User login

No link between head and neck cancers and marijuana use

Marijuana use does not seem to be a risk factor for head and neck cancer (HNC) suggests a meta-analysis including nine case-control studies.

The chance of developing head and neck cancer in individuals who had smoked marijuana in their lifetime was estimated using an odds ratio, and controlling for age, sex, race, and tobacco consumption.

Approximately 12.6% of the patients who developed HNC and 14.3% of the controls were marijuana users. No association was found between exposure to marijuana and HNC (odds ratio = 1.021).

“Despite several inferences that have made to date, there is currently insufficient epidemiological evidence to support a positive or negative association in marijuana use and the development of HNC,” the researchers said.

Future studies on the long-term effects of marijuana use and “the mechanism of action of cannabinoids in specific tissues in animal models and humans” are needed, according to the researchers.

Read the full study in Archives of Oral Biology (doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbi.2015.09.009).

Marijuana use does not seem to be a risk factor for head and neck cancer (HNC) suggests a meta-analysis including nine case-control studies.

The chance of developing head and neck cancer in individuals who had smoked marijuana in their lifetime was estimated using an odds ratio, and controlling for age, sex, race, and tobacco consumption.

Approximately 12.6% of the patients who developed HNC and 14.3% of the controls were marijuana users. No association was found between exposure to marijuana and HNC (odds ratio = 1.021).

“Despite several inferences that have made to date, there is currently insufficient epidemiological evidence to support a positive or negative association in marijuana use and the development of HNC,” the researchers said.

Future studies on the long-term effects of marijuana use and “the mechanism of action of cannabinoids in specific tissues in animal models and humans” are needed, according to the researchers.

Read the full study in Archives of Oral Biology (doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbi.2015.09.009).

Marijuana use does not seem to be a risk factor for head and neck cancer (HNC) suggests a meta-analysis including nine case-control studies.

The chance of developing head and neck cancer in individuals who had smoked marijuana in their lifetime was estimated using an odds ratio, and controlling for age, sex, race, and tobacco consumption.

Approximately 12.6% of the patients who developed HNC and 14.3% of the controls were marijuana users. No association was found between exposure to marijuana and HNC (odds ratio = 1.021).

“Despite several inferences that have made to date, there is currently insufficient epidemiological evidence to support a positive or negative association in marijuana use and the development of HNC,” the researchers said.

Future studies on the long-term effects of marijuana use and “the mechanism of action of cannabinoids in specific tissues in animal models and humans” are needed, according to the researchers.

Read the full study in Archives of Oral Biology (doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbi.2015.09.009).

FROM ARCHIVES OF ORAL BIOLOGY

ECC: Pembrolizumab hits mark in heavily pretreated nasopharngeal cancer

VIENNA – Programmed cell death 1 blockade with pembrolizumab proved a good match for nasopharngeal carcinoma, a notoriously difficult-to-treat cancer, in the phase Ib KEYSTONE-028 study.

The objective response rate among 27 heavily pretreated patients with metastatic or recurrent nasopharngeal cancer was 22.2%, including 6 partial responses.

Six patients progressed and 15 had stable disease, bringing the disease control rate to 77.8%, Dr. Chiun Hsu, of National Taiwan University Hospital in Taipei, reported at the European Cancer Congress.

Almost two-thirds of patients (67%) experienced a decrease in target lesions with pembrolizumab (Keytruda). Tumor shrinkage seen in responders at the first assessment.

The median time to response was quite short at 1.8 months, but the responses were quite durable, lasting a median of 10.8 months, he said.

Invited discussant Dr. Ulrich Keilholz, director of the Charité Comprehensive Cancer Center in Berlin, commented, “In those patients with regression, we see quite long-lasting responses. This is very rewarding and interesting.”

There were no late responses after the initial progression or evidence of pseudoprogression, which has been seen with other immunotherapies.

“So the question is really whether we need to keep patients on study if they have progression since we did not see something we saw with ipilimumab (Yervoy) in other diseases, where we had an initial progression and then late response,” he said.

Median progression-free survival was 5.6 months, but ranged from 3.6 months to 11 months, Dr. Hsu said. The PFS rate at 6 months was 49.7% and at 12 months 29%.

“This study is the first demonstration of robust clinical activity of a PD-1 inhibitor in patients with recurrent and metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma,” he said.

Recent studies have shown that about a third of patients with nasopharngeal carcinoma will recur after primary treatment and that progression-free survival is typically less than 6 months in recurrent and metastatic disease after failure of platinum-based chemotherapy, Dr. Keilholz observed.

Pembrolizumab has shown clinical activity in more than a dozen tumor types and works by binding to the programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) receptor and blocking its interaction with PD-1 ligand 1 (PD-L1) and 2 (PD-L2). Nasopharyngeal cancer almost universally expresses PD-L1, Dr. Keilholz said.

The 27 patients were drawn from the ongoing, multicohort KEYSTONE-028 study of pembrolizumab in PD-L1-positive advanced solid tumors and received pembrolizumab 10 mg/kg intravenously every two weeks for a maximum of 24 weeks or until disease progression or intolerable toxicity. Their median age was 52 years, 78% were male, 63% Asian, 66.6% had WHO class 2/3 tumors, and 29.6% had received 3 prior lines of therapy for advanced disease.

The safety profile was manageable, Dr. Hsu said. The most common treatment-related adverse event of any grade were pruritus (26%), fatigue (18.5%), and hypothyroidism (18.5%). The most notable grade 3-5 adverse events were two cases each of hepatitis and pneumonitis. There was one treatment-related death due to sepsis and four patients discontinued treatment due to adverse events.

Further investigation of pembrolizumab in this setting is planned, Dr. Hsu said.

On Twitter @pwendl

VIENNA – Programmed cell death 1 blockade with pembrolizumab proved a good match for nasopharngeal carcinoma, a notoriously difficult-to-treat cancer, in the phase Ib KEYSTONE-028 study.

The objective response rate among 27 heavily pretreated patients with metastatic or recurrent nasopharngeal cancer was 22.2%, including 6 partial responses.

Six patients progressed and 15 had stable disease, bringing the disease control rate to 77.8%, Dr. Chiun Hsu, of National Taiwan University Hospital in Taipei, reported at the European Cancer Congress.

Almost two-thirds of patients (67%) experienced a decrease in target lesions with pembrolizumab (Keytruda). Tumor shrinkage seen in responders at the first assessment.

The median time to response was quite short at 1.8 months, but the responses were quite durable, lasting a median of 10.8 months, he said.

Invited discussant Dr. Ulrich Keilholz, director of the Charité Comprehensive Cancer Center in Berlin, commented, “In those patients with regression, we see quite long-lasting responses. This is very rewarding and interesting.”

There were no late responses after the initial progression or evidence of pseudoprogression, which has been seen with other immunotherapies.

“So the question is really whether we need to keep patients on study if they have progression since we did not see something we saw with ipilimumab (Yervoy) in other diseases, where we had an initial progression and then late response,” he said.

Median progression-free survival was 5.6 months, but ranged from 3.6 months to 11 months, Dr. Hsu said. The PFS rate at 6 months was 49.7% and at 12 months 29%.

“This study is the first demonstration of robust clinical activity of a PD-1 inhibitor in patients with recurrent and metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma,” he said.

Recent studies have shown that about a third of patients with nasopharngeal carcinoma will recur after primary treatment and that progression-free survival is typically less than 6 months in recurrent and metastatic disease after failure of platinum-based chemotherapy, Dr. Keilholz observed.

Pembrolizumab has shown clinical activity in more than a dozen tumor types and works by binding to the programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) receptor and blocking its interaction with PD-1 ligand 1 (PD-L1) and 2 (PD-L2). Nasopharyngeal cancer almost universally expresses PD-L1, Dr. Keilholz said.

The 27 patients were drawn from the ongoing, multicohort KEYSTONE-028 study of pembrolizumab in PD-L1-positive advanced solid tumors and received pembrolizumab 10 mg/kg intravenously every two weeks for a maximum of 24 weeks or until disease progression or intolerable toxicity. Their median age was 52 years, 78% were male, 63% Asian, 66.6% had WHO class 2/3 tumors, and 29.6% had received 3 prior lines of therapy for advanced disease.

The safety profile was manageable, Dr. Hsu said. The most common treatment-related adverse event of any grade were pruritus (26%), fatigue (18.5%), and hypothyroidism (18.5%). The most notable grade 3-5 adverse events were two cases each of hepatitis and pneumonitis. There was one treatment-related death due to sepsis and four patients discontinued treatment due to adverse events.

