotic lesions. Up to half of patients may develop multiple ECM lesions. Palms and soles are spared. Differential diagnoses include arthropod reactions, pyoderma gangrenosum, cellulitis, herpes simplex virus and varicella zoster virus, contact dermatitis, or granuloma annulare. The rash is often accompanied by systemic symptoms including fatigue, myalgia, headache, and fever.

The next two stages include early and late disseminated infection. Early disseminated infection often occurs 3-12 weeks after infection and is characterized by muscle pain, dizziness, headache, and cardiac symptoms. CNS involvement occurs in about 20% of patients. Joint involvement may include the knee, ankle, and wrist. If symptoms are only in one joint, septic arthritis is part of the differential diagnosis, so clinical correlation and labs must be considered. Late disseminated infection occurs months or years after initial infection and includes neurologic and rheumatologic symptoms including meningitis, Bell’s palsy, arthritis, and dysesthesia. Knee arthritis is a key feature of this stage. Patients commonly have radicular pain and fibromyalgia-type pain. More severe disease processes include encephalomyelitis, arrhythmias, and heart block.

ECM is often a clinical diagnosis because serologic testing may not be positive during the first 2 weeks of infection. The screening serologic test is the ELISA, and a Western blot confirms the results. Skin histopathology for Lyme disease is often nonspecific and reveals a perivascular infiltrate of histiocytes, plasma cells, and lymphocytes. Silver stain or antibody testing may be used to identify the spirochete. In acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans, late Lyme disease presenting on the distal extremities, lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltrates are present. In borrelial lymphocytoma, a dense dermal lymphocytic infiltrate is present.

The standard for treatment of early localized disease is oral doxycycline in adults. Alternatives may be used if a patient is allergic or for children under 9. Disseminated disease may be treated with IV ceftriaxone and topical steroids are used if ocular symptoms are involved. Early treatment is often curative.

This patient’s antibodies were negative initially, but became positive after 6 weeks. He was treated empirically at the time of his office visit with doxycycline for 1 month.

This case and the photo were submitted by Lucas Shapiro, BS, of Nova Southeastern University College of Osteopathic Medicine, Fort Lauderdale, Fla., and Susannah Berke, MD, Three Rivers Dermatology, Coraopolis, Pa. The column was edited by Donna Bilu Martin, MD.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at MDedge.com/Dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

Carriveau A et al. Nurs Clin North Am. 2019 Jun;54(2):261-75.

Skar GL and Simonsen KA. Lyme Disease. [Updated 2023 May 31]. In: “StatPearls” [Internet]. Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan.

Tiger JB et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014 Oct;71(4):e133-4.

Lyme disease is the most commonly transmitted tick-borne illness in the United States. This infection is typically transmitted through a bite by the Ixodes tick commonly found in the Midwest, Northeast, and mid-Atlantic regions; however, the geographical distribution continues to expand over time in the United States. Ticks must be attached for 24-48 hours to transmit the pathogen. There are three general stages of the disease: early localized, early disseminated, and late disseminated.

The most common presentation is the early localized disease, which manifests between 3 and 30 days after an infected tick bite. Approximately 70%-80% of cases feature a targetlike lesion that expands centrifugally at the site of the bite. Most commonly, lesions appear on the abdomen, groin, axilla, and popliteal fossa. The diagnosis of ECM requires lesions at least 5 cm in size. Lesions may be asymptomatic, although burning may occur in half of patients. Atypical presentations include bullous, vesicular, hemorrhagic, or necrotic lesions. Up to half of patients may develop multiple ECM lesions. Palms and soles are spared. Differential diagnoses include arthropod reactions, pyoderma gangrenosum, cellulitis, herpes simplex virus and varicella zoster virus, contact dermatitis, or granuloma annulare. The rash is often accompanied by systemic symptoms including fatigue, myalgia, headache, and fever.

The next two stages include early and late disseminated infection. Early disseminated infection often occurs 3-12 weeks after infection and is characterized by muscle pain, dizziness, headache, and cardiac symptoms. CNS involvement occurs in about 20% of patients. Joint involvement may include the knee, ankle, and wrist. If symptoms are only in one joint, septic arthritis is part of the differential diagnosis, so clinical correlation and labs must be considered. Late disseminated infection occurs months or years after initial infection and includes neurologic and rheumatologic symptoms including meningitis, Bell’s palsy, arthritis, and dysesthesia. Knee arthritis is a key feature of this stage. Patients commonly have radicular pain and fibromyalgia-type pain. More severe disease processes include encephalomyelitis, arrhythmias, and heart block.

ECM is often a clinical diagnosis because serologic testing may not be positive during the first 2 weeks of infection. The screening serologic test is the ELISA, and a Western blot confirms the results. Skin histopathology for Lyme disease is often nonspecific and reveals a perivascular infiltrate of histiocytes, plasma cells, and lymphocytes. Silver stain or antibody testing may be used to identify the spirochete. In acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans, late Lyme disease presenting on the distal extremities, lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltrates are present. In borrelial lymphocytoma, a dense dermal lymphocytic infiltrate is present.

The standard for treatment of early localized disease is oral doxycycline in adults. Alternatives may be used if a patient is allergic or for children under 9. Disseminated disease may be treated with IV ceftriaxone and topical steroids are used if ocular symptoms are involved. Early treatment is often curative.

This patient’s antibodies were negative initially, but became positive after 6 weeks. He was treated empirically at the time of his office visit with doxycycline for 1 month.

This case and the photo were submitted by Lucas Shapiro, BS, of Nova Southeastern University College of Osteopathic Medicine, Fort Lauderdale, Fla., and Susannah Berke, MD, Three Rivers Dermatology, Coraopolis, Pa. The column was edited by Donna Bilu Martin, MD.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at MDedge.com/Dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

Carriveau A et al. Nurs Clin North Am. 2019 Jun;54(2):261-75.

Skar GL and Simonsen KA. Lyme Disease. [Updated 2023 May 31]. In: “StatPearls” [Internet]. Treasure Island, Fla.: StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan.

Tiger JB et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014 Oct;71(4):e133-4.

A worthwhile tool in evaluating worrisome lesions

ABSTRACT

Background: We sought to examine whether electrical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), a diagnostic tool approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the evaluation of pigmented skin lesions (PSLs), is beneficial to primary care providers (PCPs) by comparing the accuracy of PCPs’ management decisions for PSLs based on visual examination alone with those based on concurrent visual and EIS evaluation.

Methods: Physicians and nurse practitioners (NPs) participated in an anonymous online survey in which they viewed clinical images of PSLs and were asked to make 2 clinical decisions before and after being provided an EIS score that indicated the likelihood that the lesion was a melanoma. They were asked (1) if they would biopsy the lesion/refer the patient out and (2) what they expected the pathology results would show.

Results: Forty-four physicians and 17 NPs participated, making clinical decisions for 1354 presented lesions. Overall, with the addition of EIS to visual inspection of clinical images, the sensitivity of biopsy/referral decisions for melanomas and severely dysplastic nevi (SDN) increased from 69.2% to 90.0% (P < .001), while specificity increased from 44.0% to 72.6% (P < .001). Physicians and NPs, regardless of years of experience, each saw significant improvements in sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic accuracy with the addition of EIS scores.

Conclusions: The incorporation of EIS data into clinical decision-making by PCPs significantly increased the sensitivity and specificity of biopsy/referral decisions for melanomas and SDN and overall diagnostic accuracy compared with visual inspection alone. The results of this study suggest that diagnostic accuracy for PSLs by PCPs may be improved with adjunctive use of EIS with visual inspection.

Primary care providers (PCPs) are often the first line of defense in detecting skin cancers. For patients with concerning skin lesions, PCPs may choose to perform a biopsy or facilitate access to specialty services (eg, Dermatology). Consequently, PCPs play a critical role in the timely detection of skin cancers, and it is paramount to employ continually improving detection methods, such as the application of technologic advances.1

Differentiating benign nevi from melanoma and severely dysplastic nevi (SDN), both of which warrant excision, poses a unique challenge to clinicians examining pigmented skin lesions (PSLs). PCPs often rely on visual inspection to differentiate benign skin lesions from malignant skin cancers. In some primary care practices, dermoscopy, which involves using a handheld device to evaluate lesions with polarized light and magnification, is used to improve melanoma detection. However, while visual inspection and dermoscopy are valid, effective techniques for the diagnosis of melanocytic lesions, in many instances they still can lead to missed cancers or unnecessary biopsies and specialty referrals. Adjunctive use of dermoscopy with visual inspection has been shown to increase the probability of skin cancer detection, but it fails to achieve a near-100% success rate.2 Furthermore, dermoscopy is heavily user-dependent, requiring significant training and experience for appropriate use.3

Another option is an electrical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) device (Nevisense, Scibase, Stockholm, Sweden), which has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to assist in the detection of melanoma and differentiation from benign PSLs.4 EIS is a noninvasive, rapidly applied technology designed to accompany the visual examination of melanocytic lesions in office, with or without dermoscopy. Still relatively new, the technology is employed today by many dermatologists, increasing diagnostic accuracy for PSLs.5 The lightweight and portable instrument features a handheld probe, which is held against a lesion to obtain a reading. EIS uses a low-voltage electrode to apply a harmless electrical current to the skin at various frequencies.6 As benign and malignant tissues vary in cell shape, size, and composition, EIS distinguishes differential electrical resistance of the tissue to aid in diagnosis.7

Continue to: EIS provides high-sensitivity...

