User login

How should we monitor for ovarian cancer recurrence?

Several practice-changing developments in the treatment of ovarian cancer were seen in 2019, including the results of the pivotal trial Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG)-213, which were published in November in the New England Journal of Medicine.1 This trial randomly assigned women with ovarian cancer who had achieved a remission of more than 6 months after primary therapy (“platinum sensitive”) to either a repeat surgical cytoreduction followed by chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone. It found that the addition of surgery provided no benefit in overall survival, challenging the notion that repeat surgical “debulking” should be routinely considered for the treatment of women with platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer.

The primary treatment of ovarian cancer includes a combination of surgery and chemotherapy, after which the vast majority of patients will experience a complete clinical response, a so-called “remission.” At that time patients enter surveillance care, in which their providers evaluate them, typically every 3 months in the first 2-3 years. These visits are designed to address ongoing toxicities of therapy in addition to evaluation for recurrence. At these visits, it is common for providers to assess tumor markers, such as CA 125 (cancer antigen 125), if they had been elevated at original diagnosis. As a gynecologic oncologist, I can vouch for the fact that patients “sweat” on this lab result the most. No matter how reassuring my physical exams or their symptom profiles are, there is nothing more comforting as a normal, stable CA 125 value in black and white. However, and may, in fact, be harmful.

Providers have drawn tumor markers at surveillance exams under the working premise that abnormal or rising values signal the onset of asymptomatic recurrence, and that earlier treatment will be associated with better responses to salvage therapy. However, this has not been shown to be the case in randomized, controlled trials. In a large European cooperative-group trial, more than 500 patients with a history of completely treated ovarian cancer were randomized to either reinitiation of chemotherapy (salvage therapy) when CA 125 values first doubled or to reinitiation of therapy when they became symptomatic without knowledge of their CA 125 values.2 In this trial the mean survival of both groups was the same (26 months for the early initiation of chemotherapy vs. 27 for late initiation). However, what did differ were the quality of life scores, which were lower for the group who initiated chemotherapy earlier, likely because they received toxic therapies for longer periods of time.

The results of this trial were challenged by those who felt that this study did not evaluate the role that surgery might play. Their argument was that surgery in the recurrent setting would improve the outcomes from chemotherapy for certain patients with long platinum-free intervals (duration of remission since last receiving a platinum-containing drug), oligometastatic disease, and good performance status, just as it had in the primary setting. Retrospective series seemed to confirm this phenomenon, particularly if surgeons were able to achieve a complete resection (no residual measurable disease).3,4 By detecting asymptomatic patients with early elevations in CA 125, they proposed they might identify patients with lower disease burden in whom complete debulking would be more feasible. Whereas, in waiting for symptoms alone, they might “miss the boat,” and discover recurrence when it was too advanced to be completely resected.

The results of the GOG-213 study significantly challenge this line of thought, although with some caveats. Because this new trial showed no survival benefit for women with secondary debulking prior to chemotherapy, one could question whether there is any benefit in screening for asymptomatic, early recurrence. The authors of the study looked in subgroup analyses to attempt to identify groups who might benefit over others, such as women who had complete surgical cytoreduction (no residual disease) but still did not find a benefit to surgery. The trial population as a whole included women who had very favorable prognostic factors, including very long disease-free intervals (median, 20.4 months), and most women had only one or two sites of measurable recurrence. Yet it is remarkable that, in this group of patients who were predisposed to optimal outcomes, no benefit from surgery was observed.

However, it is important to recognize that the equivalent results of single-modality chemotherapy were achieved with the majority of women receiving bevacizumab with their chemotherapy regimen. An additional consideration is that the chemotherapy for platinum-sensitive, recurrent ovarian cancer has changed in recent years as we have learned the benefit of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor drugs as maintenance therapy following complete or partial response to chemotherapy.5 It is unclear how the addition of PARP inhibitor maintenance therapy might have influenced the results of GOG-213. Further advancements in targeted therapies and consideration of hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy at the time of surgery also are being developed, and so, the answer of optimal therapy for platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer is a fluid one and might include a role for surgery for some of these patients.

However, in the meantime, before routinely ordering that tumor marker assessment in the surveillance period, it is important to remember that, if secondary cytoreduction is not beneficial and early initiation of chemotherapy is not helpful either, then these tumor marker results might provide more hindrance than help. Why search for recurrence at an earlier time point with CA 125 elevations if there isn’t a benefit to the patient in doing so? There certainly appears to be worse quality of life in doing so, and most likely also additional cost. Perhaps we should wait for clinical symptoms to confirm recurrence?

In the meantime, we will continue to have discussions with patients after primary therapy regarding how to best monitor them in the surveillance period. We will educate them about the limitations of early initiation of chemotherapy and the potentially limited role for surgery. Hopefully with individualized care and shared decision making, patients can guide us as to how they best be evaluated. While receiving a normal CA 125 result is powerfully reassuring, it is just as powerfully confusing and difficult for a patient to receive an abnormal one followed by a period of “doing nothing,” otherwise known as expectant management, if immediate treatment is not beneficial.

Dr. Rossi is assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. N Engl J Med. 2019 Nov 14;381(20):1929-39.

2. Lancet. 2010 Oct 2;376(9747):1155-63.

3. Gynecol Oncol. 2009 Jan;112(1):265-74.

4. Br J Cancer. 2011 Sep 27;105(7):890-6.

5. N Engl J Med. 2016 Dec 1;375(22):2154-64.

Several practice-changing developments in the treatment of ovarian cancer were seen in 2019, including the results of the pivotal trial Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG)-213, which were published in November in the New England Journal of Medicine.1 This trial randomly assigned women with ovarian cancer who had achieved a remission of more than 6 months after primary therapy (“platinum sensitive”) to either a repeat surgical cytoreduction followed by chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone. It found that the addition of surgery provided no benefit in overall survival, challenging the notion that repeat surgical “debulking” should be routinely considered for the treatment of women with platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer.

The primary treatment of ovarian cancer includes a combination of surgery and chemotherapy, after which the vast majority of patients will experience a complete clinical response, a so-called “remission.” At that time patients enter surveillance care, in which their providers evaluate them, typically every 3 months in the first 2-3 years. These visits are designed to address ongoing toxicities of therapy in addition to evaluation for recurrence. At these visits, it is common for providers to assess tumor markers, such as CA 125 (cancer antigen 125), if they had been elevated at original diagnosis. As a gynecologic oncologist, I can vouch for the fact that patients “sweat” on this lab result the most. No matter how reassuring my physical exams or their symptom profiles are, there is nothing more comforting as a normal, stable CA 125 value in black and white. However, and may, in fact, be harmful.

Providers have drawn tumor markers at surveillance exams under the working premise that abnormal or rising values signal the onset of asymptomatic recurrence, and that earlier treatment will be associated with better responses to salvage therapy. However, this has not been shown to be the case in randomized, controlled trials. In a large European cooperative-group trial, more than 500 patients with a history of completely treated ovarian cancer were randomized to either reinitiation of chemotherapy (salvage therapy) when CA 125 values first doubled or to reinitiation of therapy when they became symptomatic without knowledge of their CA 125 values.2 In this trial the mean survival of both groups was the same (26 months for the early initiation of chemotherapy vs. 27 for late initiation). However, what did differ were the quality of life scores, which were lower for the group who initiated chemotherapy earlier, likely because they received toxic therapies for longer periods of time.

The results of this trial were challenged by those who felt that this study did not evaluate the role that surgery might play. Their argument was that surgery in the recurrent setting would improve the outcomes from chemotherapy for certain patients with long platinum-free intervals (duration of remission since last receiving a platinum-containing drug), oligometastatic disease, and good performance status, just as it had in the primary setting. Retrospective series seemed to confirm this phenomenon, particularly if surgeons were able to achieve a complete resection (no residual measurable disease).3,4 By detecting asymptomatic patients with early elevations in CA 125, they proposed they might identify patients with lower disease burden in whom complete debulking would be more feasible. Whereas, in waiting for symptoms alone, they might “miss the boat,” and discover recurrence when it was too advanced to be completely resected.

