User login

CDC: United States has hit a plateau with HIV

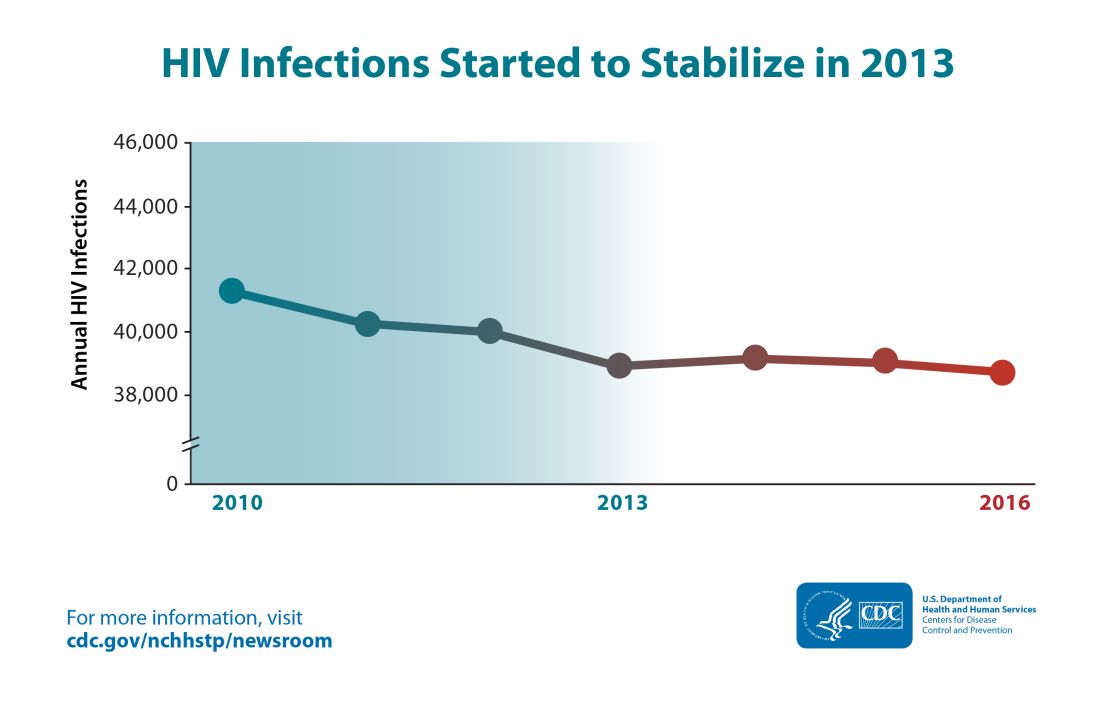

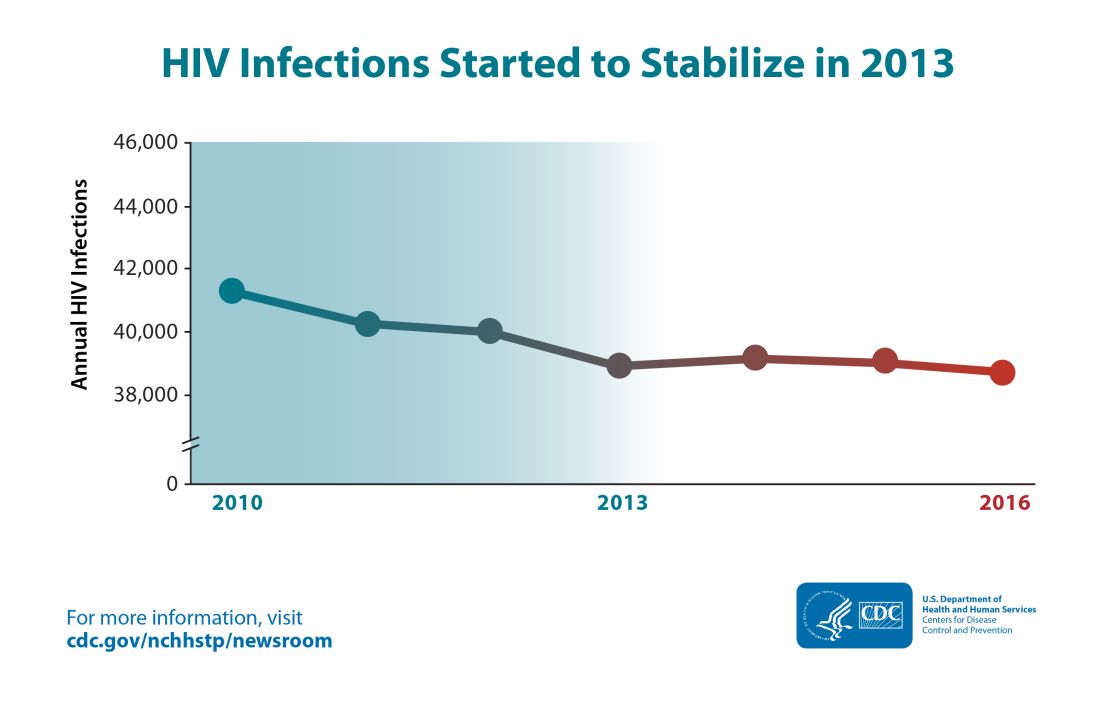

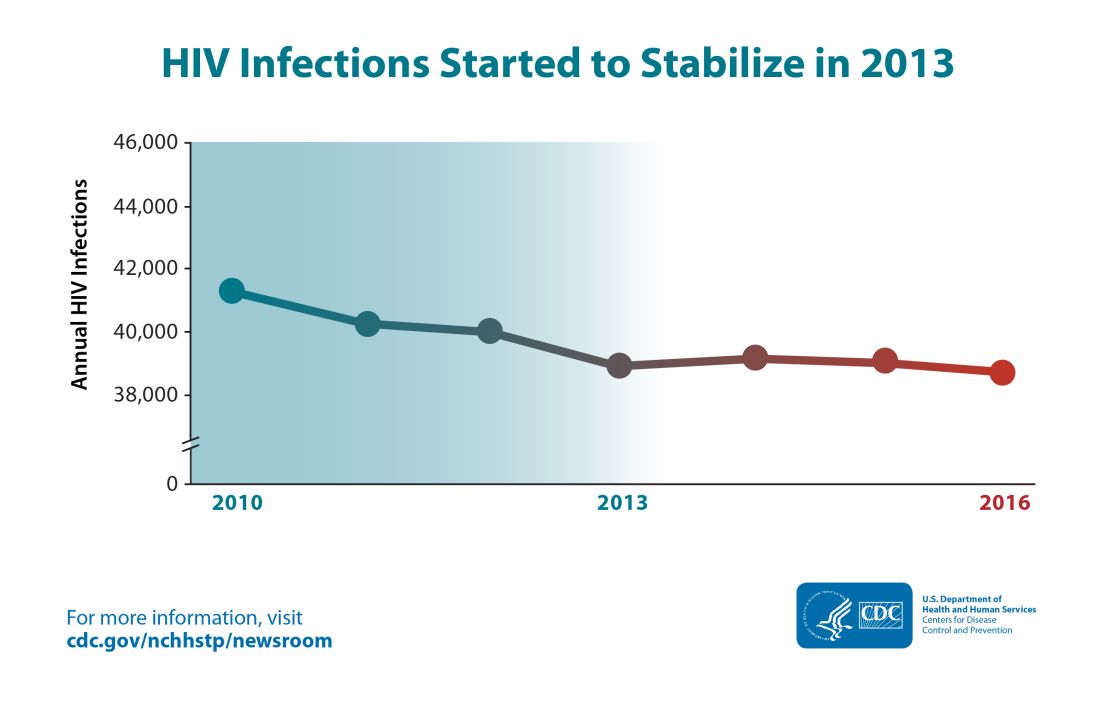

The annual number of new HIV infections has remained stable in recent years, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says that’s not good – but solutions are at hand.

Though the estimated number of new HIV infections declined from just under 42,000 per year in 2010 to about 39,000 annually in 2013, that figure was essentially unchanged by 2016, with 38,700 new HIV infections seen that year.

“CDC estimates that the decline in HIV infections has plateaued because effective HIV prevention and treatment are not adequately reaching those who could most benefit from them. These gaps remain particularly troublesome in rural areas and in the South and among disproportionately affected populations like African Americans and Latinos,” said the CDC in a press release accompanying the report.

The report comes soon after President Trump’s State of the Union address, which announced a new multiagency initiative to eliminate the HIV epidemic in the United States, with the goal of reducing new HIV infections by 90% over the next 10 years. The multipronged initiative will implement geographically targeted HIV elimination teams in areas with high HIV prevalence, pulling together federal agencies, local and state governments, and community-level resources.

The initiative, called “Ending the Epidemic: A Plan for America” will combine an intensified approach to early diagnosis and treatment with efforts to boost uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis for individuals at high risk for HIV infection.

