User login

Clinical Impact of Initiation of U-500 Insulin vs Continuation of U-100 Insulin in Subjects With Diabetes

More than 70% of Americans are overweight or obese and 1 in 10 has type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). In the last 20 years, the prevalence of obesity and DM has each increased drastically according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.1,2 Thus, an increase in severe insulin-resistant DM is predicted. Severe insulin resistance occurs when insulin doses exceed 200 units per day or 2 units/kg per day.3-5 Treating this condition demands large volumes of U-100 insulin and a high frequency of injections (usually 4-7 per day), which can lead to reduced patient adherence.8-10 Likewise, large injected volumes are more painful and can lead to altered absorption.3,9-11

U-500 insulin (500 units/mL) is 5 times more concentrated than U-100 insulin and has advantages in the management of severe insulin-resistant DM.11-13 Its pharmacokinetic profile is unique, for the clinical effect can last for up to 24 hours.4-6 U-500 can replace basal-bolus and other complex insulin regimens, offering convenient, effective glycemic control with 2 or 3 injections per day.11,14-20 U-500 can also improve the quality of life and adherence compared with formulations that require more frequent injections.7,14,21 Historically, only exceptional or “special” cases were treated with U-500, but demand for concentrated insulins has increased in the last decade as clinicians adjust their care for this growing patient population.17

The purpose of this study was to determine whether a population of subjects with severe insulin-resistant T2DM would benefit from the use of U-500 vs U-100 insulin regimens. The hypothesis was that this population would obtain equal or better glycemic control while achieving improved adherence. Other studies have demonstrated that U-500 yields improvements in glycemic control but also potentially increases hypoglycemic episodes.15-18,22-24 To our knowledge, this study is the first to evaluate the clinical outcomes of subjects with severe insulin-resistant T2DM who changed from U-100 to U-500 vs subjects who remained on high-dose U-100 insulin.

Methods

This was a single-site, retrospective chart review of subjects with T2DM who attended the endocrinology specialty clinic at the James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital (JAHVA) in Tampa, Florida, between July 2002 and June 2011. The study included a group of subjects using U-500 insulin and a comparison group using U-100 insulin. The study was approved by the JAHVA Research & Development Committee and by the University of South Florida Institutional Review Board.

Inclusion criteria included diagnosis of T2DM, body mass index (BMI) of more than 30, use of U-500 insulin, or > 200 units daily of U-100 insulin. Exclusion criteria included hypoglycemia unawareness, type 1 DM, and use of an insulin pump. A total of 142 subjects met the inclusion criteria (68 in the U-500 group and 74 in the U-100 group).

All study subjects had at least 1 DM education session. U-500 subjects used insulin vials and 1-mL volumetric hypodermal syringes. All U-500 prescriptions were issued electronically in units and volume (U-500 insulin was available exclusively in vials during the time frame from which data were collected). Subjects in the U-100 group used insulin vials or pen devices. Laboratory studies were processed in house by the institution using high-pressure liquid chromatography to determine hemoglobin A1C (Hb A1C) levels. All study subjects required at least 2 Hb A1C measurements over the observed 12 months for inclusion.

Transition to U-500 Insulin

U-500 transition was considered routinely and presented as an option for patients requiring > 200 units of insulin daily. The transition criteria included adherence to medications, follow-up appointments, and glucose monitoring recommendations, and ability to learn and apply insulin self-adjustment instructions. All subjects were given an additional U-500 insulin education session before transition. The endocrinologist calculated all starting doses by reducing the total daily dose by 20%.

Data Collection

Data were collected using the automatic data mining tools within the JAHVA Computerized Patient Record System and confirmed individually by clinical staff. Demographic data included age, race, and sex. Other parameters were weight; BMI; Hb A1C; estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR); duration of DM; use of metformin and other oral agents; total daily insulin dose; number of daily injections; prior history of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), including coronary artery disease (CAD), cerebrovascular accident (CVA), or peripheral vascular disease (PVD); occurrence of severe hypoglycemia (symptomatic hypoglycemia requiring treatment assistance from another individual) and of new cardiovascular events, classified as CAD, CVA, or PVD.

For the U-500 group, data were collected and analyzed for the 3 months before (baseline) and the 12 months after the initiation of concentrated insulin. For the U-100 group, data were collected and analyzed for the comparable 3 months before (baseline) and the 12 months after the first clinic visit in which the subject started using more than 200 units per day of U-100. Frequency of follow-up visits was individualized according to clinical needs.

Clinical Endpoints

Primary outcomes included changes in Hb A1C from baseline to the following 12 months, and the occurrence of severe hypoglycemia. Secondary outcomes included the occurrence of new ASCVD events during the study, and changes in weight, BMI, and number of injections.

Statistical Analysis

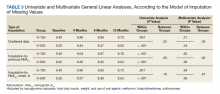

The primary and secondary outcomes were assessed through univariate and multivariate general linear models. Multivariate models were used to compare differences in the variation of Hb A1C over time. Data were incomplete for the Hb A1C in 27 subjects, 6% of the dataset (Each subject had more than one variable or observation). Therefore, a multiple imputation was used to account for the incompleteness on Hb A1C (value substitutions by the mean and by the prior Hb A1C and models were balanced against the unaltered data). A P value of ≤ .05 was used to determine statistical significance. The statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 21.

Results

Most patients were male (94%) of white race (86%), with a mean age of 57 years and comparable duration of DM (Table 1). Demographics were balanced between the groups, except for weight and BMI, both higher in the U-500 group (P < .001). Use of oral antidiabetic agents was not significantly different between groups, nor were comorbid conditions, with nearly 50% of subjects in each group affected by CKD and ASCVD, of which CAD was the most common (approximately 40% of both groups). Only about one-third of subjects used metformin and/or other oral agents, likely due to the high prevalence of CKD (contraindicating metformin) and high insulin requirements (due to correlation with β cell failure). A subgroup analysis of subjects on metformin did not demonstrate significant differences in risk of severe hypoglycemia or in Hb A1C levels (data not shown).

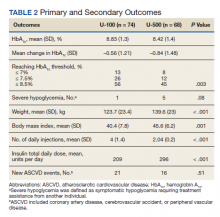

Both groups had similar initial Hb A1C baselines (> 9%) and both improved glycemic control during the study period. However, the Hb A1C reduction was greater in the U-500 group (P= .034), 0.84% vs 0.56% for U-100 and the between-groups difference was 0.4%. (Figure 1, Tables 2 and 3).

The univariate general linear model shows a statistically significant difference in the levels of Hb A1C within each treatment group, regardless of the imputation strategy. However, the differences were not significant when comparing postintervention Hb A1C means between groups with unaltered data (P = .23), because the U-500 group Hb A1C improvement gap narrowed at the end of study. In the multivariate analysis, irrespective of imputation method, the differences in Hb A1C between group treated with U-100 and U-500 were statistically significant (Table 3).

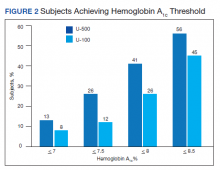

Overall, more subjects in the U-500 group than in the U-100 group achieved Hb A1C levels < 8.5% (56% vs 46%, respectively, P = .003) and the proportion of subjects achieving Hb A1C levels < 7.5% doubled that of the U-100 group (26% vs 12%; Figure 2). Five subjects in the U-500 group experienced severe hypoglycemia, compared with 1 in the U-100 group (P = .08). The total daily insulin dose was significantly higher in the U-500 group (296 units daily) than in the U-100 group (209 units daily) (P < .001) (Table 2). Baseline weight and BMI differences were also significant for the U-500 and U-100 groups (P < .001). Weight gain of approximately 2 kg occurred in both groups, a change that was not statistically significant (P = .79)

There were 21 new ASCVD events in the U-100 and 16 in the U-500 group (P = .51) and there were no statistically significant differences in the incidence of new CAD, PVD or CVA events. The U-500 group required significantly fewer injections than U-100 insulin users (2 vs 4; P < .001).

Discussion

The purpose of the study was to compare subjects with obesity and T2DM using U-500 concentrated insulin with similarly matched subjects using U-100 insulin. Available studies using U-500 insulin, including prospective trials, have reported the experience after transitioning patients who “failed” U-100 regimens.13-16,18,21-24 This failure is a relative and transient condition that, in theory, could be improved with medical intervention and lifestyle changes. Such changes cannot be easily quantified in a clinical trial or retrospective study without a control group. This study was an attempt to fill this knowledge gap.

