User login

Testing lab asks FDA to recall NDMA-tainted metformin

Valisure, an online pharmacy and analytical laboratory based in New Haven, Conn., has asked the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to request recalls of the diabetes drug metformin from 11 companies after its own testing found levels of the probable carcinogen N-nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA) exceeded those recognized by the agency as being safe, according to a petition filed with the FDA.

“The presence of this probable carcinogen in a medication that is taken daily by adults and adolescents for a chronic condition like diabetes, makes [these findings] particularly troubling,” the pharmacy said in the petition. It noted that NDMA is classified by the World Health Organization and the International Agency for Research on Cancer as a Group 2A compound, meaning that it is “probably carcinogenic to humans.”

The Valisure findings are in contrast to those from the FDA’s own testing of metformin from eight companies. In results released Feb. 2, the agency found no NDMA in metformin from seven of the companies, and elevations within the safe limit in metformin from the remaining company. Based on those results, the FDA did not issue a recall.

The FDA declined to comment on the petition, pending a formal written response, a spokesman said.

Valisure said in its petition that one reason it found NDMA at concerning levels, and the FDA did not, could be that the pharmacy’s testing was more thorough than the agency’s because it had used its proprietary analytical technologies in addition to FDA standard assays. The pharmacy said it also cast a wider net, testing samples from 22 companies instead of 8, as the FDA had.

“At least one company that consistently displayed high levels of NDMA in all Valisure-tested batches was a company whose metformin products, to Valisure’s knowledge, were not tested by FDA,” Valisure said in the petition.

The pharmacy tested 38 batches of metformin from 22 companies, and found 16 contaminated batches from 11 companies. Results from one company were confirmed by an independent laboratory in California.

In addition, “there was significant variability from batch to batch, even within a single company, underscoring the importance of batch-level chemical analysis and the necessity of overall increased quality surveillance of medications,” the pharmacy stated in the petition.

David Light, Valisure founder and CEO, said in a press release that the results “indicate that contaminated batches of drugs are scattered and intermixed with clean [batches] throughout the American pharmaceutical supply chain. This strongly suggests that neither the limited testing FDA is able to conduct nor the pharmaceutical companies’ self-reporting of analytical results is sufficient to protect American consumers.”

He explained in an interview that metformin contamination probably comes from poor manufacturing, as NDMA can form during the manufacturing process. Companies are supposed to have processes in place to limit its formation and to check for and remove it before products are shipped. The contaminated batches might have come from China, which makes the bulk of U.S. active pharmaceutical ingredients, he said.

Recently, Apotex and Ranbaxy Pharmaceuticals recalled specific metformin lots in Canada after Canadian health authorities requested NDMA testing. Metformin versions have also been recalled in Singapore. European health authorities are also looking into the issue, according to a Mar. 3 press release from the European Medicines Agency.

Over the past 2 years, NDMA contamination has led to recalls of angiotensin receptor blockers, such as valsartan and losartan, because of NDMA in excess of the daily limit, and ranitidine-containing products such as Zantac. Valisure said it hopes the FDA will avoid the “year-long rolling recalls” that have occurred for angiotensin receptor blockers.

Metformin, which is used to treat type 2 diabetes, is the fourth-most prescribed drug in the United States. About 80 million prescriptions were written for it during 2019, according to the press release.

Valisure launched its investigation after it found NDMA in metformin a client asked it to check.

Valisure, an online pharmacy and analytical laboratory based in New Haven, Conn., has asked the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to request recalls of the diabetes drug metformin from 11 companies after its own testing found levels of the probable carcinogen N-nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA) exceeded those recognized by the agency as being safe, according to a petition filed with the FDA.

“The presence of this probable carcinogen in a medication that is taken daily by adults and adolescents for a chronic condition like diabetes, makes [these findings] particularly troubling,” the pharmacy said in the petition. It noted that NDMA is classified by the World Health Organization and the International Agency for Research on Cancer as a Group 2A compound, meaning that it is “probably carcinogenic to humans.”

The Valisure findings are in contrast to those from the FDA’s own testing of metformin from eight companies. In results released Feb. 2, the agency found no NDMA in metformin from seven of the companies, and elevations within the safe limit in metformin from the remaining company. Based on those results, the FDA did not issue a recall.

The FDA declined to comment on the petition, pending a formal written response, a spokesman said.

Valisure said in its petition that one reason it found NDMA at concerning levels, and the FDA did not, could be that the pharmacy’s testing was more thorough than the agency’s because it had used its proprietary analytical technologies in addition to FDA standard assays. The pharmacy said it also cast a wider net, testing samples from 22 companies instead of 8, as the FDA had.

“At least one company that consistently displayed high levels of NDMA in all Valisure-tested batches was a company whose metformin products, to Valisure’s knowledge, were not tested by FDA,” Valisure said in the petition.

The pharmacy tested 38 batches of metformin from 22 companies, and found 16 contaminated batches from 11 companies. Results from one company were confirmed by an independent laboratory in California.

In addition, “there was significant variability from batch to batch, even within a single company, underscoring the importance of batch-level chemical analysis and the necessity of overall increased quality surveillance of medications,” the pharmacy stated in the petition.

David Light, Valisure founder and CEO, said in a press release that the results “indicate that contaminated batches of drugs are scattered and intermixed with clean [batches] throughout the American pharmaceutical supply chain. This strongly suggests that neither the limited testing FDA is able to conduct nor the pharmaceutical companies’ self-reporting of analytical results is sufficient to protect American consumers.”

He explained in an interview that metformin contamination probably comes from poor manufacturing, as NDMA can form during the manufacturing process. Companies are supposed to have processes in place to limit its formation and to check for and remove it before products are shipped. The contaminated batches might have come from China, which makes the bulk of U.S. active pharmaceutical ingredients, he said.

Recently, Apotex and Ranbaxy Pharmaceuticals recalled specific metformin lots in Canada after Canadian health authorities requested NDMA testing. Metformin versions have also been recalled in Singapore. European health authorities are also looking into the issue, according to a Mar. 3 press release from the European Medicines Agency.

Over the past 2 years, NDMA contamination has led to recalls of angiotensin receptor blockers, such as valsartan and losartan, because of NDMA in excess of the daily limit, and ranitidine-containing products such as Zantac. Valisure said it hopes the FDA will avoid the “year-long rolling recalls” that have occurred for angiotensin receptor blockers.

Metformin, which is used to treat type 2 diabetes, is the fourth-most prescribed drug in the United States. About 80 million prescriptions were written for it during 2019, according to the press release.

Valisure launched its investigation after it found NDMA in metformin a client asked it to check.

Valisure, an online pharmacy and analytical laboratory based in New Haven, Conn., has asked the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to request recalls of the diabetes drug metformin from 11 companies after its own testing found levels of the probable carcinogen N-nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA) exceeded those recognized by the agency as being safe, according to a petition filed with the FDA.

“The presence of this probable carcinogen in a medication that is taken daily by adults and adolescents for a chronic condition like diabetes, makes [these findings] particularly troubling,” the pharmacy said in the petition. It noted that NDMA is classified by the World Health Organization and the International Agency for Research on Cancer as a Group 2A compound, meaning that it is “probably carcinogenic to humans.”

The Valisure findings are in contrast to those from the FDA’s own testing of metformin from eight companies. In results released Feb. 2, the agency found no NDMA in metformin from seven of the companies, and elevations within the safe limit in metformin from the remaining company. Based on those results, the FDA did not issue a recall.

The FDA declined to comment on the petition, pending a formal written response, a spokesman said.

Valisure said in its petition that one reason it found NDMA at concerning levels, and the FDA did not, could be that the pharmacy’s testing was more thorough than the agency’s because it had used its proprietary analytical technologies in addition to FDA standard assays. The pharmacy said it also cast a wider net, testing samples from 22 companies instead of 8, as the FDA had.

“At least one company that consistently displayed high levels of NDMA in all Valisure-tested batches was a company whose metformin products, to Valisure’s knowledge, were not tested by FDA,” Valisure said in the petition.

The pharmacy tested 38 batches of metformin from 22 companies, and found 16 contaminated batches from 11 companies. Results from one company were confirmed by an independent laboratory in California.

In addition, “there was significant variability from batch to batch, even within a single company, underscoring the importance of batch-level chemical analysis and the necessity of overall increased quality surveillance of medications,” the pharmacy stated in the petition.