The new CDC report used CD4 counts reported to the National HIV Surveillance System at the time of diagnosis to identify new (incident) cases and to track prevalence. Much of the report is devoted to finely detailed reporting of HIV incidence across sex, age, race/ethnicity, and transmission mode.

Though some groups, such as people who inject drugs, have seen a decrease of about 30% in the annual rate of new HIV cases, new cases have jumped for other groups. In particular, Latino gay and bisexual men saw new cases climb from 6,400 per year in 2010 to 8,300 in 2016. The incidence rate has stayed high and stable among African American gay and bisexual men, with 9,800 new cases reported in 2010; the same number was seen in 2016.

Among gay and bisexual men overall, the rate has also stayed stable, with about 26,000 new HIV infections reported at the beginning and end of the studied period. White heterosexual women saw about 1,000 new cases per year in 2010 and in 2016.

Some groups saw declines in new cases: African American and Latina heterosexual women each saw a falling incidence of new HIV cases. For the former group, new cases fell from 4,700 to 4,000, while the latter group of women saw new cases drop from 1,200 to 980 per year from 2010 to 2016.

Within these broad groups, HIV incidence also rose among some age groups and fell among others. Decreases were seen for younger African American gay and bisexual men (those aged 13-24 years), but rates increased by about two-thirds for men in this group aged 25-34 years. A similar increase was seen for Latino men in the 25-34 years age group, a change which drove the overall 30% increase in new infections for Latino gay and bisexual men.

White gay and bisexual men saw across-the-board decreases in new infections, though the overall decrease was less than 20%.

For heterosexual individuals as a group, new infections dropped by about 17%, from 10,900 to 9,100 annually. This change was driven mostly by decreases in women identifying as heterosexual.

“After a decades-long struggle, the path to eliminate America’s HIV epidemic is clear,” said Eugene McCray, MD, director of CDC’s Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention, in the press release. “Expanding efforts across the country will close gaps, overcome threats, and turn around troublesome trends.”

The press release cited local work in Washington and New York as evidence that targeted resources can make a difference in reducing new HIV cases. In these two areas, new infections dropped by 23% and 40% respectively from 2010 to 2016.

SOURCE: Centers for Disease Control. CDC Report: www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html.

The annual number of new HIV infections has remained stable in recent years, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says that’s not good – but solutions are at hand.

Though the estimated number of new HIV infections declined from just under 42,000 per year in 2010 to about 39,000 annually in 2013, that figure was essentially unchanged by 2016, with 38,700 new HIV infections seen that year.

“CDC estimates that the decline in HIV infections has plateaued because effective HIV prevention and treatment are not adequately reaching those who could most benefit from them. These gaps remain particularly troublesome in rural areas and in the South and among disproportionately affected populations like African Americans and Latinos,” said the CDC in a press release accompanying the report.

The report comes soon after President Trump’s State of the Union address, which announced a new multiagency initiative to eliminate the HIV epidemic in the United States, with the goal of reducing new HIV infections by 90% over the next 10 years. The multipronged initiative will implement geographically targeted HIV elimination teams in areas with high HIV prevalence, pulling together federal agencies, local and state governments, and community-level resources.

The initiative, called “Ending the Epidemic: A Plan for America” will combine an intensified approach to early diagnosis and treatment with efforts to boost uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis for individuals at high risk for HIV infection.

The new CDC report used CD4 counts reported to the National HIV Surveillance System at the time of diagnosis to identify new (incident) cases and to track prevalence. Much of the report is devoted to finely detailed reporting of HIV incidence across sex, age, race/ethnicity, and transmission mode.

Though some groups, such as people who inject drugs, have seen a decrease of about 30% in the annual rate of new HIV cases, new cases have jumped for other groups. In particular, Latino gay and bisexual men saw new cases climb from 6,400 per year in 2010 to 8,300 in 2016. The incidence rate has stayed high and stable among African American gay and bisexual men, with 9,800 new cases reported in 2010; the same number was seen in 2016.

Among gay and bisexual men overall, the rate has also stayed stable, with about 26,000 new HIV infections reported at the beginning and end of the studied period. White heterosexual women saw about 1,000 new cases per year in 2010 and in 2016.

Some groups saw declines in new cases: African American and Latina heterosexual women each saw a falling incidence of new HIV cases. For the former group, new cases fell from 4,700 to 4,000, while the latter group of women saw new cases drop from 1,200 to 980 per year from 2010 to 2016.

Within these broad groups, HIV incidence also rose among some age groups and fell among others. Decreases were seen for younger African American gay and bisexual men (those aged 13-24 years), but rates increased by about two-thirds for men in this group aged 25-34 years. A similar increase was seen for Latino men in the 25-34 years age group, a change which drove the overall 30% increase in new infections for Latino gay and bisexual men.

White gay and bisexual men saw across-the-board decreases in new infections, though the overall decrease was less than 20%.

For heterosexual individuals as a group, new infections dropped by about 17%, from 10,900 to 9,100 annually. This change was driven mostly by decreases in women identifying as heterosexual.

“After a decades-long struggle, the path to eliminate America’s HIV epidemic is clear,” said Eugene McCray, MD, director of CDC’s Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention, in the press release. “Expanding efforts across the country will close gaps, overcome threats, and turn around troublesome trends.”

The press release cited local work in Washington and New York as evidence that targeted resources can make a difference in reducing new HIV cases. In these two areas, new infections dropped by 23% and 40% respectively from 2010 to 2016.

SOURCE: Centers for Disease Control. CDC Report: www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html.

The annual number of new HIV infections has remained stable in recent years, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says that’s not good – but solutions are at hand.

Though the estimated number of new HIV infections declined from just under 42,000 per year in 2010 to about 39,000 annually in 2013, that figure was essentially unchanged by 2016, with 38,700 new HIV infections seen that year.

“CDC estimates that the decline in HIV infections has plateaued because effective HIV prevention and treatment are not adequately reaching those who could most benefit from them. These gaps remain particularly troublesome in rural areas and in the South and among disproportionately affected populations like African Americans and Latinos,” said the CDC in a press release accompanying the report.

The report comes soon after President Trump’s State of the Union address, which announced a new multiagency initiative to eliminate the HIV epidemic in the United States, with the goal of reducing new HIV infections by 90% over the next 10 years. The multipronged initiative will implement geographically targeted HIV elimination teams in areas with high HIV prevalence, pulling together federal agencies, local and state governments, and community-level resources.

The initiative, called “Ending the Epidemic: A Plan for America” will combine an intensified approach to early diagnosis and treatment with efforts to boost uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis for individuals at high risk for HIV infection.

The new CDC report used CD4 counts reported to the National HIV Surveillance System at the time of diagnosis to identify new (incident) cases and to track prevalence. Much of the report is devoted to finely detailed reporting of HIV incidence across sex, age, race/ethnicity, and transmission mode.

Though some groups, such as people who inject drugs, have seen a decrease of about 30% in the annual rate of new HIV cases, new cases have jumped for other groups. In particular, Latino gay and bisexual men saw new cases climb from 6,400 per year in 2010 to 8,300 in 2016. The incidence rate has stayed high and stable among African American gay and bisexual men, with 9,800 new cases reported in 2010; the same number was seen in 2016.

Among gay and bisexual men overall, the rate has also stayed stable, with about 26,000 new HIV infections reported at the beginning and end of the studied period. White heterosexual women saw about 1,000 new cases per year in 2010 and in 2016.

Some groups saw declines in new cases: African American and Latina heterosexual women each saw a falling incidence of new HIV cases. For the former group, new cases fell from 4,700 to 4,000, while the latter group of women saw new cases drop from 1,200 to 980 per year from 2010 to 2016.

Within these broad groups, HIV incidence also rose among some age groups and fell among others. Decreases were seen for younger African American gay and bisexual men (those aged 13-24 years), but rates increased by about two-thirds for men in this group aged 25-34 years. A similar increase was seen for Latino men in the 25-34 years age group, a change which drove the overall 30% increase in new infections for Latino gay and bisexual men.

White gay and bisexual men saw across-the-board decreases in new infections, though the overall decrease was less than 20%.

For heterosexual individuals as a group, new infections dropped by about 17%, from 10,900 to 9,100 annually. This change was driven mostly by decreases in women identifying as heterosexual.

“After a decades-long struggle, the path to eliminate America’s HIV epidemic is clear,” said Eugene McCray, MD, director of CDC’s Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention, in the press release. “Expanding efforts across the country will close gaps, overcome threats, and turn around troublesome trends.”

The press release cited local work in Washington and New York as evidence that targeted resources can make a difference in reducing new HIV cases. In these two areas, new infections dropped by 23% and 40% respectively from 2010 to 2016.

SOURCE: Centers for Disease Control. CDC Report: www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html.

Caring for aging HIV-infected patients requires close attention to unrelated diseases

A substantial proportion of non–AIDS-defining cancers, and other noninfectious comorbid diseases, could be prevented with interventions on traditional risk factors in HIV-infected patients, according to the results of large database analysis published online in The Lancet HIV.