The U-500 intervention resulted in a 0.8% overall reduction in Hb A1C and a significant 0.4% reduction compared to subjects using U-100. While both groups had improvement in Hb A1C , U-500 was associated with superior reductions in Hb A1C . This finding confirms prior assertions that U-500, compared with U-100, is associated with larger Hb A1C improvement.14-16

The preintervention and postintervention Hb A1C means were > 8% in both groups. This finding suggests that lowering Hb A1C is challenging, similar to published results demonstrating that Hb A1C levels < 7% are achieved by fewer than one-third of U-500 users.16-18 The explanation for this finding remains elusive, due to the methodologic limitations of a retrospective analysis. A possible explanation is the high prevalence of CKD and ASCVD among the study population, conditions which, according to guidelines justify less aggressive glycemic control efforts.25 Multiple prior studies using retrospective data8,13-16 and 2 prospective trials18,22 demonstrated similar Hb A1C reductions after failure of U-100 regimens.

In this study, U-500 resulted in a nominal increase in the risk of severe hypoglycemic episodes. A detailed review of the events found that most of these patients had preestablished CKD and ASCVD, and half of the subjects with sever hypoglycemic episodes had new vascular events during the study (Appendix). These findings suggest a possible correlation between CKD and ASCVD complications and the risk of severe hypoglycemic events. Pharmacokinetic profiles for U-500 have not been studied in subjects with CKD, but the clinical effect of CKD is likely prolonged by the expected reduction in insulin clearance. Similarly, the frailty associated with preexisting ASCVD, or the related polypharmacy, could be factors increasing the risk of hypoglycemia and deserve further study.

Most of the U-500 subjects used it twice daily in this study, which could have contributed to the higher hypoglycemia rate. In a prospective randomized trial Hood and colleagues reported a rate of symptomatic hypoglycemia exceeding 90% in the 2 study groups, and 8 subjects (of 325 total) had severe hypoglycemia during the 6-month observation. The group assigned to 2 daily injections had a significantly higher rate of hypoglycemic events compared with a group that had 3 injections per day.18 Additional studies are required to ascertain whether U-500, compared with specific U-100 regimens (basal-bolus vs premixed; human vs insulin analogs), results in a higher risk of severe hypoglycemia.

This study also investigated the incidence of new cardiovascular events, and no difference was found between the 2 groups. A longer observation would be required to better assess whether U-500 therapy can reduce the incidence of microvascular and macrovascular complications. The similar incidence of complications is further evidence of the similarity between the 2 studied groups. It was also reassuring to find that weight gains were small and nearly identical in both insulin groups.

Strengths and Limitations

This study has several limitations. Data about hospitalizations for congestive heart failure, amputations, progression of diabetic retinopathy, neuropathy, and nephropathy were not collected for this analysis. As both groups of subjects were relatively small, statistical power to assess outcomes is a concern. Retrospective chart reviews may also be affected by incomplete data collections and multiple biases. No data were available for other hypoglycemic episodes, especially to calculate the rate of the more common forms of hypoglycemia. The period of data analyzed spanned only about 15 months. A longer, longitudinal assessment of the differences between these 2 groups may yield more differences, and clearer results and conclusions. Moreover, the data set had aged before publication of this report; however, the authors think that the analysis and information remain highly clinically relevant. The uncommon use of U-500, and prominence as a “special case” insulin may also lead to a detection bias for severe hypoglycemia in the U-500 group. In contrast, lapses in documentation of hypoglycemia in subjects using U-100 could have occurred. Finally, the differences in total daily dose and body weight among groups were significant and may reflect on important physiologic differences between the 2 groups that may affect the reproducibility of our results.

Nevertheless, this study had notable strengths. Comparing U-500 insulin users with similar subjects using U-100 over a period of time provides head-to-head data with potentially important clinical utility. Also, we collected and analyzed a sizable number of clinically important variables, including cardiovascular risk factors, the occurrence of new cardiovascular events, and prevalence of renal disease. The use of linear regression and multivariate analysis using multiple models also strengthened the results. Previous studies compared the outcomes in subjects using U-500 insulin with only their historical selves.8,13-16,18,19,22-25 Therefore, these studies analyzed the data for preconversion and postconversion of U-500 only and consistently favored U-500. This design in a retrospective study cannot eliminate the selection and/or intervention biases, as the subjects of study had inevitably “failed” prior therapies. Similarly, there is no prospective clinical trial data comparing patients on U-500 with patients on high doses of U-100 insulin. Finally, the patients in our study had high rates of comorbidities, which may have increased the applicability of our results to those of “real-life” patients in the community. To our knowledge, no other study has attempted a similar study design approach either prospectively or retrospectively.

Conclusions

In this population of elderly veterans with severely insulin-resistant T2DM, with a high incidence of CKD and ASCVD, U-500 insulin was associated with significantly greater reductions in Hb A1C than U-100 insulin-based regimens, while requiring fewer injections. No difference was noted in the incidence of new ASCVD events. More studies are needed to assess whether U-500 may increase the risk of severe hypoglycemic episodes.

Acknowledgments

The authors recognize the invaluable help provided by the editorial staff of University of South Florida IMpact, the Intramural Review to Support Research and Scientific Publication, and especially to Richard F. Lockey, MD, who has mentored us in this beautiful journey of scientific writing and for his editorial assistance. A portion of this study preliminary data was presented as an abstract at ENDO 2013, The Endocrine Society Annual meeting in San Francisco, CA, June 15-18, 2013.

Appendix. Severe Hypoglycemic Events

Subject 1: U-500 user, 61-year-old African American male. Hypoglycemia occurred during fasting and was associated with a seizure-like event 9 months after transition to concentrated insulin. He was taken by ambulance to a local hospital. No additional data were obtained. Hb A1C was 8.2% in the month before the episode (lowest of the studied period) and increased to 9.1% in the last segment of the study.

Subject 2: U-500 user, 57-year-old white male. The severe hypoglycemic episode occurred approximately 8 months after transition. His Hb A1C was 5.6% around the time of the event, the lowest of the studied period, and increased to 6.8% over the next 4 months. No other data were available.

Subject 3: U-500 user, 67-year-old white male. The event occurred at home in the morning while fasting, 3 months after transition. He was assisted by his family. Hb A1C was 7.1% 10 weeks after the event and was 7% at the end of the studied period. He had a history of CKD and PVD.

Subject 4: U-500 user, 68-year-old white male. He presented with altered consciousness, hypoglycemia, and elevated troponin levels, which was later confirmed as a non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), 7 months after transition. Hb A1C during the events was 7.1% and was followed by a 9.3% level 9 weeks later. He had history of CKD and PVD.

Subject 5: U-500 user, 67-year-old white man. Hypoglycemia occurred 6 months after transition to U-500. Hb A1C was 8.4% 2 months prior, and was followed by a 7% during the admission for severe hypoglycemia. 3 months later, his HbA1c rose to 8.2%. He had an extensive history of CAD and had a NSTEMI during the study period.

Subject 6: U-100 user, 65-year-old white man. He was found unconscious in the morning while fasting, 6 months after his first clinic visit. He had CKD and advanced ASCVD with prior CAD, PVD, and CVA. He had also had a recent CVA that had affected his movement and cognition.

1. Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2015–2016. NCHS data brief no. 288. Published October 2017. Accessed January 29, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db288.htm

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diabetes and prediabetes: CDC works to prevent type 2 diabetes and improve the health of all people with diabetes. Updated November 30, 2020. Accessed February 17, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/resources/publications/factsheets/diabetes-prediabetes.htm

3. Cochran E, Gorden P. Use of U-500 insulin in the treatment of severe insulin resistance. Insulin. 2008;3(4):211-218 [Published correction appears in Insulin. 2009;4(1):81]. doi:10.1016/S1557-0843(08)80049-8

4. Shrestha RT, Kumar AF, Taddese A, et al. Duration and onset of action of high dose U-500 regular insulin in severely insulin resistant subjects with type 2 diabetes. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab. 2018;1(4):e00041. Published 2018 Sep 10. doi:10.1002/edm2.41

5. Dailey AM, Tannock LR. Extreme insulin resistance: indications and approaches to the use of U-500 insulin in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Curr Diab Rep. 2011;11(2):77-82. doi:10.1007/s11892-010-0167-6

6. de la Peña A, Riddle M, Morrow LA, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of high-dose human regular U-500 insulin versus human regular U-100 insulin in healthy obese subjects [published correction appears in Diabetes Care. 2014 Aug;37(8):2414]. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(12):2496-2501. doi:10.2337/dc11-0721

7. Brusko C, Jackson JA, de la Peña A. Comparative properties of U-500 and U-100 regular human insulin. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70(15):1283-1284. doi:10.2146/130117

8. Dailey AM, Williams S, Taneja D, Tannock LR. Clinical efficacy and patient satisfaction with U-500 insulin use. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;88(3):259-264. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2010.02.012