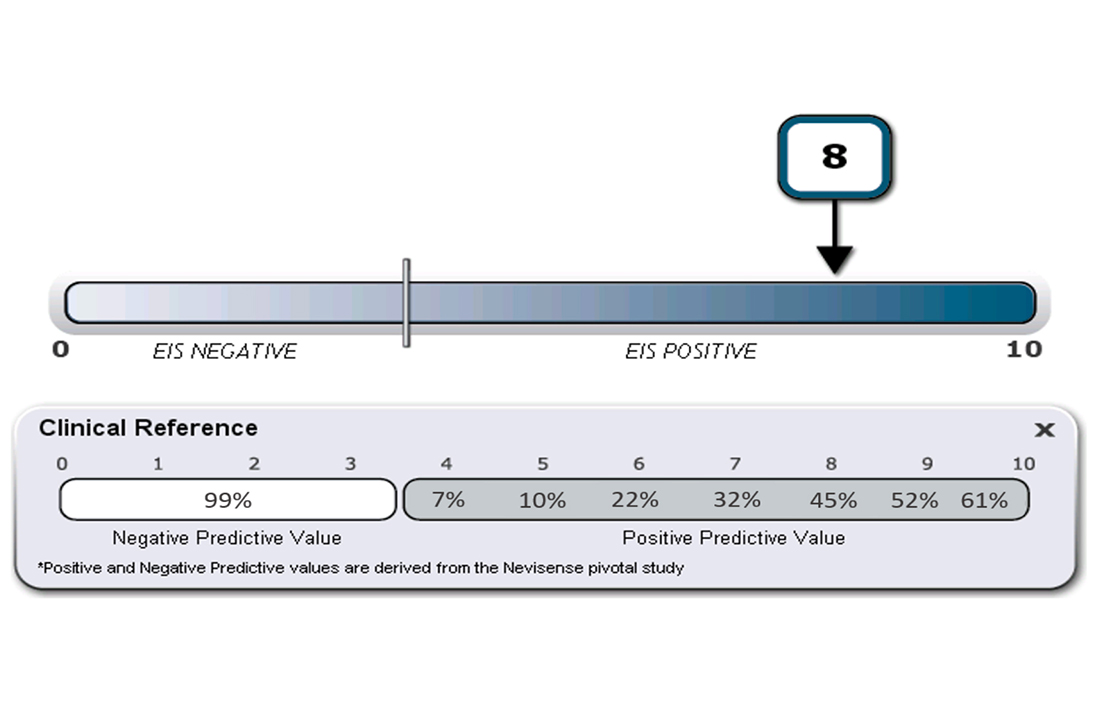

EIS provides high-sensitivity melanoma diagnosis vs histopathologic confirmation from biopsies, with 1 study showing a 96.6% sensitivity rating, detecting 256 of 265 melanomas.4 The EIS device, by measuring differences in electrical resistance between benign and cancerous cells, outputs a simple integer score ranging from 0 to 10 associated with the likelihood of the lesion being a melanoma.8 Based on data from the Nevisense pivotal trial,4 Nevisense reports that scores of 0 to 3 carry a negative predictive value of 99% for melanoma, whereas scores of 4 to 10 signify increasingly greater positive predictive values from 7% to 61%.

We aimed to assess whether EIS may be beneficial to PCPs by comparing the accuracy of clinical decision-making for PSLs based on visual examination alone with that based on concurrent visual and EIS evaluation.

METHODS

A questionnaire was distributed via email to 142 clinicians at clinics affiliated with either of 2 organizations delivering care to the New York City area through a network of community health centers: the Institute for Family Health (IFH) and the Community Healthcare Network (CHN). Of these recipients, 72 were affiliated with IFH across 27 community health centers and 70 were affiliated with CHN across 14 community health centers. Recipients were physicians and nurse practitioners (NPs) practicing at primary health care facilities.

Survey instrument. The first section of the survey instrument (APPENDIX) solicited demographic information and explained how to apply the EIS scores for diagnostic decision-making. The second featured images of 12 randomly selected, histologically confirmed, and EIS-evaluated PSLs from a previously published prospective blinded trial of 2416 lesions.4 The Institutional Review Board of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai reviewed and approved the study and survey instrument.

Clinical images of these lesions, comprising 4 melanocytic nevi, 4 dysplastic nevi (including 3 mild-moderately dysplastic and 1 severely dysplastic nevus), and 4 melanomas

Continue to: Analysis

Analysis. A biopsy or referral rating of 4 or 5 was considered a decision to biopsy or refer (ie, a diagnostic decision consistent with melanoma or SDN warranting excision), whereas a selection of 1 to 3 was considered a decision not to biopsy or refer (ie, a diagnostic decision consistent with a benign PSL). The sensitivity and specificity of biopsy/referral decisions for melanomas and SDN, the proportion of missed melanomas and SDN, and the proportion of biopsy/referral decisions for benign lesions were separately determined for visual inspection alone and visual inspection with EIS score. Similarly, diagnostic accuracy was calculated for these clinical scenarios. These metrics were further stratified among different subsets of the respondent population. Differences in sensitivity, specificity, biopsy/referral decision proportions, and diagnostic accuracy were calculated using McNemar’s test for paired proportions.

RESULTS

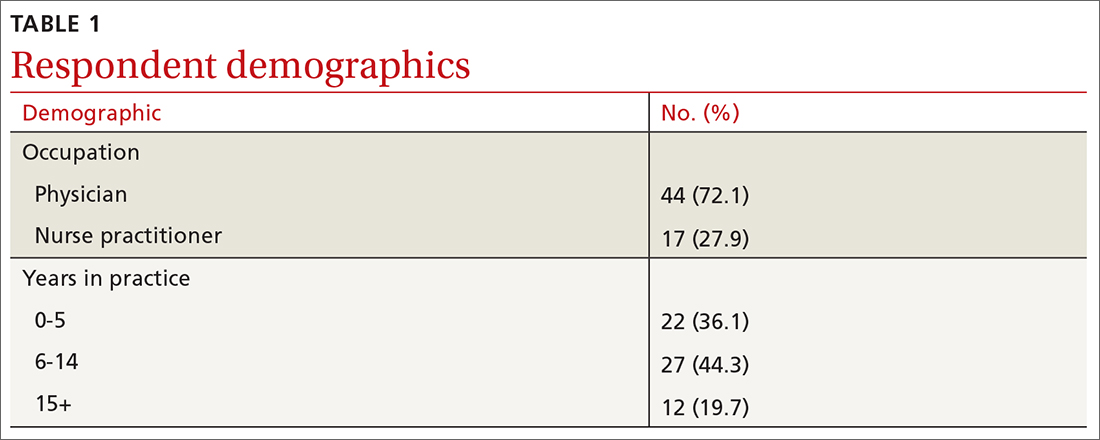

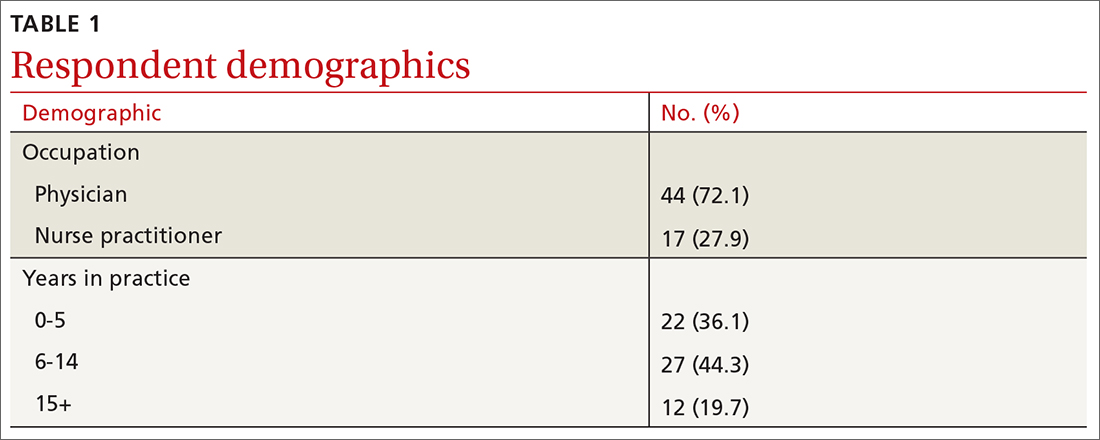

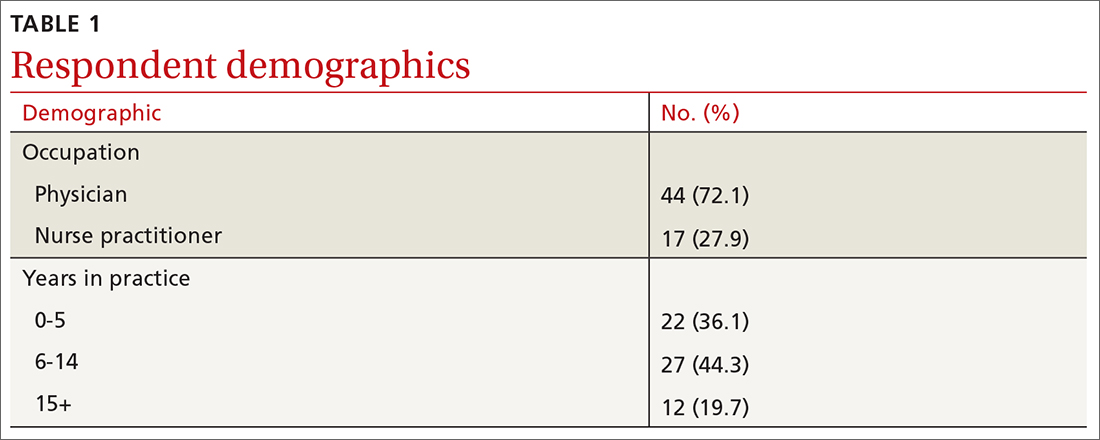

Sixty-one respondents, comprising 44 physicians and 17 NPs, completed the survey, yielding a response rate of 43% (TABLE 1). In total, 1354 clinical decisions (677 based on visual inspection alone and 677 based on visual inspection plus EIS) were made. A biopsy/referral decision was made after assessing 416 of 677 cases (61%) with visual inspection alone and 360 of 677 cases (53%) when relying on visual inspection plus EIS. None of the respondents reported any prior experience with EIS.