The researchers analyzed traditional and HIV-related risk factors for four validated noncommunicable disease outcomes (non–AIDS-defining cancers, myocardial infarction, end-stage liver disease, and end-stage renal disease) among participants of the North American AIDS Cohort Collaboration on Research and Design (NA-ACCORD), according to Keri N. Althoff, PhD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and her colleagues on behalf of the NA-ACCORD.

The study comprised individuals with the assessed disease conditions from among more than 180,000 adults (aged 18 years or older) with HIV from more than 200 sites who had at least two care visits within 12 months. The researchers used a population attributable fraction (PAF) approach to quantify the proportion of noncommunicable diseases that could be eliminated if particular risk factors were not present. According to the researchers, PAF can be used to inform prioritization of interventions.

Dr. Althoff and her colleagues found that, for non–AIDS-defining cancer, the significant preventable or modifiable risk factors were smoking, low CD4 cell count, detectable HIV RNA, a history of clinical AIDS diagnosis, and hepatitis B infection.

For myocardial infarction, the significant factors were smoking, elevated total cholesterol, hypertension, stage 4 chronic kidney disease, a low CD4 cell count, detectable HIV RNA, and hepatitis C infection.

For end-stage liver disease, the significant factors were low CD4 cell count, detectable HIV RNA, a history of a clinical AIDS diagnosis, and hepatitis B or C infection.

For end-stage renal disease, the significantly associated risk factors were elevated total cholesterol, hypertension, diabetes, low CD4 cell count, detectable HIV RNA, and a history of clinical AIDS diagnosis.

The most substantial PAF for each of the respective diseases was as follows: smoking for non–AIDS-related cancers (24%; 95% confidence interval, 13%-35%), elevated total cholesterol for myocardial infarction (44%; 95% CI, 30%-58%), and hepatitis C infection for end-stage liver disease (30%; 95% CI, 21%-39%). In addition, hypertension had the highest PAF for end-stage renal disease (39%; 95% CI, 26%-51%).

“Modifications to individual-level interventions and models of HIV care, and the implementation of structural and policy-level interventions that focus on prevention and modification of traditional risk factors are necessary to avoid noncommunicable diseases and preserve health among successfully antiretroviral-treated adults aging with HIV,” the researchers concluded.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health and the NA-ACCORD. Dr. Althoff reported having no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Althoff KN et al. The Lancet HIV. 2019 Jan 22. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(18)30295-9.

A substantial proportion of non–AIDS-defining cancers, and other noninfectious comorbid diseases, could be prevented with interventions on traditional risk factors in HIV-infected patients, according to the results of large database analysis published online in The Lancet HIV.

The researchers analyzed traditional and HIV-related risk factors for four validated noncommunicable disease outcomes (non–AIDS-defining cancers, myocardial infarction, end-stage liver disease, and end-stage renal disease) among participants of the North American AIDS Cohort Collaboration on Research and Design (NA-ACCORD), according to Keri N. Althoff, PhD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and her colleagues on behalf of the NA-ACCORD.

The study comprised individuals with the assessed disease conditions from among more than 180,000 adults (aged 18 years or older) with HIV from more than 200 sites who had at least two care visits within 12 months. The researchers used a population attributable fraction (PAF) approach to quantify the proportion of noncommunicable diseases that could be eliminated if particular risk factors were not present. According to the researchers, PAF can be used to inform prioritization of interventions.

Dr. Althoff and her colleagues found that, for non–AIDS-defining cancer, the significant preventable or modifiable risk factors were smoking, low CD4 cell count, detectable HIV RNA, a history of clinical AIDS diagnosis, and hepatitis B infection.

For myocardial infarction, the significant factors were smoking, elevated total cholesterol, hypertension, stage 4 chronic kidney disease, a low CD4 cell count, detectable HIV RNA, and hepatitis C infection.

For end-stage liver disease, the significant factors were low CD4 cell count, detectable HIV RNA, a history of a clinical AIDS diagnosis, and hepatitis B or C infection.

For end-stage renal disease, the significantly associated risk factors were elevated total cholesterol, hypertension, diabetes, low CD4 cell count, detectable HIV RNA, and a history of clinical AIDS diagnosis.

The most substantial PAF for each of the respective diseases was as follows: smoking for non–AIDS-related cancers (24%; 95% confidence interval, 13%-35%), elevated total cholesterol for myocardial infarction (44%; 95% CI, 30%-58%), and hepatitis C infection for end-stage liver disease (30%; 95% CI, 21%-39%). In addition, hypertension had the highest PAF for end-stage renal disease (39%; 95% CI, 26%-51%).

“Modifications to individual-level interventions and models of HIV care, and the implementation of structural and policy-level interventions that focus on prevention and modification of traditional risk factors are necessary to avoid noncommunicable diseases and preserve health among successfully antiretroviral-treated adults aging with HIV,” the researchers concluded.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health and the NA-ACCORD. Dr. Althoff reported having no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Althoff KN et al. The Lancet HIV. 2019 Jan 22. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(18)30295-9.

A substantial proportion of non–AIDS-defining cancers, and other noninfectious comorbid diseases, could be prevented with interventions on traditional risk factors in HIV-infected patients, according to the results of large database analysis published online in The Lancet HIV.

The researchers analyzed traditional and HIV-related risk factors for four validated noncommunicable disease outcomes (non–AIDS-defining cancers, myocardial infarction, end-stage liver disease, and end-stage renal disease) among participants of the North American AIDS Cohort Collaboration on Research and Design (NA-ACCORD), according to Keri N. Althoff, PhD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and her colleagues on behalf of the NA-ACCORD.

The study comprised individuals with the assessed disease conditions from among more than 180,000 adults (aged 18 years or older) with HIV from more than 200 sites who had at least two care visits within 12 months. The researchers used a population attributable fraction (PAF) approach to quantify the proportion of noncommunicable diseases that could be eliminated if particular risk factors were not present. According to the researchers, PAF can be used to inform prioritization of interventions.

Dr. Althoff and her colleagues found that, for non–AIDS-defining cancer, the significant preventable or modifiable risk factors were smoking, low CD4 cell count, detectable HIV RNA, a history of clinical AIDS diagnosis, and hepatitis B infection.

For myocardial infarction, the significant factors were smoking, elevated total cholesterol, hypertension, stage 4 chronic kidney disease, a low CD4 cell count, detectable HIV RNA, and hepatitis C infection.

For end-stage liver disease, the significant factors were low CD4 cell count, detectable HIV RNA, a history of a clinical AIDS diagnosis, and hepatitis B or C infection.

For end-stage renal disease, the significantly associated risk factors were elevated total cholesterol, hypertension, diabetes, low CD4 cell count, detectable HIV RNA, and a history of clinical AIDS diagnosis.

The most substantial PAF for each of the respective diseases was as follows: smoking for non–AIDS-related cancers (24%; 95% confidence interval, 13%-35%), elevated total cholesterol for myocardial infarction (44%; 95% CI, 30%-58%), and hepatitis C infection for end-stage liver disease (30%; 95% CI, 21%-39%). In addition, hypertension had the highest PAF for end-stage renal disease (39%; 95% CI, 26%-51%).

“Modifications to individual-level interventions and models of HIV care, and the implementation of structural and policy-level interventions that focus on prevention and modification of traditional risk factors are necessary to avoid noncommunicable diseases and preserve health among successfully antiretroviral-treated adults aging with HIV,” the researchers concluded.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health and the NA-ACCORD. Dr. Althoff reported having no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Althoff KN et al. The Lancet HIV. 2019 Jan 22. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(18)30295-9.

FROM THE LANCET HIV

Heart failure outcomes are worse in select HIV-infected individuals

People living with HIV (PLHIV) who have a low CD4 count or detectable viral load (VL) have an increased 30-day heart failure (HF) readmission rate as well as increased cardiovascular and all-cause mortality, compared with uninfected controls, according to Raza M. Alvi, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, and his colleagues.

Overall, the 30-day HF hospital readmission rate was higher among PLHIV versus non-HIV–infected individuals (49% vs. 32%, P less than .001), according to the results of their cohort study of 2,308 individuals admitted to the hospital with decompensated HF.

PLHIV and the non-HIV control groups were both followed over 2 years with a median follow-up period of 19 months, the authors wrote in the American Heart Journal. Demographic make-up of the two groups was similar; in particular, there was no difference in blood pressure and heart rate between the PLHIV and non-HIV controls, suggesting that adherence with HF medications may be similar between groups. The cohorts differed primarily in that pulmonary artery systolic pressure was significantly higher (45 vs. 40 mm Hg; P less than .001) in the HIV group, as was cocaine use (36% vs. 19%; P less than .001) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection (13% vs. 7%; P less than .001).

The differing results between the two cohorts were primarily caused by the fact that, for PLHIV with HF, CD4 count and VL were risk factors for adverse outcomes among patients with all types of HF. (30-day HF readmission, cardiovascular [CV] mortality, and all-cause mortality), compared with those with CD4 count greater than or equal to 200 cells/mm3. In addition, a low CD4 count/high VL independently related to an increased 30-day HF readmission rate even after the researchers controlled for major traditional and nontraditional HF risk factors.