Further investigation of pembrolizumab in this setting is planned, Dr. Hsu said.

On Twitter @pwendl

VIENNA – Programmed cell death 1 blockade with pembrolizumab proved a good match for nasopharngeal carcinoma, a notoriously difficult-to-treat cancer, in the phase Ib KEYSTONE-028 study.

The objective response rate among 27 heavily pretreated patients with metastatic or recurrent nasopharngeal cancer was 22.2%, including 6 partial responses.

Six patients progressed and 15 had stable disease, bringing the disease control rate to 77.8%, Dr. Chiun Hsu, of National Taiwan University Hospital in Taipei, reported at the European Cancer Congress.

Almost two-thirds of patients (67%) experienced a decrease in target lesions with pembrolizumab (Keytruda). Tumor shrinkage seen in responders at the first assessment.

The median time to response was quite short at 1.8 months, but the responses were quite durable, lasting a median of 10.8 months, he said.

Invited discussant Dr. Ulrich Keilholz, director of the Charité Comprehensive Cancer Center in Berlin, commented, “In those patients with regression, we see quite long-lasting responses. This is very rewarding and interesting.”

There were no late responses after the initial progression or evidence of pseudoprogression, which has been seen with other immunotherapies.

“So the question is really whether we need to keep patients on study if they have progression since we did not see something we saw with ipilimumab (Yervoy) in other diseases, where we had an initial progression and then late response,” he said.

Median progression-free survival was 5.6 months, but ranged from 3.6 months to 11 months, Dr. Hsu said. The PFS rate at 6 months was 49.7% and at 12 months 29%.

“This study is the first demonstration of robust clinical activity of a PD-1 inhibitor in patients with recurrent and metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma,” he said.

Recent studies have shown that about a third of patients with nasopharngeal carcinoma will recur after primary treatment and that progression-free survival is typically less than 6 months in recurrent and metastatic disease after failure of platinum-based chemotherapy, Dr. Keilholz observed.

Pembrolizumab has shown clinical activity in more than a dozen tumor types and works by binding to the programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) receptor and blocking its interaction with PD-1 ligand 1 (PD-L1) and 2 (PD-L2). Nasopharyngeal cancer almost universally expresses PD-L1, Dr. Keilholz said.

The 27 patients were drawn from the ongoing, multicohort KEYSTONE-028 study of pembrolizumab in PD-L1-positive advanced solid tumors and received pembrolizumab 10 mg/kg intravenously every two weeks for a maximum of 24 weeks or until disease progression or intolerable toxicity. Their median age was 52 years, 78% were male, 63% Asian, 66.6% had WHO class 2/3 tumors, and 29.6% had received 3 prior lines of therapy for advanced disease.

The safety profile was manageable, Dr. Hsu said. The most common treatment-related adverse event of any grade were pruritus (26%), fatigue (18.5%), and hypothyroidism (18.5%). The most notable grade 3-5 adverse events were two cases each of hepatitis and pneumonitis. There was one treatment-related death due to sepsis and four patients discontinued treatment due to adverse events.

Further investigation of pembrolizumab in this setting is planned, Dr. Hsu said.

On Twitter @pwendl

AT THE EUROPEAN CANCER CONGRESS 2015

Key clinical point: Pembrolizumab is clinically active and produces durable responses in patients with recurrent or metastatic nasopharyngeal cancer.

Major finding: The objective response rate was 22%.

Data source: Phase 1b study in 27 patients with recurrent or metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma.

Disclosures: KEYNOTE-028 is supported by Merck, Sharp & Dohme. Dr. Hsu reported having no conflicts to disclose.

Epidemiology of Stage IV Thyroid Cancer Patients: A Review of the National Cancer Database, 2000-2012

Background: Patients with thyroid cancer often have distinctive characteristics that change as the cancer progresses to stage IV and warrants varied treatment. A Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results-based study reported that men with thyroid cancer of follicular cell origin are more likely to present with advanced disease compared with that of female patients. This is the largest study to evaluate stage IV thyroid cancer.

Methods: A population-based study was conducted using the National Cancer Database (NCDB), which captures nearly 70% of incident cancers in the U.S. For the accession years 2000 to 2012, NCDB took epidemiologic information for a sample of 343,386 thyroid cancer cases and used data from the 2012 U.S. census. The diagnosis of stage IV disease represented 6.88% (23,613) of the total patient population. The demographics of stage IV patients were compared with patients with all other stages using the chi-square test.

Results: There was an increased incidence of stage IV thyroid cancer in Medicare, lower high school graduation rates, annual median household income < $44,000, aged ≥ 70 years, male, more comorbidities, and further distance from a treatment facility (P < .0001). Ethnicity/race had little impact on the incidence of stage IV disease. Stage IV cancer incidence is higher in males (12.14%) compared with that of females (5.15%), and stage IV patients are more likely have Medicare (14.60%) or be uninsured (8.72%) than have private insurance (4.63%). Patients with ≥ 2 comorbidities (14.23%) are more than twice as likely to have stage IV as those without comorbidities (6.77%). Medullary and anaplastic cancers (20.08%) are much more likely to be stage IV than papillary (5.76%) or follicular cancers (3.94%, P < .0001).

Conclusions: Patients with the following characteristics are more likely to present with stage IV thyroid cancer: Medicare, less education, low income, older age, male, comorbidities, far from a treatment facility, and medullary or anaplastic thyroid cancer.

Background: Patients with thyroid cancer often have distinctive characteristics that change as the cancer progresses to stage IV and warrants varied treatment. A Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results-based study reported that men with thyroid cancer of follicular cell origin are more likely to present with advanced disease compared with that of female patients. This is the largest study to evaluate stage IV thyroid cancer.

Methods: A population-based study was conducted using the National Cancer Database (NCDB), which captures nearly 70% of incident cancers in the U.S. For the accession years 2000 to 2012, NCDB took epidemiologic information for a sample of 343,386 thyroid cancer cases and used data from the 2012 U.S. census. The diagnosis of stage IV disease represented 6.88% (23,613) of the total patient population. The demographics of stage IV patients were compared with patients with all other stages using the chi-square test.

Results: There was an increased incidence of stage IV thyroid cancer in Medicare, lower high school graduation rates, annual median household income < $44,000, aged ≥ 70 years, male, more comorbidities, and further distance from a treatment facility (P < .0001). Ethnicity/race had little impact on the incidence of stage IV disease. Stage IV cancer incidence is higher in males (12.14%) compared with that of females (5.15%), and stage IV patients are more likely have Medicare (14.60%) or be uninsured (8.72%) than have private insurance (4.63%). Patients with ≥ 2 comorbidities (14.23%) are more than twice as likely to have stage IV as those without comorbidities (6.77%). Medullary and anaplastic cancers (20.08%) are much more likely to be stage IV than papillary (5.76%) or follicular cancers (3.94%, P < .0001).

Conclusions: Patients with the following characteristics are more likely to present with stage IV thyroid cancer: Medicare, less education, low income, older age, male, comorbidities, far from a treatment facility, and medullary or anaplastic thyroid cancer.

Background: Patients with thyroid cancer often have distinctive characteristics that change as the cancer progresses to stage IV and warrants varied treatment. A Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results-based study reported that men with thyroid cancer of follicular cell origin are more likely to present with advanced disease compared with that of female patients. This is the largest study to evaluate stage IV thyroid cancer.

Methods: A population-based study was conducted using the National Cancer Database (NCDB), which captures nearly 70% of incident cancers in the U.S. For the accession years 2000 to 2012, NCDB took epidemiologic information for a sample of 343,386 thyroid cancer cases and used data from the 2012 U.S. census. The diagnosis of stage IV disease represented 6.88% (23,613) of the total patient population. The demographics of stage IV patients were compared with patients with all other stages using the chi-square test.

Results: There was an increased incidence of stage IV thyroid cancer in Medicare, lower high school graduation rates, annual median household income < $44,000, aged ≥ 70 years, male, more comorbidities, and further distance from a treatment facility (P < .0001). Ethnicity/race had little impact on the incidence of stage IV disease. Stage IV cancer incidence is higher in males (12.14%) compared with that of females (5.15%), and stage IV patients are more likely have Medicare (14.60%) or be uninsured (8.72%) than have private insurance (4.63%). Patients with ≥ 2 comorbidities (14.23%) are more than twice as likely to have stage IV as those without comorbidities (6.77%). Medullary and anaplastic cancers (20.08%) are much more likely to be stage IV than papillary (5.76%) or follicular cancers (3.94%, P < .0001).