The results of the GOG-213 study significantly challenge this line of thought, although with some caveats. Because this new trial showed no survival benefit for women with secondary debulking prior to chemotherapy, one could question whether there is any benefit in screening for asymptomatic, early recurrence. The authors of the study looked in subgroup analyses to attempt to identify groups who might benefit over others, such as women who had complete surgical cytoreduction (no residual disease) but still did not find a benefit to surgery. The trial population as a whole included women who had very favorable prognostic factors, including very long disease-free intervals (median, 20.4 months), and most women had only one or two sites of measurable recurrence. Yet it is remarkable that, in this group of patients who were predisposed to optimal outcomes, no benefit from surgery was observed.

However, it is important to recognize that the equivalent results of single-modality chemotherapy were achieved with the majority of women receiving bevacizumab with their chemotherapy regimen. An additional consideration is that the chemotherapy for platinum-sensitive, recurrent ovarian cancer has changed in recent years as we have learned the benefit of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor drugs as maintenance therapy following complete or partial response to chemotherapy.5 It is unclear how the addition of PARP inhibitor maintenance therapy might have influenced the results of GOG-213. Further advancements in targeted therapies and consideration of hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy at the time of surgery also are being developed, and so, the answer of optimal therapy for platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer is a fluid one and might include a role for surgery for some of these patients.

However, in the meantime, before routinely ordering that tumor marker assessment in the surveillance period, it is important to remember that, if secondary cytoreduction is not beneficial and early initiation of chemotherapy is not helpful either, then these tumor marker results might provide more hindrance than help. Why search for recurrence at an earlier time point with CA 125 elevations if there isn’t a benefit to the patient in doing so? There certainly appears to be worse quality of life in doing so, and most likely also additional cost. Perhaps we should wait for clinical symptoms to confirm recurrence?

In the meantime, we will continue to have discussions with patients after primary therapy regarding how to best monitor them in the surveillance period. We will educate them about the limitations of early initiation of chemotherapy and the potentially limited role for surgery. Hopefully with individualized care and shared decision making, patients can guide us as to how they best be evaluated. While receiving a normal CA 125 result is powerfully reassuring, it is just as powerfully confusing and difficult for a patient to receive an abnormal one followed by a period of “doing nothing,” otherwise known as expectant management, if immediate treatment is not beneficial.

Dr. Rossi is assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. N Engl J Med. 2019 Nov 14;381(20):1929-39.

2. Lancet. 2010 Oct 2;376(9747):1155-63.

3. Gynecol Oncol. 2009 Jan;112(1):265-74.

4. Br J Cancer. 2011 Sep 27;105(7):890-6.

5. N Engl J Med. 2016 Dec 1;375(22):2154-64.

Several practice-changing developments in the treatment of ovarian cancer were seen in 2019, including the results of the pivotal trial Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG)-213, which were published in November in the New England Journal of Medicine.1 This trial randomly assigned women with ovarian cancer who had achieved a remission of more than 6 months after primary therapy (“platinum sensitive”) to either a repeat surgical cytoreduction followed by chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone. It found that the addition of surgery provided no benefit in overall survival, challenging the notion that repeat surgical “debulking” should be routinely considered for the treatment of women with platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer.

The primary treatment of ovarian cancer includes a combination of surgery and chemotherapy, after which the vast majority of patients will experience a complete clinical response, a so-called “remission.” At that time patients enter surveillance care, in which their providers evaluate them, typically every 3 months in the first 2-3 years. These visits are designed to address ongoing toxicities of therapy in addition to evaluation for recurrence. At these visits, it is common for providers to assess tumor markers, such as CA 125 (cancer antigen 125), if they had been elevated at original diagnosis. As a gynecologic oncologist, I can vouch for the fact that patients “sweat” on this lab result the most. No matter how reassuring my physical exams or their symptom profiles are, there is nothing more comforting as a normal, stable CA 125 value in black and white. However, and may, in fact, be harmful.

Providers have drawn tumor markers at surveillance exams under the working premise that abnormal or rising values signal the onset of asymptomatic recurrence, and that earlier treatment will be associated with better responses to salvage therapy. However, this has not been shown to be the case in randomized, controlled trials. In a large European cooperative-group trial, more than 500 patients with a history of completely treated ovarian cancer were randomized to either reinitiation of chemotherapy (salvage therapy) when CA 125 values first doubled or to reinitiation of therapy when they became symptomatic without knowledge of their CA 125 values.2 In this trial the mean survival of both groups was the same (26 months for the early initiation of chemotherapy vs. 27 for late initiation). However, what did differ were the quality of life scores, which were lower for the group who initiated chemotherapy earlier, likely because they received toxic therapies for longer periods of time.

The results of this trial were challenged by those who felt that this study did not evaluate the role that surgery might play. Their argument was that surgery in the recurrent setting would improve the outcomes from chemotherapy for certain patients with long platinum-free intervals (duration of remission since last receiving a platinum-containing drug), oligometastatic disease, and good performance status, just as it had in the primary setting. Retrospective series seemed to confirm this phenomenon, particularly if surgeons were able to achieve a complete resection (no residual measurable disease).3,4 By detecting asymptomatic patients with early elevations in CA 125, they proposed they might identify patients with lower disease burden in whom complete debulking would be more feasible. Whereas, in waiting for symptoms alone, they might “miss the boat,” and discover recurrence when it was too advanced to be completely resected.

The results of the GOG-213 study significantly challenge this line of thought, although with some caveats. Because this new trial showed no survival benefit for women with secondary debulking prior to chemotherapy, one could question whether there is any benefit in screening for asymptomatic, early recurrence. The authors of the study looked in subgroup analyses to attempt to identify groups who might benefit over others, such as women who had complete surgical cytoreduction (no residual disease) but still did not find a benefit to surgery. The trial population as a whole included women who had very favorable prognostic factors, including very long disease-free intervals (median, 20.4 months), and most women had only one or two sites of measurable recurrence. Yet it is remarkable that, in this group of patients who were predisposed to optimal outcomes, no benefit from surgery was observed.

However, it is important to recognize that the equivalent results of single-modality chemotherapy were achieved with the majority of women receiving bevacizumab with their chemotherapy regimen. An additional consideration is that the chemotherapy for platinum-sensitive, recurrent ovarian cancer has changed in recent years as we have learned the benefit of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor drugs as maintenance therapy following complete or partial response to chemotherapy.5 It is unclear how the addition of PARP inhibitor maintenance therapy might have influenced the results of GOG-213. Further advancements in targeted therapies and consideration of hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy at the time of surgery also are being developed, and so, the answer of optimal therapy for platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer is a fluid one and might include a role for surgery for some of these patients.

However, in the meantime, before routinely ordering that tumor marker assessment in the surveillance period, it is important to remember that, if secondary cytoreduction is not beneficial and early initiation of chemotherapy is not helpful either, then these tumor marker results might provide more hindrance than help. Why search for recurrence at an earlier time point with CA 125 elevations if there isn’t a benefit to the patient in doing so? There certainly appears to be worse quality of life in doing so, and most likely also additional cost. Perhaps we should wait for clinical symptoms to confirm recurrence?

In the meantime, we will continue to have discussions with patients after primary therapy regarding how to best monitor them in the surveillance period. We will educate them about the limitations of early initiation of chemotherapy and the potentially limited role for surgery. Hopefully with individualized care and shared decision making, patients can guide us as to how they best be evaluated. While receiving a normal CA 125 result is powerfully reassuring, it is just as powerfully confusing and difficult for a patient to receive an abnormal one followed by a period of “doing nothing,” otherwise known as expectant management, if immediate treatment is not beneficial.

Dr. Rossi is assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. N Engl J Med. 2019 Nov 14;381(20):1929-39.

2. Lancet. 2010 Oct 2;376(9747):1155-63.

3. Gynecol Oncol. 2009 Jan;112(1):265-74.

4. Br J Cancer. 2011 Sep 27;105(7):890-6.

5. N Engl J Med. 2016 Dec 1;375(22):2154-64.

In recurrent ovarian cancer, secondary surgery does not extend survival

Phase 3 findings ‘call into question’ merits of surgical cytoreduction

Secondary surgical cytoreduction was feasible but did not extend overall survival among women with platinum-sensitive, recurrent ovarian cancer in a prospective, randomized, phase 3 clinical trial, investigators report.

