User login

Veliparib improves PFS in high-grade serous epithelial ovarian cancer

BARCELONA – (HGSC) in the phase 3 VELIA/GOG-3005 trial.

The benefit associated with the oral poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor was seen in all women with newly diagnosed HGSC included in the randomized, placebo-controlled trial, regardless of BRCA mutation (BRCAm) status or homologous recombination deficiency (HRD) status, Robert L. Coleman, MD, reported at the European Society for Medical Oncology Congress.

Of 1,140 patients enrolled in the international, multicenter trial, 26% had a BRCAm and 55% were HRD positive. In the intent-to-treat population, median progression-free survival (PFS) was 23.5 months in 382 patients who received carboplatin/paclitaxel (CP) plus veliparib followed by veliparib maintenance (veliparib group 1) versus 17.3 months in 375 patients treated with CP alone followed by placebo maintenance (the control group) (hazard ratio, 0.68), according to Dr. Coleman, professor and Ann Rife Cox Chair in Gynecology in the department of gynecologic oncology and reproductive medicine in the division of surgery at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

Among 200 patients with a deleterious BRCAm, including 108 in the veliparib 1 group and 92 in the control group, median PFS was 34.7 and 22.0 months, respectively (HR, 0.44), and among 421 patients with HRD and BRCAm, including 214 in the veliparib 1 group and 207 in the control group, median PFS was 31.9 versus 20.5 months (HR, 0.57).

In the non-HRD population of 249 patients (125 in the veliparib 1 arm and 124 in the control arm), median PFS was 15.0 and 11.5 months, respectively.

The PFS for an additional group of 383 patients treated with CP plus veliparib followed by placebo maintenance (veliparib group 2) didn’t differ significantly from either the veliparib 1 or the control group (HR, 1.07 vs. the control group in the intent-to-treat population), and the PFS rates were also similar for the BRCAm and HRD-positive patients in the veliparib 2 group and control group, he noted, explaining that the main focus of his presentation was the primary study endpoint of median PFS in the veliparib 1 versus control group.

The overall response rates at the end of treatment in the intent-to-treat populations were 84% in the veliparib 1 group, 74% in the control group, and 79% in the veliparib 2 group, Dr. Coleman said, adding that response rates were numerically higher in both veliparib-containing arms.

Additional analyses, including overall survival, will be reported at a future date, he noted.

Study participants were adults with a mean age of 62 years who had previously untreated stage III-IV HGSC. Treatment included six cycles of CP at 21-day intervals, with paclitaxel given either weekly or every 3 weeks following primary cytoreduction or neoadjuvant chemotherapy with interval cytoreduction. The veliparib dose when given with CP was 150 mg twice daily, and the veliparib maintenance dose was 400 mg twice daily for 30 cycles.

Relative CP dose intensities were similar between arms, and grade 3-4 adverse events were similar in the veliparib 1 and control groups during CP – with the exception of thrombocytopenia, which occurred in 27% and 8% of patients in the groups, respectively. During maintenance, the rates of any grade 3-4 adverse events were higher in the veliparib 1 group versus the control group (45% vs. 32%), but serious adverse event rates were similar in the groups (17% and 19%).

Observed toxicities were consistent with the known veliparib safety profile, Dr. Coleman said.

The findings are notable, as PARP inhibitors have proven effective in ovarian cancer, but their use in combination with chemotherapy has been challenging because of hematologic toxicity, he added, explaining, however, that veliparib has not only been shown to have single agent activity in germline BRCAm recurrent ovarian cancer patients, but also has binding characteristics – namely increased protein poly ADP-ribosylation and decreased PARP trapping – that could allow for its use in combination with chemotherapy.

VELIA/GOG-3005 is the first randomized trial designed to enroll only untreated patients with advanced-stage HGSC regardless of BRCA status, surgical management, or response to treatment, and the findings suggest that veliparib can be safely administered with CP and should be considered a new treatment option for women with newly diagnosed, advanced-stage serous ovarian cancer, he concluded.

In an ESMO press release, Ana Oaknin, MD, PhD, head of the gynecologic cancer program at Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology, Vall d’Hebron University Hospital, Barcelona, said that this trial, along with others such as the SOLO-1 trial, the PAOLA-1/ENGOT-Ov25 trial, and the PRIMA/ENGOT-OV26/GOG-3012 trial, which each looked at integrating PARP inhibitors into first-line treatment, represents “a milestone for patients.”

“After decades studying different chemotherapy approaches, it is the first time we have meaningfully prolonged progression free survival and hopefully we will improve long-term outcome,” she said.

The study was sponsored by AbbVie. Dr. Coleman and Dr. Oaknin reported relationships with numerous pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Coleman RL et al. ESMO 2019, Abstract LBA3-PR.

BARCELONA – (HGSC) in the phase 3 VELIA/GOG-3005 trial.

The benefit associated with the oral poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor was seen in all women with newly diagnosed HGSC included in the randomized, placebo-controlled trial, regardless of BRCA mutation (BRCAm) status or homologous recombination deficiency (HRD) status, Robert L. Coleman, MD, reported at the European Society for Medical Oncology Congress.

Of 1,140 patients enrolled in the international, multicenter trial, 26% had a BRCAm and 55% were HRD positive. In the intent-to-treat population, median progression-free survival (PFS) was 23.5 months in 382 patients who received carboplatin/paclitaxel (CP) plus veliparib followed by veliparib maintenance (veliparib group 1) versus 17.3 months in 375 patients treated with CP alone followed by placebo maintenance (the control group) (hazard ratio, 0.68), according to Dr. Coleman, professor and Ann Rife Cox Chair in Gynecology in the department of gynecologic oncology and reproductive medicine in the division of surgery at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

Among 200 patients with a deleterious BRCAm, including 108 in the veliparib 1 group and 92 in the control group, median PFS was 34.7 and 22.0 months, respectively (HR, 0.44), and among 421 patients with HRD and BRCAm, including 214 in the veliparib 1 group and 207 in the control group, median PFS was 31.9 versus 20.5 months (HR, 0.57).

In the non-HRD population of 249 patients (125 in the veliparib 1 arm and 124 in the control arm), median PFS was 15.0 and 11.5 months, respectively.

The PFS for an additional group of 383 patients treated with CP plus veliparib followed by placebo maintenance (veliparib group 2) didn’t differ significantly from either the veliparib 1 or the control group (HR, 1.07 vs. the control group in the intent-to-treat population), and the PFS rates were also similar for the BRCAm and HRD-positive patients in the veliparib 2 group and control group, he noted, explaining that the main focus of his presentation was the primary study endpoint of median PFS in the veliparib 1 versus control group.

The overall response rates at the end of treatment in the intent-to-treat populations were 84% in the veliparib 1 group, 74% in the control group, and 79% in the veliparib 2 group, Dr. Coleman said, adding that response rates were numerically higher in both veliparib-containing arms.

Additional analyses, including overall survival, will be reported at a future date, he noted.

Study participants were adults with a mean age of 62 years who had previously untreated stage III-IV HGSC. Treatment included six cycles of CP at 21-day intervals, with paclitaxel given either weekly or every 3 weeks following primary cytoreduction or neoadjuvant chemotherapy with interval cytoreduction. The veliparib dose when given with CP was 150 mg twice daily, and the veliparib maintenance dose was 400 mg twice daily for 30 cycles.

Relative CP dose intensities were similar between arms, and grade 3-4 adverse events were similar in the veliparib 1 and control groups during CP – with the exception of thrombocytopenia, which occurred in 27% and 8% of patients in the groups, respectively. During maintenance, the rates of any grade 3-4 adverse events were higher in the veliparib 1 group versus the control group (45% vs. 32%), but serious adverse event rates were similar in the groups (17% and 19%).

Observed toxicities were consistent with the known veliparib safety profile, Dr. Coleman said.

The findings are notable, as PARP inhibitors have proven effective in ovarian cancer, but their use in combination with chemotherapy has been challenging because of hematologic toxicity, he added, explaining, however, that veliparib has not only been shown to have single agent activity in germline BRCAm recurrent ovarian cancer patients, but also has binding characteristics – namely increased protein poly ADP-ribosylation and decreased PARP trapping – that could allow for its use in combination with chemotherapy.

VELIA/GOG-3005 is the first randomized trial designed to enroll only untreated patients with advanced-stage HGSC regardless of BRCA status, surgical management, or response to treatment, and the findings suggest that veliparib can be safely administered with CP and should be considered a new treatment option for women with newly diagnosed, advanced-stage serous ovarian cancer, he concluded.

In an ESMO press release, Ana Oaknin, MD, PhD, head of the gynecologic cancer program at Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology, Vall d’Hebron University Hospital, Barcelona, said that this trial, along with others such as the SOLO-1 trial, the PAOLA-1/ENGOT-Ov25 trial, and the PRIMA/ENGOT-OV26/GOG-3012 trial, which each looked at integrating PARP inhibitors into first-line treatment, represents “a milestone for patients.”

