User login

Despite HCV cure, liver cancer-associated genetic changes persist

A new study showed that liver tissue from hepatitis C virus (HCV)–infected humans with and without sustained virologic response found epigenetic and gene expression alterations associated with the risk for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), according to Nourdine Hamdane, PHD, of the Institut de Recherche sur les Maladies Virales et Hépatiques, Strasbourg, France, and colleagues.

The researchers analyzed liver tissue from 6 noninfected control patients, 18 patients with chronic HCV infection, 21 patients with cured chronic HCV, 4 patients with hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, and 7 patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), as well as 8 paired HCC samples with HCV-induced liver disease (Gastroenterology 2019;156:2313–29).

They found that several altered pathways related to carcinogenesis persisted after cure, including TNF-alpha signaling, inflammatory response, G2M checkpoint, epithelial–mesenchymal transition, and phosphoinositide 3-kinase, Akt, and mammalian target of rapamycin.

They also observed lower levels of H3K27ac mapping to genes related to oxidative phosphorylation pathways, providing evidence supporting a functional role for H3K27ac changes in establishing gene expression patterns that persist after cure and contribute to carcinogenesis, according to the authors.

“Our study exposes a previously undiscovered paradigm showing that chronic HCV infection induces H3K27ac modifications that are associated with HCC risk and that persist after HCV cure,” the authors wrote. “[This study] provides a unique opportunity to uncover novel biomarkers for HCC risk, that is, from plasma through the detection of epigenetic changes of histones bound to circulating DNA complexes. Furthermore, by uncovering virus-induced epigenetic changes as therapeutic targets, our findings offer novel perspectives for HCC prevention – a key unmet medical need,” the researchers concluded.

The authors declared that they had no conflicts.

SOURCE: Hamdane N, et al. 2019; Gastroenterology 156:2313–29.

A new study showed that liver tissue from hepatitis C virus (HCV)–infected humans with and without sustained virologic response found epigenetic and gene expression alterations associated with the risk for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), according to Nourdine Hamdane, PHD, of the Institut de Recherche sur les Maladies Virales et Hépatiques, Strasbourg, France, and colleagues.

The researchers analyzed liver tissue from 6 noninfected control patients, 18 patients with chronic HCV infection, 21 patients with cured chronic HCV, 4 patients with hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, and 7 patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), as well as 8 paired HCC samples with HCV-induced liver disease (Gastroenterology 2019;156:2313–29).

They found that several altered pathways related to carcinogenesis persisted after cure, including TNF-alpha signaling, inflammatory response, G2M checkpoint, epithelial–mesenchymal transition, and phosphoinositide 3-kinase, Akt, and mammalian target of rapamycin.

They also observed lower levels of H3K27ac mapping to genes related to oxidative phosphorylation pathways, providing evidence supporting a functional role for H3K27ac changes in establishing gene expression patterns that persist after cure and contribute to carcinogenesis, according to the authors.

“Our study exposes a previously undiscovered paradigm showing that chronic HCV infection induces H3K27ac modifications that are associated with HCC risk and that persist after HCV cure,” the authors wrote. “[This study] provides a unique opportunity to uncover novel biomarkers for HCC risk, that is, from plasma through the detection of epigenetic changes of histones bound to circulating DNA complexes. Furthermore, by uncovering virus-induced epigenetic changes as therapeutic targets, our findings offer novel perspectives for HCC prevention – a key unmet medical need,” the researchers concluded.

The authors declared that they had no conflicts.

SOURCE: Hamdane N, et al. 2019; Gastroenterology 156:2313–29.

A new study showed that liver tissue from hepatitis C virus (HCV)–infected humans with and without sustained virologic response found epigenetic and gene expression alterations associated with the risk for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), according to Nourdine Hamdane, PHD, of the Institut de Recherche sur les Maladies Virales et Hépatiques, Strasbourg, France, and colleagues.

The researchers analyzed liver tissue from 6 noninfected control patients, 18 patients with chronic HCV infection, 21 patients with cured chronic HCV, 4 patients with hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, and 7 patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), as well as 8 paired HCC samples with HCV-induced liver disease (Gastroenterology 2019;156:2313–29).

They found that several altered pathways related to carcinogenesis persisted after cure, including TNF-alpha signaling, inflammatory response, G2M checkpoint, epithelial–mesenchymal transition, and phosphoinositide 3-kinase, Akt, and mammalian target of rapamycin.

They also observed lower levels of H3K27ac mapping to genes related to oxidative phosphorylation pathways, providing evidence supporting a functional role for H3K27ac changes in establishing gene expression patterns that persist after cure and contribute to carcinogenesis, according to the authors.

“Our study exposes a previously undiscovered paradigm showing that chronic HCV infection induces H3K27ac modifications that are associated with HCC risk and that persist after HCV cure,” the authors wrote. “[This study] provides a unique opportunity to uncover novel biomarkers for HCC risk, that is, from plasma through the detection of epigenetic changes of histones bound to circulating DNA complexes. Furthermore, by uncovering virus-induced epigenetic changes as therapeutic targets, our findings offer novel perspectives for HCC prevention – a key unmet medical need,” the researchers concluded.

The authors declared that they had no conflicts.

SOURCE: Hamdane N, et al. 2019; Gastroenterology 156:2313–29.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Are ObGyns knowledgeable about the risk factors for hepatitis C virus in pregnancy?

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends risk-based screening for hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection during pregnancy.1 However, the prevalence of HCV among pregnant women in the United States is on the rise. From 2009 to 2014, HCV infection present at delivery increased 89%.2 In addition, the risk of an HCV-infected mother transmitting the infection to her baby is about 4% to 7% per pregnancy.3 Currently, the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases recommend universal HCV screening in pregnancy.4

Researchers at Tufts Medical Center in Boston, Massachusetts, a tertiary care center, presented survey findings on HCV screening among ObGyns at ACOG’s 2019 Annual Clinical and Scientific Meeting in Nashville, Tennessee.5 Katherine G. Koniares, MD, and colleagues sought to assess the opinions and clinical practices of ObGyns by emailing a 10-question electronic survey to providers. A total of 38 of 41 providers (93%) responded to the survey.

Survey results show lack of knowledge on risk factors

In response to the question, “Which pregnant patients do you believe should be screened for HCV,” 43.2% of providers stated “all pregnant women,” while 54.1% said “only pregnant women with risk factors for HCV.” A small percentage (2.7%) responded that they were not sure.

Providers also were asked which patients in their practice they screen for HCV. In response, 77.8% stated that they screen pregnant women for HCV based on risk factors, while 13.9% screen all pregnant patients for HCV; 8.3% do not screen for HCV.

When asked which risk factors providers use to screen patients for HCV, 42% to 85% said they screen for each indicated risk factor. Only 36% of providers, however, correctly identified all risk factors (for example, receiving blood products from donors who later tested positive for HCV; unexplained liver disease; and percutaneous/parenteral exposures in an unregulated setting, such as receiving tattoos outside a licensed parlor).

Further study needed on universal screening

The researchers assert that risk-based screening for HCV is not effective and that further research on universal HCV screening in pregnant patients is needed.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin no. 86: Viral hepatitis in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:941-956.

- Patrick SW, Bauer AM, Warren MD, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection among women giving birth—Tennessee and the United States, 2009-2014. MMWR Morbid Mortal Weekly Rep. 2017;66:470-473.

- Koneru A, Nelson N, Hariri S, et al. Increased hepatitis C virus (HCV) detection in women of childbearing age and potential risk for vertical transmission—United States and Kentucky, 2011-2014. MMWR Morbid Mortal Weekly Rep. 2016;65:705-710.

- American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). Recommendations for testing, management, and treating, hepatitis C. HCV testing and linkage to care. https://www.hcvguidelines.org/.

- Koniares KG, Fadlallah H, Kolettis DS, et al. A survey of hepatitis C virus (HCV) screening in pregnancy among ObGyns at a tertiary care center. Poster presented at: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Annual Clinical and Scientific Meeting; May 3-6, 2019; Nashville, TN.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends risk-based screening for hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection during pregnancy.1 However, the prevalence of HCV among pregnant women in the United States is on the rise. From 2009 to 2014, HCV infection present at delivery increased 89%.2 In addition, the risk of an HCV-infected mother transmitting the infection to her baby is about 4% to 7% per pregnancy.3 Currently, the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases recommend universal HCV screening in pregnancy.4

Researchers at Tufts Medical Center in Boston, Massachusetts, a tertiary care center, presented survey findings on HCV screening among ObGyns at ACOG’s 2019 Annual Clinical and Scientific Meeting in Nashville, Tennessee.5 Katherine G. Koniares, MD, and colleagues sought to assess the opinions and clinical practices of ObGyns by emailing a 10-question electronic survey to providers. A total of 38 of 41 providers (93%) responded to the survey.