David Light, Valisure founder and CEO, said in a press release that the results “indicate that contaminated batches of drugs are scattered and intermixed with clean [batches] throughout the American pharmaceutical supply chain. This strongly suggests that neither the limited testing FDA is able to conduct nor the pharmaceutical companies’ self-reporting of analytical results is sufficient to protect American consumers.”

He explained in an interview that metformin contamination probably comes from poor manufacturing, as NDMA can form during the manufacturing process. Companies are supposed to have processes in place to limit its formation and to check for and remove it before products are shipped. The contaminated batches might have come from China, which makes the bulk of U.S. active pharmaceutical ingredients, he said.

Recently, Apotex and Ranbaxy Pharmaceuticals recalled specific metformin lots in Canada after Canadian health authorities requested NDMA testing. Metformin versions have also been recalled in Singapore. European health authorities are also looking into the issue, according to a Mar. 3 press release from the European Medicines Agency.

Over the past 2 years, NDMA contamination has led to recalls of angiotensin receptor blockers, such as valsartan and losartan, because of NDMA in excess of the daily limit, and ranitidine-containing products such as Zantac. Valisure said it hopes the FDA will avoid the “year-long rolling recalls” that have occurred for angiotensin receptor blockers.

Metformin, which is used to treat type 2 diabetes, is the fourth-most prescribed drug in the United States. About 80 million prescriptions were written for it during 2019, according to the press release.

Valisure launched its investigation after it found NDMA in metformin a client asked it to check.

MACE benefits with dapagliflozin improve with disease duration

Treatment with the sodium-glucose transporter 2 inhibitor dapagliflozin reduced the risk for cardiovascular disease or hospitalization for heart failure (CVD/HHF) in patients with diabetes, regardless of the duration of the disease, but had a greater protective benefit against major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and renal events in patients with longer disease duration, according to new findings from a post hoc analysis of the DECLARE-TIMI 58 trial.

The positive effect of dapagliflozin in patients with MACE – which includes myocardial infarction (MI), CVD, and ischemic stroke – may have been driven by lower rates of MI and ischemic stroke with the drug, compared with placebo, in patients with longer disease duration, wrote Harpreet S. Bajaj, MD, and colleagues. Their report is in Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism (2020 Feb 23. doi: 10.1111/dom.14011).

It has been previously reported that the risk for complications in diabetes increases with increasing duration of the disease. Recent studies with SGLT-2 inhibitors have shown that the drugs improve cardiovascular and renal outcomes in diabetes, and they are recommended by the American Diabetes Association as second-line therapy in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, or heart failure. The European Society of Cardiology and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes recommend that patients with diabetes patients who have three or more risk factors, or those with a disease duration of more than 20 years, should be deemed very high risk and be considered for early treatment with SGLT2 inhibitors.

“The MACE benefit observed with dapagliflozin in this study in patients with diabetes duration of [more than] 20 years, clearly supports that notion,” the authors wrote.

In DECLARE-TIMI 58, 17,160 patients with type 2 diabetes received dapagliflozin or placebo and were followed for a median of 4.2 years. Of those patients, 22.4% had a disease duration of fewer than 5 years; 27.6%, a duration of 5-10 years; 23.0%, 10-15 years; 14.2%, 10-15 years; and 12.9%, more than 20 years. The median duration of disease was 11 years.

Patients in all the age groups had similar reductions in CVD/HHF, compared with placebo, with hazard ratios of 0.79 (disease duration of 5 or fewer years), 0.86, 0.92, 0.81, and 0.75 (duration of 20 years), respectively (interaction trend P = .760).

Treatment with dapagliflozin reduced the incidence of MACE, but the benefit was more apparent in patients with longer-term disease: HR, 1.08; 1.02; 0.94; 0.92; and 0.67, respectively (interaction trend P = .004). Similar trends were seen with MI (interaction trend P = .019) and ischemic stroke (interaction trend P = .015).

The researchers also reported improved benefits in renal-specific outcome with increasing disease duration, with HRs ranging from 0.79 in patients with diabetes duration of fewer than 5 years, to 0.42 in those with a duration of more than 20 years (interaction trend P = .084).

Limitations of the study include the fact that the information about diabetes duration relied on patient reports, and that the original trial was not powered for all subgroup interactions. This authors emphasized that this was a post hoc analysis and as such, should be considered hypothesis generating.

All but two of the authors reported relationships with Astra Zeneca, which funded the study, and other drug companies.

SOURCE: Bajaj HS et al. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2020 Feb 23. doi: 10.1111/dom.14011.

Treatment with the sodium-glucose transporter 2 inhibitor dapagliflozin reduced the risk for cardiovascular disease or hospitalization for heart failure (CVD/HHF) in patients with diabetes, regardless of the duration of the disease, but had a greater protective benefit against major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and renal events in patients with longer disease duration, according to new findings from a post hoc analysis of the DECLARE-TIMI 58 trial.

The positive effect of dapagliflozin in patients with MACE – which includes myocardial infarction (MI), CVD, and ischemic stroke – may have been driven by lower rates of MI and ischemic stroke with the drug, compared with placebo, in patients with longer disease duration, wrote Harpreet S. Bajaj, MD, and colleagues. Their report is in Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism (2020 Feb 23. doi: 10.1111/dom.14011).

It has been previously reported that the risk for complications in diabetes increases with increasing duration of the disease. Recent studies with SGLT-2 inhibitors have shown that the drugs improve cardiovascular and renal outcomes in diabetes, and they are recommended by the American Diabetes Association as second-line therapy in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, or heart failure. The European Society of Cardiology and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes recommend that patients with diabetes patients who have three or more risk factors, or those with a disease duration of more than 20 years, should be deemed very high risk and be considered for early treatment with SGLT2 inhibitors.

“The MACE benefit observed with dapagliflozin in this study in patients with diabetes duration of [more than] 20 years, clearly supports that notion,” the authors wrote.

In DECLARE-TIMI 58, 17,160 patients with type 2 diabetes received dapagliflozin or placebo and were followed for a median of 4.2 years. Of those patients, 22.4% had a disease duration of fewer than 5 years; 27.6%, a duration of 5-10 years; 23.0%, 10-15 years; 14.2%, 10-15 years; and 12.9%, more than 20 years. The median duration of disease was 11 years.

Patients in all the age groups had similar reductions in CVD/HHF, compared with placebo, with hazard ratios of 0.79 (disease duration of 5 or fewer years), 0.86, 0.92, 0.81, and 0.75 (duration of 20 years), respectively (interaction trend P = .760).

Treatment with dapagliflozin reduced the incidence of MACE, but the benefit was more apparent in patients with longer-term disease: HR, 1.08; 1.02; 0.94; 0.92; and 0.67, respectively (interaction trend P = .004). Similar trends were seen with MI (interaction trend P = .019) and ischemic stroke (interaction trend P = .015).

The researchers also reported improved benefits in renal-specific outcome with increasing disease duration, with HRs ranging from 0.79 in patients with diabetes duration of fewer than 5 years, to 0.42 in those with a duration of more than 20 years (interaction trend P = .084).

Limitations of the study include the fact that the information about diabetes duration relied on patient reports, and that the original trial was not powered for all subgroup interactions. This authors emphasized that this was a post hoc analysis and as such, should be considered hypothesis generating.

All but two of the authors reported relationships with Astra Zeneca, which funded the study, and other drug companies.

SOURCE: Bajaj HS et al. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2020 Feb 23. doi: 10.1111/dom.14011.

Treatment with the sodium-glucose transporter 2 inhibitor dapagliflozin reduced the risk for cardiovascular disease or hospitalization for heart failure (CVD/HHF) in patients with diabetes, regardless of the duration of the disease, but had a greater protective benefit against major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and renal events in patients with longer disease duration, according to new findings from a post hoc analysis of the DECLARE-TIMI 58 trial.

The positive effect of dapagliflozin in patients with MACE – which includes myocardial infarction (MI), CVD, and ischemic stroke – may have been driven by lower rates of MI and ischemic stroke with the drug, compared with placebo, in patients with longer disease duration, wrote Harpreet S. Bajaj, MD, and colleagues. Their report is in Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism (2020 Feb 23. doi: 10.1111/dom.14011).

