User login

VIDEO: Triple therapy study and new recommendations provide guidance on CAPS

MADRID – Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS) is associated with a high mortality rate, but new research presented at the European Congress of Rheumatology shows that patient survival can be significantly improved by a triple therapy treatment approach.

Researchers at the Congress also presented clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of the rare disease, which accounts for just 1% of patients with antiphospholipid syndrome (APS).

CAPS is characterized by a fast onset of widespread thrombosis, mainly in the small vessels, and, often, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia is seen in the laboratory. If undiagnosed or left untreated, patients may present with multiorgan failure needing intensive care treatment, which can be fatal in up to 50% of cases.

At the Congress, Ignasi Rodríguez-Pintó, MD, presented new data from the CAPS Registry that looks at the combined effect of anticoagulation, corticosteroids, and plasma exchange or intravenous immunoglobulins on the survival of patients with CAPS as well as the new clinical practice guidelines.

CAPS Registry study

The aim of the study Dr. Rodríguez-Pintó presented on behalf of the CAPS Registry Project Group was to determine what, if any, survival benefit would be incurred from a triple therapy approach when compared with other different combinations of anticoagulation, corticosteroids, and plasma exchange or intravenous immunoglobulins, or none of these treatments.

Although the triple therapy treatment approach is already being used in practice, its use is largely empirical, Dr. Rodríguez-Pintó of the department of autoimmune disease at the Hospital Clinic, Barcelona, explained in a video interview.

The investigators derived their data from episodes of CAPS occurring in patients in the CAPS Registry from the European Forum on Antiphospholipid Antibodies. This international registry was set up in 2000 and has been assembling the clinical, laboratory, and therapeutic findings of patients with CAPS for almost 20 years.

“We observed 525 episodes of CAPS in 502 patients. That means that some patients had two to three episodes of CAPS,” Dr. Rodríguez-Pintó said. Data on 38 episodes of CAPS had to be excluded from the analysis because of missing information, which left 487 episodes occurring in 471 patients.

The mean age of the 471 patients included in the analysis was 38 years. The majority (67.9%) were female and had primary (68.8%) APS. Triple therapy was given to about 40% of patients who experienced CAPS, with about 57% receiving other combinations of drugs and 2.5% receiving no treatment for CAPS.

Overall, 177 of the 487 (36.3%) episodes of CAPS were fatal.

“Triple therapy was associated with a higher chance of survival when compared to other combinations or to none of these treatments,” Dr. Rodríguez-Pintó said.

While 28% of patients with CAPS died in the triple therapy group, mortality was 41% with other combinations of treatments and 75% with none of these treatments.

All-cause mortality was reduced by 47% with triple therapy, compared with none of these treatments. The adjusted odds ratio (aOR) when comparing survival between triple therapy and no treatment was 7.7, with a 95% confidence interval of 2.0 to 29.7. The aOR comparing other drug combinations versus none of these treatments was 6.8 (95% CI, 1.7-29.6).

“For a long time, we have been saying that triple therapy would probably be the best approach, but we had no firm evidence,” Dr. Rodríguez-Pintó said.

“So, this is the first time that we have clear clinical evidence of the benefit of these approaches, and I think that these results are important because they will give us more confidence in how we treat patients and help develop guidance on [the treatment’s] use in the future.”

Guidelines

A steering committee composed of representatives from the European Commission–funded RARE-BestPractices project and McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont., used GRADE methodology to develop the guidelines for CAPS diagnosis and management. The committee answered three diagnostic and seven treatment questions that originated from a panel of 19 international stakeholders, including Dr. Rodríguez-Pintó, through systematic reviews of the literature that used Cochrane criteria.

Although the review of studies did not include the study of CAPS Registry data that Dr. Rodríguez-Pintó and his colleagues conducted, he said that the recommendations still confirm the value of using a triple therapy approach to treatment.

The panel created three diagnostic recommendations for patients suspected of having CAPS, all of which were conditional and based on very low certainty of evidence: use preliminary CAPS classification criteria to diagnose CAPS; use or nonuse of biopsy, depending on the circumstances, because of its high specificity but possibly low sensitivity for thrombotic microangiopathy; and test for antiphospholipid antibodies, which should not delay initiation of treatment.

All seven first-line treatment recommendations that the panel developed relied on a very low certainty of evidence, and most were conditional:

- Triple therapy combination treatment with corticosteroids, heparin, and plasma exchange or intravenous immunoglobulins instead of a single agent or other combination treatments.

- Therapeutic dose anticoagulation was one of only two treatment recommendations to be considered “strong,” but use of direct oral anticoagulants is not advised.

- Therapeutic plasma exchange is recommended for use with other therapies and should be strongly considered for patients with microangiopathic hemolytic anemia.

- Intravenous immunoglobulin is advised for use in conjunction with other therapies and should be given special consideration for patients with immune thrombocytopenia or renal insufficiency.

- Antiplatelet agents are conditionally recommended as an add-on therapy, but their potential mortality benefit is tempered by increased risk of bleeding when used with anticoagulants. Strong consideration should be given to their use as an alternative therapy to anticoagulation when anticoagulation is contraindicated for a reason other than bleeding.

- Rituximab (Rituxan) should not be used because of little available data on its use, uncertainty regarding long-term consequences, and its expense – except for refractory cases where other therapies have been insufficient.

- Corticosteroids should not be used because of their lack of efficacy in CAPS when used alone and potential for adverse effects, except for certain circumstances where they may be indicated.

The authors of the guidelines emphasized that these recommendations are not meant to apply to every CAPS patient. They also noted that the available evidence did not allow for temporal analysis of treatments and that conclusions could not be drawn regarding “first-line” versus “second-line” therapies.

None of the authors of the registry study or the guidelines had relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

MADRID – Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS) is associated with a high mortality rate, but new research presented at the European Congress of Rheumatology shows that patient survival can be significantly improved by a triple therapy treatment approach.

Researchers at the Congress also presented clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of the rare disease, which accounts for just 1% of patients with antiphospholipid syndrome (APS).

CAPS is characterized by a fast onset of widespread thrombosis, mainly in the small vessels, and, often, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia is seen in the laboratory. If undiagnosed or left untreated, patients may present with multiorgan failure needing intensive care treatment, which can be fatal in up to 50% of cases.

At the Congress, Ignasi Rodríguez-Pintó, MD, presented new data from the CAPS Registry that looks at the combined effect of anticoagulation, corticosteroids, and plasma exchange or intravenous immunoglobulins on the survival of patients with CAPS as well as the new clinical practice guidelines.

CAPS Registry study

The aim of the study Dr. Rodríguez-Pintó presented on behalf of the CAPS Registry Project Group was to determine what, if any, survival benefit would be incurred from a triple therapy approach when compared with other different combinations of anticoagulation, corticosteroids, and plasma exchange or intravenous immunoglobulins, or none of these treatments.

Although the triple therapy treatment approach is already being used in practice, its use is largely empirical, Dr. Rodríguez-Pintó of the department of autoimmune disease at the Hospital Clinic, Barcelona, explained in a video interview.

The investigators derived their data from episodes of CAPS occurring in patients in the CAPS Registry from the European Forum on Antiphospholipid Antibodies. This international registry was set up in 2000 and has been assembling the clinical, laboratory, and therapeutic findings of patients with CAPS for almost 20 years.

“We observed 525 episodes of CAPS in 502 patients. That means that some patients had two to three episodes of CAPS,” Dr. Rodríguez-Pintó said. Data on 38 episodes of CAPS had to be excluded from the analysis because of missing information, which left 487 episodes occurring in 471 patients.

The mean age of the 471 patients included in the analysis was 38 years. The majority (67.9%) were female and had primary (68.8%) APS. Triple therapy was given to about 40% of patients who experienced CAPS, with about 57% receiving other combinations of drugs and 2.5% receiving no treatment for CAPS.

Overall, 177 of the 487 (36.3%) episodes of CAPS were fatal.

“Triple therapy was associated with a higher chance of survival when compared to other combinations or to none of these treatments,” Dr. Rodríguez-Pintó said.

While 28% of patients with CAPS died in the triple therapy group, mortality was 41% with other combinations of treatments and 75% with none of these treatments.

All-cause mortality was reduced by 47% with triple therapy, compared with none of these treatments. The adjusted odds ratio (aOR) when comparing survival between triple therapy and no treatment was 7.7, with a 95% confidence interval of 2.0 to 29.7. The aOR comparing other drug combinations versus none of these treatments was 6.8 (95% CI, 1.7-29.6).