Survey results show lack of knowledge on risk factors

In response to the question, “Which pregnant patients do you believe should be screened for HCV,” 43.2% of providers stated “all pregnant women,” while 54.1% said “only pregnant women with risk factors for HCV.” A small percentage (2.7%) responded that they were not sure.

Providers also were asked which patients in their practice they screen for HCV. In response, 77.8% stated that they screen pregnant women for HCV based on risk factors, while 13.9% screen all pregnant patients for HCV; 8.3% do not screen for HCV.

When asked which risk factors providers use to screen patients for HCV, 42% to 85% said they screen for each indicated risk factor. Only 36% of providers, however, correctly identified all risk factors (for example, receiving blood products from donors who later tested positive for HCV; unexplained liver disease; and percutaneous/parenteral exposures in an unregulated setting, such as receiving tattoos outside a licensed parlor).

Further study needed on universal screening

The researchers assert that risk-based screening for HCV is not effective and that further research on universal HCV screening in pregnant patients is needed.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends risk-based screening for hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection during pregnancy.1 However, the prevalence of HCV among pregnant women in the United States is on the rise. From 2009 to 2014, HCV infection present at delivery increased 89%.2 In addition, the risk of an HCV-infected mother transmitting the infection to her baby is about 4% to 7% per pregnancy.3 Currently, the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases recommend universal HCV screening in pregnancy.4

Researchers at Tufts Medical Center in Boston, Massachusetts, a tertiary care center, presented survey findings on HCV screening among ObGyns at ACOG’s 2019 Annual Clinical and Scientific Meeting in Nashville, Tennessee.5 Katherine G. Koniares, MD, and colleagues sought to assess the opinions and clinical practices of ObGyns by emailing a 10-question electronic survey to providers. A total of 38 of 41 providers (93%) responded to the survey.

Survey results show lack of knowledge on risk factors

In response to the question, “Which pregnant patients do you believe should be screened for HCV,” 43.2% of providers stated “all pregnant women,” while 54.1% said “only pregnant women with risk factors for HCV.” A small percentage (2.7%) responded that they were not sure.

Providers also were asked which patients in their practice they screen for HCV. In response, 77.8% stated that they screen pregnant women for HCV based on risk factors, while 13.9% screen all pregnant patients for HCV; 8.3% do not screen for HCV.

When asked which risk factors providers use to screen patients for HCV, 42% to 85% said they screen for each indicated risk factor. Only 36% of providers, however, correctly identified all risk factors (for example, receiving blood products from donors who later tested positive for HCV; unexplained liver disease; and percutaneous/parenteral exposures in an unregulated setting, such as receiving tattoos outside a licensed parlor).

Further study needed on universal screening

The researchers assert that risk-based screening for HCV is not effective and that further research on universal HCV screening in pregnant patients is needed.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin no. 86: Viral hepatitis in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:941-956.

- Patrick SW, Bauer AM, Warren MD, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection among women giving birth—Tennessee and the United States, 2009-2014. MMWR Morbid Mortal Weekly Rep. 2017;66:470-473.

- Koneru A, Nelson N, Hariri S, et al. Increased hepatitis C virus (HCV) detection in women of childbearing age and potential risk for vertical transmission—United States and Kentucky, 2011-2014. MMWR Morbid Mortal Weekly Rep. 2016;65:705-710.

- American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). Recommendations for testing, management, and treating, hepatitis C. HCV testing and linkage to care. https://www.hcvguidelines.org/.

- Koniares KG, Fadlallah H, Kolettis DS, et al. A survey of hepatitis C virus (HCV) screening in pregnancy among ObGyns at a tertiary care center. Poster presented at: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Annual Clinical and Scientific Meeting; May 3-6, 2019; Nashville, TN.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin no. 86: Viral hepatitis in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:941-956.

- Patrick SW, Bauer AM, Warren MD, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection among women giving birth—Tennessee and the United States, 2009-2014. MMWR Morbid Mortal Weekly Rep. 2017;66:470-473.

- Koneru A, Nelson N, Hariri S, et al. Increased hepatitis C virus (HCV) detection in women of childbearing age and potential risk for vertical transmission—United States and Kentucky, 2011-2014. MMWR Morbid Mortal Weekly Rep. 2016;65:705-710.

- American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). Recommendations for testing, management, and treating, hepatitis C. HCV testing and linkage to care. https://www.hcvguidelines.org/.

- Koniares KG, Fadlallah H, Kolettis DS, et al. A survey of hepatitis C virus (HCV) screening in pregnancy among ObGyns at a tertiary care center. Poster presented at: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Annual Clinical and Scientific Meeting; May 3-6, 2019; Nashville, TN.

DOPPS participation associated with lower HCV rates in dialysis patients

Dialysis patients are commonly infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV), and such infections are associated with increased morbidity and mortality. A team of international researchers assessed trends in the prevalence, incidence, and risk factors for HCV infection among more than 82,000 dialysis patients as defined by a documented diagnosis or antibody positivity using the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study.

They found that overall, among prevalent hemodialysis patients, HCV prevalence was nearly 10% during 2012-2015. The prevalence ranged from a low of 4% in Belgium to as high as 20% in the Middle East, with intermediate prevalence in China, Japan, Italy, Spain, and Russia. However, the prevalence of HCV decreased over time in most countries participating in more than one phase of DOPPS, and prevalence was around 5% among patients who had initiated dialysis within less than 4 months.

The incidence of . Although most units reported no seroconversions, 10% of units experienced three or more cases over a median of 1.1 years.

The researchers also found that high HCV prevalence in the hemodialysis unit was a powerful facility-level risk factor for seroconversion, but the use of isolation stations for HCV-positive patients was not associated with significantly lower seroconversion rates.

“Overall, despite a trend toward lower HCV prevalence among hemodialysis patients, the prevalence of HCV infection remains higher than in the general population,” wrote Michel Jadoul, MD, Cliniques universitaires Saint-Luc, Université Catholique de Louvain, Brussels, and colleagues.

Their report, sponsored by Merck, appeared in Kidney International. A number of the authors reported being speakers or consultants for a variety of pharmaceutical companies; two of the authors are employees of Merck. Support for the ongoing DOPPS Program is provided without restriction on publications.

SOURCE: Jadoul M et al. Kidney Int. 2019;95:939-47.

Dialysis patients are commonly infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV), and such infections are associated with increased morbidity and mortality. A team of international researchers assessed trends in the prevalence, incidence, and risk factors for HCV infection among more than 82,000 dialysis patients as defined by a documented diagnosis or antibody positivity using the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study.

They found that overall, among prevalent hemodialysis patients, HCV prevalence was nearly 10% during 2012-2015. The prevalence ranged from a low of 4% in Belgium to as high as 20% in the Middle East, with intermediate prevalence in China, Japan, Italy, Spain, and Russia. However, the prevalence of HCV decreased over time in most countries participating in more than one phase of DOPPS, and prevalence was around 5% among patients who had initiated dialysis within less than 4 months.

The incidence of . Although most units reported no seroconversions, 10% of units experienced three or more cases over a median of 1.1 years.

The researchers also found that high HCV prevalence in the hemodialysis unit was a powerful facility-level risk factor for seroconversion, but the use of isolation stations for HCV-positive patients was not associated with significantly lower seroconversion rates.

“Overall, despite a trend toward lower HCV prevalence among hemodialysis patients, the prevalence of HCV infection remains higher than in the general population,” wrote Michel Jadoul, MD, Cliniques universitaires Saint-Luc, Université Catholique de Louvain, Brussels, and colleagues.

Their report, sponsored by Merck, appeared in Kidney International. A number of the authors reported being speakers or consultants for a variety of pharmaceutical companies; two of the authors are employees of Merck. Support for the ongoing DOPPS Program is provided without restriction on publications.

SOURCE: Jadoul M et al. Kidney Int. 2019;95:939-47.

Dialysis patients are commonly infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV), and such infections are associated with increased morbidity and mortality. A team of international researchers assessed trends in the prevalence, incidence, and risk factors for HCV infection among more than 82,000 dialysis patients as defined by a documented diagnosis or antibody positivity using the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study.