9. Wysham C, Hood RC, Warren ML, Wang T, Morwick TM, Jackson JA. Effect of total daily dose on efficacy, dosing, and safety of 2 dose titration regimens of human regular U-500 insulin in severely insulin-resistant patients with type 2 diabetes. Endocr Pract. 2010;22(6):653-665. doi:10.4158/EP15959.OR

10. Gagnon-Auger M, du Souich P, Baillargeon JP, et al. Dose-dependent delay of the hypoglycemic effect of short-acting insulin analogs in obese subjects with type 2 diabetes: a pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(12):2502-2507. doi:10.2337/dc10-1126

11. Schloot NC, Hood RC, Corrigan SM, Panek RL, Heise T. Concentrated insulins in current clinical practice. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2019;148:93-101. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2018.12.007

12. Lane WS, Cochran EK, Jackson JA, et al. High-dose insulin therapy: is it time for U-500 insulin?. Endocr Pract. 2009;15(1):71-79. doi:10.4158/EP.15.1.71

13. Boldo A, Comi RJ. Clinical experience with U500 insulin: risks and benefits. Endocr Pract. 2012;18(1):56-61. doi:10.4158/EP11163.OR

14. Granata JA, Nawarskas AD, Resch ND, Vigil JM. Evaluating the effect of u-500 insulin therapy on glycemic control in veterans with type 2 diabetes. Clin Diabetes. 2015;33(1):14-19. doi:10.2337/diaclin.33.1.14

15. Eby EL, Zagar AJ, Wang P, et al. Healthcare costs and adherence associated with human regular U-500 versus high-dose U-100 insulin in patients with diabetes. Endocr Pract. 2014;20(7):663-670. doi:10.4158/EP13407.OR

16. Eby EL, Curtis BH, Gelwicks SC, et al. Initiation of human regular U-500 insulin use is associated with improved glycemic control: a real-world US cohort study. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2015;3(1):e000074. Published 2015 Apr 30. doi:10.1136/bmjdrc-2014-000074

17. Jones P, Idris I. The use of U-500 regular insulin in the management of patients with obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2013;15(10):882-887. doi:10.1111/dom.12094

18. Hood RC, Arakaki RF, Wysham C, Li YG, Settles JA, Jackson JA. Two treatment approaches for human regular U-500 insulin in patients with type 2 diabetes not achieving adequate glycemic control on high-dose U-100 insulin therapy with or without oral agents: a randomized, titration-to-target clinical trial. Endocr Pract. 2015;21(7):782-793. doi: 10.4158/EP15612.OR

19. Ballani P, Tran MT, Navar MD, Davidson MB. Clinical experience with U-500 regular insulin in obese, markedly insulin-resistant type 2 diabetic patients [published correction appears in Diabetes Care. 2007 Feb;30(2):455]. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(11):2504-2505. doi:10.2337/dc06-1478

20. Davidson MB, Navar MD, Echeverry D, Duran P. U-500 regular insulin: clinical experience and pharmacokinetics in obese, severely insulin-resistant type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(2):281-283. doi:10.2337/dc09-1490

21. Bulchandani DG, Konrady T, Hamburg MS. Clinical efficacy and patient satisfaction with U-500 insulin pump therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes. Endocr Pract. 2007;13(7):721-725. doi:10.4158/EP.13.7.721

22. Lane WS, Weinrib SL, Rappaport JM, Przestrzelski T. A prospective trial of U500 insulin delivered by Omnipod in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and severe insulin resistance [published correction appears in Endocr Pract. 2010 Nov-Dec;16(6):1082]. Endocr Pract. 2010;16(5):778-784. doi:10.4158/EP10014.OR

23. Martin C, Perez-Molinar D, Shah M, Billington C. U500 Disposable Patch Insulin Pump: Results and Discussion of a Veterans Affairs Pilot Study. J Endocr Soc. 2018;2(11):1275-1283. Published 2018 Sep 17. doi:10.1210/js.2018-00198

24. Ziesmer AE, Kelly KC, Guerra PA, George KG, Dunn FL. U500 regular insulin use in insulin-resistant type 2 diabetic veteran patients. Endocr Pract. 2012;18(1):34-38. doi:10.4158/EP11043.OR

25. American Diabetes Association. 6. Glycemic Targets: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(Suppl 1):S61-S70. doi:10.2337/dc19-S006

More than 70% of Americans are overweight or obese and 1 in 10 has type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). In the last 20 years, the prevalence of obesity and DM has each increased drastically according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.1,2 Thus, an increase in severe insulin-resistant DM is predicted. Severe insulin resistance occurs when insulin doses exceed 200 units per day or 2 units/kg per day.3-5 Treating this condition demands large volumes of U-100 insulin and a high frequency of injections (usually 4-7 per day), which can lead to reduced patient adherence.8-10 Likewise, large injected volumes are more painful and can lead to altered absorption.3,9-11

U-500 insulin (500 units/mL) is 5 times more concentrated than U-100 insulin and has advantages in the management of severe insulin-resistant DM.11-13 Its pharmacokinetic profile is unique, for the clinical effect can last for up to 24 hours.4-6 U-500 can replace basal-bolus and other complex insulin regimens, offering convenient, effective glycemic control with 2 or 3 injections per day.11,14-20 U-500 can also improve the quality of life and adherence compared with formulations that require more frequent injections.7,14,21 Historically, only exceptional or “special” cases were treated with U-500, but demand for concentrated insulins has increased in the last decade as clinicians adjust their care for this growing patient population.17

The purpose of this study was to determine whether a population of subjects with severe insulin-resistant T2DM would benefit from the use of U-500 vs U-100 insulin regimens. The hypothesis was that this population would obtain equal or better glycemic control while achieving improved adherence. Other studies have demonstrated that U-500 yields improvements in glycemic control but also potentially increases hypoglycemic episodes.15-18,22-24 To our knowledge, this study is the first to evaluate the clinical outcomes of subjects with severe insulin-resistant T2DM who changed from U-100 to U-500 vs subjects who remained on high-dose U-100 insulin.

Methods

This was a single-site, retrospective chart review of subjects with T2DM who attended the endocrinology specialty clinic at the James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital (JAHVA) in Tampa, Florida, between July 2002 and June 2011. The study included a group of subjects using U-500 insulin and a comparison group using U-100 insulin. The study was approved by the JAHVA Research & Development Committee and by the University of South Florida Institutional Review Board.

Inclusion criteria included diagnosis of T2DM, body mass index (BMI) of more than 30, use of U-500 insulin, or > 200 units daily of U-100 insulin. Exclusion criteria included hypoglycemia unawareness, type 1 DM, and use of an insulin pump. A total of 142 subjects met the inclusion criteria (68 in the U-500 group and 74 in the U-100 group).

All study subjects had at least 1 DM education session. U-500 subjects used insulin vials and 1-mL volumetric hypodermal syringes. All U-500 prescriptions were issued electronically in units and volume (U-500 insulin was available exclusively in vials during the time frame from which data were collected). Subjects in the U-100 group used insulin vials or pen devices. Laboratory studies were processed in house by the institution using high-pressure liquid chromatography to determine hemoglobin A1C (Hb A1C) levels. All study subjects required at least 2 Hb A1C measurements over the observed 12 months for inclusion.

Transition to U-500 Insulin

U-500 transition was considered routinely and presented as an option for patients requiring > 200 units of insulin daily. The transition criteria included adherence to medications, follow-up appointments, and glucose monitoring recommendations, and ability to learn and apply insulin self-adjustment instructions. All subjects were given an additional U-500 insulin education session before transition. The endocrinologist calculated all starting doses by reducing the total daily dose by 20%.

Data Collection

Data were collected using the automatic data mining tools within the JAHVA Computerized Patient Record System and confirmed individually by clinical staff. Demographic data included age, race, and sex. Other parameters were weight; BMI; Hb A1C; estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR); duration of DM; use of metformin and other oral agents; total daily insulin dose; number of daily injections; prior history of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), including coronary artery disease (CAD), cerebrovascular accident (CVA), or peripheral vascular disease (PVD); occurrence of severe hypoglycemia (symptomatic hypoglycemia requiring treatment assistance from another individual) and of new cardiovascular events, classified as CAD, CVA, or PVD.

For the U-500 group, data were collected and analyzed for the 3 months before (baseline) and the 12 months after the initiation of concentrated insulin. For the U-100 group, data were collected and analyzed for the comparable 3 months before (baseline) and the 12 months after the first clinic visit in which the subject started using more than 200 units per day of U-100. Frequency of follow-up visits was individualized according to clinical needs.