It has been previously reported that the risk for complications in diabetes increases with increasing duration of the disease. Recent studies with SGLT-2 inhibitors have shown that the drugs improve cardiovascular and renal outcomes in diabetes, and they are recommended by the American Diabetes Association as second-line therapy in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, or heart failure. The European Society of Cardiology and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes recommend that patients with diabetes patients who have three or more risk factors, or those with a disease duration of more than 20 years, should be deemed very high risk and be considered for early treatment with SGLT2 inhibitors.

“The MACE benefit observed with dapagliflozin in this study in patients with diabetes duration of [more than] 20 years, clearly supports that notion,” the authors wrote.

In DECLARE-TIMI 58, 17,160 patients with type 2 diabetes received dapagliflozin or placebo and were followed for a median of 4.2 years. Of those patients, 22.4% had a disease duration of fewer than 5 years; 27.6%, a duration of 5-10 years; 23.0%, 10-15 years; 14.2%, 10-15 years; and 12.9%, more than 20 years. The median duration of disease was 11 years.

Patients in all the age groups had similar reductions in CVD/HHF, compared with placebo, with hazard ratios of 0.79 (disease duration of 5 or fewer years), 0.86, 0.92, 0.81, and 0.75 (duration of 20 years), respectively (interaction trend P = .760).

Treatment with dapagliflozin reduced the incidence of MACE, but the benefit was more apparent in patients with longer-term disease: HR, 1.08; 1.02; 0.94; 0.92; and 0.67, respectively (interaction trend P = .004). Similar trends were seen with MI (interaction trend P = .019) and ischemic stroke (interaction trend P = .015).

The researchers also reported improved benefits in renal-specific outcome with increasing disease duration, with HRs ranging from 0.79 in patients with diabetes duration of fewer than 5 years, to 0.42 in those with a duration of more than 20 years (interaction trend P = .084).

Limitations of the study include the fact that the information about diabetes duration relied on patient reports, and that the original trial was not powered for all subgroup interactions. This authors emphasized that this was a post hoc analysis and as such, should be considered hypothesis generating.

All but two of the authors reported relationships with Astra Zeneca, which funded the study, and other drug companies.

SOURCE: Bajaj HS et al. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2020 Feb 23. doi: 10.1111/dom.14011.

FROM DIABETES, OBESITY AND METABOLISM

Latent diabetes warrants earlier, tighter glycemic control

according a post hoc analysis of a large European database.

However, Ernesto Maddaloni, MD, of Sapienza University of Rome and University of Oxford (England), and colleagues noted that the risk is less than half that in patients with type 2 disease during the first several years after diagnosis but that, after 9 years, the risk curves cross over, and patients with latent autoimmune diabetes of adulthood (LADA) matriculate to a 25% greater risk microvascular complications than do their type 2 counterparts.

The results point to a need for tighter glycemic control in patients with latent autoimmune disease and “might have relevant implications for the understanding of the differential risk of complications between type 2 diabetes and autoimmune diabetes in general,” the researchers wrote online in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology. They emphasized that the study represents the largest population of patients with latent autoimmune diabetes with the longest follow-up in a randomized controlled trial so far.

Diabetic microvascular complications are a major cause of end-stage renal disease and blindness in LADA, therefore, “implementing strict glycemic control from the time of diagnosis could reduce the later risk of microvascular complications in [these patients],” the authors wrote.

The researchers analyzed 30 years of data from the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study, focusing on 564 patients with LADA and 4,464 adults with type 2 diabetes. The primary outcome was first occurrence of renal failure, death from renal disease, blindness in one eye, vitreous hemorrhage, or retinal laser treatment.

With a median follow-up of 17.3 years, 21% of all patients (1,041) developed microvascular complications, of which there were 65 renal events and 976 retinopathy events. Secondary outcomes were nephropathy and retinopathy.

The study measured incidence in 1,000 person-years and found that the incidence for the overall primary composite microvascular outcome was 5.3% for LADA and 10% for type 2 diabetes in the first 9 years after diagnosis (P = .0020), but 13.6% and 9.2%, respectively, after that (P less than .0001). That translated into adjusted hazard ratios of 0.45 for LADA, compared with type 2 diabetes, in the first 9 years (P less than .0001) and 1.25 beyond 9 years (P = .047). The incidence of retinopathy events was 5.3% for LADA and 9.6% for type 2 diabetes up to 9 years (P = .003), and 12.5% and 8.6% thereafter (P = .001). Nephropathy rates were similar in both groups at 1.3% or less.

“The lower risk of microvascular complications during the first years after the diagnosis of latent autoimmune diabetes needs further examination,” Dr. Maddaloni and colleagues wrote.

They cautioned that LADA is often misdiagnosed as a form of type 1 diabetes. “Therefore, latent autoimmune diabetes could be the right bench test for studying differences between autoimmune diabetes and type 2 diabetes, because of fewer disparities in age and disease duration than with the comparison of type 1 diabetes and type 2 diabetes,” they wrote.

In an accompanying editorial, Didac Mauricio, MD, of the Autonomous University of Barcelona, credited Dr. Maddaloni and colleagues with presenting evidence “of major relevance” in an adequately powered study that provided “a robust conclusion” about the risk of microvascular complications in latent autoimmune diabetes.

Dr. Mauricio noted that the study adds to the literature that different subgroups of type 2 diabetes patients exist and highlights the distinct characteristics of latent autoimmune diabetes. In addition, it builds on a previous study by Dr. Maddaloni and coauthors that found cardiovascular disease outcomes did not differ between latent autoimmune and type 2 diabetes (Diabetes Obes Metab. 2019;21:2115-22), he wrote. The research team’s most recent findings “emphasize the need for early identification of latent autoimmune disease,” he stated.

The findings also raise important questions about screening all patients for antibodies upon diagnosis of diabetes, he said. “I firmly believe that it is time to take action,” first, because antibody testing is likely cost-effective and cost-saving because it facilitates better-informed, more timely decisions early in the disease trajectory, and second, it has already been well documented that patients with latent autoimmune diabetes have a higher glycemic burden.

An alternative to early universal screening for antibodies would be to raise awareness, especially among general practitioners, about the importance of timely diagnosis of LADA, Dr. Mauricio added.

The study received funding from the European Foundation for the Study of Diabetes Mentorship Program, supported by AstraZeneca. Dr. Maddaloni disclosed financial relationships with Sanofi, Eli Lilly, Abbott, and AstraZeneca. Another author disclosed financial relationships with Boehringer Ingelheim, Merck, Bayer, AstraZeneca, Novartis, and Novo Nordisk. All the other authors had no relevant financial relationships to disclose. Dr. Mauricio disclosed financial relationships with AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Merck Sharp & Dohme, NovoNordisk, Sanofi, Almirall, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Ferrer, Janssen, Menarini, and URGO.

SOURCE: Maddaloni E et al. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020 Feb 4. doi: 0.1016/S2213-8587(20)30003-6.

according a post hoc analysis of a large European database.

However, Ernesto Maddaloni, MD, of Sapienza University of Rome and University of Oxford (England), and colleagues noted that the risk is less than half that in patients with type 2 disease during the first several years after diagnosis but that, after 9 years, the risk curves cross over, and patients with latent autoimmune diabetes of adulthood (LADA) matriculate to a 25% greater risk microvascular complications than do their type 2 counterparts.

The results point to a need for tighter glycemic control in patients with latent autoimmune disease and “might have relevant implications for the understanding of the differential risk of complications between type 2 diabetes and autoimmune diabetes in general,” the researchers wrote online in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology. They emphasized that the study represents the largest population of patients with latent autoimmune diabetes with the longest follow-up in a randomized controlled trial so far.

Diabetic microvascular complications are a major cause of end-stage renal disease and blindness in LADA, therefore, “implementing strict glycemic control from the time of diagnosis could reduce the later risk of microvascular complications in [these patients],” the authors wrote.

The researchers analyzed 30 years of data from the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study, focusing on 564 patients with LADA and 4,464 adults with type 2 diabetes. The primary outcome was first occurrence of renal failure, death from renal disease, blindness in one eye, vitreous hemorrhage, or retinal laser treatment.

With a median follow-up of 17.3 years, 21% of all patients (1,041) developed microvascular complications, of which there were 65 renal events and 976 retinopathy events. Secondary outcomes were nephropathy and retinopathy.

