User login

VTE risk after bariatric surgery should be assessed

SEATTLE – Preop thromboelastometry can identify patients who need extra according to a prospective investigation of 40 patients at Conemaugh Memorial Medical Center in Johnstown, Pa.

Enoxaparin 40 mg twice daily just wasn’t enough for people who were hypercoagulable before surgery. The goal of the study was to find the best way to prevent venous thromboembolism (VTE) after weight loss surgery. At present, there’s no consensus on prophylaxis dosing, timing, duration, or even what agent to use for these patients. Conemaugh uses postop enoxaparin, a low-molecular-weight heparin. Among many other options, some hospitals opt for preop dosing with traditional heparin, which is less expensive.

The Conemaugh team turned to thromboelastometry (TEM) to look at the question of VTE risk in bariatric surgery patients. The test gauges coagulation status by measuring elasticity as a small blood sample clots over a few minutes. The investigators found that patients who were hypercoagulable before surgery were likely to be hypercoagulable afterwards. The finding argues for baseline TEM testing to guide postop anticoagulation.

The problem is that bariatric services don’t often have access to TEM equipment, and insurance doesn’t cover the $60 test. In this instance, the Lake Erie College of Osteopathic Medicine in Erie, Pa., had the equipment and covered the testing for the study.

The patients had TEM at baseline and then received 40 mg of enoxaparin about 4 hours after surgery – mostly laparoscopic gastric bypasses – and a second dose about 12 hours after the first. TEM was repeated about 2 hours after the second dose.

At baseline, 2 (5%) of the patients were hypocoagulable, 15 (37.5%) were normal, and 23 (57.5%) were hypercoagulable. On postop TEM, 17 patients (42.5%) were normal and 23 (57.5%) were hypercoagulable: “These 23 were inadequately anticoagulated,” said lead investigator Daniel Urias, MD, a general surgery resident at the medical center.

“There was an association between being normal at baseline and being normal postop, and being hypercoagulable at baseline and hypercoagulable postop. We didn’t anticipate finding such similarity between the numbers. Our suspicion that baseline status plays a major role is holding true,” Dr. Urias said at the World Congress of Endoscopic Surgery hosted by SAGES & CAGS.

When patients test hypercoagulable at baseline, “we are [now] leaning towards [enoxaparin] 60 mg twice daily,” he said.

Ultimately, anticoagulation TEM could be used to titrate patients into the normal range. For best outcomes, it’s likely that “obese patients require goal-directed therapy instead of weight-based or fixed dosing,” he said, but nothing is going to happen until insurance steps up.

The patients did not have underlying coagulopathies, and 33 (82.5%) were women; the average age was 44 years and average body mass index was 43.6 kg/m2. The mean preop Caprini score was 4, indicating moderate VTE risk. Surgery lasted about 200 minutes. Patients were out of bed and walking on postop day 0.

The investigators had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Urias D et al. World Congress of Endoscopic Surgery hosted by SAGES & CAGS abstract S023.

SEATTLE – Preop thromboelastometry can identify patients who need extra according to a prospective investigation of 40 patients at Conemaugh Memorial Medical Center in Johnstown, Pa.

Enoxaparin 40 mg twice daily just wasn’t enough for people who were hypercoagulable before surgery. The goal of the study was to find the best way to prevent venous thromboembolism (VTE) after weight loss surgery. At present, there’s no consensus on prophylaxis dosing, timing, duration, or even what agent to use for these patients. Conemaugh uses postop enoxaparin, a low-molecular-weight heparin. Among many other options, some hospitals opt for preop dosing with traditional heparin, which is less expensive.

The Conemaugh team turned to thromboelastometry (TEM) to look at the question of VTE risk in bariatric surgery patients. The test gauges coagulation status by measuring elasticity as a small blood sample clots over a few minutes. The investigators found that patients who were hypercoagulable before surgery were likely to be hypercoagulable afterwards. The finding argues for baseline TEM testing to guide postop anticoagulation.

The problem is that bariatric services don’t often have access to TEM equipment, and insurance doesn’t cover the $60 test. In this instance, the Lake Erie College of Osteopathic Medicine in Erie, Pa., had the equipment and covered the testing for the study.

The patients had TEM at baseline and then received 40 mg of enoxaparin about 4 hours after surgery – mostly laparoscopic gastric bypasses – and a second dose about 12 hours after the first. TEM was repeated about 2 hours after the second dose.

At baseline, 2 (5%) of the patients were hypocoagulable, 15 (37.5%) were normal, and 23 (57.5%) were hypercoagulable. On postop TEM, 17 patients (42.5%) were normal and 23 (57.5%) were hypercoagulable: “These 23 were inadequately anticoagulated,” said lead investigator Daniel Urias, MD, a general surgery resident at the medical center.

“There was an association between being normal at baseline and being normal postop, and being hypercoagulable at baseline and hypercoagulable postop. We didn’t anticipate finding such similarity between the numbers. Our suspicion that baseline status plays a major role is holding true,” Dr. Urias said at the World Congress of Endoscopic Surgery hosted by SAGES & CAGS.

When patients test hypercoagulable at baseline, “we are [now] leaning towards [enoxaparin] 60 mg twice daily,” he said.

Ultimately, anticoagulation TEM could be used to titrate patients into the normal range. For best outcomes, it’s likely that “obese patients require goal-directed therapy instead of weight-based or fixed dosing,” he said, but nothing is going to happen until insurance steps up.

The patients did not have underlying coagulopathies, and 33 (82.5%) were women; the average age was 44 years and average body mass index was 43.6 kg/m2. The mean preop Caprini score was 4, indicating moderate VTE risk. Surgery lasted about 200 minutes. Patients were out of bed and walking on postop day 0.

The investigators had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Urias D et al. World Congress of Endoscopic Surgery hosted by SAGES & CAGS abstract S023.

SEATTLE – Preop thromboelastometry can identify patients who need extra according to a prospective investigation of 40 patients at Conemaugh Memorial Medical Center in Johnstown, Pa.

Enoxaparin 40 mg twice daily just wasn’t enough for people who were hypercoagulable before surgery. The goal of the study was to find the best way to prevent venous thromboembolism (VTE) after weight loss surgery. At present, there’s no consensus on prophylaxis dosing, timing, duration, or even what agent to use for these patients. Conemaugh uses postop enoxaparin, a low-molecular-weight heparin. Among many other options, some hospitals opt for preop dosing with traditional heparin, which is less expensive.

The Conemaugh team turned to thromboelastometry (TEM) to look at the question of VTE risk in bariatric surgery patients. The test gauges coagulation status by measuring elasticity as a small blood sample clots over a few minutes. The investigators found that patients who were hypercoagulable before surgery were likely to be hypercoagulable afterwards. The finding argues for baseline TEM testing to guide postop anticoagulation.

The problem is that bariatric services don’t often have access to TEM equipment, and insurance doesn’t cover the $60 test. In this instance, the Lake Erie College of Osteopathic Medicine in Erie, Pa., had the equipment and covered the testing for the study.

The patients had TEM at baseline and then received 40 mg of enoxaparin about 4 hours after surgery – mostly laparoscopic gastric bypasses – and a second dose about 12 hours after the first. TEM was repeated about 2 hours after the second dose.

At baseline, 2 (5%) of the patients were hypocoagulable, 15 (37.5%) were normal, and 23 (57.5%) were hypercoagulable. On postop TEM, 17 patients (42.5%) were normal and 23 (57.5%) were hypercoagulable: “These 23 were inadequately anticoagulated,” said lead investigator Daniel Urias, MD, a general surgery resident at the medical center.

“There was an association between being normal at baseline and being normal postop, and being hypercoagulable at baseline and hypercoagulable postop. We didn’t anticipate finding such similarity between the numbers. Our suspicion that baseline status plays a major role is holding true,” Dr. Urias said at the World Congress of Endoscopic Surgery hosted by SAGES & CAGS.

When patients test hypercoagulable at baseline, “we are [now] leaning towards [enoxaparin] 60 mg twice daily,” he said.

Ultimately, anticoagulation TEM could be used to titrate patients into the normal range. For best outcomes, it’s likely that “obese patients require goal-directed therapy instead of weight-based or fixed dosing,” he said, but nothing is going to happen until insurance steps up.

The patients did not have underlying coagulopathies, and 33 (82.5%) were women; the average age was 44 years and average body mass index was 43.6 kg/m2. The mean preop Caprini score was 4, indicating moderate VTE risk. Surgery lasted about 200 minutes. Patients were out of bed and walking on postop day 0.

The investigators had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Urias D et al. World Congress of Endoscopic Surgery hosted by SAGES & CAGS abstract S023.