“For a long time, we have been saying that triple therapy would probably be the best approach, but we had no firm evidence,” Dr. Rodríguez-Pintó said.

“So, this is the first time that we have clear clinical evidence of the benefit of these approaches, and I think that these results are important because they will give us more confidence in how we treat patients and help develop guidance on [the treatment’s] use in the future.”

Guidelines

A steering committee composed of representatives from the European Commission–funded RARE-BestPractices project and McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont., used GRADE methodology to develop the guidelines for CAPS diagnosis and management. The committee answered three diagnostic and seven treatment questions that originated from a panel of 19 international stakeholders, including Dr. Rodríguez-Pintó, through systematic reviews of the literature that used Cochrane criteria.

Although the review of studies did not include the study of CAPS Registry data that Dr. Rodríguez-Pintó and his colleagues conducted, he said that the recommendations still confirm the value of using a triple therapy approach to treatment.

The panel created three diagnostic recommendations for patients suspected of having CAPS, all of which were conditional and based on very low certainty of evidence: use preliminary CAPS classification criteria to diagnose CAPS; use or nonuse of biopsy, depending on the circumstances, because of its high specificity but possibly low sensitivity for thrombotic microangiopathy; and test for antiphospholipid antibodies, which should not delay initiation of treatment.

All seven first-line treatment recommendations that the panel developed relied on a very low certainty of evidence, and most were conditional:

- Triple therapy combination treatment with corticosteroids, heparin, and plasma exchange or intravenous immunoglobulins instead of a single agent or other combination treatments.

- Therapeutic dose anticoagulation was one of only two treatment recommendations to be considered “strong,” but use of direct oral anticoagulants is not advised.

- Therapeutic plasma exchange is recommended for use with other therapies and should be strongly considered for patients with microangiopathic hemolytic anemia.

- Intravenous immunoglobulin is advised for use in conjunction with other therapies and should be given special consideration for patients with immune thrombocytopenia or renal insufficiency.

- Antiplatelet agents are conditionally recommended as an add-on therapy, but their potential mortality benefit is tempered by increased risk of bleeding when used with anticoagulants. Strong consideration should be given to their use as an alternative therapy to anticoagulation when anticoagulation is contraindicated for a reason other than bleeding.

- Rituximab (Rituxan) should not be used because of little available data on its use, uncertainty regarding long-term consequences, and its expense – except for refractory cases where other therapies have been insufficient.

- Corticosteroids should not be used because of their lack of efficacy in CAPS when used alone and potential for adverse effects, except for certain circumstances where they may be indicated.

The authors of the guidelines emphasized that these recommendations are not meant to apply to every CAPS patient. They also noted that the available evidence did not allow for temporal analysis of treatments and that conclusions could not be drawn regarding “first-line” versus “second-line” therapies.

None of the authors of the registry study or the guidelines had relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

MADRID – Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS) is associated with a high mortality rate, but new research presented at the European Congress of Rheumatology shows that patient survival can be significantly improved by a triple therapy treatment approach.

Researchers at the Congress also presented clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of the rare disease, which accounts for just 1% of patients with antiphospholipid syndrome (APS).

CAPS is characterized by a fast onset of widespread thrombosis, mainly in the small vessels, and, often, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia is seen in the laboratory. If undiagnosed or left untreated, patients may present with multiorgan failure needing intensive care treatment, which can be fatal in up to 50% of cases.

At the Congress, Ignasi Rodríguez-Pintó, MD, presented new data from the CAPS Registry that looks at the combined effect of anticoagulation, corticosteroids, and plasma exchange or intravenous immunoglobulins on the survival of patients with CAPS as well as the new clinical practice guidelines.

CAPS Registry study

The aim of the study Dr. Rodríguez-Pintó presented on behalf of the CAPS Registry Project Group was to determine what, if any, survival benefit would be incurred from a triple therapy approach when compared with other different combinations of anticoagulation, corticosteroids, and plasma exchange or intravenous immunoglobulins, or none of these treatments.

Although the triple therapy treatment approach is already being used in practice, its use is largely empirical, Dr. Rodríguez-Pintó of the department of autoimmune disease at the Hospital Clinic, Barcelona, explained in a video interview.

The investigators derived their data from episodes of CAPS occurring in patients in the CAPS Registry from the European Forum on Antiphospholipid Antibodies. This international registry was set up in 2000 and has been assembling the clinical, laboratory, and therapeutic findings of patients with CAPS for almost 20 years.

“We observed 525 episodes of CAPS in 502 patients. That means that some patients had two to three episodes of CAPS,” Dr. Rodríguez-Pintó said. Data on 38 episodes of CAPS had to be excluded from the analysis because of missing information, which left 487 episodes occurring in 471 patients.

The mean age of the 471 patients included in the analysis was 38 years. The majority (67.9%) were female and had primary (68.8%) APS. Triple therapy was given to about 40% of patients who experienced CAPS, with about 57% receiving other combinations of drugs and 2.5% receiving no treatment for CAPS.

Overall, 177 of the 487 (36.3%) episodes of CAPS were fatal.

“Triple therapy was associated with a higher chance of survival when compared to other combinations or to none of these treatments,” Dr. Rodríguez-Pintó said.

While 28% of patients with CAPS died in the triple therapy group, mortality was 41% with other combinations of treatments and 75% with none of these treatments.

All-cause mortality was reduced by 47% with triple therapy, compared with none of these treatments. The adjusted odds ratio (aOR) when comparing survival between triple therapy and no treatment was 7.7, with a 95% confidence interval of 2.0 to 29.7. The aOR comparing other drug combinations versus none of these treatments was 6.8 (95% CI, 1.7-29.6).

“For a long time, we have been saying that triple therapy would probably be the best approach, but we had no firm evidence,” Dr. Rodríguez-Pintó said.

“So, this is the first time that we have clear clinical evidence of the benefit of these approaches, and I think that these results are important because they will give us more confidence in how we treat patients and help develop guidance on [the treatment’s] use in the future.”

Guidelines

A steering committee composed of representatives from the European Commission–funded RARE-BestPractices project and McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont., used GRADE methodology to develop the guidelines for CAPS diagnosis and management. The committee answered three diagnostic and seven treatment questions that originated from a panel of 19 international stakeholders, including Dr. Rodríguez-Pintó, through systematic reviews of the literature that used Cochrane criteria.

Although the review of studies did not include the study of CAPS Registry data that Dr. Rodríguez-Pintó and his colleagues conducted, he said that the recommendations still confirm the value of using a triple therapy approach to treatment.

The panel created three diagnostic recommendations for patients suspected of having CAPS, all of which were conditional and based on very low certainty of evidence: use preliminary CAPS classification criteria to diagnose CAPS; use or nonuse of biopsy, depending on the circumstances, because of its high specificity but possibly low sensitivity for thrombotic microangiopathy; and test for antiphospholipid antibodies, which should not delay initiation of treatment.

All seven first-line treatment recommendations that the panel developed relied on a very low certainty of evidence, and most were conditional:

- Triple therapy combination treatment with corticosteroids, heparin, and plasma exchange or intravenous immunoglobulins instead of a single agent or other combination treatments.

- Therapeutic dose anticoagulation was one of only two treatment recommendations to be considered “strong,” but use of direct oral anticoagulants is not advised.

- Therapeutic plasma exchange is recommended for use with other therapies and should be strongly considered for patients with microangiopathic hemolytic anemia.

- Intravenous immunoglobulin is advised for use in conjunction with other therapies and should be given special consideration for patients with immune thrombocytopenia or renal insufficiency.

- Antiplatelet agents are conditionally recommended as an add-on therapy, but their potential mortality benefit is tempered by increased risk of bleeding when used with anticoagulants. Strong consideration should be given to their use as an alternative therapy to anticoagulation when anticoagulation is contraindicated for a reason other than bleeding.

- Rituximab (Rituxan) should not be used because of little available data on its use, uncertainty regarding long-term consequences, and its expense – except for refractory cases where other therapies have been insufficient.

- Corticosteroids should not be used because of their lack of efficacy in CAPS when used alone and potential for adverse effects, except for certain circumstances where they may be indicated.

The authors of the guidelines emphasized that these recommendations are not meant to apply to every CAPS patient. They also noted that the available evidence did not allow for temporal analysis of treatments and that conclusions could not be drawn regarding “first-line” versus “second-line” therapies.

None of the authors of the registry study or the guidelines had relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

AT THE EULAR 2017 CONGRESS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Mortality was 28% with triple therapy, 41% with other combinations of treatments, and 75% with none of these treatments.