They found that overall, among prevalent hemodialysis patients, HCV prevalence was nearly 10% during 2012-2015. The prevalence ranged from a low of 4% in Belgium to as high as 20% in the Middle East, with intermediate prevalence in China, Japan, Italy, Spain, and Russia. However, the prevalence of HCV decreased over time in most countries participating in more than one phase of DOPPS, and prevalence was around 5% among patients who had initiated dialysis within less than 4 months.

The incidence of . Although most units reported no seroconversions, 10% of units experienced three or more cases over a median of 1.1 years.

The researchers also found that high HCV prevalence in the hemodialysis unit was a powerful facility-level risk factor for seroconversion, but the use of isolation stations for HCV-positive patients was not associated with significantly lower seroconversion rates.

“Overall, despite a trend toward lower HCV prevalence among hemodialysis patients, the prevalence of HCV infection remains higher than in the general population,” wrote Michel Jadoul, MD, Cliniques universitaires Saint-Luc, Université Catholique de Louvain, Brussels, and colleagues.

Their report, sponsored by Merck, appeared in Kidney International. A number of the authors reported being speakers or consultants for a variety of pharmaceutical companies; two of the authors are employees of Merck. Support for the ongoing DOPPS Program is provided without restriction on publications.

SOURCE: Jadoul M et al. Kidney Int. 2019;95:939-47.

FROM KIDNEY INTERNATIONAL

AGA Clinical Practice Update: Direct-acting antivirals and hepatocellular carcinoma

Achieving sustained virologic response to direct-acting antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis C virus infection cuts lifetime hepatocellular carcinoma risk by approximately 70%, even when patients have baseline cirrhosis, experts wrote in Gastroenterology.

When used after curative-intent treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma, direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy also does not appear to make recurrent cancer more probable or more aggressive, wrote Amit G. Singal, MD, and associates in an American Gastroenterological Association clinical practice update. Studies that compared DAA therapy with either interferon-based therapy or no treatment have found “similar if not lower recurrence than the comparator groups,” they wrote. Rather, hepatocellular carcinoma is in itself highly recurrent: “While surgical resection and local ablative therapies are considered curative, [probability of] recurrence approaches 25%-35% within the first year, and 50%-60% within 2 years.”

Direct-acting antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis C infection improves several aspects of liver health, but experts have debated whether and how these benefits affect the risk and behavior of hepatocellular carcinoma. To explore the issue, Dr. Singal, medical director of the liver tumor program and clinical chief of hepatology at UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas and associates reviewed published clinical trials, observational studies, and systematic reviews. Among 11 studies of more than 3,000 patients in five countries, sustained virologic response (SVR) to DAA therapy was associated with about a 70% reduction in the risk of liver cancer, even after adjustment for clinical and demographic variables. “The relative reduction is similar in patients with and without cirrhosis,” the experts wrote.

Since patients with fibrosis (F3) or cirrhosis are at highest risk for hepatocellular carcinoma, they should undergo baseline imaging and remain under indefinite post-SVR surveillance as long as they are eligible for potentially curative treatment, the practice update states. The experts recommended twice-yearly ultrasound, with or without serum alpha-fetoprotein, noting that current evidence supports neither shorter surveillance intervals nor alternative imaging modalities.

“The presence of active hepatocellular carcinoma is associated with a small but statistically significant decrease in SVR with DAA therapy,” the experts confirmed, based on the results of three studies. They recommended that, when possible, patients with hepatocellular carcinoma first receive curative-intent treatment, such as with liver resection or ablation. Direct-acting antiviral therapy can begin 4-6 months later, once there has been time to confirm response to hepatocellular carcinoma treatment.

For patients who are listed for liver transplantation, timing of DAA therapy “should be determined on a case-by-case basis with consideration of median wait times for the region, availability of HCV-positive organs, and degree of liver dysfunction,” they added. “For example, DAA therapy may be beneficial pretransplant for patients in regions with long wait times or limited hepatitis C virus–positive donor organ availability, whereas therapy may be delayed until posttransplant in regions with shorter wait times or a high proportion of hepatitis C virus–positive donor organs that would otherwise go unused.”

For patients with active intermediate or advanced liver cancer, it remains unclear whether DAA therapy is usually worth the costs and risks, they noted. This is because the likelihood of complete response is lower and the competing risk of death is higher than in patients with earlier-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Pending further data, they recommend basing the decision on patients’ preferences, tumor burden, degree of liver dysfunction, and life expectancy. At their institutions, the researchers do not treat patients with DAA therapy unless their life expectancy exceeds 2 years.

The experts disclosed research funding from the National Cancer Institute, U.S. Veterans Administration, and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Dr. Singal reported personal fees or research funding from AbbVie, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eisai, Exact Sciences, Exelixis, Gilead, Glycotest, Roche, and Wako Diagnostics. His coauthors disclosed ties to AbbVie, Allergan, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Conatus, Genfit, Gilead, Intercept, and Merck.

SOURCE: Singal AG et al. Gastroenterology. 2019 Mar 13. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.02.046.

Achieving sustained virologic response to direct-acting antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis C virus infection cuts lifetime hepatocellular carcinoma risk by approximately 70%, even when patients have baseline cirrhosis, experts wrote in Gastroenterology.

When used after curative-intent treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma, direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy also does not appear to make recurrent cancer more probable or more aggressive, wrote Amit G. Singal, MD, and associates in an American Gastroenterological Association clinical practice update. Studies that compared DAA therapy with either interferon-based therapy or no treatment have found “similar if not lower recurrence than the comparator groups,” they wrote. Rather, hepatocellular carcinoma is in itself highly recurrent: “While surgical resection and local ablative therapies are considered curative, [probability of] recurrence approaches 25%-35% within the first year, and 50%-60% within 2 years.”

Direct-acting antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis C infection improves several aspects of liver health, but experts have debated whether and how these benefits affect the risk and behavior of hepatocellular carcinoma. To explore the issue, Dr. Singal, medical director of the liver tumor program and clinical chief of hepatology at UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas and associates reviewed published clinical trials, observational studies, and systematic reviews. Among 11 studies of more than 3,000 patients in five countries, sustained virologic response (SVR) to DAA therapy was associated with about a 70% reduction in the risk of liver cancer, even after adjustment for clinical and demographic variables. “The relative reduction is similar in patients with and without cirrhosis,” the experts wrote.

Since patients with fibrosis (F3) or cirrhosis are at highest risk for hepatocellular carcinoma, they should undergo baseline imaging and remain under indefinite post-SVR surveillance as long as they are eligible for potentially curative treatment, the practice update states. The experts recommended twice-yearly ultrasound, with or without serum alpha-fetoprotein, noting that current evidence supports neither shorter surveillance intervals nor alternative imaging modalities.

“The presence of active hepatocellular carcinoma is associated with a small but statistically significant decrease in SVR with DAA therapy,” the experts confirmed, based on the results of three studies. They recommended that, when possible, patients with hepatocellular carcinoma first receive curative-intent treatment, such as with liver resection or ablation. Direct-acting antiviral therapy can begin 4-6 months later, once there has been time to confirm response to hepatocellular carcinoma treatment.

For patients who are listed for liver transplantation, timing of DAA therapy “should be determined on a case-by-case basis with consideration of median wait times for the region, availability of HCV-positive organs, and degree of liver dysfunction,” they added. “For example, DAA therapy may be beneficial pretransplant for patients in regions with long wait times or limited hepatitis C virus–positive donor organ availability, whereas therapy may be delayed until posttransplant in regions with shorter wait times or a high proportion of hepatitis C virus–positive donor organs that would otherwise go unused.”

For patients with active intermediate or advanced liver cancer, it remains unclear whether DAA therapy is usually worth the costs and risks, they noted. This is because the likelihood of complete response is lower and the competing risk of death is higher than in patients with earlier-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Pending further data, they recommend basing the decision on patients’ preferences, tumor burden, degree of liver dysfunction, and life expectancy. At their institutions, the researchers do not treat patients with DAA therapy unless their life expectancy exceeds 2 years.

The experts disclosed research funding from the National Cancer Institute, U.S. Veterans Administration, and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Dr. Singal reported personal fees or research funding from AbbVie, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eisai, Exact Sciences, Exelixis, Gilead, Glycotest, Roche, and Wako Diagnostics. His coauthors disclosed ties to AbbVie, Allergan, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Conatus, Genfit, Gilead, Intercept, and Merck.

SOURCE: Singal AG et al. Gastroenterology. 2019 Mar 13. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.02.046.

Achieving sustained virologic response to direct-acting antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis C virus infection cuts lifetime hepatocellular carcinoma risk by approximately 70%, even when patients have baseline cirrhosis, experts wrote in Gastroenterology.

