User login

Noninvasive fibrosis scores not sensitive in people with fatty liver disease and T2D

Noninvasive fibrosis scores, which are widely used to predict advanced fibrosis in people with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), do not do a good job of picking up advanced fibrosis in patients with underlying diabetes, according to a new study.

Advanced fibrosis is associated with an increased risk of cirrhosis, end-stage liver disease, and liver failure. Underlying diabetes is a risk factor for both advanced fibrosis and death in patients with NAFLD.

While liver biopsy remains the gold standard for detecting advanced fibrosis, high costs and risks limit its use. Noninvasive scores such as the AST/ALT ratio; AST to platelet ratio index (APRI); fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) index; and NAFLD fibrosis score (NFS) have gained popularity in recent years, as they offer the compelling advantage of using easily and cheaply attained clinical and laboratory measures to assess likelihood of disease.

But their accuracy has come into question, particularly for people with diabetes.

In research published in the Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology, Amandeep Singh, MD, and colleagues at the Cleveland Clinic looked at their center’s records for 1,157 patients with type 2 diabetes (65% women, 88% white, 85% with obesity) who had undergone a liver biopsy for suspected advanced fibrosis between 2000 and 2015. Biopsy results revealed that a third of the cohort (32%) was positive for advanced fibrosis.

The investigators then pulled patients’ laboratory results for AST, ALT, cholesterol, triglycerides, fasting glucose, hemoglobin A1c, bilirubin, albumin, platelet count, alkaline phosphatase, albumin, and lipid levels, all collected within a year of biopsy. After plugging these into the algorithms of four different scoring systems for advanced fibrosis, they compared results with results from the biopsies.

The scores of AST/ALT greater than 1.4, APRI of at least 1.5, NFS greater than 0.676, and FIB-4 index greater than 2.67 had high specificities of 84%, 97%, 70%, and 93%, respectively, but sensitivities of only 27%, 17%, 64%, and 44%. Even when the cutoff measures were tightened, the scoring systems still missed a lot of disease. This suggests, Dr. Singh and colleagues wrote, that “the presence of diabetes could decrease the predictive value of these scores to detect advanced disease in NAFLD patients.” Reliable noninvasive biomarkers are “urgently needed” for this patient population.

In an interview, Dr. Singh advised that clinicians continue to use current noninvasive scores in patients with diabetes – preferably the NFS – “until we have a better scoring system.” If clinicians suspect advanced fibrosis based on lab tests and clinical data, then “liver biopsy should be considered,” he said.

The investigators described among the limitations of their study its retrospective, single-center design, with patients who were mostly white and from one geographic region.

Dr. Singh and colleagues reported no conflicts of interest or outside funding for their study.

SOURCE: Singh A et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2020 Mar 11. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001339.

Noninvasive fibrosis scores, which are widely used to predict advanced fibrosis in people with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), do not do a good job of picking up advanced fibrosis in patients with underlying diabetes, according to a new study.

Advanced fibrosis is associated with an increased risk of cirrhosis, end-stage liver disease, and liver failure. Underlying diabetes is a risk factor for both advanced fibrosis and death in patients with NAFLD.

While liver biopsy remains the gold standard for detecting advanced fibrosis, high costs and risks limit its use. Noninvasive scores such as the AST/ALT ratio; AST to platelet ratio index (APRI); fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) index; and NAFLD fibrosis score (NFS) have gained popularity in recent years, as they offer the compelling advantage of using easily and cheaply attained clinical and laboratory measures to assess likelihood of disease.

But their accuracy has come into question, particularly for people with diabetes.

In research published in the Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology, Amandeep Singh, MD, and colleagues at the Cleveland Clinic looked at their center’s records for 1,157 patients with type 2 diabetes (65% women, 88% white, 85% with obesity) who had undergone a liver biopsy for suspected advanced fibrosis between 2000 and 2015. Biopsy results revealed that a third of the cohort (32%) was positive for advanced fibrosis.

The investigators then pulled patients’ laboratory results for AST, ALT, cholesterol, triglycerides, fasting glucose, hemoglobin A1c, bilirubin, albumin, platelet count, alkaline phosphatase, albumin, and lipid levels, all collected within a year of biopsy. After plugging these into the algorithms of four different scoring systems for advanced fibrosis, they compared results with results from the biopsies.

The scores of AST/ALT greater than 1.4, APRI of at least 1.5, NFS greater than 0.676, and FIB-4 index greater than 2.67 had high specificities of 84%, 97%, 70%, and 93%, respectively, but sensitivities of only 27%, 17%, 64%, and 44%. Even when the cutoff measures were tightened, the scoring systems still missed a lot of disease. This suggests, Dr. Singh and colleagues wrote, that “the presence of diabetes could decrease the predictive value of these scores to detect advanced disease in NAFLD patients.” Reliable noninvasive biomarkers are “urgently needed” for this patient population.

In an interview, Dr. Singh advised that clinicians continue to use current noninvasive scores in patients with diabetes – preferably the NFS – “until we have a better scoring system.” If clinicians suspect advanced fibrosis based on lab tests and clinical data, then “liver biopsy should be considered,” he said.

The investigators described among the limitations of their study its retrospective, single-center design, with patients who were mostly white and from one geographic region.

Dr. Singh and colleagues reported no conflicts of interest or outside funding for their study.

SOURCE: Singh A et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2020 Mar 11. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001339.

Noninvasive fibrosis scores, which are widely used to predict advanced fibrosis in people with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), do not do a good job of picking up advanced fibrosis in patients with underlying diabetes, according to a new study.

Advanced fibrosis is associated with an increased risk of cirrhosis, end-stage liver disease, and liver failure. Underlying diabetes is a risk factor for both advanced fibrosis and death in patients with NAFLD.

While liver biopsy remains the gold standard for detecting advanced fibrosis, high costs and risks limit its use. Noninvasive scores such as the AST/ALT ratio; AST to platelet ratio index (APRI); fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) index; and NAFLD fibrosis score (NFS) have gained popularity in recent years, as they offer the compelling advantage of using easily and cheaply attained clinical and laboratory measures to assess likelihood of disease.

But their accuracy has come into question, particularly for people with diabetes.

In research published in the Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology, Amandeep Singh, MD, and colleagues at the Cleveland Clinic looked at their center’s records for 1,157 patients with type 2 diabetes (65% women, 88% white, 85% with obesity) who had undergone a liver biopsy for suspected advanced fibrosis between 2000 and 2015. Biopsy results revealed that a third of the cohort (32%) was positive for advanced fibrosis.

The investigators then pulled patients’ laboratory results for AST, ALT, cholesterol, triglycerides, fasting glucose, hemoglobin A1c, bilirubin, albumin, platelet count, alkaline phosphatase, albumin, and lipid levels, all collected within a year of biopsy. After plugging these into the algorithms of four different scoring systems for advanced fibrosis, they compared results with results from the biopsies.

The scores of AST/ALT greater than 1.4, APRI of at least 1.5, NFS greater than 0.676, and FIB-4 index greater than 2.67 had high specificities of 84%, 97%, 70%, and 93%, respectively, but sensitivities of only 27%, 17%, 64%, and 44%. Even when the cutoff measures were tightened, the scoring systems still missed a lot of disease. This suggests, Dr. Singh and colleagues wrote, that “the presence of diabetes could decrease the predictive value of these scores to detect advanced disease in NAFLD patients.” Reliable noninvasive biomarkers are “urgently needed” for this patient population.

In an interview, Dr. Singh advised that clinicians continue to use current noninvasive scores in patients with diabetes – preferably the NFS – “until we have a better scoring system.” If clinicians suspect advanced fibrosis based on lab tests and clinical data, then “liver biopsy should be considered,” he said.

The investigators described among the limitations of their study its retrospective, single-center design, with patients who were mostly white and from one geographic region.

Dr. Singh and colleagues reported no conflicts of interest or outside funding for their study.

SOURCE: Singh A et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2020 Mar 11. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001339.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY

Patients with preexisting diabetes benefit less from bariatric surgery

according to a retrospective review of patients receiving both sleeve gastrectomy and gastric bypass.

The difference was particularly pronounced and persistent for patients who had gastric bypass, Yingying Luo, MD, said during a virtual news conference held by the Endocrine Society. The study was slated for presentation during ENDO 2020, the society’s annual meeting, which was canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Our findings demonstrated that having bariatric surgery before developing diabetes may result in greater weight loss from the surgery, especially within the first 3 years after surgery and in patients undergoing gastric bypass surgery,” said Dr. Luo.

More than a third of U.S. adults have obesity, and more than half the population is overweight or has obesity, said Dr. Luo, citing data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Bariatric surgery not only reduces body weight, but also “can lead to remission of many metabolic disorders, including diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia,” said Dr. Luo, a visiting scholar at the University of Michigan’s division of metabolism, endocrinology, and diabetes. However, until now, it has not been known how diabetes interacts with bariatric surgery to affect weight loss outcomes.

To address that question, Dr. Luo and her colleagues looked at patients in the Michigan Bariatric Surgery Cohort who were at least 18 years old and had a body mass index (BMI) of more than 40 kg/m2, or of more than 35 kg/m2 with comorbidities.

The researchers followed 380 patients who received gastric bypass and 334 who received sleeve gastrectomy for at least 5 years. Over time, sleeve gastrectomy became the predominant type of surgery conducted, noted Dr. Luo.

At baseline, and yearly for 5 years thereafter, the researchers recorded participants’ BMI as well as their lipid levels and other laboratory values. Medication use was also tracked. Patients with a diagnosis of diabetes also had their hemoglobin A1c levels recorded at each visit.

Overall, patients in the sleeve gastrectomy group were more overweight, and those in the gastric bypass group had higher HbA1c and total cholesterol levels. The mean baseline weight for the sleeve gastrectomy recipients was 141.5 kg, compared with 133.5 kg for those receiving gastric bypass (BMI, 49.9 vs. 47.3 kg/m2, respectively; P < .01 for both measures). Mean HbA1c was 6.5% for the gastric bypass group, compared with 6.3% for the sleeve gastrectomy group (P = .03).

At baseline, 149 (39.2%) of the gastric bypass patients had diabetes, compared with 108 (32.3%) of the sleeve gastrectomy patients, but the difference was not statistically significant.

About two-thirds of the full cohort were tracked for at least 5 years, which is still considered “a good follow-up rate in a real-world study,” said Dr. Luo.

Total weight loss was defined as the difference between initial weight and postoperative weight at a given point in time. Excess weight was the difference between initial weight and an individual’s ideal weight, that is, what their weight would have been if they had a BMI of 25 kg/m2.