Women who received platinum-based chemotherapy plus surgery had a median overall survival of about 51 months, compared with 64.7 months for women who received platinum-based chemotherapy and no surgery, according to the results of the Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG)-0213 study, a multicenter, open-label, randomized, phase 3 trial.

These findings “call into question” the merits of surgical cytoreduction, said the authors, led by Robert L. Coleman, MD, of the department of gynecologic oncology and reproductive medicine at the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

Specifically, the shorter overall survival in the surgery group vs. no-surgery group emphasizes the “importance of formally assessing the value of the procedure in clinical care,” said Dr. Coleman and coauthors in the report on GOG-0213. The study was published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Clinical practice guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network currently cite secondary cytoreduction as an option for treatment of patients who experience a treatment-free interval of at least 6 months after a complete remission achieved on prior chemotherapy, the GOG-0213 investigators wrote.

Beyond GOG-0213, there are several other randomized trials underway in this setting, including DESKTOP III, a multicenter study comparing the efficacy of chemotherapy alone to chemotherapy plus additional tumor debulking surgery in women with recurrent platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer.

wrote Dr. Coleman and colleagues.

The GOG-0213 study, conducted in 67 centers, 65 of which were in the United States, had both a chemotherapy objective and a surgical objective in patients with platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer, investigators said.

Results of the chemotherapy objective, published in 2017 in Lancet Oncology, indicated that bevacizumab added to standard chemotherapy, followed by maintenance bevacizumab until progression, improved median overall survival.

The more recently reported results focused on 485 women of who 245 were randomized to receive chemotherapy alone. While 240 were randomized to receive cytoreduction prior to chemotherapy, 15 declined surgery, leaving 225 eligible patients (94%).

The adjusted hazard ratio for death was 1.29 (95% confidence interval, 0.97-1.72; P = 0.08) for surgery, compared with no surgery, which translated into median overall survival times of 50.6 months in the surgery arm and 64.7 months in the no-surgery arm, Dr. Coleman and coauthors reported.

However, 30-day morbidity and mortality were low, at 9% (20 patients) and 0.4% (1 patient), and just 4% of cases (8 patients) were aborted, they added.

Quality of life significantly declined right after secondary cytoreduction, although after recovery no significant differences were found between groups, according to the investigators.

Taken together, those findings “did not indicate that surgery plus chemotherapy was superior to chemotherapy alone,” investigators concluded.

However, several factors in GOG-0213, including longer-than-expected survival times and substantial platinum sensitivity among women in the trial, could have diluted an independent surgical effect, they said.

Dr. Coleman reported disclosures related to several pharmaceutical companies, including Agenus, AstraZeneca, Clovis, GamaMabs, Genmab, Janssen, Medivation, Merck, Regeneron, Roche/Genentech, OncoQuest, and Tesaro.

SOURCE: Coleman RL et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1929-39.

Phase 3 findings ‘call into question’ merits of surgical cytoreduction

Phase 3 findings ‘call into question’ merits of surgical cytoreduction

Secondary surgical cytoreduction was feasible but did not extend overall survival among women with platinum-sensitive, recurrent ovarian cancer in a prospective, randomized, phase 3 clinical trial, investigators report.

Women who received platinum-based chemotherapy plus surgery had a median overall survival of about 51 months, compared with 64.7 months for women who received platinum-based chemotherapy and no surgery, according to the results of the Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG)-0213 study, a multicenter, open-label, randomized, phase 3 trial.

These findings “call into question” the merits of surgical cytoreduction, said the authors, led by Robert L. Coleman, MD, of the department of gynecologic oncology and reproductive medicine at the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

Specifically, the shorter overall survival in the surgery group vs. no-surgery group emphasizes the “importance of formally assessing the value of the procedure in clinical care,” said Dr. Coleman and coauthors in the report on GOG-0213. The study was published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Clinical practice guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network currently cite secondary cytoreduction as an option for treatment of patients who experience a treatment-free interval of at least 6 months after a complete remission achieved on prior chemotherapy, the GOG-0213 investigators wrote.

Beyond GOG-0213, there are several other randomized trials underway in this setting, including DESKTOP III, a multicenter study comparing the efficacy of chemotherapy alone to chemotherapy plus additional tumor debulking surgery in women with recurrent platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer.

wrote Dr. Coleman and colleagues.

The GOG-0213 study, conducted in 67 centers, 65 of which were in the United States, had both a chemotherapy objective and a surgical objective in patients with platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer, investigators said.

Results of the chemotherapy objective, published in 2017 in Lancet Oncology, indicated that bevacizumab added to standard chemotherapy, followed by maintenance bevacizumab until progression, improved median overall survival.

The more recently reported results focused on 485 women of who 245 were randomized to receive chemotherapy alone. While 240 were randomized to receive cytoreduction prior to chemotherapy, 15 declined surgery, leaving 225 eligible patients (94%).

The adjusted hazard ratio for death was 1.29 (95% confidence interval, 0.97-1.72; P = 0.08) for surgery, compared with no surgery, which translated into median overall survival times of 50.6 months in the surgery arm and 64.7 months in the no-surgery arm, Dr. Coleman and coauthors reported.

However, 30-day morbidity and mortality were low, at 9% (20 patients) and 0.4% (1 patient), and just 4% of cases (8 patients) were aborted, they added.

Quality of life significantly declined right after secondary cytoreduction, although after recovery no significant differences were found between groups, according to the investigators.

Taken together, those findings “did not indicate that surgery plus chemotherapy was superior to chemotherapy alone,” investigators concluded.

However, several factors in GOG-0213, including longer-than-expected survival times and substantial platinum sensitivity among women in the trial, could have diluted an independent surgical effect, they said.

Dr. Coleman reported disclosures related to several pharmaceutical companies, including Agenus, AstraZeneca, Clovis, GamaMabs, Genmab, Janssen, Medivation, Merck, Regeneron, Roche/Genentech, OncoQuest, and Tesaro.

SOURCE: Coleman RL et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1929-39.

Secondary surgical cytoreduction was feasible but did not extend overall survival among women with platinum-sensitive, recurrent ovarian cancer in a prospective, randomized, phase 3 clinical trial, investigators report.

Women who received platinum-based chemotherapy plus surgery had a median overall survival of about 51 months, compared with 64.7 months for women who received platinum-based chemotherapy and no surgery, according to the results of the Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG)-0213 study, a multicenter, open-label, randomized, phase 3 trial.

These findings “call into question” the merits of surgical cytoreduction, said the authors, led by Robert L. Coleman, MD, of the department of gynecologic oncology and reproductive medicine at the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

Specifically, the shorter overall survival in the surgery group vs. no-surgery group emphasizes the “importance of formally assessing the value of the procedure in clinical care,” said Dr. Coleman and coauthors in the report on GOG-0213. The study was published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Clinical practice guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network currently cite secondary cytoreduction as an option for treatment of patients who experience a treatment-free interval of at least 6 months after a complete remission achieved on prior chemotherapy, the GOG-0213 investigators wrote.

Beyond GOG-0213, there are several other randomized trials underway in this setting, including DESKTOP III, a multicenter study comparing the efficacy of chemotherapy alone to chemotherapy plus additional tumor debulking surgery in women with recurrent platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer.

wrote Dr. Coleman and colleagues.

The GOG-0213 study, conducted in 67 centers, 65 of which were in the United States, had both a chemotherapy objective and a surgical objective in patients with platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer, investigators said.

Results of the chemotherapy objective, published in 2017 in Lancet Oncology, indicated that bevacizumab added to standard chemotherapy, followed by maintenance bevacizumab until progression, improved median overall survival.

The more recently reported results focused on 485 women of who 245 were randomized to receive chemotherapy alone. While 240 were randomized to receive cytoreduction prior to chemotherapy, 15 declined surgery, leaving 225 eligible patients (94%).

The adjusted hazard ratio for death was 1.29 (95% confidence interval, 0.97-1.72; P = 0.08) for surgery, compared with no surgery, which translated into median overall survival times of 50.6 months in the surgery arm and 64.7 months in the no-surgery arm, Dr. Coleman and coauthors reported.