“Rates of 30-day HF readmission, CV mortality, and all-cause mortality are worse among individuals with a low CD4 count or nonsuppressed viral load,” the researchers concluded.

The National Institutes of Health sponsored the study. The authors reported that they had no conflicts.

SOURCE: Alvi RM et al. Am Heart J. 2019 Apr;210:39-48.

People living with HIV (PLHIV) who have a low CD4 count or detectable viral load (VL) have an increased 30-day heart failure (HF) readmission rate as well as increased cardiovascular and all-cause mortality, compared with uninfected controls, according to Raza M. Alvi, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, and his colleagues.

Overall, the 30-day HF hospital readmission rate was higher among PLHIV versus non-HIV–infected individuals (49% vs. 32%, P less than .001), according to the results of their cohort study of 2,308 individuals admitted to the hospital with decompensated HF.

PLHIV and the non-HIV control groups were both followed over 2 years with a median follow-up period of 19 months, the authors wrote in the American Heart Journal. Demographic make-up of the two groups was similar; in particular, there was no difference in blood pressure and heart rate between the PLHIV and non-HIV controls, suggesting that adherence with HF medications may be similar between groups. The cohorts differed primarily in that pulmonary artery systolic pressure was significantly higher (45 vs. 40 mm Hg; P less than .001) in the HIV group, as was cocaine use (36% vs. 19%; P less than .001) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection (13% vs. 7%; P less than .001).

The differing results between the two cohorts were primarily caused by the fact that, for PLHIV with HF, CD4 count and VL were risk factors for adverse outcomes among patients with all types of HF. (30-day HF readmission, cardiovascular [CV] mortality, and all-cause mortality), compared with those with CD4 count greater than or equal to 200 cells/mm3. In addition, a low CD4 count/high VL independently related to an increased 30-day HF readmission rate even after the researchers controlled for major traditional and nontraditional HF risk factors.

“Rates of 30-day HF readmission, CV mortality, and all-cause mortality are worse among individuals with a low CD4 count or nonsuppressed viral load,” the researchers concluded.

The National Institutes of Health sponsored the study. The authors reported that they had no conflicts.

SOURCE: Alvi RM et al. Am Heart J. 2019 Apr;210:39-48.

People living with HIV (PLHIV) who have a low CD4 count or detectable viral load (VL) have an increased 30-day heart failure (HF) readmission rate as well as increased cardiovascular and all-cause mortality, compared with uninfected controls, according to Raza M. Alvi, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, and his colleagues.

Overall, the 30-day HF hospital readmission rate was higher among PLHIV versus non-HIV–infected individuals (49% vs. 32%, P less than .001), according to the results of their cohort study of 2,308 individuals admitted to the hospital with decompensated HF.

PLHIV and the non-HIV control groups were both followed over 2 years with a median follow-up period of 19 months, the authors wrote in the American Heart Journal. Demographic make-up of the two groups was similar; in particular, there was no difference in blood pressure and heart rate between the PLHIV and non-HIV controls, suggesting that adherence with HF medications may be similar between groups. The cohorts differed primarily in that pulmonary artery systolic pressure was significantly higher (45 vs. 40 mm Hg; P less than .001) in the HIV group, as was cocaine use (36% vs. 19%; P less than .001) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection (13% vs. 7%; P less than .001).

The differing results between the two cohorts were primarily caused by the fact that, for PLHIV with HF, CD4 count and VL were risk factors for adverse outcomes among patients with all types of HF. (30-day HF readmission, cardiovascular [CV] mortality, and all-cause mortality), compared with those with CD4 count greater than or equal to 200 cells/mm3. In addition, a low CD4 count/high VL independently related to an increased 30-day HF readmission rate even after the researchers controlled for major traditional and nontraditional HF risk factors.

“Rates of 30-day HF readmission, CV mortality, and all-cause mortality are worse among individuals with a low CD4 count or nonsuppressed viral load,” the researchers concluded.

The National Institutes of Health sponsored the study. The authors reported that they had no conflicts.

SOURCE: Alvi RM et al. Am Heart J. 2019 Apr;210:39-48.

FROM THE AMERICAN HEART JOURNAL

Protecting Older Women Against HIV Infection

Older women represent 56% of all women with HIV, and in a 2009 study, they had the highest rates of HIV- and AIDS-related deaths. But few HIV prevention and education programs focus on older women, says Christopher Coleman, PhD, MPH, department chair and professor, Department of Health Promotion and Disease Prevention, The University of Tennessee Health Science Center, College of Nursing. Moreover, sexual health studies mainly concentrate on younger women and reproductive health, not risk factors for HIV among older women.

Coleman says the “confluence of lack of knowledge and absent communication about HIV risk has created a significant health crisis” for this group. He reviewed 41 articles that provide some insight.

Ageism, biological factors, and lack of education all play a part. Some research has found that older women are less likely to engage in safe sex practices because they no longer use condoms to prevent pregnancy. The National AIDS Behavior Survey found that > 85% of respondents aged ≥ 50 years reported never using condoms or using them inconsistently. However, women in the postmenopausal age group are sexually active, and because they may be divorced or widowed, may not be in committed relationships. Also, age-related physical changes, such as thinning vaginal tissue and a weakened immune system, can make them more vulnerable to infection.

The problem is compounded when an older woman is unwilling to bring up the topic with health care providers—and health care providers are unwilling to believe that she is sexually active. Women aged > 50 years may also avoid seeking HIV testing due to social factors. And they may be prevented from traveling to health care or testing by poor physical health or other age-related issues.

We need new methods of reaching them, Coleman says. Existing HIV/AIDS instructional programs may not be effective tools for women with age-related comorbidities, such as cognitive, visual, or auditory deficits. Other options should be considered: For instance, small peer groups have been more successful than large groups, providing a sense of safety and belonging that encourages disclosure.

Health care providers should include education during routine office visits, Coleman advises, using non-ageist and nonstereotyping strategies and questions. Nurses are well positioned to educate women about the risks of HIV transmission; he says: discussing sexual activity with older women requires the “art of therapeutic communication without judgment.”

Older women represent 56% of all women with HIV, and in a 2009 study, they had the highest rates of HIV- and AIDS-related deaths. But few HIV prevention and education programs focus on older women, says Christopher Coleman, PhD, MPH, department chair and professor, Department of Health Promotion and Disease Prevention, The University of Tennessee Health Science Center, College of Nursing. Moreover, sexual health studies mainly concentrate on younger women and reproductive health, not risk factors for HIV among older women.

Coleman says the “confluence of lack of knowledge and absent communication about HIV risk has created a significant health crisis” for this group. He reviewed 41 articles that provide some insight.

Ageism, biological factors, and lack of education all play a part. Some research has found that older women are less likely to engage in safe sex practices because they no longer use condoms to prevent pregnancy. The National AIDS Behavior Survey found that > 85% of respondents aged ≥ 50 years reported never using condoms or using them inconsistently. However, women in the postmenopausal age group are sexually active, and because they may be divorced or widowed, may not be in committed relationships. Also, age-related physical changes, such as thinning vaginal tissue and a weakened immune system, can make them more vulnerable to infection.

The problem is compounded when an older woman is unwilling to bring up the topic with health care providers—and health care providers are unwilling to believe that she is sexually active. Women aged > 50 years may also avoid seeking HIV testing due to social factors. And they may be prevented from traveling to health care or testing by poor physical health or other age-related issues.

We need new methods of reaching them, Coleman says. Existing HIV/AIDS instructional programs may not be effective tools for women with age-related comorbidities, such as cognitive, visual, or auditory deficits. Other options should be considered: For instance, small peer groups have been more successful than large groups, providing a sense of safety and belonging that encourages disclosure.

Health care providers should include education during routine office visits, Coleman advises, using non-ageist and nonstereotyping strategies and questions. Nurses are well positioned to educate women about the risks of HIV transmission; he says: discussing sexual activity with older women requires the “art of therapeutic communication without judgment.”

Older women represent 56% of all women with HIV, and in a 2009 study, they had the highest rates of HIV- and AIDS-related deaths. But few HIV prevention and education programs focus on older women, says Christopher Coleman, PhD, MPH, department chair and professor, Department of Health Promotion and Disease Prevention, The University of Tennessee Health Science Center, College of Nursing. Moreover, sexual health studies mainly concentrate on younger women and reproductive health, not risk factors for HIV among older women.

Coleman says the “confluence of lack of knowledge and absent communication about HIV risk has created a significant health crisis” for this group. He reviewed 41 articles that provide some insight.

Ageism, biological factors, and lack of education all play a part. Some research has found that older women are less likely to engage in safe sex practices because they no longer use condoms to prevent pregnancy. The National AIDS Behavior Survey found that > 85% of respondents aged ≥ 50 years reported never using condoms or using them inconsistently. However, women in the postmenopausal age group are sexually active, and because they may be divorced or widowed, may not be in committed relationships. Also, age-related physical changes, such as thinning vaginal tissue and a weakened immune system, can make them more vulnerable to infection.