Clinical Endpoints

Primary outcomes included changes in Hb A1C from baseline to the following 12 months, and the occurrence of severe hypoglycemia. Secondary outcomes included the occurrence of new ASCVD events during the study, and changes in weight, BMI, and number of injections.

Statistical Analysis

The primary and secondary outcomes were assessed through univariate and multivariate general linear models. Multivariate models were used to compare differences in the variation of Hb A1C over time. Data were incomplete for the Hb A1C in 27 subjects, 6% of the dataset (Each subject had more than one variable or observation). Therefore, a multiple imputation was used to account for the incompleteness on Hb A1C (value substitutions by the mean and by the prior Hb A1C and models were balanced against the unaltered data). A P value of ≤ .05 was used to determine statistical significance. The statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 21.

Results

Most patients were male (94%) of white race (86%), with a mean age of 57 years and comparable duration of DM (Table 1). Demographics were balanced between the groups, except for weight and BMI, both higher in the U-500 group (P < .001). Use of oral antidiabetic agents was not significantly different between groups, nor were comorbid conditions, with nearly 50% of subjects in each group affected by CKD and ASCVD, of which CAD was the most common (approximately 40% of both groups). Only about one-third of subjects used metformin and/or other oral agents, likely due to the high prevalence of CKD (contraindicating metformin) and high insulin requirements (due to correlation with β cell failure). A subgroup analysis of subjects on metformin did not demonstrate significant differences in risk of severe hypoglycemia or in Hb A1C levels (data not shown).

Both groups had similar initial Hb A1C baselines (> 9%) and both improved glycemic control during the study period. However, the Hb A1C reduction was greater in the U-500 group (P= .034), 0.84% vs 0.56% for U-100 and the between-groups difference was 0.4%. (Figure 1, Tables 2 and 3).

The univariate general linear model shows a statistically significant difference in the levels of Hb A1C within each treatment group, regardless of the imputation strategy. However, the differences were not significant when comparing postintervention Hb A1C means between groups with unaltered data (P = .23), because the U-500 group Hb A1C improvement gap narrowed at the end of study. In the multivariate analysis, irrespective of imputation method, the differences in Hb A1C between group treated with U-100 and U-500 were statistically significant (Table 3).

Overall, more subjects in the U-500 group than in the U-100 group achieved Hb A1C levels < 8.5% (56% vs 46%, respectively, P = .003) and the proportion of subjects achieving Hb A1C levels < 7.5% doubled that of the U-100 group (26% vs 12%; Figure 2). Five subjects in the U-500 group experienced severe hypoglycemia, compared with 1 in the U-100 group (P = .08). The total daily insulin dose was significantly higher in the U-500 group (296 units daily) than in the U-100 group (209 units daily) (P < .001) (Table 2). Baseline weight and BMI differences were also significant for the U-500 and U-100 groups (P < .001). Weight gain of approximately 2 kg occurred in both groups, a change that was not statistically significant (P = .79)

There were 21 new ASCVD events in the U-100 and 16 in the U-500 group (P = .51) and there were no statistically significant differences in the incidence of new CAD, PVD or CVA events. The U-500 group required significantly fewer injections than U-100 insulin users (2 vs 4; P < .001).

Discussion

The purpose of the study was to compare subjects with obesity and T2DM using U-500 concentrated insulin with similarly matched subjects using U-100 insulin. Available studies using U-500 insulin, including prospective trials, have reported the experience after transitioning patients who “failed” U-100 regimens.13-16,18,21-24 This failure is a relative and transient condition that, in theory, could be improved with medical intervention and lifestyle changes. Such changes cannot be easily quantified in a clinical trial or retrospective study without a control group. This study was an attempt to fill this knowledge gap.

The U-500 intervention resulted in a 0.8% overall reduction in Hb A1C and a significant 0.4% reduction compared to subjects using U-100. While both groups had improvement in Hb A1C , U-500 was associated with superior reductions in Hb A1C . This finding confirms prior assertions that U-500, compared with U-100, is associated with larger Hb A1C improvement.14-16

The preintervention and postintervention Hb A1C means were > 8% in both groups. This finding suggests that lowering Hb A1C is challenging, similar to published results demonstrating that Hb A1C levels < 7% are achieved by fewer than one-third of U-500 users.16-18 The explanation for this finding remains elusive, due to the methodologic limitations of a retrospective analysis. A possible explanation is the high prevalence of CKD and ASCVD among the study population, conditions which, according to guidelines justify less aggressive glycemic control efforts.25 Multiple prior studies using retrospective data8,13-16 and 2 prospective trials18,22 demonstrated similar Hb A1C reductions after failure of U-100 regimens.

In this study, U-500 resulted in a nominal increase in the risk of severe hypoglycemic episodes. A detailed review of the events found that most of these patients had preestablished CKD and ASCVD, and half of the subjects with sever hypoglycemic episodes had new vascular events during the study (Appendix). These findings suggest a possible correlation between CKD and ASCVD complications and the risk of severe hypoglycemic events. Pharmacokinetic profiles for U-500 have not been studied in subjects with CKD, but the clinical effect of CKD is likely prolonged by the expected reduction in insulin clearance. Similarly, the frailty associated with preexisting ASCVD, or the related polypharmacy, could be factors increasing the risk of hypoglycemia and deserve further study.

Most of the U-500 subjects used it twice daily in this study, which could have contributed to the higher hypoglycemia rate. In a prospective randomized trial Hood and colleagues reported a rate of symptomatic hypoglycemia exceeding 90% in the 2 study groups, and 8 subjects (of 325 total) had severe hypoglycemia during the 6-month observation. The group assigned to 2 daily injections had a significantly higher rate of hypoglycemic events compared with a group that had 3 injections per day.18 Additional studies are required to ascertain whether U-500, compared with specific U-100 regimens (basal-bolus vs premixed; human vs insulin analogs), results in a higher risk of severe hypoglycemia.

This study also investigated the incidence of new cardiovascular events, and no difference was found between the 2 groups. A longer observation would be required to better assess whether U-500 therapy can reduce the incidence of microvascular and macrovascular complications. The similar incidence of complications is further evidence of the similarity between the 2 studied groups. It was also reassuring to find that weight gains were small and nearly identical in both insulin groups.

Strengths and Limitations

This study has several limitations. Data about hospitalizations for congestive heart failure, amputations, progression of diabetic retinopathy, neuropathy, and nephropathy were not collected for this analysis. As both groups of subjects were relatively small, statistical power to assess outcomes is a concern. Retrospective chart reviews may also be affected by incomplete data collections and multiple biases. No data were available for other hypoglycemic episodes, especially to calculate the rate of the more common forms of hypoglycemia. The period of data analyzed spanned only about 15 months. A longer, longitudinal assessment of the differences between these 2 groups may yield more differences, and clearer results and conclusions. Moreover, the data set had aged before publication of this report; however, the authors think that the analysis and information remain highly clinically relevant. The uncommon use of U-500, and prominence as a “special case” insulin may also lead to a detection bias for severe hypoglycemia in the U-500 group. In contrast, lapses in documentation of hypoglycemia in subjects using U-100 could have occurred. Finally, the differences in total daily dose and body weight among groups were significant and may reflect on important physiologic differences between the 2 groups that may affect the reproducibility of our results.

Nevertheless, this study had notable strengths. Comparing U-500 insulin users with similar subjects using U-100 over a period of time provides head-to-head data with potentially important clinical utility. Also, we collected and analyzed a sizable number of clinically important variables, including cardiovascular risk factors, the occurrence of new cardiovascular events, and prevalence of renal disease. The use of linear regression and multivariate analysis using multiple models also strengthened the results. Previous studies compared the outcomes in subjects using U-500 insulin with only their historical selves.8,13-16,18,19,22-25 Therefore, these studies analyzed the data for preconversion and postconversion of U-500 only and consistently favored U-500. This design in a retrospective study cannot eliminate the selection and/or intervention biases, as the subjects of study had inevitably “failed” prior therapies. Similarly, there is no prospective clinical trial data comparing patients on U-500 with patients on high doses of U-100 insulin. Finally, the patients in our study had high rates of comorbidities, which may have increased the applicability of our results to those of “real-life” patients in the community. To our knowledge, no other study has attempted a similar study design approach either prospectively or retrospectively.

Conclusions

In this population of elderly veterans with severely insulin-resistant T2DM, with a high incidence of CKD and ASCVD, U-500 insulin was associated with significantly greater reductions in Hb A1C than U-100 insulin-based regimens, while requiring fewer injections. No difference was noted in the incidence of new ASCVD events. More studies are needed to assess whether U-500 may increase the risk of severe hypoglycemic episodes.