The study measured incidence in 1,000 person-years and found that the incidence for the overall primary composite microvascular outcome was 5.3% for LADA and 10% for type 2 diabetes in the first 9 years after diagnosis (P = .0020), but 13.6% and 9.2%, respectively, after that (P less than .0001). That translated into adjusted hazard ratios of 0.45 for LADA, compared with type 2 diabetes, in the first 9 years (P less than .0001) and 1.25 beyond 9 years (P = .047). The incidence of retinopathy events was 5.3% for LADA and 9.6% for type 2 diabetes up to 9 years (P = .003), and 12.5% and 8.6% thereafter (P = .001). Nephropathy rates were similar in both groups at 1.3% or less.

“The lower risk of microvascular complications during the first years after the diagnosis of latent autoimmune diabetes needs further examination,” Dr. Maddaloni and colleagues wrote.

They cautioned that LADA is often misdiagnosed as a form of type 1 diabetes. “Therefore, latent autoimmune diabetes could be the right bench test for studying differences between autoimmune diabetes and type 2 diabetes, because of fewer disparities in age and disease duration than with the comparison of type 1 diabetes and type 2 diabetes,” they wrote.

In an accompanying editorial, Didac Mauricio, MD, of the Autonomous University of Barcelona, credited Dr. Maddaloni and colleagues with presenting evidence “of major relevance” in an adequately powered study that provided “a robust conclusion” about the risk of microvascular complications in latent autoimmune diabetes.

Dr. Mauricio noted that the study adds to the literature that different subgroups of type 2 diabetes patients exist and highlights the distinct characteristics of latent autoimmune diabetes. In addition, it builds on a previous study by Dr. Maddaloni and coauthors that found cardiovascular disease outcomes did not differ between latent autoimmune and type 2 diabetes (Diabetes Obes Metab. 2019;21:2115-22), he wrote. The research team’s most recent findings “emphasize the need for early identification of latent autoimmune disease,” he stated.

The findings also raise important questions about screening all patients for antibodies upon diagnosis of diabetes, he said. “I firmly believe that it is time to take action,” first, because antibody testing is likely cost-effective and cost-saving because it facilitates better-informed, more timely decisions early in the disease trajectory, and second, it has already been well documented that patients with latent autoimmune diabetes have a higher glycemic burden.

An alternative to early universal screening for antibodies would be to raise awareness, especially among general practitioners, about the importance of timely diagnosis of LADA, Dr. Mauricio added.

The study received funding from the European Foundation for the Study of Diabetes Mentorship Program, supported by AstraZeneca. Dr. Maddaloni disclosed financial relationships with Sanofi, Eli Lilly, Abbott, and AstraZeneca. Another author disclosed financial relationships with Boehringer Ingelheim, Merck, Bayer, AstraZeneca, Novartis, and Novo Nordisk. All the other authors had no relevant financial relationships to disclose. Dr. Mauricio disclosed financial relationships with AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Merck Sharp & Dohme, NovoNordisk, Sanofi, Almirall, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Ferrer, Janssen, Menarini, and URGO.

SOURCE: Maddaloni E et al. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020 Feb 4. doi: 0.1016/S2213-8587(20)30003-6.

according a post hoc analysis of a large European database.

However, Ernesto Maddaloni, MD, of Sapienza University of Rome and University of Oxford (England), and colleagues noted that the risk is less than half that in patients with type 2 disease during the first several years after diagnosis but that, after 9 years, the risk curves cross over, and patients with latent autoimmune diabetes of adulthood (LADA) matriculate to a 25% greater risk microvascular complications than do their type 2 counterparts.

The results point to a need for tighter glycemic control in patients with latent autoimmune disease and “might have relevant implications for the understanding of the differential risk of complications between type 2 diabetes and autoimmune diabetes in general,” the researchers wrote online in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology. They emphasized that the study represents the largest population of patients with latent autoimmune diabetes with the longest follow-up in a randomized controlled trial so far.

Diabetic microvascular complications are a major cause of end-stage renal disease and blindness in LADA, therefore, “implementing strict glycemic control from the time of diagnosis could reduce the later risk of microvascular complications in [these patients],” the authors wrote.

The researchers analyzed 30 years of data from the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study, focusing on 564 patients with LADA and 4,464 adults with type 2 diabetes. The primary outcome was first occurrence of renal failure, death from renal disease, blindness in one eye, vitreous hemorrhage, or retinal laser treatment.

With a median follow-up of 17.3 years, 21% of all patients (1,041) developed microvascular complications, of which there were 65 renal events and 976 retinopathy events. Secondary outcomes were nephropathy and retinopathy.

The study measured incidence in 1,000 person-years and found that the incidence for the overall primary composite microvascular outcome was 5.3% for LADA and 10% for type 2 diabetes in the first 9 years after diagnosis (P = .0020), but 13.6% and 9.2%, respectively, after that (P less than .0001). That translated into adjusted hazard ratios of 0.45 for LADA, compared with type 2 diabetes, in the first 9 years (P less than .0001) and 1.25 beyond 9 years (P = .047). The incidence of retinopathy events was 5.3% for LADA and 9.6% for type 2 diabetes up to 9 years (P = .003), and 12.5% and 8.6% thereafter (P = .001). Nephropathy rates were similar in both groups at 1.3% or less.

“The lower risk of microvascular complications during the first years after the diagnosis of latent autoimmune diabetes needs further examination,” Dr. Maddaloni and colleagues wrote.

They cautioned that LADA is often misdiagnosed as a form of type 1 diabetes. “Therefore, latent autoimmune diabetes could be the right bench test for studying differences between autoimmune diabetes and type 2 diabetes, because of fewer disparities in age and disease duration than with the comparison of type 1 diabetes and type 2 diabetes,” they wrote.

In an accompanying editorial, Didac Mauricio, MD, of the Autonomous University of Barcelona, credited Dr. Maddaloni and colleagues with presenting evidence “of major relevance” in an adequately powered study that provided “a robust conclusion” about the risk of microvascular complications in latent autoimmune diabetes.

Dr. Mauricio noted that the study adds to the literature that different subgroups of type 2 diabetes patients exist and highlights the distinct characteristics of latent autoimmune diabetes. In addition, it builds on a previous study by Dr. Maddaloni and coauthors that found cardiovascular disease outcomes did not differ between latent autoimmune and type 2 diabetes (Diabetes Obes Metab. 2019;21:2115-22), he wrote. The research team’s most recent findings “emphasize the need for early identification of latent autoimmune disease,” he stated.

The findings also raise important questions about screening all patients for antibodies upon diagnosis of diabetes, he said. “I firmly believe that it is time to take action,” first, because antibody testing is likely cost-effective and cost-saving because it facilitates better-informed, more timely decisions early in the disease trajectory, and second, it has already been well documented that patients with latent autoimmune diabetes have a higher glycemic burden.

An alternative to early universal screening for antibodies would be to raise awareness, especially among general practitioners, about the importance of timely diagnosis of LADA, Dr. Mauricio added.

The study received funding from the European Foundation for the Study of Diabetes Mentorship Program, supported by AstraZeneca. Dr. Maddaloni disclosed financial relationships with Sanofi, Eli Lilly, Abbott, and AstraZeneca. Another author disclosed financial relationships with Boehringer Ingelheim, Merck, Bayer, AstraZeneca, Novartis, and Novo Nordisk. All the other authors had no relevant financial relationships to disclose. Dr. Mauricio disclosed financial relationships with AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Merck Sharp & Dohme, NovoNordisk, Sanofi, Almirall, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Ferrer, Janssen, Menarini, and URGO.

SOURCE: Maddaloni E et al. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020 Feb 4. doi: 0.1016/S2213-8587(20)30003-6.