“The probability of achieving a BMI of less than 30 kg/m2 or excess weight loss of 50% or more was higher in patients who did not have diabetes diagnosis at baseline. We found that the presence of diabetes at baseline substantially impacted the probability of achieving both indicators,” said Dr. Luo. “Individuals without diabetes had a 1.5 times higher chance of achieving a BMI of under 30 kg/m2, and … [they also] had a 1.6 times higher chance of achieving excess body weight loss of 50%, or more.” Both of those differences were statistically significant on univariate analysis (P = .0249 and .0021, respectively).

The researchers conducted further statistical analysis – adjusted for age, gender, surgery type, and baseline weight – to examine whether diabetes still predicted future weight loss after bariatric surgery. After those adjustments, they still found that “the presence of diabetes before surgery is an indicator of future weight loss outcomes,” said Dr. Luo.

The differences in outcomes for those with and without diabetes tended to diminish over time in looking at the cohort as a whole. However, greater BMI reduction for those without diabetes persisted for the full 5 years of follow-up for the gastric bypass recipients. Those trends held when the researchers looked at the proportion of patients whose BMI dropped to below 30 kg/m2, and those who achieved excess weight loss of more than 50%.

Dr. Luo acknowledged that an ideal study would track patients for longer than 5 years and that studies involving more patients would also be useful. Still, she said, “our study opens the door for further research to understand why diabetes diminishes the weight loss effect of bariatric surgery.”

The research will be published in a special supplemental issue of the Journal of the Endocrine Society. In addition to a series of news conferences on March 30-31, the society will host ENDO Online 2020 during June 8-22, which will present programming for clinicians and researchers.

Dr. Luo reported no outside sources of funding and no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Luo Y et al. ENDO 2020, Abstract 590.

according to a retrospective review of patients receiving both sleeve gastrectomy and gastric bypass.

The difference was particularly pronounced and persistent for patients who had gastric bypass, Yingying Luo, MD, said during a virtual news conference held by the Endocrine Society. The study was slated for presentation during ENDO 2020, the society’s annual meeting, which was canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Our findings demonstrated that having bariatric surgery before developing diabetes may result in greater weight loss from the surgery, especially within the first 3 years after surgery and in patients undergoing gastric bypass surgery,” said Dr. Luo.

More than a third of U.S. adults have obesity, and more than half the population is overweight or has obesity, said Dr. Luo, citing data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Bariatric surgery not only reduces body weight, but also “can lead to remission of many metabolic disorders, including diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia,” said Dr. Luo, a visiting scholar at the University of Michigan’s division of metabolism, endocrinology, and diabetes. However, until now, it has not been known how diabetes interacts with bariatric surgery to affect weight loss outcomes.

To address that question, Dr. Luo and her colleagues looked at patients in the Michigan Bariatric Surgery Cohort who were at least 18 years old and had a body mass index (BMI) of more than 40 kg/m2, or of more than 35 kg/m2 with comorbidities.

The researchers followed 380 patients who received gastric bypass and 334 who received sleeve gastrectomy for at least 5 years. Over time, sleeve gastrectomy became the predominant type of surgery conducted, noted Dr. Luo.

At baseline, and yearly for 5 years thereafter, the researchers recorded participants’ BMI as well as their lipid levels and other laboratory values. Medication use was also tracked. Patients with a diagnosis of diabetes also had their hemoglobin A1c levels recorded at each visit.

Overall, patients in the sleeve gastrectomy group were more overweight, and those in the gastric bypass group had higher HbA1c and total cholesterol levels. The mean baseline weight for the sleeve gastrectomy recipients was 141.5 kg, compared with 133.5 kg for those receiving gastric bypass (BMI, 49.9 vs. 47.3 kg/m2, respectively; P < .01 for both measures). Mean HbA1c was 6.5% for the gastric bypass group, compared with 6.3% for the sleeve gastrectomy group (P = .03).

At baseline, 149 (39.2%) of the gastric bypass patients had diabetes, compared with 108 (32.3%) of the sleeve gastrectomy patients, but the difference was not statistically significant.

About two-thirds of the full cohort were tracked for at least 5 years, which is still considered “a good follow-up rate in a real-world study,” said Dr. Luo.

Total weight loss was defined as the difference between initial weight and postoperative weight at a given point in time. Excess weight was the difference between initial weight and an individual’s ideal weight, that is, what their weight would have been if they had a BMI of 25 kg/m2.

“The probability of achieving a BMI of less than 30 kg/m2 or excess weight loss of 50% or more was higher in patients who did not have diabetes diagnosis at baseline. We found that the presence of diabetes at baseline substantially impacted the probability of achieving both indicators,” said Dr. Luo. “Individuals without diabetes had a 1.5 times higher chance of achieving a BMI of under 30 kg/m2, and … [they also] had a 1.6 times higher chance of achieving excess body weight loss of 50%, or more.” Both of those differences were statistically significant on univariate analysis (P = .0249 and .0021, respectively).

The researchers conducted further statistical analysis – adjusted for age, gender, surgery type, and baseline weight – to examine whether diabetes still predicted future weight loss after bariatric surgery. After those adjustments, they still found that “the presence of diabetes before surgery is an indicator of future weight loss outcomes,” said Dr. Luo.

The differences in outcomes for those with and without diabetes tended to diminish over time in looking at the cohort as a whole. However, greater BMI reduction for those without diabetes persisted for the full 5 years of follow-up for the gastric bypass recipients. Those trends held when the researchers looked at the proportion of patients whose BMI dropped to below 30 kg/m2, and those who achieved excess weight loss of more than 50%.

Dr. Luo acknowledged that an ideal study would track patients for longer than 5 years and that studies involving more patients would also be useful. Still, she said, “our study opens the door for further research to understand why diabetes diminishes the weight loss effect of bariatric surgery.”

The research will be published in a special supplemental issue of the Journal of the Endocrine Society. In addition to a series of news conferences on March 30-31, the society will host ENDO Online 2020 during June 8-22, which will present programming for clinicians and researchers.

Dr. Luo reported no outside sources of funding and no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Luo Y et al. ENDO 2020, Abstract 590.

according to a retrospective review of patients receiving both sleeve gastrectomy and gastric bypass.

The difference was particularly pronounced and persistent for patients who had gastric bypass, Yingying Luo, MD, said during a virtual news conference held by the Endocrine Society. The study was slated for presentation during ENDO 2020, the society’s annual meeting, which was canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Our findings demonstrated that having bariatric surgery before developing diabetes may result in greater weight loss from the surgery, especially within the first 3 years after surgery and in patients undergoing gastric bypass surgery,” said Dr. Luo.

More than a third of U.S. adults have obesity, and more than half the population is overweight or has obesity, said Dr. Luo, citing data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Bariatric surgery not only reduces body weight, but also “can lead to remission of many metabolic disorders, including diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia,” said Dr. Luo, a visiting scholar at the University of Michigan’s division of metabolism, endocrinology, and diabetes. However, until now, it has not been known how diabetes interacts with bariatric surgery to affect weight loss outcomes.

To address that question, Dr. Luo and her colleagues looked at patients in the Michigan Bariatric Surgery Cohort who were at least 18 years old and had a body mass index (BMI) of more than 40 kg/m2, or of more than 35 kg/m2 with comorbidities.

The researchers followed 380 patients who received gastric bypass and 334 who received sleeve gastrectomy for at least 5 years. Over time, sleeve gastrectomy became the predominant type of surgery conducted, noted Dr. Luo.

At baseline, and yearly for 5 years thereafter, the researchers recorded participants’ BMI as well as their lipid levels and other laboratory values. Medication use was also tracked. Patients with a diagnosis of diabetes also had their hemoglobin A1c levels recorded at each visit.

Overall, patients in the sleeve gastrectomy group were more overweight, and those in the gastric bypass group had higher HbA1c and total cholesterol levels. The mean baseline weight for the sleeve gastrectomy recipients was 141.5 kg, compared with 133.5 kg for those receiving gastric bypass (BMI, 49.9 vs. 47.3 kg/m2, respectively; P < .01 for both measures). Mean HbA1c was 6.5% for the gastric bypass group, compared with 6.3% for the sleeve gastrectomy group (P = .03).

At baseline, 149 (39.2%) of the gastric bypass patients had diabetes, compared with 108 (32.3%) of the sleeve gastrectomy patients, but the difference was not statistically significant.

About two-thirds of the full cohort were tracked for at least 5 years, which is still considered “a good follow-up rate in a real-world study,” said Dr. Luo.

Total weight loss was defined as the difference between initial weight and postoperative weight at a given point in time. Excess weight was the difference between initial weight and an individual’s ideal weight, that is, what their weight would have been if they had a BMI of 25 kg/m2.

“The probability of achieving a BMI of less than 30 kg/m2 or excess weight loss of 50% or more was higher in patients who did not have diabetes diagnosis at baseline. We found that the presence of diabetes at baseline substantially impacted the probability of achieving both indicators,” said Dr. Luo. “Individuals without diabetes had a 1.5 times higher chance of achieving a BMI of under 30 kg/m2, and … [they also] had a 1.6 times higher chance of achieving excess body weight loss of 50%, or more.” Both of those differences were statistically significant on univariate analysis (P = .0249 and .0021, respectively).

The researchers conducted further statistical analysis – adjusted for age, gender, surgery type, and baseline weight – to examine whether diabetes still predicted future weight loss after bariatric surgery. After those adjustments, they still found that “the presence of diabetes before surgery is an indicator of future weight loss outcomes,” said Dr. Luo.

The differences in outcomes for those with and without diabetes tended to diminish over time in looking at the cohort as a whole. However, greater BMI reduction for those without diabetes persisted for the full 5 years of follow-up for the gastric bypass recipients. Those trends held when the researchers looked at the proportion of patients whose BMI dropped to below 30 kg/m2, and those who achieved excess weight loss of more than 50%.

Dr. Luo acknowledged that an ideal study would track patients for longer than 5 years and that studies involving more patients would also be useful. Still, she said, “our study opens the door for further research to understand why diabetes diminishes the weight loss effect of bariatric surgery.”

The research will be published in a special supplemental issue of the Journal of the Endocrine Society. In addition to a series of news conferences on March 30-31, the society will host ENDO Online 2020 during June 8-22, which will present programming for clinicians and researchers.

Dr. Luo reported no outside sources of funding and no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Luo Y et al. ENDO 2020, Abstract 590.

FROM ENDO 2020

Dapagliflozin trial in CKD halted because of high efficacy

AstraZeneca has announced that the phase 3 DAPA-CKD trial for dapagliflozin (Farxiga) in patients with chronic kidney disease has been halted early because of overwhelming efficacy of the drug, at the recommendation of an independent data monitoring committee.

