User login

When toenail onychomycosis can turn deadly

WAIKOLOA, HAWAII – Toenail onychomycosis is a common condition in the general population, but it’s three- to fourfold more prevalent in certain at risk populations where it can have serious and even life-threatening consequences, Dr. Theodore Rosen observed at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by the Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

He cited a recent systematic review led by Dr. Aditya K. Gupta, professor of dermatology at the University of Toronto, whom Dr. Rosen hailed as one of the world’s great fungal disease authorities. Dr. Gupta and coworkers concluded that while the prevalence of dermatophyte toenail onychomycosis is 3.2% worldwide in the general population, it climbs to 8.8% in diabetics, 10.2% in psoriatics, 10.3% in the elderly, 11.9% in dialysis patients, 5.2% in renal transplant recipients, and 10.4% in HIV-positive individuals. The highest prevalence of onychomycosis due to non-dermatophyte molds was seen in psoriasis patients, at 2.5%, while elderly patients had the highest prevalence of onychomycosis caused by yeasts, at 6.1% (J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015 Jun;29[6]:1039-44).

“Onychomycosis is especially important in those who are immunocompromised and immunosuppressed, for two reasons. One is that really odd organisms that aren’t Trichophyton rubrum or T. interdigitale can be involved: saprophytes like Scopulariopsis, Acremonium, Aspergillus, and Paecilomyces. And some of these saprophytes, like Fusarium, can get from the nail and nail bed into the bloodstream and can kill,” explained Dr. Rosen, professor of dermatology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston.

“Onychomycosis, aside from the fact that it looks bad and often leads to pain, can also lead to breaks in the skin which then result in secondary bacterial infections. In fact, after motor vehicle accidents, onychomycosis and tinea pedis combined are the most common cause of lower extremity cellulitis leading to hospitalization in the United States,” he continued.

The go-to treatments for onychomycosis in patients with a bad prognostic factor are oral itraconazole (Sporanox) and terbinafine. Don’t be unduly swayed by the complete cure rates reported in clinical trials and cited in the product package inserts; they don’t tell the full story because of important differences in study design, according to Dr. Rosen.

He recommended that physicians familiarize themselves with posaconazole (Noxafil) as an antifungal to consider for second-line therapy in difficult-to-cure cases of onychomycosis in immunosuppressed patients. This is off-label therapy. The approved indications for this triazole antifungal agent are prophylaxis of invasive Aspergillus and Candida infections in severely immunocompromised patients, as well as treatment of oropharyngeal candidiasis. But this is a potent agent that provides broad-spectrum coverage coupled with a favorable safety profile. It performed well in a phase IIb randomized, placebo- and active-controlled, multicenter, investigator-blinded study of 218 adults with toenail onychomycosis (Br J Dermatol. 2012 Feb;166[2]:389-98).

Dr. Rosen reported serving on scientific advisory boards for Anacor, Merz, and Valeant.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

WAIKOLOA, HAWAII – Toenail onychomycosis is a common condition in the general population, but it’s three- to fourfold more prevalent in certain at risk populations where it can have serious and even life-threatening consequences, Dr. Theodore Rosen observed at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by the Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

He cited a recent systematic review led by Dr. Aditya K. Gupta, professor of dermatology at the University of Toronto, whom Dr. Rosen hailed as one of the world’s great fungal disease authorities. Dr. Gupta and coworkers concluded that while the prevalence of dermatophyte toenail onychomycosis is 3.2% worldwide in the general population, it climbs to 8.8% in diabetics, 10.2% in psoriatics, 10.3% in the elderly, 11.9% in dialysis patients, 5.2% in renal transplant recipients, and 10.4% in HIV-positive individuals. The highest prevalence of onychomycosis due to non-dermatophyte molds was seen in psoriasis patients, at 2.5%, while elderly patients had the highest prevalence of onychomycosis caused by yeasts, at 6.1% (J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015 Jun;29[6]:1039-44).

“Onychomycosis is especially important in those who are immunocompromised and immunosuppressed, for two reasons. One is that really odd organisms that aren’t Trichophyton rubrum or T. interdigitale can be involved: saprophytes like Scopulariopsis, Acremonium, Aspergillus, and Paecilomyces. And some of these saprophytes, like Fusarium, can get from the nail and nail bed into the bloodstream and can kill,” explained Dr. Rosen, professor of dermatology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston.

“Onychomycosis, aside from the fact that it looks bad and often leads to pain, can also lead to breaks in the skin which then result in secondary bacterial infections. In fact, after motor vehicle accidents, onychomycosis and tinea pedis combined are the most common cause of lower extremity cellulitis leading to hospitalization in the United States,” he continued.

The go-to treatments for onychomycosis in patients with a bad prognostic factor are oral itraconazole (Sporanox) and terbinafine. Don’t be unduly swayed by the complete cure rates reported in clinical trials and cited in the product package inserts; they don’t tell the full story because of important differences in study design, according to Dr. Rosen.

He recommended that physicians familiarize themselves with posaconazole (Noxafil) as an antifungal to consider for second-line therapy in difficult-to-cure cases of onychomycosis in immunosuppressed patients. This is off-label therapy. The approved indications for this triazole antifungal agent are prophylaxis of invasive Aspergillus and Candida infections in severely immunocompromised patients, as well as treatment of oropharyngeal candidiasis. But this is a potent agent that provides broad-spectrum coverage coupled with a favorable safety profile. It performed well in a phase IIb randomized, placebo- and active-controlled, multicenter, investigator-blinded study of 218 adults with toenail onychomycosis (Br J Dermatol. 2012 Feb;166[2]:389-98).

Dr. Rosen reported serving on scientific advisory boards for Anacor, Merz, and Valeant.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

WAIKOLOA, HAWAII – Toenail onychomycosis is a common condition in the general population, but it’s three- to fourfold more prevalent in certain at risk populations where it can have serious and even life-threatening consequences, Dr. Theodore Rosen observed at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by the Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

He cited a recent systematic review led by Dr. Aditya K. Gupta, professor of dermatology at the University of Toronto, whom Dr. Rosen hailed as one of the world’s great fungal disease authorities. Dr. Gupta and coworkers concluded that while the prevalence of dermatophyte toenail onychomycosis is 3.2% worldwide in the general population, it climbs to 8.8% in diabetics, 10.2% in psoriatics, 10.3% in the elderly, 11.9% in dialysis patients, 5.2% in renal transplant recipients, and 10.4% in HIV-positive individuals. The highest prevalence of onychomycosis due to non-dermatophyte molds was seen in psoriasis patients, at 2.5%, while elderly patients had the highest prevalence of onychomycosis caused by yeasts, at 6.1% (J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015 Jun;29[6]:1039-44).

“Onychomycosis is especially important in those who are immunocompromised and immunosuppressed, for two reasons. One is that really odd organisms that aren’t Trichophyton rubrum or T. interdigitale can be involved: saprophytes like Scopulariopsis, Acremonium, Aspergillus, and Paecilomyces. And some of these saprophytes, like Fusarium, can get from the nail and nail bed into the bloodstream and can kill,” explained Dr. Rosen, professor of dermatology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston.

“Onychomycosis, aside from the fact that it looks bad and often leads to pain, can also lead to breaks in the skin which then result in secondary bacterial infections. In fact, after motor vehicle accidents, onychomycosis and tinea pedis combined are the most common cause of lower extremity cellulitis leading to hospitalization in the United States,” he continued.

The go-to treatments for onychomycosis in patients with a bad prognostic factor are oral itraconazole (Sporanox) and terbinafine. Don’t be unduly swayed by the complete cure rates reported in clinical trials and cited in the product package inserts; they don’t tell the full story because of important differences in study design, according to Dr. Rosen.

He recommended that physicians familiarize themselves with posaconazole (Noxafil) as an antifungal to consider for second-line therapy in difficult-to-cure cases of onychomycosis in immunosuppressed patients. This is off-label therapy. The approved indications for this triazole antifungal agent are prophylaxis of invasive Aspergillus and Candida infections in severely immunocompromised patients, as well as treatment of oropharyngeal candidiasis. But this is a potent agent that provides broad-spectrum coverage coupled with a favorable safety profile. It performed well in a phase IIb randomized, placebo- and active-controlled, multicenter, investigator-blinded study of 218 adults with toenail onychomycosis (Br J Dermatol. 2012 Feb;166[2]:389-98).

Dr. Rosen reported serving on scientific advisory boards for Anacor, Merz, and Valeant.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM SDEF HAWAII DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

Maximizing bang in topical onychomycosis therapy

WAIKOLOA, HAWAII – Two recent studies highlight several key points regarding topical therapy for onychomycosis: Treat it early for best results, and if concomitant tinea pedis is present, be sure to treat that, too, Dr. Theodore Rosen said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar.