However, 30-day morbidity and mortality were low, at 9% (20 patients) and 0.4% (1 patient), and just 4% of cases (8 patients) were aborted, they added.

Quality of life significantly declined right after secondary cytoreduction, although after recovery no significant differences were found between groups, according to the investigators.

Taken together, those findings “did not indicate that surgery plus chemotherapy was superior to chemotherapy alone,” investigators concluded.

However, several factors in GOG-0213, including longer-than-expected survival times and substantial platinum sensitivity among women in the trial, could have diluted an independent surgical effect, they said.

Dr. Coleman reported disclosures related to several pharmaceutical companies, including Agenus, AstraZeneca, Clovis, GamaMabs, Genmab, Janssen, Medivation, Merck, Regeneron, Roche/Genentech, OncoQuest, and Tesaro.

SOURCE: Coleman RL et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1929-39.

FROM NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Surgical staging improves cervical cancer outcomes

VANCOUVER – Follow-up oncologic data from the UTERUS-11 trial shows advantages to surgical staging over clinical staging in stage IIB-IVA cervical cancer, with little apparent risk.

Compared with clinical staging using CT, laparoscopic staging led to an improvement in cancer-specific survival, with no delays in treatment or increases in toxicity. It also prompted surgical up-staging and led to treatment changes in 33% of cases. There was no difference in overall survival, but progression-free survival trended towards better outcomes in the surgical-staging group.

The new study presents 5-year follow-up data from patients randomly assigned to surgical (n = 121) or clinical staging (n = 114). The original study, published in 2017 (Oncology. 2017;92[4]:213-20), reported that 33% of surgical-staging patients in the surgical staging were up-staged as a result, compared with 6% who were revealed to have positive paraaortic lymph nodes through a CT-guided core biopsy after suspicious CT results. After a median follow-up of 90 months in both arms, overall survival was similar between the two groups, and progression-free survival trended towards an improvement in the surgical-staging group (P = .088). Cancer-specific survival was better in the surgical-staging arm, compared with clinical staging (P=.028), Audrey Tsunoda, MD, PhD, reported.

Surgical staging didn’t impact the toxicity profile, said Dr. Tsunoda, a surgical oncologist focused in gynecologic cancer surgery who practices at Hospital Erasto Gaertner in Curitiba, Brazil.

The mean time to initiation of chemoradiotherapy following surgery was 14 days (range, 7-21 days) after surgery: 64% had intensity-modulated radiotherapy and 36% had three-dimensional radiotherapy. There were no grade 5 toxicities during chemoradiotherapy and both groups had similar gastrointestinal and genitourinary toxicity profiles. About 97% of the surgical staging procedures were conducted laparoscopically. Two patients had a blood loss of more than 500 cc, and two had a delay to primary chemoradiotherapy (4 days and 5 days). One patient had to be converted to an open approach because of obesity and severe adhesions, and there was no intraoperative mortality.

Previous retrospective studies examining surgical staging in these patients led to confusion and disagreements among guidelines. Surgical staging is clearly associated with increased up-staging, but the oncologic benefit is uncertain. The LiLACS study attempted to address the question with prospective data, but failed to accrue enough patients and was later abandoned. That leaves the UTERUS-11 study, the initial results of which were published in 2017, as the first prospective study to examine the benefit of surgical staging.

The new follow-up results suggest a benefit to surgical staging, but they leave an important question unanswered, according to Lois Ramondetta, MD, professor of gynecologic oncology at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, who served as a discussant at the meeting sponsored by AAGL. “Paraaortic lymph node status does connect to clinical benefit, but the question is really [whether] the removal of the lymph nodes accounts for the benefit, or is the identification of them and the change in treatment plan responsible? [If the latter is the case], a PET scan would have done a better job,” said Dr. Ramondetta. “The question remains unanswered, but I think this was huge progress in trying to answer it. Future studies need to incorporate a PET scan.”

Dr. Tsunoda has received honoraria from AstraZeneca and Roche. Dr. Ramondetta has no relevant financial disclosures.

VANCOUVER – Follow-up oncologic data from the UTERUS-11 trial shows advantages to surgical staging over clinical staging in stage IIB-IVA cervical cancer, with little apparent risk.

Compared with clinical staging using CT, laparoscopic staging led to an improvement in cancer-specific survival, with no delays in treatment or increases in toxicity. It also prompted surgical up-staging and led to treatment changes in 33% of cases. There was no difference in overall survival, but progression-free survival trended towards better outcomes in the surgical-staging group.

The new study presents 5-year follow-up data from patients randomly assigned to surgical (n = 121) or clinical staging (n = 114). The original study, published in 2017 (Oncology. 2017;92[4]:213-20), reported that 33% of surgical-staging patients in the surgical staging were up-staged as a result, compared with 6% who were revealed to have positive paraaortic lymph nodes through a CT-guided core biopsy after suspicious CT results. After a median follow-up of 90 months in both arms, overall survival was similar between the two groups, and progression-free survival trended towards an improvement in the surgical-staging group (P = .088). Cancer-specific survival was better in the surgical-staging arm, compared with clinical staging (P=.028), Audrey Tsunoda, MD, PhD, reported.

Surgical staging didn’t impact the toxicity profile, said Dr. Tsunoda, a surgical oncologist focused in gynecologic cancer surgery who practices at Hospital Erasto Gaertner in Curitiba, Brazil.

The mean time to initiation of chemoradiotherapy following surgery was 14 days (range, 7-21 days) after surgery: 64% had intensity-modulated radiotherapy and 36% had three-dimensional radiotherapy. There were no grade 5 toxicities during chemoradiotherapy and both groups had similar gastrointestinal and genitourinary toxicity profiles. About 97% of the surgical staging procedures were conducted laparoscopically. Two patients had a blood loss of more than 500 cc, and two had a delay to primary chemoradiotherapy (4 days and 5 days). One patient had to be converted to an open approach because of obesity and severe adhesions, and there was no intraoperative mortality.

Previous retrospective studies examining surgical staging in these patients led to confusion and disagreements among guidelines. Surgical staging is clearly associated with increased up-staging, but the oncologic benefit is uncertain. The LiLACS study attempted to address the question with prospective data, but failed to accrue enough patients and was later abandoned. That leaves the UTERUS-11 study, the initial results of which were published in 2017, as the first prospective study to examine the benefit of surgical staging.

The new follow-up results suggest a benefit to surgical staging, but they leave an important question unanswered, according to Lois Ramondetta, MD, professor of gynecologic oncology at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, who served as a discussant at the meeting sponsored by AAGL. “Paraaortic lymph node status does connect to clinical benefit, but the question is really [whether] the removal of the lymph nodes accounts for the benefit, or is the identification of them and the change in treatment plan responsible? [If the latter is the case], a PET scan would have done a better job,” said Dr. Ramondetta. “The question remains unanswered, but I think this was huge progress in trying to answer it. Future studies need to incorporate a PET scan.”

Dr. Tsunoda has received honoraria from AstraZeneca and Roche. Dr. Ramondetta has no relevant financial disclosures.

VANCOUVER – Follow-up oncologic data from the UTERUS-11 trial shows advantages to surgical staging over clinical staging in stage IIB-IVA cervical cancer, with little apparent risk.

Compared with clinical staging using CT, laparoscopic staging led to an improvement in cancer-specific survival, with no delays in treatment or increases in toxicity. It also prompted surgical up-staging and led to treatment changes in 33% of cases. There was no difference in overall survival, but progression-free survival trended towards better outcomes in the surgical-staging group.

The new study presents 5-year follow-up data from patients randomly assigned to surgical (n = 121) or clinical staging (n = 114). The original study, published in 2017 (Oncology. 2017;92[4]:213-20), reported that 33% of surgical-staging patients in the surgical staging were up-staged as a result, compared with 6% who were revealed to have positive paraaortic lymph nodes through a CT-guided core biopsy after suspicious CT results. After a median follow-up of 90 months in both arms, overall survival was similar between the two groups, and progression-free survival trended towards an improvement in the surgical-staging group (P = .088). Cancer-specific survival was better in the surgical-staging arm, compared with clinical staging (P=.028), Audrey Tsunoda, MD, PhD, reported.

