User login

HCC with no cirrhosis is more common in HIV patients

SEATTLE – Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is on the rise in HIV-positive individuals, its incidence having quadrupled since 1996, and HIV-positive individuals have about a 300% increase risk of HCC, compared with the general population. However, more than 40% of patients with HIV who develop HCC have a Fibrosis-4 score (FIB-4) suggesting a lack of cirrhosis, according to a new retrospective analysis. By contrast, only about 13% of typical HCC patients have no cirrhosis.

The study also revealed some of the risk factors associated with HCC in this population, including longer duration of HIV viremia and lower CD4 cell counts, as well as markers of metabolic syndrome. “There was some signal that perhaps other markers of metabolic syndrome, obesity and diabetes, were more prevalent in those [who developed HCC] without advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis, suggesting that there may be other underlying etiologies of liver disease that we should be wary of when evaluating somebody for their risk of HCC,” Jessie Torgersen, MD, said in an interview.

Dr. Torgersen is an instructor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. She presented the study at the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections.

The results of the study are tantalizing, but not yet practice changing. “I don’t think we have enough information from this study to recommend a dramatic overhaul of the current HCC screening guidelines, but with the anticipated elimination of hepatitis C, I think the emergence of [metabolic factors and their] contributions to our HIV-positive population’s risk of HCC needs to be better understood. Hopefully this will serve as a first step in further understanding those risks,” Dr. Torgersen said.

She also hopes to get a better handle on the biological mechanisms that might drive HCC in the absence of cirrhosis. “While the mechanisms are unclear as to why HCC would develop in HIV-positive patients without cirrhosis, there are a lot of biologically plausible mechanisms that seem to make [sense],” said Dr. Torgersen. The team hopes to get a better understanding of those mechanisms in order to information evaluation and screening for HCC.

The researchers analyzed data from the Veterans Affairs Cancer Registry as well as EMRs for HIV-positive veterans across the United States. The study included 2,497 participants with a FIB-4 score greater than 3.25, and 29,836 with an FIB-4 score less than or equal to 3.25. At baseline, subjects with FIB-4 greater than 3.25 were more likely to have an alcohol-related diagnosis (47% vs. 29%), be positive for hepatitis C virus RNA (59% vs. 30%), be positive for the hepatitis B surface antigen (10% versus 5%), have HIV RNA greater than or equal to 500 copies/mL (63% vs. 56%), and to have a CD4+ cell count less than 200 cells/m3 (39% vs. 26%).

A total of 278 subjects were diagnosed with HCC; 43% had an FIB-4 less than or equal to 3.25. Among those 43%, more patients had a body mass index of 30 or higher (16% vs. 12%), had diabetes (31% vs. 25%), and tested positive for the hepatitis B surface antigen (26% vs. 17%).

Among subjects with FIB-4 less than or equal to 3.25, factors associated with greater HCC risk included higher HIV RNA level (hazard ratio, 1.24 per 1.0 log10 copies/mL), CD4+ cell count less than 200 cells/m3 (HR, 1.78), hepatitis C virus infection (HR, 6.32), and positive hepatitis B surface antigen (HR, 4.93).

Among subjects with FIB-4 greater than 3.25, increased HCC risk was associated with HCV infection (HR, 6.18) and positive hepatitis B surface antigen (HR, 2.12).

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Torgersen reported no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Torgersen J et al. CROI 2019, Abstract 90.

SEATTLE – Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is on the rise in HIV-positive individuals, its incidence having quadrupled since 1996, and HIV-positive individuals have about a 300% increase risk of HCC, compared with the general population. However, more than 40% of patients with HIV who develop HCC have a Fibrosis-4 score (FIB-4) suggesting a lack of cirrhosis, according to a new retrospective analysis. By contrast, only about 13% of typical HCC patients have no cirrhosis.

The study also revealed some of the risk factors associated with HCC in this population, including longer duration of HIV viremia and lower CD4 cell counts, as well as markers of metabolic syndrome. “There was some signal that perhaps other markers of metabolic syndrome, obesity and diabetes, were more prevalent in those [who developed HCC] without advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis, suggesting that there may be other underlying etiologies of liver disease that we should be wary of when evaluating somebody for their risk of HCC,” Jessie Torgersen, MD, said in an interview.

Dr. Torgersen is an instructor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. She presented the study at the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections.

The results of the study are tantalizing, but not yet practice changing. “I don’t think we have enough information from this study to recommend a dramatic overhaul of the current HCC screening guidelines, but with the anticipated elimination of hepatitis C, I think the emergence of [metabolic factors and their] contributions to our HIV-positive population’s risk of HCC needs to be better understood. Hopefully this will serve as a first step in further understanding those risks,” Dr. Torgersen said.

She also hopes to get a better handle on the biological mechanisms that might drive HCC in the absence of cirrhosis. “While the mechanisms are unclear as to why HCC would develop in HIV-positive patients without cirrhosis, there are a lot of biologically plausible mechanisms that seem to make [sense],” said Dr. Torgersen. The team hopes to get a better understanding of those mechanisms in order to information evaluation and screening for HCC.

The researchers analyzed data from the Veterans Affairs Cancer Registry as well as EMRs for HIV-positive veterans across the United States. The study included 2,497 participants with a FIB-4 score greater than 3.25, and 29,836 with an FIB-4 score less than or equal to 3.25. At baseline, subjects with FIB-4 greater than 3.25 were more likely to have an alcohol-related diagnosis (47% vs. 29%), be positive for hepatitis C virus RNA (59% vs. 30%), be positive for the hepatitis B surface antigen (10% versus 5%), have HIV RNA greater than or equal to 500 copies/mL (63% vs. 56%), and to have a CD4+ cell count less than 200 cells/m3 (39% vs. 26%).

A total of 278 subjects were diagnosed with HCC; 43% had an FIB-4 less than or equal to 3.25. Among those 43%, more patients had a body mass index of 30 or higher (16% vs. 12%), had diabetes (31% vs. 25%), and tested positive for the hepatitis B surface antigen (26% vs. 17%).

Among subjects with FIB-4 less than or equal to 3.25, factors associated with greater HCC risk included higher HIV RNA level (hazard ratio, 1.24 per 1.0 log10 copies/mL), CD4+ cell count less than 200 cells/m3 (HR, 1.78), hepatitis C virus infection (HR, 6.32), and positive hepatitis B surface antigen (HR, 4.93).

Among subjects with FIB-4 greater than 3.25, increased HCC risk was associated with HCV infection (HR, 6.18) and positive hepatitis B surface antigen (HR, 2.12).

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Torgersen reported no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Torgersen J et al. CROI 2019, Abstract 90.

SEATTLE – Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is on the rise in HIV-positive individuals, its incidence having quadrupled since 1996, and HIV-positive individuals have about a 300% increase risk of HCC, compared with the general population. However, more than 40% of patients with HIV who develop HCC have a Fibrosis-4 score (FIB-4) suggesting a lack of cirrhosis, according to a new retrospective analysis. By contrast, only about 13% of typical HCC patients have no cirrhosis.

The study also revealed some of the risk factors associated with HCC in this population, including longer duration of HIV viremia and lower CD4 cell counts, as well as markers of metabolic syndrome. “There was some signal that perhaps other markers of metabolic syndrome, obesity and diabetes, were more prevalent in those [who developed HCC] without advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis, suggesting that there may be other underlying etiologies of liver disease that we should be wary of when evaluating somebody for their risk of HCC,” Jessie Torgersen, MD, said in an interview.

Dr. Torgersen is an instructor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. She presented the study at the Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections.

The results of the study are tantalizing, but not yet practice changing. “I don’t think we have enough information from this study to recommend a dramatic overhaul of the current HCC screening guidelines, but with the anticipated elimination of hepatitis C, I think the emergence of [metabolic factors and their] contributions to our HIV-positive population’s risk of HCC needs to be better understood. Hopefully this will serve as a first step in further understanding those risks,” Dr. Torgersen said.

She also hopes to get a better handle on the biological mechanisms that might drive HCC in the absence of cirrhosis. “While the mechanisms are unclear as to why HCC would develop in HIV-positive patients without cirrhosis, there are a lot of biologically plausible mechanisms that seem to make [sense],” said Dr. Torgersen. The team hopes to get a better understanding of those mechanisms in order to information evaluation and screening for HCC.