DAPA-CKD is an international, multicenter, randomized, double-blinded trial in 4,245 patients with stage 2-4 chronic kidney disease. Patients received either 10 mg of the dapagliflozin once-daily or a placebo. The primary composite endpoint is worsening of renal function, defined as a composite of an estimated glomerular filtration rate decline of at least 50%, onset of end-stage kidney disease, and death from cardiovascular or renal cause.

The decision to stop the trial came after a routine assessment of efficacy and safety that showed dapagliflozin’s benefits significantly earlier than expected. AstraZeneca will initiate closure of the study, and results will be published and submitted for presentation at a forthcoming medical meeting.

Dapagliflozin is a sodium-glucose transporter 2 inhibitor currently indicated for the treatment type 2 diabetes patients with inadequately controlled type 2 diabetes and for reduction of the risk of hospitalization for heart failure. In August 2019, the drug was granted Fast Track status by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of chronic kidney disease. In January 2020, the agency also granted Fast Track status for the reduction of risk of cardiovascular death or worsening of heart failure in adult patients, regardless of diabetes status, with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction.

“Chronic kidney disease patients have limited treatment options, particularly those without type-2 diabetes. We are very pleased the data monitoring committee concluded that patients experienced overwhelming benefit. Farxiga has the potential to change the management of chronic kidney disease for patients around the world,” Mene Pangalos, executive vice president of BioPharmaceuticals R&D, said in the press release.

AstraZeneca has announced that the phase 3 DAPA-CKD trial for dapagliflozin (Farxiga) in patients with chronic kidney disease has been halted early because of overwhelming efficacy of the drug, at the recommendation of an independent data monitoring committee.

DAPA-CKD is an international, multicenter, randomized, double-blinded trial in 4,245 patients with stage 2-4 chronic kidney disease. Patients received either 10 mg of the dapagliflozin once-daily or a placebo. The primary composite endpoint is worsening of renal function, defined as a composite of an estimated glomerular filtration rate decline of at least 50%, onset of end-stage kidney disease, and death from cardiovascular or renal cause.

The decision to stop the trial came after a routine assessment of efficacy and safety that showed dapagliflozin’s benefits significantly earlier than expected. AstraZeneca will initiate closure of the study, and results will be published and submitted for presentation at a forthcoming medical meeting.

Dapagliflozin is a sodium-glucose transporter 2 inhibitor currently indicated for the treatment type 2 diabetes patients with inadequately controlled type 2 diabetes and for reduction of the risk of hospitalization for heart failure. In August 2019, the drug was granted Fast Track status by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of chronic kidney disease. In January 2020, the agency also granted Fast Track status for the reduction of risk of cardiovascular death or worsening of heart failure in adult patients, regardless of diabetes status, with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction.

“Chronic kidney disease patients have limited treatment options, particularly those without type-2 diabetes. We are very pleased the data monitoring committee concluded that patients experienced overwhelming benefit. Farxiga has the potential to change the management of chronic kidney disease for patients around the world,” Mene Pangalos, executive vice president of BioPharmaceuticals R&D, said in the press release.

AstraZeneca has announced that the phase 3 DAPA-CKD trial for dapagliflozin (Farxiga) in patients with chronic kidney disease has been halted early because of overwhelming efficacy of the drug, at the recommendation of an independent data monitoring committee.

DAPA-CKD is an international, multicenter, randomized, double-blinded trial in 4,245 patients with stage 2-4 chronic kidney disease. Patients received either 10 mg of the dapagliflozin once-daily or a placebo. The primary composite endpoint is worsening of renal function, defined as a composite of an estimated glomerular filtration rate decline of at least 50%, onset of end-stage kidney disease, and death from cardiovascular or renal cause.

The decision to stop the trial came after a routine assessment of efficacy and safety that showed dapagliflozin’s benefits significantly earlier than expected. AstraZeneca will initiate closure of the study, and results will be published and submitted for presentation at a forthcoming medical meeting.

Dapagliflozin is a sodium-glucose transporter 2 inhibitor currently indicated for the treatment type 2 diabetes patients with inadequately controlled type 2 diabetes and for reduction of the risk of hospitalization for heart failure. In August 2019, the drug was granted Fast Track status by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of chronic kidney disease. In January 2020, the agency also granted Fast Track status for the reduction of risk of cardiovascular death or worsening of heart failure in adult patients, regardless of diabetes status, with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction.

“Chronic kidney disease patients have limited treatment options, particularly those without type-2 diabetes. We are very pleased the data monitoring committee concluded that patients experienced overwhelming benefit. Farxiga has the potential to change the management of chronic kidney disease for patients around the world,” Mene Pangalos, executive vice president of BioPharmaceuticals R&D, said in the press release.

Factors Associated With Lower-Extremity Amputation in Patients With Diabetic Foot Ulcers

From Northwell Health System, Lake Success, NY.

Abstract

- Objective: To explore factors associated with lower-extremity amputation (LEA) in patients with diabetic foot ulcers using data from the Online Wound Electronic Medical Record Database.

- Design: Retrospective analysis of medical records.

- Setting and participants: Data from 169 individuals with previously diagnosed diabetes mellitus who received wound care for a 6-month period within a span of 2 years was analyzed. A baseline evaluation was obtained and wound(s) were treated, managed, and monitored.

Treatment continued until the patient healed, required an LEA, or phased out of the study, neither healing nor undergoing an amputation. Of the 149 patients who completed the study, 38 had healed ulcers, 14 underwent amputation, and 97 neither healed nor underwent an amputation. All patients were treated under the care of vascular and/or podiatric surgeons. - Measurements: Variables included wound status (healed, amputated, and unhealed/non-amputated); size of wound area; age, gender, race, and ethnicity; white blood cell (WBC) count, hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), blood glucose, and body mass index (BMI); and presence of osteomyelitis, gangrene, and peripheral vascular disease.

- Results: As compared to the healed and unhealed/non-amputated group, the group of patients who underwent LEA was older and had higher percentages of males, Hispanics, and African Americans; had a higher WBC count, larger wound area, and higher rates of wound infection, osteomyelitis, and neuropathy; and had lower average values of HbA1c, blood glucose, and BMI and a lower rate of peripheral vascular disease.

- Conclusion: The association between HbA1c and LEA highlights a window of relative safety among an at-risk population. By identifying and focusing on factors associated with LEA, health care professionals may be able to decrease the prevalence of LEA in patients with diabetes.

Keywords: diabetic foot ulcer; lower-extremity amputation; risk factors; HbA1c.

An estimated 30.3 million people, or 9.4% of the US population, has diabetes. In 2014, approximately 108,000 amputations were performed on adults with diagnosed diabetes.1 Furthermore, patients with diabetes have a 10-fold increased risk for lower-extremity amputation (LEA), as compared with patients without diabetes.2 The frequency of amputations in the diabetic population is a public health crisis.

Amputation has significant, life-altering consequences. Patients who undergo LEA often face debilitation in their daily activities and must undergo intense rehabilitation to learn basic tasks. Amputations can also impact individuals’ psychological well-being as they come to terms with their altered body and may face challenges in self-perception, confidence, self-esteem, work life, and relationships. In addition, the mortality rate for patients with diabetes 5 years after undergoing LEA is 30%.2 However, public health studies estimate that more than half of LEAs in patients with diabetes are preventable.3

Although studies have explored the relationship between diabetes and LEA, few have sought to identify factors directly correlated with wound care. In the United States, patients with diabetic ulcerations are typically treated in wound care facilities; however, previous studies have concentrated on the conditions that lead to the formation of an ulcer or amputation, viewing amputation and ulcer as 2 separate entities. Our study took into account systemic variables, patient demographics, and specific wound characteristics to explore factors associated with LEA in a high-risk group of patients with diabetes. This study was designed to assess ailments that are prevalent in patients who require a LEA.

Methods

Patients and Setting

A total of 169 patients who were treated at the Comprehensive Wound Healing and Hyperbaric Center (Lake Success, NY), a tertiary facility of the Northwell Health system, participated in this retrospective study. The data for this study were obtained in conjunction with the development of the New York University School of Medicine’s Online Wound Electronic Medical Record to Decrease Limb Amputations in Persons with Diabetes (OWEMR) database. The OWEMR collects individual patient data from satellite locations across the country. Using this database, researchers can analyze similarities and differences between patients who undergo LEA.

This study utilized patient data specific to the Northwell Health facility. All of the patients in our study were enrolled under the criteria of the OWEMR database. In order to be included in the OWEMR database, patients had to be diagnosed with type 1 or type 2 diabetes; have a break in the skin ≥ 0.5 cm2; be 18 years of age or older; and have a measured hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) value within the past 120 days. Study patients signed an informed consent and committed to being available for follow-up visits to the wound care facility for 6 months after entering the study. Patients were enrolled between 2012 and 2014, and each patient was monitored for a period of 6 months within this time period. Participants were treated with current standards of care using diet, lifestyle, and pharmacologic interventions. This study was approved by the Northwell Health System Institutional Review Board Human Research Protection Program (Manhasset, NY).

Data Collection

On their first visit to the facility, patients were given a physical examination and initial interview regarding their medical history. Clinicians were required to select 1 ulcer that would be examined for the duration of the study. The selection of the ulcer was based on a point system that awarded points for pedal pulses, the ability to be probed to the bone, the location of the ulcer (ie, located on the foot rather than a toe), and the presence of multiple ulcerations. The ulcer with the highest score was selected for the study. If numerous ulcers were evaluated with the same score, the largest and deepest was selected. Wagner classification of the wound was recorded at baseline and taken at each subsequent patient visit. In addition, peripheral sensation was assessed for signs of neuropathy using Semmes-Weinstein monofilament testing.

Once selected, the wound was clinically evaluated, samples for culture were obtained, and blood tests were performed to detect the presence of wound infection. The patient’s blood was drawn for a full laboratory analysis, including white blood cell (WBC) count and measurement of blood glucose and HbA1c levels. Bone biopsy, magnetic resonance imaging, and bone scans were used to detect the presence of osteomyelitis at the discretion of the health care provider. Wounds suspected of infection, underlying osteomyelitis, or gangrene at baseline were excluded. Patients would then return for follow-up visits at least once every 6 weeks, plus or minus 2 weeks, for a maximum of 6 months.