Surgical staging didn’t impact the toxicity profile, said Dr. Tsunoda, a surgical oncologist focused in gynecologic cancer surgery who practices at Hospital Erasto Gaertner in Curitiba, Brazil.

The mean time to initiation of chemoradiotherapy following surgery was 14 days (range, 7-21 days) after surgery: 64% had intensity-modulated radiotherapy and 36% had three-dimensional radiotherapy. There were no grade 5 toxicities during chemoradiotherapy and both groups had similar gastrointestinal and genitourinary toxicity profiles. About 97% of the surgical staging procedures were conducted laparoscopically. Two patients had a blood loss of more than 500 cc, and two had a delay to primary chemoradiotherapy (4 days and 5 days). One patient had to be converted to an open approach because of obesity and severe adhesions, and there was no intraoperative mortality.

Previous retrospective studies examining surgical staging in these patients led to confusion and disagreements among guidelines. Surgical staging is clearly associated with increased up-staging, but the oncologic benefit is uncertain. The LiLACS study attempted to address the question with prospective data, but failed to accrue enough patients and was later abandoned. That leaves the UTERUS-11 study, the initial results of which were published in 2017, as the first prospective study to examine the benefit of surgical staging.

The new follow-up results suggest a benefit to surgical staging, but they leave an important question unanswered, according to Lois Ramondetta, MD, professor of gynecologic oncology at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, who served as a discussant at the meeting sponsored by AAGL. “Paraaortic lymph node status does connect to clinical benefit, but the question is really [whether] the removal of the lymph nodes accounts for the benefit, or is the identification of them and the change in treatment plan responsible? [If the latter is the case], a PET scan would have done a better job,” said Dr. Ramondetta. “The question remains unanswered, but I think this was huge progress in trying to answer it. Future studies need to incorporate a PET scan.”

Dr. Tsunoda has received honoraria from AstraZeneca and Roche. Dr. Ramondetta has no relevant financial disclosures.

REPORTING FROM THE AAGL GLOBAL CONGRESS

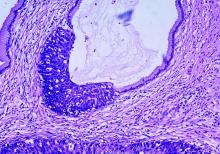

Sentinel node biopsy safe for women with vulval cancer

Women with vulval cancer who have a negative sentinel node biopsy have a low risk of recurrence and good disease-specific survival outcomes, investigators report.

One of two current standard treatment approaches for early-stage vulval cancer is radical excision of the tumor and inguinofemoral lymph node dissection, wrote Ligita P. Froeding, MD, of Copenhagen University Hospital Rigshospitalet, and coauthors. Their report is in Gynecologic Oncology. However, this procedure is associated with the disabling complication of leg lymphedema, which can significantly affect a woman’s quality of life.

Radical excision with sentinel biopsy is also an option, but the authors said large, population-based studies on the safety of this procedure when performed outside multicenter clinical trials were lacking.

In a prospective, nationwide cohort study, researchers analyzed data from 190 patients with vulval cancer who underwent the sentinel node procedure and had a negative biopsy. Of these, 73 patients had a unilateral procedure and 117 had a bilateral biopsy.

Over a median follow-up of 30 months’ follow-up, 32 patients (16.8%) died – 12 (37.5%) of vulval cancer and 20 (62.5%) from other causes. The 3-year overall survival rate was 84% and disease-specific survival was 93%.

The overall rate of recurrence in these sentinel node–negative women was 12.1% during the follow-up period. Fourteen patients (7.4%) experienced an isolated local vulval recurrence at a median time of 16 months after their primary treatment, and eight of these patients subsequently underwent inguinofemoral lymph node dissection following treatment of the recurrence. Three patients in this group died from vulval cancer, so the 3-year overall survival rate for patients with recurrent disease was 58%.

Four patients developed an isolated groin recurrence at a median of 12 months, and were treated with a combination of inguinofemoral lymph node dissection and chemoradiation. Two then developed a second recurrence.

Histopathological revision of original sentinel node specimens from the four women who experienced groin recurrences revealed that two patients actually had metastases at the time of the sentinel node procedure. In one case there were scattered tumor cells measuring less than 0.1 mm, while in the other there was a metastasis measuring 0.9 mm that was seen in six consecutive slides.

The authors noted that the failure to detect these metastases occurred despite strict adherence to histopathological procedure protocols. They suggested the first misdiagnosis may have been the result of the pathologist’s reluctance to make a histological diagnosis with so few tumor cells present. The second slide was originally screened microscopically by a specially trained medical laboratory technician, before being signed out by a pathologist, which “potentially decreases the pathologist’s diagnostic awareness,” they suggested.

“In conclusion, our study showed that the SN procedure is safe in selected VC patients when the current guidelines are strictly followed, and the procedure is performed in specialized gynecological oncology centers with a high volume of patients.”

No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Froeding L et al. Gynecol Oncol 2019 Nov 8. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2019.10.024.

Women with vulval cancer who have a negative sentinel node biopsy have a low risk of recurrence and good disease-specific survival outcomes, investigators report.

One of two current standard treatment approaches for early-stage vulval cancer is radical excision of the tumor and inguinofemoral lymph node dissection, wrote Ligita P. Froeding, MD, of Copenhagen University Hospital Rigshospitalet, and coauthors. Their report is in Gynecologic Oncology. However, this procedure is associated with the disabling complication of leg lymphedema, which can significantly affect a woman’s quality of life.

Radical excision with sentinel biopsy is also an option, but the authors said large, population-based studies on the safety of this procedure when performed outside multicenter clinical trials were lacking.

In a prospective, nationwide cohort study, researchers analyzed data from 190 patients with vulval cancer who underwent the sentinel node procedure and had a negative biopsy. Of these, 73 patients had a unilateral procedure and 117 had a bilateral biopsy.

Over a median follow-up of 30 months’ follow-up, 32 patients (16.8%) died – 12 (37.5%) of vulval cancer and 20 (62.5%) from other causes. The 3-year overall survival rate was 84% and disease-specific survival was 93%.

The overall rate of recurrence in these sentinel node–negative women was 12.1% during the follow-up period. Fourteen patients (7.4%) experienced an isolated local vulval recurrence at a median time of 16 months after their primary treatment, and eight of these patients subsequently underwent inguinofemoral lymph node dissection following treatment of the recurrence. Three patients in this group died from vulval cancer, so the 3-year overall survival rate for patients with recurrent disease was 58%.

Four patients developed an isolated groin recurrence at a median of 12 months, and were treated with a combination of inguinofemoral lymph node dissection and chemoradiation. Two then developed a second recurrence.

Histopathological revision of original sentinel node specimens from the four women who experienced groin recurrences revealed that two patients actually had metastases at the time of the sentinel node procedure. In one case there were scattered tumor cells measuring less than 0.1 mm, while in the other there was a metastasis measuring 0.9 mm that was seen in six consecutive slides.

The authors noted that the failure to detect these metastases occurred despite strict adherence to histopathological procedure protocols. They suggested the first misdiagnosis may have been the result of the pathologist’s reluctance to make a histological diagnosis with so few tumor cells present. The second slide was originally screened microscopically by a specially trained medical laboratory technician, before being signed out by a pathologist, which “potentially decreases the pathologist’s diagnostic awareness,” they suggested.

“In conclusion, our study showed that the SN procedure is safe in selected VC patients when the current guidelines are strictly followed, and the procedure is performed in specialized gynecological oncology centers with a high volume of patients.”

No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Froeding L et al. Gynecol Oncol 2019 Nov 8. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2019.10.024.

Women with vulval cancer who have a negative sentinel node biopsy have a low risk of recurrence and good disease-specific survival outcomes, investigators report.

One of two current standard treatment approaches for early-stage vulval cancer is radical excision of the tumor and inguinofemoral lymph node dissection, wrote Ligita P. Froeding, MD, of Copenhagen University Hospital Rigshospitalet, and coauthors. Their report is in Gynecologic Oncology. However, this procedure is associated with the disabling complication of leg lymphedema, which can significantly affect a woman’s quality of life.