Acknowledgments

The authors recognize the invaluable help provided by the editorial staff of University of South Florida IMpact, the Intramural Review to Support Research and Scientific Publication, and especially to Richard F. Lockey, MD, who has mentored us in this beautiful journey of scientific writing and for his editorial assistance. A portion of this study preliminary data was presented as an abstract at ENDO 2013, The Endocrine Society Annual meeting in San Francisco, CA, June 15-18, 2013.

Appendix. Severe Hypoglycemic Events

Subject 1: U-500 user, 61-year-old African American male. Hypoglycemia occurred during fasting and was associated with a seizure-like event 9 months after transition to concentrated insulin. He was taken by ambulance to a local hospital. No additional data were obtained. Hb A1C was 8.2% in the month before the episode (lowest of the studied period) and increased to 9.1% in the last segment of the study.

Subject 2: U-500 user, 57-year-old white male. The severe hypoglycemic episode occurred approximately 8 months after transition. His Hb A1C was 5.6% around the time of the event, the lowest of the studied period, and increased to 6.8% over the next 4 months. No other data were available.

Subject 3: U-500 user, 67-year-old white male. The event occurred at home in the morning while fasting, 3 months after transition. He was assisted by his family. Hb A1C was 7.1% 10 weeks after the event and was 7% at the end of the studied period. He had a history of CKD and PVD.

Subject 4: U-500 user, 68-year-old white male. He presented with altered consciousness, hypoglycemia, and elevated troponin levels, which was later confirmed as a non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), 7 months after transition. Hb A1C during the events was 7.1% and was followed by a 9.3% level 9 weeks later. He had history of CKD and PVD.

Subject 5: U-500 user, 67-year-old white man. Hypoglycemia occurred 6 months after transition to U-500. Hb A1C was 8.4% 2 months prior, and was followed by a 7% during the admission for severe hypoglycemia. 3 months later, his HbA1c rose to 8.2%. He had an extensive history of CAD and had a NSTEMI during the study period.

Subject 6: U-100 user, 65-year-old white man. He was found unconscious in the morning while fasting, 6 months after his first clinic visit. He had CKD and advanced ASCVD with prior CAD, PVD, and CVA. He had also had a recent CVA that had affected his movement and cognition.

More than 70% of Americans are overweight or obese and 1 in 10 has type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). In the last 20 years, the prevalence of obesity and DM has each increased drastically according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.1,2 Thus, an increase in severe insulin-resistant DM is predicted. Severe insulin resistance occurs when insulin doses exceed 200 units per day or 2 units/kg per day.3-5 Treating this condition demands large volumes of U-100 insulin and a high frequency of injections (usually 4-7 per day), which can lead to reduced patient adherence.8-10 Likewise, large injected volumes are more painful and can lead to altered absorption.3,9-11

U-500 insulin (500 units/mL) is 5 times more concentrated than U-100 insulin and has advantages in the management of severe insulin-resistant DM.11-13 Its pharmacokinetic profile is unique, for the clinical effect can last for up to 24 hours.4-6 U-500 can replace basal-bolus and other complex insulin regimens, offering convenient, effective glycemic control with 2 or 3 injections per day.11,14-20 U-500 can also improve the quality of life and adherence compared with formulations that require more frequent injections.7,14,21 Historically, only exceptional or “special” cases were treated with U-500, but demand for concentrated insulins has increased in the last decade as clinicians adjust their care for this growing patient population.17

The purpose of this study was to determine whether a population of subjects with severe insulin-resistant T2DM would benefit from the use of U-500 vs U-100 insulin regimens. The hypothesis was that this population would obtain equal or better glycemic control while achieving improved adherence. Other studies have demonstrated that U-500 yields improvements in glycemic control but also potentially increases hypoglycemic episodes.15-18,22-24 To our knowledge, this study is the first to evaluate the clinical outcomes of subjects with severe insulin-resistant T2DM who changed from U-100 to U-500 vs subjects who remained on high-dose U-100 insulin.

Methods

This was a single-site, retrospective chart review of subjects with T2DM who attended the endocrinology specialty clinic at the James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital (JAHVA) in Tampa, Florida, between July 2002 and June 2011. The study included a group of subjects using U-500 insulin and a comparison group using U-100 insulin. The study was approved by the JAHVA Research & Development Committee and by the University of South Florida Institutional Review Board.

Inclusion criteria included diagnosis of T2DM, body mass index (BMI) of more than 30, use of U-500 insulin, or > 200 units daily of U-100 insulin. Exclusion criteria included hypoglycemia unawareness, type 1 DM, and use of an insulin pump. A total of 142 subjects met the inclusion criteria (68 in the U-500 group and 74 in the U-100 group).

All study subjects had at least 1 DM education session. U-500 subjects used insulin vials and 1-mL volumetric hypodermal syringes. All U-500 prescriptions were issued electronically in units and volume (U-500 insulin was available exclusively in vials during the time frame from which data were collected). Subjects in the U-100 group used insulin vials or pen devices. Laboratory studies were processed in house by the institution using high-pressure liquid chromatography to determine hemoglobin A1C (Hb A1C) levels. All study subjects required at least 2 Hb A1C measurements over the observed 12 months for inclusion.

Transition to U-500 Insulin

U-500 transition was considered routinely and presented as an option for patients requiring > 200 units of insulin daily. The transition criteria included adherence to medications, follow-up appointments, and glucose monitoring recommendations, and ability to learn and apply insulin self-adjustment instructions. All subjects were given an additional U-500 insulin education session before transition. The endocrinologist calculated all starting doses by reducing the total daily dose by 20%.

Data Collection

Data were collected using the automatic data mining tools within the JAHVA Computerized Patient Record System and confirmed individually by clinical staff. Demographic data included age, race, and sex. Other parameters were weight; BMI; Hb A1C; estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR); duration of DM; use of metformin and other oral agents; total daily insulin dose; number of daily injections; prior history of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), including coronary artery disease (CAD), cerebrovascular accident (CVA), or peripheral vascular disease (PVD); occurrence of severe hypoglycemia (symptomatic hypoglycemia requiring treatment assistance from another individual) and of new cardiovascular events, classified as CAD, CVA, or PVD.

For the U-500 group, data were collected and analyzed for the 3 months before (baseline) and the 12 months after the initiation of concentrated insulin. For the U-100 group, data were collected and analyzed for the comparable 3 months before (baseline) and the 12 months after the first clinic visit in which the subject started using more than 200 units per day of U-100. Frequency of follow-up visits was individualized according to clinical needs.

Clinical Endpoints

Primary outcomes included changes in Hb A1C from baseline to the following 12 months, and the occurrence of severe hypoglycemia. Secondary outcomes included the occurrence of new ASCVD events during the study, and changes in weight, BMI, and number of injections.

Statistical Analysis

The primary and secondary outcomes were assessed through univariate and multivariate general linear models. Multivariate models were used to compare differences in the variation of Hb A1C over time. Data were incomplete for the Hb A1C in 27 subjects, 6% of the dataset (Each subject had more than one variable or observation). Therefore, a multiple imputation was used to account for the incompleteness on Hb A1C (value substitutions by the mean and by the prior Hb A1C and models were balanced against the unaltered data). A P value of ≤ .05 was used to determine statistical significance. The statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 21.

Results

Most patients were male (94%) of white race (86%), with a mean age of 57 years and comparable duration of DM (Table 1). Demographics were balanced between the groups, except for weight and BMI, both higher in the U-500 group (P < .001). Use of oral antidiabetic agents was not significantly different between groups, nor were comorbid conditions, with nearly 50% of subjects in each group affected by CKD and ASCVD, of which CAD was the most common (approximately 40% of both groups). Only about one-third of subjects used metformin and/or other oral agents, likely due to the high prevalence of CKD (contraindicating metformin) and high insulin requirements (due to correlation with β cell failure). A subgroup analysis of subjects on metformin did not demonstrate significant differences in risk of severe hypoglycemia or in Hb A1C levels (data not shown).

Both groups had similar initial Hb A1C baselines (> 9%) and both improved glycemic control during the study period. However, the Hb A1C reduction was greater in the U-500 group (P= .034), 0.84% vs 0.56% for U-100 and the between-groups difference was 0.4%. (Figure 1, Tables 2 and 3).

The univariate general linear model shows a statistically significant difference in the levels of Hb A1C within each treatment group, regardless of the imputation strategy. However, the differences were not significant when comparing postintervention Hb A1C means between groups with unaltered data (P = .23), because the U-500 group Hb A1C improvement gap narrowed at the end of study. In the multivariate analysis, irrespective of imputation method, the differences in Hb A1C between group treated with U-100 and U-500 were statistically significant (Table 3).