The studies were separate secondary analyses of the pooled results of two large, double blind, vehicle-controlled, 48-week, phase III randomized trials of efinaconazole 10% topical solution (Jublia) for onychomycosis. But the same lessons probably apply to any topical antifungal, according to Dr. Rosen, professor of dermatology at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

Early treatment: This makes a big difference in outcome, as demonstrated in Dr. Phoebe Rich’s analysis of 1,655 patients in the phase III studies. Dr. Rich, director of the nail disorders clinic at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, divided participants into three groups based upon disease duration: less than a year, 1-5 years, or more than 5 years. The complete cure rate was much better in the group with less than 1 year of onychomycosis, even though the extent of nail involvement of the target toenail didn’t differ significantly between the three groups (J Drugs Dermatol. 2015;Jan 14[1]:58-62).

“Now we have data: Don’t wait to treat until it has been there for 35 years. It’s easier to treat if it’s early,” Dr. Rosen commented at the seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

When onychomycosis and tinea pedis coexist, treat both: Dr. Leon H. Kircik of Indiana University, Indianapolis, and associates reported in a poster at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar that one in five participants in the two phase III trials had tinea pedis as well as onychomycosis, and nearly half of them were treated for their athlete’s foot using their physician’s choice of topical antifungals.

The primary endpoint in the two trials was the week 53 complete cure rate, defined as no clinical involvement of the target toenail, a negative potassium hydroxide exam, and a negative fungal culture. Among subjects with concomitant onychomycosis and tinea pedis, the onychomycosis complete cure rate was 28.2% if they received efinaconazole for their onychomycosis and got treatment for their tinea pedis, compared with 20.9% if they got efinaconazole but no treatment for their tinea pedis. The complete/almost complete cure rate was 35.5% with dual therapy versus 29.6% if they only received efinaconazole. Both differences were significant.

“Doesn’t that make logical sense? If you leave the fungus on the foot or between the toes, it’s going to say, ‘Wow, that’s steak up there on the nail. That’s real food. I’m just going to crawl back onto the nail because all my brothers up there are dead and there’s wide-open space,” Dr. Rosen explained.

He added that the reverse is also true: if a patient presents seeking treatment for athlete’s foot but also has onychomycosis, the best treatment results for the tinea pedis are obtained by also treating the nail infection.

Dr. Rosen offered a money-saving tip for effective OTC therapy for tinea pedis. Two words: Lotrimin Ultra. That’s the brand name for butenafine cream 1%, not to be confused with plain old Lotrimin, which is clotrimazole.

“Clotrimazole has been around since the dawn of man, and it’s not very effective. Many of the fungi are actually resistant to it. But they’re not resistant to butenafine, which is a very good topical antifungal now available over the counter. It costs $9 or $10 dollars for a tube the size of a baseball bat. It’s a good, effective, cheap way of treating concomitant tinea pedis,” he said.

Dr. Rosen reported serving on scientific advisory boards for Anacor, Merz, and Valeant.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

WAIKOLOA, HAWAII – Two recent studies highlight several key points regarding topical therapy for onychomycosis: Treat it early for best results, and if concomitant tinea pedis is present, be sure to treat that, too, Dr. Theodore Rosen said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar.

The studies were separate secondary analyses of the pooled results of two large, double blind, vehicle-controlled, 48-week, phase III randomized trials of efinaconazole 10% topical solution (Jublia) for onychomycosis. But the same lessons probably apply to any topical antifungal, according to Dr. Rosen, professor of dermatology at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

Early treatment: This makes a big difference in outcome, as demonstrated in Dr. Phoebe Rich’s analysis of 1,655 patients in the phase III studies. Dr. Rich, director of the nail disorders clinic at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, divided participants into three groups based upon disease duration: less than a year, 1-5 years, or more than 5 years. The complete cure rate was much better in the group with less than 1 year of onychomycosis, even though the extent of nail involvement of the target toenail didn’t differ significantly between the three groups (J Drugs Dermatol. 2015;Jan 14[1]:58-62).

“Now we have data: Don’t wait to treat until it has been there for 35 years. It’s easier to treat if it’s early,” Dr. Rosen commented at the seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

When onychomycosis and tinea pedis coexist, treat both: Dr. Leon H. Kircik of Indiana University, Indianapolis, and associates reported in a poster at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar that one in five participants in the two phase III trials had tinea pedis as well as onychomycosis, and nearly half of them were treated for their athlete’s foot using their physician’s choice of topical antifungals.

The primary endpoint in the two trials was the week 53 complete cure rate, defined as no clinical involvement of the target toenail, a negative potassium hydroxide exam, and a negative fungal culture. Among subjects with concomitant onychomycosis and tinea pedis, the onychomycosis complete cure rate was 28.2% if they received efinaconazole for their onychomycosis and got treatment for their tinea pedis, compared with 20.9% if they got efinaconazole but no treatment for their tinea pedis. The complete/almost complete cure rate was 35.5% with dual therapy versus 29.6% if they only received efinaconazole. Both differences were significant.

“Doesn’t that make logical sense? If you leave the fungus on the foot or between the toes, it’s going to say, ‘Wow, that’s steak up there on the nail. That’s real food. I’m just going to crawl back onto the nail because all my brothers up there are dead and there’s wide-open space,” Dr. Rosen explained.

He added that the reverse is also true: if a patient presents seeking treatment for athlete’s foot but also has onychomycosis, the best treatment results for the tinea pedis are obtained by also treating the nail infection.

Dr. Rosen offered a money-saving tip for effective OTC therapy for tinea pedis. Two words: Lotrimin Ultra. That’s the brand name for butenafine cream 1%, not to be confused with plain old Lotrimin, which is clotrimazole.

“Clotrimazole has been around since the dawn of man, and it’s not very effective. Many of the fungi are actually resistant to it. But they’re not resistant to butenafine, which is a very good topical antifungal now available over the counter. It costs $9 or $10 dollars for a tube the size of a baseball bat. It’s a good, effective, cheap way of treating concomitant tinea pedis,” he said.

Dr. Rosen reported serving on scientific advisory boards for Anacor, Merz, and Valeant.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

WAIKOLOA, HAWAII – Two recent studies highlight several key points regarding topical therapy for onychomycosis: Treat it early for best results, and if concomitant tinea pedis is present, be sure to treat that, too, Dr. Theodore Rosen said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar.

The studies were separate secondary analyses of the pooled results of two large, double blind, vehicle-controlled, 48-week, phase III randomized trials of efinaconazole 10% topical solution (Jublia) for onychomycosis. But the same lessons probably apply to any topical antifungal, according to Dr. Rosen, professor of dermatology at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

Early treatment: This makes a big difference in outcome, as demonstrated in Dr. Phoebe Rich’s analysis of 1,655 patients in the phase III studies. Dr. Rich, director of the nail disorders clinic at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, divided participants into three groups based upon disease duration: less than a year, 1-5 years, or more than 5 years. The complete cure rate was much better in the group with less than 1 year of onychomycosis, even though the extent of nail involvement of the target toenail didn’t differ significantly between the three groups (J Drugs Dermatol. 2015;Jan 14[1]:58-62).

“Now we have data: Don’t wait to treat until it has been there for 35 years. It’s easier to treat if it’s early,” Dr. Rosen commented at the seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

When onychomycosis and tinea pedis coexist, treat both: Dr. Leon H. Kircik of Indiana University, Indianapolis, and associates reported in a poster at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar that one in five participants in the two phase III trials had tinea pedis as well as onychomycosis, and nearly half of them were treated for their athlete’s foot using their physician’s choice of topical antifungals.

The primary endpoint in the two trials was the week 53 complete cure rate, defined as no clinical involvement of the target toenail, a negative potassium hydroxide exam, and a negative fungal culture. Among subjects with concomitant onychomycosis and tinea pedis, the onychomycosis complete cure rate was 28.2% if they received efinaconazole for their onychomycosis and got treatment for their tinea pedis, compared with 20.9% if they got efinaconazole but no treatment for their tinea pedis. The complete/almost complete cure rate was 35.5% with dual therapy versus 29.6% if they only received efinaconazole. Both differences were significant.

“Doesn’t that make logical sense? If you leave the fungus on the foot or between the toes, it’s going to say, ‘Wow, that’s steak up there on the nail. That’s real food. I’m just going to crawl back onto the nail because all my brothers up there are dead and there’s wide-open space,” Dr. Rosen explained.

He added that the reverse is also true: if a patient presents seeking treatment for athlete’s foot but also has onychomycosis, the best treatment results for the tinea pedis are obtained by also treating the nail infection.

Dr. Rosen offered a money-saving tip for effective OTC therapy for tinea pedis. Two words: Lotrimin Ultra. That’s the brand name for butenafine cream 1%, not to be confused with plain old Lotrimin, which is clotrimazole.