Data source: A registry study of 471 CAPS patients and clinical practice guidelines for CAPS.

Disclosures: None of the authors of the registry study or the guidelines had relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

Cerebral Venous Thrombosis

Cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT) is a rare cerebrovascular disease that affects about 5 in 1 million people each year and accounts for 0.5% of all strokes.1 Previously it was thought to be caused most commonly by infections (eg, mastoiditis, otitis, meningitis) affecting the superior sagittal sinus and often resulting in focal neurologic deficits, seizures, coma, and death. Although local and systemic infections are still prominent risk factors in its development, CVT is now primarily recognized as a nonseptic disease with a wide spectrum of clinical presentations.

Cerebral venous thrombosis causes reduced outflow of blood and cerebrospinal fluid, which in half of affected patients leads to significant venous infarct. As opposed to arterial infarctions, CVT mainly affects children and young adults; it is an important cause of stroke in the younger population.2 There is significant overlap of the many risk factors for CVT and those for venous thromboembolism (VTE): cancer, obesity, genetic thrombophilia, trauma, infection, and prior neurosurgery. However, the most common acquired risk factors for CVT are oral contraceptive use and pregnancy, which explains why CVT is 3 times more likely to occur in young and middle-aged women.3

Cerebral venous thrombosis was first recognized by a French physician in the 19th century, a time when the condition was diagnosed at autopsy, which typically showed hemorrhagic lesions at the thrombus site.4 For many years heparin was contraindicated in the treatment of CVT, and only within the past 25 years did advances in neuroimaging allow for earlier diagnosis and change perspectives on the management of this disease.

Cerebral venous thrombosis occurs from formation of a thrombus within the cerebral venous sinuses, leading to elevated intracranial pressure and eventually ischemia or intracranial hemorrhage. Improved imaging techniques, notably magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) venography, allow physicians to identify thrombus formation earlier and begin anticoagulation therapy with heparin before infarction. A meta-analysis of studies found that heparin was safer and more efficacious in treating CVT compared with placebo.5 Furthermore, several small randomized trials found treatment with unfractionated heparin (UFH) or low-molecularweight heparin (LMWH) was not associated with higher risk of hemorrhagic stroke in these patients.6-8

Despite improvements in imaging modalities, in many cases diagnosis is delayed, as most patients with CVT have a wide spectrum of presentations with nonspecific symptoms, such as headache, seizure, focal sensorimotor deficits, and papilledema.9 Clinical presentations of CVT depend on a variety of factors, including age, time of onset, CVT location, and presence of parenchymal lesions. Isolated headache is the most common initial symptom, and in many cases is the only presenting manifestation of CVT.1 Encephalopathy with multifocal signs, delirium, or dysfunction in executive functions most commonly occurs in elderly populations.

Cavernous sinus thrombosis most commonly produces generalized headaches, orbital pain, proptosis, and diplopia, whereas cortical vein thrombosis often produces seizures and focal sensorimotor deficits. Aphasia may be present in patients with isolated left transverse sinus thrombosis. In the presence of deep cerebral venous occlusion, patients can present in coma or with severe cognitive deficits and widespread paresis.10 Thrombosis of different veins and sinuses results in a wide spectrum of diverse clinical pictures, posing a diagnostic challenge and affecting clinical outcomes.

Given the variable and often nonspecific clinical presentations of these cases, unenhanced CT typically is the first imaging study ordered. According to the literature, noncontrast CT is not sensitive (25%-56%) in detecting CVT, and findings are normal in up to 26% of patients, rarely providing a specific diagnosis.11 Furthermore, visualization on MRI can be difficult during the acute phase of CVT, as the thrombus initially appears isointense on T1-weighted images and gradually becomes hyperintense over the course of the disease process.12 These difficulties with the usual first-choice imaging examinations often result in a delay in diagnosing CVT. However, several points on close examination of these imaging studies may help physicians establish a high index of clinical suspicion and order the appropriate follow-up studies for CVT.

The authors report the case of a patient who presented with a 1-week history of confusion, headaches, and dizziness. His nonspecific presentation along with the absence of obvious signs of CVT on imaging prolonged his diagnosis and the initiation of an appropriate treatment plan.

Case Report

A 57-year-old white air-conditioning mechanic presented to the emergency department (ED) with a 1-week history of gradual-onset confusion, severe headaches, dizziness, light-headedness, poor memory, and increased sleep. Two days earlier, he presented with similar symptoms to an outside facility, where he was admitted and underwent a workup for stroke, hemorrhage, and cardiac abnormalities—including noncontrast CT of the head. With nothing of clinical significance found, the patient was discharged and was advised to follow up on an outpatient basis.

Persisting symptoms brought the patient to the ED 1 day later, and he was admitted. He described severe, progressive, generalized headaches that were more severe when he was lying down at night and waking in the morning. He did not report that the headaches worsened with coughing or straining, and he reported no history of trauma, neck stiffness, vision change, seizures, and migraines. His medical history was significant for hypertension, dyslipidemia, and in 2011, an unprovoked deep vein thrombosis (DVT) in the right leg. He reported no history of tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drug use. He had served in the U.S. Navy, working in electronics, intelligence, data systems, and satellite communications.

On initial physical examination, the patient was afebrile and lethargic, and his blood pressure was mildly elevated (144/83 mm Hg). Cardiopulmonary examination was normal. Neurologic examination revealed no severe focal deficits, and cranial nerves II to XII were intact. Funduscopic examination was normal, with no papilledema noted. Motor strength was 5/5 bilaterally in the deltoids, biceps, triceps, radial and ulnar wrist extensors, iliopsoas, quadriceps, hamstrings, tibialis anterior and posterior, fibulares, and gastrocnemius. Pinprick sensation and light-touch sensation were decreased within the lateral bicipital region of the left upper extremity. Pinprick sensation was intact bilaterally in 1-inch increments at all other distributions along the medial and lateral aspects of the upper and lower extremities. Muscle tone and bulk were normal in all extremities. Reflexes were 2+ bilaterally in the biceps, brachioradialis, triceps, quadriceps, and Achilles. The Babinski sign was absent bilaterally, the finger-tonose and heel-to-shin tests were normal, the Romberg sign was absent, and there was no evidence of pronator drift. Laboratory test results were normal except for slightly elevated hemoglobin (17.5 g/dL) and D-dimer (588 ng/mL) levels.

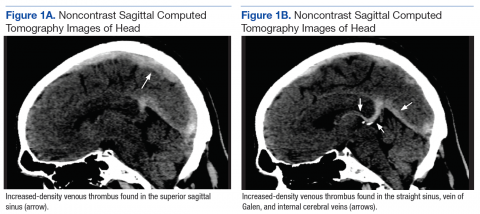

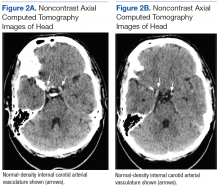

Although noncontrast CT of the head initially showed no acute intracranial abnormalities, retrospective close comparison with the arterial system revealed slightly increased attenuation in the superior sagittal sinus, straight sinus, vein of Galen, and internal cerebral veins (Figures 1A and 1B) relative to the arterial carotid anterior circulation (Figures 2A and 2B).

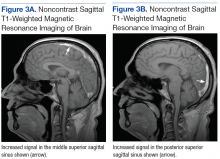

Subsequent brain MRI without contrast showed a hyperintense T1 signal involving the superior sagittal sinus (Figures 3A and 3B), extending into the straight sinus and the vein of Galen. Magnetic resonance imaging with contrast demonstrated a prominent filling defect primarily in the superior sagittal sinus, in the right transverse sinus, and in the vein of Galen. Diffusion-weighted brain MRI sequence showed restricted diffusion localized to the right thalamic area (Figure 4) and no evidence of hemorrhage.

Treatment

International guidelines recommend using heparin to achieve rapid anticoagulation, stop the thrombotic process, and prevent extension of the thrombus.13 Theoretically, more rapid recanalization may have been achieved by performing endovascular thrombectomy in the present case. However, severe bleeding complications, combined with higher cost and the limited availability of clinicians experienced in treating this rare disease, convince physicians to rely on heparin as first-line treatment for CVT.14 A small randomized clinical trial found LMWH safer and more efficacious than UFH in treating CVT.15 After stabilization, oral anticoagulation therapy is used to maintain an international normalized ratio (INR) between 2.0 and 3.0 for at least 3 months.14

Given these findings, the patient was initially treated with LMWH. Eventually he was switched to oral warfarin and showed signs of clinical improvement. A hypercoagulability state workup revealed that the patient was heterozygous for the prothrombin G20210A mutation, and he was discharged and instructed to continue the oral warfarin therapy.