“After decades studying different chemotherapy approaches, it is the first time we have meaningfully prolonged progression free survival and hopefully we will improve long-term outcome,” she said.

The study was sponsored by AbbVie. Dr. Coleman and Dr. Oaknin reported relationships with numerous pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Coleman RL et al. ESMO 2019, Abstract LBA3-PR.

BARCELONA – (HGSC) in the phase 3 VELIA/GOG-3005 trial.

The benefit associated with the oral poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor was seen in all women with newly diagnosed HGSC included in the randomized, placebo-controlled trial, regardless of BRCA mutation (BRCAm) status or homologous recombination deficiency (HRD) status, Robert L. Coleman, MD, reported at the European Society for Medical Oncology Congress.

Of 1,140 patients enrolled in the international, multicenter trial, 26% had a BRCAm and 55% were HRD positive. In the intent-to-treat population, median progression-free survival (PFS) was 23.5 months in 382 patients who received carboplatin/paclitaxel (CP) plus veliparib followed by veliparib maintenance (veliparib group 1) versus 17.3 months in 375 patients treated with CP alone followed by placebo maintenance (the control group) (hazard ratio, 0.68), according to Dr. Coleman, professor and Ann Rife Cox Chair in Gynecology in the department of gynecologic oncology and reproductive medicine in the division of surgery at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

Among 200 patients with a deleterious BRCAm, including 108 in the veliparib 1 group and 92 in the control group, median PFS was 34.7 and 22.0 months, respectively (HR, 0.44), and among 421 patients with HRD and BRCAm, including 214 in the veliparib 1 group and 207 in the control group, median PFS was 31.9 versus 20.5 months (HR, 0.57).

In the non-HRD population of 249 patients (125 in the veliparib 1 arm and 124 in the control arm), median PFS was 15.0 and 11.5 months, respectively.

The PFS for an additional group of 383 patients treated with CP plus veliparib followed by placebo maintenance (veliparib group 2) didn’t differ significantly from either the veliparib 1 or the control group (HR, 1.07 vs. the control group in the intent-to-treat population), and the PFS rates were also similar for the BRCAm and HRD-positive patients in the veliparib 2 group and control group, he noted, explaining that the main focus of his presentation was the primary study endpoint of median PFS in the veliparib 1 versus control group.

The overall response rates at the end of treatment in the intent-to-treat populations were 84% in the veliparib 1 group, 74% in the control group, and 79% in the veliparib 2 group, Dr. Coleman said, adding that response rates were numerically higher in both veliparib-containing arms.

Additional analyses, including overall survival, will be reported at a future date, he noted.

Study participants were adults with a mean age of 62 years who had previously untreated stage III-IV HGSC. Treatment included six cycles of CP at 21-day intervals, with paclitaxel given either weekly or every 3 weeks following primary cytoreduction or neoadjuvant chemotherapy with interval cytoreduction. The veliparib dose when given with CP was 150 mg twice daily, and the veliparib maintenance dose was 400 mg twice daily for 30 cycles.

Relative CP dose intensities were similar between arms, and grade 3-4 adverse events were similar in the veliparib 1 and control groups during CP – with the exception of thrombocytopenia, which occurred in 27% and 8% of patients in the groups, respectively. During maintenance, the rates of any grade 3-4 adverse events were higher in the veliparib 1 group versus the control group (45% vs. 32%), but serious adverse event rates were similar in the groups (17% and 19%).

Observed toxicities were consistent with the known veliparib safety profile, Dr. Coleman said.

The findings are notable, as PARP inhibitors have proven effective in ovarian cancer, but their use in combination with chemotherapy has been challenging because of hematologic toxicity, he added, explaining, however, that veliparib has not only been shown to have single agent activity in germline BRCAm recurrent ovarian cancer patients, but also has binding characteristics – namely increased protein poly ADP-ribosylation and decreased PARP trapping – that could allow for its use in combination with chemotherapy.

VELIA/GOG-3005 is the first randomized trial designed to enroll only untreated patients with advanced-stage HGSC regardless of BRCA status, surgical management, or response to treatment, and the findings suggest that veliparib can be safely administered with CP and should be considered a new treatment option for women with newly diagnosed, advanced-stage serous ovarian cancer, he concluded.

In an ESMO press release, Ana Oaknin, MD, PhD, head of the gynecologic cancer program at Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology, Vall d’Hebron University Hospital, Barcelona, said that this trial, along with others such as the SOLO-1 trial, the PAOLA-1/ENGOT-Ov25 trial, and the PRIMA/ENGOT-OV26/GOG-3012 trial, which each looked at integrating PARP inhibitors into first-line treatment, represents “a milestone for patients.”

“After decades studying different chemotherapy approaches, it is the first time we have meaningfully prolonged progression free survival and hopefully we will improve long-term outcome,” she said.

The study was sponsored by AbbVie. Dr. Coleman and Dr. Oaknin reported relationships with numerous pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Coleman RL et al. ESMO 2019, Abstract LBA3-PR.

REPORTING FROM ESMO 2019

The law of unintended consequences

In this edition of “How I will treat my next patient,” I focus on a recent presentation at the American Society for Radiation Oncology meeting regarding the association of recent closures in women’s health clinics with cervical cancer outcomes and on a publication regarding guideline-concordant radiation exposure and organizational characteristics of lung cancer screening programs.

Cervical cancer screening and outcomes

Between 2010 and 2013, nearly 100 women’s health clinics closed in the United States because of a variety of factors, including concerns by state legislatures about reproductive services. Amar J. Srivastava, MD, and colleagues, performed a database search to determine the effect of closures on cervical cancer screening, stage, and mortality (ASTRO 2019, Abstract 202). The researchers used the Behavioral Risk Factors Surveillance Study, which provided data from 197,143 cases, to assess differences in screening availability in 2008-2009 (before the closures). They used the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registry data from 2014-2015 (after) on 10,652 patients to compare stage at diagnosis and disease-specific mortality in states with women’s health clinic closures and states without closures.

They found that the cervical cancer screening rate in states that had a decline in the number of women’s health clinics was 1.63% lower than in states that did not lose clinics. The disparity was greater in medically underserved subgroups: Hispanic women, women aged 21-34 years, unmarried women, and uninsured women.

Early-stage diagnosis was also significantly less common in states that had a decreased number of women’s health clinics – a 13.2% drop – and the overall mortality rate from cervical cancer was 36% higher. The difference was even higher (40%) when comparing only metro residents. All of these differences between states with and without closures were statistically significant.

How these results influence clinical practice

The law of unintended consequences is that the actions of people, and especially of governments, will have effects that are unanticipated or unintended. All oncologists understand this law – we live it every day.

The data generated by Dr. Srivastava and colleagues bring to mind two presentations at the 2019 annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology: the impact of Medicaid Expansion on racial disparities in time to cancer treatment (LBA 1) and the impact of the Affordable Care Act on early-stage diagnosis and treatment for women with ovarian cancer (LBA 5563). Collectively, they remind us that health care policy changes influence the timeliness of cancer care delivery and disparities in cancer care. Of course, these analyses describe associations, not necessarily causation. Large databases have quality and completeness limitations. Nonetheless, these abstracts and the associated presentations and discussions support the concept that improved access can be associated with improved cancer care outcomes.

In 1936, American sociologist Robert K. Merton described “imperious immediacy of interest,” referring to instances in which an individual wants the intended consequence of an action so badly that he or she purposefully chooses to ignore unintended effects. As a clinical and research community, we are obliged to highlight those effects when they influence our patients’ suffering.

Lung cancer screening

As a component of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ requirements for lung cancer screening payment, institutions performing screening must use low-dose techniques and participate in a dose registry. The American College of Radiology (ACR) recommends the dose levels per CT slice (CTDIvol; 3 mGy or lower) and the effective dose (ED; 1 mSr or lower) that would qualify an examination as “low dose,” thereby hoping to minimize the risk of radiation-induced cancers.

Joshua Demb, PhD, and colleagues prospectively collected lung cancer screening examination dose metrics at U.S. institutions in the University of California, San Francisco, International Dose Registry (JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Sep 23. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.3893). Only U.S. institutions that performed more than 24 lung cancer screening scans from 2016-2017 were included in the survey (n = 72, more than 12,500 patients). Institution-level factors were collected via the Partnership for Dose trial, including how CT scans are performed and how CT protocols are established at the institutional level.

In a data-dense analysis, the authors found that 65% of institutions delivered, and more than half of patients received, radiation doses above ACR targets. This suggests that both the potential screening benefits and the margins of benefits over risks might be reduced for patients at those institutions. Factors associated with exceeding ACR guidelines for radiation dose were using an “external” medical physicist, although having a medical physicist of any type was more beneficial than not having one; allowing any radiologist to establish or modify the screening protocol, instead of limiting that role to “lead” radiologists; and updating CT protocols as needed, compared with updating the protocols annually.