The researchers analyzed data from the Veterans Affairs Cancer Registry as well as EMRs for HIV-positive veterans across the United States. The study included 2,497 participants with a FIB-4 score greater than 3.25, and 29,836 with an FIB-4 score less than or equal to 3.25. At baseline, subjects with FIB-4 greater than 3.25 were more likely to have an alcohol-related diagnosis (47% vs. 29%), be positive for hepatitis C virus RNA (59% vs. 30%), be positive for the hepatitis B surface antigen (10% versus 5%), have HIV RNA greater than or equal to 500 copies/mL (63% vs. 56%), and to have a CD4+ cell count less than 200 cells/m3 (39% vs. 26%).

A total of 278 subjects were diagnosed with HCC; 43% had an FIB-4 less than or equal to 3.25. Among those 43%, more patients had a body mass index of 30 or higher (16% vs. 12%), had diabetes (31% vs. 25%), and tested positive for the hepatitis B surface antigen (26% vs. 17%).

Among subjects with FIB-4 less than or equal to 3.25, factors associated with greater HCC risk included higher HIV RNA level (hazard ratio, 1.24 per 1.0 log10 copies/mL), CD4+ cell count less than 200 cells/m3 (HR, 1.78), hepatitis C virus infection (HR, 6.32), and positive hepatitis B surface antigen (HR, 4.93).

Among subjects with FIB-4 greater than 3.25, increased HCC risk was associated with HCV infection (HR, 6.18) and positive hepatitis B surface antigen (HR, 2.12).

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Torgersen reported no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Torgersen J et al. CROI 2019, Abstract 90.

REPORTING FROM CROI 2019

ICYMI: Noninferior tuberculosis prevention in HIV has shorter duration

The primary endpoint – first case of tuberculosis or death from tuberculosis or unknown cause among patients with HIV – was reported in 2% of both arms in the open-label, phase 3, noninferiority trial BRIEF TB (NCT01404312).

In the New England Journal of Medicine (2019 Mar 14;380[11]:1001-11), 3,000 patients with HIV were randomized to receive either 1 month of rifapentine/isoniazid or 9 months of isoniazid monotherapy for prevention of tuberculosis. Although safety was also similar between arms, the completion rate was significantly higher in the combination treatment arm, compared with the monotherapy arm (97% vs. 90%; P less than .001).

We covered this story at the annual Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections. See our coverage at the link below.

The primary endpoint – first case of tuberculosis or death from tuberculosis or unknown cause among patients with HIV – was reported in 2% of both arms in the open-label, phase 3, noninferiority trial BRIEF TB (NCT01404312).

In the New England Journal of Medicine (2019 Mar 14;380[11]:1001-11), 3,000 patients with HIV were randomized to receive either 1 month of rifapentine/isoniazid or 9 months of isoniazid monotherapy for prevention of tuberculosis. Although safety was also similar between arms, the completion rate was significantly higher in the combination treatment arm, compared with the monotherapy arm (97% vs. 90%; P less than .001).

We covered this story at the annual Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections. See our coverage at the link below.

The primary endpoint – first case of tuberculosis or death from tuberculosis or unknown cause among patients with HIV – was reported in 2% of both arms in the open-label, phase 3, noninferiority trial BRIEF TB (NCT01404312).

In the New England Journal of Medicine (2019 Mar 14;380[11]:1001-11), 3,000 patients with HIV were randomized to receive either 1 month of rifapentine/isoniazid or 9 months of isoniazid monotherapy for prevention of tuberculosis. Although safety was also similar between arms, the completion rate was significantly higher in the combination treatment arm, compared with the monotherapy arm (97% vs. 90%; P less than .001).

We covered this story at the annual Conference on Retroviruses & Opportunistic Infections. See our coverage at the link below.

FROM NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Descovy noninferior to Truvada for PrEP

SEATTLE – Descovy [emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide (F/TAF]) was noninferior to Truvada [emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (F/TDF)] for preexposure HIV prophylaxis in a blinded, randomized trial involving more than 5,000 men at high risk for the infection.

Both nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors are made by Gilead, and the company funded the trial.

F/TDF (Truvada) has been a blockbuster for the company, both for HIV treatment and, since 2012, for preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP); it’s the only medication to carry the indication. However, F/TDF is set to go off patent in 2021, so the company has turned its development efforts to a successor, F/TAF (Descovy), a prodrug of tenofovir that is already approved for HIV treatment.

The new study builds a case for F/TAF for PrEP, but whether the results are strong enough to persuade people to opt for it over a much less expensive generic version of F/TDF remains to be seen.

The trial randomized 2,694 men who have sex with men to F/TAF, and 2,693 to F/TDF for up to 96 weeks. Entrance criteria included at least two episodes of unprotected anal sex in the previous 12 weeks, or a diagnosis of rectal gonorrhea, chlamydia, or syphilis in the previous 6 months.

More than half the men contracted at least one sexually transmitted infection during the trial, “which indicated to us that these were the right patients to be enrolled in the study,” lead investigator Charles Hare, MD, an infectious disease specialist at the University of California, San Francisco, said at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections.

There were 15 new HIV infections in the F/TDF group (0.34 per 100 person-years), versus 7 in the F/TAF group (0.16 per 100 person-years). Almost all of the new infections were due to poor adherence – as proven by blood levels and dry blood spot testing – and most of the rest were in men who probably entered the trial with newly acquired HIV.

When those subjects were excluded, there were just two new onset HIV cases in subjects adherent to dosing, one in each arm. Infection rates were far lower than would have been expected had the subjects not been on PrEP.

One of Gilead’s main selling points for F/TAF over F/TDF is that the newer drug has better bone and renal safety, and there were slight biomarker differences in the trial that supported the assertion.

For instance, spine bone mineral density decreased 3% or greater from baseline in 10 F/TAF patients, but 27 men on F/TDF (P less than .001). Results were similar with hip bone density.

On the renal front, estimated glomerular filtration rates fell a median of 2.3 mL/min per 1.73 m2 in the F/TDF arm, but rose 1.8 mL/min per 1.73 m2 in men on F/TAF (P less than .001). Proximal tubular protein to creatinine ratios were largely unchanged from baseline with F/TAF, but slightly higher in the F/TDF group, at 48 weeks.

There were no statistically significant differences on actual safety outcomes – as opposed to biomarkers – between the two drugs or discontinuations due to side effects, which were rare and most often due to gastrointestinal issues. F/TAF patients gained about 1.1 kg in the trial, while weight held steady in the F/TDF arm. The study team plans to analyze lipid profile differences between the groups, since concern has been raised about F/TAF’s effect on them.

In a press conference at the conference, there was quite a bit of discussion about whether the results would justify using F/TAF for PrEP when less expensive generic versions of F/TDF become available.

“That’s a great question,” Dr. Hare said. “Both drugs actually performed quite well,” and both “do pretty well in terms of safety in this population.”

It’s not known at this point if the biomarker differences will prove to be clinically relevant. Hip fractures, kidney failure, and other problems are so rare in young, relatively healthy PrEP users that a trial to demonstrate clinical relevance would have to be huge, with years-long follow-up, Dr. Hare noted.

The average age of the men in this study was 36 years. Most were white, and about 60% lived in the United States. Other participants were from Canada or Europe.

The work was funded by Gilead; five investigators, including the senior investigator, were employees. Dr. Hare is an investigator for the company.

SOURCE: Hare CB et al. CROI 2019, Abstract 104 LB.

SEATTLE – Descovy [emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide (F/TAF]) was noninferior to Truvada [emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (F/TDF)] for preexposure HIV prophylaxis in a blinded, randomized trial involving more than 5,000 men at high risk for the infection.

Both nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors are made by Gilead, and the company funded the trial.

F/TDF (Truvada) has been a blockbuster for the company, both for HIV treatment and, since 2012, for preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP); it’s the only medication to carry the indication. However, F/TDF is set to go off patent in 2021, so the company has turned its development efforts to a successor, F/TAF (Descovy), a prodrug of tenofovir that is already approved for HIV treatment.