REPORTING FROM SAGES 2018

Key clinical point: Preoperative thromboelastometry identifies patients who need extra anticoagulation against venous thromboembolism following bariatric surgery.

Major finding: Baseline and postop coagulation were similar: 37.5% vs. 42.5% were normal and 57.5% vs 57.5% were hypercoagulable.

Study details: Prospective study of 40 bariatric surgery patients.

Disclosures: The investigators did not have any relevant disclosures. The Lake Erie College of Osteopathic Medicine paid for the testing.

Source: Urias D et al. World Congress of Endoscopic Surgery hosted by SAGES & CAGS abstract S023.

Few acutely ill hospitalized patients receive VTE prophylaxis

SAN DIEGO – Among patients hospitalized for acute medical illnesses, the risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) remained elevated 30-40 days after discharge, results from a large analysis of national data showed.

Moreover, only 7% of at-risk patients received VTE prophylaxis in both the inpatient and outpatient setting.

“The results of this real-world study imply that there is a significantly unmet medical need for effective VTE prophylaxis in both the inpatient and outpatient continuum of care among patients hospitalized for acute medical illnesses,” researchers led by Alpesh Amin, MD, wrote in a poster presented at the biennial summit of the Thrombosis & Hemostasis Societies of North America.

According to Dr. Amin, who chairs the department of medicine at the University of California, Irvine, hospitalized patients with acute medical illnesses face an increased risk for VTE during hospital discharge, mainly within 40 days following hospital admission. However, the treatment patterns of VTE prophylaxis in this patient population have not been well studied in the “real-world” setting. In an effort to improve this area of clinical practice, the researchers used the Marketscan database between Jan. 1, 2012, and June 30, 2015, to identify acutely ill hospitalized patients, such as those with heart failure, respiratory diseases, ischemic stroke, cancer, infectious diseases, and rheumatic diseases. The key outcomes of interest were the proportion of patients receiving inpatient and outpatient VTE prophylaxis and the proportion of patients with VTE events during and after the index hospitalization. They used Kaplan-Meier analysis to examine the risk for VTE events after the index inpatient admission.

The mean age of the 17,895 patients was 58 years, 55% were female, and most (77%) were from the Southern area of the United States. Their mean Charlson Comborbidity Index score prior to hospitalization was 2.2. Nearly all hospitals (87%) were urban based, nonteaching (95%), and large, with 68% having at least 300 beds. Nearly three-quarters of patients (72%) were hospitalized for infectious and respiratory diseases, and the mean length of stay was 5 days.

Dr. Amin and his associates found that 59% of hospitalized patients did not receive any VTE prophylaxis, while only 7% received prophylaxis in both the inpatient and outpatient continuum of care. At the same time, cumulative VTE rates within 40 days of index admission were highest among patients hospitalized for infectious diseases and cancer (3.4% each), followed by those with heart failure (3.1%), respiratory diseases (2%), ischemic stroke (1.5%), and rheumatic diseases (1.3%). The cumulative VTE event rate for the overall study population within 40 days from index hospitalization was nearly 3%, with 60% of VTE events having occurred within 40 days.

The study was funded by Portola Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Amin reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Amin A et al. THSNA 2018, Poster 51.

SAN DIEGO – Among patients hospitalized for acute medical illnesses, the risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) remained elevated 30-40 days after discharge, results from a large analysis of national data showed.

Moreover, only 7% of at-risk patients received VTE prophylaxis in both the inpatient and outpatient setting.

“The results of this real-world study imply that there is a significantly unmet medical need for effective VTE prophylaxis in both the inpatient and outpatient continuum of care among patients hospitalized for acute medical illnesses,” researchers led by Alpesh Amin, MD, wrote in a poster presented at the biennial summit of the Thrombosis & Hemostasis Societies of North America.

According to Dr. Amin, who chairs the department of medicine at the University of California, Irvine, hospitalized patients with acute medical illnesses face an increased risk for VTE during hospital discharge, mainly within 40 days following hospital admission. However, the treatment patterns of VTE prophylaxis in this patient population have not been well studied in the “real-world” setting. In an effort to improve this area of clinical practice, the researchers used the Marketscan database between Jan. 1, 2012, and June 30, 2015, to identify acutely ill hospitalized patients, such as those with heart failure, respiratory diseases, ischemic stroke, cancer, infectious diseases, and rheumatic diseases. The key outcomes of interest were the proportion of patients receiving inpatient and outpatient VTE prophylaxis and the proportion of patients with VTE events during and after the index hospitalization. They used Kaplan-Meier analysis to examine the risk for VTE events after the index inpatient admission.

The mean age of the 17,895 patients was 58 years, 55% were female, and most (77%) were from the Southern area of the United States. Their mean Charlson Comborbidity Index score prior to hospitalization was 2.2. Nearly all hospitals (87%) were urban based, nonteaching (95%), and large, with 68% having at least 300 beds. Nearly three-quarters of patients (72%) were hospitalized for infectious and respiratory diseases, and the mean length of stay was 5 days.

Dr. Amin and his associates found that 59% of hospitalized patients did not receive any VTE prophylaxis, while only 7% received prophylaxis in both the inpatient and outpatient continuum of care. At the same time, cumulative VTE rates within 40 days of index admission were highest among patients hospitalized for infectious diseases and cancer (3.4% each), followed by those with heart failure (3.1%), respiratory diseases (2%), ischemic stroke (1.5%), and rheumatic diseases (1.3%). The cumulative VTE event rate for the overall study population within 40 days from index hospitalization was nearly 3%, with 60% of VTE events having occurred within 40 days.

The study was funded by Portola Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Amin reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Amin A et al. THSNA 2018, Poster 51.

SAN DIEGO – Among patients hospitalized for acute medical illnesses, the risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) remained elevated 30-40 days after discharge, results from a large analysis of national data showed.

Moreover, only 7% of at-risk patients received VTE prophylaxis in both the inpatient and outpatient setting.

“The results of this real-world study imply that there is a significantly unmet medical need for effective VTE prophylaxis in both the inpatient and outpatient continuum of care among patients hospitalized for acute medical illnesses,” researchers led by Alpesh Amin, MD, wrote in a poster presented at the biennial summit of the Thrombosis & Hemostasis Societies of North America.

According to Dr. Amin, who chairs the department of medicine at the University of California, Irvine, hospitalized patients with acute medical illnesses face an increased risk for VTE during hospital discharge, mainly within 40 days following hospital admission. However, the treatment patterns of VTE prophylaxis in this patient population have not been well studied in the “real-world” setting. In an effort to improve this area of clinical practice, the researchers used the Marketscan database between Jan. 1, 2012, and June 30, 2015, to identify acutely ill hospitalized patients, such as those with heart failure, respiratory diseases, ischemic stroke, cancer, infectious diseases, and rheumatic diseases. The key outcomes of interest were the proportion of patients receiving inpatient and outpatient VTE prophylaxis and the proportion of patients with VTE events during and after the index hospitalization. They used Kaplan-Meier analysis to examine the risk for VTE events after the index inpatient admission.

The mean age of the 17,895 patients was 58 years, 55% were female, and most (77%) were from the Southern area of the United States. Their mean Charlson Comborbidity Index score prior to hospitalization was 2.2. Nearly all hospitals (87%) were urban based, nonteaching (95%), and large, with 68% having at least 300 beds. Nearly three-quarters of patients (72%) were hospitalized for infectious and respiratory diseases, and the mean length of stay was 5 days.

Dr. Amin and his associates found that 59% of hospitalized patients did not receive any VTE prophylaxis, while only 7% received prophylaxis in both the inpatient and outpatient continuum of care. At the same time, cumulative VTE rates within 40 days of index admission were highest among patients hospitalized for infectious diseases and cancer (3.4% each), followed by those with heart failure (3.1%), respiratory diseases (2%), ischemic stroke (1.5%), and rheumatic diseases (1.3%). The cumulative VTE event rate for the overall study population within 40 days from index hospitalization was nearly 3%, with 60% of VTE events having occurred within 40 days.

The study was funded by Portola Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Amin reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Amin A et al. THSNA 2018, Poster 51.

REPORTING FROM THSNA 2018

Key clinical point: There is a significant unmet medical need for VTE prophylaxis in the continuum of care of patients hospitalized for acute medical illnesses.

Major finding: Of the overall study population, only 7% received both inpatient and outpatient VTE prophylaxis.

Study details: An analysis of national data from 17,895 acutely ill hospitalized patients.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Portola Pharmaceuticals. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts.

Source: Amin A et al. THSNA 2018, Poster 51.

JAK inhibitors for RA: Is VTE risk overblown?