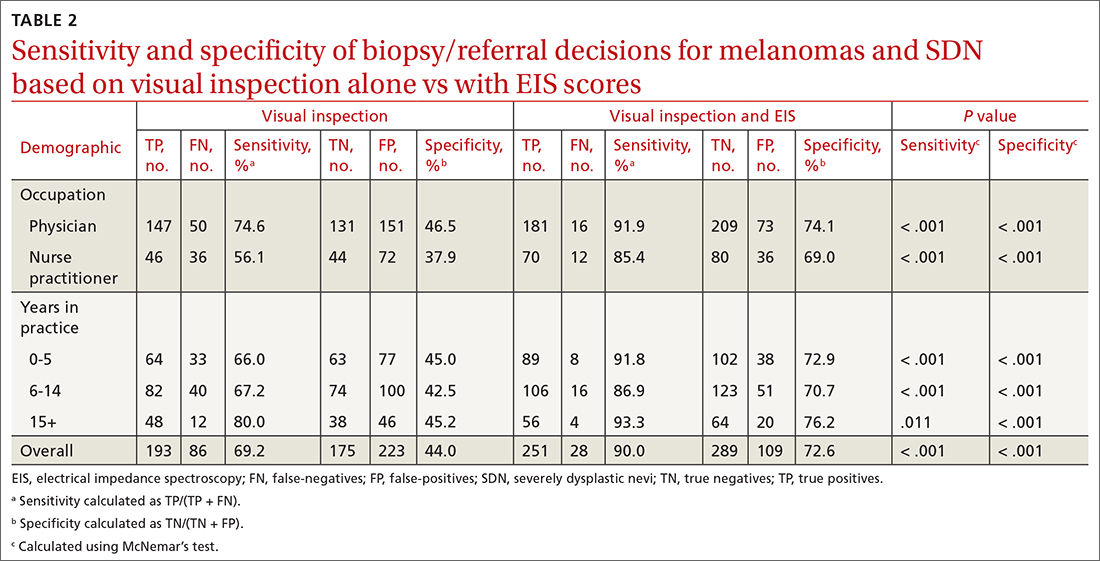

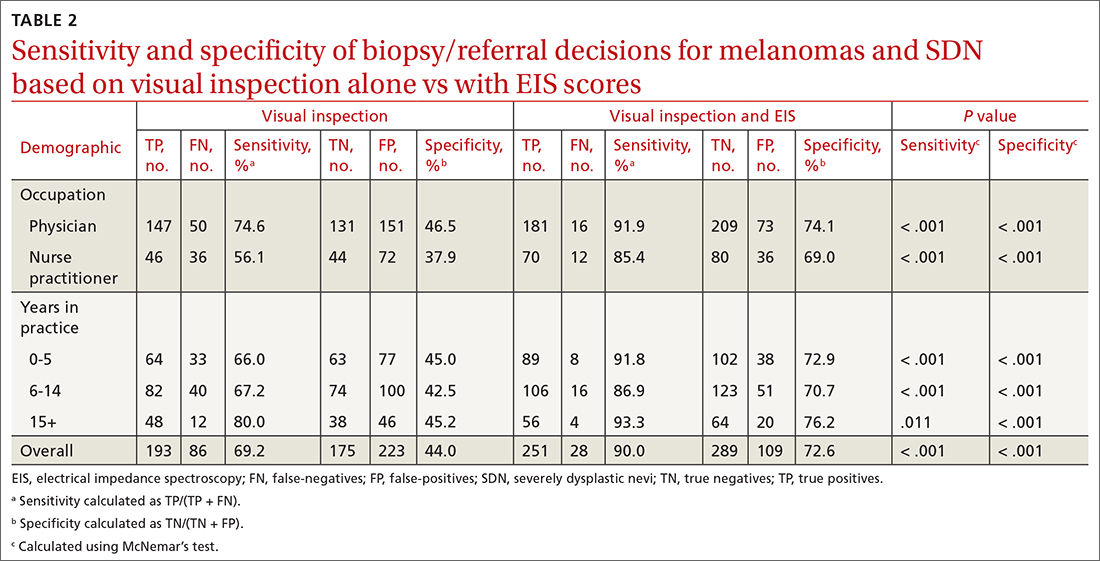

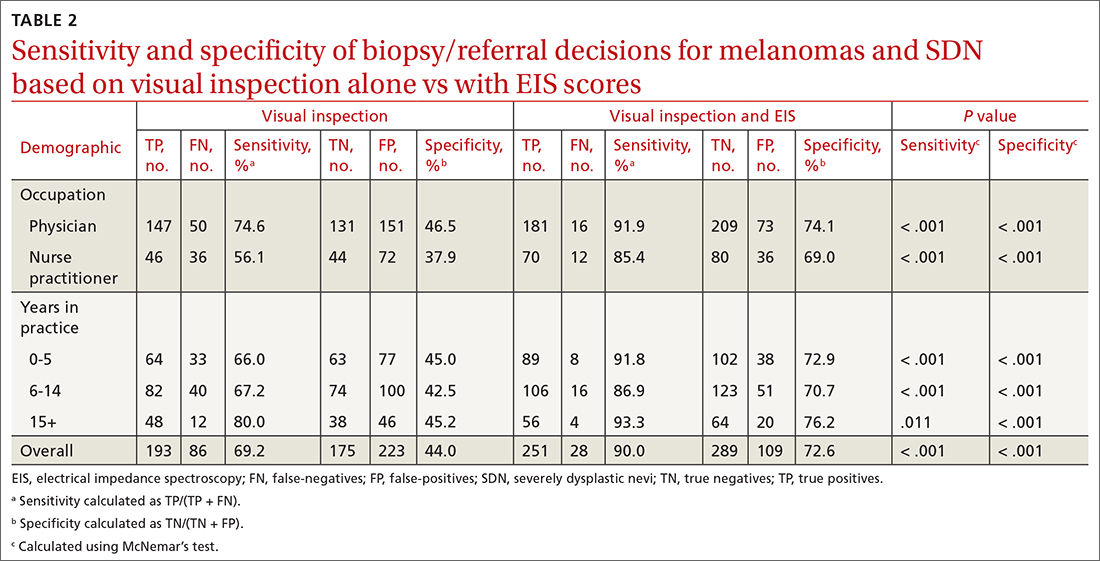

When incorporating EIS scores, respondents’ mean sensitivity for melanomas and SDN increased from 69.2% to 90.0% (P < .001) and specificity from 44.0% to 72.6% (P < .001; TABLE 2). At baseline, physicians demonstrated a sensitivity and specificity of 74.6% and 46.5%, respectively, while NPs demonstrated a sensitivity and specificity of 56.1% and 37.9%, respectively.

All respondent subgroups stratified by occupation and years of experience saw significant increases in both sensitivity and specificity upon the incorporation of EIS scores, with NPs seeing a greater increase in sensitivity (56.1% vs 85.4%; P < .001) and specificity (37.9% vs 69.0%; P < .001) than physicians (sensitivity: 74.6% vs 91.9%; P < .001; specificity: 46.5% vs 74.1%; P < .001). The only difference in diagnostic performance based on years of experience was a greater pre-EIS sensitivity by clinicians who had been in practice for ≥ 15 years, compared with those in practice for shorter periods (TABLE 2).