Radical excision with sentinel biopsy is also an option, but the authors said large, population-based studies on the safety of this procedure when performed outside multicenter clinical trials were lacking.

In a prospective, nationwide cohort study, researchers analyzed data from 190 patients with vulval cancer who underwent the sentinel node procedure and had a negative biopsy. Of these, 73 patients had a unilateral procedure and 117 had a bilateral biopsy.

Over a median follow-up of 30 months’ follow-up, 32 patients (16.8%) died – 12 (37.5%) of vulval cancer and 20 (62.5%) from other causes. The 3-year overall survival rate was 84% and disease-specific survival was 93%.

The overall rate of recurrence in these sentinel node–negative women was 12.1% during the follow-up period. Fourteen patients (7.4%) experienced an isolated local vulval recurrence at a median time of 16 months after their primary treatment, and eight of these patients subsequently underwent inguinofemoral lymph node dissection following treatment of the recurrence. Three patients in this group died from vulval cancer, so the 3-year overall survival rate for patients with recurrent disease was 58%.

Four patients developed an isolated groin recurrence at a median of 12 months, and were treated with a combination of inguinofemoral lymph node dissection and chemoradiation. Two then developed a second recurrence.

Histopathological revision of original sentinel node specimens from the four women who experienced groin recurrences revealed that two patients actually had metastases at the time of the sentinel node procedure. In one case there were scattered tumor cells measuring less than 0.1 mm, while in the other there was a metastasis measuring 0.9 mm that was seen in six consecutive slides.

The authors noted that the failure to detect these metastases occurred despite strict adherence to histopathological procedure protocols. They suggested the first misdiagnosis may have been the result of the pathologist’s reluctance to make a histological diagnosis with so few tumor cells present. The second slide was originally screened microscopically by a specially trained medical laboratory technician, before being signed out by a pathologist, which “potentially decreases the pathologist’s diagnostic awareness,” they suggested.

“In conclusion, our study showed that the SN procedure is safe in selected VC patients when the current guidelines are strictly followed, and the procedure is performed in specialized gynecological oncology centers with a high volume of patients.”

No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Froeding L et al. Gynecol Oncol 2019 Nov 8. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2019.10.024.

FROM GYNECOLOGIC ONCOLOGY

Molecule exhibits activity in heavily pretreated, HER2-positive solid tumors

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD – PRS-343, a 4-1BB/HER2 bispecific molecule, has demonstrated safety and antitumor activity in patients with heavily pretreated, HER2-positive solid tumors, an investigator reported at the annual meeting of the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer.

In a phase 1 trial of 18 evaluable patients, PRS-343 produced partial responses in 2 patients and enabled 8 patients to maintain stable disease. PRS-343 was considered well tolerated at all doses and schedules tested.

“PRS-343 is a bispecific construct targeting HER2 as well as 4-1BB,” said Geoffrey Y. Ku, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York. “The HER2 component of the molecule localizes it into the tumor microenvironment of any HER2-positive cells. If the density of the HER2 protein is high enough, that facilitates cross-linkage of 4-1BB.

“4-1BB is an immune agonist that’s present in activated T cells, and cross-linkage helps to improve T-cell exhaustion and is also critical for T-cell expansion. The idea is that, by localizing 4-1BB activation to the tumor microenvironment, we can avoid some of the systemic toxicities associated with naked 4-1BB antibodies,” Dr. Ku added.

The ongoing, phase 1 trial of PRS-343 (NCT03330561) has enrolled 53 patients with a range of HER2-positive malignancies. To be eligible, patients must have progressed on standard therapy or have a tumor for which no standard therapy is available.

The most common diagnosis among enrolled patients is gastroesophageal cancer (n = 19), followed by breast cancer (n = 14), gynecologic cancers (n = 6), colorectal cancer (n = 5), and other malignancies.

The patients’ median age at baseline was 61 years (range, 29-92 years), and a majority were female (62%). Most patients (79%) had received three or more prior lines of therapy, including anti-HER2 treatments. Breast cancer patients had received a median of four anti-HER2 treatments, and gastric cancer patients had received a median of two.

The patients have been treated with PRS-343 at 11 dose levels, ranging from 0.0005 mg/kg to 8 mg/kg, given every 3 weeks. The highest dose, 8 mg/kg, was also given every 2 weeks.

Treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) included infusion-related reactions (9%), fatigue (9%), chills (6%), flushing (6%), nausea (6%), diarrhea (6%), vomiting (5%), and noncardiac chest pain (4%).

“This was an extremely well-tolerated drug,” Dr. Ku said. “Out of 111 TRAEs, only a tiny proportion were grade 3, and toxicities mostly clustered around infusion-related reactions, constitutional symptoms, as well as gastrointestinal symptoms.”

Grade 3 TRAEs included infusion-related reactions (2%), fatigue (1%), flushing (3%), and noncardiac chest pain (1%). There were no grade 4-5 TRAEs.

At the data cutoff (Oct. 23, 2019), 18 patients were evaluable for a response at active dose levels (2.5 mg/kg, 5 mg/kg, and 8 mg/kg).

Two patients achieved a partial response, and eight had stable disease. “This translates to a response rate of 11% and a disease control rate of 55%,” Dr. Ku noted.

Both responders received PRS-343 at 8 mg/kg every 2 weeks. One of these patients had stage 4 gastric adenocarcinoma, and one had stage 4 gynecologic carcinoma.

Of the eight patients with stable disease, three received PRS-343 at 8 mg/kg every 2 weeks, two received 8 mg/kg every 3 weeks, one received the 5 mg/kg dose, and two received the 2.5 mg/kg dose.

Dr. Ku noted that the average time on treatment significantly increased in patients who received PRS-343 at 8 mg/kg every 2 weeks. Additionally, both responders and patients with stable disease had a “clear increase” in CD8+ T cells.

“[PRS-343] has demonstrated antitumor activity in heavily pretreated patients across multiple tumor types, and the treatment history, specifically the receipt of prior anti-HER2 therapy, indicates this is a 4-1BB-driven mechanism of action,” Dr. Ku said. “Based on these results, future studies are planned for continued development in defined HER2-positive indications.”

The current study is sponsored by Pieris Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Ku disclosed relationships with Arog Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, Eli Lilly, Merck, Zymeworks, and Pieris Pharmaceuticals.

SOURCE: Ku GY et al. SITC 2019, Abstract O82.

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD – PRS-343, a 4-1BB/HER2 bispecific molecule, has demonstrated safety and antitumor activity in patients with heavily pretreated, HER2-positive solid tumors, an investigator reported at the annual meeting of the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer.

In a phase 1 trial of 18 evaluable patients, PRS-343 produced partial responses in 2 patients and enabled 8 patients to maintain stable disease. PRS-343 was considered well tolerated at all doses and schedules tested.

“PRS-343 is a bispecific construct targeting HER2 as well as 4-1BB,” said Geoffrey Y. Ku, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York. “The HER2 component of the molecule localizes it into the tumor microenvironment of any HER2-positive cells. If the density of the HER2 protein is high enough, that facilitates cross-linkage of 4-1BB.

“4-1BB is an immune agonist that’s present in activated T cells, and cross-linkage helps to improve T-cell exhaustion and is also critical for T-cell expansion. The idea is that, by localizing 4-1BB activation to the tumor microenvironment, we can avoid some of the systemic toxicities associated with naked 4-1BB antibodies,” Dr. Ku added.

The ongoing, phase 1 trial of PRS-343 (NCT03330561) has enrolled 53 patients with a range of HER2-positive malignancies. To be eligible, patients must have progressed on standard therapy or have a tumor for which no standard therapy is available.

The most common diagnosis among enrolled patients is gastroesophageal cancer (n = 19), followed by breast cancer (n = 14), gynecologic cancers (n = 6), colorectal cancer (n = 5), and other malignancies.

The patients’ median age at baseline was 61 years (range, 29-92 years), and a majority were female (62%). Most patients (79%) had received three or more prior lines of therapy, including anti-HER2 treatments. Breast cancer patients had received a median of four anti-HER2 treatments, and gastric cancer patients had received a median of two.