“Clotrimazole has been around since the dawn of man, and it’s not very effective. Many of the fungi are actually resistant to it. But they’re not resistant to butenafine, which is a very good topical antifungal now available over the counter. It costs $9 or $10 dollars for a tube the size of a baseball bat. It’s a good, effective, cheap way of treating concomitant tinea pedis,” he said.

Dr. Rosen reported serving on scientific advisory boards for Anacor, Merz, and Valeant.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM SDEF HAWAII DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

VIDEO: Study links hair loss in black women with genetics

WASHINGTON – Almost 41% of black women surveyed described hair loss that was consistent with central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA), but only about 9% said they had been diagnosed with the condition, Dr. Yolanda Lenzy reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

In a video interview at the meeting, Dr. Lenzy of the University of Connecticut, Farmington, discussed the results of a hair survey she conducted with the Black Women’s Health Study at Boston University’s Slone Epidemiology Center. Nearly 6,000 women have completed the survey to date.

“For many years, it was thought to be due to hair styling practices,” but there are new data showing that genetics can be an important cause, she said, referring to research from South Africa indicating that CCCA can be inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion.

Dr. Lenzy, who practices dermatology in Chicopee, Mass., used a central hair loss photographic scale in the study, which also can be helpful in the office to monitor hair loss and “to quantify how much hair loss a person has … in terms of: Are they getting worse? Do they go from stage 3 to stage 5 or stage 1 to stage 3?”

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

WASHINGTON – Almost 41% of black women surveyed described hair loss that was consistent with central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA), but only about 9% said they had been diagnosed with the condition, Dr. Yolanda Lenzy reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

In a video interview at the meeting, Dr. Lenzy of the University of Connecticut, Farmington, discussed the results of a hair survey she conducted with the Black Women’s Health Study at Boston University’s Slone Epidemiology Center. Nearly 6,000 women have completed the survey to date.

“For many years, it was thought to be due to hair styling practices,” but there are new data showing that genetics can be an important cause, she said, referring to research from South Africa indicating that CCCA can be inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion.

Dr. Lenzy, who practices dermatology in Chicopee, Mass., used a central hair loss photographic scale in the study, which also can be helpful in the office to monitor hair loss and “to quantify how much hair loss a person has … in terms of: Are they getting worse? Do they go from stage 3 to stage 5 or stage 1 to stage 3?”

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

WASHINGTON – Almost 41% of black women surveyed described hair loss that was consistent with central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA), but only about 9% said they had been diagnosed with the condition, Dr. Yolanda Lenzy reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

In a video interview at the meeting, Dr. Lenzy of the University of Connecticut, Farmington, discussed the results of a hair survey she conducted with the Black Women’s Health Study at Boston University’s Slone Epidemiology Center. Nearly 6,000 women have completed the survey to date.

“For many years, it was thought to be due to hair styling practices,” but there are new data showing that genetics can be an important cause, she said, referring to research from South Africa indicating that CCCA can be inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion.

Dr. Lenzy, who practices dermatology in Chicopee, Mass., used a central hair loss photographic scale in the study, which also can be helpful in the office to monitor hair loss and “to quantify how much hair loss a person has … in terms of: Are they getting worse? Do they go from stage 3 to stage 5 or stage 1 to stage 3?”

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT AAD 16

VIDEO: Which patients are best for new onychomycosis topicals?

WAIKOLOA, HAWAII – Two new topical treatments for nail fungal infections are more effective than previous topical therapies, but the key to successful results is picking the right onychomycosis patient, according to Dr. Theodore Rosen.

The two new agents, tavaborole and efinaconazole, “are both better than what we had previously, especially considering topical agents don’t do quite as well as oral agents do,” explained Dr. Rosen, professor of dermatology at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

The new topicals are “very convenient, in that it’s an easy-to-do regimen, once a day,” Dr. Rosen noted. But “they are inconvenient, in that they both have to be used about 48 weeks. So, that’s about a year’s worth of therapy.”

In an interview at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation, Dr. Rosen discussed approaches to achieving the best outcomes with the new agents, and he outlined other practical steps patients can take to prevent the return of nail fungal infections.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

WAIKOLOA, HAWAII – Two new topical treatments for nail fungal infections are more effective than previous topical therapies, but the key to successful results is picking the right onychomycosis patient, according to Dr. Theodore Rosen.

The two new agents, tavaborole and efinaconazole, “are both better than what we had previously, especially considering topical agents don’t do quite as well as oral agents do,” explained Dr. Rosen, professor of dermatology at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

The new topicals are “very convenient, in that it’s an easy-to-do regimen, once a day,” Dr. Rosen noted. But “they are inconvenient, in that they both have to be used about 48 weeks. So, that’s about a year’s worth of therapy.”

In an interview at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation, Dr. Rosen discussed approaches to achieving the best outcomes with the new agents, and he outlined other practical steps patients can take to prevent the return of nail fungal infections.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

WAIKOLOA, HAWAII – Two new topical treatments for nail fungal infections are more effective than previous topical therapies, but the key to successful results is picking the right onychomycosis patient, according to Dr. Theodore Rosen.

The two new agents, tavaborole and efinaconazole, “are both better than what we had previously, especially considering topical agents don’t do quite as well as oral agents do,” explained Dr. Rosen, professor of dermatology at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

The new topicals are “very convenient, in that it’s an easy-to-do regimen, once a day,” Dr. Rosen noted. But “they are inconvenient, in that they both have to be used about 48 weeks. So, that’s about a year’s worth of therapy.”

In an interview at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation, Dr. Rosen discussed approaches to achieving the best outcomes with the new agents, and he outlined other practical steps patients can take to prevent the return of nail fungal infections.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT SDEF HAWAII DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

SDEF: New, aggressive strategies show promise in alopecia areata

Alopecia areata’s mysterious appearances, regressions, and recurrences frustrate patients and stymie physicians, but new treatments may be around the corner.

Tofacitinib, along with other medications that target the autoimmune etiology of alopecia areata, have shown complete alopecia reversal in case studies, Dr. Maria Hordinsky said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation. “There’s a lot of excitement bubbling up in hair disease research because of these new potential topical and oral treatments.”

Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, including tofacitinib, baricitinib, and ruxolitinib, have also been reported to reverse alopecia areata.

“There’s been a surge of enthusiasm for using more aggressive systemic therapies, including not only tobacitinib and ruxolitinib but also methotrexate and interleukin-2,” Dr. Hordinsky said, noting that these are still investigational uses.

The new treatment targets are welcome for physicians treating patients with alopecia areata, since currently there are no FDA-approved treatments, Dr. Hordinsky said.

A review by Dr. Hordinsky and colleague found a total of 29 trials investigating more than a dozen topical and oral treatments. Most trials were of moderate or lower quality, and most had major limitations. Treatments that were effective included topical and oral corticosteroids, as well as the sensitizing agents diphenylcyclopropenone and dinitrochlorobenzene (Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;15:231-46).

In the absence of high-quality evidence for effective treatments, patient characteristics and preference, as well as disease activity and location, can guide treatment. In some cases, a scalp biopsy can give more information about follicle differentiation, inflammation, and the stage of the hair cycle at the time of assessment, Dr. Hordinsky said.

It’s important to set expectations for patients, so they know that treatments will take time, she said. Providers should be alert to the possibility that hair loss may also be associated with an underlying medical problem, so a thorough workup is indicated.

Patients should be given the opportunity to enroll in clinical trials, where available, and should also be directed to the National Alopecia Areata Foundation (NAAF). Their website provides information and resources for patients and families, information for local support groups, and information on a national registry.

Dr. Hordinsky reported receiving grant or research support from a number of pharmaceutical and consumer product companies in the dermatology space. She serves on the scientific advisory board of the National Alopecia Areata Foundation.

This news organization and SDEF are owned by the same parent company.

On Twitter @karioakes

Alopecia areata’s mysterious appearances, regressions, and recurrences frustrate patients and stymie physicians, but new treatments may be around the corner.

Tofacitinib, along with other medications that target the autoimmune etiology of alopecia areata, have shown complete alopecia reversal in case studies, Dr. Maria Hordinsky said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation. “There’s a lot of excitement bubbling up in hair disease research because of these new potential topical and oral treatments.”

Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, including tofacitinib, baricitinib, and ruxolitinib, have also been reported to reverse alopecia areata.

“There’s been a surge of enthusiasm for using more aggressive systemic therapies, including not only tobacitinib and ruxolitinib but also methotrexate and interleukin-2,” Dr. Hordinsky said, noting that these are still investigational uses.

The new treatment targets are welcome for physicians treating patients with alopecia areata, since currently there are no FDA-approved treatments, Dr. Hordinsky said.