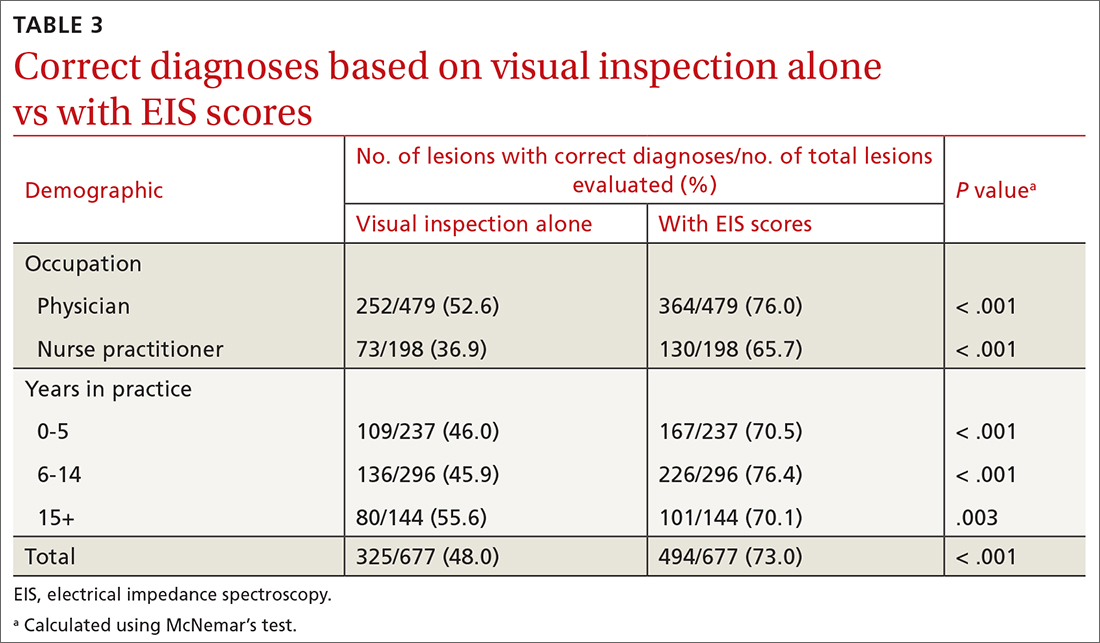

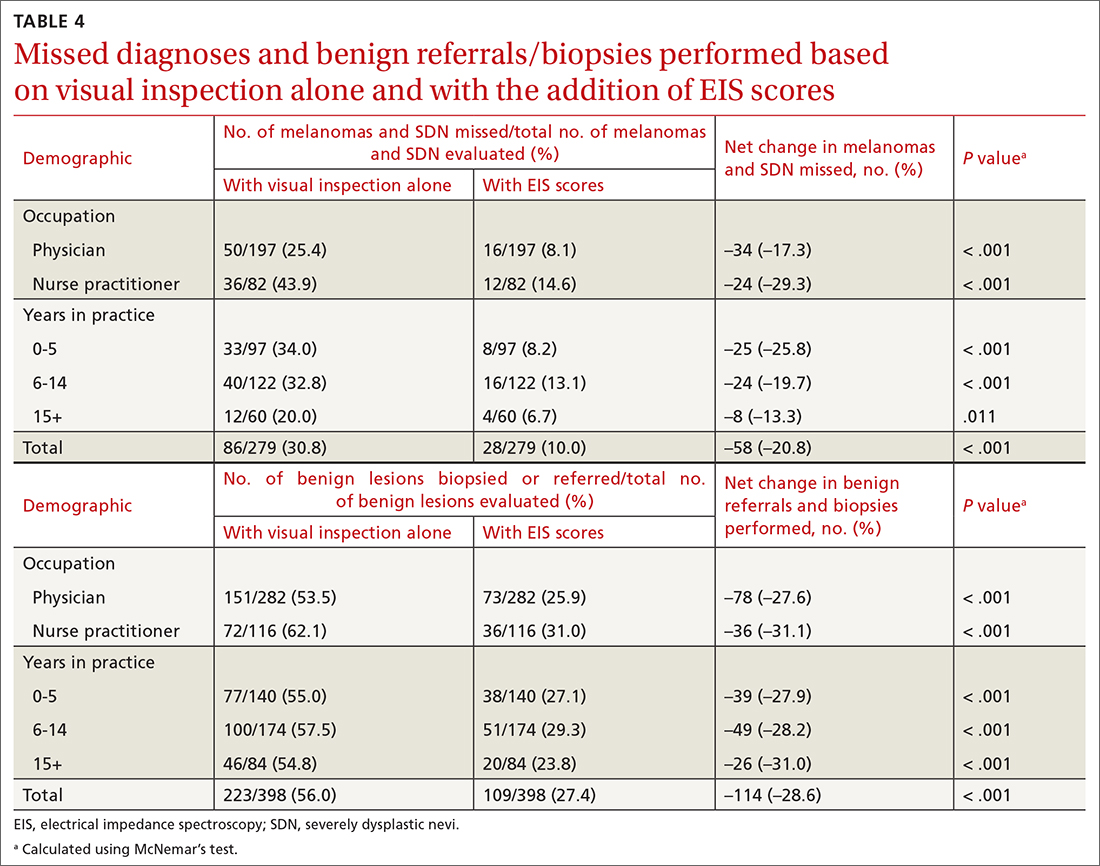

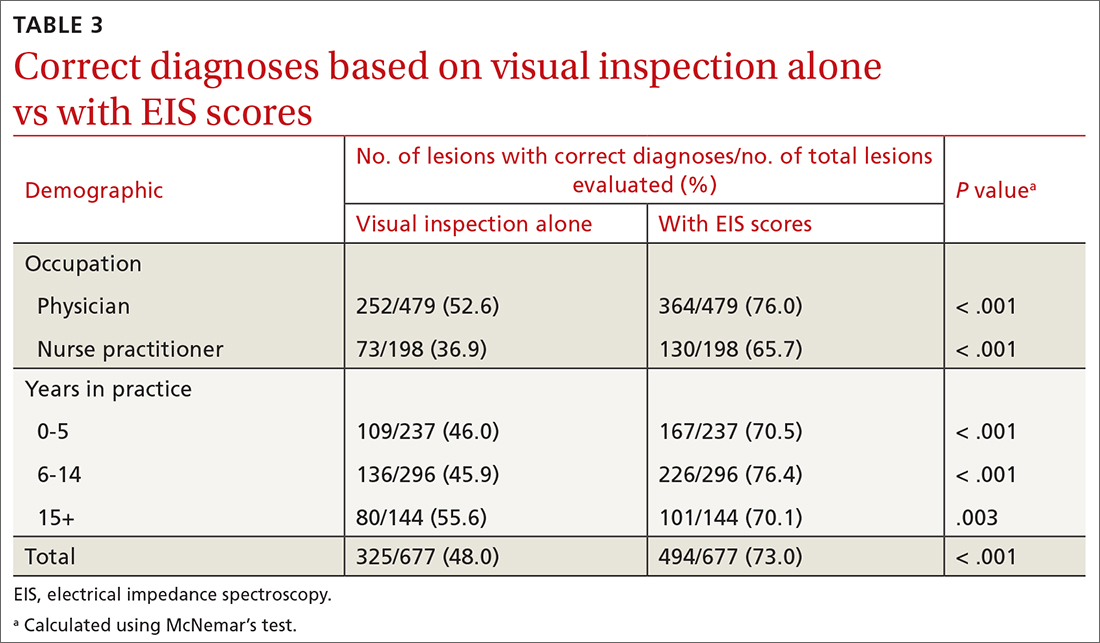

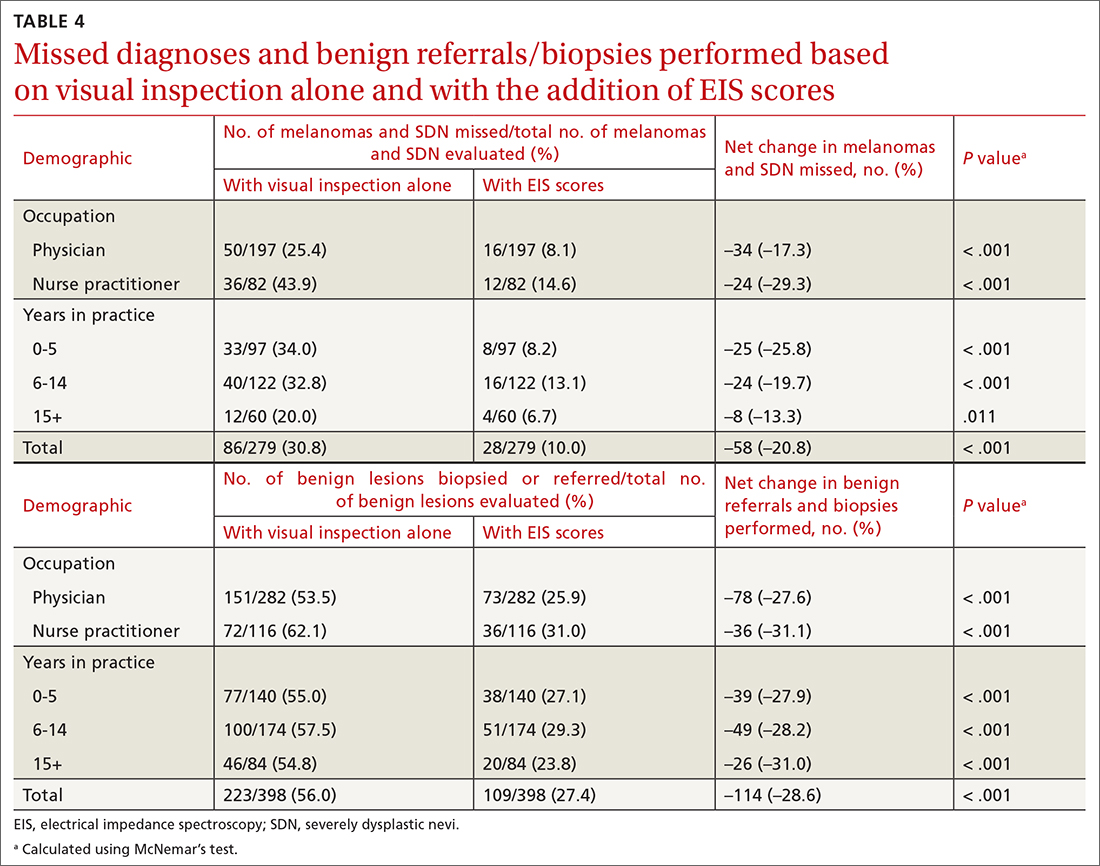

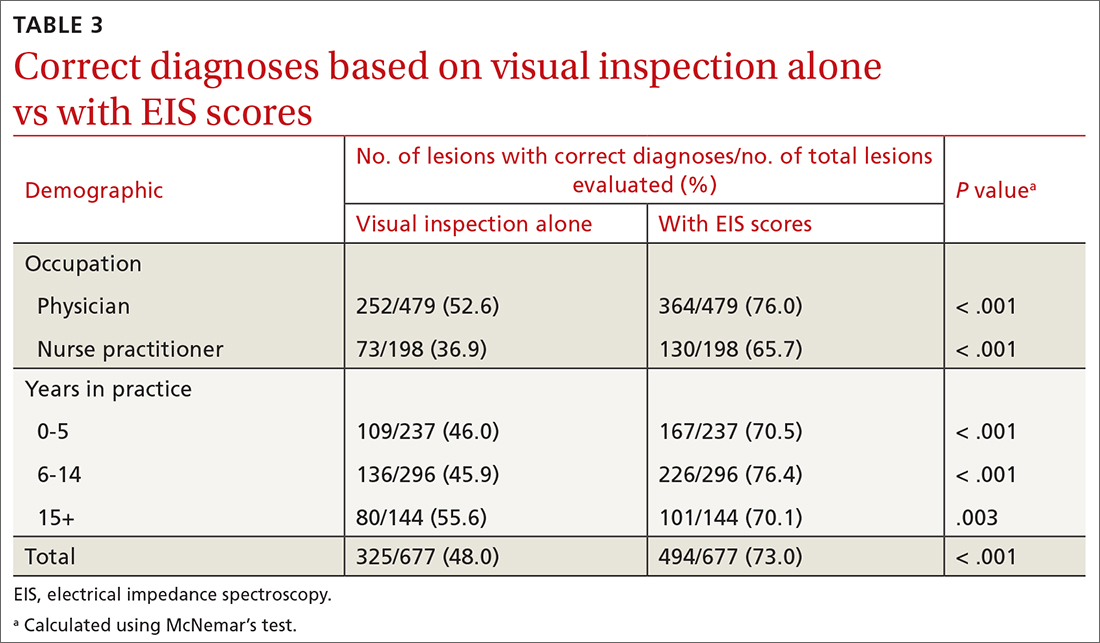

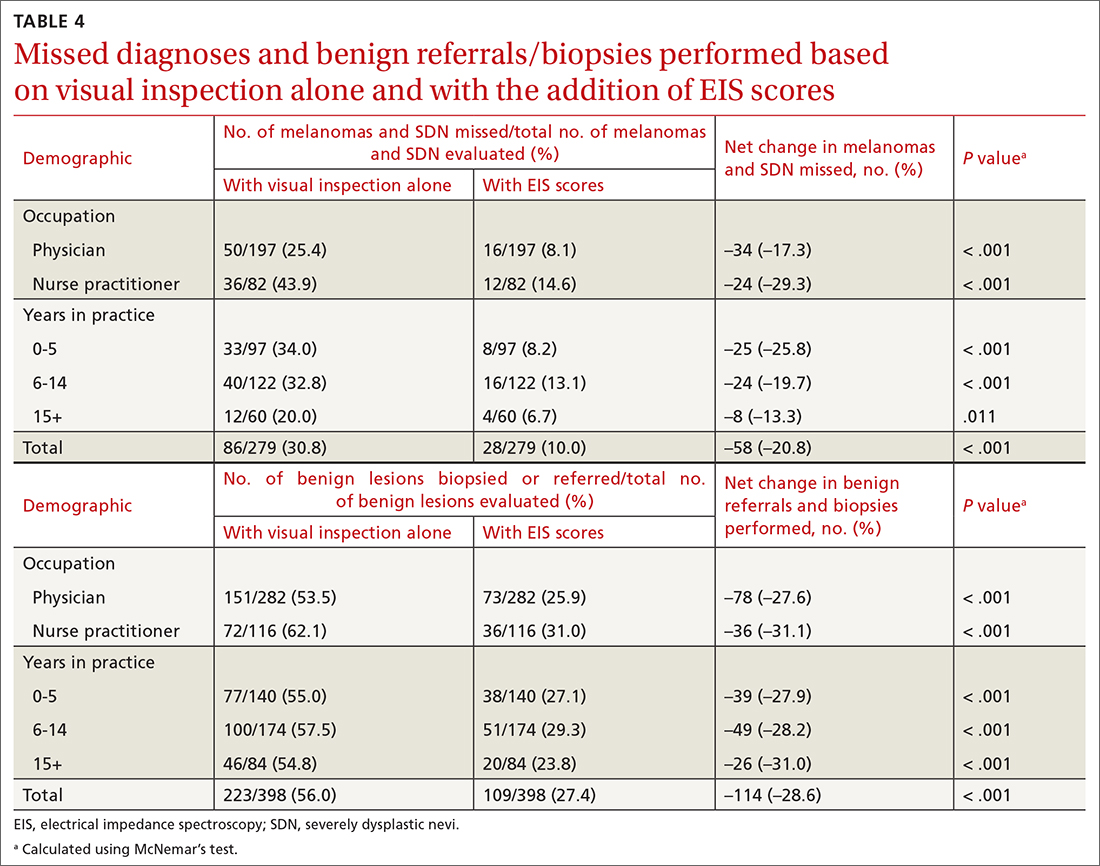

Diagnostic accuracy increased significantly from 48% when based on visual inspection alone to 73% with the addition of EIS scores (P < .001; TABLE 3). Physicians and NPs each significantly increased their diagnostic accuracy upon the incorporation of EIS, with NPs exhibiting the greatest increase (from 36.9% to 65.7%; P < .001). PCPs with 6 to 14 years of experience saw the greatest increase in diagnostic accuracy when adding EIS (45.9% vs 76.4%; P < .001). Overall, the addition of EIS scores resulted in 58 fewer missed melanomas and SDN and 114 fewer benign referrals or biopsies (TABLE 4).