On follow-up, the hematology and neurology team initiated indefinite treatment with warfarin for his genetic hypercoagulability state. Monitoring of the dose of anticoagulation therapy was started to maintain INR between 2.0 and 3.0. The patient began coming to the office for INR monitoring every 2 to 3 weeks, and his most recent INR, in May 2017, was 2.66. He is taking 7.5 mg of warfarin on Wednesdays and Sundays and 5 mg on all other days and currently does not report any progressive neurologic deficits.

Discussion

The clinical findings of CVT and the hypercoagulability state workup revealed that the patient was heterozygous for the prothrombin G20210A mutation. Prothrombin is the precursor to thrombin, which is a key regulator of the clotting cascade and a promoter of coagulation. Carriers of the mutation have elevated levels of blood plasma prothrombin and have been associated with a 4 times higher risk for VTE.16

Several large studies and systematic reviews have confirmed that the prothrombin G20210A mutation is associated with higher rates of VTE, leading to an increased risk for DVT of the leg or pulmonary embolism.17-19 More specifically, a metaanalysis of 15 case–control studies found strong associations between the mutation and CVT.20 Despite this significant association, studies are inconclusive about whether heterozygosity for the mutation is associated with increased rates of recurrent CVT or other VTE in the absence of other risk factors, such as oral contraceptive use, trauma, malignancy, and infection.21-23 Therefore, the optimal duration of anticoagulation therapy for CVT is not well established in patients with the mutation. However, the present patient was started on indefinite anticoagulation therapy because the underlying etiology of the CVT was not reversible or transient, and this CVT was his second episode of VTE, following a 2011 DVT in the right leg.

The case discussed here illustrates the clinical presentation and diagnostic complexities of CVT. Two days before coming to the ED, the patient presented to an outside facility and underwent a workup for nonspecific symptoms (eg, confusion, headaches). Due to the nonspecific presentation associated with CVT, a detailed history is imperative to distinguish symptoms suggesting increased intracranial pressure, such as headaches worse when lying down or present in the morning, with a high clinical suspicion of CVT. The ability to attain these specific details leads clinicians toward obtaining the necessary imaging studies for potential CVT patients, and may prevent delay in diagnosis and treatment. The thrombus in CVT initially consists of deoxyhemoglobin and appears on MRI as an isointense signal on T1-weighted images and a hypointense signal on T2-weighted images; over subsequent days, the thrombus changes to methemoglobin and appears as a slightly hyperintense signal on both T1- and T2-weighted images.24

During this phase, there are some false negatives, as the thrombus can be mistaken for imaging artifacts, hematocrit elevations, or low flow of normal venous blood. Given the clinical findings and imaging studies, it is essential to distinguish CVT from other benign etiologies. Earlier diagnosis and initiation of anticoagulation therapy may have precluded the small amount of localized ischemic changes in this patient’s right thalamus, thus preventing the mild sensory loss in the left upper extremity. With the variable and nonspecific clinical presentations and the difficulties in identifying CVT with first-line imaging, progression of thrombus formation may lead to severe focal neurologic deficits, coma, or death.

Using CT imaging studies to compare the blood in the draining cerebral sinuses with the blood in the arterial system can help distinguish CVT from other etiologies of hyperdense abnormalities, such as increased hematocrit or decreased flow. Retrospective close examination of the present patient’s noncontrast CT images of the head and brain revealed slight hyperdensity in the cerebral sinuses compared with the arterial blood, suggesting the presence of thrombus formation in the cerebral veins. As CT is often the first study used to evaluate the nonspecific clinical presentations of these patients, identifying subtle signaldensity differences between the arterial and venous systems could guide physicians in identifying CVT earlier.

The authors reiterate the importance of meticulous imaging interpretation in light of the entire clinical picture: In these patients, it is imperative to have a high index of clinical suspicion for CVT in order to prevent more serious complications, such as ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke.

1. Bousser MG, Ferro JM. Cerebral venous thrombosis: an update. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(2):162-170.

2. Coutinho JM. Cerebral venous thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2015;13(suppl 1):S238-S244.

3. Coutinho JM, Ferro JM, Canhão P, et al. Cerebral venous and sinus thrombosis in women. Stroke. 2009;40(7):2356-2361.

4. Zuurbier SM, Coutinho JM. Cerebral venous thrombosis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;906:183-193.

5. Einhäupl KM, Villringer A, Meister W, et al. Heparin treatment in sinus venous thrombosis. Lancet. 1991;338(8767):597-600.

6. de Bruijn SF, Stam J. Randomized, placebocontrolled trial of anticoagulant treatment with lowmolecular-weight heparin for cerebral sinus thrombosis. Stroke. 1999;30(3):484-488.

7. Nagaraja D, Haridas T, Taly AB, Veerendrakumar M, SubbuKrishna DK. Puerperal cerebral venous thrombosis: therapeutic benefit of low dose heparin. Neurol India. 1999;47(1):43-46.

8. Coutinho JM, de Bruijn SF, deVeber G, Stam J. Anticoagulation for cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. Stroke. 2012;43(4):e41-e42.

9. Sassi SB, Touati N, Baccouche H, Drissi C, Romdhane NB, Hentati F. Cerebral venous thrombosis. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2016:1076029616665168. [Epub ahead of print.]

10. Ferro JM, Canhão P. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis: update on diagnosis and management. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2014;16(9):523.

11. Albright KC, Freeman WD, Kruse BT. Cerebral venous thrombosis. J Emerg Med. 2010;38(2):238-239.

12. Lafitte F, Boukobza M, Guichard JP, et al. MRI and MRA for diagnosis and follow-up of cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT). Clin Radiol. 1997;52(9):672-679.

13. Saposnik G, Barinagarrementeria F, Brown RD Jr, et al; American Heart Association Stroke Council and Council on Epidemiology and Prevention. Diagnosis and management of cerebral venous thrombosis: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2011;42(4):1158-1192.

14. Coutinho JM, Middeldorp S, Stam J. Advances in the treatment of cerebral venous thrombosis. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2014;16(7):299.

15. Coutinho JM, Ferro JM, Canhão P, Barinagarrementeria F, Bousser MG, Stam J; ISCVT Investigators. Unfractionated or low-molecular weight heparin for the treatment of cerebral venous thrombosis. Stroke. 2010;41(11):2575-2580.

16. Rosendaal FR. Venous thrombosis: the role of genes, environment, and behavior. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2005:1-12.

17. Dentali F, Crowther M, Ageno W. Thrombophilic abnormalities, oral contraceptives, and risk of cerebral vein thrombosis: a meta-analysis. Blood.2006;107(7):2766-2773.

18. Salomon O, Steinberg DM, Zivelin A, et al. Single and combined prothrombotic factors in patients with idiopathic venous thromboembolism: prevalence and risk assessment. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19(3):511-518.

19. Emmerich J, Rosendaal FR, Cattaneo M, et al. Combined effect of factor V Leiden and prothrombin 20210A on the risk of venous thromboembolism— pooled analysis of 8 case–control studies including 2310 cases and 3204 controls. Study Group for Pooled-Analysis in Venous Thromboembolism. Thromb Haemost. 2001;86(3):809-816.

20. Lauw MN, Barco S, Coutinho JM, Middeldorp S. Cerebral venous thrombosis and thrombophilia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2013;39(8):913-927.

21. Dentali F, Poli D, Scoditti U, et al. Long-term outcomes of patients with cerebral vein thrombosis: a multicenter study. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10(7):1297-1302.

22. Martinelli I, Bucciarelli P, Passamonti SM, Battaglioli T, Previtali E, Mannucci PM. Long-term evaluation of the risk of recurrence after cerebral sinus-venous thrombosis. Circulation. 2010;121(25):2740-2746.

23. Gosk-Bierska I, Wysokinski W, Brown RD Jr, et al. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis: incidence of venous thrombosis recurrence and survival. Neurology. 2006;67(5):814-819.

24. Galidie G, Le Gall R, Cordoliani YS, Pharaboz C, Le Marec E, Cosnard G. Thrombosis of the cerebral veins. X-ray computed tomography and MRI imaging. 11 cases [in French]. J Radiol. 1992;73(3):175-190

Cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT) is a rare cerebrovascular disease that affects about 5 in 1 million people each year and accounts for 0.5% of all strokes.1 Previously it was thought to be caused most commonly by infections (eg, mastoiditis, otitis, meningitis) affecting the superior sagittal sinus and often resulting in focal neurologic deficits, seizures, coma, and death. Although local and systemic infections are still prominent risk factors in its development, CVT is now primarily recognized as a nonseptic disease with a wide spectrum of clinical presentations.