The problem is compounded when an older woman is unwilling to bring up the topic with health care providers—and health care providers are unwilling to believe that she is sexually active. Women aged > 50 years may also avoid seeking HIV testing due to social factors. And they may be prevented from traveling to health care or testing by poor physical health or other age-related issues.

We need new methods of reaching them, Coleman says. Existing HIV/AIDS instructional programs may not be effective tools for women with age-related comorbidities, such as cognitive, visual, or auditory deficits. Other options should be considered: For instance, small peer groups have been more successful than large groups, providing a sense of safety and belonging that encourages disclosure.

Health care providers should include education during routine office visits, Coleman advises, using non-ageist and nonstereotyping strategies and questions. Nurses are well positioned to educate women about the risks of HIV transmission; he says: discussing sexual activity with older women requires the “art of therapeutic communication without judgment.”

A New Way to Measure How HIV Drugs Are Working

One of the tricky parts of HIV drug therapy is determining how well the drugs have worked. The HIV DNA (provirus) in resting cells is usually too defective to replicate itself the way intact provirus can. But most current tests cannot tell the difference between the two. However, researchers from Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore have developed an accurate and scalable assay to easily count the cells in the HIV reservoir.

A stable, latent reservoir for HIV-1 in resting CD4+ T cells is “the principle barrier to a cure,” the researchers say. Quantitative outgrowth assays and assays for cells that produce viral RNA after T-cell activation may underestimate the reservoir size because 1 round of activation does not induce all proviruses. Many studies, the researchers say, rely on simple assays based on polymerase chain reaction to detect proviral DNA regardless of transcriptional status, but the clinical relevance of those assays is unclear since the vast majority of proviruses are defective.

In their study, supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the researchers analyzed DNA sequences from > 400 HIV proviruses from 28 people with HIV. They mapped 2 types of flaws: deletions and lethal mutations. They then developed strategically placed “genetic probes” that could distinguish between deleted or highly mutated proviruses and intact ones. Finally, they developed a nanotechnology-based method to analyze 1 provirus at a time to determine how many in a sample are intact.

The researchers say their findings show that the dynamics of cells that carry intact and defective proviruses are different in vitro and in vivo. Their hope is that their method will speed HIV research by allowing scientists to easily quantify the number of proviruses in an individual, which must be eliminated to achieve a cure.

One of the tricky parts of HIV drug therapy is determining how well the drugs have worked. The HIV DNA (provirus) in resting cells is usually too defective to replicate itself the way intact provirus can. But most current tests cannot tell the difference between the two. However, researchers from Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore have developed an accurate and scalable assay to easily count the cells in the HIV reservoir.

A stable, latent reservoir for HIV-1 in resting CD4+ T cells is “the principle barrier to a cure,” the researchers say. Quantitative outgrowth assays and assays for cells that produce viral RNA after T-cell activation may underestimate the reservoir size because 1 round of activation does not induce all proviruses. Many studies, the researchers say, rely on simple assays based on polymerase chain reaction to detect proviral DNA regardless of transcriptional status, but the clinical relevance of those assays is unclear since the vast majority of proviruses are defective.

In their study, supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the researchers analyzed DNA sequences from > 400 HIV proviruses from 28 people with HIV. They mapped 2 types of flaws: deletions and lethal mutations. They then developed strategically placed “genetic probes” that could distinguish between deleted or highly mutated proviruses and intact ones. Finally, they developed a nanotechnology-based method to analyze 1 provirus at a time to determine how many in a sample are intact.

The researchers say their findings show that the dynamics of cells that carry intact and defective proviruses are different in vitro and in vivo. Their hope is that their method will speed HIV research by allowing scientists to easily quantify the number of proviruses in an individual, which must be eliminated to achieve a cure.

One of the tricky parts of HIV drug therapy is determining how well the drugs have worked. The HIV DNA (provirus) in resting cells is usually too defective to replicate itself the way intact provirus can. But most current tests cannot tell the difference between the two. However, researchers from Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore have developed an accurate and scalable assay to easily count the cells in the HIV reservoir.

A stable, latent reservoir for HIV-1 in resting CD4+ T cells is “the principle barrier to a cure,” the researchers say. Quantitative outgrowth assays and assays for cells that produce viral RNA after T-cell activation may underestimate the reservoir size because 1 round of activation does not induce all proviruses. Many studies, the researchers say, rely on simple assays based on polymerase chain reaction to detect proviral DNA regardless of transcriptional status, but the clinical relevance of those assays is unclear since the vast majority of proviruses are defective.

In their study, supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the researchers analyzed DNA sequences from > 400 HIV proviruses from 28 people with HIV. They mapped 2 types of flaws: deletions and lethal mutations. They then developed strategically placed “genetic probes” that could distinguish between deleted or highly mutated proviruses and intact ones. Finally, they developed a nanotechnology-based method to analyze 1 provirus at a time to determine how many in a sample are intact.

The researchers say their findings show that the dynamics of cells that carry intact and defective proviruses are different in vitro and in vivo. Their hope is that their method will speed HIV research by allowing scientists to easily quantify the number of proviruses in an individual, which must be eliminated to achieve a cure.

Adult HIV patients should receive standard vaccinations, with caveats

Patients infected with HIV have an increased risk of mortality and morbidity from diseases that are preventable with vaccines. Undervaccination of these patients poses a major concern, according to a literature review of the vaccine response in the adult patient with HIV published in The American Journal of Medicine.

Despite the fact that data are limited, patients infected with HIV are advised to receive their age-specific and risk group−based vaccines, according to Firas El Chaer, MD, of the University of Maryland, Baltimore, and his colleague.

HIV patients are of particular concern regarding vaccination, because, despite the use of retroviral therapy, CD4+ T-lymphocytes in individuals infected with HIV remain lower than in those without HIV. In addition, HIV causes an inappropriate response to B-cell stimulation, which results in suboptimal primary and secondary response to vaccination, according to Dr. El Chaer and his colleague. Despite this and initial concerns about vaccine safety in this population, it is now recommended that adult patients infected with HIV receive their age-specific and risk group−based vaccines, they stated.

Inactivated or subunit vaccines

Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine is not recommended under current guidelines for individuals older than age 18 with HIV infection, unless they have a clinical indication.

Vaccination against hepatitis A virus is recommended for HIV-infected patients who are hepatitis A virus seronegative and have chronic liver disease, men who have sex with men, intravenous drug users, and travelers to endemic regions. However, research has shown that the immunogenicity of the vaccine is lower in patients with HIV than in uninfected individuals. It was found that the CD4 count at the time of vaccination, not the CD4 low point, was the major predictor of the immune response.

Patients coinfected with HIV and hepatitis B virus have an 8-fold and 19-fold increase in mortality, respectively, compared with either virus monoinfection. Although vaccination is recommended, the optimal hepatitis B virus vaccination schedule in patients with HIV remains controversial, according to the authors. They indicated that new strategies to improve hepatitis B virus vaccine immunogenicity for those infected with HIV are needed.

Individuals infected with HIV have been found to have a higher risk of human papillomavirus (HPV) infection. The safety and immunogenicity results and prospect of benefits has led to a consensus on the benefit of vaccinating HIV-infected patients who meet the HPV vaccine age criteria, the authors indicated.

With regard to standard flu vaccinations: “An annual inactivated influenza vaccine is recommended during the influenza season for all adult individuals with HIV; however, a live attenuated influenza vaccine is contraindicated in this population,” according to the review.

Patients with HIV have a more than 10-fold increased risk of invasive meningococcal disease, compared with the general population, with the risk being particularly higher in those individuals with CD4 counts less than 200 cells/mm3 and in men who have sex with men in cities with meningococcal outbreaks. For these reasons, the “quadrivalent meningococcal vaccine is recommended for all patients with HIV regardless of their CD4 count, with 2-dose primary series at least 2 months apart and with a booster every 5 years.”

Pneumonia is known to be especially dangerous in the HIV-infected population. With regard to pneumonia vaccination, the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine is recommended for all patients with HIV, regardless of their CD4 cell counts. According to Dr. El Chaer and his colleague, it should be followed by the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine at least 8 weeks later as a prime-boost regimen, preferably when CD4 counts are greater than 200 cells/mm3 and in patients receiving ART.

“Tetanus toxoid, diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis vaccines are recommended once for all individuals infected with HIV, regardless of the CD4 count, with a tetanus toxoid and diphtheria toxoid booster every 10 years,” according to the review.

Live vaccines

Live vaccines are a concerning issue for HIV-infected adults and recommendations for use are generally tied to the CD4 T-cell count. The measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine seems to be safe in patients infected with HIV with a CD4 count greater than 200 cells/mm3, according to Dr. El Chaer and his colleague. Similarly, patients with HIV with CD4 counts greater than 200 cells/mm3 and no evidence of documented immunity to varicella should receive the varicella vaccine.