A review by Dr. Hordinsky and colleague found a total of 29 trials investigating more than a dozen topical and oral treatments. Most trials were of moderate or lower quality, and most had major limitations. Treatments that were effective included topical and oral corticosteroids, as well as the sensitizing agents diphenylcyclopropenone and dinitrochlorobenzene (Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;15:231-46).

In the absence of high-quality evidence for effective treatments, patient characteristics and preference, as well as disease activity and location, can guide treatment. In some cases, a scalp biopsy can give more information about follicle differentiation, inflammation, and the stage of the hair cycle at the time of assessment, Dr. Hordinsky said.

It’s important to set expectations for patients, so they know that treatments will take time, she said. Providers should be alert to the possibility that hair loss may also be associated with an underlying medical problem, so a thorough workup is indicated.

Patients should be given the opportunity to enroll in clinical trials, where available, and should also be directed to the National Alopecia Areata Foundation (NAAF). Their website provides information and resources for patients and families, information for local support groups, and information on a national registry.

Dr. Hordinsky reported receiving grant or research support from a number of pharmaceutical and consumer product companies in the dermatology space. She serves on the scientific advisory board of the National Alopecia Areata Foundation.

This news organization and SDEF are owned by the same parent company.

On Twitter @karioakes

Alopecia areata’s mysterious appearances, regressions, and recurrences frustrate patients and stymie physicians, but new treatments may be around the corner.

Tofacitinib, along with other medications that target the autoimmune etiology of alopecia areata, have shown complete alopecia reversal in case studies, Dr. Maria Hordinsky said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation. “There’s a lot of excitement bubbling up in hair disease research because of these new potential topical and oral treatments.”

Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, including tofacitinib, baricitinib, and ruxolitinib, have also been reported to reverse alopecia areata.

“There’s been a surge of enthusiasm for using more aggressive systemic therapies, including not only tobacitinib and ruxolitinib but also methotrexate and interleukin-2,” Dr. Hordinsky said, noting that these are still investigational uses.

The new treatment targets are welcome for physicians treating patients with alopecia areata, since currently there are no FDA-approved treatments, Dr. Hordinsky said.

A review by Dr. Hordinsky and colleague found a total of 29 trials investigating more than a dozen topical and oral treatments. Most trials were of moderate or lower quality, and most had major limitations. Treatments that were effective included topical and oral corticosteroids, as well as the sensitizing agents diphenylcyclopropenone and dinitrochlorobenzene (Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;15:231-46).

In the absence of high-quality evidence for effective treatments, patient characteristics and preference, as well as disease activity and location, can guide treatment. In some cases, a scalp biopsy can give more information about follicle differentiation, inflammation, and the stage of the hair cycle at the time of assessment, Dr. Hordinsky said.

It’s important to set expectations for patients, so they know that treatments will take time, she said. Providers should be alert to the possibility that hair loss may also be associated with an underlying medical problem, so a thorough workup is indicated.

Patients should be given the opportunity to enroll in clinical trials, where available, and should also be directed to the National Alopecia Areata Foundation (NAAF). Their website provides information and resources for patients and families, information for local support groups, and information on a national registry.

Dr. Hordinsky reported receiving grant or research support from a number of pharmaceutical and consumer product companies in the dermatology space. She serves on the scientific advisory board of the National Alopecia Areata Foundation.

This news organization and SDEF are owned by the same parent company.

On Twitter @karioakes

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM SDEF HAWAII DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

SDEF: New clues emerge in scarring alopecias

Some kinds of scarring alopecia may also be related to lipid metabolism, pointing the way to novel therapeutic targets for this class of hair diseases, Dr. Maria Hordinsky said at the Hawaii Dermatology Symposium.

While the scarring alopecias are broadly divided into lymphocytic and neutrophilic alopecias, clinically, they are a heterogeneous group, said Dr. Hordinsky, chair of the department of dermatology at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis.

Two lymphocytic cicatricial alopecias, lichen planopilaris and frontal fibrosing alopecia, have been associated with peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARG) deficiency. This finding suggests that they may be a type of lipid metabolism disorder; the theory is bolstered by case reports of improvement with the use of pioglitazone, Dr. Hordinsky said at the meeting provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

In both of these cicatricial alopecias, patients may also have significant discomfort including scalp burning, pain, paresthesias, and itching. Patients may even say they feel as though their scalp is on fire.

Dr. Hordinsky and her collaborators are currently conducting a clinical trial of the efficacy of a compounded formulation of 6% topical gabapentin to address the scalp discomfort associated with the cicatricial alopecias. The study is ongoing and recruiting patients. “FFA has been described as an emerging disease, and participation of FFA patients in a national registry focused on improving our understanding of the epidemiology of this disease is highly recommended,” said Dr. Hordinsky.

Currently, stepwise treatment for the lymphocytic cicatricial alopecias can be divided into 3 tiers:

• Tier 1: Topical high potency corticosteroids and/or intralesional steroids, as well as non-steroidal topical anti-inflammatory medications, such as tacrolimus and pemicrolimus.

• Tier 2: Hydroxychloroquine and acetretin, as well as low-dose antibiotics, which are used for anti-inflammatory effect.

• Tier 3: Cyclosporin, mycophenolate mofetil, and prednisone.

Low-level light therapy – approved by the Food and Drug Administration to treat thinning hair in men and women – may also be of benefit for those with inflammatory scalp diseases, Dr. Hordinsky added.

Dr. Hordinsky reported financial relationships with a number of pharmaceutical and consumer product companies in the dermatologic space.

This news organization and SDEF are owned by the same parent company.

On Twitter @karioakes

Some kinds of scarring alopecia may also be related to lipid metabolism, pointing the way to novel therapeutic targets for this class of hair diseases, Dr. Maria Hordinsky said at the Hawaii Dermatology Symposium.

While the scarring alopecias are broadly divided into lymphocytic and neutrophilic alopecias, clinically, they are a heterogeneous group, said Dr. Hordinsky, chair of the department of dermatology at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis.

Two lymphocytic cicatricial alopecias, lichen planopilaris and frontal fibrosing alopecia, have been associated with peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARG) deficiency. This finding suggests that they may be a type of lipid metabolism disorder; the theory is bolstered by case reports of improvement with the use of pioglitazone, Dr. Hordinsky said at the meeting provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

In both of these cicatricial alopecias, patients may also have significant discomfort including scalp burning, pain, paresthesias, and itching. Patients may even say they feel as though their scalp is on fire.

Dr. Hordinsky and her collaborators are currently conducting a clinical trial of the efficacy of a compounded formulation of 6% topical gabapentin to address the scalp discomfort associated with the cicatricial alopecias. The study is ongoing and recruiting patients. “FFA has been described as an emerging disease, and participation of FFA patients in a national registry focused on improving our understanding of the epidemiology of this disease is highly recommended,” said Dr. Hordinsky.

Currently, stepwise treatment for the lymphocytic cicatricial alopecias can be divided into 3 tiers:

• Tier 1: Topical high potency corticosteroids and/or intralesional steroids, as well as non-steroidal topical anti-inflammatory medications, such as tacrolimus and pemicrolimus.

• Tier 2: Hydroxychloroquine and acetretin, as well as low-dose antibiotics, which are used for anti-inflammatory effect.

• Tier 3: Cyclosporin, mycophenolate mofetil, and prednisone.

Low-level light therapy – approved by the Food and Drug Administration to treat thinning hair in men and women – may also be of benefit for those with inflammatory scalp diseases, Dr. Hordinsky added.

Dr. Hordinsky reported financial relationships with a number of pharmaceutical and consumer product companies in the dermatologic space.

This news organization and SDEF are owned by the same parent company.

On Twitter @karioakes

Some kinds of scarring alopecia may also be related to lipid metabolism, pointing the way to novel therapeutic targets for this class of hair diseases, Dr. Maria Hordinsky said at the Hawaii Dermatology Symposium.

While the scarring alopecias are broadly divided into lymphocytic and neutrophilic alopecias, clinically, they are a heterogeneous group, said Dr. Hordinsky, chair of the department of dermatology at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis.

Two lymphocytic cicatricial alopecias, lichen planopilaris and frontal fibrosing alopecia, have been associated with peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARG) deficiency. This finding suggests that they may be a type of lipid metabolism disorder; the theory is bolstered by case reports of improvement with the use of pioglitazone, Dr. Hordinsky said at the meeting provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

In both of these cicatricial alopecias, patients may also have significant discomfort including scalp burning, pain, paresthesias, and itching. Patients may even say they feel as though their scalp is on fire.