Statistical Analysis

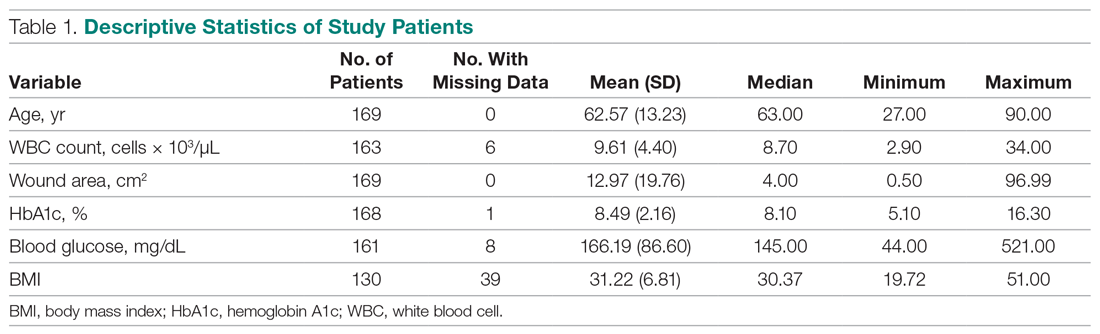

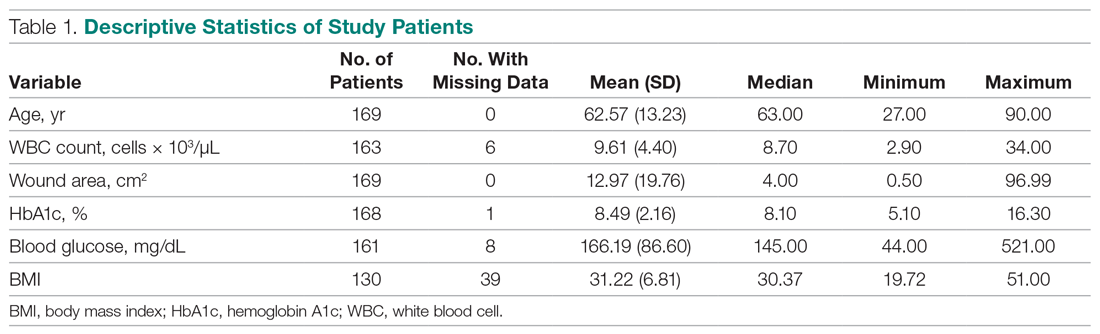

Utilizing SAS version 9.3 (Cary, NC), descriptive statistics (minimum, maximum, mean, median, and SD) were calculated for the following variables: age, WBC count, wound area, HbA1c, blood glucose, and body mass index (BMI). These variables were collected for each patient as per the OWEMR protocol and provided a basis for which to compare patients who underwent amputation and those who did not. Twenty patients were lost to follow-up, and therefore we altered the window of our statistics from 6 months to 3 months to provide the most accurate data, as 6-month follow-up data were limited. The patients were classified into the following categories: healed, amputated, and unhealed/non-amputated. Descriptive statistics were calculated for these 3 groups, analyzing the same variables (age, WBC count, wound area, HbA1c, blood glucose, and BMI). Additional statistical computations were utilized in order to show the prevalence and frequency of our categorical variables: gender, race, ethnicity, osteomyelitis, gangrene, and peripheral vascular disease. The baseline values of WBC count, HbA1c, wound area, and BMI of the 3 groups were analyzed with descriptive statistics for comparison. A multinomial logistic regression was then performed using a 3-level outcome variable: healed, amputated, or unhealed/non-amputated. Each predictor variable was analyzed independently due to the small sample size.

Results

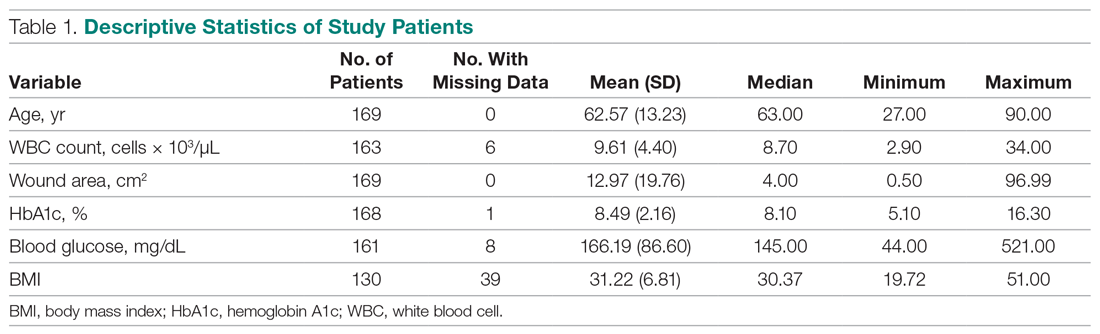

Of the 169 registered patients treated at the Northwell Health facility, all qualified for the OWEMR study and met the study criteria. In the original 169 patients, there were 19 amputations: 6 toe, 6 trans-metatarsal, 6 below knee, and 1 above knee (Table 1).