Continue to: DISCUSSION

DISCUSSION

Primary care evaluation plays a significant role in the diagnosis and management of PSLs, ultimately shaping outcomes for patients with melanoma. Improved accuracy of PSL classification could yield greater sensitivity for the diagnosis of melanomas and high-risk melanocytic lesions at earlier stages, while also reducing the number of unnecessary biopsies and referrals—leading to decreased patient morbidity and mortality and reduced health care spending.9

Diagnostic tools are valuable insofar as they can improve accuracy and positively impact clinical management and patient outcomes.10 In this case, increased sensitivity reduced missed melanoma diagnoses, while increased specificity avoided the additional costs and patient toll associated with a biopsy or referral for a benign lesion.

Dermoscopy has been shown to improve the sensitivity and specificity of PSL diagnosis compared with visual inspection alone; however, without substantial training and experience, accuracy with dermoscopy can be no better than examination with the naked eye.3,11,12 The dropout rates are high for training PCPs in its use, given that several months of training may be needed for competent use.13,14 To improve the clinical management of PSLs broadly in primary care, a need exists for easy-to-use adjunctive tools that increase diagnostic accuracy.15

In this study, with only a brief explanation of how to interpret EIS scores, clinicians without any prior experience using EIS demonstrated significantly improved accuracy in deciding appropriate management and classifying melanocytic lesions with the addition of EIS to visual inspection. These improvements, seen in clinicians of varying training and experience, suggest that the learning curve of EIS may not be as steep as that of dermoscopy.

The greater baseline sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic accuracy of physicians’ clinical decision-making compared with NPs before the incorporation of EIS in the study may be a product of comparatively more extensive medical training. In addition, EIS yielded a greater benefit to NPs than to physicians, with greater increases in sensitivity and specificity noted. This suggests that the use of EIS is particularly advantageous to clinicians who are less proficient in assessing melanocytic lesions. Using visual inspection alone, more experienced respondents made biopsy/referral decisions with greater sensitivity but similar specificity to those with less experience. With the incorporation of EIS scores, the sensitivity and specificity of respondents’ clinical decision-making rose to comparable levels across all experience groups, providing further indication of EIS’s particular value to clinicians who are less proficient in PSL evaluation.

Continue to: This technology holds the potential...

This technology holds the potential to be seamlessly implemented into primary care practice, given that dermatology expertise training is not required to use the EIS device; this could allow for EIS measurement of lesions to be delegated to office staff (eg, nurses, medical assistants).16 Future studies are needed to assess EIS use among PCPs in a real-world setting, where factors such as its application on nonmelanocytic lesions (eg, seborrheic keratoses) and its pairing with patient historical data could produce varying results.

Limitations. While revealing, this study had its limitations. Respondents did not have access to additional pertinent clinical information, such as patients’ histories and risk factors. Clinical decisions in this survey were made based on digital images rather than in vivo examination. This may not represent a real-life evaluation; there is the potential for minimization of the true consequences of a missed melanoma or unnecessary biopsy in the minds of participants, and this does not factor in the operation of the actual EIS device. The Hawthorne effect may also have influenced PCPs’ diagnostic selections. Also, the limited sample size constitutes another limitation.

Of note, in this survey format, respondents rated their inclination to biopsy or refer each lesion from 1 to 5. For statistical analyses, lesions rated 1 to 3 were considered as not biopsied/referred and those rated 4 to 5 as biopsied/referred. The sensitivity and specificity values observed, for both visual examination and concurrent visual and EIS evaluation, are therefore based on this classification system of participants’ provided ratings. It is conceivable that differing sensitivity and specificity values might have been detected if clinicians were instead given a binary choice for referral/biopsy decisions.

CONCLUSIONS

Among PCPs tasked with evaluating melanocytic lesions, the incorporation of EIS data into clinical decision-making in this study significantly increased the sensitivity, specificity, and overall diagnostic accuracy of biopsy or referral decisions for melanomas and SDN compared with visual inspection alone. Overall, the results of this preliminary study suggest that diagnostic accuracy for PSLs by PCPs may be improved with the adjunctive use of EIS with visual inspection. This would ultimately improve patient care and reduce the morbidity and mortality of a melanoma diagnosis.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jonathan Ungar, MD, Kimberly and Eric J. Waldman Department of Dermatology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, 5 East 98th Street, 5th Floor, New York, NY 10029; [email protected]

1. Goetsch NJ, Hoehns JD, Sutherland JE, et al. Assessment of postgraduate skin lesion education among Iowa family physicians. SAGE Open Med. 2017;5:2050312117691392. doi: 10.1177/2050312117691392

2. Dinnes J, Deeks JJ, Chuchu N, et al. Dermoscopy, with and without visual inspection, for diagnosing melanoma in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;12:CD011902. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011902.pub2

3. Jones OT, Jurascheck LC, van Melle MA, et al. Dermoscopy for melanoma detection and triage in primary care: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e027529. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027529

4. Malvehy J, Hauschild A, Curiel-Lewandrowski C, et al. Clinical performance of the Nevisense system in cutaneous melanoma detection: an international, multicentre, prospective and blinded clinical trial on efficacy and safety. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:1099-1107. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13121

5. Svoboda RM, Prado G, Mirsky RS, et al. Assessment of clinician accuracy for diagnosing melanoma on the basis of electrical impedance spectroscopy score plus morphology versus lesion morphology alone. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:285-287. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.08.048

6. Mohr P, Birgersson U, Berking C, et al. Electrical impedance spectroscopy as a potential adjunct diagnostic tool for cutaneous melanoma. Skin Res Technol. 2013;19:75-83. doi: 10.1111/srt.12008

7. Rocha L, Menzies SW, Lo S, et al. Analysis of an electrical impedance spectroscopy system in short-term digital dermoscopy imaging of melanocytic lesions. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:1432-1438. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15595

8. Litchman GH, Teplitz RW, Marson JW, et al. Impact of electrical impedance spectroscopy on dermatologists’ number needed to biopsy metric and biopsy decisions for pigmented skin lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:976-979. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.09.011

9. Greenwood-Lee J, Jewett L, Woodhouse L, et al. A categorisation of problems and solutions to improve patient referrals from primary to specialty care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:1-16. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3745-y

10. Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Linnet K, et al. Beyond diagnostic accuracy: the clinical utility of diagnostic tests. Clin Chem. 2012;58:1636-1643. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2012.182576

11. Argenziano G, Cerroni L, Zalaudek I , et al. Accuracy in melanoma detection: a 10-year multicenter survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:54-59. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.07.019

12. Menzies SW, Vestergaard ME, Macaskill P, et al. Dermoscopy compared with naked eye examination for the diagnosis of primary melanoma: a meta-analysis of studies performed in a clinical setting. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:669-676. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08713.x

13. Menzies SW, Emery J, Staples M, et al. Impact of dermoscopy and short-term sequential digital dermoscopy imaging for the management of pigmented lesions in primary care: a sequential intervention trial. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:1270-1277. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09374.x

14. Noor O, Nanda A, Rao BK. A dermoscopy survey to assess who is using it and why it is or is not being used. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:951-952. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.04095.x

15. Weigl BH, Boyle DS, de los Santos T, et al. Simplicity of use: a critical feature for widespread adoption of diagnostic technologies in low-resource settings. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2009;6:461-464. doi: 10.1586/erd.09.31

16. Sarac E, Meiwes A, Eigentler T, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of electrical impedance spectroscopy in non-melanoma skin cancer. Acta Derm Venereol. 2020;100:adv00328. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3689

ABSTRACT

Background: We sought to examine whether electrical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), a diagnostic tool approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the evaluation of pigmented skin lesions (PSLs), is beneficial to primary care providers (PCPs) by comparing the accuracy of PCPs’ management decisions for PSLs based on visual examination alone with those based on concurrent visual and EIS evaluation.

Methods: Physicians and nurse practitioners (NPs) participated in an anonymous online survey in which they viewed clinical images of PSLs and were asked to make 2 clinical decisions before and after being provided an EIS score that indicated the likelihood that the lesion was a melanoma. They were asked (1) if they would biopsy the lesion/refer the patient out and (2) what they expected the pathology results would show.

Results: Forty-four physicians and 17 NPs participated, making clinical decisions for 1354 presented lesions. Overall, with the addition of EIS to visual inspection of clinical images, the sensitivity of biopsy/referral decisions for melanomas and severely dysplastic nevi (SDN) increased from 69.2% to 90.0% (P < .001), while specificity increased from 44.0% to 72.6% (P < .001). Physicians and NPs, regardless of years of experience, each saw significant improvements in sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic accuracy with the addition of EIS scores.

Conclusions: The incorporation of EIS data into clinical decision-making by PCPs significantly increased the sensitivity and specificity of biopsy/referral decisions for melanomas and SDN and overall diagnostic accuracy compared with visual inspection alone. The results of this study suggest that diagnostic accuracy for PSLs by PCPs may be improved with adjunctive use of EIS with visual inspection.

Primary care providers (PCPs) are often the first line of defense in detecting skin cancers. For patients with concerning skin lesions, PCPs may choose to perform a biopsy or facilitate access to specialty services (eg, Dermatology). Consequently, PCPs play a critical role in the timely detection of skin cancers, and it is paramount to employ continually improving detection methods, such as the application of technologic advances.1

Differentiating benign nevi from melanoma and severely dysplastic nevi (SDN), both of which warrant excision, poses a unique challenge to clinicians examining pigmented skin lesions (PSLs). PCPs often rely on visual inspection to differentiate benign skin lesions from malignant skin cancers. In some primary care practices, dermoscopy, which involves using a handheld device to evaluate lesions with polarized light and magnification, is used to improve melanoma detection. However, while visual inspection and dermoscopy are valid, effective techniques for the diagnosis of melanocytic lesions, in many instances they still can lead to missed cancers or unnecessary biopsies and specialty referrals. Adjunctive use of dermoscopy with visual inspection has been shown to increase the probability of skin cancer detection, but it fails to achieve a near-100% success rate.2 Furthermore, dermoscopy is heavily user-dependent, requiring significant training and experience for appropriate use.3

Another option is an electrical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) device (Nevisense, Scibase, Stockholm, Sweden), which has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to assist in the detection of melanoma and differentiation from benign PSLs.4 EIS is a noninvasive, rapidly applied technology designed to accompany the visual examination of melanocytic lesions in office, with or without dermoscopy. Still relatively new, the technology is employed today by many dermatologists, increasing diagnostic accuracy for PSLs.5 The lightweight and portable instrument features a handheld probe, which is held against a lesion to obtain a reading. EIS uses a low-voltage electrode to apply a harmless electrical current to the skin at various frequencies.6 As benign and malignant tissues vary in cell shape, size, and composition, EIS distinguishes differential electrical resistance of the tissue to aid in diagnosis.7

Continue to: EIS provides high-sensitivity...