How these results influence clinical practice

As with the ASTRO 2019 presentation, the law of unintended consequences applies here. Whenever potentially healthy people are subjected to medical procedures to prevent illness or detect disease at early stages, protecting safety is paramount. For that reason, National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines are explicit that all lung cancer screening and follow-up scans should use low-dose techniques, unless evaluating mediastinal abnormalities or adenopathy.

The study by Dr. Demb and colleagues critically examined the proportion of lung cancer screening participants receiving guideline-concordant, low-dose examinations and several factors that could influence conformance with ACR guidelines. The results are instructive despite some of the study’s limits including the fact that the database used did not enable long-term follow-up of screened individuals for lung cancer detection or mortality, the survey relied on self-reporting, and the institutional level data was not solely focused on lung cancer screening examinations.

The survey reminds us that the logistics, quality control, and periodic review of well-intentioned programs like lung cancer screening require the thoughtful, regular involvement of teams of professionals who are cognizant of, adherent to, and vigilant about the guidelines that protect the individuals who entrust their care to us.

Dr. Lyss has been a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years, practicing in St. Louis. His clinical and research interests are in the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of breast and lung cancers and in expanding access to clinical trials to medically underserved populations.

In this edition of “How I will treat my next patient,” I focus on a recent presentation at the American Society for Radiation Oncology meeting regarding the association of recent closures in women’s health clinics with cervical cancer outcomes and on a publication regarding guideline-concordant radiation exposure and organizational characteristics of lung cancer screening programs.

Cervical cancer screening and outcomes

Between 2010 and 2013, nearly 100 women’s health clinics closed in the United States because of a variety of factors, including concerns by state legislatures about reproductive services. Amar J. Srivastava, MD, and colleagues, performed a database search to determine the effect of closures on cervical cancer screening, stage, and mortality (ASTRO 2019, Abstract 202). The researchers used the Behavioral Risk Factors Surveillance Study, which provided data from 197,143 cases, to assess differences in screening availability in 2008-2009 (before the closures). They used the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registry data from 2014-2015 (after) on 10,652 patients to compare stage at diagnosis and disease-specific mortality in states with women’s health clinic closures and states without closures.

They found that the cervical cancer screening rate in states that had a decline in the number of women’s health clinics was 1.63% lower than in states that did not lose clinics. The disparity was greater in medically underserved subgroups: Hispanic women, women aged 21-34 years, unmarried women, and uninsured women.

Early-stage diagnosis was also significantly less common in states that had a decreased number of women’s health clinics – a 13.2% drop – and the overall mortality rate from cervical cancer was 36% higher. The difference was even higher (40%) when comparing only metro residents. All of these differences between states with and without closures were statistically significant.

How these results influence clinical practice

The law of unintended consequences is that the actions of people, and especially of governments, will have effects that are unanticipated or unintended. All oncologists understand this law – we live it every day.

The data generated by Dr. Srivastava and colleagues bring to mind two presentations at the 2019 annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology: the impact of Medicaid Expansion on racial disparities in time to cancer treatment (LBA 1) and the impact of the Affordable Care Act on early-stage diagnosis and treatment for women with ovarian cancer (LBA 5563). Collectively, they remind us that health care policy changes influence the timeliness of cancer care delivery and disparities in cancer care. Of course, these analyses describe associations, not necessarily causation. Large databases have quality and completeness limitations. Nonetheless, these abstracts and the associated presentations and discussions support the concept that improved access can be associated with improved cancer care outcomes.

In 1936, American sociologist Robert K. Merton described “imperious immediacy of interest,” referring to instances in which an individual wants the intended consequence of an action so badly that he or she purposefully chooses to ignore unintended effects. As a clinical and research community, we are obliged to highlight those effects when they influence our patients’ suffering.

Lung cancer screening

As a component of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ requirements for lung cancer screening payment, institutions performing screening must use low-dose techniques and participate in a dose registry. The American College of Radiology (ACR) recommends the dose levels per CT slice (CTDIvol; 3 mGy or lower) and the effective dose (ED; 1 mSr or lower) that would qualify an examination as “low dose,” thereby hoping to minimize the risk of radiation-induced cancers.

Joshua Demb, PhD, and colleagues prospectively collected lung cancer screening examination dose metrics at U.S. institutions in the University of California, San Francisco, International Dose Registry (JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Sep 23. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.3893). Only U.S. institutions that performed more than 24 lung cancer screening scans from 2016-2017 were included in the survey (n = 72, more than 12,500 patients). Institution-level factors were collected via the Partnership for Dose trial, including how CT scans are performed and how CT protocols are established at the institutional level.

In a data-dense analysis, the authors found that 65% of institutions delivered, and more than half of patients received, radiation doses above ACR targets. This suggests that both the potential screening benefits and the margins of benefits over risks might be reduced for patients at those institutions. Factors associated with exceeding ACR guidelines for radiation dose were using an “external” medical physicist, although having a medical physicist of any type was more beneficial than not having one; allowing any radiologist to establish or modify the screening protocol, instead of limiting that role to “lead” radiologists; and updating CT protocols as needed, compared with updating the protocols annually.

How these results influence clinical practice

As with the ASTRO 2019 presentation, the law of unintended consequences applies here. Whenever potentially healthy people are subjected to medical procedures to prevent illness or detect disease at early stages, protecting safety is paramount. For that reason, National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines are explicit that all lung cancer screening and follow-up scans should use low-dose techniques, unless evaluating mediastinal abnormalities or adenopathy.

The study by Dr. Demb and colleagues critically examined the proportion of lung cancer screening participants receiving guideline-concordant, low-dose examinations and several factors that could influence conformance with ACR guidelines. The results are instructive despite some of the study’s limits including the fact that the database used did not enable long-term follow-up of screened individuals for lung cancer detection or mortality, the survey relied on self-reporting, and the institutional level data was not solely focused on lung cancer screening examinations.

The survey reminds us that the logistics, quality control, and periodic review of well-intentioned programs like lung cancer screening require the thoughtful, regular involvement of teams of professionals who are cognizant of, adherent to, and vigilant about the guidelines that protect the individuals who entrust their care to us.

Dr. Lyss has been a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years, practicing in St. Louis. His clinical and research interests are in the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of breast and lung cancers and in expanding access to clinical trials to medically underserved populations.

In this edition of “How I will treat my next patient,” I focus on a recent presentation at the American Society for Radiation Oncology meeting regarding the association of recent closures in women’s health clinics with cervical cancer outcomes and on a publication regarding guideline-concordant radiation exposure and organizational characteristics of lung cancer screening programs.

Cervical cancer screening and outcomes

Between 2010 and 2013, nearly 100 women’s health clinics closed in the United States because of a variety of factors, including concerns by state legislatures about reproductive services. Amar J. Srivastava, MD, and colleagues, performed a database search to determine the effect of closures on cervical cancer screening, stage, and mortality (ASTRO 2019, Abstract 202). The researchers used the Behavioral Risk Factors Surveillance Study, which provided data from 197,143 cases, to assess differences in screening availability in 2008-2009 (before the closures). They used the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registry data from 2014-2015 (after) on 10,652 patients to compare stage at diagnosis and disease-specific mortality in states with women’s health clinic closures and states without closures.

They found that the cervical cancer screening rate in states that had a decline in the number of women’s health clinics was 1.63% lower than in states that did not lose clinics. The disparity was greater in medically underserved subgroups: Hispanic women, women aged 21-34 years, unmarried women, and uninsured women.

Early-stage diagnosis was also significantly less common in states that had a decreased number of women’s health clinics – a 13.2% drop – and the overall mortality rate from cervical cancer was 36% higher. The difference was even higher (40%) when comparing only metro residents. All of these differences between states with and without closures were statistically significant.

How these results influence clinical practice

The law of unintended consequences is that the actions of people, and especially of governments, will have effects that are unanticipated or unintended. All oncologists understand this law – we live it every day.

The data generated by Dr. Srivastava and colleagues bring to mind two presentations at the 2019 annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology: the impact of Medicaid Expansion on racial disparities in time to cancer treatment (LBA 1) and the impact of the Affordable Care Act on early-stage diagnosis and treatment for women with ovarian cancer (LBA 5563). Collectively, they remind us that health care policy changes influence the timeliness of cancer care delivery and disparities in cancer care. Of course, these analyses describe associations, not necessarily causation. Large databases have quality and completeness limitations. Nonetheless, these abstracts and the associated presentations and discussions support the concept that improved access can be associated with improved cancer care outcomes.