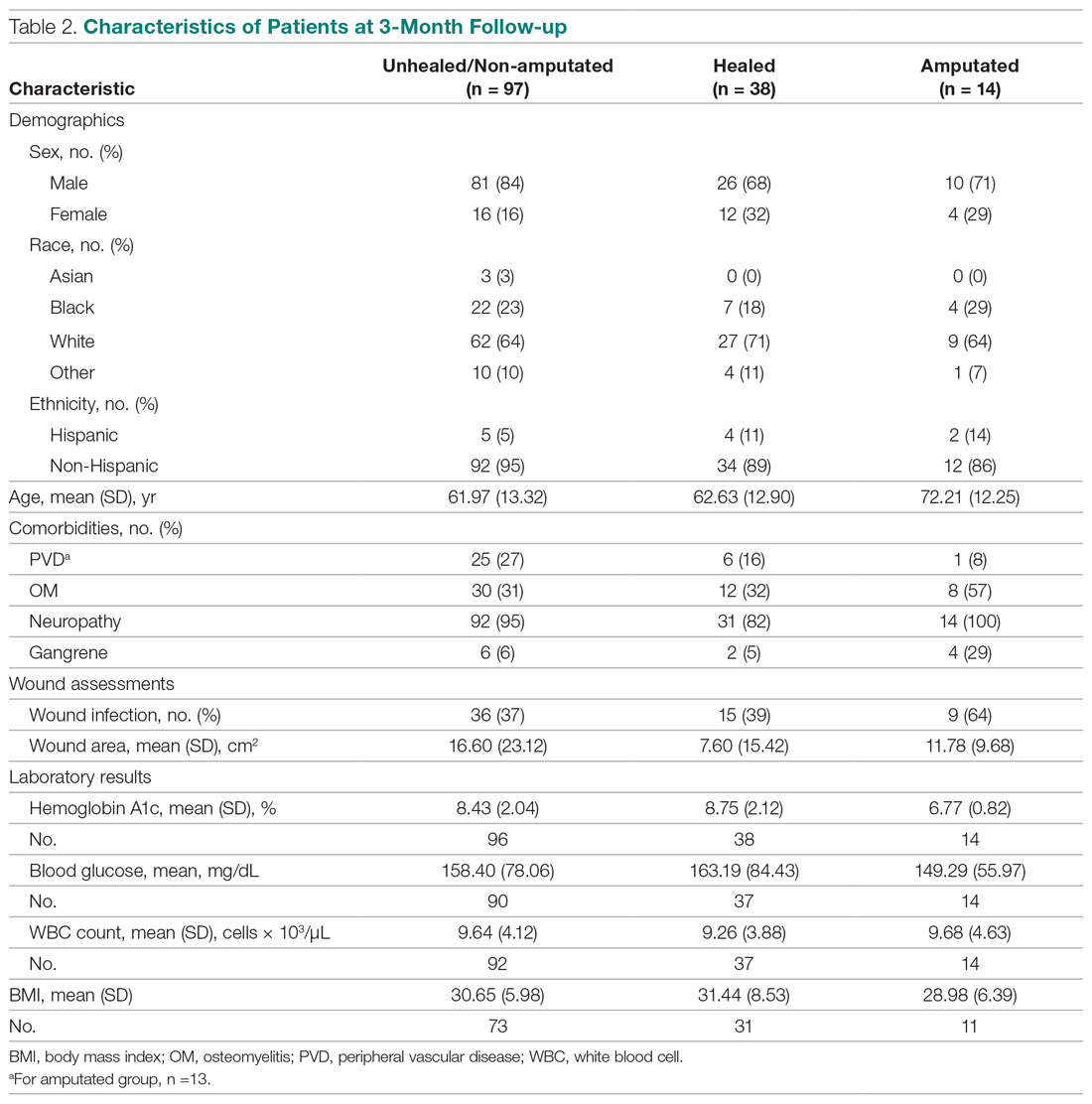

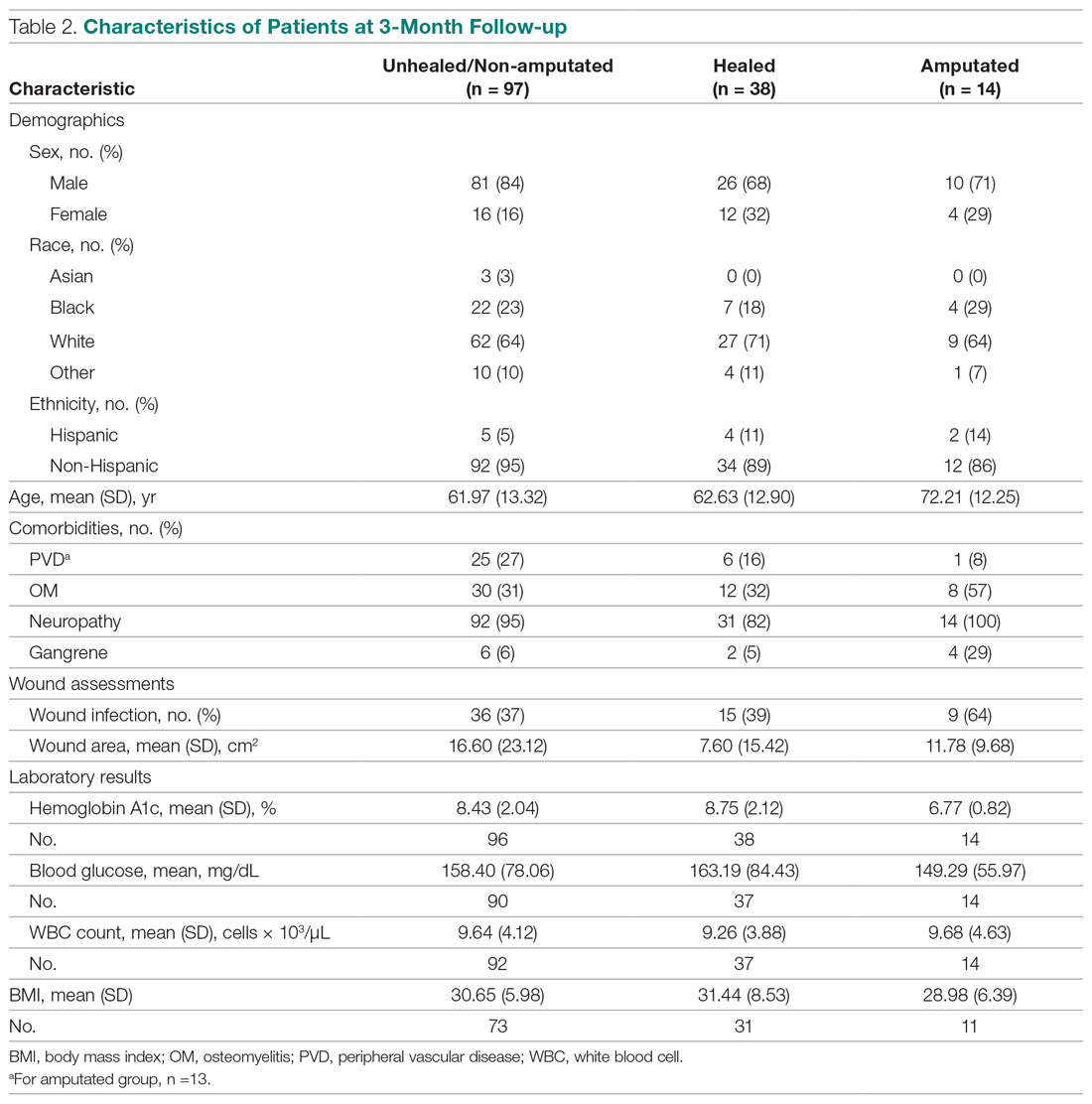

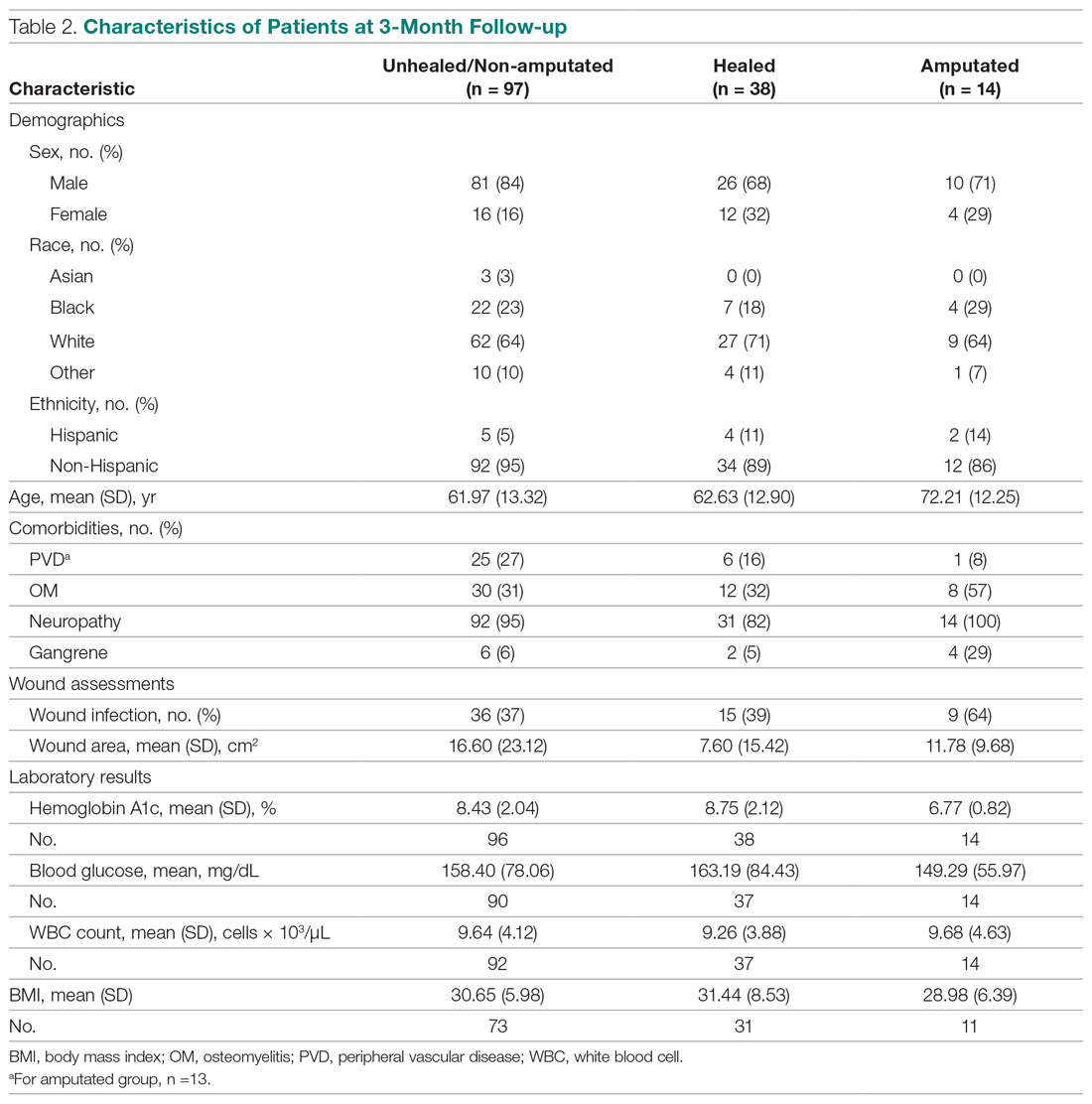

The descriptive statistics of 149 patients grouped into 3 categories (healed, amputated, unhealed/non-amputated) are shown in Table 2.

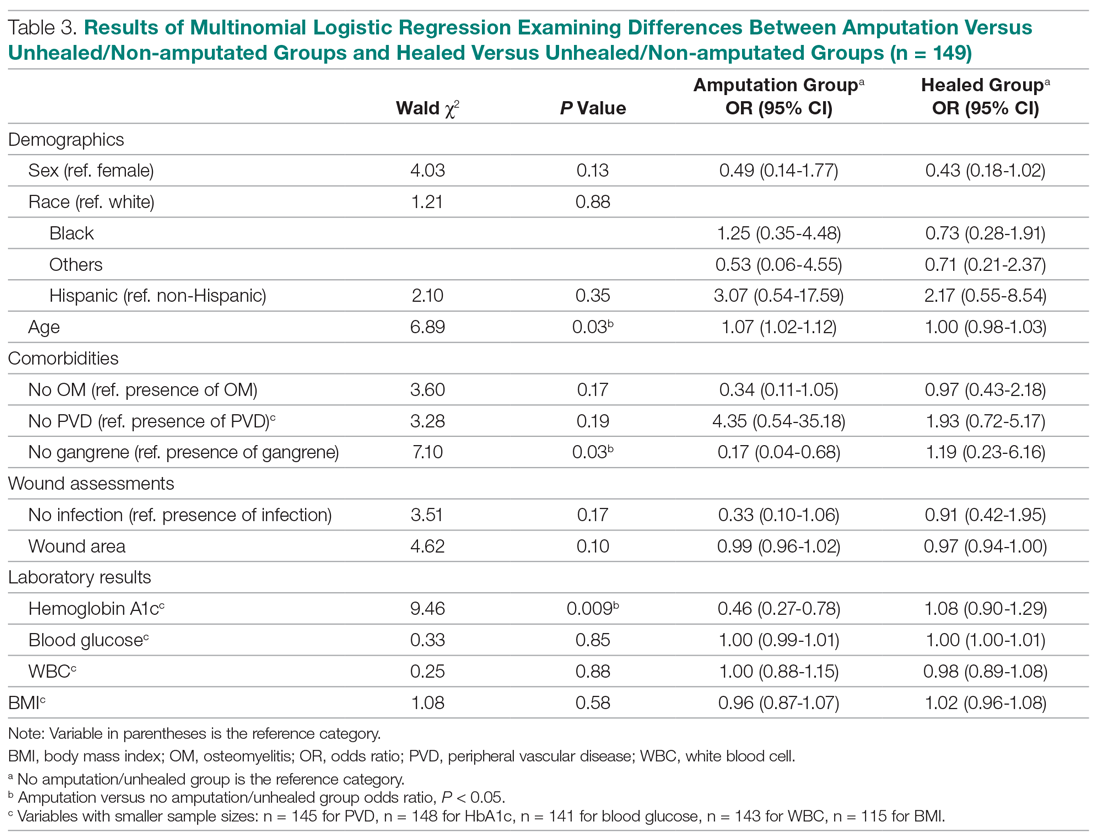

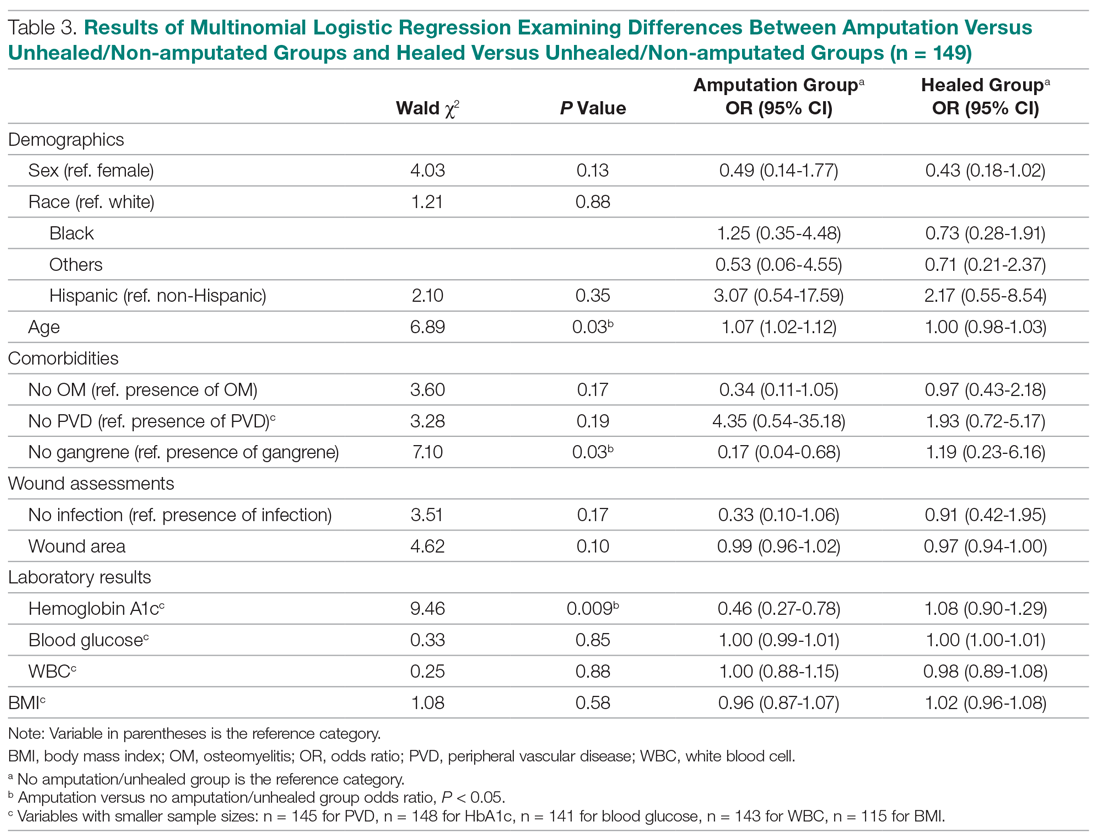

The results of the logistic regression exploring the differences between the amputation and healed groups and the unhealed/non-amputated group are shown in Table 3. The amputation group had a higher mean age and WBC count and greater wound area. Increased age was determined to be a significant predictor of the odds of amputation (P = 0.0089). For each year increase in age, the odds of amputation increased by 6.5% (odds ratio, 1.07 [95% confidence interval {CI}, 1.02-1.12]). Patients in the amputation group were more likely to be male, Hispanic, and African American and to have wound infections and comorbidities (osteomyelitis, neuropathy, and gangrene).