Conclusions: Patients with the following characteristics are more likely to present with stage IV thyroid cancer: Medicare, less education, low income, older age, male, comorbidities, far from a treatment facility, and medullary or anaplastic thyroid cancer.

Patterns of Failure and Survival Analysis of Advanced Tonsillar Cancer Treated With IMRT Radiation Therapy and Chemotherapy and Implications of HPV-Positive Tumors in Management

Purpose/Objectives: To evaluate the outcomes of patients with tonsillar cancer treated at G.V. Sonny Montgomery VA Medical Center between 2006 and 2014 and to compare survival and patterns of failure between human papillomavirus (HPV)-positive tonsillar cancer and HPV-negative tonsillar cancer.

Methods: There were 70 patients with biopsy proven squamous cell carcinoma of the tonsil in the retrospective review. Sixty-one of 70 patients had stage III/IV disease. Forty-seven of 70 patients had their HPV status evaluated. There were 22 HPV-positive and 25 HPV-negative patients. The majority of patients were treated with concurrent chemoradiotherapy, consisting of either weekly cisplatin 45 mg/m2 or weekly cetuximab 400 mg/m2 loading dose and 250 mg/m2 once a week for 7 weeks. Radiation therapy was given using intensity modulated radiation therapy to 70 Gy at 2 Gy per fraction over 7 weeks. The median radiation dose was 70 Gy. We evaluated the outcomes, including loco-regional failure, distant metastases, and survival. Rates were estimated by Kaplan-Meier method, and comparisons between HPV groups were evaluated using the Fisher exact test for categorical variables and Kruskal-Wallis test. Intermediate risk was defined as having ≥ 10 pack-years smoking history in the HPV-positive group (11 patients) and < 10 pack-years in the HPV-negative group (5 patients).

Results: Follow-up ranged from 14 to 88 months (median 22 mo). Overall survival (OS) for the entire group was 68% at 3 years with a disease-free survival (DFS) rate of 56%. At 3 years, the OS and DFS were 73% and 59% in the HPV-positive group and 50% and 50%, respectively, in the HPV-negative group. In the HPV-positive group, the failure rate was 2/11(16%) in the low-risk group and 8/11 (72%) in the intermediate-risk group. Six of 11 (55%) of the failures in the HPV-positive intermediate-risk group were local. Failure in the HPV-negative group was 3/5 (60%) in the intermediate-risk group and 12/20 (60%) in the high-risk group.

Conclusions: The results for the entire tonsillar group were comparable with that found in published literature. Patients with HPV-positive tumors had improved OS compared with HPV-negative tonsillar cancer, although not statistically significant due to small numbers.

Purpose/Objectives: To evaluate the outcomes of patients with tonsillar cancer treated at G.V. Sonny Montgomery VA Medical Center between 2006 and 2014 and to compare survival and patterns of failure between human papillomavirus (HPV)-positive tonsillar cancer and HPV-negative tonsillar cancer.

Methods: There were 70 patients with biopsy proven squamous cell carcinoma of the tonsil in the retrospective review. Sixty-one of 70 patients had stage III/IV disease. Forty-seven of 70 patients had their HPV status evaluated. There were 22 HPV-positive and 25 HPV-negative patients. The majority of patients were treated with concurrent chemoradiotherapy, consisting of either weekly cisplatin 45 mg/m2 or weekly cetuximab 400 mg/m2 loading dose and 250 mg/m2 once a week for 7 weeks. Radiation therapy was given using intensity modulated radiation therapy to 70 Gy at 2 Gy per fraction over 7 weeks. The median radiation dose was 70 Gy. We evaluated the outcomes, including loco-regional failure, distant metastases, and survival. Rates were estimated by Kaplan-Meier method, and comparisons between HPV groups were evaluated using the Fisher exact test for categorical variables and Kruskal-Wallis test. Intermediate risk was defined as having ≥ 10 pack-years smoking history in the HPV-positive group (11 patients) and < 10 pack-years in the HPV-negative group (5 patients).

Results: Follow-up ranged from 14 to 88 months (median 22 mo). Overall survival (OS) for the entire group was 68% at 3 years with a disease-free survival (DFS) rate of 56%. At 3 years, the OS and DFS were 73% and 59% in the HPV-positive group and 50% and 50%, respectively, in the HPV-negative group. In the HPV-positive group, the failure rate was 2/11(16%) in the low-risk group and 8/11 (72%) in the intermediate-risk group. Six of 11 (55%) of the failures in the HPV-positive intermediate-risk group were local. Failure in the HPV-negative group was 3/5 (60%) in the intermediate-risk group and 12/20 (60%) in the high-risk group.

Conclusions: The results for the entire tonsillar group were comparable with that found in published literature. Patients with HPV-positive tumors had improved OS compared with HPV-negative tonsillar cancer, although not statistically significant due to small numbers.

Purpose/Objectives: To evaluate the outcomes of patients with tonsillar cancer treated at G.V. Sonny Montgomery VA Medical Center between 2006 and 2014 and to compare survival and patterns of failure between human papillomavirus (HPV)-positive tonsillar cancer and HPV-negative tonsillar cancer.

Methods: There were 70 patients with biopsy proven squamous cell carcinoma of the tonsil in the retrospective review. Sixty-one of 70 patients had stage III/IV disease. Forty-seven of 70 patients had their HPV status evaluated. There were 22 HPV-positive and 25 HPV-negative patients. The majority of patients were treated with concurrent chemoradiotherapy, consisting of either weekly cisplatin 45 mg/m2 or weekly cetuximab 400 mg/m2 loading dose and 250 mg/m2 once a week for 7 weeks. Radiation therapy was given using intensity modulated radiation therapy to 70 Gy at 2 Gy per fraction over 7 weeks. The median radiation dose was 70 Gy. We evaluated the outcomes, including loco-regional failure, distant metastases, and survival. Rates were estimated by Kaplan-Meier method, and comparisons between HPV groups were evaluated using the Fisher exact test for categorical variables and Kruskal-Wallis test. Intermediate risk was defined as having ≥ 10 pack-years smoking history in the HPV-positive group (11 patients) and < 10 pack-years in the HPV-negative group (5 patients).

Results: Follow-up ranged from 14 to 88 months (median 22 mo). Overall survival (OS) for the entire group was 68% at 3 years with a disease-free survival (DFS) rate of 56%. At 3 years, the OS and DFS were 73% and 59% in the HPV-positive group and 50% and 50%, respectively, in the HPV-negative group. In the HPV-positive group, the failure rate was 2/11(16%) in the low-risk group and 8/11 (72%) in the intermediate-risk group. Six of 11 (55%) of the failures in the HPV-positive intermediate-risk group were local. Failure in the HPV-negative group was 3/5 (60%) in the intermediate-risk group and 12/20 (60%) in the high-risk group.

Conclusions: The results for the entire tonsillar group were comparable with that found in published literature. Patients with HPV-positive tumors had improved OS compared with HPV-negative tonsillar cancer, although not statistically significant due to small numbers.

Assessment of Body Weight After Completion of Radiotherapy With or Without Chemotherapy and With or Without Prophylactic Feeding Tube Placement in Head and Neck Cancer

Purpose: A majority of the patients with a diagnosis of locally advanced head and neck cancer receiving combined chemoradiotherapy experience mucositis, odynophagia, and dysphagia resulting in reduced oral intake and weight loss during the treatment. A prophylactic feeding tube is generally recommended for these patients to maintain body weight during the treatment. The purpose of this retrospective study is to understand the change in body weight from baseline to last follow-up after completion of radiotherapy or combined chemoradiotherapy and to assess the role of prophylactic feeding tube placement in maintaining body weight.

Methods: Thirty-seven patients with a diagnosis of locally advanced head and neck cancers were treated either with adjuvant or definitive radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy at Kansas City VA Medical Center during 2013. Eleven patients did not receive chemotherapy, and a majority of the patients did not receive prophylactic percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube placement. Twenty-six patient received cisplatin-based chemotherapy during radio-therapy; of these, 9 patients had no feeding tube and 17 patients received a prophylactic feeding tube. The radiation dose ranged from 60 to 70 Gy in 30 to 35 fractions. All these patients were followed on a regular basis, and weights were recorded on each visit. The follow-up period ranged from a minimum of 6 months to a maximum of 18 months. Results: Five patients died either from locoregional recurrence or distant metastases. The average weight loss for patients with combined modality treatments was 9.7% vs 6.3% for patients receiving no chemotherapy. The average weight loss for patients receiving concurrent chemotherapy and with prophylactic feeding tube placement was 7.4% com-pared with average weight loss of 16% for patients receiving chemotherapy and no prophylactic feeding tube placement. The majority of these patients both in the chemotherapy and the no chemotherapy groups never regained their baseline weight.