The new study builds a case for F/TAF for PrEP, but whether the results are strong enough to persuade people to opt for it over a much less expensive generic version of F/TDF remains to be seen.

The trial randomized 2,694 men who have sex with men to F/TAF, and 2,693 to F/TDF for up to 96 weeks. Entrance criteria included at least two episodes of unprotected anal sex in the previous 12 weeks, or a diagnosis of rectal gonorrhea, chlamydia, or syphilis in the previous 6 months.

More than half the men contracted at least one sexually transmitted infection during the trial, “which indicated to us that these were the right patients to be enrolled in the study,” lead investigator Charles Hare, MD, an infectious disease specialist at the University of California, San Francisco, said at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections.

There were 15 new HIV infections in the F/TDF group (0.34 per 100 person-years), versus 7 in the F/TAF group (0.16 per 100 person-years). Almost all of the new infections were due to poor adherence – as proven by blood levels and dry blood spot testing – and most of the rest were in men who probably entered the trial with newly acquired HIV.

When those subjects were excluded, there were just two new onset HIV cases in subjects adherent to dosing, one in each arm. Infection rates were far lower than would have been expected had the subjects not been on PrEP.

One of Gilead’s main selling points for F/TAF over F/TDF is that the newer drug has better bone and renal safety, and there were slight biomarker differences in the trial that supported the assertion.

For instance, spine bone mineral density decreased 3% or greater from baseline in 10 F/TAF patients, but 27 men on F/TDF (P less than .001). Results were similar with hip bone density.

On the renal front, estimated glomerular filtration rates fell a median of 2.3 mL/min per 1.73 m2 in the F/TDF arm, but rose 1.8 mL/min per 1.73 m2 in men on F/TAF (P less than .001). Proximal tubular protein to creatinine ratios were largely unchanged from baseline with F/TAF, but slightly higher in the F/TDF group, at 48 weeks.

There were no statistically significant differences on actual safety outcomes – as opposed to biomarkers – between the two drugs or discontinuations due to side effects, which were rare and most often due to gastrointestinal issues. F/TAF patients gained about 1.1 kg in the trial, while weight held steady in the F/TDF arm. The study team plans to analyze lipid profile differences between the groups, since concern has been raised about F/TAF’s effect on them.

In a press conference at the conference, there was quite a bit of discussion about whether the results would justify using F/TAF for PrEP when less expensive generic versions of F/TDF become available.

“That’s a great question,” Dr. Hare said. “Both drugs actually performed quite well,” and both “do pretty well in terms of safety in this population.”

It’s not known at this point if the biomarker differences will prove to be clinically relevant. Hip fractures, kidney failure, and other problems are so rare in young, relatively healthy PrEP users that a trial to demonstrate clinical relevance would have to be huge, with years-long follow-up, Dr. Hare noted.

The average age of the men in this study was 36 years. Most were white, and about 60% lived in the United States. Other participants were from Canada or Europe.

The work was funded by Gilead; five investigators, including the senior investigator, were employees. Dr. Hare is an investigator for the company.

SOURCE: Hare CB et al. CROI 2019, Abstract 104 LB.

SEATTLE – Descovy [emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide (F/TAF]) was noninferior to Truvada [emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (F/TDF)] for preexposure HIV prophylaxis in a blinded, randomized trial involving more than 5,000 men at high risk for the infection.

Both nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors are made by Gilead, and the company funded the trial.

F/TDF (Truvada) has been a blockbuster for the company, both for HIV treatment and, since 2012, for preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP); it’s the only medication to carry the indication. However, F/TDF is set to go off patent in 2021, so the company has turned its development efforts to a successor, F/TAF (Descovy), a prodrug of tenofovir that is already approved for HIV treatment.

The new study builds a case for F/TAF for PrEP, but whether the results are strong enough to persuade people to opt for it over a much less expensive generic version of F/TDF remains to be seen.

The trial randomized 2,694 men who have sex with men to F/TAF, and 2,693 to F/TDF for up to 96 weeks. Entrance criteria included at least two episodes of unprotected anal sex in the previous 12 weeks, or a diagnosis of rectal gonorrhea, chlamydia, or syphilis in the previous 6 months.

More than half the men contracted at least one sexually transmitted infection during the trial, “which indicated to us that these were the right patients to be enrolled in the study,” lead investigator Charles Hare, MD, an infectious disease specialist at the University of California, San Francisco, said at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections.

There were 15 new HIV infections in the F/TDF group (0.34 per 100 person-years), versus 7 in the F/TAF group (0.16 per 100 person-years). Almost all of the new infections were due to poor adherence – as proven by blood levels and dry blood spot testing – and most of the rest were in men who probably entered the trial with newly acquired HIV.

When those subjects were excluded, there were just two new onset HIV cases in subjects adherent to dosing, one in each arm. Infection rates were far lower than would have been expected had the subjects not been on PrEP.

One of Gilead’s main selling points for F/TAF over F/TDF is that the newer drug has better bone and renal safety, and there were slight biomarker differences in the trial that supported the assertion.

For instance, spine bone mineral density decreased 3% or greater from baseline in 10 F/TAF patients, but 27 men on F/TDF (P less than .001). Results were similar with hip bone density.

On the renal front, estimated glomerular filtration rates fell a median of 2.3 mL/min per 1.73 m2 in the F/TDF arm, but rose 1.8 mL/min per 1.73 m2 in men on F/TAF (P less than .001). Proximal tubular protein to creatinine ratios were largely unchanged from baseline with F/TAF, but slightly higher in the F/TDF group, at 48 weeks.

There were no statistically significant differences on actual safety outcomes – as opposed to biomarkers – between the two drugs or discontinuations due to side effects, which were rare and most often due to gastrointestinal issues. F/TAF patients gained about 1.1 kg in the trial, while weight held steady in the F/TDF arm. The study team plans to analyze lipid profile differences between the groups, since concern has been raised about F/TAF’s effect on them.

In a press conference at the conference, there was quite a bit of discussion about whether the results would justify using F/TAF for PrEP when less expensive generic versions of F/TDF become available.

“That’s a great question,” Dr. Hare said. “Both drugs actually performed quite well,” and both “do pretty well in terms of safety in this population.”

It’s not known at this point if the biomarker differences will prove to be clinically relevant. Hip fractures, kidney failure, and other problems are so rare in young, relatively healthy PrEP users that a trial to demonstrate clinical relevance would have to be huge, with years-long follow-up, Dr. Hare noted.

The average age of the men in this study was 36 years. Most were white, and about 60% lived in the United States. Other participants were from Canada or Europe.

The work was funded by Gilead; five investigators, including the senior investigator, were employees. Dr. Hare is an investigator for the company.

SOURCE: Hare CB et al. CROI 2019, Abstract 104 LB.

REPORTING FROM CROI 2019

Raltegravir safe, effective in late pregnancy

SEATTLE – In HIV-positive pregnant women, an antiretroviral therapy (ART) regimen that included the integrase inhibitor raltegravir (RAL-ART) led to faster viral load (VL) reduction and a greater proportion of women with a VL of less than 200 copies/mL at delivery, compared with patients treated with an efavirenz-based ART (EFV-ART). There were no statistically significant differences between the two arms with respect to percentage of stillbirths, preterm delivery, or rates of HIV infection in the newborn.

“There are lots of advantages of these [integrase inhibitor] drugs, and we’d like to have pregnant women take advantage of them. The problem is, there’s no requirement of drug manufacturers to study the drugs in pregnancy. So these studies are put off until after the drug is licensed, and we’re playing catch-up,” Mark Mirochnick, MD, professor of pediatrics at Boston University, said in an interview. Dr. Mirochnick presented the results at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections.

Another integrase inhibitor, dolutegravir, has a better resistance profile than that of raltegravir, but concerns over neural tube defects observed during a study in Botswana led both the Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency to issue safety warnings for that drug. The current study did not raise concern, since it began at 20 weeks’ gestation, well after the period when neural tube defects might occur. “I think it just demonstrates that [integrase inhibitors] are safe in mid- to late-pregnancy,” said Dr. Mirochnick.