When used after curative-intent treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma, direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy also does not appear to make recurrent cancer more probable or more aggressive, wrote Amit G. Singal, MD, and associates in an American Gastroenterological Association clinical practice update. Studies that compared DAA therapy with either interferon-based therapy or no treatment have found “similar if not lower recurrence than the comparator groups,” they wrote. Rather, hepatocellular carcinoma is in itself highly recurrent: “While surgical resection and local ablative therapies are considered curative, [probability of] recurrence approaches 25%-35% within the first year, and 50%-60% within 2 years.”

Direct-acting antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis C infection improves several aspects of liver health, but experts have debated whether and how these benefits affect the risk and behavior of hepatocellular carcinoma. To explore the issue, Dr. Singal, medical director of the liver tumor program and clinical chief of hepatology at UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas and associates reviewed published clinical trials, observational studies, and systematic reviews. Among 11 studies of more than 3,000 patients in five countries, sustained virologic response (SVR) to DAA therapy was associated with about a 70% reduction in the risk of liver cancer, even after adjustment for clinical and demographic variables. “The relative reduction is similar in patients with and without cirrhosis,” the experts wrote.

Since patients with fibrosis (F3) or cirrhosis are at highest risk for hepatocellular carcinoma, they should undergo baseline imaging and remain under indefinite post-SVR surveillance as long as they are eligible for potentially curative treatment, the practice update states. The experts recommended twice-yearly ultrasound, with or without serum alpha-fetoprotein, noting that current evidence supports neither shorter surveillance intervals nor alternative imaging modalities.

“The presence of active hepatocellular carcinoma is associated with a small but statistically significant decrease in SVR with DAA therapy,” the experts confirmed, based on the results of three studies. They recommended that, when possible, patients with hepatocellular carcinoma first receive curative-intent treatment, such as with liver resection or ablation. Direct-acting antiviral therapy can begin 4-6 months later, once there has been time to confirm response to hepatocellular carcinoma treatment.

For patients who are listed for liver transplantation, timing of DAA therapy “should be determined on a case-by-case basis with consideration of median wait times for the region, availability of HCV-positive organs, and degree of liver dysfunction,” they added. “For example, DAA therapy may be beneficial pretransplant for patients in regions with long wait times or limited hepatitis C virus–positive donor organ availability, whereas therapy may be delayed until posttransplant in regions with shorter wait times or a high proportion of hepatitis C virus–positive donor organs that would otherwise go unused.”

For patients with active intermediate or advanced liver cancer, it remains unclear whether DAA therapy is usually worth the costs and risks, they noted. This is because the likelihood of complete response is lower and the competing risk of death is higher than in patients with earlier-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Pending further data, they recommend basing the decision on patients’ preferences, tumor burden, degree of liver dysfunction, and life expectancy. At their institutions, the researchers do not treat patients with DAA therapy unless their life expectancy exceeds 2 years.

The experts disclosed research funding from the National Cancer Institute, U.S. Veterans Administration, and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Dr. Singal reported personal fees or research funding from AbbVie, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eisai, Exact Sciences, Exelixis, Gilead, Glycotest, Roche, and Wako Diagnostics. His coauthors disclosed ties to AbbVie, Allergan, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Conatus, Genfit, Gilead, Intercept, and Merck.

SOURCE: Singal AG et al. Gastroenterology. 2019 Mar 13. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.02.046.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Ribavirin boosts HCV genotype 3 eradication in compensated cirrhotic patients

VIENNA – In patients with compensated cirrhosis infected with genotype 3 hepatitis C virus, adding ribavirin to a usual antiviral regimen of sofosbuvir and velpatasvir significantly boosted the rate of sustained virologic response in a review of more than 14,000 English residents entered in a national registry starting in 2017.

With ribavirin added to a sofosbuvir plus velpatasvir regimen for 12 weeks of treatment, the three-drug combination produced a 98% rate of sustained virologic response after 12 weeks (SVR12) in 196 treated patients, Kate Drysdale, MBBCh, said at the meeting sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver. In contrast, 218 compensated cirrhosis patients who received a 12-week regimen of sofosbuvir plus velpatasvir (Epclusa) but without ribavirin had an SVR12 rate of just under 92%, a statistically significant difference, compared with the rate among patients who also received ribavirin, said Dr. Drysdale, a gastroenterologist at Bart’s Health and Queen Mary University of London. The SVR12 rate among 167 compensated cirrhotic patients treated for 12 weeks with the combination of glecaprevir plus pibrentasvir (Mavyret) was 96%, and not statistically different from the patients who received three drugs including ribavirin. The sofosbuvir, velpatasvir, ribavirin combination also outperformed the combination of sofosbuvir plus daclatasvir (Daklinza) and ribavirin, which produced an SVR12 of 92% in 868 patients. The SVR12 rate is the percentage of patients with undetectable hepatitis C virus (HCV) 12 or more weeks after the end of treatment.

Dr. Drysdale cautioned that the data have not yet been put through a multivariate analysis, but the results so far provide “a strong indication that ribavirin may not be as insignificant” as many have recently presumed. “Ribavirin has been set aside because it was thought not to add to the SVR12, but if patients get only one go at treatment, we must be sure their first treatment is the best one,” Dr. Drysdale said in an interview. If ribavirin can be shown to make a significant contribution to treatment efficacy “then we should think more widely about using it when patients tolerate it.”

The analysis included too few patients with either current decompensated cirrhosis or a history of decompensated cirrhosis to make any statistically meaningful comparisons of the treatment subgroups among these patients. And among patients with genotype 3 HCV infection and without cirrhosis, none of the treatments used in practice showed any statistically significant differences in the SVR12 rates they produced. Among patients without cirrhosis the most commonly used regimens by far were an 8-week course of glecaprevir plus pibrentasvir in 731 patients or a 12-week course of sofosbuvir plus velpatasvir in 1,184 patients. Both regimens had SVR12 rates in noncirrhotic patients of 97%, regardless of whether patients had no, mild, or moderate liver fibrosis.

The study used data collected in an English national registry of HCV-infected patients treated with direct-acting antiviral drugs starting in 2017. Dr. Drysdale and her associates narrowed down the total database of more than 37,000 English adults who received some HCV therapy during the period to 14,603 who received a complete, valid regimen and had follow-up SVR12 information available. The overall SVR12 rate among all these patients was 95.59%, and among the patients infected by genotype 3 virus the SVR12 rate was 95.03%. Dr. Drysdale’s analysis focused primarily on the roughly one-third of patients in the study group infected with genotype 3 HCV, the genotype that historically has presented unique treatment challenges (Drugs. 2017 Feb;77[2]:131-44).

Another finding Dr. Drysdale reported was that as liver disease severity worsened from no fibrosis to mild or moderate fibrosis, and then to compensated cirrhosis or decompensation, the SVR12 rate steadily diminished. Among genotype 3 patients, the SVR12 rate fell from about 97% among patients without any fibrosis to about 87% among those with decompensated cirrhosis. Although this observation had been made before, this finding in such a large number of treated patients adds significant new evidence to support this pattern. It also adds further support to the idea of screening for HCV infection among higher-risk, asymptomatic people to optimize their prospects for virus eradication with treatment.

“If patients get much better treatment outcomes before they become cirrhotic then we should try to find these HCV-infected people before they develop symptoms,” Dr. Drysdale said.

Dr. Drysdale reported no disclosures.

SOURCE: Drysdale K et al. J Hepatol. 2019 April;70(1):e131.

The results from Dr. Drysdale’s analysis confirm what had previously been proposed by other investigators that, in a subgroup of patients with cirrhosis and infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotype 3, adding ribavirin to a regimen of direct-acting antiviral drugs can increase efficacy. But the new study included no data to address the prevalence of HCV genetic variants with resistance mutations that necessitate adding ribavirin. We have known that, in patients with cirrhosis and infected with resistant genotype 3 HCV, adding ribavirin is necessary. In many locations resistance testing is not possible; in those circumstances, adding ribavirin to the treatment should be routinely done.

Thomas Berg, MD, is professor and head of hepatology at University Hospital in Leipzig, Germany. He has received personal fees and research support from several companies. He made these comments in an interview.

The results from Dr. Drysdale’s analysis confirm what had previously been proposed by other investigators that, in a subgroup of patients with cirrhosis and infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotype 3, adding ribavirin to a regimen of direct-acting antiviral drugs can increase efficacy. But the new study included no data to address the prevalence of HCV genetic variants with resistance mutations that necessitate adding ribavirin. We have known that, in patients with cirrhosis and infected with resistant genotype 3 HCV, adding ribavirin is necessary. In many locations resistance testing is not possible; in those circumstances, adding ribavirin to the treatment should be routinely done.