Cerebral venous thrombosis causes reduced outflow of blood and cerebrospinal fluid, which in half of affected patients leads to significant venous infarct. As opposed to arterial infarctions, CVT mainly affects children and young adults; it is an important cause of stroke in the younger population.2 There is significant overlap of the many risk factors for CVT and those for venous thromboembolism (VTE): cancer, obesity, genetic thrombophilia, trauma, infection, and prior neurosurgery. However, the most common acquired risk factors for CVT are oral contraceptive use and pregnancy, which explains why CVT is 3 times more likely to occur in young and middle-aged women.3

Cerebral venous thrombosis was first recognized by a French physician in the 19th century, a time when the condition was diagnosed at autopsy, which typically showed hemorrhagic lesions at the thrombus site.4 For many years heparin was contraindicated in the treatment of CVT, and only within the past 25 years did advances in neuroimaging allow for earlier diagnosis and change perspectives on the management of this disease.

Cerebral venous thrombosis occurs from formation of a thrombus within the cerebral venous sinuses, leading to elevated intracranial pressure and eventually ischemia or intracranial hemorrhage. Improved imaging techniques, notably magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) venography, allow physicians to identify thrombus formation earlier and begin anticoagulation therapy with heparin before infarction. A meta-analysis of studies found that heparin was safer and more efficacious in treating CVT compared with placebo.5 Furthermore, several small randomized trials found treatment with unfractionated heparin (UFH) or low-molecularweight heparin (LMWH) was not associated with higher risk of hemorrhagic stroke in these patients.6-8

Despite improvements in imaging modalities, in many cases diagnosis is delayed, as most patients with CVT have a wide spectrum of presentations with nonspecific symptoms, such as headache, seizure, focal sensorimotor deficits, and papilledema.9 Clinical presentations of CVT depend on a variety of factors, including age, time of onset, CVT location, and presence of parenchymal lesions. Isolated headache is the most common initial symptom, and in many cases is the only presenting manifestation of CVT.1 Encephalopathy with multifocal signs, delirium, or dysfunction in executive functions most commonly occurs in elderly populations.

Cavernous sinus thrombosis most commonly produces generalized headaches, orbital pain, proptosis, and diplopia, whereas cortical vein thrombosis often produces seizures and focal sensorimotor deficits. Aphasia may be present in patients with isolated left transverse sinus thrombosis. In the presence of deep cerebral venous occlusion, patients can present in coma or with severe cognitive deficits and widespread paresis.10 Thrombosis of different veins and sinuses results in a wide spectrum of diverse clinical pictures, posing a diagnostic challenge and affecting clinical outcomes.

Given the variable and often nonspecific clinical presentations of these cases, unenhanced CT typically is the first imaging study ordered. According to the literature, noncontrast CT is not sensitive (25%-56%) in detecting CVT, and findings are normal in up to 26% of patients, rarely providing a specific diagnosis.11 Furthermore, visualization on MRI can be difficult during the acute phase of CVT, as the thrombus initially appears isointense on T1-weighted images and gradually becomes hyperintense over the course of the disease process.12 These difficulties with the usual first-choice imaging examinations often result in a delay in diagnosing CVT. However, several points on close examination of these imaging studies may help physicians establish a high index of clinical suspicion and order the appropriate follow-up studies for CVT.

The authors report the case of a patient who presented with a 1-week history of confusion, headaches, and dizziness. His nonspecific presentation along with the absence of obvious signs of CVT on imaging prolonged his diagnosis and the initiation of an appropriate treatment plan.

Case Report

A 57-year-old white air-conditioning mechanic presented to the emergency department (ED) with a 1-week history of gradual-onset confusion, severe headaches, dizziness, light-headedness, poor memory, and increased sleep. Two days earlier, he presented with similar symptoms to an outside facility, where he was admitted and underwent a workup for stroke, hemorrhage, and cardiac abnormalities—including noncontrast CT of the head. With nothing of clinical significance found, the patient was discharged and was advised to follow up on an outpatient basis.

Persisting symptoms brought the patient to the ED 1 day later, and he was admitted. He described severe, progressive, generalized headaches that were more severe when he was lying down at night and waking in the morning. He did not report that the headaches worsened with coughing or straining, and he reported no history of trauma, neck stiffness, vision change, seizures, and migraines. His medical history was significant for hypertension, dyslipidemia, and in 2011, an unprovoked deep vein thrombosis (DVT) in the right leg. He reported no history of tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drug use. He had served in the U.S. Navy, working in electronics, intelligence, data systems, and satellite communications.

On initial physical examination, the patient was afebrile and lethargic, and his blood pressure was mildly elevated (144/83 mm Hg). Cardiopulmonary examination was normal. Neurologic examination revealed no severe focal deficits, and cranial nerves II to XII were intact. Funduscopic examination was normal, with no papilledema noted. Motor strength was 5/5 bilaterally in the deltoids, biceps, triceps, radial and ulnar wrist extensors, iliopsoas, quadriceps, hamstrings, tibialis anterior and posterior, fibulares, and gastrocnemius. Pinprick sensation and light-touch sensation were decreased within the lateral bicipital region of the left upper extremity. Pinprick sensation was intact bilaterally in 1-inch increments at all other distributions along the medial and lateral aspects of the upper and lower extremities. Muscle tone and bulk were normal in all extremities. Reflexes were 2+ bilaterally in the biceps, brachioradialis, triceps, quadriceps, and Achilles. The Babinski sign was absent bilaterally, the finger-tonose and heel-to-shin tests were normal, the Romberg sign was absent, and there was no evidence of pronator drift. Laboratory test results were normal except for slightly elevated hemoglobin (17.5 g/dL) and D-dimer (588 ng/mL) levels.

Although noncontrast CT of the head initially showed no acute intracranial abnormalities, retrospective close comparison with the arterial system revealed slightly increased attenuation in the superior sagittal sinus, straight sinus, vein of Galen, and internal cerebral veins (Figures 1A and 1B) relative to the arterial carotid anterior circulation (Figures 2A and 2B).

Subsequent brain MRI without contrast showed a hyperintense T1 signal involving the superior sagittal sinus (Figures 3A and 3B), extending into the straight sinus and the vein of Galen. Magnetic resonance imaging with contrast demonstrated a prominent filling defect primarily in the superior sagittal sinus, in the right transverse sinus, and in the vein of Galen. Diffusion-weighted brain MRI sequence showed restricted diffusion localized to the right thalamic area (Figure 4) and no evidence of hemorrhage.

Treatment

International guidelines recommend using heparin to achieve rapid anticoagulation, stop the thrombotic process, and prevent extension of the thrombus.13 Theoretically, more rapid recanalization may have been achieved by performing endovascular thrombectomy in the present case. However, severe bleeding complications, combined with higher cost and the limited availability of clinicians experienced in treating this rare disease, convince physicians to rely on heparin as first-line treatment for CVT.14 A small randomized clinical trial found LMWH safer and more efficacious than UFH in treating CVT.15 After stabilization, oral anticoagulation therapy is used to maintain an international normalized ratio (INR) between 2.0 and 3.0 for at least 3 months.14

Given these findings, the patient was initially treated with LMWH. Eventually he was switched to oral warfarin and showed signs of clinical improvement. A hypercoagulability state workup revealed that the patient was heterozygous for the prothrombin G20210A mutation, and he was discharged and instructed to continue the oral warfarin therapy.

On follow-up, the hematology and neurology team initiated indefinite treatment with warfarin for his genetic hypercoagulability state. Monitoring of the dose of anticoagulation therapy was started to maintain INR between 2.0 and 3.0. The patient began coming to the office for INR monitoring every 2 to 3 weeks, and his most recent INR, in May 2017, was 2.66. He is taking 7.5 mg of warfarin on Wednesdays and Sundays and 5 mg on all other days and currently does not report any progressive neurologic deficits.