FROM THE LANCET DIABETES & ENDOCRINOLOGY

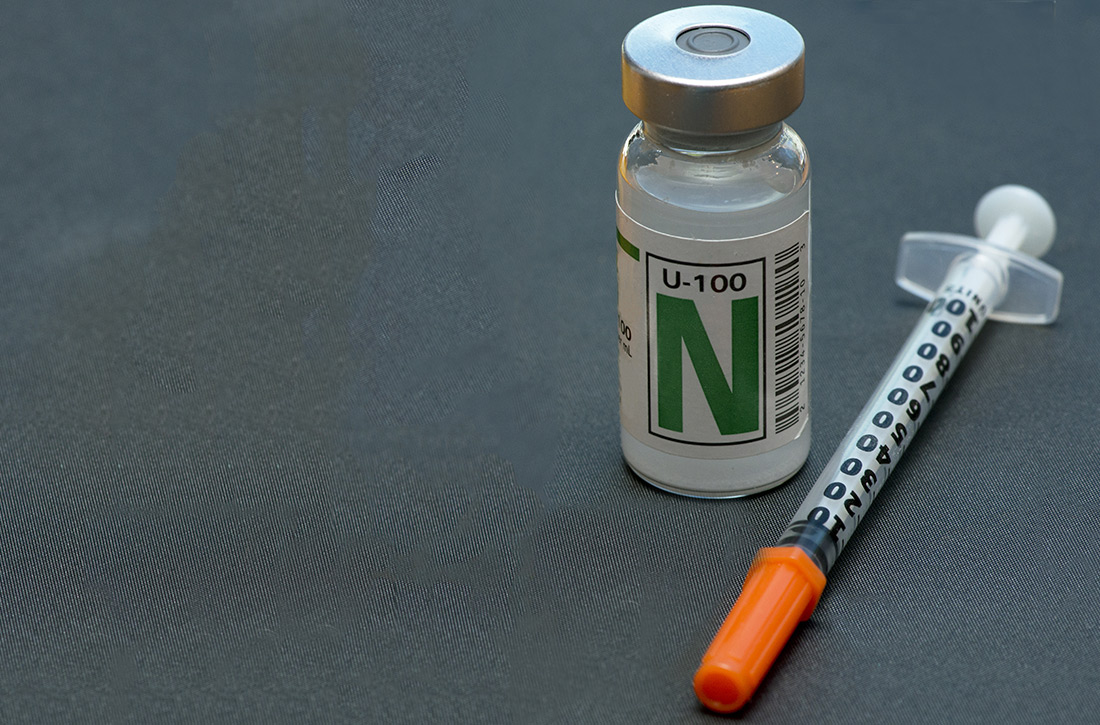

NPH insulin: It remains a good option

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

Blanche is a 54-year-old overweight woman who has had type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) for 5 years. She has been optimized on both metformin (1000 mg bid) and exenatide (2 mg weekly). While taking these medications, her hemoglobin A1C (HbA1C) has dropped from 11.2 to 8.4, and her body mass index (BMI) has declined from 35 to 31. However, she is still not at goal. You decide to start her on long-acting basal insulin. She has limited income, and she currently spends $75/month for her metformin, exenatide, atorvastatin, and lisinopril. What insulin do you prescribe?

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that the prevalence of diabetes in the United States was 9.4% (30.3 million people) in 2015.2 Among those affected, approximately 95.8% had T2DM.2 The same report estimated that 1.5 million new cases of diabetes (6.7 per 1000 persons) were diagnosed annually among US adults ≥ 18 years of age, and that about $7900 of annual medical expenses for patients diagnosed with diabetes was directly attributable to diabetes.2

In the United States, neutral protamine Hagedorn (NPH) insulin was the most commonly used intermediate- to long-acting insulin until the introduction of the long-acting insulin analogs (insulin glargine in 2000 and insulin detemir in 2005).3 Despite being considerably more expensive than NPH insulin, long-acting insulin analogs had captured more than 80% of the total long-acting insulin market by 2010.4 The market share for NPH insulin dropped from 81.9% in 2001 to 16.2% in 2010.4

While the newer insulin analogs are significantly more expensive than NPH insulin, with higher corresponding out-of-pocket costs to patients, researchers have had a difficult time demonstrating greater effectiveness or any definitive differences in any long-term outcomes between NPH and the insulin analogs. A 2007 Cochrane review comparing NPH insulin to both glargine and detemir showed little difference in metabolic control (as measured by HbA1C) or in the rate of severe hypoglycemia. However, the rates of symptomatic, overall, and nocturnal hypoglycemia were statistically lower with the insulin analogs.5

A 2015 retrospective observational study from the Veterans Health Administration (N = 142,940) covering a 10-year period from 2000 to 2010 found no consistent differences in long-term health outcomes when comparing the use of long-acting insulin analogs to that of NPH insulin.3,6

STUDY SUMMARY

Study compares performance of basal insulin analogs to that of NPH

This retrospective, observational study included 25,489 adult patients with T2DM who were enrolled in Kaiser Permanente of Northern California, had full medical and prescription coverage, and initiated basal insulin therapy with either NPH or an insulin analog between 2006 and 2015.

The primary outcome was the time from basal insulin therapy initiation to a hypoglycemia-related emergency department (ED) visit or hospital admission. The secondary outcome was the change in HbA1C level within 1 year of initiation of basal insulin therapy.

Continue to: Per 1000 person-years...

Per 1000 person-years, there was no significant difference in hypoglycemia-related ED visits or hospital admissions between the analog and NPH groups (11.9 events vs 8.8 events, respectively; between-group difference, 3.1 events; 95% confidence interval [CI], –1.5 to 7.7). HbA1C reduction was statistically greater with NPH, but most likely not clinically significant between insulin analogs and NPH (1.26 vs 1.48 percentage points; between group difference, –0.22%; 95% CI, –0.09% to –0.37%).

WHAT’S NEW?

No clinically relevant differences between insulin analogs and NPH

This study revealed that there is no clinically relevant difference in HbA1C levels and no difference in patient-focused outcomes of hypoglycemia-related ED visits or hospital admissions between NPH insulin and the more expensive insulin analogs. This makes a strong case for a different approach to initial basal insulin therapy for patients with T2DM who need insulin for glucose control.

CAVEATS

Demographics and less severe hypoglycemia might be at issue

This retrospective, observational study has broad demographics (but moderate under-representation of African-Americans), minimal patient health care disparities, and good access to medications. But generalizability outside of an integrated health delivery system may be limited. The study design also is subject to confounding, as not all potential impacts on the results can be corrected for or controlled in an observational study. Also, less profound hypoglycemia that did not require an ED visit or hospital admission was not captured.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Convenience and marketing factors may hinder change

Insulin analogs may have a number of convenience and marketing factors that may make it hard for providers and systems to change and use more NPH. However, the easy-to-use insulin analog pens are matched in availability and convenience by the much less advertised NPH insulin pens produced by at least 3 major pharmaceutical companies. In addition, while the overall cost for the insulin analogs continues to be 2 to 3 times that of non-human NPH insulin, insurance often covers up to, or more than, 80% of the cost of the insulin analogs, making the difference in the patient’s copay between the 2 not as severe. For example, patients may pay $30 to $40 per month for insulin analogs vs $10 to $25 per month for cheaper versions of NPH.7,8

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. Lipska KJ, Parker MM, Moffet HH, et al. Association of initiation of basal insulin analogs vs neutral protamine Hagedorn insulin with hypoglycemia-related emergency department visits or hospital admissions and with glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes. JAMA. 2018;320:53-62.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2017. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Dept of Health and Human Services; 2017. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf. Accessed January 15, 2020.

3. Prentice JC, Conlin PR, Gellad WF, et al. Long-term outcomes of analogue insulin compared with NPH for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21:e235-e243.

4. Turner LW, Nartey D, Stafford RS, et al. Ambulatory treatment of type 2 diabetes in the U.S., 1997-2012. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:985-992.

5. Horvath K, Jeitler K, Berghold A, et al. Long-acting insulin analogues versus NPH insulin (human isophane insulin) for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(2):CD005613.

6. Chamberlain JJ, Herman WH, Leal S, et al. Pharmacologic therapy for type 2 diabetes: synopsis of the 2017 American Diabetes Association standards of medical care in diabetes. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:572-578.

7. GoodRx.com. Insulins. www.goodrx.com/insulins. Accessed January 20, 2020. 8. Cefalu WT, Dawes DE, Gavlak G, et al. Insulin access and affordability working group: conclusions and recommendations. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:1299-1311.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

Blanche is a 54-year-old overweight woman who has had type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) for 5 years. She has been optimized on both metformin (1000 mg bid) and exenatide (2 mg weekly). While taking these medications, her hemoglobin A1C (HbA1C) has dropped from 11.2 to 8.4, and her body mass index (BMI) has declined from 35 to 31. However, she is still not at goal. You decide to start her on long-acting basal insulin. She has limited income, and she currently spends $75/month for her metformin, exenatide, atorvastatin, and lisinopril. What insulin do you prescribe?