It remains to be seen whether a potential link to neural tube defects, if it is a real effect, is due to a specific drug or the mechanism of action of integrase inhibitors more generally. “It’s a question we don’t have an answer to. So you have to balance the potential benefits and potential risks, and that’s probably a decision best made by an individual woman and her care provider. Some women do very well on a particular regimen and they don’t want to change, and you run the risk when you change that you’ll get a viral rebound. What do you tell women who are on dolutegravir and are thinking about becoming pregnant? That’s a controversial question. There are risks with both courses,” said Dr. Mirochnick.

The study comprised 408 patients recruited from centers in Brazil, Tanzania, South Africa, Thailand, Argentina, and the United States. The patients were between 20 and 37 weeks’ gestation and had not previously received ART. They were randomized to RAL-ART or EFV-ART. About 12% of patients were Asian, 36% were black, 52% were Hispanic, and 1% were white.

Overall, 94% of patients on RAL-ART had a VL less than 200 copies/mL at delivery, compared to 84% of EFV-ART patients (P = .001). The effect appeared to be driven by patients who enrolled later in pregnancy: There was no significant difference in those enrolled in weeks 20-28, but suppression occurred in 93% of the RAL-ART group versus 71% of the EFV-ART group among those enrolled in weeks 29-37 (P = .04).

Tolerability was slightly better in the RAL-ART group, with 99% versus 97% of patients staying on their assigned therapy (P = .05). In both groups, 30% of women experienced an adverse event of grade 3 or higher, as did 25% of live-born infants in both groups.

A total of 92% of women in the RAL-ART group had a sustained VL response through delivery, compared with 64% in the EFV-ART group (P less than .001). The median time to achieving a VL less than 200 copies/mL was 8 days in the RAL-ART group and 15 days in the EFV-ART group (generalized log-rank test P less than .001).

There was one stillbirth in the EFV-ART arm and three in the RAL-ART arm, with 11% in the EFV-ART group having preterm delivery compared with 12% in the RAL-ART group. In addition, the proportion of HIV-infected infants was lower in the RAL-ART arm (1% versus 3%). These differences were not significant.

The National Institutes of Health funded the study. Glaxo/ViiV, Merck, and Bristol-Myers Squibb supplied study drugs. Dr. Mirochnick has received research funding from those companies.

SOURCE: Mark Mirochnick et al. CROI 2019, Abstract 39 LB.

SEATTLE – In HIV-positive pregnant women, an antiretroviral therapy (ART) regimen that included the integrase inhibitor raltegravir (RAL-ART) led to faster viral load (VL) reduction and a greater proportion of women with a VL of less than 200 copies/mL at delivery, compared with patients treated with an efavirenz-based ART (EFV-ART). There were no statistically significant differences between the two arms with respect to percentage of stillbirths, preterm delivery, or rates of HIV infection in the newborn.

“There are lots of advantages of these [integrase inhibitor] drugs, and we’d like to have pregnant women take advantage of them. The problem is, there’s no requirement of drug manufacturers to study the drugs in pregnancy. So these studies are put off until after the drug is licensed, and we’re playing catch-up,” Mark Mirochnick, MD, professor of pediatrics at Boston University, said in an interview. Dr. Mirochnick presented the results at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections.

Another integrase inhibitor, dolutegravir, has a better resistance profile than that of raltegravir, but concerns over neural tube defects observed during a study in Botswana led both the Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency to issue safety warnings for that drug. The current study did not raise concern, since it began at 20 weeks’ gestation, well after the period when neural tube defects might occur. “I think it just demonstrates that [integrase inhibitors] are safe in mid- to late-pregnancy,” said Dr. Mirochnick.

It remains to be seen whether a potential link to neural tube defects, if it is a real effect, is due to a specific drug or the mechanism of action of integrase inhibitors more generally. “It’s a question we don’t have an answer to. So you have to balance the potential benefits and potential risks, and that’s probably a decision best made by an individual woman and her care provider. Some women do very well on a particular regimen and they don’t want to change, and you run the risk when you change that you’ll get a viral rebound. What do you tell women who are on dolutegravir and are thinking about becoming pregnant? That’s a controversial question. There are risks with both courses,” said Dr. Mirochnick.

The study comprised 408 patients recruited from centers in Brazil, Tanzania, South Africa, Thailand, Argentina, and the United States. The patients were between 20 and 37 weeks’ gestation and had not previously received ART. They were randomized to RAL-ART or EFV-ART. About 12% of patients were Asian, 36% were black, 52% were Hispanic, and 1% were white.

Overall, 94% of patients on RAL-ART had a VL less than 200 copies/mL at delivery, compared to 84% of EFV-ART patients (P = .001). The effect appeared to be driven by patients who enrolled later in pregnancy: There was no significant difference in those enrolled in weeks 20-28, but suppression occurred in 93% of the RAL-ART group versus 71% of the EFV-ART group among those enrolled in weeks 29-37 (P = .04).

Tolerability was slightly better in the RAL-ART group, with 99% versus 97% of patients staying on their assigned therapy (P = .05). In both groups, 30% of women experienced an adverse event of grade 3 or higher, as did 25% of live-born infants in both groups.

A total of 92% of women in the RAL-ART group had a sustained VL response through delivery, compared with 64% in the EFV-ART group (P less than .001). The median time to achieving a VL less than 200 copies/mL was 8 days in the RAL-ART group and 15 days in the EFV-ART group (generalized log-rank test P less than .001).

There was one stillbirth in the EFV-ART arm and three in the RAL-ART arm, with 11% in the EFV-ART group having preterm delivery compared with 12% in the RAL-ART group. In addition, the proportion of HIV-infected infants was lower in the RAL-ART arm (1% versus 3%). These differences were not significant.

The National Institutes of Health funded the study. Glaxo/ViiV, Merck, and Bristol-Myers Squibb supplied study drugs. Dr. Mirochnick has received research funding from those companies.

SOURCE: Mark Mirochnick et al. CROI 2019, Abstract 39 LB.

SEATTLE – In HIV-positive pregnant women, an antiretroviral therapy (ART) regimen that included the integrase inhibitor raltegravir (RAL-ART) led to faster viral load (VL) reduction and a greater proportion of women with a VL of less than 200 copies/mL at delivery, compared with patients treated with an efavirenz-based ART (EFV-ART). There were no statistically significant differences between the two arms with respect to percentage of stillbirths, preterm delivery, or rates of HIV infection in the newborn.

“There are lots of advantages of these [integrase inhibitor] drugs, and we’d like to have pregnant women take advantage of them. The problem is, there’s no requirement of drug manufacturers to study the drugs in pregnancy. So these studies are put off until after the drug is licensed, and we’re playing catch-up,” Mark Mirochnick, MD, professor of pediatrics at Boston University, said in an interview. Dr. Mirochnick presented the results at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections.

Another integrase inhibitor, dolutegravir, has a better resistance profile than that of raltegravir, but concerns over neural tube defects observed during a study in Botswana led both the Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency to issue safety warnings for that drug. The current study did not raise concern, since it began at 20 weeks’ gestation, well after the period when neural tube defects might occur. “I think it just demonstrates that [integrase inhibitors] are safe in mid- to late-pregnancy,” said Dr. Mirochnick.

It remains to be seen whether a potential link to neural tube defects, if it is a real effect, is due to a specific drug or the mechanism of action of integrase inhibitors more generally. “It’s a question we don’t have an answer to. So you have to balance the potential benefits and potential risks, and that’s probably a decision best made by an individual woman and her care provider. Some women do very well on a particular regimen and they don’t want to change, and you run the risk when you change that you’ll get a viral rebound. What do you tell women who are on dolutegravir and are thinking about becoming pregnant? That’s a controversial question. There are risks with both courses,” said Dr. Mirochnick.

The study comprised 408 patients recruited from centers in Brazil, Tanzania, South Africa, Thailand, Argentina, and the United States. The patients were between 20 and 37 weeks’ gestation and had not previously received ART. They were randomized to RAL-ART or EFV-ART. About 12% of patients were Asian, 36% were black, 52% were Hispanic, and 1% were white.