MAUI, HAWAII – Rheumatologists, regulatory agencies, and the pharmaceutical industry all have gone off the deep end in their fretting over what appears to be a low rate of venous thromboembolic events in the major randomized trials of the oral Janus kinase inhibitors for RA, Mark C. Genovese, MD, asserted at the 2018 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

“The reality is all of our drugs pose potential risks. Unfortunately, I think that at least for the moment, the field has turned all attention in one direction: VTE [venous thromboembolic] events. I suspect there’s some truth [to the possible associated risk]. Certainly we are seeing these events. The question is, how overdone is this?” according to Dr. Genovese, professor of medicine and cochief of the division of immunology and rheumatology at Stanford (Calif.) University.

“I think the upadacitinib data has been entirely overshadowed by concerns about VTEs,” he said. “In the last year, we saw three significant phase 3 studies on upadacitinib arrive in the rheumatology community, and I think the only thing we talked about was VTEs.”

All parties interested in developing Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors for the treatment of RA began to freak out about a possible increase in VTEs when in April 2017 the Food and Drug Administration turned down Eli Lilly and Incyte’s initial application for marketing approval of the JAK inhibitor baricitinib. Among the problems the agency cited was evidence of potential thrombotic risk.

The VTE rate in baricitinib clinical trials up to 48 weeks in duration was 0.53 events/100 patient-years, with no significant difference in risk between the2-mg and 4-mg doses. This appears to be a class effect for the oral JAK inhibitors, as low rates of VTE, albeit numerically higher than in placebo-treated controls, have also been recorded in the RA development programs for tofacitinib (Xeljanz) as well as the investigational agents filgotinib and upadacitinib, the rheumatologist noted.

This begs the question of whether these VTE rates are significantly higher than background rates in patients with RA or other rheumatologic diseases, which are known to be elevated relative to the general population. Indeed, a retrospective study of insurance claims data by investigators at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, concluded that the VTE rate in RA patients was 0.61 events/100 patient-years, 120% greater than in a matched patient population without RA. After fully adjusting for comorbid conditions and demographics, the relative risk increase associated with RA dropped to 40%, still significantly higher than in controls (Arthritis Care Res [Hoboken]. 2013 Oct;65[10]:1600-7).

Similarly, Canadian investigators conducted a meta-analysis of 25 studies with VTE data in patients with RA, systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren’s syndrome, systemic sclerosis, or inflammatory myositis. This meta-analysis included 10 studies of more than 5.2 million RA patients and nearly 900,000 controls. The conclusion: each of these rheumatic diseases was associated with a VTE rate more than three times higher than in the general population (Arthritis Res Ther. 2014 Sep 25;16[5]:435).

“Patients with RA are at higher risk for VTE than those without RA. It’s unfortunate, and it’s certainly something I don’t think many of us have thought much about before. It’s something we don’t often get to see and something we don’t like to think about,” the rheumatologist observed.

Dr. Genovese admitted to a degree of personal frustration with the current tunnel vision focus on VTEs in JAK inhibitor trials. At the 2017 annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology he presented the results of the phase 3 SELECT-BEYOND study in which 499 RA patients who had previously failed to respond or were intolerant to biologic therapy were randomized to once daily upadacitinib at 15 or 30 mg or placebo on top of background methotrexate. At week 12, the ACR 20 response rate was 65% for upadacitinib at 15 mg, 56% at 30 mg, and 28% in placebo-treated controls.

“That’s almost a 40% placebo-adjusted response rate. In fact, it’s the highest response I’ve ever seen in a biologic inadequate-responder population. This really looked pretty good, but I don’t think anyone ever took notice. Why not? Because we were all worried about VTE,” he said.

There were in fact a handful of VTEs in upadacitinib-treated patients, Dr. Genovese was quick to note. But he was more impressed by the week 12 ACR 20 responses in patients who had previously failed on three or more biologics: 71% with upadacitinib at 15 mg and 50% at 30 mg, compared with 23% in controls. Moreover, among patients with a baseline history of failure to respond to anti–interleukin-6 therapy, the week 12 ACR 20 rate was 56% with upadacitinib at 15 mg and 58% at 30 mg, versus 20% in controls.

“This looks like a pretty effective drug for patients who’ve failed everything else in our practice,” he commented.

Dr. Genovese reminded his audience that the rheumatology community has a history of overreacting to safety signals in the early days after introduction of new therapies. Examples: tuberculosis with tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, lymphoma with abatacept (Orencia), lymphoma with anti–tumor necrosis factor agents, and cardiovascular events with anti–interleukin-6 inhibition.

“PML [progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy] is a breathtaking side effect with rituximab [Rituxan], but we’ve gotten over that. We recognize that it’s a potential problem, but we still prescribe rituximab,” the rheumatologist noted. “We’re probably going to need to address the issue of which of our patients are potentially at higher risk for VTE, and maybe we avoid this class in those patients. Like we now do as we look at patients we think are at increased risk for infection, or multiple sclerosis, or TB, we may also need to think of VTE risk.”

But , he argued. There is a pressing unmet need for new therapies for RA with novel mechanisms of action. Only about one-half of patients on contemporary biologic therapies are still on that agent 5 years after initiating therapy.

“Virtually all our patients are partial responders. Everybody gets some benefit. But true remission is achieved by only a minority,” Dr. Genovese said. “The gap between where we are and where we want to be is actually much greater than we often perceive.”

He reported having financial relationships with AbbVie, which is developing upadacitinib, and more than a dozen other medical companies.

MAUI, HAWAII – Rheumatologists, regulatory agencies, and the pharmaceutical industry all have gone off the deep end in their fretting over what appears to be a low rate of venous thromboembolic events in the major randomized trials of the oral Janus kinase inhibitors for RA, Mark C. Genovese, MD, asserted at the 2018 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

“The reality is all of our drugs pose potential risks. Unfortunately, I think that at least for the moment, the field has turned all attention in one direction: VTE [venous thromboembolic] events. I suspect there’s some truth [to the possible associated risk]. Certainly we are seeing these events. The question is, how overdone is this?” according to Dr. Genovese, professor of medicine and cochief of the division of immunology and rheumatology at Stanford (Calif.) University.

“I think the upadacitinib data has been entirely overshadowed by concerns about VTEs,” he said. “In the last year, we saw three significant phase 3 studies on upadacitinib arrive in the rheumatology community, and I think the only thing we talked about was VTEs.”

All parties interested in developing Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors for the treatment of RA began to freak out about a possible increase in VTEs when in April 2017 the Food and Drug Administration turned down Eli Lilly and Incyte’s initial application for marketing approval of the JAK inhibitor baricitinib. Among the problems the agency cited was evidence of potential thrombotic risk.

The VTE rate in baricitinib clinical trials up to 48 weeks in duration was 0.53 events/100 patient-years, with no significant difference in risk between the2-mg and 4-mg doses. This appears to be a class effect for the oral JAK inhibitors, as low rates of VTE, albeit numerically higher than in placebo-treated controls, have also been recorded in the RA development programs for tofacitinib (Xeljanz) as well as the investigational agents filgotinib and upadacitinib, the rheumatologist noted.

This begs the question of whether these VTE rates are significantly higher than background rates in patients with RA or other rheumatologic diseases, which are known to be elevated relative to the general population. Indeed, a retrospective study of insurance claims data by investigators at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, concluded that the VTE rate in RA patients was 0.61 events/100 patient-years, 120% greater than in a matched patient population without RA. After fully adjusting for comorbid conditions and demographics, the relative risk increase associated with RA dropped to 40%, still significantly higher than in controls (Arthritis Care Res [Hoboken]. 2013 Oct;65[10]:1600-7).

Similarly, Canadian investigators conducted a meta-analysis of 25 studies with VTE data in patients with RA, systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren’s syndrome, systemic sclerosis, or inflammatory myositis. This meta-analysis included 10 studies of more than 5.2 million RA patients and nearly 900,000 controls. The conclusion: each of these rheumatic diseases was associated with a VTE rate more than three times higher than in the general population (Arthritis Res Ther. 2014 Sep 25;16[5]:435).

“Patients with RA are at higher risk for VTE than those without RA. It’s unfortunate, and it’s certainly something I don’t think many of us have thought much about before. It’s something we don’t often get to see and something we don’t like to think about,” the rheumatologist observed.

Dr. Genovese admitted to a degree of personal frustration with the current tunnel vision focus on VTEs in JAK inhibitor trials. At the 2017 annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology he presented the results of the phase 3 SELECT-BEYOND study in which 499 RA patients who had previously failed to respond or were intolerant to biologic therapy were randomized to once daily upadacitinib at 15 or 30 mg or placebo on top of background methotrexate. At week 12, the ACR 20 response rate was 65% for upadacitinib at 15 mg, 56% at 30 mg, and 28% in placebo-treated controls.