Dr. Hordinsky and her collaborators are currently conducting a clinical trial of the efficacy of a compounded formulation of 6% topical gabapentin to address the scalp discomfort associated with the cicatricial alopecias. The study is ongoing and recruiting patients. “FFA has been described as an emerging disease, and participation of FFA patients in a national registry focused on improving our understanding of the epidemiology of this disease is highly recommended,” said Dr. Hordinsky.

Currently, stepwise treatment for the lymphocytic cicatricial alopecias can be divided into 3 tiers:

• Tier 1: Topical high potency corticosteroids and/or intralesional steroids, as well as non-steroidal topical anti-inflammatory medications, such as tacrolimus and pemicrolimus.

• Tier 2: Hydroxychloroquine and acetretin, as well as low-dose antibiotics, which are used for anti-inflammatory effect.

• Tier 3: Cyclosporin, mycophenolate mofetil, and prednisone.

Low-level light therapy – approved by the Food and Drug Administration to treat thinning hair in men and women – may also be of benefit for those with inflammatory scalp diseases, Dr. Hordinsky added.

Dr. Hordinsky reported financial relationships with a number of pharmaceutical and consumer product companies in the dermatologic space.

This news organization and SDEF are owned by the same parent company.

On Twitter @karioakes

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM SDEF HAWAII DERMATOLOGY SYMPOSIUM

A Case of Bloom Syndrome With Uncommon Clinical Manifestations Confirmed on Genetic Testing

Bloom syndrome, also called congenital telangiectatic erythema and stunted growth, was first described by David Bloom in 1954.1 It is a rare autosomal-recessive disorder (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man 210900) characterized by specific clinical manifestations including photosensitivity, telangiectatic facial erythema, proportionate growth deficiency, hypogonadism, immunodeficiency, and a tendency to develop various malignancies.2 Linkage analysis revealed that the Bloom syndrome gene locus resides on chromosome arm 15q26.1,3 and the BLM gene in this region has been identified as being responsible for the development of Bloom syndrome.4,5 We report the case of a 12-year-old Chinese girl with Bloom syndrome and detected BLM gene. The evaluation was approved by the Institutional Ethical Review Boards of Institute of Dermatology, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College (Beijing, China).

Case Report

We evaluated a Bloom syndrome family, which consisted of the patient and her parents. The patient was a 12-year-old Chinese girl who was apparently healthy until 3 months of age when her parents noticed an erythematous eruption with blisters on the face. Exacerbation after exposure to sunlight is usual, which results in the eruption becoming prominent in summer and fainter in winter.2 Gradually, the patient’s skin lesions became more progressive, extending to the forehead, nose, and ears, with oozing, crusting, atrophy, and telangiectases developing on the face despite treatment. In the last 3 years, no blisters were present on the patient’s face because of her efforts to avoid sun exposure. She had no history of recurrent infections.

On physical examination, the patient was generally healthy with normal intelligence and short stature. She weighed 26 kg and was approximately 122-cm tall. Telangiectatic erythema and slight scaling were noted on the face, which simulated lupus erythematosus (Figures 1A and 1B). She had additional abnormalities including alopecia areata (Figure 1C), eyebrow hair loss, flat nose, reticular pigmentation on the forehead and trunk, and finger swelling. The distal phalanges on all 10 fingers became short and sharpened and the fingernails became wider than they were long (Figure 1D). Laboratory investigations, including a complete blood cell count, liver and kidney function tests, stool examination, serum complement, and albumin and globulin levels, were within reference range.

After informed consent was obtained, a mutation analysis of the BLM gene was performed in the patient and her parents. We used a genomic DNA purification kit to extract genomic DNA from peripheral blood according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Genomic DNA was used to amplify the exons of the BLM gene with intron flanking sequences by polymerase chain reaction with the primer described elsewhere.6 After the amplification, the polymerase chain reaction products were purified and the BLM gene was sequenced. Sequence comparisons and analysis were performed using Phred/Phrap/Consed version 12.0.

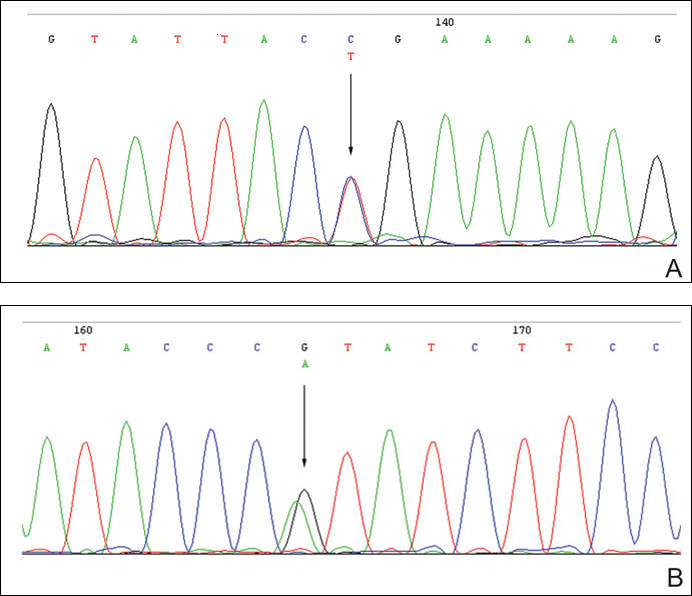

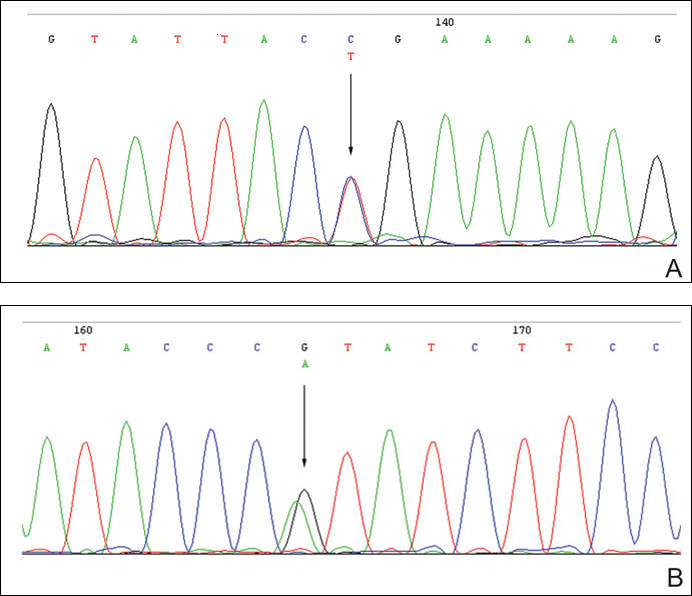

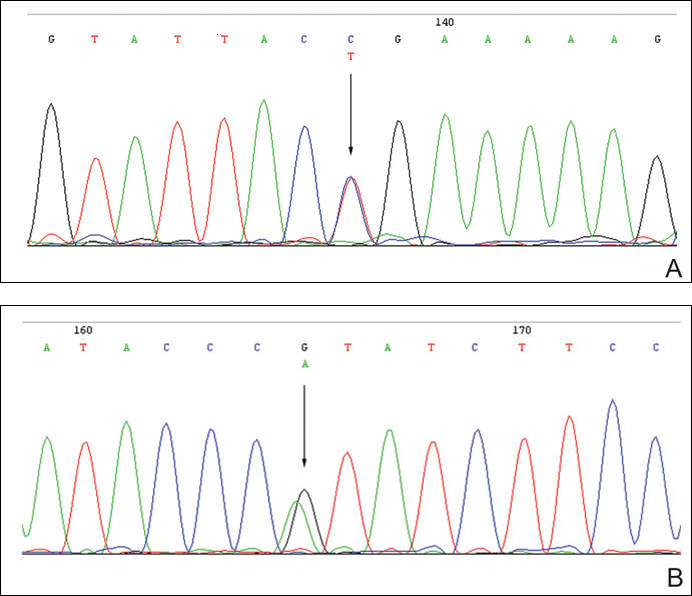

The patient was found to carry changes in 2 heterozygous nucleotide sites, including c.2603C>T in exon 13 and c.3961G>A in exon 21 of the BLM gene. The patient’s father was found to carry c.2603C>T and her mother carried c.3961G>A (Figure 2).