Overall, 94% of patients on RAL-ART had a VL less than 200 copies/mL at delivery, compared to 84% of EFV-ART patients (P = .001). The effect appeared to be driven by patients who enrolled later in pregnancy: There was no significant difference in those enrolled in weeks 20-28, but suppression occurred in 93% of the RAL-ART group versus 71% of the EFV-ART group among those enrolled in weeks 29-37 (P = .04).

Tolerability was slightly better in the RAL-ART group, with 99% versus 97% of patients staying on their assigned therapy (P = .05). In both groups, 30% of women experienced an adverse event of grade 3 or higher, as did 25% of live-born infants in both groups.

A total of 92% of women in the RAL-ART group had a sustained VL response through delivery, compared with 64% in the EFV-ART group (P less than .001). The median time to achieving a VL less than 200 copies/mL was 8 days in the RAL-ART group and 15 days in the EFV-ART group (generalized log-rank test P less than .001).

There was one stillbirth in the EFV-ART arm and three in the RAL-ART arm, with 11% in the EFV-ART group having preterm delivery compared with 12% in the RAL-ART group. In addition, the proportion of HIV-infected infants was lower in the RAL-ART arm (1% versus 3%). These differences were not significant.

The National Institutes of Health funded the study. Glaxo/ViiV, Merck, and Bristol-Myers Squibb supplied study drugs. Dr. Mirochnick has received research funding from those companies.

SOURCE: Mark Mirochnick et al. CROI 2019, Abstract 39 LB.

REPORTING FROM CROI 2019

Opioid overdose risk greater among HIV patients

SEATTLE – People with HIV are more likely to die from an opioid overdose than the general public, according to investigators from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“We looked into this because we know persons with HIV are more likely to have chronic pain and more likely to receive opioid analgesic treatments, and receive higher doses. In addition, they are more likely to have substance use disorders and mental illness than the U.S. general populations,” CDC epidemiologist Karin A. Bosh, PhD, said at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections.

To see how that played out in terms of unintentional opioid overdose deaths, they turned to the National HIV Surveillance System and focused on overdose deaths during 2011-2015, the latest data available at the time of the work.

There were 1,363 overdose deaths among persons with HIV during that period, with the rate increasing 42.7% – from 23.2/100,000 HIV patients in 2011 to 33.1/100,000 in 2015.

Although the rate of increase was comparable to the general population, the crude rate was “actually substantially higher among persons with HIV,” Dr. Bosh said. Deaths were highest among persons aged 50-59 years (41.9/100,000), whites (49.1/100,000), injection drug users (137.4/100,000), and people who live in the Northeast (60.6/100,000).

Surprisingly, there was no increase in the rate of overdose deaths among HIV patients on the West Coast, possibly because heroin there was less likely to be cut with fentanyl.

Also, the rate of opioid overdose deaths was higher among women with HIV (35.2/100,000) than among men, perhaps because women are more likely to contract HIV by injection drug use, so they are more likely to be injection drug users at baseline, while the vast majority of men are infected through male-male sex, the investigators said.

The findings underscore the importance of intensifying overdose prevention in the HIV community, and better integrating HIV and substance use disorder treatment, they concluded.

That comes down to screening people for problems, especially in the subgroups identified in the study, and connecting them to drug treatment services. If HIV and substance disorder services were in the same clinic it would help, as would an increase in the number of buprenorphine providers, according to Sheryl B. Lyss, PhD, a coinvestigator and CDC epidemiologist.

“Obviously, when substance use is addressed, people can be much more adherent with their [HIV] medications,” she noted.

The work was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The investigators had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Bosh KA et al. CROI 2019, Abstract 147.

SEATTLE – People with HIV are more likely to die from an opioid overdose than the general public, according to investigators from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“We looked into this because we know persons with HIV are more likely to have chronic pain and more likely to receive opioid analgesic treatments, and receive higher doses. In addition, they are more likely to have substance use disorders and mental illness than the U.S. general populations,” CDC epidemiologist Karin A. Bosh, PhD, said at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections.

To see how that played out in terms of unintentional opioid overdose deaths, they turned to the National HIV Surveillance System and focused on overdose deaths during 2011-2015, the latest data available at the time of the work.

There were 1,363 overdose deaths among persons with HIV during that period, with the rate increasing 42.7% – from 23.2/100,000 HIV patients in 2011 to 33.1/100,000 in 2015.

Although the rate of increase was comparable to the general population, the crude rate was “actually substantially higher among persons with HIV,” Dr. Bosh said. Deaths were highest among persons aged 50-59 years (41.9/100,000), whites (49.1/100,000), injection drug users (137.4/100,000), and people who live in the Northeast (60.6/100,000).

Surprisingly, there was no increase in the rate of overdose deaths among HIV patients on the West Coast, possibly because heroin there was less likely to be cut with fentanyl.

Also, the rate of opioid overdose deaths was higher among women with HIV (35.2/100,000) than among men, perhaps because women are more likely to contract HIV by injection drug use, so they are more likely to be injection drug users at baseline, while the vast majority of men are infected through male-male sex, the investigators said.

The findings underscore the importance of intensifying overdose prevention in the HIV community, and better integrating HIV and substance use disorder treatment, they concluded.

That comes down to screening people for problems, especially in the subgroups identified in the study, and connecting them to drug treatment services. If HIV and substance disorder services were in the same clinic it would help, as would an increase in the number of buprenorphine providers, according to Sheryl B. Lyss, PhD, a coinvestigator and CDC epidemiologist.

“Obviously, when substance use is addressed, people can be much more adherent with their [HIV] medications,” she noted.

The work was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The investigators had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Bosh KA et al. CROI 2019, Abstract 147.

SEATTLE – People with HIV are more likely to die from an opioid overdose than the general public, according to investigators from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“We looked into this because we know persons with HIV are more likely to have chronic pain and more likely to receive opioid analgesic treatments, and receive higher doses. In addition, they are more likely to have substance use disorders and mental illness than the U.S. general populations,” CDC epidemiologist Karin A. Bosh, PhD, said at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections.

To see how that played out in terms of unintentional opioid overdose deaths, they turned to the National HIV Surveillance System and focused on overdose deaths during 2011-2015, the latest data available at the time of the work.

There were 1,363 overdose deaths among persons with HIV during that period, with the rate increasing 42.7% – from 23.2/100,000 HIV patients in 2011 to 33.1/100,000 in 2015.

Although the rate of increase was comparable to the general population, the crude rate was “actually substantially higher among persons with HIV,” Dr. Bosh said. Deaths were highest among persons aged 50-59 years (41.9/100,000), whites (49.1/100,000), injection drug users (137.4/100,000), and people who live in the Northeast (60.6/100,000).

Surprisingly, there was no increase in the rate of overdose deaths among HIV patients on the West Coast, possibly because heroin there was less likely to be cut with fentanyl.

Also, the rate of opioid overdose deaths was higher among women with HIV (35.2/100,000) than among men, perhaps because women are more likely to contract HIV by injection drug use, so they are more likely to be injection drug users at baseline, while the vast majority of men are infected through male-male sex, the investigators said.

The findings underscore the importance of intensifying overdose prevention in the HIV community, and better integrating HIV and substance use disorder treatment, they concluded.

That comes down to screening people for problems, especially in the subgroups identified in the study, and connecting them to drug treatment services. If HIV and substance disorder services were in the same clinic it would help, as would an increase in the number of buprenorphine providers, according to Sheryl B. Lyss, PhD, a coinvestigator and CDC epidemiologist.

“Obviously, when substance use is addressed, people can be much more adherent with their [HIV] medications,” she noted.

The work was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The investigators had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Bosh KA et al. CROI 2019, Abstract 147.

REPORTING FROM CROI 2019

Accessibility and Uptake of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis for HIV Prevention in the VHA (FULL)

Despite important advances in treatment and prevention over the past 30 years, HIV remains a significant public health concern in the US, with nearly 40,000 new HIV infections. annually.1 Among the estimated 1.1 million Americans currently living with HIV, 1 in 8 remains undiagnosed, and only half (49%) are virally suppressed.2 Although data demonstrate that viral suppression virtually eliminates the risk of transmission among people living with HIV, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV remains an integral part of a coordinated effort to reduce transmission. Uptake of PrEP is particularly vital considering the large percentage of people in the US living with HIV who are not virally suppressed because they have not started, are unable to stay on HIV antiretroviral treatment, or have not been diagnosed.