In contrast, the live, attenuated varicella zoster virus vaccine is not recommended for patients infected with HIV, and it is contraindicated if CD4 count is less than 200 cells/mm3. Recently, a herpes zoster subunit vaccine (HZ/su) was tested in a phase 1/2a randomized, placebo-controlled study and was found to be safe and immunogenic regardless of CD4 count, although it has not yet been given a specific recommendation for immunocompromised patients.

“With the widespread use of ART resulting in better HIV control, ,” the authors concluded.

The study was not sponsored. Dr. El Chaer and his colleague reported that they had no conflicts.

SOURCE: El Chaer F et al. Am J Med. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2018.12.011.

Patients infected with HIV have an increased risk of mortality and morbidity from diseases that are preventable with vaccines. Undervaccination of these patients poses a major concern, according to a literature review of the vaccine response in the adult patient with HIV published in The American Journal of Medicine.

Despite the fact that data are limited, patients infected with HIV are advised to receive their age-specific and risk group−based vaccines, according to Firas El Chaer, MD, of the University of Maryland, Baltimore, and his colleague.

HIV patients are of particular concern regarding vaccination, because, despite the use of retroviral therapy, CD4+ T-lymphocytes in individuals infected with HIV remain lower than in those without HIV. In addition, HIV causes an inappropriate response to B-cell stimulation, which results in suboptimal primary and secondary response to vaccination, according to Dr. El Chaer and his colleague. Despite this and initial concerns about vaccine safety in this population, it is now recommended that adult patients infected with HIV receive their age-specific and risk group−based vaccines, they stated.

Inactivated or subunit vaccines

Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine is not recommended under current guidelines for individuals older than age 18 with HIV infection, unless they have a clinical indication.

Vaccination against hepatitis A virus is recommended for HIV-infected patients who are hepatitis A virus seronegative and have chronic liver disease, men who have sex with men, intravenous drug users, and travelers to endemic regions. However, research has shown that the immunogenicity of the vaccine is lower in patients with HIV than in uninfected individuals. It was found that the CD4 count at the time of vaccination, not the CD4 low point, was the major predictor of the immune response.

Patients coinfected with HIV and hepatitis B virus have an 8-fold and 19-fold increase in mortality, respectively, compared with either virus monoinfection. Although vaccination is recommended, the optimal hepatitis B virus vaccination schedule in patients with HIV remains controversial, according to the authors. They indicated that new strategies to improve hepatitis B virus vaccine immunogenicity for those infected with HIV are needed.

Individuals infected with HIV have been found to have a higher risk of human papillomavirus (HPV) infection. The safety and immunogenicity results and prospect of benefits has led to a consensus on the benefit of vaccinating HIV-infected patients who meet the HPV vaccine age criteria, the authors indicated.

With regard to standard flu vaccinations: “An annual inactivated influenza vaccine is recommended during the influenza season for all adult individuals with HIV; however, a live attenuated influenza vaccine is contraindicated in this population,” according to the review.

Patients with HIV have a more than 10-fold increased risk of invasive meningococcal disease, compared with the general population, with the risk being particularly higher in those individuals with CD4 counts less than 200 cells/mm3 and in men who have sex with men in cities with meningococcal outbreaks. For these reasons, the “quadrivalent meningococcal vaccine is recommended for all patients with HIV regardless of their CD4 count, with 2-dose primary series at least 2 months apart and with a booster every 5 years.”

Pneumonia is known to be especially dangerous in the HIV-infected population. With regard to pneumonia vaccination, the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine is recommended for all patients with HIV, regardless of their CD4 cell counts. According to Dr. El Chaer and his colleague, it should be followed by the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine at least 8 weeks later as a prime-boost regimen, preferably when CD4 counts are greater than 200 cells/mm3 and in patients receiving ART.

“Tetanus toxoid, diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis vaccines are recommended once for all individuals infected with HIV, regardless of the CD4 count, with a tetanus toxoid and diphtheria toxoid booster every 10 years,” according to the review.

Live vaccines

Live vaccines are a concerning issue for HIV-infected adults and recommendations for use are generally tied to the CD4 T-cell count. The measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine seems to be safe in patients infected with HIV with a CD4 count greater than 200 cells/mm3, according to Dr. El Chaer and his colleague. Similarly, patients with HIV with CD4 counts greater than 200 cells/mm3 and no evidence of documented immunity to varicella should receive the varicella vaccine.

In contrast, the live, attenuated varicella zoster virus vaccine is not recommended for patients infected with HIV, and it is contraindicated if CD4 count is less than 200 cells/mm3. Recently, a herpes zoster subunit vaccine (HZ/su) was tested in a phase 1/2a randomized, placebo-controlled study and was found to be safe and immunogenic regardless of CD4 count, although it has not yet been given a specific recommendation for immunocompromised patients.

“With the widespread use of ART resulting in better HIV control, ,” the authors concluded.

The study was not sponsored. Dr. El Chaer and his colleague reported that they had no conflicts.

SOURCE: El Chaer F et al. Am J Med. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2018.12.011.

Patients infected with HIV have an increased risk of mortality and morbidity from diseases that are preventable with vaccines. Undervaccination of these patients poses a major concern, according to a literature review of the vaccine response in the adult patient with HIV published in The American Journal of Medicine.

Despite the fact that data are limited, patients infected with HIV are advised to receive their age-specific and risk group−based vaccines, according to Firas El Chaer, MD, of the University of Maryland, Baltimore, and his colleague.

HIV patients are of particular concern regarding vaccination, because, despite the use of retroviral therapy, CD4+ T-lymphocytes in individuals infected with HIV remain lower than in those without HIV. In addition, HIV causes an inappropriate response to B-cell stimulation, which results in suboptimal primary and secondary response to vaccination, according to Dr. El Chaer and his colleague. Despite this and initial concerns about vaccine safety in this population, it is now recommended that adult patients infected with HIV receive their age-specific and risk group−based vaccines, they stated.

Inactivated or subunit vaccines

Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine is not recommended under current guidelines for individuals older than age 18 with HIV infection, unless they have a clinical indication.

Vaccination against hepatitis A virus is recommended for HIV-infected patients who are hepatitis A virus seronegative and have chronic liver disease, men who have sex with men, intravenous drug users, and travelers to endemic regions. However, research has shown that the immunogenicity of the vaccine is lower in patients with HIV than in uninfected individuals. It was found that the CD4 count at the time of vaccination, not the CD4 low point, was the major predictor of the immune response.

Patients coinfected with HIV and hepatitis B virus have an 8-fold and 19-fold increase in mortality, respectively, compared with either virus monoinfection. Although vaccination is recommended, the optimal hepatitis B virus vaccination schedule in patients with HIV remains controversial, according to the authors. They indicated that new strategies to improve hepatitis B virus vaccine immunogenicity for those infected with HIV are needed.

Individuals infected with HIV have been found to have a higher risk of human papillomavirus (HPV) infection. The safety and immunogenicity results and prospect of benefits has led to a consensus on the benefit of vaccinating HIV-infected patients who meet the HPV vaccine age criteria, the authors indicated.

With regard to standard flu vaccinations: “An annual inactivated influenza vaccine is recommended during the influenza season for all adult individuals with HIV; however, a live attenuated influenza vaccine is contraindicated in this population,” according to the review.

Patients with HIV have a more than 10-fold increased risk of invasive meningococcal disease, compared with the general population, with the risk being particularly higher in those individuals with CD4 counts less than 200 cells/mm3 and in men who have sex with men in cities with meningococcal outbreaks. For these reasons, the “quadrivalent meningococcal vaccine is recommended for all patients with HIV regardless of their CD4 count, with 2-dose primary series at least 2 months apart and with a booster every 5 years.”

Pneumonia is known to be especially dangerous in the HIV-infected population. With regard to pneumonia vaccination, the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine is recommended for all patients with HIV, regardless of their CD4 cell counts. According to Dr. El Chaer and his colleague, it should be followed by the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine at least 8 weeks later as a prime-boost regimen, preferably when CD4 counts are greater than 200 cells/mm3 and in patients receiving ART.

“Tetanus toxoid, diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis vaccines are recommended once for all individuals infected with HIV, regardless of the CD4 count, with a tetanus toxoid and diphtheria toxoid booster every 10 years,” according to the review.

Live vaccines

Live vaccines are a concerning issue for HIV-infected adults and recommendations for use are generally tied to the CD4 T-cell count. The measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine seems to be safe in patients infected with HIV with a CD4 count greater than 200 cells/mm3, according to Dr. El Chaer and his colleague. Similarly, patients with HIV with CD4 counts greater than 200 cells/mm3 and no evidence of documented immunity to varicella should receive the varicella vaccine.