Thomas Berg, MD, is professor and head of hepatology at University Hospital in Leipzig, Germany. He has received personal fees and research support from several companies. He made these comments in an interview.

The results from Dr. Drysdale’s analysis confirm what had previously been proposed by other investigators that, in a subgroup of patients with cirrhosis and infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotype 3, adding ribavirin to a regimen of direct-acting antiviral drugs can increase efficacy. But the new study included no data to address the prevalence of HCV genetic variants with resistance mutations that necessitate adding ribavirin. We have known that, in patients with cirrhosis and infected with resistant genotype 3 HCV, adding ribavirin is necessary. In many locations resistance testing is not possible; in those circumstances, adding ribavirin to the treatment should be routinely done.

Thomas Berg, MD, is professor and head of hepatology at University Hospital in Leipzig, Germany. He has received personal fees and research support from several companies. He made these comments in an interview.

VIENNA – In patients with compensated cirrhosis infected with genotype 3 hepatitis C virus, adding ribavirin to a usual antiviral regimen of sofosbuvir and velpatasvir significantly boosted the rate of sustained virologic response in a review of more than 14,000 English residents entered in a national registry starting in 2017.

With ribavirin added to a sofosbuvir plus velpatasvir regimen for 12 weeks of treatment, the three-drug combination produced a 98% rate of sustained virologic response after 12 weeks (SVR12) in 196 treated patients, Kate Drysdale, MBBCh, said at the meeting sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver. In contrast, 218 compensated cirrhosis patients who received a 12-week regimen of sofosbuvir plus velpatasvir (Epclusa) but without ribavirin had an SVR12 rate of just under 92%, a statistically significant difference, compared with the rate among patients who also received ribavirin, said Dr. Drysdale, a gastroenterologist at Bart’s Health and Queen Mary University of London. The SVR12 rate among 167 compensated cirrhotic patients treated for 12 weeks with the combination of glecaprevir plus pibrentasvir (Mavyret) was 96%, and not statistically different from the patients who received three drugs including ribavirin. The sofosbuvir, velpatasvir, ribavirin combination also outperformed the combination of sofosbuvir plus daclatasvir (Daklinza) and ribavirin, which produced an SVR12 of 92% in 868 patients. The SVR12 rate is the percentage of patients with undetectable hepatitis C virus (HCV) 12 or more weeks after the end of treatment.

Dr. Drysdale cautioned that the data have not yet been put through a multivariate analysis, but the results so far provide “a strong indication that ribavirin may not be as insignificant” as many have recently presumed. “Ribavirin has been set aside because it was thought not to add to the SVR12, but if patients get only one go at treatment, we must be sure their first treatment is the best one,” Dr. Drysdale said in an interview. If ribavirin can be shown to make a significant contribution to treatment efficacy “then we should think more widely about using it when patients tolerate it.”

The analysis included too few patients with either current decompensated cirrhosis or a history of decompensated cirrhosis to make any statistically meaningful comparisons of the treatment subgroups among these patients. And among patients with genotype 3 HCV infection and without cirrhosis, none of the treatments used in practice showed any statistically significant differences in the SVR12 rates they produced. Among patients without cirrhosis the most commonly used regimens by far were an 8-week course of glecaprevir plus pibrentasvir in 731 patients or a 12-week course of sofosbuvir plus velpatasvir in 1,184 patients. Both regimens had SVR12 rates in noncirrhotic patients of 97%, regardless of whether patients had no, mild, or moderate liver fibrosis.

The study used data collected in an English national registry of HCV-infected patients treated with direct-acting antiviral drugs starting in 2017. Dr. Drysdale and her associates narrowed down the total database of more than 37,000 English adults who received some HCV therapy during the period to 14,603 who received a complete, valid regimen and had follow-up SVR12 information available. The overall SVR12 rate among all these patients was 95.59%, and among the patients infected by genotype 3 virus the SVR12 rate was 95.03%. Dr. Drysdale’s analysis focused primarily on the roughly one-third of patients in the study group infected with genotype 3 HCV, the genotype that historically has presented unique treatment challenges (Drugs. 2017 Feb;77[2]:131-44).

Another finding Dr. Drysdale reported was that as liver disease severity worsened from no fibrosis to mild or moderate fibrosis, and then to compensated cirrhosis or decompensation, the SVR12 rate steadily diminished. Among genotype 3 patients, the SVR12 rate fell from about 97% among patients without any fibrosis to about 87% among those with decompensated cirrhosis. Although this observation had been made before, this finding in such a large number of treated patients adds significant new evidence to support this pattern. It also adds further support to the idea of screening for HCV infection among higher-risk, asymptomatic people to optimize their prospects for virus eradication with treatment.

“If patients get much better treatment outcomes before they become cirrhotic then we should try to find these HCV-infected people before they develop symptoms,” Dr. Drysdale said.

Dr. Drysdale reported no disclosures.

SOURCE: Drysdale K et al. J Hepatol. 2019 April;70(1):e131.

VIENNA – In patients with compensated cirrhosis infected with genotype 3 hepatitis C virus, adding ribavirin to a usual antiviral regimen of sofosbuvir and velpatasvir significantly boosted the rate of sustained virologic response in a review of more than 14,000 English residents entered in a national registry starting in 2017.

With ribavirin added to a sofosbuvir plus velpatasvir regimen for 12 weeks of treatment, the three-drug combination produced a 98% rate of sustained virologic response after 12 weeks (SVR12) in 196 treated patients, Kate Drysdale, MBBCh, said at the meeting sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver. In contrast, 218 compensated cirrhosis patients who received a 12-week regimen of sofosbuvir plus velpatasvir (Epclusa) but without ribavirin had an SVR12 rate of just under 92%, a statistically significant difference, compared with the rate among patients who also received ribavirin, said Dr. Drysdale, a gastroenterologist at Bart’s Health and Queen Mary University of London. The SVR12 rate among 167 compensated cirrhotic patients treated for 12 weeks with the combination of glecaprevir plus pibrentasvir (Mavyret) was 96%, and not statistically different from the patients who received three drugs including ribavirin. The sofosbuvir, velpatasvir, ribavirin combination also outperformed the combination of sofosbuvir plus daclatasvir (Daklinza) and ribavirin, which produced an SVR12 of 92% in 868 patients. The SVR12 rate is the percentage of patients with undetectable hepatitis C virus (HCV) 12 or more weeks after the end of treatment.

Dr. Drysdale cautioned that the data have not yet been put through a multivariate analysis, but the results so far provide “a strong indication that ribavirin may not be as insignificant” as many have recently presumed. “Ribavirin has been set aside because it was thought not to add to the SVR12, but if patients get only one go at treatment, we must be sure their first treatment is the best one,” Dr. Drysdale said in an interview. If ribavirin can be shown to make a significant contribution to treatment efficacy “then we should think more widely about using it when patients tolerate it.”

The analysis included too few patients with either current decompensated cirrhosis or a history of decompensated cirrhosis to make any statistically meaningful comparisons of the treatment subgroups among these patients. And among patients with genotype 3 HCV infection and without cirrhosis, none of the treatments used in practice showed any statistically significant differences in the SVR12 rates they produced. Among patients without cirrhosis the most commonly used regimens by far were an 8-week course of glecaprevir plus pibrentasvir in 731 patients or a 12-week course of sofosbuvir plus velpatasvir in 1,184 patients. Both regimens had SVR12 rates in noncirrhotic patients of 97%, regardless of whether patients had no, mild, or moderate liver fibrosis.

The study used data collected in an English national registry of HCV-infected patients treated with direct-acting antiviral drugs starting in 2017. Dr. Drysdale and her associates narrowed down the total database of more than 37,000 English adults who received some HCV therapy during the period to 14,603 who received a complete, valid regimen and had follow-up SVR12 information available. The overall SVR12 rate among all these patients was 95.59%, and among the patients infected by genotype 3 virus the SVR12 rate was 95.03%. Dr. Drysdale’s analysis focused primarily on the roughly one-third of patients in the study group infected with genotype 3 HCV, the genotype that historically has presented unique treatment challenges (Drugs. 2017 Feb;77[2]:131-44).