In 1936, American sociologist Robert K. Merton described “imperious immediacy of interest,” referring to instances in which an individual wants the intended consequence of an action so badly that he or she purposefully chooses to ignore unintended effects. As a clinical and research community, we are obliged to highlight those effects when they influence our patients’ suffering.

Lung cancer screening

As a component of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ requirements for lung cancer screening payment, institutions performing screening must use low-dose techniques and participate in a dose registry. The American College of Radiology (ACR) recommends the dose levels per CT slice (CTDIvol; 3 mGy or lower) and the effective dose (ED; 1 mSr or lower) that would qualify an examination as “low dose,” thereby hoping to minimize the risk of radiation-induced cancers.

Joshua Demb, PhD, and colleagues prospectively collected lung cancer screening examination dose metrics at U.S. institutions in the University of California, San Francisco, International Dose Registry (JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Sep 23. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.3893). Only U.S. institutions that performed more than 24 lung cancer screening scans from 2016-2017 were included in the survey (n = 72, more than 12,500 patients). Institution-level factors were collected via the Partnership for Dose trial, including how CT scans are performed and how CT protocols are established at the institutional level.

In a data-dense analysis, the authors found that 65% of institutions delivered, and more than half of patients received, radiation doses above ACR targets. This suggests that both the potential screening benefits and the margins of benefits over risks might be reduced for patients at those institutions. Factors associated with exceeding ACR guidelines for radiation dose were using an “external” medical physicist, although having a medical physicist of any type was more beneficial than not having one; allowing any radiologist to establish or modify the screening protocol, instead of limiting that role to “lead” radiologists; and updating CT protocols as needed, compared with updating the protocols annually.

How these results influence clinical practice

As with the ASTRO 2019 presentation, the law of unintended consequences applies here. Whenever potentially healthy people are subjected to medical procedures to prevent illness or detect disease at early stages, protecting safety is paramount. For that reason, National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines are explicit that all lung cancer screening and follow-up scans should use low-dose techniques, unless evaluating mediastinal abnormalities or adenopathy.

The study by Dr. Demb and colleagues critically examined the proportion of lung cancer screening participants receiving guideline-concordant, low-dose examinations and several factors that could influence conformance with ACR guidelines. The results are instructive despite some of the study’s limits including the fact that the database used did not enable long-term follow-up of screened individuals for lung cancer detection or mortality, the survey relied on self-reporting, and the institutional level data was not solely focused on lung cancer screening examinations.

The survey reminds us that the logistics, quality control, and periodic review of well-intentioned programs like lung cancer screening require the thoughtful, regular involvement of teams of professionals who are cognizant of, adherent to, and vigilant about the guidelines that protect the individuals who entrust their care to us.

Dr. Lyss has been a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years, practicing in St. Louis. His clinical and research interests are in the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of breast and lung cancers and in expanding access to clinical trials to medically underserved populations.

Pilot program benefits gynecologic cancer patients with malignant bowel obstruction

A pilot program that aims to optimize the care of patients with malignant bowel obstruction is associated with longer survival and shorter cumulative hospital length of stay in the first 60 days after a malignant bowel obstruction diagnosis, according to research published in Journal of Oncology Practice.

Yeh Chen Lee, MBBS, of Princess Margaret Cancer Centre in Toronto, and colleagues retrospectively compared the outcomes of 106 women with advanced gynecologic cancer who were admitted to the hospital with malignant bowel obstruction before the program was implemented, with those of 63 women who were admitted after the program was implemented.

Patients’ median age at diagnosis of malignant bowel obstruction was 62 years (range, 31-91 years). Primary cancer diagnoses included ovarian cancer (73%), uterine cancer (18%), and cervical cancer (9%), and most patients had stage III-IV disease. Most patients had small-bowel obstruction (78%).

In the 2 years before the program, women had an average cumulative length of stay in the hospital of 22 days within the first 60 days of malignant bowel obstruction diagnosis. In the 2 years after, the average length of stay was 13 days. Furthermore, median overall survival, adjusted for initial cancer stage and lines of chemotherapy, increased by about 5 months, from 99 days before the program to 243 days after the program was implemented.

Patients who were treated during the malignant bowel obstruction program were more likely than were patients in the baseline group to receive chemotherapy (83% vs. 56%) and to receive two or more interventions for malignant bowel obstruction, such as surgery, chemotherapy, or total parenteral nutrition (42% vs. 33%). Complications included bowel perforation (13% in the program group vs. 5% in the baseline group) and fistulizing disease (6% in the program group vs. 12% in the baseline group).

In addition, the program was associated with lower costs.

The pilot program was designed “to provide a systematic framework to coordinate care and consensus decision-making among different specialties relevant to [malignant bowel obstruction] management,” Dr. Lee and colleagues said. It includes outpatient care led by oncology nurses through telephone consultations. “Standardized clinical processes, assessment tools, and documentation in the electronic medical record are incorporated to facilitate seamless transition between in- and outpatient care,” the authors said. “Patient educational materials have been developed to empower patients to recognize and effectively communicate their symptoms.”

It is unclear whether other institutions could implement this program, Dr. Lee and colleagues noted. It also is not possible to determine whether differences in survival relate to earlier recognition of malignant bowel obstruction, more effective management, or other factors.

Dr. Lee was supported by funding from Princess Margaret Cancer Foundation and an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship. Coauthors disclosed financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies and pending patents related to percutaneous procedures and a surgical device.

SOURCE: Lee YC et al. J Oncol Pract. 2019 Sep 24. doi: 10.1200/JOP.18.00793.

A pilot program that aims to optimize the care of patients with malignant bowel obstruction is associated with longer survival and shorter cumulative hospital length of stay in the first 60 days after a malignant bowel obstruction diagnosis, according to research published in Journal of Oncology Practice.

Yeh Chen Lee, MBBS, of Princess Margaret Cancer Centre in Toronto, and colleagues retrospectively compared the outcomes of 106 women with advanced gynecologic cancer who were admitted to the hospital with malignant bowel obstruction before the program was implemented, with those of 63 women who were admitted after the program was implemented.

Patients’ median age at diagnosis of malignant bowel obstruction was 62 years (range, 31-91 years). Primary cancer diagnoses included ovarian cancer (73%), uterine cancer (18%), and cervical cancer (9%), and most patients had stage III-IV disease. Most patients had small-bowel obstruction (78%).

In the 2 years before the program, women had an average cumulative length of stay in the hospital of 22 days within the first 60 days of malignant bowel obstruction diagnosis. In the 2 years after, the average length of stay was 13 days. Furthermore, median overall survival, adjusted for initial cancer stage and lines of chemotherapy, increased by about 5 months, from 99 days before the program to 243 days after the program was implemented.

Patients who were treated during the malignant bowel obstruction program were more likely than were patients in the baseline group to receive chemotherapy (83% vs. 56%) and to receive two or more interventions for malignant bowel obstruction, such as surgery, chemotherapy, or total parenteral nutrition (42% vs. 33%). Complications included bowel perforation (13% in the program group vs. 5% in the baseline group) and fistulizing disease (6% in the program group vs. 12% in the baseline group).

In addition, the program was associated with lower costs.

The pilot program was designed “to provide a systematic framework to coordinate care and consensus decision-making among different specialties relevant to [malignant bowel obstruction] management,” Dr. Lee and colleagues said. It includes outpatient care led by oncology nurses through telephone consultations. “Standardized clinical processes, assessment tools, and documentation in the electronic medical record are incorporated to facilitate seamless transition between in- and outpatient care,” the authors said. “Patient educational materials have been developed to empower patients to recognize and effectively communicate their symptoms.”

It is unclear whether other institutions could implement this program, Dr. Lee and colleagues noted. It also is not possible to determine whether differences in survival relate to earlier recognition of malignant bowel obstruction, more effective management, or other factors.

Dr. Lee was supported by funding from Princess Margaret Cancer Foundation and an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship. Coauthors disclosed financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies and pending patents related to percutaneous procedures and a surgical device.

SOURCE: Lee YC et al. J Oncol Pract. 2019 Sep 24. doi: 10.1200/JOP.18.00793.

A pilot program that aims to optimize the care of patients with malignant bowel obstruction is associated with longer survival and shorter cumulative hospital length of stay in the first 60 days after a malignant bowel obstruction diagnosis, according to research published in Journal of Oncology Practice.

Yeh Chen Lee, MBBS, of Princess Margaret Cancer Centre in Toronto, and colleagues retrospectively compared the outcomes of 106 women with advanced gynecologic cancer who were admitted to the hospital with malignant bowel obstruction before the program was implemented, with those of 63 women who were admitted after the program was implemented.

Patients’ median age at diagnosis of malignant bowel obstruction was 62 years (range, 31-91 years). Primary cancer diagnoses included ovarian cancer (73%), uterine cancer (18%), and cervical cancer (9%), and most patients had stage III-IV disease. Most patients had small-bowel obstruction (78%).