The presence of gangrene was significantly associated with LEA (P = 0.03). Specifically, the odds of patients without gangrene undergoing a LEA were substantially lower compared with their counterparts with gangrene (odds ratio, 0.17; 95% CI, 0.04-0.68; P = 0.0131). However, the presence of gangrene was not associated with the odds of healing compared with the odds of neither healing nor undergoing amputation (P = 0.84; not shown in Table 3).

The amputation group had lower mean values for HbA1c, BMI, and blood glucose levels and a lower rate of peripheral vascular disease. Only the relationship between lower HbA1c and increased odds of amputation versus not healing/non-amputation was found to be statistically significant (95% CI, 0.27-0.78; P = 0.009).

Discussion

This retrospective study was undertaken to evaluate factors associated with LEA in patients with diabetic foot ulcers. Patients with diabetes being treated at a wound care facility often require continuous surgical and metabolic intervention to promote optimal healing: drainage, surgical debridement, irrigation, culturing for infection, and monitoring of blood glucose levels. This treatment requires strict compliance with medical directions and, oftentimes, additional care, such as home-care nursing visits, to maintain a curative environment for the wound. Frequently, wounds on the lower extremity further complicate the healing process by reducing the patient’s mobility and daily life. Due to these factors, many patients progress to LEA. The link between diabetic ulcers and amputation has already been well described in previous studies, with studies showing that history of diabetic foot ulcer significantly predisposes an individual to LEA.4 However, few studies have further investigated demographic factors associated with risk for an amputation. Our study analyzed several categories of patient data taken from a baseline visit. We found that those with highly elevated HbA1c values were less likely to have an amputation than persons with relatively lower levels, a finding that is contrary to previous studies.

Our study’s findings suggest a higher risk for LEA with increased age. The amputation group was, on average, 7 years older than the other 2 groups. A recent study showed that risk for amputation is directly correlated to patient age, as is the mortality rate after undergoing LEA (2.3%; P < 0.05).5 Our study found that with each increase in age of 1 year, the odds of amputation increased by 6.5%. However, recent evidence on LEA risk and aging suggests that age is of less consequence than the duration of diabetes. One study found that the propensity to develop diabetic foot ulcers increases with the duration of diabetes.6 The same study found that prevalence of ulceration was correlated with age, but the relationship between age and LEA was less significant. A follow-up study for LEA could be done to examine the role of disease duration versus age in LEA.

A consensus among previous studies is that men have a higher risk for LEA.5,7 Men comprised the majority in all 3 groups in our study. In addition, the amputation group in our study had the lowest BMI. Higher BMI generally is associated with an increased risk for health complications. However, a past study conducted in Taiwan reported that obese patients with diabetes were less likely to undergo LEA than those within the normal range for BMI.8 Neither study suggests that obesity is a deterrent for LEA, but both studies may suggest that risk of amputation may approach a maximum frequency at a specific BMI range, and then decrease. This unconfirmed “cyclic” relationship should be evaluated further in a larger sample size.

Most patients in our analysis were Caucasian, followed by African American and South Asian. African Americans were the only racial group with an increased frequency in the amputation group. This finding is supported by a previous study that found that the rate of LEA among patients with diabetes in low-income, predominantly African-American neighborhoods was nearly double that in wealthier, predominantly Caucasian areas.9 A potential problem in the comparison between our data with previous studies is that the studies did not analyze patients with our inclusion criteria. All patients with diabetes in previous investigations were grouped by race, but were not necessarily required to have 1 or more ulcers. Multiple ulcers may predispose an individual to a greater risk for amputation.

Multinomial logistic regression did not suggest an association between initial size of a patient’s wound and the risk of amputation. However, the descriptive data suggests a trend. Patients who did not heal or require an amputation had the largest average wound area. This finding is not surprising in that our study followed individuals for only 3 months. Many wounds require a long course of treatment, especially in patients with diabetes, who may have poor vascularization. However, in comparison to the healed patients, the patients who required an amputation had a larger average wound area. A larger wound requires a plentiful vascular supply for the delivery of clotting factors and nutrients to the damaged area. As wound size increases, an individual’s body must transmit an increased quantity of these factors and nutrients for the regeneration of tissue. In addition, wounds that possess a larger surface area require more debridement and present a greater opportunity for infection. This may also foreshadow a longer, more costly course of treatment. Additionally, individuals coping with large ulcerations are burdened by more elaborate and complex wound dressings.

Elevated levels of HbA1c are associated with increased adverse effects of diabetes, including end-stage renal disease, neuropathy, and infection.10 In a previous study, the risk for amputation was 1.2 times higher in patients with elevated HbA1c.11 In contrast, our study suggested the odds of LEA versus not healing/not undergoing amputation decreased as HbA1c increased. As a patient’s HbA1c level increased by a value of 1, their odds for LEA decreased by 54.3%. This finding contradicts prior studies that have found a positive association between HbA1c and LEA risk, including a study where each percentage increase in HbA1c correlated with a 13% to 15% increased risk of LEA.12 The finding that patients who underwent amputation in our study had lower levels of HbA1c and blood glucose cannot be fully explained. The maximum HbA1c value in the amputated group was 7.9%. The average values for healed patients and those who underwent LEA were 8.75% and 6.77%, respectively.

Blood glucose levels were also found to be the lowest in the amputated group in our study (mean, 149.29 mg/dL vs 163.19 mg/dL in the healed group). Similar results were found in a Brazilian study, in which patients who did not require amputation had higher HbA1c levels. This study also found an association between blood glucose levels above 200 mg/dL and amputations.3 These findings provide interesting opportunities for repeat studies, preferably with a larger number of participants.

Our study is limited by the small sample size. The sample population had to be reduced, as many patients were lost to follow-up. Although this paring down of the sample size can introduce bias, we are confident that our study is representative of the demographic of patients treated in our facility. The loss of patients to follow-up in turn caused the window of analysis to be narrowed, as long-term outcome data were not available. A multisite study observing various population samples can better explore the relationship between HbA1c and risk of amputation.

Conclusion

This retrospective study exploring factors associated with LEA was unique in that all our participants had 1 or more diabetic foot ulcerations, and thus already had an extremely high risk for amputation, in contrast to previous studies that followed persons at risk for developing diabetic foot ulcerations. In contrast to several previous studies, we found that the risk for amputation actually decreased as baseline measurements of HbA1c increased. The results of this study offer many opportunities for future investigations, preferably with a larger sample size. By further isolating and scrutinizing specific factors associated with LEA, researchers can help clinicians focus on providing wound care that promotes limb salvage.

Corresponding author: Alisha Oropallo, MD, MS, Northwell Health Comprehensive Wound Care Healing Center and Hyperbarics, 1999 Marcus Avenue, Suite M6, Lake Success, NY 11042; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: Funding for this research was provided by a multi-institutional AHRQ governmental grant.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report: Estimates of Diabetes and Its Burden in the United States, 2017. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2017.

2. Uccioli L, Giurato L, Meloni M, et al. Comment on Hoffstad et al. Diabetes, lower-extremity amputation, and death. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:1852-1857.

3. Gamba MA, Gotlieb SLD, Bergamaschi DP, Vianna LAC. Lower extremity amputations in diabetic patients: a case-control study. Rev Saúde Pública. 2004;38:399-404.

4. Martins-Mendes D, Monteiro-Soares M, Boyko EJ, et al. The independent contribution of diabetic foot ulcer on lower extremity amputation and mortality risk. J Diabetes Complications. 2014;28:632-638.

5. Lipsky BA, Weigelt JA, Sun X, et al. Developing and validating a risk score for lower-extremity amputation in patients hospitalized for a diabetic foot infection. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:1695-1700.

6. Al-Rubeaan K, Al Derwish M, Ouizi S, et al. Diabetic foot complications and their risk factors from a large retrospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0124446.

7. Pickwell K, Siersma V, Kars M, et al. Predictors of lower-extremity amputation in patients with an infected diabetic foot ulcer. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:852-857.

8. Lin C, Hsu BR, Tsai J, et al. Effect of limb preservation status and body mass index on the survival of patients with limb-threatening diabetic foot ulcers. J Diabetes Complications. 2017;31:180-185.

9. Stevens CD, Schriger DL, Raffetto B, et al. Geographic clustering of diabetic lower-extremity amputations in low-income regions of California. Health Aff. 2014;33:1383-1390.

10. Liao L, Li C, Liu C, et al. Extreme levels of HbA1c increase incident ESRD risk in Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes: competing risk analysis in national cohort of Taiwan diabetes study. PLoS One. 2015; 10:e0130828.

11. Miyajima S, Shirai A, Yamamoto S, et al. Risk factors for major limb amputations in diabetic foot gangrene patients. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2006;71:272-279.

12. Zhao W, Katzmarzyk PT, Horswell R, et al. HbA1c and lower-extremity amputation risk in low-income patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:3591-3598.

From Northwell Health System, Lake Success, NY.

Abstract

- Objective: To explore factors associated with lower-extremity amputation (LEA) in patients with diabetic foot ulcers using data from the Online Wound Electronic Medical Record Database.