Comment

Patients with Bloom syndrome have a characteristic clinical appearance that typically includes photosensitivity, telangiectatic facial erythema, and growth deficiency. Telangiectatic erythema of the face develops during infancy or early childhood as red macules or plaques and may simulate lupus erythematosus. The lesions are described as a butterfly rash affecting the bridge of the nose and cheeks but also may involve the margins of the eyelids, forehead, ears, and sometimes the dorsa of the hands and forearms. Moderate and proportionate growth deficiencies develop both in utero and postnatally. Patients with Bloom syndrome characteristically have narrow, slender, distinct facial features with micrognathism and a relatively prominent nose. They usually may have mild microcephaly, meaning the head is longer and narrower than normal.2,7-10

German and Takebe11 reported 14 Japanese patients with Bloom syndrome. The phenotype differs somewhat from most cases recognized elsewhere in that dolichocephaly was a less constant feature, the facial skin was less prominent, and life-threatening infections were less common. Our patient had typical telangiectatic facial erythema without microcephaly, dolichocephaly, or any infections. She also had some uncommon manifestations such as alopecia areata, eyebrow hair loss, flat nose, reticular pigmentation, and short sharpened distal phalanges with fingernails that were wider than they were long. Although she had no recurrent infections and laboratory tests were within reference range, the alopecia areata and eyebrow hair loss may be associated with an abnormal immune response. The reasons for the short sharpened distal phalanges and the fingernail findings are unclear. The presence of reticular pigmentation also is unclear but may be associated with photosensitivity. Since the BLM gene was discovered to be the disease-causing gene of Bloom syndrome in 1995,4,5 approximately 70 mutations were reported. The BLM gene encodes for the Bloom syndrome protein, a DNA helicase of the highly conserved RecQ subfamily of helicases, a group of nuclear proteins important in the maintenance of genomic stability.12

Mutation analysis of the BLM gene in our patient showed changes in 2 heterozygous nucleotide sites, including c.2603C>T in exon 13 and c.3961G>A in exon 21 of the BLM gene, which altered proline residue with leucine residue at 868 and valine residue with isoleucine residue at 1321, respectively. According to GenBank,13,14 c.2603C>T and c.3961G>A are single nucleotide polymorphisms of the BLM gene. The genotypic distribution of International HapMap Project15 showed that C=602/602 and T=0/602 on c.2603 in 301 unrelated Chinese patients and G=585/602 and A=17/602 on c.3961 in 301 unrelated Chinese patients. Because of the low prevalence of genotypes c.2603T and c.3961A in China, the relationship between clinical features and c.2603C>T and c.3961G>A of the BLM gene in our patient requires further study.

In conclusion, we report a patient with Bloom syndrome with uncommon clinical manifestations. Our findings indicate that c.2603C>T and c.3961G>A of the BLM gene may be the pathogenic nature for Bloom syndrome in China.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the patient and her family for their participation in the study. The authors also thank Li Qi, BA, Beijing, China, for his contribution to the review of the data in the literature.

- Bloom D. Congenital telangiectatic erythema resembling lupus erythematosus in dwarfs; probably a syndrome entity. AMA Am J Dis Child. 1954;88:754-758.

- German J. Bloom’s syndrome, I: genetical and clinical observations in the first twenty-seven patients. Am J Hum Genet. 1969;21:196-227.

- German J, Roe AM, Leppert MF, et al. Bloom syndrome: an analysis of consanguineous families assigns the locus mutated to chromosome band 15q26.1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:6669-6673.

- Passarge E. A DNA helicase in full Bloom. Nat Genet. 1995;11:356-357.

- Ellis NA, Groden J, Ye TZ, et al. The Bloom’s syndrome gene product is homologous to RecQ helicases. Cell. 1995;83:655-666.

- German J, Sanz MM, Ciocci S, et al. Syndrome-causing mutations of the BLM gene in persons in the Bloom’s Syndrome Registry. Hum Mutat. 2007;28:743-753.

- Landau JW, Sasaki MS, Newcomer VD, et al. Bloom’s syndrome: the syndrome of telangiectatic erythema and growth retardation. Arch Dermatol. 1966;94:687-694.

- Gretzula JC, Hevia O, Weber PJ. Bloom’s syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:479-488.

- Passarge E. Bloom’s syndrome: the German experience. Ann Genet. 1991;34:179-197.

- German J. Bloom’s syndrome. Dermatol Clin. 1995;13:7-18.

- German J, Takebe H. Bloom’s syndrome, XIV: the disorder in Japan. Clin Genet. 1989;35:93-110.

- Bennett RJ, Keck JL. Structure and function of RecQ DNA helicases. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;39:79-97.

- Reference SNP (refSNP) Cluster Report: rs2227935. National Center for Biotechnology Information website. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP/snp_ref.cgi?rs=2227935. Accessed February 3, 2016.

- Reference SNP (refSNP) Cluster Report: rs7167216. National Center for Biotechnology Information website. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP/snp_ref.cgi?rs=7167216. Accessed February 3, 2016.

- Homo sapiens:GRCh37.p13 (GCF_000001405.25)Chr 1 (NC_000001.10):1 - 249.3M. National Center for Biotechnology Information website. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/variationtools/1000genomes/?=%EF%BC%86=. Accessed February 3, 2016.

Bloom syndrome, also called congenital telangiectatic erythema and stunted growth, was first described by David Bloom in 1954.1 It is a rare autosomal-recessive disorder (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man 210900) characterized by specific clinical manifestations including photosensitivity, telangiectatic facial erythema, proportionate growth deficiency, hypogonadism, immunodeficiency, and a tendency to develop various malignancies.2 Linkage analysis revealed that the Bloom syndrome gene locus resides on chromosome arm 15q26.1,3 and the BLM gene in this region has been identified as being responsible for the development of Bloom syndrome.4,5 We report the case of a 12-year-old Chinese girl with Bloom syndrome and detected BLM gene. The evaluation was approved by the Institutional Ethical Review Boards of Institute of Dermatology, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College (Beijing, China).

Case Report

We evaluated a Bloom syndrome family, which consisted of the patient and her parents. The patient was a 12-year-old Chinese girl who was apparently healthy until 3 months of age when her parents noticed an erythematous eruption with blisters on the face. Exacerbation after exposure to sunlight is usual, which results in the eruption becoming prominent in summer and fainter in winter.2 Gradually, the patient’s skin lesions became more progressive, extending to the forehead, nose, and ears, with oozing, crusting, atrophy, and telangiectases developing on the face despite treatment. In the last 3 years, no blisters were present on the patient’s face because of her efforts to avoid sun exposure. She had no history of recurrent infections.

On physical examination, the patient was generally healthy with normal intelligence and short stature. She weighed 26 kg and was approximately 122-cm tall. Telangiectatic erythema and slight scaling were noted on the face, which simulated lupus erythematosus (Figures 1A and 1B). She had additional abnormalities including alopecia areata (Figure 1C), eyebrow hair loss, flat nose, reticular pigmentation on the forehead and trunk, and finger swelling. The distal phalanges on all 10 fingers became short and sharpened and the fingernails became wider than they were long (Figure 1D). Laboratory investigations, including a complete blood cell count, liver and kidney function tests, stool examination, serum complement, and albumin and globulin levels, were within reference range.

After informed consent was obtained, a mutation analysis of the BLM gene was performed in the patient and her parents. We used a genomic DNA purification kit to extract genomic DNA from peripheral blood according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Genomic DNA was used to amplify the exons of the BLM gene with intron flanking sequences by polymerase chain reaction with the primer described elsewhere.6 After the amplification, the polymerase chain reaction products were purified and the BLM gene was sequenced. Sequence comparisons and analysis were performed using Phred/Phrap/Consed version 12.0.

The patient was found to carry changes in 2 heterozygous nucleotide sites, including c.2603C>T in exon 13 and c.3961G>A in exon 21 of the BLM gene. The patient’s father was found to carry c.2603C>T and her mother carried c.3961G>A (Figure 2).

Comment

Patients with Bloom syndrome have a characteristic clinical appearance that typically includes photosensitivity, telangiectatic facial erythema, and growth deficiency. Telangiectatic erythema of the face develops during infancy or early childhood as red macules or plaques and may simulate lupus erythematosus. The lesions are described as a butterfly rash affecting the bridge of the nose and cheeks but also may involve the margins of the eyelids, forehead, ears, and sometimes the dorsa of the hands and forearms. Moderate and proportionate growth deficiencies develop both in utero and postnatally. Patients with Bloom syndrome characteristically have narrow, slender, distinct facial features with micrognathism and a relatively prominent nose. They usually may have mild microcephaly, meaning the head is longer and narrower than normal.2,7-10

German and Takebe11 reported 14 Japanese patients with Bloom syndrome. The phenotype differs somewhat from most cases recognized elsewhere in that dolichocephaly was a less constant feature, the facial skin was less prominent, and life-threatening infections were less common. Our patient had typical telangiectatic facial erythema without microcephaly, dolichocephaly, or any infections. She also had some uncommon manifestations such as alopecia areata, eyebrow hair loss, flat nose, reticular pigmentation, and short sharpened distal phalanges with fingernails that were wider than they were long. Although she had no recurrent infections and laboratory tests were within reference range, the alopecia areata and eyebrow hair loss may be associated with an abnormal immune response. The reasons for the short sharpened distal phalanges and the fingernail findings are unclear. The presence of reticular pigmentation also is unclear but may be associated with photosensitivity. Since the BLM gene was discovered to be the disease-causing gene of Bloom syndrome in 1995,4,5 approximately 70 mutations were reported. The BLM gene encodes for the Bloom syndrome protein, a DNA helicase of the highly conserved RecQ subfamily of helicases, a group of nuclear proteins important in the maintenance of genomic stability.12

Mutation analysis of the BLM gene in our patient showed changes in 2 heterozygous nucleotide sites, including c.2603C>T in exon 13 and c.3961G>A in exon 21 of the BLM gene, which altered proline residue with leucine residue at 868 and valine residue with isoleucine residue at 1321, respectively. According to GenBank,13,14 c.2603C>T and c.3961G>A are single nucleotide polymorphisms of the BLM gene. The genotypic distribution of International HapMap Project15 showed that C=602/602 and T=0/602 on c.2603 in 301 unrelated Chinese patients and G=585/602 and A=17/602 on c.3961 in 301 unrelated Chinese patients. Because of the low prevalence of genotypes c.2603T and c.3961A in China, the relationship between clinical features and c.2603C>T and c.3961G>A of the BLM gene in our patient requires further study.