Another finding Dr. Drysdale reported was that as liver disease severity worsened from no fibrosis to mild or moderate fibrosis, and then to compensated cirrhosis or decompensation, the SVR12 rate steadily diminished. Among genotype 3 patients, the SVR12 rate fell from about 97% among patients without any fibrosis to about 87% among those with decompensated cirrhosis. Although this observation had been made before, this finding in such a large number of treated patients adds significant new evidence to support this pattern. It also adds further support to the idea of screening for HCV infection among higher-risk, asymptomatic people to optimize their prospects for virus eradication with treatment.

“If patients get much better treatment outcomes before they become cirrhotic then we should try to find these HCV-infected people before they develop symptoms,” Dr. Drysdale said.

Dr. Drysdale reported no disclosures.

SOURCE: Drysdale K et al. J Hepatol. 2019 April;70(1):e131.

REPORTING FROM ILC 2019

Mavyret approved for children with any HCV genotype

The Food and Drug Administration has approved glecaprevir/pibrentasvir tablets (Mavyret) for treating any of six identified genotypes of hepatitis C virus in children ages 12-17 years.

The agency noted in its press announcement that, Dosing information now will be provided for patients aged 12 years and older or weighing at least 99 lbs, without cirrhosis or who have compensated cirrhosis. It is not recommended for patients with moderate cirrhosis, and it is contraindicated in patients with severe cirrhosis, as well as patients taking atazanavir and rifampin.

In clinical trials of 47 patients with genotype 1, 2, 3, or 4 HCV without cirrhosis or with only mild cirrhosis, results at 12 weeks after 8 or 16 weeks’ treatment suggested patients’ infections had been cured – 100% had no virus detected in their blood. Adverse reactions observed were consistent with those previously observed in adults during clinical trials.

The most common reactions were headache and fatigue. Hepatitis B virus reactivation has been reported in coinfected adults during or after treatment with direct-acting antivirals, and in those who were not receiving HBV antiviral treatment. Full prescribing information can be found on the FDA website, and more information about this approval can be found in the agency’s announcement.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved glecaprevir/pibrentasvir tablets (Mavyret) for treating any of six identified genotypes of hepatitis C virus in children ages 12-17 years.

The agency noted in its press announcement that, Dosing information now will be provided for patients aged 12 years and older or weighing at least 99 lbs, without cirrhosis or who have compensated cirrhosis. It is not recommended for patients with moderate cirrhosis, and it is contraindicated in patients with severe cirrhosis, as well as patients taking atazanavir and rifampin.

In clinical trials of 47 patients with genotype 1, 2, 3, or 4 HCV without cirrhosis or with only mild cirrhosis, results at 12 weeks after 8 or 16 weeks’ treatment suggested patients’ infections had been cured – 100% had no virus detected in their blood. Adverse reactions observed were consistent with those previously observed in adults during clinical trials.

The most common reactions were headache and fatigue. Hepatitis B virus reactivation has been reported in coinfected adults during or after treatment with direct-acting antivirals, and in those who were not receiving HBV antiviral treatment. Full prescribing information can be found on the FDA website, and more information about this approval can be found in the agency’s announcement.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved glecaprevir/pibrentasvir tablets (Mavyret) for treating any of six identified genotypes of hepatitis C virus in children ages 12-17 years.

The agency noted in its press announcement that, Dosing information now will be provided for patients aged 12 years and older or weighing at least 99 lbs, without cirrhosis or who have compensated cirrhosis. It is not recommended for patients with moderate cirrhosis, and it is contraindicated in patients with severe cirrhosis, as well as patients taking atazanavir and rifampin.

In clinical trials of 47 patients with genotype 1, 2, 3, or 4 HCV without cirrhosis or with only mild cirrhosis, results at 12 weeks after 8 or 16 weeks’ treatment suggested patients’ infections had been cured – 100% had no virus detected in their blood. Adverse reactions observed were consistent with those previously observed in adults during clinical trials.

The most common reactions were headache and fatigue. Hepatitis B virus reactivation has been reported in coinfected adults during or after treatment with direct-acting antivirals, and in those who were not receiving HBV antiviral treatment. Full prescribing information can be found on the FDA website, and more information about this approval can be found in the agency’s announcement.

Tenofovir disoproxil treated HBV with fewer future HCCs

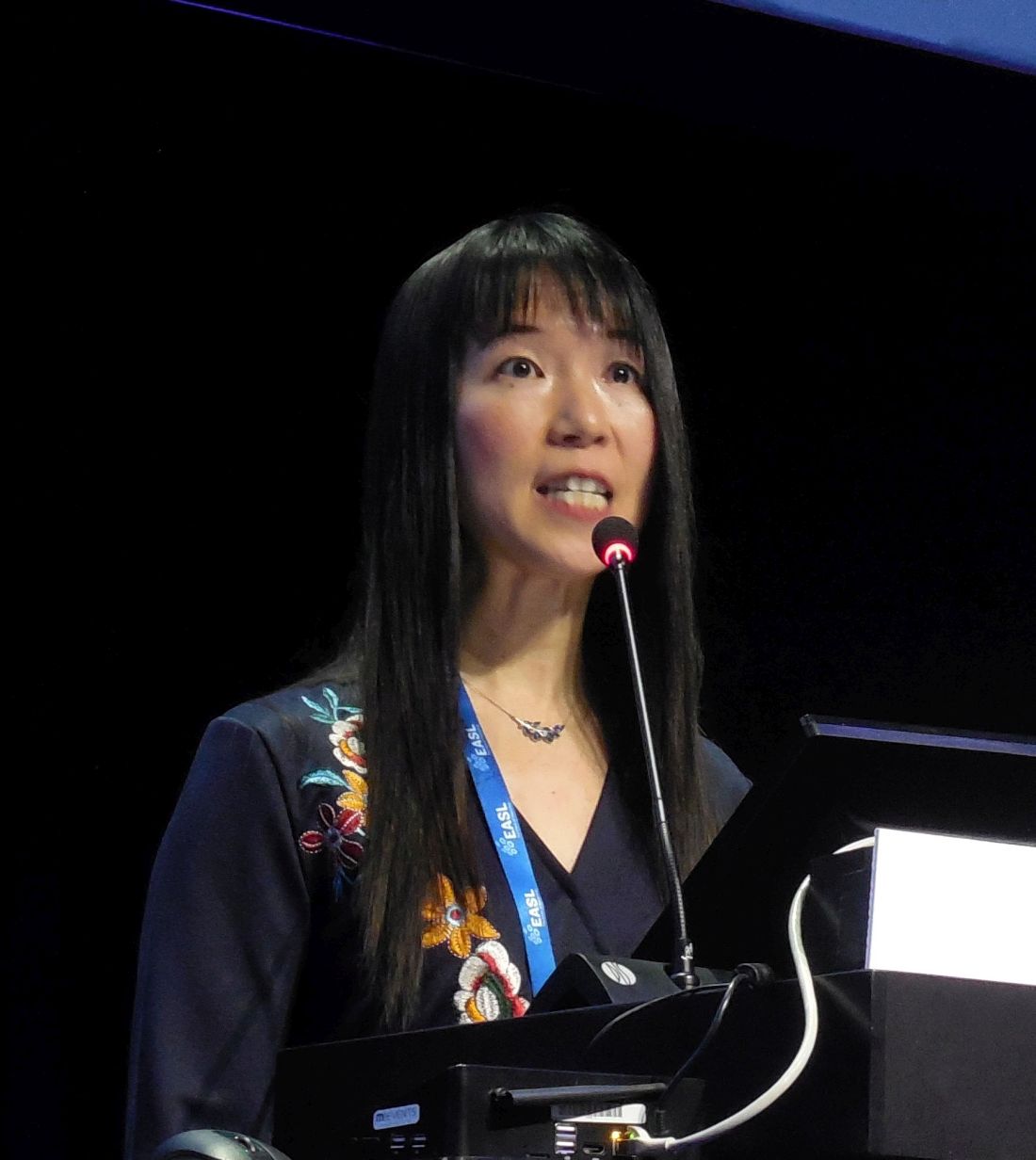

VIENNA – Treatment of individuals chronically infected with hepatitis B virus (HBV) with the nucleotide analog tenofovir disoproxil fumarate significantly linked with a substantial cut in the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) compared with those who received the nucleoside analog entecavir, according to a review of more than 29,000 Hong Kong patients.

This is the second reported study to find that association. In January 2019, a study of more than 24,000 Korean residents chronically infected with HBV showed a similar, statistically significant link between treatment with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (Viread) and a lower incidence of HCC compared with patients treated with entecavir (Baraclude) (JAMA Oncol. 2019 Jan;5[1]:30-6), Grace L.H. Wong, MD, said at the meeting, sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL).