Conclusions: Patients receiving chemotherapy benefited from prophylactic feeding tube placement in maintaining body weight similar to patients receiving no chemotherapy.

Purpose: A majority of the patients with a diagnosis of locally advanced head and neck cancer receiving combined chemoradiotherapy experience mucositis, odynophagia, and dysphagia resulting in reduced oral intake and weight loss during the treatment. A prophylactic feeding tube is generally recommended for these patients to maintain body weight during the treatment. The purpose of this retrospective study is to understand the change in body weight from baseline to last follow-up after completion of radiotherapy or combined chemoradiotherapy and to assess the role of prophylactic feeding tube placement in maintaining body weight.

Methods: Thirty-seven patients with a diagnosis of locally advanced head and neck cancers were treated either with adjuvant or definitive radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy at Kansas City VA Medical Center during 2013. Eleven patients did not receive chemotherapy, and a majority of the patients did not receive prophylactic percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube placement. Twenty-six patient received cisplatin-based chemotherapy during radio-therapy; of these, 9 patients had no feeding tube and 17 patients received a prophylactic feeding tube. The radiation dose ranged from 60 to 70 Gy in 30 to 35 fractions. All these patients were followed on a regular basis, and weights were recorded on each visit. The follow-up period ranged from a minimum of 6 months to a maximum of 18 months. Results: Five patients died either from locoregional recurrence or distant metastases. The average weight loss for patients with combined modality treatments was 9.7% vs 6.3% for patients receiving no chemotherapy. The average weight loss for patients receiving concurrent chemotherapy and with prophylactic feeding tube placement was 7.4% com-pared with average weight loss of 16% for patients receiving chemotherapy and no prophylactic feeding tube placement. The majority of these patients both in the chemotherapy and the no chemotherapy groups never regained their baseline weight.

Conclusions: Patients receiving chemotherapy benefited from prophylactic feeding tube placement in maintaining body weight similar to patients receiving no chemotherapy.

Purpose: A majority of the patients with a diagnosis of locally advanced head and neck cancer receiving combined chemoradiotherapy experience mucositis, odynophagia, and dysphagia resulting in reduced oral intake and weight loss during the treatment. A prophylactic feeding tube is generally recommended for these patients to maintain body weight during the treatment. The purpose of this retrospective study is to understand the change in body weight from baseline to last follow-up after completion of radiotherapy or combined chemoradiotherapy and to assess the role of prophylactic feeding tube placement in maintaining body weight.

Methods: Thirty-seven patients with a diagnosis of locally advanced head and neck cancers were treated either with adjuvant or definitive radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy at Kansas City VA Medical Center during 2013. Eleven patients did not receive chemotherapy, and a majority of the patients did not receive prophylactic percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube placement. Twenty-six patient received cisplatin-based chemotherapy during radio-therapy; of these, 9 patients had no feeding tube and 17 patients received a prophylactic feeding tube. The radiation dose ranged from 60 to 70 Gy in 30 to 35 fractions. All these patients were followed on a regular basis, and weights were recorded on each visit. The follow-up period ranged from a minimum of 6 months to a maximum of 18 months. Results: Five patients died either from locoregional recurrence or distant metastases. The average weight loss for patients with combined modality treatments was 9.7% vs 6.3% for patients receiving no chemotherapy. The average weight loss for patients receiving concurrent chemotherapy and with prophylactic feeding tube placement was 7.4% com-pared with average weight loss of 16% for patients receiving chemotherapy and no prophylactic feeding tube placement. The majority of these patients both in the chemotherapy and the no chemotherapy groups never regained their baseline weight.

Conclusions: Patients receiving chemotherapy benefited from prophylactic feeding tube placement in maintaining body weight similar to patients receiving no chemotherapy.

Travel Burden and Distress in Veterans With Head and Neck Cancer

Purpose: To investigate whether traveling long distances to a cancer treatment facility increases self-reported distress among veterans with head and neck cancer.

Background: Veterans within VISN 20 receive radiation therapy for head and neck cancer in Portland, Oregon, or Seattle, Washington. Given the geography, many travel and stay in lodging for the duration of treatment. As they cannot access usual sources of support within their communities, these veterans may be at risk for greater distress while undergoing cancer treatment.

Methods: The National Comprehensive Cancer Network Distress Thermometer (DT) is a validated tool for self-reported distress by cancer patients. Respondents report distress on a 0 to 10 scale and answer 28 questions regarding physical, emotional, and practical problems. In Seattle, the DT is completed shortly before starting treatment. Patient demographics, treatment plan (chemoradiation vs radiation alone), and DT data for veterans with head and neck cancer were abstracted from the Computerized Patient Record System. A DT score of 7 or higher was considered significant distress. Distance to the VA was calculated by zip code from the veteran’s address. Data were analyzed with logistic regression to control for possible effects of cancer stage, age category, or treatment plan.

Results: Sixty veterans with head and neck cancer completed the DT between April 2014 and April 2015. The average age was 65.4 years (range 39-91), all were male, 77% were white, 77% had stage III or IV cancer at diagnosis, and 47% traveled > 50 miles. The average DT score was 5.4. Veterans traveling > 50 miles were more likely to report significant distress compared with those who traveled < 50 miles (odds ratio (OR) = 1.6, P = .02). Sleep was the only problem significantly more likely for veterans traveling > 50 miles (OR = 1.71, P = .01).

Implications: Veterans with head and neck cancer traveling > 50 miles for cancer care are more likely to report significant distress or distress related to sleep. This small study suggests travel burden may be an underappreciated source of distress for veterans with cancer. Further research is warranted to better understand how travel burden affects distress and identify opportunities for intervention

Purpose: To investigate whether traveling long distances to a cancer treatment facility increases self-reported distress among veterans with head and neck cancer.

Background: Veterans within VISN 20 receive radiation therapy for head and neck cancer in Portland, Oregon, or Seattle, Washington. Given the geography, many travel and stay in lodging for the duration of treatment. As they cannot access usual sources of support within their communities, these veterans may be at risk for greater distress while undergoing cancer treatment.

Methods: The National Comprehensive Cancer Network Distress Thermometer (DT) is a validated tool for self-reported distress by cancer patients. Respondents report distress on a 0 to 10 scale and answer 28 questions regarding physical, emotional, and practical problems. In Seattle, the DT is completed shortly before starting treatment. Patient demographics, treatment plan (chemoradiation vs radiation alone), and DT data for veterans with head and neck cancer were abstracted from the Computerized Patient Record System. A DT score of 7 or higher was considered significant distress. Distance to the VA was calculated by zip code from the veteran’s address. Data were analyzed with logistic regression to control for possible effects of cancer stage, age category, or treatment plan.

Results: Sixty veterans with head and neck cancer completed the DT between April 2014 and April 2015. The average age was 65.4 years (range 39-91), all were male, 77% were white, 77% had stage III or IV cancer at diagnosis, and 47% traveled > 50 miles. The average DT score was 5.4. Veterans traveling > 50 miles were more likely to report significant distress compared with those who traveled < 50 miles (odds ratio (OR) = 1.6, P = .02). Sleep was the only problem significantly more likely for veterans traveling > 50 miles (OR = 1.71, P = .01).

Implications: Veterans with head and neck cancer traveling > 50 miles for cancer care are more likely to report significant distress or distress related to sleep. This small study suggests travel burden may be an underappreciated source of distress for veterans with cancer. Further research is warranted to better understand how travel burden affects distress and identify opportunities for intervention

Purpose: To investigate whether traveling long distances to a cancer treatment facility increases self-reported distress among veterans with head and neck cancer.

Background: Veterans within VISN 20 receive radiation therapy for head and neck cancer in Portland, Oregon, or Seattle, Washington. Given the geography, many travel and stay in lodging for the duration of treatment. As they cannot access usual sources of support within their communities, these veterans may be at risk for greater distress while undergoing cancer treatment.

Methods: The National Comprehensive Cancer Network Distress Thermometer (DT) is a validated tool for self-reported distress by cancer patients. Respondents report distress on a 0 to 10 scale and answer 28 questions regarding physical, emotional, and practical problems. In Seattle, the DT is completed shortly before starting treatment. Patient demographics, treatment plan (chemoradiation vs radiation alone), and DT data for veterans with head and neck cancer were abstracted from the Computerized Patient Record System. A DT score of 7 or higher was considered significant distress. Distance to the VA was calculated by zip code from the veteran’s address. Data were analyzed with logistic regression to control for possible effects of cancer stage, age category, or treatment plan.