Overall, more subjects in the U-500 group than in the U-100 group achieved Hb A1C levels < 8.5% (56% vs 46%, respectively, P = .003) and the proportion of subjects achieving Hb A1C levels < 7.5% doubled that of the U-100 group (26% vs 12%; Figure 2). Five subjects in the U-500 group experienced severe hypoglycemia, compared with 1 in the U-100 group (P = .08). The total daily insulin dose was significantly higher in the U-500 group (296 units daily) than in the U-100 group (209 units daily) (P < .001) (Table 2). Baseline weight and BMI differences were also significant for the U-500 and U-100 groups (P < .001). Weight gain of approximately 2 kg occurred in both groups, a change that was not statistically significant (P = .79)

There were 21 new ASCVD events in the U-100 and 16 in the U-500 group (P = .51) and there were no statistically significant differences in the incidence of new CAD, PVD or CVA events. The U-500 group required significantly fewer injections than U-100 insulin users (2 vs 4; P < .001).

Discussion

The purpose of the study was to compare subjects with obesity and T2DM using U-500 concentrated insulin with similarly matched subjects using U-100 insulin. Available studies using U-500 insulin, including prospective trials, have reported the experience after transitioning patients who “failed” U-100 regimens.13-16,18,21-24 This failure is a relative and transient condition that, in theory, could be improved with medical intervention and lifestyle changes. Such changes cannot be easily quantified in a clinical trial or retrospective study without a control group. This study was an attempt to fill this knowledge gap.

The U-500 intervention resulted in a 0.8% overall reduction in Hb A1C and a significant 0.4% reduction compared to subjects using U-100. While both groups had improvement in Hb A1C , U-500 was associated with superior reductions in Hb A1C . This finding confirms prior assertions that U-500, compared with U-100, is associated with larger Hb A1C improvement.14-16

The preintervention and postintervention Hb A1C means were > 8% in both groups. This finding suggests that lowering Hb A1C is challenging, similar to published results demonstrating that Hb A1C levels < 7% are achieved by fewer than one-third of U-500 users.16-18 The explanation for this finding remains elusive, due to the methodologic limitations of a retrospective analysis. A possible explanation is the high prevalence of CKD and ASCVD among the study population, conditions which, according to guidelines justify less aggressive glycemic control efforts.25 Multiple prior studies using retrospective data8,13-16 and 2 prospective trials18,22 demonstrated similar Hb A1C reductions after failure of U-100 regimens.

In this study, U-500 resulted in a nominal increase in the risk of severe hypoglycemic episodes. A detailed review of the events found that most of these patients had preestablished CKD and ASCVD, and half of the subjects with sever hypoglycemic episodes had new vascular events during the study (Appendix). These findings suggest a possible correlation between CKD and ASCVD complications and the risk of severe hypoglycemic events. Pharmacokinetic profiles for U-500 have not been studied in subjects with CKD, but the clinical effect of CKD is likely prolonged by the expected reduction in insulin clearance. Similarly, the frailty associated with preexisting ASCVD, or the related polypharmacy, could be factors increasing the risk of hypoglycemia and deserve further study.

Most of the U-500 subjects used it twice daily in this study, which could have contributed to the higher hypoglycemia rate. In a prospective randomized trial Hood and colleagues reported a rate of symptomatic hypoglycemia exceeding 90% in the 2 study groups, and 8 subjects (of 325 total) had severe hypoglycemia during the 6-month observation. The group assigned to 2 daily injections had a significantly higher rate of hypoglycemic events compared with a group that had 3 injections per day.18 Additional studies are required to ascertain whether U-500, compared with specific U-100 regimens (basal-bolus vs premixed; human vs insulin analogs), results in a higher risk of severe hypoglycemia.

This study also investigated the incidence of new cardiovascular events, and no difference was found between the 2 groups. A longer observation would be required to better assess whether U-500 therapy can reduce the incidence of microvascular and macrovascular complications. The similar incidence of complications is further evidence of the similarity between the 2 studied groups. It was also reassuring to find that weight gains were small and nearly identical in both insulin groups.

Strengths and Limitations

This study has several limitations. Data about hospitalizations for congestive heart failure, amputations, progression of diabetic retinopathy, neuropathy, and nephropathy were not collected for this analysis. As both groups of subjects were relatively small, statistical power to assess outcomes is a concern. Retrospective chart reviews may also be affected by incomplete data collections and multiple biases. No data were available for other hypoglycemic episodes, especially to calculate the rate of the more common forms of hypoglycemia. The period of data analyzed spanned only about 15 months. A longer, longitudinal assessment of the differences between these 2 groups may yield more differences, and clearer results and conclusions. Moreover, the data set had aged before publication of this report; however, the authors think that the analysis and information remain highly clinically relevant. The uncommon use of U-500, and prominence as a “special case” insulin may also lead to a detection bias for severe hypoglycemia in the U-500 group. In contrast, lapses in documentation of hypoglycemia in subjects using U-100 could have occurred. Finally, the differences in total daily dose and body weight among groups were significant and may reflect on important physiologic differences between the 2 groups that may affect the reproducibility of our results.

Nevertheless, this study had notable strengths. Comparing U-500 insulin users with similar subjects using U-100 over a period of time provides head-to-head data with potentially important clinical utility. Also, we collected and analyzed a sizable number of clinically important variables, including cardiovascular risk factors, the occurrence of new cardiovascular events, and prevalence of renal disease. The use of linear regression and multivariate analysis using multiple models also strengthened the results. Previous studies compared the outcomes in subjects using U-500 insulin with only their historical selves.8,13-16,18,19,22-25 Therefore, these studies analyzed the data for preconversion and postconversion of U-500 only and consistently favored U-500. This design in a retrospective study cannot eliminate the selection and/or intervention biases, as the subjects of study had inevitably “failed” prior therapies. Similarly, there is no prospective clinical trial data comparing patients on U-500 with patients on high doses of U-100 insulin. Finally, the patients in our study had high rates of comorbidities, which may have increased the applicability of our results to those of “real-life” patients in the community. To our knowledge, no other study has attempted a similar study design approach either prospectively or retrospectively.

Conclusions

In this population of elderly veterans with severely insulin-resistant T2DM, with a high incidence of CKD and ASCVD, U-500 insulin was associated with significantly greater reductions in Hb A1C than U-100 insulin-based regimens, while requiring fewer injections. No difference was noted in the incidence of new ASCVD events. More studies are needed to assess whether U-500 may increase the risk of severe hypoglycemic episodes.

Acknowledgments

The authors recognize the invaluable help provided by the editorial staff of University of South Florida IMpact, the Intramural Review to Support Research and Scientific Publication, and especially to Richard F. Lockey, MD, who has mentored us in this beautiful journey of scientific writing and for his editorial assistance. A portion of this study preliminary data was presented as an abstract at ENDO 2013, The Endocrine Society Annual meeting in San Francisco, CA, June 15-18, 2013.

Appendix. Severe Hypoglycemic Events

Subject 1: U-500 user, 61-year-old African American male. Hypoglycemia occurred during fasting and was associated with a seizure-like event 9 months after transition to concentrated insulin. He was taken by ambulance to a local hospital. No additional data were obtained. Hb A1C was 8.2% in the month before the episode (lowest of the studied period) and increased to 9.1% in the last segment of the study.

Subject 2: U-500 user, 57-year-old white male. The severe hypoglycemic episode occurred approximately 8 months after transition. His Hb A1C was 5.6% around the time of the event, the lowest of the studied period, and increased to 6.8% over the next 4 months. No other data were available.

Subject 3: U-500 user, 67-year-old white male. The event occurred at home in the morning while fasting, 3 months after transition. He was assisted by his family. Hb A1C was 7.1% 10 weeks after the event and was 7% at the end of the studied period. He had a history of CKD and PVD.

Subject 4: U-500 user, 68-year-old white male. He presented with altered consciousness, hypoglycemia, and elevated troponin levels, which was later confirmed as a non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), 7 months after transition. Hb A1C during the events was 7.1% and was followed by a 9.3% level 9 weeks later. He had history of CKD and PVD.

Subject 5: U-500 user, 67-year-old white man. Hypoglycemia occurred 6 months after transition to U-500. Hb A1C was 8.4% 2 months prior, and was followed by a 7% during the admission for severe hypoglycemia. 3 months later, his HbA1c rose to 8.2%. He had an extensive history of CAD and had a NSTEMI during the study period.

Subject 6: U-100 user, 65-year-old white man. He was found unconscious in the morning while fasting, 6 months after his first clinic visit. He had CKD and advanced ASCVD with prior CAD, PVD, and CVA. He had also had a recent CVA that had affected his movement and cognition.

1. Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2015–2016. NCHS data brief no. 288. Published October 2017. Accessed January 29, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db288.htm

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diabetes and prediabetes: CDC works to prevent type 2 diabetes and improve the health of all people with diabetes. Updated November 30, 2020. Accessed February 17, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/resources/publications/factsheets/diabetes-prediabetes.htm

3. Cochran E, Gorden P. Use of U-500 insulin in the treatment of severe insulin resistance. Insulin. 2008;3(4):211-218 [Published correction appears in Insulin. 2009;4(1):81]. doi:10.1016/S1557-0843(08)80049-8

4. Shrestha RT, Kumar AF, Taddese A, et al. Duration and onset of action of high dose U-500 regular insulin in severely insulin resistant subjects with type 2 diabetes. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab. 2018;1(4):e00041. Published 2018 Sep 10. doi:10.1002/edm2.41

5. Dailey AM, Tannock LR. Extreme insulin resistance: indications and approaches to the use of U-500 insulin in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Curr Diab Rep. 2011;11(2):77-82. doi:10.1007/s11892-010-0167-6

6. de la Peña A, Riddle M, Morrow LA, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of high-dose human regular U-500 insulin versus human regular U-100 insulin in healthy obese subjects [published correction appears in Diabetes Care. 2014 Aug;37(8):2414]. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(12):2496-2501. doi:10.2337/dc11-0721

7. Brusko C, Jackson JA, de la Peña A. Comparative properties of U-500 and U-100 regular human insulin. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70(15):1283-1284. doi:10.2146/130117

8. Dailey AM, Williams S, Taneja D, Tannock LR. Clinical efficacy and patient satisfaction with U-500 insulin use. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;88(3):259-264. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2010.02.012

9. Wysham C, Hood RC, Warren ML, Wang T, Morwick TM, Jackson JA. Effect of total daily dose on efficacy, dosing, and safety of 2 dose titration regimens of human regular U-500 insulin in severely insulin-resistant patients with type 2 diabetes. Endocr Pract. 2010;22(6):653-665. doi:10.4158/EP15959.OR

10. Gagnon-Auger M, du Souich P, Baillargeon JP, et al. Dose-dependent delay of the hypoglycemic effect of short-acting insulin analogs in obese subjects with type 2 diabetes: a pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(12):2502-2507. doi:10.2337/dc10-1126

11. Schloot NC, Hood RC, Corrigan SM, Panek RL, Heise T. Concentrated insulins in current clinical practice. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2019;148:93-101. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2018.12.007

12. Lane WS, Cochran EK, Jackson JA, et al. High-dose insulin therapy: is it time for U-500 insulin?. Endocr Pract. 2009;15(1):71-79. doi:10.4158/EP.15.1.71

13. Boldo A, Comi RJ. Clinical experience with U500 insulin: risks and benefits. Endocr Pract. 2012;18(1):56-61. doi:10.4158/EP11163.OR

14. Granata JA, Nawarskas AD, Resch ND, Vigil JM. Evaluating the effect of u-500 insulin therapy on glycemic control in veterans with type 2 diabetes. Clin Diabetes. 2015;33(1):14-19. doi:10.2337/diaclin.33.1.14

15. Eby EL, Zagar AJ, Wang P, et al. Healthcare costs and adherence associated with human regular U-500 versus high-dose U-100 insulin in patients with diabetes. Endocr Pract. 2014;20(7):663-670. doi:10.4158/EP13407.OR

16. Eby EL, Curtis BH, Gelwicks SC, et al. Initiation of human regular U-500 insulin use is associated with improved glycemic control: a real-world US cohort study. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2015;3(1):e000074. Published 2015 Apr 30. doi:10.1136/bmjdrc-2014-000074

17. Jones P, Idris I. The use of U-500 regular insulin in the management of patients with obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2013;15(10):882-887. doi:10.1111/dom.12094

18. Hood RC, Arakaki RF, Wysham C, Li YG, Settles JA, Jackson JA. Two treatment approaches for human regular U-500 insulin in patients with type 2 diabetes not achieving adequate glycemic control on high-dose U-100 insulin therapy with or without oral agents: a randomized, titration-to-target clinical trial. Endocr Pract. 2015;21(7):782-793. doi: 10.4158/EP15612.OR

19. Ballani P, Tran MT, Navar MD, Davidson MB. Clinical experience with U-500 regular insulin in obese, markedly insulin-resistant type 2 diabetic patients [published correction appears in Diabetes Care. 2007 Feb;30(2):455]. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(11):2504-2505. doi:10.2337/dc06-1478

20. Davidson MB, Navar MD, Echeverry D, Duran P. U-500 regular insulin: clinical experience and pharmacokinetics in obese, severely insulin-resistant type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(2):281-283. doi:10.2337/dc09-1490

21. Bulchandani DG, Konrady T, Hamburg MS. Clinical efficacy and patient satisfaction with U-500 insulin pump therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes. Endocr Pract. 2007;13(7):721-725. doi:10.4158/EP.13.7.721

22. Lane WS, Weinrib SL, Rappaport JM, Przestrzelski T. A prospective trial of U500 insulin delivered by Omnipod in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and severe insulin resistance [published correction appears in Endocr Pract. 2010 Nov-Dec;16(6):1082]. Endocr Pract. 2010;16(5):778-784. doi:10.4158/EP10014.OR

23. Martin C, Perez-Molinar D, Shah M, Billington C. U500 Disposable Patch Insulin Pump: Results and Discussion of a Veterans Affairs Pilot Study. J Endocr Soc. 2018;2(11):1275-1283. Published 2018 Sep 17. doi:10.1210/js.2018-00198

24. Ziesmer AE, Kelly KC, Guerra PA, George KG, Dunn FL. U500 regular insulin use in insulin-resistant type 2 diabetic veteran patients. Endocr Pract. 2012;18(1):34-38. doi:10.4158/EP11043.OR

25. American Diabetes Association. 6. Glycemic Targets: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(Suppl 1):S61-S70. doi:10.2337/dc19-S006

1. Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2015–2016. NCHS data brief no. 288. Published October 2017. Accessed January 29, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db288.htm

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diabetes and prediabetes: CDC works to prevent type 2 diabetes and improve the health of all people with diabetes. Updated November 30, 2020. Accessed February 17, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/resources/publications/factsheets/diabetes-prediabetes.htm

3. Cochran E, Gorden P. Use of U-500 insulin in the treatment of severe insulin resistance. Insulin. 2008;3(4):211-218 [Published correction appears in Insulin. 2009;4(1):81]. doi:10.1016/S1557-0843(08)80049-8

4. Shrestha RT, Kumar AF, Taddese A, et al. Duration and onset of action of high dose U-500 regular insulin in severely insulin resistant subjects with type 2 diabetes. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab. 2018;1(4):e00041. Published 2018 Sep 10. doi:10.1002/edm2.41

5. Dailey AM, Tannock LR. Extreme insulin resistance: indications and approaches to the use of U-500 insulin in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Curr Diab Rep. 2011;11(2):77-82. doi:10.1007/s11892-010-0167-6

6. de la Peña A, Riddle M, Morrow LA, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of high-dose human regular U-500 insulin versus human regular U-100 insulin in healthy obese subjects [published correction appears in Diabetes Care. 2014 Aug;37(8):2414]. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(12):2496-2501. doi:10.2337/dc11-0721

7. Brusko C, Jackson JA, de la Peña A. Comparative properties of U-500 and U-100 regular human insulin. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70(15):1283-1284. doi:10.2146/130117

8. Dailey AM, Williams S, Taneja D, Tannock LR. Clinical efficacy and patient satisfaction with U-500 insulin use. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;88(3):259-264. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2010.02.012

9. Wysham C, Hood RC, Warren ML, Wang T, Morwick TM, Jackson JA. Effect of total daily dose on efficacy, dosing, and safety of 2 dose titration regimens of human regular U-500 insulin in severely insulin-resistant patients with type 2 diabetes. Endocr Pract. 2010;22(6):653-665. doi:10.4158/EP15959.OR

10. Gagnon-Auger M, du Souich P, Baillargeon JP, et al. Dose-dependent delay of the hypoglycemic effect of short-acting insulin analogs in obese subjects with type 2 diabetes: a pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(12):2502-2507. doi:10.2337/dc10-1126

11. Schloot NC, Hood RC, Corrigan SM, Panek RL, Heise T. Concentrated insulins in current clinical practice. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2019;148:93-101. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2018.12.007

12. Lane WS, Cochran EK, Jackson JA, et al. High-dose insulin therapy: is it time for U-500 insulin?. Endocr Pract. 2009;15(1):71-79. doi:10.4158/EP.15.1.71