Discussion

The clinical findings of CVT and the hypercoagulability state workup revealed that the patient was heterozygous for the prothrombin G20210A mutation. Prothrombin is the precursor to thrombin, which is a key regulator of the clotting cascade and a promoter of coagulation. Carriers of the mutation have elevated levels of blood plasma prothrombin and have been associated with a 4 times higher risk for VTE.16

Several large studies and systematic reviews have confirmed that the prothrombin G20210A mutation is associated with higher rates of VTE, leading to an increased risk for DVT of the leg or pulmonary embolism.17-19 More specifically, a metaanalysis of 15 case–control studies found strong associations between the mutation and CVT.20 Despite this significant association, studies are inconclusive about whether heterozygosity for the mutation is associated with increased rates of recurrent CVT or other VTE in the absence of other risk factors, such as oral contraceptive use, trauma, malignancy, and infection.21-23 Therefore, the optimal duration of anticoagulation therapy for CVT is not well established in patients with the mutation. However, the present patient was started on indefinite anticoagulation therapy because the underlying etiology of the CVT was not reversible or transient, and this CVT was his second episode of VTE, following a 2011 DVT in the right leg.

The case discussed here illustrates the clinical presentation and diagnostic complexities of CVT. Two days before coming to the ED, the patient presented to an outside facility and underwent a workup for nonspecific symptoms (eg, confusion, headaches). Due to the nonspecific presentation associated with CVT, a detailed history is imperative to distinguish symptoms suggesting increased intracranial pressure, such as headaches worse when lying down or present in the morning, with a high clinical suspicion of CVT. The ability to attain these specific details leads clinicians toward obtaining the necessary imaging studies for potential CVT patients, and may prevent delay in diagnosis and treatment. The thrombus in CVT initially consists of deoxyhemoglobin and appears on MRI as an isointense signal on T1-weighted images and a hypointense signal on T2-weighted images; over subsequent days, the thrombus changes to methemoglobin and appears as a slightly hyperintense signal on both T1- and T2-weighted images.24

During this phase, there are some false negatives, as the thrombus can be mistaken for imaging artifacts, hematocrit elevations, or low flow of normal venous blood. Given the clinical findings and imaging studies, it is essential to distinguish CVT from other benign etiologies. Earlier diagnosis and initiation of anticoagulation therapy may have precluded the small amount of localized ischemic changes in this patient’s right thalamus, thus preventing the mild sensory loss in the left upper extremity. With the variable and nonspecific clinical presentations and the difficulties in identifying CVT with first-line imaging, progression of thrombus formation may lead to severe focal neurologic deficits, coma, or death.

Using CT imaging studies to compare the blood in the draining cerebral sinuses with the blood in the arterial system can help distinguish CVT from other etiologies of hyperdense abnormalities, such as increased hematocrit or decreased flow. Retrospective close examination of the present patient’s noncontrast CT images of the head and brain revealed slight hyperdensity in the cerebral sinuses compared with the arterial blood, suggesting the presence of thrombus formation in the cerebral veins. As CT is often the first study used to evaluate the nonspecific clinical presentations of these patients, identifying subtle signaldensity differences between the arterial and venous systems could guide physicians in identifying CVT earlier.

The authors reiterate the importance of meticulous imaging interpretation in light of the entire clinical picture: In these patients, it is imperative to have a high index of clinical suspicion for CVT in order to prevent more serious complications, such as ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke.

Cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT) is a rare cerebrovascular disease that affects about 5 in 1 million people each year and accounts for 0.5% of all strokes.1 Previously it was thought to be caused most commonly by infections (eg, mastoiditis, otitis, meningitis) affecting the superior sagittal sinus and often resulting in focal neurologic deficits, seizures, coma, and death. Although local and systemic infections are still prominent risk factors in its development, CVT is now primarily recognized as a nonseptic disease with a wide spectrum of clinical presentations.

Cerebral venous thrombosis causes reduced outflow of blood and cerebrospinal fluid, which in half of affected patients leads to significant venous infarct. As opposed to arterial infarctions, CVT mainly affects children and young adults; it is an important cause of stroke in the younger population.2 There is significant overlap of the many risk factors for CVT and those for venous thromboembolism (VTE): cancer, obesity, genetic thrombophilia, trauma, infection, and prior neurosurgery. However, the most common acquired risk factors for CVT are oral contraceptive use and pregnancy, which explains why CVT is 3 times more likely to occur in young and middle-aged women.3

Cerebral venous thrombosis was first recognized by a French physician in the 19th century, a time when the condition was diagnosed at autopsy, which typically showed hemorrhagic lesions at the thrombus site.4 For many years heparin was contraindicated in the treatment of CVT, and only within the past 25 years did advances in neuroimaging allow for earlier diagnosis and change perspectives on the management of this disease.

Cerebral venous thrombosis occurs from formation of a thrombus within the cerebral venous sinuses, leading to elevated intracranial pressure and eventually ischemia or intracranial hemorrhage. Improved imaging techniques, notably magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) venography, allow physicians to identify thrombus formation earlier and begin anticoagulation therapy with heparin before infarction. A meta-analysis of studies found that heparin was safer and more efficacious in treating CVT compared with placebo.5 Furthermore, several small randomized trials found treatment with unfractionated heparin (UFH) or low-molecularweight heparin (LMWH) was not associated with higher risk of hemorrhagic stroke in these patients.6-8

Despite improvements in imaging modalities, in many cases diagnosis is delayed, as most patients with CVT have a wide spectrum of presentations with nonspecific symptoms, such as headache, seizure, focal sensorimotor deficits, and papilledema.9 Clinical presentations of CVT depend on a variety of factors, including age, time of onset, CVT location, and presence of parenchymal lesions. Isolated headache is the most common initial symptom, and in many cases is the only presenting manifestation of CVT.1 Encephalopathy with multifocal signs, delirium, or dysfunction in executive functions most commonly occurs in elderly populations.

Cavernous sinus thrombosis most commonly produces generalized headaches, orbital pain, proptosis, and diplopia, whereas cortical vein thrombosis often produces seizures and focal sensorimotor deficits. Aphasia may be present in patients with isolated left transverse sinus thrombosis. In the presence of deep cerebral venous occlusion, patients can present in coma or with severe cognitive deficits and widespread paresis.10 Thrombosis of different veins and sinuses results in a wide spectrum of diverse clinical pictures, posing a diagnostic challenge and affecting clinical outcomes.

Given the variable and often nonspecific clinical presentations of these cases, unenhanced CT typically is the first imaging study ordered. According to the literature, noncontrast CT is not sensitive (25%-56%) in detecting CVT, and findings are normal in up to 26% of patients, rarely providing a specific diagnosis.11 Furthermore, visualization on MRI can be difficult during the acute phase of CVT, as the thrombus initially appears isointense on T1-weighted images and gradually becomes hyperintense over the course of the disease process.12 These difficulties with the usual first-choice imaging examinations often result in a delay in diagnosing CVT. However, several points on close examination of these imaging studies may help physicians establish a high index of clinical suspicion and order the appropriate follow-up studies for CVT.

The authors report the case of a patient who presented with a 1-week history of confusion, headaches, and dizziness. His nonspecific presentation along with the absence of obvious signs of CVT on imaging prolonged his diagnosis and the initiation of an appropriate treatment plan.

Case Report

A 57-year-old white air-conditioning mechanic presented to the emergency department (ED) with a 1-week history of gradual-onset confusion, severe headaches, dizziness, light-headedness, poor memory, and increased sleep. Two days earlier, he presented with similar symptoms to an outside facility, where he was admitted and underwent a workup for stroke, hemorrhage, and cardiac abnormalities—including noncontrast CT of the head. With nothing of clinical significance found, the patient was discharged and was advised to follow up on an outpatient basis.

Persisting symptoms brought the patient to the ED 1 day later, and he was admitted. He described severe, progressive, generalized headaches that were more severe when he was lying down at night and waking in the morning. He did not report that the headaches worsened with coughing or straining, and he reported no history of trauma, neck stiffness, vision change, seizures, and migraines. His medical history was significant for hypertension, dyslipidemia, and in 2011, an unprovoked deep vein thrombosis (DVT) in the right leg. He reported no history of tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drug use. He had served in the U.S. Navy, working in electronics, intelligence, data systems, and satellite communications.