In the 2 years before the program, women had an average cumulative length of stay in the hospital of 22 days within the first 60 days of malignant bowel obstruction diagnosis. In the 2 years after, the average length of stay was 13 days. Furthermore, median overall survival, adjusted for initial cancer stage and lines of chemotherapy, increased by about 5 months, from 99 days before the program to 243 days after the program was implemented.

Patients who were treated during the malignant bowel obstruction program were more likely than were patients in the baseline group to receive chemotherapy (83% vs. 56%) and to receive two or more interventions for malignant bowel obstruction, such as surgery, chemotherapy, or total parenteral nutrition (42% vs. 33%). Complications included bowel perforation (13% in the program group vs. 5% in the baseline group) and fistulizing disease (6% in the program group vs. 12% in the baseline group).

In addition, the program was associated with lower costs.

The pilot program was designed “to provide a systematic framework to coordinate care and consensus decision-making among different specialties relevant to [malignant bowel obstruction] management,” Dr. Lee and colleagues said. It includes outpatient care led by oncology nurses through telephone consultations. “Standardized clinical processes, assessment tools, and documentation in the electronic medical record are incorporated to facilitate seamless transition between in- and outpatient care,” the authors said. “Patient educational materials have been developed to empower patients to recognize and effectively communicate their symptoms.”

It is unclear whether other institutions could implement this program, Dr. Lee and colleagues noted. It also is not possible to determine whether differences in survival relate to earlier recognition of malignant bowel obstruction, more effective management, or other factors.

Dr. Lee was supported by funding from Princess Margaret Cancer Foundation and an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship. Coauthors disclosed financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies and pending patents related to percutaneous procedures and a surgical device.

SOURCE: Lee YC et al. J Oncol Pract. 2019 Sep 24. doi: 10.1200/JOP.18.00793.

FROM JOURNAL OF ONCOLOGY PRACTICE

PRIMA study: Niraparib maintenance improves PFS in advanced OC

BARCELONA – Niraparib significantly improves progression-free survival when given after first-line chemotherapy in patients with advanced ovarian cancer, according to “potentially practice-changing” results from the phase 3 PRIMA/ENGOT-OV26/GOG-3012 study.

Overall progression-free survival (PFS) in 484 patients randomized to receive the poly-ADP ribose polymerase inhibitor (PARPi) niraparib was 13.8 months, compared with 8.2 months in 244 patients who received placebo (hazard ratio, 0.62), Antonio González-Martin, MD, PhD, reported at the European Society for Medical Oncology Congress.

The findings were published simultaneously online in the New England Journal of Medicine (N Engl J Med. 2019 Sep 28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1910962).

In patients at high risk for progression based on homologous recombination deficiency (HRd) – defined by certain tumor factors or the presence of BRCA mutation (BRCAm), PFS was 21.9 vs. 10.4 months in the treatment (n = 245) vs. placebo (n = 125) groups, respectively (HR, 0.43), said Dr. González-Martin of Grupo Español de Investigación en Cáncer de Ovario (GEICO), medical oncology department, Clínica Universidad de Navarra, Madrid.

“At 18 months, which means approximately 2 years after the initiation of chemotherapy, 42% of patients treated with niraparib remained alive and progression free,” he said, adding that 59% of the HRd patients remained alive and progression free at 18 months.

Exploratory analyses showed that the niraparib benefits occurred across all prespecified patient subgroups, including those aged 65 and older vs. those under age 65, those with stage III vs. stage IV disease at diagnosis, those receiving vs. not receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy, those with complete response (CR) vs. partial response (PR) as their best response to platinum chemotherapy, and those with HRd who had BRCAm vs. BRCA wild type (BRCAwt) tumors, he said.

The hazard ratios for the HRd BRCAm vs. BRCAwt tumors were 0.40 and 0.50, respectively.

“So the benefit of niraparib in the HRd tumor is not driven only by the BRCA-mutated patients,” he said. “Importantly, we also saw benefit in the group of patients with tumors that were [homologous recombination] proficient (HRp), with a reduction in the risk of progression of 32%.”

For the key secondary endpoint of overall survival, a preplanned interim analysis showed that 84% vs. 77% in the niraparib and placebo groups, respectively, were alive at 2 years; in the HRd and HRp groups, those rates were 91% vs. 85% and 81% vs. 59%, respectively.

Participants in the double-blind trial had newly diagnosed, advanced high-grade serous or endometrioid ovarian, primary peritoneal, or fallopian tube cancer; their mean age was 62 years; and they had experienced a CR (69%) or PR (31%) to first-line platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall, 35% had stage IV disease and 67% received neoadjuvant chemotherapy. They were randomized 2:1 to once-daily niraparib at a starting dose of 300 mg or 200 mg depending on body weight and platelet count, with those weighing 77 kg or greater and with platelet count of 150,000/mcL or less starting at the higher dose, and those weighing less than 77 kg and/or with platelet count less than 150,000/mcL starting at the lower dose.

All subgroups showed a sustained and durable treatment effect, and although most patients experienced treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs), those were “manageable with dose interruption or dose reduction,” Dr. González-Martin said.

Discontinuations due to TRAEs occurred in 12% vs. 2.5% in the treatment vs. placebo groups, and this was consistent with prior niraparib experience, he said, adding that no niraparib-related deaths were reported and no new safety signals were identified.

The findings are notable, because the recurrence rate after standard first-line platinum-based chemotherapy in women with advanced ovarian cancer is estimated at up to 85%, and while certain subgroups of patients have options for maintenance therapy, there remains a high unmet need for others, he explained.

For example olaparib is an option, but only for tumors with BRCA mutation, and bevacizumab can be used, but “may be limited due to safety concerns in some patients and also due to limited data from randomized trials in the neoadjuvant setting,” he said.

As a result, surveillance after chemotherapy is the approach used for many patients, he added.

Niraparib is the first oral PARPi approved for maintenance in patients with recurrent ovarian cancer, regardless of BRCA mutation status; in the NOVA study, it demonstrated efficacy after platinum chemotherapy in all biomarker populations, and in the QUADRA study it showed benefit in patients who received at least three prior therapies.

The current study was designed to test the efficacy and safety of niraparib therapy after response to platinum-based chemotherapy in patients with newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer, including those at high risk of relapse.

“Niraparib is the first PARP inhibitor that has demonstrated benefit after front-line platinum-based chemotherapy across all the biomarker subgroups, regardless of BRCA status, consistent with data from the recurrent setting,” Dr. González-Martin said, adding that patients with ovarian cancer at the highest risk of early disease progression obtained significant benefit. “What does this mean for our patients and our practice? Based on these results, niraparib after first-line platinum chemotherapy should be considered a new standard of care.”

Invited discussant Ana Oaknin, MD, PhD, head of the gynecologic cancer program at Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology, Vall d’Hebron University Hospital, Barcelona, called the findings “striking” and noted that they, along with those from the PAOLA-1/ENGOT-Ov25 trial demonstrating a PFS benefit with the addition of olaparib to bevacizumab maintenance therapy after first-line platinum-based chemotherapy in advanced ovarian cancer, represent important advances.

“We are witnessing a paradigm shift in the first-line treatment of advanced ovarian cancer patients,” she said.

Are the findings of these trials clinically meaningful enough to justify the addition of PARPi maintenance therapy after first-line chemotherapy therapy as a new standard of care?

“Yes, but while the benefit is clinically meaningful in the overall population, we should consider PFS outcomes according to the biomarker status in the selection of optimal therapy; companion diagnostic tests will be needed,” she said.

The PRIMA/ENGOT-OV26/GOG-3012 study was sponsored by TESARO. Dr. González-Martin reported relationships with numerous pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: González-Martin A et al. ESMO 2019: Abstract LBA1.

BARCELONA – Niraparib significantly improves progression-free survival when given after first-line chemotherapy in patients with advanced ovarian cancer, according to “potentially practice-changing” results from the phase 3 PRIMA/ENGOT-OV26/GOG-3012 study.

Overall progression-free survival (PFS) in 484 patients randomized to receive the poly-ADP ribose polymerase inhibitor (PARPi) niraparib was 13.8 months, compared with 8.2 months in 244 patients who received placebo (hazard ratio, 0.62), Antonio González-Martin, MD, PhD, reported at the European Society for Medical Oncology Congress.

The findings were published simultaneously online in the New England Journal of Medicine (N Engl J Med. 2019 Sep 28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1910962).

In patients at high risk for progression based on homologous recombination deficiency (HRd) – defined by certain tumor factors or the presence of BRCA mutation (BRCAm), PFS was 21.9 vs. 10.4 months in the treatment (n = 245) vs. placebo (n = 125) groups, respectively (HR, 0.43), said Dr. González-Martin of Grupo Español de Investigación en Cáncer de Ovario (GEICO), medical oncology department, Clínica Universidad de Navarra, Madrid.