In conclusion, we report a patient with Bloom syndrome with uncommon clinical manifestations. Our findings indicate that c.2603C>T and c.3961G>A of the BLM gene may be the pathogenic nature for Bloom syndrome in China.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the patient and her family for their participation in the study. The authors also thank Li Qi, BA, Beijing, China, for his contribution to the review of the data in the literature.

Bloom syndrome, also called congenital telangiectatic erythema and stunted growth, was first described by David Bloom in 1954.1 It is a rare autosomal-recessive disorder (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man 210900) characterized by specific clinical manifestations including photosensitivity, telangiectatic facial erythema, proportionate growth deficiency, hypogonadism, immunodeficiency, and a tendency to develop various malignancies.2 Linkage analysis revealed that the Bloom syndrome gene locus resides on chromosome arm 15q26.1,3 and the BLM gene in this region has been identified as being responsible for the development of Bloom syndrome.4,5 We report the case of a 12-year-old Chinese girl with Bloom syndrome and detected BLM gene. The evaluation was approved by the Institutional Ethical Review Boards of Institute of Dermatology, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College (Beijing, China).

Case Report

We evaluated a Bloom syndrome family, which consisted of the patient and her parents. The patient was a 12-year-old Chinese girl who was apparently healthy until 3 months of age when her parents noticed an erythematous eruption with blisters on the face. Exacerbation after exposure to sunlight is usual, which results in the eruption becoming prominent in summer and fainter in winter.2 Gradually, the patient’s skin lesions became more progressive, extending to the forehead, nose, and ears, with oozing, crusting, atrophy, and telangiectases developing on the face despite treatment. In the last 3 years, no blisters were present on the patient’s face because of her efforts to avoid sun exposure. She had no history of recurrent infections.

On physical examination, the patient was generally healthy with normal intelligence and short stature. She weighed 26 kg and was approximately 122-cm tall. Telangiectatic erythema and slight scaling were noted on the face, which simulated lupus erythematosus (Figures 1A and 1B). She had additional abnormalities including alopecia areata (Figure 1C), eyebrow hair loss, flat nose, reticular pigmentation on the forehead and trunk, and finger swelling. The distal phalanges on all 10 fingers became short and sharpened and the fingernails became wider than they were long (Figure 1D). Laboratory investigations, including a complete blood cell count, liver and kidney function tests, stool examination, serum complement, and albumin and globulin levels, were within reference range.

After informed consent was obtained, a mutation analysis of the BLM gene was performed in the patient and her parents. We used a genomic DNA purification kit to extract genomic DNA from peripheral blood according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Genomic DNA was used to amplify the exons of the BLM gene with intron flanking sequences by polymerase chain reaction with the primer described elsewhere.6 After the amplification, the polymerase chain reaction products were purified and the BLM gene was sequenced. Sequence comparisons and analysis were performed using Phred/Phrap/Consed version 12.0.

The patient was found to carry changes in 2 heterozygous nucleotide sites, including c.2603C>T in exon 13 and c.3961G>A in exon 21 of the BLM gene. The patient’s father was found to carry c.2603C>T and her mother carried c.3961G>A (Figure 2).

Comment

Patients with Bloom syndrome have a characteristic clinical appearance that typically includes photosensitivity, telangiectatic facial erythema, and growth deficiency. Telangiectatic erythema of the face develops during infancy or early childhood as red macules or plaques and may simulate lupus erythematosus. The lesions are described as a butterfly rash affecting the bridge of the nose and cheeks but also may involve the margins of the eyelids, forehead, ears, and sometimes the dorsa of the hands and forearms. Moderate and proportionate growth deficiencies develop both in utero and postnatally. Patients with Bloom syndrome characteristically have narrow, slender, distinct facial features with micrognathism and a relatively prominent nose. They usually may have mild microcephaly, meaning the head is longer and narrower than normal.2,7-10

German and Takebe11 reported 14 Japanese patients with Bloom syndrome. The phenotype differs somewhat from most cases recognized elsewhere in that dolichocephaly was a less constant feature, the facial skin was less prominent, and life-threatening infections were less common. Our patient had typical telangiectatic facial erythema without microcephaly, dolichocephaly, or any infections. She also had some uncommon manifestations such as alopecia areata, eyebrow hair loss, flat nose, reticular pigmentation, and short sharpened distal phalanges with fingernails that were wider than they were long. Although she had no recurrent infections and laboratory tests were within reference range, the alopecia areata and eyebrow hair loss may be associated with an abnormal immune response. The reasons for the short sharpened distal phalanges and the fingernail findings are unclear. The presence of reticular pigmentation also is unclear but may be associated with photosensitivity. Since the BLM gene was discovered to be the disease-causing gene of Bloom syndrome in 1995,4,5 approximately 70 mutations were reported. The BLM gene encodes for the Bloom syndrome protein, a DNA helicase of the highly conserved RecQ subfamily of helicases, a group of nuclear proteins important in the maintenance of genomic stability.12

Mutation analysis of the BLM gene in our patient showed changes in 2 heterozygous nucleotide sites, including c.2603C>T in exon 13 and c.3961G>A in exon 21 of the BLM gene, which altered proline residue with leucine residue at 868 and valine residue with isoleucine residue at 1321, respectively. According to GenBank,13,14 c.2603C>T and c.3961G>A are single nucleotide polymorphisms of the BLM gene. The genotypic distribution of International HapMap Project15 showed that C=602/602 and T=0/602 on c.2603 in 301 unrelated Chinese patients and G=585/602 and A=17/602 on c.3961 in 301 unrelated Chinese patients. Because of the low prevalence of genotypes c.2603T and c.3961A in China, the relationship between clinical features and c.2603C>T and c.3961G>A of the BLM gene in our patient requires further study.

In conclusion, we report a patient with Bloom syndrome with uncommon clinical manifestations. Our findings indicate that c.2603C>T and c.3961G>A of the BLM gene may be the pathogenic nature for Bloom syndrome in China.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the patient and her family for their participation in the study. The authors also thank Li Qi, BA, Beijing, China, for his contribution to the review of the data in the literature.

- Bloom D. Congenital telangiectatic erythema resembling lupus erythematosus in dwarfs; probably a syndrome entity. AMA Am J Dis Child. 1954;88:754-758.

- German J. Bloom’s syndrome, I: genetical and clinical observations in the first twenty-seven patients. Am J Hum Genet. 1969;21:196-227.

- German J, Roe AM, Leppert MF, et al. Bloom syndrome: an analysis of consanguineous families assigns the locus mutated to chromosome band 15q26.1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:6669-6673.

- Passarge E. A DNA helicase in full Bloom. Nat Genet. 1995;11:356-357.

- Ellis NA, Groden J, Ye TZ, et al. The Bloom’s syndrome gene product is homologous to RecQ helicases. Cell. 1995;83:655-666.

- German J, Sanz MM, Ciocci S, et al. Syndrome-causing mutations of the BLM gene in persons in the Bloom’s Syndrome Registry. Hum Mutat. 2007;28:743-753.

- Landau JW, Sasaki MS, Newcomer VD, et al. Bloom’s syndrome: the syndrome of telangiectatic erythema and growth retardation. Arch Dermatol. 1966;94:687-694.

- Gretzula JC, Hevia O, Weber PJ. Bloom’s syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:479-488.

- Passarge E. Bloom’s syndrome: the German experience. Ann Genet. 1991;34:179-197.

- German J. Bloom’s syndrome. Dermatol Clin. 1995;13:7-18.