In contrast, the live, attenuated varicella zoster virus vaccine is not recommended for patients infected with HIV, and it is contraindicated if CD4 count is less than 200 cells/mm3. Recently, a herpes zoster subunit vaccine (HZ/su) was tested in a phase 1/2a randomized, placebo-controlled study and was found to be safe and immunogenic regardless of CD4 count, although it has not yet been given a specific recommendation for immunocompromised patients.

“With the widespread use of ART resulting in better HIV control, ,” the authors concluded.

The study was not sponsored. Dr. El Chaer and his colleague reported that they had no conflicts.

SOURCE: El Chaer F et al. Am J Med. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2018.12.011.

FROM THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Undervaccination is too common among HIV-infected patients.

Major finding: Data on vaccine effectiveness in HIV patients are limited, but do not contraindicate the need for vaccination.

Study details: Literature review of immunogenicity and vaccine efficacy in HIV-infected adults.

Disclosures: The study was unsponsored and the authors reported they had no conflicts.

Source: El Chaer F et al. Am J Med. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2018.12.011.

Marijuana smoking is an independent risk factor for lung disease in HIV+

Long-term marijuana smoking was associated with lung disease in HIV-infected (HIV+) but not HIV uninfected (HIV–) men who have sex with men (MSM), according to the results of a large, prospective cohort study.

“There were no significant interactions between marijuana and tobacco smoking in any multivariable model tested for HIV+ participants, indicating independent effects of these factors,” wrote David R. Lorenz, PhD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, and his colleagues.

These findings are especially important given that the proportion of HIV+ individuals who frequently smoke marijuana is higher than in the general population in the United States, and has increased in recent years, according to the report, published online in EClinicalMedicine.

The study examined 2,704 MSM who met eligibility criteria (1,352 HIV+ and 1,352 HIV− individuals), with a median age of 44 years at baseline and a median follow-up of 10.5 years. A total of 27% of HIV+ participants reported daily or weekly marijuana smoking for 1 year or more during follow-up, compared with 18% of the HIV− participants.

HIV+ participants who smoked marijuana were more likely to report one or more pulmonary diagnoses, versus nonsmoking HIV+ individuals during follow-up (41.0% vs. 30.0% infectious, and 24.8% vs. 19.0% noninfectious), according to the authors. In contrast, there was no association between marijuana smoking and either an infectious or noninfectious pulmonary diagnosis among HIV− participants (24.2% vs. 20.9%, and 14.8% vs. 17.7%, respectively).

For HIV+ individuals, each 10 days/month increase in marijuana smoking in the prior 2-year period was found to be associated with a 6% increased risk of infectious pulmonary diagnosis (hazard risk 1.06 [95% confidence interval 1.00-1.11]; P = .041). Overall, they found that from the 53,000 person-visits in the study, marijuana smoking was associated with increased risk of both infectious and noninfectious pulmonary diagnoses among the 1,352 HIV-infected participants independent of CD4 count, antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence, and demographic factors as well.

In particular, viral suppression did not seem to interfere with this association between marijuana smoking and infectious pulmonary diagnoses, as it remained significant in models restricted to those person-visits with suppressed HIV viral load (HR 1.41 [1.03-1.91], P = .029).

The authors suggested that HIV-specific factors such as lung immune cell depletion and dysfunction, persistent immune cell activation, systemic inflammation, respiratory microbiome alterations, and oxidative stress, or a combination of these effects, may interact with the alveolar macrophage dysfunction seen in both humans and mouse models exposed to marijuana smoke. Thus, “a potential additive risk of marijuana smoking and HIV disease may explain the increased prevalence of infectious pulmonary diagnoses in our adjusted analyses,” Dr. Lorenz and his colleagues stated.

“These findings suggest that marijuana smoking is a modifiable risk factor that healthcare providers should consider when seeking to prevent or treat lung disease in people infected with HIV, particularly those with other known risk factors including heavy tobacco smoking, and low CD4 T cell count or advanced HIV disease,” they concluded.

The National Institutes of Health funded the study. The authors reported that they had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Lorenz DR et al. EClinicalMedicine. 2019 Jan 24. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2019.01.003.

Long-term marijuana smoking was associated with lung disease in HIV-infected (HIV+) but not HIV uninfected (HIV–) men who have sex with men (MSM), according to the results of a large, prospective cohort study.

“There were no significant interactions between marijuana and tobacco smoking in any multivariable model tested for HIV+ participants, indicating independent effects of these factors,” wrote David R. Lorenz, PhD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, and his colleagues.

These findings are especially important given that the proportion of HIV+ individuals who frequently smoke marijuana is higher than in the general population in the United States, and has increased in recent years, according to the report, published online in EClinicalMedicine.

The study examined 2,704 MSM who met eligibility criteria (1,352 HIV+ and 1,352 HIV− individuals), with a median age of 44 years at baseline and a median follow-up of 10.5 years. A total of 27% of HIV+ participants reported daily or weekly marijuana smoking for 1 year or more during follow-up, compared with 18% of the HIV− participants.

HIV+ participants who smoked marijuana were more likely to report one or more pulmonary diagnoses, versus nonsmoking HIV+ individuals during follow-up (41.0% vs. 30.0% infectious, and 24.8% vs. 19.0% noninfectious), according to the authors. In contrast, there was no association between marijuana smoking and either an infectious or noninfectious pulmonary diagnosis among HIV− participants (24.2% vs. 20.9%, and 14.8% vs. 17.7%, respectively).

For HIV+ individuals, each 10 days/month increase in marijuana smoking in the prior 2-year period was found to be associated with a 6% increased risk of infectious pulmonary diagnosis (hazard risk 1.06 [95% confidence interval 1.00-1.11]; P = .041). Overall, they found that from the 53,000 person-visits in the study, marijuana smoking was associated with increased risk of both infectious and noninfectious pulmonary diagnoses among the 1,352 HIV-infected participants independent of CD4 count, antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence, and demographic factors as well.

In particular, viral suppression did not seem to interfere with this association between marijuana smoking and infectious pulmonary diagnoses, as it remained significant in models restricted to those person-visits with suppressed HIV viral load (HR 1.41 [1.03-1.91], P = .029).

The authors suggested that HIV-specific factors such as lung immune cell depletion and dysfunction, persistent immune cell activation, systemic inflammation, respiratory microbiome alterations, and oxidative stress, or a combination of these effects, may interact with the alveolar macrophage dysfunction seen in both humans and mouse models exposed to marijuana smoke. Thus, “a potential additive risk of marijuana smoking and HIV disease may explain the increased prevalence of infectious pulmonary diagnoses in our adjusted analyses,” Dr. Lorenz and his colleagues stated.

“These findings suggest that marijuana smoking is a modifiable risk factor that healthcare providers should consider when seeking to prevent or treat lung disease in people infected with HIV, particularly those with other known risk factors including heavy tobacco smoking, and low CD4 T cell count or advanced HIV disease,” they concluded.

The National Institutes of Health funded the study. The authors reported that they had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Lorenz DR et al. EClinicalMedicine. 2019 Jan 24. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2019.01.003.

Long-term marijuana smoking was associated with lung disease in HIV-infected (HIV+) but not HIV uninfected (HIV–) men who have sex with men (MSM), according to the results of a large, prospective cohort study.

“There were no significant interactions between marijuana and tobacco smoking in any multivariable model tested for HIV+ participants, indicating independent effects of these factors,” wrote David R. Lorenz, PhD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, and his colleagues.

These findings are especially important given that the proportion of HIV+ individuals who frequently smoke marijuana is higher than in the general population in the United States, and has increased in recent years, according to the report, published online in EClinicalMedicine.

The study examined 2,704 MSM who met eligibility criteria (1,352 HIV+ and 1,352 HIV− individuals), with a median age of 44 years at baseline and a median follow-up of 10.5 years. A total of 27% of HIV+ participants reported daily or weekly marijuana smoking for 1 year or more during follow-up, compared with 18% of the HIV− participants.

HIV+ participants who smoked marijuana were more likely to report one or more pulmonary diagnoses, versus nonsmoking HIV+ individuals during follow-up (41.0% vs. 30.0% infectious, and 24.8% vs. 19.0% noninfectious), according to the authors. In contrast, there was no association between marijuana smoking and either an infectious or noninfectious pulmonary diagnosis among HIV− participants (24.2% vs. 20.9%, and 14.8% vs. 17.7%, respectively).

For HIV+ individuals, each 10 days/month increase in marijuana smoking in the prior 2-year period was found to be associated with a 6% increased risk of infectious pulmonary diagnosis (hazard risk 1.06 [95% confidence interval 1.00-1.11]; P = .041). Overall, they found that from the 53,000 person-visits in the study, marijuana smoking was associated with increased risk of both infectious and noninfectious pulmonary diagnoses among the 1,352 HIV-infected participants independent of CD4 count, antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence, and demographic factors as well.

In particular, viral suppression did not seem to interfere with this association between marijuana smoking and infectious pulmonary diagnoses, as it remained significant in models restricted to those person-visits with suppressed HIV viral load (HR 1.41 [1.03-1.91], P = .029).