“At 18 months, which means approximately 2 years after the initiation of chemotherapy, 42% of patients treated with niraparib remained alive and progression free,” he said, adding that 59% of the HRd patients remained alive and progression free at 18 months.

Exploratory analyses showed that the niraparib benefits occurred across all prespecified patient subgroups, including those aged 65 and older vs. those under age 65, those with stage III vs. stage IV disease at diagnosis, those receiving vs. not receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy, those with complete response (CR) vs. partial response (PR) as their best response to platinum chemotherapy, and those with HRd who had BRCAm vs. BRCA wild type (BRCAwt) tumors, he said.

The hazard ratios for the HRd BRCAm vs. BRCAwt tumors were 0.40 and 0.50, respectively.

“So the benefit of niraparib in the HRd tumor is not driven only by the BRCA-mutated patients,” he said. “Importantly, we also saw benefit in the group of patients with tumors that were [homologous recombination] proficient (HRp), with a reduction in the risk of progression of 32%.”

For the key secondary endpoint of overall survival, a preplanned interim analysis showed that 84% vs. 77% in the niraparib and placebo groups, respectively, were alive at 2 years; in the HRd and HRp groups, those rates were 91% vs. 85% and 81% vs. 59%, respectively.

Participants in the double-blind trial had newly diagnosed, advanced high-grade serous or endometrioid ovarian, primary peritoneal, or fallopian tube cancer; their mean age was 62 years; and they had experienced a CR (69%) or PR (31%) to first-line platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall, 35% had stage IV disease and 67% received neoadjuvant chemotherapy. They were randomized 2:1 to once-daily niraparib at a starting dose of 300 mg or 200 mg depending on body weight and platelet count, with those weighing 77 kg or greater and with platelet count of 150,000/mcL or less starting at the higher dose, and those weighing less than 77 kg and/or with platelet count less than 150,000/mcL starting at the lower dose.

All subgroups showed a sustained and durable treatment effect, and although most patients experienced treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs), those were “manageable with dose interruption or dose reduction,” Dr. González-Martin said.

Discontinuations due to TRAEs occurred in 12% vs. 2.5% in the treatment vs. placebo groups, and this was consistent with prior niraparib experience, he said, adding that no niraparib-related deaths were reported and no new safety signals were identified.

The findings are notable, because the recurrence rate after standard first-line platinum-based chemotherapy in women with advanced ovarian cancer is estimated at up to 85%, and while certain subgroups of patients have options for maintenance therapy, there remains a high unmet need for others, he explained.

For example olaparib is an option, but only for tumors with BRCA mutation, and bevacizumab can be used, but “may be limited due to safety concerns in some patients and also due to limited data from randomized trials in the neoadjuvant setting,” he said.

As a result, surveillance after chemotherapy is the approach used for many patients, he added.

Niraparib is the first oral PARPi approved for maintenance in patients with recurrent ovarian cancer, regardless of BRCA mutation status; in the NOVA study, it demonstrated efficacy after platinum chemotherapy in all biomarker populations, and in the QUADRA study it showed benefit in patients who received at least three prior therapies.

The current study was designed to test the efficacy and safety of niraparib therapy after response to platinum-based chemotherapy in patients with newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer, including those at high risk of relapse.

“Niraparib is the first PARP inhibitor that has demonstrated benefit after front-line platinum-based chemotherapy across all the biomarker subgroups, regardless of BRCA status, consistent with data from the recurrent setting,” Dr. González-Martin said, adding that patients with ovarian cancer at the highest risk of early disease progression obtained significant benefit. “What does this mean for our patients and our practice? Based on these results, niraparib after first-line platinum chemotherapy should be considered a new standard of care.”

Invited discussant Ana Oaknin, MD, PhD, head of the gynecologic cancer program at Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology, Vall d’Hebron University Hospital, Barcelona, called the findings “striking” and noted that they, along with those from the PAOLA-1/ENGOT-Ov25 trial demonstrating a PFS benefit with the addition of olaparib to bevacizumab maintenance therapy after first-line platinum-based chemotherapy in advanced ovarian cancer, represent important advances.

“We are witnessing a paradigm shift in the first-line treatment of advanced ovarian cancer patients,” she said.

Are the findings of these trials clinically meaningful enough to justify the addition of PARPi maintenance therapy after first-line chemotherapy therapy as a new standard of care?

“Yes, but while the benefit is clinically meaningful in the overall population, we should consider PFS outcomes according to the biomarker status in the selection of optimal therapy; companion diagnostic tests will be needed,” she said.

The PRIMA/ENGOT-OV26/GOG-3012 study was sponsored by TESARO. Dr. González-Martin reported relationships with numerous pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: González-Martin A et al. ESMO 2019: Abstract LBA1.

BARCELONA – Niraparib significantly improves progression-free survival when given after first-line chemotherapy in patients with advanced ovarian cancer, according to “potentially practice-changing” results from the phase 3 PRIMA/ENGOT-OV26/GOG-3012 study.

Overall progression-free survival (PFS) in 484 patients randomized to receive the poly-ADP ribose polymerase inhibitor (PARPi) niraparib was 13.8 months, compared with 8.2 months in 244 patients who received placebo (hazard ratio, 0.62), Antonio González-Martin, MD, PhD, reported at the European Society for Medical Oncology Congress.

The findings were published simultaneously online in the New England Journal of Medicine (N Engl J Med. 2019 Sep 28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1910962).

In patients at high risk for progression based on homologous recombination deficiency (HRd) – defined by certain tumor factors or the presence of BRCA mutation (BRCAm), PFS was 21.9 vs. 10.4 months in the treatment (n = 245) vs. placebo (n = 125) groups, respectively (HR, 0.43), said Dr. González-Martin of Grupo Español de Investigación en Cáncer de Ovario (GEICO), medical oncology department, Clínica Universidad de Navarra, Madrid.

“At 18 months, which means approximately 2 years after the initiation of chemotherapy, 42% of patients treated with niraparib remained alive and progression free,” he said, adding that 59% of the HRd patients remained alive and progression free at 18 months.

Exploratory analyses showed that the niraparib benefits occurred across all prespecified patient subgroups, including those aged 65 and older vs. those under age 65, those with stage III vs. stage IV disease at diagnosis, those receiving vs. not receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy, those with complete response (CR) vs. partial response (PR) as their best response to platinum chemotherapy, and those with HRd who had BRCAm vs. BRCA wild type (BRCAwt) tumors, he said.

The hazard ratios for the HRd BRCAm vs. BRCAwt tumors were 0.40 and 0.50, respectively.

“So the benefit of niraparib in the HRd tumor is not driven only by the BRCA-mutated patients,” he said. “Importantly, we also saw benefit in the group of patients with tumors that were [homologous recombination] proficient (HRp), with a reduction in the risk of progression of 32%.”

For the key secondary endpoint of overall survival, a preplanned interim analysis showed that 84% vs. 77% in the niraparib and placebo groups, respectively, were alive at 2 years; in the HRd and HRp groups, those rates were 91% vs. 85% and 81% vs. 59%, respectively.

Participants in the double-blind trial had newly diagnosed, advanced high-grade serous or endometrioid ovarian, primary peritoneal, or fallopian tube cancer; their mean age was 62 years; and they had experienced a CR (69%) or PR (31%) to first-line platinum-based chemotherapy. Overall, 35% had stage IV disease and 67% received neoadjuvant chemotherapy. They were randomized 2:1 to once-daily niraparib at a starting dose of 300 mg or 200 mg depending on body weight and platelet count, with those weighing 77 kg or greater and with platelet count of 150,000/mcL or less starting at the higher dose, and those weighing less than 77 kg and/or with platelet count less than 150,000/mcL starting at the lower dose.

All subgroups showed a sustained and durable treatment effect, and although most patients experienced treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs), those were “manageable with dose interruption or dose reduction,” Dr. González-Martin said.

Discontinuations due to TRAEs occurred in 12% vs. 2.5% in the treatment vs. placebo groups, and this was consistent with prior niraparib experience, he said, adding that no niraparib-related deaths were reported and no new safety signals were identified.

The findings are notable, because the recurrence rate after standard first-line platinum-based chemotherapy in women with advanced ovarian cancer is estimated at up to 85%, and while certain subgroups of patients have options for maintenance therapy, there remains a high unmet need for others, he explained.

For example olaparib is an option, but only for tumors with BRCA mutation, and bevacizumab can be used, but “may be limited due to safety concerns in some patients and also due to limited data from randomized trials in the neoadjuvant setting,” he said.

As a result, surveillance after chemotherapy is the approach used for many patients, he added.