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that the prevalence of diabetes in the United States was 9.4% (30.3 million people) in 2015.2 Among those affected, approximately 95.8% had T2DM.2 The same report estimated that 1.5 million new cases of diabetes (6.7 per 1000 persons) were diagnosed annually among US adults ≥ 18 years of age, and that about $7900 of annual medical expenses for patients diagnosed with diabetes was directly attributable to diabetes.2

In the United States, neutral protamine Hagedorn (NPH) insulin was the most commonly used intermediate- to long-acting insulin until the introduction of the long-acting insulin analogs (insulin glargine in 2000 and insulin detemir in 2005).3 Despite being considerably more expensive than NPH insulin, long-acting insulin analogs had captured more than 80% of the total long-acting insulin market by 2010.4 The market share for NPH insulin dropped from 81.9% in 2001 to 16.2% in 2010.4

While the newer insulin analogs are significantly more expensive than NPH insulin, with higher corresponding out-of-pocket costs to patients, researchers have had a difficult time demonstrating greater effectiveness or any definitive differences in any long-term outcomes between NPH and the insulin analogs. A 2007 Cochrane review comparing NPH insulin to both glargine and detemir showed little difference in metabolic control (as measured by HbA1C) or in the rate of severe hypoglycemia. However, the rates of symptomatic, overall, and nocturnal hypoglycemia were statistically lower with the insulin analogs.5

A 2015 retrospective observational study from the Veterans Health Administration (N = 142,940) covering a 10-year period from 2000 to 2010 found no consistent differences in long-term health outcomes when comparing the use of long-acting insulin analogs to that of NPH insulin.3,6

STUDY SUMMARY

Study compares performance of basal insulin analogs to that of NPH

This retrospective, observational study included 25,489 adult patients with T2DM who were enrolled in Kaiser Permanente of Northern California, had full medical and prescription coverage, and initiated basal insulin therapy with either NPH or an insulin analog between 2006 and 2015.

The primary outcome was the time from basal insulin therapy initiation to a hypoglycemia-related emergency department (ED) visit or hospital admission. The secondary outcome was the change in HbA1C level within 1 year of initiation of basal insulin therapy.

Continue to: Per 1000 person-years...

Per 1000 person-years, there was no significant difference in hypoglycemia-related ED visits or hospital admissions between the analog and NPH groups (11.9 events vs 8.8 events, respectively; between-group difference, 3.1 events; 95% confidence interval [CI], –1.5 to 7.7). HbA1C reduction was statistically greater with NPH, but most likely not clinically significant between insulin analogs and NPH (1.26 vs 1.48 percentage points; between group difference, –0.22%; 95% CI, –0.09% to –0.37%).

WHAT’S NEW?

No clinically relevant differences between insulin analogs and NPH

This study revealed that there is no clinically relevant difference in HbA1C levels and no difference in patient-focused outcomes of hypoglycemia-related ED visits or hospital admissions between NPH insulin and the more expensive insulin analogs. This makes a strong case for a different approach to initial basal insulin therapy for patients with T2DM who need insulin for glucose control.

CAVEATS

Demographics and less severe hypoglycemia might be at issue

This retrospective, observational study has broad demographics (but moderate under-representation of African-Americans), minimal patient health care disparities, and good access to medications. But generalizability outside of an integrated health delivery system may be limited. The study design also is subject to confounding, as not all potential impacts on the results can be corrected for or controlled in an observational study. Also, less profound hypoglycemia that did not require an ED visit or hospital admission was not captured.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Convenience and marketing factors may hinder change

Insulin analogs may have a number of convenience and marketing factors that may make it hard for providers and systems to change and use more NPH. However, the easy-to-use insulin analog pens are matched in availability and convenience by the much less advertised NPH insulin pens produced by at least 3 major pharmaceutical companies. In addition, while the overall cost for the insulin analogs continues to be 2 to 3 times that of non-human NPH insulin, insurance often covers up to, or more than, 80% of the cost of the insulin analogs, making the difference in the patient’s copay between the 2 not as severe. For example, patients may pay $30 to $40 per month for insulin analogs vs $10 to $25 per month for cheaper versions of NPH.7,8

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

Blanche is a 54-year-old overweight woman who has had type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) for 5 years. She has been optimized on both metformin (1000 mg bid) and exenatide (2 mg weekly). While taking these medications, her hemoglobin A1C (HbA1C) has dropped from 11.2 to 8.4, and her body mass index (BMI) has declined from 35 to 31. However, she is still not at goal. You decide to start her on long-acting basal insulin. She has limited income, and she currently spends $75/month for her metformin, exenatide, atorvastatin, and lisinopril. What insulin do you prescribe?

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that the prevalence of diabetes in the United States was 9.4% (30.3 million people) in 2015.2 Among those affected, approximately 95.8% had T2DM.2 The same report estimated that 1.5 million new cases of diabetes (6.7 per 1000 persons) were diagnosed annually among US adults ≥ 18 years of age, and that about $7900 of annual medical expenses for patients diagnosed with diabetes was directly attributable to diabetes.2

In the United States, neutral protamine Hagedorn (NPH) insulin was the most commonly used intermediate- to long-acting insulin until the introduction of the long-acting insulin analogs (insulin glargine in 2000 and insulin detemir in 2005).3 Despite being considerably more expensive than NPH insulin, long-acting insulin analogs had captured more than 80% of the total long-acting insulin market by 2010.4 The market share for NPH insulin dropped from 81.9% in 2001 to 16.2% in 2010.4

While the newer insulin analogs are significantly more expensive than NPH insulin, with higher corresponding out-of-pocket costs to patients, researchers have had a difficult time demonstrating greater effectiveness or any definitive differences in any long-term outcomes between NPH and the insulin analogs. A 2007 Cochrane review comparing NPH insulin to both glargine and detemir showed little difference in metabolic control (as measured by HbA1C) or in the rate of severe hypoglycemia. However, the rates of symptomatic, overall, and nocturnal hypoglycemia were statistically lower with the insulin analogs.5

A 2015 retrospective observational study from the Veterans Health Administration (N = 142,940) covering a 10-year period from 2000 to 2010 found no consistent differences in long-term health outcomes when comparing the use of long-acting insulin analogs to that of NPH insulin.3,6

STUDY SUMMARY

Study compares performance of basal insulin analogs to that of NPH

This retrospective, observational study included 25,489 adult patients with T2DM who were enrolled in Kaiser Permanente of Northern California, had full medical and prescription coverage, and initiated basal insulin therapy with either NPH or an insulin analog between 2006 and 2015.

The primary outcome was the time from basal insulin therapy initiation to a hypoglycemia-related emergency department (ED) visit or hospital admission. The secondary outcome was the change in HbA1C level within 1 year of initiation of basal insulin therapy.

Continue to: Per 1000 person-years...

Per 1000 person-years, there was no significant difference in hypoglycemia-related ED visits or hospital admissions between the analog and NPH groups (11.9 events vs 8.8 events, respectively; between-group difference, 3.1 events; 95% confidence interval [CI], –1.5 to 7.7). HbA1C reduction was statistically greater with NPH, but most likely not clinically significant between insulin analogs and NPH (1.26 vs 1.48 percentage points; between group difference, –0.22%; 95% CI, –0.09% to –0.37%).

WHAT’S NEW?

No clinically relevant differences between insulin analogs and NPH

This study revealed that there is no clinically relevant difference in HbA1C levels and no difference in patient-focused outcomes of hypoglycemia-related ED visits or hospital admissions between NPH insulin and the more expensive insulin analogs. This makes a strong case for a different approach to initial basal insulin therapy for patients with T2DM who need insulin for glucose control.

CAVEATS

Demographics and less severe hypoglycemia might be at issue

This retrospective, observational study has broad demographics (but moderate under-representation of African-Americans), minimal patient health care disparities, and good access to medications. But generalizability outside of an integrated health delivery system may be limited. The study design also is subject to confounding, as not all potential impacts on the results can be corrected for or controlled in an observational study. Also, less profound hypoglycemia that did not require an ED visit or hospital admission was not captured.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Convenience and marketing factors may hinder change

Insulin analogs may have a number of convenience and marketing factors that may make it hard for providers and systems to change and use more NPH. However, the easy-to-use insulin analog pens are matched in availability and convenience by the much less advertised NPH insulin pens produced by at least 3 major pharmaceutical companies. In addition, while the overall cost for the insulin analogs continues to be 2 to 3 times that of non-human NPH insulin, insurance often covers up to, or more than, 80% of the cost of the insulin analogs, making the difference in the patient’s copay between the 2 not as severe. For example, patients may pay $30 to $40 per month for insulin analogs vs $10 to $25 per month for cheaper versions of NPH.7,8

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. Lipska KJ, Parker MM, Moffet HH, et al. Association of initiation of basal insulin analogs vs neutral protamine Hagedorn insulin with hypoglycemia-related emergency department visits or hospital admissions and with glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes. JAMA. 2018;320:53-62.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2017. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Dept of Health and Human Services; 2017. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf. Accessed January 15, 2020.