The patients have been treated with PRS-343 at 11 dose levels, ranging from 0.0005 mg/kg to 8 mg/kg, given every 3 weeks. The highest dose, 8 mg/kg, was also given every 2 weeks.

Treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) included infusion-related reactions (9%), fatigue (9%), chills (6%), flushing (6%), nausea (6%), diarrhea (6%), vomiting (5%), and noncardiac chest pain (4%).

“This was an extremely well-tolerated drug,” Dr. Ku said. “Out of 111 TRAEs, only a tiny proportion were grade 3, and toxicities mostly clustered around infusion-related reactions, constitutional symptoms, as well as gastrointestinal symptoms.”

Grade 3 TRAEs included infusion-related reactions (2%), fatigue (1%), flushing (3%), and noncardiac chest pain (1%). There were no grade 4-5 TRAEs.

At the data cutoff (Oct. 23, 2019), 18 patients were evaluable for a response at active dose levels (2.5 mg/kg, 5 mg/kg, and 8 mg/kg).

Two patients achieved a partial response, and eight had stable disease. “This translates to a response rate of 11% and a disease control rate of 55%,” Dr. Ku noted.

Both responders received PRS-343 at 8 mg/kg every 2 weeks. One of these patients had stage 4 gastric adenocarcinoma, and one had stage 4 gynecologic carcinoma.

Of the eight patients with stable disease, three received PRS-343 at 8 mg/kg every 2 weeks, two received 8 mg/kg every 3 weeks, one received the 5 mg/kg dose, and two received the 2.5 mg/kg dose.

Dr. Ku noted that the average time on treatment significantly increased in patients who received PRS-343 at 8 mg/kg every 2 weeks. Additionally, both responders and patients with stable disease had a “clear increase” in CD8+ T cells.

“[PRS-343] has demonstrated antitumor activity in heavily pretreated patients across multiple tumor types, and the treatment history, specifically the receipt of prior anti-HER2 therapy, indicates this is a 4-1BB-driven mechanism of action,” Dr. Ku said. “Based on these results, future studies are planned for continued development in defined HER2-positive indications.”

The current study is sponsored by Pieris Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Ku disclosed relationships with Arog Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, Eli Lilly, Merck, Zymeworks, and Pieris Pharmaceuticals.

SOURCE: Ku GY et al. SITC 2019, Abstract O82.

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD – PRS-343, a 4-1BB/HER2 bispecific molecule, has demonstrated safety and antitumor activity in patients with heavily pretreated, HER2-positive solid tumors, an investigator reported at the annual meeting of the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer.

In a phase 1 trial of 18 evaluable patients, PRS-343 produced partial responses in 2 patients and enabled 8 patients to maintain stable disease. PRS-343 was considered well tolerated at all doses and schedules tested.

“PRS-343 is a bispecific construct targeting HER2 as well as 4-1BB,” said Geoffrey Y. Ku, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York. “The HER2 component of the molecule localizes it into the tumor microenvironment of any HER2-positive cells. If the density of the HER2 protein is high enough, that facilitates cross-linkage of 4-1BB.

“4-1BB is an immune agonist that’s present in activated T cells, and cross-linkage helps to improve T-cell exhaustion and is also critical for T-cell expansion. The idea is that, by localizing 4-1BB activation to the tumor microenvironment, we can avoid some of the systemic toxicities associated with naked 4-1BB antibodies,” Dr. Ku added.

The ongoing, phase 1 trial of PRS-343 (NCT03330561) has enrolled 53 patients with a range of HER2-positive malignancies. To be eligible, patients must have progressed on standard therapy or have a tumor for which no standard therapy is available.

The most common diagnosis among enrolled patients is gastroesophageal cancer (n = 19), followed by breast cancer (n = 14), gynecologic cancers (n = 6), colorectal cancer (n = 5), and other malignancies.

The patients’ median age at baseline was 61 years (range, 29-92 years), and a majority were female (62%). Most patients (79%) had received three or more prior lines of therapy, including anti-HER2 treatments. Breast cancer patients had received a median of four anti-HER2 treatments, and gastric cancer patients had received a median of two.

The patients have been treated with PRS-343 at 11 dose levels, ranging from 0.0005 mg/kg to 8 mg/kg, given every 3 weeks. The highest dose, 8 mg/kg, was also given every 2 weeks.

Treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) included infusion-related reactions (9%), fatigue (9%), chills (6%), flushing (6%), nausea (6%), diarrhea (6%), vomiting (5%), and noncardiac chest pain (4%).

“This was an extremely well-tolerated drug,” Dr. Ku said. “Out of 111 TRAEs, only a tiny proportion were grade 3, and toxicities mostly clustered around infusion-related reactions, constitutional symptoms, as well as gastrointestinal symptoms.”

Grade 3 TRAEs included infusion-related reactions (2%), fatigue (1%), flushing (3%), and noncardiac chest pain (1%). There were no grade 4-5 TRAEs.

At the data cutoff (Oct. 23, 2019), 18 patients were evaluable for a response at active dose levels (2.5 mg/kg, 5 mg/kg, and 8 mg/kg).

Two patients achieved a partial response, and eight had stable disease. “This translates to a response rate of 11% and a disease control rate of 55%,” Dr. Ku noted.

Both responders received PRS-343 at 8 mg/kg every 2 weeks. One of these patients had stage 4 gastric adenocarcinoma, and one had stage 4 gynecologic carcinoma.

Of the eight patients with stable disease, three received PRS-343 at 8 mg/kg every 2 weeks, two received 8 mg/kg every 3 weeks, one received the 5 mg/kg dose, and two received the 2.5 mg/kg dose.

Dr. Ku noted that the average time on treatment significantly increased in patients who received PRS-343 at 8 mg/kg every 2 weeks. Additionally, both responders and patients with stable disease had a “clear increase” in CD8+ T cells.

“[PRS-343] has demonstrated antitumor activity in heavily pretreated patients across multiple tumor types, and the treatment history, specifically the receipt of prior anti-HER2 therapy, indicates this is a 4-1BB-driven mechanism of action,” Dr. Ku said. “Based on these results, future studies are planned for continued development in defined HER2-positive indications.”

The current study is sponsored by Pieris Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Ku disclosed relationships with Arog Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, Eli Lilly, Merck, Zymeworks, and Pieris Pharmaceuticals.

SOURCE: Ku GY et al. SITC 2019, Abstract O82.

REPORTING FROM SITC 2019

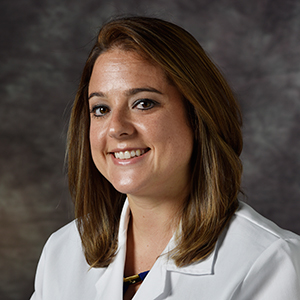

Does BSO status affect health outcomes for women taking estrogen for menopause?

Do health effects of menopausal estrogen therapy differ between women with bilateral oophorectomy versus those with conserved ovaries? To answer this question a group of investigators performed a subanalysis of the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) Estrogen-Alone Trial,1 which included 40 clinical centers across the United States. They examined estrogen therapy outcomes by bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) status, with additional stratification by 10-year age groups in 9,939 women aged 50 to 79 years with prior hysterectomy and known oophorectomy status. In the WHI trial, women were randomly assigned to conjugated equine estrogens (CEE) 0.625 mg/d or placebo for a median of 7.2 years. Investigators assessed the incidence of coronary heart disease and invasive breast cancer (the trial’s 2 primary end points), all-cause mortality, and a “global index”—these end points plus stroke, pulmonary embolism, colorectal cancer, and hip fracture—during the intervention phase and 18-year cumulative follow-up.

OBG Management caught up with lead author JoAnn E. Manson, MD, DrPH, NCMP, to discuss the study’s results.

OBG Management : How many women undergo BSO with their hysterectomy?

Dr. JoAnn E. Manson, MD, DrPH, NCMP: Of the 425,000 women who undergo hysterectomy in the United States for benign reasons each year,2,3 about 40% of them undergo BSO—so between 150,000 and 200,000 women per year undergo BSO with their hysterectomy.4,5

OBG Management : Although BSO is performed with hysterectomy to minimize patients’ future ovarian cancer risk, does BSO have health risks of its own, and how has estrogen been shown to affect these risks?