“That’s almost a 40% placebo-adjusted response rate. In fact, it’s the highest response I’ve ever seen in a biologic inadequate-responder population. This really looked pretty good, but I don’t think anyone ever took notice. Why not? Because we were all worried about VTE,” he said.

There were in fact a handful of VTEs in upadacitinib-treated patients, Dr. Genovese was quick to note. But he was more impressed by the week 12 ACR 20 responses in patients who had previously failed on three or more biologics: 71% with upadacitinib at 15 mg and 50% at 30 mg, compared with 23% in controls. Moreover, among patients with a baseline history of failure to respond to anti–interleukin-6 therapy, the week 12 ACR 20 rate was 56% with upadacitinib at 15 mg and 58% at 30 mg, versus 20% in controls.

“This looks like a pretty effective drug for patients who’ve failed everything else in our practice,” he commented.

Dr. Genovese reminded his audience that the rheumatology community has a history of overreacting to safety signals in the early days after introduction of new therapies. Examples: tuberculosis with tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, lymphoma with abatacept (Orencia), lymphoma with anti–tumor necrosis factor agents, and cardiovascular events with anti–interleukin-6 inhibition.

“PML [progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy] is a breathtaking side effect with rituximab [Rituxan], but we’ve gotten over that. We recognize that it’s a potential problem, but we still prescribe rituximab,” the rheumatologist noted. “We’re probably going to need to address the issue of which of our patients are potentially at higher risk for VTE, and maybe we avoid this class in those patients. Like we now do as we look at patients we think are at increased risk for infection, or multiple sclerosis, or TB, we may also need to think of VTE risk.”

But , he argued. There is a pressing unmet need for new therapies for RA with novel mechanisms of action. Only about one-half of patients on contemporary biologic therapies are still on that agent 5 years after initiating therapy.

“Virtually all our patients are partial responders. Everybody gets some benefit. But true remission is achieved by only a minority,” Dr. Genovese said. “The gap between where we are and where we want to be is actually much greater than we often perceive.”

He reported having financial relationships with AbbVie, which is developing upadacitinib, and more than a dozen other medical companies.

MAUI, HAWAII – Rheumatologists, regulatory agencies, and the pharmaceutical industry all have gone off the deep end in their fretting over what appears to be a low rate of venous thromboembolic events in the major randomized trials of the oral Janus kinase inhibitors for RA, Mark C. Genovese, MD, asserted at the 2018 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

“The reality is all of our drugs pose potential risks. Unfortunately, I think that at least for the moment, the field has turned all attention in one direction: VTE [venous thromboembolic] events. I suspect there’s some truth [to the possible associated risk]. Certainly we are seeing these events. The question is, how overdone is this?” according to Dr. Genovese, professor of medicine and cochief of the division of immunology and rheumatology at Stanford (Calif.) University.

“I think the upadacitinib data has been entirely overshadowed by concerns about VTEs,” he said. “In the last year, we saw three significant phase 3 studies on upadacitinib arrive in the rheumatology community, and I think the only thing we talked about was VTEs.”

All parties interested in developing Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors for the treatment of RA began to freak out about a possible increase in VTEs when in April 2017 the Food and Drug Administration turned down Eli Lilly and Incyte’s initial application for marketing approval of the JAK inhibitor baricitinib. Among the problems the agency cited was evidence of potential thrombotic risk.

The VTE rate in baricitinib clinical trials up to 48 weeks in duration was 0.53 events/100 patient-years, with no significant difference in risk between the2-mg and 4-mg doses. This appears to be a class effect for the oral JAK inhibitors, as low rates of VTE, albeit numerically higher than in placebo-treated controls, have also been recorded in the RA development programs for tofacitinib (Xeljanz) as well as the investigational agents filgotinib and upadacitinib, the rheumatologist noted.

This begs the question of whether these VTE rates are significantly higher than background rates in patients with RA or other rheumatologic diseases, which are known to be elevated relative to the general population. Indeed, a retrospective study of insurance claims data by investigators at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, concluded that the VTE rate in RA patients was 0.61 events/100 patient-years, 120% greater than in a matched patient population without RA. After fully adjusting for comorbid conditions and demographics, the relative risk increase associated with RA dropped to 40%, still significantly higher than in controls (Arthritis Care Res [Hoboken]. 2013 Oct;65[10]:1600-7).

Similarly, Canadian investigators conducted a meta-analysis of 25 studies with VTE data in patients with RA, systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren’s syndrome, systemic sclerosis, or inflammatory myositis. This meta-analysis included 10 studies of more than 5.2 million RA patients and nearly 900,000 controls. The conclusion: each of these rheumatic diseases was associated with a VTE rate more than three times higher than in the general population (Arthritis Res Ther. 2014 Sep 25;16[5]:435).

“Patients with RA are at higher risk for VTE than those without RA. It’s unfortunate, and it’s certainly something I don’t think many of us have thought much about before. It’s something we don’t often get to see and something we don’t like to think about,” the rheumatologist observed.

Dr. Genovese admitted to a degree of personal frustration with the current tunnel vision focus on VTEs in JAK inhibitor trials. At the 2017 annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology he presented the results of the phase 3 SELECT-BEYOND study in which 499 RA patients who had previously failed to respond or were intolerant to biologic therapy were randomized to once daily upadacitinib at 15 or 30 mg or placebo on top of background methotrexate. At week 12, the ACR 20 response rate was 65% for upadacitinib at 15 mg, 56% at 30 mg, and 28% in placebo-treated controls.

“That’s almost a 40% placebo-adjusted response rate. In fact, it’s the highest response I’ve ever seen in a biologic inadequate-responder population. This really looked pretty good, but I don’t think anyone ever took notice. Why not? Because we were all worried about VTE,” he said.

There were in fact a handful of VTEs in upadacitinib-treated patients, Dr. Genovese was quick to note. But he was more impressed by the week 12 ACR 20 responses in patients who had previously failed on three or more biologics: 71% with upadacitinib at 15 mg and 50% at 30 mg, compared with 23% in controls. Moreover, among patients with a baseline history of failure to respond to anti–interleukin-6 therapy, the week 12 ACR 20 rate was 56% with upadacitinib at 15 mg and 58% at 30 mg, versus 20% in controls.

“This looks like a pretty effective drug for patients who’ve failed everything else in our practice,” he commented.

Dr. Genovese reminded his audience that the rheumatology community has a history of overreacting to safety signals in the early days after introduction of new therapies. Examples: tuberculosis with tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, lymphoma with abatacept (Orencia), lymphoma with anti–tumor necrosis factor agents, and cardiovascular events with anti–interleukin-6 inhibition.

“PML [progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy] is a breathtaking side effect with rituximab [Rituxan], but we’ve gotten over that. We recognize that it’s a potential problem, but we still prescribe rituximab,” the rheumatologist noted. “We’re probably going to need to address the issue of which of our patients are potentially at higher risk for VTE, and maybe we avoid this class in those patients. Like we now do as we look at patients we think are at increased risk for infection, or multiple sclerosis, or TB, we may also need to think of VTE risk.”

But , he argued. There is a pressing unmet need for new therapies for RA with novel mechanisms of action. Only about one-half of patients on contemporary biologic therapies are still on that agent 5 years after initiating therapy.

“Virtually all our patients are partial responders. Everybody gets some benefit. But true remission is achieved by only a minority,” Dr. Genovese said. “The gap between where we are and where we want to be is actually much greater than we often perceive.”

He reported having financial relationships with AbbVie, which is developing upadacitinib, and more than a dozen other medical companies.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM RWCS 2018

Controversy surrounds calf vein thrombosis treatment

CHICAGO – The use of therapeutic-dose anticoagulation in hospitalized patients with calf vein thrombosis significantly reduces the risk of venous thromboembolic complications, compared with lower-dose prophylactic anticoagulation or surveillance alone, Heron E. Rodriguez, MD, said at a symposium on vascular surgery sponsored by Northwestern University.

Moreover, placement of an inferior vena cava filter in patients with calf vein thrombosis when anticoagulation is contraindicated accomplishes nothing beneficial and had a 10% complication rate in a large retrospective single-center study, added Dr. Rodriguez of Northwestern University, Chicago.