EIS provides high-sensitivity melanoma diagnosis vs histopathologic confirmation from biopsies, with 1 study showing a 96.6% sensitivity rating, detecting 256 of 265 melanomas.4 The EIS device, by measuring differences in electrical resistance between benign and cancerous cells, outputs a simple integer score ranging from 0 to 10 associated with the likelihood of the lesion being a melanoma.8 Based on data from the Nevisense pivotal trial,4 Nevisense reports that scores of 0 to 3 carry a negative predictive value of 99% for melanoma, whereas scores of 4 to 10 signify increasingly greater positive predictive values from 7% to 61%.

We aimed to assess whether EIS may be beneficial to PCPs by comparing the accuracy of clinical decision-making for PSLs based on visual examination alone with that based on concurrent visual and EIS evaluation.

METHODS

A questionnaire was distributed via email to 142 clinicians at clinics affiliated with either of 2 organizations delivering care to the New York City area through a network of community health centers: the Institute for Family Health (IFH) and the Community Healthcare Network (CHN). Of these recipients, 72 were affiliated with IFH across 27 community health centers and 70 were affiliated with CHN across 14 community health centers. Recipients were physicians and nurse practitioners (NPs) practicing at primary health care facilities.

Survey instrument. The first section of the survey instrument (APPENDIX) solicited demographic information and explained how to apply the EIS scores for diagnostic decision-making. The second featured images of 12 randomly selected, histologically confirmed, and EIS-evaluated PSLs from a previously published prospective blinded trial of 2416 lesions.4 The Institutional Review Board of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai reviewed and approved the study and survey instrument.

Clinical images of these lesions, comprising 4 melanocytic nevi, 4 dysplastic nevi (including 3 mild-moderately dysplastic and 1 severely dysplastic nevus), and 4 melanomas

Continue to: Analysis

Analysis. A biopsy or referral rating of 4 or 5 was considered a decision to biopsy or refer (ie, a diagnostic decision consistent with melanoma or SDN warranting excision), whereas a selection of 1 to 3 was considered a decision not to biopsy or refer (ie, a diagnostic decision consistent with a benign PSL). The sensitivity and specificity of biopsy/referral decisions for melanomas and SDN, the proportion of missed melanomas and SDN, and the proportion of biopsy/referral decisions for benign lesions were separately determined for visual inspection alone and visual inspection with EIS score. Similarly, diagnostic accuracy was calculated for these clinical scenarios. These metrics were further stratified among different subsets of the respondent population. Differences in sensitivity, specificity, biopsy/referral decision proportions, and diagnostic accuracy were calculated using McNemar’s test for paired proportions.

RESULTS

Sixty-one respondents, comprising 44 physicians and 17 NPs, completed the survey, yielding a response rate of 43% (TABLE 1). In total, 1354 clinical decisions (677 based on visual inspection alone and 677 based on visual inspection plus EIS) were made. A biopsy/referral decision was made after assessing 416 of 677 cases (61%) with visual inspection alone and 360 of 677 cases (53%) when relying on visual inspection plus EIS. None of the respondents reported any prior experience with EIS.

When incorporating EIS scores, respondents’ mean sensitivity for melanomas and SDN increased from 69.2% to 90.0% (P < .001) and specificity from 44.0% to 72.6% (P < .001; TABLE 2). At baseline, physicians demonstrated a sensitivity and specificity of 74.6% and 46.5%, respectively, while NPs demonstrated a sensitivity and specificity of 56.1% and 37.9%, respectively.

All respondent subgroups stratified by occupation and years of experience saw significant increases in both sensitivity and specificity upon the incorporation of EIS scores, with NPs seeing a greater increase in sensitivity (56.1% vs 85.4%; P < .001) and specificity (37.9% vs 69.0%; P < .001) than physicians (sensitivity: 74.6% vs 91.9%; P < .001; specificity: 46.5% vs 74.1%; P < .001). The only difference in diagnostic performance based on years of experience was a greater pre-EIS sensitivity by clinicians who had been in practice for ≥ 15 years, compared with those in practice for shorter periods (TABLE 2).

Diagnostic accuracy increased significantly from 48% when based on visual inspection alone to 73% with the addition of EIS scores (P < .001; TABLE 3). Physicians and NPs each significantly increased their diagnostic accuracy upon the incorporation of EIS, with NPs exhibiting the greatest increase (from 36.9% to 65.7%; P < .001). PCPs with 6 to 14 years of experience saw the greatest increase in diagnostic accuracy when adding EIS (45.9% vs 76.4%; P < .001). Overall, the addition of EIS scores resulted in 58 fewer missed melanomas and SDN and 114 fewer benign referrals or biopsies (TABLE 4).

Continue to: DISCUSSION

DISCUSSION

Primary care evaluation plays a significant role in the diagnosis and management of PSLs, ultimately shaping outcomes for patients with melanoma. Improved accuracy of PSL classification could yield greater sensitivity for the diagnosis of melanomas and high-risk melanocytic lesions at earlier stages, while also reducing the number of unnecessary biopsies and referrals—leading to decreased patient morbidity and mortality and reduced health care spending.9

Diagnostic tools are valuable insofar as they can improve accuracy and positively impact clinical management and patient outcomes.10 In this case, increased sensitivity reduced missed melanoma diagnoses, while increased specificity avoided the additional costs and patient toll associated with a biopsy or referral for a benign lesion.

Dermoscopy has been shown to improve the sensitivity and specificity of PSL diagnosis compared with visual inspection alone; however, without substantial training and experience, accuracy with dermoscopy can be no better than examination with the naked eye.3,11,12 The dropout rates are high for training PCPs in its use, given that several months of training may be needed for competent use.13,14 To improve the clinical management of PSLs broadly in primary care, a need exists for easy-to-use adjunctive tools that increase diagnostic accuracy.15

In this study, with only a brief explanation of how to interpret EIS scores, clinicians without any prior experience using EIS demonstrated significantly improved accuracy in deciding appropriate management and classifying melanocytic lesions with the addition of EIS to visual inspection. These improvements, seen in clinicians of varying training and experience, suggest that the learning curve of EIS may not be as steep as that of dermoscopy.

The greater baseline sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic accuracy of physicians’ clinical decision-making compared with NPs before the incorporation of EIS in the study may be a product of comparatively more extensive medical training. In addition, EIS yielded a greater benefit to NPs than to physicians, with greater increases in sensitivity and specificity noted. This suggests that the use of EIS is particularly advantageous to clinicians who are less proficient in assessing melanocytic lesions. Using visual inspection alone, more experienced respondents made biopsy/referral decisions with greater sensitivity but similar specificity to those with less experience. With the incorporation of EIS scores, the sensitivity and specificity of respondents’ clinical decision-making rose to comparable levels across all experience groups, providing further indication of EIS’s particular value to clinicians who are less proficient in PSL evaluation.

Continue to: This technology holds the potential...

This technology holds the potential to be seamlessly implemented into primary care practice, given that dermatology expertise training is not required to use the EIS device; this could allow for EIS measurement of lesions to be delegated to office staff (eg, nurses, medical assistants).16 Future studies are needed to assess EIS use among PCPs in a real-world setting, where factors such as its application on nonmelanocytic lesions (eg, seborrheic keratoses) and its pairing with patient historical data could produce varying results.

Limitations. While revealing, this study had its limitations. Respondents did not have access to additional pertinent clinical information, such as patients’ histories and risk factors. Clinical decisions in this survey were made based on digital images rather than in vivo examination. This may not represent a real-life evaluation; there is the potential for minimization of the true consequences of a missed melanoma or unnecessary biopsy in the minds of participants, and this does not factor in the operation of the actual EIS device. The Hawthorne effect may also have influenced PCPs’ diagnostic selections. Also, the limited sample size constitutes another limitation.

Of note, in this survey format, respondents rated their inclination to biopsy or refer each lesion from 1 to 5. For statistical analyses, lesions rated 1 to 3 were considered as not biopsied/referred and those rated 4 to 5 as biopsied/referred. The sensitivity and specificity values observed, for both visual examination and concurrent visual and EIS evaluation, are therefore based on this classification system of participants’ provided ratings. It is conceivable that differing sensitivity and specificity values might have been detected if clinicians were instead given a binary choice for referral/biopsy decisions.

CONCLUSIONS

Among PCPs tasked with evaluating melanocytic lesions, the incorporation of EIS data into clinical decision-making in this study significantly increased the sensitivity, specificity, and overall diagnostic accuracy of biopsy or referral decisions for melanomas and SDN compared with visual inspection alone. Overall, the results of this preliminary study suggest that diagnostic accuracy for PSLs by PCPs may be improved with the adjunctive use of EIS with visual inspection. This would ultimately improve patient care and reduce the morbidity and mortality of a melanoma diagnosis.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jonathan Ungar, MD, Kimberly and Eric J. Waldman Department of Dermatology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, 5 East 98th Street, 5th Floor, New York, NY 10029; [email protected]

ABSTRACT

Background: We sought to examine whether electrical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), a diagnostic tool approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the evaluation of pigmented skin lesions (PSLs), is beneficial to primary care providers (PCPs) by comparing the accuracy of PCPs’ management decisions for PSLs based on visual examination alone with those based on concurrent visual and EIS evaluation.

Methods: Physicians and nurse practitioners (NPs) participated in an anonymous online survey in which they viewed clinical images of PSLs and were asked to make 2 clinical decisions before and after being provided an EIS score that indicated the likelihood that the lesion was a melanoma. They were asked (1) if they would biopsy the lesion/refer the patient out and (2) what they expected the pathology results would show.

Results: Forty-four physicians and 17 NPs participated, making clinical decisions for 1354 presented lesions. Overall, with the addition of EIS to visual inspection of clinical images, the sensitivity of biopsy/referral decisions for melanomas and severely dysplastic nevi (SDN) increased from 69.2% to 90.0% (P < .001), while specificity increased from 44.0% to 72.6% (P < .001). Physicians and NPs, regardless of years of experience, each saw significant improvements in sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic accuracy with the addition of EIS scores.

Conclusions: The incorporation of EIS data into clinical decision-making by PCPs significantly increased the sensitivity and specificity of biopsy/referral decisions for melanomas and SDN and overall diagnostic accuracy compared with visual inspection alone. The results of this study suggest that diagnostic accuracy for PSLs by PCPs may be improved with adjunctive use of EIS with visual inspection.