Results: Sixty veterans with head and neck cancer completed the DT between April 2014 and April 2015. The average age was 65.4 years (range 39-91), all were male, 77% were white, 77% had stage III or IV cancer at diagnosis, and 47% traveled > 50 miles. The average DT score was 5.4. Veterans traveling > 50 miles were more likely to report significant distress compared with those who traveled < 50 miles (odds ratio (OR) = 1.6, P = .02). Sleep was the only problem significantly more likely for veterans traveling > 50 miles (OR = 1.71, P = .01).

Implications: Veterans with head and neck cancer traveling > 50 miles for cancer care are more likely to report significant distress or distress related to sleep. This small study suggests travel burden may be an underappreciated source of distress for veterans with cancer. Further research is warranted to better understand how travel burden affects distress and identify opportunities for intervention

Radiation field optimization may preserve salivary gland function

Preservation of saliva production in patients undergoing radiotherapy for head and neck cancer may be improved by use of radiation technologies that spare regions of the salivary gland abundant in stem cells, according to researchers.

By tracking the stem cell marker c-Kit, investigators determined that stem cells were not uniformly distributed throughout the parotid gland, but were most abundant in the major ducts in the central region. In rats, irradiation of the center area of the parotid gland, compared with the exterior, resulted in a greater loss, and progressive loss, of saliva production after 1 year. Tissue morphology indicated clear differences in long-term regenerative capacities of the different regions of the gland (Sci Trans Med. 2015 Sep 16. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aac4441).

The findings suggest that irradiation localized to the central region where the major ducts are found may result in gland dysfunction. The radiation dose to this area predicted dysfunction.

Stem cell distribution and parotid gland regeneration studies were done in mice and rats. A retrospective study of 74 patients with head and neck cancer correlated radiotherapy dose by region with salivary gland function.

To further evaluate the effects of radiation to the central gland region, the researchers compared two treatment plans in 22 patients. The first plan used a minimum mean dose to the entire gland, and the second minimized the dose to the critical region. The results indicated the second treatment plan resulted in dose redistribution that spared the stem cell region and was predicted to result in better posttreatment gland function.

Radiotherapy of tumors in the head and neck area often leads to irreversible hyposalivation, which severely compromises quality of life for patients. Whether radiation field optimization will eventually result in less xerostomia, or dry mouth, among patients remains to be determined, and a clinical trial is currently underway.

These findings confirm the importance of stem cells in long-term salivary gland function, according to Peter van Luijk, Ph.D., of the department of radiation oncology, University Medical Center, Groningen, the Netherlands, and his colleagues.

“It also suggests that autologous transductal stem cell transplantation may be a viable treatment strategy in patients where sparing this specific subvolume of the salivary glands is not feasible,” they wrote.

Dr. van Luijk reported having no disclosures.

Preservation of saliva production in patients undergoing radiotherapy for head and neck cancer may be improved by use of radiation technologies that spare regions of the salivary gland abundant in stem cells, according to researchers.

By tracking the stem cell marker c-Kit, investigators determined that stem cells were not uniformly distributed throughout the parotid gland, but were most abundant in the major ducts in the central region. In rats, irradiation of the center area of the parotid gland, compared with the exterior, resulted in a greater loss, and progressive loss, of saliva production after 1 year. Tissue morphology indicated clear differences in long-term regenerative capacities of the different regions of the gland (Sci Trans Med. 2015 Sep 16. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aac4441).

The findings suggest that irradiation localized to the central region where the major ducts are found may result in gland dysfunction. The radiation dose to this area predicted dysfunction.

Stem cell distribution and parotid gland regeneration studies were done in mice and rats. A retrospective study of 74 patients with head and neck cancer correlated radiotherapy dose by region with salivary gland function.

To further evaluate the effects of radiation to the central gland region, the researchers compared two treatment plans in 22 patients. The first plan used a minimum mean dose to the entire gland, and the second minimized the dose to the critical region. The results indicated the second treatment plan resulted in dose redistribution that spared the stem cell region and was predicted to result in better posttreatment gland function.

Radiotherapy of tumors in the head and neck area often leads to irreversible hyposalivation, which severely compromises quality of life for patients. Whether radiation field optimization will eventually result in less xerostomia, or dry mouth, among patients remains to be determined, and a clinical trial is currently underway.

These findings confirm the importance of stem cells in long-term salivary gland function, according to Peter van Luijk, Ph.D., of the department of radiation oncology, University Medical Center, Groningen, the Netherlands, and his colleagues.

“It also suggests that autologous transductal stem cell transplantation may be a viable treatment strategy in patients where sparing this specific subvolume of the salivary glands is not feasible,” they wrote.

Dr. van Luijk reported having no disclosures.

Preservation of saliva production in patients undergoing radiotherapy for head and neck cancer may be improved by use of radiation technologies that spare regions of the salivary gland abundant in stem cells, according to researchers.

By tracking the stem cell marker c-Kit, investigators determined that stem cells were not uniformly distributed throughout the parotid gland, but were most abundant in the major ducts in the central region. In rats, irradiation of the center area of the parotid gland, compared with the exterior, resulted in a greater loss, and progressive loss, of saliva production after 1 year. Tissue morphology indicated clear differences in long-term regenerative capacities of the different regions of the gland (Sci Trans Med. 2015 Sep 16. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aac4441).

The findings suggest that irradiation localized to the central region where the major ducts are found may result in gland dysfunction. The radiation dose to this area predicted dysfunction.

Stem cell distribution and parotid gland regeneration studies were done in mice and rats. A retrospective study of 74 patients with head and neck cancer correlated radiotherapy dose by region with salivary gland function.

To further evaluate the effects of radiation to the central gland region, the researchers compared two treatment plans in 22 patients. The first plan used a minimum mean dose to the entire gland, and the second minimized the dose to the critical region. The results indicated the second treatment plan resulted in dose redistribution that spared the stem cell region and was predicted to result in better posttreatment gland function.

Radiotherapy of tumors in the head and neck area often leads to irreversible hyposalivation, which severely compromises quality of life for patients. Whether radiation field optimization will eventually result in less xerostomia, or dry mouth, among patients remains to be determined, and a clinical trial is currently underway.

These findings confirm the importance of stem cells in long-term salivary gland function, according to Peter van Luijk, Ph.D., of the department of radiation oncology, University Medical Center, Groningen, the Netherlands, and his colleagues.

“It also suggests that autologous transductal stem cell transplantation may be a viable treatment strategy in patients where sparing this specific subvolume of the salivary glands is not feasible,” they wrote.

Dr. van Luijk reported having no disclosures.

FROM SCIENCE TRANSLATIONAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Optimized radiotherapy that spares salivary gland stem cells during treatment for head and neck cancer may preserve patients’ saliva production.

Major finding: Salivary gland stem cells carry long-term regenerative capacity, and the cells are most abundant in major ducts at the central part of the gland, which can be spared with current radiotherapy technology.

Data source: Stem cell distribution and parotid gland regeneration studies were done in mice and rats. A retrospective study of 74 patients with head and neck cancer correlated radiotherapy dose by region with salivary gland function. Radiation field optimization was prospectively studied in 22 patients.

Disclosures: Mr. van Luijk reported having no disclosures.

JCO publishes special issue on head and neck cancers

The Journal of Clinical Oncology has published a special series issue on head and neck cancers, with a major focus on squamous cell carcinomas arising from the upper aerodigestive tract mucosa.

“In addition, we also address nasopharyngeal cancer, nonmelanoma cutaneous head and neck cancer, and squamous carcinoma of the neck of unknown primary origin,” writes Dr. Danny Rischin of the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre and University of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, and associates in an overview for the issue.

The 16 articles in the issue provide the reader with an overview of current evidence and management, recent developments, and insights into future directions, they write.

It was only recently that human papillomavirus was identified as a cause of oropharyngeal cancer and that HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer was found to have its own unique biologic signature. Three articles are included in the series that review the rapidly evolving understanding of HPV-related head and neck cancers.

Find the overview and series of 16 articles in the Sept. 7 issue of the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The Journal of Clinical Oncology has published a special series issue on head and neck cancers, with a major focus on squamous cell carcinomas arising from the upper aerodigestive tract mucosa.