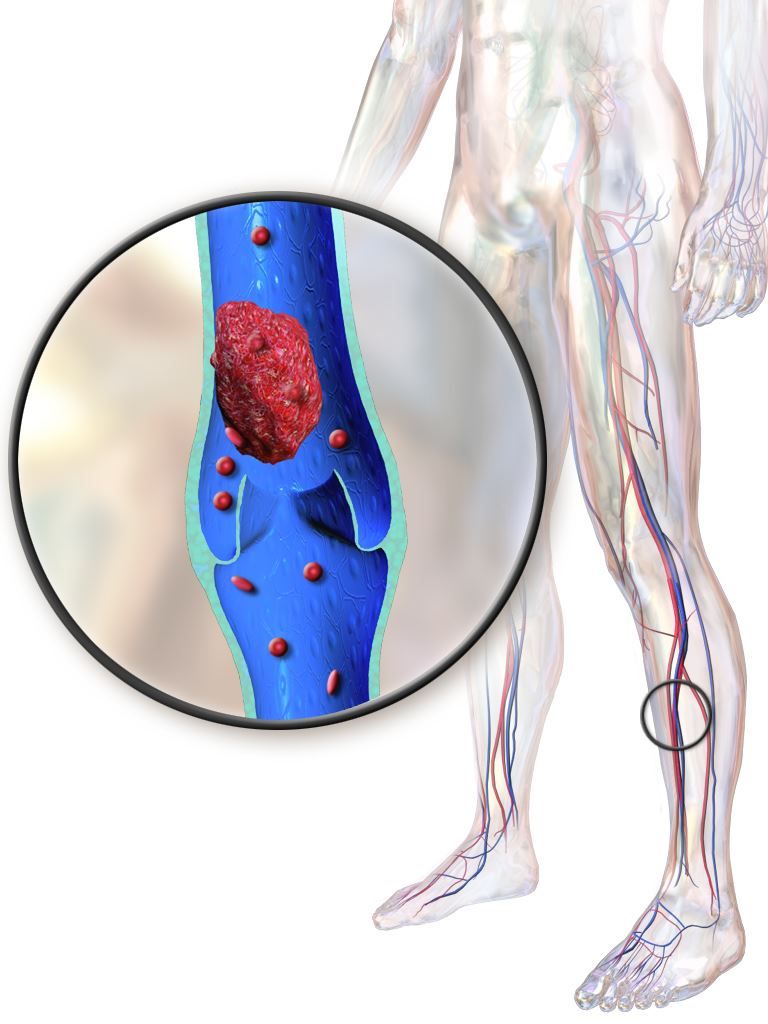

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) remains a significant source of morbidity and mortality despite worldwide awareness of the problem.

“Specifically, calf vein thrombosis [CVT] is very common, and we know that in some series up to 30% of patients end up propagating proximally if they’re not treated, and a good number of them develop chronic venous insufficiency, with long-term consequences,” he noted.

“Unfortunately there is no consensus regarding treatment. The guidelines are very vague. For example, there is no mention [in current American College of Chest Physicians guidelines] of how to manage muscular vein thrombosis and much ambiguity on how to treat calf vein thrombosis,” he continued.

Dr. Rodriguez cited as an indication of the lack of consensus on management of CVT a single-institution survey by other investigators of the practices of physicians in various specialties. Forty-nine percent of respondents indicated they anticoagulate patients with CVT; 51% don’t. Of those who did, 62% prescribed low-molecular-weight heparin and 11% intravenous heparin. Fifty-eight percent of physicians who anticoagulated did so for 3 months, 30% for 6. And 46% of physicians used an inferior vena cava (IVC) filter when anticoagulation was contraindicated (Vascular. 2014 Apr;22[2]:93-7).

That rate of IVC placement “seemed really high” given the paucity of supporting evidence for safety and efficacy of filter placement in the setting of CVT, so Dr. Rodriguez and coinvestigators decided to conduct a retrospective review of practices at Northwestern Memorial Hospital. He explained the study hypothesis: “Our thinking was that these kinds of thrombi are associated with low risk of propagation and pulmonary embolism, and they can and should be managed conservatively.”

Of 647 patients with isolated thrombosis of the anterior and posterior tibial, soleal, peroneal, or gastrocnemius veins, 44% received an IVC filter, and the rest got medical treatment alone. Of the 362 patients managed medically, 49% received therapeutic anticoagulation, 12% got low-dose prophylactic anticoagulation, and 39% underwent surveillance without anticoagulation.

The primary outcome was the incidence of venous thromboembolic complications – that is, propagation of DVT or pulmonary embolism. The incidence was 35% in the surveillance-only group, 30% with prophylactic anticoagulation, and 10% in patients who got therapeutic anticoagulation.

Of note, the rate of the most feared complication, pulmonary embolism, was low and similar in the filter recipients and medically managed group: 2.5% in the IVC group, 3.3% with medical management.

“Distal vein thromboses have low rates of pulmonary embolism, regardless of whether or not they are so-called protected with a filter. On the other hand, a filter was associated with a 10% rate of complications. I have to make clear that these were radiographic abnormalities – tilting, migration, caval perforation – that didn’t have clinical consequences, but we were very aggressive in removing the IVC filters, and I’m guessing if they’d been left inside they would create problems in the long term,” Dr. Rodriguez said.

An important point about this study is that these were all sick patients, and most were hospitalized. The filter recipients and medical groups differed in key ways. For example, 49% of the filter patients had a malignancy, and 56% had a baseline history of venous thromboembolic events, compared with 26% and 16%, respectively, of the medical group. For that reason, the investigators performed propensity score matching and came up with 157 closely matched patient pairs. The outcomes remained unchanged.

Of course, this was a retrospective study, with its inherent limitations, but Dr. Rodriguez characterized the published randomized trials on management of CVT as “small and limited.” The most frequently quoted study is the double-blind multicenter CACTUS trial, which randomized 252 outpatients with symptomatic CVT to 6 weeks of low-molecular-weight heparin or placebo and found no difference in the rates of proximal extension of venous thromboembolic events (Lancet Haematol. 2016 Dec;3[12]:e556-62). But these were all low-risk patients. Prior DVT or malignancy were exclusion criteria, so this was a very different population than treated at Northwestern.

Based upon the results of the retrospective study at Northwestern, which have been published (J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2017 Jan;5[1]:25-32), the vascular surgery service has developed a management algorithm for DVT management based upon the lesion site. If a patient is unable to undergo anticoagulation, venous duplex ultrasound is repeated at 1 week. If the imaging shows propagation into the popliteal vein and anticoagulation remains contraindicated, only then is placement of an IVC filter warranted.

Dr. Rodriguez reported serving as a paid speaker for Abbott, Endologix, and W.L. Gore.

CHICAGO – The use of therapeutic-dose anticoagulation in hospitalized patients with calf vein thrombosis significantly reduces the risk of venous thromboembolic complications, compared with lower-dose prophylactic anticoagulation or surveillance alone, Heron E. Rodriguez, MD, said at a symposium on vascular surgery sponsored by Northwestern University.

Moreover, placement of an inferior vena cava filter in patients with calf vein thrombosis when anticoagulation is contraindicated accomplishes nothing beneficial and had a 10% complication rate in a large retrospective single-center study, added Dr. Rodriguez of Northwestern University, Chicago.

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) remains a significant source of morbidity and mortality despite worldwide awareness of the problem.

“Specifically, calf vein thrombosis [CVT] is very common, and we know that in some series up to 30% of patients end up propagating proximally if they’re not treated, and a good number of them develop chronic venous insufficiency, with long-term consequences,” he noted.

“Unfortunately there is no consensus regarding treatment. The guidelines are very vague. For example, there is no mention [in current American College of Chest Physicians guidelines] of how to manage muscular vein thrombosis and much ambiguity on how to treat calf vein thrombosis,” he continued.

Dr. Rodriguez cited as an indication of the lack of consensus on management of CVT a single-institution survey by other investigators of the practices of physicians in various specialties. Forty-nine percent of respondents indicated they anticoagulate patients with CVT; 51% don’t. Of those who did, 62% prescribed low-molecular-weight heparin and 11% intravenous heparin. Fifty-eight percent of physicians who anticoagulated did so for 3 months, 30% for 6. And 46% of physicians used an inferior vena cava (IVC) filter when anticoagulation was contraindicated (Vascular. 2014 Apr;22[2]:93-7).

That rate of IVC placement “seemed really high” given the paucity of supporting evidence for safety and efficacy of filter placement in the setting of CVT, so Dr. Rodriguez and coinvestigators decided to conduct a retrospective review of practices at Northwestern Memorial Hospital. He explained the study hypothesis: “Our thinking was that these kinds of thrombi are associated with low risk of propagation and pulmonary embolism, and they can and should be managed conservatively.”

Of 647 patients with isolated thrombosis of the anterior and posterior tibial, soleal, peroneal, or gastrocnemius veins, 44% received an IVC filter, and the rest got medical treatment alone. Of the 362 patients managed medically, 49% received therapeutic anticoagulation, 12% got low-dose prophylactic anticoagulation, and 39% underwent surveillance without anticoagulation.