Primary care providers (PCPs) are often the first line of defense in detecting skin cancers. For patients with concerning skin lesions, PCPs may choose to perform a biopsy or facilitate access to specialty services (eg, Dermatology). Consequently, PCPs play a critical role in the timely detection of skin cancers, and it is paramount to employ continually improving detection methods, such as the application of technologic advances.1

Differentiating benign nevi from melanoma and severely dysplastic nevi (SDN), both of which warrant excision, poses a unique challenge to clinicians examining pigmented skin lesions (PSLs). PCPs often rely on visual inspection to differentiate benign skin lesions from malignant skin cancers. In some primary care practices, dermoscopy, which involves using a handheld device to evaluate lesions with polarized light and magnification, is used to improve melanoma detection. However, while visual inspection and dermoscopy are valid, effective techniques for the diagnosis of melanocytic lesions, in many instances they still can lead to missed cancers or unnecessary biopsies and specialty referrals. Adjunctive use of dermoscopy with visual inspection has been shown to increase the probability of skin cancer detection, but it fails to achieve a near-100% success rate.2 Furthermore, dermoscopy is heavily user-dependent, requiring significant training and experience for appropriate use.3

Another option is an electrical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) device (Nevisense, Scibase, Stockholm, Sweden), which has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to assist in the detection of melanoma and differentiation from benign PSLs.4 EIS is a noninvasive, rapidly applied technology designed to accompany the visual examination of melanocytic lesions in office, with or without dermoscopy. Still relatively new, the technology is employed today by many dermatologists, increasing diagnostic accuracy for PSLs.5 The lightweight and portable instrument features a handheld probe, which is held against a lesion to obtain a reading. EIS uses a low-voltage electrode to apply a harmless electrical current to the skin at various frequencies.6 As benign and malignant tissues vary in cell shape, size, and composition, EIS distinguishes differential electrical resistance of the tissue to aid in diagnosis.7

Continue to: EIS provides high-sensitivity...

EIS provides high-sensitivity melanoma diagnosis vs histopathologic confirmation from biopsies, with 1 study showing a 96.6% sensitivity rating, detecting 256 of 265 melanomas.4 The EIS device, by measuring differences in electrical resistance between benign and cancerous cells, outputs a simple integer score ranging from 0 to 10 associated with the likelihood of the lesion being a melanoma.8 Based on data from the Nevisense pivotal trial,4 Nevisense reports that scores of 0 to 3 carry a negative predictive value of 99% for melanoma, whereas scores of 4 to 10 signify increasingly greater positive predictive values from 7% to 61%.

We aimed to assess whether EIS may be beneficial to PCPs by comparing the accuracy of clinical decision-making for PSLs based on visual examination alone with that based on concurrent visual and EIS evaluation.

METHODS

A questionnaire was distributed via email to 142 clinicians at clinics affiliated with either of 2 organizations delivering care to the New York City area through a network of community health centers: the Institute for Family Health (IFH) and the Community Healthcare Network (CHN). Of these recipients, 72 were affiliated with IFH across 27 community health centers and 70 were affiliated with CHN across 14 community health centers. Recipients were physicians and nurse practitioners (NPs) practicing at primary health care facilities.

Survey instrument. The first section of the survey instrument (APPENDIX) solicited demographic information and explained how to apply the EIS scores for diagnostic decision-making. The second featured images of 12 randomly selected, histologically confirmed, and EIS-evaluated PSLs from a previously published prospective blinded trial of 2416 lesions.4 The Institutional Review Board of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai reviewed and approved the study and survey instrument.

Clinical images of these lesions, comprising 4 melanocytic nevi, 4 dysplastic nevi (including 3 mild-moderately dysplastic and 1 severely dysplastic nevus), and 4 melanomas

Continue to: Analysis

Analysis. A biopsy or referral rating of 4 or 5 was considered a decision to biopsy or refer (ie, a diagnostic decision consistent with melanoma or SDN warranting excision), whereas a selection of 1 to 3 was considered a decision not to biopsy or refer (ie, a diagnostic decision consistent with a benign PSL). The sensitivity and specificity of biopsy/referral decisions for melanomas and SDN, the proportion of missed melanomas and SDN, and the proportion of biopsy/referral decisions for benign lesions were separately determined for visual inspection alone and visual inspection with EIS score. Similarly, diagnostic accuracy was calculated for these clinical scenarios. These metrics were further stratified among different subsets of the respondent population. Differences in sensitivity, specificity, biopsy/referral decision proportions, and diagnostic accuracy were calculated using McNemar’s test for paired proportions.

RESULTS

Sixty-one respondents, comprising 44 physicians and 17 NPs, completed the survey, yielding a response rate of 43% (TABLE 1). In total, 1354 clinical decisions (677 based on visual inspection alone and 677 based on visual inspection plus EIS) were made. A biopsy/referral decision was made after assessing 416 of 677 cases (61%) with visual inspection alone and 360 of 677 cases (53%) when relying on visual inspection plus EIS. None of the respondents reported any prior experience with EIS.

When incorporating EIS scores, respondents’ mean sensitivity for melanomas and SDN increased from 69.2% to 90.0% (P < .001) and specificity from 44.0% to 72.6% (P < .001; TABLE 2). At baseline, physicians demonstrated a sensitivity and specificity of 74.6% and 46.5%, respectively, while NPs demonstrated a sensitivity and specificity of 56.1% and 37.9%, respectively.

All respondent subgroups stratified by occupation and years of experience saw significant increases in both sensitivity and specificity upon the incorporation of EIS scores, with NPs seeing a greater increase in sensitivity (56.1% vs 85.4%; P < .001) and specificity (37.9% vs 69.0%; P < .001) than physicians (sensitivity: 74.6% vs 91.9%; P < .001; specificity: 46.5% vs 74.1%; P < .001). The only difference in diagnostic performance based on years of experience was a greater pre-EIS sensitivity by clinicians who had been in practice for ≥ 15 years, compared with those in practice for shorter periods (TABLE 2).

Diagnostic accuracy increased significantly from 48% when based on visual inspection alone to 73% with the addition of EIS scores (P < .001; TABLE 3). Physicians and NPs each significantly increased their diagnostic accuracy upon the incorporation of EIS, with NPs exhibiting the greatest increase (from 36.9% to 65.7%; P < .001). PCPs with 6 to 14 years of experience saw the greatest increase in diagnostic accuracy when adding EIS (45.9% vs 76.4%; P < .001). Overall, the addition of EIS scores resulted in 58 fewer missed melanomas and SDN and 114 fewer benign referrals or biopsies (TABLE 4).

Continue to: DISCUSSION

DISCUSSION

Primary care evaluation plays a significant role in the diagnosis and management of PSLs, ultimately shaping outcomes for patients with melanoma. Improved accuracy of PSL classification could yield greater sensitivity for the diagnosis of melanomas and high-risk melanocytic lesions at earlier stages, while also reducing the number of unnecessary biopsies and referrals—leading to decreased patient morbidity and mortality and reduced health care spending.9

Diagnostic tools are valuable insofar as they can improve accuracy and positively impact clinical management and patient outcomes.10 In this case, increased sensitivity reduced missed melanoma diagnoses, while increased specificity avoided the additional costs and patient toll associated with a biopsy or referral for a benign lesion.

Dermoscopy has been shown to improve the sensitivity and specificity of PSL diagnosis compared with visual inspection alone; however, without substantial training and experience, accuracy with dermoscopy can be no better than examination with the naked eye.3,11,12 The dropout rates are high for training PCPs in its use, given that several months of training may be needed for competent use.13,14 To improve the clinical management of PSLs broadly in primary care, a need exists for easy-to-use adjunctive tools that increase diagnostic accuracy.15

In this study, with only a brief explanation of how to interpret EIS scores, clinicians without any prior experience using EIS demonstrated significantly improved accuracy in deciding appropriate management and classifying melanocytic lesions with the addition of EIS to visual inspection. These improvements, seen in clinicians of varying training and experience, suggest that the learning curve of EIS may not be as steep as that of dermoscopy.

The greater baseline sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic accuracy of physicians’ clinical decision-making compared with NPs before the incorporation of EIS in the study may be a product of comparatively more extensive medical training. In addition, EIS yielded a greater benefit to NPs than to physicians, with greater increases in sensitivity and specificity noted. This suggests that the use of EIS is particularly advantageous to clinicians who are less proficient in assessing melanocytic lesions. Using visual inspection alone, more experienced respondents made biopsy/referral decisions with greater sensitivity but similar specificity to those with less experience. With the incorporation of EIS scores, the sensitivity and specificity of respondents’ clinical decision-making rose to comparable levels across all experience groups, providing further indication of EIS’s particular value to clinicians who are less proficient in PSL evaluation.

Continue to: This technology holds the potential...

This technology holds the potential to be seamlessly implemented into primary care practice, given that dermatology expertise training is not required to use the EIS device; this could allow for EIS measurement of lesions to be delegated to office staff (eg, nurses, medical assistants).16 Future studies are needed to assess EIS use among PCPs in a real-world setting, where factors such as its application on nonmelanocytic lesions (eg, seborrheic keratoses) and its pairing with patient historical data could produce varying results.

Limitations. While revealing, this study had its limitations. Respondents did not have access to additional pertinent clinical information, such as patients’ histories and risk factors. Clinical decisions in this survey were made based on digital images rather than in vivo examination. This may not represent a real-life evaluation; there is the potential for minimization of the true consequences of a missed melanoma or unnecessary biopsy in the minds of participants, and this does not factor in the operation of the actual EIS device. The Hawthorne effect may also have influenced PCPs’ diagnostic selections. Also, the limited sample size constitutes another limitation.

Of note, in this survey format, respondents rated their inclination to biopsy or refer each lesion from 1 to 5. For statistical analyses, lesions rated 1 to 3 were considered as not biopsied/referred and those rated 4 to 5 as biopsied/referred. The sensitivity and specificity values observed, for both visual examination and concurrent visual and EIS evaluation, are therefore based on this classification system of participants’ provided ratings. It is conceivable that differing sensitivity and specificity values might have been detected if clinicians were instead given a binary choice for referral/biopsy decisions.