The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is the largest single provider of care to HIV-infected individuals in the US, with more than 28,000 veterans in care with HIV in 2016 (data from the VA National HIV Clinical Registry Reports, written communication from Population Health Service, Office of Patient Care Services, January 2018).

The only FDA-approved medication for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis is tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine (TDF/FTC), a fixed-dose combination of 2 antiretroviral medications that are also used to treat HIV. Its efficacy has been proven among numerous populations at risk for HIV, including those with sexual and injection drug use risk factors.4,5 Use of TDF/FTC for PrEP has been available at the VA since its July 2012 FDA approval. In May 2014, the US Public Health Service (PHS) and the US Department of Health and Human Services released the first comprehensive clinical practice guidelines for PrEP. Soon after, in September 2014, the VA released more formal guidance on the use of TDF/FTC for HIV PrEP as outlined by the PHS.6 Similar to patterns outside the VA, PrEP uptake across the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) has been modest and variable.

A recent VHA analysis of the variability in PrEP uptake identified about 1,600 patients who had been prescribed PrEP in the VA as of June 2017 among about 6 million veterans in care. Across VA medical facilities, the absolute number of PrEP initiations ranged from 0 to 109 with the maximum PrEP initiation rate at 146.4/100,000 veterans in care. Eight facilities did not initiate a single PrEP prescription over the 5-year period. This study presents strategicefforts undertaken by the VA to increase access to and uptake of PrEP across the health care system and to decrease disparities in HIV prevention care.

VA National Pr EP Working Group

In the beginning of 2017, the HIV, Hepatitis, and Related Conditions (HHRC) programs within the VHA Office of Specialty Care Services convened a national working group to better measure and address the gaps in PrEP usage across the health care system. This multidisciplinary PrEP Working Group was composed of more than 40 members with expertise in HIV clinical care and PrEP, including physicians, clinical pharmacists, advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs), physician assistants (PAs), social workers, psychologists, implementation scientists, and representatives from other VA programs with a relevant programmatic or policy interest in PrEP.

Implementation Targets

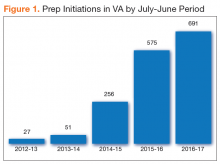

The National PrEP Working Group identified increased PrEP uptake across the VHA system as the primary implementation target with a specific focus on increasing PrEP use in primary care clinics and among those at highest risk. As noted earlier, overall uptake of PrEP across VHA medical facilities has been modest; however, new PrEP initiations have increased in each 12-month period since FDA approval (Figure 1).

To rapidly understand barriers to accessing PrEP, the National PrEP Working Group developed and deployed an informal survey to HIV clinicians at all VA facilities, with nearly half responding (n = 68). These frontline providers identified several important and common barriers inhibiting PrEP uptake, including knowledge gaps among providers without infectious diseases training

Patient adherence was not identified by providers as a significant barrier to PrEP uptake in this informal survey. A recent analysis of adherence among a national cohort of veterans on HIV PrEP in VA care between July 2012 and June 2016 found that adherence in the first year of PrEP was high with some differences detected by age, race, and gender.8

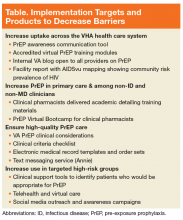

As an initial step in addressing these identified barriers to prescribing PrEP in the VHA, the National PrEP Working Group developed several provider education materials, trainings, and support tools to impact the overarching goal, and identified implementation targets of increasing access outside of primary care and among noninfectious disease and nonphysician clinicians, ensuring high-quality PrEP care in all settings, and targeting PrEP uptake to at-risk populations (Table).

Increasing PrEP Use in Primary Care and Women’s Health Clinics

As of June 2017, physicians (staff, interns, residents, and fellows) accounted for more than three-quarters of VA PrEP index prescriptions. Among staff physicians, infectious diseases specialists initiated 67% of all prescriptions. Clinical pharmacists prescribed only 6%; APRNs and PAs prescribed 16% of initiations. This is unsurprising, as the field survey identified lack of awareness and specific training on PrEP care among providers without infectious diseases training as a common barrier.

The VA is the largest US employer of nurses, including more than 5,500 APRNs. In December 2016, the VA granted full practice authority to APRNs across the health care system, regardless of state restrictions in most cases.9

In 2015, the VA employed about 7,700 clinical pharmacists, 3,200 of whom had an active SOP that allowed for prescribing authority. In fiscal year 2015, clinical pharmacists were responsible for at least 20% of all hepatitis C virus (HCV) prescriptions and 69% of prescriptions for anticoagulants across the system.10 Clinical pharmacists are increasingly recognized for their extensive contributions to increasing access to treatment in the VA across a broad spectrum of clinical issues. With this infrastructure and expertise, clinical pharmacists also are well positioned to expand their scope to include PrEP.

To that end, the National PrEP Working Group worked closely with clinical pharmacists in the field and from the VA Academic Detailing Service (ADS) within the VA Pharmacy Benefits Management Services office. The ADS supports the development of scholarly, balanced, evidence-based educational tools and information for frontline VA providers using one-on-one social marketing techniques to impact specific clinical targets. These interventions are delivered by clinical pharmacists to empower VA clinicians and promote evidence-based clinical care to help reduce variability in practice across the system.11 An ADS module for PrEP has been developed and will be available in 2018 across the VHA to facilities participating in the ADS.

A virtual accredited training program on prescribing PrEP and monitoring patients on PrEP designed for clinical pharmacists will be delivered early in 2018 to complement these materials and will be open to all prescribers interested in learning more about PrEP. By offering a complement of training and clinical support tools, most of which are detailed in other sections of this article, the National PrEP Working Group is creating educational opportunities that are accessible in a variety of different formats to decrease knowledge barriers over PrEP prescribing and build over time a broader pool of VA clinicians trained in PrEP care.

Ensuring High-Quality PrEP Care

One system-level concern about expanding PrEP to providers without infectious diseases training is the quality of follow-up care. In order to aid noninfectious diseases clinicians, and nonphysician providers who are not as familiar with PrEP, several clinical support tools have been created, including (1) VA’s Clinical Considerations for PrEP to Prevent HIV Infection, which is aligned with CDC clinical guidance12; (2) a PrEP clinical criterion check list; (3) clinical support tools, such as prepopulated electronic health record (EHR) templates and order menus to facilitate PrEP prescribing and monitoring in busy primary care clinical settings; and (4) PrEP-specific texts in the Annie App, an automated text-messaging application developed by the VA Office of Connected Care, which supports medication adherence, appointment attendance, vitals tracking, and education.13

Available evidence indicates that there is potential for disparities in PrEP effectiveness in the VA related to varying medication adherence. Analysis of pharmacy refill records found that adherence with TDF/FTC was high in the first year after PrEP initiation (median proportion of days covered in the first year was 74%), but adherence was lower among veterans in VA care who were African American, women, and/or under age 45 years.8 This highlights the importance of enhanced services, such as Annie, to support PrEP adherence in at-risk groups as well as monitoring of HIV risk factors to ensure PrEP is still indicated.

Targeting PrEP Uptake for High-Risk Veterans

Although the VA’s overarching goal is to increase access to and uptake of PrEP across the VHA, it also is important to direct resources to those at greatest risk of acquiring HIV infection. The National PrEP Working Group has focused on the following critical implementation issues in the VA’s strategic approach to HIV prevention, with a specific focus on the geographic disparities between PrEP uptake and HIV risk across the VHA as well as disparities based on rurality, race/ethnicity, and gender.