The primary outcome was the incidence of venous thromboembolic complications – that is, propagation of DVT or pulmonary embolism. The incidence was 35% in the surveillance-only group, 30% with prophylactic anticoagulation, and 10% in patients who got therapeutic anticoagulation.

Of note, the rate of the most feared complication, pulmonary embolism, was low and similar in the filter recipients and medically managed group: 2.5% in the IVC group, 3.3% with medical management.

“Distal vein thromboses have low rates of pulmonary embolism, regardless of whether or not they are so-called protected with a filter. On the other hand, a filter was associated with a 10% rate of complications. I have to make clear that these were radiographic abnormalities – tilting, migration, caval perforation – that didn’t have clinical consequences, but we were very aggressive in removing the IVC filters, and I’m guessing if they’d been left inside they would create problems in the long term,” Dr. Rodriguez said.

An important point about this study is that these were all sick patients, and most were hospitalized. The filter recipients and medical groups differed in key ways. For example, 49% of the filter patients had a malignancy, and 56% had a baseline history of venous thromboembolic events, compared with 26% and 16%, respectively, of the medical group. For that reason, the investigators performed propensity score matching and came up with 157 closely matched patient pairs. The outcomes remained unchanged.

Of course, this was a retrospective study, with its inherent limitations, but Dr. Rodriguez characterized the published randomized trials on management of CVT as “small and limited.” The most frequently quoted study is the double-blind multicenter CACTUS trial, which randomized 252 outpatients with symptomatic CVT to 6 weeks of low-molecular-weight heparin or placebo and found no difference in the rates of proximal extension of venous thromboembolic events (Lancet Haematol. 2016 Dec;3[12]:e556-62). But these were all low-risk patients. Prior DVT or malignancy were exclusion criteria, so this was a very different population than treated at Northwestern.

Based upon the results of the retrospective study at Northwestern, which have been published (J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2017 Jan;5[1]:25-32), the vascular surgery service has developed a management algorithm for DVT management based upon the lesion site. If a patient is unable to undergo anticoagulation, venous duplex ultrasound is repeated at 1 week. If the imaging shows propagation into the popliteal vein and anticoagulation remains contraindicated, only then is placement of an IVC filter warranted.

Dr. Rodriguez reported serving as a paid speaker for Abbott, Endologix, and W.L. Gore.

CHICAGO – The use of therapeutic-dose anticoagulation in hospitalized patients with calf vein thrombosis significantly reduces the risk of venous thromboembolic complications, compared with lower-dose prophylactic anticoagulation or surveillance alone, Heron E. Rodriguez, MD, said at a symposium on vascular surgery sponsored by Northwestern University.

Moreover, placement of an inferior vena cava filter in patients with calf vein thrombosis when anticoagulation is contraindicated accomplishes nothing beneficial and had a 10% complication rate in a large retrospective single-center study, added Dr. Rodriguez of Northwestern University, Chicago.

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) remains a significant source of morbidity and mortality despite worldwide awareness of the problem.

“Specifically, calf vein thrombosis [CVT] is very common, and we know that in some series up to 30% of patients end up propagating proximally if they’re not treated, and a good number of them develop chronic venous insufficiency, with long-term consequences,” he noted.

“Unfortunately there is no consensus regarding treatment. The guidelines are very vague. For example, there is no mention [in current American College of Chest Physicians guidelines] of how to manage muscular vein thrombosis and much ambiguity on how to treat calf vein thrombosis,” he continued.

Dr. Rodriguez cited as an indication of the lack of consensus on management of CVT a single-institution survey by other investigators of the practices of physicians in various specialties. Forty-nine percent of respondents indicated they anticoagulate patients with CVT; 51% don’t. Of those who did, 62% prescribed low-molecular-weight heparin and 11% intravenous heparin. Fifty-eight percent of physicians who anticoagulated did so for 3 months, 30% for 6. And 46% of physicians used an inferior vena cava (IVC) filter when anticoagulation was contraindicated (Vascular. 2014 Apr;22[2]:93-7).

That rate of IVC placement “seemed really high” given the paucity of supporting evidence for safety and efficacy of filter placement in the setting of CVT, so Dr. Rodriguez and coinvestigators decided to conduct a retrospective review of practices at Northwestern Memorial Hospital. He explained the study hypothesis: “Our thinking was that these kinds of thrombi are associated with low risk of propagation and pulmonary embolism, and they can and should be managed conservatively.”

Of 647 patients with isolated thrombosis of the anterior and posterior tibial, soleal, peroneal, or gastrocnemius veins, 44% received an IVC filter, and the rest got medical treatment alone. Of the 362 patients managed medically, 49% received therapeutic anticoagulation, 12% got low-dose prophylactic anticoagulation, and 39% underwent surveillance without anticoagulation.

The primary outcome was the incidence of venous thromboembolic complications – that is, propagation of DVT or pulmonary embolism. The incidence was 35% in the surveillance-only group, 30% with prophylactic anticoagulation, and 10% in patients who got therapeutic anticoagulation.

Of note, the rate of the most feared complication, pulmonary embolism, was low and similar in the filter recipients and medically managed group: 2.5% in the IVC group, 3.3% with medical management.

“Distal vein thromboses have low rates of pulmonary embolism, regardless of whether or not they are so-called protected with a filter. On the other hand, a filter was associated with a 10% rate of complications. I have to make clear that these were radiographic abnormalities – tilting, migration, caval perforation – that didn’t have clinical consequences, but we were very aggressive in removing the IVC filters, and I’m guessing if they’d been left inside they would create problems in the long term,” Dr. Rodriguez said.

An important point about this study is that these were all sick patients, and most were hospitalized. The filter recipients and medical groups differed in key ways. For example, 49% of the filter patients had a malignancy, and 56% had a baseline history of venous thromboembolic events, compared with 26% and 16%, respectively, of the medical group. For that reason, the investigators performed propensity score matching and came up with 157 closely matched patient pairs. The outcomes remained unchanged.

Of course, this was a retrospective study, with its inherent limitations, but Dr. Rodriguez characterized the published randomized trials on management of CVT as “small and limited.” The most frequently quoted study is the double-blind multicenter CACTUS trial, which randomized 252 outpatients with symptomatic CVT to 6 weeks of low-molecular-weight heparin or placebo and found no difference in the rates of proximal extension of venous thromboembolic events (Lancet Haematol. 2016 Dec;3[12]:e556-62). But these were all low-risk patients. Prior DVT or malignancy were exclusion criteria, so this was a very different population than treated at Northwestern.

Based upon the results of the retrospective study at Northwestern, which have been published (J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2017 Jan;5[1]:25-32), the vascular surgery service has developed a management algorithm for DVT management based upon the lesion site. If a patient is unable to undergo anticoagulation, venous duplex ultrasound is repeated at 1 week. If the imaging shows propagation into the popliteal vein and anticoagulation remains contraindicated, only then is placement of an IVC filter warranted.

Dr. Rodriguez reported serving as a paid speaker for Abbott, Endologix, and W.L. Gore.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM NORTHWESTERN VASCULAR SYMPOSIUM

Thrombosis risk is elevated with myeloproliferative neoplasms

Patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) have a higher rate of arterial and venous thrombosis than does the general population, with the greatest risk occurring around the time of diagnosis, according to results of a retrospective study.

Hazard ratios at 3 months after diagnosis were 3.0 (95% CI, 2.7-3.4) for arterial thrombosis and 9.7 (95% CI, 7.8-12.0) for venous thrombosis, compared with matched controls, Malin Hultcrantz, MD, PhD, of the Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, and her coauthors reported in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

Although previous studies have suggested patients with MPNs are at increased risk for thrombotic events, this large, population-based analysis is believed to be the first study to provide estimates of excess risk compared with matched control participants.

“These results are encouraging, and we believe that further refinement of risk scoring systems (such as by including time since MPN diagnosis and biomarkers); rethinking of recommendations for younger patients with MPNs; and emerging, more effective treatments will further improve outcomes for patients with MPNs,” the researchers wrote.

The retrospective, population-based cohort study included 9,429 Swedish patients diagnosed with MPNs between 1987 and 2009 and 35,820 matched control participants. Patient follow-up through 2010 was included in the analysis.

Thrombosis risk was highest near the time of diagnosis but decreased during the following year “likely because of effective thromboprophylactic and cytoreductive treatment of the MPN;”still, the risk remained elevated, the researchers wrote.

“This novel finding underlines the importance of initiating phlebotomy as well as thromboprophylactic and cytoreductive treatment, when indicated, as soon as the MPN is diagnosed,” they added.

Arterial thrombosis hazard ratios for MPN patients, compared with control participants, were 3.0 at 3 months after diagnosis, 2.0 at 1 year, and 1.5 at 5 years. Similarly, venous thrombosis hazard ratios were 9.7 at 3 months, 4.7 at 1 year, and 3.2 at 5 years.