CONCLUSIONS

Among PCPs tasked with evaluating melanocytic lesions, the incorporation of EIS data into clinical decision-making in this study significantly increased the sensitivity, specificity, and overall diagnostic accuracy of biopsy or referral decisions for melanomas and SDN compared with visual inspection alone. Overall, the results of this preliminary study suggest that diagnostic accuracy for PSLs by PCPs may be improved with the adjunctive use of EIS with visual inspection. This would ultimately improve patient care and reduce the morbidity and mortality of a melanoma diagnosis.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jonathan Ungar, MD, Kimberly and Eric J. Waldman Department of Dermatology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, 5 East 98th Street, 5th Floor, New York, NY 10029; [email protected]

1. Goetsch NJ, Hoehns JD, Sutherland JE, et al. Assessment of postgraduate skin lesion education among Iowa family physicians. SAGE Open Med. 2017;5:2050312117691392. doi: 10.1177/2050312117691392

2. Dinnes J, Deeks JJ, Chuchu N, et al. Dermoscopy, with and without visual inspection, for diagnosing melanoma in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;12:CD011902. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011902.pub2

3. Jones OT, Jurascheck LC, van Melle MA, et al. Dermoscopy for melanoma detection and triage in primary care: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e027529. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027529

4. Malvehy J, Hauschild A, Curiel-Lewandrowski C, et al. Clinical performance of the Nevisense system in cutaneous melanoma detection: an international, multicentre, prospective and blinded clinical trial on efficacy and safety. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:1099-1107. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13121

5. Svoboda RM, Prado G, Mirsky RS, et al. Assessment of clinician accuracy for diagnosing melanoma on the basis of electrical impedance spectroscopy score plus morphology versus lesion morphology alone. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:285-287. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.08.048

6. Mohr P, Birgersson U, Berking C, et al. Electrical impedance spectroscopy as a potential adjunct diagnostic tool for cutaneous melanoma. Skin Res Technol. 2013;19:75-83. doi: 10.1111/srt.12008

7. Rocha L, Menzies SW, Lo S, et al. Analysis of an electrical impedance spectroscopy system in short-term digital dermoscopy imaging of melanocytic lesions. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:1432-1438. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15595

8. Litchman GH, Teplitz RW, Marson JW, et al. Impact of electrical impedance spectroscopy on dermatologists’ number needed to biopsy metric and biopsy decisions for pigmented skin lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:976-979. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.09.011

9. Greenwood-Lee J, Jewett L, Woodhouse L, et al. A categorisation of problems and solutions to improve patient referrals from primary to specialty care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:1-16. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3745-y

10. Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Linnet K, et al. Beyond diagnostic accuracy: the clinical utility of diagnostic tests. Clin Chem. 2012;58:1636-1643. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2012.182576

11. Argenziano G, Cerroni L, Zalaudek I , et al. Accuracy in melanoma detection: a 10-year multicenter survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:54-59. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.07.019

12. Menzies SW, Vestergaard ME, Macaskill P, et al. Dermoscopy compared with naked eye examination for the diagnosis of primary melanoma: a meta-analysis of studies performed in a clinical setting. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:669-676. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08713.x

13. Menzies SW, Emery J, Staples M, et al. Impact of dermoscopy and short-term sequential digital dermoscopy imaging for the management of pigmented lesions in primary care: a sequential intervention trial. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:1270-1277. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09374.x

14. Noor O, Nanda A, Rao BK. A dermoscopy survey to assess who is using it and why it is or is not being used. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:951-952. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.04095.x

15. Weigl BH, Boyle DS, de los Santos T, et al. Simplicity of use: a critical feature for widespread adoption of diagnostic technologies in low-resource settings. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2009;6:461-464. doi: 10.1586/erd.09.31

16. Sarac E, Meiwes A, Eigentler T, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of electrical impedance spectroscopy in non-melanoma skin cancer. Acta Derm Venereol. 2020;100:adv00328. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3689

1. Goetsch NJ, Hoehns JD, Sutherland JE, et al. Assessment of postgraduate skin lesion education among Iowa family physicians. SAGE Open Med. 2017;5:2050312117691392. doi: 10.1177/2050312117691392

2. Dinnes J, Deeks JJ, Chuchu N, et al. Dermoscopy, with and without visual inspection, for diagnosing melanoma in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;12:CD011902. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011902.pub2

3. Jones OT, Jurascheck LC, van Melle MA, et al. Dermoscopy for melanoma detection and triage in primary care: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e027529. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027529

4. Malvehy J, Hauschild A, Curiel-Lewandrowski C, et al. Clinical performance of the Nevisense system in cutaneous melanoma detection: an international, multicentre, prospective and blinded clinical trial on efficacy and safety. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:1099-1107. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13121

5. Svoboda RM, Prado G, Mirsky RS, et al. Assessment of clinician accuracy for diagnosing melanoma on the basis of electrical impedance spectroscopy score plus morphology versus lesion morphology alone. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:285-287. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.08.048

6. Mohr P, Birgersson U, Berking C, et al. Electrical impedance spectroscopy as a potential adjunct diagnostic tool for cutaneous melanoma. Skin Res Technol. 2013;19:75-83. doi: 10.1111/srt.12008

7. Rocha L, Menzies SW, Lo S, et al. Analysis of an electrical impedance spectroscopy system in short-term digital dermoscopy imaging of melanocytic lesions. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:1432-1438. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15595

8. Litchman GH, Teplitz RW, Marson JW, et al. Impact of electrical impedance spectroscopy on dermatologists’ number needed to biopsy metric and biopsy decisions for pigmented skin lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:976-979. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.09.011

9. Greenwood-Lee J, Jewett L, Woodhouse L, et al. A categorisation of problems and solutions to improve patient referrals from primary to specialty care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:1-16. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3745-y

10. Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Linnet K, et al. Beyond diagnostic accuracy: the clinical utility of diagnostic tests. Clin Chem. 2012;58:1636-1643. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2012.182576

11. Argenziano G, Cerroni L, Zalaudek I , et al. Accuracy in melanoma detection: a 10-year multicenter survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:54-59. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.07.019

12. Menzies SW, Vestergaard ME, Macaskill P, et al. Dermoscopy compared with naked eye examination for the diagnosis of primary melanoma: a meta-analysis of studies performed in a clinical setting. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:669-676. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08713.x

13. Menzies SW, Emery J, Staples M, et al. Impact of dermoscopy and short-term sequential digital dermoscopy imaging for the management of pigmented lesions in primary care: a sequential intervention trial. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:1270-1277. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09374.x

14. Noor O, Nanda A, Rao BK. A dermoscopy survey to assess who is using it and why it is or is not being used. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:951-952. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.04095.x

15. Weigl BH, Boyle DS, de los Santos T, et al. Simplicity of use: a critical feature for widespread adoption of diagnostic technologies in low-resource settings. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2009;6:461-464. doi: 10.1586/erd.09.31

16. Sarac E, Meiwes A, Eigentler T, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of electrical impedance spectroscopy in non-melanoma skin cancer. Acta Derm Venereol. 2020;100:adv00328. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3689

Persistent ‘postherpetic neuralgia’ and well-demarcated plaque

A 75-YEAR-OLD MAN presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of localized, persistent burning pain and discomfort attributed to shingles and postherpetic neuralgia. He had received a diagnosis of shingles on his left upper back about 3 years prior to this presentation.

In the ensuing years, the patient had been evaluated and treated by his primary care physician, a pain management team, and a neurologist. These clinicians treated the symptoms as postherpetic neuralgia, with no consensus explanation for the skin findings. The patient reported that his symptoms were unresponsive to trials of gabapentin 800 mg tid, duloxetine 60 mg PO qd, and acetaminophen 1 to 3 g/d PO. He also had undergone several rounds of acupuncture, thoracic and cervical spine steroid injections, and epidurals, without resolution of symptoms. The patient believed the only treatment that helped was a lidocaine 4% patch, which he had used nearly every day for the previous 3 years.

Physical exam by the dermatologist revealed a lidocaine patch applied to the patient’s left upper back. Upon its removal, skin examination showed a well-demarcated, erythematous, hyperpigmented, lichenified plaque with excoriations and erosions where the patch had been (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Contact dermatitis

The patient’s history and skin exam provided enough information to diagnose contact dermatitis. The pruritus, burning, and pain the patient had experienced were due to continuous application of the lidocaine patch to the area rather than postherpetic neuralgia.

There are 2 types of contact dermatitis: irritant and allergic. Irritant contact dermatitis is an inflammatory reaction caused directly by a substance, while allergic contact dermatitis is a delayed hypersensitivity reaction to specific allergens.1 While data to elucidate the incidence and prevalence of allergic contact dermatitis are unknown, common causes include latex, dyes, oils, resins, and compounds in textiles, rubber, cosmetics, and other products used in daily life.1

Allergic contact dermatitis due to lidocaine is becoming more prevalent with increased use and availability of over-the-counter products.2 A retrospective chart review of 1819 patch-tested patients from the University of British Columbia Contact Dermatitis Clinic showed a significant proportion of patients (2.4%) were found to have

The differential varies by area affected

The differential diagnosis for contact dermatitis varies by area affected and the distribution of rash. Atopic dermatitis, lichen planus, and psoriasis are a few dermatologic conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis. They can look similar to contact dermatitis, but the patient’s history can help to discern the most likely diagnosis.1

Atopic dermatitis is a complex dysfunction of the skin barrier and immune factors that often begins in childhood and persists in some patients throughout their lifetime. Atopic dermatitis is associated with other forms of atopy including asthma, allergic rhinitis, and food and contact allergies. Atopic dermatitis in the absence of contact allergies may manifest with chronic, diffuse, scaly patches with poorly defined borders. The patches appear in a symmetrical distribution and favor the flexural surfaces, such as the antecubital fossa, wrists, and neck.

Continue to: Lichen planus

Lichen planus most often manifests in the fourth through sixth decade of life as flat-topped itchy pink-to-purple polygonal papules to plaques. Lesions range from 2 to 10 mm and favor the volar wrists, shins, and lower back, although they may be widespread. Oral lesions manifesting as ulcers or white lacy patches in the buccal mucosa are common and may be a clue to the diagnosis. Unlike more generalized contact dermatitis, lichen planus lesions are discrete.

Psoriasis manifests as well-demarcated scaly plaques distributed symmetrically over extensor surfaces. The plaques commonly are found on the elbows, knees, and scalp. When psoriasis manifests in a very limited form (as just a single plaque or limited number of plaques), it can be hard to confidently exclude other etiologies. In these circumstances, look for psoriasis signs in more unique locations (eg, pitting in the nails or plaques on the scalp or in the gluteal cleft). Adding those findings to an otherwise solitary plaque significantly adds to diagnostic certainty.

Diagnosis entails getting the shape of things

Diagnosis is based on history of exposure to irritating or allergic substances, as well as a clinical exam. Skin examination of contact dermatitis can vary based on how long it has been present: Acute manifestations include erythema, oozing, scale, vesicles, and bullae, while chronic contact dermatitis tends to demonstrate lichenification and scale.1

Distinctive findings. The most distinctive physical exam findings in patients with contact dermatitis are often shape and distribution of the rash, which reflect points of contact with the offending agent. This clue helped to elucidate the diagnosis in our patient: his rash was perfectly demarcated within the precise area where the patch was applied daily.

Irritant vs allergic. Patch testing can be performed to differentiate irritant vs allergic contact dermatitis.1 Irritant contact dermatitis usually is apparent when removing a patch and will resolve over a day, whereas allergic contact dermatitis forms over time and the skin rash is most prominent several days after the patch has been removed.1

Continue to: Treatment

Treatment: First, stop the offense

Treatment of both variants of contact dermatitis includes avoidance of the causative substance and symptomatic treatment with topical steroids, antihistamines, and possibly oral steroids depending on the severity.1

For our patient, a viral swab was taken and submitted for varicella zoster virus polymerase chain reaction testing to rule out persistent herpes zoster infection; the result was negative. The patient was counseled to discontinue use of the lidocaine patch.