On initial physical examination, the patient was afebrile and lethargic, and his blood pressure was mildly elevated (144/83 mm Hg). Cardiopulmonary examination was normal. Neurologic examination revealed no severe focal deficits, and cranial nerves II to XII were intact. Funduscopic examination was normal, with no papilledema noted. Motor strength was 5/5 bilaterally in the deltoids, biceps, triceps, radial and ulnar wrist extensors, iliopsoas, quadriceps, hamstrings, tibialis anterior and posterior, fibulares, and gastrocnemius. Pinprick sensation and light-touch sensation were decreased within the lateral bicipital region of the left upper extremity. Pinprick sensation was intact bilaterally in 1-inch increments at all other distributions along the medial and lateral aspects of the upper and lower extremities. Muscle tone and bulk were normal in all extremities. Reflexes were 2+ bilaterally in the biceps, brachioradialis, triceps, quadriceps, and Achilles. The Babinski sign was absent bilaterally, the finger-tonose and heel-to-shin tests were normal, the Romberg sign was absent, and there was no evidence of pronator drift. Laboratory test results were normal except for slightly elevated hemoglobin (17.5 g/dL) and D-dimer (588 ng/mL) levels.

Although noncontrast CT of the head initially showed no acute intracranial abnormalities, retrospective close comparison with the arterial system revealed slightly increased attenuation in the superior sagittal sinus, straight sinus, vein of Galen, and internal cerebral veins (Figures 1A and 1B) relative to the arterial carotid anterior circulation (Figures 2A and 2B).

Subsequent brain MRI without contrast showed a hyperintense T1 signal involving the superior sagittal sinus (Figures 3A and 3B), extending into the straight sinus and the vein of Galen. Magnetic resonance imaging with contrast demonstrated a prominent filling defect primarily in the superior sagittal sinus, in the right transverse sinus, and in the vein of Galen. Diffusion-weighted brain MRI sequence showed restricted diffusion localized to the right thalamic area (Figure 4) and no evidence of hemorrhage.

Treatment

International guidelines recommend using heparin to achieve rapid anticoagulation, stop the thrombotic process, and prevent extension of the thrombus.13 Theoretically, more rapid recanalization may have been achieved by performing endovascular thrombectomy in the present case. However, severe bleeding complications, combined with higher cost and the limited availability of clinicians experienced in treating this rare disease, convince physicians to rely on heparin as first-line treatment for CVT.14 A small randomized clinical trial found LMWH safer and more efficacious than UFH in treating CVT.15 After stabilization, oral anticoagulation therapy is used to maintain an international normalized ratio (INR) between 2.0 and 3.0 for at least 3 months.14

Given these findings, the patient was initially treated with LMWH. Eventually he was switched to oral warfarin and showed signs of clinical improvement. A hypercoagulability state workup revealed that the patient was heterozygous for the prothrombin G20210A mutation, and he was discharged and instructed to continue the oral warfarin therapy.

On follow-up, the hematology and neurology team initiated indefinite treatment with warfarin for his genetic hypercoagulability state. Monitoring of the dose of anticoagulation therapy was started to maintain INR between 2.0 and 3.0. The patient began coming to the office for INR monitoring every 2 to 3 weeks, and his most recent INR, in May 2017, was 2.66. He is taking 7.5 mg of warfarin on Wednesdays and Sundays and 5 mg on all other days and currently does not report any progressive neurologic deficits.

Discussion

The clinical findings of CVT and the hypercoagulability state workup revealed that the patient was heterozygous for the prothrombin G20210A mutation. Prothrombin is the precursor to thrombin, which is a key regulator of the clotting cascade and a promoter of coagulation. Carriers of the mutation have elevated levels of blood plasma prothrombin and have been associated with a 4 times higher risk for VTE.16

Several large studies and systematic reviews have confirmed that the prothrombin G20210A mutation is associated with higher rates of VTE, leading to an increased risk for DVT of the leg or pulmonary embolism.17-19 More specifically, a metaanalysis of 15 case–control studies found strong associations between the mutation and CVT.20 Despite this significant association, studies are inconclusive about whether heterozygosity for the mutation is associated with increased rates of recurrent CVT or other VTE in the absence of other risk factors, such as oral contraceptive use, trauma, malignancy, and infection.21-23 Therefore, the optimal duration of anticoagulation therapy for CVT is not well established in patients with the mutation. However, the present patient was started on indefinite anticoagulation therapy because the underlying etiology of the CVT was not reversible or transient, and this CVT was his second episode of VTE, following a 2011 DVT in the right leg.

The case discussed here illustrates the clinical presentation and diagnostic complexities of CVT. Two days before coming to the ED, the patient presented to an outside facility and underwent a workup for nonspecific symptoms (eg, confusion, headaches). Due to the nonspecific presentation associated with CVT, a detailed history is imperative to distinguish symptoms suggesting increased intracranial pressure, such as headaches worse when lying down or present in the morning, with a high clinical suspicion of CVT. The ability to attain these specific details leads clinicians toward obtaining the necessary imaging studies for potential CVT patients, and may prevent delay in diagnosis and treatment. The thrombus in CVT initially consists of deoxyhemoglobin and appears on MRI as an isointense signal on T1-weighted images and a hypointense signal on T2-weighted images; over subsequent days, the thrombus changes to methemoglobin and appears as a slightly hyperintense signal on both T1- and T2-weighted images.24

During this phase, there are some false negatives, as the thrombus can be mistaken for imaging artifacts, hematocrit elevations, or low flow of normal venous blood. Given the clinical findings and imaging studies, it is essential to distinguish CVT from other benign etiologies. Earlier diagnosis and initiation of anticoagulation therapy may have precluded the small amount of localized ischemic changes in this patient’s right thalamus, thus preventing the mild sensory loss in the left upper extremity. With the variable and nonspecific clinical presentations and the difficulties in identifying CVT with first-line imaging, progression of thrombus formation may lead to severe focal neurologic deficits, coma, or death.

Using CT imaging studies to compare the blood in the draining cerebral sinuses with the blood in the arterial system can help distinguish CVT from other etiologies of hyperdense abnormalities, such as increased hematocrit or decreased flow. Retrospective close examination of the present patient’s noncontrast CT images of the head and brain revealed slight hyperdensity in the cerebral sinuses compared with the arterial blood, suggesting the presence of thrombus formation in the cerebral veins. As CT is often the first study used to evaluate the nonspecific clinical presentations of these patients, identifying subtle signaldensity differences between the arterial and venous systems could guide physicians in identifying CVT earlier.

The authors reiterate the importance of meticulous imaging interpretation in light of the entire clinical picture: In these patients, it is imperative to have a high index of clinical suspicion for CVT in order to prevent more serious complications, such as ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke.

1. Bousser MG, Ferro JM. Cerebral venous thrombosis: an update. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(2):162-170.

2. Coutinho JM. Cerebral venous thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2015;13(suppl 1):S238-S244.

3. Coutinho JM, Ferro JM, Canhão P, et al. Cerebral venous and sinus thrombosis in women. Stroke. 2009;40(7):2356-2361.

4. Zuurbier SM, Coutinho JM. Cerebral venous thrombosis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;906:183-193.

5. Einhäupl KM, Villringer A, Meister W, et al. Heparin treatment in sinus venous thrombosis. Lancet. 1991;338(8767):597-600.

6. de Bruijn SF, Stam J. Randomized, placebocontrolled trial of anticoagulant treatment with lowmolecular-weight heparin for cerebral sinus thrombosis. Stroke. 1999;30(3):484-488.

7. Nagaraja D, Haridas T, Taly AB, Veerendrakumar M, SubbuKrishna DK. Puerperal cerebral venous thrombosis: therapeutic benefit of low dose heparin. Neurol India. 1999;47(1):43-46.

8. Coutinho JM, de Bruijn SF, deVeber G, Stam J. Anticoagulation for cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. Stroke. 2012;43(4):e41-e42.

9. Sassi SB, Touati N, Baccouche H, Drissi C, Romdhane NB, Hentati F. Cerebral venous thrombosis. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2016:1076029616665168. [Epub ahead of print.]

10. Ferro JM, Canhão P. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis: update on diagnosis and management. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2014;16(9):523.

11. Albright KC, Freeman WD, Kruse BT. Cerebral venous thrombosis. J Emerg Med. 2010;38(2):238-239.

12. Lafitte F, Boukobza M, Guichard JP, et al. MRI and MRA for diagnosis and follow-up of cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT). Clin Radiol. 1997;52(9):672-679.

13. Saposnik G, Barinagarrementeria F, Brown RD Jr, et al; American Heart Association Stroke Council and Council on Epidemiology and Prevention. Diagnosis and management of cerebral venous thrombosis: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2011;42(4):1158-1192.

14. Coutinho JM, Middeldorp S, Stam J. Advances in the treatment of cerebral venous thrombosis. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2014;16(7):299.

15. Coutinho JM, Ferro JM, Canhão P, Barinagarrementeria F, Bousser MG, Stam J; ISCVT Investigators. Unfractionated or low-molecular weight heparin for the treatment of cerebral venous thrombosis. Stroke. 2010;41(11):2575-2580.