13. Boldo A, Comi RJ. Clinical experience with U500 insulin: risks and benefits. Endocr Pract. 2012;18(1):56-61. doi:10.4158/EP11163.OR

14. Granata JA, Nawarskas AD, Resch ND, Vigil JM. Evaluating the effect of u-500 insulin therapy on glycemic control in veterans with type 2 diabetes. Clin Diabetes. 2015;33(1):14-19. doi:10.2337/diaclin.33.1.14

15. Eby EL, Zagar AJ, Wang P, et al. Healthcare costs and adherence associated with human regular U-500 versus high-dose U-100 insulin in patients with diabetes. Endocr Pract. 2014;20(7):663-670. doi:10.4158/EP13407.OR

16. Eby EL, Curtis BH, Gelwicks SC, et al. Initiation of human regular U-500 insulin use is associated with improved glycemic control: a real-world US cohort study. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2015;3(1):e000074. Published 2015 Apr 30. doi:10.1136/bmjdrc-2014-000074

17. Jones P, Idris I. The use of U-500 regular insulin in the management of patients with obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2013;15(10):882-887. doi:10.1111/dom.12094

18. Hood RC, Arakaki RF, Wysham C, Li YG, Settles JA, Jackson JA. Two treatment approaches for human regular U-500 insulin in patients with type 2 diabetes not achieving adequate glycemic control on high-dose U-100 insulin therapy with or without oral agents: a randomized, titration-to-target clinical trial. Endocr Pract. 2015;21(7):782-793. doi: 10.4158/EP15612.OR

19. Ballani P, Tran MT, Navar MD, Davidson MB. Clinical experience with U-500 regular insulin in obese, markedly insulin-resistant type 2 diabetic patients [published correction appears in Diabetes Care. 2007 Feb;30(2):455]. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(11):2504-2505. doi:10.2337/dc06-1478

20. Davidson MB, Navar MD, Echeverry D, Duran P. U-500 regular insulin: clinical experience and pharmacokinetics in obese, severely insulin-resistant type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(2):281-283. doi:10.2337/dc09-1490

21. Bulchandani DG, Konrady T, Hamburg MS. Clinical efficacy and patient satisfaction with U-500 insulin pump therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes. Endocr Pract. 2007;13(7):721-725. doi:10.4158/EP.13.7.721

22. Lane WS, Weinrib SL, Rappaport JM, Przestrzelski T. A prospective trial of U500 insulin delivered by Omnipod in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and severe insulin resistance [published correction appears in Endocr Pract. 2010 Nov-Dec;16(6):1082]. Endocr Pract. 2010;16(5):778-784. doi:10.4158/EP10014.OR

23. Martin C, Perez-Molinar D, Shah M, Billington C. U500 Disposable Patch Insulin Pump: Results and Discussion of a Veterans Affairs Pilot Study. J Endocr Soc. 2018;2(11):1275-1283. Published 2018 Sep 17. doi:10.1210/js.2018-00198

24. Ziesmer AE, Kelly KC, Guerra PA, George KG, Dunn FL. U500 regular insulin use in insulin-resistant type 2 diabetic veteran patients. Endocr Pract. 2012;18(1):34-38. doi:10.4158/EP11043.OR

25. American Diabetes Association. 6. Glycemic Targets: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(Suppl 1):S61-S70. doi:10.2337/dc19-S006

Semaglutide for meaningful weight loss in obesity and diabetes?

A 2.4-mg weekly injection of the glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist semaglutide led to a clinically meaningful 5% loss in weight for roughly two-thirds of patients with both overweight/obesity and type 2 diabetes, researchers report.

These findings from the Semaglutide Treatment Effect in People With Obesity 2 (STEP 2) trial, one of four phase 3 trials of this drug, which is currently under regulatory review for weight loss, were published March 2 in The Lancet.

More than 1,000 patients (mean initial weight, 100 kg [220 pounds]) were randomly assigned to receive a lifestyle intervention plus a weekly injection of semaglutide 2.4 mg or semaglutide 1.0 mg or placebo. At 68 weeks, they had lost a mean of 9.6%, 7.0%, and 3.4%, respectively, of their starting weight.

In addition, 69% of patients who had received semaglutide 2.4 mg experienced a clinically meaningful 5% loss of weight, compared with 57% of patients who had received the lower dose and 29% of patients who had received placebo.

The higher dose of semaglutide was associated with a greater improvement in cardiometabolic risk factors. The safety profile was similar to that seen with other drugs in this class.

“By far the best results with any weight loss medicine in diabetes”

Importantly, “more than a quarter of participants lost over 15% of their body weight,” senior author Ildiko Lingvay, MD, stressed. This “is by far the best result we had with any weight loss medicine in patients with diabetes,” Dr. Lingvay, of the University of Texas, Dallas, said in a statement from the university.

“The drug works by suppressing appetite centers in the brain to reduce caloric intake,” she explained. “The medication continually tells the body that you just ate, you’re full.”

Similarly, lead author Melanie J. Davies, MD, said that the STEP 2 results “are exciting and represent a new era in weight management in people with type 2 diabetes.

“They mark a real paradigm shift in our ability to treat obesity,” with results closer to those achieved with bariatric surgery, Dr. Davies, of the University of Leicester, England, said in a statement from her institution.

“It is really encouraging,” she continued, “that along with the weight loss we saw real improvements in general health, with significant improvement in physical functioning scores, blood pressure, and blood glucose control.”

Dr. Lingvay noted that on average, patients in the four STEP clinical trials lost 10%-17% of their body weight, “which is a huge step forward compared with all other medications currently available to treat obesity.” She stressed that these results are comparable to the 20%-30% weight loss seen with bariatric surgery.

One of four trials under review

More than 90% of people with type 2 diabetes are overweight or have obesity, and more than 20% of people with obesity have diabetes, wrote Dr. Davies and colleagues.

Semaglutide (Ozempic), administered subcutaneously at a dose of 0.5 mg to 1 mg weekly, is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Dosing studies indicated that it is associated with weight loss.

As previously reported, four trials of the use of semaglutide for weight loss (STEP 1, 2, 3, and 4) have been completed. The combined data were submitted to the FDA on Dec. 4, 2020 (a decision is expected within 6 months) and to the European Medicines Agency on Dec. 18, 2020.

The STEP 1 and STEP 3 trials of semaglutide 2.4 mg vs. placebo were recently published. The STEP 1 trial involved 1,961 adults with obesity or overweight; the STEP 3 trial, 611 adults with obesity or overweight. In each of the trials, some patients also underwent an intensive lifestyle intervention, and some did not. In both trials, patients with type 2 diabetes were excluded.

Topline results from STEP 2 were reported in June 2020.

STEP 2 enrolled patients with type 2 diabetes

STEP 2 involved 1,210 adults in 149 outpatient clinics in 12 countries in Europe, North America, South America, the Middle East, South Africa, and Asia. All participants had type 2 diabetes.

For all patients, the body mass index was ≥27 kg/m2, and the A1c concentration was 7%-10%. The mean BMI was 35.7 kg/m2, and the mean A1c was 8.1%.

The mean age of the patients was 55 years, and 51% were women; 62% were White, 26% were Asian, 13% were Hispanic, 8% were Black, and 4% were of other ethnicity.

Participants were managed with diet and exercise alone or underwent treatment with a stable dose of up to three oral glucose-lowering agents (metformin, sulfonylureas, SGLT2 inhibitors, or thiazolidinediones) for at least 90 days. They were then randomly assigned in 1:1:1 ratio to receive semaglutide 2.4 mg, semaglutide 1.0 mg, or placebo.

The starting dose of semaglutide was 0.25 mg/wk; the dose was escalated every 4 weeks to reach the target dose.

All patients received monthly counseling from a dietitian about calories (the goal was a 500-calorie/day deficit) and activity (the goal was 150 minutes of walking or stair climbing per week).

The mean A1c dropped by 1.6% and 1.5% in the semaglutide groups and by 0.4% in the placebo group.

Adverse events were more frequent among the patients who received semaglutide (88% and 82%) than in the placebo group (77%).

Gastrointestinal events that were mainly mild to moderate in severity were reported by 64% of patients in the 2.4-mg semaglutide group, 58% in the 1.0-mg semaglutide group, and 34% in the placebo group.

Semaglutide (Rybelsus) is approved in the United States as a once-daily oral agent for use in type 2 diabetes in doses of 7 mg and 14 mg to improve glycemic control along with diet and exercise. It is the first GLP-1 agonist available in tablet form.

The study was supported by Novo Nordisk. The authors’ relevant financial relationships are listed in the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.