“In addition, we also address nasopharyngeal cancer, nonmelanoma cutaneous head and neck cancer, and squamous carcinoma of the neck of unknown primary origin,” writes Dr. Danny Rischin of the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre and University of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, and associates in an overview for the issue.

The 16 articles in the issue provide the reader with an overview of current evidence and management, recent developments, and insights into future directions, they write.

It was only recently that human papillomavirus was identified as a cause of oropharyngeal cancer and that HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer was found to have its own unique biologic signature. Three articles are included in the series that review the rapidly evolving understanding of HPV-related head and neck cancers.

Find the overview and series of 16 articles in the Sept. 7 issue of the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The Journal of Clinical Oncology has published a special series issue on head and neck cancers, with a major focus on squamous cell carcinomas arising from the upper aerodigestive tract mucosa.

“In addition, we also address nasopharyngeal cancer, nonmelanoma cutaneous head and neck cancer, and squamous carcinoma of the neck of unknown primary origin,” writes Dr. Danny Rischin of the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre and University of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, and associates in an overview for the issue.

The 16 articles in the issue provide the reader with an overview of current evidence and management, recent developments, and insights into future directions, they write.

It was only recently that human papillomavirus was identified as a cause of oropharyngeal cancer and that HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer was found to have its own unique biologic signature. Three articles are included in the series that review the rapidly evolving understanding of HPV-related head and neck cancers.

Find the overview and series of 16 articles in the Sept. 7 issue of the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

New Treatment Options for Metastatic Thyroid Cancer

Thyroid cancer is the ninth most common malignancy in the U.S. At the time of diagnosis, thyroid cancer is mostly confined to the thyroid gland and regional lymph nodes. However, around 4% of patients with thyroid cancer present with metastatic disease. When compared with localized and regional thyroid cancer, 5-year survival rates for metastatic thyroid cancer are significantly worse (99.9%, 97.6%, and 54.7%, respectively).1 Treatment options for metastatic thyroid cancer are limited and largely depend on the pathology and the type of thyroid cancer.

Thyroid cancer can be divided into differentiated, medullary, and anaplastic subtypes based on pathology. The treatment for metastatic differentiated thyroid cancer (DTC) consists of radioactive iodine therapy, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) suppression (thyroxine hormone) therapy, and external beam radiotherapy. Systemic therapy is considered in patients with metastatic DTC who progress despite the above treatment modalities. In the case of metastatic medullary thyroid cancer (MTC), patients who are not candidates for surgery or radiation are considered for systemic therapy, because MTC does not respond to radioactive iodine or TSH suppressive therapy. On the other hand, metastatic anaplastic thyroid cancer is a very aggressive subtype with no effective therapy available to date. Palliation of symptoms is the main goal for these patients, which can be achieved by loco-regional resection and palliative irradiation.2,3

This review focuses on the newer treatment options for metastatic DTC and MTC that are based on inhibition of cellular kinases.

Differentiated Thyroid Cancer

Differentiated thyroid cancer is the most common histologic type of thyroid cancer, accounting for 95% of all thyroid cancers and consists of papillary, follicular, and poorly differentiated thyroid cancer.2,3 Surgery is the treatment of choice for DTC. Based on tumor size and its local extension in the neck, treatment options include unilateral lobectomy and isthmectomy, total thyroidectomy, central neck dissection, and more extensive resection.2,3 After surgery, radioactive iodine is recommended in patients with known metastatic disease; locally invasive tumor, regardless of size; or primary tumor > 4 cm, in the absence of other high-risk features.2 This should be followed by TSH suppressive hormone therapy.2

About 7% to 23% of patients with DTC develop distant metastases.4 Two-thirds of these patients become refractory to radioactive iodine.5 Prognosis remains poor in these patients, with a 10-year survival rate from the time detection of metastasis of only 10%.5-7 Treatment options are limited. However, recently the understanding of cell biology in terms of key signaling pathways called kinases has been elucidated. The kinases that can stabilize progressive metastatic disease seem to be attractive therapeutic targets in treating patients whose disease no longer responds to radioiodine and TSH suppressive hormone therapy.

Papillary thyroid cancers frequently carry gene mutations and rearrangements that lead to activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), which promotes cell division. The sequential components leading to activation of MAPK include rearrangements of RET and NTRK1 tyrosine kinases, activating mutations of BRAF, and activating mutations of RAS.8,9 Similarly, overexpression of normal c-myc and c-fos genes, as well as mutations of HRAS, NRAS, and KRAS genes, is found in follicular adenomas, follicular cancers, and occasionally papillary cancers.10-14 Increased expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptors (VEGFRs) might have a role in thyroid carcinoma as well.15

These kinases (the serine kinase BRAF and tyrosine kinases RET and RAS, and the contributory roles of tyrosine kinases in growth factor receptors such as the VEGFR) stimulate tumor proliferation, angiogenesis, invasion, metastasis, and inhibit tumor cell apoptosis. Kinase inhibitors target these signaling kinases, affecting tumor cell biology and its microenvironment.16,17

A wide variety of multitargeted kinase inhibitors (MKIs) have entered clinical trials for patients with advanced or progressive metastatic thyroid cancers. Two such agents, sorafenib and lenvatinib, are approved by the FDA for use in selected patients with refractory metastatic DTC, whereas many other drugs remain investigational for this disease. In phase 2 and 3 trials, most of the treatment responses for MKIs were partial. Complete responses were rare, and no study has reported a complete analysis of overall survival (OS) outcomes. Results from some new randomized trials indicate an improvement in progression-free survival (PFS) compared with placebo, and additional trials are underway.

Sorafenib

Sorafenib was approved by the FDA in 2013 for the treatment of locally recurrent or metastatic, progressive DTC that no longer responds to radioactive iodine treatment.18 Sorafenib is an oral, small molecule MKI. It works on VEGFRs 1, 2, and 3; platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR); common RET/PTC subtypes; KIT; and less potently, BRAF.19 The recommended dose is 400 mg orally twice a day.

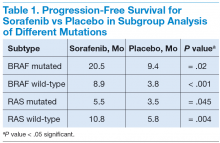

In April 2014, Brose and colleagues published the phase 3 DECISION study on sorafenib.20 It was a multicenter, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial of 417 patients with radioactive iodine-refractory locally advanced or metastatic DTC that had progressed within the previous 14 months.20 The results of the trial were promising. The median PFS was 5 months longer in the sorafenib group (10.8 mo) than in the placebo group (5.8 mo; hazard ratio [HR], 0.59; 95% conidence interval [CI], 0.45-0.76; P < .0001). The primary endpoint of the trial was PFS, and crossover from placebo to sorafenib was permitted upon progression. Overall survival did not differ significantly between the treatment groups (placebo vs sorafenib) at the time of the primary analysis data cutoff. However, OS results may have been confounded by postprogression crossover from placebo to open-label sorafenib by the majority of placebo patients.

In subgroup analysis, patients with BRAF and RAS mutations and wild-type BRAF and RAS subgroups had a significant increase in median PFS in the sorafenib treatment group compared with the placebo group (Table 1).20

Adverse events (AEs) occurred in 98.6% of patients receiving sorafenib during the double-blind period and in 87.6% of patients receiving placebo. Most AEs were grade 1 or 2. The most common AEs were hand-foot-skin reactions (76.3%), diarrhea (68.6%), alopecia (67.1%), and rash or desquamation (50.2%). Toxicities led to dose modification in 78% of patients and permanent discontinuation of therapy in 19%.20 Like other BRAF inhibitors, sorafenib has been associated with an increased incidence of cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas (5%), keratoacanthomas, and other premalignant actinic lesions.21

Lenvatinib

In February 2015, lenvatinib was approved for the treatment of locally recurrent or metastatic, progressive DTC that no longer responds to radioactive iodine treatment.22 Lenvatinib is a MKI of VEGFRs 1, 2, and 3; fibroblast growth factor receptors 1 through 4; PDGFR-α; RET, and KIT.23,24 The recommended dose is 24 mg orally once daily.