16. Rosendaal FR. Venous thrombosis: the role of genes, environment, and behavior. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2005:1-12.

17. Dentali F, Crowther M, Ageno W. Thrombophilic abnormalities, oral contraceptives, and risk of cerebral vein thrombosis: a meta-analysis. Blood.2006;107(7):2766-2773.

18. Salomon O, Steinberg DM, Zivelin A, et al. Single and combined prothrombotic factors in patients with idiopathic venous thromboembolism: prevalence and risk assessment. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19(3):511-518.

19. Emmerich J, Rosendaal FR, Cattaneo M, et al. Combined effect of factor V Leiden and prothrombin 20210A on the risk of venous thromboembolism— pooled analysis of 8 case–control studies including 2310 cases and 3204 controls. Study Group for Pooled-Analysis in Venous Thromboembolism. Thromb Haemost. 2001;86(3):809-816.

20. Lauw MN, Barco S, Coutinho JM, Middeldorp S. Cerebral venous thrombosis and thrombophilia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2013;39(8):913-927.

21. Dentali F, Poli D, Scoditti U, et al. Long-term outcomes of patients with cerebral vein thrombosis: a multicenter study. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10(7):1297-1302.

22. Martinelli I, Bucciarelli P, Passamonti SM, Battaglioli T, Previtali E, Mannucci PM. Long-term evaluation of the risk of recurrence after cerebral sinus-venous thrombosis. Circulation. 2010;121(25):2740-2746.

23. Gosk-Bierska I, Wysokinski W, Brown RD Jr, et al. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis: incidence of venous thrombosis recurrence and survival. Neurology. 2006;67(5):814-819.

24. Galidie G, Le Gall R, Cordoliani YS, Pharaboz C, Le Marec E, Cosnard G. Thrombosis of the cerebral veins. X-ray computed tomography and MRI imaging. 11 cases [in French]. J Radiol. 1992;73(3):175-190

1. Bousser MG, Ferro JM. Cerebral venous thrombosis: an update. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(2):162-170.

2. Coutinho JM. Cerebral venous thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2015;13(suppl 1):S238-S244.

3. Coutinho JM, Ferro JM, Canhão P, et al. Cerebral venous and sinus thrombosis in women. Stroke. 2009;40(7):2356-2361.

4. Zuurbier SM, Coutinho JM. Cerebral venous thrombosis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;906:183-193.

5. Einhäupl KM, Villringer A, Meister W, et al. Heparin treatment in sinus venous thrombosis. Lancet. 1991;338(8767):597-600.

6. de Bruijn SF, Stam J. Randomized, placebocontrolled trial of anticoagulant treatment with lowmolecular-weight heparin for cerebral sinus thrombosis. Stroke. 1999;30(3):484-488.

7. Nagaraja D, Haridas T, Taly AB, Veerendrakumar M, SubbuKrishna DK. Puerperal cerebral venous thrombosis: therapeutic benefit of low dose heparin. Neurol India. 1999;47(1):43-46.

8. Coutinho JM, de Bruijn SF, deVeber G, Stam J. Anticoagulation for cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. Stroke. 2012;43(4):e41-e42.

9. Sassi SB, Touati N, Baccouche H, Drissi C, Romdhane NB, Hentati F. Cerebral venous thrombosis. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2016:1076029616665168. [Epub ahead of print.]

10. Ferro JM, Canhão P. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis: update on diagnosis and management. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2014;16(9):523.

11. Albright KC, Freeman WD, Kruse BT. Cerebral venous thrombosis. J Emerg Med. 2010;38(2):238-239.

12. Lafitte F, Boukobza M, Guichard JP, et al. MRI and MRA for diagnosis and follow-up of cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT). Clin Radiol. 1997;52(9):672-679.

13. Saposnik G, Barinagarrementeria F, Brown RD Jr, et al; American Heart Association Stroke Council and Council on Epidemiology and Prevention. Diagnosis and management of cerebral venous thrombosis: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2011;42(4):1158-1192.

14. Coutinho JM, Middeldorp S, Stam J. Advances in the treatment of cerebral venous thrombosis. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2014;16(7):299.

15. Coutinho JM, Ferro JM, Canhão P, Barinagarrementeria F, Bousser MG, Stam J; ISCVT Investigators. Unfractionated or low-molecular weight heparin for the treatment of cerebral venous thrombosis. Stroke. 2010;41(11):2575-2580.

16. Rosendaal FR. Venous thrombosis: the role of genes, environment, and behavior. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2005:1-12.

17. Dentali F, Crowther M, Ageno W. Thrombophilic abnormalities, oral contraceptives, and risk of cerebral vein thrombosis: a meta-analysis. Blood.2006;107(7):2766-2773.

18. Salomon O, Steinberg DM, Zivelin A, et al. Single and combined prothrombotic factors in patients with idiopathic venous thromboembolism: prevalence and risk assessment. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19(3):511-518.

19. Emmerich J, Rosendaal FR, Cattaneo M, et al. Combined effect of factor V Leiden and prothrombin 20210A on the risk of venous thromboembolism— pooled analysis of 8 case–control studies including 2310 cases and 3204 controls. Study Group for Pooled-Analysis in Venous Thromboembolism. Thromb Haemost. 2001;86(3):809-816.

20. Lauw MN, Barco S, Coutinho JM, Middeldorp S. Cerebral venous thrombosis and thrombophilia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2013;39(8):913-927.

21. Dentali F, Poli D, Scoditti U, et al. Long-term outcomes of patients with cerebral vein thrombosis: a multicenter study. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10(7):1297-1302.

22. Martinelli I, Bucciarelli P, Passamonti SM, Battaglioli T, Previtali E, Mannucci PM. Long-term evaluation of the risk of recurrence after cerebral sinus-venous thrombosis. Circulation. 2010;121(25):2740-2746.

23. Gosk-Bierska I, Wysokinski W, Brown RD Jr, et al. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis: incidence of venous thrombosis recurrence and survival. Neurology. 2006;67(5):814-819.

24. Galidie G, Le Gall R, Cordoliani YS, Pharaboz C, Le Marec E, Cosnard G. Thrombosis of the cerebral veins. X-ray computed tomography and MRI imaging. 11 cases [in French]. J Radiol. 1992;73(3):175-190

Idarucizumab reversed dabigatran completely and rapidly in study

One IV 5-g dose of idarucizumab completely, rapidly, and safely reversed the anticoagulant effect of dabigatran, according to final results for 503 patients in the multicenter, prospective, open-label, uncontrolled RE-VERSE AD study.

Uncontrolled bleeding stopped a median of 2.5 hours after 134 patients received idarucizumab. In a separate group of 202 patients, 197 were able to undergo urgent procedures after a median of 1.6 hours, Charles V. Pollack Jr., MD, and his associates reported at the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis congress. The report was simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Idarucizumab was specifically developed to reverse the anticoagulant effect of dabigatran. Many countries have already licensed the humanized monoclonal antibody fragment based on interim results for the first 90 patients enrolled in the Reversal Effects of Idarucizumab on Active Dabigatran (RE-VERSE AD) study (NCT02104947), noted Dr. Pollack, of Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia.

The final RE-VERSE AD cohort included 301 patients with uncontrolled gastrointestinal, intracranial, or trauma-related bleeding and 202 patients who needed urgent procedures. Participants from both groups typically were white, in their late 70s (age range, 21-96 years), and receiving 110 mg (75-150 mg) dabigatran twice daily. The primary endpoint was maximum percentage reversal within 4 hours after patients received idarucizumab, based on diluted thrombin time and ecarin clotting time.

The median maximum percentage reversal of dabigatran was 100% (95% confidence interval, 100% to 100%) in more than 98% of patients, and the effect usually lasted 24 hours. Among patients who underwent procedures, intraprocedural hemostasis was considered normal in 93% of cases, mildly abnormal in 5% of cases, and moderately abnormal in 2% of cases, the researchers noted. Seven patients received another dose of idarucizumab after developing recurrent or postoperative bleeding.

A total of 24 patients had an adjudicated thrombotic event within 30 days after receiving idarucizumab. These events included pulmonary embolism, systemic embolism, ischemic stroke, deep vein thrombosis, and myocardial infarction. The fact that many patients did not restart anticoagulation could have contributed to these thrombotic events, the researchers asserted. They noted that idarucizumab had no procoagulant activity in studies of animals and healthy human volunteers.