Niraparib is the first oral PARPi approved for maintenance in patients with recurrent ovarian cancer, regardless of BRCA mutation status; in the NOVA study, it demonstrated efficacy after platinum chemotherapy in all biomarker populations, and in the QUADRA study it showed benefit in patients who received at least three prior therapies.

The current study was designed to test the efficacy and safety of niraparib therapy after response to platinum-based chemotherapy in patients with newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer, including those at high risk of relapse.

“Niraparib is the first PARP inhibitor that has demonstrated benefit after front-line platinum-based chemotherapy across all the biomarker subgroups, regardless of BRCA status, consistent with data from the recurrent setting,” Dr. González-Martin said, adding that patients with ovarian cancer at the highest risk of early disease progression obtained significant benefit. “What does this mean for our patients and our practice? Based on these results, niraparib after first-line platinum chemotherapy should be considered a new standard of care.”

Invited discussant Ana Oaknin, MD, PhD, head of the gynecologic cancer program at Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology, Vall d’Hebron University Hospital, Barcelona, called the findings “striking” and noted that they, along with those from the PAOLA-1/ENGOT-Ov25 trial demonstrating a PFS benefit with the addition of olaparib to bevacizumab maintenance therapy after first-line platinum-based chemotherapy in advanced ovarian cancer, represent important advances.

“We are witnessing a paradigm shift in the first-line treatment of advanced ovarian cancer patients,” she said.

Are the findings of these trials clinically meaningful enough to justify the addition of PARPi maintenance therapy after first-line chemotherapy therapy as a new standard of care?

“Yes, but while the benefit is clinically meaningful in the overall population, we should consider PFS outcomes according to the biomarker status in the selection of optimal therapy; companion diagnostic tests will be needed,” she said.

The PRIMA/ENGOT-OV26/GOG-3012 study was sponsored by TESARO. Dr. González-Martin reported relationships with numerous pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: González-Martin A et al. ESMO 2019: Abstract LBA1.

REPORTING FROM ESMO 2019

National HPV vaccination rates among teens according to provider recommendation

Ovarian tumor markers: What to draw and when

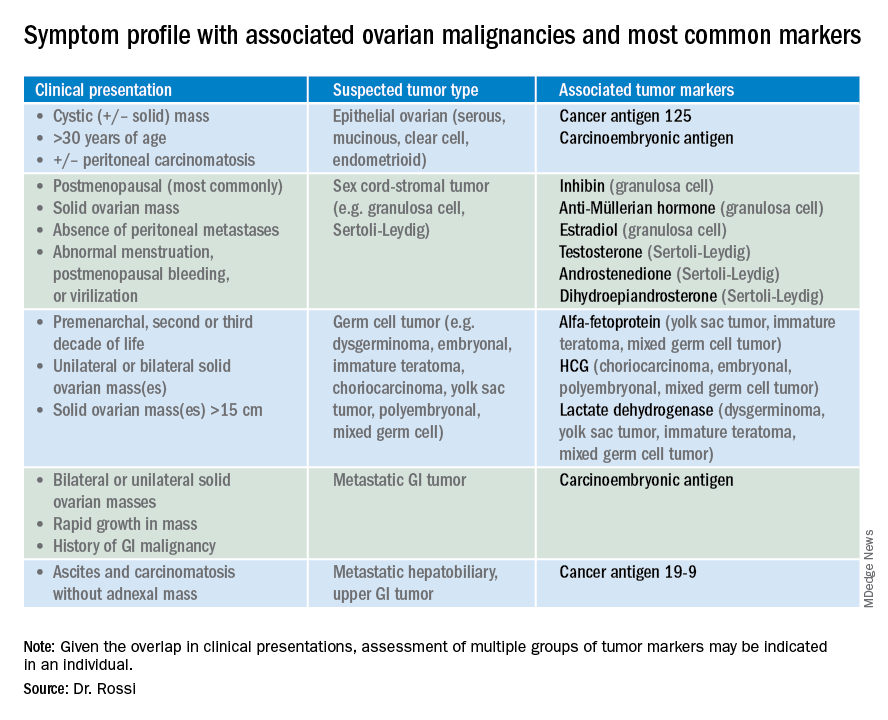

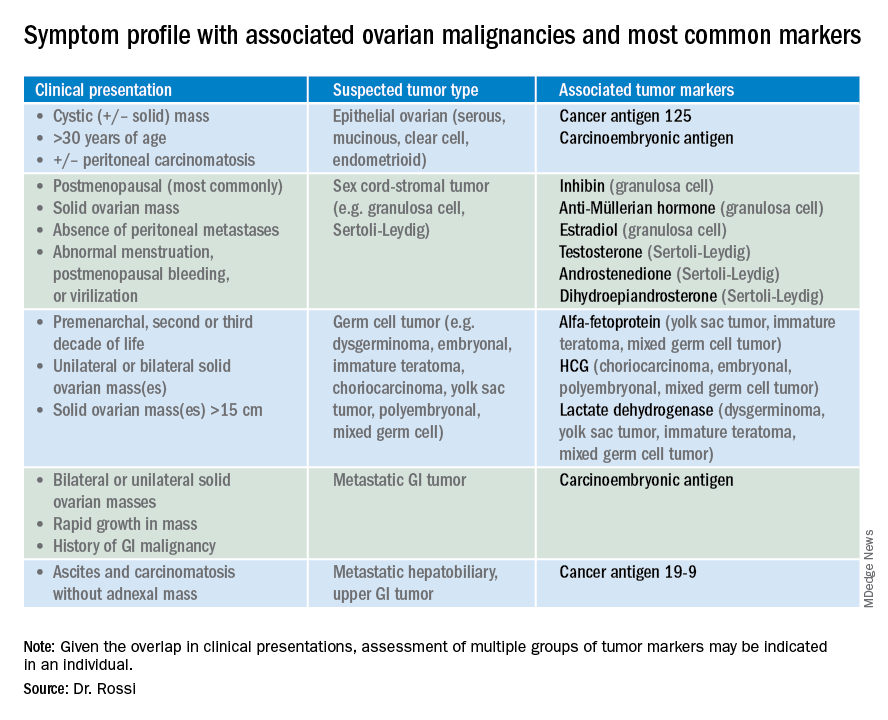

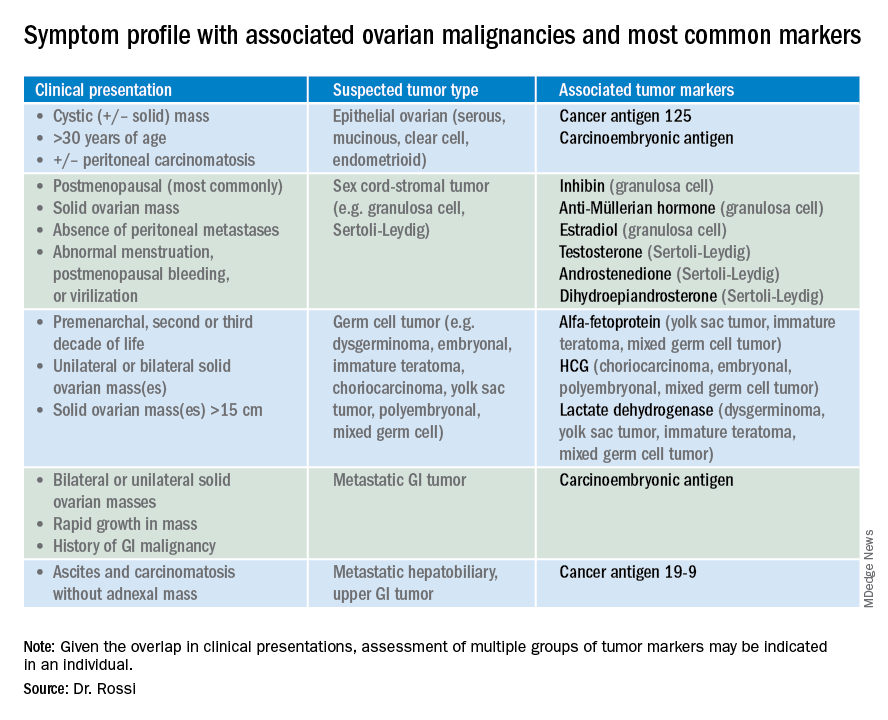

Tumor markers are serum measures that are valuable in the discrimination of an adnexal mass. However, given the long list from which to choose, it can be confusing to know exactly which might best serve your diagnostic needs. I am commonly asked by obstetrician/gynecologists and primary care doctors for guidance on this subject. In this column I will explore some of the decision making that I use when determining which markers might be most helpful for individual patients.

So which tumor markers should you order when you have diagnosed an adnexal mass? Because tumor marker profiles can differ dramatically based on the cell type of the neoplasm, perhaps the first question to ask is what is the most likely category of neoplasm based on other clinical data? Ovarian neoplasms fit into the following subgroups: epithelial (including the most common cell type, serous ovarian cancer, but also the less common mucinous and low malignant potential tumors), sex cord-stromal tumors, germ cell tumors, and metastatic tumors. Table 1 summarizes which tumor markers should be considered based on the clinical setting.