Schlumberger and colleagues published results from the SELECT trial, a randomized, double-blinded, multicenter phase 3 study involving 392 patients with progressive thyroid cancer that was refractory to iodine-131.25 A total of 261 patients received lenvatinib, and 131 patients received a placebo. Upon disease progression, patients in the placebo group were allowed to receive open-label lenvatinib. The study’s primary endpoint was PFS. Secondary endpoints were the response rate (RR), OS, and safety. The median PFS was 18.3 months in the lenvatinib group and 3.6 months in the placebo group (HR, 0.21; 99% CI, 0.14-0.31; P < .001). The RR was 64.8% in the lenvatinib group (4 complete and 165 partial responses) and 1.5% in the placebo group (P < .001). There was no significant difference in OS between the 2 groups (HR for death, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.50-1.07; P = .10). This difference became larger when a potential crossover bias was considered (rank-preserving structural failure time model; HR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.40-1.00; P = .05).25

In a subgroup analysis, median PFS was about 14 months in the absence of prior anti-VEGFR therapy and 11 months of prior therapy. The treatmentrelated AEs were 97.3% in the lenvatinib group, and 75.9% were grade 3 or higher. Common treatmentrelated AEs of any grade in the lenvatinib group included hypertension (67.8%), diarrhea (59.4%), fatigue or asthenia (59.0%), decreased appetite (50.2%), decreased weight (46.4%), and nausea (41.0%). The study drug had to be discontinued because of AEs in 14% of patients who received lenvatinib and 2% of patients who received placebo. In the lenvatinib group, 2.3% patients had treatment-related fatal events (6 patients).25

Summary

Patients with DTC who progress after radioactive iodine therapy, TSH suppressive therapy, and external beam radiotherapy should be considered for systemic therapy. Systemic therapy consists of MKIs, which can stabilize progressive metastatic disease. These newer drugs have significant toxicities. Therefore, it is important to limit the use of systemic treatments to patients at significant risk for morbidity or mortality due to progressive metastatic disease. Patients treated with systemic agents should have a good baseline performance status, such as being ambulatory at least 50% (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance score of 2) of the day to tolerate these treatments.

Patients who have disease progression or are unable to tolerate sorafenib and lenvatinib can choose to participate in clinical trials with investigational multitarget inhibitors. Other alternatives include vandetinib, pazopanib, and sunitinib, which finished phase 2 trials and showed some partial responses.26-30 If the patients are unable to tolerate MKIs, they can try doxorubicin-based conventional chemotherapy regimens.31

Medullary Thyroid Cancer

Medullary thyroid cancer is a neuroendocrine tumor arising from the thyroid parafollicular cells, accounting for about 4% of thyroid carcinomas, most of which are sporadic. However, some are familial as part of the multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 (MEN 2) syndromes, which are transmitted in an autosomal dominant fashion.32,33 Similar to DTC, the primary treatment option is surgery. Medullary thyroid cancer can be cured only by complete resection of the thyroid tumor and any local and regional metastases. Compared with DTC, metastatic MTC is unresponsive to radioiodine or TSH

suppressive treatment, because this cancer neither concentrates iodine nor is TSH dependent.34,35

The 10-year OS rate in MTC is ≤ 40% in patients with locally advanced or metastatic disease.32,36,37 In hereditary MTC, germline mutations in the c-ret proto-oncogene occur in virtually all patients. In sporadic MTC, 85% of patients have the M918T mutation, and somatic c-ret mutations are seen in about 50% of patients.38-42

Similar to DTC, due to the presence of mutations involving RET receptor tyrosine kinase, molecular targeted therapeutics with activity against RET demonstrate a potential therapeutic target in MTC.43-45 Other signaling pathways likely to contribute to the growth and invasiveness of MTC include VEGFR-dependent tumor angiogenesis and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-dependent tumor cell proliferation.46

In 2011 and 2012, the FDA approved tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) vandetanib and cabozantinib for metastatic MTC. Similar to treatment for DTC, systemic therapy is mainly based on targeted therapies. Patients with progressive or symptomatic metastatic disease who are not candidates for surgery or radiotherapy should be considered for TKI therapy.

Vandetanib

Vandetanib is approved for unresectable, locally advanced or metastatic sporadic or hereditary MTC.47 The daily recommended dose is 300 mg/d. It is an oral MKI that targets VEGFR, RET/PTC, and the EGFR.48

The ZETA trial was an international randomized phase 3 trial involving patients with unresectable locally advanced or metastatic sporadic or hereditary MTC.48 In a ZETA trial study by Wells Jr and colleagues, patients with advanced MTC were randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio to receive vandetanib 300 mg/d or placebo. After objective disease progression, patients could elect to receive openlabel vandetanib. The primary endpoint was PFS, determined by independent central Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors assessments.

A total of 331 patients were randomly assigned to receive vandetanib (231 patients) or placebo (100 patients). At data cutoff, with median follow-up of 24 months, PFS was significantly prolonged in patients randomly assigned to vandetanib vs placebo (30.5 mo vs 19.3 mo; HR, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.31-0.69). The objective RR was significantly higher in the vandetanib group (45% vs 13%). The presence of a somatic RET M918T mutation predicted an improved PFS.

Common AEs (any grade) noted with vandetanib vs placebo include diarrhea (56% vs 26%), rash (45% vs 11%), nausea (33% vs 16%), hypertension (32% vs 5%), and headache (26% vs 9%). Torsades de pointes and sudden death were reported in patients receiving vandetanib. Data on OS were immature at data cutoff (HR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.48-1.65). A final survival analysis will take place when 50% of the patients have died.48

Vandetanib is currently approved with a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy to inform health care professionals about serious heart-related risks. Electrocardiograms and serum potassium, calcium, magnesium, and TSH should be taken at 2 to 4 weeks and 8 to 12 weeks after starting treatment and every 3 months after that. Patients with diarrhea may require more frequent monitoring.

Cabozantinib

In 2012, the FDA approved cabozantinib for the treatment of progressive, metastatic MTC.49 It is an oral, small molecule TKI that targets VEGFRs 1 and 2, MET, and RET. The inhibitory activity against MET, the cognate receptor for the hepatocyte growth factor, may provide additional synergistic benefit in MTC.50 The daily recommended dose is 140 mg/d. A phase 3 randomized EXAM trial in patients with progressive, metastatic, or unresectable locally advanced MTC.51 Three hundred thirty patients were randomly assigned to receive either cabozantinib 140 mg or placebo once daily. Progressionfree survival was improved with cabozantinib compared with that of placebo (11.2 vs 4.0 mo; HR, 0.28; 95% CI, 0.19-0.40). Partial responses were observed in 27% vs 0% in placebo. A planned interim analysis of OS was conducted, including 96 (44%) of the 217 patient deaths required for the final analysis, with no statistically significant difference observed between the treatment arms (HR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.63-1.52). Survival follow-up is planned to continue until at least 217 deaths have been observed.

There was markedly improved PFS in the subset of patients treated with cabozantinib compared with placebo whose tumors contained RET M918T mutations (61 vs 17 wk; HR, 0.15; 95% CI, 0.08-0.28) or RAS mutations (47 vs 8 wk; HR, 0.15; 95% CI, 0.02-1.10).51

The most common AEs, occurring in ≥ 25% of patients, were diarrhea, stomatitis, hand and foot syndrome, hypertension, and abdominal pain. Although uncommon, clinically significant AEs also included fistula formation and osteonecrosis of the jaw.

Summary

Patients with progressive or symptomatic metastatic disease who are not candidates for surgery or radiotherapy should be considered for TKI therapy. Though not curative, TKIs can only stabilize disease progression. Initiation of TKIs should be considered in rapidly progressive disease, because these drugs are associated with considerable AEs affecting the quality of life (QOL).

Patients who progressed or were unable to tolerate vandetanib or cabozantinib can choose to participate in clinical trials with investigational multitarget inhibitors. Other alternatives include pazopanib, sunitinib, and sorafenib, which finished phase 2 trials and showed some partial responses.29,52-57 If patients are unable to tolerate MKIs, they can try conventional chemotherapy consisting of dacarbazine with other agents or doxorubin.58-60

Conclusions

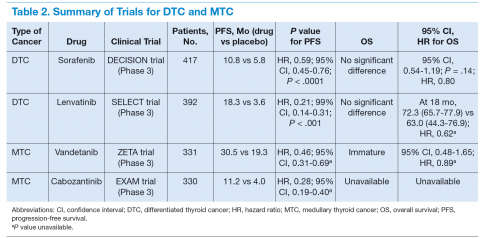

Molecular targeted therapy is an emerging treatment option for patients with metastatic thyroid cancer (Table 2). The authors suggest that such patients participate in clinical trials in the hope of developing more effective and tolerable drugs and recommend oral TKIs for patients with rapidly progressive disease who cannot participate in a clinical trial. For patients who cannot tolerate or fail one TKI, the authors recommend trying other TKIs before initiating cytotoxic chemotherapy.