Thrombosis risk was elevated in all age groups and all MPN subtypes, including primary myelofibrosis, polycythemia vera, and essential thrombocythemia. Of note, the study confirmed prior thrombosis and older age (60 years or older) as risk factors. Among patients with both of those risk factors, risk of thrombosis was increased 7-fold, according to the researchers.

Hazard ratios for thrombosis decreased during more recent time periods, suggesting a “positive effect” of improved treatment strategies, including increased use of aspirin as primary prophylaxis, better cardiovascular risk management, and better adherence to recommendations for cytoreductive treatment and phlebotomy, the researchers noted. Additionally, treatment with interferon and Janus kinase 2 inhibitors, such as ruxolitinib, “may be effective in further reducing risk for thrombosis,” the researchers wrote.

The study was funded by the Cancer Research Foundations of Radiumhemmet, the Swedish Research Council, and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, among other sources. The researchers reported having no financial disclosures relevant to the study.

SOURCE: Hultcrantz M et al. Ann Intern Med. 2018. doi: 10.7326/M17-0028.

The most notable contribution of the large cohort study by Hultcrantz and her colleagues is quantification of the magnitude of thrombotic risk that MPNs confer, according to Alison R. Moliterno, MD, and Elizabeth V. Ratchford, MD.

“Hultcrantz and colleagues have opened our eyes to the magnitude of thrombotic risk MPNs bring to affected patients,” Dr. Moliterno and Dr. Ratchford wrote in an editorial in Annals of Internal Medicine. “Their study shows us that the traditional approach to assessing thrombotic risk in patients with MPNs [who are age 60 years and older, have prior thrombotic event, and have traditional cardiovascular risk factors] lacks precision and personalization.”

Both arterial and venous thrombotic events were increased throughout patients’ lifetimes, though the highest risk was around the time of MPN diagnosis. According to study results, 10% of patients had a thrombotic event in the 30 days before or after diagnosis.

“Patients and clinicians should be keenly aware of this particularly risky period, during which risk for thrombosis is similar to that in the month after a transient ischemic attack,” Dr. Moliterno and Dr. Ratchford wrote.

Unfortunately, the study did not include data on genomics, they noted. The acquired JAK2 V617F mutation, which drives MPN phenotypes, is associated with elevated inflammatory cytokines, and inflammation is a recognized risk factor for thrombosis, according to the editorial authors.

Alison R. Moliterno, MD, and Elizabeth V. Ratchford, MD, are with Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (Ann Intern Med. 2018. doi: 10.7326/M17-3153). The authors reported having no relevant conflicts related to the study.

The most notable contribution of the large cohort study by Hultcrantz and her colleagues is quantification of the magnitude of thrombotic risk that MPNs confer, according to Alison R. Moliterno, MD, and Elizabeth V. Ratchford, MD.

“Hultcrantz and colleagues have opened our eyes to the magnitude of thrombotic risk MPNs bring to affected patients,” Dr. Moliterno and Dr. Ratchford wrote in an editorial in Annals of Internal Medicine. “Their study shows us that the traditional approach to assessing thrombotic risk in patients with MPNs [who are age 60 years and older, have prior thrombotic event, and have traditional cardiovascular risk factors] lacks precision and personalization.”

Both arterial and venous thrombotic events were increased throughout patients’ lifetimes, though the highest risk was around the time of MPN diagnosis. According to study results, 10% of patients had a thrombotic event in the 30 days before or after diagnosis.

“Patients and clinicians should be keenly aware of this particularly risky period, during which risk for thrombosis is similar to that in the month after a transient ischemic attack,” Dr. Moliterno and Dr. Ratchford wrote.

Unfortunately, the study did not include data on genomics, they noted. The acquired JAK2 V617F mutation, which drives MPN phenotypes, is associated with elevated inflammatory cytokines, and inflammation is a recognized risk factor for thrombosis, according to the editorial authors.

Alison R. Moliterno, MD, and Elizabeth V. Ratchford, MD, are with Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (Ann Intern Med. 2018. doi: 10.7326/M17-3153). The authors reported having no relevant conflicts related to the study.

The most notable contribution of the large cohort study by Hultcrantz and her colleagues is quantification of the magnitude of thrombotic risk that MPNs confer, according to Alison R. Moliterno, MD, and Elizabeth V. Ratchford, MD.

“Hultcrantz and colleagues have opened our eyes to the magnitude of thrombotic risk MPNs bring to affected patients,” Dr. Moliterno and Dr. Ratchford wrote in an editorial in Annals of Internal Medicine. “Their study shows us that the traditional approach to assessing thrombotic risk in patients with MPNs [who are age 60 years and older, have prior thrombotic event, and have traditional cardiovascular risk factors] lacks precision and personalization.”

Both arterial and venous thrombotic events were increased throughout patients’ lifetimes, though the highest risk was around the time of MPN diagnosis. According to study results, 10% of patients had a thrombotic event in the 30 days before or after diagnosis.

“Patients and clinicians should be keenly aware of this particularly risky period, during which risk for thrombosis is similar to that in the month after a transient ischemic attack,” Dr. Moliterno and Dr. Ratchford wrote.

Unfortunately, the study did not include data on genomics, they noted. The acquired JAK2 V617F mutation, which drives MPN phenotypes, is associated with elevated inflammatory cytokines, and inflammation is a recognized risk factor for thrombosis, according to the editorial authors.

Alison R. Moliterno, MD, and Elizabeth V. Ratchford, MD, are with Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (Ann Intern Med. 2018. doi: 10.7326/M17-3153). The authors reported having no relevant conflicts related to the study.

Patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) have a higher rate of arterial and venous thrombosis than does the general population, with the greatest risk occurring around the time of diagnosis, according to results of a retrospective study.

Hazard ratios at 3 months after diagnosis were 3.0 (95% CI, 2.7-3.4) for arterial thrombosis and 9.7 (95% CI, 7.8-12.0) for venous thrombosis, compared with matched controls, Malin Hultcrantz, MD, PhD, of the Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, and her coauthors reported in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

Although previous studies have suggested patients with MPNs are at increased risk for thrombotic events, this large, population-based analysis is believed to be the first study to provide estimates of excess risk compared with matched control participants.

“These results are encouraging, and we believe that further refinement of risk scoring systems (such as by including time since MPN diagnosis and biomarkers); rethinking of recommendations for younger patients with MPNs; and emerging, more effective treatments will further improve outcomes for patients with MPNs,” the researchers wrote.

The retrospective, population-based cohort study included 9,429 Swedish patients diagnosed with MPNs between 1987 and 2009 and 35,820 matched control participants. Patient follow-up through 2010 was included in the analysis.

Thrombosis risk was highest near the time of diagnosis but decreased during the following year “likely because of effective thromboprophylactic and cytoreductive treatment of the MPN;”still, the risk remained elevated, the researchers wrote.

“This novel finding underlines the importance of initiating phlebotomy as well as thromboprophylactic and cytoreductive treatment, when indicated, as soon as the MPN is diagnosed,” they added.

Arterial thrombosis hazard ratios for MPN patients, compared with control participants, were 3.0 at 3 months after diagnosis, 2.0 at 1 year, and 1.5 at 5 years. Similarly, venous thrombosis hazard ratios were 9.7 at 3 months, 4.7 at 1 year, and 3.2 at 5 years.

Thrombosis risk was elevated in all age groups and all MPN subtypes, including primary myelofibrosis, polycythemia vera, and essential thrombocythemia. Of note, the study confirmed prior thrombosis and older age (60 years or older) as risk factors. Among patients with both of those risk factors, risk of thrombosis was increased 7-fold, according to the researchers.

Hazard ratios for thrombosis decreased during more recent time periods, suggesting a “positive effect” of improved treatment strategies, including increased use of aspirin as primary prophylaxis, better cardiovascular risk management, and better adherence to recommendations for cytoreductive treatment and phlebotomy, the researchers noted. Additionally, treatment with interferon and Janus kinase 2 inhibitors, such as ruxolitinib, “may be effective in further reducing risk for thrombosis,” the researchers wrote.

The study was funded by the Cancer Research Foundations of Radiumhemmet, the Swedish Research Council, and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, among other sources. The researchers reported having no financial disclosures relevant to the study.

SOURCE: Hultcrantz M et al. Ann Intern Med. 2018. doi: 10.7326/M17-0028.

Patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) have a higher rate of arterial and venous thrombosis than does the general population, with the greatest risk occurring around the time of diagnosis, according to results of a retrospective study.