Dr. Manson: First, yes, BSO has been associated with health risks, especially when it is performed at a young age, such as before age 45. It has been linked to an increased risk of heart disease, osteoporosis, cognitive decline, and all-cause mortality. According to observational studies, estrogen therapy appears to offset many of these risks, particularly those related to heart disease and osteoporosis (the evidence is less clear on cognitive deficits).5

OBG Management : What did you find in your trial when you randomly assigned women in the age groups of 50 to 79 who underwent hysterectomy with and without BSO to estrogen therapy or placebo?

Dr. Manson: The WHI is the first study to be conducted in a randomized trial setting to analyze the health risks and benefits of estrogen therapy according to whether or not women had their ovaries removed. What we found was that the woman’s age had a strong influence on the effects of estrogen therapy among women who had BSO but only a negligible effect among women who had conserved ovaries. Overall, across the full age range, the effects of estrogen therapy did not differ substantially between women who had a BSO and those who had their ovaries conserved.

However, there were major differences by age group among the women who had BSO. A significant 32% reduction in all-cause mortality emerged during the 18-year follow-up period among the younger women (below age 60) who had BSO when they received estrogen therapy as compared with placebo. By contrast, the women who had conserved ovaries did not have this significant reduction in all-cause mortality, or in most of the other outcomes on estrogen compared with placebo. Overall, the effects of estrogen therapy tended to be relatively neutral in the women with conserved ovaries.

Now, the reduction in all-cause mortality with estrogen therapy was particularly pronounced among women who had BSO before age 45. They had a 40% statistically significant reduction in all-cause mortality with estrogen therapy compared with placebo. Also, among the women with BSO, there was a strong association between the timing of estrogen initiation and the magnitude of reduction in mortality. Women who started the estrogen therapy within 10 years of having the BSO had a 34% significant reduction in all-cause mortality, and those who started estrogen more than 20 years after having their ovaries removed had no reduction in mortality.

Continue to:

OBG Management : Do your data give support to the timing hypothesis?

Dr. Manson: Yes, our findings do support a timing hypothesis that was particularly pronounced for women who underwent BSO. It was the women who had early surgical menopause (before age 45) and those who started the estrogen therapy within 10 years of having their ovaries removed who had the greatest reduction in all-cause mortality and the most favorable benefit-risk profile from hormone therapy. So, the results do lend support to the timing hypothesis.

By contrast, women who had BSO at hysterectomy and began hormone therapy at age 70 or older had net adverse effects from hormone therapy. They posted a 40% increase in the global index—which is a summary measure of adverse effects on cardiovascular disease, cancer, and other major health outcomes. So, the women with BSO who were randomized in the trial at age 70 and older, had unfavorable results from estrogen therapy and an increase in the global index, in contrast to the women who were below age 60 or within 10 years of menopause.

OBG Management : Given your study findings, in which women would you recommend estrogen therapy? And are there groups of women in which you would advise avoiding estrogen therapy?

Dr. Manson: Current guidelines6,7 recommend estrogen therapy for women who have early menopause, particularly an early surgical menopause and BSO prior to the average age at natural menopause. Unless the woman has contraindications to estrogen therapy, the recommendations are to treat with estrogen until the average age of menopause—until about age 50 to 51.

Our study findings provide reassurance that, if a woman continues to have indications for estrogen (vasomotor symptoms, or other indications for estrogen therapy), there is relative safety of continuing estrogen-alone therapy through her 50s, until age 60. For example, a woman who, after the average age of menopause continues to have vasomotor symptoms, or if she has bone health problems, our study would suggest that estrogen therapy would continue to have a favorable benefit-risk profile until at least the age of 60. Decisions would have to be individualized, especially after age 60, with shared decision-making particularly important for those decisions. (Some women, depending on their risk profile, may continue to be candidates for estrogen therapy past age 60.)

So, this study provides reassurance regarding use of estrogen therapy for women in their 50s if they have had BSO. Actually, the women who had conserved ovaries also had relative safety with estrogen therapy until age 60. They just didn’t show the significant benefits for all-cause mortality. Overall, their pattern of health-related benefits and risks was neutral. Thus, if vasomotor symptom management, quality of life benefits, or bone health effects are sought, taking hormone therapy is a quite reasonable choice for these women.

By contrast, women who have had a BSO and are age 70 or older should really avoid initiating estrogen therapy because it would follow a prolonged period of estrogen deficiency, or very low estrogen levels, and these women appeared to have a net adverse effect from initiating hormone therapy (with increases in the global index found).

Continue to:

OBG Management : Did taking estrogen therapy prior to trial enrollment make a difference when it came to study outcomes?

Dr. Manson: We found minimal if any effect in our analyses. In fact, even the women who did not have prior (pre-randomization) use of estrogen therapy tended to do well on estrogen-alone therapy if they were younger than age 60. This was particularly true for the women who had BSO. Even if they had not used estrogen previously, and they were many years past the BSO, they still did well on estrogen therapy if they were below age 60.

1. Manson JE, Aragaki AK, Bassuk SS. Menopausal estrogen-alone therapy and health outcomes in women with and without bilateral oophorectomy: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2019 September 10. doi:10.7326/M19-0274.

2. Einarsson J. Are hysterectomy volumes in the US really falling? Contemporary OB/GYN. 1 September 2017. www.contemporaryobgyn.net/gynecology/are-hysterectomy-volumes-us-really-falling. November 4, 2019.

3. Temkin SM, Minasian L, Noone AM. The end of the hysterectomy epidemic and endometrial cancer incidence: what are the unintended consequences of declining hysterectomy rates? Front Oncol. 2016;6:89.

4. Doll KM, Dusetzina SB, Robinson W. Trends in inpatient and outpatient hysterectomy and oophorectomy rates among commercially insured women in the United States, 2000-2014. JAMA Surg. 2016;151:876-877.

5. Adelman MR, Sharp HT. Ovarian conservation vs removal at the time of benign hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218:269-279.

6. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 141: management of menopausal symptoms [published corrections appear in: Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(1):166. and Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(3):604]. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:202-216.

7. The 2017 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2017;24:728-753.

Do health effects of menopausal estrogen therapy differ between women with bilateral oophorectomy versus those with conserved ovaries? To answer this question a group of investigators performed a subanalysis of the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) Estrogen-Alone Trial,1 which included 40 clinical centers across the United States. They examined estrogen therapy outcomes by bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) status, with additional stratification by 10-year age groups in 9,939 women aged 50 to 79 years with prior hysterectomy and known oophorectomy status. In the WHI trial, women were randomly assigned to conjugated equine estrogens (CEE) 0.625 mg/d or placebo for a median of 7.2 years. Investigators assessed the incidence of coronary heart disease and invasive breast cancer (the trial’s 2 primary end points), all-cause mortality, and a “global index”—these end points plus stroke, pulmonary embolism, colorectal cancer, and hip fracture—during the intervention phase and 18-year cumulative follow-up.

OBG Management caught up with lead author JoAnn E. Manson, MD, DrPH, NCMP, to discuss the study’s results.

OBG Management : How many women undergo BSO with their hysterectomy?

Dr. JoAnn E. Manson, MD, DrPH, NCMP: Of the 425,000 women who undergo hysterectomy in the United States for benign reasons each year,2,3 about 40% of them undergo BSO—so between 150,000 and 200,000 women per year undergo BSO with their hysterectomy.4,5

OBG Management : Although BSO is performed with hysterectomy to minimize patients’ future ovarian cancer risk, does BSO have health risks of its own, and how has estrogen been shown to affect these risks?

Dr. Manson: First, yes, BSO has been associated with health risks, especially when it is performed at a young age, such as before age 45. It has been linked to an increased risk of heart disease, osteoporosis, cognitive decline, and all-cause mortality. According to observational studies, estrogen therapy appears to offset many of these risks, particularly those related to heart disease and osteoporosis (the evidence is less clear on cognitive deficits).5

OBG Management : What did you find in your trial when you randomly assigned women in the age groups of 50 to 79 who underwent hysterectomy with and without BSO to estrogen therapy or placebo?