However, another report published just a few days before Dr. Wong spoke failed to find an association between tenofovir disoproxil treatment of HBV and the subsequent rate of HCC compared with patients treated with entecavir. That study comprised nearly 2,900 HBV patients treated at any of four Korean medical centers (J Hepatol. 2019 Apr. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.03.028).

Dr. Wong noted that although current guidelines from EASL cite both tenofovir disoproxil and entecavir (as well as tenofovir alafenamide [Vemlidy]) as first-line treatments for chronic HBV infection (J Hepatol. 2017 Aug;67[2]:370-98), some evidence suggests that tenofovir disoproxil might produce effects subtly different from those of entecavir.

At the meeting in Vienna, for example, a report on 176 Japanese patients with chronic HBV showed that those who were treated with a nucleotide analog such as tenofovir disoproxil produced higher serum levels of interferon-lamda3 compared with patients treated with entecavir, and increased levels of this interferon could improve clearance of HBV surface antigen (J Hepatol. 2019 April;70[1]:e477). The most recent EASL guidelines for treatment of chronic hepatitis B infection also list tenofovir disoproxil, entecavir, and tenofovir alafenamide as preferred agents (Hepatology. 2018 April;67[4]:1560-99).

The data Dr. Wong and her associates analyzed came from health records kept for about 80% of Hong Kong’s population in the Clinical Data Analysis and Recording System of the Hospital Authority of Hong Kong. From January 2010 to June 2018, this database included 28,041 consecutive patients chronically infected with HBV and treated with entecavir, and 1,309 consecutive patients treated with tenofovir disoproxil. These numbers excluded patients treated for less than 6 months, patients coinfected with hepatitis C or D virus, patients with cancer diagnosed or a liver transplanted before or during their first 6 months on treatment, and patients previously treated with an interferon or nucleos(t)ide.

During an average follow-up of 2.8 years of tenofovir disoproxil treatment, 8 patients developed HCC, and during an average follow-up of 3.7 years of entecavir treatment, 1,386 patients developed HCC, reported Dr. Wong, a hepatologist and professor of medicine at the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

In a multivariate analysis that adjusted for demographic and clinical differences, treatment with tenofovir disoproxil linked with a statistically significant 68% reduced rate of HCC development compared with the entecavir-treated patients, she said. In a propensity score–weighted analysis, tenofovir disoproxil linked with a statistically significant 64% reduced rate of incident HCC, and in a propensity score–matched analysis tenofovir disoproxil linked with a 58% reduced rate of HCC, although in this analysis, which excluded many of the entecavir-treated patients and hence had less statistical power, the difference just missed statistical significance.

As an additional step to try to rule out the possible effect of unadjusted confounders, Dr. Wong and associates analyzed the links between tenofovir disoproxil and entecavir treatment and two negative-control outcomes, the incidence of lung cancer and the incidence of acute myocardial infarction. Neither of these outcomes showed a statistically significant link with one of the HBV treatments, suggesting that the link between treatment and HCC incidence did not appear because of an unadjusted confounding bias, Dr. Wong said. The Hong Kong database did not include enough patients treated with tenofovir alafenamide to allow assessment of this drug, she added.

Dr. Wong has been an adviser to Gilead and a speaker for Abbott, AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Janssen, and Roche. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate is marketed by Gilead, and entecavir is marketed by Bristol-Myers Squibb.

SOURCE: Wong GL et al. J Hepatol. 2019 April;70[1]:e128.

VIENNA – Treatment of individuals chronically infected with hepatitis B virus (HBV) with the nucleotide analog tenofovir disoproxil fumarate significantly linked with a substantial cut in the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) compared with those who received the nucleoside analog entecavir, according to a review of more than 29,000 Hong Kong patients.

This is the second reported study to find that association. In January 2019, a study of more than 24,000 Korean residents chronically infected with HBV showed a similar, statistically significant link between treatment with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (Viread) and a lower incidence of HCC compared with patients treated with entecavir (Baraclude) (JAMA Oncol. 2019 Jan;5[1]:30-6), Grace L.H. Wong, MD, said at the meeting, sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL).

However, another report published just a few days before Dr. Wong spoke failed to find an association between tenofovir disoproxil treatment of HBV and the subsequent rate of HCC compared with patients treated with entecavir. That study comprised nearly 2,900 HBV patients treated at any of four Korean medical centers (J Hepatol. 2019 Apr. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.03.028).

Dr. Wong noted that although current guidelines from EASL cite both tenofovir disoproxil and entecavir (as well as tenofovir alafenamide [Vemlidy]) as first-line treatments for chronic HBV infection (J Hepatol. 2017 Aug;67[2]:370-98), some evidence suggests that tenofovir disoproxil might produce effects subtly different from those of entecavir.

At the meeting in Vienna, for example, a report on 176 Japanese patients with chronic HBV showed that those who were treated with a nucleotide analog such as tenofovir disoproxil produced higher serum levels of interferon-lamda3 compared with patients treated with entecavir, and increased levels of this interferon could improve clearance of HBV surface antigen (J Hepatol. 2019 April;70[1]:e477). The most recent EASL guidelines for treatment of chronic hepatitis B infection also list tenofovir disoproxil, entecavir, and tenofovir alafenamide as preferred agents (Hepatology. 2018 April;67[4]:1560-99).

The data Dr. Wong and her associates analyzed came from health records kept for about 80% of Hong Kong’s population in the Clinical Data Analysis and Recording System of the Hospital Authority of Hong Kong. From January 2010 to June 2018, this database included 28,041 consecutive patients chronically infected with HBV and treated with entecavir, and 1,309 consecutive patients treated with tenofovir disoproxil. These numbers excluded patients treated for less than 6 months, patients coinfected with hepatitis C or D virus, patients with cancer diagnosed or a liver transplanted before or during their first 6 months on treatment, and patients previously treated with an interferon or nucleos(t)ide.

During an average follow-up of 2.8 years of tenofovir disoproxil treatment, 8 patients developed HCC, and during an average follow-up of 3.7 years of entecavir treatment, 1,386 patients developed HCC, reported Dr. Wong, a hepatologist and professor of medicine at the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

In a multivariate analysis that adjusted for demographic and clinical differences, treatment with tenofovir disoproxil linked with a statistically significant 68% reduced rate of HCC development compared with the entecavir-treated patients, she said. In a propensity score–weighted analysis, tenofovir disoproxil linked with a statistically significant 64% reduced rate of incident HCC, and in a propensity score–matched analysis tenofovir disoproxil linked with a 58% reduced rate of HCC, although in this analysis, which excluded many of the entecavir-treated patients and hence had less statistical power, the difference just missed statistical significance.

As an additional step to try to rule out the possible effect of unadjusted confounders, Dr. Wong and associates analyzed the links between tenofovir disoproxil and entecavir treatment and two negative-control outcomes, the incidence of lung cancer and the incidence of acute myocardial infarction. Neither of these outcomes showed a statistically significant link with one of the HBV treatments, suggesting that the link between treatment and HCC incidence did not appear because of an unadjusted confounding bias, Dr. Wong said. The Hong Kong database did not include enough patients treated with tenofovir alafenamide to allow assessment of this drug, she added.

Dr. Wong has been an adviser to Gilead and a speaker for Abbott, AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Janssen, and Roche. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate is marketed by Gilead, and entecavir is marketed by Bristol-Myers Squibb.

SOURCE: Wong GL et al. J Hepatol. 2019 April;70[1]:e128.

VIENNA – Treatment of individuals chronically infected with hepatitis B virus (HBV) with the nucleotide analog tenofovir disoproxil fumarate significantly linked with a substantial cut in the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) compared with those who received the nucleoside analog entecavir, according to a review of more than 29,000 Hong Kong patients.

This is the second reported study to find that association. In January 2019, a study of more than 24,000 Korean residents chronically infected with HBV showed a similar, statistically significant link between treatment with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (Viread) and a lower incidence of HCC compared with patients treated with entecavir (Baraclude) (JAMA Oncol. 2019 Jan;5[1]:30-6), Grace L.H. Wong, MD, said at the meeting, sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL).

However, another report published just a few days before Dr. Wong spoke failed to find an association between tenofovir disoproxil treatment of HBV and the subsequent rate of HCC compared with patients treated with entecavir. That study comprised nearly 2,900 HBV patients treated at any of four Korean medical centers (J Hepatol. 2019 Apr. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.03.028).