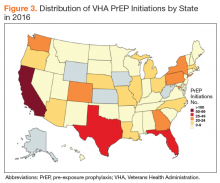

The majority of the VHA patient population is male (91% in 2016).14 A VHA analysis of PrEP initiations in the VA indicates that in June 2017, 97% of veterans in VA care receiving PrEP were male, 69% were white, 88% resided in urban areas, and the average age was 41.6 years. An analysis of PrEP initiation in the VA indicates that current PrEP uptake is clustered in a few geographic areas and that some areas with high HIV incidence had low uptake.15 States with the highest risk of HIV infection are in the Southeast, followed by parts of the West, Midwest, and Northeast (Figure 2).16,17

Rural areas are increasingly impacted by the HIV epidemic in the US, but access to PrEP is often limited in rural communities.19 Several rural counties in the Southeastern US now have rates of new HIV infection comparable with those historically seen in only the largest cities.1 In addition, recent outbreaks of HIV and hepatitis C virus infection related to needle sharing highlight the need for HIV prevention programs in rural areas impacted by the opioid epidemic.20

About 1 in 4 veterans overall—and 16% of veterans in care who are HIV-positive—reside in rural areas, but only 4.3% of veterans who had initiated PrEP through 2017 resided in rural areas.21,22 In order to address the need to improve access to PrEP in many rural-serving VHA facilities, the PrEP Working Group has emphasized the increased utilization of virtual care (telehealth, Annie App, the Virtual Medical Room) and broadening the pool of available PrEP prescribers to include noninfectious diseases physicians, pharmacists, and APRNs.

Important racial and ethnic disparities also exist in PrEP access nationally. For example, in the US as a whole, African American MSM, followed by Latino MSM continue to be at highest risk for HIV infection.1 In 2015, 45% of all new HIV infections in the US were among African Americans, 26% of whom were women and 58% identified as gay or bisexual.23 A recent analysis of US retail pharmacies that dispensed FTC/TDF analyzed the racial demographics of PrEP uptake and found that the majority of PrEP initiations were among whites (74%), followed by Hispanics (12%) and African Americans (10%); and females of all races made up 20.7%.24 The VA is performing better than these national averages. Of the 688 PrEP prescriptions in the VA in 2016, 64% of recipients identified themselves as white and 23% as African American. Hispanic ethnicity was reported by 13%.

There are several limitations to identifying a specific implementation target for PrEP across the VA system, including the challenge of accurately identifying the population at risk via the EHR or clinical informatics tools. For example, strong risk factors for HIV acquisition include IV drug use, receptive anal intercourse without a condom, and needlesticks.

Behaviors that pose lower risk, such as vaginal intercourse or insertive anal intercourse could contribute to a higher overall lifetime risk if these behaviors occur frequently.25 Behavioral risk factors are not well captured in the VA EHR, making it difficult to identify potential PrEP candidates through population health tools. Additionally, stigma and discrimination may make it difficult for a patient to disclose to their clinician and for a clinician to inquire into behavioral risk factors. The criminalization of HIV-related risk behaviors in some states also may complicate the identification of potential PrEP candidates.26,27 These issues contribute to the challenges that providers face in screening for HIV risk and that patients face in disclosing their personal risk.

To address these regional, rural, and ethnic disparities and enhance the identification of potential PrEP recipients, the National PrEP Working Group is developing a suite of tools to support frontline providers in identifying potential PrEP recipients and expanding care to those at highest risk and who may be more difficult to reach due to rurality, concerns about stigma, or other issues.

- Clinical support tools to identify potential PrEP recipients, such as a clinical reminder that identifies patients at high risk for HIV based on diagnosis codes, and a PrEP clinical dashboard;

- A telehealth protocol for PrEP care and promotion of the VA Virtual Medical Room, which allows providers to video conference with patients in their home; and

- Social media outreach and awareness campaigns targeted at veterans to increase PrEP awareness are being shared through VA Facebook and Twitter accounts, blog posts, and www.hiv.va.gov posts (Figure 4).

Implementation Strategy & Evaluation

During the calendar year 2017, the PrEP Working Group met monthly and in smaller subcommittees to develop the strategic plan, products, and tools described earlier. On World AIDS Day, a virtual live meeting on PrEP was made available to all providers across the system and will be made available for continuing education training through the VA online employee education system. During 2018, the primary focus of the PrEP Working Group will be the continued development and refinement of provider education materials, clinical tools, and data tracking as well as increasing veteran outreach through social media and other awareness campaigns planned throughout the year.

Annual assessment of PrEP uptake will evaluate progress on the primary implementation target and areas of clinical practice: (1) increase number of PrEP prescriptions overall; (2) ensure PrEP is prescribed at all VA facilities; (3) increase preciptions by noninfectious diseases provider; (4) increase prescriptions by clinical pharmacists and APRNs; (5) monitor quality of care, including by discipline/practice setting; (6) increase PrEP prescriptions in facilities in endemic areas; and (7) increase the proportion of PrEP prescriptions for veterans of color.

In 2019 and 2020, additional targeted intervention and outreach plans will be developed for sites with difficulty meeting implementation targets. Sites in highly HIV-endemic areas will be a priority, and outreach will be designed to assist in the identification of facility-level barriers to PrEP use.

Conclusion

HIV remains an important public health issue in the US and among veterans in VA care, and prevention is a critical component to combat the epidemic. The VHA is the largest single provider of HIV care in the US with facilities and community-based outpatient clinics in all states and US territories.

The VA seems to be performing better in terms of the proportion of PrEP uptake among racial groups at highest risk for HIV compared with a US sample from retail pharmacies, which may be, in part, driven by the cost of PrEP and follow-up sexually transmitted infection testing.24 However, a considerable gap remain in VHA PrEP uptake among populations at highest risk for HIV in the US.

With the investment of a National PrEP Working Group, the VA is charting a course to augment its HIV prevention services to exceed the US nationally. The National PrEP Working Group will continue to develop specific, measurable, and impactful targets guided by state-of-the-art scientific evidence and surveillance data and a suite of educational and clinical resources designed to assist frontline providers, facilities, and patients in meeting clearly defined implementation targets.

Click here to read the digital edition.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV surveillance report, 2016; Vol 28. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance -report-2016-vol-28.pdf. Published November 2017. Accessed February 12, 2018.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV continuum of care, US, 2014, overall and by age, race/ethnicity, transmission route and sex. https://www.cdc .gov/nchhstp/newsroom/2017/HIV-Continuum-of-Care.html. Updated September 12, 2017. Accessed February 12, 2018.

3. Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-14):1-17.

4. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves first medication to reduce HIV risk [press release]. https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/news/1254/fda-approves-first-drug -for-reducing-the-risk-of-sexually-acquired-hiv-infection. Published July 12, 2012. Accessed February 14, 2018.

5. Fonner VA, Dalglish SL, Kennedy CE, et al. Effectiveness and safety of oral HIV preexposure prophylaxis for all populations. AIDS. 2016;30(12):1973-1983.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Public Health Service. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States—2014: a clinical practice guideline. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/PrEPguidelines2014.pdf. Published 2014. Accessed February 12, 2018.

7. Smith DK, Mendoza MC, Stryker JE, Rose CE. PrEP awareness and attitudes in a national survey of primary care clinicians in the United States, 2009-2015. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0156592.

8. Van Epps P, Maier M, Lund B, et al. Medication adherence in a nationwide cohort of veterans initiating pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) to prevent HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2018;77(3):272-278.

9. US Department of Veterans Affairs. 38 CFR Part 17, RIN 2900-AP44. Advance Practice Registered Nurses. Federal Register, Rules and Regulations. 81(240) December 14, 2016

10. Ourth H, Groppi J, Morreale AP, Quicci-Roberts K. Clinical pharmacist prescribing activities in the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2016;73(18):1406-1415.

11. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Pharmacy Benefits Management Academic Detailing Service. VA academic detailing implementation guide. https://www.pbm.va.gov/PBM/AcademicDetailingService/Documents/VA_Academic_Detailing_Implementation_Guide.pdf. Published September 2016. Accessed February 12, 2018.

12. Veterans Health Administration US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Specialty Services, HIV, Hepatitis, and Related Conditions Programs. Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) to prevent HIV infection: clinical considerations from the Department of Veterans Affairs National HIV Program. https://www.hiv.va.gov/pdf/PrEP-considerations.pdf. Published September 2016. Accessed January 4, 2018.

13. US Department of Veterans Affairs, VA Mobile Health. Annie app for clinicians. https://mobile.va.gov/app/annie-app-clinicians. Published September 2016. Accessed January 4, 2018.