The authors suggested that HIV-specific factors such as lung immune cell depletion and dysfunction, persistent immune cell activation, systemic inflammation, respiratory microbiome alterations, and oxidative stress, or a combination of these effects, may interact with the alveolar macrophage dysfunction seen in both humans and mouse models exposed to marijuana smoke. Thus, “a potential additive risk of marijuana smoking and HIV disease may explain the increased prevalence of infectious pulmonary diagnoses in our adjusted analyses,” Dr. Lorenz and his colleagues stated.

“These findings suggest that marijuana smoking is a modifiable risk factor that healthcare providers should consider when seeking to prevent or treat lung disease in people infected with HIV, particularly those with other known risk factors including heavy tobacco smoking, and low CD4 T cell count or advanced HIV disease,” they concluded.

The National Institutes of Health funded the study. The authors reported that they had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Lorenz DR et al. EClinicalMedicine. 2019 Jan 24. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2019.01.003.

FROM ECLINICALMEDICINE

Key clinical point: HIV+ but not HIV– marijuana smokers had an increased rate of pulmonary diagnoses.

Major finding: HIV+ marijuana smokers were more likely to report one or more infectious or noninfectious pulmonary diagnoses, compared with nonsmoking HIV+ individuals (41.0% vs. 30.0%, and 24.8% vs. 19.0%, respectively).

Study details: A prospective cohort study of 1,352 HIV+ vs. 1,352 HIV– men who have sex with men.

Disclosures: The National Institutes of Health funded the study. The authors reported that they had no relevant disclosures.

Source: Lorenz DR et al. EClinicalMedicine. 2019 Jan 24. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2019.01.003.

Checkpoint inhibitors ‘viable treatment option’ in HIV-infected individuals

Immune checkpoint inhibitors are safe and effective in HIV-infected patients with advanced cancers, according to authors of a recently published systematic review.

The treatment was well tolerated and associated with a 9% rate of grade 3 or higher immune-related adverse events, according to results of the review of 73 patient cases.

There were no adverse impacts on HIV load or CD4 cell count detected in the patients, according to researchers Michael R. Cook, MD, and Chul Kim, MD, MPH, of Georgetown University, Washington.

Antitumor activity of the checkpoint inhibitors in lung cancer patients was comparable to what has been seen in previous randomized clinical trials that excluded HIV-infected individuals, Dr. Cook and Dr. Kim reported in JAMA Oncology.

“Based on the results of the present systematic review, and in the absence of definitive prospective data suggesting an unfavorable risk-to-benefit ratio, immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy may be considered as a viable treatment option for HIV-infected patients with advanced cancer,” they said.

There are preclinical data suggesting that immune checkpoint modulation could improve function of HIV-specific T cells, the investigators added.

“Prospective trials of immune checkpoint inhibitors are necessary to elucidate the antiviral efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy in patients with HIV infection and cancer,” they said.

Several such trials are underway to evaluate the role of the pembrolizumab, nivolumab, nivolumab plus ipilimumab, and durvalumab in HIV-infected patients with advanced-stage cancers, according to the review authors.

In the present systematic review, Dr. Cook and Dr. Kim conducted a literature search and reviewed presentations from major annual medical conferences.

Of the 73 HIV-infected patients they identified, most had non–small cell lung cancer (34.2%), melanoma (21.9%), or Kaposi sarcoma (12.3%), while the rest had anal cancer, head and neck cancer, or other malignancies. Most patients had received either nivolumab (39.7%) or pembrolizumab (35.6%).

There were “no concerning findings” among these patients with regard to immune-mediated toxicities or changes in HIV-related parameters.

Six of 70 patients had immune-related adverse events of grade 3 or greater.

Thirty-four patients had documented HIV loads before and after receiving an immune checkpoint inhibitor. Of those, 28 had undetectable HIV loads at baseline, and all but 2 (7%) maintained undetectable loads in the posttreatment evaluation.

Of the remaining six with detectable HIV loads before treatment, five had a decrease in viral load, to the point that four had undetectable HIV viral load in the posttreatment evaluation, the investigators reported.

The overall response rate was 30% for the lung cancer patients, 27% for melanoma, and 63% for Kaposi sarcoma.

In the non–small cell lung cancer subset, response rates were 26% for those who had received previous systemic treatment, and 50% for those who had not, which was similar to findings from major checkpoint inhibitor trials that excluded HIV-infected individuals, the investigators said.

The American Society of Clinical Oncology Conquer Cancer Foundation and Georgetown University supported the study. Dr. Kim reported disclosures related to CARIS Life Science and AstraZeneca.

SOURCE: Cook MR and Kim C. JAMA Oncol. 2019 Feb 7. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.6737.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors are safe and effective in HIV-infected patients with advanced cancers, according to authors of a recently published systematic review.

The treatment was well tolerated and associated with a 9% rate of grade 3 or higher immune-related adverse events, according to results of the review of 73 patient cases.

There were no adverse impacts on HIV load or CD4 cell count detected in the patients, according to researchers Michael R. Cook, MD, and Chul Kim, MD, MPH, of Georgetown University, Washington.

Antitumor activity of the checkpoint inhibitors in lung cancer patients was comparable to what has been seen in previous randomized clinical trials that excluded HIV-infected individuals, Dr. Cook and Dr. Kim reported in JAMA Oncology.

“Based on the results of the present systematic review, and in the absence of definitive prospective data suggesting an unfavorable risk-to-benefit ratio, immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy may be considered as a viable treatment option for HIV-infected patients with advanced cancer,” they said.

There are preclinical data suggesting that immune checkpoint modulation could improve function of HIV-specific T cells, the investigators added.

“Prospective trials of immune checkpoint inhibitors are necessary to elucidate the antiviral efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy in patients with HIV infection and cancer,” they said.

Several such trials are underway to evaluate the role of the pembrolizumab, nivolumab, nivolumab plus ipilimumab, and durvalumab in HIV-infected patients with advanced-stage cancers, according to the review authors.

In the present systematic review, Dr. Cook and Dr. Kim conducted a literature search and reviewed presentations from major annual medical conferences.

Of the 73 HIV-infected patients they identified, most had non–small cell lung cancer (34.2%), melanoma (21.9%), or Kaposi sarcoma (12.3%), while the rest had anal cancer, head and neck cancer, or other malignancies. Most patients had received either nivolumab (39.7%) or pembrolizumab (35.6%).

There were “no concerning findings” among these patients with regard to immune-mediated toxicities or changes in HIV-related parameters.

Six of 70 patients had immune-related adverse events of grade 3 or greater.

Thirty-four patients had documented HIV loads before and after receiving an immune checkpoint inhibitor. Of those, 28 had undetectable HIV loads at baseline, and all but 2 (7%) maintained undetectable loads in the posttreatment evaluation.

Of the remaining six with detectable HIV loads before treatment, five had a decrease in viral load, to the point that four had undetectable HIV viral load in the posttreatment evaluation, the investigators reported.

The overall response rate was 30% for the lung cancer patients, 27% for melanoma, and 63% for Kaposi sarcoma.

In the non–small cell lung cancer subset, response rates were 26% for those who had received previous systemic treatment, and 50% for those who had not, which was similar to findings from major checkpoint inhibitor trials that excluded HIV-infected individuals, the investigators said.

The American Society of Clinical Oncology Conquer Cancer Foundation and Georgetown University supported the study. Dr. Kim reported disclosures related to CARIS Life Science and AstraZeneca.

SOURCE: Cook MR and Kim C. JAMA Oncol. 2019 Feb 7. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.6737.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors are safe and effective in HIV-infected patients with advanced cancers, according to authors of a recently published systematic review.

The treatment was well tolerated and associated with a 9% rate of grade 3 or higher immune-related adverse events, according to results of the review of 73 patient cases.

There were no adverse impacts on HIV load or CD4 cell count detected in the patients, according to researchers Michael R. Cook, MD, and Chul Kim, MD, MPH, of Georgetown University, Washington.

Antitumor activity of the checkpoint inhibitors in lung cancer patients was comparable to what has been seen in previous randomized clinical trials that excluded HIV-infected individuals, Dr. Cook and Dr. Kim reported in JAMA Oncology.

“Based on the results of the present systematic review, and in the absence of definitive prospective data suggesting an unfavorable risk-to-benefit ratio, immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy may be considered as a viable treatment option for HIV-infected patients with advanced cancer,” they said.

There are preclinical data suggesting that immune checkpoint modulation could improve function of HIV-specific T cells, the investigators added.

“Prospective trials of immune checkpoint inhibitors are necessary to elucidate the antiviral efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy in patients with HIV infection and cancer,” they said.

Several such trials are underway to evaluate the role of the pembrolizumab, nivolumab, nivolumab plus ipilimumab, and durvalumab in HIV-infected patients with advanced-stage cancers, according to the review authors.

In the present systematic review, Dr. Cook and Dr. Kim conducted a literature search and reviewed presentations from major annual medical conferences.