- Design: Retrospective analysis of medical records.

- Setting and participants: Data from 169 individuals with previously diagnosed diabetes mellitus who received wound care for a 6-month period within a span of 2 years was analyzed. A baseline evaluation was obtained and wound(s) were treated, managed, and monitored.

Treatment continued until the patient healed, required an LEA, or phased out of the study, neither healing nor undergoing an amputation. Of the 149 patients who completed the study, 38 had healed ulcers, 14 underwent amputation, and 97 neither healed nor underwent an amputation. All patients were treated under the care of vascular and/or podiatric surgeons. - Measurements: Variables included wound status (healed, amputated, and unhealed/non-amputated); size of wound area; age, gender, race, and ethnicity; white blood cell (WBC) count, hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), blood glucose, and body mass index (BMI); and presence of osteomyelitis, gangrene, and peripheral vascular disease.

- Results: As compared to the healed and unhealed/non-amputated group, the group of patients who underwent LEA was older and had higher percentages of males, Hispanics, and African Americans; had a higher WBC count, larger wound area, and higher rates of wound infection, osteomyelitis, and neuropathy; and had lower average values of HbA1c, blood glucose, and BMI and a lower rate of peripheral vascular disease.

- Conclusion: The association between HbA1c and LEA highlights a window of relative safety among an at-risk population. By identifying and focusing on factors associated with LEA, health care professionals may be able to decrease the prevalence of LEA in patients with diabetes.

Keywords: diabetic foot ulcer; lower-extremity amputation; risk factors; HbA1c.

An estimated 30.3 million people, or 9.4% of the US population, has diabetes. In 2014, approximately 108,000 amputations were performed on adults with diagnosed diabetes.1 Furthermore, patients with diabetes have a 10-fold increased risk for lower-extremity amputation (LEA), as compared with patients without diabetes.2 The frequency of amputations in the diabetic population is a public health crisis.

Amputation has significant, life-altering consequences. Patients who undergo LEA often face debilitation in their daily activities and must undergo intense rehabilitation to learn basic tasks. Amputations can also impact individuals’ psychological well-being as they come to terms with their altered body and may face challenges in self-perception, confidence, self-esteem, work life, and relationships. In addition, the mortality rate for patients with diabetes 5 years after undergoing LEA is 30%.2 However, public health studies estimate that more than half of LEAs in patients with diabetes are preventable.3

Although studies have explored the relationship between diabetes and LEA, few have sought to identify factors directly correlated with wound care. In the United States, patients with diabetic ulcerations are typically treated in wound care facilities; however, previous studies have concentrated on the conditions that lead to the formation of an ulcer or amputation, viewing amputation and ulcer as 2 separate entities. Our study took into account systemic variables, patient demographics, and specific wound characteristics to explore factors associated with LEA in a high-risk group of patients with diabetes. This study was designed to assess ailments that are prevalent in patients who require a LEA.

Methods

Patients and Setting

A total of 169 patients who were treated at the Comprehensive Wound Healing and Hyperbaric Center (Lake Success, NY), a tertiary facility of the Northwell Health system, participated in this retrospective study. The data for this study were obtained in conjunction with the development of the New York University School of Medicine’s Online Wound Electronic Medical Record to Decrease Limb Amputations in Persons with Diabetes (OWEMR) database. The OWEMR collects individual patient data from satellite locations across the country. Using this database, researchers can analyze similarities and differences between patients who undergo LEA.

This study utilized patient data specific to the Northwell Health facility. All of the patients in our study were enrolled under the criteria of the OWEMR database. In order to be included in the OWEMR database, patients had to be diagnosed with type 1 or type 2 diabetes; have a break in the skin ≥ 0.5 cm2; be 18 years of age or older; and have a measured hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) value within the past 120 days. Study patients signed an informed consent and committed to being available for follow-up visits to the wound care facility for 6 months after entering the study. Patients were enrolled between 2012 and 2014, and each patient was monitored for a period of 6 months within this time period. Participants were treated with current standards of care using diet, lifestyle, and pharmacologic interventions. This study was approved by the Northwell Health System Institutional Review Board Human Research Protection Program (Manhasset, NY).

Data Collection

On their first visit to the facility, patients were given a physical examination and initial interview regarding their medical history. Clinicians were required to select 1 ulcer that would be examined for the duration of the study. The selection of the ulcer was based on a point system that awarded points for pedal pulses, the ability to be probed to the bone, the location of the ulcer (ie, located on the foot rather than a toe), and the presence of multiple ulcerations. The ulcer with the highest score was selected for the study. If numerous ulcers were evaluated with the same score, the largest and deepest was selected. Wagner classification of the wound was recorded at baseline and taken at each subsequent patient visit. In addition, peripheral sensation was assessed for signs of neuropathy using Semmes-Weinstein monofilament testing.

Once selected, the wound was clinically evaluated, samples for culture were obtained, and blood tests were performed to detect the presence of wound infection. The patient’s blood was drawn for a full laboratory analysis, including white blood cell (WBC) count and measurement of blood glucose and HbA1c levels. Bone biopsy, magnetic resonance imaging, and bone scans were used to detect the presence of osteomyelitis at the discretion of the health care provider. Wounds suspected of infection, underlying osteomyelitis, or gangrene at baseline were excluded. Patients would then return for follow-up visits at least once every 6 weeks, plus or minus 2 weeks, for a maximum of 6 months.

Statistical Analysis

Utilizing SAS version 9.3 (Cary, NC), descriptive statistics (minimum, maximum, mean, median, and SD) were calculated for the following variables: age, WBC count, wound area, HbA1c, blood glucose, and body mass index (BMI). These variables were collected for each patient as per the OWEMR protocol and provided a basis for which to compare patients who underwent amputation and those who did not. Twenty patients were lost to follow-up, and therefore we altered the window of our statistics from 6 months to 3 months to provide the most accurate data, as 6-month follow-up data were limited. The patients were classified into the following categories: healed, amputated, and unhealed/non-amputated. Descriptive statistics were calculated for these 3 groups, analyzing the same variables (age, WBC count, wound area, HbA1c, blood glucose, and BMI). Additional statistical computations were utilized in order to show the prevalence and frequency of our categorical variables: gender, race, ethnicity, osteomyelitis, gangrene, and peripheral vascular disease. The baseline values of WBC count, HbA1c, wound area, and BMI of the 3 groups were analyzed with descriptive statistics for comparison. A multinomial logistic regression was then performed using a 3-level outcome variable: healed, amputated, or unhealed/non-amputated. Each predictor variable was analyzed independently due to the small sample size.

Results

Of the 169 registered patients treated at the Northwell Health facility, all qualified for the OWEMR study and met the study criteria. In the original 169 patients, there were 19 amputations: 6 toe, 6 trans-metatarsal, 6 below knee, and 1 above knee (Table 1).

The descriptive statistics of 149 patients grouped into 3 categories (healed, amputated, unhealed/non-amputated) are shown in Table 2.

The results of the logistic regression exploring the differences between the amputation and healed groups and the unhealed/non-amputated group are shown in Table 3. The amputation group had a higher mean age and WBC count and greater wound area. Increased age was determined to be a significant predictor of the odds of amputation (P = 0.0089). For each year increase in age, the odds of amputation increased by 6.5% (odds ratio, 1.07 [95% confidence interval {CI}, 1.02-1.12]). Patients in the amputation group were more likely to be male, Hispanic, and African American and to have wound infections and comorbidities (osteomyelitis, neuropathy, and gangrene).

The presence of gangrene was significantly associated with LEA (P = 0.03). Specifically, the odds of patients without gangrene undergoing a LEA were substantially lower compared with their counterparts with gangrene (odds ratio, 0.17; 95% CI, 0.04-0.68; P = 0.0131). However, the presence of gangrene was not associated with the odds of healing compared with the odds of neither healing nor undergoing amputation (P = 0.84; not shown in Table 3).

The amputation group had lower mean values for HbA1c, BMI, and blood glucose levels and a lower rate of peripheral vascular disease. Only the relationship between lower HbA1c and increased odds of amputation versus not healing/non-amputation was found to be statistically significant (95% CI, 0.27-0.78; P = 0.009).

Discussion

This retrospective study was undertaken to evaluate factors associated with LEA in patients with diabetic foot ulcers. Patients with diabetes being treated at a wound care facility often require continuous surgical and metabolic intervention to promote optimal healing: drainage, surgical debridement, irrigation, culturing for infection, and monitoring of blood glucose levels. This treatment requires strict compliance with medical directions and, oftentimes, additional care, such as home-care nursing visits, to maintain a curative environment for the wound. Frequently, wounds on the lower extremity further complicate the healing process by reducing the patient’s mobility and daily life. Due to these factors, many patients progress to LEA. The link between diabetic ulcers and amputation has already been well described in previous studies, with studies showing that history of diabetic foot ulcer significantly predisposes an individual to LEA.4 However, few studies have further investigated demographic factors associated with risk for an amputation. Our study analyzed several categories of patient data taken from a baseline visit. We found that those with highly elevated HbA1c values were less likely to have an amputation than persons with relatively lower levels, a finding that is contrary to previous studies.

Our study’s findings suggest a higher risk for LEA with increased age. The amputation group was, on average, 7 years older than the other 2 groups. A recent study showed that risk for amputation is directly correlated to patient age, as is the mortality rate after undergoing LEA (2.3%; P < 0.05).5 Our study found that with each increase in age of 1 year, the odds of amputation increased by 6.5%. However, recent evidence on LEA risk and aging suggests that age is of less consequence than the duration of diabetes. One study found that the propensity to develop diabetic foot ulcers increases with the duration of diabetes.6 The same study found that prevalence of ulceration was correlated with age, but the relationship between age and LEA was less significant. A follow-up study for LEA could be done to examine the role of disease duration versus age in LEA.

A consensus among previous studies is that men have a higher risk for LEA.5,7 Men comprised the majority in all 3 groups in our study. In addition, the amputation group in our study had the lowest BMI. Higher BMI generally is associated with an increased risk for health complications. However, a past study conducted in Taiwan reported that obese patients with diabetes were less likely to undergo LEA than those within the normal range for BMI.8 Neither study suggests that obesity is a deterrent for LEA, but both studies may suggest that risk of amputation may approach a maximum frequency at a specific BMI range, and then decrease. This unconfirmed “cyclic” relationship should be evaluated further in a larger sample size.

Most patients in our analysis were Caucasian, followed by African American and South Asian. African Americans were the only racial group with an increased frequency in the amputation group. This finding is supported by a previous study that found that the rate of LEA among patients with diabetes in low-income, predominantly African-American neighborhoods was nearly double that in wealthier, predominantly Caucasian areas.9 A potential problem in the comparison between our data with previous studies is that the studies did not analyze patients with our inclusion criteria. All patients with diabetes in previous investigations were grouped by race, but were not necessarily required to have 1 or more ulcers. Multiple ulcers may predispose an individual to a greater risk for amputation.