Hazard ratios at 3 months after diagnosis were 3.0 (95% CI, 2.7-3.4) for arterial thrombosis and 9.7 (95% CI, 7.8-12.0) for venous thrombosis, compared with matched controls, Malin Hultcrantz, MD, PhD, of the Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, and her coauthors reported in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

Although previous studies have suggested patients with MPNs are at increased risk for thrombotic events, this large, population-based analysis is believed to be the first study to provide estimates of excess risk compared with matched control participants.

“These results are encouraging, and we believe that further refinement of risk scoring systems (such as by including time since MPN diagnosis and biomarkers); rethinking of recommendations for younger patients with MPNs; and emerging, more effective treatments will further improve outcomes for patients with MPNs,” the researchers wrote.

The retrospective, population-based cohort study included 9,429 Swedish patients diagnosed with MPNs between 1987 and 2009 and 35,820 matched control participants. Patient follow-up through 2010 was included in the analysis.

Thrombosis risk was highest near the time of diagnosis but decreased during the following year “likely because of effective thromboprophylactic and cytoreductive treatment of the MPN;”still, the risk remained elevated, the researchers wrote.

“This novel finding underlines the importance of initiating phlebotomy as well as thromboprophylactic and cytoreductive treatment, when indicated, as soon as the MPN is diagnosed,” they added.

Arterial thrombosis hazard ratios for MPN patients, compared with control participants, were 3.0 at 3 months after diagnosis, 2.0 at 1 year, and 1.5 at 5 years. Similarly, venous thrombosis hazard ratios were 9.7 at 3 months, 4.7 at 1 year, and 3.2 at 5 years.

Thrombosis risk was elevated in all age groups and all MPN subtypes, including primary myelofibrosis, polycythemia vera, and essential thrombocythemia. Of note, the study confirmed prior thrombosis and older age (60 years or older) as risk factors. Among patients with both of those risk factors, risk of thrombosis was increased 7-fold, according to the researchers.

Hazard ratios for thrombosis decreased during more recent time periods, suggesting a “positive effect” of improved treatment strategies, including increased use of aspirin as primary prophylaxis, better cardiovascular risk management, and better adherence to recommendations for cytoreductive treatment and phlebotomy, the researchers noted. Additionally, treatment with interferon and Janus kinase 2 inhibitors, such as ruxolitinib, “may be effective in further reducing risk for thrombosis,” the researchers wrote.

The study was funded by the Cancer Research Foundations of Radiumhemmet, the Swedish Research Council, and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, among other sources. The researchers reported having no financial disclosures relevant to the study.

SOURCE: Hultcrantz M et al. Ann Intern Med. 2018. doi: 10.7326/M17-0028.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Hazard ratios (HRs) at 3 months were 3.0 (95% confidence interval, 2.7-3.4) for arterial thrombosis and 9.7 (95% CI, 7.8-12.0) for venous thrombosis, compared with matched controls.

Study details: A Swedish retrospective, population-based study including 9,429 patients with MPNs and 35,820 matched control participants.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Cancer Research Foundations of Radiumhemmet, the Swedish Research Council, and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, among other sources. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Source: Hultcrantz M et al. Ann Intern Med. 2018. doi: 10.7326/M17-0028.

Edoxaban noninferior to dalteparin for cancer-associated VTE

ATLANTA – Twelve months of daily treatment with the novel oral factor Xa inhibitor edoxaban was noninferior to standard subcutaneous therapy with dalteparin for treatment of venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer, according to late-breaking results from a randomized, open-label, blinded-outcomes trial.

Throughout follow-up, trial arms had nearly identical rates of survival free from recurrent VTE or major bleeding, Gary E. Raskob, PhD, reported during a late-breaking oral presentation at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology. “Edoxaban was associated with a lower rate of recurrent VTE, which was offset by a similar increase in risk of major bleeding,” he said. “Therefore, oral edoxaban was noninferior to subcutaneous dalteparin for the [combined] primary outcome.”

Venous thromboembolism affects about one in five patients with active cancer and is difficult to treat because patients face increased risks of recurrence and bleeding. The struggle to balance these risks fuels morbidity and mortality and can hamper cancer treatment, said Dr. Raskob of the University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City.

Pharmacy and medical oncology societies recommend long-term low-molecular-weight heparin for cancer patients with VTE, but the daily burden of subcutaneous injections leads many to stop after about 2-4 months of treatment, Dr. Raskob said. “Direct oral anticoagulants may be an attractive alternative.”

For the trial, 1,446 adults with cancer and lower limb VTE from 114 clinics in North America, Europe, Australia, and New Zealand received either edoxaban (60 mg daily) or dalteparin (200 IU/kg for 30 days, followed by 150 IU/kg) for up to 12 months. Nearly all patients had active cancer. Tumor types reflected what’s most common in practice, such as malignancies of the lung, colon, and breast. About 50 patients had primary or metastatic brain cancers. Approximately two-thirds had pulmonary embolism with or without deep-vein thrombosis, while the rest had isolated deep-vein thrombosis.

After 12 months of follow-up, 12.8% of edoxaban patients had at least one recurrence of VTE or a major bleed, compared with 13.5% of dalteparin patients (hazard ratio, 0.97; 95% confidence interval, 0.70-1.36; P = .006 for noninferiority). Edoxaban also was noninferior to dalteparin after the first 6 months of treatment and in the per-protocol analysis (HRs, 1.0; P = .02 for noninferiority in each analysis). Thus, differences in efficacy did not only reflect better compliance to oral therapy, Dr. Raskob said.

He also reported on individual outcomes. In all, 10.3% of dalteparin recipients had a VTE recurrence, as did 6.5% of edoxaban recipients, for a risk difference of 3.8% (95% CI, 7.1%-0.4%). More than half of recurrences in each group were symptomatic, and none were fatal. Bleeding caused no deaths in either study arm, and each therapy conferred an identical chance of a grade 3-4 major bleed (2.3%).

Edoxaban was associated, however, with a greater frequency of major bleeds (33 events; 6.3%) than was dalteparin (17 events; 3.2%; risk difference, 3.1%; 95% CI, 0.5%-5.7%). In particular, patients who received edoxaban had a slightly higher rate of upper gastrointestinal bleeds. Most had gastric cancer.

Future studies should evaluate whether these patients should receive a lower dose of edoxaban, said Dr. Raskob. “We don’t yet fully know the minimum effective dose [of edoxaban] in cancer patients.”

He also addressed the idea that heparin has antineoplastic activity, calling it “one we should probably abandon. The concept originates from older trials in which researchers probably did not recognize that heparin was preventing fatal pulmonary embolism, he said.

The investigators soon will begin deeper analyses that should inform patient selection, he said. For now, he recommends discussing these findings with patients to help them make an informed choice between oral anticoagulation, with its ease of use but slightly higher rate of major bleeds, and subcutaneous heparin, with its lower bleeding rate and treatment burden.

Daiichi Sankyo provided funding. Dr. Raskob disclosed consulting relationships and honoraria from Daiichi Sankyo, Eli Lilly, Janssen, and several other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Raskob G et al. ASH Abstract LBA-6.

ATLANTA – Twelve months of daily treatment with the novel oral factor Xa inhibitor edoxaban was noninferior to standard subcutaneous therapy with dalteparin for treatment of venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer, according to late-breaking results from a randomized, open-label, blinded-outcomes trial.

Throughout follow-up, trial arms had nearly identical rates of survival free from recurrent VTE or major bleeding, Gary E. Raskob, PhD, reported during a late-breaking oral presentation at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology. “Edoxaban was associated with a lower rate of recurrent VTE, which was offset by a similar increase in risk of major bleeding,” he said. “Therefore, oral edoxaban was noninferior to subcutaneous dalteparin for the [combined] primary outcome.”

Venous thromboembolism affects about one in five patients with active cancer and is difficult to treat because patients face increased risks of recurrence and bleeding. The struggle to balance these risks fuels morbidity and mortality and can hamper cancer treatment, said Dr. Raskob of the University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City.

Pharmacy and medical oncology societies recommend long-term low-molecular-weight heparin for cancer patients with VTE, but the daily burden of subcutaneous injections leads many to stop after about 2-4 months of treatment, Dr. Raskob said. “Direct oral anticoagulants may be an attractive alternative.”

For the trial, 1,446 adults with cancer and lower limb VTE from 114 clinics in North America, Europe, Australia, and New Zealand received either edoxaban (60 mg daily) or dalteparin (200 IU/kg for 30 days, followed by 150 IU/kg) for up to 12 months. Nearly all patients had active cancer. Tumor types reflected what’s most common in practice, such as malignancies of the lung, colon, and breast. About 50 patients had primary or metastatic brain cancers. Approximately two-thirds had pulmonary embolism with or without deep-vein thrombosis, while the rest had isolated deep-vein thrombosis.