- German J, Takebe H. Bloom’s syndrome, XIV: the disorder in Japan. Clin Genet. 1989;35:93-110.

- Bennett RJ, Keck JL. Structure and function of RecQ DNA helicases. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;39:79-97.

- Reference SNP (refSNP) Cluster Report: rs2227935. National Center for Biotechnology Information website. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP/snp_ref.cgi?rs=2227935. Accessed February 3, 2016.

- Reference SNP (refSNP) Cluster Report: rs7167216. National Center for Biotechnology Information website. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP/snp_ref.cgi?rs=7167216. Accessed February 3, 2016.

- Homo sapiens:GRCh37.p13 (GCF_000001405.25)Chr 1 (NC_000001.10):1 - 249.3M. National Center for Biotechnology Information website. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/variationtools/1000genomes/?=%EF%BC%86=. Accessed February 3, 2016.

- Bloom D. Congenital telangiectatic erythema resembling lupus erythematosus in dwarfs; probably a syndrome entity. AMA Am J Dis Child. 1954;88:754-758.

- German J. Bloom’s syndrome, I: genetical and clinical observations in the first twenty-seven patients. Am J Hum Genet. 1969;21:196-227.

- German J, Roe AM, Leppert MF, et al. Bloom syndrome: an analysis of consanguineous families assigns the locus mutated to chromosome band 15q26.1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:6669-6673.

- Passarge E. A DNA helicase in full Bloom. Nat Genet. 1995;11:356-357.

- Ellis NA, Groden J, Ye TZ, et al. The Bloom’s syndrome gene product is homologous to RecQ helicases. Cell. 1995;83:655-666.

- German J, Sanz MM, Ciocci S, et al. Syndrome-causing mutations of the BLM gene in persons in the Bloom’s Syndrome Registry. Hum Mutat. 2007;28:743-753.

- Landau JW, Sasaki MS, Newcomer VD, et al. Bloom’s syndrome: the syndrome of telangiectatic erythema and growth retardation. Arch Dermatol. 1966;94:687-694.

- Gretzula JC, Hevia O, Weber PJ. Bloom’s syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:479-488.

- Passarge E. Bloom’s syndrome: the German experience. Ann Genet. 1991;34:179-197.

- German J. Bloom’s syndrome. Dermatol Clin. 1995;13:7-18.

- German J, Takebe H. Bloom’s syndrome, XIV: the disorder in Japan. Clin Genet. 1989;35:93-110.

- Bennett RJ, Keck JL. Structure and function of RecQ DNA helicases. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;39:79-97.

- Reference SNP (refSNP) Cluster Report: rs2227935. National Center for Biotechnology Information website. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP/snp_ref.cgi?rs=2227935. Accessed February 3, 2016.

- Reference SNP (refSNP) Cluster Report: rs7167216. National Center for Biotechnology Information website. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP/snp_ref.cgi?rs=7167216. Accessed February 3, 2016.

- Homo sapiens:GRCh37.p13 (GCF_000001405.25)Chr 1 (NC_000001.10):1 - 249.3M. National Center for Biotechnology Information website. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/variationtools/1000genomes/?=%EF%BC%86=. Accessed February 3, 2016.

Certain hairstyles can predispose patients to traction alopecia

ORLANDO – When it comes to preventing alopecia, it may be best to advise patients against certain trendy hairstyles that can cause early hair loss.

At the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference, Dr. Wendy Roberts, a dermatologist practicing in Rancho Mirage, Calif., spoke about the risks of traction alopecia associated with some hairstyles and why it’s in patients’ best interest to avoid them if they don’t want to experience premature hair loss.

Dr. Roberts brings up the topic of hair loss with patients during the full-body exam. Full-body skin exams are “opportunities for us, as the skin and hair experts, to speak to our patients about hair loss, [but] it’s rarely asked about,” she said. “Typically, what I do is start my full-body skin exam from the head and I always ask the question right away ‘How’s your hair? Are you having any problems with your hair? How’s your scalp?’ And about 50% of the time, there’s a positive answer or an interest in learning more about it.”

To avoid traction alopecia, caused frequently by intense pulling or pressure on the hair follicles, patients should be advised against braiding their hair or, for male patients, styling their hair in a “man bun.” For braids, the tightness of the braid and pulling along the hairlines will cause intense pressure on follicles over time that can lead to hair loss. For the man bun, Dr. Roberts noted that dermatologists will likely see an uptick in male patients with traction alopecia as this hairstyle becomes more popular.

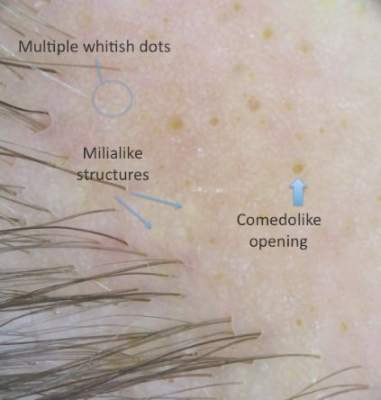

In the evaluation and treatment of traction alopecia – as with any form of alopecia – clinical presentation, ethnicity, and the age of the patient should be considered, Dr. Roberts said. Additionally, collection of evidence – hair pulls, biopsy, dermoscopy, and lab work should be obtained.

Labs will check for iron levels and anemia, thyroid disease, vitamin D deficiency, and perhaps signs of a connective tissue disorder, she noted. “It’s staggering the amount of African-American women who are deficient in vitamin D, [and] there is some soft evidence that perhaps vitamin D deficiency may be a culprit in some of the clinical signs of discoid lupus erythematosus, [so] check the vitamin D and zinc levels.”

After making a diagnosis, it is important to quickly begin rigorous treatment of the alopecia. Aggressive treatment is “the bottom line,” Dr. Roberts emphasized, “because people are losing their hair and when they come to you, they’ve really had enough.”

She did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

ORLANDO – When it comes to preventing alopecia, it may be best to advise patients against certain trendy hairstyles that can cause early hair loss.

At the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference, Dr. Wendy Roberts, a dermatologist practicing in Rancho Mirage, Calif., spoke about the risks of traction alopecia associated with some hairstyles and why it’s in patients’ best interest to avoid them if they don’t want to experience premature hair loss.

Dr. Roberts brings up the topic of hair loss with patients during the full-body exam. Full-body skin exams are “opportunities for us, as the skin and hair experts, to speak to our patients about hair loss, [but] it’s rarely asked about,” she said. “Typically, what I do is start my full-body skin exam from the head and I always ask the question right away ‘How’s your hair? Are you having any problems with your hair? How’s your scalp?’ And about 50% of the time, there’s a positive answer or an interest in learning more about it.”

To avoid traction alopecia, caused frequently by intense pulling or pressure on the hair follicles, patients should be advised against braiding their hair or, for male patients, styling their hair in a “man bun.” For braids, the tightness of the braid and pulling along the hairlines will cause intense pressure on follicles over time that can lead to hair loss. For the man bun, Dr. Roberts noted that dermatologists will likely see an uptick in male patients with traction alopecia as this hairstyle becomes more popular.

In the evaluation and treatment of traction alopecia – as with any form of alopecia – clinical presentation, ethnicity, and the age of the patient should be considered, Dr. Roberts said. Additionally, collection of evidence – hair pulls, biopsy, dermoscopy, and lab work should be obtained.

Labs will check for iron levels and anemia, thyroid disease, vitamin D deficiency, and perhaps signs of a connective tissue disorder, she noted. “It’s staggering the amount of African-American women who are deficient in vitamin D, [and] there is some soft evidence that perhaps vitamin D deficiency may be a culprit in some of the clinical signs of discoid lupus erythematosus, [so] check the vitamin D and zinc levels.”

After making a diagnosis, it is important to quickly begin rigorous treatment of the alopecia. Aggressive treatment is “the bottom line,” Dr. Roberts emphasized, “because people are losing their hair and when they come to you, they’ve really had enough.”

She did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

ORLANDO – When it comes to preventing alopecia, it may be best to advise patients against certain trendy hairstyles that can cause early hair loss.

At the Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference, Dr. Wendy Roberts, a dermatologist practicing in Rancho Mirage, Calif., spoke about the risks of traction alopecia associated with some hairstyles and why it’s in patients’ best interest to avoid them if they don’t want to experience premature hair loss.

Dr. Roberts brings up the topic of hair loss with patients during the full-body exam. Full-body skin exams are “opportunities for us, as the skin and hair experts, to speak to our patients about hair loss, [but] it’s rarely asked about,” she said. “Typically, what I do is start my full-body skin exam from the head and I always ask the question right away ‘How’s your hair? Are you having any problems with your hair? How’s your scalp?’ And about 50% of the time, there’s a positive answer or an interest in learning more about it.”