Before initiation of treatment for metastatic disease, an important factor to consider is the pace of disease progression. Patients who are asymptomatic and have the very indolent disease may postpone kinase inhibitor therapy until they become rapidly progressive or symptomatic, because the AEs of treatment will adversely affect the patient’s QOL. In patients with symptomatic and rapidly progressive disease, initiation of treatment with kinase inhibitor therapy can lead to stabilization of disease, although at the cost of some AEs. More structured clinical trials are needed, along with an evaluation of newer molecular targets for the management of this progressive metastatic disease with a dismal prognosis.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Click here to read the digital edition.

1. Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al, eds. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2012. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2015.

2. Cooper DS, Doherty GM, Haugen BR, et al; American Thyroid Association (ATA) Guidelines Taskforce on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Revised American Thyroid Association management guidelines for patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2009;19(11):1167-1214.

3. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: thyroid carcinoma. National Comprehensive Cancer Network Website. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/thyroid.pdf. Updated May 11, 2015. Accessed July 10, 2015.

4. Shoup M, Stojadinovic A, Nissan A, et al. Prognostic indicators of outcomes in patients with distant metastases from differentiated thyroid carcinoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;197(2):191-197.

5. Durante C, Haddy N, Baudin E, et al. Long-term outcome of 444 patients with distant metastases from papillary and follicular thyroid carcinoma: benefits and limits of radioiodine therapy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(8):2892-2899.

6. Busaidy NL, Cabanillas ME. Differentiated thyroid cancer: management of patients with radioiodine nonresponsive disease. J Thyroid Res. 2012;2012:618985.

7. Schlumberger M, Brose M, Elisei R, et al. Definition and management of radioactive iodine-refractory differentiated thyroid cancer. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2(5):356-358.

8. Melillo RM, Castellone MD, Guarino V, et al. The RET/PTC-RAS-BRAF linear signaling cascade mediates the motile and mitogenic phenotype of thyroid cancer cells. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(4):1068-1081.

9. Ciampi R, Nikiforov YE. RET/PTC rearrangements and BRAF mutations in thyroid tumorigenesis. Endocrinology. 2007;148(3):936-941.

10. Lemoine NR, Mayall ES, Wyllie FS, et al. High frequency of ras oncogene activation in all stages of human thyroid tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 1989;4(2):159-164.

11. Namba H, Rubin SA, Fagin JA. Point mutations of ras oncogenes are an early event in thyroid tumorigenesis. Mol Endocrinol. 1990;4(10):1474-1479.

12. Suarez HG, du Villard JA, Severino M, et al. Presence of mutations in all three ras genes in human thyroid tumors. Oncogene. 1990;5(4):565-570.

13. Karga H, Lee JK, Vickery AL Jr, Thor A, Gaz RD, Jameson JL. Ras oncogene mutations in benign and malignant thyroid neoplasms. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1991;73(4):832-836.

14. Terrier P, Sheng ZM, Schlumberger M, et al. Structure and expression of c-myc and c-fos proto-oncogenes in thyroid carcinomas. Br J Cancer. 1988;57(1):43-47.

15. Klein M, Vignaud JM, Hennequin V, et al. Increased expression of the vascular endothelial growth factor is a pejorative prognosis marker in papillary thyroid carcinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86(2):656-658.

16. Zhang J, Yang PL, Gray NS. Targeting cancer with small molecule kinase inhibitors. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9(1):28-39.

17. Haugen BR, Sherman SI. Evolving approaches to patients with advanced differentiated thyroid cancer. Endocr Rev. 2013;34(3):439-455.

18. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves Nexavar to treat type of thyroid cancer [press release]. Silver Spring, MD: U.S. Food and Drug Administration; November 22, 2013.

19. Wilhelm SM, Carter C, Tang L, et al. BAY 43-9006 exhibits broad spectrum oral antitumor activity and targets the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway and receptor tyrosine kinases involved in tumor progression and angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 2004;64(19):7099-7109.

20. Brose MS, Nutting CM, Jarzab B, et al; DECISION investigators. Sorafenib in radioactive iodine-refractory, locally advanced or metastatic differentiated thyroid cancer: a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2014;384(9940):319-328.

21. Dubauskas Z, Kunishige J, Prieto VG, Jonasch E, Hwu P, Tannir NM. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and inflammation of actinic keratoses associated with sorafenib. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2009;7(1):20-23.

22. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves Lenvima for a type of thyroid cancer [press release]. Silver Spring, MD: U.S. Food and Drug Administration; February 13, 2015.

23. Matsui J, Yamamoto Y, Funahashi Y, et al. E7080, a novel inhibitor that targets multiple kinases, has potent antitumor activities against stem cell factor producing human small cell lung cancer H146, based on angiogenesis inhibition. Int J Cancer. 2008;122(3):664-671.

24. Matsui J, Funahashi Y, Uenaka T, Watanabe T, Tsuruoka A, Asada M. Multi-kinase inhibitor E7080 suppresses lymph node and lung metastases of human mammary breast tumor MDA-MB-231 via inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factorreceptor (VEGF-R) 2 and VEGF-R3 kinase. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(17):5459-5465.

25. Schlumberger M, Tahara M, Wirth LJ, et al. Lenvatinib versus placebo in radioiodine- refractory thyroid cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(7):621-630.

26. Leboulleux S, Bastholt L, Krause T, et al. Vandetanib in locally advanced or metastatic differentiated thyroid cancer: a randomised, double-blind, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(9):897-905.

27. A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multi-centre phase III study to assess the efficacy and safety of vandetanib (CAPRELSA) 300 mg in patients with differentiated thyroid cancer that is either locally advanced or metastatic who are refractory or unsuitable for radioiodine (RAI) therapy. Trial number NCT01876784. ClinicalTrials.gov Website. https://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01876784. Updated June 26, 2015. Accessed July 22, 2015.

28. Bible KC, Suman VJ, Molina JR, et al; Endocrine Malignancies Disease Oriented Group; Mayo Clinic Cancer Center; Mayo Phase 2 Consortium. Efficacy of pazopanib in progressive, radioiodine-refractory, metastatic differentiated thyroid cancers: results of a phase 2 consortium study. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(10):962-972.

29. Kim DW, Jo YS, Jung HS, et al. An orally administered multitarget tyrosine kinase inhibitor, SU11248, is a novel potent inhibitor of thyroid oncogenic RET/papillary thyroid cancer kinases. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(10):4070-4076.

30. Dawson SJ, Conus NM, Toner GC, et al. Sustained clinical responses to tyrosine kinase inhibitor sunitinib in thyroid carcinoma. Anticancer Drugs. 2008;19(5):547-552.

31. Carter SK, Blum RH. New chemotherapeutic agents—bleomycin and adriamycin. CA Cancer J Clin. 1974;24(6):322-331.

32. Hundahl SA, Fleming ID, Fremgen AM, Menck HR. A National Cancer Data Base report on 53,856 cases of thyroid carcinoma treated in the U.S., 1985-1995 [see comments]. Cancer. 1998;83(12):2638-2648.

33. Lakhani VT, You YN, Wells SA. The multiple endocrine neoplasia syndromes. Annu Rev Med. 2007;58:253-265.

34. Martins RG, Rajendran JG, Capell P, Byrd DR, Mankoff DA. Medullary thyroid cancer: options for systemic therapy of metastatic disease? J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(11):1653-1655.

35. American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force; Kloos RT, Eng C, Evans DB, et al. Medullary thyroid cancer: management guidelines of the American Thyroid Association. Thyroid. 2009;19(6):565-612.

36. Roman S, Lin R, Sosa JA. Prognosis of medullary thyroid carcinoma: demographic, clinical, and pathologic predictors of survival in 1252 cases. Cancer. 2006;107(9):2134-2142.

37. Modigliani E, Cohen R, Campos JM, et al. Prognostic factors for survival and for biochemical cure in medullary thyroid carcinoma: results in 899 patients. The GETC Study Group. Groupe d’étude des tumeurs à calcitonine. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1998;48(3):265-273.

38. Donis-Keller H, Dou S, Chi D, et al. Mutations in the RET proto-oncogene are associated with MEN 2A and FMTC. Hum Mol Genet. 1993;2(7):851-856.

39. Mulligan LM, Kwok JB, Healey CS, et al. Germ-line mutations of the RET protooncogene in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2A. Nature. 363(6428):458-460.

40. Carlson KM, Dou S, Chi D, et al. Single missense mutation in the tyrosine kinase catalytic domain of the RET protooncogene is associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91(4):1579-1583.