You should suspect an epithelial tumor if there is an adnexal mass with significant cystic components in older, postmenopausal patients, or the presence of peritoneal carcinomatosis on imaging. The tumor markers most commonly elevated in this clinical setting are cancer antigen 125 (CA 125), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), and possibly CA 19-9. The CA 125 antigen is a glycoprotein derived from the epithelium of peritoneum, pleura, pericardium, and Müllerian tissues. The multiple sites of origin of this glycoprotein speaks to the poor specificity associated with its elevation, as it is well known to be elevated in both benign conditions such as endometriosis, fibroids, pregnancy, ovulation, cirrhosis, and pericarditis as well as in nongynecologic malignancies, particularly those metastatic to the peritoneal cavity. Multiple different assays are available to measure CA 125, and each is associated with a slightly different reference range. Therefore, if measuring serial values, it is best to have these assessed by the same laboratory. Similarly, as it can be physiologically elevated during the menstrual cycle, premenopausal women should have serial assessments at the same point in their menstrual cycle or ideally within the first 2 weeks of their cycle.

The sensitivity of CA 125 in detecting ovarian cancer is only 78%, which is limited by the fact that not all epithelial ovarian cancer cell types (including some clear cell, carcinosarcoma, and mucinous) express elevations in this tumor marker, and because CA 125 is elevated in less than half of stage I ovarian cancers.1 Therefore, given the lack of sensitivity and specificity for this tumor marker, you should integrate other clinical data, such as imaging findings, age of the patient, and associated benign medical conditions, when evaluating the likelihood of cancer. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends that in the setting of an adnexal mass, referral to gynecologic oncology is recommended when the CA 125 value is greater than 200 U/mL in premenopausal women, or greater than 35U/mL in postmenopausal women.2

CEA is a protein that can be expressed in the colon but not in other normal tissues after birth, and therefore its elevation is commonly associated with metastatic GI tumors to the ovary and peritoneum, or mucinous ovarian tumors, including borderline tumors. Metastatic GI tumors typically are suspected when there are bilateral ovarian solid masses. Right-sided ovarian cysts also can be associated with appendiceal pathology and checking a CEA level can be considered in these cases. I will commonly draw both CA 125 and CEA tumor markers in the setting of cystic +/– solid ovarian masses. This allows the recognition of CA 125-negative/CEA-positive ovarian cancers, such as mucinous tumors, which aids in later surveillance or increases my suspicion for an occult GI tumor (particularly if there is a disproportionately higher elevation in CEA than CA 125).3 If tumor marker profiles are suggestive of an occult GI tumor, I often will consider a preoperative colonoscopy and upper GI endoscopic assessment.

CA 19-9 is a much less specific tumor marker which can be elevated in a variety of solid organ tumors including pancreatic, hepatobiliary, gastric and ovarian tumors. I typically reserve adding this marker for atypical clinical presentations of ovarian cancer, such as carcinomatosis in the absence of pelvic masses.

Ovarian sex cord-stromal neoplasms most commonly present as solid tumors in the ovary. The ovarian stroma includes the bland fibroblasts and the hormone-producing sex-cord granulosa, Sertoli and Leydig cells. Therefore the sex cord-stromal tumors commonly are associated with elevations in serum inhibin, anti-Müllerian hormone, and potentially androstenedione and dehydroepiandrosterone.4 These tumors rarely have advanced disease at diagnosis. Granulosa cell tumors should be suspected in women with a solid ovarian mass and abnormal uterine bleeding (including postmenopausal bleeding), and the appropriate tumor markers (inhibin and anti-Müllerian hormone) can guide this diagnosis preoperatively.4 Androgen-secreting stromal tumors such as Sertoli-Leydig tumors often present with virilization or menstrual irregularities. Interestingly, these patients may have dramatic clinical symptoms with corresponding nonvisible or very small solid adnexal lesions seen on imaging. In the case of fibromas, these solid tumors have normal hormonal tumor markers but may present with ascites and pleural effusions as part of Meigs syndrome, which can confuse the clinician who may suspect advanced-stage epithelial cancer especially as this condition may be associated with elevated CA 125.

Germ cell tumors make up the other main group of primary ovarian tumors, and typically strongly express tumor markers. These tumors typically are solid and highly vascularized on imaging, can be bilateral, and may be very large at the time of diagnosis.5 They most commonly are unilateral and arise among younger women (including usually in the second and third decades of life). Table 1 demonstrates the different tumor markers associated with different germ cell tumors. It is my practice to order a panel of all of these germ cell markers in young women with solid adnexal masses in whom germ cell tumors are suspected, but I will not routinely draw this expansive panel for older women with cystic lesions.

Tumor marker panels (such as OVA 1, Overa, Risk of Malignancy Algorithm or ROMA) have become popular in recent years. These panels include multiple serum markers (such as CA 125, beta-2 microglobulin, human epididymis secretory protein 4, transferrin, etc.) evaluated in concert with the goal being a more nuanced assessment of likelihood for malignancy.6,7 These assays typically are stratified by age or menopausal status given the physiologic differences in normal reference ranges that occur between these groups. While these studies do improve upon the sensitivity and specificity for identifying malignancy, compared with single-assay tests, they are not definitively diagnostic for this purpose. Therefore, I typically recommend these assays if a referring doctor needs additional risk stratification to guide whether or not to refer to an oncologist for surgery.

Not all tumor markers are of equal value in all patients with an adnexal mass. I recommend careful consideration of other clinical factors such as age, menopausal status, ultrasonographic features, and associated findings such as GI symptoms or manifestations of hormonal alterations when considering which markers to assess.

Dr. Rossi is assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. Hum Reprod. 1989 Jan;4(1):1-12.

2. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Nov;128(5):e210-e26.

3. Dan Med Bull. 2011 Nov;58(11):A4331.

4. Int J Cancer. 2015 Oct 1;137(7):1661-71.

5. Obstet Gynecol. 2000 Jan;95(1):128-33.

6. Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Jun;117(6):1289-97.

7. Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Aug;118(2 Pt 1):280-8.

Tumor markers are serum measures that are valuable in the discrimination of an adnexal mass. However, given the long list from which to choose, it can be confusing to know exactly which might best serve your diagnostic needs. I am commonly asked by obstetrician/gynecologists and primary care doctors for guidance on this subject. In this column I will explore some of the decision making that I use when determining which markers might be most helpful for individual patients.

So which tumor markers should you order when you have diagnosed an adnexal mass? Because tumor marker profiles can differ dramatically based on the cell type of the neoplasm, perhaps the first question to ask is what is the most likely category of neoplasm based on other clinical data? Ovarian neoplasms fit into the following subgroups: epithelial (including the most common cell type, serous ovarian cancer, but also the less common mucinous and low malignant potential tumors), sex cord-stromal tumors, germ cell tumors, and metastatic tumors. Table 1 summarizes which tumor markers should be considered based on the clinical setting.

You should suspect an epithelial tumor if there is an adnexal mass with significant cystic components in older, postmenopausal patients, or the presence of peritoneal carcinomatosis on imaging. The tumor markers most commonly elevated in this clinical setting are cancer antigen 125 (CA 125), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), and possibly CA 19-9. The CA 125 antigen is a glycoprotein derived from the epithelium of peritoneum, pleura, pericardium, and Müllerian tissues. The multiple sites of origin of this glycoprotein speaks to the poor specificity associated with its elevation, as it is well known to be elevated in both benign conditions such as endometriosis, fibroids, pregnancy, ovulation, cirrhosis, and pericarditis as well as in nongynecologic malignancies, particularly those metastatic to the peritoneal cavity. Multiple different assays are available to measure CA 125, and each is associated with a slightly different reference range. Therefore, if measuring serial values, it is best to have these assessed by the same laboratory. Similarly, as it can be physiologically elevated during the menstrual cycle, premenopausal women should have serial assessments at the same point in their menstrual cycle or ideally within the first 2 weeks of their cycle.

The sensitivity of CA 125 in detecting ovarian cancer is only 78%, which is limited by the fact that not all epithelial ovarian cancer cell types (including some clear cell, carcinosarcoma, and mucinous) express elevations in this tumor marker, and because CA 125 is elevated in less than half of stage I ovarian cancers.1 Therefore, given the lack of sensitivity and specificity for this tumor marker, you should integrate other clinical data, such as imaging findings, age of the patient, and associated benign medical conditions, when evaluating the likelihood of cancer. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends that in the setting of an adnexal mass, referral to gynecologic oncology is recommended when the CA 125 value is greater than 200 U/mL in premenopausal women, or greater than 35U/mL in postmenopausal women.2