Dr. Wong noted that although current guidelines from EASL cite both tenofovir disoproxil and entecavir (as well as tenofovir alafenamide [Vemlidy]) as first-line treatments for chronic HBV infection (J Hepatol. 2017 Aug;67[2]:370-98), some evidence suggests that tenofovir disoproxil might produce effects subtly different from those of entecavir.

At the meeting in Vienna, for example, a report on 176 Japanese patients with chronic HBV showed that those who were treated with a nucleotide analog such as tenofovir disoproxil produced higher serum levels of interferon-lamda3 compared with patients treated with entecavir, and increased levels of this interferon could improve clearance of HBV surface antigen (J Hepatol. 2019 April;70[1]:e477). The most recent EASL guidelines for treatment of chronic hepatitis B infection also list tenofovir disoproxil, entecavir, and tenofovir alafenamide as preferred agents (Hepatology. 2018 April;67[4]:1560-99).

The data Dr. Wong and her associates analyzed came from health records kept for about 80% of Hong Kong’s population in the Clinical Data Analysis and Recording System of the Hospital Authority of Hong Kong. From January 2010 to June 2018, this database included 28,041 consecutive patients chronically infected with HBV and treated with entecavir, and 1,309 consecutive patients treated with tenofovir disoproxil. These numbers excluded patients treated for less than 6 months, patients coinfected with hepatitis C or D virus, patients with cancer diagnosed or a liver transplanted before or during their first 6 months on treatment, and patients previously treated with an interferon or nucleos(t)ide.

During an average follow-up of 2.8 years of tenofovir disoproxil treatment, 8 patients developed HCC, and during an average follow-up of 3.7 years of entecavir treatment, 1,386 patients developed HCC, reported Dr. Wong, a hepatologist and professor of medicine at the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

In a multivariate analysis that adjusted for demographic and clinical differences, treatment with tenofovir disoproxil linked with a statistically significant 68% reduced rate of HCC development compared with the entecavir-treated patients, she said. In a propensity score–weighted analysis, tenofovir disoproxil linked with a statistically significant 64% reduced rate of incident HCC, and in a propensity score–matched analysis tenofovir disoproxil linked with a 58% reduced rate of HCC, although in this analysis, which excluded many of the entecavir-treated patients and hence had less statistical power, the difference just missed statistical significance.

As an additional step to try to rule out the possible effect of unadjusted confounders, Dr. Wong and associates analyzed the links between tenofovir disoproxil and entecavir treatment and two negative-control outcomes, the incidence of lung cancer and the incidence of acute myocardial infarction. Neither of these outcomes showed a statistically significant link with one of the HBV treatments, suggesting that the link between treatment and HCC incidence did not appear because of an unadjusted confounding bias, Dr. Wong said. The Hong Kong database did not include enough patients treated with tenofovir alafenamide to allow assessment of this drug, she added.

Dr. Wong has been an adviser to Gilead and a speaker for Abbott, AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Janssen, and Roche. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate is marketed by Gilead, and entecavir is marketed by Bristol-Myers Squibb.

SOURCE: Wong GL et al. J Hepatol. 2019 April;70[1]:e128.

REPORTING FROM ILC 2019

HCC linked to mitochondrial damage, iron accumulation from HCV

according to an extensive literature review.

Although the mechanisms underlying the hepatocellular carcinoma development are not fully understood, it is known that oxidative stress exists to a greater degree in hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, compared with other inflammatory liver diseases. Such stress has been proposed as a major mechanism of liver injury in patients with chronic HCV, the authors reported in Free Radical Biology and Medicine.

Patients with HCV have significant hepatocellular mitochondrial alterations, and iron accumulation is also a well-known characteristic in patients with chronic HCV. Such alterations in mitochondria and iron accumulation are closely related to oxidative stress, since the mitochondria are the main site of reactive oxygen species generation, and iron produces hydroxy radicals via the Fenton reaction, according to the review.

“The greatest concern is whether mitochondrial damage and iron metabolic dysregulation persist even after HCV eradication and to what extent such pathological conditions affect the development of HCC. Determining the molecular signaling that underlies the mitophagy induced by iron depletion is another topic of interest and is expected to lead to potential therapeutic approaches for multiple diseases,” the researchers concluded.

Support was from the Research Program on Hepatitis from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development. The authors reported no disclosures.

SOURCE: Keisuke H et al. Free Radic Biol Med. 2019;133:193-9.

according to an extensive literature review.

Although the mechanisms underlying the hepatocellular carcinoma development are not fully understood, it is known that oxidative stress exists to a greater degree in hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, compared with other inflammatory liver diseases. Such stress has been proposed as a major mechanism of liver injury in patients with chronic HCV, the authors reported in Free Radical Biology and Medicine.

Patients with HCV have significant hepatocellular mitochondrial alterations, and iron accumulation is also a well-known characteristic in patients with chronic HCV. Such alterations in mitochondria and iron accumulation are closely related to oxidative stress, since the mitochondria are the main site of reactive oxygen species generation, and iron produces hydroxy radicals via the Fenton reaction, according to the review.

“The greatest concern is whether mitochondrial damage and iron metabolic dysregulation persist even after HCV eradication and to what extent such pathological conditions affect the development of HCC. Determining the molecular signaling that underlies the mitophagy induced by iron depletion is another topic of interest and is expected to lead to potential therapeutic approaches for multiple diseases,” the researchers concluded.

Support was from the Research Program on Hepatitis from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development. The authors reported no disclosures.

SOURCE: Keisuke H et al. Free Radic Biol Med. 2019;133:193-9.

according to an extensive literature review.

Although the mechanisms underlying the hepatocellular carcinoma development are not fully understood, it is known that oxidative stress exists to a greater degree in hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, compared with other inflammatory liver diseases. Such stress has been proposed as a major mechanism of liver injury in patients with chronic HCV, the authors reported in Free Radical Biology and Medicine.

Patients with HCV have significant hepatocellular mitochondrial alterations, and iron accumulation is also a well-known characteristic in patients with chronic HCV. Such alterations in mitochondria and iron accumulation are closely related to oxidative stress, since the mitochondria are the main site of reactive oxygen species generation, and iron produces hydroxy radicals via the Fenton reaction, according to the review.

“The greatest concern is whether mitochondrial damage and iron metabolic dysregulation persist even after HCV eradication and to what extent such pathological conditions affect the development of HCC. Determining the molecular signaling that underlies the mitophagy induced by iron depletion is another topic of interest and is expected to lead to potential therapeutic approaches for multiple diseases,” the researchers concluded.

Support was from the Research Program on Hepatitis from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development. The authors reported no disclosures.

SOURCE: Keisuke H et al. Free Radic Biol Med. 2019;133:193-9.

FROM FREE RADICAL BIOLOGY AND MEDICINE

The VA vs HCV: Making a Deadly Disease a Memory

“This is terrific news,” said US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Secretary Robert Wilkie, noting that the VA is the largest single provider of hepatitis C virus (HCV) care in the US. “Diagnosing, treating, and curing hepatitis C virus infection among veterans has been a significant priority for VA.” According to the Review of Hepatitis C Virus Care within the Veterans Health Administration, published last month by the VA Office of Inspector General (OIG), the VA cares for more than 180,000 confirmed patients who are disproportionately affected by HCV infection, at rates about 3 times that of the national average.

As of March, nearly 116,000 veterans had started all-oral HCV medications. Almost 100,000 have completed treatment and are now cured. As an article in Forbes magazine pointed out, that is a story very different from the one reported just a few years earlier, when HCV treatment was out of reach for the tens of thousands of service members seriously ill with HCV, most of whom contracted it during blood transfusions in the Vietnam War.

The good news is due largely to the use of highly effective direct-acting antivirals (DAAs), which have revolutionized HCV treatment. Before 2014, HCV treatment required weekly interferon injections for up to a year, with low cure rates (35%-55%) and significant physical and psychiatric adverse effects (AEs), leading to frequent early discontinuation. Of the approximately 180,000 veterans in VA care at that time who had been diagnosed with chronic HCV infection, only 12,000 had been treated and cured. More than 30,000 had advanced liver disease.

In 2014, the VA launched an “aggressive program” to identify all undiagnosed veterans with HCV, link them to care, and offer them treatment with the new medications: sofosbuvir (Sovaldi) and simeprevir (Olysio). They have few AEs and can be administered once daily for as few as 8 weeks.

However, those drugs were incredibly expensive, prohibitively so for many people. Sovaldi cost $1,000 a pill. But the VA, allowed by law to negotiate prices, brought down the price. The VA estimated that the drugs would cost roughly $750 million and provide about 60,000 treatments over 2017 and 2018, at about $25,300 per service member .