14. US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. VA utilization profile FY 2016. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/Quickfacts/VA_Utilization_Profile.pdf. Published . November 2017. Accessed March 5, 2018.

15. Van Epps P. Pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention: the use and effectiveness of PrEP in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA). Abstract presented at: Infectious Diseases Week 2016; October 26-30, 2016; New Orleans, LA. https://idsa.confex.com/idsa/2016/webprogram/Paper60122.html. Accessed February 12, 2018.

16. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2016 conference on retroviruses and opportunistic infections, lifetime risk of HIV diagnosis by state: https://www.cdc .gov/nchhstp/newsroom/images/2016/CROI_lifetime_risk_state.jpg. Published February 24, 2016. Accessed February 12, 2018.

17. Elopre L, Kudroff K, Westfall AO, Overton ET, Mugavero MJ. Brief report: the right people, right places, and right practices: disparities in PrEP access among African American men, women, and MSM in the Deep South. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;74(1):56-59.

18. Wu H, Mendoza MC, Huang YA, Hayes T, Smith DK, Hoover KW. Uptake of HIV preexposure prophylaxis among commercially insured persons-United States, 2010-2014. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(2):144-149.

19. Schafer KR, Albrecht H, Dillingham R, et al. The continuum of HIV care in rural communities in the United States and Canada: what is known and future research directions. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;75(1):355-344.

20. Conrad C, Bradley HM, Broz D, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). community outbreak of hiv infection linked to injection drug use of oxymorphone—Indiana, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(16):443-444.

21. Ohl ME, Richardson K, Kaboli P, Perencevich E, Vaughan-Sarrazin M. Geographic access and use of infectious diseases specialty and general primary care services by veterans with HIV infection: implications for telehealth and shared care programs. J Rural Health. 2014;30(4):412-421.

22. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Rural Health. Rural veterans’ health care challenges. https://www.ruralhealth.va.gov/aboutus/ruralvets.asp. Updated February 9, 2018. Accessed on February 12, 2018.

23. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV among African Americans. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/racialethnic/africanamericans/index.html. Updated February 9, 2018. Accessed on February 12, 2018.

24. Bush S, Magnuson D, Rawlings K, et al. Racial characteristics of FTC/TDF for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) users in the US. Paper presented at: ASM Microbe Conference 2016; June 16-20, 2016; Boston, MA.

25. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV risk behaviors. https://www.cdc .gov/hiv/pdf/risk/estimates/cdc-hiv-risk-behaviors.pdf. Published December 2015. Accessed on February 12, 2018.

26. Lehman JS, Carr MH, Nichol AJ, et al. Prevalence and public health implications of state laws that criminalize potential HIV exposure in the United States. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(6):997-1006.

27. US Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division. Best practices guide to reform HIV-specific criminal laws to align with scientifically-supported factors. https://www.hivlawandpolicy.org/sites/default/files/DOj-HIV-Criminal-Law-Best-Practices-Guide.pdf. March 2014. Accessed on February 12, 2018.

28. Backus L, Czarnogorski M, Yip G, et al. HIV care continuum applied to the US Department of Veterans Affairs: HIV virologic outcomes in an integrated health care system. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;69(4):474-480.

Despite important advances in treatment and prevention over the past 30 years, HIV remains a significant public health concern in the US, with nearly 40,000 new HIV infections. annually.1 Among the estimated 1.1 million Americans currently living with HIV, 1 in 8 remains undiagnosed, and only half (49%) are virally suppressed.2 Although data demonstrate that viral suppression virtually eliminates the risk of transmission among people living with HIV, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV remains an integral part of a coordinated effort to reduce transmission. Uptake of PrEP is particularly vital considering the large percentage of people in the US living with HIV who are not virally suppressed because they have not started, are unable to stay on HIV antiretroviral treatment, or have not been diagnosed.

The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is the largest single provider of care to HIV-infected individuals in the US, with more than 28,000 veterans in care with HIV in 2016 (data from the VA National HIV Clinical Registry Reports, written communication from Population Health Service, Office of Patient Care Services, January 2018).

The only FDA-approved medication for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis is tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine (TDF/FTC), a fixed-dose combination of 2 antiretroviral medications that are also used to treat HIV. Its efficacy has been proven among numerous populations at risk for HIV, including those with sexual and injection drug use risk factors.4,5 Use of TDF/FTC for PrEP has been available at the VA since its July 2012 FDA approval. In May 2014, the US Public Health Service (PHS) and the US Department of Health and Human Services released the first comprehensive clinical practice guidelines for PrEP. Soon after, in September 2014, the VA released more formal guidance on the use of TDF/FTC for HIV PrEP as outlined by the PHS.6 Similar to patterns outside the VA, PrEP uptake across the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) has been modest and variable.

A recent VHA analysis of the variability in PrEP uptake identified about 1,600 patients who had been prescribed PrEP in the VA as of June 2017 among about 6 million veterans in care. Across VA medical facilities, the absolute number of PrEP initiations ranged from 0 to 109 with the maximum PrEP initiation rate at 146.4/100,000 veterans in care. Eight facilities did not initiate a single PrEP prescription over the 5-year period. This study presents strategicefforts undertaken by the VA to increase access to and uptake of PrEP across the health care system and to decrease disparities in HIV prevention care.

VA National Pr EP Working Group

In the beginning of 2017, the HIV, Hepatitis, and Related Conditions (HHRC) programs within the VHA Office of Specialty Care Services convened a national working group to better measure and address the gaps in PrEP usage across the health care system. This multidisciplinary PrEP Working Group was composed of more than 40 members with expertise in HIV clinical care and PrEP, including physicians, clinical pharmacists, advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs), physician assistants (PAs), social workers, psychologists, implementation scientists, and representatives from other VA programs with a relevant programmatic or policy interest in PrEP.

Implementation Targets

The National PrEP Working Group identified increased PrEP uptake across the VHA system as the primary implementation target with a specific focus on increasing PrEP use in primary care clinics and among those at highest risk. As noted earlier, overall uptake of PrEP across VHA medical facilities has been modest; however, new PrEP initiations have increased in each 12-month period since FDA approval (Figure 1).

To rapidly understand barriers to accessing PrEP, the National PrEP Working Group developed and deployed an informal survey to HIV clinicians at all VA facilities, with nearly half responding (n = 68). These frontline providers identified several important and common barriers inhibiting PrEP uptake, including knowledge gaps among providers without infectious diseases training

Patient adherence was not identified by providers as a significant barrier to PrEP uptake in this informal survey. A recent analysis of adherence among a national cohort of veterans on HIV PrEP in VA care between July 2012 and June 2016 found that adherence in the first year of PrEP was high with some differences detected by age, race, and gender.8

As an initial step in addressing these identified barriers to prescribing PrEP in the VHA, the National PrEP Working Group developed several provider education materials, trainings, and support tools to impact the overarching goal, and identified implementation targets of increasing access outside of primary care and among noninfectious disease and nonphysician clinicians, ensuring high-quality PrEP care in all settings, and targeting PrEP uptake to at-risk populations (Table).

Increasing PrEP Use in Primary Care and Women’s Health Clinics

As of June 2017, physicians (staff, interns, residents, and fellows) accounted for more than three-quarters of VA PrEP index prescriptions. Among staff physicians, infectious diseases specialists initiated 67% of all prescriptions. Clinical pharmacists prescribed only 6%; APRNs and PAs prescribed 16% of initiations. This is unsurprising, as the field survey identified lack of awareness and specific training on PrEP care among providers without infectious diseases training as a common barrier.

The VA is the largest US employer of nurses, including more than 5,500 APRNs. In December 2016, the VA granted full practice authority to APRNs across the health care system, regardless of state restrictions in most cases.9

In 2015, the VA employed about 7,700 clinical pharmacists, 3,200 of whom had an active SOP that allowed for prescribing authority. In fiscal year 2015, clinical pharmacists were responsible for at least 20% of all hepatitis C virus (HCV) prescriptions and 69% of prescriptions for anticoagulants across the system.10 Clinical pharmacists are increasingly recognized for their extensive contributions to increasing access to treatment in the VA across a broad spectrum of clinical issues. With this infrastructure and expertise, clinical pharmacists also are well positioned to expand their scope to include PrEP.