3. Prentice JC, Conlin PR, Gellad WF, et al. Long-term outcomes of analogue insulin compared with NPH for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21:e235-e243.

4. Turner LW, Nartey D, Stafford RS, et al. Ambulatory treatment of type 2 diabetes in the U.S., 1997-2012. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:985-992.

5. Horvath K, Jeitler K, Berghold A, et al. Long-acting insulin analogues versus NPH insulin (human isophane insulin) for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(2):CD005613.

6. Chamberlain JJ, Herman WH, Leal S, et al. Pharmacologic therapy for type 2 diabetes: synopsis of the 2017 American Diabetes Association standards of medical care in diabetes. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:572-578.

7. GoodRx.com. Insulins. www.goodrx.com/insulins. Accessed January 20, 2020. 8. Cefalu WT, Dawes DE, Gavlak G, et al. Insulin access and affordability working group: conclusions and recommendations. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:1299-1311.

1. Lipska KJ, Parker MM, Moffet HH, et al. Association of initiation of basal insulin analogs vs neutral protamine Hagedorn insulin with hypoglycemia-related emergency department visits or hospital admissions and with glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes. JAMA. 2018;320:53-62.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2017. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Dept of Health and Human Services; 2017. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf. Accessed January 15, 2020.

3. Prentice JC, Conlin PR, Gellad WF, et al. Long-term outcomes of analogue insulin compared with NPH for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21:e235-e243.

4. Turner LW, Nartey D, Stafford RS, et al. Ambulatory treatment of type 2 diabetes in the U.S., 1997-2012. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:985-992.

5. Horvath K, Jeitler K, Berghold A, et al. Long-acting insulin analogues versus NPH insulin (human isophane insulin) for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(2):CD005613.

6. Chamberlain JJ, Herman WH, Leal S, et al. Pharmacologic therapy for type 2 diabetes: synopsis of the 2017 American Diabetes Association standards of medical care in diabetes. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:572-578.

7. GoodRx.com. Insulins. www.goodrx.com/insulins. Accessed January 20, 2020. 8. Cefalu WT, Dawes DE, Gavlak G, et al. Insulin access and affordability working group: conclusions and recommendations. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:1299-1311.

PRACTICE CHANGER

Consider NPH insulin for patients who require initiation of long-acting insulin therapy because it is as safe as, and more cost-effective than, basal insulin analogs.

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

B: Based on a single, large, retrospective, observational study.

Lipska KJ, Parker MM, Moffet HH, et al. Association of initiation of basal insulin analogs vs neutral protamine Hagedorn insulin with hypoglycemia-related emergency department visits or hospital admissions and with glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes. JAMA. 2018;320:53-62.1

Glucocorticoid use linked to mortality in RA with diabetes

Glucocorticoid use is associated with greater mortality and cardiovascular risk in RA patients, and the associated risk is greater still in patients with RA and comorbid diabetes. The findings come from a new retrospective analysis derived from U.K. primary care records.

Although patients with diabetes actually had a lower relative risk for mortality than the nondiabetes cohort, they had a greater mortality difference because of a greater baseline risk. Ultimately, glucocorticoid (GC) use was associated with an additional 44.9 deaths per 1,000 person-years in the diabetes group, compared with 34.4 per 1,000 person-years in the RA-only group.

The study, led by Ruth Costello and William Dixon, MBBS, PhD of the University of Manchester (England), was published in BMC Rheumatology.

The findings aren’t particularly surprising, given that steroid use and diabetes have associated cardiovascular risks, and physicians generally try to reduce or eliminate their use. “There’s a group [of physicians] saying that we don’t need to use steroids at all in rheumatoid arthritis, except maybe for [a] short time at diagnosis to bridge to other therapies, or during flares,” Gordon Starkebaum, MD, professor emeritus of rheumatology at the University of Washington, Seattle, said in an interview. He recounted a session at last year’s annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology that advocated for only injectable steroid use during flare-ups. “That was provocative,” Dr. Starkebaum said.

“It’s a retrospective study, so it has some limitations, but it provides good insight, and some substantiation to what we already think,” added Brett Smith, DO, a rheumatologist practicing in Knoxville, Tenn.

Dr. Smith suggested that the study further underscores the need to follow treat-to-target protocols in RA. He emphasized that lifetime exposure to steroids is likely the greatest concern, and that steady accumulating doses are a sign of trouble. “If you need that much steroids, you need to go up on your medication – your methotrexate, or sulfasalazine, or your biologic,” said Dr. Smith. “At least 50% of people will need a biologic to [achieve] disease control, and if you get them on it, they’re going to have better disease control, compliance is typically better, and they’re going to have less steroid exposure.”

Dr. Smith also noted that comorbid diabetes shouldn’t affect treat-to-target strategies. In fact, in such patients “you should probably be following it more tightly to reduce the cardiovascular outcomes,” he said.

The retrospective analysis included 9,085 patients with RA and with or without type 2 diabetes, with a mean follow-up of 5.2 years. They were recruited to the study between 1998 and 2011. Among patients with comorbid diabetes, those exposed to GC had a mortality of 67.4 per 1,000 person-years, compared with 22.5 among those not exposed to GC. Among those with RA alone, mortality was 44.6 versus 10.2 with and without GC exposure, respectively. Those with diabetes had a lower risk ratio for mortality (2.99 vs. 4.37), but a higher mortality difference (44.9 vs. 34.4 per 1,000 person-years).

“The increased absolute hazard for all-cause mortality indicates the greater public health impact of people with RA using GCs if they have [diabetes],” the researchers wrote. “Rheumatologists should consider [diabetes] status when prescribing GCs to patients with RA given this potential impact of GC therapy on glucose control and mortality.”

The study was limited by a lack of information on GC dose and cumulative exposure. Given its retrospective nature, the study could have been affected by confounding by indication, as well as unknown confounders.

The study was funded by the Centre for Epidemiology Versus Arthritis and the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre. Dr. Starkebaum has no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Smith is on the speaker’s bureau for AbbVie and serves on the company’s advisory board. He is also on the advisory boards of Regeneron and Sanofi Genzyme.

SOURCE: Costello R et al. BMC Rheumatol. 2020 Feb 19. doi: 10.1186/s41927-019-0105-4.

Glucocorticoid use is associated with greater mortality and cardiovascular risk in RA patients, and the associated risk is greater still in patients with RA and comorbid diabetes. The findings come from a new retrospective analysis derived from U.K. primary care records.

Although patients with diabetes actually had a lower relative risk for mortality than the nondiabetes cohort, they had a greater mortality difference because of a greater baseline risk. Ultimately, glucocorticoid (GC) use was associated with an additional 44.9 deaths per 1,000 person-years in the diabetes group, compared with 34.4 per 1,000 person-years in the RA-only group.

The study, led by Ruth Costello and William Dixon, MBBS, PhD of the University of Manchester (England), was published in BMC Rheumatology.

The findings aren’t particularly surprising, given that steroid use and diabetes have associated cardiovascular risks, and physicians generally try to reduce or eliminate their use. “There’s a group [of physicians] saying that we don’t need to use steroids at all in rheumatoid arthritis, except maybe for [a] short time at diagnosis to bridge to other therapies, or during flares,” Gordon Starkebaum, MD, professor emeritus of rheumatology at the University of Washington, Seattle, said in an interview. He recounted a session at last year’s annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology that advocated for only injectable steroid use during flare-ups. “That was provocative,” Dr. Starkebaum said.

“It’s a retrospective study, so it has some limitations, but it provides good insight, and some substantiation to what we already think,” added Brett Smith, DO, a rheumatologist practicing in Knoxville, Tenn.

Dr. Smith suggested that the study further underscores the need to follow treat-to-target protocols in RA. He emphasized that lifetime exposure to steroids is likely the greatest concern, and that steady accumulating doses are a sign of trouble. “If you need that much steroids, you need to go up on your medication – your methotrexate, or sulfasalazine, or your biologic,” said Dr. Smith. “At least 50% of people will need a biologic to [achieve] disease control, and if you get them on it, they’re going to have better disease control, compliance is typically better, and they’re going to have less steroid exposure.”