Multinomial logistic regression did not suggest an association between initial size of a patient’s wound and the risk of amputation. However, the descriptive data suggests a trend. Patients who did not heal or require an amputation had the largest average wound area. This finding is not surprising in that our study followed individuals for only 3 months. Many wounds require a long course of treatment, especially in patients with diabetes, who may have poor vascularization. However, in comparison to the healed patients, the patients who required an amputation had a larger average wound area. A larger wound requires a plentiful vascular supply for the delivery of clotting factors and nutrients to the damaged area. As wound size increases, an individual’s body must transmit an increased quantity of these factors and nutrients for the regeneration of tissue. In addition, wounds that possess a larger surface area require more debridement and present a greater opportunity for infection. This may also foreshadow a longer, more costly course of treatment. Additionally, individuals coping with large ulcerations are burdened by more elaborate and complex wound dressings.

Elevated levels of HbA1c are associated with increased adverse effects of diabetes, including end-stage renal disease, neuropathy, and infection.10 In a previous study, the risk for amputation was 1.2 times higher in patients with elevated HbA1c.11 In contrast, our study suggested the odds of LEA versus not healing/not undergoing amputation decreased as HbA1c increased. As a patient’s HbA1c level increased by a value of 1, their odds for LEA decreased by 54.3%. This finding contradicts prior studies that have found a positive association between HbA1c and LEA risk, including a study where each percentage increase in HbA1c correlated with a 13% to 15% increased risk of LEA.12 The finding that patients who underwent amputation in our study had lower levels of HbA1c and blood glucose cannot be fully explained. The maximum HbA1c value in the amputated group was 7.9%. The average values for healed patients and those who underwent LEA were 8.75% and 6.77%, respectively.

Blood glucose levels were also found to be the lowest in the amputated group in our study (mean, 149.29 mg/dL vs 163.19 mg/dL in the healed group). Similar results were found in a Brazilian study, in which patients who did not require amputation had higher HbA1c levels. This study also found an association between blood glucose levels above 200 mg/dL and amputations.3 These findings provide interesting opportunities for repeat studies, preferably with a larger number of participants.

Our study is limited by the small sample size. The sample population had to be reduced, as many patients were lost to follow-up. Although this paring down of the sample size can introduce bias, we are confident that our study is representative of the demographic of patients treated in our facility. The loss of patients to follow-up in turn caused the window of analysis to be narrowed, as long-term outcome data were not available. A multisite study observing various population samples can better explore the relationship between HbA1c and risk of amputation.

Conclusion

This retrospective study exploring factors associated with LEA was unique in that all our participants had 1 or more diabetic foot ulcerations, and thus already had an extremely high risk for amputation, in contrast to previous studies that followed persons at risk for developing diabetic foot ulcerations. In contrast to several previous studies, we found that the risk for amputation actually decreased as baseline measurements of HbA1c increased. The results of this study offer many opportunities for future investigations, preferably with a larger sample size. By further isolating and scrutinizing specific factors associated with LEA, researchers can help clinicians focus on providing wound care that promotes limb salvage.

Corresponding author: Alisha Oropallo, MD, MS, Northwell Health Comprehensive Wound Care Healing Center and Hyperbarics, 1999 Marcus Avenue, Suite M6, Lake Success, NY 11042; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: Funding for this research was provided by a multi-institutional AHRQ governmental grant.

From Northwell Health System, Lake Success, NY.

Abstract

- Objective: To explore factors associated with lower-extremity amputation (LEA) in patients with diabetic foot ulcers using data from the Online Wound Electronic Medical Record Database.

- Design: Retrospective analysis of medical records.

- Setting and participants: Data from 169 individuals with previously diagnosed diabetes mellitus who received wound care for a 6-month period within a span of 2 years was analyzed. A baseline evaluation was obtained and wound(s) were treated, managed, and monitored.

Treatment continued until the patient healed, required an LEA, or phased out of the study, neither healing nor undergoing an amputation. Of the 149 patients who completed the study, 38 had healed ulcers, 14 underwent amputation, and 97 neither healed nor underwent an amputation. All patients were treated under the care of vascular and/or podiatric surgeons. - Measurements: Variables included wound status (healed, amputated, and unhealed/non-amputated); size of wound area; age, gender, race, and ethnicity; white blood cell (WBC) count, hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), blood glucose, and body mass index (BMI); and presence of osteomyelitis, gangrene, and peripheral vascular disease.

- Results: As compared to the healed and unhealed/non-amputated group, the group of patients who underwent LEA was older and had higher percentages of males, Hispanics, and African Americans; had a higher WBC count, larger wound area, and higher rates of wound infection, osteomyelitis, and neuropathy; and had lower average values of HbA1c, blood glucose, and BMI and a lower rate of peripheral vascular disease.

- Conclusion: The association between HbA1c and LEA highlights a window of relative safety among an at-risk population. By identifying and focusing on factors associated with LEA, health care professionals may be able to decrease the prevalence of LEA in patients with diabetes.

Keywords: diabetic foot ulcer; lower-extremity amputation; risk factors; HbA1c.

An estimated 30.3 million people, or 9.4% of the US population, has diabetes. In 2014, approximately 108,000 amputations were performed on adults with diagnosed diabetes.1 Furthermore, patients with diabetes have a 10-fold increased risk for lower-extremity amputation (LEA), as compared with patients without diabetes.2 The frequency of amputations in the diabetic population is a public health crisis.

Amputation has significant, life-altering consequences. Patients who undergo LEA often face debilitation in their daily activities and must undergo intense rehabilitation to learn basic tasks. Amputations can also impact individuals’ psychological well-being as they come to terms with their altered body and may face challenges in self-perception, confidence, self-esteem, work life, and relationships. In addition, the mortality rate for patients with diabetes 5 years after undergoing LEA is 30%.2 However, public health studies estimate that more than half of LEAs in patients with diabetes are preventable.3

Although studies have explored the relationship between diabetes and LEA, few have sought to identify factors directly correlated with wound care. In the United States, patients with diabetic ulcerations are typically treated in wound care facilities; however, previous studies have concentrated on the conditions that lead to the formation of an ulcer or amputation, viewing amputation and ulcer as 2 separate entities. Our study took into account systemic variables, patient demographics, and specific wound characteristics to explore factors associated with LEA in a high-risk group of patients with diabetes. This study was designed to assess ailments that are prevalent in patients who require a LEA.

Methods

Patients and Setting

A total of 169 patients who were treated at the Comprehensive Wound Healing and Hyperbaric Center (Lake Success, NY), a tertiary facility of the Northwell Health system, participated in this retrospective study. The data for this study were obtained in conjunction with the development of the New York University School of Medicine’s Online Wound Electronic Medical Record to Decrease Limb Amputations in Persons with Diabetes (OWEMR) database. The OWEMR collects individual patient data from satellite locations across the country. Using this database, researchers can analyze similarities and differences between patients who undergo LEA.

This study utilized patient data specific to the Northwell Health facility. All of the patients in our study were enrolled under the criteria of the OWEMR database. In order to be included in the OWEMR database, patients had to be diagnosed with type 1 or type 2 diabetes; have a break in the skin ≥ 0.5 cm2; be 18 years of age or older; and have a measured hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) value within the past 120 days. Study patients signed an informed consent and committed to being available for follow-up visits to the wound care facility for 6 months after entering the study. Patients were enrolled between 2012 and 2014, and each patient was monitored for a period of 6 months within this time period. Participants were treated with current standards of care using diet, lifestyle, and pharmacologic interventions. This study was approved by the Northwell Health System Institutional Review Board Human Research Protection Program (Manhasset, NY).

Data Collection

On their first visit to the facility, patients were given a physical examination and initial interview regarding their medical history. Clinicians were required to select 1 ulcer that would be examined for the duration of the study. The selection of the ulcer was based on a point system that awarded points for pedal pulses, the ability to be probed to the bone, the location of the ulcer (ie, located on the foot rather than a toe), and the presence of multiple ulcerations. The ulcer with the highest score was selected for the study. If numerous ulcers were evaluated with the same score, the largest and deepest was selected. Wagner classification of the wound was recorded at baseline and taken at each subsequent patient visit. In addition, peripheral sensation was assessed for signs of neuropathy using Semmes-Weinstein monofilament testing.

Once selected, the wound was clinically evaluated, samples for culture were obtained, and blood tests were performed to detect the presence of wound infection. The patient’s blood was drawn for a full laboratory analysis, including white blood cell (WBC) count and measurement of blood glucose and HbA1c levels. Bone biopsy, magnetic resonance imaging, and bone scans were used to detect the presence of osteomyelitis at the discretion of the health care provider. Wounds suspected of infection, underlying osteomyelitis, or gangrene at baseline were excluded. Patients would then return for follow-up visits at least once every 6 weeks, plus or minus 2 weeks, for a maximum of 6 months.

Statistical Analysis

Utilizing SAS version 9.3 (Cary, NC), descriptive statistics (minimum, maximum, mean, median, and SD) were calculated for the following variables: age, WBC count, wound area, HbA1c, blood glucose, and body mass index (BMI). These variables were collected for each patient as per the OWEMR protocol and provided a basis for which to compare patients who underwent amputation and those who did not. Twenty patients were lost to follow-up, and therefore we altered the window of our statistics from 6 months to 3 months to provide the most accurate data, as 6-month follow-up data were limited. The patients were classified into the following categories: healed, amputated, and unhealed/non-amputated. Descriptive statistics were calculated for these 3 groups, analyzing the same variables (age, WBC count, wound area, HbA1c, blood glucose, and BMI). Additional statistical computations were utilized in order to show the prevalence and frequency of our categorical variables: gender, race, ethnicity, osteomyelitis, gangrene, and peripheral vascular disease. The baseline values of WBC count, HbA1c, wound area, and BMI of the 3 groups were analyzed with descriptive statistics for comparison. A multinomial logistic regression was then performed using a 3-level outcome variable: healed, amputated, or unhealed/non-amputated. Each predictor variable was analyzed independently due to the small sample size.

Results

Of the 169 registered patients treated at the Northwell Health facility, all qualified for the OWEMR study and met the study criteria. In the original 169 patients, there were 19 amputations: 6 toe, 6 trans-metatarsal, 6 below knee, and 1 above knee (Table 1).

The descriptive statistics of 149 patients grouped into 3 categories (healed, amputated, unhealed/non-amputated) are shown in Table 2.