Dr. Smith also noted that comorbid diabetes shouldn’t affect treat-to-target strategies. In fact, in such patients “you should probably be following it more tightly to reduce the cardiovascular outcomes,” he said.

The retrospective analysis included 9,085 patients with RA and with or without type 2 diabetes, with a mean follow-up of 5.2 years. They were recruited to the study between 1998 and 2011. Among patients with comorbid diabetes, those exposed to GC had a mortality of 67.4 per 1,000 person-years, compared with 22.5 among those not exposed to GC. Among those with RA alone, mortality was 44.6 versus 10.2 with and without GC exposure, respectively. Those with diabetes had a lower risk ratio for mortality (2.99 vs. 4.37), but a higher mortality difference (44.9 vs. 34.4 per 1,000 person-years).

“The increased absolute hazard for all-cause mortality indicates the greater public health impact of people with RA using GCs if they have [diabetes],” the researchers wrote. “Rheumatologists should consider [diabetes] status when prescribing GCs to patients with RA given this potential impact of GC therapy on glucose control and mortality.”

The study was limited by a lack of information on GC dose and cumulative exposure. Given its retrospective nature, the study could have been affected by confounding by indication, as well as unknown confounders.

The study was funded by the Centre for Epidemiology Versus Arthritis and the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre. Dr. Starkebaum has no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Smith is on the speaker’s bureau for AbbVie and serves on the company’s advisory board. He is also on the advisory boards of Regeneron and Sanofi Genzyme.

SOURCE: Costello R et al. BMC Rheumatol. 2020 Feb 19. doi: 10.1186/s41927-019-0105-4.

Glucocorticoid use is associated with greater mortality and cardiovascular risk in RA patients, and the associated risk is greater still in patients with RA and comorbid diabetes. The findings come from a new retrospective analysis derived from U.K. primary care records.

Although patients with diabetes actually had a lower relative risk for mortality than the nondiabetes cohort, they had a greater mortality difference because of a greater baseline risk. Ultimately, glucocorticoid (GC) use was associated with an additional 44.9 deaths per 1,000 person-years in the diabetes group, compared with 34.4 per 1,000 person-years in the RA-only group.

The study, led by Ruth Costello and William Dixon, MBBS, PhD of the University of Manchester (England), was published in BMC Rheumatology.

The findings aren’t particularly surprising, given that steroid use and diabetes have associated cardiovascular risks, and physicians generally try to reduce or eliminate their use. “There’s a group [of physicians] saying that we don’t need to use steroids at all in rheumatoid arthritis, except maybe for [a] short time at diagnosis to bridge to other therapies, or during flares,” Gordon Starkebaum, MD, professor emeritus of rheumatology at the University of Washington, Seattle, said in an interview. He recounted a session at last year’s annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology that advocated for only injectable steroid use during flare-ups. “That was provocative,” Dr. Starkebaum said.

“It’s a retrospective study, so it has some limitations, but it provides good insight, and some substantiation to what we already think,” added Brett Smith, DO, a rheumatologist practicing in Knoxville, Tenn.

Dr. Smith suggested that the study further underscores the need to follow treat-to-target protocols in RA. He emphasized that lifetime exposure to steroids is likely the greatest concern, and that steady accumulating doses are a sign of trouble. “If you need that much steroids, you need to go up on your medication – your methotrexate, or sulfasalazine, or your biologic,” said Dr. Smith. “At least 50% of people will need a biologic to [achieve] disease control, and if you get them on it, they’re going to have better disease control, compliance is typically better, and they’re going to have less steroid exposure.”

Dr. Smith also noted that comorbid diabetes shouldn’t affect treat-to-target strategies. In fact, in such patients “you should probably be following it more tightly to reduce the cardiovascular outcomes,” he said.

The retrospective analysis included 9,085 patients with RA and with or without type 2 diabetes, with a mean follow-up of 5.2 years. They were recruited to the study between 1998 and 2011. Among patients with comorbid diabetes, those exposed to GC had a mortality of 67.4 per 1,000 person-years, compared with 22.5 among those not exposed to GC. Among those with RA alone, mortality was 44.6 versus 10.2 with and without GC exposure, respectively. Those with diabetes had a lower risk ratio for mortality (2.99 vs. 4.37), but a higher mortality difference (44.9 vs. 34.4 per 1,000 person-years).

“The increased absolute hazard for all-cause mortality indicates the greater public health impact of people with RA using GCs if they have [diabetes],” the researchers wrote. “Rheumatologists should consider [diabetes] status when prescribing GCs to patients with RA given this potential impact of GC therapy on glucose control and mortality.”

The study was limited by a lack of information on GC dose and cumulative exposure. Given its retrospective nature, the study could have been affected by confounding by indication, as well as unknown confounders.

The study was funded by the Centre for Epidemiology Versus Arthritis and the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre. Dr. Starkebaum has no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Smith is on the speaker’s bureau for AbbVie and serves on the company’s advisory board. He is also on the advisory boards of Regeneron and Sanofi Genzyme.

SOURCE: Costello R et al. BMC Rheumatol. 2020 Feb 19. doi: 10.1186/s41927-019-0105-4.

REPORTING FROM BMC RHEUMATOLOGY

In gestational diabetes, early postpartum glucose testing is a winner

GRAPEVINE, TEX. – Early postpartum glucose tolerance testing for women with gestational diabetes resulted in a 99% adherence rate, with similar sensitivity and specificity as the currently recommended 4- to 12-week postpartum testing schedule.

“Two-day postpartum glucose tolerance testing has similar diagnostic utility as the 4- to 12-week postpartum glucose tolerance test to identify impaired glucose metabolism and diabetes at 1 year postpartum,” said Erika Werner, MD, speaking at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Overall, 29% of women studied had impaired glucose metabolism at 2 days postpartum, as did 25% in the 4- to 12-weeks postpartum window. At 1 year, that figure was 35%. The number of women meeting diagnostic criteria for diabetes held steady at 4% for all three time points.

The findings warrant “consideration for the 2-day postpartum glucose tolerance test (GTT) as the initial postpartum test for women who have gestational diabetes, with repeat testing at 1 year,” said Dr. Werner, a maternal-fetal medicine physician at Brown University, Providence, R.I.

Glucose testing for women with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is recommended at 4-12 weeks postpartum by both the American Diabetes Association and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Testing can allow detection and treatment of impaired glucose metabolism, seen in 15%-40% of women with a history of GDM. Up to 1 in 20 women with GDM will receive a postpartum diagnosis of type 2 diabetes.

However, fewer than one in five women will actually have postpartum glucose testing, representing a large missed opportunity, said Dr. Werner.

Several factors likely contribute to those screening failures, she added. In addition to the potential for public insurance to lapse at 6 weeks postpartum, the logistical realities and time demands of parenting a newborn are themselves a significant barrier.

“What if we changed the timing?” and shifted glucose testing to the early postpartum days, before hospital discharge, asked Dr. Werner. Several pilot studies had already compared glucose screening in the first few days postpartum with the routine schedule, finding good correlation between the early and routine GTT schedule.

Importantly, the earlier studies achieved an adherence rate of more than 90% for early GTT. By contrast, fewer than half of the participants in the usual-care arms actually returned for postpartum GTT in the 4- to 12-week postpartum window, even under the optimized conditions associated with a medical study.

The single-center prospective cohort study conducted by Dr. Werner and collaborators enrolled 300 women with GDM. Women agreed to participate in glucose tolerance testing as inpatients, at 2 days postpartum, in addition to receiving a GTT between 4 and 12 weeks postpartum, and additional screening that included a glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) test at 1 year postpartum.

The investigators obtained postpartum day 2 GTTs for all but four of the patients. A total of 201 patients returned in the 4- to 12-week postpartum window, and 168 of those participants returned for HbA1c testing at 1 year. Of the 95 patients who didn’t come back for the 4- to 12-week test, 33 did return at 1 year for HbA1c testing.

Dr. Werner and her coinvestigators included adult women who spoke either fluent Spanish or English and had GDM diagnosed by the Carpenter-Coustan criteria, or by having a blood glucose level of 200 mg/dL or more in a 1-hour glucose challenge test.